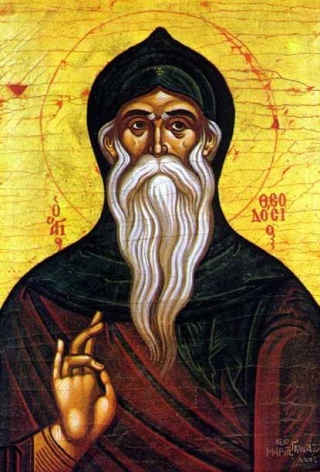

Saint Théodose

Abbé

(423-529)

Théodose naquit, l'an 423, dans une petite ville de la Cappadoce. Jeune encore, il se sentit inspiré de visiter les Lieux Saints. En route, il voulut voir saint Siméon Stylite et le consulter sur le genre de vie qu'il devait choisir. Siméon le distingua dans la foule des pèlerins, et, l'appelant par son nom: "Théodose, homme de Dieu, lui dit-il, soyez le bienvenu." Il le fit monter sur la haute colonne qui lui servait de demeure, le bénit et lui annonça qu'il serait le père d'un grand peuple de moines.

Théodose, après son pèlerinage, se fixa dans la Terre Sainte et chercha la solitude sur une haute montagne, où il vécut dans les jeûnes et la prière. L'éclat de sa vertu lui attira des disciples; il en reçut d'abord un tout petit nombre, mais bientôt sa charité lui fit accepter tous les sujets de bonne volonté. Il les exerçait à la vertu par la parole et par l'exemple. Pour leur rendre toujours présente la pensée de la mort, il leur fit creuser une tombe; puis, se tenant au milieu d'eux, il leur dit en souriant: "Voici tout prêt le lieu du repos, qui de nous en fera la dédicace?" Un prêtre, nommé Basile, fléchit le genou: "Veuillez me bénir, mon Père, ce sera moi!" On lut pendant quarante jours l'office des funérailles, et au quarantième jour, sans fièvre, sans douleur, sans agonie, Basile s'endormit du dernier sommeil.

Théodose, sur un avis céleste, fit bâtir un monastère si vaste, qu'il avait l'aspect d'une cité. Outre les bâtiments réservés aux moines, il y avait de grands établissements pour tous les métiers, et plusieurs hôpitaux pour les foules d'infirmes et de malades; l'enceinte de ce monastère ne renfermait pas moins de quatre églises.

Dieu récompensa l'immense charité de son serviteur. Certain jour, il y eut cent tables dressées dans le monastère pour les étrangers; la Providence pourvoyait à tous les besoins. Une fois, les provisions étant épuisées, les frères se mirent à murmurer, Théodose leur dit: "Confiance, Dieu ne nous oubliera pas." Bientôt arrivèrent des mulets chargés de vivres. Le Saint vit venir avec joie la mort, dans la pensée de laquelle il avait puisé le principe d'une vie si parfaite; il était arrivé à l'âge de cent six ans.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

THÉODOSE le CÉNOBIARQUE

Saint Théodose, chef et pilote de ceux qui menaient la vie communautaire en Palestine (cénobiarque = «chef des cénobites») et astre brillant pour l'éternité dans le firmament spirituel, naquit vers 423 dans le village de Garissos, en Cappadoce, de parents pieux et craignant Dieu, qui lui inspirèrent l'amour des saintes vertus et de l'application aux Saintes Ecritures. Devenu lecteur dès son jeune âge, il aimait à méditer sur l'histoire d'Abraham, le modèle de tous ceux qui s'exilent par amour du Seigneur (Gen. 12), et sur les paroles de l'Evangile qui recommandent de quitter parents, biens et amis pour hériter la vie éternelle (Mat. 19:29). L'âme brûlante d'une divine ardeur il décida un jour d'appliquer ces préceptes et prit la route de Jérusalem. Passant dans la région d'Antioche, il alla prendre la bénédiction de l'illustre Saint Syméon le Stylite (mémoire le 1er septembre). Le vieillard le salua de loin, en disant: «Théodose, homme de Dieu, sois le bienvenu! » Il le fit monter en haut de sa colonne, l'embrassa tendrement et lui prédit qu'il deviendrait le pasteur d'un immense troupeau de brebis spirituelles.

