Vitrail représentant saint Chad, monastère de la Sainte-Croix de West Park (État de New York).

Saint Chad ou Ceadda

de Liechfield, évêque

Frère de saint Cédric,

abbé de Lastingham, à York en Angleterre, il y pratiqua la stricte observance

de la règle de saint Columba. Evêque d'York, il sut s'effacer humblement

lorsque cette charge lui fut retirée par saint Théodore, archevêque de Cantorbéry,

et il fixa son siège épiscopal à Lichflield où il mourut peu après, en

672. Ses reliques sont conservées dans la cathédrale de Birmingham.

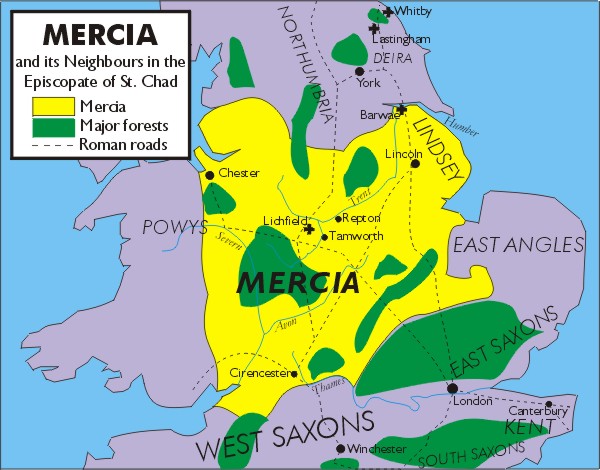

Mercia in time of Chad

Saint Chad de Liechfield

Évêque d'York (+ 672)

ou Ceadda.

Nous le fêtons avec la

Communion anglicane.

Frère de saint Cédric, abbé de Lastingham, à York en

Angleterre, il y pratiqua la stricte observance de la règle de saint Colomba. Evêque

d'York, il sut s'effacer humblement lorsque cette charge lui fut retirée

par saint Théodore,

archevêque de Cantorbery, et il fixa son siège épiscopal à Lichflield où il

mourut peu après. Ses reliques sont conservées dans la cathédrale de

Birmingham.

À Lichfield en

Angleterre, l’an 677, saint Céadde ou Chad, évêque. Dans des circonstances

difficiles, il exerça son ministère épiscopal dans la province de Mercie et de

Lindsey, et prit soin d’administrer son peuple selon les exemples des anciens

Pères, en se montrant humble, pieux, zélé et apostolique.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/731/Saint-Chad-de-Liechfield.html

St

Chad depicted holding Lichfield Cathedral 4'

figure carved in Honduras mahogany by Denis Parsons.

Location unknown.

Also

known as

Chad of Lichfield

Ceadda of….

Apostle of Mercia

Profile

Brother of Saint Cedd and Saint Cynibild. Missionary monk to Ireland with Saint Egbert. Ordained in 653. Studied Latin

and astronomy. Abbot at

Lastingham monastery,

Yorkshire, England; abbot to Saint Owen.

Not long after Chad

became abbot, Saint Wilfrid of

York was chosen Bishop of Lindisfarne,

a see which

was soon moved to York. Wilfrid went to Gaul for

consecration, and stayed so long that King Oswiu

declared the see vacant

and procured the election of Chad as bishop of York.

Chad felt unworthy, but threw himself into the new vocation, travelling his diocese on

foot, evangelizing where

he could. When Wilfrid returned in 666, Saint Theodore, Archbishop of Canterbury,

decided that Chad’s episcopal consecration

was invalid, and that Chad must give up the diocese to Wilfrid.

Chad replied that he had never thought himself worthy of the position, that he

took it through obedience, and he would surrender it through obedience.

Theodore, astonished at this humility, consecrated Chad himself, and appointed

him bishop of

the Mercians in Lichfield in 669.

He founded monasteries,

including those at Lindsey and Barrow-upon-Humber, evangelized, travelled and preached,

reformed monastic life

in his diocese,

and built a cathedral on

land that had been the site of the martyrdom of

1,000 Christians by

the pagan Mercians. Miraculous cures reported

at the wells he caused to be dug for the relief of travellers.

Legend says that on one

occasion two of the king‘s sons

were hunting,

were led by their quarry to the oratory of Saint Chad where

they found him praying.

They were so impressed by the sight of the frail old man upon his knees, his

face glowing with rapture, that they knelt, asked his blessing, and converted.

The pagan King Wulfhere

was so angry that he slew his

sons, and hunted down Saint Chad for

some of the same. But as he approached the bishop‘s cell, a great light

shone through its single window, and the king was

almost blinded by its brightness; he abandoned his plan for revenge.

During storms,

Chad would go to chapel and pray continually.

He explained, “God thunders

forth from heaven to rouse people to fear the Lord, to call them to remember

the future judgment…when God will come in the

clouds in great power and majesty to judge the living and the dead. And so we

ought to respond to God‘s

heavenly warning with due fear and love so that as often as God disturbs the

sky, yet spares us still, we should implore God‘s mercy, examining

the innermost recesses of our hearts and purging out the dregs of our sins, and

behave with such caution that we may never deserve to be struck down.”

NOTE:

I still get email from visitors asking if Chad is the patron of elections,

disputes, disputed elections, losers, or some other element related to 2000‘s

disputed American presidential election. I have absolutely no evidence that

there are patrons of

elections, and certainly none that Chad has anything to do with it. It was not

until 31

October 2000 that politicians and

elected officials received a patron, and

that’s Saint Thomas More.

Times were rough in 7th century England,

but I have no record of Chad hanging, dangling, dimpled or pregnant. As you see

above, he was involved in a disputed election, but no patronage

tradition resulted. Also note that when a dispute arose, Chad stepped aside for

the greater good. Wish our current politicians had

such grace; but no one ever accused them of being saints. – Terry

Born

c.620 in Northumbria, England

2 March 672 at Lichfield, England of

natural causes after a brief illness, probably the plague

his initial tomb was in

the form of a small wooden house

some relics preserved

in the cathedral of Saint Chad

in Birmingham, England

in England

Lichfield,

city of

bishop holding Lichfield Cathedral and

a branch, usually a vine

bishop holding

the cathedral in

the midst of a battlefield with the dead surrounding him

man with a hart leading hunters to

him by a pool

converting Saint Wulfhald

and Saint Rufinus

who converted on

finding him in chapel while

they were hunting

Additional

Information

An

Old English Martyrology, by George Herzfeld

Book of

Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban Butler

Roman

Martyrology, 1914 edition

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

Prayers of the Saints,

edited by Cecil Headlam

Saints

and Their Attributes, by Helen Roeder

other

sites in english

Christian

Biographies, by James Keifer

Early British Kingdoms, by David Nash Ford

Ecclesiastical

History of the English Nation, Book IV by the Venerable Bede

Parish of Oystermouth, Swansea, Wales

R W Morrell,

an article about Saint Chad’s Well

images

video

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

nettsteder

i norsk

Readings

King Oswy

sent to Kent a holy man of modest character, well versed in the Scriptures, and

practicing with diligence what he had learned from them, to be ordained bishop of

the church of York…. But when they reached Kent, they found that Archbishop Deusdedit

had departed this life and that as yet no other had been appointed in his

place.

Thereupon they turned

aside to the province of the West Saxons, where Wine was bishop,

and by him the above mentioned Chad was consecrated bishop, two bishops of the

British nation, who kept Easter in

contravention of the canonical custom from the 14th to the 20th of the moon,

being associated with him, for at that time there was no other bishop in

all Britain canonically ordained besides Wine. Saint Theodore of

Canterbury had not yet arrived.

As soon as Chad had been

consecrated bishop, he

began most strenuously to devote himself to ecclesiastical truth and purity of

doctrine and to give attention to the practice of humility, self- denial and

study: to travel about, not on horseback,

but on foot, after the manner of the apostles, preaching the Gospel in the

towns and the open country, in cottages, villages and castles, for he was one of

Aidan’s disciples and tried to instruct his hearers by acting and behaving

after the example of his master and of his brother Cedd. – Venerable Bede

Almighty God, whose servant Chad,

for the peace of the Church, relinquished cheerfully the honors that had been

thrust upon him, only to be rewarded with equal responsibility: Keep us, we

pray, from thinking of ourselves more highly than we ought to think, and ready

at all times to step aside for others, (in honor preferring one another,) that

the cause of Christ may be advanced; in the name of him who washed his disciples’

feet, your Son Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and

the Holy

Spirit, one God,

now and for ever. – prayer on

the feast of Saint Chad

The beloved Guest who

would visit our brethren has deigned to come to me also this day and to summon

me from the world. Turn your steps to the church and bid the brethren to

commend in their prayers my going hence to God, and to remember to prepare for

their own departure, the hour of which is yet uncertain, by watching and by

praying and by good works. – having been warned of approaching death,

Saint Chad speaks to his brothers

MLA

Citation

“Saint Chad of

Mercia“. CatholicSaints.Info. 16 May 2024. Web. 24 October 2024.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-chad/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-chad/

Statue of St Chad commissioned by Lichfield Cathedral and created by sculptor Peter Walker. Unveiled and dedicated on Saturday 26 June 2021.

