Saint Bruno

Fondateur des

Chartreux (+ 1101)

Il avait tout pour faire une belle carrière d'universitaire ecclésiastique, ce fils d'un riche marchand des bords du Rhin. Originaire de Cologne, il avait étudié dans sa ville natale et puis l'avait quittée, âgé d'une quinzaine d'années pour aller se perfectionner à Reims. A 24 ans, le voilà devenu écolâtre, chargé d'étudiants. Sa réputation est si flatteuse qu'il devient chancelier de l'archevêque de Reims, Manassès de Gournay. Mais l'archevêque est indigne. Il a payé ses électeurs et Bruno le dénonce. On lui offre de lui succéder, Bruno refuse. Et c'est alors la rupture. Cette brillante carrière ne le comble pas, il ressent un vide dans son cœur, une soif le consume. Il n'est pas fait pour les 'combines', il veut être à Dieu seul. A 52 ans, en 1084, il vend tout ce qu'il possède et, avec quelques amis qui partagent ses aspirations, il tente un premier essai de vie érémitique au prieuré de Sèchefontaine*, une dépendance de l'abbaye de Molesme. La forme de vie dont il rêve ne s'y trouve pas. Il lui faut la créer. Saint Hugues, évêque de Grenoble, met à la disposition de Bruno et de ses compagnons une 'solitude' dans le massif alpin de la Grande Chartreuse. Bruno y élabore ce qui deviendra la Règle des Chartreux, faite de solitude en cellule, de liturgies communes et de travail manuel. Le pape Urbain II l'ayant appelé comme conseiller, il quitte à regret la Chartreuse pour Rome. Ne pouvant s'habituer à la vie 'du siècle', il obtient de se retirer en Calabre où il fonde une nouvelle communauté cartusienne à La Torre. C'est là qu'il mourra dans une solitude bienheureuse: "L'air y est doux, les prés verdoyants, nous avons des fleurs et des fruits, nous sommes loin des hommes, écrivait-il à un vieil ami de Reims. Comment dépeindre cette fête perpétuelle où déjà l'on savoure les fruits du ciel?".

*solitude que lui avait indiquée saint

Robert, futur fondateur de Cîteaux.

Saint Hugues et Saint Bruno:

Le diocèse de Grenoble voit naître ou s'établir de nombreuses communautés et de grandes figures religieuses.

En 1084 saint Bruno s'installe avec l'accord de saint Hugues, évêque de Grenoble, en Chartreuse et fonde l'ordre des Chartreux. Saint Hugues est lui-même connu pour avoir libéré l'Église du pouvoir des laïcs, et considéré comme le véritable fondateur du diocèse car il en fixe le territoire. Il fonde aussi le monastère de Chalais.

- Histoire du diocèse de Grenoble

Mémoire de saint Bruno, prêtre. Né à Cologne, il enseigna la théologie en

France, mais désireux d'une vie solitaire, il fonda, avec quelques disciples,

dans la vallée déserte de la Chartreuse, dans les Alpes, un Ordre où la

solitude des ermites serait tempérée par une certaine forme de cénobitisme.

Appelé à Rome par le bienheureux pape Urbain II, pour qu'il lui vienne en aide

dans les besoins que connaissait l'Église, il passa cependant les dernières

années de sa vie dans un ermitage, près du monastère de La Torre en Calabre, où

il mourut en 1101.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1969/Saint-Bruno.html

Saint

Bruno et ses six compagnons devant l'évêque Hugues de Grenoble dans la Grande

Chartreuse,

Manuscrit

du XVe siècle

Saint Bruno

Fondateur de l'Ordre des

Chartreux

(1035-1101)

Saint Bruno naquit à

Cologne d'une famille de première noblesse. Ses magnifiques succès

épouvantèrent son âme, désireuse de ne vivre que pour Dieu. Il songeait à

quitter ce monde, où il était déjà appelé aux grandeurs, quand un fait tragique

décida complètement sa vocation. Bruno comptait pour ami, à l'université de

Paris, le célèbre chanoine Raymond, dont tout le monde admirait la vertu non

moins que la science. Or cet ami vint à mourir, et pendant ses obsèques

solennelles, auxquelles Bruno assistait, à ces paroles de Job:

"Réponds-moi, quelles sont mes iniquités?" Le mort se releva et dit

d'une voix effrayante: "Je suis accusé par un juste jugement de

Dieu!" Une panique indescriptible s'empara de la foule, et la sépulture

fut remise au lendemain; mais le lendemain au même moment de l'office, le mort se

leva de nouveau et s'écria: "Je suis jugé par un juste jugement de

Dieu!" Une nouvelle terreur occasionna un nouveau retard. Enfin, le

troisième jour, le mort se leva encore et cria d'une voix plus terrible:

"Je suis condamné au juste jugement de Dieu!"

Bruno brisa dès lors les

derniers liens qui le retenaient au monde, et, inspiré du Ciel, il se rendit à

Grenoble, où le saint évêque Hugues, répondant à ses aspirations vers la

solitude la plus profonde, lui indiqua ce désert affreux et grandiose à la fois,

si connu sous le nom de Grande-Chartreuse. Il fallut franchir de dangereux

précipices, s'ouvrir un chemin à coups de hache dans des bois d'une végétation

puissante, entremêlés de ronces épaisses et d'immenses fougères; il fallut

prendre le terrain pied à pied sur les bêtes sauvages, furieuses d'être

troublées dans leur possession paisible. Quelques cellules en bois et une

chapelle furent le premier établissement. Le travail, la prière, un profond

silence du côté des hommes, tel fut pour Bruno l'emploi des premières années de

sa retraite.

Il dut aller, pendant

plusieurs années, servir de conseiller au saint Pape Urbain II, refusa avec

larmes l'archevêché de Reggio, retourna à sa vie solitaire et alla fonder en

Calabre un nouveau couvent de son Ordre. À l'approche de sa dernière heure,

pendant que ses frères désolés entouraient son lit de planches couvert de

cendres, Bruno parla du bonheur de la vie monastique, fit sa confession

générale, demanda humblement la Sainte Eucharistie, et s'endormit paisiblement

dans le Seigneur.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_bruno.html

Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652). Saint

Bruno, 1643, 38 x 27, Galleria Nazionale di Capodimonte

Vie de Saint Bruno

Bruno qui appartenait à

une famille noble (celle, croit-on, des Hartenfaust, de duro pugno), né à

Cologne entre 1030 et 1035. Il commença ses études dans sa ville natale, à la

collégiale de Saint-Cunibert, et fit ensuite des études de philosophie et de théologie

à Reims et, peut-être aussi à Paris. Vers 1055, il revint à Cologne pour

recevoir de l’archevêque Annon, avec la prêtrise, un canonicat à

Saint-Cunibert.

En 1056 ou 1057, il fut

rappelé à Reims par l’archevêque Gervais pour y devenir, avec le titre

d'écolâtre, professeur de grammaire, de philosophie et de théologie ; il devait

garder une vingtaine d'années cette chaire, où il travailla à répandre les

doctrines clunisiennes et, comme on allait dire bientôt, grégoriennes ; parmi

ses élèves, étaient Eudes de Châtillon, le futur Urbain II, Rangérius, futur

évêque de Lucques, Robert, futur évêque de Langres, Lambert, futur abbé de

Pothières, Pierre, futur abbé de Saint-Jean de Soissons, Mainard, futur prieur

de Cormery, et d'autres personnages de premier plan. Maître Bruno dont on

conserve un commentaire des psaumes et une étude sur les épitres de saint Paul

est précis, clair et concis en même temps qu’affable, bon et souriant « il est,

dire ses disciples, éloquent, expert dans tous les arts, dialecticien,

grammairien, rhéteur, fontaine de doctrine, docteur des docteurs. »

Sa situation devint

difficile quand l'archevêque Manassès de Gournay, simoniaque avéré, monta en

1067 sur le siège de Reims ; ce prélat qui n'ignorait pas l'opposition de

Bruno, tenta d'abord de se le concilier, et le désigna même comme chancelier du

Chapitre (1075), mais l'administration tyrannique de Manassès, qui pillait les

biens d'Eglise, provoqua des protestations, auxquelles Bruno s'associa ; elles

devaient aboutir à la déposition de l'indigne prélat en 1080 ; en attendant,

Manassès priva Bruno de ses charges et s'empara de ses biens qui ne lui furent

rendus que lorsque l'archevêque perdit son siège[1].

Bruno, réfugié d'abord au

château d'Ebles de Roucy, puis, semble-t-il, à Cologne, chargé de mission à

Paris, et redoutant d'être appelé à la succession de Manassès, décida de

renoncer à la vie séculière. Cette résolution aurait été fortifiée en lui, d'après

une tradition que répètent les historiens chartreux, par l'épisode parisien

(1082) des funérailles du chanoine Raymond Diocrès qui se serait trois fois

levé de son cercueil pour se déclarer jugé et condamné au tribunal de Dieu[2].

