Saint Matthieu

Un des apôtres du Christ,

martyr (1er s.)

A Capharnaüm, il y avait

un poste de douane. Le fonctionnaire qui tenait ce poste s'appelait Lévi ou

Matthieu. Il était fils d'Alphée. Un matin, Jésus l'appelle, Matthieu laisse

ses registres et suit Jésus. (Marc

2, 14 - Luc

5, 27)

A quelle attente secrète

répond-il ainsi? En tout cas, il explose de joie, suit Jésus, l'invite à dîner,

invite ses amis. Le fonctionnaire méticuleux devient missionnaire et, choisi

comme apôtre, il sera aussi le premier évangéliste(*), relevant méticuleusement

les paroles et les actions de Jésus. Ce publicain, méprisé par les scribes, est

pourtant le plus juif des quatre évangélistes: 130 citations de l'Ancien

Testament. Par la suite, la Tradition lui fait évangéliser l'Éthiopie.

(*) Evangile

de Jésus-Christ selon saint Matthieu

Des internautes nous

signalent:

- "St Matthieu est

le patron des agents des douanes, et à cette occasion dans certaines directions

les remises de la médaille des Douane aux agents a lieu le 21/09."

- "En Basse Sambre,

région de l'Arrondissement judiciaire de Namur (Belgique), les professionnels

de la comptabilité et de la fiscalité organisent le quatrième vendredi de

septembre un banquet pour la fête de la saint Matthieu."

Au 21 septembre, au

martyrologe romain, fête de saint Matthieu, Apôtre et Évangéliste. surnommé

Lévi, appelé par Jésus à le suivre, il abandonna son métier de publicain ou

collecteur d’impôts et, choisi dans le groupe des Douze, il écrivit son

Évangile, où il montre que Jésus, le Christ, fils de David, fils d’Abraham, a

porté à son terme l’ancienne Alliance.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1066/Saint-Matthieu.html

Caravaggio (1571–1610),

Vocazione di san Matteo / The Calling of Matthew, circa 1599-1600, 340 x

322, Contarelli Chapel, Church of San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome

Saint Matthieu

Apôtre

(Ier siècle)

Saint Matthieu était

probablement Galiléen de naissance. Il exerçait la profession de publicain ou

de receveur des tributs pour les Romains, profession très odieuse parmi les

Juifs. Son nom fut d'abord Lévi. Il était à son bureau, près du lac de

Génésareth, où apparemment il recevait le droit de péage, lorsque Jésus-Christ

l'aperçut et l'appela. Sa place était avantageuse; mais aucune considération ne

l'arrêta, et il se mit aussitôt à la suite du Sauveur. Celui qui l'appelait par

Sa parole le touchait en même temps par l'action intérieure de Sa grâce.

Lévi, appelé Matthieu

après sa conversion, invita Jésus-Christ et Ses disciples à manger chez lui; il

appela même au festin ses amis, espérant sans doute que les entretiens de Jésus

les attireraient aussi à Lui. C'est à cette occasion que les Pharisiens dirent

aux disciples du Sauveur: "Pourquoi votre Maître mange-t-Il avec les

publicains et les pécheurs?" Et Jésus, entendant leurs murmures, répondit

ces belles paroles: "Les médecins sont pour les malades et non pour ceux

qui sont en bonne santé. Sachez-le donc bien, Je veux la miséricorde et non le

sacrifice; car Je suis venu appeler, non les justes, mais les pécheurs."

Après l'Ascension, saint

Matthieu convertit un grand nombre d'âmes en Judée; puis il alla prêcher en

Orient, où il souffrit le martyre. Il est le premier qui ait écrit l'histoire

de Notre-Seigneur et Sa doctrine, renfermées dans l'Évangile qui porte son nom.

– On remarque, dans l'Évangile de saint Matthieu, qu'il se nomme le publicain,

par humilité, aveu touchant, et qui nous montre bien le disciple fidèle de

Celui qui a dit: "Apprenez de Moi que Je suis doux et humble de

coeur." On croit qu'il évangélisa l'Éthiopie. Là, il se rendit populaire

par un miracle: il fit le signe de la Croix sur deux dragons très redoutés, les

rendit doux comme des agneaux et leur commanda de s'enfuir dans leurs repaires.

Ce fut le signal de la

conversion d'un grand nombre. La résurrection du fils du roi, au nom de

Jésus-Christ, produisit un effet plus grand encore et fut la cause de la

conversion de la maison royale et de tout le pays. On attribue à saint Matthieu

l'institution du premier couvent des vierges. C'est en défendant contre les

atteintes d'un prince une vierge consacrée au Seigneur, que le saint Apôtre

reçut le coup de la mort sur les marches de l'autel.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_matthieu.html

Caravaggio (1571–1610),

Il martirio di San Matteo, circa 1600, 323 x 343, San Luigi dei Francesi, Ponte, Municipio I, Rome, Metropolitan City of Rome, Lazio, Italy

Matthieu est probablement d’origine juive, galiléen de naissance. Il

exerce la profession de collecteur d’impôts (publicain) pour les romains à

Capharnaüm. C’est un homme cultivé, de formation grecque (d’ où son nom Lévi).

Le jour où Jésus, de passage devant son bureau de péage, lui demande de le

suivre, il abandonne tout et devient un de ses disciples.

Evangile selon saint Luc

V 27-29 : "Et après cela il sortit, et il remarqua un publicain

du nom de Lévi, assis au bureau du péage, et il lui dit : Suis-moi. Et,

quittant tout, se levant, il le suivait. Et Lévi lui fit une grande réception

dans sa maison".

Evangile selon saint Marc II 13-14 : "Et il sortit de nouveau le

long de la mer. Et toute la foule venait vers lui, et il les enseignait. Et en

passant, il vit Lévi, le fils d’Alphée, assis au bureau du péage. Et il lui

dit : Suis-moi. Et se levant, il le suivit".

Sa profession aurait fait

de lui un homme méprisé par les autres juifs : les percepteurs étaient de

véritables oppresseurs au service des Romains et l’on savait qu’ils

escroquaient les gens pour augmenter leurs revenus. Ils étaient exclus de la

communauté religieuse, interdits de Temple et tout le monde les évitait.

Lévi, captivé par les

propos de Jésus, le suivit, quittant sa fonction de publicain. Il devint l’un

des 12 apôtres de Jésus et pris le nom de Matthieu. Afin de convaincre ses amis

de partager ses nouvelles convictions, Matthieu les convia à prendre un repas

chez lui, en compagnie de Jésus. et de ses disciples. Les Pharisiens en prirent

ombrage car il était malvenu de déjeuner avec les publicains. Jésus leur

répondit : "Les médecins sont pour les malades et non pour ceux

qui sont en bonne santé. Sachez-le donc bien, je veux la miséricorde et non le

sacrifice ; car je suis venu appeler, non les justes, mais les

pécheurs."

L’Évangile de Matthieu est un récit lucide, qui semble avoir été écrit d’abord pour montrer que Jésus répond aux attentes messianiques juives, d’où son souci de bien établir sa généalogie. En 130, Papias montra que Matthieu écrivit d’abord en araméen, comme un Juif écrivant pour des lecteurs juifs. Cependant, les fragments les plus anciens sont en grec. Le style est concis et conventionnel, particulièrement adapté aux lectures publiques et à l’enseignement.

Alors que les trois autres évangélistes sont symbolisés par des animaux,

Matthieu est représenté par un homme ailé en raison de son souci de l’humanité

et particulièrement de la famille du Christ.

Après la Pentecôte, selon la tradition orale de l’Eglise, il passe un temps en Egypte, puis part en Ethiopie.

Arrivé à Naddaver, la capitale, il prêche et combat l’influence de deux mages, convertissant une partie du peuple désabusé.

Il devient populaire en opérant la résurrection du fils du roi, au nom de Jésus Christ.

Défendant une vierge consacrée au Seigneur contre l’avidité d’un prince, Matthieu s’attire la colère du nouveau roi Hirtiacus. Il est assassiné au cours d’une célébration à Naddaver.

Ses reliques auraient été transportées d’Éthiopie dans le Finistère, en

Bretagne, d’où elles furent transférées à Salerne par Robert Guiscard. Quant à

sa tête, quatre églises différentes en France prétendent la posséder.

L’évangile araméen de

Matthieu parait avant l’an 50. Une traduction grecque circule déjà hors

Palestine, étayée des autres synoptiques parus entre-temps.

D’où vient le nom de

Matthieu ? Il s’agit d’un nom sémitique, Mattaï, signifiant « don de

Dieu » (Théodore, Dieudonné). Certains pensent que ce surnom lui vient de

Jésus.

Saint patron des

percepteurs, des comptables, des fiscalistes et des banquiers ; fêté le 21

septembre en Occident, le 16 novembre en Orient.

SOURCE : http://www.catholique-verdun.cef.fr/spip/spip.php?page=service&id_article=3227

21 septembre

Saint Matthieu

Apôtre et évangéliste

Le nom de Matthieu que

l'on a traduit du grec Maththios ou Matthios, vient de

l'hébreux Matt'yah, abréviation de Mattatyah, qui signifie don

de Yahvé, comme Matthias, Mattathias et Matthan.

On sait que saint

Matthieu, auteur du premier évangile, est un des douze apôtres du Seigneur[1], qu'il est fils d'Alphée et porte d'abord le

nom de Lévi.

