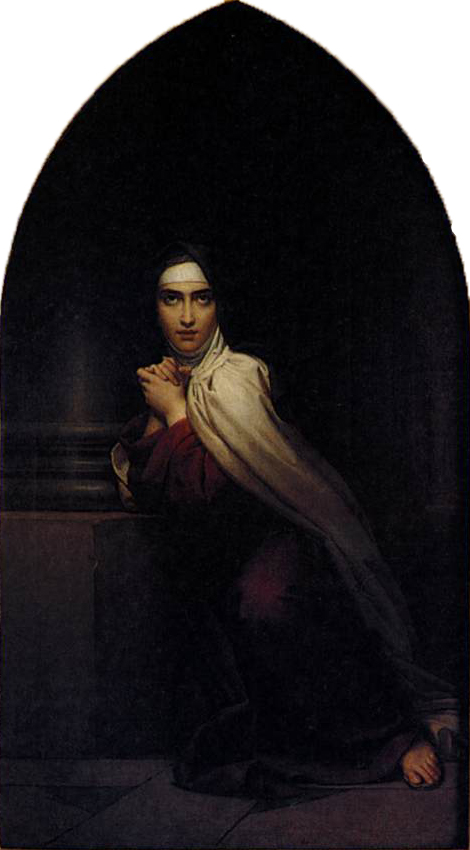

François Gérard (1770–1837), Sainte

Thérèse, 1827, Infirmerie

Marie-Thérèse, Paris

François Gérard (1770–1837), Sainte

Thérèse, 1827, 172 x 93, Infirmerie

Marie-Thérèse, Paris

Réformatrice du Carmel et docteur de l'Église (+ 1582)

Qu'il est admirable de songer que Celui dont la

grandeur emplirait mille mondes et beaucoup plus, s'enferme ainsi en nous qui

sommes une si petite chose !

Sainte Thérèse - Chemins de la Perfection

Juan Martín Cabezalero (1633–1673), La comunión de Santa Teresa, circa 1670, 248 x

222, Museo Lázaro Galdiano

Sainte Thérèse d'Avila

Vierge, Réformatrice des

Carmélites

(1515-1582)

Sainte Thérèse naquit en

Espagne, de parents nobles et chrétiens. Dès l'âge le plus tendre, un fait

révéla ce qu'elle devait être un jour. Parmi ses frères, il y en avait un

qu'elle aimait plus que les autres; ils se réunissaient pour lire ensemble la

Vie des Saints: "Quoi! lui dit-elle, les martyrs verront Dieu toujours,

toujours! Allons, mon frère, chez les cruels Maures, et soyons martyrs aussi,

nous pour aller au Ciel." Et, joignant les actes aux paroles, elle

emmenait son petit frère Rodrigue; ils avaient fait une demi-lieue, quand on

les ramena au foyer paternel.

Elle avait dès lors une

grande dévotion à la Sainte Vierge. Chaque jour elle récitait le Rosaire. Ayant

perdu sa mère, à l'âge de douze ans, elle alla se jeter en pleurant aux pieds

d'une statue de Marie et La supplia de l'accepter pour Sa fille, promettant de

La regarder toujours comme sa Mère.

Cependant sa ferveur eut

un moment d'arrêt. De vaines lectures, la société d'une jeune parente mondaine,

refroidirent son âme sans toutefois que le péché mortel la ternît jamais. Mais

ce relâchement fut court, et, une vive lumière divine inondant son âme, elle

résolut de quitter le monde. Elle en éprouva un grand déchirement de coeur;

mais Dieu, pour l'encourager, lui montra un jour la place qu'elle eût occupée

en enfer, si elle s'était attachée au monde.

Dieu, voulant faire de

Thérèse le type le plus accompli peut-être de l'union d'une âme avec l'Époux

céleste, employa vingt ans à la purifier par toutes sortes d'épreuves

terribles: maladies, sécheresses spirituelles, incapacité dans l'oraison.

Jésus-Christ, qui ne voulait pas la moindre tache en elle, ne lui laissait

aucun repos, et exigeait d'elle le sacrifice même de certaines amitiés très

innocentes. "Désormais, lui dit-Il à la fin de cette période d'expiation,

Je ne veux plus que tu converses avec les hommes!" A ces mots, elle se

sentit tout à coup établie en Dieu de manière à ne plus avoir d'autre volonté,

d'autre goût, d'autre amour que ceux de Dieu même et à ne plus aimer aucune

créature que pour Dieu, comme Dieu et selon Dieu.

Elle devint la

réformatrice de l'Ordre du Carmel, et travailla tant au salut des âmes, que,

d'après une révélation, elle convertit plus d'âmes dans la retraite de son

couvent, que saint François Xavier dans ses missions.

Un séraphin vint un jour

la percer du dard enflammé de l'amour divin: Jésus la prit pour épouse. Ses

révélations, ses écrits, ses miracles, ses oeuvres, ses vertus, tout est à la

même hauteur sublime.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/sainte_therese_d_avila.html

Guercino (1591–1666), Apparition du Christ

à sainte Thérèse, 1634, 298 x 202, Musée Granet

La lumière qui nous surprend

Durant plusieurs années, je lus beaucoup de livres

spirituels sans en avoir l’intelligence ; je passai aussi fort longtemps

sans trouver une seule parole pour faire connaître aux autres les lumières et

les grâces dont Dieu me favorisait, ce qui ne m’a pas coûté peu de peine. Mais

quand il plaît à sa divine Majesté, elle donne en un instant l’intelligence de

tout, d’une manière qui m’épouvante.

La lumière m’est venue quand je ne la cherchais pas,

quand je ne la demandais pas. Curieuse pour ce qui était vain, je ne l’étais

point pour des choses où il y aurait eu un vrai mérite à l’être. Ce Dieu de

bonté m’a donné en un instant une pleine intelligence de ces faveurs, et la grâce

de les savoir exprimer. Mes confesseurs en étaient dans l’étonnement, et moi

plus qu’eux, parce que mon incapacité m’était plus connue. Cette grâce, qui est

toute récente, fait que je ne me mets point en peine d’apprendre ce que notre

Seigneur ne m’enseigne pas. Je reviens de nouveau à cet avis si

important : on ne doit pas élever son esprit, mais attendre que le

Seigneur l’élève lui-même ; et quand c’est lui qui l’élève, on le

reconnaît à l’instant.

Ste Thérèse d’Avila

Thérèse d’Avila († 1582) travailla à la réforme de

l’ordre du Carmel et à la fondation de dix-sept monastères de carmélites.

Canonisée en 1622, elle a été proclamée docteur de l’Église par Paul VI en

1970. / Vie écrite par elle-même, Paris, Julien-Lanier-Cosnard, 1857, p.

136-137.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/jeudi-11-novembre/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

L’Esprit Saint vous

enseignera

En cette mémoire de

sainte Thérèse, les mots du pape Paul VI soulignent combien sa vie

illustre l’Évangile de ce jour.

La doctrine de sainte

Thérèse d’Avila resplendit des charismes de la vérité, de la conformité à la

foi catholique, de l’utilité pour l’érudition des âmes ; et nous pouvons

en noter particulièrement un autre : le charisme de la sagesse, qui nous

fait penser à l’aspect le plus attirant et ensemble le plus mystérieux du

doctorat de sainte Thérèse, l’influx de l’inspiration divine en ce prodigieux

écrivain mystique. D’où venait à Thérèse le trésor de sa doctrine ? Sans

nul doute, de son intelligence, de sa formation culturelle et spirituelle, de

ses lectures, de ses conversations avec de grands maîtres de la théologie et de

la spiritualité ; elle lui venait de sa sensibilité profonde, de son

habituelle et intense discipline ascétique, de sa méditation contemplative, en

un mot, de la correspondance à la grâce accueillie dans une âme

extraordinairement riche et préparée à la pratique et à l’expérience de

l’oraison. Mais était-ce là l’unique source de sa « doctrine

éminente » ? Ou ne doit-on pas chercher en sainte Thérèse des actes,

des faits, des états qui ne proviennent pas d’elle, mais qui par elles sont

subis, c’est-à-dire soufferts, passifs, mystiques au sens strict du mot, et

qu’il faut donc attribuer à une action extraordinaire de l’Esprit Saint ?

Indubitablement, nous sommes devant une âme dans laquelle se manifeste

l’initiative divine extraordinaire.

St Paul VI

Le cardinal Montini fut

élu pape en juin 1963 et occupa la chaire de saint Pierre jusqu’à son décès en

1978. Il a été canonisé en 2018. / 27 septembre 1970, Homélie prononcée le jour

de la proclamation du doctorat de sainte Thérèse d’Avila, Librairie éditrice

vaticane.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/samedi-15-octobre/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

SAINTE THÉRÈSE.

Voici la plus célèbre des contemplatives. Pourquoi la

plus célèbre ? Je n’en sais absolument rien. La plus célèbre et la plus

pardonnée. Le caractère général des contemplatifs, c’est d’arrêter la colère et

l’ironie des hommes. Le lieu où ils vivent est déjà par lui-même irritant pour

les aveugles, à cause de la lumière dont il est rempli. La nature de leurs

actes prête admirablement à l’ironie toutes les occasions d’éclater. Le principe

et la fin de leurs actions échappent tous deux aux regards des hommes. L’action

elle-même tombe seule sous ce regard, isolée, destituée de son principe, destituée

de son but, dépouillée de l’atmosphère où vit l’esprit qui l’anime. Ainsi

lancée sur le terrain du monde, sans explication, la vie du contemplatif est

une étrangère et on la prend pour une ennemie. Les hommes ne savent que penser

de ces étrangers qu’on appelle des saints, non pas étrangers par leur indifférence,

mais étrangers par leur supériorité, et, ne sachant que penser, les hommes se

mettent à rire. Ils rient parce que le rire éclate quand une chose apparaît

sans rapport avec les autres choses, de même que les larmes coulent quand le

rapport apparaît profond.

Pour faire pleurer, que faut-il? Il faut faire sentir

profondément les rapports des personnes, leurs affections, leurs amitiés, leurs

ressemblances, leurs parentés intérieures, toutes leurs intimités, toutes leurs

joies, toutes leurs douleurs ; car la joie et la douleur sont des relations

senties.