En 1083, Bruno se rendit

avec deux compagnons, Pierre et Lambert, auprès de saint Robert de Molesme,

pour lui demander l'habit monastique et l'autorisation de se retirer dans la

solitude, à Sèche-Fontaine. Mais ce n'était pas encore, si près de l'abbaye, la

vraie vie érémitique. Sur le conseil de Robert de Molesme et, semble-t-il, de

l'abbé de la Chaise-Dieu, Seguin d'Escotay, Bruno se rendit, avec six

compagnons[3] auprès du saint évêque Hugues de Grenoble qui accueillit avec

bienveillance la petite colonie. Une tradition de l'Ordre veut que saint Hugues

ait vu les sept ermites annoncés dans un songe sous l'apparence de sept

étoiles. Il conduisit Bruno et ses compagnons dans un site montagneux d'une

sévérité vraiment farouche, le désert de Chartreuse (1084) [4]. En 1085 une première

église s'y élevait. Le sol avait été cédé en propriété par Hugues aux religieux

qui en gardèrent le nom de Chartreux. Quant à l'appartenance spirituelle, il

paraît que la fondation eut d'abord quelque lien avec la Chaise-Dieu, à qui

Bruno la remit quand il dut se rendre en Italie ; mais l'abbé Seguin restitua

la Chartreuse au prieur Landuin quand celui-ci, pour obéir à saint Bruno,

rétablit la communauté, et il reconnut l'indépendance de l'ordre nouveau (1090)

[5].

Au début de cette année

1090, Bruno avait été appelé à Rome par un de ses anciens élèves, le pape

Urbain II, qui voulait s'aider de ses conseils et qui lui concéda, pour ceux de

ses compagnons qui l'avaient suivi, l'église de Saint-Cyriaque. Le fondateur

fut à plusieurs reprises convoqué à des conciles [6]. Le pape eût voulu lui

faire accepter l'archevêché de Reggio de Calabre, mais Bruno n'abandonnait pas

son rêve de vie érémitique. Il avait reçu en 1092 du comte Roger de Sicile un

terrain boisé à La Torre, près de Squillace, où Urbain II autorisa la

construction d'un ermitage et où une église fut consacrée en 1094. Roger aurait

affirmé, dans un diplôme de 1099, que Bruno l'aurait averti dans un songe d'un

complot durant le siège de Padoue en 1098.

Bruno, le 27 juillet

1101, recevait du pape Pascal II la confirmation de l'autonomie de ses ermites.

Le 6 octobre suivant, après avoir émis une profession de foi et fait devant les

frères sa confession générale, il rendit l'âme à la chartreuse de San Stefano

in Bosco, filiale de La Torre, où il fut enseveli. Les cent soixante-treize

rouleaux des morts, circulant d'abbaye en abbaye et recevant des formules

d'éloges funèbres, attestent précieusement, dès le lendemain de sa mort, sa

réputation de sainteté, accrue par les miracles attribués à son intercession.

Son corps, transféré en 1122 à Sainte-Marie du Désert, la chartreuse principale

de La Torre, y fut l'objet d'une invention en 1502 et d'une récognition en

1514. Le culte fut autorisé de vive voix dans l'ordre des Chartreux par Léon X,

le 19 juillet 1514. La fête, introduite en 1622 dans la liturgie romaine et

confirmée en 1623 comme semi-double ad libitum, est devenue de précepte et de

rite double en 1674 à la date anniversaire de sa mort, le 6 octobre ; saint

Bruno n'a donc été l'objet que d'une canonisation équipollente.

En 1257, saint Louis

demanda des moines au prieur de la Grande Chartreuse, qui lui envoya Dom Jean

de Jossaram, prieur du Val-Sainte-Marie, près de Valence, et quatre autres

religieux. Ils habitèrent d'abord Gentilly, puis vinrent près de Paris, au

château de Vauvert, dès 1258. Saint Louis fit commencer leur grande église, qui

ne fut dédiée qu'en 1325, à la Sainte Vierge et à saint Jean-Baptiste. Elle

avait sept chapelles latérales dans la clôture et une huitième chapelle extérieure,

dont l'accès était permis aux femmes. Vingt-huit cellules, chacune composée de

deux ou trois pièces et accompagnée d'un jardin, étaient groupées autour du

grand cloître. Il y vivait quarante religieux, sans compter les Frères. Le

petit cloître était décoré des fameux tableaux de la vie de saint Bruno

d'Eustache Lesueur : il n'y en avait que trois, disait-on, de sa main. La

Révolution détruisit ce monastère pour faire passer des rues et agrandir le

jardin du Luxembourg.

Les Chartreux de Paris

achetèrent une rente sur des biens sis à Saulx que saint Louis leur confirma en

1263. L’année suivante, les Chartreux achètent à Saulx la dîme du blé avec une

partie du fief des Tournelles où était le four banal. En 1265, les Chartreux

achètent à Saulx la dime du vin. En 1285, les Chartreux achètent le fief des

Tournelles avec le four banal. En 1657 le prieuré Notre-Dame de Saulx est cédé

aux Chartreux et ils nomment le curé de la paroisse.

Le 14 mai 1984,

l'occasion du neuvième centenaire de la fondation de leur Ordre le Saint-Père

adressait aux Chartreux la lettre Silentio et solitudini, rappelant qu’en l'an

1084, aux alentours de la fête de saint Jean-Baptiste, Bruno de Cologne, au

terme d’une brillante carrière ecclésiastique, marquée notamment par un courage

indomptable dans la lutte contre les abus de l'époque, entrait avec six

compagnons au désert de Chartreuse. Il s’agit d’une vallée étroite et resserrée

des Préalpes, à 1175 mètres d'altitude, où de grands sapins laissent à peine

pénétrer la lumière, et que les neiges isolent presque complètement du monde

extérieur durant l'hiver interminable. Ce cadre austère paraissait approprié à

la forme de vie entièrement centrée sur Dieu qu'ils désiraient chercher par le

moyen de la solitude. Le monastère fut fait de petits ermitages, reliés par une

galerie pour se rendre en toute saison à l'église. Les moines ne se

rencontraient habituellement qu’aux Matines et aux Vêpres, parfois à la messe

qui n’était pas alors quotidienne, mais ils prenaient ensemble le repas du dimanche,

suivi du chapitre. Saint Bruno avait en propre de savoir unir une soif intense

de la rencontre de Dieu dans la solitude, avec une capacité exceptionnelle de

se faire des amis, et de faire naître parmi eux un courant d'intense affection.

Parmi les six compagnons

de saint Bruno figuraient deux laïcs ou convers ; leur solitude devait

incorporer un certain travail hors de la cellule, principalement agricole.

Aujourd'hui encore un monastère cartusien comporte des moines du cloître, voués

à la solitude de la cellule, et des moines convers, qui partagent leur temps

entre cette solitude et la solitude du travail dans les obédiences : on

pratique ainsi deux manières, étroitement solidaires et complémentaires, de

vivre la vie de chartreux ou de chartreuse.

Les historiens de la vie

monastique ont relevé la sagesse qui a su unir les différents aspects de la vie

cartusienne en un équilibre harmonieux : le soutien de la vie fraternelle aide

à affronter l'austérité de l'érémitisme ; la coexistence de deux manières de

vivre l'érémitisme (moines du cloître et moines convers) permet à chacune des

deux de trouver sa formule la meilleure ; un facteur équilibrant, aussi, est

joué par l'importance de l'office liturgique de Matines, célébré à l'église au

cours de la nuit. Ou encore, liberté spirituelle et obéissance sont étroitement

unies... Cette sagesse de vie, les chartreux la doivent à saint Bruno lui-même,

et c'est elle qui a assuré la persévérance de leur Ordre à travers les siècles.

Sagesse et équilibre.

Il reste vrai qu'une

telle vie n'a de sens qu'en référence à Dieu. Le Saint-Père, dans sa lettre,

rappelait aux Chartreux que c'est là leur responsabilité, leur fonction propre

dans le Corps mystique, au sein duquel ils doivent exercer un rayonnement

invisible : ils sont, disait-il, des témoins de l'absolu, spécialement utiles

aux hommes d'aujourd'hui, souvent profondément troublés par le tourbillon des

idées et l'instabilité qui caractérisent la culture moderne. Pour l'Eglise

elle-même, ajoute le Pape, en tant qu'elle est absorbée dans les difficultés du

labeur apostolique, les solitaires signifient la certitude de l'Amour immuable

de Dieu ; et c'est au nom de toute l'Eglise qu'ils font monter vers Lui un

hymne de louange ininterrompue.

[1] Quelques clercs de Reims

avaient porté plainte contre Manassès de Gournay auprès de Hugues de Die, légat

du pape Grégoire VII, qui le cita à comparaître au concile d’Autun (1077).

Manassès ne parut pas au concile d’Autun qui le déposa, mais s’en fut se

plaindre à Rome où il promit tout ce que l’on voulut. C’est alors qu’il priva

de leurs charges et de leurs biens tous ses accusateurs dont Bruno. Voyant que

Manassès de Gournay ne s’amendait pas, Hugues de Die le cita à comparaître au

concile de Lyon (1080) ; l’archevêque écrivit pour se défendre mais, cette

fois, il fut déposé et, le 27 décembre 1080, Grégoire VII ordonna aux clercs de

Reims de procéder à l’élection d’un nouvel archevêque. Manassès s’enfuit et ses

accusateurs rentrèrent en possession de leurs charges et de leurs biens.