Il semble originaire de

Capharnaüm[2] où il est publicain[3] et tient le bureau de péage[4], c'est-à-dire le bureau où l'on perçoit

le portorium, à la fois douane, octroi et péage entre les états du roi

Hérode Antipas et de son frère, le tétrarque Philippe[5]. Chacun connaît les récits de son appel par

Jésus :

Évangile selon saint

Matthieu IX 9 : « Et, passant plus loin, Jésus vit, assis au bureau

du péage, un homme appelé Matthieu. Et il lui dit : Suis-moi. Et, se levant, il

le suivit. »

Évangile selon saint Luc

V 27-29 : « Et après cela il sortit, et il remarqua un publicain du

nom de Lévi, assis au bureau du péage, et il lui dit : Suis-moi. Et, quittant

tout, se levant, il le suivait. Et Lévi lui fit une grande réception dans sa

maison. »

Évangile selon saint Marc

II 13-14 : « Et il sortit de nouveau le long de la mer. Et toute la

foule venait vers lui, et il les enseignait. Et en passant, il vit Lévi, le

[fils] d'Alphée, assis au bureau du péage. Et il lui dit : Suis-moi. Et se

levant, il le suivit. »

(Textes liturgiques ©

AELF, Paris)

La tradition

hagiographique[6], reprise par Rufin, saint Eucher de Lyon et

Socrate dit qu'il passa un temps en Egypte avant que d'aller dans la capitale

d'Ethiopie, Naddaver, où il fut accueilli par cet eunuque, haut fonctionnaire

de la Candace[7], que le diacre Philippe avait baptisé. Or,

il y avait dans cette ville deux habiles magiciens, Zaroës et Arfaxat, qui

trompaient les habitants en leur causant des maladies qu'ils savaient guérir ;

saint Matthieu ne tarda pas à découvrir leurs sortilèges et à désabuser le

peuple dont beaucoup se convertirent.

Quand Matthieu eut

ressuscité le prince héritier Euphranor, le roi et la reine, avec toute la

maison royale et tout ce qui comptait dans la province reçurent le baptême.

Iphigénie, fille du roi d'Ethiopie et quelques unes de ses compagnes, firent

vœu de virginité et se retirèrent dans une maison particulière qui devint le

premier monastère du pays.

Le roi Eglippe étant

mort, son frère Hirtace s'empara du royaume et, pour mieux asseoir son pouvoir,

voulut d'épouser Iphigénie. Hirtace eut recours à saint Matthieu qui lui

répondit : Vienne votre Majesté au discours que je vais faire aux

vierges chrétiennes rassemblées avec Iphigénie et vous verrez vous-même avec

quel zèle je vais remplir vos ordres ; saint Matthieu fit un tel éloge de

la virginité, invitant ses filles à mourir plutôt qu'à y renoncer, qu'Hirtace

se résolut à le faire mourir. Les bourreaux arrivèrent alors que saint Matthieu

finissait la messe, ils montèrent à l'autel et le tuèrent.

Le corps de saint

Matthieu fut d’abord conservé avec beaucoup de vénération dans la ville de

Naddaver où il avait enduré le martyre. En 956, il fut transféré à Salerne,

dans le Royaume de Naples. Comme on se trouvait alors souvent en péril de

guerre et que l’on craignait que quelqu’un s’emparât furtivement des reliques,

on cacha le corps de saint Matthieu dans un endroit secret connu de quelques

personnes. Près de cent vingt ans plus tard, sous le pontificat de saint

Grégoire VII, on découvrit le caveau secret ce dont le Pape félicita

Alfane[8], archevêque de Salerne. De Salerne, le chef

de saint Matthieu fut transporté en France et déposé dans la cathédrale de,

Beauvais ; une partie de ce chef fut donnée au monastère de la Visitation

Sainte-Marie de Chartres. La relique de Beauvais disparut pendant la révolution

française (1793).

[1] Saint

Marc III 18, saint Luc VI 15, saint Matthieu X 3 et Actes des Apôtres I 13

[2] Capharnaüm (le

village de Nahum) aujourd'hui Tell-Hum : ville de Galilée située au

nord-ouest du lac de Gennésareth (lac de Tibériade ou mer de Galilée), à quatre

kilomètres de l'embouchure du Jourdain dans le lac, qui appartient aux

territoires du tétrarque Hérode Antipas. Capharnaüm (aux confins des états

d'Hérode Antipas et de d'Hérode Philippe II) est un poste de douane sur la

route de la Gaulanitide tenu par le publicain Lévi, fils d'Alphée, le futur

apôtre Matthieu (S. Matthieu IX 9, S. Marc II 13-17, S. Luc V 27-32) ; la ville

est gardée par une garnison romaine commandée par le centurion du Domine

non sum dignus (S. Matthieu VIII 5-13, S. Luc VII 1-10). Au début de sa

vie publique, Jésus y établit son centre d'action, y fit de nombreux miracles

et y prêcha dans la synagogue. Il vint habiter à Capharnaüm qui est au

bord de la mer, dans le territoire de Zabulon et de Nephtali, pour que

s'accomplît ce qui avait été annoncé par Isaïe, le prophète, quand il dit :

" Pays de Zabulon et pays de Nephtali, chemin de la mer, pays au-delà du

Jourdain, Galilée des nations, le peuple qui était assis dans les ténèbres a vu

une grande lumière, et pour ceux qui étaient assis dans le sombre pays de la

mort une lumière s'est levée " (S. Matthieu IV 13-16).

[3] Sous

aucun régime la levée de l'impôt n'a été un moyen de se concilier la faveur

populaire. Les exactions et les vexations dont les publicains se rendaient

coupables, n'avaient fait qu'accroître cette impopularité, inhérente à la

fonction ; Hérondas affirme que chaque demeure frissonnait de peur à leur

vue. Autant du Publicains, autant de voleurs, disait d'eux le comique

Xénon, en cela fidèle interprète du sentiment public dans le monde gréco-romain

où Lucien les assimilait à ceux qui tenaient des maisons de débauche et Cicéron

les appelait les plus vils des hommes. Le monde juif ne pensait pas

autrement : la littérature rabbinique associe les publicains, réputés traitres

et apostats puisqu'ils violent les observances de pureté légale, aux voleurs et

aux meurtriers ; on accole publicains et pécheurs (S. Matthieu IX 10),

publicains et païens (S. Matthieu XVIII 17), publicains et prostituées (S.

Matthieu XXI 31). Le Talmud leur interdit les fonctions de juges ou de témoins

dans les procès. Quand Jean-Baptiste avait commencé à prêcher, plusieurs de ces

fonctionnaires de l'impôt étaient allés le trouver pour se faire

baptiser : Maître, que devons-nous faire ? lui avait-il

demandé. N'exigez rien de plus que la taxe fixée, leur avait-il répondu,

laissant clairement entendre que telle n'était pas leur pratique habituelle (S.

Luc III 12-13). L'impopularité du métier n'empêchait pas qu'il ne fût fort

recherché, la perspective du gain imposant facilement silence aux

susceptibilités de l'amour-propre. Avec une souveraine indépendance, Jésus veut

se choisir un disciple parmi les membres de cette corporation méprisée.

[4] Capharnaüm,

située sur une des routes principales qui reliaient Damas à la Méditerranée et

à l'Égypte, elle possédait un bureau où l'on percevait à la fois les droits de

douane, d'octroi et de péage. Suivant la méthode pratiquée dans l'empire

romain, ces taxes avaient été affermées par Hérode, pour une somme déterminée,

à de riches particuliers ou à des compagnies qui se chargeaient de percevoir

directement, non sans y ajouter des taxes pour couvrir leurs frais et se

ménager un bénéfice. Ces fermiers de l'impôt public avaient reçu le nom

de publicains, qui se donnait aussi à leurs agents subalternes (ils

étaient appelés portitores à Rome). Ces impôts (portorium ou teloneum)

portaient sur les marchandises, les individus et les moyens de transport,

hormis ce qui servait à l'armée ou au fisc ; ils étaient levés aux frontières

d'un état (douane), à la sortie d'une ville (octroi) et sur des points

déterminés de passage comme l'entrée d'une route ou d'un pont (péage).

[5] Saint

Marc II 14-15, saint Luc V 27, saint Matthieu IX 9.

[6] Saint

Ambroise et saint Paulin de Nole parlent d'une prédication en Perse, d'autres

parlent du Pont, de la Syrie, de la Macédoine et même de l'Irlande.

[7] Candace

(en grec Kandake, du méroïte Kantake) que les Actes des Apôtres (VIII 27)

donnent comme nom à la reine d'Ethiopie, n'est en fait pas un nom, mais un

titre attribué aux reines de Méroé, l'Ethiopie des Romains, dont la capitale

était Napata (Pline : Histoire naturelle, XVIII 6 ; Strabon : Géographie, XVII,

1, 54).

[8] Alfano

I°, archevêque de Salerne, théologien, philosophe, poète, médecin et musicien.

Originaire de Salerne, il y étudia la médecine. Il entra au monastére de

Sainte-Sophie de Bénévent (1054), puis à celui du Mont-Cassin (1056) où il fit

des études classiques et théologiques. Il parut à la cour du pape Victor II, où

il se fit remarquer par ses connaissances musicales et médicales. Au

Mont-Cassin se trouvaient déjà Fredéric de Lorraine et Didier, ses deux amis,

comme lui savants et lettrés. Frédéric étant devenu le pape Étienne IX (1057)

et Didier l’abbé du Mont-Cassin, Alfano accepta le siège archiépiscopal de

Salerne (1058) et fut consacré par Étienne IX. Sous son épiscopat, l'Église de

Salerne fut enrichie de nombreux privilèges par les papes et les princes et

reçut de notables accroissements spirituels et matériels : droit pour ses

archevêques d'user du pallium, de nommer et de consacrer leurs onze évêques

suffragants ; droit de primauté sur les métropoles de Cosenza, Conza et

Acerenza. Sous l'épiscopat d'Alfano fut bâtie la cathédrale qui fut dédiée

à saint Matthieu, dont on venait de retrouver les restes. L'édifice fut

consacré par saint Grégoire VII (1085). L'archevéque réorganisa aussi son

chapitre, qui se composa de vingt-huit chanoines, dont vingt-quatre portèrent

le titre de cardinaux-prétres, et quatre celui de cardinaux-diacres. Alfano

prit part à plusieurs conciles où il se lia d'amitié avec Hildebrand (futur

Grégoire VII), dont il partageait les desseins de réforme ecclésiastique,

et dont il seconda les efforts dans sa lutte pour la liberté de l'Église. En

1062 ou 1063, il fit, avec l’évêque Bernard de Palestrina, un pèlerinage en

Palestine. Il rendit des services diplomatiques aux princes normands qui

gouvernaient le sud de l’Italie, et fut peu ou prou mêlé aux grandes affaires

de son temps. Lorsque Grégoire VII fut chassé de Rome, Alfano le reçut à

Salerne. Alfano mourut le 9 octobre 1085 et fut enseveli dans sa cathédrale,

près de son Grégoire VII, mort le 25 mai de la même année. Alfano jouit

d'un renom de sainteté, justifié par les pratiques d'une vie austère et

bienfaisante. « Il passait le carême sans manger plus de deux fois par

semaine et sans reposer sur un lit. Les témoins de sa vie racontèrent sa mort

comme celle des saints. On assura qu’il avait vu en songe une échelle qui, du

bord de sa couche allait jusqu'au ciel, et que deux jeunes hommes vêtus de blanc

l'invitaient à monter. » Parmi les devoirs d'une vie si remplie, Alfano trouva

le temps de cultiver la médecine, la philosophie, la poésie, l’éloquence et

l’hagiographie, laissant des œuvres dans toutes ces branches du savoir. On

conserve encore de lui un sermon sur saint Matthieu.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/09/21.php

Caravaggio (1571–1610), Saint Matthew and the Angel, circa 1602, 292 x 186, Contarelli Chapel, Church of San Luigi dei Francesi, Roma

La tradition est unanime

à reconnaître dans le publicain Matthieu (ou Lévi) l’auteur du

premier évangile. Fête attestée au IXème siècle.

