Saint Thomas More

Chancelier du roi Henri

VIII d'Angleterre, martyr (+ 1535)

Fils d'un haut magistrat londonien, il se distingue par son intelligence, sa bonne humeur et sa piété. Une apparente vocation religieuse le conduit à la Chartreuse de Londres, mais il n'est pas fait pour la solitude contemplative. Il est bâti pour la vie active dans le monde. Très vite, il se révèle un des plus grands juristes et un des humanistes les plus cultivés de son temps. L'amitié d'Erasme et la publication de "L'Utopie"* (une vision humoristique d'une république idéale) le placent au premier rang de la nouvelle culture et des aspirants à un renouveau religieux. Avec cela son réalisme, sa clairvoyance souriante le font reconnaître du roi Henri VIII d'Angleterre comme un magistrat exceptionnel. D'où sa promotion aux fonctions de Lord-chancelier du Royaume. Mais les années de rêve dans sa résidence de Chelsea, au milieu d'une nombreuse famille, débordante de gaieté, de ferveur et d'hospitalité, ne se prolongent pas longtemps. Ni sa lucide intégrité ni sa foi éclairée ne lui permettent de suivre Henri VIII dans le schisme où les errements conjugaux du roi allaient s'engager. Sir Thomas More, fidèle à la foi catholique, bien qu'ayant renoncé à ses hautes fonctions pour garder sa liberté de jugement, paiera de sa tête cette fidélité.

* L'utopie ou Le Traité de la meilleure forme de gouvernement (1516)

- Le pape Jean-Paul II fit de Thomas More le patron des ministres et des

responsables politiques car il a illustré en son temps que gouverner était une

vertu. vidéo CFRT/

France Télévisions - Jour du Seigneur.

A lire aussi: Lettre apostolique en forme de motu proprio pour la

proclamation de saint Thomas More comme patron des responsables de gouvernement

et des hommes politiques (Jean-Paul II, le 31 octobre 2000)

Mémoire des saints Jean

Fisher, évêque, et Thomas More, martyrs. Leur opposition au roi Henri VIII

dans la controverse autour de son divorce et sur la suprématie spirituelle du

pape, entraîna leur incarcération à la Tour de Londres. Jean Fisher, évêque de

Rochester, qui s'était fait remarquer par son érudition et la sainteté de sa

vie, fut décapité devant sa prison par ordre du roi lui-même. Thomas More, père

de famille d'une vie absolument intègre, et chancelier du royaume d'Angleterre,

fut décapité le 6 juillet suivant, lié au saint évêque par la même fidélité à

l'Église catholique et par le même martyre.

Martyrologe romain

On me reproche de mêler

boutades, facéties et joyeux propos aux sujets les plus graves. Avec Horace,

j'estime qu'on peut dire la vérité en riant. Sans doute aussi convient-il mieux

au laïc que je suis de transmettre sa pensée sur un mode allègre et enjoué,

plutôt que sur le mode sérieux et solennel, à la façon des prédicateurs.

(Saint Thomas More -

L'utopie)

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1372/Saint-Thomas-More.html

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/1498–1543),

Portrait of Sir Thomas More, 1527, oil on oak panel,

74.9 x 60.3, The Frick Collection

SAINT THOMAS MORE

Martyr

(1487-1535)

Saint Thomas More naquit

à Londres, le 7 février 1478. Son père remplissait la fonction de juge, dans la

capitale. Thomas passa quelques-unes de ses premières années en qualité de

page, au service du cardinal Morton, alors archevêque de Cantorbéry et chancelier

d'Angleterre. A l'âge de quatorze ans, il alla étudier à Oxford où il fit de

sérieuses études juridiques et suivit les conférences sur la Cité de Dieu, de

saint Augustin.

En 1501, Thomas More

était reçu avocat et élu membre du Parlement trois ans plus tard. Après

quelques années de mariage, il perdit sa femme et demeura seul avec ses quatre

enfants: trois filles et un fils. Il ne se remariera que beaucoup plus tard,

avec une veuve. En père vigilant, il veillait à ce que Dieu restât le centre de

la vie de ses enfants. Le soir, il récitait la prière avec eux; aux repas, une

de ses filles lisait un passage de l'Ecriture Sainte et on discutait ensuite

sur le texte en conversant gaiement. Jamais la science, ni la vertu, ne prirent

un visage austère dans sa demeure; sa piété n'en était cependant pas moins

profonde. Saint Thomas More entendait la messe tous les jours; en plus de ses

prières du matin et du soir, il récitait les psaumes quotidiennement.

Sa valeur le fit nommer

Maître des Requêtes et conseiller privé du roi. En 1529, Thomas More remplaça

le défunt cardinal Wolsey dans la charge de Lord chancelier. Celui qui n'avait

jamais recherché les honneurs ni désiré une haute situation se trouvait placé

au sommet des dignités humaines. Les succès, pas plus que les afflictions,

n'eurent de prise sur sa force de caractère.

Lorsque Henri VIII voulut

divorcer pour épouser Anne Boleyn, et qu'il prétendit devant l'opposition

formelle du pape, se proclamer chef de l'Église d'Angleterre, saint Thomas More

blâma la conduite de son suzerain. Dès lors, les bonnes grâces du roi se

changèrent en hostilité ouverte contre lui. Le roi le renvoya sans aucune

ressource, car saint Thomas versait au fur à mesure tous ses revenus dans le

sein des pauvres. Le jour où il apprit que ses granges avaient été incendiées,

il écrivit à sa femme de rendre grâces à Dieu pour cette épreuve.

Le 12 avril 1554,

l'ex-chancelier fut invité à prononcer le serment qui reconnaissait Anne Boleyn

comme épouse légitime et rejetait l'autorité du pape. Saint Thomas rejeta

noblement toute espèce de compromis avec sa conscience et refusa de donner son

appui à l'adultère et au schisme. Après un second refus réitéré le 17 avril, on

l'emprisonna à la Tour de Londres. Il vécut dans le recueillement et la prière

durant les quatorze mois de son injuste incarcération.

Comme il avait fait de

toute sa vie une préparation à l'éternité, la sérénité ne le quittait jamais.

Il avoua bonnement: «Il me semble que Dieu fait de moi Son jouet et qu'Il me

berce.» L'épreuve de la maladie s'ajouta bientôt à celle de la réclusion.

Devenu semblable à un squelette, il ne cessa cependant de travailler en

écrivant des traités moraux, un traité sur la Passion, et même de joyeuses

satires.

L'intensité de sa prière

conservait sa force d'âme: «Donne-moi Ta grâce, Dieu bon, pour que je compte

pour rien le monde et fixe mon esprit sur Toi.» Il disait à sa chère fille

Marguerite: «Si je sens la frayeur sur le point de me vaincre, je me

rappellerai comment un souffle de vent faillit faire faire naufrage à Pierre

parce que sa foi avait faibli. Je ferai donc comme lui, j'appellerai le Christ

à mon secours.»

On accusa saint Thomas

More de haute trahison parce qu'il niait la suprématie spirituelle du roi.

Lorsque le simulacre de jugement qui le condamnait à être décapité fut terminé,

le courageux confesseur de la foi n'eut que des paroles de réconfort pour tous

ceux qui pleuraient sa mort imminente et injuste. A la foule des spectateurs,

il demanda de prier pour lui et de porter témoignage qu'il mourait dans la foi

et pour la foi de la Sainte Église catholique. Sir Kingston, connu pour son

coeur impitoyable, lui fit ses adieux en sanglotant. Il récita pieusement le

Miserere au pied de l'échafaud. Il demanda de l'aide pour monter sur l'échafaud:

«Pour la descente, ajouta-t-il avec humour, je m'en tirerai bien tout seul.» Il

embrassa son bourreau: «Courage, mon brave, n'aie pas peur, mais comme j'ai le

cou très court, attention! il y va de ton honneur.» Il se banda les yeux et se

plaça lui-même sur la planche.

Béatifié par Léon XIII le

29 décembre 1886, sa canonisation eut lieu le 19 mai 1935.

Tiré de: Frères des Écoles Chrétiennes, Vies des Saints, Edition 1932, p. 234-235 -- Marteau

de Langle de Cary, 1959, tome II, p. 37-42.

SOURCE : https://livres-mystiques.com/partieTEXTES/Jaud_Saints/calendrier/Vies_des_Saints/07-06.htm

LETTRE APOSTOLIQUE

EN FORME DE MOTU PROPRIO

POUR LA PROCLAMATION DE

SAINT THOMAS MORE

COMME PATRON DES

RESPONSABLES DE GOUVERNEMENT

ET DES HOMMES POLITIQUES

JEAN-PAUL II

EN PERPÉTUELLE MÉMOIRE

1. De la vie et du

martyre de saint Thomas More se dégage un message qui traverse les siècles et

qui parle aux hommes de tous temps de la dignité inaliénable de la conscience,

dans laquelle, comme le rappelle le Concile Vatican II, réside «le centre le

plus secret de l’homme et le sanctuaire où il est seul avec Dieu dont la voix

se fait entendre dans ce lieu le plus intime» (Gaudium et spes, n. 16). Quand

l’homme et la femme écoutent le rappel de la vérité, la conscience oriente avec

sûreté leurs actes vers le bien. C’est précisément pour son témoignage de la

primauté de la vérité sur le pouvoir, rendu jusqu’à l’effusion du sang, que

saint Thomas More est vénéré comme exemple permanent de cohérence morale. Même

en dehors de l’Église, particulièrement parmi ceux qui sont appelés à guider

les destinées des peuples, sa figure est reconnue comme source d’inspiration

pour une politique qui se donne comme fin suprême le service de la personne

humaine.

