Saint Bède le Vénérable

Moine, Docteur de l'Eglise (+ 735)

On disait de lui: "C'est l'homme le plus savant de notre temps. Pourtant

Bède n'est jamais sorti de son monastère anglais." C'était un petit

orphelin de Wearmouth dans le Northamberland quand, à sept ans, on le confie à

saint Benoît Biscop, abbé du monastère local. Le petit Bède trouve là sa vraie

famille, la famille bénédictine. Quand il fut grand, l'abbé l'envoya fonder

avec saint Ceolfrid l'abbaye-sœur de Jarrow. Il y demeura toute sa vie,

réalisant en sa personne le modèle du moine bénédictin, partageant son temps

entre le travail manuel (on dit de lui qu'il exerçait l'office de boulanger),

l'étude et la prière. Son oeuvre, qu'il appelle lui-même une compilation

d'extraits des anciens (la bibliothèque de monastère était d'une richesse

étonnante pour un nouveau monastère) est considérable: œuvres exégétiques,

historiques, liturgiques, poétiques. Il fut le premier historien de

l'Angleterre, des origines à l'année 731, et nul historien de l'Europe ne peut

s'en passer. Il introduisit la connaissance des Pères latins dans ce pays et

fut le premier auteur à s'être servi de l'anglais dans ses écrits. Son oeuvre

lui valut le surnom de vénérable. Sa mort fut humble et tranquille comme toute

sa vie. La veille, il dictait encore, assis sur son lit, une traduction anglaise

de l'évangile selon saint Jean.

Au cours de l'audience générale du 18 février 2009, Benoît XVI a tracé un

portrait de Bède le vénérable, un saint anglais né vers 672 en Northumbrie. A

sept ans ses parents le confièrent à un monastère bénédictin où il fut éduqué.

Saint Bède est considéré comme un des principaux érudits du haut moyen-âge.

"Son enseignement et la célébrité de ses écrits lui acquirent l'amitié des

principaux personnages de son temps, qui encouragèrent des travaux qui

profitaient à tant de personnes".

L'Ecriture, a rappelé le Pape, fut la source des réflexions théologiques de

Bède qui voyait dans les évènements de l'Ancien comme du Nouveau Testament un

chemin conduisant au Christ. Evoquant le premier Temple de Jérusalem, à la

construction duquel prirent part des païens, en offrant les matériaux de prix

et l'expérience de leurs maîtres, il a rappelé que les apôtres ont contribué à

bâtir l'Eglise, qui a grandi ensuite grâce aux apports juifs, grecs et latins,

puis grâce aux peuples comme les Celtes irlandais ou les Anglo-Saxons comme

aimait à le souligner Bède.

Puis le Saint-Père a cité certaines œuvres de Bède le vénérable comme sa Grande

Chronique dont la chronologie servit de base à un calendrier universel, ou son

Histoire ecclésiastique des peuples angles, qui fit de lui le père de

l'historiographie anglaise. L'Eglise dont Bède fit le portrait se caractérisait

par sa catholicité, sa fidélité à la tradition et son ouverture au monde, mais

aussi par sa "recherche de l'unité dans la diversité..., par son

apostolicité et sa romanité. C'est pourquoi Bède considéra-t-il capital de

convaincre les diverses Eglises celtiques irlandaises et pictes de célébrer

ensemble Pâques selon le calendrier romain".

Bède fut aussi un "maître de premier ordre en théologie liturgique".

Ses homélies habituèrent "les fidèles à célébrer dans la joie les mystères

de la foi et de la vivre de manière cohérente dans l'attente de leur

dévoilement final avec le retour du Seigneur... Grâce à un travail théologique

intégrant Bible, liturgie et histoire, l’œuvre de Bède contient un message

encore actuel pour les divers aspects de la vie chrétienne. Ainsi rappelle-t-il

aux chercheurs leurs deux principaux devoirs, étudier les merveilles de la

Parole de manière à les rendre attrayantes aux fidèles, et puis exposer les

vérités dogmatiques hors de toute complication hérétique, en s'en tenant à la

simplicité catholique qui est la vertu des petits et des humbles auxquels il

plaît à Dieu de révéler les mystères du Royaume".

Selon l'enseignement de Bède, les pasteurs "doivent se consacrer avant

tout à la prédication, qui ne doit pas se limiter aux sermons mais recourir à

la vie des saints et aux images religieuses, aux processions et aux

pèlerinages". Les personnes consacrées doivent s'occuper de l'apostolat,

"en collaborant à l'action pastorale des évêques en faveur des jeunes

communautés et en s'engageant dans l'évangélisation". Pour le saint érudit

le Christ attend "une Eglise active...qui défriche de nouveaux terrains de

culture..., qui insère l'Evangile dans le tissu social et dans les institutions

culturelles". Il encourageait aussi "les laïcs à l'assiduité dans la

formation religieuse...et leur expliquait comment prier de manière

constante...en faisant de leurs actions une offrande spirituelle en union avec

le Christ". L’œuvre de Bède le vénérable, qui mourut en mai 735, contribua

fortement à la construction de l'Europe chrétienne. (source: VIS 090218)

Mémoire de saint Bède le Vénérable, prêtre et docteur de l’Église qui passa toute

sa vie au service du Christ. Orphelin à l’âge de sept ans, il fut confié, au

monastère de Wearmouth, à saint Benoît Biscop, puis par celui-ci à saint

Céolfrid, au monastère de Jarrow en Northumbrie où il vécut comme moine tout le

reste de sa vie, tout occupé à méditer et à commenter les saintes Écritures, à

pratiquer avec soin l’observance régulière, à chanter chaque jour les louanges

divines, trouvant son plaisir à apprendre, à enseigner et à écrire, jusqu’à sa

mort en 735.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1213/Saint-Bede-le-Venerable.html

SAINT BÈDE LE VÉNÉRABLE

Confesseur et Docteur

(673-735)

Saint Bède naquit en Écosse,

au bourg appelé aujourd'hui Girvan. A l'âge de sept ans, il fut donné au

célèbre moine anglais saint Benoît Biscop, pour être élevé et instruit selon

l'usage bénédictin. Son nom, en anglo-saxon, signifie prière, et qualifie bien

toute la vie de cet homme de Dieu, si vénéré de ses contemporains qu'il en

reçut le surnom de Vénérable, que la postérité lui a conservé.

A sa grande piété

s'ajouta une science extraordinaire. A dix-neuf ans, il avait parcouru le

cercle de toutes les sciences religieuses et humaines: latin, grec poésie,

sciences exactes, mélodies grégoriennes, liturgie sacrée, Écriture Sainte

surtout, rien ne lui fut étranger. Mais la pensée de Dieu présidait à tous ses

travaux: "O bon Jésus, s'écriait-il, Vous avez daigné m'abreuver des ondes

suaves de la science, accordez-moi surtout d'atteindre jusqu'à Vous, source de

toute sagesse."

D'élève passé maître, il

eut jusqu'à 600 disciples et plus à instruire; ce n'est pas un petit éloge que

de citer seulement saint Boniface, Alcuin, comme des élèves par lesquels sa

science rayonna jusqu'en France et en Allemagne. Étudier, écrire était sa vie;

mais l'étude ne desséchait point son coeur tendre et pieux; il rédigeait tous

ses immenses écrits de sa propre main: les principaux monuments de sa science sont

ses vastes commentaires sur l'Écriture Sainte et son Histoire ecclésiastique

d'Angleterre.

Le Saint eut à porter

longtemps la lourde Croix de la jalousie et fut même accusé d'hérésie: ainsi

Dieu perfectionne Ses Saints et les maintient dans l'humilité. Il n'avait que

soixante-deux ans quand il se sentit pris d'une extrême faiblesse. Jusqu'à la

fin, son esprit fut appliqué à l'étude et son coeur à la prière; tourné vers le

Lieu saint, il expira en chantant: Gloria Patri et Filio et Spiritui Sancto.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_bede_le_venerable.html

Ni Dieu sans le prochain,

ni le prochain sans Dieu

Le parfait amour est

celui par lequel il nous est commandé d’aimer le Seigneur de tout notre cœur,

de toute notre âme et de toute notre force et le prochain comme nous-mêmes. Et

l’amour de l’un ne peut être parfait sans l’amour de l’autre, car on ne peut

aimer vraiment ni Dieu sans le prochain ni le prochain sans Dieu. Aussi, chaque

fois que le Seigneur demande à Pierre s’il l’aime et que celui-ci répond qu’il

l’aime en le prenant lui-même à témoin, à chaque reprise il

conclut : « Pais mes brebis » ou « Pais mes

agneaux » (Jn 21, 17.15) ; c’est comme s’il disait ouvertement

qu’il n’y a qu’une véritable preuve d’amour total de Dieu, l’ardeur à prendre

bien soin des frères.

Car celui qui néglige

l’acte de piété qu’il peut accomplir en faveur d’un frère montre bien qu’il

aime moins son Créateur, dont il méprise le commandement de venir en aide aux

besoins du prochain. Oui, il ne peut y avoir de charité sans la grâce de l’inspiration

divine : le Seigneur le laisse penser d’une manière voilée lorsque,

interrogeant Pierre au sujet d’elle, il l’appelle « Simon, fils de

Jean », un nom que personne ne lui donne nulle part ailleurs.

St Bède le Vénérable

(Traduction de G. Bady

pour Magnificat.)

