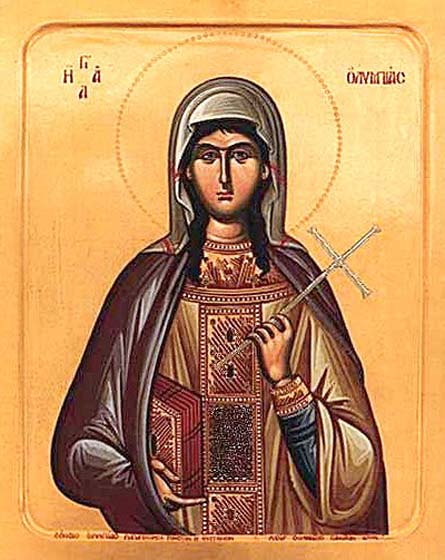

Sainte Olympiade

Veuve, diaconesse à

Constantinople (+ v. 410)

ou Olympias.

Elle avait épousé le préfet de Constantinople, mais elle perdit son époux après vingt mois de mariage. Elle prit alors le voile de diaconesse, utilisa son immense fortune pour fonder un hôpital et un orphelinat desservis par une communauté religieuse. Fille spirituelle de saint Jean Chrysostome, elle le soutint quand il fut exilé par l'impératrice Eudoxie, qui d'ailleurs dispersa la communauté de sainte Olympiade. Elle supporta ces harcèlements et ces persécutions avec patience. Nous avons dix-sept lettres de saint Jean Chrysostome qui, durant son exil, lui écrivait pour la soutenir. Il ne se plaint pas de son état, il ne la plaint pas non plus. Il la félicite d'être patiente et d'aimer ses persécuteurs: "Tu as fortifié et entraîné par ton exemple ceux qui t'entouraient."

Née à Constantinople, elle connut saint Grégoire le théologien et saint Grégoire de Nysse. Après la mort de son époux, préfet de Constantinople, elle refusa un second mariage et consacra son immense fortune à édifier des hôpitaux pour les malades, des hôtelleries pour les pauvres et des monastères pour les religieuses. Elle-même vivait très pauvrement. Ordonnée diaconesse, elle fut la conseillère du patriarche saint Nectaire puis de saint Jean Chrysostome qu'elle défendit au moment de son exil. Ce qui lui valut de lourdes amendes et, comme son patriarche, l'exil qu'elle endura avec foi et patience. Nous avons plusieurs lettres que saint Jean Chrysostome lui adressa à cette époque. Elle mourut en exil, à Nicomédie.

À Nicomédie de Bithynie, le trépas de sainte Olympiade, veuve. Encore jeune

quand elle perdit son mari, elle passa le reste de sa vie à Constantinople

parmi les femmes consacrées à Dieu, venant en aide aux pauvres et entièrement

fidèle à saint Jean Chrysostome, jusque dans son exil.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/274/Sainte-Olympiade.html

Sainte Olympiade

Veuve

(+ v. 419)

Sainte Olympiade ou

Olympie, la gloire des veuves de l'Église d'Orient, naquit à Constantinople, de

parents très illustres, dont la mort prématurée la laissa de bonne heure à la

tête d'une fortune considérable. Élevée au milieu des plus saints exemples,

elle était, à dix-huit ans, le modèle des vertus chrétiennes. C'est à cette

époque qu'elle fut mariée à Nébridius, jeune homme digne d'une telle épouse. Il

se promirent l'un à l'autre une continence parfaite; mais après vingt mois

seulement de cette union angélique, Nébridius alla recevoir au Ciel la

récompense de ses vertus. A l'empereur, qui voulait l'engager dans un nouveau

mariage: "Si Dieu, dit-elle, m'eût destinée à vivre dans le mariage, il ne

m'aurait pas enlevé mon premier époux. L'événement qui a brisé mes liens me

montre la voie que la Providence m'a tracée."

Depuis la mort de son

époux, Olympiade avait rendu sa vie plus austère. Ses jeûnes devinrent

rigoureux et continuels; elle se fit une loi de ne jamais manger de viande.

Elle s'interdit également le bain, qui était dans les moeurs du pays; elle

affranchit tous ses esclaves, qui voulurent continuer néanmoins à la servir;

elle administrait sa fortune en qualité d'économe des pauvres; les villes les

plus lointaines, les îles, les déserts, les églises pauvres, ressentaient tour

à tour les effets de sa libéralité.