Article

CHAD (CEADDA) (Saint)

Bishop (March 2) (7th century) An Anglo-Saxon, brother of Saint Cedd, Bishop of

London. He was educated at Lindisfarne and in Ireland. He governed for some

years the monastery of Lestingay in Yorkshire, acquiring thereby a great reputation

for ability and for holiness of life. Through a mistake occasioned by the

prolonged absence of Saint Wilfrid in France, Saint Chad was consecrated

Archbishop of York in his place; but on the Saint’s return passed to the

Bishopric of the Mercians, of which he fixed the See at Lichfield. He died two

years later in the great pestilence of A.D. 673, leaving an imperishable memory

for zeal and devotedness. A portion of his Sacred Belies are venerated in

Birmingham Cathedral, which is dedicated to him.

MLA

Citation

Monks of Ramsgate.

“Chad”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info. 2 October 2012.

Web. 24 October 2024. <http://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-chad/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-chad/

Saint Chad, Holy Trinity, Northwood, Stained glass window

St. Chad of Mercia

Feastday: March 2

Patron: of Mercia; Lichfield; of astronomers

Birth: 634

Death: 672

Irish archbishop and

brother of St. Cedd, also called Ceadda. He was trained by St. Aidan in

Lindisfarne and in England. He also spent time with

St. Egbert in

Ireland. Made the archbishop of

York by King Oswy, Chad was disciplined by Theodore, the newly arrived archbishop of

Canterbury, in 669. Chad accepted Theodore's charges of impropriety with

such humility and grace that

Theodore regularized his consecration and

appointed him the bishop of

Mercia. He established a see at Lichfield. His relics are

enshrined in Birmingham. In liturgical art he is depicted as a bishop,

holding a church.

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=2656

Saint

Chad, stained glass window, Chadwell Heath, London Borough of Barking and

Dagenham

St Chad

Celebrated on March

2nd

Bishop. Chad was the

first bishop of Mercia and Lindsay at Lichfield. Born in Northumbria in the 7th

century, he was a pupil of St Aidan at Lindisfarne, who sent him to Ireland for

part of his education. He later became abbot of Lastingham in Yorkshire, but

was then called to be bishop of York. In 669, St Theodore of Canterbury judged

him to have been irregularly consecrated. Chad accepted the decision and humbly

went back to his monastery. Theodore was so impressed by his character he made

him bishop of Mercia with his see at Lichfield.

St Chad lived only three years longer, but during that time, according to Bede:

"he administered his diocese in great holiness of life, following the

example of the ancient fathers."

St Chad always travelled on foot, until Archbishop Theodore insisted that he

rode a horse. He founded a monastery in Lincolnshire, probably at Barrow upon

Humber and another near Lichfield Cathedral. He died on this day in 672 and was

very soon venerated as a saint. There were many reports of healings at his tomb

which became a popular centre for pilgrimage.

Several shrines were built to him at the cathedral church of St Peter - each

more elaborate until the last one, built by the bishop of Lichfield Robert

Stretton in the late 1300s, which was decorated in gold and precious jewels.

Rowland Lee, the last Catholic bishop of Lichfield from 1534 - 53, begged Henry

VIII to spare the shrine but it was destroyed by reformers. Some bones were

later discovered, apparently preserved by recusants. These are now in St Chad's

Catholic Cathedral in Birmingham. They were recently carbon-tested and date to

the seventh century.

An illuminated Gospel of St Chad, that probably belonged to the shrine, is now

in Lichfield Cathedral library. Thirty-nine ancient churches and several wells

mainly in the Midlands were dedicated to St Chad. There are also several modern

dedications.

SOURCE : https://www.indcatholicnews.com/saint/067

Saint

Chad et Saint Alban, stained glass window, Chadwell Heath, London Borough of

Barking and Dagenham

An

Old English Martyrology – March 2 – Saint Chad

Article

On the second day of the

month is the departure of Saint Chad; his miracles and life were recorded by

the learned Bede in his English History. The archbishop took this Chad from the

northern frontier in the monastery of Lastingham and sent him as a bishop to

the Mercians and the Middle Angles and the people of Lindisfarne; and God’s

angels openly conducted him to heaven with delightful singing; and one of the

servants of God whose name was Owine heard this, and the hermit Saint Egbert

told the abbot Hygebald that the soul of the bishop Cedd had come from heaven

with a crowd of angels and brought his brother’s soul to heaven. The body of

this bishop rests in the minster at Lichfield.

MLA

Citation

George Herzfeld. “March 2

– Saint Chad”. An Old English Martyrology, 1900. CatholicSaints.Info.

16 May 2024. Web. 24 October 2024.

<https://catholicsaints.info/an-old-english-martyrology-march-2-saint-chad/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/an-old-english-martyrology-march-2-saint-chad/

Caption

from page 31 of Modern English Silverwork

(1909), by C. R. Ashbee: "Altar cross, designed and made for Miss Sophia

Lonsdale as a gift to Lichfield Cathedral. The base of this piece was made to

harmonise with the bases of the Cathedral candlesticks. The cross itself is

designed with an elaborate nimbus, richly chased, partly enamelled and set with

moonstones and pearl blisters. Ten chased angels, with enamelled wings,

surround the nimbus, and a small cast figure of St. Chad occupies a niche in

the head. A large azurite is set in the vesica which occupies the centre, from

which gilded rays diverge to the nimbus. The St. Chad was modelled by Alec

Miller. The cross stands 47 inches high and is here drawn to two-thirds of its

full size."

St. Ceada, or Chad, Bishop and Confessor

HE was brother to St.

Cedd, bishop of London, and the two holy priests Celin and Cymbel, and had his

education in the monastery of Lindisfarne, under St. Aidan. For his greater

improvement in sacred letters and divine contemplation he passed into Ireland,

and spent a considerable time in the company of Saint Egbert, till he was

called back by his brother St. Cedd to assist him in settling the monastery of

Lestingay, which he had founded in the mountains of the Deiri, that is, the

Woulds of Yorkshire. St. Cedd being made bishop of London, or of the East

Saxons, left to him the entire government of this house. Oswi having yielded up

Bernicia, or the northern part of his kingdom, to his son Alcfrid, this prince

sent St. Wilfrid into France, that he might be consecrated to the bishopric of

the Northumbrian kingdom, or of York; but he staid so long abroad that Oswi

himself nominated St. Chad to that dignity, who was ordained by Wini, bishop of

Winchester, assisted by two British prelates, in 666. Bede assures us that he

zealously devoted himself to all the laborious functions of his charge,

visiting his diocess on foot, preaching the gospel, and seeking out the poorest

and most abandoned persons to instruct and comfort in the meanest cottages, and

in the fields. When St. Theodorus, archbishop of Canterbury, arrived in

England, in his general visitation of all the English churches, he adjudged the

see of York to St. Wilfrid. Saint Chad made him this answer: “If you judge that

I have not duly received the episcopal ordination, I willingly resign this

charge, having never thought myself worthy of it; but which, however unworthy,

I submitted to undertake in obedience.” The archbishop was charmed with his

candour and humility, would not admit his abdication, but supplied certain

rites which he judged defective in his ordination: and St. Chad, leaving the

see of York, retired to his monastery of Lestingay, but was not suffered to

bury himself long in that solitude. Jaruman, bishop of the Mercians, dying, St.

Chad was called upon to take upon him the charge of that most extensive

diocess. 1 He

was the fifth bishop of the Mercians, and first fixed that see at Litchfield,

so called from a great number of martyrs slain and buried there under

Maximianus Herculeus; the name signifying the field of carcasses. Hence this

city bears for its arms a landscape, covered with the bodies of martyrs. St.

Theodorus considering St. Chad’s old age, and the great extent of his diocess,

absolutely forbade him to make his visitations on foot, as he used to do at

York. When the laborious duties of his charge allowed him to retire, he enjoyed

God in solitude with seven or eight monks, whom he had settled in a place near

his cathedral. Here he gained new strength and fresh graces for the discharge

of his functions: he was so strongly affected with the fear of the divine

judgments, that as often as it thundered he went to the church and prayed

prostrate all the time the storm continued, in remembrance of the dreadful day

on which Christ will come to judge the world. By the bounty of king Wulfere, he

founded a monastery at a place called Barrow, in the province of Lindsay, (in

the northern part of Lincolnshire,) where the footsteps of the regular life

begun by him remained to the time of Bede. Carte conjectures that the foundation

of the great monastery of Bardney, in the same province, was begun by him. St.

