Saint

Vincent de Paul

Fondateur

de la congrégation de la Mission et des Filles de la Charité (+ 1660)

Monsieur Vincent n'oubliera jamais que, quand il était petit, il gardait les porcs dans la campagne landaise. Il en rougissait à l'époque et s'il voulut devenir prêtre, ce fut surtout pour échapper à sa condition paysanne. Plus tard, non seulement il l'assumera, mais il en fera l'un des éléments de sa convivialité avec les pauvres et les humiliés. A 19 ans, c'est chose faite, il monte à Paris parce qu'il ne trouve pas d'établissement qui lui convienne. Le petit pâtre devient curé de Clichy un village des environs de Paris, aumônier de la reine Margot, précepteur dans la grande famille des Gondi. Entre temps, il rencontre Bérulle qui lui fait découvrir ce qu'est la grâce sacerdotale et les devoirs qui s'y rattachent. Il appellera cette rencontre "ma conversion". Il renonce à ses bénéfices, couche sur la paille et ne pense plus qu'à Dieu. Dès lors son poste de précepteur des Gondi lui pèse. Il postule pour une paroisse rurale à Châtillon-les-Dombes et c'est là qu'il retrouve la grande misère spirituelle et physique des campagnes françaises. Sa vocation de champion de la charité s'affermit. Rappelé auprès des Gondi, il accepte et enrichit son expérience comme aumônier des galères dont Monsieur de Gondi est le général. Ami et confident de saint François de Sales, il trouve en lui l'homme de douceur dont Monsieur Vincent a besoin, car son tempérament est celui d'un homme de feu. Pour les oubliés de la société (malades, galériens, réfugiés, illettrés, enfants trouvés) il fonde successivement les Confréries de Charité, la Congrégation de la Mission (Lazaristes) et avec sainte Louise de Marillac, la Compagnie des Filles de la Charité. Plus que l'importance de ses fondations, c'est son humilité, sa douceur qui frappe désormais ses contemporains. Auprès de lui chacun se sent des envies de devenir saint. Il meurt, assis près du feu, en murmurant le secret de sa vie: "Confiance! Jésus!".

- Le Pape François rend hommage à saint Vincent de Paul dans un message adressé aux membres de l'Association internationale des Charités, à l'occasion des 400 ans des premières Confréries de Charité, le 15 mars 2017. (Le Pape encourage une 'culture de la miséricorde' à la suite de saint Vincent de Paul)

- Saint Vincent de Paul (1581 - 1660) est un géant de la charité. Sa vie est une synthèse de la prière et de l'action. Elle se résume en un triptyque:

+ Une riche spiritualité propre à approfondir notre foi.

+ Une vie toute donnée à Dieu et aux pauvres.

+ Un amour profond pour le sacerdoce et la mission. Car "l'Amour est

inventif jusqu'à l'infini!"

(Diocèse d'Aire et Dax -

saints et martyrs landais - l'Église dans les Landes)

- Saint Vincent de Paul (1581-1660) Monsieur Vincent, géant de la charité, nous échappera toujours et ne se laissera pas appréhender facilement. Mais il nous dit avec son air malicieux de gascon: «le temps change tout». Alors, que nous dit-il, 350 ans après et toujours vivant? Figures de sainteté - site de l'Eglise catholique en France

- "A Saintes précisément, il établit aussi la Congrégation de la Mission.

De nombreuses lettres qu'il adressa au supérieur de la maison sont conservées :

à Louis Thibault, Claude Dufour, Pierre Watebled et surtout Louis Rivet. Elles

témoignent du soin extrême que Monsieur Vincent apporte au déroulement des

missions dans nos régions charentaises." (diocèse de La Rochelle Saintes -

Saint Vincent de Paul)

- En 1885, le pape Léon XIII le déclare «patron de toutes les œuvres

charitables»... Saint Vincent de Paul (1581-1660)... (diocèse de Paris)

- ...saint Vincent de Paul devient pour quelques mois curé de Châtillon sur Chalaronne. C'est là qu'il fonde les dames de la Charité, dont le règlement a été conservé dans la chambre qu'il occupait... (Diocèse de Belley-Ars - 2000 ans de vie chrétienne)

- Vidéo: le berceau de Saint Vincent de Paul, reportage réalisé par Le Jour du Seigneur dans un village qui porte son nom près de Dax.

- A lire: Monsieur Vincent «La vie à sauver», prix 2011 de la Bande

Dessinée Chrétienne d'Angoulême.

Un internaute brésilien nous suggère de rendre Saint Vincent de Paul patron du

football, ce sport étant un maillon important de la socialisation, de la paix

et de l'inclusion.

Mémoire de saint Vincent de Paul, prêtre.

Rempli d'esprit sacerdotal et entièrement donné aux pauvres à Paris, il

reconnaissait sur le visage de n'importe quel malheureux la face de son

Seigneur ; pour retrouver la forme de l'Église primitive, éduquer le clergé à

la sainteté et soulager les pauvres, il fonda la Congrégation de la Mission et,

avec l'aide de sainte Louise de Marillac, la Congrégation des Filles de la

Charité. Il mourut, épuisé, à Paris en 1660.

Martyrologe

romain

S'il s'en trouve parmi vous qui pensent qu'ils sont envoyés pour "évangéliser" les prisonniers et non pour les soulager, pour remédier à leurs besoins spirituels et non aux temporels, je réponds que nous devons les assister en toutes manières par nous et par autrui: faire cela, c'est évangéliser par paroles et par œuvres, et c'est cela le plus juste...

Saint-Vincent de Paul

(1581-1660) - (Premier aumônier des prisonniers)

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1927/Saint-Vincent-de-Paul.html

Émilien

Cabuchet. Monument de Saint Vincent de Paul. Châtillon-sur-Chalaronne,

SAINT VINCENT de PAUL

Prêtre, Fondateur d'Ordres

(1576-1660)

Ce Saint, dont le nom est devenu synonyme de charité,

est l'une des plus pures gloires de la France et de l'humanité tout entière. Il

naquit à Pouy, près de Dax, le 24 août 1576. Ses parents faisaient valoir une

petite ferme et vivaient du travail de leurs mains. Les premières années de

Vincent se passèrent à la garde des troupeaux. Un jour qu'il avait ramassé

jusqu'à trente sous, somme considérable pour lui, il la donna au malheureux qui

lui parut le plus délaissé. Quand ses parents l'envoyaient au moulin, s'il

rencontrait des pauvres sur sa route, il ouvrait le sac de farine et leur en

donnait à discrétion.

Son père, témoin de sa charité et devinant sa rare

intelligence, résolut de s'imposer les plus durs sacrifices pour le faire

étudier et le pousser au sacerdoce: "Il sera bon prêtre, disait-il, car il

a le coeur tendre." A vingt ans, il étudie la théologie à Toulouse et

reçoit bientôt le grade de docteur.

Un an après son ordination au sacerdoce, il se rend à

Marseille pour recueillir un legs que lui a laissé un de ses amis. Au retour,

voyageant par mer pour se rendre à Narbonne, il est pris par des pirates et

emmené captif en Afrique. Sa captivité, d'abord très dure et accompagnée de

fortes épreuves pour sa foi, se termina par la conversion de son maître, qui

lui rendit la liberté. C'est alors que Vincent va se trouver dans sa voie.

Les circonstances le font nommer aumônier général des

galères, et il se dévoue au salut de ces malheureux criminels avec une charité

couronnée des plus grands succès. La Providence semble le conduire partout où

il y a des plaies de l'humanité à guérir.

A une époque où la famine et les misères de toutes

sortes exercent les plus affreux ravages, il fait des prodiges de dévouement;

des sommes incalculables passent par ses mains dans le sein des pauvres, il

sauve à lui seul des villes et des provinces entières. Ne pouvant se multiplier,

il fonde, en divers lieux, des Confréries de Dames de la Charité, qui se

transforment bientôt dans cette institution immortelle et incomparable des

Filles de la Charité, plus connues sous le nom des Soeurs de

Saint-Vincent-de-Paul. Nulle misère ne le laisse insensible; il trouve le moyen

de ramasser lui-même et de protéger partout des multitudes d'enfants, fruits du

libertinage, exposés à l'abandon et à la mort, et mérite le nom de Père des

enfants trouvés.

Il a formé des légions d'anges de charité; mais il lui

faut des légions d'apôtres, et il fonde les Prêtres de la Mission, destinés à

évangéliser la France et même les peuples infidèles.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours

de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950.

Mort à Paris le 27 septembre 1660. Canonisé en 1737

par Clément XII, fête fixée comme semidouble au 19 juillet. Benoît XIV l’érigea

en fête double en 1753.

SOURCE : https://livres-mystiques.com/partieTEXTES/Jaud_Saints/calendrier/Vies_des_Saints/07-19.htm

Saint Vincent de Paul s’adresse aux Filles de la

Charité.

Voilà donc, mes chères filles, de fortes raisons pour

vous inciter à faire estime de votre vocation et à vous en acquitter avec

plaisir, puisque cela plaît à Dieu et que le prochain en est secouru, et sans

crainte, puisque Dieu même vous préserve.

Un moyen de le faire comme Dieu veut, c’est de le

faire en charité, en charité, mes filles. Oh ! que cela rendra votre

service excellent ! Mais savez-vous ce que c’est que le faire en

charité ? C’est le faire en Dieu, car Dieu est charité, c’est le faire pour

Dieu tout purement ; c’est le faire en la grâce de Dieu, car le péché nous

sépare de la charité de Dieu.

Servant les pauvres, on sert Jésus Christ. Ô mes

filles, que cela est vrai ! Vous servez Jésus Christ en la personne des

pauvres. Et cela est aussi vrai que nous sommes ici. Une sœur ira dix fois le

jour voir les malades, et dix fois par jour elle y trouvera Dieu. Comme dit

saint Augustin, ce que nous voyons n’est pas si assuré, parce que nos sens

nous peuvent tromper ; mais les vérités de Dieu ne trompent jamais. Allez

voir de pauvres forçats à la chaîne, vous y trouverez Dieu ; servez ces

petits enfants, vous y trouverez Dieu. Ô mes filles, que cela est

obligeant ! Vous allez en de pauvres maisons, mais vous y trouvez Dieu. Ô

mes filles, que cela est obligeant encore une fois ! Il agrée le service

que vous rendez à ces malades et le tient fait à lui-même, comme vous avez dit.

St Vincent de Paul

Figure majeure du renouveau spirituel du XVIIe

siècle français, saint Vincent de Paul († 1660) a fondé, avec Louise de

Marillac, les Filles de la Charité. Il fut aussi formateur de prêtres et fonda

la société des Prêtres de la Mission (lazaristes). / Correspondance,

entretiens, documents, II – Entretiens, tome IX, Paris, Gabalda, 1923, p.

