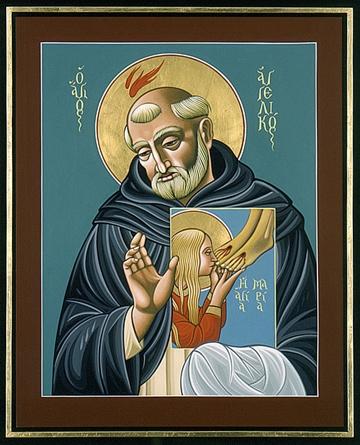

Bienheureux Fra Angelico, prêtre

Guido di Piero est né en Toscane à la fin du XIVème siècle. Adolescent, il va à Florence où il apprend à peindre, mais c'est la vie religieuse qui l'attire. Avec son frère Benoît, il entre au couvent des Dominicains de Fiesole où il reçoit le nom de Jean. Ordonné prêtre, il devient le prieur du couvent de Fiesole où il peint plusieurs retables. Puis on l'envoie au couvent Saint Marc de Florence pour le décorer. Il y couvre de fresques le cloître, la salle du chapitre, les cellules et les couloirs du dortoir. Il décore aussi les murs de deux chapelles dans la basilique Saint-Pierre du Vatican, puis la chapelle privée du pape. Il est simple et droit, pauvre et humble. Il meurt en 1455, à Rome, au couvent de Santa Maria sopra Minerva. Frère Jean de saint Dominique, passé à l’histoire sous le nom de Fra Angelico, sut créer l’harmonie entre l’art de la Renaissance naissante et la pureté de cœur d’un vrai chercheur de Dieu.

Bienheureux Fra Angelico

Frère prêcheur italien et peintre (+ 1455)

Confesseur.

Guido est né en Toscane. Adolescent, il va à Florence

où il apprend à peindre, mais c'est la vie religieuse qui l'attire. Les deux ne

sont pas incompatibles. Avec son frère Benoît, il entre au couvent des

Dominicains de Fiesole où il reçoit le nom de Jean. Ordonné prêtre, il devient

le prieur du couvent de Fiesole où il peint plusieurs retables. Puis on

l'envoie au couvent Saint Marc de Florence pour le décorer. Il y couvre de

fresques le cloître, la salle du chapitre, les cellules et les couloirs du

dortoir. Il décore aussi les murs de deux chapelles dans Saint Pierre de Rome

au Vatican, puis la chapelle privée du Pape. "Quiconque fait les choses du

Christ, doit être tout entier au Christ" aime à dire frère Jean de Fiesole

qu'on appelle aussi Fra Angelico. Il est simple et droit, pauvre et

humble.

Ses tableaux témoignent de sa ferveur. Ils s'éclairent et nous éclairent de la lumière divine qui l'habite et qui lui valut ce surnom.

Une légende veut que les anges qu'il avait peints, pleurèrent ce jour-là.

Le Pape Jean-Paul II a accordé son culte liturgique en 1982 à l'Ordre des Frères Prêcheurs et en a fait le patron des artistes.

À Rome, en 1455, le bienheureux Jean de Fiesole, surnommé l’Angélique, prêtre de l’Ordre des Prêcheurs, qui, toujours attaché au Christ, exprima dans sa peinture ce qu’il contemplait intérieurement, pour élever l’esprit des hommes vers les réalités d’en-haut.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/5772/Bienheureux-Fra-Angelico.html

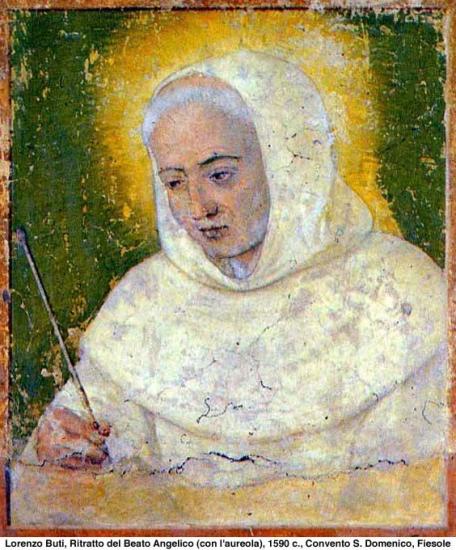

Bienheureux Fra Angelico da Fiesole († 1455)

S'il fallait un exemple pour faire comprendre comment la grâce sait s'appuyer sur la nature, ici le don de peindre, c'est bien l'oeuvre d'un Fra Angelico qui pourrait le faire comprendre. Guido di Pietro, né vers 1400 en Toscane, doit sa première formation artistique à un atelier d'enluminure. Vers l'âge de vingt ans, il entre au couvent observant de San Domenico de Fiesole, sur cette hauteur embaumée qui surplombe Florence.

Lorsque les dominicains prennent possession du couvent de Saint-Marc, les Médicis, en puissants mécènes, proposent de financer une nouvelle église. C'est Fra Angelico qui est chargé de décorer les bâtiments conventuels sous la direction de son maître, le futur archevêque de Florence, saint Antonin. Il est appelé à Rome par les papes Eugène IV et Nicolas V. Il travaille beaucoup, retourne à Fiesole puis de nouveau à Rome où il meurt en 1455, sans avoir eu le temps d'achever les fresques du cloître de Sainte-Marie de la Minerve où il repose, non loin du tombeau de sainte Catherine de Sienne.

Les historiens de l'art n'ont pas cessé d'interroger son oeuvre picturale, plus énigmatique que sa lumineuse limpidité ne le ferait supposer de prime abord. Si on s'attache moins maintenant à montrer dans le détail sa conformité à la théologie thomiste - comme si la Somme pouvait être illustrée -, on admire la manière dont cette peinture se penche sur le mystère de l'Incarnation et de la Rédemption, et comment la lumière délicate qu'elle irradie, manifeste le renouvellement du monde dans le Christ. C'est bien cela qui est conforme à la théologie de saint Thomas d'Aquin.

L'alliage que fait Fra Angelico du jeu des couleurs, des décors et des attitudes, de l'ordre et d'une certaine dissemblance - comme l'a montré récemment l'historien de l'art Georges Didi-Huberman -, du réalisme de la terre et des beautés du ciel, du concret et de l'abstrait, lui permet de suggérer la transfiguration de la nature. Cette lecture théologique de l'oeuvre peut s'accompagner d'une lecture dominicaine en quelque sorte. En effet à San Marco, à Fiesole, terre dominicaine, Fra Angelico répond aux besoins des communautés observantes auxquelles il appartient. Car, et en cela il est bien encore médiéval, Fra Angelico ne conçoit pas de dissociation entre le beau et le fonctionnel.

Il s'agit pour le peintre dominicain de rappeler à ses frères qui vont vivre, étudier, prier, dormir, manger, déambuler, le sens de ce qu'ils font, et comment leur prière, leur pénitence et toute leur existence doivent être polarisées par les mystères du salut, qu'en outre, par profession, ils devront prêcher. Ce que Fra Angelico nous propose, ce sont des homélies picturales, et c'est bien l'idéal, sous des formes et des intuitions évidemment différentes, de tout artiste dominicain. (Source : Quilici, Alain; Bedouelle, Guy. Les frères prêcheurs autrement dits Dominicains. Le Sarment/Fayard, 1997)

SOURCE : http://www.dominicains.ca/Histoire/Figures/angelico.htm

Jean-Paul II évoque le bienheureux Fra Angelico,

patron des artistes

18 février 2004

CITE DU VATICAN, MERCREDI 18 février 2004 (ZENIT.org) – Jean-Paul II a évoqué le bienheureux Fra Angelico, patron des artistes, en saluant à la fin de l’audience générale de ce mercredi les représentant de l’Union catholique italienne des Artistes.

Le pape leur indiquait comme "modèle" le bienheureux peintre de Fiesole dont l’Eglise célèbre aujourd’hui la mémoire liturgique, tandis que la France, et Lourdes en particulier, fête sainte Bernadette.

"Que l’exemple et l’intercession de cet humble disciple de saint Dominique soient pour vous, chers jeunes, ajoutait le pape, un encouragement à vivre fidèlement votre vocation chrétienne".

Aux malades, le pape disait: "Que le bienheureux Angelico vous aide, chers malades, à offrir vos souffrances en union avec celles du Christ pour le salut de l’humanité".

"Qu’il vous soutienne, chers jeunes mariés, concluait le pape, dans votre engagement quotidien à la fidélité réciproque".

Le bienheureux frère dominicain italien Angelico de Fiesole (1377-1435) s’appelait à son baptême Jean. Il est né dans la province de Mugello, près de Florence. Il est devenu dominicain à Fiesole en 1407. Il résida quelque temps au couvent Saint-Marc de florence où il a orné les cellules de ses frères de fresques représentant des scènes de la vie du Christ: un véritable Evangile médité. Il est mort au couvent de la Minerve, à Rome, où il repose après avoir peint de nombreux autres chefs d’œuvres inspirés.

Il a été béatifié en 1982 par Jean-Paul II qui l’a donné comme saint patron aux artistes en 1984.

(18 février 2004) © Innovative Media Inc.

