Fra Angelico (circa 1395–1455), Crucifixion avec des saints, détail, 1441, 550 x 950, Museum of San Marco

Saint Benoît

Benoît de Nursie, patriarche des moines d'Occident (+ v. 547)

C'était un jeune noble de Nursie en Ombrie. A 15 ans, on l'envoie à Rome faire ses études, accompagné de sa nourrice. Rome est terrible aux âmes pures : tentations charnelles, tentations intellectuelles et politiques.

Benoît s'enfuit, car c'est "Dieu seul" qu'il cherche et il ne veut pas courir le risque de le perdre. Il aboutit à une caverne de Subiaco où un ermite accepte de lui servir de guide dans sa quête de Dieu. Benoît y médite de la meilleure façon de vivre pour trouver Dieu. Mais il est difficile de passer inaperçu quand on rayonne de sainteté.

Les moines d'un monastère voisin l'invitent à devenir leur Père abbé. Bien mal leur en a pris : il veut les sanctifier et les réformer. Ils en sont décontenancés et tentent de l'empoisonner.

Il retourne à sa caverne de Subiaco où des disciples mieux intentionnés viennent le rejoindre. Il les organise en prieuré et c'est ainsi que va naître la Règle bénédictine. La jalousie d'un prêtre les en chasse, lui et ses frères, et ils se réfugient au Mont-Cassin qui deviendra le premier monastère bénédictin.

Il y mourra la même année que sa soeur sainte Scholastique. Emportées au Moyen Age d'une manière assez frauduleuse, leurs reliques sont désormais sur les bords de la Loire, à Fleury sur Loire, devenu Saint Benoît sur Loire-45730.

Saint patron de l'Europe: "Messager de paix, fondateur de la vie monastique en Occident...

Lui et ses fils avec la Croix, le livre et la charrue, apporteront le progrès chrétien aux populations s'étendant de la Méditerranée à la Scandinavie, de l'Irlande aux plaines de Pologne" (Paul VI 1964)

Père du monachisme, patron de l'Europe: La catéchèse le 9 avril 2008 a été consacrée à la figure de saint Benoît de Nursie, "le père du monachisme occidental, dont la vie et les oeuvres imprimèrent un mouvement fondamental à la civilisation et à la culture occidentale. La source principale pour approcher la vie de Benoît est le second livre des Dialogues de saint Grégoire le grand, qui présente le moine comme un astre brillant indiquant comment sortir "de la nuit ténébreuse de l'histoire", d'une crise des valeurs et des institutions découlant de la fin de l'empire romain. Son œuvre et la règle bénédictine ont exercé une influence fondamentale pendant des siècles dans le développement de la civilisation et de la culture en occident, bien au-delà de son pays et de son temps. Après la fin de l'unité politique il favorisa la naissance d'une nouvelle Europe, spirituelle et culturelle, unie par la foi chrétienne commune aux peuples du continent".

"Benoît naquit vers 480 dans une famille aisée qui l'envoya étudier à Rome. Mais avant de les avoir terminées, il gagna une communauté monastique dans les Abruzzes. Trois ans plus tard il gagnait une grotte de Subiaco dans laquelle il vécut isolé trois ans... résistant aux habituelles tentations humaines comme l'auto-affirmation de soi et le nombrilisme, la sensualité, la colère et la vengeance. Sa conviction -a précisé le Saint-Père- était que seul après avoir dominé ces épreuves" il aurait été en mesure d'aider autrui. En 529, Benoît fonda l'ordre monastique qui porte son nom et se transporta à Montecassino, site élevé et visible de loin. "Selon saint Grégoire, ce choix symbolique voulait dire que si la vie monastique trouve sa raison d'être dans l'isolement, le monastère a également une fonction publique dans la vie de l'Église comme de la société".

Toute l'existence de Benoît de Nursie, a dit le Pape, "est imprégnée de la prière, qui fut le fondement de son œuvre, car sans elle il n'y a pas expérience de Dieu. Son intériorité n'était cependant pas détachée de la réalité et, dans l'inquiétude et la confusion de son temps, Benoît vivait sous le regard de Dieu, tourné vers lui, tout en étant attentif aux devoirs quotidiens envers les besoins concrets des gens". Il mourut en 547 et sa règle donne des conseils qui, au-delà des moines, sont utiles pour qui chemine vers Dieu. "Par sa mesure, son humanité et son clair discernement entre l'essentiel et le secondaire en matière spirituelle, ce texte reste éclairant jusqu'à nos jours".

