Bienheureuse Olympie

(Olga) Bidà, vierge et martyre

Née en Ukraine en 1903,

elle entre chez les sœurs de Saint Joseph et sert comme catéchiste dans divers

villes et villages. Elle a un charisme envers les jeunes. Devenue supérieure du

couvent de Kheriv, elle fait de son mieux pour assurer les besoins spirituels

de la société malgré le régime communiste. Arrêtée avec d'autres sœurs en 1951,

emprisonnée puis déportée au camp de détention de Kharsk près de Tomsk, en

Sibérie, elle est soumise aux travaux forcés. Elle organise ses sœurs et

d'autres religieuses du camp pour s'entraider et prier ensemble et supporte,

pour l’amour du Christ, toutes les adversités infligées, qui la conduisent à la

mort le 28 janvier 1952, après une grave

maladie.

Bienheureuse Olympia

(Olga Bida)

Martyre du régime

communiste (+ 1952)

Née en 1903, elle entre chez les sœurs de Saint Joseph et sert comme catéchiste dans divers villes et villages. Elle a un charisme envers les jeunes. Devenue supérieure du couvent de Kheriv, elle fait de son mieux pour assurer les besoins spirituels de la société malgré le régime communiste. Arrêtée avec d'autres sœurs en 1951, emprisonnée puis exilée en Sibérie, aux travaux forcés, elle organise ses sœurs et d'autres religieuses du camp pour s'entraider et prier ensemble. Elle meurt après une grave maladie le 28 janvier 1952.

Béatifiée le 27 juin 2001 avec 24 autres grecs-catholiques dont Nicolas Carneckyj par Jean-Paul II lors de son voyage en Ukraine.

Biographie en anglais - homélie du Pape - site du Vatican.

Au camp de détention de Kharsk près de Tomsk en Sibérie, l'an 1952, la

bienheureuse Olympie (Olga Bida), vierge, de la Congrégation des Sœurs de Saint

Joseph, et martyre, qui supporta, pour l'amour du Christ, toutes les adversités

infligées par le régime communiste soviétique.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/11393/Bienheureuse-Olympia-%28Olga-Bida%29.html

Bienheureuse Olympia BIDÀ

Nom: BIDÀ

Prénom: Olga (Olha)

Nom de religion: Olympia

Pays: Ukraine

Naissance:

. .1903 à Tsebliv (Lviv)

Mort: 28.01,1952 à

Tomsk (Sibérie)

Etat: Religieuse -

Martyre du Groupe des 25

martyrs d'Ukraine 2

Note: Sœur de Saint

Joseph. Sœur Olympia. Catéchiste, maîtresse des novices, éducatrice. Supérieure

du couvent de Kheriv. Déportée à Tomsk en Sibérie en 1951. Elle y meurt en

1952.

Béatification:

27.06.2001 à Lviv (Ukraine) par Jean Paul II

Canonisation:

Fête: 27 juin

Réf. dans l’Osservatore

Romano: 2001 n.26 p.1-5 - n.27 p.9-10 - n.28 p.12

- n.29 p.2.5

Réf. dans la Documentation

Catholique: 2001 n.15 p.747-749

Notice

Olha Bidà naît en 1903 au

village de Tsebliv dans la région de Lviv. Elle entre chez les Sœurs de Saint

Joseph et prend le nom d'Olympia. Elle sert dans de nombreuses villes ou

villages comme catéchiste. Elle est maîtresse des novices et prend soin des

personnes âgées et infirmes. Elle a un charisme spécial pour les jeunes et

s'occupe personnellement de l'éducation d'un grand nombre de jeunes femmes.

Nommée supérieure du couvent de la ville de Kheriv, elle fait de son mieux pour

discerner les besoins spirituels et sociaux de la population en dépit de la

pression exercée par les communistes pour entraver leur travail. En 1951 elle

est arrêtée avec deux autres religieuses, emprisonnée pendant un certain temps,

puis envoyée en exil dans la région de Tomsk en Sibérie. Soumise à de rudes

travaux forcés, Sœur Olympia essaie de remplir ses devoirs de supérieure auprès

de ses Sœurs, faisant venir des Sœurs isolées dans d'autres camps afin de prier

et de s'entraider; mais peu de temps après son arrivée, elle succombe à la

maladie et meurt le 28 janvier 1952.

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/hagiographie/fiches/f0569.htm

Also

known as

Olga

Olha

Ol’ha

Olimpia

27 June as

one of the Martyrs

Killed Under Communist Regimes in Eastern Europe

Profile

Greek

Catholic. Joined the Congregation of the Sisters of Saint Joseph.

Worked in several towns as a catechist and novice

director, and with the aged and sick. Taught and

helped to raise several young women. Convent superior

in Kheriv where the Communists worked against her. Arrested for

her faith in 1951,

and exiled to

a forced labour camp in the Tomsk region of Siberia in Russia.

In the camp she continued her duties as superior, and organised other exiled nuns into prayer and

support groups. Martyr.

Born

1903 at

Tsebliv, L’vivs’ka oblast’, Ukraine

28 January 1952 in

Kharsk, Tomskaya oblast’, Russia

24 April 2001 by Pope John

Paul II (decree of martyrdom)

27 June 2001 by Pope John

Paul II in Ukraine

Additional

Information

other

sites in english

images

fonti

in italiano

Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

nettsteder

i norsk

MLA

Citation

“Blessed Olympia

Bida“. CatholicSaints.Info. 1 October 2021. Web. 28 February 2022.

<https://catholicsaints.info/blessed-olympia-bida/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/blessed-olympia-bida/

SOURCE : https://www.vatican.va/news_services/liturgy/saints/ns_lit_doc_20010627_carneckyj_en.html

Martyrs of Communism: Blessed

Olympia Bida

The saints and blesseds

who died under Communism can help us see why someone would choose death rather

than blindly follow an ideology that not only denies the existence of God, but

also denies human dignity.

January 28, 2022 Dawn Beutner Features, History 10Print

Left: Blessed Olympia Bida (Image:

https://catholicsaints.info/); right: A fence at an old Gulag camp (Image:

Gerald Praschl/Wiklpedia)

How many people have died

as a result of Communism? The Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation makes

the bold statement on the front page of their web site that 100 million human

beings have been killed by Communism. Could this be true?

Obviously, simply living

your entire life in a Communist state doesn’t mean that you were killed by

Communism.1 However, there are some unique

features of Communism as a form of government that make it easy to believe that

such a staggering human cost is not unlikely. For example, the Communist

government in Russia instituted prison camps where death was almost a certainty

for its prisoners; letting someone know that you believed in God was sufficient

cause to be sentenced to one of them.

When Communist countries

invaded other countries for the sake of their ideological goals, those who died

in the resulting wars were clearly victims of Communism. People who died by

starvation due to the poor economic policies which are inherent in Communism

were also obviously victims of Communism. These three categories alone start to

make 100 million victims sound reasonable.

But how can we measure

such an immense loss? Who can fathom the joys, sorrows, and inherent worth of

100 million individual human lives? Only God can. That’s why the saints and

blesseds of the Church who died under Communism can help us see not only the

tragedy of an individual life cut short, but why someone would choose death

rather than blindly follow the ideology of a form of government that not only

denies the existence of God, but also denies human dignity.

Olga Bida was born in

1903 in the little village of Tsebliv in Ukraine. She was raised in the Greek

Catholic Church. To understand her life, it helps to understand a little of the

history of her native country.

For about two hundred

years prior to Olga’s birth, Ukraine had been under the control of czarist

Russia. A revolution in Russia in early 1917, when Olga was only a teenager, gave

the Ukrainian people hope for independence, but that hope was in vain. When

Vladimir Lenin took control of Russia several months later, Lenin was unwilling

to give up control over the food produced by the fertile land of Ukraine. It

took four years of fierce fighting, but Lenin eventually won, and Ukraine fell

under Communist control in 1921. Lenin loosened his tight grip over the country

for a few years to avoid grumbling from the nation’s farmers, and Ukraine

briefly experienced a national revival in folk customs, religion, and the arts.

At about that time, Olga

discerned that God was calling her to religious life. It is always difficult

for a person to discern a religious vocation, and living under a regime that

denied the existence of God couldn’t have made it easier to make such a choice.

However, Olga entered the Sisters of Saint Joseph and took the name in

religious life of Olympia.