[2] Jean Long d'Ypres :

Chronique de Saint-Bertin.

[3] Les six compagnons de

Bruno étaient le toscan Landuin, théologien réputé, qui lui succéda comme

prieur de la Chartreuse, Etienne de Bourg et Etienne de Die, chanoines de

Saint-Ruf en Dauphiné, le prêtre Hugues qui fut leur chapelain, André et

Guérin. Les deux derniers des six compagnons de saint Bruno étaient deux laïcs

ou convers ; leur solitude devait incorporer un certain travail hors de la

cellule, principalement agricole. Aujourd'hui encore un monastère cartusien

comporte des moines du cloître, voués à la solitude de la cellule, et des

moines convers, qui partagent leur temps entre cette solitude et la solitude du

travail dans les obédiences : on pratique ainsi deux manières, étroitement

solidaires et complémentaires, de vivre la vie de chartreux ou de chartreuse.

[4] Il s’agit d’une

vallée étroite et resserrée des Préalpes, à 1175 mètres d'altitude, où de

grands sapins laissent à peine pénétrer la lumière, et que les neiges isolent

presque complètement du monde extérieur durant l'hiver interminable. Ce cadre

austère paraissait approprié à la forme de vie entièrement centrée sur Dieu

qu'ils désiraient chercher par le moyen de la solitude. Le monastère fut fait

de petits ermitages, reliés par une galerie pour se rendre en toute saison à

l'église. Les moines ne se rencontraient habituellement qu’aux Matines et aux

Vêpres, parfois à la messe qui n’était pas alors quotidienne, mais ils

prenaient ensemble le repas du dimanche, suivi du chapitre. Saint Bruno avait

en propre de savoir unir une soif intense de la rencontre de Dieu dans la

solitude, avec une capacité exceptionnelle de se faire des amis, et de faire

naître parmi eux un courant d'intense affection.

[5] Les historiens de la

vie monastique ont relevé la sagesse qui a su unir les différents aspects de la

vie cartusienne en un équilibre harmonieux : le soutien de la vie fraternelle

aide à affronter l'austérité de l'érémitisme ; la coexistence de deux manières

de vivre l'érémitisme (moines du cloître et moines convers) permet à chacune

des deux de trouver sa formule la meilleure ; un facteur équilibrant, aussi,

est joué par l'importance de l'office liturgique de Matines, célébré à l'église

au cours de la nuit. Ou encore, liberté spirituelle et obéissance sont

étroitement unies... Cette sagesse de vie, les chartreux la doivent à saint

Bruno lui-même, et c'est elle qui a assuré la persévérance de leur Ordre à

travers les siècles. Sagesse et équilibre. Il reste vrai qu'une telle vie n'a

de sens qu'en référence à Dieu. Le Saint-Père, dans sa lettre, rappelait aux

Chartreux que c'est là leur responsabilité, leur fonction propre dans le Corps

mystique, au sein duquel ils doivent exercer un rayonnement invisible : ils

sont, disait-il, des témoins de l'absolu, spécialement utiles aux hommes

d'aujourd'hui, souvent profondément troublés par le tourbillon des idées et

l'instabilité qui caractérisent la culture moderne. Pour l'Eglise elle-même,

ajoute le Pape, en tant qu'elle est absorbée dans les difficultés du labeur

apostolique, les solitaires signifient la certitude de l'Amour immuable de Dieu

; et c'est au nom de toute l'Eglise qu'ils font monter vers Lui un hymne de

louange ininterrompue.

[6] Bénévent, 1091 ; Troja,

1093 ; Plaisance, 1095.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/10/06.php

HOMÉLIE DU PAPE BENOÎT

XVI

Chers frères et soeurs,

Je n'ai pas préparé de

véritable homélie, mais seulement quelques notes pour guider la méditation. La

mission de saint Bruno, le saint du

jour, apparaît avec clarté, elle est - pouvons-nous dire - interprétée dans la

prière de ce jour qui, même si elle est assez différente dans le texte italien,

nous rappelle que sa mission fut faite de silence et de contemplation. Mais

silence et contemplation ont un but: ils servent à conserver, dans la

dispersion de la vie quotidienne, une union permanente avec Dieu. Tel est le

but: que dans notre âme soit toujours présente l'union avec Dieu et

qu'elle transforme tout notre être.

Silence et contemplation

- une caractéristique de saint Bruno

- servent à pouvoir trouver dans la dispersion de chaque jour cette union

profonde, continuelle, avec Dieu. Silence et contemplation: la belle

vocation du théologien est de parler. Telle est sa mission: dans la

logorée de notre époque, et d'autres époques, dans l'inflation des paroles,

rendre présentes les paroles essentielles. Dans les paroles, rendre présente la

Parole, la Parole qui vient de Dieu, la Parole qui est Dieu.

Mais comment pourrions-nous,

en faisant partie de ce monde avec toutes ses paroles, rendre présente la

Parole dans les paroles, sinon à travers un processus de purification de notre

pensée, qui doit surtout être également un processus de purification de nos

paroles? Comment pourrions-nous ouvrir le monde, et tout d'abord nous-mêmes, à

la Parole sans entrer dans le silence de Dieu, duquel procède sa Parole? Pour

la purification de nos paroles, et donc pour la purification des paroles du

monde, nous avons besoin de ce silence qui devient contemplation, qui nous fait

entrer dans le silence de Dieu et arriver ainsi au point où naît la Parole, la

Parole rédemptrice.

Saint Thomas d'Aquin,

s'inscrivant dans une longue tradition, dit que, dans la théologie, Dieu n'est

pas l'objet dont nous parlons. Telle est notre conception normale. En réalité,

Dieu n'est pas l'objet; Dieu est le sujet de la théologie. Celui qui parle dans

la théologie, le sujet parlant, devrait être Dieu lui-même. Et nos paroles et

nos pensées devraient uniquement servir pour que Dieu qui parle, la Parole de

Dieu puisse être écoutée, puisse trouver un espace dans le monde. Et ainsi,

nous sommes invités à nouveau sur ce chemin du renoncement à nos propres

paroles; sur ce chemin de la purification, pour que nos paroles ne soient que

l'instrument par l'intermédiaire duquel Dieu puisse parler, et que Dieu soit

ainsi réellement non pas l'objet, mais le sujet de la théologie.

Dans ce contexte, il me

vient à l'esprit une très belle parole de la Première Lettre de saint Pierre,

dans le premier chapitre, verset 22. En latin, elle dit ceci: "Castificantes

animas nostras in oboedentia veritatis". L'obéissance à la vérité doit

"rendre chaste" notre âme, et conduire ainsi à la parole juste et à

l'action juste. En d'autres termes, parler pour susciter les applaudissements,

parler en fonction de ce que les hommes veulent entendre, parler en obéissant à

la dictature des opinions communes, cela est considéré comme une sorte de

prostitution de la parole et de l'âme. La "chasteté" à laquelle fait

allusion l'Apôtre Pierre est de ne pas se soumettre à ces règles, ne pas

rechercher les applaudissements, mais rechercher l'obéissance à la vérité.

Telle est, selon moi, la vertu fondamentale du théologien, cette discipline

quelquefois difficile de l'obéissance à la vérité qui fait de nous des

collaborateurs de la vérité, bouche de la vérité, parce que nous ne parlons pas

nous-mêmes dans ce fleuve de paroles d'aujourd'hui, mais réellement purifiés et

rendus chastes par l'obéissance à la vérité, pour que la vérité parle en nous.

Et nous pouvons vraiment être ainsi des porteurs de la vérité.

Cela me fait penser à

saint Ignace d'Antioche et à l'une de ses belles expressions: "Qui a

compris les paroles du Seigneur comprend son silence, parce que le Seigneur

doit être connu dans son silence". L'analyse des paroles de Jésus arrive

jusqu'à un certain point, mais elle demeure dans notre pensée. C'est uniquement

lorsque nous arrivons à ce silence du Seigneur, dans sa présence avec le Père

dont proviennent les paroles, que nous pouvons réellement commencer à

comprendre la profondeur de ces paroles. Les paroles de Jésus sont nées dans

son silence sur la Montagne, comme le dit l'Ecriture, dans sa présence avec le

Père. C'est de ce silence de la communion avec le Père, de l'immersion dans le

Père, que naissent les paroles et ce n'est qu'en arrivant à ce point, et en

partant de ce point, que nous arrivons à une véritable profondeur de la Parole

et que nous pouvons être d'authentiques interprètes de la Parole. Le Seigneur

nous invite, en parlant, à gravir avec Lui la Montagne, et dans son silence, à

apprendre ainsi, à nouveau, le véritable sens des paroles.

En disant cela, nous

sommes arrivés aux deux lectures d'aujourd'hui. Job avait crié vers Dieu, il

avait également combattu avec Dieu face aux évidentes injustices avec

lesquelles il le traitait. A présent, il est confronté à la grandeur de Dieu.