Pour faire rire, que faut-il ? Il faut isoler une

personne ou une chose, la présenter toute seule, en supprimant tout ce qui l’avoisine,

en détruisant toutes les relations d’esprit, de lumière et d’amour par lesquelles

elle tient au monde visible ou au monde invisible. Le spectacle d’un individu

qui ne ressemble pas à ceux au milieu desquels il vit, plus isolé que dans un

désert, est l’occasion et l’élément du rire.

Voilà pourquoi le monde rit des saints, surtout des

saints contemplatifs, parce que la contemplation est, de toutes les choses

saintes, celle qu’il comprend le moins. Eh bien ! par une exception bizarre, il

rit peu, ou ne rit pas de sainte Thérèse. M. Renan la déclare admirable. Toutes

les femmes à imagination ont un certain penchant pour elle. Tous les artistes

la respectent; toutes les fois que son nom paraît, une louange assez vive est

dans le voisinage.

Saint Augustin et sainte Thérèse partagent ce privilège

: ils sont estimés. Saint Augustin et sainte Thérèse jouissent d’une immunité.

Pourquoi cette immunité ? à quoi tient-elle ? Sainte

Thérèse est cependant, autant que qui que ce soit, dans les voies

extraordinaires. Sa vie est pleine de visions, de révélations. Elle nage dans

le surnaturel comme un poisson dans l’eau.

Pourquoi donc le monde ne s’en moque-t-il pas? Cette

question très profonde trouverait peut-être sa solution dans la nature du rire

telle que je viens de l’indiquer tout à l’heure.

Saint Augustin et sainte Thérèse ne paraissent pas

ridicules, comme les autres saints, aux yeux des hommes, parce qu’ils semblent

montrer entre les hommes et eux des relations évidentes et subsistantes, au

sommet même de leur sainteté. Les hommes les trouvent moins isolés sur la terre

que beaucoup d’autres. C’est qu’en effet ces deux saints mettent dans leurs

récits leurs faiblesses en évidence.

Saint Augustin et sainte Thérèse racontent si bien

leurs faiblesses, qu’ils établissent entre le lecteur et eux une espèce de

trait d'union. Les vanités de celle-ci, les erreurs de celui-là, permettent au lecteur de trouver en lui et en elle une certaine ressemblance de lui-même. Les

deux conversions, différentes comme leurs fautes, semblent les avoir préservés

sans les avoir séparés, et quelque chose persiste au fond de ce saint, au fond

de cette sainte, qui, sans flatter la nature déchue, l’invite cependant à

regarder. Leur éloquence est à peu près du même genre : naïve, pénétrante,

intime et véridique. Tous deux ont écrit leur vie, dans la pureté profonde de

leur esprit et de leur âme. Tous deux sont agités, inquiets, même au lieu d’où

semblent bannies l’agitation et l’inquiétude. Saint Augustin garde dans la paix

religieuse des doutes philosophiques. Cet esprit remuant cherche, cherche

toujours. Il remue, il questionne. Il ne s’endort jamais. Sainte Thérèse, poursuivie

sur les hauteurs du Carmel par des doutes d’une autre espèce, moins philosophiques

et plus déchirants, se demande si elle est dans la voie de Dieu ou si elle est

la victime des illusions de l’ennemi.

Saint Augustin représente assez bien la recherche de l’homme

: quelle est la vérité de mon esprit ? Sainte Thérèse représente assez bien la recherche

de la femme : quelle est la vérité de mon âme ? Saint Augustin cherche hors de

lui ; sainte Thérèse au fond d’elle-même : tous deux ingénieux, tous deux

profonds, tous deux habiles dans les choses divines, habiles aussi dans les choses

humaines, tous deux subtils, tous deux troublés.

La simplicité ne les caractérise ni l’un ni l’autre.

La simplicité accompagne très bien le génie, elle accompagne rarement l’esprit,

dans le sens français du mot. Or saint Augustin et sainte Thérèse étaient, au plus

haut point, des gens d’esprit. L'amabilité humaine les distingue et les suit. On

voudrait les connaître, même indépendamment de leur sainteté. C’est apparemment

ce parfum terrestre qui leur donne le privilège, étrange pour des saints, de

trouver grâce aux yeux des hommes. Leurs siècles à tous les deux étaient des

siècles subtils, chercheurs, métaphysiciens, et ils respirèrent l’air qu’il

fallait pour nourrir à la fois leurs qualités et leurs défauts.

Toute la vie de sainte Thérèse, avant sa conversion, se

résume en un mot : Vanité. Il est vrai que ce mot contient tout, puisqu’il

signifie le vide. La vanité, qui est le vide, s’oppose directement à la plénitude,

qui est Dieu, et ceux qui comprennent ces mystères intérieurs ne s’étonneront pas

des repentirs longs et profonds, qui, portant sur les fautes que le monde croit

légères, pourront paraître exagérés aux esprits superficiels. Le monde ! tel

était en effet l’ennemi personnel et le tentateur intime de sainte Thérèse.

J’ai expliqué quelque part quelle différence il y a entre le péché et l’esprit

du monde (Voyez l’Homme, par Ernest

Hello) : l’esprit du monde est essentiellement le péché, mais le péché n’est

pas toujours l’esprit du monde. Eh bien ! saint Augustin luttait directement

contre le péché, sainte Thérèse contre l’esprit du monde, et ces tentations si

subtiles que lui donnaient, même au comble de sa hauteur, les conversations du

parloir, conversations mondaines, mais non pas scandaleuses, montrent bien de

quelle nature était 1’ennemi, petit, mais robuste, qui la poursuivait sur la

montagne sans être complétement tué par l’atmosphère dévorante et brûlante du

Carmel.

Je ne raconterai pas ici la vie de sainte Thérèse ;

elle est beaucoup trop connue., grâce au privilège dont je parlais tout à l’heure,

pour avoir besoin de narration. Mais j’indiquerai volontiers la nature de son

combat. C’’est le combat de l’âme et de l’esprit. L’âme chez elle veut être

toute à Dieu. L’esprit est retenu, poursuivi et tenté par le souvenir humain et

même mondain des choses humaines et même mondaines. Jamais rien de grossier dans

ces tentations : ce sont des nuances, des finesses, des délicatesses spirituelles

et intellectuelles ! L'âme veut être toute à Dieu. L’esprit semble par

moments accepter l’ombre d'un partage. L’âme croit, sent, voit qu’elle est

toute á Dieu. L’esprit, plein de réflexions et de troubles, admet l’illusion comme

possible et probable. Tout favorise en elle et autour d’elle le doute. La

longue illusion de ses directeurs semble le reflet de ses propres tentations

qui s’extériorisent et lui parlent par des voix étrangères. D'un côté Dieu

l’emporte, et voilà la part de l’âme transportée, ravie, qui voit sur la montagne,

dans la liberté de l’amour qui l’appelle. D’un autre côté, elle hésite, elle

doute ; on hésite, on doute; personne ne sait plus le chemin; on regarde de

tous côtés avec une agitation stérile ; plus on regarde, moins on voit, et

voilà la part de l’esprit. L’obéissance fut la voie par où l’esprit passa pour

rejoindre l’âme sur la hauteur. Quand Jésus-Christ apparaissait á sainte

Thérèse et qu’elle refusait, par obéissance, l’apparition méconnue préparait sa

délivrance ; elle acceptait le mystère terrible qui lui était préparé ; la

vérité allait se faire jour, et saint Pierre d’Alcantara approchait, appelé par

l’obéissance.

C’est la réflexion, dépourvue de lumière et de

simplicité, qui enchaînait l’esprit, le séparait de l’âme, et ce déchirement

terrible fut le supplice de sainte Thérèse. Son confesseur ayant consulté cinq

ou six maîtres, tous furent d’avis que les phénomènes spirituels dont sainte

Thérèse était l’objet venaient du démon. L’oraison lui fut interdite, et la communion

retranchée. On lui défendit la solitude. On prit contre Dieu toutes les mesures

possibles. Il lui fallut insulter de tontes les manières celui qui

apparaissait. L’absence des grâces sensibles devint aussi pour elle une torture

singulière. A une certaine époque, elle désirait la fin de l’heure marquée pour la

prière. Car le don de la prière facile lui était refusé. Le temps et l’éternité

semblent représenter les deux aspects de la vie de sainte Thérèse. Elle passa

des heures horribles, et elle avait le sentiment profond du jour qui ne doit

pas finir. Dans son enfance, lisant la Vie des saints, elle s’arrêtait pour

s’écrier : Éternellement ! éternellement ! - Et elle sentait une impression

spéciale et étrange quand on chantait au credo

: Cujus non erit finis. Elle avait

besoin de l’assurance que le règne n’aura pas de fin.

Enfin saint Pierre d’Alcantara apporta la lumière, et

avec elle l’activité, et avec elle le repos. Il jugea et décida que les

lumières de sainte Thérèse étaient des lumières divines. Louis Bertrand, Jean

d’Avila et Louis de Grenade partagèrent ce sentiment. La question fut décidée.

Sainte Thérèse écrivit sa vie et les Sept

châteaux de l’âme. Ceux qui croient que les saints se ressemblent devraient

dire aussi qu’il n’y a dans la création qu’une fleur. Rien de plus différent

que les types des Élus, même de ceux qui offrent entre eux au premier coup d’oeil

le plus de ressemblance. Pendant qu’Angèle de Foligno, ravie tout à coup d’une

façon imprévue et terrible, perd le sentiment des choses qu’elle ne sait pas,

étrangère à tout, à cause de sa hauteur, ne pouvant plus parler de Dieu, ne

sachant plus quel nom lui donner, ravie dans un amour qui prend la ressemblance

de l’horreur, d’une horreur défaillante et transportée où le cri se mêle au

silence; sainte Thérèse, elle, garde la vue constante et claire des états qu’elle

traverse, des étapes qu'elle parcourt, des phases par où elle passe, des

résidences où habite son âme. Peut-être les doutes, les questions, les

analyses, les lenteurs, les études qu’on faisait autour d’elle, à propos

d’elle, et qu’on lui faisait faire sur elle-même, ont-elles développé dans son

intelligence cette lucidité méthodique. Dans les Sept châteaux de l’âme elle détermine avec précision le point où cette

région finit, le point où cette région commence. On dirait une carte de

géographie. Peut-être cette faculté d’analyse la rend-elle plus supportable aux

lecteurs ordinaires. Comme elle raconte son ascension, on lui pardonne même de

s’être laissée enlever.

