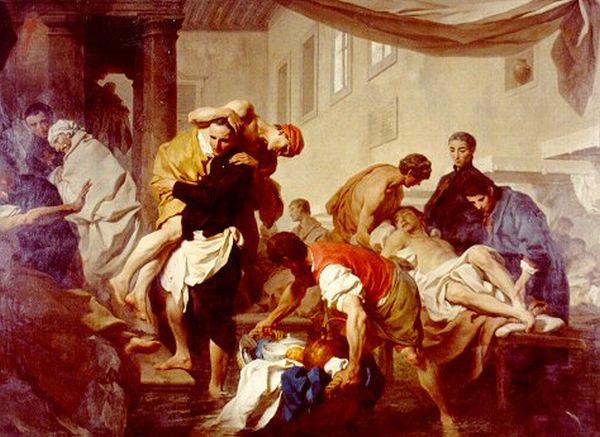

Saint Camillo de Lellis, Chiesa Santa Maria Maddalena

Saint Camille de Lellis

Fondateur des Clercs réguliers pour le service des

malades (+1614)

Cet adolescent italien, orphelin et sans fortune, eut une jeunesse dissipée. Il s'engagea dans l'armée espagnole pour combattre les Turcs. Un jour de malchance, il perd au jeu tout ce qu'il possède. On le renvoie de l'armée. Il fait alors tous les métiers pour aboutir comme homme de service dans un couvent de capucins. Et c'est là qu'il se convertit. Comme il ne fait rien à moitié, il y demande son admission. Mais un ulcère incurable à la jambe lui interdit l'état religieux. Camille entre à l'hôpital Saint-Jacques de Rome pour se faire soigner. Il est si frappé par la détresse des autres malades qu'il s'y engage comme infirmier. L'indifférence de ses collègues vis-à-vis des malades le bouleverse. Il entreprend de réformer tout cela. En prenant soin des malades, ce sont les plaies du Christ qu'il soigne. Sa charité rayonnante lui attire de jeunes disciples. Ces volontaires, qui se réunissent pour prier ensemble et rivalisent de tendresse envers les malades, constituent le noyau initial des Clercs Réguliers des Infirmes que l'on appellera familièrement par la suite les "Camilliens". La mission de ces nouveaux religieux, pères et frères, est "l'exercice des œuvres spirituelles et corporelles de miséricorde envers les malades, même atteints de la peste, tant dans les hôpitaux et prisons que dans les maisons privées, partout où il faudra." Pour mieux établir son Institut, Camille devint prêtre. Partout où se déclare une peste, il accourt ou envoie ses frères. Il finit par mourir d'épuisement à Rome.

Martyrologe romain

La musique que je préfère, c'est celle que font les pauvres malades lorsque l'un demande qu'on lui refasse son lit, l'autre qu'on lui rafraîchisse la langue ou qu'on lui réchauffe les pieds.

Saint Camille de Lellis à ses frères

Igreja São Sebastião, Porto Alegre : São Camilo

de Lellis

SAINT CAMILLE de LELLIS

Fondateur d'Ordre

(1549-1614)

Saint Camille de Lellis, Napolitain, fut privé de sa mère dès le berceau. Malgré les heureux présages donnés par un songe qu'avait eu sa mère avant sa naissance, il eut une enfance peu vertueuse; sa jeunesse fut même débauchée. Jusque vers l'âge de vingt-cinq ans, on le voit mener une vie d'aventures; il se livre au jeu avec frénésie, et un jour en particulier il joue tout, jusqu'à ses vêtements. Sa misère le fait entrer dans un couvent de Capucins, où il sert de commissionnaire.

Un jour, en revenant d'une course faite à cheval, pour le service du monastère, il est pénétré d'un vif rayon de la lumière divine et se jette à terre, saisi d'un profond repentir, en versant un torrent de larmes: "Ah! Malheureux que je suis, s'écria-t-il, pourquoi ai-je connu si tard mon Dieu? Comment suis-je resté sourd à tant d'appels? Pardon, Seigneur, pardon pour ce misérable pécheur! Je renonce pour jamais au monde!"

Transformé par la pénitence, Camille fut admis au nombre des novices et mérita, par l'édification qu'il donna, le nom de frère Humble. Dieu permit que le frottement de la robe de bure rouvrît une ancienne plaie qu'il avait eue à la jambe, ce qui l'obligea de quitter le couvent des Capucins. Lorsque guéri de son mal, il voulut revenir chez ces religieux, saint Philippe de Néri, consulté par lui, lui dit: "Adieu, Camille, tu retournes chez les Capucins, mais ce ne sera pas pour longtemps." En effet, peu après, la plaie se rouvrit, et Camille, obligé de renoncer à la vie monastique, s'occupa de soigner et d'édifier les malades dans les hôpitaux.

C'est en voyant la négligence des employés salariés de ces établissements que sa vocation définitive de fondateur d'un Ordre d'infirmiers se révéla en lui: "Nous porterons, se dit-il, la Croix sur la poitrine; sa vue nous soutiendra et nous récompensera." Les commencements de cet Institut nouveau furent faibles et biens éprouvés; mais bientôt le nombre des religieux s'étendit au-delà de toute espérance.

Camille, après des études opiniâtres, s'était fait ordonner prêtre, et il était en mesure de soutenir sa tâche. Pendant une peste affreuse, le Saint fit des prodiges de charité; il allait partout à la recherche de la misère, se dépouillait lui-même et donnait jusqu'aux dernières ressources de son monastère. Dieu bénissait le désintéressement de Son serviteur, car des mains généreuses arrivaient toujours à temps pour renouveler les provisions épuisées.

Plein de vertus, épuisé de travaux, Camille mourut à Rome, les bras en croix, la prière sur les lèvres.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours

de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950.

SOURCE : https://livres-mystiques.com/partieTEXTES/Jaud_Saints/calendrier/Vies_des_Saints/07-18.htm

Saint Camille de Lellis

Saint Camille de Lellis (mort le 14 juillet 1614) est

le fondateur des Clercs réguliers ministres des infirmes, plus connus sous le

nom de Camilliens, qu'il institue à Rome, le 8 septembre 1584, que le pape

Sixte V approuve le 18 mars 1586 et que le pape Grégoire XIV érige en ordre

religieux le 21 septembre 1591. Fortement centralisé sous son préfet général,

l'ordre qui comprend déjà trois cents membres répartis en cinq provinces à la

mort de son fondateur, connaît au XVII° siècle un essor rapide en Italie, en

Espagne, au Portugal et aux Amériques. Les Camilliens portent l'habit clérical

ordinaire (soutane noire) surchargée d'une croix latine rouge cousue.

Fils d’un officier au service de Charles-Quint qui

avait pris part au sac de Rome (1527), Camille de Lellis naquit à Bocchianico,

au sud de Chieti, dans les Abruzzes (royaume de Naples) le 25 mai 1550.

Orphelin de mère, à treize ans, et de père, à dix-neuf ans, ce géant, joueur

invétéré qui s’était ruiné dans les jeux de hasard, était sans ressource

lorsque, atteint d’une plaie au pied, il alla se faire soigner à l’hôpital

romain de Saint-Jacques des Incurables où, ne pouvant payer, il fut employé un

mois comme infirmier. Comme il avait transformé sa chambre en salle de jeux, on

le chassa de l’hôpital et, à la fin de 1569, il s’enrôla dans l’armée

vénitienne qui allait combattre le sultan Sélim II, puis il servit sous don

Juan d’Autriche mais la dysenterie l’empêcha de participer à la bataille de

Lépante (1571). Il embarqua sur les galères napolitaines en route vers Tunis.

Libéré du service, il vécut plus ou moins bien du jeu.

Ayant rencontré deux franciscains dans les rues de Zermo, il fit vœu de

renoncer aux désordres de sa vie mais il oublia très vite ses bonnes

dispositions qui le reprirent, sans plus d’effet, lorsqu’il fut près de périr

dans une tempête qui dura trois jours et trois nuits. Ayant perdu au jeu son

épée, son arquebuse, son manteau et sa chemise, il fut réduit à la mendicité

jusqu’au début de 1575 où il se fit engager comme manœuvre chez un entrepreneur

qui construisait le couvent des Capucins de Manfredonia.

Un soir que l’entrepreneur l’avait envoyé faire une

course au couvent, le père gardien le prit à part et l’entretint de la

nécessité de se donner à Dieu ; le lendemain, alors qu’il revenait à

cheval, songeant à la conversation de la veille, il tomba de sa monture et,

dans une intense lumière intérieure, il vit ses péchés avec le jugement de Dieu

: « Ah ! malheureux, misérable que je suis, pourquoi ai-je connu si

tard mon Seigneur et mon Dieu ? Comment suis-je resté sourd à tant

d’appels ? Que de crimes ! Ne vaudrait-il pas mieux que je ne fusse

jamais né ? Pardon, Seigneur, pardon pour ce misérable pécheur :

laissez-lui le temps de faire une vraie pénitence. Je ne veux plus rester dans

le monde, j’y renonce à jamais. » Admis par les capucins de Manfredonia,

il se montra si bien converti qu’on l’envoya faire son noviciat à Trivento. En

chemin, un soir, comme il s’apprêtait à traverser une rivière, il entendit une

voix lui crier du haut d’une montagne : « Ne va pas plus loin, ne

passe pas ! » Il regarda pour voir qui lui parlait, et, n’apercevant

personne, il continua d’avancer ; la même voix l’appela trois fois et parvint

enfin à l’arrêter ; il revint sur ses pas et s’endormit sous un

arbre : le lendemain, il apprit que la rivière était là si profonde qu’il

y eût certainement perdu la vie s’il ne se fût arrêté. Au couvent de Trivento,

sa vie fut parfaite mais la plaie de sa jambe s’étant rouverte et envenimée, il

dut retourner à l’hôpital romain de Saint-Jacques des Incurables où il se mit

sous la direction de saint Philippe Néri. Guéri, il resta, comme infirmier et

devint le maître de maison (économe). Bon gestionnaire, il fit passer

les revenus annuels de l’hôpital de cent à quatorze cent quatre-vingt-seize

écus bien qu’il exigeât la meilleure marchandise et qu’il refusât le blé de

mauvaise qualité.

