Saint

Jean-Gabriel Perboyre

Lazariste, martyr en Chine (+ 1840)

Fils d'un laboureur, il est né dans le Quercy. En 1820, il entra chez les Pères Lazaristes. Après avoir été maître des novices, à Paris, rue de Sèvres, il est envoyé en Chine. Il apprend les langues locales, adopte les coutumes chinoises et s'établit au cœur du Kiang-Si, une province montagneuse interdite aux Européens. Après quatre années de prédication, il est arrêté en vertu d'une loi de l'empereur Kien-long qui interdit le christianisme. Fouetté, suspendu par les cheveux à un chevalet, brûlé au fer rouge, on lui grave sur le front: "Propagateur d'une secte abominable". Ces tourments se prolongent plusieurs mois, lentement et avec raffinement. Sur vingt chrétiens arrêtés en même temps que lui, douze renièrent le Christ. Les bourreaux avaient reçu toute liberté: ils le chargèrent de chaînes, lui broyèrent les pieds dans un étau, lui firent boire du sang de chien, le tourmentèrent jusque dans sa pudeur la plus intime. Alors même qu'il agonisait, les membres écartelés sur une croix, ils lui donnaient encore des coups de pieds dans le ventre. Ils l'achevèrent en l'étranglant.

Jean-Gabriel Perboyre (1802-1840) martyr, de la Congrégation de la Mission canonisé le 2 juin 1996, Place Saint-Pierre - site internet du Vatican.

C'est à Mongesty en 1802 que naquit Saint Jean-Gabriel Perboyre. Ce fils de laboureur entra chez les Lazaristes en 1820, fut ordonné prêtre en 1825 et attendit 10 ans avant de s'embarquer pour la Chine. En 1839 il alla exercer son ministère dans les montagnes du Hou-Pei où il fut arrêté le 16 septembre de cette même année. Il mourut martyr le 11 septembre 1840 à Ou-Tchang-Fou et fut canonisé par Jean-Paul II en 1996. (présentation du diocèse de Cahors)

- Fête de Saint Jean-Gabriel Perboyre à Montgesty(diocèse de Cahors)

- La maison natale de Jean Gabriel Perboyre, à Montgesty (Lot) et la statue de Jean Gabriel - Le Quercy sur le net

- Saint Jean-Gabriel Perboyre et sa vie - site Internet de l'Abbaye Saint Benoît de Port-Valais.

- Site du pèlerinage à Montgesty.

À Wuchang, dans la province chinoise de Hebei, en 1840, saint Jean-Gabriel

Perboyre, prêtre de la Congrégation de la Mission et martyr. Pour annoncer

l'Évangile, il adopta l'apparence et les coutumes chinoises, mais, quand vint

la persécution, il fut longtemps détenu en prison et soumis à des tortures

diverses, enfin attaché à une croix et étranglé.

Martyrologe romain

Siang-Yang-Fou, j'ai subi quatre interrogatoires, à l'un desquels je fus obligé de rester une demi-journée les genoux sur des chaînes de fer et suspendu à une poutre de bambou... A Ou-Tchang-Fou, j'ai reçu 110 coups de bambou parce que je n'ai pas voulu fouler aux pieds la croix.

Lettres de Jean-Gabriel

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1834/Saint-Jean-Gabriel-Perboyre.html

San Giovanni Gabriele Perboyre

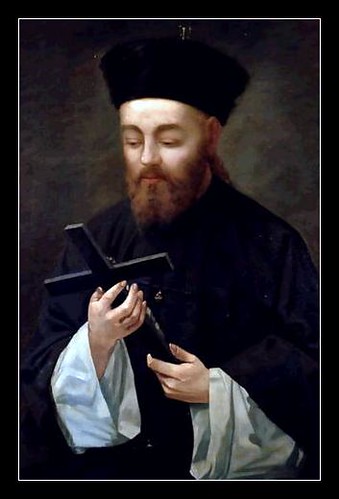

Gravure

de 1889 représentant Saint Jean-Gabriel Perboyre, jeune prêtre, avant son

départ en Chine

Engraving

of 1889, representing Saint Jean-Gabriel Perboyre, a young priest, before

leaving for China

Saint Jean-Gabriel Perboyre

Lazariste, Martyr en

Chine

(1802-1840)

Jean-Gabriel Perboyre

naquit au diocèse de Cahors. Dès l'âge le plus tendre, il se fit remarquer par

sa piété. Au petit séminaire, il fut aimé et vénéré de tous ses condisciples,

qui le surnommèrent le petit Jésus. En rhétorique se décida sa vocation:

"Je veux être missionnaire," dit-il dès lors. Il entra chez les Pères

Lazaristes de Montauban. "Depuis bien des années, dit un des novices

confiés plus tard à ses soins, j'avais désiré rencontrer un saint; en voyant M.

Perboyre, il me sembla que Dieu avait exaucé mes désirs. J'avais dit plusieurs

fois: "Vous verrez que M. Perboyre sera canonisé." Lui seul ne se

doutait pas des sentiments qu'il inspirait, et il s'appelait "la balayure

de la maison". Ses deux maximes étaient: "On ne fait du bien dans les

âmes que par la prière... Dans tout ce que vous faites, ne travaillez que pour

plaire à Dieu; sans cela vous perdriez votre temps et vos peines."

Jean-Gabriel était

remarquable par une tendre piété envers le Saint-Sacrement, il y revenait sans

cesse et passait des heures entières en adoration: "Je ne suis jamais plus

content, disait-il, que quand j'ai offert le Saint Sacrifice." Son action

de grâces durait ordinairement une demi-heure. Envoyé dans les missions de

Chine, M. Perboyre se surpassa lui-même.

Après quatre ans

d'apostolat, trahi comme son Maître, il subit les plus cruels supplices.

L'athlète de la foi, digne de Jésus-Christ, ne profère pas un cri de douleur;

les assistants ne cachent pas leur étonnement et peuvent à peine retenir leurs

larmes: "Foule aux pieds ton Dieu et je te rends la liberté, lui crie le

mandarin. – Oh! répond le martyr, comment pourrais-je faire cette injure à mon

Sauveur?" Et, saisissant le crucifix, il le colle à ses lèvres. Après neuf

mois d'une horrible prison, il fut étranglé sur un gibet en forme de Croix.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_jean-gabriel_perboyre.html

San Giovanni Gabriele Perboyre

Saint

Joannes-Gab. Perboyre. Salzburg, Riedenburg, Herz-Jesu-Asylkirche

Jean-Gabriel Perboyre

(1802-1840)

Martyr, de la

Congrégation de la Mission

Les années de formation

Rien n'arrive par hasard.

Ni la vie, ni la mort, ni la vocation. JEAN-GABRIEL PERBOYRE naquit à Mongesty,

près de Cahors, dans la France méridionale, le 6 janvier 1802, dans une famille

qui donna à l'Église trois Lazaristes et deux Filles de la Charité. Dans un tel

environnement, il respira la foi, il reçut des valeurs simples et saines et

comprit le sens de la vie comme un don.

Dans l'adolescence, celui

" qui appelle chacun par son nom " semblait l'ignorer. Il s'adressa à

son frère cadet pour qu'il entre au séminaire. On demanda à Jean-Gabriel

d'accompagner le petit frère durant quelque temps, en attendant qu'il s'habitue

à son nouveau cadre. Il y était arrivé par hasard et il aurait dû en sortir

vite. Mais le hasard révéla aux yeux étonnés du jeune homme des horizons

insoupçonnés et que sa voie était ici au séminaire.

L'Église de France était

alors à peine sortie de l'expérience de la Révolution française, avec les

vêtements empourprés du martyre de quelques-uns et avec la souffrance de

l'apostasie d'un certain nombre. Le panorama offert par les premières années du

XIX` siècle était désolant: édifices détruits, couvents saccagés, âmes sans

pasteurs. Ce ne fut donc pas un hasard si l'idéal sacerdotal apparut au jeune

homme, non comme un état de vie agréable, mais comme le destin des héros.

Ses parents, surpris,

acceptèrent le choix de leur fils et l'accompagnèrent de leurs encouragements.

Ce n'est pas un hasard si l'oncle Jacques était Lazariste. Cela explique qu'en

1818 mûrit chez le jeune Jean-Gabriel l'idéal missionnaire. À cette époque la

mission signifiait principalement la Chine.

Mais la Chine était un

mirage lointain. Partir voulait dire ne plus retrouver l'atmosphère de la

maison, ni en sentir les parfums, ni en goûter l'affection. Ce fut naturel pour

lui de choisir la Congrégation de la Mission, fondée par saint Vincent de Paul

en 1625 pour évangéliser les pauvres et former le clergé, mais d'abord pour

inciter ses propres membres à la sainteté. La mission n'est pas une propagande.

Depuis toujours l'Église a voulu que ceux qui annoncent la Parole soient des

personnes intérieures, mortifiées, remplies de Dieu et de la charité. Pour

illuminer les ténèbres, il ne suffit pas d'avoir une lampe si l'huile vient à

manquer.

Jean-Gabriel n'y alla pas

par demi-mesure. S'il fut martyr, c'est parce qu'il fut saint.

De 1818 à 1835, il fut

missionnaire dans son pays. Tout d'abord, durant le temps de la formation, il

fut un modèle de novice et de séminariste. Après l'ordination sacerdotale

(1826), il fut chargé de la formation des séminaristes.

L'attrait pour la mission

Un fait nouveau, mais non

fortuit certes, vint changer le cours de sa vie. Le protagoniste en fut encore

une fois son frère Louis. Lui aussi était entré dans la Congrégation de la

Mission et il avait demandé à être envoyé en Chine, où, entre temps, les fils

de saint Vincent avaient eu un nouveau martyr en la personne du bienheureux

François-Régis Clet (18 février 1820). Mais, durant le voyage, le jeune Louis,

alors qu'il n'avait que 24 ans, fut appelé à la mission du ciel.