Moine de l’abbaye de

Jarrow, en Angleterre, saint Bède le Vénérable († 735) fut l’auteur de

l’Histoire ecclésiastique du peuple anglais, ainsi qu’un fécond exégète. /

Homélie 22, trad. de G. Bady pour Magnificat

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/jeudi-8-juin-2/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

Saint Bède le Vénérable

docteur de l'église

catholique

672-735

Dictionnaire de Théologie

Catholique

I. VIE.

Bède, le plus grand

personnage intellectuel de son pays et de son siècle, l’émule des Cassiodore et

des Isidore de Séville, naquit en 673, à Jarrow, sur les terres de l’abbaye de

Wearmouth, dans le Northumberland. Orphelin, il fut confié, dès l’âge de sept

ans, par ses proches au saint et savant évêque abbé de Wearmouth, Benoit

Biscop. Mais, trois ans après, celui-ci confia l’enfant à son coadjuteur

Ceolfrid, qui allait fonder avec quelques religieux, près de l’embouchure de la

Tyne, la colonie de Jarrow. C’est à que Bède reçut, à dix-neuf ans, le

diaconat, et à trente ans, la prêtrise des mains de saint Jean de Beverley.

C’est là qu’élève tour à tour et maître, il passa, sauf les voyages nécessités

par ses études, le reste de sa vie, au milieu de ses confrères et de la foule

des disciples qu’attirait sa renommée, en relations familières, sinon intimes,

avec ce que l’Angleterre avait de plus grand et de meilleur, Ceowulf, roi de

Northumbriens, saint Acca, évêque d’Hexham, Albin, le premier abbé anglo-saxon du

monastère de saint Augustin à Cantorbéry, l’archevêque d’York, Egbert, etc.,

sans autre récréation que le chant quotidien du chœur, sans autre plaisir, à ce

qu’il dit lui-même, que d’apprendre, d’enseigner et d’écrire. Bède mourut à

Jarrow en odeur de sainteté, le 27 mai 735 ; ses reliques dérobées au XIe

siècle et transportées à Durham, pour être réunie à celles de saint Cuthbert,

n’échappèrent pas, sous Henri VIII, à la profanation générale des ossements des

saints de la Northumbrie. La voix populaire, en saluant Bède, au IXe siècle, du

nom de Vénérable, l’avait canonisé. Par un décret du 13 novembre 1899, Léon

XIII l’a honoré du titre de docteur et a étendu sa fête à toute l’Eglise, en la

fixant au 27 mai, jour de sa mort. Canoniste contemporain, 1900, p. 109-110.

Cf. Analecta juris pontificii, Rome, 1855, t. I, col. 1317-1320.

II. OUVRAGES.

A la sincérité, à

l’ardeur de la foi chrétienne, Bède allie, comme plus tard Alcuin,

l’admiration, le goût, dirai-je le regret de la littérature classique. Saint Ambroise,

saint Jérôme, saint Augustin, saint Grégoire le Grand, lui sont très familiers

; mais Aristote, Hippocrate, Cicéron, Sénèque et Pline, Lucrèce, Virgile,

Ovide, Lucain, Stace, reviennent aussi dans sa mémoire. Il est théologien de

profession ; mais l’astronomie et la météorologie, la physique et la musique,

la chronologie et l’histoire, les mathématiques, la rhétorique, la grammaire,

la versification le préoccupent vivement. C’est un moine, un prêtre, la lumière

de l’Eglise contemporaine ; mais c’est en même temps un érudit, un lettré.

L’humble moine de Jarrow maniait également le vers et la prose, l’anglo-saxon

et le latin ; et nul doute qu’il sût le grec.

1° Vers.

Les œuvres poétiques de

Bède sont, relativement, de peu de valeur. Dans la liste que Bède a rédigée

lui-même, Hist. eccl., l. V, c. XXIV, P. L., t. XCV, col. 289-290, trois ans

avant sa mort, de ses quarante-cinq ouvrages antérieurs, il mentionne deux

recueils de poésies, un livre d’hymnes, les unes métriques, les autres

rythmiques, et un livre d’épigrammes. Le Liber epigrammatum est perdu ; quant

aux hymnes qui ont trouvé place dans les éditions de Bède, P. L., t. XCIV, col.

606-638, l’authenticité en est contestée. Un Martyrologe en vers, attribué à

Bède, est tenu pareillement pour apocryphe, Ibid., col. 603-606. Le poème Vita

metrica sancti Cuthberti episcopi Lindisfarnensis, ibid., col. 575-596,

témoigne, sinon du génie poétique de l’auteur, du moins de son goût et de sa

rare culture d’esprit. Bède nous a conservé, en l’insérant dans son Histoire,

l. IV, c. XX, P. L., t. XCV, col. 204-205, l’hymne métrique, hymnus

virginitatis, qu’il avait dédié à la reine Etheldrida, l’épouse vierge

d’Egfrid, un bienfaiteur insigne de l’abbaye de Wearmouth. Des vers

anglo-saxons de Bède il ne nous reste rien, hormis les dix vers qu’un de ses

disciples, témoin oculaire de ses derniers jours, avait recueillis sur les

lèvres du moribond.

2° Prose.

Bien autre est

l’importance de ses ouvrages en prose. On peut les diviser en quatre classes :

1. œuvres théologiques ;

2. œuvres scientifiques

et littéraires ;

3. œuvres historiques ;

4. lettres.

1. Les œuvres

théologiques de Bède, avant que la théologie chrétienne n’eût revêtu le

caractère et la forme d’une vaste synthèse, ne pouvaient guère être que des

études d’exégèse sacrée. De fait, ce sont, ou des commentaires sur divers

livres de l’Ecriture, ou des dissertations soit sur quelques parties isolées,

soit sur quelques passages difficiles du texte sacré, ou des homélies,

destinées primitivement aux religieux de Jarrow et vite répandues dans les

autres cloîtres bénédictins. Selon Mabillon, nous n’avons plus de Bède que

quarante-neuf homélies authentiques, P. L., t. XCIV, col. 9-268 ; de ce nombre

n’est pas la soi-disant homélie LXX, ibid., col. 450 sq., que le bréviaire

romain fait lire le jour et dans l’octave de la Toussaint. Partout

l’interprétation allégorique et morale prédomine ; les pensées et les textes

des Pères fournissent la trame et le fond du travail. Dans la matière de la

grâce, Bède suit saint Augustin et le transcrit presque mot à mot.

Les écrits exégétiques de

Bède embrassaient l’Ancien et le Nouveau Testament et formaient une somme

biblique complète. Tous ne sont pas parvenus jusqu’à nous. Ceux qui sont

publiés, P. L., t. XCI-XCIII, sont ou bien des résumés substantiels, clairs et

méthodiques des commentaires antérieurs des Pères grecs et latins, ou bien des

œuvres personnelles, dans lesquelles le sens allégorique et moral est recherché

au détriment de l’interprétation littérale. Pour les détails, voir le

Dictionnaire de la Bible, de M. Vigouroux, t. I, col. 1539-1541.

Aux œuvres théologiques

on peut rattacher un Martyrologe en prose, où il est assez malaisé de

reconnaître la main de Bède sous les retouches et les additions postérieures,

P. L., t. XCIV, col. 797-1148 ; ? le Pénitentiel qui porte le nom de Bède, sans

que celui-ci, dans le catalogue précité, en dise mot ; voir Martène, Thesaurus

novus anedoctum, Paris, 1717, t. IV, p. 31-56 ; Mansi, Concil., supplément, t.

I, col. 563-596 ; le Liber de locis sacris, qui probablement ne fait qu’un avec

l’abrégé, composé par l’infatigable travailleur, Hist. eccles., l. V, c.

XV-XVII, P. L., t. XCV, col. 256-258, du livre d’Adamnan, abbé d’Iona, De situ

urbis Jerusalem.

2. Les ouvrages

scientifiques et littéraires sont au nombre de quatre :

a. De orthographia

liber, P. L., t. XC, col. 123-150.

b. De arte metrica

liber ad Wigbertum levitam, ibid., col. 149-176, rédigés tous les deux par Bède

à l’usage des disciples monastiques ; le second, offre par les citations des

poètes chrétiens latins comme par les explications que Bède en propose, un

intérêt particulier. ?

c. Un petit traité de

rhétorique pratique est intitulé De schematis et tropis sacræ Scripturæ

liber, ibid., col. 175-186 ; l’auteur en appuie les préceptes sur des exemples

de la Bible et y relève notamment, après Cassiodore, les beautés littéraires

des psaumes. ?

d. Un autre ouvrage de la

même classe a pour titre, De natura verum, ibid., 187-278, et date de l’an

703. C’est un résumé méthodique et précis de ce qui survivait alors de

l’astronomie et de la cosmographie des anciens, en même temps qu’un premier

essai de géographie générale.

3. Les travaux

chronologiques et historiques de Bède sont d’une très haute valeur.

En 703, le docte

Anglo-Saxon, prélude par l’opuscule De temporibus, ibid., col. 277-292, à son

grand ouvrage, De temporum ratione, ibid., col. 293-518, lequel en est une

refonte et nous donne, au témoignage d’Ideler, Handbuch der Chronologie, t. II,

p. 292, " un manuel complet de chronologie pour les dates et les fêtes.

" Ici et là, Bède se prononce nettement contre le comput pascal des

Eglises d’Ecosse et d’Irlande, et tient pour le comput alexandrin, suivi par

Denys le petit. Au De temporum ratione il rattacha, en 725 et en 726, son

Chronicon sive de sex ætatibus mundi, ibid., col. 520-571. Comme saint Isidore,

il y divise l’histoire du monde en six âges ; mais, à la différence de saint

Isidore, il calcule les années depuis Adam jusqu’à Abraham selon l’original

hébreu, non pas selon le texte des Septante. Saint Augustin est son guide,

Eusèbe et saint Jérôme sont les sources auxquelles il vient puiser.