Il envisagea de réformer les soins et, avec le

chapelain et quatre infirmiers, de créer une association d’infirmiers (août

1582) mais il échoua devant l’incompréhension des directeurs de

l’hôpital ; c’est alors qu’il songea à fonder une congrégation entièrement

consacrée au soin des malades. Pour mettre en œuvre son projet, il comprit

qu’il lui fallait être prêtre, aussi, tout en continuant son travail d’économe

de l’hôpital, alla-t-il suivre les cours du Collège Romain.

Ordonné prêtre, il célébra sa première messe dans la

chapelle de l’hôpital Saint-Jacques des Incurables (10 juin 1584) dont les

directeurs le nommèrent chapelain de la Madonnina des Miracles. Contre l’avis

de saint Philippe Néri, il abandonna sa charge d’économe, quitta l’hôpital et,

dans sa chapelle, le 8 septembre 1584, il reçut ses premiers disciples qui

furent employés à l’hôpital du Saint-Esprit : « Parfois, il y a

jusqu’à deux cents lits occupés, et c’est à qui vomira, toussera, criera,

tirera le souffle, rendra l’âme, se démènera frénétiquemenl tant qu’il faut le

lier; et c’est à qui gémira et qui se lamentera... Se pourvoir de pain, de

viande, d’épices, de draps et de couvertures, c’est à quoi l’argent réussit

sans grande fatigue. Mais le service est mauvais superlativement, abominable.

Pensez si on tient a venir vider les vases de ces gens-là, à six giuli par

mois ; on en donnerait dix que ce serait la même chose. »

Les nouveaux religieux n’ayant pas de chapelle, ils

obtinrent le couvent de la Madeleine et les logis adjacents (1586). Approuvé

par les papes, Camille de Lellis fut le premier préfet général de son ordre,

charge qu’il abandonna en 1607. Après que Grégoire XIV eut fulminé la bulle qui

érigeait l’Ordre des Ministres des infirmes sous la règle de

Saint-Augustin (21 septembre 1591), le 8 septembre 1591, fête de la Nativité de

la Sainte Vierge, en l’église du couvent de la Madeleine, les vingt-cinq

premières professions purent être faites où chaque camillien disait à

Dieu : « Je vous promets de servir les pauvres malades, vos fils et

mes frères, tout le temps de ma vie, avec le plus de charité possible. »

Atteint de graves infirmités, épuisé par de nombreux

voyages, Camille de Lellis mourut à Rome, au couvent de la Madeleine, le 14

juillet 1614, un heure après le commencement de la nuit. Quand le cardinal

Ginnasio lui porta le viatique, il dit : « Je reconnais, Seigneur,

que je suis le plus grand des pécheurs et que je ne mérite pas de recevoir la

faveur que vous daignez me faire; mais sauvez-moi par votre infinie

miséricorde. Je mets toute ma confiance dans les mérites de votre précieux

sang. » Il laissait 15 maisons et 8 hôpitaux à 242 profès, répartis

en 5 provinces. Benoît XIV béatifia (2 février 1742) et canonisa (29 juin 1746)

Camille de Lellis. Un décret de la congrégation des Rites (15 décembre 1762),

signé par Clément XIII le 18 juillet, étend sa fête à toute l’Église. Avec

saint Jean de Dieu, Léon XIII le proclame patron des malades et des hôpitaux

(22 juin 1886), Pie XI le proclame patron du personnel des hôpitaux (28 août

1930).

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/07/14.php

Camille de Lellis, le saint qui guérit les blessures

Timothée

Dhellemmes - Publié le 14/07/20

Fêté le 14 juillet par l’Église catholique, Camille de

Lellis n’a pas vraiment eu l’itinéraire tout tracé pour devenir saint… Habitué

des jeux de hasard et menant une vie dissipée, sa conversion inattendue et sa

propre maladie l’ont mené au chevet des plus fragiles.

De mercenaire et habitué des jeux de hasard, à saint

patron des infirmes et des hôpitaux. L’itinéraire de saint Camille de Lellis

est l’histoire d’une conversion inattendue, alors qu’il était homme de service

et ouvrier dans un couvent de capucins, à Rome. Le jeune homme, orphelin dès

l’âge de 13 ans puis simple soldat, s’était retrouvé là par hasard, après

s’être ruiné aux jeux d’argent…

Lire aussi :

Dix versets bibliques pour surmonter l’épreuve de la maladie

C’est alors qu’il gagne la confiance et l′estime des

religieux. Derrière ses faiblesses et son manque d’éducation, les religieux

voient rapidement en lui un homme pieux et sage. Et ils voient juste : le 2

février 1575, Camille de Lellis se repent officiellement de tous ses péchés et

décide de devenir frère capucin. Il pense alors avoir trouvé sa vocation, mais

un ulcère incurable à la jambe l’empêche de terminer son noviciat et d’être

admis.

À l’hôpital, Camille de Lellis découvre sa propre

vocation

C’est une grande épreuve pour lui et pour les frères,

mais cette étape est pourtant l’occasion d’affiner encore un peu plus la

manière dont il souhaite répondre à l’appel de Dieu. Dans les hôpitaux qu’il a

l’habitude de fréquenter, Camille est toujours très touché par la détresse des

autres malades qu’il croise, et par l’indifférence de certains infirmiers.

À sa sortie, il décide de s’engager à son tour dans le

service des malades. Son charisme et l’immense désir de charité qu’il dégage

attirent de nombreux volontaires à ses côtés, désireux de porter secours aux

malades, en particulier de la peste. C’est ainsi que né l’ordre des Clercs

Réguliers des Infirmes, que l’on appelle aussi familièrement les

« Camilliens ».

« Servir ceux qui souffrent, c’est servir le

Christ lui-même »

En parallèle de ses actions après des souffrants,

Camille termine sa formation de prêtre à l’âge de 32 ans. « Servir ceux

qui souffrent, c’est servir le Christ lui-même », ne cessait-il de

répéter. Il prend soin de chaque malade comme le ferait une mère avec son fils

unique. À la fin de sa vie, l’Ordre des Clercs Réguliers des Infirmes ne compte

pas moins de 14 couvents, 8 hôpitaux et plus de 300 religieux. Epuisé, Camille

de Lellis meurt le 14 juillet 1614 à Rome.

Il est canonisé 132 ans plus tard par Benoît XV, et

obtient le titre de « Protecteur des hôpitaux et des malades » le 22

juin 1886, en même temps que saint Jean de Dieu.

Mosaik Hl. Kamillus einen Kranken pflegend an der Camillianerkirche Maria Heil der Kranken in der Versorgungsheimstraße 72 in Wien-Hietzing.

Camille de Lellis, le saint qui tendait l’oreille à la

voix des anges

Anne Bernet - Publié le 13/07/21

Bagarreur professionnel et joueur impénitent, Camille

de Lellis, fêté par l'Église catholique le 14 juillet, fait l’expérience de la

souffrance avant d’exceller dans le métier d’infirmier. Devenu prêtre,

l’assistance des anges lui vaut de belles aventures.

Àn’en pas douter, c’est un drôle de miracle que le Bon

Dieu a fait en faveur des Lellis quand Il se décide à leur donner le fils

qu’ils lui réclament depuis longtemps ! Lorsque Mme de Lellis se trouve

enfin enceinte, ce à quoi aucun médecin n’a d’abord voulu croire, elle a la

soixantaine, ce qui, en cette année 1550, fait d’elle une vieille femme. Quant

à son mari, « le vieux Lellis », dit-on dans leur village de

Bacchianicco dans les Abruzzes, il est septuagénaire. Et pourtant, le garçon

qui leur est né n’a rien d’un « enfant de vieux ».

À 16 ans, Camillo frôle les deux mètres de haut, et,

taillé en hercule, effraie tout le pays pour son goût immodéré des bagarres. Au

lieu de canaliser cette violence qui explose à tout propos, son père laisse

faire, trop heureux des « exploits » de son fils. Enfin, jouant de

ses relations, il se décide à lui ouvrir la carrière des armes et le fait

entrer dans l’armée vénitienne. Camille ne se révèle pas bon soldat :

indiscipliné, gros buveur, querelleur, il n’occasionne que des problèmes,

d’autant qu’il a la passion du jeu, joue sa solde, et l’argent que son père lui

envoie pour éponger ses dettes, perd sans cesse et se met dans des rages

terribles…

La Providence veille

Et puis un jour, le vieux Lellis meurt et il n’y a

plus personne ni pour payer les dettes de son fils ni pour apaiser le

mécontentement des supérieurs. Au début des années 1570, la Sérénissime donne

congé au jeune homme qui, ayant mangé la fortune paternelle, se retrouve réduit

aux expédients. Il ne sait que jouer et se battre. Alors il se fait joueur

professionnel, tricheur aussi, pour survivre, et sans doute spadassin. Camille

de Lellis survit ainsi une dizaine d’années. Jusqu’au jour où, dans une affaire

douteuse, il est sérieusement blessé au pied. Infectée, la plaie refuse de

guérir et le laisse infirme. Désormais incapable de gagner sa vie, réduit à la

mendicité, il reprend le chemin du Sud, dans l’illusion qu’au pays natal, il se

trouverait des proches pour lui venir en aide. La route est longue, Camille

tombe d’épuisement en chemin, mais, la Providence veillant, c’est près d’un

couvent de capucins, celui de San Giovanni Rotondo, où les Pères recueillent le

blessé et le soignent. Comme il va mieux, ils lui offrent un emploi de

jardinier. C’est tout ce que cet infirme semble capable de faire, ayant peu

fréquenté l’école.

Son expérience de la douleur et de l’humiliation l’a

rendu doux et compatissant ; son amour grandissant du Christ l’amène à tout

faire afin de lui plaire.

