Saint Auguste

Chapdelaine, prêtre et martyr

Auguste Chapdelaine, né

en Normandie en 1814, quitte bientôt la ferme paternelle pour entrer à la

Société des Missions étrangères de Paris ; il est envoyé en Chine où,

après deux années d’activités missionnaires, il est arrêté par des soldats

à Xilinxian, dans la province chinoise de Guangni, avec plusieurs néophytes,

parce qu’il avait, le premier, semé la foi chrétienne dans cette région ;

il fut, sur l’ordre du grand mandarin, frappé de trois cents coups de rotin,

enfermé dans une cage étroite et enfin décapité en 1856.

Saint Auguste Chapdelaine

Missionnaire, martyr en

Chine (+ 1856)

et ses compagnons,

martyrs.

Ils étaient membres de la

Société des Missions Étrangères de Paris et, après deux années d'activités

missionnaires, ils sont arrêtés et torturés dans une Chine qui n'avait pas vu

de prêtres catholiques depuis plus d'un siècle et demi.

Auguste Chapdelaine a été

béatifié par Léon XIII le 27 mai 1900 et canonisé par Jean-Paul II le 1er

octobre 2000.

"Auguste Chapdelaine

naquit en 1814 dans une famille d'agriculteurs de la Rochelle Normande. Il

aurait pu y demeurer: il travailla d'ailleurs jusqu'à vingt ans dans la ferme

familiale. Mais autre chose le préoccupait, qui se précisa: il se sentait

appelé à partir loin, bien loin au delà des frontières verdoyantes de son pays

natal; Dieu lui donnait le désir et la force d'être missionnaire en Chine,

alors même que là-bas, depuis 1814 justement, l'année de sa naissance, les

martyrs se succédaient. A-t-il entendu, enfant, parler des trente-trois

chrétiens, chinois et prêtres français des Missions étrangères, exécutés

le jour de la Sainte-Croix, le 14 septembre 1815? Il semble que sa vocation ait

toujours été axée autour de la signification même du martyr: être témoin,

jusqu'à l'extrême..."

Source: Liturgie

des heures du diocèse de Coutances et Avranches 1993.

Voir aussi sur

le site des missions étrangères de Paris, sur notre site saint

Augustin Zhao Rong et sur le site du Vatican Agostino

Zhao Rong et 119 compagnons, martyrs en Chine

À Xilinxian, dans la

province chinoise de Guangni, en 1856, saint Auguste Chapdelaine, prêtre de la

Société des Missions étrangères de Paris et martyr. Arrêté par des soldats avec

plusieurs néophytes, parce qu’il avait, le premier, semé la foi chrétienne dans

cette région, il fut, sur l’ordre du grand mandarin, frappé de trois cents

coups de rotin, enfermé dans une cage étroite et enfin décapité. (éloge omis le

28 février des années bissextiles)

Martyrologe romain

"Il vous est utile

que votre pasteur meure pour vous". (Auguste Chapdelaine)

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/5894/Saint-Auguste-Chapdelaine.html

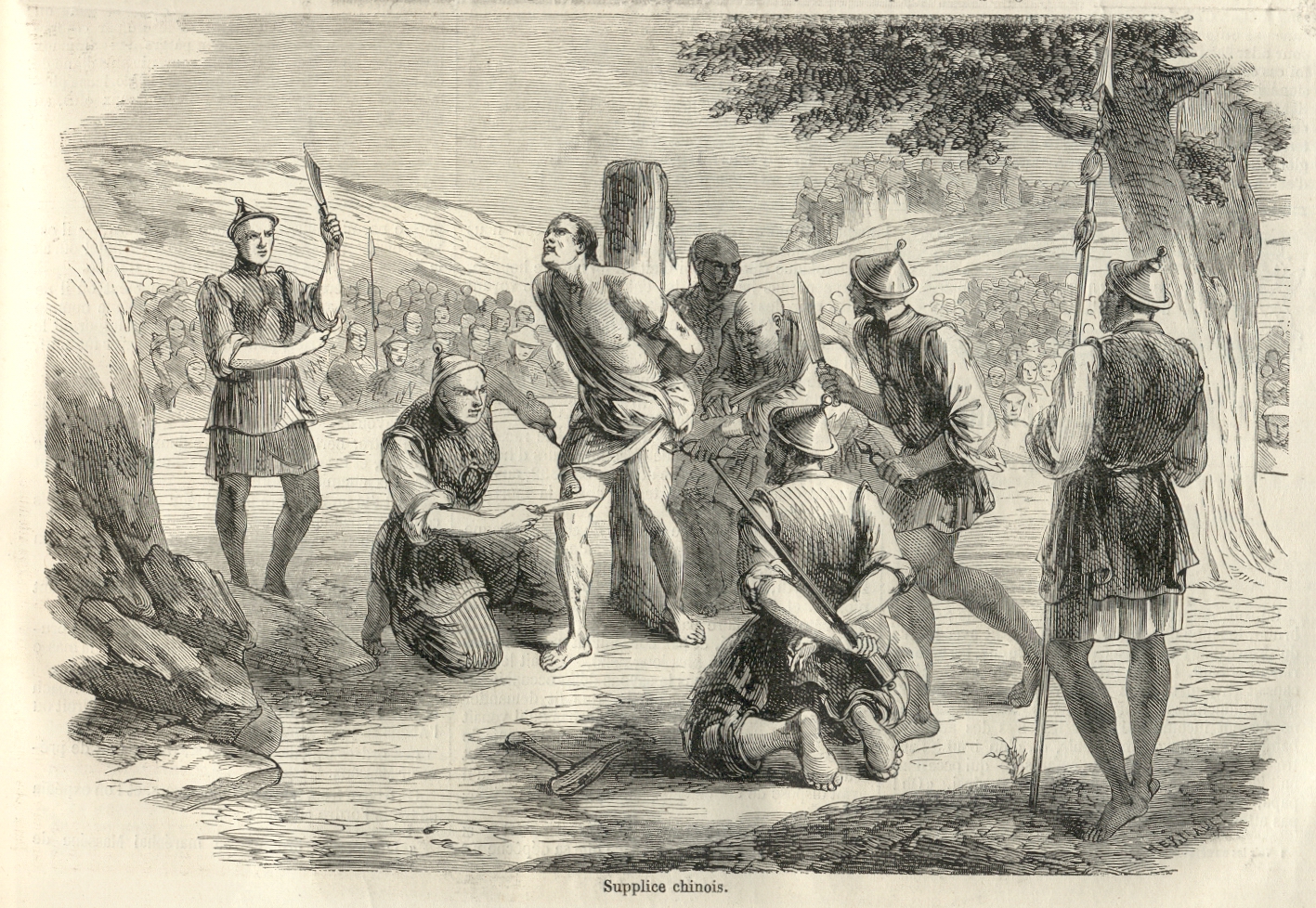

-Chinese “slow-slicing” torture, Lingchi, literally meaning “death-by-a-thousand-cuts”, an 1858 illustration from the French newspaper Le Monde Illustré, of the lingchi execution of a French missionary, Auguste Chapdelaine, in China. In fact, Chapdelaine died from physical abuse in prison, and was beheaded after death. Please click on the image for greater detail.

Tortures

subies par le R. P. Chapedelaine, missionnaire en Chine, martyrisé dans la

province de Quang-si

Illustrations de la torture et de l'exécution d'Auguste Chapdelaine en Chine par le supplice du lingchi, Le Monde illustré, de 1858

Chapdelaine,

further torture in a box where the victim can neither stand nor rest. If

painful exertions are not made, the victim will suffocate. Please click on the

image for greater detail.

Martyre du R. P.

Chapedelaine et de ses compagnons

Àl’extrémité de la longue

et sinueuse rue du Bac, au fond d’un préau qu’égayent quelques arbustes, dans

un bâtiment spacieux dont un collège de jeunes lévites avive la paisible

solitude, existe un… que dirai-je ?… une chambre de question ?…

non ; un musée… mais un musée sans précédent, un musée unique : ce

sont des haches, des casse-tête, des poignards, des glaives de toutes grandeurs

et de toutes formes, des lames droites, courbes, barbelées, ondoyantes comme

des flammes, tordues comme des spirales, des fers à cautérisation des formes le

plus bizarrement horribles, des cangues écrasantes, des entraves, des carcans,

des rotins, des fouets, des tenailles hideuses, des chaînes énormes dont la

rouille ensanglantée accuse éloquemment l’emploi sinistre… que sais-je ?

tous les instruments de torture et de supplice qu’a jamais pu inventer la rage

des persécuteurs et des bourreaux.

Cette galerie, nous

pourrions dire ce sanctuaire, est le reliquaire du martyre auquel se prépare,

par l’étude de la science et par la pratique de la vertu, cette jeunesse calme

et sereine qu’attendent les austères et glorieux devoirs de l’apostolat.

