Exaltation

de la Sainte Croix, Les Très Riches Heures du duc de

Berry (musée Condé, Chantilly).

Exaltation de la sainte

Croix

Fête de la Croix

glorieuse

Quand, à Jérusalem, la

reine sainte Hélène, mère

de l'empereur Constantin, fut convaincue d'avoir retrouvé sur le Mont Calvaire

la vraie croix du Christ, elle fit édifier en ce lieu, avec l'aide de son fils,

une basilique englobant le Calvaire et le Saint Sépulcre. Cette basilique qui

eut pour nom "Résurrection" fut consacrée un 14 septembre. Par la

suite, ce jour fut choisi pour célébrer une fête qu'on appela "Exaltation

de la précieuse et vivifiante Croix" parce que son rite principal

consistait en une ostension solennelle d'une relique de la vraie croix. Ce

geste manifestait devant tous que la Croix est glorieuse parce qu'en elle la

mort est vaincue par la vie. La fête se répandit à Constantinople où elle

connut un éclat nouveau à partir du VIIe siècle parce que les Perses infidèles

s'étaient emparés de Jérusalem et avaient emporté dans leur pays la vraie Croix

comme trophée de victoire. L'empereur Heraclius alla la reprendre et ramena

triomphalement à Constantinople le symbole de la victoire du Christ sur la

mort. Progressivement la fête fut célébrée dans toute l'Église et des parcelles

de cette relique furent distribuées à travers le monde chrétien.

"Ô Croix mon refuge,

ô Croix mon chemin et ma force, ô Croix étendard imprenable, ô Croix arme

invincible. La Croix repousse tout mal, la Croix met les ténèbres en fuite; par

cette Croix je parcourrai le chemin qui mène à Dieu."

(Invocation

à la Croix par Saint Odilon - Église catholique en France)

Fête de la Croix

glorieuse. Au lendemain de la dédicace de la basilique de la Résurrection,

érigée sur le tombeau du Christ, la sainte Croix est exaltée et honorée, comme

le trophée de sa victoire pascale et le signe qui apparaîtra dans le ciel,

annonçant déjà d’avance à tous son glorieux avènement.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1850/Exaltation-de-la-sainte-Croix.html

Tableau-reliquaire

de la Vraie Croix et couvercle à glissière. Reliquaire de Byzance, xie siècle, musée du Louvre.

Exaltation de la Sainte

Croix

627

Sous le règne de

l'empereur Héraclius Ier, les Perses s'emparèrent de Jérusalem et y enlevèrent

la principale partie de la vraie Croix de Notre-Seigneur, que sainte Hélène,

mère de l'empereur Constantin, y avait laissée. Héraclius résolut de

reconquérir cet objet précieux, nouvelle Arche d'alliance du nouveau peuple de

Dieu. Avant de quitter Constantinople, il vint à l'église, les pieds chaussés

de noir, en esprit de pénitence; il se prosterna devant l'autel et pria Dieu de

seconder son courage; enfin il emporta avec lui une image miraculeuse du

Sauveur, décidé à combattre avec elle jusqu'à la mort. Le Ciel aida

sensiblement le vaillant empereur, car son armée courut de victoire en

victoire; une des conditions du traité de paix fut la reddition de la Croix de

Notre-Seigneur dans le même état où elle avait été prise.

Héraclius, à son retour,

fut reçu à Constantinople par les acclamations du peuple; on alla au-devant de

lui avec des rameaux d'oliviers et des flambeaux, et la vraie Croix fut

honorée, à cette occasion, d'un magnifique triomphe. L'empereur lui-même, en

action de grâce, voulut retourner à Jérusalem ce bois sacré, qui avait été

quatorze ans au pouvoir des barbares. Quand il fut arrivé dans la Cité Sainte,

il chargea la relique précieuse sur ses épaules; mais lorsqu'il fut à la porte

qui mène au Calvaire, il lui fut impossible d'avancer, à son grand étonnement

et à la stupéfaction de tout: "Prenez garde, ô empereur! lui dit alors le

patriarche Zacharie; sans doute le vêtement impérial que vous portez n'est pas

assez conforme à l'état pauvre et humilié de Jésus portant Sa Croix."

Héraclius, touché de ces paroles, quitta ses ornements impériaux, ôta ses

chaussures, et, vêtu en pauvre, il put gravir sans difficulté jusqu'au Calvaire

et y déposer son glorieux fardeau.

Pour donner plus d'éclat

à cette marche triomphale, Dieu permit que plusieurs miracles fussent opérés

par la vertu de ce bois sacré: un mort fut ressuscité, quatre paralytiques

guéris; dix lépreux recouvrèrent la santé, quinze aveugles la vue; une quantité

de possédés furent délivrés du malin esprit, et un nombre considérable de

malades trouvèrent une complète guérison. A la suite de ces événements fut

instituée la fête de l'Exaltation de la Sainte Croix, pour en perpétuer le

souvenir.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/exaltation_de_la_sainte_croix.html

Assumption

of Mary Church Fresco, 1834 - Frescos in

the Assumption of Mary Church, Pchelino

[HOMÉLIE] La Croix

glorieuse, une parole à écouter

Jean-Thomas

de Beauregard - publié le 13/09/25

Dominicain du couvent de

Bordeaux, le frère Jean-Thomas de Beauregard commente les lectures du dimanche

de la Croix glorieuse. La croix du Christ ne se contemple pas seulement, elle

s’écoute : les yeux voient l’humanité du Christ anéantie, et les oreilles

entendent le Verbe de Dieu accomplir l’œuvre souveraine de la miséricorde.

Le 12 septembre 1901,

sainte Élisabeth de la Trinité écrit

à sa sœur : "Prends ton Crucifix, regarde, écoute." Au spectacle

du crucifié, le risque serait de regarder seulement, sans écouter, ou

d’entendre sans voir. Parce que la Passion du Christ est le drame où se joue

notre salut, nous ne pouvons nous permettre d’être aveugles ou sourds au

moindre détail.

La foi vient de l’écoute

Au Calvaire, les yeux

voient l’horreur du supplice de la Croix : "Reconnu homme à son

aspect, il s’est abaissé, devenant obéissant jusqu’à la mort, et la mort de la

croix" (Ph 2, 7-8). Mais les oreilles perçoivent l’écho encore ténu de la

gloire : "C’est pourquoi Dieu l’a souverainement élevé et lui a

conféré le nom qui est au-dessus de tout nom" (Ph 2, 9). Tous nos sens en

éveil, il faut tenir les deux : la Croix et la Gloire. Sans doute en

raison de la relation intime qui les lie, il en va du témoin du Calvaire comme

du baptisé devant le mystère de l’Eucharistie, où les yeux ne voient que du

pain et du vin, tandis que les oreilles entendent "ceci est mon corps,

ceci est mon sang". Devant l’autel de la Croix comme devant l’autel

eucharistique, la foi vient de l’écoute (fides ex auditu). En réalité, c’est

tout l’organisme des sacrements de l’Église qui procède de cette logique :

l’humilité du signe visible est parée de la gloire du ciel en vertu de la

parole qui l’accompagne.

Les yeux voient

l’humanité du Christ humiliée, torturée, épuisée, et finalement anéantie, et

les oreilles entendent le Verbe de Dieu accomplir l’œuvre la plus

souveraine qu’est la miséricorde : "Père, pardonne-leur, ils ne savent pas

ce qu’ils font" (Lc 23, 34). Celui qui ne verrait pas l’humanité du Christ

blessée à mort ne comprendrait pas le réalisme de l’Incarnation et jusqu’à quel

abaissement l’amour veut se livrer. Celui qui n’entendrait pas la parole du

Verbe incarné ne comprendrait pas combien cet amour et cette souffrance, l’un

et l’autre inextricablement liés, sauvent le monde et le font entrer dans une

gloire qui est celle de Dieu lui-même. Sans la Croix, comment Jésus nous

rejoindrait-il dans nos souffrances ? Et sans la gloire, comment nous en libèrerait-il ?

Quarante jours après la

fête de la Transfiguration

La liturgie de l’Église

ne s’y trompe pas en situant la fête de la Croix glorieuse quarante jours après

la fête de la Transfiguration. Sur la montagne du Golgotha, le bon et le

mauvais larron ont pris la place de Moïse et d’Élie, intégrant toute l’humanité

sainte et pécheresse dans le dessein rédempteur du Christ, mais c’est encore

d’une transfiguration qu’il s’agit avec la Croix glorieuse. Avec une différence

toutefois : au mont Thabor, la gloire était éclatante ; au Golgotha,

la foi seule perçoit la gloire.

Attention à ne pas

décoller trop vite de la Croix vers la gloire ! Dans La Femme pauvre,

Léon Bloy fulminait contre la Transfiguration de Raphaël qui "n’a pas

compris qu’il était absolument indispensable que les Pieds de Jésus touchassent

le sol pour que sa transfiguration fut terrestre". On pourrait en dire

autant de bien des représentations contemporaines du Crucifié, où la croix est

parfois escamotée, soi-disant pour éviter l’écueil d’un dolorisme jansénisant.

Cette croix était une

école

Mais attention à ne voir

que la Croix sans la gloire ! La typologie vient alors à notre aide. Les

Pères de l’Église avaient l’imagination fertile, et ils n’ont pas manqué de

voir dans la Croix la figure de quelque gloire divine qu’un déguisement de

misère ne suffit pas à cacher au croyant dont la foi pénètre au cœur du

mystère. Que faut-il voir dans la Croix ? Mettons-nous à l’école de saint Augustin.

L’évêque d’Hippone

écrit : "Cette croix était une école. C’est là que le Maître a

instruit le larron. Le bois auquel il était pendu est devenu la chaire de

l’enseignant." Où l’on voit qu’Élisabeth de la Trinité et Augustin ont la

même intuition : la Croix n’est pas seulement un spectacle à regarder,

c’est une parole à écouter, celle que Jésus adresse depuis sa chaire de douleur

pour enseigner le larron, et par lui, tous les hommes. C’est là qu’il nous dit

jusqu’où va l’amour de Dieu, jusqu’où va sa miséricorde. Une telle parole

devait être vécue pour être crue, et c’est pour cela qu’elle devait culminer

dans la chaire de la Croix.

