Corrado Giaquinto (1703–1766). Sainte Marguerite Marie Alacoque contemplant le Sacré Cœur de Jésus, 1765, 171 x 123

Sainte Marguerite-Marie Alacoque

Religieuse visitandine à Paray-le-Monial (✝ 1690)

Elle est née, le 22 juillet 1647, en

Bourgogne Elle devient orpheline alors qu'elle a douze ans et ses tantes

qui gèrent la famille font d'elle un véritable souffre-douleur. A 24 ans, elle

peut enfin réaliser sa vocation: répondre à l'amour intense de Dieu. Les grâces

mystiques qui accompagnent ses épreuves culminent en 1673 dans plusieurs

visions du Christ: Voici le cœur qui a tant aimé les hommes jusqu'à s'épuiser

et se consumer pour leur témoigner son amour. Guidée par le Saint jésuite Claude

de La Colombière, elle parviendra à promouvoir le culte du Sacré-Cœur

d'abord dans son monastère de la Visitation, puis dans toute l'Église

Catholique latine. Elle meurt le 16 octobre 1690.

Béatifiée d'abord par l'opinion populaire à cause de tous les miracles obtenus

par son intercession, les pressions jansénistes puis la Révolution retarderont

sa béatification jusqu'en 1864 puis sa canonisation en 1920. Les foules

continuent d'affluer à Paray le Monial. Plusieurs Papes ont souligné

l'importance de son message: l'immensité de l'Amour de Dieu révélé dans un cœur

d'homme, et proposé à tous.

- vidéo de la webTV de la CEF, Chronique des saints: Marguerite-Marie Alacoque.

Mémoire de sainte Marguerite-Marie Alacoque, vierge. Entrée à vingt-quatre ans

au monastère de la Visitation à Paray-le-Monial en Bourgogne, elle avança de manière

admirable sur le chemin de la perfection. Pourvue de dons mystiques, elle se

préoccupa avant tout de la dévotion envers le Sacré-Cœur de Jésus, et fit

beaucoup pour promouvoir son culte dans l'Église. Elle mourut le 17 octobre

1690.

Martyrologe romain

En vous oubliant de vous-même, vous le posséderez. En

vous abandonnant à lui, il vous possédera. Allez donc, pleine de foi et d'une

amoureuse confiance, vous livrer à la merci de sa Providence, pour lui être un

fonds qu'il puisse cultiver à son gré et sans résistance de votre part,

demeurant dans une humble et paisible adhérence à son bon plaisir.

Lettre à une religieuse

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/2028/Sainte-Marguerite-Marie-Alacoque.html

Santa Margherita Maria Alacoque

Le

Sacré-Coeur de Jésus et Marguerite-Marie Alacoque. Vitrail, 1916.

Maitre-verrier : Charles Champigneulle, Eglises d'Ivry sur

Seine

Sainte Marguerite-Marie

Alacoque

Confidente du Sacré-Coeur

(1648-1690)

C'est pour instituer et

propager le culte de Son Sacré Coeur que Jésus-Christ Se choisit, au monastère

de la Visitation de Paray-le-Monial, une servante dévouée en Marguerite-Marie

Alacoque: une des gloires de la France est de lui avoir donné naissance.

Prévenue par la grâce

divine dès ses premières années, elle conçut de la laideur du péché une idée si

vive, que la moindre faute lui était insupportable; pour l'arrêter dans les

vivacités de son âge, il suffisait de lui dire: "Tu offenses Dieu!"

Elle fit le voeu de virginité à un âge où elle n'en comprenait pas encore la

portée.

On raconte qu'elle

aimait, tout enfant, à réciter le Rosaire, en baisant la terre à chaque Ave

Maria. Après sa Première Communion, elle se sentit complètement dégoûtée du

monde; Dieu, pour la purifier, l'affligea d'une maladie qui l'empêcha de

marcher pendant quatre ans, et elle dut sa guérison à la Sainte Vierge, en

échange du voeu qu'elle fit d'entrer dans un Ordre qui Lui fût consacré.

Revenue à la santé, elle oublia son voeu, et, gaie d'humeur, expansive,

aimante, elle se livra, non au péché, mais à une dissipation exagérée avec ses

compagnes.

De nouvelles épreuves

vinrent la détacher des vanités mondaines; les bonnes oeuvres, le soin des

pauvres, la communion, faisaient sa consolation. Enfin elle entra à la

Visitation de Paray-le-Monial. C'est là que Jésus l'attendait pour la préparer

à sa grande mission.

Le divin Époux la forma à

Son image dans le sacrifice, les rebuts, l'humiliation; Il la soutenait dans

ses angoisses, Il lui faisait sentir qu'elle ne pouvait rien sans Lui, mais

tout avec Lui. "Vaincre ou mourir!" tel était le cri de guerre de

cette grande âme.

Quand la victime fut

complètement pure, Jésus lui apparut à plusieurs reprises, lui montra Son Coeur

Sacré dans Sa poitrine ouverte: "Voilà, lui dit-Il, ce Coeur qui a tant

aimé les hommes et qui en est si peu aimé!" On sait l'immense expansion de

dévotion au Sacré Coeur qui est sortie de ces Révélations. La canonisation de

la Sainte a eu lieu le 13 mai 1920.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/sainte_marguerite-marie_alacoque.html

National Shrine of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Solemnly Consecrated June 15, 1985, on July 2, 2000, Dedication of New Altar Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Manila Sacred Heart Street List of barangays of Metro Manila, Legislative districts of Makati, Barangay San Antonio, Makati City.

16 octobre

Sainte Marguerite Marie Alacoque

Santa Margherita Maria Alacoque

Joseph-Hugues Fabisch, L'apparition du Sacré-Cœur ou Le Christ et Marguerite-Marie Alacoque, 1877, retable, Chapelle de l'Hôtel-Dieu /Chapelle du Sacré-Cœur, Lyon 2e

Ce divin Coeur est un abîme de bien où les pauvres

doivent abîmer leurs nécessités ; un abîme de joie où il faut abîmer toutes nos

tristesses ; un abîme d'humiliation pour notre orgueil, un abîme de miséricorde

pour les misérables, et un abîme d'amour où il nous faut abîmer toutes nos

misères.

Dites dans chacune de vos actions : " Mon Dieu, je

vais faire ou souffrir cela dans le Sacré Coeur de votre divin Fils et selon

ses saintes intentions que je vous offre pour réparer tout ce qu'il y a d'impur

ou d'imparfait dans les miennes. " Et ainsi de tout le reste.

Ne nous troublons pas, car les troubles ne servent

qu'à augmenter notre mal. L'Esprit de Dieu fait tout en paix. Recourons à Lui

avec amour et confiance, et il nous recevra entre les bras de sa miséricorde.

Vous demandez quelque courte prière pour lui témoigner

votre amour ; pour moi je n'en connais point d'autre et n'en trouve point de

meilleur que ce même amour, car tout parle quand on aime, et même les plus

grandes préoccupation sont des preuves de notre amour.

A la vérité, je crois que tout se change en amour, et

une âme qui est une fois embrasée de ce feu sacré, n'a plus d'autre exercice ni

d'autre emploi que d'aimer en souffrant.

Le Seigneur ne fait sa demeure que dans la paix d'une

âme qui aime fortement de se voir anéantie, pour demeurer comme toute perdue

dans l'amour à son abjection.

Vous ne trouverez de paix ni de repos que lorsque vous

aurez tout sacrifié à Dieu.

Ne nous troublons pas, car les troubles ne servent

qu'à augmenter notre mal. L'Esprit de Dieu fait tout en paix. Recourons à Lui

avec amour et confiance, et il nous recevra entre les bras de sa miséricorde.

La sainteté d'amour donne à l'âme un désir si ardent

d'être unie à Dieu qu'elle n'a de repos ni jour ni nuit ... Dieu se faisant

voir à l'âme et lui découvrant les trésors dont il l'enrichit et l'ardent amour

qu'il a pour elle.

Sainte Marguerite-Marie Alacoque

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/10/16.php

Santa Margherita Maria Alacoque

Margaretha

Maria Alacoque. Kath. Pfarrkirche St. Gordian und Epimachus, Merazhofen, Stadt

Leutkirch im Allgäu, Landkreis Ravensburg. Chorgestühl, 1896, Bildhauer: Peter

Paul Metz

Margaret

Mary Alacoque. Catholic parish church of St. Gordian and Epimachus, Merazhofen.

Sculptor: Peter Paul Metz, 1896

Małgorzata

Maria Alacoque. Rzeźba z kościoła parafialnego pw. św. Gordona i Epimachusa w

Merazhofen (Niemcy). Autor dzieła: Peter Paul Metz, 1896

MARIE ALACOQUE.

Quand l’homme veut agir, il choisit l’instrument le

plus capable de la fin qu’il se propose. Si un souverain souverain choisit un

ministère, il le prend ou essaye de le prendre tel que ses fonctions le réclament.

Si un homme veut faire son portrait, il s’adresse à un peintre, pas à un

cordonnier.

