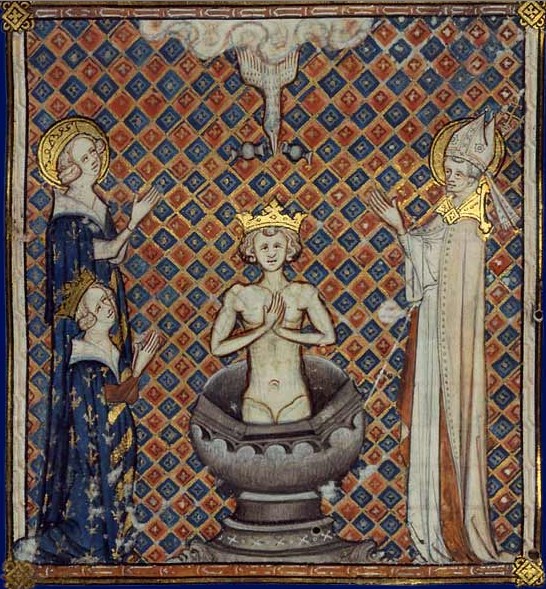

Maître de Saint Gilles, Baptême de Clovis 1er, roi des Francs, par Saint Rémi, vers 1500, National Gallery of Art de Washington.

Master of Saint Giles, The Baptism of

Clovis , circa 1500, 61,5 x 45,5, National Gallery of Art

Maestro

di Saint Gilles, San Remigio di Reims battezza il re Clodoveo (1500 ca.), olio

su tavola, Washington, National Gallery

Saint Remi

Évêque de Reims (+ 530)

Au propre de France, Rémi

est fêté le 15 janvier (dies natalis).

Au propre du diocèse de

Reims, il est fêté le 1er octobre, jour de la "translation" des

reliques pour y être vénéré par les rémois à l'emplacement où s'élèvera

l'actuelle basilique (attesté dès 585 - installation d'un monastère vers

750-760).

Issu d'une grande famille

gallo-romaine de la région de Laon, il avait pour mère sainte

Céline. A 22 ans, il est choisi comme évêque de Reims et son activité

missionnaire s'étend jusqu'à la Belgique. Il fonde les diocèses de Thérouanne,

Laon et Arras, crée tout un réseau d'assistance pour les pauvres et joue un

rôle de médiateur auprès des Barbares. Quand le chef franc Clovis prend le

pouvoir, saint Rémi lui envoie un message "Soulage tes concitoyens,

secours les affligés, protège les veuves, nourris les orphelins."

La reine sainte Clotilde,

tout naturellement, se tournera vers saint Rémi et vers un autre évêque

contemporain, saint Vaast, pour

acheminer le roi vers la foi. Après le baptême de Reims, saint Rémi restera,

jusqu'à sa mort, l'un des conseillers écoutés du roi et sera l'un des artisans,

en Gaule, du retour à la vérité catholique des Burgondes après le bataille de

Dijon et des Wisigoths à Vouillé, deux populations contaminées par

l'arianisme.

Voir

aussi sur le site du diocèse de Reims.

Au 13 janvier au

martyrologe romain: À Reims, vers 530, la naissance au ciel de saint Remi,

évêque, qui, après avoir lavé le roi Clovis dans la fontaine baptismale et

l’avoir initié aux sacrements de la foi, il convertit au Christ le peuple des

Francs. Il quitta cette vie, célèbre par sa sainteté après plus de soixante ans

d’épiscopat. (En France, sa mémoire est célébrée le 15, jour de sa mise au tombeau.)

Martyrologe romain

Secourez les malheureux,

protégez les veuves, nourrissez les orphelins… Que votre tribunal reste ouvert

à tous et que personne n’en sorte triste ! Toutes les richesses de vos

ancêtres, vous les emploierez à la libération des captifs et au rachat des

esclaves. Admis en votre palais, que nul ne s’y sente étranger ! Plaisantez

avec les jeunes, délibérez avec les vieillards !

Lettre de saint Rémi au

roi Clovis - 482

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/439/Saint-Remi.html

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867),

Saint Rémi, évêque de Reims, carton pour les vitraux de la chapelle Saint-Louis

à Dreux, Eure-et--Loir, France

Saint Remi

Évêque de Reims

La Tradition nous apprend

que Remi naquit dans une famille pieuse et emplie de la crainte de Dieu. Son

père, Émile, comte de Laon, fut dit-on un extraordinaire administrateur, tandis

que sa mère, sainte Céline, alliait toutes les qualités de mère et de grande

dame. Émile et Céline eurent d'abord deux garçons : saint Principe, évêque de

Soissons, et un autre, père de saint Loup, successeur de son oncle à Soissons.

On raconte que l'ermite

Montan reçut trois fois de Dieu l'ordre d'aller avertir Émile et Céline qu'ils

auraient encore un fils et que celui-ci serait l'apôtre des Francs en même

temps que le reconstructeur de l'Église des Gaules. C'est ainsi que naquit

Remi, à Laon, vers le milieu du V° siècle.

Très vite, dit-on, Remi

montra une grande piété et beaucoup d'humilité, en même temps qu'une grande

intelligence ; aussi le mit-on très tôt à l'étude où il progressa vivement.

Vers sa vingtième année, il se claustra dans une petite maison proche du

château de Laon où il continua d'étudier en menant une vie de prière, ne

sortant que pour les offices et l'exercice de la charité. Sa réputation grandit

au point que lorsque mourut Bennadius, évêque de Reims, le clergé et le peuple

de cette ville demandèrent qu'il soit leur évêque bien qu'il n'eût que

vingt-deux ans.

Remi fit toutes les

représentations possibles et imaginables pour échapper à l'élection ; rien n'y

fit, les rémois n'en démordirent pas et répondaient à tout, jusqu'à ce que Dieu

lui-même s'en vint ratifier leur choix lorsqu'Il envoya un rayon de lumière sur

le front de Remi en l'embaumant d'un céleste parfum. Les gens de Reims

enlevèrent alors l'élu et le firent sacrer leur XV° évêque.

À peine sacré, il se mit

à exercer son épiscopat avec l'autorité et le discernement d'un vieil évêque :

homme de prière et de célébration, de pénitence et de charité ; prédicateur de

talent et parfait instructeur du peuple. De plus, il ne tarda guère à opérer

des miracles comme délivrer des possédés de l'emprise du démon, rendre la vue

aux aveugles, préserver de l'incendie et de la mort, changer de l'eau en vin et

même ressusciter des morts.

Or, il advint que Clovis

monta sur un trône des Francs et Remi ne manqua pas de lui écrire promptement

pour le féliciter et aussi pour lui adresser ses conseils :

L'important, c'est que la

justice de Dieu ne chancelle point chez nous.

... Vous devez vous

servir de conseillers capables d'orner votre réputation.

... Vous devrez avoir de

la déférence pour nos prêtres et recourir toujours à leurs conseils : si

l'harmonie règne entre Vous et eux, notre pays en profitera.

... Secourez les

affligés, ayez soin des veuves, nourrissez les orphelins.

... Que tous vous aiment

et vous craignent.

Clovis ne tarda pas à

nourrir une grande estime pour les qualités humaines de l'évêque Remi dont il

fit un de ses conseillers privilégiés. Le chroniqueur Frégédaire affirme que

Remi fut le bénéficiaire de l'histoire du ‘ vase de Soissons ’.

Enfin lorsque la Gaule du

Nord fut conquise, il est vraisemblable que Remi fut l'intermédiaire entre la

population et les Francs, d'autant plus que les autres évêques reconnaissaient

Remi pour leur porte-parole et leur défenseur.

Cependant, il convenait

au plus tôt de réaliser la prophétie de Montan et de convertir Clovis dont

l'épouse, Clotilde, était déjà chrétienne. Remi fit alors le siège de Clovis et

l'encercla par des arguments politiques (les ennemis qu'il restait à vaincre -

Wisigoths, Burgondes, Ostrogoths - étaient hérétiques et le Roi devenu

catholique serait reçu comme un libérateur venu restituer la vraie foi), en

même temps que par des démonstrations spirituelles et intellectuelles. Clovis

se décida lors de la bataille de Tolbiac qu'il gagna, pensa-t-il,

miraculeusement. L'ennemi ayant fait volte-face, Clovis fut acclamé par ses

guerriers et, publiquement, commença le chemin de la conversion sous la

conduite de saint Remi. Le baptême eut lieu à Noël 496 dans la cathédrale de

Reims et une colombe apporta le Saint Chrême du ciel. Trois mille guerriers se

firent baptiser avec leur roi. Clovis devint le nouveau Constantin et rallia

les populations catholiques des Gaules.

Brisé par la maladie,

saint Remi mourut après plus de 70 ans d'épiscopat, le 13 janvier 533, et fut

déposé au tombeau le 15 janvier. La translation solennelle de ses reliques eut

lieu le 1° octobre de la même année.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/01/15.php

Miracle

de saint Remi, école de Reims, XIVe siècle.

Saint Rémi

Archevêque de Reims,

Apôtre des Francs

(438-533)

La naissance de saint

Rémi fut prédite à ses parents déjà avancés en âge par un vieux moine aveugle.

