Saint Jean de Dieu, religieux

A huit ans, pour des raisons que l'on ignore, le petit portugais Joao Ciudad fait une fugue et se retrouve, vagabond, sur les routes. Pendant 33 ans, il va mener une vie d'errance : enfant-volé puis abandonné par un prêtre-escroc, il parcourt l'Espagne. Tour à tour berger, soldat, valet, mendiant, journalier, infirmier, libraire... Le vagabond, un moment occupé à guerroyer contre les Turcs en Hongrie, se retrouve à Gibraltar. Et c'est là qu'un sermon de saint Jean d'Avila le convertit. Il en est si exalté qu'on le tient pour fou et qu’on l'enferme. Puis son dévouement éclot en œuvres caritatives. Tout ce qu'il a découvert et souffert, va le faire devenir bon et miséricordieux pour les misérables. Il collecte pour eux, ouvre un hôpital, crée un Ordre de religieux, l'Ordre de la Charité. L'hôpital qu'il a fondé à Grenade donnera naissance aux Frères Hospitaliers de Saint Jean de Dieu. Au moment de mourir, en 1550, il dira: "Il reste en moi trois sujets d'affliction : mon ingratitude envers Dieu, le dénuement où je laisse les pauvres, les dettes que j'ai contractées pour les soutenir."

Pompeo Marchesi (1783-1858), Monument to Saint John of God (1827) in Milan, Italy. It stands in the courtyard of the former Hospital "Fatebenesorelle" in Milan, currently absorbed by the Hospital "Fatebenefratelli", in whose original building it stood previously. Picture by Giovanni Dall'Orto, October 22 2008.

Saint Jean de Dieu

Fondateur des Frères de la Charité (+ 1550)

A huit ans, pour des raisons que l'on ignore, le petit portugais Joao Ciudad fait une fugue et se retrouve, vagabond, sur les routes. Pendant 33 ans, il va mener une vie d'errance: enfant-volé puis abandonné par un prêtre-escroc, il parcourt l'Espagne. Tour à tour berger, soldat, valet, mendiant, journalier, infirmier, libraire... Le vagabond, un moment occupé à guerroyer contre les Turcs en Hongrie, se retrouve à Gibraltar. Et c'est là qu'un sermon de saint Jean d'Avila le convertit. Il en est si exalté qu'on l'enferme avec les fous. Puis son dévouement éclot en œuvres caritatives. Tout ce qu'il a découvert et souffert, va le faire devenir bon et miséricordieux pour les misérables. Il collecte pour eux, ouvre un hôpital, crée un Ordre de religieux, l'Ordre de la Charité. L'hôpital qu'il a fondé à Grenade donnera naissance aux Frères Hospitaliers de Saint Jean de Dieu. Au moment de mourir, il dira: "Il reste en moi trois sujets d'affliction : mon ingratitude envers Dieu, le dénuement où je laisse les pauvres, les dettes que j'ai contractées pour les soutenir."

- vidéo Saint Jean de Dieu - l'hospitalité (WebTv de la CEF)

- site internet de l'Ordre Hospitalier de Saint Jean de Dieu - Province de France.

- site de la Fondation Saint Jean de Dieu, en 2016, cette fête a pris un sens tout particulier du fait qu'elle coïncidait avec l'Année de la miséricorde voulue par le pape François.

- Un internaute nous signale que St Jean de Dieu, a été déclaré Protecteur des hôpitaux et des malades, en même temps que St Camille de Lellis, par Léon XIII le 22 juin 1886. Pie XI les proclame, tous deux, patrons du personnel des hôpitaux.

Mémoire de saint Jean de Dieu, religieux. Né au Portugal, après une vie pleine

d'aventures et de périls, où il fut tour à tour en Espagne berger, régisseur,

soldat, pèlerin et marchand d'images, mais avec le désir d'une vie meilleure,

il construisit à Grenade un hôpital où il servit et soigna avec une constante

charité les pauvres et les malades, et s'adjoignit des compagnons qui

constituèrent plus tard l'Ordre des Hospitaliers de Saint Jean de Dieu. Il s'en

alla vers le repos éternel en 1550.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/772/Saint-Jean-de-Dieu.html

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617–1682). San Juan de Dios (1495-1550), circa 1672, 79 x 62, Hospital de la Santa Caridad (de orígen portugués y fundador de la Orden Hospitalaria de San Juan de Dios. En la obra, el santo cae a tierra por llevar a un enfermo, y el Arcángel Gabriel aparece milagrosamente para ayudarle)

Fondateur des Frères de la Charité

(1495-1550)

Saint Jean de Dieu naquit en Portugal, de parents pauvres, mais chrétiens. Sa

jeunesse, à la différence de celle de la plupart des Saints, fut très orageuse.

Âgé de huit ans, il suivit, à l'insu de ses parents, les traces d'un voyageur

qui se rendait à Madrid; mais il se perdit et fut réduit à se faire le valet

d'un berger. Plus tard, il s'enrôla dans l'armée de Charles-Quint et subit

l'entraînement et le mauvais exemple. Il ne fallut pas moins qu'un coup de la

Providence pour l'arracher au péril.

Après quelques nouvelles aventures, il apprit la nouvelle de la mort de sa mère

et résolut de se convertir. Il tint parole, et dès lors il passa la plus grande

partie de ses jours et de ses nuits dans la prière et la pénitence, exerçant à

toute occasion, malheureux, lui-même, la charité envers les malheureux. Ce ne

fut point là toutefois le terme de ses pérégrinations incertaines; il ne trouva

sa voie que plus tard, à l'âge de quarante-cinq ans.

Il s'établit à Grenade, s'y livra à quelque commerce et employa ses économies

et les dons de la charité à la fondation d'un hôpital qui prit bientôt de

prodigieux accroissements. On vit bien alors que cet homme, traité partout

d'abord comme un fou, était un saint.

Pour procurer des aliments à ses nombreux malades, Jean, une hotte sur le dos

et une marmite à chaque bras, parcourait les rues de Grenade en criant:

"Mes frères, pour l'amour de Dieu, faites-vous du bien à vous-mêmes."

Sa sollicitude s'étendait à tous les malheureux qu'il rencontrait; il se

dépouillait de tout pour les couvrir et leur abandonnait tout ce qu'il avait,

confiant en la Providence, qui ne lui manqua jamais.

Mais Jean, appelé par la voix populaire Jean de Dieu, ne suffisait pas à son

oeuvre; les disciples affluèrent; un nouvel Ordre se fondait, qui prit le nom

de Frères Hospitaliers de Saint-Jean-de-Dieu, et s'est répandu en l'Europe

entière. Peu de Saints ont atteint un pareil esprit de mortification,

d'humilité et de mépris de soi-même.

Un jour, la Mère de Dieu lui apparut, tenant en mains une couronne d'épines, et

lui dit: "Jean, c'est par les épines que tu dois mériter la couronne du

Ciel. -- Je ne veux, répondit-il, cueillir d'autres fleurs que les épines de la

Croix; ces épines sont mes roses."

Une autre fois, un pauvre qu'il soignait disparut en lui disant: "Tout ce

que tu fais aux pauvres, c'est à Moi que tu le fais." Quand on lit

l'histoire émouvante de telles vies, on ne peut s'empêcher de s'écrier: Dieu

est admirable dans Ses Saints !

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame,

1950.

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_jean_de_dieu.html

Statue of St. John of God at the Church of Vilar de Frades, Barcelos, Portugal. The inscription reads: All things pass, only good works last

Saint Jean de Dieu

Jean de Dieu est

né en 1495 à Montemor-o-Novo au Portugal, au sein d’une famille pauvre. Quand

il n’avait pas encore 10 ans, ses parents s’établirent à Oropesa en Espagne.

Il commença par mener une

vie des plus aventureuses : enlevé enfant par un inconnu, puis abandonné, il

devint berger puis, en 1523 s’engagea dans l’armée et participa à de nombreuses

guerres, la dernière en 1532 avec Charles Quint contre les Turcs. Ce fut pour

lui une dure expérience.

En 1535 il se mit à

travailler comme tailleur de pierre pour la fortification de la ville de Ceuta.

Il aida, avec ses maigres revenus une noble famille portugaise qui vivait

ruiné. Plus tard il alla à Gibraltar, où il se dit vendeur ambulant de livres

et de timbres. Il déménagea définitivement à Grenade en 1538 et ouvrit une

petite librairie.

C’est là qu’il eut ses

premiers contacts avec des livres religieux.

Le 20 janvier 1539, à

l’âge de 42 ans il se rendit à un sermon de Jean d'Avila, au cours duquel il

eut sa conversion. Les propos de Jean d'Avila provoquèrent en lui un si grand

choc qu’il se mit à détruire les livres qu’il vendait, se mit à traverser nu la

ville sous les huées des enfants qui le suivaient. Son comportement fut

considéré comme celui d'un aliéné et il fut incarcéré dans l’hôpital

psychiatrique de l’Hopital Real, avec les fous et les mendiants. Il prend alors

la résolution de s’occuper et de servir les malades. Jean d'Avila fut son

directeur spirituel, et le poussa faire un pèlerinage au sanctuaire de la

Vierge de Guadeloupe, en Estrémadure.

