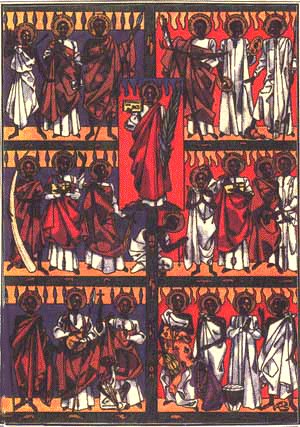

San Carlo Lwanga et ses compagnons martyrs

Saint Charles Lwanga et ses compagnons, martyrs

Avec les vingt-deux martyrs de l'Ouganda on revit une page des Actes des Martyrs des premiers siècles. Plusieurs étaient chrétiens depuis peu. Quatre d'entre eux furent baptisés par Charles Lwanga juste avant le supplice. La plupart de ceux qui furent brûlés vifs à Numumgongo (1886) avaient entre seize et vingt-quatre ans. Le plus jeune, Kizito, en avait treize.

Reliquiario di San Carlo Lwanga contenente un frammento osseo

Saint Charles Lwanga

Martyr en Ouganda (+ 1886)

L'Eglise ougandaise était

toute jeune : à peine dix ans depuis que les Pères Blancs avaient évangélisé le

pays, avec l'appui du roi. Mais le roi était mort et son successeur Mwanga

était un homme sans moralité et tyrannique. Il avait renvoyé les missionnaires

de la religion étrangère. Or voici que certains de ses pages refusaient de se

plier à ses désirs contre-nature sous prétexte que leur baptême leur faisait un

devoir de rester purs.

Le roi fit arrêter ceux

de ses pages qui étaient chrétiens, catholiques et protestants mélés dans le

même témoignage : une vingtaine, âgés de 13 à 30 ans, avec leur meneur Charles

Lwanga. Ils furent longuement torturés, mais sans qu'on pût les forcer à renier

leur baptême. Ils furent brûlés vifs, à petit feu, sur une colline afin qu'on

puisse les voir de loin, pour l'exemple. Un an plus tard, le nombre des

baptisés et des catéchumènes avait plus que triplé, signe de la fécondité de

leur martyre.

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/7140/Saint-Charles-Lwanga.html

Uganda

Martyrs Church in Munyonyo, Kampala built on the spot where future Uganda

Martyrs were imprisoned and taken for execution in Namugongo.

Shrine in Munyonyo constructed as thanksgiving for the canonisation of Uganda Martyrs

Saints Martyrs de

l'Ouganda

Charles Lwanga et ses 21

compagnons (+ 1886)

La liste de ces saints

sur le site Afrique Espoir.

Charles Lwanga, mort le 3

Juin 1886

Laïc - Converti par les

Pères Blancs, Charles Lwanga, serviteur du roi Mwanga d’Ouganda, fut baptisé en

novembre 1885 et brûlé vif au mois de juin de l’année suivante, à Namuyongo.

Martyr du Groupe des 22

martyrs de l'Ouganda

Les martyrs (†1885,

†1886, †1887) - les 22 martyrs de l’Ouganda. Martyrs de la persécution du roi

Mwanga de 1885 à 1887 durant laquelle périrent une centaine de jeunes

chrétiens, catholiques et anglicans. A cause de la prière et de la chasteté,

ils périrent dans d’atroces supplices, dont celui du feu.

Marchant à la mort Kizito

(13 ans) demandait à son aîné, Charles Lwanga: «Donne-moi la main: j’aurai

moins peur». Tous les deux ont été proclamés patrons de la jeunesse africaine.

Un autre, arrivant au

lieu du supplice, déclara : «C’est ici que nous verrons Jésus!».

Béatifiés par la brève de

Benoît XV le 6 juin 1920 (en italien), canonisés par Paul VI, le 18 octobre

1964 à Rome.

Album de la canonisation des

22 martyrs de l'Ouganda le 18 octobre 1964 - site des Pères Blancs : http://www.africamission-mafr.org/canonization_martyrs_uganda.htm

Mémoire des saints

Charles Lwanga et ses douze compagnons: les saints Mbaga Tuzindé, Bruno

Serunkerma, Jacques Buzabaliawo, Kizito, Ambroise Kibuka, Mgagga, Gyavira,

Achille Kiwanuka, Adolphe Ludigo Mkasa, Mukasa Kiriwawanvu, Anatole

Kiriggwajjo; Luc Banabakintu, martyrs en Ouganda l’an 1886. Âgés entre quatorze

et trente ans, ils faisaient partie du groupe des pages ou de la garde du roi

Mwanga. Néophytes et fermement attachés à la foi catholique, ils refusèrent de

se soumettre aux désirs impurs du roi et furent soit égorgés par l’épée, soit

jetés au feu sur la colline Nemugongo. Avec eux sont commémorés neuf autres:

les saints Joseph Mukasa Balikuddembe, Denis Sebuggwawo, André Kaggwa, Pontien

Ngondwe, Athanase Bazzekuketta, Gonzague Gonza, Matthias Kalemba, Noé Mawaggali,

Jean-Marie Muzei. qui subirent le martyre dans la même persécution, à des jours

différents, entre 1885 et 1889.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1267/Saints-Martyrs-de-l-Ouganda.html

LES SAINTS MARTYRS de

L'OUGANDA

(1885-1887)

Ces Saints habitaient une

contrée au milieu de l'Afrique, appelée Ouganda. Personne n'y avait jamais

prononcé le nom de Dieu et le démon y régnait par l'esclavage, la sorcellerie

et le cannibalisme. Deux Pères Blancs, le P. Lourdel et le P. Livinhac

débarquèrent un jour chez ces pauvres indigènes. Ils se présentèrent aussitôt

au roi Mutesa qui les accueillit pacifiquement et leur accorda droit de cité.

Les dévoués missionnaires

se faisaient tout à tous en rendant tous les services possibles. Sept mois à

peine après l'ouverture du catéchuménat, ils désignaient quelques sujets dignes

d'être préparés au baptême. Le roi Mutesa s'intéressait à ce que prêchait les

Pères, mais leur prédication alluma bientôt la colère des sorciers jaloux et

des Arabes qui pratiquaient le commerce des Noirs.

Pressentant la

persécution, les Pères Lourdel et Livinhac baptisèrent les indigènes déjà

préparés et se retirèrent au sud du lac Victoria avec quelques jeunes Noirs

qu'ils avaient rachetés. Comme la variole décimait la population de cette

contrée, les missionnaires baptisèrent un grand nombre d'enfants près de

mourir.

Après trois ans d'exil,

le roi Mutesa vint à mourir. Son fils Mwanga, favorable à la nouvelle religion,

rappela les Pères Blancs au pays. Le 12 juillet 1885, la population ougandaise

qui n'avait rien oublié des multiples bienfaits des missionnaires, accueillait

triomphalement les Pères Lourdel et Livinhac. Les Noirs qu'ils avaient baptisés

avant de partir, en avaient baptisé d'autres; l'apostolat s'avérait florissant.

Le ministre du nouveau roi prit ombrage du succès des chrétiens, surtout du

chef des pages, Joseph Mukasa, qui combattait leur immoralité.

Ami et confident du roi,

supérieurement doué, il aurait pu devenir le second personnage du royaume, mais

sa seule ambition était de réaliser en lui et autour de lui, les enseignements

du Christ. Le ministre persuada le jeune roi que les chrétiens voulaient

s'emparer de son trône; les sorciers insistaient pour que les prétendus

conspirateurs soient promptement punis de mort. Mwanga céda à ces fausses

accusations et fit brûler Joseph Mukasa, le 15 novembre 1885.

«Quand j'aurai tué

celui-là, dit le tyran, tous les autres auront peur et abandonneront la

religion des Pères.» Contrairement à ces prévisions, les conversions ne

cessèrent de se multiplier. La nuit qui suivit le martyre de Joseph, douze

catéchumènes sollicitèrent la grâce du baptême. Cent cinq autres catéchumènes

furent baptisés dans la semaine qui suivit la mort de Joseph, parmi lesquels

figuraient onze des futurs martyrs.

Le 25 mai 1886, six mois

après l'odieux meurtre de Joseph, le roi revenant de chasse fit appeler un de

ses pages, nommé Denis, âgé de quatorze ans. En l'interrogeant, Mwanga apprit

qu'il étudiait le catéchisme avec Muwafu, un jeune baptisé. Transporté de rage,

il l'égorgea avec sa lance empoisonnée. Les bourreaux l'achevèrent le lendemain

matin, 26 mai, jour où le despote déclara officiellement la persécution ouverte

contre les chrétiens.

Le même jour, Mwanga fit

mutiler et torturer le jeune Honorat, mit la congue au cou à un néophyte appelé

Jacques qui avait essayé autrefois de le convertir à la religion chrétienne.

Ensuite, il fit assembler tous les pages chrétiens et ordonna qu'on les amena

pour être brûlés vifs sur le bûcher de Namugongo. Jacques périt sur ce bûcher

en compagnie des autres martyrs, le 3 juin 1886, fête de l'Ascension.