Certains Chefs d’État et

de gouvernement, de nombreux responsables politiques, quelques Conférences

épiscopales et des évêques individuellement m’ont récemment adressé des

pétitions en faveur de la proclamation de saint Thomas More comme Patron des

Responsables de gouvernement et des hommes politiques. Parmi les signataires de

la demande, on trouve des personnalités de diverses provenances politiques,

culturelles et religieuses, ce qui témoigne d’un intérêt à la fois vif et très

répandu pour la pensée et le comportement de cet insigne homme de gouvernement.

2. Thomas More a connu

une carrière politique extraordinaire dans son pays. Né à Londres en 1478 dans

une famille respectable, il fut placé dès sa jeunesse au service de

l’Archevêque de Cantorbéry, John Morton, Chancelier du Royaume. Il étudia

ensuite le droit à Oxford et à Londres, élargissant ses centres d’intérêts à de

vastes secteurs de la culture, de la théologie et de la littérature classique.

Il apprit à fond le grec et il établit des rapports d’échanges et d’amitié avec

d’importants protagonistes de la culture de la Renaissance, notamment Didier

Érasme de Rotterdam.

Sa sensibilité religieuse

le conduisit à rechercher la vie vertueuse à travers une pratique ascétique

assidue: il cultiva l’amitié avec les Frères mineurs de la stricte observance

du couvent de Greenwich, et pendant un certain temps il logea à la Chartreuse

de Londres, deux des principaux centres de ferveur religieuse dans le Royaume.

Se sentant appelé au mariage, à la vie familiale et à l’engagement laïc, il

épousa en 1505 Jane Colt, dont il eut quatre enfants. Jane mourut en 1511 et

Thomas épousa en secondes noces Alice Middleton, qui était veuve et avait une

fille. Durant toute sa vie, il fut un mari et un père affectueux et fidèle,

veillant avec soin à l’éducation religieuse, morale et intellectuelle de ses

enfants. Dans sa maison, il accueillait ses gendres, ses belles-filles et ses

petits-enfants, et sa porte était ouverte à beaucoup de jeunes amis à la

recherche de la vérité ou de leur vocation. D’autre part, la vie familiale

faisait une large place à la prière commune et à la lectio divina, comme aussi

à de saines formes de récréation. Thomas participait chaque jour à la messe

dans l’église paroissiale, mais les pénitences austères auxquelles il se

livrait n’étaient connues que de ses proches les plus intimes.

3. En 1504, sous le roi

Henri VII, il accéda pour la première fois au parlement. Henri VIII renouvela

son mandat en 1510 et il l’établit également représentant de la Couronne dans

la capitale, lui ouvrant une carrière remarquable dans l’administration

publique. Dans la décennie qui suivit, le roi l’envoya à diverses reprises,

pour des missions diplomatiques et commerciales, dans les Flandres et dans le

territoire de la France actuelle. Nommé membre du Conseil de la Couronne, juge

président d’un tribunal important, vice-trésorier et chevalier, il devint en

1523 porte-parole, c’est-à-dire président, de la Chambre des Communes.

Universellement estimé

pour son indéfectible intégrité morale, pour la finesse de son intelligence,

pour son caractère ouvert et enjoué, pour son érudition extraordinaire, en

1529, à une époque de crise politique et économique dans le pays, il fut nommé

par le roi Chancelier du Royaume. Premier laïc à occuper cette charge, Thomas

fit face à une période extrêmement difficile, s’efforçant de servir le roi et

le pays. Fidèle à ses principes, il s’employa à promouvoir la justice et à

endiguer l’influence délétère de ceux qui poursuivaient leur propre intérêt au

détriment des plus faibles. En 1532, ne voulant pas donner son appui au projet

d’Henri VIII qui voulait prendre le contrôle de l’Église en Angleterre, il

présenta sa démission. Il se retira de la vie publique, acceptant de supporter

avec sa famille la pauvreté et l’abandon de beaucoup de personnes qui, dans

l’épreuve, se révélèrent de faux amis.

Constatant la fermeté

inébranlable avec laquelle il refusait tout compromis avec sa conscience, le

roi le fit emprisonner en 1534 dans la Tour de Londres, où il fut soumis à

diverses formes de pression psychologique. Thomas More ne se laissa pas

impressionner et refusa de prêter le serment qu’on lui demandait parce qu’il

comportait l’acceptation d’une plate-forme politique et ecclésiastique qui

préparait le terrain à un despotisme sans contrôle. Au cours du procès intenté

contre lui, il prononça une apologie passionnée de ses convictions sur

l’indissolubilité du mariage, le respect du patrimoine juridique inspiré par les

valeurs chrétiennes, la liberté de l’Église face à l’État. Condamné par le

Tribunal, il fut décapité.

Au cours des siècles qui

suivirent, la discrimination à l’égard de l’Église s’atténua. En 1850, la

hiérarchie catholique fut rétablie en Angleterre. Il fut alors possible

d’engager les causes de canonisation de nombreux martyrs. Thomas More fut

béatifié par le Pape Léon XIII en 1886, en même temps que cinquante-trois

autres martyrs, dont l’évêque John Fischer. Avec ce dernier, il fut canonisé

par Pie XI en 1935, à l’occasion du quatrième centenaire de son martyre.

4. De nombreuses raisons

militent en faveur de la proclamation de saint Thomas More comme Patron des

Responsables de gouvernement et des hommes politiques. Entre autres, le besoin

ressenti par le monde politique et administratif d’avoir des modèles crédibles

qui indiquent le chemin de la vérité en une période historique où se

multiplient de lourds défis et de graves responsabilités. Aujourd’hui, en

effet, des phénomènes économiques fortement innovateurs sont en train de

modifier les structures sociales; d’autre part, les conquêtes scientifiques

dans le secteur des biotechnologies renforcent la nécessité de défendre la vie

humaine sous toutes ses formes, tandis que les promesses d’une société nouvelle,

proposées avec succès à une opinion publique déconcertée, requièrent d’urgence

des choix politiques clairs en faveur de la famille, des jeunes, des personnes

âgées et des marginaux.

Dans ce contexte, il est

bon de revenir à l’exemple de saint Thomas More, qui se distingua par sa

constante fidélité à l’autorité et aux institutions légitimes, précisément

parce qu’il entendait servir en elles non le pouvoir mais l’idéal suprême de la

justice. Sa vie nous enseigne que le gouvernement est avant tout un exercice de

vertus. Fort de cette rigoureuse assise morale, cet homme d’État anglais mit

son activité publique au service de la personne, surtout quand elle est faible

ou pauvre; il géra les controverses sociales avec un grand sens de l’équité; il

protégea la famille et la défendit avec une détermination inlassable; il promut

l’éducation intégrale de la jeunesse. Son profond détachement des honneurs et

des richesses, son humilité sereine et joviale, sa connaissance équilibrée de

la nature humaine et de la vanité du succès, sa sûreté de jugement enracinée

dans la foi, lui donnèrent la force intérieure pleine de confiance qui le

soutint dans l’adversité et face à la mort. Sa sainteté resplendit dans le

martyre, mais elle fut préparée par une vie entière de travail dans le dévouement

à Dieu et au prochain.

Mentionnant des exemples

semblables de parfaite harmonie entre la foi et les œuvres, j’ai écrit dans

l’exhortation apostolique post-synodale Christifideles laici que «l’unité de la

vie des fidèles laïcs est d’une importance extrême : ils doivent en effet se

sanctifier dans la vie ordinaire, professionnelle et sociale. Afin qu’ils

puissent répondre à leur vocation, les fidèles laïcs doivent donc considérer

les activités de la vie quotidienne comme une occasion d’union à Dieu et

d’accomplissement de sa volonté, comme aussi de service envers les autres

hommes» (n. 17).

Cette harmonie entre le

naturel et le surnaturel est l’élément qui décrit peut-être plus que tout autre

la personnalité du grand homme d’État anglais : il vécut son intense vie

publique avec une humilité toute simple, marquée par son humour bien connu,

même aux portes de la mort.

Tel est le but où le

conduisit sa passion pour la vérité. On ne peut séparer l’homme de Dieu, ni la

politique de la morale; telle est la lumière qui éclaira sa conscience. Comme

j’ai déjà eu l’occasion de le dire, «l’homme est une créature de Dieu, et c’est

pourquoi les droits de l’homme ont en Dieu leur origine, ils reposent dans le

dessein de la création et ils entrent dans le plan de la rédemption. On

pourrait presque dire, d’une façon audacieuse, que les droits de l’homme sont

aussi les droits de Dieu» (Discours du 7 avril 1998 aux participants à la

Rencontre universitaire internationale UNIV’98).