Olympiade méritait

assurément d'être mise au nombre des diaconesses de Constantinople. Les

diaconesses étaient appelées à aider les prêtres dans l'administration des

sacrements et les oeuvres de charité; elles étaient chargées d'instruire les

catéchumènes de leur sexe et de préparer le linge qui servait à l'autel; en

prenant le voile, elles faisaient voeu de chasteté perpétuelle. Il y avait déjà

seize ans qu'Olympiade remplissait ces fonctions, quand saint Jean Chrysostome

fut élevé sur le siège de Constantinople.

La sainte veuve n'avait

pas manqué d'épreuves jusqu'à ce moment; des maladies cruelles, de noires

calomnies, lui avaient fait verser des larmes continuelles. Sous le nouveau

patriarche elle allait faire un pas de plus dans le sacrifice et dans la

sainteté. Saint Jean Chrysostome sut utiliser pour le bien les qualités et la

fortune de l'illustre diaconesse. C'est par elle qu'il éleva un hôpital pour

les malades et un hospice pour les vieillards et les orphelins. Quand le

patriarche partit pour l'exil où il devait mourir, Olympiade reçut une de ses

dernières bénédictions. Elle fut entretenue dans ses oeuvres par les lettres du

pontife, et acheva en exil une vie toute de charité, de patience et de prière.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/sainte_olympiade.html

11.

St. Olympias. The 140 Saints of the Colonnade St. Olympias. Born – 361 Died

- 25 July 408 at Nicomedia. Feastday - 25 July (previous 17 December).

Statue Installed - 1667-1668. Sculptor - Giovanni Maria De Rossi

There are similarities with other sculptures in this area (8, 12, 13, 15, 16,

30, 38) that allow attribution to De Rossi. Height - 3.1 m. (10ft 4in) travertine.

The saint is dressed in classical robes with her left hand raised. She was a

noble widow of Constantinople who was a friend of St John Chrysostom. Her

charitable works include building a hospital and orphanage attached to the

church of St Sofia. Her support for John Chrysostom led to her being exiled

from Constantinople in 404.

Saint Olympias of

Constantinople

Also

known as

Olympiada

25

July on some calendars

Profile

Born to a wealthy Constantinople noble

family. Orphaned as

a child. Married to

Nebridius, prefect of Constantinople. Widowed,

she refused several offers of marriage,

and devoted herself to the Church. Deaconess.

She led a non-cloistered group

of prayerful women in

her home, and devoted herself to charity.

She built a hospital and orphanage,

sheltered monks expelled

from Nitria, and gave away so much of her wealth that her friend, Saint John

Chrysostom, told her she was over-doing. In 404,

due to her support of Saint John,

she was persecuted, her community disbanded, her house seized and sold, and she

spent the rest of her days in exile in

Nicomedia.

Born

25

July 408 at

Nicomedia following a long illness

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

video

fonti

in italiano

MLA

Citation

‘Saint Olympias of

Constantinople‘. CatholicSaints.Info. 18 December 2022. Web. 4 January

2026. <https://catholicsaints.info/saint-olympias-of-constantinople/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-olympias-of-constantinople/

Book of

Saints – Olympias – 17 December

Article

(Saint) Widow (December

17) (5th

century) A lady of

noble birth at Constantinople who lost her

husband after only twenty months of married life,

and thenceforward devoted herself to works of religion and charity.

She was appointed a deaconess of the Church at Constantinople,

and, devotedly attached as she was to the cause of the exiled Saint John

Chrysostom, was herself persecuted on his account. Several Greek Fathers

of her time speak in her praise. She passed

away, as would seem, soon after A.D. 400.

MLA

Citation

Monks of Ramsgate.

“Olympias”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info.

1 May 2016. Web. 5 January 2026.

<https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-olympias-17-december/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-olympias-17-december/

St. Olympias

Feastday: December 17

Olympias born into a

wealthy noble Constantinople family.

