Saint François de Borgia

Duc de Gandie, général de

la Compagnie de Jésus (+ 1572)

L'Histoire retient

surtout les scandales de son grand-père, le pape Alexandre VI Borgia. La mère

de François est fille illégitime d'un archevêque de Saragosse lequel d'ailleurs

est un bâtard du roi Ferdinand le Catholique. Dans cette famille va naître une

fleur de sainteté. A 19 ans, Charles-Quint en personne le marie à la portugaise

Eleonore de Castro. François est un grand personnage: duc de Gandie,

grand-veneur de l'Empereur, écuyer de l'Impératrice, gouverneur de Catalogne.

Père de huit enfants, il perd son épouse alors qu'il a 36 ans. Deux ans plus

tard, il change de cap, entre chez les jésuites et devient "maître général

de la Compagnie" à 55 ans. Il s'impose comme "second fondateur",

un père indulgent et ferme, profondément aimé de ses frères. Sous son

gouvernement, les Jésuites se répandent dans toute l'Europe et dans les

missions lointaines. Il leur donne un grand dynamisme et fait de son Ordre l'un

des grands artisans de la Contre-Réforme.

Fils aîné du duc Jean de

Borgia, François naquit en 1510 à Gandie, dans le royaume de Valence. Après une

éducation raffinée à la cour de l'empereur Charles-Quint, il épousa en 1529

Éléonore de Castro, dont il eut huit fils. En 1542, il succéda à son père comme

duc de Gandie; mais après la mort de sa femme il renonça à son duché. Il entra

dans la Compagnie de Jésus, et, ses études de théologie achevées, y fut ordonné

prêtre en 1551. il fut élu troisième Général en 1565. Il fit beaucoup pour la

formation et la vie spirituelle de ses religieux, pour les collèges qu'il fit

fonder en divers lieux et pour les missions, remarquable par l'austérité de sa

vie et son don d'oraison. Il meurt à Rome le 30 septembre 1572 et fut canonisé

par Clément X en 1671.

Un internaute nous

signale:

'Ici, en Espagne, on

célèbre la festivité de saint François Borja / Borgia ("San Francisco de

Borja) le 3 octobre'

Voir aussi sur le site

de la province de France des Jésuites où il est fêté le 3 octobre.

30 septembre au

martyrologe romain: À Rome, en 1572, saint François de Borja, prêtre. Après la

mort de sa femme, dont il avait eu huit enfants, il quitta les dignités du

siècle et refusa celles de l'Église, entrant dans la Compagnie de Jésus, dont

il fut élu préposé général, vraiment remarquable par l'austérité de sa vie et

son don d'oraison.

Martyrologe romain

Quel grand remède pour

tous nos maux que de méditer la Croix du Christ!

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/8492/Saint-Francois-de-Borgia.html

SAINT FRANÇOIS DE BORGIA

Jésuite

(1510-1572)

Saint François de Borgia

était Espagnol et fils de prince. À peine put-il articuler quelques mots, que

sa pieuse mère lui apprit à prononcer les noms sacrés de Jésus et de Marie. Âgé

de cinq ans, il retenait avec une merveilleuse mémoire les sermons, le ton, les

gestes des prédicateurs, et les répétait dans sa famille avec une onction

touchante. Bien que sa jeunesse se passât dans le monde, à la cour de Charles-Quint,

et dans le métier des armes, sa vie fut très pure et toute chrétienne; il

tenait même peu aux honneurs auxquels l'avaient appelé son grand nom et ses

mérites.

A vingt-huit ans, la vue

du cadavre défiguré de l'impératrice Isabelle le frappa tellement, qu'il se dit

à lui-même: "François, voilà ce que tu seras bientôt... A quoi te

serviront les grandeurs de la terre?..." Toutefois, cédant aux instances

de l'empereur, qui le fit son premier conseiller, il ne quitta le monde qu'à la

mort de son épouse, Éléonore de Castro. Il avait trente-six ans; encore dut-il

passer quatre ans dans le siècle, afin de pourvoir aux besoins de ses huit

enfants.

François de Borgia fut

digne de son maître saint Ignace; tout son éloge est dans ce mot. L'humilité

fut la vertu dominante de ce prince revêtu de la livrée des pauvres du Christ.

A plusieurs reprises, le Pape voulut le nommer cardinal; une première fois il

se déroba par la fuite; une autre fois, saint Ignace conjura le danger.

Étant un jour en voyage

avec un vieux religieux, il dut coucher sur la paille avec son compagnon, dans

une misérable hôtellerie. Toute la nuit, le vieillard ne fit que tousser et cracher;

ce ne fut que le lendemain matin qu'il s'aperçut de ce qui lui était arrivé; il

avait couvert de ses crachats le visage et les habits du Saint. Comme il en

témoignait un grand chagrin: "Que cela ne vous fasse point de peine, lui

dit François, car il n'y avait pas un endroit dans la chambre où il fallût

cracher plutôt que sur moi." Ce trait peint assez un homme aux vertus

héroïques.

Plus l'humble religieux

s'abaissait, plus les honneurs le cherchaient. Celui qui signait toutes ses

lettres de ces mots: François, pécheur; celui qui ne lisait qu'à genoux les

lettres de ses supérieurs, devint le troisième général de la Compagnie de

Jésus.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_francois_de_borgia.html

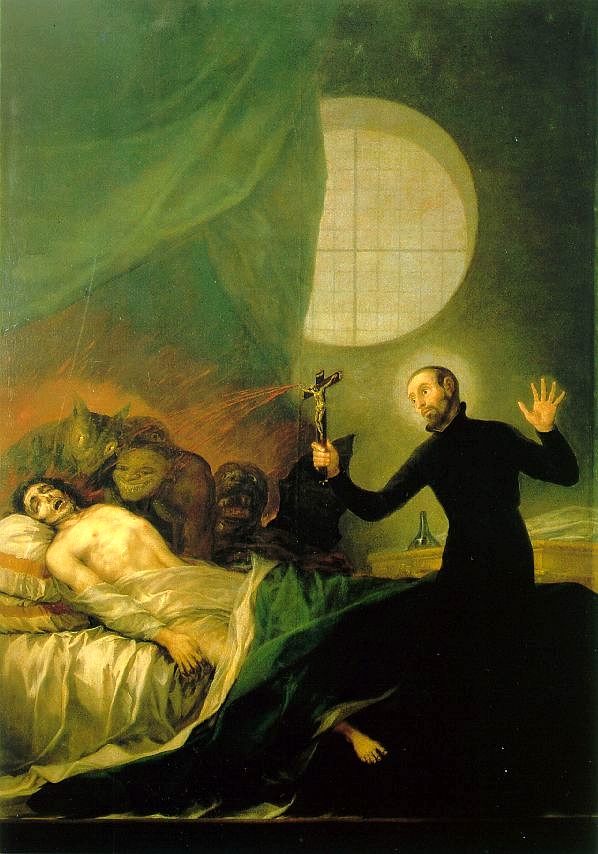

Francisco

de Goya, San

Francisco de Borja y el moribundo impenitente / Saint François de Borgia et

le Moribond impénitent, 1788, 300 x 300, cathédrale de Valence.

François de Borgia, un

saint issu de la plus sulfureuse des familles

Anne Bernet - publié

le 02/10/23

Vocation étonnante que

celle de François de Borgia, petit-fils bâtard d’archevêque, petit-fils d’un

bâtard de pape… qui devînt général des jésuites et fut canonisé pour ses réels

mérites par la sainte Église.

Le 1er mai 1539, la reine

Isabelle d’Espagne, épouse de Charles Quint, meurt à Tolède en donnant le jour à son cinquième

enfant. Drame d’une banalité absolue qui n’épargne ni grandes dames ni

bourgeoises, ni paysannes, ni pauvresses ; une femme sur deux, à l’époque et

pour longtemps encore, succombe à ses maternités. Les reines comme les autres.

Cette cruelle évidence n’empêche pas, en pareil cas, d’immenses chagrins. Très

épris de sa belle princesse portugaise, Charles Quint s’enferme dans un

monastère pour la pleurer en paix. Quant aux obsèques, qui seront célébrées,

selon l’usage des Rois catholiques, dans la chapelle funéraire de la dynastie,

à Grenade, il charge de s’en occuper l’un de ses plus fidèles serviteurs, le

marquis de Lombay, et l’épouse de celui-ci, Éléonore de Castro, dame d’atours

de la disparue, venue avec elle du Portugal.

Une ascendance bizarre

Qui est le marquis de

Lombay ? Premier-né du duc de Gandie et de Jeanne d’Aragon, fille bâtarde

de l’archevêque de Saragosse, lui-même fils bâtard du roi Ferdinand d’Aragon,

le marquis est le petit-fils de Juan de Gandie, un bâtard, lui aussi, né d’une

des maîtresses du cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, futur pape Alexandre VI, et neveu du

défunt pape Calixte III… Si la situation nous semble passablement choquante,

elle l’est, en fait, beaucoup moins aux yeux des contemporains qui jugent le

gouvernement de l’Église affaire aussi politique que celui de n’importe quel

État laïque ; cardinaux et souverains pontifes sont des administrateurs et des

guerriers, non des saints et rares sont ceux qui ont embrassé la vie religieuse

par vocation. L’on ferme les yeux sur leurs mœurs et leur vie privée, quand

même elle serait peu édifiante, voire choquante. Cela dit, Alexandre VI, malgré

ses liaisons et ses enfants adultérins, qu’il exhibe sans vergogne et marie

princièrement, est un homme de foi, qui craint Dieu, de temps en temps, et ne

plaisante pas avec les enseignements catholiques.