Les talents et les vertus de Rémi le firent consacrer archevêque de Reims, à

l'âge de vingt-deux ans; sa consécration fut marquée par un prodige: le front

de Rémi parut brillant de lumière et fut embaumé d'un parfum tout céleste.

Il montra dès l'abord

toutes les vertus des grands pontifes. Les miracles relevèrent encore l'éclat

de sa sainteté: pendant ses repas, les oiseaux venaient prendre du pain dans

ses mains; il guérit un aveugle possédé du démon; il remplit de vin, par le

signe de la Croix, un vase presque vide; il éteignit, par sa seule présence, un

terrible incendie; il délivra du démon une jeune fille que saint Benoît n'avait

pu délivrer.

L'histoire de sainte

Clotilde nous apprend comment Clovis se tourna vers le Dieu des chrétiens, à la

bataille de Tolbiac, et remporta la victoire. Ce fut saint Rémi qui acheva

d'instruire le prince. Comme il lui racontait, d'une manière touchante, la

Passion du Sauveur: "Ah! s'écria le guerrier, que n'étais-je là avec mes

Francs pour Le délivrer!" La nuit avant le baptême, saint Rémi alla

chercher le roi, la reine et leur suite dans le palais, et les conduisit à

l'église, où il leur fit un éloquent discours sur la vanité des faux dieux et

les grands mystères de la religion chrétienne. Alors l'église se remplit d'une

lumière et d'une odeur célestes, et l'on entendit une voix qui disait: "La

paix soit avec vous!"

Le Saint prédit à Clovis

et à Clotilde les grandeurs futures des rois de France, s'ils restaient fidèles

à Dieu et à l'Église. Quand fut venu le moment du baptême, il dit au roi:

"Courbe la tête, fier Sicambre; adore ce que tu as brûlé, et brûle ce que

tu as adoré." Au moment de faire l'onction du Saint Chrême, le pontife,

s'apercevant que l'huile manquait, leva les yeux au Ciel et pria Dieu d'y

pourvoir. Tout à coup, on aperçut une blanche colombe descendre d'en haut,

portant une fiole pleine d'un baume miraculeux; le saint prélat la prit, et fit

l'onction sur le front du prince. Cette fiole, appelée dans l'histoire la

sainte Ampoule, exista jusqu'en 1793, époque où elle fut brisée par les

révolutionnaires. Outre l'onction du baptême, saint Rémi avait conféré au roi

Clovis l'onction royale. Deux soeurs du roi, trois mille seigneurs, une foule

de soldats, de femmes et d'enfants furent baptisés le même jour.

Saint Rémi devint aveugle

dans sa vieillesse. Ayant recouvré la vue par miracle, il célébra une dernière

fois le Saint Sacrifice et s'éteignit, âgé de quatre-vingt-seize ans.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_remi.html

Saint

Remy et Clovis Ier. Cote : Français 241 ,

Fol.

266v. Jacobus de Voragine, Legenda aurea (traduction de Jean de

Vignay),

France,

Paris, XIVe siècle, Richard de Montbaston.

SAINT REMI

Remi vient de rameur, qui

conduit et dirige le navire. Ou de rames, instruments à l’aide desquels on mène

le vaisseau. Il vient de plus de gyon, lutte. En effet saint Remi gouverna

l’église et la préserva du naufrage ; il la conduisit à la porte du paradis, et

il combattit pour elle contre les embûches du diable.

Saint Remi convertit à

J.-C. le roi et la nation des Francs. En effet ce roi avait épousé une femme

très chrétienne nommée Clotilde qui employait inutilement tous les moyens pour

convertir son mari à la foi: Ayant mis au monde un fils, elle voulut qu'il fût baptisé;

le roi s'y opposa formellement : or, comme elle n'avait pas de plus pressant

désir, elle finit par obtenir le consentement de Clovis; et l’enfant fut

baptisé; mais peu de temps après, il mourut subitement. Le roi dit à Clotilde :

« On voit maintenant que le Christ est un dieu de maigre valeur, puisqu'il n'a

pu conserver à la vie celui par lequel sa croyance pouvait être accrue. »

Clotilde lui dit : « Bien au contraire, c'est en cela que je me sens

singulièrement aimée de mon Dieu, puisque je sais qu'il a repris le premier

fruit de mon sein ; il a donné à mon fils. un royaume infiniment meilleur que

le tien. » Or, elle conçut de nouveau et mit au monde un second fils qu'elle

fit baptiser au plus tôt ainsi que le premier; quand tout à coup, il tomba si gravement

malade qu'on désespéra de sa vie. Alors le roi dit à son épouse : « Vraiment

ton dieu (142) est bien faible pour ne pouvoir conserver à la vie quelqu'un

baptisé en son nom : quand tu en engendrerais un mille et que tu les ferais

baptiser, tous ils périront de même. Cependant l’enfant entra en convalescence

et recouvra la santé ; il régna même après son père. Or, cette femme fidèle

s'efforçait d'amener son mari à 1a foi, mais celui-ci résistait d'une manière

absolue. (Dans une autre fête de saint Remi qui se trouve après l’Épiphanie, on

a dit comment il fut converti,) Et quand le roi Clovis eut été fait chrétien,

il voulut doter l’église de Reims, et dit à saint Remi : « Je vous veux donner

tout le terrain dont vous pourrez faire le, tour pendant ma méridienne

(Flodoard, c. XIV). »Ainsi fut fait. Mais sur un point du terrain que Remi

parcourait, se trouvait un moulin, et le meunier repoussa le saint avec

indignation. Saint Remi lui dit : « Mon ami, souffre sans te plaindre que nous

partagions ce moulin. » Cet homme le repoussa encore, mais aussitôt la roue du

moulin se mit à tourner à rebours ; il appela alors saint Remi en lui disant :

« Serviteur de Dieu, venez, et possédons le moulin en commun. » Le saint lui

répondit : « Ce ne sera ni à toi, ni à moi. » Et à l’instant la terre

s'entr'ouvrit et engloutit entièrement le moulin. Saint Remi, prévoyant qu'il y

aurait une famine, amassa beaucoup de blé ; des paysans ivres, pour se moquer

de la prudence du vieillard mirent le feu au magasin. Quand saint Remi apprit

cela, à raison des glaces de l’âge et du soir qui était arrivé il se mit à Se

chauffer et dit tranquillement : « Le feu est bon en tout temps, cependant les

hommes qui ont agi ainsi, et leurs descendants auront les membres virils rompus

et leurs femmes seront goitreuses. » Il en fut ainsi jusqu'au temps où ils

furent dispersés par Charlemagne (Flodoard (c. XVII) rapporte cette malédiction

du saint ; les hommes auraient eu une affliction qui n'aurait été autre qu'une

hernie. Il se sert du mot ponderosi). Or, il faut noter que la fête de saint

Remi qui se célèbre au mois de janvier est le jour de son bienheureux trépas

tandis que ce jour est la fête de sa translation. Après son décès, son corps

était porté dans un cercueil en l’église des saints Timothée et Apollinaire ;

mais arrivé à l’église de saint Christophe, il devint tellement pesant qu'il

n'y eut plus possibilité de le mouvoir. On fut donc forcé de prier le Seigneur

de daigner indiquer si, par hasard, il ne voulait pas que Remi fût inhumé dans

cette église où il n'y avait encore aucune autre relique de saint : et à

l’instant, on souleva le corps avec grande facilité, tant il était devenu

léger! et on l'y déposa avec beaucoup de pompe. Or, comme il s'y opérait une

infinité de miracles, on agrandit l’église et on construisit une crypte

derrière l’autel; mais quand il fallut lever le corps pour l’y placer, on ne

put le remuer. On passa la nuit en prières et à minuit, tout le monde s'étant

endormi, le lendemain, c'est-à-dire, le jour des calendes (1er) d'octobre, on

trouva que le cercueil avait été porté, dans cette crypte par les anges avec le

corps, de saint Remi.

Ce fut longtemps après

qu'on en fit, à pareil jour, la translation, avec une châsse d'argent, dans la

crypte qui avait reçu de riches décorations (Cf. Flodoard, passim..).

Saint Remi vécut vers

l’an du Seigneur 490.

La Légende dorée de

Jacques de VORAGINE nouvellement traduite en français avec introduction,

notices, notes et recherches sur les sources par l'Abbé J.-B. M. Roze, Chanoine

Honoraire de la cathédrale d'Amiens , Édouard Rouveyre, éditeur, 76, Rue de

Seine, 76, Paris MDCCCCII

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/voragine/tome03/148.htm

Eikenhouten

reliëf van de doop van Clovis, waarschijnlijk onderdeel van een altaarretabel,

in het Limburgs Museum in Venlo. Zuid-Nederlands of Nederrijns, ca. 1550.

Le Baptême de Clovis

(du livret « Saint Rémi,

Thaumaturge et Apôtre des Francs » par le Marquis de la Franquerie, pages 12 à

14)

« Dans la nuit de Noël

496, au jour anniversaire et à l’heure même de sa naissance, le Christ – lors

de la naissance spirituelle de notre France et de nos Rois - voulut, par un

miracle éclatant, affirmer la Mission providentielle de notre pays et de notre

Race Royale, au moment même ou Saint Rémi va proclamer cette Mission au nom du

Tout-Puissant, pour sanctionner solennellement les paroles (divinement

inspirées) de Son Ministre. A minuit, alors que le Roi, la Reine et leur suite

sont dans l’Eglise Saint Pierre ou l’Archevêque les a convoqués, ‘soudain

raconte Hincmar (1), une lumière plus éclatante que le soleil inonde l’église !