Quelques années plus

tard, Bède publiait son chef-d’œuvre, cette Historia ecclesiastica gentis

anglorum, P. L., t. XCV, col. 21-290, qui lui a mérité le titre de père de

l’histoire l’anglaise et qui suffirait pour immortaliser son nom. Elle se

partage en cinq livres ; après être remontée aux premières relations des

Bretons et des Romains et s’être faite comme l’écho de Gildas, d’Orose, de

saint Prosper d’Aquitaine, elle prend vite une allure et ton personnels et

s’arrête à l’an 731. Les affaires de l’Eglise et les affaires civiles, les

traditions religieuses et les évènements de tout genre y sont enchâssés dans

une seule narration ; pas plus que saint Grégoire de Tours, Bède ne sépare les

destinées des laïques et des clercs. Au fond, c’est une chronique, aussi bien

que les ouvrages analogues de Grégoire de Tours, des Jornandès, des Isidore de

Séville, des Paul Diacre, un recueil d’histoires, suivant l’ordre chronologique

et d’après l’ère chrétienne. Mais les juges les plus compétents reconnaissent

en Bède un chroniqueur instruit et pénétré du sentiment de sa responsabilité,

un critique habile et pénétrant, un écrivain exact, clair, élégant, qui se lit

avec plaisir et a le droit d’être cru. L’Historia ecclesiastica se continue,

pour ainsi dire, et se complète dans la biographie des cinq premiers abbés de

Wearmouth et Jarrow, que Bède avait tous personnellement connus. P. L., t.

XCIV, col. 713-730. Elle avait été précédée par un récit en prose de la vie de

saint Cuthbert, que Bède ne tenait que des moines de Lindisfarne, et qui

renferme, au milieu des miracles dont il fourmille des détails, des détails

assez curieux pour l’histoire des mœurs. Ibid., col. 733-790 ; Acta sanctorum,

martii, t. III, p. 97-117. La Vie de saint Félix, évêque de Nole, d’après les

poèmes de saint Paulin, nous reporte à l’âge des persécutions. Ibid., col.

789-798. La Vie et passion de saint Anastase semble bien perdue.

4. Seize lettres

Parmi les seize lettres

que nous avons de Bède, l’une De æquinoctio, est un opuscule scientifique ; la

lettre De Paschæ celebratione est reproduite deux fois, P. L., t. XC, col.

599-606 ; t. XCIV, col. 675-682 ; une autre, Ad pleigwinum, s’élève contre la

manie de vouloir déterminer l’année de la fin du monde, P. L.¸ t. XCIV, col.

669-675 ; sept sont adressées au plus intime ami de l’auteur, saint Acca, et

traitent de questions exégétiques ; une est écrite à l’abbé Albin, pour le

remercier de son appui dans la composition de l’Historia ecclesiastica. Ibid.,

col. 655-657. La longue lettre écrite à l’archevêque d’York, Egbert, est une

espèce de traité sur le gouvernement spirituel et temporel de la Northumbrie ;

en jetant une vive et franche lumière sur l’état de l’Eglise anglo-saxonne,

elle fait honneur à la clairvoyance comme au courage du Vénérable Bède. Ibid.,

col. 657-668.

III. INFLUENCE.

La renommée de Bède se

répandit promptement de son pays natal dans tout l’Occident, et ses ouvrages,

qui prirent place dans les bibliothèques des monastères à côté de ceux des

Ambroise, des Jérôme, des Augustin, etc., perpétuèrent son influence à travers

le moyen âge. De son vivant, ses compatriotes, saint Boniface en tête, Epist.,

XXXVIII, à Egbert, P. L., t. LXXXIX, col. 736, l’avaient tenu pour le plus

sagace des exégètes. Lui mort, ses œuvres théologiques impriment à l’exégèse

une impulsion vigoureuse et fraient la voie aux travaux d’Alcuin, de Raban Maur

et leurs plus illustres émules. S. Lull, Epist., XXV, XXXI, P. L., t. XCVI,

col. 841, 846 ; Alcuin, Epist., XIV ? XVI, LXXXV, P. L.¸ t. C, col. 164, 168,

278, 279 ; Smaragde, Collectaneum, præf., P. L., t. CII, col. 123 ; Raban Maur,

In Gen., P. L., t. CVII, col. 443 sq. ; In Matth., ibid., col. 728 sq. ; In IV

Reg., præf., P. L., t. CIX, col. 1 ; Paschase Radbert, Exposit. in Matth.,

prol., P. L., t. CXX, col. 35 ; Walafrid Strabon, Glossa ordinaria, P. L., t.

CXIII, CXIV ; Notker, De interpretibus S. Script., P. L., t. CXXXI, col. 996.

Dès le temps de Paul Diacre, on se servait en nombre de cloîtres et notamment

au mont Cassin des homélies de Bède. Dans son Institution laïque, l. I, c.

XIII, P. L., t. CVI, col. 147-148, etc., l’évêque d’Orléans, Jonas, rangera le

moine de Jarrow parmi les Pères de l’Eglise, et le vieil auteur de l’Héliand

s’inspirera ici et là des commentaires sur saint Luc et saint Marc. Vers la fin

du Xe siècle, Adelfrid de Malmesbury ne se fera pas faute, dans ses deux

premiers recueils d’homélies, d’emprunter à Bède. Le diacre Florus de Lyon

avait gagné, du moins en partie, sa réputation à remanier le Martyrologe ; ce

Martyrologe, ainsi refondu, servira de base et de canevas, vers le milieu du

IXe siècle, à celui de Raban Maur comme à celui de Wandelbert. Les liturgistes

Annalaire de Metz, De eccl. officiis, l. I, c. I, VII, VIII ; l. IV, c. I, III,

IV, VII, P. L., t. CV, col. 994, 1003, 1007, 1165, 1170, 1177, 1178 ; Florus de

Lyon, De exposit. missæ, P. L., t. CXIX, col. 15 ; les théologiens et les

canonistes, Loup de Ferrières, Epist., CXXVIII, ibid., col. 603, Collectaneum,

col. 665 ; Remi de Lyon, Liber de tribus epist., c. VII, P. L., t. CXXI, col.

1001 ; Hincmar de Reims, Epist. ad Carol., P. L., t. CXXV, col. 54 ; De

prædestinatione, c. XXVI, ibid., col. 270 ; les ascètes, saint Benoît d’Aniane,

Concordia regularum, c. XXXVI, 6, P. L., t. CIII, col. 1028 sq. recourent à

l’autorité de Bède.

Les œuvres historiques de

Bède seront également citées et mises à contribution. Paul Diacre, par exemple,

dans son Histoire romaine et dans son Histoire des Lombards, prendre pour

guide, entre autres, la Chronique ; Frékulf et saint Adon au IXe siècle,

Réginon de Prüm au Xe, en relèveront et y puiseront à pleines mains. L’Histoire

ecclésiastique sera traduite, hormis quelques coupures, en anglo-saxon par

Alfred le Grand ; elle sera aussi la grande mine exploitée par Paul Diacre,

dans sa Vie de saint Grégoire le Grand ; par Jean Diacre, cent ans plus tard,

dans sa biographie du même pontife ; par Radbod dans son panégyrique de saint

Suitbert ; par Hucbald dans sa vie de saint Lébuin ; et l’archevêque de Reims,

Hincmar, s’en autorisera pour publier les versions de Bernold. Raban Maur, dans

son traité Du comput, pillera des pages entières du De temporum ratione.

Adelfrid de Malmesbury à son tour traduira le Liber de temporibus, et le savant

Hérix d’Auxerre l’enrichira de ses gloses.

Les œuvres scientifiques

et littéraires du moine de Jarrow ne resteront pas non plus sans influence. Le

traité De l’orthographe marquera visiblement de son empreinte l’opuscule

d’Alcuin sur le même sujet ; et Bridferth, au Xe siècle, devra sa réputation de

mathématicien à ses gloses latines sur le De natura rerum et sur le De temporum

ratione, P. L., t. XC, col. 187 sq.

I. EDITIONS.

Les premières éditions

des œuvres complètes de Bède, Paris, 1544, 1554 ; Bâle, 1563 ; Cologne, 1613,

1688, fourmillaient de lacunes et d’erreurs. Grâce aux travaux de Cassandre,

d’Henri Canisius, de Mabillon, etc., le tri de l’apocryphe et de l’authentique

s’est fait peu à peu ; les lacunes ont été comblées par d’heureuses

trouvailles. Smith donna une meilleure édition à Londres en 1721 ; une autre,

supérieure encore, bien qu’elle ne dise pas le dernier mot, est celle de Giles,

6 vol., Londres, 1844, reproduite et complétée, P. L., t. XC-XCV ; nouvelle

édition par Plummer, 2 vol., 1896. L’Histoire ecclésiastique a été édité par

Robert Hussey, Oxford, 1865 ; par Mayor et Lumby, 1878 ; par Holder, 1882.

Mommsen a réédité à part le Chronicon de sex ætatibus mundi, dans Monumenta

germanica historica, Auctatores antiquissimi, Berlin, 1895, t. XIV. La vie de

saint Cuthbert a été éditée par les bollandistes, Acta sanct., martii, t. III.