She was orphaned when a child and was given over to the care of Theodosia by

her uncle, the prefect Procopius. She married Nebridius, also a prefect, was

widowed soon after, refused several offers of marriage, and had her fortune put

in trust until she was thirty by Emperor Theodosius when she also refused his

choice for a husband. When he restored her estate in 391, she was consecrated

deaconess and with several other ladies founded a community. She was so lavish

in her almsgiving that her good friend St. John Chrysostom

remonstrated with her and when he became Patriarch of Constantinople in

398, he took her under his direction. She established a hospital and an

orphanage, gave shelter to the expelled monks of Nitria, and was a firm

supporter of Chrysostom when he was expelled in 404 from Constantinople and

refused to accept the usurper Arsacius as Patriarch. She was fined by the

prefect, Optatus, for refusing to accept Arsacius, and Arsacius' successor,

Atticus, disbanded her community and ended her charitable works. She spent the

last years of her life beset

by illness and persecution but

comforted by Chrysostom from his place of exile. She died in exile in Nicomedia on

July 25, less than a year after the death of Chrysostom. Her feast day is December

17th.

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=797

St. Olympias

Born 360-5; died 25 July,

408, probably at Nicomedia.

This pious,

charitable, and wealthy disciple of St. John Chrysostom came

from an illustrious family in

Constantinople. Her father (called by the sources Secundus or Selencus) was a

"Count" of the empire; one of her ancestors, Ablabius, filled in 331

the consular office, and was also praetorian prefect of the East. As Olympias

was not thirty years of age in 390, she cannot have been born before 361.

Her parents died

when she was quite young, and left her an immense fortune. In 384 or 385 she

married Nebridius, Prefect of Constantinople. St. Gregory of Nazianzus,

who had left Constantinople in 381, was invited to the wedding, but wrote a

letter excusing his absence (Ep. cxciii, in P.G., XXXVI, 315), and sent the

bride a poem (P.G., loc. cit., 1542 sqq.). Within a short time Nebridius died,

and Olympias was left a childless widow. She steadfastly

rejected all new proposals of marriage, determining to devote herself to the

service of God and

to works of charity.

Nectarius, Bishop of

Constantinople (381-97), consecrated her deaconess. On the death

of her husband the emperor had appointed the urban prefect administrator of

her property,

but in 391 (after the war against

Maximus) restored her the administration of her large fortune. She built beside

the principal church of Constantinople a convent, into which

three relatives and a large number of maidens withdrew with her to consecrate themselves

to the service of God.

When St. John

Chrysostom became Bishop of

Constantinople (398), he acted as spiritual guide of Olympias and her

companions, and, as many undeserving approached the kind-hearted deaconess for

support, he advised her as to the proper manner of utilizing her vast fortune

in the service of the poor (Sozomen, Church History VIII.9).

Olympias resigned herself wholly to Chrysostom's direction, and placed at his

disposal ample sums for religious and charitable objects. Even to the most

distant regions of the empire extended her benefactions to churches and the

poor.

When Chrysostom was

exiled, Olympias supported him in every possible way, and remained a faithful

disciple, refusing to enter into communion with his unlawfully appointed

successor. Chrysostom encouraged and guided her through his letters, of which

seventeen are extant (P.G., LII, 549 sqq.); these are a beautiful memorial of

the noble-hearted, spiritual daughter of the great bishop. Olympias was

also exiled, and died a few months after Chrysostom. After her death she

was venerated as

a saint. A biography dating from

the second half of the fifth century, which gives particulars concerning her

from the "Historia Lausiaca" of Palladius and from

the "Dialogus de vita Joh. Chrysostomi", proves the great veneration

she enjoyed. During he riot of Constantinople in 532 the convent of St.

Olympias and the adjacent church were destroyed. Emperor Justinian had it

rebuilt, and the prioress,

Sergia, transferred thither the remains of the foundress from the ruined church of St.

Thomas in Brokhthes, where she had been buried. We possess an account of this

translation by Sergia herself. The feast of St. Olympias is celebrated in

the Greek Church on

24 July, and in the Roman

Church on 17 December.

Sources

Vita S. Olympiadis et

narratio Sergiae de eiusdem translatione in Anal. Bolland. (1896), 400 sqq.,

(1897), 44 sqq.; BOUSQUET, Vie d'Olympias la diaconesse in Revue de l'Orient

chrét. (1900), 225 sqq.; IDEM, Recit de Sergia sur Olympias, ibid. (1907), 255

sqq.; PALLADIUS, Hist. Lausiaca, LVI, ed. BUTLER (Cambridge, 1904); Synaxarium

Constantinopol., ed. DELAHAYE, Propylaeum ad Acta SS., November (Brussels,

1902), 841-2; MEURISSE, Hist. d'Olympias, diaconesse de Constantinople (Metz,

1670); VENABLES in Dict. Christ. Biog., s.v. See also the bibliography of JOHN

CHRYSOSTOM, SAINT.