Le visage de l’évêque en est irradié ! En même temps retentit une voix : ‘La

paix soit avec vous ! C’est moi ! N’ayez point peur ! Persévérez en ma

dilection ! Quand la voix eut parlé, ce fut une odeur céleste qui embauma

l’atmosphère. Le Roi, la Reine, toute l’assistance épouvantés, se jetèrent aux

pieds de Saint Rémi qui les rassura et leur déclara que c’est le propre de Dieu

d’étonner au commencement de Ses visites et de se réjouir à la fin. Puis

soudainement illuminé d’une vision d’avenir, la face rayonnante, l’œil en feu,

le nouveau Moïse s’adressant directement à Clovis, Chef du nouveau Peuple de

Dieu, lui tint le langage – identique quant au sens – de l’ancien Moïse à

l’Ancien Peuple de Dieu : ‘Apprenez, mon fils, que le royaume de France est

prédestiné par Dieu à la défense de l’Eglise Romaine, qui est la seule

véritable église du Christ. Ce Royaume sera un jour grand entre tous les

royaumes et il embrassera toutes les limites de l’empire romain ! Et il

soumettra tous les peuples à son sceptre ! Il durera jusqu’à la fin des temps !

Il sera victorieux et prospère tant qu’il sera fidèle à la foi romaine. Mais il

sera rudement châtié toutes les fois qu’il sera infidèle à sa vocation(2)’.

Remarquez le bien : la prophétie est faite directement à la race royale, pour

bien marquer que la race royale doit être aussi inséparable de la France que la

France doit être inséparable de l’Eglise ! Un nouveau miracle devait se

produire le jour même ; laissons parler Hincmar : ‘Dès qu’on fut arrivé au

baptistère, le clerc qui portait le chrême, séparé par la foule de l’officiant,

ne put arriver à le rejoindre. Le Saint Chrême fit défaut. Le Pontife alors

lève au ciel les yeux…et supplie le Seigneur de le secourir en cette nécessité

pressante. ‘Soudain apparaît, voltigeant à la portée de sa main, aux yeux ravis

et étonnés de l’immense foule, une blanche colombe tenant en son bec une

ampoule d’huile sainte dont le parfum d’une inexprimable suavité embauma toute

l’assistance. Dès que le prélat eut reçu l’ampoule, la colombe disparut (3).

C’est avec le Saint Chrême contenu dans cette Ampoule, qu’ont été sacrés nos

Rois. Le cérémonial du Sacre des Rois de France reconnaît que, comme au baptême

du Christ, c’est le ‘Saint Esprit qui, par l’effet d’une grâce singulière,

apparut sous la forme d’une colombe et donna ce baume divin au pontife’. Le

Saint Esprit voulut assister visiblement au Sacre du premier de nos Rois, pour

marquer ainsi d’un signe sacré de toute spéciale prédilection la Monarchie

Française, consacrer tous nos Rois et imprimer sur leur front un caractère

indélébile qui leur assurerait la Primauté sur tous les autres Souverains de la

terre ; enfin pour les munir de Ses sept dons afin qu’ils pussent accomplir

leur Mission providentielle dans le monde. Très véritablement le Roi de France

était l’Oint, le consacré du Seigneur. Ce privilège unique était reconnu dans

le monde entier. Dans toutes les cérémonies diplomatiques, en effet,

l’Ambassadeur du Roi de France avait le pas sur ceux de tous les autres

Souverains parce que son Maître était ‘Sacré d’une huile apportée du Ciel’,

ainsi que le reconnaît un Décret de la République de Venise, daté de 1558 ».

Notes :

(1) : « Migne ‘Patrologie

Latine’, tome 125, page 1159. Hincmar : ‘Vita Sancti Remigii’, chapitre 36 ».

(2) : « Migne ‘Patrologie

Latine’, tome 135, page 51 ; Flodoard : ‘Historia Ecclesiae Remensis, livre 1,

chapitre 13 ».

(3) : « Hincmar :

‘Vita Sancti Remigii’, chapitre 38. Migne ‘Patrologie Latine’, tome 125, page

1160 ».

SOURCE : http://viens-seigneur-jesus.forumactif.com/t1417-le-bapteme-de-clovis-par-saint-remi

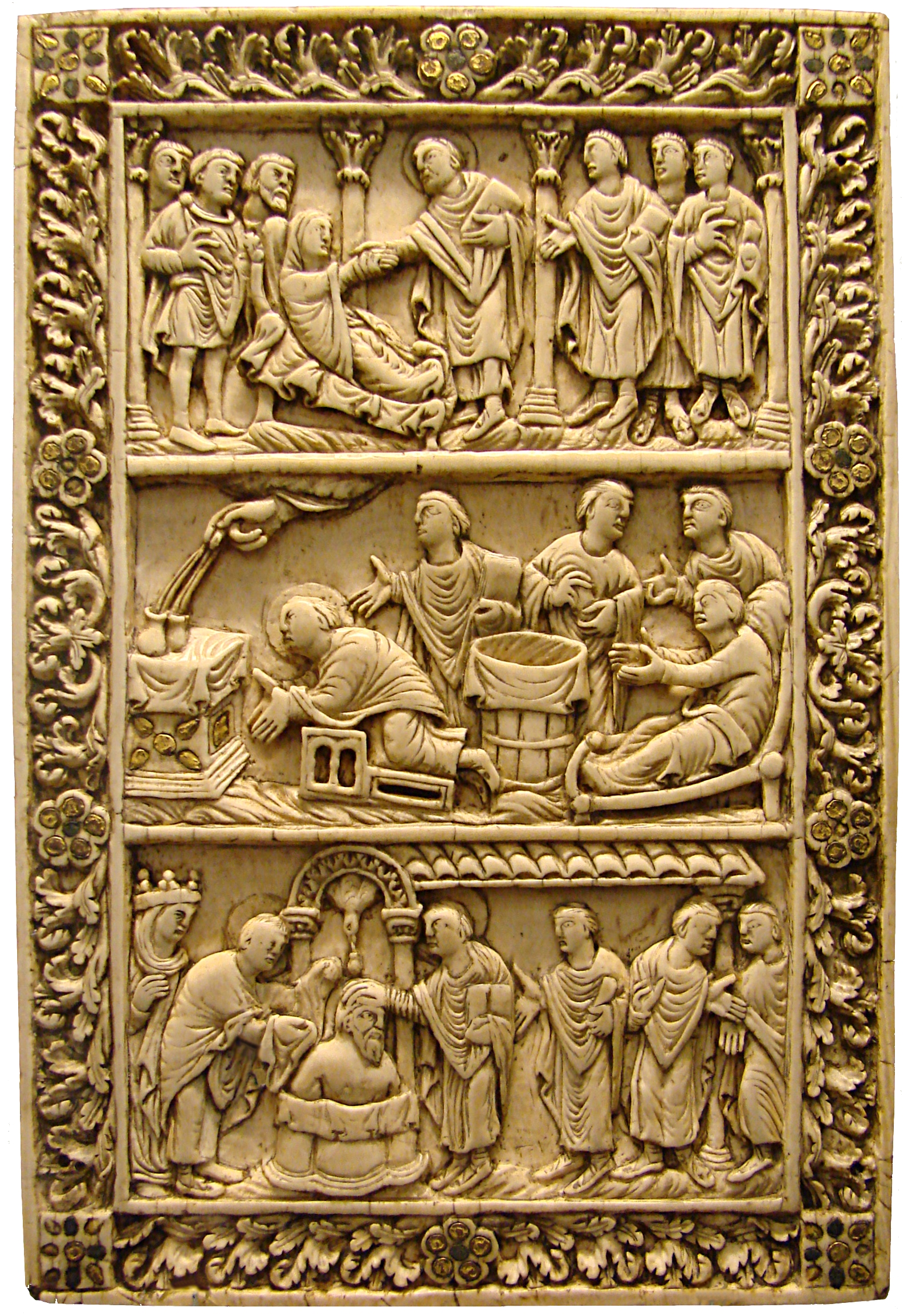

Plaque

de reliure en ivoire, Reims, dernier quart du IXème siècle. Musée de Picardie à

Amiens.

Scènes

de la vie de St Remi :

au

registre supérieur, St Remi ressuscite une jeune fille ;

au

centre : la Main de Dieu remplit deux flacons ;

au

registre inférieur, le baptême de Clovis avec le miracle de la Sainte Ampoule.

Also

known as

Apostle of the Franks

Remigius of Reims

Remi…

Remigio…

Remigiusz…

Romieg…

Rémi…

Rémy…

1

October (translation of relics)

15

January (France,

general calendar)

3rd Sunday in September (Arignano, Italy)

Profile

Born to the Gallo-Roman

nobility, the son of Emilius, count of

Laon, and of Saint Celina;

younger brother of Saint Principius

of Soissons; uncle of Saint Lupus

of Soissons. A speaker noted

for his eloquence, he was selected bishop of Rheims (in

modern France)

at age 22 while still a layman,

and served his diocese for

74 years. He evangelized throughout Gaul,

working with Saint Vaast.