Quand Dieu veut agir, il prend le procédé directement

contraire. Il choisit l’instrument le plus absolument incapable. Il est jaloux

de montrer qu’il agit seul et va chercher la faiblesse la plus extrême pour que

nous ne soyons tentés d’attribuer la force à l’instrument. Déjà du temps de

saint Paul, il avait choisi la faiblesse pour confondre la force, Saint

Pierre, qui devait le représenter, lui à qui la puissance allait être donnée, la

puissance officielle, le gouvernement, Saint Pierre qui allait lier et délier,

saint Pierre, le maître des clefs, chargé d’ouvrir et de fermer le ciel, saint

Pierre est désigné par une faiblesse incalculable : il renie trois fois, par

peur d’une servante, celui dont il avait vu la face resplendir sur la montagne

du Thabor. II faut scruter cette faiblesse et pénétrer dans cet abîme, si l’on

veut savoir à quel point saint Pierre représente la force ; car l’abîme appelle

l’abîme, et il représente la force avec une réalité divine d’autant plus grande

que sa faiblesse humaine fut plus incommensurable.

Un jour saint François d’Assise rencontra un religieux

qui lui dit : - Pourquoi donc, pourquoi donc ce concours de monde vers vous ?

Pourquoi cette foule ? Pourquoi ce respect ? Pourquoi se presse-t-on sur vos

pas ?

Saint François répondit :

-Dieu a regardé le monde, cherchant par quel misérable

il pourrait bien manifester sa puissance. Ses yeux très saints, en tombant sur

la terre, n’ont rien trouvé de si vil, de si bas, de si petit, de si ignoble

que moi. Voilà la raison de son choix.

Vous voyez que c’est toujours le même procédé.

Cependant il restait dans Pierre et dans François de

grands dons naturels. C’étaient des âmes élevées. François avait quelque chose

de naturellement sublime dans l’esprit et de naturellement héroïque dans le

coeur.

Mais si nous regardons Marie Alacoque, qui fut

chargée d’une grande oeuvre, nous contemplerons un des chefs-d'oeuvre de la

misère humaine sans compensation. Ce n’est pas une grande nature égarée par de

grandes passions ; c’est une petite nature, étroite, sans attrait, sans lumière

naturelle, sans style, sans parole. Elle n’avait qu’une chose, l’amour, le

dévouement. Mais telle est la pauvreté de ses moyens naturels que l’amour même

la rend rarement éloquente. Elle bégaye, elle ânonne, elle hésite. Elle ne sait

pas. Seulement, elle aime et elle obéit. La voilà dans la gloire. Elle est

choisie.

« Je t’ai choisie, lui dit Jésus-Christ, comme un abîme

d’indignité et d’ignorance pour l’accomplissement de ce grand dessein, afin que

tout soit fait par moi. »

En fait d’ignorance, il est difficile d’aller plus

loin

M. Louis Veuillot a fait le parallèle de Dante et

d’Angèle de Foligno.

Même comme oeuvre humaine et comme poésie, il préfère

infiniment Angèle de Foligno, et il a raison.

Les foudres du coeur éclatent dans Angèle.

« Si un ange, dit-elle, me prédisait la mort de mon

amour, je lui dirais : C’est toi qui est tombé du ciel Et si quelqu’un,

n’importe qui, me racontait la Passion de Jésus-Christ, comme je la sens, je

lui dirais ; C’est toi qui l’as soufferte (Visions

et révélations d’Angèle de Foligno). »

Ses anéantissements, quand le nom de Dieu est prononcé

devant elle, dépassent les transports des plus grands poètes anciens ou

modernes.

Sainte Thérèse, quoique très inférieure à Angèle, est

cependant une femme hors ligne. Renan l’admire beaucoup. L’imagination de

sainte Thérèse est ardente et son esprit est subtil.

Mais Marie Alacocque est un défi jeté à l’esprit

humain. Personne n’eût songé à la choisir, personne excepté Dieu, qui voulut

priver ici son instrument de toutes les splendeurs humaines, sans en excepter

une. Aussi pauvre d’intelligence que de fortune, elle ne sait comment rendre

compte de ce qui se passe en elle. Son dévouement est sans bornes, son amour

est généreux jusqu’au plus complet et au plus déchirant sacrifice d’elle-même

tout entière. Et cependant son biographe, le R. Père Giraud, supérieur des

missionnaires de la Salette, dit à propos d’une de ses révélations :

« Ce langage paraîtra peut-être au pieux lecteur peu

digne de Notre-Seigneur. Il faut l’éclaircir sur ce point, afin de dissiper en

lui toute impression défavorable...

« Ce qui a paru petit et puéril dans l’expression, au

jugement de quelques censeurs, ne sera pas attribué à Jésus-Christ, mais à la

simplicité de la personne qui fait parler Jésus-Christ, et on n’attribuera au

divin Maître que le fond et la substance des pensées et des sentiments. »

Pour les détails de sa vie, nous renvoyons le lecteur

au livre du père Giraud (1), qui, s’effaçant autant que possible, a laissé parler

la Bienheureuse elle-même, s'appliquant seulement à expliquer et à commenter sa

vie et ses paroles. Il serait difficile de rencontrer un plus digne

commentateur ; car l’esprit de la Bienheureuse le pénètre si parfaitement que

c’est à peine si elle cesse de parler, quand le père Giraud parle.

Cette pauvre fille, absolument dépourvue

d'imagination, voit Jésus-Christ et l’entend lui dire :

« Mon divin Coeur est si passionné d’amour pour les

hommes et pour toi en particulier, que ne pouvant contenir en soi les flammes

de son ardente charité, il faut qu’il les répande par ton moyen. »

Quelques-uns croiront que la pauvre religieuse

travaillait à s’exalter et qu’on travaillait autour d’elle à l’exalter ; c’est

le contraire qui arrivait.

Ses voies extraordinaires ne convenaient pas, lui

disait-on à la Visitation de Sainte-Marie, et il fallait y renoncer.

On lui donne à garder une ânesse et son ânon, pour

occuper et distraire son esprit. Elle répond : « Puisque Saül, en gardant des

ânesses, a trouvé le royaume d’Israël, il faut que j’acquière le royaume du

ciel en courant après de tels animaux. »

Suivant la remarque intéressante du père Giraud, cette

pauvre fille, qui ne sait rien, cite sans cesse l’Écriture. Elle en a même une

intelligence tout à fait au-dessus de sa nature.

On attribue tantôt à la nature, tantôt au démon les

phénomènes qui se passent en elle. On lutte par tous les moyens possibles

contre elle et contre eux. Elle se fait, par obéissance, la complice des

erreurs que l’on commet sur elle. Tout conspire contre elle, y compris elle-même.

Elle n’a ni talent, ni intelligence, ni autorité, ni prestige. On intéresse sa

conscience à lutter contre ses visions.

Contre elle, elle a tout. Pour elle, elle n’a rien. Cependant

elle a triomphé, elle triomphe et surtout elle triomphera. Sans armes, sans

industrie, sans génie, sans allié, elle a conquis la gloire, qu’elle fuyait. La

gloire la fuyait ; elle fuyait la gloire, et cependant les voilà unies l’une à

l’autre dans le temps et dans l’éternité.

Son nom est connu partout ; beaucoup s’en moquent, il

est vrai. Mais ceux-là même le connaissent. Leur moquerie, comme leur colère,

est un hommage d’autant plus frappant qu’il est involontaire. C’est un hommage

rendu de force à cette inconcevable

célébrité, qui n’a pas d’explication humaine. Si ce n’est pas Dieu qui l’a

glorifiée, qui donc l’a glorifiée, et par quel prodige une telle petite fille,

si parfaitement dépourvue de dons naturels, par sa pauvreté intellectuelle, par

sa pauvreté sociale, par sa pauvreté religieuse, incapable de toutes les

manières, désirant en outre l’obscurité, qui semblait à tous les points de vue

lui être assurée ; comment cette pauvre fille, dont nous ne devrions pas savoir

le nom, est-elle à la fois glorieuse et célèbre, glorieuse dans l’Église,

célèbre dans le monde ? On se moque d’elle, bien entendu. Mais, si elle eût été

livrée à l’oubli naturel qui l’attendait nécessairement, il serait aussi

impossible de s’en moquer que de la vanter. Car on ne se moque pas, après deux

siècles, dans le monde entier, de la première petite fille venue. On l’ignore,

et voilà tout. Si Marie Alacocque eût cherché, par une maladresse insigne, la

réputation, jamais elle ne l’eût rencontrée. Par dessus toutes les disgrâces

réunies de la nature et de la société, elle porte un nom qui dit lui-même une

disgrâce. Ce mot : Alacocque, prête à la plaisanterie.

Toute la vie de la bienheureuse Marguerite-Marie

Alacocque est une lutte entre la grossièreté de sa nature et l’élévation qui

lui est conférée. Un jour, elle veut faire une pénitence corporelle sur la

nature de laquelle elle ne s’explique pas, mais qui lui donnait, dit-elle, grand

appétit par sa rigueur. Jésus-Christ le lui défend ; car, dit-elle, étant Esprit,

il veut aussi les sacrifices de l’Esprit.

C’est simple et clair ; mais elle était incapable de

penser cela naturellement.

