Reliquienbüste des Hl. Paulus, between circa 1220 and circa 1250, 42 × 30.5 × 15.5, Westphalian State Museum of Art and Cultural History, Münster. Leihgabe des Bistums Münster

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 2 juillet 2008

L'Apôtre Paul, un maître

pour notre temps

Chers frères et sœurs,

Je voudrais entamer aujourd'hui un nouveau cycle de catéchèses, dédié au grand

Apôtre saint Paul. C'est à lui, comme vous le savez, qu'est consacrée cette

année qui s'étend de la fête liturgique des saints Pierre et Paul du 29 juin

2008 jusqu'à la même fête de 2009. L'apôtre Paul, figure extraordinaire et

presque inimitable, mais pourtant stimulante, se présente à nous comme un

exemple de dévouement total au Seigneur et à son Eglise, ainsi que de grande

ouverture à l'humanité et à ses cultures. Il est donc juste que nous lui

réservions une place particulière, non seulement dans notre vénération, mais

également dans l'effort de comprendre ce qu'il a à nous dire à nous aussi,

chrétiens d'aujourd'hui. Au cours de cette première rencontre, nous voulons

nous arrêter pour prendre en considération le milieu dans lequel il vécut et

œuvra. Un thème de ce genre semblerait nous conduire loin de notre époque, vu

que nous devons nous replacer dans le monde d'il y a deux mille ans. Mais

toutefois cela n'est vrai qu'en apparence et seulement en partie, car nous

pourrons constater que, sous divers aspects, le contexte socio-culturel

d'aujourd'hui ne diffère pas beaucoup de celui de l'époque.

Un facteur primordial et fondamental qu'il faut garder à l'esprit est le

rapport entre le milieu dans lequel Paul naît et se développe et le contexte

global dans lequel il s'inscrit par la suite. Il provient d'une culture bien

précise et circonscrite, certainement minoritaire, qui est celle du peuple

d'Israël et de sa tradition. Dans le monde antique et particulièrement au sein

de l'empire romain, comme nous l'enseignent les spécialistes en la matière, les

juifs devaient correspondre à environ 10% de la population totale; mais ici à

Rome, vers la moitié du I siècle, leur nombre était encore plus faible,

atteignant au maximum 3% des habitants de la ville. Leurs croyances et leur

style de vie, comme cela arrive encore aujourd'hui, les différenciaient

nettement du milieu environnant; et cela pouvait avoir deux résultats: ou la

dérision, qui pouvait conduire à l'intolérance, ou bien l'admiration, qui

s'exprimait sous diverses formes de sympathie comme dans le cas des

"craignants Dieu" ou des "prosélytes", païens qui

s'associaient à la Synanogue et partageaient la foi dans le Dieu d'Israël.

Comme exemples concrets de cette double attitude nous pouvons citer, d'une

part, le jugement lapidaire d'un orateur tel que Cicéron, qui méprisait leur

religion et même la ville de Jérusalem (cf. Pro Flacco, 66-69) et, de l'autre,

l'attitude de la femme de Néron, Popée, qui est rappelée par Flavius Josèphe

comme "sympathisante" des Juifs (cf. Antiquités juives 20, 195.252;

Vie 16), sans oublier que Jules César leur avait déjà officiellement reconnu

des droits particuliers qui nous ont été transmis par l'historien juif Flavius

Josèphe (cf. ibid. 4, 200-216). Il est certain que le nombre de juifs, comme du

reste c'est le cas aujourd'hui, était beaucoup plus important en dehors de la

terre d'Israël, c'est-à-dire dans la diaspora, que sur le territoire que les

autres appelaient Palestine.

Il n'est donc pas étonnant que Paul lui-même ait été l'objet de la double

évaluation, opposée, que nous avons évoquée. Une chose est certaine: le

particularisme de la culture et de la religion juive trouvait sans difficulté

place au sein d'une institution aussi omniprésente que l'était l'empire romain.

Plus difficile et plus compliquée sera la position du groupe de ceux, juifs ou

païens, qui adhéreront avec foi à la personne de Jésus de Nazareth, dans la

mesure où ceux-ci se distingueront aussi bien du judaïsme que du paganisme

régnant. Quoi qu'il en soit, deux facteurs favorisèrent l'engagement de Paul.

Le premier fut la culture grecque ou plutôt hellénistique, qui après Alexandre

le Grand était devenue le patrimoine commun de l'ouest méditerranéen et du

Moyen-Orient, tout en intégrant en elle de nombreux éléments des cultures de

peuples traditionnellement jugés barbares. A cet égard, l'un des écrivains de

l'époque affirme qu'Alexandre "ordonna que tous considèrent comme patrie

l'œkoumène tout entier... et que le Grec et le Barbare ne se différencient

plus" (Plutarque De Alexandri Magni fortuna aut virtute, 6.8). Le deuxième

facteur fut la structure politique et administrative de l'empire romain, qui

garantissait la paix et la stabilité de la Britannia jusqu'à l'Egypte du sud,

unifiant un territoire aux dimensions jamais vues auparavant. Dans cet espace,

il était possible de se déplacer avec une liberté et une sécurité suffisantes,

en profitant, entre autres, d'un système routier extraordinaire, et en trouvant

en chaque lieu d'arrivée des caractéristiques culturelles de base qui, sans

aller au détriment des valeurs locales, représentaient cependant un tissu

commun d'unification vraiment super partes, si bien que le philosophe juif Philon

d'Alexandrie, contemporain de Paul, loue l'empereur Auguste car "il a

composé en harmonie tous les peuples sauvages... en se faisant le gardien de la

paix" (Legatio ad Caium, 146-147).

La vision universaliste typique de la personnalité de saint Paul, tout au moins

du Paul chrétien après l'événement du chemin de Damas, doit certainement son

impulsion de base à la foi en Jésus Christ, dans la mesure où la figure du

Ressuscité se place désormais au-delà de toute limitation particulariste; en

effet, pour l'apôtre "il n'y a plus ni juif ni païen, il n'y a plus

esclave ni homme libre, il n'y a plus l'homme et la femme, car tous vous ne

faites plus qu'un dans le Christ Jésus" (Ga 3, 28). Toutefois, la

situation historique et culturelle de son époque et de son milieu ne peut elle

aussi qu'avoir influencé ses choix et son engagement. Certains ont défini Paul

comme l'"homme des trois cultures", en tenant compte de son origine

juive, de sa langue grecque, et de sa prérogative de "civis romanus",

comme l'atteste également le nom d'origine latine. Il faut en particulier

rappeler la philosophie stoïcienne, qui dominait à l'époque de Paul et qui

influença, même si c'est de manière marginale, également le christianisme. A ce

propos, nous ne pouvons manquer de citer plusieurs noms de philosophes

stoïciens comme Zénon et Cléanthe, et ensuite ceux chronologiquement plus

proches de Paul comme Sénèque, Musonius et Epictète: on trouve chez eux des

valeurs très élevées d'humanité et de sagesse, qui seront naturellement

accueillies par le christianisme. Comme l'écrit très justement un chercheur

dans ce domaine, "la Stoa... annonça un nouvel idéal, qui imposait en

effet des devoirs à l'homme envers ses semblables, mais qui dans le même temps

le libérait de tous les liens physiques et nationaux et en faisait un être

purement spirituel" (M. Pohlenz, La Stoa, I, Florence 1978, pp. 565sq).

Que l'on pense, par exemple, à la doctrine de l'univers entendu comme un unique

grand corps harmonieux, et en conséquence à la doctrine de l'égalité entre tous

les hommes sans distinctions sociales, à l'équivalence tout au moins de

principe entre l'homme et la femme, et ensuite à l'idéal de la frugalité, de la

juste mesure et de la maîtrise de soi pour éviter tout excès. Lorsque Paul

écrit aux Philippiens: "Tout ce qui est vrai et noble, tout ce qui est

juste et pur, tout ce qui est digne d'être aimé et honoré, tout ce qui

s'appelle vertu et qui mérite des éloges, tout cela, prenez-le à votre

compte" (Ph 4, 8), il ne fait que reprendre une conception typiquement

humaniste propre à cette sagesse philosophique.

A l'époque de saint Paul, était également en cours une crise de la religion

traditionnelle, tout au moins dans ses aspects mythologiques et également

civiques. Après que Lucrèce, déjà un siècle auparavant, avait de manière

polémique affirmé que "la religion a conduit à tant de méfaits" (De

rerum natura, 1, 101), un philosophe comme Sénèque, en allant bien au-delà de

tout ritualisme extérieur, enseignait que "Dieu est proche de toi, il est

avec toi, il est en toi" (Lettres à Lucilius, 41, 1). De même, quand Paul

s'adresse à un auditoire de philosophes épicuriens et stoïciens dans l'Aréopage

d'Athènes, il dit textuellement que "Dieu... n'habite pas les temples

construits par l'homme... En effet, c'est en lui qu'il nous est donné de vivre,

de nous mouvoir, d'exister" (Ac 17, 24.28). Avec ces termes, il fait

certainement écho à la foi juive dans un Dieu qui n'est pas représentable en

termes anthropomorphiques, mais il se place également sur une longueur d'onde

religieuse que ses auditeurs connaissaient bien. Nous devons, en outre, tenir

compte du fait que de nombreux cultes païens n'utilisaient pas les temples

officiels de la ville, et se déroulaient dans des lieux privés qui favorisaient

l'initiation des adeptes. Cela ne constituait donc pas un motif d'étonnement si

les réunions chrétiennes (les ekklesíai), comme nous l'attestent en particulier

les lettres pauliniennes, avaient lieu dans des maisons privées. A cette

époque, du reste, il n'existait encore aucun édifice public. Les réunions des

chrétiens devaient donc apparaître aux contemporains comme une simple variante

de leur pratique religieuse plus intime. Les différences entre les cultes

païens et le culte chrétien ne sont pourtant pas de moindre importance et

concernent aussi bien la conscience de l'identité des participants que la

participation en commun d'hommes et de femmes, la célébration de la "cène

du Seigneur" et la lecture des Ecritures.

En conclusion, de cette rapide vue d'ensemble du milieu culturel du premier

siècle de l'ère chrétienne il ressort qu'il n'est pas possible de comprendre

comme il se doit saint Paul sans le placer sur la toile de fond, aussi bien

juive que païenne, de son temps. De cette manière, sa figure acquiert une force

historique et idéale, en révélant à la fois les points communs et l'originalité

par rapport au milieu. Mais cela vaut également pour la christianisme en

général, dont l'apôtre Paul est un paradigme de premier ordre, dont nous avons

encore tous beaucoup à apprendre. Tel est l'objectif de l'Année paulinienne :

apprendre de saint Paul, apprendre la foi, apprendre le Christ, apprendre enfin

la route d'une vie juste.