Spiritual teacher of Saint Theodoric. Converted Clovis, king of

the Franks, baptising him

on 24

December 496;

this opened the way to the conversion of

all the Franks and

the establishment of the Church throughout France. Blind at

the time of his death.

Born

c.438

13

January 533 of

natural causes

interred on 15

January 533

relics transferred

to the Basilica Saint-Rémy 1

October 1049

against

religious indifference

Rheims, France, archdiocese of

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Golden

Legend: Life of Saint Remigius

Golden

Legend: Translation of Saint Remigius

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Francis

Xavier Weninger

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

books

Our

Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

Champions

of Catholic Orthodoxy

Dictionary

of Christian Biography, by Henry Wace

New

Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge

images

webseiten

auf deutsch

sitios

en español

Martirologio

Romano, 2001 edición

sites

en français

fonti

in italiano

nettsteder

i norsk

spletne

strani v slovenšcini

MLA

Citation

“Saint Remigius of

Rheims“. CatholicSaints.Info. 26 July 2020. Web. 13 January 2021. <https://catholicsaints.info/saint-remigius-of-rheims/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-remigius-of-rheims/

Vitrail

de saint Remi et saint Waast.

St. Remigius

Apostle of the Franks, Archbishop of Reims,

b. at Cerny or Laon, 437; d. at Reims,

13 January 533. His feast is

celebrated 1 October. His father was Emile, Count of Laon. He

studied literature at Reims and

soon became so noted for learning and sanctity that

he was elected Archbishop of Reims in

his twenty-second year. Thence-forward his chief aim was the propagation

of Christianity in

the realm of the Franks.

The story of the return of the sacred

vessels, which had been stolen from

the Church of Soissons testifies

to the friendly relations existing between him and Clovis,

King of the Franks,

whom he converted to Christianity with

the assistance of St. Waast (Vedastus, Vaast) and St.

Clotilda, wife of Clovis.

Even before he embraced Christianity Clovis had

showered benefits upon both

the Bishop and Cathedral of Reims,

and after the battle of Tolbiac, he requested Remigius to baptize him

at Reims (24

December, 496) in presence of several bishops of

the Franks and Alemanni and

great numbers of the Frankish army. Clovis granted

Remigius stretches of territory, in which the latter established andendowed many churches.

He erected, with the papal consent, bishoprics at Tournai; Cambrai; Terouanne,

where he ordained the

first bishop in

499; Arras, where he placed St. Waast; Laon, which he gave to

his nephew Gunband. The authors of "Gallia

Christiana" record numerous and

munificent donations made to St. Remigius by members of

the Frankish nobility,

which he presented to the cathedral at Reims.

In 517 he held a synod, at which after a heated discussion he converted a bishop of Arian views.

In 523 he wrote congratulating Pope Hormisdas upon

his election. St.

Medardus, Bishop of

Noyon, was consecrated by

him in 530. Although St. Remigius's influence over people and prelates was

extraordinary, yet upon one occasion, the history of which has come

down to us, his course of action was attacked. His condonement of

the offences of one Claudius, a priest,

brought upon him the rebukes of his episcopal brethren, who

deemed Claudius deserving of degradation. The reply of St.

Remigius, which is still extant, is able and convincing (cf. Labbe,

"Concilia", IV). His relics were

kept in the cathedral of Reims,

whence Hincmar had

them translated to Epernay during the period of the invasion by

the Northmen,

thence, in 1099, at the instance of Leo

IX, to the Abbey of Saint-Remy. His sermons, so much admired

by Sidonius Apollinaris (lib. IX, cap. lxx), are not extant. On

his other works we have four letters, the one containing his defence in

the matter of Claudius, two written to Clovis,

and a fourth to the Bishop of

Tongres. According to several biographers, the Testament of St.

Remigius is apocryphal; Mabillon and Ducange,

however, argue for its authenticity. The attribution of other works

to St. Remigius, particularly a commentary upon St.

Paul's Epistles,

is entirely without foundation.

Sources

Acta Sanct. I October,

59-187; Hist. litt. France, III (Paris, 1735), 155-163; DE

CERIZIERS, Les heureux commencements de la France chrétienne sous St. Remi (Reims,

1633); MARLOT, Tombeau de St. Remi (Reims, 1647); DORIGNY, Vie

de St Remi (Paris, 1714); AUBERT, Vie de St. Remi (Paris, 1849);

MEYER, Notice de deux MSS. de la vie de St. Remi in Notes et extraits de

MSS., XXXV (Paris, 1895), 117-30; D'AVENAY, St. Remi de Reims (Lille,

1896); CARLIER, Vie de St Remi (Tours, 1896).

Dedieu-Barthe,

Joseph. "St. Remigius." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol.

12. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 20 May

2015 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12763b.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Thomas M. Barrett. Dedicated to

the memory of St. Remigius.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. June 1, 1911. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2020 by Kevin

Knight. Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12763b.htm

Remigiusdarstellung am

Gemeindehaus St. Remigius, Königswinter

Remigius (Rémy, Remi) of

Reims B (RM) +

Born at Cerny near Laon, France, c. 437; died at Rheims on January 13, 530. The

name St. Rémy is intimately connected with that of King Clovis of the Franks,

the bloodthirsty general and collector of vases. Rémy was the son of Count

Emilius of Laon and Saint Celina, daughter of Principius, bishop of Soissons.

Even as a child Rémy was devoted to books and God. These two loves developed

the future saint into a famous preacher. Saint Sidonius Apollinaris, who knew

him, testified to his virtue and eloquence as a preacher.

So great was his renown

that, in 459, when he was only 22 and still a layman, he was elected bishop of

Rheims. Hincmar, testifying that Rémy "was forced into being bishop rather

than elected," adds to our impression of a virtuous man the added quality

of modesty. Other sources note that the saint was refined, tall (over seven

feet(!) in height), with an austere forehead, an aquiline nose, fair hair, a

solemn walk, and stately bearing.

After his ordination and

consecration, he reigned for 74 years--all the time devoting himself to the

evangelization of the Franks. It was said that "by his signs and miracles,

Rémy brought low the heathen altars everywhere." Foregoing the alternative

episcopal path, Rémy chose the way of self-sacrifice. He became a model for his

clergy and was indefatigable in his good works.

At some point between 481

and 486, Rémy wrote to the pagan King Clovis: "May the voice of justice be

heard from your mouth. . . . Respect your bishops and seek their advice. . . .

Be the protector of your subjects, the support of the afflicted, the comfort of

widows, the father of orphans and the master of all, that they might learn to

love you and fear you. . . . Let your court fe open to all and let no one leave

with the grief of not being heard. . . . Divert yourself with young people, but

if you wish truly to reign transact important matters with those who are older.

. . ."

Clovis must have

respected Rémy's advice even if he did not follow it: During his march on

Chalons and Troyes, Clovis bypassed Rheims, Rémy's see. It is possible, though,

that only his wife's civilizing influence prevented him from burning Rheims.

Clovis married the

radiant and beautiful Christian, Saint Clotildis, by proxy at Chalons-sur-

Saone, while she was still living in Lyons under the tutelage of Saint

Blandine. It was not a peaceful union. Clovis, an ambitious autocrat, allowed

his rage to lead to ill-planned actions. The young, pious Clotildis showed him

how much wiser it was to struggle with this wild beast than to give way to his

emotions. At first Clovis resisted being tamed by his wife.

In 496, Clovis,

supposedly in response to a suggestion from his wife, invoked the Christian God

when the invading Alemanni were on the verge of defeating his forces, whereupon

the tide of battle turned and Clovis was victorious at Tolbiac. St. Rémy, aided

by Saint Vedast, instructed him and his chieftains in Christianity. At the

Easter Vigil (or Christmas Day) in 496, Rémy baptized Clovis, his two sisters,

and 3,000 of his subjects. (Most seem to agree on the year, but not the day or

place.)

Though he never took part

in any of the councils held during his life, Rémy was a zealous proponent of

orthodoxy, opposed Arianism, and converted an Arian bishop at a synod of Arian

bishops in 517. He was censured by a group of bishops for ordaining one

Claudius, whom they felt was unworthy of the priesthood, but St. Rémy was

generally held in great veneration for his holiness, learning, and miracles. He

is said to have healed a blind man. Another time, like Jesus, he was confronted

with a host who ran out of wine at a dinner party. Rémy went down to the

cellar, prayed, and at once wine began to spread over the floor!

Rémy's last act was to

draw up a will in which he distributed all his lands and wealth and ordered

that "generous alms be given the poor, that liberty be given to the serfs

on his domain," and concluded by asking God to bless the family of the

first Christian king.

Because he was the most

influential prelate of Gaul and is considered the apostle of the Franks, Rémy

has been the subject of many tales. Rémy's notoriety sometimes difficult to

distinguish the reliable from the untrustworthy in his biographies (Attwater,

Benedictines, Delaney, Encyclopedia).