Et c’est précisément dans

la défense des droits de la conscience que l’exemple de Thomas More brilla

d’une lumière intense. On peut dire qu’il vécut d’une manière singulière la

valeur d’une conscience morale qui est «témoignage de Dieu lui-même, dont la

voix et le jugement pénètrent l'intime de l'homme jusqu'aux racines de son âme»

(Encyclique Veritatis splendor, n. 58), même si, en ce qui concerne l’action

contre les hérétiques, il fut tributaire des limites de la culture de son

temps.

Le Concile œcuménique

Vatican II, dans la constitution Gaudium et spes, remarque que, dans le monde

contemporain, grandit «la conscience de l’éminente dignité qui revient à la

personne humaine, du fait qu’elle l’emporte sur toute chose et que ses droits

et devoirs sont universels et inviolables» (n. 26). L’histoire de saint Thomas

More illustre clairement une vérité fondamentale de l’éthique politique. En

effet, la défense de la liberté de l’Église contre des ingérences indues de

l’État est en même temps défense, au nom de la primauté de la conscience, de la

liberté de la personne par rapport au pouvoir politique. C’est là le principe

fondamental de tout ordre civil, conforme à la nature de l’homme.

5 Je suis donc certain

que l’élévation de l’éminente figure de saint Thomas More au rang de Patron des

Responsables de gouvernement et des hommes politiques pourvoira au bien de la

société. C’est là d’ailleurs une initiative qui est en pleine syntonie avec

l’esprit du grand Jubilé, qui conduit au troisième millénaire chrétien.

En conséquence, après

mûre considération, accueillant volontiers les demandes qui m’ont été

adressées, j’établis et je déclare Patron céleste des Responsables de

gouvernement et des hommes politiques saint Thomas More, et je décide que

doivent lui être attribués tous les honneurs et les privilèges liturgiques qui

reviennent, selon le droit, aux Patrons de catégories de personnes.

Béni et glorifié soit

Jésus Christ, Rédempteur de l’homme, hier, aujourd’hui, à jamais.

Donné à Rome, près de

Saint-Pierre, le 31 octobre 2000, en la vingt-troisième année de mon

Pontificat.

IOANNES PAULUS PP. II

© Copyright 2000 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

RENCONTRE AVEC LE

PARLEMENT ET LA BRITISH SOCIETY

ALLOCUTION DU SAINT-PÈRE

BENOÎT XVI*

Monsieur le Speaker,

Je vous remercie des

paroles de bienvenue que vous venez de m’adresser au nom des membres distingués

de cette assemblée. En m’adressant à vous, j’ai bien conscience du privilège

qui m’est ainsi donné d’adresser la parole au peuple britannique et à ses

Représentants au Palais de Westminster, édifice auréolé d’une signification

unique dans l’histoire civile et politique du peuple de ces Iles. Permettez-moi

d’exprimer mon estime pour le Parlement qui siège en ce lieu depuis des siècles

et qui a eu une influence si profonde pour le développement du gouvernement

participatif dans les nations, en particulier au sein du Commonwealth et dans

le monde de l’anglophonie en général. Votre tradition de droit commun sert de

base aux systèmes législatifs en bien des régions du monde, et votre conception

particulière des droits et des devoirs respectifs de l’État et des citoyens,

ainsi que de la séparation des pouvoirs, continue d’en inspirer beaucoup sur

notre planète.

Tandis que je vous parle

en cette enceinte chargée d’histoire, je pense aux hommes et aux femmes

innombrables des siècles passés ayant joué un rôle important en des événements

marquants qui se sont déroulés dans ces murs ; ils ont laissé leur empreinte

sur des générations de Britanniques et de bien d’autres aussi. En particulier,

j’évoque la figure de saint Thomas More, intellectuel et homme d’État anglais

de grande envergure, qui est admiré aussi bien par les croyants que par les

non-croyants pour l’intégrité avec laquelle il a suivi sa conscience, fusse au

prix de déplaire au Souverain dont il était le « bon serviteur », et cela parce

qu’il avait choisi de servir Dieu avant tout. Le dilemme que More a dû

affronter en des temps difficiles, l’éternelle question du rapport entre ce qui

est dû à César et ce qui est dû à Dieu, m’offre l’opportunité de réfléchir

brièvement avec vous sur la juste place de la croyance religieuse à l’intérieur

de la vie politique.

La tradition

parlementaire de ce pays doit beaucoup à la tendance naturelle de votre nation

pour la modération, au désir d’arriver à un équilibre véritable entre les

exigences légitimes du gouvernement et les droits de ceux qui y sont soumis.

Tandis que des mesures décisives ont été prises à plusieurs époques de votre

histoire afin de définir des limites dans l’exercice du pouvoir, les

institutions politiques de la nation ont pu évoluer dans un espace remarquable

de stabilité. Dans ce processus, la Grande-Bretagne est apparue comme une

démocratie pluraliste qui attache une grande valeur à la liberté de parole, à

la liberté d’obédience politique et au respect de la primauté du droit comme

règle de conduite, accompagné d’un sens très fort des droits et des devoirs de

chacun, ainsi que de l’égalité de tous les citoyens devant la loi. S’il

s’exprime d’une manière différente, l’enseignement social de l’Église

catholique a bien des points communs avec cette approche, aussi bien quand il

s’agit de protéger avec fermeté la dignité unique de toute personne humaine,

créée à l’image et à la ressemblance de Dieu, que lorsqu’il souligne avec force

le devoir qu’ont les autorités civiles de promouvoir le bien commun.

Et pourtant, les

questions fondamentales qui étaient en jeu dans le procès de Thomas More,

continuent à se présenter, même si c’est de manière différente, à mesure

qu’apparaissent de nouvelles conditions sociales. Chaque génération, en

cherchant à faire progresser le bien commun, doit à nouveau se poser la

question : quelles sont les exigences que des gouvernements peuvent

raisonnablement imposer aux citoyens, et jusqu’où cela peut-il aller ? En

faisant appel à quelle autorité les dilemmes moraux peuvent-ils être résolus ?

et le bien commun promu ? Ces questions nous mènent directement aux fondements

éthiques du discours civil. Si les principes moraux qui sont sous-jacents au

processus démocratique ne sont eux-mêmes déterminés par rien de plus solide

qu’un consensus social, alors la fragilité du processus ne devient que trop

évidente – là est le véritable défi pour la démocratie.

L’inaptitude des

solutions pragmatiques, à court-terme, devant les problèmes sociaux et éthiques

complexes a été amplement démontrée par la récente crise financière mondiale.

Il existe un large consensus pour reconnaître que le manque d’un solide

fondement éthique de l’activité économique a contribué aux graves difficultés

qui éprouvent des millions de personnes à travers le monde entier. De même que

« toute décision économique a une conséquence de caractère moral » (Caritas

in veritate, 37), ainsi, dans le domaine politique, la dimension éthique a

des conséquences de longue portée qu’aucun gouvernement ne peut se permettre

d’ignorer. Nous trouvons un exemple positif de cela dans l’un des succès

particulièrement remarquable du Parlement britannique : l’abolition de la

traite des esclaves. La campagne qui a abouti à cette législation reposait sur

des principes éthiques solides, enracinés dans la loi naturelle, et fut ainsi

rendue une contribution à la civilisation dont votre nation peut justement être

fière.

Mais alors la question

centrale qui se pose est celle-ci : où peut-on trouver le fondement éthique des

choix politiques ? La tradition catholique soutient que les normes objectives

qui dirigent une action droite sont accessibles à la raison, même sans le

contenu de la Révélation. Selon cette approche, le rôle de la religion dans le

débat politique n’est pas tant celui de fournir ces normes, comme si elles ne

pouvaient pas être connues par des non-croyants – encore moins de proposer des

solutions politiques concrètes, ce qui de toute façon serait hors de la

compétence de la religion – mais plutôt d’aider à purifier la raison et de

donner un éclairage pour la mise en œuvre de celle-ci dans la découverte de

principes moraux objectifs. Ce rôle « correctif » de la religion à l’égard de la

raison n’est toutefois pas toujours bien accueilli, en partie parce que des

formes déviantes de religion, telles que le sectarisme et le fondamentalisme,

peuvent être perçues comme susceptibles de créer elles-mêmes de graves

problèmes sociaux. A leur tour, ces déformations de la religion surgissent

quand n’est pas accordée une attention suffisante au rôle purifiant et

structurant de la raison à l’intérieur de la religion. Il s’agit d’un processus

à deux sens. Sans le correctif apporté par la religion, d’ailleurs, la raison

aussi peut tomber dans des distorsions, comme lorsqu’elle est manipulée par

l’idéologie, ou lorsqu’elle est utilisée de manière partiale si bien qu’elle

n’arrive plus à prendre totalement en compte la dignité de la personne humaine.

C’est ce mauvais usage de la raison qui, en fin de compte, fut à l’origine du

trafic des esclaves et de bien d’autres maux sociaux dont les idéologies

totalitaires du 20ème siècle ne furent pas les moindres. C’est pourquoi,

je voudrais suggérer que le monde de la raison et de la foi, le monde de la

rationalité séculière et le monde de la croyance religieuse reconnaissent

qu’ils ont besoin l’un de l’autre, qu’ils ne doivent pas craindre d’entrer dans

un profond dialogue permanent, et cela pour le bien de notre civilisation.

