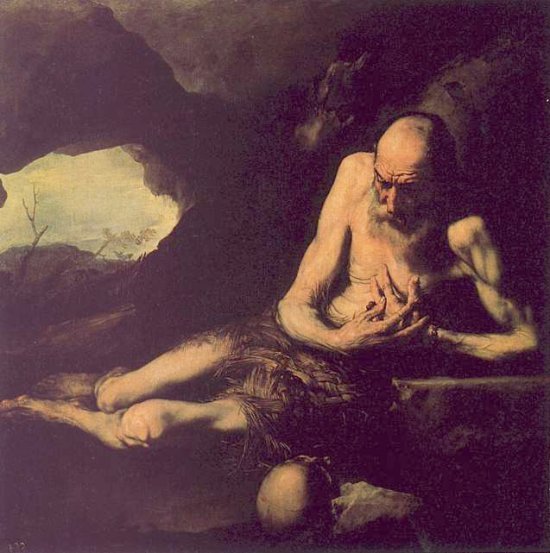

Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652), Saint Paul of Thebes, 1640, 143 x 143, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Saint Paul l'Ermite

Ermite en

Thébaïde (+ 345)

On l'appelle aussi le

premier ermite, car il serait plus ancien que saint Antoine,

le père des moines. C'est du moins ce qu'affirme son biographe, saint Jérôme.

Issu d'une famille de notables égyptiens, il reçut une éducation soignée, à la

différence du fruste paysan qu'était saint Antoine. Orphelin à seize ans, il se

retrouve à la tête d'une belle fortune. Mais il est chrétien et l'empereur Dèce

déclenche une persécution. Paul fuit au désert et c'est là qu'il rencontre Dieu

dans la solitude d'une grotte où il restera pendant quatre-vingt-dix ans. Agé

de 113 ans, il reçoit la visite de saint Antoine et ils conversent tous deux

toute la nuit. Au petit matin, saint Paul meurt. Antoine l'enveloppe dans le

manteau que lui avait donné saint Athanase

d'Alexandrie. Des gestes qui sont tout un symbole de la tradition de

l'Église.

En Thébaïde, au IVe

siècle, saint Paul, ermite, un des premiers à mener la vie monastique.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/437/Saint-Paul-l-Ermite.html

Saint Paul

Premier Ermite

(229-342)

La gloire de ce grand

Saint est d'avoir frayé la voie du désert à d'innombrables générations de

solitaires et de n'avoir été surpassé par personne dans la pratique de la

prière et de la pénitence. Il naquit dans la Basse-Thébaïde, en Égypte.

Orphelin dès l'âge de quinze ans et possesseur d'un très riche patrimoine, il

abandonna tout pour obéir à l'impulsion divine. S'enfonçant dans la solitude,

il arriva à une caverne creusée dans les flancs d'une montagne, et dans

laquelle coulait une source limpide. Il prit ce lieu en affection et résolut

d'y passer sa vie. Un palmier voisin lui fournissait son repas et son vêtement;

l'eau claire de la fontaine était son unique boisson.

Paul avait vingt-deux ans

quand il se retira du monde; il vécut dans le désert jusqu'à l'âge de cent

treize ans; il passa donc quatre-vingt-onze ans sous le regard de Dieu et loin

de la vue des hommes, et nul ne pourra jamais nous dire ni les merveilles de

vertu qu'il a accomplies, ni les ineffables douceurs de sa vie pénitente et

contemplative. Deux faits cependant nous sont connus.

Paul avait quarante-trois

ans quand Dieu se chargea de le nourrir lui-même en lui envoyant

miraculeusement chaque jour, par un corbeau, la moitié d'un pain. A l'âge de

cent treize ans, il reçut la visite du saint solitaire Antoine.

Antoine, âgé de

quatre-vingt-dix ans, avait été éprouvé par une tentation de vaine gloire, le

démon essayant de lui suggérer qu'il était le plus parfait des solitaires. Mais

Dieu lui avait ordonné en songe d'aller plus avant dans le désert, à la

rencontre d'un solitaire bien plus parfait que lui. Après deux jours et une

nuit de marche, Antoine suivit la trace d'une louve qui le conduisit jusqu'à la

grotte où habitait Paul. Ce fut à grand peine que le Saint voulut ouvrir sa

porte au voyageur inconnu. Il ouvrit enfin; les deux vieillards s'embrassèrent

en s'appelant par leur nom et passèrent de longues heures à bénir Dieu.

Ce jour-là, le corbeau

leur apporta un pain entier; ils rendirent grâces au Seigneur, et s'assirent au

bord de la fontaine pour prendre leur frugal repas. Antoine, de retour dans sa

solitude, disait à ses disciples: "Malheur à moi, pécheur, qui suis indigne

d'être appelé serviteur de Dieu! J'ai vu Élie, j'ai vu Jean dans le désert; en

un mot, j'ai vu Paul dans le Paradis." Paul mourut cette même année, et sa

fosse fut creusée par deux lions du désert. Sa vie parfaitement authentique,

fut écrite par saint Jérôme.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_paul_ermite.html

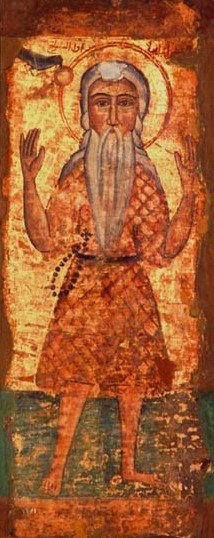

Icône

copte de Saint-Paul. XVII-XVIII s.

Icons of Paul of Thebes ; Coptic icons ; Cilice in icons

Saint Paul l'ermite

Il naquit en haute Egypte

près de la ville de Thèbes (Louxor), sous le règne de l'empereur Alexandre

Sévère, vers l'an 230. Ses parents chrétiens lui donnèrent une solide éducation

religieuse. Il maitrisait la langue grecque et égyptienne. A l'âge de 16 ans il

perdit sa mère puis son père. Il ne lui restait plus qu'une soeur marié avec un

beau frère qui voulait s'accaparer de l'héritage du jeune garçon. Vers l'an 248,

Décius un militaire romain se révolte contre l'empereur Philippe l'Arabe, qui,

d'après Eusèbe, s'était converti au christianisme et l'assassine. En 249 après

la bataille de Vérone où Philippe l'Arabe est tué, Décius prend sa succession,

et lance une nouvelle persécution contre les chrétiens de l'empire. La

persécution fut si féroce, que les bourreaux ne tuaient pas les pauvres

victimes mais essayaient de les faire souffrir le plus longtemps possible avant

de les achever.

Les églises d'Egypte

furent abandonnées. Paul qui n'était qu'un adolescent préféra se cacher dans

une cabane, dans les champs de ses parents, restant à l'écart de ces évènements

mais son beau-fère le dénonça en pensant profiter de cette occasion pour se

débarrasser de lui et prendre tout l'héritage. Mais sa soeur pu le prévenir à

temps et il s'enfonça seul dans le désert. Au début, il ne s'éloigna pas

beaucoup, car il espérait revenir quand la persécution aurait cessée pour

réclamer son dû à son beau-frère.

Mais face à la faim, la

soif, le froid, la fièvre et à son désir de vengeance qui le rongeait, il cria

du fond de sa détresse et appela Jésus à son secours. Egaré dans cet immense

désert et à bout de force, il se croyait perdu quand il arriva devant une

colline où se trouvait une caverne dont l'entrée était caché par un palmier. A

côté de cette tanière se trouvait aussi une source d'eau limpide. Il put enfin

étancher sa soif et se rassasier des dattes qui murissaient sur le palmier. Il

trouva dans cet endroit une paix profonde et passa toute la nuit en prière pour

remercier Dieu de sa sollicitude. Plus le temps passait plus, il se sentait

heureux dans cette solidude qui le raprochait de Dieu. Quand ses habits furent

usés, il se fit une tunique de feuilles de palmier. Trouvant dans ce lieu tout

le nécessaire pour vivre, il ne désira rien de plus, et tourna toute son

attention au salut de son âme et le rachat de ses fautes. Ainsi caché au regard

des hommes, il passa 90 ans dans ce désert. C'est déjà l'époque où les

Chrétiens connaissent une paix relative dans l'empire romain et le début des

hérésies. Dieu voulu révéler à son église et au monde la vie cachée de ce saint

égyptien pour qu'il sert d'exemple aux générations suivantes. C'est à Saint

Antoine le Grand que fut confié cette tâche et jusqu'à ce jour cette tradition,

l'ermite du désert, est toujours vivante parmi les moines coptes.

SOURCE : http://orient.chretien.free.fr/PaulErmite.htm

Sassetta (1392–1450),

The meeting of Saint Anthony the Great and Saint Paul the Anchorite, circa

1445, tempera on wood, 47.5 x

34.5, National Gallery of Art, Washington,

D.C.,

SAINT PAUL

Plusieurs ont douté quel

a été celui d'entre tous les solitaires qui a le premier habité les déserts; et

il y en a qui, remontant bien loin jusque dans les siècles passés, veulent que

les premiers auteurs d'une si sainte retraite soient le bienheureux Hélie et

saint Jean-Baptiste ; dont l'un me semble devoir plutôt être considéré comme un

prophète que comme un solitaire, et l'autre a commencé à prophétiser avant même

que de naître. D'autres assurent, et c'est la commune opinion, que saint Antoine

doit être considéré comme le maître de ce projet; ce qui est vrai en partie

puisque, bien qu'il n'ait pas été le premier de tous les solitaires qui en

fuyant le monde ait passé dans le désert, il a été le premier qui par son

exemple a montré le chemin et excité l'ardeur de tous ceux qui se sont portés à

embrasser une vie si sainte; car Amatas et Macaire, deux de ses disciples dont

le premier l'a mis en terre, nous assurent encore aujourd'hui qu'un nommé Paul

Thébéen a été celui qui a commencé à vivre de cette sorte, en quoi je suis bien

de leur avis. Il y en a aussi d'autres qui, feignant sur cela tout ce qui leur

vient en fantaisie, voudraient nous faire croire que Paul vivait dans un antre

souterrain, et que les cheveux lui tombaient jusque sur les talons; à quoi ils

ajoutent d'autres semblables contes faits à plaisir, et que je n'estime pas

devoir prendre la peine de réfuter, puisque ce sont des mensonges ridicules et

sans apparence.