Sorti de l'asile, il

fonde à Grenade en Espagne, en 1537, son premier hôpital, selon des conceptions

très hardies pour son temps. Des disciples se joignent à lui ; ensemble, ils

posent les fondements d'un ordre hospitalier au service des pauvres malades :

les Frères de la Charité, appelé de nos jours l'Ordre hospitalier de Saint Jean

de Dieu.

Rainer Maria Rilke

raconte, dans ses Cahiers de Malte

Laurids Brigge (Die Aufzeichnungen

des Malte Laurids Brigge), qu'en train d'agoniser, Saint Jean-de-Dieu se

leva soudain pour aller détacher dans un jardin proche un homme qui venait de

se pendre.

Il a été proclamé par

Léon XIII patron des malades et des hôpitaux en 1886, et par Pie XI, patron des

infirmiers et infirmières en 1930.

SOURCE : http://auto23652.centerblog.net/6583297-Jean-de-Dieu

Manuel Gómez-Moreno González (1880). San Juan de Dios salvando a los enfermos de incendio del Hospital Real (St. John of God saving the Sick from a Fire at the Royal Hospital in 1549), circa 1880, 310 x 195, Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes, Granada

Saint Jean de Dieu

Saint Jean de Dieu naquit

le 8 mars 1495 à Montemor-O-Novo, au diocèse d’Evora, dans la province

portugaise d'Alemtéjo, des artisans André et Thérèse Ciudad. Ses parents

l’élevèrent dans des sentiments chrétiens. Jean avait huit ans lorsque ses

parents donnèrent l’hospitalité à un prêtre qui se rendait à Madrid ; ce prêtre

dit tant de bien des œuvres de bienfaisances qui s’accomplissaient en Espagne,

que l’enfant s’enfuit en secret de la maison paternelle pour le rejoindre. Ses

parents le rechèrent sans succès puis sa mère tomba malade. Un soir, elle dit à

son mari : « André, ne le cherche plus, nous ne reverrons pas notre enfant en

ce monde ; son ange gardien m’est apparu pour me dire : Ne vous désespérez pas,

mais bénissez le Seigneur, je suis chargé de le garder et il est en lieu sûr. »

Thérèse ajouta : « Pour moi, je quitte ce monde sans regret ; lorsque je ne

serai plus, André, pense à assurer ton salut, consacre-toi à Dieu. » Vingt

jours après la disparition de son fils, Thérèse mourut et André, renonçant au

monde, entra dans un couvent franciscain de Lisbonne.

Cependant, Jean avait

rejoint le prêtre sur la route de Madrid mais, arrivé à Oropeza

(Nouvelle-Castille), il fut incapable d’aller plus loin ; le prêtre le confia

au mayoral du comte dont il devint l’un des bergers. Dix ans plus tard, Jean

qui avait appris à lire, à écrire et à calculer se vit confier l’administration

de la ferme du mayoral qui prospéra au delà de toute attente ; son maître fut

si content de lui qu’il lui proposa d’épouser sa fille. Or, comme Jean avait

fait le vœu de se consacrer uniquement à Dieu et que, malgré ses refus, le

mayoral revenait à la charge, il prit la fuite pour s'engager dans les armées

de Charles Quint.

Le comte d’Oropeza avait

reçu l’ordre de lever des troupes pour débloquer Fontarabie qu’assiégeait une

armée française. Pendant cette campagne, sans imiter les mauvais exemples des

soudards espagnols, Jean perdit tout de même un peu des pratiques spéciales de

la dévotion qu’il avait pour la Sainte Vierge. Alors qu’il était tombé de

cheval et laissé sans connaissance sur le bord du chemin où les Français

avaient bien des chances de le faire prisonnier, réveillé, il invoqua Marie qui

lui apparut pour le ramener sain et sauf dans le camp espagnol. Après avoir été

faussement accusé d’avoir volé le butin dont il avait la garde, Jean, sauvé de

la pendaison par un officier supérieur, quitta l’armée espagnole. Il passa deux

jours à genoux, au bord de la route, à méditer au pied d’un calvaire et se

résolut à revenir dans la maison du mayoral qui l’accueillit comme un fils et

lui rendit l’administration de ses biens.

S’avisant que les animaux

de la ferme étaient mieux traités que les hommes et que l’on n’hésitait pas à

dépenser pour eux tandis que les mendiants étaient renvoyés, Jean pensa que son

temps serait mieux employé à soigner les pauvres qu’à engraisser les bêtes,

sans pour autant savoir comment s’y prendre. Le mayoral étant revenu à ses

anciens projets de mariage, Jean s’enrôla de nouveau dans les armées. En 1522,

après avoir participé à la défense victorieuse de Vienne contre Soliman II, il

quitta l'armée et, après avoir fait un pèlerinage à Saint-Jacques de

Compostelle, retourna au Portugal où il apprit d’un vieil oncle maternel,

dernier survivant de sa famille, la mort de ses parents. Il résolut d’aller en

Afrique pour soulager les chrétiens que les musulmans retenaient en esclavage.

A Gibraltar, il se fit serviteur bénévole du comte Sylva que Jean III venait

d’exiler à Ceuta (Afrique). Il passa en Afrique où il soigna jusqu’à la mort le

comte Sylva.

Jean se proposait de

ramener à l’Eglise les chrétiens qui avaient apostasié, mais un franciscain de

Ceuta lui ordonna de retourner en Espagne où Dieu lui communiquerait ses

volontés. Jean se fit alors marchand d’images pieuses. Dans une de ses

tournées, il rencontra un petit garçon misérable qu’il chargea sur ses épaules

; au repos, le petit garçon se transforma en Enfant Jésus qui lui tendit une

grenade entr’ouverte d’où sortait une croix, et lui dit : « Jean de Dieu,

Grenade sera ta croix ! »

Jean s’en fut donc à

Grenade où, le 20 janvier 1537, il entendit prêcher Jean d’Avila ; il s'imposa

une telle pénitence publique qu'on l'enferma avec les fous de l'hôpital royal.

Libéré sur les instances de Jean d’Avila, il resta comme infirmier, puis fit un

pèlerinage à Notre-Dame de Guadalupe d’Estramadure. Tandis qu’il priait devant

une image de la Vierge, Marie daigna se pencher vers lui pour déposer sur ses

bras l’Enfant Jésus avec des langes et des vêtements pour le couvrir. Il alla

en Andalousie, chercher les conseils de saint Jean d'Avila qui le conforta dans

l’idée de se consacrer au service des miséreux et lui donna une règle de

conduite.

De retour à Grenade, il

se fit marchand de bois pour entretenir une maison qu’il avait louée pour la

transformer en hôpital (1538). Les dons lui vinrent et aussi les disciples,

avec lesquels il fonda une congrégation d’hospitaliers que Pie V mettra sous la

règle de saint Augustin (1572). Jean de Dieu mourut à Grenade, le 8 mars 1550 ;

il fut béatifié par Urbain VIII, en 1630, et canonisé par Alexandre VIII, en

1690 ; il a été proclamé patron des hôpitaux par Léon XIII, à quoi Pie XI

ajouta les infirmiers et les malades, le 28 août 1930.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/03/08.php

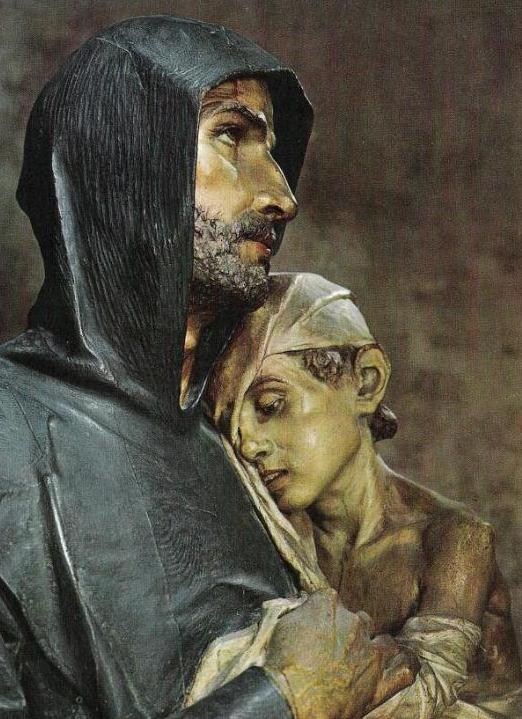

Pietní socha při kostele svatého Leopolda v Brně (podle Samek: Umělecké

památky, s. 211 jde o Jana z Boha

Statue de Saint Jean de Dieu, l'église Saint-Léopold de Brno

Saint Jean de Dieu

Jean de Dieu, de son vrai

nom Joao Ciudad, est né en 1495 à Montémor o Novo au Portugal. A l’âge de huit

ans, il quitte brusquement sa famille pour suivre un mystérieux gyrovague et

commence une vie errante. Les raisons de ce départ restent un mystère. Il

arrive assez rapidement en Espagne, à Oropesa (Tolède) où il est accueilli dans

la famille de Francisco Cid, dénommé « el Mayoral ». La famille du Mayoral fait

de l’élevage, et jusqu’à l’âge de 20 ans Jean se consacre au métier de berger.

Il est apprécié de tous.

