Saint Brendan

Abbé de Clonfert, en

Irlande (+ 583)

Il pilota ses nombreux

disciples à travers les flots de ce monde, "vers la terre promise des

saints." Il doit sa réputation à la légende qui l'aurait fait naviguer

vers les îles Canaries et l'Amérique du Sud.

Moine irlandais, rendu

célèbre par ses "navigations aux îles fortunées", quelque part entre

les Canaries et le Groenland. Né en 484 à Clonfert, au sud-ouest de l'Irlande,

il entre au monastère de Llancarvan, fondé par saint Cado dans le pays de

Galles. La tradition rapporte qu'il débarqua avec des compagnons dans

l'estuaire du Léguer et qu'il fonda un monastère à Ploulec'h; Lanvellec est

sous son patronage. Deux paroisses, dans le Finistère, prétendent garder le

souvenir de ce saint, Kerlouan* et Loc-Brévalaire, mais l'identification de

Brendan avec Brévalaire est sujette à caution. A Loc-Brévalaire, le saint

patron est représenté en évêque (ou en abbé?), un dragon à ses pieds (diocèse

de Quimper et Léon)

* L'église

Saint-Brévalaire fut nommée du nom du saint patron de Kerlouan: Brévalaire,

moine navigateur irlandais. (ensemble paroissial La Côte des Légendes)

Saint Brendan est

également saint patron du diocèse de Kerry en Irlande -

En Irlande, vers 577,

saint Brendan, abbé de Clonfert et propagateur valeureux de la vie monastique,

devenu le héros d’exploits fabuleux racontés dans la célèbre Navigation de

saint Brendan.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1166/Saint-Brendan.html

BRENDAN (Bréanainn),

saint, abbé et missionnaire irlandais que la tradition associe à des voyages à

l’Ouest vers l’Amérique du Nord et peut-être même le Canada actuel, né vers

484, mort vers 578.

On croit qu’il naquit

près de Tralee, dans le comté de Kerry, en Irlande, de parents chrétiens. Il

fut ordonné prêtre à l’âge de 26 ans et, plus tard, il fonda le grand monastère

de Clonfert, dans le comté de Galway, dont il fut abbé. Le mont Brandon, dans

la péninsule de Dingle, porte son nom, et on pense que « l’île de Saint-Brendan

» se trouvait à l’est de cette montagne.

Saint Brendan est censé

avoir visité des lieux tels que les îles Féroé, l’Islande, l’île de Jan-Mayen,

les Antilles, les Açores, les Canaries et même le Groenland et le continent

américain. Bien que les Irlandais aient atteint l’Islande et y aient établi une

communauté religieuse avant l’an 800 de notre ère, rien ne permet d’associer

Brendan à cette aventure. Il n’existe pas non plus de preuve digne de foi qui

indique que Brendan ou un de ses compatriotes ait jamais atteint le Groenland

ou l’Amérique.

Une Vita Sancti

Brendani apparut très tôt. Elle fut suivie plus tard de la Navigatio

Sancti Brendani, dans laquelle des parties de la Vita avaient été incluses. Il

y a controverse sur l’époque de la parution de la Navigatio (Selmer pense que

le premier manuscrit fut rédigé vers la fin du xe ou au début du xie siècle).

La Navigatio raconte le ou les voyages du saint dans sa recherche du paradisum

terrestre (tir tairgirne) ou de la Terre promise des saints. Elle connut une

diffusion considérable et fut traduite en plusieurs langues ; il en existe un

grand nombre de manuscrits.

Il est bien plus

raisonnable de soutenir que les renseignements relatifs à des mers et à des

terres situées à l’ouest de l’Islande, que l’on peut dégager de certains

passages de la Navigatio Sancti Brendani, proviennent de récits de voyages des

Norvégiens dans l’Atlantique Nord (ou, dans les cas où il paraît être question

de l’Islande, de moines irlandais qui avaient fui l’Islande à l’approche des

Normands en 870) transmis par les nombreux Scandinaves qui se rendirent ou

s’établirent en Irlande pendant les années 800–1200.

Un examen attentif des

sagas islandaises pertinentes, la Saga d’Érik le Rouge (chap. XII), la Saga

d’Eyrbyggja (chap. LXIV) et le Landnámabok (chap. clxxi), mène nécessairement à

la conclusion qu’elles ne peuvent s’appliquer à aucune « Terre des Hommes

blancs » en Amérique ; et, certes, on ne peut découvrir aucune terre à six

jours de navigation à voile à l’ouest de l’Irlande. Saint Brendan ou d’autres

comme lui peuvent avoir traversé l’Atlantique, mais cette affirmation ne

s’appuie sur aucune preuve véritable. S’ils l’ont fait, ils n’y ont laissé

aucun souvenir même passager, tels que ceux dont on s’attend à trouver la

description dans les sagas islandaises. Nous pouvons donc supposer que les

Scandinaves ne sont pas entrés en contact avec, une colonie irlandaise

florissante sur la côte orientale du Canada ou des États-Unis d’Amérique.

T. J. OLESON

Navigatio Sancti Brendani

abbatis, ed. Carl Selmer (Notre Dame, Indiana, 1959), contient une

bibliographie complète sur le sujet.— Geoffrey Ashe, Land to the west (London,

1962).— Eugène Beauvois, La découverte du Nouveau Monde par les Irlandais,

et les premières traces du christianisme en Amérique avant l’an 1 000 (Congrès

international des Américanistes, Nancy, 1875).— R.-Y. Creston, Journal de

bord de Saint-Brendan (Paris, 1957).— Jón Dúason, Landkönnun og

Landnám Íslendinga i Vesturheimi (Reykjavik, 1941–47), 292–297, 665–670.—

Richard Hennig, Terrae incognitae.— Lanctot, Histoire du Canada, I :

45–59, 62.— G. A. Little, St. Brendan the navigator (Dublin, 1945).—

Fridtjof Nansen, In northern mists : arctic exploration in early times (2

vol., London, 1911), II : 42–56.— Denis O’Donoghue, Brendaniana ; St.

Brendan the voyager (Dublin, 1893).— Oleson, Early voyages, 100,

125.— E. G. R. Waters, The Anglo-Norman voyage of St. Brendan (Oxford,

1928).

© 2000 University of

Toronto/Université Laval

SOURCE : http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-f.php?BioId=34209

Ary

Renan (1857-1900). Saint Brandan tenant ses attributs (ancre, cloche). Ary

Renan. Lápiz sobre papel. s/f.

Saint Brendan de Clonfert nait

dans le royaume du Munster en 484, et connaît une enfance très vite bercée par

le christianisme. Il se rend dans le monastère de Llancarfan dans le Royaume de

Gwent (Pays de Galles) pour y apprendre le latin, le grec, les mathématiques,

la médecine et l’astronomie, et s’initie aux textes chrétiens.

Dès 515, Saint Brendan

voyage beaucoup, et part pour une quête de 7 ans afin de rechercher le jardin

d’Eden (comme le veut une tradition celte dictée par L’Immram, un ancien conte

mythologique). Il n’hésite pas à naviguer, s’aventurant sur l’océan Atlantique

sur un curragh, accompagnés d’autres moines. A la fin de sa quête, Brendan

retourne en Irlande, et conte son périple en affirmant avoir trouvé une île

assimilable au Paradis… Très vite, la nouvelle se propage et la légende se

forme : Brendan est alors surnommé « Le Navigateur », et de nombreux pèlerins

se rassemblent autour d’Aldfert, village où aurait démarré le périple du moine.

Mais Saint Brendan de

Clonfert ne s’arrête pas là et reprend la mer, à la recherche de nouveaux

territoires à découvrir… D’après le récit médiéval « Navigatio Sancti Brendani

abbatis », le moine aurait effectué 2 voyages importants, l’un le menant aux

îles Canaries, l’autre vers les Antilles. Il voyagera ensuite durant plus de 25

ans entre les îles Britanniques et la Bretagne. De nos jours, beaucoup de

spécialistes semblent douter de ces voyages, considérant la plupart des récits

vantant ses périples comme inexacts et incohérents.

C’est en 561 que Brendan

retourne en Irlande, et décide de fonder le monastère de Clonfert dans la

région de Galway. Il meurt ensuite entre 574 et 578 et fut canonisé par le Pape

Zacharie en 1243, fixant sa fête au 16 mai.