Angèle de Foligno, parlant de la Passion de Jésus-Christ,

s’écrie : « Si quelqu’un me la racontait, je lui dirais : C’est toi qui l’as

soufferte ; et si un ange me prédisait la fin de mon amour, je lui dirais : C’est

toi qui es tombé du ciel. »

L’acte surnaturel d’Angèle de Foligno ressemble un peu

à l’acte naturel du génie, qui arrive sans qu’on l’ait vu marcher. L’acte

surnaturel de sainte Thérèse ressemble un peu à l’acte naturel du talent, qui raconte

son voyage et dit par où il passe.

Jamais la pratique de la contemplation ne fait oublier

longtemps de suite à sainte Thérèse la théorie. La fondation de ses couvents

marche simultanément avec ses illuminations intérieures. Elle opère extérieurement

sa réforme visible du Carmel, comme elle en opère elle-même l’invisible

ascension. Elle bâtit des couvents, comme elle construit spirituellement et

décrit minutieusement les châteaux de l’âme. Elle est analytique ; elle est

savante ; elle dessine ; l’architecture lui est familière. Enfin c’est par elle

que se propage la dévotion à saint Joseph, qui est appelé le patron des âmes

intérieures, et qui est aussi fréquemment invoqué, quand les intérêts

pécuniaires sont en jeu.

C’est à saint Joseph que sainte Thérèse attribua la

grâce d’avoir enfin obtenu saint Pierre d’Alcantara. Saint Pierre d’Alcantara

coupa en deux la vie de sainte Thérèse. Avant lui, les ténèbres; après lui, la

lumière. C’est lui qui porta le flambeau dans l’abîme.

Saint Jean de la Croix se joignit à ce groupe

illustre. Sainte Thérèse, saint Pierre d’Alcantara, saint Jean de la Croix,

inséparables dans l’histoire, brillent comme trois étoiles de première grandeur

dans le ciel invisible. Ce ciel a sans doute comme l’autre ses constellations.

Sainte Thérèse, saint Pierre d’Alcantara, saint Jean de la Croix forment une

constellation.

Ces trois étoiles sont fort différentes entre elles.

Sainte Thérèse avait une vivacité rare d’esprit et d’imagination. Saint Jean de

la Croix, homme sévère et purement intérieur, avait une défiance inouïe de

l’esprit et de l'imagination. Et cependant il lui fut favorable, parce qu’il

était éclairé. Et tous deux, un jour, parlant de la Trinité, tombèrent en

extase.

Ernest HELLO, Physionimies de saints

SOURCE : https://archive.org/stream/PhysionomiesDeSaintsParErnestHello/physionomies%20de%20saints_djvu.txt

Sorni (Lavis, Trentino) - Chiesa di Santa Maria

Assunta, interno - Statua di santa Teresa d'Ávila

Sorni (Lavis, Trentino, Italy) - Church of the

Assumption, interior - Statue of saint Teresa of Ávila

15 octobre

Personne ne s’étonnera que sainte Thérèse d’Avila

attachât une importance primordiale à la présence de Jésus dans l’Hostie

consacrée qu’elle se réjouissait d’étendre en multipliant les chapelles par ses

fondations. Ainsi, à propos de l’érection du monastère Saint-Joseph d’Avila

(1562), elle écrivait : « Ce fut pour moi comme un état de gloire

quand je vis qu’on mettait le très saint Sacrement dans le tabernacle » ;

en se rappelant la fondation du monastère Saint-Joseph de Medina del Campo (1567),

elle confiait : « Ma joie fut extrême jusqu’à la fin de la cérémonie.

C’est pour moi, d’ailleurs, une consolation très vive de voir une église de

plus où se trouve le très saint Sacrement » ; se souvenant de la fondation

du monastère Saint-Joseph de Salamanque (1570), elle notait : « A peine

mise en route, toutes les fatigues me paraissent peu de chose ; je considère

celui pour la gloire de qui je travaille ; je songe que dans la nouvelle

fondation le Seigneur sera fidèlement servi, et que le très saint Sacrement y

résidera. C’est toujours une consolation spéciale pour moi, de voir s’élever

une église de plus (...). Beaucoup sans doute ne songent pas que Jésus-Christ,

vrai Dieu et vrai homme, se trouve réellement présent au très saint Sacrement

de l’autel dans une foule d’endroits ; et cependant ce devrait être là pour

nous un grand sujet de consolation. Et certes j’en éprouve souvent une très

vive, quand je suis au chœur et que je considère ces âmes si pures tout

occupées de la louange de Dieu. »

Cependant, sainte Thérèse d’Avila redoutait beaucoup

que le Saint Sacrement fût profané : « Allant un jour à la communion, je

vis des yeux de l’âme, beaucoup plus clairement que je n’aurais pu le faire des

yeux du corps, deux démons d’un aspect horrible. Ils semblaient serrer avec

leurs cornes la gorge d’un pauvre prêtre. En même temps que cet infortuné

tenait en ses mains l’hostie qu’il allait me donner, je vis mon Seigneur

m’apparaître avec cette majesté dont je viens de parler. Evidemment mon

Seigneur était entre des mains criminelles, et je compris que cet âme se

trouvait en état de péché mortel (...). Je fus si troublée que je ne sais

comment il me fut possible de communier. Une grande crainte s’empara de moi ;

si cette vision venait de Dieu, sa Majesté, me semblait-il, ne m’aurait pas

montré l’état malheureux de cette âme. Mais le Seigneur me recommanda de prier

pour elle. Il ajouta qu’il avait permis cela pour me faire comprendre quelle

est la vertu des paroles de la consécration, et comment il ne laisse pas d’être

présent sous l’hostie, quelque coupable que soit le prêtre qui prononce ces

paroles. » Lors de la fondation du monastère Saint-Joseph de Medina del

Campo (1567), la chapelle n’était pas protégée : « J’étais le jour et

la nuit dans les plus grandes anxiétés. J’avais cbargé, il est vrai, des hommes

de veiller toujours à la garde du Saint Sacrement ; mais je craignais qu’ils ne

vinssent à s’endormir. Je me levais la nuit, et par une fenêtre je pouvais me

rendre compte de tout, à la faveur d’un beau clair de lune. »

Etant en oraison, je me trouvai en un instant, sans

savoir de quelle manière, transportée dans l'Enfer. Je compris que Dieu voulait

me faire voir la place que les démons m'y avaient préparée, et que j'avais

méritée par mes péchés. Cela dura très peu, mais quand je vivrais encore de

longues années, il me serait impossible d'en perdre le souvenir.

Je demeurai épouvantée, et quoique six ans à peu près

se soient écoulés depuis cette vision, je suis en cet instant saisie d'un tel

effroi en l'écrivant, que mon sang se glace dans mes veines. Au milieu des

épreuves et des douleurs, j'évoque ce souvenir, et dès lors tout ce qu'on peut

endurer ici-bas ne me semble plus rien, je trouve même que nous nous plaignons

sans sujet.

Je le répète, cette vision est à mes yeux, une des

plus grandes grâces que Dieu m'ait faite, elle a contribué admirablement à

m'enlever la crainte des tribulations et des contradictions de cette vie, elle

m'a donné du courage pour les souffrir, enfin, elle a mis dans mon coeur la

plus vive reconnaissance envers Dieu qui m'a délivrée, comme j'ai maintenant

sujet de le croire, de maux si terribles dont la durée doit être éternelle.

Je m'arrête souvent à cette pensée ; nous sommes

naturellement touchés de compassion quand nous voyons souffrir une personne qui

nous est chère, et nous ne pouvons nous empêcher de ressentir vivement sa

douleur quand elle est grande. Qui pourrait donc soutenir la vue d'une âme en

proie pour une éternité à un tourment qui surpasse tous les tourments ? Quel

coeur n'en serait déchiré ? Emus d'une commisération si grande pour des

souffrances qui finiront avec la vie, que devons-nous sentir pour des douleurs

sans terme ? Et pouvons-nous prendre un moment de repos, en voyant la perte

éternelle de tant d'âmes que le démon entraîne chaque jour avec lui dans

l'Enfer ?

Sainte Thérèse d'Avila

Trento, santuario della Madonna delle Laste - Statua

di santa Teresa d'Avila

Trento (Italy), Madonna delle Laste sanctuary - Statue of saint Theresa of Avila

Il y a longtemps que j'ai écrit ce qui précède,

sans avoir jamais eu le loisir de le continuer. Si je voulais savoir ce que

j'ai dit, je devrais me relire ; mais pour ne pas perdre de temps, je

continuerai comme je pourrai, sans me préoccuper de mettre une liaison avec ce

qui précède.

Les deux voies

La méditation

Les personnes qui ont un jugement rassis, qui sont

déjà exercées à la méditation et peuvent se recueillir, ont à leur disposition

une foule de livres excellents, composés par des auteurs de mérite. Celles

d'entre vous qui sont dans ce cas se tromperaient donc si elles faisaient

quelque cas de ce que je vais dire sur l'oraison. Elles ont en effet sous la

main des livres qui leur retracent pour chaque jour de la semaine les mystères

de la vie et de la Passion de Notre-Seigneur, des méditations sur le jugement,

sur l'enfer, sur notre néant renferment une doctrine et une méthode excellentes

en ce qui concerne le fondement et le but de l'oraison. Je n'ai rien à dire à

celle qui suivent ce genre d'oraison, ou qui y sont déjà habituées. Par un

chemin aussi sûr, le Seigneur les conduira au port de la lumière, et des

commencements aussi bons les amèneront à une fin excellente. Quiconque suivra

cette voie trouvera repos et sécurité : quand la pensée a une assiette

stable, on connaît une paix entière.

