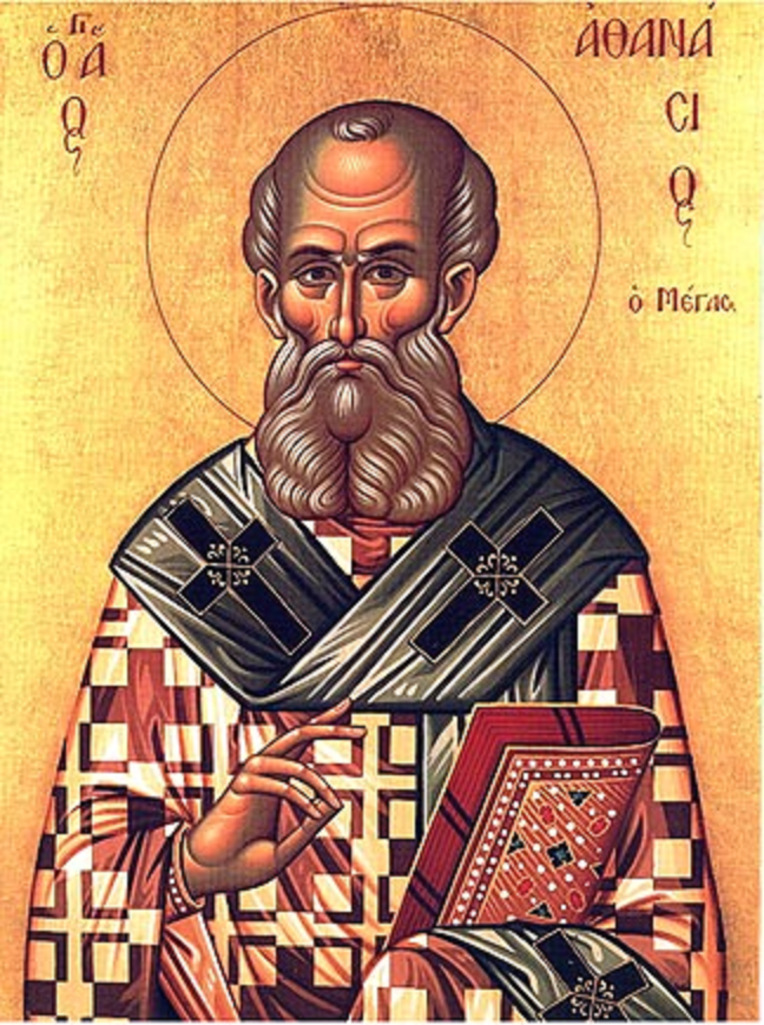

Maestro de San Ildefonso. San Atanasio de Alejandría, huile sur toile, 155 x 72, National Sculpture Museum

Le Verbe de Dieu s'est

fait homme pour que nous devenions Dieu ;

il s'est rendu visible

dans le corps pour que nous ayons une idée du Père invisible,

et il a lui-même supporté

la violence des hommes pour que nous héritions de l'incorruptibilité

Saint Athanase. Sur

l'Incarnation du Verbe, 54,3.

Saint

Athanase, évêque et docteur de l'Église

Evêque d'Alexandrie de

328 à 373, Athanase n'eut qu'un objectif : défendre la foi en la divinité du

Christ, qui avait été définie à Nicée, mais se trouvait battue en brèche de

partout. Ni la pusillanimité des évêques, ni les tracasseries policières, ni

cinq exils ne vinrent à bout de son caractère et surtout de son amour pour le

Seigneur Jésus, Dieu fait homme.

Saint Athanase

d'Alexandrie

Patriarche d'Alexandrie,

Père de l'Église (+373)

Les Églises d'Orient le

fêtent aussi en janvier.

Nul ne contribua

davantage à la défaite de l'arianisme. Il n'écrivit, ne souffrit, ne vécut que

pour défendre la divinité du Christ. Petit de taille, prodigieusement

intelligent, nourri de culture grecque, il n'était encore que diacre lorsqu'il

accompagna l'évêque d'Alexandrie au concile de Nicée en 325. Il y contribua à

la condamnation de son compatriote Arius et à la formulation des dogmes de

l'Incarnation et de la Sainte Trinité. Devenu lui-même évêque d'Alexandrie en

328, il fut, dès lors et pour toujours, en butte à la persécution des ariens,

semi-ariens et anti-nicéens de tout genre qui pullulaient en Égypte et dans

l'Église entière. Ces ariens étaient soutenus par les empereurs qui

rêvaient d'une formule plus souple que celle de Nicée, d'une solution de

compromis susceptible de rallier tous les chrétiens et de rendre la paix à

l'empire. C'est ce qui explique que sur les quarante-cinq années de son

épiscopat, saint Athanase en passa dix-sept en exil: deux années à Trèves, sept

années à Rome, le reste dans les cavernes des déserts de l'Égypte. Il fut même

accusé d'avoir assassiné l'évêque Arsène d'Ypsélé. Il ne dut la reconnaissance

de son innocence qu'au fait qu'Arsène revint en plein jour et se montra vivant

aux accusateurs de saint Athanase.

Son œuvre théologique est

considérable.

- A découvrir: ses œuvres

publiées aux éditions du Cerf.

Mémoire de saint

Athanase, évêque et docteur de l'Église. Homme très éminent en sainteté et en

doctrine, placé sur le siège d'Alexandrie, il défendit la foi orthodoxe avec

une vigueur intrépide, depuis le temps de Constantin jusqu'à celui de Valens,

contre les empereurs, les gouverneurs de province, contre un nombre infini d'évêques

ariens, qui lui tendirent toutes sortes de pièges et le forcèrent plusieurs

fois à l'exil ; enfin, après bien des combats et des triomphes qu'il remporta

par sa patience, il rentra dans son Église et s'endormit dans la paix du Christ

la quarante-neuvième année de son épiscopat, en 373.

Martyrologe romain

Athanase a été sans aucun

doute l'un des Pères de l'Église antique les plus importants et les plus

vénérés... Nous avons de nombreux motifs de gratitude envers Athanase. Sa vie,

comme celle d'Antoine et

d'innombrables autres saints, nous montre que "celui qui va vers Dieu ne

s'éloigne pas des hommes, mais qu'il se rend au contraire proche d'eux" (Saint

Athanase - audience du 20 juin 2007 - Benoît XVI)

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1076/Saint-Athanase-d-Alexandrie.html

SAINT ATHANASE

Docteur de l'Église

(296-375)

Saint Athanase naquit à

Alexandrie, métropole de l'Égypte. Sa première éducation fut excellente; il ne

quitta le foyer paternel que pour être élevé, nouveau Samuel, dans le temple du

Seigneur, par l'évêque d'Alexandrie.

Athanase était simple

diacre, quand son évêque le mena au concile de Nicée, dont il fut à la fois la

force et la lumière. Cinq mois après, le patriarche d'Alexandrie mourut, et

Athanase, malgré sa fuite, se vit obligé d'accepter le lourd fardeau de ce

grand siège. Dès lors, ce fut une guerre acharnée contre lui. Les accusations

succèdent aux accusations, les perfidies aux perfidies; Athanase, inébranlable,

invincible dans la défense de la foi, fait à lui seul trembler tous ses

ennemis.

La malice des hérétiques

ne servit qu'à faire ressortir l'énergie de cette volonté de fer, la sainteté

de ce grand coeur, les ressources de cet esprit fécond, la splendeur de ce fier

génie. Exilé par l'empereur Constantin, il lui fit cette réponse:

"Puisque vous cédez

à mes calomniateurs, le Seigneur jugera entre vous et moi."

Avant de mourir,

Constantin le rappela, et Athanase fut reçu en triomphe dans sa ville

épiscopale. Le vaillant champion de la foi eut à subir bientôt un nouvel exil,

et deux conciles ariens ne craignirent pas de pousser la mauvaise foi et

l'audace jusqu'à le déposer de son siège.

Toujours persécuté et

toujours vainqueur, voilà la vie d'Athanase; il vit périr l'infâme Arius d'une

mort honteuse et effrayante et tous ses ennemis disparaître les uns après les

autres. Jamais les adversaires de ce grand homme ne purent le mettre en défaut,

il déjoua toutes leurs ruses avec une admirable pénétration d'esprit. En voici

quelques traits.

En plein concile, on le

fit accuser d'infamie par une courtisane; mais il trouve le moyen de montrer

que cette femme ne le connaissait même pas de vue, puisqu'elle prit un de ses

prêtres pour lui.

Au même concile, on

l'accusa d'avoir mis à mort un évêque nommé Arsène, et coupé sa main droite;

comme preuve on montrait la main desséchée de la victime; mais voici qu'à

l'appel d'Athanase, Arsène paraît vivant et montre ses deux mains.

Une autre fois, Athanase,

poursuivi, s'enfuit sur un bateau; puis bientôt il rebrousse chemin, croise ses

ennemis, qui lui demandent s'il a vu passer l'évêque d'Alexandrie:

"Poursuivez, leur dit-il, il n'est pas très éloigné d'ici."

Ses dernières années furent

les seules paisibles de sa vie. Enfin, après avoir gouverné pendant

quarante-six ans l'Église d'Alexandrie, après avoir soutenu tant de combats, il

alla recevoir au Ciel la récompense de "ceux qui souffrent persécution

pour la justice".

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950.

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_athanase.html

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 20 juin 2007

Saint Athanase

Chers frères et sœurs,

En poursuivant notre

évocation des grands Maîtres de l'Église antique, nous voulons aujourd'hui

tourner notre attention vers saint Athanase d'Alexandrie. Cet authentique

protagoniste de la tradition chrétienne, déjà quelques années avant sa mort,

fut célébré comme "la colonne de l'Église" par le grand théologien et

Évêque de Constantinople Grégroire de Nazianze (Discours 21, 26), et il a

toujours été considéré comme un modèle d'orthodoxie, aussi bien en Orient qu'en

Occident. Ce n'est donc pas par hasard que Gian Lorenzo Bernini en plaça la

statue parmi celles des quatre saints Docteurs de l'Église orientale et

occidentale - avec Ambroise, Jean Chrysostome et Augustin -, qui dans la

merveilleuse abside la Basilique vaticane entourent la Chaire de saint Pierre.

