Saturnino Gatti, Trasporto della della Santa Casa a Loreto (fine XV - inizio XVI secolo; New York, Metropolitan Museum

Notre Dame de Lorette

La Bienheureuse Vierge Marie de Lorette inscrite au calendrier romain: un décret de la Congrégation du Culte divin établit au 10 décembre la mémoire liturgique de la Vierge de Lorette, vénérée et célébrée chaque année par des milliers de pèlerins. (Vatican News le 31 octobre 2019)

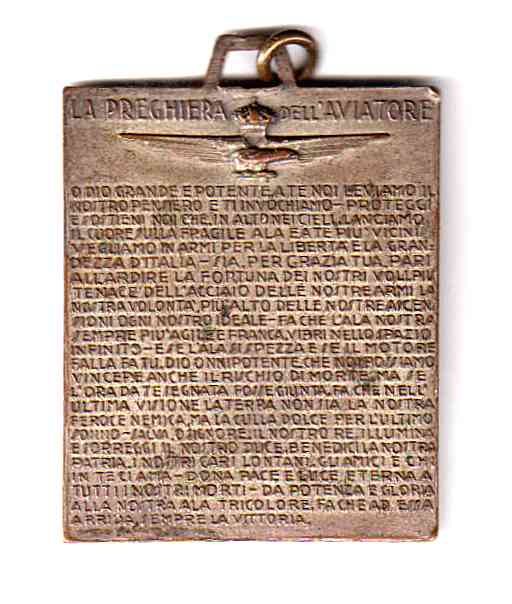

La légende dit que la Sainte Maison de Joseph, Marie et Jésus vola à travers les airs, portée par des anges, de Galilée jusque en Italie en traversant ce qui est aujourd'hui l'ex-Yougoslavie. Notre-Dame de Lorette semblait donc tout indiquée pour devenir patronne de tous ceux qui travaillent dans l'aviation. Cette décision fut officiellement approuvée par un décret de la Congrégation Pontificale pour les Sacrements du 24 mars 1920. (Diocèse aux Armées françaises)

Des internautes nous signalent

- "Notre Dame de Loretto est devenue patronne des aviateurs d'après une légende qui dit que des anges auraient transporté sa maison en Italie. Lors du pèlerinage et la fête, des patrouilles aériennes de divers pays passent à basse altitude sur la ville, le défilé est ouvert de droit par la patrouille acrobatique italienne "les flèches tricolores" car elle est chez elle et après suivent les autres patrouilles, les aviateurs italiens font bénir ce jour-là leur arme de cérémonie."

- Dans l'église de Sancé, à quelques kilomètres au nord de Mâcon un

important retable illustre le transport de la maison de la Vierge jusqu'à

Loretto. (Pastourisme71)

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/12348/Notre-Dame-de-Lorette.html

La Bienheureuse Vierge

Marie de Lorette inscrite au calendrier romain

Un décret de la

Congrégation du Culte divin établit au 10 décembre la mémoire liturgique de la

Vierge de Lorette, vénérée et célébrée chaque année par des milliers de

pèlerins.

Le cardinal Robert Sarah,

Préfet de la Congrégation pour le Culte Divin et la discipline des Sacrements a

signé un décret inscrivant la Bienheureuse Vierge de Lorette au calendrier

romain général. C'est désormais le 10 décembre, jour où Notre-Dame de Lorette

est fêtée dans son sanctuaire italien des Marches, que cette mémoire liturgique

sera célébrée, rappelle le décret.

Situé non loin de la côte

adriatique, le sanctuaire marial de Lorette est célèbre dans le monde entier

pour abriter la "Maison sainte", celle où la Vierge Marie reçut

l’Annonciation de l’Archange Gabriel.

Le Pape François s'était

rendu le 25 mars dernier au sanctuaire de Lorette, jour de la solennité de

l’Annonciation du Seigneur. En confiant à la Vierge toutes les vocations, le

Saint-Père y avait signé l'exhortation apostolique post-synodale, rédigée suite

au synode d'octobre 2018 sur "les jeunes, la foi et le discernement

vocationnel".

«Cette célébration aidera

tout le monde, en particulier les familles, les jeunes, les religieux et les

religieuses, à imiter les vertus de celle qui a été disciple parfaite de

l’Évangile, la Vierge Marie qui, en concevant le chef de l’Église, nous a

également accueillis chez elle» peut-on lire dans le décret.

Lire aussi

25/03/2019

Le

Pape à Notre-Dame de Lorette: la Vierge Marie, reine des vocations

En voici la traduction

française:

DÉCRET d’inscription

de la célébration de la bienheureuse Vierge Marie de Lorette dans le

Calendrier Romain Général

La vénération de la

Sainte Maison de Lorette a été, depuis le Moyen Âge, à l’origine de ce

sanctuaire particulier, fréquenté, encore aujourd’hui, par de nombreux pèlerins

pour nourrir leur foi en la Parole de Dieu faite chair pour nous.

Ce sanctuaire rappelle le

mystère de l’Incarnation et pousse tous ceux qui le visitent à considérer la

plénitude du temps, quand Dieu a envoyé son Fils, né d’une femme, et à méditer

à la fois sur les paroles de l’Ange qui annonce l’Evangile et sur les paroles

de Vierge qui a répondu à l'appel divin. Adombrée par le Saint-Esprit, l'humble

servante du Seigneur est devenue la maison de Dieu, l'image la plus pure de la

sainte Église.

Le sanctuaire

susmentionné, étroitement lié au Siège apostolique, loué par les Souverains

Pontifes et connu dans le monde entier, a su illustrer de manière excellente au

fil du temps, autant que Nazareth en Terre Sainte, les vertus évangéliques de

la Sainte Famille.

Dans la Sainte Maison,

devant l'effigie de la Mère du Rédempteur et de l'Église, les Saints et les

Bienheureux ont répondu à leur vocation, les malades ont demandé la consolation

dans la souffrance, le peuple de Dieu a commencé à louer et à supplier Sante

Marie avec les Litanies de Lorette, connues dans le monde entier. D’une manière

particulière, ceux qui voyagent en avion ont trouvé en elle leur patronne

céleste.

En raison de tout cela,

le Souverain Pontife François a décrété avec son autorité que la mémoire

facultative de la Bienheureuse Vierge Marie de Lorette soit inscrite dans le

calendrier romain le 10 décembre, jour de la fête à Lorette, et célébrée chaque

année. Cette célébration aidera tout le monde, en particulier les familles, les

jeunes, les religieux et les religieuses, à imiter les vertus de celle qui a

été disciple parfaite de l’Évangile, la Vierge Marie qui, en concevant le chef

de l’Église, nous a également accueillis chez elle.

La nouvelle mémoire doit

donc apparaître dans tous les calendriers et livres liturgiques pour la

célébration de la Messe et de la Liturgie des Heures; les textes liturgiques

relatifs à cette célébration sont joints à ce décret et leurs traductions,

approuvées par les Conférences épiscopales, seront publiées après la

confirmation de ce Dicastère.

Nonobstant toute

disposition contraire.

De la Congrégation pour

le Culte Divin et la Discipline des Sacrements, le 7 octobre 2019, mémoire de

la Bienheureuse Vierge Marie du Rosaire.

Robert Card. Sarah,

Prefet

Arthur Roche, Archevêque

Secrétaire

Un Jubilé pour Lorette

Le prochain 8 décembre

débutera avec l'ouverture de la Porte Sainte le Jubilé de Lorette, convoqué

pour célébrer les 100 ans de la proclamation de Notre-Dame-de-Lorette comme

patronne des aviateurs. Cette Année Sainte se tiendra jusqu'au 10 décembre

2020. Ce 1er novembre, jour de la Toussaint, aura lieu la célébration de

l'indiction du Jubilé, présidé par Mgr Krystof Nikiel.

Merci d'avoir lu cet

article. Si vous souhaitez rester informé, inscrivez-vous à la lettre

d’information en cliquant ici

Sainte

Maison, en la basilique de Lorette.

Santuario

della Santa Casa w Loreto - Święty Domek

Santuario della Santa Casa in Loreto - Casa Santa

Sainte

Maison, en la basilique de Lorette.

Santuario

della Santa Casa w Loreto - Święty Domek

Santuario della Santa Casa in Loreto - Casa Santa

Partie

du revêtement marmoréen de la Sainte Maison de Lorette sous la coupole de Giuliano Sangallo peinte par Cesare

Maccari.

Translation de la Maison de la Sainte Famille à Lorette

(1291 et 1294)

La nouvelle terrible que la Terre Sainte était perdue pour les chrétiens répandit une profonde tristesse dans toute l'Église; mais en même temps une autre nouvelle vint consoler les âmes chrétiennes: la sainte Maison de Nazareth, où la Vierge Marie avait conçu le Verbe fait chair, avait été transportée par les Anges en Dalmatie.

Au lever de l'aurore, les habitants du pays ne remarquèrent pas sans étonnement un nouvel édifice qui reposait sur la terre sans fondements, et attestait, par sa forme, une origine étrangère. Quel pouvait être ce monument? Pendant que l'on s'interrogeait avec curiosité, Marie apportait Elle-même du Ciel la réponse à l'évêque du diocèse qui, gravement malade, demandait au Ciel sa guérison pour aller voir le prodige: "Mon fils, lui dit Marie en lui apparaissant, cette maison est la maison de Nazareth où a été conçu le Fils de Dieu. Ta guérison fera foi du prodige."

Trois ans plus tard, la

sainte Maison, portée par les mains des Anges, s'éleva de nouveau dans les airs

et disparut aux yeux du peuple désolé, le 10 décembre 1294. Or, le lendemain

matin, les habitants de Récanati, en Italie, voyaient sur la montagne voisine

de Lorette une maison inconnue, à l'aspect extraordinaire. On eut bientôt

constaté que cette maison était celle de Nazareth, que les habitants de la

Dalmatie avaient vue soudain disparaître dans le même temps. De là un concours

immense de peuples.