Chad governed his diocess of Litchfield two years and a half, and died in the

great pestilence on the 2nd of March, in 673. Bede gives the following relation

of his passage: “Among the eight monks whom he kept with him at Litchfield, was

one Owini, who came with queen Ethelred, commonly called St. Audry, from the

province of the East Angles, and was her major-domo, and the first officer of

her court, till quitting the world, clad in a mean garment, and carrying an axe

and a hatchet in his hand, he went to the monastery of Lestingay, signifying

that he came to work, and not to be idle; which he made good by his behaviour

in the monastic state. This monk declared, that he one day heard a joyful

melody of some persons sweetly singing, which descended from heaven into the

bishop’s oratory, filled the same for about half an hour, then mounted again to

heaven. After this, the bishop opening his window, and seeing him at his work,

bade him call the other seven brethren. When the eight monks were entered his

oratory, he exhorted them to preserve peace, and religiously observe the rules

of regular discipline; adding, that the amiable guest who was wont to visit

their brethren, had vouchsafed to come to him that day, and to call him out of

this world. Wherefore he earnestly recommended his passage to their prayers,

and pressed them to prepare for their own, the hour of which is uncertain, by

watching, prayer, and good works.”

The bishop fell presently

into a languishing distemper, which daily increased, till, on the seventh day,

having received the body and blood of our Lord, he departed to bliss, to which

he was invited by the happy soul of his brother St. Cedd, and a company of

angels with heavenly music. He was buried in the church of St. Mary, in

Litchfield; but his body was soon after removed to that of St. Peter, in both

places honoured by miraculous cures, as Bede mentions. His relics were

afterwards translated into the great church which was built in 1148, under the

invocation of the B. Virgin and St. Chad, which is now the cathedral, and they

remained there till the change of religion. See Bede, l. 3. c. 28. l. 4.

c. 2 and 3.

Note 1. The first

bishop of the Mercians was Diuma a Scot; the second Keollach, of the same

nation; the third Tramhere, who had been abbot of Gethling, in the kingdom of

the Northumbrians; the fourth Jaruman. [back]

Rev. Alban

Butler (1711–73). Volume III: March. The Lives of the

Saints. 1866.

SOURCE : http://www.bartleby.com/210/3/022.html

First item late copy of The old Englisch Homely on the life of St. Chad. Hatton MS 116, formally Junius 24 (10,5 X 7,5 inch). 1200AD Language: Old English. (MS given by H. Wanley, 1705.)

De una copia tardía del viejo English Homely en la vida de St. Chad, c. 1200,

en el Bodleian Biblioteca, Oxford.

St. Ceadda

(Commonly known as ST.

CHAD.)

Abbot of

Lastingham, Bishop successively

of York and Lichfield, England; date of

birth uncertain, died 672.

He is often confounded

with his brother, St.

Cedd, also Abbot of

Lastingham and the Bishop of

the East Saxons. He had two other brothers, Cynibill and Caelin, who also

became priests.

Probably Northumbrian by birth, he was educated at Lindisfarne under St.

Aidan, but afterwards went to Ireland,

where he studied with St.

Ecgberht in the monastery of

Rathmelsige (Melfont).

There he returned to help his brother St.

Cedd to establish the monastery of

Laestingaeu, now Lastingham in Yorkshire. On his brother's death in 664, he

succeeded him as abbot.

Shortly afterwards St.

Wilfrid, who had been chosen to succeed Tudi, Bishop of Lindisfarne,

went to Gaul for consecration and

remained so long absent that King Oswiu determined to wait no longer, and

procured the election of

Chad as Bishop of York,

to which place the Bishopric of Lindisfarne had

been transferred. As Canterbury was

vacant, he was consecrated by

Wini of Worcester,

assisted by two British bishops.

As bishop he

visited his diocese on

foot, and laboured in an apostolic spirit until the arrival of St.

Theodore, the newly elected Archbishop of Canterbury who

was making a general

visitation. St.

Theodore decided that St. Chad must give up the diocese to St.

Wilfrid, who had now returned. When he further intimated that St. Chad's

episcopal consecration had

not been rightly performed, the Saint replied, "If you decide that I have

not rightly received the episcopal character, I willingly lay down the office;

for I have never thought myself worthy of it, but under obedience, I, though

unworthy, consented to undertake it". St.

Theodore, however, desired him not to relinquish the episcopate and himself

supplied what was lacking ("ipse ordinationem ejus denuo catholica ratione

consummavit" — Bede,

Hist. Eccl. IV, 2). Ceadda then returned to Lastingham, where he remained

till St.

Theodore called him in 669 to become Bishop of

the Mercians. He built a church and monastery at Lichfield,

where he dwelt with seven or eight monks,

devoting to prayer and

study time he could spare from his work as bishop.

He received warning of his death in a vision.

His shrine,

which was honoured by miracles,

was removed in the twelfth century to the cathedral at Lichfield,

dedicated to Our

Lady and the Saint himself. At the Reformation his relics were

rescued from profanation by Catholics,

and they now lie in the Catholic cathedral at Birmingham,

which is dedicated to him. His festival is

kept on the 2nd of March. All accounts of his life are based on that given

by Venerable

Bede, who had been instructed in Holy

Scripture by Trumberct, one of St. Chad's monks and

disciples.

Burton,

Edwin. "St. Ceadda." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol.

3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 2 Mar.

2016<http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03470c.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Joseph P. Thomas.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. November 1, 1908. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2023 by Kevin Knight.

Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03470c.htm

Saint Chad of Lichfield B

(RM)

(also known as Ceadda)

Born in Northumbria,

England; died at Lichfield in 673.

The Venerable Bede writes

that:

King Oswy sent to Kent a

holy man of modest character, well versed in the Scriptures, and practicing

with diligence what he had learned from them, to be ordained bishop of the

church of York. . . . But when they reached Kent, they found that Archbishop Deusdedit

had departed this life and that as yet no other had been appointed in his

place.

Thereupon they turned

aside to the province of the West Saxons, where Wine was bishop, and by him the

above mentioned Chad was consecrated bishop, two bishops of the British nation,

who kept Easter in contravention of the canonical custom from the 14th to the

20th of the moon, being associated with him, for at that time there was no

other bishop in all Britain canonically ordained besides Wine. [St. Theodore of

Canterbury had no yet arrived.]

As soon as Chad had been

consecrated bishop, he began most strenuously to devote himself to

ecclesiastical truth and purity of doctrine and to give attention to the

practice of humility, self- denial and study: to travel about, not on

horseback, but on foot, after the manner of the apostles, preaching the Gospel

in the towns and the open country, in cottages, villages and castles, for he

was one of Aidan's disciples and tried to instruct his hearers by acting and

behaving after the example of his master and of his brother Cedd.

During the tenure of

Saint Aidan as abbot, when the abbey of Lindisfarne in northern Britain was a

hive of Christian activity and the center of a brave and eager company of

evangelists, among them was St. Chad, an Angle by birth, one of four brothers

all of whom became priests, including Saint Cedd and Saint Cynibild.

As a young monk Chad had

spent some years as a missionary monk in Ireland with Saint Egbert at

Rathmelsigi, but was recalled to England to replace his brother Cedd as abbot

of Lastingham Monastery, when Cedd was appointed bishop of London. Lastingham

was a small community under the Rule of St. Columba in a remote, beautiful

village on the very edge of the north York Moors near Whitby.

As described by Bede,

within a year of his abbatial appointment Chad was named bishop of York by King

Oswy. Meanwhile, King Oswy's son King Alcfrid had appointed Wilfrid, bishop of

the same see. But Wilfrid, considering the northern bishops who had refused to

accept the decrees of Whitby as schismatic, went to France to be ordained

(consecrated?). Delayed until 666 in his return, Wilfrid found that St. Chad

had been appointed. Rather than contest the election of Chad, Wilfrid returned

to his monastery at Ripon.

When Saint Theodore became

archbishop of Canterbury in 669, he removed Chad from the see of York on the

grounds that he was improperly consecrated by Wine, and restored St. Wilfrid.

Chad's humility in accepting this change was evidenced in his reply to

Theodore: "If you consider that I have not been properly consecrated, I

willingly resign this charge of which I never thought myself worthy. I

undertook it, though unworthy, under obedience."

With that, the astonished

Theodore supplied what he thought was wanting in Chad's consecration, and soon

after made him bishop of the Mercians with his see at Lichfield. This was

Chad's greatest achievement: The creation of the see of Lichfield, which

covered 17 counties and stretched from the Severn to the North Sea. At

Lichfield, or the Field of the Dead, where once a thousand Christians had been

martyred, Chad founded his cathedral. Here, too, he built himself a simple

oratory not far from the church, where he lived and prayed when not travelling

on foot throughout his wide diocese, and here also he gathered around him a

missionary band of eight of his brethren from Lastingham.

