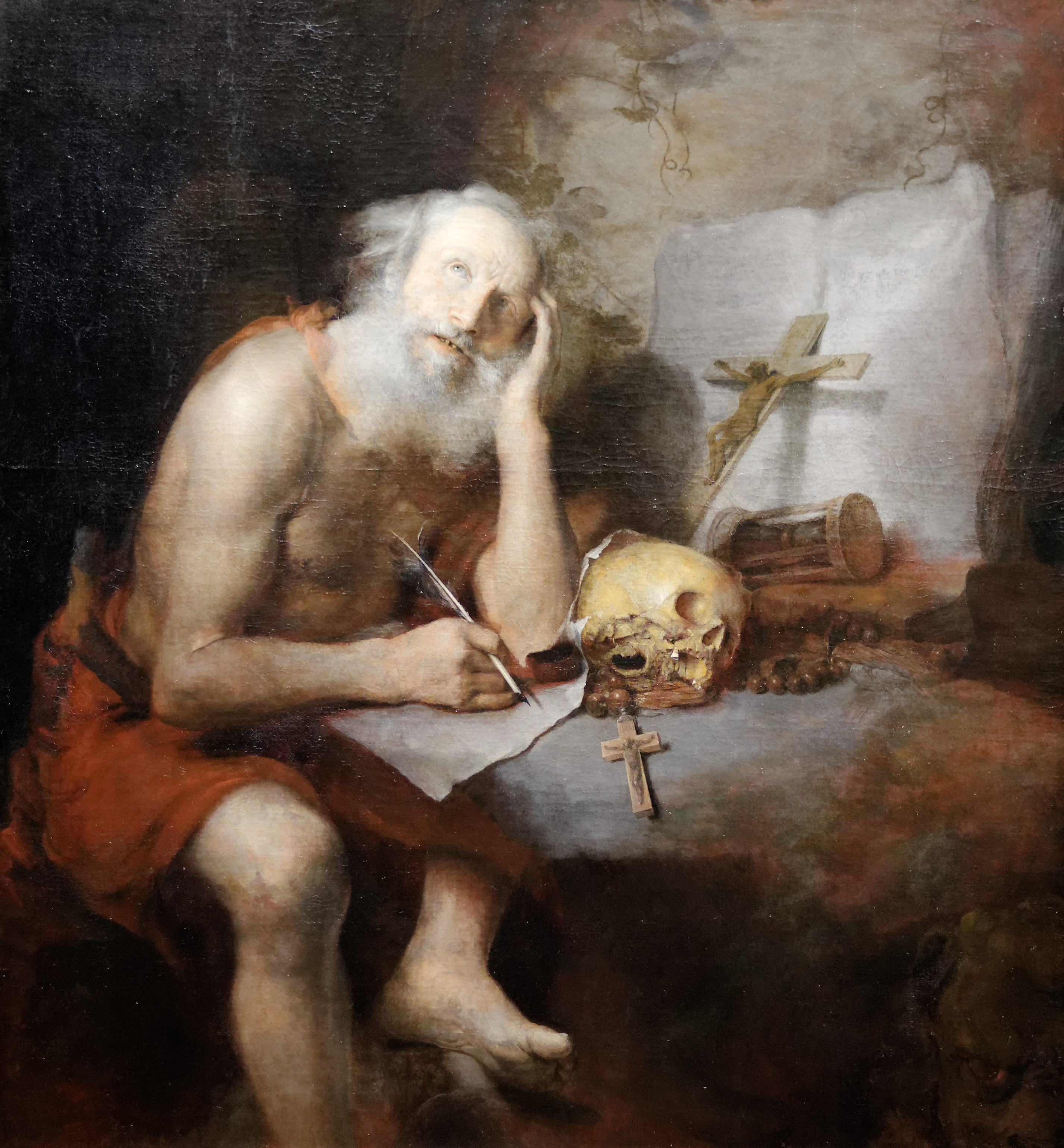

Christopher Paudiß (circa 1618–1666/1667), Jérôme de Stridon (Saint Jérôme). circa 1656, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienne (Autriche). Inv Nr GG 395.

Saint Jérôme

Père et Docteur de l'Église (+ 420)

Martyrologe

romain

Priez-vous ? vous parlez au Seigneur. Lisez-vous

l'Ecriture sainte ? C'est Lui qui vous parle. - Ignorer les Ecritures, c'est

ignorer le Christ. - On ne naît pas chrétien. On le devient. - Ce qui a de la

valeur, c'est d'être chrétien et non de le paraître.

Paroles de saint Jérôme

Anonimo

pittore Veneto-Bizantino, San Gerolamo e il leone, XIV secolo, collezione

Palazzo Roverella, Rovigo

« Que le jeûne du

corps nous prépare au festin de l’âme »

« Les invités de la

noce pourraient-ils donc être en deuil pendant le temps où l’Époux est avec

eux ? Mais des jours viendront où l’Époux leur sera enlevé ; alors

ils jeûneront. » L’époux, c’est le Christ, l’épouse, l’Église :

union sainte et spirituelle qui donna naissance aux Apôtres, et ils ne peuvent

être en deuil tant qu’ils voient l’épouse dans la chambre, tant qu’ils savent

l’époux avec l’épouse. Mais une fois le temps des noces fini, quand sera venu

celui de la Passion et de la Résurrection, alors les fils de l’Époux jeûneront.

La coutume de l’Église est de s’acheminer à la Passion de notre Seigneur et à

la Résurrection en humiliant la chair, pour que le jeûne du corps nous prépare

au festin de l’âme.

« Personne ne pose

une pièce d’étoffe neuve sur un vieux vêtement, car le morceau ajouté tire sur

le vêtement, et la déchirure s’agrandit. » Voici le sens de ces

paroles : qui n’est pas encore rené, qui n’a pas encore dépouillé le vieil

homme et, par l’effet de ma Passion, revêtu l’homme nouveau ne peut supporter

les jeûnes trop austères et les préceptes de la continence, de peur que l’excès

d’austérité ne lui fasse perdre même la foi qu’il montre maintenant.

Saint Jérôme

Prêtre de Rome, saint

Jérôme († 420) partit pour Bethléem, où il vécut comme moine. Il est connu

notamment comme exégète et traducteur de la Bible en latin. / Commentaire

sur s. Matthieu 9, 15-16, trad. É. Bonnard, Paris, Cerf, 1977, Sources

Chrétiennes 242, p. 173-175.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/samedi-2-juillet/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

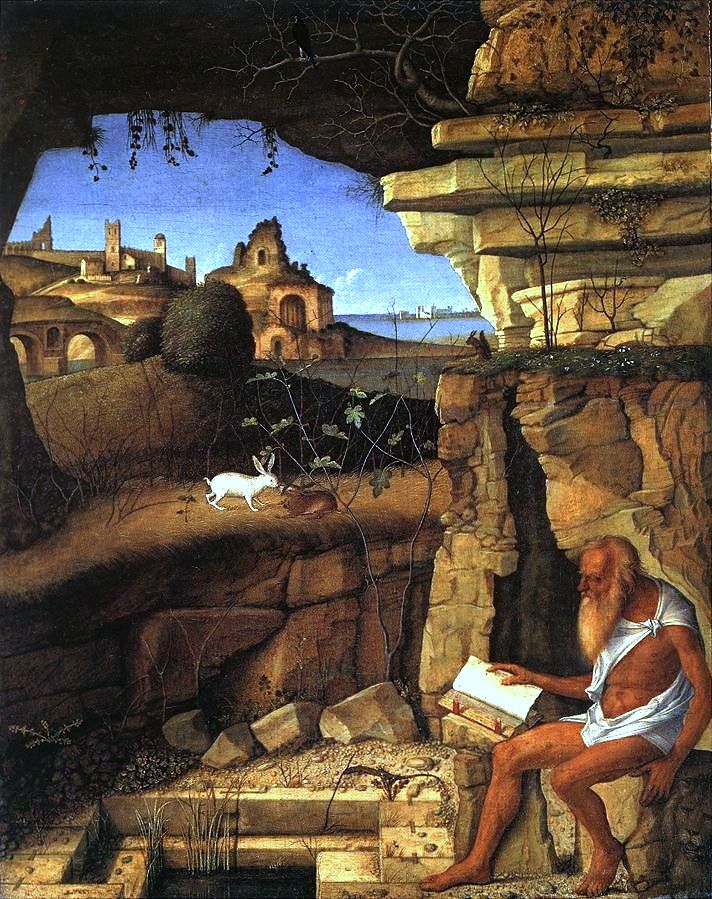

Antonello de Messine, Saint Jérôme (Panneaux

de Palerme), 1472-1473,

Tempera

grasse sur bois transférée sur toile, 39 x 41, Palerme, Galleria Regionale

della Sicilia di Palazzo Abatellis

Saint Jérôme

Docteur de l'Eglise

Je suis à la fois, disait

Jérôme, philosophe, rhéteur, grammairien, dialecticien, expert en hébreu, grec

et latin ; il fut aussi un polémiste redoutable, parfois injuste, tel ce jour

où il invectiva saint Augustin, son cadet d’à peine cinq ans : Ecoute mon

conseil, jeune homme : ne viens pas, dans l'arène des Ecritures, provoquer un

vieillard ! Tu troubles mon silence. Tu fais la roue avec ta science.

« Hierônumos en grec

(celui dont le nom est sacré) ; Hieronymus, en latin, fils d'Eusèbe, je naquis

à Stridon, ville maintenant détruite par les Goths, mais qui se situait alors

sur les confins de la Dalmatie et de la Pannonie (Hongrie) », écrit-il, en 392,

à la dernière page du De viris illustribus, ajoutant : « Je suis né chrétien,

de parents chrétiens. Dès le berceau, je fus nourri du lait catholique. » Il

dit encore de lui-même : « Je suis à la fois philosophe, rhéteur, grammairien,

dialecticien, expert en hébreu, grec et latin. »

Enfant unique pendant

treize ans, Jérôme fut terriblement gâté par les siens jusqu’à ce que

naquissent sa sœur et son frère. Il étudia à Milan, puis à Rome où il suivit

les cours du célèbre grammairien Aelius Donatus. Elève doué mais difficile et

facétieux, Jérôme respira les parfums de cette ville puissante, maîtresse du

monde, alors gouvernée par Julien l'Apostat. Admirateur de Cicéron, il

déclamait les grands plaidoyers les exordes sonores qui lui servirent lors d’un

stage auprès des tribunaux. Il se lia avec Bonose et Rufin, deux compagnons

d'étude. Avec soin et à grands frais, il acquit des livres et, peut-être,

goûta-t-il de furtifs amours au milieu des danses des jeunes filles romaines.

Cependant, confia-t-il

dans son commentaire d’Ezéchiel (XI 5) « Quand j’étais à Rome, jeune étudiant

ès-arts libéraux, j’avais accoutumé, le dimanche, avec d’autres de même âge et

de même résolution, de visiter les tombeaux des apôtres et des martyrs. Souvent

nous entrions dans ces cryptes creusées dans les profondeurs de la terre où

l’on avance entre des morts ensevelis à droite et à gauche le long des parois.