On ignore trop dans notre

siècle, si ardemment voué au culte des intérêts matériels, tous les mystères

d’humble dévouement et d’abnégation sublime qui s’élaborent dans ces pieuses

retraites, et tous les avantages qui, à part des résultats bien autrement

précieux, en rejaillissent sur le pays si le nom de la France éveille, tant de

sympathies dans les contrées les plus éloignées, les peuples de l’extrême

Orient ou de l’Afrique centrale, au sein des archipels sauvages de l’Océanie, à

qui le doit-il? Qu’on ne s’imagine pas que ce soit aux lés d’étamine qui

apparaissent au mât d’un croiseur et que le vent qui les a apportés remporte

presque aussitôt. Non sans doute… C’est aux missionnaires qui partent chaque

année de cette maison et de quelques autres semblables pour aller éclairer des

rayons de la civilisation et de la foi ces contrées perdues dans les ténèbres,

c’est aux missionnaires qui fondent incessamment de nouvelles chrétientés sur

ces plages lointaines. Que d’îles, comme l’archipel Gambier, déjà

régénérées ! Ce sont là leurs palmes terrestres, mais aussi ils y en

trouvent souvent de plus glorieuses ; les palmes du martyre. Alors, ce que

revient d’eux à la maison d’où ils sont partis, c’est le sang coagulé sur les

fers, les chevalets et les haches, qui grossissent de temps à autre les panoplies

de ce musée, les joyaux de ce glorieux écrin c’est là que viennent d’arriver

quelques reliques du R. P. Chapedelaine, du sang de qui la France demande

aujourd’hui compte à la Chine.

Nous touchons à

l’anniversaire de la mort de ce généreux confesseur de la foi. Ce fut le

dernier jour de février 1856 qu’il baptisa de son sang la province de Quang-Si,

qu’il était allé conquérir à vérité.

Depuis deux ans déjà, il

exerçait son apostolat dans cette province, où n’avait pas retenti, de temps

immémorial, la parole sainte, lorsqu’il fut accusé, auprès du mandarin de

Si-Ling-Hien, de porter les peuples à la révolte et de les séduire par des

opérations magiques.

Le magistrat, inquiet des

progrès du christianisme, donna l’ordre de l’arrêter. Le père Chapedelaine, prévenu

aussitôt du danger qui le menaçait par un néophyte de Si-Ling-Hien, pouvait

fuir et trouver un refuge assuré au sein des chrétientés florissantes, de

provinces voisines ; mais, par sa fuite, il livrait aux erreurs le

troupeau fidèle qu’il avait réuni sous son bâton pastoral. N’était-il pas à

craindre que cet acte de prudence ne fût interprété comme un acte de

pusillanimité par ceux qu’il eût abandonnés aux persécutions ? Loin de

fuir, il se rendit à Si-Ling-Hien même ; ce fut là qu’il fût saisi et conduit

devant le mandarin. Interrogé sur la doctrine qu’il prêchait au peuple, le

généreux apôtre confessa sa foi avec une telle ardeur, que le juge se hâta

d’étouffer cette éloquente protestation sous des questions portant sur ses

richesses et sur ses sortilèges. Le Révérend Père, imitant alors son divin

Maître devant Hérode, n’opposa à ces imputations que son silence. Le juge

irrité lui fit frapper cent coups d’une semelle de cuir sur le visage. Sous ces

coups appliqués par la main du bourreau, les dents de l’apôtre sautèrent de sa

mâchoire brisée.

Ce n’était que la

première épreuve des tortures à travers lesquelles il devait arriver à la mort.

Dépouillé de ses vêtements et couché sur le sol, il reçut trois cent coups de

rotin sur le dos, dont les chairs broyées ne formaient plus à la fin qu’une

plaie. Pas un soupir… pas une plainte n’échappa de ses lèvres. Le mandarin,

étonné d’abord, ne vit bientôt après dans cette constance héroïque qu’une

preuve du pouvoir magique de sa victime. Un chien fut égorgé par ses ordres,

et, pour rompre la puissance des sortilèges du patient, il fit arroser son

corps avec ce sang encore chaud. La flagellation recommença avec plus de

violence. Cette fois, on ne compta plus les coups, le bourreau frappa jusqu’à

ce que le corps restât immobile. Alors il fut porté dans la prison, où on le

jeta sanglant et brisé sur le sol.

Ici ce ne fut plus

l’ineffable patience du martyr qui vint frapper de stupeur ses bourreaux, ce

fut un de ces miracles qui forment comme le nimbe rayonnant de l’antiquité

chrétienne au temps des Césars ! Voilà que le cadavre pantelant du martyr

se ranime ; le P. Chapedelaine se relève et se promène dans son cachot, le

calme sur le front, la ferveur dans le regard, la prière sur les lèvres.

Ce prodige est rapporté

au mandarin, qui se croit bravé et n’en devient que plus furieux. Il saura bien

épuiser ce qu’il regarde comme la science cabalistique de cet étranger. Le

génie inventeur des Chinois s’est surtout signalé dans la création des

tortures ; il possède là un arsenal où il trouvera bien une arme pour

vaincre son ennemi. Il dédaigne le supplice vulgaire qui consiste à découper le

patient en milliers de morceaux (supplice représenté par l’une de nos

gravures). Il lui faut des tourments dont les angoisses épuisent plus lentement

la vie, l’épuisent soupir à soupir.

Le lendemain, 27 février,

le père Chapedelaine est de nouveau conduit sur la place des supplices. Au

moyen de cordes et de poteaux, il est établi en équilibre et placé à genoux sur

une énorme chaîne de fer dont les anneaux, tout le jour et la nuit suivante

dans cette situation cruelle, exposé aux regards de la multitude.

Le surlendemain, nouveau

supplice : il est placé dans une cage d’un mètre environ de hauteur, la

tête prise dans la plate-forme de manière à ce que le corps ne pouvant reposer

complètement ni sur la plante des pieds, ni sur les genoux, le martyr subissait

toutes les douleurs de la strangulation sans en éprouver la crise suprême.

L’heure si ardemment espérée par le pieux confesseur approchait enfin, il avait

été jugé par Dieu digne de recevoir la couronne de la justification

sanglante ; mais le souverain Maître lui réservait une autre joie : à

celui qui avait sacrifié pour lui patrie et famille, il allait rendre patrie et

famille à la fois, la patrie céleste et une famille de martyrs engendrée par

lui à la vie de la grâce. Déjà un de ses néophytes, Laurent Pe-mou, avait eu la

tête tranchée sous ses yeux, en proclamant généreusement ses croyances. C’était

le tour d’une jeune veuve, Agnès Tsaou-Kong, qui s’était vouée à

l’éducation : « Si tu ne renonces à l’instant même à la religion de

ton prêtre Ma, lui dit le mandarin en terminant son interrogatoire, je te fais

mourir. — Je ne renoncerai pas la religion du Seigneur du ciel… La mort

plutôt ! — Soit ! Alors, choisis toi-même ton supplice. » La jeune

femme portant un regard attendri vers le missionnaire dont la pâleur de

l’agonie voilait les traits : « Le même supplice que mon

maître. » Elle fut aussitôt placée dans une cage semblable à celle du père

Chapedelaine. Elle avait voulu partager ses souffrances, elle allait partager

sa gloire.

Cependant la vie du

missionnaire se prolongeait au delà de toutes les prévisions de ses

bourreaux ; le mandarin, prévenu qu’il respirait encore le 29 au matin,

craignit qu’il ne lui échappât par quelque enchantement inconnu, et ordonna

qu’on lui tranchât la tête.

Rapporterons-nous les

horribles excès dont fut suivi ce supplice ?… Le cœur du missionnaire,

jeté dans un bassin de fer, sur un feu ardent, et dévoré par ces

forcenés ; son cadavre abandonné en pâture aux animaux immondes de la

voirie ? Il est un souvenir plus digne de cet apôtre : reportons

notre pensée vers la glorieuse phalange des martyrs recevant les trois nouveaux

élus, au milieu des Hosannah du ciel.

Fulgence Girard, Le Monde illustré, 27 février 1858

SOURCE : http://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Martyre_du_R._P._Chapedelaine_et_de_ses_compagnons

Bienheureux Auguste Chapdelaine, portrait, crypte de la chapelle des MEP.

Auguste Chapdelaine, un

saint doublement martyr

Isabelle

Cousturié | 28 février 2018

En Chine, l’humiliation

subie après la cruelle exécution en 1856 d’Auguste Chapdelaine est encore très

vive de nos jours.

Sa vocation, être témoin

jusqu’à l’extrême. Auguste Chapdelaine (1814-1856), fils d’agriculteur à la

Rochelle, en Normandie, aurait pu rester dans la ferme familiale. Mais non, il

a préféré se faire prêtre et partir en Chine sous l’égide des Missions

étrangères de Paris avec d’autres compagnons. Nous sommes en 1852. Dans la

province du Guangxi où il est envoyé, après deux années passées à Hong Kong,

pas l’ombre d’un prêtre catholique depuis plus d’un siècle et demi, comme dans

le reste du pays. Les villages de la province sont secoués par des révoltes

musulmanes. Il n’a pas le droit d’y aller, mais lui s’y aventure et tente d’y

semer la foi.