Or, d'autant que l'on a

écrit très exactement, tant en grec qu'en latin, la vie de saint Antoine, j'ai

résolu de dire quelque chose du commencement et de la fin de celle de saint

Paul, plutôt à cause que personne ne l'a fait jusqu'ici que par la créance d'y

pouvoir bien réussir; car quant à ce qui s'est passé depuis sa jeunesse jusqu'à

sa vieillesse, et aux tentations du diable qu'il a soutenues et surmontées,

personne n'en a connaissance.

Du temps de la

persécution de Decius et de Valérien, lorsque le pape Corneille à Rome et saint

Cyprien à Carthage répandirent leur sang bienheureux, cette cruelle tempête

dépeupla plusieurs Eglises dans l'Egypte et dans la Thébaïde. Le plus grand

souhait des chrétiens était alors d'avoir la tête tranchée pour la confession

du nom de Jésus-Christ. Mais la malice de leur ennemi le rendait ingénieux à

inventer des supplices qui leur donnassent une longue mort, parce que son

dessein était de tuer leurs âmes et non pas leurs corps; ainsi que saint

Cyprien, qui l'a éprouvé en sa propre personne, le témoigne lui-même par ces

paroles: « On refusait de donner la mort à ceux qui la désiraient.» Et afin de

faire connaître jusqu'à quel excès allait cette cruauté, j'en veux rapporter

ici deux exemples pour en conserver la mémoire.

Un magistrat païen,

voyant un martyr demeurer ferme et triompher des tourments au milieu des

chevalets et des lames de fer sortant de la fournaise, commanda qu'on lui

frottât tout le corps de miel, et qu'après lui avoir lié les mains derrière le

dos on le mit à la renverse, et qu'on l'exposât ainsi aux plus ardents rayons du

soleil, afin que celui qui avait surmonté tant d'autres douleurs cédât à celles

que lui feraient sentir les aiguillons d'une infinité de mouches.

Il ordonna que l'on menât

un autre qui était en la fleur de son âge dans un jardin très délicieux, et que

là, au milieu des lis et des roses, et le long d'un petit ruisseau qui avec un

doux murmure serpentait à l'entour de ces fleurs, et où le vent en soufflant

agréablement agitait un peu les feuilles des arbres, on le couchât sur un lit,

et qu'après l'y avoir attaché doucement avec des rubans de soie pour lui ôter

tout moyen d'en sortir, on le laissât seul. Chacun s'étant retiré, il fit venir

une fort belle courtisane qui se jetta à son cou avec des embrassements

lascifs, et, ce qui est horrible seulement à dire, porta ses mains en des lieux

que la pudeur ne permet pas de nommer, afin qu'après avoir excité en lui le

désir d'un plaisir criminel, son impudence victorieuse triomphât de sa

chasteté. Ce généreux soldat de Jésus-Christ ne savait en cet état ni que faire

ni à quoi se résoudre, car se fût-il laissé vaincre par les délices après avoir

résisté à tant de tourments ? Enfin par une inspiration divine il se coupa la

langue avec les dents, et en la crachant au visage de cette, effrontée qui le

baisait il éteignit, par l'extrême douleur qu'il se fit à lui-même, les

sentiments de volupté qui eussent pu s'allumer dans sa chair fragile.

Au temps que ces choses

se passaient Paul, n'étant âgé que de quinze ans et n'ayant plus ni père ni

mère mais seulement une soeur déjà mariée, se trouva maître d'une grande

succession en la basse Thébaïde. Il était fort savant dans les lettres grecques

et égyptiennes, de fort douce humeur et plein d'un grand amour de Dieu. La

tempête de cette persécution éclatant de tous, côtés, il se retira en une

maison des champs assez éloignée et assez à l'écart.

Son beau-frère se résolut

de découvrir celui qu'il était si obligé de cacher, sans que les larmes de sa

femme, les devoirs d’une si étroite alliance ni la crainte de Dieu, qui du haut

du ciel regarde toutes nos actions, fussent capables de le détourner d’un si

grand crime; et la cruauté qui le portait à cela se couvrait même d'un prétexte

de religion.

Ce jeune garçon qui était

très sage, ayant appris ce dessein et se résolvant à faire volontairement ce

qu'il était obligé de faire par force, s'enfuit dans les déserts des montagnes

pour y attendre que la persécution fût cessée ; et en s'y avançant peu à peu,

et puis encore davantage, et continuant souvent à faire la même chose, enfin il

trouva une montagne pierreuse au pied de laquelle était une grande caverne dont

l'entrée était fermée avec une pierre, qu'il retira; et, regardant

attentivement de tous côtés par cet instinct naturel qui porte l'homme à

désirer de connaître les choses cachées, il aperçut au-dedans , comme un grand

vestibule qu'un vieux palmier avait formé de ses branches en les étendant et

les entrelaçant les unes dans les autres, et qui n'avait rien que le ciel

au-dessus de soi. Il y avait là une fontaine très claire d'où il sortait un

ruisseau, qui à peine commençait à couler qu'on le voyait se perdre dans un

petit trou, et être englouti par la même terre qui le produisait. Il y avait

aussi aux endroits de la montagne les plus difficiles à aborder diverses

petites maisonnettes où l'on voyait encore des burins, des enclumes et des

marteaux dont on s'était autrefois servi pour faire de la monnaie ; et quelques

mémoires égyptiens portent que c'avait été une fabrique de fausse monnaie,

durant le temps des amours d'Antoine et de Cléopâtre.

Notre saint, concevant de

l'attrait pour cette demeure qu'il considérait comme lui ayant été présentée de

la main de Dieu, y passa toute sa vie en oraisons et en solitude ; et le

palmier dont ,j'ai parlé lui fournissait tout ce qui,lui était nécessaire pour

sa nourriture et son vêlement; ce qui ne doit pas passer pour impossible,

puisque je prends à témoin Jésus-Christ et ses anges que, dans cette partie du

désert qui en joignant la Syrie tient aux terres des Arabes, j'ai vu parmi des

solitaires un frère qui, étant reclus, il y avait trente ans, ne vivait que de

pain d'orge et d'eau bourbeuse, et un autre qui, étant enfermé dans une vieille

citerne, vivait de cinq figues par jour. Je ne doute pas néanmoins que cela ne

semble incroyable aux personnes qui manquent de foi, parce « qu'il n'y a que

ceux qui croient, à qui telles, choses soient possibles. »

Mais pour retourner à ce

que j'avais commencé de dire, il y avait déjà cent treize axis que le

bienheureux Paul menait sur la terre, une vie toute céleste; et Antoine, âgé de

quatre-vingt-dix ans ( comme il l'assurait souvent ), demeurant dans, une autre

solitude, il lui vint en pensée que nul autre que lui n'avait passé dans le

désert la vie d'un parlait et véritable solitaire; mais lorsqu'il dormait il

lui fut, la nuit, révélé en songe qu'à y en avait un autre, plus, avant dans le

désert, meilleur que lui, et qu'il se devait hâter d'aller voir.

Dès la pointe du jour ce

vénérable vieillard, soutenant son corps faible et exténué avec mi bâton qui

lui servait aussi à se conduire, commença à marcher sans savoir où il allait;

et déjà le, soleil, arrivé à son midi, avait échauffé l'air de telle sorte

qu'il paraissait tout enflammé, sans que néanmoins il se pût résoudre à

différer son voyage, disant en lui-même:

« Je me confie en mon

Dieu, et ne doute point qu'il ne me fasse voir son serviteur ainsi qu'il me l'a

promis.» Comme il achevait ces paroles il vit un Homme qui avait en partie le

corps d'un cheval, et était comme ceux que les poètes nomment Hippocentaures.

Aussitôt qu'il l'eut aperçu il arma son front du signe salutaire de la croix et

lui cria: « Holà! En quel lieu demeure ici le serviteur de Dieu ?» Alors ce

monstre, marmottant je ne sais quoi de barbare et entrecoupant plutôt ses

paroles qu'il ne les proférait distinctement, s'efforça de faire sortir une

voix douce de ses lèvres toutes hérissées de poil, et, étendant sa main droite,

lui montra le chemin tant désiré; puis en fuyant il traversa avec une

incroyable vitesse toute une grande campagne, et s'évanouit devant les yeux de

celui qu'il avait rempli d'étonnement. Quant à savoir si le diable pour

épouvanter le saint avait pris cette figure, ou si ces déserts si fertiles en

monstres avaient produit celui-ci, je ne saurais en rien assurer.