A typical story is of how

on one occasion when two of the king's sons were out hunting, they were led by

their quarry to the oratory of St. Chad, where they found him praying, and were

so impressed by the sight of the frail old man upon his knees, his face glowing

with rapture, that they knelt and asked his blessing, and were later baptized

and confirmed. All who encountered him were similarly impressed, and many made pilgrimage

to Lichfield and to his holy well outside the city, which still remains.

He had great qualities of

mind and spirit, but greatest of all was his sense of the presence of God and

the influence it had upon others, for it is said that all who met him were

aware of God's glory. It was this experience, no doubt, which underlies the

story that Wulfhere was so angry when his sons were converted that he slew them

and, breathing fury, sought out St. Chad, but as he approached the bishop's

cell a great light shone through its single window, and the king was almost

blinded by its brightness.

In his early days in

Northumbria, St. Chad had trudged on foot on his long missionary journeys until

Archbishop Theodore with his own hands lifted him on horseback, insisting that

he conserve his strength. This was typical of St. Chad, and he brought to his

work at Lichfield the same grace and simplicity.

In Lichfield Chad founded

monasteries including possibly Barrow (Barton) upon Humber, improved the

discipline of the cloisters, preached everywhere, and reformed the churches of

the diocese.

Many legends gathered

round his name, and the familiar one which relates to his death reflects at

least the inner beauty of his life. After two and one half years of steady, unremitting

labor, when Chad came to die, his oratory was filled with the sound of music.

First a laborer heard it, outside in the fields, and drew near in wonder, then

ran and told others. St. Chad's followers gathered outside, and when they asked

what it was, he told them that it meant that his hour had come and it was the

angels calling him home. Then he gave each of them a blessing, begged them to

keep together, to live in peace, and faithfully fulfill their calling. St.

Chad's body simply wore out.

Some of his relics are

preserved in the cathedral of Birmingham, which is named for him (Attwater,

Benedictines, Delaney, Encyclopedia, Gill).

In art, St. Chad is a

bishop holding Lichfield Cathedral and a branch (usually a vine). He may also

be found (1) holding the cathedral in the midst of a battlefield with the dead

surrounding him, (2) with a hart leading hunters to him by a pool, or (3) at

the time of the conversion of the hunters (SS. Wulfhald and Ruffinus) (Roeder).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0302.shtml

Sculpture de saint. Chad, St. Chad's Church, Lichfield, Staffordshire, 1930

Biography of St.

Chad (623-672), Bishop of Lichfield

S T. C H A D

Born: c.AD 623 in Northumbria

Abbot of Lastingham

Bishop of York

Bishop of Lichfield

Died: 2nd March AD 672 at Lichfield, Staffordshire

Part 1: Training & Abbacy of Lastingham

St. Chad, or Ceadda,

was the youngest of the four brothers: Cedd,

Cynebil, Celin and Chad, all eminent priests. Despite attempts to claim him as

both a Scottish and an Irish saint, he was certainly an Angle, born of noble

parents in Northumbria around AD 623. Bede tells us that St. Chad, along with

his elder brothers, was a pupil of St. Aidan at his Lindisfarne school. The

bishop required the young men who studied with him to spend much time in

reading Holy Writ and in learning, by heart, large portions of the Psalter,

which they would require in their devotions. Upon the death of Aidan, in AD

651, the four young men were to Ireland to complete their training. The Emerald

Isle was then full of men of learning and piety, and Chad, there, made the

acquaintance of Egbert, afterwards Abbot of Iona.

Meanwhile, Chad's

brother, Cedd, had returned to England and evangelised the East Saxons. In AD

658, at the request of King Aethelwald of Deira, he also established a

monastery at Lastingham in

Yorkshire, standing just on the edge of the North York Moors. Though often

absent, he frequently returned thither from his London diocese and, at a time

of the AD 664 plague, he died there. Upon his death-bed, Cedd bequeathed the

care of the monastery to his brother, Chad, who was then still in Ireland.

On his return, St. Chad

ruled the Lastingham Abbey with great care and prudence, and received all who

sought his hospitality with kindness and humility. However, he arrived in

Northumbria during a period of religious change and political upheaval. Having,

at the Synod of Whitby, rejected the ways of the Irish Church in favour of

those of Rome, the Northern diocese quickly found itself short of a Bishop.

Eventually, the heavily pro-Roman and, therefore to some factions,

unpopular St.

Wilfred given the Northumbrian Bishopric which he transferred to York.

Arrogant to the last, he insisted on being consecrated by true followers of the

Roman rule, as only to be found in France and was absent some months.

Part 2: Episcopate of York

The following year (AD

665), while St.

Wilfred was still abroad, King Oswiu of Northumbria became impatient

for some religious guidance in his kingdom and decided to send Chad to Kent to

be ordained Bishop of the Northern Church. He was accompanied by the King's

Chaplain, Edhed, who was, some years afterwards, made Abbot of Ripon. However,

upon their arrival in Canterbury, the two priests found that Archbishop

Deusdedit had died of the Plague. His successor, Wigheard, was journeying to

Rome for his consecration and Bishop Ithamar of Rochester was too close to

death to be of any help. So they turned aside to Wessex where, at

Dorchester-on-Thames, they were greeted by Bishop Wine. He was the only

canonically ordained bishop available in England, yet the required ceremony

demanded three. Wine therefore called upon two Welsh and/or Cornish Bishops to

help him and St. Chad was duly consecrated Bishop of York in Dorchester

Cathedral.

Bishop Chad began, at

once, to apply himself to the practice of humility, continence and study. He

travelled about his new diocese, not on horseback, but after the manner of the

apostles, on foot, to preach the gospel in the towns and the open countryside,

according to the example of both St. Aidan and his late brother, Cedd. Wilfred

returned to England in AD 666 and, finding himself, deposed, quietly retired to

his Abbey at Ripon. He remained, however, an opponent of Chad who was

constantly criticised for the manner of his consecration. Three years

later, Theodore of

Tarsus, a new Archbishop arrived in Canterbury from the Continent. Being

naturally a staunch supporter of the Roman doctrine, he soon charged Chad with

holding an uncanonical office. The northern prelate humbly replied that if this

were true, he would willingly resign for he never thought himself worthy of the

position and had only consented out of a sense of duty. Theodore was so moved

that he completed Chad's ordination himself in the Roman manner. Though the

latter still preferred to resign in favour of Wilfred and he thus retired to

Lastingham. Though Chad was Bishop of York for so short a time, he left his

mark on the affections of the people, for we find that at least one chantry was

dedicated in his name at York Minster.

Part 3: Episcopate of Lichfield

In AD 669, Bishop Jaruman

of Mercia died and King Wulfhere asked Archbishop

Theodore to send his people a new Christian leader. The primate did

not wish to consecrate a fresh bishop, so he persuaded King Oswiu to release

Chad from the Abbacy of Lastingham to

be the new Mercian Bishop. Soon after his election, Chad set out for Repton in

Derbyshire, where Diuma, the first Bishop of Mercia, had established his see.

Theodore, knowing that it was Chad's custom to travel on foot, bade him ride,

whenever he had a long journey to perform. However, finding Chad unwilling to

comply, the archbishop was forced to lift him onto his horse, with his own

hands, and oblige him to ride.

Chad did not stay long at

Repton, but removed the centre of the Mercian See to Lichfield in

Staffordshire. Whether this was through a desire for a more central position or

was influenced by a wish to do honour to a spot enriched with the blood of

martyrs is unknown. For Licetfield was then thought to translate as "Field

of the Dead" where one thousand British Christians were said to have been

butchered. Possibly also, he wished to be closer to the popular Royal Palace at

Tamworth.

Chad's new diocese was

not much less in extent than that of Northumbria. It comprised seventeen

counties and stretched from the banks of the Severn to the shores of the North

Sea. For the dioceses of Worcester, Leicester, Lindsey and Hereford had still

to be detached. Though such an area may be thought far beyond the power of one

man to administer effectively, Chad apparently rose to the challenge. King

Wulfhere gave him the land of fifty families upon which to build a monastery,

at the place called Ad Barve (At the Wood) in Lindsey, conjectured to

be Barton-on-Humber, where the ancient Saxon church still stands. Though it was

almost certainly Barrow in the same region.