Athanase a été sans aucun

doute l'un des Pères de l'Église antique les plus importants et les plus

vénérés. Mais ce grand saint est surtout le théologien passionné de l'incarnation,

du Logos, le Verbe de Dieu, qui - comme le dit le prologue du quatrième

Évangile - "se fit chair et vint habiter parmi nous" (Jn 1, 14).

C'est précisément pour cette raison qu'Athanase fut également l'adversaire le

plus important et le plus tenace de l'hérésie arienne, qui menaçait alors la

foi dans le Christ, réduit à une créature "intermédiaire" entre Dieu

et l'homme, selon une tendance récurrente dans l'histoire et que nous voyons en

œuvre de différentes façons aujourd'hui aussi. Probablement né à Alexandrie

vers l'an 300, Athanase reçut une bonne éducation avant de devenir diacre et

secrétaire de l'Évêque de la métropole égyptienne, Alexandre. Proche

collaborateur de son Évêque, le jeune ecclésiastique prit part avec lui au

Concile de Nicée, le premier à caractère œcuménique, convoqué par l'empereur

Constantin en mai 325 pour assurer l'unité de l'Eglise. Les Pères nicéens

purent ainsi affronter diverses questions et principalement le grave problème

né quelques années auparavant à la suite de la prédication du prêtre alexandrin

Arius.

Celui-ci, avec sa

théorie, menaçait l'authentique foi dans le Christ, en déclarant que le Logos

n'était pas le vrai Dieu, mais un Dieu créé, un être "intermédiaire"

entre Dieu et l'homme, ce qui rendait ainsi le vrai Dieu toujours inaccessible

pour nous. Les Évêques réunis à Nicée répondirent en mettant au point et en

fixant le "Symbole de la foi" qui, complété plus tard par le premier

Concile de Constantinople, est resté dans la tradition des différentes

confessions chrétiennes et dans la liturgie comme le Credo de

Nicée-Constantinople. Dans ce texte fondamental - qui exprime la foi de

l'Église indivise, et que nous répétons aujourd'hui encore, chaque dimanche,

dans la célébration eucharistique - figure le terme grec homooúsios, en latin

consubstantialis: celui-ci veut indiquer que le Fils, le Logos est "de la

même substance" que le Père, il est Dieu de Dieu, il est sa substance, et

ainsi est mise en lumière la pleine divinité du Fils, qui était en revanche

niée par le ariens.

A la mort de l'Évêque

Alexandre, Athanase devint, en 328, son successeur comme Évêque d'Alexandrie,

et il se révéla immédiatement décidé à refuser tout compromis à l'égard des

théories ariennes condamnées par le Concile de Nicée. Son intransigeance,

tenace et parfois également très dure, bien que nécessaire, contre ceux qui

s'étaient opposés à son élection épiscopale et surtout contre les adversaires

du Symbole de Nicée, lui valut l'hostilité implacable des ariens et des

philo-ariens. Malgré l'issue sans équivoque du Concile, qui avait clairement

affirmé que le Fils est de la même substance que le Père, peu après, ces idées

fausses prévalurent à nouveau - dans ce contexte, Arius lui-même fut réhabilité

-, et elles furent soutenues pour des raisons politiques par l'empereur

Constantin lui-même et ensuite par son fils Constance II. Celui-ci, par

ailleurs, qui ne se souciait pas tant de la vérité théologique que de l'unité

de l'empire et de ses problèmes politiques, voulait politiser la foi, la rendant

plus accessible - à son avis - à tous ses sujets dans l'empire.

La crise arienne, que

l'on croyait résolue à Nicée, continua ainsi pendant des décennies, avec des

événements difficiles et des divisions douloureuses dans l'Église. Et à cinq

reprises au moins - pendant une période de trente ans, entre 336 et 366 - Athanase

fut obligé d'abandonner sa ville, passant dix années en exil et souffrant pour

la foi. Mais au cours de ses absences forcées d'Alexandrie, l'Évêque eut

l'occasion de soutenir et de diffuser en Occident, d'abord à Trèves puis à

Rome, la foi nicéenne et également les idéaux du monachisme, embrassés en

Égypte par le grand ermite Antoine, à travers un choix de vie dont Athanase fut

toujours proche. Saint Antoine, avec sa force spirituelle, était la personne

qui soutenait le plus la foi de saint Athanase. Réinstallé définitivement dans

son Siège, l'Evêque d'Alexandrie put se consacrer à la pacification religieuse

et à la réorganisation des communautés chrétiennes. Il mourut le 2 mai 373,

jour où nous célébrons sa mémoire liturgique.

L'oeuvre doctrinale la plus

célèbre du saint Évêque alexandrin est le traité Sur l'incarnation du Verbe, le

Logos divin qui s'est fait chair en devenant comme nous pour notre salut. Dans

cette œuvre, Athanase dit, avec une affirmation devenue célèbre à juste titre,

que le Verbe de Dieu "s'est fait homme pour que nous devenions Dieu; il

s'est rendu visible dans le corps pour que nous ayons une idée du Père

invisible, et il a lui-même supporté la violence des hommes pour que nous

héritions de l'incorruptibilité" (54, 3). En effet, avec sa résurrection

le Seigneur a fait disparaître la mort comme "la paille dans le feu"

(8, 4). L'idée fondamentale de tout le combat théologique de saint Athanase

était précisément celle que Dieu est accessible. Il n'est pas un Dieu

secondaire, il est le vrai Dieu, et, à travers notre communion avec le Christ,

nous pouvons nous unir réellement à Dieu. Il est devenu réellement "Dieu

avec nous".

Parmi les autres œuvres

de ce grand Père de l'Église - qui demeurent en grande partie liées aux

événements de la crise arienne - rappelons ensuite les autres lettres qu'il

adressa à son ami Sérapion, Évêque de Thmuis, sur la divinité de l'Esprit

Saint, qui est affirmée avec netteté, et une trentaine de lettres festales,

adressées en chaque début d'année aux Églises et aux monastères d'Égypte pour

indiquer la date de la fête de Pâques, mais surtout pour assurer les liens

entre les fidèles, en renforçant leur foi et en les préparant à cette grande

solennité.

Enfin, Athanase est

également l'auteur de textes de méditation sur les Psaumes, ensuite largement

diffusés, et d'une œuvre qui constitue le best seller de la littérature

chrétienne antique: la Vie d'Antoine, c'est-à-dire la biographie de saint

Antoine abbé, écrite peu après la mort de ce saint, précisément alors que

l'Évêque d'Alexandrie, exilé, vivait avec les moines dans le désert égyptien.

Athanase fut l'ami du grand ermite, au point de recevoir l'une des deux peaux

de moutons laissées par Antoine en héritage, avec le manteau que l'Évêque

d'Alexandrie lui avait lui-même donné. Devenue rapidement très populaire,

traduite presque immédiatement en latin à deux reprises et ensuite en diverses

langues orientales, la biographie exemplaire de cette figure chère à la

tradition chrétienne contribua beaucoup à la diffusion du monachisme en Orient

et en Occident. Ce n'est pas un hasard si la lecture de ce texte, à Trèves, se

trouve au centre d'un récit émouvant de la conversion de deux fonctionnaires

impériaux, qu'Augustin place dans les Confessions (VIII, 6, 15) comme prémisses

de sa conversion elle-même.

Du reste, Athanase

lui-même montre avoir clairement conscience de l'influence que pouvait avoir

sur le peuple chrétien la figure exemplaire d'Antoine. Il écrit en effet dans

la conclusion de cette œuvre: "Qu'il fut partout connu, admiré par tous et

désiré, également par ceux qui ne l'avaient jamais vu, est un signe de sa vertu

et de son âme amie de Dieu. En effet, ce n'est pas par ses écrits ni par une

sagesse profane, ni en raison de quelque capacité qu'Antoine est connu, mais

seulement pour sa piété envers Dieu. Et personne ne pourrait nier que cela soit

un don de Dieu. Comment, en effet, aurait-on entendu parler en Espagne et en

Gaule, à Rome et en Afrique de cet homme, qui vivait retiré parmi les

montagnes, si ce n'était Dieu lui-même qui l'avait partout fait connaître,

comme il le fait avec ceux qui lui appartiennent, et comme il l'avait annoncé à

Antoine dès le début? Et même si ceux-ci agissent dans le secret et veulent

rester cachés, le Seigneur les montre à tous comme un phare, pour que ceux qui

entendent parler d'eux sachent qu'il est possible de suivre les commandements

et prennent courage pour parcourir le chemin de la vertu" (Vie d'Antoine

93, 5-6).

Oui, frères et soeurs!

Nous avons de nombreux motifs de gratitude envers Athanase. Sa vie, comme celle

d'Antoine et d'innombrables autres saints, nous montre que "celui qui va

vers Dieu ne s'éloigne pas des hommes, mais qu'il se rend au contraire proche

d'eux" (Deus caritas est, n. 42).

* * *

Rencontre avec des groupes

dans la Basilique Saint-Pierre

Chers pèlerins de langue

française,

je vous accueille avec

joie auprès de la tombe de Pierre. Que la démarche spirituelle que vous

accomplissez ici affermisse votre foi au Christ et votre lien avec l’Église.

En vous confiant à

l’intercession de la Bienheureuse Vierge Marie, je vous assure de ma prière

pour vous, pour vos familles et à toutes vos intentions.

* * *

Aula Paolo VI

Je salue cordialement les

pèlerins de langue française. À la lumière de l’enseignement et de la vie des

saints, puissiez-vous découvrir que ceux qui vont vers Dieu ne s’éloignent pas

des hommes, mais qu’ils se rendent au contraire vraiment proches d’eux.

