Saint Augustin de

Cantorbéry

Évêque (+ 604)

Augustin était prieur du

monastère de Saint-André du Mont Coelius, l'une des sept collines de Rome quand

le pape saint Grégoire le Grand vint le soustraire à la paix du cloître. Le

pape se souciait fort du salut des Anglo-Saxons, ces barbares païens qui

avaient envahi le brumeux pays des Bretons et que ces Bretons refusaient

d'évangéliser. Pour eux, ils étaient leurs occupants envahisseurs. Avec

quarante compagnons, moines comme lui, saint Augustin est envoyé par le pape en

Angleterre, avec une escale à Lérins, une à Paris et d'autres encore, car la

route est longue de Rome à Cantorbery. La mission romaine reçoit l'appui

d'Ethelbert, roi du Kent dont la femme est chrétienne. Il les installe à

Cantorbery. La ferveur et l'éloquence des moines romains impressionnent le roi

qui demande, à son tour, le baptême. Saint Augustin échoua par contre auprès

des Celtes chrétiens du pays de Galles par manque de tact selon saint Bède le

Vénérable. Lorsqu'il convoqua leurs évêques pour les amener à le reconnaître

comme primat nommé par le pape et à adopter la liturgie romaine, il crut bon de

rester sur son siège au lieu d'aller à leur rencontre. Les clercs bretons,

irrités par l'ingérence de ces moines romains dans leur pays, repartirent sans

rien céder. Saint Augustin continua d'opérer de nombreuses conversions chez les

Anglais et fonda le siège de Cantorbery dont il devient l'évêque. Il se dépense

alors pour asseoir la jeune Église d'Angleterre et multiplie les tentatives

pour réconcilier les chrétiens bretons et anglais. Il y faudra cent ans.

Life of St

Augustine of Canterbury (video en anglais) racontée d'après les

vitraux de l'église saint Augustin de Wembley Park

Mémoire de saint

Augustin, évêque de Cantorbéry en Angleterre. Envoyé avec d’autres moines

romains par le pape saint Grégoire le Grand pour annoncer l’Évangile au peuple

des Angles, il fut accueilli avec bienveillance par le roi du Kent, Éthelbert,

et imitant la vie apostolique de l’Église primitive, il convertit à la foi

chrétienne le roi lui-même et beaucoup de son peuple, et établit plusieurs

sièges épiscopaux sur cette terre. Il mourut le 26 mai, vers 604.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1228/Saint-Augustin-de-Cantorbery.html

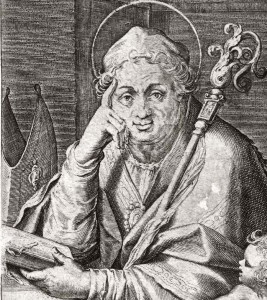

Lettera miniata con Sant'Agostino

di Canterbury, tratta dal Beda di Leningrado

Scriptorium

de l'abbaye de Wearmouth-Jarrow Lettrines historiées HIS représentant un

portrait de Grégoire le Grand

Historiated

initial, portrait of St Gregory

SAINT AUGUSTIN de

CANTORBÉRY

Moine bénédictin et

archevêque de Cantorbéry

(+ 605)

Aux Ve et VIe siècles,

l'île de la Grande-Bretagne évangélisée dès les premiers siècles du

christianisme, était retombée dans le paganisme à la suite de l'invasion des

Saxons. Le jeune roi de ce temps, Ethelbert, épousa Berthe, princesse chrétienne,

fille de Caribert Ier, roi de Paris et petit-fils de Clovis.

Berthe consentit à ce

mariage à la condition d'avoir sa chapelle et de pouvoir observer librement les

préceptes et les pratiques de sa foi avec l'aide et l'appui d'un évêque

gallo-franc. L'âme du roi de Kent subissait la salutaire influence de sa pieuse

épouse qui le préparait sans le savoir à recevoir le don de la foi. Le pape

Grégoire le Grand jugea le moment opportun pour tenter l'évangélisation de

l'Angleterre qu'il souhaitait depuis longtemps. Pour réaliser cet important

projet, le souverain pontife choisit le moine Augustin alors prieur du

monastère de St-André à Rome.

On ne sait absolument

rien de la vie de saint Augustin de Cantorbéry avant le jour solennel du

printemps 596, où pour obéir aux ordres du pape saint Grégoire le Grand qui

avait été son abbé dans le passé, il dut s'arracher à la vie paisible de son

abbaye avec quarante de ses moines pour devenir missionnaire.

A Lérins, première étape

des moines missionnaires, ce qu'on leur rapporta de la cruauté des Saxons

effraya tellement les compagnons d'Augustin, qu'ils le prièrent de solliciter

leur rappel du pape. Augustin dut retourner à Rome pour supplier saint Grégoire

de dispenser ses moines d'un voyage si pénible, si périlleux et si inutile. Le

souverain pontife renvoya Augustin avec une lettre où il prescrivait aux

missionnaires de reconnaître désormais le prieur de St-André pour leur abbé et

de lui obéir en tout. Il leur recommanda surtout de ne pas se laisser terrifier

par tous les racontars et les encouragea à souffrir généreusement pour la

gloire de Dieu et le salut des âmes. Ainsi stimulés, les religieux reprirent

courage, se remirent en route et débarquèrent sur la plage méridionale de la

Grande-Bretagne.

Le roi Ethelbert

n'autorisa pas les moines romains à venir le rencontrer dans la cité de

Cantorbéry qui lui servait de résidence, mais au bout de quelques jours, il

s'en alla lui-même visiter les nouveaux venus. Au bruit de son approche, les

missionnaires, avec saint Augustin à leur tête, s'avancèrent

processionnellement au-devant du roi, en chantant des litanies. Ethelbert

n'abandonna pas tout de suite les croyances de ses ancêtres. Cependant, il

établit libéralement les missionnaires à Cantorbéry, capitale de son royaume,

leur assignant une demeure qui s'appelle encore Stable Gate: la porte de

l'Hôtellerie, et ordonna qu'on leur fournit toutes les choses nécessaires à la

vie.

Vivant de la vie des

Apôtres dans la primitive Eglise, saint Augustin et ses compagnons étaient

assidus à l'oraison, aux vigiles et aux jeûnes. Ils prêchaient la parole de vie

à tous ceux qu'ils abordaient, se comportant en tout selon la sainte doctrine

qu'ils propageaient, prêts à tout souffrir et à mourir pour la vérité.

L'innocence et la simplicité de leur vie, la céleste douceur de leur

enseignement, parurent des arguments invincibles aux Saxons qui embrassèrent le

christianisme en grand nombre.

Charmé comme tant

d'autres par la pureté de la vie de ces hommes, séduit par les promesses dont

plus d'un miracle attestait la vérité, le noble et vaillant Ethelbert demanda

lui aussi le baptême qu'il reçut des mains de saint Augustin. Sa conversion

amena celle d'une grande partie de ses sujets. Comme le saint pape Grégoire le

Grand lui recommanda de le faire, le roi proscrivit le culte des idoles,

renversa leurs temples et établit de bonnes moeurs par ses exhortations, mais

encore plus par son propre exemple.

En 1597, étant désormais

à la tête d'une chrétienté florissante, saint Augustin de Cantorbéry se rendit

à Arles, afin d'y recevoir la consécration épiscopale, selon le désir du pape

saint Grégoire. De retour parmi ses ouailles, à la Noël de la même année, dix

mille Saxons se présentèrent pour recevoir le baptême.

De plus en plus pénétré

de respect et de dévouement pour la sainte foi, le roi abandonna son propre

palais de Cantorbéry au nouvel archevêque. A côté de cette royale demeure, on

construisit une basilique destinée à devenir la métropole de l'Angleterre.

Saint Augustin en devint le premier archevêque et le premier abbé. En le

nommant primat d'Angleterre, le pape saint Grégoire le Grand lui envoya douze

nouveaux auxiliaires, porteurs de reliques et de vases sacrés, de vêtements

sacerdotaux, de parements d'autels et de livres destinés à former une

bibliothèque ecclésiastique.

Le souverain pontife

conféra aussi au nouveau prélat le droit de porter le pallium en célébrant la

messe, pour le récompenser d'avoir formé la nouvelle Église d'Angleterre par

ses inlassables travaux apostoliques. Cet honneur insigne devait passer à tous

ses successeurs sur le siège archiépiscopal d'Angleterre. Le pape lui donna

également le pouvoir d'ordonner d'autres évêques afin de constituer une

hiérarchie régulière dans ce nouveau pays catholique. Il le constitua aussi

métropolitain des douze évêchés qu'il lui ordonna d'ériger dans l'Angleterre

méridionale.

Les sept dernières années

de sa vie furent employées à parcourir le pays des Saxons de l'Ouest. Même

après sa consécration archiépiscopale, saint Augustin voyageait en véritable

missionnaire, toujours à pied et sans bagage, entremêlant les bienfaits et les

prodiges à ses prédications. Rebelles à la grâce, les Saxons de l'Ouest

refusèrent d'entendre Augustin et ses compagnons, les accablèrent d'avanies et

d'outrages et allèrent jusqu'à attenter à leur vie afin de les éloigner.