Tout ce que le jeune

prêtre avait espéré et fait serait devenu inutile si Jean-Gabriel n'avait pas

fait la demande de remplacer son frère sur la brèche.

Jean-Gabriel atteignit la

Chine en août 1835. En Occident, à cette époque, on ne connaissait presque rien

de l'Empire Céleste, et l'ignorance était mutuelle. Les deux mondes se

sentaient attirés l'un par l'autre, mais le dialogue était difficile. Dans les

pays européens, on ne parlait pas d'une civilisation chinoise, mais seulement

de superstitions, de rites et d'usages " ridicules ". Les jugements

étaient en fait des préjugés. L'appréciation que portait la Chine sur l'Europe

et le Christianisme n'était pas meilleure.

Entre les deux

civilisations, il y avait comme un rayon d'obscurité. Il fallait quelqu'un pour

le traverser et pour prendre sur lui le mal de beaucoup pour le brûler dans la

charité.

Jean-Gabriel, après un

temps d'acclimatation à Macao, entreprit un long voyage en jonque, à pieds ou à

cheval qui, après 8 mois, le conduisit dans le Honan, à Nanyang, où il se remit

à l'étude de la langue.

Après 5 mois, malgré

quelques difficultés, il était capable de s'exprimer en bon chinois et,

aussitôt, il se lança dans le ministère, visitant les petites communautés

chrétiennes. Puis, il fut envoyé dans le Hubei, qui fait partie de la région

des lacs formés par le Yangtze Kiang (Fleuve Bleu). Quoiqu'il fit un apostolat

intense, il souffrait beaucoup dans son corps et dans son esprit. Dans une

lettre, il écrit: " Non, je ne suis pas plus un homme de merveilles en

Chine qu'en France... demandez premièrement ma conversion et ma sanctification

et ensuite la grâce de ne pas trop laisser gâter son oeuvre " (Lettre 94).

Pour celui qui voit les choses de l'extérieur, il est difficile d'imaginer

qu'un missionnaire comme lui puisse se trouver dans une nuit obscure. Mais

l'Esprit-Saint le préparait, dans le vide de l'humilité et dans le silence de

Dieu, au témoignage suprême.

Enchaîné pour le Christ

Deux faits, apparemment

sans lien entre eux, vinrent troubler l'horizon en 1839. Le premier est le

déclenchement des persécutions, après que l'Empereur manchou Quinlong

(1736-1795) eût proscrit en 17941a religion chrétienne.

Le second est le

déclenchement de la guerre sino-britannique, connue sous le nom de "guerre

de l'opium" (1839-1842). La fermeture des frontières de la Chine et la

prétention du gouvernement chinois d'exiger un acte de vassalité de la part des

ambassadeurs étrangers avait créé une situation explosive. L'étincelle vint de

la confiscation de chargements d'opium sur des bateaux amarrés dans le port de

Canton, au préjudice de marchants en grande partie anglais. La flotte

britannique intervint et ce fut la guerre.

Les missionnaires,

directement concernés seulement par le premier aspect, étaient constamment sur

leurs gardes. Comme cela arrive souvent, les alertes trop fréquentes diminuent

la vigilance. C'est ce qui arriva le 15 septembre 1839 à Cha-yuen-ken, où résidait

Perboyre. Ce jour-là, il se trouvait avec deux Lazaristes, un Chinois, le P.

Wang, et un Français, le P. Baldus, ainsi qu'un Franciscain, le P. Rizzolati.

On signala la présence d'un colonne d'une centaine de soldats. Les

missionnaires sous-évaluèrent les informations. Peut-être allaient-ils dans une

autre direction. Et, au lieu d'être prudents, ils poursuivirent leur

fraternelle conversation. Quand il n'y eut plus de doutes sur la direction des

soldats, il était trop tard. Baldus et Rizzolati décidèrent de s'enfuir au

loin. Perboyre choisit de se cacher dans les environs, étant donné que les

montagnes voisines étaient couvertes de forêts de bambou et de grottes cachées.

Mais, les soldats, sous la menace, comme cela a été attesté par le P. Baldus, contraignirent

un catéchumène à révéler le lieu où le missionnaire se cachait. Il fut un

faible, mais pas un Judas.

Alors commença le rude

calvaire de Jean-Gabriel. Le prisonnier n'avait aucun droit, il n'était pas

protégé par la loi, mais il était soumis à l'arbitraire de ses gardiens et de

ses juges. Comme il était en état d'arrestation, on présumait qu'il était

coupable; et s'il était coupable, il pouvait être puni.

Alors commença la série

des procès. Le premier se tint à KouChing-Hien. Les réponses du martyr furent

admirables:

- Es-tu un prêtre

chrétien?

- Oui, je suis prêtre et

je prêche cette religion.

- Veux-tu renoncer à ta

foi?

- Je ne renoncerai jamais

à la foi en Jésus-Christ.

Ils lui demandèrent de

livrer ses frères dans la foi et de dire les raisons pour lesquelles il avait

transgressé les lois de la Chine. En fait, on voulait transformer la victime en

coupable. Mais un témoin du Christ n'est pas un délateur. Aussi, il se tut.

Le prisonnier fut ensuite

transféré à Siang-Yang. Les interrogatoires devinrent plus brutaux. On le mit

durant plusieurs heures à genoux sur des chaînes de fer rouillées, il fut

suspendu par les pouces et les cheveux à une poutre (supplice du hangtzé), il

fut battu à plusieurs reprises avec des cannes de bambou. Mais, plus que par la

violence physique, il fut blessé de ce qu'on tourna en ridicule les valeurs

dans lesquelles il croyait: l'espérance en la vie éternelle, les sacrements, la

foi.

Le troisième procès se

tint à Wuchang. Il fut cité devant quatre tribunaux et fut soumis à 20

interrogatoires. Aux questions s'ajoutaient les tortures et les moqueries les

plus cruelles. On poursuivait en justice un missionnaire, mais, en même temps,

on piétinait l'homme. Des chrétiens furent contraints à l'abjuration et quelques-uns

d'entre eux à cracher et à frapper sur le missionnaire qui leur avait apporté

la foi. Il reçut 110 coups de pantsé pour ne pas avoir voulu piétiner le

crucifix.

Parmi les diverses

accusations dont il fut l'objet, la plus terrible fut celle d'avoir eu des

relations immorales avec une jeune chinoise, Anna Kao, qui avait fait voeu de

virginité. Le martyr se défendit. Elle n'était ni son amante ni sa servante. La

femme est respectée, elle n'est pas outragée par le Christianisme. Tel fut le

sens de la réponse de Jean-Gabriel Perboyre. Mais il fut perturbé parce qu'on

faisait souffrir des innocents à cause de lui.

Durant un interrogatoire,

il fut contraint de revêtir les ornements de la Messe. Ils voulaient l'accuser

de mettre le charme du sacerdoce au service d'intérêts personnels. Mais le

missionnaire, revêtu des vêtements sacerdotaux, impressionna les assistants et

deux chrétiens s'approchèrent de lui pour lui demander l'absolution.

Le juge le plus cruel fut

le vice-roi. Le missionnaire était désormais devenu une ombre. La colère de cet

homme sans scrupule s'acharna contre cet être frêle. Aveuglé par sa toute

puissance, il voulait des aveux, des reconnaissances, des dénonciations. Mais

si son corps était faible, son âme s'était renforcée. E n'attendait plus

désormais que la rencontre avec Dieu, qu'il sentait chaque jour plus proche.

Lorsque, pour la dernière

fois, Jean-Gabriel lui dit: " Plutôt mourir que renier ma foi! ", le

juge prononça sa sentence. Ce serait la mort par strangulation.

Avec le Christ prêtre et

victime

Vint alors une période

d'attente de confirmation de la sentence par l'Empereur. Peut-être pouvait-on

espérer dans la clémence du souverain. Mais la guerre contre les anglais

interdit toute possibilité de geste de bienveillance. Et c'est ainsi que le 11

septembre 1840, un émissaire impérial arriva à bride abattue, portant le décret

de confirmation de la condamnation.

Avec sept bandits, le

missionnaire fut conduit sur une hauteur appelée la " Montagne Rouge

". Les bandits furent tout d'abord exécutés, puis Perboyre se recueillit

en prière, à l'étonnement des spectateurs.

Quand son tour fut venu,

les bourreaux le dépouillèrent de sa tunique rouge et le lièrent à un poteau en

forme de croix. Ils lui passèrent la corde au cou et ils l'étranglèrent.

C'était la sixième heure. Tel Jésus, Jean-Gabriel mourut comme le grain de blé

tombé en terre. II mourut, ou plutôt il naquit au ciel, pour faire descendre

sur la terre la rosée des bénédictions de Dieu.

Bien des circonstances de

sa détention (trahison, arrestation, mort sur une croix, jour et heure) le

rapprochent de la Passion du Christ, En réalité toute sa vie fut celle d'un

témoin et d'un disciple fidèle du Christ. Saint Ignace d'Antioche écrivait:

" Je cherche celui qui est mort pour nous; je veux celui qui est

ressuscité pour nous. Voici qu'approche le moment où je serai enfanté à la vie.

Ayez compassion de moi, frères, ne m'empêchez pas de naître à la vie! ".

Jean-Gabriel " naquit à la vie " le 11 septembre 1840, parce qu'il avait toujours cherché " celui qui est mort pour nous". Son corps repose en France, mais son cœur est resté dans sa patrie d'élection, en terre de Chine. C'est là qu'il a donné rendez-vous aux fils et aux filles de saint Vincent, dans l'attente qu'eux aussi, après une vie dépensée au service de l'Évangile et des pauvres, ils naissent au ciel.

