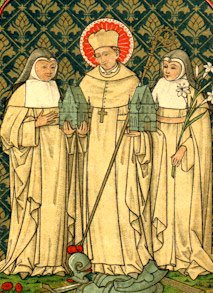

Saint Gilbert de Sempringham, prêtre

Fils d'un chevalier normand,

compagnon de Guillaume le Conquérant, né à Sempringham dans le Lincolnshire en

1083, il est envoyé par son père pour faire ses études à Paris et c'est là

qu'il rencontre saint Bernard. A vingt-quatre ans, il est mis en prison pour

avoir soutenu saint Thomas Beckett contre les exigences du roi Henri II

d'Angleterre. C’est alors qu’il est curé de son village natal où il est revenu,

en 1123 qu’il est sollicité et reçoit l’intuition d’une fondation

originale : l'ordre des Gilbertins, qui comprit des moines selon la règle

de saint Augustin et des moniales selon la règle de saint Benoît. A sa mort, en

1189, alors qu’il est devenu aveugle et s’est retiré de sa responsabilité de

supérieur général pour se consacrer uniquement à la prière, l’ordre comptait 13

monastères et 22 quand la Réforme d’Henry VIII les supprima.

Saint Gilbert de Sempringham

Fondateur de l'ordre

des Gilbertins (✝ 1189)

Fils d'un chevalier

normand, compagnon de Guillaume le Conquérant, son père l'avait envoyé faire

ses études à Paris et c'est là qu'il rencontre saint

Bernard. A vingt-quatre ans, il est mis en prison pour avoir soutenu

saint

Thomas Beckett contre les exigences exagérées du roi Henri II

d'Angleterre. Il fonda un type de monastères originaux qui comprenaient dans

l'un, des chanoines réguliers, dans l'autre, des moniales, le tout formant une

petite agglomération avec des sœurs et des frères "convers",

c'est-à-dire, à l'époque, d'humble origine et sans instruction. Ceux-ci et

celles-ci s'occupaient des soucis matériels des monastères, des orphelinats et

des léproseries qui leur étaient joints. A la mort de saint Gilbert, il y en

eut treize de ce type. Et plus de vingt quand le roi Henri VIII les supprima.

Un internaute nous signale que 'The Book of Saints', rédigé par les

Bénédictins de Ramsgate depuis 1921, apporte les précisions suivantes :

"1083-1189: anglais, né à Sempringham dans le Lincolnshire, il devint

prêtre de la paroisse de son village natal en 1123. Sept demoiselles de la

paroisse voulant vivre en communauté, il leur rédigea un ensemble de préceptes.

Ceci est à l'origine de l'ordre des gilbertins, qui comprit des moines selon la

règle de saint Augustin et des moniales selon la règle de saint Benoît. Gilbert

était leur maître général, jusqu'à ce qu'il devînt aveugle. A l'époque de la

Réforme, l'ordre comptait 22 maisons."

À Sempringham en Angleterre, l’an 1190, saint Gilbert, prêtre. Il fonda,

avec l’approbation du pape Eugène III, un Ordre monastique double, où il imposa

une double discipline de vie: la Règle de saint Benoît pour les moniales, et

celle de saint Augustin pour les clercs.

Martyrologe romain

ST.

GILBERT A., FOUNDER OF THE GILBERTINS—1084-1190

|

Feast: February 16

|

He was born at

Sempringham in Lincolnshire, and, after a clerical education, was ordained

priest by the bishop of Lincoln. For some time he taught a free-school,

training up youth in regular exercises of piety and learning. The advowson of

the parsonages of Sempringham and Tirington being the right of his father, he

was presented by him to those united livings, in 1123. He gave all the

revenues of them to the poor, except a small sum for bare necessaries, which

he reserved out of the first living. By his cafe his parishioners seemed to

lead the lives of religious men, and were known to be of his flock, by their

conversation, wherever they went. He gave a rule to seven holy virgins. who

lived in strict enclosure in a house adjoining to the wall of his parish

church of St. Andrew at Sempringham, and another afterwards to a community of

men, who desired to live under his direction. The latter was drawn from the

rule of the canon regulars; rut that given to his nuns, from St. Bennet's:

but to both he added many particular constitutions. Such was the origin of

the Order of the Gilbertins, he approbation of which he procured from Pope

Eugenius III. At length he entered the Order himself, but resigned the

government of it some time before his death, when he lost his sight. His diet

was chiefly roots and pulse, and so sparing, that others wondered how he

could subsist. He had always at table a dish which he called, The plate of

the Lord Jesus, in which he put all that was best of what was served up; and

this was for the poor. He always wore a hair shirt, took his short rest

sitting, and spent great part of the night in prayer. In this, his favorite

exercise, his soul found those wings on which she continually soared to God.

During the exile of St. Thomas of Canterbury, he and the other superiors of

his Order were accused of having sent him succors abroad. The charge was

false; yet the saint chose rather to suffer imprisonment. and the danger of

the suppression of his Order, than to deny it, lest he should seem to condemn

what would have been good and just. He departed to our Lord on the 3d of

February, 1190, being one hundred and six years old. Miracles wrought at his

tomb were examined and approved by Hubert, archbishop of Canterbury, and the

commissioners of Pope Innocent III. In 1201, and he was canonized by that

pope the year following. The Statutes of the Gilbertins, and Exhortations to

his Brethren, are ascribed to him. See his life by a contemporary writer, in

Dugdale's Monasticon, t. 2, p. 696; and the same in Henschenius, with another

from Capgrave of the same age. See also,. Harpsfield, Hist. Angl. cent. 12,

c. 37. De Visch, Bibl. Cisterc. Henschenius, p. 567. Helyot,

&c.

|

Provided Courtesy of:

Eternal Word Television Network 5817 Old Leeds Road Irondale, AL 35210 www.ewtn.com |

St. Gilbert of Sempringham

Founder of the Order of Gilbertines, b. at Sempringham, on the border

of the Lincolnshire fens, between Bourn and Heckington. The exact date of his

birth is unknown, but it lies between 1083 and 1089; d. at Sempringham, 1189.

His father, Jocelin, was a wealthy Norman knight holding lands in Lincolnshire; his mother,

name unknown, was an Englishwoman of humble rank. Being ill-favoured and deformed, he was

not destined for a military or knightly career, but was sent to France to study. After spending some time abroad,

where he became a teacher, he returned as a young man to his Lincolnshire home,

and was presented to the livings of Sempringham and Tirington, which were

churches in his father's gift. Shortly afterwards he betook himself to

the court of Robert Bloet, Bishop of Lincoln, where he became a clerk in the

episcopal household. Robert was succeeded in 1123 by Alexander, who retained

Gilbert in his service ordaining him deacon and priest much against his will. The revenues of

Sempringham had to suffice for his maintenance in the court of the bishop; those of Tirington he devoted to the poor.

Offered the archdeaconry of Lincoln, he refused, saying that he knew no surer way to perdition. In 1131 he returned

to Sempringham and, is father being dead, became lord of the manor and lands.

It was in this year that he founded the Gilbertine Order, which he was the

first is "Master", and constructed at Sempringham, with the help of

Alexander, a dwelling and cloister for his nuns, at the north of the church of St. Andrew.

His life henceforth became

one of extraordinary austerity, its strictness not diminishing as he grew

older, though the activity and fatigue caused by the government of the order

were considerable. In 1147 he travelled to Cîteaux, in Burgundy, where he met Eugene III, St Bernard, and St. Malachy, Archbishop of Armagh. The pope expressed regret at not having known of him

some years previously when choosing a successor to the deposed Archbishop of York. In 1165 he was summoned before Henry II's

justices at Westminster and was charged with having sent

help to the exiled St. Thomas a Becket. To clear himself he was invited to take

an oath that he had not done so. He refused, for,

though as a matter of fact he had not sent help, an oath to that effect might make him appear an enemy

to the archbishop. He was prepared for a sentence of

exile, when letters came from the king in Normandy, ordering the judges to await his return. In