La messe du jour lit

l’évangile de l’appel de St Matthieu dans son évangile. La messe de la Vigile

(voir au 20/09, vigile supprimée en 1955) faisait lire l’appel de Lévi selon St

Luc.

(Leçons des Matines)

AU DEUXIÈME NOCTURNE.

Quatrième leçon. L’apôtre

et Évangéliste Matthieu, appelé aussi Lévi, était assis à son comptoir, lorsque

le Christ lui fit entendre son appel. Il le suivit sans tarder et le reçut à sa

table, lui et les autres disciples. Après la résurrection du Christ, avant de

quitter la Judée pour la contrée qui lui était échue à évangéliser, il écrivit

le premier, en hébreu, l’Évangile de Jésus-Christ, pour les Juifs convertis.

Puis il partit pour l’Éthiopie, où il prêcha la bonne nouvelle, confirmant sa

doctrine par de nombreux miracles.

Cinquième leçon. On doit

citer en première ligne le miracle qu’il opéra en ressuscitant la fille du roi

; ce prodige convertit à la foi du Christ le roi, père de la jeune fille, la

reine, et toute la contrée. A la mort du roi, Hirtacus, son successeur, voulut

épouser la princesse Iphigénie, de race royale. Mais comme celle-ci avait voué

à Dieu sa virginité, sur le conseil de Matthieu, et qu’elle persistait dans son

pieux dessein, Hirtacus donna l’ordre de tuer l’Apôtre, tandis qu’il célébrait

à l’autel les saints Mystères. La gloire du martyre couronna sa carrière

apostolique, le onze des calendes d’octobre. Son corps fut transporté à

Salerne, et déposé peu après, Grégoire VII étant souverain Pontife, dans

l’église consacrée sous son vocable, et il y reçoit de la part de nombreux

fidèles, un culte de pieuse vénération.

On lit pour 6ème Leçon,

la 4ème Leçon du Commun.

AU TROISIÈME NOCTURNE.

Lecture du saint Évangile

selon saint Matthieu.

En ce temps-là : Jésus

vit un homme nommé Matthieu assis au bureau des impôts, et lui dit : Suis-moi.

Et le reste.

Homélie de saint Jérôme,

Prêtre.

Septième leçon. Les

autres Évangélistes, par respect et honneur pour Matthieu, se sont abstenus de

lui donner son nom populaire et ils l’ont appelé Lévi ; il eut en effet ces

deux noms. Quant à lui, suivant ce que dit Salomon : « Le juste est le premier

accusateur de lui-même ; » et : « Confesse tes péchés, afin d’être justifié, »

il s’appelle Matthieu et se déclare publicain, pour montrer à ceux qui le

liront que nul ne doit désespérer du salut, pourvu qu’il embrasse une vie

meilleure, puisqu’on voit en sa personne un publicain tout à coup changé en

Apôtre.

Huitième leçon. Porphyre

et l’empereur Julien relèvent ici sous forme d’accusation, ou l’ignorance d’un

historien inexact ou la folie de ceux qui suivirent immédiatement le Sauveur,

comme s’ils avaient inconsidérément obéi à l’appel du premier venu ; tandis

qu’au contraire, Jésus avait déjà opéré beaucoup de miracles et de grands

prodiges, que les Apôtres avaient certainement vus avant de croire. D’ailleurs

l’éclat et la majesté de la divinité cachée en lui reflétés jusque sur sa face,

pouvaient dès le premier aspect, attirer à lui ceux qui le voyaient ; car si

l’on dit que l’aimant et l’ambre ont la propriété d’attirer les anneaux de fer,

les tiges de blé, les brins de paille, combien plus le Seigneur de toutes

choses pouvait-il attirer à lui ceux qu’il appelait ?

Neuvième leçon. « Or il arriva que Jésus étant à table dans la maison, beaucoup de publicains et de pécheurs vinrent s’y asseoir avec lui. » Ils voient que ce publicain, passé d’un état de péché à une vie meilleure, avait été admis à la pénitence ; et c’est pour cela qu’eux-mêmes ne désespèrent pas de leur salut. Mais ce n’est pas en demeurant dans leurs mauvaises habitudes qu’ils viennent à Jésus, ainsi que les Pharisiens et les Scribes le disent avec murmure. C’est en faisant pénitence, comme le marque le Seigneur dans la réponse qui suit : « Je veux la miséricorde et non le sacrifice ; car je ne suis pas venu appeler les justes, mais les pécheurs. » Aussi le Seigneur allait-il aux repas des pécheurs, pour avoir l’occasion de les instruire et de servir à ceux qui l’invitaient, des aliments spirituels.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/21-09-St-Matthieu-apotre-et

Michelangelo

Merisi da Caravaggio, Saint Matthew and the Angel, c.1602, formerly the

Kaiser Friedrich Museum, Berlin, destroyed 1945 in Flakturm Friedrichshain

fire, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library,

Washington, DC

L'évangile de Matthieu

a-t-il un original hébreu ?

L'apôtre Matthieu ou Lévi

?

Appelé par Jésus (Mt 9,

9-10), Matthieu était percepteur des impôts à Capharnaüm, aux frontières du

territoire de Hérode Antipas et de son frère Philippe.

Marc et Luc cependant

l'appellent Lévi (Mc 2, 13-14; Lc 5, 27-28).

Le témoignage de Papias

(vers l'an 130).

Papias fut évêque de

Hiérapolis en Phrygie vers l'an 110, et il était un disciple personnel de

l'apôtre Jean et un compagnon de Polycarpe[1].

L'œuvre de Papias est

perdue, mais Eusèbe de Césarée nous apprend que Papias « ordonna des logia ».

Le mot « logia » vient du mot « logos », mot, parole, sentence. Il s'agit d'un

recueil de sentences. Et dans un autre passage, Eusèbe parle d'un Evangile de

Matthieu, dans sa langue maternelle. Le pape commente cette tradition :

« La tradition de

l'Eglise antique s'accorde de façon unanime à attribuer à Matthieu la paternité

du premier Evangile. Cela est déjà le cas à partir de Papias, évêque de

Hiérapolis en Phrygie, autour de l'an 130. Il écrit:

"Matthieu recueillit

les paroles (du Seigneur) en langue hébraïque, et chacun les interpréta comme

il le pouvait"

(in Eusèbe de Césarée,

Hist. eccl. III, 39, 16).

L'historien Eusèbe ajoute

cette information:

"Matthieu, qui avait

tout d'abord prêché parmi les juifs, lorsqu'il décida de se rendre également

auprès d'autres peuples, écrivit dans sa langue maternelle l'Evangile qu'il

avait annoncé; il chercha ainsi à remplacer par un écrit, auprès de ceux dont

il se séparait, ce que ces derniers perdaient avec son départ"

(Ibid., III, 24, 6).

Nous ne possédons plus

l'Evangile écrit par Matthieu en hébreu ou en araméen, mais, dans l'Evangile

grec que nous possédons, nous continuons à entendre encore, d'une certaine

façon, la voix persuasive du publicain Matthieu qui, devenu Apôtre, continue à

nous annoncer la miséricorde salvatrice de Dieu et écoutons ce message de saint

Matthieu, méditons-le toujours à nouveau pour apprendre, nous aussi, à nous

lever et à suivre Jésus de façon décidée. »

(Benoît XVI, audience du

30 août 2006).

Le témoignage de saint

Irénée (vers l'an 180).

En pleine cohérence avec

la tradition de Papias, vers la fin du II° siècle, saint Irénée écrit :

"Ainsi Matthieu

publia-t-il chez les Hébreux, dans leur propre langue, une forme écrite

d'Evangile, à l'époque où Pierre et Paul évangélisaient Rome et y fondaient

l'Eglise"[2].

Hébreu ou araméen ? [3].

La première ébauche

était-elle en hébreu, langue traditionnelle du peuple juif ? Ou en araméen (qui

n'est pas un dialecte mais une langue tout aussi vénérable que l'hébreu),

beaucoup plus répandu en Galilée et dans la plupart des villages juifs a 1°

siècle de notre ère ? L'hébreu est possible et semble plus conforme aux

indications de Papias et d'Irénée. Pourtant, il est courant dans les textes

chrétiens rédigés en grec d'appeler « langue hébraïque » la langue des juifs,

même lorsqu'il s'agit explicitement d'araméen. Il y en a trois exemples dans

l'évangile de Jean (Jn 5,2 ; 19, 13.17). L'araméen est alors plus probable.

Matthieu : de qui

parle-t-on ? [4]

Nous expliquons ailleurs

que l'évangile de Matthieu fut achevé plus tard que celui de Marc.

