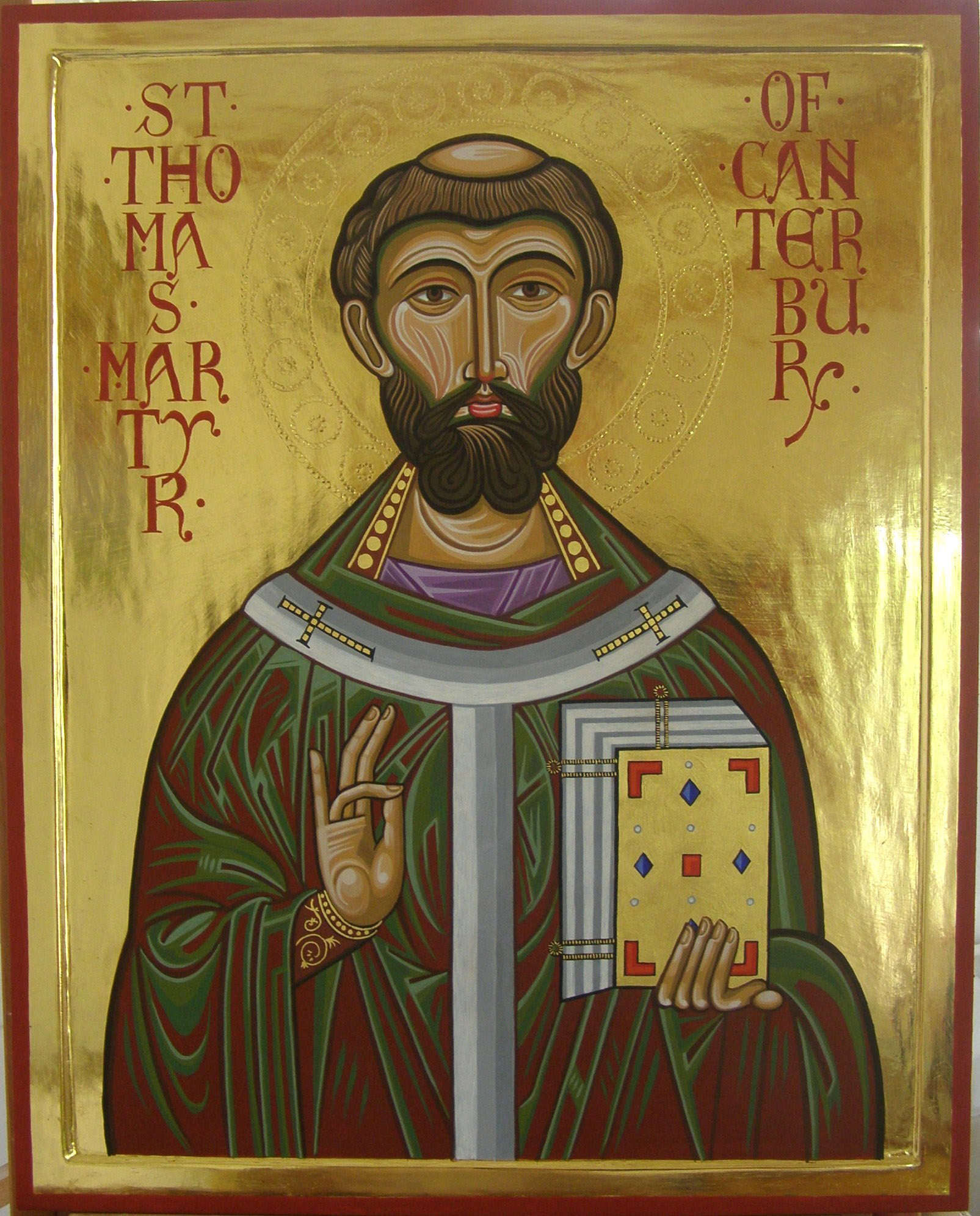

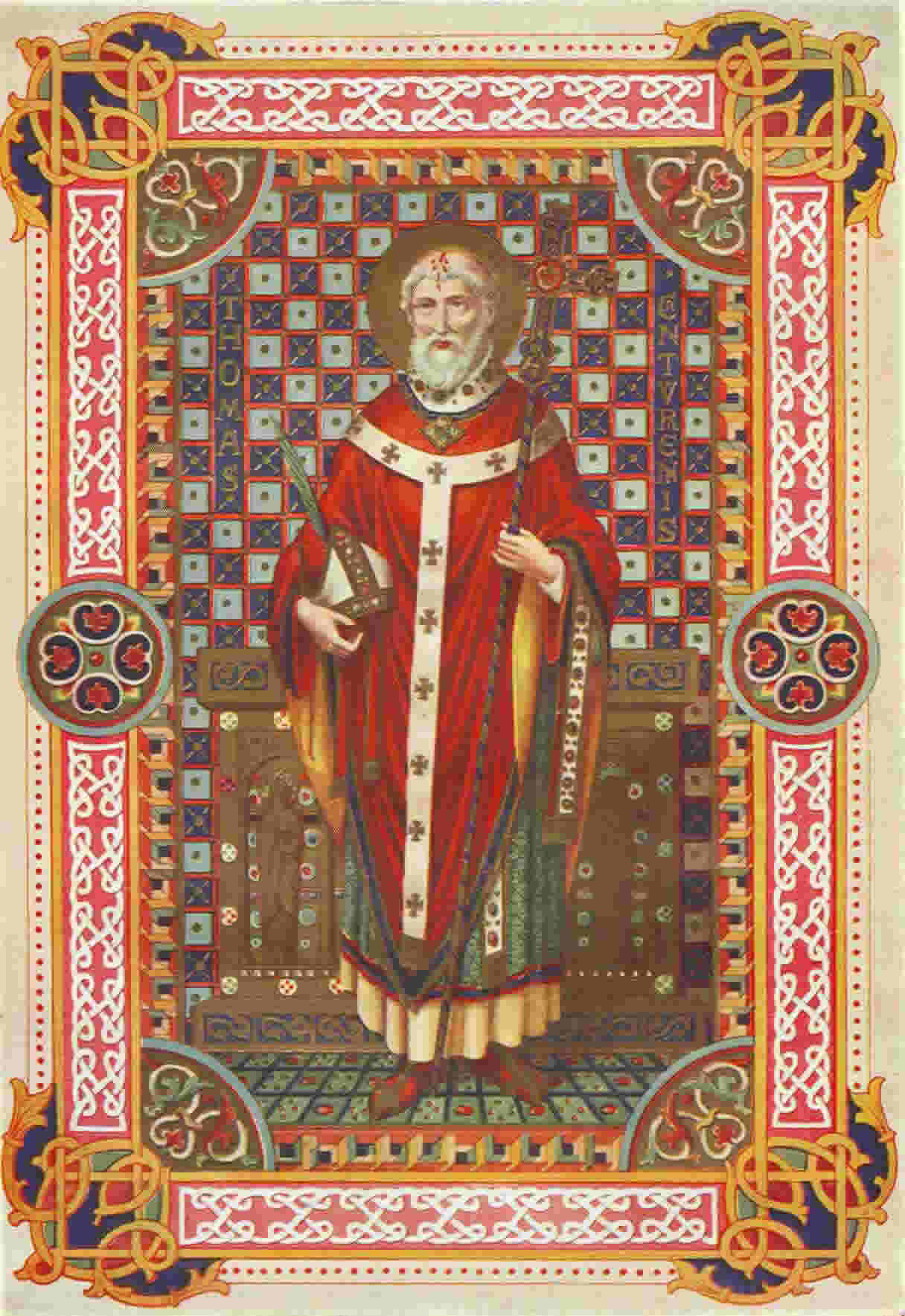

Saint Thomas Becket

Archevêque de Cantorbéry,

martyr (+ 1170)

Il était né à Londres d'une famille normande. Il fit de bonnes études à Londres et à Paris et le roi Henri II Plantagenêt choisit ce brillant sujet comme chancelier. Enchanté de son administration, il le fait nommer archevêque de Canterbury, pensant ainsi résoudre les difficultés qu'il connaît avec les évêques de son royaume. Thomas change du tout au tout. De fastueux, il devient ascétique; de servile, il se trouve bientôt en conflit avec le roi, qui veut imposer sa loi par-dessus celle de l'Église romaine. Il invite les pauvres à sa table et prend l'habit de moine. La querelle s'envenime au point qu'il doit s'enfuir en France. Il rejoint alors l'abbaye cistercienne de Pontigny en Bourgogne. Il regagne Canterbury en novembre 1170, et c'est là que, dans sa cathédrale, peu après Noël, quatre familiers de roi vont l'abattre devant l'autel après qu'il eût refusé de lever les excommunications qu'il avait portées contre les évêques trop dociles à l'égard du roi.

De souche normande, Thomas Becket est né à Londres. Archidiacre de Coutances et chancelier d'Angleterre, il est élu évêque de Cantorbéry. Face à son ami le roi Henry II, il défend les intérêts de l'Eglise. Calomnié et poursuivi dans sa cathédrale, il est massacré, avec la complicité du roi.

Un an plus tard, Henry II vient recevoir le pardon du pape à la porte de la cathédrale d'Avranches. Thomas Becket est canonisé et le diocèse de Coutances est un des premiers à lui rendre un culte. Une église lui est dédiée dans le faubourg de Saint Lô, ainsi qu'un croisillon de la cathédrale.

Source: Liturgie des heures du diocèse de Coutances et Avranches 1993 où il est fêté le 7 mai.

Saint Thomas Becket naquit à Londres le 21 décembre 1117. Il fit ses études à Oxford et Paris, puis vint étudier le Droit Canon à Auxerre. De retour en Angleterre, il fut ordonné prêtre. En 1162, il fut nommé archevêque de Cantorbéry. Le roi Henri II s'opposait alors de multiples façons à l'indépendance de l'Église dans son royaume et l'archevêque Thomas lui résista. Il fut contraint de s'exiler en France et se retira à l'abbaye de Pontigny où il demeura deux ans. Puis il se rendit à Sens où il resta quatre années, prêchant dans les églises et les couvents des environs.

Retourné en Angleterre, il fut assassiné dans sa cathédrale le 29 décembre 1170.

* Au siècle suivant, un autre archevêque de Cantorbéry, saint Edme,

viendra aussi se réfugier à l'abbaye de Pontigny. Il mourra en France en 1240:

son corps repose à Pontigny.

Saint Thomas Becket - diocèse de Sens-Auxerre

- L'église de Cuiseaux (71) est dédiée à St Thomas Becket, archevêque de Cantorbery. Elle renferme une statue de ce saint.

Au 29 décembre au martyrologe romain, mémoire de saint Thomas Becket, évêque et

martyr. Pour la défense de la justice et de la liberté de l'Église, il fut

contraint de quitter le siège de Cantorbéry et même le royaume d'Angleterre et

de vivre en exil en France. Revenu en Angleterre au bout de six ans, il eut

encore beaucoup à supporter jusqu'à ce que, en 1170, des chevaliers du roi

Henri II le frappent de l'épée dans sa cathédrale et qu'ainsi il s'en aille

vers le Christ.