L'eau vive

Mais il est un point dont je voudrais parler afin de

donner quelques conseils, si Dieu m'en accorde la grâce. S'il ne me l'accorde

pas, je voudrais du moins vous faire comprendre que beaucoup d'âmes souffrent

du tourment dont je vais parler, afin que vous ne vous attristiez point dans le

cas où vous seriez de ce nombre.

Il y a des âmes dont l'esprit est très instable ;

elles ressemblent à des chevaux qui ne sentent plus le frein et qu'on ne

saurait arrêter. Elles vont ici ou là, et son toujours dans l'agitation, soit

que cela provienne de leur nature, soit que Dieu le permette ainsi. J'en suis

touchée de la plus vive compassion. On dirait des personnes desséchées par une

soif brûlante qui aperçoivent au loin une source d'eau vive et qui, quand elles

veulent en approcher, trouvent des ennemis qui leur barrent l'accès au

commencement, au milieu et au bout du chemin qui y conduit. Il arrive qu'à

force de lutter, et lutter ferme, elles triomphent des premiers ennemis ;

mais elles se laissent vaincre par les seconds, et elles aiment mieux mourir de

soif que de lutter encore pour boire un eau qui doit leur coûter si cher. Elles

cessent tout effort, elles perdent courage. D'autres âmes qui ont assez de

valeur pour vaincre les seconds ennemis, n'en n'ont plus aucune devant les

troisièmes, et peut-être n'étaient-elles plus qu'à deux pas de la source d'eau

vive dont Notre-Seigneur a dit à la Samaritaine : Celui qui en boira

n'aura plus jamais soif.

Oh ! qu'elle est juste, qu'elle est vraie, cette

parole prononcée par Celui qui est la Vérité même ! L'âme qui boit de

cette eau n'a plus soif des choses de cette vie ; elle sent en elle une

autre soif qui va croissant pour les choses de l'autre vie et dont la soif

naturelle ne saurait nous donner la moindre idée. Mais qui dira combien l'âme

est altérée de cette soif ! Car elle en comprend tout le prix, et bien que

cette soif soit un supplice terrible, elle apporte avec elle une suavité qui

est son propre apaisement. Elle ne tue point ; elle éteint seulement le

désir des choses de la terre, et rassasie l'âme des eau, une des plus grandes

grâces qu'il puisse accorder à l'âme, c'est de la laisser encore tout altérée.

Chaque fois qu'elle boit de cette eau, elle désire toujours plus ardemment en

boire encore.

Les effets de l'eau vive

L'eau vive rafraîchit

Parmi les nombreuses propriétés que doit avoir l'eau,

il y en a trois qui se présentent maintenant à mon esprit et qui conviennent à

mon sujet. L'une, c'est de rafraîchir. Quelle que soit la chaleur que nous

ayons, elle disparaît dès que nous nous mettons à l'eau. Un grand feu même ne

résiste pas à son action - si ce n'est celui qui, étant produit par le goudron,

n'en devient que plus actif. O grand Dieu ! quelle merveille qu'un feu qui

s'enflamme davantage par l'eau quand il est fort, puissant et au-dessus des

éléments, car l'eau qui lui est opposée, loin de l'éteindre, l'active encore

plus ! Ce me serait un grand secours de pouvoir m'entretenir ici avec

quelqu'un qui sût la philosophie et qui me rendît compte de la propriété des choses.

Je pourrais alors m'expliquer su ce sujet qui m'émerveille. Mais je ne sais

comment l'exposer, et peut-être même que je ne l'ai pas bien compris.

Lorsque Dieu vous appelle, mes sœurs, à boire de cette

eau, en compagnie de celles d'entre vous qui jouissent déjà d'une pareille

faveur, vous goûterez ce que je dis. Vous comprendrez comment le véritable

amour de Dieu, s'il est fort, s'il est libre des choses de la terre et plane

au-dessus d'elle, est incontestablement le maître des éléments et du monde. Quant

à l'eau qui tire son origine d'ici-bas, soyez sans crainte, elle n'éteindra pas

ce feu de l'amour de Dieu. Ce n'est point là son affaire, bien qu'elle lui soit

opposée ; car ce feu est déjà maître absolu et il ne lui est soumis en

rien. Ne vous étonnez donc point, mes sœurs, si j'ai tant insisté dans ce livre

pour vous stimuler à acquérir une telle liberté.

N'est-ce pas une chose merveilleuse qu'une pauvre sœur

de Saint-Joseph puisse arriver à exercer un empire sur la terre et les

éléments ? Quoi d'étonnant que les saints en aient disposé à leur gré,

avec la grâce de Dieu ? Saint Martin voyait le feu et les eaux lui obéir.

Saint François commandait même aux oiseaux et aux poissons. Beaucoup d'autres

saint ont eu le même pouvoir. On comprenait clairement qu'ils n'avaient tant

d'empire sur toutes les choses de la terre, que parce qu'ils s'étaient

appliqués à les mépriser et s'étaient soumis eux-mêmes de tout leur cœur et de

toutes leurs forces au souverain Maître du monde. Ainsi donc, je le répète,

l'eau qui jaillit d'ici-bas n'a aucun pouvoir contre ce feu de l'amour divin.

Les flammes de ce dernier sont trop hautes ; il ne prend pas son origine

dans une chose si basse.

Il y a d'autres feux qui proviennent d'un faible amour

de Dieu. Le premier accident les éteint. Mais il n'en est pas de même de celui

dont je parle. La mer tout entière des tentations viendrait-elle à se

précipiter sur lui, qu'il continuerait du ciel, elle saurait encore moins

l'éteindre, car cette eau et de ce feu ne sont point opposés. Ils sont du même

pays. Ne craignez pas qu'ils se fassent aucun mal ; chacun de ces deux

éléments contribuera, au contraire, à l'effet de l'autre. Car les larmes qui

coulent à l'heure de la véritable oraison sont une eau qui, envoyée par le roi

du ciel, active ce feu et le fait durer. A son tour, ce feu aide l'eau à

rafraîchir. O grand Dieu, quel spectacle ! quelle merveille ! Un feu

qui rafraîchit ! Eh oui, il en est ainsi. Il glace même toutes les

affections du monde, quand il est arrosé par les eaux vives du ciel, je veux

dire, par cette source d'où découlent les larmes dont je viens de parler,

larmes qui sont un pur don, et non le fruit de notre industrie.

Il est donc bien clair que cette eau nous enlève toute

fièvre et toute affection pour les choses du monde. Elle nous empêche, en

outre, de nous y arrêter, à moins que ce ne soit pour chercher à embraser les

autres de ce feu ; car ce feu ne se contente pas de sa nature d'agir dans

une sphère étroite ; il voudrait, si c'était possible, consumer le monde

entier.

L'eau vive purifie

La seconde propriété de l'eau est de laver ce qui est

sale. Sans eau pour nettoyer, dans quel état serait le monde ! Or,

sachez-le, il y a autant de vertu dans cette eau vive, cette eau céleste, cette

eau claire, quand elle est très limpide et sans aucune fange, et qu'elle tombe

du ciel ; il suffit d'en boire une seule fois, et je regarde comme certain

qu'elle rend l'âme nette et pure de toutes ses fautes. Car, ainsi que je l'ai

dit, cette eau, je veux dire l'oraison d'union, est une faveur entièrement

surnaturelle, qui ne dépend point de notre volonté. Dieu ne la donne à l'âme

que pour la purifier, la rendre nette, et la délivrer de toute la fange ainsi

que de toutes les misères où ses fautes l'avaient plongée.

Les douceurs dont nous jouissons par l'entremise de

l'entendement dans la méditation ordinaire seront, malgré tout, comme une eau

qui coule sur la terre. On ne la boit pas à sa source même ; elle

rencontre forcément des impuretés sur sa route, auxquelles nous nous arrêtons ;

elle rencontre forcément des impuretés sur sa route, auxquelles nous nous

arrêtons ; elle n'est plus aussi pure ni aussi limpide. Le nom d'eau vive

ne convient donc pas, d'après moi, à cette oraison que l'on fait lorsque l'on

discourt à l'aide de l'entendement ; car l'âme a beau faire des efforts,

elle s'attache toujours, malgré elle, à quelque chose de terrestre, entraînée

qu'elle est par son corps et la bassesse de sa nature.

Je veux expliquer davantage ma pensée. Nous méditons

sur le monde ou la fragilité de ses biens pour les mépriser ; et, sans

nous en douter, nous nous occupons de plusieurs choses qui nous plaisent en

lui. Nous souhaitons les fuir, mais nous nous arrêtons au moins quelque peu à

la pensée de ce qui a été, ou sera, de ce que nous avons fait ou de ce que nous

ferons ; il en résulte alors qu'en songeant à nous délivrer du danger,

nous nous y exposons parfois de nouveau. Ce n'est pas à dire qu'il faille

renoncer à ces considérations ; mais il faut nous tenir dans la crainte et

ne pas cesser d'être sur nos gardes.

Ici, dans l'oraison surnaturelle, le Seigneur se

charge de ce soin, parce qu'il ne veut pas de fier à nous sur ce point. Telle

est l'estime qu'il a de notre âme que, dans le temps où il lui réserve quelque

faveur, il ne la laisse pas se mêler de choses capables de nuire à son progrès.

Dans l'espace d'un instant, il la met à ses côtés, et lui révèle plus de

vérités, lui communique sur toutes les choses du monde des connaissances plus

claires qu'elle n'aurait pu en acquérir après bien des années, parce que notre

vue n'est pas dégagée et que nous sommes aveuglés par la poussière de la

marche. Mais dans l'oraison surnaturelle, le Seigneur nous transporte au but de

notre course, sans que nous sachions comment.

L'eau vive désaltère

L'autre propriété de l'eau consiste à nous désaltérer

et à étancher notre soif. La soif, en effet, exprime, ce me semble, le désir

d'une chose dont le besoin est tellement pressant que nous mourons si nous en

sommes privés. Chose étrange, si l'eau nous manque, c'est la mort ; et

d'un autre côté, si nous en buvons avec excès, c'est encore la mort : car

c'est ainsi que meurent beaucoup de noyés.