A la recherche

d'aventures, il décide ensuite de s’enrôler dans les troupes que lève Charles

Quint pour combattre François 1er. Après cette expérience militaire, il

redevient berger mais très vite, nous le retrouvons aux portes de Vienne en

Autriche avec l’armée impériale qui entend stopper l’invasion des turcs de

Soliman le Magnifique. Il ira même jusqu’aux Pays Bas avec sa compagnie.

Quittant définitivement

l’armée, il se met au service d’une noble famille espagnole condamnée à l’exil

à Ceuta, sur la côte marocaine. De retour en Espagne après un passage sur sa

terre natale, il erre sur les routes d’Andalousie, s’installe à Grenade et se

fait marchand ambulant de livres de piété et de chevalerie.

Un jour de 1539, il

écoute une prédication du célèbre Jean d’Avila qu’on surnomme l’apôtre de

l’Andalousie. Et c’est la conversion. Bouleversé par ce qu'il vient d'entendre,

il parcourt les rues de la ville en criant « Miséricorde ! Miséricorde ! », il

arrache ses vêtements, se roule dans la boue. Les enfants le poursuivent en

criant « el loco ! el loco ! », « le fou ! le fou ! ». Il est alors enfermé à

l’hôpital Royal de Grenade. Il connaît le sort des malades mentaux de l’époque

: jeûne, coups fouets, jets d’eau glacée… pour chasser le mal. C’est à ce

moment que naît sa vocation. Il décide de passer le reste de sa vie à secourir

ceux qu’il a côtoyés à l’hôpital Royal : paralytiques, vagabonds, prostituées,

et surtout malades mentaux.

Il fonde une première «

maison de Dieu » qui s’avère très vite trop petite, il en fonde donc une

deuxième plus grande. Pour subvenir aux besoins de sa « maison de Dieu », il

quête chaque jour en criant : « Frères, faites-vous du bien à vous-mêmes en

donnant aux pauvres ! » Très vite, les habitants de Grenade le surnomment Jean

de Dieu. Cinq compagnons, gagnés par son exemple, le rejoignent.

Il meurt le 8 mars 1550,

laissant derrière lui une renommée de sainteté qui traverse les frontières. Ses

compagnons vont très vite se réunir pour fonder l’Ordre Hospitalier des frères

de Saint Jean de Dieu, grâce au pape saint Pie V qui, le 1er janvier 1572,

approuve la congrégation et lui donne la règle de saint Augustin, et au pape

Sixte V qui, le 1er octobre 1586, l’élève au rang d’Ordre religieux.

Six lettres manuscrites

de saint Jean de Dieu ont été conservées précieusement. Parmi les nombreuses

citations, on peut y lire notamment « Dieu avant tout et par-dessus tout ce qui

est au monde ! », « Je suis endetté et captif pour Jésus-Christ seul ! », ou

encore, « Mettez votre confiance en Jésus-Christ seul ! »

Jean de Dieu est canonisé

en 1690, déclaré patron des malades et des hôpitaux en 1886 et protecteur des

infirmiers et infirmières en 1930.

Aujourd’hui, l’Ordre

Hospitalier est présent sur les cinq continents, les frères y ont fondés des

hôpitaux, des maisons de santé, des centres de réhabilitation, des accueils de

nuit, des écoles de formation…

SOURCE : http://www.saintjeandedieu.com/ewb_pages/b/biographie.php

Saint Jean de Dieu, les « fous », et sa

vocation

Aliénor Goudet - published on 07/03/21

La conversion renversante de Jean de Dieu (1495-1550)

survient après un sermon de Jean d'Avila. S'ensuit une extase telle qu’on le

prend pour un fou et qu'il est enfermé quelque temps dans un asile. C’est dans

celui-ci que le futur saint patron des malades va découvrir sa vocation.

Grenade, 20 janvier 1537. Dans une rue grouillante de

Grenade, la foule s’écarte pour laisser passer trois hommes. Deux soldats en

armure traînent un individu à moitié nu et crotté. Des murmures se répandent.

Est-ce lui, l’énergumène qui s’est soudainement mis à se rouler dans la boue en

criant le nom de Dieu ? Celui qui a déchiré ses vêtements ? N’est-ce pas Jean,

le marchand d’ouvrages ambulant ? La folie l’a donc bel et bien frappé.

Mais le fou en question n’a que faire de ces murmures.

Même traîné ainsi comme un malpropre, il ne peut s’empêcher de regarder vers le

ciel. Le Dieu qui aime et qui règne l’a saisi au cœur et ne le lâchera plus

jamais. Comment a-t-il pu ignorer un tel amour pendant plus de quarante ans ?

Il ne peut s’empêcher de sourire et de verser des larmes.

– Miséricorde, crie-t-il sans arrêt. Miséricorde !

Les soldats s’arrêtent enfin. On ouvre les portes de

l’hôpital Royal et on explique au physicien la situation. Un coup d’œil plus

tard, on l’asperge d’eau glacée. Puis on le fouette pour chasser le mal avant

de le jeter dans une pièce sombre. Une minuscule fenêtre sous le plafond laisse

passer quelques rayons de soleil. Et l’extase de Jean retombe bien vite. Il

n’est pas seul.

Une femme ne cesse de crier qu’on lui rende son

enfant. Elle griffe de ses ongles ensanglantés le mur comme pour essayer

d’atteindre la fenêtre. Recroquevillé dans un coin, un homme au regard perdu se

balance d’avant en arrière et bave. Un enfant, ligoté sur le sol, gémit comme

un animal pris dans un piège. Le sang de Jean ne fait qu’un tour. Il s’approche

pour libérer l’enfant mais une voix l’arrête.

– Ça ne sert à rien, lui dit un cul-de-jatte au sol.

Le petit se frappe la tête jusqu’au sang et mord s’il n’est pas attaché.

La pièce empeste la moisissure et l’urine. Il n’y a

même pas de paille pour dormir confortablement. Et la porte, fermée à double

tour, ne s’ouvre que pour laisser entrer les soignants.

Dans les jours qui suivent, Jean constate avec effroi

les traitements de ses compagnons de chambre. On ne les sort que pour leur

faire prendre des bains glacés. Personne ne bronche quand ils crient la

journée. Mais s’ils crient la nuit, on les bat jusqu’à ce qu’ils se taisent.

Ils vivent dans leurs vêtements souillés des jours entiers avant qu’on ne

daigne les changer. Et la lumière du jour ne leur vient que par cette minuscule

fenêtre. Le cœur de Jean se serre à chaque cri de faim, de douleur et de folie

pure.

– C’est entendu Seigneur, dit-il dans sa prière. Ce

sont eux dont je prendrai soin.

Le lendemain, Jean demande aux soignants de quoi

nettoyer les plaies de ses compagnons. Ils ont besoin de vêtements chauds, de

matelas et de nourriture. On lui répond que rien n’est disponible à part de

l’eau et des bandages. Alors Jean lave un à un ses compagnons. Il échange sa

tunique propre et bande les plaies de ceux qui ont été battus la veille.

Quelques temps plus tard, voyant que la lucidité lui est revenue, l’hôpital le

relâche.

– Je reviendrai les chercher, dit-il avant de partir.

À dater de ce jour, Jean mendie pour récolter de quoi

subvenir aux besoins de ses « fous ». Tous les jours, il fait

l’aumône dans la rue. Il fonde une « maison de Dieu » pour accueillir

tous les affligés dont personne ne prend soin.

– Frères, dit-il. Faites-vous du bien à vous-mêmes en

donnant !

Jean d’Avila l’encourage dans cette vocation. Touchés

par son altruisme, les habitants de Grenade le surnomment rapidement

« Jean de Dieu ». Petit à petit, des disciples le rejoignent pour

former l’Ordre des hospitaliers.

Saint Jean de Dieu rend l’âme le 8 mars 1550 après

treize ans de service auprès des affligés. Il est canonisé par le pape

Alexandre VIII en 1690. On dit que le saint patron des malades et des hôpitaux

a également porté la couronne du Christ.

Lire aussi :Charles de Foucauld : « Plus on aime Dieu, plus on

aime les hommes »

Aguijarro (Antonio Guijarro Morales), pintor y cardiólogo natural de Guadix (Granada), San Juan de Dios

Saint Jean de Dieu,

l’inventeur de l’hôpital moderne qu’on prenait pour un fou

Anne Bernet - publié

le 07/03/24

Pris pour un fou, c’est à

l’asile qu’il prend conscience de l’horrible souffrance des malades mentaux

maltraités. Fondateur de l’ordre des Hospitaliers, Jean de Dieu est le

véritable inventeur de l’hôpital moderne. L’Église le fête le 8 mars.

Grenade, 20 janvier 1538

: la foule se presse pour entendre Jean d’Avila, grand prédicateur venu parler

du martyre de saint Sébastien. Le sermon est brillant, bouleversant, beaucoup

de gens pleurent en l’écoutant. Soudain, au premier rang, un homme d’âge mûr,

car il a passé la quarantaine, se dresse, ruisselant de larmes, se frappant

violemment la poitrine ; il hurle : « Ayez pitié d’un pauvre pécheur, mon

Dieu, ayez pitié de moi ! » Il paraît frappé de démence, conviction qui

grandit dans les jours suivants tant son comportement semble insensé.