249-252.

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/daily-prayer/lundi-27-septembre/meditation-de-ce-jour-1/

[VIDEO] Quand saint Vincent de Paul était esclave

Retour sur un épisode de la vie de saint Vincent de

Paul, patron de toutes les œuvres charitables et des prisonniers, qui changea

le sort de milliers de chrétiens persécutés.

L’humilité de saint Vincent de Paul (1581-1660), sa

bonté, sa convivialité, son abandon à la Providence sont bien connus. Des

qualités qui ont fait de lui un géant de la charité auprès des plus pauvres,

des marginalisés, des orphelins, reconnaissant en eux « la face de son

Seigneur ». Cette humilité, cette douceur et cet empressement à soulager

de leur détresse tous les « oubliés de la société » frappent

tous ses contemporains et rayonnent aujourd’hui encore à travers le

monde. Il doit certainement ces facultés à son tempérament naturel et à

son enfance paysanne dans les Landes — dont il rougissait à l’époque mais qu’il

assumera au contact de la misère du monde rural. Mais il la doit aussi très

certainement à ses 23 mois de captivité et de travaux forcés passés en

Barbarie, où il s’est retrouvé en condition d’esclave. Vendu à divers

« maîtres », il prendra conscience de la condition insupportable des

milliers d’esclaves chrétiens en terre d’islam.

Lire aussi :

Saint Vincent de Paul : « Les pauvres sont nos

maîtres »

Nous sommes en 1605, c’est-à-dire cinq ans après son

ordination sacerdotale, lorsque Vincent est fait prisonnier avec tant d’autres

passagers lors d’un voyage en Méditerranée, et emmené à Tunis. À cette époque,

le piratage barbaresque, non loin des côtes européennes, est au plus fort. Les

captifs sont entassés dans les bagnes de Tunis et d’Alger. 36 000 chrétiens

sont alors répartis entre les deux villes. Durant ces deux années, et à son

retour, après une traversée périlleuse à bord d’une simple barque, le jeune

homme déploiera tous les efforts possibles pour les soulager de leurs souffrances.

Des galères aux bagnes d’Alger

Le premier réflexe de Vincent à son retour est d’aller

partager son souci avec les autorités françaises et de venir en aide à tous les

captifs qui, s’aperçoit-il, dans son propre pays, vivent dans des conditions

déplorables. Nommé aumônier général des galères du roi en 1619, il découvre

vite qu’on traite les galériens comme des bêtes. Le sort des

« chiourmes », comme on appelait les équipages d’une galère,

enchainés et fouettés sans arrêt durant les traversées, sont d’une atrocité qui

lui fait honte. Il va alors de port en port, de galère en galère, constater

l’horreur de leur traitement. On raconte même qu’un jour, révolté par la brutalité

d’un gardien, il a voulu prendre la place d’un de ces pauvres malheureux et

ramer à sa place. Grâce à lui et à de bonnes dames charitables, il arrivera peu

à peu à améliorer les conditions de vie des prisonniers en général.

Lire aussi :

« Pour saint Vincent de Paul là où se trouve le pauvre, se

trouve le Christ »

Parallèlement, saint Vincent pense aux bagnes d’Alger

et de Tunis et à tous ces captifs en terre d’islam. Le temps de fonder sa

Congrégation de la Mission, en 1625, puis la Société des prêtres de la Mission

(lazaristes) en 1627, et de les voir grandir, il lance, en 1646, son premier

projet à l’étranger, envoyant plusieurs missionnaires à Constantinople, au

centre de l’Empire ottoman. Il arrivera à faire délivrer plusieurs milliers de

captifs chrétiens en échange de rançons, et à mettre en place une sorte

d’aumônerie pour apporter soulagement et réconfort aux captifs face aux

pressions morales et parfois physiques auxquelles ils étaient soumis dans la

tentative de les faire apostasier.

Pour Vincent, envisager des missions sur ces terres

était comme le prolongement normal des missions en France. Même si la

congrégation de la mission ne prévoyait pas dans ses statuts l’envoi de

missionnaires à l’extérieur, saint Vincent n’eut aucun mal à convaincre la

communauté que le service des pauvres englobe « toutes les missions, même

les plus lointaines ». En revanche il dut braver toutes sortes de

réticences et pressions de l’extérieur pour ne pas devoir arrêter ses missions

en Barbarie.

La cathédrale de Tunis, érigée entre 1893 et 1897, lui rend

hommage en portant son nom. L’un des vitraux retrace la scène du saint apôtre

de la charité présentant à Richelieu des négociants français esclaves à

Tunis, et montrant au cardinal le contrat signé avec le Bey de Tunis pour le

rachat des captifs.

Découvrez les huit plus belles citations de saint

Vincent de Paul :

Lire aussi :Saint Vincent de Paul, discrète star du street-art parisien

Entre Vincent de Paul et Catherine Labouré, une amitié

d’éternité

Anne Bernet - Publié le 26/09/21

Entre Catherine Labouré et Monsieur Vincent fêté le 27

septembre, s’est tissée au fil des années une relation affective et spirituelle

d’autant plus forte que, reniée par son père, la jeune fille se sent orpheline.

Leurs mystérieux échanges sont-ils à l’origine de la visite de la Vierge Marie…

à l’origine de la diffusion de la Médaille miraculeuse ?

Pour les chrétiens, ainsi que le disent les prières

des funérailles, au moment de la mort, « la vie n’est pas ôtée, mais

changée » et les défunts continuent d’exister, dans une autre dimension

que celle où nous nous mouvons. Ce qui est vrai des simples fidèles qui, en

général, ont encore besoin d’un temps de purification, l’est évidemment plus

encore des saints entrés directement dans la gloire céleste. Cette réalité

explique pourquoi certains d’entre eux, après leur trépas, se manifestent

familièrement, d’une manière ou d’une autre, aux vivants, qu’ils se soient ou

non connus sur cette terre. Ce fut le cas, à maintes reprises, pour Martin de

Porrès, Thérèse de Lisieux ou Padre Pio mais savez-vous que saint Vincent de Paul prit en personne, au début du

XIXe siècle, la peine de former à sa mission mariale la future voyante de la rue du Bac ?

Le songe de Zoé

Nous sommes en 1824, à Fain-les-Moutiers, un gros

bourg bourguignon. Depuis 1815, et la mort prématurée de sa mère, Zoé Labouré,

18 ans, s’occupe seule de faire tourner la grosse ferme familiale et d’élever

ses cadets, tâche écrasante dont son père a jugé bon de l’accabler alors

qu’elle n’était encore qu’une enfant. Depuis longtemps, il feint d’ignorer que

sa fille, qu’il aime autant qu’il l’esclavage, a entendu l’appel divin et

aspire au cloître ; d’ailleurs quand, à sa majorité, elle ose le lui dire, elle

se heurte à un refus formel, accompagné de la confiscation de sa dot et de sa

part d’héritage maternel. Pour l’heure, Zoé, comme on l’appelle en famille,

préférant ce prénom, celui du jour de sa naissance, à celui donné à l’état

civil, Catherine, garde son secret pour elle et s’interroge sur l’ordre où elle

doit entrer. Elle n’a qu’une certitude : ce ne sera pas chez les Filles de la

Charité de saint Vincent de Paul, où se trouve déjà sa sœur aînée.

Lire aussi :Saint Vincent de Paul, discrète star du street-art parisien

Et voilà qu’une nuit, Zoé fait un rêve. Elle se voit

dans l’église de Fain assistant à la messe, chose impossible car, depuis la

Révolution, l’église n’est plus desservie, ce qui l’oblige à faire des

kilomètres tous les jours pour s’y rendre et communier. À l’autel, un vieux

prêtre qu’elle ne connaît pas et qui la regarde, avec une attention si

particulière, et tant de bonté, qu’elle en est toute remuée, au point, dès la

dernière bénédiction, de s’enfuir pour échapper à ces yeux qui semblent lire en

elle. Puis Zoé entre dans une maison voisine, pour visiter une malade ; au

chevet de celle-ci, revoici le vieux prêtre ; il lui parle : « Ma fille,

c’est bien de soigner les malades. Vous me fuyez maintenant mais un jour, vous

serez heureuse de venir à moi. Dieu a des desseins sur vous. Ne l’oubliez

pas. »

Elle sait maintenant

Zoé se réveille en proie à un trouble immense, mais,

fille de bon sens, elle cherche où elle a pu rencontrer ce prêtre ou en voir le

portrait. Impossible : elle est sûre de ne pas le connaître, ni de près ni de

loin. Pourtant, son visage amical et souriant reste ancré dans son souvenir.

Un an plus tard, Zoé obtient de son père, qui n’a

jamais jugé utile de scolariser ses filles, de l’autoriser à entrer quelques

mois chez l’une de ses cousines qui tient un pensionnat à Châtillon-sur-Seine,

afin d’apprendre au moins à lire et écrire. Sans quoi, mais elle s’est gardée

de le dire, aucun noviciat ne voudra d’elle analphabète. Ce séjour tourne au

cauchemar : elle est déplacée dans ce milieu d’adolescentes riches qui se

moquent de cette paysanne incapable d’apprendre à lire… Découragée, Zoé ne sait

plus ce que Dieu attend d’elle.

Lire aussi :« Pour saint Vincent de Paul là où se trouve le pauvre, se

trouve le Christ »

Un jour, sa cousine, pour lui changer les idées,

l’emmène chez les Filles de la Charité et là, accroché au mur du parloir, le

portrait d’un vieux prêtre que Zoé reconnaît aussitôt puisque c’est l’inconnu

de son rêve. Quand elle demande de qui il s’agit, les religieuses lui répondent

que c’est saint Vincent de Paul, leur fondateur. D’un coup, tous les doutes et

les réticences de Zoé disparaissent ; elle sait maintenant où Dieu l’appelle.

Ses parents de substitution

En fait, à cause de l’obstination mauvaise de son

père, il faudra presque cinq ans pour que Zoé Labouré réussisse, en avril 1830,

à entrer au noviciat des Filles de la Charité, rue du Bac à Paris. On n’y fait

guère attention à cette « fermière » au fort accent bourguignon,

presque illettrée et dont la dot minimale laisse croire qu’elle est pauvre.

Personne ne devine l’étonnante vertu de cette novice, ni sa familiarité réelle

avec les choses divines.

Comme jadis après la mort de sa maman, elle a élu la

Sainte Vierge pour Mère adoptive, Mademoiselle Labouré a reporté sur Vincent

l’affection dont son père ne veut plus.

