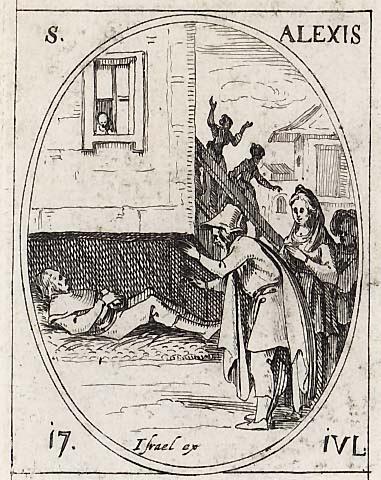

Saint

Alexius

św.

Aleksy, Człowiek Boży (XVII w.). http://days.pravoslavie.ru/Images/ii134&393.htm

Saint Alexis

Légende (Ve siècle)

Ce mendiant fort populaire, dont la légende remplace l'histoire, était l'objet d'un culte populaire extraordinaire au point que le Pape Innocent XII dut déclarer le jour de sa fête, jour chômé au 17ème siècle. Fiancé contre son gré, il s'était enfui de Rome en pleine cérémonie nuptiale et s'embarqua pour la Syrie. Il gagna Edesse, mendiant sous les porches. Devant la popularité qui l'entourait, il reprit la mer. Le navire, à cause des vents contraires, le ramena à Rome. Sa fiancée lui était restée fidèle. Ni ses parents ni elle ne le reconnurent dans ce miséreux couvert de loques. Il resta dix-sept ans, dormant sous l'escalier extérieur de la maison paternelle, visitant les églises, maltraité par les esclaves qui lui jetaient des détritus. Une voix céleste révéla sa présence à l'empereur et au pape qui vinrent sous l'escalier et le trouvèrent mort, serrant un manuscrit racontant ses origines.

L'histoire est belle, trop belle peut-être, mais elle n'est pas sans fondement.

La 'Chanson de Roland' a amélioré la guerre de Charlemagne, mais Roland

existait bien ... Alors il en est sans doute ainsi pour saint Alexis.

À Rome, dans une église

située sur l'Aventin, au VIe siècle, on célèbre sous le nom de saint Alexis, un

homme de Dieu qui, selon la tradition, quitta sa maison pour se faire pauvre

et, inconnu de tous, mendia l'aumône.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/10013/Saint-Alexis.html

SAINT ALEXIS

Confesseur, Pèlerin et

Mendiant

(+ 404)

Saint Alexis fut un rare

modèle de mépris du monde. Fils unique d'un des plus illustres sénateurs de

Rome nommé Euphémien, il reçut une éducation brillante et soignée.

L'exemple de ses parents

apprit au jeune Alexis que le meilleur usage des richesses consistait à les

partager avec les pauvres. Cédant aux désirs de sa famille, le jeune Alexis dut

choisir une épouse. Mais le jour même de ses noces, se sentant pénétré du désir

d'être uniquement à Dieu et de L'aimer sans partage, il résolut de s'enfuir

secrètement, s'embarqua sur un vaisseau qui se dirigeait vers Laodicée, et

gagna la ville d'Edesse.

Là, distribuant aux

indigents tout ce qui lui restait d'argent, il se mit à mendier son pain. Il

passait la plus grande partie de son temps à prier sous le portail du

sanctuaire de Notre-Dame d'Edesse, devant une image de la Vierge. Après

dix-sept années passées dans l'abjection et l'oubli le plus total, il plut à

Marie de glorifier Son serviteur par un éclatant miracle. Un jour, comme le

trésorier de l'église passait sous le porche, l'image de Notre-Dame s'illumina

d'une clarté soudaine. Frappé de ce merveilleux spectacle, le trésorier se

prosterna devant la Madone. La Très Sainte Vierge lui montra Alexis et lui dit:

«Allez préparer à ce pauvre un logement convenable. Je ne puis souffrir qu'un

de Mes serviteurs aussi dévoué soit délaissé de la sorte.»

La nouvelle de cette

révélation se répandit aussitôt dans la ville. L'humilité du Saint s'alarma

devant les témoignages de vénération dont il était devenu subitement l'objet.

Il quitta donc la ville d'Edesse pour se rendre à Tarse, mais une tempête

poussa l'embarquation sur les rivages d'Italie. L'Esprit-Saint lui inspira

l'idée de retourner à Rome, sa ville natale, et de mendier une petite place

dans la maison paternelle. A la requête de l'humble pèlerin, le sénateur

Euphémien consentit à le laisser habiter sous l'escalier d'entrée de son

palais, lui demandant, en reconnaissance de ce bienfait, de prier pour le

retour de son fils disparu.

Saint Alexis vécut

inconnu, pauvre et méprisé, à l'endroit même où il avait été entouré de tant

d'estime et d'honneurs. Tous les jours, il voyait couler les larmes du vieux

patricien, il entendait les soupirs d'une mère inconsolable et entrevoyait

cette noble fiancée dont la beauté s'était empreinte d'une indicible tristesse.

Malgré ce déchirant spectacle, saint Alexis eut le courage surhumain de garder

son secret et de renouveler perpétuellement son sacrifice à Dieu.

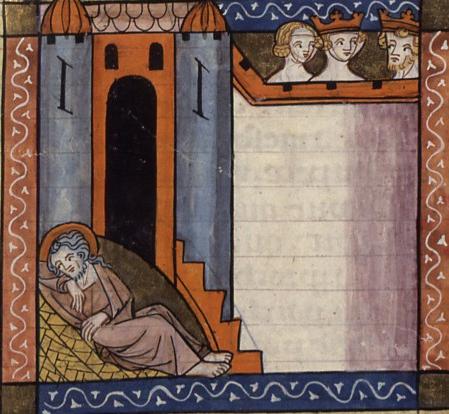

Ce Saint, plus

qu'admirable, demeura dix-sept nouvelles années dans le plus complet oubli,

vivant caché sous les marches de cet escalier que tous gravissaient pour entrer

dans une maison qui était la sienne, en sorte qu'il semblait foulé aux pieds de

tous. Avec une humilité consommée, il subit sans jamais se plaindre, les odieux

procédés et les persécutions des valets qui l'avaient servi autrefois avec tant

de respect et d'égards. Saint Alexis passa donc trente-quatre ans dans une âpre

et héroïque lutte contre lui-même. Ce temps écoulé, Dieu ordonna à Son

serviteur d'écrire son nom et de rédiger l'histoire de sa vie. Alexis comprit

qu'il allait mourir bientôt, et obéit promptement.

Le dimanche suivant, au

moment où le pape Innocent Ier célébrait la messe dans la basilique St-Pierre

de Rome, en présence de l'empereur Honorius, tout le peuple entendit une voix

mystérieuse qui partait du sanctuaire: «Cherchez l'homme de Dieu, dit la voix,

il priera pour Rome, et le Seigneur lui sera propice. Du reste, il doit mourir

vendredi prochain.»

Durant cinq jours, tous

les habitants de la ville s'épuisèrent en vaines recherches. Le vendredi

suivant, dans la même basilique, la même voix se fit entendre de nouveau au

peuple assemblé: «Le Saint est dans la maison du sénateur Euphémien.» On y

courut, et on trouva le pauvre pèlerin, qui venait de mourir. Quand le Pape eu

fait donner lecture du parchemin que le mort tenait en sa main, ce ne fut de

toutes parts, dans Rome, qu'un cri d'admiration. Innocent Ier ordonna d'exposer

le corps de saint Alexis à la basilique St-Pierre, pendant sept jours. Ses

funérailles eurent lieu au milieu d'un immense concours de peuple.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950. -- F. Paillart,

édition 1900, p. 209-201 -- L'abbé Jouve, édition 1886, p. 87-89 -- Les

Petits Bollandistes, Paris, 1874, tome XIII, p. 403-405 -- l'Abbé J. Sabouret,

édition 1922, p. 275-277

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/alexis-de-rome.html

Saint Alexis de Rome

Fête saint : 17 Juillet

Date : 404

Pape : Innocent Ier

Empereur : Arcadius ; Honorius

Pensée

Les voies extraordinaires

par lesquelles Dieu se plaît à conduire quelques âmes privilégiées sont moins

l’objet de notre imitation que de notre admiration. Mais ce que nous pouvons et

devons imiter, c’est le souverain mépris du monde et de ses vanités, qui en a

été le principe.

Pratique

Aimez à être ignoré et

méprisé.

Priez

Pour la conversion des

faux dévots.

Hagiographie

Saint Alexis fut un

rare modèle du mépris du monde. Il vivait au commencement du cinquième siècle ;

il était fils unique d’un riche sénateur de Rome, et reçut une excellente

éducation. Il apprit, par l’exemple de ses parents, qu’on ne pouvait faire un

meilleur usage de ses richesses que de les partager avec les pauvres, parce

qu’étant ainsi distribuées en aumônes, elles forment dans le ciel un trésor

pour l’éternité. La manière dont il soulageait l’indigence ajoutait un nouveau

prix à ses charités. On eût dit qu’il regardait les pauvres comme ses

bienfaiteurs, et qu’il se tenait pour obligé envers ceux qui avaient part à ses

libéralités, tant il leur montrait d’affection et de tendresse. Ses parents

voulant absolument qu’il s’engageât dans le mariage, il se rendit, par

condescendance, à leurs désirs ; mais, sans doute par une inspiration de Dieu,

le jour même de ses noces, il s’enfuit secrètement dans un pays éloigné, où il

se fixa dans le voisinage d’une église, dédiée sous l’invocation de la sainte Vierge.