Tout est si obscur que la parole du Prophète est presque réalisée : qu’ils

descendent vivants dans les enfers ! Ici et là, une clarté venue d’en-haut

tempère l’horreur des ténèbres : moins une fenêtre qu’un trou foré,

croirait-on, par la clarté qui tombe. Puis, pas à pas, on revient, et dans la

nuit noire qui vous entoure, le vers de Virgile est obsédant : Tout suscite

l’horreur et le silence même. » Il reçut le baptême, en 366, sans doute des

mains du pape Libère.

Jérôme, hébergé par son

ami Bonose, séjourna d'abord à Trèves, résidence impériale de Valentinien I°,

où il approfondit la théologie ; en 373, il était à Aquilée, centre économique

et littéraire, où, avec Rufin et Bonose, il fonda une académie sous l'égide de

l'évêque Chromatius ; « les clercs d’Aquilée forment comme un chœur de

bienheureux », dira-t-il dans la Chronique.

Quand, pour d’obscures

raisons, le groupe se disloqua, Jérôme partit à Antioche de Syrie où, un jour

du carême 375, il tomba si gravement malade qu'on le crut aux portes de la

mort. Ce lui fut une expérience mystique : « En esprit, je m'imaginai

transporté devant le tribunal du Souverain Juge. Voici la confrontation.

Interrogé sur ma conduite, je déclare : Je suis chrétien. - Tu mens, me

réplique le Juge suprême : Tu es cicéronien, non pas chrétien ; là où est ton

trésor, là aussi est ton cœur. Je m'exclame alors : Seigneur, si jamais je

retiens les livres du siècle, c'est que je t'aurai renié. » (Epître XX 30).

Rétabli mais sans cesse taraudé par fautes passées, il se retira dans la

solitude de Chalcis, au sud de Beroea (Alep) ; il s’imposait une rude ascèse

mais, en même temps, il s’adonnait à l’étude du grec et de l'hébreu. « Combien

de fois, installé au désert, en cette vaste solitude torréfiée d'un ardent

soleil, affreux habitat offert aux moines, je me suis cru mêlé aux plaisirs de

Rome ! ... Les jeûnes avaient pâli mon visage, mais les désirs enflammaient mon

esprit, le corps restant glacé. Devant ce pauvre homme déjà moins chair vivante

que cadavre, grondaient seulement les incendies de la volupté. » (Lettre

CCXXVII, à Eustochium)

Dans sa solitude, les

âpres controverses sur la Trinité, ne manquèrent pas de lui parvenir ; il

écrivit par deux fois au pape Damase, sans recevoir la moindre réponse. Pour

accepter d’être ordonné prêtre par Paulin d'Antioche, en 378, Jérôme, soucieux

de son indépendance, avait posé deux conditions aussi singulières que

paradoxales : ne pas être astreint aux fonctions ministérielles pastorales et

demeurer libre de ses mouvements. Cependant, se jugeant indigne de monter à

l'autel, il ne célébra jamais la messe.

En 379, il partit auprès

de saint Grégoire de Nazianze qui réorganisait l’Eglise de Constantinople.

Jérôme traduisit et compléta la Chronique d'Eusèbe de Césarée et les Homélies

d’Origène. Epiphane de Salamine et Paulin d’Antioche, convoqués à Rome pour un

concile sur les affaires d'Orient, emmenèrent Jérôme qu’ils présentèrent au

Pape (382). Le pape Damase vit tout le parti qu’il pouvait tirer de ce moine

érudit, en provenance de Constantinople qui venait de lui dédier une traduction

des Deux homélies d'Origène sur le Cantique ; il l’engagea comme conseiller

pour les affaires d'Orient et consulteur biblique : Révisez donc le texte peu

satisfaisant des Evangiles, lui demanda-t-il : Je m'y appliquerai d'après les

sources complémentaires : manuscrits grecs et textes en hébreu. Ce fut fait,

avec une correction complète du Psautier.

Connaissez-vous Jérôme,

demandait-on à Rome, ce stupéfiant érudit ? Savez-vous qu'il donne des

conférences très doctes et fort suivies ? - En quel lieu je vous prie ? - Mais

sur l'Aventin, au palais de la veuve Marcella et de la noble Albine, sa mère.

Bientôt, les dames de la société dont Paula et ses deux filles, Eustochium et

Blésilia, coururent se faire conseiller par le savant personnage, rassembleur

de matrones qui ne manqua pas de se faire de solides ennemis parmi les jaloux

qui, à la mort de Damase (11 décembre 384) dénoncèrent ce moine, coqueluche des

dames ; ulcéré, Jérôme qui proclamait que la virginité consacrée doit rester

reine, rugit contre Helvidius qui prétendait que tous les états de vie se

valent. Sois la cigale des nuits ! Veille comme le passereau, sur un toit

désert... Ne faut-il pas pleurer et gémir, quand le serpent nous présente

encore le fruit défendu ? Que me veux-tu, volupté qui passe si vite ? ... Je t'en

conjure, ma chère Eustochium, ma fille, ma souveraine, ma compagne, ma soeur...

Je t'appelle de ces noms puisque mon âge, ta vertu, notre profession, me le

permettent ... Laisse, au-dehors, errer les vierges folles (S. Matthieu XXV

8-13). Reste au dedans. Ferme la porte et prie(Epître XXII 18 : Voeux à

Eustochium, vierge fidèle).

Au mois d’août 385,

calomnié et persécuté, à bout de patience, il secoua sur l'ingrate Rome la

poussière de sessandales (Matthieu VI 11) : D'après eux, je serais donc : fourbe,

séducteur, suppôt de Satan... Il en est qui me baisent les mains et, d'autre

part, me déchirent d'une langue de vipère. Ils affectent de me plaindre mais,

au tréfonds, ils se réjouissent de mon malheur... l'un calomnie ma démarche et

mon rire ; l'autre soupçonne ma simplicité... Et je vécus près de trois ans

avec ces Romains ! C'est à la hâte que je vous confie ces souffrances. Je

m'embarque aujourd'hui, triste et les yeux gonflés de larmes (Epître XLV à

Asella).

Parti vers la Palestine

avec une dizaine de dames romaines, il logea chez Epiphane de Salamine, à

Chypre, où Paula et Eustochium vinrent le rejoindre avant qu’il partît pour

l’Egypte. En Alexandrie, il consulta Didyme l'aveugle, voyant spirituel,

exégète subtil et vulgarisateur génial (Lettre CXII 4). Les pèlerins

enthousiasmèrent et édifièrent les monastères de Nitrie, puis ils entrèrent en

Terre-Sainte. Notre chère Paula y fit visite de la crèche du Sauveur. Quand

elle vit la sainte retraite de la Vierge et l'étable, elle protesta en ma présence

qu'elle voyait, comme si elle les eût sous les yeux : l'Enfant enveloppé de

langes, le Seigneur vagissant dans l'étable, les mages l'adorant, l'étoile

brillant sur la crèche, la Vierge devenue mère, Joseph lui prodiguant ses

soins, les pasteurs veillant de nuit, pour contempler la vérité du Verbe

(Epître CVIII 6, 14 : éloge funèbre de Paula).

Depuis 377, après avoir

séjourné six ans en Egypte, près de Didyme l’aveugle, Tyrannius Rufin

d'Aquilée, l’ami de Jérôme, ordonné prêtre par l’évêque Jean, s’était établi à

Jérusalem comme conseiller spirituel de Mélanie l'ancienne, noble dame romaine,

avec qui, sur le Mont des Oliviers, il animait un monastère double (moines d'un

côté et moniales de l'autre) ; en 386, Jérôme et Paula imitèrent son exemple à

Bethléem : Jérôme priait, se mortifiait, étudiait, travaillait manuellement,

faisait la direction spirituelle de ses moniales : Cette solitude m'est un vrai

paradis !

Dès 389, il a révisé la

version latine de l'Ancien Testament, selon les Hexaples d'Origène (du grec

Hexaplos, sextuple : texte en hébreu, même version en lettres grecques, quatre

versions grecques différentes). Vint ensuite un seconde révision du Psautier

pour le rendre plus conforme à la Septante (version grecque établie, entre 250

et 130 avant J. C., par 70 rabins d'Alexandrie), puis le Livre de Job, les

Paralipomènes et les livres salomoniens.

En même temps, sous la

conduite du juif Baranina, Jérôme se remit à l'étude systématique de l'hébreu

et entreprit une nouvelle relecture annotée de l'Ancien Testament, recherchant

à en rendre le mot, la pensée et le style, mais se heurtant à la pauvreté du

latin, soit pour sauvegarder l'hebraïca veritas, soit pour rendre la nuance

grecque. Pour ma part, non seulement je confesse mais encore je professe, sans

gêne et tout haut : quand je traduis les Grecs - sauf dans les Saintes

Ecritures où l'ordre des mots est aussi un mystère - ce n'est pas un mot par un

mot mais une idée par une idée que j'exprime. (Lettre LVII 5, adressée à

Pammachius ).

Origène (+ 254), fut un

puissant génie dont l'œuvre gigantesque fut amplement exploitée par les Pères

cappadociens et latins : saint Athanase l’opposa aux ariens, saint Grégoire de

Nysse y puisa sa mystique, saint Hilaire de Poitiers s’en imprégna, saint

Ambroise le plagia, et saint Augustin s'en pénétra ; saint Jérôme lui-même se

déclara tributaire d’Origène le Grand, après que saint Grégoire de Naziance le

réputa la pierre qui nous aiguise tous, et que Didyme l’aveugle l’appela le

maître des églises après l’apôtre. Il n’en reste pas moins que la doctrine

origéniste, conservée par Evagre le Pontique et professée par des moines

égyptiens et palestiniens est hétérodoxe[1].

Au début de 393, le moine

Artabius visitant les monastères, présenta un formulaire accablant contre

Origène qui erra, sur les questions dogmatiques : trinité, incarnation,

résurrection, jugement dernier. Jérôme signa la condamnation que Rufin refusa.

A Pâque, Epiphane de Salamine, en pèlerinage à Jérusalem, accusa l'évêque Jean

d'origénisme. L'opinion publique s'agita, des bagarres éclatèrent dans la

basilique du Saint-Sépulcre entre moines de clans opposés. Soutenu par Rufin

Jean durcit sa position, tandis qu’Epiphane se retirait à Bethléem, dans un

monastère hiéronymite. Pour conjurer le schisme, le subtil Théophile,

patriarche d'Alexandrie, força Rufin et Jérôme à la réconciliation, mais, en

réalité, tous deux campaient sur leurs positions.

Retourné à Rome, Rufin

publia une traduction des Principes d'Origène, en biffant les passages qu'il

jugeait contraires à la foi chrétienne, réputés simples interpolations faites

par des mains étrangères. Il écrivit à Jérôme : Jadis admiratif d'un génie,

premier mainteneur de l'Eglise après les apôtres, tu le pourfends aujourd'hui !

Indigne volte-face ! A quoi Jérôme répliqua : J'ai loué sa doctrine et son

intelligence, non pas sa foi : j'approuve le philosophe et je désapprouve

l'apôtre. Rufin adressa sa première Apologie au pape Anastase (400) et, cinq

ans plus tard, il rédigea la deuxième pour répondre aux objections de Jérôme.

