Pachomius le Grand, Curtea Veche, Bucharest

Saint Pacôme le Grand

Fondateur du cénobitisme

chrétien (+ 346)

A 20 ans, l'égyptien Pacôme est enrôlé de force dans l'armée romaine. A Thèbes, alors qu'il se morfond dans une caserne où on l'a enfermé avec les autres conscrits récalcitrants, des chrétiens charitables viennent les visiter et leur apportent de quoi manger.

Une fois libéré, Pacôme se fait baptiser. Il se met au service des pauvres et des malades, puis obéit à l'appel de la solitude en se faisant ermite pendant sept ans.

Un jour qu'il se trouve à Tabennesi dans le désert, une voix mystérieuse lui dit: "Pacôme, reste ici, bâtis un monastère."

Une autre fois, un ange lui dit: "Pacôme, voici la volonté de Dieu: servir le genre humain et le réconcilier avec Dieu."

Pacôme a compris: on ne se sauve pas tout seul. Il bâtit un monastère pour aider d'autres hommes à trouver Dieu. Les disciples y viendront petit à petit.

Ce premier essai de vie commune est un échec: on n'improvise pas une communauté. Pacôme en tirera la leçon et rédigera un règlement strict: "la Règle de saint Pacôme". Il devient ainsi le père du monachisme communautaire ou cénobitique.

Le grand saint Athanase d'Alexandrie veut le faire prêtre. Par humilité, il refuse. Il continue à fonder et à multiplier les monastères chez les coptes de la Haute-Égypte.

Il mourut lors d'une épidémie qui frappa les couvents égyptiens en 346.

Saint

Pacôme est fêté le 15 mai par les Eglises d'Orient.

En Thébaïde, l'an 347 ou 348, saint Pacôme, abbé. Soldat encore païen, témoin

de la charité chrétienne envers les recrues de l'armée détenues, il en fut ému,

se convertit à la vie chrétienne, reçut de l'anachorète Palémon l'habit

monastique et, sept années plus tard, sur un avertissement divin, il édifia un

grand nombre de monastères pour accueillir des frères, et écrivit une célèbre

Règle des moines.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1127/Saint-Pacome-le-Grand.html

Saint

Pachomius, Iconostasis in Blaj, XVIIIth Century

SAINT PACÔME

Abbé

(292-348)

Pacôme naquit en 292,

dans la Haute-Thébaïde, au sein de l'idôlatrie, comme une rose au milieu des

épines. A l'âge de vingt ans, il était soldat dans les troupes impériales,

quand l'hospitalité si charitable des moines chrétiens l'éclaira et fixa ses

idées vers le christianisme et la vie religieuse. A peine libéré du service

militaire, il se fit instruire, reçut le baptême et se rendit dans un désert,

où il pria un solitaire de le prendre pour son disciple. "Considérez, mon

fils, dit le vieillard, que du pain et du sel font toute ma nourriture; l'usage

du vin et de l'huile m'est inconnu. Je passe la moitié de la nuit à chanter des

psaumes ou à méditer les Saintes Écritures; quelques fois il m'arrive de passer

la nuit entière sans sommeil." Pacôme, étonné, mais non découragé,

répondit qu'avec la grâce de Dieu, il pourrait mener ce genre de vie jusqu'à la

mort. Il fut fidèle à sa parole. Dès ce moment, il se livra généreusement à

toutes les rudes pratiques de la vie érémitique.

Un jour qu'il était allé

au désert de Tabenne, sur les bords du Nil, un Ange lui apporta du Ciel une

règle et lui commanda, de la part de Dieu, d'élever là un monastère. Dans sa

Règle, le jeûne et le travail étaient proportionnés aux forces de chacun; on

mangeait en commun et en silence; tous les instants étaient occupés; la loi du

silence était rigoureuse; en allant d'un lieu à un autre, on devait méditer

quelque passage de l'Écriture; on chantait des psaumes même pendant le travail.

Bientôt le monastère devint trop étroit, il fallut en bâtir six autres dans le

voisinage. L'oeuvre de Pacôme se développait d'une manière aussi merveilleuse

que celle de saint Antoine, commencée vingt ans plus tôt.

L'obéissance était la

vertu que Pacôme conseillait le plus à ses religieux; il punissait sévèrement

les moindres infractions à cette vertu. Un jour, il avait commandé à un saint

moine d'abattre un figuier couvert de fruits magnifiques, mais qui était pour

les novices un sujet de tentation: "Comment, saint Père, lui dit celui-ci,

vous voulez abattre ce figuier, qui suffit à lui tout seul à nourrir tout le

couvent?" Pacôme n'insista pas; mais, le lendemain, le figuier se trouvait

desséché: ainsi Dieu voulait montrer le mérite de la parfaite obéissance. Le

saint abbé semblait avoir toute puissance sur la nature: il marchait sur les

serpents et foulait aux pieds les scorpions sans en recevoir aucun mal;

lorsqu'il lui fallait traverser quelque bras du Nil pour la visite de ses

monastères, les crocodiles se présentaient à lui et le passaient sur leur dos.

Sur le point de mourir, il vit son bon Ange près de lui.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950.

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_pacome.html,

http://viechretienne.catholique.org/saints/1430-saint-pacome

The

phenomenon of an angel to Sacred Pahomiju (fresco). XIVth centuryChurch of

a monastery Zrze (Macedonia).

Явление

ангела Святому Пахомию (фреска).Церковь монастыря Зрзе (Македония).

SAINT PACÔME

Haute-Egypte au début du IVe siècle. Il fut un homme d'ascensions en quête de

Dieu plus haut que toutes cimes. D'origine païenne, soldat dans l'armée

impériale, frappé par la fraternité des chrétiens, il se donne au Christ et

quitte tous ses biens pour lui. Attiré par l'appel du Désert, il se fixe vers

325 en un lieu retiré, près de Thèbes. Depuis lors, le mot Thébaïde désignera

une solitude radicale, comme le mentionne le "Larousse". Bientôt

affluent autour de lui ses disciples. Pour eux, Pacôme connaîtra d'abord un

échec : ses premiers compagnons, dégagés des soucis matériels, consacraient

beaucoup plus de temps au repos et au sommeil qu'au travail, à la pénitence et

à la prière !

Pacôme lance un appel aux plus généreux et gagne le désert de Tabennêsi. Il

édifie avec eux une grande Famille où ensemble on prie, on travaille de ses

mains et on se sanctifie : des moines vaillants engagés aussi bien dans les

exercices spirituels que dans les tâches de la vie en commun. Naîtront neuf

monastères, la plus grande source de la vie monastique en Orient puis en

Occident. Saint Pacôme remet son âme à Dieu vers 346. Avec Antoine le grand et

Macaire, Pacôme constitue la trilogie des Pères du Désert en Egypte. Leur

grande maxime de sagesse afin de vivre pour Dieu l'Unique se traduit en latin

"fuge, tace, quiesce" : viens à l'écart, habite le silence, reçois la

paix du coeur. A chacun de chercher la voie royale du Désert en respirant par

l'Esprit.

Pâcome vient du latin "paix".

Rédacteur : Frère Bernard Pineau, OP

SOURCE : http://www.lejourduseigneur.com/Web-TV/Saints/Pacome

Saint

Pacôme le Grand recevant de l'ange la Règle de son Ordre (icône Byzantine).

Saint Pacôme

(pacificateur)

Avec saint Antoine , saint Pacôme fut le fondateur du monachisme.

Au moment de sa mort, les 9 monastères qu’il avait créés devaient contenir de 6

à 8.000 moines répartis sur les deux rives du Nil, en Égypte.

Quand il allait les visiter et qu’il devait traverser le Nil, il se mettait sur

un crocodile qui le transportait de l’autre côté.

Il est né en 286, à Esneh (actuellement Isna) en Égypte, non loin de Thèbes au

sein d’un milieu païen. Il sacrifiait aux Dieu mais vomissait le vin du

sacrifice et ne pouvait ingurgiter aucune nourriture sacrifiée. Quand il

entrait dans un temple, les idoles s’arrêtaient de prophétiser.

A vingt ans, il fut enrôlé de force dans l’armée romaine où il découvrit les

martyrs chrétiens. Après avoir quitté l’armée, il se rendit à Sheneset où

vivait un ermite du nom de l’apa Palemon et demanda à vivre avec lui. Il frappa

à la porte et palémon lui dit : en été, je jeune tous les jours, et en hiver,

je mange tous les deux jours. Je ne prends que de l’eau, du pain et du sel et

je dors rarement.

Qu’à cela ne tienne, Pacôme fut conquit par le programme et s’installa avec

l’apa Palémon auprès duquel il restera sept ans.