Martyrologe romain

Saint Thomas Becket,

priez pour nous ! A la manière des coulisses du théâtre, soufflez-nous comment

s'y prendre Pour ne tolérer ni l'intolérable, ni l'abus de pouvoir, ni

l'iniquité. Après vous et avec vous, apprenez-nous l'intransigeance Sans

renoncer à l'amitié Sans détruire l'amour du conjoint Encore moins l'amour de

l'enfant. Gardez-nous de murer l'avenir, de voiler nos propres contradictions.

Au nom de la communion des saints, Saint Thomas Becket, Avec le vent du large,

Soufflez-nous le pardon, Celui que l'on reçoit et celui que l'on donne. Saint

Thomas Becket, priez pour nous

(L. Malle)

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/329/Saint-Thomas-Becket.html

Saint Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket ou Thomas

de Londres comme on l'appelait alors, naquit probablement en 1118 dans une

famille de la bourgeoisie londonienne qui connut des revers de fortune. Le

soutien d’un de ses parents lui permit de faire de brillantes études à Paris.

Il entra au service de l'archevêque Thibaud de Cantorbéry qui lui fit faire

d'intéressants voyages à Rome (1151-1153) et aux écoles de Bologne et d’Auxerre

où l’on formait des juristes. Finalement il se lia avec le futur Henri II

Plantagenêt, qui, un an après son accession au trône d’Angleterre, le nomma

chancelier d’Angleterre, après que l’archevêque l’eut nommé archidiacre de

Cantorbéry.

Thomas, fastueux

ministre, seconda efficacement Henri II dans son œuvre générale de restauration

monarchique après les troubles du règne d'Etienne de Blois (1135-1154).

L'Eglise d'Angleterre avait profité de cette période de faiblesse pour sortir

de la soumission où la tenait jadis la monarchie normande, pour conquérir ses «

libertés » que le Roi entendait rogner. Croyant trouver un auxiliaire docile en

son chancelier, Henri II nomma Thomas archevêque de Cantorbéry (mai 1162),

réunissant entre les mêmes mains la chancellerie et une province ecclésiastique

qui comprenait dix-sept des dix-neuf diocèses anglais. Thomas qui avait reçu en

deux jours l’ordination sacerdotale et le sacre épiscopal, abandonna sa charge

séculière, changea sa vie du tout au tout et se voua sans réserve à la défense

des droits de l'Eglise. Lorsqu’en janvier 1164 Henri II voulut imposer à

l’Eglise les Constitutions de Clarendon qui prétendaient revenir aux anciennes

coutumes du royaume contre le droit canon, Thomas Becket fut un adversaire

résolu. Après de multiples péripéties juridiques où l’archevêque-primat fut

trahi par ses confrères d’York et de Londres, il dut s'exiler en France où il

demeura six ans (1164-1170), notamment à l'abbaye cistercienne de Pontigny où

il s’imposa l’observance monastique. Lorsqu'il rentra dans sa patrie après une

paix boiteuse conclue à Fréteval dans le Maine (22 juillet 1170), les

difficultés recommencèrent d’autant plus qu’avant de s’embarquer il avait frappé

de suspense tous ses suffragants plus ou moins coupables de rébellion contre

lui (1° décembre 1170).

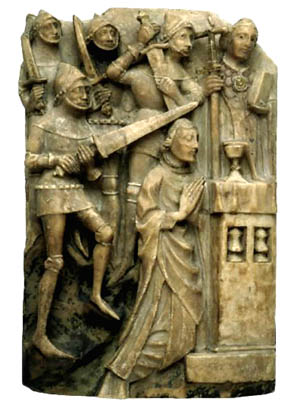

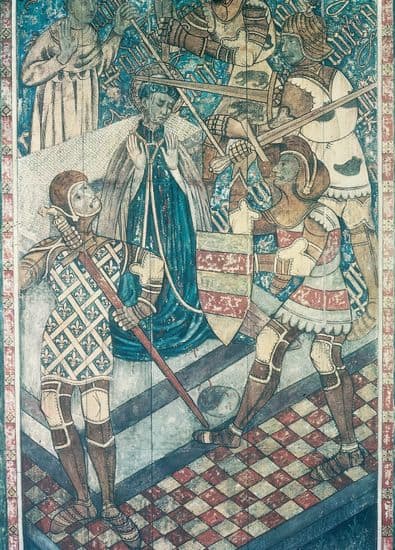

Une phrase ambiguë

d'Henri II (« N'y aura-t-il donc personne pour me débarrasser de ce clerc

outrecuidant ? ») amena quatre chevaliers normands à assassiner l'archevêque

dans sa cathédrale le 29 décembre 1170.

Dans la nuit de Noël

1170, après avoir célébré la messe, Thomas Becket, archevêque de Cantorbéry et

primat d'Angleterre, monta en chaire et, en termes formels, prédit qu'il serait

bientôt massacré par les impies ; puis, comme l'auditoire se récriait, il

invectiva vivement ceux qui mettaient la division entre le Roi et le Pasteur et

les excommunia « comme les pestes du genre humain et les ennemis du bien

public. » Le lendemain de la fête des saints Innocents, vers onze heures du

matin, quatre personnages vinrent le menacer chez lui et lui dirent que sa

résistance lui coûterait la vie ; il répondit avec douceur et fermeté : « Je ne

fuirai pas, j'attendrai avec joie le coup de la mort, je suis prêt à la

recevoir », et montrant sa tête, il ajouta : « c'est là que vous me frapperez !

» Après dîner, il était à l'église pour les vêpres, les quatre assassins

forcèrent l'entrée du cloître et comme les moines cherchaient à les empêcher

d'entrer dans l'église, l'archevêque dit : « Il ne faut pas garder le temple de

Dieu comme on garde une forteresse ; nous ne triompherons pas de nos ennemis en

combattant, mais en souffrant. Pour moi, je suis prêt à être sacrifié pour la

cause de l'Eglise dont je défends les droits. » Les quatre assassins entrèrent

donc dans l'église en criant : « Où est Thomas Becket ? Où est ce traître au

Roi et à l'Etat ? Où est l'Archevêque ? » L’archevêque se présenta : « Me voici

! Non pas traître à l'Etat, mais prêtre de Jésus-Christ. » Les assassins lui

crièrent : « Sauve-toi, autrement tu es mort ! » Thomas répondit : « Je n'ai

garde de fuir ; tout ce que je demande, c'est de donner mon âme pour celles en

faveur desquelles mon Sauveur a donné tout son sang. Cependant, je vous défends,

de la part de Dieu tout-puissant, de maltraiter qui que ce soit des miens. » Ne

pouvant arriver à le traîner dehors, les quatre assassins le frappèrent dans

l'église : « Je meurs volontiers pour le nom de Jésus et la défense de

l'Eglise. »

Thomas Becket triompha

dans sa mort. Ce qu'il n'avait pu obtenir par l'effort de sa vie, il le réalisa

par son martyre. Le peuple le vénéra aussitôt comme un saint, et le pape

Alexandre III frappa Henri II, compromis dans ce meurtre, d’interdit personnel

; pour obtenir son pardon, le Roi dut faire un pèlerinage humiliant au tombeau

de Thomas Becket et se soumettre à la pénitence publique de la flagellation (21

mai 1172). Des miracles ayant attesté la glorification de Thomas Becket,

Alexandre III le canonisa le 21 février 1173. Toujours est-il que la châsse du

martyr devint le but d'un des pèlerinages les plus célèbres de la chrétienté.

En 1538, Henri VIII se donna le ridicule de procéder à la « décanonisation » de

saint Thomas Becket.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/12/29.php

Martyrdom

of Thomas Becket, English Alabaster

Saint Thomas Beckett,

Dieu et l’Église avant tout

Publié le 29

décembre 2016 par Camille Meyer

Thomas Beckett

(1120-1170) n’a rien gardé de la cour quand il est nommé évêque de Cantorbéry

par Henri II de Plantagenêt. Il va vivre une incroyable conversion faisant de

lui un fervent défenseur et martyr de l’Église.

Né en 1117 et originaire

de Londres, Thomas Beckett est le fils de riches marchands roturiers. Après des

études à Cantorbéry puis à Bologne (Italie), le jeune homme rentre en

Angleterre. Talentueux, il attire l’attention de Thibaut du Bec, archevêque de

Cantorbéry qui l’envoie à Rome en mission puis le nomme archidiacre de la cité

royale du Kent.

Le conseiller d’Henri II

d’Angleterre

La place de conseiller du

roi d’Angleterre est vacante. Avec l’appui de l’archevêque, Thomas va

devenir le nouveau chancelier du royaume. Grand ami du roi, ferme

diplomate, administrateur efficace et redouté, ceux qui entourent Beckett

obéissent au roi. Âgé d’une dizaine d’années de plus qu’Henri, il sait

gouverner et a un fort ascendant sur lui, ce qui déplaît fortement à Aliénor

d’Aquitaine, mère de Richard Cœur de Lion et reine d’Angleterre. Cette dernière

va d’ailleurs tout faire pour l’évincer. En 1162, Thibaut du Bec meurt. Henri

II s’arrange alors pour nommer (ce qui va à l’encontre du droit ecclésiastique

et canonique) Thomas Beckett archevêque de Cantorbéry, le 3 juin 1162,

charge la plus importante de l’Église anglaise. Dès lors, les deux amis

détiennent l’un le pouvoir spirituel et l’autre le pouvoir temporel. Cette

décision aurait dû faire d’Henri II un monarque absolu .

Sa conversion

Mais Thomas Beckett

change. Il va vivre une réelle conversion en recevant les ordres

sacerdotaux et épiscopaux. Il prend conscience de toute la signification de sa

charge et souhaite poursuivre sur le chemin du Christ. Il ne veut plus servir

Henri II mais l’Église et cela, le roi va très mal le prendre. Portant le

cilice, l’homme mondain devient austère et donne tous ses biens aux plus

démunis. Désormais il veut vivre modestement et se consacre entièrement aux

affaires de son Église. A l’époque, un archevêque à la charge d’un vaste

territoire et de beaucoup de biens. Beckett est donc garant de l’éducation, de

la santé et de l’assistance données à tous ceux qui vivent sur le comté de

Cantorbéry.

Beckett prend position

L’Église est divisée au

12ième siècle, Alexandre III est élu pape à la suite d’Adrien IV. Mais une

petite minorité d’évêque pro germanique préfère le cardinal prêtre

Octavien. Beckett prend position et se soumet à l’autorité d’Alexandre III.

De retour en Angleterre, il souhaite mettre en place les recommandations faites

par le nouveau pape: libérer l’Église d’Angleterre de la monarchie en demandant

l’exemption complète de toute juridiction civile et demandant le contrôle

exclusif de sa juridiction par le clergé. Henri II est furieux. Il convoque

l’assemblée à Clarendon et lui soumet seize demandes, limitant notamment le

pouvoir ecclésial et revenant sur les accords passés par Henri Ier en 1107 et

par Étienne d’Angleterre en 1136. Si le clergé accepte, Beckett refuse de

signer, la guerre entre les deux est déclarée.