Il faut donc accepter que

son rédacteur final soit distinct de l'un des Douze. En effet, il est

invraisemblable qu'un témoin oculaire prenne modèle sur un homme apostolique

qui n'a pas été témoin oculaire (Marc).

Ce rédacteur final (que

nous appelons Matthieu) s'est donc placé sous l'autorité apostolique de l'apôtre

(Matthieu-Lévi) et il a écrit un évangile complet. Ce dédoublement des rôles

peut expliquer que Matthieu soit appelé Lévi dans les autres évangiles (Mc 2,

13-14; Lc 5, 27-28).

Ce rédacteur final est

très probablement judéo-chrétien, car il fait un bon usage de l'Ancien

Testament, il connaît les légendes juives, il fait un parallèle entre Moïse et

Jésus, etc... Et il aura très probablement utilisé le recueil de sentences dont

parle Papias. Car nous n'avons aucune raison de disqualifier Papias.

Ceci dit, n'y a-t-il pas

eu un évangile hébreu complet ? [5]

Irénée parle bien d'un

évangile. Dans l'antiquité, il est légitime de penser qu'il y avait un évangile

juif, probablement araméen, utilisé par les chrétiens palestiniens.

Mais il n'a pas été retrouvé.

• Les quelques citations

chez les pères de l'Eglise.

Saint Jérôme affirmait

l'avoir traduit en grec. Pourtant quand on les compare à l'évangile canonique

de Matthieu, les quelques passages conservés dans les citations des pères de

l'Eglise semblent être des ajouts secondaires ou des interpolations.

• Les versions

médiévales.

Il existe des versions

médiévales hébraïques de Matthieu et la plupart des spécialistes considèrent

qu'il s'agit des rétroversions du grec du Matthieu canonique, souvent destinées

au débat entre chrétiens et juifs.

Certains affirment

cependant que ces textes peuvent conduire à l'original hébreu de Matthieu[7].

• D'autres pensent

pouvoir reconstruire l'original hébreu ou araméen sous-jacent à tout ou partie

du texte grec du Matthieu canonique.

La grande majorité des

exégètes, toutefois, soutient que l'évangile que nous connaissons sous le nom

de Matthieu fut originellement composé en grec (puisque par exemple il corrige

le style de Marc et se livre à des jeux de mots grecs).

Conclusion.

L'Eglise croit que

l'Esprit Saint a guidé tout le processus de la rédaction de la Bible et ne

dévalue pas l'influence des apôtres.

Benoît XVI, dans la

catéchèse sur Matthieu, rapporte la tradition de Papias sur l'évangile en

langue hébraïque attribué à Matthieu, mais il ajoute que nous n'en avons plus

la trace. Il se garde bien d'attribuer directement à Matthieu l'évangile canonique

(grec) que nous possédons, il dit simplement que « nous continuons à entendre,

d'une certaine façon, la voix persuasive du publicain Matthieu ».

La tradition de Papias,

reprise par saint Irénée, avait l'intention de montrer comme plausible et authentique

l'origine apostolique de ce qui avait été écrit en bel ordre dans « l'évangile

selon Matthieu ».[7]

Benoît XVI ne s'en

éloigne nullement. Mais il autorise aussi les recherches récentes qui pensent

que notre évangile de Matthieu ne soit pas une traduction et qu'il ait eu aussi

une source « Q », en grec, commune avec Luc.

[1] IRENEE, Contre

les hérésies, V, 33, 4. ; EUSEBES, Histoire eccl., III, 39, 1

[2] IRENEE, Contre

les hérésies, III, 1, 1

[3] Michel QUESNEL, Histoire

des Evangiles, Cerf, Paris 1987, p. 56.

[4] Cf. R. E.

Brown, Que sait-on du Nouveau Testament ? Bayard, Paris 2000, p.

252-253

[5] Cf. R. E.

Brown, Que sait-on du Nouveau Testament ? Bayard, Paris 2000, p.

250-252

[6] Auteurs récents ayant

travaillé ce thème : Cl. Tresmontrant ; O. Grelot ; G.E. Howard ; G.A.Mercer.

[7] SEGALLA G., Evangelo

e vangeli, EDB, Bologna 1993, pp. 116-117.

Françoise Breynaert

SOURCE : http://www.mariedenazareth.com/6733.0.html?&L=0

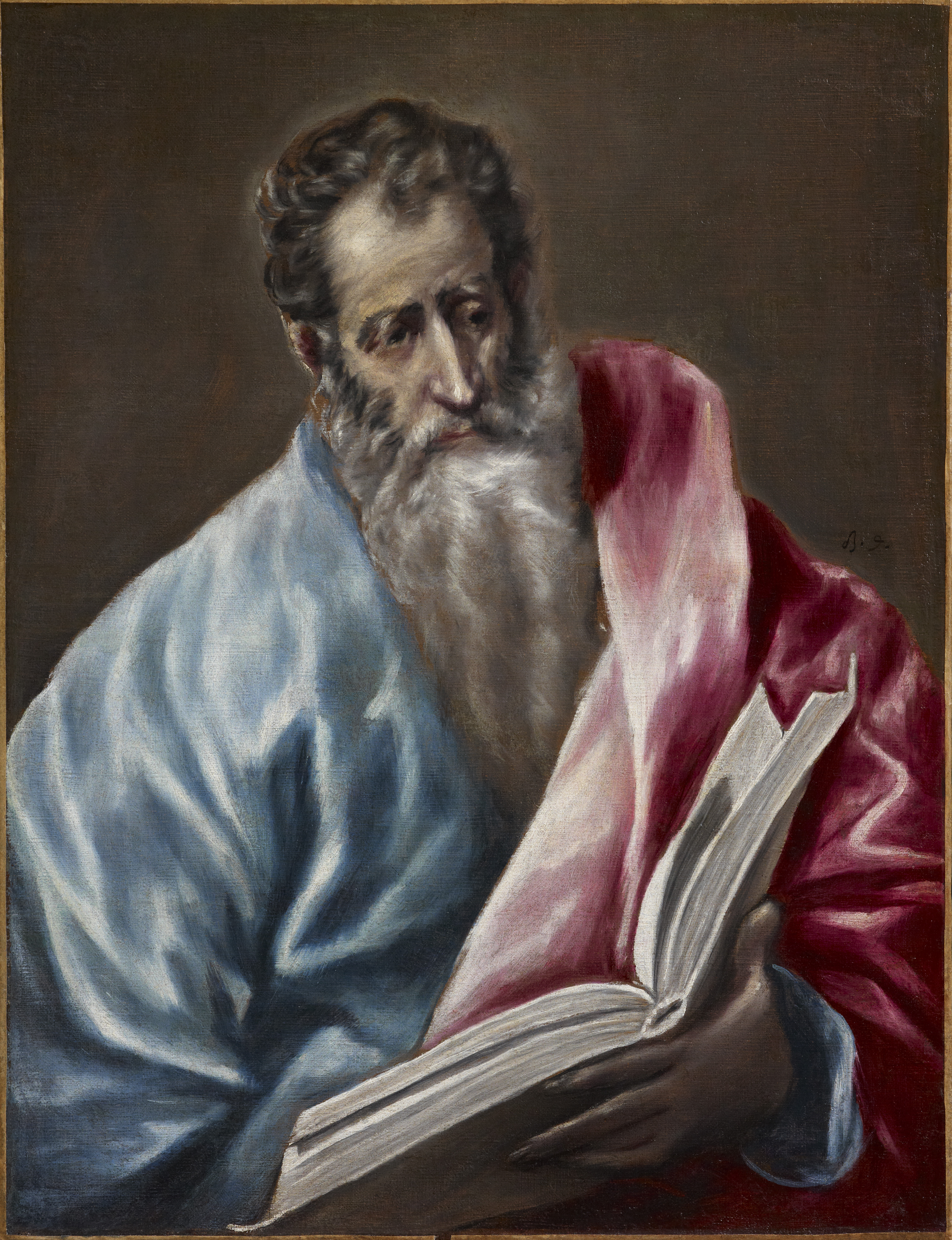

El Greco (1541–1614),

San Mateo Apóstol, circa 1610, 62 x 50, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Arthur

W. Herrington Collection, Indianapolis, Indiana

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 30 août 2006

Matthieu

Chers frères et soeurs,

En poursuivant la série

de portraits des douze Apôtres, que nous avons commencée il y a quelques

semaines, nous nous arrêtons aujourd'hui sur Matthieu. En vérité, décrire

entièrement sa figure est presque impossible, car les informations qui le

concernent sont peu nombreuses et fragmentaires. Cependant, ce que nous pouvons

faire n'est pas tant de retracer sa biographie, mais plutôt d'en établir le

profil que l'Evangile nous transmet.

Pour commencer, il est

toujours présent dans les listes des Douze choisis par Jésus (cf. Mt 10, 3; Mc

3, 18; Lc 6, 15; Ac 1, 13). Son nom juif signifie "don de Dieu". Le

premier Evangile canonique, qui porte son nom, nous le présente dans la liste

des Douze avec une qualification bien précise: "le publicain"

(Mt 10, 3). De cette façon, il est identifié avec l'homme assis à son bureau de

publicain, que Jésus appelle à sa suite: "Jésus, sortant de Capharnaüm,

vit un homme, du nom de Matthieu, assis à son bureau de publicain. Il lui

dit: "Suis-moi". L'homme se leva et le suivit" (Mt 9, 9).

Marc (cf. 2, 13-17) et Luc (cf. 5, 27-30) racontent eux aussi l'appel de

l'homme assis à son bureau de publicain, mais ils l'appellent "Levi".

Pour imaginer la scène décrite dans Mt 9, 9, il suffit de se rappeler le

magnifique tableau du Caravage, conservé ici, à Rome, dans l'église

Saint-Louis-des-Français. Dans les Evangiles, un détail biographique supplémentaire

apparaît: dans le passage qui précède immédiatement le récit de l'appel,

nous est rapporté un miracle accompli par Jésus à Capharnaüm (cf. Mt 9, 1-8; Mc

2, 1-12) et l'on mentionne la proximité de la mer de Galilée, c'est-à-dire du

Lac de Tibériade (cf. Mc 2, 13-14). On peut déduire de cela que Matthieu

exerçait la fonction de percepteur à Capharnaüm, ville située précisément

"au bord du lac" (Mt 4, 13), où Jésus était un hôte permanent dans la

maison de Pierre.