Ses vertus ayant attiré sur lui l’attention, il revint à la maison de son père,

où il se présenta comme un pauvre pèlerin, et à ce titre on lui accorda un

petit logement, où il passa le reste de ses jours sans se faire connaître, ni

se plaindre des mauvais traitements qu’il essuyait quelquefois de la part des

domestiques. Ce ne fut que sur le point de rendre le dernier soupir qu’il fit

connaître à ses parents qui il était.

Jamais nous ne serons

véritablement humbles, si nous ne saisissons toutes les occasions de déraciner

de nos cœurs l’orgueil qui le tyrannise. 1° Le fatal poison de ce

vice infecte tous les états ; il se glisse dans toutes les conditions ; les

plus secrets replis de nos âmes lui servent de retraite : de tous nos ennemis,

c’est toujours le dernier vaincu. 2° Les actions les plus louables en

elles-mêmes sont souvent dénaturées par la malignité de l’amour-propre : sans

cesse il faut être en garde contre ses assauts.

Oraison

O Dieu qui nous

réjouissez par la solennité annuelle de la fête du bienheureux Alexis,

votre confesseur ; faites que nous imitions les saintes actions de celui dont

nous célébrons le triomphe au ciel. Par J.-C. N.-S. Ainsi soit-il.

Comment représente-t-on saint

Alexis ?

On le représente tenant

entre ses mains, après sa mort, un écrit qui le fit reconnaître. Le légendaire

vénitien le représente couché sous un escalier de la maison paternelle, où il

passa ses dernières années comme un pauvre inconnu. Il est quelquefois

représenté avec une pèlerine, un bourdon et le chapeau orné d’une coquille.

SOURCE : https://www.laviedessaints.com/saint-alexis/

Leçons des Matines avant 1960.

Au deuxième nocturne.

Quatrième leçon. Alexis,

Romain de très noble origine, poussé par un vif amour de Jésus-Christ, et

docile à un avertissement divin tout particulier, partit le premier soir de ses

noces laissant son épouse vierge, et entreprit à travers le monde le pèlerinage

des plus célèbres sanctuaires. Pendant ces voyages, il resta dix-sept ans

inconnu, jusqu’au jour où une image de la sainte Vierge Marie divulgua son nom.

C’était à Édesse, en Syrie. Ayant pris la mer pour s’éloigner, il aborda au

port Romain et fut reçu chez son père, à titre de pauvre étranger. Il vécut

dix-sept ans sous le toit paternel sans être connu de personne. Mais, en

mourant, il laissa par écrit, avec l’indication de son nom et de sa naissance,

le récit abrégé de toute sa vie. Il passa de la terre au ciel, sous le

Pontificat d’Innocent 1er.

Du livre des Morales de

saint Grégoire, Pape. (du commun)

Cinquième leçon. « La

simplicité du juste est tournée en dérision » [1]. La sagesse de ce monde

consiste à employer toutes sortes de ruses pour cacher le fond de son cœur, à

se servir de la parole pour déguiser sa pensée, à faire paraître vrai ce qui

est faux et faux ce qui est vrai. Cette sagesse, les jeunes gens l’acquièrent

par l’usage ; les enfants l’apprennent à prix d’argent ; ceux qui la savent

s’enorgueillissent et méprisent le reste des hommes ; ceux qui l’ignorent sont

un objet d’étonnement pour les autres, qui les regardent comme des êtres

timides et dégradés. Ils aiment cette inique duplicité sous le nom qui la

recouvre, car on qualifie d’urbanité une telle perversité d’esprit. La sagesse

mondaine enseigne à ses disciples à rechercher le faîte des honneurs, à se

réjouir, par vanité, de l’acquisition d’une gloire temporelle, à rendre

abondamment aux autres le mal qu’ils nous ont fait ; à ne jamais céder, tant

qu’ils sont assez forts pour cela, aux adversaires qui leur résistent ; mais,

si le courage leur fait défaut, à dissimuler sous des apparences de bonté et de

douceur, l’impuissance de leur malice.

Sixième leçon. La sagesse

des justes consiste, au contraire, à ne jamais agir par ostentation, à dire ce

que l’on pense, à aimer le vrai tel qu’il est, à éviter le faux, à faire le

bien gratuitement, à souffrir très volontiers des peines plutôt que d’en causer

aux autres, à ne pas tirer vengeance des injures reçues, à estimer comme un

gain l’outrage qu’on endure pour J’amour de la vérité. « Mais cette simplicité

des justes est tournée en dérision ». Car les sages de ce monde regardent la

pureté de la vertu comme une sottise. Tout ce qu’on fait innocemment, ils le

taxent de folie, tout ce que la vérité approuve dans nos œuvres paraît insensé

à cette sagesse charnelle. Rien semble-t-il, en effet, plus stupide aux yeux du

monde, que de montrer sa pensée .quand on parle, de ne rien feindre par d’habiles

expédients, de ne pas rendre des affronts pour des injures, de prier pour ceux

qui nous maudissent, de rechercher la pauvreté, d’abandonner ses biens, de ne

pas résister à ceux qui nous pillent, de présenter l’autre joue à ceux qui nous

frappent.

Au troisième nocturne.

Lecture du saint Évangile

selon saint Matthieu. Cap. 19, 27-29.

En ce temps-là : Pierre

dit à Jésus : Voici que nous avons tout quitté, et que nous vous avons suivi ;

qu’y aura-t-il donc pour nous ? Et le reste.

Homélie de saint Jérôme,

Prêtre. Lib. 3 in Matth. Cap. 19

Septième leçon. Confiance

admirable ! Pierre était pêcheur, il était loin d’être riche, il gagnait sa vie

par le travail de ses mains, et cependant il dit avec la plus grande assurance

: « Nous avons tout quitté ». Et, comme tout quitter ne suffit pas, il ajoute

ce qui est parfait : « Et nous vous avons suivi » ; nous avons fait ce que vous

avez commandé, que nous donnerez-vous en récompense ? Jésus leur répondit : «

Je vous dis en vérité que pour vous qui m’avez suivi, lorsqu’au temps de la

régénération le Fils de l’homme sera assis sur le trône de sa gloire, vous

serez aussi assis sur douze trônes et vous jugerez les douze tribus d’Israël. »

Le Sauveur ne dit pas : vous qui avez tout quitté ; car cela le philosophe

Cratès l’a fait, et une foule d’autres ont méprisé les richesses, mais il dit :

« vous qui m’avez suivi », ce qui est le propre des Apôtres et des fidèles.

Huitième leçon. Lorsqu’au

jour de la résurrection, le Fils de l’homme sera assis sur le trône de sa

gloire, quand les morts sortiront, incorruptibles désormais, de la corruption

du tombeau, vous serez, vous aussi, assis sur des trônes de juges et vous

condamnerez les douze tribus d’Israël, parce que, tandis que vous embrassiez la

foi, elles l’ont repoussée. « Et quiconque aura quitté pour moi, ou maison, ou

frères, ou sœurs, ou père, ou mère, ou femme, ou enfants, ou terres, recevra le

centuple et possédera la vie éternelle ». Ce passage concorde avec cette autre

déclaration du Sauveur : « Je ne suis pas venu apporter la paix, mais le glaive

; car je suis venu séparer le fils d’avec le père, la fille d’avec la mère, la

belle-fille d’avec la belle-mère, et l’homme aura pour ennemis ceux de sa

propre maison ». Ceux donc qui pour la foi de Jésus-Christ et la prédication de

l’Évangile, auront sacrifié toutes les affections, renoncé aux richesses et aux

plaisirs du monde, recevront le centuple et posséderont la vie éternelle.

Neuvième leçon. Certains

esprits s’appuient sur cette promesse pour imaginer une période de mille ans

après la résurrection, période pendant laquelle nous recevrions le centuple de

ce que nous avons quitté et ensuite la vie éternelle ; ils ne réfléchissent pas

que si cela paraît convenable pour la plupart des biens, il serait ridicule,

sous le rapport des femmes, que celui qui aurait quitté son épouse pour le

Seigneur, en reçoive cent dans la vie future. Voici dons le sens de cette

promesse : celui qui, pour l’amour du Sauveur aura quitté les biens charnels

recevra des biens spirituels, lesquels, par leur valeur propre et comparés aux

premiers, leur sont aussi supérieurs que le nombre cent l’est à un petit

nombre.

[1] Job. 12, 4.