«On avait lié ensemble

les jeunes de 18 à 25 ans, écrira le Père Lourdel; les enfants étaient

également liés, et si étroitement serrés les uns près des autres qu'ils ne

pouvaient marcher sans se heurter un peu. Je vis le petit Kizito rire de cette

bousculade comme s'il eût été en train de jouer avec ses compagnons.» Ils sont

en tout quinze catholiques. Trois seront graciés à la dernière minute. On

compte officiellement vingt-deux martyrs catholiques canonisés dont le martyre

s'échelonne de l'année 1885 à 1887.

Le groupe des condamnés

marchait vers le lieu de leur supplice, lorsqu'ils rencontrèrent un Noir nommé

Pontien. «Tu sais prier?» questionna le bourreau; sur la réponse affirmative de

Pontien, le bourreau lui trancha la tête d'un coup de lance. C'était le 26 mai

1886. Le soir venu, on immobilisa les martyrs dans une cangue et on ramena de

force à la maison, le fils du bourreau, au nombre des victimes. Après une

longue marche exténuante, doublée de mauvais traitements, les captifs

arrivèrent, le 27 mai, à Namugongo. Les bourreaux, au nombre d'une centaine,

répartirent les prisonniers entre eux.

Les cruels exécuteurs

travailleront jusqu'au 3 juin afin de rassembler tout le bois nécessaire au

bûcher. Les prisonniers doivent donc attendre six longues journées de

privations et de souffrances, nuits de froid et d'insomnie, mais plus encore

d'ardentes prières, avant que la mort ne vienne couronner leur héroïque combat.

Le martèlement frénétique des tam-tams qui se fit entendre toute la nuit du 2

juin indiqua aux martyrs qui languissaient, garottés dans des huttes, que

l'immense brasier de leur suprême holocauste s'allumerait très bientôt.

Charles Lwanga,

magnifique athlète d'une vigueur peu commune, à qui le roi avait confié un

groupe de pages auxquels il avait enseigné le catéchisme en cachette, fut

séparé de ses compagnons afin d'être brûlé à part, d'une manière

particulièrement atroce. Le bourreau alluma les branchages de manière à ne

brûler d'abord que les pieds de sa victime. «Tu me brûles, dit Charles, mais c'est

comme si tu versais de l'eau pour me laver!» Lorsque les flammes attaquèrent la

région du coeur, avant d'expirer, Charles murmura: «Mon Dieu! mon Dieu!»

Comme le groupe des

martyrs avançait vers le bûcher, un cri de triomphe retentit: Nwaga, le fils du

chef des bourreaux, avait réussi à s'enfuir de la maison pour voler au martyre!

Il bondissait de joie en se retrouvant dans la compagnie de ses amis. On

l'assomma d'abord d'un coup de massue, puis il fut roulé avec les autres dans

des claies de roseaux pour devenir dans un instant la proie des flammes.

Après leur avoir brûlé

les pieds, ils reçurent la promesse d'une prompte délivrance s'ils renonçaient

à la prière. Mais ces héros ne craignaient pas la mort de leur corps et devant

leur refus catégorique d'apostasier, on commença à incendier le bûcher.

Par-dessus le crépitement du brasier et les clameurs des bourreaux

sanguinaires, la prière des saints martyrs s'éleva calme, ardente et sereine:

«Notre Père qui êtes aux cieux...» On sut qu'ils étaient morts lorsqu'ils

cessèrent de prier.

Le dernier des martyrs

s'appelait Jean-Marie. Longtemps obligé de se cacher, las de sa vie vagabonde,

il désirait ardemment mourir pour sa foi. Malgré les conseils de ses amis qui

essayaient de le dissuader de ce projet, Jean-Marie résolut d'aller voir le roi

Mwanga. Nul ne le revit plus jamais, car le 27 janvier 1887, Mwanga le fit

décapiter et jeter dans un étang.

La dévotion populaire aux

martyrs de l'Ouganda prit un essor universel, après que saint Pie X les proclama

Vénérables, le 16 août 1912. Leur béatification eut lieu le 6 juin 1920 et ils

reçurent les honneurs de la canonisation, le 18 octobre 1964.

Tiré de Marteau de Langle

de Cary, 1959, tome II, p. 305-308 -- Vivante Afrique, No 234 - Bimestriel

- Sept - Oct. – 1964

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/les_saints_martyrs_de_l_ouganda.html

Monument at Munyonyo Martyrs Shrine marking the spot from where future martyrs walked for death

Le pays de l’Ouganda se

situe en Afrique du centre-est, au sud du Soudan, à l’est du Zaïre et du

Rwanda, bordé par une grappe de grands lacs, dont l’immense Lac Victoria, qui

touche l’Ouganda, le Kenya, la Tanzanie. Ce beau pays est à peu près grand

comme la moitié de la France, et compte actuellement une trentaine de millions

d’habitants. Pays agricole essentiellement, grâce à un climat tempéré qui ne

connaît pas de températures en-dessous de 13° ni au-dessus de 30°, on y vit

d’élevage et de cultures diverses : banane, patate, manioc, café, thé, canne à

sucre, tabac.

Les premiers

missionnaires y arrivèrent en 1879 et furent très bien reçus. Mais le kabaka

(le roi) en prit ensuite ombrage ; son successeur, Mouanga, rappela les

missionnaires, et soutint ouvertement le travail des missionnaires, nommant aux

charges les meilleurs des néophytes.

Ceux-ci avertirent le roi

qu’une conspiration se tramait contre lui ; il arrêta son katikiro (premier

ministre), qui lui mentit en protestant de sa fidélité ; pardonné, ce dernier

jura la mort des chrétiens et s’ingénia à les faire mépriser du roi comme

dangereux, conspirateurs, etc. La toute première victime fut le conseiller

intime du roi, Joseph Mkasa, qui était aimé de tous. Même le bourreau cherchait

à retarder de l’exécuter, mais il reçut l’ordre du katikiro de le tuer sur place

; il fut ainsi décapité, avec deux ou trois pages de la cour.

Auparavant, Joseph, très

calmement, confia au bourreau cette commission : “Tu diras de ma part à Mouanga

qu’il m’a condamné injustement, mais que je lui pardonne de bon cœur. Tu

ajouteras que je lui conseille fort de se repentir, car, s’il ne se repent, il

aura à plaider avec moi au tribunal de Dieu”.

Quelques mois plus tard,

le roi transperce de sa lance le jeune Denis Sebuggwawo, qui était en train

d’instruire un compagnon. Ce fut le signal de la persécution proprement dite :

désormais devront être massacrés “tous ceux qui prient”. C’était le 25 mai

1886. Un chrétien courut de nuit avertir les missionnaires de ce qui s’était

passé et qui allait se produire, de sorte que l’un d’eux, le père Lourdel, vite

accouru, fut lui-même témoin des faits suivants, à l’intérieur de la résidence

royale.

Charles Lwanga, chef du

groupe des pages, est appelé le premier avec sa bande ; ils reçoivent une pluie

de reproches sur leur religion, puis sont enlacés de grosses cordes, d’un côté

le groupe des jeunes de dix-huit à vingt-cinq ans, de l’autre les enfants.

Charles et Kizito se tiennent par la main, pour s’encourager l’un l’autre à ne

pas faiblir ; Kizito, quatorze ans, demande le baptême depuis longtemps, et le

père Lourdel lui avait enfin promis de le baptiser dans un mois ; en fait, il

sera baptisé en prison, la veille de son martyre. C’est le plus jeune de tous

ces martyrs.

Après les employés de la

cour, on convoque un jeune soldat, Jacques Buzabaliawo. Le roi ironise sur lui

et ajoute : “C’est celui-là qui a voulu autrefois me faire embrasser la

religion ! … Bourreaux, enlevez-le et tuez-le bien vite. C’est par lui que je veux

commencer.” A quoi Jacques répond sans s’émouvoir : “Adieu ! je m’en vais

là-haut, au paradis, prier Dieu pour toi.” Passant devant le père, il lève ses

mains enchaînées vers le ciel, souriant comme s’il allait à une fête.

Inquiet pour la mission,

le père revient sur ses pas ; apercevant une source où se désaltérer, il

s’entend dire : “Le cadavre d’une des victimes de la nuit a été traîné dans

cette eau.” Car des pillards avaient été lancés dans toute la contrée pour

saccager les villages où se trouvaient des chrétiens.

André Kaggwa était un

chef parmi les plus influents et les plus fidèles au roi. C’était l’un des

trois qui l’avaient en effet averti de la conspiration qui le menaçait. Il

devait devenir le général en chef de toute l’armée, car le roi avait en lui une

confiance absolue, le gardant toujours à ses côtés. Le premier ministre le

dénonça bientôt comme le plus dangereux de tous, et, de guerre lasse, le roi

finit par le laisser faire ce qu’il voulait. Immédiatement garrotté, André est

“interrogé” et le premier ministre insiste auprès du bourreau : “Je ne mangerai

pas que tu ne m’aies apporté sa main coupée, comme preuve de sa mort”. Et

André, au bourreau : “Hâte-toi d’accomplir les ordres que tu viens de recevoir…

Tue-moi donc vite, pour t’épargner les reproches du ministre. Tu lui porteras

ma main, puisqu’il ne peut manger avant de l’avoir vue.”