Pour s’accrocher dans la

tempête

Saint Augustin écrit

encore : "Le mystère du déluge, dans lequel les justes ont été sauvés

par la croix, figurait l’Église à venir que le Christ, son roi et son Dieu, a

tenue, par le sacrement de sa croix, au-dessus de l’inondation de ce

siècle." Le bois de l’arche de Noé préfigure le bois de la Croix, l’une et

l’autre devenant ce à quoi les hommes peuvent s’accrocher dans la tempête pour

échapper au péché et à la mort. Claudel s’en souviendra au début du Soulier

de satin, en lui donnant une dimension plus dramatique encore. L’écrivain fait

dire à son personnage dont le bateau est en train de couler et qui s’est arrimé

au mât du vaisseau en désespoir de cause : "Et c’est vrai que je suis

attaché à la croix, mais la croix où je suis n’est plus attachée à rien. Elle

flotte sur la mer."

Saint Augustin écrit

enfin : "Jésus recommandait la croix qu’il portait sur ses

épaules ; il portait le candélabre pour la lampe qui devait brûler et

qu’il ne fallait pas mettre sous le boisseau." La croix est le candélabre

qui porte la lumière, Jésus le soleil de justice, lampe qui brûle d’amour et

illumine les hommes depuis la montagne du Calvaire. Les romains installaient

les suppliciés sur une hauteur, aux yeux de tous, pour que leur torture

dissuade les spectateurs de commettre d’autres crimes. Mais le Père veut que

Jésus soit "élevé de terre" pour qu’il "attire tout à lui"

(Jn 12, 32), et que les rayons qui s’échappent de son cœur transpercé

illuminent le monde.

Sans rougir de cette

croix

La Croix glorieuse est

celle du Christ, elle doit devenir celle du chrétien. Signe d’infamie, la croix

devient par la foi notre signe de ralliement. C’est pour

cela qu’il nous est bon, en nous signant, d’en faire mémoire, mais plus encore

d’en témoigner fièrement à la face du monde. C’est encore Augustin qui

conclut : "Glorifions-nous, nous aussi, dans la croix de notre

Seigneur Jésus Christ, par qui le monde est crucifié pour nous et nous pour le

monde ; sans rougir de cette croix, nous l’avons placée sur notre front,

c’est-à-dire au siège même de la honte." En cette fête de la Croix glorieuse,

nous chassons, avec le péché et la mort, toute honte, et proclamons fièrement

notre appartenance au Christ crucifié et glorifié par le Père dans l’Esprit.

Lectures de la fête de la

Croix glorieuse : Nb 21, 4b-9 ; Ph

2, 6-11 ; Jn 3, 13-17

Lire aussi :Cette

prière qui relie le sacrifice de la Croix à nos vies quotidiennes

Lire aussi :La

plus belle des prières ? Le cri vers Dieu, assure Léon XIV

Lire aussi :Le

“martyre blanc” de Jean Paul II, un chemin inspirant pour la traversée de la

souffrance ?

Staurothèque byzantine du début du IXe siècle

L'EXALTATION DE LA SAINTE CROIX

L'Exaltation de la Sainte Croix est ainsi appelée parce que à pareil jour la foi et la sainte Croix furent singulièrement exaltées. Il faut observer qu'avant la passion de J.-C., le bois de la croix fut un bois méprisé, parce que ces croix étaient faites avec du bois de bas prix ; il ne portait point de fruit tout autant de fois qu'il était planté sur le mont du Calvaire ; c'était un bois ignoble, parce que c'était l’instrument du supplice des larrons ; c'était un bois de ténèbres et sans aucune beauté ; c'était un bois de mort, puisque les hommes y étaient attachés pour mourir; c'était un bois infect, parce qu'il était planté au milieu des cadavres. Mais après la passion, il fut exalté de bien des manières, parce que au lieu d'être vil, il devint précieux ; ce qui a fait dire à saint André : « Salut, croix précieuse, etc. » Sa stérilité fut convertie en fertilité c'est pour cela qu'il est dit au ch. VII des Cantiques : « Je monterai sur le palmier, et j'en cueillerai les fruits. » Son ignominie devint excellence. « La croix, dit saint Augustin, qui était l’instrument de supplice des larrons, a passé sur le front des empereurs. » Ses ténèbres ont été converties en clarté. « La croix et les cicatrices de J.-C., dit saint Chrysostome, seront au jugement plus brillantes que les rayons du soleil. » La mort est devenue une vie sans fin : Ce qui fait dire à l’Église : « La source de la mort devint la source de la vie. » Son infection fut changée en odeur suave : Pendant que le roi se reposait, est-il dit au Cantique, le nard dont j'étais parfumé, c'est-à-dire, la Sainte Croix, a répandu son odeur. »

L'Exaltation de la Sainte Croix est célébrée solennellement dans l’Église, parce que la foi en reçut une admirable gloire. En effet, l’an du Seigneur 615, Dieu permit que son peuple fût affligé par les mauvais traitements des païens, quand Chosroës, roi des Perses, soumit à sa domination tous les royaumes de la terre. Lorsqu'il vint à Jérusalem, il sortit effrayé du sépulcre du Seigneur, mais pourtant il emporta la partie de la Sainte Croix que sainte Hélène y avait laissée. Or, sa volonté étant de se faire adorer par tous ses sujets comme un dieu : il fit construire une tour d'or et d'argent entremêlés de pierres précieuses, dans laquelle il plaça les imagés du soleil, de la lune et des étoiles. A l’aide de conduits minces et cachés, il faisait tomber la pluie d'en haut comme Dieu, et dans un souterrain, il plaça des chevaux qui traînaient des, chariots en tournant, comme pour ébranler la tour et simuler le tonnerre. Il remit donc le soin de son royaume à son fils, et le profane réside dans un temple de cette nature, où après avoir placé auprès de soi la Croix du Seigneur, il ordonne que tous l’appellent Dieu. D'après ce qu'on lit dans le livre Mitral (Sicardus, c. XLIV) lui-même, Chosroës, résidant sur un trône comme le Père, plaça à sa droite le bois de la Croix au lieu dit Fils, et à sa gauche, un coq, au lieu du Saint-Esprit, et il se fit nommer le Père. Alors l’empereur Héraclius rassembla une armée nombreuse et vint pour livrer bataille au fils de Chosroës auprès du Danube. Les deux princes convinrent de se mesurer seul à seul sur le pont, à la condition que celui qui resterait vainqueur aurait l’empire sans que ni l’une ni l’autre armée n'eût à en souffrir. Il fut encore convenu que celui qui aurait la présomption de quitter les rangs pour porter aide à son prince, aurait les jambes et les bras brisés aussitôt et serait noyé dans le fleuve. Or, Héraclius s'offrit tout entier à Dieu et se recommanda à la Sainte Croix avec toute la dévotion possible. Les deux princes en étant venus aux mains, le Seigneur accorda la victoire à Héraclius, qui soumit l’armée ennemie à son commandement, de telle sorte que tout le peuple de Chosroës embrassa la foi chrétienne et reçut le saint baptême. Or, Chosroës ignorait l’issue de la guerre, car étant généralement haï, personne ne lui en donna connaissance. Mais Héraclius parvint jusqu'à lui et le trouvant assis sur son trône d'or, il lui dit : « Puisque tu as honoré à ta façon le bois de la Sainte Croix, si tu veux recevoir le baptême et la foi de J.-C., tu conserveras la vie et ton royaume, en me donnant quelques otages ; mais si tu rejettes ma proposition, je te frapperai de mon épée et te trancherai la tète. » Chosroës ne voulut pas acquiescer à ces conditions. Héraclius dégaina alors son épée et le décapita sans merci : et comme il avait été roi, il commanda de l’ensevelir. Pour son fils, âgé de dix ans, qu'il trouva avec lui, il le fit baptiser, et le levant (Le parrain retirait lui-même de l’eau la personne qui y avait été plongée par le prêtre quand le baptême se donnait par trois immersions successives.) lui-même des fonts sacrés, il lui laissa le royaume de son père. Il détruisit ensuite la. tour, dont il donna l’argent à son armée pour sa part du butin : mais l’or et les pierreries, il les réserva afin de réparer les églises que le tyran avait détruites. Après quoi il prit la Sainte Croix qu'il reporta à Jérusalem.