Il parcourt les rues en

se flagellant

L’homme se nomme Joao

Cidade, est né près d’Evora au Portugal le 8 mars 1495, s’est récemment établi

libraire à Grenade. C’est d’ailleurs vers sa boutique que, toujours en proie à

cette excitation fiévreuse, il se dirige maintenant. Rentré dans sa librairie,

il arrache les livres des rayons. Ceux qui traitent de religion, il les pose

sur le seuil, incitant à les emporter gratuitement ; quant aux romans et autres

sottises, il les déchire à pleines mains et, quand la reliure résiste,

l’arrache avec les dents… Ses affaires personnelles et vêtements connaissent le

même sort, il distribue tout, restant habillé d’un pantalon et d’une chemise

usés. Puis il se met à parcourir les rues en se flagellant, se traînant par

terre, en larmes, refusant de manger.

Les premiers jours, les

enfants lui jettent des pierres, puis l’on s’écarte de son chemin, on le chasse

en criant au fou. La rumeur qu’un dément se promène en ville, dangereux pour

lui-même et pour autrui se répand, les autorités se décident à l’interner. Joao

se laisse faire sans protester, même quand il expérimente les tristes méthodes

destinées à « soigner » les aliénés : douches glacées et fouet,

chaînes et privations de nourriture. Il supporte tout, offre tout à Dieu pour

la rémission de péchés dont on ne sait rien.

Une seule idée :

fonder un hôpital

Peu à peu, cette crise

mystique semble s’apaiser : Joao reprend un comportement normal, se fait

apprécier des gardiens de l’asile, leur demande la permission de les aider à

soigner ses frères d’infortune, besogne à laquelle sans l’avoir apprise il se

consacre avec une douceur étonnante, obtenant plus d’amélioration de leur état

que les brutalités. Au bout de quelques mois, convaincues de sa guérison, les

autorités le relâchent. Rendu à la liberté, Joao ne parvient pas à oublier, non

cette pénible expérience car il en a vu d’autres, mais l’horrible souffrance de

ces malades mentaux maltraités.

Il n’a plus qu’une idée :

fonder un établissement pour les recevoir où ils seront chrétiennement traités.

Il n’a pas un sou. Qu’importe, il mendiera, au cri lancinant de « Frères,

pour l’amour de Dieu, faites-vous du bien, donnez aux pauvres ! » Quelques

bonnes âmes lui donnent de quoi louer un local, y mettre des paillasses, une

table, des ustensiles de cuisine. Ce ne sont pas seulement les aliénés que Joao

recueille mais toutes les détresses croisées dans la rue, y compris un vieil

Arabe à l’agonie dont la présence, en ces lendemains de la Reconquista, est

fort peu appréciée… Des disciples lui viennent, qui seront avec lui à l’origine

de l’Ordre des Hospitaliers. Pourtant, quel que soit son dévouement, son total

oubli de lui-même, Joao est hanté par son passé sur lequel il laissera planer

une certaine pénombre.

Les stigmates de la

couronne d’épines

Fils d’une honorable

famille portugaise ruinée, il l’a abandonnée à 8 ans sans que l’on sache s’il a

fugué pour se rendre à Madrid ou s’il a été enlevé par un vagabond, peut-être

prêtre défroqué, qui l’a abandonné en rase campagne. Recueilli par l’intendant

du comte d’Oropesa, l’enfant devient berger. À 27 ans, il s’engage dans

l’armée, en est chassé pour manquement à ses devoirs, retourne à son métier de

berger, se réengage. Après avoir servi en Hongrie et en Hollande, vieillissant,

libéré des obligations militaires, il veut retrouver sa famille, découvre que

sa mère est morte du chagrin de sa disparition et que son père l’a suivie dans

la tombe, après avoir enfoui sa peine dans un couvent où il a prié jusqu’à son

dernier jour pour son fils. Sans autre but qu’oublier ses malheurs, pires sans

doute que ce qu’il en livre, Joao va à Ceuta, à Gibraltar, échoue à Grenade où sa

vie a enfin trouvé sa raison d’être. Est-il le grand pécheur dépravé qu’il se

croit, ou une victime ?

Quoiqu’il en soit, il n’y

a plus de place dans son existence que pour l’amour de Dieu et du prochain, qui

lui fait prendre tous les risques comme la nuit où le feu ravageant son

hôpital, il se jette dans le brasier pour en arracher un à un ses malades, au risque

de périr avec eux. L’évêque reconnaît sa fondation, lui donne un habit

monastique de couleur grise et le nom de Jean de Dieu. Peu après, ses proches

constatent sur son front d’étranges traces de piqûres qui font le tour de sa

tête : les stigmates de la couronne d’épines apportée par Notre-Dame lors

d’une extase ; ils ne s’effaceront plus. Qu’il communique avec le monde

invisible, l’on en a une autre preuve le jour où il abandonne en toute hâte ce

qu’il fait pour courir vers la maison d’un de ses amis et le secourir in

extremis alors qu’il venait de se pendre… À ceux qui demanderont comment

il a su, il avoue avoir été averti par un ange qui a soutenu le pendu le temps

qu’il arrive et coupe la corde.

Une conception nouvelle

des soins aux malades

Début mars 1550, alors

que le fleuve sorti de son lit inonde Grenade, Jean se jette à l’eau pour

sauver un homme qui se noie. Il échoue à l’arracher à la mort, regagne

péniblement la rive. Cette baignade glaciale achève son organisme brisé par les

jeûnes, privations, pénitences. Jean de Dieu meurt le 8, jour de son 55e

anniversaire. Ses derniers mots à son confesseur sont :

Il me reste trois sujets

d’affliction : mon ingratitude envers Dieu, le dénuement où je laisse mes

pauvres et n’avoir pas remboursé les dettes contractées pour les secourir.

Son œuvre lui survivra,

répandant sa conception neuve et humaine des soins aux malades et de l’hôpital.

Canonisé en 1690, saint Jean de Dieu est le patron des malades hospitalisés, du

personnel hospitalier, des infirmiers mais aussi, en souvenir de ses premières

activités des imprimeurs, relieurs et libraires.

Lire aussi :Depuis 500 ans, cet ordre est un champion de l’hospitalité

Statue of Saint John of God. Concathedral of the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, right of the the Holy Spirit altar

St Jean de Dieu, confesseur

Mort le 8 mars 1550.

Canonisé en 1690. Fête en 1714.

Leçons des Matines avant

1960

Quatrième leçon. Jean de

Dieu naquit de parents catholiques et pieux, dans la ville de Monte-Mayor, au

royaume de Portugal. Au moment de sa naissance une clarté extraordinaire parut

sur sa maison, et une cloche sonna d’elle-même ; ces prodiges firent clairement

présager que le Seigneur avait choisi cet enfant pour de glorieuses destinées.

Dans sa jeunesse il fut retiré, par la puissance de la grâce divine, d’une vie

trop relâchée et il commença à donner l’exemple d’une grande sainteté. Un jour,

entendant la parole de Dieu, il se sentit tellement excité au bien, que dès

lors il sembla avoir atteint une perfection consommée, quoiqu’il ne fût encore

qu’au début d’une vie très sainte. Après avoir donné tout ce qu’il avait aux

pauvres prisonniers, il devint pour tout le peuple un spectacle de pénitence,

et de mépris de soi-même, ce qui lui attira les plus mauvais traitements de la

part de beaucoup de personnes qui le regardaient comme un fou, et on alla

jusqu’à l’enfermer dans une maison de santé. Mais Jean, enflammé de plus en

plus d’une charité céleste, parvint à faire construire dans la ville de

Grenade, avec les aumônes des personnes pieuses, deux vastes hôpitaux, et jeta

les fondements d’un nouvel Ordre, donnant à l’Église l’institut des Frères

hospitaliers, qui servent les malades au grand profit des âmes et des corps, et

qui se sont répandus dans le monde entier.

Cinquième leçon. Il ne

négligeait rien pour procurer le salut de l’âme et du corps aux pauvres

malades, que souvent il portait chez lui sur ses épaules. Sa chanté ne se

renfermait pas dans les limites d’un hôpital : il procurait secrètement des

aliments à de pauvres veuves, à des jeunes filles dont la vertu était en

danger, et mettait un soin infatigable à délivrer du vice ceux qui en étaient

souillés. Un grand incendie s’étant déclaré dans l’hôpital de Grenade, Jean se

jeta intrépidement au milieu du feu, courant ça et là dans l’enceinte embrasée

jusqu’à ce qu’il eût transporté sur ses épaules tous les malades, et jeté les

lits par les fenêtres pour les préserver du feu. Il resta ainsi pendant une

demi-heure au milieu des flammes qui s’étendaient avec une rapidité

extraordinaire ; il en sortit sain et sauf par le secours divin, à l’admiration

de tous les habitants de Grenade ; montrant par cet exemple de charité que le

feu qui le brûlait au dehors était moins ardent que celui qui l’embrasait

intérieurement.