Henri II veut se

débarrasser cet archevêque gênant. Il tente de le faire condamner et le

convoque à Northampton le 8 octobre 1164, l’accusant de contester l’autorité

royale. L’autre désaccord vient du refus de l’archevêque de marier Guillaume

Plantagenêt (frère d’Henri II) et Isabelle de Warenne pour consanguinité.

Beckett doit alors

quitter l’Angleterre. Il s’embarque incognito pour la France où le pape

Alexandre III (exilé de Rome) et Louis VII, roi de France, l’accueillent. La

France voyant aussi et surtout le moyen de se venger d’Aliénor d’Aquitaine. Il

passera par l’abbaye cistercienne de Pontigny et à l’Abbaye Sainte Colombe de

Saint Denis les Sen

La tentative de

réconciliation

Voyant le mécontentement

du clergé anglais, Henri II doit se réconcilier avec Thomas Beckett. Un

seul moyen au Moyen-Age, le « baiser de paix » mais le roi refuse. Le

« baiser de paix » se fait sur la bouche, le principe étant

d’échanger les souffles et de permettre aux âmes de chacun de se rencontrer. En

soit, un geste hautement symbolique. Il faudra qu’Alexandre III menace Henri II

d’excommunication, pour qu’un semblant de paix se fasse. L’archevêque

revient donc en Angleterre.

Son assassinat

Le roi refuse de rendre à

l’Église les propriétés ecclésiastiques malgré les demandes de Beckett. Henri

II a alors cette phrase malheureuse: « n’y aura-t-il personne

pour me débarrasser de ce clerc roturier ? ». Quatre chevaliers du roi le

prirent comme un ordre. Pénétrant dans la cathédrale de Cantorbéry le 29

décembre 1170, ils massacrèrent Thomas Beckett peu avant l’office des vêpres.

Les témoins accuseront immédiatement le roi d’avoir commandité cet assassinat.

Henri II, mal vu par

l’Église, malmené par son peuple, n’a d’autres choix, en 1172, que d’obéir à

Alexandre III et de faire pénitence en public, à genoux sur la tombe du futur

saint. Canonisé en 1173, Saint Thomas Beckett est mort sans se défendre et pour

la liberté de l’Église d’Angleterre.

Camille Meyer

Diplômée de l'Institut

Européen de Journalisme (IEJ) de Paris, ancienne de Secrets d'Histoire sur

France 2 . Aujourd'hui, Camille est rédactrice web et responsable des réseaux

sociaux.

Enseigne

de pèlerinage en plomb représentant Thomas Becket, vendue aux pèlerins se

rendant sur sa tombe à Canterbury, XIVe siècle, 3.9 x 1.5

Saint Thomas Becket

Archevêque de Cantorbéry,

Martyr

(1117-1170)

Saint Thomas de

Cantorbéry, par son courage indomptable à défendre les droits de l'Église, est

devenu l'un des plus célèbres évêques honorés du nom de saints et de martyrs.

Dès sa jeunesse, il fut élevé aux plus hautes charges de la magistrature; mais

l'injustice des hommes détacha du monde ce coeur plein de droiture et de

sincérité, et il entra dans l'état ecclésiastique. Là encore, son mérite

l'éleva aux honneurs, et le roi Henri II le nomma son chancelier. Il ne fit que

croître en vertu, donnant le jour aux affaires et passant la meilleure partie

de la nuit en oraison. Il n'était que le distributeur de ses immenses revenus:

les familles ruinées, les malades abandonnés, les prisonniers, les monastères

pauvres, en avaient la meilleure part.

Le roi l'obligea

d'accepter l'archevêché de Cantorbéry. Thomas eut beau dire au prince, pour le

dissuader, qu'il s'en repentirait bientôt: celui-ci persista, et le chancelier

reçut le sacerdoce (car il n'était encore que diacre) et l'onction épiscopale.

Sa sainteté s'accrut en raison de la sublimité de ses fonctions. On ne le

voyait jamais dire la Sainte Messe, sinon les yeux baignés de larmes; en

récitant le Confiteor, il poussait autant de soupirs qu'il prononçait de mots.

Il servait les pauvres à table trois fois par jour; à la première table, il y

avait treize pauvres; à la seconde, douze; à la troisième, cent.

Thomas avait bien prévu:

les exigences injustes du roi obligèrent l'archevêque à défendre avec fermeté

les droits et les privilèges de l'Église. Henri II, mal conseillé et furieux de

voir un évêque lui résister, exerça contre Thomas une persécution à outrance.

Le pontife, abandonné par les évêques d'Angleterre, chercha un refuge en

France. Il rentra bientôt en son pays, avec la conviction arrêtée qu'il allait

y chercher la mort; mais il était prêt.

Un jour les émissaires du

roi se présentèrent dans l'église où Thomas priait; il refusa de fuir, et fut

assommé si brutalement, que sa tête se brisa et que sa cervelle se répandit sur

le pavé du sanctuaire. C'est à genoux qu'il reçut le coup de la mort. Il

employa ce qui lui restait de force pour dire: "Je meurs volontiers pour

le nom de Jésus et pour la défense de l'Église."

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_thomas_becket.html

SAINT THOMAS DE CANTORBÉRY *

Thomas veut dire abyme,

jumeau, et coupé. Abyme, c'est-à-dire, profond en humilité, ce qui est clair

par son cilice, et, en lavant les pieds des pauvres ; jumeau, car dans sa

prélature, il eut deux qualités éminentes, celle de la parole et celle de l’exemple.

Il fut coupé dans son martyre.

Thomas de Cantorbéry,

restant à la cour du roi d'Angleterre vit commettre différentes actions

contraires à la religion; il se retira alors pour se mettre sous la conduite de

l’archevêque de Cantorbéry qui le nomma son archidiacre. Il se rendit cependant

aux instances de l’archevêque qui lui conseilla de conserver la charge de

chancelier du roi, afin que, par la prudence, dont il était excellemment doué,

il devînt un obstacle au mal que les méchants pourraient exercer contre

l’église. Le roi avait pour lui tant d'affection que, lors du décès de

l’archevêque, il voulut l’élever sur le siège épiscopal. Après de longues

résistances, il consentit à recevoir ce fardeau sur les épaules. Mais tout

aussitôt il fut changé en un autre homme: il était devenu parfait, il

mortifiait sa chair par le cilice et parles jeûnes ; car il portait non

seulement un cilice au lieu de chemise, mais il avait des caleçons de poil de

chèvre qui le couvraient jusqu'aux genoux. Il employait une telle adresse à

cacher sa sainteté que, tout en conservant une honnêteté exquise, sous des

habits convenables et n'ayant que des meubles décents, il se conformait aux

moeurs de chacun. Tous les jours, il lavait à genoux les pieds de treize

pauvres auxquels il donnait un repas et quatre pièces d'argent. Le roi

s'efforçait de le faire plier à sa volonté au détriment de l’église, en

exigeant qu'il sanctionnât; lui aussi, des coutumes dont ses prédécesseurs

avaient joui contre les libertés ecclésiastiques. Il n'y voulut jamais

consentir, et il s'attira ainsi la haine du roi et des princes. Pressé un jour

par le roi, lui et quelques évêques, sous l’influence de la mort dont on les

menaçait et trompé par les conseils de plusieurs grands personnages, il

consentit de bouche à céder au voeu du monarque; mais s'apercevant qu'il

pourrait en résulter bientôt un grand détriment pour les âmes, il s'imposa dès

lors de plus rigoureuses mortifications il cessa de dire la messe, jusqu'à ce

qu'il eût pu obtenir d'être relevé, par le souverain Pontife, des suspenses

qu'il croyait avoir encourues. Requis de confirmer par écrit ce qu'il avait

promis de bouche, il résista au roi avec énergie, prit lui-même sa croix pour

sortir de la cour, aux clameurs des impies qui disaient : « Saisissez le

voleur, à mort le traître: » Deux personnages éminents et pleins de foi vinrent

alors lui assurer avec serment qu'une foule de grands avaient juré sa mort.

L'homme de Dieu, qui craignait pour l’église plus encore que pour lui, prit la

fuite, et vint trouver à Sens le juge Alexandre, et avec des recommandations

pour le monastère de Pontigny, il arriva en France. De son côté, le roi envoya

à Rome demander des légats afin de terminer le différend mais il n'éprouva que

dés refus, ce qui l’irrita plus encore contre le prélat. Il mit la saisie sur

tous ses biens et sur ceux de ses amis, exila tous es membres de sa famille,

sans avoir aucun égard pour la condition ou le sexe, le rang ou l’âge des

individus. Quant au saint, tous les jours, il priait pour le roi et pour le

royaume d'Angleterre. Il eut alors une révélation qu'il rentrerait dans son

église, et qu'il recevrait du Christ la palme du martyre. Après sept ans

d'exil, il lui fut accordé de revenir et fut reçu avec de grands honneurs.

Quelques jours avant le

martyre de Thomas, un jeune homme mourut et ressuscita miraculeusement et il

disait avoir été conduit jusqu'au rang le plus élevé des saints où il avait vu

une place vide parmi les apôtres. Il demanda à qui appartenait cette place, un

ange lui répondit qu'elle était réservée par le Seigneur à un illustre prêtre

anglais. Un ecclésiastique qui tous les jours célébrait la messe en l’honneur

de, la Bienheureuse Vierge, fut accusé auprès de l’archevêque qui le fit

comparaître devant lui et le suspendit de son office, comme idiot et ignorant.

Or, le bienheureux Thomas avait caché sous son lit son cilice qu'il, devait

recoudre quand il en aurait le temps; la bienheureuse Marie apparut au prêtre

et lui dit : « Allez dire à l’archevêque que celle pour l’amour de laquelle

vous disiez vos messes a recousu son cilice qui est à tel endroit et qu'elle y

a laissé le fil rouge dont elle s'est servi. Elle vous envoie pour qu'il ait à

lever, l’interdit dont il vous a frappé. » Thomas en entendant cela et trouvant

tout ainsi qu'il avait été dit, fut saisi, et en relevant le prêtre de son

interdit, il lui recommanda de tenir cela sous le secret. Il défendit, comme

auparavant les droits de l’Église et il ne se laissa fléchir ni par la

violence, ni par les prières du roi. Comme donc on ne pouvait l’abattre en

aucune manière, voici venir avec leurs armes des soldats du roi qui demandent à

grands cris où est l’archevêque. Il alla au-devant d'eux et leur dit : «Me

voici, que voulez-vous? » «Nous venons, répondent-ils, pour te tuer tu n'as pas

plus long temps à vivre. » Il leur dit : « Je suis prêt à mourir pour Dieu,

pour la défense de la justice et la liberté de l’Église. Donc si c'est, à moi

que vous en voulez, de la part du Dieu tout-puissant et sous peine d'anathème,

je vous défends de faire tel marque ce soit à ceux qui sont ici, et je,

recommande la cause de l’Église et moi-même à Dieu, à la bienheureuse Marie, à

tous les saints et à saint Denys. » Après quoi sa tête vénérable tombe sous le

glaive des impies, la couronne de son chef est coupée, sa cervelle jaillit sur

le pavé de l’église et il est sacré martyr du Seigneur l’an 1174. Comme les

clercs commençaient Requiem aeternam de la messe des morts qu'ils allaient

célébrer pour lui, tout aussitôt, dit-on, les choeurs des anges interrompent la

voix des chantres et entonnent la messe d'un martyr : Laetabitur justus in

Domino, que les autres clercs continuent. Ce changement est vraiment l’ouvrage

de la droite du TrèsHaut, que le chant de la tristesse ait été changé en un

cantique de louange, quand celui pour lequel on venait de commencer les prières

des morts, se trouve à l’instant partager les honneurs des hymnes des martyrs.