Parvenu à Jérusalem, après avoir vénéré les Lieux Saints, Théodose se demanda comment il pouvait commencer dans la vie ascétique. Certes, il désirait mener la vie solitaire; mais, averti des dangers d'entrer dans la lutte contre les ennemis invisibles sans avoir été préalablement exercé au combat par un maître expérimenté, il se mit à la recherche d'un tel guide et le trouva en la personne d'un vieillard originaire de Cappadoce, nommé Longin, qui brillait de toutes sortes de vertus parmi les moines consacrés au service de la basilique de la Résurrection (les spoudaioi). Une fois instruit, par l'obéissance, à ne faire, comme le Christ, que la volonté de Dieu le Père et à discerner avec science le bien et le mal, il s'installa seul dans une église située sur le chemin de Bethléem. Lorsque la riche et pieuse fondatrice de cette église voulut le mettre à la tête d'une communauté de moines, il se retira dans une grotte située sur une montagne déserte, où, disait-on, les Mages avaient logé après avoir vénéré l'Enfant-Dieu. Tendu avec ardeur vers le ciel et oubliant tout ce qui est de la terre, Théodose y purifiait son âme par la mortification sans relâche des plaisirs de la chair, par la station debout durant toute la nuit, soutenu par des cordes qu'il avait suspendues au plafond, par la psalmodie et la prière incessantes. Il demeura trente ans sans manger un morceau de pain, en ne se nourrissant que de dattes, de fèves et de quelques herbes qui poussaient dans la grotte. La renommée de ses combats et de la vie divine qui brillait en lui attirèrent bientôt vers la grotte de nombreux disciples. Il n'en reçut d'abord que six, puis douze, et enfin accepta tous ceux que Dieu lui envoyait.

En premier lieu, il leur enseignait à tenir toujours devant leurs yeux la pensée de la mort, comme fondement de la vie en Christ. Un jour, il leur fit creuser un vaste sépulcre et leur dit: «Voici votre tombeau, qui de vous veut l'inaugurer?» Un prêtre, nommé Basile, tomba à genoux et demanda au Saint sa bénédiction pour partir le premier vers le Seigneur. Théodose ordonna alors de célébrer les offices de commémoration du 3e, du 9e et du 40e jour, comme il est coutume jusqu'à nos jours pour les défunts. Sitôt venu le 40e jour, Basile expira, et pendant les 40 jours suivants Théodose le vit se tenir spirituellement au milieu des frères pendant la psalmodie.

Une veille de Pâques, les frères, manquant de toute nourriture et même de pain pour célébrer la Sainte Liturgie, s'agitaient inquiets. Théodose, recueilli en lui-même dans un endroit isolé, leur recommanda de ne mettre leur espérance qu'en Dieu. De fait, la nuit venue, deux mulets arrivèrent à la porte du Monastère chargés de provisions qui durèrent jusqu'à la Pentecôte.