Sur la base de ces

simples constatations, qui apparaissent dans l'Evangile, nous pouvons effectuer

deux réflexions. La première est que Jésus accueille dans le groupe de ses

proches un homme qui, selon les conceptions en vigueur à l'époque en Israël,

était considéré comme un pécheur public. En effet, Matthieu manipulait non

seulement de l'argent considéré impur en raison de sa provenance de personnes

étrangères au peuple de Dieu, mais il collaborait également avec une autorité

étrangère odieusement avide, dont les impôts pouvaient également être déterminés

de manière arbitraire. C'est pour ces motifs que, plus d'une fois, les

Evangiles parlent à la fois de "publicains et pécheurs" (Mt 9, 10; Lc

15, 1), de "publicains et de prostituées" (Mt 21, 31). En outre, ils

voient chez les publicains un exemple de mesquinerie (cf. Mt 5, 46: ils

aiment seulement ceux qui les aiment) et ils mentionnent l'un d'eux, Zachée,

comme le "chef des collecteurs d'impôts et [...] quelqu'un de riche"

(Lc 19, 2), alors que l'opinion populaire les associait aux "voleurs,

injustes, adultères" (Lc 18, 11). Sur la base de ces éléments, un premier

fait saute aux yeux: Jésus n'exclut personne de son amitié. Au contraire,

alors qu'il se trouve à table dans la maison de Matthieu-Levi, en réponse à

ceux qui trouvaient scandaleux le fait qu'il fréquentât des compagnies peu

recommandables, il prononce cette déclaration importante: "Ce ne

sont pas les gens bien portants qui ont besoin du médecin, mais les malades. Je

suis venu appeler non pas les justes, mais les pécheurs" (Mc 2, 17).

La bonne annonce de

l'Evangile consiste précisément en cela: dans l'offrande de la grâce de

Dieu au pécheur! Ailleurs, dans la célèbre parabole du pharisien et du

publicain montés au Temple pour prier, Jésus indique même un publicain anonyme

comme exemple appréciable d'humble confiance dans la miséricorde divine:

alors que le pharisien se vante de sa propre perfection morale, "le

publicain... n'osait même pas lever les yeux vers le ciel, mais il se frappait

la poitrine en disant: "Mon Dieu, prends pitié du pécheur que je

suis!"". Et Jésus commente: "Quand ce dernier rentra chez

lui, c'est lui, je vous le déclare, qui était devenu juste. Qui s'élève sera

abaissé; qui s'abaisse sera élevé" (Lc 18, 13-14). Dans la figure de

Matthieu, les Evangiles nous proposent donc un véritable paradoxe: celui

qui est apparemment le plus éloigné de la sainteté peut même devenir un modèle

d'accueil de la miséricorde de Dieu et en laisser entrevoir les merveilleux

effets dans sa propre existence. A ce propos, saint Jean Chrysostome formule

une remarque significative: il observe que c'est seulement dans le récit

de certains appels qu'est mentionné le travail que les appelés effectuaient.

Pierre, André, Jacques et Jean sont appelés alors qu'ils pêchent, Matthieu

précisément alors qu'il lève l'impôt. Il s'agit de fonctions peu importantes -

commente Jean Chrysostome - "car il n'y a rien de plus détestable que le

percepteur d'impôt et rien de plus commun que la pêche" (In Matth.

Hom.: PL 57, 363). L'appel de Jésus parvient donc également à des

personnes de basse extraction sociale, alors qu'elles effectuent un travail

ordinaire.

Une autre réflexion, qui

apparaît dans le récit évangélique, est que Matthieu répond immédiatement à

l'appel de Jésus: "il se leva et le suivit". La concision de la

phrase met clairement en évidence la rapidité de Matthieu à répondre à l'appel.

Cela signifiait pour lui l'abandon de toute chose, en particulier de ce qui lui

garantissait une source de revenus sûrs, même si souvent injuste et peu

honorable. De toute évidence, Matthieu comprit qu'être proche de Jésus ne lui

permettait pas de poursuivre des activités désapprouvées par Dieu. On peut

facilement appliquer cela au présent: aujourd'hui aussi, il n'est pas

admissible de rester attachés à des choses incompatibles avec la

"sequela" de Jésus, comme c'est le cas des richesses malhonnêtes. A

un moment, Il dit sans détour: "Si tu veux être parfait, va, vends

ce que tu possèdes, donne-le aux pauvres, et tu auras un trésor dans les cieux.

Puis viens, suis-moi" (Mt 19, 21). C'est précisément ce que fit

Matthieu: il se leva et le suivit! Dans cette action de "se

lever", il est légitime de lire le détachement d'une situation de péché

et, en même temps, l'adhésion consciente à une nouvelle existence, honnête,

dans la communion avec Jésus.

Rappelons enfin que la

tradition de l'Eglise antique s'accorde de façon unanime à attribuer à Matthieu

la paternité du premier Evangile. Cela est déjà le cas à partir de Papia,

Evêque de Hiérapolis en Phrygie, autour de l'an 130. Il écrit:

"Matthieu recueillit les paroles (du Seigneur) en langue hébraïque, et

chacun les interpréta comme il le pouvait" (in Eusèbe de Césarée, Hist.

eccl. III, 39, 16). L'historien Eusèbe ajoute cette information:

"Matthieu, qui avait tout d'abord prêché parmi les juifs, lorsqu'il

décida de se rendre également auprès d'autres peuples, écrivit dans sa langue

maternelle l'Evangile qu'il avait annoncé; il chercha ainsi à remplacer par un

écrit, auprès de ceux dont il se séparait, ce que ces derniers perdaient avec

son départ" (Ibid., III, 24, 6). Nous ne possédons plus l'Evangile écrit

par Matthieu en hébreu ou en araméen, mais, dans l'Evangile grec que nous

possédons, nous continuons à entendre encore, d'une certaine façon, la voix

persuasive du publicain Matthieu qui, devenu Apôtre, continue à nous annoncer

la miséricorde salvatrice de Dieu et écoutons ce message de saint Matthieu,

méditons-le toujours à nouveau pour apprendre nous aussi à nous lever et à

suivre Jésus de façon décidée.

* * *

Je salue cordialement les

pèlerins francophones présents ce matin, en particulier les séminaristes de

l’archidiocèse de Lyon, accompagnés par le Cardinal Philippe Barbarin, ainsi

que le pèlerinage œcuménique d’Athènes. Puisse la figure de l’Apôtre Matthieu

vous inviter à devenir toujours plus des témoins de la miséricorde du Seigneur,

en vous donnant tout entiers pour son service et pour celui de vos frères !

© Copyright 2006 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

SOURCE : http://w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/fr/audiences/2006/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20060830.html

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), L’Apôtre

Matthieu, circa 1618, 83,5 x 72,5, Rubenshuis,

Fonds Generet, 2016, King Baudouin Foundation

SAINT MATHIEU, APÔTRE

Saint Mathieu eut deux

noms, Mathieu et Lévi. Mathieu veut dire don hâtif, ou bien donneur de conseil.

Ou Mathieu vient de magnus, grand, et Theos, Dieu, comme si on disait grand à

Dieu, ou bien de main et de Theos, main de Dieu. En effet il fut un don hâtif

puisque sa conversion fut prompte. Il donna des conseils par ses prédications

salutaires. II fut grand devant Dieu par la perfection de sa vie, et il fut la

main dont Dieu se servit pour écrire son Evangile. Lévi veut dire, enlevé, mis,

ajouté, apposé. Il fut enlevé à son bureau d'impôts, mis au nombre des apôtres,

ajouté à la société des Evangélistes, et apposé au catalogue des martyrs.

Saint Mathieu, apôtre,

prêchait. en Ethiopie (Honorius d'Autun.) dans une ville nommée Nadaber, où il

trouva deux mages Zaroïs et Arphaxus qui ensorcelaient les hommes par de tels

artifices que tous ceux qu'ils voulaient paraissaient avoir perdu la santé avec

l’usage de leurs membres. Ce qui enfla tellement leur orgueil qu'ils se

faisaient adorer comme des dieux par les hommes. L'apôtre Mathieu étant entré

dans cette ville où il reçut l’hospitalité de l’eunuque de la reine de Candace

baptisé par Philippe (Actes, vin), découvrait si adroitement les prestiges de

ces mages qu'il changeait eu bien le mal qu'ils faisaient aux hommes. Or,

l’eunuque, ayant demandé à saint Mathieu comment il se faisait qu'il parlât et comprit

tant de langages différents, Mathieu lui exposa qu'après la descente du

Saint-Esprit, il s'était trouvé posséder la science de toutes les langues, afin

que, comme ceux qui avaient essayé par orgueil d'élever une tour jusqu'au ciel,

s'étaient vus forces d'interrompre leurs travaux par la confusion des langues,

de même les apôtres, par la connaissance de tous les idiomes, construisissent,

non plus avec des pierres, mais avec des vertus, une tour au moyen de laquelle

tous ceux qui croiraient pussent monter au ciel. Alors quelqu'un vint annoncer

l’arrivée des deux mages accompagnés de dragons qui, en vomissant un feu de

soufre par la gueule et par les naseaux, tuaient, tous les hommes. L'apôtre, se

munissant du signe de la croix, alla avec assurance vers eux. Les dragons ne

l’eurent pas plutôt aperçu qu'ils vinrent à l’instant s'endormir à ses pieds.

Alors saint Mathieu dit aux mages : « Où donc est votre art ? Eveillez-les, si

vous pouvez : quant à moi, si je n'avais prié le Seigneur, j'aurais de suite tourné

contre vous ce que vous aviez la pensée de me faire. » Or, comme le peuple

s'était rassemblé, Mathieu commanda de par le nom de J.-C. aux dragons de

s'éloigner, et ils s'en allèrent de suite sans nuire à personne. Ensuite saint

Mathieu commença à adresser un grand discours au peuple sur la gloire da

paradis terrestre, avançant qu'il était plus élevé que toutes les montagnes et

voisin du ciel, qu'il n'Y avait là ni épines ni ronces, que les lys ni les

roses ne s'y flétrissaient, que la vieillesse n'y existait pas, mais que les

hommes y restaient constamment jeunes, que les concerts des anges s'y faisaient

entendre, et que quand on appelait les oiseaux, ils obéissaient tout de suite.