Cette ascendance bizarre

ne nuit donc en rien au marquis de Lombay, lequel, d’ailleurs, n’y peut rien.

Et puis, cela n’empêche pas d’être, de ce côté-là de la famille, chrétiens

exemplaires. La preuve en est que la grand-mère de M. de Lombay, après la mort

tragique de son époux, le premier duc de Gandie, Juan, fils aîné du Pape,

vraisemblablement occis sur ordre de son jeune frère, le cardinal César

Borgia…, a pris le voile chez les clarisses.

Une mission qui va

bouleverser sa vie

Cet exemple, comme celui

de ses parents, a fait de Francisco Borgia de Gandie, marquis de Lombay, un

garçon remarquablement pieux. S’il n’était l’aîné, il serait entré dans les

ordres, choix auquel son père s’est véhémentement opposé. Le mariage d’amour de

son fils et sa brillante réussite à la Cour semblent avoir écarté cette lubie.

Francisco ne le sait pas encore, mais la funèbre mission dont son roi l’a

chargé va bouleverser sa vie du tout au tout. De Tolède à Grenade, il y a 500

kilomètres, ce qui demande plus d’un mois de voyage, au rythme du char funèbre,

et, en mai, en Espagne, il fait chaud. En dépit du cercueil de plomb dans

lequel il a été placé, le cadavre de la reine se décompose. Or, l’étiquette

prévoit qu’à l’arrivée à la nécropole royale la bière soit ouverte afin de

s’assurer que la dépouille est bien celle confiée à la garde de l’escorte.

Lorsque le couvercle est enlevé, et les Grands invités à attester de l’identité

de la défunte, Isabelle est dans un tel état de pourriture que nul n’ose ni

s’approcher pour la reconnaître ni attester qu’il s’agit bien de la radieuse et

ravissante jeune femme qu’ils ont connue.

Nul, sauf Francisco

Borgia, esclave de son sens du devoir. Le choc est atroce. Confronté à la

réalité du trépas, il atteste que cette « chose qui n’a de nom en aucune

langue » est pourtant bien la reine d’Espagne, ce dont il peut jurer car

il n’a pas quitté le cercueil du regard un instant. Puis, blême, le marquis de

Lombay murmure :

Je ne servirai plus jamais

un seigneur qui puisse mourir.

Il respectera ce serment,

dès qu’on lui en accordera le loisir.

Une prière d’offrande et

d’abandon

Devenu duc de Gandie à la

mort de son père en 1542, Borgia perd sa femme quatre ans plus tard. Toujours

amoureux d’elle, il a supplié le Ciel de la lui laisser. À quoi le Crucifié

devant lequel il prie répond : « Si tu désires profondément que je te

laisse plus longtemps ta duchesse, je t’en fais seul juge mais je t’avertis que

ce choix ne serait pas convenable. » Brisé mais résigné, Francisco répond

par une prière d’offrande et d’abandon :

Seigneur, je ne puis rien

faire de moins pour répondre à Ton infinie et gracieuse générosité que t’offrir

ma vie, celle de mon épouse, celle de mes enfants et tout ce que je possède en ce

monde. C’est de Ta main que j’ai tout reçu, je Te rends donc le tout en Te

priant d’en disposer selon Ton bon plaisir.

Deux ans plus tard, il

entrera dans la Compagnie de Jésus, en deviendra Général et l’une des plus grandes

figures de l’Ordre.

Lire aussi :Gabriel de l’Addolorata, le patron des séminaristes, était un

noceur

Lire aussi :Saint Calixte, la miséricorde et le pécheur qui voulait servir

Dieu

Lire aussi :« Saint Pierre est un signe d’espérance pour les

pécheurs »

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/2023/10/02/francois-de-borgia-un-saint-dans-la-plus-sulfureuse-des-familles/

Francisco Goya (1746–1828). San

Francisco de Borja asiste a un moribundo impenitente,

vers

1788, 29 x 38, Colección Marquesa de Santa Cruz (Madrid, España).

SAINT FRANÇOIS DE BORGIA,

CONFESSEUR.

Né en 1510, mort le 30

septembre 1572. Canonisé en 1671, fête en 1688.

Leçons des Matines (avant

1960)

Quatrième leçon.

François, quatrième duc de Gandie, fils de Jean de Borgia et de Jeanne

d’Aragon, petite-fille de Ferdinand le Catholique, après avoir passé au sein de

sa famille une enfance admirable d’innocence et de piété, se montra plus

admirable encore par la pratique exemplaire des vertus chrétiennes et l’austérité

de sa vie, à la cour de l’empereur Charles-Quint, et ensuite dans le

gouvernement de la Catalogne. A la mort de l’impératrice Isabelle, il fut

chargé de conduire son corps à Grenade, pour y recevoir la sépulture. En voyant

le changement opéré sur le visage de l’impératrice, il réfléchit à la vanité de

tout ce qui est mortel, et s’engagea par vœu à se dépouiller de tous ses biens

dès qu’il le pourrait, pour ne plus servir que le Roi des rois. Dès lors il

avança tellement dans la vertu, qu’au milieu des affaires du siècle, il

reproduisait tous les traits de la perfection religieuse, et qu’on l’appelait

le prodige des princes.

Cinquième leçon. Éléonore

de Castro, son épouse étant morte, il entra dans la Compagnie de Jésus, afin

d’y mener plus sûrement une vie cachée, et de s’interdire l’accès aux dignités

par l’engagement sacré d’un vœu. Il mérita que son exemple portât plusieurs

princes à embrasser un genre de vie plus austère, et que Charles-Quint

lui-même, en abdiquant l’empire, déclarât que François avait été son

inspirateur et son guide. Dans cette profession de vie rigoureuse, François

réduisit son corps à une maigreur extrême par le jeûne, les chaînes de fer, le

cilice, des flagellations longues et sanglantes et la privation de sommeil.

D’ailleurs, il ne s’épargnait aucune fatigue pour se vaincre et pour sauver les

âmes. Orné de tant de vertus, il fut nommé, par saint Ignace, commissaire

général de la Compagnie en Espagne, et quelques années après, on l’élut, malgré

lui, troisième général de la Compagnie. Dans cette charge, il se rendit

extrêmement cher aux princes temporels et aux souverains Pontifes, par sa

prudence et sa sainteté. Il fonda ou développa en divers lieux nombre

d’établissements, envoya des membres de sa Compagnie en Pologne, dans les îles

de l’Océan, au Mexique et au Pérou, dirigea vers d’autres contrées des

missionnaires qui, par leurs prédications, leurs sueurs et leur sang, propagèrent

la foi catholique et romaine

Sixième leçon. Il avait de lui-même une si basse opinion qu’il s’appropriait le nom de pécheur, comme étant le sien. Il refusa avec une humilité qui ne se démentit jamais, la pourpre romaine que les souverains Pontifes lui offrirent à différentes reprises. Balayer la maison, mendier son pain aux portes, servir les malades dans les hôpitaux, par mépris de soi-même et du monde, il en faisait ses délices. Tous les jours il consacrait de longues heures, ordinairement huit et quelquefois dix, à la méditation des choses du ciel. Cent fois par jour, il faisait la génuflexion pour adorer Dieu. Jamais il n’omit de célébrer la sainte Messe. L’ardeur divine qui le consumait, se manifestait par l’éclat de son visage lorsqu’il offrait le saint Sacrifice, et quelquefois même pendant qu’il prêchait. Un instinct céleste lui marquait les lieux où le très saint corps de Jésus Christ, caché dans l’Eucharistie, se trouvait en réserve. Sur l’ordre de saint Pie V, il accompagna le Cardinal Alexandrin, légat du Siège apostolique, que le Pape envoyait auprès des princes chrétiens, pour former une ligue contre les Turcs. Ce fut donc par obéissance qu’il entreprit ce long voyage, malgré l’affaiblissement de ses forces. Il mourut à son retour à Rome, où il avait désiré achever sa vie, à l’âge de soixante-deux ans, en l’année mil cinq cent soixante-douze. Sainte Thérèse, qui recourait à ses conseils, l’appelait un saint, et Grégoire XIII, un fidèle administrateur. Enfin, de nombreux et grands miracles l’ayant glorifié, Clément X l’inscrivit au nombre des Saints.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/10-10-St-Francois-de-Borgia

SAINT FRANÇOIS DE BORGIA,

CONFESSEUR.

Vanité des vanités, tout

n'est que vanité (Ecclc. I, 1) ! Il n'eut besoin d'aucun discours pour s'en

convaincre, le descendant des rois célébré en ce jour, lorsqu'à l'ouverture du

cercueil où l'on disait qu'était endormi ce que l'Espagne renfermait de

jeunesse et de grâces, la mort lui révéla soudain ses réalités. Beautés de tous

les temps, la mort seule ne meurt pas ; sinistre importune qui s'invite de vos

danses et de vos plaisirs, elle assiste à tous les triomphes, elle entend les

serments qui se disent éternels. Combien vite elle saura disperser vos

adorateurs ! Quelques années, sinon quelques jours, peut-être moins, séparent

vos parfums d'emprunt de la pourriture de la tombe.