Il était vraiment doué d'une haute sainteté ce martyr glorieux du Seigneur

auquel les anges donnent ce témoignage d'honneur si éclatant en l’inscrivant

eux-mêmes par avance au catalogue des martyrs. Ce saint souffrit donc la mort

pour l’Église, dans une église; dans le lieu saint, dans un temps saint, entre

les mains des prêtres et des religieux, afin que parussent au grand jour et la

sainteté du patient et la cruauté des persécuteurs. Le Seigneur daigna opérer

beaucoup d'autres miracles par son saint, car en considération de ses mérites,

furent rendus aux aveugles la vue, aux sourds l’ouïe, aux boiteux le marcher,

aux morts la vie. L'eau dans laquelle on lavait les linges trempés de son sang,

guérit beaucoup de malades. Par coquetterie et afin de paraître plus belle, une

dame d'Angleterre désirait avoir des yeux vairons et pour cela elle vint, après

en avoir fait le veau, nu-pieds au tombeau de saint Thomas. En se levant après

sa prière, elle se trouva tout à fait aveugle; elle se repentit alors et

commença à prier saint Thomas de lui rendre au moins les yeux tels qu'elle les

avait, sans parler d'yeux vairons, et ce fut à peine si elle put l’obtenir.

Un plaisant avait apporté

dans un vase, à son maître à table, de l’eau ordinaire au lieu de l’eau de

saint Thomas. Ce maître lui dit : « Si tu ne m’as jamais rien volé, que saint

Thomas te laisse apporter l’eau, mais si tu es coupable de vol, que cette eau

s'évapore aussitôt. » Le serviteur, qui savait avoir rempli le vase; il n'y

avait qu'un instant, y consentit. Chose merveilleuse ! On découvrit le vase, et

il fut trouvé vide et de cette manière le serviteur fut reconnu menteur et

convaincu d'être fin voleur. Un oiseau, auquel on avait appris à parler, était

poursuivi par un aide, quand il se mit à crier ces mots qu'on lui avait fait

retenir: « Saint Thomas, au secours, aide-moi. L'aigle tomba mort à l’instant

et l’oiseau fut sauvé. Un particulier que saint Thomas avait beaucoup aimé

tomba gravement malade; il alla à son tombeau prier pour recouvrer la santé :

ce qu'il obtint à souhait. Mais en revenant guéri, il se prit à penser que

cette guérison n'était peut-être pas avantageuse à son âme. Alors il retourna

prier au tombeau et demanda que si sa guérison ne devait pas lui être utile

pour son salut, son infirmité lui revînt, et il en fut ainsi qu'auparavant. La

vengeance divine s'exerça sur ceux qui l’avaient massacré : les uns se

mettaient les doigts en lambeaux avec les dents, le corps des autres: tombait

en pourriture ; ceux-ci moururent de paralysie, ceux-là succombèrent

misérablement dans des accès de folie.

*Tirée de sa vie écrite

par plus de dix auteurs contemporains.

La Légende dorée de

Jacques de Voragine nouvellement traduite en français avec introduction,

notices, notes et recherches sur les sources par l'abbé J.-B. M. Roze, chanoine

honoraire de la Cathédrale d'Amiens, Édouard Rouveyre, éditeur, 76, rue de

Seine, 76, Paris mdccccii

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/voragine/tome01/014.htm

Saint Thomas Beckett,

Archevêque de Canterbury, Martyr (+ 1170)

Autre biographie:

Fils de Gilbert et Matilda, un couple issu de la noblesse de Normandie et installé à Londres, où son père occupe un emploi dans le commerce.

Thomas est d’abord confié aux Moines de l’abbaye Merton, puis il étudie à

Londres et à Paris, avant de rentrer en Angleterre à l’âge de 21 ans.

Lorsque son père décède, il se retrouve dans une situation financière difficile et commence à travailler comme clerc pour l’Archevêque Thibaud de Canterbury, lui aussi originaire de Normandie.

Ce dernier s’attache rapidement à Thomas et décide de le prendre à son service

régulier. Dès lors, il lui demande de l’accompagner dans ses déplacements à la

cour, où le jeune Henry II Plantagenêt ne tarde pas lui aussi à le prendre en

sympathie.

Thomas décide de partir étudier le droit canon et le droit civil successivement à Bologne et Auxerre.

De retour dans son pays, il est consacré archidiacre de Canterbury et est

bientôt chargé de plusieurs missions diplomatiques auprès du roi de France.

En 1155, il est nommé chancelier d’Angleterre et il s’acquitte de sa charge avec beaucoup de sagesse et d’intelligence.

Sept ans plus tard, et après avoir été ordonné Prêtre, il abandonne sa charge à

la chancellerie pour succéder à Thibaud (décédé en 1161) comme Archevêque de

Canterbury.

Dès lors, il modifie son style de vie, délaissant les habits luxueux pour se vêtir à la manière des Moines.

Il prend bientôt des mesures pour régler les nombreux problèmes qui perdurent

au sein du clergé, ce qui provoque des frictions avec le monarque.

Les divergences de points

de vue débouchent bientôt sur un véritable conflit, qui oppose les deux hommes

sur deux points principaux : la juridiction de l’Église et de l’état sur les

membres du clergé soupçonnés d’avoir commis des délits et sur la liberté d’en

appeler à Rome.

Toute tentative d’en arriver à un accord s’avérant impossible, Thomas choisit de s’exiler en France, où il demeure pendant 6 ans, installé au Monastère Cistercien de Pontigny.

Henry ayant menacé de chasser de son royaume tous les Moines Cisterciens s’ils

continuent à offrir l’hospitalité à Thomas, celui-ci déménage chez les

Bénédictines de l’Abbaye Sainte-Colombe de Sens, qui bénéficient de la

protection du roi de France, Louis VII.

Plusieurs tentatives de médiation avec le Pape Alexandre III échouent et c’est

finalement après avoir fait couronner son fils par l’Archevêque d’York qu’Henry

propose la paix.

Thomas rentre alors en Angleterre, où il est accueilli avec réticence par le

clergé, mais la situation se dégrade à nouveau très rapidement après que le

Pape ait décidé d’excommunier tous les Évêques d’Angleterre déclarés coupables

d’avoir usurper les droits de l’Archevêque de Canterbury.

Henry se trouve alors en Normandie lorsqu’il apprend la nouvelle. Dans un terrible accès de colère, il fait alors une déclaration qui sera lourde de conséquences : « mais personne ne réussira donc jamais à me débarrasser de ce Prêtre turbulent! ».

Quatre chevaliers qui assistent à la scène décident alors de traverser la Manche pour se rendre directement à Canterbury.

Le 29 Décembre 1170, accompagnés d’un bataillon de soldats, ils se présentent à

la Cathédrale et demandent à parler à l’Archevêque, bien décidés à

l’assassiner, croyant ainsi obéir à la volonté du souverain et convaincus

d’avoir son appui.

Ils pénètrent dans la Cathédrale et se saisissent de Thomas, qu’ils traînent

jusque sur les marches de son autel avant d’abattre à plusieurs reprises une

lourde épée sur sa tête.

Durant les quelques minutes que dure son agonie, il est en Prière.

La mort de Thomas provoque un choc très grand dans toute la chrétienté et Henry est alors contraint de faire acte public de pénitence.

Thomas est Canonisé seulement deux ans après sa mort par le Pape Alexandre III.

Saint-Thomas Becket est le patron du clergé séculier.

Lecture

Quelle est donc la raison de la mort de Thomas Becket ?

A y bien regarder, il est mort pour ce qui est la cause de l’antagonisme entre le monde et l’Église.

L’Église est établie dans tous les pays pour s’adresser à tous, aux grands et aux petits, aux personnes de tout rang et de toute condition.

Pour diriger et, en un certain sens intervenir en conscience, et dans le cas de misère morale des princes que le monde adule dès leur petite enfance, pour promulguer aussi la loi et enseigner, ce faisant, la Foi.

Là est le conflit : le monde n’aime pas recevoir de leçons. Les rois d’Israël n’aimaient pas les prophètes. L’Église peut, elle aussi, en venir à s’opposer au monde et à s’élever comme témoin contre lui.

Tel fut le conflit entre le monde et Thomas Becket

John Henry Newman, Sermon

SOURCE : https://www.reflexionchretienne.fr/pages/vie-des-saints/decembre/saint-thomas-becket-archeveque-de-cantorbery-martyr-1117-1170-fete-le-29-decembre.html

et http://jubilatedeo.centerblog.net/6573900-Les-saints-du-jour-mardi-29-Decembre

Saint Thomas Becket

Quatrième leçon. Thomas,

né à Londres, en Angleterre, succéda à Théobald, Évêque de Cantorbéry. Il avait

exercé auparavant, et avec honneur, la charge de chancelier et il se montra

fort et invincible dans les devoirs de l’épiscopat. Henri II, roi d’Angleterre,

ayant voulu, dans une assemblée des prélats et des grands de son royaume,

porter des lois contraires à l’intérêt et à la dignité de 1’ Église, Thomas

s’opposa à.la cupidité du roi avec tant de constance, que, n’ayant voulu fléchir,

ni devant les promesses ni devant les menaces, il se vit obligé de se retirer

secrètement, parce qu’il allait être emprisonné. Bientôt tous ses parents, ses

amis et ses partisans furent chassés du royaume, après qu’on eut fait jurer à

tous ceux dont l’âge le permettait, d’aller trouver Thomas, afin d’ébranler,

par la vue de l’état pitoyable des siens, cette sainte résolution, dont ne

l’avaient nullement détourné ses propres souffrances. Il n’eut égard ni à la

chair ni au sang, et aucun sentiment trop humain n’ébranla sa constance

pastorale.

Répons du Commun d’un

Martyr

Cinquième leçon. Il se

rendit auprès du Pape Alexandre III, qui le reçut avec bonté et le recommanda

aux moines du monastère de Pontigny, de l’Ordre de Cîteaux, vers lequel il se dirigea.