Rufin poursuivit ses travaux jusqu'à sa mort (410), laissant vociférer le lion

de Bethléem qui le qualifiait de scorpion, hydre, serpent, porc aux grognements

indécents. La question dogmatique ne sera close qu'en 553, au II° concile de Constantinople.

Voilà qu’un dangereux

exalté, le moine Pélage (360-422), venu de Grande-Bretagne, s’établit

successivement à Rome, en Afrique et en Palestine. C’était un disciple

d'Origène qui commentait les épîtres de saint Paul selon une exégèse fallacieuse

dont on pouvait conclure que le péché originel ne serait qu'un mythe, puisque,

même avant sa faute, Adam aurait été créé mortel et déjà sujet à la

concupiscence ; donc, après la chute, parce que le vouloir et le faire de

l'homme serait demeurés intacts, le baptême n’effacerait que les péchés actuels

et ce serait une simple d'entrée dans l'Eglise.

Dans les Dialogues contre

les pélagiens, Jérôme réfuta ces propositions hérétiques et accentua ses

critiques dans la Lettre à Ctésiphon. Il félicitera saint Augustin de ses

pamphlets antipélagiens. Les hérétiques réagirent vivement, surtout Julien

d'Eclane, réfugié en Orient, et la lutte fut si féroce que certains

commentateurs attribuèrent aux troupes pélagiennes une expédition punitive

contre les monastères hiéronymiens (416) où l’on tua un diacre et incendia les

bâtiments ; assiégé dans une tour fortifiée, Jérôme échappa de justesse : Notre

maison, par rapport aux ressources matérielles, fut complètement ruinée par les

persécutions des hérétiques. Toutefois, le Christ est avec nous. La demeure

reste donc remplie de richesses spirituelles. Mieux vaut mendier son pain que

de perdre la foi (Conclusion de l'épîtreCXXIV).

Pendant quinze ans, de

rudes coups accablèrent le vieil exégète acharné à son travail, mais taraudé

par des maux d'estomac. Paula mourut le 26 janvier 404 : Adieu, Paula. Par tes

prières, tu soutenais la viellesse défaillante d'un homme qui tant te vénéra.

Maintenant que ta foi et tes oeuvres t'unissent au Christ, tu intercèderas plus

facilement pour lui. En 410, quand le wisigoth Alaric envahit l'Italie et pilla

Rome. le vieux patriote vit, dans ce crépuscule des aigles, l'écroulement d'un

monde : Elle s'est donc éteinte, la lumière la plus brillante de tous les

continents. Plus précisément, l'empire vient d'avoir la tête tranchée. Pour

dire l'entière vérité : en une ville, c'est l'univers entier qui périt

(Prologue au commentaire sur Ezéchiel ", XXV 16 a). A la fin de l'année

418, la deuxième fille de Paula, Eustochium, meurt subitement : Cette mort

soudaine me laisse désemparé. Elle a changé ma vie. Effectivement, à partir de

là, et pendant deux ans, Jérôme, d'ordinaire si loquace, se tait. Nous ne

savons rien des derniers jours de Jérôme qui mourut en 419 ou en 420, âgé, dit

la Chronique de Prosper, de quatre-vingt-onze ans.

[1] La création est

conçue comme un acte éternel. La toute puissance et la bonté de Dieu ne

peuvent jamais rester sans objet d’activité. Dans une émanation éternelle, le

Fils procède de Dieu et du Fils procède le Saint-Esprit. Un monde d’esprits

également parfaits a précédé le monde visible actuel, mais a fait défection une

partie de ces esprits à qui appartenaient aussi les âmes préexistantes, et

c’est pourquoi ces esprits ont été exilés dans la matière créée seulement

alors. Les différences entre les hommes sur la terre et la mesure des grâces

que Dieu donne à chacun, se règlent sur leur culpabilité dans un monde

antérieur. Les âmes de ceux qui ont commis des péchés sur la terre, vont après

la mort dans un feu de purification, mais peu à peu toutes, aussi les démons,

montent de degré en degré pour, finalement, entièrement purifiées, ressusciter

dans des corps éthérés, et Dieu sera tout en tous.

Antonio da Fabriano (1420–1490), Saint Jerome in His Study, tempera on wood, 88 x 52, Walters Art Museum

Lettre à Fabiola

Quiconque est versé dans

la science des divines écritures et reconnaît dans leurs lois et leurs

témoignages des liens de vérité, pourra combattre ses adversaires, les

enchaîner, les réduire en captivité, puis, d'anciens ennemis et de misérables

captifs, faire des enfants de Dieu.

Saint Jérôme

Giovanni Angelo d'Antonio (–1481), Saint

Jerome, circa 1463, tempera and gold on panel, 154 x

43, Pinacoteca di Brera

C'est dans les eaux profondes et vivifiantes de la Vulgate que nos littérateurs se sont abreuvés... L'auteur a inventé cette syntaxe, ce style et cette langue à la fois très populaire et très noble, qui anticipe sur les langues romanes et a sûrement joué un grand rôle dans leur constitution... Pontife, en vérité, celui qui a donné la Bible hébraïque au monde occidental et construit un large viaduc qui relie Jérusalem à Rome et Rome à tous les peuples

Valéry Larbaud : Sous l'invocation de Saint Jérôme

Michael Pacher (1435–1498), Szene innen: Hl. Hieronymus, Kirchenväteraltar (Altarpiece of the Church Fathers), 1471-1475, color on wood, Bavarian State Painting Collections, Alte Pinakothek

Michael Pacher (1435–1498), Les Pères de l'Église : Jérôme, Augustin, Grégoire, Ambroise -Kirchenväteraltar (Altarpiece of the

Church Fathers), 1471-1475, color on wood, Bavarian State Painting

Collections, Alte Pinakothek

« Celui qui hait son

frère est un meurtrier » (S. Jean III 15). Telle est la claire affirmation de

Jean, apôtre et évangéliste, et il la fait à juste titre car il n’est que trop

vrai que le meurtre naît souvent de la haine. Son épée peut n’avoir jamais

frappé un coup et pourtant celui qui hait, est déjà, dans son cœur, un

meurtrier. Je vous en prie, dites-vous, pourquoi tout ce préambule ? Simplement

pour vous demander avec insistance que nous enterrions les vieux ressentiments

et préparions à Dieu un cœur pur où il puisse établir sa demeure. « Frémissez,

nous dit David, mais ne péchez pas » (Psaume IV 5). L’apôtre explique ce verset

avec plus de détails : « Que le soleil ne se couche pas sur votre colère » (S.

Paul aux Ephésiens IV 26). Dites-moi, comment allons-nous affronter le jour du

jugement ? Le soleil est témoin qu’il s’est couché sur notre co1ère non pas un

jour, mais pendant bien des années. « Si tu présentes ton offrande à l’autel,

dit Notre-Seigneur dans l’Evangile et que là tu te souviennes que ton frère a

quelque chose contre toi, laisse là ton offrande devant l’autel et va d’abord

te réconcilier avec ton frère, puis viens présenter ton offrande » (S. Matthieu

V 23). Malheur à moi, vil misérable ! dois-je dire. Mais malheur également à

vous ? Pendant tant d’années, ou nous n’avons point présenté d’offrandes à

l’autel, ou nous en avons présenté tout en continuant à nourrir des griefs sans

motif. Comment avons-nous jamais pu faire nôtre la prière quotidienne «

Pardonnez-nous nos offenses comme nous pardonnons à ceux qui nous ont offensés

» (S. Matthieu VI 12), alors que le cœur et la langue étaient tellement en

désaccord, la supplication en contradiction avec la conduite ? C’est pourquoi

je renouvelle maintenant la requête que je vous ai adressée dans ma précédente

lettre l’an dernier. Conservons tous deux cette paix que nous a léguée

Notre-Seigneur, et puisse le Christ jeter un regard favorable sur mon désir et

sur votre intention. Bientôt l’harmonie rétablie ou l’harmonie brisée recevra

sa récompense ou sa punition devant son Tribunal. Mais si vous me repoussez

maintenant, ce qu’à Dieu ne plaise, la faute n’en retombera pas sur moi ; car

une fois que vous l’aurez lue, cette lettre assurera mon acquittement.

Lettre de saint Jérôme à la sœur de sa mère, Castorina

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/09/30.php

Theodoric of Prague (fl. 1359–1368),

Hl. Hieronymus / Saint Jerome, circa 1370, 114 x 105, National gallery in

Prague

Saint Jérôme

Prêtre, Docteur de

l'Église

(340-420)

Saint Jérôme naquit en

Dalmatie, de parents riches et illustres, qui ne négligèrent rien pour son

éducation. Le jeune homme profita si bien de ses années d'études, qu'on put

bientôt, à la profondeur de son jugement, à la vigueur de son intelligence, à

l'éclat de son imagination, deviner l'homme de génie qui devait un jour remplir

le monde de son nom. Les séductions de Rome entraînèrent un instant Jérôme hors

des voies de l'Évangile; mais bientôt, revenant à des idées plus sérieuses, il

ne songea plus qu'à pleurer ses péchés et se retira dans une solitude profonde,

près d'Antioche, n'ayant pour tout bagage qu'une collection de livres précieux

qu'il avait faite dans ses voyages.

L'ennemi des âmes

poursuivit Jérôme jusque dans son désert, et là, lui rappelant les plaisirs de

Rome, réveilla dans son imagination de dangereux fantômes. Mais l'athlète du

Christ, loin de se laisser abattre par ces assauts continuels, redoubla

d'austérités; il se couchait sur la terre nue, passait les nuits et les jours à

verser des larmes, refusait toute nourriture pendant des semaines entières. Ces

prières et ces larmes furent enfin victorieuses, et les attaques de Satan ne

servirent qu'à faire mieux éclater la sainteté du jeune moine.

Avec des auteurs sacrés,

Jérôme avait emporté au désert quelques auteurs profanes; il se plaisait à

converser avec Cicéron et Quintillien. Mais Dieu, qui réservait pour Lui seul

les trésors de cet esprit, ne permit plus au solitaire de goûter à ces sources

humaines, et, dans une vision célèbre, Il lui fit comprendre qu'il devait se

donner tout entier aux études saintes: "Non, lui disait une voix pendant

son sommeil, tu n'es pas chrétien, tu es cicéronien!" Et Jérôme s'écriait

en pleurant: "Seigneur, si désormais je prends un livre profane, si je le

lis, je consens à être traité comme un apostat."

Son unique occupation fut

la Sainte Écriture. À Antioche, puis en Palestine, puis à Rome, puis enfin à

Bethléem, où il passa les années de sa vieillesse, il s'occupa du grand travail

de la traduction des Saints Livres sur le texte original, et il a la gloire

unique d'avoir laissé à l'Église cette version célèbre appelée la Vulgate,

version officielle et authentique, qu'on peut et doit suivre en toute sécurité.

Une autre gloire de saint Jérôme, c'est d'avoir été le secrétaire du concile de Constantinople, puis le secrétaire du Pape saint Damase. Après la mort de ce Pape, l'envie et la calomnie chassèrent de Rome ce grand défenseur de la foi, et il alla terminer ses jours dans la solitude, à Bethléem, près du berceau du Christ.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame,

1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_jerome.html

Jacopo Bassano (1510–1592), Saint Jerome,

1556, oil on canvas, 119 x 154, Gallerie dell'Accademia

Jérôme, un géant de la

foi qui avait le sang chaud

La

rédaction d'Aleteia | 29 septembre 2019

Fêté par l'Église le 30

septembre, saint Jérôme a vécu au Ve siècle après Jésus-Christ. Il laisse

l'image d'un intellectuel brillant assaisonné d'un tempérament bouillonnant. Sa

façon d'être peut encore nous inspirer aujourd'hui.