La religion, en d’autres

termes, n’est pas un problème que les législateurs doivent résoudre, mais elle

est une contribution vitale au dialogue national. Dans cette optique, je ne

puis que manifester ma préoccupation devant la croissante marginalisation de la

religion, particulièrement du christianisme, qui s’installe dans certains

domaines, même dans des nations qui mettent si fortement l’accent sur la

tolérance. Certains militent pour que la voix de la religion soit étouffée, ou

tout au moins reléguée à la seule sphère privée. D’autres soutiennent que la

célébration publique de certaines fêtes, comme Noël, devrait être découragée,

en arguant de manière peu défendable que cela pourrait offenser de quelque

manière ceux qui professent une autre religion ou qui n’en ont pas. Et d’autres

encore soutiennent – paradoxalement en vue d’éliminer les discriminations – que

les chrétiens qui ont des fonctions publiques devraient être obligés en

certains cas d’agir contre leur conscience. Ce sont là des signes inquiétants

de l’incapacité d’apprécier non seulement les droits des croyants à la liberté

de conscience et de religion, mais aussi le rôle légitime de la religion dans

la vie publique. Je voudrais donc vous inviter tous, dans vos domaines

d’influence respectifs, à chercher les moyens de promouvoir et d’encourager le

dialogue entre foi et raison à tous les niveaux de la vie nationale.

Votre disponibilité en ce

sens est déjà manifeste par l’invitation exceptionnelle que vous m’avez offerte

aujourd’hui. Et elle trouve aussi une expression dans les questions sur

lesquelles votre Gouvernement a engagé un dialogue avec le Saint-Siège. En ce

qui concerne la paix, il y a eu des échanges à propos de l’élaboration d’un

traité international sur le trafic d’armes ; à propos des droits de l’homme, le

Saint-Siège et le Royaume-Uni se sont réjouis des progrès de la démocratie,

spécialement au cours des soixante-cinq dernières années ; en ce qui concerne

le développement, des collaborations se sont mises en place pour l’allègement

de la dette, pour un marché équitable et pour le financement du développement,

en particulier à travers l’International Finance Facility, l’International

Immunisation Bond et l’Advanced Market Commitment. Le Saint-Siège espère

aussi pouvoir explorer avec le Royaume-Uni de nouvelles voies pour promouvoir

une mentalité responsable vis-à-vis de l’environnement, pour le bien de tous.

Je remarque aussi que

l’actuel Gouvernement a engagé le Royaume-Uni à consacrer 0,7% du revenu

national pour l’aide au développement d’ici à 2013. C’est dernières années des

signes encourageants ont pu être observés de par le monde concernant un souci

plus grand de solidarité avec les pauvres. Mais pour que cette solidarité

s’exprime en actions effectives, il est nécessaire de repenser les moyens qui

amélioreront les conditions de vie dans de nombreux domaines, allant de la

production alimentaire, à l’eau potable, à la création d’emplois, à

l’éducation, au soutien des familles, spécialement les migrants, et aux soins

médicaux de base. Là où des vies humaines sont en jeu, le temps est toujours

court : toutefois le monde a été témoin des immenses ressources que les

gouvernements peuvent mettre à disposition lorsqu’il s’agit de venir au secours

d’institutions financières retenues comme « trop importantes pour être vouées à

l’échec ». Il ne peut être mis en doute que le développement humain intégral

des peuples du monde n’est pas moins important : voilà bien une entreprise qui

mérite l’attention du monde, et qui est véritablement « trop importante pour

être vouée à l’échec ».

Ce panorama de récents

aspects de la coopération entre le Royaume-Uni et le Saint-Siège montre bien

tout les progrès qui ont été accomplis, au long des années qui se sont écoulées

depuis l’établissement de relations diplomatiques bilatérales, afin de

promouvoir, à travers le monde, les nombreuses valeurs fondamentales que nous

partageons. J’espère et je prie pour que ces relations continuent à être

fructueuses, et pour qu’elles se reflètent dans une acceptation croissante du

besoin de dialogue et de respect à tous les niveaux de la société entre le

monde de la raison et le monde de la foi. Je suis convaincu que, dans ce pays

également, il y a de nombreux domaines où l’Église et les autorités civiles

peuvent travailler ensemble pour le bien des habitants, en harmonie avec la

pratique historique de ce Parlement d’invoquer la guidance du Saint-Esprit sur

ceux qui cherchent à améliorer la condition de tous. Afin que cette coopération

soit possible, les groupes religieux – incluant des institutions en relation

avec l’Église catholique – ont besoin d’être libres pour agir en accord avec

leurs propres principes et leurs convictions spécifiques basés sur la foi et

l’enseignement officiel de l’Église. Ainsi, ces droits fondamentaux que sont la

liberté religieuse, la liberté de conscience et la liberté d’association,

seront garantis.

Les anges qui nous

regardent depuis le magnifique plafond de cet antique Palais, nous rappellent

la longue tradition à partir de laquelle le Parlement britannique a évolué. Ils

nous rappellent que Dieu veille constamment sur nous pour nous guider et nous

protéger. Et ils nous invitent à faire nôtre la contribution essentielle que la

croyance religieuse a apportée et continue d’apporter à la vie de la nation.

Monsieur le Speaker, je

vous remercie encore de cette invitation à m’adresser brièvement à cette

assemblée distinguée. Permettez-moi de vous assurer, vous-même et le Lord

Speaker, de mes vœux les meilleurs et de ma prière pour vous et pour les

travaux féconds des deux Chambres de cet antique Parlement. Merci, et que Dieu

vous bénisse !

*L'Osservatore Romano.

Edition hebdomadaire en langue française n°38 p.10, 11.

© Copyright 2010 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Copyright © Dicastero per

la Comunicazione - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Chelsea Old Town Hall, Sir Thomas More by Ludwig Cauer. Exhibited at the RA in

1895 and acquired for the library in 1896

INTRODUCTION

Thomas More écrivit en

latin et en anglais. Au début de sa carrière, il semble hésiter entre les deux

langues. La Vie (inachevée) de Richard III existe dans une version latine et

dans une version anglaise. On a de lui des poésies en anglais et d'autres en

latin. Puis, le latin l'emporte. C'est en latin qu'il écrit l'Utopie, commencée

aux Pays-Bas pendant l'été de 1515, achevée à Londres l'année suivante,

imprimée pour la première fois à Louvain par Thierry Martens en 1516. L'ouvrage

eut un tel succès qu'on pouvait s'attendre à voir l'auteur continuer dans cette

veine, et dans la langue qui faisait de l'Europe humaniste une seule et même

patrie intellectuelle. Il n'en est rien. Dès 1520, il revient exclusivement à

la préoccupation essentielle de sa jeunesse, qui avait été toute tournée vers

la vie religieuse, à telle enseigne qu'il avait songé à entrer dans les ordres.

À 42 ans (il est né en 1480), More est l'un des premiers avocats de Londres,

très apprécié de Henry VIII qui a 29 ans et qui est encore un fervent

catholique, au point de vouloir ferrailler contre Luther. Ce dernier ayant

publié la Captivité de Babylone, le roi y répondit par une Défense des Sept

Sacrements, à laquelle More a probablement collaboré. Sous le nom de Gulielmus

Rosseus, More publia encore une Réponse aux injures de Martin Luther, où il se

montre aussi peu modéré que son adversaire. C'était le ton en usage à cette

époque. Toutes ces polémiques sont en latin. Elles expriment mal le génie

véritable de More. Celui-ci n'était nullement fait pour la querelle, fût-elle

théologique. Il était fait pour s'adresser aux gens de son pays, et pour leur

exprimer, avec toute sa courtoisie, toute sa gentillesse naturelle, ce qu'il

pensait de la religion du Christ et du rôle qu'elle devait jouer dans la vie de

chacun.

Le désir de propager une

doctrine religieuse a joué un rôle capital dans le développement des langues

que l'on appelait alors, par opposition au latin, les langues vulgaires. C'est

pour atteindre le peuple que Luther a écrit en allemand, Calvin en français,

que Tyndale, bientôt passé à l'hérésie, traduisit la Bible en anglais. Si

Érasme avait suivi le mouvement, toute l'histoire des lettres néerlandaises

aurait été modifiée. Thomas More, dès 1522, renonce au latin et il écrit en

anglais, ce qui revient à dire qu'il préfère toucher les simples plutôt que de

rester dans le cercle des doctes. Ce choix a fait de lui un des fondateurs de

la prose anglaise. Il écrit une série d'œuvres, souvent conçues sous forme de

dialogues, qui circulèrent certainement de son vivant, au moins en manuscrits.

Mais, à partir de 1530, les rapports se tendirent entre Henry VIII et le pape.

Le roi voulait divorcer d'avec Catherine d'Aragon pour épouser Anne Boleyn et

le pape s'y opposait. More, dans l'intervalle, était devenu Sir Thomas et

chancelier d'Angleterre. Il ne pouvait admettre que l'on désobéît au pape, et

il finit par remettre au roi sa démission de chancelier. Puis, ce qui était

plus grave, il refusa le serment d'obéissance en matière religieuse, que le roi

exigeait. Cela lui valut d'être jugé, condamné pour trahison envers son

souverain, enfermé pendant quinze mois à la Tour et finalement décapité, sa

tête plongée ensuite dans l'eau bouillante pour qu'elle ne pût devenir objet de

vénération. Cela se passait le 6 juillet 1535. Henry vécut jusqu'en 1547. Les

œuvres religieuses de Thomas More ne purent donc pas être imprimées à Londres

avant la parenthèse catholique marquée par le règne de Marie Tudor. Elles

parurent en 1557. C'est un gros volume en lettres gothiques où figurent

seulement les textes anglais.