SOURCE : http://www.zenit.org/fr/articles/jean-paul-ii-evoque-le-bienheureux-fra-angelico-patron-des-artistes

Fra Angelico (circa 1395 –1455). Armadio degli argenti, vers 1450, Museum of San Marco

« L'art exige beaucoup de calme, et pour peindre les choses du Christ il faut vivre avec le Christ »

Fra ANGELICO

Angélique et génial

Le saint patron des peintres - (Anita Bourdin

- Zenit.org)

Le martyrologe romain fait mémoire, le 18 février, du bienheureux prêtre dominicain, peintre de la Renaissance italienne, Fra Angelico, prêtre (†1455).

Jean de Fiesole est cet "angélique" peintre dont Jean-Paul II a dit qu'il avait écrit avec son pinceau une "somme" théologique. Il était né à Vecchio, et il reçut au baptême le nom de Guido. Attiré de bonne heure par lavie religieuse, Guido entre chez les Frères prêcheurs à Florence: il reçoit le nom de frère Jean, "Fra Giovanni". Dès lors, il ne cesse de peindre tout en étant économe, vicaire, prieur.

Il peindra les fameuses fresques du couvent Saint-Marc de Florence, inspirées par les mystères de la vie du Christ, pour les cellules de ses frères dominicains, mais aussi la salle du chapitre, les couloirs, le parvis et le retable de l'autel de l'église. Et l'Annonciation si célèbre devant laquelle on ne saurait passer sans prier la Vierge Marie. Le pape Eugène IV le fit venir à Rome, en 1445, et il lui confia la mission de décorer un oratoire et la chapelle du Saint-Sacrement au Vatican.

De l'avis de ses frères dominicains, "Fra Angelico" fut un homme modeste et religieux, doux, pieux et honnête. Il s'éteignit à Rome le 18 février 1455 au couvent romain de Sainte-Marie-sur-la-Minerve où son corps repose aujourd'hui. Après sa mort, il reçut le surnom d'"Angelico", pour la beauté de sa peinture inspirée, pour sa bonté, et pour son élévation mystique dans la contemplation des mystères de la vie du Christ.

Son culte a été confirmé en 1982 par Jean-Paul II qui l'a ensuite proclamé saint patron des artistes et spécialement des peintres, le 18 février 1984, lors du Jubilé des artistes. Pour le bienheureux pape, Fra Angelico a été "un chant extraordinaire pour Dieu": "par toute sa vie, il a chanté la Gloire de Dieu qu'il portait comme un trésor au fond de son coeur et exprimait dans ses oeuvres d'art. Religieux, il a su transmettre par son art les valeurs typiques du style de vie chrétien. Il fut un "prophète" de l'image sacrée : il a su atteindre le sommet de l'art en s'inspirant des Mystères de la Foi".

"Sa vie fut un extraordinaire chant

pour Dieu!".

Pape Jean-Paul II.

Attiré par la vie religieuse alors qu' il est encore un jeune adolescent, Guido entre chez les Frères prêcheurs dominicains qui, sur les hauteurs de Florence, aspirent à un renouveau spirituel de leur Ordre.

Le désormais "Fra Giovanni" ne cesse alors de peindre, tout en s' acquittant avec beaucoup de zèle des charges qui lui sont confiées : économe, vicaire, prieur.

Tandis qu' il vaquait aux différentes fonctions qui lui étaient assignées, sa renommée de peintre talentueux commença de se répandre. Dans le couvent saint Marc de Florence, le Frère donne la pleine mesure de son art : il décore les cellules, la salle du chapitre, les couloirs, le parvis et le retable de l' autel de l' église : aucun recoin n' échappe à son immense talent!

Le Pape Eugène IV fut tellement enthousiasmé par cette oeuvre qu' il le fit veni à Rome, en 1445, et lui confia la mission de décorer un oratoire et la chapelle du Saint-Sacrement au Vatican.

De l' avis de ses frères en religion, "Fra Angelico" fut un homme pleinement modeste et religieux, doux par l' esprit, honnête par la piété.

Il s' éteignit à Rome le 18 février 1455 dans le couvent de Santa Maria sopra Minerva.

C' est après sa mort qu' on le surnomma "Angelico", en raison de la bonté de son coeur et de la beauté de sa peinture par lesquelles il "chantait" la Gloire de Dieu comme les Anges du Ciel.

Le Pape Jean-Paul II le proclama "Patron des artistes" et spécialement des peintres, le 18 février 1984.

Ce jour-là, dans son homélie, le Saint-Père rappela que la vie de Fra Angelico "fut un extraordinaire "chant" pour Dieu". Par toute sa vie, il a chanté la Gloire de Dieu qu' il portait comme un trésor au fond de son coeur et exprimait dans ses oeuvres d' art... Il fut un religieux qui a su transmettre par son art, les valeurs qui sont à la base du style de vie chrétien. Il fut un "prophète" de l' image sacrée : il a su atteindre le sommet de l' art en s' inspirant des Mystères de la Foi".

En rencontrant des artistes, le Pape Benoit XVI disait :

"L' histoire de l' humanité est mouvement et

ascension, elle est une tension inépuisable vers la plénitude, vers le

Bonheur ultime, vers un horizon qui dépasse toujours le présent alors qu'

il le traverse... La beauté, de celle qui se manifeste dans l' univers et dans

la nature à celle qui s' exprime à travers les créations artistiques...

peut devenir une voie vers le Transcendant, vers le Mystère ultime, vers

Dieu".

(Pape Benoit XVI. Discours aux artistes du samedi 21 novembre 2009 à la Chapelle Sixtine).

Bienheureux Fra Angelico,

prie pour nous et en particulier pour les artistes et

les peintres, afin qu' à travers leur art,

ils aident les hommes de ce temps

à contempler le Dieu de Bonté et de Beauté qui S' est

révélé en Jésus,

"le plus Beau des enfants des hommes"

qui est aussi la Grande Espérance qui soutient toute

chose!

Amen

Le

Sermon sur la montagne, fresque de Fra Angelico sur le mur de la cellule 32 du

couvent dominicain de Saint-Marc, Florence, Toscane, Italie.

Fra Angelico, ce peintre

bienheureux qui ne retouchait jamais ses œuvres

Anne Bernet - publié

le 17/02/23

Nous connaissons le

peintre, mais bien peu le bienheureux. Ce dominicain qui peignait comme un

ange, était d’abord un homme de prière et de pauvreté. Béatifié par le pape

Jean Paul II, l’Église fête sa mémoire le 18 février.

Pour Bernadette, la séance, une de plus, est interminable.

Depuis des semaines, prêtres, religieux, évêques, théologiens de renom ou

prétendus tels, mais aussi journalistes et simples curieux, parfois d’ailleurs

vraiment en quête de Dieu, défilent à Lourdes,

demandent à la voir et l’éreintent de questions, toujours les mêmes. Il en est

une qui revient régulièrement : à quoi ressemble la Sainte Vierge ?

Consciencieusement, l’adolescente tente de répondre, allant même, un jour, pour

un visiteur plus malheureux que les autres, à « lui faire le sourire de

Notre-Dame », se transfigurant au point que cet agnostique se retirera

converti. Aujourd’hui, les ecclésiastiques venus la voir ont apporté un gros

livre présentant les reproductions des plus célèbres images mariales. Il y a là

les plus grands peintres et sculpteurs de l’histoire de l’art chrétien mais

rien n’y fait et Bernadette se contente de tourner les pages avec une grimace

de dépit : cela ne ressemble ni de près ni de loin à ce qu’elle a vu. En

comparaison, tout est laid. Soudain, elle suspend son geste, se penche vers

l’image, hésitante, murmure : « Il y a quelque chose, là… » puis

soupire que « Non, ce n’est pas cela ».

Un reflet du paradis

Cette planche sur

laquelle Bernadette s’est arrêtée, la seule de tout l’album, il semble qu’il

s’agisse d’une reproduction d’une Madone de Fra Angelico, l’une de ses Vierges

d’humilité peut-être parce que, assise par terre, à jouer avec son Fils,

Notre-Dame rappelle la toute petite jeune fille d’une quinzaine d’années

qu’elle a vue dix-huit fois. Ce qui manque à cette reproduction, impossible à

rendre à l’époque à travers une gravure inférieure à l’originale, c’est

l’infinie délicatesse, la beauté hors de ce monde, et surtout l’explosion de

couleurs exquises qui sont la marque du religieux dominicain, ce fra Giovanni

que l’on rebaptisera, après sa mort, Fra Angelico, le frère angélique, pour son

incroyable capacité à donner à voir un reflet du paradis.