Au XIVè siècle, un temple

magnifique fut bâti pour garder la maison miraculeuse. Ce temple existe encore

et voit chaque jour de nombreux pèlerins de toutes les parties du monde. Que ne

dit pas au coeur du chrétien ce monument vénérable! Combien il rappelle de

mystères! Combien il a vu de merveilles de sainteté! Combien sa présence à

Lorette et son existence aujourd'hui supposent de miracles! Le pèlerin aime à

se dire: "Là pria Marie, là travailla Joseph, là vécut Jésus!" Il

aime à baiser un objet de bien peu de valeur par lui-même, mais plus précieux

que tous les trésors, par les souvenirs qui y sont attachés: on l'appelle la

sainte Écuelle; c'est le petit vase de terre où le Sauveur, dit la tradition,

prenait Sa nourriture.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950.

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/translation_de_la_maison_de_lorette.html

Annibale

Carracci, Translation de la Sainte Maison, 1605,

133 x 90, église Sant'Onofrio au Janicule de Rome. Commissioned by

cardinal Carlo Gaudenzio Madruzzo for the

Church of Sant' Onofrio, Rome, between 1604 and 1605

La translation de la

Sainte Maison de Lorette

En 1291, sous le pontificat de Nicolas IV, les chrétiens avaient entièrement

perdu les saints lieux de la Palestine. L’église élevée à Nazareth par

l’impératrice Hélène venait de tomber sous le marteau destructeur, et la Sainte

Maison qu’elle renfermait allait bientôt avoir le même sort, lorsque, selon le

récit traditionnel, Dieu ordonna à ses anges de la transporter ailleurs. Le 10

mai, à la seconde veille de la nuit, le sanctuaire de Nazareth avait été déposé

non loin des rivages de l’Adriatique, entre Tersatz et Fiume, sur un petit mont

appelé Rauniza, en Dalmatie. A l’intérieur de la Sainte Maison, on découvrit

une statue de cèdre, représentant la Vierge Marie couronnée de perles, vêtue d’une

robe dorée et d’un manteau bleu, debout, portant dans ses bras l’Enfant Jésus

qui levait les trois premiers doigts de main droite pour bénir, tandis que sa

main gauche soutenait un globe.

Lorsqu’on lui rapporta la nouvelle, l’évêque Alexandre était fort malade ; dans

la nuit, il était au plus mal et priait la Vierge Marie, espérant pouvoir aller

contempler le prodige qu’on lui avait décrit. Soudain le ciel s’est ouvert à

ses yeux, la très-sainte Vierge se montre au milieu des anges qui

l’environnent, et d’une voix dont la douceur ravit intérieurement le cœur dit :

« Mon fils, tu m’as appelée ; me voici pour te donner un efficace secours et te

dévoiler le secret dont tu souhaites la connaissance. Sache donc que la sainte

demeure apportée récemment sur ce territoire est la maison même où j’ai pris

naissance et où je reçu presque toute mon éducation. C’est là qu’à la nouvelle

apportée par l’archange Gabriel, j’ai conçu par l’opération du Saint-Esprit le

Divin Enfant. C’est là que le Verbe s’est fait chair. Aussi, après mon trépas,

les apôtres ont-ils consacré ce toit illustre par de si hauts mystères, et se

sont-ils disputé l’honneur d’y célébrer l’auguste sacrifice. L’autel,

transporté au même pays, est celui même que dressa l’apôtre saint Pierre. Le

crucifix que l’on y remarque, y fut placé autrefois par les apôtres. La statue

de cèdre est mon image faite par la main de l’évangéliste saint Luc qui, guidé

par l’attachement qu’il avait pour moi, a exprimé, par les ressources de l’art,

la ressemblance de mes traits, autant qu’il est possible à un mortel. Cette

maison, aimée du ciel, environnée pendant tant de siècles d’honneur dans la

Galilée, mais aujourd’hui privée d’hommages au milieu de la défaillance de la

foi, a passé de Nazareth sur ces rivages. Ici point de doute : l’auteur de ce

grand évènement est ce Dieu près duquel nulle parole n’est impossible. Du

reste,afin que tu en sois toi-même le témoin et le prédicateur, reçois ta

guérison. Ton retour subit à la santé au milieu d’une si longue maladie fera

foi de ce prodige.

L’enquête juridique que l’évêque Alexandre et deux députés du pays (Sigismond

Orsich et Jean Grégoruschi) allèrent faire jusqu’à Nazareth, pour constater sa

translalion en Dalmatie, la persuasion universelle des peuples qui venaient la

vénérer de toutes parts, semblaient être des preuves incontestables de la

vérité du prodige.

Après trois ans et sept mois, la Sainte Maison fut à nouveau transportée par

les Anges et fut déposée dans la marche d’Ancône, au territoire de Récanati,

dans une forêt appartenant a une dame appelée Lorette ; c’était le 10 décembre

1294. Les peuples de Dalmatie furent tellement désolés qu’ils semblaient ne

pouvoir survivre à l’évènement. Pour se consoler, ils bâtirent sur le même

terrain une église consacrée à la Mère de Dieu, qui fut desservie depuis par

les Franciscains et, chaque année, les fidèles dalmates se rendent par troupe à

Lorette.

En 1464, Pie II offrit au sanctuaire de Lorette un calice d’or pour avoir été

guéri d’une maladie. En 1470, une bulle de Paul II célèbre à Lorette une statue

de la Vierge apportée par les anges dans un édifice fondé miraculeusement. Deux

ans plus tard, Pietro di Giorgio Tolomei, dit Teramano, recteur de l’église de

Lorette, raconte, dans une notice, comment la Sainte Maison (Santa Casa) de

Nazareth vint à Rauniza puis à Lorette. Sixte IV déclare Lorette propriété du

Saint-Siège. En 1489, le bienheureux Baptiste Spagnuoli, dit le Mantouan,

rédige une nouvelle notice qui reprend celle de Teramano. Après qu’une bulle de

Jules II (1507) a consacré ces pieuses croyances, Erasme compose une messe pour

la Vierge de Lorette (1525) sans pourtant faire allusion au vol de la maison

dans les cieux dont parle le récit que Jérôme Angelita adressa à Clément VII

(1531). Les Carmes furent députés à la garde de la Sainte Maison. Léon X

étendit les indulgences des stations apostoliques à Rome au sanctuaire de

Lorette. En 1483, le cardinal Savelli composa les litanies dites de Lorette

dont l’Eglise fait usage aujourd’hui pour prier la Vierge Marie. Sixte V, en

1585, éleva Lorette au rang de cité, donna le titre de cathédrale à son église

et y établit un siège épiscopal.

A Liesse et au séminaire Saint-Sulpice d’Issy-les-Moulineaux, ont voit une

chapelle construite sur le modèle de la Sainte Maison de Lorette. A travers la

France, on rencontre des sanctuaires et des églises dédiés à Notre-Dame de

Lorette. Dans le diocèse de Nancy on visite les sanctuaires de Notre-Dame de

Lorette de Baudrecourt, bâti en 1578, et de Saint-Martin qui fut reconstruit

après la Révolution. Au diocèse de Saint-Claude, à Conliège où l’on avait

édifié une chapelle pour abriter une statue de la Sainte Vierge qu’un petit

berger avait découverte dans un rocher, on établit une confrérie sous le titre

de Notre-Dame de Lorette (1653). Au diocèse de Luçon, à la Flocellière,

Elisabeth Hamilton, femme de Jacques de Maillé-Brézé, morte en 1617, léga ses

bijoux pour fonder un couvent de Carmes et une chapelle dédiée à Notre-Dame de

Lorette, achevée dix-huit ans après sa mort ; détruite par la Révolution, la

chapelle fut relevée en 1867. Au diocèse de Rodez, on trouve, en plus de celui

de Millau, un sanctuaire que Louis d’Arpajon, marquis de Séverac, éleva à

Notre-Dame de Lorette, en 1648, pour expier un crime ; la statue fut sauvée de

la Révolution et la chapelle fut rendue au culte en 1854. Au diocèse de Tours,

à Montrésor, au XVI° siècle, René de Bastarnay, seigneur de Montrésor, baron du

Bouchage et d’Authon, en souvenir d’un pélerinage à Notre-Dame de Lorette, fit

édifier une chapelle qui, ruinée par la Révolution, fut rétablie en 1877 ; à

Tauxigny, une chapelle dédiée à Notre-Dame de Lorette, élevée en 1542 par

Guillaume, abbé de Baugerais, fut vendue à la Révolution et ne fut pas rendue

au culte. Au diocèse de Séez, à Montsort, près d’Alençon, on voit un ancien

oratoire construit sur le modèle de Notre-Dame de Lorette qui reçut, en 1888,

un office particulier. Au diocèse d’Autun, à Morlet, près d’Epinac, au XIV°

siècle, le seigneur des Loges, en remerciement pour avoir été délivré des Turcs,

construisit une chapelle en l’honneur de Notre-Dame de Lorette. Au diocèse de

Strasbourg, à Murbach, on vénère une Notre-Dame de Lorette construite à la fin

du XVII° siècle. A Nantes, l’église Sainte-Croix est affiliée à Notre-Dame de

Lorette. Au diocèse de Saint-Brieuc, dans le canton d’Uzel, au Quillio, on

vénérait déjà sous l’Ancien Régime Notre-Dame de Lorette. Dans l’archidiocèse

de Bordeaux, à Saint-Michel de la Pujade, près de Lamothe-Landeron, Eléonore

d’Aquitaine, après l’apparition de la Vierge à deux petits pâtres, avait fondé

une chapelle qui, au XIV° siècle, prit le nom et la forme de Notre-Dame de

Lorette ; ruinée par la Révolution, la chapelle fut restaurée au siècle

suivant. Au diocèse de Saint-Flour, à Salers, on célèbre Notre-Dame de Lorette

: l’antique statue ayant été brûlée par les révolutionnaires, la nouvelle fut

bénite en 1813 par le cardinal Gabrielli et la nouvelle église consacrée en

1887.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/12/10.php

Giambattista Tiepolo, Esquisse pour Le

Transport de la Sainte Maison de Lorette, 1743, Getty

Museum, Los Angeles

Lorette : la sainte

maison

Le rayonnement de ce

sanctuaire italien est si grand que le calendrier liturgique catholique romain

propose une mémoire liturgique pour célébrer la "Translation de la Sainte

Maison de Lorette", le 10 décembre.