Le temps passa et, dans la paix de la maison

franciscaine, Camille opère un retour sur lui-même. Son passé se met à lui

faire horreur et, bouleversé d’avoir tant offensé Dieu, il demande à entrer au

noviciat. L’usage est d’aller pour cela dans une autre maison, on l’envoie à

Trivento. C’est un long voyage et Camille, que son pied fait toujours souffrir,

peine. Depuis des lieues, il suit une rivière paisible mais qui ne présente

aucun gué et que ne franchit aucun pont. Il lui faut pourtant la passer pour arriver

à destination. Craignant d’être surpris par la nuit loin du couvent, Camille

décide de traverser à la nage. Il s’apprête à se mettre à l’eau lorsque, venue

de nulle part, une voix se fait entendre : « Ne traverse pas,

Camille ! » Constatant qu’il n’y a personne, Camille attribue cette

voix mystérieuse à son ange gardien et, obéissant, cherche un endroit où

dormir. Bien lui en prend !

Étonnant infirmier

À l’aube, s’étant remis en route, il croise des

paysans auprès desquels il s’enquiert des moyens de passer la rivière. Ils lui

disent que sous ses airs tranquilles, le cours d’eau est profond, plein de

courants cachés, et que tous les imprudents qui ont voulu passer à la nage se

sont noyés. Cette intervention providentielle prouve que la main de Dieu s’étend

sur Camille, mais sa vie n’en est pas facilitée. À Trivento, sa blessure se

rouvre, et le Père Gardien, après des mois de soins inutiles, déclare à Lellis

que les Capucins ne peuvent le recevoir. Il quitte le couvent désolé, se dirige

vers Rome sans savoir ce qu’il va devenir, y arrive si mal en point qu’on le

fait admettre à l’hôpital Saint-Jacques, qui reçoit les pèlerins malades.

Camille n’a pas d’argent pour payer ses soins et, dès qu’il se sent mieux, il

propose d’aider à entretenir les salles, faire les lits et changer les patients

pour s’acquitter de sa pension. On accepte. C’est une besogne ingrate et

méprisée mais Camille y excelle.

Lire aussi :Connaissez-vous vraiment toutes les missions de votre ange

gardien ?

Son expérience de la douleur et de l’humiliation l’a

rendu doux et compatissant ; son amour grandissant du Christ l’amène à tout

faire afin de lui plaire. Cet étonnant infirmier attire bientôt l’attention

d’un habitué de la maison, un prêtre célèbre dans tout Rome, Philippe

Néri. Il devint le directeur de conscience de Camille et, quand celui-ci,

guéri, lui annonce son intention de retourner à Trivento accomplir son noviciat

capucin, le saint lui déclare que ce n’est pas là l’endroit où Dieu l’appelle.

Camille s’entête. En le voyant partir, Philippe Néri lui déclare : « Tu

verras, ta plaie va se rouvrir et ils te chasseront de nouveau… » Ce fut

exactement ce qui arriva. Plus infirme que jamais, Camille revient à Rome et

reprend ses fonctions à Saint-Jacques, mais, cette fois, il comprend les

raisons de son échec chez les fils de saint François.

« Poursuis cette affaire ! »

Depuis quelques temps, le grand crucifix de sa chambre

s’anime quand il prie et le Christ l’entretient des projets qu’Il nourrit pour

lui : Camille, qui a vu la détresse des patients des hôpitaux romains, doit se

consacrer à la fondation d’un ordre religieux qui se dévouerait au soulagement

de ces malheureux, fussent-ils galériens ou pestiférés, leur prodiguant des

soins avec toute la charité chrétienne nécessaire, les aidant à offrir leurs

souffrances pour le salut des âmes, et d’abord de la leur, les assistant à

l’approche de la mort. Camille réunit autour de lui quelques soignants de bonne

volonté et s’applique à satisfaire le Christ ; mais on l’accuse de chercher à

s’emparer de la direction de l’établissement, on lui fait mille avanies, tant

et si bien qu’il veut renoncer. Alors, le Crucifié lui déclare : « Poursuis

cette affaire et ne t’afflige pas, je viendrai à ton aide car cette œuvre est

la mienne, non la tienne. »

Lire aussi :Comment les anges communiquent-ils entre eux ?

Peu à peu, la communauté prend forme sous sa houlette.

On lui fait comprendre que, pour le bien de tous, il doit, s’il veut assumer

ses responsabilités de fondateur, se préparer au sacerdoce. Il a 32 ans, sait

tout juste lire et écrire, a toujours entendu ses maîtres dire qu’il a une

cervelle de moineau. Néanmoins, il entre au collège comme un écolier, étudie en

dépit de tous les obstacles, arrive aux ordres sacrés. En réponse à ceux qui se

moquent de ce séminariste trop âgé, un supérieur déclare : « Il est venu

tard, certes, mais il fera de grandes choses dans l’Église. » Le 9 juin

1584, Camille de Lellis devient prêtre et se voit confier l’aumônerie de

l’hôpital du Saint Esprit. Sa congrégation, qui ne compte avec lui que trois

membres, s’appelle « les pieux serviteurs des malades » et se donne

pour but de soigner les corps et les âmes en étant tour à tour domestiques,

infirmiers et prêtres. Très vite, ils n’ont plus un sou et les huissiers aux

portes. À ses frères consternés, Camille assure que, « sous un mois,

toutes leurs dettes seraient payées » et la fondation tirée d’affaire. Il

l’affirme aussi à ses créanciers qui lui répondent que « le temps des

miracles est terminé ». Il se contente de sourire.

Une singulière aventure

Un mois après, un cardinal dont il a sollicité le

patronage meurt en lui laissant toute sa fortune, laquelle est considérable.

C’en est fini des ennuis d’argent. « Il ne faut jamais douter de la

Providence », dit-il seulement. C’est si vrai que, même pendant le

terrible hiver 1590, l’un des plus froids que l’Italie ait connus, tandis que

l’on meurt de faim à Rome, le pain ne manque jamais dans les maisons

camilliennes, alors même que le Père de Lellis dépense sans compter pour

soulager toutes les misères qui s’étalent devant lui, affirmant à ceux qui

l’incitent à la prudence : « Ne savez-vous pas que Notre Seigneur est

peut-être caché sous les haillons de ce miséreux ? Comment oserais-je refuser

la charité à mon Seigneur ? » Ce fut en ces circonstances qu’il lui arriva

une singulière aventure.

Assister les agonisants, leur porter les derniers

sacrements est pour Camille mission essentielle.

Les Pauvres Serviteurs des Malades gèrent alors

l’église Sainte-Madeleine, non loin du Panthéon, quartier parmi les plus

pauvres de la Ville. Un soir, tard, on frappe à la porte de Camille. Quand il

ouvre, il trouve sur le seuil un adolescent qui lui demande de venir tout de

suite au chevet de sa grand-mère sur le point de mourir. Assister les

agonisants, leur porter les derniers sacrements est pour Camille mission

essentielle. Il suit le garçon, monte à sa suite l’escalier d’un immeuble

vétuste, et, derrière lui, pénètre dans un galetas sordide au dernier étage. Là

se trouve en effet une vieille femme à l’article de la mort, qui, en voyant le

prêtre, s’écrie : « Padre, c’est le Ciel qui vous envoie ! J’ai eu si

peur de mourir toute seule et sans les sacrements ! » Comme la

malheureuse crie au miracle, Camille affirme qu’il n’y a là aucun miracle et

qu’elle doit remercier son petit-fils d’être venu le chercher. Alors, la

moribonde regarde le prêtre et dit : « Padre, je n’ai pas de petit-fils.

Toute ma famille est morte. » Et elle explique que, seule, abandonnée de

tous, se sentant partir, elle s’est tournée vers celui dont elle savait qu’il

demeure toujours près d’elle : son ange gardien et lui a demandé d’aller

chercher un prêtre.

Interloqué, Camille se retourne. Il n’y a aucun jeune

homme dans la mansarde. Il comprend que l’ange a fait son travail et que, dans

un souci de discrétion, peu désireux, comme le sont souvent les esprits

bienheureux, d’être reconnu pour ce qu’il était, il a pris apparence humaine et

s’est fait passer pour un petit-fils en peine pour sa grand-mère chérie.

FLEURS D’ORAISON

Que j’ai été aveugle en

ne reconnaissant pas mon Dieu ! Pourquoi n’ai-je pas dépensé toute ma vie à son

service? Seigneur, donne-moi au moins du temps pour faire pénitence.

Ne croyons pas que

l’Esprit Saint, dans son ésir d’élever nos âmes au-dessus de la terre, n’ait

que mépris pour le corps.

Ce crucifix m’a soutenu

et consolé, certes je ne méritais pas toutes ces grâces qu’il m’a faites. Aussi

je ne passe pas une heure du jour sans me souvenir du crucifix et sans prier

avec une grande confiance.

La musique que je

préfère, c’est celle que font les pauvres malades lorsque l’un demande qu’on

lui refasse son lit, l’autre que l’on lui rafraichisse la langue ou qu’on lui

réchauffe les pieds.

Tous les péchés du monde,

comparés à la grande miséricorde de Deu et aux mérites infinis du sang du

Christ, sont moins qu’une goutte d’eau dans le sein de la mer.

Seigneur, tout ce que

j’ai été, tout ce que je suis, tout ce que je serai, tout m’est venu et me

vient de votre grâce.

Non pas pour un salaire, mais volontairement et pour l’amour de Dieu, soignez

les malades avec la tendresse d’une mère pour son unique fils malade.

Dieu est tout. Le reste

n’est rien. Il faut sauver l’âme qui ne meurt pas.

Toute mauvaise action, a

dit un grand écrivain, laisses en notre cœur d’immondes racines, qu’il faut

arracher avec des tenailles ardentes.

Le bon soldat meurt au

combat, le bon marin, en mer, et le bon serviteur des malades, à l’hôpital.