Au début de l'an 605,

deux mois après la mort de saint Grégoire le Grand, son ami et son père, saint

Augustin, fondateur de l'Église anglo-saxonne, alla recueillir le fruit de ses

multiples travaux. Avant de mourir, il nomma son successeur sur le siège de

Cantorbéry. Selon la coutume de Rome, le grand missionnaire fut enterré sur le

bord de la voie publique, près du grand chemin romain qui conduisait de

Cantorbéry à la mer, dans l'église inachevée du célèbre monastère qui allait

prendre et garder son nom.

Boll., Paris, éd. 1874,

tome 6, p. 193-199 -- Marteau de Langle de Cary, 1959, tome II, p. 277-279 --

l'Abbé J. Sabouret, édition 1922, p. 199-200

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_augustin_de_cantorbery.html

Le baptême d'Æthelberht de Kent, détail d'une miniature d'un manuscrit du Roman de Brut abrégé, circa 1325-1350 BL Egerton3028 folio 55r : Ethelbert baptized by St. Augustine British Library

Le baptême d'Æthelberht de Kent, détail d'une miniature d'un manuscrit du Roman de Brut abrégé, circa 1325-1350 BL Egerton3028 folio 55r : Ethelbert baptized by St. Augustine British Library

C’est cet homme qui a

fait de Cantorbéry le centre spirituel de l’Angleterre

Aliénor

Goudet - Publié le 27/05/21

Pourtant heureux de son

rôle de prieur au monastère de Saint-André de Rome, Augustin reçoit

soudainement une mission du Pape. Celle d’aller évangéliser la Grande-Bretagne.

Cette mission va donner racine au célèbre archevêché de Cantorbéry.

Grande-Bretagne, 597.

Lorsque Augustin quitte enfin la demeure d’Ethelbert, roi du Kent, un long

soupir de soulagement lui échappe. Ses quarante compagnons moines se

précipitent vers lui pour qu’il leur donne le verdict.

– N’ayez crainte, mes

frères, leur dit-il. Le roi nous permet de rester.

Bien que païen et méfiant

à l’égard des chrétiens, Ethelbert a permis aux envoyés du pape de s’installer

dans le Kent. Sans doute grâce à son épouse, la reine Berthe, fille du roi de

Paris et fervente chrétienne. On les emmène alors vers le lieu que le roi leur

a offert. Sur le chemin, Augustin laisse ses pensées retourner dans le temps.

La grande mission d’un

petit prieur

Quelle a été sa surprise

lorsque le pape Grégoire I lui-même est venu le trouver pour lui confier

l’évangélisation des Anglo-Saxons. Lui, petit prieur qui s’apprêtait à passer

le reste de sa vie au calme dans son monastère ? Le saint pontife lui avait

alors assuré que ses connaissances bibliques et ses compétences

d’administrateur étaient requises. Le Seigneur avait donc une mission pour lui.

Et par la grâce de Dieu, ce voyage de Rome à la Grande Bretagne s’est déroulé

sans trop des périls.

Lire aussi :Le

plus grand pape de l’Histoire… ne voulait pas être pape

Leur guide tire Augustin

de sa rêverie lorsqu’ils atteignent enfin les lieux. Le bâtiment que le roi leur

a offert est un vestige abandonné de l’occupation romaine. Un bon ménage ne

serait pas de trop, mais l’endroit est parfait ! De suite, les moines se

mettent au travail.

Très vite, sous la

direction d’Augustin, la petite communauté prend racine. Les moines qui suivent

la règle de saint Benoît deviennent vite indépendants. Le bâtiment est

transformé en l’église Saint-Martin, devenant ainsi la première église de

Grande Bretagne. Augustin et ses frères prennent également bien soin

d’appliquer l’Evangile qu’ils prêchent auprès des habitants du Kent. Ils

soignent les malades, aident à la récolte et nourrissent les pauvres tout en

prêchant les valeurs du Christ. Tout ça sous l’œil bienveillant d’Augustin.

Un échec pas total

Mais le contact avec le

reste des Anglo-saxons n’est pas aussi facile. Les peuples païens sont

dangereusement attachés à leurs traditions. Quant à ceux qui ont été

christianisés au IIIe siècle, ils se sont repliés dans leurs petites

communautés, coupé du reste du monde chrétien. Par conséquent, de nombreux de

petits clergés se sont formés sans liens entre eux ou avec Rome. Les contacter

demande énormément de patience et de lettres à l’envoyé du pape. Augustin passe

de longues heures à rédiger sur son bureau.

Lire aussi :Anglicans

et catholiques appelés à ne pas sous-estimer leur foi commune

Le travail acharné

d’Augustin et de ses compagnons ne passe pas inaperçus. Impressionné par le

savoir et la serviabilité des moines, le roi Ethelbert demande le baptême moins

d’un an après leur arrivée. L’influence du souverain fait que le Kent et les

provinces sous son règne ne tardent pas à se convertir. Selon les écrits du

pape Grégoire I, la mission d’Augustin entraine la conversion de plus de 10.000

bretons.

Alors qu’on érige le

monastère bénédictin Saints-Pierre-et-Paul, Augustin s’applique à unifier

l’Angleterre. Il rassemble les évêques bretons et leur prêche l’importance de

l’unité de l’Église.

– Travaillons ensemble à

l’annonce de l’Évangile de Jésus-Christ et préservons l’unité catholique.

Malheureusement, outre

les régions dépendantes d’Ethelbert, son appel reste sans réponse. Même les

renforts que lui envoie le pape ne parviennent pas à convaincre tous les bretons.

Il faudra encore du temps avant l’unification de la Grande Bretagne sous la

bannière du Christ.

Le premier archevêque de

Cantorbéry s’éteint le 26 mai 604. Mais même sans avoir vu l’Angleterre

convertie de son vivant, c’est lui qui a érigé le lieu qui deviendra la

capitale de la chrétienté en Angleterre.

Lire aussi :Saint

Thomas Becket, martyr pour l’honneur de Dieu

Lire aussi :Anselme,

le « docteur magnifique » qui faisait rayonner l’abbaye du Bec

Saint Augustin de

Cantorbéry, évêque et confesseur

A Cantorbéry, déposition

de saint Augustin, premier évêque de cette ville, le 26 mai 604 ou 605. Culte

local immédiat. Le concile de Cloveshoë décrète en 747 son natale jour férié et

l’inscription de son nom dans les litanies après celui de saint Grégoire le

Grand.

Diffusion du culte dans

le nord de la France à partir du XIe siècle.

Léon XIII introduit la

fête sous le rite double à la date du 28 mai en 1882.

Leçons des Matines avant

1960

Quatrième leçon. L’an

cinq cent quatre-vingt-dix-sept, Augustin, moine du monastère de Latran à Rome,

fut envoyé par Grégoire le Grand en Angleterre, avec environ quarante moines de

sa communauté, pour convertir au Christ les populations de cette contrée. Il y

avait alors dans le pays de Kent un roi très puissant, nommé Ethelbert. Ayant

appris le motif de l’arrivée d’Augustin, il l’invita à venir avec ses

compagnons à Cantorbéry, capitale de son royaume, et lui accorda de bonne grâce

l’autorisation d’y demeurer et d’y prêcher le Christ. Le Saint bâtit donc près

de Cantorbéry un oratoire où il résida quelque temps, et où ses compagnons et

lui menèrent à l’envi un genre de vie tout apostolique.

Cinquième leçon.

L’exemple de sa vie, joint à la prédication de la céleste doctrine que

confirmaient de nombreux miracles, gagna les insulaires, puis amena à embrasser

le christianisme la plupart d’entre eux et finalement le roi lui-même, qui

reçut le baptême, ainsi qu’un nombre considérable des gens de son entourage ;

ces faits comblèrent de joie la reine Berthe, qui était chrétienne. Il arriva

qu’un jour de Noël Augustin baptisa plus de dix mille Anglais dans les eaux

d’une rivière qui coule à York, et l’on rapporte que tous ceux qui se

trouvaient atteints de quelque maladie recouvrèrent la santé du corps, en même

temps qu’ils recevaient le salut de l’âme. Ordonné Évêque par l’ordre de

Grégoire, Augustin établit son siège à Cantorbéry dans l’église du Sauveur

qu’il avait élevée, et y plaça des moines pour seconder ses travaux ; il

construisit dans un faubourg le monastère de Saint-Pierre, qui porta même plus

tard le nom d’Augustin. Ce même Pape Grégoire lui accorda l’usage du pallium,

avec le pouvoir d’établir en Angleterre la hiérarchie ecclésiastique. Il lui

envoya aussi de nouveaux ouvriers apostoliques, parmi lesquels Méliton, Just,

Paulin et Rufin.