Antoine, pensant tout

étonné à ce qu'il venait de voir, ne laissa pas de continuer son chemin ; et à

peine avait-il commencé à marcher qu'il aperçut dans un vallon pierreux un fort

petit homme qui avait les narines crochues, des cornes au front et des pieds de

chèvre. Ce nouveau spectacle ayant augmenté son admiration, il eut recours,

comme un vaillant soldat de Jésus-Christ, aux armes de la foi et de

l'espérance; mais cet animal, pour gage de son affection, lui offrit des dattes

pour le nourrir durant son voyage. Le saint s'arrêta et lui demanda qui il

était. Il répondit : « Je suis mortel et l'un des habitants des déserts que les

païens, qui se laissent emporter à tant de diverses erreurs, adorent sous le

nom de Faunes, de Satyres et d'Incubes. Je suis envoyé vers vous comme

ambassadeur par ceux de mon espèce, et nous Vous supplions tous de prier pour

nous celui qui est également notre Dieu, lequel nous avons su être venu pour le

salut du monde, et dont le nom et la réputation se sont répandus par toute la terre.

»

A ces paroles ce sage

vieillard et cet heureux pèlerin trempa son visage des larmes que l’excès de sa

joie lui faisait répandre, en abondance, et qui étaient des marques évidentes

de ce qui se passait dans son coeur; car il se réjouissait de la gloire de

Jésus-Christ et de la destruction de celle du diable, et admirait en même temps

comment il avait pu entendre le langage de cet animal et être entendu de lui.

En cet état, frappant la terre de son bâton, il disait: « Malheur à toi,

Alexandrie, qui adores des monstres en qualité de dieux ! Malheur à toi, ville

adultère qui es devenue la retraite des démons répandus en toutes les parties

du monde. De quelle sorte t'excuseras-tu maintenant? Les bêtes parlent des

grandeurs de Jésus-Christ, et tu rends à des bêtes les honneurs et les hommages

qui ne sont dus qu'à Dieu seul! » A peine avait-il achevé ces paroles, que cet

animal si léger s'enfuit avec autant de vitesse que s'il avait eu des ailes. Et

s'il se trouve quelqu'un à qui cela semple si incroyable qu'il fasse difficulté

d'y ajouter foi, il en pourra voir un exemple dont tout le monde a été témoin

et qui est arrivé sous le règne de Constance; car un homme de cette sorte,

ayant été mené vivant à Alexandrie, l'ut vu avec admiration de tout le peuple ;

et, étant mort, son corps, après avoir été salé de crainte que la chaleur de

l'été ne le corrompit, fut porté à Antioche pour le faire voir à l'empereur.

Mais, pour revenir à mon

discours, Antoine, continuant à marcher dans le chemin où il s'était engagé, ne

considérai autre chose que la piste des bêtes sauvages et la vaste solitude de

ce désert, sans savoir ce qu'il devait faire ni de quel côté il devait tourner.

Déjà le second jour était

passé depuis qu'il était parti, et il en restait encore un troisième afin qu'il

acquit par cette épreuve une entière confiance de ne pouvoir être abandonné de

Jésus-Christ. Il employa toute cette seconde nuit en oraisons, et à peine le

jour commençait à poindre qu'il aperçut de loin une louve qui, toute haletante

de soif, se coulait le long du pied de la montagne. Il la suivit des yeux et,

lorsqu'elle fut fort éloignée, s'étant approché de la caverne et voulant

regarder dedans, sa curiosité lui fut inutile, à cause due son obscurité était

si grande que ses yeux ne la pouvaient pénétrer; mais, comme dit l'Écriture, «

le parfait amour bannissant la crainte, » après s’être un peu arrêté et avoir

repris Baleine, ce saint et habile espion entra dans cet antre en s'avançant

peu à peu et s'arrêtant souvent pour écouter s'il n'entendrait point de bruit.

Enfin, à travers l'horreur de ces épaisses ténèbres, il aperçut de la lumière

assez loin de là. Alors, redoublant ses pas et marchant sur des cailloux, il

fit du bruit. Paul l'ayant entendu, il tira sur lui sa porte qui était ouverte,

et la ferma au verrou.

Antoine, se jetant contre

terre sur le seuil de la porte, y demeura jusqu'à l'heure de Sexte et

davantage, le conjurant toujours de lui ouvrir et lui disant : « Vous savez qui

je suis, d'où je viens, et le sujet qui m'amène. J'avoue que je ne suis pas

digne de vous voir, mais je ne partirai néanmoins jamais d'ici jusqu'à ce due

j'aie revu ce bonheur. Est-il possible que, ne refusant pas aux bêtes l'entrée

de votre caverne, vous la refusiez aux hommes? Je vous ai cherché, je vous ai

trouvé; et,je frappe à votre porte afin qu'elle me soit ouverte : que si je ne

puis obtenir cette grâce, je suis résolu de mourir en la demandant; et j'espère

qu'au moins vous aurez assez de charité pour m'ensevelir. »

« Personne ne supplie en

menaçant et ne mêle des injures avec des larmes, » lui répondit Paul « vous

étonnez-vous donc si je ne veux pas vous recevoir, puisque vous dites n'être

venu ici que pour mourir?» Ainsi Paul en souriant lui ouvrit la porte; et

alors, s'étant embrassés à diverses fois, ils se saluèrent et se nommèrent tous

deux par leurs propres noms. Ils rendirent ensemble grâces à Dieu; et, après

s'être donné le saint baiser, Paul, s'étant assis auprès d'Antoine, lui parla

en cette sorte :

« Voici celui que vous

avez cherché avec tant de peine, et dont le corps flétri de vieillesse est

couvert par des cheveux blancs tout pleins de crasse; voici cet homme qui est

sur le point d'être réduit en poussière; mais, puisque la charité ne trouve

rien de difficile, dites-moi, je vous supplie, comment va le monde : fait-on de

nouveaux bâtiments dans les anciennes villes? qui est celui qui règne

aujourd'hui ? et se trouve-t-il encore des hommes si aveuglés d'erreur que

d'adorer les démons? »

Comme ils s'entretenaient

de la sorte ils virent un corbeau qui, après s'être reposé sur une branche

d'arbre, vint de là, en volant tout doucement, apporter à terre devant eux un

pain tout entier. Aussitôt qu'il fut parti Paul commença à dire : « Voyez, je

vous supplie, comme Dieu, véritablement tout bon et tout miséricordieux, nous a

envoyé à dîner. Il y a déjà soixante ans que je reçois chaque jour de cette

sorte une moitié de pain; mais depuis que vous êtes arrivé Jésus-Christ a

redoublé ma portion, pour faire voir par là le soin qu'il daigne prendre de

ceux qui, en qualité de ses soldats, combattent pour son service. »

Ensuite, ayant tous deux

rendu grâces à Dieu, ils s'assirent sur le bord d'une fontaine aussi claire que

du cristal, et voulant se déférer l'un à l'autre l'honneur de rompre le pain,

cette dispute dura quasi jusqu'à vêpres, Paul insistant sur ce que

l'hospitalité et la coutume l'obligeaient à cette civilité, et Antoine la

refusant à cause de l'avantage que l'âge de Paul lui donnait sur lui. Enfin ils

résolurent que chacun de son côté, prenant le pain et le tirant à soi, en

retiendrait la portion qui lui demeurerait entre les mains. Après, en se

baissant sur la fontaine et mettant leur bouche sur l'eau, ils en burent chacun

un peu, et puis, offrant à Dieu un sacrifice de louanges, ils passèrent toute

la nuit en prières.

Le jour étant venu, Paul

parla ainsi à Antoine : « Il y a longtemps, mon frère, que je savais votre

séjour en ce désert; il y a longtemps que Dieu m'avait promis que vous

emploieriez comme moi votre vie à son service; mais parce que l'heure de mon

heureux sommeil est arrivé, et qu'ayant toujours désiré avec ardeur d'être

délivré de ce corps mortel pour m'unir à Jésus-Christ, il ne me reste plus,

après avoir achevé ma course, que de recevoir la couronne de justice, notre

Seigneur vous a envoyé pour couvrir de terre ce pauvre corps, ou, pour mieux

dire, pour rendre la terre à la terre. »

A ces paroles Antoine,

fondant en pleurs et jetant mille soupirs, le conjurait de ne le point

abandonner et de demander à Dieu qu'il lui tint compagnie en ce voyage; à quoi

il lui répondit : «Vous ne devez pas désirer ce qui vous est plus avantageux,

mais ce qui est plus utile à votre prochain : il n'y a point de doute que ce ne

vous fût un extrême bonheur d'être déchargé du fardeau ennuyeux de cette chair

pour suivre l'agneau sans tache, mais il importe au bien de vos frères d'être

encore instruits par votre exemple. Ainsi, si ce ne vous est point trop

d'incommodité, je vous supplie d'aller quérir le manteau que l'évêque Athanase

vous donna, et de me l'apporter pour m'ensevelir. » Or si le bienheureux Paul

lui faisait cette prière, ce n'est pas qu'il se souciât beaucoup que son corps

fût plutôt enseveli que de demeurer nu, puisqu'il devait être réduit en

pourriture, lui qui depuis tant d'années n'était revêtu que de feuilles de

palmier entrelacées, mais afin que, Antoine étant éloigné de lui, il ressentit

avec moins de violence l'extrême douleur qu'il recevrait de sa mort.

Antoine fut rempli d'un

merveilleux étonnement de ce qu'il lui venait de dire de saint Athanase et du

manteau qu'il lui avait donné; et, comme s'il eût vu Jésus-Christ dans Paul et

adorant Dieu résidant dans son coeur, il n'osa plus lui rien répliquer; mais,

pleurant sans dire une seule parole, après lui avoir baisé les yeux et les

mains il partit pour s'en retourner à son monastère, qui fut depuis occupé par

les Arabes; et, bien que son esprit fit faire à son corps affaibli de jeûnes et

cassé de vieillesse une diligence beaucoup plus grande que son âge ne le

pouvait permettre, il s'accusait néanmoins de marcher trop lentement. Enfin

après avoir achevé ce long chemin, il arriva tout fatigué et tout hors

d'haleine à son monastère.