Dom Guéranger, l’Année

Liturgique

S’il n’est commandé à

personne de suivre les Saints jusqu’aux extrémités où les conduit l’héroïsme de

leurs vertus, ils n’en demeurent pas moins, du haut de ces inaccessibles

sommets, les guides de ceux qui marchent par les sentiers moins laborieux de la

plaine. Comme l’aigle en présence de l’astre du jour, ils ont fixé de leur

regard puissant le Soleil de justice ; et s’enivrant de ses divines splendeurs,

ils ont vers lui dirigé leur vol bien au delà de la région des nuages sous

lesquels nos faibles yeux se réjouissent de pouvoir tempérer la lumière. Mais,

si différent que puisse être son éclat pour eux et pour nous, celle-ci ne

change pas de nature, à la condition d’être pour nous comme pour eux de

provenance authentique. Quand la débilité de notre vue nous expose à prendre de

fausses lueurs pour la vérité, considérons ces amis de Dieu ; si le courage

nous fait défaut pour les imiter en tout dans l’usage de la liberté que les

préceptes nous laissent, conformons du moins pleinement notre manière de voir à

leurs appréciations : leur vue est plus sûre, car elle porte plus loin ; et

leur sainteté n’est autre chose que la rectitude avec laquelle ils suivent sans

vaciller, jusqu’à son foyer même, le céleste rayon dont nous ne pouvons

soutenir qu’un reflet amoindri. Que surtout les feux follets de ce monde de

ténèbres [2] ne nous égarent pas au point de prétendre contrôler à leur vain

éclat les actes des Saints : l’oiseau de nuit préférera-t-il son jugement à

celui de l’aigle touchant la lumière ?

Descendant du ciel très

pur de la sainte Liturgie jusqu’aux plus humbles conditions de la vie

chrétienne, la lumière qui conduit Alexis par les sommets du plus haut

détachement se traduit pour tous dans cette conclusion que formule l’Apôtre : «

Quiconque prend femme ne pèche pas, ni non plus la vierge qu’il épouse ;

ceux-là pourtant connaîtront les tribulations de la chair, et je voudrais vous

les épargner. Voici donc ce que je dis, mes Frères : le temps est court ; en

conséquence, que ceux qui ont des épouses soient comme n’en ayant pas, et ceux

qui pleurent comme ne pleurant pas, et ceux qui se réjouissent comme ne se

réjouissant pas, et ceux qui achètent comme ne possédant pas, et ceux qui usent

de ce monde comme n’en usant point ; car la figure de ce monde passe » [3].

Elle ne passe point si

vite cependant cette face changeante du monde et de son histoire, que le

Seigneur ne se réserve toujours de montrer en sa courte durée que ses paroles à

lui ne passent jamais [4]. Cinq siècles après la mort glorieuse d’Alexis, le

Dieu éternel pour qui les distances ne sont rien dans l’espace et les temps,

lui rendait au centuple la postérité à laquelle il avait renoncé pour son

amour. Le monastère qui sur l’Aventin garde encore son nom joint à celui du

martyr Boniface, était devenu le patrimoine commun de l’Orient et de l’Occident

dans la Ville éternelle ; les deux grandes familles monastiques de Basile et de

Benoît unissaient leurs rameaux sous le toit d’Alexis ; et la semence féconde

cueillie à son tombeau par l’évêque-moine saint Adalbert engendrait à la foi

les nations du Nord.

Homme de Dieu, c’est le

nom que vous donna le ciel, ô Alexis, celui sous lequel l’Orient vous

distingue, et que Rome même a consacré par le choix de l’Épître accompagnant

aujourd’hui l’oblation du grand Sacrifice [5] ; nous y voyons en effet l’Apôtre

appliquer ce beau titre à son disciple Timothée, en lui recommandant les vertus

que vous avez si éminemment pratiquées. Titre sublime, qui nous montre la

noblesse des cieux à la portée des habitants de la terre ! Vous l’avez préféré

aux plus beaux que le monde puisse offrir. Il vous les présentait avec le

cortège de tous les bonheurs permis par Dieu à ceux qui se contentent de ne pas

l’offenser. Mais votre âme, plus grande que le monde, dédaigna ses présents

d’un jour. Au milieu de l’éclat des fêtes nuptiales, vous entendîtes ces

harmonies qui dégoûtent de la terre, que, deux siècles plus tôt, la noble

Cécile écoutait elle aussi dans un autre palais de la cité reine. Celui qui

voilant sa divinité quitta les joies de la céleste Jérusalem et n’eut pas même

où reposer sa tête [6] se révélait à votre cœur si pur [7] ; et, en même temps

que son amour, entraient en vous les sentiments qu’avait Jésus-Christ [8].

Usant de la liberté qui vous restait encore d’opter entre la vie, parfaite et

la consommation d’une union de ce monde, vous résolûtes de n’être plus

qu’étranger et pèlerin sur la terre [9], pour mériter de posséder dans la

patrie l’éternelle Sagesse [10]. O voies admirables ! ô mystérieuse direction

de cette Sagesse du Père pour tous ceux qu’a conquis son amour [11] ! On vit la

Reine des Anges applaudir à ce spectacle digne d’eux [12], et révéler aux

hommes sous le ciel d’Orient le nom illustre que leur cachaient en vous les

livrées de la sainte pauvreté. Ramené par une fuite nouvelle après dix-sept ans

dans la patrie de votre naissance, vous sûtes y demeurer par la vaillance de

votre foi comme dans une terre étrangère [13]. Sous cet escalier de la maison

paternelle aujourd’hui l’objet d’une vénération attendrie, en butte aux avanies

de vos propres esclaves, mendiant inconnu pour le père, la mère, l’épouse qui

vous pleuraient toujours, vous attendîtes dix-sept autres années, sans vous

trahir jamais, votre passage à la céleste et seule vraie patrie [14]. Aussi

Dieu s’honora-t-il lui-même d’être appelé votre Dieu [15], lorsque, au moment

de votre mort précieuse, une voix puissante retentit dans Rome, ordonnant à

tous de chercher l’Homme de Dieu.

Souvenez-vous, Alexis, que la voix ajouta au sujet de cet Homme de Dieu qui était vous-même : « Il priera pour Rome, et sera exaucé ». Priez donc pour l’illustre cité qui vous donna le jour, qui vous dut son salut sous le choc des barbares, et vous entoure maintenant de plus d’honneurs a coup sûr qu’elle n’eût fait, si vous vous étiez borné à continuer dans ses murs les traditions de vos nobles aïeux ; l’enfer se vante de l’avoir arrachée pour jamais à la puissance des successeurs de Pierre et d’Innocent : priez, et que le ciel vous exauce à nouveau contre les modernes successeurs d’Alaric. Puisse le peuple chrétien, à la lumière de vos actes sublimes, s’élever toujours plus au-dessus de la terre ; conduisez-nous sûrement par l’étroit sentier [16] à la maison du Père qui est aux cieux.

[2] Eph VI, 12.

[3] I Cor. VII, 28-31.

[4] Matth. XXIV, 33.

[5] 1 Tim, VI, 11.

[6] Matth. VIII, 20.

[7] Ibid. V, 8.

[8] Philip. II, 5.

[9] Heb. XI, 13.

[10] Prov. IV, 7.

[11] Rom. XI, 33.

[12] I Cor. IV, 9.

[13] Heb. XI. 9.

[14] Ibid. 16.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Matth. VII, 14.

Kath.

Pfarrkirche hl. Georg und Friedhof in Großklein, Steiermark - Statue hl.

Alexius.

Parish

church St. George and cemetery in Großklein, Styria - statue of saint Alexius.

Bhx cardinal

Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

Le culte de saint Alexis

vint à Rome de l’Orient où l’Homme de Dieu, ou Mar-Risà — ainsi en effet

l’appellent les Syriens — fut l’objet d’une grande vénération. Ses Actes sont

très douteux ; et quant à la résidence de saint Alexis à Rome, il semble qu’il

s’agisse d’une adaptation de la légende importée de Syrie sur les rives du

Tibre et localisée ensuite sur le Mont Aventin par un métropolite nommé Serge

de Damas, qui s’y installa avec la permission de Benoît VII et y fonda un

monastère gréco-latin. Le phénomène d’une vie cachée, passée dans la pénitence

et les pèlerinages, et embrassée spontanément pour l’amour du Christ, n’est ni

nouveau ni rare dans les fastes de l’Église. Au siècle dernier, saint Benoît-Joseph

Labre reproduisit à Rome la vie héroïque décrite dans les Actes de saint Jean

Calybite et de saint Alexis, — si toutefois ces deux saints sont deux

personnages distincts.

L’homme de Dieu, selon la

narration syriaque primitive qui semble postérieure d’un demi-siècle à peine

aux événements, vécut à Édesse sous l’évêque Rabula (412-435). Sa sainteté fut

reconnue seulement après sa mort, mais son culte se répandit immédiatement dans

l’Orient grec, qui, nous ne savons pourquoi, donna au pèlerin anonyme le nom

d’Alexis.

Son histoire fut chantée

au IXe siècle par Joseph l’Hymnographe, et, transportée à Rome sur l’Aventin,

elle trouva un panégyriste enthousiaste en saint Adalbert, évêque de Prague,

devenu moine au monastère de Saint-Boniface.

Les Grecs célèbrent la

fête d’Alexis le 17 mars : Ἀλεξίου τοῦ άνθρώπου τοῦ Θεοῦ.

La messe est du Commun,

sauf les deux lectures. L’Évangile est celui de la fête des Abbés ; — le titre

: homme de Dieu, chez les Syriens, désigne probablement la profession

monastique du saint mendiant. Quant à l’épître (I Timot., VI, 6-12), l’Apôtre y

traite des périls qu’entraîné la possession des richesses. Tel un hydropique

altéré, plus le riche possède, plus il veut posséder. Il n’a jamais assez, et

pour thésauriser davantage, il sacrifie parfois l’honnêteté, l’amitié, la santé

corporelle et jusqu’à la religion et au salut de son âme. L’apôtre conclut donc

en observant que l’intime racine de tout péché est la cupidité.