Sixième leçon. Les

affaires de son Église étant réglées, Augustin réunit en synode les Évêques et

les docteurs des anciens Bretons, depuis longtemps en désaccord avec l’Église

romaine par rapport à la célébration de la fête de Pâques et à d’autres

questions de rite. Mais comme il ne parvenait à les ramener à l’unité, ni par

l’autorité du siège apostolique ni par des miracles, un esprit prophétique

l’inspirant, il leur prédit leur perte. Enfin, après avoir accompli de nombreux

travaux pour le Christ et d’éclatants prodiges, après avoir préposé Méliton à

l’Église de Londres, Just à celle de Rochester, il désigna Laurent pour son

successeur, et partit pour le ciel, le sept des calendes de juin, sous le règne

d’Ethelbert. Il fut enterré au monastère de Saint-Pierre, qui devint le lieu de

sépulture des Archevêques de Cantorbéry et de plusieurs rois. Les Anglais lui

rendirent un culte fervent, et le souverain Pontife Léon XILI a étendu son

Office et sa Messe à l’Église universelle.

Dom Guéranger, l’Année

Liturgique

Quatre cents ans étaient

à peine écoulés, depuis le départ d’Éleuthère pour la patrie céleste, qu’un

second apôtre de la grande île britannique s’élevait de ce monde, au même jour,

vers la gloire éternelle. La rencontre de ces deux pontifes sur le cycle est

particulièrement touchante, en même temps qu’elle nous révèle la prévoyance

divine qui règle le départ de chacun de nous, en sorte que le jour et l’heure

en sont fixés avec une sagesse admirable. Plus d’une fois nous avons reconnu

avec évidence ces coïncidences merveilleuses qui forment un des principaux

caractères du cycle liturgique. Aujourd’hui, quel admirable spectacle dans ce

premier archevêque de Cantorbéry, saluant sur son lit de mort le jour où le

saint pape à qui l’Angleterre doit la première prédication de l’Évangile, monta

dans les cieux, et se réunissant à lui dans un même triomphe ! Mais aussi qui

n’y reconnaîtrait un gage de la prédilection dont le ciel a favorisé cette

contrée longtemps fidèle, et devenue depuis hostile à sa véritable gloire ?

L’œuvre de saint

Éleuthère avait péri en grande partie dans l’invasion des Saxons et des Angles,

et une nouvelle prédication de l’Évangile était devenue nécessaire. Rome y

pourvut comme la première fois. Saint Grégoire le Grand conçut cette noble

pensée ; il eût désiré assumer sur lui-même les fatigues de l’apostolat dans

cette contrée redevenue infidèle ; un instinct divin lui révélait qu’il était

destiné à devenir le père de ces insulaires, dont il avait vu quelques-uns

exposés comme esclaves sur les marchés de Rome. Mais du moins il fallait à

Grégoire des apôtres capables d’entreprendre ce labeur auquel il ne lui était

pas donné de se livrer en personne. Il les trouva dans le cloître bénédictin,

où lui-même avait abrité sa vie durant plusieurs années. Rome alors vit partir

Augustin à la tête de quarante moines se dirigeant vers l’île des Bretons, sous

l’étendard de la croix.

Ainsi la nouvelle race

qui peuplait cette île recevait à son tour la foi par les mains d’un pape ; des

moines étaient ses initiateurs à la doctrine du salut. La parole d’Augustin et

de ses compagnons germa sur ce sol privilégié. Il lui fallut, sans doute, du

temps pour s’étendre à l’île tout entière ; mais ni Rome, ni l’ordre monastique

n’abandonnèrent l’œuvre commencée ; les débris de l’ancien christianisme breton

finirent par s’unir aux nouvelles recrues, et l’Angleterre mérita d’être

appelée longtemps l’île des saints.

Les gestes de l’apostolat

d’Augustin dans cette île ravissent la pensée. Le débarquement des

missionnaires romains qui s’avancent sur cette terre infidèle en chantant la

Litanie ; l’accueil pacifique et même bienveillant que leur fait dès l’abord le

roi Ethelbert ; l’influence de la reine Berthe, française et chrétienne, sur l’établissement

de la foi chez les Saxons ; le baptême de dix mille néophytes dans les eaux

d’un fleuve au jour de Noël, la fondation de l’Église primatiale de Cantorbéry,

l’une des plus illustres de la chrétienté par la sainteté et la grandeur de ses

évêques : toutes ces merveilles montrent dans l’évangélisation de l’Angleterre

un des traits les plus marqués de la bienveillance céleste sur un peuple. Le

caractère d’Augustin, calme et plein de mansuétude, son attrait pour la

contemplation au milieu de tant de labeurs, répandent un charme de plus sur ce

magnifique épisode de l’histoire de l’Église ; mais on a le cœur serré quand on

vient à songer qu’une nation prévenue de telles grâces est devenue infidèle à

sa mission, et qu’elle a tourné contre Rome, sa mère, contre l’institut

monastique auquel elle est tant redevable, toutes les fureurs d’une haine

parricide et tous les efforts d’une politique sans entrailles.

Nous plaçons ici cette

Hymne qui a été approuvée par le Saint-Siège, en l’honneur de l’apôtre de l’Angleterre.

HYMNE.

Ile féconde des saints,

célèbre ton apôtre, exalte dans tes pieux concerts le fils de Grégoire.

Rendue fertile par ses

labeurs, tu donnas une moisson abondante ; et longtemps les fleurs de sainteté

qui couvraient ton sol répandirent sur toi un éclat supérieur.

Suivi d’une troupe de

quarante moines, il débarqua sur tes rivages, ô terre des Anglais ! Il portait

l’étendard du Christ ; messager de la paix, il venait en apporter les gages.

Bientôt la croix est

plantée sur ton sol comme un éclatant trophée, la parole du salut se répand de

toutes parts ; et un roi barbare reçoit lui-même la foi d’un cœur docile.

La nation renonce à ses

coutumes sauvages ; elle se plonge dans les eaux sanctifiées d’un fleuve, et

renaît à la vie de l’âme le jour même où le Soleil de justice se leva sur le

monde.

O Pasteur auguste, du

haut du ciel, gouverne toujours tes fils ; ramène dans les bras de la mère

désolée l’ingrat troupeau qui s’est éloigné d’elle.

Heureuse Trinité, qui

envoyez sans cesse sur votre vigne la rosée de la grâce, daignez faire renaître

l’antique foi, afin qu’elle fleurisse comme aux anciens jours.

Amen.

Vous êtes, ô Jésus

ressuscité, la vie des peuples, comme vous êtes la vie de nos âmes. Vous

appelez les nations à vous connaître, à vous aimer et à vous servir ; car «

elles vous ont été données en héritage [1] », et vous les possédez tour à tour.

Votre amour vous inclina de bonne heure vers cette île de l’Occident que, du

haut de la croix du Calvaire, votre regard divin considérait avec miséricorde.

Dès le deuxième siècle, votre bonté dirigea vers elle les premiers envoyés de

la parole ; et voici qu’à la fin du sixième, Augustin, votre apôtre, délégué

par Grégoire, votre vicaire, vient au secours d’une nouvelle race païenne qui

s’est rendue maîtresse de cette île appelée à de si hautes destinées.

Vous avez régné

glorieusement sur cette région, ô Christ ! Vous lui avez donné des pontifes,

des docteurs, des rois, des moines, des vierges, dont les vertus et les

services ont porté au loin la renommée de l’Ile des saints ; et la grande part

d’honneur dans une si noble conquête revient aujourd’hui à Augustin, votre

disciple et votre héraut. Votre empire a duré longtemps, ô Jésus, sur ce peuple

dont la foi fut célèbre dans le monde entier ; mais, hélas ! des jours funestes

sont venus, et l’Angleterre n’a plus voulu que vous régniez sur elle [2], et elle

a contribué à égarer d’autres nations soumises à son influence. Elle vous a haï

dans votre vicaire, elle a répudié la plus grande partie des vérités que vous

avez enseignées aux hommes, elle a éteint la foi, pour y substituer une raison

indépendante qui a produit dans son sein toutes les erreurs. Dans sa rage

hérétique, elle a foulé aux pieds et brûlé les reliques des saints qui étaient

sa gloire, elle a anéanti l’ordre monastique auquel elle devait le bienfait du

christianisme, elle s’est baignée dans le sang des martyrs, encourageant

l’apostasie et poursuivant comme le plus grand des crimes la fidélité à

l’antique foi.

En retour, elle s’est

livrée avec passion au culte de la matière, à l’orgueil de ses flottes et de

ses colonies ; elle voudrait tenir le monde entier sous sa loi. Mais le

Seigneur renversera un jour ce colosse de puissance et de richesse. La petite

pierre détachée de la montagne l’atteindra à ses pieds d’argile, et les peuples

seront étonnés du peu de solidité qu’avait cet empire géant qui s’était cru

immortel. L’Angleterre n’appartient plus à votre empire, ô Jésus ! Elle s’en

est séparée en rompant le lien de communion qui l’unit si longtemps à votre

unique Église. Vous avez attendu son retour, et elle ne revient pas ; sa

prospérité est le scandale des faibles, et c’est pour cela que sa chute, que

l’on peut déjà prévoir, sera lamentable et sans retour.