Deux de ses disciples qui

le servaient depuis plusieurs années ayant couru au-devant de lui et lui disant

: « Mon père, où avez-vous demeuré si longtemps?» il leur répondit : «Malheur à

moi, misérable pécheur, qui porte si indignement le nom de solitaire! J'ai vu

Hélie, j'ai vu Jean dans le désert, et, pour parler selon la vérité, j'ai vu

Paul dans un paradis. »Sans en dire davantage et en se frappant la poitrine il

tira le manteau de sa cellule; et ses disciples le suppliant de les informer

plus particulièrement de ce que c'était, il leur répondit : « Il y a temps de

parler et temps de se taire ; » et, sortant ainsi de la maison sans prendre

aucune nourriture, il s'en retourna par le même chemin qu'il était venu, ayant

le coeur tout rempli de Paul, brûlant d'ardeur de le voir et l'ayant toujours

devant les yeux et dans l'esprit, parce qu'il craignait, ainsi qu'il arriva,

qu'il ne rendit son âme à Dieu durant son absence.

Le lendemain au point du

jour, lorsqu'il y avait déjà trois heures qu'il était en chemin, il vit au

milieu des troupes des anges et entre les chœurs des prophètes et des apôtres

Paul, tout éclatant d'une blancheur pure et lumineuse, monter dans le ciel.

Soudain, se jetant le visage contre terre, il se couvrit la tête de sable et s'écria

en pleurant : « Paul, pourquoi m'abandonnez-vous ainsi? Pourquoi partez-vous

sans me donner le loisir de vous dire adieu? Vous ayant connu si tard, faut-il

que vous me quittiez si tôt? »

Le bienheureux Antoine

contait, depuis, qu'il acheva avec tant de vitesse ce qui lui restait de chemin

qu'il semblait qu'il eût des ailes, et non sans sujet puisque, étant entré dans

la caverne, il y vit le corps mort du saint qui avait les genoux en terre, la

tête levée et les mains étendues vers le ciel. Il crut d'abord qu'il était

vivant et qu'il priait, et se mit de son côté en prières; mais, ne l'entendant

point soupirer ainsi qu'il avait coutume de le faire en priant, il s'alla jeter

à son cou pour lui donner un triste baiser, et reconnut que par une posture si dévote

le corps de ce saint homme, tout mort qu'il était, priait encore Dieu auquel

toutes choses sont vivantes.

Ayant roulé et tiré ce

corps dehors, et chanté des hymnes et des psaumes selon la tradition de

l'Eglise catholique, il était fort fâché de n'avoir rien pour fouiller la

terre, et pensant et repensant à cela avec inquiétude d'esprit, il disait : «

Si je retourne au monastère il me faut trois jours pour revenir, et si je

demeure ici, je n'avancerai rien : il vaut donc beaucoup mieux que je meure et

que, suivant votre vaillant soldat, ô Jésus-Christ, mon cher maître, je rende

auprès de lui les derniers soupirs. »

Comme il parlait ainsi en

lui-même, voici deux lions qui, sortant en courant dis fond du désert,

faisaient flotter leurs longs crins dessus le cou. Ils lui donnèrent d'abord de

la frayeur, mais, élevant son esprit à Dieu, il demeura aussi, tranquille que s'ils

eussent été dés colombes, lis vinrent droit au corps du bienheureux vieillard,

et, s'arrêtant là et le flattant avec leurs queues, ils se couchèrent à ses

pieds, puis jetèrent de grands rugissements pour lui témoigner qu'ils le

pleuraient en la manière qu'ils le pouvaient. Ils commencèrent ensuite à

gratter la terre avec leurs ongles, en un lieu assez proche de là, et, jetant,

à l'envi le sable. de côté et d'autre, firent une fosse capable de recevoir le

corps d'un homme; et aussitôt après, comme s'ils eussent demandé récompense de

leur travail, ils vinrent, en remuant les oreilles et la tête basse, vers

Antoine, et lui léchaient les pieds et les mains. Il reconnut qu'ils lui

demandaient sa bénédiction, et soudain, rendant des louanges infinies à Jésus-Christ

de ce que même les animaux irraisonnables avaient quelque sentiment de la

divinité, il dit : « Seigneur, sans la volonté duquel il ne tombe pas même une

seule feuille des arbres ai le moindre oiseau ne perd la vie, donnez à ces

lions ce que vous savez leur être nécessaire ; » et après, leur faisant signe

de la main, il leur commanda de s'en aller.

Lorsqu'ils furent partis

il courba ses épaules affaiblies par la vieillesse sous le fardeau de ce saint

corps, et, l'ayant porté dans la fosse, jeta du sable dessus pour l'enterrer

selon la coutume de l’Eglise. Le jour suivant étant venu, ce pieux héritier, ne

voulant, rien perdre de la succession de celui qui était mort sans faire de

testament, prit pour soi la tunique qu'il avait tissue de ses propres mains

avec des feuilles de palmier, en la même sorte qu'on l'ait des paniers d'osier,

et retournant ainsi à son monastère, il conta particulièrement à ses disciples

tout ce qui lui était arrivé; et aux jours solennels de Pâques et de la

Pentecôte il se revêtait toujours de la tunique du bienheureux Paul.

Je ne saurais m'empocher,

sur la fin de cette histoire, de demander à ceux qui ont tant de biens qu'ils

n'en savent pas le compte, qui bâtissent des palais de marbre, qui enferment

dans un seul collier de diamants ou de perles le prix, de plusieurs riches

héritages, ce qui a jamais manqué à ce, vieillard tout nu. Vous buvez dans des

coupes de pierres précieuses; et lui avec le creux de sa main satisfaisait, au

besoin de la nature; vous vous parez, avec des robes tissues d'or, et lui n'a

pas eu le plus vil habit qu'eût pu porter le moindre de vos esclaves; mais, par

un changement étrange, le paradis a été ouvert à cet homme si pauvre, et vous,

avec votre magnificence, serez précipités dans les flammes éternelles; tout nu

qu'il était, il a conservé cette robe blanche dont Jésus-Christ l'avait revêtu

au baptême, et vous, avec ces habits somptueux, vous l'avez perdue; Paul,

n'étant couvert que d'une vile poussière, se relèvera un jour pour ressusciter

en gloire, et ces tombeaux si élaborés et si superbes qui vous enferment

aujourd'hui ne vous empêcheront pas de braver misérablement avec toutes vos

richesses. Ayez pitié de vous-mêmes, je vous prie, et épargnez au moins ces

biens que vous aimez tant. Pourquoi ensevelissez-vous vos morts dans des draps

d'or et de soie? Pourquoi votre vanité ne cesse-t-elle pas même au milieu de

vos soupirs et de vos larmes? Est-ce que vous croyez que les corps des riches

ne sauraient pourrir que dans des étoffes précieuses?

Qui que vous soyez qui

lirez ceci, je vous conjure de vous souvenir du pécheur Jérôme, lequel, si Dieu

lui en avait donné le choix, aimerait incomparablement mieux la tunique de Paul

avec ses mérites due la pourpre des rois avec toute leur puissance.

Saint Jérôme. Vies de

quelques Pères du désert. Vie de Saint Paul ermite. : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/saints/jerome/mystiques/019.htm

Illumination

depicting the Story of Saints Anthony and Paul the Hermit from the Belles

Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry, XVth century

SAINT PAUL, ERMITE *

Paul, premier ermite, au

témoignage de saint Jérôme qui a écrit sa vie, se retira, pendant la

persécution violente de Dèce, dans un vaste désert où il demeura 60 ans, au

fond d'une caverne, tout à fait inconnue des hommes. Ce Dèce, qui eut, deux

noms, pourrait bien être Gallien qui commença à régner l’an du Seigneur 256.

Saint Paul voyant donc les chrétiens en butte à toutes sortes de supplices,

s'enfuit au désert. A la même époque, en effet, deux jeunes chrétiens sont

pris, l’un d'eux a tout le corps enduit de miel et est exposé sous l’ardeur du

soleil aux piqûres des mouches, des insectes et des guêpes ; l’autre est mis

sur un lit des plus mollets, placé dans un jardin charmant, où une douce

température, le murmure des ruisseaux, le chant des oiseaux, l’odeur des fleurs

étaient enivrants. Le jeune homme est attaché avec des cordes tissées de la

couleur des fleurs, de sorte qu'il ne pouvait s'aider ni des mains, ni des

pieds. Vient une jouvencelle d'une exquise beauté, mais impudique, qui caresse

impudiquement le jeune homme rempli de l’amour de Dieu. Or, comme il sentait

dans sa chair des mouvements contraires à la raison, mais qu'il était privé

d'armes, pour se soustraire à son ennemi, il se coupa la langue avec les dents

et la cracha au visage de cette courtisane : il vainquit ainsi la tentation par

la douleur, et mérita un trophée digne de louanges. Saint Paul effrayé par de

pareils tourments et par d'autres encore, alla au désert. Antoine se croyait

alors le premier des moines qui vécût en ermite; mais averti en songe qu'il y

en a un meilleur que lui de beaucoup, lequel vivait dans un ermitage, il se mit

à le chercher à travers les forêts; il rencontra un hippocentaure cet être

moitié homme, moitié cheval, lui indiqua qu'il fallait prendre à droite.