Ce 25 avril 1830 est une grande date : cachées durant

la Terreur, les reliques de saint Vincent de Paul seront

solennellement ramenées rue de Sèvres dans l’église des Lazaristes, l’autre

ordre, masculin, fondé par Monsieur Vincent afin d’évangéliser les campagnes et

former le clergé. Cette translation sera suivie d’une octave de prière en

l’honneur du fondateur et les novices pourront chaque jour aller prier devant

les reliques de leur bon père. Zoé, devenue en religion sœur Catherine, n’a

jamais oublié les paroles du vieux prêtre de son rêve : « Un jour, ma

fille, vous serez heureuse de venir à moi. » Entre elle et le saint, au

fil des années, s’est tissée une relation affective d’autant plus forte que,

reniée par son père qui l’a chassée de sa maison parce qu’elle persistait dans

sa vocation, la jeune fille n’a plus d’autre soutien que le saint. Comme jadis

après la mort de sa maman, elle a élu la Sainte Vierge pour Mère adoptive,

Mademoiselle Labouré a reporté sur Vincent l’affection dont son père ne veut

plus. Et elle attend tout de ses parents de substitution.

La vision du cœur de Monsieur Vincent

Toute une semaine, à ses moindres moments de loisir,

Catherine va prier devant les reliques : « Je demandais à saint Vincent

toutes les grâces qui m’étaient nécessaires, et aussi pour les deux familles

(les filles de la Charité et les Lazaristes), et la France entière. Il me

semblait qu’elles en avaient le plus grand besoin. Enfin, je priais Monsieur

Vincent de m’enseigner ce qu’il fallait que je demande avec une foi

vive. » Demander à Dieu ce qu’il faut lui demander et non ce que l’on

souhaiterait obtenir de lui, telle est le secret de la prière des saints. À

chacune de ses stations devant les reliques, Catherine a le sentiment de la

présence quasi physique de Vincent, au point qu’elle souffre de devoir le

quitter. Heureusement, dans la chapelle de la rue du Bac se trouve un autre

reliquaire contenant « des petites reliques » du fondateur. « Et

toutes les fois que je revenais de Saint-Lazare, j’avais tant de peine qu’il me

semblait retrouver à la communauté saint Vincent, ou du moins son cœur, il

m’apparaissait toutes les fois que je revenais de Saint-Lazare. J’avais la

douce consolation de le voir… »

L’annonce de la révolution

La première fois qu’elle a la vision du cœur de saint

Vincent, Catherine le voit « blanc couleur de chair » et elle éprouve

de la douceur et du réconfort ; elle comprend intérieurement que ce blanc

symbolise « la paix, le calme, l’innocence et l’union ». Le

lendemain, nouvelle vision mais cette fois, le cœur du saint est « rouge

feu, ce qui doit allumer la charité dans les cœurs. Il me semblait que toute la

communauté devait se renouveler et s’étendre jusqu’aux extrémités du

monde ». Pourquoi faut-il qu’à ces promesses succède, le troisième jour,

la vision d’un cœur « rouge noir, ce qui me mettait de la tristesse dans

le cœur ; il me venait de la tristesse que j’avais de la peine à surmonter. Je

ne savais ni comment ni pourquoi cette tristesse se portait sur le changement

de gouvernement ». C’est l’annonce de la révolution qui, en juillet,

renversera la monarchie et déclenchera contre le catholicisme de nouvelles

violences en France…

Lire aussi :Apparition mariale : le message de la rue du Bac

Quand, à sa prochaine confession, Catherine s’ouvrira

de ces visions, elle se fera rabrouer de la belle manière par son jeune

confesseur, le père Aladel, avec qui elle aura toute sa vie des rapports

compliqués… Cela ne s’arrangera pas quand elle viendra lui dire, en tremblant

de ses réactions, qu’elle voit aussi le Christ présent dans l’hostie pendant la

messe, qu’Il lui apparaît dans sa royauté bafouée, et ce sera bien pire lorsque

les révélations de Notre-Dame commenceront !

La visite nocturne

À la fin de l’octave, les manifestations de saint

Vincent cessent, mais pas l’affection que Catherine lui porte. Dans le

calendrier de l’époque, la fête du fondateur est au 19 juillet. Le 18, sœur

Marthe, responsable des novices, leur parle de la grande dévotion mariale du

fondateur et, en cadeau, leur partage une relique précieuse du saint, un petit

morceau de son rochet. Catherine a reçu ce présent avec joie, mais elle a une

idée en tête. Si elle se meut à l’aise dans le monde invisible, avec lequel ses

contacts vont croissants, elle éprouve un regret de n’avoir pas encore vu

la Sainte Vierge… Saint

Vincent ne pourrait-il, profitant du regain de grâces occasionnées par sa fête,

lui obtenir celle de rencontrer enfin la Mère qu’elle s’est donnée, dans un

grand élan de tendresse et de confiance, au lendemain de la mort de la sienne ?

« Comme on nous avait distribué un morceau de linge d’un rochet de saint

Vincent, j’en ai coupé la moitié que j’ai avalée, et je me suis endormie dans

la pensée que saint Vincent m’obtiendrait la grâce de voir la Sainte

Vierge. »

Quelques heures plus tard, en pleine nuit, son ange

gardien réveillera sœur Catherine pour l’informer que la Sainte Vierge l’attend

à la chapelle.

Lire aussi :Catherine Labouré, une adoratrice silencieuse qui a vu Jésus

dans l’Hostie

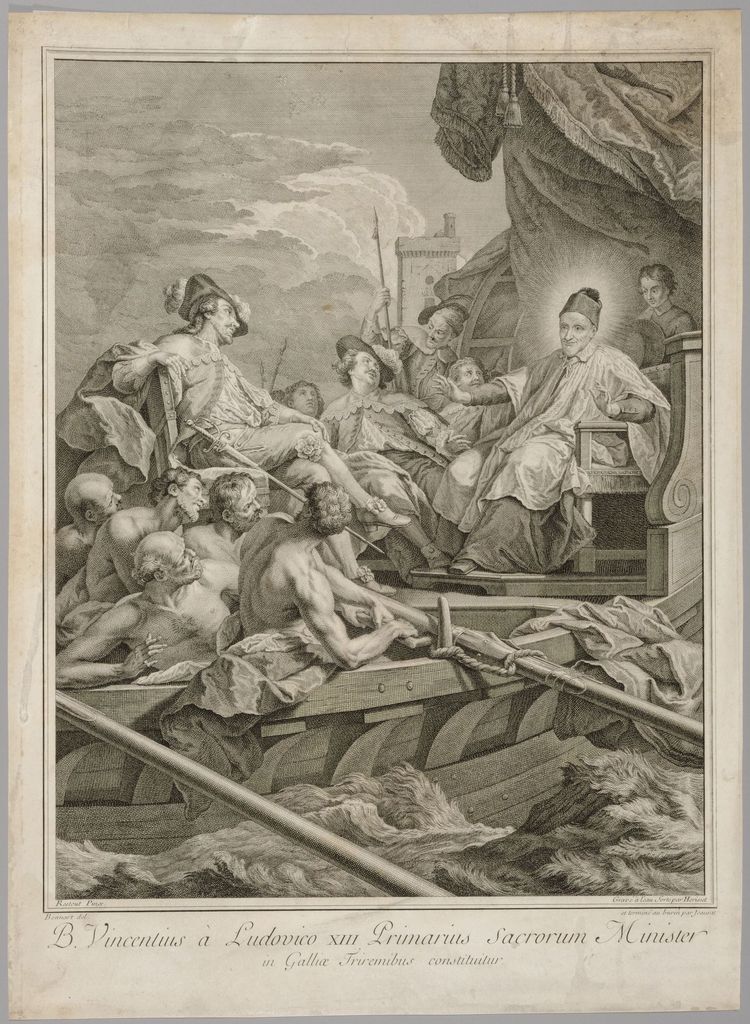

Restout (d'après), HERISSET (graveur), Jeaurat Edme (graveur), Bonnart (dessinateur). Rencontre de Saint Vincent de Paul et de Louis XIII sur un trirème, illustration de la nomination de saint Vincent de Paul comme aumonier royal des galères, vers 1740, Musées départementaux de la Haute-Saône

Leçons des Matines avant 1960.

Au deuxième nocturne.

Quatrième leçon. Vincent de Paul, français de nation, naquit à Pouy, non loin de Dax, en Aquitaine, et manifesta dès son enfance une grande charité pour les pauvres. Étant passé de la garde du troupeau paternel à la culture des lettres, il étudia la littérature à Aix, et la théologie à Toulouse et à Saragosse. Ordonné Prêtre et reçu bachelier en théologie, il tomba aux mains des Turcs qui l’emmenèrent captif en Afrique. Pendant sa captivité, il gagna son maître lui-même à Jésus-Christ ; grâce au secours de la Mère de Dieu, il put s’échapper avec lui de ces pays barbares, et prit le chemin de Rome. De retour en France, il gouverna très saintement les paroisses de Clichy et de Châtillon. Nommé par le roi grand aumônier des galères de France, il apporta dans cette fonction un zèle merveilleux pour le salut des officiers et des rameurs ; saint François de Sales le donna comme supérieur aux religieuses de la Visitation, et, pendant près de quarante ans, il remplit cette charge avec tant de prudence, qu’il justifia de tout point le jugement du saint Prélat, qui déclarait ne pas connaître de Prêtre plus digne que Vincent.

Cinquième leçon. Il s’appliqua avec une ardeur infatigable jusqu’à un âge très avancé à évangéliser les pauvres, et surtout les paysans, et astreignit spécialement à cette œuvre apostolique, par un vœu perpétuel que le Saint-Siège a confirmé, et lui-même et les membres de la congrégation qu’il avait instituée, sous le titre de Prêtres séculiers de la Mission. Combien Vincent eut à cœur de favoriser la discipline ecclésiastique, on en a la preuve par les séminaires qu’il érigea pour les Clercs aspirant aux Ordres, par le soin qu’il mit à rendre fréquentes les réunions où les Prêtres conféraient entre eux sur les sciences sacrées, et à faire précéder la sainte ordination d’exercices préparatoires. Pour ces exercices et ces réunions, comme aussi pour les retraites des laïques, il voulut que les maisons de son institut s’ouvrissent facilement. De plus, afin de développer la foi et la piété, il envoya des ouvriers évangéliques, non seulement dans les provinces de la France, mais en Italie, en Pologne, en Écosse, en Irlande, et même chez les Barbares et les Indiens. Quant à lui, après avoir assisté Louis XIII à ses derniers moments, il fut appelé par la reine Anne d’Autriche, mère de Louis XIV, à faire partie d’un conseil ecclésiastique. Il apporta tout son zèle à ne laisser placer que les plus dignes à la tête des Églises et des monastères, à mettre fin aux discordes civiles, aux duels, aux erreurs naissantes, aussitôt détestées de lui que découvertes ; enfin, à ce que les jugements apostoliques fussent reçus de tous avec l’obéissance qui leur est due.