Ces ouvrages, le Traité

des fins dernières, le Dialogue concernant les hérésies et plusieurs sujets

religieux, la Supplique des âmes du purgatoire, la Réfutation contre Tyndale,

le Dialogue sur le réconfort dans les tribulations enfin, tous ont les mêmes

qualités. Une bonhomie, une humanité charmantes s'y marquent constamment, le

goût le plus simple et le plus vif pour la vie quotidienne observée d'un regard

amusé et pénétrant. Le Dialogue concernant les hérésies traite de diverses

matières telles que la vénération des images et reliques, les prières aux

saints, les pèlerinages, toutes questions brûlantes puisque la propagande

protestante portait précisément sur ces points. On y trouvera aussi, dit le

titre, « bien d'autres choses touchant la pestilentielle secte de Luther et

Tyndale ». Voilà, semble-t-il, une déclaration de guerre. Mais ouvrons le

volume. L'auteur suppose qu'un de ses amis lui communique par l'intermédiaire

d'un messager certains doutes concernant le catholicisme orthodoxe. More reçoit

le messager, l'écoute attentivement, cherche à comprendre son point de vue et

le réfute fermement, mais jamais sans se déprendre d'une parfaite tolérance. En

cours de route, il raconte des anecdotes, comme celle du faux miraculé

Saint-Alban, que Shakespeare a repris dans la seconde partie Henry VII (II, I).

On trouvera dans le présent ouvrage plus d'un intermède de ce genre, empreint

tantôt de la gaillardise des fabliaux, tantôt de la sagesse populaire des

contes d'animaux. Voyez la charmante fable de l'Âne et du Loup qui s'en vont à

confesse. More semble bien y avoir réuni deux histoires différentes : l'Âne

avec son sage confesseur et le Renard confesseur du Loup, aussi peu

recommandable que son pénitent. Elles s'accordent vaille que vaille pour

illustrer cette morale qu'il n'est pas bon d'avoir, trop de scrupules, mais que

cela vaut mieux encore que de n'en avoir point du tout.

Partout rayonne le

profond, le tonique optimisme de More en matière de religion et de morale, sa

confiance dans la raison humaine et dans la bonté de Dieu.

« Ces luthériens sont

fous qui voudraient maintenant tout balayer, excepté l'Écriture, toute science,

laquelle me paraît devoir être et avoir toujours été rangée opportunément au

service de la théologie. Et, comme l'a dit saint Jérôme, les Hébreux ont bien

pris les dépouilles des Égyptiens, les sages du Christ ont pris des auteurs

païens la richesse, la science et la sagesse que Dieu leur avait données et les

ont employées au service de la théologie pour le bénéfice des enfants choisis

par Dieu en Israël pour être l'Église du Christ, païens au cœur dur devenus

enfants d'Abraham » (English Works, p. 154).

Pour More en effet, la

tradition chrétienne n'est pas seulement constituée par l'Écriture, comme le

veulent les protestants, mais aussi par toute l'interprétation qu'en a donnée

et qu'en donne encore l'Église éternelle, et, enfin, par la foi vécue et

pratiquée à l'intérieur de la communauté chrétienne. C'est pourquoi celui qui

veut retourner aux sources de la vie religieuse ne peut se dispenser de lire,

avec les deux Testaments, les Pères et les Docteurs. Contre l'orgueil des

mystiques qui prétendent trouver Dieu dans un élan autonome venu du fond de

leur être, More établit la nécessité des études et l'utilité de la raison mise

au service de la foi. Puis, toujours, il revient à la vie quotidienne et tire

de l'expérience des leçons modestes et justes.

Parmi tous les ouvrages

religieux de More en langue anglaise, le Dialogue du réconfort contre la

tribulation occupe une place toute particulière. More l'a écrit à la Tour en

1534, pendant la longue et pénible captivité qui devait se terminer par son

supplice. On pouvait difficilement imaginer une tribulation plus accablante et

moins méritée. Nul doute qu'il n'ait souvent pensé à lui-même et demandé à Dieu

la grâce de faire servir l'épreuve à son salut. Et cependant, nulle part

n'affleure la moindre préoccupation personnelle, la moindre revendication, la

moindre aigreur. Repris comme au temps de l'Utopie par le goût de la fiction,

More veut que l'ouvrage ait été écrit en latin par un Hongrois, traduit du latin

en français puis du français en anglais, après quoi il parle de Budapest le

plus sérieusement du monde, comme s'il y avait été. Il avait un certain mérite

à monter cette mystification dans les conditions où il était. Au cours de tout

le traité, sa malicieuse bonhomie est aussi allègre que dans ses livres

précédents. La Tour était cependant un séjour terrible et le prisonnier ne

gardait aucune illusion sur le sort qui l'attendait. C'est bien l'homme qui

écrivait à sa fille, à la fin de sa détention :

« Le Seigneur me garde

véridique, fidèle et loyal. Sans cela, je le prie de tout mon cœur de ne pas me

laisser vivre. Car pour ce qui est d'une longue vie, comme je vous l'ai souvent

dit, Meg, je ne l'ai jamais envisagée ni désirée et je suis prêt à m'en aller

si Dieu m'appelle d'ici demain. Et grâce à Dieu je ne connais aucune personne

vivante que je voudrais voir affligée d'une chiquenaude pour ma vie sauve : de

cela je suis plus heureux que de tout le reste. »

Et ailleurs il lui donne

rendez-vous dans le ciel, « pour y être tous gais ensemble », « merry together

»... Jamais il ne perdit cette sérénité.

Le Dialogue n'est pas la

dernière des œuvres qu'il écrivit pendant sa captivité. Au cours des dernières

semaines de sa vie, il rédigea des méditations sur la Passion du Sauveur. Pour

cette Expositio Passionis, il revint au latin de ses jeunes années. Il ne put

terminer l'ouvrage. Les dernières lignes qu'il écrivit sont des réflexions sur

le moment où les soldats s'emparent de Jésus après la nuit au Mont des

Oliviers. Il faut s'imaginer Sir Thomas interrompu à cet endroit, posant la

plume, se levant et suivant, avec sa courtoisie habituelle, les soldats qui

l'emmènent vers le bourreau et le supplice.