Comme le sommeil entraîne le moine dans un monde d’illusion, il fallait ne pas

dormir sauf le strict nécessaire. Il dormait donc accroupi ou assis en

s’appuyant légèrement contre un mur. Lorsqu’il rentrait le soir et voulait

s’allonger pour dormir, l’apa Palemon l’envoyait se promener dans le désert en

portant une grosse pierre pendant des heures entières. Il mangeait des herbes

cuites auxquelles Palémon ajoutait un peu de cendres pour leur donner mauvais

goût.

Les prières se faisaient debout, les bras en croix, immobile et abolissant

toute perception du monde extérieur.

Un jour, il partit dans le désert et aboutit à un village nommé Tabennesi. Un

ange lui apparut et lui ordonna de s’installer en ce lieu. Il y fondera son

premier monastère.

Tout était fait pour éliminer l’orgueil et tuer “l’homme mondain”.

Les moines étaient regroupés par métiers. De plus, Pacôme avait institué ce

qu’on appelait la “règle de l’ange”: les moines étaient répartis en 24 groupes

selon les 24 lettres de l’alphabet grec. Chaque lettre désignait un certains

type de moine. Ainsi, la lettre iota, i, regroupait les niais et un peu innocents,

le chi, les moines au caractère difficiles etc.

Seul Pacôme connaissait la répartition. Les moines ne la connaissaient pas.

Il luttait contre toute ostention de l’ascèse. Ainsi, chaque moine mangeait

avec un grand capuchon qui ne permettait pas au voisin de voir ce qu’il

laissait par mortification : pas de jalousie, pas de culpabilité. Si un moine

sortait avant la fin du repas, personne ne pouvait voir ce qui restait dans son

assiette et se prévaloir d’une mortification plus intense que celle de son voisin.

Chacun était tenu de tresser une natte par jour. Par ostentation, un moine en

fit deux. Pacôme l’enferma cinq mois dans sa cellule avec obligation de faire

deux nattes par jour.

(Cf. “Les hommes ivres de Dieu”, Jacques Lacarrière, Points Sagesse, Arthème

Fayard)

Le tempérament des moines Coptes se pliait difficilement à cette discipline et

souvent des querelles surgissait que Pacôme s’efforçait de calmer.

Un jour, un moine lui demanda : “Pourquoi, saint père, lorsqu’on m’adresse des

paroles dures, suis-je tout de suite en colère ?”. Pacôme répondit :”Parce que

lorsqu’on donne un coup de hache à l’acacia, il émet aussitôt de la gomme !”.

Pacôme mourut à l’âge de soixante ans lors d’une épidémie de peste.

Mais le cénobitisme (moines vivant en communauté) était né et se répandit en

Cappadoce, en Grèce et dans tout l’Occident.

SOURCE : http://carmina-carmina.com/carmina/Mytholosaints/pacome.htm

Saint Pacôme le Grand

Fondateur du cénobitisme

chrétien (+ 346)

A 20 ans, l’égyptien

Pacôme est enrôlé de force dans l’armée romaine. A Thèbes, alors qu’il se

morfond dans une caserne où on l’a enfermé avec les autres conscrits

récalcitrants, des chrétiens charitables viennent les visiter et leur apportent

de quoi manger.

Une fois libéré, Pacôme

se fait baptiser. Il se met au service des pauvres et des malades, puis obéit à

l’appel de la solitude en se faisant ermite pendant sept ans. Un jour qu’il se

trouve à Tabennesi dans le désert, une voix mystérieuse lui dit: « Pacôme,

reste ici, bâtis un monastère. » Une autre fois, un ange lui dit:

« Pacôme, voici la volonté de Dieu: servir le genre humain et le

réconcilier avec Dieu. » Pacôme a compris: on ne se sauve pas tout seul.

Il bâtit un monastère pour aider d’autres hommes à trouver Dieu. Les disciples

y viendront petit à petit.

Ce premier essai de vie

commune est un échec: on n’improvise pas une communauté. Pacôme en tirera la

leçon et rédigera un règlement strict: « la Règle de saint Pacôme ».

Il devient ainsi le père du monachisme communautaire ou cénobitique. Le

grand saint Athanase d’Alexandrie veut le faire prêtre. Par

humilité, il refuse. Il continue à fonder et à multiplier les monastères chez

les coptes de la Haute-Égypte.

Il mourut lors d’une

épidémie qui frappa les couvents égyptiens en 346. Saint

Pacôme est fêté le 15 mai par les Eglises d’Orient.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/samedi-9-mai/&daily_prayer_section=evangile-du-jour-3/

Monastery

of Saint Abraam

Also

known as

Pachomius the Elder

Pachomius the Great

Pachome…

Pakhomius…

Pacomius..

Pacomio…

9 May (Roman

Martyrology; Coptic church)

15 May (in

the east)

14 May on

some calendars

3 July on

some calendars

Profile

Soldier in

the imperial Roman army. Convert in 313.

He left the army in 314 and

became a spiritual student of Saint Palaemon.

Lived as a hermit from 316.

During a retreat into the deep desert, he received a vision telling him to

build a monastery on

the spot and leave the life of a hermit for

that of a monk in

community. He did in 320,

and devised a Rule that let fellow hermits ease

from solitary to communal living; legend says that the Rule was dictated to him

by an angel. Abbot.

His first house expanded to eleven monasteries and convents with

over 7,000 monks and nuns in

religous life by the time of Pachomius’s death.

Spiritual teacher of Saint Abraham

the Poor and Saint Theodore

of Tabennísi. Considered the founder of Christian cenobitic

(communal) monasticism, whose rule for monks is

the earliest extant.

Born

c.346 of

natural causes

buried in

an unknown location by Saint Theodore

of Tabennísi

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Roman

Martyrology, 1914 edition

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

Coptic

Orthodox Church Network

History

of Monastic Spirituality

Lausiac History, by Palladius

Patristics

in English, Rule, part 1

Patristics

in English, Rule, part 2

Patristics

in English, Rule, part 3

Patristics

in English, Rule, part 4

images

video

sites

en français

fonti

in italiano

notitia

in latin

MLA

Citation

“Saint Pachomius of

Tabenna“. CatholicSaints.Info. 8 December 2021. Web. 9 May 2023.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-pachomius-of-tabenna/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-pachomius-of-tabenna/

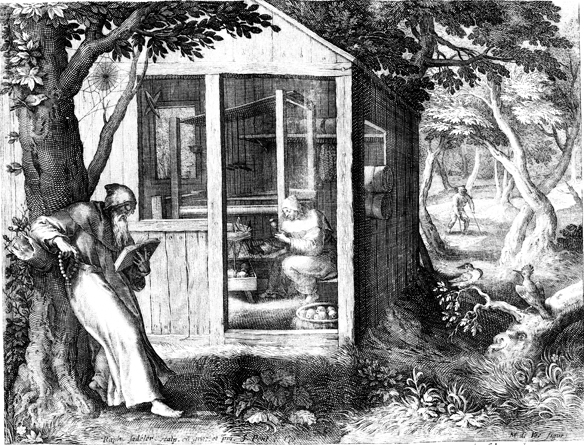

Plate

from the 1619 book Sylva anachoretica Aegypti et Palaestinae. Plate design

by Abraham Bloemaert (1564/66-1651); engraving by Boetius à Bolswert (ca.

1580-1633). Scan from the original work - Bloemaert, Abraham (1619) Sylva

anachoretica Ægypti et Palæstinæ. : Figuris æneis et brevibvs vitarvm

elogiis expressa. / Abrahamo Blommaert inuentore. Boetio a Bolsvvert sculptore, Antwerp:

ex typographi^a Henrici Ærtss ij, Sumptibus auctoris. University

Library - Radboud University

St. Pachomius

Died about 346. The main facts of his life will be found in MONASTICISM (Section

II: Eastern Monasticismbefore Chalcedon). Having spent some time

with Palemon, he went to a deserted village

named Tabennisi, notnecessarily with the intention of

remaining there permanently. A hermit would

often withdraw for a time to some more remote spot in the desert,

and afterwards return to his old abode. But Pachomius never returned;

a vision bade him stay and erect a monastery;

"very many eager to embrace the monastic life will come hither

to thee". Although from the first Pachomius seems to have realized his

mission to substitute the cenobiticalfor the eremitical life,

some time elapsed before he could realize his idea.

First his elder brother joined him, then others, but all were bent upon

pursuing the eremitical life with

some modifications proposed by Pachomius (e.g., meals in common). Soon,

however, disciples came who were able to enter into his plans. In his

treatment of these earliest recruits Pachomius displayed great wisdom. He

realized that men, acquainted only with the eremitical life,

might speedily become disgusted, if the distracting cares of

the cenobitical lifewere thrust too abruptly upon them. He therefore

allowed them to devote their whole time to spiritualexercises,

undertaking himself all the burdensome work which community life entails.