SOURCE : http://www.vatican.va/news_services/liturgy/saints/ns_lit_doc_19960602_perboyre_fr.html

San Giovanni Gabriele Perboyre

Gravure

du martyr de Saint Jean-Gabriel Perboyre, le 11 septembre 1840 à Ou-Tchang-Fou

(Chine)

Engraving

of the martyr of Saint Jean-Gabriel Perboyre, September 11, 1840 in

Ou-Tchang-Fou (China)

Salle Paul VI

Lundi 3 juin 1996

Venerati Fratelli nell’Episcopato e nel Sacerdozio,

Fratelli e Sorelle nel Signore!

1. Sono lieto di

rivolgervi un cordiale benvenuto in occasione di questa Udienza speciale,

all’indomani della canonizzazione di Jean-Gabriel Perboyre, sacerdote

della Congregazione della Missione, Egidio Maria di San Giuseppe, frate

minore francescano, e Juan Grande Román, religioso dell’Ordine

ospedaliero.

L’incontro di quest’oggi

rinnova ed approfondisce in ciascuno la gioia ed i sentimenti di lode e di

gratitudine al Signore per l’iscrizione di questi nostri fratelli nell’albo dei

Santi. La Chiesa intera è invitata a contemplarli come luminosi esempi di

fedele risposta alla grazia divina e ad invocarli quali intercessori nelle

necessità materiali e spirituali.

Mentre ringraziamo il

Signore per le meraviglie che ha compiuto in loro, ci soffermiamo a riflettere

sull’attualità del messaggio che essi continuano ad indirizzare a noi e al

mondo intero.

2. Il mio pensiero

va, innanzitutto, al francescano Egidio Maria di San Giuseppe, umile

figlio di quel meridione d’Italia che tanti Santi ha dato alla Chiesa. Saluto

voi, carissimi Fratelli e Sorelle venuti a Roma da Taranto, Lecce, Napoli e da

altre città, per partecipare alla sua solenne Canonizzazione. Il mio saluto

s’estende ai vostri Pastori ed ai cari Religiosi dell’Ordine Francescano dei

Frati Minori.

Il nuovo santo, pugliese

d’origine e napoletano d’adozione, fu docile strumento nelle mani di Dio per spronare

gli uomini alla conversione e rivelare loro l’infinita tenerezza del Padre

celeste, ricco di bontà e di misericordia. Con francescana semplicità in

un’esistenza autenticamente povera, sant’Egidio Maria di San Giuseppe fu

efficace annunciatore del Vangelo, da lui comunicato ai propri contemporanei

soprattutto con la testimonianza della carità, mediante la quale seppe farsi

carico delle sofferenze dei più bisognosi.

Il " Consolatore

di Napoli", come veniva chiamato mentr’era ancora in vita, condusse la

sua vicenda umana nella famiglia spirituale del Poverello d’Assisi, ispirandosi

in particolare agli esempi della Madre del Signore. Egli cantò con Maria

il "Magnificat", lodando con la sua stessa esistenza Colui che

riempie di beni gli affamati e semina gioia nel cuore degli oppressi e dei

sofferenti. Ci aiuti il nuovo santo ad essere lieti dispensatori della gioia

che viene dall’Alto, testimoniando coraggiosamente nella società la presenza

viva di Cristo e la forza trasformante del Vangelo.

3. Je suis heureux de

vous accueillir, chers amis pèlerins venus à Rome pour la canonisation de saint

Jean-Gabriel Perboyre. Je salue cordialement mes frères dans l'épiscopat,

notamment Sa Béatitude le Patriarche Stephanos II, les Évêques venus de Chine,

de Macao, de France et de plusieurs autres pays. J'adresse aussi un salut

chaleureux au Révérend Père Robert Maloney, Supérieur général de la

Congrégation de la Mission, à ses confrères venus de toutes les provinces du

monde, à la famille du nouveau saint, ainsi qu'aux membres et aux amis de la

famille spirituelle de Saint Vincent de Paul.

Dans la personne de

Jean-Gabriel Perboyre, originaire du diocèse de Cahors, se trouve résumée la

vocation missionnaire vincentienne: se donner totalement au Christ dans

l'annonce de la Bonne Nouvelle aux pauvres et la formation du clergé. Pendant

près de dix ans, Jean-Gabriel a mis à profit ses talents d'éducateur des jeunes

dans le diocèse d'Amiens, puis dans la formation des futurs prêtres diocésains

à Saint-Flour, et enfin des novices de sa Congrégation à Paris. Mais,

ressentie, très jeune, la vocation d'aller jusqu'aux extrémités de la terre

annoncer l'Évangile, dans l'esprit même de Monsieur Vincent, se réalisera enfin

lorsqu'il sera appelé à partir vers la Chine. « Priez Dieu, disait-il, que ma

santé se fortifie et que puisse aller en Chine, afin d'y prêcher Jésus-Christ

et de mourir pour lui ». Il partira sur les traces de son propre frère et sur

celles du bienheureux François-Régis Clet, son confrère martyrisé en 1820 dans

la même région. Dans ce pays, qu'il a aimé, il vivra jusqu'à l'héroïsme son

engagement de se mettre pour toujours à la suite du Christ. Jean-Gabriel

achèvera ce témoignage de foi dans le partage saisissant des étapes de la

Passion du Christ sur un semblable chemin de la croix.

Prêtres de la Mission, et

membres de la famille vincentienne, je vous encourage vivement à garder l'amour

qui animait votre frère Jean-Gabriel à l'égard du peuple chinois, à maintenir

intacte en vous la même aspiration à y annoncer la Bonne Nouvelle du Seigneur

Jésus, qui se manifeste avec tant de force dans le martyre de Jean-Gabriel et

de ceux qui, aujourd'hui comme hier, acceptent d'aller jusqu'au bout de leur

témoignage.

Dans notre monde marqué

par tant de pauvretés, de détresses et de désespoirs, la famille vincentienne

que vous représentez ici se doit de continuer avec générosité l'œuvre commencée

par Monsieur Vincent. Prêtres de la Mission, Filles de la Charité, associations

de laïcs qu'il a fondées ou qui sont nées de son esprit, les conditions

actuelles vous invitent à coordonner de mieux en mieux les divers services que

vous accomplissez. La belle figure de Jean-Gabriel Perboyre demeure une source

d'inspiration missionnaire, un арреl à avancer toujours plus loin sur les

chemins de l'Évangile.

4. Deseo saludar ahora

cordialmente a los Hermanos de San Juan de Dios, a los Colaboradores de la

Orden y a los numerosos peregrinos de lengua española.

En san Juan Grande,

religioso hospitalario y Patrono de la diócesis de Jerez, se da una síntesis

espléndida de consagración total a Dios y de servicio incondicional a los

hermanos, especialmente a los que se encuentran en mayores dificultades. En

efecto, queriendo hacer propias las palabras de su fundador: « Dios ante todo y

sobre todas las cosas del mundo », el nuevo Santo emprendió muy pronto el

camino de la vida consagrada y, cimentado en una profunda vida de oración y de

piedad, lo siguió con ejemplar fidelidad hasta el fin.

En la intimidad con el

Señor aprendió el respeto y el aprecio por toda persona humana, de cualquier

condición y en cada momento de su existencia. Siguiendo de cerca a Jesús

descubrió, como el buen Samaritano, la belleza de encontrar al prójimo

necesitado y socorrerlo con todos los medios, mostrando así el rostro

infinitamente misericordioso de Dios. Como contemplativo y asiduo adorador de

la Eucaristía, alimentó constantemente en el Sacramento del amor su espíritu de

servicio y fidelidad inquebrantable a los enfermos y menesterosos, por encima

de dificultades y de riesgos incluso para su propia vida, llegando a morir

víctima de su acción caritativa. En la Virgen María, de la cual era ferviente

devoto, halló siempre maternal cobijo, así como una insuperable Maestra

de dulzura y delicadeza en el trato con los demás, tan importante en el

cuidado de los enfermos, y en el arte de saber llevar consuelo en las

situaciones más adversas.

Hombre totalmente de Dios

y, como Jesús, entregado enteramente a los hermanos, san Juan Grande es un

modelo de vida cristiana y una llamada viviente a la santidad. Vosotros, peregrinos

jerezanos que, acompañados por vuestro Obispo, Monseñor Rafael Bellido,

habéis querido participar en la canonización de quien es un magnífico don de

Dios a vuestra tierra, llevad junto con mi cordial saludo este mensaje a los

demás fieles diocesanos; y vosotros, religiosos de la Orden Hospitalaria,

que con gozo habéis asistido a la elevación a los altares de uno de vuestros

más insignes hermanos, seguid su ejemplo para alcanzar el ideal de vida

indicado por vuestro fundador, y continuad enriquecίendo a la Iglesia con el

don de la vida consagrada y el específico carisma de los Hermanos de San Juan

de Dios, aportando espléndidos frutos de testimonio evangélico, de caridad

cristiana y de santidad.

5. Cari Fratelli e

Sorelle! Il Signore, che chiama tutti indistintamente sulla via della santità,

compie continuamente grandi cose in coloro che si sforzano di rispondere

generosamente alla sua grazia. Facendo ritorno alle vostre terre, portate con

voi il lieto ricordo della partecipazione alla Liturgia di Canonizzazione di

Jean-Gabriel Perboyre, Egidio Maria di San Giuseppe e Juan Grande Roman,

insieme con l'impegno di imitarne gli esempi di vita evangelica. Vi conforti in

questi propositi la celeste protezione di Maria, Regi-na di tutti i Santi. E vi

accompagni anche la Benedizione, che di cuore imparto a ciascuno di voi ed alle

vostre Comunità ecclesiali e religiose, in particolare ai giovani, agli

ammalati ed alle famiglie.

© Copyright 1996 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Copyright © Dicastero per

la Comunicazione - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

San Giovanni Gabriele Perboyre

Statue

de Jean-Gabriel Perboyre devant l'église de Montgesty

La vocation du Bx. J. J. G. Perboyre

Auteur: G. Van Winsen .

Année de la première publication : 1977 · La source : Vicentiana.