1170, when Gilbert was already a very old man, some of his lay-brothers

revolted and spread serious calumnies against him. After some years of fierce

controversy on the subject, in which Henry II took his part, Alexander III freed him from suspicion, and confirmed the

privileges granted to the order. Advancing age induced Gilbert to give up the

government of his order. He appointed as his successor Roger, prior of Malton. Very infirm and almost blind, he

now made his religious profession, for though he had founded an order

and ruled it for many years he had never become a religious in the strict

sense. Twelve years after his death, at the earnest request of Hubert Walter, Archbishop of Canterbury, he was canonized by Innocent III, and his relics were solemnly translated to an honourable

place in the church at Sempringham, his shrine becoming a centre of pilgrimage. Besides the compilation of his rule, he has

left in little treatise entitled "De constructione monasteriorum".

His feast is kept in the Roman calendar on 11 February.

Butler, Richard Urban. "St. Gilbert of Sempringham." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 16 Feb. 2017 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06557b.htm>.

Transcription. This article was transcribed for

New Advent by Joseph P. Thomas.

Ecclesiastical approbation. Nihil Obstat. September 1, 1909. Remy Lafort, Censor. Imprimatur. +John M. Farley, Archbishop of New

York.

Gilbert was born in Sempringham, England, into a

wealthy family, but he followed a path quite different from that expected of

him as the son of a Norman knight. Sent to France for his higher education, he

decided to pursue seminary studies.

He returned to England not yet ordained a priest,

and inherited several estates from his father. But Gilbert avoided the easy

life he could have led under the circumstances. Instead he lived a simple life

at a parish, sharing as much as possible with the poor. Following his

ordination to the priesthood he served as parish priest at Sempringham.

Among the congregation were seven young women who

had expressed to him their desire to live in religious life. In response,

Gilbert had a house built for them adjacent to the Church. There they lived an

austere life, but one which attracted ever more numbers; eventually lay sisters

and lay brothers were added to work the land. The religious order formed

eventually became known as the Gilbertines, though Gilbert had hoped the

Cistercians or some other existing order would take on the responsibility of

establishing a rule of life for the new order. The Gilbertines, the only

religious order of English origin founded during the Middle Ages, continued to

thrive. But the order came to an end when King Henry VIII suppressed all

Catholic monasteries.

Over the years a special custom grew up in the

houses of the order called "the plate of the Lord Jesus." The best

portions of the dinner were put on a special plate and shared with the poor,

reflecting Gilbert's lifelong concern for less fortunate people.

Throughout his life Gilbert lived simply, consumed

little food and spent a good portion of many nights in prayer. Despite the

rigors of such a life he died at well over age 100.

Comment:

When he came into his father’s wealth, Gilbert could

have lived a life of luxury, as many of his fellow priests did at the time.

Instead, he chose to share his wealth with the poor. The charming habit of

filling “the plate of the Lord Jesus” in the monasteries he established

reflected his concern. Today’s Operation Rice Bowl echoes that habit: eating a

simpler meal and letting the difference in the grocery bill help feed the

hungry.

SOURCE

: http://www.americancatholic.org/Features/Saints/saint.aspx?id=1293

Gilbert of Sempringham, Founder (RM)

Born at Sempringham, Lincolnshire, England, c. 1083-85; died there, February 4, 1189; canonized 1202 by Pope Innocent III at Anagni; feast day formerly on February 4.

Saint Gilbert, son of Jocelin, a wealthy Norman knight, and his Anglo-Saxon wife, was regarded as unfit for ordinary feudal life because of some kind of physical deformity. For this reason, he was sent to France to study and took a master's degree.

Upon his return to England, Gilbert started a school for both boys and girls. From his father, he received the hereditary benefices of Sempringham and Torrington in Lincolnshire, but he gave all the revenues from them to the poor, except a small sum for bare necessities. As he was not yet ordained, he appointed a vicar for the liturgies and lived in poverty in the vicarage.

In 1122, Gilbert became a clerk in the household of Bishop Robert Bloet of Lincoln and was ordained by Robert's successor Alexander, and was offered, but refused, a rich archdeaconry. Instead, upon the death of his father in 1131, Gilbert returned to Sempringham as lord of the manor and parson. By his care his parishioners seemed to lead the lives of religious men and, wherever they went, were known to be of his flock by their conversation.