* * *

Je salue cordialement les pèlerins francophones présents à cette audience, en

particulier ceux de l’École Notre Dame de Lourdes de Paris et du Collège Saint

François de Sales de Dijon, et les membres de l’Association Charles de Foucauld

de la Principauté de Monaco. Avec ma Bénédiction apostolique.

© Copyright 2008 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Premier

voyage (45-49) C'est un voyage aller-retour qu'il effectue en compagnie

de Barnabé et de Jean Marc (cousin de Barnabé). Il visite Chypre (Paphos), la Pamphylie (Pergé) et prêche autour d'Antioche de Pisidie. Paul et Barnabé cherchent à convertir des Juifs, prêchent dans les synagogues, sont souvent mal reçus et obligés de partir

précipitamment – à cause de leur annonce du salut et de la résurrection

en Jésus (Actes 13:15-41) mais pas forcément

mal reçus (Actes 13:42-49). Sur le chemin du retour, ils ne repassent pas

par Chypre et se rendent directement de Pergé

à Antioche.

Deuxième

voyage (50=52) Paul effectue ce deuxième voyage en compagnie de Silas. Son premier objectif est de rencontrer à

nouveau les communautés qui se sont créées en Cilicie et Pisidie. À Lystre, il rencontre Timothée qui continue le voyage avec eux.

Ils parcourent la Phrygie, la Galatie, la Mysie. À Troie, ils s'embarquent pour la Macédoine. Paul séjourne quelque temps

à Athènes puis à Corinthe. Il retourne ensuite à Antioche en passant par Éphèse et Césarée.

Troisième

voyage (53-58) C'est un voyage de consolidation : Paul retourne voir les

communautés qui se sont créées en Galatie, Phrygie, à Éphèse, en Macédoine jusqu'à Corinthe. Puis il retourne à Troie en passant par la Macédoine. De là, il embarque et finit

son trajet par bateau jusqu'à Tyr, Césarée et Jérusalem où il est arrêté.

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 27 août 2008

Les voyages de saint Paul

Chers frères et sœurs,

Dans la dernière catéchèse avant les vacances - il y a deux mois, au début de

juillet - j'avais commencé une nouvelle série de thématiques à l'occasion de

l'année paulinienne, en considérant le monde dans lequel vécut saint Paul. Je

voudrais aujourd'hui reprendre et continuer la réflexion sur l'apôtre des

nations, en proposant une brève biographie. Etant donné que nous consacrerons

mercredi prochain à l'événement extraordinaire qui eut lieu sur la route de

Damas, la conversion de Paul, tournant fondamental de son existence à la suite

de sa rencontre avec le Christ, nous nous arrêtons aujourd'hui brièvement sur

l'ensemble de sa vie. Les informations sur la vie de Paul se trouvent

respectivement dans la Lettre à Philémon, dans laquelle il se déclare

"vieux" (Fm 9: Presbytes) et dans les Actes des Apôtres, qui au

moment de la lapidation d'Etienne le qualifient de "jeune" (7, 58:

neanías). Les deux désignations sont évidemment génériques, mais, selon la

manière antique de calculer l'âge d'un homme, l'homme autour de trente ans

était qualifié de "jeune", alors que celui qui arrivait à soixante

ans était appelé "vieux". En termes absolus la date de la naissance

de Paul dépend en grande partie de la datation de la Lettre à Philémon.

Traditionnellement sa rédaction est datée de son emprisonnement à Rome, au

milieu des années soixante. Paul serait né en l'an 8, donc il aurait eu plus ou

moins soixante ans, alors qu'au moment de la lapidation d'Etienne il en avait

trente. Telle devrait être la chronologie exacte. Et la célébration de l'année

paulinienne en cours suit cette chronologie. L'année 2008 a été choisie en

pensant à la naissance autour de l'an 8.

Il naquit en tous les cas à Tarse, en Cilicie (cf. Ac 22, 3). La ville était le

chef-lieu administratif de la région et, en 51 av. J.C., son proconsul n'avait

été autre que Marc Tullius Cicéron, alors que dix ans plus tard, en 41, Tarse

avait été le lieu de la première rencontre entre Marc Antoine et Cléopâtre.

Juif de la diaspora, il parlait grec tout en ayant un nom d'origine latine, qui

dérive par ailleurs par assonance du nom originel hébreu Saul/Saulos, et il

avait reçu la citoyenneté romaine (cf. Ac 22, 25-28). Paul apparaît donc se

situer à la frontière de trois cultures différentes - romaine, grecque et juive

- et peut-être est-ce aussi pour cela qu'il était disponible à des ouvertures

universelles fécondes, à une médiation entre les cultures, à une véritable

universalité. Il apprit également un travail manuel, peut-être transmis par son

père, qui consistait dans le métier de "fabricant de tentes" (cf. Ac

18, 3: skenopoiòs), qu'il faut comprendre probablement comme tisseur de laine

brute de chèvre ou de fibres de lin pour en faire des nattes ou des tentes (cf.

Ac 20, 33-35). Vers 12 ou 13 ans, l'âge auquel un jeune garçon juif devient bar

mitzvà ("fils du précepte"), Paul quitta Tarse et s'installa à

Jérusalem pour recevoir l'enseignement du rabbin Gamaliel l'Ancien, neveu du

grand rabbin Hillèl, selon les règles les plus rigides du pharisianisme et

acquérant une grand dévotion pour la Toràh mosaïque (cf. Ga 1, 14; Ph 3, 5-6;

Ac 22, 3; 23, 6; 26, 5).

Sur la base de cette profonde orthodoxie, qu'il avait apprise à l'école de

Hillèl à Jérusalem, il entrevit dans le nouveau mouvement qui se réclamait de

Jésus de Nazareth un risque, une menace pour l'identité juive, pour la vraie

orthodoxie des pères. Cela explique le fait qu'il ait "fièrement persécuté

l'Eglise de Dieu", comme il l'admet à trois reprises dans ses lettres ( 1

Co 15, 9; Ga 1, 13; Ph 3, 6). Même s'il n'est pas facile de s'imaginer

concrètement en quoi consista cette persécution, son attitude fut cependant

d'intolérance. C'est ici que se situe l'événement de Damas, sur lequel nous

reviendrons dans la prochaine catéchèse. Il est certain qu'à partir de ce

moment sa vie changea et qu'il devint un apôtre inlassable de l'Evangile. De

fait, Paul passa à l'histoire davantage pour ce qu'il fit en tant que chrétien,

ou mieux en tant qu'apôtre, qu'en tant que pharisien. On divise

traditionnellement son activité apostolique sur la base de ses trois voyages

missionnaires, auxquels s'ajoute le quatrième lorsqu'il se rendit à Rome en

tant que prisonnier. Ils sont tous racontés par Luc dans les Actes. A propos des

trois voyages missionnaires, il faut cependant distinguer le premier des deux

autres.

En effet, Paul n'eut pas la responsabilité directe du premier (cf. Ac 13, 14),

qui fut en revanche confié au chypriote Barnabé. Ils partirent ensemble

d'Antioche sur l'Oronte, envoyés par cette Eglise (cf. Ac 13, 1-3), et, après

avoir pris la mer du port de Séleucie sur la côte syrienne, ils traversèrent

l'île de Chypre de Salamine à Paphos; de là ils parvinrent sur les côtes

méridionales de l'Anatolie, l'actuelle Turquie, et arrivèrent dans les villes

d'Attalìa, de Pergè en Pamphylie, d'Antioche de Pisidie, d'Iconium, de Lystres

et Derbé, d'où ils revinrent à leur point de départ. C'est ainsi que naquit

l'Eglise des peuples, l'Eglise des païens. Et entre temps, en particulier à

Jérusalem, une âpre discussion était née pour savoir jusqu'à quel point ces

chrétiens provenant du paganisme étaient obligés d'entrer également dans la vie

et dans la loi d'Israël (diverses observances et prescriptions qui séparaient

Israël du reste du monde) pour faire réellement partie des promesses des

prophètes et pour entrer effectivement dans l'héritage d'Israël. Pour résoudre

ce problème fondamental pour la naissance de l'Eglise future, ce que l'on

appelle le Concile des apôtres se réunit à Jérusalem pour trancher sur ce

problème dont dépendait la naissance effective d'une Eglise universelle. Et il

fut décidé de ne pas imposer aux païens convertis l'observance de la loi

mosaïque (cf. Ac 15, 6, 30): c'est-à-dire qu'ils n'étaient pas obligés de se

conformer aux prescriptions du judaïsme; la seule nécessité était d'appartenir

au Christ, de vivre avec le Christ et selon ses paroles. Ainsi, appartenant au

Christ, ils appartenaient aussi à Abraham, à Dieu et faisaient partie de toutes

les promesses. Après cet événement décisif Paul se sépara de Barnabé; il

choisit Silas et commença son deuxième voyage missionnaire (cf. Ac 15, 36-18,

22). Ayant dépassé la Syrie et la Cilicie, il revit la ville de Lystres, où il

accueillit Timothée (figure très importante de l'Eglise naissante, fils d'une

juive et d'un païen), et il le fit circoncire; il traversa l'Anatolie centrale

et rejoint la ville de Troas sur la côte nord de la mer Egée. C'est là qu'eut à

nouveau lieu un événement important: il vit en rêve un macédonien de l'autre

côté de la mer, c'est-à-dire en Europe, qui disait "Viens et

aide-nous!". C'était la future Europe qui demandait l'aide et la lumière

de l'Evangile. De là il prit la mer pour la Macédoine, entrant ainsi en Europe.

Ayant débarqué à Neapoli, il arriva à Philippes, où il fonda une belle

communauté, puis il passa ensuite à Thessalonique, et, ayant quitté ce lieu à

la suite de difficultés créés par les juifs, il passa par Bérée, parvint à

Athènes.