Les artistes accourus à

Florence (…) gagnent des sommes énormes, tirent gloire de leur talent et leur

renommée. Tous, sauf un

Son prieur, Antonino

Pierozzi, futur saint Antonin, spécialiste de Thomas d’Aquin, gloire de

l’Ordre, et qui, en bon fils de la Renaissance florentine, s’y entend en fait

d’art lorsqu’il regarde les merveilles sorties des mains de fra Giovanni, dit :

« On ne peut peindre le Christ sans vivre à l’imitation du Christ. »

C’est vrai aussi de la Vierge, des saints, des anges et de tout cet univers à

la fois très proche et très lointain, immatériel en même temps que réel dans

les moindres détails né sous le pinceau de l’artiste et jamais retouché car le

peintre, qui ne travaille qu’après avoir prié, a la conviction d’avoir œuvré

sous la conduite du Saint Esprit, de n’avoir donc pas le droit de corriger ce

qui ne vient pas de lui. C’est ainsi que travaillent, dans les monastères

orthodoxes, les iconographes absorbés dans l’oraison et la méditation. Reste

que, dans l’Italie du Rinascimento, cette façon de faire n’est pas

commune. Les artistes accourus à Florence, sous contrat avec les puissantes

familles de la ville, gagnent des sommes énormes, tirent gloire de leur talent

et leur renommée. Tous, sauf un, et cela fait toute la différence, donnant aux

créations de frère Giovanni ce supplément d’âme qui frappera Bernadette et lui

fera retrouver, jusque dans une piètre reproduction en noir et blanc, le reflet

de la lumière divine.

Ceux qui rêvent d’une

grande réforme

Cette humilité vraie,

cette volonté de s’effacer derrière ce qu’il montre, si elle est une marque de

sainteté, a pour inconvénient que nous en savons peu concernant la vie du

peintre. Même sa date de naissance est controversée : 1387 ? 1395 ? 1400 ? Sans

doute faut-il s’en tenir à la première, qu’indique Vasari, son premier

biographe. Lorsqu’il naît près de Vicchio, dans la vallée du Mugello, à 30

kilomètres de Florence, fra Angelico s’appelle Guido di Pietro ; les patronymes

ne sont pas encore fixés et l’on ajoute encore seulement au prénom de baptême

celui du père. Ce père doit posséder une certaine fortune puisqu’il a les

moyens d’offrir de bonnes études à ses deux fils, Guido et Benedetto. Guido a

une dizaine d’années quand ses parents s’installent à Florence ; là, il est

placé en apprentissage au couvent camaldule Santa Maria degli Angeli, près d’un

moine peintre très apprécié, Lorenzo di Monaco, un maître des couleurs.

L’adolescent se révèle remarquablement doué mais, bien que l’on pressente en

lui un très grand artiste, ce n’est pas cela qui l’intéresse.

Chez les frères

prêcheurs, la règle de saint Dominique n’est plus observée, surtout en ce qui

concerne la pauvreté voulue par le fondateur.

En ce début du XVe

siècle, alors que l’Église est déchirée par le grand schisme d’Occident qui

donne à la chrétienté le sidérant spectacle de deux, voire trois papes en même

temps, nombreux sont ceux qui rêvent d’une grande réforme qui restaurerait la

catholicité dans sa splendeur première. Car si une pareille crise a pu se

produire et durer, il faut que le mal soit ancien, profond et généralisé,

n’épargnant pas même les Ordres mendiants voulus à l’origine pour en finir avec

le relâchement de la vie religieuse. Chez les frères prêcheurs, la règle de

saint Dominique n’est plus observée, surtout en ce qui concerne la pauvreté

voulue par le fondateur. Certes, un courant réformateur, né dans l’entourage de

Catherine de Sienne, parcourt l’Ordre, mais il est loin d’être majoritaire tant

l’abandon des plaisirs terrestres est odieux à bien des religieux.

Un couvent où l’on est

pauvre

Au temps de

l’apprentissage de Guido, l’on entend, dans les églises et les rues de

Florence, un fils de Dominique, Giovanni Dominici, prédicateur au verbe de feu

que les Florentins surnomment « le voleur d’enfants » tant il suscite

de vocations. Guido et Benedetto, son frère, vers 1407, après l’avoir entendu,

entrent au couvent Saint-Dominique de Fiesole, fondation de Dominici qui a dû

rompre avec le riche et puissant couvent florentin Santa Maria Novella, car il

rejette toute tentative de réforme. Au conventino de Fiesole, l’on

est pauvre, ne vivant que du travail des frères. Celui de Guido, devenu Fra

Giovanni lors de sa prise d’habit, et celui de Benedetto, enlumineur habile,

seraient précieux mais l’usage est que les novices se consacrent à leurs

études. Giovanni s’y plie et, cinq années durant, jusqu’à son ordination en

1412, ne touchera plus un pinceau, ne cherchant en tout que la volonté de

Dieu.

Très vite, l’atelier de

Fra Giovanni, car il doit s’adjoindre des assistants, devient le plus réputé de

Toscane, voire d’Italie

Tout est difficile

pourtant. Aux difficultés financières s’ajoute le soutien apporté par les

dominicains de Fiesole au pape de Rome, Grégoire XII, choix qui les oblige à se

réfugier à Foligno en Ombrie. C’est dans cette ville que Giovanni devient

prêtre en 1412, là aussi peut-être qu’il réalise son premier chef d’œuvre, en

l’honneur d’une des grandes figures de son Ordre, saint Pierre martyr. Ainsi

commence une carrière hors du commun, ponctuée de merveilles, qui transcrit en

images les grands enseignements thomistes. Très vite, l’atelier de Fra

Giovanni, car il doit s’adjoindre des assistants, devient le plus réputé de

Toscane, voire d’Italie après que le peintre ait été découvert par la cour

pontificale lors d’un long séjour florentin. Avec la réalisation de son Jugement

dernier, et son admirable ronde des élus qui, à travers la danse, main dans la

main, des hommes sauvés et de leurs anges gardiens, le peintre, qui illustre

cette affirmation de saint Thomas d’Aquin, « il y aura une seule société

des hommes et des anges », s’impose en effet comme le frère angélique.

Il ne veut rien garder

Il se partage entre le

couvent San Domenico de Fiesole, et le nouveau couvent réformé de San Marco à

Florence, dont il ornera chapelle, réfectoire, corridors et cellules, dans un

dépouillement propre à soutenir la prière, sans provoquer des distractions aux

religieux. Il assure l’économat des deux maisons car l’artiste inspiré a les

pieds sur terre et gère efficacement, pour le bien de l’ordre et des pauvres,

les sommes colossales que rapporte sa peinture. Il n’empêche que cet argent,

qu’il gagne, lui brûle les mains et qu’il hésite à se faire payer à sa juste

valeur. Il ne veut rien garder, rappelle à temps et à contretemps que les

prêcheurs sont un ordre mendiant, n’hésite pas à figurer sur l’une de ses

fresques saint Dominique assurant de la malédiction de Dieu et de la sienne

quiconque introduira la propriété dans l’Ordre.

Cet idéal de pauvreté

devient difficile mais les supérieurs, admiratifs des saintes exigences du

frère Giovanni, attendront sa mort pour autoriser à recevoir des héritages et

posséder des propriétés immobilières. Giovanni regagne Fiesole, où la rigueur

réformatrice est plus facile à soutenir qu’à Florence. En 1445, le pape Eugène

IV le fait venir à Rome. Pour l’employer dans l’immense chantier de

restauration entrepris après tant d’années durant lesquelles la papauté,

réfugiée en Avignon, a laissé la Ville abandonnée, mais aussi, murmure-t-on,

pour lui proposer l’archevêché de Florence… Giovanni refuse et conseille au

souverain pontife d’y nommer plutôt son prieur, Antonin, ce qui sera fait.

Une Annonciation peinte

par un ange

S’il est ainsi écouté,

c’est que l’on admire autant le saint homme que l’artiste. Lors de ses nombreux

déplacements afin d’honorer des contrats, Giovanni ne dort que dans un couvent

dominicain mais, à Orvieto, celui-ci est trop éloigné de son chantier et ses commanditaires

lui louent une maison plus commode. Quand ils lui demandent de quoi il a

besoin, il répond : « De la paille et un drap. » Alors qu’il

travaille pour le pape Nicolas V, celui-ci, inquiet de voir l’artiste épuisé

par les jeûnes et les pénitences, les flagellations qu’il s’impose chaque

semaine depuis qu’il a, jeune prêtre, adhéré à la confrérie de San Nicolo in

Carmine, lui sert un plat de viande, strictement interdit par la Règle

dominicaine. Giovanni repousse l’assiette en s’excusant : « Très Saint

Père, je ne puis, je n’ai pas demandé dispense à mon Prieur » et le Pape

de rétorquer, édifié : « Je pense pouvoir vous l’accorder à sa

place. »

Sexagénaire, Giovanni,

tordu de rhumatismes, a de plus en plus de mal à se hisser sur un échafaudage

pour peindre, ou à cheminer à pied comme Dominique le demande à ses fils lors

de ses déplacements professionnels. Pour la première fois de sa vie, il doit

renoncer à certains contrats, pourtant aménagés afin de lui faciliter la

besogne. En 1450, il est rappelé à Fiesole afin de remplacer comme prieur son

frère Benedetto, emporté par la peste. Il assume cette tâche deux années

durant, parvient encore à peindre, notamment pour l’église florentine de la

Santissima Annunziata, célèbre pour une représentation de l’Annonciation

réputée miraculeusement peinte par un ange. Seul un frère angélique est en

effet capable d’achever la décoration du sanctuaire. À l’automne 1454, Nicolas

V rappelle fra Giovanni à Rome. Est-ce pour travailler aux fresques de la

chapelle Nicoline du Vatican, ou à des embellissements au couvent dominicain de

Santa Maria sopra Minerva ? On ne sait mais c’est là que, le 18 février 1455,

le peintre meurt et est enterré, avec des honneurs jamais accordés à un simple

frère, rejoignant pour l’éternité la ronde des élus. Jean Paul II l’a

béatifié le 3 octobre 1982.