Une autre fois, Jésus-Christ lui dit : « Je te rendrai

si pauvre, si vile et si abjecte à tes yeux, et je te détruirai si fort dans la

pensée de ton coeur, que je pourrai m’édifier sur ce néant ».

Remarquez ce mot : dans

la pensée de ton coeur ; c’est le style de l’Écriture. Voilà Marguerite-Marie

qui parle admirablement. Comment donc s’y prend-elle ? Et qui donc lui apprend

à penser comme saint Paul ?

Mais qui donc lui apprend aussi à penser comme Moïse ?

Jésus-Christ lui montre un jour les châtiments qu’il

réserve à certaines âmes, ennemies de Marguerite-Marie.

« Je me jetai, reprend Marguerite-Marie, à ses pieds

sacrés, en lui disant : - O mon Sauveur ! déchargez sur moi toute votre colère,

et m’effacez du livre de vie plutôt

que de perdre ces âmes qui vous ont couté si cher ! Et il me répondit : - Mais

elles ne t'aiment pas et ne cesseront pas de t’affliger. - Il n’importe, mon

Dieu ! pourvu qu’elles vous aiment, je ne veux cesser de vous prier de leur

pardonner. - Laisse-moi faire, je ne les peux souffrir davantage. - Et l’embrassant

encore plus fortement : Non, mon Seigneur, je ne vous quitterai point que vous

ne leur ayez pardonné. - Et il me disait : Je le veux bien si tu veux répondre

pour elles. - Oui, mon Dieu, mais je ne vous paierai toujours qu'avec vos

propres biens, qui sont les trésors de votre Sacré Coeur. - C’est de quoi il se

tint content. »

Ne reconnaissez-vous pas Moïse? « Lâche-moi ? - Non je

ne vous lâcherai pas. »

La vie de la bienheureuse Marguerite-Marie, commencée

par elle, est terminée par le P. Giraud. Il n’eût pas été facile de choisir un

plus digne historien. On pourrait croire que le P. Giraud a été le directeur de

la Bienheureuse, tant il la connaît profondément. Il ne la connaît pas seulement

avec la pensée de son esprit, il la connaît avec

la pensée de son coeur. Il a puisé aux mêmes sources. Il ne faut pas

insister plus longtemps sur lui, dans la crainte de lui déplaire, car il est de

ceux qui aiment le secret.

1. (1) La Vie de la bienheureuse Marguerite-

Marie, religieuse de la Visitation, écrite par elle-même. Texte authentique de ce précieux écrit, accompagné de notes historiques et

théologiques, et suivi du récit des dernières années de la vie de la Bienheureuse

et d’une neuvaine en son honneur, par le Père S. M. Giraud.

Ernest

HELLO. Physionomies de saints.

SOURCE : https://archive.org/stream/PhysionomiesDeSaintsParErnestHello/physionomies%20de%20saints_djvu.txt

Cinéma : “Sacré-Cœur”, la

plus belle histoire d’amour portée à l’écran

Anne-Sophie

Retailleau - publié le 30/09/25

Le film

"Sacré-Cœur", de Sabrina et Steven J. Gunnell, en salles ce 1er

octobre, dirige les projecteurs sur le Sacré Cœur de Jésus et sur ceux qui, de

toute époque jusqu’à aujourd’hui, lui ont consacré leur vie. Un docu-fiction

brillamment porté par des témoignages édifiants et de superbes scènes

cinématographiques.

C’est un ovni qui

s’apprête à débarquer dans les salles de cinéma, le 1er octobre 2025. Les

réalisateurs Sabrina et Steven J. Gunnell ont

consacré un film au Sacré-Cœur de Jésus, 350 ans après les apparitions

de Marguerite-Marie

Alacoque à Paray-le-Monial. Dans un docu-fiction d’1h30, ils retracent

l’histoire de la dévotion au Sacré-Coeur à

travers les siècles, jusqu’à aujourd’hui. Et ils montrent, avec des témoignages

poignants, l’incroyable actualité de son message.

"Le monde meurt de

ne pas se savoir aimé", assure un prêtre intervenant dans le film. Quoi de

mieux, pour y remédier, que de porter sur grand écran ce cœur "qui a tant

aimé les hommes", selon les propres paroles du Christ à sainte

Marguerite-Marie Alacoque ?

Les deux réalisateurs ont

relevé le défi haut la main avec un film puissant, tant par son message que par

la grande qualité des images de reconstitutions historiques. On retrouve ainsi

la figure emblématique de sainte Marguerite-Marie, incarnée avec grâce et

justesse, alternant avec des images de la Passion du Christ. Le public

découvrira aussi la dévotion au Sacré-Cœur dans l’enfer des tranchées, à

travers l’histoire du peintre George Desvallières.

Ces personnages

historiques ont porté l’étendard du Sacré-Cœur, qui touche encore aujourd’hui

les cœurs et change des vies. Ainsi, face à la caméra, des témoins de tous

horizons et de toutes conditions racontent avec la même ferveur comment l’amour

du cœur de Jésus a bouleversé leur existence. La force du film est de montrer

l’universalité du message du Sacré Cœur, qui rejoint chacun dans son histoire

propre. Du prêtre à l’étudiante, du “charismatique” au “traditionaliste”… Tous

les états de vie et toutes les sensibilités dans l’Église sont représentés. Non

pas pour dresser une liste exhaustive des cœurs conquis, mais plutôt comme un

écho à l’invitation de saint Paul à ne faire "plus qu’un dans le Christ

Jésus" (Gal, 3, 28).

Pacifier les cœurs et les unir en lui, c’est le pouvoir du Sacré Cœur, qui

continue de se déployer. Et le film invite à se laisser transformer par lui.

Pratique

Sacré-Cœur, 1 h 35.

Un film de Sabrina et Steven J. Gunnell

En salles le 1er octobre.

En partenariat avec SAJE

Distribution

Le film “Sacré-Cœur”

poursuit son ascension au box office

La rédaction d'Aleteia - publié

le 14/10/25

Le succès du film

"Sacré Cœur" diffusé en France depuis le 1er octobre, se confirme

avec 100.000 entrées au 14 octobre, un record pour ce film au petit budget

ayant démarré avec 155 salles. Il sera présent sur plus de 336 écrans à compter

du mercredi 15 octobre.

100.000 : c'est le nombre

de personnes qui sont allées voir le film Sacré Cœur : son règne n'aura pas de fin depuis sa

sortie en salles, le 1er octobre. Ce film documentaire s'offre un succès inédit

alors qu'il était programmé à travers seulement 155 salles dans toute la

France. Il se positionne N°9 au box-office global, alors qu’il n’a bénéficié

que de 910 séances (contre 4.200 à 10.000 séances pour les 8 premiers films).

Devant la demande et les

files d'attente toujours plus grandes, le nombre de copies avait déjà augmenté une première fois lors de la deuxième semaine

de diffusion : cumulant 43.620 entrées au 7 octobre, le film avait été

diffusé sur 223 copies supplémentaires. Pour cette troisième semaine, de

nombreux cinémas ont donc répondu à la demande pressante d'accueillir le film

dans leurs salles, comme à Lyon, à Toulouse, à Bordeaux, à Créteil, ou encore à

Lisieux. De plus petites villes comme Saint-Jean-de-Luz, Les Sables-d'Olonne ou

Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume font également partie des nouvelles salles

proposant le film. Pour cette troisième semaine, le film sera présent sur plus

de 336 écrans à compter du mercredi 15 octobre.

Dévotion au Cœur de Jésus

Réalisé par Steven et

Sabrina Gunnel, diffusé par Saje distribution, le film raconte l’histoire de

sainte Marguerite Marie Alacoque, religieuse visitandine du XVIIe siècle,

à laquelle le Christ est apparu pour lui délivrer la dévotion à son Cœur

brûlant d'amour pour les hommes. Face à la caméra, des témoins de tous horizons

et de toutes conditions témoignent de la puissance de cette dévotion dans leur

vie. Le film s'attache ainsi à montrer l'universalité du message du Sacré Cœur,

qui rejoint chacun dans son histoire propre. Tous les états de vie et toutes

les sensibilités dans l’Église sont représentés. "C’est un vrai mystère

qui nous dépasse, parce qu’il nous devance. Quand nous avons démarré la production,

nous avons découvert que le Sacré-Cœur est dans nos vies depuis le début. Il ne

nous a jamais lâchés", confiait à Aleteia Steven J. Gunnell avant la

diffusion du film.

Santa Margherita Maria Alacoque

Sainte

Marguerite Marie, église Saint Augustin de Paris

Sainte Marguerite Marie

Alacoque

Morte le 17 octobre 1690.

Canonisée en 1920, fête en 1929

Leçons des Matines (avant

1960)

Quatrième leçon.

Marguerite-Marie Alacoque, née d’une famille honorable dans un bourg du diocèse

d’Autun, donna dès son enfance des signes de sa sainteté future. Brûlant

d’amour pour la Vierge Mère de Dieu et pour l’auguste sacrement de

l’Eucharistie, la jeune adolescente voua à Dieu sa virginité ; Avant toute

chose, elle s’efforce de réaliser dans sa vie l’exercice des vertus

chrétiennes. Elle a le plaisir de dépenser des heures dans les prières et dans

la méditation sur les choses du ciel. Elle était humble et patiente dans

l’adversité. Elle a exercé la pénitence physique. Elle a montré sa charité

envers son prochain, en particulier les pauvres. Par tous les moyens dans les

limites de son pouvoir, elle s’employa avec diligence à imiter les plus saints

exemples a laissé par notre divin Rédempteur.