Dans cette capitale de l'antique culture grecque il prêcha d'abord dans

l'Agorà, puis dans l'Aréopage aux païens et aux grecs. Et le discours de

l'aréopage rapporté dans les Actes des apôtres est le modèle de la manière de

traduire l'Evangile dans la culture grecque, de la manière de faire comprendre aux

grecs que ce Dieu des chrétiens, des juifs, n'était pas un Dieu étranger à leur

culture mais le Dieu inconnu qu'ils attendaient, la vraie réponse aux questions

les plus profondes de leur culture. Puis d'Athènes il arriva à Corinthe, où il

s'arrêta une année et demi. Et nous avons ici un événement chronologiquement

très sûr, le plus sûr de toute sa biographie, parce que durant ce premier

séjour à Corinthe il dut se présenter devant le gouverneur de la province

sénatoriale d'Achaïe, le proconsul Gallion, accusé de culte illégitime. A

propos de Gallion et de son époque à Corinthe il existe une inscription antique

retrouvée à Delphes, où il est dit qu'il était proconsul à Corinthe de l'an 51

à l'an 53. Nous avons donc une date absolument certaine. Le séjour de Paul à

Corinthe se déroula dans ces années-là. Par conséquent nous pouvons supposer

qu'il est arrivé plus ou moins en 50 et qu'il est resté jusqu'en 52. Puis de

Corinthe en passant par Cencrées, port oriental de la ville, il se dirigea vers

la Palestine rejoignant Césarée maritime, de là il remonta à Jérusalem pour

revenir ensuite à Antioche sur l'Oronte.

Le troisième voyage missionnaire (cf. Ac 18, 23-21, 16) commença comme toujours

par Antioche, qui était devenue le point de départ de l'Eglise des païens, de

la mission aux païens, et c'était aussi le lieu où naquit le terme

"chrétiens". Là pour la première fois, nous dit saint Luc, les

disciples de Jésus furent appelés "chrétiens". De là Paul alla

directement à Ephèse, capitale de la province d'Asie, où il séjourna pendant

deux ans, exerçant un ministère qui eut de fécondes répercussions sur la

région. D'Ephèse Paul écrivit les lettres aux Thessaloniciens et aux

Corinthiens. La population de la ville fut cependant soulevée contre lui par

les orfèvres locaux, qui voyaient diminuer leurs entrées en raison de

l'affaiblissement du culte d'Artémis (le temple qui lui était dédié à Ephèse,

l'Artemysion, était l'une des sept merveilles du monde antique); il dut donc

fuir vers le nord. Ayant retraversé la Macédoine, il descendit de nouveau en

Grèce, probablement à Corinthe, où il resta trois mois et écrivit la célèbre

Lettre aux Romains.

De là il revint sur ses pas: il repassa par la Macédoine, rejoignit Troas en

bateau et, ensuite, touchant à peine les îles de Mytilène, Chios, et Samos, il

parvint à Milet où il tint un discours important aux Anciens de l'Eglise

d'Ephèse, traçant un portrait du vrai pasteur de l'Eglise: cf. Ac 20. Il

repartit de là en voguant vers Tyr, d'où il rejoint Césarée Maritime pour remonter

encore une fois vers Jérusalem. Il y fut arrêté à cause d'un malentendu:

plusieurs juifs avaient pris pour des païens d'autres juifs d'origine grecque,

introduits par Paul dans l'aire du temple réservée uniquement aux Israélites.

La condamnation à mort prévue lui fut épargnée grâce à l'intervention du tribun

romain de garde dans l'aire du temple (cf. Ac 21, 27-36); cet événement eut

lieu alors qu'Antoine Félix était gouverneur impérial en Judée. Après une

période d'emprisonnement (dont la durée est discutée), et Paul ayant fait appel

à César (qui était alors Néron) en tant que citoyen romain, le gouverneur

suivant Porcius Festus l'envoya à Rome sous surveillance militaire.

Le voyage vers Rome aborda les îles méditerranéennes de Crète et Malte, et

ensuite les villes de Syracuse, Reggio Calabria et Pozzuoli. Les chrétiens de

Rome allèrent à sa rencontre sur la via Appia jusqu'au forum d'Appius (environ

à 70km au sud de la capitale) et d'autres jusqu'aux Tre Taverne (environ 40km).

A Rome, il rencontra les délégués de la communauté juive, à qui il confia que

c'était à cause de "l'espérance d'Israël" qu'il portait ces chaînes

(cf. Ac 28, 20). Mais le récit de Luc se termine sur la mention de deux années

passées à Rome sous une légère surveillance militaire, sans mentionner aucune

sentence de César (Néron) pas plus que la mort de l'accusé. Des traditions

successives parlent de sa libération, qui aurait permis un voyage missionnaire

en Espagne, ainsi qu'un passage en Orient et spécifiquement à Crète, à Ephèse

et à Nicopolis en Epire. Toujours sur une base hypothétique, on parle d'une

nouvelle arrestation et d'un deuxième emprisonnement à Rome (d'où il aurait

écrit les trois Lettres appelés pastorales, c'est-à-dire les deux Lettres à

Timothée et celle à Tite) avec un deuxième procès, qui lui aurait été

défavorable. Toutefois, une série de motifs pousse de nombreux spécialistes de

saint Paul à terminer la biographie de l'apôtre par le récit des Actes de Luc.

Nous reviendrons plus avant sur son martyre dans le cycle de nos catéchèses. Il

est pour le moment suffisant dans cette brève revue des voyages de Paul de

prendre acte de la façon dont il s'est consacré à l'annonce de l'Evangile sans

épargner ses énergies, en affrontant une série d'épreuves difficiles, dont il nous

a laissé la liste dans la deuxième Lettre aux Corinthiens (cf. 11, 21-28). Du

reste, c'est lui qui écrit: "Je le fais à cause de l'Evangile" (1 Co

9, 23), exerçant avec une générosité absolue ce qu'il appelle le "souci de

toutes les Eglises" (2 Co 11, 28). Nous voyons un engagement qui ne

s'explique que par une âme réellement fascinée par la lumière de l'Evangile,

amoureuse du Christ, une âme soutenue par une conviction profonde: il est

nécessaire d'apporter au monde la lumière du Christ, d'annoncer l'Evangile à

tous. Tel est, me semble-t-il, ce qui reste de cette brève revue des voyages de

saint Paul: sa passion pour l'Evangile, avoir ainsi l'intuition de la grandeur,

de la beauté et même de la nécessité profonde de l'Evangile pour nous tous.

Prions afin que le Seigneur qui a fait voir à Paul sa lumière, lui a fait

entendre sa Parole, a touché intimement son cœur, nous fasse également voir sa

lumière, pour que notre cœur aussi soit touché par sa Parole et que nous

puissions ainsi donner nous aussi au monde d'aujourd'hui, qui en a soif, la

lumière de l'Evangile et la vérité du Christ.

* * *

Je salue cordialement les pèlerins francophones présents, en particulier les

pèlerins venus d’Égypte, les pèlerins belges de Louvain et de

Lavaux-Sainte-Anne ainsi que le groupe du sanctuaire « Notre-Dame des Anges »

de Pignans en France. Avec ma Bénédiction apostolique.

Appel face à la grave situation en Inde

J'ai appris avec une profonde tristesse les nouvelles concernant les violences

contre les communautés chrétiennes dans l'Etat indien de l'Orissa, qui ont

explosé suite au déplorable assassinat du leader hindou Swami Lakshmananda

Saraswati. Jusqu'à présent plusieurs personnes ont été tuées et plusieurs

autres blessées. On a assisté en outre à la destruction de centres de culte,

propriété de l'Eglise, et d'habitations privées.

Tandis que je condamne avec fermeté toute attaque contre la vie humaine, dont

le caractère sacré exige le respect de tous, j'exprime ma proximité spirituelle

et ma solidarité aux frères et sœurs dans la foi si durement mis à l'épreuve.

J'implore le Seigneur de les accompagner et de les soutenir en cette période de

souffrance et de leur donner la force de continuer dans le service d'amour en

faveur de tous.

J'invite les responsables religieux et les autorités civiles à travailler

ensemble pour rétablir parmi les membres des diverses communautés la

coexistence pacifique et l'harmonie qui ont toujours été la marque distinctive

de la société indienne.

© Copyright 2008 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

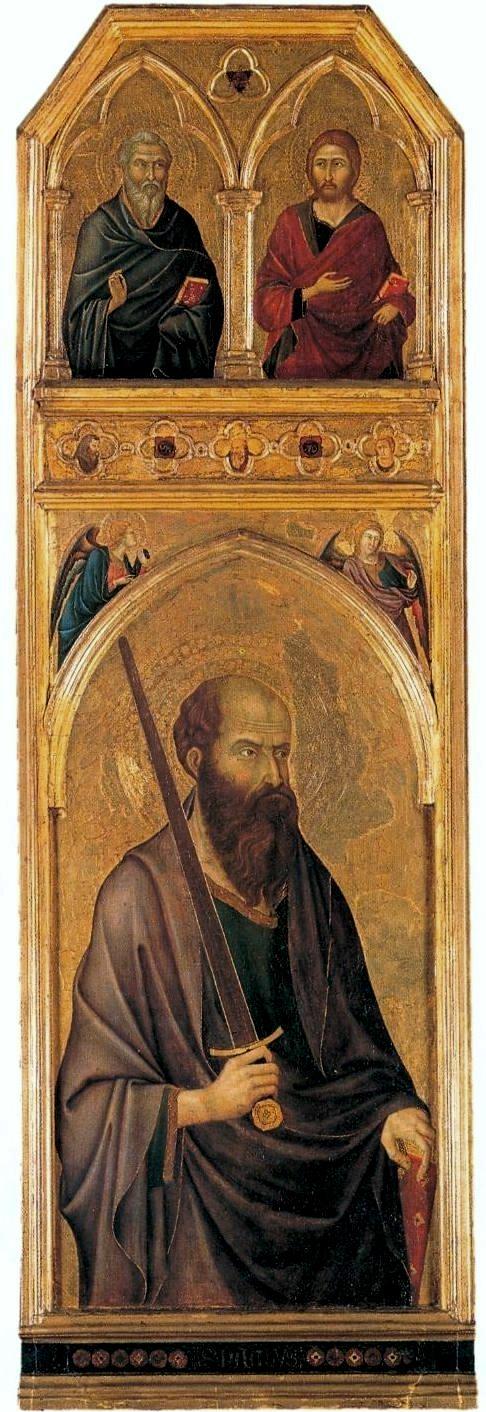

Luca

di Tommè. Conversión de Saulo. Seattle Art Museum.

Paintings by Luca di Tommè ; Religious

paintings in the Seattle Art Museum ; 14th-century paintings of

Saint Paul

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 3 septembre 2008

La conversion de Paul

Chers frères et sœurs,

La catéchèse d'aujourd'hui sera consacrée à l'expérience que saint Paul fit sur le chemin de Damas et donc sur ce que l'on appelle communément sa conversion. C'est précisément sur le chemin de Damas, au début des années 30 du i siècle, et après une période où il avait persécuté l'Eglise, qu'eut lieu le moment décisif de la vie de Paul. On a beaucoup écrit à son propos et naturellement de différents points de vue. Il est certain qu'un tournant eut lieu là, et même un renversement de perspective. Alors, de manière inattendue, il commença à considérer "perte" et "balayures" tout ce qui auparavant constituait pour lui l'idéal le plus élevé, presque la raison d'être de son existence (cf. Ph 3, 7-8). Que s'était-il passé?