En attendant cette

épreuve terrible que votre justice fera subir à l’île coupable, votre

miséricorde, ô Jésus, glane dans son sein des milliers d’âmes, heureuses de

voir la lumière, et remplies pour la vérité qui leur apparaît, d’un amour

d’autant plus ardent, qu’elles en avaient été plus longtemps privées. Vous vous

créez un peuple nouveau au sein même de l’infidélité, et chaque année la moisson

est abondante. Poursuivez votre œuvre miséricordieuse, afin qu’au jour suprême

ces restes d’Israël proclament, au milieu des désastres de Babylone,

l’immortelle vie de cette Église dont les nations qu’elle a nourries ne

sauraient se séparer impunément.

Saint apôtre de

l’Angleterre, Augustin, votre mission n’est donc pas terminée. Le Seigneur a

résolu de compléter le nombre de ses élus, en glanant parmi l’ivraie qui couvre

le champ que vos mains ont ensemencé. Venez en aide au labeur des nouveaux envoyés

du Père de famille. Par votre intercession, obtenez ces grâces qui éclairent

les esprits et changent les cœurs. Révélez à tant d’aveugles que l’Épouse de

Jésus est « unique », comme il l’appelle lui-même [3] ; que la foi de Grégoire

et d’Augustin n’a pas cessé d’être la foi de l’Église catholique, et que trois

siècles de possession ne sauraient créer un droit à l’hérésie sur une terre

qu’elle n’a conquise que par la séduction et la violence, et qui garde toujours

le sceau ineffaçable de la catholicité.

[1] Psalm. II.

[2] Luc. XIX, 14.

[3] Cant. VI, 8.

Bhx Cardinal

Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

Cette fête fut introduite

dans le calendrier par Léon XIII, et, dans l’intention de ce grand Pontife,

elle était comme un cri d’immense amour et un tendre appel de l’Église Mère à

cette glorieuse île Britannique jadis si féconde en saints. Saint Augustin était

un moine romain, et il fut envoyé en Angleterre par saint Grégoire le Grand,

avec quarante de ses compagnons, pour convertir ce royaume à la foi. Le succès

surpassa de beaucoup l’attente du Pape, car Dieu authentiqua la prédication

d’Augustin par un si grand nombre de miracles qu’on semblait revenu au temps

des Apôtres. Le roi de Kent, Ethelbert, accompagné des grands de sa cour, reçut

le baptême des mains du Saint qui, un jour de Noël, baptisa dans un fleuve des

milliers de personnes. A ceux qui étaient malades, les ondes baptismales

donnèrent la santé du—corps en même temps que celle de l’âme. Sur l’ordre de

saint Grégoire, Augustin fut consacré premier évêque des Anglais par Virgile

d’Arles. Revenu ensuite dans la Grande-Bretagne, il consacra des évêques pour

d’autres sièges, et il établit sa chaire primatiale à Cantorbéry où il érigea

aussi un célèbre monastère. Il mourut le 26 mai 609 et reçut immédiatement le

culte des saints.

De même que durant sa vie

saint Grégoire avait partagé la consolation de son disciple Augustin lors de la

régénération chrétienne de tout ce florissant royaume, après sa mort il fut

aussi associé à ses mérites, et c’est surtout par les Anglais qu’il fut

proclamé l’Apôtre de l’Angleterre ; ce titre honorifique se trouve même dans

l’épigraphe tombale de saint Grégoire :

AD • CHRISTVM • ANGLOS •

CONVERTIT • PIETATE • MAGISTRA

ADQVIRENS • FIDEI •

AGMINA • GENTE • NOVA

Les Anglais attribuent

aussi la gloire de leur conversion au patriarche saint Benoît dont la Règle fut

introduite chez eux par Augustin et ses compagnons. Voici comment s’exprime à

ce sujet saint Aldhelm : Huius (Benedicti) alumnorum numéro glomeramus ovantes

… A quo iam nobis baptismi gratia fluxit Atque Magistrorum (Augustin et les 40

moines) veneranda caterva cucurrit. La lecture de l’Apôtre est tirée de la Ire

Épître aux Thessaloniciens (II, 2-9). Saint Paul rappelle en quelles

circonstances il avait commencé sa prédication dans leur ville ; quel avait été

son infatigable labeur durant ces premiers jours, la pureté de sa doctrine et

enfin son désintéressement puisqu’il avait renoncé à recevoir des fidèles même

ce modeste entretien corporel auquel d’ailleurs le prédicateur évangélique a

droit. Une si grande pureté d’intention et un labeur si difficile ne doivent

pourtant pas être inutiles ; c’est pourquoi il faut que les fidèles gardent

avec un grand zèle ce dépôt de foi catholique qui leur fut confié jadis.

Le répons-graduel est

tiré du psaume : « Je revêtirai ses prêtres de salut, et ses saints exulteront

dans la joie. ». « Là je ferai paraître la puissance de David, et je tiendrai

allumé un flambeau devant mon Oint. »

Ces splendides promesses

messianiques sont appliquées par l’Église aux saints Pontifes, en tant qu’ils

participent à la dignité du sacerdoce du Christ. Ce sacerdoce catholique sera

pour beaucoup comme un vêtement de salut éternel, car ils assureront leur

prédestination par la fidélité avec laquelle ils correspondront à leur

vocation. Et que comporte donc cette vocation sacerdotale ? La vertu commune ne

suffit pas ; une seule chose est requise : sainteté, et sainteté éminente.

La lecture évangélique,

en la fête de ce grand apôtre de l’Angleterre, ne peut être autre que celle qui

se présente lors de la solennité des premiers compagnons des apôtres : Marc,

Luc, Tite, etc.

La prédication

d’Augustin, comme celle des premiers Apôtres à qui Jésus, dans l’Évangile de ce

jour, ordonne de faire des miracles et de guérir les malades, fut authentiquée

par le Seigneur par de nombreux prodiges. La renommée de ceux-ci parvint

jusqu’à saint Grégoire à Rome et on aime voir le très humble Pontife, écrivant

à son disciple, l’exhorter à conserver la vertu d’humilité malgré la grandeur

des miracles qu’il opérait [4].

Les deux collectes avant

l’anaphore et après la Communion sont les suivantes :

Sur les oblations. — «

Nous vous offrons, Seigneur, le Sacrifice en la fête du bienheureux pontife

Augustin, vous suppliant de faire que les brebis séparées retournent l’unité de

la foi et participent ainsi à ce banquet de salut. » Claire allusion à la

conversion, tant désirée par l’Église, de l’Angleterre à la foi de ses pères,

et à l’invalidité de l’Eucharistie et des Ordinations chez les Anglicans.

Après la Communion. — «

Après avoir participé à la Victime du salut, nous vous prions, par les mérites

de votre bienheureux pontife Augustin, de permettre que cette même Hostie vous

soit offerte toujours et partout. » — La pensée est empruntée à Malachie, mais

l’allusion concerne la grande île Britannique.

Nous ne saurions nous

séparer aujourd’hui de saint Augustin sans évoquer la scène suggestive et

impressionnante de son premier atterrissage en Angleterre. Tandis que les

Barbares mettaient sens dessus dessous l’Italie, brûlaient les églises et

massacraient les évêques, Grégoire le Grand décide un coup audacieux. Il envoie

ses pacifiques troupes conquérantes dans la lointaine Bretagne, là où les

Césars eux-mêmes n’avaient jamais pu établir solidement les aigles romaines. Le

groupe psalmodiant des quarante moines missionnaires pose donc, courageux, le

pied sur le sol anglais, et en prenant possession au nom de l’Église

catholique, il se met en ordre de procession. Le pieux cortège est précédé

d’une croix d’argent et d’une image du Divin Sauveur suivies par Augustin et

les moines, qui chantent cette belle prière romaine de la procession des

Robigalia : Deprecamur te, Domine, in omni misericordia tua, ut auferatur furor

tuus et ira tua a civitate ista et de domo sancta tua, quia peccavimus tibi.

Y eut-il jamais conquête

plus pacifique que celle-là ?

[4] Registr. xi, Ep. 28.

P. L., LXXVII, col. 1138.

Dom Pius Parsch, le Guide

dans l’année liturgique

Pour le retour des

Anglicans.

Saint Augustin. — Jour de

mort : 26 mai 604. — Tombeau : dans le monastère Saint Pierre, à Cantorbéry.

Image : On le représente en Bénédictin et en évêque. Vie : Le saint était moine

au monastère de Saint-André, près du Latran, à Rome. Le pape saint Grégoire 1er

le chargea, en 597, avec 40 compagnons, d’aller évangéliser les Anglo-Saxons.