« Assez des vains

fantômes ; assez servi les rois mortels ; éveille-toi, mon âme. » C'est la

réponse de François de Borgia aux enseignements du trépas. L'ami de

Charles-Quint, le grand seigneur dont la noblesse, la fortune, les brillantes

qualités ne sont dépassées par aucun, abandonne dès qu'il peut la cour. Ignace,

l'ancien soldat du siège de Pampelune, voit le vice-roi de Catalogne se jeter à

ses pieds, lui demandant de le protéger contre les honneurs qui le poursuivent

jusque sous le pauvre habit de jésuite où il a mis sa gloire.

L'Église emploie les

lignes suivantes à raconter sa vie.

François, quatrième duc

de Gandie, naquit de Jean de Borgia et de Jeanne d'Aragon, petite-fille de

Ferdinand le Catholique. Admirable avait été parmi les siens l'innocence et la

piété de son enfance ; plus admirable fut-il encore dans les exemples de vertu

chrétienne et d'austérité qu'il donna par la suite, à la cour d'abord de

l'empereur Charles-Quint, plus tard comme vice-roi de Catalogne. Ayant dû

conduire le corps de l'impératrice Isabelle à Grenade pour l'y remettre aux

sépultures royales, l'affreux changement des traits de la défunte le pénétra

tellement de la fragilité de ce qui doit mourir, qu'il s'engagea par vœu à

laisser tout dès qu'il le pourrait pour servir uniquement le Roi des rois. Si

grands furent dès lors ses progrès, qu'il retraçait au milieu du tourbillon des

affaires une très fidèle image de la perfection religieuse, et qu'on l'appelait

la merveille des princes.

A la mort d'Eléonore de

Castro son épouse, il entra dans la Compagnie de Jésus. Son but était de s'y

cacher plus sûrement, et de se fermer la route aux dignités par le voeu qu'on y

fait à l’encontre. Nombre de personnages princiers s'honorèrent de marcher

après lui sur le chemin du renoncement, et Charles-Quint lui-même ne fit pas

difficulté de reconnaître que c'étaient son exemple et ses conseils qui

l'avaient porté à abdiquer l'empire. Tel était le zèle de François dans la voie

étroite, que ses jeûnes, l'usage qu'il s'imposait des chaînes de fer et du plus

rude cilice, ses sanglantes et longues flagellations, ses privations de sommeil

réduisirent à la dernière maigreur son corps; ce pendant qu'il n'épargnait

aucun labeur pour se vaincre lui-même et sauver les âmes. Tant de vertu porta

saint Ignace à le nommer son vicaire général pour l'Espagne, et peu après la

Compagnie entière l'élisait pour troisième Général malgré ses résistances. Sa

prudence, sa sainteté le rendirent particulièrement cher en cette charge aux

Souverains Pontifes et aux princes. Beaucoup de maisons furent augmentées ou

fondées par lui en tous lieux ; il introduisit la Compagnie en Pologne, dans

les îles de l'Océan, au Mexique, au Pérou ; il envoya en d'autres contrées des

missionnaires dont la prédication, les sueurs, le sang propagèrent la foi

catholique romaine.

Si humbles étaient ses

sentiments de lui-même, qu'il se nommait le pécheur. Souvent la pourpre romaine

lui fut offerte par les Souverains Pontifes ; son invincible humilité la refusa

toujours. Balayer les ordures, mendier de porte en porte, servir les malades

dans les hôpitaux, étaient les délices de ce contempteur du monde et de

lui-même. Chaque jour, il donnait de nombreuses heures ininterrompues, souvent

huit, quelquefois dix, à la contemplation des choses célestes. Cent fois le

jour, il fléchissait le genou, adorant Dieu. Jamais il n'omit de célébrer le

saint Sacrifice, et l'ardeur divine qui l'embrasait se trahissait alors sur son

visage ; parfois, quand il offrait la divine Hostie ou quand il prêchait, on le

voyait entouré de rayons. Un instinct du ciel lui révélait les lieux où l'on

gardait le très saint corps du Christ caché dans l'Eucharistie. Saint Pie V

l'ayant donné comme compagnon au cardinal Alexandrini dans la légation qui

avait pour but d'unir les princes chrétiens contre les Turcs, il entreprit par

obéissance ce pénible voyage, les forces déjà presque épuisées ; ce fut ainsi

que, dans l'obéissance, et pourtant selon son désir à Rome où il était de

retour, il acheva heureusement la course de la vie, dans la soixante-deuxième

année de son âge, l'an du salut mil cinq cent soixante-douze. Sainte Thérèse

qui recourait à ses conseils l'appelait un saint, Grégoire XIII un serviteur

fidèle. Clément X, à la suite de ses grands et nombreux miracles, l'inscrivit

parmi les Saints.

« Seigneur Jésus-Christ,

modèle de l'humilité véritable et sa récompense ; en la manière que vous avez

fait du bienheureux François votre imitateur glorieux dans le mépris des

honneurs de la terre, nous vous en supplions, faites que vous imitant

nous-mêmes, nous partagions sa gloire (Collecte du jour). » C'est la prière que

l'Église présente sous vos auspices à l'Époux. Elle sait que, toujours grand

près de Dieu, le crédit des Saints l'est surtout pour obtenir à leurs dévots

clients la grâce des vertus qu'ils ont plus spécialement pratiquées.

Combien précieuse

apparaît en vous cette prérogative, ô François, puisqu'elle s'exerce dans le

domaine de la vertu qui attire toute grâce ici-bas, comme elle assure toute

grandeur au ciel ! Depuis que l'orgueil précipita Lucifer aux abîmes et que les

abaissements du Fils de l'homme ont amené son exaltation par delà les deux

(Philipp. II, 6, 11), l'humilité, quoi qu'on ait dit dans nos temps, n'a rien

perdu de sa valeur inestimable ; elle reste l'indispensable fondement de tout

édifice spirituel ou social aspirant à la durée, la base sans laquelle nulles

autres vertus, fût-ce leur reine à toutes, la divine charité, ne sauraient

subsister un jour. Donc, ô François, obtenez-nous d'être humbles ;

pénétrez-nous de la vanité des honneurs du monde et de ses faux plaisirs.

Puisse la sainte Compagnie dont vous sûtes, après Ignace même, augmenter encore

le prix pour l'Eglise, garder chèrement cet esprit qui fut vôtre, afin de

grandir toujours dans l'estime du ciel et la reconnaissance de la terre.

Dom Guéranger. L'Année liturgique

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/gueranger/anneliturgique/pentecote/pentecote05/046.htm

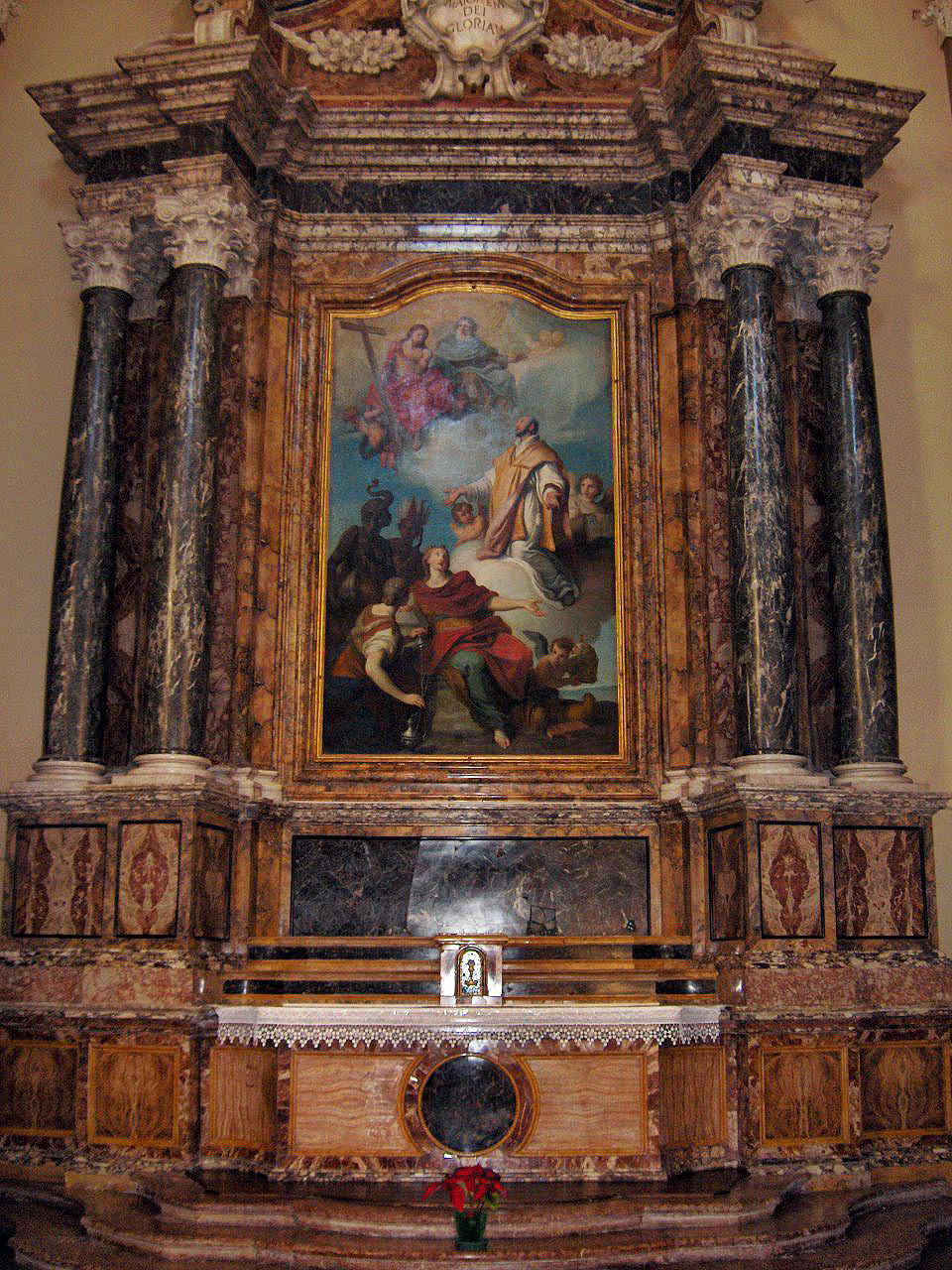

Church

of São Jerónimo de Real, Braga, Portugal.