Le mot

"translation" signifie "transport" : l'actuel sanctuaire,

construit au XV° et XVI° siècle, abrite une maison, "la sainte

Maison", dont les pierres sont une relique de la maison de la Vierge Marie

de Nazareth.

Sixte V (pape de 1585 à

1590), fit graver en lettres d'or sur façade de la Basilique à peine achevée :

« Maison de la Mère de Dieu où le Verbe s'est fait chair ».

Il est tout à fait

saisissant d’entrer en ce lieu, de se prosterner là, et de penser qu’entre ses

pierres, quand la Vierge prononça son Oui, le Verbe s’est fait chair dans son

sein virginal, et qu’il a vécu parmi nous.

FÊTES

• Le 10 décembre, mémoire

liturgique de la translation de la sainte maison.

• 25 mars, fête de

l’Annonciation : l’Annonciation a eu lieu à Nazareth, et les murs de cette

maison si simple rendent ce mystère palpable.

• 8 septembre, fête de la

Nativité de Marie : il est particulièrement juste d’honorer la naissance de

Marie dont la sainteté est toute orientée vers sa mission exceptionnelle :

devenir la mère de Jésus le Christ, vrai Dieu et vrai homme.

Accès facile par le train

sur la ligne Milan-Lecce.

Le sanctuaire a une

double administration : pontificale et franciscaine (les Capucins).

LE FAMEUX RÉCIT DE 1472,

LA TRANSLATIO MIRACULOSA

On entend encore parler

aujourd'hui de l’ouvrage Translatio miraculosa (Translation miraculeuse),

composé vers 1472 par Pietro Giorgio di Tolomei, dit « le Teramano », qui fut

recteur du sanctuaire de Lorette de 1450 à 1473. On y raconte comment, lorsque

les habitants de Nazareth accueillirent la religion musulmane, la « chambre de

la maison de Marie » fut transportée par les anges d’abord à Tersatto, près de

Fiume (Rijeka) en Croatie, puis sur le territoire de Recanati en trois sites

différents : dans la forêt d’une certaine Loreta, sur la colline de deux frères

qui se disputèrent pour le partage des offrandes recueillies, et enfin au

milieu d’une voie publique.

Certains mystiques ont

repris cette idée, ce qui ajoute à la confusion car les lecteurs ne savent pas

toujours discerner dans leurs "révélations" ce qui vient des

connaissances de leur temps et ce qui vient de la lumière divine.

En tout cas, au fil du

temps, cet ouvrage a généré de nombreuses polémiques, jusqu’à ce que la

recherche moderne situe les choses plus sérieusement, et plus sereinement.

LES FOUILLES

ARCHÉOLOGIQUES SOUS LA SAINTE MAISON ENTRE 1962 ET 1968

- La maison est sans

fondations : elle repose directement sur la voie publique.

- On a retrouvé des

monnaies de 1452 dans le sous-sol de la Sainte Maison, dont certaines très

importantes. Elles nous ramènent à l’année 1294, retenue par la tradition comme

date du commencement de la présence à Lorette de la Sainte Maison.

- Certains graffitis

tracés sur les pierres de la Sainte Maison ont causé une grande surprise. Ils

représentent des croix de forme inhabituelle (croix avec « waw », « cosmiques

», monogrammes, à double taille, à deux ou trois cornes...) qu’Emmanuele Testa

et Bellarmino Bagatti, experts franciscains de Terre sainte, ont déclaré

d’origine palestinienne et judéo-chrétienne. De telles croix sont identiques à

celles trouvées à Nazareth et remontant au IIIe siècle. Ce sont des symboles

christologiques qui proclament la puissance de la croix de Jésus. Ces pierres

couvertes de graffitis évoquent la patrie de Marie et rendent plausible leur

transport de la Palestine à Lorette.

- La position et

l’orientation de la maison de Lorette, très surprenante par rapport aux usages

locaux, devient lumineuse lorsqu’elle est rapprochée de la position avec la

grotte de Nazareth qui en constituait le prolongement.

LE TÉMOIGNAGE DE L'ART

Contrairement à ce que

l’on pensait, les premiers témoignages iconographiques concernant le

déplacement de la maison de Marie depuis Nazareth jusqu’à Lorette ne

représentent pas un vol aérien par des "anges", mais un transport

maritime. Ainsi en est-il de deux bas-reliefs de la fin du XV° siècle les anges

portent la Sainte Maison non pas dans les airs, mais immergée dans les flots.

LES DOCUMENTS

ADMINISTRATIFS

- Les notes de frais d’un

transport par bateau au compte de la famille « Angeli »,

- La mention des «

saintes pierres extraites de la maison de notre Dame la vierge mère de Dieu »

dans un acte notarié concernant un mariage dans entre la famille « De Angelis »

et celle de Philippe d’Anjou,

- La présence d’une pièce

de monnaie de la famille d’Anjou, murée dans les murs de la maison.

IL S'AGIT DONC D'UN

TRANSPORT DE RELIQUES PAR UNE FAMILLE CHRÉTIENNE

Le transport aurait ainsi

été organisé par une famille noble, De Angeli, dans le but de préserver ces

précieuses pierres contre les attaques des turcs. Les résultats permettent

aussi de comprendre comment on est passé du transport par la famille « Angelis

» (ange), à la légende d’un transport par les anges

Il ne faut pas s’étonner

de ce transport des reliques de Terre sainte jusqu’en Italie. Il suffit de

penser aux reliques de la Croix et à la Scala Santa qui furent acheminées à

Rome par sainte Hélène, la mère de Constantin.

Jean Paul II au

sanctuaire de Lorette (1994)

• "Une

relique", une précieuse “icône concrète”.

A l’occasion du VIIe centenaire

du sanctuaire de Lorette (1994), Jean Paul II, tout en «laissant [...] pleine

liberté à la recherche historique pour enquêter sur l’origine du sanctuaire et

sur la tradition de Lorette», a évoqué la signification de la Sainte Maison

quand il a affirmé : celle-ci «n’est pas seulement une relique, mais aussi une

précieuse “icône concrète”». Le pape retient implicitement comme une donnée

historique minima que la Sainte Maison contient quelque élément de la chambre

de Marie à Nazareth ; autrement elle ne pourrait pas être considérée comme une

« relique » (ce qui reste d’une personne ou d’une chose sacrée, ou un objet

venu en contact avec elles). Sans un « quelque chose » de relationnel avec la

maison de Marie, sans allonger les «racines... dans l’Orient chrétien» (n° 9).

• Le mystère de

l'Incarnation

Or, insiste le pape, le

mystère de l’Incarnation s’est accompli en trois moments qui « renferment

chacun à son tour les grands messages que le sanctuaire de Lorette est appelé à

tenir vivants dans l’Eglise ».

Ce sont :

– 1. La salutation de

l’ange, c’est-à-dire l’Annonciation ;

– 2. La réponse de foi,

le « fiat » de Marie ;

– 3. Le sublime événement

du Verbe qui se fait chair. Nous pourrions les résumer dans les trois paroles :

« grâce, foi et salut... » (no 3).

• Un lieu pour la famille

Le souvenir de la vie

cachée de Nazareth « réveille le sens de la sainteté de la famille, exposant

d’un seul coup tout un monde de valeurs, aujourd’hui tellement menacées, comme

la fidélité, le respect de la vie, l’éducation des enfants, la prière, que les

familles chrétiennes peuvent redécouvrir à l’intérieur des murs de la Sainte

Maison, première et exemplaire “église domestique” de l’histoire » (no 8).

• Un sanctuaire qui porte

de bons fruits

Jean Paul II établit

aussi un sage principe qui s’applique à Lorette : « L’importance du sanctuaire

lui-même ne se mesure pas selon la base d’où il a tiré ses origines, mais aussi

sur la base de ce qu’il a produit », selon le critère évangélique qui juge

l’arbre à ses fruits (no 2). Le même pontife reconnaît que le sanctuaire de la

Sainte Maison « a eu une part très active dans la vie du peuple chrétien

pendant quasiment tout le cours du second millénaire » (no 9).

Benoît XVI, le 4 octobre

2012, à Lorette.

« La foi nous fait

habiter, demeurer, mais nous fait aussi marcher sur le chemin de la vie. À ce

propos aussi, la Sainte Maison de Lorette nous donne un enseignement important.

Comme nous le savons, elle était située sur une route. La chose pourrait

apparaître plutôt étrange : de notre point de vue en effet, la maison et la

route semblent s'exclure. [...]

Ainsi, nous trouvons ici

à Lorette, une maison qui nous fait demeurer, habiter et qui en même temps nous

fait cheminer, nous rappelle que nous sommes tous pèlerins, que nous devons

toujours être en chemin vers une autre maison, vers la maison définitive, celle

de la Cité éternelle, la demeure de Dieu avec l'humanité rachetée. (cf. Ap 21,

3). »

Extrait de Benoît XVI,

Homélie du 4 octobre 2012, à Lorette.

Autres visiteurs

illustres

Vers 1462/64, le cardinal

Pietro Barbo (1417- 1471), d’origine vénitienne, est atteint de la peste. Il se

fait porter au sanctuaire de Notre-Dame de Lorette. Là, « il s’endormit, et vit

dans son sommeil la bienheureuse Vierge qui lui promit non seulement qu’il

guérirait, mais que très prochainement il serait élevé sur la chaire de saint

Pierre ». Il guérit et fut élu pape en 1464, sous le nom de Paul II.

Saint François de Sales,

saint Louis- Marie Grignion de Montfort, saint Alphonse de Liguori... ne se

sont pas privés d’un séjour à Lorette pour se raffermir dans l’esprit et

contempler dans la joie le grand mystère de l’Incarnation.

Parfois, comme cela s’est

passé dans le mouvement des Focolari, Lorette représente une expérience

fondamentale, comme en témoigne Chiara Lubich, la fondatrice.

Stefano DE FIORES,

article « LORETTE I », dans : René LAURENTIN et Patrick SBALCHIERO,

Dictionnaire encyclopédique des apparitions de la Vierge. Inventaire des

origines à nos jours. Méthodologie, prosopopée, approche interdisciplinaire,

Fayard, Paris 2007.