Sixième leçon. Jean de

Dieu pratiqua, dans un degré éminent de perfection, des mortifications de tous

genres, la plus humble obéissance, une extrême pauvreté, le zèle de la prière,

la contemplation des choses divines ainsi que la dévotion à la sainte Vierge ;

il fut aussi favorisé du don des larmes. Enfin, atteint d’une grave maladie, il

reçut, selon l’usage, tous les sacrements de l’Église dans tes plus saintes

dispositions, puis, malgré sa faiblesse, il se leva de son lit, couvert de ses

vêtements, se jeta à genoux, et, pressant sur son cœur l’image de Jésus-Christ

crucifié, il mourut ainsi dans le baiser du Seigneur, le huit des ides de mars,

l’an mil cinq cent cinquante. Même après son dernier soupir, ses mains

retinrent encore le crucifix, et son corps resta dans la même position pendant

environ six heures, répandant une odeur merveilleusement suave jusqu’à ce qu’on

l’eût enlevé de ce lieu. La ville entière fut témoin de ces prodiges. Illustre

par de nombreux miracles, pendant sa vie et après sa mort, Jean de Dieu a été

mis au nombre des Saints par le souverain Pontife Alexandre VIII. Léon XIII,

agissant selon le désir des saints Évêques de l’Univers catholique et après

avoir consulté la Congrégation des Rites, l’a déclaré le céleste Patron de tous

les hospitaliers et des malades du monde entier, et il a ordonné qu’on invoquât

son nom dans les Litanies des agonisants.

Statue

of Saint John of God in Saint Peter's Basilica

Statue

of Saint John of God in Saint Peter's Basilica

Dom Guéranger, l’Année

Liturgique

Le même esprit qui avait

inspire Jean de Matha se reposa sur Jean de Dieu, et le porta à se faire le

serviteur de ses frères les plus délaissés. Tous deux, dans ce saint temps, se

montrent à nous comme les apôtres de la charité fraternelle. Ils nous

enseignent, par leurs exemples, que c’est en vain que nous nous flatterions

d’aimer Dieu, si la miséricorde envers le prochain ne règne pas dans notre cœur,

selon l’oracle du disciple bien-aimé qui nous dit : « Celui qui aura reçu en

partage les biens de ce monde, et qui, voyant son frère dans la nécessité,

tiendra pour lui ses entrailles fermées, comment la charité de Dieu

demeurerait-elle en lui [1] ? » Mais, s’il n’est point d’amour de Dieu sans

l’amour du prochain, l’amour des hommes, quand il ne se rattache pas à l’amour

du Créateur et du Rédempteur, n’est aussi lui-même qu’une déception. La

philanthropie, au nom de laquelle un homme prétend s’isoler du Père commun, et

ne secourir son semblable qu’au nom de l’humanité, cette prétendue vertu n’est

qu’une illusion de l’orgueil, incapable de créer un lien entre les hommes,

stérile dans ses résultats. Il n’est qu’un seul lien qui unisse les hommes :

c’est Dieu, Dieu qui les a tous produits, et qui veut les réunir à lui. Servir

l’humanité pour l’humanité même, c’est en faire un Dieu ; et les résultats ont

montré si les ennemis de la charité ont su mieux adoucir les misères auxquelles

l’homme est sujet en cette vie, que les humbles disciples de Jésus-Christ qui

puisent en lui les motifs et le courage de se vouer à l’assistance de leurs

frères. Le héros que nous honorons aujourd’hui fut appelé Jean de Dieu, parce

que le saint nom de Dieu était toujours dans sa bouche. Ses œuvres sublimes

n’eurent pas d’autre mobile que celui de plaire à Dieu, en appliquant à ses

frères les effets de cette tendresse que Dieu lui avait inspirée pour eux.

Imitons cet exemple ; et le Christ nous assure qu’il réputera fait à lui-même tout

ce que nous aurons fait en faveur du dernier de nos semblables.

Le patronage des hôpitaux

a été dévolu par l’Église à Jean de Dieu, de concert avec Camille de Lellis que

nous retrouverons au Temps après la Pentecôte.

Qu’elle est belle, ô Jean

de Dieu ! Votre vie consacrée au soulagement de vos frères ! Qu’elle est grande

en vous, la puissance de la charité ! Sorti, comme Vincent de Paul, de la

condition la plus obscure, ayant comme lui passé vos premières années dans la

garde des troupeaux, la charité qui consume votre cœur arrive à vous faire

produire des œuvres qui dépassent de beaucoup l’influence et les moyens des

puissants selon le monde. Votre mémoire est chère à l’Église ; elle doit l’être

à l’humanité tout entière, puisque vous l’avez servie au nom de Dieu, avec un

dévouement personnel dont n’approchèrent jamais ces économistes qui savent

disserter, sans doute, mais pour qui le pauvre ne saurait être une chose

sacrée, tant qu’ils ne veulent pas voir en lui Dieu lui-même. Homme de charité,

ouvrez les yeux de ces aveugles, et daignez guérir la société des maux qu’ils

lui ont faits. Longtemps on a conspiré pour effacer du pauvre la ressemblance

du Christ ; mais c’est le Christ lui-même qui l’a établie et déclarée, cette

ressemblance ; il faut que le siècle la reconnaisse, ou il périra sous la

vengeance du pauvre qu’il a dégradé. Votre zèle, ô Jean de Dieu, s’exerça, avec

une particulière prédilection, sur les infirmes ; protégez-les contre les

odieux attentats d’une laïcisation qui poursuit leurs âmes jusque dans les

asiles que leur avait préparés la charité chrétienne. Prenez pitié des nations

modernes qui, sous prétexte d’arriver à ce qu’elles appelaient la

sécularisation, ont chassé Dieu de leurs mœurs et de leurs institutions : la

société, elle aussi, est malade, et ne sent pas encore assez distinctement son

mal ; assistez-la, éclairez-la, et obtenez pour elle la santé et la vie. Mais

comme la société se compose des individus, et qu’elle ne reviendra à Dieu que

par le retour personnel des membres qui la composent, réchauffez la sainte

charité dans le cœur des chrétiens : afin que, dans ces jours où nous voulons

obtenir miséricorde, nous nous efforcions d’être miséricordieux, comme vous

l’avez été, à l’exemple de celui qui, étant notre Dieu offensé, s’est donné

lui-même pour nous, en qui il a daigné voir ses frères. Protégez aussi du haut

du ciel le précieux institut que vous avez fondé, et auquel vous avez donné

votre esprit, afin qu’il s’accroisse et puisse répandre en tous lieux la bonne

odeur de cette charité de laquelle il emprunte son beau nom.

[1] I Johan. III, 17.

Bhx Cardinal

Schuster, Liber Sacramentorum

Ce fut Clément XI qui

introduisit dans le Missel, sous le rite semi-double, la fête de cet insigne

patron des hôpitaux catholiques (+ 1550) et de tous ceux qui, dans les douleurs

de la maladie et de l’agonie, accomplissent ici-bas les dernières phases de leur

purification avant de comparaître au tribunal divin. Plus tard, Innocent XIII

accorda à la fête de saint Jean de Dieu le rite double, et Léon XIII prescrivit

d’insérer son nom dans les litanies des agonisants, avec celui de saint Camille

de Lellis.

La messe est celle du

Commun des Confesseurs non Pontifes, sauf la première collecte et l’Évangile,

qui sont propres. La collecte fait allusion non seulement à la fondation de l’Ordre des Hospitaliers, mais aussi au miracle de saint Jean de Dieu, alors que,

l’hôpital de Grenade étant la proie des flammes, il circula près d’une

demi-heure, intrépide, dans cette fournaise, transportant en lieu sûr les

malades et jetant les lits par les fenêtres pour les soustraire au feu.

Le culte particulier de

ce Saint est assuré à Rome chrétienne par les religieux de son Ordre, qui

desservent l’antique église de Saint-Jean de Insula, dans l’île Tibérine. Il

est en outre dans les traditions de la cour papale que la pharmacie des Palais

apostoliques soit administrée par un religieux de l’Ordre de Saint-Jean de

Dieu, qui remplit aussi les fonctions d’infirmier du Souverain Pontife.

La lecture de l’Évangile

est celle du XVIIe dimanche après la Pentecôte (Matth., XXII, 34-36) où Jésus

promulgue le grand précepte de la perfection chrétienne, qui consiste

essentiellement dans l’amour. A la vérité, étant donné le caractère historique

de l’inspiration liturgique moderne, on se serait plutôt attendu à trouver ici

le récit du bon Samaritain, prototype de l’infirmier chrétien. Néanmoins la

péricope choisie s’adapte bien, elle aussi, à notre Saint, puisque en lui

l’amour du prochain, et plus encore l’amour de Dieu, s’élevèrent à des hauteurs

si vertigineuses qu’ils atteignirent la sublime folie de la Croix, jusqu’à le

pousser à se faire passer pour fou, à subir des coups et à se laisser enfermer

dans un hôpital d’aliénés. Ce fut le bienheureux Maître Jean d’Avila qui

pénétra le mystère et rappela le Saint de ce singulier genre de vie à une règle

plus discrète, telle que Dieu l’exigeait de lui, pour qu’il arrivât à

constituer une nouvelle et stable congrégation religieuse.

A notre lit de mort, dans

les litanies des agonisants, le prêtre et les assistants invoqueront pour nous

l’intercession de saint Jean de Dieu. Très probablement, nous ne serons plus

alors en mesure de le faire, et peut-être pas même de l’entendre ; il est donc

opportun de l’implorer dès maintenant, en recommandant au Saint le moment

suprême d’où dépend le sort de notre éternité.

Hospital

de Nuestra Señora de la Paz, Sevilla

Dom Pius Parsch, le Guide

dans l’année liturgique

« Dieu est amour. Celui

qui demeure dans l’amour, demeure en Dieu et Dieu en lui. » (Devise de son

Ordre).