Marie Delcourt. «

Introduction » à SAINT THOMAS MORE. Dialogue du réconfort dans les

tribulations

SOURCE : https://livres-mystiques.com/partieTEXTES/Thomas_More/table.htm

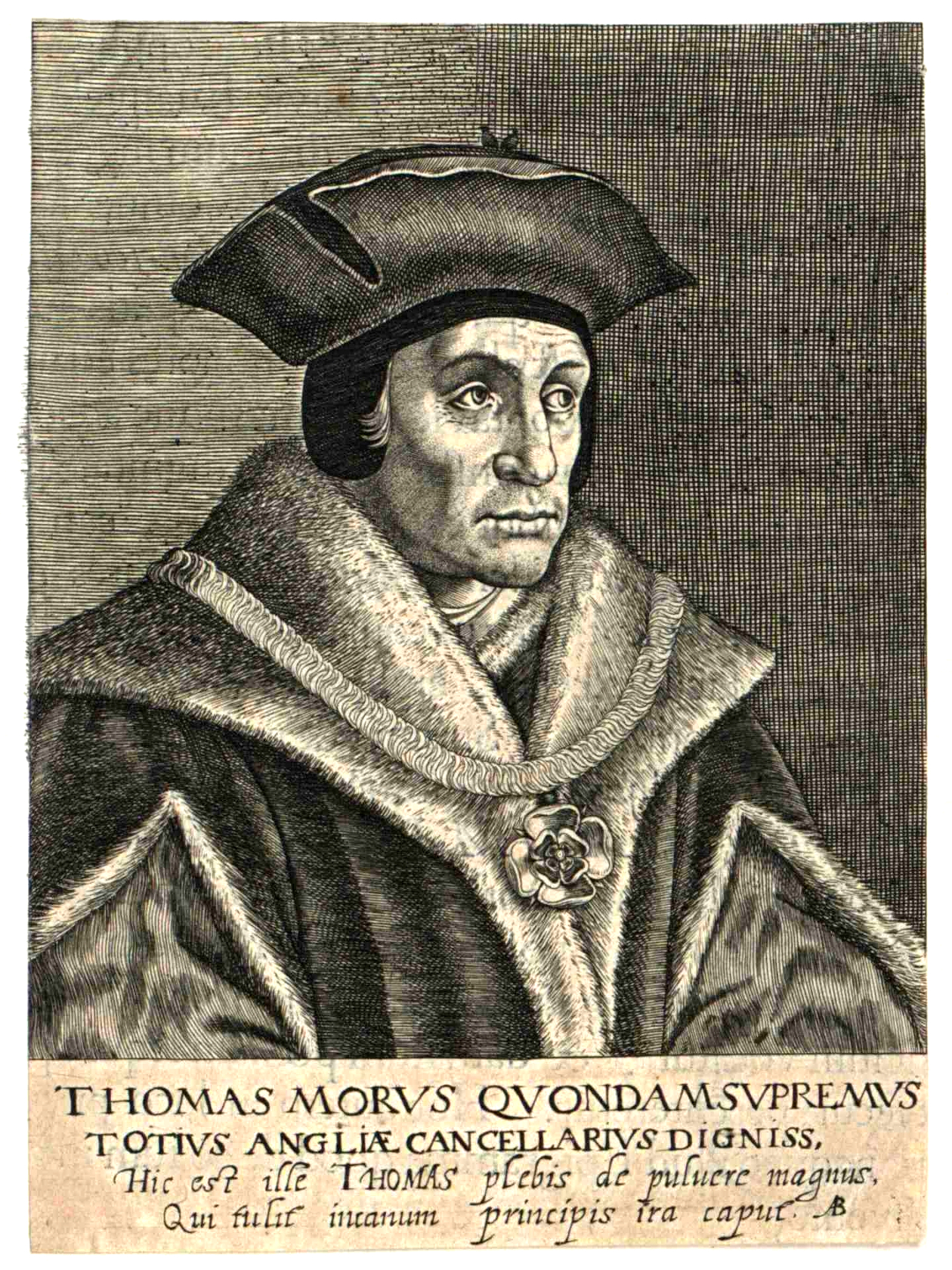

Academie des sciences et des arts, contenant les vies, et les eloges

historiques des hommes illustres [...] avec leurs pourtraits tirez sur des

originaux au naturel, et plusieurs inscriptions funebres, exactement

recueïllies de leurs tombeaux / par Isaac Bullart [...]. T. 1. Amsterdam, 1682.

National Library of Poland

Saint Thomas More

(1478 - 1535)

Saint Thomas More naquit

à Londres, le 7 février 1478. Son père remplissait la fonction de juge, dans la

capitale. Thomas passa quelques-unes de ses premières années en qualité de

page, au service du cardinal Morton, alors archevêque de Cantorbéry et

chancelier d’Angleterre. A l’âge de quatorze ans, il alla étudier à Oxford où

il fit de sérieuses études juridiques et suivit les conférences sur la Cité de

Dieu, de saint Augustin.

En 1501, Thomas More

était reçu avocat et élu membre du Parlement trois ans plus tard. Après

quelques années de mariage, il perdit sa femme et demeura seul avec ses quatre

enfants : trois filles et un fils. Il ne se remariera que beaucoup plus tard,

avec une veuve. En père vigilant, il veillait à ce que Dieu restât le centre de

la vie de ses enfants. Le soir, il récitait la prière avec eux ; aux repas, une

de ses filles lisait un passage de l’Ecriture Sainte et on discutait ensuite

sur le texte en conversant gaiement. Jamais la science, ni la vertu, ne prirent

un visage austère dans sa demeure ; sa piété n’en était cependant pas moins

profonde. Saint Thomas More entendait la messe tous les jours ; en plus de ses

prières du matin et du soir, il récitait les psaumes quotidiennement.

Sa valeur le fit nommer

Maître des Requêtes et conseiller privé du roi. En 1529, Thomas More remplaça

le défunt cardinal Wolsey dans la charge de Lord chancelier. Celui qui n’avait

jamais recherché les honneurs ni désiré une haute situation se trouvait placé

au sommet des dignités humaines. Les succès, pas plus que les afflictions,

n’eurent de prise sur sa force de caractère.

Lorsque Henri VIII voulut

divorcer pour épouser Anne Boleyn, et qu’il prétendit devant l’opposition

formelle du pape, se proclamer chef de l’Eglise d’Angleterre, saint Thomas More

blâma la conduite de son suzerain. Dès lors, les bonnes grâces du roi se

changèrent en hostilité ouverte contre lui. Le roi le renvoya sans aucune

ressource, car saint Thomas versait au fur à mesure tous ses revenus dans le

sein des pauvres. Le jour où il apprit que ses granges avaient été incendiées,

il écrivit à sa femme de rendre grâces à Dieu pour cette épreuve.

Le 12 avril 1554,

l’ex-chancelier fut invité à prononcer le serment qui reconnaissait Anne Boleyn

comme épouse légitime et rejetait l’autorité du pape. Saint Thomas rejeta

noblement toute espèce de compromis avec sa conscience et refusa de donner son

appui à l’adultère et au schisme. Après un second refus réitéré le 17 avril, on

l’emprisonna à la Tour de Londres. Il vécut dans le recueillement et la prière

durant les quatorze mois de son injuste incarcération.

Comme il avait fait de toute

sa vie une préparation à l’éternité, la sérénité ne le quittait jamais. Il

avoua bonnement : « Il me semble que Dieu fait de moi Son jouet et qu’Il me

berce. » L’épreuve de la maladie s’ajouta bientôt à celle de la réclusion.

Devenu semblable à un squelette, il ne cessa cependant de travailler en

écrivant des traités moraux, un traité sur la Passion, et même de joyeuses

satires.

L’intensité de sa prière

conservait sa force d’âme : « Donne-moi Ta grâce, Dieu bon, pour que je compte

pour rien le monde et fixe mon esprit sur Toi. » Il disait à sa chère fille

Marguerite : « Si je sens la frayeur sur le point de me vaincre, je me

rappellerai comment un souffle de vent faillit faire faire naufrage à Pierre

parce que sa foi avait faibli. Je ferai donc comme lui, j’appellerai le Christ

à mon secours. »

On accusa saint Thomas

More de haute trahison parce qu’il niait la suprématie spirituelle du roi.

Lorsque le simulacre de jugement qui le condamnait à être décapité fut terminé,

le courageux confesseur de la foi n’eut que des paroles de réconfort pour tous

ceux qui pleuraient sa mort imminente et injuste. A la foule des spectateurs,

il demanda de prier pour lui et de porter témoignage qu’il mourait dans la foi

et pour la foi de la Sainte Église catholique. Sir Kingston, connu pour son

coeur impitoyable, lui fit ses adieux en sanglotant. Il récita pieusement le

Miserere au pied de l’échafaud. Il demanda de l’aide pour monter sur l’échafaud

: « Pour la descente, ajouta-t-il avec humour, je m’en tirerai bien tout seul.

» Il embrassa son bourreau : « Courage, mon brave, n’aie pas peur, mais comme

j’ai le cou très court, attention ! il y va de ton honneur. » Il se banda les

yeux et se plaça lui-même sur la planche.

Béatifié par Léon XIII le

29 décembre 1886, sa canonisation eut lieu le 19 mai 1935.

SOURCE : http://viechretienne.catholique.org/saints/8-saint-thomas-more

John Rogers Herbert (1810–1890), Sir Thomas

More and his Daughter (Margaret Roper) , 1844, 110.5 x 85.1, Tate, National Gallery

Also

known as

omnium horarum homo (a

man for all seasons, referring to his wide scholarship and knowledge)

6 July (London, England;

Church of England)

1 December as

one of the Martyrs

of Oxford University

Profile

Studied at London and Oxford, England. Page for

the Archbishop of Canterbury. Lawyer.

Twice married,

and a widower he

was the father of

one son and three daughters, and a devoted family man. Writer,

most famously of the novel which coined the word Utopia. Translated with

works of Lucian. Known during his own day for his scholarship and

the depth of his knowledge. Friend of King Henry VIII.

Lord Chancellor of England from 1529 to 1532, a

position of political power second only to the king.

Fought any form of heresy,

especially the incursion of Protestantism into England.

Opposed the king on

the matter of royal divorce, and refused to swear the Oath of Supremacy which

declared the king the

head of the Church in England.

Resigned the Chancellorship,

and was imprisoned in

the Tower of London. Martyred for

his refusal to bend his religious beliefs to the king‘s

political needs.

Born

7 February 1478 at London, England

beheaded on 6 July 1535 on

Tower Hill, London, England

body taken to Saint Peter

ad Vincula, Tower of London, England

his head was parboiled

and then exposed on London Bridge for a month as a warning to other “traitors”;

Margaret Roper bribed the man whose was supposed to throw it into the river to

give it to her instead

in 1824 a

lead box was found in the Roper vault at Saint Dunstan’s Church Canterbury, England;

it contained a head presumed to be More’s

29 December 1886 by Pope Leo XIII

–

politicians (proclaimed

on 31

October 2000 by Pope John

Paul II)

statesmen (proclaimed

on 31

October 2000 by Pope John

Paul II)

–

Society

of Our Lady of Good Counsel

University

of Santo Tomas Faculty of Arts and Letters

–

Arlington, Virginia, diocese of

Pensacola-Tallahassee, Florida, diocese of

–

English Lord Chancellor carrying

a book

English Lord Chancellor carrying

an axe

Additional

Information

A

Catholic of the Renaissance, by Father Henry

Browne, S.J.

A

Great Lord Chancellor, by Lord Justice Russell

A

National Bulwark Against Tyranny, by Father Bede

Jarrett, O.P.

A

Saint Who Was A Lawyer, by Eileen Taylor

A

Turning Point in History, by G K Chesterton

Book

of Saints, by Father Lawrence

George Lovasik, S.V.D.