Et il comprend que, face à la véritable grandeur de Dieu, toutes nos paroles ne

sont que pauvreté et elles sont même très loin d'arriver à la grandeur de son

être et il dit ceci: "J'ai parlé deux fois, je n'ajouterai

rien" (Jb 40, 5). Silence devant la grandeur de Dieu, parce que nos

paroles deviennent trop petites. Cela me fait penser aux dernières semaines de

la vie de saint Thomas. Au cours de ces dernières semaines, il n'a plus écrit,

il n'a plus parlé. Ses amis lui demandent: Maître, pourquoi ne parles-tu

plus, pourquoi n'écris-tu pas? Et il dit: Devant ce que j'ai vu, à

présent, toutes mes paroles me semblent comme paille. Le grand spécialiste de

saint Thomas, le Père Jean-Pierre Torrel, nous dit de ne pas mal interpréter

ces paroles. La paille, ce n'est pas rien. La paille porte le blé et cela est

la grande valeur de la paille. Elle porte le blé. Et la paille des paroles

aussi demeure valable comme porteuse de blé. Mais cela est aussi pour nous,

dirais-je, une relativisation de notre travail et, en même temps, une

valorisation de celui-ci. C'est aussi une indication, afin que notre manière de

travailler, notre paille, porte réellement le blé de la Parole de Dieu.

L'Evangile finit avec les

mots: "Qui vous écoute, m'écoute" (Lc 10, 16). Quelle mise

en garde, quel examen de conscience que ces paroles! Est-il vrai que celui qui

m'écoute, écoute réellement le Seigneur? Prions et travaillons pour qu'il soit

toujours plus vrai que celui qui nous écoute, écoute le Christ. Amen!

© Copyright 2006 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Copyright © Dicastero per

la Comunicazione - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Nicolas

MIGNARD. Saint Bruno en prière dans le désert,

1638,

huile sur toile, 220 x 144,5, Avignon, Musée Calvet

Prières

"O Dieu,

montrez-nous votre visage

qui n'est autre que votre

Fils,

puisque c'est par lui que

vous vous faites connaître

de même que l'homme tout

entier est connu par son seul visage.

Et par ce visage que vous

nous aurez montré,

convertissez-nous ;

convertissez les morts

que nous sommes

des ténèbres à la

lumière,

convertissez-nous des

vices aux vertus,

de l'ignorance à la

parfaite connaissance de vous."

Saint Bruno

"Vous êtes mon

Seigneur,

vous dont je préfère les

volontés aux miennes propres ;

puisque je ne puis

toujours prier avec des paroles,

si quelque jour j'ai prié

avec une vraie dévotion,

comprenez mon cri :

prenez en gré cette

dévotion

qui vous prie comme une

immense clameur ;

et pour que mes paroles

soient de plus en plus

dignes d'être exaucées de vous,

donnez intensité et

persévérance à la voix de ma prière.

O Dieu, qui êtes puissant

et dont je me suis fait le serviteur,

quant à moi je vous prie

et vous prierai avec persévérance

afin de mériter et de

vous obtenir ;

ce n'est pas pour obtenir

quelque bien terrestre :

je demande ce que je dois

demander, Vous seul."

Saint Bruno

SOURCE : http://jubilatedeo.centerblog.net/6069037-Saint-Bruno-Fondateur-des-Chartreux-p-1101

Saint BRUNO

Né vers 1030, mort en

1101. Culte autorisé en 1514, fête en 1674.

Leçons des Matines (avant

1960)

Quatrième leçon. Bruno,

fondateur de l’Ordre des Chartreux, naquit à Cologne. Dès le berceau, il montra

de tels indices de sa sainteté future, par la gravité de ses mœurs, par le soin

qu’il mettait, avec le secours de la grâce divine, à fuir les amusements

frivoles de cet âge, qu’on pouvait déjà reconnaître en lui le père des moines,

en même temps que le restaurateur de la vie anachorétique. Ses parents, qui se

distinguaient autant par leur noblesse que par leurs vertus, l’envoyèrent à

Paris, et il y fit de tels progrès dans l’étude de la philosophie et de la

théologie, qu’il obtint le titre de docteur et de maître dans l’une et l’autre

faculté. Peu après, il se vit, en raison de ses remarquables vertus, appelé à

faire partie du Chapitre de l’Église de Reims.

Cinquième leçon. Quelques

années s’étant écoulées, Bruno renonçant au monde avec six de ses amis se

rendit auprès de saint Hugues, Évêque de Grenoble. Instruit du motif de leur

venue, et comprenant que c’était eux qu’il avait vus en songe, la nuit

précédente, sous l’image de sept étoiles se prosternant à ses pieds, il leur

concéda, dans son diocèse, des montagnes très escarpées connues sous le nom de

Chartreuse. Hugues lui-même accompagna Bruno et ses compagnons jusqu’à ce

désert, où le Saint mena pendant plusieurs années la vie érémitique. Urbain II,

qui avait été son disciple, le fit venir à Rome, et s’aida quelques années de

ses conseils dans les difficultés du gouvernement de l’Église, jusqu’à ce que,

Bruno ayant refusé l’archevêché de Reggio, obtint du Pape la permission de

s’éloigner.

Sixième leçon. Poussé par l’amour de la solitude, il se retira dans un lieu désert, sur les confins de la Calabre, près de Squillace. Ce fut là que Roger, comte de Calabre, étant à la chasse, le découvrit en prière, au fond d’une caverne où ses chiens s’étaient précipités à grand bruit. Le comte, frappé de sa sainteté, commença à l’honorer et à le favoriser beaucoup, lui et ses disciples. Les libéralités de Roger ne demeurèrent pas sans récompense. En effet, tandis qu’il assiégeait Capoue, Sergius, un de ses officiers, ayant formé le dessein de le trahir, Bruno, vivant encore dans le désert susdit, apparut en songe au comte et, lui découvrant tout le complot, le délivra d’un péril imminent. Enfin, plein de mérites et de vertus, non moins illustre par sa sainteté que par sa science, Bruno s’endormit dans le Seigneur et fut enseveli dans le monastère de Saint-Etienne, construit par Roger, où son culte est resté jusqu’ici en grand honneur.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/06-10-St-Bruno-confesseur

Profile

Educated in Paris and

the seminary of Rheims, France, Bruno

was ordained a priest c.1055, and

began to teach theology;

one of his students later became Pope Blessed Urban II. Father Bruno

presided over the cathedral school at Rheims from 1057 to 1075. He

criticized the worldliness he saw in his fellow clergy,

and opposed Manasses, Archbishop of Rheims,

because of his laxity and mismanagement. He served as chancellor of

the archdiocese of Rheims.

Following a vision he

received of a secluded hermitage where

he could spend his life becoming closer to God, he retired to a mountain near

Chartreuse in Dauphiny (in modern France)

in 1084,

and with the help of Saint Hugh of

Grenoble, he founded what became the first house of the Carthusian Order.

He and his brother Carthusians supported

themselves as manuscript copyists. Bruno became an assistant to Pope Urban II in 1090, and

supported the pope‘s

efforts at reform.

Retiring from public

life, Bruno and his companions built a hermitage at Torre, Italy where, 1095,

the monastery of Saint Stephen

was built.

Bruno combined in the religious life the eremetical and

the cenobitic,

both hermit and monk. His

learning and insight are apparent from his scriptural

commentaries.

Born

1101 at Torre, Calabria, Italy of

natural causes

buried in

the church of

Saint Stephen at Torre

death’s head

man holding a book and being

illuminated by a ray of light

crucifix with leaves and flowers

star on his breast

globe under his

feet

chalice with

the Sacred Host

man refusing a mitre

Additional

Information

A

Garner of Saints, by Allen Banks Hinds, M.A.

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Francis

Xavier Weninger

Saints

and Saintly Dominicans, by Blessed Hyacinthe-Marie

Cormier, O.P.

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

Upon

God’s Holy Hills, by Father Cyril

Charles Martindale, S.J.

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

images

video

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites

en français

Abbé

Christian-Philippe Chanut

fonti

in italiano

Readings

Rejoice, my dearest

brothers, because you are blessed and because of the bountiful hand of God’s

grace upon you. Rejoice, because you have escaped the various dangers and

shipwrecks of the stormy world. Rejoice because you have reached the quiet and

safe anchorage of a secret harbor. Many wish to come into this port, and many

make great efforts to do so, yet do not achieve it. Indeed many, after reaching

it, have been thrust out, since it was not granted them from above. By your

work you show what you love and what you know. When you observe true obedience

with prudence and enthusiasm, it is clear that you wisely pick the most

delightful and nourishing fruit of divine Scripture. – from a letter by

Saint Bruno to the Carthusians

MLA

Citation

“Saint Bruno“. CatholicSaints.Info.