II. TRAVAUX.

Prolegomena de

l’édition de Migne, P. L., t. XC, col. 9-124, où se trouvent réunies plusieurs

vies de Bède, avec les jugements de divers critiques :

Gehle, De Bedæ

venerabilis vita et scriptis, Leyde, 1838 (dis.) ; Montalembert, Les

moines d’Occident, Paris, 1867, t. V, p. 59-104 ; Werner, Beda der

Ehrwürdige une seine Zeit, Vienne, 1881 ; A. Ebert, Histoire générale de

la littérature du moyen âge en Occident, trad. franç, Paris, 1883, p. 666-684 ;

Kraus, Histoire de l’Eglise, trad. franç., Paris, 1902, t. II, p. 100-101

; dom Plaine, Le vénérable Bède, docteur de l’Eglise, dans la Revue

anglo-romaine, 1896, t. III, p. 49-96 ; H. Quentin, Les martyrologes

historiques, Paris, 1908.

P. GODET. Dictionnaire

de Théologie Catholique

JesusMarie.com

SOURCE : http://jesusmarie.free.fr/bede_le_venerable.html

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 18 février 2009

Bède le vénérable

Chers frères et sœurs,

Le saint que nous

évoquons aujourd'hui s'appelle Bède et naquit dans le Nord-Est de l'Angleterre,

plus exactement dans le Northumberland, en 672/673. Il raconte lui-même que ses

parents, à l'âge de sept ans, le confièrent à l'abbé du proche monastère bénédictin,

afin qu'il l'instruise: "Depuis lors - rappelle-t-il -, j'ai toujours vécu

dans ce monastère, me consacrant intensément à l'étude de l'Ecriture et, alors

que j'observais la discipline de la Règle et l'engagement quotidien de chanter

à l'église, il me fut toujours doux d'apprendre, d'enseigner ou d'écrire"

(Historia eccl. Anglorum, v, 24). De fait, Bède devint l'une des plus éminentes

figures d'érudit du haut Moyen-Age, pouvant utiliser les nombreux manuscrits

précieux que ses abbés, revenant de leurs fréquents voyages sur le continent et

à Rome, lui portaient. L'enseignement et la réputation de ses écrits lui

valurent de nombreuses amitiés avec les principales personnalités de son

époque, qui l'encouragèrent à poursuivre son travail, dont ils étaient nombreux

à tirer bénéfice. Etant tombé malade, il ne cessa pas de travailler, conservant

toujours une joie intérieure qui s'exprimait dans la prière et dans le chant.

Il concluait son œuvre la plus importante, la Historia ecclesiastica gentis

Anglorum, par cette invocation: "Je te prie, ô bon Jésus, qui avec

bienveillance m'a permis de puiser aux douces paroles de ta sagesse,

accorde-moi, dans ta bonté, de parvenir un jour à toi, source de toute sagesse,

et de me trouver toujours face à ton visage". La mort le saisit le 26 mai

735: c'était le jour de l'Ascension.

Les Saintes Ecritures

sont la source constante de la réflexion théologique de Bède. Après une étude

critique approfondie du texte (une copie du monumental Codex Amiatinus de la

Vulgate, sur lequel Bède travailla, nous est parvenue), il commente la Bible,

en la lisant dans une optique christologique, c'est-à-dire qu'il réunit deux

choses: d'une part, il écoute ce que dit exactement le texte, il veut

réellement écouter, comprendre le texte lui-même; de l'autre, il est convaincu

que la clef pour comprendre l'Ecriture Sainte comme unique Parole de Dieu est

le Christ et avec le Christ, dans sa lumière, on comprend l'Ancien et le

Nouveau Testament comme "une" Ecriture Sainte. Les événements de

l'Ancien et du Nouveau Testament vont de pair, ils sont un chemin vers le

Christ, bien qu'ils soient exprimés à travers des signes et des institutions

différentes (c'est ce qu'il appelle la concordia sacramentorum). Par exemple,

la tente de l'alliance que Moïse dressa dans le désert et le premier et le

deuxième temple de Jérusalem sont des images de l'Eglise, nouveau temple édifié

sur le Christ et sur les Apôtres avec des pierres vivantes, cimentées par la

charité de l'Esprit. Et de même qu'à la construction de l'antique temple

contribuèrent également des populations païennes, mettant à disposition des

matériaux précieux et l'expérience technique de leurs maîtres d'œuvre, à

l'édification de l'Eglise contribuent les apôtres et les maîtres provenant non

seulement des antiques souches juive, grecque et latine, mais également des

nouveaux peuples, parmi lesquels Bède se plaît à citer les celtes irlandais et

les Anglo-saxons. Saint Bède voit croître l'universalité de l'Eglise qui ne se

restreint pas à une culture déterminée, mais se compose de toutes les cultures

du monde qui doivent s'ouvrir au Christ et trouver en Lui leur point d'arrivée.

L'histoire de l'Eglise

est un autre thème cher à Bède. Après s'être intéressé à l'époque décrite dans

les Actes des Apôtres, il reparcourt l'histoire des Pères et des Conciles,

convaincu que l'œuvre de l'Esprit Saint continue dans l'histoire. Dans la

Chronica Maiora, Bède trace une chronologie qui deviendra la base du Calendrier

universel "ab incarnatione Domini". Déjà à l'époque, on calculait le

temps depuis la fondation de la ville de Rome. Bède, voyant que le véritable

point de référence, le centre de l'histoire est la naissance du Christ, nous a

donné ce calendrier qui lit l'histoire en partant de l'Incarnation du Seigneur.

Il enregistre les six premiers Conciles œcuméniques et leurs développements,

présentant fidèlement la doctrine christologique, mariologique et

sotériologique, et dénonçant les hérésies monophysite et monothélite,

iconoclaste et néo-pélagienne. Enfin, il rédige avec beaucoup de rigueur

documentaire et d'attention littéraire l'Histoire ecclésiastiques des peuples

Angles, pour laquelle il est reconnu comme le "père de l'historiographie

anglaise". Les traits caractéristiques de l'Eglise que Bède aime souligner

sont: a) la catholicité, comme fidélité à la tradition et en même temps

ouverture aux développements historiques, et comme recherche de l'unité dans la

multiplicité, dans la diversité de l'histoire et des cultures, selon les

directives que le Pape Grégoire le Grand avait données à l'Apôtre de

l'Angleterre, Augustin de Canterbury; b) l'apostolicité et la romanité: à cet

égard, il considère comme d'une importance primordiale de convaincre toutes les

Eglises celtiques et des Pictes à célébrer de manière unitaire la Pâque selon

le calendrier romain. Le Calcul qu'il élabora scientifiquement pour établir la

date exacte de la célébration pascale, et donc tout le cycle de l'année

liturgique, est devenu le texte de référence pour toute l'Eglise catholique.

Bède fut également un

éminent maître de théologie liturgique. Dans les homélies sur les Evangiles du

dimanche et des fêtes, il accomplit une véritable mystagogie, en éduquant les

fidèles à célébrer joyeusement les mystères de la foi et à les reproduire de

façon cohérente dans la vie, dans l'attente de leur pleine manifestation au

retour du Christ, lorsque, avec nos corps glorifiés, nous serons admis en

procession d'offrande à l'éternelle liturgie de Dieu au ciel. En suivant le

"réalisme" des catéchèses de Cyrille, d'Ambroise et d'Augustin, Bède

enseigne que les sacrements de l'initiation chrétienne constituent chaque

fidèle "non seulement chrétien, mais Christ". En effet, chaque fois

qu'une âme fidèle accueille et conserve avec amour la Parole de Dieu, à l'image

de Marie, elle conçoit et engendre à nouveau le Christ. Et chaque fois qu'un

groupe de néophytes reçoit les sacrements de Pâques, l'Eglise

s'"auto-engendre" ou, à travers une expression encore plus hardie,

l'Eglise devient "Mère de Dieu" en participant à la génération de ses

fils, par l'œuvre de l'Esprit Saint.

Grâce à sa façon de faire

de la théologie en mêlant la Bible, la liturgie et l'histoire, Bède transmet un

message actuel pour les divers "états de vie": a) aux experts

(doctores ac doctrices), il rappelle deux devoirs essentiels: sonder les

merveilles de la Parole de Dieu pour les présenter sous une forme attrayante

aux fidèles; exposer les vérités dogmatiques en évitant les complications

hérétiques et en s'en tenant à la "simplicité catholique", avec

l'attitude des petits et des humbles auxquels Dieu se complaît de révéler les

mystères du royaume; b) les pasteurs, pour leur part, doivent donner la

priorité à la prédication, non seulement à travers le langage verbal ou

hagiographique, mais en valorisant également les icônes, les processions et les

pèlerinages. Bède leur recommande l'utilisation de la langue vulgaire, comme il

le fait lui-même, en expliquant en dialecte du Northumberland le "Notre

Père", le "Credo" et en poursuivant jusqu'au dernier jour de sa

vie le commentaire en langue vulgaire de l'Evangile de Jean; c) aux personnes

consacrées qui se consacrent à l'Office divin, en vivant dans la joie de la

communion fraternelle et en progressant dans la vie spirituelle à travers

l'ascèse et la contemplation, Bède recommande de soigner l'apostolat - personne

ne reçoit l'Evangile que pour soi, mais doit l'écouter comme un don également

pour les autres - soit en collaborant avec les évêques dans des activités

pastorales de divers types en faveur des jeunes communautés chrétiennes, soit

en étant disponibles à la mission évangélisatrice auprès des païens, hors de

leur pays, comme "peregrini pro amore Dei".

En se plaçant dans cette

perspective, dans le commentaire du Cantique des Cantiques, Bède présente la

synagogue et l'Eglise comme des collaboratrices dans la diffusion de la Parole

de Dieu. Le Christ Epoux veut une Eglise industrieuse, "le teint hâlé par

les efforts de l'évangélisation" - il y a ici une claire évocation de la

parole du Cantique des Cantiques (1, 5) où l'épouse dit: "Nigra sum sed

formosa" (je suis noire, et pourtant belle) -, occupée à défricher

d'autres champs ou vignes et à établir parmi les nouvelles populations

"non pas une cabane provisoire, mais une demeure stable", c'est-à-dire

à insérer l'Evangile dans le tissu social et dans les institutions culturelles.