Lire aussi :Les clés d’une œuvre : le retable de San Domenico de Fra

Angelico

Lire aussi :Les clefs d’une œuvre : « L’annonciation » de Fra

Angelico

Fra Angelico

A famous painter of

the Florentine school,

born near Castello di Vicchio in the province of Mugello, Tuscany,

1387; died at Rome,

1455. He was christened Guido, and his father's name

being Pietro he was known as Guido, or Guidolino, di Pietro, but his full

appellation today is that of "Blessed Fra Angelico Giovanni da

Fiesole". He and his supposed younger brother, Fra Benedetto da Fiesole,

or da Mugello, joined the order of Preachers in 1407, entering the Dominican convent at Fiesole.

Giovanni was twenty years old at the time the brothers began their art careers

as illustrators of manuscripts,

and Fra Benedetto, who had considerable talent as an illuminator and

miniaturist, is supposed to have assisted his more celebrated brother in his

famous frescoes in the convent of

San Marco in Florence.

Fra Benedetto was superior at San Dominico at Fiesole for

some years before his death in 1448. Fra Angelico, who during a residence

at Foligno had

come under the influence of Giotto whose

work at Assisi was

within easy reach, soon graduated from the illumination of missals and

choir books into a remarkably naive and inspiring maker of religious

paintings, who glorified the quaint naturalness of his types with a

peculiarly pious mysticism.

He was convinced that to picture Christ perfectly

one must need be Christlike, and Vasari says

that he prefaced his paintings by prayer.

His technical equipment was somewhat slender, as was natural for an artist with

his beginnings, his work being rather thin dry and hard. His spirit, however,

glorified his paintings.

His noble holy figures, his beautiful angels,

human but in form, robed with the hues of the sunrise and sunset, and his

supremely earnest saints and martyrs are

permeated with the sincerest of religious feeling. His early training in

miniature and illumination had its influence in his more important works, with

their robes of golden embroidery,

their decorative arrangements and details, and pure, brilliant colours. As for

the early studies in art of Fra Angelico, nothing is known.

His painting shows

the influence of the Siennese school,

and it is thought he may have studied under Gherardo, Starnina, or Lorenzo

Monaco.

On account of the

struggle for the pontifical throne between Gregory

XII, Benedict

XIII, and Alexander

V, Fra Giovanni and his brother, being adherents of the first named, had in

1409 to leave Fiesole, taking refuge in the convent of

their order established at Foligno in

Umbria. The pest devastating that place in 1414, the brothers went to Cortona,

where they spent four years and then returned to Fiesole. There Fra Angelico

remained for sixteen years. He was then invited to Florence to decorate the new

Convent of San Marco which had just been allotted to his order, and of which

Cosmo de' Medici was a munificent patron. At Cortona are found some of his best

pictures. It was at Florence,

however, where he spent nine years, that he painted his

most important works. In 1445, Pope

Eugenius IV invited Fra Angelico to Rome and

gave him work to do in the Vatican, where he painted for

him and for his successor, Pope

Nicholas V, the frescoes of two chapels.

That of the cappella del Sacramento, in the Vatican, was destroyed later

by Paul

III. Eugenius

IV than asked him to go to Orvieto to

work in the chapel of

the Madonna di San Brizio in the cathedral.

This work he began in 1447, but did not finish, returning to Rome in

the autumn of that year. Much later the chapel was

finished by Luca

Signorelli. Pope Eugenius is said to have offered the painter the

place of Archbishop of Florence,

which through modesty and devotion to his art he declined. At Rome,

besides his great paintings in

the chapels of

the Vatican, he executed some beautiful miniatures for choral books. He is

buried in Rome in

the church of Santa

Maria sopra Minerva.

Among the thirty works of

Fra Angelico in the cloisters and chapter

house of the convent of

San Marco in Florence (which has been converted into a national museum) is

notable the famous "Crucifixion", with the Saviour between

the two thieves surrounded by a group of twenty saints,

and with bust portraits of seventeen Dominican fathers

below. Here is shown to the full the mastery of the painter in

depicting in the faces of the monks the

emotions evoked by the contemplation of heavenly mysteries. In the Uffizi

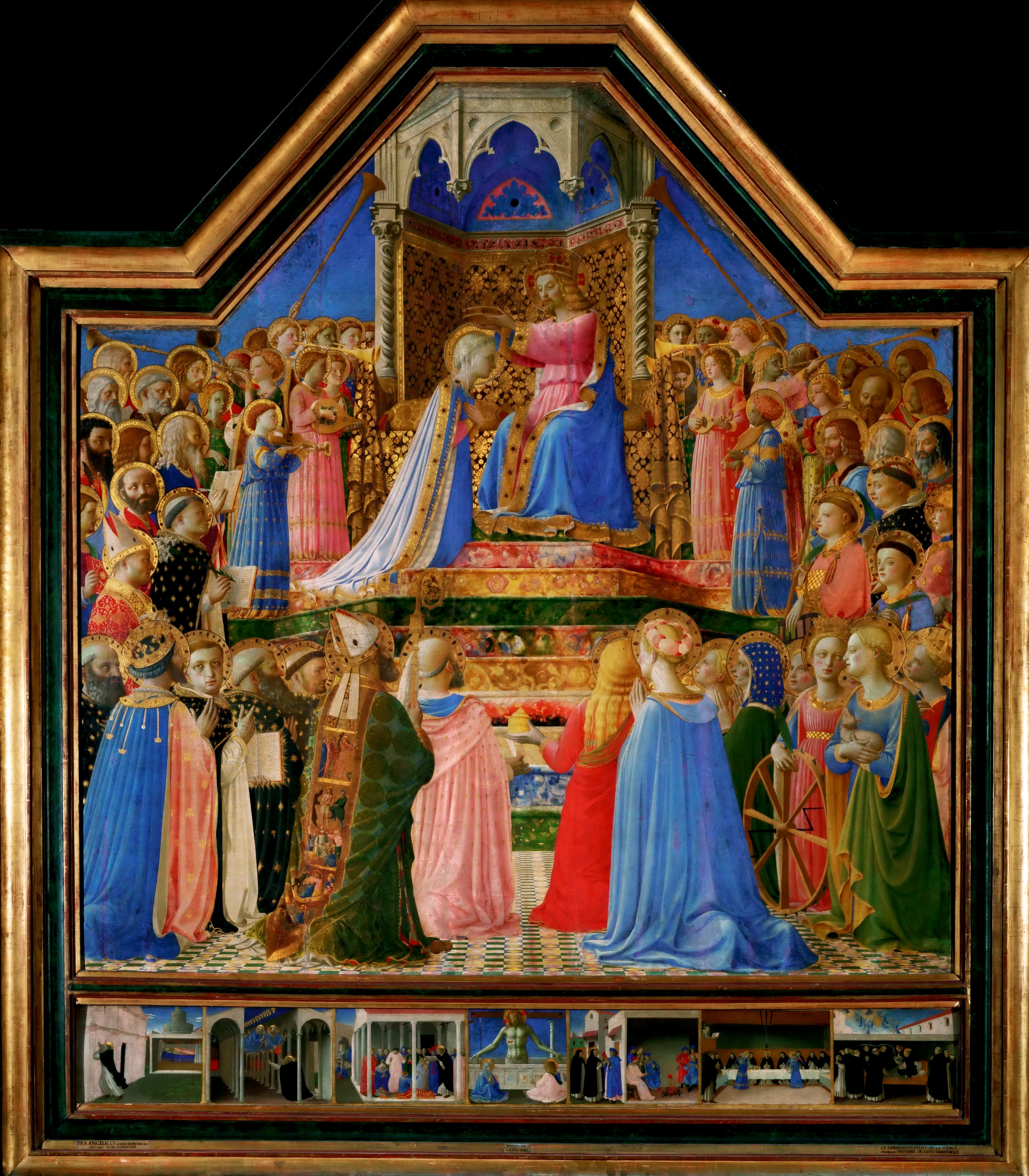

Gallery are "The Coronation of the Virgin", "The Virgin and

Child with Saints", "Naming of John the Baptist", "The

Preaching of St. Peter", "The Martyrdom of St. Mark", and

"The Adoration of the Magi", while among the examples at the Florence

Academy are "The Last Judgement", "Paradise", "The

Deposition from the Cross", "The Entombment", scenes from the

lives of St. Cosmas and St. Damian, and various subjects from the life of

Christ. At Fiesole are a "Madonna and Saints" and a

"Crucifixion". The predella in London is

in five compartments and shows Christ with

the Banner of the Resurrection surrounded

by a choir of angels and

a great throng of the blessed. There is also there an "Adoration of the

Magi". At Cortona appear at the Convent of San Domenico the fresco

"The Virgin and Child with four Evangelists"

and the altar-piece "Virgin

and Child with Saints", and at the baptistry an "Annunciation"

with scenes from the life of the Virgin and a "Life of St. Dominic".