Le bonheur que j’espère

est si grand, que toutes les peines et toutes les soffrances deviennent pour

moi des sources de joie.

Je reconnais, Seigneur, que je suis le plus grand des pécheurs et que je ne mérite pas la faveur que vous daignez me faire, mais sauvez-moi par votre infinie miséricorde. Je mets toute ma confiance dans votre Précieux Sang.

Jésus Marie et Notre Temps, 55e Année, 595e numéro, avril 2025

Leçons des Matines avant 1960.

Au deuxième nocturne.

Quatrième leçon. Camille naquit à Bucchianico au diocèse de Chieti, de la noble famille des Lellis et d’une mère sexagénaire qui, tandis qu’elle le portait encore dans son sein, crut voir, durant son sommeil, qu’elle avait donné le jour à un petit enfant, muni du signe de la croix sur la poitrine et précédant une troupe d’enfants qui portaient le même signe. Camille ayant embrassé dans son adolescence la carrière militaire, se laissa pendant quelque temps gagner par les vices du siècle. Mais dans sa vingt-cinquième année, il fut soudain éclairé d’une telle lumière surnaturelle et saisi d’une si profonde douleur d’avoir offensé Dieu, qu’ayant versé des larmes abondantes, il prit la ferme résolution d’effacer sans retard les souillures de sa vie passée et de revêtir l’homme nouveau. Le jour même où ceci arriva, c’est-à-dire en la fête de la Purification de la très sainte Vierge, il s’empressa d’aller trouver les Frères Mineurs, appelés Capucins, et les pria très instamment de l’admettre parmi eux. On lui accorda ce qu’il désirait, une première fois, puis une deuxième, mais un horrible ulcère, dont il avait autrefois souffert à la jambe, s’étant ouvert de nouveau, Camille, humblement soumis à la divine Providence qui le réservait pour de plus grandes choses, et vainqueur de lui-même, quitta deux fois l’habit de cet Ordre, qu’à deux reprises il avait sollicité et reçu.

Cinquième leçon. Il partit pour Rome et fut admis dans l’hôpital dit des incurables, dont on lui confia l’administration, à cause de sa vertu éprouvée. Il s’acquitta de cette charge avec la plus grande intégrité et une sollicitude vraiment paternelle. Se regardant comme le serviteur de tous les malades, il avait coutume de préparer leurs lits, de nettoyer les salles, de panser les ulcères, de secourir les mourants à l’heure du suprême combat, par de pieuses prières et des exhortations, et il donna dans ces fonctions, des exemples d’admirable patience, de force invincible et d’héroïque charité. Mais ayant compris que la connaissance des lettres l’aiderait beaucoup à atteindre son but unique qui était de venir en aide aux âmes des agonisants, il ne rougit pas, à l’âge de trente-deux ans, de se mêler aux enfants pour étudier les premiers éléments de la grammaire. Initié dans la suite au sacerdoce, il jeta, de concert avec quelques amis associés à lui pour cette œuvre, les fondements de la congrégation des Clercs réguliers consacrés au service des infirmes ; et cela, malgré l’opposition et les efforts irrités de l’ennemi du genre humain. Miraculeusement encouragé par une voix céleste partant d’une mage du Christ en croix, qui, par un prodige admirable, tendait vers lui ses mains détachées du bois, Camille obtint du Siège apostolique l’approbation de son Ordre, où, par un quatrième vœu très méritoire, les religieux s’engagent à assister les malades, même atteints de la peste. Il parut que cet institut était singulièrement agréable à Dieu et profitable au salut des âmes ; car saint Philippe de Néri, confesseur de Camille, attesta avoir assez souvent vu les Anges suggérer des paroles aux disciples de ce dernier, lorsqu’ils portaient secours aux mourants.

Sixième leçon. Attaché par des liens si étroits au service des malades, et s’y dévouant jour et nuit jusqu’à son dernier soupir, Camille déploya un zèle admirable à veiller à tous leurs besoins, sans se laisser rebuter par aucune fatigue, sans s’alarmer du péril que courait sa vie. Il se faisait tout à tous et embrassait les fonctions les plus basses d’un cœur joyeux et résolu, avec la plus humble condescendance ; le plus souvent il les remplissait à genoux, considérant Jésus-Christ lui-même dans la personne des infirmes. Afin de se trouver prêt à secourir toutes les misères, il abandonna de lui-même le gouvernement général de son Ordre et renonça aux délices célestes dont il était inondé dans la contemplation. Son amour paternel à l’égard des pauvres éclata surtout pendant que les habitants de Rome eurent à souffrir d’une maladie contagieuse, puis d’une extrême famine, et aussi lorsqu’une peste affreuse ravagea Nole en Campanie. Enfin il brûlait d’une si grande charité pour Dieu et pour le prochain, qu’il mérita d’être appelé un ange et d’être secouru par des Anges au milieu des dangers divers courus dans ses voyages. Il était doué du don de prophétie et de guérison, et découvrait les secrets des cœurs grâce à ses prières, tantôt les vivres se multipliaient, tantôt l’eau se changeait en vin. Épuisé par les veilles, les jeûnes, les fatigues continuelles, et semblant ne plus avoir que la peau et les os, il supporta courageusement cinq maladies longues et fâcheuses, qu’il appelait des miséricordes du Seigneur. A l’âge de soixante cinq ans, au moment où il prononçait les noms si suaves de Jésus et de Marie, et ces paroles : « Que le visage du Christ Jésus t’apparaisse doux et joyeux » il s’endormit dans le Seigneur, muni des sacrements de l’Église, à Rome, à l’heure qu’il avait prédite, la veille des ides de juillet, l’an du salut mil six cent quatorze. De nombreux miracles l’ont rendu illustre, et Benoît XIV l’a inscrit solennellement dans les fastes des Saints. Léon XIII, se rendant au vœu des saints Évêques de l’Univers catholique, après avoir consulté la Congrégation des rites, l’a déclaré le céleste Patron de tous les hospitaliers et des malades du monde entier, et il a ordonné que l’on invoquât son nom dans les Litanies des agonisants.

Au troisième nocturne.

Lecture du saint Évangile selon saint Jean. Cap. 15, 12-16.

En ce temps-là : Jésus dit à ses disciples : Ceci est mon commandement : que vous vous aimiez les uns les autres, comme je vous ai aimés. Et le reste.

Homélie de saint Augustin, Évêque. Tract. 83 in Joannem

Septième leçon. Que pensons-nous, mes frères ? Est-ce que le précepte qui veut qu’on s’entr’aime est le seul ? Et n’y en a-t-il pas un autre plus grand, celui d’aimer Dieu ? Ou plutôt Dieu ne nous a-t-il rien commandé de plus que la dilection, en sorte que nous n’ayons aucun souci du reste ? Évidemment l’Apôtre recommande trois choses, quand il dit : « La foi, l’espérance, la charité demeurent ; elles sont trois, mais la plus grande des trois, c’est la charité » [1]. Et si la charité ou dilection, parce qu’elle renferme ces deux préceptes, est donnée comme étant plus grande, elle n’est pas donnée comme étant seule. Ainsi au sujet de la foi, quel nombre de commandements y a-t-il ? Quel nombre aussi en ce qui touche l’espérance ? Qui peut les rassembler tous ? Qui peut suffire à les énumérer ? Mais étudions cette parole du même Apôtre : « La charité est la plénitude de la loi » [2].

Huitième leçon. Là où se trouve la charité, que peut-il donc manquer ? et où elle n’existe pas, que peut-il y avoir de profitable ? Le démon croit, mais il n’aime pas, l’homme qui ne croit pas, n’aime pas non plus. De même l’homme qui n’aime pas, quoique l’espérance du pardon ne lui soit pas enlevée, l’espère en vain ; mais celui qui aime, ne peut désespérer. Ainsi où est la dilection, se trouvent la foi et l’espérance ; et là où est l’amour du prochain se trouve nécessairement aussi l’amour de Dieu. En effet, comment celui qui n’aime pas Dieu aimerait-il le prochain comme lui-même ; puisqu’il ne s’aime pas soi-même, impie qu’il est et ami de l’iniquité ? Or celui qui aime l’iniquité, celui-là, à coup sûr, n’aime pas son âme, il la hait au contraire [3].

Neuvième leçon. Observons donc le précepte d’aimer le Seigneur afin de nous entr’aimer, et par là nous accomplirons tout le reste, puisque tout le reste y est compris. Car l’amour de Dieu se distingue de l’amour du prochain, et le Sauveur a marqué cette distinction en ajoutant : « Comme je vous ai aimés » [4] ; or à quelle fin le Christ nous aime-t-il, si ce n’est pour que nous puissions régner avec lui ? Aimons-nous donc les uns les autres de manière à nous distinguer du reste des hommes, qui ne peuvent aimer les autres, par la raison qu’ils ne s’aiment pas eux-mêmes. Quant à ceux qui s’aiment en vue de posséder Dieu, ils s’aiment véritablement. Ainsi donc, qu’ils aiment Dieu pour s’aimer. Un tel amour n’existe pas chez tous les hommes ; il en est peu qui s’aiment afin que Dieu soit tout en tous.

[1] I Cor. 13, 13.

[2] Rom. 13, 10.

[3] Ps. 10, 6.

[4] Jn. 15, 12.