Il ajouta que l’homme avait été chassé de ce paradis terrestre, mais que par la

naissance de J.-C. il avait été rappelé au Paradis du ciel. Pendant qu'il

parlait au peuple, tout à coup s'éleva mi grand tumulte ; car l’on pleurait la

mort du fils du roi. Comme les magiciens ne pouvaient le ressusciter, ils

persuadaient au roi qu'il avait été enlevé en la compagnie des dieux et qu'il

fallait en conséquence lui élever une statue et un temple. Mais l’eunuque, dont

il a été parlé plus haut, fit garder les magiciens et manda l’apôtre qui, après

avoir fait une prière, ressuscita à l’instant le jeune homme (Bréviaire.).

Alors le roi, qui se nommait Egippus, ayant vu cela, envoya publier dans toutes

ses provinces : « Venez voir un Dieu caché sous les traits d'un homme. » On

vint donc avec des couronnes d'or et différentes victimes dans l’intention

d'offrir des sacrifices à Mathieu, mais celui-ci les en empêcha en disant : « O

hommes, que faites-vous? Je ne suis pas un Dieu, je suis seulement le serviteur

de N.-S. J.-C. » Alors avec l’argent et l’or qu'ils avaient apportés avec eux,

ces gens bâtirent, par l’ordre de l’apôtre, une grande église qu'ils

terminèrent en trente jours; et dans laquelle saint Mathieu siégea trente-trois

ans; il convertit l’Egypte toute entière; le roi Egippus, avec sa femme et tout

le peuple, se fit baptiser. Iphigénie, la fille du roi, qui avait été consacrée

à Dieu, fut mise à la tête de plus de deux cents vierges.

Après quoi Hirtacus

succéda au roi ; il s'éprit d'Iphigénie et promit à l’apôtre la moitié de son

royaume s'il la faisait consentir à accepter sa main. L'apôtre lui dit de venir

le dimanche à l’église comme son prédécesseur, pour entendre, en présence

d'Iphigénie et des autres vierges, quels avantages procurent les mariages

légitimes. Le roi s'empressa de venir avec joie, dans la pensée que l’apôtre voudrait

conseiller le mariage à Iphigénie. Quand les vierges et tout le peuple furent

assemblés, saint Mathieu parla longtemps des avantages du mariage et mérita les

éloges du roi, qui croyait que l’apôtre parlait ainsi afin d'engager la vierge

à se marier. Ensuite, ayant demandé qu'on fit silence, il reprit son discours

en disant « Puisque le mariage est une bonne chose, quand on en conserve

inviolablement les promesses, sachez-le bien, sous qui êtes ici présents, que

si un esclave avait la présomption d'enlever l’épouse du roi, non seulement il

encourrait la colère du prince, mais, il mériterait encore la mort, non parce

qu'il serait convaincu de s'être marié, mais parce qu'en prenant l’épouse de

son seigneur, il aurait outragé son prince dans sa femme. Il en serait de même

de vous, ô roi; vous savez qu'Iphigénie est devenue l’épouse du roi éternel, et

qu'elle est consacrée par le voile sacré; comment donc pourrez-vous prendre

l’épouse de plus puissant que vous et vous unir à elle par le mariage ? » Quand

le roi eut entendu cela, il se retira furieux de colère (Bréviaire.). Mais

l’apôtre intrépide et constant exhorta tout le monde à la patience et à la

constance; ensuite il bénit Iphigénie, qui, tremblante de peur, s'était jetée à

genoux devant lui avec les autres vierges. Or, quand la messe solennelle fut

achevée, le roi envoya. un bourreau qui tua Mathieu en prières debout devant

l’autel et les bras étendus vers le ciel. Le bourreau le frappa par derrière et

en fit ainsi un martyr. A cette nouvelle, le peuple courut, au palais du roi

pour y mettre le feu, et ce fut à peine si les prêtres et les diacres purent le

contenir; puis on célébra avec joie le martyre de l’apôtre. Or, comme le roi ne

pouvait par aucun moyen faire changer Iphigénie de résolution, malgré les

instances des dames qui lui furent envoyées, et celles des magiciens, il fit

entourer sa demeure tout entière d'un feu immense afin de la brûler avec les

autres vierges. Mais l’apôtre leur apparut, et il repoussa l’incendie de leur

maison. Ce feu en jaillissant se jeta sur le palais du roi qu'il consuma en

entier; le roi seul parvint avec peine à s'échapper avec son fils unique.

Aussitôt après ce fils fut saisi par le démon, et courut au tombeau de l’apôtre

en confessant les crimes de son père, qui lui-même fut attaqué d'une lèpre

affreuse ; et comme il ne put être guéri, il se tua de sa propre main en se

perçant avec une épée. Alors le peuple établit roi le frère d'Iphigénie qui

avait été baptisé par l’apôtre. Il régna soixante-dix ans, et après s'être

substitué son fils, il procura de l’accroissement au culte chrétien, et remplit

toute la province de l’Ethiopie d'églises en l’honneur de J.-C. Pour Zaroës et

Arphaxat, dès le jour ou l’apôtre ressuscita le fils du roi, ils s'enfuirent en

Perse; mais saint Simon et saint Jude les y vainquirent.

Dans saint Mathieu, il

faut considérer quatre vertus : 1° La promptitude de son obéissance : car à

l’instant où J.-C. l’appela, il quitta immédiatement son bureau, et sans

craindre ses maîtres, il laissa les états d'impôts inachevés pour s'attacher

entièrement à J.-C. Cette promptitude dans son obéissance a donné à

quelques-uns l’occasion de tomber en erreur, selon que le rapporte saint Jérôme

dans son commentaire sur cet endroit de l’Evangile : « Porphyre, dit-il, et

l’empereur Julien accusent l’historien de mensonge et de maladresse, comme

aussi il taxe de folie la conduite de ceux qui se mirent aussitôt à la suite du

Sauveur, comme ils auraient fait à l’égard de n'importe quel homme qu'ils

auraient suivi sans motifs. J.-C. opéra auparavant de si grands prodiges et de

si grands miracles qu'il n'y a pas de doute que les apôtres ne les aient vus

avant de croire. Certainement l’éclat même et la majesté de la puissance divine

qui était cachée, et qui brillait sur sa face humaine, pouvait au premier

aspect attirer à soi ceux qui le voyaient. Car si on attribue à l’aimant la

force d'attirer des anneaux et de la paille, à combien plus forte raison le

maître de toutes les créatures pouvait-il attirer à soi ceux qu'il voulait. »

2° Considérons ses largesses et sa libéralité, puisqu'il donna de suite au

Sauveur un grand repas dans sa maison. Or, ce repas ne fut pas grand par cela

seul qu'il fut splendide, mais il le fut : a) par la résolution qui lui fit

recevoir J.-C. avec grande affection et désir; b) par le mystère dont il fut la

signification; mystère que la glose sur saint Luc explique en disant : « Celui

qui reçoit J.-C. dans l’intérieur de sa maison est rempli d'un torrent de

délices et de volupté » ; c) par les instructions que J.-C. ne cessa d'y

adresser comme, par exemple : « Je veux la miséricorde et non le sacrifice » et

encore : « Ce ne sont pas ceux qui se portent bien qui ont besoin de médecins;

» d) par la qualité des invités, qui furent de grands personnages, comme J.-C.

et ses disciples. 3° Son humilité qui parut en deux circonstances : la première

en ce qu'il avoua être un publicain. Les autres évangélistes, dit là glose, par

un sentiment de pudeur, et par respect pour saint Matthieu, ne lui donnent pas

son nom ordinaire. Mais, d'après ce qui est écrit du Juste, qu'il est son

propre accusateur, il se nomme lui-même Mathieu et publicain, pour montrer à

celui qui se convertit qu'il ne doit jamais désespérer de son salut, car de

publicain il fut fait de suite apôtre et évangéliste. La seconde, en ce qu'il

supporta avec patience les injures qui lui furent adressées. En effet quand les

pharisiens murmuraient de ce que J.-C. eût été loger chez un pécheur, il aurait

pu à bon droit leur répondre et leur dire : « C'est vous plutôt: qui êtes des

misérables et des pécheurs puisque vous refusez les secours du médecin en vous

croyant justes : mais moi je ne puis plus être désormais appelé pécheur, quand

j'ai recours au médecin du salut et que je lui découvre mes plaies. »

4° L'honneur que reçoit

dans l’église son évangile qui se lit plus souvent que celui des autres

évangélistes comme les psaumes de David et les épîtres de saint Paul, qu'on lit

plus fréquemment que les autres livres de la sainte Ecriture. En voici la

raison : Selon saint Jacques, il y a trois sortes de péchés, savoir: l’orgueil,

la luxure et l’avarice. Saul, ainsi appelé de Saül le plus orgueilleux des

rois, commit le péché d'orgueil quand il persécuta l’église au delà de toute

mesure. David se livra au péché de luxure en commettant un adultère et en

faisant tuer par suite de ce premier crime Urie le plus fidèle de ses soldats.