Voilà les motifs

surnaturels sur quoi se fonde la pauvreté évangélique que professent par vœu

les religieux. Selon l’observation du Docteur angélique, ceux-ci, moyennant un

tel renoncement, éloignent efficacement d’eux-mêmes tout ce qui aurait pu créer

un obstacle au développement de la charité et de la grâce de Dieu dans leur

âme.

Les Menées des Grecs

contiennent les vers suivants en l’honneur de l’homme de Dieu :

Toi seul portas sur la

terre le nom d’homme de Dieu.

Toi seul au ciel

également as obtenu, ô Père, un nom nouveau.

Le dix-septième jour

t’apporte la mort, ô Alexis.

Dom Pius Parsch, Le

guide dans l’année liturgique

Il quitta sa maison, son

père et son épouse pour l’amour de Dieu.

1. Saint Alexis. — Qui

fut-il exactement et dans quelle mesure les faits qu’on lui attribue sont-ils

exacts ? Cet « homme de Dieu », comme on l’appelle en Orient, a-t-il vécu en

Orient ou à Rome ? Ce sont des questions que nous n’avons pas à discuter ici.

La légende de saint

Alexis compte parmi les plus touchantes que nous possédions. Fort instructive

et édifiante, elle illustre à merveille l’idéal de la perfection chrétienne :

savoir endurer pour le Sauveur la pauvreté et les humiliations. Peut-il y avoir

héroïsme plus grand que d’habiter pendant dix-sept ans sous l’escalier de la

demeure paternelle, exposé aux railleries de ses propres esclaves, de passer

pour un mendiant inconnu aux yeux de son père, de sa mère et de son épouse

inconsolable ? Et tout cela, résultat de l’amour du Christ qui triomphe de

tout. En supposant que la légende soit dépourvue de fondement historique, il y

aurait encore lieu d’admirer la foi capable de concevoir un tel idéal.

« Alexis, lisons-nous

dans le bréviaire, romain de très noble origine, poussé par un vif amour de

Jésus-Christ, et sur un avertissement particulier de Dieu, partit le premier

soir de ses noces, laissant vierge son épouse, et entreprit à travers le monde

le pèlerinage des plus célèbres sanctuaires. Pendant ces voyages, il resta

dix-sept ans inconnu, jusqu’au jour où à Édesse, en Syrie, son nom fut divulgué

par une image de la Très Sainte Vierge. Quittant donc ce pays, il aborda au

port de Rome et fut reçu chez son père comme un pauvre étranger. Il y vécut

dix-sept ans sans que personne ne le reconnût ; mais, à sa mort, il laissa un

écrit où il révélait son nom, sa naissance et les diverses circonstances de son

existence. Il passa de la terre au ciel sous le pontificat d’Innocent 1er (17

juillet 417) ».La vie de ce saint offre un exemple extraordinaire des voies et

des volontés divines que nous pouvons sinon suivre, du moins admirer. Il montre

à quel héroïsme peut conduire l’amour de Dieu. Efforçons-nous aujourd’hui de

nous laisser pénétrer de cet amour, et qu’il nous incite à l’accomplissement de

multiples bonnes actions.

2. Messe (Os justi). — La

messe, composée en partie de textes du commun et en partie de textes propres,

parle de la pauvreté (Épître et Évangile) : « Nous n’avons rien apporté en ce

monde, et nul doute que nous n’en pouvons rien emporter. Ayant donc la

nourriture et le vêtement, estimons-nous satisfaits. Les avides de richesses

deviennent victimes des tentations et des filets du diable... Car la cupidité

est la racine de tous les vices » (Ép.). Quelle force en ces paroles dans la

bouche d’un saint qui en a tiré les conséquences les plus dures ! Son séjour

dans la demeure paternelle fut une grande « épreuve qu’il supporta » (All.). Il

a « tout quitté et suivi le Sauveur » ; c’est pourquoi « lorsque, au jour du

renouvellement, le Fils de l’homme sera assis sur le trône de sa gloire », il

régnera avec lui. Il a suivi à la lettre la parole du Maître, et, « ayant

quitté pour l’amour du Christ sa maison, son père, son épouse, il a reçu le

centuple et la vie éternelle ». Nous aussi nous pouvons, à la messe, participer

à cette gloire. L’église de Saint-Bonaventure et Saint-Alexis, à Rome, sur

l’Aventin, conserve un certain nombre de souvenirs de notre saint : on y montre

dans la crypte le lieu de sa mort ; plus loin la fontaine de sa maison, et,

enfin, l’escalier sous lequel il a longtemps habité.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/17-07-St-Alexis-confesseur

Statua

di Sant'Alessio nella Chiesa di Sant'Alessio in Vico Sant'Alessio,

Rione

Lavinaio, Quartiere Pendino, a Napoli.

Photographie : Delehaye

SAINT ALEXIS *

Alexis vient de a, qui veut dire beaucoup, et lexis, qui signifie sermon. De là

Alexis, qui est très fort sur la parole de Dieu.

Alexis fut le fils

d'Euphémien, homme d'une haute noblesse à Rome, et le premier à la cour de

l’empereur : il avait pour serviteurs trois mille jeunes esclaves revêtus de

ceintures d'or et d'habits de soie. Or, le préfet Euphémien était rempli de

miséricorde, et tous les jours, dans sa maison, on dressait trois tables pour

les pauvres, les orphelins, les veuves et les pèlerins qu'il servait avec

empressement; et à l’heure de none, il prenait lui-même son repas dans la

crainte du Seigneur avec des personnages religieux. Sa femme nommée Aglaë avait

la même dévotion et les mêmes goûts. Or, comme ils n'avaient point d'enfant, à

leurs prières Dieu accorda un fils, après la naissance duquel ils prirent la

ferme résolution de vivre désormais dans la chasteté. L'enfant fut instruit

dans les sciences libérales, et après avoir brillé dans tous les arts de la

philosophie, et avoir atteint l’âge de puberté, on lui choisit une épouse de la

maison de; l’empereur et on le maria. Arriva l’heure de la nuit où il alla avec

son épouse dans la chambre nuptiale : alors le saint jeune homme commença par

instruire cette jeune personne de la crainte de Dieu, et à la porter à conserver

la pudeur de la virginité. Ensuite il lui donna son anneau d'or et le bout de

la ceinture qu'il portait en lui disant de les conserver: « Reçois ceci, et

conserve-le tant qu'il plaira à Dieu, et que le Seigneur soit entre nous. »

Après quoi il prit de ses biens, alla. à la mer et s'embarqua à la dérobée sur

un vaisseau qui faisait voile pour Laodicée, d'où il partit pour Edesse, ville

de Syrie, dans laquelle on conservait un portrait de Notre-Seigneur J.-C. peint

sur .un linge sans que l’homme y ait mis la main. Quand il y fut arrivé, il

distribua aux pauvres tout ce qu'il avait apporté avec soi, puis se revêtant de

mauvais habits, il commença par se joindre aux autres pauvres qui restaient

sous le porche de l’église de la Vierge Marie. Il gardait des aumônes ce qui

pouvait lui suffire; le reste, il le donnait aux pauvres. Cependant, son père;

inconsolable de la disparition de son fils, envoya ses serviteurs par tous

pays, afin de le chercher avec soin. Quelques-uns vinrent à Edesse et Alexis

les reconnut; mais eux ne le reconnurent point, et même ils lui donnèrent

l’aumône comme aux autres pauvres. En l’acceptant, il rendit grâces à Dieu en

disant « Je vous rends grâces, dit-il, Seigneur, de ce que vous m’avez

fait recevoir l’aumône de mes serviteurs. » A leur retour, ils annoncèrent au

père qu'on n'avait pu le trouver en aucun lieu. Quant à sa mère, à partir du

Jour de son départ, elle étendit un sac sur le pavé de sa chambre, où au milieu

de ses veilles, elle poussait ces cris lamentables : « Toujours je demeurerai

ici dans le deuil, jusqu'à ce que j'aie retrouvé mon fils. » Pour son épouse,

elle dit à sa belle-mère : « Jusqu'à ce que j'entende parler de mon très cher

époux, semblable à une tourterelle; je resterai dans la solitude avec vous.»