O mon Seigneur ! Que ne m'est-il donné d'être

engloutie dans cette eau vive pour y perdre la vie ! Mais, comment ?

cela est-il possible ? Oui. Notre amour pour Dieu, notre désir de Dieu

peuvent grandir au point que notre nature y succombe ; aussi y a-t-il des

personnes qui en sont mortes. Pour moi, j'en connais une qui eût été dans ce

cas si Dieu ne s'était empressé de la secourir en lui donnant de cette eau vive

avec tant d'abondance qu'il la tira pour ainsi dire hors d'elle-même pour la

faire entrer dans le ravissement. Je dis qu'il la tira, pour ainsi dire, hors

d'elle-même, car elle trouve alors le repos qu'elle désire. Il lui semble

étouffer, tant elle éprouve d'aversion pour le monde, et elle ressuscite en

Dieu ; Sa Majesté la rend alors capable de jouir d'un bien qu'elle

n'aurait pu posséder sans mourir, si elle n'eût été n'y a rien en notre

souverain Bien qui ne soit parfait, il ne nous donne rien qui ne soit pour

notre avantage. Il peut donner l'eau en très grande abondance, car il n'y a

jamais d'excès dans ce qui vient de sa main. S'il en donne beaucoup, il rend

l'âme apte, comme je l'ai dit, à en boire beaucoup, semblable au verrier qui

donne au vase la capacité nécessaire pour contenir ce qu'il veut y mettre.

Quant au désir, comme il vient de nous, il n'est

jamais sans quelque imperfection, s'il contient quelque chose de bon il le doit

à l'assistance du Seigneur ; et comme nous manquons de discernement, la

peine où nous sommes étant suave et pleine de délices, nous croyons ne pouvoir

jamais nous rassasier de cette peine. Nous prenons cette nourriture sans

mesure ; nous excitons encore ce désir autant que nous le pouvons ;

et quelquefois on en meurt. Heureuse mort, certes ! mais si l'on avait

continué à vivre, on eût peut-être aidé d'autres personnes à mourir du désir de

cette mort. Selon moi, nous devons redouter les ruses du démon. Il voit les

dommages que cette sorte de personnes de lui occasionnent en restant sur la

terre. Il les tente, les pousse à des mortifications inopportunes pour ruiner

leur santé, c'est là un grand point pour lui.

L'âme arrivée à cette soif ardente de Dieu doit donc

se tenir avec soin sur ses gardes, parce qu'elle aura cette tentation ; si

elle ne meurt pas de cette soif, elle ruinera sa santé. Elle laissera malgré

elle transpirer au dehors les sentiments qui l'animent et qu'elle devrait à

tout prix tenir secrets. Parfois ses efforts seront inutiles, et elle ne pourra

les tenir aussi cachés qu'elle le voudrait. Néanmoins, elle doit prendre garde

à ne pas exciter ces ardents désirs pour ne pas les augmenter, et y couper

court doucement par quelque autre considération. Peut-être notre nature elle-même

se montrera-t-elle parfois aussi active que l'amour de Dieu, car il y a des

personnes qui se portent avec une extrême ardeur vers tout ce qu'elles

désirent, alors même que ce serait quelque chose de mauvais ; celles-là, à

mon avis, ne sont pas très conformes à la mortification, qui pourtant nous est

utile en tout. Mais ne semble-t-il pas déraisonnable de mettre un frein à une

chose de mauvais ; celles-là, à mon avis, ne sont pas très conformes à la

mortification, qui pourtant nous est utile en tout. Mais me semble-t-il pas

déraisonnable de mettre un frein à une chose si excellente ? Non, car je

ne dis pas qu'il faille étouffer ce désir, mais que nous devons le modérer par

une autre qui nous aidera peut-être à gagner autant de mérite.

Je veux vous donner une explication qui fera mieux

comprendre ma pensée. Il nous vient un vif désir, comme à S. Paul, d'être

délivrés de cette prison du corps et de nous voir avec Dieu. Pour modérer une

peine qui part d'un motif si élevé et bien grande mortification ; et

encore on n'y réussit pas complètement. Parfois cette angoisse sera telle

qu'elle enlèvera presque le jugement. C'est ce que j'ai constaté, il n'y a pas

si longtemps, chez une personne impétueuse par nature et cependant habituée à

briser sa volonté, et qui me semble avoir perdu tout bon sens, comme on a pu le

voir dans certaines circonstances. Je l'ai vue un instant comme hors

d'elle-même, tant sa peine était profonde et tant elle faisait d'efforts pour

la dissimuler. Quand ces souffrances étreignent l'âme, il faut, alors même

qu'elles viendraient de Dieu, pratiquer l'humilité et craindre. Nous ne devons

pas nous imaginer que notre charité est assez vive pour nous jeter dans de

telles angoisses. De plus, il ne serait pas mal, à mon avis, que l'âme, si elle

le peut, et elle ne le pourra pas toujours, change l'objet de son désir.

Qu'elle se persuade que si elle continuait à

vivre sur cette terre, elle servirait Dieu davantage et éclairerait quelque âme

qui sans cela était perdue ; si elle travaillait à servir Dieu ainsi, elle

acquerrait de nouveaux mérites et pourrait un jour posséder Dieu plus

pleinement ; enfin elle doit être remplie de crainte à la pensée qu'elle l'a

encore bien peu servi. Ce sont là de bons motifs de consolation pour l'aider à

supporter une telle épreuve et calmer son chagrin. Elle gagnera, en outre, de

nombreux mérites, puisqu'elle veut demeurer sur la terre avec sa peine afin de

glorifier Dieu davantage. Je la compare à une personne qui se trouverait sous

le coup d'une terrible épreuve ou d'un chagrin profond, et que je consolerais

par ces paroles : Prenez patience, et remettez-vous entre les mains de

Dieu ; que sa volonté s'accomplisse en vous, car le plus sûr est de nous

abandonner en tout à sa Providence.

Mais le démon ne favorise-t-il pas de quelque manière

un tel désir de voir Dieu ? C'est là une chose possible. Cassien, si je ne

me trompe, rapporte en effet qu'un ermite de vie très austère se laissa

persuader qu'il devait se jeter dans un puits afin d'aller voir Dieu au plus

tôt. A mon avis, cet ermite ne devait pas avoir servi le Seigneur avec

perfection et humilité. Le Seigneur, en effet, est fidèle, et il n'aurait pas

permis que cet homme fût assez aveuglé pour ne pas comprendre une chose aussi

évidente. Il est clair que, lorsque le désir vient de Dieu, loin de pousser au

mal il apporte avec lui la lumière, le discernement, la mesure ; cela est

évident ; mais le démon, notre mortel ennemi, ne néglige rien pour

chercher à nous nuire ; et dès lors qu'il déploie tant d'activités, ne

cessons jamais d'être en garde contre lui. C'est là un point très important

pour beaucoup de choses ; il l'est en particulier pour abréger le temps de

l'oraison, si douce qu'elle soit, lorsque les forces du corps nous trahissent

ou que la tête n'y trouve que fatigue ; la modération est très nécessaire

en tout.

Pourquoi, mes filles ai-je voulu vous montrer le but à

atteindre et vous exposer la récompense avant le combat lui-même, en vous

parlant du bonheur que goûte l'âme quand elle boit à cette fontaine céleste, et

s'abreuve à ces eaux vives ? C'est afin que vous ne vous affligiez pas des

travaux ni des obstacles de la route, que vous marchiez avec courage et que

vous ne succombiez pas à la fatigue ; car, ainsi que je l'ai dit, il peut

se faire qu'étant déjà arrivés jusqu'au bord de la fontaine, vous n'ayez plus

qu'à vous pencher pour y boire, mais que vous abandonniez tout et perdiez un

bien si précieux, en vous imaginant que vous n'avez pas la force d'y parvenir

et que vous n'y êtes point appelées.

Veuillez considérer que le Seigneur appelle tout le

monde. Or, il est la Vérité même ; on ne saurait douter de sa parole. Si

son banquet n'était pas pour tous, il ne nous appellerait pas tous, ou alors

même qu'il nous appellerait, il ne dirait pas :

Je vous donnerai à boire. Il aurait pu

dire : Venez tous, car enfin vous n'y perdrez rien, et je donnerai à

boire à ceux qu'il me plaira. Mais, je le répète, il ne met pas de

restriction ; oui, il nous appelle tous. Je regarde donc comme certain que

tous ceux qui ne resteront pas en chemin boiront de cette eau vive. Plaise au

Seigneur, qui nous le promet, de nous donner la grâce de le chercher comme il

faut ! Je le lui demande par sa bonté infinie.

Imagen de Santa Teresa de Jesús en la parroquia de los

frailes Carmelitas Descalzos en la Ciudad de Panamá

Imatge de Santa Teresa de Jesús a Ciutat de Panamà.

Ô mon Seigneur et mon Bien ! Je ne puis parler de la

sorte sans verser des larmes et sentir mon âme inondée de bonheur. Vous voulez,

Seigneur, demeurer avec nous comme vous demeurez au Sacrement de l'autel. Je

puis le croire en toute vérité, puisque c'est un point de notre foi, et c'est à

bon droit que je puis me servir de cette comparaison. Et si nous n'y mettons

obstacle par notre faute, nous pouvons mettre en vous notre bonheur. Vous-même,

vous mettez votre bonheur à demeurer en nous, puisque vous nous l'assurez en

disant : " Mes délices sont d'être avec les enfants des hommes !