Après l’assassinat,

l’humiliation

Deux ans plus tard

(1856), celui que les habitants ruraux et pauvres de la zone appellent déjà

affectueusement Ma Lai (Père Ma) – Ma étant la première

syllabe de Mahomet chez les musulmans de Chine – est dénoncé, accusé de

propagande pour une religion interdite, et arrêté à Dingan dans la nuit du 24

au 25 février. Condamné à mort, il est violemment battu de 300 coups de rotin,

puis enfermé dans une cage accrochée au portail du tribunal, et enfin décapité,

selon la peine prévue par le code chinois contre les missionnaires clandestins.

Lire aussi :

Le

Nigeria, pays où le plus de missionnaires ont été tués en 2017

Aussitôt, une ferme

protestation est adressée au gouverneur de la province par la France qui lui

demande des excuses solennelles. Mais le gouverneur refuse de s’excuser, et

Napoléon III, sans attendre, se lance alors aux côtés du Royaume-Uni, dans la

seconde guerre de l’opium, de 1856 à 1860. Au cours de la guerre, le palais

d’été de Pékin est mis à sac. C’est l’humiliation nationale. Humiliation

vivement ressentie en Chine et entretenue par l’historiographie communiste

encore aujourd’hui. La canonisation d’Auguste Chapdelaine en 2000 par Jean Paul

II avec 119 autres martyrs provoque de très violente réactions du Parti

communiste chinois (PCC).

Hommages cruels

En 2016, année des 160

ans de la mort du missionnaire français, les autorités locales ouvrent à Dingan

un musée présentant Auguste Chapdelaine comme un « violeur » et un

« espion ». On y célèbre l’ »esprit patriotique » du

magistrat qui l’a fait torturer et exécuter. L’année précédente, c’est un

concours du meilleur poème célébrant la décapitation du missionnaire qui avait

été organisé, ainsi que le tournage d’un documentaire de deux heures contre le

prêtre. Les reliques de saint Auguste Chapdelaine sont aujourd’hui exposées

dans la salle des martyrs de la Chapelle des Missions étrangères de Paris.

Lire aussi :

Pourquoi

le Vatican tend la main à la Chine ?

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/2018/02/28/auguste-chapdelaine-un-saint-doublement-martyr/

Saint Auguste CHAPDELAINE

Nom: CHAPDELAINE

Prénom: Auguste

Pays: France - Chine

Naissance:

06.01.1814 au diocèse de Coutances

Mort: 29.02.1856

(Province du Kouang-si)

Etat: Prêtre des Missions

Étrangères de Paris - Martyr du Groupe des 120

martyrs de Chine 2

Note: Prêtre en 1843 pour

les Missions Étrangères de Paris. Part pour la Chine en 1851. Subit le martyre

en 1856 avec toutes sortes de tortures. Cf notice du groupe spécialement

le §2)

Béatification:

27.05.1900 à Rome par Léon XIII

Canonisation:

01.10.2000 à Rome par Jean Paul II

Fête: 9 juillet

Réf. dans l’Osservatore

Romano: 2000 n.39 p.9-10 - n. 40 p.1-7 - n.41 p.7.10

Réf. dans la Documentation

Catholique: 2000 n.19 p.906-908

Notice

Auguste Chapdelaine naît

en 1814 au diocèse de Coutances dans une famille paysanne dont il est le 9e enfant.

Il est ordonné prêtre en 1843 pour son diocèse. En 1851 il est agrégé à la

société des Missions Étrangères de Paris et part pour la Chine. Après deux ans

il quitte Hong-Kong pour le Kouang-si, une province qui n'avait plus de prêtre

depuis un siècle et demi: "Au départ de cette mission, une ardeur de

néophyte!" Récit du Père Chapdelaine: "Un habitant du Kouang-si venu

au Kouei-tchéou pour affaires, rencontre par hasard un de ses parents

nouvellement converti qui l'initie aux vérités de notre sainte religion; il

renonce à ses idoles, adore le vrai Dieu et, de retour dans sa famille, se met

à exercer l'apostolat auprès de ses parents et de ses amis. Quarante ou

cinquante familles se convertissent. Le nouvel apôtre repart alors au

Kouei-tchéou pour demander un chrétien qui pourra le seconder. Je viens

moi-même d'arriver et je peux l'aider de mes conseils. Trois mois après, au

terme d'un pénible voyage, je célèbre la sainte messe au milieu de ces

néophytes.. Mais le démon ne tarde pas à nous susciter des obstacles." En

effet, les chrétiens sont dénoncés et le Père est incarcéré avec six autres. Le

mandarin est impressionné par la fière attitude du missionnaire et, la

Providence aidant, ils sont tous relâchés. Pendant deux ans, le Père exerce

librement son ministère dans le Kouang-si. Mais en 1856 il est de nouveau

dénoncé. Malheureusement, c'est un nouveau mandarin qui dirige, animé d'une

haine implacable contre les chrétiens. Le Père est pris. En tout 25 confesseurs

de la foi sont arrêtés et frappés, dont la très jeune veuve Agnès (née en 1833)

chargée de la formation des femmes catéchistes. Quant à Laurent Pé-mou, baptisé

depuis 5 jours, il est le premier à comparaître à la barre du tribunal et à

confesser sa foi. Le mandarin voulant lui faire abandonner le maître Ma (nom

chinois du Père Chapdelaine), Laurent rétorque: "Je ne l'abandonnerai

jamais!" Irrité d'une déclaration aussi ferme et du refus d'apostasier que

lui oppose Laurent, le mandarin le fait décapiter. Puis c'est le tour de la

jeune Agnès. Enfermée dans une cage, mutilée, consumée par la faim et la soif,

elle meurt au bout de quatre jours. Le Père comparaît à son tour. Il répond aux

premières questions, mais oppose le silence à des questions impertinentes qui

s'ensuivent. Il reçoit 300 coups de rotin dans le dos sans proférer aucune

plainte. Sa cruelle et longue agonie se termine par le supplice de la cage

suspendue (strangulation lente). Le 29 février au matin, comme il respire

encore, le mandarin le fait sortir de sa cage et ordonne à un satellite de le

décapiter.

Incidence politique du

martyre du Père Chapdelaine: Au même moment, des commerçants et marins

anglais sont molestés. Napoléon III propose à l'Angleterre d'intervenir. Une

escadre alliée menace; la Chine signe le traité de Tim-tsin (1858) contenant

aussi des clauses autorisant les missions. Cette imbrication des affaires

politiques et de l'apostolat inquiète. Il faut cependant reconnaître que les

résultats purement chrétiens de ces traités imposés par la force sont

excellents. Dans la paix - une paix toute relative d'ailleurs - les chrétientés

chinoises se reforment et se réorganisent. (Cf Fiche générale, début du §3)

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/hagiographie/fiches/f0502.htm

Also

known as

Augustus Chapdelaine

Father Ma

Papa Chapdelaine

29

February (in leap years)

28

September (as one of the Martyrs

of China)

Profile

Youngest of nine children born

to Nicolas Chapdelaine and Madeleine Dodeman. Following grammar school,

Auguste dropped out to work on the family farm.

He early felt a call to the priesthood,

but his family opposed it, needing his help on the farm.

However, the sudden death of

two of his brothers caused them to re-think forcing him to ignore his life’s

vocation, and they finally approved. He entered the minor seminary at

Mortain on 1

October 1834, studying with boys half

his age. It led to his being nicknamed Papa Chapdelaine, which stuck with

him the rest of his life.

Ordained on 10 June 1843 at

age 29. Associate pastor from 1844 to 1851.

He finally obtained permission from his bishop to

enter the foreign missions,

and was accepted by French Foreign Missions; he was two years past their

age limit, but his zeal for the missions made

them approve him anyway. He stayed long enough to say a final Mass,

bury his sister, and say good-bye to his family, warning them that he would

never see them again. Left Paris, France for

the Chinese missions on 30 April 1852,

landing in Singapore on 5

September 1852.

Due to being robbed on

the road by bandits, Auguste lost everything he had, and had to fall back and

regroup before making his way to his missionary assignment.