Charles Lwanga fut séparé

des autres, sans doute dans le but de les impressionner davantage. Le bourreau

le fit brûler lentement, en commençant par les pieds et en le méprisant : “Que

Dieu vienne et te retire du brasier !”. Mais Charles lui répondit bravement :

“Pauvre insensé ! Tu ne sais pas ce que tu dis. En ce moment c’est de l’eau que

tu verses sur mon corps, mais pour toi, le Dieu que tu insultes te plongera un

jour dans le véritable feu.” Après quoi, recueilli en prière, il supporta son

long supplice sans proférer aucune plainte.

Il y avait là aussi trois

jeunes pages, qu’on fit assister au supplice des autres, dans l’espoir de les

voir apostasier. Non seulement ils ne cédèrent pas, mais l’un deux protesta de

ne pas être enfermé dans un fagot comme les autres pour être brûlé ; puis quand

on les reconduisit tous trois en prison sans les torturer, ils demandèrent :

“Pourquoi ne pas nous tuer ? Nous sommes chrétiens aussi bien que ceux que vous

venez de brûler ; nous n’avons pas renoncé à notre religion, nous n’y

renoncerons jamais. Inutile de nous remettre à plus tard.” Mais le bourreau fut

sourd à leurs plaintes, sans doute par permission de Dieu, pour que ces

trois-là nous fournissent ensuite les détails du martyre de tous les autres.

Parmi les condamnés se

trouvait le propre fils du bourreau, le jeune catéchumène Mbaga. Son père était

désespéré et cherchait par tous les moyens de le faire changer d’avis, ou de

lui extorquer un mot qu’on aurait pu interpréter comme une apostasie ; inutile.

L’enfant ajoute même : “Père, tu n’es que l’esclave du roi. Il t’a ordonné de

me tuer : si tu ne me tues pas, tu t’attireras des désagréments et je veux te les

épargner. Je connais la cause de ma mort : c’est la religion. Père, tue-moi !”

Alors le père ordonne à un de ses hommes de lui accorder la mort des “amis”, en

lui assénant un fort coup de bâton à la nuque. Puis le corps fut enfermé dans

un fagot de roseaux, au milieu des autres.

On enferma donc chacun

des condamnés dans un fagot, et l’on y mit le feu du côté des pieds, pour faire

durer plus longtemps le supplice, et aussi pour tenter de faire apostasier ces

garçons. En fait, s’ils ouvrent la bouche, c’est pour prier. Une demi-heure

après, les roseaux étaient consumés, laissant à terre une rangée de cadavres à

moitié brûlés et couverts de cendres.

Un autre chrétien qui fut

arrêté, fut le juge de paix Mathias Mulumba ; il avait connu l’Islam puis le

protestantisme ; devenu catholique, c’était un homme très pieux qui vivait

paisiblement avec son épouse et ses enfants. Amené devant le premier ministre,

il répondait calmement aux vilaines questions qu’il lui posait. Furieux, le

ministre crie : “Emmenez-le, tuez-le. Vous lui couperez les pieds et les mains,

et lui enlèverez des lanières de chair sur le dos. Vous les ferez griller sous

ses yeux. Dieu le délivrera !” Mathias, blessé par cette injure faite à Dieu,

répond : “Oui, Dieu me délivrera, mais vous ne verrez pas comment il le fera ;

car il prendra avec lui mon être raisonnable, et ne vous laissera entre les

mains que l’enveloppe mortelle.” Le bourreau accomplit scrupuleusement les

ordres reçus : de sa hache, il coupe les pieds et les mains de Mathias, les fait

griller sous ses yeux ; l’ayant fait coucher face contre terre, il lui fait

enlever des lanières de chair qu’ils grillent ensuite, usant de tout leur art

pour empêcher l’écoulement du sang, et prolonger ainsi l’agonie de leur

victime, qui ne proféra mot. Effectivement, trois jours après, d’autres

esclaves passaient par là et entendirent des gémissements : c’était Mathias qui

demandait un peu d’eau à boire ; mais épouvantés par l’horrible spectacle, ils

s’enfuirent, le laissant consommer atrocement son martyre.

Avec lui fut aussi

conduit au supplice un de ses amis, Luc Banabakintu, qui eut “seulement” la

tête tranchée.

Pendant ces exécutions,

des pillards allèrent s’emparer du peu qu’il y avait à voler chez Mathias et

voulurent ravir son épouse et ses enfants. Il y avait là un serviteur très

fidèle et pieux, Noé Mawaggali. Son chef n’eut pas le courage de le refuser aux

pillards, qui le percèrent de leurs lances.

La sœur de ce dernier

fallit être ravie par le chef des pillards, mais elle leur parla très fermement

: “Vous avez tué mon frère parce qu’il priait ; je prie comme lui, tuez-moi

donc aussi.” Au contraire, ils l’épargnèrent et la conduisirent en cachette

chez les missionnaires, où elle s’occupa maternellement des enfants de Mathias,

dont l’un n’avait que deux ans.

Il y eut aussi

Jean-Marie, surnommé Muzéï, “vieillard”, à cause de la maturité de son

caractère. Baptisé à la Toussaint de 1885, on disait qu’il avait appris tout le

catéchisme en un jour. Il donnait aux pauvres, s’occupait des malades,

rachetait des captifs. Confirmé le 3 juin 1886, il fut noyé dans un étang le 27

janvier 1887.

Tels sont les plus

marquants des vingt-deux martyrs ougandais, qui furent béatifiés en 1920, et

canonisés en 1964. Ils sont fêtés le 3 juin, jour du martyre de la majeure

partie d’entre eux. Voici maintenant les noms de ces vaillants soldats du

Christ, avec l’indication de leur prénom dans leur langue propre et la date

respective de leur martyre :

Joseph (Yosefu) Mukasa

Balikuddembe, chef des pages, décapité puis brûlé, martyrisé le 15 novembre

1885

Denis Ssebuggwawo Wasswa,

première victime de la grande persécution, martyrisé le 25 mai 1886

André (Anderea) Kaggwa,

page, celui qui devait être le général en chef du roi ; le bourreau lui trancha

le poignet et la tête ; martyrisé le 26 mai 1886

Pontien (Ponsiano)

Ngondwé, page, mis en prison, percé de coups de lance, martyrisé le 26 mai 1886

Gonzague Gonza, page du

roi, percé d’une lance après avoir forcé l’admiration du bourreau lui-même,

martyrisé le 27 mai 1886

Athanase (Antanansio)

Bazzekuketta, page, accablé de coups, martyrisé le 27 mai 1886

Mathias (Matiya) Kalemba

Mulumba Wante, dont on a parlé plus haut, martyrisé le 30 mai 1886

Noé (Nowa) Mawaggali,

martyrisé le 31 mai 1886

Les treize suivants sont

tous martyrisés le 3 juin 1886, tous brûlés vifs :

Charles (Karoli) Lwanga

Bruno Serunkuma, soldat

du roi, roué de coups de bâton

Mugagga Lubowa, qui s’est

offert spontanément aux bourreaux

Jacques (Yakobo)

Buzabaliawo, soldat, qu’on entendit prier pour ses persécuteurs

Kizito, le benjamin de

quatorze ans

Ambroise (Ambrosio)

Kibuka, page

Gyavira Musoke, page,

catéchumène, jeté en prison le jour même où Charles le baptiza

Achille (Achileo)

Kiwanuka, page

Adolphe (Adolofu) Mukasa

Ludigo, page

Mukasa Kiriwawanvu, page

et catéchumène

Anatole (Anatoli)

Kiriggwajjo, page, qui refusa la charge honorifique proposée par le roi

Mbaga Tuzinde, page, fils

du bourreau, baptisé par Charles juste avant d’être enchaîné avec lui, roué de

coups, assommé avant d’être brûlé.

Luc (Lukka) Banabakintu,

décapité puis brûlé

Enfin :

Jean-Marie (Yohana Maria)

Muzeyi, saint homme, longtemps recherché, arrêté, décapité le 27 janvier 1887.

C’est la dernière victime de la persécution.

On aurait pu croire que

le christianisme aurait été ainsi dangereusement menacé d’extinction. Il n’en

fut rien. Trente ans après, l’évêque du lieu pouvait compter sur 88 prêtres, 11

frères coadjuteurs, 38 Religieuses et 1244 (!) catéchistes.

Actuellement, la religion

catholique y est majoritaire à 45 %, suivie de l’anglicanisme (39 %) et de

l’Islam (10%).

Bruno Kiefer

SOURCE : http://alexandrina.balasar.free.fr/martyrs_ouganda.htm

Uganda

Martyrs Catholic Shrine Namugongo. The photo depicts how the martyrs died. The

metallic pillars covering the church depicts the fire woods that were used to

burn the martyrs

Les pages martyrs de

l’Ouganda

Auteur : Daniel-Rops | Ouvrage : Légende dorée de mes filleuls .

— Non, je ne trahirai pas

le serment de mon baptême ! Non, je n’accepterai pas de revenir aux

idoles, aux fétiches ! Non, non… je préfère mourir !

À quel moment de

l’histoire sommes-nous donc ? À Rome, à l’époque des

grandes persécutions, et cette jeune voix qui proclame ainsi sa foi, est-ce

celle d’un frère de sainte Agnès, de sainte Blandine ; celle d’un martyr

du IIIe ou du IVe siècle ? Nullement, nous sommes en plein XIXe siècle. Il

y a environ soixante-cinq ans. Et où donc ? Regardez.