La grotte devint vite trop étroite pour le nombre grandissant de disciples, et de riches amis, prêts à contribuer à toutes les dépenses, pressaient le Saint de choisir un emplacement convenable pour édifier un grand monastère, conformément à la prophétie de Saint Syméon. Dabord hésitant, de peur de perdre les fruits de la vie solitaire, Théodose parvint à la conclusion, qu'avec l'aide de Dieu, il pourrait garder son âme dans une paix imperturbable, tout en menant un grand nombre d'hommes sur la voie du Salut. Il prit donc un encensoir, l'emplit de charbon, et s'avança droit devant lui, en priant Dieu d'allumer» Lui-même l'encens lorsqu'il parviendrait à l'endroit convenable. Le Seigneur accorda ce signe à son serviteur dans un lieu situé à environ 7 km de Bethléem. On y construisit bientôt de vastes bâtiments pour les moines, avec des ateliers et tout ce qui est nécessaire pour les libérer des distractions causées par les relations avec le monde extérieur. A cette cité évangélique étaient jointes plusieurs annexes: une hôtellerie pour les moines étrangers, une autre pour recevoir les pauvres et les indigents, un hôpital pour les malades, un hospice pour les moines âgés et un asile pour les aliénés. Oeil pour les aveugles, pied pour les boiteux, toit pour les sans-toit, vêtement pour ceux qui étaient nus, le Saint se faisait tout pour tous, il soignait lui-même les plaies les plus répugnantes et embrassait tendrement les lépreux. Les indigents accourraient en si grand nombre au monastère, en ces temps de disette, qu'on allait jusqu'à dresser la table cent fois par jour. Pour subvenir à de tels besoins, Dieu intervenait fréquemment par des miracles et multipliait le pain et les vivres.

La communauté était composée de plus de 400 moines de nationalités différentes. C'est pourquoi le Saint avait fait construire quatre églises dans l'enceinte du monastère: une où l'on célébrait la louange de Dieu en grec, l'autre en syriaque, une autre en arménien, et la quatrième était réservée aux aliénés et aux possédés. Sept fois le jour les hymnes s'élevaient vers le ciel en un accord harmonieux de diverses langues, et tous se réunissaient dans l'église des Grecs, après la lecture de l'Evangile, pour célébrer en commun la Sainte Eucharistie. Père unique, Théodose prenait soin de chacun et montrait à tous, par sa conduite et ses enseignements, une vivante image du Christ. A la mort de Gérontios, le supérieur du monastère fondé par Sainte Mélanie (31 décembre), il fut élu comme supérieur (archimandrite) et chef de tous les moines vivant en communautés, alors que Saint Sabas (5 décembre) était placé à la tête des ermites et de ceux qui vivaient dans les laures. Les deux Saints étaient unis par une grande charité, ils se rencontraient souvent pour s'entretenir de sujets spirituels et luttèrent de concert contre les hérétiques.

En ce temps-là (513), l'Eglise était en effet troublée par l'empereur Anastase, qui avait pris la défense des monophysites, ennemis du Concile de Chalcédoine. Il déposa le Patriarche de Jérusalem Elie, lui substitua un hérétique, et tenta d'attirer à lui tous les moines éminents de Palestine, en particulier Saint Sabas et Saint Théodose. Si, par humilité, saint Théodose se laissait vaincre et contrarier en toute chose, il se montrait toutefois intraitable en ce qui concernait Dieu et les Saints Dogmes de l'Eglise. Il rassembla tous les habitants des déserts, leur déclara que le temps était venu pour le «doux de se changer en guerrier» (Joël 3:11), et écrivit au souverain une lettre, où il annonçait la ferme décision des moines de rester fidèles jusqu'au sang à la doctrine des Saints Conciles OEcuméniques. Impressionné par ce courage, Anastase relâcha pour un peu de temps ses persécutions, mais les reprit bientôt de plus belle. Théodose se rendit alors à la basilique de la Résurrection et, du haut de l'ambon, s'écria: «Si quelqu'un refuse d'accepter les quatre Saints Conciles au même titre que les quatre Saints Evangiles, qu'il soit anathème!» Puis, à la tête d'une armée de moines, il parcourut la ville en confirmant le peuple dans la foi par sa parole et ses miracles. Envoyé en exil sur ordre de l'empereur, il put regagner son monastère, deux ans plus tard, lors de l'avènement de Justin 1er, favorable à l'Orthodoxie (518).