Life in Ukraine changed

when Lenin died. Joseph Stalin wanted greater control over the troublesome

Ukrainian people, so in 1929, he ordered thousands of their scholars, leaders,

and scientists summarily shot or sent to prison camps. He took land away from

their farmers, and he sent those farmers—and many others—to work in mines as

virtual slaves.

When the people unsurprisingly

continued to resent his propaganda and threats, Stalin punished the entire

country. In 1933, he stole all the food produced in Ukraine and conspired with

Communist sympathizers all over the world to pretend that the Ukrainian people

were not starving to death, when, of course, they were. Descriptions of

emaciated children and the sight of people dropping dead in the streets were

conveniently omitted by the foreign press corps while 25% of the Ukrainian

people—several million human beings—died of starvation.

During the famine of

1932-1933, how many people did Sister Olympia personally know—other sisters in

her community, family members, friends, classmates—who died from starvation? We

don’t know. But everyone who survived the Holodomor, the name which was given

to this event and which means, roughly, “killing by starvation”, experienced a

deep personal suffering as a direct result of Communist ideology and politics.

In 1938, Olympia became

the superior of her community in the town of Khyriv. She and her sisters cared

for the sick and the elderly, taught young women about the faith, and quietly

did what all religious sisters do: prayed to God and witnessed to the grace and

beauty of a life lived solely for Him. Persecution of believers continued as

control of the country changed from the Soviet Union, to Nazi Germany, and then

back to the Soviet Union after World War II.

In 1950, the NKVD (Soviet

secret police) decided that Olympia was engaged in “anti-Soviet activities”;

her only crime was probably that she was a Catholic and a leader of other

Catholics. Olympia was sentenced to hard labor in Boryslav (Ukraine) and then

lifelong exile in Russia. The almost subarctic conditions of the Tomsk region

of Siberia, combined with the inhuman conditions of her prison camp, made life

extremely harsh. Olympia served as the superior of the other sisters who had

also been sentenced to the camp, she cared for those in need, and she led other

prisoners in prayer.

She died less than two

years after her arrest, in early 1952, having inspired those around her with

her faith. The Church considers her a martyr. After all, it was her faith in

God, not her political opinions, that caused her early death. Blessed Olympia’s

feast day is celebrated on January 28.

What did she accomplish

by being a Catholic and a religious sister, when her life could have been much

easier and much longer if she had simply given up her vocation, her

responsibilities to others in need, and her faith in God? In a letter she wrote

to her superior before her death, Blessed Olympia spoke of God’s providence.

She expressed her trust that God continues to care for every single one of His

children, even those who are far from home and imprisoned for their faith.

Blessed Olympia knew God,

loved God, and served God. Even Communist prisons cannot prevent a person from

fulfilling the purpose for which God made every single one of us. And

fulfilling that purpose can make any one of us a saint.

Endnotes:

1 For

historical information about Communism from a Catholic perspective, see Dr.

Warren Carroll’s The Rise and Fall

of the Communist Revolution. For information about Communism and Socialism as a form of government

from a Catholic perspective, see Trent Horn and Catherine R. Pakaluk’s Can a Catholic Be a Socialist ?

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report

provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your

contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers

worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more

information on donating to CWR. Click here to

sign up for our newsletter.

About Dawn Beutner 31 Articles

Dawn Beutner is the

author of Saints:

Becoming an Image of Christ Every Day of the Year from Ignatius Press

and blogs at dawnbeutner.com.

SOURCE : https://www.catholicworldreport.com/2022/01/28/martyrs-of-communism-blessed-olympia-bida/

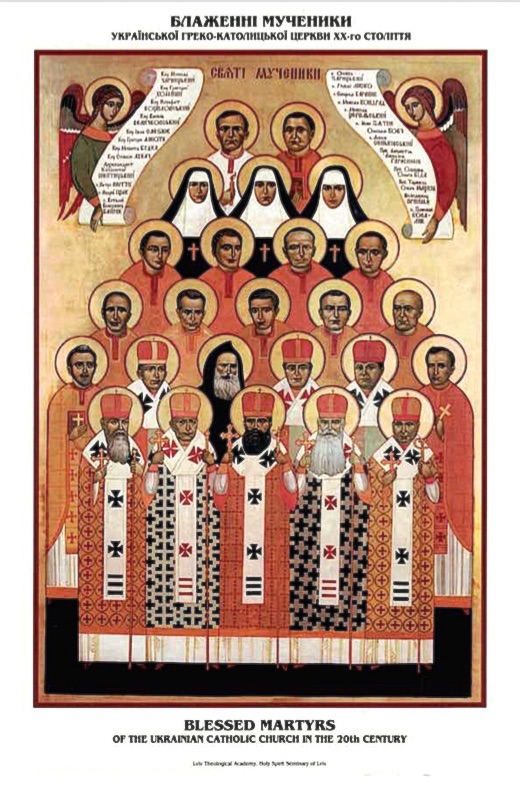

The New Martyrs of the

Ukrainian Greco-Catholic Church

His Beatitude Patriarch

Sviatoslav blessed the transfer of the relics of new martyrs of Ukrainian

Greek-Catholic Church to venerate in the projected Immaculate Conception Ukrainian

Byzantine Catholic Shrine.

Pope John Paul II’s

solemn proclamation of the new martyrs and faithful servants of God of the

Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church as blessed is another divine manifestation to

our people. During more than 1,000 years of salvation history on our land,

Ukrainian Christians have rejoiced in various signs of God’s presence. The Word

has become incarnate among us has been changed into visible sacraments: the

healing water of baptism, the oil of the Holy Spirit, the bread and wine of the

Lord’s paschal feast. They lead us to the divine life. “God is with us!”

He has built His house

here. Great Church councils throughout the ages and quiet little chapels speak

to us. The warm and hospitable face of the Lord looks into our souls from

childhood. His image is embroidered on our decorative cloths at home. The

feasts of the liturgical year sanctify our time, invite us to overcome our lack

of faith and our doubts, and to feel that we live in the age of the Kingdom of

God.

We receive this mercy of

the Lord through the blessing of hierarchs and priests, on whose heads we can

still feel the warm hands of the priests and martyrs Hryhorii, Theodore,

Josaphat, Nykyta, Hryhorii, Mykola, Semeon, Ivan and Vasyl. We celebrate

together with monks and nuns who still today remember the sanctifying

righteousness of Sister Josaphata and the “aristocracy of spirit” of priest and

martyr Klymentii. They remember these fathers and sisters of their communities

– kind, welcoming and, at the same time, brave and constant in the faith. We

rejoice with Neonila Lysko, who can still today tell us about the eyes of her

good husband, full of troubles: Neonila who for such a short time was comforted

by his close presence but his glory will last. Together with Father Emilian

Kovch’s children, who are with us, we pass on his testament of love of neighbor

and love of enemy.

From now on from our

midst, for us and for the world, the universal Church raises them up as

examples of holiness, as heavenly friends of the Lord, humble figures of mortal

human beings. Yesterday they lived among us or among our parents in our cities

and villages, bravely fought with the greatest tyrants of human history,

against wrongs and injustices done to their brothers and sisters. They also

struggled with their own imperfections and with the simple worries of daily

life. Their presence here was and now is, incredibly, still felt.

They walked our streets

and rode on our roads, sat on our episcopal thrones and in our confessionals.

They gave lectures at solemn conferences and reports from their professorial

chairs, and studied in our Theological Academy and seminaries. They probably

did not think that the terrible trial of martyrdom and its everlasting crown

was waiting for them. They wore priestly vestments and the habits of our

religious communities and heard stirring words from their spiritual directors

about self-giving and self-dedication, which we often hear but receive as

something everyday, as an abstraction, something unreal and far away in time

and space.

Now their figures are

strangely close, visible. Through them holiness itself is closer. They bring

heaven closer to us – sometimes so unattainable – heaven, where they have

gloriously found their place at the hand of the Almighty Father and Our

Creator. And the land on which they walked only yesterday has itself become

holier, receiving their hot blood and tortured bodies. Walking on this same

earth we feel the grandeur of this holiness and the depth of this drama which

they lived through and to which the Lord can call you and me.

Finally, we were all

called long ago-called to love our neighbour, forgive our enemies, feed the

hungry, tend to the wounded, comfort the weary, give hope to the hopeless and

die to self in order to live for others. Today on our earth and in our Ukraine

there is no lack of opportunities to dedicate yourself to God.