Saint Jean : Jour de mort

: 8 mars 1550. — Tombeau : à Grenade. Image : On le représente avec une

couronne d’épines et avec une corne autour du cou à laquelle sont suspendus

deux vases (pour recueillir les aumônes). Vie : Saint Jean de Dieu naquit en

1493. A l’âge de huit ans, il s’enfuit de la maison paternelle pour une raison

inconnue. Dans sa jeunesse, il fut successivement bouvier et libraire et mena

une vie chrétienne assez tiède. Un sermon du bienheureux Jean d’Avila le

convertit soudain. Sa conversion fut si complète qu’on le prit pour un fou. Il

sauva, au péril de sa vie, dans un incendie, les malades d’un hôpital

(Oraison). Cette action manifesta sa vertu et lui révéla à lui-même la grande

tâche de sa vie. Il fonda l’Ordre des Frères de la miséricorde (approuvé en

1572 par Saint Pie V). Le but de cet Ordre est la charité miséricordieuse pour

les malades. Les membres de cet Ordre s’engagent, par un quatrième vœu, à se

consacrer toute leur vie au soin des malades. Le saint est le patron des

hôpitaux et des mourants. Son nom est invoqué dans les litanies dés agonisants.

Pratique : Notre temps ne

sait plus, comme l’ancienne Église, unir harmonieusement, dans une vie intime

et organique, ces deux choses : la liturgie et le soin des malades. Notre saint

peut nous en indiquer les moyens. — Nous prenons la messe du Carême et faisons

mémoire du saint.

Quelques traits de sa

vie. — Dans le grand hôpital de Grenade fondé par les souverains Ferdinand et

Isabelle, un incendie avait éclaté. Parti de la cuisine, le feu avait gagné les

autres pièces. Il menaçait d’envahir aussi les grandes salles dans lesquelles

étaient couchés des centaines de malades. On sonna le tocsin. De toutes parts,

le peuple se précipita : Jean était en tête. Les pompiers et les charpentiers

étaient impuissants. Personne n’osait se lancer dans la maison en feu. On

entendait les gémissements désespérés des pauvres malades. Ceux qui pouvaient

se lever, se tenaient auprès des fenêtres, se tordant les mains. C’était à

devenir fou. Jean, alors, ne peut plus se contenir. Sans tenir compte de la

fumée et des flammes, il se précipite dans ces salles qu’il connaît bien,

arrache portes et fenêtres, donne quelques indications, quelques ordres brefs à

ceux qui peuvent se sauver eux-mêmes, puis guidant, poussant et traînant les

autres, en portant souvent deux à la fois, dans ses bras, sur ses épaules,

montant et descendant les escaliers, il met tous les malades dehors, à l’abri.

Quand tous sont sauvés, il s’occupe du mobilier ; il jette, par la fenêtre, les

couvertures et les lits, les habits et les chaises, les autres meubles et

arrache ainsi au feu le bien sacré des pauvres. Puis, il prend une hache et

monte sur le toit. Tout là-haut, on le voit frapper avec acharnement. Soudain,

une gerbe de flammes jaillit à côté de lui. Il s’enfuit et cherche à se sauver

dans l’édifice adjacent. Mais là aussi une vague de flammes jaillit en face de

lui. Il est entre deux feux. Quelques instants et il disparaît dans le brasier

et la fumée. L’incendie se limite à son foyer. On déplore à haute voix la mort

de l’homme courageux quand, soudain, il se précipite hors de la maison, noir de

fumée, mais sain et sauf, n’ayant que les sourcils brûlés. La foule l’entoure

en poussant des cris d’allégresse et félicite le sauveur des malades et de

l’hôpital. Mais Jean chercha modestement à s’arracher aux remerciements et à la

reconnaissance.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/08-03-St-Jean-de-Dieu-confesseur

Templo

de la Virgen del Carmen, Celaya, Guanajuato, México

Also

known as

Giovanni di Dio

Juan de Dios

Juan Ciudad

Profile

Juan grew up working as

a shepherd in

the Castile region of Spain.

He led a wild and misspent youth,

and travelled over

much of Europe and

north Africa as

a soldier in

the army of Charles

V, and as a mercenary. Fought through a brief period of insanity.

Peddled religious books and

pictures in Gibraltar,

though without any religious conviction himself. In his 40’s he received a

vision of the Infant Jesus who called him John of God. To make up for the

misery he had caused as a soldier,

he left the military, rented a house in Granada, Spain,

and began caring for the sick, poor, homeless and

unwanted. He gave what he had, begged for

those who couldn’t, carried those who could not move on their own, and converted both

his patients and those who saw him work with them. Friend of Saint John

of Avila, on whom he tried to model his life. John founded the Order

of Charity and the Order

of Hospitallers of Saint John of God.

Born

8

March 1495 at

Montemoro Novo, Evora, Portugal

8

March 1550 at Granada, Spain while praying before

a crucifix from

a illness he had contracted while saving a drowning man

21

September 1630 by Pope Urban

VIII

16

October 1690 by Pope Alexander

VIII

hospitals (proclaimed

on 22

June 1886 by Pope Leo

XIII)

nurses (proclaimed

in 1930 by Pope Pius

XI)

alms

box around his neck

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by Father Lawrence

George Lovasik, S.V.D.

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Catholic

Encyclopedia: Brothers Hospitaller of Saint John of God, by Louis Gaudet

Catholic

Encyclopedia: Saint John of God, by F M Rudge

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Saint

John of God, Champion of Charity, by Benedict O’Grady, O.H.

Saints

for Sinners, by Father Alban

Goodier, SJ

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

The

Servant of the Poor, by Leonora Blanche Lang

Wild

Juano, by Mary F. Nixon-Roulet

books

Our

Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

1001

Patron Saints and Their Feast Days, Australian Catholic Truth Society

Conference

of the Polish Episcopate

History

of the life and holy works of John of God

Ordine

Ospedaleior de San Giovanni di Dio

images

video

sitios

en español

Martirologio

Romano, 2001 edición

sites

en français

Abbé

Christian-Philippe Chanut

Ordre

Hospitalier Saint Jean de Dieu

fonti

in italiano

Ordine

Ospedaliero di San Giovanni di Dio

spletne

strani v slovenšcini

Readings

Labour without stopping;

do all the good works you can while you still have the time. – Saint John

of God

If we look forward to

receiving God’s mercy, we can never fail to do good so long as we have the

strength. For if we share with the poor, out of love for God, whatever he has

given to us, we shall receive according to his promise a hundredfold in eternal

happiness. What a fine profit, what a blessed reward! With outstretched arms he

begs us to turn toward him, to weep for our sins, and to become the servants of

love, first for ourselves, then for our neighbors. Just as water extinguishes a

fire, so love wipes away sin.

So many poor people

come here that I very often wonder how we can care for them all, but Jesus

Christ provides all things and nourishes everyone. Many of them come to the

house of God, because the city of Granada is

large and very cold, especially now in winter. More than a hundred and ten are

now living here, sick and healthy, servants and pilgrims.

Since this house is open to everyone, it receives the sick of every type and

condition: the crippled, the disabled, lepers, mutes, the insane, paralytics,

those suffering from scurvy and those bearing the afflictions of old age, many

children, and above all countless pilgrims and travelers,

who come here, and for whom we furnish the fire, water, and salt, as well as

the utensils to cook their food. And for all of this no payment is requested,

yet Christ provides.

I work here on borrowed

money, a prisoner for the sake of Jesus Christ. And often my debts are so

pressing that I dare not go out of the house for fear of being seized by my

creditors. Whenever I see so many poor brothers and neighbours of mine

suffering beyond their strength and overwhelmed with so many physical or mental

ills which I cannot alleviate, then I become exceedingly sorrowful; but I trust

in Christ, who knows my heart. And so I say, “Woe to the man who trusts in men

rather than in Christ.” – from a letter written by Saint John

of God

MLA

Citation

“Saint John of

God“. CatholicSaints.Info. 8 July 2020. Web. 1 February 2021.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-john-of-god/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-john-of-god/

Saint

John of God Church, León, Guanajuato State, Mexico

St. John of God

Born at Montemoro

Novo, Portugal,

8 March, 1495, of devout Christian parents;

died at Granada,

8 March, 1550. The wonders attending the saints birth

heralded a life many-sided in its interests, but dominated

throughout by implicit fidelity to the grace

of God. A Spanish priest whom

he followed to Oropeza, Spain,

in his ninth year left him in charge of the chief shepherd of the place, to

whom he gradually endeared himself through his punctuality and fidelity

to duty,

as well as his earnest piety.

When he had reached manhood, to escape his mastery well-meant, but

persistent, offer of his daughter's hand

in marriage, John took service for a time in the army of Charles

V, and on the renewal of the proposal he enlisted in a regiment on its way

to Austria to

do battle with the Turks. Succeeding years

found him first at his birthplace, saddened by the news of his mother's

premature death, which had followed close upon

his mysterious disappearance; then a shepherd at Seville and

still later at Gibraltar,

on the way to Africa,

to ransom with his liberty Christians heldcaptive by

the Moors.