Dom Guéranger, l’Année Liturgique

Ne croyons pas que l’Esprit-Saint, dans son désir d’élever nos âmes au-dessus de la terre, n’ait que mépris pour les corps. C’est l’homme tout entier qu’il a reçu mission de conduire à l’éternité bienheureuse, comme tout entier l’homme est sa créature et son temple [5]. Dans l’ordre de la création matérielle, le corps de l’Homme-Dieu fut son chef d’œuvre ; et la divine complaisance qu’il prend dans ce corps très parfait du chef de notre race, rejaillit sur les nôtres dont ce même corps, formé par lui au sein de la Vierge toute pure, a été dès le commencement le modèle. Dans l’ordre de réhabilitation qui suivit la chute, le corps de l’Homme-Dieu fournit la rançon du monde ; et telle est l’économie du salut, que la vertu du sang rédempteur n’arrive à l’âme de chacun de nous qu’en passant par nos corps avec les divins sacrements, qui tous s’adressent aux sens pour leur demander l’entrée. Admirable harmonie de la nature et de la grâce, qui fait qu’elle-même celle-ci honore l’élément matériel de notre être au point de ne vouloir élever l’âme qu’avec lui vers la lumière et les cieux ! Car dans cet insondable mystère de la sanctification, les sens ne sont point seulement un passage : eux-mêmes éprouvent l’énergie du sacrement, comme les facultés supérieures dont ils sont les avenues ; et l’âme sanctifiée voit dès ce monde l’humble compagnon de son pèlerinage associé à cette dignité de la filiation divine, dont l’éclat de nos corps après la résurrection ne sera que l’épanouissement.

C’est la raison qui élève à la divine noblesse de la sainte chargé les soins donnés au prochain dans son corps ; car, inspirés par ce motif, ils ne sont autres que l’entrée en participation de l’amour dont le Père souverain entoure ces membres, qui sont pour lui les membres d’autant de fils bien-aimés. J’ai été malade et vous m’avez visité [6], dira le Seigneur au dernier des jours, montrant bien qu’en effet, dans les infirmités mêmes de la déchéance et de l’exil, le corps de ceux qu’il daigne appeler ses frères [7] participe de la propre dignité du Fils unique engendré au sein du Père avant tous les âges. Aussi l’Esprit, chargé de rappeler les paroles du Sauveur à l’Église [8], n’a-t-il eu garde d’oublier celle-ci ; tombée dans la bonne terre des âmes d’élite [9] elle a produit cent pour un en fruits de grâce et d’héroïque dévouement. Camille de Lellis l’a recueillie avec amour ; et par ses soins la divine semence est devenue un grand arbre [10] offrant son ombre aux oiseaux fatigués qu’arrête plus ou moins longuement la souffrance, ou pour lesquels l’heure du dernier repos va sonner. L’Ordre des Clercs réguliers Ministres des infirmes, ou du bien mourir, mérite la reconnaissance de la terre ; depuis longtemps celle des cieux lui est acquise, et les Anges sont ses associés, comme on l’a vu plus d’une fois au chevet des mourants.

Ange de la charité, quelles voies ont été les vôtres sous la conduite du divin Esprit ! Il fallut un long temps avant que la vision de votre pieuse mère, quand elle vous portait, se réalisât : avant de paraître orné du signe de la Croix et d’enrôler des compagnons sous cette marque sacrée, vous connûtes la tyrannie du maître odieux qui ne veut que des esclaves sous son étendard, et la passion du jeu faillit vous perdre. O Camille, à la pensée du péril encouru alors, ayez pitié des malheureux que domine l’impérieuse passion, arrachez-les à la fureur funeste qui jette en proie au hasard capricieux leurs biens, leur honneur, leur repos de ce monde et de l’autre. Votre histoire montre qu’il n’est point de liens que la grâce ne brise, point d’habitude invétérée qu’elle ne transforme : puissent-ils comme vous retourner vers Dieu leurs penchants, et oublier pour les hasards de la sainte charité ceux qui plaisent à l’enfer ! Car, elle aussi, la charité a ses risques, périls glorieux qui vont jusqu’à exposer sa vie comme le Seigneur a donné pour nous la sienne : jeu sublime, dans lequel vous fûtes maître, et auquel plus d’une fois applaudirent les Anges. Mais qu’est-ce donc que l’enjeu de cette vie terrestre, auprès du prix réservé au vainqueur ?

Selon la recommandation de l’Évangile que l’Église nous fait lire aujourd’hui en votre honneur, puissions-nous tous à votre exemple aimer nos frères comme le Christ nous a aimés [11] ! Bien peu, dit saint Augustin [12], ont aujourd’hui cet amour qui accomplit toute la loi ; car bien peu s’aiment pour que Dieu soit tout en tous [13]. Vous l’avez eu cet amour, ô Camille ; et de préférence vous l’avez exercé à l’égard des membres souffrants du corps mystique de l’Homme-Dieu, en qui le Seigneur se révélait plus à vous, en qui son règne aussi approchait davantage. A cause de cela, l’Église reconnaissante vous a choisi pour veiller, de concert avec Jean de Dieu, sur ces asiles de la souffrance qu’elle a fondés avec les soins que seule une mère sait déployer pour ses fils malades. Faites honneur à la confiance de la Mère commune. Protégez les Hôtels-Dieu contre l’entreprise d’une laïcisation inepte et odieuse qui sacrifie jusqu’au bien-être des corps à la rage de perdre les âmes des malheureux livrés aux soins d’une philanthropie de l’enfer. Pour satisfaire à nos misères croissantes, multipliez vos fils ; qu’ils soient toujours dignes d’être assistés des Anges. Qu’en quelque lieu de cette vallée d’exil vienne à sonner pour nous l’heure du dernier combat, vous usiez de la précieuse prérogative qu’exalte aujourd’hui la Liturgie sacrée, nous aidant par l’esprit de la sainte dilection à vaincre l’ennemi et à saisir la couronne céleste [14].

[5] I Cor. VI, 19, 20.

[6] Matth. XXV, 36.

[7] Heb. II, 11-17.

[8] Johan. XIV, 26.

[9] Luc. VIII, 8, 15.

[10] Ibid. XIII, 19.

[11] Johan XV, 12.

[12] Homilia diei Aug. In Joh. tract. LXXXIII.

[13] I Cor. XV, 28.

[14] Collecta diei.

Bhx cardinal Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

La gloire et l’importance historique de saint Camille de Lellis proviennent de ce qu’il appartient à ce groupe choisi d’apôtres doués d’une charité sublime et héroïque, humblement soumis à l’Église, et qui, en son nom, réalisèrent dans son sein cette réforme générale dont, au XVIe siècle, on sentait partout le besoin, et dont on parlait parfois dans un sens fort peu catholique.

Saint Camille, après une vie laborieusement dépensée à assister les malades dans les hôpitaux publics de Saint-Jacques des Incurables et du Saint-Esprit, mourut à Rome le 14 juillet 1614. Saint Philippe Néri, qui fut son confesseur, avait vu les anges eux-mêmes mettre sur les lèvres des religieux institués par saint Camille les paroles les plus aptes à réconforter les mourants, et Léon XIII le proclama céleste Patron des agonisants.

La messe suivante s’inspire de la pensée du sublime mérite de la charité chrétienne, laquelle atteint son sommet le plus héroïque quand on méprise sa propre vie pour venir au secours de son frère en danger, comme cela fut imposé par le Saint à la Congrégation qu’il fonda.

L’antienne d’introït est tirée de l’Évangile selon saint Jean (XV, 13) : « Personne n’aime davantage que celui qui donne sa vie pour ses amis ». — Saint Bernard fait à ce propos une charmante remarque : « Seigneur, on peut concevoir une charité encore plus grande, et c’est la vôtre, vous qui avez donné votre vie pour vos ennemis ». Suit le premier verset du psaume 40 : « Bienheureux celui qui se souvient du pauvre et du misérable ; le Seigneur le sauvera au jour du malheur ». — L’aumône, c’est la compassion qu’on a pour le pauvre (à la vérité, la Vulgate parle ici de l’intelligence de la pauvreté) ; c’est comme un capital qu’on donne à Dieu, et qui produit un intérêt de cent pour un.

Voici la première collecte : « Seigneur, qui avez orné le bienheureux Camille d’une charité spéciale pour assister les malades dans les angoisses de l’agonie ; accordez-nous par ses mérites l’esprit de dilection, afin qu’au moment de notre trépas, nous arrivions à surmonter l’adversaire et à mériter la céleste couronne ».

La première lecture, tirée de saint Jean (I, III, 13-18) est commune au deuxième dimanche après la Pentecôte. La charité est une flamme qui s’éteint, si elle ne consume ; elle vit donc de sacrifice.

Le graduel et le verset alléluiatique sont empruntés à la messe Os iusti.

La lecture évangélique est identique à celle de la vigile de saint Thomas. La charité est le précepte spécial du Christ, en sorte que la foi catholique et l’espérance ne nous serviraient de rien, si ces deux vertus n’agissaient pas ensuite au moyen de l’amour. Præceptum Domini est — répétait à Éphèse le Disciple bien-aimé, quand, à la fin du premier siècle, il était porté à cause de son grand âge par ses disciples dans les synaxes liturgiques — et si hoc solum fiat, sufficit.

Voici la collecte sur les oblations : « Que l’Hostie immaculée qui renouvelle ici sur l’autel l’excès d’amour de notre Seigneur Jésus, par l’intercession de saint Camille nous protège contre tous les maux du corps et de l’esprit et soit aussi pour les agonisants réconfort et salut ».

Le génie chrétien a donné un nom très expressif à la divine Eucharistie reçue parles malades près de mourir : elle s’appelle le viatique, c’est-à-dire la nourriture qui sert pour le voyage du temps à l’éternité. Il existe une mystérieuse relation entre l’Eucharistie et notre passage à l’autre vie. En effet, comme l’agneau pascal et les pains azymes furent mangés pour la première fois par les Hébreux à leur départ d’Égypte ; comme Jésus lui-même, la veille de sa mort, institua le divin Sacrement, et y participa lui-même le premier ; ainsi voulut-il que l’Eucharistie fût aussi pour nous le Sacrement qui consacre notre sacrifice suprême et couronne notre vie chrétienne.

L’antienne pour la Communion est tirée de saint Matthieu (XXV, 36 et 40) : « J’ai été malade et vous m’avez visité. Je vous le dis en vérité : ce que vous avez fait à un seul de mes plus petits frères, vous me l’avez fait à moi ». Le malade reflète d’une manière spéciale l’image de Jésus, parce que celui-ci dans sa charité languores nostros ipse tulit et dolores nostros ipse portavit, comme le dit Isaïe [15].