Dès qu’Henri l’eut appris, il envoya des lettres menaçantes au Chapitre de

Cîteaux, dans le but de faire chasser Thomas du monastère de Pontigny. Le saint

homme, craignant que cet Ordre ne souffrît quelque persécution à cause de lui,

se retira spontanément, et sur l’invitation de Louis, roi de France, il alla

demeurer auprès de lui. Il y resta jusqu’à ce que, par l’intervention du

Souverain Pontife et du roi, il fut rappelé de l’exil, et rentra en Angleterre

à la grande satisfaction du royaume entier. Comme il s’appliquait, sans rien

craindre, à remplir les devoirs d’un bon pasteur, des calomniateurs vinrent

rapporter au roi qu’il entreprenait beaucoup de choses contre le royaume et la

tranquillité publique : en sorte que ce prince se plaignait souvent de ce que,

dans son royaume, il y avait un Évêque avec lequel il ne pouvait avoir la paix.

Sixième leçon. Ces

paroles du roi ayant fait croire à quelques détestables satellites qu’ils lui

causeraient un grand plaisir s’ils faisaient mourir Thomas, ils se rendirent

secrètement à Cantorbéry, et allèrent attaquer l’Évêque, dans l’église même où

il célébrait l’Office des Vêpres. Les clercs voulant leur fermer l’entrée du

temple, Thomas accourut aussitôt, et ouvrit lui-même la porte, en disant aux

siens : « L’église de Dieu ne doit pas être gardée comme un camp ; pour moi, je

souffrirai volontiers la mort pour l’Église de Dieu. » Puis, s’adressant aux

soldats : « De la part de Dieu, dit-il, je vous défends de toucher à aucun des

miens. » Il se mit ensuite à genoux, et après avoir recommandé l’Église et son

âme à Dieu, à la bienheureuse Marie, à saint Denys et aux autres patrons de sa

cathédrale, il présenta sa tête au fer sacrilège, avec la même constance qu’il

avait mise à résister aux lois très injustes du roi. Ceci arriva le quatre des

Calendes de janvier, l’an du Seigneur onze cent soixante et onze ; et la

cervelle du Martyr jaillit sur le pavé du temple. Dieu l’ayant bientôt illustré

par un grand nombre de miracles, le même Pape Alexandre l’inscrivit au nombre

des Saints.

Au troisième nocturne.

Lecture du saint Évangile

selon saint Jean.

En ce temps-là : Jésus

dit aux pharisiens : Je suis le bon pasteur. Le bon pasteur donne sa vie pour

les brebis. Et le reste.

Homélie de saint Jean

Chrysostome.

Septième leçon. Elle est

grande, mes très chers frères, elle est grande, dis-je, la dignité de prélat

dans l’Église, et elle exige beaucoup de sagesse et de force en celui qui en

est revêtu ! Notre courage doit selon l’exemple proposé par Jésus-Christ, être

tel que nous donnions notre vie pour nos brebis, que jamais nous ne les

abandonnions, et que nous résistions généreusement au loup. C’est en cela que

le pasteur diffère du mercenaire. L’un s’inquiète peu de ses brebis, et n’a de

vigilance que pour ses propres intérêts ; mais l’autre s’oublie lui-même et

veille constamment au salut de son troupeau. Jésus-Christ donc, après avoir

caractérisé le pasteur, signale deux sortes de personnes qui nuisent au

troupeau : le voleur, qui ravit et égorge les brebis, et le mercenaire, qui ne

repousse pas le voleur et ne défend pas les brebis confiées à sa garde.

Huitième leçon. C’est là

ce qui arrachait autrefois à Ézéchiel ces invectives : « Malheur aux pasteurs

d’Israël ! Ne se paissaient-ils pas eux-mêmes ? N’est-ce pas les troupeaux que

les pasteurs font paître ? » Mais eux, ils faisaient le contraire : conduite

des plus criminelles, et source de calamités nombreuses. Ainsi, ajoute le

Prophète : « Ils ne ramenaient pas (au bercail les brebis) égarées ; celles qui

étaient perdues, ils ne les cherchaient pas ; ils ne bandaient point les plaies

de celles qui étaient blessées ; ils ne fortifiaient pas celles qui étaient

faibles ou malades, parce qu’ils le paissaient eux-mêmes et non leur troupeau.

» Saint Paul exprime la même vérité en d’autres termes : « Tous cherchent leurs

propres intérêts et non ceux de Jésus-Christ. »

Neuvième leçon. Le Christ

il se fait voir bien différent du voleur et du mercenaire : différent d’abord

de ceux qui viennent pour la perte des autres, quand il dit « être venu pour

qu’ils aient la vie, et l’aient très abondamment » ; différent ensuite des

pasteurs négligents qui ne se souciaient pas de voir des loups ravir les

brebis, en disant qu’il « donne sa vie pour ses brebis, afin qu’elles ne

périssent pas ». En effet, bien que les Juifs cherchassent à le faire mourir,

il continuait à répandre sa doctrine ; il n’a point abandonné ni trahi ceux qui

croyaient en lui, mais il est demeuré ferme et il a souffert la mort. C’est

pourquoi souvent il dit : « Je suis le bon pasteur. » Comme on ne voyait pas de

preuve de ce qu’il avançait (car cette parole : « Je donne ma vie », n’eut son

accomplissement que peu de temps après, et celle-ci : « afin qu’elles aient la

vie, et qu’elles l’aient très abondamment », ne devait se réaliser qu’au siècle

futur), que fait-il ? Il confirme une des assertions par l’autre.

Dom Guéranger, l’Année

Liturgique

Un nouveau Martyr vient

réclamer sa place auprès du berceau de l’Enfant-Dieu. Il n’appartient point au

premier âge de l’Église ; son nom n’est point écrit dans les livres du Nouveau

Testament, comme ceux d’Étienne, de Jean, et des enfants de Bethléhem.

Néanmoins, il occupe un des premiers rangs dans cette légion de Martyrs qui n’a

cessé de se recruter à chaque siècle, et qui atteste la fécondité de l’Église

et la force immortelle dont l’a douée son divin auteur. Ce glorieux Martyr n’a

pas versé son sang pour la foi ; il n’a point été amené devant les païens, ou

les hérétiques, pour confesser les dogmes révélés par Jésus-Christ et proclamés

par l’Église. Des mains chrétiennes l’ont immolé ; un roi catholique a prononcé

son arrêt de mort ; il a été abandonné et maudit par le grand nombre de ses

frères, dans son propre pays : comment donc est-il Martyr ? Comment a-t-il

mérité la palme d’Étienne ? C’est qu’il a été le Martyr de la Liberté de

l’Église.

En effet, tous les

fidèles de Jésus-Christ sont appelés à l’honneur du martyre, pour confesser les

dogmes dont ils ont reçu l’initiation au Baptême. Les droits du Christ qui les

a adoptés pour ses frères s’étendent jusque-là. Ce témoignage n’est pas exigé

de tous ; mais tous doivent être prêts de rendre, sous peine de la mort

éternelle dont la grâce du Sauveur les a rachetés. Un tel devoir est, à plus

forte raison, imposé aux pasteurs de l’Église ; il est la garantie de

l’enseignement qu’ils donnent à leur propre troupeau : aussi, les annales de

l’Église sont-elles couvertes, à chaque page, des noms triomphants de tant de

saints Évêques qui ont, pour dernier dévouement, arrosé de leur sang le champ

que leurs mains avaient fécondé, et donné, en cette manière, le suprême degré

d’autorité à leur parole.

Mais si les simples

fidèles sont tenus d’acquitter la grande dette de la foi par l’effusion de leur

sang ; s’ils doivent à l’Église de confesser, à travers toute sorte de périls,

les liens sacrés qui les unissent à elle, et par elle, à Jésus-Christ, les

pasteurs ont un devoir de plus à remplir, le devoir de confesser la Liberté de

l’Église. Ce mot de Liberté de l’Église sonne mal aux oreilles des politiques.

Ils y voient tout aussitôt l’annonce d’une conspiration ; le monde, de son

côté, y trouve un sujet de scandale, et répète les grands mots d’ambition

sacerdotale ; les gens timides commencent à trembler, et vous disent que tant

que la foi n’est pas attaquée, rien n’est en péril. Malgré tout cela, l’Église

place sur ses autels et associe à saint Étienne, à saint Jean, aux saints

Innocents, cet Archevêque anglais du XIIe siècle, égorgé dans sa Cathédrale

pour la défense des droits extérieurs du sacerdoce. Elle chérit la belle maxime

de saint Anselme, l’un des prédécesseurs de saint Thomas, que Dieu n’aime rien

tant en ce monde que la Liberté de son Église ; et au XIXe siècle, comme au

XIIe, le Siège Apostolique s’écrie, par la bouche de Pie VIII, comme elle l’eût

fait par celle de saint Grégoire VII : C’est par l’institution même de Dieu que

l’Église, Épouse sans tache de l’Agneau immaculé Jésus-Christ, est LIBRE, et

qu’elle n’est soumise à aucune puissance terrestre [7].

Or, cette Liberté sacrée

consiste en la complète indépendance de l’Église à l’égard de toute puissance

séculière, dans le ministère de la Parole, qu’elle doit pouvoir prêcher, comme

parle l’Apôtre, à temps et à contre-temps, à toute espèce de personnes, sans

distinction de nations, de races, d’âge, ni de sexe ; dans l’administration de

ses Sacrements, auxquels elle doit appeler tous les hommes sans exception, pour

les sauver tous ; dans la pratique, sans contrôle étranger, des conseils aussi

bien que des préceptes évangéliques ; dans les relations, dégagées de toute

entrave, entre les divers degrés de sa divine hiérarchie ; dans la publication

et l’application des ordonnances de sa discipline ; dans le maintien et le

développement des institutions qu’elle a créées ; dans la conservation et

l’administration de son patrimoine temporel ; enfin dans la défense des privilèges

que l’autorité séculière elle-même lui a reconnus, pour assurer l’aisance et la

considération de son ministère de paix et de charité sur les peuples.