Giuseppe SANTARELLI,

Nuove fonti letterarie, in Theotokos 1997, n° 2, pp. 707-724, extraits des

pages 716-724 (Giuseppe SANTARELLI, basilica della « santa Casa », 60025

Loreto).

Synthèse par F. Breynaert

SOURCE : http://www.mariedenazareth.com/9128.0.html?&L=0

Raphaël, La Vierge de Lorette, 1509-1510, 120 x 90, Musée Condé, Rotonde de la galerie de peinture, Chantilly

HOMÉLIE DU PAPE BENOÎT

XVI

Place Madonna di Loreto

Jeudi 4 octobre 2012

Messieurs les Cardinaux,

Vénérés frères dans

l’épiscopat,

Chers frères et sœurs !

Le 4 octobre 1962, le

bienheureux Jean XXIII est venu en pèlerinage dans ce sanctuaire pour confier à

la Vierge Marie le Concile Œcuménique Vatican II, qui devait être inauguré une

semaine plus tard. Lui qui nourrissait une dévotion filiale et profonde à la

Vierge s’est tourné vers elle avec ces mots : « Aujourd’hui encore une fois, et

au nom de tout l’épiscopat, à Vous, très douce mère, que l’on salue du titre de

« Auxilium Episcoporum », Nous demandons pour Nous, évêque de Rome et pour tous

les évêques du monde entier de Nous obtenir la grâce d’entrer dans la salle

conciliaire de la basilique Saint-Pierre comme sont entrés les Apôtres et

premiers disciples de Jésus dans le Cénacle : avec un seul cœur, un seul

battement d’amour envers le Christ et les âmes, un seul but de vivre et de se

sacrifier pour le salut des individus et des peuples. Ainsi, que par votre

intercession maternelle, dans les années et les siècles à venir, on puisse dire

que la grâce de Dieu a préparé, accompagné et couronné le vingtième Concile

Œcuménique, en donnant à tous les fils de la Sainte Église une nouvelle

ferveur, un nouvel élan de générosité et de fermes résolutions » (AAS 54

(1962), 727).

À cinquante ans de

distance, après avoir été appelé par la divine Providence à succéder au siège

de Pierre à ce Pape inoubliable, je suis venu ici moi aussi en pèlerin pour

confier à la Mère de Dieu deux importantes initiatives ecclésiales : l’Année de

la Foi, qui s’ouvrira dans une semaine, le 11 octobre, à l’occasion du

cinquantième anniversaire de l’ouverture du Concile Vatican II, et l’Assemblée

Générale ordinaire du Synode des Évêques que j’ai convoquée au mois d’octobre

sur le thème « La nouvelle évangélisation pour la transmission de la foi

chrétienne ».

Chers amis ! À vous tous

j’adresse mon plus cordial salut. Je remercie l’archevêque de Lorette, Mgr

Giovanni Tonnuci, pour ses chaleureuses paroles d’accueil. Je salue les autres

évêques présents, les prêtres, les pères Capucins, qui ont la charge pastorale

du sanctuaire, et les religieuses. J’adresse une pensée respectueuse au maire,

M. Paolo Nicoletti, que je remercie pour ses paroles courtoises, au

représentant du gouvernement et aux autorités civiles et militaires présentes.

Ma reconnaissance va aussi à tous ceux qui ont offert généreusement leur

collaboration pour la réalisation de mon pèlerinage ici.

Comme je le rappelais

dans la Lettre Apostolique de promulgation de l’Année de la Foi, « j’entends

inviter les confrères Évêques du monde entier à s’unir au Successeur de Pierre,

en ce temps de grâce spirituelle que le Seigneur nous offre, pour faire mémoire

du don précieux de la foi. » (Porta Fidei, 8). Et justement ici à Lorette, nous

avons l’opportunité de nous mettre à l’école de Marie, de celle qui a été

proclamée bienheureuse parce qu’elle a cru (Lc 1, 45).Ce sanctuaire, construit

autour de sa maison terrestre, abrite la mémoire du moment où l’Ange du

Seigneur est venu à Marie avec la grande annonce de l’Incarnation, et où elle a

donné sa réponse. Cette humble habitation est un témoignage concret et tangible

du plus grand évènement de notre histoire : l’Incarnation, le Verbe qui se fait

chair, et Marie, la servante du Seigneur est la voie privilégiée par laquelle

Dieu est venu habiter parmi nous (cf Jn 1, 14). Marie a offert sa propre chair,

s’est mise tout entière à disposition de la volonté de Dieu, devenant un « lieu

» de sa présence, « lieu » dans lequel demeure le Fils de Dieu. Ici, nous pouvons

rappeler la parole du Psaume par laquelle, d’après la Lettre aux Hébreux, le

Christ a commencé sa vie terrestre en disant au Père : « Tu n'as voulu ni

sacrifice ni offrande, Mais tu m'as formé un corps… Alors j'ai dit : Voici, je

viens pour faire, ô Dieu, ta volonté » (10, 5.7). Marie prononce des paroles

similaires devant l’Ange qui lui révèle le plan de Dieu sur elle : « Je suis la

servante du Seigneur, qu’il me soit fait selon ta parole » (Lc 1, 38). La

volonté de Marie coïncide avec la volonté du Fils dans l’unique projet d’amour

du Père, et en elle, s’unissent le ciel et la terre, le Dieu créateur et sa

créature. Dieu devient homme, et Marie se fait « maison vivante » du Seigneur,

temple où habite le Très-Haut. Ici à Lorette, il y a cinquante ans, le

Bienheureux Jean XXIII invitait à contempler ce mystère, à « réfléchir sur ce

lien entre le ciel et la terre, qui est l’objectif de l’Incarnation et de la

Rédemption », et il continuait en affirmant que le Concile avait pour but

d’étendre toujours plus les bienfaits de l’Incarnation et la Rédemption du

Christ à toutes les formes de la vie sociale (cf. AAS 54, (1962), 724). C’est

une invitation qui résonne encore aujourd’hui avec une force particulière. Dans

la crise actuelle, qui ne concerne pas seulement l’économie, mais plusieurs

secteurs de la société. L’Incarnation du Fils de Dieu nous dit combien l’homme

est important pour Dieu et Dieu pour l’homme. Sans Dieu, l’homme finit par

faire prévaloir son propre égoïsme sur la solidarité et sur l’amour, les choses

matérielles sur les valeurs, l’avoir sur l’être. Il faut revenir à Dieu pour

que l’homme redevienne homme. Avec Dieu, même dans les moments difficiles, de

crise, apparait un horizon d’espérance : l’Incarnation nous dit que nous ne

sommes jamais seuls, que Dieu entre dans notre humanité et nous accompagne.

Mais la demeure du Fils

de Dieu dans la « maison vivante », dans le temple qu’est Marie nous amène à

une autre réflexion : là où habite Dieu, nous devons reconnaitre que nous

sommes tous « à la maison » : là où habite le Christ, ses frères et sœurs ne

sont plus des étrangers. Marie, qui est la mère du Christ et aussi notre mère,

nous ouvre la porte de sa maison, nous aide à entrer dans la volonté de son

Fils. C’est la foi, ainsi, qui nous donne une maison en ce monde, qui nous unit

en une seule famille et qui nous rend tous frères et sœurs. En contemplant

Marie, nous devons nous demander si nous aussi nous voulons être ouverts au

Seigneur, si nous voulons offrir notre vie pour qu’elle soit une demeure pour

Lui ; ou si nous avons peur que la présence du Seigneur puisse être une limite

à notre liberté, et si nous voulons nous réserver une part de notre vie qui

n’appartienne qu’à nous-mêmes. Mais c’est précisément Dieu qui libère notre

liberté, la libère du repli sur elle-même, de la soif du pouvoir, de la

possession, de la domination, et la rend capable de s’ouvrir à la dimension qui

lui donne tout son sens : celle du don de soi, de l’amour, qui se fait service

et partage.

La foi nous fait habiter,

demeurer, mais nous fait aussi marcher sur le chemin de la vie. À ce propos

aussi, la Sainte Maison de Lorette nous donne un enseignement important. Comme

nous le savons, elle était située sur une route. La chose pourrait apparaître

plutôt étrange : de notre point de vue en effet, la maison et la route semblent

s’exclure. En réalité, justement sur cet aspect particulier, un message

singulier est gardé dans cette maison. Elle n’est pas une maison privée, elle

n’appartient pas à une personne ou à une famille, mais elle est au contraire

une habitation ouverte à tous, qui est, pourrait-on dire, sur notre chemin à

tous. Ainsi, nous trouvons ici à Lorette, une maison qui nous fait demeurer,

habiter et qui en même temps nous fait cheminer, nous rappelle que nous sommes

tous pèlerins, que nous devons toujours être en chemin vers une autre maison,

vers la maison définitive, celle de la Cité éternelle, la demeure de Dieu avec

l’humanité rachetée. (cf. Ap 21, 3).

Il y a encore un point

important du récit évangélique de l’Annonciation que je voudrais souligner, un

aspect qui ne finit pas de nous étonner : Dieu demande le « oui » de l’homme,

il a crée un interlocuteur libre, il demande que sa créature Lui réponde en

toute liberté. Saint Bernard de Clairvaux, dans un de ses sermons les plus

célèbres, « représente » l’attente de la part de Dieu et de l’humanité du « oui

» de Marie, en se tournant vers elle avec une supplique : « L’ange attend ta

réponse, parce qu’il est déjà temps pour lui de retourner vers Dieu qui l'a envoyé.

Donne ta réponse, ô Vierge, hâte-toi, ô Souveraine, donne cette réponse que la

terre, que les enfers, que les cieux aussi attendent. Autant il a convoité ta

beauté, autant il désire à cette heure le « oui » de ta réponse, ce oui par

lequel il a résolu de sauver le monde. Lève-toi, cours, ouvre ! Lève-toi par la

foi, cours par la ferveur, ouvre-lui par ton consentement (In laudibus Virginis

Matris, Hom. IV, 8). Dieu demande la libre adhésion de Marie pour devenir

homme. Certes, le « oui » de Marie est le fruit de la grâce divine. Mais la

grâce n’élimine pas la liberté, au contraire elle la crée et la soutient. La

foi n’enlève rien à la créature humaine, mais ne permet pas la pleine et

définitive réalisation.