Sixième leçon. Il n’y avait aucun genre d’infortune qu’il ne secourût paternellement. Les Chrétiens gémissant sous le joug des Turcs, les enfants abandonnés, les jeunes gens indisciplinés, les jeunes filles dont la vertu était exposée, les religieuses dispersées, les femmes tombées, les hommes condamnés aux galères, les étrangers malades, les artisans invalides, les fous même et d’innombrables mendiants, furent secourus par lui, reçus et charitablement soignés dans des établissements hospitaliers qui subsistent encore. Il vint largement en aide à la Lorraine et à la Champagne, à la Picardie et à d’autres régions ravagées par la peste, la famine et la guerre. Pour rechercher et soulager les malheureux, il fonda plusieurs congrégations, entre autres celles des Dames et des Filles de la Charité, que l’on connaît et qui sont répandues partout ; il institua aussi les Filles de la Croix, de la Providence, de sainte Geneviève, pour l’éducation des jeunes filles. Au milieu de ces importantes affaires et d’autres encore il était continuellement occupé de Dieu, affable envers tous, toujours semblable à lui-même, simple, droit et humble : son éloignement pour les honneurs, les richesses, les plaisirs, ne se démentit jamais, et on l’a entendu dire que rien ne lui plaisait, si ce n’est dans le Christ Jésus, qu’il s’étudiait à imiter en toutes choses. Enfin, âgé de quatre vingt-cinq ans et usé par les mortifications, les fatigues et la vieillesse, il s’endormit paisiblement, le vingt-septième jour de septembre, l’an du salut mil six cent soixante. C’est à Paris qu’il mourut, dans la maison de Saint-Lazare, qui est la maison-mère de la congrégation de la Mission. L’éclat de ses vertus, de ses mérites et de ses miracles ont porté Clément XII à le mettre au nombre des Saints, en fixant sa Fête annuelle au dix-neuvième jour du mois de juillet. Sur les instances de plusieurs Évêques, Léon XIII a déclaré et constitué cet illustre héros de la divine charité, qui a si bien mérité de tout le genre humain, le patron spécial auprès de Dieu de toutes les associations de charité existant dans l’univers catholique et lui devant en quelque manière leur origine.

Au troisième nocturne. [1]

Lecture du saint Évangile selon saint Luc. Cap. 10, 1-9.

En ce temps-là : Le Seigneur désigna encore soixante-douze autres disciples, et les envoya deux à deux devant lui dans toutes les villes et tous les lieux où lui-même devait venir. Et le reste.

Homélie de saint Grégoire, Pape. Homilía 17 in Evangelia

Septième leçon. Notre Seigneur et Sauveur nous instruit, mes bien-aimés frères, tantôt par ses paroles, et tantôt par ses œuvres. Ses œuvres elles-mêmes sont des préceptes, et quand il agit, même sans rien dire, il nous apprend ce que nous avons à faire. Voilà donc que le Seigneur envoie ses disciples prêcher ; il les envoie deux à deux, parce qu’il y a deux préceptes de la charité : l’amour de Dieu et l’amour du prochain, et qu’il faut être au moins deux pour qu’il y ait lieu de pratiquer la charité. Car, à proprement parler, on n’exerce pas la chanté envers soi-même ; mais l’amour, pour devenir charité, doit avoir pour objet une autre personne.

Huitième leçon. Voilà donc que le Seigneur envoie ses disciples deux à deux pour prêcher ; il nous fait ainsi tacitement comprendre que celui qui n’a point de charité envers le prochain ne doit en aucune manière se charger du ministère de la prédication. C’est avec raison que le Seigneur dit qu’il a envoyé ses disciples devant lui, dans toutes les villes et tous les lieux où il devait venir lui-même. Le Seigneur suit ceux qui l’annoncent. La prédication a lieu d’abord ; et le Seigneur vient établir sa demeure dans nos âmes, quand les paroles de ceux qui nous exhortent l’ont devancé, et qu’ainsi la vérité a été reçue par notre esprit.

Neuvième leçon. Voilà pourquoi Isaïe a dit aux mêmes prédicateurs : « Préparez la voie du Seigneur ; rendez droits les sentiers de notre Dieu » [2]. A son tour le Psalmiste dit aux enfants de Dieu : « Faites un chemin à celui qui monte au-dessus du couchant » [3]. Le Seigneur est en effet monté au-dessus du couchant ; car plus il s’est abaissé dans sa passion, plus il a manifesté sa gloire en sa résurrection. Il est vraiment monté au-dessus du couchant : car, en ressuscitant, il a foulé aux pieds la mort qu’il avait endurée [4]. Nous préparons donc le chemin à Celui qui est monté au-dessus du couchant quand nous vous prêchons sa gloire, afin que lui-même, venant ensuite, éclaire vos âmes par sa présence et son amour.

[1] L’évangile de la Messe reprenant celui des Messes

des Évangélistes, les lectures du 3ème nocturne sont celles de ce Commun.

[2] Is. 40, 3.

[3] Ps 67, 5.

[4] La passion du Christ peut être comparée au couchant parce que la gloire de

cet astre divin y a comme disparu et la mort du Sauveur également puisqu’elle

l’a couché inanimé dans le tombeau.

Vincent

De Paul présentant Louise de Marillac et les premières Filles de la Charité à la

reine Anne d'Autriche. Tableau de frère

André, religieux dominicain, dans l'église de sainte Marguerite à Paris, XVIIIe

siècle. À droite, Anne d'Autriche est assise. Saint-Vincent, debout,

présente à la reine une religieuse agenouillée, peut-être Mlle Le Gras,

qui tient à la main un livre ouvert, les constitutions des filles de la

charité. Reproduction issue de : Arthur Loth, Saint Vincent et

sa mision locale, Paris, Dumoulin, 1880

Dom Guéranger, l’Année Liturgique

Vincent fut l’homme de la foi qui opère par la charité

[5]. Venu au monde sur la fin du siècle où naquit Calvin, il trouvait l’Église

en deuil de nombreuses nations que l’erreur avait récemment séparées de la

catholicité. Sur toutes les côtes de la Méditerranée, le Turc, ennemi perpétuel

du nom chrétien, redoublait ses brigandages. La France, épuisée par quarante

années de guerres religieuses, n’échappait à la domination de l’hérésie au

dedans que pour bientôt lui prêter main forte à l’extérieur par le contraste

d’une politique insensée. Sur ses frontières de l’Est et du Nord d’effroyables

dévastations promenaient la ruine, et gagnaient jusqu’aux provinces de l’Ouest

et du Centre à la faveur des luttes intestines qu’entretenait l’anarchie. Plus

lamentable que toute situation matérielle était dans cette confusion l’état des

âmes. Les villes seules gardaient encore, avec un reste de tranquillité

précaire, quelque loisir de prier Dieu. Le peuple des campagnes, oublié,

sacrifié, disputant sa vie à tous les fléaux, n’avait pour le relever dans tant

de misères qu’un clergé le plus souvent abandonné comme lui de ses chefs,

indigne en trop de lieux, rivalisant presque toujours avec lui d’ignorance.

Ce fut alors que pour conjurer ces maux et, du même

coup, mille autres anciens et nouveaux, l’Esprit-Saint suscita Vincent dans une

immense simplicité de foi, fondement unique d’une charité que le monde,

ignorant du rôle de la foi, ne saurait comprendre. Le monde admire les œuvres

qui remplirent la vie de l’ancien pâtre de Buglose ; mais le ressort secret de

cette vie lui échappe. Il voudrait lui aussi reproduire ces œuvres ; et comme

les enfants qui s’évertuent dans leurs jeux à élever des palais, il s’étonne de

trouver en ruines au matin les constructions de la veille : le ciment de sa

philanthropie ne vaut pas l’eau bourbeuse dont les enfants s’essaient à lier

les matériaux de leurs maisons d’un jour ; et l’édifice qu’il prétendait

remplacer est toujours debout, défiant la sape, répondant seul aux multiples

besoins de l’humanité souffrante. C’est que la foi connaît seule en effet le

mystère de la souffrance, que seule elle peut sonder ces profondeurs sacrées

dont le Fils de Dieu même a parcouru les abîmes, qu’elle seule encore,

associant l’homme aux conseils du Très-Haut, l’associe tout ensemble à sa force

et à son amour. De là viennent aux œuvres bienfaisantes qui procèdent de la foi

leur puissance et leur durée. La solidarité tant prônée de nos utopistes

modernes n’a point ce secret ; et pourtant elle descend aussi de Dieu, quoi

qu’ils veuillent ; mais elle enchaîne plus qu’elle ne lie : elle regarde plus

la justice que l’amour ; et à ce titre, dans l’opposition qu’on en fait à la

divine charité venue du ciel, elle semble une lugubre ironie montant du séjour

des châtiments.

Vincent aima les pauvres d’un amour de prédilection,

parce qu’il aimait Dieu et que la foi lui révélait en eux le Seigneur. « O

Dieu, disait-il, qu’il fait beau voir les pauvres, si nous les considérons en

Dieu et dans l’estime que Jésus-Christ en a faite ! Bien souvent ils n’ont pas

presque la figure ni l’esprit de personnes raisonnables, tant ils sont

grossiers et terrestres. Mais tournez la médaille, et vous verrez, par les

lumières de la foi, que le Fils de Dieu, qui a voulu être pauvre, nous est

représenté par ces pauvres ; qu’il n’avait presque pas la figure d’un homme en

sa passion, et qu’il passait pour fou dans l’esprit des Gentils, et pour pierre

de scandale dans celui des Juifs ; et avec tout cela il se qualifie l’évangéliste

des pauvres, evangelizare pauperibus misit me [6] ».

Ce titre d’évangéliste des pauvres est l’unique que

Vincent ambitionna pour lui-même, le point de départ, l’explication de tout ce

qu’il accomplit dans l’Église. Assurer le ciel aux malheureux, travailler au

salut des abandonnés de ce monde, en commençant par les pauvres gens des champs

si délaissés : tout le reste pour lui, déclarait-il, « n’était qu’accessoire ».

Et il ajoutait, parlant à ses fils de Saint-Lazare : « Nous n’eussions jamais

travaillé aux ordinands ni aux séminaires des ecclésiastiques, si nous

n’eussions jugé qu’il était nécessaire, pour maintenir les peuples en bon état,

et conserver les fruits des missions, de faire en sorte qu’il y eût de bons

ecclésiastiques parmi eux ». C’est afin de lui donner l’occasion d’affermir son

œuvre à tous les degrés, que Dieu conduisit l’apôtre des humbles au conseil

royal de conscience, où Anne d’Autriche remettait en ses mains l’extirpation

des abus du haut clergé et le choix des chefs des Églises de France. Pour

mettre un terme aux maux causés par le délaissement si funeste des peuples, il

fallait à la tête du troupeau des pasteurs qui entendissent reprendre pour eux

la parole du chef divin : « Je connais mes brebis, et mes brebis me connaissent

» [7].