Quand en descendant du Mont des Oliviers, il voulut entrer, sur son cheval et revêtu de ses ornements impériaux, par la porte sous laquelle J.-C. avait passé en allant au supplice, tout à coup les pierres de la porte descendirent et se fermèrent comme un mur ou comme une paroi. Tout le monde en était dans la stupeur, quand un ange du Seigneur, tenant une crois dans ses mains, apparut au-dessus de la porte et dit : « Lorsque le roi des cieux entrait par cette porte en allant au lieu de sa passion, ce n'était pas avec un appareil royal ; mais il est entré monté sur un pauvre !ne, pour laisser à ses adorateurs un exemple d'humilité. » Après avoir dit ces mots, l’ange disparut. Alors l’empereur, tout couvert de larmes, ôta lui-même sa chaussure, et se dépouilla de ses vêtements jusqu'à sa chemise, et prenant la croix du Seigneur, il la porta avec humilité jusqu'à la porte. Aussitôt la dureté de la pierre fut sensible à l’ordre du ciel, et à l’instant la porte se releva et laissa l’entrée libre. Or, l’odeur extraordinairement suave avait cessé d'émaner de la Sainte Croix à partir du jour et de l’instant où elle avait été enlevée de Jérusalem pour être transportée à travers toute l’étendue de la terre, dans la Perse, à la cour de Chosroës; elle se fit sentir de nouveau, et enivra tout le monde d'une admirable suavité. Alors (47) le roi, dans la ferveur de sa dévotion, adressa les hommages suivants à la Croix : « O croix plus brillante que chacun des astres, célèbre au monde, digne de l’amour des hommes, plus sainte que tout, qui seule avez été digne de porter la rançon de l’univers ; bois aimable, clous précieux, doux glaive, douce lance, qui portez un doux fardeau, sauvez cette assemblée réunie aujourd'hui pour chanter vos louanges, et marquée du signe de votre étendard (c'est l’Antienne de Magnificat des premières vêpres de la fête.). » C'est ainsi que cette précieuse Croix est remise en son lieu, et les anciens miracles se renouvellent. Plusieurs morts sont rendus à la vie, quatre paralytiques sont guéris, dix lépreux sont purifiés, quinze aveugles reçoivent la vue, les démons sont mis en fuite, et plusieurs sont délivrés de diverses maladies. Alors l’empereur fit réparer les églises qu'il combla en outre de présents dignes d'un monarque; après quoi, il revint dans ses propres états. Ces faits sont rapportés autrement dans les chroniques. On y dit que Chosroës dominait sur toute la terre, et qu'ayant pris Jérusalem avec le patriarche Zacharie et le bois de la Croix, Héraclius voulait faire la paix avec lui. Chosroës jura qu'il ne conclurait la paix avec les Romains s'ils reniaient le crucifix et s'ils adoraient le soleil. Mais Héraclius enflammé de zèle leva une armée contre lui, défit les Perses dans plusieurs batailles et força Chosroës de fuir jusqu'à Clésyphonte. Enfin, Chosroës, malade de la dyssenterie, voulut faire couronner roi son fils Médasas. A cette nouvelle, Syroïs, son aîné, fit alliance avec Héraclius, et s'étant mis avec les nobles à la poursuite de son père, il le jeta dans les chaînes, où après l’avoir sustenté de pain de douleur et d'eau d'affliction, il le fit enfin périr à coups de flèches. Dans la suite, il fit rendre à Héraclius tous les prisonniers avec le patriarche et le bois de la croix. Héraclius porta d'abord à Jérusalem le précieux bois de la croix qu'il transporta dans la suite à Constantinople. C'est ce qu'on lit dans une quantité de chroniques. — Voici d'après l’Histoire tripartite (Lib. II, ch. XVII.) comment s'exprime la Sybille des païens au sujet du bois de la croix : « O bois trois fois heureux sur lequel Dieu a été étendu! » Ce qui peut s'entendre peut-être de la vie de la nature, de la grâce et de la gloire qui vient de la croix.

Un juif étant entré dans l’église de Sainte-Sophie à Constantinople, y aperçut une image de J.-C. Voyant qu'il était seul, il saisit une épée, s'approche et frappe l’image à la gorge. Tout aussitôt il en jaillit du sang et la figure ainsi que la tête du juif en furent couvertes. Celui-ci effrayé saisit l’image, la jeta dans un puits et prit la fuite. Un chrétien le rencontra et lui dit : « D'où viens-tu, juif? tu as tué un homme. » Le juif répondit : « C'est faux. » « Tu as certainement commis un homicide, reprit le chrétien, puisque tu portes des taches de sang. » Le juif répondit : « Véritablement le Dieu des chrétiens est grand, et sa foi se trouve confirmée par tous les moyens : car ce n'est pas un homme que j'ai tué, mais l’image du Christ; et aussitôt le sang a jailli de sa gorge. » Alors le juif conduisit cet homme au puits d'où ils retirèrent la sainte image. On rapporte que la blessure faite au gosier de J.-C. est encore visible aujourd'hui. Le juif se convertit de suite à la foi (Denys le Chartr., Sermon I de l’Exaltation de la Sainte Croix.). — Dans la ville de Bérith, en Syrie, un chrétien était logé dans une maison, moyennant une pension annuelle : il avait attaché pieusement une image de N.-S. en croix à la tête de son lit et ne manquait pas d'y faire ses prières. L'année étant expirée, il loua une autre maison, et oublia d'emporter son image. Or, un juif loua la maison quittée par le chrétien et un jour il invita à dîner un homme de sa tribu. Pendant le repas, celui qui avait été invité vint à examiner l’appartement et aperçut l’image attachée à la muraille; alors frémissant de colère contre son hôte, il lui adresse des menaces parce qu'il ose garder une image de J.-C. de Nazareth. Or, l’autre juif, qui n'avait pas vu cette image, affirmait par tous les serments possibles qu'il ne savait pas de quelle image il voulait parler. Le juif faisant alors comme s'il était apaisé dit adieu à son hôte et alla trouver le chef de sa nation et accusa l’autre de ce qu'il avait vu. Les juifs, s'étant donc réunis, vont à la maison et après avoir vu l’image, ils accablent le locataire des plus durs outrages, le jettent à demi mort hors de la synagogue, et foulant aux pieds l’image, ils renouvelèrent sur elle tous les opprobres de la passion du Seigneur. Mais quand ils eurent percé le côté avec une lance, le sang et l’eau en sortirent en abondance et un vase qu'on mit pour les recevoir en fut rempli. Les juifs stupéfaits portèrent ce sang dans les synagogues et tous les malades qui en furent oints étaient aussitôt guéris. Alors les juifs racontèrent toutes les circonstances de ces faits à l’évêque du pays et reçurent tous ensemble le baptême et la foi de J.-C. Or, l’évêque conserva ce sang dans des ampoules de cristal et de verre. Il fit venir ensuite le chrétien et lui: demanda quel était l’artiste qui avait exécuté une si belle image. Le chrétien répondit : « C'est Nicodème qui l’a faite, et en mourant, il la laissa à Gamaliel, Gamaliel à Zachée, Zachée à Jacques et Jacques à Simon. Elle est restée à Jérusalem jusqu'à la destruction de la ville ; elle fut transportée dans la suite par les fidèles au royaume d'Agrippa ; de là dans ma patrie par mes parents, et elle m’est échue par droit d'héritage.» Cela arriva l’an du Seigneur 750 (Saint Athanase, De imag. Salv. D. N. J. C., 7e Conc. oecum., act. IV; — Vincent de B., l. XXIV, c. CVII. - Sigebert, Chron. an 764; — Hélinand, an 764). Alors tous les juifs changèrent leurs synagogues en églises ; et à partir de cette époque, ce fut la coutume de consacrer les églises, car auparavant on ne consacrait que les autels. C'est à cause de ce miracle que l’Église ordonna de faire au 5 des calendes de décembre, d'autres disent, au 5 des ides de novembre, la mémoire de la Passion du Seigneur. De là encore, à Rome; on consacra en l’honneur du Sauveur une église où se conserve une ampoule de ce sang, et la fête en est solennelle.

Chez les infidèles, la vertu extraordinaire de la croix fut aussi attestée en toutes sortes de circonstances. En effet, saint Grégoire raconte au IIIe livre de ses Dialogues (ch. III) que, André, évêque de Fondi, ayant permis qu'une religieuse demeurât avec lui, l’antique ennemi commença à imprimer dans les yeux de son âme la beauté de cette femme, en sorte qu'il pensait dans le lit à des choses affreuses. Or, un jour, un juif venu à Rome, voyant qu'il se faisait tard, et n'ayant pas trouvé où loger, entra pour y rester dans un temple d'Apollon. Comme il craignait de passer la nuit dans ce lieu sacrilège, bien qu'il n'eut pas du tout confiance dans la croix, il eut soin cependant de se signer. Or, au milieu de la nuit, il s'éveilla et vit une foule d'esprits malins qui semblaient s'avancer sous la direction de quelque autorité; alors le chef qui commandait aux autres s'assit au milieu d'eux, et se mit à discuter les affaires et les actes de chacun des esprits placés sous son obéissance, afin de s'assurer de tout ce que chacun d'eux avait commis d'iniquités. Saint Grégoire a passé sous silence, pour abréger, le mode de cette discussion : mais ou peut s'en rendre compte par un exemple semblable qu'on lit dans la Vie des Pères (Honorius d'Autun). En effet quelqu'un étant entré dans un temple d'idoles, vit Satan assis et toute sa milice présente devant lui. Alors entra un des malins esprits qui l’adora. Satan lui dit : « D'oùt viens-tu ? » Et il répondit : «J'ai été dans telle province et j'y ai suscité quantité de guerres; j'y ai soulevé beaucoup de troubles, J'y ai versé du sang en abondance, et je suis venu te l’annoncer. » Et Satan reprit : « En combien de temps as-tu fait cela? » L'autre dit : « En trente jours. » « Pourquoi, dit le prince des ténèbres, si peu en tant de temps? » et s'adressant aux assistants : « Allez, dit-il, fouettez-le et frappez dur. » Un second vint et l’adora en disant : « J'étais dans la mer, maître, et j'ai excité d'épouvantables tempêtes, j'ai englouti beaucoup de navires, j'ai fait périr grand nombre d'hommes. » Et Satan dit : « En combien de temps as-tu fait cela? » « En vingt jours, répondit l’autre. » Et Satan le fit fouetter comme le premier en disant : « C'est en tant de temps que tu as fait si peu ! » Alors vint un troisième qui dit : « Je suis allé dans une ville, et j'ai excité des querelles pendant certaine noce, j'y ai fait répandre beaucoup de sang, j'ai tué l’époux lui-même, et je suis venu te l’annoncer. » Satan dit : « En combien de temps as-tu fait cela ! » « En dix jours, répondit-il. » Et Satan lui dit : « Et tu n'as pas fait plus en tant de jours ? » Et il le fit frapper par ceux qui étaient autour de lui. Ensuite vint un quatrième : « Je suis resté, dit-il, dans le désert, et pendant quarante ans, j'ai travaillé autour d'un moine, et c'est. à peine si enfin je l’ai fait tomber dans le péché de la chair. » Quand Satan entendit cela, il se leva de son trône, et embrassant ce démon, il ôta la couronne de dessus son front, et la lui mit sur la tête, puis il le fit asseoir avec lui en disant : « C'est une grande chose que tu as eu le courage de faire là, et tu as travaillé plus que tous les autres. » C'est là ou à peu près le mode de la discussion que saint Grégoire a passée sous silence. Quand chacun des esprits eut exposé ce qu'il avait fait, il y (53) en eut un, qui s'élança au milieu de l’assemblée, et qui fit connaître de quelle tentation charnelle il avait agité l’esprit d'André par rapport à cette religieuse, ajoutant que la veille, à l’heure des vêpres, il en était venu jusqu'à amener son esprit à donner un coup sur le dos de cette femme en signe de caresse. Alors le malin esprit l’engagea à accomplir ce qu'il avait commencé afin que ce fût lui qui eût la palme la plus remarquable pour avoir fait succomber André : il commanda ensuite qu'on cherchât à savoir quel était celui qui avait été si présomptueux pour se coucher dans ce temple. Et comme cet homme tremblait de plus en plus fort, et que les esprits envoyés pour le reconnaître voyaient' qu'il était signé du mystère de la croix, aussitôt ils se mirent à crier avec effroi : « Le vase est vide, il est vrai, mais il est scellé. » A ce cri, la troupe de malins esprits disparut aussitôt. Mais le juif se hâta de venir trouver l’évêque et lui raconta tout de point en point. L'évêque, en entendant cela, se mit .à gémir grandement; et il Renvoya de suite toutes les femmes hors de sa maison, puis il baptisa le Juif. — Saint Grégoire rapporte encore au livre des Dialogues (ch. IV), qu'une religieuse en entrant dans un jardin, et y apercevant une laitue, en conçut un violent désir, et, oubliant de la bénir avec le signe de la croix; elle la mordit avec avidité, mais elle fut saisie par le démon et tomba à l’instant. Saint Equitius étant venu auprès d'elle, le diable se mit à crier en disant: « Qu'ai-je fait, moi, qu'ai-je fait? J'étais assis sur la laitue; celle-ci est venue et elle m’a mordu. » Mais sur l’ordre du saint homme, le démon sortit de suite. — On lit au livre XIe de (54) l’Histoire ecclésiastique que les Gentils avaient peint sur les murs d'Alexandrie les armes de Sérapis ; mais Théodose les fit effacer et y substitua le signe de la croix. Alors, les gentils et les prêtres des idoles se firent baptiser, en disant que c'était une tradition des anciens, que ce qu'ils vénéraient subsisterait jusqu'à ce que soit venu ce signe dans lequel est la vie. Ils avaient dans leur alphabet une lettre, à laquelle ils donnaient le nom de sacrée : elle avait la forme d'une croix qu'ils disaient signifier la vie future (Eusèbe de Césarée, 1. II, c. XX; — Rufin, l. II, c. XXIX.).