Bientôt après, il rencontra un animal portant des fruits de palmier, dont la

partie supérieure du corps avait la figure d'un homme et la partie inférieure,

la forme d'une chèvre. Antoine le conjura de la part de Dieu de lui dire qui il

était; l’animal répondit qu'il était un satyre, le Dieu des bois, d'après la

croyance erronée des gentils. Enfin il rencontra un loup qui le conduisit à la

cellule de saint Paul. Mais celui-ci ayant deviné que c'était Antoine qui

venait, ferma sa porte. Alors Antoine le prie de lui ouvrir, l’assurant qu'il

ire s'en ira pas de là, mais qu'il y mourra plutôt. Paul cède et lui ouvre, et

aussitôt ils se jetèrent dans les bras l’un de l’autre en s'embrassant. Quand

l’heure du repas fut arrivée, un corbeau apporta une double ration de pain : or,

comme Antoine était dans l’admiration, Paul répondit que Dieu le servait tous

les jours de la sorte, mais qu'il avait doublé la pitance en faveur de son

hôte. Il y eut un pieux débat entre eux pour savoir qui était le plus digne de

rompre ce pain : saint Paul voulait déférer cet honneur à son hôte et saint

Antoine à son ancien. Enfin ils tiennent. le pain chacun d'une main et le

partagent égaleraient en deux. Saint Antoine, à son retour, était déjà près de

sa cellule, quand il vit des anges portant l’âme de Paul, il s'empressa de

revenir, et trouva le corps de Paul droit sur ses genoux fléchis, comme s'il

priait; en sorte qu'il le pensait vivant ; mais s'étant assuré qu'il était

mort, il dit : « O sainte âme, tu as montré par ta mort ce que tu étais dans ta

vie. » Or, comme Antoine était dépourvu de ce qui était nécessaire pour creuser

une fosse, voici venir deux lions qui en creusèrent une, puis s'en retournèrent

à la forêt, après l’inhumation. Antoine prit à Paul sa tunique tissue avec da

palmier, et il s'en revêtit dans la suite aux jours de solennité. Il mourut

environ l’an 287.

* Tiré de saint Jérôme.

La Légende dorée de

Jacques de Voragine nouvellement traduite en français avec introduction,

notices, notes et recherches sur les sources par l'abbé J.-B. M. Roze, chanoine

honoraire de la Cathédrale d'Amiens, Édouard Rouveyre, éditeur, 76, rue de

Seine, 76, Paris mdccccii

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/voragine/tome01/018.htm

Leçons des Matines avant 1960

AU DEUXIÈME NOCTURNE.

Quatrième leçon. Paul, l’instituteur et le maître des Ermites, naquit dans la basse Thébaïde ; il n’avait que quinze ans lorsqu’il perdit son père et sa mère. Quelque temps après, pour fuir la persécution de Dèce et de Valérien et pour servir Dieu avec plus de liberté, il se retira dans une caverne du désert. C’est là qu’un palmier lui fournissant de quoi se nourrir et se vêtir, il vécut jusqu’à l’âge de cent treize ans : alors saint Antoine, qui en avait quatre-vingt-dix, le visita, d’après un avertissement de Dieu. Ils se saluèrent de leurs propres noms, bien qu’ils ne se connussent point auparavant, et pendant qu’ils se complaisaient à s’entretenir du royaume de Dieu, un corbeau, qui jusqu’alors avait toujours apporté à Paul la moitié d’un pain, en déposa un tout entier auprès d’eux.

Cinquième leçon. Après le départ du corbeau : « Voyez, dit Paul, comment le Seigneur vraiment bon, vraiment miséricordieux, nous a envoyé notre repas. Il y a déjà soixante ans que je reçois chaque jour la moitié d’un pain, et maintenant, à votre arrivée, Jésus-Christ a donné une ration double pour ses soldats. » Ils prirent donc leur nourriture avec action de grâces, au bord d’une fontaine ; ayant ainsi réparé leurs forces et rendu de nouveau grâces à Dieu, selon la coutume, ils passèrent la nuit dans les louanges divines. Au point du jour, Paul, sachant que sa mort était proche, en avertit Antoine, et le pria d’aller chercher, pour ensevelir son corps, le manteau qu’il avait reçu de saint Athanase. Antoine, étant en route pour revenir, vit l’âme de Paul monter au ciel parmi les chœurs des Anges et dans la compagnie des Prophètes et des Apôtres.

Sixième leçon. Quand il

fut arrivé à la cellule de Paul, il le trouva à genoux, la tête levée, les

mains étendues vers le ciel et le corps inanimé. Il l’enveloppa du manteau et

chanta des hymnes et des Psaumes, selon la tradition chrétienne. Comme il n’avait

pas d’instrument pour creuser la terre, deux lions accoururent du fond du

désert et s’arrêtèrent près du corps du bienheureux vieillard, donnant à

entendre qu’ils le pleuraient à leur manière. Ils creusèrent la terre avec

leurs griffes à l’envi l’un de l’autre et firent une fosse capable de contenir

un homme. Lorsqu’ils furent partis, Antoine déposa le saint corps en ce lieu,

et le couvrant de terre, il lui dressa un tombeau à la manière des chrétiens.

Quant à la tunique de Paul, qu’il avait tissue de feuilles de palmier comme on

fait les corbeilles, il l’emporta avec lui, et tant qu’il vécut, il se servit

de ce vêtement aux jours solennels de Pâques et de la Pentecôte.

Dom Guéranger, l’Année Liturgique

L’Église honore aujourd’hui la mémoire d’un des hommes le plus spécialement choisis pour représenter la pensée de ce détachement sublime que l’exemple du Fils de Dieu, né dans une grotte, à Bethlehem, révéla au monde. L’ermite Paul a tant estimé la pauvreté de Jésus-Christ, qu’il s’est enfui au désert, loin de toute possession humaine et de toute convoitise. Une caverne pour habitation, un palmier pour sa nourriture et son vêtement, une fontaine pour y désaltérer sa soif, un pain journellement apporté du ciel par un corbeau pour prolonger cette vie merveilleuse : c’est ainsi que Paul servit, pendant soixante ans, étranger aux hommes, Celui qui n’avait pas trouvé de place dans la demeure des hommes, et qui fut contraint d’aller naître dans une étable abandonnée.

Mais Paul habitait avec Dieu dans sa grotte ; et en lui commence la race sublime des Anachorètes, qui, pour converser avec le Seigneur, ont renoncé à la société et même à la vue des hommes : anges terrestres dans lesquels a éclaté, pour l’instruction des siècles suivants, la puissance et la richesse du Dieu qui suffit lui seul aux besoins de sa créature. Admirons un tel prodige ; et considérons, avec reconnaissance, à quelle hauteur le mystère d’un Dieu incarné a pu élever la nature humaine tombée dans la servitude des sens, et tout enivrée de l’amour des biens terrestres.

N’allons pas croire cependant que cette vie de soixante ans passée au désert, cette contemplation surhumaine de l’objet de la béatitude éternelle, eussent désintéressé Paul de l’Église et de ses luttes glorieuses. Nul n’est assuré d’être dans la voie qui conduit à la vision et à la possession de Dieu, qu’autant qu’il se tient uni à l’Épouse que le Christ s’est choisie, et qu’il a établie pour être la colonne et le soutien de la vérité [1]. Or, parmi les enfants de l’Église, ceux qui doivent le plus étroitement se presser contre son sein maternel, sont les contemplatifs ; car ils parcourent des voies sublimes et ardues, où plusieurs ont rencontré le péril Du fond de sa grotte, Paul, éclairé d’une lumière supérieure, suivait les luttes de l’Église contre l’arianisme ; il se tenait uni aux défenseurs du Verbe consubstantiel au Père : et afin de montrer sa sympathie pour saint Athanase, le vaillant athlète de la foi, il pria saint Antoine, à qui il laissait sa tunique de feuilles de palmier, de l’ensevelir dans un manteau dont l’illustre patriarche d’Alexandrie, qui aimait tendrement le saint abbé, lui avait fait présent.

Le nom de Paul, père des Anachorètes, est donc enchaîné à celui d’Antoine, père des Cénobites ; les races fondées par ces deux apôtres de la solitude sont sœurs ; toutes deux émanent de Bethlehem comme d’une source commune. La même période du Cycle réunit, à un jour d’intervalle, les deux fidèles disciples de la crèche du Sauveur.

Nous donnons ici les trois strophes suivantes, consacrées par l’Église Grecque, dans ses Menées, à la louange du premier des Ermites :

Quand, par l’inspiration divine, tu as abandonné avec sagesse, ô Père, les sollicitudes de la vie pour embrasser les travaux de l’ascèse ; alors, enflammé de l’amour du Seigneur , plein de joie, tu t’es emparé du désert, laissant derrière toi les passions de l’homme , et poursuivant avec persévérance ce qu’il y a de meilleur, semblable à un Ange, tu as accompli ta vie.

Séparé volontairement de

toute société humaine, dès ton adolescence, ô Paul, notre Père, tu as, le

premier de tous, embrassé la complète solitude , dépassant tous les autres

solitaires, et tu as été inconnu pendant toute ta vie : c’est pourquoi Antoine,

par un mouvement divin, t’a découvert, toi qui étais comme caché, et il t’a

manifesté à l’univers.

Livré, ô Paul, à un genre

de vie inaccoutumé sur la terre, tu as habité avec les bêtes, assisté du

ministère d’un oiseau, par la volonté divine ; à cette vue, le grand Antoine

stupéfait, au jour où il te découvrit, te célébra sans relâche, comme le

Prophète et le Maître de tous comme un être divin.