Dans cette perspective, le saint docteur exhorte les fidèles laïcs à être

assidus à l'instruction religieuse, en imitant les "insatiables foules

évangéliques, qui ne laissaient pas même le temps aux apôtres de manger un

morceau de nourriture". Il leur enseigne comment prier continuellement,

"en reproduisant dans la vie ce qu'ils célèbrent dans la liturgie",

en offrant toutes les actions comme sacrifice spirituel en union avec le

Christ. Aux parents, il explique que même dans leur petit milieu familial, ils

peuvent exercer "la charge sacerdotale de pasteurs et de guides", en

formant de façon chrétienne leurs enfants et affirme connaître de nombreux

fidèles (hommes et femmes, mariés ou célibataires), "capables d'une

conduite irrépréhensible, qui, s'ils sont suivis de façon adéquate, pourraient

s'approcher chaque jour de la communion eucharistique" (Epist. ad

Ecgberctum, ed. Plummer, p. 419).

La renommée de sainteté

et de sagesse dont, déjà au cours de sa vie, Bède jouit, lui valut le titre de

"vénérable". C'est ainsi également que l'appelle le Pape Serge i,

lorsqu'en 701, il écrit à son abbé en lui demandant qu'il le fasse venir pour

un certain temps à Rome afin de le consulter sur des questions d'intérêt

universel. Après sa mort, ses écrits furent diffusés largement dans sa patrie

et sur le continent européen. Le grand missionnaire d'Allemagne, l'Evêque saint

Boniface (+ 754), demanda plusieurs fois à l'archevêque de York et à l'abbé de

Wearmouth de faire transcrire certaines de ses œuvres et de les lui envoyer de

sorte que lui-même et ses compagnons puissent aussi bénéficier de la lumière

spirituelle qui en émanait. Un siècle plus tard, Notkero Galbulo, abbé de

Saint-Gall (+ 912), prenant acte de l'extraordinaire influence de Bède, le

compara à un nouveau soleil que Dieu avait fait lever non de l'orient, mais de

l'occident pour illuminer le monde. Hormis l'emphase rhétorique, il est de fait

que, à travers ses œuvres, Bède contribua de façon efficace à la construction

d'une Europe chrétienne, dans laquelle les diverses populations et cultures se

sont amalgamées, lui conférant une physionomie unitaire, inspirée par la foi

chrétienne. Prions afin qu'aujourd'hui également, se trouvent des personnalités

de la stature de Bède pour maintenir uni tout le continent; prions afin que

nous soyons tous prêts à redécouvrir nos racines communes, pour être les

bâtisseurs d'une Europe profondément humaine et authentiquement chrétienne.

* * *

Je salue cordialement les

pèlerins de langue française, particulièrement les groupes du diocèse de

Créteil, avec leur Évêque Mgr Michel Santier, les prêtres du diocèse de

Grenoble-Vienne, avec Mgr Guy de Kérimel, les nombreux jeunes des lycées et des

aumôneries ainsi que les groupes provenant de diverses paroisses. À l’exemple

de Bède le Vénérable, prenez le temps de scruter les merveilles de la Parole de

Dieu, pour en faire votre nourriture. Que Dieu vous bénisse!

© Copyright 2009 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Saint Bède le vénérable

La vie paisible et laborieuse de saint Bède le Vénérable s’écoula toute entière

à l’ombre du cloître où, orphelin, il fut recueilli dès l’âge de huit ans. Les

principales dates de sa vie sont connues par quelques lignes qu’il écrivit à la

fin de son Histoire ecclésiastique où il se donne cinquante-neuf ans ;

l’ouvrage étant achevé en 731, on peut en déduire qu’il naquit en 672 ou 673.

Accueilli à l’abbaye de Wearmouth par saint Benoît Biscop, Bède fut, trois ans

plus tard, confié à saint Ceolfrid qui allait fonder l’abbaye de Jarrow où il

passa toute sa vie ; diacre à dix-neuf ans, prêtre à trente ans, il mourut à

Jarrow le 26 mai 735. Il se décrit lui-même « Tout occupé de l’étude des

saintes Ecritures, de l’observance de la disciline régulière, du souci de

chanter chaque jour la louange divine dans l’église, trouvant son plaisir à

apprendre, à enseigner et à écrire. »

Initié à la culture classique, Bède le Vénérable connaît le latin et le grec ;

il possède Aristote et Hippocrate, Cicéron, Sénèque, Pline, Virgile, Ovide et

Lucain ; il manie la prose et les vers ; encore qu’il fut surtout exégète et

historien, son œuvre contient à peu près toute la science de son temps

(orthographe, métrique, cosmologie...), au point que Burke l’appelle le père de

l’érudition anglaise. Grand lecteur des Pères de l’Eglise, il se fit surtout le

disciple de saint Ambroise, de saint Jérôme, de saint Augustin et de saint

Grégoire le Grand. Outre ses récits hagiographiques, ses œuvres grammaticales,

ses écrits scientifiques, ses lettres, ses prières et ses ouvrages historiques

dont son Histoire ecclésiastique, on a de lui des commentaires de presque toute

l’Ecriture (48 livres) et des sermons dont deux groupes de vingt-cinq homélies

qu’il prêcha aux moines de Jarrow. Il s’inspire de saint Jérôme pour le sens

littéral, de saint Augustin pour le sens moral et de saint Grégoire le Grand

pour le sens allégorique.

Bède le Vénérable, parfait moine, qui était mort en disant : Gloire au Père, au

Fils, et au Saint-Esprit, comme il était au commencement, maintenant et

toujours, pour les siècles des siècles, fut enterré dans l’église abbatiale

Saint-Paul de Jarrow. En 1020, ses reliques furent portées à Durham et mises

dans une châsse que l’évêque Hugues fit somptueusement refaire en 1155. Henri

VIII fit détruire les reliques dont il ne reste plus qu’un vieux siège de bois

que l’on montre à Jarrow.

Commentaire de l'évangile

selon saint Luc

Le Seigneur m'a fait une telle grâce qu'aucune parole humaine ne saurait

l'exprimer et que je puis à peine, au fond de ma conscience, la comprendre :

c'est pourquoi j'offrirai à mon Dieu, pour lui exprimer ma reconnaissance,

toutes les forces de mon âme ; et tout ce que j'ai de vie, de sentiment,

d'intelligence, je l'emploierai de tout coeur à contempler la grandeur de celui

qui est infini ... Le psalmiste avait indiqué une disposition semblable quand

il disait : Mon âme a tressailli dans le Seigneur et elle se délectera dans son

salut. (...) Un seul regard de Dieu sur sa créature la plus pauvre (et ceci

elle le dit encore à la gloire de Dieu), suffit pour amener cette créature à la

grandeur et à la béatitude. C'est pourquoi elle sait, qu'à cause de ce regard

de Dieu sur elle, on l'appellera bienheureuse.

Saint Bède le Vénérable

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/05/25.php

St Bède le vénérable,

confesseur et docteur

Mort à l’abbaye de Jarrow le 25 mai 835, veille de l’Ascension. Son nom est

joint à celui de saint Augustin de Cantorbéry le 26 mai dans les calendriers

anglais du XIe siècle.

Baronius l’inscrivit à la date du 27 mai dans le martyrologe en 1584. C’est ce

jour qui fut choisi en 1899 pour inscrire sa fête au calendrier sous le rite

double quand Léon XIII le proclama docteur.

Leçons des Matines avant 1960

Quatrième leçon. Bède, prêtre de Jarrow, né sur les confins de la Grande-Bretagne

et de l’Écosse, n’avait que sept ans quand son éducation fut confiée à saint

Benoît Biscop, abbé de Wearmouth. Devenu moine, il régla sa vie de telle sorte

que, tout en se donnant entièrement à l’étude des arts et des sciences, il n’a

jamais rien omis des règles monastiques. Il n’est pas de science qu’il n’ait

acquise, grâce à des études approfondies ; mais il apporta surtout ses soins

les plus assidus aux divines Écritures ; et, pour les posséder plus pleinement,

il apprit le grec et l’hébreu. A trente ans, sur l’ordre de son supérieur, il

fut ordonné prêtre et aussitôt, à la demande d’Acca, évêque d’Exham, il donna

des leçons d’Écriture sainte ; il les appuyait si bien sur la doctrine des

Saints Pères, qu’il n’avançait rien qui ne fût fortifié par leur témoignage, se

servant souvent presque des mêmes expressions. Le repos lui était en horreur il

passait de ses leçons à l’oraison pour retourner de l’oraison à ses leçons ; il

était si enflammé par les sujets qu’il traitait, que souvent les larmes accompagnaient

ses explications. Pour ne pas être distrait par les soucis temporels, il ne

voulut jamais accepter la charge d’abbé qui lui fut bien des fois offerte.

Cinquième leçon. Bède s’acquit un tel renom de science et de piété, que la

pensée vint à Saint Sergius, pape, de le faire venir à Rome, pour qu’il

travaillât à la solution des difficiles questions que la science sacrée avait

alors à étudier. Il fit plusieurs ouvrages, dans le but de corriger les mœurs

des fidèles, d’exposer et de défendre la foi, ce qui lui valut à un tel point

l’estime générale que saint Boniface, évêque et martyr, l’appelait la lumière

de l’Église ; Lanfranc, docteur des Angles, et le concile d’Aix-la-Chapelle,

docteur admirable. Bien plus, ses écrits étaient lus publiquement dans les

églises, même de son vivant. Et quand le fait avait lieu, comme il n’était pas

permis de lui donner le nom de saint, on l’appelait vénérable, et ce titre lui

a été attribué dans les siècles suivants. Sa doctrine avait d’autant plus de

force et d’efficacité qu’elle était confirmée par la sainteté de sa vie et la

pratique des plus belles vertus religieuses. Aussi, grâce à ses leçons et à ses

exemples, ses disciples, qui étaient nombreux et remarquables, se

distinguèrent-ils autant par leur sainteté que par leurs progrès dans les

sciences et dans les lettres.