He reached Kwang-si province in 1854,

and was arrested in

Su-Lik-Hien ten days later. He spent two to three weeks in prison,

but was released, and ministered to the locals for two years, converting hundreds. Arrested on 26

February 1856 during

a government crackdown, he was returned to Su-Lik-Hien and sentenced to death for

his work. Tortured with

and died with Saint Lawrence

Pe-Man and Saint Agnes

Tsau Kouy. One of the Martyrs

of China

Born

6

January 1814 at

La Rochelle-Normande, France

beheaded on 29

February 1856 in

Su-Lik-Hien, Kwang-Si province, China

2 July 1899 by Pope Leo

XIII (decree of martyrdom)

1

October 2000 by Pope John

Paul II

Additional

Information

The

Holiness of the Church in the 19th Century

other

sites in english

images

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

MLA

Citation

“Saint Auguste

Chapdelaine“. CatholicSaints.Info. 21 February 2023. Web. 29 February

2024. <https://catholicsaints.info/saint-auguste-chapdelaine/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-auguste-chapdelaine/

Statue d'Auguste Chapdelaine en l'église de Boucey (50).

Statue

d'Auguste Chapdelaine en l'église de Boucey (50).

St. Auguste Chapdelaine

(Feast: February 29)

(1814-1856)

Auguste was born in La

Rochelle, on January 6, 1814, the eighth of nine children of Nicolas

Chapdelaine and Madeleine Dodeman. The ancestral cradle of the Chapdelaines was

located in Lower Normandy, near Mont Saint Michael, and the family could trace

their Gallo-Roman and Viking ancestry back to the mid-thirteenth century.

After grammar school,

Auguste worked on the family farm. Being physically strong, it is

understandable that his parents, needing him at home, would object to his

desire to become a priest. But, with the sudden death of two of his brothers

including the youngest, they realized that God wanted their Auguste as a priest

and acquiesced to his wish. On October 1, 1834, at the age of 20, he entered

the minor seminary of Mortain, studying with boys only 12 and 13 years

old.

His father died the

following year. Making up for lost time by arduous study, Auguste entered the

Seminary of Coutances and was ordained to the priesthood on June 10, 1843. He

spent the next eight months with his family in La Rochelle before being

appointed as associate pastor in Boucey, on February 23, 1844.

Before his assignment in

Boucey, Father Chapdelaine confided to his brother that he “had not become a

priest for those who already know God, but for those who don’t.” He wished to

enter the French Foreign Missions immediately after ordination but submitted

humbly to the will of his superiors. For seven years, he would remain in

Boucey, under the guidance of the elderly and infirm pastor, Father Oury.

Despite his parish work, Father Auguste never wavered in his desire: to found a

mission church, then die! Still, he was not getting any younger.

When Father Oury died in

April, 1849, Father Chapdelaine was already 35 years old, the age limit to

enter the French Foreign Missions. Yet, despite his ardent desire to enter, he

would serve under the new pastor, Father Poupinet, for another two years. Then,

in January, 1851, Bishop Robiou authorized him to leave the diocese for the

Foreign Missions – if they would have a 37-year-old priest! Despite his age,

Father Chapdelaine immediately reapplied for admission. In face of such zeal,

he was accepted. Returning to La Rochelle he found his entire family assembled,

not to bid him farewell but to his sister, Victoria, who had just died. After

the funeral, Auguste announced his departure for Paris and let it be known he

would never see his family again. Eight days later, he boarded the train for

Paris. On March 15, 1851, the young man who had entered minor seminary at age

20 was now entering the French Foreign Missions two years over the age limit,

not only was his a late vocation but one that would be forever delayed in the

attainment of its goals.

The motherhouse of the

French Foreign Missions on Rue du Bac had produced so many martyrs for the

Faith in Indochina and China that it was termed the “Polytechnic Institute of

Martyrs." Directed by veteran missionaries, the seminary would evaluate

Father Chapdelaine for his zeal, devotion and stamina to withstand the rigors

of missionary life. Upon the completion of his probationary year, on March 29,

1852, Father Chapdelaine met with his director. For a long time after this

meeting, he knelt before the altar, lost in prayer, then he penned a letter to

his mother.

“... I am being sent to

China. You must make the sacrifice for God and He will reward you in eternity.

You shall appear before Him in confidence, at your death, remembering your

generosity, for His greatest glory, in sacrificing what is dearest to you. As a

sign of your consent, please sign the letter you will send me as soon as

possible, and as a sign of your forgiveness for all the sorrow I have caused

you, and as sign of your blessing, please add a cross after your name.” He then

wrote to his brother, Nicolas. “I thank God for the wonderful family He has

given me, and for the conduct of all its members.... It has been my greatest

happiness on earth to have had such an honorable family.” Still, he made a

final trip to Normandy, meeting his brother, Nicolas, and sister-in-law, Marie,

in Caen on April 22, to make arrangements for Masses to be offered for his

parents, for himself and for all his family members. On April 29, the imposing

departure ceremony was held in the chapel of Our Lady, Queen of Martyrs. The

next day, accompanied by five other missionaries, Father Chapdelaine left

Paris. Being the oldest, he was given charge of the group and control of its

purse.

After a few days in

Brussels, the six apostles boarded the Dutch ship, Henri-Joseph, at Anvers on

May 5, 1852. Violent storms, seasickness, and unfavorable winds dogged and

delayed their voyage. They were not to set foot on dry land for four months,

landing in Singapore on September 5. While in Singapore, the aspiring and

zealous missionary was delayed in his quest yet again, robbed by bandits who

took everything he had. He spent the next two years trying to replenish his

wardrobe and the necessary supplies for his mission in China.

On October 15, a

Portuguese vessel offered them passage north towards Hong-Kong. However, the

torrential rains and fierce winds of the monsoon forced them to return to

Borneo and then head towards the Philippines in a voyage filled with storms and

hurricanes. Their vessel finally anchored in the harbor of Macao on the evening

of Christmas Day, 1852. Hong-Kong lay only sixty kilometers away in the estuary

of the Canton River, but it too was a dangerous undertaking, the area being

infested with naval pirates. It took them another twelve hours to reach

Hong-Kong, the gateway of the Celestial Empire. Received at the house of the

French Foreign Missions, Father Chapdelaine and his companions were to remain

with his missionary confreres in Hong-Kong for ten and a half months while

perfecting their command of the Chinese language.

On October 12, 1853,

accompanied by some Christians, he set out for the missionary territory

assigned to him in the Chinese province of Guangxi. All the hardships of his

journeys by sea were now replaced by those on land: fast-flowing rivers, high

mountain ranges, and bandits. Encouraged by the small groups of Christians they

encountered on their way, they reached the mission at Kouy-Yang in February,

1854 where they were received by three missionary confreres. While resting and

awaiting the opportunity of penetrating into Guangxi, he was given the pastoral

care of three villages. During this time, he adopted the dress and appearance

of the Chinese: black suit, moustache and long thin beard, and his long hair

bound in a queue down his back. He also wore the black hat common to Chinese

scholars.

Finally, in 1854, Father

Chapdelaine made the acquaintance of a young widow who was well versed in

Sacred Scripture and knowledgeable of the Faith. Agnès Tsao-Kouy agreed to

accompany him to Guangxi, located on the northeast border of Vietnam, and to

catechize the 30-40 Christian families living there. In 1854, the authorities

still held that no evangelizing by Christians was permitted. Father Auguste

celebrated his first Mass in Guangxi on December 8, 1854. Nine days later, the

authorities arrested him in Su-lik-hien. He spent the next 5 months in close

confinement before his release was secretly obtained in April, 1855. His

apostolic endeavors during the next 8 months bore abundant fruits, but were by

no means uncontested.

In December, 1855, Father

Chapdelaine secretly returned to Guangxi, living in hiding among the Christian

families of Su-lik-hien, ministering to their spiritual needs and converting

hundreds of others. He was arrested on the night of February 25, 1856 and

returned to the prison in Su-lik-hien where the Chinese magistrate had him

sentenced to death. The French missionary had been denounced by Bai San, a

relative of one of the new converts. He was subjected to excruciating tortures

and indignities and then suspended in an iron cage outside the jail. He died

from the severity of his sufferings; his head was decapitated and kept on

public display for some time, his body was thrown to the dogs.

Two others accompanied

him to his martyrdom: the widow-catechist, Agnès Tsao-Kouy, and another devout

layman, Laurent Pe-man, an unassuming laborer. All three were beatified by Pope

Leo XIII on May 27, 1900 and canonized together a century later. His feast day

is February 29th.

SOURCE : https://www.americaneedsfatima.org/Saints-Heroes/st-auguste-chapdelaine.html

Catholic

Heroes . . . St. Augustus Chapdelaine

February 24, 2015

By CAROLE BRESLIN

Christianity has never been warmly welcomed by the authorities in China, but that did not stop the missionaries over the centuries who have gone there to save souls. Christianity has existed in various forms since the Tang Dynasty (eighth century).

The first reports of Catholic priests going to China go back to the 13th century. John of Montecorvino, an Italian Franciscan, arrived in Beijing in 1294. Although he made many converts, and he began to translate the Holy Bible into Mandarin, the official Chinese language, the mission did not thrive.

In 1582 Matteo Ricci was sent to China. His subtle approach and his diplomacy met with some small success with the emperor and with Chinese authorities. Even though he died in 1610, the Jesuit mission continued finding favor with many Chinese until the middle of the 18th century. Jesuits were appointed to prestigious positions such as painters, musicians, mechanics, and instrument makers.