In art, St. Remigius is generally portrayed as a bishop carrying holy oils, though he may have other representations. At times he may be shown (1) as a dove brings him the chrism to anoint Clovis; (2) with Clovis kneeling before him; (3) preaching before Clovis and his queen; (4) welcoming another saint led by an angel from prison; (5) exorcising; or (6) contemplating the veil of Saint Veronica (Roeder).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/1001.shtml

Anonyme, Saint Remigius Replenishing the Barrel of Wine; (interior) Saint Remigius and the Burning Wheat, Oil, gold, and white metal on wood, circa 1500–1505, 13,8 x 77,5, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Anonyme,

Saint Remigius Replenishing the Barrel of Wine; (interior) Saint Remigius and

the Burning Wheat, Oil, gold, and white metal on wood, circa 1500–1505, 13,8 x

77,5, Metropolitan Museum of Art

St. Remigius, Archbishop

of Rheims, Confessor

From his ancient life now

lost, but abridged by Fortunatus, and his life compiled by Archbishop Hincmar,

with a history of the translation of his relics. See also St. Gregory of Tours,

l. 2; Fleury, l. 29, n. 44, &c.; Ceillier, t. 16; Rivet, Hist. Littér.

de la Fr. t. 3, p. 155; Suysken the Bollandist, t. 1, Octob. pp. 59, 187.

A.D. 533.

ST. REMIGIUS, the great

apostle of the French nation, was one of the brightest lights of the Gaulish

church, illustrious for his learning, eloquence, sanctity, and miracles. An

episcopacy of seventy years, and many great actions have rendered his name

famous in the annals of the church. His very birth was wonderful, and his life

was almost a continued miracle of divine grace. His father Emilius, and his

mother Cilinia, both descended of noble Gaulish families, enjoyed an affluent

fortune, lived in splendour suitable to their rank at the castle of Laon, and

devoted themselves to the exercise of all Christian virtues. St. Remigius seems

to have been born in the year 439. 1 He

had two brothers older than himself, Principius, bishop of Soissons, and

another whose name is not known, but who was father of St. Lupus, who was

afterwards one of his uncle’s successors in the episcopal see of Soissons. A

hermit named Montanus foretold the birth of our saint to his mother; and the

pious parents had a special care of his education, looked upon him as a child

blessed by heaven, and were careful to put him into the best hands.

His nurse Balsamia is

reckoned among the saints, and is honoured at Rheims in a collegiate church

which bears her name. She had a son called Celsin, who was afterwards a

disciple of our saint, and is known at Laon by the name of St. Soussin. St.

Remigius had an excellent genius, made great progress in learning, and in the

opinion of St. Apollinaris Sidonius, who was acquainted with him in the earlier

part of his life, he became the most eloquent person in that age. 2 He

was remarkable from his youth for his extraordinary devotion and piety, and for

the severity of his morals. A secret apartment in which he spent a great part

of his time in close retirement, in the castle of Laon, whilst he lived there,

was standing in the ninth century, and was visited with devout veneration when

Hincmar wrote. Our saint, earnestly thirsting after greater solitude, and the

means of a more sublime perfection, left his father’s house, and made choice of

a retired abode, where, having only God for witness, he abandoned himself to

the fervour of his zeal in fasting, watching, and prayer. The episcopal see of

Rheims 3 becoming

vacant by the death of Bennagius, Remigius, though only twenty-two years of

age, was compelled, notwithstanding his extreme reluctance, to take upon him

that important charge; his extraordinary abilities seeming to the bishops of

the province a sufficient reason for dispensing with the canons in point of

age. In this new dignity, prayer, meditation on the holy scriptures, the

instruction of the people, and the conversion of infidels, heretics, and

sinners were the constant employment of the holy pastor. Such was the fire and

unction with which he announced the divine oracles to all ranks of men, that he

was called by many a second St. Paul. St. Apollinaris Sidonius 4 was

not able to find terms to express his admiration of the ardent charity and

purity with which this zealous bishop offered at the altar an incense of sweet

odour to God, and of the zeal with which by his words he powerfully subdued the

wildest hearts, and brought them under the yoke of virtue, inspiring the

lustful with the love of purity, and moving hardened sinners to bewail their

offences with tears of sincere compunction. The same author, who, for his

eloquence and piety was one of the greatest lights of the church in that age,

testifies, 5 that

he procured copies of the sermons of this admirable bishop, which he esteemed

an invaluable treasure; and says that in them he admired the loftiness of the

thoughts, the judicious choice of the epithets, the gracefulness and propriety

of the figures, and the justness, strength, and closeness of the reasoning,

which he compares to the vehemence of thunder; the words flowed like a gentle

river, but every part in each discourse was so naturally connected, and the

style so even and smooth, that the whole carried with it an irresistible force.

The delicacy and beauty of the thoughts and expression were at the same time

enchanting, this being so smooth, that it might be compared to the smoothest

ice or crystal upon which a nail runs without meeting with the least rub or

unevenness. Another main excellency of these sermons consisted in the sublimity

of the divine maxims which they contained, and the unction and sincere piety

with which they were delivered; but the holy bishop’s sermons and zealous

labours derived their greatest force from the sanctity of his life, which was

supported by an extraordinary gift of miracles. Thus was St. Remigius qualified

and prepared by God to be made the apostle of a great nation.

The Gauls, who had

formerly extended their conquests by large colonies in Asia, had subdued a

great part of Italy, and brought Rome itself to the very brink of utter

destruction, 6 were

at length reduced under the Roman yoke by Julius Cæsar, fifty years before the

Christian era. It was the custom of those proud conquerors, as St. Austin

observes, 7 to

impose the law of their own language upon the nations which they subdued. 8 After

Gaul had been for the space of about five hundred years one of the richest and

most powerful provinces of the Roman empire, it fell into the hands of the

French; but these new masters, far from extirpating or expelling the old Roman

or Gaulish inhabitants, became, by a coalition with them, one people and took

up their language and manners. 9 Clovis,

at his accession to the crown, was only fifteen years old: he became the

greatest conqueror of his age, and is justly styled the founder of the French

monarchy. Even whilst he was a pagan he treated the Christians, especially the

bishops, very well, spared the churches, and honoured holy men, particularly

St. Remigius, to whom he caused one of the vessels of his church, which a

soldier had taken away, to be returned, and because the man made some demur,

slew him with his own hand. St. Clotildis, whom he married in 493, earnestly

endeavoured to persuade him to embrace the faith of Christ. The first fruit of

their marriage was a son, who, by the mother’s procurement, was baptized, and

called Ingomer. This child died during the time of his wearing the white habit,

within the first week after his baptism. Clovis harshly reproached Clotildis,

and said: “If he had been consecrated in the name of my gods, he had not died;

but having been baptized in the name of yours, he could not live.” The queen

answered: “I thank God, who has thought me worthy of bearing a child whom he

has called to his kingdom.” She had afterwards another son, whom she procured

to be baptized, and who was named Chlodomir. He also fell sick, and the king

said in great anger: “It could not be otherwise: he will die presently in the

same manner his brother did, having been baptized in the name of your Christ.”

God was pleased to put the good queen to this trial; but by her prayers this child

recovered. 10 She

never ceased to exhort the king to forsake his idols, and to acknowledge the

true God; but he held out a long time against all her arguments, till, on the

following occasion, God was pleased wonderfully to bring him to the confession

of his holy name, and to dissipate that fear of the world which chiefly held

him back so long, he being apprehensive lest his pagan subjects should take

umbrage at such a change.

The Suevi and Alemanni in

Germany assembled a numerous and valiant army, and under the command of several

kings, passed the Rhine, hoping to dislodge their countrymen the Franks, and

obtain for themselves the glorious spoils of the Roman empire in Gaul. Clovis

marched to meet them near his frontiers, and one of the fiercest battles

recorded in history was fought at Tolbiac. Some think that the situation of

these German nations, the shortness of the march of Clovis, and the route which

he took, point out the place of this battle to have been somewhere in Upper

Alsace. 11 But

most modern historians agree that Tolbiac is the present Zulpich, situated in

the duchy of Juliers, four leagues from Cologne, between the Meuse and the

Rhine; and this is demonstrated by the judicious and learned d’Anville. 12 In

this engagement the king had given the command of the infantry to his cousin

Sigebert, fighting himself at the head of the cavalry. The shock of the enemy

was so terrible, that Sigebert was in a short time carried wounded out of the

field, and the infantry was entirely routed, and put to flight. Clovis saw the

whole weight of the battle falling on his cavalry; yet stood his ground,

fighting himself like a lion, covered with blood and dust: and encouraging his

men to exert their utmost strength, he performed with them wonderful exploits

of valour. Notwithstanding these efforts, they were at length borne down, and

began to flee and disperse themselves; nor could they be rallied by the

commands and entreaties of their king, who saw the battle upon which his empire

depended, quite desperate. Clotildis had said to him in taking leave: “My lord,

you are going to conquest; but in order to be victorious, invoke the God of the

Christians: he is the sole Lord of the universe, and is styled the God of

armies. If you address yourself to him with confidence, nothing can resist you.

Though your enemies were a hundred against one, you would triumph over them.”