Through these blessed and

martyrs, whom we are honouring today, the Lord has shown us that for us mere

mortals, who are neighbours, fellow workers or students, relatives and family

members or just friends, for us such accomplishments are possible. God reveals

Himself always and everywhere: in the quiet of a monastic cell and in an

inspiring sermon in church, among the Siberian snows and in the burning oven of

Majdanek, in the joy of motherhood and in the cries of an orphaned child …

Will we be able here and

now, and then tomorrow and elsewhere, to respond to this appearance of our

Lord? Are we ready to give witness to Christ in everyday life or, God forbid,

in the face of mortal danger? We hope in the Lord that this is so. And our

first step in this direction is our joyful celebration of these abundant

blessings which have come to us through the solemn glorification of the new martyrs

and faithful servants of God. Let us be glad with them and with certainty

follow in their footsteps!

Father Borys Gudziak,

Ph.D. is rector of the Lviv Theological Academy and director of the Institute

of Church History. Written in 2001.

Church of the Martyrs

Following are

biographical materials prepared by the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church. The

information is organized in chronological order.

Sanctifying righteousness

Sister Josaphata (Michaelina) Hordashevska was

born in Lviv on November 20, 1869. At the age of 18, influenced by the retreats

of the Basilian Fathers, she felt the call to consecrate her life to God.

Together with Father Kyryl Seletskyi, pastor in Zhuzhel, and Father Yeremia

Lomnytskyi OSBM, she established a new congregation, the Sisters Servants of

Mary Immaculate, called to an active apostolate among the people. Today the

Sisters Servants is the biggest female religious community in the Ukrainian

Greek-Catholic Church.

Sister Josaphata’s

holiness showed itself in her total dedication to her calling, in constantly

embodying in her life Christ’s command to love God and neighbor and in humbly

bearing all her difficulties and sufferings. She died on April 7, 1919, after a

long and severe illness, prophesying the day of her death, which she accepted

consciously, with prayer on her lips.

“She showed her love for

her people through her heart-felt desire to lift them up morally and

spiritually: she taught children, youth and women, served the sick, visited the

poor and needy, taught liturgical chant and looked after the church’s

beauty.” – From the testimony of Sister Filomena Yuskiv.

Apostle of unity

Priest and

martyr Father Leonid Feodorov was born to a Russian Orthodox family

on November 4, 1879, in St. Petersburg, Russia. In 1902, he left his studies at

the Petersburg Spiritual Academy and went abroad. In Rome he converted to

Catholicism. He studied in Anagni, Rome and Frieburg. Contact with Metropolitan

Andrey Sheptytsky had a great influence on Father Leonid’s spiritual

development. On March 25, 1911, he was ordained a Greek-Catholic priest. In

1913 he became a monk of the Studite order in Bosnia.

After his return to

tsarist Russia, in connection with the beginning of World War One he was exiled

to Tobolsk, Siberia because he was a Catholic. In 1917 he was released and

appointed head of the Russian Greek-Catholic Church, with the title of exarch.

His second imprisonment came in 1923, now by the Bolsheviks, for 10 years. From

1926 to 1929 he served his term in Solovky and later in exile in Pinieza,

Kotlas and Viatka. He died as a martyr for the faith and Church unity on March

7, 1935.

“We expect that the

exarch is on the road to glorification through beatification. Of course, it is

much too early to talk about this, but all of us were strongly impressed by his

holiness, strengthened by the crown of martyrdom and death; this certainly

supports our expectations. On the other hand, as a Russian Catholic, as exarch,

as someone who died at the hands of the Bolsheviks, it seems to us that he will

be right in the centre of attention of the entire Church.” – From

Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky’s letter to Prince P. Volkonski of May 4, 1935.

Bloody Unification

Stalin’s attack on the

Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church (UGCC) began immediately after the first

occupation of western Ukraine in September 1939. This occupation was in

accordance with the Soviet-Nazi Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and lasted until June

1941. In this period all UGCC property was confiscated, and schools and

hospitals were nationalized. Church publications and religious organizations

were forbidden, religious educational institutions and presses were closed, the

activities of religious congregations were limited, brutal atheist propaganda and

mass terror, and the deportation of a peaceful population began.

“It is absolutely clear

that under the Bolsheviks we all felt destined for death; they did not conceal

their intention to destroy, to strangle Christianity, to erase its smallest

traces.” – From Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky’s letter to the nuncio,

Rotti, of August 30, 1941.

Patron of Students

Priest and

martyr Father Mykola Konrad was born on May 16, 1876 in the village

of Strusiv, Ternopil District. He finished his philosophical and theological

studies in Rome, where he defended his doctoral dissertation. In 1899, he was

ordained to the priesthood. He taught in a high school in Berezhany and

Terebovlia. In 1929 in Lviv he founded Obnova (Renewal), the first Ukrainian

association of Catholic students.

In 1930 Metropolitan

Andrey Sheptytsky invited him to teach at the Lviv Theological Academy and

later appointed him to be a parish priest in the village of Stradch, near

Yaniv. There, as in previous years, he showed his great diligence and responsibility,

fulfilling his pastoral duties, in particular, spiritual guidance for youth.

Returning from visiting a sick woman, who had requested the sacrament of

reconciliation, he died tragically as a martyr for the faith at the hands of

the NKVD on June 26, 1941, near Stradch.

“Doctor Konrad, a

professor at the academy, my catechist … O, he was a distinguished person. An

ideal man. He was very involved with youth; he had a heart for youth – and for

his people. He wanted us to be patriots, to be good and aware students. That

was Father Konrad…” – From an interview with Father Mykola Markevych.

Sacrificial Cantor

Martyr Volodymyr

Pryima was born on July 17, 1906, in the village of Stradch, Yavoriv

District. After graduating from a school for cantors he became the cantor and

choir director in the local church. He took active part in the life of his

parish. Always and in everything he respected human dignity and built his life

on the principles of the gospel. On June 26, 1941, agents of the NKVD

mercilessly tortured and murdered him along with Father Mykola Konrad.

“Father Konrad went with

the holy sacraments to fulfil his sacred obligation, hearing a woman’s

confession in the neighbouring village. He felt he had to go, though he was

stopped. I know that they stopped him and said: ‘Father, don’t go. Look what’s

happening: the war has started, anything could happen.’ He said that this was

his sacred duty and he had to go. He got dressed and left together with

Volodymyr Pryima, the cantor. They didn’t come back. After a week they were

found there, murdered. People thought something was wrong. So they went to look

for them and they found them there. It was awful. The cantor’s wife had two

children. One was three, the other was four. Mama told me how when they were found

everyone was overcome by what they saw. The cantor was especially cut up, his

chest stabbed with a bayonet many times.” – From an interview with Yuriy

Skavronskyi.

Professor and Pastor

Priest and

martyr Father Andrii Ischak was born on September 20, 1887, in

Mykolaiv, in the Lviv District. He finished his theological studies at the

universities in Lviv and Innsbruck (Austria). In 1914 he received his Ph.D. in

theology and was ordained. Beginning in 1928 he taught dogmatic theology and

canon law at the Lviv Theological Academy.

He was able to combine

his professorial duties with his pastoral work in the village of Sykhiv near

Lviv, where he met his death. Even under the threat of great danger he did not

leave his parishioners without spiritual guidance. He was faithful to the end.

On June 26, 1941, he died a martyr for the faith at the hands of soldiers of

the retreating Soviet army.

“As the war began, the

priest was taken at Persenkivka, the neighbouring station. Sometime in the

afternoon they took him, detained him until the evening, then they let him go.

My dad, because they knew each other well, told him: ‘Father, when they let you

go, I would advise you to hide for a few days.’ Because it was already clear

that the Germans were coming and the Bolsheviks would be fleeing. ‘Hide

yourself and we’ll survive.’ But the priest said: ‘Ivan, the shepherd doesn’t

abandon his flock. And I can’t leave my parishioners and conceal myself.’ In

two days the military came and took him from his home. It was overgrown there

with bushes, some distance from the parish, maybe a half-kilometre. They

brought him there and killed him. They shot him in the stomach, and it looked

like they also stabbed him with a knife.” – From the testimony of Ivan

Kulchytskyi.

Benevolent Prior

Priest and

martyr Father Severian Baranyk was born on July 18, 1889, place of

birth unknown. On September 24, 1904, he entered the monastery of the Basilian

Fathers in Krekhiv. He was ordained to the priesthood on February 14, 1915. In

1932 he became the hegumen (prior) of the monastery in Drohobych. In life he

was noted for his special kindnesses to youth and orphans. He inspired all with

his joy and was famous for his preaching.