" 0 mon Seigneur, quelle parole que celle-là. Chaque fois que je l'ai

entendue, elle a toujours été pour moi, même au milieu de mes grandes

infidélités, la source des consolations les plus vives. Mais, ô mon Dieu,

serait-il possible de trouver une âme qui, après avoir reçu de vous des faveurs

si élevées, des joies si, intimes, et compris que vous mettiez en elle vos

délices, vous ait offensé de nouveau, et ait oublié tant de faveurs et tant de

marques de votre amour dont elle ne pouvait douter puisqu'elle en voyait les

effets merveilleux ? Oui, cela est possible, je l'affirme. Il y a une âme qui

vous a offensé, non pas une fois seulement, mais souvent, et cette coupable,

c'est moi, ô mon Dieu. Plaise à votre Bonté, Seigneur que je sois la seule âme

de cette sorte, la seule qui soit tombée dans une malice si profonde et qui ait

manifesté un tel excès d'ingratitude ! Sans doute, vous avez daigné dans votre

infinie Bonté en tirer quelque bien et plus ma misère a été profonde, plus

aussi elle fait resplendir le trésor incomparable de vos miséricordes. Et avec

combien de raison ne puis-je pas les chanter éternellement ! Je vous en

supplie, ô mon Dieu, qu'il en soit ainsi, que je puisse les chanter et les

chanter sans fin ! Vous avez daigné me les prodiguer avec tant de magnificence

! Ceux qui le voient en sont étonnés. Moi-même j'en suis souvent ravie, et je

puis mieux alors vous adresser mes louanges ! Si une fois revenue à moi je me

trouvais sans vous, ô Seigneur, je ne pourrais rien. … Ne le permettez pas,

Seigneur. Ne laissez pas se perdre une âme que vous avez achetée au prix de

tant de souffrances.

Autobiographie,

chapitre XIV,10

Ô mon espérance ! ô mon Père et mon Créateur, et

mon vrai Seigneur et Frère ! Quand je songe que vous dites que vos délices sont

d'être avec les enfants des hommes, mon âme se réjouit énormément. 0 Seigneur

du ciel et de la terre, et quelles paroles que celles-là pour qu'aucun pécheur

ne perde confiance ! Vous manque-t-il, Seigneur, par hasard, quelqu'un avec qui

prendre vos délices, pour que vous cherchiez un petit ver aussi malodorant que

moi ? Cette voix qui s'est fait entendre lors du Baptême de Votre Fils, a dit

que vous mettiez en Lui vos complaisances. Alors, Seigneur, devons-nous lui

être tous égaux ? Ô quelle infinie miséricorde, et quelle faveur tellement

au-dessus de nos mérites. Et tout cela, nous l'oublierions, nous les mortels ?

Vous, ô mon Dieu, souvenez-vous de notre extrême misère, et regardez notre

faiblesse car vous savez tout.

Exclamation

N°7/A

Ô mon âme, considère la grande joie et le grand amour

qu'éprouve le Père à connaître son Fils, et le Fils à connaître son Père, et

l'ardeur avec laquelle le Saint-Esprit s'unit à eux, et comment aucune de ces

trois Personnes ne peut se départir de cet amour ni de cette connaissance,

parce qu'elles sont toutes les trois une même chose. Ces souveraines personnes

se connaissent, elles s'aiment et elles sont les délices les unes des autres.

De quelle utilité peut donc être mon amour ? Pourquoi le voulez-vous, ô mon

Dieu, quel gain y trouvez-vous ? 0, Vous, soyez béni, soyez béni, vous, ô mon

Dieu, pour toujours. Que toutes les choses chantent vos louanges, Seigneur,

éternellement, car vous êtes éternel.

Exclamation

N°7/B

Réjouis-toi, ô mon âme, de ce qu'il y ait quelqu'un

qui aime Dieu comme Il le mérite. Réjouis-toi, de ce qu'il y ait quelqu'un qui

connaisse sa bonté et sa souveraineté. Remercie-le de nous avoir donné sur

terre quelqu'un qui le connaît comme le connaît son Fils unique. Sous cette

protection, tu pourras t'approcher de ton Dieu et le supplier, puisque Sa

Majesté prend en toi ses délices. Que toutes les choses d'ici-bas soient

impuissantes à t'empêcher de prendre tes délices et à te réjouir dans les

grandeurs de ton Dieu, en voyant combien il mérite d'être aimé et loué

demande-lui de t'aider, afin que tu contribues quelque peu à ce que son nom

soit béni, et que tu puisses dire avec vérité : "Mon âme chante les

grandeurs et les louanges du Seigneur".

Exclamation

N°7/C

Ô Seigneur, ô mon Dieu, comme vous avez les paroles de

vie ! Tous les mortels y trouveraient ce qu'ils désirent, s'ils voulaient l'y

chercher. Mais quoi d'étonnant, ô mon Dieu, que nous oubliions vos paroles, dès

lors que nos œuvres mauvaises nous rendent aliénés et malades ? 0 mon Dieu, mon

Dieu, Dieu créateur de tout l'univers, qu'est-ce que tout le créé, si vous,

Seigneur, vouliez créer encore ? Vous êtes le Tout-Puissant, vos œuvres sont

incompréhensibles. Faites donc, Seigneur, que ma pensée ne s'éloigne jamais de

vos paroles. Vous dites : " Venez à moi, vous tous qui souffrez et

pliez sous le fardeau, et je vous consolerai ". Que voulons-nous de

plus, Seigneur ? Que demandons-nous, que cherchons-nous ? Pourquoi les gens du

monde se perdent-ils, si ce n'est parce qu'ils cherchent du repos ? 0 grand

Dieu, ô grand Dieu, qu'est-ce que cela, Seigneur ? Oh ! quelle pitié, oh ! quel

aveuglement que nous cherchions le repos là où il est impossible de le trouver.

Exclamation

N°8/A

Ayez pitié, Créateur, de vos pauvres créatures.

Considérez que nous ne nous comprenons pas, que nous ne savons pas ce que nous

désirons, ni ne parvenons à trouver ce que nous demandons. Donnez-nous,

Seigneur, la lumière, considérez qu'elle nous est plus nécessaire qu'à

l'aveugle-né, car celui-ci désirait voir la lumière, et ne le pouvait pas.

Maintenant, Seigneur, on ne veut pas voir. Oh ! est-il mal plus incurable ?

C'est ici, ô mon Dieu, que doit se montrer votre pouvoir, ici doit se

manifester votre miséricorde. Oh ! quelle chose âpre je vous demande, ô mon

vrai Dieu, que vous aimiez celui qui ne vous aime pas, que vous ouvriez à celui

qui ne vous appelle pas, que vous donniez la santé à celui qui se plaît à être

malade et recherche la maladie. Vous dites, ô mon Seigneur, que vous venez

chercher les pécheurs. Eh bien, les voilà, Seigneur, les vrais pécheurs. Ne

regardez pas notre aveuglement, mon Dieu, mais le sang que votre Fils a versé

abondamment pour nous. Que resplendisse votre miséricorde au milieu d'une si

insondable malignité. Considérez, Seigneur, que nous sommes votre œuvre, que

votre bonté et votre miséricorde nous secourent.

Exclamation

N°8/B

Statue of Teresa of Ávila in the Sagrada Família

Souveraine Majesté,

Éternelle Sagesse,

Bonté douce à mon âme,

Dieu, mon Seigneur,

Qu'ordonnez-vous qu'il

soit fait de moi ?

Je suis vôtre puisque

vous m'avez créée,

Vôtre, puisque vous

m'avez rachetée,

Vôtre, puisque vous

m'avez supportée,

Vôtre, puisque vous

m'avez appelée,

Vôtre, puisque vous

m'avez attendue,

Vôtre, puisque je ne me

suis pas perdue..

Voici mon cœur, Je le

remets entre vos mains

Voici mon corps, ma vie,

mon âme,

Ma tendresse et mon

amour…

Si vous me voulez dans la

joie,

Par amour pour vous je

veux me réjouir

Si vous me commandez des

travaux,

Je veux mourir à

l'ouvrage.

Dites-moi seulement où,

comment et quand.

Parlez, ô doux Amour,

parlez.

Je suis vôtre, pour vous

je suis née,

Que voulez-vous faire de

moi ?

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/10/15.php

L’importance de l’oraison

Je voudrais être douée d’une grande force de

persuasion pour qu’on croie ce que je dis ; je supplie le Seigneur de me

la donner. J’insiste pour que nul de ceux qui ont commencé à faire oraison ne

flanche, en disant : « Si je retombe dans le mal et que je continue

l’oraison, ce sera bien pis. » Je crois qu’il en serait ainsi, si on

abandonnait l’oraison sans corriger le mal ; mais si on ne l’abandonne

point, croyez qu’elle vous conduira au port de lumière. Le démon me livra dans

ce but un tel combat, je crus si longtemps que faire oraison serait, dans ma

misère, un manque d’humilité, que, comme je l’ai dit, j’y ai renoncé pendant un

an et demi, un an au moins, car je ne suis pas sûre de la demi-année ;

cela eût été suffisant, et fut suffisant, pour que je me précipite moi-même en

enfer, sans que le démon ait à m’y pousser. Ô Dieu secourable, l’immense

aveuglement ! Et que le démon a raison, pour atteindre son but, de ne pas

y aller de main morte sur ce point ! Il sait, le traître, que l’âme qui

persévère dans l’oraison est perdue pour lui, que toutes les chutes qu’il

provoque l’aident, avec la bonté de Dieu, à rebondir beaucoup plus haut et à mieux

servir le Seigneur.

Ste Thérèse d’Avila

Thérèse d’Avila († 1583), première femme docteur de

l’Église, incarne la vitalité mystique du Siècle d’or espagnol, tant par ses

écrits que par la réforme du Carmel qu’elle entreprit avec saint Jean de la

Croix. / Œuvres complètes, Paris, DDB, 1964, p. 123

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/vendredi-15-octobre/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

CHRONOLOGIE DE SAINTE THÉRÈSE DE JÉSUS

1515

• 28 mars, Naissance de Teresa de Cepeda y Ahumada,

• 4 avril, Baptême de Teresa, Inauguration du carmel de l’Incarnation.

1522

• Teresa et Rodrigo s’enfuient au pays des Maures “pour voir Dieu”.

1528

• Mort de Béatrice de Ahumada, mère de Teresa.

1531

• Teresa est pensionnaire au couvent de Notre Dame de Grâce.

1535

• 3 août, Rodrigo, le frère très aimé, part pour l’Amérique.

• 2 novembre, Teresa s’enfuit et entre au couvent de l’Incarnation.

1536

• 2 novembre, Teresa prend l’habit du Carmel.

1537

• 3 novembre, Profession religieuse de Teresa.