Les jeunes enfants sont

noirs, absolument noirs, oui de jeunes nègres de quatorze ou quinze ans.

Alignés les uns à côté des autres, une quarantaine, ils sont enfermés dans

des cages en bambous ; leur cou est pris dans une fourche et de lourdes

pièces de bois leur emprisonnent un pied et un poignet. Devant eux s’agitent

des sortes de monstres grotesques et horribles en grand nombre ; le visage

enduit d’argile rouge, zébré de traînées de suie, la tête hérissée de plumes,

des peaux de bêtes attachées autour des reins, un collier d’ossements battant

sur la poitrine et des grelots tintant à leurs chevilles, ce sont des

sorciers. Mais leurs gesticulations menaçantes, leurs cris, leurs chants

sauvages, pas plus que les préparatifs du grand bûcher qu’on élève non loin de

là, rien ne peut faire fléchir le courage de ces jeunes héros du Christ.

Ils mourront tous, sans

un moment de faiblesse, sans qu’un seul abandonne la foi et trahisse. Cette

histoire des petits martyrs de l’Ouganda est un des plus beaux chapitres de

toute la grande histoire de l’Église… Écoutez-la !

* * *

L’immense continent noir,

l’Afrique, a été pénétré par le Christianisme surtout depuis un siècle… Et

cette pénétration a été l’œuvre d’hommes admirables, les Missionnaires,

prêtres et moines d’un dévouement sans trêve, d’un courage à toute

épreuve, d’une merveilleuse bonté. Aussi braves quand il s’agit d’aller, en des

pays hostiles, parmi des peuples encore sauvages, pour y semer la bonne

parole du Christ, l’Évangile, que patients et bons organisateurs quand il

s’agit ensuite de vivre au milieu des noirs, pour leur apporter non seulement

l’enseignement chrétien, mais toutes sortes de secours, les missionnaires ont

été, dans toute l’Afrique, de véritables conquérants pacifiques qui, sans

armes, ont gagné à la civilisation des espaces géants. Aujourd’hui, il

n’est contrée si lointaine, si perdue, qui n’ait ses Missionnaires. Au Père,

les indigènes viennent demander tout : un conseil, un médicament, une

protection. Si l’Église a désormais des milliers de fidèles dans le

continent noir, c’est aux Missionnaires que ce grand succès est dû.

Parmi ceux qui ont

participé le mieux à cette grande tâche se trouvent au premier rang les

Pères Blancs. Ils ont été fondés par un homme de génie, le Cardinal Lavigerie,

tout exprès pour vivre la même vie que les indigènes, s’habillant comme eux, parlant

leur langue, aidés aussi par les Sœurs Blanches qui, vivant de la même façon,

s’occupent spécialement des femmes et des enfants. « II y a là-bas

cent millions d’êtres humains qui attendent le Christ ; je veux les donner

à Lui ! » s’était écrié un jour Lavigerie devant le Pape Pie IX. Et,

fidèles à cette promesse, Pères blancs et Sœurs blanches n’ont pas cessé,

depuis lors, de travailler à sa réalisation.

Vers 1880, les Pères

blancs avaient pénétré dans l’Ouganda. Savez-vous où se trouve, sur la carte

d’Afrique, ce pays ? Regardez au sud du Soudan et de l’Éthiopie,

c’est-à-dire à l’est du continent. Là s’étend un immense plateau, grand

à peu près comme la France, que domine la puissante masse du volcan Elgon.

Une magnifique nappe d’eau, le lac Victoria, — si vaste qu’il s’y produit de

petites marées,— en occupe le sud, et c’est de ce lac que sort une des deux

rivières qui, en s’unissant, vont former le Nil. Ce haut plateau, où le climat

est frais, où les pluies sont suffisantes sans être excessives, ne manque pas

de richesses : bananiers, épices, café, maïs, sorgho, bœufs et moutons

y font vivre à l’aise une population qui se développe. Cette

population est formée de nègres ; des nègres intelligents, travailleurs,

qu’on appelle « bantous ».

Comme la presque totalité

des nègres d’Afrique, les bantous de l’Ouganda étaient, il y a

quatre-vingts ans, fétichistes, c’est-à-dire qu’ils adoraient des sortes de

divinités grossières représentées par des pieux sculptés, des idoles

nombreuses, auxquels ils faisaient des sacrifices sanglants. Cependant les

Arabes de la côte exerçaient sur eux une certaine influence et cherchaient

à les gagner à leur religion : l’Islam, la doctrine de Mahomet.

Aussi, pour les missionnaires du Christ, la situation n’était-elle pas commode.

* * *

Et cependant, ils

réussirent d’éclatante façon. Après moins de cinq ans d’évangélisation, dans

maints districts de l’Ouganda des groupes de chrétiens se formèrent,

extrêmement fervents et dévoués. En certaines bourgades, on en comptait deux

cent cinquante et davantage. Leur nombre croissait de mois en mois. Avant même

d’avoir reçu le baptême, les catéchumènes commençaient déjà à faire de la

propagande parmi leurs amis, dans leurs familles, et il n’était guère d’entre

eux qui n’amenât avec lui une nouvelle recrue.

Bientôt même, il

y eut des chrétiens dans l’entourage du roi, parmi les jeunes gens des

meilleures familles qui servaient autour de lui comme autrefois, chez les rois

d’Europe, servaient les pages. Le chef des pages, quelque chose comme le

régisseur du Palais royal, Charles Louanga, étant devenu chrétien, un grand

nombre des pages l’avaient suivi. Et ainsi, à deux pas du roitelet, encore

fétichiste, on célébrait les cérémonies chrétiennes avec foi.

Or ce roi, nommé Mouanga,

était un garçon jeune, violent, qui se laissait aller à de terribles

mouvements de colère et qui, de plus, était fort influençable : ceux qui

avaient sa confiance lui faisaient faire à peu près tout ce qu’ils

voulaient. À cette époque, celui qui avait toute sa confiance était son

premier ministre, lequel haïssait Charles Louanga et les chrétiens. En toute

occasion, il répétait au roitelet que ces missionnaires n’étaient que des

agents chargés par les Blancs de ruiner son autorité, que, s’il les laissait

continuer leur propagande, il verrait bientôt les Anglais, les Français, les

Allemands envahir ses États, venant de toutes les directions. Et les

commerçants arabes auxquels l’Ouganda vendait ses marchandises, répétaient

au triste Mouanga qu’il ferait bien mieux d’embrasser la religion de Mahomet.

Au début, Mouanga hésita.

Un jour, il annonça qu’il allait faire de l’Islam la religion obligatoire de

tous ses sujets ; mais un des Pères Blancs qui vivaient dans le pays se

présenta devant lui avec courage et réclama le droit pour tous de prier Dieu de

la façon qui lui plairait, et il obtint gain de cause. Mouanga n’osait pas

s’attaquer aux Blancs, de peur de provoquer une expédition d’une puissance

européenne. Seulement, il n’en mûrissait pas moins sa colère contre ceux de son

peuple qui avaient accepté le baptême. Un jour cette colère éclata.

* * *

À l’automne de 1885,

dans un accès de fureur, il fit brûler vif un de ses conseillers, Joseph

Moukassa, qui était chrétien. En mourant, le martyr avait prononcé des paroles sublimes,

celles de Jésus sur la croix : « Allez dire à Mouanga que je lui

pardonne de tout mon cœur et que je lui conseille de se repentir. » Ce

supplice, au lieu d’effrayer les chrétiens, n’avait fait qu’exalter leur

courage. La situation était si tendue que les Pères Blancs, avant de donner le

baptême à ceux qui le demandaient, leur disaient très franchement qu’ils

risquaient leur vie, qu’il fallait bien réfléchir avant de recevoir l’Eau

Sainte du sacrement. Mais le nombre des baptisés n’en croissait pas moins,

très vite.

Parmi les pages, c’était

une véritable émulation à qui se montrerait meilleur chrétien ! Sans

cesse des groupes de ces jeunes gens, à qui l’excellent Charles Louanga

avait parlé du Christ et de la vérité chrétienne, arrivaient chez les missionnaires

et demandaient à être baptisés. Le souvenir de leur martyr, de Joseph

Moukassa, les exaltait dans leur détermination. Une fois c’étaient vingt-deux

baptêmes, une autre fois quinze. Tant et si bien que presque tous les pages du

roi furent chrétiens.

Celui-ci, bien entendu,

ne l’ignorait pas. Un jour, comme il passait en revue le bataillon des pages,

le petit despote cria : « Que ceux qui ne prient pas avec les Blancs

sortent des rangs ! » II y en eut trois seulement. Tous les autres

étaient baptisés ou avaient résolu de l’être. Le roi entra dans une de ces

fureurs terribles dont il avait le secret. Il ordonna au premier ministre

d’enfermer tous ces jeunes gens dans un camp, bien gardé par des sentinelles,

en attendant qu’il eût décidé de leur sort. Et il se mit à hurler :

« II faut que je me débarrasse de ces scélérats qui veulent me

détrôner ! Il faut que je les massacre tous ! » Et comme une de ses

sœurs essayait d’implorer leur grâce, il saisit un des jeunes pages dont on lui

avait dit qu’il apprenait le catéchisme et il le tua de sa propre main.