Or, la dix-septième année qu'Alexis demeurait dans le. service de Dieu sous le

porche dont il a été question plus haut, une image de la Sainte Vierge qui se

trouvait là, dit enfin au custode de l’église : « Fais entrer l’homme de Dieu,

parce qu'il est digne du royaume du ciel et l’Esprit divin repose sur lui : sa

prière s'élève comme l’encens en la présence de Dieu. » Et comme le custode ne

savait de qui la Vierge parlait, elle ajouta : « C'est celui qui est assis

dehors sous le porche. » Alors le custode se hâta de sortir et fit entrer

Alexis dans l’église. Ce fait étant venu à la connaissance du public, on se mit

à lui donner dés marques de vénération; mais Alexis, fuyant la vaine gloire,

quitta Edesse et vint à Laodicée, où il s'embarqua dans l’intention d'aller à Tharse

de Cilicie ; cependant Dieu en disposa autrement, car le navire, poussé par le

vent, aborda au port de Rome. Quand Alexis eut vu cela, il se dit en lui-même :

« Je resterai inconnu dans la maison de mon père et je ne serai à charge à

aucun autre. » Il rencontra son père qui revenait du palais entouré d'une

multitude de gens obséquieux, et il se mit à lui crier : « Serviteur de Dieu,

je suis un pèlerin, fais-moi recevoir dans ta maison, et laisse-moi me nourrir

des miettes de ta table, afin que le Seigneur daigne avoir pitié de toi, à ton

tour, qui es pèlerin aussi. » En entendant ces mots, le père, par amour pour

son fils, l’introduisit chez lui ; il lui donna un lieu particulier dans sa

maison, lui envoya de la nourriture de sa table; en chargeant quelqu'un d'avoir

soin de lui. Alexis persévérait dans la prière, macérait son corps par les

jeûnes et par les veilles. Les serviteurs de la maison se moquaient de lui à

tout instant; souvent ils lui jetaient sur la tête l’eau qui avait servi, et

l’accablaient d'injures : mais il supportait tout avec une grande patience. Il

demeura donc inconnu de la sorte pendant dix-sept ans dans la maison de son

père.

Ayant vu en esprit que le

terme de sa vie était proche, il demanda du papier, et de l’encre; et il

écrivit le récit de toute sa vie. Un jour de dimanche, après la messe

solennelle, une voix se fit entendre dans le sanctuaire en disant : « Venez à

moi, vous tous qui travaillez et qui êtes fatigués et je vous soulagerai. »,

Quand on entendit cela, on fut effrayé; tout le monde e jeta la face contre

terre, quand pour la seconde fois, la voix se fit entendre et dit : « Cherchez

l’homme de Dieu afin qu'il prie pour Rome. » Les recherches n'ayant abouti à

rien, la voix dit de nouveau: « C'est dans la maison d'Euphémien que vous devez

chercher. » On s'informa auprès de lui, et il dit qu'il ne savait pas de qui on

voulait parler. Alors les empereurs Arcadius et Honorius vinrent avec le pape

Innocent à la maison d'Euphémien : et voilà que celui qui était chargé d'Alexis

vint trouver son maître et lui dire : « Voyez, Seigneur, si ce ne serait pas

notre pèlerin ; car vraiment c'est un homme d'une grande patience. » Euphémien

courut aussitôt, mais il le trouva mort: il vit sa figure toute resplendissante

comme celle d'un ange: ensuite il voulut prendre le papier qu'il avait dans la

main, mais il ne put l’ôter. En sortant il raconta ces détails aux empereurs et

aux pontifes qui, étant entrés dans le lieu où gisait le pèlerin, dirent : «

Quoique pécheurs, nous avons cependant le gouvernement du royaume; et l’un de

nous a la charge du gouvernement pastoral de l’Eglise universelle, donne-nous

donc ce papier :afin que nous sachions ce qui y est écrit: » Le pape

s'approchant prit le papier, que le défunt laissa aussitôt échapper, et il le

fit lire devant tout le peuple, en présence du père lui-même. Alors Euphémien,

qui entendait cela, fut saisi d'une violente douleur; il perdit connaissance et

tomba pâmé sur la terre. Revenu un peu à lui, il déchira ses vêtements,

s'arracha les cheveux blanchis, se tira la barbe, et se déchira lui-même de ses

propres mains, puis se jetant sur le corps de son fils, il criait : «

Malheureux que je suis ! pourquoi, mon fils, pourquoi m’as-tu contristé

de la sorte ? pourquoi pendant tant d'années m’as-tu plongé dans la

douleur et les gémissements ? Ah! que je suis malheureux de te voir, toi, le

bâton de ma vieillesse, étendu sur un grabat! tu ne parles pas : ah! misérable

que je suis ! quelle consolation pourrai-je jamais goûter maintenant? » Sa mère

en entendant cela, semblable à une lionne qui a brisé le piège où elle était

prise, s'arrache les vêtements, se rue échevelée, lève les yeux au ciel, et

comme la foule était si épaisse qu'elle ne pouvait arriver jusqu'au saint

corps, elle criait: « Laissez-moi passer, que je voie mon fils, que je voie la

consolation de mon âme, celui qui a,sucé mes mamelles. » Arrivée au corps, elle

se jeta sur, lui en criant : « Quel malheur pour moi! mon fils,, la lumière de

mes yeux, qu'as-tu fait là? pourquoi avoir agi si cruellement envers nous? Tu

voyais ton père et ta malheureuse mère en larmes, et tu ne te faisais pas

connaître à nous ! Tes esclaves t'injuriaient et tu le supportais ! » Et à

chaque instant elle se jetait sur le corps, tantôt étendant les bras sur lui, tantôt

caressant de ses mains ce visage angélique, tantôt l’embrassant : « Pleurez

tous avec moi, s'écriait-elle ; puisque, pendant dix-sept ans, je l’ai eu dans

ma maison et je n'ai pas su que ce fût mon fils. Et encore il y avait des

esclaves qui l’insultaient et qui l’outrageaient en le souffletant! Suis-je

malheureuse! qui donnera à mes yeux une fontaine de larmes pour pleurer nuit et

jour celui qui est la douleur de mon âme ? » La femme d'Alexis, vêtue d'habits

de deuil, accourut baignée de larmes. « Quel malheur pour moi! quelle

désolation! me voici veuve, je n'ai plus personne à regarder et sur lequel

j'aie à lever les yeux. » Mon miroir est brisé, l’objet de mon espoir a

péri. Aujourd'hui. commence pour moi une douleur qui n'aura point de fin. » Le

peuple témoin de ce spectacle versait d'abondantes larmes. Alors le pontife et

les empereurs avec lui placèrent le corps sur un riche brancard, et le

conduisirent au milieu de la ville. On annonçait au peuple qu'on avait trouvé

l’homme de Dieu que tous les citoyens recherchaient. Tout le monde courait

au-devant du saint. Y avait-il un infirme? il touchait ce très saint corps, et

aussitôt il était guéri ; les aveugles recouvraient la vue, les possédés du

démon étaient délivrés; tous ceux qui étaient souffrants de n'importe quelle

infirmité recevaient guérison. Les empereurs, à la vue de tous ces prodiges,

voulurent porter eux-mêmes, avec le souverain pontife, le lit funèbre, pour

être sanctifiés aussi par ce corps saint. Alors les empereurs firent jeter une

grande quantité d'or et d'argent sur les places publiques, afin que la foule,

attirée par l’appât de cette monnaie, laissât parvenir le corps du saint

jusqu'à l’église. Mais la populace qui ne tint aucun compte de l’argent, se

portait de plus en plus auprès du corps saint pour le toucher. Enfin ce fut

après de grandes difficultés qu'on parvint à le conduire à l’église de saint

Boniface, martyr; on l’y laissa sept jours qui furent consacrés à la prière.

Pendant ce temps on éleva un tombeau avec de l’or et des pierres précieuses de

toute nature, et on y plaça le saint corps avec grande vénération. Il en

émanait une odeur si suave que tout le monde le pensait plein d'aromates. Or,

saint Alexis mourut le 16 des calendes d'août, vers l’an 398.

* Sigebert de Gemblours, Chron,

an., 405.

La Légende dorée de Jacques de Voragine nouvellement traduite en français avec introduction, notices, notes et recherches sur les sources par l'abbé J.-B. M. Roze, chanoine honoraire de la Cathédrale d'Amiens, Édouard Rouveyre, éditeur, 76, rue de Seine, 76, Paris mdcccci

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/voragine/tome02/094.htm

SAINT ALEXIS

Sanctus Alexis | Alexius

Fête: 17 juillet

Latines :

Gautier

de Châtillon, Vita sancti Alexii

Vincent

de Beauvais, Speculum historiale, livre XIX, ch. 43-46 (prose)

Iacopo

da Varazze, Legenda aurea, ch. 90 (prose)

Diverses

versions anonymes en vers et en prose

Allemandes :

Konrad

von Würzburg, Alexius

Diverses

versions anonymes en vers et en prose

Françaises :

Versions

anonymes en vers et prose

Jean

de Vignay, Le miroir historial, livre XIX, ch. 43-46

Jean

de Vignay, La legende dorée, ch. 89 (prose)

Jean

Batallier, La legende dorée, ch. 89 (prose)

Le

tombel de Chartreuse, conte n° 18 (vers)

Italiennes :

Bonvesin

da la Riva, La vita di sant'Alessio

Versions

anonymes en vers et en prose

Néerlandaises :

Sente

Alexis legende (prose)

Occitane :

Portugaise :

A

vida de sancto Alexo confesor

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

Répertoires

bibliographiques

Bossuat,

Robert, Manuel bibliographique de la littérature française du Moyen Âge,

Melun, Librairie d'Argences (Bibliothèque elzévirienne. Nouvelle série. Études

et documents), 1951, xxxiv + 638 p. (ici p. 8-10, nos 39-65bis)

Dictionnaires: DEAF

Boss

Storey,

Christopher, An Annotated Bibliography and Guide to Alexis Studies (La vie

de saint Alexis), Genève, Droz (Histoire des idées et critique littéraire,

251), 1987, 126 p.

Généralités

Addonizio,

Francesco, La leggenda di S. Alessio nella letteratura e

nell'arte. Saggio critico, Napoli, Leone, 1930, 106 p.