In the Turin Gallery

"Two Angels kneeling on Clouds", and at Rome,

in the Corsini Palace, "The Ascension", "The Last

Judgment", and "Pentecost". At the Louvre in Paris are

"The Coronation of the Virgin", "The Crucifixion", and

"The Martyrdom of St. Cosmas and St. Damian". Berlin has, at the

Museum, a "Last Judgment", and Dublin, at the National Gallery,

"The Martyrdom of St. Cosmas and St. Damian". At Madrid is

"The Annunciation", in Munich "Scenes

from the Lives of St. Cosmas and St. Damian", and in St. Petersburg a

"Madonna and Saints". Mrs. John L. Gardner has in the art gallery of

her Boston residence

an "Assumption" and a "Dormition of the Virgin". There are

other works at Parma, Perugia,

and Pisa.

At San Marco, Florence,

in addition to the works already mentioned are "Madonna della

Stella", "Coronation of the Virgin", "Adoration of the

Magi", and "St. Peter Martyr". The Chapel of St. Nicholas in the

Vatican at Rome contains

frescoes of the "Lives of St. Lawrence and St. Stephen", "The

Four Evangelists", and "The Teachers of the Church".

In the gallery of the Vatican are "St. Nicholas of Bari",

and "Madonna and Angels". The work at Orvieto finished

by Signorelli shows Christ in

"a glory of angels with

sixteen saints and prophets".

Bryan, Dictionary of Painters and Engravers; Edgecombe-Haley, Fra

Angelico.

Van Cleef,

Augustus. "Fra Angelico." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol.

1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 22 Feb.

2016 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01483b.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Nicolette Ormsbee.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. March 1, 1907. Remy Lafort, S.T.D., Censor. Imprimatur. +John

Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2020 by Kevin

Knight. Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

Also known as

Angelico of Fiesole

Beato Angelico

Fra Giovanni

Giovanni da Fiesole

Giovanni de Fiesole

Guido di Pietro

John of Fiesole

Painter of the Angels

Profile

Joined the Dominicans in Fiesole, Italy in 1407,

taking the name Fra Giovanna. He was taught to

illuminate missals and manuscripts, and immediately exhibited a natural talent

as an artist.

Today his works can be seen in the Italian cities Cortona, Fiesole, Florence,

and in the Vatican. His dedication to religious

art earned him the title Angelico.

Born

1387 in Vicchio di

Mugello near Florence, Italy as Guido

di Pietro

18 February 1455 in

the Dominican convent in Rome, Italy of

natural causes

3 October 1982 by Pope John

Paul II

Additional Information

Fra

Angelico, by I B Supino

Fra

Angelico, by James White

Giovanni

da Fiesole, by Langton Robert Douglas

Illustrated

Catholic Family Annual

Knights

in Art, by Amy Steedman

Lives

of the Painters, by Giorgio Vasari

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

The

Art of Fra Angelico, by Langton Robert Douglas

Voyage

in Italie: Florence et Venise

Fra Angelico, by George Charles Williamson

The Works of Fra Angelico, from the book series Masters

in Art

Angels from

the frame of The Madonna deil Linajuoli

Dance

of the Angels, from The Last Judgment

Scenes

from the Life of Saint Laurence

books

Book of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other sites in english

Saint Charles Borromeo Church, Picayune, Mississippi

video

sitios en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti in italiano

spletne strani v slovenšcini

Readings

Though Fra Angelico completed the cycle of purely

supernatural art, he also led the way to that wonderful fusion of the

supernatural and the natural in which Italian art culminated a century later.

He was the last disciple of Giotto, the first harbinger of Raphael. –

Cosmo Monkhouse

To Fra Angelico belongs the glory of fixing, in a

series of imperishable visions, the religious ideal of the Middle Ages, just at

the moment when it was about to disappear forever. – Georges Lafenestre

While the artists about him were absorbed in mastering

the laws of geometry and anatomy, Fra Angelico sought to express the inner life

of the adoring soul. The message that his pictures convey might have been told

almost as perfectly upon the lute or viol. His world is a strange one – a world

not of hills and fields and flowers and men of flesh and blood, but one where

the people are embodied ecstasies, the colors tints from evening clouds or

apocalyptic jewels, the scenery a flood of light or a background of illuminated

gold. His mystic gardens, where the ransomed souls embrace, and dance with

angels on the lawns outside the City of the Lamb, are such as were never

trodden by the foot of man in any paradise of earth. – John Addington

Symonds

MLA Citation

“Blessed Fra Angelico“. CatholicSaints.Info. 23

December 2020. Web. 18 February 2021.

<https://catholicsaints.info/blessed-fra-angelico/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/blessed-fra-angelico/

Fra

Angelico (circa 1395 –1455), Couronnement de la Vierge Résurrection de Jésus / Coronation of the Virgin - Resurrection of Jesus, from 1425 until

1450, altarpiece, tempera on wood, 213 x 211, Louvre

Museum

Article

Fra Giovanni Angelico of

the order of Friars Preachers, of Fiesole, is renowned as much for his

excellence as a painter as for his high character as a friar. Indeed, it is

through the manifestation of his artistic life that his virtue was revealed.

However he ranked in heaven, amongst those who understand the art of painting

he is looked upon as one of the noblest and sweetest artists ever to be

inspired by God. For that reason the true and simple record of his life and

creation has been seriously distorted by writers, carried away by the romance

of his pictures, who have imagined experiences and interpretations which can

never be verified. Less than a hundred years after his death, the historian

Vasari wrote about him only in general terms indicating that the man was the

artist and that his life was happily and fruitfully occupied in making works to

glorify God. Who could hope to better the following description by Vasari?

“Fra Giovanni was a

simple and most holy man in his habits, and it is a sign of his goodness that

one morning, when Pope Nicholas V wished him to dine with him, he excused himself

from eating flesh without the permission of his prior, not thinking of the

papal authority. He avoided all worldly intrigues, living in purity and

holiness, and was as benign to the poor as I believe Heaven must be to him now.

He was always busy with his paintings, but would never do any but holy

subjects. He might have become rich, but cared nothing about it, for he used to

say that true riches consist in being contented with little. He might have

ruled many but would not, saying that there was less trouble and error in

obeying others. He could have obtained high rank in his Order and in the world,

but he did not esteem it, saying that he wished for no other dignity than to

escape hell and win Paradise. In truth, not only the religious, but all men ought

to seek that dignity, which is only to be found in good and virtuous living. He

was most gentle and temperate, living chastely, removed from the cares of the

world. He would often say that whoever practiced art needed a quiet life and

freedom from care, and that he who occupies himself with the things of Christ

ought always to be with Christ. He was never seen in anger among the Friars,

which seems to be an extraordinary thing and almost impossible to believe; his

habit was to smile and reprove his friends. To those who wished works of him he

would gently say that they must first obtain the consent of the prior, and

after that he would not fail. I cannot bestow too much praise on this Holy

Father, who was so humble and modest in all his conversation and works, so

facile and devout in his painting, the saints by his hand being more like those

blessed beings than those of any other. He never retouched or repaired any of

his pictures, always leaving them in the condition in which they were first

seen, believing, so he said, that this was the will of God. Some say that Fra

Giovanni never took his brush without first making a prayer. He never made a

Crucifix when the tears did not course down his cheeks, while the goodness of

his sincere and great soul in religion may be seen in the faces and attitudes

of his figures.”

He was born in the valley

of Mugello near Vechio in 1387. His real name was Guido or Guidolino. Van Marle

says that it was quite likely that he and his brother Benedetto, a miniature

painter, heard the sermons of Fra Giovanni Dominici, the founder of the

Dominican monastery at Fiesole, already an old man whom Saint Catherine of

Siena visited in his dreams and who preached against the new spirit of

humanism, inciting his audiences to a mysticism of quite a medieval character.

It is not very surprising then that Fra Angelico and his brother entered the

monastery of Fiesole in the year 1407. Owning to the conflict between rival

claimants to the papacy and later to an outbreak of plague, the young monks and

the community spent the next eleven years in, alternatively, Foligno and

Cortona, and it is not until 1418 that they finally returned to the monastery

at Fiesole. Whatever Fra Angelico lost in the way of stability by these flights

he must have gained in experience and contact with the work of artists in the

these districts and his first dated work, the Linauoli Altarpiece (1433), shows

him to have been so mature that his holy spirit was clearly communicated in

this painting.

In 1436 San Marco was obtained

for the Dominicans by Cosimo de Medicit from Pope Eugenius. The reconstruction

of this Florentine convent was immediately begun and was placed in the hands of

Michelozzo Michelozzi. Fra Angelico had by now reached such a point of eminence

as an artist that he was given complete charge of the interior decoration.

According to Muratoff his principal work consisted of studying the scheme of

composition, of giving fundamental ideas and superintending the execution of

the work. At the same time he had to attend to the scaffolding; the preparation

of the mural surface, the quality of the paints and other materials, and

perhaps also the bookkeeping and cashier duties. Nevertheless in seven years it

was finished. Some seventy compositions had been carried out, each one a visual

sermon filled with incident. No decorative scheme had been followed but the

monastic nature of the cells and larger rooms had dictated to the artist

subject which recalled the monks to their vows but which nevertheless provided

them with colour and ornament in the jeweled nature of the designs and the

necessarily bright range of tones called for by the tempera medium.