Appel du Pape Benoît XVI

pour la Journée mondiale des Réfugiés

On célèbre aujourd'hui la

Journée mondiale des Réfugiés, promue par les Nations unies pour que

l'attention de l'opinion publique ne manque pas à ceux qui ont été obligés de

fuir de leurs pays à la suite de réels dangers pour leur vie. Accueillir les

réfugiés et leur accorder l'hospitalité représente pour tous un geste juste de

solidarité humaine, afin que ces derniers ne se sentent pas isolés à cause de

l'intolérance et du manque d'intérêt. En outre, il s'agit pour les chrétiens de

manifester l'amour évangélique d'une manière concrète. Je souhaite de tout cœur

que soient garantis l'asile et la reconnaissance de leurs droits à nos frères

et sœurs durement éprouvés par la souffrance, et j'invite les responsables des

nations à offrir leur protection à ceux qui se trouvent dans une situation de

besoin aussi délicate.

© Copyright 2007 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Le Créateur devenu

serviteur

Il n’était pas digne de

la bonté de Dieu que des êtres suscités par lui fussent détruits à cause de la

ruse pratiquée par le diable à l’encontre des hommes. D’ailleurs, il eût été

d’une inconvenance totale que l’art mis par Dieu à susciter les hommes fût

anéanti par leur négligence ou par la ruse des démons. Ainsi, les êtres

raisonnables périssant et de telles œuvres étant vouées à leur perte, que

fallait-il que Dieu fît, lui qui est bon ? Permettre à la corruption de

prévaloir sur eux et à la mort de les dominer ? Mais quel profit pour ces

êtres d’avoir été suscités à l’origine ? Il valait mieux ne pas être que

de se trouver abandonnés, et de périr, une fois dans l’être. Car de la négligence

de Dieu on conclurait à sa faiblesse plutôt qu’à sa bonté, si après avoir créé

il laissait périr son œuvre, et cela bien plus que s’il n’avait pas fait

l’homme au commencement.

De qui avait-on besoin

pour cette grâce et cette restauration, sinon du Verbe de Dieu qui au

commencement avait créé toutes choses de rien ? C’était à lui de ramener

le corruptible à l’incorruptibilité, et de trouver ce qui en toutes choses

convenait au Père. Étant le Verbe de Dieu, au-dessus de tout, seul par

conséquent il était capable de recréer toutes choses, de souffrir pour tous les

hommes et d’être au nom de tous un digne ambassadeur auprès du Père.

St Athanase d’Alexandrie

Saint Athanase, évêque

d’Alexandrie († 373) et docteur de l’Église, a été au ive siècle l’un

des plus combattifs défenseurs de la divinité du Christ. / Sur

l’Incarnation du Verbe, 6,5-8, 7,4-5, trad. C. Kannengiesser, Paris, Cerf,

1973, Sources Chrétiennes 199, p. 285.289.

Le Fils de l’homme

aurait-il pu ne pas être livré ?

Dieu a

dit : « Tu es terre et à la terre tu retourneras » (Gn

3, 19). « Mais, dira-t-on, sans même que le Sauveur ne vînt du tout, Dieu

pouvait se contenter de parler et d’annuler la malédiction. » Cependant il

faut noter ce qui bénéficie aux hommes et non ce qui est en toute éventualité

possible à Dieu, puisqu’il pouvait, avant l’arche de Noé, détruire les hommes

qui avaient alors transgressé, mais il le fit après que l’arche fut construite.

Il pouvait, en se dispensant de Moïse, tout juste dire un mot et conduire

le peuple hors d’Égypte, mais il valait mieux le faire par Moïse. Le Sauveur

pouvait venir dès le commencement ou, une fois venu, ne pas être livré à

Pilate, mais c’est à la fin des temps qu’il vint et, quand on le cherchait, il

dit : « C’est moi » (Jn 18, 5).

Si Dieu avait parlé en

vertu de son pouvoir et que la malédiction eut été levée, la puissance de celui

qui émettait l’ordre aurait été montrée, mais l’homme serait néanmoins resté le

même, tel qu’était Adam avant la transgression, recevant la grâce de

l’extérieur et sans l’avoir ajustée au corps (car tel il était, lorsqu’il fut

placé au paradis) ; peut-être même se serait-il détérioré, lorsqu’il

aurait appris à transgresser. Dans cet état, s’il était encore séduit par le

serpent, le besoin survenait à nouveau que Dieu commande et lève la malédiction ;

et de cette façon le besoin survenait à perpétuité, et les hommes n’en

demeuraient pas moins réduits en esclavage, toujours soumis au péché.

St Athanase d’Alexandrie

Saint Athanase, évêque

d’Alexandrie († 373) et docteur de l’Église, a été au ive siècle l’un

des plus combatifs défenseurs de la divinité du Christ. / Traités contre

les ariens, t. II, 67-68, trad. C. Kannengiesser, Paris, Cerf, 2019, Sources

Chrétiennes 599, p. 229-233.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/samedi-30-septembre-2/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

Saint

Athanase d’Alexandrie, Fresque, Hosios Loukas,

Saint Athanase

Fête saint : 02 Mai

Présentation

Titre : Docteur de

l’Église

Date : 373

Pape : Saint Marcellin ;

saint Damase

Empereur : Valentinien ;

Valens

Il était, dit saint

Grégoire de Nazianze, d'une humilité si profonde que nul ne portait cette vertu

plus loin que lui. Doux et affable, il n'y avait personne qui n'eût auprès de

lui un accès facile. Il joignait à une bonté inaltérable, une tendre compassion

pour les malheureux. Ses discours avaient je ne sais quoi d'aimable qui

captivait tous les cœurs ; mais ils faisaient encore moins d'impression que sa

manière de vivre. Ses réprimandes étaient sans amertume, et ses louanges

servaient de leçon ; il savait si bien mesurer les unes et les autres, qu'il

reprenait avec la tendresse d'un père et louait avec la gravité d'un maître. Il

était tout à la fois indulgent sans faiblesse et ferme sans dureté.

La Vie des Saints :

Saint Athanase

Auteur

Mgr Paul Guérin

Les Petits Bollandistes

- Vies des Saints - Septième édition - Bloud et Barral - 1876 -

Saint Athanase

À Alexandrie, le

bienheureux décès de saint Athanase, évêque de la même ville, très-célèbre par

sa sainteté et sa doctrine. L'univers presque entier semblait s'être conjuré

pour le persécuter. De retour, à la fin, dans son église, après beaucoup de

combats et autant de victoires dues à sa constance, il rendit son âme au

Seigneur, la quarante-sixième année de son épiscopat, au temps des empereurs

Valentinien et Valens. ✞ 373

Hagiographie

Une lutte perpétuelle est

l’inévitable condition du bien dans l’humanité déchue. Dieu le fit voir à son

Église, lorsque, après avoir si glorieusement vaincu la persécution, elle eut à

repousser les attaques non moins formidables de l’hérésie. Celle-ci, il est

vrai, dès l’apparition du christianisme, avait cherché à troubler les conquêtes

de la foi ; mais, devant le glaive des tyrans et la gloire des martyrs, elle

avait fait peu de bruit et obtenu peu de succès.

Le lecteur, pour

comprendre la vie d’Athanase, a besoin de connaitre le schisme Mélécien et

l’hérésie arienne. Saint Pierre, prédécesseur d’Achillas sur le siège

d’Alexandrie, par son indulgence envers les chrétiens qui avaient offert de

l’encens aux idoles pour éviter la mort, et qui s’en repentaient, avait déplu

à Mélece, évêque de Lycopolis ; ce dernier se sépara de la communion de Pierre

et forma un schisme ; ses partisans prirent le nom de Méléciens. Arius, qui des

sables de la Libye était venu chercher fortune dans la capitale de l’Égypte, se

joignit à ces schismatiques.

Néanmoins, il parvint à

gagner, par un faux repentir, les bonnes grâces d’Achillas, patriarche

d’Alexandrie, qui l’éleva au sacerdoce et lui confia le gouvernement d’une des

paroisses, nommée Baucolis.

Ce n’était pas assez pour

son ambition : il aspirait au patriarcat ; mais saint Alexandre lui fut

justement préféré, pour sa piété, sa charité envers les pauvres, sa science

sacrée et son éloquence. Blessé dans son orgueil et voulant à toute fin jouer

un rôle dans le monde, il se fit le chef d’une nouvelle doctrine, qui fut

bientôt déclarée hérétique. Il enseignait que Jésus-Christ n’est point Dieu,

mais une simple créature, plus parfaite à la vérité que les autres, et formée

avant elles, non pas cependant de toute éternité. Or, si Jésus-Christ n’est pas

Dieu, à quoi aboutissent les espérances des chrétiens ? Il ne négligea rien

pour répandre ces erreurs dans le peuple ; il les mit en chansons pour les

ouvriers, les meuniers, les matelots, les voyageurs. Alexandre, n’ayant pu

ramener cet hérésiarque par les voies de la douceur, le fit condamner par un

concile tenu à Alexandrie, et écrivit aux évêques qui n’avaient pu y assister,

pour leur en faire connaitre les décisions.

Jamais, peut-être, aucun

chef d’hérésie ne posséda à un plus haut degré qu’Arius les qualités propres à

ce maudit et funeste rôle. Instruit dans les lettres et dans la philosophie des

Grecs, doué d’une rare souplesse de dialectique et de langage, il excellait à

donner à l’erreur les traits et le charme de la vérité. Son extérieur aidait à

la séduction. D’un âge déjà avancé, il joignait à l’avantage d’une haute taille

la dignité du vieillard. Son orgueil se dérobait sous un vêtement simple, sous

un visage modeste, recueilli, mortifié, qui lui donnait un faux air de

sainteté, et avec lequel il savait allier un abord gracieux, un ton doux et

insinuant.