The king called to mind these her words in his present extremity, and lifting

up his eyes to heaven, said, with tears: “O Christ, whom Clotildas invokes as

Son of the living God, I implore thy succour. I have called upon my gods, and

find they have no power. I therefore invoke thee; I believe in thee. Deliver me

from my enemies, and I will be baptized in thy name.” No sooner had he made

this prayer than his scattered cavalry began to rally about his person; the

battle was renewed with fresh vigour, and the chief king and generalissimo of

the enemy being slain, the whole army threw down their arms, and begged for quarter.

Clovis granted them their lives and liberty upon condition that the country of

the Suevi in Germany should pay him an annual tribute. He seems to have also

subdued and imposed the same yoke upon the Boioarians or Bavarians; for his

successors gave that people their first princes or dukes, as F. Daniel shows at

large. This miraculous victory was gained in the fifteenth year of his reign,

of Christ 496.

Clovis, from that

memorable day, thought of nothing but of preparing himself for the holy laver

of regeneration. In his return from this expedition he passed by Toul, and

there took with him St. Vedast, a holy priest who led a retired life in that

city, that he might be instructed by him in the faith during his journey; so

impatient was he to fulfil his vow of becoming a Christian, that the least

wilful delay appeared to him criminal. The queen, upon this news, sent

privately to St. Remigius to come to her, and went with him herself to meet the

king in Champagne. Clovis no sooner saw her, but he cried out to her: “Clovis

has vanquished the Alemanni, and you have triumphed over Clovis. The business

you have so much at heart is done; my baptism can be no longer delayed.” The

queen answered: “To the God of hosts is the glory of both these triumphs due.”

She encouraged him forthwith to accomplish his vow, and presented to him St.

Remigius as the most holy bishop in his dominions. This great prelate continued

his instruction, and prepared him for baptism by the usual practices of

fasting, penance, and prayer. Clovis suggested to him that he apprehended the

people who obeyed him would not be willing to forsake their gods, but said he

would speak to them according to his instructions. He assembled the chiefs of

his nation for this purpose; but they prevented his speaking, and cried out

with a loud voice: “My lord, we abandon mortal gods, and are ready to follow

the immortal God, whom Remigius teaches.” St. Remigius and St. Vedast therefore

instructed and prepared them for baptism. Many bishops repaired to Rheims for this

solemnity, which they judged proper to perform on Christmas-day, rather than to

defer it till Easter. The king set the rest an example of compunction and

devotion, laying aside his purple and crown, and, covered with ashes, imploring

night and day the divine mercy. To give an external pomp to this sacred action,

in order to strike the senses of a barbarous people, and impress a sensible awe

and respect upon their minds, the good queen took care that the streets from

the palace to the great church should be adorned with rich hangings, and that

the church and baptistery should be lighted up with a great number of perfumed

wax tapers, and scented with exquisite odours. The catechumens marched in

procession, carrying crosses, and singing the Litany. St. Remigius conducted

the king by the hand, followed by the queen and the people. Coming near the

sacred font, the holy bishop, who had with great application softened the heart

of this proud barbarian conqueror into sentiments of Christian meekness and

humility, said to him: “Bow down your neck with meekness, great Sicambrian

prince: adore what you have hitherto burnt; and burn what you have hitherto

adored.” Words which may be emphatically addressed to every penitent, to

express the change of his heart and conduct, in renouncing the idols of his

passions, and putting on the spirit of sincere Christian piety and humility.

The king was baptized by St. Remigius on Christmas-day, as St. Avitus assures

us. 13 St.

Remigius afterwards baptized Albofleda, the king’s sister, and three thousand

persons of his army, that is, of the Franks, who were yet only a body of troops

dispersed among the Gauls. Albofleda died soon after, and the king being

extremely afflicted at her loss, St. Remigius wrote him a letter of

consolation, representing to him the happiness of such a death in the grace of

baptism, by which we ought to believe she had received the crown of virgins. 14 Lantilda,

another sister of Clovis, who had fallen into the Arian heresy, was reconciled

to the Catholic faith, and received the unction of the holy chrism, that is,

says Fleury, confirmation; though some think it only a rite used in the reconciliation

of certain heretics. The king, after his baptism, bestowed many lands on St.

Remigius, who distributed them to several churches, as he did the donations of

several others among the Franks, lest they should imagine he had attempted

their conversion out of interest. He gave a considerable part to St. Mary’s

church at Laon, where he had been brought up; and established Genebald, a

nobleman skilled in profane and divine learning, first bishop of that see. He

had married a niece of St. Remigius, but was separated from her to devote

himself to the practices of piety. Such was the original of the bishopric of

Laon, which before was part of the diocess of Rheims. St. Remigius also

constituted Theodore bishop of Tournay in 487. St. Vedast, bishop of Arras in

498, and of Cambray in 510. He sent Antimund to preach the faith to the Morini,

and to found the church of Terouenne. Clovis built churches in many places,

conferred upon them great riches, and by an edict invited all his subjects to

embrace the Christian faith. St. Avitus, bishop of Vienne, wrote to him a

letter of congratulation, upon his baptism, and exhorts him to send ambassadors

to the remotest German nations beyond the Rhine, to solicit them to open their

hearts to the faith.

When Clovis was preparing

to march against Alaric, in 506, St. Remigius sent him a letter of advice how

he ought to govern his people so as to draw down upon himself the divine

blessings.” 15 “Choose,”

said he, “wise counsellors, who will be an honour to your reign. Respect the

clergy. Be the father and protector of your people; let it be your study to

lighten as much as possible all the burdens which the necessities of the state

may oblige them to bear: comfort and relieve the poor; feed the orphans;

protect widows; suffer no extortion. Let the gate of your palace be open to

all, that every one may have recourse to you for justice: employ your great

revenues in redeeming captives,” &c. 16 Clovis

after his victories over the Visigoths, and the conquest of Toulouse, their

capital in Gaul, sent a circular letter to all the bishops in his dominions, in

which he allowed them to give liberty to any of the captives he had taken, but

desired them only to make use of this privilege in favour of persons of whom

they had some knowledge. 17 Upon

the news of these victories of Clovis over the Visigoths, Anastatius, the

eastern emperor, to court his alliance against the Goths, who had principally

concurred to the extinction of the western empire, sent him the ornaments and

titles of Patrician, Consul, and Augustus: from which time he was habited in

purple, and styled himself Augustus. This great conqueror invaded Burgundy to

compel King Gondebald to allow a dower to his queen, and to revenge the murder

of her father and uncle; but was satisfied with the yearly tribute which the

tyrant promised to pay him. The perfidious Arian afterwards murdered his third

brother; whereupon Clovis again attacked and vanquished him; but at the entreaty

of Clotildis, suffered him to reign tributary to him, and allowed his son

Sigismund to ascend the throne after his death. Under the protection of this

great monarch St. Remigius wonderfully propagated the gospel of Christ by the

conversion of a great part of the French nation; in which work God endowed him

with an extraordinary gift of miracles, as we are assured not only by Hincmar,

Flodoard, and all other historians who have mentioned him, but also by other

incontestable monuments and authorities. Not to mention his Testament, in which

mention is made of his miracles, the bishops who were assembled in the

celebrated conference that was held at Lyons against the Arians in his time,

declared they were stirred up to exert their zeal in defence of the Catholic

faith by the example of Remigius, “Who,” say they, 18 “hath

every where destroyed the altars of the idols by a multitude of miracles and

signs.” The chief among these prelates were Stephen bishop of Lyons, St. Avitus

of Vienne, his brother Apollinaris of Valence, and Eonius of Arles. They all

went to wait upon Gondebald, the Arian king of the Burgundians, who was at

Savigny, and entreated him to command his Arian bishops to hold a public

conference with them. When he showed much unwillingness they all prostrated

themselves before him, and wept bitterly. The king was sensibly affected at the

sight, and kindly raising them up, promised to give them an answer soon after.

They went back to Lyons, and the king returning thither the next day, told them

their desire was granted. It was the eve of St. Justus, and the Catholic bishops

passed the whole night in the church of that saint in devout prayer; the next

day, at the hour appointed by the king, they repaired to his palace, and,

before him and many of his senators, entered upon the disputation, St. Avitus

speaking for the Catholics, and one Boniface for the Arians. The latter

answered only by clamours and injurious language, treating the Catholics as

worshippers of three Gods. The issue of a second meeting, some days after, was

the same with that of the first: and many Arians were converted. Gondebald

himself, sometime after, acknowledged to St. Avitus, that he believed the Son

and the Holy Ghost to be equal to the Father, and desired him to give him

privately the unction of the holy chrism. St. Avitus said to him, “Our Lord declares, Whoever

shall confess me before men, him will I confess before my Father. You are

a king, and have no persecution to fear, as the apostles had. You fear a

sedition among the people, but ought not to cherish such a weakness. God does

not love him, who, for an earthly kingdom, dares not confess him before the

world.” 19 The

king knew not what to answer; but never had the courage to make a public

profession of the Catholic faith. 20 St.