Il est connu pour son

caractère bien trempé. Père et docteur de l’Église, saint Jérôme est pourvu

d’un tempérament explosif. Il passe d’ailleurs dans l’histoire de l’Église pour

l’un des plus mauvais caractères de la communion des saints ! On peut dire, en

d’autres mots, qu’il était habité par une intransigeance associée à une nature

de feu qui ne supportait pas la demi-mesure.

Après avoir demandé le

baptême à 19 ans, le jeune Romain fougueux n’a plus qu’une idée en tête :

consacrer sa vie à Dieu. Tel un Gulliver des premiers siècles, il fait son

balluchon et passe d’abord deux années dans le désert de Chalcis en Syrie.

Là-bas, il expérimente la vie d’ermite. Mais Jérôme a besoin d’action : il

reprend donc son bardas et part cette fois pour Antioche, où il apprend le grec

et l’hébreu et reçoit le sacerdoce.

Être chrétien tel que

l’on est

Après un passage à

Constantinople, le brillant intellectuel revient à Rome où il devient le

secrétaire du pape Damase. Il est particulièrement aimé des laïcs, et notamment

d’un petit cercle de dames de la noblesse chrétienne dont il est le père

spirituel. À la mort dudit pape, Jérôme doit quitter les lieux. Il faut dire

que son sang chaud lui a valu beaucoup d’ennemis. Il se retire alors à Bethléem

où il trouve enfin sa vocation : étudier la Bible et la traduire en latin —

c’est ce qu’on appelle la « Vulgate ». Il fait de nombreux

commentaires des Écritures et s’applique à les vivre quotidiennement. Saint

Jérôme peut nous inspirer. Son émotivité exacerbée ne l’a pas empêché d’aimer

Dieu de tout son cœur. Il témoigne que l’on peut être chrétien avec la nature

qui est la sienne, en s’accueillant humblement tel que l’on est.

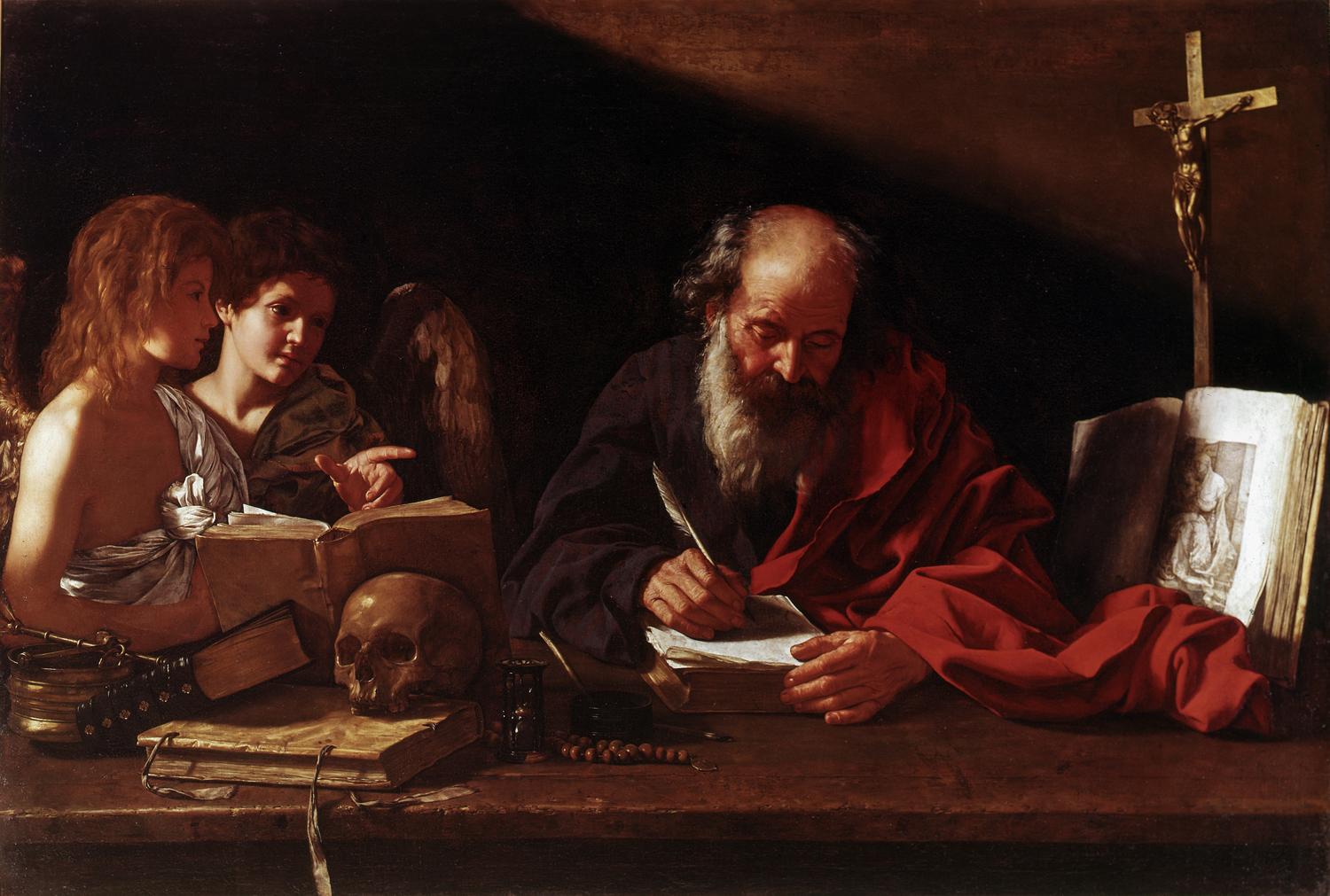

Antonello de Messine, Saint Jérôme dans son étude, 1474-1475, peinture à l'huile sur panneau de tilleul, 45,7 x 36,2, National Gallery, Londres

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 7 novembre 2007

Saint Jérôme

Chers frères et soeurs!

Nous porterons

aujourd'hui notre attention sur saint Jérôme, un Père de l'Eglise qui a placé

la Bible au centre de sa vie: il l'a traduite en langue latine, il l'a

commentée dans ses œuvres, et il s'est surtout engagé à la vivre concrètement

au cours de sa longue existence terrestre, malgré le célèbre caractère

difficile et fougueux qu'il avait reçu de la nature.

Jérôme naquit à Stridon

vers 347 dans une famille chrétienne, qui lui assura une formation soignée,

l'envoyant également à Rome pour perfectionner ses études. Dès sa jeunesse, il

ressentit l'attrait de la vie dans le monde (cf. Ep 22, 7), mais en lui

prévalurent le désir et l'intérêt pour la religion chrétienne. Après avoir reçu

le Baptême vers 366, il s'orienta vers la vie ascétique et, s'étant rendu à

Aquilée, il s'inséra dans un groupe de fervents chrétiens, qu'il définit comme

un "chœur de bienheureux" (Chron. ad ann. 374) réuni autour de

l'Evêque Valérien. Il partit ensuite pour l'Orient et vécut en ermite dans le

désert de Calcide, au sud d'Alep (cf. Ep 14, 10), se consacrant sérieusement

aux études. Il perfectionna sa connaissance du grec, commença l'étude de

l'hébreu (cf. Ep 125, 12), transcrivit des codex et des œuvres patristiques

(cf. Ep 5, 2). La méditation, la solitude, le contact avec la Parole de Dieu

firent mûrir sa sensibilité chrétienne. Il sentit de manière plus aiguë le

poids de ses expériences de jeunesse (cf. Ep 22, 7), et il ressentit vivement

l'opposition entre la mentalité païenne et la vie chrétienne: une opposition

rendue célèbre par la "vision" dramatique et vivante, dont il nous a

laissé le récit. Dans celle-ci, il lui sembla être flagellé devant Dieu, car

"cicéronien et non chrétien" (cf. Ep 22, 30).

En 382, il partit

s'installer à Rome: là, le Pape Damase, connaissant sa réputation d'ascète et

sa compétence d'érudit, l'engagea comme secrétaire et conseiller; il

l'encouragea à entreprendre une nouvelle traduction latine des textes bibliques

pour des raisons pastorales et culturelles. Quelques personnes de l'aristocratie

romaine, en particulier des nobles dames comme Paola, Marcella, Asella, Lea et

d'autres, souhaitant s'engager sur la voie de la perfection chrétienne et

approfondir leur connaissance de la Parole de Dieu, le choisirent comme guide

spirituel et maître dans l'approche méthodique des textes sacrés. Ces nobles

dames apprirent également le grec et l'hébreu.

Après la mort du Pape

Damase, Jérôme quitta Rome en 385 et entreprit un pèlerinage, tout d'abord en

Terre Sainte, témoin silencieux de la vie terrestre du Christ, puis en Egypte,

terre d'élection de nombreux moines (cf. Contra Rufinum 3, 22; Ep 108, 6-14).

En 386, il s'arrêta à Bethléem, où, grâce à la générosité de la noble dame

Paola, furent construits un monastère masculin, un monastère féminin et un hospice

pour les pèlerins qui se rendaient en Terre Sainte, "pensant que Marie et

Joseph n'avaient pas trouvé où faire halte" (Ep 108, 14). Il resta à

Bethléem jusqu'à sa mort, en continuant à exercer une intense activité: il

commenta la Parole de Dieu; défendit la foi, s'opposant avec vigueur à

différentes hérésies; il exhorta les moines à la perfection; il enseigna la

culture classique et chrétienne à de jeunes élèves; il accueillit avec une âme

pastorale les pèlerins qui visitaient la Terre Sainte. Il s'éteignit dans sa

cellule, près de la grotte de la Nativité, le 30 septembre 419/420.

Sa grande culture

littéraire et sa vaste érudition permirent à Jérôme la révision et la

traduction de nombreux textes bibliques: un travail précieux pour l'Eglise

latine et pour la culture occidentale. Sur la base des textes originaux en grec

et en hébreu et grâce à la confrontation avec les versions précédentes, il

effectua la révision des quatre Evangiles en langue latine, puis du Psautier et

d'une grande partie de l'Ancien Testament. En tenant compte de l'original

hébreu et grec, des Septante et de la version grecque classique de l'Ancien

Testament remontant à l'époque pré-chrétienne, et des précédentes versions

latines, Jérôme, ensuite assisté par d'autres collaborateurs, put offrir une

meilleure traduction: elle constitue ce qu'on appelle la "Vulgate",

le texte "officiel" de l'Eglise latine, qui a été reconnu comme tel

par le Concile de Trente et qui, après la récente révision, demeure le texte

"officiel" de l'Eglise de langue latine. Il est intéressant de

souligner les critères auxquels ce grand bibliste s'est tenu dans son œuvre de

traducteur. Il le révèle lui-même quand il affirme respecter jusqu'à l'ordre

des mots dans les Saintes Ecritures, car dans celles-ci, dit-il, "l'ordre

des mots est aussi un mystère" (Ep 57, 5), c'est-à-dire une révélation. Il

réaffirme en outre la nécessité d'avoir recours aux textes originaux:

"S'il devait surgir une discussion entre les Latins sur le Nouveau

Testament, en raison des leçons discordantes des manuscrits, ayons recours à

l'original, c'est-à-dire au texte grec, langue dans laquelle a été écrit le

Nouveau Pacte. De la même manière pour l'Ancien Testament, s'il existe des

divergences entre les textes grecs et latins, nous devons faire appel au texte

original, l'hébreu; de manière à ce que nous puissions retrouver tout ce qui

naît de la source dans les ruisseaux" (Ep 106, 2). En outre, Jérôme

commenta également de nombreux textes bibliques. Il pensait que les

commentaires devaient offrir de nombreuses opinions, "de manière à ce que

le lecteur avisé, après avoir lu les différentes explications et après avoir

connu de nombreuses opinions - à accepter ou à refuser -, juge celle qui était

la plus crédible et, comme un expert en monnaies, refuse la fausse

monnaie" (Contra Rufinum 1, 16).