Banni du sanctuaire, il

quitte Alexandrie, où il s’est déjà fait de nombreux partisans, et va demander

asile à Eusèbe, évêque de Césarée, métropole de la Palestine. Celui-ci était

l’un des plus savants hommes de son siècle, et auteur d’excellents ouvrages,

pour lesquels la postérité a partagé l’admiration de ses contemporains. Arius

sut lui faire goûter sa doctrine et l’intéresser à sa cause avec plusieurs

autres évêques. Parmi eux se signala un second Eusèbe, parent, dit-on, de la

famille impériale, qui, de sa propre autorité, avait osé abandonner le siège

dédaigné de Béryte, en Judée, pour celui de Nicomédie, séjour ordinaire des

empereurs d’Orient. Sa naissance, sa position, ses talents, ses qualités

extérieures lui donnaient un crédit et un ascendant dont ses sentiments le

rendaient indigne. Il avait apostasié dans la persécution. Condisciple d’Arius,

on l’a soupçonné d’avoir été son secret conseiller, avant de se faire son

protecteur déclaré. Quoi qu’il en soit, bravant encore une fois les règles de

la discipline et de l’ordre hiérarchique, il prit hautement le parti du

sectaire contre le digne patriarche, dont la réputation et le rang offusquaient

son orgueil. Ayant fait venir Arius à Nicomédie, il se concerta avec lui, et

écrivit en sa faveur aux évêques pour obtenir son rétablissement. Alexandre fut

inébranlable dans sa décision, comme il l’était dans sa foi.

Cette scission

scandaleuse agita et troubla l’église d’Orient. Constantin en fut sensiblement

affligé. Mais l’évêque courtisan de Nicomédie lui fit entendre qu’il ne

s’agissait entre Alexandre et Arius que d’une vaine dispute de mots, dont le

tort devait être surtout attribué au zèle amer et inflexible du premier. Ce

fut dans ces préjugés que l’empereur écrivit à l’un et à l’autre, par Osius,

évêque de Cordoue, qu’il députa en Égypte pour régler ce différend. Osius était

le prélat le plus vénéré de cette époque. Il avait souffert courageusement pour

la foi, avait initié Constantin à la connaissance des vérités du

christianisme, et l’on croit qu’il était venu alors en Orient de la part de

l’évêque de Rome, traiter avec l’empereur des affaires de l’Église. La lettre du

prince se terminait par de touchantes exhortations, qui attestent son zèle

sincère pour la foi ainsi que la bonté de son cœur :

« Rendez-moi des jours

sereins et des nuits tranquilles. Si vos divisions continuent, je serai réduit

à gémir, à verser des larmes ; il n’y aura plus pour moi de repos. Où en

trouverais-je, si ceux qui servent avec moi le vrai Dieu, se déchirent si

opiniâtrement ? Je voulais vous aller visiter, mon cœur était déjà avec vous ;

vos discordes m’ont fermé le chemin de l’Orient. Réunissez vous pour me le

rouvrir, donnez-moi la joie de vous voir heureux, comme tous les peuples de mon

empire ».

Ces accents d’un père ne

furent point écoutés. Le désordre augmentait de jour en jour. L’hérésie, comme

partout et toujours, se montra violente et rebelle. Il y eut des émeutes.

Constantin prononça, à cette occasion, un mot justement célèbre. Dans une

ville, les Ariens s’étaient emportés jusqu’à jeter des pierres à la face d’une

de ses statues. Comme ses ministres l’excitaient à tirer vengeance de cet

affront, lui, portant la main à son visage, leur répondit en souriant :

« Je ne me sens pas

blessé ».

La mission de l’évêque de

Cordoue ne fut pas néanmoins sans résultat. Il comprit, d’un côté, toute la

gravité de la controverse ; de l’autre, l’erreur et la mauvaise foi d’Arius ;

et, en les faisant connaître à l’empereur, il lui inspira une grande pensée :

celle de convoquer les évêques de toute la chrétienté, pour donner à la vérité

attaquée l’autorité d’une irrécusable décision. Les Apôtres n’avaient-ils pas

agi ainsi pour terminer la contestation sur les observances mosaïques ?

Au reste, c’était la

première fois, depuis l’extension de l’Évangile, que les circonstances

permettaient de, recourir à ce moyen extraordinaire. On se trouvait à la fin de

324, l’année même de la défaite et de la mort de Licinius, indigne beau-frère

de Constantin, le dernier des survivants de cette funeste ligue de pâtres

parvenus, de monstres débauchés et cruels, qui, pendant près d’un demi-siècle,

s’enivrèrent à l’envi du sang chrétien et dévorèrent la substance des peuples.

Maintenant, sous le doux et glorieux sceptre de Constantin, l’empire se

réjouissait d’une liberté, d’une prospérité inaccoutumée, et s’étonnait de voir

réunis autour de ce prince les ambassadeurs de toutes les nations de

l’univers, qui admiraient ses vertus et redoutaient ses armes, auxquelles la

victoire ne fut jamais infidèle. Dans un de ces moments trop rares et trop

courts pour le bonheur de l’humanité, le monde entier était en paix.

Dès le printemps de

l’année 325, sur l’invitation et avec l’aide du puissant empereur, qui s’était

concerté avec le chef de l’Église, les évêques de toutes les parties du monde

se rendirent en Asie, dans la ville de Nicée, voisine de Nicomédie. Le peuple

fidèle, ému par la nouveauté et l’importance du débat qu’ils allaient

terminer, et la réputation de leurs vertus, accourait sur leur passage, se

prosternait devant eux et les accompagnait de ses vœux et de ses espérances.

Constantin, qui les avait précédés à Nicée, les y accueillit avec la dignité

qui le caractérisait, et, en même temps, avec les plus touchants témoignages de

foi, de déférence et d’affection. Combien ils méritaient cet empressement, ces

hommages des populations et du premier empereur chrétien, des hommes dont la

plupart, outre leur caractère sacré, commandaient le respect et l’admiration

par leur âge, leur courageuse fidélité dans la persécution, leur science et

leur sainteté ! Celui-ci, ancien solitaire, avait été arraché malgré lui au

désert, dont il conservait, dans les dignités, les habitudes simples et

austères ; celui-là était célèbre par ses miracles ; plusieurs portaient encore

sur leurs membres ou sur leur visage les stigmates du martyre. Quels plus

dignes interprètes du grand mystère de la sainte Trinité !

Ces prélats, sans compter

les prêtres, les diacres et les laïques éclairés qui les assistaient, se

trouvèrent réunis au nombre de trois cent dix-huit, parmi lesquels on n’en

compta que dix-sept infectés d’arianisme. Pendant deux mois, depuis le 19 juin

jusqu’au 25 août, ils tinrent, sur différentes questions de dogme et de

discipline, de nombreuses et longues conférences. Arius exposa sa doctrine. En

l’entendant proférer ces nouveautés impies, les Pères du concile se bouchaient

les oreilles. Il leur fallut un grand effort de raison et de prudence pour

consentir à les examiner. Enfin, la question fut approfondie et discutée des

deux côtés avec toute la science et toute l’habileté que chacun pouvait

désirer. On en remit la décision à une séance solennelle, qui eut lieu, en

présence de l’empereur, dans la plus vaste salle de son palais. Les évêques

étaient rangés sur des sièges disposés autour de cette enceinte. Un trône

s’élevait au milieu : on y déposa le livre des Évangiles. Osius présidait

l’assemblée au nom du Pape, que son âge, ses infirmités et les exigences de son

rang avaient retenu à Rome. Dans le fond de la salle, un siège vide, moins

élevé que les autres, mais tout resplendissant d’or, était destiné à

l’empereur. À neuf heures du matin, il se présente sans armes, sans soldats,

accompagné seulement de quelques dignitaires qui professaient le christianisme.

À sa vue, les Pères du concile, qui l’attendaient en silence, se lèvent et se

tiennent debout. Tout, dans le maintien, l’air et la taille de Constantin,

montrait l’homme supérieur aux autres hommes par les heureux dons de la

nature ; comme il l’était par l’éminence de sa dignité. À cinquante ans, il

avait encore l’éclat et les grâces de la jeunesse. La franchise de son

caractère et la pureté de ses mœurs reluisaient sur son front serein. Il

s’avance au milieu de cette assemblée la plus sainte et la plus auguste qu’on

eût jamais vue sous le ciel, avec une magnificence de vêtement qui annonce le

maître de l’empire, avec un respect et une modestie qui révèlent le chrétien.

Arrivé devant son siège, il attendit, pour y prendre place, d’y être invité par

les évêques, qui s’assirent après lui. Alors s’engagea entre les Pères du

concile une discussion d’où sortit la foudre qui terrassa l’hérésie. Les

blasphèmes d’Arius ne tinrent plus devant le terme de consubstantiel,

expression aussi concise qu’énergique de l’unité de nature dans les trois

personnes divines. L’univers répéta avec transport le symbole de Nicée,

magnifique développement du symbole des Apôtres, hymne sublime de foi, d’amour

et de reconnaissance. Les évêques ariens le souscrivirent, après plus ou moins

de résistance, avec plus au moins de bonne foi, à l’exception de deux, qui

furent déposés par le concile, et, avec Arius, condamnés, par l’empereur, au

bannissement : châtiment dû aux téméraires violateurs des lois de la plus haute

société qui ait paru sur la terre.

Dans ce débat solennel,

au milieu de ces vénérables et savants prélats, de ces glorieux athlètes de la

foi, on vit se lever, par leur conseil et à leur grande joie, un jeune lévite,

qui lutta corps à corps avec Arius. Par la supériorité de sa raison, par la

connaissance approfondie et l’intelligence des livres saints, par la lucidité

et la force de l’argumentation, par la chaleur d’une éloquence simple, vraie et

naturelle, il repoussa les audacieuses attaques de ce redoutable adversaire,

déjoua toutes ses ruses, le poursuivit dans tous ses détours, et le confondit,

en éclairant de la plus vive lumière ses plus ténébreux retranchements. Il ne

charma pas moins le concile par sa modestie, par la sincérité de sa foi et de

son dévouement que par l’éclat de sa victoire ; car ce jeune homme aimait

l’Église plus que le plus tendre fils n’aime sa mère, plus que jamais ni Grec

ni Romain n’aima sa patrie : nous avons nommé Athanase.

Enfant d’une famille

distinguée et chrétienne d’Alexandrie, il s’était attaché de bonne heure à

saint Alexandre, qui l’avait élevé et le chérissait comme un fils.