Nous avons à ce propos deux types de sources. Le premier type, le plus connu, est constitué par des récits dus à la plume de Luc, qui à trois reprises raconte l'événement dans les Actes des Apôtres (cf. 9, 1-19; 22, 3-21; 26, 4-23). Le lecteur moyen est peut-être tenté de trop s'arrêter sur certains détails, comme la lumière du ciel, la chute à terre, la voix qui appelle, la nouvelle condition de cécité, la guérison comme si des écailles lui étaient tombées des yeux et le jeûne. Mais tous ces détails se réfèrent au centre de l'événement: le Christ ressuscité apparaît comme une lumière splendide et parle à Saul, il transforme sa pensée et sa vie elle-même. La splendeur du Ressuscité le rend aveugle: il apparaît ainsi extérieurement ce qui était sa réalité intérieure, sa cécité à l'égard de la vérité, de la lumière qu'est le Christ. Et ensuite son "oui" définitif au Christ dans le baptême ouvre à nouveau ses yeux, le fait réellement voir.

Dans l'Eglise antique le baptême était également appelé "illumination", car ce sacrement donne la lumière, fait voir réellement. Ce qui est ainsi indiqué théologiquement, se réalise également physiquement chez Paul: guéri de sa cécité intérieure, il voit bien. Saint Paul a donc été transformé, non par une pensée, mais par un événement, par la présence irrésistible du Ressuscité, de laquelle il ne pourra jamais douter par la suite tant l'évidence de l'événement, de cette rencontre, avait été forte. Elle changea fondamentalement la vie de Paul; en ce sens on peut et on doit parler d'une conversion. Cette rencontre est le centre du récit de saint Luc, qui a sans doute utilisé un récit qui est probablement né dans la communauté de Damas. La couleur locale donnée par la présence d'Ananie et par les noms des rues, ainsi que du propriétaire de la maison dans laquelle Paul séjourna (cf. Ac 9, 11) le laisse penser.

Le deuxième type de sources sur la conversion est constitué par les Lettres de saint Paul lui-même. Il n'a jamais parlé en détail de cet événement, je pense que c'est parce qu'il pouvait supposer que tous connaissaient l'essentiel de cette histoire, que tous savaient que de persécuteur il avait été transformé en apôtre fervent du Christ. Et cela avait eu lieu non à la suite d'une réflexion personnelle, mais d'un événement fort, d'une rencontre avec le Ressuscité. Bien que ne mentionnant pas de détails, il mentionne plusieurs fois ce fait très important, c'est-à-dire que lui aussi est témoin de la résurrection de Jésus, de laquelle il a reçu directement de Jésus lui-même la révélation, avec la mission d'apôtre. Le texte le plus clair sur ce point se trouve dans son récit sur ce qui constitue le centre de l'histoire du salut: la mort et la résurrection de Jésus et les apparitions aux témoins (cf. 1 Co 15). Avec les paroles de la très ancienne tradition, que lui aussi a reçues de l'Eglise de Jérusalem, il dit que Jésus mort crucifié, enseveli, ressuscité, apparut, après la résurrection, tous d'abord à Céphas, c'est-à-dire à Pierre, puis aux Douze, puis à cinq cents frères qui vivaient encore en grande partie à cette époque, puis à Jacques, puis à tous les Apôtres. Et à ce récit reçu de la tradition, il ajoute: "Et en tout dernier lieu, il est même apparu à l'avorton que je suis" (1 Co 15, 8). Il fait ainsi comprendre que cela est le fondement de son apostolat et de sa nouvelle vie. Il existe également d'autres textes dans lesquels la même chose apparaît: "Nous avons reçu par lui [Jésus] grâce et mission d'Apôtre" (cf. Rm 1, 5); et encore: "N'ai-je pas vu Jésus notre Seigneur?" (1 Co 9, 1), des paroles avec lesquelles il fait allusion à une chose que tous savent. Et finalement le texte le plus diffusé peut être trouvé dans Ga 1, 15-17: "Mais Dieu m'avait mis à part dès le sein de ma mère, dans sa grâce il m'avait appelé, et, un jour, il a trouvé bon de mettre en moi la révélation de son Fils, pour que moi, je l'annonce parmi les nations païennes. Aussitôt, sans prendre l'avis de personne, sans même monter à Jérusalem pour y rencontrer ceux qui étaient les Apôtres avant moi, je suis parti pour l'Arabie; de là, je suis revenu à Damas". Dans cette "auto-apologie" il souligne de manière décidée qu'il est lui aussi un véritable témoin du Ressuscité, qu'il a une mission reçue directement du Ressuscité.

Nous pouvons ainsi voir que les deux sources, les Actes des Apôtres et les Lettres de saint Paul, convergent et s'accordent sur un point fondamental: le Ressuscité a parlé à Paul, il l'a appelé à l'apostolat, il a fait de lui un véritable apôtre, témoin de la résurrection, avec la charge spécifique d'annoncer l'Evangile aux païens, au monde gréco-romain. Et dans le même temps, Paul a appris que, malgré le caractère direct de sa relation avec le Ressuscité, il doit entrer dans la communion de l'Eglise, il doit se faire baptiser, il doit vivre en harmonie avec les autres apôtres. Ce n'est que dans cette communion avec tous qu'il pourra être un véritable apôtre, ainsi qu'il l'écrit explicitement dans la première Epître aux Corinthiens: "Eux ou moi, voilà ce que nous prêchons. Et voilà ce que vous avez cru" (15, 11). Il n'y a qu'une seule annonce du Ressuscité car le Christ est un.

Comme on peut le voir, dans tous ces passages Paul n'interprète jamais ce moment comme un fait de conversion. Pourquoi? Il y a beaucoup d'hypothèses, mais selon moi le motif était tout à fait évident. Ce tournant dans sa vie, cette transformation de tout son être ne fut pas le fruit d'un processus psychologique, d'une maturation ou d'une évolution intellectuelle et morale, mais il vint de l'extérieur: ce ne fut pas le fruit de sa pensée, mais de la rencontre avec Jésus Christ. En ce sens, ce ne fut pas simplement une conversion, une maturation de son "moi", mais ce fut une mort et une résurrection pour lui-même: il mourut à sa vie et naquit à une autre vie nouvelle avec le Christ ressuscité. D'aucune autre manière on ne peut expliquer ce renouveau de Paul. Toutes les analyses psychologiques ne peuvent pas éclairer et résoudre le problème. Seul l'événement, la rencontre forte avec le Christ, est la clé pour comprendre ce qui était arrivé; mort et résurrection, renouveau de la part de Celui qui s'était montré et avait parlé avec lui. En ce sens plus profond, nous pouvons et nous devons parler de conversion. Cette rencontre est un réel renouveau qui a changé tous ses paramètres. Maintenant il peut dire que ce qui auparavant était pour lui essentiel et fondamental, est devenu pour lui "balayures"; ce n'est plus un "gain", mais une perte, parce que désormais seul compte la vie dans le Christ.

Nous ne devons toutefois pas penser que Paul ait été ainsi enfermé dans un événement aveugle. Le contraire est vrai, parce que le Christ ressuscité est la lumière de la vérité, la lumière de Dieu lui-même. Cela a élargi son cœur, l'a ouvert à tous. En cet instant il n'a pas perdu ce qu'il y avait de bon et de vrai dans sa vie, dans son héritage, mais il a compris de manière nouvelle la sagesse, la vérité, la profondeur de la loi et des prophètes, il se l'est réapproprié de manière nouvelle. Dans le même temps, sa raison s'est ouverte à la sagesse des païens; s'étant ouvert au Christ de tout son cœur, il est devenu capable d'un large dialogue avec tous, il est devenu capable de se faire tout pour tous. C'est ainsi qu'il pouvait réellement devenir l'apôtre des païens.

Si l'on en revient à présent à nous-mêmes, nous nous demandons: qu'est-ce que tout cela veut dire pour nous? Cela veut dire que pour nous aussi le christianisme n'est pas une nouvelle philosophie ou une nouvelle morale. Nous ne sommes chrétiens que si nous rencontrons le Christ. Assurément, il ne se montre pas à nous de manière irrésistible, lumineuse, comme il l'a fait avec Paul pour en faire l'apôtre de toutes les nations. Mais nous aussi nous pouvons rencontrer le Christ, dans la lecture de l'Ecriture Sainte, dans la prière, dans la vie liturgique de l'Eglise. Nous pouvons toucher le cœur du Christ et sentir qu'il touche le nôtre. C'est seulement dans cette relation personnelle avec le Christ, seulement dans cette rencontre avec le Ressuscité que nous devenons réellement chrétiens. Et ainsi s'ouvre notre raison, s'ouvre toute la sagesse du Christ et toute la richesse de la vérité. Prions donc le Seigneur de nous éclairer, de nous offrir dans notre monde de rencontrer sa présence: et qu'ainsi il nous donne une foi vivace, un cœur ouvert, une grande charité pour tous, capable de renouveler le monde.

* * *

Je suis heureux de vous accueillir chers pèlerins francophones. A l’exemple de

saint Paul laissez-vous saisir par le Christ. C’est en lui que se trouve le

sens ultime de votre vie. Vous aussi, soyez des témoins ardents du Sauveur des

hommes, parmi vos frères et vos sœurs. Que Dieu vous bénisse !

© Copyright 2008 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

San

Paolo, Tomba particolare, Chiesa di Santa Maria della Consolazione

Reliefs of Saint Paul in Italy ; Santa Maria della Consolazione (Altomonte) - Interior

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 10 septembre

2008

Audience générale du 10

septembre 2008

L'apostolat de saint Paul

Chers frères et sœurs,

Mercredi dernier, j'ai parlé du grand tournant qui eut lieu dans la vie de

saint Paul à la suite de sa rencontre avec le Christ ressuscité. Jésus entra

dans sa vie et le transforma de persécuteur en apôtre. Cette rencontre marqua

le début de sa mission: Paul ne pouvait pas continuer à vivre comme avant, à

présent il se sentait investi par le Seigneur de la mission d'annoncer son

Evangile en qualité d'apôtre. Et c'est précisément de cette nouvelle condition

de vie, c'est-à-dire d'être apôtre du Christ, que je voudrais vous parler

aujourd'hui. Normalement, en suivant les Evangiles, nous identifions les Douze

avec le titre d'apôtres, entendant ainsi indiquer ceux qui étaient les

compagnons de vie et les auditeurs de l'enseignement de Jésus. Mais Paul aussi

se sent un véritable apôtre et il apparaît donc clair que le concept paulinien

d'apostolat ne se limite pas au groupe des Douze. Naturellement Paul sait bien

distinguer son propre cas de celui de ceux "qui étaient Apôtres

avant" lui (Ga 1, 17): il leur reconnaît une place toute particulière dans

la vie de l'Eglise. Et pourtant, comme chacun le sait, saint Paul s'interprète

lui aussi comme Apôtre au sens strict. Il est certain que, à l'époque des

origines chrétiennes, personne ne parcourut autant de kilomètres que lui, sur

la terre et sur la mer, dans le seul but d'annoncer l'Evangile.