Chad built himself a

small oratory beside Stowe Pool at Lichfield. It adjoined a large well and a

small church (St. Chad's), not far from his new cathedral. He would emerse

himself naked in the deep well every morning and meditate in the icy waters

before setting out around his diocese to care for the needy. When time allowed,

Chad was also wont to pray and read with seven or eight other brethren in his

cell. If it happened that there blew a strong gust of wind, when he was reading

or doing anything else, he at once called upon the Lord for mercy. If it blew

stronger, he, prostrating himself, prayed more earnestly. But if it proved a

violent storm of wind or rain, or of thunder and lightning, he would pray and

repeat Psalms in the church till the weather became calm. He explained to his

followers that the Lord moves the air, raises the winds, darts lightning and

thunders from heaven to excite the inhabitants of the Earth to fear him, to

dispel their pride, vanquish their boldness and to put them in mind of their

future judgement.

It was to Bishop Chad's

little cell that Prince Wulfade of Mercia happened to chase a handsome deer

whilst out hunting one day. Struck by the words of the pious holyman, the

prince allowed himself to be baptised in the Bishop's well. His brother,

Rufine, soon followed suit. Their father, King Wulfhere, had relapsed into

Paganism and was furious at his sons. Having his mind further poisoned by their

enemy - a thane named Werbode - he rode out and slew them both with his own

hands. Immediately stung with remorse, however, the King fell ill and was

counselled by his queen to ask Chad to give him absolution. As a penance, the

saint told him to build several abbeys and, amongst the number, he completed

Peterborough Minster (Cathedral), which his brother had begun. He was converted

to Christianity and, often afterwards, sought the Bishop's advice.

After a rule of two and a

half years, a deadly plague began to ravage the Midlands. Many of the Lichfield

brethren were felled by the disease and it was not long before Bishop Chad's

time came near. This was heralded by a heavenly audition, witnessed by Owin, a

monk of great merit who had joined Chad at Lastingham from the entourage of St.

Etheldreda, whilst he worked outside the Bishop's oratory. Chad immediately

called upon him to gather the brethren, then praying in the church, around him.

He encouraged them to preserve the virtue of peace amongst them and follow his

example in all things when he had gone. He explained to Owin that his death

would come to pass within seven days, and so it did.

Chad died on the 2nd

March AD 672 and was first buried in St. Mary's Church at Lichfield. Like many

cathedrals of the time, however, there were many churches in the Episcopal

complex and when the Church of St. Peter was completed, his bones were

translated thither. Frequent miraculous cures were attested in both places.

Though Chad's episcopate

was short, it was abundantly esteemed by the warm-hearted Mercians, for

thirty-one churches are dedicated in his honour, all in the midland counties,

either in or near the ancient diocese of Lichfield. His relics were translated

to the present Cathedral, when it was rebuilt by Bishop Roger, in honour of SS.

Mary and Chad. There, they reposed in a beautiful shrine erected by Bishop

Walter Langton in his newly-built Lady Chapel from the early 14th century until

the Reformation. Some of them were saved from destruction and are now on

display in Birmingham Roman Catholic Cathedral.

Chad's emblem is a

branch, perhaps this was suggested by the Gospel of St. John which speaks of

the fruitful branches of the vine. This was formerly read on the Feast of

Chad's Translation, which was celebrated with great pomp at Lichfield every 2nd

August. However, he is most easily recognised in art through his cradling a

little church with three spires, ie. Lichfield Cathedral.

Partly Edited from S.

Baring-Gould's "The Lives of the Saints" (1877).

SOURCE : https://web.archive.org/web/20150906220301/http://www.britannia.com/bios/saints/chad1.html

Saint Chad, Saint Peada et Saint Wulfhere, entrée occidentale de la Cathédrale de Lichfield

St

Chad (left), alongside Mercian kings Peada and Wulfhere, as portrayed in 19th century sculpture

above the western entrance to Lichfield Cathedral.

St

Chad - Patron Saint of Medicinal Springs

Dr Bruce Osborne -

revised Spring 2009

The Archaeological record

There are a number of

significant sites in England that celebrate the cult of St Chad. This

interesting phenomenon first identified by James Rattue in Living Stream,

(1995) is the preponderance of St Chads Wells. This list has subsequently been

consolidated by Harte (2008). The value of Harte’s work as an authoritative

publication is that it provides a gazetteer of sources and their recording over

the centuries and as such is a new prime reference point for anyone wishing to

locate and conduct further research on particular sites or cults. The

bibliography in particular gives students of Holy Wells a substantial guide

with regard to source material. Harte identifies the following early

spring/well sites dedicated to St Chad in addition to Lichfield Cathedral

itself.

In the examples the

locations are given with an indication of the date of known first recording.

Tushingham in Cheshire 1301 (p.27); Lastingham in Yorkshire 19th century (p43,

v2p356); Stowe near Lichfield 14th century (p44,101, v2p325); Abbots Bromley in

Staffordshire c.1300 (p.64, v2p321); Wilne in Derbyshire medieval (p64.

v2p190); Chadkirk in Cheshire c.1306 (p64, v2p178); Chadshunt in Warwickshire

1695 (p64,79, v2p331); St Pancras in London (p.64, v2p266); Bedhampton in

Hampshire (v3p443); Stepney in London (v3p448). Chadwell in Essex 19th century

(v3p388); Chadwell Heath in Essex 19th century (v3p388); Birdbrook in Essex

19th century (v3p388); Brettenham in Norfolk 19th century (v3p402);

Peterborough in Northamptonshire 17th century (v3p403); Warmington in

Northamptonshire 20th century (v3p404); Chadswell in Shropshire 19th century

(v3p407); Midsomer Norton in Somerset 19th century (v3p413); Chaigley in

Lancashire 20th century (v3p430); together with a number of doubtful and

spurious wells as follows: Pertenhall in Bedfordshire (v3p436); Shodwell in

Cheshire (v3p437); Prestbury in Gloucestershire 1201 (v3p442); Twyning in

Gloucestershire (v3p443); Ware in Hertfordshire (v3p444); Chaigley in

Lancashire (v3p446); Barton-upon-Humber in Lincolnshire (v3p447); South Ferriby

in Lincolnshire (v3p.448); Shadwell in Norfolk (v3p449); Broughton in

Oxfordshire (v3p450); Chatwall in Shropshire (v3p451); Shrewsbury in Shropshire

(v3p.451); Birmingham in Warwickshire (v3p454). With such an array of recorded

St Chad sites now consolidated by Harte into a single directory it raises the question:

what is the background to this popular well cult?

Early background to Chad

Ceadda was actually a

pre-Christian deity of healing springs and holy wells whose symbol was Crann

Bethadh, the Tree of Life. There is some confusion as to whether Ceadda was a

god or a goddess and the celebration may also have been originally Norse, not

Celtic. Chieftains were inaugurated at the Tree of Life. Through its roots and

branches the tree connected with the power both of the heavens and the worlds

below. St Chad represents a Christianisation of this healing spring deity.

St Chad (Anglo Saxon -

Ceadda) is regarded as the missionary who introduced Christianity to Mercia.

Born circa 620 in Northumbria, he was educated at the monastery of Lindisfarne,

or Holy Island, of which he became the bishop. Upon his canonization, St Chad

became the patron saint of medicinal springs. His year of consecration is

recorded in Anglo-Saxon Chronicles at 664.

Litchfield Established AD

669

In the year AD 669, the

year that the church in Lichfield, Staffordshire, UK was established, St Chad

came to Lichfield to be its first bishop. His appointment as Bishop of Mercia

was by King Wulfhere. Here he founded a monastery beside a well of spring

water. The spring was where he baptized the converts and the church that he

built was dedicated to St Mary.

The nature of St Chads

appointment as a bishop gave rise to the more recent and unfortunate use of the

word Chad to signify a false election result. From Mercia, Chad’s brother Cedd

had gone to work first with the East Saxons before going north to Lastingham

(in modern-day Yorkshire) where he had been given land for a monastery. On

Cedd’s death from plague in 664, Chad succeeded his brother as Abbot of

Lastingham and both brothers have a well there named after them.

The following year,

Wilfrid, Abbot of Ripon, was sent to France to be consecrated as bishop of the

Northumbrians. Wilfrid, however, lingered in France and Chad was summoned from

Lastingham to be consecrated in his place. Bishop Wini of the West Saxons was

the only bishop of the Roman tradition left in England, but, as three bishops

were required for a consecration, two others still following the British

traditions assisted.

In 669, Theodore of

Tarsus became Archbishop of Canterbury and immediately set about reforming the

English church. On discovering two bishops in Northumbria, he declared Chad’s

consecration invalid because of the participation of the two British bishops.

Chad’s reply revealed his deep humility: “If you know I have not duly received

episcopal ordination, I willingly resign the office, for I never thought myself

worthy of it; but, though unworthy, in obedience submitted to undertake it.”

Moved by this reply, Theodore completed Chad’s consecration according to Roman

rites. However, Wilfrid remained as Bishop of York and so Chad returned to

Lastingham.