Il réfuta avec énergie et

vigueur les hérétiques qui contestaient la tradition et la foi de l'Eglise. Il

démontra également l'importance et la validité de la littérature chrétienne,

devenue une véritable culture désormais digne d'être comparée avec la

littérature classique: il le fit en composant le De viris illustribus, une

œuvre dans laquelle Jérôme présente les biographies de plus d'une centaine

d'auteurs chrétiens. Il écrivit également des biographies de moines, illustrant

à côté d'autres itinéraires spirituels également l'idéal monastique; en outre,

il traduisit diverses œuvres d'auteurs grecs. Enfin, dans le fameux

Epistolario, un chef-d'œuvre de la littérature latine, Jérôme apparaît avec ses

caractéristiques d'homme cultivé, d'ascète et de guide des âmes.

Que pouvons-nous

apprendre de saint Jérôme? Je pense en particulier ceci: aimer la Parole de

Dieu dans l'Ecriture Sainte. Saint Jérôme dit: "Ignorer les Ecritures,

c'est ignorer le Christ". C'est pourquoi, il est très important que chaque

chrétien vive en contact et en dialogue personnel avec la Parole de Dieu qui

nous a été donnée dans l'Ecriture Sainte. Notre dialogue avec elle doit

toujours revêtir deux dimensions: d'une part, il doit être un dialogue

réellement personnel, car Dieu parle avec chacun de nous à travers l'Ecriture

Sainte et possède un message pour chacun. Nous devons lire l'Ecriture Sainte

non pas comme une parole du passé, mais comme une Parole de Dieu qui s'adresse

également à nous et nous efforcer de comprendre ce que le Seigneur veut nous

dire. Mais pour ne pas tomber dans l'individualisme, nous devons tenir compte

du fait que la Parole de Dieu nous est donnée précisément pour construire la

communion, pour nous unir dans la vérité de notre chemin vers Dieu. C'est

pourquoi, tout en étant une Parole personnelle, elle est également une Parole

qui construit une communauté, qui construit l'Eglise. Nous devons donc la lire

en communion avec l'Eglise vivante. Le lieu privilégié de la lecture et de

l'écoute de la Parole de Dieu est la liturgie, dans laquelle, en célébrant la

parole et en rendant présent dans le Sacrement le Corps du Christ, nous

réalisons la parole dans notre vie et la rendons présente parmi nous. Nous ne

devons jamais oublier que la Parole de Dieu transcende les temps. Les opinions

humaines vont et viennent. Ce qui est très moderne aujourd'hui sera très vieux

demain. La Parole de Dieu, au contraire, est une Parole de vie éternelle, elle

porte en elle l'éternité, ce qui vaut pour toujours. En portant en nous la

Parole de Dieu, nous portons donc en nous l'éternel, la vie éternelle.

Et ainsi, je conclus par

une parole de saint Jérôme à saint Paulin de Nola. Dans celle-ci, le grand

exégète exprime précisément cette réalité, c'est-à-dire que dans la Parole de

Dieu, nous recevons l'éternité, la vie éternelle. Saint Jérôme dit:

"Cherchons à apprendre sur la terre les vérités dont la consistance

persistera également au ciel" (Ep 53, 10).

* * *

Je salue cordialement les

personnes de langue française, particulièrement les pèlerins de la diaconie du

Var et les jeunes. À la suite de saint Jérôme, je vous invite à lire et à

méditer la Parole de Dieu, qui nous est donnée dans la Bible. Faites-en tous

les jours votre nourriture spirituelle ! Que Dieu vous bénisse et vous garde

dans l’espérance !

© Copyright 2007 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Vittore Crivelli (1440–1501),

Saint Jerome,

75,9 x 38,3, Harvard Art Museums, Fogg

Museum

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 14 novembre 2007

Saint Jérôme

Chers frères et sœurs,

Nous poursuivons

aujourd'hui la présentation de la figure de saint Jérôme. Comme nous l'avons

dit mercredi dernier, il consacra sa vie à l'étude de la Bible, au point d'être

reconnu par l'un de mes prédécesseurs, le Pape Benoît XV, comme "docteur

éminent dans l'interprétation des Saintes Ecritures". Jérôme soulignait la

joie et l'importance de se familiariser avec les textes bibliques: "Ne te

semble-t-il pas habiter - déjà ici, sur terre - dans le royaume des cieux,

lorsqu'on vit parmi ces textes, lorsqu'on les médite, lorsqu'on ne connaît ni

ne recherche rien d'autre?" (Ep 53, 10). En réalité, dialoguer avec Dieu,

avec sa Parole, est dans un certain sens une présence du Ciel, c'est-à-dire une

présence de Dieu. S'approcher des textes bibliques, surtout du Nouveau

Testament, est essentiel pour le croyant, car "ignorer l'Ecriture, c'est

ignorer le Christ". C'est à lui qu'appartient cette phrase célèbre,

également citée par le Concile Vatican II dans la Constitution Dei Verbum (n.

25).

Réellement

"amoureux" de la Parole de Dieu, il se demandait: "Comment

pourrait-on vivre sans la science des Ecritures, à travers lesquelles on

apprend à connaître le Christ lui-même, qui est la vie des croyants" (Ep

30, 7). La Bible, instrument "avec lequel Dieu parle chaque jour aux

fidèles" (Ep 133, 13), devient ainsi un encouragement et la source de la

vie chrétienne pour toutes les situations et pour chaque personne. Lire

l'Ecriture signifie converser avec Dieu: "Si tu pries - écrit-il à une

noble jeune fille de Rome -, tu parles avec l'Epoux; si tu lis, c'est Lui qui

te parle" (Ep 22, 25). L'étude et la méditation de l'Ecriture rendent

l'homme sage et serein (cf. In Eph., prol.). Assurément, pour pénétrer toujours

plus profondément la Parole de Dieu, une application constante et progressive

est nécessaire. Jérôme recommandait ainsi au prêtre Népotien: "Lis avec

une grande fréquence les divines Ecritures; ou mieux, que le Livre Saint reste

toujours entre tes mains. Apprends-là ce que tu dois enseigner" (Ep 52,

7). Il donnait les conseils suivants à la matrone romaine Leta pour l'éducation

chrétienne de sa fille: "Assure-toi qu'elle étudie chaque jour un passage

de l'Ecriture... Qu'à la prière elle fasse suivre la lecture, et à la lecture

la prière... Au lieu des bijoux et des vêtements de soie, qu'elle aime les

Livres divins" (Ep 107, 9.12). Avec la méditation et la science des

Ecritures se "conserve l'équilibre de l'âme" (Ad Eph., prol.). Seul

un profond esprit de prière et l'assistance de l'Esprit Saint peuvent nous

introduire à la compréhension de la Bible: "Dans l'interprétation des

Saintes Ecritures, nous avons toujours besoin de l'assistance de l'Esprit

Saint" (In Mich. 1, 1, 10, 15).

Un amour passionné pour

les Ecritures imprégna donc toute la vie de Jérôme, un amour qu'il chercha

toujours à susciter également chez les fidèles. Il recommandait à l'une de ses

filles spirituelles: "Aime l'Ecriture Sainte et la sagesse t'aimera;

aime-la tendrement, et celle-ci te préservera; honore-la et tu recevras ses

caresses. Qu'elle soit pour toi comme tes colliers et tes boucles

d'oreille" (Ep 130, 20). Et encore: "Aime la science de l'Ecriture,

et tu n'aimeras pas les vices de la chair" (Ep 125, 11).

Pour Jérôme, un critère

de méthode fondamental dans l'interprétation des Ecritures était l'harmonie

avec le magistère de l'Eglise. Nous ne pouvons jamais lire l'Ecriture seuls.

Nous trouvons trop de portes fermées et nous glissons facilement dans l'erreur.

La Bible a été écrite par le Peuple de Dieu et pour le Peuple de Dieu, sous

l'inspiration de l'Esprit Saint. Ce n'est que dans cette communion avec le

Peuple de Dieu que nous pouvons réellement entrer avec le "nous" au

centre de la vérité que Dieu lui-même veut nous dire. Pour lui, une

interprétation authentique de la Bible devait toujours être en harmonieuse

concordance avec la foi de l'Eglise catholique. Il ne s'agit pas d'une exigence

imposée à ce Livre de l'extérieur; le Livre est précisément la voix du Peuple

de Dieu en pèlerinage et ce n'est que dans la foi de ce Peuple que nous sommes,

pour ainsi dire, dans la juste tonalité pour comprendre l'Ecriture Sainte. Il

admonestait donc: "Reste fermement attaché à la doctrine traditionnelle

qui t'a été enseignée, afin que tu puisses exhorter selon la saine doctrine et réfuter

ceux qui la contredisent" (Ep 52, 7). En particulier, étant donné que

Jésus Christ a fondé son Eglise sur Pierre, chaque chrétien - concluait-il -

doit être en communion "avec la Chaire de saint Pierre. Je sais que sur

cette pierre l'Eglise est édifiée" (Ep 15, 2). Par conséquent, et de façon

directe, il déclarait: "Je suis avec quiconque est uni à la Chaire de

saint Pierre" (Ep 16).

Jérôme ne néglige pas,

bien sûr, l'aspect éthique. Il rappelle au contraire souvent le devoir

d'accorder sa propre vie avec la Parole divine et ce n'est qu'en la vivant que

nous trouvons également la capacité de la comprendre. Cette cohérence est

indispensable pour chaque chrétien, et en particulier pour le prédicateur, afin

que ses actions, si elles étaient discordantes par rapport au discours, ne le

mettent pas dans l'embarras. Ainsi exhorte-t-il le prêtre Népotien: "Que

tes actions ne démentent pas tes paroles, afin que, lorsque tu prêches à

l'église, il n'arrive pas que quelqu'un commente en son for intérieur:

"Pourquoi n'agis-tu pas précisément ainsi?" Cela est vraiment

plaisant de voir ce maître qui, le ventre plein, disserte sur le jeûne; même un

voleur peut blâmer l'avarice; mais chez le prêtre du Christ, l'esprit et la

parole doivent s'accorder" (Ep 52, 7). Dans une autre lettre, Jérôme

réaffirme: "Même si elle possède une doctrine splendide, la personne qui

se sent condamnée par sa propre conscience se sent honteuse" (Ep 127, 4).