On June 26, 1941, the

NKVD arrested him. They brought him to a prison in Drohobych, after which he

was never seen alive again. His body, mutilated by tortures, was found among

other dead prisoners. He died a martyr for the faith at the end of June 1941.

“Behind the prison I saw

a big hole which had been covered up, filled with sand. When the Bolsheviks

retreated the Germans came and people rushed to the prison to find their

relatives. The Germans allowed people into the area of the prison in small

groups to claim their murdered relatives, but most people stood by the gates. I

was a little boy and didn’t see anything from the gates, so I went to the side

and climbed a tree. There was a terrible stink … I saw how the Germans sent

people to uncover the hole which was filled with sand. The hole was new,

because the people uncovered it with their hands. They dragged out the murdered

bodies. There was a little covering near the hole, and under it I saw the dead

body of Father Severian Baranyk, Basilian, with visible marks of his prison

tortures; his body had unnaturally swelled, black, his face terrible. Dad later

said that on his chest the sign of the cross had been slashed.” – From the

testimony of Yosyf Lastoviak.

Loving Monk

Priest and

martyr Father Yakym Senkivskyi was born on May 2, 1896, in the

village of Hayi Velyki, Ternopil District. After completing his theological

studies in Lviv, he was ordained as a priest on December 4, 1921. He received a

Ph.D. in theology in Innsbruck (Austria). In 1923 he became a novice in the

Basilian order in Krekhiv. After professing his first vows he was assigned to

serve in the village of Krasnopuscha, and later in the village of Lavriv, in

the area of Starosambir. From 1931 to 1938 at St. Onufry monastery in Lviv he

was chaplain of the Marian Society, he ministered to children and youth and

organized a Eucharistic Society. In 1939, he was appointed proto-hegumen

(abbot) at the monastery in Drohobych.

He was arrested by the

Bolsheviks on June 26, 1941. According to the testimony of various prisoners,

he was boiled to death in a cauldron in the Drohobych prison on June 29.

Because of his righteous life the faithful held him up as a model of service to

Church and nation. He died a martyr for the faith.

“From the first days of

his time in Drohobych he became the favourite of the whole town. He gained the

affection of the population with his remarkable talent, his ability to speak to

the scholar and the labourer, young and old, and even to the little child. He

was always polite and with a warm smile on his face. In your soul you felt that

this person had no malice, and in addition to the impression of humility and

dignity, a true servant of Christ was evident.” – From the memories of

Father Orest Kupranets.

Fearless Preacher

Priest and

martyr Father Zenovii Kovalyk was born on August 18, 1903, in the

village of Ivakhiv near Ternopil. He entered the Congregation of the

Redemptorists and on August 28, 1926, he made his religious vows. He received

his philosophical and theological education in Belgium. He returned to Ukraine

and on September 4, 1937, was ordained to the priesthood. He served as a

missionary in Volyn.

On December 20, 1940, he

was arrested in church while giving a homily. After terrible tortures he was

murdered by the Communists in a mock crucifixion against a wall in a prison on

Zamarstynivska Street, in Lviv in June 1941. He died a martyr for the faith.

“[His] sermons made an

incredible impression on the listeners. But in the prevailing system of

denunciations and terror this was very dangerous for a preacher. So I often

tried to convince Father Kovalyk … that he needed to be more careful about the

content of his sermons, that he shouldn’t provoke the Bolsheviks, because here

was a question of his own safety. But it was all in vain. Father Kovalyk only

had one answer: ‘If that is God’s will, I will gladly accept death, but as a

preacher I will never act against my conscience.’” – From the memories of

Yaroslav Levytskyi.

A New Order

The beginning of the

Nazi-Soviet war on June 22, 1941, for many western Ukrainians meant, first of

all, the liquidation of the hated Bolshevik domination and led to unfulfilled

expectations for the revival of religious freedom and the achievement of their

national aspirations. However, it was soon apparent that changing one bloody

regime for another would not change the essence of totalitarianism.

“… The terror is growing.

During the last two months in Lviv more than 40,000 Jews were murdered. The

authorities conducted searches in the church, in my residence and in parts of

the monastery … Two monks were imprisoned, and perhaps there will be attempts

to create some ‘show trials.’ The arrests continue. This is a regime of raving

madmen.” – From a letter of Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky to Cardinal

Tisserand of December 28, 1942.

Rescuer of the Doomed

Priest and

Martyr Father Emilian Kovch was born on August 20, 1884, in Kosmach

near Kosiv. After graduating from the College of Ss. Sergius and Bacchus in

Rome, he was ordained to the priesthood in 1911. In 1919 he became field

chaplain for the Ukrainian Galician Army. After the war and until his

imprisonment he conducted his priestly ministry in Przemysl (Peremyshl), at the

same time tending to his parishioners’ social and cultural life. He helped the

poor and orphans, though he had six children of his own.

During World War II he

bravely carried out his priestly duties, preaching love to people of all

nationalities and rescuing Jews from destruction. He was arrested by the

Gestapo on December 30, 1942. He displayed heroic bravery in the concentration

camp, protecting the prisoners sentenced to death from falling into despair. He

was burned to death in the ovens of the Majdanek Nazi death camp on March 25,

1944. He was recognized as a “Righteous Ukrainian” by the Jewish Council of

Ukraine on September 9, 1999.

“I understand that you

are trying to free me. But I am asking you not to do anything. Yesterday they

killed 50 persons here. If I were not here, who would help them to endure these

sufferings? I thank God for His kindness to me. Except heaven this is the only

place I would like to be. Here we are all equal: Poles, Jews, Ukrainians,

Russians, Latvians and Estonians. I am the only priest here. I couldn’t even

imagine what would happen here without me. Here I see God, Who is the same for

everybody, regardless of religious distinctions which exist among us. Maybe our

Churches are different, but they are all ruled by the same all-powerful God.

When I am celebrating the Holy Mass, everyone prays … Don’t worry and don’t

despair about my fate. Instead of this, rejoice with me. Pray for those who

created this concentration camp and this system. They are the only ones who

need prayers May God have mercy on them…” – From Father Emilian Kovch’s

letters written in the concentration camp to relatives.

Second Assault

The prospect of the

return of Soviet power to western Ukraine after the defeat of the German Army

on the Eastern Front led the hierarchy and faithful of the UGCC to fear for the

fate of the Church. All too painful were the still fresh memories of the

violence of the Communist regime against the conscience of the faithful during

the previous Soviet conquest of less than two years.

“The Bolshevik Army is

approaching … This news fills all the faithful with fear. Everyone … is

convinced that they are destined for certain death.” – From a letter of

Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky to Cardinal Tisserand on March 22, 1944.

“Because she was a nun”

Nun and

Martyr Sister Tarsykiya Matskiv was born on March 23, 1919 in the

village of Khodoriv, Lviv District. On May 3, 1938 she entered the Sisters

Servants of Mary Immaculate. After professing her first vows on November 5,

1940, she worked in the convent, sewing clothes for the sisters and teaching

the skill to others. Even prior to the Bolshevik arrival in Lviv, Sister

Tarsykiya had made a private oath to her spiritual director, Father Volodymyr

Kovalyk OSBM, that she would sacrifice her life for the conversion of Russia

and for the good of the Catholic Church.

On July 17, 1944 Soviet

soldiers surrounded the monastery, determined to destroy it. At 8 a.m. Sister

opened the door, expecting a priest who was supposed to celebrate the liturgy.

Without warning an automatic shot her dead. All her life she witnessed to the

authenticity of the consecrated life. She died a martyr for the faith.

“Suddenly the bell at the

gate rang. We thought it was the priest. Sister Tarsykia opened the door, asked

Sister Maria for the key to the front door and went to the main entrance. Then

a shot rang out and Sister Tarsykia fell down dead. The soldier who shot her

did not really explain why he did it. Later they said that he said he killed

her because she was a nun.” – From the testimony of Sister Daria Hradiuk.

Friendly missionary

Priest and

Martyr Father Vitalii Bairak was born on February 24, 1907 in the

village of Shvaikivtsy, Ternopil District. In 1924 he entered the Basilian

monastery. He was ordained a priest on August 13, 1933. In 1941 he was

appointed superior of the Drohobych monastery, in place of the recently

martyred Father Yakym (Senkivskyi).