La collecte d’action de grâces a les mêmes caractères que les précédentes. Elle manque de rythme, ne suit pas les lois du cursus et, pour vouloir dire trop, elle se soutient mal. La piété seule supplée à ces lacunes de style. « Par ce divin Sacrement que nous avons pieusement reçu en la fête de saint Camille votre confesseur ; accordez-nous, Seigneur, qu’au moment de mourir, munis des Sacrements et absous de tout péché, nous soyons heureusement accueillis au sein de votre miséricorde ».

Voilà le dernier réconfort d’une âme chrétienne : la douce espérance dans l’ineffable miséricorde de Dieu ; parce que, comme le dit l’Apôtre : spes autem non confondit [16] ; et Celui qui alimente dans notre cœur la douce espérance est le même qui veut ensuite la réaliser au ciel.

[15] LIII, 4 : Il a porté nos langueurs, et Il s’est chargé Lui-même de nos douleurs.

[16] Rom. 5, 5 : l’espérance n’est point trompeuse.

Dom Pius Parsch, Le guide dans l’année liturgique

J’étais malade et vous m’avez visité.

L’Église célèbre, les 18, 19 et 20 juillet, trois héros de la charité : saint Camille de Lellis, saint Vincent de Paul et saint Jérôme Émilien. Leur fête n’arrive pas le jour de leur mort, et l’intention de l’Église en les rapprochant apparaît manifeste : C’est que le premier pratiqua une charité héroïque envers les malades, le second envers les pauvres, et le troisième envers les orphelins.

1. Saint Camille. — Jour de mort : 14 juillet 1614. Tombeau : à Rome, dans l’église de Sainte-Marie Madeleine (sous un autel latéral du côté de l’Épître). Saint Camille naquit d’une mère déjà sexagénaire. Dans sa jeunesse, il se laissa, quelque temps, aller aux vices du siècle, mais, à vingt-cinq ans, le jour de la Purification, il se convertit. A deux reprises il voulut se faire admettre chez les Frères Mineurs Capucins ; un ulcère à la jambe l’en empêcha. A Rome, on le reçoit à l’hôpital des Incurables. Tel est l’éclat de ses vertus qu’on lui en confie l’administration. De mille manières il prodigue aux malades ses soins spirituels et corporels. A trente-deux ans, il commence ses études, sans rougir d’avoir pour condisciples des enfants. Prêtre, il fonde la Congrégation des Clercs réguliers ministres des infirmes qui, en plus des trois vœux ordinaires, font celui de soigner les pestiférés au péril de leur vie. Les malades le voient, nuit et jour, inlassable à leur service, s’acquittant des plus serviles besognes. Mais c’est surtout aux heures où une épidémie, suivie de la famine, éprouve Rome, et où la peste exerce à Nole ses ravages, que brille sa charité. Il supporte courageusement cinq maladies. Il les appelle des miséricordes du Seigneur, et expire à Rome, âgé de soixante-cinq ans, avec aux lèvres ces paroles de la prière des agonisants : « Que le visage du Christ Jésus t’apparaisse doux et joyeux ! » Léon XIII l’a déclaré le céleste patron des hôpitaux, et a prescrit l’invocation de son nom aux litanies des mourants.

2. Messe (Majórem hac). — Elle est un exemple d’un formulaire nouveau qui retrace la vie et les vertus du saint. L’Introït fournit le titre et le thème de la messe : « Personne ne peut donner une plus grande marque d’amour que de donner sa vie pour ses amis ». Suit le psaume 40, le psaume des malades. Le thème reparaît dans l’Épître et l’Évangile tirés de saint Jean, l’apôtre de la charité.

L’Épître parle de l’amour du prochain : l’amour du prochain est la marque de la vie divine en nous. « Nous savons que nous sommes passés de la mort à la vie parce que nous aimons nos frères... Quiconque hait son frère est un homicide... A ceci nous avons connu l’amour (du Christ), c’est que Lui a donné sa vie pour nous. Nous aussi ; nous devons donner notre vie pour nos frères. Mes petits enfants, n’aimons pas de parole et de langue, mais en action et en vérité ». Ces mots de l’Épître contiennent, dans toute sa profondeur, le précepte de la charité.

A l’Évangile ; nous entendons le Maître lui-même dans son discours d’adieu : « C’est mon commandement que vous vous aimiez les uns les autres comme je vous ai aimés. Personne ne peut avoir de plus grand amour que de donner sa vie pour ses amis ». Paroles à graver profondément en nous, et qui ne doivent pas être de simples formules.

Au Saint-Sacrifice elles deviennent « action et vérité » : nous y « renouvelons cette œuvre de l’immense amour de Notre-Seigneur Jésus-Christ » (Secrète), le sacrifice de la Croix. La Communion est également très expressive : la sainte communion est une anticipation du retour du Sauveur. « J’ai été malade, dit-il, et vous m’avez visité... Ce que vous avez fait au plus petit de mes frères, c’est à moi que vous l’avez fait ».

A la Postcommunion, nous demandons la grâce d’une bonne mort ; que notre communion d’aujourd’hui soit un viatique pour notre trépas !

3. La prière liturgique pour les agonisants. — « Puissions-nous à l’heure de notre mort triompher de l’ennemi et recevoir la couronne céleste ! » Voici le vœu que nous formulons aujourd’hui dans notre prière. Connaît-on bien la prière liturgique pour les agonisants ? En prévision de la mort, avons-nous chez nous un cierge bénit ? Nous devons également tenir prêts, pour l’administration des derniers sacrements, un crucifix, des bougies et une nappe blanche. Sait-on que l’Église a composé pour qu’on les récite à l’approche de la mort des prières spéciales, la « recommandation de l’âme » ? Malheureusement, ce sont des prières que les prêtres ne récitent presque jamais. Dès maintenant demandons donc à l’un ou à l’autre de ceux que nous connaissons de nous rendre ce service, le moment venu. Dès maintenant aussi, pendant que nous jouissons de la santé, familiarisons-nous avec les prières des agonisants. Elles commencent par une litanie spéciale où sont invoqués les patrons de la bonne mort. Vient ensuite l’oraison bien connue : « Quitte ce monde, âme chrétienne, au nom de Dieu, le Père tout-puissant, qui t’a créée ; au nom de Jésus-Christ, le Fils du Dieu vivant, qui a souffert pour toi ; au nom du Saint-Esprit, qui a été répandu en toi... » Puis, c’est encore une prière de forme litanique dans laquelle on rappelle à Dieu les circonstances de l’Ancien et du Nouveau Testament où les justes furent sauvés de la détresse et du danger ; cette évocation, par exemple : « Délivre, Seigneur, l’âme de ton serviteur, comme tu as déchargé Suzanne d’une fausse accusation ». Lorsque le mourant a rendu le dernier soupir, on supplie Dieu aussitôt de lui faire bon accueil : « Venez à son aide, saints de Dieu ; accourez à sa rencontre, anges du Seigneur, Recevez son âme et présentez-la devant la face du Très-Haut. » C’est en nous familiarisant ainsi avec ces prières que notre âme sera prête pour l’heure de la mort.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/18-07-St-Camille-de-Lellis

Saint Camille de Lellis

Camille de Lellis est un religieux catholique italien,

canonisé en 1746. Il est le fondateur des Clercs réguliers ministres des

infirmes, plus connus sous le nom de Camilliens, qu’il institue à Rome, le 8

septembre 1584, que le pape Sixte V approuve le 18 mars 1586 et que le pape

Grégoire XIV érige en ordre religieux le 21 septembre 1591. Fortement

centralisé sous son préfet général, l’ordre qui comprend déjà trois cents

membres répartis en cinq provinces à la mort de son fondateur, connaît au XVII°

siècle un essor rapide en Italie, en Espagne, au Portugal et aux Amériques. Les

Camilliens portent l’habit clérical ordinaire surchargée d’une croix latine

rouge cousue. Fils d’un officier au service de Charles-Quint qui avait pris

part au sac de Rome (1527), Camille de Lellis naquit à Bocchianico, au sud de

Chieti, dans les Abruzzes (royaume de Naples) le 25 mai 1550. Orphelin de mère,

à treize ans, et de père, à dix-neuf ans, ce géant, joueur invétéré qui s’était

ruiné dans les jeux de hasard, était sans ressource lorsqu’atteint d’une plaie

au pied, il alla se faire soigner à l’hôpital romain de Saint-Jacques des

Incurables où, ne pouvant payer, il fut employé un mois comme infirmier. Comme

il avait transformé sa chambre en salle de jeux, on le chassa de l’hôpital et,

à la fin de 1569, il s’enrôla dans l’armée vénitienne qui allait combattre le

sultan Sélim II, puis il servit sous don Juan d’Autriche mais la dysenterie

l’empêcha de participer à la bataille de Lépante (1571). Il embarqua sur les

galères napolitaines en route vers Tunis.

Libéré du service, il vécut plus ou moins bien du jeu.

Ayant rencontré deux franciscains dans les rues de Zermo, il fit vœu de

renoncer aux désordres de sa vie mais il oublia très vite ses bonnes

dispositions qui le reprirent, sans plus d’effet, lorsqu’il fut près de périr

dans une tempête qui dura trois jours et trois nuits. Ayant perdu au jeu son

épée, son arquebuse, son manteau et sa chemise, il fut réduit à la mendicité

jusqu’au début de 1575 où il se fit engager comme manœuvre chez un entrepreneur

qui construisait le couvent des Capucins de Manfredonia.