Il est facile, documents

en main, de retracer l’évolution de la vocation sacerdotale et missionnaire de

Jean-Gabriel Perboyre.D’après une lettre de son ancien professeur de latin,

Jean Gabriel n’est venu en novembre 1816 au Petit séminaire de Montauban que

pour accompagner son frère Louis qui était élève de la maison. Au bout de

quelque temps, Jean-Gabriel devait en principe regagner le foyer paternel. Mais

ses professeurs ayant reconnu dans ce garçon une vocation sacerdotale

pressèrent son père de lui faire apprendre le latin.

Le père en fit la

proposition á son fils lors d’une visite á Montauban. Celui-ci réagit quelque

temps après dans une lettre en ces termes:

« Après votre départ de

cette ville, j’ai réfléchi sur la proposition que vous m’aviez faite d’étudier

le latin. J’ai consulté Dieu sur l’état que je devais embrasser pour aller plus

sûrement au ciel. Après bien des prières, j’ai cru que le Seigneur voulait que

j’entrasse dans l’état ecclésiastique. En conséquence, j’ai commencé á étudier

le latin, bien résolu de l’abandonner si vous n’approuvez pas ma démarche… si

le bon Dieu m’appelle á l’état ecclésiastique, je ne puis pas prendre d’autre

chemin pour arriver á l’éternité bienheureuse. Je continuerai ce que j’ai

commencé jusqu’á ce que j’aie votre réponse…».

D’après une autre lettre

de son ancien professeur de latin datée de la fin de 1817, une mission avait

lieu á Montauban. Un sermon frappa le jeune Jean-Gabriel, et revenu á la maison

dit á son oncle: « Je veux être missionnaire ». Celui-ci en rit. Mais ces

premiers moments de sa vocation missionnaire avaient fait une profonde

impression sur Jean-Gabriel. Vingt ans plus tard, quand enfin il a atteint son

but et qu’il est envoyé comme missionnaire apostolique en Chine, fi se remémore

tous les détails.

Il écrit á son oncle en

février 1835 ces lignes:

«J’ai une grande nouvelle

á vous annoncer. Le bon Dieu vient de me favoriser d’une grâce bien précieuse

et dont j’étais bien indigne. Quand il daigna me donner la vocation pour l’état

ecclésiastique, le principal motif qui me détermina á répondre á sa voix, fut

l’espoir de pouvoir prêcher aux infidèles la bonne nouvelle du salut. Depuis je

n’avais jamais tout á fait perdu cette perspective et l’idée seule des

Missions, de Chine surtout, a toujours fait palpiter mon cœur».

Dans une lettre écrite du

Honan en Chine le 18 août 1836, il nous livre un autre détail sur sa vocation.

«Pour moi, me voilà

aussi lancé dans une nouvelle carrière. Il y a quelques raisons de croire que

c’est celle que le bon Dieu me destinait á parcourir. C’est celle qu’il me

montrait de loin en m’appellant á l’état ecclésiastique, c’est celle que je lui

demandais avec instante dans une neuvaine que je fis á St. François Xavier, il

y a près d’une vingtaine d’année… ».

Au cours de sa jeunesse,

Jean-Gabriel a employé tous les moyens pour connaitre sa vocation. L’influence

de diverses personnes sur cette vocation est manifeste: son oncle, ses

professeurs, le prédicateur de mission.

Étant élève de

rhétorique, le jeune homme trouva á s’exprimer dans une composition littéraire.

Il la lut au cours des exercices publics qui précédèrent la distribution des

prix. Le titre en était: « La Croix est le plus beau des monuments».

Citons une phrase de

cette composition: « Ah qu’elle est belle cette croix plantée au milieu des

terres infidèles et souvent arrosée du sang des ap6tres de Jésus-Christ».

Ainsi préparé,

Jean-Gabriel voulut entrer dans la Congrégation de la Mission. Il demanda son

admission aux supérieurs par l’entremise de son oncle Jacques: c’est ce

qu’écrit M. Châtelet dans sa biographie. Au dire de M. Châtelet, l’oncle

Jacques fut victime de son propre faible pour la Chine en cédant á la demande

persistante de son neveu. Malgré l’affirmation de

M. Châtelet, p. 34, nous

n’avons pas trouvé de documents pour confirmer cette opinion.

Nous pouvons á nouveau

suivre l’évolution de la vocation missionnaire de Jean-Gabriel depuis l’année

1829. Son frère Louis est désigné pour la Chine. Dans la conscience de notre

bienheureux prend corps l’idée qu’il a perdu par ses péchés sa vocation pour

la Chine. Il exprime cette pensée dans la lettre du 28 novembre 1829:

«Je crains beaucoup, mon

cher Frère, d’avoir étouffé par mon infidélité á la grâce le germe d’une

vocation semblable á la vôtre. Priez Dieu, qu’il me pardonne mes péchés, qu’il

me fasse connaître sa volonté et qu’il me donne la force de la suivre».

Jean-Gabriel exprime de

nouveau son angoisse á son frère dans une lettre du 11 octobre 1830: «Je crains

de n’avoir pas été fidèle á la vocation que le Seigneur m’a donnée. Priez-le de

me faire connaître sa sainte volonté et de m’y faire correspondre. Obtenez-moi

de sa miséricordieuse bonté le pardon de mes misères et l’esprit de notre saint

état, afin que je devienne un bon chrétien, un bon prêtre, un bon

missionnaire».

Dans une lettre d’un

missionnaire chinois, M. Peschaud, écrite á M ». Etienne le 30 janvier

1844 nous lisons:

«Un jour, dans une

conférence où il nous parlait des vocations, il disait qu’il y avait une

vocation générale á la Mission qu’il fallait conserver avec soin, mais qu’il y

en avait aussi de particulières á tel emploi que la moindre infidélité pouvait

faire perdre. Pour moi —disait-il— j’ai certainement perdu cette vocation

particulière par mes misères et infidélités. Il parlait de sa vocation á la

Chine, que sa faible santé et la volonté des supérieurs ne lui permettaient pas

encore d’espérer».

Il a donné cette

conférence comme sous-directeur du séminaire interne á la Maison-Mère; par

conséquent entre août 1832 et février 1835.

La pensée d’avoir perdu

sa vocation pour la Chine, a causé bien des peines spirituelles á Jean-Gabriel.

Il semble le confesser dans une lettre á son ancien directeur de conscience, M.

Grappin, alors assistant de la Congrégation, en date du 18 août 1836 (il est

déjà missionnaire en Chine).

«Le souvenir (de la

neuvaine á St. François Xavier) est souvent venu depuis exciter mes remords ou

ranimer mon espoir, car il me semblait que j’avais été exaucé».

Il faut aussi se

ressouvenir que Jean-Gabriel a connu des périodes de sécheresse spirituelle.

Dans ces occasions, son humilité profonde lui cachait tout le bien qui était

en lui, dans sa pensée, il ne voyait que défauts et imperfections.

Nous pouvons supposer

qu’une période de sécheresse coïncidait avec sa souffrance á cause de sa

vocation particulière pour la Chine.

Citons plusieurs lettres

écrites á son frère Louis:

Le 28 nov. 1829:

«Je ne sais où aboutira

un malaise général que j’éprouve depuis longtemps et qui est toujours

progressif. Je m’en mettrais peu en peine, si je pouvais bien remplir mes

devoirs religieux. Ayez compassion d’un misérable qui ne fait qu’amasser des

trésors de colère pour l’éternité, priez pour un frère qui est tout á vous en

Notre-Seigneur».

Les 24 février-11 mars

1830:

«…mon esprit s’abrutit de

jour en jour; bientôt il sera tout matériel et entièrement nul pour toute

fonction intellectuelle. Vous pouvez m’obtenir du moins de l’Esprit qui éclaire

tout homme venant en ce monde, les lumières dont j’ai besoin pour bien remplir

mes devoirs».

Le 12 avril 1830:

«Je ne crois pas avoir

passé deux jours depuis six mois sans avoir senti ma tête rompue, tous membres

brisés et mon sang tout en feu. Rien ne me fatigue, comme le détail de l’administration,

rien ne me mine comme la sollicitude».

Devant les difficultés et

les incertitudes, la réaction de Jean- Gabriel est tout á fait dans la ligne

d’une saine doctrine spirituelle. Il connait sa situation et il adopte les

moyens opportuns. D’une part il sait qu’il n’est pas assez prêt ni assez décidé

par lui-même pour s’embarquer pour la Chine, (lettre du 24 août 1830) (17). Il

sait que sa santé n’est guère solide (10 mars 1834). D’autre part il demande

des prières, comme cette fois où devant les reliques du Bx. Clet, il dit á ses

séminaristes:

Priez donc bien que ma

santé se fortifie et que je puisse aller en Chine, afin d’y prêcher

Jésus-Christ et de mourir pour Lui».

Il connaît l’importance

de son office.

Lettre du 10 mars 1834:

«Ma position de Directeur

des Novices me met á mémé de vous dédommager amplement de vous avoir fait faute

de moi-même: je seconderai de mon mieux les vocations qui se manifesteront

pour la Chine. J’espère que par là j’aurai quelque peu de part au bien qui s’y

fera, sans avoir l’honneur de partager vos travaux».

Nous pensons quant á nous

que le Bienheureux acquit la certitude de sa vocation pour la Chine au moment

où il apprit la nouvelle de la mort de Louis (février 1832). Déjà alors il écrivait

á son oncle:

«Que ne suis-je trouvé

digne d’aller remplir la place qu’il laisse vacante! que ne puis-je aller

expier mes péchés par le martyre après lequel son âme innocente soupirait si

ardemment?

Hélas j’ai déjà plus de

trente ans, qui se sont écoulés comme un songe, et je n’ai pas encore appris á

vivre! Quand donc aurai-je appris á mourir?».