Cinquième leçon. Entrée

dans l’Ordre de la Visitation, elle commença aussitôt à resplendir du

rayonnement de la vie religieuse. Elle fut gratifiée par Dieu d’un don

d’oraison très élevée, d’autres faveurs spirituelles et de visions fréquentes.

La plus célèbre fut celle où, tandis qu’elle priait devant le Saint-Sacrement,

Jésus se présenta lui-même à sa vue, lui montra, sur sa poitrine ouverte, son

Divin Cœur tout embrasé et entouré d’épines et lui ordonna de faire en sorte,

en raison d’un tel amour et pour réparer les outrages des hommes ingrats, qu’un

culte public fût institué en l’honneur de son Cœur ; il promettait en retour de

grandes récompenses puisées dans le trésor céleste. Lorsque, par l’humilité,

elle a hésité d’entreprendre une telle tâche, son Sauveur très aimant l’a

encouragé. En même temps, il a désigné Claude de la Colombière, un homme de

grande sainteté, comme celui qui pourrait la guider et l’aider. Notre Seigneur

l’a également conforté avec l’assurance qu’une très grande bénédiction

s’étendrait sur l’Église grâce au culte de son divin Coeur.

Sixième leçon. Marguerite s’est ardemment dépensée à accomplir l’ordre du Rédempteur. Vexations, insultes ne lui manquèrent pas de la part de certains qui maintenaient qu’elle faisait l’objet d’aberrations mentales. Elle a non seulement porté ces souffrances patiemment, elle a même tiré profit, s’offrant elle-même dans l’angoisse et les douleurs comme une victime agréable à Dieu, supportant toute ces choses comme un moyen plus sûr de réaliser son but. Très estimée pour la perfection de sa vie religieuse et chaque jour plus unie au céleste Époux par la contemplation des réalités éternelles, elle s’envola vers lui, en la quarante-troisième année de son âge, l’an 1690 de la Rédemption. Elle fut glorifiée par des miracles ; Benoît XV l’inscrivit parmi les saints et Pie XI étendit son Office à l’Église universelle.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/17-10-Ste-Marguerite-Marie

Santa Margherita Maria Alacoque

Hombourg

Kirche St. Brice, Fenster von 1892 mit Darstellung der Heiligen Margareta-Maria

Alacoque, Begründerin des Festes zu Ehren des “Heiligsten Herzens Jesu”

Hombourg

church window from 1892 showing Holy Marguerite-Marie Alacoque

Hombourg,

eglise Saint Brice, vitrail datent de 1892: le “Sacré-cœur” et Ste

Marguerite-Marie Alacoque

Sainte Marguerite-Marie

Alacoque (1647-1690)

Sainte Marguerite-Marie

Alacoque (1647-1690) est née à Verosvre en Charolais et elle se fit visitandine

à Paray le Monial (1672) et y fut maîtresse des novices.

Elle fut canonisée le 13

mai 1920.

Sainte Marguerite Marie

Alacoque et la Vierge Marie.

Durant son enfance,

Marguerite fut guérie après quatre années de grave maladie par l'intercession

de Marie. En remerciement, le jour de sa confirmation, elle ajouta alors le nom

de « Marie » à « Marguerite ».

« J'allais à elle avec

tant de confiance qu'il me semblait n'avoir rien à craindre sous sa protection

maternelle. Je me consacrai à Elle pour être à jamais son esclave, la suppliant

de ne pas me refuser en cette qualité. Je lui parlais comme une enfant, avec

simplicité, tout comme à ma bonne Mère pour laquelle je me sentais pressé dès

lors d'un amour tendre. Si je suis entrée à la Visitation, c'est que j'étais

attirée par le nom tout aimable de Marie. Je sentais que c'était là ce que je

cherchais. »[1]

Religieuse, elle tombe

malade, et c'est encore la Vierge Marie qui la guérit : la sainte Vierge

apparut à Marguerite-Marie, lui « fit de grandes caresses, » l'entretint

longtemps et lui dit : « Prends courage, ma chère fille, dans la santé que je

te donne de la part de mon divin [Fils], car [tu as] encore un long et pénible

chemin à faire, toujours dessus la croix, percée de clous et d'épines, et

déchirée de fouets ; mais ne crains rien, je ne t'abandonnerai et te promets ma

protection. »[2]

La dévotion au Sacré-Cœur

existait déjà[3].

La dévotion au Sacré Cœur

était déjà chère au XII° siècle à saint Antoine de Padoue, saint Bonaventure,

saint Claire d'Assise, ou encore, au XVII° siècle, à Bérulle et à saint Jean

Eudes. Au milieu du XVII° siècle existent déjà des images du Christ montrant

son cœur dans son corps entrouvert.

L'idée centrale de la

dévotion au Sacré Cœur se résume ainsi : « Quel bonheur d'être uni à

Jésus-Christ dans le Sacré Cœur qui a été continuellement uni à Dieu ».

Chez certaines personnes

(dont Marguerite-Marie), la dévotion au Sacré-Cœur devient une prière pour les

pécheurs ou une prière de réparation.

Un nouvel élan pour la

dévotion au Sacré-Cœur.

Sœur Marguerite-Marie

évoque plusieurs apparitions du Christ.

- C'était le 27 décembre

1673, fête de saint Jean l'Évangéliste. Sœur Marguerite-Marie, ayant un peu

plus de loisir qu'à l'ordinaire, priait devant le saint Sacrement.

« Il me dit : - Mon divin

Cœur est si passionné d'amour pour les hommes, et pour toi en particulier, que,

ne pouvant plus contenir en lui-même les flammes de son ardente charité, il

faut qu'il les répande par ton moyen, et qu'il se manifeste à eux, pour les enrichir

de ses précieux trésors que je te découvre, et qui contiennent les grâces

sanctifiantes et salutaires nécessaires pour les retirer de l'abîme de

perdition ; et je t'ai choisie comme un abîme d'indignité et d'ignorance pour

l'accomplissement de ce grand dessein, afin que tout soit fait par moi. »

Après, il me demanda mon

cœur, lequel je le suppliai de prendre, ce qu'il fit, et le mit dans le sien

adorable, dans lequel il me le fit voir comme un petit atome, qui se consommait

dans cette ardente fournaise, d'où le retirant comme une flamme ardente en

forme de coeur, il [le] remit dans le lieu où il l'avait pris, en me disant

:

« Voilà, ma bien-aimée,

un précieux gage de mon amour, qui renferme dans ton côté une petite étincelle

de ses plais vives flammes, pour te servir de cœur et te consommer jusqu'au

dernier moment [...] »

« J'ai une soif ardente

d'être honoré des hommes dans le saint Sacrement, et je ne trouve presque

personne qui s'efforce, selon mon désir, de me désaltérer, usant envers moi de

quelque retour. » [4]

- Un premier vendredi

d'un mois de 1674, le Christ demande la réparation des offenses envers le Saint

Sacrement par l'heure sainte (le jeudi de 23h à minuit) et la communion du

premier vendredi du mois.

- Un jour de l'octave du

Saint Sacrement 1675, le Christ demande la fête annuelle du Sacré-Cœur. [5]

- Un jour de l'année

1689, le Christ lui dit qu'il désire du roi (Louis XIV) une consécration à son

Sacré-Cœur, la représentation du Sacré-Cœur sur le drapeau français et un sanctuaire

national dédié au Sacré-Cœur dans lequel il consacrerait la France Sacré-Cœur.

Mais Louis XIV n'en fera rien et la basilique du Sacré-Cœur de Montmartre ne

sera inaugurée qu'en 1919...

[1] Marquis de la

Franquerie, La Vierge Marie dans l'Histoire de France, Éditions Saint Rémi, p.

174

[2] Cf.

http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/saints/margueritemarie.

[3] Cf. E. Préclin et E. Jarry,

Histoire de l'Église, tome 19 , Bloud & Gay, Paris 1955, p. 288-289. Lire

aussi : H. De Barenton, La dévotion au Sacré-Coeur. Ce qu'elle est et comment

les saints la pratiquèrent, Paris 1914. L. Garriguet, Le Sacré-coeur de Jésus.

Exposé historique et dogmatique de la dévotion au Sacré Coeur de Jésus, Paris

1920.

[4] Cf.

http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/saints/margueritemarie. Citation de

l'Autobiographie, p. 75.

[5] Cf. E. Préclin et E. Jarry,

Histoire de l'Eglise, tome 19 , Bloud & Gay, Paris 1955, p. 288-289

Synthèse Françoise

Breynaert

SOURCE : http://www.mariedenazareth.com/17415.0.html?&L=0

Also known as

Margarita Mary Alacoque

Margherita Mary Alacoque

Marguerite Mary Alacoque

Profile

Healed from

a crippling disorder

by a vision of the Blessed

Virgin, which prompted her to give her life to God.