Un soir que l’entrepreneur l’avait envoyé faire une

course au couvent, le père gardien le prit à part et l’entretint de la

nécessité de se donner à Dieu ; le lendemain, alors qu’il revenait à

cheval, songeant à la conversation de la veille, il tomba de sa monture et,

dans une intense lumière intérieure, il vit ses péchés avec le jugement de

Dieu. Admis par les capucins de Manfredonia, il se montra si bien converti

qu’on l’envoya faire son noviciat à Trivento. En chemin, un soir, comme il

s’apprêtait à traverser une rivière, il entendit une voix lui crier du haut

d’une montagne : « Ne va pas plus loin, ne passe pas ! » Il

regarda pour voir qui lui parlait, et, n’apercevant personne, il continua

d’avancer ; la même voix l’appela trois fois et parvint enfin à

l’arrêter ; il revint sur ses pas et s’endormit sous un arbre : le

lendemain, il apprit que la rivière était là si profonde qu’il y eût

certainement perdu la vie s’il ne se fût arrêté. Au couvent de Trivento, sa vie

fut parfaite mais la plaie de sa jambe s’étant rouverte et envenimée, il dut

retourner à l’hôpital romain de Saint-Jacques des Incurables où il se mit sous

la direction de saint Philippe Néri. Guéri, il resta, comme infirmier et devint

le maître de maison (économe). Bon gestionnaire, il fit passer les revenus

annuels de l’hôpital de cent à quatorze cent quatre-vingt-seize écus bien qu’il

exigeât la meilleure marchandise et qu’il refusât le blé de mauvaise qualité.

Il envisagea de réformer les soins et, avec le

chapelain et quatre infirmiers, de créer une association d’infirmiers (août

1582) mais il échoua devant incompréhension des directeurs de l’hôpital ;

c’est alors qu’il songea à fonder une congrégation entièrement consacrée au

soin des malades. Pour mettre en œuvre son projet, il comprit qu’il lui fallait

être prêtre, aussi, tout en continuant son travail d’économe de l’hôpital,

alla-t-il suivre les cours du Collège Romain.

Ordonné prêtre, il célébra sa première messe dans la

chapelle de l’hôpital Saint-Jacques des Incurables (10 juin 1584) dont les

directeurs le nommèrent chapelain de la Madonnina des Miracles. Contre l’avis

de saint Philippe Néri, il abandonna sa charge d’économe, quitta l’hôpital et,

dans sa chapelle, le 8 septembre 1584, il reçut ses premiers disciples qui

furent employés à l’hôpital du Saint-Esprit : « Parfois, il y a

jusqu’à deux cents lits occupés, et c’est à qui vomira, toussera, criera,

tirera le souffle, rendra l’âme, se démènera frénétiquement tant qu’il faut le

lier ; et c’est à qui gémira et qui se lamentera... Se pourvoir de pain,

de viande, d’épices, de draps et de couver-tures, c’est à quoi l’argent réussit

sans grande fatigue. Mais le service est mauvais superlativement, abominable.

Pensez si on tient a venir vider les vases de ces gens-là, à six giuli par

mois ; on en donnerait dix que ce serait la même chose. »

Les nouveaux religieux n’ayant pas de chapelle, ils

obtinrent le couvent de la Madeleine et les logis adjacents (1586). Approuvé par

les papes, Camille de Lellis fut le premier préfet général de son ordre, charge

qu’il abandonna en 1607. Après que Grégoire XIV eut fulminé la bulle qui

érigeait l’Ordre des Ministres des infirmes sous la règle de Saint-Augustin (21

septembre 1591), le 8 septembre 1591, fête de la Nativité de la Sainte Vierge,

en l’église du couvent de la Madeleine, les vingt-cinq premières professions

purent être faites où chaque camillien disait à Dieu : « Je vous

promets de servir les pauvres malades, vos fils et mes frères, tout le temps de

ma vie, avec le plus de charité possible. »

Atteint de graves infirmités, épuisé par de nombreux

voyages, Camille de Lellis mourut à Rome, au couvent de la Madeleine, le 14

juillet 1614, un heure après le commencement de la nuit. Quand le cardinal

Ginnasio lui porta le viatique, il dit : « Je reconnais, Seigneur,

que je suis le plus grand des pécheurs et que je ne mérite pas de recevoir la

faveur que vous daignez me faire ; mais sauvez-moi par votre infinie

miséricorde. Je mets toute ma confiance dans les mérites de votre précieux

sang. » Il laissait 15 maisons et 8 hôpitaux à 242 profès, répartis en 5

provinces. Benoît XIV béatifia (2 février 1742) et canonisa (29 juin 1746)

Camille de Lellis. Un décret de la congrégation des Rites (15 décembre 1762),

signé par Clément XIII le 18 juillet, étend sa fête à toute l’Église. Avec

saint Jean de Dieu, Léon XIII le proclame patron des malades et des hôpitaux

(22 juin 1886), Pie XI le proclame patron du personnel des hôpitaux (28 août

1930).

SOURCE : https://cybercure.fr/grandes-figures/article/saint-camille-de-lellis

SAINT CAMILLE DE LELLIS

« Toute mauvaise action », a dit un grand

écrivain, laisse en notre cœur d’immondes racines, qu’il faut arracher avec des

tenailles ardentes ».

Que dire donc des habitudes criminelles ?

Ne dévorent-elles pas fatalement tout ce qu’il y a de

bon dans l’âme ?

Ne sont-elles pas une chaîne ignoble qu’il faut

traîner jusqu’à la tombe ?

On le dirait.

On dirait qu’il n’y a pas d’esclave plus asservi que

le pécheur d’habitude.

Pourtant les habitudes mauvaises — même contractées

dès l’enfance — n’empêchent pas d’arriver à la sainteté. La vie de Camille de

Lellis le prouve, elle prouve aussi que les rechutes ne doivent point

décourager.

L’héroïque servant des malades, le fondateur des Frères

du bien mourir ne rompit point d’un coup ses honteuses chaînes.

Loin de là. Plusieurs années durant, il lutta faiblement contre lui-même et la force de l’habitude triompha bien des fois de ses résolutions. Cependant ce libertin, ce joueur est devenu saint Camille de Lellis.

***

Il naquit en 1550, dans une petite ville des Abruzzes.

Sa mère mourut quand il était encore au berceau, et son père, qui était

officier, négligea fort son éducation. Il envoya pourtant son fils à l’école.

L’enfant y apprit à lire et à écrire, mais, abandonné à lui-même, il se lia

avec de jeunes vauriens et fit des jeux de dés et de cartes son occupation

principale.

À dix-huit ans, Camille de Lellis embrassa la carrière

des armes. Passionné pour le jeu au-delà de tout ce qui se peut dire, il ne

tarda pas à perdre aux cartes toute sa fortune et, au bout de trois ans, un

ulcère à la jambe, suite d’une égratignure négligée, l’obligea de quitter

le service.

L’hôpital des Incurables de saint Jacques, à Rome,

était alors desservi par les meilleurs chirurgiens. Dans l’espoir de faire

guérir plus vite sa jambe, le jeune Napolitain s’y rendit, et sa fierté et

son dénuement lui firent demander une place d’infirmier.

Le néant des choses humaines lui apparaissait souvent

dans une vive lumière, il aurait voulu se faire capucin.

Mais, malgré les graves pensées qui le travaillaient,

malgré les pertes énormes qu’il avait faites au jeu, la vue des cartes et des

dés exerçait encore sur lui une fascination irrésistible.

Le futur fondateur des Frères du bien mourir abandonnait

le service des malades pour aller jouer. Aussi on ne tarda pas à le renvoyer,

non seulement comme joueur, mais encore comme fantasque, emporté et cherchant

querelle, sur le moindre prétexte, aux employés de la maison.

Tels furent les débuts du saint dans une carrière où

il devait aller jusqu’au bout des forces humaines dans l’abnégation et la

charité.

Réduit par ses folies à gagner misérablement sa vie et

tourmenté à certaines heures du désir de la perfection, Camille de Lellis fut

tour à tour novice franciscain, aide-maçon, infirmier par nécessité et soldat.

L’extrême misère et ses essais de vie religieuse ne l’avaient point guéri de

son amour du jeu et, à Naples, on le vit, emporté par sa passion, jouer jusqu’à

sa chemise — qu’il perdit.

L’infortuné jeune homme semblait condamné à finir ses

jours dans quelque misérable querelle. Mais, malgré son naturel emporté, malgré

tous ses excès, ce joueur frénétique et malheureux n’avait jamais souillé ses

lèvres d’un blasphème. Ce fut là sans doute, dit l’un de ses biographes, ce qui

lui fit trouver grâce devant Dieu.

Un jour qu’il cheminait à pied, seul et sans

ressource, l’injure faite par ses péchés à la Majesté divine lui apparut

tout à coup dans une lumière si terrible qu’il tomba la face contre terre. Il

se releva changé, transformé, résolu à ne plus vivre que pour expier ses folies

et ses crimes. Il se rendit à Rome et s’offrit, en qualité d’infirmier

volontaire et gratuit, à l’hôpital des Incurables d’où on l’avait renvoyé.

Là, Camille de Lellis parut un homme nouveau et, tout

en pratiquant des mortifications terribles, il servit nuit et jour les malades,

avec un dévouement aussi tendre qu’infatigable.

Il s’attachait surtout aux mourants et, comme un ange

du ciel, les préparait à paraître devant Dieu. Son incomparable charité et ses

hautes capacités le firent bientôt nommer directeur de l’hôpital. Le saint eut

bien des occasions de constater que l’argent seul ne fait pas les bons

infirmiers et il souffrait cruellement de se voir si mal secondé par les

employés mercenaires.

Afin de porter remède à ce mal, il résolut de fonder

une congrégation d’hommes charitables qui serviraient les malades pour le seul

amour de Jésus-Christ.

Pendant qu’il méditait ce grand projet, un Christ,

détachant ses mains de la croix, les tendit suppliantes vers lui et

l’encouragea dans son dessein.

Du cœur du saint, cet appel du Christ fit jaillir les

énergies irrésistibles.

Il triompha de tous les obstacles ; il trouva des

compagnons tels qu’il en désirait et, afin d’être plus utile aux malades, il

résolut, sur l’ordre de saint Philippe de Néri, son directeur et son ami, de se

préparer au sacerdoce. Il apprit le latin avec une ardeur incroyable, fit ses

études théologiques au collège romain et reçut la prêtrise.