In 1445 he was summoned

to Rome by the Pope for whom he carried out a number of works. He stayed there

until 1447 when he travelled to Orvieto where he rested and commenced an

altarpiece which was completed by Bennozo Gozzoli. In 1449 he was recalled to

Florence as prior, largely, it has been suggested, because this was the only

way in which the Dominican friars could secure him from the patronage of the

Holy Father. However, at the end of this three years ministry he was once more

sought by the Pope and returned to Rome to complete his cycle of pictures. He

died there in 1455. These facts set out practically all that is known of Fra

Angelico the man. But from his pictures his character and nature can be gleaned

as freshly as if he were still laboring with love on the embellishment of San

Marco; naïve and simple in his inability to handle or describe the reality of

life convincingly; profoundly moving in the depiction of holiness and beauty

and exciting in his modernism – ready to adopt the most recent theories and

inventions; one of the first artists of his time to introduce the nude figure

and to paint landscape which was taken from the countryside in which he lived.

When he came to Fiesole

at the age of 20, Fra Angelico had already been trained. According to the

record of his entry, “he excelled as a painter and adorned many panels and

walls before taking the habit of a cleric.” Before he commenced the interior of

San Marco, he must have reached a very advanced stage of development because he

was then surrounded with many assistants and pupils. Yet, little knowledge of

his original master can be elicited even by the most scientific of historians.

These have been variously stated to have been Gherardo Starnina, Lorenzo

Monaco, and Spinello, but none can afford to overlook the importance of the

influence of the great sculptors, Donatello, Ghiberti, and Luca della Robbia,

each of whom was closely associated with Michellozi, the architect of San

Marco. The soft and rounded figures of Fra Angelicoc’s compositions suggest not

so much anatomically-realized bodies as the bronze bas-relief of Ghiberti’s

door or of the flowing planes of Donatello. Reflect also the correspondence of

feeling between the gentle Madonnas of Luca della Robbias’ enameled

terra-cottas in gleaming blue and white which this sculptor first invented in

the year 1443 and the lovely Coronations in the Uffizi, the Louvre and in San

Marco. The calm medieval monasticism of these static figures can then be seen

to be a blend of the inherited Byzantine spirit and the visual equivalent of

Fra Angelico’s contemplation of Heaven. He was able to call the romanticism of

his age to this assistance and to introduce gestures of movement and conflict

into his subjects as can be seen in our National Gallery version of “The

Martydom of Saints Cosmas and Damian,” but he was always separated from the

greatest of his contemporaries by his own spirituality. It was his total

immersion in love, his inability to conceive the material man on the sensual

plane, which gives his works an idyllic sweetness that takes them a little out

of the tradition and makes them the epitome of innocence and, let us admit it,

utterly desirable.

Truly to grasp the

significance of Fra Angelico one must carefully compare him with one whom

Bernard Berenson calls the greatest painter since Giotto. Massacio completed

his work in the Brancacci Chapel in 1427. He seized on all the remarkable

aspects of Giotto’s art and pushed forward the science of painting in the 28

years which was all that was given to him of life. He created a sense of space

in which his figures could live and appear to breathe and he made these figures

so big and heavy, with yet a brooding and profound dignity, that the citizens

of Florence were said to gasp with amazement when first they saw his

Crucifixion one the walls of the Dominican monastery of Santa Maria Novella.

The reality which Massacio painted was that of one of Brunellechi’s new

churches containing a figure of Christ which confounded the viewer into

mistaking the representation for the very Flesh itself. Fra Angelico had

nothing of this quality, neither the overwhelming force of the figures nor the

convincing appearance of interior space. Indeed, it is doubtful if the holy

friar would have wished to deceive any one’s eye or to make them imagine even

for one moment that they were seeing anything other than an idealized

conception of the reward of virtue. He was not able even to suggest the horror

of hell, although he frequently applied himself to the task. Like that other

painter of love and tenderness in Sienna, Simone Martini, he was imbued with a

power to make images of God’s saints that man might be moved, by very desire

for beauty, into loving God, since beauty is merely a synonym for God.

Those contemplatives,

those mystics who succeed in subjecting their bodies to their minds, in order

to achieve unity of God, must come in the end almost to forget what a healthy,

perfect physique feels and looks like. If, as we believe, Fra Angelico was of

such an order of men, he was surely incapable of conceiving the human body in

the classic or idealized physical type and of reproducing it as did Massacio

and later Michaelangelo. One turns then to Fra Angelico’s art fully realizing

that the perfection he achieved was in the direction of simple love and

goodness. It dealt with the drama of daily life only in so far as such drama

assisted him to demonstrate the New Testament. Consider ‘The Crucifixion’ from

San Marco. Here the figures of Christ and the thieves are painted as symbols of

the Redemption. We feel the tragedy and the suffering only in a limited way.

Turn away from the top half of the picture to the group of Saints below and

observe how all of them are connected by expression and direction of

countenance with the grief of Our Lady. As far as they are concerned the

figures above might be merely statues. Fra Angelico has placed the Crucifix high

but the mourners below are, so to speak, in the world with us and we join them

in grief, not at what we see above, but at our realization of what it means.

Fra Angelico, the preacher, dominates Fra Angelico, the artist.

In the “Coronation of The

Virgin” from San Marco, one comes into contact with the master at his greatest.

In the Louvre “Coronation” he freely gives expression to a range of colours

against a gold background which sets up a chord of emotion in the heart of the

viewer to be likened only to the blissful relief of a child re-united with its

mother after a nightmare separation. Like a tumultuous song of joy in blues and

pinks and gold the range of saints wing out on either side while in the centre

a comparatively young King of Heaven crowns His beloved Mother. Note

particularly that while the saints are drawn in characteristic poses and

shapes, this ageless and pure symbol of Womankind who is Our Lady is described

as a simple geometric form practically without bodily description except for the

beautifully modeled head and tender hands.

In the San Marco

‘Coronation’, however, a new and probably original shape for the crown is

introduced which by its dark and pointed form becomes a symbol for the whole

altarpiece of the earlier work in the Louvre. The polygonal altar has been

replaced by abstract planes – clouds which separate th six saints from the

objects of their adoration. The Holy Virgin is more precisely defined and this

time is seated as She gracefully leans forward to receive the crown. However

much one admires the complication and dexterity and brilliant colour of the

first Coronation it must be seen that the simpler balance of the figures here

and the mystery, tenderness and more direct expression of emotion makes this

one of the supreme achievements of art. In particular, one cannot help pointing

out how the consciousness of the harmony of bodily form here adds to the poetry

of religious feeling which permeates the action and thought expressed in the

eloquent movements of all the figures.

In the San Marco

‘Transfiguration’, the artist returns once more to his Byzantine origins and

releases himself from the necessity of justifying the position of each saint in

the picture. He surrounds the figure of Christ with saints in earthly

astonishment and with others formally worshipping. Creating with these a

spacious plan of design, he allows the superbly modeled figure of Christ to

extend over the oval of light and thus to enter our consciousness, in reversal,

one might say, of the plan of The Coronation. The Head and Hands of Our Saviour

now take on the nature of The Flesh and the aspect is one of kindly

benevolence. Here one sees the painter pay tribute to Massacio.

It has been said

repeatedly that Fra Angelico was a medieval classic rather than a Renaissance

classic. Surely it would have been more truly to say that the spirit of pagan

classicism which grew apace with the development of humanism was so far removed

from the mind and the heart of our painter that his work remained pure and

unsullied by a quality which however enlivening had also the elements of death.

Undoubtedly Fra Angelico was unable to consider the problem of death. He

perfectly solved problems of symmetry and harmony, of form and colour. In short

he was an artist dedicated to Heavenly images and he only understood sin in so

far as he could convert sinners. For over 500 years all those sinners who are

able to consider his pictures, have come to regard them as poems of love, and

by virtue of their quality, find themselves hushed and silent, knowing they are

in saintly company.

MLA

Citation

James White. “Fra

Angelico”. The Irish Rosary, July –

August 1955. CatholicSaints.Info.

3 December 2015. Web. 18 February 2020.

<https://catholicsaints.info/fra-anglico-by-james-white/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/fra-anglico-by-james-white/

Amy Steedman –

Saint Fra Angelico

Nearly a hundred years

had passed by since Giotto lived and worked in Florence, and in the same hilly

country where he used to tend his sheep another great painter was born.

Many other artists had

come and gone, and had added their golden links of beauty to the chain of Art

which bound these years together. Some day you will learn to know all their

names and what they did. But now we will only single out, here and there, a few

of those names which are perhaps greater than the rest. Just as on a clear

night, when we look up into the starlit sky, it would bewilder us to try and

remember all the stars, so we learn first to know those that are most easily

recognised – the Plough, or the Great Bear, as they shine with a clear steady

light against the background of a thousand lesser stars.