Le roi Ethelbert l’accueillit amicalement et lui permit de s’établir dans le

voisinage de Cantorbéry. Bientôt, il put baptiser le roi et 10.000 de ses

sujets. Augustin fut alors nommé par le pape primat d’Angleterre et reçut le

pallium. Il mourut le 26 mai 604 et fut enterré dans le monastère de

Saint-Pierre, qui fut désormais le lieu de sépulture des évêques de Cantorbéry.

Pratique : Nous avons

devant les yeux, aujourd’hui, l’Apôtre de l’Angleterre. Malheureusement, ce

pays est en grande partie, aujourd’hui, séparé de l’unité de l’Église, tout en

gardant toujours des sentiments religieux profonds. Les Anglicans ont, par

exemple, un bréviaire laïc avec la récitation quotidienne des psaumes et la

lecture de la bible ; ils ont un idéal liturgique semblable au nôtre. L’oraison

du jour demande que ce peuple religieux revienne à l’unité de l’Église.

La messe (Sacerdotes) est composée en partie de textes du commun et en partie de textes propres. Nous avons devant nous l’évêque (Intr., Grad., Alléluia) et le missionnaire (Ép. et Évang.). L’Évangile est celui des saints missionnaires qui sont les successeurs des 72 disciples que le Seigneur envoie devant lui. L’Épître est très belle. Saint Paul y décrit, d’une manière touchante, en s’adressant aux Thessaloniciens, ses travaux, pastoraux. Avec les paroles de l’Apôtre, saint Augustin décrit son zèle pour les âmes : « Vous le savez, nous avons été pour chacun de vous comme est un père pour ses enfants, vous priant, vous exhortant et vous adjurant ». L’évêque Augustin a été le serviteur vigilant que le Seigneur au moment de la mort a trouvé veillant Qu’il en soit ainsi pour nous aujourd’hui et à l’heure de notre mort !

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/28-05-St-Augustin-de-Cantorbery#nh1

Saint Augustin de

Cantorbéry

Le saint Pape Grégoire le

Grand avait toute sa vie rêvé de s'en aller porter l'Évangile en Angleterre

mais, attaché au service du Pape Pélage dont il fut le successeur, il ne put y

aller. Monté sur le trône pontifical (590), il choisit, pour cette mission,

Augustin, prieur du monastère Saint-André, dont on ne sait rien avant son

départ pour l'Angleterre.

Comme l'affirment

Tertullien et Origène, la Grande-Bretagne avait jadis été christianisée, mais

les invasions saxonnes avaient repoussé les chrétiens (Bretons) en Cornouailles

et dans le Pays de Galles sans que l'on pût espérer la conversion des

envahisseurs, jusqu'à ce que le jeune roi du Kent, Ethelbert, chef de la

confédération des royaumes saxons, épousât une princesse catholique, Berthe,

fille de Caribert I° Roi de Paris.

Au printemps 596, à la

tête d'une quarantaine de moines missionnaires, Augustin s'en alla au monastère

de Lérins pour étudier la langue et les mœurs des Saxons. Les descriptions

furent si horribles que la peur prit le pas sur le zèle et que les

missionnaires renvoyèrent leur chef à Rome pour qu'il obtînt du Pape d'être

déchargé de cette impossible mission.

Grégoire le Grand

accueillit fraîchement Augustin et pendant le temps où il le retint auprès de

lui, souffla le chaud et le froid, maniant tour à tour les menaces et les

encouragements jusqu'à ce qu'il acceptât de repartir. On lui conféra la dignité

abbatiale et, dûment nanti de lettres pour les évêques, les princes et la reine

Brunehaut, on le renvoya en Gaule.

Merveilleusement

accueilli par l'évêque d'Arles qui était alors le légat pontifical pour la

Gaule, Augustin retourna chercher ses moines qu'il installa en Arles.

L'Archevêque leur fournit des professeurs enthousiastes de saxon et les envoya

à travers la Gaule en leur faisant remonter le Rhône. Ils étaient à Autun

pendant l'hiver puis ils longèrent la Loire, passèrent à Orléans, à Tours et

s'embarquèrent à l'embouchure de la Loire pour débarquer à l'île de Thanet

(proche de Ramsgate), au printemps 597.

A peine touché le sol du

Royaume du Kent, au chant des litanies, les missionnaires formèrent une

procession devant Augustin, crosse en main et mitre en tête. Ainsi arrivé

devant le roi Ethelbert, Augustin fit son premier sermon, écouté avec

bienveillance ; il n'obtint pas encore la conversion du Roi mais l'autorisation

de prêcher et de construire sous la protection de la Reine.

Les résultats ne se

firent guère attendre puisque, dès la Pentecôte 597, on inaugura la cathédrale

de Cantorbéry (capitale du Royaume) où le Roi lui-même s'installa parmi les

fidèles enthousiasmés par les pompes et les chants de la liturgie romaine.

L'Église du Kent étant

constituée, selon les ordres du Pape Grégoire, Augustin s'en retourna en Arles

où l'évêque lui donna la consécration épiscopale.

Au comble de la joie,

enthousiaste, le Pape envoya vers l'Angleterre courrier sur courrier et conçut

un vaste plan d'organisation ecclésiastique qu'on mit quelques siècles à

réaliser.

De nouveaux moines furent

dépêchés dans le Kent et l'on commença l'évangélisation de l'Essex. Or, si

Augustin, évêque de Cantorbéry et primat d'Angleterre, réussit à merveille chez

les païens Saxons, il eut contre lui l'antique église celtique qui refusait de

le reconnaître et d'adopter les coutumes et les usages romains.

Ayant posé les solides

bases du catholicisme romain en Grande Bretagne, Augustin mourut en son

archevêché le 26 mai 604.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/05/27.php

Sculpture

of St. Augustine of Canterbury, the first archbishop of Canterbury, on

Canterbury Cathedral in England.

Sculpture

de St. Augustin de Cantorbéry, premier archevêque de Cantorbéry, sur la

Cathédrale de Cantorbéry en Angleterre.

Also

known as

Apostle to the

Anglo-Saxons

Apostle to the English

Austin of Canterbury

28 May on

some calendars

Profile

Monk and abbot of

Saint Andrew’s abbey in Rome, Italy.

Sent by Pope Saint Gregory

the Great with 40 brother monks,

including Saint Lawrence

of Canterbury to evangelize the

British Isles in 597.

Before he reached the islands, terrifying tales of the Celts sent him back

to Rome in

fear, but Gregory told

him he had no choice, and so he went. He established and spread the faith throughout England;

one of his earliest converts was King AEthelberht

who brought 10,000 of his people into the Church.

Ordained as a bishop in Gaul (modern France)

by the archbishop of Arles.

First Archbishop of Canterbury, England.

Helped re-establish contact between the Celtic and Latin churches, though he

could not establish his desired uniformity of liturgy and practices between

them. Worked with Saint Justus

of Canterbury. Anglican Archbishops

of Canterbury are still referred to as occupying the Chair of Augustine.

Born

26 May 605 in Canterbury, England of

natural causes

relics interred

outside the church of Saints Peter and Paul, Canterbury,

a building project he had started

in England

Southwark, archdiocese of

–

Personal

Ordinariate of Our Lady of the Southern Cross

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

In

God’s Garden, by Amy Steedman

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Our

Island Saints, by Amy Steedman

Saints

and Their Symbols, by E A Greene

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

The

Child’s Name, by Julian McCormick

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

Saints

and Their Attributes, by Helen Roeder

other

sites in english

images

video

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites

en français

Abbé

Christian-Philippe Chanut

fonti

in italiano

nettsteder

i norsk

MLA

Citation

“Saint Augustine of

Canterbury“. CatholicSaints.Info. 28 May 2024. Web. 27 May 2025. <https://catholicsaints.info/saint-augustine-of-canterbury/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-augustine-of-canterbury/

Book of

Saints – Augustine of Canterbury

Article

AUGUSTINE of CANTERBURY

(Saint) Bishop (May 26) (7th century) Saint Augustine shares with Saint Gregory

the Great the title of Apostle of the English. Saint Gregory himself, hefore

his advancement to the Papal See, set out to convert the English, but was

recalled to Rome. Five years after his election to the Pontifical Chair, he

sent forth a band of forty monks from the monastery of Saint Andrew in Rome, under

their Prior Augustine, to begin a mission in England. They landed at or near

Ebbsfleet in the Isle of Thanet, where they were received and listened to by

King Saint Ethelbert, who received Baptism and established the holy

missionaries at Canterbury (A.D. 597). Saint Augustine was consecrated the

first Archbishop of Canterbury, it is said, by Virgilius, the Metropolitan of

Aries. Saint Gregory, on hearing of the success of the mission, sent the

pallium (an ornament distinctive of Archbishops) to Augustine, together with a

reinforcement of labourers, among whom were Mellitus, Paulinus and Justus.