Nous ne pourrions, on le comprend, raconter dans ces

pages l’histoire de l’homme en qui la plus universelle charité fut comme

personnifiée. Mais du reste, il n’eut point non plus d’autre inspiration que

celle de l’apostolat dans ces immortelles campagnes où, depuis le bagne de

Tunis où il fut esclave jusqu’aux provinces ruinées pour lesquelles il trouva

des millions, on le vit s’attaquer à tous les aspects de la souffrance physique

et faire reculer sur tous les points la misère ; il voulait, par les soins

donnés aux corps, arriver à conquérir l’âme de ceux pour lesquels le Christ a

voulu lui aussi embrasser l’amertume et l’angoisse. On ne peut que sourire de

l’effort par lequel, dans un temps où l’on rejetait l’Évangile en retenant ses

bienfaits, certains sages prétendirent faire honneur de pareilles entreprises à

la philosophie de leur auteur. Les camps aujourd’hui sont plus tranchés ; et

l’on ne craint plus de renier parfois jusqu’à l’œuvre, pour renier logiquement

l’ouvrier. Mais aux tenants d’un philosophisme attardé, s’il en est encore, il

sera bon de méditer ces mots, où celui dont ils font un chef d’école déduisait

les principes qui devaient gouverner les actes de ses disciples et leurs

pensées : « Ce qui se fait pour la charité se fait pour Dieu. Il ne nous suffit

pas d’aimer Dieu, si notre prochain ne l’aime aussi ; et nous ne saurions aimer

notre prochain comme nous-mêmes, si nous ne lui procurons le bien que nous

sommes obligés de nous vouloir a nous-mêmes, c’est à savoir, l’amour divin, qui

nous unit à celui qui est notre souverain bien. Nous devons aimer notre

prochain comme l’image de Dieu et l’objet de son amour, et faire en sorte que

réciproquement les hommes aiment leur très aimable Créateur, et qu’ils

s’entr’aiment les uns les autres d’une charité mutuelle pour l’amour de Dieu,

qui les a tant aimés que de livrer son propre Fils à la mort pour eux. Mais

regardons, je vous prie, ce divin Sauveur comme le parfait exemplaire de la

charité que nous devons avoir pour notre prochain ».

On le voit : pas plus que la philosophie déiste ou

athée, la théophilanthropie qui apporta plus tard à la déraison du siècle

dernier l’appoint de ses fêtes burlesques, n’eut de titre à ranger Vincent,

comme elle fit, parmi les grands hommes de son calendrier. Ce n’est point la

nature, ni aucune des vaines divinités de la fausse science, mais le Dieu des

chrétiens, le Dieu fait homme pour nous sauver en prenant sur lui nos misères,

qui fut l’unique guide du plus grand des bienfaiteurs de l’humanité dans nos temps.

Rien ne me plaît qu’en Jésus-Christ, aimait-il à dire. Non seulement, fidèle

comme tous les Saints à l’ordre de la divine charité, il voulait voir régner en

lui ce Maître adoré avant de songer à le faire régner dans les autres ; mais,

plutôt que de rien entreprendre de lui-même par les données de la seule raison,

il se fût réfugié à tout jamais dans le secret de la face du Seigneur [8], pour

ne laisser de lui qu’un nom ignoré.

« Honorons, écrivait-il, l’état inconnu du Fils de

Dieu. C’est là notre centre, et c’est ce qu’il demande de nous pour le présent

et pour l’avenir, et pour toujours, si sa divine majesté ne nous fait

connaître, en sa manière qui ne peut tromper, qu’il veuille autre chose de

nous. Honorons particulièrement ce divin Maître dans la modération de son agir.

Il n’a pas voulu faire toujours tout ce qu’il a pu, pour nous apprendre à nous

contenter, lorsqu’il n’est pas expédient de faire tout ce que nous pourrions

faire, mais seulement ce qui est convenable à la charité, et conforme, aux

ordres de la divine volonté... Que ceux-là honorent souverainement notre

Seigneur qui suivent la sainte Providence, et qui n’enjambent pas sur elle !

N’est-il pas vrai que vous voulez, comme il est bien raisonnable, que votre

serviteur n’entreprenne rien sans vous et sans votre ordre ? Et si cela est

raisonnable d’un homme à un autre, à combien plus forte raison du Créateur à la

créature ? »

Vincent s’attachait donc, selon son expression, à

côtoyer la Providence, n’ayant point de plus grand souci que de ne jamais la

devancer. Ainsi fut-il sept années avant d’accepter pour lui les avances de la

Générale de Gondi et de fonder son établissement de la Mission. Ainsi

éprouva-t-il longuement sa fidèle coadjutrice, Mademoiselle Le Gras, quand elle

se crut appelée à se dévouer au service spirituel des premières Filles de la

Charité, sans lien entre elles jusque-là ni vie commune, simples aides

suppléantes des dames de condition que l’homme de Dieu avait assemblées dans

ses Confréries. « Quant à cet emploi, lui mandait-il après instances réitérées

de sa part, je vous prie une fois pour toutes de n’y point penser, jusqu’à ce

que notre Seigneur fasse paraître ce qu’il veut. Vous cherchez à devenir la

servante de ces pauvres filles, et Dieu veut que vous soyez la sienne. Pour

Dieu, Mademoiselle, que votre cœur honore la tranquillité de celui de notre

Seigneur, et il sera en état de le servir. Le royaume de Dieu est la paix au

Saint-Esprit ; il régnera en vous, si vous êtes en paix. Soyez-y donc, s’il

vous plaît, et honorez souverainement le Dieu de paix et de dilection ».

Grande leçon donnée au zèle fiévreux d’un siècle comme

le nôtre par cet homme dont la vie fut si pleine ! Que de fois, dans ce qu’on

nomme aujourd’hui les œuvres, l’humaine prétention stérilise la grâce en

froissant l’Esprit-Saint ! Tandis que, « pauvre ver rampant sur la terre et ne

sachant où il va, cherchant seulement à se cacher en vous, ô mon Dieu ! Qui

êtes tout son désir », Vincent de Paul voit l’inertie apparente de son humilité

fécondée plus que l’initiative de mille autres, sans que pour ainsi dire il en

ait conscience. « C’est la sainte Providence qui a mis votre Compagnie sur le

pied où elle est, disait-il vers la fin de son long pèlerinage à ses filles.

Car qui a-ce été, je vous supplie ? Je ne saurais me le représenter. Nous n’en

eûmes jamais le dessein. J’y pensais encore aujourd’hui, et je me disais :

Est-ce toi qui as pensé à faire une Compagnie de Filles de la Charité ? Oh !

Nenni. Est-ce Mademoiselle Le Gras ? Aussi peu. Oh ! Mes filles, je n’y pensais

pas, votre sœur servante n’y pensait pas, aussi peu Monsieur Portail (le

premier et plus fidèle compagnon de Vincent dans les missions) : c’est donc

Dieu qui y pensait pour vous ; c’est donc lui que nous pouvons dire être

l’auteur de votre Compagnie, puisque véritablement nous ne saurions en

reconnaître un autre ».

Mais autant son incomparable délicatesse à l’égard de

Dieu lui faisait un devoir de ne le jamais prévenir plus qu’un instrument ne le

fait pour la main qui le porte ; autant, l’impulsion divine une fois donnée, il

ne pouvait supporter qu’on hésitât à la suivre, ou qu’il y eût place dans l’âme

pour un autre sentiment que celui de la plus absolue confiance. Il écrivait

encore, avec sa simplicité si pleine de charmes, à la coopératrice que Dieu lui

avait donnée : « Je vous vois toujours un peu dans les sentiments humains,

pensant que tout est perdu dès lors que vous me voyez malade. O femme de peu de

foi, que n’avez-vous plus de confiance et d’acquiescement à la conduite et à l’exemple

de Jésus-Christ ! Ce Sauveur du monde se rapportait à Dieu son Père pour l’état

de toute l’Église ; et vous, pour une poignée de filles que sa Providence a

notoirement suscitées et assemblées, vous pensez qu’il vous manquera ! Allez,

Mademoiselle, humiliez-vous beaucoup devant Dieu ».

Faut-il s’étonner que la foi, seule inspiratrice d’une

telle vie, inébranlable fondement de ce qu’il était pour le prochain et pour

lui-même, fût aux yeux de Vincent de Paul le premier des trésors ? Lui

qu’aucune souffrance même méritée ne laissait indifférent, qu’on vit un jour

par une fraude héroïque remplacer un forçat dans ses fers, devenait impitoyable

en face de l’hérésie, et n’avait de repos qu’il n’eût obtenu le bannissement

des sectaires ou leur châtiment. C’est le témoignage que lui rend dans la bulle

de sa canonisation Clément XII, parlant de cette funeste erreur du jansénisme

que notre saint dénonça des premiers et poursuivit plus que personne. Jamais

peut-être autant qu’en cette rencontre, ne se vérifia le mot des saints Livres

: La simplicité des justes les guidera sûrement, et l’astuce des méchants sera

leur perte [9]. La secte qui, plus tard, affectait un si profond dédain pour

Monsieur Vincent, n’en avait pas jugé toujours de même. « Je suis, déclarait-il

dans l’intimité, obligé très particulièrement de bénir Dieu et de le remercier

de ce qu’il n’a pas permis que les premiers et les plus considérables d’entre

ceux qui professent cette doctrine, que j’ai connus particulièrement, et qui

étaient de mes amis, aient pu me persuader leurs sentiments. Je ne vous saurais

exprimer la peine qu’ils y ont prise, et les raisons qu’ils m’ont proposées

pour cela ; mais je leur opposais entre autres choses l’autorité du concile de

Trente, qui leur est manifestement contraire ; et voyant qu’ils continuaient

toujours, au lieu de leur répondre je récitais tout bas mon Credo : et voilà

comme je suis demeuré ferme en la créance catholique ».

L’année 1883, cinquantième anniversaire de la

fondation des Conférences de Saint-Vincent-de-Paul à Paris, voyait notre Saint

proclamé le Patron de toutes les sociétés de charité de France ; ce patronage

fut, deux ans plus tard, étendu aux sociétés de charité de l’Église entière.

Quelle gerbe, ô Vincent, vous emportez au ciel [10] !