Une fois la paix rétablie, le bienheureux continua de répandre la bénédiction de Dieu sur les hommes: il guérit des maladies incurables, d'un seul grain de blé il remplit un grenier entier, il rendit fécondes des femmes stériles, chassa des nuées de sauterelles, fit venir la pluie, délivra des voyageurs en danger, annonça sept ans à l'avance le séisme qui détruisit la ville d'Antioche (526). Mais ne comptant pour rien tant de grâces, il montait sans cesse vers Dieu, en s'enfonçant dans l'abîme de l'humilité. Voyant un jour deux de ses disciples qui se disputaient, il se jeta à leurs pieds et refusa de se relever tant qu'ils ne se furent pas réconciliés. Une autre fois, comme il avait interdit la communion à un moine responsable d'une faute grave, celui-ci répliqua en faisant la même défense au Père. Théodose obéit, et ne se présenta à la communion que lorsque le moine se fût rétracté.

Affligé, vers la fin de ses jours, d'une longue et douloureuse maladie, il supportait tout, comme Job, avec action de grâces, refusait de prier Dieu d'en être délivré et ne relâchait en rien sa règle d'ascèse et de prière. Un peu avant son trépas, il exhorta ses moines à la persévérance dans les épreuves, leur promit de toujours intercéder au ciel pour son monastère; puis, après avoir rassemblé tous les Higoumènes de Palestine, il les bénit et remit son âme à Dieu. Il était âgé de 105 ans (529). Ses funérailles furent célébrées avec tous les honneurs possibles par le Patriarche, en présence d'une foule immense de moines et de laïcs. On ensevelit son corps dans la première grotte où il avait demeuré, et peu de temps après les miracles commencèrent à abonder.

De toutes les vertus de Saint Théodose, trois restèrent à ses disciples comme un vivant héritage: une sévère ascèse jusqu'à la mort, accompagnée d'une foi inébranlable; la miséricorde envers les pauvres et les malades, et l'assiduité continuelle à la prière et à la louange de Dieu.

THEODOSIUS was born in Cappadocia in 423. The example of Abraham urged him to leave his country, and his desire to follow Jesus Christ attracted him to the religious life. He placed himself under Longinus, a very holy hermit, who sent him to govern a monastery near Bethlehem. Unable to bring himself to command others, he fled to a cavern, where he lived in penance and prayer. His great charity, however, forbade him to refuse the charge of some disciples, who, few at first, became in time a vast number, and Theodosius built a large monastery and three churches for them. He became eventually Superior of the religious communities of Palestine. Theodosius accommodated himself so carefully to the characters of his subjects, that his reproofs were loved rather than dreaded. But once he was obliged to separate from the communion of the others a religious guilty of a grave fault. Instead of humbly accepting his sentence, the monk was arrogant enough to pretend to excommunicate Theodosius in revenge. Theodosius thought not of indignation, nor of his own position but meekly submitted to this false and unjust excommunication. This so touched the heart of his disciple that he submitted at once and acknowledged his fault. Theodosius never refused assistance to any in poverty or affliction; on some days, the monks laid more than a hundred tables for those in want. In times of famine Theodosius forbade the alms to be diminished, and often miraculously multiplied the provisions. He also built five hospitals, to which he lovingly served the sick, while by assiduous spiritual reading he maintained himself in perfect recollection. He successfully opposed the Eutychian heresy in Jerusalem, and for this was banished by the emperor. He suffered a long and painful malady, and refused to pray to be cured, calling it a salutary penance for his former successes. He died at the age of a hundred and six.

REFLECTION.—St. Theodosius, for the sake of charity, sacrificed all he most prized—his home for the love of God, and his solitude for the love of his neighbor. Can ours be true charity if it costs us little or nothing?