The monastery atTabennisi,

though several times enlarged, soon became too small and a second was founded

at Pabau (Faou). A monastery at

Chenoboskion (Schenisit) next joined the order, and, before Pachomius died,

there were nine monasteries of

his order for men, and two for women.

How did Pachomius get

his idea of

the cenobitical life? Weingarten (Der Ursprung des

Möncthums, Gotha, 1877) held that Pachomius was once a pagan monk,

on the ground that Pachomius after his baptism took

up his abode in a building which old people said had once been a temple of

Serapis. In 1898 Ladeuze (LeCénobitisme pakhomien, 156) declared this

theory rejected by Catholics and Protestants alike.

In 1903 Preuschen published a monograph (Möncthum und Serapiskult, Giessen,

1903), which his reviewer in the "Theologische Literaturzeitung"

(1904, col. 79), and Abbot Butler in the "Journal of

Theological Studies" (V, 152) hoped would put an end to this

theory. Preuschen showed that the supposed monks of

Serapis were notmonks in

any sense whatever. They were dwellers in the temple who practised

"incubation", i.e. sleeping in the temple to

obtain oracular dreams. But theories of this kind die hard. Mr.

Flinders Petrie in his "Egypt in Israel" (published by the Soc.

for the Prop. of Christ. Knowl., 1911) proclaims Pachomius simply

a monk of

Serapis. Another theory is that Pachomius's relations with

the hermits became

strained, and that he recoiled from their extreme austerities. This theory

also topples over when confronted with

facts. Pachomius's relationswere always affectionate with the

old hermit Palemon,

who helped him to build his monastery.

There was never any rivalry between the hermits and

the cenobites. Pachomius wished his monks to

emulate theausterities of the hermits;

he drew up a rule which made things easier for the less proficient, but did not

check the most extreme asceticism in the more

proficient. Common meals were provided, but those who wished to

absent themselves from them were encouraged to do so, and bread, salt, and

water were placed in their cells. It seems that Pachomius found the solitude of

the eremitical life a

bar to vocations, and held thecenobitical life to be in itself the

higher (Ladeuze, op. cit., 168). The main features

of Pachomius's rule are described in the article already referred to,

but a few words may be said about the rule supposed to have been dictated by

an angel (Palladius,

"Hist. Lausiaca", ed. Butler, pp. 88 sqq.), of which use is

often made in describing a monastery.

According to Ladeuze (263 sqq.), all accounts of this rule go back to Palladius;

and in some most important points it can be shown that it was never followed by

either Pachomius or his monks.

It is unnecessary to discuss the charges brought by Amelineau on the

flimsiest grounds against the morality of the Pachomian monks.

They have been amply refuted by Ladeuze and Schiwietz (cf. also Leipoldt,

"Schneute von Atripe", 147).

Sources

In addition to the

bibliography already given (Eastern Monasticism before Chalcedon) consult

CABROL, Dict. d'archeol. chrét., s.v. Cenobitisme; BOUSQUET AND NAU, Hist.

de S. Pacomus in Ascetica. . .patrologia orient., IV (Paris, 1908).

Bacchus, Francis Joseph. "St. Pachomius." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton

Company, 1911.13 May

2015 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11381a.htm>.

Transcription. This article was transcribed for New Advent by Herman F.

Holbrook. Benedictus Deus in sanctis suis.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. February 1, 1911. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2021 by Kevin Knight. Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11381a.htm

Article

(Saint) Abbot (May 14)

(4th

century) One of the most celebrated of the “Fathers of the Desert.” He was

a hermit in

the Thebaid (Upper Egypt)

from soon after his conversion to Christianity,

and there became a disciple of the Abbot Palaemon. Saint Pachomius

founded several monasteries governed

by a very austere Rule, which he himself had compiled. He seems to have been

the first to group Religious Houses subject to one Rule under the jurisdiction

of a Father General or Head Abbot. At

the time of his holy death (A.D. 348)

seven thousand monks were

in this manner governed by him.

MLA

Citation

Monks of Ramsgate.

“Pachomius”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info.

27 May 2016. Web. 10 May 2023.

<https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-pachomius/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-pachomius/

Lives

of Illustrious Men – Pachomius the presbyter-monk

Article

Pachomius the monk, a man

endowed with apostolic grace both in teaching and in performing miracles, and

founder of the Egyptian monasteries, wrote an Order of discipline suited to

both classes of monks, which he received by angelic dictation. He wrote letters

also to the associated bishops of his district, in an alphabet concealed by

mystic sacraments so as to surpass customary human knowledge and only manifest

to those of special grace or desert, that is To the Abbot Cornelius one, To the

Abbot Syrus one, and one To the heads of all monasteries exhorting that,

gathered together to one very ancient monastery which is called in the Egyptian

language Bau, they should celebrate the day of the Passover together as by

everlasting law. He urged likewise in another letter that on the day of

remission, which is celebrated in the month of August, the chief bishops should

be gathered together to one place, and wrote one other letter to the brethren

who had been sent to work outside the monasteries.

MLA

Citation

Saint Jerome.

“Pachomius the presbyter-monk”. Lives of

Illustrious Men, with the Authors whom Gennadius Added after the Death of the

Blessed Jerome, translated by Ernest Cushing Richardson. CatholicSaints.Info.

17 April 2014. Web. 10 May 2023.

<http://catholicsaints.info/lives-of-illustrious-men-/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/lives-of-illustrious-men-pachomius-the-presbyter-monk/

Miniature

Lives of the Saints – Saint Pachomius, Abbot

Article

In the beginning of the

fourth century great levies of troops were made throughout Egypt for the

service of the Roman emperor. Among the recruits was Pachomius, a young

heathen, then in his twenty-first year. On his way down the Nile he passed a

village whose inhabitants gave him food and money. Marvelling at this kindness,

Pachomius was told they were Christians, and hoped for a reward in the life to

come. He then prayed God to show him the truth, and promised to devote his life

to His service. On being discharged, he returned to a Christian village in

Egypt where he was instructed and baptized. Instead of going home he sought

Palemon, an aged solitary, to learn from him a perfect life, and with great joy

embraced the most severe austerities. Their food was bread and water, once a

day in summer and once in two days in winter; sometimes they added herbs, but

mixed ashes with them. They only slept one hour each night, and this short

repose Pachomius took sitting upright without support. Three times God revealed

to him that he was to found a religious Order at Tabenna, and an angel gave him

a rule of life. Trusting in God he built a monastery, although he had no

disciples; but vast multitudes soon flocked to him, and he trained them in

perfect detachment from creatures and from self. His visions and miracles were

innumerable, and he read all hearts. His holy death occurred in 348.

“To live in great

simplicity, and in a wise ignorance, is exceeding wise.” – Saint Pachomius

“Most men look for

miracles as a sign of sanctity, but I prefer a solid and heartfelt humility to

raising the dead.” – Saint Pachomius

One day a monk, by dint

of great exertions, contrived to make two mats instead of the one which was the

usual daily task, and set them both out in front of his cell, that Pachomius

might see how diligent he had been. But the Saint, perceiving the vainglory

which had prompted the act, said, “This brother has taken a great deal of pains

from morning till night to give his work to the devil.” Then, to cure him of

his delusion, Pachomius imposed on him as a penance to keep his cell for five

months and to taste no food but bread and water.

“Take heed, therefore,

that you do not your justice before men to be seen by them; otherwise you shall

not have a reward of your Father who is in heaven.” – Matthew 6:i

MLA

Citation

Henry Sebastian Bowden.

“Saint Pachomius, Abbot”. Miniature Lives of the

Saints for Every Day of the Year, 1877. CatholicSaints.Info.

23 February 2015. Web. 10 May 2023.

<https://catholicsaints.info/miniature-lives-of-the-saints-saint-pachomius-abbot/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/miniature-lives-of-the-saints-saint-pachomius-abbot/

Saint

Pachomius fresco, Monastery of the Cross - Interior

ST. PACHOMIUS, ABBOT.