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Catholic

Tradition in English Literature, by George Carver

Conscience

or King?, by Mrs Lang

Franciscan

Herald, by Father Francis

Borgia, O.F.M.

Life

of Sir Thomas More, by William Roper

Margaret

Roper, Daughter of Sir Thomas More, Chancellor of England, by Anna Theresa

Sadlier

Mementoes

of the English Martyrs and Confessors, by Father Henry

Sebastian Bowden

Relics

of Saints John Fisher and Thomas More, by Monsignor P

E Hallett

Roman

Martyrology, 1914 edition

Saint

Thomas More Today, by Marie and Tony Shannon

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

Sir

Thomas More’s Fame Among His Countrymen, by Professor R

W Chambers

The

Charge of Religious Intolerance, by Father Ronald

Knox

The

Glory of Chelsea, by Reginald Blunt

The

Witness to Abstract Truth, by Hilaire Belloc

—

Dialogue

of Comfort Against Tribulation, by Saint Thomas

Treatise

on the Blessed Sacrament, by Saint Thomas

books

Catholic Martyrs of

England and Wales 1535-1680, by the Catholic Truth Society

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

Oxford Dictionary of Saints, by David Hugh Farmer

Saints

and Their Attributes, by Helen Roeder

other

sites in english

1001 Patron Saints and Their Feast Days, Australian

Catholic Truth Society

American Catholic: Patron Saint of Politicians

Center for

Thomas More Studies

Saint Thomas

More Church, Cherry Hill, New Jersey

images

audio

Catholic Culture: Dialogue on Conscience, by Saint Thomas

More

Utopia –

librivox audio book

video

A Dialogue of Comfort in Tribulation, by Saint Thomas More

(audio book)

e-books

on other sites

Life

and Letters of Sir Thomas More, by Agnes M Stewart

Life

and Writings of Sir Thomas More, by Father T E Bridgett

Life

of Sir Thomas More, by Cresacre More

Life

of Sir Thomas More, by William Roper

Memoirs

of Sir Thomas More, volume 1, by Arthur Cayley

Memoirs

of Sir Thomas More, volume 2, by Arthur Cayley

Sir Thomas

More, by Henry Bremond

Sir

Thomas More, His Life and Times, by W Joseph Walter

The

Story of Blessed Thomas More, by a Nun of Tyburn Convent

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites

en français

Dicastero delle Cause dei Santi

Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

Readings

What does it avail to

know that there is a God, which you not only believe by Faith, but also know by

reason: what does it avail that you know Him if you think little of Him? –

Saint Thomas More

What men call fame is,

after all, but a very windy thing. A man things that many are praising him, and

talking of him alone, and yet they spend but a very small part of the day

thinking of him, being occupied with things of their own. – Saint Thomas

More

Although I know well,

Margaret, that because of my past wickedness I deserve to be abandoned by God,

I cannot but trust in his merciful goodness. His grace has strengthened me

until now and made me content to lose goods, land, and life as well, rather than

to swear against my conscience. God’s grace has given the king a gracious frame

of mind toward me, so that as yet he has taken from me nothing but my liberty.

In doing this His Majesty has done me such great good with respect to spiritual

profit that I trust that among all the great benefits he has heaped so

abundantly upon me I count my imprisonment the very greatest. I cannot,

therefore, mistrust the grace of God. By the merits of his bitter passion

joined to mine and far surpassing in merit for me all that I can suffer myself,

his bounteous goodness shall release me from the pains of purgatory and shall

increase my reward in heaven besides. I will not mistrust him, Meg, though I

shall feel myself weakening and on the verge of being overcome with fear. I shall

remember how Saint Peter at a blast of wind began to sink because of his lack

of faith, and I shall do as he did: call upon Christ and pray to him for help.

And then I trust he shall place his holy hand on me and in the stormy seas hold

me up from drowning. And finally, Margaret, I know this well: that without my

fault he will not let me be lost. I shall, therefore, with good hope commit

myself wholly to him. And if he permits me to perish for my faults, then I

shall serve as praise for his justice. But in good faith, Meg, I trust that his

tender pity shall keep my poor soul safe and make me commend his mercy. And,

therefore, my own good daughter, do not let you mind be troubled over anything

that shall happen to me in this world. Nothing can come but what God wills. And

I am very sure that whatever that be, however bad it may seem, it shall indeed

be the best. – from a letter written by Saint Thomas More from prison to

his daughter Margaret

Grant me, O Lord, good

digestion, and also something to digest. Grant me a healthy body, and the

necessary good humor to maintain it. Grant me a simple soul that knows to

treasure all that is good and that doesn’t frighten easily at the sight of

evil, but rather finds the means to put things back in their place. Give me a

soul that knows not boredom, grumblings, sighs and laments, nor excess of

stress, because of that obstructing thing called “I”. Grant me, O Lord, a sense

of good humor. Allow me the grace to be able to take a joke to discover in life

a bit of joy, and to be able to share it with others. Amen. – Saint Thomas

More

O God, who in martyrdom

have brought true faith to its highest expression, graciously grant that,

strengthened through the intercession of Saints John Fisher and Thomas More, we

may confirm by the witness of our life the faith we profess with our lips.

Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the

unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. – liturgical collect

MLA

Citation

“Saint Thomas

More“. CatholicSaints.Info. 6 January 2025. Web. 13 May 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-thomas-more/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-thomas-more/

Statue

of Thomas More, Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, London. Chelsea Old Church in background.

21 January 2006. Photographer: Fin Fahey.

Statua

di Tommaso Moro vicino alla chiesa vecchia di Chelsea,

Londra

Statue

of Thomas More, Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, London. Chelsea Old Church in background.

21 January 2006. Photographer: Fin Fahey.

Statua

di Tommaso Moro vicino alla chiesa vecchia di Chelsea,

Londra

APOSTOLIC LETTER

ISSUED MOTU PROPRIO

PROCLAIMING SAINT THOMAS

MORE

PATRON OF STATESMEN AND

POLITICIANS

POPE JOHN PAUL II

FOR PERPETUAL REMEMBRANCE

1. The life and martyrdom

of Saint Thomas More have been the source of a message which spans the

centuries and which speaks to people everywhere of the inalienable dignity of

the human conscience, which, as the Second Vatican Council reminds us, is "the

most intimate centre and sanctuary of a person, in which he or she is alone

with God, whose voice echoes within them" (Gaudium et Spes, 16). Whenever

men or women heed the call of truth, their conscience then guides their actions

reliably towards good. Precisely because of the witness which he bore, even at

the price of his life, to the primacy of truth over power, Saint Thomas More is

venerated as an imperishable example of moral integrity. And even outside the

Church, particularly among those with responsibility for the destinies of

peoples, he is acknowledged as a source of inspiration for a political system

which has as its supreme goal the service of the human person.

Recently, several Heads

of State and of Government, numerous political figures, and some Episcopal

Conferences and individual Bishops have asked me to proclaim Saint Thomas More

the Patron of Statesmen and Politicians. Those supporting this petition include

people from different political, cultural and religious allegiances, and this

is a sign of the deep and widespread interest in the thought and activity of

this outstanding Statesman.

2. Thomas More had a

remarkable political career in his native land. Born in London in 1478 of a

respectable family, as a young boy he was placed in the service of the

Archbishop of Canterbury, John Morton, Lord Chancellor of the Realm. He then

studied law at Oxford and London, while broadening his interests in the spheres

of culture, theology and classical literature. He mastered Greek and enjoyed

the company and friendship of important figures of Renaissance culture,

including Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam.

His sincere religious

sentiment led him to pursue virtue through the assiduous practice of

asceticism: he cultivated friendly relations with the Observant Franciscans of

the Friary at Greenwich, and for a time he lived at the London Charterhouse,

these being two of the main centres of religious fervour in the Kingdom.

Feeling himself called to marriage, family life and dedication as a layman, in

1505 he married Jane Colt, who bore him four children. Jane died in 1511 and

Thomas then married Alice Middleton, a widow with one daughter. Throughout his

life he was an affectionate and faithful husband and father, deeply involved in

his children’s religious, moral and intellectual education. His house offered a

welcome to his children’s spouses and his grandchildren, and was always open to

his many young friends in search of the truth or of their own calling in life.

Family life also gave him ample opportunity for prayer in common and lectio

divina, as well as for happy and wholesome relaxation. Thomas attended daily

Mass in the parish church, but the austere penances which he practised were

known only to his immediate family.

3. He was elected to

Parliament for the first time in 1504 under King Henry VII. The latter’s

successor Henry VIII renewed his mandate in 1510, and even made him the Crown’s

representative in the capital. This launched him on a prominent career in

public administration. During the following decade the King sent him on several

diplomatic and commercial missions to Flanders and the territory of present-day

France. Having been made a member of the King’s Council, presiding judge of an

important tribunal, deputy treasurer and a knight, in 1523 he became Speaker of

the House of Commons.

Highly esteemed by

everyone for his unfailing moral integrity, sharpness of mind, his open and

humorous character, and his extraordinary learning, in 1529 at a time of

political and economic crisis in the country he was appointed by the King to

the post of Lord Chancellor. The first layman to occupy this position, Thomas

faced an extremely difficult period, as he sought to serve King and country. In

fidelity to his principles, he concentrated on promoting justice and

restraining the harmful influence of those who advanced their own interests at

the expense of the weak. In 1532, not wishing to support Henry VIII’s intention

to take control of the Church in England, he resigned. He withdrew from public

life, resigning himself to suffering poverty with his family and being deserted

by many people who, in the moment of trial, proved to be false friends.