Toujours sur le thème de la cohérence, il observe: l'Evangile doit se traduire

par des attitudes de charité véritable, car en chaque être humain, la Personne

même du Christ est présente. En s'adressant, par exemple, au prêtre Paulin (qui

devint ensuite Evêque de Nola et saint), Jérôme le conseillait ainsi: "Le

véritable temple du Christ est l'âme du fidèle: orne-le, ce sanctuaire,

embellis-le, dépose en lui tes offrandes et reçois le Christ. Dans quel but

revêtir les murs de pierres précieuses, si le Christ meurt de faim dans la

personne d'un pauvre?" (Ep 58, 7). Jérôme concrétise: il faut "vêtir

le Christ chez les pauvres, lui rendre visite chez les personnes qui souffrent,

le nourrir chez les affamés, le loger chez les sans-abris" (Ep 130, 14).

L'amour pour le Christ, nourri par l'étude et la méditation, nous fait

surmonter chaque difficulté: "Aimons nous aussi Jésus Christ, recherchons

toujours l'union avec lui: alors, même ce qui est difficile nous semblera

facile" (Ep 22, 40).

Jérôme, défini par

Prospère d'Aquitaine comme un "modèle de conduite et maître du genre

humain" (Carmen de ingratis, 57), nous a également laissé un enseignement

riche et varié sur l'ascétisme chrétien. Il rappelle qu'un courageux engagement

vers la perfection demande une vigilance constante, de fréquentes

mortifications, toutefois avec modération et prudence, un travail intellectuel

ou manuel assidu pour éviter l'oisiveté (cf. Epp 125, 11 et 130, 15), et

surtout l'obéissance à Dieu: "Rien... ne plaît autant à Dieu que

l'obéissance..., qui est la plus excellente et l'unique vertu" (Hom. de

oboedientia: CCL 78,552). La pratique des pèlerinages peut également appartenir

au chemin ascétique. Jérôme donna en particulier une impulsion à ceux en Terre

Sainte, où les pèlerins étaient accueillis et logés dans des édifices élevés à

côté du monastère de Bethléem, grâce à la générosité de la noble dame Paule,

fille spirituelle de Jérôme (cf. Ep 108, 14).

Enfin, on ne peut pas

oublier la contribution apportée par Jérôme dans le domaine de la pédagogie

chrétienne (cf. Epp 107 et 128). Il se propose de former "une âme qui doit

devenir le temple du Seigneur" (Ep 107, 4), une "pierre très

précieuse" aux yeux de Dieu (Ep 107, 13). Avec une profonde intuition, il

conseille de la préserver du mal et des occasions de pécher, d'exclure les

amitiés équivoques ou débauchées (cf. Ep 107, 4 et 8-9; cf. également Ep 128,

3-4). Il exhorte surtout les parents pour qu'ils créent un environnement serein

et joyeux autour des enfants, pour qu'ils les incitent à l'étude et au travail,

également par la louange et l'émulation (cf. Epp 107, 4 et 128, 1), qu'ils les

encouragent à surmonter les difficultés, qu'ils favorisent entre eux les bonnes

habitudes et qu'ils les préservent d'en prendre de mauvaises car - et il cite

là une phrase de Publilius Syrus entendue à l'école - "difficilement tu

réussiras à te corriger de ces choses dont tu prends tranquillement

l'habitude" (Ep 107, 8). Les parents sont les principaux éducateurs des

enfants, les premiers maîtres de vie. Avec une grande clarté, Jérôme,

s'adressant à la mère d'une jeune fille et mentionnant ensuite le père,

admoneste, comme exprimant une exigence fondamentale de chaque créature humaine

qui commence son existence: "Qu'elle trouve en toi sa maîtresse, et que sa

jeunesse inexpérimentée regarde vers toi avec émerveillement. Que ni en toi, ni

en son père elle ne voie jamais d'attitudes qui la conduisent au péché, si

elles devaient être imitées. Rappelez-vous que... vous pouvez davantage

l'éduquer par l'exemple que par la parole" (Ep 107, 9). Parmi les

principales intuitions de Jérôme comme pédagogue, on doit souligner

l'importance attribuée à une éducation saine et complète dès la prime enfance,

la responsabilité particulière reconnue aux parents, l'urgence d'une sérieuse

formation morale et religieuse, l'exigence de l'étude pour une formation humaine

plus complète. En outre, un aspect assez négligé à l'époque antique, mais

considéré comme vital par notre auteur, est la promotion de la femme, à

laquelle il reconnaît le droit à une formation complète: humaine, scolaire,

religieuse, professionnelle. Et nous voyons précisément aujourd'hui que

l'éducation de la personnalité dans son intégralité, l'éducation à la

responsabilité devant Dieu et devant l'homme, est la véritable condition de

tout progrès, de toute paix, de toute réconciliation et d'exclusion de la

violence. L'éducation devant Dieu et devant l'homme: c'est l'Ecriture Sainte

qui nous indique la direction de l'éducation et ainsi, du véritable humanisme.

Nous ne pouvons pas

conclure ces rapides annotations sur cet éminent Père de l'Eglise sans mentionner

la contribution efficace qu'il apporta à la préservation d'éléments positifs et

valables des antiques cultures juive, grecque et romaine au sein de la

civilisation chrétienne naissante. Jérôme a reconnu et assimilé les valeurs

artistiques, la richesse des sentiments et l'harmonie des images présentes chez

les classiques, qui éduquent le cœur et l'imagination à de nobles sentiments.

Il a en particulier placé au centre de sa vie et de son activité la Parole de

Dieu, qui indique à l'homme les chemins de la vie, et lui révèle les secrets de

la sainteté. Nous ne pouvons que lui être profondément reconnaissants pour tout

cela, précisément dans le monde d'aujourd'hui.

* * *

Je suis heureux de saluer

les francophones, notamment les jeunes prêtres de Belley-Ars, avec leur Évêque,

Mgr Bagnard. J’adresse un salut tout particulier aux pèlerins de France venus

avec les reliques de sainte Thérèse de l’Enfant Jésus et de la Sainte-Face,

accompagnés par Mgr Pican, Évêque de Bayeux et Lisieux. Nous nous souvenons qu’il

y a cent vingt ans, la petite Thérèse est venue rencontrer le Pape Léon XIII,

pour lui demander la permission d’entrer au Carmel malgré son jeune âge. Il y a

quatre-vingt ans, le Pape Pie XI la proclamait Patronne des Missions et, en

1997, le Pape Jean-Paul II la déclarait Docteur de l’Église. Après cette

audience, j’aurai la joie de prier devant ses reliques, comme de nombreux

fidèles peuvent le faire pendant toute la semaine dans différentes églises de

Rome. Sainte Thérèse aurait voulu apprendre les langues bibliques pour mieux

lire l’Écriture. À sa suite et à l’exemple de saint Jérôme, puissiez-vous

prendre du temps pour lire la Bible de manière régulière. En devenant familiers

de la Parole de Dieu, vous y rencontrerez le Christ pour demeurer en intimité

avec lui. Avec ma Bénédiction apostolique.

© Copyright 2007 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Saint Jérôme de Stridon,

exégète et patron des traducteurs

Publié le 18/2/24

Chapeau rouge de

cardinal, face amaigrie de vieillard usé par les jeûnes, un lion à ses pieds,

le livre des Saintes Ecritures dans les mains, le canon iconographique de saint

Jérôme est des plus constants. Difficile de démêler la part d’amplification légendaire

et la part de vérité historique.

Saint Jérôme « a

placé la Bible au centre de sa vie, disait Benoît XVI ; il l’a traduite en

langue latine, il l’a commentée dans ses œuvres, et il s’est surtout engagé à

vivre concrètement en conformité avec elle au cours de sa longue existence

terrestre, malgré le célèbre caractère difficile et fougueux qu’il avait reçu

de la nature » (Audience générale du 7 novembre 2007). Ce

Père de l’Église (ainsi sont désignés les saints qui, par leur doctrine et leur

exemple, ont comme nourri l’Église dans son enfance) se définit

lui-même en ces termes : « Je suis à la fois philosophe, rhéteur,

grammairien, dialecticien, expert en hébreu, grec et latin. » Voilà les armes

du polémiste dont la fougue va jusqu’à invectiver l’évêque d’Hippone, saint

Augustin – son benjamin de dix ans –, comme s’il s’adressait à un étudiant : «

Écoute mon conseil, jeune homme. Ne viens pas, dans l’arène des Écritures,

provoquer un vieillard ! Tu troubles mon silence. Tu fais la roue avec ta

science. »

Saint Jérôme est né vers

345, à Stridon, bourgade fortifiée située aux confins des provinces de Dalmatie

et de Pannonie (actuelle Hongrie). Son père, Eusèbe, est un riche propriétaire

foncier. Jérôme mentionne avec fierté : « Je suis né chrétien de parents

chrétiens, et portant sur mon front l’étendard de la Croix. » On lui

donne pourtant un nom païen, Hieronymus (qui signifie : celui dont le nom est

sacré), en français : Jérôme. Conformément à une pratique courante à l’époque,

l’enfant n’est pas baptisé, mais simplement inscrit sur le registre des

catéchumènes. De son enfance, Jérôme dira : « Je me rappelle avoir gambadé

à travers les chambrettes des petits esclaves, avoir passé à jouer mon jour de

congé et m’être fait arracher aux bras de ma grand-mère pour être livré captif

à la fureur d’un Olibrius. » Cet Olibrius est, en effet, un maître

d’école aux méthodes d’éducation brutales, et l’enfant « a pleuré sous le

claquement de la férule ». Élève turbulent, espiègle, à

l’intelligence très vive, à la mémoire fidèle, Jérôme possède un caractère

extrêmement sensible, qui le rendra susceptible, ombrageux, mais aussi

profondément affectueux et ouvert aux rencontres.

« Un chœur de bienheureux

»

Ses parents l’envoient à

Rome pour y parachever sa formation. Là, sous la conduite des meilleurs

professeurs, il s’initie aux secrets de la rhétorique (art de bien parler)

et de la dialectique (art de la discussion). Il se constitue une

bibliothèque en recopiant de sa main, « avec beaucoup de soin et de peine

», quelques œuvres de ses auteurs préférés : Plaute, Virgile, Cicéron.

Toutefois, il est aussi avide de distractions : sa nature ardente le porte à

s’extérioriser, et, s’il ne se jette pas dans le plaisir avec l’ardeur

d’un Augustin, il sacrifie cependant quelque peu à ses passions naissantes. Il

évoquera plus tard son égarement d’alors, « au milieu des danses des

jeunes filles romaines ». Malgré cela, son esprit religieux le porte,

le dimanche, à visiter les catacombes, avec des amis. Finalement, touché par la

grâce, il se décide en 366 à recevoir le Baptême. Puis il se rend à

Trèves, où l’empereur Valentinien s’est installé. Pour répondre aux vœux de sa

famille, Jérôme cherche, en effet, un poste dans l’administration. Mais

là, il découvre la vie monastique qui lui inspire de graves pensées.