LA LÉGENDE DORÉE de Jacques de Voragine nouvellement traduite en

français avec introduction, notices, notes et recherches sur les sources par

l'abbé J.-B. M. Roze, chanoine honoraire de la Cathédrale d'Amiens, Édouard

Rouveyre, éditeur, 76, rue de Seine, 76, Paris MDCCCCII

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/voragine/tome03/136.htm

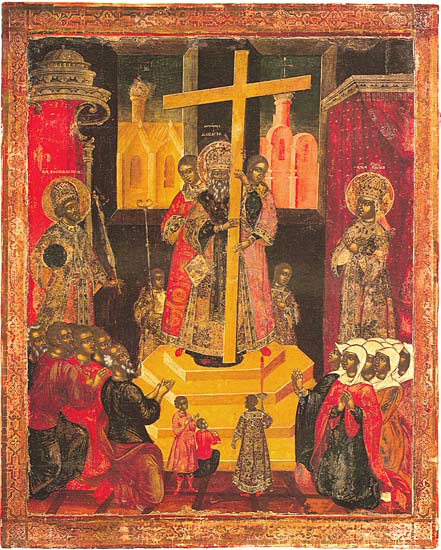

Russian

icon of the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross (icon from Yaroslavl by

Gury Nikitin, 1680. Tretyakov

Gallery, Moscow).

Icône russe de l'Exaltation de la Croix.

(Icône de Iaroslavl par Goury Nikitine, 1680. Galerie Tretiakov, Moscou)

Prière d’invocation à la « Sainte Croix de

Jésus-Christ »

Voici la « Prière d’invocation à la Sainte

Croix de Jésus-Christ» trouvée en l'an 802 dans le tombeau de Jésus-Christ

et envoyée par le Saint pape Léon III (795-816) à l'Empereur Charlemagne quand

il partit avec son armée pour combattre les ennemis de Saint Michel en France.

La « Prière d’invocation à la Sainte

Croix » :

« Dieu tout-puissant, qui avez souffert la mort à

l'arbre patibulaire pour tous nos péchés, soyez avec moi ; Sainte Croix de

Jésus-Christ, ayez pitié de moi ; Sainte Croix de Jésus-Christ, soyez mon

espoir ; Sainte Croix de Jésus-Christ, repoussez de moi toute arme

tranchante ; Sainte Croix de Jésus-Christ, versez en moi tout bien ;

Sainte Croix de Jésus-Christ, détournez de moi tout mal ; Sainte Croix de

Jésus-Christ, faites que je parvienne au chemin du salut ; Sainte Croix de

Jésus-Christ, repoussez de moi toute atteinte de mort ; Sainte Croix de

Jésus-Christ, préservez moi des accidents corporels et temporels, que j'adore

la Sainte Croix de Jésus-Christ à jamais. Jésus de Nazareth crucifié, ayez

pitié de moi, faites que l'esprit malin et nuisible fuie de moi, dans tous les

siècles des siècles. Ainsi soit-il ! En l'honneur du Sang Précieux de

Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ, en l'honneur de Son Incarnation, par où Il peut

nous conduire à la vie éternelle, aussi vrai que Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ

est né le jour de Noël et qu'Il a été crucifié le Vendredi Saint. Amen. »

Celui qui lira cette « Prière d’invocation à la

Sainte Croix », qui l'entendra ou qui la portera sur lui ne mourra pas

subitement, ne se noiera pas et ne sera pas brûlé, aucun venin ne pourra

l'empoisonner et ne tombera pas entre les mains des ennemis et ne sera pas

vaincu dans les combats.

Quand une femme se trouvera en enfantement, qu'elle

entendra lire ou lira cette « Prière d’invocation à la Sainte Croix »

ou la portera sur elle, elle sera promptement délivrée, elle restera tendre

mère et quand l'enfant sera né, posez cette « Prière d’invocation à la

Sainte Croix » sur son côté droit et il sera préservé d'un grand nombre

d'accidents.

Celui qui portera cette « Prière d’invocation à

la Sainte Croix » sur lui sera préservé du mal d'épilepsie et lorsque dans

les rues, vous verrez une personne attaquée de ce mal, posez cette

« Prière d’invocation à la Sainte Croix » sur son côté droit et elle

se lèvera joyeusement.

Celui qui écrit cette « Prière d’invocation à la

Sainte Croix » pour lui ou pour d'autres, Je le bénirai, dit le Seigneur,

et celui qui s'en moquera en fera pénitence.

Lorsque cette « Prière d’invocation à la Sainte

Croix » sera déposée dans une maison, elle sera préservée de la foudre et

du tonnerre ; celui qui journellement lira cette « Prière

d’invocation à la Sainte Croix » sera prévenu trois jours avant sa mort

par un signe divin de l'heure du trépas.

SOURCE : http://site-catholique.fr/index.php?post/Priere-invocation-a-la-Sainte-Croix

Fête de la Croix glorieuse : la Croix attire, car elle

promet et réalise l’union à Dieu

Fr.

Jean-Thomas de Beauregard, op | 10 septembre 2020

La fête de la Croix glorieuse invite à contempler la

beauté de la Croix, mais aussi le drame de la Passion. Le piège serait de

rester spectateur : être acteur du drame, c’est supplier comme le bon larron,

intercéder comme Marie ou témoigner comme Jean.

L’Église fête aujourd’hui 14 septembre la

Croix glorieuse. Lorsqu’il annonce à Nicodème qu’il sera élevé en Croix (Jn

3, 13-17), Jésus se compare au serpent d’airain de l’Exode. Les Hébreux au

désert devaient fixer ce serpent des yeux pour guérir et vivre, malgré

l’horreur qu’il leur inspirait. En arrière-plan se dessine l’antique serpent de

la Genèse, le démon, enroulé, incurvé, autour de l’arbre du péché originel.

Jésus, cloué à l’arbre de vie, l’arbre de la Croix, droit et tendu de tout son

être vers sa mission de sauveur, se présente comme l’antidote au serpent de la

Genèse, et comme la réalité parfaite dont le serpent de l’Exode n’était que la

figure. Les trois images se superposent, et la vérité de la Croix apparaît

comme par transparence.

Cette image du serpent nous donne à contempler Jésus

en Croix sur le mode de la fascination. La fascination, ce mélange d’attraction et

de répulsion qui saisit le spectateur à la vue d’un serpent. De

fait, la

Croix attire, car elle promet, et même, elle réalise l’union

à Dieu et la vie éternelle : le bois de la Croix est ce pont dressé entre

la terre et le ciel ; mais la Croix nous repousse, de toute notre sensibilité,

parce que Jésus y souffre atrocement, et parce qu’il nous invite à le suivre

sur ce chemin : le bois de la Croix est celui d’un gibet, un instrument de

torture à l’usage des criminels.

La fascination comme attraction/répulsion, jeu d’ombre

et de lumière, forme la toile de fond de l’existence chrétienne. Et il en va

ainsi de la Croix comme il en va du Christ, comme il en va du prêtre, comme il

en va de tout baptisé qui prend au sérieux sa vie théologale : à les voir,

on est irrésistiblement attiré, mais aussi invinciblement repoussé. C’est

d’ailleurs un indice de sainteté, qui simultanément attire et repousse, avec la

même intensité. Il y a, de ce point de vue, une esthétique de la

Révélation chrétienne.

La beauté de la Croix

Attention toutefois à ne pas se complaire dans une

contemplation purement esthétique de la Croix : jouir du contraste, du

paradoxe, chercher le beau dans le laid, la grâce dans l’ignominie… La Croix ne

peut pas être, pour un chrétien, le prétexte à un exercice de style, quand bien

même elle semble s’y prêter. Saint Augustin ou Bossuet, lorsqu’ils jouent des

paradoxes de la Croix, ne sont virtuoses que parce que la foi les anime et

donne vie à leurs mots.