Vous contemplez

maintenant dans sa gloire, ô prince des Anachorètes, le Dieu dont vous avez

médité, durant soixante années, la faiblesse et les abaissements volontaires ;

votre conversation avec lui est éternelle. Pour cette caverne, qui fut le

théâtre de votre pénitence, vous avez l’immensité des cieux ; pour cette

tunique de feuilles de palmier, un vêtement de lumière ; pour ce pain matériel,

l’éternel Pain de vie ; pour cette humble fontaine, la source de ces eaux qui

jaillissent jusque dans l’éternité. Dans votre isolement sublime, vous imitiez

le silence du Fils de Dieu en Bethlehem ; maintenant, votre langue est déliée,

et la louange s’échappe à jamais de votre bouche avec le cri de la félicité.

Souvenez-vous cependant de cette terre dont vous n’avez connu que les déserts ;

rappelez à l’Emmanuel qu’il ne l’a visitée que dans son amour, et faites

descendre sur nous ses bénédictions. Obtenez-nous la grâce d’un parfait

détachement des choses périssables, l’estime de la pauvreté, l’amour de la

prière, et une continuelle aspiration vers la patrie céleste.

[1] II Tim. III, 15.

Bhx Cardinal

Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

La fête de ce patriarche

de l’ascèse monastique orientale est entrée très tard dans le calendrier

romain, puisque ce fut seulement sous l’influence d’une Congrégation religieuse

portant son nom, et qui, après le XIVe siècle, avait pris en Occident un développement

considérable, qu’Innocent XIII éleva la fête de saint Paul au rite double pour

l’Église universelle. Rome elle-même avait, au XVIe siècle, sur le mont

Viminal, un temple en l’honneur de cet admirable fils du désert. Aujour d’hui

cet édifice a été confisqué et profané.

L’insigne des Ermites de

Saint-Paul était le palmier. De là viennent, dans la messe, les gracieuses et

fréquentes allusions à cet arbre providentiel qui fournit à notre saint la

nourriture et le vêtement, et qui, par l’extension de ses branches, symbolise si

bien dans les Écritures l’activité surnaturelle des justes.

L’histoire de saint Paul,

premier ermite, fut écrite vers 376 par saint Jérôme. Son identité avec le

moine Paul, que les deux prêtres lucifériens Marcellin et Faustin dans une

lettre aux empereurs Valentinien, Théodose et Arcadius (entre 383 et 384), nous

décrivent comme un invincible champion de l’orthodoxie de Nicée à Oxyrhynque,

n’est pas entièrement démontrée. Si le Paul de ce deuxième document était le

même que celui dont saint Jérôme fit l’éloge, le premier ermite nous serait

montré sous un jour tout à fait nouveau. Les besoins de la foi l’eussent

temporairement transformé en un courageux apôtre. Le document en question

ajoute que la fête de saint Paul était dès lors célébrée chaque année par le

peuple d’Oxyrhynque [2].

La messe, sauf un verset

d’Osée, n’a aucun élément propre, mais emprunte ses diverses parties aux messes

du Commun des simples confesseurs.

L’introït est tiré du

psaume 91 : « Le juste fleurira comme le palmier et croîtra comme le cèdre sur

le Liban. Il sera transplanté dans la maison de Dieu, dans les cours du temple

de Yahweh. » — Au juste est promise la fécondité et la force, parce qu’il agit,

non par lui-même, mais en Dieu, unique principe de vie. Voilà le secret du succès

des œuvres des saints.

La collecte est la

suivante : « O Dieu qui réjouissez ce jour par la solennité de votre

bienheureux confesseur Paul ; de grâce, accordez-nous d’imiter les œuvres de

celui dont nous célébrons la naissance à la vie éternelle. »

La lecture est tirée de

l’épître aux Philippiens (III, 7-12) où l’Apôtre rappelle à ses correspondants

que, pour gagner le Christ et sa croix, il a abdiqué ces avantages que lui

promettait sa situation sociale antérieure vis-à-vis de la Synagogue ; lui, de

la tribu de Benjamin, pharisien, disciple de rabbi Gamaliel, zélé gardien de la

Thora, jusqu’à devenir persécuteur des chrétiens. Toutes ces circonstances dont

se seraient tant glorifiés les émules de l’Apôtre, furent par lui comptées pour

rien, et il n’ambitionna plus d’autre gloire que celle de porter en lui-même

l’empreinte du Crucifié. C’est seulement à cette condition que Paul se promet

d’avoir part avec le Christ à la gloire de la résurrection.

Le graduel est presque

semblable à l’introït. Le second verset est le suivant : « Pour célébrer de bon

matin votre bonté, et votre vérité au cœur de la nuit. »

Le verset alléluiatique

s’inspire du prophète Osée (xiv, 6) : « Le Juste fleurira comme le lis, et sans

fin il germera devant le Seigneur. »

Après la Septuagésime, on

omet le verset alléluiatique et l’on récite à sa place le psaume tractus, qui,

à l’origine, suivait, aux jours de fête, la deuxième lecture de l’Écriture.

Quand, au moyen âge, l’on perdit la notion historique de l’origine du tractus,

les liturgistes y découvrirent un chant lugubre de pénitence. Au contraire, le

Missel n’assigne le tractus qu’aux dimanches de la Septuagésime pascale, à

quelques fériés quadragésimales solennelles, et aux fêtes des saints que l’on

célèbre durant cette période de préparation à la fête de Pâques. Tous les

autres jours de la semaine qui sont sanctifiés par le jeûne n’ont point le

tractus — le psaume Domine, non secundum, récité trois fois par semaine en

Carême, est d’introduction tardive — précisément parce que le tractus

représente encore dans le Missel actuel l’ancien psaume in directum.

Celui-ci, les jours

festifs, suivait la seconde lecture, régulièrement tirée du Nouveau Testament —

en général des épîtres de saint Paul — mais il disparut quand saint Grégoire le

Grand prescrivit, aux messes dominicales en dehors du Carême, le chant de

l’Alléluia, jusqu’alors réservé à Rome au seul temps pascal.

Saint Grégoire voulut

ainsi égaler le dimanche à la solennité pascale dont il est vraiment, depuis

l’antiquité, la commémoration hebdomadaire. Il ne prévit pas, toutefois, toutes

les conséquences de cette mesure. Les fêtes des martyrs commencèrent à être

placées sur le même plan que le dimanche ; vinrent ensuite celles des

confesseurs et des vierges, et il arriva ceci, que ce qui était à l’origine le

chant pascal par excellence et que saint Jean, dans l’Apocalypse, met sur les

lèvres des bienheureux dans le ciel, devint le chant quotidien du chœur.

L’alléluia perdit ainsi toute cette éclatante beauté qu’il avait pour les

anciens, lesquels l’entonnaient à l’aube de la nuit de Pâques, quand, avec le

Christ triomphateur de la mort, la blanche armée des néophytes sortait

processionnellement du baptistère, pour s’approcher pour la première fois de

l’autel eucharistique du Seigneur. Le trait est tiré du psaume 111, qui célèbre

l’éloge du Juste : « Bienheureux l’homme qui craint Yahweh, et qui trouve son

bonheur dans l’observance de ses préceptes. Sa postérité sera puissante sur la

terre, parce que la descendance des justes est en bénédiction. La gloire et les

richesses sont dans sa maison, et sa justice demeurera à travers tous les

siècles. » C’est l’éloge messianique du Juste par excellence, c’est-à-dire du

Christ, à qui les saints ont tâché de se conformer.

La lecture évangélique

est prise en saint Matthieu (XI, 25-30). Jésus exulte et, rendant grâces au

Père, il entonne le chant de l’humilité : Je te remercie, ô Père, parce que tu

as caché tes mystères aux sages et aux puissants de ce monde pour révéler au

contraire l’Évangile du Royaume, la joyeuse nouvelle, aux pauvres. Venez, vous

tous, ô pauvres, vous qui travaillez et êtes fatigués, et je vous dédommagerai

de vos peines. Le monde proclame bienheureux ceux qui jouissent ; bienheureux,

an contraire, ceux qui, d’eux-mêmes, mettent sur leur cou mon joug, joug

d’humilité, de douceur, joug suave, qui est gage de vraie liberté d’esprit et

qui contient le secret de la joie intime du cœur.

L’antienne pour

l’oblation est tirée du psaume 20 : « Seigneur, par votre puissance le juste

exulte et se délecte dans votre salut qu’il reconnaît bien venir de vous. Vous

avez rempli le vœu de son cœur. » Voilà comment la louange catholique des

saints n’enlève rien à l’adoration que tous nous devons à Dieu ; car si

l’Église magnifie la vertu de ses membres de choix, elle en attribue néanmoins

toute la gloire, toute la louange et toutes les grâces au Seigneur, devant le

trône duquel les saints de l’Apocalypse déposent avec respect leurs couronnes.

La secrète est la

suivante : « Seigneur, nous vous offrons ce sacrifice de louange en la fête de

vos saints, le cœur plein de confiance qu’il nous servira à échapper aux maux

présents et à éviter les périls futurs. »

Le verset pour la

communion est tiré du psaume 63. « Le Juste se réjouira parce qu’il met dans le

Seigneur son espérance. Tous ceux qui ont le cœur droit seront loués. » Voici

donc comment la source de la joie, de la justice et de la gloire est la céleste

confiance en Dieu. Se fier à Dieu et faire en sorte que Dieu se fie à nous, la

sainteté est toute en cela.

La prière d’action de

grâces est la suivante : « Rassasiés par une nourriture et un breuvage divins,

nous vous demandons que toujours nous protègent les prières de celui en

l’honneur duquel nous avons participé au céleste Sacrifice. »

Un auteur sacré donne une

belle définition d’un saint. Un saint, dit-il, est un chrétien qui prend au

sérieux les obligations de son baptême et la nature des relations existant

entre le Créateur et la créature. Ainsi s’explique-t-on que saint Paul ermite,

par exemple, ait pu soutenir près d’un siècle de vie solitaire et pénitente,

croyant encore donner trop peu pour conquérir le paradis et Dieu.