Quelles bénédictions vous accompagnent, montant de cette terre à la vraie

patrie [11] ! O le plus simple des hommes qui furent en un siècle tant célébré

pour ses grandeurs, vous dépassez maintenant les renommées dont l’éclat bruyant

fascinait vos contemporains. La vraie gloire de ce siècle, la seule qui restera

de lui quand le temps ne sera plus [12], est d’avoir eu dans sa première partie

des saints d’une pareille puissance de loi et d’amour, arrêtant les triomphes

de Satan, rendant au sol de France stérilisé par l’hérésie la fécondité des

beaux jours. Et voici que deux siècles et plus après vos travaux, la moisson

qui n’a point cessé continue par les soins de vos fils et de vos filles, aidés

d’auxiliaires nouveaux qui vous reconnaissent eux aussi pour leur inspirateur

et leur père. Dans ce royaume du ciel qui ne connaît plus la souffrance et les

larmes [13], chaque jour pourtant comme autrefois voit monter vers vous

l’action de grâces de ceux qui souffrent et qui pleurent.

Reconnaissez par des bienfaits nouveaux la confiance

de la terre. Il n’est point de nom qui impose autant que le vôtre le respect de

l’Église, en nos temps de blasphème. Et pourtant déjà les négateurs du Christ

en viennent, par haine de sa divine domination [14], à vouloir étouffer le

témoignage que le pauvre à cause de vous lui rendait toujours. Contre ces

hommes en qui s’est incarné l’enfer, usez du glaive à deux tranchants remis aux

saints pour venger Dieu au milieu des nations [15] : comme jadis les hérétiques

en votre présence, qu’ils méritent le pardon ou connaissent la colère ; qu’ils

changent, ou soient réduits d’en haut à l’impuissance de nuire. Gardez surtout

les malheureux que leur rage satanique s’applaudit de priver du secours suprême

au moment du trépas ; eussent-ils un pied déjà dans les flammes, ces

infortunés, vous pouvez les sauver encore [16]. Élevez vos filles à la hauteur

des circonstances douloureuses où l’on voudrait que leur dévouement reniât son

origine céleste ou dissimulât sa divine livrée ; si la force brutale des ennemis

du pauvre arrache de son chevet le signe du salut, il n’est règlements ni lois,

puissance de ce monde ou de l’autre, qui puissent expulser Jésus de l’âme d’une

Fille de chanté, ou l’empêcher de passer de son cœur à ses lèvres : ni la mort,

ni l’enfer, ni le feu, ni le débordement des grandes eaux, dit le Cantique, ne

sauraient l’arrêter [17].

Vos fils aussi poursuivent votre œuvre

d’évangélisation ; jusqu’en nos temps leur apostolat se voit couronné du

diadème de la sainteté et du martyre. Maintenez leur zèle ; développez en eux

votre esprit d’inaltérable dévouement à l’Église et de soumission au Pasteur

suprême. Assistez toutes ces œuvres nouvelles de charité qui sont nées de vous

dans nos jours, et dont, pour cette cause, Rome vous défère le patronage et

l’honneur ; qu’elles s’alimentent toujours à l’authentique foyer que vous avez

ravivé sur la terre [18] ; qu’elles cherchent avant tout le royaume de Dieu et

sa justice [19], ne se départant jamais, pour le choix des moyens, du principe

que vous leur donnez de « juger, parler et opérer, comme la Sagesse éternelle

de Dieu, revêtue de notre faible chair, a jugé, parlé et opéré ».

[5] Gal. V, 6.

[6] Luc. IV, 18.

[7] Johan. X, 14.

[8] Psalm. XXX, 2 1.

[9] Prov. XI, 3.

[10] Psalm. CXXV, 6.

[11] Prov. XXII, 9 ; Eccli. XXXI, 28.

[12] Apoc. X, 6.

[13] Ibid. XXI, 4.

[14] Jud. 4.

[15] Psalm. CXLIX, 6-9.

[16] Jud. 23.

[17] Cant. VIII, 6-7.

[18] Luc. XII, 40.

[19] Matth. VI, 33.

Bhx cardinal

Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

Alors que la France était

désolée par la peste, la famine et la guerre, la Providence sembla avoir chargé

saint Vincent de Paul de la représenter. Cela ne suffit-il pas pour louer ce

Saint, l’un de ceux qui, aux siècles derniers, cherchèrent davantage à exprimer

en eux-mêmes les vertus du Christ.

Par les mains de ce

pauvre Monsieur Vincent, comme on l’appelait, passèrent des sommes

considérables et des secours de tout genre, distribués ensuite aux foules

affamées.

L’autorité de saint

Vincent était immense et indiscutée dans tout le royaume. Il faisait partie du

conseil royal de conscience, en sorte que les nominations aux évêchés et aux

plus riches bénéfices de l’Église de France étaient soumises à son contrôle.

Néanmoins Vincent, doux et humble de cœur, gravissait les splendides escaliers

du palais royal et prenait part aux conseils de la couronne avec la même

évangélique simplicité et les mêmes vêtements pauvres et négligés que lorsqu’il

circulait dans les rues de Paris pour y recueillir les orphelins et les malades

abandonnés.

Saint Vincent de Paul

fonda la Congrégation des Prêtres de la Mission et la Compagnie des Filles de

la Charité, et mourut dans une vieillesse avancée le 27 septembre 1660.

La messe est du Commun,

sauf les parties suivantes :

Voici la première

collecte, où sont bien mis en relief les deux champs spéciaux où se déroula

l’activité de Vincent : le soin matériel et spirituel des pauvres, et la

réforme de l’esprit ecclésiastique : « Seigneur qui avez conféré une force

apostolique au bienheureux Vincent, pour qu’il évangélisât vos pauvres et

rappelât les ecclésiastiques au sentiment de leur dignité ; accordez-nous,

comme aujourd’hui nous vénérons ses mérites, d’imiter aussi ses illustres

exemples ».

Puisqu’il s’agit du

fondateur de la Congrégation de la Mission, la lecture de l’Évangile ne peut

être autre en ce jour que celle où est narrée la vocation des soixante-douze

disciples à l’apostolat, et que nous avons déjà rencontrée le 3 décembre.

Arrêtons-nous de

préférence sur une vertu de saint Vincent de Paul et tâchons de l’imiter. Il

est dit que rien ne plaisait à ce cher Saint, sinon en Jésus-Christ, en qui il

vivait, et conformément à l’esprit de qui il agissait. C’est pourquoi, dans les

cas un peu douteux, il s’arrêtait un instant pour réfléchir, se demandant : en

cette circonstance, qu’aurait fait Jésus ? Et selon l’inspiration intérieure du

Saint-Esprit, ainsi il agissait.

Dom Pius Parsch, Le

guide dans l’année liturgique

« Vincent était toujours

égal à lui-même » (sibi semper constans), dit le bréviaire.

1. Saint Vincent. — Jour

de mort : 27 septembre 1660. Tombeau : à Paris, dans la chapelle des Prêtres de

la Mission. Vie : saint Vincent est le fondateur des Lazaristes et des Filles

de la Charité, le patron de toutes les sociétés charitables. « Vincens »

signifie « vainqueur » : il a vaincu le monde par sa charité. Tout enfant, il

montra une grande tendresse envers les pauvres. Il commença par être berger,

puis il étudia la théologie. Prêtre, il tomba aux mains des « Turcs », devint

esclave, convertit son maître et s’enfuit avec lui à Rome et en France. Il fut

d’abord curé, puis grand aumônier des galères. Pendant quarante ans environ, il

dirigea les religieuses de la Visitation. Innombrables sont ses entreprises

charitables : rachat des esclaves chrétiens, aide aux enfants abandonnés, aux

garçons exposés au danger, aux filles tombées, aux forçats, aux pèlerins

malades, aux fous, aux mendiants... Comme conseiller du roi, il exerça une

grande influence sur la distribution des dignités ecclésiastiques. Bien qu’il

eût à disposer de cinquante millions, il pratiqua toujours la douceur,

l’humilité et la pauvreté. A lui seul, a-t-on dit, il retarda la Révolution

Française.

2. La messe (Justus ut

palma). — C’est celle du commun avec l’Évangile qui relate la mission des

Apôtres.

La messe des fondateurs

d’ordres nous met en présence non seulement du saint, mais de l’œuvre dont il

fut le promoteur : elle est comme un grand rameau qui s’élance de l’arbre du

Christ chargé de fleurs toujours nouvelles. A la messe s’accomplit l’œuvre de

la rédemption de cette façon encore : nous nous embrasons au feu de la vive

charité de ces héros, et puisons dans l’Eucharistie les grâces nécessaires pour

tendre à un semblable amour. Il est également important de concrétiser les

textes du commun en y reconnaissant les traits de la vie du saint.

Saint Vincent de Paul nous apparaît comme le palmier et le cèdre dans le vaste jardin de Dieu (Introït). A l’Épître, il s’adresse à nous pour notre confusion : il fut méprisé, persécuté, traité comme le rebut du monde, et nous, nous recherchons les honneurs, l’admiration... A l’Évangile, nous le voyons avec les prêtres de la Mission (Lazaristes) se répandre à travers le monde ; nous, nous les accompagnons du moins par notre prière (« Priez le maître de la moisson d’envoyer des ouvriers ») et par nos aumônes. La Communion est « le gage de la récompense au centuple et de la vie éternelle ».

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/19-07-St-Vincent-de-Paul

Antoine

Hérisset. Prédication de saint Vincent de Paul

27 septembre

Saint Vincent de Paul

Lettre

à un prêtre de la Mission

Lettre

à Louise de Marillac (2)

Lettre

II de Bossuet à St Vincent

Lettre

IV de Bossuet à St Vincent

Extraits

de la lettre de Paul VI...

Lettre

à Louise de Marillac (entre 1626 et 1629)

Tâchez à vivre contente

parmi vos sujets de mécontentement et honorez toujours le non-faire et l'état

inconnu du Fils de Dieu. C'est là votre centre et ce qu'il demande de vous pour

le présent et pour l'avenir, pour toujours. Si sa divine Majesté ne vous fait

connaître, de la manière qui ne peut tromper, qu'il veut quelque autre chose de

vous, ne pensez point et n'occupez point votre esprit en cette chose-là.

Saint Vincent de Paul

Lettre

à Bernard Codoing (16 mars 1644)

Au nom de Dieu, Monsieur,

retranchez de vos sollicitudes les choses absentes éloignées et qui ne vous

regardent pas, et appliquez tous vos soins à la discipline domestique. Le reste

viendra en son temps. La grâce a ses moments. Abandonnons-nous à la providence

de Dieu et gardons-nous bien de la devancer. S'il plaît à Notre-Seigneur me

donner quelque consolation en notre vocation, c'est ceci : que je pense qu'il

me semble que nous avons tâché de suivre en toutes choses la grande providence

et que nous avons tâché de ne mettre le pied que là où elle nous a marqué.