Kirsch, Johann Peter. "St. Olympias." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11248b.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Herman F. Holbrook. O Saint Olympias,

and all ye holy Virgins and Widows, pray for us.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. February 1, 1911. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2023 by Kevin Knight.

Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-olympias-of-constantinople/

December 17

St. Olympias, Widow

From St. Chrysostom’s

seventeen letters to her. Palladius in his life. Another Palladius in Lausiac,

c. 43. Sozom. l. 8, c. 2. Leo Imp. in Encomio S. Joan. Chrysostomi. See

Tillemont, t. 11, p. 416.

About the Year 410

ST. OLYMPIAS, the glory

of the widows in the Eastern church, was a lady of illustrious descent and a

plentiful fortune. She was born about the year 368, and left an orphan under

the care of Procopius, who seems to have been her uncle; but it was her

greatest happiness that she was brought up under the care of Theodosia, sister

to St. Amphilochius, a most virtuous and prudent woman, whom St. Gregory

Nazianzen called a perfect pattern of piety, in whose life the tender virgin

saw as in a glass the practice of all virtues, and it was her study faithfully

to transcribe them into the copy of her own life. From this example which was

placed before her eyes, she raised herself more easily to contemplate and to

endeavour to imitate Christ, who in all virtues is the divine original which

every Christian is bound to act after. Olympias, besides her birth and fortune,

was, moreover, possessed of all the qualifications of mind and body which

engage affection and respect. She was very young when she married Nebridius,

treasurer of the Emperor Theodosius the Great, and for some time prefect of

Constantinople; but he died within twenty days after his marriage. Our saint

was addressed by several of the most considerable men of the court, and

Theodosius was very pressing with her to accept for her husband Elpidius, a

Spaniard, and his near relation. She modestly declared her resolution of

remaining single the rest of her days. The emperor continued to urge the

affair, and after several decisive answers of the holy widow, put her whole

fortune in the hands of the prefect of Constantinople, with orders to act as

her guardian till she was thirty years old. At the instigation of the

disappointed lover, the prefect hindered her from seeing the bishops or going

to church, hoping thus to tire her into a compliance. She told the emperor that

she was obliged to own his goodness in easing her of the heavy burden of

managing and disposing of her own money; and that the favour would be complete

if he would order her whole fortune to be divided between the poor and the church.

Theodosius, struck with her heroic virtue, made a further inquiry into her

manner of living, and conceiving an exalted idea of her piety, restored to her

the administration of her estate in 391. The use which she made of it, was to

consecrate the revenues to the purposes which religion and virtue prescribe. By

her state of widowhood, according to the admonition of the apostle, she looked

upon herself as exempted even from what the support of her rank seemed to

require in the world, and she rejoiced that the slavery of vanity and luxury

was by her condition condemned even in the eyes of the world itself. With great

fervour she embraced a life of penance and prayer. Her tender body she

macerated with austere fasts, and never ate flesh or anything that had life: by

habit, long watchings became as natural to her as much sleep is to others; and

she seldom allowed herself the use of a bath, which is thought a necessary

refreshment in hot countries, and was particularly so before the ordinary use

of linen. By meekness and humility she seemed perfectly crucified to her own

will, and to all sentiments of vanity, which had no place in her heart, nor

share in any of her actions. The modesty, simplicity, and sincerity from which

she never departed in her conduct, were a clear demonstration what was the sole

object of her affections and desires. Her dress was mean, her furniture poor,

her prayers assiduous and fervent, and her charities without bounds. These St.

Chrysostom compares to a river which is open to all, and diffuses its waters to

the bounds of the earth, and into the ocean itself. The most distant towns,

isles, and deserts received plentiful supplies by her liberality, and she

settled whole estates upon remote destitute churches. Her riches indeed were

almost immense, and her mortified life afforded her an opportunity of

consecrating them all to God: yet St. Chrysostom found it necessary to exhort

her sometimes to moderate her alms, or rather to be more cautious and reserved

in bestowing them, that she might be enabled to succour those whose distresses

deserved a preference.