Blau, Max

Friedrich, Zur Alexiuslegende, Wien, Gerold's Sohn, 1888, [iii] + 39

p. [GB] [HT] [IA]

Compte rendu:

Brauns, Julius, Über

Quelle und Entwicklung der altfranzösischen "Cançun de saint Alexis",

verglichen mit der provenzalischen Vida sowie den altenglischen und

mittelhochdeutschen Darstellungen, Kiel, Lipsius und Tischer, 1884, x + 58

p. [GB] [IA]

Cseppentő, István, « Une

légende médiévale au XVIIIe siècle: Le nouvel Alexis de Rétif de

La Bretonne », La joie des cours. Études médiévales et humanistes, éd.

Krisztina Horváth, Budapest, Elte Eötvös Kiadó, 2012, p. 30-38. [eltereader.hu]

Eis, Gerhard, «

Alexiuslied und christliche Askese », Zeitschrift für französische Sprache

und Literatur, 59:3-4, 1935, p. 232-236.

Gaiffier, B. de,

??, Analecta Bollandiana, 62, 1944, p. 281-283.

Hürsch, Melitta, «

Alexiuslied und christliche Askese », Zeitschrift für französische Sprache

und Literatur, 58, 1934, p. 414-418.

Johnson, Phyllis, et

Brigitte Cazelles, Le Vain Siècle Guerpir: A Literary Approach to

Sainthood Through Old French Hagiography of the 12th Century, Chapel Hill,

University of North Carolina Press (North Carolina Studies in the Romance

Languages and Literatures, 205), 1979, 321 p.

Comptes rendus:

A. Gier, dans Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie, 96, 1980, p. 405-407.

M. Thiry-Stassin, dans Le Moyen Âge, 88, 1982, p. 360-361.

K. D. Uitti,

dans The Modern Language Review, 76, 1981, p. 458-460. — R. Vermette,

dans Speculum, 56, 1981, p. 144-147.

Mölk, Ulrich, «

La Chanson de saint Alexis et le culte du saint en France aux

XIe et XIIe siècles », Cahiers de civilisation médiévale, 21,

1978, p. 339-355. [Pers] [Acad] DOI: 10.3406/ccmed.1978.2088

Pauphilet, Albert, et

Anne-Françoise Labie-Leurquin, « Saint Alexis (Vie

de) », Dictionnaire des lettres françaises: le Moyen Âge, éd.

Geneviève Hasenohr et Michel Zink, Paris, Fayard, 1992, p.

1330. Réimpr.: Paris, Fayard (La Pochothèque), 1994.

Rösler, Margarete, «

Beziehungen der Celestina zur Alexiuslegende », Zeitschrift für

romanische Philologie, 58, 1938, p. 365-367. [Gallica] DOI: 10.1515/zrph.1938.58.1.331

Rösler, Margarete, «

Versiones españolas de la leyenda de san Alejo », Nueva revista de

filología hispánica, 3, 1949, p. 329-352.

Stebbins, C. E., « Les

origines de la légende de Saint Alexis », Revue belge de philologie et

d'histoire, 51:3, 1973, p. 497-507. DOI: 10.3406/rbph.1973.2970

Stebbins, Charles E., «

Les grandes versions de la légende de saint Alexis », Revue belge de

philologie et d'histoire, 53:3, 1975, p. 679-695. DOI: 10.3406/rbph.1975.3049

Permalien: https://arlima.net/no/200

Archives de littérature

du Moyen Âge

Rédaction: Laurent Brun

Dernière mise à jour: 28 septembre 2018

SOURCE : https://www.arlima.net/ad/alexis_saint.html

Sant’Alessio

di Roma, fresque, XIe siècle, chiesa di San Clemente

Ambito

romano, Storie della vita di sant'Alessio di Roma (ultimo

quarto dell'XI

secolo), affresco; Roma, Basilica di San Clemente al

Laterano

Also

known as

Alexius of Edessa

Alexius the Beggar

Alexis…

Alessio…

The Man of God

17 July (Western

calendar)

17 March (Eastern

calendar)

Profile

The only son of a

wealthy Christian Roman senator.

The young man wanted to devote himself to God, but his

parents arranged a marriage for

him. On his wedding day his fiancee agreed to release him and let him follow

his vocation. He fled his parent‘s

home disguised as a beggar,

and lived near a church in Syria.

A vision of Our

Lady at the church pointed him out as exceptionally holy, calling him

the “Man of God”. This drew attention to him, which caused him to return

to Rome, Italy where

he would not be known. He came as a beggar to

his own home. His parents did

not recognize him, but were kind to all the poor,

and let him stay there. Alexis lived for seventeen years in a corner under the

stairs, praying,

and teaching catechism to

small children.

At his death an

unseen voice was heard to proclaim him ‘The Man of God’, and afterwards his

family found a note on his body which told them who he was and how he had lived

his life of penance from the day of his wedding until

then, for the love of God.

early 5th

century

dying man

with a letter in

his hand

man holding a ladder

man in a pilgrim‘s habit holding

a staff

man lying beneath a staircase

man lying on a mat

old and very ragged beggar with

a dish

old man dressed as

a pilgrim

palm (his

sufferings and patience led some to consider him a martyr)

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Francis

Xavier Weninger

Saints

and Their Symbols, by E A Greene

Saints

in Art, by Margaret Tabor

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

1001 Patron Saints and Their Feast Days, Australian

Catholic Truth Society

Saint

Charles Borromeo Church, Picayune, Mississippi

images

video

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

MLA

Citation

“Saint Alexius of

Rome“. CatholicSaints.Info. 23 January 2022. Web. 19 March 2023.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-alexius-of-rome/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-alexius-of-rome/

Saint

Alexis, détail d'un vitrail de l'église Saint-Pierre-ès-Liens, Pomport,

Dordogne, France.

Saint Alexis

Saint Alexis was the only

son of a rich Roman senator. From his good Christian parents, he learned to be

charitable to the poor. Alexis wanted to give up his wealth and honors but his

parents had chosen a rich bride for him. Because it was their will, he married

her. Yet right on his wedding day, he obtained her permission to leave her for

God. Then, in disguise, he traveled to Syria in the East and lived in great

poverty near a Church of Our Lady.

One day, after seventeen

years, a picture of our Blessed Mother spoke to tell the people that this

beggar was very holy. She called him “The man of God.” when he became famous,

which was the last thing he wanted, he fled back to Rome. He came as a beggar

to his own home. His parents did not recognize him, but they were very kind to

all poor people and so they let him stay there. In a corner under the stairs,

Alexis lived for seventeen years.

He used to go out only to

pray in church and to teach little children about God. The servants were often

very mean to him, and though he could have ended all these sufferings just by

telling his father who he was, he chose to say nothing. What great courage and

strength of will that took!

After Alexis died, his family found a note on his body which told them who he was and how he had lived his life of penance from the day of his wedding until then, for the love of God.

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/alexis/

Pfarrkirche

St. Martin, Langenargen, Bodenseekreis

St. Alexius

Confessor.

According to the most recent researches he was

an Eastern saint whose veneration was transplanted

from the Byzantine empire to Rome,

whence it spread rapidly throughout western

Christendom. Together with the name and veneration of

the Saint, his legend was made known to Rome and

the West by means of Latin versions and recensions based on

the form current in the Byzantine Orient. This process was

facilitated by the fact that according to the

earlier Syriac legend of the Saint, the "Man of

God," of Edessa (identical

with St. Alexius) was a native of Rome.

The Greek legend, which antedates the ninth century and is the basis

of all later versions, makes Alexius the son of a

distinguished Roman named Euphemianus. The night of

his marriage he secretly left his father's house

and journeyed to Edessa in

the Syrian Orient where, for seventeen years, he led the life of

a pious ascetic.

As the fame of his sanctity grew,

he left Edessa and

returned to Rome,

where, for seventeen years, he dwelt as a beggar under the stairs of his father's palace,

unknown to his father or

wife. After his death, assigned to the year 417, a document was found on his

body, in which he revealed his identity. He was forthwith honoured as

a saint and his father's house

was converted into a church placed under

the patronage of Alexius. In this

expanded form the legend is first found in a hymn (canon)

of the Greek hymnographer Josephus (d. 883). It also occurs in

a Syrian biography

of Alexius, written not later than the ninth century, and which presupposes

the existence of a Greek life of the Saint. The

latter is in turn based on an earlier Syriac legend (referred to

above), composed at Edessa between

450 and 475. Although in this latter document the name of Alexius is not

mentioned, he is manifestly the same as the "Man of God" of whom

this earlier Syriac legend relates that he lived in Edessa during

the episcopate of Bishop Rabula (412-435) as

a poor beggar, and solicited alms at

the church door. These he divided among the rest of the poor,

after reserving barely enough for the absolute necessities

of life. He died in the hospital and

was buried in the common grave of the poor. Before his death,

however, he revealed to one of the church servants that he

was the only son of distinguished Roman parents.

After the Saint's death, the servant told this to the Bishop.