1538

• Séjour à Becedas.

1543

• 26 décembre, Mort d’Alonso de Cepeda, père de Teresa.

1555

• Conversion de Teresa (Saint Augustin, Christ aux plaies, …).

1556

• au printemps, Les fiançailles mystiques de Teresa.

1558

• “La contradiction des gens de biens” commence. Les uns attribuent les grâces

dont jouit Teresa au démon, les autres à Dieu.

• Première rencontre avec Pierre d’Alcántara.

1560

• 25 janvier, Vision du Christ ressuscité,

• avril, Grâce de la transverbération,

• août, Vision de l’enfer,

• septembre, Au cours d’une conversation, on parle de “réforme”,

• octobre, Teresa rédige sa première Relation.

1561

• Le père Garcia de Toledo lui demande d’écrire sa Vida et sa manière de faire

oraison.

1562

• 24 août, Fondation de Saint Joseph d’Avila,

• décembre, Teresa commence Le Chemin de Perfection.

1563

• Première rédaction des Constitutions.

1567

• février, Visite du Père Général, Rubeo de Ravenne,

Avril, Patentes autorisant d’autres fondations,

• 15 Août, Fondation du couvent de Medina del Campo, Première rencontre avec

Jean de la Croix.

1568

• 11 avril, Fondation du couvent de Malagón,

• 15 août, Fondation du couvent de Valladolid,

• 28 novembre, Fondation du couvent masculin de Duruelo.

1569

• 14 mai, Fondation du couvent de Tolède,

• 23 juin, Fondation du couvent de Pastrana.

1570

• 1er novembre, Fondation du couvent de Salamanque.

1571

• 25 janvier, Fondation du couvent d’Alba de Tormes,

• 6 octobre, Teresa arrive à l’Incarnation comme prieure.

1572

• 16 novembre, Grâce du mariage spirituel.

1573

• 25 août, Commencement du récit des Fondations.

1574

• 19 mars, Fondation du couvent de Ségovie.

1575

• L’Inquisition ordonne la saisie de la Vida de Teresa,

• 24 février, Fondation du couvent de Beas de Segura,

• Printemps, Première rencontre avec le P. Jérôme Gratien,

• 29 mai, Fondation du couvent de Séville, Teresa reçoit l’ordre de se retirer

dans un couvent de son choix et de n’en plus sortir. “La grande tempête”

commence pour la “Réforme”.

1576

• 1er janvier, Fondation du couvent de Caravaca, (par Anne de Saint-Albert).

1577

• mai, À Tolède, Teresa commence Le Livre des Demeures.

• 29 novembre, À Avila, elle achève son ouvrage.

• 24 décembre, Elle se casse le bras gauche en tombant dans l’escalier.

1578/79

• Grandes souffrances de la Réforme et de la réformatrice.

1580

• 21 Février, Fondation du couvent de Villanueva de la Jara,

• 26 juin, Mort de Lorenzo, frère de Teresa,

• 25 Décembre, Fondation du couvent de Palencia.

1581

• 14 juin, Fondation du couvent de Soria.

1582

• 20 janvier, Fondation du couvent de Grenade (par Anne de Jésus)

• 19 avril, Fondation du couvent de Burgos

• 21 septembre, Arrivée à Alba de Tormes.

• 4 (15) octobre, Teresa meurt “fille de l’Église”.

1614

• 14 avril, Béatification, par Paul V.

1622

• 12 mars, Canonisation, par Grégoire XV.

1917

• 30 novembre, Patronne de l’Espagne.

1965

• 18 septembre, Patronne des écrivains espagnols, par Paul VI.

1970

• 27 septembre, Docteur de l’Église, par Paul VI. Teresa est également patronne

: du Corps de l’Intendance militaire, du Royaume de Naples, des joueurs

d’échec, etc.

SOURCE : http://www.carmel.asso.fr/Chronologie-Therese-de-Jesus.html

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Salle Paul VI

Mercredi 2 février 2011

Sainte Thérèse de Jésus

Chers frères et sœurs,

Au cours des catéchèses

que j’ai voulu consacrer aux Pères de l’Eglise et aux grandes figures de

théologiens et de femmes du Moyen-âge, j’ai eu l’occasion de m’arrêter

également sur certains saints et saintes qui ont été proclamés docteurs de

l’Eglise en raison de leur éminente doctrine. Aujourd’hui, je voudrais

commencer une brève série de rencontres pour compléter la présentation des

docteurs de l’Eglise. Et je commence par une sainte qui représente l’un des

sommets de la spiritualité chrétienne de tous les temps: sainte Thérèse d’Avila

(de Jésus).

Elle naît à Avila, en

Espagne, en 1515, sous le nom de Teresa de Ahumada. Dans son autobiographie,

elle mentionne elle-même certains détails de son enfance: la naissance de

«parents vertueux et craignant Dieu», au sein d’une famille nombreuse, avec

neuf frères et trois sœurs. Encore enfant, alors qu’elle n’avait pas encore 9

ans, elle a l’occasion de lire les vies de certains martyrs, qui lui inspirent

le désir du martyre, si bien qu’elle improvise une brève fugue de chez elle

pour mourir martyre et monter au Ciel (cf. Vie, 1, 4): «Je veux voir Dieu»

déclare la petite fille à ses parents. Quelques années plus tard, Thérèse

parlera de ses lectures d’enfance, et affirmera y avoir découvert la vérité,

qu’elle résume dans deux principes fondamentaux: d’un côté, «le fait que tout

ce qui appartient au monde ici bas passe» et de l’autre, que seul Dieu est

«pour toujours, toujours, toujours», un thème qui revient dans la très célèbre

poésie «Que rien ne te trouble,/ que rien ne t’effraie;/ tout passe. Dieu ne

change pas:/ la patience obtient tout;/ celui qui possède Dieu/ ne manque de

rien/ Dieu seul suffit!». Orpheline de mère à l’âge de 12 ans, elle demande à

la Très Sainte Vierge de lui servir de mère (cf. Vie, 1, 7).

Si, au cours de son

adolescence, la lecture de livres profanes l’avait conduite aux distractions

d’une vie dans le monde, l’expérience comme élève des moniales augustiniennes

de Sainte-Marie-des-Grâces d’Avila, ainsi que la lecture de livres spirituels, en

particulier des classiques de la spiritualité franciscaine, lui enseignent le

recueillement et la prière. A l’âge de 20 ans, elle entre au monastère

carmélite de l’Incarnation, toujours à Avila; dans sa vie religieuse, elle

prend le nom de Thérèse de Jésus. Trois ans plus tard, elle tombe gravement

malade, au point de rester quatre jours dans le coma, apparemment morte (cf.

Vie, 5, 9). Même dans la lutte contre ses maladies, la sainte voit le combat

contre les faiblesses et les résistances à l’appel de Dieu: «Je désirais vivre

— écrit-elle — car je le sentais, ce n'était pas vivre que de me débattre ainsi

contre une espèce de mort; mais nul n'était là pour me donner la vie, et il

n'était pas en mon pouvoir de la prendre. Celui qui pouvait seul me la donner

avait raison de ne pas me secourir; il m'avait tant de fois ramenée à lui, et

je l'avais toujours abandonné» (Vie, 8, 2) En 1543, sa famille s’éloigne: son

père meurt et tous ses frères émigrent l’un après l’autre en Amérique. Au cours

du carême 1554, à l’âge de 39 ans, Thérèse atteint le sommet de sa lutte contre

ses faiblesses. La découverte fortuite de la statue d’«un Christ couvert de

plaies» marque profondément sa vie (cf. Vie, 9). La sainte, qui à cette époque

trouvait un profond écho dans les Confessions de saint Augustin, décrit ainsi

le jour décisif de son expérience mystique: «Le sentiment de la présence de

Dieu me saisissait alors tout à coup. Il m'était absolument impossible de

douter qu'il ne fût au dedans de moi, ou que je ne fusse toute abîmée en lui»

(Vie, 10, 1).

Parallèlement au

mûrissement de son intériorité, la sainte commence à développer concrètement

l'idéal de réforme de l'ordre du carmel: en 1562, elle fonde à Avila, avec le

soutien de l'évêque de la ville, don Alvaro de Mendoza, le premier carmel

réformé, et peu après, elle reçoit aussi l'approbation du supérieur général de

l'ordre, Giovanni Battista Rossi. Dans les années qui suivent, elle continue à

fonder de nouveaux carmels, dix-sept au total. La rencontre avec saint Jean de la

Croix, avec lequel, en 1568, elle fonde à Duruelo, non loin d'Avila, le premier

couvent de carmélites déchaussées, est fondamentale. En 1580, elle obtient de

Rome l'érection en Province autonome pour ses carmels réformés, point de départ

de l'ordre religieux des carmélites déchaussées. Thérèse termine sa vie

terrestre au moment où elle est engagée dans l'activité de fondation. En 1582,

en effet, après avoir fondé le carmel de Burgos et tandis qu'elle est en train

d'effectuer son voyage de retour à Avila, elle meurt la nuit du 15 octobre à

Alba de Tormes, en répétant humblement ces deux phrases: «A la fin, je meurs en

fille de l'Eglise» et «L'heure est à présent venue, mon Epoux, que nous nous

voyons». Une existence passée en Espagne, mais consacrée à l'Eglise tout

entière. Béatifiée par le Pape Paul V en 1614 et canonisée en 1622 par Grégoire

XV, elle est proclamée «Docteur de l'Eglise» par le Serviteur de Dieu Paul VI

en 1970.