He accompanied to Africa a Portuguese family just expelled

from the country, to whomcharity impelled him to offer his

services. On the advice of his confessor he soon returned to Gilbratar,

where,brief as had been the time since the invention of the

printing-press, he inaugurated the Apostolate of the printed page, by making

the circuit of the towns and villages about Gilbratar,

selling religious books and pictures, with practically no margin of

profit, in order to place them within the reach of all.

It was during this period

of his life that he is said to have been granted the vision of the

Infant Jesus,

Who bestowed on him the name by which he was later known, John of

God, also bidding him to go to Granada.

There he was so deeply impressed by the preaching of Blessed

John of Avila that he distributed his worldlygoods and went

through the streets of the city, beating his breast and calling on God for

mercy. For some time his sanity was doubted by

the people and he was dealt with as a madman, until the zealous preacher obligedhim

to desist from his lamentations and take some other method

of atoning for his past life. He then made apilgrimage to

the shrine of Our Lady of Guadeloupe,

where the nature of his vocation was revealed to

him by the Blessed Virgin. Returning to Granada,

he gave himself up to the service of the sick and poor, renting a house in

which to care for them and after furnishing it with what was necessary,

he searched the city for those afflicted with all manner of disease, bearing on

his shoulders any who were unable to walk.

For some time he was

alone in his charitable work soliciting by night the

needful supplies, and by day attending scrupulously to the needs of his

patients and the rare of the hospital;

but he soon received the co-operation of charitable priests and

physicians. Many beautiful stories are related of the heavenly guests

who visited him during the early days of herculean tasks, which were lightened

at times by St.Raphael in

person. To put a stop to the saint's habit of

exchanging his cloak with any beggar he chanced to meet,

Don SebastianRamirez, Bishop of Tuy,

had made for him a habit, which was later adopted in all

its essentials as the religiousgarb of his followers, and he

imposed on him for all time the name given him by the Infant Jesus, John

of God. The saint's first two

companions, Antonio Martin and Pedro Velasco, once bitter

enemies who had scandalisedall Granada with

their quarrels and dissipations, were converted through his prayers and

formed the nucleus of a flourishing congregation. The former advanced so far on

the way of perfection that the saint on

his death-bed commended him to his followers as his successor in the

government of the order. The latter, Peter the Sinner, as he

called himself, became a model of humility and charity.

Among the many miracles which

are related of the saint the

most famous is the one commemorated in theOffice of his feast, his

rescue of all the inmates during a fire in the

Grand Hospital at Granada,

he himself passing through the flames unscathed. His

boundless charity extended to widows and orphans,

those out of employment, poor students, and fallen women.

After thirteen years of severe mortification,

unceasing prayer,

and devotion to his patients, he died amid

the lamentations of all the inhabitants of Granada.

His last illness had resulted from an heroic but futile effort to save a

young man from drowning. The magistrates and nobility of the city crowded about

his death-bed to express their gratitude for his services to the poor,

and he wasburied with the pomp usually reserved for princes. He was beatified by Urban

VIII, 21 September, 1638, and canonized by Alexander

VIII, 16 October, 1690. Pope

Leo XIII made St. John of God patron of hospitals and

the dying. (See also BROTHERS

HOSPITALLERS OF ST. JOHN OF GOD.)

Sources

Acta SS. 1 March, I, 813:

De CASTRO, Miraculosa vida y santas obras del. b. Juan Dios (Granada,

1588); GIRARD DE VILLE-THIERY, Vie de s. Jean de Dieu (Paris, 1691);

BUTLER, Lives of the Saints, 8 March; BEISSEL in Kircheslex., s.v.

Johannes von Gott.

Rudge,

F.M. "St. John of God." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol.

8. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 8 Mar.

2016<http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08472c.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Joseph P. Thomas. In memory of

Fr. George Kanatt M.C.B.S.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. October 1, 1910. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2020 by Kevin

Knight. Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08472c.htm

Saint

John of God. Engraving by C. Galle.

John De Dieu

John De Dieu (JOHANNES A

DEO), saint, founder of the order of charity, was born at Monte-Mor-el-Novo,

Portugal, March 8, 1495. An unknown priest stole him from his father, a poor

man called Andrea Ciudad, and afterwards abandoned him at Oropesa, in Castile.

After roving about many years, he was led to dedicate himself to a religious

life by the preaching of John of Avila, whom he heard at Grenada. So excited

became he, that, according to Richard and Glraud, he went through the town

flogging himself, and never stopped till he went, half dead, to the hospital.

He resolved to devote himself to the care of the sick, and changed his family

name for de Dieu (a Deo), by permission of the bishop of Tui. In 1540

he opened the first house of his order at Seville, and died March 8, 1550,

without leaving any set rules for his disciples. In 1572 pope Pius V subjected

them to the rule of St. Augustine, adding a vow to devote themselves to the

care of the sick, and sundry other regulations. SEE CHARITY,

BROTHERS OF. John de Dieu was canonized by pope Alexander VIII, October 16,

1690. He is commemorated on the 8th of March. See Castro et Girard de

Ville-Thierri, Vies de St. Jean de Dieu; Baillet, Vies des

Saints, March 8; Heliot, Histoire des Ordres Monastiques, vol.

4, ch. 18; Hoefer, Nouv. Biog. Générale, 26, 442 sq.

SOURCE : https://www.biblicalcyclopedia.com/J/john-de-dieu.html

ST. JOHN OF GOD. (1495 - 1550)

NOTHING in John's early

life foreshadowed his future sanctity. He ran away as a boy from his home in

Portugal, tended sheep and cattle in Spain, and served as a soldier against the

French, and afterwards against the Turks. When about forty years of age, feeling

remorse for his wild life, he resolved to devote himself to the ransom of the

Christian slaves in Africa, and went thither with the family of an exiled

noble, which he maintained by his labor. On his return to Spain he sought to do

good by selling holy pictures and books at low prices. At. length the hour of

grace struck. At Granada a sermon by the celebrated John of Avila shook his

soul to its depths, and his expressions of self-abhorrence were so

extraordinary that he was taken to the asylum as one mad. There he employed

himself in ministering to the sick. On leaving he began to collect homeless

poor, and to support them by his work and by begging. One night St. John found

in the streets a poor man who seemed near death, and, as was his wont, he carried

him to the hospital, laid him on a bed, and went to fetch water to wash his

feet. When he had washed them, he knelt to kiss them, and started with awe: the

feet were pierced, and the print of the nails bright with an unearthly

radiance. He raised his eyes to look, and heard the words, "John, to Me

thou doest all that thou doest to the poor My name: I reach forth My hand for

the alms thou givest; Me dost thou clothe, Mine are the feet thou dost

wash." And then the gracious vision disappeared, leaving St. John filled

at once with confusion and consolation. The bishop became the Saint's patron,

and gave him the name of John of God. When his hospital was on fire, John was

seen rushing about uninjured amidst the flames until he had rescued all his

poor. After ten years spent in the service of the suffering, the Saint's life

was fitly closed. He plunged into the river Xenil to save a drowning boy, and

died A.D. 1550 of an illness brought on by the attempt, at the age of

fifty-five.

Reflection.--God often

rewards men for works that are pleasing in His sight by giving them grace and

opportunity to do other works higher still. St. John of God used to attribute

his conversion, and the graces which enabled him to do such great works, to his

self-denying charity in Africa.

SOURCE : http://jesus-passion.com/saint_john_of_god.htm

St. John of God

St. John of God (1495-1550) having given up active Christian belief while a soldier, was 40 before the depth of his sinfulness began to dawn on him. He decided to give the rest of his life to God’s service, and headed at once for Africa, where he hoped to free captive Christians and, possibly, be martyred.

He was soon advised that

his desire for martyrdom was not spiritually well based, and returned to Spain

and the relatively prosaic activity of a religious goods store. Yet he was

still not settled. Moved initially by a sermon of Blessed John of Avila, he one

day engaged in a public beating of himself, begging mercy and wildly repenting

for his past life.

Committed to a mental hospital for these actions, John was

visited by Blessed John, who advised him to be more actively involved in

tending to the needs of others rather than in enduring personal hardships. John

gained peace of heart, and shortly after left the hospital to begin work among

the poor.

He established a house

where he wisely tended to the needs of the sick poor, at first doing his own

begging. But excited by the saint’s great work and inspired by his devotion,

many people began to back him up with money and provisions. Among them were the

archbishop and marquis of Tarifa.

Behind John’s outward

acts of total concern and love for Christ’s sick poor was a deep interior

prayer life which was reflected in his spirit of humility. These qualities

attracted helpers who, 20 years after John’s death, formed the Brothers

Hospitallers, now a worldwide religious order.

One mark of honor to his

labors is that this order has been officially entrusted with the medical care

of the Popes.

John became ill after 10

years of service but tried to disguise his ill health. He began to put the

hospital’s administrative work into order and appointed a leader for his

helpers. He died on March 8, 1550, his 55th birthday. He was canonized by Pope

Alexander VIII on October 16, 1690, and later named the patron saint of

hospitals, the sick, nurses, firefighters, alcoholics, and booksellers. St.

John’s feast day is commemorated on March 8.

SOURCE : http://www.ucatholic.com/saints/saint-john-of-god/

John of God, Religious

(RM)

Born at Montemoro Nuovo (diocese of Evora), Portugal, March 8, 1495; died in

Granada, Spain, on March 8, 1550; canonized by Pope Alexander VIII in 1690; Leo

XIII in 1886 declared him to be "patron of all hospitals and sick,"

along with Camillus de Lellis.