After receiving a vision of Christ fresh from the Scourging, she was moved to

join the Order

of the Visitation at Paray-le-Monial in 1671.

Received a revelation from Our Lord in 1675,

which included 12 promises to her and to those who practiced a true to devotion

to His Sacred

Heart, whose crown

of thorns represent his sacrifices. The devotion encountered violent

opposition, especially in Jansenist areas,

but has become widespread and popular.

Born

22 July 1647 at

L’Hautecourt, Burgundy, France

17

October 1690 of

natural causes

body incorrupt

18

September 1864 by Pope Blessed Pius

IX

13 May 1920 by Pope Benedict

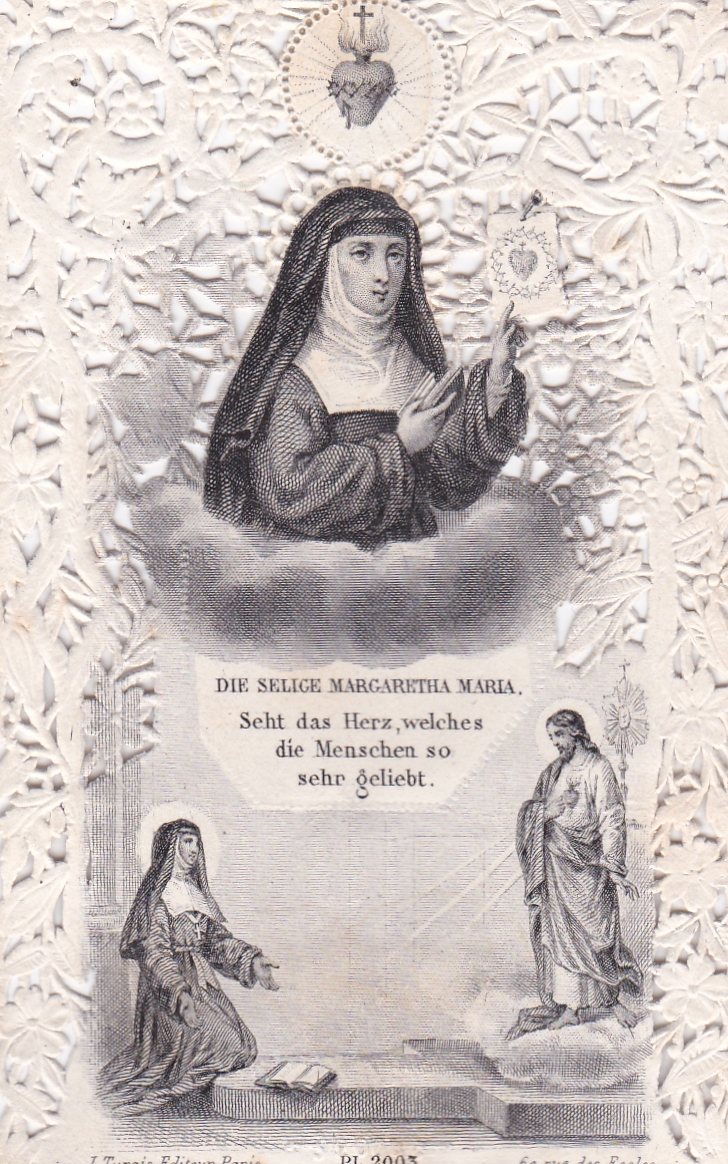

XV

woman wearing

the habit of

the Order

of the Visitation and holding a flaming heart

woman wearing

the habit of

the Order

of the Visitation and kneeling before Jesus who exposes His heart to

her

Readings

What a weakness it is to love Jesus Christ only when

He Caresses us, and to be cold immediately once He afflicts us. This is not

true love. Thouse who love thus, love themselves too much to love God with all

their heart. – Saint Margaret

Mary Alacoque

The Twelve Promises of Jesus to Saint Margaret Mary

for those devoted to His Sacred Heart

I will give them all the graces necessary for their

state of life.

I will establish peace in their families.

I will console them in all their troubles.

They shall find in My Heart an assured refuge during

life and especially at the hour of their death.

I will pour abundant blessings on all their

undertakings.

Sinners shall find in My Heart the source of an

infinite ocean of mercy.

Tepid souls shall become fervent.

Fervent souls shall speedily rise to great perfection.

I will bless the homes where an image of My Heart

shall be exposed and honored.

I will give to priests the power of touching the most

hardened hearts.

Those who propagate this devotion shall have their

names written in My Heart, never to be effaced.

The all-powerful love of My Heart will grant to all

those who shall receive Communion on

the First Friday of nine consecutive months the grace of final repentance; they

shall not die under my displeasure, nor without receiving their Sacraments; My

heart shall be their assured refuge at that last hour.

– from Saint Margaret Mary Alacoque’s vision of Jesus

Look at this Heart which has loved men so much, and

yet men do not want to love Me in return. Through you My divine Heart wishes to

spread its love everywhere on earth.” – from Saint Margaret Mary

Alacoque’s vision of Jesus

The sacred heart of Christ is an inexhaustible

fountain and its sole desire is to pour itself out into the hearts of the

humble so as to free them and prepare them to lead lives according to his good

pleasure. From this divine heart three streams flow endlessly. The first is the

stream of mercy for sinners; it pours into their hearts sentiments of contrition

and repentance. The second is the stream of charity which helps all in need and

especially aids those seeking perfection in order to find the means of

surmounting their difficulties. From the third stream flow love and light for

the benefit of his friends who have attained perfection; these he wishes to

unit to himself so that they may share his knowledge and commandments and, in

their individual ways, devote themselves wholly to advancing his glory. This

divine heart is an abyss filled

with all blessings, and into the poor should submerge all their needs. It is an

abyss of joy in which all of us can immerse our sorrows. It is an abyss of

lowliness to counteract our foolishness, an abyss of mercy for the wretched, an

abyss of love to meet our every need. Are you making no progress in prayer? The

you need only offer God the prayers which the Savior has poured out for us in

the sacrament of the altar. Offer God his fervent love in reparation for your

sluggishness. In the course of every activity pray as follows: “My God, I do

this or I endure that in the heart of your Son and according to his holy

counsels. I offer it to you in reparation for anything blameworthy or imperfect

in my actions.” Continue to do this in every circumstance of life. But above

all preserve peace of heart. This is more valuable than any treasure. In order

to preserve it there is nothing more useful than renouncing your own will and

substituting for it the will of the divine heart. In this way his will can

carry out for us whatever contributes to his glory, and we will be happy to be

his subjects and to trust entirely in him. – from a letter by Saint

Margaret Mary Alacoque

MLA Citation

“Saint Margaret Mary Alacoque“. CatholicSaints.Info. 17 August 2020. Web. 16 October 2020. <https://catholicsaints.info/saint-margaret-mary-alacoque/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-margaret-mary-alacoque/

Santa Margherita Maria Alacoque

Eglise Saint-Martin de Lamballe, Côtes d'Armor, baie 5

St. Margaret Mary

Alacoque

St. Margaret Mary

Alacoque – Religious of the Visitation Order. Apostle of the Devotion to the

Sacred Heart of Jesus, born at Lhautecour, France, 22 July, 1647; died at

Paray-le-Monial, 17 October, 1690.

Her parents, Claude

Alacoque and Philiberte Lamyn, were distinguished less for temporal possessions

than for their virtue, which gave them an honourable position. From early

childhood Margaret showed intense love for the Blessed Sacrament, and preferred

silence and prayer to childish amusements. After her first communion at the age

of nine, she practised in secret severe corporal mortifications, until

paralysis confined her to bed for four years. At the end of this period, having

made a vow to the Blessed Virgin to consecrate herself to religious life, she

was instantly restored to perfect health. The death of her father and the

injustice of a relative plunged the family in poverty and humiliation, after

which more than ever Margaret found consolation in the Blessed Sacrament, and

Christ made her sensible of His presence and protection. He usually appeared to

her as the Crucified or the Ecce Homo, and this did not surprise her, as she

thought others had the same Divine assistance. When Margaret was seventeen, the

family property was recovered, and her mother besought her to establish herself

in the world. Her filial tenderness made her believe that the vow of childhood

was not binding, and that she could serve God at home by penance and charity to

the poor. Then, still bleeding from her self-imposed austerities, she began to

take part in the pleasures of the world. One night upon her return from a ball,

she had a vision of Christ as He was during the scourging, reproaching her for

infidelity after He had given her so many proofs of His love. During her entire

life Margaret mourned over two faults committed at this time–the wearing of

some superfluous ornaments and a mask at the carnival to please her brothers.

On 25 May, 1671, she

entered the Visitation Convent at Paray, where she was subjected to many trials

to prove her vocation, and in November, 1672, pronounced her final vows. She

had a delicate constitution, but was gifted with intelligence and good

judgement, and in the cloister she chose for herself what was most repugnant to

her nature, making her life one of inconceivable sufferings, which were often

relieved or instantly cured by our Lord, Who acted as her Director, appeared to

her frequently and conversed with her, confiding to her the mission to establish

the devotion to His Sacred Heart. These extraordinary occurrences drew upon her

the adverse criticism of the community, who treated her as a visionary, and her

superior commanded her to live the common life. But her obedience, her

humility, and invariable charity towards those who persecuted her, finally

prevailed, and her mission, accomplished in the crucible of suffering, was

recognized even by those who had shown her the most bitter opposition.