Thereupon the grave was opened, but only his pauper's rags were now

found therein. How far this account is based

on historical tradition is hard to determine. Perhaps the only

basis for the story is the fact that a certain pious ascetic at Edessa lived

the life of a beggar and was later venerated as

a saint. In addition to this earlier Syriac legend,

the Greek author of the later biography of St. Alexius, which we

have mentioned above as having been written before the ninth century, probably

had in mind also the events related in the life of St. John Calybata,

a young Roman patrician, concerning whom a similar story is told. In

the West we find no trace of the name Alexius in any martyrology or

other liturgical

book previous to the end of the tenth century; he seems to have been

completely unknown. He first appears in connection with St.

Boniface as titular saint of a church on the

Aventine at Rome.

On the site now occupied by the church of

Sant' Alessio there was at one time a diaconia, i.e. an

establishment for the care of the poor of the Roman

Church. Connected with this was a church which by the eighth

century had been in existence for some time and

was dedicated to St.

Boniface. In 972 Pope

Benedict VII transferred the almost abandoned church to

the exiled Greek metropolitan,

Sergius of Damascus. The latter erected beside the church a monastery for Greek and Latin monks,

soon made famous for the austere life of its inmates. To the name

of St.

Boniface was now added that of St. Alexius as

titular saint of the church and monastery.

It is evidently Sergius and his monks who

brought to Rome the veneration of St.

Alexius. The Oriental Saint, according to his legend a

native of Rome,

was soon very popular with the folk of that city. Among the

frescoes executed towards the end of the eleventh century in

the Roman basilica of St. Clement (now the lower

church of San Clemente) are very interesting representations of

events in the life of St. Alexius. His feast is

observed on the 17th of July, in the West; in the East, on the 17th of

March. The church of Sts. Alexius and Boniface on the

Aventine has been renovated in modern times but several medieval monuments

are still preserved there. Among them the visitor is shown the

alleged stairs of the house of Euphemianus under which Alexius is

said to have lived.

Sources

Acta SS., July, IV, 238

sqq.; Analecta Bollandiana, XIX, 241 sqq. (1900); DUCHESNE, Les

légendes chrétiennes de l'Aventin; Notes sur la topographie de Rome au

moyen-age, N. VII, in Mélanges d'archeol. et d'hist., X, 234 sqq. (1890);

AMIAND, La légende Syriaque de S. Alexis, l'Homme de Dieu (Paris,

1899); KONRAD VON WURZBURG, Das Leben des hl. Alexius (Berlin, 1898);

MASSMANN, St. Alexius Leben (Quedlinburg and Leipzig, 1843);

NERINIUS, De templo et coenobio Sanctorum Bonifatii et Alexii (Rome,

1752); BUTLER, Lives, 17 July.

Kirsch, Johann

Peter. "St. Alexius." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol.

1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 23 Apr.

2015 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01307b.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Laura Ouellette.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. March 1, 1907. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2021 by Kevin Knight.

Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01307b.htm

Saint

Alexius. Coloured engraving by C. Klauber after J.B Baumgartner.

July 17

St. Alexius, Confessor

From Joseph the Younger,

in a poem of the ninth age, divided into Odes, an anonymous writer of his Life

in the tenth century, noted by the Bollandists, a homily of St. Adalbert,

bishop of Prague, and martyr, of the same age, and from other monuments, free from

later interpolations; on all which see Pinius the Bollandist, t. 4, Julij, p.

239, who confutes at large the groundless and inconsistent surmises of Baillet.

Above all, see Nerinio, abbot of the Hieronymites at Rome, who has fully

vindicated the memory of St. Alexius in his Dissertation De Templo et Cœnobio,

SS. Bonifacii et Alexii, in 4to. Romæ, 1752. On his Chaldaic Acts, see Jos.

Assemani, ad 17 Martii, in Calend. Univ. t. 6, pp. 187, 189; and Bibl. Orient.

t. 1, p. 401.

In the Fifth Century.

ST. ALEXIUS or

Alexis is a perfect model of the most generous contempt of the world. He was

the only son of a rich senator of Rome, born and educated in that capital, in

the fifth century. From the charitable example of his pious parents he learned,

from his tender years, that the riches which are given away to the poor, remain

with us for ever; and that alms-deeds are a treasure transferred to heaven,

with the interest of an immense reward. And whilst yet a child, not content to

give all he could, he left nothing unattempted to compass or solicit the relief

of all whom he saw in distress. But the manner in which he dealt about his

liberal alms was still a greater proof of the noble sentiments of virtue with

which his soul was fired; for by this he showed that he thought himself most

obliged to those who received his charity, and regarded them as his greatest

benefactors. The more he enlarged his views of eternity, and raised his

thoughts and desires to the bright scene of immortal bliss, the more did he daily

despise all earthly toys; for, when once the soul is thus upon the wing, and

soars upwards, how does the glory of this world lessen in her eye! and how does

she contemn the empty pageantry of all that worldlings call great!

Fearing lest the

fascination, or at least the distraction of temporal honours might at length

divide or draw his heart too much from those only noble and great objects, he

entertained thoughts of renouncing the advantages of his birth, and retiring

from the more dangerous part of the world. Having, in compliance with the will

of his parents, married a rich and virtuous lady, he on the very day of the

nuptials, making use of the liberty which the laws of God and his church give a.person

before the marriage be consummated, of preferring a more perfect state,

secretly withdrew, in order to break all the ties which held him in the world.

In disguise he travelled into a distant country, embraced extreme poverty, and

resided in a hut adjoining to a church dedicated to the Mother of God. Being,

after some time there, discovered to be a stranger of distinction, he returned

home, and being received as a poor pilgrim, lived some time unknown in his

father’s house, bearing the contumely and ill treatment of the servants with

invincible patience and silence. A little before he died, he by a letter

discovered himself to his parents. He flourished in the reign of the emperor

Honorius, Innocent the First being bishop of Rome; and is honoured in the

calendars of the Latins, Greeks, Syrians, Maronites, and Armenians. His

interment was celebrated with the greatest pomp by the whole city of Rome, on

the Aventin hill. His body was found there in 1216, in the ancient church of

St. Boniface, whilst Honorius III. sat in St. Peter’s chair, and at this day is

the most precious treasure of a sumptuous church on the same spot, which bears

his name jointly with that of St. Boniface, gives title to a cardinal, and is

in the hands of the Hieronymites

The extraordinary paths

in which the Holy Ghost is pleased sometimes to conduct certain privileged

souls are rather to be admired than imitated. If it cost them so much to seek

humiliations, how diligently ought we to make a good use of those at least

which providence sends us! It is only by humbling ourselves on all occasions

that we can walk in the path of true humility, and root out of our hearts all

secret pride. The poison of this vice infects all states and conditions: it

often lurks undiscovered in the foldings of the heart even after a man has got

the mastery over all his other passions. Pride always remains even for the most

perfect principally to fight against; and unless we watch continually against

it, nothing will remain sound or untainted in our lives; this vice will creep even

into our best actions, infect the whole circle of our lives, and become a main

spring of all the motions of our heart; and what is the height of our

misfortune, the deeper its wounds are, the more is the soul stupified by its

venom, and the less capable is she of feeling her most grievous disease and

spiritual death. St. John Climacus writes, 1 that

when a young novice was rebuked for his pride, he said: “Pardon me, father, I

am not proud.” To whom the experienced director replied: “And how could you

give me a surer proof of your pride than by not seeing it yourself?”

Note 1. Gr. 22, p.

548. [back]

Rev. Alban Butler

(1711–73). Volume VII: July. The Lives of the Saints. 1866.

SOURCE : https://www.bartleby.com/lit-hub/lives-of-the-saints/volume-vii-july/st-alexius-confessor

Église de Saint Alexios, Patras

Article

Here beginneth the Life

of Saint Alexis.

Alexis is as much to say

as going out of the law of marriage for to keep virginity for God’s sake, and

to renounce all the pomp and riches of the world for to live in poverty.

Of Saint Alexis.

In the time that Arcadius

and Honorius were emperors of Rome, there was in Rome a right noble lord named

Euphemius which was chief and above all other lords about the emperors, and had

under his power a thousand knights. He was a much just man unto all men, and

also he was piteous and merciful unto the poor, for he had daily three tables

set and covered for to feed the orphans, poor widows, and pilgrims, and he ate

at the hour of noon with good and religious persons. His wife, that was named

Aglaia, led a religious life, but because they had no child, they prayed unto God

to send them a son that might be their heir after them of their havoir and

goods. It was so that God heard their prayers and beheld their bounty and good

living, and gave unto them a son, which was named Alexis, whom they did to be

taught and enformed in all sciences and honours. After this they married him

unto a fair damoisel which was of the lineage of the emperor of Rome. When the

day of the espousals was come to even, Alexis, being in the chamber with his

wife alone, began to inform and induce her to dread God and serve him, and were

all that night together in right good doctrine. And finally, he gave to his

wife his ring and the buckle of gold of his girdle, both bound in a little

cloth of purple, and said to her: Fair sister, take this and keep it as long as

it shall please our Lord God, and it shall be a token between us, and he give

you grace to keep truly your virginity.