En 1964 Paul VI fit de Benoît le saint patron de l'Europe, de ce continent qui, profondément blessé car "à peine sorti de deux guerres et de deux idéologies tragiques, était à la recherche d'une nouvelle identité. Pour forger une nouvelle unité stable les moyens politiques, économiques et juridiques sont importants. Mais il faut trouver un renouveau éthique et spirituel tiré des racines chrétiennes de l'Europe. Sans cette lymphe vitale, l'homme reste exposé au danger de succomber à la vieille tentation de se racheter tout seul...ce qui est que la vielle utopie du XXe siècle européen...qui a provoqué un recul sans précédent dans une histoire humaine déjà tourmentée". (Source: VIS 080409 540)

L'église abbatiale de Fleury a pris le vocable de St-Benoît lorsque les reliques du Saint furent ramenées du Mont Cassin en 703. La première en France a avoir suivi la règle de St-Benoît. (diocèse d'Orléans)

(…)

Mémoire (en Europe: Fête) de saint Benoît, abbé. Né à Nursie en Ombrie, après des études à Rome, il commença par vivre en ermite à Subiaco, rassembla autour de lui de nombreux disciples, puis s’établit au Mont-Cassin, où il fonda un monastère célèbre et composa une Règle, qui se répandit dans toutes les régions, au point qu’il mérite d’être appelé patriarche des moines d’Occident. La tradition place sa mort le 21 mars 547, mais dès le VIIIe siècle, on a célébré sa mémoire en ce jour.

Martyrologe romain

Quand tu entreprends une bonne action, demande lui par une très instante prière qu’il la parachève. Alors celui qui a daigné nous compter au nombre de ses fils n’aura pas un jour à s’attrister de nos mauvaises actions.

Règle de saint Benoît - Prologue

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1483/Saint-Benoit.html

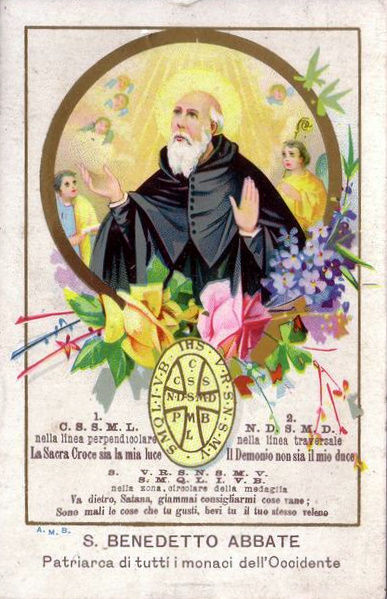

Benediktusmedaille

von Desiderius Lenz, Mönch im Kloster Beuron, geschaffen zum 1400.

Geburtsjubiläum von Benedikt im Jahre 1880, im Auftrag gegeben von Erzabt

Nikolaus d'Orgement vom Montecassino - heute die am weitestens verbreitete Form

der Benediktusmedaille.

Benedict

depicted on a Jubilee Saint Benedict Medal for the 1,400th

anniversary of his birth in 1880

Saint Benoît, abbé

Benoît naquit à Norcia (Ombrie). Après avoir étudié à Rome, il se retira dans une grotte de Subiaco, « ne préférant rien à l'amour de Dieu ». Des disciples vinrent à lui. Mais, au bout d'un certain temps, Benoît dut quitter Subiaco et s'établir avec eux au Mont-Cassin. C'est là qu'il écrivit sa Règle monastique et mérita d'être appelé le Patriarche des moines d'Occident. Il y mourut vers 547. L'œuvre évangélisatrice et culturelle des bénédictins qui façonnèrent l'Europe au Moyen-Age lui valut encore d'être choisi par le pape Paul VI pour être le premier patron de l'Europe. Il est aussi le nom que choisit le cardinal Ratzinger lors de son élection au Siège de Pierre en 2005.

Giovanni

Bellini, Triptych Madonna and Child. Benedict of Nursia and Saint Mark the Evangelist Oil on panel

1488. Size: 2.75 x 2.50, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari,

Sacristy

Giovanni Bellini, Triptyque Vierge à

l'Enfant. Benoît de Nursie et Marc l’évangéliste . Huile sur panneaux

de bois 1488, 2,75 x 2,50, Basilique Santa Maria

Gloriosa dei Frari, Sacristie

Giovanni Bellini, Trittico Madonna col

Bambino . Benedetto da Norcia e Marco Evangelista Olio su pannelli di legno

1488, 2.75 x 2.50, Basilica di Santa Maria

Gloriosa dei Frari, Sacrestia

SAINT BENOÎT

Père des Moines

d'Occident

(480-543)

Benoît naquit dans une

petite ville des montagnes de l'Ombrie, d'une des plus illustres familles de ce

pays. Le Pape saint Grégoire assure que le nom de Benoît lui fut

providentiellement donné comme gage des bénédictions célestes dont il devait

être comblé.

Craignant la contagion du

monde, il résolut, à l'âge de quatorze ans, de s'enfuir dans un désert pour

s'abandonner entièrement au service de Dieu. Il parvint au désert de Subiaco, à

quarante milles de Rome, sans savoir comment il y subsisterait; mais Dieu y

pourvut par le moyen d'un pieux moine nommé Romain, qui se chargea de lui faire

parvenir sa frugale provision de chaque jour.