Theodosius the

Cenobiarch, Abbot (RM)

Born in Garissus, Cappadocia, c. 423; died near Bethlehem 529. Theodosius was

born and raised in a devout Christian family. While still young, he decided to

consecrate himself to God and to become a student of the Scripture. Eventually,

he was ordained a reader. In the course of his studies, he was moved by the

example of Abraham who "obeyed when he was called to go out to a place

that he was to receive as an inheritance; he went out, not knowing where he was

to go. By faith he sojourned in the promised land as in a foreign country . . .

for he was looking forward to the city with foundations, whose architect and

maker is God" (Hebrews 11:8-10). And so it happened that when Theodosius

was about 30, he left home to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem to the places of

the Savior's Passion.

When he reached

Antioch, he visited Simeon Stylites, a living statue of prayer and

renunciation, to receive his blessing. Theodosius did not visit Simeon like the

curious who came in great numbers to disturb his prayer, or the mockers who

came to make fun of the saint; and Simeon, foretelling the future glory of his

youthful visitor, called to him, saying: "Theodosius, man of God, you are

welcome here." Theodosius climbed upon the pillar of Simeon to receive his

advice and blessing.

Untrustworthy

tradition says that after visiting the holy places of Jerusalem, Theodosius

placed himself in the care of Saint Longinus, the centurion who pierced the

Savior's side, was converted, and became a monk at Caesarea in Cappadocia.

Longinus soon saw that his charge was unusually committed to the ways of Jesus.

This story line continues that a rich woman had built a monastery near

Jerusalem and needed someone to lead it. Longinus persuaded Theodosius to take

the job.

Another tradition

says that Theodosius tried eremitical life and decided that it was not his

calling. With some companions he went to a mountain, where they lived in

extreme privation, constant prayer, and charitable works. With or without

Longinus, their fame reached the ears of many young people who came to their

monastery asking permission to remain with them. It grew rapidly, its monks

being of several peoples and languages.

Eventually,

Theodosius had to undertake the construction of an immense monastery at

Catismus, near Bethlehem, that could provide quarters for the throng of

pilgrims, religious, and sick. Thereby, he became the founder of monasticism in

Palestine, and built a monastery on the shores of the Dead Sea 'like a city of

saints in the midst of the desert.' There were four churches--one for each of

three different languages and a fourth for penitents--and three hospitals. One

hospital cared for the aged, another for the physically ill, and the third for

the mentally ill. Greeks, Armenians, and Persians worked and prayed happily

together. And no one was ever turned away without a meal and good

hospitality--no matter how little the monks themselves had to eat.

Sallus, patriarch

of Jerusalem appointed Theodosius's friend and fellow-countryman, Saint Sabas,

head of all hermit-monks in Palestine and set Saint Theodosius over those

living in communities: This explains his surname 'Cenobiarch,' i.e., chief of

those leading a life in common. Theodosius was a staunch opponent of

Monophysitism, which led to his being removed from office for a short time by

the Emperor Anastasius.

Emperor Anastasius

patronized the Eutychian heresy, and tried to win Theodosius over to his own

views. In 513, he deposed Elias, patriarch of Jerusalem, just as he had

previously banished Flavian II of Antioch, and intruded Severus into that see.

Theodosius and Sabas maintained the rights of Elias, and of his successor John;

whereupon the imperial officers thought it advisable to connive at their

proceedings, considering the great authority they had merited by their

sanctity. Soon after, the emperor sent Theodosius a considerable amount of

money, for charitable uses in appearance, but in reality as a bribe. The saint

accepted it, and distributed it all among the poor.

Of course, the

emperor thought that he had finally persuaded Theodosius. Anastasius sent the

saint a heretical profession of faith, in which the divine and human natures of

Christ were confounded into one, and wanted Theodosius to sign it. Our saint

responded to Anastasius with apostolic zeal, and for some time the emperor was

more peaceable. But soon he renewed his persecuting edicts against the

orthodox, despatching troops to execute them. When Theodosius heard about this,

he travelled throughout Palestine urging everyone to stand fast in the faith of

the four general councils. Thereupon the emperor banished Theodosius. He was

recalled by Anastasius's successor within a short time.