Durant des mois, de longs

et sévères mois, les pages furent maintenus dans le camp de concentration,

à peine nourris, menacés sans cesse. Tous les jours on leur annonçait

qu’ils allaient être torturés, brûlés vifs, déchiquetés, jetés aux fauves.

Aucun ne fléchit. Derrière les grilles de bambous, ils priaient tous ensemble

et leur grand chef, le bon Charles Louanga, baptisait même, dans le camp,

quatre d’entre eux qui n’avaient pas encore reçu l’Eau Sainte avant d’être

arrêtés.

Quand il apprit cette

nouvelle, le roi fut au comble de l’exaspération. Il réunit son conseil et

annonça que les jeunes pages qui persisteraient à être chrétiens

mourraient. Il était si menaçant que les parents mêmes de la plupart des pages

se soumirent, épouvantés, et s’écrièrent : « Roi, tues-les donc, ces

enfants ingrats et rebelles ! Nous t’en donnerons d’autres ! »

« Qu’ils meurent tous ! » cria le roitelet. Et se tournant vers les

petits chrétiens, il ajouta avec un rire sinistre : « Allez manger

votre vache chez votre Père du ciel ! »

Mais, même devant la

menace imminente de la mort, aucun ne trahit. Tous déclarèrent qu’ils

préféraient le supplice au parjure. Il y avait parmi eux le petit Mbaga,

âgé de quatorze ans, le fils du bourreau en chef, à qui son père proposa

de le faire fuir et qui refusa, à qui sa mère demanda, avec des

supplications, de déclarer qu’il ne priait plus avec les Blancs, et qui refusa

encore… Ces enfants héroïques n’étaient-ils pas dignes des martyrs de jadis ?

* * *

Leur mort fut aussi

admirable. On commença par les emmener, à pied, enchaînés, entravés,

à plus de soixante kilomètres de la capitale, en pleine forêt, — sans

doute de peur que le spectacle de toutes ces jeunes victimes exaspérât la

passion du peuple et provoquât une révolte. Ceux qui, le long de cette dure

route, se montrèrent trop faibles, ceux qui tombèrent, ceux dont les chevilles

enflèrent, furent abattus d’un coup de sagaie, sur place. La nuit, on les

attachait encore davantage, on les enfermait dans les cages de bambou. Comme

s’ils avaient eu envie de fuir ! Ils ne faisaient que chanter des

cantiques et trois d’entre eux, qui avaient eu l’occasion de s’enfuir, étaient

revenus rejoindre leurs camarades, volontairement.

Arrivés au lieu du supplice,

en vue du bûcher gigantesque sur lequel ils devaient périr, une fois encore

invités à renier leur foi chrétienne, ils refusèrent, tous, sans aucune

exception. « Qu’on vous rôtisse, criait un des bourreaux, pour voir si

votre Dieu sera assez fort pour venir vous délivrer ! »

Et l’un des jeunes pages,

Bruno, répondait avec calme : « Vous pouvez bien brûler notre corps.

Notre âme, vous ne la brûlerez pas. Elle ira en Paradis. »

Et la funèbre cérémonie

commença. L’un après l’autre, on enfermait les martyrs dans une claie de

roseaux, puis on les portait sur le bûcher, comme de vivants fagots. Quand vint

le tour du petit Mbaga, son père, le chef des bourreaux, n’eut quand même pas

le triste courage de faire brûler son enfant tout vivant : il l’emmena

à l’écart et l’abattit d’un coup de massue. Puis la flamme jaillit et l’on

entendit de grands cris, des chants d’actions de grâces qui se mêlèrent au

tam-tam effréné des sorciers indigènes dansant autour du bûcher : les

petits martyrs de l’Ouganda avaient donné leur vie pour le Christ.

* * *

Ainsi le temps de

l’héroïsme n’est-il pas fini dans l’Église. Ainsi, comme aux jours où, dans les

amphithéâtres de Rome, les martyrs d’autrefois mouraient sous la dent des

bêtes, des enfants ont donné l’exemple.

Des martyrs, d’aussi

admirables figures, on en connaît bien d’autres à notre époque. Il

y en eut en Indochine au siècle passé, où plus de trente missionnaires

moururent dans d’affreux supplices pour avoir voulu porter à l’Asie la

parole de vérité. Il y en eut dans maints pays, le Mexique, par exemple,

où des persécutions éclatèrent, où des prêtres furent pourchassés, où l’Église

dut se cacher comme à l’époque des Catacombes. Il y en

a certainement à cette heure même… Et l’on peut être bien convaincu

que si, un jour, une persécution religieuse éclatait chez nous, — ce qu’à Dieu

ne plaise ! — innombrables seraient ceux qui préféreraient la mort

à la trahison.

Sacrifices héroïques,

indispensables, qui ne cessent de travailler à accroître l’Église et

à préparer les voies de Dieu ! Vous vous souvenez du mot d’un

écrivain chrétien du IVe siècle : « Le sang des martyrs est la

semence des chrétiens ! » Partout où il y a eu des martyrs, il est

bien vrai que le bon grain a germé, que les moissons ont été magnifiques.

Ainsi en a‑t-il été en Afrique Orientale, où les jeunes saints de l’Ouganda

ont, au ciel, imploré le Seigneur pour leurs parents et ont été écoutés. Le

Saint Père les a proclamés Saints et la cathédrale de Roubaga, dans leur

patrie, leur rend un culte. Aujourd’hui, l’Ouganda, sur deux millions

d’habitants, a près de six cent mille baptisés, et un clergé indigène,

prêtres et religieuses, travaille à convertir le reste de leurs frères.

Puissance de l’exemple ! Leçon du sacrifice ! Le sang des pages héroïques,

ici comme partout et toujours, a vraiment ensemencé des chrétiens !

SOURCE : https://www.maintenantunehistoire.fr/les-pages-martyrs-de-louganda/

Saint Kizito baptisé par saint Charles

Lwanga. Cathédrale Sainte-Marie de Kampala.

Stained

glass at Munyonyo Martyrs Shrine Church (Kampala) at place were St. Kizito was

baptised.

Also

known as

Carolus Lwanga

Karoli Lwanga

Profile

Ngabi clan. Servant of King Mwanga

of Uganda. Convert,

joining the Church in

June 1885.

One of the Martyrs

of Uganda who died in

the Mwangan persecutions.

Born

1865 at

Bulimu, Buganda, Uganda

burned

to death on 3 June 1886 at

Namugongo, Uganda

29 February 1920 by Pope Benedict

XV (decree of martyrdom)

6 June 1920 by Pope Benedict

XV

18 October 1964 by Pope Paul

VI at Rome, Italy

African

Catholic Youth Action (proclaimed by Pope Pius XII on 23 June 1950)

Additional

Information

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

audio

video

fonti

in italiano

Dicastero delle Cause dei Santi

Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

Readings

It is as if you are

pouring water on me. Please repent and become a Christian like me. – Saint

Charles Lwanga as he was being burned

MLA

Citation

“Saint Charles

Lwanga“. CatholicSaints.Info. 13 April 2024. Web. 2 June 2024. <https://catholicsaints.info/saint-charles-lwanga/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-charles-lwanga/

HOMILY OF HIS HOLINESS

JOHN PAUL II

Kampala (Uganda)

Sunday, 7 February 1993

Baana bange abaagalwa,

Mbalamusizza mwenna.

Mwebale okujja.

Katonda Kitaffe tumugulumize.

(My beloved sons and

daughters,

I greet you all.

Thanks for coming.

Let us praise God our Father).

"The effects of the

light are seen in complete goodness and right living and truth" (Eph.

5: 9).

1. Today is Sunday. Jesus

Christ, the Light of the world (Cf. Jn. 8: 12), is risen from the

dead! At the Shrine of the Holy Martyrs of Uganda, we have gathered to

celebrate Christ the Light of the world.

Christ’s Resurrection

fulfilled the words spoken to the Holy City Jerusalem by the Prophet Isaiah:

"Your light has come, the glory of the Lord is rising on you... above you

the Lord now rises and above you his glory appears" (Is. 60: 1-2).

Isaiah then said: "The

nations come to your light... your sons from far away" (Ibid. 60:

3-4). Yes. From far away the nations have come: from countless lands and

peoples of the earth. For two thousand years. You too have come, people of

Uganda, sons and daughters of Africa. You too have seen the light of Christ’s

Resurrection. The light which produces "complete goodness and right living

and truth".

2. This is the place

where Christ’s light shone on your land with a particular splendour. This was

the place of darkness, Namugongo, where Christ’s light shone bright in the

great fire which consumed Saint Charles Lwanga and his companions. May the

light of that holocaust never cease to shine in Africa!

The heroic sacrifice of

the Martyrs helped to draw Uganda and all of Africa to Christ, the true light

which enlightens all men (Cf. ibid. 1: 9). Men and women of every race,

language, people and nation (Cf. Rev. 5: 9) have answered Christ’s call,

have followed him and have become members of his Church, like the crowds which

come on pilgrimage, year after year, to Namugongo.

Today, the Bishop of

Rome, the Successor of Saint Peter, has also come on pilgrimage to the Shrine

of the Holy Uganda Martyrs. Following in the footsteps of Pope Paul VI, who

raised these sons of your land to the glory of the altars and later was the

first Pope to visit Africa, I too wish to plant a special kiss of peace on this

holy ground.