La première rencontre de

saint Athanase avec saint Alexandre eut un caractère tout providentiel. Dans

les premiers temps de son pontificat, dit Rufin, le saint patriarche Alexandre

avait convié tous les clercs de son église, un dimanche soir, à un repas qu’il

voulait leur donner dans sa maison, située sur le bord de la mer. Après les

solennités du jour, Alexandre, en attendant ses hôtes, avait les yeux fixés sur

le rivage, lorsqu’il aperçut un groupe d’enfants qui se livraient aux jeux de

leur âge. Ils avaient élu un évêque ; ils le firent asseoir au milieu d’eux et

écoutèrent gravement ses paroles ; puis ils s’inclinèrent sous sa main

bénissante, et le pontife-enfant imita sur quelques-uns de ses compagnons

toutes les cérémonies du baptême. À cette vue, Alexandre craignit une

profanation ; il envoya son diacre, avec ordre de lui amener les enfants. En

présence du véritable évêque, ceux-ci eurent peur et ne répondirent qu’en

balbutiant à toutes ses interrogations. Enfin, rassurés par l’air de douceur et

de bonté qui se peignait sur son visage, ils lui dirent qu’ils avaient élu un

d’entre eux, Athanase, pour évêque ; que celui-ci avait des catéchumènes

instruits par ses soins, auxquels il venait de conférer le baptême. L’enfant

qui répondait au nom d’Athanase parut alors, mais avec une confusion facile à

deviner. Le patriarche lui demanda s’il avait réellement administré le baptême

selon les rites de l’Église et avec l’intention de conférer un sacrement. La

réponse d’Athanase fut affirmative ; il répéta devant le patriarche les

formules qu’il avait employées. Saint Alexandre donna l’ordre à ses prêtres de

suppléer aux néophytes ainsi baptisés les autres cérémonies de l’Église, mais

sans renouveler le baptême, « parce qu’il avait été validement conféré ».

À partir de ce jour, Athanase et ceux de ses compagnons qui remplissaient près

de sa personne les fonctions de prêtres et de diacre, furent élevés, du

consentement de leurs parents, dans l’école ecclésiastique d’Alexandrie.

Athanase y fit de rapides progrès.

Athanase s’occupa de

bonne heure à bien écrire. Il n’accorda que peu de temps aux lettres profanes,

assez cependant pour ne pas y rester complétement étranger, et pour que l’on

ne pût attribuer à l’ignorance le rang subalterne où elles étaient reléguées

dans son estime. Ce noble et mâle génie répugnait à consumer ses efforts dans

des études vaines.

Les études qui se

rapportaient à la religion employaient la plus grande partie de son temps. La

suite de sa vie et la lecture de ses écrits feront voir jusqu’à quel point il y

excellait. Il cite si souvent et si à propos les livres saints qu’on croirait

qu’il les savait par cœur : au moins conviendra-t-on que la méditation les lui

avait rendus très-familiers. C’était là qu’il avait puisé cette rare piété et

cette profonde intelligence des mystères de la foi. Quant au vrai sens des

oracles divins, il le cherchait dans la tradition de l’Église, et il nous

apprend lui-même qu’il lisait avec soin les commentaires des anciens Pères. Il

dit dans un autre endroit, qu’il apprenait la tradition des saints maitres

inspirés et des martyrs de la divinité de Jésus-Christ. Comme il avait beaucoup

de zèle pour la discipline de l’Église, il acquit aussi une grande connaissance

du droit canonique. On voit encore par ses ouvrages qu’il savait le droit

civil, et c’est ce qui lui a fait donner par Sulpice-Sévère le titre de

jurisconsulte.

Pour aliment de sa

pensée, il choisit l’Ancien et le Nouveau Testament. A ces habitudes de

contemplation se joignirent des trésors de vertu, chaque jour augmentés. La

science et les mœurs brillant chez Athanase d’un éclat pareil et se fortifiant

mutuellement, formèrent cette chaîne d’or, dont si peu d’hommes réussirent à

ourdir le double et précieux fil. La pratique du bien l’initiait à la

contemplation, et la contemplation à son tour lé guidait dans la pratique du

bien.

Quand il eut achevé ses

études littéraires, le désir d’avancer dans les voies de la perfection le

conduisit aux pieds du fameux solitaire saint Antoine. Il resta quelques années

sous sa direction, et revint près du patriarche Alexandre, qui l’éleva au

diaconat et l’employa comme secrétaire. C’est ainsi, ajoute Rufin, qu’Athanase,

nouveau Samuel, fut attaché à la personne du grand prêtre, jusqu’à ce qu’il fut

plus tard appelé à l’honneur de revêtir lui-même l’éphod pontifical.

Athanase n’était encore

que diacre, lorsque le patriarche l’amena avec lui au concile de Nicée. Mais,

aussitôt après, il fut ordonné prêtre, et, l’année suivante, l’auguste

vieillard, se sentant près de mourir, le désigna pour son successeur. Athanase

se cacha, pour se dérober, lui si jeune, à une telle dignité.

« Tu fuis » ; dit le

saint avant d’expirer, « tu fuis, Athanase, mais tu n’échapperas pas ».

Ces paroles furent un

oracle. Le peuple demanda instamment et obtint des évêques assemblés que le jeune

prêtre fût nommé évêque d’Alexandrie. Il avait à peine trente ans ; mais, dans

les circonstances où se trouvait cette église, le génie, la science et la

sainteté n’avaient pas besoin du nombre des années. Ce choix fit frémir

l’hérésie, qui, pour être vaincue, n’avait pas renoncé à ses espérances. Le

jour n’est pas loin, où, par de cauteleuses démarches, par d’artificieuses

professions de foi, elle saura gagner la faveur du prince : et, une fois armée

de l’autorité publique, jusqu’où n’iront pas son audace et ses excès ?

Athanase, quels combats, quelles épreuves vous attendent !

Athanase signala les

commencements de son épiscopat par son attention à pourvoir aux besoins

spirituels des Éthiopiens. Il sacra Frumence évêque, et le leur envoya, afin

qu’il pût achever l’œuvre de leur conversion, qu’il avait si heureusement

commencée ; et lorsqu’il eut établi un bon ordre dans l’intérieur de la ville,

il entreprit la visite générale des églises de sa dépendance.

Les Méléciens donnèrent

beaucoup d’exercice à son zèle. Ils continuèrent, après la mort de Mélèce,

leur chef, de tenir des assemblées et d’ordonner des évêques de leur propre

autorité. Partout ils soufflaient le feu de la discorde, et par là ils

entretenaient le peuple dans l’esprit de révolte. Athanase essaya tous les

moyens possibles pour les ramener à l’unité ; mais il n’y en eut aucun qui lui

réussit. Austères dans leur morale, ils s’étaient fait un grand nombre de

partisans, surtout parmi les gens simples, auxquels ils en avaient imposé. Les

Ariens résolurent de profiter des dispositions où ils les voyaient : ils

s’empressèrent donc de rechercher leur amitié. Les Méléciens n’avaient d’abord

erré dans aucun article de la foi ; ils avaient même été des premiers et des

plus ardents à combattre la doctrine d’Arius ; mais bientôt après ils s’unirent

aux partisans de cet hérésiarque pour calomnier et persécuter Athanase. Il se

forma entre eux une ligue solennelle, afin que les coups qu’ils lui porteraient

fussent plus efficaces. Saint Athanase fait observer à ce sujet, que comme

Hérode et Pilate oublièrent la haine qu’ils se portaient mutuellement pour se

réunir contre le Sauveur, de même les Méléciens et les Ariens dissimulèrent

leur animosité réciproque afin de former une espèce de confédération contre la

vérité. Au reste, voilà l’esprit de tous les sectaires ; ils font cesser leurs

divisions lorsqu’il s’agit de déchirer le sein de l’Église et de déclarer la

guerre à ceux qui tiennent pour la doctrine catholique.

Constantin donna bientôt

de nouvelles preuves de son attachement à la foi de Nicée. Trois mois après la

conclusion du concile, il exila avec indignation Eusèbe de Nicomédie, qui

osait en attaquer les décisions et communiquait ouvertement avec ceux qui s’y

montraient rebelles.

Mais quels sombres nuages

ont voilé tout à coup la gloire jusque-là si pure et si brillante du grand

Constantin ! Quoi I d’un prince ordinairement si doux et si prudent, l’histoire

raconte des actes irréfléchis et barbares, des meurtres domestiques ! Et puis,

sous ce même prince, qui, jusqu’à son dernier soupir, ne cessa d’avoir horreur

de l’hérésie, les hérétiques sont honorés, triomphants et les catholiques

repoussés, persécutés ! Quelle est donc la triste condition de l’humanité

déchue ? Quel impur alliage est venu souiller tout à coup en lui l’or pur de la

charité chrétienne ?

Pour comble de malheur,

il perdit sa mère, la glorieuse sainte Hélène, lorsque, à la veille des plus

astucieuses machinations de l’erreur, les conseils et l’influence de cette

mère plus éclairée que lui dans la foi, eussent été si nécessaires et auraient

prévenu sans doute de nouvelles fautes.

Lorsque sainte Hélène ne

fut plus, toute la tendresse de famille et la confiance de l’empereur se

concentrèrent sur sa sœur Constancie, veuve de Licinius. Celle-ci d’ailleurs,

femme de mérite et de vertu, s’était depuis longtemps laissé entêter de l’arianisme

par Eusèbe de Nicomédie, qui avait été le partisan de Licinius, et par un

prêtre dont l’histoire a dédaigné le nom. Près de rendre le dernier soupir, un

an environ après la mort de sainte Hélène, ·elle signala à Constantin ce prêtre

obscur comme le plus propre à le diriger dans les affaires de la religion.

« Suivez ses avis »,

dit-elle, « je meurs, aucun intérêt ne m’attache plus à la terre, mais je

crains pour vous la colère de Dieu, je crains qu’il ne vous punisse de l’exil

auquel vous avez condamné des hommes justes et vertueux ».