Aux vacances qui

suivirent la mort de son frère Louis, Jean- Gabriel se rendit auprès de ses

parents. Il leur annonça alors que son intention était d’aller en Chine, que

Dieu le pressait intérieurement pour cela, et qu’il ferait tout ce qui

dépendrait de lui pour répondre á sa volonté. Il parla aussi á son oncle de son

projet.

Dans ces circonstances,

Jean-Gabriel est appelé á Paris en août 1832. Dans une lettre á son ancien

directeur, M. Grappin, écrite du Honan le 18 août 1836, il dit:

«…c’est celle (la

vocation pour la Chine) qui s’est comme d’elle-même ouverte devant moi quand le

moment de la Providence a été venu. Il est vrai que soit vous, soit mes autres

Directeurs me dissuadiez de mon projet toutes les fois que j’en parlais. Mais

la principale raison que vous mettiez en avant était celle du défaut de santé

et l’expérience a montré qu’elle avait moins de fondement qu’on ne lui en

supposait».

D’après M. Etienne, le

combat entre Jean-Gabriel et son directeur dura six mois, á la suite desquels

le directeur se sentit tout á coup changé et comme forcé de donner la main á

l’exécution du projet. Jean-Gabriel demanda (á genoux) au Supérieur Général la

permission de partir en Chine.

Ici le premier biographe,

M. Etienne, nous place devant un petit mystère.

Il a écrit que

Jean-Gabriel fit « inopinément » la demande d’être missionnaire en Chine, et

encore, que sa proposition étonna beaucoup tous ceux qui en eurent

connaissance. A la lumière des documents on ne comprend pas ce qu’a voulu

écrire M. Etienne sur ce point.

Quoi qu’il en soit ce

serait le même M. Etienne qui proposa au Supérieur hésitant, de s’en remettre

au jugement du médecin de la maison.

C’est alors que nous

sommes devant un autre petit mystère. M. Etienne écrit:

«En un mot le docteur

n’hésita pas á prononcer qu’on pouvait sans inconvénient lui permettre de

réaliser ses désirs».

Mais le biographe de 1853

écrit, lui que «le jugement du médecin était premièrement négatif, mais ayant

réfléchi, il crut s’être trompé et donna á Jean-Gabriel la permission de partir».

Laissons Jean-Gabriel

lui-même raconter son bonheur:

«Eh bien, mon cher oncle,

mes vœux sont aujourd’hui enfin exaucés. Ce fut le jour de la Purification que

me fut accordée la mission pour la Chine, ce qui me fait croire que dans cette

affaire, je dois beaucoup á la Ste Vierge. Aidez-moi s’il vous plait á la remercier

et á la prier de remercier Notre-Seigneur pour moi».

Le 21 mars 1835, le

Bienheureux partit pour la Chine, le but de son grand désir.

SOURCE : http://vincentians.com/fr/la-vocation-du-bx-j-j-g-perboyre/

San Giovanni Gabriele Perboyre

Statue of Jean-Gabriel Perboyre in the Saint Bartholomew church in Varaire, Lot, France

Une Semence d’Éternité :

Saint Jean-Gabriel Perboyre : Prêtre de la Mission, Martyr, Premier Saint de

Chine

Auteur: Jean-Yves Ducourneau,

CM · Année de la première publication : 1996.

Quinze jours après l’exécution

de Jean-Gabriel, son confrère, Jean-Henri Baldus, relit l’histoire et donne

quelques éléments de réflexion intéressants à son Supérieur Jean-Baptiste

Torrette : « Si vous me demandiez ce que l’on dit de MM. Rameaux et

Perboyre, croyez-vous que je n’aurais que des éloges à vous écrire de la part

des chrétiens et des confrères ? Pour ne parler ici que du dernier, sur qui à

Macao vous mettiez tant de confiance et d’espérance, je ne sais pas ce qui

déplaisait en lui aux chinois, mais de tous les européens que j’ai vus en

Chine, je n’en connais pas dont le genre fut moins de leur goût » Sur la

fatigue qui pesait sur Jean-Gabriel, les mots sont amers : » Ce sont les

propres paroles de M. Rameaux qui disait que quand on ne savait pas mieux se

remuer, il ne fallait pas venir en Chine. En plusieurs endroits les chrétiens

ont montré une grande répugnance à l’avoir, fait de grandes instances, usé de

beaucoup d’artifices, afin d’en avoir un autre, européen aussi… Je sais que la

raison de son extérieur physique n’y entrait pour rien ». Cette lettre

sévère est différente de tout ce que l’on peut déjà entendre sur le martyr.

Conscient d’aller à contre courant de l’opinion générale de l’époque, le père

Baldus, cependant, poursuit : « Hélas ! je vais peut-être aller trop loin

!..Selon moi, qui étais présent, et selon tous les autres confrères européens

et chinois, si la persécution a été si violente, c’est à cause de la prise de

M. Perboyre. S’il a été pris, humainement parlant, c’est parce qu’il était une

poule mouillée et par sa seule bêtise… Il n’était pas précisément question

d’avoir des jambes, mais d’être plus avisé ». Ne pouvant plus arrêter sa

pensée, il poursuit d’une plume alerte : « Tout le monde s’accorde à le

dire et les chrétiens savent bien répéter : M. Rameaux en pareil cas n’aurait

pas été embarrassé… De pareils événements, quand c’est la Providence qui seule

les détermine n’ont rien de fâcheux pour des chrétiens ; mais lorsqu’il y entre

de sa faute, il y a toujours quelque chose qui fait de la peine ». Se reprenant

un peu et reconnaissant en Jean-Gabriel un foi profonde, il conclut :

« Cependant connaissant la belle âme de M. Perboyre, je suis bien persuadé

qu’il n’est pas coupable devant Dieu, et je voudrai bien faire échange avec

lui. » Mais c’est bien Jean-Gabriel qui a souffert jusqu’au bout et est

mort sur le gibet planté en terre païenne comme une semence, le 11 septembre

1840 à midi, heure de la mort du Christ, son Seigneur et Maître du Ciel.

La main de Dieu ne tarde

pas à faire lever le grain de la semence. Le signe de sa présence divine germe

par delà le monde et en particulier en Chine, dès l’annonce du martyre héroïque

du missionnaire français.

Le premier signe perçu

par les chrétiens comme une action de la Providence répondant au martyre est

d’abord la révocation du Vice-Roi cruel et sanguinaire par l’Empereur

Tao-Kouang. Tous ses biens sont confisqués en punition des supplices

effroyables qu’il faisait endurer à ses prisonniers contrairement aux lois de

l’Empire. Dans cette région blessée, les chrétiens se remettent à espérer et à

prospérer sous la conduite de leur nouvel évêque, Mgr Rizzolati. Plus tard, ce

pasteur se souviendra de l’accueil que lui avait réservé Jean-Gabriel, lors de

sa visite à la résidence. Il l’avait reçu avec la plus grande déférence comme

on recevait un évêque.

Les chrétiens, méditant

sur la Passion de leur prêtre martyr, se souviennent aussi de la force

spirituelle qui avait envahi l’homme et qui lui avait fait garder foi dans les

nombreuses souffrances infligées. Ce n’était plus le même missionnaire. Il

semblait transfiguré, transformé. Sa crainte naturelle, sa réserve bien connue,

son effacement constaté, tout cela avait laissé place à une vigueur incroyable.

La puissance de Dieu se laissait toucher du bout des doigts lorsque l’on

remarquait les rapides guérisons des plaies ensanglantées alors que les

conditions hygiéniques de la prison empêchaient un tel rétablissement.

Certains se rappellent

aussi la beauté et le calme qui ont envahi son corps lors de sa mort tragique.

De plus, même des païens en ont été troublés.

D’autres évoquent encore

ce qui semble être le premier miracle du martyr. On raconte que l’homme païen

qui l’avait transporté en palanquin durant la période de la torture se trouvait

au plus mal. Ce riche personnage du nom de Liéou-Kiou-Lin, qui avait sans le

savoir exercé le ministère de Simon de Cyrène, eut une vision durant sa

maladie. Il vit deux échelles, l’une blanche et l’autre rouge. Sur cette

dernière se tenait Jean-Gabriel l’invitant à gravir la blanche, malgré

l’opposition farouche du démon qui était là. Le malade se souvint alors des

invocations des chrétiens qu’il avait entendu : « Ô Dieu, ayez pitié de

moi ! Ô Jésus, ayez pitié de moi ! » Puis la vision disparut et une

rémission arriva. Sans tarder, il devint catéchumène et reçut le baptême. Prêt

pour le grand voyage, la maladie le frappa de nouveau et c’est, assisté dans

son agonie par la communauté chrétienne, qu’il s’endormit dans la mort.

Bien sûr, on reparle de

cette croix aperçue dans les ciel au moment où le martyr a remis son esprit à

Dieu. On évoque aussi celle que l’on a vu au-dessus du cimetière, quelque temps

plus tard.

La vénération croît à une

vitesse que personne ne contrôle. Bien vite, les fidèles nomment le prêtre

défunt : « le grand martyr ». Mgr Rizzolati semble dépassé par les

événements. Avec fermeté, il demande de tempérer un peu cet élan populaire et

de ne pas devancer une possible décision du Saint-Siège.

Rien n’y fait. La tombe

du martyr devient rapidement un lieu de pèlerinage, dépassant en visites la

dévotion attribuée aux autres martyrs. On se met à raconter la vie du

« grand martyr » partout. Les limites de la province du Houkouang

sont allégrement franchies. On se souvient des lieux de son passage. La

renommée traverse les océans.

En France, on apprend le

martyre de Jean-Gabriel avec émotion. Connaissant les risques encourus par les

missionnaires de Chine, on ne s’étonne pas outre mesure de cette fin tragique.

On dit ça et là que cette fin tant désirée puisqu’ouvertement exprimée

correspond bien au personnage mais on reste surpris de la force avec laquelle

ce prêtre a su résister aux nombreux sévices. Lui que l’on disait si faible et

de petite nature a su montrer que c’est justement de sa faiblesse que Dieu lui

a permis de tirer sa force.