The devil assailed her by

many trials, which God permitted for the exercise and perfecting of her virtue.

The contradictions of the world served only to increase her meekness, humility,

and patience, and with her merits to multiply her crowns. Frequent severe

sicknesses, most outrageous slanders and unjust persecutions succeeded one

another. St. Chrysostom, in one of his letters, writes to her as follows. 1 “As

you are well acquainted with the advantages and merits of sufferings, you have

reason to rejoice, inasmuch as by having lived constantly in tribulation you

have walked in the road of crowns and laurels. All manner of corporal

distempers have been your portion, often more cruel and harder to be endured

than ten thousand deaths; nor have you ever been free from sickness. You have

been perpetually overwhelmed with slanders, insults, and injuries. Never have

you been free from some new tribulation; torrents of tears have always been

familiar to you. Among all these one single affliction is enough to fill your

soul with spiritual riches.” Her virtue was the admiration of the whole church,

as appears by the manner in which almost all the saints and great prelates of

that age mention her. St. Amphilochius, St. Epiphanius, St. Peter of Sebaste,

and others were fond of her acquaintance, and maintained a correspondence with

her, which always tended to promote God’s glory, and the good of souls.

Nectarius, archbishop of Constantinople, had the greatest esteem for her

sanctity, and created her deaconess to serve that church in certain remote

functions of the ministry, of which that sex is capable, as in preparing linen

for the altars, and the like. A vow of perpetual chastity was always annexed to

this state. St. Chrysostom, who was placed in that see in 398, had not less

respect for the sanctity of Olympias than his predecessor, and as his

extraordinary piety, experience, and skill in sacred learning, made him an

incomparable guide and model of a spiritual life, he was so much the more

honoured by her; but he refused to charge himself with the distribution of her

alms as Nectarius had done. She was one of the last persons whom St. Chrysostom

took leave of when he went into banishment on the 20th of June in 404. She was

then in the great church, which seemed the place of her usual residence; and it

was necessary to tear her from his feet by violence. After his departure she

had a great share in the persecution in which all his friends were involved.

She was convened before Optatus, the prefect of the city, who was a heathen.

She justified herself as to the calumnies which were shamelessly alleged in

court against her; but she assured the governor that nothing should engage her

to hold communion with Arsacius, a schismatical usurper of another’s see. She

was dismissed for that time, and was visited with a grievous fit of sickness,

which afflicted her the whole winter. In spring she was obliged by Arsacius and

the court to leave the city, and wandered from place to place. About midsummer

in 405 she was brought back to Constantinople, and again presented before

Optatus, who, without any further trial, sentenced her to pay a heavy fine

because she refused to communicate with Arsacius. Her goods were sold by a

public auction; she was often dragged before public tribunals; her clothes were

torn by the soldiers, her farms rifled by many amongst the dregs of the people,

and she was insulted by her own servants, and those who had received from her

hands the greatest favours. Atticus, successor of Arsacius, dispersed and

banished the whole community of nuns which she governed; for it seems, by what

Palladius writes, that she was abbess, or at least directress, of the monastery

which she had founded near the great church, which subsisted till the fall of

the Grecian empire. St. Chrysostom frequently encouraged and comforted her by

letters; but he sometimes blamed her grief. This indeed seemed in some degree

excusable, as she regretted the loss of the spiritual consolation and

instruction she had formerly received from him, and deplored the dreadful evils

which his unjust banishment brought upon the church. Neither did she sink into

despondency, fail in the perfect resignation of her will, or lose her

confidence in God under her affliction, remembering that God is ready to supply

every help to those who sincerely seek him, and that he abandoned not St.

Paul’s tender converts when he suffered their master to be taken from them. St.

Chrysostom bid her particularly to rejoice under her sicknesses, which she

ought to place among her most precious crowns, in imitation of Job and Lazarus.

In his distress she furnished him with plentiful supplies, wherewith he

ransomed many captives, and relieved the poor in the wild and desert countries

into which he was banished. She also sent him drugs for his own use when he

laboured under a bad state of health. Her lingering martyrdom was prolonged

beyond that of St. Chrysostom; for she was living in 408, when Palladius wrote

his Dialogue on the Life of St. Chrysostom. The other Palladius, in the Lausiac

history which he compiled in 420, tells us, that she died under her sufferings,

and, deserving to receive the recompence due to holy confessors, enjoyed the

glory of heaven among the saints. The Greeks honour her memory on the 25th of

July; but the Roman Martyrology on the 17th of December.