Chers frères et sœurs, en

ce pèlerinage, qui parcourt à nouveau celui du Bienheureux Jean XXIII – et qui

a lieu de manière providentielle, le jour de la fête de Saint François

d’Assise, véritable « évangile vivant » –, je voudrais confier à la très Sainte

Mère de Dieu toutes les difficultés que vit notre monde à la recherche de la

sérénité et de la paix, les problèmes de tant de familles qui regardent

l’avenir avec préoccupation, les désirs des jeunes qui s’ouvrent à la vie, les

souffrances de ceux qui attendent des gestes et des choix de solidarité et

d’amour. Je voudrais confier aussi à la Mère de Dieu ce temps spécial de grâce

pour l’Église, qui s’ouvre devant nous. Toi, Mère du « oui », qui a écouté

Jésus, parle-nous de Lui, raconte-nous ton chemin pour le suivre sur la voie de

la foi, aide-nous à l’annoncer pour que tout homme puisse l’accueillir et

devenir demeure de Dieu. Amen !

© Copyright 2012 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Caravage,

La Vierge de Lorette, (nommée aussi

plus descriptivement La Madone des pèlerins), 1604-1605, 260 x 150, Basilique Saint-Augustin de Rome,,

Rome

Les Litanies de Lorette,

quand l’Église chante son amour à la Vierge

Agnès

Pinard Legry | 18 août 2020

Courtes invocations

adressées à Dieu, à la Vierge, aux saints ou à un saint en particulier, les

litanies sont toutes ponctuées de la demande : « Priez pour nous ». Prier au

rythme des litanies, c’est se laisser porter et inspirer par les vertus de

celui ou celle à qui elles sont adressées. Cet été Aleteia vous propose de

(re)découvrir les cinq litanies reconnues comme prière liturgique officielle de

l’Église. Aujourd’hui les Litanies de Lorette. (3/5)

Connue depuis le XIIe siècle,

les Litanies de Lorette, du nom du sanctuaire italien de la Sainte Maison de

Lorette qui les a rendues célèbres, sont un ensemble d’invocations à la Vierge

qui se récitent habituellement après le chapelet. Elles se composent de trois

groupes d’invocations exaltant successivement la maternité divine de Marie, sa

virginité incomparable et sa glorieuse prééminence de Reine.

Lire aussi :

Pourquoi

la Vierge Marie a-t-elle autant de noms ?

Ce qui est fort dans ces

litanies, c’est qu’elles sont intimement liées à la vie de l’Église et aux

préoccupations des hommes. En effet, « elles se sont progressivement

développées dans un environnement spirituel marial dont la frontière remonte à

Byzance, au IVe siècle », précise Mgr Dominique Le Tourneau dans

son Dictionnaire

encyclopédique de Marie. « Un texte du milieu du XIVe siècle, un

missel romain traduit en arménien, pourrait faire penser que les Litanies se

seraient formées à cette époque ». Pourtant, en dépit des siècles, elles

sont d’une incroyable actualité : régulièrement, les papes y ajoutent des

vocables qui font écho aux préoccupation du moment. En juin 2020, par exemple,

le pape François a décidé d’ajouter trois vocables : Mater Misericordiae, Mater

Spei et Solacium migrantium, soit « Mère de Miséricorde »,

« Mère de l’Espérance » et « Réconfort (ou aide) des

migrants ».

D’autres papes avant lui

ont décidé d’inclure des invocations dans les litanies : Pie V, Léon XIII,

Benoît XV, Paul VI… Pie IX a par exemple autorisé l’invocation « Reine

conçue sans le péché originel » qui, après la promulgation du dogme

de L’Immaculée

Conception, se répand alors de plus en plus jusqu’à en devenir universel.

Jean Paul II a également ajouté l’invocation à la « Mère de la

famille ». « Elles répondent au moment réel, un moment qui représente

un défi pour le peuple« , a ainsi expliqué Mgr Arthur Roche, membre de la

Congrégation pour le Culte divin et la discipline des sacrements, dans un

entretien à Vatican News. « Même à l’époque actuelle, marquée par

des raisons d’incertitude et de désarroi« , le recours « plein

d’affection et de confiance » à la Vierge « est particulièrement

suivi par le peuple de Dieu ».

Seigneur, prends pitié.

Ô Christ, prends pitié.

Seigneur, prends pitié.

Christ, écoute-nous.

Christ, écoute-nous.

Père du Ciel, toi qui es Dieu,

aie pitié de nous.

Fils, Rédempteur du monde, toi qui es Dieu,

Esprit Saint, toi qui es Dieu,

Trinité sainte, toi qui es un seul Dieu,

Sainte Marie, priez pour nous.

Sainte Mère de Dieu, priez…

Sainte Vierge des vierges,

Mère du Christ,

Mère de l’Église,

Mère de la grâce divine,

Mère très pure,

Mère très chaste,

Mère toujours vierge,

Mère sans taches,

Mère très aimable,

Mère admirable,

Mère du bon conseil,

Mère du Créateur,

Mère du Sauveur,

Mère de miséricorde,

Mère très prudente,

Mère digne d’honneur,

Mère digne de louange,

Vierge puissante,

Vierge clémente,

Vierge fidèle,

Miroir de la sainteté divine,

Siège de la Sagesse,

Cause de notre joie,

Temple de l’Esprit Saint,

Tabernacle de la gloire éternelle,

Demeure toute consacrée à Dieu,

Rose mystique,

Tour de David,

Tour d’ivoire,

Maison d’or,

Arche d’alliance,

Porte du ciel,

Étoile du matin,

Salut des malades,

Refuge des pécheurs,

Consolatrice des affligés,

Secours des chrétiens,

Reine des Anges,

Reine des Patriarches,

Reine des Prophètes,

Reine des Apôtres,

Reine des Martyrs,

Reine des Confesseurs,

Reine des Vierges,

Reine de tous les Saints,

Reine conçue sans le péché originel,

Reine élevée au ciel,

Reine du Saint Rosaire,

Reine de la famille,

Reine de la paix.

Agneau de Dieu, qui enlèves le péché du monde,

pardonne-nous, Seigneur.

Agneau de Dieu, qui enlèves le péché du monde,

écoute-nous, Seigneur.

Agneau de Dieu, qui enlèves le péché du monde,

aie pitié de nous, Seigneur.

Prie pour nous, Sainte Mère de Dieu,

afin que nous devenions dignes des promesses du Christ.

Prions,

Accorde à tes fidèles,

Seigneur notre Dieu,

de bénéficier de la santé de l’âme et du corps,

par la glorieuse intercession

de la bienheureuse Marie toujours vierge,

délivre-nous des tristesse du temps présent

et conduis-nous au bonheur éternel,

Par Jésus, le Christ, notre Seigneur.

Amen.

Lire aussi :

Les

Litanies de saint Joseph, le meilleur moyen de lui demander d’intercéder pour

nous

Lire aussi :

Les

Litanies des saints, quand l’Église de la terre appelle à l’aide l’Église du

Ciel

Basilica

Pontificia della Santa Casa di Loreto

Santuario della Santa Casa, Loreto

Santuario della Santa Casa, Loreto

Loreto

veduta

Notre-Dame de Lorette :

le plus ancien sanctuaire marial international

Isabelle Cousturié ✝ - Marie de Nazareth - ZENIT - publié le

10/12/13

Sa fête, le 10 décembre,

a été l’occasion d’une pensée pour Benoit XVI qui avait confié à Notre Dame de

Lorette l’Année de la foi.

11/12/2013

Le rayonnement du

sanctuaire italien Notre-Dame de Lorette est si grand que le calendrier

liturgique catholique romain propose une mémoire liturgique pour

célébrer la « Translation de la Sainte Maison de Lorette », le

10 décembre.

Et le 10 décembre, c’est à Marie que le pape François a

consacré son tweet, en recommandant à ses followers, sur son compte Pape

François @Pontifex_fr, de s’en remettre à elle « quand cela va

mal ».

L’occasion de rappeler le pèlerinage que Benoît XVI y avait fait, en

octobre 2012, 50 ans après la visite historique de Jean XXIII qui

a depuis ce jour-là sa statue tout en haut de la colline.

C’était en 1962, le bon pape Jean s’apprêtait à ouvrir le concile Vatican

II et souhaitait confier ses travaux à la Vierge Marie. En 2012, Benoît

XVI a souhaité entreprendre la même démarche pour confier de nouveau à Notre

Dame de Lorette les 50 ans de l’ouverture du concile et l’Année de la

foi qu’il allait ouvrir une semaine plus tard (12 octobre 2012).

C’était sa deuxième visite après celle pour le rassemblement des jeunes

catholiques italiens, l’Agora des Jeunes de 2007. (zenit).

Comme pour son prédécesseur, Jean-Paul II, qui y avait effectué trois

pèlerinages, la maison de Lorette était « une maison faite pour y

demeurer, y habiter » mais « pour mieux avancer » dans la vie,

pour se rappeler que « nous sommes tous des pèlerins, que nous

devons toujours être en marche vers une autre maison, vers la maison définitive,

celle de la Cité éternelle, la demeure de Dieu avec l’humanité rachetée”.

Notre-Dame de Lorette est le tout premier sanctuaire marial international

consacré à la Vierge : « Ici à Lorette, nous avons l’opportunité de nous

mettre à l’école de Marie, de celle qui a été proclamée bienheureuse parce

qu’elle a cru », avait souligné Benoît XVI à l’homélie de

la messe célébrée sur le parvis de la basilique.

Et de poursuivre : « Marie, qui est la mère du Christ et aussi notre

mère, nous ouvre la porte de sa maison, nous aide à entrer dans la volonté de

son Fils. C’est la foi, ainsi, qui nous donne une maison en ce monde, qui nous

unit en une seule famille et qui nous rend tous frères et sœurs (…) En

contemplant Marie, nous devons nous demander si nous aussi nous voulons être

ouverts au Seigneur, si nous voulons offrir notre vie pour qu’elle soit une

demeure pour Lui ; ou si nous avons peur que la présence du Seigneur puisse

être une limite à notre liberté, et si nous voulons nous réserver une part de

notre vie qui n’appartienne qu’à nous-mêmes ».