Au Puech, c’est le

vicaire M. Laborderie qui vient annoncer la terrible nouvelle de la mort du

fils aîné. Sa mère, avec un courage admirable mais ne pouvant retenir quelques

larmes, s’exclame : » Que ferai-je en me lamentant ? Ses lettres depuis

qu’il est en Chine nous ont exprimé de manière bien vive combien il désirait le

martyre… Pourquoi hésiterai-je à faire à Dieu le sacrifice de mon fils ? La

Sainte Vierge n’a-t-elle pas généreusement sacrifié le sien pour mon salut ?

D’ailleurs je ne croirais pas aimer véritablement mon fils si je m’affligeais,

sachant qu’il est maintenant au comble de ses vœux. » Toute la famille se

joint à ses paroles et avec un sentiment de fierté mêlé à la tristesse, elle

commence à rassembler des souvenirs sur l’enfance et la jeunesse de

Jean-Gabriel.

En haut lieu, on

s’affaire. Le pape Grégoire XVI ayant appris la mort du missionnaire, fait dire

au Père Général de la Congrégation de la Mission, Jean-Baptiste Etienne, qu’il

faut entreprendre sans délai la récolte des informations sur ce martyr en vue

d’une éventuelle introduction de sa cause. Le père Etienne confie alors à celui

qui l’a bien connu, le père Rameaux, le soin de mener à bien cette enquête. Mgr

Rizzolati et le père Laribe y apportent une précieuse contribution. Le travail,

qui sera achevé en 1845, s’applique minutieusement à toutes les données, dont

la principale est celle-ci : Jean-Gabriel est-il un Martyr de la Foi?

La définition du martyre

est claire : « Le chrétien ne doit pas s’exposer de lui-même à la

persécution, soit pour épargner un crime aux infidèles soit pour ne pas exposer

sa propre faiblesse : mais lorsqu’on se trouve affronté à la lutte, nous ne pouvons

pas nous y soustraire. Il est téméraire de s’exposer, se refuser est une

lâcheté. » 10

Il sera affirmé que la

cause de la mort du père Perboyre a bien été la foi en la Personne du Christ.

Il a confessé sa foi dans son sang, comme les témoins de la Primitive Église

qui se glorifiaient de cette Parole du Sauveur : « Qui perdra sa vie à

cause de moi… la sauvera » (Marc 8, 35). Il a offert le plus beau mais en

même temps le plus difficile des témoignages : à la suite du Christ, il a donné

sa vie comme le Christ le fit pour ses frères.

Mais pour recevoir la

palme du martyre, il ne suffisait pas à Jean-Gabriel de souffrir ou même de

mourir pour la foi, il fallait que se manifeste, de la part de l’oppresseur, la

haine envers Dieu et son Christ, la haine contre l’Église ou le désir de le

forcer à commettre des actions entraînant le péché. Ensuite, il lui restait à

accepter la mort par amour du Christ : « Tuez-moi », avait-il crié au

Vice-Roi qui voulait le voir se prosterner devant une statue d’idole. En affrontant

l’épreuve du martyre, Jean-Gabriel entrait dans ce cortège d’hommes et de

femmes ayant lavé leur sang dans le sang de l’Agneau. Et Dieu n’a rien enlevé

de son caractère, il lui a seulement permis de s’accomplir en montrant une

certaine plénitude humaine. Aujourd’hui, Dieu ne demande pas de regarder

Jean-Gabriel comme une personne extraordinaire, mais de le voir avec ce qu’il

fut durant toute sa vie avec ses joies, ses peines, ses peurs et ses rêves sans

gommer ses défauts dans le catalogue trop souvent gonflé des dons et qualités.

Mgr Rizzolati, qui

s’était exprimé peu après la mort du missionnaire lazariste en ces termes :

« Le vénérable serviteur de Dieu M. Perboyre, abstraction faite de son

martyre, serait digne par ses vertus des honneurs des autels ». Le père

Laribe, qui fut un temps son compagnon, font également le nécessaire pour

qu’une stèle soit placée sur la tombe du martyr.

C’est le 23 mai 1858 que,

sur ordre du Père Général, M. Etienne, les restes de Jean-Gabriel Perboyre et

de son prédécesseur dans le martyre, François-Régis Clet, sont exhumés en

présence de Mgr Delaplace, lazariste et de Mgr Spelta, successeur de Mgr

Rizzolati, et ce n’est que le 6 janvier 1860, cinquante huit ans après le jour

communément donné comme celui de la naissance du martyr, qu’ils parviendront à

Paris pour y être exposés à la Chapelle de la Maison-Mère des lazaristes et

confiés ainsi à la dévotion populaire. Leurs tombeaux, surmontés d’une petite

statue, y sont toujours et témoignent encore, pour les gens venant s’y recueillir,

de ces signes qui germent dans le monde et qui permettent à Dieu d’ensemencer

sa Parole pour sa plus grande gloire.

San Giovanni Gabriele Perboyre

Statue

de saint Jean-Gabriel Perboyre à la chapelle Saint-Vincent-de-Paul de Paris.

Une Semence d’Eternité :

Saint Jean-Gabriel Perboyre : Prêtre de la Mission, Martyr, Premier Saint de

Chine

La moisson inachevée

La piété des fidèles est une

chose remarquable. C’est elle qui parfois, sanctifie un homme de ses prières et

autres ex-voto. Jean-Gabriel a connu le même chemin. Ses vêtements, les

instruments de son supplice, ses lettres sont passés du statut de simple objet

à celui de « reliques ». Tout est devenu comme un patrimoine sacré

nous rappelant le martyr et son passage parmi les hommes. Aujourd’hui encore,

en Chine, on possède la stèle de son tombeau. Elle est confiée maintenant au

grand séminaire régional de Wuhan comme une relique afin que les futurs prêtres

se souviennent de ceux qui les ont précédés dans la foi.

La procédure de la

Béatification s’est poursuivie simultanément en France et en Chine. En 1862, un

procès apostolique restreint fut organisé à Rome. Pour le compléter, l’institution

d’un nouveau procès apostolique en Chine fut décidée. Après quelques aléas dûs

aux troubles survenus en la Ville Éternelle ces années-là, le dossier fut enfin

complet et prêt à l’étude en 1879. Entre 1886 et 1888, la Congrégation

préparatoire chargée de la cause de Béatification rendit un jugement positif.

Le pape Léon XIII le confirmait solennellement le 12 juin 1888.

Le 12 mars 1889, une

dernière réunion précisait alors que l’Église pouvait procéder en toute sûreté,

à la Béatification tant attendue de Jean-Gabriel Perboyre. Le 30 mai suivant,

le Saint-Père promulguait le décret de Béatification et le 10 novembre de la

même année, une nombreuse assistance se pressait à Rome, dans la Chapelle

Sixtine, pour la Célébration. Parmi elle, on discernait le frère cadet de

Jean-Gabriel, le père Jacques Perboyre ainsi que sa sœur Marie-Anne, Fille de

la Charité. Une importante délégation du diocèse de Cahors avait fait également

le long déplacement. La fête réjouissait tous les cœurs. Le « grand martyr »

devint à ce moment-là le Bienheureux Jean-Gabriel. Bien des célébrations

d’action de grâce furent organisées en de nombreux pays où la famille

Vincentienne était à l’œuvre. Elles se sont attachées à mettre en relief les

grandes qualités de ce missionnaire fort apprécié dans son ministère en France

et qui a réalisé en Chine, son grand désir de donner sa vie pour le Christ.

Un des anciens

séminaristes du Bienheureux martyr n’a pas pu se joindre à cette foule en

liesse. Décédé le 7 juillet 1887, il a gardé pendant longtemps dans son cœur un

précieux souvenir. Pierre-Marie Aubert, prêtre de la Mission, devenu supérieur

de la maison de Sainte-Anne à Amiens, raconte : » Un jour, étant au

séminaire de Saint-Lazare, je servais la messe à Jean-Gabriel, lorsqu’au moment

de la consécration, je le vis élevé au-dessus de terre et ravi en extase. Le

Saint Sacrifice achevé, le serviteur de Dieu fut alarmé dans son humilité,

craignant que je ne révèle ce dont je venais d’être témoin. Aussi, de retour à

la sacristie, M. Perboyre me fit promettre là-dessus un secret inviolable tant

qu’il serait en vie. Je gardais le silence jusqu’après son martyre ».

Aujourd’hui, les fidèles peuvent trouver dans l’Église Sainte-Anne, bâtie par

le père Aubert, une chapelle latérale dédiée à Jean-Gabriel et à François-Régis

Clet, les deux martyrs de Ou-Tchang-Fou.

Dans les églises du Lot,

se sont mises à fleurir de nombreuses statues de Jean-Gabriel. Le rappel de ce

que fut sa vie peut ainsi se lire dans le visage serein du Bienheureux

représenté en martyr dans sa robe rouge de condamné. Malgré une Église rurale

qui semble souffrir de la désaffection de ses membres les plus jeunes, les plus

âgés restent accrochés à leur Bienheureux martyr. Chaque année, une grande

célébration a lieu en la petite Église de Montgesty qui résonne de la gloire de

« son » Jean-Gabriel.

Cette année 1996 voit

aboutir de longues procédures en vue de la Canonisation. La Congrégation des

Saints chargée du procès a étudié deux guérisons considérées comme miraculeuses

et en particulier celle de sœur Gabrielle Isoré, guérie à 38 ans en 1889 d’une

névrite polyradiculaire ascendante. En 1994, à Rome, une conclusion médicale

précise sans conteste le caractère miraculeux de cette guérison. Le 21 février

1995, les théologiens se réunissent à leur tour et entérinent cette décision.