The several versions of Saint John's story are hopelessly confused with regard

to a sequence of events in his early life.

Juan Ciudad was born of pious, peasant stock. His parents died when he was

young (either before or after his misadventures). He was "seduced from his

home by a priest, who abandoned him on the road" (Tabor with no further

explanation). For a while he was a shepherd. He also served the bailiff of the

count of Oroprusa in Castile for some time. After travelling for a while, he

entered military service in 1522 where, his biographers report, he was guilty

of many grievous sexual excesses and other sins. He served in the wars between

the French and the Spaniards, and in Hungary against the Turks. After the

count's company broke up, John worked as a shepherd near Seville. He even

worked as a superintendent of slaves in Morocco at some point.

When he was about 40, he was profoundly moved with remorse and decided to

dedicate himself to God's service in some special way. He initially thought of

going to Morocco in Africa to minister to and rescue Christian slaves. Instead

he accompanied a Portuguese family from Gibraltar to Ceuta, Barbary. There he

served a Portuguese nobleman, who had lost all his possessions. John maintained

the whole family by his labor. Then he returned to Gibraltar, where he peddled

religious pictures and books. He business prospered, and in 1538, in obedience

to a vision, he opened a shop in Granada.

After hearing Blessed John of Ávila preach on Saint Sebastian's Day (January

20), he was so touched that he cried aloud and beat his breast, begging for

mercy. He ran about the streets behaving like a lunatic, and the townspeople

threw sticks and stones at him. He returned to his shop, gave away his stock,

and began wandering the streets in distraction.

Some people took him to Blessed John of Ávila, who advised him and offered his

support. John was calm for a while but fell into wild behavior again and was

taken to an insane asylum, where the customary brutal treatments were applied

to bring him to sanity. John of Ávila heard of his fate and visited him,

telling him that he had practiced his penance long enough and that he should

address himself to doing something more useful for himself and his neighbor.

John was calmed by this, remained in the hospital, and attended the sick until

1539. While there he determined to spend the rest of his life working for the

poor.

On his release from the hospital, he began selling wood to earn money to feed

the poor. With the help of the archbishop of Granada, hired a house as a refuge

to care for the sick poor-- including prostitutes and vagabonds, which brought

him criticism. Although he was constantly short of money, his work prospered

because he served them with great zeal and discrimination.

On one occasion his hospital caught fire and he carried out most of the

patients on his own back, returning again and again through the flames to

rescue them. He had a good business head and was so efficient in his

administration that soon he found himself the recipient of aid from the whole

city of Granada and beyond. He found so many willing to join in helping him,

that he was forced to think of starting a religious order. This was the

beginning of the Borthers of Saint John of God, a group which was to have

enormous influence in the Church. He had not intended to found a religious

order, and so the rules were not drawn up until six years after his death.

He gave relief also to the poor in their homes and found work for the

unemployed. In his eagerness that no case of want should go unrelieved, he

instituted an inquiry into the problems and needs of the poor of the whole

area. In addition to his relief work, bearing in his hand a crucifix, he sought

out the fallen women of the city to reclaim them. The archbishop once sent for

him and complained that he harbored idle beggars and bad women, to which he

replied that the only bad person in the hospital was himself.

John of God practiced great penance, enjoyed visions and even ecstasies, but

manifested great humility through a life in which he wore himself out, trying

to aid every distressed person he met or heard of, in addition to preaching

with cross in hand to crowds throughout the city streets. He fell ill after

trying to save his wood and to rescue a drowning child from the River Ximel

during a flood. He hid his illness and continued in his duties, but the news

finally got out.

He named Antony Martin superior over his helpers. John remained so long in

front of the Blessed Sacrament that the Lady Anne Ossorio took him home with

her by force. She surrounded him with every comfort, and read to him the story

of the Passion of Jesus. He worried that while Jesus drank gall, he, a

miserable sinner, was being fed good food.

Outside, the whole city gathered at the door--nobles and beggars alike--craving

his blessing. The magistrates begged him to bless his fellow townsfolk, but he

said that he was a sinner. The archbishop finally convinced him to confer his

blessing. John died on his knees before the altar of his hospital chapel, and

was buried by the archbishop (Attwater, Benedictines, Bentley, Delaney,

Encyclopedia, Gill, Tabor, White).

In art, Saint John is portrayed as a Capuchin monk with a long beard, two bowls

hung around his neck on a cord, and a basket. At times he may be shown (1) as a

crown of thorns is brought to him by the Virgin, (2) with an alms box hung up

near him, (3) with a crucifix, rosary, and collection box, (4) holding a

pomegranate (pome de Granada) with a cross on it, (5) washing Jesus's feet as a

pilgrim, (6) carrying sick persons, or (7) with a beggar kneeling at his feet

(Roeder, Tabor). He is venerated in Granada, Spain (Roeder, White). John of God

is the patron of the sick, of hospitals, and of nurses, printers, and

booksellers (White).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0308.shtml

March 8

St. John of God, Confessor, Founder of the Order of Charity

From his life, written by Francis de Castro, twenty-five years after his death; abridged by Baillet, p. 92. and F. Helyot, Hist. des Ordres Relig. t. 4. p. 131.

A.D. 1550

ST. JOHN, surnamed of God, was born in Portugal, in 1495. His parents were of

the lowest rank in the country, but devout and charitable. John spent a

considerable part of his youth in service, under the mayoral or chief shepherd

of the count of Oropeusa in Castile, and in great innocence and virtue. In 1522

he listed himself in a company of foot raised by the count, and served in the

wars between the French and Spaniards; as he did afterwards in Hungary against

the Turks whilst the emperor Charles V. was king of Spain. By the

licentiousness of his companions he, by degrees, lost his fear of offending

God, and laid aside the greater part of his practices of devotion. The troop

which he belonged to being disbanded, he went into Andalusia in 1536, where he

entered the service of a rich lady near Seville, in quality of shepherd. Being

now about forty years of age, stung with remorse for his past misconduct, he

began to entertain very serious thoughts of a change of life, and doing penance

for his sins. He accordingly employed the greater part of his time, both by day

and night, in the exercises of prayer and mortification; bewailing almost

continually his ingratitude towards God, and deliberating how he could dedicate

himself in the most perfect manner to his service. His compassion for the

distressed moved him to take a resolution of leaving his place, and passing

into Africa, that he might comfort and succour the poor slaves there, not

without hopes of meeting with the crown of martyrdom. At Gibralter he met with

a Portuguese gentleman condemned to banishment, and whose estate had also been

confiscated by King John III. He was then in the hands of the king’s officers,

together with his wife and children, and on his way to Ceuta in Barbary, the

place of his exile. John, out of charity and compassion, served him without any

wages. At Ceuta, the gentleman falling sick with grief and the change of air,

was soon reduced to such straits as to be obliged to dispose of the small

remains of his shattered fortune for the family’s support. John, not content to

sell what little stock he was master of to relieve them, went to day-labour at

the public works, to earn all he could for their subsistence. The apostasy of

one of his companions alarmed him; and his confessor telling him that his going

in quest of martyrdom was an illusion, he determined to return, to Spain.

Coming back to Gibralter, his piety suggested to him to turn pedler, and sell

little pictures and books of devotion, which might furnish him with

opportunities of exhorting his customers to virtue. His stock increasing

considerably, he settled in Granada, where he opened a shop in 1538, being then

forty-three years of age.

The great preacher and servant of God, John D’Avila, 1 surnamed

the Apostle of Andalusia, preached that year at Granada, on St. Sebastian’s

day, which is there kept as a great festival. John, having heard his sermon,

was so affected with it, that, melting into tears, he filled the whole church

with his cries and lamentations; detesting his past life, beating his breast,

and calling aloud for mercy. Not content with this, he ran about the streets

like a distracted person, tearing his hair, and behaving in such a manner that

he was followed every where by a rabble with sticks and stones, and came home

all besmeared with dirt and blood. He then gave away all he had in the world,

and having thus reduced himself to absolute poverty, that he might die to

himself and crucify all the sentiments of the old man, he began again to

counterfeit the madman, running about the streets as before, till some had the

charity to take him to the venerable John D’Avila, covered with dirt and blood.

The holy man, full of the Spirit of God, soon discovered in John the motions of

extraordinary graces, spoke to him in private, heard his general confession,

and gave him proper advice, and promised his assistance ever after. John, out

of a desire of the greatest humiliations, returned soon after to his apparent

madness and extravagances. He was, thereupon, taken up and put into a madhouse,

on supposition of his being disordered in his senses, where the severest

methods were used to bring him to himself, all which he underwent in the spirit

of penance, and by way of atonement for the sins of his past life. D’Avila,

being informed of his conduct, came to visit him, and found him reduced almost

to the grave by weakness, and his body covered with wounds and sores; but his

soul was still vigorous, and thirsting with the greatest ardour after new

sufferings and humiliations. D’Avila however told him, that having now been

sufficiently exercised in that so singular a method of penance and humiliation,

he advised him to employ himself for the time to come in something more

conducive to his own and the public good. His exhortation had its desired

effect; and he grew instantly calm and sedate, to the great astonishment of his

keepers. He continued, however, some time longer in the hospital, serving the