Remigius by his zealous endeavours promoted the Catholic interest in Burgundy,

and entirely crushed both idolatry and the Arian heresy in the French

dominions. In a synod he converted, in his old age, an Arian bishop who came

thither to dispute against him. 21 King

Clovis died in 511. St. Remigius survived him many years, and died in the joint

reign of his four sons, on the 13th of January in the year 533, according to

Rivet, and in the ninety-fourth year of his age, having been bishop above

seventy years. The age before the irruption of the Franks had been of all

others the most fruitful in great and learned men in Gaul; but studies were

there at the lowest ebb from the time of St. Remigius’s death, till they were

revived in the reign of Charlemagne. 22 The

body of this holy archbishop was buried in St. Christopher’s church at Rheims,

and found incorrupt when it was taken up by Archbishop Hincmar in 852. Pope Leo

IX. during a council which he held at Rheims in 1049, translated it into the

church of the Benedictin abbey, which bears his name in that city, on the 1st

of October, on which day, in memory of this and other translations, he

appointed his festival to be celebrated, which, in Florus and other calendars,

was before marked on the 13th of January. In 1646 this saint’s body was again

visited by the archbishop with many honourable witnesses, and found incorrupt

and whole in all its parts; but the skin was dried, and stuck to the

winding-sheet, as it was described by Hinckmar above eight hundred years

before. It is now above twelve hundred years since his death. 23

Care, watchings, and

labours were sweet to this good pastor, for the sake of souls redeemed by the

blood of Jesus. Knowing what pains our Redeemer took, and how much he suffered

for sinners, during the whole course of his mortal life, and how tenderly his

divine heart is ever open to them, this faithful minister was never weary in preaching,

exhorting, mourning, and praying for those that were committed to his charge.

In imitation of the good shepherd and prince of pastors, he was always ready to

lay down his life for their safety: he bore them all in his heart, and watched

over them, always trembling lest any among them should perish, especially

through his neglect: for he considered with what indefatigable rage the wolf

watched continually to devour them. As all human endeavours are too weak to

discover the wiles, and repulse the assaults of the enemy, without the divine

light and strength, this succour he studied to obtain by humble supplications;

and when he was not taken up in external service for his flock, he secretly

poured forth his soul in devout prayer before God for himself and them.

Note 1. The

chronology of this saint’s life is determined by the following circumstances:

historians agree that he was made bishop when he was twenty-two years old. The

saint says, in a letter which he wrote in 512, that he had then been bishop

fifty-three years, and St. Gregory of Tours says, that he held that dignity

above seventy years. Consequently, he died in 533, in the ninety-fourth year of

his age; was born in 439, and in 512 was seventy-five years old. [back]

Note 2. L. 9, ep.

7. [back]

Note 3. The origin

of the episcopal see of Rheims is obscure. On Sixtus and Sinicius, the apostles

of that province, see Marlot. (l. 1, c. 12, t. 1; Hist. Metrop. Rhem. and

chiefly Dom Dionysius de Ste. Marthe, Gallia Christiana Nov. t. 9, p. 2.)

Sixtus and Sinicius were fellow-labourers in first planting this church;

Sinicius survived and succeeded his colleague in this see. Among their

disciples many received the crown of martyrdom under Rictius Varus, about the

year 287, namely Timotheus, Apollinaris, Maurus, a priest, Macra, a virgin, and

many others whose bodies were found in the city itself, in 1640 and 1650, near

the church of St. Nicasius: their heads and arms were pierced with huge nails,

as was St. Quintin under the same tyrant: also St. Piat, &c. St. Nicasius

is counted the eleventh, and St. Remigius, the fifteenth archbishop of this

see. [back]

Note 4. L. 8, c.

14. [back]

Note 5. L. 9, ep.

7. [back]

Note 6. See D.

Brezillac, a Maurist monk, Histoire de Gaules, et des Conquêtes des Gaulois, 2

vols. 4to. printed in 1752; and Cæsar’s Commentaries De Bello Gallico, who

wrote and fought with the same inimitable spirit; also Observations sur la

Religion des Gaulois, et sur celle des Germains, par M. Freret, t. 34, des

Mémoires de Littérature de l’Académie des Inscriptions, An. 1751. [back]

Note 7. De Civ. l.

19, c. 7. [back]

Note 8. The Gauls became so learned and eloquent, that among them several seemed almost to rival the greatest men among the Romans. Not to mention Virgil, Livy, Catullus, Cornelius Nepos, the two Plinies, and other ornaments of the Cisalpine Gaul; in the Transalpine Petronius Arbiter, Terentius Varro, Roscius, Pompeius Trogus, and others are ranked among the foremost in the list of Latin writers. How much the study of eloquence and the sacred sciences nourished in Gaul when the faith was planted there, appears from St. Martin, St. Sulpitius Severus, the two SS. Hilaries, St. Paulinus, Salvian of Marseilles, the glorious St. Remigius, St. Apollinaris Sidonius, &c.

Dom Rivet proves (Hist. Lit. t. 1,) that the Celtic tongue gave place in most parts to the Roman, and seems long since extinct, except in certain proper names, and some few other words. Samuel Bochart, the father of conjectures, (as he is called by Menage in his Phaleg,) derives it from the Phenician. Borel (Pref. sur les Recherches Gauloises) and Marcel (Hist. de l’Origine de la Monarchie Françoise, t. 1, p. 11,) from the Hebrew. The latter ingenious historian observes, that a certain analogy between all languages shows them to have sprang from one primitive tongue; which affinity is far more sensible between all the western languages. St. Jerom, who had visited both countries, assures us, that in the fourth age the language was nearly the same that was spoken at Triers and in Galatia. (in Galat. Præf. 2, p. 255.) Valerius Andræas (in Topogr. Belgic. p. 1,) pretends the ancient Celtic to be preserved in the modern Flemish; but this is certainly a bastard dialect derived from the Teutonic, and no more the Celtic than it was the language of Adam in Paradise, as Goropius Becanus pretended. The received opinion is, that the Welch tongue, and that still used in Lower Brittany (which are originally the same language) are a dialect of the Celtic, though not perfectly pure; and Tacitus assures us, that the Celtic differed very little from the language of the Britons (Vitâ Agricolæ, c. 11,) which is preserved in the Welch tongue.

Dom Pezron, in his Antiquities of the ancient Celtes, has given

abundant proofs that the Greek, Latin, and Teutonic have borrowed a great number

of words from the Celtic, as well as from the Hebrew and Egyptian. M. Bullet,

royal professor of the university of Besançon, has thrown great light on this

subject; he proves that the primeval Celts, and Scytho-Celts, have not only

occupied the western regions of Europe, but extended themselves into Spain and

Italy; that in their progress through the latter fine country, they met the

Grecian colonies who were settled in its southern provinces; and that having

incorporated with one of those colonies on the banks of the Tyber, the Latin

tongue had in course of time been formed out of the Celtic and Greek languages.

Of this coalition of Celts and Grecians in ancient Latium, and of this original

of the Latin language, that learned antiquary has given unexceptionable proofs,

and confirms them by the testimonies of Pliny and Dionysius of Halicarnassus.

In its original the Celtic, like all other eastern tongues, after

the confusion at Babel, was confined to between four and five hundred words,

mostly monosyllables. The wants and ideas of men being but few in the earliest

times, they required but few terms to express them by; and it was in proportion

to the invention of arts, and the slow progress of science, that new terms have

been multiplied, and that signs of abstract ideas have been compounded.

Language, yet in its infancy, came only by degrees to the maturity of copious

expression, and grammatical precision. In the vast regions occupied by the

ancient Celts, their language branched out into several dialects; intermixture

with new nations on the continent, and the revolutions incident to time

produced them; and ultimately these dialects were reduced to distinct tongues,

so different in texture and syntax, that the tracing them to the true stock

would not be easy, had we not an inerrable clue to lead us in the multitude of

Celtic terms common to all. The Cumaraeg of the Welch and Gadelic of the Irish,

are living proofs of this fact. The Welch and Irish tongues preserved to our

own time in ancient writings, are undoubtedly the purest remains of the ancient

Celtic. Formed in very remote periods of time, and confined to our own western

isles, they approached nearer to their original than the Celtic tongues of the

continent; and according to the learned Leibnitz, the Celtic of Ireland (a

country the longest free from all foreign intermixture) bids fairer for

originality than that of any other Celtic people.

It is certain that the Irish Celtic, as we find it in old books,

exhibits a strong proof of its being the language of a cultivated nation.

Nervous, copious, and pathetic in phraseology, it is thoroughly free from the

consonantal harshness, which rendered the Celtic dialects of ancient Gaul

grating to Roman ears; it furnishes the poet and orator very promptly with the

vocal arms, which give energy to expression, and elevation to sentiment. This

language, in use at present among the common people of Ireland, is falling into

the corruptions which ever attend any tongue confined chiefly to the illiterate

vulgar. These corruptions are increasing daily. The Erse of Scotland is still

more corrupt, as the inhabitants of the Highlands have had no schools for the

preservation of their language for several ages, and as none of the old

writings of their bards and senachies have been preserved. The poems therefore

published lately by an able writer under the name of Ossian, are undoubtedly

his own, grafted on traditions still sung among his countrymen; and similar to

the tales lathered on Oisin, the son of Fin-mac-Cumhal, sung at present among

the common people of Ireland. It was a pleasing artifice. The fame of

composition transferred to old Ossian, returned back in due time to the true

author; and criticism, recovered from the surprise of an unguarded moment, did

him justice. The works of Ossian, if any he composed, have been long since

lost, not a trace remains; and it was soon discovered that the Celtic dialect

of a prince, represented by Mr. Macpherson as an illiterate bard of the third

century, could not be produced in the eighteenth, and that a publication of

those poems in modern Erse would prove them modern compositions; for further

observations on the ancient Celtic language, and on the poems of Ossian, we

refer the reader to O’Conor’s excellent Dissertations on the history of

Ireland, Dublin, 1766.