Mathieu commit le péché, d'avarice, eu se livrant à des gains honteux, car il

était douanier. La douane, dit Isidore, est un lieu sur un port de mer où sont

reçues les marchandises des vaisseaux et les gages des matelots. Telos, en

grec, dit Bède, veut dire impôt. Or, bien que Saul, David et Mathieu eussent

été pécheurs, cependant leur pénitence fut si agréable que non seulement (85)

le Seigneur leur pardonna leurs fautes, mais qu'il les combla de toutes sortes

de bienfaits : car dit plus cruel persécuteur, il fit le plus fidèle

prédicateur; d'un adultère et d'un homicide il fit un prophète et un psalmiste;

d'un homme avide de richesses et d'un avare, il fit un apôtre et un

évangéliste. C'est pour cela que les paroles de ces trois personnages se lisent

si fréquemment : afin que personne ne désespère de son pardon, s'il veut se

convertir, eu considérant la grandeur de la race dans ceux qui ont été de si

grands coupables. D'après saint Ambroise, dans la conversion de saint Mathieu

il y a certaines particularités à considérer du côté du médecin, du côté de

l’infirme qui est guéri, et du côté de la manière de guérir. Dans le médecin il

y a eu trois qualités, savoir : la sagesse qui connut, le mal dans sa racine,

la bonté qui employa les remèdes, et la puissance qui changea saint. Mathieu si

subitement. Saint Ambroise parle ainsi de ces trois qualités dans la personne

de saint Mathieu lui-même : « Celui-là peut enlever la douleur de mon cœur et

la pâleur de mon âme qui connaît ce qui est caché. » Voici ce qui a rapport à

la sagesse. « J'ai trouvé le médecin qui habite les cieux et qui sème les

remèdes, sur la terre. » Ceci se rapporte à la bonté. « Celui-là seul peut

guérir mes blessures qui ne s'en connaît pas. » Ceci s'applique à la puissance.

Or, dans cet infirme qui est guéri, c'est-à-dire dans saint Mathieu, il y a

trois circonstances à considérer; toujours d'après saint Ambroise. Il se

dépouilla parfaitement de la maladie, il resta agréable à celui qui le

guérissait, et quand il eut reçu la santé, toujours il se conserva intact.

C'est ce qui lui fait dire : « Déjà je ne suis plus ce publicain, je ne suis

plus Lévi, je me suis dépouillé de Lévi, quand j'ai eu revêtu J.-C. », ce qui

se rapporte à la première considération. « Je hais ma race, je change de vie,

je marche seulement à votre suite, mon Seigneur Jésus, vous qui guérissez mes

plaies. » Ceci, a trait à la deuxième considération. «Quel est celui qui me

séparera de la charité de Dieu, laquelle réside en moi? Sera-ce la tribulation,

la détresse, la faim? » C'est ce qui s'applique à la troisième. D'après saint

Ambroise le mode de guérison fut triple : 1° J.-C. le lia avec des chaînes ; 2°

il le cautérisa; 3° il le débarrassa de toutes ses pourritures. Ce qui fait

dire à saint Ambroise dans la personne de saint Mathieu : « J'ai été lié avec

les clous de la croix et dans les douces entraves de la charité ; enlevez, ô

Jésus! la pourriture de mes péchés tandis que vous me tenez enchaîné dans les

liens de la charité ; tranchez tout ce que vous trouverez de vicieux. » Premier

mode. « Votre commandement, sera pour moi un caustique que je tiendrai sur moi,

et si le caustique de votre commandement brûle, toutefois il ne brûle que les

pourritures de la chair; de peur, que la contagion ne se glisse comme un virus

; et quand bien même le médicament tourmenterait, il ne laisse pas d'enlever

l’ulcère. » Deuxième mode. « Venez de. suite, Seigneur, tranchez les passions

cachées et profondes. Ouvrez vite la blessure, de peur que le mal ne s'aggrave;

purifiez tout ce qui est fétide dans un bain salutaire. » Troisième mode. —

L'évangile de, saint Mathieu fut trouvé écrit de sa main l’an du Seigneur 500,

avec les os de saint Barnabé. Cet apôtre portait cet évangile avec lui et le

posait sur les infirmes qui tous étaient guéris, tant par la foi de Barnabé que

par les mérites de Mathieu.

La Légende dorée de

Jacques de Voragine nouvellement traduite en français avec introduction,

notices, notes et recherches sur les sources par l'abbé J.-B. M. Roze, chanoine

honoraire de la Cathédrale d'Amiens, Édouard Rouveyre, éditeur, 76, rue de

Seine, 76, Paris mdccccii

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/voragine/tome03/141.htm

Theodoric

of Prague, Matthew the Apostle, circa 1360, collection of the National

Gallery in Prague

Also

known as

Levi

Apostle of Ethiopia

Matthew the Evangelist

21

September (Western calendar)

16

November (Eastern calendar)

6 May (translation

of his relics)

Profile

Son of Alphaeus, he lived

at Capenaum on Lake Genesareth. He was a Roman tax

collector, a position equated with collaboration with the enemy by those

from whom he collected taxes. Jesus’ contemporaries were surprised to see the

Christ with a traitor, but Jesus explained that he had come “not to call

the just, but sinners.”

Matthew’s Gospel is

given pride of place in the canon of

the New Testament, and was written to

convince Jewish readers that their anticipated Messiah had come in the person

of Jesus. He preached among

the Jews for 15 years; his audiences may have included the Jewish enclave

in Ethiopia,

and places in the East.

Worshipful

Company of Tax Advisers

Washington,

DC, archdiocese of

in Italy

angel holding

a pen or inkwell

man holding money

money box

winged man

young man

Storefront

medals and pendants –

( part

1 ) ( part

2 ) ( part

3 ) ( part

4 ) ( part

5 ) ( part

6 ) ( part

7 ) ( part

8 ) ( part

9 ) ( part

10 ) ( part

11 ) ( part

12 ) ( part

13 ) ( part

14 ) ( part

15 ) ( part

16 ) ( part

17 ) ( part

18 ) ( part

19 ) ( part

20 ) ( part

21 ) ( part

22 ) ( part

23 ) ( part

24 ) ( part

25 ) ( part

26 ) ( part

27 )

rosaries – ( part

1 ) ( part

2 )

Additional

Information

A

Garner of Saints, by Allen Banks Hinds, M.A.

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Catholic

Encyclopedia, by E. Jacquier

Encyclopaedia

Britannica, 1911 edition

Lives

of Illustrious Men, by Saint Jerome

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Francis

Xavier Weninger

Meditations

on the Gospels for Every Day in the Year, by Father Pierre

Médaille

New

Catholic Dictionary: Gospel of Saint Matthew

New

Catholic Dictionary: Saint Matthew

Pope

Benedict XVI: General Audience, 30 August 2006

Roman

Martyrology, 1914 edition

Saints

and Saintly Dominicans, by Blessed Hyacinthe-Marie

Cormier, O.P.

Saints

of the Canon, by Monsignor John

T McMahon

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

Catholic Herald: A patron saint for bankers and accountants

Christian

Biographies, by James E Keifer

Did

Matthew Invent a Prophecy about Jesus?, by Jimmy Akin

Gospel According

to Matthew New American Bible

audio

Gospel According to Matthew – New English Bible

images

video

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites

en français

Abbé

Christian-Philippe Chanut

fonti

in italiano

nettsteder

i norsk

Readings

“Jesus saw a man called

Matthew sitting at the tax office, and he said to him: Follow me.” Jesus saw

Matthew, not merely in the usual sense, but more significantly with his

merciful understanding of men.” He saw the tax collector and, because he saw

him through the eyes of mercy and chose him, he said to him: “Follow me.” This

following meant imitating the pattern of his life – not just walking after him.

Saint John tells us: “Whoever says he abides in Christ ought to walk in the

same way in which he walked.” “And he rose and followed him.” There is no

reason for surprise that the tax collector abandoned earthly wealth as soon as

the Lord commanded him. Nor should one be amazed that neglecting his wealth, he

joined a band of men whose leader had, on Matthew’s assessment, no riches at

all. Our Lord summoned Matthew by speaking to him in words. By an invisible,

interior impulse flooding his mind with the light of grace, he instructed him

to walk in his footsteps. In this way Matthew could understand that Christ, who

was summoning him away from earthly possessions, had incorruptible treasures of

heaven in his gift. – from a homily by Saint Bede the

Venerable

MLA

Citation

“Saint Matthew the

Apostle“. CatholicSaints.Info. 7 June 2023. Web. 23 September 2023.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-matthew-the-apostle/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-matthew-the-apostle/

Giovanni Girolamo Savoldo (1480–1548),

Matthew the Apostle and the Angel,

1530, 93,4 x 124,5, Metropolitan Museum of Art

St. Matthew

Apostle and evangelist.

The name Matthew is

derived from the Hebrew Mattija,

being shortened to Mattai in post-Biblical Hebrew.

In Greek it is sometimes spelled Maththaios, BD, and sometimes Matthaios,

CEKL, but grammarians do not agree as to which of the two spellings is the

original.

Matthew is spoken of five

times in the New

Testament; first in Matthew

9:9, when called by Jesus to

follow Him, and then four times in the list of the Apostles,

where he is mentioned in the seventh (Luke

6:15, and Mark

3:18), and again in the eighth place (Matthew

10:3, and Acts

1:13). The man designated in Matthew

9:9, as "sitting in the custom house", and "named

Matthew" is the same as Levi, recorded in Mark

2:14, and Luke

5:27, as "sitting at the receipt of custom". The account in the

three Synoptics is

identical, the vocation of

Matthew-Levi being alluded to in the same terms. Hence Levi was the original

name of the man who was subsequently called Matthew; the Maththaios

legomenos of Matthew

9:9, would indicate this.

The fact of one man

having two names is of frequent occurrence among the Jews.

It is true that

the same person usually

bears a Hebrew

name such as "Shaoul" and a Greek name, Paulos.

However, we have also examples of individuals with

two Hebrew

names as, for instance, Joseph-Caiaphas, Simon-Cephas,

etc. It is probable that Mattija, "gift of Iaveh", was the name

conferred upon the tax-gatherer by Jesus

Christ when He called him

to the Apostolate,

and by it he was thenceforth known among his Christian brethren,

Levi being his original name.

Matthew, the son of

Alpheus (Mark

2:14) was a Galilean,

although Eusebius informs

us that he was a Syrian.

As tax-gatherer at Capharnaum,

he collected custom duties for Herod

Antipas, and, although a Jew,

was despised by the Pharisees,

who hated all publicans.

When summoned by Jesus,

Matthew arose and followed Him and tendered Him a feast in his house, where

tax-gatherers and sinners sat

at table with Christ and

His disciples.