Ils seront suivis, le 4 avril suivant par la Session Ordinaire des Pères

Cardinaux et Évêques qui confirment cette conclusion. A son tour, Jean-Paul II

déclare : « Il résulte certain qu’il y a eu miracle, accompli par Dieu, à

l’intercession du Bienheureux Jean-Gabriel Perboyre, prêtre profès de la

Congrégation de la Mission de Saint Vincent de Paul, dans le cas de guérison

soudaine, parfaite et durable de Sœur Gabrielle Isoré ».

Le 2 juin 1996, en place

de Rome, Le Bienheureux Jean-Gabriel Perboyre devient Saint Jean-Gabriel

Perboyre. Sa fête sera célébrée chaque année le 11 septembre, jour anniversaire

de son martyre.

Notre nouveau Saint nous

invite et même nous pousse à poursuivre la Mission de la Moisson. Le champ est

immense et les ouvriers manquent à l’appel. Dieu aidant, il nous pousse à

arpenter les champs du monde, en Chine comme en Europe ou dans le reste du

globe. Jean-Gabriel n’est pas une statue d’église mais il fut un être vivant,

un chrétien, un missionnaire de la famille de Saint Vincent de Paul. Parmi bien

d’autres, à sa manière, il a été signe de l’Amour de Dieu qui comble la vie

d’un homme acceptant de se mettre au service de ses frères. Il nous fait signe

aujourd’hui d’entendre et de crier l’appel du Seigneur : « Allez, de

toutes les nations, faîtes des disciples » (Mt 28, 19). Que son exemple

nous stimule et nous rappelle que la Parole du Christ a sa place jusqu’aux

limites du monde et qu’elle est source de vie sanctifiante parce qu’elle est

Semence d’Éternité…

San Giovanni Gabriele Perboyre

Image

de la page 635 de la Vie des Saints en langue bretonne. Écrit par

Yann-Vari Perrot et publié en 1912.

Une Semence d’Éternité :

Saint Jean-Gabriel Perboyre : Prêtre de la Mission, Martyr, Premier Saint de

Chine

« Le sang des

martyrs est la semence des chrétiens » (TERTULLIEN)

La Chine, immense terre

qui a vu le sang de nombreux martyrs de la foi, a été particulièrement

ensemencée par celui des Filles de la Charité et des Lazaristes. Il est

important pour nous de ne pas isoler le sacrifice de Jean-Gabriel de celui des

autres victimes de l’oppression contre l’Église.

Le 17 février 1820 : le

père François-Régis Clet meurt étranglé. Il est proclamé Bienheureux le 27 mai

1900.

En 1825, le père François

Cheng, compagnon de route du précédent, est condamné à l’exil et massacré.

En 1840, le père

Jean-Gabriel Perboyre meurt étranglé.

En 1857, le père Fernand

Montels est décapité avec deux de ses compagnons chrétiens.

En 1870, les pères

Claude-Marie Chevalier et Vincent Ou, sont égorgés à Tientsin.

Le 21 juin de la même

année, dix Filles de la Charité sont massacrées au même endroit.

En 1900 et 1901, les

lazaristes Maurice Doré, Pascal d’Addosio et Jules Garrigues sont brûlés durant

la révolution des Boxers.

En 1903, le père André

Tsu, 28 ans, est torturé. On lui ouvre la poitrine en forme de croix.

En 1906, le père

Jean-Marie Lacruche, est massacré à Nancheng.

En 1907, le père Antoine

Canduglia est décapité.

Le 9 septembre 1937, Mgr

François-Xavier Schraven, lazariste, évêque de Tchengting, les pères lazarites

Lucien Charny, Thomas Ceska, Eugène Bertrand, Gérard Vouters, les frères

lazaristes Antoine Geerts, Vladislas Prinz, le père Emmanuel, trappiste et M.

Biscopich, laïc tchèque venu réparer les orgues de la cathédrale sont

massacrés.

En 1940, le père Laurent

Ch’enn, séculier, est enseveli vivant avec son catéchiste, à Kao-Cheng.

En 1945, le père Louis

Uao, séculier, est condamné aux travaux forcés où il est mort.

En 1947, le père

lazariste Joseph K’ung est exécuté par un jury populaire.

En 1950, les pères

Jacques Chao, lazariste et Jacques Ou, séculier ont la tête tranchée.

La même année,

l’archevêque Joseph Chow T’si-Che, lazariste, est condamné aux travaux forcés.

Il mourra en 1972.

Le

16 septembre 1951, le père Pierre Souen meurt en prison des suites de la

gangrène.

En 1952, le père Jean

Chao, lazariste, est condamné aux travaux forcés. Depuis on est sans nouvelles

de lui.

Entre 1965 et 1976, à

l’époque de la « Révolution culturelle », une persécution violente se

déploie et bon nombre de prêtres et de chrétiens n’échappent aux travaux forcés

ou à la prison.

Actuellement, la

situation est confuse. Bien des chrétiens connaissent encore la prison ou une

liberté très limitée.

Principales dates de la

vie de Saint Jean-Gabriel PERBOYRE

Naissance au Puech de

Montgesty Mardi 5 Janvier 1802,

Baptême en l’église de

Montgesty, Mercredi 6 Janvier 1802

Études secondaires au

collège de Montauban, 14 ans, Automne 1816,

Décision de se préparer

au sacerdoce à Montauban, 15 ans, Lundi 16 Juin 1817,

Entrée dans la

Congrégation de la Mission à Montauban, 16 ans, Mardi 15 Décembre 1818,

Vœux dans la Congrégation

de la Mission à Montauban, 18 ans, Jeudi 28 Décembre 1820,

Arrivée à Paris pour sa

théologie, 19 ans, Janvier 1821,

Tonsuré, Samedi 22

Décembre 1821,

4 mineurs, 20 ans, Samedi

21 Décembre 1822,

Ordonné sous-diacre dans

la chapelle de l’archevêché de Paris par Mgr de Quelen, 22 ans, Samedi 3 Avril

1824,

Envoyé comme professeur

au collège de Montdidier, Septembre 1824,

Ordonné diacre en

l’église St Sulpice par Mgr de Quelen, archevêque de Paris, 23 ans, Samedi 28

Mai 1825,

Ordonné prêtre à Paris,

140 rue du Bac, par Mgr Louis Dubourg, évêque de Montauban, 24 ans, Samedi 23

Septembre 1826,

Professeur au Grand

Séminaire de Saint-Flour, Fin Septembre 1826,

Nommé supérieur du petit

séminaire de Saint-Flour, 25 ans, Septembre 1827,

Mort de son frère Louis,

en route vers la Chine, 29 ans, Lundi 2 Mai 1831,

Appelé à Paris comme

sous-directeur du Séminaire Interne (noviciat), 30 ans, Septembre 1832,

Obtient d’être envoyé en

Chine, 33 ans, Lundi 2 Février 1835,

Départ du Havre pour la

Chine, Samedi 21 Mars 1835,

Arrivée à Macao, Samedi

29 Août 1835,

Départ de Macao pour le

Ho Nan, Lundi 21 Décembre 1835,

Arrivée à la Mission du

Ho Nan, 34 ans, mi-juillet 1836,

Envoyé au Hou Pei, 36

ans, Début 1838,

Arrestation à Tcha Yuen

Keou, 37 ans, Lundi 16 Septembre 1839,

Condamnation à mort à Ou

Tchang Fou, 38 ans, Mercredi 15 Juillet 1840,

Exécution, Vendredi 11

Septembre 1840,

Inhumation au cimetière

chrétien de la Montagne-Rouge, Dimanche 13 Septembre 1840,

Titre de Vénérable par

Grégoire XVI, Dimanche 9 Juillet 1843,

Exhumation au cimetière

de la Montagne-Rouge, Dimanche 23 Mai 1858,

Retour des Restes de Jean

Gabriel à la Maison-Mère à Paris, Vendredi 6 Janvier 1860,

Translation des reliques

dans un sarcophage dans la chapelle de la Maison-Mère, Jeudi 21 Août 1879,

Béatification par Léon

XIII à Rome, Dimanche 10 Novembre 1889,

Canonisation par

Jean-Paul II à Rome, Dimanche 2 Juin 1996.

San Giovanni Gabriele Perboyre

Ascension de Jean-Gabriel Perboyre. Église Notre-Dame-de-l'Assomption, Castelfranc

AIMER JÉSUS

Jésus-Christ est le grand

Maître de la science ; c’est lui seul qui donne la vraie lumière. Toute science

qui ne vient pas de lui et ne conduit pas à lui est vaine, inutile et

dangereuse. Il n’y qu’une seule chose importante, c’est de connaître et d’aimer

Jésus-Christ.

Nous ne pouvons parvenir

au salut que par la conformité avec Jésus-Christ. Après notre mort, on ne nous

demandera pas si nous avons été savants, si nous avons occupé des emplois

distingués, si nous avons fait parler avantageusement de nous dans le monde ;

mais on nous demandera si nous nous sommes occupés à étudier Jésus-Christ et à

l’imiter.

FAIRE BIEN SIMPLEMENT

Il n’est pas nécessaire

de faire beaucoup de choses, ni des choses bien extraordinaires, pour nous

rendre agréables à Dieu ; il suffit que nous fassions bien ce que nous faisons.

LE DÉSIR

Dans le Crucifix,

l’Évangile et l’Eucharistie, nous trouvons tout ce que nous pouvons désirer. Il

n’y a pas d’autre voie, d’autre vérité, d’autre vie.

Jean-Gabriel Perboyre

San Giovanni Gabriele Perboyre

Autel principal de l'église Notre-Dame-de-la-Nativité (Toulouse). Il conserve une relique de Jean-Gabriel Perboyre

PRIÈRE À SAINT JEAN-GABRIEL PRIÈRE DE ST JEAN-GABRIEL

Apôtre de la Chine

Témoin de la foi,

Martyr de l’Amour,

Communique – nous :

Ton enthousiasme pour la

Mission

Ta passion du Royaume,

Ton goût du risque,

Ta joie de servir ;

Obtiens – nous :

La fidélité à notre

baptême,

La constance dans la foi,

Le sens de la prière,

L’amour de l’Évangile et

de l’Église ;

Infuse en nos cœurs :

Le sel de la Sagesse,

La ferveur des Apôtres,

La force de l’Esprit

Et… la folie de la Croix.