From this place I am

pleased to greet the President of the Republic of Uganda and the

representatives of the Government who honour us by their presence.

I greet all the members

of the Church in Uganda. I rejoice to greet Archbishop Emmanuel Wamala and

all my Brother Bishops of Uganda, particularly the Bishops of the South: Bishop

Adrian Ddungu of Masaka, Bishop Joseph Willigers of Jinja and Bishop Joseph

Mukwaya of Kiyinda–Mityana. I also welcome all the Cardinals and Bishops who

have come from other countries to take part in this celebration. I greet the priests

and the men and women Religious who have devoted their lives to serving

their brothers and sisters in the faith. Today too my greetings go in a

special way to Uganda’s lay faithful. I embrace you with love in the Lord

Jesus. You are the heirs of the strong and faithful lay leaders with which the

Church in Uganda was blessed from the beginning.

3. "You were

darkness once", Saint Paul told the Ephesians, "but now you are light

in the Lord" (Eph. 5: 8).

How eloquent were the

words of Pope Paul VI in his homily at the canonization of the Uganda Martyrs!

"Who could

foresee", the Pope asked, "that with the great historical figures of

African martyrs and confessors like Cyprian, Felicity and Perpetua and the

outstanding Augustine, we should one day list the beloved names of Charles

Lwanga, Matthias Mulumba Kalemba and their twenty companions?" (Paul

VI, Homily on the occasion of the canonization of the Uganda Martyrs, 18

October 1964).

Truly the Uganda

Martyrs became light in the Lord! Their sacrifice hastened the rebirth of

the Church in Africa. In our own days, all Africa is being called to the

light of Christ! Africa is being called again to discover her true

identity in the light of faith in the Son of God. All that is truly African,

all that is true and good and noble in Africa’s traditions and cultures, is

meant to find its fulfilment in Christ. The Uganda Martyrs show this clearly:

they were the truest of Africans, worthy heirs of the virtues of their

ancestors. In embracing Jesus Christ, they opened the door of faith to their

own people (Cf. Acts. 14: 27), so that the glory of the Lord could shine on

Uganda, on Africa.

4. Here at Namugongo, it

is right that we give thanks to God for all those who have worked and prayed

and shed their blood for the rebirth of the Church on this Continent. We give

thanks for all who have carried on the work of the Martyrs by striving to build

a Church that is truly Catholic and truly African.

In the first place, I

wish to acknowledge the outstanding service provided by your catechists.

In recent times some of them, like the martyrs of old, have even been called to

give their lives for Christ. The history of the Church in Uganda clearly shows

that generations of catechists have offered "a singular and absolutely

necessary contribution to the spread of the faith and of the Church"

(Cf. Ad

Gentes, 17) in your country.

How obvious this was even

at the dawn of Christianity in Uganda! Despite the fact that they themselves

had only recently come to know Christ, your Martyrs joyfully shared with others

the good news about the One who is "the way and the truth and the

life" (Jn. 14: 6). They understood that "faith is strengthened when

it is given to others" (John Paul II, Redemptoris

Missio, 2).

Dear Catechists: What you

have freely received, you must freely give! (Cf. Mt. 10: 8) Deepen your

knowledge of the Church’s faith, so that you can share its treasures ever more

fully with others. Always strive to think with the Church. Above all else you

must be devoted to personal prayer. Only if your ministry is nourished by

prayer and sustained by genuine Christian living will it bear lasting fruit.

Your catechesis can never be only instruction about Christ and his Church. It

must also be a school of prayer, where the baptized learn to grow into an ever

deeper and more conscious relationship with God the Father, with Jesus, the

first–born of many brothers and sisters (Cf. Rom. 8: 29), and with the Holy

Spirit, the giver of eternal life.

The effects of Christ’s

light must clearly be seen in the goodness of your lives! You must be

examples of a faith that is rooted in a personal relationship to Jesus, lived

in full communion with the Church. Your faith must be clearly seen in your

obedience to the Gospel, in your lives of charity and service, and in your

missionary zeal towards those who still do not believe or who no longer live

the faith they received at Baptism.

Take to heart Saint

Paul’s lesson: be examples of patience and charity towards all people, mindful

that if you have not love, then you are nothing at all (Cf. 1Cor. 13).

5. "You are

light in the Lord!" How brightly the light of Christ shines in the

lives of the lay men and women committed to the pursuit of holiness in

the quiet and often hidden circumstances of their lives! In particular I wish

to express the Church’s esteem for the women of Uganda. I encourage you:

do not be afraid to let your voices be heard! God has given Ugandan women

important gifts to share for the building of a more human and loving society, a

society which respects the dignity of all people, especially of children and

those most in need. How important is the apostolate of Christian families for

the growth of society and of the Church! Christian married couples: be faithful

to each other! Never forget the sacred calling you have received to pass on the

faith and to train the younger generation to live in a way pleasing to God.

Africa needs the witness of Christian families, families which are schools of

generosity, patience, dialogue and respect for the needs of others!

I am pleased to see here

the representatives of the various Associations and Ecclesial Movements which

play so important a role in the life of your local Churches. Dear friends: your

desire for holiness and authentic Christian living is a great gift of God to

the Church in our time. Be of one mind and heart with the Church’s pastors.

Jesus is calling you to be missionaries of his love, and a leaven of

reconciliation and renewal in the midst of his People. I encourage your efforts

to bring the Good News of Christ to all, particularly to the lukewarm and to

those who are not reached by the Church’s ordinary pastoral care.

6. "Shine out,

for your light has come!" (Is. 60: 1).

Christ’s words are

addressed to you, the lay faithful of Uganda! To each of you Christ says:

"Your light must shine in the sight of men, so that, seeing your good

works, they may give the praise to your Father in heaven" (Mt. 5: 16).

How much the people of

Uganda need the light of the Gospel in order to dispel the darkness still

left by long years of civil unrest, violence and fear. Today, Uganda stands at

the crossroads: her people need the salt of God’s word to bring out the virtues

of honesty, goodness, justice, concern for the dignity of others, which alone

can guarantee the rebuilding of their country on a firm foundation.

Uganda needs to hear the

word of God! How many of your brothers and sisters have still not met

Christ! To all of you I repeat today that challenge which Pope Paul VI left to

you: you must become missionaries to yourselves! Let your enthusiasm for

evangelization be accompanied by an ever more sincere commitment to work for

the unity of all who profess the name of Christ. Relations between Christians

should be marked by harmony and a spirit of mutual respect. Despite divisions,

efforts to promote Christian unity are themselves a powerful sign of the

reconciliation which God wishes to accomplish in our midst (Cf. John Paul II, Redemptoris

Missio, 50).

7. Laity of Uganda! "You

must be the salt of the earth and the light of the world" (Cf. Mt. 5:

13-14). If your works contain the salt of "goodness, right living and

truth", then your lives will truly become light for your neighbours.

Christ calls you to

lead a life pleasing to God. When you were reborn in the waters of Baptism, you

were made a new creation, given a share in his divine life and sent forth to

bear witness to the One who called us out of darkness into his kingdom of light

(Cf. Col. 1: 13).

Saint Paul says it very

clearly: "Have nothing to do with the futile works of

darkness" (Eph. 5: 11). You have renounced Satan and his works. You

have been bought at the price of Christ’s Blood, so you must never deny him by

turning to idols, or by abandoning your Christian way of life for the empty

promises of a culture of death! "You were darkness once, but now you are

light in the Lord" (Ibid. 5: 9). Let the Martyrs be your

inspiration! They did not profess Christ with their lips alone. They

showed their love for God by keeping his commandments (Cf. 1Jn. 5: 3). Christ’s

image shone forth in them with a spiritual power that even now draws people to

him. In their lives and in their deaths, the Martyrs revealed the power of the

Cross, the power of a faith that is stronger than fear, a life that triumphs

over death, a hope that lights up the future, and a love that reconciles the

bitterest of enemies.

8. "The Lord will be

your everlasting light" (Is. 60: 20). I thank God for this opportunity to

celebrate the Holy Eucharist with you at the Shrine of the Holy Martyrs of

Uganda. The Martyrs were called upon, amid this beloved African people, to

"shine in the sight of men" (Mt. 5: 16). In them Christ’s parables of

salt and light have been fulfilled. In their earthly life, the Martyrs

"tried to discover what the Lord wants" (Cf. Eph. 5: 10) and acted in

a way worthy of the calling they had received. As followers of Christ, they

were ready even to give their lives for him.

The Holy Spirit "lit

this light" in Namugongo. Through the ministry of the Church, he also

ensured that the light would not remain hidden, but would "shine for

everyone in the house" (Cf. Mt. 5: 15): in your house, in Uganda and in

all Africa.

Mwebale okumpuliriza. Kristu abeere ekitangaala Mu Africa Yonna.

(Grazie per avermi ascoltato. Possa Cristo essere la luce di tutta l’Africa).

Copyright © Dicastero per

la Comunicazione - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

PASTORAL VISIT TO BENIN,

UGANDA AND KHARTOUM

JOHN PAUL II

Sunday, 17 February 1993

At the end of this Mass

we turn with love to the Blessed Virgin Mary and prepare to say the Angelus.

From his Cross, Jesus gave Mary to his followers to be their Mother (Cfr. Jn 19,25-27).