The saints all studied to

husband every moment to the best advantage, knowing that life is very short,

that night is coming on apace, in which no one will be able to work, and that

all our moments here are so many precious seeds of eternity. If we applied

ourselves with the saints to the uninterrupted exercise of good works, we

should find that short as life is, it affords sufficient time for extirpating

our evil inclinations, learning to put on the spirit of Christ, working our

souls into a heavenly temper, adorning them with all virtues, and laying in a

provision for eternity. But through our unthinking indolence, the precious time

of life is reduced almost to nothing, because the greatest part of it is

absolutely thrown away. So numerous is the tribe of idlers, and the class of

occupations which deserve no other denomination than that of idleness, that a

bare list would fill a volume. The complaint of Seneca, how much soever it

degrades men beneath the dignity of reason, and much more of religion, agrees

no less to the greater part of Christians, than to the idolaters, that “Almost

their whole lives are spent in doing nothing, and the whole in doing nothing to

the purpose.” 2 Let

no moments be spent merely to pass time; diversions and corporal exercise ought

to be used with moderation, only as much as may seem requisite for bodily

health and the vigour of the mind. Every one is bound to apply himself to some

serious employment. This and his necessary recreations must be referred to God,

and sanctified by a holy intention, and other circumstances which virtue

prescribes; and in all our actions humility, patience, various acts of secret

prayer, and other virtues ought, according to the occasions, be exercised. Thus

will our lives be a continued series of good works, and an uninterrupted holocaust

of divine praise and love. That any parts of this sacrifice should be

defective, ought to be the subject of our daily compunction and tears.

Note 1. St. Chrys.

ep. 3. [back]

Note 2. Seneca,

ep. [back]

Rev. Alban

Butler (1711–73). Volume XII: December. The Lives of the

Saints. 1866.

SOURCE : http://www.bartleby.com/210/12/171.html

Pictorial

Lives of the Saints – Saint Olympias, Widow

Article

Saint Olympias, the glory

of the widows in the Eastern Church, was of a noble and wealthy family. Left an

orphan at a tender age, she was brought up by Theodosia, sister of Saint

Amphilochius, a virtuous and prudent woman. Olympias insensibly reflected the

virtues of this estimable woman. She married quite young, but her husband dying

within twenty days of their wedding, she modestly declined any further offer

for her hand, and resolved to consecrate her life to prayer and other good

works, and to devote her forDecember tune to the poor. Nectarius, Archbishop of

Constantinople, had a high esteem for the saintly widow, and made her a

deaconess of his church, the duties of which were to prepare the altar linen

and to attend to other matters of that sort. Saint Chrysostom, who succeeded

Nectarius, had no less rerespect than his predecessor for Olympias, but refused

to attend to the distribution of her alms. Our Saint was one of the last to

leave Saint Chrysostom when he went into banishment on the 20th of June, 404.

After his departure, she suffered great persecution, and crowned a virtuous

life by a saintly death, about the year 410.

Reflection – “Lay

not up to yourselves treasures on earth, but in heaven, where neither rust nor

moth doth consume.”

MLA

Citation

John Dawson Gilmary Shea.

“Saint Olympias, Widow”. Pictorial Lives of the

Saints, 1922. CatholicSaints.Info.

15 December 2018. Web. 5 January 2026.

<https://catholicsaints.info/pictorial-lives-of-the-saints-saint-olympias-widow/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/pictorial-lives-of-the-saints-saint-olympias-widow/