However, in 1826, the Daoguang emperor published a new clause to the “fundamental laws” of China. This clause stated that Europeans would be put to death for spreading Roman Catholic Christianity among the Han Chinese and the Manchus.

Although some hoped that the Chinese government’s new law pertained only to Catholics, Protestants were also targeted. In 1835 and 1836, whenever Protestants supplied Christian books to Chinese children, they were either strangled or expelled.

Meanwhile in France, a man entered the seminary who would play a major part in European interactions with China — most of it as a result of his death.

Augustus Chapdelaine was born on January 6, 1814 to Nicholas Chapdelaine and his wife Madeleine Dodeman. Augustus was the youngest of nine children of this farming family who lived in the northwest French province of Normandy.

As soon as Augustus finished grammar school, his father insisted that he return home and work on the farm. Although Augustus felt called to the priesthood, his father refused to let him enter the seminary, claiming that he needed Augustus’ help on the farm.

By the time Augustus was 21 years old his parents changed their minds because of tragic circumstances. Being God-fearing persons, and having lost two of their other sons in death, they reconsidered their decision regarding the vocation of Augustus. They decided that he should pursue his calling to be a priest.

On October 1, 1834, Augustus entered the minor seminary at Mortain. Because of his advanced age — he was twice the age of the other students — they called him “Papa Chapdelaine,” a nickname that followed him for all his life

On June 10, 1843, Augustus made his final vows for Ordination. He then served as an associate pastor from 1844 until 1851, when he obtained permission to join the foreign missions. He was two years past the age limit to enter the French Foreign Missions, but he so impressed the men of the mission that they accepted him because of his uncommon zeal and enthusiasm.

Augustus returned home to Normandy to say a final goodbye to his family. He then said his last Mass with them and buried his sister. Having bid them farewell, he asked them to pray for him since he probably would never see them again. Then he departed for Paris, from where he left for China on April 30, 1852.

About four months later, he landed in Singapore, on September 5, 1852. His journey was interrupted in Singapore when he was robbed by bandits who took everything he had. Hence, he stayed in Singapore for almost two years, trying to replenish his wardrobe and supplies for his mission in China.

Finally, in 1854, Augustus arrived in the Chinese Guangxi province, located on the northeast border of Vietnam. This was nearly 20 years after the Protestants were expelled for their proselytizing through giving away books and preaching.

In 1854, the authorities still held that no evangelizing was allowed. Augustus celebrated his first Mass in Guangxi on December 8, 1854. Ten days after his arrival, the authorities arrested Augustus in Su-lik-hien. He spent two weeks in prison before he was released.

For the next two years, Augustus ministered to the local Christians, converting hundreds to the Catholic Church. During this time, he adopted the dress and appearance of the Chinese, wearing the black suit, growing a small but long beard, as well as letting his hair grow long, bound in a queue behind his head. He also wore the black hat common to the Chinese scholars.

On February 26, 1856, the Chinese authorities cracked down on the Christians and arrested Augustus once again. They returned him to the prison in Su-lik-hien where the Chinese magistrate had him sentenced to death for preaching to and converting the Chinese people. Augustus had been denounced by Bai San, a relative of one of the converts. He was beaten severely and hung outside the jail in an iron cage.

Along with St. Lawrence Pe-Man and St. Agnes Tsau Kouy, St. Augustus Chapdelaine was beheaded on February 29, 1856. His feast day is celebrated on February 27.

News of his death reached the head of the French mission in Hong Kong on July 12, 1856. On July 25, the charge d’affaires filed a formal and strong protest to the Chinese Imperial Viceroy Ye Mingchen, claiming the murder was a violation of the agreement the two governments had made. He demanded reparation from the Chinese.

The French officer also sent a report to the French foreign office which pursued the demand for reparation. The Chinese viceroy claimed that Chapdelaine had violated Chinese law, and catered to known rebels who had repeatedly been arrested. To appease the French, the arresting officer was arrested. It did not work — a much greater conflict was brewing.

Sometime after the martyrdom of St. Augustus, the French declared war on China. Once the French had won the war, the Chinese agreed to allow the French missionaries freedom to tend the Catholics in China. Some historians suggest that the French merely used Chapdelaine’s death as a pretext to further their colonial aspirations.

Nevertheless, St. Augustus sacrificed his life to spread the Gospel in China. Pope Leo XIII beatified him on May 27, 1900. Pope St. John Paul II canonized Augustus on October 1, 2000.

Dear St. Augustus, the Catholic sheep in China still suffer much persecution.

May our Lady watch over them as the Mother of Mercy and bring them comfort and

solace during their trials. Amen.

(Carole Breslin home-schooled her four

daughters and served as treasurer of the Michigan Catholic Home Educators for

eight years. For over ten years, she was national coordinator for the Marian

Catechists, founded by Fr. John A. Hardon, SJ.)

SOURCE : https://thewandererpress.com/saints/catholic-heroes-st-augustus-chapdelaine/

The Saint Who Helped

Start a War

St. Auguste Chapdelaine

Memorial: February 29

Auguste Chapdelaine was

born on February 6, 1814, in the tiny northwestern French village of La

Rochelle-Normande.

Not much is known of his

early life other than that his family were farmers, he was strong, and for this

reason his parents were reluctant to “lose” him to the priesthood since they

needed able-bodied people to work their land, especially as they grew older.

Ironically, it was the

sudden death of two of his brothers that made his parents realize God’s calling

for their youngest, and so they submitted to His will. Auguste entered the

minor seminary at age 20.

He was much older than

his fellow students, most of whom were ages 12-13. As a result, they called

him, “Pops.” The nickname stuck for the rest of his life.

He received ordination in

1843, and after several months waiting for an assignment at home, his bishop

appointed him as a parochial vicar in Boucey, France.

Before this appointment,

he had told another one of his brothers, “I did not become a priest for

those who already know God but for those who don’t.” Nonetheless he bided his

time, and for seven years served the roughly 650 souls in the village.

Finally, around 1851, he

was able to join the Foreign Missions of Paris (PIME) to work in one of

their mission fields. The people of Boucey had grown to love him so much, they

packed the church for his last Mass. Some didn’t understand why he wanted to

leave them when he was so well regarded and his work so valued. Others

perfectly understood his zeal to spread the Good News and blessed him on his

way.

Before leaving for

mission territory, he had to be evaluated by his PIME superiors at their

seminary in Paris, called the “Polytechnic Institute of Martyrs” due

to the huge number of its graduates who had given the ultimate witness for

the Faith.

During his stay, he wrote

a Carmelite who taught in Boucey, “If it’s true what they say, that Paris is

the center of dissoluteness, it is also the home of much virtue.”

Finally after about a

year in the French capital, he had his evaluation. Afterward he wrote his

mother, “I am being sent to China. You must treat this as a sacrifice made for

God, and He will reward you in eternity. At your death, you shall appear before

Him in confidence [and He will remember] your generosity for His greater glory

in sacrificing what is dearest to you. Please sign the letter you will send me

as soon as possible s a sign of your consent and also as a sign of your

forgiveness for all the sorrow I have caused you. And as sign of your blessing,

please add a cross after your name.”

He then wrote his

brother, Nicolas, “I thank God for the wonderful family He has given me and for

the conduct of all its members…. It has been my greatest happiness on earth to

have had such an honorable family.”

The journey was arduous.

Departing in May from Le Havre, Netherlands, it took two weeks for the

storm-tossed ship he and six other missionaries had boarded just to exit

the English Channel. Then because of unfavorable winds, rather than going

around Africa, the ship’s captain headed west at the Canary Islands and made

for Brazil, where they landed June 6, 1852. The seven men were in a 4’x6’ cabin

with no ventilation, and once they passed the Equator, their room became

unbearably hot. When they reached the southern tip of South America, of course

they were in winter. Then, once around the Horn, instead of heading straight to

China, bad winds forced them to make for Australia. They had not touched land

in three months but finally landed in Singapore in September. They then made

their way to Vietnam where, after some time, a Portuguese ship offered them

passage to Hong Kong. But being monsoon season, they had to take refuge in

Borneo and then head to the Philippines. All along the way, storms and

hurricanes buffeted their ship.

They finally landed in

Macau on Christmas Day, and reached Hong Kong on January 10, 1853.

First he stayed in Hong

Kong for a period. Then in October 1853, he took a journey of three days to the

west, during which he was beaten and robbed. Finally he arrived at the village

of Yaoshan, Xilin County, Guangxi Province. He celebrated his first Mass there

for 300 souls on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, December 8, 1854.

Accompanying him was the lay catechist and future martyr, St. Jerome (aka,

Hieronymus) Lu Tingmei († January 28, 1858). Ten days later authorities

arrested him for illegal missionary activities.

The reason was that at

this time in China’s history, Christianity was only legal in five open ports.