On September 17, 1945 the

NKVD arrested Father Vitalii and on November 13 sentenced him to eight years’

imprisonment “with confiscation of property” (though he had none). In life he

was distinguished for his friendliness, his activeness in mission and

preaching. He possessed the gift of spiritual direction. He died a martyr for

the faith just before Easter 1946 after having been severely beaten in the

Drohobych prison.

“Living in the territory

that had been temporarily occupied by German forces…, he wrote an article with

a negative position towards the Bolshevik Party, which had been published in

the anti-Soviet calendar Misionar [“Missionary”] in 1942.” – From the

personal file of V. V. Bairak in the archives of the Ministry of Internal

Affairs.

Father-Psalmist

Priest and

Martyr Father Roman Lysko was born on August 14, 1914 in Horodok,

Lviv District. He finished his theological studies at the Lviv Theological

Academy. Possessing special poetic and artistic talents, he and his wife

joyfully conducted youth ministry together. On August 28, 1941 he was ordained

to the priesthood by Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky.

He refused to sign a

statement of conversion to Orthodoxy, remaining faithful to his Church and his

people. On September 9, 1949 he was arrested by the NKVD and imprisoned in Lviv.

Until 1956, according to information given after his family had been turned

away many times, it was said that he died on October 14, 1949 from paralysis of

the heart. But many witnesses report that they saw him in prison later, or they

heard him singing psalms at the top of his lungs. It was reported that they

sealed him up, alive, in a wall. He gave his life as a martyr for the faith.

“He was imprisoned on Lontskyi Street. His mother brought him some packages.

Sometimes his grandmother came from Zhulychi to visit him. At first the

packages were accepted. The prisoner always had a right to thank the giver with

the same card [with which the package was sent]. These cards were always sent

back, even the bags in which they usually put packages. And there were always

those cards, on which he wrote, ‘Thank you. Many kisses,’ and signed it.

“After the murder of

Galan [a Communist agitator], they refused to accept the packages. But after

six months when they started to accept packages again, then the relatives found

a card with ‘Thanks’ and a signature written, but in a stranger’s hand. It was

a completely different handwriting.” – From an interview with his niece

Lidia Kupchyk.

Liquidation by the State

Immediately after the Red

Army returned to western Ukraine in the summer of 1944 the previous limitations

imposed on the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church were renewed. But the great

authority possessed by the whole Church and its head, Metropolitan Andrey

Sheptytsky, forced the state during the first period to avoid direct

confrontation. The war with Nazi Germany was finishing, and the spiritual

father of the Church and the people, Servant of God Andrey, passed into

eternity in the odor of sanctity on November 1, 1944.

Then the Soviet security

services prepared a special plan “for detachment of parishes of the

Greek-Catholic (Uniate) Church in the USSR from the Vatican and their

subsequent unification with the Russian Orthodox Church.” This plan carried out

Stalin’s direct order and received his praise. On April 11, 1945 with no proof

of guilt, Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj, Bishops Hryhorii Khomyshyn, Nykyta Budka,

Mykola Charnetskyi and Ivan Liatyshevskyi were arrested. Soon after that the

Bishops of Przemsyl, Josaphat Kotsylovsky and Hryhory Lakota, about 500 priests

all over western Ukraine, in addition, almost all eparchial officials,

professors of the Theological Academy and seminaries, the most gifted pastors.

With the combined efforts

of party and government structures, the police organs and the Orthodox

hierarchy, by means of open terror and false demagoguery, the “liquidation of

the union” was proclaimed in 1946 in western Ukraine in the so-called “Lviv

pseudo-Sobor [“Council”]” and in 1949 in Transcarpathia. Regardless of the

persecution, the authorities were not able to break the will of the bishops and

to convince one of them to renounce his Church for a career in the Church of

the “regime,” the Russian Orthodox Church. “…Then you will be handed over to be

persecuted and put to death … At that time many will turn away from the faith

and will betray and hate each other, and many false prophets will appear and

deceive many people. Because of the increase of wickedness the love of most

will grow cold, but he who stands firm to the end will be saved.” (Gospel of St.

Matthew 24: 9-14)

Unbending Fighter

Bishop and

Martyr Hryhorii Khomyshyn was born on March 25, 1867 in the village

of Hadynkivtsi, Ternopil District. After graduating from the Lviv seminary in

1893, he was ordained to the priesthood. He continued his theological studies

in Vienna (1894-1899), earning a doctorate. In 1902, Metropolitan Andrey

Sheptytsky appointed Father Hryhorii rector of the Seminary in Lviv, and in

1904 he was ordained bishop of Ivano-Frankivsk.

In 1939, he was arrested

for the first time by the NKVD. His second arrest was in April of 1945, after

which he was taken to Kyiv’s Lukianivska prison. Bishop Hryhorii remained an

example for the Church of the bravery of a soldier of Christ, showing

perseverance in God’s truth in the most difficult moments of life. He died a

martyr for the faith in the infirmary of the NKVD prison in Kyiv on January 17,

1947.

“At the Kyiv prison the

interrogations were conducted by Interrogator Dubok. He was a horrible sadist.

He investigated my case too This Dubok told me himself how he had killed the

bishop: ‘So you, Khomyshyn, spoke out against communism?’ The bishop, as

always, replied resolutely: ‘I did and I will’. ‘Did you fight against the

Soviet authority? “Yes, I did and I will!’ Then Dubok became outraged and

grabbed some books written by the bishop, which lay on the table in front of

him, and started cruelly beating His Excellency with them, on his head and

everywhere else.” – From the testimony of Father Petro

Heryliuk-Kupchynskyi.

Undying Spirit of the Carpathians

Bishop and

Martyr Theodore Romzha was born on April 14, 1911, in the village of

Velykyi Bychkiv, Zakarpattia to a family of railroad workers. He finished his

theological studies at the Papal Gregorian University in Rome. In 1938 he

became pastor in the mountain villages of Berezevo and Nyzhnii Bystryi outside

of Khust. Beginning with the fall of 1939 he taught philosophy and was

spiritual director at the Uzhorod seminary. On September 24, 1944, soon after

the arrival of the Soviet Army, he was ordained to the episcopacy.

Because Bishop Theodore

bravely refused to cooperate with the authorities in the liquidation of the

Greek-Catholic Church and separate from the Roman Apostolic See, government

organs decided to destroy him. On October 27, 1947 a military vehicle ran into

the bishop’s horse-carriage. When the soldiers saw that he didn’t die in the

accident, they beat him and his companions into unconsciousness. On November 1

of that year when Bishop Theodore was beginning to recover, he was poisoned in

the Mukachiv hospital by workers cooperating with the security services. He

died a martyr for the faith.

“According to the

instructions of Khruschev, a member of the Politburo (Central Committee of the

Communist Party) of Ukraine and the first secretary of the same, according to

the plan developed by the Ministry of State Security in Ukraine and approved by

Khruschev, Romzha was eliminated in Mukachiv. As the head of the Greek-Catholic

Church, he had actively opposed the uniting of Greek-Catholics to Orthodoxy.” –

From a letter of Pavlo Sudoplatov, general of state security, to delegates of

the 23rd Assembly of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

“Deported” into Eternity

Bishop and

Martyr Josaphat Kotsylovsky was born on March 3, 1876 in the village of

Pakoshivka, Lemkiv District. He graduated with a degree in Theology from Rome

in 1907, and later on October 9 of that year he was ordained to the priesthood.

Not long after that he was appointed vice-rector and professor of Theology at

the Ivano-Frankivsk seminary. In 1911 he entered the novitiate of the Basilian

order. He was ordained a bishop on September 23, 1917 in Przemysl (Peremyshl)

upon the return of Metropolitan Andrey (Sheptytsky) from captivity in Russia.

In September of 1945 the

Polish Communist authorities arrested him and on June 26, 1946, after his next

arrest, they forcibly took him to the USSR and placed him in a prison in Kyiv.

Throughout his life he showed his perseverance of service, to make the

Christian faith firm and to grow in human souls. He died a martyr for the faith

on November 17, 1947 in the Chapaivka concentration camp near Kyiv.

“I came to Protection

Monastery and the hegumena [prioress] told me the story. When they arrested

Bishop Kotsylovsky they arrested their Orthodox bishop of Kyiv at the same

time. When they brought a package to Chapaivka, that Orthodox bishop said:

‘Uniate Bishop Josaphat Kotsylovsky is confined in the same camp with me.’ And

he asked those nuns, if they could, to bring a package to Bishop Josaphat as well.