Sant' Olimpia

(Olimpiade) Vedova

Festa: 25 luglio

† 408

Nacque verso il 361 da

un'agiata famiglia di Costantinopoli. Divenuta orfana in giovane età, fu

affidata per l'educazione a Teodosia, sorella del vescovo di Iconio,

sant'Anfilochio. Fin da giovanissima, così, Olimpia fu istruita sulla Sacra

Scrittura. Imitando santa Melania, si dedicò alla mortificazione, e pur potendo

aspirare ad una brillante posizione nella corte imperiale, se ne allontanò. Nel

384-85 si sposò ma dopo solo venti mesi il marito morì; l'imperatore Teodosio

il Grande voleva risposarla con un suo cugino, ma Olimpia rifiutò. Teodosio

allora per vincere le sue resistenze le sequestrò tutti i suoi beni, che le

vennero restituiti nel 391. Fu così che Olimpia ne approfittò per fondare

alcune opere caritative. Il vescovo Nettario (381-397) contrariamente

all'usanza, la nominò diaconessa, dignità che allora si dava alle vedove di 60

anni. Olimpia fondò in città un monastero le cui religiose appartenevano alle

migliori famiglie della città. Al suo arrivo in città come arcivescovo,

Giovanni Crisostomo trovò in Olimpia una valida collaboratrice. Ma fu anch'essa

vittima della persecuzione contro i "giovanniti" (seguaci di san

Giovanni Crisostomo). Fu infatti esiliata a Nicomedia. Morì verso il 408.

Etimologia: Olimpia

= che abita nell'Olimpo, sede degli dèi

Martirologio

Romano: A Nicomedia in Bitinia, nell’odierna Turchia, transito di santa

Olimpiade, vedova: dopo aver perso il marito in ancor giovane età, trascorse

piamente a Costantinopoli il resto della sua vita tra le donne consacrate a

Dio, assistendo i poveri e rimanendo fedele collaboratrice di san Giovanni

Crisostomo anche durante il suo esilio.

Di questa santa dell’agiografia greca, non ci sono dubbi sulla sua ‘Vita’ perché ci sono pervenuti vari importanti documenti storici e contemporanei che la citano o descrivono; inoltre vi sono ben 17 lettere che le inviò, dal suo esilio, s. Giovanni Crisostomo.

Olimpia nacque verso il 361 da una agiata e distinta famiglia di Costantinopoli, suo nonno Ablabios godeva della stima dell’imperatore Costantino ed era stato prefetto di Oriente quattro volte, suo padre era conte di palazzo.

Divenuta orfana in giovane età, fu posta sotto la tutela di Procopio prefetto della capitale, il quale l’affidò per la sua educazione a Teodosia, donna di grande cultura e sentimenti cristiani, sorella del vescovo di Iconio s. Anfilochio; di lei avevano grande stima sia s. Basilio che s. Gregorio di Nazianzo, Dottori della Chiesa; s. Gregorio di Nissa le dedicò il suo commento al ‘Cantico dei Cantici’.

Fin da giovanissima, Olimpia ebbe lezioni sulla Sacra Scrittura, considerata da altre dame della società, come s. Melania l’Anziana, la via per giungere alla perfezione cristiana; e imitando s. Melania, si dedicò alla mortificazione, ella pur potendo aspirare ad una brillante posizione nella corte essendo ricca, istruita e nobile, invece se ne allontanò.

Nel 384-85, sposò Nebridio che fu prefetto di Costantinopoli nel 386, ma la sua felicità durò poco, dopo solo venti mesi il marito morì; l’imperatore Teodosio il Grande voleva risposarla con un suo cugino, ma Olimpia rifiutò dicendo: “Se il mio re avesse voluto che io vivessi con un uomo, non mi avrebbe tolto il mio primo”.

Teodosio considerò ciò un capriccio e per vincere le sue resistenze, le sequestrò tutti i suoi beni, finché non avesse compiuti 30 anni; il prefetto della città aggiunse il divieto di intrattenersi con i vescovi più illustri e perfino di andare in chiesa.

Ma nel 391, Teodosio visto la sua virtù e la costanza nella prova di Olimpia, che conduceva una vita di penitente povera, le restituì i suoi beni. Lei ne approfittò per fondare a Costantinopoli alcune opere caritative, fra cui un grande ospizio per ricevere gli ecclesiastici di passaggio e i viaggiatori poveri.

Avendo una grande ricchezza e proprietà, sia in città che nelle altre regioni, altrettanto grande fu la sua generosità, donò a s. Giovanni Crisostomo 10.000 denari d’oro e 20.000 d’argento per la sua chiesa di S. Sofia; il vescovo Nettario (381-397) contrariamente all’usanza, la nominò diaconessa, dignità che allora si dava alle vedove di 60 anni, mentre Olimpia ne aveva solo 30 e a lei ricorreva per consigli densi della sua scienza e saggezza.