5 October 2023. Web. 6 October 2023.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-bruno/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-bruno/

St. Bruno

St. Bruno was born in

Cologne of the prominent Hartenfaust family. He studied at the Cathedral school

at Rheims, and on his return to Cologne about 1055, was ordained and became a

Canon at St. Cunibert’s. He returned to Rheims in 1056 as professor of

theology, became head of the school the following year, and remained there

until 1074, when he was appointed chancellor of Rheims by its archbishop,

Manasses. Bruno was forced to flee Rheims when he and several other priests

denounced Manasses in 1076 as unfit for the office of Papal Legate.

Bruno later returned to

Cologne but went back to Rheims in 1080 when Manasses was deposed, and though

the people of Rheims wanted to make Bruno archbishop, he decided to pursue an

eremitical life. He became a hermit under Abbot St. Robert of Molesmes (who later

founded Citeaux) but then moved on to Grenoble with six companions in 1084.

They were assigned a place for their hermitages in a desolate, mountainous,

alpine area called La Grande Chartreuse, by Bishop St. Hugh of Grenoble, whose

confessor Bruno became.

They built an oratory and

individual cells, roughly followed the rule of St. Benedict, and thus began the

Carthusian Order. The Cathusians are one of the strictest in the Church.

Carthusians follow the Rule of St. Benedict, but accord it a most austere

interpretation; there is perpetual silence and complete abstinence from flesh

meat (only bread, legumes, and water are taken for nourishment).

Bruno sought to revive

the ancient eremitical way of life. His Order enjoys the distinction of never

becoming unfaithful to the spirit of its founder, never needing a reform.They

embraced a life of poverty, manual work, prayer, and transcribing manuscripts,

though as yet they had no written rule.

The fame of the group and

their founder spread, and in 1090, Bruno was brought to Rome, against his

wishes, by Pope Urban II as Papal Adviser in the reformation of the clergy.

Pope Urban II had been a student of Bruno’s at Rheims and is perhaps most well

known as the Pope who called for the first crusade.

Bruno persuaded Urban to

allow him to resume his eremitical state, founded St. Mary’s at La Torre in

Calabria, declined the Pope’s offer of the archbishopric of Reggio, became a

close friend of Count Robert of Sicily, and remained there until his death on

October 6.

He wrote several commentaries on the psalms and on St. Paul’s

epistles. He was never formally canonized because of the Carthusians’ aversion

to public honors but Pope Leo X granted the Carthusians permission to celebrate

his feast in 1514, and his name was placed on the Roman calendar in 1623.

His feast day is October 6. St. Bruno is the patron of diabolic possession and Ruthenia (parts of modern day Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Slovakia, & Poland).

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/saint-bruno/

San

Bruno, vetrata nel chiostro della Certosa di Serra San Bruno

São

Bruno, vitral no claustro da Cartuxa da Serra de São Bruno

St. Bruno

Confessor, ecclesiastical writer,

and founder of the Carthusian

Order. He was born at Cologne about

the year 1030; died 6 October, 1101. He is usually represented with a death's

head in his hands, a book and a cross, or crowned with

seven stars; or with a roll bearing the device O Bonitas. His feast is

kept on the 6th of October.

According

to tradition, St.

Bruno belonged to the family of Hartenfaust,

or Hardebüst, one of the principal families of

the city, and it is in remembrance of this origin that different members of

the family of Hartenfaust have

received from the Carthusians either

some special prayers

for the dead, as in the case

of Peter Bruno Hartenfaust in 1714,

and Louis Alexander Hartenfaust, Baron of Laach, in 1740;

or a personal affiliation with the order, as

with Louis Bruno of Hardevüst, Baron

of Laach and Burgomaster of the town of

Bergues-S. Winnoc, in the Diocese

of Cambrai, with whom the Hardevüst family in

the male line became extinct on 22 March, 1784.

We have little

information about the childhood and youth of St.

Bruno. Born at Cologne,

he would have studied at the city college, or collegial of St.

Cunibert. While still quite young (a pueris) he went to complete his education at Reims,

attracted by the reputation of the episcopal school and

of its director, Heriman. There he finished his classical studies

and perfected himself in the sacred

sciences which at that time consisted principally of the study

of Holy

Scripture and of the Fathers.

He became there, according to the testimony of his contemporaries, learned both

in human and in Divine science.

His education completed, St.

Bruno returned to Cologne,

where he was provided with a canonry at St.

Cunibert's, and, according to the most probable opinion, was elevated to

the priestly dignity.

This was about the year 1055. In 1056 Bishop Gervais recalled him to Reims,

to aid his former master Heriman in the direction of the school.

The latter was already turning his attention towards a

more perfect form of life, and when he at last left the

world to enter the religious

life, in 1057, St.

Bruno found himself head of the episcopal school,

or écolâtre, a post difficult as it was elevated, for it then included the

direction of the public schools and

the oversight of all the educational

establishments of the diocese.

For about twenty years, from 1057 to 1075, he maintained the prestige which

the school of Reims has

attained under its former masters, Remi

of Auxerre, Hucbald

of St. Amand, Gerbert, and lastly Heriman. Of the excellence of his

teaching we have a proof in

the funereal titles composed in his honour,

which celebrate his eloquence, his poetic, philosophical,

and above all his exegetical and theological,

talents; and also in the merits of his pupils, amongst whom

were Eudes of Châtillon, afterwards Urban

II, Rangier, Cardinal and Bishop of Reggio,

Robert, Bishop of Langres,

and a large number of prelates and abbots.

In 1075 St.

Bruno was appointed chancellor of the church of Reims,

and had then to give himself especially to the administration of the diocese.

Meanwhile the pious Bishop

Gervais, friend of St.

Bruno, had been succeeded by Manasses de Gournai, who quickly became odious

for his impiety and violence.

The chancellor and two other canons were commissioned to bear to

the papal

legate, Hugh of Die, the complaints of the indignant clergy,

and at the Council of Autun,

1077, they obtained the suspension of the unworthy prelate.

The latter's reply was to raze the houses of his accusers, confiscate

their goods, sell their benefices,

and appeal to the pope. Bruno then

absented himself from Reims for

a while, and went probably to Rome to

defend the justice of

his cause. It was only in 1080 that a

definite sentence, confirmed by a rising of the

people, compelled Manasses to withdraw and take refuge with the Emperor

Henry IV. Free then to choose another bishop,

the clergy were

on the point of uniting their vote upon the chancellor. He, however, had far

different designs in view. According to a tradition preserved in

the Carthusian

Order, Bruno was persuaded to abandon the world by the

sight of a celebrated prodigy, popularized by the brush of Lesueur--the

triple resurrection of the Parisian doctor,

Raymond Diocres. To this tradition may be opposed

the silence of contemporaries, and of the first biographers of

the saint;

the silence of Bruno himself in his letter

to Raoul le Vert, Provost of Reims;

and the impossibility of proving that he ever visited Paris.

He had no need of such an extraordinary argument to cause him to

leave the world. Some time before, when in conversation with two of his

friends, Raoul and Fulcius, canons of Reims like

himself, they had been so enkindled with the love of God and

the desire of eternal goods that they had made a vow to abandon the

world and to embrace the religious

life. This vow,

uttered in 1077, could not be put into execution until 1080, owing to

various circumstances.

The first idea of St.

Bruno on leaving Reims seems

to have been to place himself and his companions under the direction of an

eminent solitary, St. Robert, who had recently (1075) settled at Molesme in

the Diocese

of Langres, together with a band of other solitaries who were

later on (1098) to form the Cistercian

Order. But he soon found that this was not his vocation, and after a short

sojourn at Sèche-Fontaine near Molesme, he left two of his

companions, Peter and Lambert, and betook himself with six

others to Hugh of Châteauneuf, Bishop of Grenoble,

and, according to some authors, one of his pupils. The bishop,

to whom God had

shown these men in a dream, under the image of seven stars,

conducted and installed them himself (1084) in a wild spot on the Alps of Dauphiné

named Chartreuse, about four leagues from Grenoble,

in the midst of precipitous rocks and mountains almost always covered with

snow. With St.

Bruno were Landuin, the two Stephens of Bourg and

Die, canons of Sts. Rufus, and Hugh the Chaplain,

"all, the most learned men of their time", and two laymen, Andrew and Guérin,

who afterwards became the first lay

brothers. They built a little monastery where

they lived in deep retreat and poverty, entirely occupied

in prayer and

study, and frequently honoured by

the visits of St.

Hugh who became like one of themselves. Their manner of life has been

recorded by a contemporary, Guibert of Nogent, who visited them in

their solitude. (De Vitâ suâ, I, ii.)

Meanwhile, another pupil

of St.