These were appointed to the Sees of London, York and Rochester. Saint Augustine

died within a short time of Saint Gregory (A.D. 604). He was buried in the

Abbey church without the walls of Canterbury, which he had founded.

MLA

Citation

Monks of Ramsgate.

“Augustine of Canterbury”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info. 4

August 2012.

Web. 27 May 2025. <http://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-augustine-of-canterbury/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-augustine-of-canterbury/

St. Augustine of

Canterbury

In the year 596, some 40 monks set out from Rome to evangelize the Anglo-Saxons

in England. Leading the group was Augustine, the prior of their monastery in

Rome. Hardly had he and his men reached Gaul (France) when they heard stories

of the ferocity of the Anglo-Saxons and of the treacherous waters of the

English Channel. Augustine returned to Rome and to the pope who had sent them—

Pope St. Gregory the Great —only to be assured by him that their fears were

groundless.

Augustine again set out and this time the group crossed the English Channel and

landed in the territory of Kent, ruled by King Ethelbert, a pagan married to a

Christian. Ethelbert received them kindly, set up a residence for them in

Canterbury and within the year, on Pentecost Sunday, 597, was himself baptized.

After being consecrated a bishop in France, Augustine returned to Canterbury,

where he founded his see. He constructed a church and monastery near where the

present cathedral, begun in 1070, now stands. As the faith spread, additional sees

were established at London and Rochester.

Work was sometimes slow and Augustine did not always meet with success.

Attempts to reconcile the Anglo-Saxon Christians with the original Briton

Christians (who had been driven into western England by Anglo-Saxon invaders)

ended in dismal failure. Augustine failed to convince the Britons to give up

certain Celtic customs at variance with Rome and to forget their bitterness,

helping him evangelize their Anglo-Saxon conquerors

Laboring patiently, Augustine wisely heeded the missionary principles—quite

enlightened for the times—suggested by Pope Gregory the Great: purify rather

than destroy pagan temples and customs; let pagan rites and festivals be

transformed into Christian feasts; retain local customs as far as possible. The

limited success Augustine achieved in England before his death in 605, a short

eight years after he arrived in England, would eventually bear fruit long after

in the conversion of England. Truly Augustine of Canterbury can be called the “Apostle

of England.”

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/st-augustine-of-canterbury/

The

right light of the south window of the south transept of All Saints Church,

Roffey, Horsham, West Sussex. It was made by Michael Farrar Bell in 1936.

St. Augustine of

Canterbury

Feastday: May 27

Death: 605

At the end of the sixth

century anyone would have said that Augustine had found his niche in

life. Looking at this respected prior of

a monastery, almost anyone would have predicted he would spend his last days

there, instructing, governing, and settling even further into this sedentary

life.

But Pope St. Gregory the

Great had lived under Augustine's rule in that same monastery. When he decided

it was time to

send missionaries to Anglo-Saxon England, he didn't choose those with restless

natures or the young looking for new worlds to conquer. He chose Augustine and

thirty monks to make the unexpected, and dangerous, trip to England.

Missionaries had gone to

Britain years before but the Saxon conquest of England had forced these

Christians into hiding. Augustine and his monks were to bring these Christians

back into the fold and convince the warlike conquerors to become Christians

themselves.

Every step of the way

they heard the horrid stories of the cruelty and barbarity of their future

hosts. By the time they

had reached France the

stories became so frightening that the monks turned back to Rome. Gregory had

heard encouraging news that England was far more ready for Christianity than

the stories would indicate, including the marriage of King Ethelbert of

Kent to a Christian princess,

Bertha. He sent Augustine and the monks on their way again fortified with

his belief that

now was the time for

evangelization.

King Ethelbert himself

wasn't as sure, but he was a just king and curious. So he went to hear what the

missionaries had to say after they landed in England. But he was just as afraid

of them as they were of him! Fearful that they would use magic on them, he held

the meeting in the open air. There he listened to what they had to say about

Christianity. He did not convert then but was impressed enough to let them

continue to preach -- as long as they didn't force anyone to convert.

They didn't have to --

the king was baptized in 597. Unlike other kings who

forced all subjects to be baptized as soon as they were converted, Ethelbert left

religious a free choice. Nonetheless the following year many of his subjects

were baptized.

Augustine was

consecrated bishop of

the English and more missionaries arrived from Rome to

help with the new task. Augustine had to be very careful because, although the

English had embraced the new religion they

still respected the old. Under the wise orders of Gregory the Great, Augustine

aided the growth from the ancient traditions to the new life by

consecrating pagan temples

for Christian worship

and turning pagan festivals

into feast days of martyrs. Canterbury was

built on the site of an ancient church.

Augustine was more

successful with the pagans than with the Christians. He found the ancient

British Church, which had been driven into Cornwall and Wales, had strayed a

little in its practices from Rome. He met with them several times to try to

bring them back to the Roman Church but the old Church could not forgive their

conquerors and chose isolation and bitterness over community and

reconciliation.

Augustine was only in

England for eight years before he died in 605. His feast day is celebrated

on May 26 in England and May 28 elsewhere. He is also known as Austin,a name

that many locations have adopted.

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=25

James William Edmund Doyle (1822–1892) and

Edmund Evans (1826–1905), engraver, Augustine of Canterbury preaches

to Æthelberht of Kent,"The Saxons"

in A Chronicle

of England: B.C. 55 – A.D. 1485, London:

Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green, pp. p. 25

St. Augustine of

Canterbury

First Archbishop of Canterbury, Apostle of

the English; date of

birth unknown; d. 26 May, 604. Symbols: cope,pallium,

and mitre as Bishop of Canterbury,

and pastoral

staff and gospels as missionary. Nothing is known of

his youth except that he was probably a Roman of the better class,

and that early in life he become a monk in

the famous monastery of St.

Andrew erected by St.

Gregory out of his own patrimony on the Cælian Hill. It was thus amid

the religious intimacies of the Benedictine

Rule and in the bracing atmosphere of a recent foundation that

the character of the future missionary was

formed. Chance is said to have furnished the opportunity for the

enterprise which was destined to link his name for

all time with that of his friend andpatron, St.

Gregory, as the "true beginner" of one of the most

important Churches in Christendom and

the medium by which the authority of the Roman

See was established over men of the English-speaking race.

It is unnecessary to dwell here upon Bede's well-known

version of Gregory's casual

encounter with English slaves in the Roman market

place (H.E., II, i), which is treated under GREGORY

THE GREAT.

Some five years after his

elevation to the Roman

See (590) Gregory began

to look about him for ways and means to carry out the dream of his

earlier days. He naturally turned to the community he had ruled more

than a decade of years before in the monastery on

the Cælian Hill. Out of these he selected a company of about forty and

designated Augustine, at that time Prior of St. Andrew's,

to be their representative and spokesman. The appointment, as will appear later

on, seems to have been of a somewhat indeterminate character; but from

this time forward until his death in 604 it is

to Augustine as "strengthened by the confirmation of

the blessed Father Gregory (roboratus confirmatione beati patris

Gregorii, Bede,

H. E., I, xxv) that English, as distinguished from British, Christianity owes

its primary inspiration.

The event which

afforded Pope

Gregory the opportunity he had so long desired of carrying out his

greatmissionary plan in favour of the English happened in the year

595 or 596. A rumour had reached Rome that

thepagan inhabitants

of Britain were ready to embrace the Faith in great

numbers, if only preachers could be found to instruct them. The first plan

which seems to have occurred to the pontiff was to take measures for

the purchase of English captive boys of seventeen years of age

and upwards. These he would have brought up in the Catholic Faith with idea of ordaining them

and sending them back in due time as apostles to their own people. He

according wrote to Candidus, a presbyter entrusted

with the administration of a small estate belonging to the patrimony of

the Roman

Church in Gaul,

asking him to secure revenues and set them aside for this purpose.

(Greg., Epp., VI, vii in Migne,

P.L., LXXVII.) It is possible, not only to determine approximately

the dates of these events, but also to indicate the particular

quarter of Britain from which the rumour had

come. Aethelberht became King of Kent in 559 or 560, and in

less than twenty years he succeeded in establishing an overlordship that

extended from the boulders of the country of

the West Saxons eastward to the sea and as far north as

the Humber and the Trent. The Saxons of Middlesex and

of Essex, together with the men of East Anglia and of Mercia, were

thus brought to acknowledge him at Bretwalda, and he acquired a political

importance which began to be felt by the Frankish princes

on the other side of the Channel. Charibert of Paris gave

him his daughter Bertha in marriage,

stipulating, as part of the nuptial agreement, that she should be

allowed the free exercise of her religion. The condition was

accepted (Bede, H. E., I, xxv) and Luidhard, a Frankish bishop,

accompanied the princess to her new home in Canterbury,

where the ruined church of

St. Martin, situated a short distance beyond the walls, and dating from

Roman-British times, was set apart for her use (Bede, H. E., I, xxvi).