This drew forth a protest from the Pharisees whom Jesus rebuked

in these consoling words: "I came not to call the just, but sinners".

No further allusion is

made to Matthew in the Gospels,

except in the list of the Apostles.

As a disciple and

an Apostle he

thenceforth followed Christ,

accompanying Him up to the time of

His Passion and,

in Galilee,

was one of the witnesses of

His Resurrection.

He was also amongst the Apostles who

were present at the Ascension,

and afterwards withdrew to an upper chamber, in Jerusalem, praying in

union with Mary,

the Mother of Jesus,

and with his brethren (Acts

1:10 and 1:14).

Of Matthew's subsequent

career we have only inaccurate or legendary data. St.

Irenæus tells us that Matthew preached the Gospel among

the Hebrews, St.

Clement of Alexandria claiming that he did this for fifteen years,

and Eusebius maintains

that, before going into other countries, he gave them his Gospel in

the mother

tongue. Ancient writers are not as one as to the countries evangelized by

Matthew, but almost all mention Ethiopia to the south of the Caspian Sea

(not Ethiopia in Africa),

and some Persia and

the kingdom of the Parthians, Macedonia,

and Syria.

According to Heracleon,

who is quoted by Clement

of Alexandria, Matthew did not die a martyr,

but this opinion conflicts with all other ancient testimony. Let us add,

however, that the account of his martyrdom in

the apocryphal Greek

writings entitled "Martyrium S. Matthæi in Ponto" and published by

Bonnet, "Acta apostolorum apocrypha" (Leipzig, 1898), is absolutely

devoid of historic value. Lipsius holds

that this "Martyrium S. Matthæi", which contains traces of Gnosticism,

must have been published in the third century.

There is a disagreement

as to the place of St. Matthew's martyrdom and

the kind of torture inflicted on him, therefore it is not known whether

he was burned, stoned,

or beheaded. The Roman Martyrology simply

says: "S. Matthæi, qui in Æthiopia prædicans martyrium passus est".

Various writings that are

now considered apocryphal,

have been attributed to St. Matthew. In the "Evangelia

apocrypha" (Leipzig, 1876), Tischendorf reproduced a Latin document

entitled: "De Ortu beatæ Mariæ et infantia Salvatoris", supposedly

written in Hebrew by St.

Matthew the Evangelist,

and translated into Latin by Jerome,

the priest.

It is an abridged adaptation of the "Protoevangelium" of St. James,

which was a Greek apocryphal of

the second century. This pseudo-Matthew dates from the middle or the end of the

sixth century.

The Latin

Church celebrates the feast of St.

Matthew on 21 September, and the Greek

Church on 16 November. St. Matthew is represented under the symbol of

a winged man,

carrying in his hand a lance as a characteristic emblem.

Jacquier, Jacque Eugène. "St. Matthew." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 10. New York: Robert Appleton

Company, 1911.21 Sept. 2015

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Ernie Stefanik.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. October 1, 1911. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2021 by Kevin Knight. Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10056b.htm

Gospel of St. Matthew

Canonicity

The earliest Christian communities

looked upon the books of the Old

Testament as Sacred

Scripture, and read them at their religious assemblies. That

the Gospels, which contained the words of Christ and the

narrative of His life, soon enjoyed the same authority as the Old

Testament, is made clear by Hegesippus (Eusebius, Church

History IV.22.3), who tells us that in every city the Christians were faithful to

the teachings of the law,

the prophets,

and the Lord. A book was acknowledged as canonical when

the Church regarded

it as Apostolic, and had it read at her assemblies. Hence, to establish

the canonicity of the Gospel according to St. Matthew,

we must investigate primitive Christian

tradition for the use that was made of this document, and for

indications proving that it was regarded as Scripture in

the same manner as the Books of the Old

Testament.

The first traces that we

find of it are not indubitable, because post-Apostolic writers quoted the texts

with a certain freedom, and principally because it is difficult to

say whether the passages thus quoted were taken from

oral tradition or from a written Gospel. The first Christian document

whose date can be fixed with comparative certainty (95-98),

is the Epistle of St. Clement to the Corinthians. It

contains sayings of the Lord which closely resemble those recorded in

the First Gospel (Clement, 16:17 = Matthew

11:29; Clem., 24:5 = Matthew

13:3), but it is possible that they are derived

from Apostolic preaching, as, in chapter xiii, 2, we find a

mixture of sentences from Matthew, Luke, and an unknown

source. Again, we note a similar commingling of Evangelical texts

elsewhere in the same Epistle

of Clement, in the Doctrine of the Twelve

Apostles, in the Epistle of Polycarp, and in Clement

of Alexandria. Whether these these texts were thus combined in

oral tradition or emanated from a collection of Christ's utterances,

we are unable to say.

The Epistles of St.

Ignatius (martyred 110-17)

contain no literal quotation from the Holy Books;

nevertheless, St. Ignatius borrowed expressions and

some sentences from Matthew ("Ad Polyc.", 2:2

= Matthew

10:16; "Ephesians", 14:2 = Matthew

12:33, etc.). In his "Epistle to the Philadelphians" (v, 12), he

speaks of the Gospel in which he takes refuge as in the Flesh

of Jesus;

consequently, he had an evangelical collection which he regarded

as Sacred Writ, and we cannot doubt that

the Gospel of St. Matthew formed part of it.

In

the Epistle of Polycarp (110-17), we find various passages

from St. Matthew quoted literally (12:3 = Matthew

5:44; 7:2 = Matthew

26:41, etc.).

The Doctrine of

the Twelve

Apostles (Didache) contains sixty-six passages that recall

the Gospel of Matthew; some of them are literal quotations (8:2

= Matthew

6:7-13; 7:1 = Matthew

28:19; 11:7 = Matthew

12:31, etc.).

In the

so-called Epistle of Barnabas (117-30), we find a passage

from St. Matthew (xxii, 14), introduced by

the scriptural formula, os gegraptai, which proves that

the author considered the Gospel of Matthew equal in point

of authority to the writings of the Old

Testament.

The "Shepherd of

Hermas" has several passages which bear close resemblance to passages

of Matthew, but not a single literal quotation from it.

In his

"Dialogue" (xcix, 8), St.

Justin quotes, almost literally, the prayer of Christ in

the Garden of Olives, in Matthew

26:39-40.

A great number of

passages in the writings of St.

Justin recall the Gospel of Matthew,

and prove that he ranked it among the Memoirs of

the Apostles which, he said, were called Gospels (I Apol.,

lxvi), were read in the services of the Church (ibid., i),

and were consequently regarded as Scripture.

In his Plea

for the Christians 12.11, Athenagoras (177)

quotes almost literally sentences taken from the Sermon on

the Mount (Matthew

5:44).

Theophilus

of Antioch (Ad Autol., III, xiii-xiv) quotes a passage from Matthew (v,

28, 32), and, according to St.

Jerome (In Matt. Prol.), wrote a commentary on

the Gospel of St. Matthew.

We find in

the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs--drawn up,

according to some critics, about the middle of the second

century--numerous passages that closely resemble

the Gospel of Matthew (Test. Gad, 5:3; 6:6; 5:7 = Matthew

18:15, 35; Test. Joshua 1:5, 6 = Matthew

25:35-36, etc.), but Dr. Charles maintains that

the Testaments were written in Hebrew in the first century

before Jesus

Christ, and translated into Greek towards the middle of the same

century. In this event, the Gospel of Matthew would depend

upon the Testaments and not the Testaments upon

the Gospel. The question is not yet settled, but it seems to us that there

is a greater probability that the Testaments, at least in

their Greek version, are of later date than

the Gospel of Matthew, they certainly received

numerous Christian additions.

The Greek text of

the Clementine Homilies contains some quotations

from Matthew (Hom. 3:52 = Matthew

15:13); in Hom. xviii, 15, the quotation from Matthew

13:35, is literal.

Passages which suggest

the Gospel of Matthew might be quoted from heretical writings

of the second century and from apocryphal gospels--the Gospel of Peter,

the Protoevangelium of James, etc., in which the narratives, to

a considerable extent, are derived from the Gospel of Matthew.

Tatian incorporated

the Gospel of Matthew in his "Diatesseron"; we

shall quote below the testimonies of Papias and St. Irenæus. For

the latter, the Gospel of Matthew, from which he quotes numerous

passages, was one of the four that constituted the

quadriform Gospel dominated by a single spirit.

Tertullian (Adv. Marc.,

IV, ii) asserts, that the "Instrumentum evangelicum" was composed by

the Apostles,

and mentions Matthew as the author of a Gospel (De

carne Christi, xii).

Clement

of Alexandria (Stromata III.13)

speaks of the four Gospels that have been transmitted, and quotes

over three hundred passages from the Gospel of Matthew, which he

introduces by the formula, en de to kata Matthaion euaggelio or

by phesin ho kurios.

It is unnecessary to

pursue our inquiry further. About the middle of the third century,

the Gospel of Matthew was received by the whole Christian

Church as a Divinely inspired document, and consequently

as canonical. The testimony of Origen ("In

Matt.", quoted by Eusebius, Church

History III.25.4), of Eusebius (op.

cit., III, xxiv, 5; xxv, 1), and of St.

Jerome ("De Viris Ill.", iii, "Prolog.

in Matt.,") are explicit in this respect. It might be added that

this Gospel is found in the most ancient versions:

Old Latin, Syriac, and Egyptian.

Finally, it stands at the head of the Books of the New

Testament in the Canon of the Council of Laodicea (363)

and in that of St. Athanasius (326-73), and very probably it was in

the last part of the Muratorian Canon. Furthermore,

the canonicity of the Gospel of St. Matthew is

accepted by the entire Christian

world.

Authenticity of the First Gospel

The question

of authenticity assumes an altogether special aspect in regard to the

First Gospel. The early

Christian writers assert that St. Matthew wrote

a Gospel in Hebrew; this Hebrew Gospel has,

however, entirely disappeared, and the Gospel which we have, and from

which ecclesiastical writers

borrow quotations as coming from the Gospel of Matthew, is

in Greek. What connection is there between