This state of affairs did

not last long, as later in the same year King Wulfhere of Mercia requested a

bishop and Theodore sent Chad. Although there had been previous bishops working

in Mercia, it was with Chad that the see was fixed at Lichfield and so Chad can

be correctly described as the first Bishop of Lichfield.

The Stag Legend

The background to St

Chad’s ministry in Lichfield is legendary. Wulfhere was the Christian king who

had asked Theodore, the archbishop, to provide him with someone to be bishop in

Mercia, and so Chad had come to Lichfield. According to this legend, Wulfhere

later renounced his Christian faith at the persuasion of an evil counsellor

called Werbode, and two of his sons, Wulfhad and Ruffin, were brought up as

pagans.

While out hunting one

day, son Wulfhad raised a stag which he followed to St Chad's cell at

Lichfield, where it plunged into the spring there - now St Chad's Well - before

fleeing into the forest again. On reaching the spring, Wulfhad saw Chad and

asked him which way the stag had gone. Chad told him that he was to follow the

stag no further. Its purpose had been to bring him here, to Chad's cell, so

that he could be baptised in the Christian faith. Wulfhad challenged Chad, if

his God was so great, to bring the stag back by prayer. Chad knelt and prayed,

the stag returned and Wulfhad was baptised at the spring.

The next morning, Wulfhad

returned home and told his brother all that had happened. Ruffin decided that

he, too, would be baptised and the stag once more appeared, to lead them

through the forest to Chad's cell.

Thereafter, the two

brothers made frequent visits to Chad to be instructed in the Christian faith.

However, the evil Werbode became suspicious and, after a successful spying

mission, reported the brothers to their father, the king. In an uncontrollable

rage, Wulfhere went to Chad's cell and demanded of his two sons that they

renounced their new faith. When they refused, he slew them both. (Chad was

saved, we are told, because on hearing their father approaching, the brothers

had persuaded him to slip away.)

Later, realising what he

had done, Wulfhere was overcome by guilt and fell ill. Eventually, he agreed to

follow the advice of his wife and seek out Chad so that he could repent and be

absolved of his sin. The stag made its third appearance, to lead Wulfhere to

Chad. On arriving at the cell, Wulfhere could hear Chad saying Mass, and,

conscious of his guilt, was reluctant to go in.

When Mass was finished,

Chad hung his vestments on a convenient sunbeam (or so we are told) and came

out to meet Wulfhere. As a penance for his sins, Wulfhere was instructed to

replace paganism with Christianity throughout his kingdom, to found churches and

monasteries, and to lead a Christian life.

Bede indicates that St

Chad zealously devoted himself to all the laborious functions of his charge,

visiting his diocese on foot, preaching the gospel, and seeking out the poorest

and most abandoned persons in the meanest cottages and in the fields, that he

might instruct them. When old age compelled him to retire, he settled with

seven or eight monks near Lichfield. Tradition described him as greatly

affected by storms; he called thunder 'the voice of God,' regarding it as

designed to call men to repentance, and lower their self-sufficiency. On these

occasions, he would go into the church, and continue in prayer until the storm

had abated.

Stowe

There is some confusion

as to whether the original church was on the site of the Lichfield Cathedral

rather than a short walk away at nearby Stowe. It is likely that Chad’s church,

dedicated to St. Mary, was somewhere on the site of the present cathedral and

that the church nearby at Stowe was the site of the ‘house near the church,

where he used to retire privately with seven or eight brethren in order to pray

or study whenever his work and preaching permitted’.

St Chads church at Stowe

is only about a half mile from Lichfield Cathedral. The present day church is a

12th century and later construction, the original Saxon one having been

demolished. St Chads Well can be seen in the grounds of the present day church.

It lies beneath a canopy erected in 1951, replacing an earlier enclosed stone

built structure. Some say, St Chad was wont, naked, to stand in the water and

pray, a habit that likely led to his saintly patronisation of cold bathing.

Well Dressing here can be dated from the nineteenth century. This practice was

revived in 1995.

Chad’s Death and his relicts

After two and a half

years at Lichfield, there came a time of plague which ‘freed many members of

the reverend bishop’s church from the burden of the flesh’. It is related that

seven days before his death, a monk named Arvinus, who was outside the building

in which he lay, heard a sound as of heavenly music attendant upon a company of

angels, who visited the saint to forewarn him of his end. St Chad died in 672

and his body was buried near the church of St Mary’s. In 700 his bones were

relocated to the newly completed cathedral in Lichfield. His remains were

enclosed in a rich shrine, which, being resorted to by multitudes of pilgrims,

caused the gradual rise of the city of Lichfield from a small village. It is

related that the saint's tomb had a hole in it, through which the pilgrims used

to take out portions of the dust, which, mixed with holy water, they gave to

men and animals to drink.

Chad's cult was destroyed

at the Reformation and his relics were scattered, apparently in 1538. A

prebendary of Lichfield, Arthur Dudley (a relative of the Sutton Lords Dudley

and of the cadet branch of the Dudley family who held various high offices and

titles in 16th C), scooped up a few of Chad's bones. He is said, in a document

written by a Jesuit priest in mid 17th C, to have deposited them with two

sisters, members of his family, in Russells Hall, Dudley. The sisters

eventually entrusted the few bones to Henry and William Hodgetts, recusants of

Woodsetton in the neighbouring parish of Sedgley. William died first (he

apparently 'divined' thefts with a crystal ball, among other things). Just

before Henry died, in 1651 (not 1615, as the local version has it, from an

early 19th C published translation of the Latin), he gave the relics to the

Jesuit priest who administered the Last Rites. The fragments were given by the

Jesuit to a member of the Leveson family, royalists and recusants, at least one

of whom was involved in defending Dudley Castle around that time. A Puritan

raid on a Leveson house resulted in the loss of some of the bones. The rest

were hidden by other Staffordshire recusant families until religious toleration

acts were passed at the end of 18th C and beginning of 19th, and the Cathedral

for the RC Archdiocese of Birmingham was the obvious destination for them.

(supplied by Buckley C from Greenslade 1996 & 2006)

St Chad remains and are

now in the hands of the Birmingham Roman Catholic Cathedral. Carbon dating has

confirmed that the remains are contemporary with the life of St Chad.

Celebration of St Chad

and cold bathing

Sir John Floyer of

Lichfield, the celebrated physician to Charles II, in 1706 published a curious

collection of letters about the medicinal values of cold bathing. In his text

he describes St Chad as one of the first converters of our nation, who used

immersion in the baptism of the Saxons; such immersion being beneficial to the

body as well as the soul. Floyer concludes that the well near Stowe, which

bears Chad's name, was his baptistery, it being deep enough for immersion, and

conveniently seated near the church; and that it has the reputation of curing

sore eyes, scabs, &c. Sir John Floyer, it should be added, set up his own

baths at Unite’s Well. This lay about one mile north-west of Lichfield. He

appropriately named his baths after St Chad, the water of which he observes to

be the coldest in the neighbourhood. Sir John gives a table of diseases for

which St Chads Baths was efficacious (Floyer J. 1706, p.17 - 27.).

Chamber’s “Book of Days”

indicates that Chad was designated "Patron Saint of Medicinal

Springs" as a result of the miraculous healing achieved using the dust

from his shrine mixed with Holy Water. An alternative view, expressed by

Sunderland (1915) is that the designation resulted from his practice of bathing

naked in his well at Stowe, by the church.

Today’s archaeology

The cult of St Chad has

resulted in the name being adopted in up to 42 instances of springs and wells

and one may conclude that the patron saint of medicinal springs was a very

powerful endorsement of a well’s properties. This may not be as clear cut as first

assumed however. St Chad’s wells in some instances are likely a transformation

or hagiologising from “cealdwiella” or cold well. (Harte p.8) Chadwell in Essex

for example in 1578 was Chawdwell but by the 20th century had adopted the

nomenclature St Chad's Well. It is not surprising that Floyer therefore took an

interest in the well at Lichfield in view of his interest in cold bathing as a

cure. It would appear that St Chad became synonymous with cold wells.

Today we find St Chad's

name being used to name hospitals, doctor's surgeries and health centres. The

cult lives on. Meanwhile the St Chads Foundation Trust strives to protect and

enhance the site of St Chad’s Church and Spring at Stowe, near Lichfield.

St Chads Feast Day is

March 2nd.

B E Osborne 2009

General and detailed

sources:

Pictures by S Arnold and

B Osborne;

<Anglo-Saxon

Chronicles Ingram J (1912 reprint 1929). p.40.

Book of

Days Chambers R (1864) p.321.

Catholic

Staffordshire Greenslade M (2006) Gracewing Books, Leominster

The Forgotten

Cathedral Current Archaeology 205 (2006) Rodwell W, p.9-17.