Il possédait donc un concept d'apostolat qui allait au-delà de celui lié

uniquement au groupe des Douze et transmis en particulier par saint Luc dans

les Actes (cf. Ac 1,2.26; 6, 2). En effet, dans la première Lettre aux

Corinthiens Paul effectue une claire distinction entre "les Douze" et

"tous les apôtres", mentionnés comme deux groupes différents de

bénéficiaires des apparitions du Ressuscité (cf. 15, 5.7). Dans ce même texte,

il se nomme ensuite humblement lui-même comme "le plus petit des

Apôtres", se comparant même à un avorton et affirmant textuellement:

"Je ne suis pas digne d'être appelé apôtre, puisque j'ai persécuté

l'Eglise de Dieu. Mais ce que je suis, je le suis par la grâce de Dieu, et la

grâce dont il m'a comblé n'a pas été stérile. Je me suis donné de la peine plus

que tous les autres; à vrai dire ce n'est pas moi, c'est la grâce de Dieu avec

moi" (1 Co 15, 9-10). La métaphore de l'avorton exprime une extrême modestie;

on la trouvera également dans la Lettre aux Romains de saint Ignace d'Antioche:

"Je suis le dernier de tous, je suis un avorton; mais il me sera accordé

d'être quelque chose, si je rejoins Dieu" (9, 2). Ce que l'évêque

d'Antioche dira à propos de son martyre imminent, prévoyant que celui-ci

transformerait sa condition d'indignité, saint Paul le dit lui-même en relation

avec son propre engagement apostolique: c'est dans celui-ci que se manifeste la

fécondité de la grâce de Dieu, qui sait précisément transformer un homme mal

réussi en un apôtre splendide. De persécuteur à fondateur d'Eglises: c'est ce

qu'a fait Dieu chez une personne qui, du point de vue évangélique, aurait pu

être considérée comme un rebut!

Qu'est-ce donc, selon la conception de Paul, qui fait de lui et d'autres

personnes des apôtres? Dans ses Lettres apparaissent trois caractéristiques

principales, qui constituent l'apostolat. La première est d'avoir "vu le

Seigneur" (cf. 1 Co 9, 1), c'est-à-dire d'avoir eu avec lui une rencontre

déterminante pour sa propre vie. De même, dans la Lettre aux Galates (cf. 1,

15-16) il dira qu'il a été appelé, presque sélectionné par la grâce de Dieu

avec la révélation de son Fils en vue de l'heureuse annonce aux païens. En

définitive, c'est le Seigneur qui appelle à l'apostolat, et non la propre

présomption. L'apôtre ne se fait pas tout seul, mais il est fait tel par le

Seigneur; l'apôtre a donc besoin de se référer constamment au Seigneur. Ce

n'est pas pour rien que Paul dit qu'il est "apôtre par vocation" (Rm

1, 1), c'est-à-dire "envoyé non par les hommes, ni par un intermédiaire

humain, mais par Jésus Christ et par Dieu le Père" (Ga 1, 1). Telle est la

première caractéristique: avoir vu le Seigneur, avoir été appelé par Lui

La deuxième caractéristique est d'"avoir été envoyés". Le terme grec

apóstolos signifie précisément "envoyé, mandaté", c'est-à-dire

ambassadeur et porteur d'un message; il doit donc agir comme responsable et

représentant d'un mandant. Et c'est pour cela que Paul se définit "apôtre

du Christ Jésus" (1 Co 1, 1; 2 Co 1, 1), c'est-à-dire son délégué,

entièrement placé à son service, au point de s'appeler également

"serviteur de Jésus Christ" (Rm 1, 1). Encore une fois apparaît au

premier plan l'idée de l'initiative d'une autre personne, celle de Dieu dans le

Christ Jésus, à laquelle on doit une pleine obéissance; mais il est en

particulier souligné que l'on a reçu de lui une mission à accomplir en son nom,

en mettant absolument au deuxième plan tout intérêt personnel.

La troisième condition est l'exercice de l'"annonce de l'Evangile",

avec la fondation conséquente d'Eglises. En effet, le titre

d'"apôtre" n'est pas et ne peut pas être un titre honorifique. Il

engage concrètement et même dramatiquement toute l'existence du sujet concerné.

Dans la première Lettre aux Corinthiens Paul s'exclame: "Ne suis-je pas

apôtre? N'ai-je pas vu Jésus notre Seigneur? Et vous, n'êtes-vous pas mon œuvre

dans le Seigneur?" (9, 1). De même, dans la deuxième Lettre aux

Corinthiens il affirme: "C'est vous-mêmes qui êtes ce document..., vous

êtes ce document venant du Christ, confié à notre ministère, écrit non pas avec

de l'encre, mais avec l'Esprit du Dieu vivant" (3, 2-3).

Il ne faut donc pas s'étonner si saint Jean Chrysostome parle de Paul comme

d'"une âme de diamant" (Panégyriques, 1, 8), et poursuit en disant:

"De la même manière que le feu se renforce encore davantage en prenant sur

des matériaux différents..., la parole de Paul gagnait à sa propre cause tous

ceux avec qui il entrait en relation, et ceux qui lui faisaient la guerre,

capturés par ses discours, devenaient une nourriture pour ce feu

spirituel" (ibid. 7, 11). Cela explique pourquoi Paul définit les apôtres

comme des "collaborateurs de Dieu" (1 Co 3, 9; 2 Co 6, 1), dont la

grâce agit avec eux. Un élément typique du véritable apôtre, bien mis en

lumière par saint Paul, est une sorte d'identification entre Evangile et

évangélisateur, tous deux destinés au même sort. En effet, personne autant que

Paul n'a souligné que l'annonce de la croix du Christ apparaît comme

"scandale et folie" (1 Co 1, 23), à laquelle nombreux sont ceux qui

réagissent par l'incompréhension et le refus. L'apôtre Paul participe donc à ce

sort d'apparaître "scandale et folie" et il le sait: telle est

l'expérience de sa vie. Il écrit aux Corinthiens, non sans une nuance d'ironie:

"Mais nous les Apôtres, il me semble que Dieu a fait de nous les derniers

de tous, comme on expose des condamnés à mort, livrés en spectacle au monde

entier, aux anges et aux hommes. Nous passons pour des fous à cause du Christ,

et vous, pour des gens sensés dans le Christ; nous sommes faibles, et vous êtes

forts; vous êtes à l'honneur, et nous, dans le mépris. Maintenant encore, nous

avons faim, nous avons soif, nous n'avons pas de vêtements, nous sommes maltraités,

nous n'avons pas de domicile, nous peinons dur à travailler de nos mains. Les

gens nous insultent, nous les bénissons. Ils nous persécutent, nous supportons.

Ils nous calomnient, nous avons des paroles d'apaisement. Jusqu'à maintenant,

nous sommes pour ainsi dire les balayures du monde, le rebut de

l'humanité" (1 Co 4, 9-13). C'est un autoportrait de la vie apostolique de

saint Paul: dans toutes ces souffrances prévaut la joie d'être le porteur de la

bénédiction de Dieu et de la grâce de l'Evangile

Paul partage par ailleurs avec la philosophie stoïcienne de son temps l'idée

d'une constance tenace face à toutes les difficultés qui se présentent à lui;

mais il dépasse la perspective purement humaniste, rappelant la composante de

l'amour de Dieu et du Christ: "Qui pourra nous séparer de l'amour du

Christ? la détresse? l'angoisse? la persécution? la faim? le dénuement? le

danger? le supplice? L'Ecriture dit en effet: C'est pour toi qu'on nous

massacre sans arrêt, on nous prend pour des moutons d'abattoir. Oui, en tout

cela nous sommes les grands vainqueurs grâce à celui qui nous a aimés. J'en ai

la certitude: ni la mort ni la vie, ni les esprits ni les puissances, ni le

présent ni l'avenir, ni les astres, ni les cieux, ni les abîmes, ni aucune

autre créature, rien ne pourra nous séparer de l'amour de Dieu qui est en Jésus

Christ notre Seigneur" (Rm 8, 35-39). Telle est la certitude, la joie

profonde qui guide l'apôtre Paul dans tous ces événements: rien ne peut nous

séparer de l'amour de Dieu. Et cet amour est la véritable richesse de la vie

humaine.

Comme on le voit, saint Paul s'était donné à l'Evangile avec toute son

existence; nous pourrions dire vingt-quatre heures sur vingt-quatre! Et il

accomplissait son ministère avec fidélité et avec joie, "pour en sauver à

tout prix quelques-uns" (1 Co 9, 22). Et il se situait à l'égard des

Eglises, tout en sachant qu'il avait avec elles une relation de paternité (cf.

1 Co 4, 15), voire de maternité (cf. Ga 4, 19), dans une attitude de service

complet, déclarant admirablement: "Il ne s'agit pas d'exercer un pouvoir

sur votre foi, mais de collaborer à votre joie" (2 Co 1, 24). Telle

demeure la mission de tous les apôtres du Christ à toutes les époques: être les

collaborateurs de la joie véritable.

* * *

Je souhaite la bienvenue aux pèlerins de langue française présents ce matin.

Que l’exemple de saint Paul vous aide à vous laisser transformer par la grâce

de Dieu afin de devenir d’authentiques disciples du Christ, ardents à annoncer

son Évangile. Avec ma Bénédiction apostolique.