Everywhere else, it was not permitted. Because of the threats he received after

his release from jail, he traveled to neighboring Guizhou (aka, Kweichow)

Province. By the end of the year, however, he had returned to minister to his

people. His efforts led to several hundred people forswearing paganism,

embracing Christ as their Savior, and entering the Church.

In February 1855, the

pagan wife of a new convert didn’t like her husband chastising her

for not being more like the Christian wives he knew. She complained to her

brother and uncle, who denounced St. Auguste. Thus he was again arrested

sometime between February 22 and the night of February 24-25, 1856 (sources

vary), charged with the crime of propagating an illegal religion. Under Chinese

law at the time, this was a capital crime.

When the local mandarin

attempted to question him, Father, like Christ at His own trial, said very

little. Furious at what he considered to be disrespect, the official had him

flogged 150 times on the cheeks. The very first lash drew blood. We can only

imagine what damage the other 149 blows did. Next Father received 300 lashes

with a cane on his back. They stopped only when they saw he could not move.

But when they went to

drag him back to his cell, after only a few steps, he rose and began walking as

if in perfect health. The Chinese couldn’t believe their eyes. The saint told

them, “It is the good God Who protects and blesses me.”

They next placed him in a

custom made cage. His head fit through a hole in the top, and it was just tall

enough for him to barely touch his toes on the ground. Furthermore the cage was

constructed to hold his arms in place so that he could not use them to pull

himself up in order to breath more easily. Thus he was always hovering between

suffocation and barely breathing.

The mandarin offered to

spare his life, however, provided he came up with a ransom of 400 silver

talents. “I have no money,” he said, “only books.” What about 150 talents,

then? he was asked. He replied, “Let the mandarin do what he pleases with me. I

am in his hands.” Thus on February 29, 1856, they beheaded him. They needn’t

have bothered, though. He had been beaten so badly and his body had been so

tortured, he was already dead.

He had not sought out

martyrdom. Not long before his arrest, he was reputed to have said, “He Who

gives us our lives demands that we should take reasonable care of the gift. But

if the danger comes to us, then happy those who are found worthy to suffer for

His dear sake.” Nonetheless die he did.

Martyred at around this

same time was St.

Agnes Tsao Kou Ying, one of his lay catechists who had been stuck in the

same sort of cage as he had been. Their cages were placed side-by-side, and

while they could see one another, they could not talk. Doing so was impossible.

Also giving his life

was St.

Lawrence Bai Xiaoman, a layman who had promised to accompany Father to

death if need be for the sake of Jesus Christ and the salvation of souls.

Learning of his death,

the head of the French mission at Hong Kong sent this protest to Ye Ming-Chen,

governor of Guangdong:

“The captivity of Mr.

Chapdelaine, the torture he suffered, his cruel death, and the violence that

was made to his body constitute, noble Imperial Commissioner, a blatant and

odious violation of the solemn commitments to which he was consecrated. Your government

therefore needs to give [some reparation] to France. You will not hesitate to

give it me fully and entirely. You will propose the terms: I will have to then

decide if the honor, dignity, and interests of the Government of my great

Emperor allow me to accept. My desire is also to go to Canton and to confer in

person with Your Excellency. You know an hour of friendly conversation more

often than not advances the solution to important affairs than a month of

written correspondence.

The Chinese were frankly

tired of the foreign powers throwing their weight around. China, after all, has

always been a great and mighty nation. Were it not for the Europeans’ advanced

military technology—ironically, technology that had its birth in China—China

would have swatted these “bearded foreign devils” away like flies.

Thus it shouldn’t

surprise us that the Chinese government refused to apologize or offer

compensation or any satisfaction for the life of Fr. Chapdelaine. After all,

had he not clearly broken Chinese law by breaching the interior and

preaching an illegal religion? He had. And was not the punishment for this

beheading? It was. So for what was there to apologize? Abbé Chapdelaine wasn’t

the only French citizen arrested for such activity. At the time, six of his

countrymen were in custody for attempting to spread the gospel.

Furthermore, Father’s

activities took place in territory where rebels were active (see the

Christianity-inspired Taiping Rebellion here).

How could it not be that a Frenchman – whose Christian government had not shown

itself overly friendly or necessarily an ally to China – was doing something

other than preaching religion? In fact, the Chinese viceroy asserted that

Father’s activities had nothing whatsoever to do with religion. He was an

agitating agent working against the government.

This turn of affairs was

not necessarily disadvantageous to the French. Many of their countrymen had

suffered martyrdom for their missionary work, and their government had never

once taken action or retaliated. Now the sense was, “Enough is enough.” As the

aforementioned minister wrote his nation’s Foreign Office:

If, in a word, the

Representative of His Imperial Majesty would not but fail in his duty if he did

not take advantage of the opportunity offered him to fix with one blow the

errors or mistakes of the past and to bring out of the martyrdom of a

missionary the complete emancipation of Christianity [in China].

As a result of the

Chinese government’s refusal to apologize in any way, France thus used the

incident as a pretext to join the United Kingdom in the Second Opium War.

Britain’s purpose for the war was to have China legalize the opium trade

(heroin comes from opium), expand its access to near-slave-wages Chinese labor

(abuses of Chinese workers had led their government to cut off English access

to such labor), and get China to exempt foreign imports from internal transit

duties.

The war lasted until

1860. While it obtained for foreign missionaries access to China’s interior,

all in all it was a shameful mess. One could say about it what the English

politician Gladstone said about the First Opium War: “I feel in dread of the

judgments of God upon England for our national iniquity towards China…. [This

is] a war more unjust in its origin, a war more calculated in its progress to

cover this country with permanent disgrace.”

Pope St. John Paul II

canonized St. Auguste and other Chinese martyrs on October 1, 2000, the same

day (perhaps not coincidentally) as the anniversary of the People’s Republic of

China. The next day the Chinese Communist Party’s People’s Daily released

an article showing all the ways those canonized were actually bandits and other

types of miscreants. It accused St. Auguste of raping women, of living with a

woman named Cao, and of bribing officials on behalf of “bandits.”

Needless to say, the

charges were the sorts of lies and politically motivated propaganda at which

all communists excel.

God have mercy on their

piddling souls.

SOURCE : https://catholicsaintsguy.wordpress.com/2016/02/29/the-saint-who-caused-a-war/

FEBRUARY, MARTYRS OF

CHINA, SAINTS

FEB 28/29 – ST AUGUSTE

CHAPDELAINE, MEP, (1814-1856), PRIEST, MARTYR OF CHINA, “FR. MA”

-St Auguste Chapdelaine, MEP

Youngest of nine children

born to Nicolas Chapdelaine and Madeleine Dodeman, 6 January 1814 at La

Rochelle-Normande, France. Following grammar school, Auguste dropped out to

work on the family farm. He was big and strong. He early felt a call to

the priesthood, but his family opposed it, needing his help on the farm, due to

his physical abilities. However, the sudden death of two of his brothers caused

them to re-think, and they finally approved. He entered the minor seminary at

Mortain on 1 October 1834, studying with boys half his age. It led to his being

nicknamed Papa Chapdelaine, which stuck with him the rest of his life.

Ordained on 10 June 1843

at age 29. Associate pastor from 1844 to 1851, in Boucey, France. He finally

obtained permission from his bishop to enter the foreign missions, and was

accepted by French Foreign Missions; he was two years past their age limit, but

his zeal for the missions made them approve him anyway. He stayed long enough

to say a final Mass, bury his sister, and say good-bye to his family, warning

them that he would never see them again. Left Paris, France for the Chinese

missions on 30 April 1852, landing in Singapore on 5 September 1852.

Due to being robbed on

the road by bandits, Auguste lost everything he had, and had to fall back and

regroup before making his way to his missionary assignment. Chapdelaine went

illegally to the Chinese interior to proselytize Christianity. The local

mandarin Zhang Mingfeng was no doubt disposed to take such a harsh line against

this provocation by virtue of the ongoing, Christian-inspired Taiping

Rebellion, which had originated right there in Guangxi and was in the process

of engulfing all of southern China in one of history’s bloodiest conflicts.

The Taiping Rebellion,

1850–64, was a revolt against the Ch’ing (Manchu) dynasty of China. It was led

by Hung Hsiu-ch’üan, a visionary from Guangdong who evolved a political creed

and messianic religious ideology influenced by elements of Protestant

Christianity. His object was to found a new dynasty, the Taiping [great peace].

Strong discontent with the corrupt and decaying Chinese government brought him

many adherents, especially among the poorer classes, and the movement spread

with great violence through the E Chang (Yangtze) valley. The rebels captured

Nanjing in 1853 and made it their capital.

The Western powers,

particularly the British, who at first sympathized with the movement, soon

realized that the Ch’ing dynasty might collapse and with it foreign trade. They

offered military help and led the Ever-Victorious Army, which protected

Shanghai from the Taipings. The Taipings, weakened by strategic blunders and

internal dissension, were finally defeated by new provincial armies led by

Tseng Kuo-fan and Li Hung-chang. Some 20 million people died in the uprising,

which was filled with acts of barbarism on both sides.