So they brought a package for the one bishop and for the other … Once when she

brought a package, the bishop said that Kotsylovsky had died. And he asked her,

because the dead were all thrown into one hole, if they could borrow some money

or get some money somewhere. He asked her ‘to bury him in a separate grave,

because this was a holy man.” – From the testimony of Father Josaphat

Kavatsivo.

Archpastor in Three Parts

of the World

Bishop and

martyr Nykyta Budka was born on June 7, 1877, in the village of

Dobomirka, Zbarazh District. In 1905 after finishing theological studies in

Vienna and Innsbruck he was ordained to the priesthood by Metropolitan Andrey

Sheptytsky. From the very beginning he gave great attention to the ministry for

Ukrainian emigrants. The Holy See appointed him first bishop for Ukrainian

Catholics in Canada in July 1912, and he was ordained bishop on October 14,

1912. In 1928 he returned to Lviv and became vicar general of the Metropolitan

Curia in Lviv.

[Editor’s note: Since his

beatification, more information has been discovered regarding the arrest and

death of Nykyta Budka. Hence we have removed the orginal text of Fr. Borys

Gudziak. Based on recent research, we present the following account by Rev. Dr.

Athanasius McVay of the Eparchy of Edmonton who has spent years research the

life and works of Budka. Fr. Athanasius updates his work on his personal blog]

Blessed Nykyta Budka was

arrested in Lviv by the Soviets on 11 April 1945 and transported to Kyiv the

following day. For the next twelve months he was interrogated and tried for

‘crimes’ against the Soviet Union and the Communist Party. A military tribunal

sentenced him to five-years imprisonment on 29 May 1946. After that he vanished

and, for over ten years, no one knew his whereabouts or even if he was alive.

It was rumoured that Budka was being held in Siberia. Instead, he was among the

many innocent people who had been sent to prison camps near Karaganda, Kazahstan.

After Stalin’s death, Soviet authorities began to release the survivors. These

men and women were finally able to tell the stories about those who had lived

and died in the gulag. Among the survivors from Kazakhstan were Blessed Bishops

Ivan Liatyshevsky and Aleksander Khira, and future-archbishop, Father Volodymyr

Sterniuk. In 1958 Soviet authorities finally confirmed that Nykyta Budka had

died close to 1 October 1949, but more precise dates and details are still

lacking to this day.

Budka and other Ukrainian

Catholics who had been criminalized by a criminal regime were politically

rehabilitated in September 1991. This occurred less than a month after

Ukrainian independence, with the Soviet ‘Union’ still officially in existence

and the Communist Party having been declared illegal. Yet no official follow-up

to the case has ever occurred, even though Canadian Ukrainians had asked their

government for a redress to the Budka case in 1989.

Kazahstani authorities

have only recently confirmed that Budka served out his sentence at the

Karadzhar prison camp near Karaganda, where he died of heart disease on 28

September 1949. Additional documentation, obtained unofficially in 1995,

further specifies that Budka arrived at the camp on 5 July 1946 and was admitted

to a nearby hospital on 14 October 1947, the feast-day of his patron, the

Protection of the Mother of God according to the Julian calendar. That day was

also the forty-second anniversary of his priestly ordination and the

thirty-fifth of his episcopal ordination. Even the date of his death occurred

on the forty-second anniversary of his ordination to the diaconate.

Angelic Bishop

Bishop and

Martyr Hryhorii Lakota was born on January 31,1883, in the village of

Holodivka, in Lviv District. He studied theology in Lviv. He was ordained to

the priesthood in 1908 in Przemsyl (Peremyshl). In Vienna in 1911 he received

his Ph.D. in theology. In 1913 he became a professor at the Przemysl seminary,

later becoming its rector. On May 16, 1926, he was ordained to the episcopacy

and was appointed auxiliary bishop of Przemysl.

On June 9, 1946, he was

arrested and sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment. In exile in Vorkuta, Russia,

he was distinguished for his great humanness, his humility, his desire to take

the most difficult labour on himself and to make the unbearable conditions of

life easier for others. He died a martyr for the faith on November 12, 1950, in

the village of Abez near Vorkuta.

“Exiled to a labour camp,

in the middle of human misery, I also met real angels in human bodies, who by

their lives were the earthly representatives of the cherubim, glorifying

Christ, the King of Glory. Among them was the confessor of the faith, Hryhorii

Lakota, auxiliary bishop of Przemysl. From 1949 to 1950, by his example of Christian

virtues, his life witnessed to us who were weakened by life in the labour

camp.” – From the written account of Father Alfrysas Svarinskas.

Aristocrat of the Spirit

Priest and

Martyr Archimandrite Klymentii Sheptytsky, the younger brother of the Servant

of God Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky, was born on November 17, 1869, in the

village of Prylbychi, Yavoriv region. He studied law in Munich and Paris and

received a doctorate at the University of Krakow. He was a legate of the

Austrian Parliament and member of the National Council. In 1912 he entered the

Studite monastery as a late vocation; by so doing he renounced his successful

secular career. He completed his theological studies in Innsbruck. On August

28, 1915, he was ordained to the priesthood. For many years he was the hegumen

(prior) of the Studite monastery at Univ, and in 1944 he became the

archimandrite (abbot).

During World War II, he

gave refuge to persecuted Jews. On June 5, 1947, he was arrested and sentenced

to eight years’ imprisonment by a special meeting of the NKVD in Kyiv. He died

a martyr for the faith on May 1, 1951, in a harsh prison in Vladimir, Russia.

“Tall, 180-185

centimetres, rather thin, with a long white beard, a little stooped, with a

cane. Arms relaxed, calm, face and eyes friendly. He reminded me of St.

Nicholas We never expected such a rascal in our room Some sisters had passed

three apples to him, real rosy red and ripe. And he gave one apple to Roman

Novosad, who often had stomach problems. He said: ‘You need to take care of

your stomach,’ and the others he divided among us.” – From the memories of

Ivan Kryvytskyi.

Apostles of the Gulag

The unbending

faithfulness to Christ and His Church of Confessor of the Faith Metropolitan

Josyf Slipyj and all the Greek-Catholic hierarchy, their deep certainty in the

victory over evil and their special witness of fidelity to the Roman Apostolic

See served as an inspiring example and supported the faith and hope of laity

and clergy alike who had avoided arrest and exile and had not spent time in

prison.

Prayerful Parent

Priest and

Martyr Father Mykola Tsehelskyi was born on December 17, 1896, in the

village of Strusiv, Ternopil District. In 1923 he graduated from the

Theological Faculty of Lviv University. On April 5, 1925, Metropolitan Andrey

Sheptytsky ordained him to the priesthood. He was a zealous priest who cared

for the spirituality, education and welfare of his parishioners.

After the war he was

repressed by the Bolsheviks because he refused to convert to Orthodoxy. Father

Tsehelskyi drank deep from the bitter cup of intimidation, threats and

beatings. On October 28, 1946, he was arrested, and on January 27, 1947, he was

sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment. He was deported to Mordovia, Russia, but

his wife, three children and daughter-in-law were taken to Russia’s Chytynska

region. He lived in extremely horrid conditions, in a camp that was notoriously

strict and cruel. He suffered from severe pain due to illness, but this did not

break his strong spirit. He died a martyr for the faith on May 25, 1951, and is

buried in the camp cemetery.

“My dearest wife: the

feast of the Dormition was our 25th wedding anniversary. I recall fondly our

family life together, and every day in my dreams I am with you and the

children, and this makes me happy I give a fatherly kiss to all their

foreheads, and I hope to live honestly, behaving blamelessly, keeping far from

everything that is foul. I pray for this most of all.” – From the letters

of Father Mykola Tsehelskyi written in Mordovia.

Suffered on Good Friday

Priest and

Martyr Father Ivan Ziatyk was born on December 26, 1899, in the

village of Odrekhiv, near Sianok. After finishing his theology studies in

Przemysl (Peremyshl) seminary in 1923, he was ordained to the priesthood. In

1935 he entered the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer (Redemptorists). He

was a teacher of dogmatic theology and holy scripture, and also known as a good

administrator. During the Nazi occupation he was acting superior of the

monastery in Ternopil and later in Zboiski near Lviv. After the official

liquidation of the UGCC and the exile of Protohegumen Yosyf de Vokhta, Father

Ivan took on his duties.

On January 5, 1950, he

was arrested and found guilty of “preaching the ideas of the pope of Rome

regarding the spread of the Catholic faith among nations of the whole world.”