La liturgie se souvient

de saint François Borgia. C'était un "grand d'Espagne" au XVIe

siècle. Il était même vice-roi de Catalogne et un excellent administrateur.

Après la mort de son épouse vers 1548, ayant pourvu à l'établissement de ses

huit enfants, le duc François renonce au pouvoir et aux richesses. Préoccupé de

réparer les fautes de ses ancêtres et de sa famille (les Borgia !), il entre

dans la Compagnie de Jésus fondée par saint Ignace de Loyola. Il en deviendra

le 3e supérieur général.

Le Jésuite François de

Borgia va se "distinguer" par sa ferveur et son humilité : il porte

l'Évangile à travers l'Espagne et le Portugal. Il aura la tâche délicate d'être

l'exécuteur testamentaire de l'empereur Charles Quint dont il prononcera

l'oraison funèbre. Sous sa direction, mettant en oeuvre de rares qualités

administratives et humaines, la Compagnie de Jésus va se développer

considérablement par les missions en Pologne, au Pérou et au Mexique. Saint

François de Borgia (à ne pas confondre avec l'autre grand saint jésuite : saint

François Xavier) termine sa vie à Rome, au terme d'une mission épuisante, en

1572. Son corps, transporté à Madrid, a disparu dans l'émeute de 1931. Avec

saint Antoine de Padoue, saint François Borgia est le patron de l'Espagne et du

Portugal. François vient du nom latin du peuple des "Francs".

Rédacteur : Frère Bernard Pineau, OP

SOURCE : http://www.lejourduseigneur.com/Web-TV/Saints/Francois-Borgia

Chapel

with St Francis Borgia. Cathedral (Sé) of Santarém. Portugal

Saint François Borgia

Fils aîné du troisième

duc de Gandie, Francisco de Borja naquit à Gandie (sud de Valence) le 28

octobre 1510. Il était par son père, Jean de Borja, l'arrière-petit-fils du

pape Alexandre VI et, par sa mère, Jeanne d'Aragon, l'arrière-petit-fils du roi

Ferdinand le Catholique. Orphelin de mère en, 1520, il fut élevé par son oncle

maternel, Jean d'Aragon, archevêque de Saragosse, jusqu'à ce qu'on l'appelât à

la cour de la reine Jeanne la Folle, à Tordesillas, comme page de la princesse

Catherine, soeur de Charles-Quint. Quand l'infante Catherine épousa le roi Jean

III de Portugal, François retourna à Saragosse pour étudier la philosophie

(1525).

En 1528, il entra au

service de Charles-Quint qui, en 1529, lui fit épouser une dame d'honneur de

l'impératrice Isabelle, Eléonore de Castro, dont il aura huit enfants ; marquis

de Llombai en 1530, grand veneur de l'Empereur et grand écuyer de

l'Impératrice, Charles-Quint, lui confia la surveillance de la cour pendant la

victorieuse campagne contre Tunis (1536), lui demanda de l'instruire en

cosmographie, puis se l'adjoignit pendant l'expédition de Provence, et mit sous

son influence l'infant Philippe.

De nature pieuse, fidèle

à ses devoirs, le marquis de Llombai, pendant une convalescence, lut les

homélies de S. Jean Chrysostome ; lors de la campagne de Provence il assista le

poète Garcilaso de la Vega dans son agonie et, au retour, après une maladie

dont il crut mourir, il prit la résolution de la confession et de la communion

mensuelles. Quand l'Impératrice Isabelle mourut (1° mai 1539) il fut chargé de

reconnaître et de conduire à Grenade son cadavre décomposé ce qui

l'impressionna si profondément qu'il s'écria : Ah ! Je n'aurai jamais

d'attachement pour aucun maître que la mort me puisse ravir et Dieu seul sera

l'objet de mes pensées, de mes désirs et de mon amour !

Nommé par Charles-Quint

vice-roi de Catalogne (26 juin 1539) François Borgia exerça sa charge avec

prudence et énergie pendant quatre ans au bout desquels il devint grand

majordome de la princesse Marie de Portugal, femme de l'infant Philippe, mais

il ne remplit jamais les fonctions car la reine du Portugal ne voulait pas

qu'Eléonore de Castro approchât sa fille qui mourut en donnant naissance à

l'infant Don Carlos (12 juillet 1545). Quatrième duc de Gandie la mort de son

père (17 décembre 1542), il présidait à plus de trois mille familles vassales,

au marquisat de Llombai et à quatorze baronnies.

Eléonore de Castro mourut

le 27 mars 1546. Le duc de Gandie, fort lié avec les premiers Jésuites qu'il

protégeait de toute son influence, suivit les exercices de saint Ignace et

résolut de faire vœu de chasteté et d'obéissance, puis d'entrer dans la

Compagnie de Jésus (2 juin 1546) ; il fit secrètement sa profession solennelle

(1° février 1548) et s’en vint étudier la théologie à l'université de Gandie

qu'il avait fondée.

Le 31 août 1550, sous

prétexte de gagner l'indulgence jubilaire de l'Année Sainte, François Borgia se

rendit à Rome où il fut ordonné prêtre (23 mai 1551) et célébra sa première

messe (1° août). Il fut envoyé prêcher au Pays Basque, puis au Portugal. En

avril 1555, il était commissaire général de la Compagnie de Jésus en Espagne et

au Portugal. Charles-Quint le choisit, conjointement avec l'infant Philippe,

comme son exécuteur testamentaire. Appelé à Rome, il y arriva le 7 décembre

1561 et fut élu général de la Compagnie de Jésus le 2 juillet 1565.

Il mourut à Rome, le 30 septembre 1572, à minuit. Béatifié par Urbain VIII le 21 novembre 1624, il fut canonisé par Clément X le 12 avril 1671.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/10/10.php

Saint François de Borgia

François, fils aîné du

duc Jean de Borgia, naquit en 1510 à Gandie, dans le royaume de Valence. Après

une éducation raffinée à la cour de l’empereur Charles-Quint, il épousa en 1529

Éléonore de Castro, dont il eut huit fils. En 1542, il succéda à son père comme

duc de Gandie ; mais après la mort de sa femme il renonça à son duché et, ses

études de théologie achevées, fut ordonné prêtre en 1551.

Entré dans la Compagnie,

il fut élu troisième Général en 1565. Il fit beaucoup pour la formation et la

vie spirituelle de ses religieux, pour les collèges qu’il fit fonder en divers

lieux et pour les missions. Il mourut à Rome le 30 septembre 1572 et fut

canonisé par Clément X en 1671. Il est fêté le 3 octobre dans la Compagnie de

Jésus.

Biographie détaillée

François de Borgia (en

espagnol : Francisco de Borja y Trastámara), duc de Gandie, grand d’Espagne,

naît à Gandie, dans le royaume de Valence (Espagne), le 28 Octobre 1510. Il

était le fils de Juan Borgia, le 3e duc de Gandie, et de Jeanne d’Aragon, fille

d’Alphonse d’Aragon (1470-1520) ; François était aussi arrière-petit-fils

du Pape Alexandre VI.

À peine put-il articuler

quelques mots, que sa pieuse mère lui apprit à prononcer les noms sacrés de

Jésus et de Marie. Âgé de cinq ans, il retenait avec une merveilleuse

mémoire les sermons, le ton, les gestes des prédicateurs, et les répétait dans

sa famille avec une onction touchante. Bien que sa jeunesse se passât dans

le monde, à la cour de Charles-Quint, et dans le métier des armes, sa vie fut

très pure et toute chrétienne ; il tenait même peu aux honneurs auxquels

l’avaient appelé son grand nom et ses mérites.

À vingt-huit ans, la vue

du cadavre défiguré de l’impératrice Isabelle le frappa tellement, qu’il se dit

à lui-même : « François, voilà ce que tu seras bientôt… À quoi te

serviront les grandeurs de la terre ?… »

Toutefois, cédant aux

instances de l’empereur, qui le fit son premier conseiller, il ne quitta le

monde qu’à la mort de son épouse, Éléonore de Castro. Il avait trente-six

ans ; encore dut-il passer quatre ans dans le siècle, afin de pourvoir aux

besoins de ses huit enfants.

François de Borgia fut

digne de son maître saint Ignace ; tout son éloge est dans ce mot.

L’humilité fut la vertu dominante de ce prince revêtu de la livrée des pauvres

du Christ. À plusieurs reprises, le Pape voulut le nommer Cardinal ; une

première fois il se déroba par la fuite ; une autre fois, saint Ignace

conjura le danger.