St Auguste reached

Kwang-si province in 1854, and was arrested in Su-Lik-Hien ten days later. He

spent two to three weeks in prison, but was released, and ministered to the

locals for two years, converting hundreds. In February 1856, the pagan wife of

a new convert didn’t like her husband chastising her for not being more like

the Christian wives he knew. She complained to her brother and uncle, who

denounced St. Auguste to the local magistrate as a Christian and prosletyzing,

a capital crime outside the five open ports where it was allowed, but not in

the interior.

Arrested on 26 February

1856 during a government crackdown due to the Taiping Rebellion, he was

returned to Su-Lik-Hien and sentenced to death for his work.

Like his Master, Fr.

Chapdelaine said very little in his own defense. Furious at what he considered

to be disrespect, the official had him flogged 150 times on the cheeks. The

very first lash drew blood. We can only imagine what damage the other 149 blows

did. Next Father received 300 lashes with a cane on his back. They stopped only

when they saw he could not move.

But when they went to

drag him back to his cell, after only a few steps, he rose and began walking as

if in perfect health. The Chinese couldn’t believe their eyes. The saint told

them, “It is the good God Who protects and blesses me.”

They next placed him in a

custom made cage. His head fit through a hole in the top, and it was just tall

enough for him to barely touch his toes on the ground. Furthermore the cage was

constructed to hold his arms in place so that he could not use them to pull

himself up in order to breath more easily. Thus he was always hovering between

suffocation and barely breathing.

The mandarin offered to

spare his life, however, provided he came up with a ransom of 400 silver

talents. “I have no money,” he said, “only books.” What about 150 talents,

then? he was asked. He replied, “Let the mandarin do what he pleases with me. I

am in his hands.” Thus on February 29, 1856, they beheaded him. They needn’t

have bothered, though. He had been beaten so badly and his body had been so

tortured, he was already dead.

He had not sought out

martyrdom. Not long before his arrest, he was reputed to have said, “He Who

gives us our lives demands that we should take reasonable care of the gift. But

if the danger comes to us, then happy those who are found worthy to suffer for

His dear sake.” Nonetheless die he did.

Martyred at around this

same time was St. Agnes Tsao Kou Ying, one of his lay catechists who had been

stuck in the same sort of cage as he had been. Their cages were placed

side-by-side, and while they could see one another, they could not talk. Doing

so was impossible.

Also giving his life was

St. Lawrence Bai Xiaoman, a layman who had promised to accompany Father to

death if need be for the sake of Jesus Christ and the salvation of souls.

Learning of his death,

the head of the French mission at Hong Kong sent this protest to Ye Ming-Chen,

governor of Guangdong:

“The captivity of Mr.

Chapdelaine, the torture he suffered, his cruel death, and the violence that

was made to his body constitute, noble Imperial Commissioner, a blatant and

odious violation of the solemn commitments to which he was consecrated. Your

government therefore needs to give [some reparation] to France. You will not

hesitate to give it me fully and entirely. You will propose the terms: I will

have to then decide if the honor, dignity, and interests of the Government of

my great Emperor allow me to accept. My desire is also to go to Canton and to

confer in person with Your Excellency. You know an hour of friendly

conversation more often than not advances the solution to important affairs

than a month of written correspondence.”

The Chinese were frankly

tired of the foreign powers throwing their weight around. China, after all, has

always been a great and mighty nation. Were it not for the Europeans’ advanced

military technology—ironically, technology that had its birth in China—China

would have swatted these “bearded foreign devils” away like flies.

Thus it shouldn’t

surprise us that the Chinese government refused to apologize or offer

compensation or any satisfaction for the life of Fr. Chapdelaine. After all,

had he not clearly broken Chinese law by breaching the interior and preaching

an illegal religion? He had. And was not the punishment for this beheading? It

was. So for what was there to apologize? Abbé Chapdelaine wasn’t the only

French citizen arrested for such activity. At the time, six of his countrymen

were in custody for attempting to spread the gospel.

Furthermore, Father’s

activities took place in territory where rebels were active

(Christianity-inspired Taiping Rebellion). How could it not be that a Frenchman

– whose Christian government had not shown itself overly friendly or necessarily

an ally to China – was doing something other than preaching religion? In fact,

the Chinese viceroy asserted that Father’s activities had nothing whatsoever to

do with religion. He was an agitating agent working against the government.

This turn of affairs was

not necessarily disadvantageous to the French. Many of their countrymen had

suffered martyrdom for their missionary work, and their government had never

once taken action or retaliated. Now the sense was, “Enough is enough.” As the

aforementioned minister wrote his nation’s Foreign Office:

“If, in a word, the

Representative of His Imperial Majesty would not but fail in his duty if he did

not take advantage of the opportunity offered him to fix with one blow the

errors or mistakes of the past and to bring out of the martyrdom of a

missionary the complete emancipation of Christianity [in China].”

As a result of the

Chinese government’s refusal to apologize in any way, France thus used the

incident as a pretext to join the United Kingdom in the Second Opium War.

Britain’s purpose for the war was to have China legalize the opium trade

(heroin comes from opium), expand its access to near-slave-wages Chinese labor

(abuses of Chinese workers had led their government to cut off English access

to such labor), and get China to exempt foreign imports from internal transit

duties.

The war lasted until

1860. While it obtained for foreign missionaries access to China’s interior,

all in all it was a shameful mess. One could say about it what the English

politician Gladstone said about the First Opium War: “I feel in dread of the

judgments of God upon England for our national iniquity towards China…. [This

is] a war more unjust in its origin, a war more calculated in its progress to

cover this country with permanent disgrace.”

Pope St. John Paul II

canonized St. Auguste and other Chinese martyrs on October 1, 2000, the same

day (perhaps not coincidentally) as the anniversary of the People’s Republic of

China. The next day the Chinese Communist Party’s People’s Daily released an

article showing all the ways those canonized were actually bandits and other

types of miscreants. It accused St. Auguste of raping women, of living with a

woman named Cao, and of bribing officials on behalf of “bandits”.

“I am being sent to

China. You must treat this as a sacrifice made for God, and He will reward you

in eternity. At your death, you shall appear before Him in confidence [and He

will remember] your generosity for His greater glory in sacrificing what is

dearest to you. Please sign the letter you will send me as soon as possible as

sign of your consent and also as a sign of your forgiveness for all the sorrow

I have caused you. And as sign of your blessing, please add a cross after your

name.” -in a letter to his mother, making her aware his foreign

assignment, 1852, from Paris.

“I thank God for the

wonderful family He has given me and for the conduct of all its members…. It

has been my greatest happiness on earth to have had such an honorable

family.” -from a letter to his brother, Nicolas, at the same time, 1852.

Almighty and ever-living

God, You have raised the Chinese martyrs to be models of our faith. Through

Your grace, they had the courage to witness to Your Gospel by giving up their

lives. May their blood continue to nourish the seeds of faith in the Chinese

people, leading them to know and love You. We ask this through our Lord, Jesus

Christ, Your Son, Who lives and reigns with You and the Holy Spirit, one God,

for ever and ever. Amen.

Love,

Matthew

SOURCE : https://soul-candy.info/2016/07/feb-28-st-auguste-chapdelaine-mep-1814-1856/

Museum praises murderers

of a Catholic saint, “enemy of the people”

A life-size diorama

showing Saint Auguste Chapdelaine is on display in a tourist area in Guangxi.

It shows the martyr kneeling before the magistrate who sentenced him to death.

A six-metre bronze mural shows the cage in which he suffocated to death. A

poetry contest gives prize money to those who praise “iron-willed” magistrate

Zhang.

Beijing (AsiaNews) –

Village authorities in Dingan, Guangxi, plan to celebrate the expulsion of

Catholic foreigners from their area by opening a museum to celebrate Zhang

Mingfeng, a magistrate from the Qing era who sentenced a missionary saint to

death. The celebration includes a poetry contest. The new facility includes a

six metre bronze mural showing the missionary confined in a cage.

The region is a major

tourist area and local officials want "to show the evil brought by those

foreign devils" and condemn the "spiritual opium" that stifles

people.

The Maoist revolution

developed against China’s repressive imperial system, but Maoist anti-religious

propaganda has always followed the same crude narrative as the Qing era.

Now Communist leaders in

Dingan want to turn into a hero one of champions of that system that Maoism

called corrupt. A poetry contest was mounted offering a thousand yuan for the

best couplets praising the “iron-willed” judge who presided the trial against

Saint Auguste Chapdelaine.

Born on 16 January 1814

in La Rochelle (France), Auguste Chapdelaine was ordained priest in 1843. In

1851 he joined the Institute of Foreign Missions of Paris and on 29 April 1852

left Antwerp for the Chinese mission of Kuang-Si (old transliteration for Guangxi).