After this he took of

gold and silver a great sum and departed alone from Rome, and found a ship in

which he sailed into Greece, and from thence went into Syria, and came to a

city called Edessa, and gave there all his money for the love of God, and clad

him in a coat, and demanded alms for God’s sake, like a poor man, tofore the

church of our Lady, and what he had left of the alms above his necessity, he

gave it unto others for God’s sake. And every Sunday he was houseled and

received the sacrament; such a life he led long. Some of the messengers that

his father had sent to seek him through all the parts of the world, came to seek

him in the said city of Edessa, and gave unto him their alms, he sitting tofore

the church with other poor people, but they knew not him. And he knew well them

and thanked our Lord saying: I thank thee, fair Lord Jesu Christ, that vouchest

safe to call me and to take alms in thy name of my servants, I pray thee to

perform in me that which thou hast begun. When the messengers were returned to

Rome, and Euphemius, his father, saw that they had not found his son, he laid

him down upon a mattress, stretching on the earth, wailing, and said thus: I

shall hold me here and abide till that I have tidings of my son. And the wife

of his son Alexis said, weeping, to Euphemius: I shall not depart out of your

house, but shall make me semblable and like to the turtle, which after that she

hath lost her fellow will take none other but all her life after liveth chaste.

In like wise I shall refuse all fellowship unto the time that I shall know

where my right sweet friend is become.

After that Alexis had

done his penance by right great poverty in the said city and led a right holy

life by the space of seventeen years, there was a voice heard that came from

God unto the church of our Lady, and said to the porter: Make the man of God to

enter in, for he is worthy to have the kingdom of heaven, and the spirit of God

resteth on him. When the clerk could not find ne know him among other poor men,

he prayed to God to show to him who it was, and a voice came from God and said:

He sitteth without, tofore the entry of the church; and so the clerk found him,

and prayed him humbly that he would come in to the church.

When this miracle came to

the knowledge of the people, and Alexis saw that man did to him honour and

worship, anon for to eschew vain glory, he departed from thence and came into

Greece, where he took ship and entered for to go into Sicily. But, as God would,

there arose a great wind which made the ship to arrive at the port of Rome.

When Alexis saw this, anon he said to himself: By the grace of God I will

charge no man of Rome, I shall go to my father’s house in such wise as I shall

not be known of any person. And when he was within Rome he met Euphemius, his

father, which came from the palace of the emperor with a great meiny following

him. And Alexis, his son, like a poor man ran crying and said: Sergeant of of

God, have pity on me that am a poor pilgrim, and receive me into thine house

for to have my sustenance of the reliefs that shall come from thy board, that

God bless thee and have pity on thy son, which is also a pilgrim. When

Euphemius heard speak of his son, anon his heart began to melt, and said to his

servants: Which of you will have pity of this man and take the cure and charge

of him, I shall deliver him from his servage and make him free, and shall give

him of mine heritage. And anon he committed him unto one of his servants, and

commanded that his bed should be made in a corner of the hall whereas comers

and goers might see him. And the servant to whom Alexis was commanded to keep,

made anon his bed under the stair and steps of the hall, and there he lay right

like a poor wretch, and suffered many villainies and despises of the servants

of his father, which oft-times cast and threw on him the washing of dishes and

other filth, and did to him many evil turns and mocked him, but he never

complained, but suffered all patiently for the love of God. Finally, when he

had led this right holy life within his father’s house, in fasting, in praying

and in doing penance, by the space of seventeen years’ and knew that he should

soon die, he prayed the servant that kept him to give him a piece of parchment and

ink, and therein he wrote by order all his life, and how he was married by the

commandment of his father, and what he had said to his wife, and of the tokens

of his ring and buckle of his girdle that he had given to her at his departing,

and what he had suffered for God’s sake, and all this did he for to make his

father to understand that he was his son.

After this, when it

pleased God for to show and manifest the victory of our Lord Jesu Christ in his

servant Alexis, on a time on a Sunday after mass, hearing all the people in the

church, there was a voice heard from God crying and saying as is said, Matthew,

eleventh chap.: Come unto me ye that labour and be travailed, I shall comfort

you. Of which voice all the people were abashed, which anon fell down unto the

earth. And the voice said again: Seek ye the servant of God, for he prayeth for

all Rome. And they sought him, but he was not found.

Alexis in a morning, on a

Good Friday, gave his soul unto God, and departed out this world, and that same

day all the people assembled at Saint Peter’s church and prayed God that he

would show to them where the man of God might be found that prayed for Rome.

And a voice was heard that came from God that said: Ye shall find him in the

house of Euphemius. And the people said unto Euphemius: Why hast thou hid from

us that thou hast such grace in thine house? And Euphemius answered: God

knoweth that I know no thing thereof. Arcadius and Honorius that then were

emperors of Rome, and also the pope Innocent, commanded that men should go unto

Euphemius’s house for to enquire diligently tidings of the man of God.

Euphemius went tofore with his servants for to make ready his house against the

coming of the pope and emperors, and when Alexis’ wife had understood the cause

and how a voice was heard that came from God saying: Seek the man of God in

Euphemius’s house, anon she said to Euphemius: Sire, see if this poor man that

ye have so long kept and harboured be the same man of God. I have well marked

that he hath lived a right fair and holy life. He hath every Sunday received

the sacrament of the altar, he hath been right religious, in fasting, in

waking, and in prayer, and hath suffered patiently and debonairly of our

servants many villainies. And when Euphemius had heard all this, he ran towards

Alexis and found him dead. He discovered his visage, which shone and was bright

as the face of an angel. And anon he returned toward the emperors and said: We

have found the man of God that we sought, and told unto them how he had

harboured him, and how the holy man had lived, and also how he was dead, and

that he held a bill or letter in his hand which they might not draw out. Anon

the emperor with the pope went to Euphemius’s house and came tofore the bed

where Alexis lay dead, and said: How well the we be sinners, yet nevertheless

we govern the world, and lo here is the pope the general father of all the

church, give us the letter that thou holdest in thine hand for to know what is

the writing of it. And the pope went tofore and took the letter and took it to

his notary for to read, and the notary read it tofore the pope, the emperors

and all the people, and when he came to the point that made mention of his

father, and of his mother, and also of his wife, and that by the ensigns that

he had given to his wife at his departing, his ring and buckle of his girdle

wrapped in a little purple cloth, anon Euphemius fell down aswoon, and when he

came again to himself he began to draw his hair and beat his breast, and fell

down on the corpse of Alexis his son, and kissed it, weeping and crying in

right great sorrow of heart, saying: Alas! right sweet son, wherefore hast thou

made me to suffer such sorrow? Thou sawest what sorrow and heaviness we had for

thee; alas! why hadst thou no pity on us in so long time? How mightest thou

suffer thy mother and thy father to weep so much for thee and thou sawest it

well without taking pity on us? I supposed to have heard some time tidings of

thee, and now I see thee lie dead in thy bed, which shouldst be my solace in

mine age; alas! what solace may I have that see my right dear son dead ? Me

were better die than live. When the mother of Alexis saw and heard this, she

came running like a lioness and cried: Alas! alas ! drawing her hair in great

sorrow, scratching her paps with her nails, saying: These paps have given thee

suck. And when she might not come to the corpse for the foison of people that

was come thither, she cried and said: Make room and way to me, sorrowful

mother, that I may see my desire and my dear son that I have engendered and

nourished. And as soon as she came to the body of her son she fell down on it

piteously and kissed it, saying thus: Alas for sorrow! my dear son, the light

of mine age, why hast thou made us suffer so much sorrow? Thou sawest thy

father, and me thy sorrowful mother so oft weep for thee, and wouldst never

make to us semblance of son. O all ye that have the heart of a mother, weep ye

with me upon my dear son, whom I have had in my house seventeen years as a poor

man. To whom my servants have done much villainy. Ah! fair son, thou hast

suffered them right sweetly and debonairly. Alas! thou that wert my trust, my

comfort and solace in mine old age how mightest thou hide thee from me that am

thy sorrowful mother? who shall give to mine eyes from henceforth a fountain of

tears for to make pain unto the sorrow of mine heart? And after this came the

wife of Alexis in weeping, throwing herself upon the body, and with great sighs

and heaviness said: Right sweet friend and spouse, whom long I have desired to

see, and chastely I have to thee kept myself like a turtle that alone, without

make, waileth and weepeth. And lo ! here is my right sweet husband whom I have

desired to see alive, and now I see him dead; from henceforth I wot not in whom

I shall have fiance ne hope. Certes my solace is dead, and in sorrow I shall be

unto the death, for now forthon I am the most unhappy among all women, and

reckoned among the sorrowful widows. And after these piteous complaints the

people wept for the death of Alexis. The pope made the body to be taken up and

to be put into a fere-tree and borne into the church. And when it was borne

through the city, right great foison of people came against it, and said: The

man of God is found that the city sought. Whatsomever sick body might touch the

fere-tree he was anon healed of his malady. There was a blind man that

recovered his sight, and lame men and others were healed. The emperor made

great foison of gold and silver to be thrown among the people, for to make way that

the fere-tree might pass, and thus by great labour and reverence was borne the

body of Saint Alexis unto the church of Saint Boniface the glorious martyr.

And there was the body put into a shrine much honourably, made of gold and

silver, the seventeenth day of July, and all the people rendered thankings and

laud to our Lord God for his great miracles, unto whom be given honour, laud,

and glory in secula secuIorum. Amen.

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/golden-legend-saint-alexis/

Weninger’s

Lives of the Saints – Saint Alexius, Confessor

Article

The life of Alexius teaches us how great God is in His

Saints. His

parents, Euphemianus and Aglae, were rich and distinguished people, but they

were long without issue. At length, after many prayers, they were blessed with