Plus l’humble religieux

s’abaissait, plus les honneurs le cherchaient. Celui qui signait toutes ses

lettres de ces mots : François, pécheur ; celui qui ne lisait qu’à

genoux les lettres de ses supérieurs, devint le troisième général de la Compagnie

de Jésus. François de Borgia meurt à Rome, à l’âge de 62 ans, le 30 Septembre

1572 et sera canonisé en 1671 par le Pape Clément X (Emilio Altieri,

1670-1676).

“Quel grand remède pour

tous nos maux que de méditer la Croix du Christ”

Nous sommes tous en marche

vers le Seigneur ; en prononçant nos vœux, nous avons revêtu l’équipement

nécessaire à ce voyage ; notre profession religieuse est donc vaine si nous ne

marchons pas allégrement sur cette route et si nous ne courons pas dans la voie

de la perfection jusqu’à ce que nous arrivions à « la divine montagne de

l’Horeb ».

Le premier avis que j’ai

à vous donner, je le trouve formulé comme il suit au commencement de la dixième

partie des Constitutions, où il est question des moyens de conserver et

d’accroître la Compagnie : « Les moyens qui unissent un instrument à Dieu, qui

le disposent à être manié régulièrement par sa main divine, sont bien plus

efficaces que ceux qui le disposent à servir les hommes. Ces moyens sont la

justice et la générosité, la charité surtout, la pureté d’intention dans le

service divin, l’union familière avec Dieu dans les exercices spirituels, un

zèle très pur pour le salut des âmes, sans autre recherche que la gloire de

celui qui les a créées et rachetées ».

Paroles bien dignes

d’être l’objet de notre plus sérieuse attention, puisque notre bienheureux Père

les a écrites avec tant de soin et d’amour pour ses enfants. En effet, si nous

voulons y réfléchir sérieusement, nous reconnaîtrons que la négligence à

employer les moyens qui unissent l’instrument à Dieu suscite et aggrave les

dissensions et les misères qui déchirent les sociétés religieuses. Car comme la

sécheresse d’un terrain fait dépérir les fleurs et les fruits des arbres, ainsi

l’aridité habituelle dans les méditations et autres exercices de piété dévore

dans l’âme religieuse les fleurs et les fruits spirituels.

Donc le religieux qui ne

s’exerce pas à la méditation et à l’imitation de Jésus crucifié, celui-là

travaillera sans ardeur à la gloire de ce divin Maître ; bien plus, il n’y

apportera que lâcheté, et, cependant, il ne laissera pas d’être satisfait de

lui-même et de mépriser les autres.

Quel grand remède pour

tous nos maux que de méditer la Croix du Christ !

(Lettre 717 du mois

d’avril 1569 adressée à toute la Compagnie.

Texte espagnol dans MHSI

: S. Franciscus Borgia, t. 5, Madrid, 1911, pp. 78-79 ;

tr. fr. : Lettres

choisies des Généraux, t. I, Lyon, 1878, pp. 32-33).

SOURCE : https://www.jesuites.com/saint-francois-de-borgia-sj/

Also

known as

Francisco de Borja y

Aragon

10 October on

some calendars

Profile

Born to the nobility, the

great-grandson of Pope Alexander

VI; grandson of King Ferdinand

of Aragon;

son of Duke Juan

Borgia. Raised in the court of King Charles

V and educated at Saragossa, Spain. Married Eleanor

de Castro in 1529,

and the father of eight children.

Accompanied Charles on

his expedition to Africa, 1535,

and to Provence, 1536.

Viceroy of Catalonia, 1539–1543. Duke of

Gandia, 1543–1550. Widower in 1546.

Friend and advisor

of Saint Ignatius

of Loyola. Joined the Jesuits in 1548. Ordained in 1551.

Notable preacher.

Given charge of the Jesuit missions in

the East and West Indies.

Commissary-general of the Jesuits in Spain in 1560.

General of the Jesuits in 1565.

Under his generalship the Society established

its missions in Florida,

New Spain and Peru,

and greatly developed its internal structures. Concerned that Jesuits were

in danger of getting too involved in their work at the expense of their

spiritual growth, he introduced their daily hour-long meditation. His changes

and revitalization of the Society led

to him being sometimes called the “Second Founder of the Society of Jesus”. He

worked with Pope Saint Pius

V and Saint Charles

Borromeo in the Counter-Reformation.

Born

28 October 1510 at

Gandia, Valencia, Spain

30

September 1572 at Ferrara, Italy

relics translated

to the Jesuit church

in Madrid, Spain in 1901

23 November 1624 by Pope Urban

VIII in Madrid, Spain

12 April 1671 by Pope Clement

X at Saint

Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City, Rome, Italy

Rota,

Marianas

skull crowned with

an emporer’s diadem

Gallery of

images of Saint Francis

Additional

Information

An

Example of Humility and Self-Contempt, by Father Francis

Xavier Lasance

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Catholic

Encyclopedia, by Pierre Suau

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Francis

Xavier Weninger

Meditations

on the Gospels for Every Day in the Year, by Father Pierre

Médaille

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

Saints

of the Society of Jesus

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

Little

Pictorial Lives of the Saints

Order of Ignatian Spirituality

images

video

sites

en français

Abbé

Christian-Philippe Chanut

fonti

in italiano

Dicastero delle Cause dei Santi

MLA

Citation

“Saint Francis

Borgia“. CatholicSaints.Info. 11 October 2023. Web. 18 October 2023.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-francis-borgia/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-francis-borgia/

St. Francis Borgia

St. Francis Borgia was born within the Duchy of Gandia, Valencia on October 28,

1510. He was the son of Juan de Borgia, the 3rd Duke of Gandia and Joana of

Aragon, daughter of Afonso de Aragon, Archbishop of Zaragoza, who, in turn, was

the illegitimate son of Ferdinand the Catholic (King Ferdinand II of Aragon)

and his mistress Aldonza Ruiz de Iborra y Alemany. Francis was also the

paternal great-grandson of Pope Alexander VI.

The future saint was unhappy in his ancestry. His grandfather, Juan Borgia, the

second son of Pope Alexander VI, was assassinated in Rome on 14 June, 1497, by

an unknown hand, which his family always believed to be that of Cæsar Borgia.

Rodrigo Borgia, elected pope in 1402 under the name of Alexander VI, had eight children.

The eldest, Pedro Luis, had acquired in 1485 the hereditary Duchy of Gandia in

the Kingdom of Valencia, which, at his death, passed to his brother Juan, who

had married Maria Enriquez de Luna. Having been left a widow by the murder of

her husband, Maria Enriquez withdrew to her duchy and devoted herself piously

to the education of her two children, Juan and Isabel. After the marriage of

her son in 1509, she followed the example of her daughter, who had entered the

convent of Poor Clares in Gandia, and it was through these two women that

sanctity entered the Borgia family, and in the House of Gandia was begun the

work of reparation to the Borgia family name which Francis Borgia was to crown.

Although as a child he was very pious and wished to become a monk, his family

sent him instead to the court of the Emperor Charles V. He distinguished

himself there, accompanying the Emperor on several campaigns and marrying, in

Madrid in September 1526, a Portuguese noblewoman, Eleanor de Castro Melo e

Menezes, by whom he had eight children: Carlos in 1530, Isabel in 1532, Juan in

1533, Álvaro circa 1535, Juana also circa 1535, Fernando in 1537, Dorotea in

1538, and Alfonso in 1539. In 1539, he convoyed the corpse of Empress Isabella

of Portugal to her burial-place in Granada.

It is said that, when he saw the effect of death on the beautiful empress, he

decided to “never again serve a mortal master.” However, while still a young

man, he was made viceroy of Catalonia, and administered the province with great

efficiency. His true interests, however, lay elsewhere. When his father died,

the new Duke of Gandia retired to his native place and led, with his wife and

family, a life devoted entirely to Jesus Christ and The Holy Catholic Church.

In

1546 his wife Eleanor died and Francis was determined to enter the newly formed

Society of Jesus. He put his affairs in order, renounced his titles in favor of

his eldest son, Carlos, and became a Jesuit priest. Because of his high birth,

great abilities and Europe-wide fame, he was immediately offered a cardinal’s

hat. This, however, he refused, preferring the life of an itinerant preacher.

In time, however, his friends persuaded him to accept the leadership role that

nature and circumstances had destined him for: in 1554, he became the Jesuits’

commissary-general in Spain; and, in 1565, the third Father General or Superior

General of the Society of Jesus.

His successes have caused historians to describe Francis as the greatest

General after Saint Ignatius. He founded the Collegium Romanum, which was to

become the Gregorian University, dispatched missionaries to distant corners of

the globe, advised kings and popes, and closely supervised all the affairs of

the rapidly expanding order. Yet, despite the great power of his office,

Francis led a humble life, and was widely regarded in his own lifetime as a

saint.ˇ

Francis Borgia died on September 30, 1572 in Rome. He was beatified in Madrid

on November 23, 1624 by Pope Gregory XV. He was canonized nearly thirty five

years later on June 20, 1670 by Pope Clement X.