Telle est la Liberté de

l’Église : et qui ne voit qu’elle est le boulevard du sanctuaire lui-même ; que

toute atteinte qui lui serait portée peut mettre à découvert la hiérarchie, et

jusqu’au dogme lui-même ? Le Pasteur doit donc la défendre d’office, cette

sainte Liberté : il ne doit ni fuir, comme le mercenaire ; ni se taire, comme

ces chiens muets qui ne savent pas aboyer, dont parle Isaïe [8]. Il est la

sentinelle d’Israël ; il ne doit pas attendre que l’ennemi soit entré dans la

place pour jeter le cri d’alarme, et pour offrir ses mains aux chaînes, et sa

tête au glaive. Le devoir de donner sa vie pour son troupeau commence pour lui

du moment où l’ennemi assiège ces postes avancés, dont la franchise assure le

repos de la cité tout entière. Que si cette résistance entraîne de graves

conséquences, c’est alors qu’il faut se rappeler ces belles paroles de Bossuet,

dans son sublime Panégyrique de saint Thomas de Cantorbéry, que nous voudrions

pouvoir ici citer tout entier : « C’est une loi établie, dit-il, que l’Église

ne peut jouir d’aucun avantage qui ne lui coûte la mort de ses enfants, et que,

pour affermir ses droits, il faut qu’elle répande du sang. Son Époux l’a

rachetée par le sang qu’il averse pour elle, et il veut qu’elle achète par un

prix semblable les grâces qu’il lui accorde. C’est par le sang des Martyrs

qu’elle a étendu ses conquêtes bien loin au. delà de l’empire romain ; son sang

lui a procuré et la paix dont elle a joui sous les empereurs chrétiens, et la

victoire qu’elle a remportée sur les empereurs infidèles. Il paraît donc

qu’elle devait du sang à l’affermissement de son autorité, comme elle en avait

donné à l’établissement de sa doctrine ; et ainsi la discipline, aussi bien que

la foi de l’Église, a dû avoir ses Martyrs. »

Il ne s’est donc pas agi,

pour saint Thomas et pourtant d’autres Martyrs de la Liberté ecclésiastique, de

considérer la faiblesse des moyens qu’on pourrait opposer aux envahissements

des droits de l’Église. L’élément du martyre est la simplicité unie à la force

; et n’est-ce pas pour cela que de si belles palmes ont été cueillies par de

simples fidèles, par de jeunes vierges, par des enfants ? Dieu a mis au cœur du

chrétien un élément de résistance humble et inflexible qui brise toujours toute

autre force. Quelle inviolable fidélité l’Esprit-Saint n’inspire-t-il pas à

l’âme de ses pasteurs qu’il établit comme les Époux de son Église, et comme

autant de murs imprenables de sa chère Jérusalem ? « Thomas, dit encore

l’Évêque de Meaux, ne cède pas à l’iniquité, sous prétexte qu’elle est armée et

soutenue d’une main royale ; au contraire, lui voyant prendre son cours d’un

lieu éminent, d’où elle peut se répandre avec plus de force, il se croit plus

obligé de s’élever contre, comme une digue que l’on élève à mesure que l’on

voit les ondes enflées. »

Mais, dans cette lutte,

le Pasteur périra peut-être ? Et, sans doute, il pourra obtenir cet insigne

honneur. Dans sa lutte contre le monde, dans cette victoire que le Christ a

remportée pour nous, il a versé son sang, il est mort sur une croix ; et les

Martyrs sont morts aussi ; mais l’Église, arrosée du sang de Jésus-Christ, cimentée

parle sang des Martyrs, peut-elle se passer toujours de ce bain salutaire qui

ranime sa vigueur, et forme sa pourpre royale ? Thomas l’a compris ; et cet

homme, dont les sens sont mortifiés par une pénitence assidue, dont les

affections en ce monde sont crucifiées par toutes les privations et toutes les

adversités, a dans son cœur ce courage plein de calme, cette patience inouïe

qui préparent au martyre. En un mot, il a reçu l’Esprit de force, et il lui a

été fidèle.

« Selon le langage

ecclésiastique, continue Bossuet, la force a une autre signification que dans

le langage du monde. La force selon le monde s’étend jusqu’à entreprendre ; la

force selon l’Église ne va pas plus loin que de tout souffrir : voilà les

bornes qui lui sont prescrites. Écoutez l’Apôtre saint Paul : Nondum usque ad

sanguinem restitistis ; comme s’il disait : Vous n’avez pas tenu jusqu’au bout,

parce que vous ne vous êtes pas défendus jusqu’au sang. Il ne dit pas jusqu’à

attaquer, jusqu’à verser le sang de vos ennemis, mais jusqu’à répandre le

vôtre. _ « Au reste, saint Thomas n’abuse point de ces maximes vigoureuses. Il

ne prend pas par fierté ces armes apostoliques, pour se faire valoir dans le

monde : il s’en sert comme d’un bouclier nécessaire dans l’extrême besoin de l’Église.

La force du saint Évêque ne dépend donc pas du concours de ses amis, ni d’une

intrigue finement menée. Il ne sait point étaler au monde a sa patience, pour

rendre son persécuteur plus odieux, ni faire jouer de secrets ressorts pour

soulever les esprits. Il n’a pour lui que les prières des pauvres, les

gémissements des veuves et des orphelins. Voilà, disait saint Ambroise, les

défenseurs des Évêques ; voilà leurs gardes, voilà leur armée. Il est fort,

parce qu il a un esprit également incapable et de crainte et de murmure. Il

peut dire véritablement à Henri, roi d’Angleterre, ce que disait Tertullien, au

nom de toute l’Église, à un magistrat de l’Empire, grand persécuteur de

l’Église : Non te terremus, qui nec timemus. Apprends à connaître quels nous sommes,

et vois quel homme c’est qu’un chrétien : Nous ne pensons pas à te faire peur,

et nous sommes incapables de te craindre. Nous ne sommes ni redoutables ni

lâches : nous ne sommes pas redoutables, parce que nous ne savons pas cabaler ;

et nous ne sommes pas lâches, parce que nous savons mourir. »

Mais laissons encore la

parole à l’éloquent prêtre de l’Église de France, qui fut lui-même appelé aux

honneurs de l’épiscopat dans l’année qui suivit celle où il prononça ce

discours ; écoutons-le nous raconter la victoire de l’Église par saint Thomas

de Cantorbéry :

« Chrétiens, soyez

attentifs : s’il y eut jamais un martyre qui ressemblât parfaitement à un

sacrifice, c’est celui que je dois vous représenter. Voyez les préparatifs :

l’Evêque est à l’église avec son clergé, et ils sont déjà revêtus. Il ne faut

pas chercher bien loin la victime : le saint Pontife est préparé, et c’est la

victime que Dieu a choisie. Ainsi tout est prêt pour le sacrifice, et je vois

entrer dans l’église ceux qui doivent donner le coup. Le saint homme va

au-devant d’eux, à l’imitation de Jésus-Christ ; et pour a imiter en tout ce

divin modèle, il défend à son clergé toute résistance, et se contente de

demander sûreté pour les siens. Si c’est moi que vous » cherchez, laissez, dit

Jésus, retirer ceux-ci. Ces choses étant accomplies, et l’heure du sacrifice

étant arrivée, voyez comme saint Thomas en commence la cérémonie. Victime et

Pontife tout ensemble, il présente sa tête et fait sa prière. Voici les vœux

solennels et les paroles mystiques de ce sacrifice : Et ego pro Deo mori

paratus sum, et pro assertione justitiœ, et pro Ecclesiae libertate ; dummodo

effusione sanguinis mei pacem et libertatem consequatur. Je suis prêt à mourir,

dit-il, pour la cause de Dieu et de son Église ; et toute la grâce que je

demande, c’est que mon sang lui rende la paix et la liberté qu’on veut lui

ravir. Il se prosterne devant Dieu ; et comme dans le Sacrifice solennel nous

appelons les Saints nos intercesseurs, il n’omet pas une partie si considérable

de cette cérémonie sacrée : il appelle les saints Martyrs et la sainte Vierge

au secours de l’Église opprimée ; il ne parle que de l’Église ; il n’a que

l’Église dans le cœur et dans la bouche ; et, abattu par le coup, sa langue

froide et inanimée semble encore nommer l’Église. »

Ainsi ce grand Martyr, ce

type des Pasteurs de l’Église, a consommé son sacrifice ; ainsi il a remporté

la victoire ; et cette victoire ira jusqu’à l’entière abrogation de la coupable

législation qui devait entraver l’Église, et l’abaisser aux yeux des peuples.

La tombe de Thomas deviendra un autel ; et au pied de cet autel, on verra

bientôt un Roi pénitent solliciter humblement sa grâce. Que s’est-il donc passé

? La mort de Thomas a-t-elle excité les peuples à la révolte ? le Martyr a-t-il

rencontré des vengeurs ? Rien de tout cela n’est arrivé. Son sang a suffi à

tout. Qu’on le comprenne bien : les fidèles ne verront jamais de sang-froid la

mort d’un pasteur immolé pour ses devoirs ; et les gouvernements qui osent

faire des Martyrs en porteront toujours la peine. C’est pour l’avoir compris

d’instinct, que les ruses de la politique se sont réfugiées dans les systèmes

d’oppression administrative, afin de dérober habilement le secret de la guerre

entreprise contre la Liberté de l’Église. C’est pour cela qu’ont été forgées

ces chaînes non moins déliées qu’insupportables, qui enlacent aujourd’hui tant

d’Églises. Or, il n’est pas dans la nature de ces chaîner de se dénouer jamais

; elles ne sauraient être que brisées ; mais quiconque les brisera, sa gloire

sera grande dans l’Église de la terre et dans celle du ciel ; car sa gloire

sera celle du martyre. Il ne s’agira ni de combattre avec le fer, ni de

négocier par la politique ; mais de résister en face et de souffrir avec

patience jusqu’au bout.

Écoutons une dernière

fois notre grand orateur, relevant ce sublime élément qui a assuré la victoire

à la cause de saint Thomas : « Voyez, mes Frères, quels défenseurs trouve

l’Église dans sa faiblesse, et combien elle a raison de dire avec l’Apôtre : Cum

infirmor, tunc potens sum. Ce sont ces bienheureuses faiblesses qui lui donnent

cet invincible secours, et qui arment en sa faveur les plus valeureux soldats

et les plus puissants conquérants du monde, je veux dire, les saints Martyrs.

Quiconque ne ménage pas l’autorité de l’Église, qu’il craigne ce sang précieux

des Martyrs, qui la consacre et la protège. »

Or, toute cette force,

toute cette victoire émanent du berceau de l’Enfant-Dieu ; et c’est pour cela

que Thomas s’y rencontre avec Étienne. Il fallait un Dieu anéanti, une si haute

manifestation d’humilité, de constance et de faiblesse selon la chair, pour

ouvrir les yeux des hommes sur la nature de la véritable force. Jusque-là on

n’avait soupçonné d’autre vigueur que celle des conquérants à coups d’épée,

d’autre grandeur que la richesse, d’autre honneur que le triomphe ; et

maintenant, parce que Dieu venant en ce monde a apparu désarmé, pauvre et

persécuté, tout a changé de face. Des cœurs se sont rencontrés qui ont voulu

aimer, malgré tout, les abaissements de la Crèche ; et ils y ont puisé le

secret d’une grandeur d’âme que le monde, tout en restant ce qu’il est, n’a pu

s’empêcher de sentir et d’admirer.

Il est donc juste que la

couronne de Thomas et celle d’Étienne, unies ensemble, apparaissent comme un

double trophée aux côtés du berceau de l’Enfant de Bethléhem ; et quant au

saint Archevêque, la Providence de Dieu a marqué divinement sa place sur le

Cycle, en permettant que son immolation s’accomplît le lendemain de la fête des

saints Innocents, afin que la sainte Église n’éprouvât pas d’incertitude sur le

jour qu’elle devrait assigner à sa mémoire. Qu’il garde donc cette place si

glorieuse et si chère à toute l’Église de Jésus-Christ ; et que son nom reste,

jusqu’à la fin des temps, la terreur des ennemis de la Liberté de l’Église,

l’espérance et la consolation de ceux qui aiment cette Liberté que le Christ a

acquise aussi par son sang.