That same year of 1131, he organized a group of seven young women of the parish into a community under the Benedictine rule. They lived in strict enclosure in a house adjoining Sempringham's parish church of Saint Andrew. As the foundation grew, Gilbert added laysisters and, on the advice of the Cistercian Abbot William of Rievaulx, lay brothers to work the land. A second house was soon founded.

In 1148, Gilbert went to the general chapter at Cîteaux to ask the Cistercians to take on the governance of the community. When the Cistercians declined because women were included, Gilbert provided chaplains for his nuns by establishing a body of canons following the Augustinian rule with the approval of Pope Eugene III, who was present at the chapter. Saint Bernard helped Gilbert draw up the Institutes of the Order of Sempringham, of which Eugenius made him the master. Thus, the canons followed the Augustinian Rule and the lay brothers and sisters that of Cîteaux. Women formed the majority of the order; the men both governed them and ministered to their needs, temporal and spiritual. The Gilbertines are the only specifically English order, and except for one foundation in Scotland, never spread beyond its border.

This order grew rapidly to 13 foundations, including men's and women's houses side by side and also monasteries solely for canons. They also ran leper hospitals and orphanages. Gilbert imposed a strict rule on his order. An illustration of the enforced simplicity of life was the fact that the choir office was celebrated without fanfare.

As master general of the order, Saint Gilbert set an admirable example of abstemious and devoted living and concern for the poor. Gilbert's diet consisted primarily of roots and pulse in small amounts. He always set a place at the table for Jesus, in which he put all the best of what was served up, and this was for the poor. He wore a hair-shirt, took his short rest in a sitting position, and spent most of each night in prayer.

And, he was never idle. He travelled frequently from house to house (primarily in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire), forever active in copying manuscripts, making furniture, and building.

The later years of his long life were seriously disturbed. When he was about 80, he was arrested and charged with assisting Saint Thomas á Becket, who had taken refuge abroad from King Henry II after the council at Northampton (1163). (Thomas, dressed as a Sempringham lay brother, was said to have fled north to their houses in the Lincolnshire Fens before doubling back on his tracks south to Kent.) Though he was not guilty of this kindness, the saint chose to suffer rather than seem to condemn that which would have been good and just. Eventually the charge was dropped, although Gilbert still refused to deny it on oath.

Later still there was a revolt among his laybrothers, who grievously slandered the 90-year-old man, saying that there was too much work and not enough food. The rebellion was led by two skilled craftsmen who slandered Gilbert, obtained funds and support from magnates in the church and state, and took the case to Rome. There Pope Alexander III decided in Gilbert's favor, but the living conditions were improved.

Saint Gilbert lived to be 106 and passed his last years nearly blind, as a simple member of the order he had founded and governed. He had built 13 monasteries (of which nine were double) and four dedicated solely to canons encompassing about 1,500 religious. Contemporary chroniclers highly praised both Gilbert and his nuns. His cultus was spontaneous and immediate. Miracles wrought at his tomb were examined and approved by Archbishop Hubert Walter of Canterbury (who ordered the English bishops to celebrate Gilbert's feast) and the commissioners of Pope Innocent III in 1201, leading to his canonization the following year. His name was added to the calendar on the wall of the Roman church of the Four Crowned Martyrs soon after his canonization. His relics are said to have been taken by King Louis VIII to Toulouse, France, where they are kept in the Church of Saint Sernin.

Gilbert of Sempringham, Founder (RM)

Born at Sempringham, Lincolnshire, England, c. 1083-85; died there, February 4, 1189; canonized 1202 by Pope Innocent III at Anagni; feast day formerly on February 4.

Saint Gilbert, son of Jocelin, a wealthy Norman knight, and his Anglo-Saxon wife, was regarded as unfit for ordinary feudal life because of some kind of physical deformity. For this reason, he was sent to France to study and took a master's degree.

Upon his return to England, Gilbert started a school for both boys and girls. From his father, he received the hereditary benefices of Sempringham and Torrington in Lincolnshire, but he gave all the revenues from them to the poor, except a small sum for bare necessities. As he was not yet ordained, he appointed a vicar for the liturgies and lived in poverty in the vicarage.