Au cœur de ce sanctuaire, Benoît XVI avait confié à la très

Sainte Mère de Dieu « toutes les difficultés que vit notre monde à la

recherche de la sérénité et de la paix, les problèmes de tant de familles qui

regardent l’avenir avec préoccupation, les désirs des jeunes qui s’ouvrent à la

vie, les souffrances de ceux qui attendent des gestes et des choix de

solidarité et d’amour. »

L'histoire de la sainte maison déplacée dans les airs par des anges… est

devenue un point de repère familier pour les aviateurs qui ont fait de Notre-Dame

de Lorette leur sainte protectrice.

Loreto:

Facciata del Santuario (xilografia). Strafforello Gustavo, La patria, geografia

dell'Italia, III. Provincie di Ancona, Ascoli Piceno, Macerata, Pesaro e

Urbino. Unione Tipografico-Editrice, Torino, 1898

Le Pèlerinage à Lorette

de quelques voyageurs français entre Renaissance et Lumières.

Conférencier /

conférencière

Au moment de la découverte, en 1770, du voyage manuscrit de Montaigne, l’intelligentsia parisienne crut tenir dans ce récit de la visite ad limina du philosophe un texte où l’Église de Rome serait jugée d’une manière que l’on supposait être digne d’un des pères fondateurs de la pensée des Lumières. « Ce sera un véritable cadeau pour les philosophes et les gens de lettres », notait alors un anonyme correspondant des Affiches de province . Si un écrivain français passait pour être à la source d’une certaine modernité, c’était bien le seigneur de Montaigne, heureusement mis à l’index dès 1676, magnifié par l’édition du huguenot Pierre Coste comme l’alpha sinon l’oméga de la libre-pensée , celui qui, dans deux gravures célèbres, accueillait aux Champs-Élysées des Philosophes l’homme de Ferney et celui de Montmorency, le père de Candide et celui d’Émile . Accouru à Paris avec sa découverte, l’abbé Prunis, naïf « inventeur » du manuscrit, s’empressa de s’en ouvrir au coryphée de la philosophie : D’Alembert fut consterné de sa lecture et se dispensa d’en favoriser l’édition . Qu’y avait-il de si scandaleux dans ces pages sur le voyage d’Allemagne et d’Italie ? Les trois jours passés au sanctuaire de Notre-Dame de Lorette donnaient du philosophe une image que la presse de l’époque trouva bien peu conforme à celle d’un des parrains supposés du déisme moderne. Le Journal encyclopédique s’étonna « qu’un philosophe tel que Montaigne », etc., le Journal des savants nota avec quelque perfidie : « Ceux qui chercheront ici l’auteur des Essais pourraient bien ne le trouver nulle part » ; et l’Année littéraire de Fréron se réjouit de la déconvenue des philosophes et d’un Montaigne posthume qui le faisait bon chrétien . Malgré les efforts de l’éditeur Le Jay pour suggérer par une page de titre alléchante un ouvrage de contrebande antireligieuse (fausse adresse romaine et vignette représentant la basilique Saint-Pierre comme pour un vulgaire Compère Mathieu ), le Journal donnait l’impression désolante d’un catholique fort respectueux du magistère romain auquel il soumettait son œuvre et, surtout, d’une dévotion à ce qui paraissait aux esprits éclairés du temps l’une des plus grossières supercheries de l’Église d’Occident : ce conte de fées qui prétendait que les anges avaient transporté de Nazareth à Lorette la maison natale de la Vierge où eut lieu l’Annonciation et où le Christ passa avec sa mère et Joseph le charpentier l’essentiel de sa vie terrestre, sublime témoignage et preuve tangible, on s’en doute, pour tout chrétien du Dieu fait homme en Galilée pour sauver l’Humanité tout entière .

Meunier de Querlon qui se chargea de l’édition la fit précéder d’une dédicace à

Buffon destinée d’entrée de jeu à sanctifier philosophiquement le texte

montaignien et il consacra, en outre, une partie de son « Discours préliminaire

» de 1774 à justifier la faute de goût que constituait pour un esprit libéré

l’escapade dévote de Lorette :

« De tous les lieux

d’Italie propres à attirer l’attention de Montaigne, celui qu’on pourrait le moins

soupçonner qu’il eût été curieux de voir, c’est LORETTE : cependant lui qui

n’était resté qu’un jour et demi tout au plus à Tivoli, passa près de trois

jours à Lorette. Il est vrai qu’une partie de ce temps fut consacrée tant à

faire construire un riche ex-voto composé de quatre figures d’argent […] qu’à

solliciter pour son tableau une place qu’il n’obtint qu’avec beaucoup de

faveur. Il y fit de plus ses dévotions ; ce qui surprendra peut-être encore

plus que le voyage et l’ex-voto même. Si l’auteur de la Dissertation sur la

religion de Montaigne , qui vient de paraître avait lu le Journal que nous

publions, il en aurait tiré les plus fortes preuves en faveur de son

christianisme contre ceux qui croient bien l’honorer en lui refusant toute

religion » .

C’est dire combien les mentalités avaient évolué en deux siècles : car ce qui n’était que dévotion à forte coloration sociale et familiale pour le seigneur de Montaigne était devenue l’emblème de la superstition à l’âge des d’Holbach et des Voltaire. Dans les pages qui suivent nous parcourrons en compagnie de quelques pèlerins choisis les chemins de Lorette et leurs échos littéraires.

On sait qu’après un cours séjour sur la rive orientale de l’Adriatique, la Santa Casa de Nazareth toujours portée par des Anges parvint en Italie en décembre 1294 : elle y fut déposée dans un bois de lauriers (lauretum). Le Santuario de la Santa Casa fut édifié par Paul II à partir de 1468 ; ce fut au cœur de cette basilique que l’on installa dans un écrin de marbre la Santa Casa sur les murs de laquelle les pèlerins fixaient des ex-voto. La littérature sur Lorette est fortement liée à ces pèlerinages . Elle fut strictement contrôlée dès l’origine par le Saint-Siège : dès 1507, Jules II avait soustrait le sanctuaire à l’évêque du lieu et l’avait confié à l’autorité pontificale représentée par un gouverneur-légat. En 1532, Girolamo Angelita publia à Venise la Lauretanae Virginis historia: ce texte souvent réédité était inspiré de la Translatio miraculosa, récit rédigé par G. B. Spagnuoli dit: il Mantovano (Baptiste le Mantouan) à la suite de la visite qu’il avait effectuée au sanctuaire en 1489 ; l’ouvrage fut largement traduit et diffusé sous forme manuscrite et imprimée. Mais l’esprit naissant de la Réforme veillait : dès 1546, le Limousin acclimaté à Genève, Eustorg de Beaulieu, chansonne dans sa Chrétienne réjouissance ces pèlerins de l’inutile :

« Brunette, joliette,

Qu’allez-vous tant courir,

À Rome n’à Lorette

Pour de vos maux guarir » .

En 1554, Pietro Paolo

Vergerio il Giovane (Pierre Paul Verger le Jeune) publia une contestation de

l’authenticité des reliques mariales dans un De Idolo Lauretano, dont une

traduction allemande, de grande diffusion en terre luthérienne, parut cinq ans

plus tard . Fort heureusement pour le culte lorétain, on allait attribuer en

1571 la victoire navale de Lépante sur l’Infidèle à une particulière

intercession de la Madonne de Lorette : favorisant activement le culte marial -

vierge et mère - dans une relecture tridentine du culte catholique que l’on

nomma plus tard, avec le père Lemoyne, la « dévotion aisée », la Compagnie de

Jésus propagea à travers l’Europe les vertus miraculeuses de la « Santa Casa »

- symbole de la famille chrétienne - contre l’hérésie et les fausses religions

. Si la pensée humaniste de la Renaissance avait quelque méfiance pour «

l’errance pèlerine » , source de nombreuses entorses aux bonnes mœurs, l’Église

elle-même visait au contrôle de cette activité, le décret touchant les

indulgences promulgué en 1563 par la XXVe session du Concile de Trente

recommandait de « porter respect aux corps saints des martyrs et des autres

saints qui vivent en Jésus Christ » ; mais divers règlements royaux français du

XVIIe siècle limitent étroitement la liberté des pèlerins : un édit d’août 1671

stipule que :

« ceux qui voudraient

faire des pèlerinages seraient tenus de se présenter devant leur évêque

diocésain pour être par lui examinés sur les motifs de leur voyage et de

prendre de lui une attestation par écrit » .

Quelques mois après la

Révocation de l’Édit de Nantes, une déclaration de janvier 1686 interdisait :

« les pèlerinages hors du

royaume, sans une permission expresse du Roi, signée par l’un de ses

Secrétaires d’État sur l’approbation de l’évêque diocésain, à peine des galères

à perpétuité contre les hommes et contre les femmes » .