Saint Vincent de Paul

Lettre

à Claude Dufour (18 septembre 1649)

Voilà donc un peu de

patience à prendre en cette attente et de mieux mériter le bonheur d'un si

saint emploi par le bon usage des moindres où vous vous êtes appliqué, qui sont

néanmoins très grands, puisqu'en la maison de Dieu tout y est suprême et royal.

Saint Vincent de Paul

Lettre à un prêtre de la Mission

qui veut quitter la congrégation sous la pression affective de son père (probablement de 1649)

Je connais l'état

d'anxiété dans lequel vous a mis la lettre que votre père vous a écrite pour

vous presser de venir l'assister. En conséquence, je suis obligé de vous dire

ce que je pense :

1° Qu'il y a grand mal à

briser le lien par lequel vous vous êtes attaché à Dieu dans la

Compagnie ;

2° Que, en perdant votre

vocation, vous priverez Dieu des services appréciables qu'Il attend de

vous ;

3° Que vous serez

responsable devant le trône de Sa justice pour le bien que vous ne ferez pas et

que, neanmoins vous auriez pu faire en restant dans l'état où vous êtes

maintenant ;

4° Que vous risquerez

votre salut dans la société de vos parents et ne leur apporterez sans doute pas

le réconfort qu'ils désirent, pas plus que d'autres qui nous ont quittés sous

ce prétexte ne l'ont fait, car Dieu ne l'a pas permis ;

5° Que Notre-Seigneur,

connaissant le mal qui résulte de la fréquentation de la société des parents

pour ceux qui les ont quittés pour Le suivre, ne désire pas, comme nous le dit

l'Evangile, qu'un de ses disciples l'abandonne pour ensevelir son père, ou vende

ses biens afin de les donner aux pauvres.

6° Que vous donneriez le

mauvais exemple à vos confrères, et seriez une source de chagrin pour la

Compagnie, du fait de la perte d'un de ses enfants qu'elle aime et qu'elle a

éduqué avec le plus grand soin.

Tel est, Monsieur, ce à

quoi je désire que vous réfléchissiez devant Dieu. Vous invoquez, comme motif,

pour vous retirer, le besoin qu'a votre père de vos soins. Mais il est

essentiel de connaître les circonstances qui, selon les casuistes, obligent les

enfants à quitter leur communauté. Quant à moi, je pense que c'est seulement

valable quand les pères ou les mères subissent des afflictions naturelles et

non les fluctuations de leur condition sociale, comme, par exemple, lorsqu'ils

sont très vieux ou lorsque, par suite de quelque infirmité, ils ne peuvent plus

gagner leur pain. Or ce n'est pas le cas de votre père qui n'a que quarante ou

quarante-cinq ans, qui se porte parfaitement bien, qui est capable de

travailler et qui, en fait, travaille. Autrement, il ne se serait pas remarié,

comme il l'a fait tout récemment avec une jeune femme de dix-huit ans, une des

plus belles personnes de la ville. Il me l'a dit lui-même afin que je puisse

donner à cette dernière une introduction auprès de la Princesse de Longueville[1] pour

s'occuper de son fils. Je crois qu'il n'est pas très à l’aise, mais qui ne

souffre, de nos jours, de la misère des temps ? En outre, ce n'est pas la

détresse qui l'oblige à vous rappeler, car elle n'est pas, en fait, très

grande, c'est seulement l'appréhension qu'il en a par manque de confiance en

Dieu, quoique jusqu'à présent il n'ait manqué de rien et qu'il aurait toute

raison d'espérer en la bonté de Dieu qui ne l'abandonnera jamais.

Vous pensez sans doute

que c'est par votre entremise que Dieu désire en réalité l'aider et que pour

cette raison Sa Providence vous offre une cure valant six cents livres par

l'entremise de cet excellent homme. Mais vous verrez qu'il n'en est pas ainsi

si vous considérez seulement deux choses : d'abord que Dieu vous ayant

appelé à un état de vie qui honore celui de Son Fils sur terre et qui est si

utile à votre prochain, ne peut désirer vous en retirer au moment présent afin

d'aller prendre soin d'une famille qui vit dans le monde, qui ne cherche que

son propre confort, qui vous importunera continuellement, qui vous accablera de

difficultés et de désagréments, si vous ne pouvez la satisfaire. D'autre part,

il est incroyable que votre père ait reçu pour vous la promesse d'une cure

valant 600 livres l'an, étant donné que celles du diocèse de Bruges sont les

plus pauvres du royaume. Mais, même si cela était vrai, combien resterait-il

après en avoir déduit votre entretien ?

Je ne vous dis pas cela

par crainte que la tentation puisse avoir raison de vous ; non, je connais

votre fidélité envers Dieu ; mais afin que vous puissiez écrire une fois

pour toutes à votre père et lui dire vos motifs de suivre la volonté de Dieu

plutôt que la sienne. Croyez-moi, Monsieur, sa disposition naturelle est de

telle sorte qu'elle vous donnera très peu de repos lorsque vous serez auprès de

lui, pas plus qu'elle ne vous en donne maintenant alors que vous en êtes

éloigné. Les tourments qu'il a causés à votre pauvre sœur qui est auprès de

Mademoiselle Le Gras [2],

sont inimaginables. Il veut qu'elle abandonne le service de Dieu et de Ses

pauvres, comme s'il devait recevoir d'elle une aide considérable. Vous savez

qu'il est d'un tempérament naturellement inquiet et cela à un point tel que

tout ce qu'il a lui déplaît, et tout ce qu'il n'a pas excite en lui de

violentes convoitises. Finalement, le plus grand bien que vous puissiez lui

faire est de prier Dieu pour lui, gardant pour vous cette seule chose

nécessaire qui sera un jour votre récompense et fera descendre sur vos parents

les bénédictions divines. Je prie de tout mon cœur pour que la grâce de

Notre-Seigneur soit avec vous.

Saint Vincent de Paul

Notes :

[1] Anne

Geneviève de Bourbon, dite Mademoiselle de Bourbon, fille de Henri II de

Bourbon, prince de Condé, et sœur du grand Condé (Louis II) et du prince de

Conti (Armand). Née au château de Vincennes le 27 août 1619, elle épousa (2

juin 1646) Henri II d’Orléans, duc de Longueville, d’Estouville et de Coulommiers,

prince souverain de Neufchâtel et de Valengin, comte de Dunois, Tancarville et

Saint-Paul, pair et prince du sang de France (1595-1663). Elle mourut le 15

avril 1679 à Paris, au couvent des Carmélites du faubourg Saint-Jacques où elle

fut inhumée. Après s’être beaucoup agitée pendant la Fronde et avoir fait

scandale pour ses liaisons avec La Rochefoucauld et Turenne, elle fit pénitence

aux Carmélites du faubourg Saint-Jacques.

[2] Sainte

Louise de Marillac, née le 12 août 1591, à Ferrières-en-Brie, est la fille

naturelle de Louis de Marillac, enseigne d’une compagnie de gendarmes aux

ordonnances du Roi (nièce du chancelier Michel de Marillac et du maréchal

Louis de Marillac). Elle épouse Antoine Le Gras, secrétaire des commandements

de Marie de Médicis, écuyer, homme de bonne vie, fort craignant Dieu et

exact à se rendre irréprochable (6 février 1613). Antoine Le Gras

n’étant pas noble, on ne lui dira pas Madame, mais, comme à une bourgeoise

de ces temps-là, Mademoiselle. Après la mort de son mari (21 décembre

1625), elle fait vœu de viduité et mène dans le monde une vie toute religieuse

où elle conjugue à un règlement très strict, la prière et le secours des pauvres,

sans cesser d'être attentive à l'éducation de son fils. Elle s’installe rue

Saint-Victor, près du collège des Bons-Enfants que Mme. de Gondi vient de

donner à Vincent de Paul qui l’emploie dans les Charités, ces groupements

de dames et de filles pour l’assistance des malades dans les paroisses et les

visites à domicile. En 1628, lorsque son fils est entré au séminaire

Saint-Nicolas-du-Chardonnet, elle dispose de davantage de temps pour se

consacrer aux œuvres et Vincent de Paul la charge de surveiller les Charités,

de modifier leur règlement et de visiter celles des provinces. Elle persuade

Vincent de Paul que les Dames associées ne peuvent rendre aux malades

les services pénibles qu’exige leur état, et qu’il faut songer à réunir des

personnes zélées pour se dévouer entièrement à l’œuvre sans autres devoirs et

préoccupations au dehors. C’est ainsi que naissent les Filles de la Charité.

Lettre

à Louise de Marillac (2)

La grâce de

Notre-Seigneur soit toujours avec vous ! Je n’ai jamais vu une femme comme vous

pour prendre certains événements au tragique. Vous dites que le choix de votre

fils est une manifestation de la justice de Dieu à votre égard. Vous avez certainement

tort d’entretenir de pareilles idées et plus encore de les exprimer. Je vous ai

souvent prié de ne point parler de la sorte.

Au nom de Dieu,

Mademoiselle, corrigez cette faute et apprenez une fois pour toutes que les

pensées amères procèdent du démon, les douces et aimables de Notre-Seigneur.

Souvenez-vous aussi que les fautes des enfants ne sont pas toujours imputables

à leurs parents, spécialement lorsqu’ils les ont fait bien instruire et qu’ils

leur ont donné le bon exemple, comme, grâce à Dieu, vous l’avez fait. En outre,

Notre-Seigneur, dans sa merveilleuse Providence, permet aux enfants de briser

le cœur de leurs pieux parents. Celui d’Ahraham le fut par Ismaël et celui

d’Isaac par Esaü, celui de Jacob par la plupart de ses enfants, celui de David

par Absalon, celui de Salomon par Roboam et celui du Fils de Dieu par Judas.

Je puis vous dire que

votre fils a dit à Fr. de la Salle qu’il n’embrassait cette carrière que parce

que c’était votre désir, qu’il aurait préféré mourir que de le faire et qu’il

ne prendrait les ordres mineurs que pour vous plaire. Eh bien ! Est-ce là

vraiment une vocation ? Je suis certain qu’il aimerait mieux mourir lui-même

que vous faire mourir de déplaisir. Quoiqu’il en soit, sa volonté n’est pas

libre dans le choix d’une carrière si importante et vous ne devriez pas le

désirer envers et contre tout. Il y a quelque temps de cela, un excellent jeune

homme de cette ville entra comme sous-diacre dans des conditions à peu près

similaires, il n’a pas été capable de poursuivre jusqu’aux ordres superieurs ;

désirez-vous exposer votre fils aux mêmes dangers ? Laissez-le suivre la voie

que Dieu lui suggérera ; Il est son père plus que vous n’êtes sa mère, et Il

l’aime plus que vous ne l’aimez. Laissez-Le en décider. Il pourra l’appeler une

autre fois si telle est Sa volonté, ou lui donner quelque autre emploi qui le

mènera à son salut. Je me souviens d’un prêtre qui se trouvait ici et qui avait

été ordonné tout en ayant l’esprit très anxieux ; Dieu seul sait ce qu’il est

devenu !