One of the

biographers of Theodosius writes: "He did not punish the brethren with

severity, but with a sweet, agreeable, and loving flow of words which

penetrated to the depth of the heart. He was at once severe and kind; he

consoled and astonished the religious with his kindness; he governed them with

such calmness and tranquility that he seemed to be alone in a desert. He was

always the same, whether alone or in company, because he learned to keep

himself always in the presence of God."

In his old age, Theodosius

was stricken with a long illness that made his skin and body dry like a stone.

He suffered a great deal from this, but bore his pains with perfect patience,

praying continually, so much so that even at night his lips continued to move

while he slept, as if they were saying some prayer. Theodosius died about the

age of 105. Patriarch Peter of Jerusalem and the whole country were present at

his funeral, which was honored by miracles. He was buried in his first cell,

called the cave of the Magi, because the wise men who searched for Christ soon

after his birth were said to have lodged in it. Theodosius's reputation for

holiness multiplied in the many miracles that followed his death for the

benefit of those who begged his intercession (Attwater, Benedictines, Bentley,

Encyclopedia, Gill, Walsh).

In art, Saint

Theodosius is an abbot hermit with iron bands on his neck and arms, chains and

a money bag near him (Roeder). He is the patron of file makers (Roeder).

St.

Theodosius the Cenobiarch, Abbot

From

his life by Theodoras, bishop of Petra, some time his disciple, in Surius and

Bollandus, and commended by Fleury, Baillet, &c.

A.D.

529.

The monks passed a considerable part of the day and night at their devotions in the church, and at the times not set apart for public prayer and necessary rest, every one was obliged to apply himself to some trade, or manual labour, not incompatible with recollection, that the house might be supplied with conveniencies. Sallust, bishop of Jerusalem, appointed St. Sabas superior general of the hermits, and our saint of the Cenobites, or religious men living in community throughout all Palestine, whence he was styled the Cenobiarch. These two great servants of God lived in strict friendship, and had frequent spiritual conferences together; they were also united in their zeal and sufferings for the church.

The emperor Anastasius patronised the Eutychian heresy, and used all possible means to engage our saint in his party. In 513 he deposed Elias, patriarch of Jerusalem, as he had banished Flavian II. patriarch of Antioch, and intruded Severus, an impious heretic, into that see, commanding the Syrians to obey and hold communion with him. SS. Theodosius and Sabas maintained boldly the rights of Elias, and of John his successor; whereupon the imperial officers thought it most advisable to connive at their proceedings, considering the great authority they had acquired by their sanctity. Soon after, the emperor sent Theodosius a considerable sum of money, for charitable uses in appearance; but in reality to engage him in his interest. The saint accepted of it, and distributed it all among the poor. Anastasius now persuading himself that he was as good as gained over to his cause, sent him an heretical profession of faith, in which the divine and human natures in Christ were confounded into one, and desired him to sign it. The saint wrote him an answer full of apostolic spirit; in which, besides solidly confuting the Eutychian error, he added, that he was ready to lay down his life for the faith of the church. The emperor admired his courage and the strength of his reasoning, and returning him a respectful answer, highly commended his generous zeal, made some apology for his own inconsiderateness, and protested that he only desired the peace of the church. But it was not long ere he relapsed into his former impiety, and renewed his bloody edicts against the orthodox, despatching troops every where to have them put in execution. On the first intelligence of this, Theodosius went over all the deserts and country of Palestine, exhorting every one to be firm in the faith of the four general councils. At Jerusalem, having assembled the people together, he from the pulpit cried out with a loud voice: “If any one receives not the four general councils as the four gospels, let him be anathema.” So bold an action in a man of his years, inspired with courage those whom the edicts had terrified. His discourses had a wonderful effect on the people, and God gave a sanction to his zeal by miracles; one of these was, that on his going out of the church at Jerusalem, a woman was healed of a cancer on the spot, by only touching his garments. The emperor sent an order for his banishment, which was executed; but dying soon after, Theodosius was recalled by his catholic successor, Justin; who, from a common soldier, had gradually ascended the imperial throne.