Amen !

O mon divin Sauveur,

par ta toute puissance

et ton infinie

miséricorde,

que je sois changé et

tout transformé en toi.

Que mes mains soient tes

mains,

que mes yeux soient tes

yeux,

que ma langue soit ta

langue,

que tous mes sens et mon

corps

ne servent qu’à te

glorifier ;

mais surtout

transforme mon âme et

toutes ses puissances ;

que ma mémoire, mon

intelligence, mon cœur

soient ta mémoire, ton

intelligence et ton cœur ;

que mes actions, mes

sentiments

soient semblables à tes

actions, à tes sentiments,

et de même que ton Père

disait de toi :

je t’ai engendré

aujourd’hui

tu puisses le dire de moi

et ajouter aussi comme

ton Père céleste :

Voici mon Fils bien-aimé,

en lui, j’ai mis tout mon

amour.

Amen !

TOUT POUR JÉSUS

Par notre baptême, nous

sommes devenus les membres de Jésus-Christ ; par suite de notre union, nos

besoins sont, en quelque sorte, les besoins mêmes de Jésus-Christ : nous ne

pouvons rien demander qui ait rapport au salut ou à la perfection de notre âme,

que nous le demandions aussi pour Jésus-Christ lui-même ; car l’honneur, la

gloire des membres est l’honneur, la gloire du corps.

LE PORTRAIT DE JÉSUS

Jésus-Christ est la forme

des prédestinés, les saints dans le ciel ne sont que les portraits de

Jésus-Christ ressuscité et glorieux, de même que sur la terre, ils ont été les

portraits de Jésus-Christ souffrant, humilié et agissant.

PEINTRE DU CIEL

Si nous voulons parvenir

à la gloire du Ciel, il faut que nous devenions peintres ; plus nous peindrons

fidèlement en nous l’humilité de Jésus-Christ, son obéissance, sa charité et

ses autres vertus, plus nous assurerons notre salut, et plus notre gloire sera

grande dans le Ciel.

Jean-Gabriel Perboyre

Notes

1. Citation de Saint

Vincent de Paul : « Si j’avais su ce que c’était, quand j’eus la témérité

d’y entrer, comme je l’ai su depuis, j’aurais mieux aimé labourer la terre, que

de m’engager à un état si redoutable ». (V, 568)

2. Ursulines :

Congrégation religieuse enseignante d’origine italienne

3. Mr Trippier :

supérieur du pensionnat ecclésiastique de la ville de Saint-Flour

4.Aristarque :

grammairien et critique grec du IIème siècle av. JC, type du critique sévère

5. La guerre de l’opium :

« Le monopole de la culture du pavot était détenu par l’East Indian

Company… L’opium était au XIX ème siècle la plus grande source de recettes de

l’administration coloniale anglaise » (Luigi Mezzadri, cm) et était vendu

en échange de porcelaine et de thé.

6. courrier : messager,

envoyé.

7. une lieue chinoise

équivaut environ à deux kilomètres.

8. Pan-tse : Planchette.

La peine de la bastonnade était appliquée aux soldats avec une planchette de

bois. Dans les tribunaux civils, on se servait généralement d’un bâton de

bambou.

9. « Il faut nous

soyons tout à Dieu et au service du public, il faut nous donner à Dieu pour

cela, nous consumer pour cela, donner nos vies pour cela, nous dépouiller, par

manière de dire, pour le revêtir » (XI, 402)

10. Saint

Grégoire de Naziance in Oraison XLIII, 5-6

San Giovanni Gabriele Perboyre

Pomnik

Jean-Gabriel Perboyre z krakowskiego kościoła Niepokalanego Poczęcia NMP przy

ul. Kopernika 19.

Also

known as

John Gabriel Perboyre

Profile

One of eight children born

to Pierre Perboyre and Marie Rigal. At age 16 he followed his brother Louis to

the seminary,

and joined the Congregation

of the Mission of Saint Vincent on Christmas

Day 1818. Ordained in Paris on 23

September 1825. Professor of theology. Seminary rector.

Assistant director

of novices.

His brother died on

a mission to China,

and John Gabriel was asked to replace him. In March 1835 he sailed for China,

and began his mission in

Macao in June, 1836.

A widespread persecution of Christians began

in 1839,

the same year England had

attacked China. Father John

Gabriel was denounced to the authorities by one of his catachumens, arrested,

tried on 16

September 1839, tortured by

hanging by his thumbs and flogging with bamboo rods, and condemned to death on 11

September 1840. Martyr.

The first saint associated

with China.

Born

6

January 1802 at

Le Puech, near Mongesty, Cahors diocese,

southern France

lashed to a cross on a

hill named the “red mountain”, then strangled with

a rope on 11

September 1840 at

Ou-Tchang-Fou, China

10

November 1889 by Pope Leo

XIII

2 June 1996 by Pope John

Paul II

Gallery of

images of Saint John

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

On

Blessed John Gabriel Perboyre by Bishop John

Edward Cuthbert Hedley

The

Holiness of the Church in the 19th Century

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

images

video

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

Dicastero delle Cause dei Santi

Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

Readings

O my Divine Savior,

Transform me into Yourself.

May my hands be the hands of Jesus.

Grant that every faculty of my body

May serve only to glorify You.

Above all,

Transform my soul and all its powers

So that my memory, will and affection

May be the memory, will and affections

Of Jesus.

I pray You

To destroy in me all that is not of You.

Grant that I may live but in You, by You and for You,

So that I may truly say, with Saint Paul,

“I live – now not I – But Christ lives in me.

– Saint John

Gabriel

MLA

Citation

“Saint Jean-Gabriel

Perboyre“. CatholicSaints.Info. 4 May 2024. Web. 17 April 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-jean-gabriel-perboyre/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-jean-gabriel-perboyre/

San Giovanni Gabriele Perboyre

Bl. John-Gabriel Perboyre

Feastday: September 11

Birth: 1802

Death: 1840

Martyr of China: He was a

Vincentian from Puech, France, who was ordained in 1826. In 1835 he volunteered

for the missions of China and

went to Honan, where he rescued abandoned children. When the persecution started, John was arrested

and tortured for a year. On September 11, he was strangled to death. Pope Leo

XIII beatified him in

1889, making him the first martyr in China to

be so honored. Pope John Paul II canonized

him in 1996.

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=3983

San Giovanni Gabriele Perboyre

St. Jean Gabriel Perboyre

Took the place of his

brother, a priest who died on missions in China

Vincentian Priest and

Martyr: 1802-1840

His life

+ Jean Gabriel was born

in Le Peuch, France. At the age of 16, he began seminary studies and entered

the Congregation of the Missions (the Vincentians). Ordained a priest in 1825,

he served his community as theology professor, seminary rector, and assistant

director of novices.

+ Jean Gabriel had a

brother who was also a Vincentian priest who died while serving as a missionary

in China. Jean Gabriel was asked to take his place. He arrived in China in

1836.

+ A widespread

persecution of Christians began in 1839 (prompted by an English attack on China

that led to the “Opium War” [1839-1842]). Father Jean Gabriel was betrayed by

one of his catechumens and was arrested and tried for the crime of being a

Christian on September 16, 1839.

+ Imprisoned for nearly a

year, he suffered extreme torture before being lashed to a cross on a hill

called “Red Mountain” and strangled to death on September 11, 1840.

+ Saint Jean Gabriel

Perboyre was canonized in 1996.

Quote

"O my Divine Savior,

Transform me into Yourself.

Grant that I may live but in You, by You, and for You,

So that I may truly say, with Saint Paul,

"I live - now not I - But Christ lives in me."

—Saint Jean Gabriel

Perboyre

Prayer

Grant, we pray, almighty

God, that we may follow with due devotion the faith of blessed Jean Gabriel,

who, for spreading the faith, merited the crown of martyrdom. Through our Lord

Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy

Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

(from The Roman

Missal: Common of Martyrs—For One Missionary Martyr)

~

Saint profiles prepared

by Brother Silas Henderson, S.D.S.

SOURCE : https://aleteia.org/daily-prayer/monday-september-11

John Gabriel Perboyre

Following the French

Revolution, Napoleon in 1801 brought religious peace to France. The country was

still Catholic, especially rural France. Pierre Perboyre and his wife Marie on

a small farm in Puech near Cahors typified the French peasant’s faith. God

blessed them with eight children. Three sons became priests in the Congregation

of the Mission (Vincentians), and two daughters entered the Daughters of

Charity of St. Vincent de Paul.

The eldest son of Pierre

and Marie, John Gabriel, was born on the 6th of January 1802. In 1816 John

Gabriel accompanied a younger brother, Louis, to a high school in Montauban

that had been started by their uncle, Fr. Jacques Perboyre, C.M., to prepare

young men for the seminary. In the Spring of 1817, his teachers noting John

Gabriel’s intelligence and piety suggested he remain with his brother and

continue his studies. Though willing to return home if needed on the farm, John

Gabriel wrote to his father that he believed that the Lord was calling him to

the priesthood.

From his earliest days in

the seminary, John Gabriel had longed for the China mission. In 1832, however,

his superiors appointed him a novice director in the Vincentian Motherhouse.

The departure of some Vincentians to China in 1835 renewed his missionary

longing. Poor health stood in the way, but finally his doctor saw the voyage to

the Orient as a possible cure. Five months at sea brought John Gabriel to Macao

where he studied Chinese.

In December of 1835,

Father Perboyre, along with several missionaries, set sail from Macao in a Junk.

Since the Chinese law forbade the entry of Christian missionaries, the

Christian captain and crew disguised themselves as merchants and smuggled John

Gabriel on to the mainland of China.

Following a five month