Les moines irlandais et

le voyage de Saint-Brendan

L'hypothèse d'expéditions

transatlantiques menées par des moines irlandais du Moyen Âge semble

raisonnablement valide. Nous savons qu'aux 5e et 6e siècles de notre ère, l'Irlande

est le foyer d'un bouillonnement culturel. Elle est la gardienne de la

chrétienté de l'Europe du Nord à la suite du déclin et de la chute de l'Empire

romain. À cette époque, les moines irlandais prennent le risque de traverser

l'Atlantique Nord en quête d'une mission de nature divine ou spirituelle. Ils

atteignent les archipels des Hébrides et des Orcades ainsi que les îles Féroé.

Les sagas scandinaves mentionnent que des moines irlandais habitent déjà

l'Islande lorsque les Scandinaves s'y implantent vers 870 de notre ère (même si

aucune preuve archéologique ne le confirme jusqu'à présent).

De tels exploits donnent

un air d'authenticité à l'histoire de Saint-Brendan. Né en Irlande vers 489, il

fonde le monastère à Clonfert dans le comté de Galway. Selon la légende, il est

septuagénaire lorsqu'il se lance dans une expédition vers l'ouest. Il part avec

17 compagnons sur un curragh, un bateau fait de peaux de bœuf sur une armature

en bois. D'après un récit du 10e siècle, Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis (Le

voyage de Saint-Brendan), les moines naviguent pendant sept ans dans

l'Atlantique Nord.

Ils finissent par

accoster à la « Terre promise des saints ». Après l'avoir explorée, ils

repartent vers leur point de départ en emportant avec eux des fruits et des

pierres précieuses. Brendan s'est-il rendu jusqu'à Terre-Neuve en se servant

des îles de l'Atlantique Nord comme de tremplins vers sa destination? En 1976

et 1977, Tim Severin, un écrivain et explorateur britannique, fait la

démonstration qu'une telle expédition est réalisable. Il reproduit un curragh,

le Brendan, et navigue jusqu'à Terre-Neuve. Si les moines irlandais ont

réellement traversé l'Atlantique, ce qu'ils ont accompli représente un exploit

d'une grande importance historique. Avant le 8e siècle, l'Irlande subit les

attaques répétées des Vikings. C'est donc peut-être par les Irlandais que les

Scandinaves apprennent l'existence de terres lointaine à l'Ouest.

©1997, site Web du

Patrimoine de Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador

Bibliographie

- Les premières explorations (en anglais)

SOURCE : https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/en-francais/exploration/le-voyage-de-saint-brendan.php

Güstrow

(Mecklenburg-Vorpommern). Dom: Kreuzigungsaltar (ca. 1500) von Hinrik Bornemann

mit der Inschrift „SANCTVS BRNDA“ im Heiligenschein - Heiliger Brandamus (Brendan der Reisende) in der Darstellung

als Abt mit einer brennenden Kerze in der rechten Hand und einem Buch in der

linken. (Zur Ikonografie siehe V. Mayr, Brendan (Brandanus) von Clonfert

(Clúana Ferta, von Irland). In: Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie,

Band 5, S. 442–443.)

Güstrow

(Mecklenburg-Vorpommern). Cathedral: Altar of the Crucifixion (c. 1500) by

Hinrik Bornemann with the inscription “SANCTVS BRNDA” - Saint Brandamus (Brendan of Clonfert),

depicted as abbot holding a burning candle and a book.

SAINT

BRENDAN

Sanctus Brendanus |

Sanctus Brandanus | Saint Brendan of Clonfert | Saint Brandan

Fête: 16 mai

En plus de sa vita s'est

développée une biographie fabuleuse, le Voyage de saint

Brendan. Vers la fin du Moyen Âge, les deux versions se retrouvent et se

mêlent pour en former de nouvelles.

Vita

Gossuin de Metz, Image du monde

Navigatio

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

Recueils

Sanct Brandan. Ein lateinischer und drei deutsche Texte,

éd. C. Schröder, Erlangen, 1871.

Grosejan, P., « Vita s.

Brandani Clonfertensis e Codice Dubliniensi », Analecta Bollandiana, 48, 1930, p. 99-123.

Heist, W. W., Vitae Sanctorum Hiberiae ex Codice ilim

Salmanticensi nunc Bruxellensi, Bruxelles, Société des Bollandistes

(Subsidia Hagiographica, 28), 1965.

Moran, Patrick F., Acta Sancti Brendani: Original Latin

Documents Connected with the Life of Saint Brendan, Patron of Kerry and

Clonfert, Dublin, Kelly, 1872.

Plummer, Charles, Vitae Sanctorum Hiberniae, Oxford,

Clarendon Press, 1910, 2 t.

Plummer, Charles, Miscellanea Hagiographica Hibernica,

Bruxelles, Société des Bollandistes (Subsidia Hagiographica, 15), 1925.

Généralités

Burgess, Glyn S., « The life and legend of saint Brendan », The Voyage of Saint

Brendan: Representative Versions of the Legend in English Translation, éd. W.

R. J. Barron et Glyn S. Burgess, Exeter, University of Exeter Press, 2002, p.

1-11.

Comptes

rendus du recueil:

Réimpression:

Iannello, Fausto, «

Dell'oblio di un ancestrale monaco irlandese: Brendano di Birr, detto "il

Vecchio". Finzione, contaminazione o reductio funzionale? (Appendix:

"West Munster Synod", transl. from Old Irish by T. Shingurova)

», Studia monastica, 57:1, 2015,

p. 25-67.

Iannello, Fausto, «

Tradizioni e funzioni protettivo-apotropaiche di san Brendano di Clonfert in

ambito litanico ed eucologico », Revue

des sciences religieuses, 92:2, 2018, p. 179-200.

Wright, John Kirtland, The Geographical Lore of the Time of the Crusades: A Study in the

History of Medieval Science and Tradition in Western Europe, New York,

American Geographical Society (American Geographical Society Research Series,

15), 1925, xxi + 563 p. [HT] [IA]

Réimpression:

Permalien: https://arlima.net/no/78

Voir aussi:

> (aucun)

Rédaction: Mattia Cavagna

Compléments: Fausto

Iannello

Dernière mise à jour: 18 septembre 2021

SOURCE : https://www.arlima.net/ad/brendan_saint.html

LE

VOYAGE DE SAINT BRENDAN

VERSIONS

Vita sancti

Brandani abbatis (traduction latine de la version

française de Benedeit)

Actus sancti

Brandani (traduction latine de la version

française de Benedeit)

Brandans Meerfahrt (versions

en vers et en prose)

William Caxton, Golden Legende

Version courte tiréee de

la Llegenda àuria

Version catalane longue (San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Real

Biblioteca del Monasterio, N-III-5, f. 223v-226r, déb. XIV (Es 2)

Benedeit, Le voyage de saint Brendan (vers)

Gossuin de Metz,

version comprise dans l'Image du monde (vers)

Saint

Brandainne le moine (prose)

Autres

versions françaises en vers et en prose

La leggenda di

san Brandano (4 versions)

Version incluse

dans Lo libre

de las flos e de las vidas dels sans e sanctas, traduction de la Legenda aurea de Jacques de Voragine

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

RecueilsBarron, W. R. J., et Glyn S. Burgess,

éd., The Voyage of Saint Brendan:

Representative Versions of the Legend in English Translation, Exeter,

University of Exeter Press, 2002, xi + 377 p.

Comptes

rendus:

Réimpression:

Glyn S. Burgess and Clara

Strijbosch, éd., The Brendan Legend:

Texts and Versions, Brill, Leiden (The Northern World, 24), 2006, 395 p.

Généralités

Bottex-Ferragne, Ariane,

« Le "court Moyen Âge" de la Navigation de saint Brendan:

extinction et réception d'une tradition textuelle », Memini. Travaux et documents, 13, 2009,

p. 67-83. [www]

Brown, Arthur C. L., « The wonderful flower that came

to St. Brendan », The Manly

Anniversary Studies in Language and Literature, Chicago, University of

Chicago Press, 1923, p. 295-299. [HT] [IA]

Réimpression:

Burgess, Glyn S., « The life and legend of saint

Brendan », The Voyage of Saint

Brendan: Representative Versions of the Legend in English Translation, éd. W.