In the beginning of the fourth century, great levies of troops were made

throughout Egypt for the service of the Roman emperor. Among the recruits was

Pachomius, a young heathen, then in his twenty-first year. On his way down the

Nile he passed a village, whose inhabitants gave him food and money. Marvelling

at this kindness, Pachomius was told they were Christians, and hoped for a

reward in the life to come. He then prayed God to show him the truth, and

promised to devote his life to His service. On being discharged, he returned to

a Christian village in Egypt, where he was instructed and baptized. Instead of

going home, he sought Palemon, an aged solitary, to learn from him a perfect

life, and with great joy embraced the most severe austerities. Their food was

bread and water, once a day in summer, and once in two days in winter;

sometimes they added herbs, but mixed ashes with them. They only slept one hour

each night, and this short repose Pachomius took sitting upright without

support. Three times God revealed to him that he was to found a religious order

at Tabenna; and an angel gave him a rule of life. Trusting in God, he built a

monastery, although he had no disciples; but vast multitudes soon flocked to

him, and he trained them in perfect detachment from creatures and from self.

One day a monk, by dint of great exertions, contrived to make two mats instead

of the one which was the usual daily task, and set them both out in front of

his cell, that Pachomius might see how diligent he had been. But the Saint,

perceiving the vainglory which had prompted the act, said, "This brother

has taken a great deal of pains from morning till night to give his work to the

devil." Then, to cure him of his delusion, Pachomius imposed on him as

penance to keep his cell for five months and to taste no food but bread and

water. His visions and miracles were innumerable, and he read all hearts. His

holy death occurred in 348.

REFLECTION.—" To live in great simplicity," said St. Pachomius,

"and in a wise ignorance, is exceeding wise."

SOURCE : http://jesus-passion.com/Saint_Pachomius.htm

Saint Pachomius

St. Pachomius was born

about 292 in the Upeer Thebaid in Egypt and was inducted into the Emperor’s

army as a twenty-year-old. The great kindness of Christians at Thebes toward

the soldiers became embedded in his mind and led to his conversion after his

discharge. After being baptized, he became a disciple of an anchorite, Palemon,

and took the habit. The two of them led a life of extreme austerity and total

dedication to God; they combined manual labor with unceasing prayer both day

and night.

Later, Pachomius felt

called to build a monastery on the banks of the Nile at Tabennisi; so about 318

Palemon helped him build a cell there and even remained with him for a while.

In a short time some one hundred monks joined him and Pachomius organized them

on principles of community living. So prevalent did the desire to emulate the

life of Pachomius and his monks become, that the holy man was obliged to

establish ten other monasteries for men and two nunneries for women. Before his

death in 346, there were seven thousand monks in his houses, and his Order

lasted in the East until the 11th century.

St. Pachomius was the first monk to organize hermits into groups and write down a Rule for them. Both St. Basil and St. Benedict drew from his Rule in setting forth their own more famous ones. Hence, though St. Anthony is usually regarded as the founder of Christian monasticism, it was really St. Pachomius who began monasticism as we know it today.

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/pachomius/

Pachomius of Tabenna, Abbot (RM)

(also known as Pachome)

Born in the Upper Thebaîd near Esneh, Egypt, c. 290-292; died at Tabennisi,

Egypt, on May 15, c. 346-348; feast day in the East is May 15.

"It is very much better for you to be one among a crowd of a thousand

people and to possess a very little humility, than to be a man living in the

cave of a hyena in pride." --Pachomius

Pachomius, son of pagan parents, was unwillingly drafted into the Theban army

at the age of 20, probably to help Maximinus wage war against Licinius and

Constantine. When his unit reached Thebes the officers in charge, knowing the

feelings of their reluctant recruits, locked them up. They were taken down the

Nile as virtual prisoners under terrible conditions. The soldier-prisoners were

fed, given money, and treated with great kindness by the Christians of

Latopolis (Esneh) while they were being shipped down the Nile, and Pachomius

was struck by this. When the army disbanded after the overthrow of Maximinus,

he returned to Khenoboskion (Kasr as-Sayd). The kindness of the Christians to

strangers caused Pachomius to enquire about their faith and to enroll himself

as a catechumen at the local Christian church. After his baptism in 314 he

searched for the best way to respond to the grace he had received in the

sacrament. He prayed continually:

"O God, Creator of heaven and earth, cast on me an eye of pity: deliver me

from my miseries: teach me the true way of pleasing You, and it shall be the

whole employment, and most earnest study of my life to serve You, and to do

Your will."

Like many neophytes, Pachomius was in danger of the temptation to do too much.

Zeal is often an artifice of the devil to make a novice undertake too much too

fast, and run indiscreetly beyond his strength. If the sails gather too much

wind, the vessel is driven ahead, falls on some rock, and splits. Eagerness may

be a symptom of secret passion, not of true virtue if it is willful and

impatient at advice. Thus, Pachomius wanted to find a skillful conductor.

Hearing about a holy man was serving God in perfection, Pachomius finally

sought out the elderly desert hermit named Saint Palaemon and asked to be his

follower. They lived very austerely, doing manual labor to earn money for the

relief of the poor and their own subsistence, and often praying all night.

Palaemon would not use wine or oil in his food, even on Easter day, so as not

to lose sight of the meaning of Christ's suffering. He set Pachomius to

collecting briars barefoot; and the saint would often bear the pain as a

reminder of the nails that entered Christ's feet.

One day in 318 while walking in the Tabennisi Desert on the banks of the Nile

north of Thebes, Pachomius is said to have heard a voice that told him to begin

a monastery there. He also experienced a vision in which an angel set out

directions for the religious life. The two hermits constructed a cell there

together about 320, and Palaemon lived with him for a while before returning to

solitude. Pachomius's first follower was his own brother, John, and within a

short time, there were 100 monks.

Pachomius wrote the first communal rule for monks (which some say survives in a

Latin translation by Saint Jerome and others say is lost), an innovation on the

common type of eremitical monachism. The life style was severe but less

rigorous than that of typical hermits. Their habit was a sleeveless tunic of

rough white linen with a cowl that prevented them from seeing one another at

group meals taken in silence. (Silence was strictly observed at all times.) They

wore on their shoulders a white goatskin, called Melotes. The monks learned the

Bible by heart and came together daily for prayer. By his rule, the fasts and

tasks of work of each were proportioned to his strength. They received the holy

communion on the first and last days of every week. Novices were tried with

great severity before they were admitted to the habit and profession of vows.

His rule influenced SS. Basil and Benedict; 32 passages of Benedict's rule are

based on Pachomius's guidelines.

Pachomius himself went fifteen years without ever lying down, taking his short

rest sitting on a stone. He begrudged the necessity for sleep because he wished

he could have been able to employ all his moments in the actual exercises of

divine love. From the time of his conversion he never ate a full meal. The

saint, with the greatest care, comforted and served the sick himself. He

received into his community the sickly and weak, rejecting none just because he

lacked physical strength. The holy monk desired to lead all souls to heaven

that had the fervor to walk in the paths of perfection.

He opened six other monasteries and a convent for his sister on the opposite

side of the Nile (but would never visit her) in the Thebaîd, and from 336 on

lived primarily at Pabau near Thebes, which outgrew the Tabennisi community in

fame. He was an excellent administrator, and acted as superior general.

The communities were broken down into houses according to the crafts the

inhabitants practiced, such as tailoring, baking, and agriculture. Goods made

in the monasteries were sold in Alexandria. Because of his military background,

Pachomius styled himself as a general who could transfer monks from one house

to another for the good of the whole. There were local superiors and deans in

charge of the houses. All those in authority met each year at Easter and in

August to review annual accounts. Pachomius also built a church for poor

shepherds and acted as its lector, but he refused to seek ordination for the

priesthood or to present any of his monks for ordination, although he permitted

priests to join and serve the communities.

Pachomius also had an enormous sense of justice. Although the money garnered by

their labors was destined for the poor, when one of the procurators had sold

the mats at market at a higher price than the saint had bid him, he ordered him

to carry back the money to the buyers, and chastised him for his avarice.

The author of his vita tells us that the saint had the gift of tongues.

Although he never learned Latin or Greek, he could speak them fluently when the

necessity arose. Pachomius is credited with many miraculous cures with blessed

oil of the sick and those possessed by devils. But he often said that their

sickness or affliction was for the good of their souls and only prayed for

their temporal comfort, with this clause or condition, if it should not prove

hurtful to their souls. His dearest disciple, Saint Theodorus who after his

death succeeded him as superior general, was afflicted with a perpetual headache.

Pachomius, when asked by some of the brethren to pray for his health, answered:

"Though abstinence and prayer be of great merit, yet sickness, suffered

with patience, is of much greater."

One of the saints chief occupations was praying for the spiritual health of his

disciples and others. He took every opportunity to curb and heal their

passions, especially that of pride. One day a certain monk having doubled his

diligence at work, and made two mats instead of one and set them where

Pachomius might see them. The saint perceiving the snare, said "This

brother has taken a great deal of pains from morning till night, to give his

work to the devil." In order to cure the monk's vanity, Pachomius ruled

that the proud monk do penance by remaining in his cell for five months.