Bruno, Eudes of Châtillon, had become pope under

the name of Urban

II (1088). Resolved to continue the work of reform commenced

by Gregory

VII, and being obliged to

struggle against the antipope, Guibert

of Ravenna, and the Emperor

Henry IV, he sought to surround himself with devoted allies and

called his ancient master ad Sedis Apostolicae servitium. Thus

the solitary found himself obliged to

leave the spot where he had spent more than six years in retreat, followed

by a part of his community, who could not make up their minds to live

separated from him (1090). It is difficult to assign the place which he then

occupied at the pontifical court, or his influence in contemporary

events, which was entirely hidden and confidential. Lodged in the palace of

the pope himself

and admitted to his councils, and charged, moreover, with other

collaborators, in preparing matters for the numerous councils of this

period, we must give him some credit for their results. But he took care always

to keep himself in the background, and although he seems to have assisted at

the Council of Benevento (March,

1091), we find no evidence of his having been present at

the Councils of Troja (March, 1093), of Piacenza (March,

1095), or of Clermont (November,

1095). His part in history is effaced. All that we can say with certainty is

that he seconded with all his power the sovereign

pontiff in his efforts for the reform of the clergy,

efforts inaugurated at the Council of Melfi (1089) and

continued at that of Benevento.

A short time after the arrival of St.

Bruno, the pope had

been obliged to abandon Rome before

the victorious forces of the emperor and the antipope.

He withdrew with all his court to the south of Italy.

During the voyage, the

former professor of Reims attracted

the attention of the clergy of Reggio in

further Calabria, which had just lost its archbishop Arnulph (1090),

and their votes were given to him. The pope and

the Norman prince, Roger, Duke of Apulia, strongly approved of

the election and pressed St.

Bruno to accept it. In a similar juncture at Reims he

had escaped by flight; this time he again escaped

by causing Rangier, one of his former pupils, to be elected, who

was fortunately near by at the Benedictine Abbey

of La Cava near Salerno.

But he feared that such attempts would be renewed; moreover he was

weary of the agitated life imposed upon him, and solitude ever

invited him. He begged, therefore, and after much trouble obtained, the pope's permission

to return again to his solitary life. His intention was to

rejoin his brethren in Dauphiné, as a letter addressed to them makes clear. But

the will of Urban

II kept him in Italy,

near the papal court,

to which he could be called at need. The place chosen for his

new retreat by St.

Bruno and some followers who had joined him was in the Diocese

of Squillace, on the eastern slope of the great chain

which crosses Calabria from north to south, and in a high valley

three miles long and two in width, covered with forest. The

new solitaries constructed a little chapel of

planks for their pious reunions

and, in the depths of the woods, cabins covered with mud for their habitations.

A legend says that St.

Bruno whilst at prayer was

discovered by the hounds of Roger, Great Count of Sicily and

Calabria and uncle of the Duke of Apulia, who was then hunting in the

neighbourhood, and who thus learnt to know and venerate him;

but the count had no need to wait for that occasion to know him,

for it was probably upon his invitation that the

new solitaries settled upon his domains. That same year (1091) he

visited them, made them a grant of the lands they occupied, and a close

friendship was formed between them. More than once St.

Bruno went to Mileto to take part in the joys and

sorrows of the noble family,

to visit the count when sick (1098 and 1101), and to baptize his

son Roger (1097), the future King of Sicily.

But more often it was Roger who went into the desert to

visit his friends, and when, through his generosity, the monastery of St.

Stephen was built, in 1095, near the hermitage of St. Mary, there was

erected adjoining it a little country house at which he loved to

pass the time left free from governing his State.

Meanwhile the friends

of St.

Bruno died one after the other: Urban

II in 1099; Landuin, the prior of

the Grand Chartreuse, his first companion, in 1100; Count Roger in 1101.

His own time was near at hand. Before his death he gathered for the

last time his brethren round him and made in their presence a profession of

the Catholic Faith,

the words of which have been preserved. He affirms with special

emphasis his faith in the

mystery of the Holy Trinity, and in the real

presence of Our Saviour in the Holy

Eucharist--a protestation against the two heresies which

had troubled that century, the tritheism of Roscelin,

and the impanation of Berengarius.

After his death, the Carthusians of

Calabria, following a frequent custom of the Middle

Ages by which the Christian

world was associated with the death of its saints,

dispatched a rolliger, a servant of the convent laden

with a long roll of parchment, hung round his neck, who passed through Italy, France, Germany,

and England.

He stopped at the principal churches and communities to announce the

death, and in return, the churches, communities,

or chapters inscribed upon his roll, in prose or verse, the

expression of their regrets, with promises of prayers.

Many of these rolls have been preserved, but few are so extensive or so full of

praise as that about St.

Bruno. A hundred and seventy-eight witnesses, of whom many

had known the deceased, celebrated the extent of his knowledge and

the fruitfulness of his instruction. Strangers to him were above all struck by

his great knowledge and

talents. But his disciples praised his three chief virtues--his

great spirit of prayer,

an extreme mortification,

and a filial devotion

to the Blessed Virgin. Both the churches built by him in

the desert were dedicated to

the Blessed Virgin: Our Lady of Casalibus in Dauphiné,

Our Lady Della Torre in Calabria; and, faithful to his

inspirations, the Carthusian Statutes

proclaim the Mother

of God the first and chief patron of all the houses of the

order, whoever may be their particular patron.

St.

Bruno was buried in the little cemetery of the

hermitage of St. Mary, and many miracles were

worked at his tomb.

He had never been formally canonized.

His cult, authorized for the Carthusian

Order by Leo

X in 1514, was extended to the whole church by Gregory

XV, 17 February, 1623, as a semi-double feast, and elevated to the

class of doubles by Clement

X, 14 March, 1674. St.

Bruno is the popular saint of Calabria; every year a great

multitude resort to the Charterhouse of St. Stephen, on the

Monday and Tuesday of Pentecost, when his relics are

borne in procession to the hermitage of St. Mary, where he

lived, and the people visit the spots sanctified by his presence. An immense

number of medals are

struck in his honour and

distributed to the crowd, and the little Carthusian habits,

which so many children of the neighbourhood wear, are blessed. He is

especially invoked, and successfully, for the deliverance of those

possessed.

As a writer and founder

of an order, St.

Bruno occupies an important place in the history of the

eleventh century. He composed commentaries on

the Psalms and on the Epistles of St.

Paul, the former written probably during his professorship at Reims,

the latter during his stay at the Grande Chartreuse if we may believe an

old manuscript seen

by Mabillon--"Explicit

glosarius Brunonis heremitae super Epistolas B. Pauli." Two letters of his

still remain, also his profession of faith,

and a short elegy on contempt for the world which shows that he

cultivated poetry. The "Commentaries" disclose to us a man of

learning; he knows a little Hebrew and Greek and

uses it to explain, or if need be, rectify the Vulgate;

he is familiar with the Fathers, especially St.

Augustine and St.

Ambrose, his favourites. "His style", says Dom Rivet,

"is concise, clear, nervous and simple, and

his Latin as good as could be expected of that century: it

would be difficult to find a composition of this kind at once more solid and

more luminous, more concise and more clear". His writings have been

published several times: at Paris,

1509-24; Cologne, 1611-40; Migne, Latin Patrology,

CLII, CLIII, Montreuil-sur-Mer, 1891. The Paris edition

of 1524 and those of Cologne include

also some sermons and homilies which

may be more justly attributed to St.

Bruno, Bishop of Segni.

The Preface of the Blessed Virgin has also been wrongly

ascribed to him; it is long anterior, though he may have contributed to

introduce it into the liturgy.

St.

Bruno's distinction as the founder of an order was that he introduced into

the religious

life the mixed form, or union of the eremitical and cenobite modes

of monasticism, a medium between the Camaldolese Rule and

that of St. Benedict. He wrote no rule, but he left behind him two

institutions which had little connection with each other--that of Dauphiné and

that of Calabria. The foundation of Calabria, somewhat like the Camaldolese,

comprised two classes of religious: hermits,

who had the direction of the order, and cenobites who did not feel

called to the solitary life; it only lasted a century, did

not rise to more than five houses, and finally, in 1191, united with

the Cistercian

Order. The foundation of Grenoble,

more like the rule

of St. Benedict, comprised only one kind of religious, subject to a

uniform discipline, and the greater part of whose life was spent

in solitude, without, however, the complete exclusion of

the conventual life. This life spread throughout Europe,

numbered 250 monasteries,

and in spite of many trials continues to this day.