English Holy Wells – a

sourcebook Harte J (2008) Heart of Albion Loughborough. Vols 2 and 3 are

the gazetteer.

History of Cold Bathing –

both ancient and modern Floyer J (1706) Walford London.

London’s Spas, Baths and

Wells Sunderland S (1915) Bale, London. p.13-16.

On Eagles Wings The Life

and Spirit of St Chad Adam D (1999) Triangle London.

Saint Chad of Lichfield

and Birmingham Greenslade M W, (Archdiocese of Birmingham Historical

Commission, publication number 10, 1996)

The Living Stream – Holy

Wells in Historical Context Rattue J (1995) Boydell Woodbridge

Other sources include

www.stchads.org.uk together with the archives of the Spas Research Fellowship.

James Rattue and Jeremy Harte have both aided the preparation of this paper.

SOURCE : http://www.thespasdirectory.com/discover_the_spa_research_fell.asp?i=10#

Saint

Chad, vitrail de Christopher Whall. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

San Ceadda (Chad) di

Lichfield Abate e vescovo

† Lichfield, Inghilterra,

2 marzo 672

Patronato: Diocesi di

Birmingham

Martirologio Romano: A

Lichfield in Inghilterra, san Ceadda, vescovo, che nelle allora povere province

della Mercia, del Lindsey e dell’Anglia meridionale, resse l’ufficio

episcopale, impegnandosi ad amministrarlo secondo l’esempio degli antichi Padri

in grande perfezione di vita.

San Ceadda (Chad)

proveniva da una famiglia molto religiosa della Northumbria, della quale ben

quattro fratelli divennero sacerdoti, due addirittura vescovi. Egli fu

discepolo di Sant’Aidano di Lindisfarne, e proprio in quest’ultima città

soggiornò per un certo periodo e ricevette dal suo maestro un’ottima

formazione. Ancora in giovane età, si trasferì in Irlanda, dove insieme al

compagno Egberto visse da monaco, immerso nella preghiera, nel digiuno e nella

meditazione delle Sacre Scritture. Ricevette l’ordinazione presbiterale

probabilmente una volta tornato in Inghilterra. Nulla sappiamo di preciso sulla

sua vita sino alla morte del fratello San Cedda. Quest’ultimo predicò il Vangelo

agli angli del centro, fu pi vescovo ed apostolo dei sassoni orientali ed

infine fondò ed amministrò il monastero di Lastingham, che poi lasciò in

eredità al fratello.

Il nuovo abate si ritrovò

ben presto nel mezzo di una intricata questine politica, che coinvolse i

sovrani dei regni vicini e dei principali monasteri, ma che sarebbe lungo ed

inutile riportare nei dettagli. Da ciò Ceadda ne ricavò la consacrazione

episcopale, non solo in base a calcoli fatti a tavolino, ma proprio perchè

nessuno dubitava sulla sua santità e sulle lodevoli qualità, come ebbe a

testimoniare nelle sue memorie anche San Beda il Venerabile. Sorserò però dei

dubbi sulla legittimità della sua nomina e della sua ordinazione, contestata da

San Vilfrido che si rivolse al nuovo arcivescovo San Teodoro di Tarso dal quale

ebbe pieno appoggio. Ceadda non esitò allora a farsi da parte per obbedienza ed

umiltà, ma Teodoro commosso dalla sua reazione, convalidò la consacrazione

episcopale di Ceadda, che comunque preferì ritirarsi a vita monastica presso

Lastingham.

Quando però ben presto la

Mercia rimase senza vescovi, Teodoro richiamò nuovamente Ceadda che prese

possesso della sede di Lichfield. Vicino alla cattedrale il santo fece

edificare un luogo ove portersi ritirare in preghiera con altri monaci quando

era libero da altri impegni. Ricevette inoltre in dono un terreno presso Ad

Barvae, probabilmente l’odierna Barrow nella contea di Lindsey, ove fondare un

nuovo monastero. Annunciò in anticipo ai frati la prossimità della sua

scomparsa, persuadendoli a vivere in pace con tutto e con tutti, rimanendo

fedeli alle regole monastiche apprese da lui e dai suoi predecessori. Spirò

infine il 2 marzo 672, dopo aver ricevuto la comunione sotto le due specie, a

causa di quella tremenda epidemia di peste che parecchie vittime aveva già

mietuto tra i suoi fedeli.

Il suo vecchio amico

Egberto asserì che fu vista l’anima di Cedd scendere dal cielo assieme ad uno

stormo di angeli per scortare il fratello verso la vita eterna. Dopo una

primitiva sepoltura, le sue spoglie furono traslate ove oggi sorge la

cattedrale di Lichfield. Su entrambe le tombe si verificarono numerosi

miracoli, grazie ai quali il suo culto si diffuse ampiamente. Con le invasioni

normanne si pensò che le reliquie fosse andate perdute, ma alcune di esse nel 1839

furono rinvenute e deposte sopra l’altar maggiore della nuova cattedrale di

Birmingham, di cui divenne patrono. Il nome di San Chad figura nei calendari e

nelle litanie anglosassoni e ad esso vennero dedicate parecchie chiese

medioevali nell’Inghilterra centrale.

Autore: Fabio

Arduino

SOURCE : https://www.santiebeati.it/dettaglio/43620

Eglwys

Sant Chad, Hanmer, Wrecsam.

Saint

Chad's Church, Hanmer, Wrexham, Cymru, Wales

Den hellige Chad av

Lichfield (~623-672)

Minnedag: 2.

mars

Den hellige Chad (Cedda;

gmleng: Ceadda) ble født rundt 623 i Northumbria i Nord-England. Han kom fra en

adelig anglisk familie som hadde slått seg ned der. Det har vært gjort forsøk

på å hevde at han var skotsk eller irsk, men han var helt sikkert anglisk, selv

om navnet Chad skal ha vært av britisk keltisk opprinnelse snarere enn

angelsaksisk. Han hadde tre eldre brødre, den hellige Cedd av Lastingham (Ceddus)

(ca 620-64), Caelin (Celin) (f. ca 621) og den hellige Cynebill (Cynibil,

Cymbel) (ca 622-64). Alle fire ble som gutter utdannet på Lindisfarne av de

hellige Aidan (Áedán)

(d. 651) og Finan

av Lindisfarne (d. 661). Lindisfarne (nå Holy Island) er en øy utenfor

kysten av Northumbria som er landfast ved lavvann. Aidan, som var en disippel

av den hellige Kolumba

av Iona, kom til Northumbria i 635.

Ved Aidans død i 651 ble

studentene sendt til Irland for videre studier, og Chad fikk deler av sin

utdannelse i et uidentifisert kloster ved navn Rathmelsigi (Rathelmigisi,

Rathmelsige, Rathemigisi, Rathelmigisi), av noen identifisert som Clonmelsh i

grevskapet Carlow i provinsen Leinster, av andre som Mellifont i grevskapet Louth

i Leinster. Der studerte de sammen med en jevnaldrende munk fra Lindisfarne,

den hellige Egbert

av Iona. Alle fire brødrene ble prester – Cedd og Chad ble også senere

biskoper. En kilde sier at Chad ble presteviet i 653 og vendte tilbake til

England for å begynne på sin tjeneste som misjonær, en annen kilde sier at han

fortsatt var i Irland i 664.

Chads eldre bror Cedd

arbeidet som misjonær blant østsakserne i Essex, og under et besøk på

Lindisfarne hadde abbed Finan i 654 vigslet ham til misjonsbiskop. Imens hadde

Cedds og Chads bror Caelin undervist og døpt kong Ethelwald av Deira (651-656),

sønn av den hellige kong Osvald av

Northumbria (634-42), som utnevnte ham til sin kapellan. Caelin

foreslo for kongen at det ville være en god idé å grunnlegge et kloster i det

sørlige Northumbria, hvor han kunne be mens han levde og bli gravlagt når han

døde og hvor bønnene for hans sjel ville fortsette.

Caelin introduserte kong

Ethelwald for sin bror Cedd, som tilfeldigvis trengte en slik politisk base og

åndelig tilfluktssted. Han fikk et stykke land av kongen, og klosteret ble

grunnlagt i 658. Stedet ble kalt Laestingaeu, som er identifisert som

Lastingham i North Riding, like ved en av de fortsatt brukbare romerske veiene.

Her ble Cedd den første abbeden, og han kom ofte tilbake dit til tross for sine

forpliktelser som biskop. Cedd fastet i førti dager for å konsekrerte stedet, og

dette var en skikk fra Lindisfarne som stammet fra den hellige Kolumba. Men da

han var kommet til den trettiende dagen, ble han tilkalt til viktige affærer,

og da overtok broren Cynibil fasten på de resterende ti dagene. Lastingham ble

opplagt sett på som en base for familien og planlagt å være under deres

kontroll i overskuelig fremtid, noe som ikke var uvanlig i denne perioden.