Lire aussi :

Elle

console et elle juge, la double face de la Croix

Comment contempler la Croix glorieuse d’une manière

qui soit juste ? D’abord en ne faisant l’impasse ni sur la Croix, ni sur la

Gloire, c’est évident. Selon le tempérament ou l’époque, on s’attarde plus

volontiers sur l’une ou sur l’autre. Les artistes du Moyen Âge savaient

conjuguer l’une et l’autre en représentant une véritable croix, dans sa

terrible nudité, mais sertie de pierres précieuses, signes de sa gloire. C’est

le cas par exemple sur les tapisseries de l’abbatiale de la Chaise-Dieu, en

Haute-Loire.

Être acteur du drame

Mais le piège n’est pas tellement dans la préférence

pour la Croix ou pour la gloire, voire dans le refus de l’une ou de l’autre,

même si tout choix exclusif serait nécessairement une hérésie. Le piège, plus

sournois, peut-être, est de rester spectateur. Le piège, c’est, devant un tel

spectacle à la fois horrible et magnifique, d’en rester à une sorte d’effroi

sacré, qui est peut-être déjà religieux mais pas encore chrétien. Pour échapper

au piège de la fascination esthétique, pour ne pas rester extérieur au drame de

la Croix, une seule solution : être acteur du drame. Le rôle de Jésus mis

à part, il reste trois rôles possibles : le

bon larron, la

Vierge Marie, saint

Jean.

Le

bon larron, qui sait qu’il a crucifié Jésus par ses péchés, mais qui espère

le salut et l’implore en confessant sa foi. « Ils regarderont vers Celui

qu’ils ont transpercé. » La

Vierge Marie, qui se tient debout près de la Croix et intercède pour les

hommes de tous les temps en offrant sa souffrance de mère. « Je complète

en ma chair les souffrances qui manquent à la Passion du Christ. » Saint

Jean, qui se tient en retrait, scrute le mystère de la Rédemption de toute

son intelligence éclairée par la foi, et s’apprête à livrer son témoignage au

monde qui l’attend : « Dieu a tant aimé le monde qu’il a donné son Fils

unique, afin que quiconque qui croit en Lui ait la vie éternelle. »

L’Église et la Croix

Face à la Croix, nous pouvons adopter chacune de ces

trois attitudes, successivement ou simultanément : supplication pour

soi-même et espérance avec le bon larron, intercession pour les autres et

offrande de soi avec Marie, contemplation théologique et témoignage avec Jean.

Alors, fini la simple fascination esthétique, place à la participation au

mystère. En l’occurrence, c’est une participation au mystère de l’Église, qui

naît des plaies du Christ en Croix. L’Église et la Croix sont inséparables. Et

quand la barque de saint Pierre, l’Église, est emportée dans la tempête, quand

nous ne comprenons plus, quand nous sommes blessés dans notre conscience de

croyant, ce qui arrive souvent ces temps-ci, la seule issue consiste à nous

arrimer de toutes nos forces à la Croix comme au mât du bateau.

Lire aussi :

N’ayez

pas peur de prendre votre croix !

Attachons-nous à la Croix, donc à Jésus, alors nous

tiendrons. Dans la tempête, ce n’est plus nous qui portons nos croix, telle

souffrance, telle épreuve, que nous subissons ou que nous choisissons d’offrir,

non, ce n’est plus nous qui portons nos croix, dans la tempête, c’est la Croix

qui nous porte.

Wassily Sazonov, Sant'Elena presenta

la Vera Croce al figlio Costantino (1870 ca.), olio

su telaThe Elevation of the Holy Cross. Menologion of Basil II. First quarter

of XIth century. Rome, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

http://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.gr.1613/0057?sid=a7590df9b8aca22111c8359533716419

Prière d’invocation à la sainte Croix de Jésus-Christ

La "Prière

d’invocation à la sainte Croix de Jésus-Christ" a été trouvée en l'an

802 dans le tombeau de Jésus-Christ, écrite sur un parchemin en lettres d’or,

et envoyée par le saint pape Léon III (795-816) à l'empereur Charlemagne quand

il est parti avec son armée pour combattre les ennemis de saint Michel — son

saint protecteur et celui de l’Église — en France, avant d’être conservée

précisément à l’abbaye de Saint-Michel de France. Cette prière a protégé les

soldats qui la portaient sur eux, et la récitaient, pendant les deux dernières

guerres :

"Dieu tout-puissant, qui avez souffert la mort à l'arbre patibulaire pour tous nos péchés, soyez avec moi ;

Sainte Croix de Jésus-Christ, ayez pitié de moi ;

Sainte Croix de Jésus-Christ, soyez mon espoir ;

Sainte Croix de Jésus-Christ, repoussez de moi toute arme tranchante ;

Sainte Croix de Jésus-Christ, versez en moi tout bien ;

Sainte Croix de Jésus-Christ, détournez de moi tout mal ;

Sainte Croix de Jésus-Christ, faites que je parvienne au chemin du salut ;

Sainte Croix de Jésus-Christ, repoussez de moi toute atteinte de mort ;

Sainte Croix de Jésus-Christ, préservez moi des accidents corporels et temporels, que j'adore la Sainte Croix de Jésus-Christ à jamais.

Jésus de Nazareth crucifié, ayez pitié de moi, faites que l'esprit malin et

nuisible fuie de moi, dans tous les siècles des siècles.

Ainsi soit-il !

En l'honneur du Sang Précieux de Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ, en l'honneur de

Son Incarnation, par où Il peut nous conduire à la vie éternelle, aussi vrai que

Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ est né le jour de Noël et qu'Il a été crucifié le

Vendredi Saint.

Amen."

La tradition assure que

cette prière protège également les femmes enceintes qui la récitent,

l’entendent ou la portent sur elles ; préserve les maisons de la foudre et

du tonnerre, et les personnes contre certaines maladies comme l’épilepsie.

Enfin, quiconque écrit cette prière pour lui-même ou pour d’autres, de

préférence le dimanche, sera bénit par le Seigneur.

Абраз

«Узвышэнне Св. Крыжа». Сярэдзіна ХVIII ст., з Іванаўскага р-на, НММ РБ. XVIIIth century.

https://media.catholic.by/nv/n29/art4gallery.htm

Chacun se souvient

comment la vraie croix avait été retrouvée par sainte Hélène, mère de

l'empereur Constantin[1] (voir au 18 août). En 335,

l'empereur Constantin, invite pour le trentième anniversaire de son avènement,

les Pères réunis à Tyr à la dédicace des deux basiliques[2] qui doit avoir lieu le 13 septembre à

Jérusalem.

Le lendemain de la

dédicace, le dimanche 14 septembre, l'évêque de Jérusalem montre pour la

première fois à la foule le bois sacré de la Croix (l'hyposis) et, sur ordre de

Constantin, les Pères décrètent la célébration annuelle de la dédicace et de

l'exaltation, au 14 septembre. Un morceau de la Croix étant apporté à

Constantinople, on y célèbre la même fête avec l'hyposis. Cette fête est

répandue dans tout l'Orient dès le VII° siècle, et on la trouve à Rome au plus

tard au temps du pape Serge I° (687-701) à la notice duquel, dans le Liber

pontificalis, on trouve la mention suivante : En la sacristie du

bienheureux apôtre Pierre, se trouve un reliquaire où est renfermée un

précieuse et considérable portion du bois salutaire de la croix du Sauveur ...

Au jour de l'Exaltation de la sainte croix, le peuple chrétien baise et adore

cette relique dans la basilique constantinienne du Saint-Sauveur[3].

Il est aujourd’hui de bon

ton, pour prétendre être pris au sérieux, d'afficher un souverain mépris pour

les reliques en général et pour celles de la vraie Croix en particulier. La

perfide doctrine des anciens réformés, pilleurs de sacristies et ravageurs

d'œuvres d'art, est devenue celle des catholiques à la mode : « on ne

saurait adorer les os d'un martyr qu'on ne soit en danger d'adorer les os de

quelque brigand ou larron, ou bien d'un âne, ou d'un chien, ou d'un cheval.[4] » Ainsi, depuis que certains

catholiques se sont persuadés qu'ils sont les héritiers des Lumières, on enlève

les reliquaires de la vénération des fidèles pour les séquestrer dans la crasse

des arrières-sacristies quand on ne les a pas vendus à d’avides antiquaires.

Pour faire taire les

résistants, la propagande iconoclaste se réclame de l’esprit de Vatican II dont

la lettre, pourtant, dans la Constitution sur le sainte Liturgie recommande

que l’on vénère les reliques authentiques des saints (n° 111), et que le droit

de 1983, application directe de Vatican II, interdit absolument de vendre les

saintes reliques ou de les aliéner en aucune manière, voire de les transférer

définitivement (canon 1190). Dans le Catéchisme de l’Eglise catholique (1992),

l’index thématique de l’édition française a beau avoir oublié le mot, on trouve

cependant la chose dans le texte qui présente la vénération des reliques comme

une des expressions variées de la piété des fidèles dont la catéchèse doit

tenir compte (n° 1674). D’aucuns, à la vantardise plus savante, font remarquer

doctement que le culte des reliques est inconnu dans l’antiquité

chrétienne ; ils mentent effrontément puisque les actes du martyre de

saint Polycarpe, en 156, en font une attestation certaine : « prenant

les ossements plus précieux que les gemmes de grand prix et plus épurés que

l’or, nous les avons déposés dans un lieu convenable. Là même, autant que

possible, réunis dans l’allégresse et la joie, le Seigneur nous donnera de

célébrer l’anniversaire de son martyre en mémoire de ceux qui sont déjà sorti

du combat, et pour exercer et préparer ceux qui attendent le martyre. » On

se souvient aussi, en 177, d’une lettre où l’Eglise de Lyon regrettait de

n’avoir pu conserver les restes de ses martyrs[5].

La tradition, comme nous

l’avons dit plus haut, rapporte généralement que l’on doit à l’impératrice

Hélène la découverte[6] de la Vraie Croix. La mère de

Constantin, suivit son fils à Constantinople où elle souffrit durement des

excès de l’Empereur qui avait fait assassiner sa seconde femme pour avoir fait

exécuter Crispus, fils d'un premier lit. En expiation, Hélène qui venait de

fêter son soixante-dix-huitième anniversaire, s'en alla en pèlerinage à

Jérusalem.