La Liturgie de l’Église

d’Angleterre rendait à saint Thomas un culte plein de tendresse et

d’enthousiasme. Nous extrairons plusieurs pièces de l’ancien Bréviaire de

Salisbury, et nous donnerons d’abord un ensemble formé de la plupart des

Antiennes des Matines et des Laudes. Tout l’Office est rimé, suivant l’usage du

XIIIe siècle, auquel ces compositions appartiennent.

Thomas, élevé au

souverain sacerdoce, se trouve tout à coup changé en un autre homme.

Sous ses vêtements de

clerc, il revêt secrètement le cilice du moine ; plus fort que la chair, il

réprime les révoltes de la chair.

Agriculteur fidèle, il

arrache les ronces du champ du Seigneur ; de ses vignes il repousse et il

chasse les renards.

Il ne souffre point que

les loups dévorent les agneaux, ni que les animaux malfaisants traversent le

jardin confié à sa garde.

On l’exile ; ses biens

sont la proie des méchants ; mais, au milieu du feu de la tribulation, Thomas

n’est pas atteint.

Des satellites de Satan

pénètrent dans le temple ; ils en font le théâtre d’un forfait inouï.

Thomas marche au-devant

des épées menaçantes ; il ne cède ni aux menaces, ni aux glaives, pas même à la

mort.

Lieu fortuné, heureuse

église où vit la mémoire de Thomas ! heureuse terre qui a produit un tel prélat

! Heureuse contrée qui, avec amour, recueillit son exil !

Le grain tombe, et c’est

pour produire une abondance de froment ; le vase d’albâtre est brisé, et c’est

pour répandre la suavité du parfum.

L’univers entier

s’empresse à témoigner son amour pour le Martyr ; ses prodiges multipliés

excitent en tout lieu l’étonnement.

Les pièces qui suivent ne

sont pas moins dignes de mémoire, pour l’affection et la confiance qu’elles

expriment à notre grand Martyr.

Ant. Le Pasteur immolé,

au milieu de son troupeau achète la paix au prix de son sang. O douleur pleine

d’allégresse ! ô joie remplie de tristesse ! par la mort du Pasteur, le

troupeau respire ; la mère en pleurs applaudit à son fils, vivant et victorieux

sous le glaive.

R/. Cesse tes plaintes, ô

Rachel cesse de pleurer sur la fleur de ce monde, que le monde a brisée ;

Thomas immolé, enseveli est un nouvel Abel qui succède à l’ancien.

Ant. Salut, Thomas !

Sceptre de justice, splendeur du monde, vigueur de l’Église, amour du peuple,

délices du clergé. Tuteur fidèle du troupeau, salut ! Daignez sauver ceux qui

applaudissent à votre gloire.

Nous empruntons au même

Bréviaire de Salisbury le Répons qui suit. Il est remarquable, dans sa forme,

par l’insertion d’une Prose entière, en manière de Verset, après laquelle la

Réclame revient, selon l’usage du XIV° siècle. Nous n’avons pas besoin de

relever la beauté naïve de cette pièce liturgique.

L’épi succombe opprimé

par la paille ; le juste est immolé par l’épée des méchants : * Il échange

contre le ciel cette demeure de boue. V/. Le gardien de la vigne succombe dans

la vigne même, le capitaine dans son camp, le cultivateur dans son aire. * Il

échange contre le ciel cette demeure de boue.

Prose

Que le Pasteur fasse

retentir la trompette de force ;

Qu’il réclame la liberté

de la vigne du Christ,

De cette vigne que le

Christ, sous le manteau de la chair, a choisie pour sienne.

Qu’il a affranchie par le

sang de sa croix.

Une brebis égarée s’est

élevée contre Thomas,

Elle s’est baignée dans

le sang du pasteur immolé.

Le pavé de marbre de la

maison du Christ

S’est rougi d’un sang

précieux.

Le Martyr, décoré de la

couronne de vie,

Semblable au grain dégagé

de la paille,

Est transféré dans les

greniers divins.

* Il échange contre le

ciel cette demeure de boue.

L’Église de France

témoigna aussi par la Liturgie sa vive admiration pour l’illustre Martyr. Adam

de Saint-Victor composa jusqu’à trois Séquences pour célébrer un si noble

triomphe. Nous donnerons ici les deux plus belles. Elles respirent la plus

ardente sympathie pour le sublime athlète de Cantorbéry, et montrent à quel

point était chère la Liberté de l’Église aux fidèles de ces temps, et comment

la cause dont saint Thomas fut le martyr était regardée alors comme celle de la

société chrétienne tout entière. Obligé de nous restreindre, nous regrettons de

ne pouvoir insérer ici la belle Prose des Missels de Liège : Laureata novo

Thoma.

Ière SÉQUENCE.

Réjouis-toi, Sion, et

sois dans l’allégresse ; par tes chants, par tes vœux, éclate dans une

solennelle réjouissance.

Ton pasteur Thomas est

égorgé ; pour toi, ô Christ ! il est immolé, comme une hostie salutaire.

Archevêque et légat, nul

degré d’honneur n’a enflé son âme.

Dispensateur fidèle du

souverain Roi, pour avoir défendu son troupeau, il est condamné à l’exil.

Il combat avec les armes

du pasteur ; il est ceint du glaive spirituel ; il a mérité le triomphe.

Pour la loi de son Dieu,

pour le salut de ses brebis, il a voulu combattre et mourir.

Privée de son chef, veuve

de son pasteur, Cantorbéry se lamentait.

Plus heureuse et battant

des mains, la Gaule Sénonnaise saluait un si grand homme.

Par son absence est

affaiblie, foulée aux pieds, la liberté de l’Église.

Ainsi, tu nous quittas, ô

Pasteur ! Mais rien ne te fit reculer du vrai sentier de la justice.

Naguère, en la cour des

seigneurs, tu étais le premier : tu occupais le poste d’honneur au palais du

roi.

Le vent de la faveur

populaire était pour toi, et tu jouissais de ces applaudissements du siècle,

qui ne durent qu’un temps.

Élevé à la prélature, tu

changeas bientôt ; par un heureux échange, tu devins un homme nouveau.

Tu résistas à

l’adversaire, tu t’opposas comme un mur, tu offris ta tête dans un sacrifice

comme celui du Christ.

Tu as bravé la mort de ta

chair, athlète triomphant !

Une palme glorieuse est

dans tes mains ; des miracles inouïs l’attestent en grand nombre.

Illustre Thomas ! la perle

du clergé, par tes prières efficaces, dompte les assauts de notre chair.

Afin que, enracinés dans

le Christ, la vraie vigne, nous obtenions la couronne de la vie véritable.

Amen.

II° SÉQUENCE.

O Église, ô tendre Mère,

déplore dans tes chants le forfait commis naguère par la Grande-Bretagne.

O France, sois émue de

compassion ; le ciel lui-même, la terre et les mers, pleurent sur ce crime

exécrable.

Oui, l’Angleterre a

commis un crime qu’on n’ose raconter, un forfait immense et qui saisit d’horreur.

Elle a condamné son propre père ; elle l’a massacré sur son siège, auquel il

venait d’être rendu.

Thomas, lui, la fleur

vermeille de l’Angleterre, la gloire première de l’Église, a été immolé dans le

temple de Cantorbéry ; prêtre et victime, il a succombé pour la justice.

Entre le temple et

l’autel, sur le seuil même de l’église, on l’a atteint, mais non vaincu ; le

voile du temple a été fendu en deux par le glaive. Élisée a reçu le coup sur sa

tête vénérable ; Zacharie a été égorgé ; la paix qui venait de se conclure a été

violée ; et les chants d’allégresse se sont changés en lamentations.

Le lendemain de la fête

des Innocents, le Pontife innocent comme eux est traîné à la mort ; on le

frappe, on répand sa cervelle sur le pavé avec la pointe du glaive. Le temple

acquiert une nouvelle gloire par le sang qui rougit ses dalles, au moment où le

Pontife revêt la robe empourprée du martyre.

La fureur des meurtriers

est au comble ; ils ont conspiré contre la vie du juste, et leur épée s’est

abattue sur sa tête en présence même du Seigneur. Le Pontife accomplissait

l’œuvre de sanctification : là même il est sanctifié ; il immolait, et on

l’immole. Il laisse ainsi aux hommes l’exemple de son sublime courage.

Cet holocauste choisi

devient célèbre dans tout l’univers ; c’est le Pontife lui-même offert à Dieu,

comme une victime d’agréable odeur ; on a frappé sa tête à l’endroit où la

couronne la rendait plus sacrée ; en retour, il a reçu une double tunique

d’honneur ; et le privilège de son trône archiépiscopal est désormais reconnu.

Le Juif regarde avec

insolence, le païen idolâtre poursuit de ses sarcasmes des chrétiens qui ont

violé le pacte sacré, et dont la rage n’a pas su épargner même un des pères de

la chrétienté Rachel repousse les consolations ; elle pleure le fils qu’elle a

vu immoler jusque sur son sein maternel, le fils dont le trépas arrache tant de

larmes aux chrétiens pieux.

C’est là le Pontife que

le suprême architecte a placé glorieux au faite de l’édifice céleste, parce

qu’il a triomphé du glaive homicide des Anglais.

Pour n’avoir pas craint

la mort, pour avoir livré sa tête avec son sang, au sortir de ce séjour

terrestre, il est entré pour jamais dans le Saint des Saints.

Les prodiges attestent

combien fut précieuse sa mort ; que ses prières, nous soient un secours

favorable pour l’éternité.

Amen.

Ainsi s’épanchait, par la

voix sacrée de la Liturgie, l’amour du peuple catholique pour saint Thomas de

Cantorbéry. Ainsi la victoire de l’Église était-elle réputée la victoire de

l’humanité elle-même, dans les siècles catholiques. Il n’entre point dans notre

plan d’écrire la vie des Saints dans cette Année liturgique déjà si remplie ;

nous ne pourrons donc développer ici en détail le caractère de ce grand Martyr

de la plus sacrée des libertés. Cependant, nous croyons faire plaisir à nos

lecteurs, en produisant sois leurs yeux un témoignage touchant de l’affection

et de l’estime qu’avait inspirées Thomas à ceux qui avaient été témoins des

vertus évangéliques de ce prélat fidèle et désintéressé, auquel le roi son ami,

et plus tard son meurtrier, ne pardonna jamais de s’être démis des hautes

fonctions de Chancelier du royaume d’Angleterre, le jour où il fut promu à

l’archevêché de Cantorbéry. La lettre qu’on va lire fut écrite par un Français,

Pierre de Blois, Archidiacre de Bath, et adressée aux Chanoines de Beauvoir,

peu de jours après le martyre du Saint, quand son sang était encore chaud sur

le pavé de l’Église Primatiale de l’Angleterre. Cette lettre est un cri de

victoire ; mais combien la victoire de l’Église, dans laquelle elle ne verse

d’autre sang que le sien, est pure et paisible !

« Il est décédé, le

Pasteur de nos âmes, lui dont je voulais pleurer le trépas ; mais que dis-je ?

il s’est retiré plutôt qu’il n’est décédé ; il s’en est allé, il n’est pas mort.