Bonamy (Diss. sur l’Introduct. de la Langue Lantine dans les Gauls,

Mémoires de l’Acad. des Inscriptions, vol. 24,) finds fault with Rivet for

making his assertion too general, and proves that the Franks kept to their own

old Teutonic language for some time at court, and in certain towns where they

were most numerous; and always retained some Teutonic words even after the

Latin language of the old inhabitants prevailed; but he grants, that out of

thirty French words it is hard to find one that is not derived from Latin.

Rivet would probably have granted as much; for he never denied but some few

French words are of Teutonic extraction; or that the Franks for some time

retained their own language amongst themselves, though they also learned

usually the old Latin language of the Gauls, amongst whom they settled, which

is evidently the basis of all the dialects spoken in France, except of that of

Lower-Brittany, and a considerable part of the Burgundian; yet there is

everywhere some foreign alloy, which is very considerable in Gascony, and part

of Normandy. Even the differences in the Provençal and others are mostly a

corrupt Latin. [back]

Note 9. The Franks

or French have been sought for by different authors in every province of

Germany, and by some near the Palus Mœotis; but the best writers now agree with

Spener, the most judicious of the modern German historians, (Notit. Germ.

antiqu. t. 1,) that the Franks were composed of several German nations, which

entered into a confederacy together to seek new settlements, and defend their

liberty and independency; from which liberty, according to some, they took the

name of Franks, unknown among the German nations when Tacitus wrote; but the

word Frenk or Frank signified in the old German tongue Fierce or Cruel, as

Bruzen de la Martinière observes, in his additions to Puffendorf’s Introduction

to Modern History, t. 5. The Franks are first mentioned by the writers of the

Augustan History in the reign of Gallien. From Eumenius’s panegyric in praise

of Constantine, the first book of Claudian upon Stilico, and several passages

of Apollinaris Sidonius, it appears that they originally came chiefly from

nations settled beyond the Elbe, about the present duchies of Sleswick, and

part of Holstein. This opinion is set in a favourable light in a dissertation

printed at Paris in 1748; and in another written by F. Germon, published by F.

Griffet, in his new edition of F. Daniel’s History in 1755. F. Germon places

them in the countries situated between the Lower Rhine, the Maine, the Elbe,

and the Ocean, nearly the same whence the English Saxons afterwards came; after

their first migrations probably some more remote nations had filled the void

they had left. Among the Franks there were Bructeri, Cherisci, Catici, and

Sicambri; but the Salii and Ripuarii or Ansuari, were the most considerable;

the latter for their numbers, the former for their riches, nobility, and power,

say Martinière and Messieurs de Boispreaux and Sellius, in their Histoire

Générale des Provinces Unies. (in 3 vols. 4to. 1757.) Leibnitz derives the name

of Salians from the river Sala, and thinks the Salic laws, so famous among the

French, were originally established by them. F. Daniel and M. Gundling warmly

contend that they are more modern, framed since the conversion of the Franks to

Christianity. De Boispreaux and Sellius will have the laws to be as ancient as

Leibnitz advances; but acknowledge that the preface to them is of Christian

original; perhaps changed, say they, by Clovis after his baptism.

The Franks settled first on the Eastern banks of the Rhine, but soon crossed it; for Vopiscus places them on both sides of that river. The country about the Lower Rhine, from Alsace to the Germanic ocean, is the first that was called France, and afterwards distinguished by the name of Francia Germanica or Vetus, afterwards eastern France, of which the part called Franconia still retains the name. See Eccard at length in Francia Orientalis, and d’Anville, p. 18. Peutinger’s map (or the ancient topographical description of that country, published by Peutinger of Ausburg, but composed in the latter end of the fourth century) places France on the right hand bank or eastern side of the Rhine. The Franks chose their kings by lifting them upon a shield in the army. The names of the first are Pharamund, Clodion, Merovæus, and Childeric. In Merovæus the crown became hereditary, and from him the first race of the French kings is called Merovingian. F. Daniel will not allow the names of these four kings before Clovis, to belong to the history of the French monarchy, being persuaded that they reigned only in old France beyond the Rhine, and possessed nothing in Gaul, though they made frequent excursions into its provinces for plunder. This novelty gave offence to many, and is warmly exploded by Du Bos, Dom Maur, Le Gendre, and others. For it is evident from incontestable monuments produced by Bosquet and others, that the Franks from Pharamund began to extend their conquests in Belgic Gaul, though they sometimes met with checks. Henault observes, they had acquired a fixed settlement about the Rhine in 287, which was confirmed to them by the Emperor Julian in 358; that under King Clodion in 445, they became masters of Cambray and the neighbouring provinces as far as the river Somme in Picardy. Their kings seem to have made Tournay for some time their residence. At least the tomb of Childeric was discovered at Tournay in 1653, with undoubted marks, some of which are deposited in the king’s library at Paris. See the Sieur Chifflet’s relation of this curious discovery, and Mabillon’s Dissertation on the Ancient Burial-places of the kings of France.

It is an idle conceit of many painters, with Chifflet, to imagine from the figures of bees found in this monument, that they were the arms of France above seven hundred years before coat-armoury was thought of, which was a badge of noble personages first invented for the sake of distinction at the tilts and tournaments. A swarm of bees following a leader was a natural emblem for a colony seeking a new settlement. Some think the fleur-de-lis to have been first taken from some ill-shaped half figures of bees on old royal ornaments. See Addition aux Dissertations concernant le Nom Patronimique de l’Auguste Maison de France, showing that it never had a name but in each branch that of its appanage or estate. Amsterdam, 1770, with a second Diss. Extrait concernant les Armes des Princes de la Maison de France. The figure of the lis in the arms of France seems borrowed from the head of the battle-axe called Francische, the usual weapon of the ancient Franks; for it perfectly resembles it, not any of the flowers which bear the name of lis or iris; though some reduce it to the Florentine iris, others to the March lily. See their figures in the botanists. On the tomb of Queen Fredegundes in the abbey of St. Germain-des-Prez, fleur-de-luces or de-lis, are found used as ornaments in the crown and royal robes; and the same occurs in some other ornaments, as we find them sometimes employed in the monuments of the first English Norman kings, &c. See Montfaucon, Antiquités de la Monarchie Francoise, t. 1, p. 31. But Philip Augustus, or rather Lewis VII. was the first that took them for his coat of arms; and Charles VI. reduced their number to three. According to Le Gendre, Clodion began to reign over the Franks in 426, Merovæus in 446, Childeric in 450, and his son Clovis I. or the Great in 481. The Romans sometimes entered into treaties with them, and acknowledged them their allies. The King of the Franks, probably Childeric, with his army, joined Aëtius against the Huns, and was a powerful succour to him in the entire overthrow which he gave to Attila in 481.

Clovis conquered all Gaul, except the southern provinces, which

were before seized, part by the Burgundians, and part by the Goths. The western

empire was extinguished in 476, when the city of Rome and all Italy fell into

the hands of Odoacer, king of the Turcilingi and the Heruli, who marched

thither out of Pannonia. Nevertheless, Syagrius, son of the Roman governor

Ægidius in Gaul, still kept an army on foot there, though without a master,

there being no longer any Roman emperor. Clovis, who passed the five first

years of his reign in peace, marched against him in 486, defeated him in a

great battle near Soissons, and afterwards, in 489, caused his head to be cut

off. Extending his conquests, he possessed himself of Tongres in 491, and of

Rheims in 493, the same year in which he married St. Clotildis. After the

battle of Tolbiac, in 496, he subdued the whole country as far as the Rhine;

and in 497 the Roman army about the Loire, and the people of Armorica, who were

become independent and had received new colonies from Britain, submitted to

him. In 507 he vanquished and slew Alaric, king of the Visigoths, with his own

hands, in a single combat at the head of the two armies near Poitiers, and

conquered all the provinces that lie between the Loire and the Pyreneans; but

being discomfited by Theodoric before Arles in 509, he left the Visigoths in

possession of Septimania, now called Languedoc, and the neighbouring provinces;

and the Burgundians, possessed of those territories which they had seized one

hundred years before. The Abbé Dubos (Histoire Critique de l’Etablissement de

la Monarchie Françoise dans les Gauls, 2 vols. quarto) endeavours to prove that

the Franks became masters of the greater part of Gaul, not as invaders, but by

alliances with the Romans. It is certain they gained the friendship of most of

the old inhabitants, pretending they came only to rescue and protect them in

their liberties; and their government was more mild and desirable than that of

the Goths or Burgundians, to whom the Gauls must have otherwise been left a

prey. Neither did the Franks extirpate the conquered Gauls, but mixed with

them, and even learned their language. Nor did they deprive the old inhabitants

of their private estates, except in some particular cases; these forfeited

estates given to the Francs were called Salic lands, and subject to the Salic

law, by which all contests about them were to be determined by a combat of the