Des amis lui donnèrent une maison ; le pape

Sixte V approuva l’institut naissant, et, trois ans plus tard,

Grégoire XIV fit de sa congrégation un ordre religieux.

Les fils de saint Camille remplaçaient les

infirmiers mercenaires presque toujours insuffisants. Ils transformèrent

les hôpitaux et se répandirent bientôt dans les villes d’Italie et dans toute

la chrétienté. Leur saint fondateur leur avait donné pour règle de voir dans

les malades Jésus-Christ en personne. Aussi ces religieux firent partout des

prodiges de charité. Ils s’engageaient par vœu à servir les malades — même

pestiférés — et, dans les temps d’épidémie, beaucoup moururent victimes de leur

dévouement.

On aimera peut-être à savoir ce que saint Camille

recommandait surtout à ceux qui assistent les mourants. Il voulait qu’on les

exhortât discrètement et suavement à s’abandonner à Dieu, à accepter la mort en

union avec Notre-Seigneur et en esprit d’expiation.

Il voulait qu’on fît demander aux mourants

l’application du fruit de cette prière que Jésus-Christ fit sur la croix.

Dans les derniers moments, le saint recommandait

instamment qu’on rappelât souvent aux mourants l’invocation des noms de Jésus

et de Marie.

Il ordonna aussi de continuer les prières pour

les agonisants quelque temps après qu’ils paraîtraient avoir rendu le dernier

soupir.

Camille de Lellis parlait toujours aux malades avec

une douceur toute céleste. Par ses exhortations pénétrantes, il leur inspirait

la patience, la résignation, parfois même la joie de souffrir.

Il appelait les cruelles infirmités dont il

souffrait des miséricordes du bon Dieu.

On l’entendait souvent dire comme saint François

d’Assise :

« Le bonheur que j’espère est si grand, que

toutes les peines et toutes les souffrances deviennent pour moi des sources de

joie ».

Austère à lui-même jusqu’à ne se laisser que la peau

et les os, il avait pour tous les malades la tendresse d’une mère. Il poussait

la bonté jusqu’à faire faire de la musique auprès de ceux qui trouvaient,

dans cette harmonie, quelque soulagement à leurs maux.

On le voyait, épuisé de fatigues et de souffrances, se

traîner de lit en lit pour voir si rien ne manquait aux malades et pour leur

parler de l’amour de Dieu.

Même dans les conversations ordinaires, les discours

de saint Camille roulaient toujours sur l’amour de Dieu, et, s’il lui arrivait

d’entendre un sermon où il n’en fut point parlé, il disait que c’était un

anneau auquel il manquait un diamant.

Lorsqu’on lui annonça que les médecins désespéraient

de sa vie, il s’écria, ravi :

« Je me suis réjoui parce qu’on m’a dit :

Nous irons dans la maison du Seigneur ».

Quand on lui apporta le viatique, il versa des larmes

et dit avec une humilité profonde :

« Je reconnais, Seigneur, que je suis le plus

grand des pécheurs et que je ne mérite pas la faveur que vous daignez me faire,

mais sauvez-moi par votre infinie miséricorde. Je mets toute ma confiance dans

votre précieux Sang ».

Il prononçait avec tant de tendresse les noms de Jésus et de Marie, que l’amour qui le consumait embrasait aussi les assistants. Enfin, les yeux fixés sur une image de Marie et les bras en croix, il expira dans une paix céleste, en invoquant toujours ces doux noms qui furent ses dernières paroles.

Laure Conan. Physionomies de saints. Librairie Beauchemin, Limitée, 1913 (p. 128-132).

SOURCE : https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Physionomies_de_saints/Saint_Camille_de_Lellis

Fresque de Saint Camille de Lellis,

salle de conférences de la bibliothèque régionale d'Aoste.

Also known as

Camillus de Lellis

Camillo de Lellis

Profile

Son of a military officer

who had served both for Naples and France.

His mother died when

Camillus was very young.

He spent his youth as

a soldier,

fighting for the Venetians against

the Turks, and then for Naples.

Reported as a large individual, perhaps as tall as 6’6″ (2 metres), and

powerfully built, but he suffered all his life from abscesses on his feet.

A gambling

addict, he lost so much he had to take a job working construction on

a building belonging to the Capuchins;

they converted him.

Camillus entered the Capuchin noviate three

times, but a nagging leg

injury, received while fighting the Turks, each time forced him to give it

up. He went to Rome, Italy for medical treatment

where Saint Philip

Neri became his priest and confessor.

He moved into San Giacomo Hospital for

the incurable, and eventually became its administrator. Lacking education,

he began to study with children when

he was 32 years old. Priest.

Founded the Congregation of the Servants of the

Sick (the Camillians or Fathers of a Good Death) who,

naturally, care for the sick both

in hospital and

home. The Order expanded with houses in several countries. Camillus

honoured the sick as

living images of Christ, and hoped that the service he gave them did penance

for his wayward youth. Reported to have the gifts of miraculous healing and prophecy.

Born

25 May 1550 at

Bocchiavico, Abruzzi,

kingdom of Naples, Italy

14 July 1614 at Genoa, Italy of

natural causes

7 April 1742 by Pope Benedict

XIV

29 June 1746 by Pope Benedict

XIV

sick

people (proclaimed on 22 June 22 1886 by Pope Leo

XIII)

Additional Information

Book

of Saints, by Father Lawrence

George Lovasik, S.V.D.

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Francis

Xavier Weninger

Saints

for Sinners, by Father Alban

Goodier, SJ

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

Camillus de Lellis, the Hospital Saint, by Sister Mary

Camilla Lyons

Saint Camillus de Lellis, Founder of the Clerics

Regular, Ministers of the Sick, by a Camillian

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other sites in english

1001 Patron Saints and Their Feast Days, Australian

Catholic Truth Society

images

video

ebooks

Camillus

de Lellis, The Hospital Saint

sitios en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites en français

Abbé Christian-Philippe Chanut

fonti in italiano

nettsteder i norsk

Readings

Think well. Speak well. Do well. These three things,

through the mercy of God, will make a man go to Heaven. – Saint Camillus

de Lellis

Let me begin with holy charity. It is the root of all

the virtues and Camillus’ most characteristic trait. I can attest that he was

on fire with this holy virtue – not only toward God, but also toward his fellow

men, and especially toward the sick. The mere sight of the sick was enough to

soften and melt his heart and make him utterly forget all the pleasures,

enticements, and interests of this world. When he was taking care of his

parents, he seemed to spend and exhaust himself completely, so great was his

devotion and compassion. He would have loved to take upon himself all their

illness, their every affliction, could he but ease their pain and relieve their

weakness. In the sick he saw the person of Christ. His reverence in their

presence was as a great as if he were really and truly in the presence of his

Lord. To enkindle the enthusiasm of his religious brothers for this

all-important virtue, he used to impress upon them the consoling words of Jesus

Christ: “I was sick and

you visited me.” He seemed to have these words truly graven on his heart, so

often did he say them over and over again. Great and all-embracing was

Camillus’ charity. Not only the sick and dying, but every other needy or

suffering human being found shelter in his deep and kind concern. – from a

biography of Saint Camillus

by a contemporary

MLA Citation

“Saint Camillus of Lellis“. CatholicSaints.Info.

3 July 2021. Web. 14 July 2021. <https://catholicsaints.info/saint-camillus-of-lellis/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-camillus-of-lellis/

Saint Camillus de Lellis

Born at Bucchianico, Abruzzo, 1550; died at Rome,

14 July, 1614.

He was the son of an officer who had served both in the Neapolitan and French armies.

His mother died when he was a child, and he grew up absolutely neglected. When

still a youth he became a soldier in the service of Venice and

afterwards of Naples,

until 1574, when his regiment was disbanded. While in the service he became

a confirmed gambler, and in consequence of his losses at play was at

times reduced to a condition of destitution. The kindness of

a Franciscan friar induced

him to apply for admission to that order, but he was refused. He then betook

himself to Rome,

where he obtained employment in the Hospital for Incurables. He

was prompted to go there chiefly by the hope of a cure of abscesses

in both his feet from which he had been long suffering. He was dismissed from

the hospital on

account of his quarrelsome disposition and

his passion for gambling. He again became a Venetian soldier,

and took part in the campaign against the Turks in

1569. After the war he

was employed by the Capuchins at Manfredonia on

a new building which they were erecting. His

old gambling habit still pursued him, until a discourse of

the guardian of the convent so

startled him that he determined to reform. He was admitted to the order as

a lay

brother, but was soon dismissed on account of his infirmity. He betook

himself again to Rome,

where he entered the hospital in

which he had previously been, and after a temporary cure of his ailment became

a nurse, and winning the admiration of the institution by his piety and prudence,

he was appointed director of the hospital.

While in this office, he attempted to found an order

of lay infirmarians, but the scheme was opposed, and on the advice of

his friends, among whom was his spiritual guide, St.

Philip Neri, he determined to become a priest.

He was then thirty-two years of age and began the study of Latin at

the Jesuit College in Rome.

He afterwards established his order, the Fathers of

a Good Death (1584), and bound the members by vow to devote themselves

to the plague-stricken; their work was not restricted to the hospitals,

but included the care of the sick in their homes. Pope

Sixtus V confirmed the congregation in 1586,

and ordained that there should be an election of a general

superior every three years. Camillus was naturally the

first, and was succeeded by an Englishman, named Roger. Two years

afterwards a house was established in Naples,

and there two of the community won the glory of being the first martyrs of charity of

the congregation, by dying in the fleet which had

been quarantined off the harbour, and which they had visited to nurse

the sick. In 1591 Gregory

XIV erected the congregation into a religious order,

with all the privileges of the mendicants.

It was again confirmed as such by Clement

VIII, in 1592. The infirmity which had prevented his entrance among

the Capuchins continued

to afflict Camillus for forty-six years, and his other ailments

contributed to make his life one of uninterrupted suffering, but he would

permit no one to wait on him, and when scarcely able to stand would crawl out