Margaret Mary was

inspired by Christ to establish the Holy Hour and to pray lying prostrate with

her face to the ground from eleven till midnight on the eve of the first Friday

of each month, to share in the mortal sadness He endured when abandoned by His

Apostles in His Agony, and to receive holy Communion on the first Friday of

every month. In the first great revelation, He made known to her His ardent

desire to be loved by men and His design of manifesting His Heart with all Its

treasures of love and mercy, of sanctification and salvation. He appointed the

Friday after the octave of the feast of Corpus Christi as the feast of the

Sacred Heart; He called her “the Beloved Disciple of the Sacred Heart”, and the

heiress of all Its treasures. The love of the Sacred Heart was the fire which

consumed her, and devotion to the Sacred Heart is the refrain of all her

writings. In her last illness she refused all alleviation, repeating

frequently: “What have I in heaven and what do I desire on earth, but Thee

alone, O my God”, and died pronouncing the Holy Name of Jesus.

The discussion of the

mission and virtues of Margaret Mary continued for years. All her actions, her

revelations, her spiritual maxims, her teachings regarding the devotion to the

Sacred Heart, of which she was the chief exponent as well as the apostle, were

subjected to the most severe and minute examination, and finally the Sacred

Congregation of rites passed a favourable vote on the heroic virtues of this

servant of God. In March, 1824, Leo XII pronounced her Venerable, and on 18

September, 1864, Pius IX declared her Blessed. When her tomb was canonically

opened in July, 1830, two instantaneous cures took place. Her body rests under

the altar in the chapel at Paray, and many striking favours have been obtained

by pilgrims attracted thither from all parts of the world. St. Margaret Mary

was canonized by Benedict XV in 1920. Her feast is celebrated on 17

October.

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/st-margaret-mary-alacoque/

Santa Margherita Maria Alacoque

Revelation

of the Sacred Heart to Marguerite Marie Alacoque, Ballylooby Church of Our

Lady and St. Kieran South Transept South Window

St. Margaret Mary

Alacoque

Religious of

the Visitation

Order. Apostle of the Devotion

to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, born at Lhautecour, France,

22 July, 1647; died at Paray-le-Monial,

17 October, 1690.

Her parents,

Claude Alacoque and Philiberte Lamyn, were distinguished less for temporal

possessions than for their virtue,

which gave them an honourable position.

From early childhood Margaret showed intense love for

the Blessed

Sacrament, and preferred silence and prayer to

childish amusements. After her first communion at

the age of nine, she practised in secret severe corporal

mortifications, until paralysis confined her to bed for four years. At the

end of this period, having made a vow to

the Blessed

Virgin to consecrate herself

to religious

life, she was instantly restored to perfect health. The death of her father

and the injustice of

a relative plunged the family in poverty and

humiliation, after which more than ever Margaret found consolation in the Blessed

Sacrament, and Christ made

her sensible of His presence and protection. He usually appeared to

her as the Crucified or the Ecce Homo, and this did not surprise her, as

she thought others had the same Divine assistance. When Margaret was seventeen,

the family property was

recovered, and her mother besought her to establish herself in the world. Her

filial tenderness made her believe that the vow of

childhood was not binding, and that she could serve God at

home by penance and charity

to the poor. Then, still bleeding from her self-imposed austerities,

she began to take part in the pleasures of the world. One night upon her return

from a ball, she had a vision of Christ as

He was during the scourging, reproaching her for infidelity after He had given

her so many proofs of

His love.

During her entire life Margaret mourned over two faults committed at this

time--the wearing of some superfluous ornaments and a mask at the carnival to

please her brothers.

On 25 May, 1671, she

entered the Visitation Convent at Paray,

where she was subjected to many trials to prove her vocation,

and in November, 1672, pronounced her final vows.

She had a delicate constitution, but was gifted with intelligence and good

judgement, and in the cloister she

chose for herself what was most repugnant to her nature, making her life one of

inconceivable sufferings, which were often relieved or instantly cured by our

Lord, Who acted as her Director, appeared to

her frequently and conversed with her, confiding to her the mission to

establish the devotion

to His Sacred Heart. These extraordinary occurrences drew upon her the

adverse criticism of the community,

who treated her as a visionary, and her superior commanded her to live the

common life. But her obedience,

her humility,

and invariable charity towards

those who persecuted her, finally prevailed, and her mission, accomplished in

the crucible of suffering, was recognized even by those who had shown her the

most bitter opposition.

Margaret Mary was

inspired by Christ to

establish the Holy Hour and to pray lying

prostrate with her face to the ground from eleven till midnight on the eve of

the first Friday of each month, to share in the mortal sadness He endured when

abandoned by His Apostles in

His Agony,

and to receive holy

Communion on the first Friday of every month. In the first great revelation,

He made known to her His ardent desire to be loved by men and

His design of manifesting His Heart with

all Its treasures of love and

mercy, of sanctification and salvation.

He appointed the Friday after the octave of

the feast of Corpus

Christi as the feast of

the Sacred

Heart; He called her "the Beloved Disciple of the Sacred

Heart", and the heiress of all Its treasures. The love of

the Sacred

Heart was the fire which consumed her, and devotion

to the Sacred Heart is the refrain of all her writings. In her last

illness she refused all alleviation, repeating frequently: "What have I

in heaven and

what do I desire on earth, but Thee alone, O my God",

and died pronouncing the Holy

Name of Jesus.

The discussion of the

mission and virtues of

Margaret Mary continued for years. All her actions, her revelations,

her spiritual maxims, her teachings regarding the devotion

to the Sacred Heart, of which she was the chief exponent as well as the

apostle, were subjected to the most severe and minute examination, and finally

the Sacred Congregation of rites passed a favourable vote on the heroic

virtues of this servant of God.

In March, 1824, Leo

XII pronounced her Venerable, and on 18 September, 1864, Pius

IX declared her Blessed.

When her tomb was

canonically opened in July, 1830, two instantaneous cures took place. Her body

rests under the altar in

the chapel at Paray,

and many striking favours have been obtained by pilgrims attracted

thither from all parts of the world. Her feast is

celebrated on 17 October. [Editor's Note: St. Margaret Mary was canonized by

Benedict XV in 1920. Her feast is

now 16 October.]

Doll, Sister Mary

Bernard. "St. Margaret Mary Alacoque." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton

Company, 1910. 16 Oct.

2016 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09653a.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Paul T. Crowley. Dedicated to

Mrs. Margaret McHugh and Mrs. Margaret Crowley.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. October 1, 1910. Remy Lafort,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John M. Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2020 by Kevin

Knight. Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09653a.htm

Santa Margherita Maria Alacoque

Monument

of the Sacred Heart, Cerro de los Ángeles, Getafe, Madrid, Spain: "The

church in triumph"

Monumento

al Sacro Cuore, Cerro de los Ángeles, Getafe, Madrid, Spagna: "La Chiesa

trionfante"

Monumento

al Sagrado Corazón, Cerro de los Ángeles, Getafe, Madrid, Spain: "Iglesia

triunfante".

Están

representados: San Agustín, San Francisco de Asís, Santa Margarita María de Alacoque, Santa Teresa de Jesús, Santa Gertrudis y el Venerable Padre Bernardo de Hoyos

Margaret Mary Alacoque V

(RM)

Born July 22, 1647, at

L'Hautecourt, Burgundy; died at Paray-le- Monial, 1690; canonized 1920.

"Love triumphs, love

enjoys, the love of the Sacred Heart rejoices!"

Saint Margaret Mary is

nearly the antithesis of yesterday's saint, Teresa of Ávila. As joyful as

Teresa was; Margaret Mary was dour and humorless. Teresa was gregarious;

Margaret Mary self- contained. Both were sickly, but dealt with it differently.

Both were visionaries. This proves once again that no personality precludes

sanctity.

Margaret Mary was the

daughter of the respected notary Claude Alacoque and Philiberte Lamyn. Her

father died when she was around eight, leaving her family in a precarious

financial situation, so that for several years they were at the mercy of some

domineering and rapacious relatives.

She was sent to school

with the Poor Clares at Charolles. She fell ill with a painful rheumatic

condition at 12 and was bedridden until she was 15. The family home had been

taken over by her sister, and her mother and she were treated with undeserved

severity and almost like servants. Her sister often refused her permission to

attend church. "At that time," she wrote later, "all my desire

was to seek happiness and comfort in the Blessed Sacrament.

At 20, she was pressed to

marry but after a long struggle with herself decided to fulfill the vow she had

made earlier to the Virgin and entered the Order of the Visitation. She was

confirmed at 22 and took the name Mary. Her brother furnished her dowry and she

joined the convent at Paray-le-Monial. During her retreat before her

profession, which she made on November 6, 1672, she had a vision of Jesus in

which he said, "Behold the wound in my side, wherein you are to make your

abode, now and forever."

She worked in the

infirmary, and the slow-moving, awkward Margaret Mary suffered much under the

active and efficient infirmarian, Sister Catherine Marest.