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/saint-francis-borgia/

Pietro

Antonio Rotari, St. Francis Borgia in adoration, XVIIe siècle

St. Francis Borgia

(Spanish FRANCISCO DE BORJA Y ARAGON )

Francis Borgia, born 28 October, 1510, was the son of Juan Borgia, third Duke

of Gandia, and of Juana of Aragon;

died 30 September, 1572. The future saint was unhappy in his

ancestry. His grandfather, Juan Borgia, the second son of Alexander

VI, was assassinated in Rome on

14 June, 1497, by an unknown hand, which his family always believed to

be that of Cæsar Borgia. Rodrigo Borgia, elected pope in

1492 under the name of Alexander

VI, had eight children. The eldest, Pedro Luis, had acquired in 1485

the hereditary Duchy of Gandia in the Kingdom of Valencia,

which, at his death, passed to his brother Juan, who

had married Maria Enriquez de Luna. Having been left

a widow by

the murder of

her husband, Maria Enriquez withdrew to her duchy and devoted

herself piously to the education of

her two children, Juan and Isabel. After the marriage of her son

in 1509, she followed the example of her daughter, who had entered the convent of Poor

Clares in Gandia, and it was through these two women that sanctity entered

the Borgia family,

and in the House of Gandia was begun the work

of reparation which Francis Borgia was to crown.

Great-grandson of Alexander

VI, on the paternal side, he was, on his mother's side, the great-grandson

of the Catholic King Ferdinand of Aragon.

This monarch had procured the appointment of

his natural son, Alfonso, to

the Archbishopric of Saragossa at the age of nine years.

By Anna de Gurrea, Alfonso had two sons, who succeeded him

in his archiepiscopal

see, and two daughters, one of whom,

Juana, married Duke Juan of Gandia and became the mother of

our saint. By this marriage Juan had three sons and four

daughters. By a second, contracted in 1523, he had five sons and five

daughters. The eldest of all and heir to the dukedom

was Francis. Piously reared in a court which felt the influence

of the two Poor

Clares, the mother and sister of the reigning duke, Francis lost

his own mother when he was but ten. In 1521, a sedition amongst the populace

imperilled the child's life, and the position of the nobility. When the

disturbance was suppressed, Francis was sent

to Saragossa to continue his education at

the court of his uncle, the archbishop,

an ostentatious prelate who

had never been consecrated nor

even ordained priest.

Although in this court the Spanish faith retained

its fervour, it lapsed nevertheless into the inconsistencies permitted by the

times, and Francis could not disguise from himself the relation in

which his grandmother stood to the dead archbishop,

although he was much indebted to her for his

early religious training. While

at Saragossa Francis cultivated his mind and attracted

the attention of his relatives by his fervour. They being desirous of assuring

the fortune of the heir of Gandia, sent him at the age of twelve

to Tordesillas as page to the Infanta Catarina, the youngest

child and companion in solitude of the unfortunate queen, Juana the Mad.

In 1525 the Infanta married King Juan III of Portugal,

and Francis returned to Saragossa to complete his education.

At last, in 1528, the court of Charles

V was opened to him, and the most brilliant future awaited him. On the

way to Valladolid,

while passing, brilliantly escorted, through Alcalá de

Henares, Francis encountered a poor man whom the

servants of the Inquisition were

leading to prison.

It was Ignatius

of Loyola. The young nobleman exchanged a glance of emotion with the prisoner,

little dreaming that one day they should be united by the closest

ties. The emperor and empress welcomed Borgia less as a subject than as

a kinsman. He was seventeen, endowed with every charm,

accompanied by a magnificent train of followers, and, after the emperor, his

presence was the most gallant and knightly at court. In

1529, at the desire of the empress, Charles

V gave him in marriage the hand of Eleanor de Castro, at the

same time making him Marquess of Lombay, master of the hounds, and equerry

to the empress, and appointing Eleanor Camarera Mayor. The newly-created

Marquess of Lombay enjoyed a privileged station. Whenever

the emperor was travelling or conducting a campaign, he confided to the young

equerry the care of the empress, and on his return to Spain treated

him as a confidant and friend. In 1535, Charles

V led the expedition against Tunis unaccompanied

by Borgia, but in the following year the favourite followed his sovereign on

the unfortunate campaign in Provence. Besides the virtues which made

him the model of the court and the personal attractions which made him its

ornament, the Marquess of Lombay possessed a cultivated musical

taste. He delighted above all in ecclesiastical compositions,

and these display a remarkable contrapuntal style

and bear witness to the skill of the

composer, justifying indeed the assertion that, in the sixteenth

century and prior to Palestrina,

Borgia was one of the chief restorers of sacred

music.

In 1538, at Toledo, an eighth child was born to the Marquess

of Lombay, and on 1 May of the next year the

Empress Isabella died. The equerry was commissioned to convey her

remains to Granada,

where they were interred on

17 May. The death of the empress caused the first break in the

brilliant career of the Marquess and Marchioness of Lombay. It detached

them from the court and taught the nobleman the vanity of life and of

its grandeurs. Blessed

John of Avila preached the funeral sermon, and Francis,

having made known to him his desire of reforming his life, returned

to Toledo resolved to become a perfect Christian.

On 26 June, 1539, Charles

V named Borgia Viceroy of Catalonia, and the importance of the

charge tested the sterling qualities of the

courtier. Precise instructions determined his course of action.

He was to reform the administration of justice,

put the finances in order, fortify the city of Barcelona, and repress

outlawry. On his arrival at the viceregal city, on 23 August, he at once

proceeded, with an energy which no opposition could daunt, to build the

ramparts, rid the country of the brigands who terrorized it, reform

the monasteries,

and develop learning. During his vice-regency he showed himself an inflexible

justiciary, and above all an exemplary Christian.

But a series of grievous trials were destined to develop in him the

work of sanctification begun at Granada.

In 1543 he became, by the death of his father,

Duke of Gandia, and was named by the emperor master of the household

of Prince Philip of Spain,

who was betrothed to

the Princess of Portugal.

This appointment seemed to indicate Francis as the

chief minister of the future reign, but by God's permission

the sovereigns of Portugal opposed

the appointment. Francis then retired to his Duchy of Gandia, and for

three years awaited the termination of the displeasure which barred him from

court. He profited by this leisure to reorganize his duchy, to found a university in

which he himself took the degree of Doctor of Theology, and to

attain to a still higher degree of virtue.

In 1546 his wife died. The duke had invited the Jesuits to

Gandia and become their protector and disciple, and even at that time

their model. But he desired still more, and on 1 February, 1548, became one of

them by the pronunciation of the solemn vows of religion,

although authorized by the pope to

remain in the world, until he should have fulfilled his obligations towards

his children and his estates—his obligations as

father and as ruler.

On 31 August, 1550, the Duke of Gandia left his estates to see them no more. On

23 October he arrived at Rome,

threw himself at the feet of St. Ignatius, and edified by his rare humility those

especially who recalled the ancient power of the Borgias. Quick to conceive

great projects, he even then urged St. Ignatius to found

the Roman College. On 4 February, 1551, he left Rome,

without making known his intention of departure. On 4

April, he reached Azpeitia in Guipuzcoa, and chose as his abode the hermitage

of Santa Magdalena near Oñate. Charles

V having permitted him to relinquish his possessions,

he abdicated in favour of his eldest son, was ordained priest 25

May, and at once began to deliver a series of sermons in Guipuzcoa

which revived the faith of

the country. Nothing was talked of throughout Spain but

this change of life, and Oñate became the object of incessant pilgrimage.

The neophyte was obliged to

tear himself from prayer in

order to preach in the cities which called him, and which his burning words,

his example, and even his mere appearance, stirred profoundly. In 1553 he was

invited to visit Portugal.

The court received him as a messenger from God and vowed to

him, thenceforth, a veneration which it has always preserved. On his

return from this journey, Francis learned that, at the request of the

emperor, Pope

Julius III was willing to bestow on him the cardinalate. St.

Ignatius prevailed upon the pope to

reconsider this decision, but two years later the project was renewed and

Borgia anxiously inquired whether he might in conscience oppose

the desire of the pope. St.

Ignatius again relieved his embarrassment by requesting him to pronounce

the solemn vows of

profession, by which he engaged not to accept any dignities save at

the formal command of the pope.

Thenceforth the saint was

reassured. Pius

IV and Pius

V loved him

too well to impose upon him a dignity which would have caused him

distress. Gregory

XIII, it is true,

appeared resolved, in 1572, to overcome his reluctance, but on this occasion

death saved him from the elevation he had so long feared.

On 10 June, 1554, St.

Ignatius named Francis Borgia commissary-general of

the Society in Spain.

Two years later he confided to him the care of the missions of

the East and West Indies, that is to say of all the missions of

the Society.

To do this was to entrust to a recruit the future of his order in the

peninsula, but in this choice the founder displayed his rare knowledge of men,

for within seven years Francis was to transform the provinces

confided to him. He found them poor in subjects, containing but few

houses, and those scarcely known. He left them strengthened by his

influence and rich in disciples drawn from the highest

grades of society.

These latter, whom his example had done so much to attract, were assembled

chiefly in his novitiate at

Simancas, and were sufficient for numerous foundations. Everything aided Borgia

— his name, his sanctity,

his eager power of initiative, and his influence with the Princess Juana, who

governed Castile in the absence of her brother Philip. On 22

April, 1555, Queen Juana the Mad died at Tordesillas, attended

by Borgia. To the saint's presence

has been ascribed the serenity enjoyed by the queen in her last moments.

The veneration which he inspired was thereby increased, and

furthermore his extreme austerity, the care which he lavished on

the poor in the hospitals,

the marvellous graces with

which God surrounded

his apostolate contributed to augment a renown by which he profited to

further God's work.

In 1565 and 1566 he founded the missions of Florida, New

Spain, and Peru,

thus extending even to the New

World the effects of his insatiable zeal.