At first he was imprisoned in Zolochiv and later was sent to Ozerlah, Irkhutsk

region, Russia. In all he lived through 72 interrogations. On Good Friday in

1952 he was severely beaten, drenched with water and left to lie in the cold.

He died in the prison infirmary on May 17, 1952, a martyr for the faith.

“He stood and prayed the

whole day; for whole days he prayed every moment. He was such a pleasant person

to talk to. You could hear many wise and instructive words from him; this was

especially so in my case, as at that time I was a youngster.” – From an

interview with fellow prisoner Anatolii Medelian.

A Mother to Her Sisters

Nun and

Martyr Sister Olympia Olha Bida was born in 1903 in the village of

Tsebliv, Lviv District. At a young age she entered the congregation of the

Sisters of St. Joseph. In 1938 she was assigned to the town of Khyriv where she

became superior of the house. After the establishment of the Soviet regime, she

and the other sisters suffered a number of attacks on the convent. She,

nevertheless, continued to care for children, to catechize and organize

underground religious services (often without a priest).

In 1950 she was arrested

by soldiers of the NKVD and taken to a hard labour camp in Boryslav. Eventually

she was sentenced to lifelong exile in the Tomsk region of Siberia for

“anti-Soviet activities.” Even in exile, Sister Olympia tried to perform her

duties as superior. She provided support for her fellow sisters. She patiently

endured inhuman living conditions. She died a martyr’s death on January 23,

1952.

“God Almighty, God’s

Providence will not allow His little children to perish in a foreign land. For

He is with us here, in the midst of these forests and waters. He doesn’t forget

about us Because of our faith, because of a divine matter, we suffer, and what

could be better than this? Let’s follow Him bravely. Not only when all is well,

but even when times are bitter, let us say: Glory to God in all

matters.” – From Sister Olympia’s letter to her provincial superior,

Sister Neonylia.

Faith Amid Hopelessness

Nun and

Martyr Sister Lavrentia Herasymiv was born on September 31, 1911, in

the village of Rudnyky, Lviv District. In 1931 she entered the congregation of

the Sisters of St. Joseph in Tsebliv. In 1933 she made her first vows. Together

with Sister Olympia, in 1938 she went to the house in Khyriv, and their fates

were crossed until death. In 1950 she was arrested by the agents of the NKVD

and sent to Boryslav.

Eventually, together with

her fellow sister she was sentenced to lifelong exile in the Tomsk region. She

was sick with tuberculosis when she arrived to her designated place of exile

and so only one family would agree to give her a roof over her head. This was

in a room where a paralyzed man lay behind a partition. She prayed much and

performed various forms of manual labor. She patiently endured the inhuman

living conditions and the lack of medical attention. She died on August 28,

1952, as a martyr for the faith in the village of Kharsk in Siberia’s Tomsk

Region.

“The NKVD agents attacked

our convent. They spent a long time breaking down the door. It was night-time;

the sisters were terrified. Sister Lavrentia ran to the cellar and escaped into

the garden through a little window. A cold rain started to fall. When the NKVD

broke into the house they immediately noticed the open window and ran to look

for her. It was dark and with their bayonets they poked every bush. A few times

the bayonet was right in front of Sister’s eyes. Not finding her, the NKVD went

away, but sister was out in the rain until the morning. She came to the house

exhausted and frozen. After this incident she got seriously ill, and lay in

bed. They took her to prison when she was infirm.” – From the memories of a

relative, Anna Harasymiv.

Berlin Founder

Priest and

Martyr Father Petro Verhun was born on November 18, 1890, in Horodok,

Lviv District. He held a Ph.D. in philosophy. On October 30, 1927, he was

ordained to the priesthood by Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky at St. George’s

Cathedral and was appointed to be the pastor and later the apostolic visitator

for Ukrainian Catholics in Germany. Priests and all the faithful, whom fate had

brought to a foreign land, gravitated to Father Verhun because they felt he was

a good shepherd who would give his life for his sheep.

In June 1945 he was

arrested by the Soviet security services in Berlin and sent to Siberia,

sentenced to eight years of hard labour. But even there, amid unbearable living

conditions, he knew how to gather the faithful around him, giving his own

personal example of perseverance in the faith. He died as a martyr for the

faith on February 7, 1957, in exile in the village of Anharsk, in the Krasnoyar

territory.

“My life is very

monotonous. I have enough to eat. I cook for myself. My greatest joy is that I

can pray every day without disturbances Finally I don’t need anything. I feel

that my head is tending little by little to my eternal rest. But I really would

rather die in the monastery.” – From the letters of Father Petro Verhun

written in Siberian exile.

Pastor of the East

Priest and

Martyr Father Oleksii Zarytskyi was born in 1912 in the village of

Bilche, in the Lviv District. From 1931 to 1934 he studied at the Lviv

Theological Academy. He was ordained to the priesthood by Metropolitan Andrey

Sheptytsky in 1936. During his ministry in the village of Strutyna near

Zolochiv he gained the special favour of his parishioners. In 1948 he was

sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment in the camps of Siberia and Kazakstan for

refusing to convert to Orthodoxy.

After his rehabilitation

in 1957, he returned to western Ukraine a number of times but again returned to

the east. Amid inhuman conditions Father Zarytskyi had a wide field for

pastoral ministry to people in a foreign land. He tirelessly took care not only

of Ukrainians but Poles, Germans, Russians, Greek and Roman Catholics. He

visited Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj in exile.

Father Zarytskyi was

sentenced a second time: two years for “vagrancy.” The guardian of children,

youth, the poor, he will forever remain in people’s memory an example of the

embodiment in life of the commandments to love God and neighbour. He died a

martyr for the faith on October 30, 1963, in a labour camp in a village in

Karaganda. His mortal remains were reburied in 1990 in the village of

Riasna-Ruska near Lviv.

“That was in 1957 during

Lent, on Palm Sunday. Almost the whole village was waiting for him. There were

even people who went to the Orthodox Church, who hadn’t made their confession; they

were still waiting … And they waited until he came. When we told them that

Father Zarytskyi was here, everyone came to us to confess. Confessions started

in the evening and lasted almost to the morning. At dawn Father Zarytskyi

celebrated the divine liturgy. Very many people took advantage of the

opportunity: young and old. They got married, children were baptized. Father

Zarytskyi stayed with us the whole summer. But on September 21 he had to leave

for Karaganda; he had to return because they were waiting for him there” –

From an interview with Sister Konstantsia Seniuk.

Light in the Catacombs

Stalin’s death in March

1953 and Khruschev’s “thaw” began a new period in the way of the cross of the

UGCC: the catacombs. The main protagonists of this period of the Church’s life

were the bishops, priests, monks, nuns and faithful who had returned home from

the camps and exile. Having survived unspeakable physical and moral tortures,

they encountered a different western Ukraine: bloodless, frightened by the terror,

deceived by the atheist-communist ideology, but in spite of all that it was

still alive and waiting for the resurrection.

These people who knew how

to preserve in their hearts faith in Christ and faithfulness to their Church

became little islands around which the gradual renewal of Church structures

began. Thanks to the unbending character of the martyr bishops, the

perseverance of the clergy and the faithfulness of the laity, the UGCC survived

the period of official “liquidation,” organized the underground and gave birth

to a new generation of Church leaders. For almost half a century it was the

largest illegal Christian community in the world and at the same time the

largest organism of social opposition to the totalitarian system of the USSR.

“And so take up every

divine weapon so that you can stand fast during the storms and, overcoming

everything, survive. Stand up, therefore, girding your thigh with truth and

clothing yourself with the armour of justice … But above all take in your hands

the shield of faith, with which you will be able to defeat the fiery arrows of

the Evil One. And take up the helmet of salvation and the spiritual sword,

which is the word of God.” – From a letter of Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj,

written in exile, February 17, 1961.

Healer of Souls

Bishop and

Martyr Mykola Charnetskyi was born on September 14, 1884, in the

village of Semakivtsi, Ivano-Frankivsk District. After he completed his studies

at the local seminary in Rome, he was ordained to the priesthood in 1909. He

obtained his doctorate in dogmatic theology from Rome and became a spiritual

director and professor at the seminary in Ivano-Frankivsk. In 1919 he entered

the novitiate of the Redemptorist Fathers in Lviv, and in 1926 he was appointed

apostolic visitator for Ukrainian Catholics in Volyn, Polissia, Kholm and

Pidliashia. A model religious leader and missionary, he zealously worked for

the union of the Holy Church. He was ordained to the episcopacy by Bishop

Hryhorii Khomyshyn in Rome on February 2, 1931.