Il convient de rappeler

que l'empereur Adrien (76-138), après avoir détruit Jérusalem et chassé les

Juifs de leur pays (136), rebaptisa la ville Aelia Capitolina et la

fit reconstruire en y enlevant jusqu'au souvenir judéo-chrétien ; sur le

Golgotha, lieu du Calvaire, fut élevé un temple à Vénus. Sainte Hélène ne

trouva que décombres et ruines païennes dans la Ville Sainte.

« Elle apprit,

par révélation, que la croix avait été enfouie dans un des caveaux du

sépulcre de Notre Seigneur, et les anciens de la ville, qu'elle consulta avec

grand soin, lui marquèrent le lieu où ils croyaient, selon la tradition de

leurs pères, qu'était ce précieux monument ; elle fit creuser en ce lieu avec

tant d'ardeur et de diligence, qu'elle découvrit enfin ce trésor que la divine

Providence avait caché dans les entrailles de la terre durant tout le temps des

persécutions, afin qu'il ne fût point brûlé par les idolâtres, et que le monde,

étant devenu chrétien, lui pût rendre ses adorations. Dieu récompensa

cette sainte impératrice beaucoup plus qu'elle n'eût osé l'espérer : car, outre

la Croix, elle trouva encore les autres instruments de la Passion, à

savoir : les clous dont Notre Seigneur avait été attaché, et le titre qui avait

été mis au-dessus de sa tête. Cependant, une chose la mit extrêmement en peine

: les croix des deux larrons, crucifiés avec Lui, étaient aussi avec la sienne,

et l'Impératrice n'avait aucune marque pour distinguer l'une des autres. Mais

saint Macaire, alors évêque de Jérusalem, qui l'assistait dans cette action,

leva bientôt cette nouvelle difficulté. Ayant fait mettre tout le monde en

prière, et demandé à Dieu qu'il lui plût de découvrir à son Eglise quel était

le véritable instrument de sa Rédemption, il le reconnut par le miracle suivant

: une femme, prête à mourir, ayant été amenée sur le lieu, on lui fit toucher

inutilement les deux croix des larrons ; mais dès qu'elle approcha de celle du

Sauveur du monde, elle se sentit entièrement guérie, quoique son mal eût

résisté jusqu'alors à tous les remèdes humains et qu'elle fût entièrement

désespérée des médecins. Le même jour,saint Macaire rencontra un mort qu'une

grande foule accompagnait au cimetière. Il fit arrêter ceux qui le portaient et

toucha inutilement le cadavre avec deux des croix ; aussitôt qu'on eut approché

celle du Sauveur, le mort ressuscita. Sainte Hélène, ravie d'avoir trouvé le

trésor qu'elle avait tant désiré, remercia Dieu d'une grande ferveur, et fit

bâtir au même lieu une église magnifique ; elle y laissa une bonne partie de la

Croix, qu'elle fit richement orner ; une autre partie fut donnée à

Constantinople ; enfin le reste fut envoyé à Rome, pour l'église que Constantin

et sa mère avaient fondée dans le palais Sessorien (demeure de l'Impératrice)

près du Latran qui a toujours depuis le nom de Sainte-Croix-de-Jérusalem. »

Certes, Eusèbe de Césarée

(263-339), dans La Vie de Constantin le Grand, parle bien de l'édification

de la basilique, mais ne souffle mot de la découverte de la vraie Croix ;

de surcroît, transcrivant le discours de la dédicace de la Basilique, il ne

parle pas de l'évènement mais seulement du signe sauveur. Voilà qui suffit

aux iconoclastes pour dire que la tradition est une vaste blague. Avant de

courir à une telle conclusion, il serait prudent de s'aviser que ledit Eusèbe

de Césarée rejetait tout culte des images du Christ « afin que, écrit-il à

Constancia, nous ne portions pas, à la manière des païens, notre Dieu dans

une image. » Ajoutons, comme l'a si bien démontré Paschali, que la Vita

Constantini n’est pas l'œuvre originale car sa révision interrompue par la

mort d'Eusèbe, fut publiée à titre posthume avec des ajouts et des restrictions

pour justifier la politique de Constantin II. De toutes façons, un silence

d’Eusèbe de Césarée ne saurait constituer une preuve, et l’on doit considérer

d'autres témoignages. Les archives mêmes d’Eusèbe, comme celles de Théodoret de

Cyr (393-460) et celles de Socrate (380-439), conservent une lettre de

Constantin au patriarche de Jérusalem : « La grâce de Notre Sauveur

est si grande que la langue semble se refuser à dépeindre dignement le miracle

qui vient de s'opérer ; car est-il rien de plus surprenant que de voir le

monument de la Sainte Passion, resté si longtemps caché sous terre, se révélant

tout à coup aux Chrétiens, lorsqu'ils sont délivrés de leur ennemi ? »

A part quelques détails

secondaires, des auteurs dont l’enfance est contemporaine du voyage de

l’Impératrice ou ceux de la génération qui suit, attestent de l'Invention

de la Sainte Croix par sainte Hélène et de son culte ; ainsi peut-on

se référer à saint Cyrille de Jérusalem (mort en 386), à saint Paulin de Nole

(mort en 431), à saint Sulpice Sévère (mort en 420), à saint Ambroise de Milan

(mort en 397), à saint Jean Chrysostome (mort en 407), à Rufin d’Aquilée (mort

en 410), à Théodoret de Cyr ou à l'avocat de Constantinople, Socrate.

Déjà saint Cyrille,

deuxième successeur de saint Macaire au siège de Jérusalem, mentionne que des

parcelles de la Vraie Croix sont dispersées à travers le monde

entier, ce qu’attestent par ailleurs deux inscriptions datées de 359 relevées

en Algérie, l’une près de Sétif et l’autre au cap Matifou.

Si saint Ambroise de

Milan décrit l'adoration de la Crux Realis par sainte Hélène, saint

Jérôme raconte, dans une lettre à Eustochie, comment sa propre mère, sainte

Paule, vénéra le bois sacré de la Croix à Jérusalem.

Saint Jean Chrysostome

dit que les chrétiens accouraient pour vénérer le bois de la Croix et tâchaient

d'en obtenir de minuscules parcelles qu'ils faisaient sertir dans des métaux

précieux enrichis de pierreries.

Saint Paulin de Nole

envoie une de ces parcelles à saint Sulpice Sévère en lui recommandant de les

recevoir avec religion et de les garder « précieusement comme une

protection pour la vie présente et comme un gage de salut éternel. »

Le 5 mai 614, les Perses

s'emparèrent de Jérusalem, pillèrent les églises et envoyèrent ce qui restait

de la Croix à leur empereur, Chosroës II[7]. Après plus de dix ans de malchance,

Héraclius[8] battit les Perses et obligea le

successeur de Kosroës à restituer la relique de la Croix qu'il rapporta en

triomphe à Jérusalem. Héraclius entra dans la ville, pieds nus, portant la

Croix sur ses épaules (21 mars 630). Le bois de la Croix séjourna quelques

années à Sainte-Sophie de Constantinople puis retourna à Jérusalem. Le bois de

la Croix a été partagé en trois grandes parts, elles-mêmes fractionnées, pour

Jérusalem, Constantinople et Rome. Ce qui restait du morceau de Jérusalem fut

caché pendant l'occupation musulmane et ne réapparut que lorsque la ville fut

prise par les Croisés qui s'en servirent souvent comme étendard, de sorte qu'il

fut pris par Saladin à la bataille d'Hiltin (1187) et ne fut rendu qu'après la

prise de Damiette (1249) pour être partagé entre certains croisés dont Sigur de

Norvège et Waldemar de Danemark.

Le 14 septembre 1241, le

saint roi Louis IX alla solennellement au-devant des reliques de la Passion

qu'il avait achetées à l'empereur de Constantinople : c'étaient un morceau de

bois de la vraie Croix, le fer de la lance, une partie de l'éponge, un morceau

du roseau et un lambeau du manteau de pourpre. Elles furent déposées à la

Sainte-Chapelle en 1248.

Luther a dit qu'avec les

reliques de la Vraie Croix on pourrait construire la charpente d'un immense

bâtiment et Calvin affirma que cinquante hommes ne porteraient pas le bois de

la Vraie Croix. L’avis des deux hérétiques fut admis comme une vérité révélée

et chacun les répéta en souriant. Or, d'après le travail minutieux de M. Rouhault

de Fleury, on peut supposer que la Croix du Seigneur représentait cent

quatre-vingt millions de millimètres cubes. Si l'on met ensemble les parcelles

que l'on conserve et celles qui ont été détruites mais dont on connaît la

description, on totalise environ cinq millions de millimètres cubes. Rouhault

de Fleury, généreux, multiplie les résultats de son enquête par trois pour ce

qui pourrait être inconnu ; on est loin du compte !

Le 14 septembre 1241, le

saint roi Louis IX alla solennellement au-devant des reliques de la Passion

qu'il avait achetées à l'empereur de Constantinople : c'étaient un morceau de

bois de la vraie Croix, le fer de la lance, une partie de l'éponge, un morceau

du roseau et un lambeau du manteau de pourpre. Elles furent déposées à la Sainte-Chapelle

en 1248.

Il existait, à Paris, une

église Sainte-Croix de la Cité qui devint une paroisse, probablement

vers 1107, lorsque furent dispersées le moniale de Saint-Eloi qui y avaient une

chapelle dès le VII° siècle. Le curé tait à la nomination de l'abbé de

Saint-Maur-des-Fossés. L'édifice qui s'élevait à l'emplacement de l'actuel

Marché aux fleurs, avait été construit en 1450 et dédié en 1511, il fut détruit

en 1797.