The date of this marriage, so important in its results to the

future fortunes of Western

Christianity, is of course largely a matter of conjecture; but from the

evidence furnished by one or two scattered remarks in St.

Gregory's letters (Epp., VI) and from the circumstances which attended

the emergence of the kingdom of the Jutes to a position of

prominence in the Britain of this period, we may safely assume that

it had taken place fully twenty years before the plan of

sending Augustine and his companions suggested itself to the pope.

The pope was obliged to

complain of the lack of episcopal zeal among Aethelberht Christian neighbours.

Whether we are to understand the phrase ex vicinis (Greg., Epp., VI) as

referring to Gaulish prelates or

to the Celtic bishops of

northern and western Britain, the fact remains that neither Bertha's piety,

nor Luidhard's preaching, nor Aethelberht's toleration, nor the

supposedly robust faith of British or Gaulish neighbouring

peoples was found adequate to so obvious an opportunity until a Roman

pontiff, distracted with the cares of a world supposed to be

hastening to its eclipse, first exhorted forty Benedictines of Italian blood

to the enterprise. The itinerary seem to have been speedily, if

vaguely, prepared; the little company set out upon their long journey in the

month of June, 596. They were armed with letters to the bishops and Christian princes

of the countries through which they were likely to pass, and they were further

instructed to provide themselves with Frankish interpreters

before setting foot in Britain itself. Discouragement, however,

appears early to have overtaken them on their way. Tales of the uncouth

islanders to whom they were going chilled their enthusiasm, and some of their

number actually proposed that they should draw back. Augustine so far

compromised with the waverers that he agreed to return in person

to Pope

Gregory and lay before him plainly the difficulties which they might

be compelled to encounter. The band of missionaries waited for him in

the neighbourhood of Aix-en-Provence. Pope

Gregory, however, raised the

drooping spirits of Augustine and sent him back without

delay to his faint-hearted brethren, armed with more precise, and as

it appeared, more convincing authority.

Augustine was named abbot of

the missionaries (Bede, H. E., I, xxiii) and was furnished with

fresh letters in which the pope made

kindly acknowledgment of the aid thus far offered by Protasius, Bishop of Aix-en-Provence,

by Stephen, Abbot of Lérins,

and by a wealthy lay official of patrician rank called Arigius

[Greg., Epp., VI (indic. xiv) num. 52 sqq.;sc. 3,4,5 of the Benedictine series]. Augustine must

have reached Aix on his return journey some time in August;

for Gregory's message

of encouragement to the party bears the date of

July the twenty-third, 596. Whatever may have been the real source of the

passing discouragement no more delays are recorded.

The missionaries pushed on through Gaul, passing up through the

valley of the Rhone to Arles on their way

to Vienne and Autun, and thence northward, by one of several

alternatives routes which it is impossible now to fix with accuracy, until they

come to Paris.

Here, in all probability, they passed the winter months; and here, too, as is

not unlikely, considering

the relations that existed between the family of

the reigning house and that of Kent, they secured the services of the

local presbyters suggested

as interpreters in the pope's letters

to Theodoric and Theodebert and to Brunichilda, Queen of the Franks.

In the spring of the

following year they were ready to embark. The name of the port at which they

took ship has not been recorded. Boulogne was at that time a place of

some mercantile importance; and it is not improbable that they directed their

steps thither to find a suitable vessel in which they could complete the last

and not least hazardous portion of their journey. All that we know for certain is

that they landed somewhere on the Isle of Thanet (Bede, H. E.,

I, xxv) and that they waited there in obedience to King Aethelberht orders until

arrangements could be made for a formal interview. The king replied to their

messengers that he would come in person from Canterbury,

which was less than a dozen miles away. It is not easy to decide at this date between

the four rival spots, each of which has claimed the distinction of being the

place upon which St.

Augustine and his companions first set foot. The Boarded Groin,

Stonar, Ebbsfleet, and Richborough — last named, if the present

course of the Stour has not altered in thirteen hundred years, then forming

part of the mainland — each has its defenders. The curious in such matters may

consult the special literature on the subject cited at the close of

this article. The promised interview between the king and

the missionaries took place within a few days. It was held in the

open air, sub divo, says Bede (Bede,

H.E., I, xxv), on a level spot, probably under a spreading oak in deference to

the king's dread of Augustine's possible incantations. His fear,

however, was dispelled by the native grace of manner and the

kindly personality of

his chief guest who addressed him through an interpreter. The message told

"how the compassionate Jesus hadredeemed a

world of sin by

His own agony and

opened the Kingdom

of Heaven to all who would believe" (Aelfric,

ap. Haddan and Stubbs, III, ii). The king's answer, while gracious in its

friendliness, was curious lyprophetic of

the religious after-temper of his race. "Your words and promised

are very fair" he is said to have replied, "but as they are new to us

and of uncertain import, I cannot assent to them and give up what I have long

held in common with the whole English nation. But since you have come

as strangers from so great a distance, and, as I take it, are anxious to have

us also share in what you conceive to be both excellent and true,

we will not interfere with you, but receive you, rather, in

kindly hospitality and take care to provide what may be necessary for

your support. Moreover, we make no objection to your winning as

many converts as you can to your creed". (Bede, H.E., I,

xxv.)

The king more than

made good his words. He invited the missionaries to take up

their abode in the royal capital of Canterbury,

then a barbarous and half-ruined metropolis,

built by the Kentish folk upon the site of the old Roman military

town of Durovernum. In spite of the squalid character of the city,

the monks must

have made an impressive picture as they drew near the abode "over against

the King.' Street facing the north", a detail preserved in William

Thorne's (c. 1397) "Chronicle of the Abbots of St.

Augustine's Canterbury," p. 1759, assigned them for a dwelling. The striking

circumstances of their approach seem to have lingered long in popular

remembrance; for Bede,

writing fully a century and a third after the event, is at pains to describe

how they came in characteristic Roman fashion (more suo) bearing

"the holy cross together with a picture of the Sovereign

King, Our

Lord Jesus Christ and chanting in unison

this litany", as they advanced: "We beseech thee, O Lord,

in the fulness of thy pity that Thine anger and

Thy holy wrath be turned away from this city and from

Thy holy house, because we have sinned: Alleluia!"

It was an anthem out of one of the many "Rogation"litanies then

beginning to be familiar in the churches of Gaul and

possibly not unknown also at Rome.

(Martène, "De antiquis Ecclesiae ritibus", 1764, III, 189; Bede,

"H.E.", II, xx; Joanes Diac., "De Vita Gregorii",

II, 17 in Migne,

P.L., LXXXV; Duchesne's ed., "Liber

Pontificalis", II, 12.) The building set apart for their use must have

been fairly large to afford shelter to a community numbering fully forty. It

stood in the Stable Gate, not far from the ruins of an old heathen temple;

and the tradition in Thorn's day was that the parish church of

St. Alphage approximately marked the site (Chr. Aug. Abb., 1759).

Here Augustine and his companions seemed to have established without

delay the ordinary routine of the Benedictine

rule as practiced at the close of the sixth century; and to it they

seem to have added in a quiet way the apostolic ministry of

preaching. The church dedicated to St. Martin in the

eastern part of the city which had been set apart for the convenience

of Bishop Luidhard and Queen Bertha's followers

many years before was also thrown open to them until the king should permit a

more highly organized attempt at evangelization.

The evident sincerity of

the missionaries, their single-mindedness, their courage under

trial, and, above all, the disinterested character of Augustine himself

and the unworldly note of his doctrine made

a profound impression on the mind of the king. He asked to be

instructed and his baptism was

appointed to take place at Pentecost. Whether the queen and her Frankish bishop had

any real hand in the process of this comparatively sudden conversion, it

is impossible to say. St.

Gregory's letter written to Bertha herself,

when the news of the king's baptism had

reached Rome,

would lead us to infer, that, while little or nothing had been done before Augustine's arrival,

afterwards there was an endeavor on the part of the queen to make up for past

remissness. The pope writes:

"Et quoniam, Deo volente, aptum nunc tempus est, agate, ut divina

gratia co-operante, cum augmento possitis quod neglectum est

reparare". [Greg. Epp., XI (indic., iv), 29.] The remissness does seem to

have been atoned for, when we take into account the Christian activity

associated with the names of this royal pair during the next few

months. Aethelberht's conversion naturally gave a great

impetus to the enterprise of Augustine and his companions. Augustine himself

determined to act at once upon the provisional instruction he had

received from Pope

Gregory. He crossed over to Gaul and

sought episcopalconsecration at

the hands of Virgilius, the Metropolitan of Arles.

Returning almost immediately to Kent, he made preparations for that more

active and open form of propaganda for which Aethelberht's baptism had

prepared a way. It is characteristic of the spirit which

actuated Augustine and his companions that no attempt was made to

secure converts on a large scale by the employment of force. Bede tells

us that it was part of the king's uniform policy "to compel no man to

embrace Christianity"

(H. E., I, xxvi) and we know from

more than one of his extant letters what the pope though

of a method so strangely at variance with the teaching of theGospels. On Christmas

Day, 597, more than ten thousand persons were baptized by

the first "Archbishop of the English". The great ceremony probably

took place in the waters of the Swale, not far from the mouth of the Medway.