Ces conseils d’une sœur

chérie et mourante ne furent que trop écoutés. Arius est rappelé avec les

évêques exilés pour sa cause, moyennant quelque équivoque ou mensongère

profession de foi. Rétabli sur son siège de Nicomédie, et dans tout son crédit,

Eusèbe ne sera satisfait qu’autant qu’Arius aura reparu et repris ses fonctions

dans l’église d’Alexandrie. Pour l’obtenir, il emploie inutilement auprès

d’Athanase et les sollicitations et les menaces. Inutilement, il lui fait écrire

par l’empereur. Le patriarche est alors en butte à toutes les calomnies. Mandé

à la cour, il se justifie avec une telle évidence, que Constantin, en le

congédiant, lui remet une lettre adressée au peuple d’Alexandrie, où, après

avoir déploré la malice de ceux qui troublent et divisent l’Église pour

satisfaire leur jalousie et leur ambition, il ajoute que les méchants n’ont

rien pu contre leur évêque, dont il a reconnu l’innocence et la sainteté.

Il fallut donc se taire

et dissimuler pendant quelque temps. Mais bientôt les calomnies recommencent

avec un acharnement effronté. La cabale que dirige Eusèbe est en même temps la

plus fourbe et la plus audacieuse qui fût jamais. Protestant de son adhésion à

la foi catholique, ce n’est plus la doctrine, mais le caractère et la conduite

d’Athanase qu’elle attaque ; c’est de crimes qu’elle l’accuse. Et de quels

crimes ? De meurtres, d’opérations magiques, d’impures violences.

Athanase a beau se

justifier encore devant l’empereur, qui, après informations prises auprès des

magistrats d’Égypte, s’irrite de ces odieuses inventions, et menace, si elles

se renouvellent, d’en chercher les auteurs. L’intrigant Eusèbe obtient la

convocation d’un concile particulier à Césarée, résidence du second Eusèbe,

sous prétexte de mettre fin aux divisions, mais au fond pour y faire condamner

le patriarche d’Alexandrie, et il a soin d’y faire appeler en majorité ses

partisans. Aussi Athanase refuse-t-il pendant trois ans de comparaître devant

des juges qui sont ses ennemis ; mais en 344, sur les ordres formels de

l’empereur, à qui on l’a dépeint comme un homme superbe et un sujet rebelle, il

est obligé de se rendre à Tyr, où le synode a été transféré.

Parmi les imputations

déjà détruites, on osa, comme Athanase l’avait prévu, reproduire celles-là

mêmes dont l’invraisemblance seule aurait dû montrer la fausseté.

Une femme fut entendue,

qui déclara qu’elle s’était consacrée à Dieu par vœu de virginité ; mais que,

ayant logé dans sa maison l’évêque Athanase, celui-ci n’avait pas rougi d’outrager

les droits sacrés de l’hospitalité et les droits plus saints encore de la

pudeur. Athanase innocent était aussi trop habile pour se laisser confondre par

cette facile et banale accusation. L’ayant ouïe, il demeura immobile à sa

place, tandis que Timothée, un de ses prêtres, et son confident, se lève, et,

s’avançant vers l’impudente :

« Quoi », lui dit-il, «

c’est moi qui ai commis un tel crime ? »

« Oui, c’est vous

», s’écrie-t-elle avec force, « s’agitant, tout en pleurs, et les cheveux

épars, c’est vous-même, je vous reconnais ».

Et elle indiquait avec

assurance toutes les circonstances de l’attentat imaginé. Cette flagrante

imposture fut accueillie par un rire général, et la misérable ignominieusement

éconduite, malgré les instances d’Athanase, pour qu’on la retînt, afin de lui

faire révéler les auteurs de cette trame malencontreuse.

Mais voici un autre

prétendu forfait.

Arsène, évêque d’une

ville de la Thébaïde et l’un des sectateurs de Mélèce, cet évêque schismatique

dont Arius avait embrassé le parti avant de se faire lui-même chef d’hérésie,

avait disparu tout à coup. Les Méléciens, que les Ariens avaient su gagner à

leur cause, accusèrent Athanase de l’avoir fait mourir. Pour preuve, ils

portaient et montraient de ville en ville une main droite d’homme, prétendant

que c’était celle d’Arsène, dont le patriarche avait voulu se servir pour des

opérations magiques. À la vue de cette main desséchée, les membres du concile

furent saisis, les uns d’horreur, vraie ou feinte, pour l’attentat, les autres

d’indignation contre les machinateurs de l’affreuse calomnie. Athanase, qui

s’était préparé à y donner un éclatant démenti, seul ne fut point ému.

Aussitôt, il envoie prendre un homme qui attendait à la porte, et qui entre,

couvert d’un manteau. C’était Arsène lui-même, dont Athanase était parvenu à

découvrir la retraite au fond de quelque désert, et qu’il avait fait amener

secrètement à Tyr. Plusieurs des assistants connaissaient parfaitement Arsène :

sa présence fut un coup de foudre. Athanase s’étant approché de lui et

soulevant peu à peu son manteau, découvre d’abord la main gauche, puis la main

droite.

« Voilà », dit-il »,

Arsène avec ses deux mains, le Créateur ne nous en a pas donné davantage. Que

mon adversaire montre où l’on a pris la troisième ».

Cӎtait trop de confusion

pour les accusateurs d’Athanase ; à cette fois, ils ne lui pardonnèrent ni leur

supercherie et leur sottise, ni son habileté et son innocence. Cette confusion

se change tout à coup en aveugles transports de colère, et la délibération en

un affreux tumulte. Si cette main n’est pas la main d’Arsène, si Arsène est

vivant, c’est l’effet de quelque sortilège, c’est un nouveau coup de magie, un

nouveau grief contre Athanase. Leur fureur est telle qu’ils se seraient portés

contre lui aux dernières violences, sans le gouverneur de la Palestine qui

l’arracha de leurs mains, et, pour le mettre en sûreté, l’engagea à s’embarquer

la nuit suivante. Athanase fait voile vers Constantinople et va demander

justice à l’empereur.

Les autres chefs d’accusation

ne furent pas mieux établis. Qu’importe ? La décision fut telle qu’on la devait

attendre d’une assemblée délibérant sous la pression des Eusébiens et des

Méléciens réunis, et de la force armée que l’empereur avait mise à leur

disposition. Des troupes stationnaient autour de l’enceinte sacrée : ce

n’étaient plus des diacres, mais des soldats ou des geôliers qui en ouvraient

les portes. Athanase fut condamné et déposé par des juges malintentionnés,

intimidés ou trompés. Dans la crainte que l’empereur ne voulût pas croire aux

crimes qu’on lui imputait, on eut soin de donner pour dernier motif de cette

condamnation qu’Athanase, par son orgueil et l’inflexibilité de son caractère,

était une cause de division et de troubles dans l’Église d’Alexandrie.

Toutefois, de nombreuses et courageuses voix vengèrent Athanase de l’injustice

dont il était victime. Le concile se composait de cent neuf évêques ;

quarante-neuf rendirent témoignage de son innocence et de ses vertus, et

protestèrent contre l’iniquité de ce jugement.

Dès l’ouverture du

concile, le vertueux Potamon, évêque d’Héraclée sur le Nil, voyant Athanase

debout devant les autres évêques assis, dans l’attitude d’un accusé devant ses

juges, ne put retenir ses larmes et son indignation :

« Quoi, Eusèbe », dit-il

à l’évêque de Césarée, « vous êtes assis, vous, pour juger Athanase qui est

innocent ! »

« Dites-moi,

n’étions-nous pas tous deux en prison pendant la persécution ? J’y perdis un

œil, vous voilà avec tous vos membres : comment en êtes-vous sorti ? ».

Ainsi, cet Eusèbe, aussi

bien que le premier, avait apostasié pendant les dernières épreuves.

L’illustre confesseur,

saint Paphnuce, ancien disciple de saint Antoine et alors évêque dans la haute

Thébaïde, celui auquel Constantin rendit tant d’honneurs au concile de Nicée,

prenant par la main saint Maxime de Jérusalem, son compagnon de martyre,

l’entraîna hors du concile en lui disant qu’après avoir souffert ensemble pour

Jésus-Christ, ils ne devaient pas siéger dans l’assemblée des méchants. Il

l’instruisit ensuite de toute la conspiration qu’on lui avait dissimulée et

l’attacha pour toujours à la cause d’Athanase.

Il restait à lever

l’anathème dont le concile œcuménique avait frappé Arius et à le rétablir dans

l’église d’Alexandrie. Mais un ordre de l’empereur ayant appelé tout à coup

les évêques à Jérusalem pour la dédicace de l’église du Saint-Sépulcre, qui

venait d’être terminée, ils reprirent dans cette ville la suite de leurs

délibérations. Arius présenta une profession de foi accompagnée de lettres de

recommandation de l’empereur, à qui cette profession avait paru orthodoxe. Le

concile se hâta de l’approuver et de prononcer la réunion à l’Église d’Arius

et de tous ceux qui avaient suivi son parti.

Cependant, Athanase,

réfugié à Constantinople, ne pouvait arriver jusqu’à l’empereur. Les Eusébiens

lui fermaient également les avenues du palais et le cœur du prince. Mais

Athanase, par une démarche hardie, déjoua l’opposition de ses ennemis.

L’empereur entrait un jour à cheval dans la ville. Athanase s’approche de lui,

et comme l’empereur, déjà prévenu par les décisions du concile de Tyr, avait

peine à l’écouter :

« Prince », lui dit-il, «

Dieu jugera entre vous et moi, puisque, prenant parti pour mes calomniateurs,

vous refusez de m’entendre. Je ne sollicite aucune faveur. Qu’on me confronte

seulement devant vous avec ceux qui m’ont condamné ».

Cette réclamation était

trop conforme aux principes d’équité et de modération de l’empereur pour

n’être pas accueillie. L’invitation de se rendre aussitôt à Constantinople pour

y exposer les motifs de la condamnation du patriarche d’Alexandrie, consterna

les évêques qui l’avaient prononcée et qui se trouvaient encore réunis à

Jérusalem. Mais les chefs du parti furent assez habiles pour les engager à

rentrer dans leurs églises après s’être fait déléguer eux-mêmes pour

représenter leurs collègues auprès de l’empereur.