En effet, la mort par laquelle le Seigneur a glorifié son Saint n’est pas une

mort, mais un sommeil. C’est un port, c’est la porte de la vie, l’entrée dans

les délices de la patrie céleste, dans les puissances du Seigneur, dans l’abîme

de l’éternelle clarté. Prêt à partir pour un voyage lointain, il a pris a avec

lui les subsides de la route, pour revenir à la pleine lune. Son âme, qui s’est

retirée de son corps riche de mérites, rentrera, opulente, dans cette ancienne

demeure, au jour de la résurrection générale. La mort envieuse et pleine de

ruse a voulu voir si, dans ce trésor, il se trouvait quelque chose qui

appartînt à son domaine. Lui, en homme prudent et circonspect, n’avait pas

voulu risquer sa vraie vie. Dès longtemps il t désirait la dissolution de son

corps pour être avec Jésus-Christ ; dès longtemps il aspirait à sortir de ce

corps de mort. Il a donc jeté un peu de poussière à la face de cette vieille

ennemie, comme un tribut. C’est delà qu’est sortie cette rumeur populaire et

fausse qu’une bête féroce avait dévoré Joseph. La tunique dont on l’a dépouillé

n’était donc qu’une fausse messagère de sa mort ; car Joseph est vivant, et il

domine sur toute la terre d’Égypte. Sa bienheureuse âme, débarrassée de

l’enveloppe de cette poussière corruptible, s’est envolée libre au ciel.

« Oui, il a été appelé au

ciel, cet homme dont le monde n’était pas digne. Cette lumière n’est pas

éteinte ; un souffle passager l’a inclinée, afin qu’elle brillât ensuite avec

plus de clarté, afin qu’elle ne fût plus sous le boisseau, mais éclatât

davantage aux yeux de ceux qui sont dans la maison. Aux regards des insensés il

a paru mourir ; mais sa vie est cachée avec Jésus-Christ en Dieu. La mort a

semblé l’avoir vaincu et dévoré ; mais la mort a été ensevelie dans a son

triomphe. Vous lui avez accordé, Seigneur, u le désir de son cœur ; car

longtemps il milita pour vous, fidèle à votre service, à travers les voies les

plus dures. Dès son adolescence, il montra la maturité de la vieillesse ; et on

le vit réprimer les révoltes de la chair par les veilles, par les jeûnes, par

les disciplines, par le cilice et la garde d’une continence perpétuelle. Le

Seigneur se le choisit pour Pontife, afin qu’il fût, au milieu de son peuple,

un chef, un docteur, un miroir de vie, un modèle de pénitence, un exemplaire de

sainteté. Le Dieu des sciences lui » avait donné une langue éloquente, et avait

répandu en lui avec abondance l’esprit d’intelligence et de sagesse, afin qu’il

fût entre les doctes le plus docte, entre les sages le plus sage, entre les

bons le meilleur, entre les grands le plus grand. Il était le héraut de la

parole divine, la trompette de l’Évangile, l’ami de l’Époux, la colonne du

clergé, l’œil de l’aveugle, le pied du boiteux, le sel de la terre, la lumière

de la patrie, le ministre du Très-Haut, le vicaire du Christ, le Christ même du

Seigneur.

« Il était droit dans le

jugement, habile dans le gouvernement, discret dans le commandement, modeste

dans le parler, circonspect dans les conseils, tempérant dans la nourriture,

pacifique dans la colère, un ange dans la chair, doux au milieu des injures,

timide dans la prospérité, ferme dans l’adversité, prodigue dans les aumônes,

tout entier à la miséricorde. Il était la gloire des moines, les délices du

peuple, la terreur des princes, le Dieu de Pharaon. D’autres, quand ils sont

élevés sur le siège éminent de l’Épiscopat, se montrent tout aussitôt enclins à

flatter la chair ; ils craignent toute souffrance du corps comme un supplice ;

leur désir en toutes choses est de jouir longtemps de la vie. Celui-ci, au

contraire, dès le jour de sa promotion, désira avec passion la fin de cette

vie, ou plutôt le commencement d’une vie meilleure ; c’est pour cela que, se

revêtant de la livrée du pèlerin, il a bu, sur la voie, l’eau du torrent, et

pour cela, son nom est élevé en gloire dans la patrie. Ainsi, nos seigneurs et

frères, les Moines de l’Église cathédrale, sont-ils devenus tout à coup des

pupilles qui ont perdu leur Père. »

Le seizième siècle vint

encore ajouter à la gloire de saint Thomas, lorsque l’ennemi de Dieu et des

hommes, Henri VIII d’Angleterre, osa poursuivre de sa tyrannie le Martyr de la

Liberté de l’Église jusque dans la châsse splendide où il recevait depuis près

de quatre siècles les hommages de la vénération de l’univers chrétien. Les

sacrés ossements du Pontife égorgé pour la justice furent arrachés de l’autel ;

un procès monstrueux fut instruit contre le Père de la patrie, et une sentence

impie déclara Thomas criminel de lèse-majesté royale. Ces restes précieux furent

placés sur un bûcher ; et dans ce second martyre, le feu dévora la glorieuse

dépouille de l’homme simple et fort dont l’intercession attirait sur

l’Angleterre les regards et la protection du ciel. Aussi, il était juste que la

contrée qui devait perdre la foi par une désolante apostasie ne gardât pas dans

son sein un trésor qui n’était plus estimé à son prix ; et d’ailleurs le siège

de Cantorbéry était souillé. Cranmer s’asseyait sur la chaire des Augustin, des

Dunstan, des Lanfranc, des Anselme, de Thomas enfin ; et le saint Martyr,

regardant autour de lui, n’avait trouvé parmi ses frères de cette génération

que le seul Jean Fischer, qui consentît à le suivre jusqu’au martyre. Mais ce

dernier sacrifice, tout glorieux qu’il fût, ne sauva rien. Dès longtemps la

Liberté de l’Église avait péri en Angleterre : la foi n’avait plus qu’à

s’éteindre.

Invincible défenseur de

l’Église de votre Maître, glorieux Martyr Thomas ! Nous venons à vous, en ce

jour de votre fête, pour honorer les dons merveilleux que le Seigneur a déposés

en votre personne. Enfants de l’Église, nous aimons à contempler celui qui l’a

tant aimée, et qui a tenu à si grand prix l’honneur de cette Épouse du Christ,

qu’il n’a pas craint de donner sa vie pour lui assurer l’indépendance. Parce

que vous avez ainsi aimé l’Église aux dépens de votre repos, de votre bonheur

temporel, de votre vie même ; parce que votre sacrifice sublime a été le plus

désintéressé de tous, la langue des impies et celle des lâches se sont

aiguisées contre vous, et votre nom a souvent été blasphémé et calomnié. O

véritable Martyr ! digne de toute croyance dans son témoignage, puisqu’il ne

parle et qu’il ne résiste que contre ses intérêts terrestres. O Pasteur associé

au Christ dans l’effusion du sang et dans la délivrance du troupeau ! nous vous

vénérons de tout le mépris que vous ont prodigué les ennemis de l’Église ; nous

vous aimons de toute la haine qu’ils ont versée sur vous, dans leur

impuissance. Nous vous demandons pardon pour ceux qui ont rougi de votre nom,

et qui ont regardé votre martyre comme un embarras dans les Annales de

l’Église. Que votre gloire est grande, ô Pontife fidèle ! d’avoir été choisi

pour accompagner avec Étienne, Jean et les Innocents, le Christ, au moment où

il fait son entrée en ce monde ! Descendu dans l’arène sanglante à la onzième

heure, vous n’avez pas été déshérité du prix qu’ont reçu vos frères de la

première heure ; loin de là, vous êtes grand parmi les Martyrs. Vous êtes donc

puissant sur le cœur du divin Enfant qui naît en ces jours mêmes pour être le

Roi des Martyrs. Permettez que, sous votre garde, nous pénétrions jusqu’à lui.

Comme vous, nous voulons aimer son Église, cette Église chérie dont l’amour l’a

forcé à descendre du ciel ; cette Église qui nous prépare de si douces

consolations dans la célébration des grands mystères auxquels votre nom se

trouve si glorieusement mêlé. Obtenez-nous cette force qui fasse que nous ne

reculions devant aucun sacrifice, quand il s’agit d’honorer notre beau titre de

Catholiques.

Assurez l’Enfant qui nous

est né, Celui qui doit porter sur son épaule la Croix comme le signe de sa

principauté, que, moyennant sa grâce, nous ne nous scandaliserons jamais ni de

sa cause, ni de ses défenseurs ; que, dans la simplicité de notre attachement

envers la sainte Église qu’il nous a donnée pour Mère, nous placerons toujours

ses intérêts au-dessus de tous les autres ; car elle seule a les paroles de la

vie éternelle, elle seule a le secret et l’autorité de conduire les hommes vers

ce monde meilleur qui seul est notre terme, seul ne passe pas, tandis que tous

les intérêts de la terre ne sont que vanité, illusion, et le plus souvent

obstacles à l’unique fin de l’homme et de l’humanité.

Mais, afin que cette

Église sainte puisse accomplir sa mission et sortir victorieuse de tant de

pièges qui lui sont tendus dans tous les sentiers de son pèlerinage, elle a

besoin par-dessus tout de Pasteurs qui vous ressemblent, ô Martyr du Christ !

Priez donc afin que le Maître de la vigne envoie des ouvriers, capables non

seulement de la cultiver et de l’arroser, mais encore de la défendre à la fois

du renard et du sanglier qui, comme nous en avertissent les saintes Écritures,

cherchent sans cesse à y pénétrer pour la ravager. Que la voix de votre sang

devienne de plus en plus tonnante en ces jours d’anarchie, où l’Église du

Christ est asservie sur tant de points de cette terre qu’elle est venue

affranchir. Souvenez-vous de l’Église d’Angleterre qui lit un si triste

naufrage, il y a trois siècles, par l’apostasie de tant de prélats, tombés

victimes de ces mêmes maximes contre lesquelles vous aviez résisté jusqu’au

sang. Aujourd’hui qu’elle semble se relever de ses ruines, tendez-lui la main,

et oubliez les outrages qui furent prodigués à votre nom, au moment où l’Ile des

Saints allait sombrer dans l’abîme de l’hérésie. Souvenez-vous aussi de

l’Église de France qui vous reçut dans votre exil, et au sein de laquelle votre

culte fut si florissant autrefois. Obtenez pour ses Pasteurs l’esprit qui vous

anima ; revêtez-les de cette armure qui vous rendit invulnérable dans vos rudes

combats contre les ennemis de la Liberté de l’Église. Enfin, quelque part, en

quelque manière que cette sainte Liberté soit en danger, accourez au secours,

et que vos prières et votre exemple assurent une complète victoire à l’Épouse

de Jésus-Christ.

[7] Libera est

institutione divina, nullique obnox laterrenae potestati, Ecclesia intemerata

sponsa immaculati Agni Christi Jesu. Litterae Apostolicae ad Episcopos

provinciae Rhenanae, 3o Junii 183o.

[8] LVI, 10.

[9] Psalm. XCVIII.

[10] Psalm. XLIV.

Bhx Cardinal

Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

Cette fête (de St Thomas