[2] Cf. H.

DELEHAYE, La personnalité historique de saint Paul de Thèbes (Analect.

Bolland, t. XLIV, pp. 64-69).

Dom Pius Parsch, le Guide

dans l’année liturgique

Le silence et

l’obéissance sont des conditions préalables pour la bonne tenue liturgique.

Nos maîtres de vertu. —

Les saints veulent être nos guides vers le ciel. L’Église déroule devant nos

yeux la vie des saints, elle exalte leurs vertus et les propose à notre

imitation. Considérons les moyens que l’Église emploie pour cela. Aux Matines,

nous lisons avec attention la vie du saint, parfois même, l’Église nous fait

lire quelques passages de ses écrits. A l’Oraison, il n’est pas rare que

l’Église insiste sur sa vertu préférée. Dans les deux lectures de la messe (Ép.,

Év.) le saint est caractérisé par des paroles de l’Écriture, afin de nous

exciter à l’imiter. Il y a même des messes où les chants psalmodiques sont

empruntés à la vie du saint. L’Église brosse ainsi un portrait brillant du

saint, elle nous invite à le contempler toute la journée et à en reproduire les

traits en nous. C’est là le côté éducateur du culte des saints. Les deux saints

d’aujourd’hui nous enseignent l’amour de la solitude, le silence et

l’obéissance. La solitude et le silence sont la clôture de l’âme. « Pendant que

le silence enveloppait la terre », le Fils de Dieu est descendu ici-bas ; c’est

ainsi qu’il descend dans notre âme, qu’il aime environner de silence et de

solitude. Dans l’agitation du monde, la voix de Dieu ne se fait pas entendre.

L’obéissance est une condition préalable pour devenir enfants de Dieu. La

désobéissance a introduit le péché sur la terre. L’obéissance du Fils de Dieu,

portée jusqu’à la mort, nous a valu la Rédemption et le ciel.

Saint Paul : jour de mort

(d’après le martyrologe) : 15 janvier 347, à l’âge de 113 ans. Tombeau :

reliques insignes à Rome (Saint Pierre et Sainte Marie du Capitole). Image : On

le représente en ermite, vêtu de feuilles de palmier, et avec un corbeau. Sa

vie : Paul « le premier ermite » (il est rare que le Missel et le Bréviaire

fassent une mention particulière comme celle-ci) est le porte-étendard de ces

hommes courageux qui, par amour pour le Christ, quittèrent le monde et

peuplèrent le désert où ils s’adonnèrent à la contemplation, au milieu de

toutes sortes de privations. Les ermites furent les grands suppliants dans ces

jours terribles où l’Église devait, dans des combats violents, se défendre

contre les hérésies. Pendant des siècles, leur exemple fut l’école de la

perfection chrétienne. Ils furent les précurseurs de la vie monastique et

religieuse dans l’Église. Le bréviaire raconte cette légende édifiante au sujet

de saint Paul : Un jour, saint Antoine, un vieillard de quatre-vingt dix ans,

vint le visiter sur l’ordre de Dieu. Bien qu’ils ne se connussent pas, ils se

saluèrent cependant par leurs noms et s’entretinrent de conversations

spirituelles ; alors le corbeau qui avait coutume d’apporter à Paul. un

demi-pain, apporta un pain entier. Quand le corbeau se fut éloigné, Paul dit :

« Vois, le Seigneur qui est vraiment bon et bienveillant, nous a envoyé de la

nourriture. Il y a déjà soixante ans que je reçois,. tous les jours un

demi-pain, mais, à ton arrivée, le Christ a doublé la ration de ses soldats. »

Ils prirent donc, en remerciant Dieu, leur nourriture auprès d’une source, et,

après avoir pris un peu de repos, ils offrirent de nouveau leurs actions de

grâces au Seigneur, comme ils avaient toujours coutume de le faire, et

passèrent toute la nuit dans les louanges de Dieu. Le lendemain, de bonne

heure, Paul révéla à Antoine sa mort imminente et le pria de lui apporter le

manteau qu’il avait reçu de saint Athanase, pour l’ensevelir dedans. Lorsque

Antoine revint de ce voyage, il vit l’âme de Paul, entourée d’anges et au

milieu du chœur des Prophètes et des Apôtres, s’envoler au ciel. — Saint Jérôme

écrivit, en 376, la vie du premier ermite.

La messe (Justus ut

palma). — La messe reflète d’une manière très belle la vie de saint Paul.

Quand, à l’Introït, on le compare à un palmier, nous nous souvenons de sa vie

dans le désert où le palmier lui fournissait vêtement et nourriture (de même le

Graduel). L’Épître est très belle, c’est un des plus sublimes passages de saint

Paul. « Ce qui était pour moi un gain, je l’ai regardé à cause du Christ comme

une perte... tout me semble une ordure, afin que je gagne le Christ... en lui

devenant semblable dans la mort pour parvenir à la résurrection. » L’Évangile

aussi est une des plus belles pages de la Sainte Écriture. Le Christ y trace

son propre portrait. D’une part il est Dieu, d’autre part il est le Sauveur

miséricordieux, dans son humilité et sa douceur. « Venez tous à moi, vous qui

êtes fatigués... et je vous soulagerai. » Cela se réalise au Saint-Sacrifice,

mais nous devons, par contre, réaliser à l’Offrande cette parole : « Prenez mon

joug sur vous. » Considérons qu’à l’Épître c’est notre saint qui parle ; à

l’Évangile, c’est Notre-Seigneur. Tous les deux se sont caractérisés d’une

manière merveilleuse. Avec les sentiments de l’Épître, approchons-nous, au

Saint-Sacrifice, du Seigneur et du Sauveur de l’Évangile.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/15-01-St-Paul-premier-ermite-et

129.

St. Paul-First Hermit. The 140 Saints of the Colonnade. St. Paul-First Hermit

Born - c.228. Died - c.343 Egypt. Feastday - 10 January. Statue created -

c.1672

It's part of a group of 16 installed between August 1670 and March 1673.. Sculptor

- Lazzaro Morelli

Payment was made to Morelli in June 1672 for 80 scudi.. Height - 3.1 m. (10ft

4in) travertine

The old venerable saint is dressed in woven palm leaves. He holds the

bread, which according to legend, a raven brought every day to his cave. The

face is similar to the St Athanasius on the Chair of St Peter, where Morelli

had worked with Bernini from 1661 to 1663. He is regarded as the first

Christian hermit. The Life of St Paul the First Hermit was written by St

Jerome.

Also

known as

Paul the First Hermit

Paul of Thebes

Paul the Anchorite

Pavly

Pavlos

Anba Bola

Paolo di Tebe

15 January (Eastern

calendar)

Profile

Paul grew up in an

upper-class, Christian family.

He was well educated,

fluent in Greek and Egyptian.

His parents died when

the boy was 15. When the persecutions of Decius began

a few years later, Paul fled into the desert to escape both them, and the

machinations of his brother Peter and other family members who wanted his

property. He lived as a desert hermit in

a cave the remainder of his 113 year life, surviving off fruit and water,

wearing leaves or nothing, spending his time in prayer;

legend says a raven kept

him supplied with bread. Late in life he came to know, and was buried by Saint Anthony

the Abbot. His biography was written by Saint Jerome.

Born

5 January 342 of

natural causes

grave reported to have

been dug by desert lions near

his cave who guarded the body

buried by Saint Anthony

the Abbot

–

Order

of Saint Paul the First Hermit

dead man

whose grave is

being dug by a lion

man being brought food by

a bird

man clad in rough

garments made of leaves or skins

old man,

clothed with palm-leaves, and seated under a palm-tree, near which are a river

and loaf of bread

with Saint Anthony

the Abbot

Additional

Information

An

Old English Martyrology, by George Herzfeld

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Character

Calendar, by Sister Mary Fidelis and Sister Mary Charitas, S.S.N.D

First

of the Hermits, by Mrs Lang

Golden

Legend, by Jacobus

de Voragine

Life

of Paulus, the First Hermit, by Saint Jerome

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Sabine Baring-Gould

Roman

Martyrology, 1914 edition

Roman

Martyrology, 1914 edition

Saints

in Art, by Margaret E Tabor

Saints

of Italy, by Ella Noyes

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

Three

Saints for the Incredulous, by Father Robert

Emmett Holland

books

1001 Patron Saints and Their Feast Days, by Australian

Catholic Truth Society

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

images

video

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites

en français

fonti

in italiano

websites

in nederlandse

nettsteder

i norsk

spletne

strani v slovenšcini

MLA

Citation

“Saint Paul the

Hermit“. CatholicSaints.Info. 17 May 2024. Web. 20 January 2026.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-paul-the-hermit/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-paul-the-hermit/

Book of Saints – Paul

the First

Article

hermit (Saint)

(January

10) (4th

century) The Life of this Saint,

written by Saint Jerome,

tells us that he was an Egyptian of

good birth and well educated.

Still a youth, he fled into the desert country about Thebes to escape the persecution then

raging. Delighted and helped by solitude he persevered in the Eremitical life

even after the Peace of the Church, and is said to have passed ninety years in

the Desert, where he died A.D. 342,

comforted at the end by a visit from Saint Antony,

the Father of Monks.

MLA

Citation

Monks of Ramsgate. “Paul

the First”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info.

10 September 2016. Web. 21 January 2026.

<https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-paul-the-first/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-paul-the-first/

New

Catholic Dictionary – Saint Paul, the First Hermit

Article

Confessor; born Thebes,

Egypt, 230; died 342. Escaping from the persecution of Decius, he took refuge

in a mountain desert, where he lived in a cave for ninety years, in

mortification and prayer; he was visited there by Saint Anthony. Patron of

weavers. Relics at Budapest. Feast, Roman Calendar, 15 January.