In December, 1556, and three other times, Charles

V shut himself up at Yuste. He at once summoned thither his old

favourite, whose example had done so much to inspire him with the

desire to abdicate. In the following month of August, he sent him to Lisbon to

deal with various questions concerning the succession of Juan III.

When the emperor died, 21 September, 1558, Borgia was unable to be present at

his bedside, but he was one of the testamentary executors appointed

by the monarch, and it was he who, at the solemn services at Valladolid,

pronounced the eulogy of the deceased sovereign. A trial was to close this

period of success. In 1559 Philip II returned to reign in Spain.

Prejudiced for various reasons (and his prejudice was fomented by many who

were envious of

Borgia, some of whose interpolated works had been recently condemned by

the Inquisition), Philip seemed

to have forgotten his old friendship for the Marquess of Lombay, and he

manifested towards him a displeasure which increased when he learned that

the saint had

gone to Lisbon. Indifferent to

this storm, Francis continued for two years in Portugal his

preaching and his foundations, and then, at the request of Pope

Pius IV, went to Rome in

1561. But storms have their providential mission. It may be

questioned whether but for the disgrace of 1543 the Duke of Gandia would have

become a religious, and whether, but for the trial which took him away

from Spain,

he would have accomplished the work which awaited him in Italy.

At Rome it

was not long before he won the veneration of the

public. Cardinals Otho Truchsess, Archbishop of Augsburg, Stanislaus

Hosius, and Alexander

Farnese evinced towards him a sincere friendship.

Two men above all rejoiced at his coming. They were Michael Chisleri,

the future Pope

Pius V, and Charles

Borromeo, whom Borgia's example aided to become a saint.

On 16 February, 1564, Francis Borgia was named assistant general

in Spain and Portugal,

and on 20 January, 1565, was elected vicar-general of

the Society

of Jesus. He was elected general 2 July, 1565, by thirty-one

votes out of thirty-nine, to succeed Father James Laynez. Although

much weakened by his austerities, worn by attacks of gout and an affection

of the stomach, the new general still possessed much strength, which, added to

his abundant store of initiative, his daring in the conception

and execution of vast designs, and the influence which he exercised

over the Christian princes

and at Rome,

made him for the Society at

once the exemplary model and the providential head. In Spain he

had had other cares in addition to those of government. Henceforth he was to be

only the general. The preacher was silent. The director of souls ceased

to exercise his activity, except through his correspondence, which, it is true,

was immense and which carried throughout the entire world light and strength to

kings, bishops and apostles,

to nearly all who in his day served the Catholic cause.

His chief anxiety being to strengthen and develop his order, he sent visitors

to all the provinces of Europe,

to Brazil, India,

and Japan.

The instructions, with which he furnished them were models of prudence,

kindness, and breadth of mind. For the missionaries as well as

for the fathers delegated by the pope to

the Diet of Augsburg, for the confessors of princes and the

professors of colleges he mapped out wide and secure paths. While too

much a man of duty to

permit relaxation or abuse, he attracted chiefly by his kindness, and won souls to good by

his example. The edition of the rules, at which he laboured incessantly, was

completed in 1567. He published them at Rome,

dispatched them (throughout the Society),

and strongly urged their observance. The text of those now in force was edited

after his death, in 1580, but it differs little from that issued by Borgia, to

whom the Society owes

the chief edition of its rules as well as that of the Spiritual, of which

he had borne the expense in 1548. In order to ensure

the spiritual and intellectual formation

of the young religious and the apostolic character of

the whole order, it became necessary to

take other measures. The task of Borgia was to establish, first at Rome,

then in all the provinces, wisely regulated novitiates and

flourishing houses of study, and to develop the cultivation of the

interior life by establishing in all of these the custom of

a daily hour of prayer.

He completed at Rome the

house and church of S. Andrea in Quirinale, in 1567. Illustrious novices flocked

thither, among them Stanislaus Kostka (d. 1568), and the

future martyr Rudolph Acquaviva.

Since his first journey to Rome,

Borgia had been preoccupied with the idea of

founding a Roman college, and while in Spain had

generously supported the project. In 1567, he built the church of

the college, assured it even then an income of six thousand ducats, and at

the same time drew up the rule of studies, which, in

1583, inspired the compilers of the Ratio

Studiorum of the Society.

Being a man of prayer as

well as of action, the saintly general, despite overwhelming

occupations, did not permit his soul to

be distracted from continual contemplation. Strengthened by so

vigilant and holy an administration the Society could

not but develop. Spain and Portugal numbered

many foundations; in Italy Borgia created the Roman province,

and founded several colleges in Piedmont. France and

the Northern province, however, were the chief field of his triumphs.

His relations with the Cardinal

de Lorraine and his influence with the French Court made

it possible for him to put an end to numerous misunderstandings, to secure

the revocation of several hostile edicts, and to found

eight colleges in France.

In Flanders and Bohemia,

in the Tyrol and in Germany,

he maintained and multiplied important foundations.

The province of Poland was

entirely his work. At Rome everything

was transformed under his hands. He had built S. Andrea and

the church of the Roman college. He assisted generously in the

building of the Gesù, and although the official founder of

that church was Cardinal

Farnese, and the Roman College has taken the name of one of its

greatest benefactors, Gregory

XIII, Borgia contributed more than anyone towards these foundations. During

the seven years of his government, Borgia had introduced so

many reforms into his order as to deserve to be called its second

founder. Three saints of

this epoch laboured incessantly to further the renaissance of Catholicism.

They were St. Francis Borgia, St.

Pius V, and St.

Charles Borromeo.

The pontificate of Pius

V and the generalship of Borgia began within an interval of a few

months and ended at almost the same time. The saintly pope had

entire confidence in the saintly general, who conformed with intelligent devotion to

every desire of the pontiff. It was he who inspired the pope with

the idea of

demanding from the Universities of Perugia and Bologna,

and eventually from all the Catholic universities,

a profession of the Catholic faith.

It was also he who, in 1568, desired the pope to

appoint a commission of cardinals charged

with promoting the conversion of infidels and heretics,

which was the germ of the Congregation for

the Propogation of the Faith, established later by Gregory

XV in 1622. A pestilential fever invaded Rome in

1566, and Borgia organized methods of relief, established ambulances, and

distributed forty of his religious to such purpose that the same

fever having broken out two years later it was to Borgia that the pope at

once confided the task of safeguarding the city.

Francis Borgia had always greatly loved the

foreign missions. He reformed those of India and

the Far East and created those of America. Within a few years,

he had the glory of numbering among his sons sixty-six martyrs,

the most illustrious of whom were the

fifty-three missionaries of Brazil who

with their superior, Ignacio

Azevedo, were massacred by Huguenot corsairs.

It remained for Francis to terminate his

beautiful life with a splendid act of obedience to

the pope and devotion to

the Church.

On 7 June, 1571, Pius

V requested him to accompany his nephew, Cardinal Bonelli,

on an embassy to Spain and Portugal. Francis was

then recovering from a severe illness; it was feared that he had not

the strength to bear fatigue, and he himself felt that such a journey would

cost him his life, but he gave it generously. Spain welcomed

him with transports. The old distrust of Philip II was

forgotten. Barcelona and Valencia hastened to meet their

former viceroy and saintly duke. The crowds in the streets cried:

"Where is the saint?"

They found him emaciated by penance. Wherever he went, he reconciled

differences and soothed discord. At Madrid, Philip

II received him with open arms, the Inquisition approved

and recommended his genuine works. The reparation was complete, and

it seemed as though God wished

by this journey to give Spain to

understand for the last time this living sermon, the sight of

a saint. Gandia ardently desired to behold its holy duke, but he

would never consent to return thither. The embassy to Lisbon was

no less consoling to Borgia. Among other happy results

he prevailed upon the king, Don Sebastian, to ask

in marriage the hand of Marguerite of Valois, the sister of Charles

IX. This was the desire of St.

Pius V, but this project, being formulated too late, was frustrated by the

Queen of Navarre, who had meanwhile secured the hand of Marguerite for her

son. An order from the pope expressed

his wish that the embassy should also reach the French court. The

winter promised to be severe and

was destined to prove fatal to Borgia. Still more grievous

to him was to be the spectacle of the devastation which heresy had caused in

that country, and which struck sorrow to the heart of the saint.

At Blois, Charles IX and Catherine

de' Medici accorded Borgia the reception due to

a Spanish grandee, but to the cardinal legate as

well as to him they gave only fair words in which there was little sincerity.

On 25 February they left Blois. By the time they

reached Lyons, Borgia's lungs were already affected. Under

these conditions the passage of Mt. Cenis

over snow-covered roads was extremely painful. By exerting all his

strength the invalid reached Turin.

On the way the people came out of the villages crying: "We wish to see

the saint". Advised

of his cousin's condition, Alfonso of Este, Duke of Ferrara,

sent to Alexandria and had him brought to his ducal city, where he

remained from 19 April until 3 September. His recovery was despaired of and it

was said that he would not survive the autumn. Wishing to die either

at Loretto or at Rome,

he departed in a litter on 3 September, spent eight days at Loretto, and

then, despite the sufferings caused by the slightest jolt, ordered

the bearers to push forward with the utmost speed for Rome.

It was expected that any instant might see the end of his agony. They

reached the "Porta del Popolo" on 28 September. The dying man halted

his litter and thanked God that

he had been able to accomplish this act of obedience. He was

borne to his cell which was soon invaded by cardinals and prelates.