In 1855, he began his apostolate, which led to 200 conversions in a short

period of time.

His work, however,

created envy and jealousy. According to the chronicles of the time, a certain

Pé-San, a man of corrupt morals, having learnt that a woman he had seduced had

converted to Christianity, denounced the presence of the missionary to the

magistrate of Sy- Lin-Hien, an arch-enemy of Christians, accusing the clergyman

of stirring up the people and fomenting unrest.

The “heroic” magistrate

in question, Zhang Mingfeng, sent guards to Yan-Chan to arrest Fr Chapdelaine;

however, the latter, forewarned, had fled to the house of a Christian writer in

Sy-Lin-Hien. On 25 February 1856, guards surrounded and searched the house. Fr

Chapdelaine, four other Christians, and the host’s second son were arrested.

Overall some 25 people were taken into custody, beaten with bamboo sticks,

chained and collared.

On 26 February, the

missionary was questioned and accused, whipped hundreds of times with a bamboo

stick that left welts all over his body. The next day he was chained by his

knees, bent over iron bars band until the 28th, waiting for Christians to pay a

ransom.

He was sentenced to die

in a cage. On 29 February 1856, his neck in a hole in the top cover, he was

hung, and suffocated to death. Beatified on 27 May 1900 by Pope Leo XIII, he

was proclaimed saint on 1 October 2000 by Pope John Paul II.

The decision to canonise

the missionary – along with many other saints of evangelisation in China –

sparked controversy in China. An article in Xinhua in September 2000,

titled ‘Unmasking the so-called saints’, showcased the alleged crimes of three

missionaries Qing era without any supporting sources. The three were Fr

Chapdelaine, Saint Alberico Crescitelli, of the Pontifical Institute for

Foreign Missions, and Spanish Dominican Francisco Fernandez de Capillas.

The Dingan museum is not

just a nationalist tourist facility, but fits with the government’s drive to

sinicise religious activities in the country.

“Western cultural influence

highlights a certain moral vacuum in today’s Chinese society, caught between

widespread corruption and the worship of money, where the Communist Party has

lost its pivotal role,” an expert told AsiaNews.

“Thus, sinicisation is meant to provide society with ‘other values’.”

Vitrail

commémoratif du martyre d'Auguste Chapdelaine en l'église de Boucey (50).

Vetrata commemorativa del martirio di Sant'Augusto Chapdelaine nella chiesa di Boucey

Vitrail

commémoratif du martyre d'Auguste Chapdelaine en l'église de Boucey (50).

Vetrata commemorativa del martirio di Sant'Augusto Chapdelaine nella chiesa di Boucey

Sant' Augusto Chapdelaine Martire

in Cina

(negli

anni bisestili: 29 febbraio)

La Rochelle (Francia), 6

gennaio 1814 – Sy-Lin-Hien (Cina), 29 febbraio 1856

Nacque a La Rochelle in

Francia, il 6 gennaio 1814 in una famiglia di contadini. Frequentò il Seminario

diocesano e fu ordinato sacerdote nel 1843; ebbe il compito, prima di vicario e

poi di parroco del villaggio di Boucey. Nel 1851 passò al noviziato

dell'Istituto delle missioni estere di Parigi e il 29 aprile 1852 s'imbarcò ad

Anversa, diretto alla missione cinese del Kuang-Si; ma si fermò a Ta-Chan

vicino alla frontiera, per ambientarsi, imparare la lingua e aspettare il

momento propizio. Trascorsero quasi tre anni, poi nel 1855 poté entrare nello

Kuang-Si, dove si mise subito a fare apostolato, percorrendo il territorio in

lungo e in largo; in breve tempo i neofiti divennero circa duecento. Un certo

Pé-San, uomo di costumi corrotti, però, avendo saputo che una donna da lui

sedotta, si era convertita al cristianesimo, denunciò la presenza del

missionario al mandarino di Sy-Lin-Hien, acerrimo nemico dei cristiani,

accusandolo di sobillare il popolo, fomentando disordini. Il 25 febbraio 1856

padre Chapdelaine fu fatto prigioniero. interrogatom, torturato e condannato.

Morì martire il 29 febbbraio.

Martirologio

Romano: Nella città di Xilinxian nella provincia del Guangxi in Cina,

sant’Agostino Chapdelaine, sacerdote della Società per le Missioni Estere di

Parigi e martire, che, arrestato dai soldati insieme a molti neofiti per avere

per primo seminato la fede cristiana in questa regione, colpito da trecento

frustate e costretto in una piccola gabbia, morì infine decapitato.

La storia

dell’evangelizzazione della Cina è costellata da innumerevoli martiri,

missionari europei, clero locale, catechisti cinesi, fedeli convertiti, che

donarono la loro vita, durante le ricorrenti persecuzioni, che si alternarono a

periodi di pace e di proficua evangelizzazione, scatenate o sobillate da bonzi

invidiosi, fanatici ‘boxer’, crudeli mandarini e imperatori, soldataglia avida

di sangue e saccheggi.

In questa eroica schiera

di martiri caduti negli ultimi quattro secoli, è compreso s. Augusto

Chapdelaine, missionario dell’Istituto delle Missioni Estere di Parigi.

Nacque a La Rochelle

(diocesi di Coutances) in Francia, il 6 gennaio 1814; coltivò con i fratelli,

fino ai 20 anni, gli ampi poderi agricoli presi in affitto dalla famiglia; ma

dopo la morte di due di essi e la riduzione della superficie dei terreni,

lasciò l’azienda e si dedicò alla desiderata carriera ecclesiastica.

Frequentò il Seminario

diocesano e fu ordinato sacerdote nel 1843; ebbe il compito, prima di vicario e

poi di parroco del villaggio di Boucey.

Ma il suo desiderio era

quello di essere missionario, quindi nel 1851 passò al seminario – noviziato

dell’Istituto delle Missioni Estere di Parigi e il 29 aprile 1852 s’imbarcò ad

Anversa, diretto alla missione cinese del Kuang-Si; ma si fermò a Ta-Chan

vicino alla frontiera, per ambientarsi, imparare la lingua e aspettare il

momento propizio, perché il Kuang-Si era stato per più di un secolo senza la

presenza di un missionario e quindi non si era più certi dell’accoglienza dei

suoi abitanti.

Trascorsero quasi tre

anni, poi nel 1855 poté entrare nello Kuang-Si, dove si mise subito a fare

apostolato, percorrendo il territorio in lungo e in largo; in breve tempo i

neofiti divennero circa duecento e ulteriori conversioni erano prossime, quando

un certo Pé-San, uomo di costumi corrotti, avendo saputo che una donna da lui

sedotta, si era convertita al cristianesimo, denunciò la presenza del

missionario al mandarino di Sy-Lin-Hien, acerrimo nemico dei cristiani,

accusandolo di sobillare il popolo, fomentando disordini.

Il mandarino allora inviò

le sue guardie a Yan-Chan, dov’era padre Augusto Chapdelaine per arrestarlo, ma

questi avvertito in tempo, sfuggì alla cattura rifugiandosi in casa di un

letterato cristiano a Sy-Lin-Hien.

Il 25 febbraio 1856, la

casa venne circondata dalle guardie e perquisita; padre Chapdelaine fu fatto

prigioniero insieme a quattro fedeli cristiani che l’avevano accompagnato e il

secondo figlio dell’ospite.

La retata di cristiani

produsse a sera 25 prigionieri, che furono bastonati a colpi di bambù,

incatenati e con la ‘ganga’ al collo (tipica gogna dei Paese asiatici).

Il 26 febbraio il

missionario fu interrogato e accusato; ricevé per punizione centinaia di colpi

di bambù che lo resero tutto una piaga. Il giorno dopo fu incatenato con le ginocchia

piegate e strette sopra delle catene di ferro e così rimase in quella

dolorosissima posizione fino al 28, in attesa di un ingente riscatto da parte

dei cristiani, che comunque erano nascosti ed impauriti.

Fu condannato a morire

nella gabbia e il 29 febbraio 1856, con il collo entro un foro del coperchio

superiore e il corpo, tolto il fondo della gabbia, sospeso, il missionario morì

come fosse impiccato.

Padre Augusto Chapdelaine

fu beatificato il 27 maggio 1900 da papa Leone XIII e proclamato santo il 1°

ottobre 2000, da papa Giovanni Paolo II.

Autore: Antonio

Borrelli

SOURCE : http://www.santiebeati.it/dettaglio/92019

Voir aussi : https://web.archive.org/web/20040615005537/http://chapdelaine.8k.com/page2.html

_%C3%89glise_03.jpg)

_%C3%89glise_05.jpg)

_%C3%89glise_06.jpg)

_%C3%89glise_07.jpg)

_%C3%89glise_10.jpg)

_%C3%89glise_11.jpg)

_%C3%89glise_08.jpg)

_%C3%89glise_09.jpg)