MLA

Citation

“Saint Paul, the First

Hermit”. People of the Faith. CatholicSaints.Info. 17

October 2010.

Web. 21 January 2026.

<http://catholicsaints.info/new-catholic-dictionary-saint-paul-the-first-hermit/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/new-catholic-dictionary-saint-paul-the-first-hermit/

St. Paul the Hermit

Feastday: January 15

Patron: of San Pablo City, Philippines

Birth: 229

Death: 342

Also known as Paul the

First Hermit and Paul of Thebes, an Egyptian hermit and friend of St. Jerome.

Born in Lower The baid, Egypt, he was left an orphan at about the age of

fifteen and hid during the persecution of

the Church under Emperor Traj anus Decius. At the age of twenty two he went to

the desert to

circumvent a planned effort by his brother in law to

report him to authorities as a Christian and

thereby gain control of his property. Paul soon found that the eremitical life was

much to his personal taste, and so remained in a desert cave

for the rest of his reportedly very long life. His contemplative existence was

disturbed by St. Anthony, who visited the aged Paul. Anthony also buried Paul,

supposedly wrapping him in a cloak that had been given to Anthony by St.

Athanasius. According to legend, two lions assisted Anthony in digging the

grave. While there is little doubt that

Paul lived, the only source for details on his life are

found in the Vita Pauli written by St. Jerome and

preserved in both Latin and Greek versions.

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=5280

St. Paul the Hermit

St. Paul the Hermit was

reportedly born in Egypt, where he was orphaned by age 15. He was also a

learned and devout young man. During the persecution of Decius in Egypt in the

year 250, Paul was forced to hide in the home of a friend. Fearing a

brother-in-law would betray him, he fled in a cave in the desert. His plan was

to return once the persecution ended, but the sweetness of solitude and

heavenly contemplation convinced him to stay.

He went on to live in

that cave for the next 90 years. A nearby spring gave him drink, a palm tree

furnished him clothing and nourishment. After 21 years of solitude a bird began

bringing him half of a loaf of bread each day. Without knowing what was

happening in the world, Paul prayed that the world would become a better place.

St. Anthony attests to

his holy life and death. Tempted by the thought that no one had served God in

the wilderness longer than he, Anthony was led by God to find Paul and

acknowledge him as a man more perfect than himself. The raven that day brought

a whole loaf of bread instead of the usual half. As Paul predicted, Anthony

would return to bury his new friend.

Thought to have been

about 112 when he died, Paul is known as the “First Hermit.” His feast day is

celebrated in the East; he is also commemorated in the Coptic and Armenian

rites of the Mass.

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/saint-paul-the-hermit/

Paul the First Hermit (RM)

(also known as Paul of Thebes)

Born in Thebaid, Egypt c. 230; died c. 342; feast day in the West was January

10 until the cultus was suppressed in 1969; Eastern feast day is either January

5 or 15.

Saint Paul was from the

lower Thebaid in Egypt and lived during a period in which Christians were

hunted down like criminals for endangering the safety of the state. Paul,

orphaned at 15, had a property inheritance; and his pagan brother-in-law saw a

double opportunity in betraying him to the officers of Emperor Decius: first to

get the reward promised to those who turned in Christians, and second to obtain

for himself the inherited property.

The 22-year-old Paul,

already in hiding in a remote village, was warned by his sister and fled into

the desert, not so much as a permanent place to live as much as a refuge

because he feared that his faith may not be strong enough to endure

persecution. Later, however, the thought of returning to his home left him, and

the vastness of the desert surged up before him as the place where he would

find God. (Remember that this is part of our Judaic heritage. The Israelites

"found" God in the desert, where He led them as a pillar of fire.)

Silence and solitude

frighten most of us; we are afraid to be really alone. That was the first fruit

of the life in the desert for Paul: he was strengthened in spirit, he learned

to consecrate his soul to God alone, and to be alone with the alone. All masks

fall away in such a solitary place; God's voice is no longer choked.

Second, Paul learned in

the desert to trust in God to supply all his needs. Having renounced all

things, Paul needed very little: a palm tree to clothe him and perhaps to

protect him from the sun, bread to nourish his body, and water to slake his

thirst. The palm tree also provided his only food until he was 43 (about 21

years). Then, it is said that, like Elias, he was fed miraculously each day; a

raven descended carrying just the right amount of bread for the day. Whether we

trust such stories or not, life must have been difficult enough and it must

have taken an enormous simplicity and trust in God for Paul to survive.

The story of Paul is full

of the comings and goings of a 'rival' hermit of the desert: Saint Antony. How

they overcome their singular rivalry; how they sit down to eat their miraculous

banquets together; how they pray and fast in a combat of spirituality: these

are the tales biographers give us. They also suggest the profound friendship

that must have existed at the deepest possible level for these two men of

identical, yet altogether unusual, vocations.

It is said that God first

revealed Paul's existence to Antony, because he was tempted to vanity at the

thought that he had served God longest in the desert. After the revelation,

Antony searched three days to find Paul (here Jerome's narrative becomes a

little bizarre with centaurs and satyrs, etc.). Finally, he followed a thirsty

she-wolf into a cave thinking to find water for himself, and found Paul, too.

They knew each other at once and praised God.

While they were talking,

a raven flew towards them, and dropped a loaf of bread before them. Upon which

Paul said, "Our good God has sent us dinner. In this manner I have

received half a loaf every day these 60 years past; now you are come to see me,

Christ has doubled his provision for his servants."

On that first meeting, it

seemed that they would never eat. Paul insisted that his guest must have the

privilege of breaking the bread, whereas the 90-year-old youngster Antony

wanted to defer to the elder Paul. The stalemate was broken before the bread

grew too stale--they acted simultaneously.

Paul predicted to Antony

the time of his death, and asked him to wrap and bury his body in a cloak given

to Antony by Athanasius, bishop of Alexandria. Rushing to obtain the cloak,

Antony saw Paul's body in a vision carried up to heaven attended by angels,

prophets, and apostles. He found Paul's body kneeling in prayer with his arms

stretched out, as was the custom. For the rest of his own life, Saint Antony

cherished Paul's palm-leaf clothing, and wore it himself on important church

feasts.

According to Saint Jerome

who was one of the hermit's biographers, Paul died in 342 at age 113, having

spent about 90 years in the desert. It is said that two lions came and dug his

grave.

He is called Paul the

First Hermit, not because he was the first desert solitary--though he may have

been the first who was Christian, but in order to distinguish him from other

hermits named Paul. Saint Jerome's Life of Paul, based on a Greek original, is

almost the only source for the details of the hermit's life, but it is a

mixture of fact and fantasy (Attwater, Benedictines, Bentley, Butler, Delaney,

Encyclopedia, Farmer, Waddell).

In art Saint Paul can be

identified as an old man in plaited palm leaves breaking bread with Saint

Antony (). At times (1) a raven brings them bread, (2) he is naked with only a

girdle of palms leaves (not to be confused with Onuphrius) (3) with a hind by

him, or (4) buried by Saint Antony with two lions nearby (Roeder). Scenes from

Paul's life, especially the meeting with Antony, are depicted on the Ruthwell

cross (c. 700) and on some Irish crosses. He also appears on the 15th-century

rood-screen of Wolborough (Devon) with other monastic saints (Farmer).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0115.shtml

Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652), Saint Paul of Thebes, circa 1630, 197 x 153, Louvre

Museum, Paris

St. Paul the Hermit

There are three important

versions of the Life of St. Paul: (1) the Latin version (H)

of St.

Jerome; (2) a Greek version (b), much shorter than

the Latin; (3) a Greek version (a), which is either a

translation of H or an amplification of b by means of H.

The question is whether H or b is the original. Both a and b were

published for the first time by Bidez in 1900 ("Deux versions

grecques inédites de la vie des s. Paul de

Thébes", Ghent). Bidez maintains that H was the

original Life. This view has been attacked by Nau, who makes b the

original in the "Analect. Bolland." of 1901 (XX, 121-157).

The Life, minor details excepted, is the same in other versions.

When a young man of sixteen Paul fled into the desert of

the Thebaid during

the Decian persecution.

He lived in a cave in the mountain-side till he was one-hundred-and-thirteen.

The mountain, adds St.

Jerome, was honeycombed with caves.

When he was ninety St. Anthony was tempted to vain-glory,

thinking he was the first to dwell in the desert.

In obedience to a vision he set forth to find his

predecessor. On his road he met with a demon in the form of a

centaur. Later on he spied a tiny old man with horns on his head. "Who are

you?" asked Antony. "I am a corpse, one of those whom the heathen call

satyrs, and by them were snared into idolatry."

This is the Greek story (b) which makes both centaur

and satyr unmistakably demons, one of which tries to terrify

the saint,

while the other acknowledges the overthrow of the gods. With St.

Jerome the centaur may have been a demon; and may also have been

"one of those monsters of which the desert is

so prolific." At all events he tries to show the saint the

way. As for the satyr he is a harmless little mortal deputed by his

brethren to ask the saint's blessing.

One asks, on the supposition that the Greek is the original,

why St.

Jerome changes devils into centaurs and satyrs. It is not

surprising that stories of St. Anthony meeting

fabulous beasts in his mysterious journey should spring up

among people with whom belief in

such creatures lingered on, as belief in

fairies does to the present day. The stories of the meeting

of St. Paul and St. Anthony, the raven who brought them

bread, St. Anthony being sent to fetch the cloak given him by

"Athanasius the bishop"