Sixième leçon. Enfin, brisé par l’âge et les travaux, il tomba dangereusement

malade. Cette maladie, qui dura plus de cinquante jours, n’interrompit ni ses

prières, ni ses explications ordinaires des Saintes Écritures : c’est pendant

ce temps, en effet, qu’il traduisit en langue vulgaire, à l’usage du peuple des

Angles, l’Évangile de Saint Jean. La veille de l’Ascension, sentant sa fin

approcher, il voulut se fortifier par la réception des derniers sacrements de

l’église. Puis il embrassa ses frères, se coucha à terre sur son cilice, répéta

deux fois : Gloire au Père, et au Fils et au Saint-Esprit et s’endormit dans le

Seigneur. On rapporte qu’après sa mort, son corps exhalait l’odeur la plus

suave : il fut enseveli dans le monastère de Jarrow et ensuite transporté à

Dublin avec les reliques de Saint Cuthbert. Les Bénédictins, d’autres familles

religieuses et quelques diocèses l’honoraient comme docteur : le Saint Père

Léon XIII, d’après un décret de la sacrée congrégation des Rites, le déclara

Docteur de l’Église universelle et rendit obligatoires pour tous, au jour de sa

fête, la Messe et l’Office des Docteurs.

Au troisième nocturne.

Lecture du saint Évangile selon saint Matthieu. Cap. 5, 13-19.

En ce temps-là : Jésus dit à ses disciples : Vous êtes le sel de la terre. Mais

si le sel s’affadit, avec quoi le salera-t-on ?. Et le reste.

Homélie de saint Bède le Vénérable, Prêtre.

Septième leçon. Par la terre, entendez la nature humaine ; par le sel, la sagesse.

Le sel, de sa nature, fait perdre à la terre sa fécondité. Nous lisons de

certaines villes, qui ont passé par la colère des vainqueurs, qu’elles ont été

ensemencées de sel. Et ceci convient bien à la doctrine apostolique : le sel de

la sagesse, semé sur la terre de notre chair, empêche de germer, et le luxe du

siècle, et la laideur des vices. S’il n’y a plus de sel, avec quoi salera-t-on

? C’est-à-dire, si vous, qui devez servir aux peuples de condiment, vous perdez

le royaume des cieux par crainte de la persécution, par une vaine terreur, il

n’est pas douteux que, sortis de l’Église, vous ne deveniez le jouet de vos

ennemis.

Huitième leçon. « Vous êtes la lumière du monde » : c’est-à-dire, vous qui avez

été éclairés de la vraie lumière, vous devez être la lumière de ceux qui sont

dans le monde. « Une cité bâtie sur la montagne ne peut se cacher » : il s’agit

de la doctrine apostolique, fondée sur le Christ ; ou de l’Église, bâtie sur le

Christ, formée de beaucoup de nations unies par la foi, et cimentée par la

charité. Elle offre un asile sûr à ceux qui entrent, elle est d’un accès

difficile à ceux qui approchent ; elle garde ceux qui l’habitent et elle

refoule tous ses ennemis.

Neuvième leçon. « Et on n’allume point une lampe pour la mettre sous le

boisseau, mais sur un chandelier ». Or celui-là met la lumière sous le boisseau

qui obscurcit, voile la lumière de la doctrine en la faisant servir à des

avantages temporels. Et celui-là met la lumière sur le chandelier qui se soumet

de telle sorte au ministère de-Dieu, qu’il mette bien au-dessus de la servitude

du corps la doctrine de la vérité. Ou bien encore : le Sauveur allume la

lumière, lui qui a éclairé notre nature humaine par la flamme de la divinité ;

et il a placé cette lumière sur le chandelier, c’est-à-dire sur l’Église, en

marquant sur notre front la foi de son Incarnation. Cette lumière n’a pu être

placée sous le boisseau, c’est-à-dire enfermée dans les dimensions de la foi et

dans la Judée seulement, mais elle a éclairé le monde tout entier.

Dom Guéranger, l’Année Liturgique

La bénédiction que le Seigneur donnait à la terre en s’élevant au ciel atteint

les plus lointaines frontières de la gentilité. Trois jours de suite, le Cycle

nous montre les grâces qu’elle annonçait concentrant sur l’extrême Occident

leurs énergies : c’est le fleuve de Dieu [1], dont les eaux débordées se font

plus impétueuses à la limite qu’elles ne dépasseront pas.

Hier, l’expédition évangélique que le roi Lucius avait sollicitée du Pontife

Éleuthère quittait Rome pour la future Ile des Saints. Demain, dans la terre

des Bretons devenue celle des Angles, elle sera suivie par le chef du second

apostolat, Augustin, l’envoyé de Grégoire le Grand. Aujourd’hui, impatiente de

justifier ces célestes prodigalités, Albion produit devant les hommes son

illustre fils, Bède le Vénérable, l’humble et doux moine dont la vie se passe à

louer Dieu, à le chercher dans la nature et dans l’histoire, mais plus encore

dans l’Écriture étudiée avec amour, approfondie à la lumière des plus sûres

traditions. Lui qui toujours écouta les anciens prend place aujourd’hui parmi

ses maîtres, devenu lui-même Père et Docteur de l’Église de Dieu. Entendons-le,

dans ses dernières années, résumer sa vie :

« Prêtre du monastère des bienheureux Pierre et Paul, Apôtres, je naquis sur

leur territoire, et je n’ai point cessé, depuis ma septième année, d’habiter

leur maison, observant la règle, chantant chaque jour en leur église, faisant

mes délices d’apprendre, d’enseigner ou d’écrire. Depuis que j’eus reçu la

prêtrise, j’annotai pour mes frères et pour moi la sainte Écriture en quelques

ouvrages, m’aidant des expressions dont se servirent nos Pères vénérés, ou

m’attachant à leur manière d’interprétation. Et maintenant, bon Jésus, je vous

le demande : vous qui m’avez miséricordieusement donné de m’abreuver à la

douceur de votre parole, donnez-moi bénignement d’arriver à la source, ô

fontaine de sagesse, et de vous voir toujours [2]. »

La touchante mort du serviteur de Dieu ne devait pas être la moins précieuse

des leçons qu’il laisserait aux siens. Les cinquante jours de la maladie qui

l’enleva de ce monde s’étaient passés comme toute sa vie à chanter des psaumes

ou à enseigner. Comme on approchait de l’Ascension du Seigneur, il redisait

avec des larmes de joie l’Antienne de la fête : « O Roi de gloire qui êtes

monté triomphant par delà tous les cieux, ne nous laissez pas orphelins, mais

envoyez-nous l’Esprit de vérité selon la promesse du Père. » A ses élèves en

pleurs il disait, reprenant la parole de saint Ambroise : « Je n’ai pas vécu de

telle sorte que j’eusse à rougir de vivre avec vous ; mais je ne crains pas non

plus de mourir, car nous avons un bon Maître. » Puis revenant à sa traduction

de l’Évangile de saint Jean et à un travail qu’il avait entrepris sur saint

Isidore : « Je ne veux pas que mes disciples après ma mort s’attardent à des

faussetés et que leurs études soient sans fruit. »

Le mardi avant l’Ascension, l’oppression du malade augmentait les symptômes

d’un dénouement prochain se montrèrent. Plein d’allégresse, il dicta durant

toute cette journée, et passa la nuit en actions de grâces. L’aube du mercredi

le retrouvait pressant le travail de ses disciples. A l’heure de Tierce, ils le

quittèrent pour se rendre à la procession qu’on avait dès lors coutume de faire

en ce jour avec les reliques des Saints. Resté près de lui :»Bien-aimé Maître,

dit l’un d’eux, un enfant, il n’y a plus à dicter qu’un chapitre ; en

aurez-vous la force ? » — « C’est facile, répond souriant le doux Père : prends

ta plume, taille-la, et puis écris ; mais hâte-toi. » A l’heure de None, il

manda les prêtres du monastère, et leur rit de petits présents, implorant leur

souvenir à l’autel du Seigneur. Tous pleuraient. Lui, plein de joie, disait : «

Il est temps, s’il plaît à mon Créateur, que je retourne à Celui qui m’a fait

de rien quand je n’étais pas ; mon doux Juge a bien ordonné ma vie ; et voici

qu’approche maintenant pour moi la dissolution ; je la désire pour être avec le

Christ : oui, mon âme désire voir mon Roi, le Christ, en sa beauté. »

Ce ne furent de sa part jusqu’au soir qu’effusions semblables ; jusqu’à ce

dialogue plus touchant que tout le reste avec Wibert, l’enfant mentionné plus

haut : « Maître chéri, il reste encore une phrase.— Écris-la vite. » Et après

un moment : « C’est fini, dit l’enfant. —Tu dis vrai, répartit le bienheureux :

c’est fini ; prends ma tête dans tes mains et soutiens-la du côté de

l’oratoire, parce que ce m’est une grande joie de me voir en face du lieu saint

où j’ai tant prié. » Et du pavé de sa cellule où on l’avait déposé, il entonna

: Gloire au Père, et au Fils, et au Saint-Esprit ; quand il eut nommé

l’Esprit-Saint, il rendit l’âme [3].