Fondò sotto il portico meridionale di S. Sofia, un monastero le cui religiose appartenevano alle migliori famiglie della città, fra cui tre sue sorelle Elisanzia, Martiria e Palladia, in più una sua nipote chiamata anch’essa Olimpia; iniziò con circa 50 suore che in breve tempo divennero 250.

Agli inizi del 398, giunse in città s. Giovanni Crisostomo che pur non volendo, era stato nominato arcivescovo di Costantinopoli, trovando un fervore cristiano affievolito sia nei fedeli che nel clero e monaci, fino alla corte divenuta oltremodo mondana con la presenza di Eudossia moglie dell’imperatore d’Oriente Arcadio.

Ma si consolò vedendo il monastero di Olimpia, formato da anime ben disposte e adatte a servire da modello. Tra l’arcivescovo e Olimpia si instaurò una salda amicizia, le tre sorelle furono ordinate diaconesse e affiancarono in questo compito Olimpia.

Si sforzava di aiutarlo in tutto, dal cibo al suo vestire, divenne in certo modo la collaboratrice nell’opera di rinnovamento spirituale da lui iniziata. Tutto questo attirò anche su di lei il rancore di coloro che intendevano intralciare l’opera riformatrice del vescovo.

Due dei vescovi dissidenti, ottennero da Arcadio un decreto d’esilio contro s. Giovanni Crisostomo, il quale fra il tumulto dei fedeli e delle suore, dovette lasciare S. Sofia e venne condotto dai soldati a Cucusa fra i monti dell’Armenia, dove giunse affranto dal viaggio due mesi dopo, alla fine di agosto del 404.

Nello stesso giorno della partenza, il 30 giugno 404, un incendio distrusse l’episcopio e gran parte della chiesa e del senato. Furono accusati i fedeli del vescovo e la stessa Olimpia fu portata davanti al prefetto della città Optato, accusata dell’incendio, si difese dicendo che avendo dato spese considerevoli per costruire chiese, non aveva nessuna necessità di bruciarle.

Optato le offrì di lasciare in pace lei e le sue suore, se avessero riconosciuto il nuovo vescovo Arsace e Olimpia rifiutò; fu condannata a pagare una grossa somma come multa e dopodiché nello stesso anno 405 si ritirò volontariamente a Cizico.

Giacché proseguiva la persecuzione contro i “giovanniti” (seguaci di s. Giovanni Crisostomo) Olimpia fu nuovamente processata dal prefetto e esiliata a Nicomedia. In quegli anni mantenne una corrispondenza (che le era permesso) con il vescovo esiliato in Armenia, interessandosi della sua salute, inviandogli del denaro che veniva speso per i poveri della regione e per il riscatto di persone cadute nelle mani dei briganti isauriani.

Giovanni tramite questi scritti, descrive i particolari del penosissimo viaggio per giungere lì. La esorta a bandire la tristezza e a far nascere la gioia spirituale che distacca dalle cose del mondo ed eleva l’anima, raccomandandole di sostenere i suoi amici, che subivano la persecuzione per causa sua.

Olimpia morì verso il 408 in un data non documentata, secondo lo scrittore Palladio, “gli abitanti di Costantinopoli la pongono fra i confessori della fede, perché ella è morta ed è ritornata al Signore fra le battaglie sostenute per Dio”, anticamente i confessori erano i martiri.

Il suo monastero ebbe alterne vicende, le suore coinvolte nella disgrazia dell’arcivescovo, si dispersero nel 404, quando fu mandato in esilio; si riunirono solo nel 416, quando i “giovanniti” si riappacificarono con i successori del Crisostomo; sotto la guida di Onorina, parente di Olimpia; il monastero fu poi distrutto dall’incendio di S. Sofia nel 532, ritornarono poi quando Giustiniano lo ricostruì.

Le reliquie di s. Olimpia, che erano state portate da Nicomedia nella chiesa di S. Tommaso sul Bosforo, andarono perse durante l’incendio della chiesa appiccato dai Persiani nelle loro incursioni (616-626). La superiora Sergia, fu fortunata nel ritrovarle fra le macerie e le fece trasportare all’interno del monastero; in seguito non si hanno più notizie di esse.

S. Olimpia è festeggiata nella Chiesa Orientale il 24-25-29 luglio, il ‘Martirologio Romano’ che la poneva al 17 dicembre, ora la celebra il 25 luglio.

Autore: Antonio Borrelli