R. J. Barron et Glyn S. Burgess, Exeter, University of Exeter Press, 2002, p.

1-11.

Comptes

rendus du recueil:

Réimpression:

Gaffarel, Paul,

« Les voyages de saint Brandan et des Papœ dans l'Atlantique au moyen

âge », Bulletin de la Société

de géographie de Rochefort, 2, 1880-1881, p. 29-51. [Gallica]

Richard, Jean, « Voyages

réels et voyages imaginaires, instrauments de la connaissance géographique au

Moyen Âge », Culture et travail

intellectuel dans l'Occident médiéval, éd. Geneviève Hasenohr et Jean Longère,

Paris, Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 1981, p. 211-220.

Selmer, Carl, Francis Bar

et Anne-Françoise Labie-Leurquin, « Navigatio sancti Brendani », Dictionnaire des lettres françaises: le

Moyen Âge, éd. Geneviève Hasenohr et Michel Zink, Paris, Fayard, 1992, p.

1057-1058.

Réimpression:

Thurneysen, Rudolf, «

Eine Variante der Brendan-Legende », Zeitschrift

für celtische Philologie, 10, 1915, p. 408-420. [GB] [HT] [IA]

Ward, H. L. D., Catalogue of Romances in the Departement of Manuscripts in the British

Museum, London, British Museum, t. 1, 1883, xx + 955 p.; t. 2, 1893, xii +

748 p. (ici t. 2, p. 516-557) [GB: t. 1, t. 2] [HT] [IA: t. 1, t. 2]

Compte

rendu:

Répertoires

bibliographiques

Permalien: https://arlima.net/no/417

Voir aussi:

> (aucun)

Rédaction: Mattia Cavagna

Compléments: Antonio

Scolari et Laurent Brun

Dernière mise à jour: 23 septembre 2021

SOURCE : https://www.arlima.net/uz/voyage_de_saint_brendan.html#

St. James' Church, Glenbeigh, County Kerry, Ireland. Detail of right light in the hree-light window in the south-west wall of the transept, depicting Saint Brendan.

Also

known as

Brendan the Voyager

Brendan McFinlugh

Brendan of Clonfert

Brendan of Cluain Ferta

Borodon….

Brandan….

Brendain….

Breandan….

6

January as one of the Twelve

Apostles of Ireland

14 June (translation

of relics)

Profile

Son of Findloga; brother

of Saint Briga. Monk. Educated by Saint Ita

of Killeedy and Saint Erc

of Kerry. Friend of Saint Columba and Saint Brendan

of Birr, Saint Brigid,

and Saint Enda

of Arran. Ordained in 512.

Built monastic cells at

Ardfert, Shankeel, Aleth, Plouaret, Inchquin Island, and Annaghdown. Founded

Clonfert monastery and monastic school c.559.

Legend says that this community had at least three thousand monks,

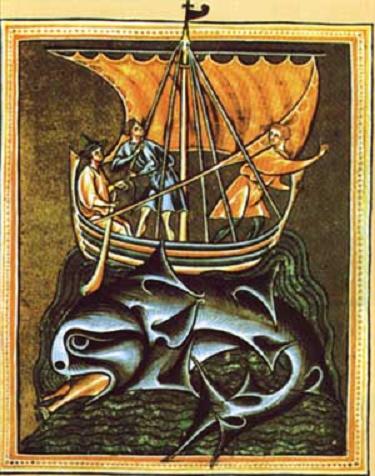

and that their Rule was dictated to Brendan by an angel.

Brendan and his brothers

figure in Brendan’s Voyage, a tale of monks travelling the

high seas of the Atlantic, evangelizing to

the islands, possibly reaching the Americas in the 6th

century. At one point they stop on a small island, celebrate Easter Mass,

light a fire – and then learn the island is an enormous whale!

Born

460 at

Tralee, County Kerry, Ireland

c.577 at

Annaghdown (Enach Duin)

Prayer

for the Spirit of Saint Brendan

priest celebrating Mass on

board ship while fish gather

to listen

one of a group of monks in

a small boat

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Brendan’s

Fabulous Voyage, by John Patrick Crichton Stuart Bute

Catholic

Encyclopedia: Saint Brendan

Catholic

Encyclopedia: Voyage of Saint Brendan

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Roman

Martyrology, 1914 edition

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

The

Book of Saints and Heroes, by Leonora Blanche Lang

books

Battersby’s Registry for

the Whole World

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

1001 Patron Saints and Their Feast Days, Australian

Catholic Truth Society

Dictionary

of Canadian Biography

images

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

Readings

Let the brothers and sisters

now sing

Of the holy life of Brendan;

In an old melody

Let it be kept in song.

Loving the jewel of

chastity,

He was the father of monastics.

He shunned the choir of the world;

Now he sings among the angels.

Let him pray that we may

be saved

As we sail upon this sea.

Let him quickly aid the fallen

Oppressed with burdensome sin.

God the Father; Most High

King

Breast-fed by a virgin mother;

Holy

Spirit: when They will it,

Let Them feed us divine honey.

– Guido of Ivrea, 11th

century; English translation from the Latin by Karen Rae Keck, 1994

MLA

Citation

“Saint Brendan the

Navigator“. CatholicSaints.Info. 31 August 2021. Web. 16 May 2022.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-brendan-the-navigator/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-brendan-the-navigator/

St. Brendan's Cathedral, Loughrea, County Galway, Ireland. Stained glass window by Sarah Purser in the western porch, depicting St. Brendan the Navigator at sea. This work is titled “Breandán Naoṁṫa ar an Muir” (see inscription at the bottom) and was created mid 1903 with dimensions 915 × 457 mm. It is her “only window she carried through all the design and craft stages with no assistant”. (See entry 374 in the list of her works at John O'Grady, The life and work of Sarah Purser, ISBN 1-85182-241-0, p. 244–245; Nicola Gordon Bowe et al, Gazetteer of Irish Stained Glass, ISBN 0-7165-2413-9, p. 57; St Brendan's Cathedral, Loughrea, ISBN 0-900346-76-0.)

St. Brendan

St. Brendan of Ardfert and Clonfert, known also as Brendan the Voyager, was

born in Ciarraighe Luachra, near the present city of Tralee, County Kerry,

Ireland, in 484; he died at Enachduin, now Annaghdown, in 577. He was baptized

at Tubrid, near Ardfert, by Bishop Erc. For five years he was educated under

St. Ita, “the Brigid of Munster”, and he completed his studies under St. Erc,

who ordained him priest in 512. Between the years 512 and 530 St. Brendan built

monastic cells at Ardfert, and at Shanakeel or Baalynevinoorach, at the foot of

Brandon Hill. It was from here that he set out on his famous voyage for the

Land of Delight.

St. Brendan belongs to

that glorious period in the history of Ireland when the island in the first

glow of its conversion to Christianity sent forth its earliest messengers of

the Faith to the continent and to the regions of the sea. It is, therefore, perhaps

possible that the legends, current in the ninth and committed to writing in the

eleventh century, have for foundation an actual sea-voyage the destination of

which cannot however be determined.

These adventures were

called the “Navigatio Brendani”, the Voyage or Wandering of St. Brendan, but

there is no historical proof of this journey. Brendan is said to have sailed in

search of a fabled Paradise with a company of monks, the number of which is

variously stated as from 18 to 150. After a long voyage of seven years they

reached the “Terra Repromissionis”, or Paradise, a most beautiful land with

luxuriant vegetation.

The narrative offers a

wide range for the interpretation of the geographical position of this land and

with it of the scene of the legend of St. Brendan. While many locations had

been speculated, in the early part of the nineteenth century belief in the

existence of the island was completely abandoned. But soon a new theory arose,

maintained by those scholars who claim for the Irish the glory of discovering

America, namely, MacCarthy, Rafn, Beamish, O’Hanlon, Beauvois, Gafarel, etc.

They rest this claim on the account of the Northmen who found a region south of

Vinland and the Chesapeake Bay called “Hvitramamaland” (Land of the White Men) or

“Irland ed mikla” (Greater Ireland), and on the tradition of the Shawano

(Shawnee) Indians that in earlier times Florida was inhabited by a white tribe

which had iron implements.

In regard to Brendan

himself the point is made that he could only have gained a knowledge of foreign

animals and plants, such as are described in the legend, by visiting the

western continent.