Là, les fourbes

eurent-ils le front de répéter les accusations auxquelles Athanase avait déjà

donné de si foudroyants démentis ? Non ; ils en improvisèrent une nouvelle

dont le succès était infaillible. Athanase, dirent-ils à l’empereur, a menacé

d’arriver en Égypte le blé destiné à l’approvisionnement de Constantinople.

C’était attaquer Constantin par l’endroit le plus sensible, lui que rien ne

préoccupait, en ce moment, comme la prospérité de la ville dont il avait jeté

les fondements, en 328, sur les rives enchantées du Bosphore, et dont il

voulait faire la première ville du monde.

Malgré les dénégations

formelles d’Athanase, l’empereur, qui connaissait l’ascendant du patriarche

dans toute l’Égypte, crut à une calomnie qu’Eusèbe accompagnait de serments et

l’exila à Trêves, alors la capitale des Gaules. Injustement accusé, Athanase

s’était défendu sans crainte ; injustement condamné, il obéit sans murmure.

La terre de l’exil fut

douce et hospitalière. La vénération des peuples, l’affection de saint Maximin,

évêque de cette ville, la bienveillance et les égards du jeune Constantin, qui

commandait pour son père dans l’Occident, consolèrent le glorieux athlète de

la vérité, de la disgrâce du prince et de l’acharnement de ses ennemis.

La nouvelle de la

condamnation et du bannissement d’Athanase répandit parmi l’ardente et fidèle

population d’Alexandrie une irritation qui put à peine se contenir. Les villes

et les· campagnes de l’Égypte, les solitudes mêmes de la Thébaïde en furent

émues. Mille voix s’élevèrent de toutes parts, et parmi ces voix, la plus

vénérée de ce temps, celle de saint Antoine, pour demander le rappel de

l’illustre patriarche ; mais rien ne put faire revenir Constantin d’une mesure

qui, justifiée par l’autorité d’un concile, lui était d’ailleurs inspirée par

son aversion pour les divisions entre les chrétiens. Il espérait que l’absence

momentanée d’Athanase calmerait les esprits et finirait par ramener l’union et

la paix dans l’église d’Orient. Au reste, Athanase lui-même s’est plu à

reconnaître sur ce point la rectitude d’intention de Constantin. Ce prince

refusa d’ailleurs de le remplacer par un évêque du choix des Eusébiens avec une

résolution et des menaces qui les firent renoncer à leur entreprise.

Les décisions du concile

de Jérusalem ne devaient pas longtemps porter bonheur au superbe Arius :

Alexandrie le repoussa avec horreur. Rappelé par l’empereur à Constantinople,

les Eusébiens se flattèrent de donner plus d’éclat à son triomphe en le faisant

rétablir dans l’église même de la résidence impériale. Mais là se rencontra,

pour s’opposer à son intrusion, un autre Alexandre qui honorait son nom par les

mêmes vertus, la même pureté et la même fermeté de foi que le patriarche

d’Égypte, qui le premier bannit de l’Église le prêtre indocile. Ni prières ni

menaces ne purent déterminer l’évêque de Constantinople à ouvrir à

l’hérésiarque les portes du sanctuaire. Nécessité fut alors aux sectaires de

recourir à l’autorité de l’empereur, qui, avant d’intervenir, voulut s’assurer

lui-même des véritables sentiments d’Arius. Celui-ci renouvelle devant le

prince ses équivoques professions de foi.

« Jurez, lui dit

Constantin, que votre croyance est conforme aux décrets de Nicée ».

Arius jura.

« S’il en est ainsi,

reprit l’empereur, allez en toute assurance ; mais si votre foi trahit votre

serment, que Dieu vous juge ».

Il fait appeler aussitôt

saint Alexandre ; lui communique les protestations d’orthodoxie qu’Arius vient

de réitérer sous la foi du serment, et ajoute qu’il faut tendre la main à un

homme qui demande à se sauver. L’évêque représente que l’hérésiarque, n’ayant

rétracté aucune de ses erreurs, le recevoir dans l’Église ce serait y

introduire l’hérésie elle-même. L’empereur s’irrite, le Saint garde un silence

tout à la fois digne et respectueux, et se retire, abandonnant de plus en plus

dans son cœur sa cause à Dieu.

Déjà, depuis sept jours,

par son conseil et, celui de l’illustre évêque de Nisibe, saint Jacques, doué

du don de prophétie et de miracles, qui se trouvait en ce moment à

Constantinople les catholiques imploraient, dans le jeûne et dans les larmes,

la protection du ciel contre l’audacieuse entreprise de l’erreur. Sorti du

palais impérial dans une profonde affliction, l’évêque va se jeter au pied des

autels et demande instamment à Dieu d’épargner à son Église un tel scandale.

C’était un samedi. Eusèbe, à la tête de ses partisans, voulut préluder par une

ovation publique à l’installation solennelle de l’intrus, fixée au lendemain.

La multitude des Ariens grossissait de rue en rue, tandis qu’Arius excitait

leur enthousiasme par de vains et insolents discours. Parvenu à l’entrée de la

place de Constantin, d’où l’on apercevait le temple où devait se consommer son

triomphe, il pâlit tout à coup, et saisi de violentes douleurs d’entrailles, il

est obligé de s’écarter de la foule. On le trouve bientôt expirant dans le lieu

secret où il s’était retiré : digne fin d’une vie d’orgueil et de sacrilège

hypocrisie. La justice et la patience de Dieu n’attendent pas toujours

l’éternité pour punir.

Plusieurs Ariens se

convertirent ; Constantin vit dans ce tragique événement le châtiment du

parjure et s’attacha de plus en plus à la foi de Nicée. Le lendemain, les

catholiques célébraient en paix et pleins de joie les divins mystères et leur

délivrance miraculeuse. Le bannissement de saint Athanase fut la dernière faute

de Constantin ; et l’ordre de le rappeler, qu’il donna un an après, le dernier

acte de sa vie.

Il laissa trois fils :

Constantin, Constance et Constant. Au premier échurent la Grande-Bretagne, les

Gaules et l’Espagne ; au second, l’Asie et l’Égypte ; au troisième l’Illyrie,

la Grèce, l’Italie et l’Afrique.

Constantin le Jeune se

hâta de remplir les intentions de son père, et de rendre la liberté à saint

Athanase, qui remonta sur son siège, l’an 338, aux acclamations du peuple

d’Alexandrie et de l’Égypte entière.

Le rétablissement

d’Athanase mortifia sensiblement les Ariens ; aussi firent-ils jouer de

nouveaux ressorts pour le perdre. Ils mirent dans leurs intérêts Constance, qui

avait eu l’Orient en partagé, et lui représentèrent Athanase comme un esprit

inquiet et turbulent qui depuis son retour avait excité des séditions et commis

des violences et des meurtres. Ils l’accusèrent encore d’avoir vendu à son

profit les grains destinés à la nourriture des veuves et des ecclésiastiques

qui habitaient les contrées où il ne venait point de blé. Ils formèrent les

mêmes accusations auprès de Constantin et de Constant ; mais leurs députés,

loin de réussir à persuader ces deux princes, furent renvoyés avec mépris. Pour

Constance, il se laissa séduire et ajouta foi au dernier chef d’accusation. Il

ne fut pas difficile au patriarche d’en démontrer la fausseté, et il n’eut

autre chose à faire pour cela que de produire les attestations des évêques de

Libye, où il était marqué qu’ils avaient reçu la quantité ordinaire de froment.

La calomnie découverte ne dissipa point les préjugés de Constance. Ce

malheureux prince était gouverné par Eusèbe de Nicomédie et par d’autres

ariens, qui lui inspiraient leurs propres sentiments, et qui l’amenèrent au

point de leur permettre d’élire un nouveau patriarche d’Alexandrie.

La permission étant

accordée, les hérétiques s’assemblèrent à Antioche sans délai ; ils déposèrent

Athanase, et élurent en sa place un prêtre égyptien de leur secte, nommé

Piste. Ce mauvais prêtre, ainsi que l’évêque qui le sacra, avait été

précédemment condamné par saint Alexandre et par le concile de Nicée. Le pape

Jules refusa de communiquer avec cet intrus, et toutes les églises catholiques

lui dirent anathème ; aussi ne peut-il jamais prendre possession d’une dignité

qu’il avait usurpée.

Athanase, de son côté,

tint à Alexandrie un concile où se trouvèrent cent évêques. On y prit la

défense de la foi, et l’on y reconnut l’innocence du patriarche. Les Pères

écrivirent ensuite une lettre circulaire à tous les évêques, et l’envoyèrent

nommément au pape Jules. Le Saint alla lui-même à Rome en 341 ; mais le long

séjour que les circonstances l’obligèrent de faire dans cette ville, donna aux

Ariens le temps de tout bouleverser en Orient.

Dans la même année 341,

il y eut un synode à Antioche, à l’occasion de la dédicace de la grande église.

On fit dans ce synode, composé d’évêques orthodoxes et hérétiques, vingt-cinq

canons de discipline ; mais les prélats orthodoxes ne furent pas plus tôt

partis, que les hérétiques y en ajoutèrent un vingt-sixième, qui regardait

évidemment saint Athanase. Il portait que si un évêque déposé justement ou

injustement dans un concile retournait à son église sans avoir été réhabilité

par un concile plus nombreux que celui qui avait prononcé la déposition, il ne

pourrait plus espérer d’être rétabli ni même d’être admis à se justifier. Ils

élurent ensuite un certain Grégoire, sorti de la Cappadoce, qui combla la

mesure de son indignité par sa monstrueuse ingratitude pour les bienfaits

d’Athanase.

Le prétendu patriarche,

escorté de soldats que commande Philagre, gouverneur de l’Égypte, fait son

entrée dans Alexandrie comme dans une ville prise d’assaut. Le peuple réclama

contre cette nomination et ces violences, si contraires aux traditions et à la

discipline de l’Église. Le gouverneur fit à ces justes plaintes l’accueil

qu’on devait attendre d’un apostat décrié pour le désordre de ses mœurs et la

dureté de son caractère. Il appelle à son aide les Juifs, les païens, la plus

vile populace, qu’il joint à ses cohortes. Cette troupe hideuse se rue sur les

fidèles assemblés dans les églises et s’y livre aux plus indécents et aux plus

cruels excès. Il y eut du sang répandu, les femmes furent outragées, les païens

offrirent à leurs divinités des sacrifices sur la table sainte. C’est ainsi que

les erreurs les plus opposées se tolèrent et s’associent pour combattre la

vérité.