In 1122, Gilbert became a clerk in the household of Bishop Robert Bloet of Lincoln and was ordained by Robert's successor Alexander, and was offered, but refused, a rich archdeaconry. Instead, upon the death of his father in 1131, Gilbert returned to Sempringham as lord of the manor and parson. By his care his parishioners seemed to lead the lives of religious men and, wherever they went, were known to be of his flock by their conversation.

That same year of 1131, he organized a group of seven young women of the parish into a community under the Benedictine rule. They lived in strict enclosure in a house adjoining Sempringham's parish church of Saint Andrew. As the foundation grew, Gilbert added laysisters and, on the advice of the Cistercian Abbot William of Rievaulx, lay brothers to work the land. A second house was soon founded.

In 1148, Gilbert went to the general chapter at Cîteaux to ask the Cistercians to take on the governance of the community. When the Cistercians declined because women were included, Gilbert provided chaplains for his nuns by establishing a body of canons following the Augustinian rule with the approval of Pope Eugene III, who was present at the chapter. Saint Bernard helped Gilbert draw up the Institutes of the Order of Sempringham, of which Eugenius made him the master. Thus, the canons followed the Augustinian Rule and the lay brothers and sisters that of Cîteaux. Women formed the majority of the order; the men both governed them and ministered to their needs, temporal and spiritual. The Gilbertines are the only specifically English order, and except for one foundation in Scotland, never spread beyond its border.

This order grew rapidly to 13 foundations, including men's and women's houses side by side and also monasteries solely for canons. They also ran leper hospitals and orphanages. Gilbert imposed a strict rule on his order. An illustration of the enforced simplicity of life was the fact that the choir office was celebrated without fanfare.

As master general of the order, Saint Gilbert set an admirable example of abstemious and devoted living and concern for the poor. Gilbert's diet consisted primarily of roots and pulse in small amounts. He always set a place at the table for Jesus, in which he put all the best of what was served up, and this was for the poor. He wore a hair-shirt, took his short rest in a sitting position, and spent most of each night in prayer.

And, he was never idle. He travelled frequently from house to house (primarily in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire), forever active in copying manuscripts, making furniture, and building.

The later years of his long life were seriously disturbed. When he was about 80, he was arrested and charged with assisting Saint Thomas á Becket, who had taken refuge abroad from King Henry II after the council at Northampton (1163). (Thomas, dressed as a Sempringham lay brother, was said to have fled north to their houses in the Lincolnshire Fens before doubling back on his tracks south to Kent.) Though he was not guilty of this kindness, the saint chose to suffer rather than seem to condemn that which would have been good and just. Eventually the charge was dropped, although Gilbert still refused to deny it on oath.

Later still there was a revolt among his laybrothers, who grievously slandered the 90-year-old man, saying that there was too much work and not enough food. The rebellion was led by two skilled craftsmen who slandered Gilbert, obtained funds and support from magnates in the church and state, and took the case to Rome. There Pope Alexander III decided in Gilbert's favor, but the living conditions were improved.

Saint Gilbert lived to be 106 and passed his last years nearly blind, as a simple member of the order he had founded and governed. He had built 13 monasteries (of which nine were double) and four dedicated solely to canons encompassing about 1,500 religious. Contemporary chroniclers highly praised both Gilbert and his nuns. His cultus was spontaneous and immediate. Miracles wrought at his tomb were examined and approved by Archbishop Hubert Walter of Canterbury (who ordered the English bishops to celebrate Gilbert's feast) and the commissioners of Pope Innocent III in 1201, leading to his canonization the following year. His name was added to the calendar on the wall of the Roman church of the Four Crowned Martyrs soon after his canonization. His relics are said to have been taken by King Louis VIII to Toulouse, France, where they are kept in the Church of Saint Sernin.

Because

the Gilbertine Order was contained within the borders of England, it came to an

end when its 26 houses were suppressed by King Henry VIII (Attwater,

Benedictines, Delaney, Encyclopedia, Farmer, Graham, Husenbeth, Walsh, White).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0216.shtml