Profondément touché, il décide de renoncer au monde, et commence à s’intéresser

à la littérature chrétienne. Animé de ces dispositions nouvelles, il retourne

en Italie, à Aquilée, où il s’insère dans un groupe de fervents chrétiens,

qu’il définit comme un « chœur de bienheureux » réuni autour de

l’évêque Valérien. En 374, il décide soudain de partir en Orient, dans le

dessein de s’y consacrer à la vie monastique.

Après un long et pénible

voyage, épuisé par la fièvre, Jérôme arrive à Antioche de Syrie chez un ami

rencontré à Aquilée, le prêtre Évagre. Il y mène avec joie une vie

paisible et studieuse ; ce n’est pourtant pas à proprement parler une vie

monastique. Lors du carême de 375, atteint par la maladie, il s’entend

reprocher, au cours d’un songe, son attachement excessif aux lettres profanes :

« En esprit, je m’imaginais transporté devant le tribunal du souverain

Juge. Interrogé sur ma religion : “Je suis chrétien, répondis-je. – Tu mens, me

réplique le Juge suprême : Tu es cicéronien, pas chrétien. Où est ton trésor,

là est ton cœur !” » Intensément tourmenté par sa conscience, Jérôme

renonce aux livres profanes. Retiré dans le désert de Chalcis, au sud d’Alep

(Syrie), il pratique une rude ascèse, se consacrant sérieusement à l’étude

du grec et de l’hébreu. La méditation, la solitude, le contact avec la

Parole de Dieu ouvrent son goût à la lecture de la Bible. Cependant, sa

santé fragile souffre des privations qu’il s’impose : « Les jeûnes

avaient fait pâlir mon visage, mais les désirs enflammaient pourtant mon esprit

dans mon corps glacé, et devant le pauvre homme que j’étais, chair à moitié

morte, seuls bouillonnaient les incendies des voluptés. »

Une direction éclairée

L’Église d’Antioche est

alors déchirée par un schisme. Jérôme, pressé de prendre position, en

appelle au Pape, mais la réponse se fait attendre. Les moines ariens, eux,

n’attendent pas : ils l’importunent par leurs querelles au point de lui

rendre le désert odieux. Désabusé, Jérôme rentre en 377 à Antioche, où

l’évêque Paulin l’ordonne prêtre. En 379, il se rend à Constantinople, où

il continue ses études bibliques sous la direction éclairée de Grégoire de

Nazianze, théologien et exégète. Une amitié sincère s’établit entre eux

deux. À cette époque, il découvre Origène, et commence à développer une exégèse (c’est-à-dire

une étude du texte sacré) à partir des textes originaux en hébreu et en grec.

En 382, l’évêque Paulin et Épiphane de Salamine l’invitent à les accompagner

jusqu’à Rome, où ils veulent informer le Pape Damase des événements qui agitent

l’Orient. Jérôme accepte de grand cœur. Le saint Pape, qui connaît sa

réputation d’ascète et sa compétence d’érudit, se l’adjoint comme secrétaire et

le consulte sur le sens de passages obscurs des Écritures. Il l’engage à

entreprendre une nouvelle traduction latine des textes bibliques.

« Sa grande culture

littéraire et sa vaste érudition permirent à Jérôme la révision et la

traduction de nombreux textes bibliques : un travail précieux pour l’Église

latine et pour la culture occidentale. Sur la base des textes originaux en

hébreu et en grec, et grâce à la confrontation avec les versions précédentes,

il effectua la révision des quatre Évangiles en langue latine, puis du Psautier

et d’une grande partie de l’Ancien Testament… Jérôme put offrir une meilleure

traduction : elle constitue ce qu’on appelle la “Vulgate”, le texte officiel de

l’Église latine, qui a été reconnu comme tel par le Concile de Trente » et qui,

après la récente révision (1979), le demeure encore aujourd’hui (Benoît

XVI, 7 novembre 2007).

Une veuve romaine,

Marcella, en quête d’un directeur spirituel et d’un maître qui puisse lui

expliquer les Écritures, s’adresse à Jérôme. Un cercle d’études formé de

riches veuves s’organise bientôt dans le palais de Marcella. On y trouve

Marcellina, la sœur d’Ambroise

de Milan, Paula et ses filles Blésilla, Eustochium et Paulina, et bien d’autres

encore. Certaines d’entre elles seront honorées comme saintes. Jérôme

dispense à ses élèves empressées la fine fleur de ses recherches et le bienfait

de sa direction spirituelle. Une lettre à Eustochium est devenue célèbre :

« L’épouse du Christ ressemble à l’arche d’Alliance, qui était dorée

extérieurement et intérieurement. Elle est la gardienne de la Loi du Seigneur.

Dans l’Arche, il n’y avait rien d’autre que les Tables de la Loi. Il ne doit y

avoir non plus en vous aucune pensée étrangère… Personne ne doit vous retenir :

ni mère, ni sœur, ni parente, ni parent. Le Seigneur a besoin de vous. S’ils

veulent vous arrêter, qu’ils craignent ces fléaux dont nous parle la Sainte

Écriture, et que Pharaon eut à subir pour avoir refusé au peuple de Dieu la

liberté de l’adorer. » Véritable plaidoyer pour la vie monastique et la

virginité, cette lettre connaît une diffusion importante ; mais elle choque la

haute société romaine. Certains clercs se sentent visés par ce manifeste pour

une vie évangélique ; ils ne pardonnent pas à son auteur de les avoir trop

vivement pris à partie en mettant ostensiblement le doigt sur leurs défauts.

Jaloux de son influence, ils le traitent de faussaire et de sacrilège pour

avoir osé introduire des modifications dans les textes bibliques reçus jusque-là.

Finalement, leur colère explose en grossières calomnies contre lui et ses

saintes amies : que vient faire ce moine au milieu de ces dames ? « Si les

hommes m’interrogeaient sur l’Écriture, répond finement Jérôme, je parlerais

moins aux femmes ! »

Voyage enthousiasmant

Après la mort du Pape

Damase, le 11 décembre 384, Jérôme décide de mettre à exécution son rêve de

toujours et s’embarque pour le Moyen-Orient en août 385, avec son frère

Paulinien et quelques moines décidés à s’installer avec lui en Terre Sainte.

Quelques temps après, Paula et sa fille Eustochium les rejoignent à

Antioche. Une caravane est mise sur pied qui doit, en plein hiver, les

acheminer vers la Judée. Jérôme décrira dans une lettre l’enthousiasme de

Paula pour la visite des lieux saints. Les pèlerins continuent ensuite

vers l’Égypte et se rendent à Alexandrie, où se trouve une grande école

biblique héritière de l’enseignement d’Origène et

d’Athanase

le Grand. Didyme l’Aveugle la dirige ; Jérôme se range parmi ses

disciples. Les pèlerins profitent de leur séjour pour rendre visite aux

moines d’Égypte, les fameux “Pères du désert”.

En 386, le petit groupe

revient s’installer à Bethléem, où, grâce à la générosité de Paula, sont

bientôt construits un monastère pour les moines, un autre pour les moniales,

une tour fortifiée et un hospice pour les pèlerins qui se rendent en Terre

Sainte, « car ils se souvenaient que Marie et Joseph n’y avaient pas

trouvé où faire halte. » À la faveur de la tranquillité dont il jouit

maintenant, Jérôme reprend avec allégresse ses travaux : traductions et

commentaires bibliques, histoire, polémique, hagiographie… Paula dirige le

monastère des femmes et Jérôme celui des hommes, mais lui-même donne à tous une

direction spirituelle appropriée, à partir de la Sainte Écriture. La Bible, qu’il

assimile au Christ, tient une place primordiale dans la vie communautaire :

« Aime les Saintes Écritures, dit-il, et la Sagesse t’aimera ; il faut que

ta langue ne connaisse que le Christ, qu’elle ne puisse dire que ce qui est

saint. »

Benoît XVI a mis en

relief l’amour du saint docteur pour la Parole de Dieu : « Pour saint

Jérôme, “ignorer les Écritures, c’est ignorer le Christ”. C’est pourquoi, il

est très important que chaque chrétien vive en contact et en dialogue personnel

avec la Parole de Dieu qui nous a été donnée dans l’Écriture Sainte. Notre

dialogue avec elle doit être réellement personnel, car Dieu parle avec chacun

de nous à travers l’Écriture Sainte et livre un message pour chacun. Nous

devons lire l’Écriture Sainte non pas comme une parole du passé, mais comme une

Parole de Dieu qui s’adresse également à nous, et nous efforcer de comprendre

ce que le Seigneur veut nous dire… La Parole de Dieu transcende les temps. Les

opinions humaines vont et viennent ; ce qui est très moderne aujourd’hui sera

très vieux demain. La Parole de Dieu, au contraire, est une Parole de vie

éternelle, elle porte en elle l’éternité, ce qui vaut pour toujours. En portant

en nous la Parole de Dieu, nous portons donc en nous l’éternel, la vie

éternelle » (7 novembre 2007).

« Aime-la tendrement »

Saint Jérôme «

recommandait à l’une de ses filles spirituelles : “Aime l’Écriture Sainte…

aime-la tendrement, et celle-ci te préservera.” Et encore : “Aime la science de

l’Écriture, et tu n’aimeras pas les vices de la chair.” Pour lui, un point

fondamental de méthode pour interpréter correctement les Écritures est

l’harmonie avec l’enseignement de l’Église. Nous ne pouvons jamais lire

l’Écriture seuls. Nous trouvons trop de portes fermées et nous glissons

facilement dans l’erreur… Pour lui, une interprétation authentique de la

Bible devait toujours être en concordance avec la foi de l’Église catholique…

Il admonestait donc : “Reste fermement attaché à la doctrine traditionnelle qui

t’a été enseignée, afin que tu puisses exhorter selon la saine doctrine et

réfuter ceux qui la contredisent.” En particulier, étant donné que Jésus-Christ

a fondé son Église sur Pierre, chaque chrétien doit être en communion “avec la

Chaire de saint Pierre. Je sais que sur cette pierre l’Église est édifiée”. Par

conséquent, et de façon directe, il déclarait : “Je suis avec quiconque est uni

à la Chaire de saint Pierre” » (Audience générale du 14 novembre 2007).

Mais bientôt les

querelles origénistes (occasionnées par les erreurs des disciples d’Origène niant

le caractère définitif du jugement de Dieu), puis la lutte contre le

pélagianisme (qui prétendait que l’initiative du salut vient de l’homme, et qui

niait le péché originel), amènent Jérôme à défendre la foi avec vigueur

: en certaines occasions, sa plume devient comme un stylet acéré. D’autre

part les invasions barbares, en faisant affluer en Terre Sainte des foules de

réfugiés, l’obligent à mettre au second plan ses chères études et à

satisfaire aux devoirs de la charité. Il n’en persévère pas moins dans

l’œuvre sainte à laquelle il s’est voué. Sa cellule devient une sorte de

phare pour le monde chrétien tout entier : vers lui se tournent les âmes avides

de perfection. Il en résulte une correspondance aussi abondante que variée

avec les meilleurs esprits de son temps. À l’un d’eux, qui demande

conseil, Jérôme montre quelle importance il donne à la vie en communauté :

« Je préférerais que tu sois dans une sainte communauté, que tu ne

t’enseignes pas toi-même et que tu ne t’engages pas sans maître dans une voie

entièrement nouvelle pour toi. » Il recommande la modération dans les

jeûnes corporels : « Une nourriture modique, mais raisonnable, est

salutaire au corps et à l’âme. » Il rappelle qu’un courageux

engagement vers la perfection demande une vigilance constante, de fréquentes

mortifications, avec discrétion toutefois, un travail intellectuel ou manuel

assidu pour éviter l’oisiveté, et surtout l’obéissance à Dieu : « Rien ne

plaît autant à Dieu que l’obéissance, qui est la plus excellente et l’unique

vertu » (Homélie sur l’obéissance : CCL 78, 552).