Our saint survived his return eleven years, never admitting the least relaxation in his former austerities. Such was his humility, that seeing two monks at variance with each other, he threw himself at their feet, and would not rise till they were perfectly reconciled; and once having excommunicated one of his subjects for a crime, who contumaciously pretended to excommunicate him in his turn, the saint behaved as if he had been really excommunicated, to gain the sinner’s soul by this unprecedented example of submission, which had the desired effect. During the last year of his life he was afflicted with a painful distemper, in which he gave proof of an heroic patience, and an entire submission to the will of God; for being advised by one that was an eye-witness of his great sufferings, to pray that God would be pleased to grant him some ease, he would give no ear to it, alleging that such thoughts were impatience, and would rob him of his crown. Perceiving the hour of his dissolution at hand, he gave his last exhortation to his disciples, and foretold many things, which accordingly came to pass after his death; this happened in the one hundred and fifth year of his age, and of our Lord 529. Peter, patriarch of Jerusalem, and the whole country, assisted with the deepest sentiments of respect at the solemnity of his interment, which was honoured by miracles. He was buried in his first cell, called the cave of the magi, because the wise men, who came to adore Christ soon after his birth, were said to have lodged in it. A certain count being on his march against the Persians, begged the hair-shirt which the saint used to wear next his skin, and believed that he owed the victory which he obtained over them, to the saint’s protection through the pledge of that relic. Both the Roman and Greek calendars mention his festival on the 11th of January.

The examples of the Nazarites and Essenes among the Jews, and of many excellent and holy persons among the Christians through every age demonstrate, that many are called by God to serve him in a retired contemplative life; nay, it is the opinion of St. Gregory the Great, that the world is to some persons so full of ambushes and snares, or dangerous occasions of sin, that they cannot be saved but by choosing a safe retreat. Those who, from experience, are conscious of their own weakness, and find themselves to be no match for the world, unable to countermine its policies, and oppose its power, ought to retire as from the face of too potent an enemy; and prefer a contemplative state to a busy and active life: not to indulge sloth, or to decline the service of God and their neighbour; but to consult their own security, and to fly from dangers of sin and vanity. Yet there are some who find the greatest dangers in solitude itself; so that it is necessary for every one to sound his own heart, take a survey of his own forces and abilities, and consult God, that he may best be able to learn the designs of his providence with regard to his soul; in doing which, a great purity of intention is the first requisite. Ease and enjoyment must not be the end of Christian retirement, but penance, labour, and assiduous contemplation; without great fervour and constancy in which, close solitude is the road to perdition. If greater safety, or an unfitness for a public station, or a life of much business (in which several are only public nuisances) may be just motives to some for embracing a life of retirement, the means of more easily attaining to perfect virtue may be such to many. Nor do true contemplatives bury their talents, or cease either to be members of the republic of mankind, or to throw in their mite towards its welfare. From the prayers and thanksgivings, which they daily offer to God for the peace of the world, the preservation of the church, the conversion of sinners, and the salvation of all men, doubtless more valuable benefits often accrue to mankind, than from the alms of the rich, or the labours of the learned. Nor is it to be imagined, how far and how powerful their spirit, and the example of their innocence and perfect virtue, often spread their influence; and how serviceable persons who lead a holy and sequestered life, may be to the good of the world; nor how great glory redounds to God, by the perfect purity of heart and charity to which many souls are thus raised.

Note 1. See Le Brun, Explic. des Cérémonies de la Messe, T. 4. p. 234, 235. dissert. 14. art. 2. [back]

Rev. Alban Butler (1711–73). Volume I: January. The Lives of the Saints. 1866.

SOURCE : http://www.bartleby.com/210/1/111.html