Gloire au Père, et au Fils, et au Saint-Esprit ! C’est le chant de l’éternité ;

l’ange et mme n’étaient pas, que Dieu, dans le concert des trois divines

personnes, suffisait à sa louange : louange adéquate, infinie, parfaite comme

Dieu, seule digne de lui. Combien le monde, si magnifiquement qu’il célébrât

son auteur par les mille voix delà nature, demeurait au-dessous de l’objet de

ses chants ! Toutefois la création elle-même était appelée à renvoyer au ciel

un jour l’écho de la mélodie trine et une ; lorsque le Verbe fut devenu par

l’Esprit-Saint fils de l’homme en Marie comme il l’était du Père, la résonance

créée du Cantique éternel répondit pleinement aux adorables harmonies dont la

Trinité gardait primitivement le secret pour elle seule. Depuis, pour l’homme

qui sait comprendre, la perfection fut de s’assimiler au fils de Marie afin de

ne faire qu’un avec le Fils de Dieu, dans le concert auguste où Dieu trouve sa

gloire.

Vous fûtes, ô Bède, cet homme à qui l’intelligence est donnée. Il était juste

que le dernier souffle s’exhalât sur vos lèvres avec le chant d’amour où

s’était consumée pour vous la vie mortelle, marquant ainsi votre entrée de

plain-pied dans l’éternité bienheureuse et glorieuse. Puissions-nous mettre à

profit la leçon suprême où se résument les enseignements de votre vie si grande

et si simple !

Gloire à la toute-puissante et miséricordieuse Trinité ! N’est-ce pas aussi le

dernier mot du Cycle entier des mystères qui s’achèvent présentement dans la

glorification du Père souverain par le triomphe du Fils rédempteur, et

l’épanouissement du règne de l’Esprit sanctificateur en tous lieux ? Qu’il

était beau dans l’Ile des Saints le règne de l’Esprit, le triomphe du Fils à la

gloire du Père, quand Albion, deux fois donnée par Rome au Christ, brillait aux

extrémités de l’univers comme un joyau sans prix de la parure de l’Épouse !

Docteur des Angles au temps de leur fidélité, répondez à l’espoir du Pontife

suprême étendant votre culte à toute l’Église en nos jours, et réveillez dans

l’âme de vos concitoyens leurs sentiments d’autrefois pour la Mère commune.

[1] Psalm. XLV, 5.

[2] BED. Hist. eccl. Cap. ultimum.

[3] Epist. CUTHBERTI.

Bhx Cardinal Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

La fête de cet ancien moine anglo-saxon fut introduite dans le calendrier de

l’Église universelle par Léon XIII, après que la Sacrée Congrégation des Rites

lui eût reconnu ce titre de docteur que, depuis de longs siècles, lui avaient

décerné les suffrages de l’univers. Cette vénération pour Bède avait même déjà

commencé à se manifester de son vivant, si bien que, lors de la lecture

publique de ses œuvres, ses contemporains ne pouvant encore lui attribuer le

titre de saint l’appelaient venerabilis presbyter, et c’est sous ce titre que

Bède est passé à la postérité.

A une science vraiment encyclopédique, Bède unit les plus éclatantes vertus du

moine bénédictin, faisant alterner dans sa vie la prière et l’étude. Ora et

labora. Il eut de nombreux disciples et laissa tant d’écrits que, durant le

haut moyen âge, ceux-ci constituèrent pour ainsi dire toute la bibliothèque

ecclésiastique des Anglo-Saxons. La vaste érudition de ce moine rappelle d’une

certaine manière celle de saint Jérôme à qui il ressemble quelque peu. Saint

Boniface, l’apôtre de l’Allemagne, salua saint Bédé comme la lumière de

l’Église, et le Concile d’Aix-la-Chapelle lui donna le titre de docteur

admirable.

Bédé mourut très âgé, le 26 mai 735, et sa dernière prière fut l’antienne de

l’office (de l’Ascension) : O Rex gloriae, qui triumphator hodie super omnes

caelos ascendisti, ne derelinquas nos orphanos, sed mitte promissum Patris in

nos Spiritum veri-tatis. Au moment d’expirer, il entonna le Gloria Patri.

Le collège ecclésiastique anglais de Rome est dédié à la mémoire de saint Bédé

le Vénérable.

La messe est du Commun des Docteurs, sauf la première collecte qui est propre :

« Seigneur, qui avez voulu illuminer votre Église au moyen de la science

merveilleuse de votre bienheureux confesseur Bédé le docteur, faites que nous,

vos serviteurs, fassions toujours notre trésor de sa doctrine, et que nous

soyons aidés par ses mérites. »

Voici ce que rapportent les historiens de saint Bédé le Vénérable : Numquam

torpebat otio, numquam a studio cessabat ; semper legit, semper scripsit,

semper docuit, semper oravit, sciens quod amator scientiae salutaris vitia

carnis facile superaret. Quelle leçon pour notre sensualité, qui se nourrit

justement dans l’oisiveté et la frivolité !

Dom Pius Parsch, le Guide dans l’année liturgique

Le docteur de la sagesse biblique.

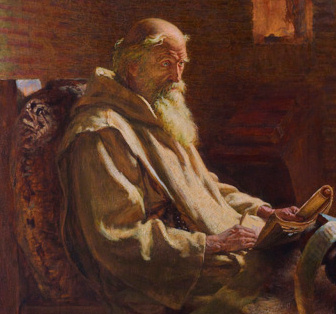

Saint Bède. — Jour de mort : 26 mai 735 à Jarrow. Tombeau : à Durham, en

Angleterre. Image : On le représente en bénédictin, avec le livre du docteur à

la main. Vie : L’importance de saint Bède réside dans ce fait qu’il forme la

transition entre l’époque des Pères de l’Église et les premiers progrès des

peuples germaniques devenus chrétiens. Il transmet les traditions de culture et

de science romano-chrétiennes au moyen âge. Ses écrits étaient lus publiquement

dans les églises, de son vivant. C’est pourquoi on le vénérait. Comme on ne

pouvait pas encore le nommer « saint », on lui donna le titre de « vénérable ».

Ce titre lui resta plus tard comme surnom. — Le jour de l’Ascension, il sentit

que la mort approchait. Il se munit alors des derniers sacrements. Il embrassa

ensuite ses frères, se fit coucher sur un dur cilice et, en prononçant

doucement ces paroles : « Gloire au Père et au Fils et au Saint-Esprit », il

s’endormit dans le Seigneur.

Pratique : Saint Bède est notre docteur dans la sagesse biblique. Celui qui

veut vivre avec l’Église doit avoir à la main le livre des Saintes Écritures,

pendant la semaine, pendant sa vie. Saint Bède a expliqué ce livre à d’autres.

Peut-être avons-nous t’occasion et la possibilité d’en faire autant. — La messe

(In medio) est du commun des docteurs.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/27-05-St-Bede-le-venerable#nh4

Br. Kenneth Hosley, O.P.C.: the Venerable Bede.

Also

known as

Venerable Bede

Father of English History

formerly 27 May

Profile

Born around the

time England was

finally completely Christianized,

Bede was raised from age seven in the abbey of

Saints Peter and Paul at Wearmouth-Jarrow,

and lived there the rest of his life. Benedictine monk.

Spiritual student of the founder, Saint Benedict

Biscop. Ordained a priest in 702 by Saint John

of Beverley.

Bede was considered the

most learned man of his day. He worked as both teacher and author, writing about history, rhetoric, mathematics, music, astronomy, poetry,

grammar, philosophy, hagiography, homiletics,

and Bible

commentary. His writings began

the tradition of dating this era from the incarnation of Christ. The central

theme of Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica is

of the Church using

the power of its spiritual, doctrinal, and cultural unity to stamp out violence

and barbarism. Our knowledge of England before

the 8th

century is mainly the result of Bede’s writing.

He was declared a Doctor

of the Church on 13

November 1899 by Pope Leo

XIII.

Born

Redemptoris

Mater Seminary, Uzhhorod, Ukraine

old monk dying amidst

his community

old monk reading

or otherwise studying

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Little

Lives of the Great Saints

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Pope

Benedict XVI: General Audience, 18

February 2009

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

Christian Classics

Ethereal Library

Ecclesiastical

History of England, by Saint Bede

Redemptoris

Mater Seminary, Uzhhorod, Ukraine

images

audio

video

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites

en français

Abbé

Christian-Philippe Chanut

fonti

in italiano

Readings

He alone loves the

Creator perfectly who manifests a pure love for his neighbour. – Saint Bede

the Venerable

On Tuesday before the

feast of the Ascension,

Bede’s breathing became labored and a slight swelling appeared in his legs.

Nevertheless, he gave us instruction all day long and dictated cheerfully the

whole time. It seemed to us, however, that he knew very well that his end was

near, and so he spent the whole night giving thanks to God. At daybreak on

Wednesday he told us to finish the writing we had begun. We worked until nine

o’clock, when we went in procession with the relics as

the custom of the day required. But one of our community, a boy named Wilbert,

stayed with him and said to him, “Dear master, there is still one more chapter to

finish in that book you were dictating. Do you think it would be too hard for

you to answer any more questions?” Bede replied: “Not at all; it will be easy.

Take up your pen and ink, and write quickly,” and he did so. At three o’clock,

Bede said to me, “I have a few treasures in my private chest, some pepper,

napkins, and a little incense. Run quickly and bring the priest of

our monastery,

and I will distribute among them these little presents that god has given me.”