On December 27, 1673, the

feast of Saint John the Evangelist, as she knelt at the grill before the

exposed Blessed Sacrament, she experienced a vision in which the Lord told her

to take the place that Saint John had occupied at the Last Supper, and that she

would act as His instrument. Jesus revealed His Sacred Heart as a symbol of His

love for mankind, saying:

"My divine Heart is

so inflamed with love for mankind . . . that it can no longer contain within

itself the flames of its burning charity and must spread them abroad by your

means."

Then it was as if He took

her heart and placed it next to his own, and then returned it burning with

divine love into her breast.

She had three more

visions over the next year and a half in which he instructed her in a devotion

that was to become known as the Nine Fridays and the Holy Hour, and in the

final revelation, the Lord asked that a feast of reparation be instituted for

the Friday after the octave of Corpus Christi.

The Wisdom of God also

told her, "Do nothing without the approval of those who guide you, so

that, having the authority of obedience, you may not be misled by Satan, who

has no power over those who are obedient."

She told her superior,

Mother de Saumaise, about the visions, was treated contemptuously and was

forbidden to carry out any of the religious devotions that had been requested

of her in her visions. She became ill from the strain, and the superior,

searching for a divine sign of what to do, vowed to believe the visions if

Margaret Mary was cured. Margaret Mary prayed and recovered, and her superior

kept her promise.

A group within the

convent remained skeptical of her experiences, especially when, in 1677, she

told them that Jesus had twice asked her to be a willing victim to expiate

their shortcomings. The superior ordered Margaret Mary to present her

experiences to theologians. They were judged to be delusions, and it was

recommended that Margaret Mary eat more.

Blessed Claude La

Colombière, a holy and experienced Jesuit, arrived as confessor to the nuns,

and in him Margaret Mary recognized the understanding guide that had been

promised to her in the visions. He became convinced that her experiences were

genuine and adopted the teaching of the Sacred Heart the visions had

communicated to her. He departed not long after for England.

During the next years,

Margaret Mary experienced periods of both despair and vanity, and she was ill a

great deal. In 1681 Claude returned; in 1682 he died. In 1684 Mother Melin

became superior and elected Margaret Mary her assistant, silencing any further

opposition.

Her revelations were made

known to the community when they were read aloud in the refectory in the course

of a book written by Blessed Claude. Margaret Mary became novice mistress and

was very successful.

Her revelations in the

open now, she encouraged devotion to the Sacred Heart, especially among her

novices, who observed the feast in 1685. The family of an expelled novice

accused her of being unorthodox, and bad feelings were revived, but this passed

and the entire house celebrated the feast that year.

A chapel was built in

1687 at Paray in honor of the Sacred Heart, and devotion began to spread in the

other convents of the Visitidines, as well as throughout France.

Margaret Mary became ill

while serving a second term as assistant to the superior and died during the

fourth anointing step of the last rites. As she received the Last Sacrament,

she said, "I need nothing but God, and to lose myself in the heart of

Jesus."

(She actually died on

October 17, but the Church celebrates her today.) She, Saint John Eudes, and

Blessed Claude are called "saints of the Sacred Heart."

Margaret Mary's patience

and trust during her trials within the convent contributed to her canonization

in 1920. The devotion was officially recognized and approved by Pope Clement

XIII in 1765, 75 years after her death. Her visions and teachings have had

considerable influence on the devotional life of Catholics, especially since

the inauguration of the Feast of the Sacred Heart of Jesus on the Roman calendar

in 1856 (Attwater, Delaney, Kerns, White).

Depicted as a nun in the

Visitation habit holding a flaming heart; or kneeling before Jesus, who exposed

his heart to her (White).

In art, Saint Margaret

Mary is portrayed as a nun to whom Christ offers His Sacred Heart

(Roeder).

Illustrated

Catholic Family Annual – Blessed Margaret Mary Alacoque

Article

The Blessed Margaret Mary Alacoque was born at Terrau,

in the province of Burgundy, France, on the 22d of July, 1647. Her family was

highly respectable; her father having held the office of judge for Terrau, as

well as for several of the neighboring towns. From an early age little Margaret

showed great devotion towards the Blessed Virgin. When eight years old she lost

her father, and, as she was the only daughter living, she was placed at school

with the Dames Urbanistes, a title given the Religious of Saint Clare who

followed the mitigated rule sanctioned by Pope Urban VIII. At the end of two

years her mother had to remove her, as she was visited with a severe illness

which lasted four years. The bones pierced her skin, and she almost lost the

use of her limbs. She says, in her own Life, that a promise was made that, if

she was cured, she would belong to the Blessed Virgin and be one of her

daughters. She had no sooner made the vow than she was cured.

In her twenty-third year she entered the little

convent of the Order of the Visitation at Paray, on 25 May 1671. It contained

at that time thirty-three choir sisters, three lay sisters, and three novices.

To go into the details of her convent life would take up too much space. A

valuable biography has been written by Father Tickell, S.J. Her whole life was

devoted to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, a devotion founded by her. All through

her life she was particularly favored by our divine Lord. She died in the odor

of sanctity, on 17 October 1690, in the forty-fourth year of her age, in the

arms of the two sisters to whom she had herself predicted this several years

before. Her body was deposited in the burial-place of the community, but in 1703

the coffin was opened, and the precious bones collected and placed in an oak

case near the same spot, where they remained until the expulsion of the Sisters

by the Revolutionists of 1792.

Paray-le-Monial has lately attracted much attention in

consequence of pilgrimages being made to the Blessed Margaret Mary’s shrine. On

16 June 1823, the present monastery was dedicated, and the relics of the

Blessed Margaret Mary placed in an oratory adjoining the choir, but were

afterwards put in a tomb, where they remained until her beatification. The

decree establishing her heroic character was prepared in May 1S46, by the

present Pope, Pius IX, who visited the monastery in August of the same year,

Orders were given for the prose cution of the cause in April 1864, and on 24

June the decree of beatification was published; on 6 September 1866 His

Holiness signed the order for resuming the cause of canonization. A pilgrimage

from England, under the lead of the Duke of Norfolk, and with the sanction of

the hierarchy of England, to Paray-le-Monial, took place in September 1873, and

attracted special attention everywhere.

MLA Citation

“Blessed Margaret Mary Alacoque”. Illustrated Catholic Family Annual, 1874. CatholicSaints.Info.

17 January 2017. Web. 16 October 2020.

<https://catholicsaints.info/illustrated-catholic-family-annual-blessed-margaret-mary-alacoque/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/illustrated-catholic-family-annual-blessed-margaret-mary-alacoque/

Christ appearing to Saint Margaret Mary, Church of the Sacred Heart, Coshocton, Ohio, stained glass

Pictorial

Lives of the Saints – Blessed Margaret Mary Alacoque

Margaret Mary was born at Terreau in Burgundy, on the

22nd July, 1647. During her infancy she showed a wonderfully sensitive horror

of the very idea of sin. In 1671 she entered the Order of the Visitation, at

Paray-le-Monial, and was professed the following year. After purifying her by

many trials, Jesus appeared to her in numerous visions, displaying to her His

Sacred Heart, sometimes burning as a furnace, and sometimes torn and bleeding

on account of the coldness and sins of men. In 1675 the great revelation was

made to her that she, in union with Father de la Colombiere, of the Society of

Jesus, was to be the chief instrument for instituting the feast of the Sacred

Heart, and for spreading that devotion throughout the world. She died on the

17th October, 1690.

Reflection – Love for the Sacred Heart especially

honors the Incarnation, and makes the soul grow rapidly in humility,

generosity, patience, and union with its Beloved.

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/pictorial-lives-of-the-saints-blessed-margaret-mary-alacoque/

Bleiglasfenster

in der katholischen Kirche Saint-Rémy (Recey-sur-Ource) in Recey-sur-Ource im

Département Côte-d’Or (Burgund/Frankreich), Darstellung: Herz Jesu und

Marguerite Marie Alacoque

Saint

Margaret Mary Alacoque, by Father Henry A. Johnston, S.J.

In the baptismal register of the parish of Verosyres

can still be read the following entry: ‘Margaret, daughter of Monsieur Claude

Alacoque, royal notary, and his wife, Philiberte Lemain, was baptized by me,

the undersigned Cure of Verosyres, Thursday, 25th of July, 1847.’ – This is the

beginning of the story of a wonderful life of grace. The child’s birth had

taken place three days previously, on July 22nd. It was in the pleasant land of

Burgundy, in the small town of Lautecour, that Margaret Alacoque was born and

grew up. She had four brothers and two sisters, one brother and one sister

being younger than herself. Two sisters died young, so she was left an only

sister among four brothers. We have very few of those details about her home,

her early years and later, about her surroundings when she was a religious,

which gave such a human interest to the life of Saint Therese of Lisieux, for

instance. In the account of her life, which she wrote when she was 38, at the

command of Pere Rolin, S.J., her director, she confined herself almost entirely

to the relations between her soul and God.