Thérèse de Jésus n'avait

pas de formation universitaire, mais elle a tiré profit des enseignements de

théologiens, d'hommes de lettres et de maîtres spirituels. Comme écrivain, elle

s'en est toujours tenu à ce qu'elle avait personnellement vécu ou avait vu dans

l'expérience des autres (cf. Prologue au Chemin de perfection), c'est-à-dire en

partant de l'expérience. Thérèse a l'occasion de nouer des liens d'amitié

spirituelle avec un grand nombre de saints, en particulier avec saint Jean de

la Croix. Dans le même temps, elle se nourrit de la lecture des Pères de

l'Eglise, saint Jérôme, saint Grégoire le Grand, saint Augustin. Parmi ses

œuvres majeures, il faut rappeler tout d'abord son autobiographie, intitulée

Livre de la vie, qu'elle appelle Livre des Miséricordes du Seigneur. Composée

au Carmel d'Avila en 1565, elle rapporte le parcours biographique et spirituel,

écrit, comme l'affirme Thérèse elle-même, pour soumettre son âme au

discernement du «Maître des spirituels», saint Jean d'Avila. Le but est de

mettre en évidence la présence et l'action de Dieu miséricordieux dans sa vie:

c'est pourquoi l’œuvre rappelle souvent le dialogue de prière avec le Seigneur.

C'est une lecture fascinante, parce que la sainte non seulement raconte, mais

montre qu'elle revit l'expérience profonde de sa relation avec Dieu. En 1566,

Thérèse écrit le Chemin de perfection, qu'elle appelle Admonestations et

conseils que donne Thérèse de Jésus à ses moniales. Les destinataires en sont

les douze novices du carmel de saint Joseph d’Avila. Thérèse leur propose un

intense programme de vie contemplative au service de l'Église, à la base duquel

se trouvent les vertus évangéliques et la prière. Parmi les passages les plus

précieux, figure le commentaire au Notre Père, modèle de prière. L’œuvre

mystique la plus célèbre de sainte Thérèse est le Château intérieur, écrit en

1577, en pleine maturité. Il s'agit d’une relecture de son chemin de vie

spirituelle et, dans le même temps, d'une codification du déroulement possible

de la vie chrétienne vers sa plénitude, la sainteté, sous l'action de l'Esprit

Saint. Thérèse fait appel à la structure d'un château avec sept pièces, comme

image de l'intériorité de l'homme, en introduisant, dans le même temps, le

symbole du ver à soie qui renaît en papillon, pour exprimer le passage du

naturel au surnaturel. La sainte s'inspire des Saintes Écritures, en

particulier du Cantique des cantiques, pour le symbole final des «deux Époux»,

qui lui permet de décrire, dans la septième pièce, le sommet de la vie

chrétienne dans ses quatre aspects: trinitaire, christologique, anthropologique

et ecclésial. A son activité de fondatrice des carmels réformés, Thérèse

consacre le Livre des fondations, écrit entre 1573 et 1582, dans lequel

elle parle de la vie du groupe religieux naissant. Comme dans son

autobiographie, le récit tend à mettre en évidence l'action de Dieu dans

l’œuvre de fondation des nouveaux monastères.

Il n’est pas facile de

résumer en quelques mots la spiritualité thérésienne, profonde et articulée. Je

voudrais mentionner plusieurs points essentiels. En premier lieu, sainte

Thérèse propose les vertus évangéliques comme base de toute la vie chrétienne

et humaine: en particulier, le détachement des biens ou pauvreté évangélique,

et cela nous concerne tous; l’amour des uns pour les autres comme élément

essentiel de la vie communautaire et sociale; l’humilité comme amour de la

vérité; la détermination comme fruit de l’audace chrétienne; l’espérance

théologale, qu’elle décrit comme une soif d’eau vive. Sans oublier les vertus

humaines: amabilité, véracité, modestie, courtoisie, joie, culture. En deuxième

lieu, sainte Thérèse propose une profonde harmonie avec les grands personnages

bibliques et l’écoute vivante de la Parole de Dieu. Elle se sent surtout en

harmonie avec l’épouse du Cantique des Cantiques et avec l’apôtre Paul, outre

qu’avec le Christ de la Passion et avec Jésus eucharistie.

La sainte souligne

ensuite à quel point la prière est essentielle: prier, dit-elle, «signifie

fréquenter avec amitié, car nous fréquentons en tête à tête Celui qui, nous le

savons, nous aime» (Vie 8, 5). L’idée de sainte Thérèse coïncide avec la

définition que saint Thomas d’Aquin donne de la charité théologale, comme

amicitia quaedam hominis ad Deum, un type d’amitié de l’homme avec Dieu, qui le

premier a offert son amitié à l’homme; l’initiative vient de Dieu (cf. Summa

Theologiae -II, 21, 1). La prière est vie et se développe graduellement en

même temps que la croissance de la vie chrétienne: elle commence par la prière

vocale, elle passe par l’intériorisation à travers la méditation et le

recueillement, jusqu’à parvenir à l’union d’amour avec le Christ et avec la

Très Sainte Trinité. Il ne s’agit évidemment pas d’un développement dans lequel

gravir les plus hautes marches signifie abandonner le type de prière précédent,

mais c’est plutôt un approfondissement graduel de la relation avec Dieu qui

enveloppe toute la vie. Plus qu’une pédagogie de la prière, celle de Thérèse

est une véritable «mystagogie»: elle enseigne au lecteur de ses œuvres à prier

en priant elle-même avec lui; en effet, elle interrompt fréquemment le récit ou

l’exposé pour se lancer dans une prière.

Un autre thème cher à la

sainte est le caractère central de l’humanité du Christ. En effet, pour Thérèse

la vie chrétienne est une relation personnelle avec Jésus, qui atteint son

sommet dans l’union avec Lui par grâce, par amour et par imitation. D’où

l’importance que celle-ci attribue à la méditation de la Passion et à

l’Eucharistie, comme présence du Christ, dans l’Eglise, pour la vie de chaque

croyant et comme cœur de la liturgie. Sainte Thérèse vit un amour inconditionné

pour l’Eglise: elle manifeste un vif sensus Ecclesiae face aux épisodes de

division et de conflit dans l’Eglise de son temps. Elle réforme l’Ordre des

carmélites avec l’intention de mieux servir et de mieux défendre la «Sainte

Eglise catholique romaine », et elle est disposée à donner sa vie pour celle-ci

(cf. Vie 33, 5).

Un dernier aspect

essentiel de la doctrine thérésienne, que je voudrais souligner, est la

perfection, comme aspiration de toute la vie chrétienne et objectif final de

celle-ci. La sainte a une idée très claire de la «plénitude» du Christ, revécue

par le chrétien. A la fin du parcours du Château intérieur, dans la dernière

«pièce», Thérèse décrit cette plénitude, réalisée dans l’inhabitation de la

Trinité, dans l’union au Christ à travers le mystère de son humanité.

Chers frères et sœurs,

sainte Thérèse de Jésus est une véritable maîtresse de vie chrétienne pour les

fidèles de chaque temps. Dans notre société, souvent en manque de valeurs

spirituelles, sainte Thérèse nous enseigne à être des témoins inlassables de

Dieu, de sa présence et de son action, elle nous enseigne à ressentir

réellement cette soif de Dieu qui existe dans la profondeur de notre cœur, ce

désir de voir Dieu, de chercher Dieu, d’être en conversation avec Lui et d’être

ses amis. Telle est l’amitié qui est nécessaire pour nous tous et que nous

devons rechercher, jour après jour, à nouveau. Que l’exemple de cette sainte,

profondément contemplative et efficacement active, nous pousse nous aussi à

consacrer chaque jour le juste temps à la prière, à cette ouverture vers Dieu,

à ce chemin pour chercher Dieu, pour le voir, pour trouver son amitié et

trouver ainsi la vraie vie; car réellement, un grand nombre d’entre nous

devraient dire: «Je ne vis pas, je ne vis pas réellement, car je ne vis pas

l’essence de ma vie». C’est pourquoi, le temps de la prière n’est pas du temps

perdu, c’est un temps pendant lequel s’ouvre la voie de la vie, s’ouvre la voie

pour apprendre de Dieu un amour ardent pour Lui, pour son Eglise, c’est une

charité concrète pour nos frères. Merci.

***

Je salue cordialement les

pèlerins francophones et plus particulièrement la Communauté Saint-Martin et le

lycée Sacré-Cœur. Que l’exemple de sainte Thérèse de Jésus nous encourage à

donner chaque jour du temps à la prière pour apprendre à aimer Dieu et son

Eglise! Avec ma bénédiction.

© Copyright 2011 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Les sept étapes de la vie mystique selon Thérèse

d’Avila

Père Denis

Marie Ghesquières - Publié le 14/10/20

Par sa présence, Dieu veut révéler notre vrai désir

d’aimer. Thérèse d’Avila nous montre comment Il conduit notre vie spirituelle à

travers l’expérience de sept traversées successives. Progressivement, nous

sommes rendus plus libres pour aimer et communier à son désir de sauver tous

les hommes.

Au terme de son parcours spirituel, Thérèse d’Avila

compare notre âme — où Dieu demeure — à un château. Dans son livre Le Livre des Demeures ou Le Château

intérieur, elle écrit en 1577 l’expérience du « mariage spirituel » vécu

en 1572. Ses demeures correspondent à quatre citations bibliques. Elle y décrit

avec précision chacune des étapes de la croissance de la vie spirituelle en

détaillant davantage les dernières étapes qui correspondent à des réalités

moins claires pour ses lectrices (ses propres sœurs carmélites). Elle écrit

tout cela après être arrivée à sa pleine maturité spirituelle et avoir reçu la

grâce de traverser toutes les « demeures ».

Du chemin vers Dieu à la vie de Dieu en nous

Les premières demeures vont permettre approfondir la

vie spirituelle comprise comme un chemin vers Dieu, puis, à partir des

cinquièmes demeures il y aura comme un renversement qui se fait où nous

percevons notre vie comme la vie de Dieu en nous. Dieu fait alors vivre

l’expérience que saint Paul décrit en ces termes : « Ce n’est plus moi qui

vis, c’est le Christ qui vit en moi » (Gal 2, 20). Une

conscience nouvelle de la relation à Dieu nous habite. Sur ce chemin spirituel,

les premières demeures sont le lieu de transformation de nos relations :

dans la deuxième demeure, la relation au monde ; dans la troisième, la

relation à soi-même ; dans la quatrième, la relation à Dieu. Nous allons

ainsi de ce qui est le plus extérieur, le monde, à ce qui est le plus intérieur

en nous : Dieu.

Lire aussi :

Cinq

choses que vous ignorez peut-être sur sainte Thérèse d’Avila