When the priests arrived

he spoke to them and asked each one to offer Masses and prayers for him

regularly. They gladly promised to do so. The priests were sad, however, and

they all wept, especially because Bede had said that he thought they would not

see his face much longer in this world. Yet they rejoiced when he said, “If it

so please my Maker, it is time for me to return to him who created me and

formed me out of nothing when I did not exist. I have lived a long time, and

the righteous Judge has taken good care of me during my whole life. The time

has come for my departure, and I long to die and be with Christ. My soul yearns

to see Christ, my King, in all his glory.” He said many other things which

profited us greatly, and so he passed the day joyfully till evening. When

evening came, young Wilbert said to Bede, “Dear master, there is still one

sentence that we have not written down.” Bede said, “Quick, write it down.” In

a little while, Wilbert said, “There; now it is written down.” Bede said,

“Good. You have spoken the truth; it is finished. Hold my head in your hands,

for I really enjoy sitting opposite the holy place where I used to pray; I can

call upon my Father as I sit there.” And so Bede, as he lay upon the floor of

his cell,

sang, “Glory be to the Father, and to the Son and to the Holy

Spirit.” And when he had named the Holy

Spirit, he breathed his last breath. – from a letter on the death of Saint Bede written by

the monk Cuthbert

“My soul proclaims the

greatness of the Lord, any my spirit rejoices in God my savior.” With these

words Mary first

acknowledges the special gifts she has been given. Above all other saints, she

alone could truly rejoice in Jesus, her savior, for she knew that he who was

the source of eternal salvation would be born in time in her body, in one

person both her own son and her Lord. “For the Almighty has done great things

for me, and holy is his name.” Mary attributes nothing to her own merits. She

refers all her greatness to the gift of one whose essence is power and whose

nature is greatness, for he fill with greatness and strength the small and the

weak who believe in him. She did well to add: “and holy is his name,” to warn

those who heard, and indeed all who would receive his words, that they must

believe and call upon his name. For they too could share in everlasting

holiness and true salvation according to the words of the prophet: “and it will

come to pass, that everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.”

This is the name she spoke of earlier when she said “and my spirit rejoices in

God my savior.” – from a homily by Saint Bede

MLA

Citation

“Saint Bede the

Venerable“. CatholicSaints.Info. 23 March 2022. Web. 8 June 2023. <https://catholicsaints.info/saint-bede-the-venerable/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-bede-the-venerable/

BENEDICT XVI

GENERAL AUDIENCE

Bede, the Venerable

Dear Brothers and

Sisters,

The Saint we are

approaching today is called Bede and was born in the north-east of England, to

be exact, Northumbria, in the year 672 or 673. He himself recounts that when he

was seven years old his parents entrusted him to the Abbot of the neighbouring

Benedictine monastery to be educated: "spending all the remaining time of

my life a dweller in that monastery". He recalls, "I wholly applied

myself to the study of Scripture; and amidst the observance of the monastic

Rule and the daily charge of singing in church, I always took delight in

learning, or teaching, or writing" (Historia eccl. Anglorum, v, 24).

In fact, Bede became one of the most outstanding erudite figures of the early

Middle Ages since he was able to avail himself of many precious manuscripts

which his Abbots would bring him on their return from frequent journeys to the

continent and to Rome. His teaching and the fame of his writings occasioned his

friendships with many of the most important figures of his time who encouraged

him to persevere in his work from which so many were to benefit. When Bede fell

ill, he did not stop working, always preserving an inner joy that he expressed

in prayer and song. He ended his most important work, the Historia

Ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, with this invocation: "I beseech you,

O good Jesus, that to the one to whom you have graciously granted sweetly to

drink in the words of your knowledge, you will also vouchsafe in your loving

kindness that he may one day come to you, the Fountain of all wisdom, and

appear for ever before your face". Death took him on 26 May 737: it was

the Ascension.

Sacred Scripture was the

constant source of Bede's theological reflection. After a critical study of the

text (a copy of the monumental Codex Amiatinus of the Vulgate on

which Bede worked has come down to us), he comments on the Bible, interpreting

it in a Christological key, that is, combining two things: on the one hand he

listens to exactly what the text says, he really seeks to hear and understand

the text itself; on the other, he is convinced that the key to understanding

Sacred Scripture as the one word of God is Christ, and with Christ, in his

light, one understands the Old and New Testaments as "one" Sacred

Scripture. The events of the Old and New Testaments go together, they are the

way to Christ, although expressed in different signs and institutions (this is

what he calls the concordia sacramentorum). For example, the tent of the

covenant that Moses pitched in the desert and the first and second temple of

Jerusalem are images of the Church, the new temple built on Christ and on the

Apostles with living stones, held together by the love of the Spirit. And just

as pagan peoples also contributed to building the ancient temple by making

available valuable materials and the technical experience of their master

builders, so too contributing to the construction of the Church there were

apostles and teachers, not only from ancient Jewish, Greek and Latin lineage,

but also from the new peoples, among whom Bede was pleased to list the Irish

Celts and Anglo-Saxons. St Bede saw the growth of the universal dimension of

the Church which is not restricted to one specific culture but is comprised of

all the cultures of the world that must be open to Christ and find in him their

goal.

Another of Bede's

favourite topics is the history of the Church. After studying the period

described in the Acts of the Apostles, he reviews the history of the Fathers

and the Councils, convinced that the work of the Holy Spirit continues in

history. In the Chronica Maiora, Bede outlines a chronology that was

to become the basis of the universal Calendar "ab incarnatione

Domini". In his day, time was calculated from the foundation of the City

of Rome. Realizing that the true reference point, the centre of history, is the

Birth of Christ, Bede gave us this calendar that interprets history starting

from the Incarnation of the Lord. Bede records the first six Ecumenical

Councils and their developments, faithfully presenting Christian doctrine, both

Mariological and soteriological, and denouncing the Monophysite and

Monothelite, Iconoclastic and Neo-Pelagian heresies. Lastly he compiled with

documentary rigour and literary expertise the Ecclesiastical History of

the English Peoples mentioned above, which earned him recognition as

"the father of English historiography". The characteristic features

of the Church that Bede sought to emphasize are: a) catholicity, seen as

faithfulness to tradition while remaining open to historical developments, and

as the quest for unity in multiplicity, in historical and cultural diversity

according to the directives Pope Gregory the Great had given to Augustine of

Canterbury, the Apostle of England; b) apostolicity and Roman

traditions: in this regard he deemed it of prime importance to convince

all the Irish, Celtic and Pict Churches to have one celebration for Easter in

accordance with the Roman calendar. The Computo, which he worked out

scientifically to establish the exact date of the Easter celebration, hence the

entire cycle of the liturgical year, became the reference text for the whole

Catholic Church.

Bede was also an eminent

teacher of liturgical theology. In his Homilies on the Gospels for Sundays and

feast days he achieves a true mystagogy, teaching the faithful to celebrate the

mysteries of the faith joyfully and to reproduce them coherently in life, while

awaiting their full manifestation with the return of Christ, when, with our

glorified bodies, we shall be admitted to the offertory procession in the

eternal liturgy of God in Heaven. Following the "realism" of the

catecheses of Cyril, Ambrose and Augustine, Bede teaches that the sacraments of

Christian initiation make every faithful person "not only a Christian but

Christ". Indeed, every time that a faithful soul lovingly accepts and

preserves the Word of God, in imitation of Mary, he conceives and generates

Christ anew. And every time that a group of neophytes receives the Easter

sacraments the Church "reproduces herself" or, to use a more daring

term, the Church becomes "Mother of God", participating in the

generation of her children through the action of the Holy Spirit.

By his way of creating

theology, interweaving the Bible, liturgy and history, Bede has a timely

message for the different "states of life": a) for scholars (doctores

ac doctrices) he recalls two essential tasks: to examine the marvels of the

word of God in order to present them in an attractive form to the faithful; to

explain the dogmatic truths, avoiding heretical complications and keeping to

"Catholic simplicity", with the attitude of the lowly and humble to

whom God is pleased to reveal the mysteries of the Kingdom; b) pastors, for

their part, must give priority to preaching, not only through verbal or

hagiographic language but also by giving importance to icons, processions and

pilgrimages. Bede recommends that they use the vulgate as he himself does,

explaining the "Our Father" and the "Creed" in Northumbrian

and continuing, until the last day of his life, his commentary on the Gospel of

John in the vulgate; c) Bede recommends to consecrated people who devote

themselves to the Divine Office, living in the joy of fraternal communion and

progressing in the spiritual life by means of ascesis and contemplation that

they attend to the apostolate no one possesses the Gospel for himself alone but

must perceive it as a gift for others too both by collaborating with Bishops in

pastoral activities of various kinds for the young Christian communities and by

offering themselves for the evangelizing mission among the pagans, outside

their own country, as "peregrini pro amore Dei".

Making this viewpoint his

own, in his commentary on the Song of Songs Bede presents the Synagogue and the

Church as collaborators in the dissemination of God's word. Christ the

Bridegroom wants a hard-working Church, "weathered by the efforts of

evangelization" there is a clear reference to the word in the Song of

Songs (1: 5), where the bride says "Nigra sum sed formosa" ("I

am very dark, but comely") intent on tilling other fields or vineyards and

in establishing among the new peoples "not a temporary hut but a permanent

dwelling place", in other words, intent on integrating the Gospel into

their social fabric and cultural institutions. In this perspective the holy

Doctor urges lay faithful to be diligent in religious instruction, imitating

those "insatiable crowds of the Gospel who did not even allow the Apostles

time to take a mouthful". He teaches them how to pray ceaselessly,

"reproducing in life what they celebrate in the liturgy", offering

all their actions as a spiritual sacrifice in union with Christ. He explains to

parents that in their small domestic circle too they can exercise "the