Pour ce qui est du domaine littéraire français , le père Louis Richeome, s. j., publia en 1597 à Bordeaux chez Simon Millanges – le premier éditeur des Essais dix-sept ans auparavant - Trois discours pour la religion catholique, des miracles, des saints et des images, qui magnifiaient le culte lorétain. Il y revint en 1604 chez le même libraire par un volume de 983 pages, le Pèlerin de Lorette, vœu à la glorieuse Vierge Marie , ouvrage central de la dévotion jésuite récemment analysé avec finesse par Marie-Christine Gomez-Géraud . Nous emprunterons la conclusion de ce savant à un livre traduit en plusieurs langues et dont extraits et abrégés entretinrent longtemps l’influence : « En ces heures de reconquête catholique, le voyageur de Dieu selon Louis Richeome œuvre à sa sanctification personnelle pour gagner d’autres âmes, en devenant un guide spirituel et un apôtre » . Quelques années auparavant, la littérature lorétaine avait été dotée de sa première « histoire », l’Historia Lauretana d’Orazio Torsellini publiée à Rome en 1597, un grand classique réédité et traduit jusqu’au XIXe siècle qui précéda de plus d’un siècle la première bibliographie lorétaine, le Teatro storico della Santa Casa Nazarena (Roma, 1735) par Pietro Valerio Martorelli. Les pèlerins de Lorette avaient donc à leur disposition des livres et des brochures qui ne leur celaient rien de ce morceau de Terre Sainte acclimaté dans la Marche d’Ancône, tels du père Antoine de Saint-Michel les Fumées de la Cour par dialogue entre un Récollet et un gentilhomme faisant ensemble le voyage de Notre-Dame de Lorette […] Avec une exhortation à Messieurs les courtisans (Béziers, 1615) ou de Nicolas de Bralion, la Sainte Chapelle de Laurette ou l’histoire admirable de ce sacré sanctuaire imprimé à Paris en 1665 pour l’édification des voyageurs. Le pèlerinage à Lorette faisait partie, plus généralement, des excursions du Grand Tour, et pas seulement pour les catholiques. Des guides de Rome inclurent dès le XVIIe siècle le sanctuaire lorétain dans les annexes dévotes de la Ville éternelle, comme les Merveilles de la ville de Rome […] Le tout traduit d’Italien en français par Pompée de Launay (Rome, De l’Imprimerie de feu Mascardi, 1668), qui comporte en fin de volume un « Guide de Rome à Notre-Dame de Lorette », illustré de gravures sur bois assez naïves : un pur produit pour pèlerin de moyenne extraction.

Mais le véritable ancêtre des Baedeker et des Joanne, le guide de Maximilien Misson, qui fut l’ouvrage dont presque tous les voyageurs du XVIIIe siècle emportaient un exemplaire – une mine d’érudition pour les relations qu’ils en rédigeaient -, renvoie une autre image du sanctuaire lorétain et des pratiques de pèlerinage. C’est avec Misson que ce qui, depuis le XVIe siècle, formait la vulgate réformée de Lorette atteint le plus vaste public des voyageurs. La Lettre XXe du Nouveau Voyage d’Italie est datée du 26 février 1688 – quelques mois avant le début de la Glorieuse Révolution, le détail a son importance. Dans ce recueil d’un voyageur qui écrit à un correspondant britannique, la lettre consacrée à Lorette est particulièrement illustrée : cinq planches dépliantes hors-texte représentent les quatre faces externes du magnifique écrin et le « dedans de la Santa Casa », plus la statue miraculeuse de Notre-Dame placée dans le même lieu. L’habillage extérieur de marbre de Carrare qui sert de protection à la Santa Casa, avec ses colonnes, ses bas-reliefs et ses statues sculptés par les plus grands artistes, forme contraste – et ce n’est pas une nouvelle fois innocent – avec la médiocrité de la Santa Casa elle-même construite de mauvaises briques et assez délabrée. C’est toute la pompe de l’Église romaine qui est là et qui travestit, une fois de plus, la modeste, mais sublime, vérité du mystère de l’Annonciation. Des numéros renvoient dans la gravure à des lieux ou à des objets où le quotidien prend un sens mystique pour le dévot pèlerin et suscite interrogation sceptique chez l’observateur malveillant: c’est en 12 la « fenêtre par où l’on dit que l’Ange passa » et en 13 l’« armoire où l’on garde quelque vaisselle de terre que l’on dit avoir servi à la Vierge » . On verra que ce dernier vestige sacré intrigua spécialement les voyageurs.

À n’en pas douter, Maximilien Misson, huguenot français réfugié en Angleterre, se montrait fort peu sensible, trois ans après la Révocation de l’Édit de Nantes, à l’idolâtrie romaine : sa lettre sur Lorette est un modèle de rouerie et d’un esprit que l’on pourrait déjà qualifier de voltairien. Le voyageur rapporte d’abord l’histoire de la translation de la Santa Casa sur un ton de naïve crédulité et même avec un enthousiasme suspect : « toute la Nature tressaillit de joie », « les chênes de la forêt » firent chorus, « il ne leur manqua que la voix de ceux de Dodone » (p. 303). Cette présence des mystères du paganisme mise sur le même pied que les divins mystères du christianisme rappelle les débats contemporains sur les « oracles » . Après d’assez extravagants épisodes racontés d’un ton pénétré sur les divers lieux qu’occupa la Santa Casa à Lorette et après avoir suggéré que sa translation sous le pontificat de Boniface VIII, « ce fameux renard » très capable de « fourberie » , pouvait laisser à penser, Misson compose une scène grandiose où il se met en scène dans le sanctuaire lui-même avec un « jésuite anglais » évoquant la naissance miraculeuse du prince de Galles par l’intercession directe de la Madonne et de l’Archange dont Misson reproduit d’après le jésuite le dialogue qu’ils eurent … en latin (p. 309-314). L’allusion au catholicisme de Marie de Modène, qui mit au monde le 10 juin 1688 le futur Jacques III Stuart, seul garçon survivant de la famille royale, ne manquait pas d’humour rétrospectif, car l’année 1688 fut aussi celle de la Glorieuse Révolution qui exila d’Angleterre Jacques II soupçonné de vouloir y rétablir la confession de Rome. De toute évidence, la Madonne et l’Archange avaient abandonné en cours d’année leur dévote princesse. Sans y faire référence, Misson consacre des pages à un commentaire sur la latinité du dialogue entre la Vierge et l’Ange dont le pédantisme burlesque, un peu hors de propos, ravale le séjour de Lorette au niveau d’une parade de superstitions en action et d’absurdités papistes. Le portrait qu’il fait des pèlerins achève de rendre le ridicule de ces entreprises d’autosuggestions collectives : « Il est difficile d’imaginer une chose plus plaisante que les caravanes de pèlerins, quand ces caravanes arrivent ensemble en corps de confréries. […] Ces pèlerins ainsi équipés montent tous sur des ânes. Ces ânes sont réputés avoir quelque odeur de sainteté, à cause de leurs fréquents pèlerinages » (p. 315). En définitive, Lorette n’est qu’un lieu de négoce et l’emblème de cette Église romaine qui a trahi la leçon du Christ . Au cours du siècle des Lumières, les voyageurs anglais de confession réformée en pensèrent ou en écrivirent de même, et parfois avec quelque talent .

La révélation du Journal de Montaigne, en contraste avec ce qu’il faut bien

appeler une avalanche de sarcasmes sceptiques sur la « relique » de Lorette, ne

pouvait que choquer les esprits un peu philosophes. Qu’on en juge : si l’auteur

des Essais n’avait pas la naïveté de croire que le sanctuaire était vierge de

pensées mercantiles, si l’on peut même dire que sa relation prouve une dévotion

sincère mais sans excès de ferveur mystique , une dévotion uniquement

préoccupée de réaliser un « vœu » familial et d’en laisser le témoignage sous

forme d’une plaque d’argent compartimentée à son image et à celle de sa famille

entourant celle de la Vierge où se reconnaît bien là le seigneur de Montaigne,

ce « civis romanus » d’une altière modestie, il n’en demeure pas moins vrai

qu’il évoque sans la moindre ironie les divers « remuements » de la Santa Casa

et, surtout, le miracle dont la Madonne favorisa un Français, « l’archiligueur

» Michel Marteau, seigneur de la Chapelle dont il fit connaissance à Lorette .

On est assez loin d’un Érasme, l’un des pères spirituels de Montaigne, qui dans

une Virginis Matris apud Lauretum cultæ Liturgia (Bâle, Froben, 1523) passe

sous silence le premier « miracle », celui de la « translation » . Montaigne se

met commodément à l’abri de la tradition pour authentifier – d’ailleurs avec

une curieuse erreur - cette « maisonnette qu’ils tiennent être celle-là propre

où en Nazareth naquit Jésus Christ » [sic] . Contrairement à d’autres

voyageurs, il n’évoque pas le fabuleux trésor du sanctuaire, sujet d’admiration

pour les uns et de scandale pour les autres. De fait, ce qu’il semble penser de

Lorette n’est guère éloigné du discours tenu huit ans plus tard sur le même

sujet par un « guisard » de la suite du cardinal de Joyeuse qui décrit assez

précisément, d’autre part, l’endroit de la Santa Casa où l’on fixait les

ex-votos :

« J’ai souvenance qu’il y

a l’un des côtés de ladite chapelle qui est le lieu où est la cheminée , lequel

est tout couvert depuis le haut jusques en bas d’une infinité de tables

d’argent massif, épaisses d’un doigt, esquelles sont les vœux de ceux qui les

ont présentées » .

Dans de très nombreux

récits ou compilations de voyageurs français (voire « belges » ) imprimés ou

restés manuscrits qui évoquent un séjour à Lorette, on rencontre souvent cette

discrétion – fruit d’une foi sincère ou d’un scepticisme censuré - sur l’authenticité

de la Santa Casa . Il est évident que les voyageurs de confession réformée ou

de sensibilité libertine vont moins à Lorette en pèlerins qu’en touristes et

jugent sévèrement les marchands du Temple qui prospèrent sur la crédulité

publique. Bien souvent, les catholiques font, sans s’interroger trop, provision

de médailles et d’agnus-Dei , et les plus curieux insistent sur la splendeur du

sanctuaire et de l’écrin de marbre qui sert de cache-misère à la Santa Casa.