News of these extraordinary events was at once dispatched to the pope,

who wrote in turn to express his joy to

his friend Eulogius, Bishop of Alexandria,

to Augustine himself, and to the king and queen. (Epp., VIII, xxx;

XI, xxviii; ibid., lxvi; Bede,

H. E., I, xxxi, xxxii.) Augustine's message to Gregory was

carried by Lawrence the Presbyter, afterwards Archbishop of Canterbury,

and Peter one of the original colony of missionary monks.

They were instructed to ask for more Gospel labourers, and, if we

may trust Bede's account

in this particular and the curious group of letters embodied in his narrative,

they bore with them a list ofdubia, or questions, bearing upon several points

of discipline and ritual with regard to

which Augustineawaited the pope's answer.

The genuineness of

the document or libellus, as Bede calls

it (H.E., II, i), in which the pope is

alleged to have answered the doubts of

the new archbishop has

not been seriously called in question; though scholars have felt the force of the

objection which St.

Boniface, writing in the second quarter of the eighth century, urges,vis,

that no trace of it could be found in the official collection of St.

Gregory's correspondence preserved in the registry of the Roman

Church.(Haddan and Stubbs, III, 336; Dudden, "Gregory the Great",

II, 130, note; Mason, "Mission of St. Augustine", preface, pp. viii

and ix; Duchesne, "Origines", 3d ed., p. 99, note.) It contains

nine responsa, the most important of which are those that touch upon the

local differences of ritual, the question of jurisdiction,

and the perpetually recurring problem of marriage relationships.

"Why", Augustinehad asked "since the faith is

one, should there be different usages in different churches; one way of

sayingMass in

the Roman

Church, for instance, and another in the Church

of Gaul?" The pope's reply

is, that while "Augustine is not to forget the Church in which

he has been brought up", he is at liberty to adopt from the

usage of other Churches whatever is most likely

to prove pleasing to Almighty

God. "For institutions", he adds, "are not to be loved for

the sake of places; but places, rather, for the sake of institutions".

With regard to the delicate question of jurisdiction Augustine is

informed that he is to exercise no authority over the churches of

Gaul; but that "all the bishops of Britain are

entrusted to him, to the end that the unlearned may be instructed, the wavering

strengthened by persuasion and the perverse corrected with authority".

[Greg., Epp., XI (indic., iv), 64; Bede,

H. E., I, xxvii.] Augustine seized the first convenient opportunity

to carry out the graver provisions of this last enactment. He had already

received the pallium on

the return of Peter andLawrence from Rome in

601. The original band of missionaries had also been reinforced by

fresh recruits, among whom "the first and most distinguished"

as Bede notes,

"were Mellitus, Justus, Paulinus,

andRuffinianus". Of these Ruffinianus was afterwards

chosen abbot of

the monastery established

by Augustine in honour of St.

Peter outside the eastern walls of the Kentish capital. Mellitus became

the first English Bishop of London; Justus was

appointed to the new see of Rochester, and Paulinus became

the Metropolitan of York.

Aethelberht,

as Bretwalda, allowed his wider territory to be mapped out into dioceses,

and exerted himself in Augustine's behalf to bring about a meeting with

the Celtic bishops of

Southern Britain. The conference took place in Malmesbury, on the

borders of Wessex, not far from the Severn, at a spot long described in

popular legend as Austin's Oak. (Bede,

H.E., II, ii.) Nothing came of this attempt to introduce ecclesiastical uniformity. Augustine seems

to have been willing enough to yield certain points; but on three important

issues he would not compromise. He insisted on an unconditional surrender on

the Easter

controversy; on the mode of administering the Sacrament

of Baptism; and on the duty of

taking active measures in concert with him for the evangelization of

the Saxon conquerors. The Celtic bishops refused

to yield, and the meeting was broken up. A second conference was afterwards

planned at which only seven of the British bishops convened.

They were accompanied this time by a group of their "most

learned men" headed by Dinoth, the abbot of

the celebrated monastery of

Bangor-is-coed. The result was, if anything, more discouraging than before.

Accusations of unworthy motives were freely bandied on both

sides. Augustine's Roman regard for form, together with his

punctiliousness for personal precedence as Pope

Gregory's representative, gave umbrage to the Celts.

They denounced the Archbishop for

his pride,

and retired behind their mountains. As they were on the point of withdrawing,

they heard the only angry threat that is recorded of the saint:

"If ye will not have peace with the brethren, ye shall have war from

your enemies; and if ye will not preach the way of life to

theEnglish, ye shall suffer the punishment of death at their hands".

Popular imagination,

some ten years afterwards, saw a terrible fulfilment of

the prophecy in the butchery of the Bangor monks at

the hands of Aethelfrid the Destroyer in the great battle won by him

at Chester in

613.

These efforts toward Catholic unity with the Celtic bishops and the constitution of a well-defined hierarchy for the Saxon Church are the last recorded acts of the saint's life. His death fell in the same year says a very early tradition (which can be traced back to Archbishop Theodore's time) as that of his beloved father andpatron, Pope Gregory. Thorn, however, who attempts always to give the Canterbury version of these legends, asserts — somewhat inaccurately, it would appear, if his coincidences be rigorously tested — that it took place in 605. He was buried, in true Roman fashion, outside the walls of the Kentish capital in a grave dug by the side of the great Roman road which then ran from Deal to Canterbury over St. Martin's Hill and near the unfinished abbey church which he had begun in honour of Sts. Peter and Paul and which was afterwards to bededicated to his memory. When the monastery was completed, his relics were translated to a tomb prepared for them in the north porch. A modern hospital is said to occupy the site of his last resting place. [Stanley, "Memorials of Canterbury" (1906), 38.] His feast day in the Roman Calendar is kept on 28 May; but in the proper of the English office it occurs two days earlier, the true anniversary of his death.

Sources

Bede, Hist. Eccl. I and II; Paulus Diaconus, Johannes Diaconus, and St.

Gall MSS., Lives of St. Gregory in P.L., LXXV; Epistlae

Gregorii, ibid.; Gregory of Tours, Historia Francorum, ibid.,

LXXI; Goscelin, Life of St. Gregory in Acta SS., May, VI, 370 sqq.; Wm.

Thorne, Chron. Abbat. S. Aug. in Twysden's Decem Scriptores (London,

1652), pp 1758-2202; Haddan and Stubbs, Councils and Ecclesiastical

Documents relating to Great Britain and Ireland (Oxford, 1869-1873, 3

vols.); Mason (ed.), The Mission of St. Augustine according to the

Original Documents (Cambridge, 1897); Dudden, Gregory the Great, His

Place in the History of Thought (London, New York, Bombay, 1905); St

Gallen MS., ed, Gasquet (1904) ;Stanley, Memorials of

Canterbury (London, 1855, 1906); Bassenge, Die Sendung Augustins zur

Bekehrung d. Angelsachsen (Leipzig, 1890); Brou, St. Augustin de

Canterbury et ses Compagnons (Paris, 1897); Lévèque, St Augustin de

Canterbury, in Rev. des Quest. Hist. (1899), xxi, 353-423;

Martielli, Récits des fêtes célébrées a l'occ. du 13e centenaire de l'arrivée

de St. Aug. en Angleterre (Paris, 1899)

Clifford,

Cornelius. "St. Augustine of Canterbury." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company,1907. 27

May 2017 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02081a.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Rev. Dave Maher. Dedicated to

Rev. Louis McCorkle.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. 1907. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John M. Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2020 by Kevin

Knight. Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02081a.htm

Golden Legend –

Life of Saint Austin

Of Saint Austin that

brought Christendom to England.

Saint Austin was a holy

monk and sent in to England, to preach the faith of our Lord Jesu Christ, by

Saint Gregory, then being pope of Rome. The which had a great zeal and love

unto England, as is rehearsed all along in his legend, how that he saw children

of England in the market of Rome for to be sold, which were fair of visage, for

which cause he demanded licence and obtained to go into England for to convert

the people thereof to christian faith. And he being on the way the pope died

and he was chosen pope, and was countermanded and came again to Rome. And

after, when he was sacred into the papacy, he remembered the realm of England,

and sent Saint Austin, as head and chief, and other holy monks and priests

with him, to the number of forty persons, unto the realm of England. And as

they came toward England they came in the province of Anjou, purposing to have

rested all night at a place called Pounte, say a mile from the city and river

of Ligerim, but the women scorned and were so noyous to them that they drove

them out of the town, and they came unto a fair broad elm, and purposed to have

rested there that night, but one of the women which was more cruel than the

other purposed to drive them thence, and came so nigh them that they might not

rest there that night. And then Saint Austin took his staff for to remove from