[1] Elle

commença par visiter les Lieux saints ; l’Esprit lui souffla de chercher le

bois de la croix. Elle s’approcha du Golgotha et dit : « Voici le

lieu du combat; où est la victoire ? Je cherche l’étendard du salut et ne le

vois pas. » Elle creuse donc le sol, en rejette au loin les

décombres. Voici qu’elle trouve pêle-mêle trois gibets sur lesquels la ruine

s’était abattue et que l’ennemi avait cachés. Mais le triomphe du Christ

peut-il rester dans l’oubli ? Troublée, Hélène hésite, elle hésite comme

une femme. Mue par l’Esprit-Saint, elle se rappelle alors que deux larrons furent

crucifiés avec le Seigneur. Elle cherche donc le croix du milieu. Mais,

peut-être, dans la chute, ont-elles été confondues et interverties. Elle

revient à la lecture de l’Evangile et voit que la croix du milieu portait

l’inscription : « Jésus de Nazareth, Roi des Juifs ». Par

là fut terminée la démonstration de la vérité et, grâce au titre, fut reconnue

la croix du salut (saint Ambroise).

[2] Les

basiliques du Mont des Oliviers et du Saint-Sépulcre.

[3] La

basilique du Saint-Sauveur est depuis devenue la basilique Saint-Jean de

Latran, cathédrale de Rome.

[4] Calvin : Traité

des reliques

[5] Voir

au 2 juin ; « Lettre des serviteurs du Christ qui habitent Vienne et

Lyon, en Gaule, aux frères qui sont en Asie et en Phrygie, ayant la même foi et

la même espérance de la rédemption. »

[6] On

disait autrefois : « L’invention de la sainte Croix » ;

invention vient du latin inventio qui signifie : « acte de

trouver, de découvrir » ; il y avait d’ailleurs une fête particulière

de L’invention de la sainte Croix qui était célébrée le 3 mai. Dans

certains calendriers, on célèbre l'Invention, c'est-à-dire la découverte du

corps ou des reliques d'un saint.

[7] Chosroès

II le Victorieux, roi sassanide de Perse de 590 à 628) qui fut élevé

au trône par une révolte des féodaux, durant les troubles provoqués par le

soulèvement de Vahram Tchubin. Celui-ci, qui prétendait descendre des

Arsacides, se proclama roi sous le nom de Vahram VI, et Chosroès dut aller se

placer sous la protection de l'empereur Maurice. Avec l'aide militaire des

Byzantins, il réussit à reconquérir son trône (591) et maintint pendant plus de

dix ans la paix avec Byzance. En 602, après l'assassinat de l’empereur Maurice

par Phocas, il rouvrit les hostilités contre l'empire d'Orient, sous prétexte

de venger Maurice. Ses armées envahirent la Syrie et l'Anatolie, atteignirent

la Chalcédoine et le Bosphore et menacèrent directement Constantinople (608).

En 6l4, elles firent la conquête de Jérusalem, qui fut mise au pillage pendant

trois jours, puis les Perses pénétrèrent en Egypte et s'emparèrent d'Alexandrie

(616). Chosroès II avait ainsi reconstitué l'ancien Empire perse des

Achéménides et porté à son apogée la puissance sassanide. Allié des Avars, il

vint bloquer Constantinople (626), mais l'Empire byzantin se ressaisit avec

Héraclius. Après la victoire des Byzantins à Ninive (628), Chosroès dut fuir

Ctésiphon, sa capitale, et fut déposé par son fils Khavad II, qui le fit tuer

quelques jours plus tard.

[8] Héraclius,

né en Cappadoce vers 575, fut empereur d'Orient 610 à 641. Venu au pouvoir en

renversant l'usurpateur Phocas, il trouva l'Empire au bord de la ruine. Les

Perses envahissaient l'Asie Mineure, s'emparaient de Jérusalem (614) et de

l'Egypte (619) ; les Avars parvenaient sous les murs de Constantinople.

Heraclius déclencha contre les Perses une véritable croisade (622-628),

remporta sur Chosroès II la victoire décisive de Ninive (12 décembre 627) et

reconquit tous les territoires perdus en Orient ; en mars 630, il rapporta

en grande pompe à Jérusalem la Vraie Croix, qui avait été enlevée par

Chosroès II. Mais cet effort offensif avait épuisé l'Empire, qui se

retrouva impuissant devant le déferlement de l'invasion arabe :

l'écrasement de l'armée byzantine à Yarmouk (636) provoqua la perte, cette fois

définitive, de la Syrie, de Jérusalem (638), de la Mésopotamie (639), de

l'Egypte (639-642) Le règne d'Héraclius s'achevait ainsi par un désastre,

qu'avait préparé, à l'intérieur, la grande querelle religieuse du monophysisme.

Il mourut à Constantinople le 10 février 641.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/09/14.php

Icône de la fête de la Croix, musée de Warmia

et Mazury, Olsztyn, Pologne.

Olsztyn

- Muzeum Warmii i Mazur Podwyższenie Krzyża - tempera na desce, złocenie

Olsztyn

- Museum of Warmia and Masuria Feast of the Cross - temper on board, gilding

EXALTATION DE LA SAINTE CROIX

L’Église de Rome fêtait

le 3 mai l’invention de la Ste Croix (fête supprimée par Jean XXIII

en 1960) : c’est à dire l’anniversaire de son retour à Jérusalem par Héraclius

(630), la date du 14 septembre étant déjà celle de la célébration des

Sts Corneille et Cyprien. Puis par un glissement de mémoire, la fête du 3 mai

devint celle de la découverte par Ste Hélène (320) et l’événement d’Héraclius

fut commémoré le 14 septembre.

Cette fête commémore

aussi la dédicace des basiliques du Calvaire et du St Sépulcre (335). La

réforme de Jean XXIII, ayant supprimée la fête du 3 mai, a élevé celle du 14

septembre au rang de IIème classe.

(Leçons des Matines)

AU PREMIER NOCTURNE.

Du livre des Nombres.

Première leçon. Lorsque

le roi d’Arad, Chananéen, qui habitait vers le midi, eut appris cela,

c’est-à-dire qu’Israël était venu par le chemin des espions, il combattit

contre lui, et étant vainqueur, il en emporta le butin. Mais Israël se liant

par un vœu au Seigneur, dit : Si vous livrez ce peuple à ma main, je détruirai

toutes ses villes. Et le Seigneur exauça les prières d’Israël, et il livra le

Chananéen qu’Israël fit périr, ses villes ayant été renversées ; et il appela

ce lieu du nom de Horma, c’est-à-dire anathème.

R/. La sainte Église

vénère le jour glorieux où fut exalté le bois triomphal, * Sur lequel notre

Rédempteur, rompant les liens de la mort, a vaincu le perfide serpent. V/. Le

Verbe du Père nous a ouvert le chemin du salut, étant suspendu au bois. * Sur

lequel.

Deuxième leçon. Or, ils

partirent aussi du mont Hor par la voie qui conduit à la mer Rouge, pour aller

autour de la terre d’Edom. Et le peuple commença à s’ennuyer du chemin et de la

fatigue ; et il parla contre Dieu et contre Moïse, et dit : Pourquoi nous as-tu

retirés de l’Égypte, pour que nous mourions dans le désert ? Le pain nous

manque, il n’y a pas d’eau ; notre âme a déjà des nausées à cause de cette

nourriture très légère. C’est pourquoi le Seigneur envoya contre le peuple des

serpents brûlants.

R/. O Croix, l’appui de

notre confiance, arbre seul illustre entre tous les autres, nulle forêt n’a

produit ton pareil pour le feuillage la fleur et le fruit : * Il nous est cher,

ce bois ; ils nous sont chers, ces clous ; et combien est doux le fardeau

qu’ils soutiennent. V/. Tu es seule plus élevée que tous les cèdres. * Il nous

est cher.

Troisième leçon. A cause

des blessures et de la mort d’un grand nombre, on vint à Moïse et on dit : Nous

avons péché, parce que nous avons parlé contre le Seigneur et contre toi : prie

pour qu’il éloigne de nous les serpents. Et Moïse pria pour le peuple, et le

Seigneur lui dit : Fais un serpent d’airain, et expose-le comme un signe :

celui qui, ayant été blessé, le regardera, vivra. Moïse fit donc un serpent

d’airain et l’exposa comme un signe : lorsque les blessés le regardaient, ils

étaient guéris.

R/. Voici l’arbre très

digne placé au milieu du paradis, * Sur lequel l’auteur du salut a vaincu, par

sa mort, la mort de tous les hommes. V/. Croix excellente et d’une éclatante

beauté. * Sur. Gloire au Père. * Sur.

AU DEUXIÈME NOCTURNE.

Quatrième leçon. Vers la

fin du règne de Phocas, Chosroës, roi des Perses, après avoir envahi l’Égypte

et l’Afrique et s’être emparé de Jérusalem, où il fit périr plusieurs milliers

de Chrétiens, emporta en Perse la Croix de notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ,

qu’Hélène avait déposée sur le mont Calvaire. Fatigué des vexations et des

calamités innombrables de la guerre, Héraclius, successeur de Phocas, demanda

la paix. Mais Chosroës, enorgueilli par ses victoires, ne voulut à aucun prix

la lui accorder. Dans cette extrémité, Héraclius eut recours aux jeûnes et aux

prières multipliées, implorant avec beaucoup de ferveur le secours de Dieu. Sur

l’inspiration du ciel, il rassembla une armée et, ayant engagé le combat, il

défit les trois généraux de Chosroës avec leurs trois armées.

R/. Il faut que nous nous

glorifiions dans la Croix de notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ, en qui est le salut,

la vie et notre résurrection : * Par qui nous avons été sauvés et délivrés. V/.

Nous adorons votre Croix, Seigneur, et nous honorons le souvenir de votre

glorieuse passion. * Par qui.

Cinquième leçon. Abattu

par ces défaites, Chosroës prit la fuite ; et lorsqu’il se disposait à

traverser le Tigre, il désigna son fils Médarsès, comme devant partager avec

lui l’autorité royale. Son fils aîné ne supporta pas cet affront sans un cruel

dépit, et en vint à méditer la perte commune de son père et de son frère :

dessein qu’il exécuta bientôt au retour de ces deux fugitifs. Après quoi il

sollicita d’Héraclius le droit de régner et l’obtint à certaines conditions,

dont la première était la restitution de la Croix du Seigneur. C’est ainsi que

la Croix fut recouvrée, quatorze ans après qu’elle était tombée en la

possession des Perses. De retour à Jérusalem, Héraclius la prit sur ses épaules

et la reporta, en grande pompe, sur la montagne où le Sauveur l’avait lui-même

portée.