Etter Ethelwald ble

tronen overtatt av Oswiu (Oswy), som var konge av Bernicia fra 642 og av hele

Northumbria (Bernicia og Deira) fra 655 til sin død i 670. Hans sønn Alcfrid

(Alchfrith) av Deira (656-64) var medregent for Deira under sin far. Som ung

mann hadde Oswiu tilbrakt en tid i eksil i Skottland og Irland, og han fikk

opplæring og ble døpt klosteret på øya Iona i De indre Hebridene på vestkysten

av Skottland. Øya het opprinnelig Hy, men fikk senere navnet Iona etter den

hellige Kolumba (=

due på latin; hebr: iona). I Irland fikk han sønnen Aldfrid (Aldfrith) med

den irske kvinnen Fina. Aldfrid ble senere konge av Northumbria (685-704).

Nord-England var kristnet

både fra Irland og fra Sør-England, og dette skapte visse konflikter, for det

oppsto strid i den angelsaksiske Kirken om beregningen av påsken og andre

«irske» kirkelige skikker, som formen på tonsuren og etter hvert biskopenes

rolle og forholdet mellom lokalkirkene og Roma. Disse «irske» skikkene kunne

like gjerne kalles skotske, piktiske, britiske, northumbriske eller ganske

enkelt «keltiske».

Kong Oswiu hadde

oppmuntret munker fra Nord-Irland til å komme til landet. De holdt fast på den

keltiske tidsfastsettelse av påsken fra Iona, og kongen fulgte de irske

skikkene. Det samme gjorde Finan av Lindisfarne (d. 661), som på det sterkeste

motsatte seg fornyerne fra Kent eller utlandet, som ville innføre de romerske

skikkene som ble fulgt i resten av Europa. Finan motsto alle argumenter, men

han gikk til slutt med på at den hellige Wilfrid av York fikk

reise fra Lindisfarne til Roma.

Men kong Oswiu var gift

med den hellige Enfleda, datter

av den hellige kong Edwin av Northumbria (616-33)

og hans dronning, den hellige Ethelburga, en

prinsesse fra Kent. Hun var trofast mot sine lærere, som var opplært i Roma, og

hun var beskytter for Wilfrid av York da han var en ung mann. Hun holdt fast

ved den europeiske beregningsmåten for påsken, og dermed feiret kongen og

dronningen påsken på forskjellig tidspunkt, og det absurde i denne situasjonen

hjalp til å få avgjort spørsmålet

Kongen innkalte synoden i

Whitby (Streaneshalch) i 664 (eller 663), hvor det deltok kirkeledere fra hele

England. Finans etterfølger, den hellige biskop Colman av

Lindisfarne, var den viktigste forsvareren av de keltiske skikkene, sammen

med den mektige abbedisse Hilda av Whitby og

biskop Cedd av Lastingham, som imidlertid prøvde å opptre som megler mellom de

to sidene. Det romerske partiet ble ledet av den hellige Agilbert av Paris,

som tidligere var biskop av Dorchester, men han ba Wilfrid, som han nylig hadde

viet til prest, til å være hovedtalsmann på hans vegne, ettersom hans eget

kjennskap til gammelengelsk var ufullkommen. Andre på den romerske siden var

den hellige Ronan,

dronningens kapellan Romanus og Jakob Diakonen, som hadde blitt værende i

Swaledale etter at den hellige Paulinus av York flyktet

fra Yorkshire.

Wilfrid talte varmt for

den romerske og vesteuropeiske tradisjonen. Ingen av de to sidene kunne bevise

sitt syn historisk, men kong Oswiu aksepterte til slutt Wilfrids argumenter om

at de romerske tradisjonene ble fulgt i resten av Europa, og det ble vedtatt at

de romerske skikkene skulle følges i hele kongeriket. Hilda og Cedd aksepterte

avgjørelsen, noe som bidro til å hindre splittelse. En irsk synode hadde

akseptert den romerske beregningsmåten allerede noen år tidligere, og etter

hvert var den innført i hele England. Men biskop Colman av Lindisfarne gikk av

i protest mot vedtakene på synoden i Whitby og vendt tilbake til Iona sammen

med alle de irske munkene og tretti av de engelske, og de tok levningene av den

hellige Aidan

av Lindisfarne med seg. Den hellige Tuda ble

konsekrert til northumbrisk biskop i stedet, men han døde kort etter.

Etter synoden i Whitby i

663/64 trakk Cedd seg tilbake til sin grunnleggelse i Lastingham, i følge

historien for å dø under monastisk lydighet, men han var nok alt for ung til å

vente på døden ennå. Men uheldigvis herjet det en pest i Nord-England på den

tiden, og både Cedd og broren Cynebill ble smittet. Etter å ha utnevnt deres

yngste bror Chad til ny abbed i Lastingham, døde de begge, Cedd den 26. oktober

664, en dato vi kjenner fra Florence av Worcester. Beda forteller at da nyheten

om Cedds død nådde munkene i Essex, reiste tretti av dem nordover, «enten, hvis

Gud vil, å bo nær legemet av deres Far, eller å dø og bli lagt til hvile sammen

med ham». De var til stede i begravelsen, men de ble smittet av den samme

pesten og døde i Lastingham, bortsett fra en gutt, som etterpå ble funnet å ha

vært udøpt. Han levde og ble prest og en nidkjær misjonær. Cedd ble først

gravlagt utenfor murene i Lastingham, men senere ble han overført til koret i

en nybygd steinkirke viet til Jomfru Maria og

bisatt til høyre for alteret.

Chad var fortsatt i

Irland da hans to brødre døde i pesten, men han dro straks til Lastingham og

overtok som abbed i tråd med brorens ønske. Lastingham var en liten kommunitet

under den hellige Kolumbas regel i en avsidesliggende, vakker landsby helt i

utkanten av de nordlige York Moors nær Whitby i North Yorkshire. Men Chad fikk

bare være abbed der i ett år.

Kong Alcfrid grunnla et

kloster i Ripon, hvor romerske skikker ble innført. Ifølge Beda ble Tuda

etterfulgt som abbed av Lindisfarne av den hellige abbed Eata av

Melrose. Kong Alcfrid ønsket å ha en egen biskop for sitt folk i Deira, og han

vendte seg til Wilfrid, abbeden i Ripon, og utnevnte ham i 664 til biskop.

Wilfrid flyttet det northumbriske bispesetet fra Lindisfarne til York (da

Eoforwyc), hovedstad i Deira og Northumbria, og dermed ble embetene som abbed

og biskop av Lindisfarne delt. Senere, da den hellige erkebiskop Theodor av Canterbury delte

det enorme bispedømmet Northumbria i 678 over hodet på biskop Wilfrid, ble Eata

biskop av Bernicia, den nordlige halvparten, med sete i Hexham. Tre år senere

ble også dette bispedømmet delt i bispedømmene Hexham og Lindisfarne, og Eata

styrte Lindisfarne som biskop fra 681 til 684.

Mange nordlige biskoper

hadde avvist vedtaket fra Whitby, så den rimelig arrogante Wilfrid betraktet

dem temmelig urettferdig som skismatikere. Derfor insisterte han på å dra til det

frankiske kongeriket Neustria for å motta bispevielsen der. Med samtykke av

kong Oswiu sendte Alcfrid Wilfrid sørover for å bispevies. Wilfrid oppsøkte sin

egen lærer og beskytter Agilbert, en talsmann for den romerske linjen på

synoden i Whitby, som var blitt utnevnt til biskop av Paris. Han satte i gang

prosessen for å få bispeviet Wilfrid kanonisk, og han innkalte flere biskoper

til Compiègne for seremonien. Beda forteller at Wilfrid deretter ble værende en

tid utenlands, men han nevner ikke noen grunn til dette.

Til slutt mistet kong

Oswiu tålmodigheten og grep inn og insisterte på å få valgt en ny biskop. Vi

vet ikke om han ville irettesette Alcfrid eller om abbeden for Lastingham, det

andre kongelige klosteret i Deira, var det eneste åpenbare alternativet i

Wilfrids stadige fravær. I 665 utnevnte i alle fall kong Oswiu Chad til biskop.

Det var mangel på

biskoper i Nord-England, så Chad fikk de samme problemene som Wilfrid hadde

hatt. Han dro derfor sørover til Canterbury for å bispevies. Han ble fulgt av

kongens kapellan Edhed, som senere ble abbed i Ripon. Men da Chad kom til Kent,

fant han at den hellige erkebiskop Deusdedit (655-64)

var død i pesten og hans valgte etterfølger, Wighard (Wigheard), var i Roma for