From the very beginning of the Church’s presence in this land, Uganda’s

Christians have been sustained in their witness to the Gospel by the prayers of

the Mother of God. The Uganda’s Martyrs gave proof of their profound devotion

to Mary by their daily recitation of the Angelus and the Rosary during the time

of their imprisonment. In union with them and with all the Saints, let us now

entrust to Mary’s maternal protection this beloved country of Uganda and its

people.

Mary, Queen of Peace! To

you we commend the men, women and children of Uganda. Through your prayers, may

the Spirit of God grant lasting peace and prosperity to their nation. May the

light of Christ cast out the spiritual darkness which breeds selfishness,

violence, hatred for others and contempt for their rights. May all hearts be

opened to the power of God’s love. May those divided by ethnic or political

antagonisms learn to work together in order to build a society of justice,

peace and freedom for their children.

Mary, Queen of Martyrs! To

you we commend the Christians of this country. May the noble example of Saints

Charles Lwanga and the Uganda’s Martyrs inspire them to offer their lives as a

sacrifice pleasing to God. May their faith in Christ be seen in the holiness of

their lives and in their charity towards their brothers and sisters. Strengthen

priests and Religious in fidelity and apostolic zeal, and grant that more and

more young people may respond generously to God’s call to serve him in the

Church. By your loving intercession, may Christians be beacons of hope, letting

their light shine before men, a leaven of Gospel values working for the

spiritual and moral renewal of Ugandan society.

Mary, Mother of all who

believe! May all Christ’s followers in this country draw ever closer

together in a spirit of mutual respect and cooperation. May they bear ever more

fraternal witness to the reconciling love of Jesus the Redeemer. Impelled by

the Spirit of love, may they help spread the light of the Gospel to all the

people of Uganda.

Mary, Mother of

Sorrows! Look with mercy on those who suffer. Be close to the victims of

violence and terror, and console those who mourn. May Jesus your Son grant

comfort and peace to all the sick and dying, and may he strengthen those

devoted to their physical and spiritual care.

Mary, Queen of Africa! Lead

all people into the Lord’s Kingdom of holiness, truth and life. You who freely

said "yes" to God and became the Virgin Mother of his only Son,

remain ever close to your children in Uganda. May they be reborn in hope, and

may God’s saving plan be fulfilled in them. Through them, may all Africa come

to know and love the name of Jesus Christ our Saviour.

Copyright © Dicastero per

la Comunicazione - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

SOURCE : https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/angelus/1993/documents/hf_jp-ii_ang_19930207.html

St. Charles Lwanga and

Companions

St. Charles was one of 22 Ugandan martyrs who converted from paganism. Though

he was baptized the night before being put to death, he became a moral leader.

He was the chief of the royal pages and was considered the strongest athlete of

the court. He was also known as “the most handsome man of the Kingdom of the

Uganda.” He instructed his friends in the Catholic Faith and he personally

baptized boy pages. He inspired and encouraged his companions to remain chaste

and faithful. He protected his companions, ages 13-30, from the immoral acts

and ritualistic homosexual demands of the Babandan ruler, Mwanga.

Mwanga was a superstitious pagan king who originally was tolerant of

Catholicism. However, his chief assistant, Katikiro, slowly convinced him that

Christians were a threat to his rule. The premise was if these Christians would

not bow to him, nor make sacrifices to their pagan god, nor pillage, massacre,

nor make war, what would happen if his whole kingdom converted to Catholicism?

When Charles was sentenced to death, he seemed very peaceful, one might even

say, cheerful. He was to be executed by being burnt to death. While the pyre

was being prepared, he asked to be untied so that he could arrange the sticks.

He then lay down upon them. When the executioner said that Charles would be

burned slowly so death, Charles replied by saying that he was very glad to be

dying for the True Faith. He made no cry of pain but just twisted and moaned,

“Kotanda! (O my God!).” He was burned to death by Mwanga’s order on June 3,

1886. Pope Paul VI canonized Charles Lwanga and his companions on June 22,1964.

We celebrate his memorial on June 3rd of the Roman Calendar. Charles is the

Patron of the African Youth of Catholic Action.

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/saint-charles-lwanga/

LWANGA, CHARLES, ST.

One of the 22 uganda

martyrs; b. Buddu County, Uganda, c. 1860; d. Namugongo, Uganda, June

3, 1886. Lwanga first learned of the Catholic faith from two retainers in the

court of chief Mawulugungu. While a catechumen he entered the royal household

of the Kabaka of Buganda in 1884 as the assistant to Joseph Mukasa, the

majordomo in charge of the young court pages. On the night of Mukasa's martyrdom

by order of the new Kabaka, Mwanga, Lwanga requested and received baptism (Nov.

15, 1885). During the succeeding months, when it was most difficult to

communicate with priests, he protected the pages from Mwanga's perverted

demands. He instructed and encouraged the youths and, at the moment of crisis,

baptized the catechumens. When persecution started anew (May 1886), Lwanga was

arrested with the Christian pages, after making with them a public profession

of faith. During the march to Namugongo he was roughly treated. He was singled

out for a particularly cruel death by slow fire. With 21 others he was

beatified (June 6, 1920) and canonized (Oct. 18, 1964). Pius

XI declared him patron of youth and Catholic Action for most of

tropical Africa (June 22, 1934).

Feast: June 3.

Bibliography: J. P.

THOONEN, Black Martyrs (London 1941). J. F. FAUPEL, African

Holocaust (New

York 1962). Acta Apostolicae Sedis 56 (Rome 1964) 901–912.

[J. F. Faupel]

New Catholic Encyclopedia

SOURCE : https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/lwanga-charles-st

Charles Lwanga

Roman Catholic Saint. Also

known as Carl or Karoli Lwanga. He was born possibly in Birinzi Village in

Buddu County, somewhere in Buganda, Uganda, though his parentage is unknown,

and he was of the Ngabi clan of the tribe of Muganda. He was brought up by

Kaddu at an early age, and in August 1878, he was placed in the service of

Mawulugungu, chief of Kirwanyi (who later died in 1882). He became the chief of

the royal pages who lived in the time of King Mutesa I and his son Mwanga II

when Christianity came into Uganda between 1877 and 1879. After Mutesa's death

on October 19, 1884, Mwanga came to power at age 16 and demanded that Christians

renounce their faith on pain of torture or death, and that his pages engage in

pedophilic activities. Many pages, including Lwanga, refused to engage in such

activities and went into hiding with some Christian missionaries, while Mwanga

had many missionaries, including archbishop James Hannington, slaughtered.

Lwanga was baptized by Pere Ludovic Girault and Pere Simeon Lourdel on November

15, 1885, on the same day that Joseph Mukasa Balikuddembe was martyred; and

Lwanga assumed Balikuddembe's duties. Even after the events of the fire of the

royal palace on February 22, 1886, he rebuked Mwanga for such actions but fell

into disfavor. On May 25, Lwanga and his fellow pages were discovered by

Mwanga, arrested and put in jail. The next day, while Denis Ssebuggwawo,

Anderea Kaggwa and Ponsiano Ngondwe were martyred, Lwanga secretly baptized his

four fellow pages: Gyavire, Kizito, Mbaga Tuzinde, and Muggaga. The next

morning, May 27, Lwanga and his 15 fellow Catholic pages were condemned to

death. Three of them (Antanansio Bazzekuketta, Gonzaga Gonza and Nowa

Mawaggali) were martyred both on the way to Namugongo and during their

imprisonment there for a week. Lwanga encouraged the remaining pages to remain

faithful until death. On the day of their execution (that is, June 3, the

Ascension of the Lord), he and the 11 remaining pages were wrapped in reed mats

and laid down on a furnace pyre, joined in by the body of his fellow page

Tuzinde, who had been beaten to death for refusing to renounce Christianity;

and they were burned alive. As Lwanga (who was not yet 26 years old) was being

burned, one executioner, Ssenkoole, urged him to save himself, but Lwanga

replied, "Poor madman, you are burning me, but it's as if you are pouring

water over my body. Please repent and become a Christian like me." His

death, along with 21 other martyrs, resulted in the eventual rebellion against

and exile of Mwanga. In 1920, Lwanga and his 21 other companions were beatified

by Pope Benedict XV, and on October 18, 1964, they were canonized by Pope Paul

VI, and a shrine or basilica church was built in Namugongo in their honor.

Lwanga is the patron saint of African Catholic Youth Action, converts and

torture victims, and his joint feast day with 21 others is June 3.

SOURCE : https://fr.findagrave.com/memorial/29118251/charles-lwanga

Charles Lwanga, a young page in the royal court of Buganda (now part of

Uganda), was burned to death in 1886 at the order of King Mwanga, after

refusing to renounce his faith in Jesus Christ. Lwanga, who was in his mid

twenties, had become the protector and pastor to a group of young men who

worked in the royal court, many of whom had been led to faith and baptized by

him. Mwanga's wrath was fueled by what he perceived to be divided loyalty among

the pages because of their devotion to God and their growing unwillingness,

under Lwanga's guidance, to submit to his homosexual abuse. Mwanga ordered

twenty nine pages, including Lwanga, to parade before him to recant their faith

or die. Three recanted, and the remaining twenty six were sent out to be burnt

alive.