R/. Tandis que par une

grâce céleste on exalte le gage sacré, la foi dans le Christ est fortifiée : *

On voit s’accomplir les divins prodiges opérés figurativement autrefois par le

bâton de Moïse. V/. Au contact de la Croix, les morts ressuscitent, et les

grandeurs de Dieu se révèlent. * On voit.

Sixième leçon. Cette

action fut marquée par un éclatant miracle. Héraclius, tout chargé d’or et de

pierreries, sentit une force invincible l’arrêter à la porte qui donnait accès

au mont Calvaire ; plus il faisait d’efforts pour avancer, plus il semblait

être fortement retenu. Comme l’empereur et avec lui tous les témoins de cette

scène étaient stupéfaits, Zacharie, Évêque de Jérusalem, lui dit : « Prenez

garde, ô empereur, qu’avec ces ornements de triomphe, vous n’imitiez point

assez la pauvreté de Jésus-Christ et l’humilité avec laquelle il a porté sa

Croix. » Héraclius se dépouillant alors de ses splendides vêtements, et

détachant ses chaussures, jeta sur ses épaules un vulgaire manteau et se remit

en route. Cela fait, il accomplit facilement le reste du trajet et replaça la

Croix sur le mont Calvaire, à l’endroit même d’où les Perses l’avaient enlevée.

La solennité de l’exaltation de la sainte Croix, que l’on célébrait chaque

année en ce même jour, prit alors une grande importance, en mémoire de ce

qu’elle avait été remise, par Héraclius, au lieu même où on l’avait dressée la

première fois pour le Sauveur.

R/. Ce signe de la Croix

sera dans le ciel lorsque le Seigneur viendra pour juger : * Alors seront

manifestés les secrets de notre cœur. V/. Quand le Fils de l’homme sera assis

sur le siège de sa majesté, et commencera à juger le siècle par le feu. *

Alors. Gloire au Père. * Alors.

AU TROISIÈME NOCTURNE.

Lecture du saint Évangile

selon saint Jean.

En ce temps-là : Jésus

dit à la foule des Juifs : C’est maintenant le jugement du monde, maintenant le

prince de ce monde sera jeté dehors. Et le reste.

Homélie de saint Léon,

Pape.

Septième leçon. A la vue

du Christ élevé en croix, il ne faut pas, mes bien-aimés, que votre pensée

s’arrête à ce seul aspect extérieur qui frappa les yeux des impies, auxquels il

a été dit par Moïse : « Ta vie sera comme en suspens devant tes yeux, et tu

craindras jour et nuit, et tu ne croiras pas à ta vie. » En effet, à la vue du

Seigneur en Croix, les impies ne pouvaient apercevoir en lui autre chose que

leur crime ; ils tremblèrent de crainte, non pas de la crainte qui justifie

dans la vraie foi, mais de celle qui torture une conscience coupable. Pour

nous, ayant l’intelligence éclairée par l’esprit de vérité, embrassons d’un

cœur pur et libre la Croix dont la gloire resplendit au ciel et sur la terre,

et appliquons toute l’attention de notre âme à pénétrer le mystère que le

Seigneur, parlant de sa passion prochaine, annonçait ainsi : « C’est maintenant

le jugement du monde, maintenant le prince de ce monde sera jeté dehors. Et

moi, quand j’aurai été élevé de terre, j’attirerai tout à moi. »

R/. Doux bois, doux clous,

ils ont soutenu un doux fardeau : * Ce bois a seul été digne de porter la

rançon du monde. V/. Ce signe de la Croix sera dans le ciel, lorsque le

Seigneur viendra pour juger. * Ce bois.

Huitième leçon. O vertu

admirable de la Croix ! ô gloire ineffable de la passion ! où l’on voit, et le

tribunal du Seigneur, et le jugement du monde, et la puissance du Crucifié.

Oui, Seigneur, vous avez attiré tout à vous, lorsque, ayant « vos mains tout le

jour étendues vers un peuple incrédule et rebelle, » l’univers entier comprit

qu’il devait rendre hommage à votre majesté. Vous avez, Seigneur, attiré tout à

vous, lorsque tous les éléments n’eurent qu’une seule voix pour exécrer le

forfait des Juifs ; lorsque les astres étant obscurcis, la clarté du jour

changée en ténèbres, la terre fut à son tour ébranlée par des secousses

extraordinaires et la création tout entière se refusa à servir des impies. Vous

avez, Seigneur, attiré tout à vous, parce que le voile du temple s’étant

déchiré, le saint des saints rejeta ses indignes pontifes, pour montrer que la

figure se transformait en réalité, la prophétie en déclarations manifestes, la

loi en Évangile.

R/. Comme Moïse a élevé

le serpent dans le désert, il faut de même que le Fils de l’homme soit élevé :

* Afin que quiconque croit en lui ne périsse point, mais qu’il ait la vie

éternelle. V/. Dieu n’a pas envoyé son Fils dans le monde pour condamner le

monde, mais pour que le monde soit sauvé par lui. * Afin. Gloire au Père. *

Afin.

Neuvième leçon. Vous avez, Seigneur, attiré tout à vous, afin que la piété de toutes les nations qui peuplent la terre célébrât, comme un mystère plein de réalité et dégagé de tout voile, ce que vous teniez caché dans un temple de la Judée, sous l’ombre des figures. Maintenant, en effet, l’ordre des Lévites a plus d’éclat, la dignité des Prêtres plus de grandeur, et l’onction qui sacre les Pontifes plus de sainteté. Et cela, parce que la source de toute bénédiction et le principe de toutes les grâces se trouvent en votre Croix, laquelle fait passer les croyants de la faiblesse à la force, de l’opprobre à la gloire, de la mort à la vie. C’est maintenant aussi que les divers sacrifices d’animaux charnels étant abolis, la seule oblation de votre corps et de votre sang tient lieu de toutes les différentes victimes qui la représentaient. Car vous êtes le véritable « Agneau de Dieu qui effacez les péchés du monde, » et tous les mystères s’accomplissent tellement en vous, que, de même que toutes les hosties qui vous sont offertes ne font qu’un seul sacrifice, ainsi toutes les nations de la terre ne font plus qu’un seul royaume.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/14-09-Exaltation-de-la-Ste-Croix

Feast of

the Exaltation of the Holy Cross

Also

known as

Feast of the Holy Cross

Feast of the Triumph of

the Cross

Roodmas

3

May (Gallican Rite)

About

the Feast

The feast was

celebrated in Rome before

the end of the 7th

century. Its purpose is to commemorate the recovering of that portion of

the Holy Cross which was preserved at Jerusalem,

and which had fallen into the hands of the Persians. Emperor Heraclius

recovered this precious relic and

brought it back to Jerusalem on 3

May 629.

Las

Cruces, New

Mexico, diocese of

–

in Brazil

–

in Italy

Additional

Information

Light

From the Altar, edited by Father James

J McGovern

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Francis

Xavier Weninger

Meditations

on the Gospels for Every Day in the Year, by Father Pierre

Médaille

New Catholic Dictionary

Saints

and Saintly Dominicans, by Blessed Hyacinthe-Marie

Cormier, O.P.

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

other

sites in english

Brother Albert Thomas Dempsey, OP

New Liturgical Movement: The Story of the True Cross

New Liturgical Movement: Durandus on Exaltation of the

Cross

images

video

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites

en français

Abbé

Christian-Philippe Chanut

fonti

in italiano

Readings

O merciful God, grant thy

gracious presence to this thy family, that both in prosperity and adversity

thou mayest be ready to hear their prayers; and by the standard of the holy

Cross do thou vouchsafe to bring to nought all the wicked devices of our

enemies: that through thy protection we may be counted worthy to attain unto

everlasting joy in thy salvation. – Milanese Sacramentary

MLA

Citation

“Feast of the Exaltation

of the Holy Cross“. CatholicSaints.Info. 4 February 2024. Web. 13 September

2024.

<https://catholicsaints.info/feast-of-the-exaltation-of-the-holy-cross/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/feast-of-the-exaltation-of-the-holy-cross/

Reliquary of the True Cross at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem

Feast of The Exaltation

of the Holy Cross

On the Feast of the

Exaltation of the Cross (or Triumph of the Cross) we honor the Holy Cross by

which Christ redeemed the world. The public veneration of the Cross of Christ

originated in the fourth century, according to early accounts. The miraculous

discovery of the True Cross on September 14, 326, by Saint Helen, mother of

Constantine, while she was on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, is the origin of the

tradition of celebrating the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross on this date.

Constantine later built the Church of the Holy Sepulchre on the site of her

discovery of the cross. On this same pilgrimage she ordered two other churches

built: one in Bethlehem near the Grotto of the Nativity, the other on the Mount

of the Ascension, near Jerusalem.

In the Western Church the

feast came into prominence in the seventh century — after 629, when the

Byzantine emperor Heraclitus restored the Holy Cross to Jerusalem, after

defeating the Persians who had stolen it.

It remained in Christian

hands until the Battle of Hattin in 1187, when the Moslem leader Saladin

captured the relic. Saladin after the Battle of Hattin and the capture of

Jerusalem, would ride his horse through the streets with the Holy Relic

dragging behind his mount’s tail.

Christians “exalt” (raise

on high) the Cross of Christ as the instrument of our salvation. Adoration of

the Cross is, thus, adoration of Jesus Christ, the God Man, who suffered and

died on this Roman instrument of torture for our redemption from sin and death.

The cross represents the One Sacrifice by which Jesus, obedient even unto

death, accomplished our salvation. The cross is a symbolic summary of the

Passion, Crucifixion and Resurrection of Christ — all in one image.

The Cross — because of

what it represents — is the most potent and universal symbol of the Christian

faith. It has inspired both liturgical and private devotions: for example, the