Message à la France en vue de la Visite Apostolique

Chers Frères et Sœurs,

Vendredi prochain j’entreprendrai mon premier voyage pastoral en France en tant

que Successeur de Pierre. A la veille de mon arrivée, je tiens à adresser mon cordial

salut au peuple français et à tous les habitants de cette Nation bien-aimée. Je

viens chez vous en messager de paix et de fraternité. Votre pays ne m’est pas

inconnu. A plusieurs reprises j’ai eu la joie de m’y rendre et d’apprécier sa

généreuse tradition d’accueil et de tolérance, ainsi que la solidité de sa foi

chrétienne comme sa haute culture humaine et spirituelle. Cette fois,

l’occasion de ma venue est la célébration du cent cinquantième anniversaire des

apparitions de la Vierge Marie à Lourdes. Après avoir visité Paris, la capitale

de votre pays, ce sera une grande joie pour moi de m’unir à la foule des

pèlerins qui viennent suivre les étapes du chemin du Jubilé, à la suite de

sainte Bernadette, jusqu’à la grotte de Massabielle. Ma prière se fera intense

aux pieds de Notre Dame aux intentions de toute l’Église, particulièrement pour

les malades, les personnes les plus délaissées, mais aussi pour la paix dans le

monde. Que Marie soit pour vous tous, et particulièrement pour les jeunes, la

Mère toujours disponible aux besoins de ses enfants, une lumière d’espérance

qui éclaire et guide vos chemins ! Chers amis de France, je vous invite à vous

unir à ma prière pour que ce voyage porte des fruits abondants. Dans l’heureuse

attente d’être prochainement parmi vous, j’invoque sur chacun, sur vos familles

et sur vos communautés, la protection maternelle de la Vierge Marie, Notre Dame

de Lourdes. Que Dieu vous bénisse !

© Copyright 2008 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

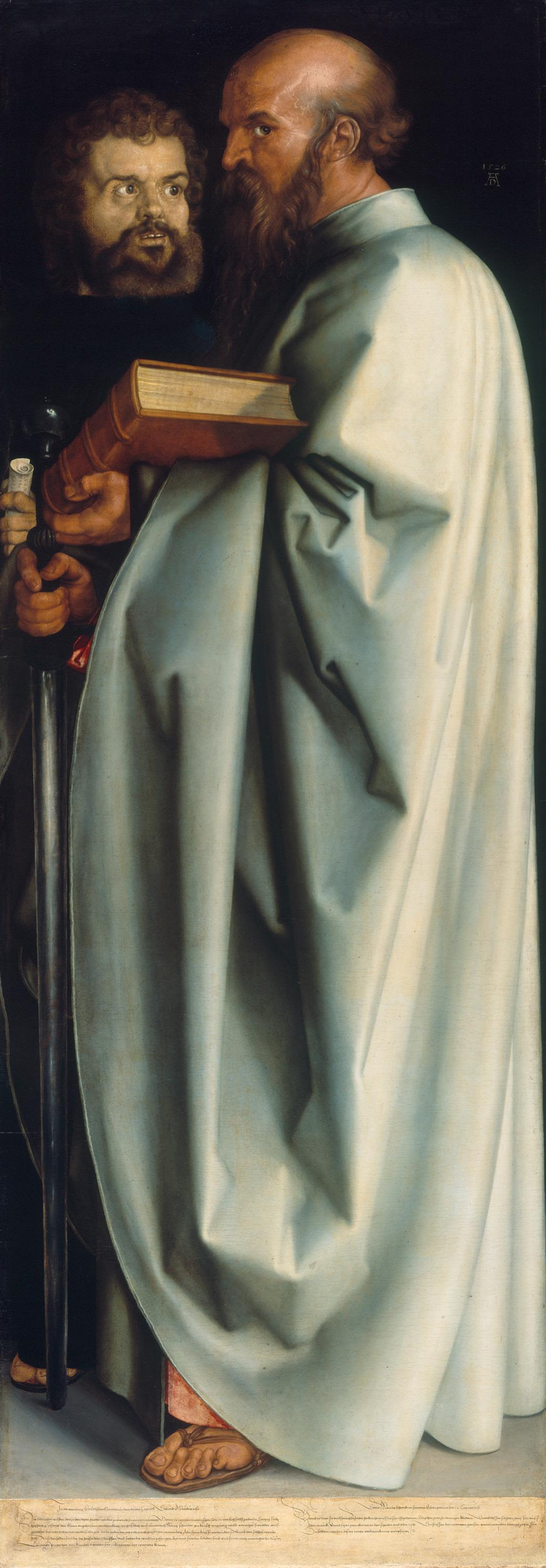

Master

of the Worms Panels, A wormsi táblák, bal szárny, Szt. Pál / Die Worms Tafeln,

Linker Flügel, Hl. Paulus / The Worms Panels - Left Wing - St. Paulus, circa

1260. oil on panel. Städel Museum, acquired in 1910. On loan from

Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt. oto by Szilas in the Städel

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 24 septembre

2008

Les relations entre saint

Paul et les apôtres

Chers frères et sœurs,

Je voudrais parler aujourd'hui des relations entre saint Paul et les Apôtres

qui l'avaient précédé à la suite de Jésus. Ces relations furent toujours

marquées par un profond respect et par une franchise qui, chez saint Paul,

dérive de la défense de la vérité de l'Evangile. Même s'il était, dans les

faits, contemporain de Jésus de Nazareth, il n'eut jamais l'occasion de le

rencontrer, au cours de sa vie publique. C'est pourquoi, après avoir été

foudroyé sur le chemin de Damas, il ressentit le besoin de consulter les

premiers disciples du Maître, qui avaient été choisis par Lui pour en porter

l'Evangile jusqu'aux extrémités de la terre.

Dans la Lettre aux Galates, Paul rédige un compte-rendu important sur les

contacts entretenus avec plusieurs des Douze: avant tout avec Pierre qui avait

été choisi comme Kephas, le terme araméen qui signifie le roc sur lequel l'on

édifiait l'Eglise (cf. Ga 1, 18), avec Jacques, "le frère du

Seigneur" (cf. Ga 1, 19), et avec Jean (cf. Ga 2, 9): Paul n'hésite pas à

les reconnaître comme "les colonnes" de l'Eglise. La rencontre avec

Céphas (Pierre), qui eut lieu à Jérusalem, est particulièrement significative:

Paul resta chez lui pendant 15 jours pour "le consulter" (cf. Ga 1,

19), c'est-à-dire pour être informé sur la vie terrestre du Ressuscité, qui

l'avait "saisi" sur la route de Damas et qui était en train de lui

changer, de manière radicale, l'existence: de persécuteur à l'égard de l'Eglise

de Dieu, il était devenu évangélisateur de cette foi dans le Messie crucifié et

Fils de Dieu, que par le passé il avait cherché à détruire (cf. Ga 1, 23).

Quel genre d'informations Paul obtint-il sur Jésus Christ pendant les trois

années qui suivirent la rencontre de Damas? Dans la première Lettre aux

Corinthiens nous pouvons noter deux passages, que Paul a connus à Jérusalem, et

qui avaient déjà été formulés comme éléments centraux de la tradition

chrétienne, tradition constitutive. Il les transmet verbalement, tels qu'il les

a reçus, avec une formule très solennelle: "Je vous ai transmis ceci, que

j'ai moi-même reçu". C'est-à-dire qu'il insiste sur la fidélité à ce qu'il

a lui-même reçu et qu'il transmet fidèlement aux nouveaux chrétiens. Ce sont

des éléments constitutifs et ils concernent l'Eucharistie et la Résurrection;

il s'agit de passages déjà formulés dans les années trente. Nous arrivons ainsi

à la mort, la sépulture au cœur de la terre et à la résurrection de Jésus (cf.

1 Co 15, 3-4). Prenons l'un et l'autre: les paroles de Jésus au cours de la

Dernière Cène (cf. 1 Co 11, 23-25) sont réellement pour Paul le centre de la

vie de l'Eglise: l'Eglise s'édifie à partir de ce centre, en devenant ainsi

elle-même. Outre ce centre eucharistique, dans lequel naît toujours à nouveau

l'Eglise - également pour toute la théologie de saint Paul, pour toute sa

pensée - ces paroles ont eu une profonde répercussion sur la relation

personnelle de Paul avec Jésus. D'une part, elles attestent que l'Eucharistie

illumine la malédiction de la croix, la transformant en bénédiction (Ga 3,

13-14) et, de l'autre, elles expliquent la portée de la mort et de la

résurrection de Jésus. Dans ses Lettres le "pour vous" de

l'institution eucharistique devient le "pour moi" (Ga 2, 20),

personnalisant, sachant qu'en ce "vous" il était lui-même connu et

aimé de Jésus et d'autre part "pour tous" (2 Co 5, 14): ce "pour

vous" devient "pour moi" et "pour l'Eglise (Ep 5,

25)", c'est-à-dire également "pour tous" du sacrifice expiatoire

de la croix (cf. Rm 3, 25). A partir de l'Eucharistie et dans celle-ci,

l'Eglise s'édifie et se reconnaît comme "Corps du Christ" (1 Co 12,

27), nourrie chaque jour par la puissance de l'Esprit du Ressuscité.

L'autre texte sur la Résurrection nous transmet à nouveau la même formule de

fidélité. Saint Paul écrit: "Avant tout, je vous ai transmis ceci, que

j'ai moi-même reçu: le Christ est mort pour nos péchés conformément aux

Ecritures, et il a été mis au tombeau; il est ressuscité le troisième jour

conformément aux Ecritures, et il est apparu à Pierre, puis aux Douze" (1

Co 15, 3-5). Dans cette tradition transmise à Paul revient également ce

"pour nos péchés", qui met l'accent sur le don que Jésus a fait de

lui-même au Père, pour nous libérer des péchés et de la mort. De ce don de soi,

Paul tirera les expressions les plus captivantes et fascinantes de notre

relation avec le Christ: "Celui qui n'a pas connu le péché, Dieu l'a pour

nous identifié au péché des hommes, afin que, grâce à lui, nous soyons

identifiés à la justice de Dieu" (2 Co 5, 21); "Vous connaissez en

effet la générosité de notre Seigneur Jésus Christ: lui qui est riche, il est

devenu pauvre à cause de vous, pour que vous deveniez riches par sa

pauvreté" (2 Co 8, 9). Il vaut la peine de rappeler le commentaire par

lequel celui qui était alors un moine augustin, Martin Luther, accompagnait ces

expressions paradoxales de Paul: "Tel est le mystère grandiose de la grâce

divine envers les pécheurs: que par un admirable échange nos péchés ne sont

plus les nôtres, mais du Christ, et la justice du Christ n'est plus du Christ,

mais la nôtre" (Commentaire sur les Psaumes de 1513-1515). Et ainsi nous

sommes sauvés.

Dans le kerygma original, transmis de bouche à oreille, il faut souligner

l'usage du verbe "il est ressuscité", au lieu de "il fut

ressuscité" qu'il aurait été plus logique d'utiliser, en continuité avec

"il mourut... et fut enseveli". La forme verbale est choisie pour

souligner que la résurrection du Christ influence jusqu'à l'heure actuelle

l'existence des croyants: nous pouvons le traduire par "il est ressuscité

et continue à vivre" dans l'Eucharistie et dans l'Eglise. Ainsi toutes les

Ecritures rendent témoignage de la mort et de la résurrection du Christ car -

comme l'écrira Ugo di San Vittore - "toute la divine Ecriture constitue un

unique livre et cet unique livre est le Christ, car toute l'Ecriture parle du

Christ et trouve dans le Christ son accomplissement" (De arca Noe, 2, 8).