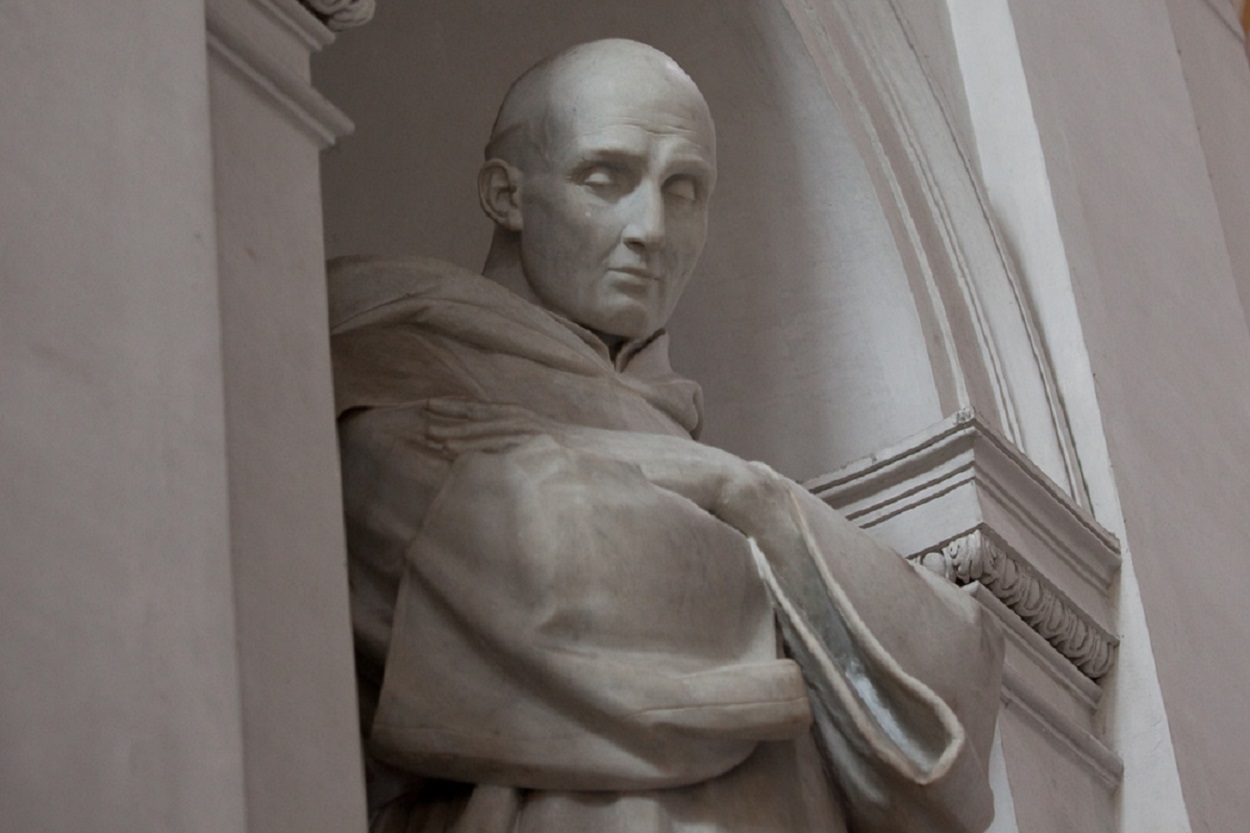

The great figure of St.

Bruno has been often sketched by artists and

has inspired more than one masterpiece: in sculpture,

for example, the famous statue by Houdon,

at St. Mary of the Angels in Rome,

"which would speak if his rule did not compel him to silence";

in painting,

the fine picture by Zurbaran,

in the Seville museum, representing Urban

II and St.

Bruno in conference; the Apparition of the Blessed

Virgin to St.

Bruno, by Guercino at Bologna; and above all the twenty-two pictures

forming the gallery of St.

Bruno in the museum of the Louvre, "a masterpiece of Le

Sueur and of the French school".

Mougel,

Ambrose. "St. Bruno." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol.

3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 31 Mar.

2015 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03014b.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Donald Jacob Uitvlugt.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. November 1, 1908. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2021 by Kevin Knight.

Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03014b.htm

HOMILY OF HIS HOLINESS

BENEDICT XVI

At the beginning of the

Liturgy, Cardinal William J. Levada, Prefect of the Congregation for the

Doctrine of the Faith, greeted the Holy Father, who responded:

Thank you, Your Eminence,

for your deeply cordial words. Thank you for your work and for your prayers. In

the joy of our common faith, let us now begin the Celebration of the Holy

Mysteries.

Dear Brothers and

Sisters,

I have not prepared a

real Homily, only a few ideas for meditation.

As clearly appears, the

mission of St Bruno, today's saint,

is, we might say, interpreted in the prayer for this day, which reminds us,

despite being somewhat different in the Italian text, that his mission was

silence and contemplation.

But silence and

contemplation have a purpose: they serve, in the distractions of daily life, to

preserve permanent union with God. This is their purpose: that union with God

may always be present in our souls and may transform our entire being.

Silence and

contemplation, characteristic of St

Bruno, help us find this profound, continuous union with God in the

distractions of every day. Silence and contemplation: speaking is the beautiful

vocation of the theologian. This is his mission: in the loquacity of our day

and of other times, in the plethora of words, to make the essential words

heard. Through words, it means making present the Word, the Word who comes from

God, the Word who is God.

Yet, since we are part of

this world with all its words, how can we make the Word present in words other

than through a process of purification of our thoughts, which in addition must

be above all a process of purification of our words?

How can we open the

world, and first of all ourselves, to the Word without entering into the

silence of God from which his Word proceeds? For the purification of our words,

hence, also for the purification of the words of the world, we need that

silence which becomes contemplation, which introduces us into God's silence and

brings us to the point where the Word, the redeeming Word, is born.

St Thomas Aquinas, with a

long tradition, says that in theology God is not the object of which we speak.

This is our own normal conception.

God, in reality, is not

the object but the subject of theology. The one who speaks through theology,

the speaking subject, must be God himself. And our speech and thoughts must

always serve to ensure that what God says, the Word of God, is listened to and

finds room in the world.

Thus, once again we find

ourselves invited to this process of forfeiting our own words, this process of

purification so that our words may be nothing but the instrument through which

God can speak, and hence, that he may truly be the subject and not the object

of theology.

In this context, a

beautiful phrase from the First Letter of St Peter springs to my mind. It is

from verse 22 of the first chapter. The Latin goes like this:

"Castificantes animas nostras in oboedentia veritatis". Obedience to

the truth must "purify" our souls and thus guide us to upright speech

and upright action.

In other words, speaking

in the hope of being applauded, governed by what people want to hear out of

obedience to the dictatorship of current opinion, is considered to be a sort of

prostitution: of words and of the soul.

The "purity" to

which the Apostle Peter is referring means not submitting to these standards,

not seeking applause, but rather, seeking obedience to the truth.

And I think that this is

the fundamental virtue for the theologian, this discipline of obedience to the

truth, which makes us, although it may be hard, collaborators of the truth,

mouthpieces of truth, for it is not we who speak in today's river of words, but

it is the truth which speaks in us, who are really purified and made chaste by

obedience to the truth. So it is that we can truly be harbingers of the truth.

This reminds me of St

Ignatius of Antioch and something beautiful he said: "Those who have

understood the Lord's words understand his silence, for the Lord should be

recognized in his silence". The analysis of Jesus' words reaches a certain

point but lives on in our thoughts.

Only when we attain that

silence of the Lord, his being with the Father from which words come, can we

truly begin to grasp the depth of these words.

Jesus' words are born in

his silence on the Mountain, as Scripture tells us, in his being with the

Father.

Words are born from this

silence of communion with the Father, from being immersed in the Father, and

only on reaching this point, on starting from this point, do we arrive at the

real depth of the Word and can ourselves be authentic interpreters of the Word.

The Lord invites us verbally to climb the Mountain with him and thus, in his

silence, to learn anew the true meaning of words.

In saying this, we have

arrived at today's two Readings. Job had cried out to God and had even argued

with God in the face of the glaring injustice with which God was treating him.

He is now confronted with God's greatness. And he understands that before the

true greatness of God all our speech is nothing but poverty and we come nowhere

near the greatness of his being; so he says: "I have spoken... twice, but

I will proceed no further" [Jb 40: 5].

We are silent before the

grandeur of God, for it dwarfs our words. This makes me think of the last weeks

of St Thomas' life. In these last weeks, he no longer wrote, he no longer

spoke. His friends asked him: "Teacher, why are you no longer speaking?

Why are you not writing?". And he said: "Before what I have seen now

all my words appear to me as straw".

Fr Jean-Pierre Torrel,

the great expert on St Thomas, tells us not to misconstrue these words. Straw

is not nothing. Straw bears grains of wheat and this is the great value of

straw. It bears the ear of wheat. And even the straw of words continues to be

worthwhile since it produces wheat.

For us, however, I would

say that this is a relativization of our work; yet, at the same time, it is an

appreciation of our work. It is also an indication in order that our way of

working, our straw, may truly bear the wheat of God's Word.

The Gospel ends with the

words: "He who hears you, hears me". What an admonition! What an

examination of conscience those words are! Is it true that those who hear me

are really listening to the Lord? Let us work and pray so that it may be ever

more true that those who hear us hear Christ. Amen!