The oldest account of the

legend is in Latin, “Navigatio Sancti Brendani”, and belongs to the tenth or

eleventh century; the first French translation dates from 1125; since the

thirteenth century the legend has appeared in the literatures of the

Netherlands, Germany, and England.

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/saint-brendan/

St. Brendan

St. Brendan of Ardfert

and Clonfert,

known also as Brendan the Voyager, was born in Ciarraighe Luachra, near

the present city of Tralee, County Kerry, Ireland,

in 484; he died at Enachduin, now Annaghdown, in 577. He was baptized at Tubrid,

near Ardfert, by Bishop Erc. For five years he was educated under St.

Ita, "the Brigidof Munster", and he completed his

studies under St. Erc, who ordained him priest in

512. Between the years 512 and 530 St. Brendan

built monastic cells at Ardfert, and at Shanakeel or

Baalynevinoorach, at the foot of Brandon Hill. It was from here that he set out

on his famous voyage for the Land of Delight. The old Irish

Calendars assigned a special feast for the "Egressio

familiae S. Brendani", on 22 March;

and St Aengus theCuldee, in his Litany, at the close of the

eighth century, invokes "the sixty who accompanied St.

Brendan in his quest of the Land of Promise". Naturally, the

story of the seven years' voyage was carried about, and, soon, crowds of pilgrims and

students flocked to Ardfert. Thus, in a few years, many religious

houses were formed at Gallerus, Kilmalchedor, Brandon Hill, and the

Blasquet Islands, in order to meet the wants of those who came

for spiritual guidance to St. Brendan.

Having established

the See of Ardfert, St. Brendan proceeded to Thomond, and founded

a monastery at

Inis-da-druim (now Coney Island, County Clare), in the present parish of

Killadysert, about the year 550. He then journeyed to Wales,

and thence to Iona,

and left traces of his apostolic

zeal at Kilbrandon (near Oban) and Kilbrennan Sound. After a

three years' mission in Britain he returned to Ireland,

and did much good work in various parts of Leinster, especially at

Dysart (Co. Kilkenny), Killiney (Tubberboe), and Brandon Hill. He

founded the Sees of Ardfert, and of Annaghdown, and

established churches at Inchiquin, County Galway,

and at Inishglora, County Mayo. His most

celebrated foundation was Clonfert,

in 557, over which he appointed St. Moinenn as Prior and

Head Master. St. Brendan was interred in Clonfert,

and his feast is

kept on 16 May.

Voyage of St. Brendan

St. Brendan belongs to

that glorious period in the history of Ireland when

the island in the first glow of itsconversion to Christianity sent

forth its earliest messengers of the Faith to the continent and to

the regions of the sea. It is, therefore, perhaps possible that the legends,

current in the ninth and committed to writing in the eleventh century, have

for foundation an actual sea-voyage the destination of

which cannot however be determined. These adventures were called the

"Navigatio Brendani", the Voyage or Wandering of St.

Brendan, but there is no historical proof of

this journey. Brendan is said to have sailed in search of a fabled Paradisewith

a company of monks,

the number of which is variously stated as from 18 to 150. After a long voyage

of seven years they reached the "Terra Repromissionis", or Paradise,

a most beautiful land with luxuriant vegetation. The

narrative offers a wide range for the interpretation of

the geographical position of this land and with it of the scene of

the legend of St.

Brendan. On the Catalonian chart (1375) it is placed not very far west

of the southern part of Ireland.

On other charts, however, it is identified with the "Fortunate Isles"

of the ancients and is placed towards the south. Thus it is put among the Canary

Islands on the Herford chart of the world (beginning of the

fourteenth century); it is substituted for the island of Madeira on the chart

of the Pizzigani (1367), on the Weimar chart (1424), and on the chart

of Beccario (1435). As the increase inknowledge of

this region proved the

former belief to

be false the

island was pushed further out into the ocean. It is found 60 degrees west of

the first meridian and very near the equator on Martin

Behaim's globe. The inhabitants of Ferro, Gomera, Madeira, and

the Azores positively

declared to Columbus that

they had often seen the island and continued to make the assertion up to a far

later period. At the end of the sixteenth century the failure to find the

island led the cartographers Apianus and Ortelius to

place it once more in the ocean west of Ireland;

finally, in the early part of the nineteenth century belief in

the existence of the island was completely abandoned. But soon a

new theory arose, maintained by those scholars who claim for the Irishthe glory of

discovering America, namely, MacCarthy, Rafn, Beamish, O'Hanlon,

Beauvois, Gafarel, etc. They rest this claim on the account of the Northmen who

found a region south of Vinland and the Chesapeake Bay called

"Hvitramamaland" (Land of the White Men) or "Irland ed

mikla" (Greater Ireland),

and on the tradition of

the Shawano (Shawnee) Indians that in earlier times Florida was

inhabited by a white tribe which had iron implements. In regard to Brendan

himself the point is made that he could only have gained a knowledge of

foreign animals and plants, such as are described in the legend,

by visiting the western continent. On the other hand, doubt was

very early expressed as to the value of the narrative for

the history of discovery. Honorius

of Augsburg declared that the island had vanished; Vincent

of Beauvais denied the authenticity of the entire pilgrimage,

and the Bollandists do

not recognize it. Among the geographers, Alexander von

Humboldt, Peschel, Ruge, and Kretschmer, place the story

among geographical legends, which are of interestfor

the history of civilization but which can lay no claim to

serious consideration from the point of view ofgeography. The oldest account of

the legend is in Latin, "Navigatio

Sancti Brendani", and belongs to the tenth or eleventh century; the

first French translation dates from 1125; since the thirteenth

century the legend has appeared in the literatures of the Netherlands, Germany,

and England.

A list of the numerous manuscripts is

given by Hardy, "Descriptive Catalogue of Materials Relating to the

History of Great Britain and Ireland" (London, 1862), I, 159 sqq. Editions

have been issued by : Jubinal, "La Legende latine de S. Brandaines avec

une traduction inedite en prose et en poésie romanes" (Paris, 1836);

Wright, "St. Brandan, a Medieval Legend of the Sea, in English Verse, and

Prose" (London, 1844); C. Schroder, "Sanct Brandan, ein

latinischer und drei deutsche Texte" (Erlangen, 1871); Brill, "Van

Sinte Brandane" (Gronningen, 1871); Francisque Michel, Les Voyages

merveilleux de Saint Brandan a la recherche du paradis

terrestre" (Paris, 1878); Fr. Novati, "La Navigatio

Sancti Brandani in antico Veneziano" (Bergamo, 1892); E. Bonebakker,

"Van Sente Brandane" (Amsterdam, 1894); Carl Wahland gives a list of

the rich literature on the subject and the

old French prose translation of Brendan's voyage (Upsala,

1900), XXXVI-XC.

Sources

Beamish, The

Discovery of America (1881), 210-211; O'Hanlon, Lives of the Irish

Saints (Dublin, 1875), V, 389; Peschel, Abhandlungen zur Erd- und

Volkerkunde (Leipzig, 1877), I, 20-28; Gaffarel, Les Voyages de Saint

Brandan et des Papœ dans l'Atlantique au Moyen Age in Bulletin de la

Societé de Géographie de Rochefort (1880-1881), II, 5; Ruge, Geschichte

des Zeitalters der Entdeckungen (Leipzig, 1881); Schirmer, Zur

Brendanus Legende (Leipzig, 1888); Zimmer, Keltische Beiträge in

Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und deutsche Litteratur (1888-89), 33;

Idem, Die frühesten Berührungen der Iren mit den Nordgermanen in Berichte

der Akademie der Wissenschaft (Berlin, 1891); Kretschmer, Die

Entdeckung Amerikas (Berlin, 1892, Calmund, 1902), 186-195;

Brittain, The History of North America (Philadelphia, 1907), I, 10;

Rafn, Ant. Amer., XXXVII, and 447-450; Avezac, Les Îles fantastiques de

l'océan occidental in Nouv. An. des voyages et de science geogr.,

(1845), I, 293; MacCarthy, The voyage of St. Brendan, in Dublin University

Magazine (Jan. 1848), 89 sqq.

Grattan-Flood, William,

and Otto Hartig. "St. Brendan." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol.