The deaths ignited

astonishing growth in Buganda, so that 25 years after the martyrdoms 40% of the

tribe had been baptized. Bugandan missionaries in turn spread the gospel to the

rest of East Africa and the whole continent.

Background

The African kingdom of

Buganda was "discovered" by British explorer, J. H. Speke in 1862 and

visited by Henry M. Stanley, a British journalist, in 1875. Both Speke and

Stanley wrote books that praised the Baganda for their organizational skills,

massive army and navy, and willingness to modernize. Stanley described a town

of about 40,000 surrounding the king's palace, which was situated atop a

commanding hill. He noted a corps of young pages who served the king while

training to become future chiefs.

Anglican and Roman

Catholic missionaries soon followed, as well as Arab muslims. Mutesa allowed

his people to join any religion, but he remained a traditionalist. By the mid

1880s there had been substantial conversions among the Baganda, especially in

the royal court, where the missionaries had focused their attention for

strategic reasons. When Mutesa died and was succeeded by his son Mwanga,

however, the cost of being a Christian rose dramatically and tragically.

Lwanga's life

Charles Lwanga was born

around 1860 in Ssmgo County and was raised in Buddu in the southwest. At age

18, Lwanga started working for the chief of Kirwanyi and travelled with him to

the capital of Buganda in 1880. Lwanga became interested in the teaching of the

Catholic missionaries and began to attend their instructions. When freed from

service to the chief, Lwanga joined a group of recently baptised Christians in

Bulemezi County.

When Mwanga became king

in 1884, Lwanga entered his royal service. A natural leader, he was immediately

put in charge of the royal pages and quickly won their confidence and

affection, not least because of his skill as a wrestler. Lwanga understood his

job to be to give instruction and guidance to the royal pages and shield them

from the evil influences at court. With his encouragement and under his

mentorship, many pages turned to Christ.

The martyrdoms

King Mwanga was concerned

that the converts had diverted their loyalty to some other authority so that he

could no longer rely on their allegiance at all costs. The ultimate humiliation

for him was that they resisted his homosexual advances - it was unheard of for

mere pages to reject the wishes of a king. Mwanga was thus determined to rid

his kingdom of the new teaching and its followers.

The first three martyrs

were killed at Busega Natete on January 31, 1885. The executions reached their

peak with the death of Lwanga and twenty five other "Ugandan Martyrs"

on June 3, 1886. Lwanga was burned first and burned more slowly to increase the

suffering. Throughout most of it he prayed quietly, and just before the end, he

cried out in a loud voice `Katonda,' - `My God.' By Jan 27, 1887, when the last

death in Mwanga's campaign occurred, a total of at least forty five young

Africans had been killed.

Impact of the martyrs

The martyrdoms drove the

infant East African church underground but not into retreat. There was dramatic

growth in the churches, even during the oppression. More people were baptized

than martyred, and at the very peak of the terror, congregations of fifty and

more attended services [1]. Within two months of Lwanda's death, Anglicans had

baptized two hundred and twenty-seven people, and the Catholics may well have

baptized even more. Baptisms included prominent members of the royal court such

as the admiral of the fleet.

The oppression eased in

1888 when Mwanga was deposed, but the astonishing growth continued. Soon the

missionaries were far outnumbered by local church leaders, and church growth

was led by the Africans. In the 1890s revival swept the Ugandan Protestant

community, which then sent out large numbers of missionary evangelists. Their

work was so successful that Baganda was 40% Christian and the rest of Uganda 7%

Christian by 1911, ready for the even more dramatic East African Revival that

began in 1929.

References

• Aylward Shorter

"Slow death by burning", Quarterly Review of Mission January

2004 [2]

• "The Christian

Martyrs of Uganda", The Buganda Home Page [3]

• John Bauer, 2000

Years of Christianity in Africa (Nairobi: Paulines, 1994) pp. 233-44.

• Ashe, Robert P. Two

kings of Uganda London, 1889

• Ashe, Robert P. Chronicles

of Uganda New York, 1895

• Neil Lettinga,

"19th Century Missions in the African Interior: Buganda" African

Christianity Homepage, [4]

SOURCE : http://www.theopedia.com/Charles_Lwanga

St. Charles Lwanga and

Companions

Feastday: June 3

For those of us who think

that the faith and zeal of

the early Christians died out as the Church grew more safe and powerful through

the centuries, the martyrs of Uganda are a reminder that persecution of

Christians continues in modern times, even to the present day.

The Society of

Missionaries of Africa (known

as the White Fathers) had only been in Uganda for 6 years and yet they had

built up a community of converts whose faith would

outshine their own. The earliest converts were soon instructing and leading new

converts that the White Fathers couldn't

reach. Many of these converts lived and taught at King Mwanga's court.

King Mwanga was a violent

ruler and pedophile who forced himself on the young boys and men who served him

as pages and attendants. The Christians at Mwanga's court who tried to protect

the pages from King Mwanga.

The leader of the small

community of 200 Christians, was the chief steward of Mwanga's court, a

twenty-five-year-old Catholic named Joseph Mkasa

(or Mukasa).

When Mwanga killed a

Protestant missionary and his companions, Joseph Mkasa

confronted Mwanga and condemned his action. Mwanga had always liked Joseph but

when Joseph dared

to demand that Mwanga change his lifestyle, Mwanga forgot their long

friendship. After striking Joseph with

a spear, Mwanga ordered him killed. When the executioners tried to tie Joseph's

hands, he told them, "A Christian who

gives his life for God is

not afraid to die." He forgave Mwanga with all his heart but made one

final plea for his repentance before he was beheaded and then burned on

November 15, 1885.

Charles Lwanga took over

the instruction and leadership of the Christian community

at court -- and the charge of keeping the young boys and men out of Mwanga's

hands. Perhaps Joseph's plea for repentance had had some affect on Mwanga

because the persecution died

down for six months.

Anger and suspicion must

have been simmering in Mwanga, however. In May 1886 he called one of his pages

named Mwafu and asked what the page had been doing that kept him away from

Mwanga. When the page replied that he had been receiving religious instruction

from Denis Sebuggwawo, Mwanga's temper boiled over. He had Denis brought to him

and killed him himself by thrusting a spear through his throat.

He then ordered that the

royal compound be sealed and guarded so that no one could escape and summoned

the country's executioners. Knowing what was coming, Charles Lwanga baptized

four catechumens that night, including a thirteen-year-old named Kizito. The

next morning Mwanga brought his whole court before him and separated the

Christians from the rest by saying, "Those who do not pray stand by me,

those who do pray stand over there." He demanded of the fifteen boys and

young men (all under 25) if they were Christians and intended to remain

Christians. When they answered "Yes" with strength and

courage Mwanga condemned them to death.

He commanded that the

group be taken on a 37 mile trek to the place of execution at Namugongo. The

chief executioner begged one of the boys, his own son, Mabaga, to escape and

hide but Mbaga refused. The cruelly-bound prisoners passed the home of

the White

Fathers on their way to execution. Father Lourdel remembered

thirteen-year-old Kizito laughing and chattering. Lourdel almost fainted at the

courage and joy these condemned converts, his friends, showed on their way to

martyrdom. Three of these faithful were killed on road.

A Christian soldier

named James Buzabaliawo

was brought before the king. When Mwanga ordered him to be killed with the

rest, James said,

"Goodbye, then. I am going to Heaven, and I will pray

to God for

you." When a griefstricken Father Lourdel raised his hand in absolution as James passed, James lifted his

own tied hands and pointed up to show that he knew he was going to heaven and

would meet Father Lourdel there. With a smile he said to Lourdel, "Why are

you so sad? This nothing to the joys you have taught us to look forward

to."

Also condemned were

Andrew Kagwa, a Kigowa chief, who had converted his wife and several others,

and Matthias Murumba (or Kalemba) an assistant judge. The chief counsellor was

so furious with Andrew that he proclaimed he wouldn't eat until he knew Andrew

was dead. When the executioners hesitated Andrew egged them on by saying,

"Don't keep your counsellor hungry -- kill me." When the same

counsellor described what he was going to do with Matthias, he added,

"No doubt his god will rescue

him." "Yes," Matthias replied, "God will rescue

me. But you will not

see how he does it, because he will take

my soul and

leave you only my body." Matthias was cut up on the road and left to die

-- it took him at least three days.

The original caravan

reached Namugongo and the survivors were kept imprisoned for seven days. On

June 3, they were brought out, wrapped in reed mats, and placed on the pyre.

Mbaga was killed first by order of his father, the chief executioner, who had

tried one last time to

change his son's mind. The rest were burned to death. Thirteen Catholics and

eleven Protestants died. They died calling on the name of Jesus and proclaiming,

"You can burn our bodies, but you cannot harm our souls."

When the White Fathers were

expelled from the country, the new Christians carried on their work,

translating and printing the catechism into their natively language and

giving secret instruction

on the faith. Without priests, liturgy, and sacraments their

faith, intelligence, courage, and wisdom kept

the Catholic Church

alive and growing in Uganda. When the White Fathers returned

after King Mwanga's death, they found five hundred Christians and one thousand

catchumens waiting for them. The twenty-two Catholic martyrs

of the Uganda persecution were

canonized.

Prayer:

Martyrs of Uganda, pray

for the faith where

it is danger and for Christians who must suffer because of their faith. Give

them the same courage, zeal, and joy you showed. And help those of us who live