For two days Francis Borgia, fully conscious, awaited death,

receiving those who visited him and blessing through his younger

brother, Thomas Borgia, all his children and grandchildren. Shortly

after midnight on 30 September, his beautiful life came to a peaceful

and painless close. In the Catholic Church he

had been one of the most striking examples of the conversion of souls after

the Renaissance,

and for the Society

of Jesus he had been the protector chosen by Providence to

whom, after St. Ignatius, it owes most.

In 1607

the Duke of Lerma, minister of Philip III

and grandson of the holy religious,

having seen his granddaughter miraculously cured

through the intercession of Francis, caused the

process for his canonization to

be begun. The ordinary process, begun at once in several cities, was followed,

in 1637, by the Apostolic process. In 1617 Madrid received

the remains of the saint.

In 1624 the Congregation of Rites announced that his beatification

and canonization might be proceeded with. The beatification was

celebrated at Madrid with

incomparable splendour. Urban

VIII having decreed, in 1631, that a Blessed might not

be canonized without

a new procedure, a new process was begun. It was reserved for Clement

X to sign the Bull of canonization of St.

Francis Borgia, on 20 June, 1670. Spared from the decree of Joseph Bonaparte

who, in 1809, ordered the confiscation of all shrines and precious

objects, the silver shrine containing the remains of the saint,

after various vicissitudes, was removed, in 1901, to the church of

the Society at Madrid,

where it is honoured at

the present time.

It is with good reason that Spain and

the Church venerate in St.

Francis Borgia a great man and a great saint. The highest nobles of Spain are proud of

their descent from, or their connexion with him. By his penitent

and apostolic life he repaired the sins of

his family and

rendered glorious a name, which but for him, would have remained a

source of humiliation for the Church. His feast is

celebrated 10 October.

Sources

Sources: Archives of

Osuna (Madrid), of Simancas; National Archives of Paris; Archives of the

Society of Jesus; Regeste du généralat de Laynez et de Borgia, etc.

Literature: Monumenta historica S. J. (Madrid); Mon. Borgiana; Chronicon

Polanci; Epistolæ Mixtæ; Quadrimetres; Epistolæ Patris Nadal, etc.; Epistolæ

et instructiones S. Ignatii; ORLANDINI AND SACCHINI, Historia Societatis

Jesu; ALCÁZAR, Chrono-historia de la provincia de Toledo; Lives of

the saint by VASQUEZ (1586; manuscript, still unedited), RIBADENEYRA, (1592),

NIEREMBERG (1643), BARTOLI (1681), CIENFUEGOS (1701); Acta SS., Oct.,

V; ASTRAIN, Historia de la Compañía de Jesús en la Asistencia de España, I

and II (1902, 1905); BÉTHENCOURT, Historia genealógica y heráldica de la

monarchía española (Madrid, 1902), IV, Gandia, Casa de Borja; Boletín

de la Academia de la Historia (Madrid), passim; SUAU, S. François de

Borgia in Les Saints (Paris, 1905); IDEM, Histoire de S.

François de Borgia (Paris, 1909).

Suau, Pierre. "St. Francis Borgia." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton

Company, 1909. 10 Oct.

2015 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06213a.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by WGKofron. In honor of David J.

Collins, S.J.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. September 1, 1909. Remy Lafort,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John M. Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2020 by Kevin Knight. Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06213a.htm

Weninger’s

Lives of the Saints – Saint Francis Borgia, Confessor

Article

Saint Francis Borgia, a

bright example of virtue, both for ecclesiastics and laymen, was born in 1510,

at Gandia, in Spain. His father was John Borgia, the third Duke of Gandia; and

his mother, Joanna of Aragon, grand-daughter to Ferdinand the Catholic.

Francis, when only a child, was already remarkable for his virtue and piety.

When scarcely seventeen years, old he came to the Court of the Emperor Charles

V, where, notwithstanding the many and great dangers to which he was exposed,

he preserved his innocence by frequently partaking of the Blessed Sacrament, by

great devotion to the Blessed Virgin, and the practice of mortification. His

talents and his edifying life gained him the esteem of the Emperor; hence the

Empress gave him in marriage a very virtuous lady, who was a great favorite of

hers. Francis was then made chief equerry to the Emperor, and created Marquis

of Lombay. The court which Francis kept after he was married might have served

as a model to all Christian princes. He distributed the hours of the day, so

that certain times were devoted to prayer, to business, and to recreation. He,

at the same time, began the praiseworthy practice of selecting every month a

Saint for especial veneration. He was much opposed to gaming, and did not allow

his servants to indulge in it. He used to say: “Gaming is accompanied by great

losses; loss of money, loss of time, loss of devotion, and loss of conscience.”

The same aversion he had for the reading of frivolous books, even if they were

not immoral. He found his greatest delight in reading devout books, and said:

“The reading of devout books is the first step towards a better life.” At the

period in which he lived the principal enjoyments of the higher classes were

music and hawking; and, as he could not abstain from them entirely, he took

care, at such times, to raise his thoughts to the Almighty, and to mortify

himself. Thus, when he went hawking, he closed his eyes at the very moment when

the hawk swooped; the sight of which, they say, was the chief pleasure of this

kind of hunting.

The Almighty, to draw His

servant entirely away from the world, sent him several severe maladies, which

made him recognize the instability of all that is earthly. He became more fully

aware of this after the death of the Empress, whose wondrous beauty was

everywhere extolled. By the order of the Emperor, it becarhe the duty of

Francis to escort the remains to the royal vault at Granada. There the coffin

was opened before the burial took place, and the sight that greeted the

beholders was most awful. Nothing was left of the beautiful Empress but a

corpse, so disfigured, that all averted their eyes, whilst the odor it exhaled

was so offensive that most of the spectators were driven away.

Saint Francis was most

deeply touched, and when, after the burial, he went into his room, prostrated

himself before the crucifix, and having given vent to his feelings, he

exclaimed: “No, no, my God! in future 1 will have no master whom death can take

from me.” He then made a vow that he would enter a religious order, should he

survive his consort. He often used to say afterwards: “The death of the Empress

awakened me to life.” When Francis returned from Granada the Emperor created

him Viceroy of Catalonia, and in this new dignity the holy Duke continued to

lead rather a religious than a worldly life. He had a fatherly care for his

subjects, and every one had at all hours admittance to him. Towards the poor he

manifested great kindness. He daily gave four or five hours to prayer. He

fasted almost daily, and scourged himself to blood. He assisted at Mass, and

received Holy Communion every day. When he heard that disputes had arisen among

the theologians at the universities, in regard to the frequent use of Holy

Communion, he wrote to Saint Ignatius, at Rome, and asked his opinion on the

subject. Saint Ignatius wrote back to him, approving of the frequent use of

Holy Communion, and strengthening him in his thoughts about it Meanwhile, the

death of his father brought upon him the administration of his vast estates,

without, however, in the least changing his pious manner of living. Scon after

his pious consort, who was his equal in virtue, became sick. Francis prayed

most fervently to God for her recovery. One da y, while he was thus praying, he

heard an interior voice, which said these words: “If you desires that thy

consort should recover, thy wish shall be fulfilled, but it will not benefit

thee.” Frightened at these words, he immediately conformed his own will in all

things to the Divine will. From that moment the condition of the Duchess grew

worse, and she died, as she had lived, piously and peacefully. Saint Francis,

remembering his vow, determined to execute it without delay. Taking counsel of

God and of his confessor, he chose the Society of Jesus, which had recently

been instituted. Writing to Saint Ignatius, he asked for admittance, which was

cheerfully granted. But, to settle his affairs satisfactorily, he was obliged

to remain four years longer in his offices. Having at length, by the permission

of the Emperor, resigned his possessions to his eldest son, he took the

religious habit, and proceeded to Rome. Scarcely four months had elapsed since

his arrival, when he was informed that the Pope wished to make him a cardinal;

and, to avoid this dignity, he returned to Spain- Being ordained priest, he

said his first Mass in the chapel of the Castle of Loyola, where Saint Ignatius

had been born; and then spent a few years in preaching and instructing the

people. It would take more space than is allowed to us to relate how many

sinners he converted, and how much he labored for the honor of God and the

salvation of souls. During this time he visited Charles V., in the solitude

which this great Emperor had chosen to pass his last days, after he had

abdicated his throne. At length, Saint Francis was recalled to Rome, where he

was, much against his will, elected General of the Society of Jesus. He

fulfilled the many and arduous duties of this office with the utmost diligence;

his greatest care being to further the honor of God and the salvation of souls.

To effect this he founded colleges in many cities, and sent apostolic men into

all parts of the world to convert the heathen. In all the persecutions of the

Society he placed his trust in God. He used to say that the Society was hated

and persecuted, first by the heretics and infidels; secondly, by those who led

a godless life; and thirdly, by those who were not well informed as to the end

and aim which its members had in view. When he had for seven years most wisely

governed the Society, the Pope sent him, on most important business of the

Church, to Spain, Portugal, and France. This long and painful journey, with the

labors of his mission, exhausted his strength so that he fell ill before he had

reached Rome on his return. Perceiving the danger in which he was, he made all

possible haste, but visited on his way the holy house of Loretto, to commend

himself to the protection of the Blessed Virgin. When at last he arrived at

Rome, more dead than alive, he prepared himself without delay to receive the

last Sacraments. The time still left him on earth he passed in devout

exercises; and therefore declined to receive the visits even of bishops and

cardinals, saying that he had now to do only with God, the Lord of life and