2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 16 May

2015 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02758c.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Kieran O'Shea.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. 1907. Remy Lafort, S.T.D., Censor. Imprimatur. +John

M. Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2021 by Kevin Knight.

Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02758c.htm

Sculpture of St Brendan, The Square Bantry, County Cork, Ireland

Brendan the Voyager,

Abbot (RM)

Born c. 484-489; died at Annaghdown, Ireland, c. 577-583.

"I fear that I shall journey alone, that the way will be dark; I fear the

unknown land, the presence of my King and the sentence of my judge."--The

dying words of Saint Brendan to his sister Abbess Brig.

Like the wanderings of Ulysses, the story of Saint Brendan voyaging over

perilous waters was a popular story in the Middle Ages. We see him as only a

shadow in the old Celtic world, and who he was or where he came from is

uncertain, though it is supposed that he was born the son of Findlugh on Fenit

Peninsula in Kerry, Ireland, of an ancient and noble line. It is said that he

studied theology under Saint Ita (f.d. January 15) at Killeedy, that he was a

contemporary and disciple of Saint Finian (f.d. December 12) and later Saint

Gildas at Llancarfan in Wales, and that later he founded a monastery at Saint

Malo.

Another version of his early life says that the infant Saint Brendan was given

into the care of Saint Ita, who taught him three things that God really loves:

"the true faith of a pure heart; the simple religious life; and

bountifulness inspired by Christian charity." She would have added the

three things God hates are "a scowling face; obstinate wrong-doing; and

too much confidence in money." When he was six he was sent to Saint

Jarlath's monastery school at Tuam for his education, and was ordained by

Bishop Saint Erc in 512.

Though Brendan was a real person, fabulous stories are told how his wanderings

in search of an unknown land, perhaps the Faroes, the Canaries, or the Azores.

For seven years he voyaged to find the Promised Land of the saints.

On the Kerry coast, with 14 chosen monks, he built a coracle of wattle, covered

it with hides tanned in oak bark softened with butter, and set up a mast and a

sail, and after a prayer upon the shore, he embarked in the name of the

Trinity. After strange wanderings he returned to Ireland and, about 559,

founded a great monastery at Clonfert in Galway of 3,000 monks and a convent

under his sister Briga (f.d. January 21). He gave his monks a rule of

remarkable austerity.

Later he visited the holy island of Iona, which was the center of much

missionary activity. He founded numerous other monasteries in Ireland and

several sees. And he himself made missionary journeys into England and

Scotland.

From Ireland's Eye

It is said that Columbus, to whom Brendan's story would have been familiar, may

have been inspired by the saint's epic saga Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis.

Long before Columbus, the Irish monks were renowned as travellers and

explorers. Tradition says that they reached Iceland and explored even farther

afield in the Atlantic--perhaps as far as America.

Scholars long doubted the voyage to the Promised Land described by Brendan could

have been to North America, but some modern scholars now believe that he may

have done just that. In 1976-77, Tim Severin, an expert on exploration,

following the instructions in the Navigatio built a hide-covered curragh and

then sailed it from Ireland to Newfoundland via Iceland and Greenland,

demonstrating the accuracy of its directions and descriptions of the places

Brendan mentioned in his epic.

Brendan himself stands out in a dark age as the captain of a Christian crew.

Like the Greeks and the Vikings, he had a craving for the sea, but he built his

boat, and launched it in the name of the Lord and sailed it under the ensign of

the Cross. It is a thrilling saga, for all its strangeness, and set many a

sailor later to search in vain for Saint Brendan's Island; but none ever found

it, though it was said at times to be seen, like an Isle of Paradise, riding

above the surface of the sea.

Now the great mountain that juts out into the Atlantic in County Kerry is

called Mount Brandon, because he had a little chapel atop it, and the bay at

the foot of the mountain is Brandon Bay. Brendan probably died while visiting

his sister Briga, abbess of a convent at Enach Duin (Annaghdown) (Attwater,

Benedictines, Bentley, Delaney, Gill, Little, Severin, Webb).

Below I've recounted some of the many legends surrounding Saint Brendan:

There is a graphic description of one of their expeditions: "Three Scots

came to King Alfred, in a boat without oars, from Ireland, whence they had

stolen away, because for the love of God they desired to be on pilgrimage, they

recked not whither. The boat in which they came was made of two hides and a

half; and they took with them provisions for seven days; and about the seventh

day they came on shore in Cornwall, and soon after went to King Alfred"

(Gill).

Saint Brendan was chanting the office for the Feast of Saint Paul the Apostle,

when his brethren asked him to do so quietly for fear of disturbing the sea

monsters. He laughed, "What has driven out your faith? Fear naught but the

Lord our God, and love Him in fear. Many perils have tried you, but the Lord

brought you safely out of them all. There is no danger here. What are you

afraid of?" And he celebrated Mass more solemnly than before.

"Thereupon the monsters of the deep began to rise on all sides, and making

merry for joy of the Feast, followed after the ship. Yet when the office of the

day was ended, they straightway turned back and went their way" (Plummer).

They sailed to another small, lovely island, in which there was a whirlpool.

"They went across the island, and found a church built of stone, and in it

a venerable old man at his prayers. . . . And the old man said to them, 'O holy

men of God, make haste to flee from this island. For there is a sea-cat here,

of old time, inveterate in wiles, that hath grown huge through eating

excessively of fish.' Thereupon they turned back in haste to their ship, and

abandoned the island.

"But lo, behind them they saw that beast swimming through the sea, and it

had great eyes like vessels of glass. Thereupon they all fell to prayer, and

Brendan said, 'Lord Jesus Christ, hinder Thy beast.' And straightway arose

another beast from the depths of the sea, and approaching fell to battle with

the first; and both went down to the depth of the sea, nor were they further

seen. Then they gave thanks to God, and turned back to the old man, to question

him as to his way of living and whence he had come.

"And he said to them, 'We were twelve men from the island of Ireland that

came to this place, seeking the place of our resurrection. Eleven be dead; and

I alone remain, awaiting, O Saint of God, the Host from thy hands. We brought

with us in the ship a cat, a most amiable cat and greatly loved by us; but he

grew to great bulk through eating of fish, as I said; yet our Lord Jesus Christ

did not suffer him to harm us.'

"And then he showed them the way to the land which they sought; and

receiving the Host at the hands of Brendan, he fell joyfully asleep in the

Lord; and he was buried beside his companions" (Plummer).

Then they came to an island filled with flowers and fruit trees and found

harbor. "The Brendan said to his brethren, 'Behold, our Lord Jesus Christ,

the good, the merciful, hath given us this place wherein to abide His holy

resurrection. My brothers, if we had naught else to restore our bodies, this

spring alone would suffice us for meat and drink.'

"Now there was above the spring a tree of strange height, covered with

birds of dazzling white, so crowded on the tree that scarcely could it be seen

by human eyes. And looking upon it the man of God began to ponder within

himself what cause had brought so great a multitude of birds together on one

tree."

[He prayed with tears that God might reveal the mystery of the birds to him.]

"And the bird spoke to him. 'We are,' it said, 'of that great ruin of the

ancient foe, who did not consent to him wholly. Yet because we consented in

part to his sin, our ruin also befell. For God is just, and keeps truth and

mercy. And so by His judgment He sent us to this place, where we know no other

pain than that we cannot see the presence of God, and so hath He estranged us

from the fellowship of those who stood firm. On the solemn feasts and on the

Sabbaths we take such bodies as you see, and abide here, praising our Maker.

And as other spirits who are sent through the divers regions of the air and the

earth, so may we speed also.

"'Now hast thou with thy brethren been one year upon thy journey; and six

years yet remain. Where this day thou dost keep the Easter Feast, there shalt

thou keep it throughout every year of thy pilgrimage, and thereafter shalt thou

find the thing that thou hast set in thy heart, the land that was promised to

the saints.' And when the bird had spoken thus, it raised itself up from the

prow, and took its flight to the rest.

"And when the hour of evening drew on, then began all the birds that were

on the tree to sing as with one voice, beating their wings and saying, 'Praise

waiteth for Thee, O Lord, in Sion: and unto Thee shall the vow be performed.'

And they continued repeating that verse, for the space of one hour.