Le Saint-Siège, lui, s’émut

de tendresse et d’admiration à l’arrivée d’un fils si dévoué, d’un si glorieux

défenseur de la foi et des traditions apostoliques. Les Eusébiens, pendant que

Constance était occupée à la guerre contre les Perses, avaient accusé Athanase

devant le chef de l’Église, dont ils proclamaient ainsi eux-mêmes la

suprématie ; et Athanase, pour répondre à leurs calomnies, lui avait adressé

par écrit une complète justification de sa conduite, confirmée par les

suffrages des évêques d’Égypte, témoins oculaires des faits. Jules Ier

accueillit donc Athanase avec les égards, l’affection et l’honneur dus à son

innocence, à son zèle, à son génie et à ses malheurs.

Le patriarche prit rang

au concile convoqué par le Pape, pour instruire pleinement ce grand procès qui

divisait l’Orient. Sa présence, la bienveillance méritée dont il était

l’objet, déconcertèrent ses accusateurs. Ils n’osèrent pas lui tenir tête

devant un tribunal purement ecclésiastique, où l’absence de la force armée et

des ordres du prince laisserait la vérité et l’innocence se produire en toute

liberté, et ils refusèrent de paraître au concile, afin d’échapper au jugement

qu’ils avaient provoqué les premiers. Ce jugement eut lieu malgré leur

abstention, et saint Jules le proclama, dans une lettre adressée aux Eusébiens,

avec ce ton d’autorité calme et de fermeté affectueuse qui caractérise le

suprême gardien de la foi, le père commun des fidèles. Les condamnations

prononcées contre Athanase dans les conciles de Tyr et d’Antioche, la

nomination et l’installation de Grégoire furent reconnues entachées de passion

et de violence, irrégulières dans la forme, injustes au fond. On invoqua en

même temps l’autorité irréfragable du concile œcuménique de Nicée, l’anathème

fulminé par ce concile contre Arius et ses partisans, et enfin les prérogatives

de l’Église de Rome, son droit traditionnel et incontestable d’intervenir dans

toutes les affaires majeures qui intéressent le dogme et la discipline.

Les orgueilleux sectaires

ne se rendent point à ces arrêts, et, sous l’égide de Constance, ils continuent

à exclure des principaux sièges les évêques orthodoxes, jusqu’à ce que, en

347, à la demande du Pape et des illustres évêques de Trêves et de Cordoue,

Constant obtient de son frère le consentement à une réunion des évêques

d’Orient et d’Occident, dans la ville de Sardique, située en Illyrie, sur les

confins des deux empires.

Dans ce concile, où le

Pape envoya ses légats, auquel présida le grand Osius, l’Église, indépendante

et unie à son chef, prononça les mêmes oracles qu’à Rome, et prit, dès le

premier jour, pour principe et pour règle de ses délibérations, le symbole de

Nicée. Le droit d’appel et de recours au Saint-Siège contre les décisions des

conciles particuliers fut de nouveau proclamé, Athanase déclaré seul évêque

légitime d’Alexandrie, et l’intrus Grégoire exclu de la communion de l’Église.

Deux évêques eusébiens, abandonnant leur parti, vinrent en dévoiler toute la

mauvaise foi et les trames coupables.

Ici encore les ennemis

d’Athanase, n’osant affronter la discussion, s’obstinèrent à n’y prendre

aucune part, renouvelèrent leurs protestations, et, rentrés en Orient, le

troublèrent par leur audace toujours croissante. Dans la ville d’Andrinople,

dix catholiques, qui avaient refusé de communiquer avec eux, furent mis à mort

par ordre des magistrats. Partout les évêques catholiques étaient bannis,

maltraités, odieusement calomniés.

Le puissant empereur

d’Occident, instruit et indigné de ces excès, en écrivit à son frère sur un ton

qui annonçait qu’il serait dangereux de lui résister. Les emportements des

Eusébiens ouvrirent d’ailleurs un instant les yeux â Constance, et lui-même se

sentit saisi tout à coup d’admiration pour le grand évêque d’Alexandrie.

Il lui écrivit de sa main

à plusieurs reprises, non seulement pour l’inviter à rentrer dans son église,

mais encore pour lui exprimer combien il serait heureux de le voir, et le presser,

le conjurer de venir à la cour. Athanase se défia d’abord d’une bienveillance

si imprévue et si subite, mais il dut céder à ces instances réitérées,

qu’accompagnaient d’ailleurs les mesures les plus décisives. La persécution

avait cessé dans toutes les provinces ; les prêtres d’Alexandrie, bannis pour

leur fidélité à leur évêque, étaient rappelés. Ayant pris congé, à Milan, de

l’empereur Constant, et à Rome, du pape Jules, Athanase reprend le chemin de

l’Orient, et voit Constance dans Antioche. Cet empereur l’accueillit avec

bonté, l’entoura, pendant son séjour, de considération et de respect, et à son

départ, lui promit avec serment de ne plus ouvrir l’oreille aux calomnies, de

ne plus souffrir qu’on le troublât dans son ministère.

Alexandrie le reçut avec

les mêmes transports de joie qui avaient éclaté à son premier retour ; le

souvenir des cruautés de l’intrus en doublait la vivacité. Sa présence eut des

effets plus importants. Elle refoula autour de lui les mauvaises passions,

excita la passion du bien et de toutes les vertus évangéliques. Les œuvres de

miséricorde se multiplièrent et s’étendirent à tous les infortunés. Que de

jeunes hommes, que de jeunes filles, sous l’influence de ses exemples,

embrassèrent une vie de sacrifices et d’héroïque dévouement !

Malheureusement, les

bienveillantes dispositions de Constance ne furent pas de longue durée. Le

principal appui des catholiques, l’infortuné Constant, perdit le trône et la

vie, en 350, à l’âge de vingt-sept ans, victime d’une conspiration ourdie par

Magnence, un de ses généraux. Délivré de la crainte des Perses par leur déroute

sous les murs de Nisibe, qu’il dut moins à ses armes qu’aux conseils et aux

miracles de saint Jacques, illustre évêque de cette ville, Constance vengea

bientôt la mort de son frère. La victoire qu’il remporta sur l’usurpateur, dans

les champs de la Pannonie, mit le monde à ses pieds. La prospérité est funeste

aux âmes vaines et faibles. Il rougit d’avoir cédé aux remontrances de son

frère en faveur d’Athanase. Il oublia ses serments. Les orthodoxes sont en

butte, sur tous les points de l’empire, à une violente persécution, qui, sous

le fils de Constantin, rappelle l’ère sanglante des martyrs.

Dans la capitale de

l’Égypte, un chef militaire à la tête de cinq mille soldats, envahit, la nuit,

l’église où priait Athanase avec une multitude considérable de peuple. L’épée

est tirée, des flèches sont lancées contre cette foule agenouillée. À cette

subite et farouche attaque, le peuple se presse autour de son évêque, qu’on

veut lui enlever, ou plutôt qu’on veut immoler au pied des autels. Dans cet

affreux tumulte, le patriarche élève sa voix toujours obéie, il ordonne aux

fidèles de se retirer et de se mettre en sûreté eux-mêmes. Pour lui, il ne

sortit que des derniers, enveloppé, emporté par un groupe dévoué, qui vint à

bout de le dérober aux traits de la troupe homicide.

Proscrit et fugitif,

Athanase ne peut croire que Constance ait commandé ces sacrilèges violences ;

il compte d’ailleurs encore sur ses anciennes protestations et sur sa ·bonne

foi. Pour l’éclairer, il lui adressa une grande apologie où il réfute un à un

tous les griefs des Ariens. Écoutons-le répondre à l’accusation d’une

prétendue correspondance avec l’usurpateur Magnence :

« Le reproche d’avoir

voulu irriter contre vous votre frère, d’heureuse mémoire, avait du moins

quelque prétexte aux yeux des calomniateurs. En effet, j’avais le privilège de

le voir librement, et il me défendait contre vous. Présent, il m’honorait,

absent, il m’a souvent appelé. Mais cet infernal Magnence, Dieu m’est témoin

que je ne le connais pas. Quelle familiarité pouvait donc s’établir d’un

inconnu à un inconnu ? Par où pouvais-je commencer une lettre à lui ? Était-ce

ainsi : Tu as bien fait de tuer celui qui me comblait d’honneurs et dont je

n’oublierai jamais l’amitié ? Je t’aime d’avoir égorgé ceux qui, dans Rome,

m’ont accueilli avec tant de faveur ? ».

Cette justification,

étincelante d’éloquence et de vérité, n’eut pas de prise sur l’âme prévenue de

Constance. Il n’en devint que plus obstiné, et son fanatisme plus violent. Un

nouvel intrus du nom de Georges, autrefois chargé de fournir la viande de porc

à l’armée, et pire que Grégoire, déshonora, fit frémir d’indignation par sa

grossièreté, par son ignorance, par son avarice et sa cruauté, l’illustre siège

d’Alexandrie que réjouissaient naguère les nobles qualités, le génie et les

vertus d’Athanase. Constance assemble conciles sur conciles, auxquels il

impose, avec d’astucieuses formules de foi, plus ou moins favorables à

l’hérésie, l’inévitable condition de la condamnation du patriarche. Il en fut

ainsi à Sirmich en Hongrie, à Rimini en Italie, à Arles en France. Les évêques

qui refusent de les souscrire sont envoyés dans de lointains et rigoureux

exils.

Athanase lui-même errait

de déserts en déserts, toujours recherché et souvent poursuivi de près par les

soldats et les espions des gouverneurs romains. Quelquefois, pour leur

échapper, il rentrait dans les populeuses cités de l’Égypte, où la foule ne le

cachait pas moins que la solitude. Mais sa retraite préférée était dans les