The name by which this

second great painter is known is Fra Angelico, but that was only the name he

earned in later years. His baby name was Guido, and his home was in a village

close to where Giotto was born.

He was not a poor boy,

and did not need to work in the fields or tend the sheep on the hillside.

Indeed, he might have soon become rich and famous, for his wonderful talent for

painting would have quickly brought him honours and wealth if he had gone out

into the world. But instead of this, when he was a young man of twenty he made

up his mind to enter the convent at Fiesole, and to become a monk of the Order

of Saint Dominic.

Every brother, or frate,

as he is called, who leaves the world and enters the life of the convent is

given a new name, and his old name is never used again. So young Guido was

called Fra Giovanni, or Brother John. But it is not by that name that he is

known best, but that of Fra Angelico, or the angelic brother – a name which was

given him afterwards because of his pure and beautiful life, and the heavenly

pictures which he painted.

With all his great gifts

in his hands, with all the years of youth and pleasure stretching out green and

fair before him, he said good-bye to earthly joys, and chose rather to serve

his Master Christ in the way he thought was right.

The monks of Saint

Dominic were the great preachers of those days – men who tried to make the

world better by telling people what they ought to do, and teaching them how to

live honest and good lives. But there are other ways of teaching people besides

preaching, and the young monk who spent his time bending over the illuminated

prayer- book, seeing with his dreamy eyes visions of saints and white-robed

angels, was preparing to be a greater teacher than them all. The words of the

preacher monks have passed away, and the world pays little heed to them now,

but the teaching of Fra Angelico, the silent lessons of his wonderful pictures,

are as fresh and clear to-day as they were in those far-off years.

Great trouble was in

store for the monks of the little convent at Fiesole, which Fra Angelico and

his brother Benedetto had entered. Fierce struggles were going on in Italy

between different religious parties, and at one time the little band of

preaching monks were obliged to leave their peaceful home at Fiesole to seek

shelter in other towns. But, as it turned out, this was good fortune for the

young painter-monk, for in those hill towns of Umbria where the brothers sought

refuge there were pictures to be studied which delighted his eyes with their

beauty, and taught him many a lesson which he could never have learned on the

quiet slopes of Fiesole.

The hill towns of Italy

are very much the same to-day as they were in those days. Long winding roads

lead upwards from the plain below to the city gates, and there on the summit of

the hill the little town is built. The tall white houses cluster close

together, and the overhanging eaves seem almost to meet across the narrow paved

streets, and always there is the great square, with the church the centre of

all.

It would be almost a

day’s journey to follow the white road that leads down from Perugia across the

plain to the little hill town of Assisi, and many a spring morning saw the

painter-monk setting out on the convent donkey before sunrise and returning

when the sun had set. He would thread his way up between the olive-trees until

he reached the city gates, and pass into the little town without hindrance. For

the followers of Saint Francis in their brown robes would be glad to welcome a

stranger monk, though his black robe showed that he belonged to a different

order. Any one who came to see the glory of their city, the church where their

saint lay, which Giotto had covered with his wonderful pictures, was never

refused admittance.

How often then must Fra

Angelico have knelt in the dim light of that lower church of Assisi, learning

his lesson on his knees, as was ever his habit. Then home again he would wend

his way, his eyes filled with visions of those beautiful pictures, and his hand

longing for the pencil and brush, that he might add new beauty to his own work

from what he had learned.

Several years passed by,

and at last the brothers were allowed to return to their convent home of San

Dominico at Fiesole, and there they lived peaceably for a long time. We cannot

tell exactly what pictures our painter-monk painted during those peaceful

years, but we know he must have been looking out with wise, seeing eyes,

drinking in all the beauty that was spread around him.

At his feet lay Florence,

with its towers and palaces, the Arno running through it like a silver thread,

and beyond, the purple of the Tuscan hills. All around on the sheltered

hillside were green vines and fruit-trees, olives and cypresses, fields flaming

in spring with scarlet anemones or golden with great yellow tulips, and hedges

of rose-bushes covered with clusters of pink blossoms. No wonder, then, such

beauty sunk into his heart, and we see in his pictures the pure fresh colour of

the spring flowers, with no shadow of dark or evil things.

Soon the fame of the

painter began to be whispered outside the convent walls, and reached the ears

of Cosimo da Medici, one of the powerful rulers of Florence. He offered the

monks a new home, and, when they were settled in the convent of San Marco in

Florence, he invited Fra Angelico to fresco the walls.

One by one the heavenly

pictures were painted upon the walls of the cells and cloister of the new home.

How the brothers must have crowded round to see each new fresco as it was

finished, and how anxious they would be to see which picture was to be near

their own particular bed. In all the frescoes, whether he painted the gentle

Virgin bending before the angel messenger, or tried to show the glory of the

ascended Lord, the artist- monk would always introduce one or more of the

convent’s special saints, which made the brothers feel that the pictures were

their very own. Fra Angelico had a kind word and smile for all the brothers. He

was never impatient, and no one ever saw him angry, for he was as humble and

gentle as the saints whose pictures he loved to paint.

It is told of him, too,

that he never took a brush or pencil in his hand without a prayer that his work

might be to the glory of God. Often when he painted the sufferings of our Lord,

the tears would be seen running down his cheeks and almost blinding his eyes.

There is an old legend

which tells of a certain monk who, when he was busily illuminating a page of

his missal, was called away to do some service for the poor. He went

unwillingly, the legend says, for he longed to put the last touches to the holy

picture he was painting; but when he returned, lo! he found his work finished

by angel hands.

Often when we look at

some of Fra Angelico’s pictures we are reminded of this legend, and feel that

he too might have been helped by those same angel hands. Did they indeed touch

his eyes that he might catch glimpses of a Heaven where saints were swinging

their golden censers, and white-robed angels danced in the flowery meadows of

Paradise? We cannot tell; but this we know, that no other painter has ever shown

us such a glory of heavenly things.

Best of all, the

angel-painter loved to paint pictures of the life of our Lord; and in the

picture I have shown you, you will see the tender care with which he has drawn

the head of the Infant Jesus with His little golden halo, the Madonna in her

robe of purest blue, holding the Baby close in her arms, Saint Joseph the

guardian walking at the side, and all around the flowers and trees which he

loved so well in the quiet home of Fiesole.

He did not care for fame

or power, this dreamy painter of angels, and when the Pope invited him to Rome

to paint the walls of a chapel there, he thought no more of the glory and

honour than if he was but called upon to paint another cell at San Marco.

But when the Pope had

seen what this quiet monk could do, he called the artist to him.

‘A man who can paint such

pictures,’ he said, ‘must be a good man, and one who will do well whatever he

undertakes. Will you, then, do other work for me, and become my Archbishop at

Florence?’ But the painter was startled and dismayed.

‘I cannot teach or preach

or govern men,’ he said, ‘I can but use my gift of painting for the glory of

God. Let me rather be as I am, for it is safer to obey than to rule.’

But though he would not

take this honour himself, he told the Pope of a friend of his, a humble

brother, Fra Antonino, at the convent of San Marco, who was well fitted to do

the work. So the Pope took the painter’s advice, and the choice was so wise and

good, that to this day the Florentine people talk lovingly of their good bishop

Antonino.

It was while he was at

work in Rome that Fra Angelico died, so his body does not rest in his own

beloved Florence. But if his body lies in Rome, his gentle spirit still seems

to hover around the old convent of San Marco, and there we learn to know and

love him best. Little wonder that in after ages they looked upon him almost as

a saint, and gave him the title of ‘Beato,’ or the blessed angel-painter.

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/amy-steedman-saint-fra-angelico/

New Catholic

Dictionary – Fra Angelico

Also

known as

Guido di Pietro

Giovanni da Fiesole

Profile

Religious painter, born

near Castello di Vicchio, Tuscany, Italy; died Rome,Italy.

Entering the Dominican

Order as Fra Giovanni, in Fiesole, 1407,

the illumination of missals and manuscripts furnished his first training in

art. For the Dominican convent

in Cortona where he lived, 1414-1418, he painted the well-known “Madonna and

Four Saints,” and for the baptistery a first “Annunciation.” Returning to

Fiesole in 1418,

he painted the “Christ in Glory Surrounded by Saints and Angels,” now in

the National Gallery of London.

He was invited to Florence in 1436 to decorate the new convent of San Marco.

Among the paintings and frescos still to be seen in the galleries of the city

and in the national museum established in the former convent are the “Crucifixion,”

“Madonna of the Star,” “Coronation of the Virgin,” and “Christ as a Pilgrim.”

His finest work is in the chapel of Nicholas V in the Vatican, a series of

frescos depicting the lives of Saint Stephen and Saint Lawrence. The dedication

of his art to religious subjects earned him the title of “Angelico,” and the

holiness of his life caused him to be beatified, so that he is also known as

“Il Beato” (the Blessed). His work is noted for an extraordinary spiritual

quality, bright decorative detail, and exquisite coloring.

Born

MLA

Citation

“Fra Anglico”. New Catholic Dictionary. CatholicSaints.Info. 16

August 2012.