© Copyright 2006 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Copyright © Dicastero per

la Comunicazione - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Manuel

Pereira (1588–1683), Saint Bruno, 1652, 169 × 70 × 60, Real Academia de Bellas

Artes de San Fernando, Madrid

October 6

St. Bruno, Confessor,

Founder of the Carthusians

From the short chronicle

of the four first priors of the Chartreuse, compiled by Guigo, the fifth prior,

as it seems, whose eulogy is added in MSS. ap. Labb. Bibl. MSS. t. 1, p. 638,

and the Bollandists; from the larger chronicle called Chronica de exordio

Ordinis Carthusiensis, or Tr. de Narratione historiæ inchoationis et

promotionis Ordinis Carthus, containing the history of the five first priors,

written about the year 1250, according to F. Bye; from St. Bruno’s life by Fr.

du Puitz or Puteanus, general of the Order, in 1508, printed at Basil in 1515;

from his life compiled by Guibert of Nogent, in 1101, and the life of St. Hugh

of Grenoble, written by Guy, the fifth general of the Carthusians. See

Mabillon, Annal. Bened. t. 5, p. 202, et Act. Ben. t. 9. Camillus Tutinus, in

Ordinis Carth. historiæ prospectu; Columbius, Diss. de Carthusianorum initiis;

Masson, the learned general of the Order, l. 1. Annalium Carthus. Hercules

Zanotti in Italica historia S. Brunonis, printed at Bologna in

1741. Continuators of the Hist. Littéraire de la France, t. 9, p. 233. F.

Longueval, Hist. de l’Eglise de France, l. 22, t. 8, p. 117. Bye the

Bollandist, t. 3, Oct. p. 491 to 777.

A.D. 1101.

THE MOST pious and learned Cardinal Bona, one of the greatest lights, not only of the Cistercian Order, but of the whole church, speaking of the Carthusian monks, of whose institute St. Bruno was the founder, calls them, “the great miracles of the world; men living in the flesh as out of the flesh; the angels of the earth, representing John the Baptist in the wilderness; the principal ornament of the church; eagles soaring up to heaven, whose state is justly preferred to the institutes of all other religious Orders.” 1 St. Bruno was descended of an ancient and honourable family, and born at Cologn, not after the middle of the eleventh century, as some mistake, but about the year 1030, as the sequel of his life demonstrates. In his infancy he seemed above the usual weaknesses of that age, and nothing childish ever appeared in his manners. His religious parents hoping to secure his virtue by a good education, placed him very young in the college of the clergy of St. Cunibert’s church, where he gave extraordinary proofs of his piety, capacity, and learning, insomuch that St. Anno, then bishop of Cologn, preferred him to a canonry in that church. He was yet young when he left Cologn, and went to Rheims for his greater improvement in his studies, moved probably by the reputation of the school kept by the clergy of that church. 2 Bruno was received by them with great marks of distinction. He took in the whole circle of the sciences; was a good poet for that age, but excelled chiefly in philosophy and theology, so that these titles of poet, philosopher, and divine, were given him by contemporary writers by way of eminence, and he was regarded as a great master and model of the schools. The historians of that age speak still with greater admiration of his singular piety. 3 Heriman, canon and scolasticus of Rheims, resigning his dignities, and renouncing the world to make the study of true wisdom his whole occupation, Gervasius, who was made archbishop of Rheims in 1056, made Bruno scholasticus, to which dignity then belonged the direction of the studies and all the great schools of the diocess. The prudence and extraordinary learning of the saint shone with great lustre in this station; in all his lessons and precepts he had chiefly in view to conduct men to God, and to make them know and respect his holy law. Many eminent scholars in philosophy and divinity did him honour by their proficiency and abilities, and carried his reputation into distant parts; among these Odo became afterwards cardinal bishop of Ostia, and at length pope, under the name of Urban II. Robert of Burgundy, bishop of Langres, brother to two dukes of Burgundy, and grandson to King Robert; Rangier, cardinal archbishop of Reggio, (after St. Bruno had refused that dignity,) and many other learned prelates and abbots of that age mention it as a particular honour and happiness, that they had been Bruno’s scholars. Such was his reputation that he was looked upon as the light of churches, the doctor of doctors, the glory of the two nations of Germany and France, the ornament of the age, the model of good men, and the mirror of the world, to use the expressions of an ancient writer. He taught a considerable time in the church of Rheims; and is said, by the author of his life to have been a long time the support of that great diocess; by which expression he seems to have borne the weight of the spiritual government under the archbishop Gervasius. That prelate dying in 1067, Manasses I. by open simony got possession of that metropolitical church, and oppressed it with most tyrannical vexations and enormities. Bruno retained under him his authority and dignities, particularly that of chancellor of the diocess, in which office he signed with him the charter of the foundations of St. Martin aux Jumeaux, and some other deeds of donations to monasteries. Yet he vigorously opposed his criminal projects. Hugh of Die, the pope’s legate, summoned Manasses to appear at a council which he held at Autun in 1077, and upon his refusing to obey the summons, declared him suspended from his functions. St. Bruno, Manasses the provost, and Poncius, a canon of Rheims, accused him in this council; in which affair our saint behaved with so much prudence and piety, that the legate writing to the pope, exceedingly extolled his virtue and wisdom, styling him the most worthy doctor of the church of Rheims, 4 and recommending him to his holiness as one excellently qualified to give him good counsel, and to assist him in the churches of France in promoting the cause of God. The simoniacal usurper, exasperated against the three canons who appeared in the council against him, caused their houses to be broken open and plundered, and sold their prebends. The persecuted canons took refuge in the castle of the count of Rouci, and remained there till August 1078, as appears by a letter which the simoniacal archbishop at that time wrote against them to the pope.

Before this time St.

Bruno had concerted the project of his retreat, of which he gives the following

account in his letter to Raoul or Ralph, provost of Rheims, to which dignity he

was raised in 1077, upon the resignation of Manasses. St. Bruno, this Ralph,

and another canon of Rheims named Fulcius, in a conversation which they had one

day together in one Adam’s garden, discoursed on the vanity and false pleasures

of the world, and on the joys of eternal life, and being strongly affected with

their serious reflections, promised one another to forsake the world. They

deferred the execution of this engagement till Fulcius should return from Rome,

whither he was going; and he being detained there, Ralph slackened in his

resolution, and continuing at Rheims, was afterwards made archbishop of that

see. But Bruno persevered in his resolution of embracing a state of religious

retirement. Serious meditation increased in him daily his sense of the

inestimable happiness of a glorious eternity, and his abhorrence of the world.

Thus he forsook it in a time of the most flattering prosperity, when he enjoyed

in it riches, honours, and the favour of men, and when the church of Rheims was

ready to choose him archbishop in the room of Manasses, who had been then

convicted of simony and deposed. He resigned his benefice, quitted his friends,

and renounced whatever held him in the world, and persuaded some of his friends

to accompany him into solitude, who were men of great endowments and virtue,

and who abundantly made up the loss of his two first companions in this design;

he seems first to have retired to Reciac or Roe, a fortified town and castle on

the Axona or Aisne in Champagne, the seat of Count Ebal, who had zealously

joined St. Bruno and others in opposing the impiety of Manasses. After some

time he went to Cologn, his native country; and some time after, was called

back to his canonry at Rheims; but making there a very short stay, he repaired

to Saisse-Fontaine, in the diocess of Langres, where he lived some time with

some of his scholars and companions. Two of these, named Peter and Lambert,

built there a church, which was afterwards united to the abbey of Molesme.

In this solitude Bruno,

with an earnest desire of aiming at true perfection in virtue, considered with

himself, and deliberated with his companions, what it was best for him to do,

spending his time in the exercises of holy solitude, penance, and prayer. He

addressed himself for advice to a monk of great experience and sanctity, that

is, to St. Robert, abbot of Molesme, who exhorted him to apply to Hugh, bishop

of Grenoble, who was truly a servant of God, and a person better qualified than

any other to assist him in his design. 5 St.

Bruno followed this direction, being informed that in the diocess of Grenoble,

there were woods, rocks, and deserts most suitable to his desires of finding

perfect solitude, and that this holy prelate would certainly favour his design.

Six of those who had accompanied him in his retreat, attended him on this

occasion, namely, Landwin, who afterwards succeeded him in the office of prior

of the great Chartreuse; Stephen of Bourg, and Stephen of Die, both canons of

St. Rufus in Dauphine; Hugh, whom they called the chaplain, because he was the

only priest among them, and two laymen, Andrew and Guerin. St. Bruno and these

six companions arrived at Grenoble about midsummer in 1084, and cast themselves

at the feet of St. Hugh, begging of him some place in his diocess, where they

might serve God, remote from worldly affairs, and without being burdensome to

men. The holy prelate understanding their errand, rejoiced exceedingly, and

received them with open arms, not doubting but these seven strangers were

represented to him in a vision he had the night before in his sleep; wherein he

thought he saw God himself building a church in the desert of his diocess

called the Chartreuse, and seven stars rising from the ground, and forming a

circle which went before him to that place, as it were, to shew him the way to

that church. 6 He

embraced them very lovingly, thinking he could never sufficiently commend their

generous resolution; and assigned them that desert of Chartreuse for their

retreat, promising his utmost assistance to establish them there; but to the

end they might be armed against the difficulties they would meet with, lest

they should enter upon so great an undertaking without having well considered

it: he, at the same time, represented to them the dismal situation of that

solitude, beset with very high craggy rocks, almost all the year covered with snow

and thick fogs, which rendered them not habitable. This relation did not daunt

the servants of God: on the contrary, joy, painted on their faces, expressed

their satisfaction for having found so convenient a retirement, cut off from

the society of men. St. Hugh having kept them some days in his palace,

conducted them to this place, and made over to them all the right he had in

that forest; and some time after, Siguin, abbot of Chaise-Dieu in Auvergne, who