CHILDHOOD’S HAPPY HOURS

She was a happy and lively child. But God early showed

that He had special designs in her regard. Our Lord, when on earth, had special

affection for little children, and He remains the same always. Children seem

often to be in close touch with God and the supernatural. So it was with little

Margaret. Sin appeared to her something horrible, as indeed it really is. An

ebullition of natural high spirits on the part of the child could always be

checked by telling her that she would offend God. When she was quite small, she

repeated one day at Mass the words, ‘My God, I consecrate to You my purity, and

I make a vow to You of perpetual chastity.’ Where the child got the idea, we do

not know. She tells us herself that she did not know the meaning of ‘vow’ or

‘chastity’ at the time. It may have been the result of some pious conversation

which she listened to in the family circle, or an echo of her catechism; but,

more likely still, God was speaking to her heart in secret.

Her godmother, a great lady who lived in the castle of

Corcheval, four miles away, often had Margaret with her between her fourth and

eighth year. The pine-clad hills, the rocky gorges, the music-making streams

about Corcheval, must all have had an effect on the child’s bright

intelligence. The castle contained a chapel, and the facilities this gave for

prayer tended to strengthen the bonds, which were being woven between her soul

and God. ‘O my only Love,’ she wrote twenty-five years later, ‘how much I owe

You for having granted me Your benedictions from my most tender years, making

Yourself the master and owner of my heart.’

When she was eight and a half years of age, her father

died. He had been a thoroughly good Christian man; even today, we can see a

cross traced at the head of all the documents written by him as judge and Royal

Notary. His death necessitated a change in the family. The mother could not

look after the property and give proper attention to her five surviving

children. Margaret was sent to school to the Urbanists at Charolles. Her close

contact with religious naturally strengthened the ideals of piety when she already

possessed. She was found sufficiently developed spiritually to make her First

Communion at the then early age of nine. Like many another little girl, she

begins to plan to be a nun. But she does not lose her gaiety. She is full of

fun and fond of amusement. Then God begins to work out His plans in her. She is

good; more, she is holy. But unless God intervenes in a special way, she is not

likely to love Him with her whole heart and her whole soul. And He wants the

whole of her heart. When she is eleven she falls ill, and for four years, she

is unable to walk. She is worn away nearly to a skeleton.

This was a hard cross for one of her years. Suffering

later became a joy to her, but it was not so at the age of eleven. It is only

through the virtues of later years that we can estimate the change it worked in

her soul.

Margaret had during her early years a real child’s

love for Mary, Mother of God. She tells us that Mary saved her from ‘very great

dangers’ during her girlhood. When her illness persisted in spite of all

remedies, a vow was made that if the child recovered she would be ‘one of

Mary’s daughters.’ This brought about her cure, and gave Our Blessed Lady an

even more important place in her life. ‘She made herself so entirely mistress

of my heart that she took upon herself the absolute government of me; she

reproved me for my faults, and taught me to do the will of God.’

The restoration of her health had another effect,

however, on Margaret. At fourteen, the memory of pain is soon effaced, and the

girl’s natural vivacity and love of enjoyment quickly asserted themselves. She

felt the attraction of pleasant things around her, and the affection, which her

mother and brothers had for her, encouraged her in giving herself a good time

(her own. words: A me donner du bon temps). In later life, she reproached

herself bitterly for levity and especially for once, in company with some of

her young friends, appearing disguised during the time of carnival. It was not

a great crime, but it was resistance to the urging of grace. God was not yet

master of the heart He had made for Himself. Bodily suffering had not

succeeded; suffering of mind and spirit was to follow.

THE HAND OF GOD

Some of the property of Monsieur Alacoque had not

passed entirely to his widow. His mother, who lived with the family, and a

married sister had an interest in it. This sister and her husband, Toussaint

Delaroche, were hostile to the Alacoques, and seem to have been of a coarse and

bitter disposition. They usurped all authority in the Alacoque household, and

the life of mother and daughter became a misery. The Saint’s own words portray

it clearly enough. ‘My mother and I were soon reduced to hard captivity. . . .

We had no longer any power in the house, and we dare not do anything without

permission. It was a state of continual war. Everything was kept under lock and

key, so that I could not even dress myself in order to go to Holy Mass. . . . I

acknowledge that I felt keenly this state of slavery. . . .

‘I should have thought myself happy to go and beg my

bread rather than live as I was living.’ Continual nagging went on in the

house, and it was not easy to escape. She could not leave the house without

permission of three persons, and when she wanted to go to the church to Mass or

Benediction and was refused, the tears, which sometimes followed, were

attributed to vexation at not being able to keep some secret appointment. She

was not given enough to eat; she worked like a servant. And God’s design in it

all? ‘Jesus Christ gave me to understand when I was in this state that He

wished to make Himself the absolute Master of my heart.’ Such suffering would

have embittered many a young girl. But earnest prayer and constant meditation

on the sufferings, which Our Lord had to endure for her enabled Margaret

Alacoque to drive every unkind thought from her mind. – In the end, she came to

look upon her persecutors as real benefactors.

Gradually things changed. Her brothers grew up and

acquired more authority. Margaret herself was eighteen, her mother looked

forward to a good marriage for her, which would help still further towards

their emancipation. It was a new trial of a different kind. The love of

pleasure, so long suppressed, revealed itself once more. – The world began to

smile on Margaret, and she quickly responded. She began to pay more attention

to dress. She mixed more in society. Eligible young men were encouraged to come

to the Alacoque house. The girl felt she was being unfaithful to God’s call and

a struggle raged in her soul. She had made a vow of chastity; but then she had

not understood what she was doing. She had decided to become a nun but now she

felt that she could not persevere. True, she had made a promise to the Blessed

Virgin during her illness, but her mother was ill now and wanted her to settle

in the world. Could she break her mother’s heart?

Then she tried to compromise. She increased her

mortifications, but at the same time, she did not give up the round of

pleasure. She inflicted cruel sufferings on herself, but she would not give Our

Lord what He wanted. His grace pursued her, however, and just when she seemed

likely to yield to her mother’s wishes, and agree to be married, He spoke so

strongly to her one day after Communion, representing how unworthy it would be

if, after all His favours, she would turn her back on Him and give herself to

another, that she was finally conquered. It was like the snapping of a chain,

like the dawning of the day after a troubled night.

The story of the struggle between God and the world in

the heart of Saint Margaret Mary during the early part of her life has its

counterpart in the heart of many a young girl at the present day here in our

own country. God is near her in childhood, and she gives her young heart to

Him. She passes to a convent school, and opportunities for frequent Communion

lead to more intimate friendship with Our Lord. Vacations sometimes bring

forgetfulness and carelessness, but Our Lord wins her heart once more to

Himself. Fifteen or sixteen comes, and the beauty and worth of religious life

make a strong appeal. She becomes conscious, with a little surprise and perhaps

fear, that she has a vocation, that Our Lord is calling her to follow Him. But

the dangerous years are at hand. She begins to feel more strongly the

attraction of pleasure and amusement. Admiration and flattery bring new and

exhilarating sensations. The Voice of God is not heard so clearly. Perhaps, she

thinks, she was mistaken in thinking she had a vocation.

If she ventures to mention the idea, her friends

pooh-pooh it. At any rate, she must wait for a few years and enjoy herself

first. Intercourse with the world does the rest and often, very often, Our Lord

has lost a friend, the Church an apostle, and a soul the grandest opportunity

in this life, and a crown of wondrous beauty in life everlasting.

THE SNARE IS BROKEN

Margaret Alacoque was not twenty years of age. Her

mind was fully made up, and she began to live as devoted a life as she could in

preparation for her entry into religion. She prayed much, knowing her own

weakness; she gave herself to works of charity; she went to extremes, having no

one to guide her in the matter of mortification. Not that her troubles were

over.

Four years were to pass before she could give herself

to God in religious life. Her mother, and still more her brother, Chrysostom,

opposed her wish. The Delaroche family resumed their rough treatment. Her

relative and godfather, the cure of the parish, who seems to have been infected

with Jansenism, was a further obstacle to her, instead of being a help, in the

way of God. Then pressure was brought to bear on her to force her against her judgement

and God’s wish into a convent where she had a cousin. ‘I am going to be a

religious solely for love of God,’ she said. She prayed earnestly that God

would send her help. ‘Is it possible,’ was the reply, ‘that a child so fondly

loved as you are should be lost in the arms of an all-powerful Father?’

In 1669, when she was twenty-two, she was confirmed

and took the name of Mary. The following year, God sent a Franciscan Father to

Verosyres, and Margaret Mary opened her heart to him. He checked her extravagances,

as, for instance, when she naively transcribed whole pages of sins from manuals

of the examinations of conscience and accused herself of them all; but with

regard to her vocation, he took her side at once, and spoke strongly to her

brother Chrysostom. So the path was cleared at last, and she entered the

Visitation Convent at Paray-le-Monial in June, 1671. She was then 24 years of

age.

She tells us herself of the joy with which she left

her home. Even her mother’s tears did not sadden her. But when she was on the

point of entering the convent, sadness and fear assailed her, and she felt as

if she would die. It had often been thus, before and since, with those who were

giving themselves completely to God. The great Saint Teresa, writing later in

life, says: ‘I can remember, as if it were today, how, as I was leaving my

father’s house, I felt in such a state that I think if I had been at the point

of death I could not have felt greater pain.’ But the pain soon passed, and the

joy which followed was lasting.

A NOVICE