"It seemed to the brethren that the melody and the sound of the wings was

like a lament that is sweetly sung. Then said Saint Brendan to the brethren,

'Do ye refresh your bodies, for this day have your souls been filled with the

heavenly bread.' And when the Feast was ended, the brethren began to sing the

office; and thereafter they rested in quiet until the third watch of the night.

"Then the man of God awaking, began to rouse the brethren for the Vigils

of the Holy Night. And when he had begun the verse, 'Lord, open Thou my lips,

and my heart shall show forth Thy praise,' all the birds rang out with voice

and wing, singing, 'Praise the Lord, all ye His angels; praise ye Him, all His

hosts.' And even as at Vespers, they sang for the space of one hour.

"Then, when dawn brought the ending of the night, they all began to sing,

'And let the beauty of the Lord our God be upon us,' with equal melody and

length of chanting, as had been at Matins.

"At Tierce they sang this verse: 'Sing praises to God, sing praises; sing

ye praises with understanding.' And at Sext they sang, 'Lord, lift up the light

of Thy countenance upon us, and have mercy upon us.' At Nones they said,

'Behold how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in

unity.' And so day and night the birds sang praises to God. And throughout the

octaves of the Feast they continued in the praises of God.

"Here then the brethren remained until the Whitsun Feast; for the sweet

singing of the birds was their delight and their reviving. . . . But when the

octave of the feast was ended, the Saint bade his brethren to make ready the

ship, and fill their vessels with water from the spring. And when all was made

ready, came the aforesaid bird in swift flight, and rested on the prow of the

ship, and said, as if to comfort them against the perils of the sea: 'Know that

where ye held the Lord's Supper, in the year that is past, there in like

fashion shall ye be on that same night this year. . . . After eight months ye

shall find an island . . . whereon ye shall celebrate the Lord's Nativity.' And

when the bird had foretold these things, it returned to its own place.

"Then the brethren began to spread their sails and go out to sea. And the

birds were singing as with one voice, saying, 'Hear us, O God of our salvation,

Who art the confidence of all the ends of the earth, and of them that are afar

off upon the sea.' And so for three months they were borne on the breadth of ocean,

and saw nothing beyond the sea and sky" (Plummer; these stories are also

told in Curtayne).

In art, Saint Brendan is shown saying Mass on ship as the fish crowd round to

listen to him. He may also be shown holding a candle. Just inside the main doors

of Saint Patrick's, across from Saint Brigid (f.d. February 1), stands a statue

of Saint Brendan holding his ship. Brendan is the patron of seafarers and

travellers, and is venerated in Ireland (Roeder).

Interested in learning

more about Saint Brendan? Visit The Voyage of Brendan the Navigator and La Isla

Fantasma: San Borondon (in Spanish but some great pictures). The first

discusses the possibility that Brendan reached the New World. The second speaks

of the legend of Brendan's visit to the Canary Islands. Enjoy!

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0516.shtml

St.

Benin's Church, Kilbennan, County Galway, Ireland. Stained glass window

depicting Saint Brendan.

St. Brendan the Elder,

Abbot in Ireland

[Abbot of Cluain-fearta,

or Clonfert, upon the river Shannon.] HE was son of Findloga, and a

disciple of St. Finian at Clonard. Passing afterwards into Wales he lived some

time under the discipline of St. Gildas, also several years in the abbey of

Llan-carven, in Glamorganshire. He built in Britain the monastery of Ailech,

and another church in a territory called Heth. Returning into Ireland he

founded there several schools and monasteries, the chief of which was that of

Cluain-fearta. 1 He

wrote a monastic rule which was long famous in Ireland, taught some time at

Ros-carbre, and died at Enachduin, a monastery which he had built for his

sister Briga, in Connaught. He is named in the Roman Martyrology on the 16th of

May, on which he passed to bliss, in the year 578, in the ninety-fourth year of

his age. His life extant in MS. in the Cottonian Library is filled with apochryphal

relations of miracles; see Usher’s Antiq. p. 271, 471, 494; Smith’s Natural and

Civil History of Kerry, p. 412, and 68.

Note 1. Two

great monasteries in Ireland, the heads of their respective Orders, had the

same name of Cluainfearta: this on the Shannon, in Connaught, in the county of

Galway, where now is the episcopal see of Clonfert: the other founded by St.

Luan or Molua in Leinster, called from him Cluain-fearta-Molua. Cluain, in the

old Irish language signifies a retired or hidden place; and Fearta, wonders or

miracles. [back]

Rev. Alban

Butler (1711–73). Volume V: May. The Lives of the Saints. 1866.

SOURCE : http://www.bartleby.com/210/5/167.html

Le départ de Saint-Brendan et de ses compagnons, s.d. Artiste inconnu. Tiré de St. Brendan the Voyager du révérend Denis O'Donoghue, Brown & Nolan, Dublin, 1893) frontispice.

BRENDAN (Bréanainn), SAINT, Irish abbot and missionary, traditionally connected with voyages westward towards North America and possibly even to present-day Canada; b. c. 484; d. c. 578.

It is believed that he

was born near Tralee, County Kerry, Ireland, the son of Christian parents. He

was ordained at the age of 26 and later founded the important monastery at

Clonfert, County Galway, of which he was abbot. Mt. Brandon, on Dingle peninsula,

is named after the saint, and to the west of it is the supposed location of

“St. Brendan’s Isle.”

St. Brendan is reputed to

have visited such places as the Faeroe Islands, Iceland, Jan Mayen Island, the

Antilles, the Azores, the Canaries, and even Greenland and the mainland of

America. Although the Irish had reached and even established a religious

community in Iceland before A.D. 800, there is nothing to connect Brendan with

this venture. Nor is there any reliable evidence to show that either Brendan or

any of his countrymen had ever reached Greenland or America. Very early a Vita

Sancti Brendani was written and then later a Navigatio which incorporated parts

of the Vita and the date of which is disputed (Selmer dates the earliest

manuscript at the turn of the 10th to the 11th century). This Navigatio relates

the voyage or voyages of the saint in search of the paradisum terrestre (tir

tairgirne) or Promised Land of the saints. It was circulated in numerous

manuscripts and translated into many languages.

It is a much more

reasonable argument that, where the Navigatio Sancti Brendani contains what

might be construed as information about the seas or lands west of Iceland, this

was derived from accounts of the voyages of the Norsemen in the north Atlantic

(or, in cases where Iceland seems to be indicated, from the Irish monks who

fled Iceland at the approach of the Norsemen in 870) transmitted by the

numerous Scandinavians who visited or settled in Ireland in the years 800–1200.

A close scrutiny of the

relevant Icelandic sagas (Saga of Eric the Red, (chap. 12); Eyrbyggja saga

(chap. 64); and the Landnámabok (chap. 171)) can lead only to the conclusion

that they are inapplicable to any “White Men’s Land” in America, and indeed no

land is to be found in six days’ sailing west of Ireland. St. Brendan or others

like him may have crossed the Atlantic but there is no real evidence for this

view. If they did, they left not even transient memorials, such as one would

expect to find described in the Icelandic sagas. Therefore we may assume that

the Norsemen did not come into contact with a flourishing Irish colony on the

east coast of Canada or of the United States of America.

T. J. OLESON

Navigatio Sancti Brendani

abbatis, ed. Carl Selmer (Notre Dame, Ind., 1959) contains a full bibliography

and account of the MSS material. Geoffrey Ashe, Land to the west (London,

1962). Eugène Beauvois, La découverte du Nouveau Monde par les Irlandais,

et les premières traces du christianisme en Amérique avant l’an 1000 (Congrès

international des Américanistes, Nancy, 1875). R.-Y. Creston, Journal de

bord de Saint-Brendan (Paris, 1957). Jón Dúason, Landkönnun og

Landnám Íslendinga i Vesturheimi (Reykjavík, 1941–47), 292–97, 665–70.

Hennig, Terrae incognitae. Lanctot, Histoire du Canada, I, 45–59, 62. G.

A. Little, St. Brendan the navigator (Dublin, 1945). Fridtjof

Nansen, In northern mists: arctic exploration in early times (2v.,

London, 1911), II, 42–56. Denis O’Donoghue, Brendaniana: St. Brendan the

voyager (Dublin, 1893). Oleson, Early voyages, 100, 125. E. G. R.

Waters, The Anglo-Norman voyage of St. Brendan (Oxford, 1928).