Another time a young actor named Silvanus entered the monastery to do penance,

but continued to live an undisciplined life by trying to entertain his fellows.

Pachomius had a difficult time curbing his youthful playfulness until he explained

the dreadful punishments awaiting those who mock God. From that moment divine

grace touched Saint Silvanus, he led an exemplary life and was moved by the

gift of tears.

Pachomius was an opponent of Arianism and for this reason was denounced to a council

of bishops at Latopolis, but was completely exonerated. Though he was never

ordained, he was highly respected and even visited by Saint Athanasius in 333.

By the time of his death, there were 3,000 (7,000 according to one source)

monks in nine monasteries and two convents for women. He died in an epidemic.

Pachomiusis one of the best-known figures in the history of monasticism

(Attwater, Benedictines, Bentley, Delaney, Farmer, Husenbeth, Walsh, White).

The vita of Saint Pachomius was translated into Latin from the Greek in the 6th

century by the abbot Dionysus Exiguus, so called not because of his height but

because of his great humility. Dionysus includes this story:

"At another time the cohorts of the devils plotted to tempt the man of God

by a certain phantasy. For a crowd of them assembling together, were seen by

him tying up the leaf of a tree with great ropes and tugging it along with

immense exertion, ranking in order on the right and left: and the one side

would exhort the other, and strain and tug, as if they were moving a stone of

enormous weight. And this the wicked spirits were doing so as to move him, if

they could, to loud laughter, and so they might cast it in his teeth. But

Pachome, seeing their impudence, groaned and fled to the Lord with his

accustomed prayers: and straightway by the virtue of Christ all their

triangular array was brought to naught. . . . "After this, so much trust

had the blessed Pachome learned to place in God . . . that many a time he trod

on snakes and scorpions, and passed unhurt through all: and the crocodiles, if

ever he had necessity to cross the river, would carry him with the utmost

subservience, and set him down at whatever spot he indicated" (Dionysus).

In art, Saint Pachomius

is a hermit holding the tablets of his rule. He might also be shown (1) as an

angel brings him the monastic rule; (2) being tempted by a she-devil; (3) in a

hairshirt; (4) with Saint Palaemon (Roeder), or (5) walking among serpents

(White).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0509.shtml

St. Pachomius, Abbot

From his authentic life compiled by a monk of Tabenna soon after his death. See Tillemont, t. 7. Ceillier, t. 4. Helyot, t. 1. Rosweide, l. 1. p. 114, and Papebroke, t. 3, Maij. p. 287.

A.D. 348.

THOUGH St. Antony be

justly esteemed the institutor of the cenobitic life, or that of religious

persons living in community under a certain rule, St. Pachomius was the first

who drew up a monastic rule in writing. He was born in Upper Thebais about the

year 292, of idolatrous parents, and was educated in their blind superstition,

and in the study of the Egyptian sciences. From his infancy, he was meek and

modest, and had an aversion to the profane ceremonies used by the infidels in

the worship of their idols. Being about twenty years of age, he was pressed

into the emperor’s troops, probably the tyrant Maximinus, 1 who

was master of Egypt from the year 310; and in 312 made great levies to carry on

a war against Licinius and Constantine. He was, with several other recruits,

put on board a vessel that was sailing down the river. They arrived in the

evening at Thebes or Diospolis, the capital of Thebais, a city in which dwelt

many Christians. Those true disciples of Christ sought every opportunity of

relieving and comforting all who were in distress, and were moved with

compassion towards the recruits, who were kept close confined, and very

ill-treated. The Christians of this city showed them the same tenderness as if

they had been their own children; took all possible care of them, and supplied

them liberally with money and necessaries. Such an uncommon example of

disinterested virtue made a great impression on the mind of Pachomius. He

inquired who their pious benefactors were, and when he heard that they believed

in Jesus Christ the only Son of God, and that in the hope of a reward in the

world to come they laboured continually to do good to all mankind, he found kindled

in his heart a great love of so holy a law, and an ardent desire of serving the

God whom these good men adored. The next day, when he was continuing his

journey down the river, the remembrance of this purpose strengthened him to

resist a carnal temptation. From his infancy he had been always a lover of

chastity and temperance; but the example of the Christians had made those

virtues appear to him far more amiable, and in a new light. After the overthrow

of Maximinus, his forces were disbanded. Pachomius was no sooner returned home,

but he repaired to a town in Thebais, in which there was a Christian church,

and there he entered his name among the catechumens, or such as were preparing

for baptism; and having gone through the usual course of preliminary instructions

and practices with great attention and fervour, he received that sacrament at

Chenoboscium, with great sentiments of piety and devotion. From his first

acquaintance with our holy faith at Thebes, he had always made this his prayer:

“O God, Creator of heaven and earth, cast on me an eye of pity: deliver me from

my miseries: teach me the true way of pleasing you, and it shall be the whole

employment, and most earnest study of my life to serve you, and to do your

will.” The perfect sacrifice of his heart to God, was the beginning of his

eminent virtue. The grace by which God reigns in his soul, is a treasure

infinitely above all price. We must give all to purchase it. 2 To

desire it faintly is to undervalue it. He is absolutely disqualified and unfit

for so great a blessing, and unworthy ever to receive it, who seeks it by

halves, or who does not esteem all other things as dung that he may gain

Christ.

When Pachomius was

baptized, he began seriously to consider with himself how he should most

faithfully fulfil the obligations which he had contracted, and attain to the

great end to which he aspired. There is danger even in fervour itself. It is

often an artifice of the devil to make a novice undertake too much at first,

and run indiscreetly beyond his strength. If the sails gather too much wind,

the vessel is driven a-head, falls on some rock and splits. Eagerness is a

symptom of secret passion, not of true virtue, where it is wilful and impatient

at advice. Pachomius was far from so dangerous a disposition, because his

desire was pure, therefore his first care was to find a skilful conductor.

Hearing that a venerable old man named Palemon served God in the desert in

great perfection, he sought him out, and with great earnestness begged to live

under his direction. The hermit having set before him the difficulties and

austerities of his way of life, which several had already attempted in vain to

follow, advised him to make a trial of his strength and fervour in some

monastery; and, to give him a sketch of the difficulties he had to encounter in

the life he aspired to, he added: “Consider, my son, that my diet is only bread

and salt: I drink no wine, use no oil, watch one half of the night, spending

that time in singing psalms or in meditating on the holy scriptures, and

sometimes pass the whole night without sleeping.” Pachomius was amazed at this

account, but not discouraged. He thought himself able to undertake everything

that might be a means to render his soul pleasing to God, and readily promised

to observe whatever Palemon should think fit to enjoin him; who thereupon

admitted him into his cell, and gave him the monastic habit. Pachomius was by

his example enabled to bear solitude, and an acquaintance with himself. They

sometimes repeated together the psalter, at other times they exercised

themselves in manual labours (which they accompanied with interior prayer) with

a view to their own subsistence and the relief of the poor. Pachomius prayed

above all things for perfect purity of heart, that being disengaged from all

secret attachment to creatures, he might love God with all his affections. And

to destroy the very roots of all inordinate passions, it was his first study to

obtain the most profound humility, and perfect patience and meekness. He prayed

often with his arms stretched out in the form of a cross; which posture was

then much used in the church. He was in the beginning often drowsy at the night

office. Palemon used to rouse him, and say: “Labour and watch, my dear

Pachomius, lest the enemy overthrow you and ruin all your endeavours.” Against

this weakness and temptation he enjoined him, on such occasions, to carry sand

from one place to another, till his drowsiness was overcome. By this means the

novice strengthened himself in the habit of watching. Whatever instructions he

read or heard, he immediately endeavoured fervently to reduce to practice. One

Easter-day Palemon bade the disciple prepare a dinner for that great festival.

Pachomius took a little oil, and mixed it with the salt which he pounded small,

and added a few wild herbs, which they were to eat with their bread. The holy

old man having made his prayer, came to table; but at the sight of the oil he

struck himself on the forehead, and said with tears: “My Saviour was crucified,

and shall I indulge myself so far as to eat oil?” Nor could he be prevailed

upon to taste it. Pachomius used sometimes to go into a vast uninhabited

desert, on the banks of the Nile, called Tabenna, in the diocess of Tentyra, a

city between the Great and Little Diospolis. Whilst he was there one day in

prayer, he heard a voice which commanded him to build a monastery in that

place, in which he should receive those who should be sent by God to serve him

faithfully. He received, about the same time, from an angel who appeared to

him, certain instructions relating to a monastic life. 3 Pachomius

going back to Palemon, imparted to him this vision; and both of them coming to

Tabenna built there a little cell towards the year 325, about twenty years

after St. Antony had founded his first monastery. After a short time, Palemon

returned to his former dwelling, having promised his disciple a yearly visit,

but he died soon after, and is honoured in the Roman Martyrology on the 11th of

January.