He was arrested by the

NKVD on April 11, 1945, and sentenced to six years of hard labour in Siberia.

According to official data, he underwent 600 hours of interrogation and torture

and spent time in 30 different prisons and camps. Terminally ill, in 1956 he

was permitted to return to western Ukraine, where he secretly continued to

fulfil his episcopal obligations. In the midst of the cruelty and oppression

which he suffered in imprisonment and in exile, he was distinguished for his

evangelical patience, gentleness and limitless goodness; already during his

life he was considered a holy man. As a consequence of his sufferings, he died

a martyr for the faith on April 2, 1959, in Lviv.

“I saw him. He was a very

humble person. The first time I came for instruction from the bishop, he was

sweeping the house. I wanted to help him, to take the broom, but he didn’t let

me. He himself swept. ‘Have a seat,’ he said. I was embarrassed that the bishop

was sweeping, but I was sitting, because he wouldn’t let me. He told how many

priests who had signed over to Orthodoxy, came to him to confess nearly 300

priests, they repented and came to him.” – From an interview with Father

Vasyl Voronovskyi.

Discrete Member of the

Underground

Bishop and

Martyr Semeon Lukach was born on July 7, 1893, in the village of

Starunia, Ivano-Frankivsk District. In 1913 he entered the seminary. He

finished the seminary in Ivano-Frankivsk and was ordained a priest in 1919. In

December 1920 he was appointed professor of moral theology at the seminary

where he had earlier studied. He secretly received episcopal ordination in the

spring of 1945 before the arrest of Bishop Hryhorii Khomyshyn. On October 26,

1949, he was arrested by the Soviet secret police. Sentenced in August 1950 to

10 years of imprisonment, he carried out hard labour in a lumber camp in

Krasnoyarsk. He was freed on February 11, 1955, and returned to his native

land. In July 1962 he was arrested for a second time and was sentenced to five

years in a severe colony. During his interrogations he showed his unbroken

perseverance, discretion and faithfulness to the Catholic Church. In March 1964

because of his critical condition, tuberculosis of the lungs, he was taken to

his native village, Starunia. He died a martyr for the faith on August 22,

1964.

“I celebrated divine

liturgy in an apartment and in a few houses. From one to 30 people took part in

the services I also baptized and celebrated marriages But conscience does not

allow me to mention their names, so that my mistake will not cause those people

who sought spiritual help from me to suffer. I acted in good faith, serving

God’s will, so I was in danger of colliding with state laws. If the state finds

me guilty, I myself will take the responsibility.” – From the

autobiography in the court case written after his arrest in 1949.

Unbroken

“Conversationalist”

Bishop and

Martyr Ivan Sleziuk was born on January 14, 1896, in the village of

Zhyvachiv, Ivano-Frankivsk District. After graduating from the eparchial

seminary in 1923 he was ordained to the priesthood. He served as a catechist

and spiritual director in Ivano-Frankivsk. In April of 1945 Bishop Hryhory

Khomyshyn secretly ordained him a bishop. On June 2, 1945, Bishop Sleziuk was

arrested, and a year later he was sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment. He served

his sentence in camps in Vorkuta and Mordovia, Russia. Released from prison, he

returned to Ivano-Frankivsk and carried out the duties of administrator of the

eparchy.

In 1962 he was arrested

for the second time, together with Bishop Semeon Lukach, and was sentenced to

five years’ imprisonment in harsh camps. After his release in 1968 he ordained

Basilian Sofron Dmyterko a bishop. Bishop Dmyterko succeeded him in guiding the

eparchy. In his final years Bishop Sleziuk was often called to the KGB for regular

“conversations.” After one of these “conversations” he fell ill and never

recovered. He died a martyr for the faith on December 2, 1973, in

Ivano-Frankivsk.

“As the deceased himself

said, they locked him in a separate isolated area, and no one visited him. He

stayed there for two hours. Then they told him: ‘You’re free to go.’ It was

difficult for him to walk because, as he himself said, after this he felt

dizzy, as if he had a fever, his skin was burning. The Sisters of St. Vincent,

who helped him out, also said that the bishop returned from this ‘conversation’

with a very red face, he felt exhausted, stayed in bed and died two weeks

later. There was and still is a suspicion that the KGB used radiation to get

rid of one more Uniate bishop.” – From the testimony of Bishop Sofron

Dmyterko.

Worthy Acting Head

Bishop and

Martyr Vasyl Velychkovsky was born June 1, 1903, in Ivano-Frankivsk. In

1920 he entered the seminary in Lviv. In 1925 in Holosko, near Lviv, he took

his first religious vows in the Order of the Most Holy Redeemer and was

ordained a priest. Father Vasyl became a missionary in Volyn. In 1942 he became

the hegumen (prior) of the monastery in Ternopil, where he was arrested in

1945. He was then taken to Kyiv. His death sentence was soon commuted to 10

years of imprisonment and hard labor. He returned to Lviv in 1955, where he

continued his pastoral work.

In 1963 he was secretly

ordained an archbishop in a Moscow hotel by Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj, who, on

his way to exile in Rome, passed Bishop Velychkovsky the responsibility for the

catacomb Church. Predicting his own possible arrest, he ordained new

underground bishops in 1964. Among them was his successor, Archbishop Volodymyr

Sterniuk, who eventually led the Church out of the underground. In 1969 Bishop

Velychkovsky was arrested a second time, but after three years of imprisonment

he was deported outside the USSR. He died in Winnipeg on June 30, 1973, as a

consequence of serious heart disease which began when he was in prison.

“After many years spent

in prisons and labour camps, how pleasant it is to be free with my fellow

Ukrainians. What joy to go to pray freely in a Ukrainian church, where no one

will send you to the camps or prison because of your prayers The prisons and

camps ruined my health and my strength, but this was my fate, the Lord God

placed this cross on my shoulders.” – From the last speech of Bishop Vasyl

Velychkovsky to the faithful in Canada, June 17, 1973.

In Lieu of an Epilogue

“The metropolitan lay

calmly with eyes shut and breathed with difficulty, as he had previously. Then

he began to pray again. He opened his eyes and began to talk to us: ‘Our Church

will be ruined, destroyed by the Bolsheviks, but you will hold on, do not

renounce the faith, the Catholic Church. A difficult trial will fall on our

Church, but it is passing. I see the rebirth of our Church, it will be more

beautiful, more glorious than of old, and it will embrace all our people.

‘Ukraine,’ the metropolitan continued, ‘will rise again from her destruction and

will become a mighty state, united, great, comparable to other highly-developed

countries. Peace, well-being, happiness, high culture, mutual love and harmony

will rule here. It will all be as I say. It is only necessary to pray that the

Lord God and the mother of God will care for our poor tired people, who have

suffered so much and that God’s care will last forever.’” – From an

interview with Father Yosyf Kladochnyi about Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky’s

last moments of earthly life.

Source

The official website of

the papal visit to Ukraine, http://www.papalvisit.org.ua. Oleh Turii, candidate of

historical studies and acting director of the Institute of Church History at

the Lviv Theological Academy, prepared this text on the basis of materials of

the Postulation Center for the Beatification and Canonization of Saints of the

UGCC and the archives of the Institute of Church History at the LTA.

The Beatified

Sister Josaphata

(Michaelina) Hordashevska

Father Leonid Feodorov

Father Mykola Konrad

Volodymyr Pryima

Father Andrii Ischak

Father Severian Baranyk

Father Yakym Senkivskyi

Father Zenovii Kovalyk

Father Emilian Kovch

Sister Tarsykia Matskiv

Father Vitalii Bairak

Father Roman Lysko

Bishop Hryhorii Khomyshyn

Bishop Theodore Romzha

Bishop Josaphat

Kotsylovsky

Bishop Mykyta Budka

Bishop Hryhorii Lakota

Archimandrite Klymentii

Sheptytsky

Father Mykola Tsehelskyi

Father Ivan Ziatyk

Sister Olympia Olha Bida

Sister Lavrentia

Herasymiv

Fahter Petro Verhun

Father Oleksii Zarytskyi

Bishop Mykola Charnetskyi

Bishop Semeon Lukach

Bishop Ivan Sleziuk

Bishop Vasyl Velychkovsky

SOURCE : https://icshrine.org/new-martyrs-of-ukrainian-church/

Beata Olimpia

(Olga) Bidà Vergine e martire

>>> Visualizza la

Scheda del Gruppo cui appartiene