« Orne ce sanctuaire ! »

«L’Évangile, disait

Benoît XVI, doit se traduire par des attitudes de charité véritable… En s’adressant,

par exemple, au prêtre Paulin (qui devint ensuite le saint évêque de Nole),

Jérôme le conseillait ainsi : “Le véritable temple du Christ est l’âme du

fidèle : orne-le, ce sanctuaire, embellis-le, dépose en lui tes offrandes et

reçois le Christ. Dans quel but revêtir les murs de pierres précieuses, si le

Christ meurt de faim dans la personne d’un pauvre ?” Jérôme est concret : il

faut “vêtir le Christ chez les pauvres, lui rendre visite chez les personnes

qui souffrent, le nourrir chez les affamés, le loger chez les sans-abri.”

L’amour pour le Christ, nourri par l’étude et la méditation, nous fait

surmonter chaque difficulté : “Aimons, nous aussi, Jésus-Christ, recherchons

toujours l’union avec lui : alors, même ce qui est difficile nous semblera facile” »

(14 novembre 2007).

Le Pape émérite

soulignait aussi la contribution de saint Jérôme « dans le domaine de

la pédagogie chrétienne. Il se propose de former “une âme qui doit devenir le

temple du Seigneur”, une “pierre très précieuse” aux yeux de Dieu. Avec une

profonde intuition, il conseille de la préserver du mal et des occasions de

pécher, d’exclure les amitiés équivoques ou débauchées. Il exhorte surtout les

parents pour qu’ils créent un environnement serein et joyeux autour des

enfants, les incitent à l’étude et au travail, également par la louange et

l’émulation, les encouragent à surmonter les difficultés, favorisent entre eux

les bonnes habitudes et les préservent d’en prendre de mauvaises… Les parents

sont les principaux éducateurs des enfants, les premiers maîtres de vie. Avec

une grande clarté, Jérôme, s’adressant à la mère d’une jeune fille, admoneste :

“Qu’elle trouve en toi sa maîtresse, et que sa jeunesse inexpérimentée regarde

vers toi avec émerveillement. Que ni en toi, ni en son père, elle ne voie

jamais d’attitudes qui la conduisent au péché, si elles devaient être imitées.

Rappelez-vous que vous pouvez davantage l’éduquer par l’exemple que par la

parole.”… En outre, un aspect assez négligé à l’époque antique, mais considéré

comme vital par notre auteur, est la promotion de la femme, à laquelle il

reconnaît le droit à une formation complète : humaine, scolaire, religieuse,

professionnelle. Et nous voyons précisément aujourd’hui que l’éducation de la

personnalité dans son intégralité, l’éducation à la responsabilité devant Dieu

et devant l’homme, est la véritable condition de tout progrès, de toute paix,

de toute réconciliation et d’exclusion de la violence. L’éducation devant Dieu

et devant l’homme : c’est l’Écriture Sainte qui nous en indique la direction et

ainsi celle du véritable humanisme » (Ibid.).

Mendier son pain plutôt

que perdre la foi

Dans les dernières années

de sa vie, Jérôme est assailli par une accumulation d’épreuves. En 404,

sainte Paula, l’amie fidèle, meurt. En 410, le Wisigoth Alaric Ier envahit

l’Italie et met Rome à sac. Dans cette tragédie, Jérôme perçoit l’écroulement

d’un monde et il en gémit : « L’Empire vient d’avoir la tête tranchée.

Pour dire l’entière vérité : en une seule ville, c’est l’univers entier qui périt. »

Le couvent de sainte Marcella est pillé ; elle-même est torturée et meurt peu

après. En 416, des moines favorables à Pélage organisent en Judée une

expédition punitive contre les monastères hiéronymiens. Un diacre est tué,

les bâtiments sont incendiés. On se réfugie dans la tour fortifiée ; Jérôme

échappe de justesse à la mort. Non sans fierté, il écrit : « Notre

maison, pour ce qui est des ressources matérielles, fut complètement ruinée par

les persécutions des hérétiques. Toutefois, le Christ est avec nous. La demeure

reste donc remplie de richesses spirituelles. Mieux vaut mendier son pain que

de perdre la foi. » En 418, la mort imprévue d’Eustochium, qui avait

succédé à sa mère Paula à la tête du monastère féminin, l’accable. Elle

était son soutien dans ses travaux. Cette mort, écrit-il, « a presque

changé les conditions de notre existence, parce que bien des choses que nous

voudrions faire, nous en sommes maintenant incapable : l’esprit est ardent,

mais il est vaincu par la débilité de la vieillesse. »

Sa dernière lettre sera

pour Augustin et pour son ami Alypius : « Pour moi, écrit-il, je suis

ravi de trouver quelque occasion de vous écrire, et je n’en laisse échapper

aucune. Dieu m’est témoin que, si je pouvais, je prendrais des ailes de colombe

pour satisfaire à l’empressement que j’ai de vous embrasser. C’est ce que j’ai

toujours ardemment souhaité, tant je fais de cas de votre vertu ; mais je le

souhaite aujourd’hui avec plus de force que jamais, pour me réjouir avec vous

de la victoire que vous avez remportée sur l’hérésie de Célestius (disciple de

l’hérétique Pélage), que vous avez entièrement étouffée par votre zèle et par

vos soins… Je vous conjure aussi, mes saints et vénérables pères, de ne me pas

oublier, et je prie le Seigneur de vous conserver en santé » (Lettre

143). Perclus d’infirmités, presque aveugle, le serviteur fidèle s’endort

paisiblement en Dieu le 30 septembre 420. Il est enterré près de la grotte

de la Nativité à Bethléem. Ses restes, ramenés à Rome au VIIIe siècle, reposent

dans la basilique Sainte-Marie-Majeure, près des reliques de la Crèche du

Seigneur que Jérôme avait précieusement rassemblées.

Davide Ghirlandaio (1452–1525),

Saint Jérôme, fresco,

circa 1475, Vatican Library

Saint JÉRÔME

I. Vie

- 1. Naissance et famille

- 2. Brillant étudiant à Rome

- 3. Passant distrait en Gaule

- 4. Apprenti ascète à Aquilée

- 5. Anachorète novice en Syrie

- 6. Étudiant ecclésiastique à Constantinople

- 7. Secrétaire du pape Damase

- 8. Il se lie d’amitié avec de saintes femmes

- 9. Il regagne l’Orient

- 10. Il se fixe à Bethléem

II. Œuvres

- 1. L’œuvre essentielle : les travaux bibliques

- 2. Traductions d’auteurs ecclésiastiques

- 3. Œuvres polémiques

- 4. Œuvres historiques

- 5. Homélies

- 6. Lettres

- Conclusion : L’homme des Écritures et un maître de d’ascèse

• Ignorer les Écritures, c’est ignorer le Christ.

Commentaire sur Isaïe, prologue

• Lis assez souvent et étudie le plus possible. Que le sommeil te surprenne un

livre à la main ; qu’en tombant, ton visage rencontre l’accueil d’une page

sainte.

Lettre 22 à Eustochium

• Pour ce qui est des Écritures saintes, fixe-toi un certain nombre de versets.

Acquitte-toi de cette tâche envers ton Maître et n’accorde pas de repos à tes

membres avant d’avoir rempli de ce tissu la corbeille de travail qu’est ton

cœur. Après les Écritures saintes, lis les traités des savants, mais de ceux-là

seulement dont la foi est notoire. Tu n’as pas besoin de chercher de l’or dans

la boue ; au prix de perles nombreuses, achète la perle unique. Comme dit

Jérémie (6, 16), tiens-toi au débouché de plusieurs chemins, mais pour arriver

à ce chemin qui conduit au Père.

Lettre 54 à la veuve Furia

I. Vie

1. Naissance et famille

Saint Jérôme nous

l’apprend lui-même : il est « né chrétien de parents chrétiens » [1]. Les

savants, tout en renonçant à dater sa naissance, la situent entre 340 et 347.

Tout en avouant de même qu’il n’est pas possible de trouver l’emplacement de sa

ville natale Stridon, détruite de fond en comble par les Goths en 392, ils la

localisent aux confins de la Pannonie ou Hongrie actuelle et de la Dalmatie. De

toute façon, par sa culture, Jérôme est un Romain. Aîné de trois enfants, il

eut un frère Paulinien et une sœur. Un des meilleurs connaisseurs de saint

Jérôme, Dom Paul Antin, résume si bien sa vie en la survolant que nous le

citons et que nous en reprendrons les termes comme divisions caractérisées de

cette notice :

• « Brillant étudiant à

Rome, passant distrait en Gaule, apprenti ascète à Aquilée, anachorète novice

en Syrie, derechef étudiant mais étudiant ecclésiastique à Constantinople sous

Grégoire de Nazianze, secrétaire du pape Damase à Rome où il se lie d’amitié avec

de saintes femmes, il regagne l’Orient définitivement en 385 et se fixe à

Bethléem » [2].

2. Brillant étudiant à

Rome

Jeune encore, peut-être

même vers l’âge de douze ans déjà, Jérôme est à Rome pour y étudier. Toute sa

vie, il aima l’étude et étudia fort bien. Il ne se lassera pas de vanter le

maître très aimé qui le forma à la grammaire, le célèbre Donat. De chers condisciples

allaient devenir de grands amis, Bonose et Rufin. Ce dernier est le futur

traducteur d’Origène et… le futur ennemi de Jérôme !

Jérôme s’accusera de la

vie dissolue qu’il mena à Rome et le souvenir des tentations que lui offrait la

grande ville aux mœurs décadentes le hantera souvent :

• Combien de fois moi qui étais installé dans le désert, dans cette vaste solitude torréfiée d’un soleil ardent, affreux habitat offert aux moines, je me suis cru mêlé aux plaisirs de Rome ! J’étais assis, solitaire… et moi-même qui, par crainte de la géhenne, m’étais personnellement infligé une si dure prison, sans autre société que les scorpions et les bêtes sauvages, souvent je croyais assister aux danses des jeunes filles.

Lettre 22 à Eustochium (vers 384)

Jérôme reçut le baptême à

Rome, sans doute en 366.

3. Passant distrait en

Gaule

Ses études finies, Jérôme

inaugure par la Gaule une longue suite de voyages. Il parcourt la Gaule et fait

étape à Trèves, la capitale de l’Occident. Il y découvre la vie monastique et

en ressent l’attrait. La Vie d’Antoine avait été traduite en latin à Trèves,

lors de l’exil de saint Athanase dans cette ville [3], par un certain Evagrios

dont nous allons bientôt devoir reparler. L’ami Bonose est auprès de Jérôme et