Si saint Ambroise de Milan peut dire que "dans l'Ecriture nous lisons le

Christ", c'est parce que l'Eglise des origines a relu toutes les Ecritures

d'Israël en partant du Christ et en revenant à Lui.

L'énumération des apparitions du Ressuscité à Céphas, aux Douze, à plus de cinq

cent frères et à Jacques se termine par la mention de l'apparition personnelle,

reçue par Paul sur le chemin de Damas: "Et en tout dernier lieu, il est

même apparu à l'avorton que je suis" (1 Co 15, 8). Ayant persécuté

l'Eglise de Dieu, il exprime dans cette confession son indignité à être

considéré apôtre, au même niveau que ceux qui l'ont précédé: mais la grâce de

Dieu en lui n'a pas été vaine (1 Co 15, 10). C'est pourquoi l'affirmation

puissante de la grâce divine unit Paul aux premiers témoins de la résurrection

du Christ: "Bref, qu'il s'agisse de moi ou des autres, voilà notre

message, et voilà notre foi" (1 Co 15, 11). L'identité et le caractère

unique de l'Evangile sont importants: aussi bien eux que moi prêchons la même

foi, le même Evangile de Jésus Christ mort et ressuscité qui se donne dans la

Très Sainte Eucharistie.

L'importance qu'il confère à cette Tradition vivante de l'Eglise, qu'il

transmet à ses communautés, démontre à quel point est erronée la vision de ceux

qui attribuent à Paul l'invention du christianisme: avant de porter l'évangile

de Jésus Christ, son Seigneur, il l'a rencontré sur le chemin de Damas et il

l'a fréquenté dans l'Eglise, en observant sa vie chez les Douze et chez ceux

qui l'ont suivi sur les routes de la Galilée. Dans les prochaines catéchèses,

nous aurons l'opportunité d'approfondir les contributions que Paul a apportées

à l'Eglise des origines; mais la mission reçue par le Ressuscité en vue

d'évangéliser les païens a besoin d'être confirmée et garantie par ceux qui lui

donnèrent leur main droite, ainsi qu'à Barnabé, en signe d'approbation de leur

apostolat et de leur évangélisation et d'accueil dans l'unique communion de

l'Eglise du Christ (cf. Ga 2, 9). On comprend alors que l'expression "nous

avons compris le Christ à la manière humaine" ( 2 Co 5, 16) ne signifie

pas que son existence terrestre ait eu une faible importance pour notre maturation

dans la foi, mais qu'à partir du moment de sa Résurrection, notre façon de nous

rapporter à Lui se transforme. Il est, dans le même temps, le Fils de Dieu,

"né de la race de David; selon l'Esprit qui sanctifie, il a été établi

dans sa puissance de Fils de Dieu par sa résurrection d'entre les morts, lui,

Jésus Christ, notre Seigneur", comme le rappellera Paul au début de la

Lettres aux Romains (1, 3-4).

Plus nous cherchons à nous mettre sur les traces de Jésus de Nazareth sur les

routes de la Galilée, plus nous pouvons comprendre qu'il a pris en charge notre

humanité, la partageant en tout, hormis le péché. Notre foi ne naît pas d'un

mythe, ni d'une idée, mais bien de la rencontre avec le Ressuscité, dans la vie

de l'Eglise.

* * *

Je suis heureux de vous accueillir, chers pèlerins francophones, en particulier

les pèlerins du Diocèse de Chartres avec leur Évêque Monseigneur Michel

Pansard, ainsi que les pèlerins du Diocèse de Tournai, avec leur Évêque

Monseigneur Guy Harpigny. A la suite de saint Paul, prions afin que le Seigneur

envoie beaucoup d’ouvriers apostoliques dans sa vigne. Avec ma Bénédiction

Apostolique.

© Copyright 2008 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Pietro Lorenzetti (1280–1348), Christ

Between Saints Peter and Paul. Circa 1320, Ferens Art Gallery. Kingston upon Hull.

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 1 octobre 2008

Saint Paul, le

"Concile" de Jérusalem et l'incident d'Antioche

Chers frères et sœurs,

Le respect et la vénération que Paul a toujours cultivés à l'égard des Douze ne

font pas défaut lorsqu'il défend avec franchise la vérité de l'Evangile, qui

n'est autre que Jésus Christ, le Seigneur. Nous voulons aujourd'hui nous

arrêter sur deux épisodes qui démontrent la vénération et, dans le même temps,

la liberté avec laquelle l'Apôtre s'adresse à Céphas et aux autres Apôtres: ce

qu'on appelle le "Concile" de Jérusalem et l'incident d'Antioche de

Syrie, rapportés dans la Lettre aux Galates (cf. 2, 1-10; 2, 11-14).

Chaque Concile et Synode de l'Eglise est "un événement de l'Esprit"

et contient dans son accomplissement les instances de tout le peuple de Dieu:

ceux qui ont reçu le don de participer au Concile Vatican II en ont fait

personnellement l'expérience. C'est pourquoi saint Luc, en nous informant sur

le premier Concile de l'Eglise, qui s'est déroulé à Jérusalem, commence ainsi

la lettre que les Apôtres envoyèrent en cette circonstance aux communautés

chrétiennes de la diaspora: "L'Esprit Saint et nous-mêmes avons

décidé..." (Ac 15, 28). L'Esprit, qui agit dans toute l'Eglise, conduit

les Apôtres par la main pour entreprendre de nouvelles routes en vue de

réaliser ses projets: c'est Lui l'artisan principal de l'édification de

l'Eglise.

L'assemblée de Jérusalem se déroula pourtant à un moment de tension importante

au sein de la Communauté des origines. Il s'agissait de répondre à la question

de savoir s'il fallait demander aux païens qui adhéraient à Jésus Christ, le

Seigneur, la circoncision ou s'il était licite de les laisser libres de la Loi

mosaïque, c'est-à-dire de l'observance des normes nécessaires pour être des

hommes justes, qui obtempèrent à la Loi, et surtout libres des normes

concernant les purifications cultuelles, les aliments purs et impurs et le

Sabbat. Saint Paul parle également de l'assemblée de Jérusalem dans Ga 2, 1-10:

quatorze ans après la rencontre avec le Ressuscité à Damas - nous sommes dans

la deuxième moitié des années 40 ap. J.C. - Paul part avec Barnabé d'Antioche

de Syrie et se fait accompagner par Tite, son fidèle collaborateur qui, bien

qu'étant d'origine grecque, n'avait pas été obligé de se faire circoncire pour

entrer dans l'Eglise. A cette occasion, Paul expose aux Douze, définis comme

les personnes les plus remarquables, son évangile de la liberté de la Loi (cf.

Ga 2, 6). A la lumière de la rencontre avec le Christ ressuscité, il avait

compris qu'au moment du passage à l'Evangile de Jésus Christ, pour les païens

n'étaient plus nécessaire la circoncision, les règles sur la nourriture, sur le

sabbat comme signes de la justice: le Christ est notre justice et

"juste" est tout ce qui lui est conforme. Il n'y pas besoin d'autres

signes pour être des justes. Dans la Lettre aux Galates, en quelques lignes, il

rapporte le déroulement de l'assemblée: il rappelle avec enthousiasme que

l'évangile de la liberté à l'égard de la Loi fut approuvé par Jacques, Céphas

et Jean, "les colonnes", qui lui offrirent ainsi qu'à Barnabé la main

droite de la communion ecclésiale dans le Christ (cf. Ga 2, 9). Si, comme nous

l'avons remarqué, pour Luc le Concile de Jérusalem exprime l'action de l'Esprit

Saint, pour Paul il représente la reconnaissance décisive de la liberté

partagée entre tous ceux qui y participèrent: une liberté des obligations provenant

de la circoncision et de la Loi; cette liberté pour laquelle "le Christ

nous a libérés, pour que nous restions libres" et pour que nous ne nous

laissions plus imposer le joug de l'esclavage (cf. Ga 5, 1). Les deux modalités

avec lesquelles Paul et Luc décrivent l'assemblée de Jérusalem ont en commun

l'action libératrice de l'Esprit, car "là où l'Esprit du Seigneur est

présent, là est la liberté", dira-t-il dans la deuxième Lettre aux

Corinthiens (cf. 3, 17).

Toutefois, comme il apparaît avec une grande clarté dans les Lettres de saint

Paul, la liberté chrétienne ne s'identifie jamais avec le libertinage ou avec

le libre arbitre de faire ce que l'on veut; elle se réalise dans la conformité

au Christ et donc dans le service authentique pour les frères, en particulier

pour les plus indigents. C'est pourquoi, le compte-rendu de Paul sur

l'assemblée se termine par le souvenir de la recommandation que les Apôtres lui

adressèrent: "Ils nous demandèrent seulement de penser aux pauvres de leur

communauté, ce que j'ai toujours fait de mon mieux" (Ga 2, 10). Chaque

Concile naît de l'Eglise et retourne à l'Eglise: en cette occasion, il y

retourne avec une attention pour les pauvres qui, selon les diverses

annotations de Paul dans ses Lettres, sont tout d'abord ceux de l'Eglise de

Jérusalem. Dans sa préoccupation pour les pauvres, attestée en particulier dans

la deuxième Lettre aux Corinthiens (cf. 8-9) et dans la partie finale de la

Lettre aux Romains (cf. Rm 15), Paul démontre sa fidélité aux décisions qui ont

mûri pendant l'assemblée.

Peut-être ne sommes-nous plus en mesure de comprendre pleinement la

signification que Paul et ses communautés attribuèrent à la collecte pour les

pauvres de Jérusalem. Ce fut une initiative entièrement nouvelle dans le cadre

des activités religieuses: elle ne fut pas obligatoire, mais libre et

spontanée; toute les Eglises fondées par Paul vers l'Occident y prirent part.