Pachomius received

first his own eldest brother John, and after his death many others, so that he

enlarged his house; and the number of his monks in a short time amounted to a

hundred. Their clothing was of rough linen; that of St. Pachomius himself often

hair-cloth. He passed fifteen years without ever lying down, taking his short

rest sitting on a stone. He even grudged himself the least time which he

allowed to necessary sleep, because he wished he could have been able to employ

all his moments in the actual exercises of divine love. From the time of his

conversion he never ate a full meal. By his rule, the fasts and tasks of work

were proportioned to every one’s strength; though all are together in one

common refectory, in silence, with their cowl or hood drawn over their heads

that they might not see one another at their meals. Their habit was a tunic of

white linen without sleeves, with a cowl of the same stuff; they wore on their

shoulders a white goat-skin, called a Melotes. They received the holy communion

on the first and last days of every week. Novices were tried with great

severity before they were admitted to the habit, the taking of which was then

deemed the monastic profession, and attended with the vows. St. Pachomius

preferred none of his monks to holy orders, and his monasteries were often

served by priests from abroad; though he admitted priests when any presented

themselves to the habit, and he employed them in the functions of their

ministry. All his monks were occupied in various kinds of manual labour: no

moment was allowed for idleness. The saint, with the greatest care, comforted and

served the sick himself. Silence was so strictly observed at Tabenna, that a

monk, who wanted anything necessary, was only to ask for it by signs. In going

from one place to another, the monks were ordered always to meditate on some

passage of the holy scripture, and sing psalms at their work. The sacrifice of

the mass was offered for every monk who died, as we read in the life of St.

Pachomius. 4 His

rule was translated into Latin by St. Jerom, and is still extant. He received

the sickly and weak, rejecting none for the want of corporal strength, being

desirous to conduct to heaven all souls which had fervour to walk in the paths

of perfection. He built six other monasteries in Thebais, not far asunder, and

from the year 336 chose often to reside in that of Pabau or Pau, near Thebes,

in its territory, though not far from Tabenna, situated in the neighbouring

province of Diospolis, also in Thebais. Pabau became a more numerous and more

famous monastery than Tabenna itself. By the advice of Serapion, bishop of

Tentyra, he built a church in a village for the benefit of the poor shepherds,

in which for some time he performed the office of Lector, reading to the people

the word of God with admirable fervour, in which function he appeared rather

like an angel than a man. He converted many infidels, and zealously opposed the

Arians, but could never be induced by his bishop to receive the holy order of

priesthood. In 333 he was favoured with a visit of St. Athanasius at Tabenna.

His sister at a certain time came to his monastery desiring to see him; but he

sent her word at the gate, that no woman could be allowed to enter his

inclosure, and that she ought to be satisfied with hearing that he was alive.

However, it being her desire to embrace a religious state, he built her a

nunnery on the other side of the Nile, which was soon filled with holy virgins.

St. Pachomius going one day to Pané, one of his monasteries, met the funeral

procession of a tepid monk deceased. Knowing the wretched state in which he

died, and to strike a terror into the slothful, he forbade his monks to proceed

in singing psalms, and ordered the clothes which covered the corpse to be

burnt, saying: “Honours could only increase his torments; but the ignominy with

which his body was treated, might move God to show more mercy to his soul; for

God forgives some sins not only in this world, but also in the next.” When the

procurator of the house had sold the mats at market at a higher price than the

saint had bid him, he ordered him to carry back the money to the buyers, and

chastised him for his avarice.

Among many miracles

wrought by him, the author of his life assures us, that though he had never

learned the Greek or Latin tongue, he sometimes miraculously spoke them; he

cured the sick and persons possessed by devils with blessed oil. But he often

told sick or distressed persons, that their sickness or affliction was an

effect of the divine goodness in their behalf; and he only prayed for their

temporal comfort, with this clause or condition, if it should not prove hurtful

to their souls. His dearest disciple St. Theodorus, who after his death

succeeded him in the government of his monasteries, was afflicted with a

perpetual head-ache. St. Pachomius, when desired by some of the brethren to

pray for his health, answered: “Though abstinence and prayer be of great merit,

yet sickness, suffered with patience, is of much greater.” He chiefly begged of

God the spiritual health of the souls of his disciples and others, and took

every opportunity to curb and heal their passions, especially that of pride.

One day a certain monk having doubled his diligence at work, and made two mats

instead of one, set them where St. Pachomius might see them. The saint

perceiving the snare, said, “This brother hath taken a great deal of pains from

morning till night, to give his work to the devil.” And, to cure his vanity by

humiliations, he enjoined him by way of penance, to keep his cell five months,

with no other allowance than a little bread, salt, and water. A young man named

Sylvanus, who had been an actor on the stage, entered the monastery of St.

Pachomius with the view of doing penance, but led for some time an

undisciplined life, often transgressing the rules of the house, and still fond

of entertaining himself and others with buffooneries. The man of God

endeavoured to make him sensible of his danger by charitable remonstrances, and

also employed his more potent arms of prayer, sighs, and tears, for his poor

soul. Though for some time he found his endeavours fruitless, he did not desist

on that account; and having one day represented to this impenitent sinner, in a

very pathetic manner, the dreadful judgments which threaten those who mock God,

the divine grace touching the heart of Sylvanus, he from that moment began to

lead a life of great edification to the rest of the brethren; and being moved

with the most feeling sentiments of compunction, he never failed, wheresoever

he was, and howsoever employed, to bewail with bitterness his past

misdemeanours. When others entreated him to moderate the floods of his tears,

“Ah,” said he, “how can I help weeping, when I consider the wretchedness of my

past life, and that by my sloth I have profaned what was most sacred? I have

reason to fear lest the earth should open under my feet, and swallow me up, as

it did Dathan and Abiron. Oh! suffer me to labour with ever-flowing fountains

of tears, to expiate my innumerable sins. I ought, if I could, even to pour

forth this wretched soul of mine in mourning; it would be all too little for my

offences.” In these sentiments of contrition he made so great progress in

virtue, that the holy abbot proposed him as a model of humility to the rest;

and when, after eight years spent in this penitential course, God had called

him to himself by a holy death, St. Pachomius was assured by a revelation, that

his soul was presented by angels a most agreeable sacrifice to Christ. The

saint was favoured with a spirit of prophecy, and with great grief foretold the

decay of monastic fervour in his Order in succeeding ages. In 348 he was cited

before a council of bishops at Latopolis, to answer certain matters laid to his

charge. He justified himself against the calumniators, but in such a manner

that the whole council admired his extraordinary humility. The same year, God

afflicted his monasteries with a pestilence, which swept off a hundred monks.

The saint himself fell sick, and during forty days suffered a painful distemper

with incredible patience and cheerfulness, discovering a great interior joy at

the approach of the end of his earthly pilgrimage. In his last moments he

exhorted his monks to fervour, and having armed himself with the sign of the

cross, resigned his happy soul into the hands of his Creator in the

fifty-seventh year of his age. He lived to see in his different monasteries

seven thousand monks. His Order subsisted in the East till the eleventh

century; for Anselm, bishop of Havelburgh, writes, that he saw five hundred

monks of this institute in a monastery at Constantinople. St. Pachomius formed

his disciples to an eminent a degree of perfection chiefly by his own fervent

spirit and example; for he always appeared the first, the most exact, and the

most fervent in all the exercises of the community. To the fervour and

watchfulness of the superior it was owing that in so numerous a community

discipline was observed with astonishing regularity, as Palladius and Cassian

observe. The former says that they eat with their cowl drawn so as to hide the

greater part of their faces, and with their eyes cast down, never looking at

one another. Many contented themselves with taking a very few mouthfuls of

bread and oil, or of such like dish; others of pottage only. So great was the

silence that reigned amongst them whilst every one followed his employment,

that in the midst of so great a multitude, a person seemed to be in a solitude.

Cassian tells us, 5 that

the more numerous the monastery was, the more perfect and rigorous was regular

observance of discipline, and all constantly obeyed their superior more readily

than a single person is found to do in other places. Nothing so much weakens

the fervour of inferiors as the example of a superior who easily allows himself

exemptions or dispensations in the rule. The relaxation of monastic discipline

is often owing to no other cause. How enormous is the crime of such a scandal.

Note 1. Those who

place the conversion of St. Pachomius later, think this emperor was

Constantine. But for our account see Tillemont, Hist. Eccl. note 2, t. 7, p. 675. [back]

Note 2. Matt. xiii.