© 2000 University of

Toronto/Université Laval

SOURCE : http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?&id_nbr=87

St.

Michael's Church, Ballinasloe, County Galway, Ireland. Detail of the east

window by Frederick Settle Barff (1822–1866),

depicting Saint Brendan.

St. Brendan (Brendan the

Voyager, Brendan the Navigator) belongs to that glorious period in the

history of Ireland when the island, in the first glow of conversion to

Christianity, sent forth its earliest messengers of the Faith to the continent

and to the regions of the sea. The stories of Saint Brendan voyaging over

perilous waters were popular in the Middle Ages, and his travels were as well

known as the wanderings of Ulysses.

He was born on the Fenit Peninsula in Ciarraighe Luachra, near the present city

of Tralee, in the diocese of Ardfert and Aghadoe, County Kerry, Ireland, in

484. Many accounts agree that he was the son of Findlugh, from an ancient and

noble family. He was baptized at Tubrid, near Ardfert, by Bishop Erc. One

version of his early life says that the infant Saint Brendan was given into the

care of Saint Ita of Killeedy, "The Brigid of Munster," who taught

him three things that God really loves: "the true faith of a pure heart;

the simple religious life; and bountifulness inspired by Christian

charity." When he was six he was sent to Saint Jarlath's monastery school

at Tuam for more childhood education. In 512 Bishop Erc ordained Brendan to the

priesthood; between the years 512 and 530 he built monastic cells at Ardfert,

at Shanakeel or Baalynevinoorach, and at the foot of Brandon Hill. It was from

here that he set out on his most famous voyage.

On the Kerry coast, he built a coracle of wattle, covered it with hides tanned

in oak bark softened with butter, set up a mast and a sail, and after a prayer

upon the shore, embarked in the name of the Trinity. For seven years he voyaged

to find the Promised Land of the saints, and fabulous stories are told of his

wanderings. The great seafaring legends attached to St. Brendan, first

committed to writing in the eleventh century, have for foundation an actual

sea-voyage the destination of which cannot ever be determined. These adventures

were called the "Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis" the Voyage or

Wandering of St. Brendan, commonly known as the Navigatio. Brendan set forth

with a company of monks, the number of which is variously stated as from 18 to

150, and after a long voyage of seven years they reached the "Terra

Repromissionis", the Paradise or Promised Land, a most beautiful island

with luxuriant vegetation.

Over the years there have been many interpretations of the possible

geographical position of this island. Various pre-Columbian sea-charts

indicated it everywhere from the southern part of Ireland, to the Canary

Islands, Faroes or Azores, to the island of Madeira, to a point 60 degrees west

of the first meridian and very near the equator. Belief in the existence of the

island was almost completely abandoned when a new theory arose, maintained by

those who claim for the Irish the glory of discovering America. This claim

rests in part on the account of the Vikings who found a region south of the

Chesapeake Bay called "Irland ed mikla" (Greater Ireland), and on

stone carvings discovered in West Virginia dated between 500 and 1000 A.D.

Analysis by archaeologist Robert Pyle and language expert Barry Fell indicate

that these carvings are written in Old Irish using the Ogham alphabet.

According to Fell, "the West Virginia Ogham texts are the oldest Ogham

inscriptions anywhere in the world. They exhibit the grammar and vocabulary of

Old Irish in a manner previously unknown in such early rock-cut inscriptions in

any Celtic language."

Brendan himself stands out in a dark age as the captain of a Christian crew.

Like the Greeks and the Vikings, he had a craving for the sea, but when he

built his boat, he launched it in the name of the Lord, and sailed it under the

ensign of the Cross. Dr. Fell goes on to speculate that, "It seems

possible that the scribes that cut the West Virginia inscriptions may have been

Irish missionaries in the wake of Brendan's voyage, for these inscriptions are

Christian. Early Christian symbols such as Chi-Rho monograms (Name of Christ)

and the Dextra Dei (Right Hand of God) appear at the sites together with the

Ogham texts."

It is true that the Irish monks were renowned as travellers and explorers

centuries before Columbus. Tradition says that they reached Iceland and

explored even farther afield in the Atlantic. Some scholars who long doubted

that the voyage described by Brendan could have made it to North America have

reconsidered their position based on the research and pilgrimage of British

navigation scholar Tim Severin. Severin, over several years in the late 1970s,

did an extraordinary thing: he built a hide-covered boat following the

instructions in the Navigatio, and sailed it from Ireland to Newfoundland via

Iceland and Greenland, demonstrating the accuracy of its directions and

descriptions of the places Brendan mentioned in his epic, and proving that a

small boat could have sailed from Ireland to North America.

After many years of seafaring Brendan at last returned to Ireland. As the story

of the seven years' voyage was carried about, crowds of pilgrims and students

flocked to Ardfert. In a few years, many religious houses were formed at

Gallerus, Kilmalchedor, Brandon Hill, and the Blasquet Islands to serve the

many people who sought spiritual guidance from St. Brendan. Brendan then

founded a monastery at Inis-da-druim (now Coney Island, County Clare), in the

present parish of Killadysert, about the year 550. He journeyed to Wales, and

studied under Saint Gildas at Llancarfan. He visited Iona, and was a

contemporary and disciple of St. Finian. He left traces of his apostolic zeal

at Kilbrandon (near Oban) and Kilbrennan Sound. After three years in Britain he

returned to Ireland and did much good work in various parts of Leinster,

especially at Dysart (Co. Kilkenny), Killiney (Tubberboe), and Brandon Hill.

The great mountain that juts out into the Atlantic in County Kerry is called

Mount Brandon, because he built a little chapel atop it, and the bay at the

foot of the mountain is Brandon Bay. He also founded the Sees of Ardfert, and

of Annaghdown, and established churches at Inchiquin, County Galway, and at

Inishglora, County Mayo. Brendan's most celebrated foundation was Clonfert in

Galway, in 557, over which he appointed St. Moinenn as Prior and Head Master.

The great monastery at Clonfert housed 3,000 monks, whose rule of life was

constructed with remarkable austerity, and also included a convent for women

initially placed under the charge of his sister, St. Briga.

Brendan died at Enach Duin, now called Annaghdown, in 577, on a visit to his

sister while she was abbess of a convent there. Despite a life of exceeding

piety and many dangerous travels, he had great anxiety about the holy Journey

of death. His dying words to Briga are reported to have been: "I fear that

I shall journey alone, that the way will be dark; I fear the unknown land, the

presence of my King and the sentence of my judge."

Brendan's feast day is celebrated on May 16.

SOURCE : http://www.allsaintsbrookline.org/celtic_saints/brendan.html

St.

Brendan statue, Fenit Without, Co. Kerry, Ireland

St. Brendan the Navigator. This modern statue to St Brendan stands on Samphire Island which can be reached by a causeway from Fenit.

The statue is 12 feet tall and is placed at Great Samphire Rock in Fenit Harbour, Tralee. Brendan is pointing West to the mouth of Tralee Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, one knee bent and the other foot pushed back, bracing his body against "a force 10 gale" which blows his cloak out behind him.

San Brendano di

Cluain Ferta Abate

Tralee, County Kerry,

Irlanda, 460 - Luachair Dedad, 577-583?

In irlandese è chiamato

Brénnain Clúana Ferta, ma è conosciuto anche come Brendan di Clonfert o

Brandano il Navigatore. Negli Annali irlandesi è nominato varie volte, ma la

prima notizia certa la troviamo nella «Cronaca» compilata verso il 740; essa

ricorda la fondazione della chiesa di Clúain Ferta (baronia di Longford, contea

di Galway) a opera di Brendano, avvenimento risalente al 558. La morte, invece,

si colloca tra il 577 e il 583. Brendano fu certamente un abate, ma non fu mai

consacrato vescovo, e avrebbe fondato il monastero di Enach Dúin (Annaghdown)

su una terra donata dal re del Connacht Aíd Abrat (578). Nel X secolo un

irlandese compose l'opera letteraria «Navigatio Brendani» in cui sono

raccontati i viaggi apostolici e le avventure occorse al santo abate; seguendo

il filone delle leggende di viaggi. Un'altra «Vita» afferma che Brendano aveva

una sorella, Bríg, ricordata nel Martirologio di Donegal al 7 gennaio e che

morì mentre le rendeva visita in Luachair Dedad; inoltre sembra che fosse parente

di altri santi irlandesi. (Avvenire)

Martirologio

Romano: In Irlanda, san Brendano, abate di Clonfert, fervido propagatore

della vita monastica, del quale è celebre il racconto di una leggendaria

navigazione.