Given his inflexible

firmness in rejecting any compromise with his own conscience, in 1534 the King

had him imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he was subjected to various

kinds of psychological pressure. Thomas More did not allow himself to waver,

and he refused to take the oath requested of him, since this would have

involved accepting a political and ecclesiastical arrangement that prepared the

way for uncontrolled despotism. At his trial, he made an impassioned defence of

his own convictions on the indissolubility of marriage, the respect due to the

juridical patrimony of Christian civilization, and the freedom of the Church in

her relations with the State. Condemned by the Court, he was beheaded.

With the passing of the

centuries discrimination against the Church diminished. In 1850 the English

Catholic Hierarchy was re-established. This made it possible to initiate the

causes of many martyrs. Thomas More, together with 53 other martyrs, including

Bishop John Fisher, was beatified by Pope Leo XIII in 1886. And with John

Fisher, he was canonized by Pius XI in 1935, on the fourth centenary of his

martyrdom.

4. There are many reasons

for proclaiming Thomas More Patron of statesmen and people in public life.

Among these is the need felt by the world of politics and public administration

for credible role models able to indicate the path of truth at a time in

history when difficult challenges and crucial responsibilities are increasing.

Today in fact strongly innovative economic forces are reshaping social

structures; on the other hand, scientific achievements in the area of

biotechnology underline the need to defend human life at all its different

stages, while the promises of a new society — successfully presented to a

bewildered public opinion — urgently demand clear political decisions in favour

of the family, young people, the elderly and the marginalized.

In this context, it is

helpful to turn to the example of Saint Thomas More, who distinguished himself

by his constant fidelity to legitimate authority and institutions precisely in

his intention to serve not power but the supreme ideal of justice. His life

teaches us that government is above all an exercise of virtue. Unwavering in

this rigorous moral stance, this English statesman placed his own public

activity at the service of the person, especially if that person was weak or

poor; he dealt with social controversies with a superb sense of fairness; he

was vigorously committed to favouring and defending the family; he supported

the all-round education of the young. His profound detachment from honours and

wealth, his serene and joyful humility, his balanced knowledge of human nature

and of the vanity of success, his certainty of judgement rooted in faith: these

all gave him that confident inner strength that sustained him in adversity and

in the face of death. His sanctity shone forth in his martyrdom, but it had

been prepared by an entire life of work devoted to God and neighbour.

Referring to similar

examples of perfect harmony between faith and action, in my Post-Synodal

Apostolic Exhortation Christifideles Laici I wrote: "The unity of life of

the lay faithful is of the greatest importance: indeed they must be sanctified

in everyday professional and social life. Therefore, to respond to their

vocation, the lay faithful must see their daily activities as an occasion to

join themselves to God, fulfil his will, serve other people and lead them to

communion with God in Christ" (No. 17).

This harmony between the

natural and the supernatural is perhaps the element which more than any other

defines the personality of this great English statesman: he lived his intense

public life with a simple humility marked by good humour, even at the moment of

his execution.

This was the height to

which he was led by his passion for the truth. What enlightened his conscience

was the sense that man cannot be sundered from God, nor politics from morality.

As I have already had occasion to say, "man is created by God, and

therefore human rights have their origin in God, are based upon the design of

creation and form part of the plan of redemption. One might even dare to say

that the rights of man are also the rights of God" (Speech, 7 April 1998).

And it was precisely in

defence of the rights of conscience that the example of Thomas More shone

brightly. It can be said that he demonstrated in a singular way the value of a

moral conscience which is "the witness of God himself, whose voice and

judgment penetrate the depths of man’s soul" (Encyclical Letter Veritatis

Splendor, 58), even if, in his actions against heretics, he reflected the

limits of the culture of his time.

In the Constitution

Gaudium et Spes, the Second Vatican Council notes how in the world today there

is "a growing awareness of the matchless dignity of the human person, who

is superior to all else and whose rights and duties are universal and

inviolable" (No. 26). The life of Saint Thomas More clearly illustrates a

fundamental truth of political ethics. The defence of the Church’s freedom from

unwarranted interference by the State is at the same time a defence, in the

name of the primacy of conscience, of the individual’s freedom vis-à-vis

political power. Here we find the basic principle of every civil order

consonant with human nature.

5. I am confident

therefore that the proclamation of the outstanding figure of Saint Thomas More

as Patron of Statesmen and Politicians will redound to the good of society. It

is likewise a gesture fully in keeping with the spirit of the Great Jubilee

which carries us into the Third Christian Millennium.

Therefore, after due

consideration and willingly acceding to the petitions addressed to me, I

establish and declare Saint Thomas More the heavenly Patron of Statesmen and

Politicians, and I decree that he be ascribed all the liturgical honours and

privileges which, according to law, belong to the Patrons of categories of

people.

Blessed and glorified be

Jesus Christ, the Redeemer of man, yesterday, today and for ever.

Given at Saint Peter’s,

on the thirty-first day of October in the year 2000, the twenty-third of my

Pontificate.

IOANNES PAULUS PP. II

© Copyright 2000 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS

BENEDICT XVI*

Mr Speaker,

Thank you for your words

of welcome on behalf of this distinguished gathering. As I address you, I am

conscious of the privilege afforded me to speak to the British people and their

representatives in Westminster Hall, a building of unique significance in the

civil and political history of the people of these islands. Allow me also to

express my esteem for the Parliament which has existed on this site for

centuries and which has had such a profound influence on the development of

participative government among the nations, especially in the Commonwealth and

the English-speaking world at large. Your common law tradition serves as the

basis of legal systems in many parts of the world, and your particular vision

of the respective rights and duties of the state and the individual, and of the

separation of powers, remains an inspiration to many across the globe.

As I speak to you in this

historic setting, I think of the countless men and women down the centuries who

have played their part in the momentous events that have taken place within

these walls and have shaped the lives of many generations of Britons, and

others besides. In particular, I recall the figure of Saint Thomas More, the

great English scholar and statesman, who is admired by believers and non-believers

alike for the integrity with which he followed his conscience, even at the cost

of displeasing the sovereign whose “good servant” he was, because he chose to

serve God first. The dilemma which faced More in those difficult times, the

perennial question of the relationship between what is owed to Caesar and what

is owed to God, allows me the opportunity to reflect with you briefly on the

proper place of religious belief within the political process.

This country’s

Parliamentary tradition owes much to the national instinct for moderation, to

the desire to achieve a genuine balance between the legitimate claims of

government and the rights of those subject to it. While decisive steps have

been taken at several points in your history to place limits on the exercise of

power, the nation’s political institutions have been able to evolve with a

remarkable degree of stability. In the process, Britain has emerged as a

pluralist democracy which places great value on freedom of speech, freedom of

political affiliation and respect for the rule of law, with a strong sense of

the individual’s rights and duties, and of the equality of all citizens before

the law. While couched in different language, Catholic social teaching has much

in common with this approach, in its overriding concern to safeguard the unique

dignity of every human person, created in the image and likeness of God, and in

its emphasis on the duty of civil authority to foster the common good.

And yet the fundamental

questions at stake in Thomas More’s trial continue to present themselves in

ever-changing terms as new social conditions emerge. Each generation, as it

seeks to advance the common good, must ask anew: what are the requirements that

governments may reasonably impose upon citizens, and how far do they extend? By

appeal to what authority can moral dilemmas be resolved? These questions take

us directly to the ethical foundations of civil discourse. If the moral

principles underpinning the democratic process are themselves determined by

nothing more solid than social consensus, then the fragility of the process

becomes all too evident - herein lies the real challenge for democracy.

The inadequacy of

pragmatic, short-term solutions to complex social and ethical problems has been

illustrated all too clearly by the recent global financial crisis. There is

widespread agreement that the lack of a solid ethical foundation for economic

activity has contributed to the grave difficulties now being experienced by

millions of people throughout the world. Just as “every economic decision has a

moral consequence” (Caritas

in Veritate, 37), so too in the political field, the ethical dimension of

policy has far-reaching consequences that no government can afford to ignore. A

positive illustration of this is found in one of the British Parliament’s

particularly notable achievements – the abolition of the slave trade. The campaign

that led to this landmark legislation was built upon firm ethical principles,

rooted in the natural law, and it has made a contribution to civilization of

which this nation may be justly proud.

The central question at

issue, then, is this: where is the ethical foundation for political choices to

be found? The Catholic tradition maintains that the objective norms governing

right action are accessible to reason, prescinding from the content of

revelation. According to this understanding, the role of religion in political

debate is not so much to supply these norms, as if they could not be known by

non-believers – still less to propose concrete political solutions, which would

lie altogether outside the competence of religion – but rather to help purify

and shed light upon the application of reason to the discovery of objective

moral principles. This “corrective” role of religion vis-à-vis reason is not

always welcomed, though, partly because distorted forms of religion, such as

sectarianism and fundamentalism, can be seen to create serious social problems

themselves. And in their turn, these distortions of religion arise when