44. [back]

Note 3. Some late

editions say the angel gave St. Pachomius the whole rule in writing which he

prescribed to his monks; but this is an interpolation not found in the genuine

life published by the Bollandists, Maij. t. 3, 10, p. 201. [back]

Note 4. Acta

Sanctorum, Maij. t. 3, p. 321. [back]

Note 5. Cassian, l.

4; Instit. c. 1. [back]

Rev. Alban

Butler (1711–73). Volume V: May. The Lives of the Saints. 1866.

SOURCE : http://www.bartleby.com/210/5/142.html

Saint Pachomius

the Great

May 28th (May 15th old

calendar).

Saint Pachomius was an

Egyptian by birth and was a pagan in his youth. As a soldier, he took part in

the Emperor Constantine's war against Maxentius. After that, learning from

Christians about the one God and seeing their devout life, Pachomius was baptized

and went to the Tabennisiot desert, to the famous ascetic Palamon, with whom he

lived in asceticism for ten years. Then an angel appeared to him in the robes

of a monk of the Great Habit at the place called Tabennisi and gave him a

tablet on which was written the rule of a cenobitic monastery, commanding him

to found such a monastery in that place and prophesying to him that many monks

would come to it seeking the salvation of their souls. Obeying the angel of

God, Pachomius began building many cells, although there was no-one in that

place but himself and his brother John. When his brother grumbled at him for

doing this unnecessary building, St. Pachomius simply told him that he was

following God's command, without explaining who would live there, or when. But

many men soon assembled in that place, moved by the Spirit of God, and began to

live in asceticism under the rule that Pachomius had received from the angel.

When

the number of monks had increased greatly, Pachomius, step by step, founded six

further monasteries. The number of his disciples grew to seven thousand. St.

Antony is regarded as the founder of the eremitic life, and St. Pachomius of

the monastic, communal life. The humility, love of toil and abstinence of this

holy father were and remain a rare example for the imitation of monks. St.

Pachomius performed innumerable miracles, and also endured innumerable

temptations from demons and men. And he served men as both father and brother.

He roused many to set out on the way of salvation, and brought many into the

way of truth. He was and remains a great light in the Church and a great

witness to the truth and righteousness of Christ. He entered peacefully into

rest in 346, at the age of sixty. The Church has raised many of his followers to

the ranks of the saints: Theodore, Job, Paphnutius, Pecusius, Athenodorus,

Eponichus, Soutus, Psois, Dionysius, Petronius and others.

Troparion Tone 5

As

a pastor of the Chief Shepherd/ thou didst guide flocks of monks into the

heavenly sheepfold / thyself illumined, thou didst instruct others concerning

the Habit and Rule./ And now thou dost rejoice with them in the heavenly

mansions.

Kontakion Tone 2

O

Godbearing Pachomius, after living the life of Angels in thy body/ thou wast

granted their glory./ Now thou art standing with them before God's throne/ and

praying that we all may be forgiven.

SOURCE : http://www.fatheralexander.org/booklets/english/saints/pachomius_great.htm

San Pacomio Abate

Alto Egitto, 287 - 347

Nacque nell'Alto Egitto,

nel 287, da genitori pagani. Arruolato a forza nell'esercito imperiale all'età

di vent'anni, finì in prigione a Tebe con tutte le reclute. Protetti

dall'oscurità, la sera alcuni cristiani recarono loro un po' di cibo. Il gesto

degli sconosciuti commosse Pacomio, che domandò loro chi li spingesse a far

questo. «Il Dio del cielo» fu la risposta dei cristiani. Quella notte Pacomio

pregò il Dio dei cristiani di liberarlo dalle catene, promettendogli in cambio

di dedicare la propria vita al suo servizio. Tornato in libertà, adempì al voto

aggregandosi a una comunità cristiana di un villaggio del sud, l'attuale

Kasr-es-Sayad, dove ebbe l'istruzione necessaria per ricevere il battesimo. Per

qualche tempo condusse vita da asceta, dedicandosi al servizio della gente del

luogo, poi si mise per sette anni sotto la guida di un vecchio monaco,

Palamone. Durante una parentesi di solitudine nel deserto, una voce misteriosa

lo invitò a fissare la sua dimora in quel luogo, al quale presto sarebbero convenuti

numerosi discepoli. Alla morte dell'abate Pacomio, i monasteri maschili erano

nove, più uno femminile. Del santo restò sconosciuto il luogo della

sepoltura. (Avvenire)

Emblema: Bastone

pastorale

Martirologio Romano:

Nella Tebaide, in Egitto, san Pacomio, abate, che, ancora pagano, spinto da un

gesto di carità cristiana nei confronti dei soldati suoi compagni con lui

detenuti, si convertì al cristianesimo, ricevendo dall’anacoreta Palémone

l’abito monastico; dopo sette anni, per divina ispirazione, istituì molti

cenobi per accogliere fratelli e scrisse per i monaci una regola divenuta

famosa.

Come ti converto uno che non crede? Con l’esempio di una carità viva. Prendete un giovanotto pagano, arruolato a forza nell’esercito imperiale e subito fatto prigioniero insieme a tutte le reclute. Pensate allo sconcerto, alla delusione e alla sofferenza dei giorni di prigionia, insieme all’incertezza di quella che sarà la sua sorte. Immaginate l’incontro furtivo nella notte con alcuni uomini, che di nascosto vengono a confortarlo, sfamarlo e incoraggiarlo e che, insieme all’aiuto materiale, gli sussurrano parole di Cielo e dicono di fare tutto ciò in nome del “Dio dei cristiani”. Il giovanotto ne resta così colpito ed ammirato da rivolgersi all’ancora ignoto “Dio dei cristiani”, promettendo di dedicare a lui tutta la sua vita se riuscirà a liberarsi da quelle catene. E quando ciò avviene, al giovanotto restando solo due cose da fare: imparare a credere in quel Dio che lo ha liberato e, poi, studiare il modo per sciogliere il suo voto. E’ questa, in sintesi, l’origine dell’esperienza religiosa di San Pacomio, nato nell’Alto Egitto nel 287 e convertitosi al cristianesimo come abbiamo appena descritto. Dopo il battesimo, la vita spirituale di Pacomio cerca modi per esprimersi: prima all’interno di una comunità cristiana di cui si mette a servizio, quasi a voler subito mettere in pratica l’insegnamento di carità che quegli sconosciuti cristiani gli avevano trasmesso in carcere; poi attraverso l’esperienza eremitica, cioè l’incontro con Dio nella solitudine del deserto, di cui il grande Antonio è stato maestro un secolo prima. Pacomio, però, apre una strada nuova: all’imitazione di Gesù, solo nel deserto, in un rapporto esclusivo con il Padre e alle prese con le tentazioni del demonio, egli preferisce imitare Gesù che vive con i suoi discepoli ed insegna loro a pregare. Ecco nascere così attorno a lui un’interessante ed inedita esperienza di monachesimo: il cenobitismo o vita comune, dove la disciplina e l’autorità sostituiscono l’anarchia degli anacoreti. Quindi, non più e non solo la solitudine degli eremiti precedenti,con le astinenze, i digiuni e le penitenze corporali che li caratterizzano ma che possono anche nascondere l’insidia della bizzarria e dell’orgoglio; piuttosto, una comunità cristiana sul modello di quella fondata da Gesù con gli apostoli, basata sulla comunione nella preghiera, nel lavoro e nella refezione e concretizzata nel servizio reciproco. Il documento su cui Pacomio vuole regolare la vita della comunità è la Sacra Scrittura, che i monaci imparano a memoria e recitano a bassa voce mentre svolgono il loro lavoro: un contatto diretto con Dio attraverso il “sacramento della Parola”. Pacomio muore il 14 maggio 346, lasciando in eredità una decina di monasteri, di cui un paio anche femminili. Il luogo della sua sepoltura è sempre stato sconosciuto, perché un punto di morte aveva raccomandato al discepolo più fedele di seppellirlo in un posto segreto, per evitare la venerazione dei suoi seguaci.

Autore: Gianpiero Pettiti

L’esempio di un gesto di generosità e di altruismo può cambiare l’anima e il destino di una persona: da malvagia può diventare compassionevole, da avara prodiga, da collerica mite, da pigra laboriosa, da atea credente. È quello che è capitato al giovane pagano Pacomio, nato in Egitto nel 287, mai entrato in contatto con il Cristianesimo. Costretto ad arruolarsi nell’esercito romano, viene fatto prigioniero assieme ai suoi compagni a Tebe (Grecia). Pacomio è disperato perché non sa che cosa gli riserverà il futuro. Di notte vede arrivare furtivamente alcune persone che offrono ai prigionieri cibo e parole di conforto. Il soldato si stupisce e chiede il motivo di questo comportamento. «Siamo cristiani – si sente rispondere – discepoli di Gesù, il Figlio di Dio che ci ha insegnato ad aiutare il prossimo». Parole che colpiscono profondamente Pacomio che, con fiducia, chiede a Gesù di essere liberato. In cambio consacrerà la sua vita a Dio, farà quello che a lui è gradito e offrirà il Bene a tutti gli uomini.