In irlandese è chiamato Brénnain Clúana Ferta, ma è conosciuto anche come Brendan di Clonfert o Brandano il Navigatore. Negli Annali irlandesi s. Brendano è nominato varie volte, ma la prima notizia certa la troviamo nella ‘Cronaca’ compilata verso il 740; essa ricorda la fondazione della chiesa di Clúain Ferta (baronia di Longford, contea di Galway) ad opera di Brendano e questo avvenimento è posto in date diverse nelle opere letterarie successive, ma ne citiamo solo la prima, nel 558.

La ‘Cronaca’ riporta anche la notizia della sua morte, che anch’essa negli annali successivi è variamente interpretata dal 577 al 583; Brendano fu certamente un abate, ma non fu mai consacrato vescovo, era il figlio di Find Loga (486) e fu educato da s. M’Íte (570) dei Déissi.

La fonte a cui facciamo riferimento per queste notizie è la “Bibliotheca Sanctorum” e l’articolo biografico è a firma dell’irlandese Cuthbert Mc Grath, purtroppo lo scritto è talmente infarcito di notizie collaterali al santo, al punto che esso viene descritto in pochissimo spazio, mentre per il resto si parla del padre, delle fonti agiografiche e storiche irlandesi in cui è menzionato, del paese d’origine e dei suoi usi, ecc. il tutto nominando continuamente nomi lunghi e composti e la loro origine nella etimologia irlandese, che è difficile seguire e riportare; per chi fosse interessato, si può consultare il III vol. di detta Opera alla pagina 404-409, in cui è riportata anche la bibliografia.

Brendano avrebbe fondato il monastero di Enach Dúin (Annaghdown) su una terra donata dal re del Connacht Aíd Abrat (578) e sarebbe morto a 94 anni.

Prendendo altre notizie sparse, sappiamo che Cummian nella sua famosa ‘Lettera Pasquale’ lo chiama Brénnain moccu Alta stabilendo così la tribù a cui apparteneva e che fece visita a Columb Cille a Hinba accompagnato da altri santi fondatori di cenobi.

Nel X secolo un irlandese compose l’opera letteraria “Navigatio Brendani” in cui sono raccontati i viaggi apostolici e le avventure occorse al santo abate; seguendo il filone delle leggende di viaggi, in generale descritti nell’Immrama.

Un’altra ‘Vita’ afferma che Brendano aveva una sorella s. Bríg, ricordata nel Martirologio di Donegal al 7 gennaio e che morì mentre le rendeva visita in Luachair Dedad; inoltre sembra che fosse parente di altri santi irlandesi.

In seguito il culto per s. Brendano si diffuse in Scozia, nel Galles, in Inghilterra, in Bretagna, in Normandia, nelle Fiandre, raggiungendo perfino le coste del Mar Baltico.

La festa nei Martirologi irlandesi, poi riportata anche dal ‘Martyrologium Romanum’ è al 16 maggio; quadri e vetrate che lo raffigurano e sue reliquie, sono nel convento della Poterie (sec. XV-XVI) di Bruges in Fiandra (Belgio).

Autore: Antonio Borrelli

SOURCE : http://santiebeati.it/dettaglio/53375

Europe

and the discoveries: Brendan discovering the Faroe

Islands

Stamp

FR 252 of Postverk Føroya, Faroe Islands (common edition with

Ireland and Iceland)

Date

of issue: 18 April 1994

Artist: Colin Harrison

Europe

and the discoveries: Brendan discovering Iceland

Stamp

FR 253 of Postverk Føroya, Faroe

Islands (common edition with Ireland and Iceland)

Date

of issue: 18 April 1994

Artist: Colin Harrison

BRANDANO, San

di Raymond Lantier - Enciclopedia

Italiana (1930)

, Irlandese, nato

verso il 484 a Tralee (Kerry). Fondò numerosi conventi in Irlanda, tra cui

quello di Clonfert, ove divenne abate e morì verso il 578. È soprattutto

celebre per il racconto - popolarissimo nel Medioevo - del suo viaggio

settennale alla ricerca del Paradiso. Lo possediamo in una redazione

latina, Navigatio sancti Brandani, verosimilmente della fine del sec. XI,

e in numerose versioni, tanto nelle quattro lingue celtiche, quanto in

francese, inglese, sassone, fiammingo, italiano.

La leggenda di S.

Brandano si ricollega a tutta una serie di viaggi mitici verso i paesi

d'oltremare: tema favorito nella letteratura celtica dei primi secoli dell'era

cristiana. Alcuni episodî della navigazione di S. Brandano si ritrovano nel

viaggio di Bran figlio di Febal, e nella saga di Maelduin. Ma ci possiamo

chiedere se questa leggenda non contenga anche vestigia di tradizioni relative

a spedizioni marittime irlandesi e a stabilimenti in Islanda e in America, ai

quali sembrano alludere le saghe islandesi. La leggenda di Brandano, poi, si è

diffusa ben presto anche fuori dei paesi celti; e sembra l'abbiano conosciuta

anche gli Arabi, che ne hanno introdotto qualche episodio nella storia di

Sindbad il marinaio. L'isola di S. Brandano è stata indicata sulle principali

carte medievali fino ad epoca relativamente recente, per es. sopra una carta

veneziana del 1367, su quella anonima di Weimar del 1424; in quella di Beccario

(1435) è confusa con Madera, e Martino Behaim (1492) la pone ad ovest delle

Canarie. Nel trattato con cui la Corona di Portogallo cede ai Castigliani i

suoi diritti sulle Canarie, è detta "l'isola non ancora scoperta".

Dal 1526 al 1721 non meno di quattro spedizioni salparono dalle Canarie alla

ricerca dell'isola di S. Brandano.

Bibl.: A. Jubinal, La

légende latine de Saint-Brandan, Parigi 1836; Zimmer, Keltische Beiträge,

II, Brandans Meerfahrt, Berlino 1889; P. F. Moran, Acta Sancti

Brandani, Dublino 1872; O' Donoghue, Brandaniana, Dublino 1893; A.

D'Ancona, Scritti danteschi, Firenze 1913, pp. 45-46; C. Wahlund, Eine

altfranzösische prosaübersetzung von Brandans Meerfahrt, in Festgabe W.

Förster, Halle 1901, p. 129 segg.; id., in Skrifter utgifna af K.

Humanistika Vetenskaps-Samfundet i Uppsala, IV, 3 (1902); F. Novati, La

Navigatio S. Brandani in antico veneziano, Bergamo 1893, 2ª ed. 1896; J. K.

Wright, The geographical Lore of the Time of the Crusades, New York 1925.

SOURCE : https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/san-brandano_(Enciclopedia-Italiana)/

A woodcut which shows the scene from Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis where the saint celebrates a mass on the body of a sea monster. 15th century

Jean Larmat (Université de Nice). Le réel et l’imaginaire dans la Navigation de Saint Brandan in Voyage, quête, pèlerinage dans la littérature et la civilisation médiévales, Presses universitaires de Provence, 1976 : https://books.openedition.org/pup/4330?lang=fr

Jean

Larmat (Université de Nice). L'eau

dans la Navigation de saint Brandan de Benedeit in L’eau au

Moyen Âge, Presses universitaires de Provence, 1985 : https://books.openedition.org/pup/2947

Glyn S. Burgess. »Les fonctions des quatre éléments dans le Voyage de saint Brendan par Benedeit »Cahiers de Civilisation Médiévale Année 1995 38-149 pp. 3-22 : https://www.persee.fr/doc/ccmed_0007-9731_1995_num_38_149_2602

Silvère Menegaldo, « W.R.J. Barron, Glyn S. Burgess (éds.), The Voyage of Saint Brendan », Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes [En ligne], Recensions par année de publication, mis en ligne le 29 août 2008, consulté le 16 mai 2022. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/crm/1003 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/crm.1003

Le Voyage de Saint

Brendan : http://saintbrendan.d-t-x.com/

Saint Brendan The Navigator : https://www.irelandseye.com/irish/people/saints/brendan.shtm

.jpg)

.jpg)