La collecte exprimait la dette de ses communautés à l'égard de l'Eglise mère de

la Palestine, dont elles avaient reçu le don extraordinaire de l'Evangile. La

valeur que Paul attribue à ce geste de partage est tellement grande que

rarement il l'appelle simplement "collecte": pour lui celle-ci est

plutôt "service", "bénédiction", "amour",

grâce", et même "liturgie" (2 Co 9). On est en particulier

surpris par ce dernier terme, qui confère à la collecte d'argent une valeur

également cultuelle: d'une part, celle-ci est un geste liturgique ou

"service", offert par chaque communauté à Dieu, de l'autre, elle est

une action d'amour accomplie en faveur du peuple. Amour pour les pauvres et

liturgie divine vont ensemble, l'amour pour les pauvres est liturgie. Les deux

horizons sont présents dans chaque liturgie célébrée et vécue dans l'Eglise,

qui par sa nature s'oppose à la séparation entre le culte et la vie, entre la

foi et les oeuvres, entre la prière et la charité pour les frères. Le Concile

de Jérusalem naît ainsi pour résoudre la question sur la façon de se comporter

avec les païens qui adhéraient à la foi, en optant pour la liberté à l'égard de

la circoncision et des observances imposées par la Loi, et elle se résout dans

l'instance ecclésiale et pastorale, qui place en son centre la foi dans le

Christ et l'amour pour les pauvres de Jérusalem et de toute l'Eglise.

Le deuxième épisode est le célèbre incident d'Antioche, en Syrie, qui atteste

la liberté intérieure dont Paul jouissait: comment se comporter à l'occasion de

la communion à la table entre les croyants d'origine juive et ceux d'origine

païenne? Ici se fait jour l'autre épicentre de l'observance mosaïque: la

distinction entre les aliments purs et impurs, qui divisaient profondément les

juifs observants des païens. Au début, Céphas, Pierre partageait sa table avec

les uns et les autres; mais avec l'arrivée de plusieurs chrétiens liés à

Jacques, "le frère du Seigneur" (Ga 1, 19), Pierre avait commencé à

éviter les contacts à table avec les païens, pour ne pas scandaliser ceux qui

continuaient à observer les lois sur les aliments purs; et le choix avait été

partagé par Barnabé. Ce choix divisait profondément les chrétiens venus de la

circoncision et les chrétiens venus du paganisme. Ce comportement, qui menaçait

réellement l'unité et la liberté de l'Eglise, suscita les réactions enflammées

de Paul, qui parvint à accuser Pierre et les autres d'hypocrisie; "Toi,

tout juif que tu es, il t'arrive de suivre les coutumes des païens et non

celles des juifs; alors, pourquoi forces-tu les païens à faire comme les

juifs?" (Ga 2, 14). En réalité, les préoccupations de Paul, d'une part, et

celles de Pierre et Barnabé, de l'autre, étaient différentes: pour ces derniers

la séparation des païens représentait une manière de protéger et de ne pas

scandaliser les croyants provenant du judaïsme; pour Paul, elle constituait en

revanche un danger de mauvaise compréhension du salut universel en Christ,

offert aussi bien aux païens qu'aux juifs. Si la justification ne se réalise

qu'en vertu de la foi dans le Christ, de la conformité avec lui, sans aucune

œuvre de la Loi, quel sens cela a-t-il d'observer la pureté des aliments à

l'occasion du partage de la table? Les perspectives de Pierre et de Paul

étaient probablement différentes: pour le premier ne pas perdre les juifs qui

avaient adhéré à l'Evangile, pour le deuxième ne pas réduire la valeur salvifique

de la mort du Christ pour tous les croyants.

Cela paraît étrange, mais en écrivant aux chrétiens de Rome, quelques années

après (vers le milieu des années 50 ap. J.C.), Paul lui-même se trouvera face à

une situation analogue et demandera aux forts de ne pas manger de nourriture

impure pour ne pas perdre ou pour ne pas scandaliser les faibles: "C'est

bien de ne pas manger de viande, de ne pas boire de vin, bref de ne rien faire

qui fasse tomber ton frère" (Rm 14, 21). L'incident d'Antioche se révéla

donc une leçon aussi bien pour Pierre que pour Paul. Ce n'est que le dialogue

sincère, ouvert à la vérité de l'Evangile, qui put orienter le chemin de

l'Eglise: "En effet, le Royaume de Dieu ne consiste pas en des questions

de nourriture ou de boisson; il est justice, paix et joie dans l'Esprit

Saint" (Rm 14, 17). C'est une leçon que nous devons apprendre nous aussi:

avec les différents charismes confiés à Pierre et à Paul, laissons-nous guider

par l'Esprit, en cherchant à vivre dans la liberté qui trouve son orientation

dans la foi en Christ et se concrétise dans le service à nos frères. Ce qui est

essentiel c'est d'être toujours plus conforme au Christ. C'est ainsi qu'on

devient réellement libre, c'est ainsi que s'exprime en nous le noyau le plus

profond de la Loi: l'amour pour Dieu et pour notre prochain. Prions le Seigneur

pour qu'il nous enseigne à partager ses sentiments, pour apprendre de Lui la

vraie liberté et l'amour évangélique qui embrasse tout être humain.

* * *

Je salue tous les pèlerins francophones présents à cette audience, en

particulier les participants au pèlerinage œcuménique Saint-Paul présidé par

Monseigneur Robert Le Gall, archevêque de Toulouse, ainsi que les pèlerins

venus du Canada et de la Guadeloupe. Puisse la méditation des lettres de Paul

faire aimer toujours davantage l’Église en son mystère. Bon pèlerinage à tous !

© Copyright 2008 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Luca

di Tommè, Tre Santi dal polittico di San Paolo, circa 1374, da Ufficio

Biccherna a Siena

Paintings by Luca di Tommè ; 14th-century paintings of

Saint Paul ; Paintings in

the Villa medicea di Cerreto Guidi

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 8 octobre 2008

Saint Paul et la vie

terrestre de Jésus

Chers frères et sœurs!

Dans les dernières catéchèses sur saint Paul, j'ai parlé de sa rencontre avec

le Christ ressuscité, qui a changé profondément sa vie, puis de sa relation

avec les douze Apôtres, appelés par Jésus - en particulier avec Jacques, Céphas

et Jean - et de sa relation avec l'Eglise de Jérusalem. Il reste à présent la

question de ce que saint Paul a su du Jésus terrestre, de sa vie, de ses

enseignements, de sa passion. Avant d'aborder cette question, il peut être

utile d'avoir à l'esprit que saint Paul lui-même distingue deux façons de

connaître Jésus et plus généralement deux façons de connaître une personne. Il

écrit dans la Deuxième Lettre aux Corinthiens: "Ainsi donc, désormais nous

ne connaissons personne selon la chair. Même si nous avons connu le Christ

selon la chair, maintenant ce n'est plus ainsi que nous le connaissons"

(5, 16). Connaître "selon la chair", de manière charnelle, cela veut

dire connaître de manière seulement extérieure, avec des critères extérieurs:

on peut avoir vu une personne plusieurs fois, connaître ainsi son aspect et les

divers détails de son comportement: la manière dont il parle, la manière dont

il bouge, etc. Toutefois, même en connaissant quelqu'un de cette manière on ne

le connaît pas réellement, on ne connaît pas le noyau de la personne. C'est

seulement avec le cœur que l'on connaît vraiment une personne. De fait, les

pharisiens et les saducéens ont connu Jésus de manière extérieure, ils ont

appris son enseignement, beaucoup de détails sur lui, mais ils ne l'ont pas

connu dans sa vérité. Il y a une distinction analogue dans une parole de Jésus.

Après la Transfiguration, il demande aux apôtres: "Le Fils de l'homme qui

est-il, d'après ce que disent les gens?" (Mt 16, 13) "Et vous que

dites-vous? Pour vous qui suis-je?" (Mt 16, 15). Les gens le connaissent,

mais de manière superficielle; ils savent plusieurs choses de lui, mais ils ne

l'ont pas réellement connu. En revanche, les Douze, grâce à l'amitié qui fait

participer le cœur, ont au moins compris dans la substance et ont commencé à

connaître qui est Jésus. Aujourd'hui aussi existe cette manière différente de

connaître: il y a des personnes savantes qui connaissent Jésus dans ses

nombreux détails et des personnes simples qui n'ont pas connaissance de ces

détails, mais qui l'ont connu dans sa vérité: "le cœur parle au

cœur". Et Paul veut dire essentiellement qu'il faut connaître Jésus ainsi,

avec le cœur et connaître essentiellement de cette manière la personne dans sa

vérité; puis, dans un deuxième temps, en connaître les détails.

Cela dit, demeure toutefois la question: qu'a connu saint Paul de la vie

concrète, des paroles, de la passion, des miracles de Jésus? Il semble confirmé

qu'il ne l'a pas rencontré pendant sa vie terrestre. A travers les apôtres et

l'Eglise naissante il a assurément connu aussi les détails sur la vie terrestre

de Jésus. Dans ses Lettres, nous pouvons trouver trois formes de référence au

Jésus pré-pascal.

En premier lieu, on trouve des références explicites et directes. Paul parle de

l'ascendance davidique de Jésus (cf. Rm 1, 3), il connaît l'existence de ses

"frères" ou consanguins (1 Co 9, 5; Ga 1, 19), il connaît le

déroulement de la Dernière Cène (cf. 1 Co 11, 23), il connaît d'autres paroles

de Jésus, par exemple, sur l'indissolubilité du mariage (cf. 1 Co 7, 10 avec Mc

10, 11-12), sur la nécessité que celui qui annonce l'Evangile soit nourri par

la communauté dans la mesure où l'ouvrier est digne de son salaire (cf. 1 Co 9,

14 et Lc 10, 7); Paul connaît les paroles prononcées par Jésus lors de la

Dernière Cène (cf. 1 Co 11, 24-25 et Lc 22, 19-20) et il connaît aussi la croix

de Jésus. Telles sont les références directes à des paroles et des faits de la

vie de Jésus.

En deuxième lieu, nous pouvons entrevoir dans certaines phrases des Lettres

pauliniennes plusieurs allusions à la tradition attestée dans les Evangiles

synoptiques. Par exemple, les paroles que nous lisons dans la première Lettre

aux Thessaloniciens, selon lesquelles "le jour du Seigneur viendra comme

un voleur dans la nuit" (5, 2), ne s'expliqueraient pas comme un renvoi

aux prophéties vétéro-testamentaires, car la comparaison avec le voleur

nocturne ne se trouve que dans l'Evangile de Matthieu et de Luc, donc elle est

tirée précisément de la tradition synoptique. Ainsi, quand nous lisons que: "ce

qu'il y a de faible dans le monde, voilà ce que Jésus a choisi..." (1 Co

1, 27-28), on entend l'écho fidèle de l'enseignement de Jésus sur les simples

et sur les pauvres (cf. Mt 5, 3; 11, 25; 19, 30). Il y a ensuite les paroles

prononcée par Jésus dans la joie messianique: "Père, Seigneur du ciel et

de la terre, je proclame ta louange: ce que tu as caché aux sages et aux

savants, tu l'as révélé aux tout-petits" (Mt 11, 25). Paul sait - c'est