Pacomio ritrova la libertà e tiene fede alla solenne promessa. Si reca in un villaggio dove aiuta i poveri e cura gli ammalati. Dopo aver ricevuto il Battesimo si dedica alla vita solitaria per alcuni anni, imitando gli eremiti del deserto. Un giorno, però, una visione Celeste gli suggerisce di fondare una comunità per “chiamare” gli altri uomini a Dio. Pacomio capisce che deve pregare insieme agli altri e lavorare con loro per mantenersi e per aiutare il prossimo. Il santo segue l’esempio degli apostoli che lavoravano, mangiavano e pregavano insieme. Egli raduna i monaci, diventati sempre più numerosi, che mettono tutti i loro beni in comune e si aiutano vicendevolmente. Detta alcune norme di comportamento per regolare la vita della comunità: una disciplina che va rispettata, un’autorità alla quale si deve obbedienza per sostituire l’anarchia (libertà di fare quello che si vuole). Una di queste regole, per stare sempre a contatto con Dio, è di imparare a memoria la Bibbia e di recitarla sottovoce mentre si lavora.

Pacomio muore nel 347 dopo aver fondato otto monasteri maschili e due femminili. Dove dimora il suo corpo non è dato saperlo, poiché, tenendo fede alla sua grande umiltà, in punto di morte l’ex soldato chiede e ottiene dal suo discepolo Teodoro di essere sepolto in un posto sconosciuto a tutti, onde evitare di essere ricordato e venerato.

Autore: Mariella Lentini

SOURCE : http://www.santiebeati.it/dettaglio/52450

PACOMIO, abate di Tabennesi santo. Nato nella diocesi di Snē (Latopolis dei Greci) nel 287, P. mori a Phbōou nel 347, dopo aver istituito nell'Alto Egitto una Congregazione di nove fiorenti monasteri. Fu profondamente venerato dai suoi discepoli che lo considerarono come padre del cenobitismo egiziano.

Sommario: I. Fonti.

- II. Vita. - III. Spiritualità. - IV. Culto. - V. Iconografia.

I. FONTI. Tra i

diversi testi della documentazione pacomiana, la Vita costituisce

certamente il documento piú importante e piú prezioso per la conoscenza del

personaggio e della prima generazione del monachismo da lui istaurato.

Piú d'una volta P.

raccontò ai suoi primi discepoli la storia della propria infanzia, della

conversione, delle lotte contro i demoni e degli inizi della Congregazione e,

dopo la morte del « padre », Teodoro, il discepolo prediletto, narrò ancora

ai fratelli queste stesse cose e tutto ciò che P. aveva fatto per lo

stabilimento della Congregazione; esortati ripetutamente da Teodoro, i fratelli

«interpreti» scrissero la prima Vita di P. Non si sa con certezza se fu scritta

in copto o in greco, poiché i fratelli « interpreti », dunque bilingui,

poterono scriverla nell'una e nell'altra lingua. Tuttavia un fatto è certo:

tutte le grandi compilazioni che ci restano della Vita di P. si

fondano su documenti copri e non esiste alcuna valida ragione per supporre che

questi abbiano avuto dei modelli greci.

Da lungo tempo due

particolari compilazioni sono state riconosciute essere le piú importanti: la

prima Vita greca e la compilazione copra del tipo della Vita

bohairica, mentre si è molto discusso sulle relazioni esistenti tra i due

documenti e sulla priorità dell'uno rispetto all'altro. Un attento confronto

con un testo arabo ancora inedito ci ha dimostrato che non si tratta in realtà

di un vero e proprio problema. Le due compilazioni si fondano sugli

stessi due documenti base: una Vita breve di P. ed un altro documento

da noi considerato come una Vita di Teodoro; un primo compilatore

maldestro inserí in blocco la prima parte della Vita di Teodoro in

quella di P. ed il risultante testo sahidico ci è pervenuto soltanto in una

traduzione araba inedita (ms. 116 della Biblioteca Universitaria di Gottínga).

La Vita breve di P. non è stata conservata distinta mentre quella

di Teodora si conserva in ampi frammenti sahidici. Un rimaneggiamento di questa

compilazione, dunque, fu la fonte comune che l'autore della prima Vita greca

e quello della Vita copta del tipo della Vita bohairica

rimaneggiarono leggermente e completarono indipendentemente l'uno dall'altro.

A parte qualche frammento

molto antico (S1 - S2 - S8) la Vita araba del ms. di Gottinga (inedita,

ma incorporata nella grande compilazione araba pubblicata da Amélineau)

rimane il documento piú importante per la conoscenza della vita di P., mentre

tutti gli altri, sia greci sia copri, o ne dipendono o hanno un interesse

secondario.

Accanto alla fonte

fondamentale costituita dalla Vita, è il caso di citare la Regola di

P., le sue catechesi e le sue lettere, oltre che alcune opere dei suoi

discepoli e successori immediati, Teodoro e Orsiesio.

In realtà s. P. non scrisse

una regola o per lo meno non nel senso in cui si intende la parola quando si

parla ad es, della Regula Magistri o di quella di s.

Benedetto, né ha scritto regole sul tipo di quelle « morali » di s. Basilio.

La Vita, tuttavia ci parla a piú riprese dei precetti o

regolamenti che egli andava tracciando per i suoi discepoli, precetti e

regolamenti che, redatti in occasione della fondazione di nuovi monasteri,

riguardavano soprattutto l'organizzazione materiale del lavoro durante la

sinassi, la cura dei malati, il lavoro dei campi e dei forni, ecc.; alcuni di

tali precetti, scritti in circostanze diverse, furono riuniti ad altri di data

posteriore opera probabilmente di Orsiesio. Questo insieme eterogeneo fu

tradotto dal greco in latino da s. Girolamo con il titolo Regola di s.

Pacomio ed è inutile dire che questo amalgama, per quanto prezioso possa

essere per lo storico, non è di natura tale da darci una idea esatta

della spiritualità pacomiana, né della vita pacomiana della prima generazione.

Dopo la Vita, quindi, i documenti piú importanti a tale scopo sono

invece le poche catechesi di Teodoro conservate in copto ed il testamento di

Orsiesio (Liber Orsiesii) conservato in latino.

L'Historia Lausiaca di

Palladio, che comprende alcuni capitoli (32-34) dedicati ai Tabennesioti, ha

avuto una straordinaria popolarità attraverso tutto lo svolgersi

della tradizione sino ai nostri giorni ed ha contribuito non poco a creare e

conservare una falsa immagine del cenobitismo pacomiano, In effetti, questo

strano testo e soprattutto la fantasiosa regola del cap. 32 (che si dice

dettata da un angelo) non hanno praticamente niente in comune con questa forma

di cenobitismo. Palladio ha semplicemente utilizzato in questi capitoli un

testo preesistente, d'origine copra, nel quale un monaco in possesso di una

vaga conoscenza dell'ambiente pacomiano aveva tentato di descriverlo nel

quadro delle pratiche dei centri semianacoretici del Basso Egitto.

II. VITA. P. nacque,

come si è detto, a Snē, regione dell'Alto Egitto, nel 287, da genitori pagani.

Verso i vent'anni fu arruolato di forza nelle armate imperiali e,

giunto a Tebe, fu gettato in prigione con le altre reclute; a sera però i cittadini

del luogo vennero a portate loro dei viveri. Commosso da tanta bontà, P. chiese

chi fossero ed essi risposero di essere cristiani e di trattare cosí i

prigionieri « per il Dio del cielo »: questo fu il primo contatto di P. con il

Cristianesimo. Durante la notte, pregò il Dio di quei cristiani di liberarlo

dalla servitú promettendogli di servire il genere umano per tutti i giorni

della propria vita.

La sua preghiera fu

esaudita e poco dopo fu congedato. Messosi in cammino verso Sud, si fermò

presso la comunità cristiana del villaggio di Šenesēt (Khenoboskion per i

Greci, l'attuale Kasr-es-Sayad), dove fu catechizzato e ricevette il

Battesimo. Durante la notte nella quale fu iniziato ai santi misteri

una visione gli fece comprendere che egli doveva espandere la grazia allora

ricevuta su tutto il genere umano che si era impegnato a servire: vide in sogno