Web. 18 February 2020. <http://catholicsaints.info/new-catholic-dictionary-fra-angelico/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/new-catholic-dictionary-fra-angelico/

Blessed Fra Angelico, OP

(PC)

Born in Mugello near Florence, Italy, in 1386 or 1387; died in Rome, Italy, in

1455.

Guido da Vicchio's innate talent for art was supplemented by the natural beauty

of his native Tuscany. He studied under several master artists when Italy was

most conscious of the spirit of Giotto and Cimabue, and their influence was

always to give a certain unearthly aspect to his paintings.

When he was still quite young, and already a recognized artist, he entered the

Dominican monastery at Fiesole with his brother Benedetto in 1407. It is a

tribute to the ability and sanctity of both brothers that their names stand out

in such distinguished company, for some of the greatest men of the order were

housed in the same priory: Blesseds John Dominici, Peter Capucci, and Lawrence

of Ripafratta (f.d. September 28), and St. Antoninus of Florence. The latter,

when he was appointed archbishop, was to commission some of the two artists'

finest work.

Few personal details are known about Brother John of the Angels, who is known

as Fra Angelico in secular history. He was a priest. His painting in Florence

was sufficiently well-known and admired to merit his being called to Rome to

decorate the Chapel of Nicholas V at the Vatican. In 1449, he was appointed

prior of San Marco, which he decorated with his wonderful paintings, and held that

office for three years.

He may have been recalled to Rome in 1454; he died there in 1455 at the

Dominican friary of La Minerva. In much the same way as St. Thomas Aquinas was

obscured by his writings for centuries, Fra Angelico seems to have disappeared

behind his art. We know that he was the painter par excellence of the Queen of

Angels and of her court.

St. Antoninus, who must have known him well, said: "No one could paint

like that without first having been to heaven." The sincerity of his

paintings and the depth of their theological and devotional teaching makes this

statement believable.

Fra Angelico and Fra Benedetto were both artists of skill and originality.

Perhaps God wished them to work together to make Fiesole and San Marco treasure

houses of art, where some innocence and beauty might remain untouched by the

storm of Renaissance humanism loomed on the horizon. Benedetto painted and

illuminated an exquisite set of choir books, reputed to be the loveliest in the

world. If he had lived out his career, he might have rivalled his famous

brother, but he was accidentally killed in a street battle during one of the

frequent political upheavals in Florence, and his work was left unfinished.

Fra Angelico himself did some illumination; in fact, he probably began his

career as an illuminator. There is in his altarpieces a definite touch of the

illuminator's talent for extracting the gist of the matter and leaving out

extraneous details. His work is never cluttered, which might, of course, be the

result of a mind trained in theology, as well as of a hand trained in

illuminating.

His frescoes were done on wet plaster, with clay colors, which means that he

could not see any exact color relationship until the wall had dried, and it was

too late to touch it up. This makes it all the more remarkable that his colors

are so exquisitely blended, and that they still glow with such unfaded

loveliness after 400 years. Some of his best works are in the convent of San

Marco, which is now a state museum.

Here in Washington, D.C., we have a wonderful wood panel enamelled by Fra

Angelico, "The Madonna of Humility," which shows, much better than

the prints we are accustomed to seeing, the almost heavenly radiance that

glowed through his paintings. The figures of the Madonna and Child have a

quaint, awkward attitude; yet no one looking at them can possibly mistake that

fact that he is depicting the Queen of Heaven.

Part of the ethereal look of his Madonna comes from the fact that Fra Angelico

did not use models for his pictures. This alone was remarkable in a time when

painters were flinging themselves into the study of anatomy, sometimes at the

cost of other qualities. Perhaps he was revolted by the practice of some of his

contemporary painters who chose beautiful women with bad reputations to pose

for their Madonnas. Perhaps it was simply that he saw, with the clear vision of

a theologian, that nothing--painting, statue, sermon, poem, or building--should

obstruct one's view of God, drawing the attention away from that vision.

Fra Angelico's greatest complete work was his "Life of Christ," a

series of 35 paintings in Fiesole. They began with the vision of the Prophet

Ezekiel and ended with the lovely Coronation of the Virgin, which we sometimes

see reproduced in print. These pictures tell us what the records leave unsaid:

that Brother John of the Angels was a capable theologian and a splendid

Scripture scholar. He was also a devoted son of St. Dominic, whom he dearly

loved and never tired of painting.

In America, we are most familiar with his paintings of the Annunciation, which

was obviously one of his favorite subjects, since he painted it dozens of

times. Most of his subjects were chosen from the life of Our Lord; the famous

"angels," which one so often sees, are parts of much larger

altarpieces, having much more serious subjects than the colorful and joyful

angels decorating them.

Some have said that Fra Angelico in art, Dante in poetry, and St. Thomas in the

Summa Theologica, have each presented the same truth in three different ways.

Whether or not this is completely true, it is an indication of the veneration

in which history has held this man. His motto was: "To paint Christ, one

must live Christ." He is the best example we have of one who preaches with

a brush as eloquently as his brothers do with voice or pen. Today he still

preaches, in places where no other would be heard. Perhaps his mission is still

alive, to help bring into the fold those who love art but know nothing of God.

The cause of Fra Angelico was resumed on the 500th anniversary of his death and

has been active since then. Although he is usually called il Beato Angelico, he

has never officially been beatified (Benedictines, Dorcy).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0318.shtml

Tradition shows us Fra

Angelico absorbed in his work, and either caressing with his brush one of those

graceful angelic figures which have made him immortal, or reverently outlining

the sweet image of the Virgin before which he himself would kneel in adoration.

Legend pictures him devoutly prostrate in prayer before beginning work, that

his soul might be purified, and fitted to understand and render the divine

subject. But has tradition any foundation in fact? Why not? Through his

numberless works we may easily divine the soul of the artist, and can well

understand how the calm and serene atmosphere of the monastic cell, the church

perfumed with incense, the cloister vibrating with psalms, would develop the

mystic sentiment in such a mind.

Among all the masters who

have attempted to imbue the human form with the divine spirit, Fra Angelico is

perhaps the only one who succeeded in producing purely celestial figures, and

this with such marvelous simplicity of line that they have become the glory of

his art. He put into his work the flame of an overpowering passion; under his

touch features were beautified and figures animated with a new mystic grace.

His forms are often, it is true, conventional, and there is a certain sameness

in his heads, with their large oval countenances; his small eyes, outlined

around the upper arch of the eyebrow, with black spots for pupils, sometimes

lack expression; his mouths are always drawn small, with a thickening of the

lips in the center, and the corners strongly accentuated; the color of his

faces is either too pink or too yellow; the folds of his robes (often

independent of the figure, especially in the lower part) fall straight, and, in

the representations of the seated Virgin, expand on the ground as if to form

the foot of a chalice. But in his frescos these faults of conventional manner

almost entirely disappear, giving place to freer drawing, more lifelike

expression, and a character of greater power.

There is no doubt that

Fra Angelico felt the beneficent influx of the new style, of which Masaccio was

the greatest champion, and that he followed it, abandoning, up to a certain

point, the primitive Giottesque forms. There is in his art the great medieval

ideal, rejuvenated and reinvigorated by the spirit of newer times. Being in the

beginning of his career, as is generally believed, only an illuminator, he continued,

with subtle delicacy, and accurate, almost timid design, to illuminate in

larger proportions on his panels. But in his later works, while still

preserving the simplicity of handling and the innate character of his style, he

displays a new tendency, and learns to give life to his figures, not only by

the expression of purity and sweet ecstasy, but in finer particularization of

form and action.

His clear diaphanous

transparency of coloring is not used from lack of technical ability, but to

approach more nearly to his ideal of celestial visions – a species of pictorial

religious symbolism. In the midst of his calm and serene compositions Fra

Angelico gives us figures in which a healthy realism is strongly accentuated;

figures drawn with decision, strong chiaroscuro, and robust coloring, which

show that he did not deliberately disdain the progress made in art by his

contemporaries. Indeed we should err in believing that he was unwilling to

recognize the artistic developments going on around him; but he profited by the

movement only as far as he deemed possible without losing his own sentiment and

character. Perhaps he divined that if he had followed the new current too

closely it would have carried him farther than he wished to go; that the new

manner would have removed him forever from his ideal – in a word, that too

intense study of the real would have diminished or entirely impeded fantasy and

feeling, and therefore kept himself constant to his old style, and while

perfecting himself in it, still remained what he always had been, and what he

felt he should be.

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/fra-angelico-by-i-b-supino/

Blessed Giovanni da Fiesole, more popularly known as

Fra Angelico.

Fra Angelico is well

known as an Italian painter of the early Renaissance who combined the life of a

devout Dominican friar with that of an accomplished painter. Originally named

Guido di Pietro, he was born in Vicchio, Tuscany, in 1395. He discovered his God-given gifts as a child, and as a

young teenager was already a much sought-after artist.

Angelico was a devout

young man who entered a Dominican friary in Fiesole in 1418. He took his religious

vows, and about 1425 became a friar using the name Giovanni da Fiesole. He was

called “Brother Angel” by his peers, and was praised for his kindness to others

and hours devoted to prayer.

He spent most of his

early life in Florence decorating the Dominican monastery of San Marco. In

1445, he was called to Rome. But before leaving, he completed one of his most