Je vous prie de faire

votre prière en pensant à la femme de Zébédée à qui Notre-Seigneur répondit,

lorsqu’elle voulait établir ses fils : « Vous ne savez Pas ce que vous

demandez ».

Saint Vincent de Paul

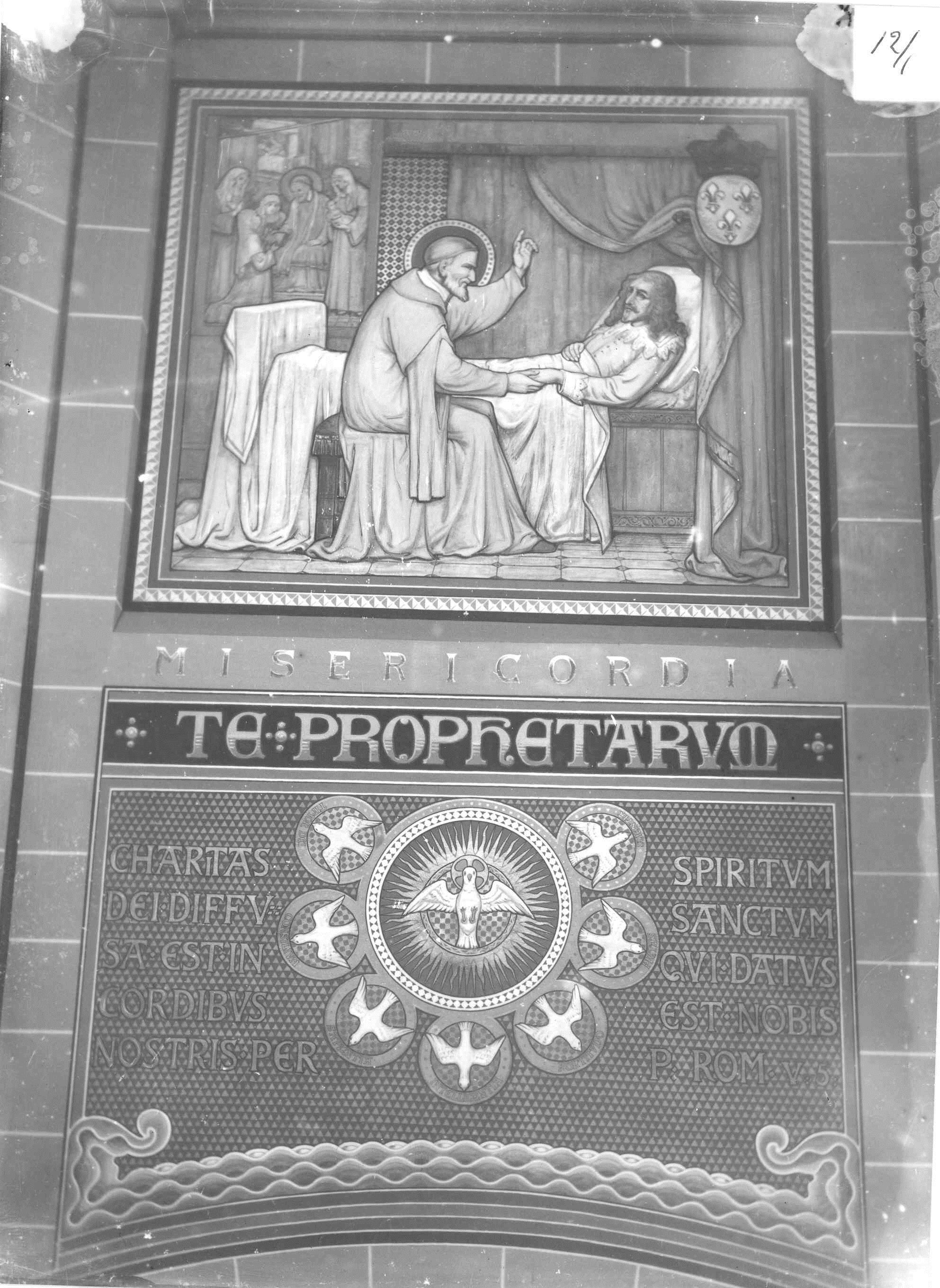

Détail

de l'autel dédié à Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, église Saint Julien,

Château-l'Évêque, Dordogne, France

Lettre II de Bossuet à St Vincent A Metz, ce 12 janvier 1658 [3]

Monsieur,

J'ai appris de M. de

Champin [4] la

charité que vous aviez pour ce pays, qui vous obligeait à y envoyer une mission

considérable ; que vous l'aviez proposé à la Compagnie [5],

et que vous et tous ces Messieurs aviez eu assez bonne opinion de moi pour

croire que je m'emploierais volontiers à une œuvre si salutaire. Sur l'avis

qu'il m'en a donné, je le supliais de vous assurer que je n'omettrais rien de

ma part, pour y coopérer dans toutes les choses dont on me jugerait capable. Et

comme Monseigneur l'évêque d'Auguste et moi devions faire un petit voyage à

Paris, je le priais aussi de savoir le temps de l'arrivée de ces Messieurs,

afin que nous pussions prendre nos mesures sur cela ; jugeant bien l'un et

l'autre que nous serions fort coupables devant Dieu, si nous abandonnions la

moisson dans le temps où sa bonté souveraine nous envoie des ouvriers si fidèles

et si charitables. Je ne sais, Monsieur, par quel accident je n'ai reçu aucune

réponse à cette lettre : mais je ne suis pas fâché que cette occasion se

présente de vous renouveler mes respects, en vous assurant avant toutes choses

de l'excellente disposition en laquelle est Monseigneur l'évêque d'Auguste pour

coopérer à cette œuvre.

Pour ce qui me regarde,

Monsieur, je me reconnais fort incapable d'y rendre le service que je voudrais

bien : mais j'espère de la bonté de Dieu que l'exemple de tant de saints

ecclésiastiques, et les leçons que j'ai autrefois apprises en la

Compagnie [6],

me donneront de la force pour agir avec de si bons ouvriers, si je ne puis rien

de moi-même. Je vous demande la grâce d'en assurer la Compagnie, que je salue

de tout mon cœur en Notre-Seigneur, et la prie de me faire part de ses oraisons

et saints sacrifices.

S'il y a quelque chose

que vous jugiez ici nécessaire pour la préparation des esprits, je recevrai de

bon cœur et exécuterai fidèlement, avec la grâce de Dieu, les ordres que vous

me donnerez. Je suis, Monsieur, votre très humble et très obéissant serviteur,

Bossuet, prêtre,

grand-archidiacre de Metz

Notes :

[3] La

Reine mère ayant fait en 1657 un voyage à Metz, fut sensiblement touchée du

triste état de cette ville. De retour à Paris, elle témoigna à saint Vincent de

Paul, qu'elle honorait de sa confiance, le désir qu'elle aurait de faire

instruire son peuple de Metz ; et pour cet effet, il fut conclu que saint

Vincent y enverrait une mission. Il en choisit les ouvriers, principalement

parmi les ecclésiastiques qu'on appelait Messieurs de la Conférence des

Mardis, parce qu'ils s'assemblaient ce jour-là pour conférer entre eux sur

les matières ecclésiastiques. Saint Vincent avait formé cette espèce

d'association, dans laquelle l'abbé Sossuet était entré. La mission fut ainsi

composée de vingt prêtres d'un mérite distingé, qui avaient à leur tête M.

l'abbé de Chandenier, neveu de M. le cardinal de La Rochefoucauld.

[4] C'était

un docteur de la Conférence des Mardis.

[5] A Messieurs

de la Conférence des Mardis.

[6] Il

parle de la Compagnie de Messieurs de la Conférence des Mardis, dont

il était membre.

Lettre IV de Bossuet à St Vincent, A Metz, ce 1er février 1658.

J'ai été extrêmement

consolé que celui de vos prêtres qui est venu ici ait été M. de Monchy : mais

j'ai beaucoup de déplaisir qu'il y ait fait si peu de séjour. Il pourra,

Monsieur, vous avoir appris que les lettres de la Reine ont été reçues avec le

respect dû à Sa Majesté, et que M. l'évêque d'Auguste et M. de la Contour ont

fait leur devoir en cette rencontre.

Je rends compte à M. de

Monchy de l'état des choses depuis son départ ; et je me remets à lui à vous en

instruire, pour ne pas vous importuner par des redites : mais je me sens

obligé, Monsieur, à vous informer d'une chose qui s'est passée ici depuis

quelque temps, et qui sera bientôt portée à la Cour.

Une servante catholique,

qui est décédée chez un huguenot, marchand considérable et accommodé, a été

étrangement violentée dans sa conscience. Il est contant par la propre

déposition de son maître, qu'elle avait fait toute sa vie profession de la

religion catholique : il paraît même certain qu'elle avait communié peu de

temps avant que de tomber malade. Elle n'a jamais été aux prêches, ni n'a fait

aucun exercice de la religion prétendue réformée. Son maître prétend que cinq

jours avant sa mort elle a changé de religion : Il lui a fait, dit-il, venir

des ministres pour recevoir sa déclaration, sans avoir appelé à cette action ni

le curé, ni li magistrat, ni aucun catholique qui pût rendre témoignage du

fait. Le jour que cette pauvre fille mourut, un jésuite averti par un des

voisins de la violence qu'on lui faisait, se présente pour la consoler. On lui refuse

l'entrée ; et il est certain qu'elle était vivante. Il retourne quelque temps

après avec l'ordre d magistrat, et il la trouve décédée dans cet intervalle.

Tous ces faits sont constants et avérés : il y a même des indices si forts

qu'elle a demandé un prêtre, et les parties ont si fort varié dans leur

réponses sur ce sujet-là, que cela peut passer pour certain.

Je ne vous exagère pas,

Monsieur, ni les circonstances de cette affaire, ni de quelle conséquence elle

est ; vous le voyez assez de vous-même, et quelle est l'imprudence de ceux qui,

ayant reçu par grâce du Roi la liberté de conscience dans son État, la

ravissent dans leurs maisons à ses sujets leurs serviteurs. Certainement cela

crie vengeance : cependant les ministres et le consistoire soutiennent cette

entreprise ; et M. de la Contour m'a dit aujourd'hui qu'un député de ces

Messieurs avait bien eu le front de lui dire que cet homme n'avait rien fait

sans ordre. Bien plus, ils ont ajouté qu'ils allaient se plaindre à la Cour, de