C’est le cas, par exemple, de Montesquieu qui resta, semble-t-il, une seule

journée à Lorette en juillet 1729 : il se limite à des remarques sur les

morceaux les plus considérables de la décoration du sanctuaire et sur le trésor

– mais sans le moindre jugement critique. Une seule allusion incidente aux

Carmes qui auraient fait « voyager » la Santa Casa pourrait passer pour une

infraction à l’honnête discrétion qui préside à ce récit . Le président de

Brosses n’a pas, quelques années plus tard, cette courtoise cécité. Le fougueux

Bourguignon fit un bref séjour à Lorette en février 1740 qu’il traite, dans une

lettre récemment publiée, de « belle boutique d’orfèvrerie » . Il consacre au

sanctuaire une partie d’une autre lettre à son ami dijonnais Jacques-Philippe

Fyot de Neuilly, missive rédigée le « mercredi des cendres » à Modène et qui

n’en est pas plus catholique pour cela . Le renvoi que Brosses fait à Misson

pour la description intérieure du sanctuaire donne le ton et l’orientation

critique de ces pages d’une ironie jubilatoire. Il ne manque pas de faire un

sort aux « deux vieilles écuelles ébréchées » (p. 1178), ces restes de la

vaisselle familiale dont les voyageurs révéraient dévotement les débris

ceinturés d’argent. Mais il se livre surtout à ce que l’on pourrait appeler une

enquête scientifique sur la Santa Casa qu’on disait généralement avoir été

maçonnée de mauvaises briques : Brosses analyse ce matériau comme de la pierre,

et de la pierre de provenance régionale, ce qui ruine l’origine galiléenne de

la « relique » : « Cette pierre, fort reconnaissable par son grain singulier et

par sa couleur, est commune aux environs de Lorette et de Recanati, comme je

l’ai facilement remarqué » (p. 1177). Devant la « robe de la Sainte Vierge »

conservée dans la Santa Casa, il opère la même inspection désacralisante: elle

est faite d’un « tabis de soie ponceau à gros grains comme du gros de Naples ».

Et il poursuit :

« N’allez pas, je vous

prie, chicaner cette robe, sur ce que la soie était alors, même en Orient, une

marchandise trop rare et trop chère pour servir aux vêtements des gens du

commun » (p. 1178).

Que reste-t-il de ces

saintes reliques ? Rien sinon un parfum de mystification, qu’un autre voyageur,

après Fougeret de Monbron , le marquis de Sade retrouve dans la « Note sur

Lorette » de son Voyage d’Italie . C’est au retour de Naples, où règne une

superstition très orientale, que Sade passe en mai 1776 deux jours à Lorette

sur la route qui le conduit à Modène et à Parme. Se fondant sur des documents

anciens, il avance qu’une église Notre-Dame existait à Lorette plus de cent ans

avant la translation, que les croisés avaient l’habitude de reproduire en

Europe les hauts lieux de la Terre Sainte, que le récit de la seconde

translation copie étroitement la première. Et il conclut :

«Cette inconstance, cette

légèreté ne prouvent guère la sagesse d’un Dieu qui permet le déplacement d’une

maison dans laquelle on prétend qu’il s’est fait homme pour nous, et dans tout

ceci, je reconnais plus l’esprit d’un politique italien que la sagesse de celui

et de celle qui en sont l’objet ».

L’esprit critique n’a évidemment que faire en ce siècle éclairé de ces reliques dont l’analyse objective et la pratique d’une méthode historique naissante anéantissent le caractère sacré. Il détruit aussi la part de rêve et de ferveur mystique qui peut être attachée à ce qui n’est, après tout, qu’une pieuse allégorie de l’insondable mystère du Dieu fait homme. C’est pourquoi, plus que pour ces illustres en littérature, le pèlerinage à Lorette d’un prince catholique allemand qui écrivait en français pourrait recentrer le jugement moyen, mais non indifférent, des hommes des Lumières. L’électeur Charles-Albert de Bavière, empereur romain germanique de 1742 à 1745 sous le nom de Charles VII, est l’ultime Wittelsbach monté sur le trône impérial . Fils de l’électeur Max Emmanuel qui vécut un long exil en France, neveu par alliance du Grand Dauphin, c’était un francophile déclaré et un amateur raffiné d’art et de musique. Il avait épousé en 1722 la fort dévote archiduchesse Marie-Amélie qui ne dédaignait pas cependant l’opéra comme leur voyage de noces à Naples en témoigne. Du premier séjour italien, qui dura de décembre 1715 à la fin du mois d’août de l’année suivante, subsistent une relation allemande rédigée par un secrétaire et une traduction partielle française . Le voyage de mai-juin 1737 est, en revanche, totalement en français et de la plume de Charles-Albert. : nous en connaissons des copies confectionnées par Thérèse de Gombert, femme de chambre et confidente de l’Électrice.

En prince très catholique, Charles-Albert sait alterner dans une même journée les devoirs du chrétien et les plaisirs du mélomane, et l’électrice n’est pas la dernière à l’imiter. De son enfance ballottée entre l’exil et la rude éducation militaire qu’il reçut du prince Eugène complétant celle, plus mondaine, des jésuites autrichiens, Charles-Albert avait acquis un sens de l’humour très peu commun dans sa caste et une certaine distance à l’égard des « grandeurs du monde ». Le voyage de 1715 (f. 5) semble mettre en perspective dans une succession sobrement chronologique le pèlerinage « dans l’église de Sainte-Catherine de Bologne, où il a vu le corps de cette sainte » immédiatement suivi d’une représentation d’opéra: télescopage que nous retrouverons souvent sous la plume de Charles-Albert. Le journal de 1737 est composé à la Ich-Form, à la première personne, ce qui élimine d’entrée de jeu la présence de cet intermédiaire, secrétaire ou auteur masqué, qui faisait du voyageur de 1715 le héros muet d’un spectacle de convention. « Nous quittâmes les plaisirs et les masques en quittant les États de Venise et avons entamé le chemin de Lorette qui était le véritable but de notre voyage » (p. 93), note un peu triste, mais déterminé, un Charles-Albert qui sait où est son devoir. Se rendant aux fêtes de saint Antoine à Padoue, il avait déjà évoqué cette singulière dramaturgie « métamorphosant les coureurs de masques en dévots pèlerins » (p. 87). Les Électeurs ne manquent jamais la messe matinale qui est comme l’ouverture de la journée. Marie-Amélie, archiduchesse d’Autriche, a cette religiosité à l’espagnole que la Cour de Vienne conserve de la tradition des Habsbourg du XVIe siècle. Charles-Albert fait mine de s’y plier: « La dévotion de la comtesse de Camb [pseudonyme de voyage de l’Électrice] fut sans doute ce qui me procura une prompte guérison » (p. 92), constate avec une délicate ironie son mari relevant de maladie à Padoue, où l’humour du prince à l’égard de cette très convenable manière de vivre transparaît dans des remarques fines sur la princesse: on fait mine de s’inquiéter de perdre Marie-Amélie dans les jardins-labyrinthes du « noble Papafava » (p. 32); elle n’a pas la chance de son ancêtre l’empereur Maximilien, d’avoir été, comme le rapporte Charles-Albert, remise sur le bon chemin par un aimable ange conducteur (p. 9); ailleurs, on joue à cache-cache avec la princesse pour échapper à quelque cérémonie surnuméraire qui priverait de l’opéra.

Charles-Albert rapporte avec un sérieux un peu trop appuyé les légendes les plus extravagantes qui courent sur les saints personnages que l’on honore ici ou là ; cela commence très tôt, dès les premiers jours du voyage: pour s’en protéger, il va à Benediktbeuern « toucher la tête de sainte Anastasie, grande patronne contre les maux de tête » (p. 2-3). Peu de temps après, il inaugure ces longs récits de miracles et d’épouvantables fantaisies divines dont il aimera émailler son récit et qui forment un contrepoint surnaturel aux plates réalités du voyage. Sans lasser apparemment le mémorialiste, les anecdotes pieuses se succèdent et se font écho d’une présence permanente d’un Dieu qui semble néanmoins avoir oublié depuis un siècle ou deux d’intervenir dans la vie des hommes. À titre d’exception malheureusement invérifiable, on affirme aux princes, lors du second séjour à Padoue, que saint Antoine vient de ressusciter un homme « assassiné et enterré »: hélas! si le miraculé est « actuellement » dans la ville, « cependant, [il] n’en parle à personne » (p. 92). Plus convaincant si l’on veut, au milieu de la cathédrale de Trente, lieu sacré du Concile, un crucifix miraculeux « confirme » pourtant par « un mouvement de tête » les belles vérités qu’on y a proférées (p. 14-15). En contrepoint, l’évocation du saint « enfant de Trente » martyrisé par les juifs « à coups d’épingles, de pincettes et couteaux » rappelle que Satan et la Synagogue font bon ménage et que la vigilance est toujours de mise (p. 15-16). Mais en général, récits fabuleux et achats variés destinées à perpétuer l’effet bénéfique de la protection des saints se complètent harmonieusement dans un discours dont seul l’imperturbable sérieux du narrateur peut faire soupçonner la part de dérision. À Padoue encore, les deux princes rendent hommage de concert à la langue de saint Antoine, puis « font des emplettes consistant en chapelets et médailles qui ont touché les saintes reliques » (p. 33). Par autorisation spéciale - seul le Pape a ce privilège -, ils se rendent au Couvent de Sainte-Catherine à Bologne pour y contempler le corps de la sainte: « [...] c’est certainement un grand miracle de voir cette sainte assise dans un fauteuil sans être appuyée; on dit que se relevant de son tombeau, c’est par obéissance qu’elle s’est mise dans cette situation; tout son Saint Corps se trouve très bien conservé, hormis la peau [qui] est noire; on y voit encore les ongles aux mains et aux pieds, les dents dans la bouche et toutes les parties du visage dans leur entier depuis trois cents ans que cette sainte est morte; nous lui avons baisé les pieds » (p. 124).

Mais c’est à Lorette, que, du 16 au 19 juin, le couple princier et sa suite

arrivés fort simplement en chaise de poste déploient une dévotion de la plus

belle eau; la tension ironique du récit se note seulement dans l’accumulation

de détails d’une trop parfaite convention et par de brusques et singulières

ruptures de ton. Lors de son premier voyage en 1716, Charles-Albert avait déjà

visité le sanctuaire, mais le secrétaire qui tenait sa plume n’avait rien écrit

que de très banal sur le sujet . En 1737, il est encore question assez

platement de cette « sainte maison » - « une vraie consolation interne » (p.

98) -, de «cette chapelle déplacée deux fois par les Anges et apportée dans ce

lieu » (p. 99). Visites dévotes, dons propitiatoires et achats de précaution se

succèdent au cours de quatre journées uniquement consacrées à ces exercices: «

[...] cette maison est toute miraculeuse, car tout ce qu’on y observe à

présent, et tout ce qui en reste ne subsiste que miraculeusement » (p. 107),

remarque très sobrement Charles-Albert. L’Électrice écoute quatre messes, fait