Le jeune solitaire excita

bientôt par sa vertu la rage de Satan; celui-ci apparut sous la forme d'un

merle et l'obséda d'une si terrible tentation de la chair, que Benoît fut un

instant porté à abandonner sa retraite; mais, la grâce prenant le dessus, il

chassa le démon d'un signe de la Croix et alla se rouler nu sur un buisson

d'épines, tout près de sa grotte sauvage. Le sang qu'il versa affaiblit son

corps et guérit son âme pour toujours. Le buisson s'est changé en un rosier

qu'on voit encore aujourd'hui: de ce buisson, de ce rosier est sorti l'arbre

immense de l'Ordre bénédictin, qui a couvert le monde.

Les combats de Benoît

n'étaient point finis. Des moines du voisinage l'avaient choisi pour maître

malgré lui; bientôt ils cherchèrent à se débarrasser de lui par le poison; le

saint bénit la coupe, qui se brisa, à la grande confusion des coupables.

Cependant il était dans

l'ordre de la Providence que Benoît devînt le Père d'un grand peuple de moines,

et il ne put se soustraire à cette mission; de nombreux monastères se fondèrent

sous sa direction, se multiplièrent bientôt par toute l'Europe et devinrent une

pépinière inépuisable d'évêques, de papes et de saints.

Parmi ses innombrables

miracles, citons les deux suivants: Un de ses moines avait, en travaillant,

laissé tomber le fer de sa hache dans la rivière; Benoît prit le manche de

bois, le jeta sur l'eau, et le fer, remontant à la surface, revint prendre sa

place. Une autre fois, cédant aux importunes prières d'un père qui le

sollicitait de ressusciter son fils, Benoît se couche sur l'enfant et dit:

"Seigneur, ne regardez pas mes péchés, mais la foi de cet homme!"

Aussitôt l'enfant s'agite et va se jeter dans les bras paternels.

La médaille de saint

Benoît est très efficace contre toutes sortes de maux. On l'emploie avec un

grand succès pour la guérison et la conservation des animaux.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950.

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_benoit.html

Saint

Benoît donnant sa règle à son disciple saint Maur

St.

Benedict delivering his Rule to St. Maurus and other monks of his order. France,

Monastery of St. Gilles, Nimes, 1129

Saint Benoît de Nursie

Chers frères et sœurs,

Je voudrais parler aujourd'hui de saint Benoît, fondateur du monachisme

occidental, et aussi Patron de mon pontificat. Je commence par une parole de

saint Grégoire le Grand, qui écrit à propos de saint Benoît: "L'homme de

Dieu qui brilla sur cette terre par de si nombreux miracles, ne brilla pas

moins par l'éloquence avec laquelle il sut exposer sa doctrine" (Dial. II,

36). Telles sont les paroles que ce grand Pape écrivit en l'an 592; le saint

moine était mort à peine 50 ans auparavant et il était encore vivant dans la

mémoire des personnes et en particulier dans le florissant Ordre religieux

qu'il avait fondé. Saint Benoît de Nursie, par sa vie et par son œuvre, a

exercé une influence fondamentale sur le développement de la civilisation et de

la culture européenne. La source la plus importante à propos de la vie de ce

saint est le deuxième livre des Dialogues de saint Grégoire le Grand. Il ne

s'agit pas d'une biographie au sens classique. Selon les idées de son temps, il

voulut illustrer à travers l'exemple d'un homme concret - précisément saint

Benoît - l'ascension au sommet de la contemplation, qui peut être réalisée par

celui qui s'abandonne à Dieu. Il nous donne donc un modèle de la vie humaine

comme ascension vers le sommet de la perfection. Saint Grégoire le Grand

raconte également dans ce livre des Dialogues de nombreux miracles accomplis

par le saint, et ici aussi il ne veut pas raconter simplement quelque chose

d'étrange, mais démontrer comment Dieu, en admonestant, en aidant et aussi en

punissant, intervient dans les situations concrètes de la vie de l'homme. Il

veut démontrer que Dieu n'est pas une hypothèse lointaine placée à l'origine du

monde, mais qu'il est présent dans la vie de l'homme, de tout homme.

Cette perspective du "biographe" s'explique également à la lumière du

contexte général de son époque: entre le V et le VI siècle, le monde était

bouleversé par une terrible crise des valeurs et des institutions, causée par

la chute de l'Empire romain, par l'invasion des nouveaux peuples et par la

décadence des mœurs. En présentant saint Benoît comme un "astre

lumineux", Grégoire voulait indiquer dans cette situation terrible,

précisément ici dans cette ville de Rome, l'issue de la "nuit obscure de

l'histoire" (Jean-Paul II, Insegnamenti, II/1, 1979, p. 1158). De fait,

l'œuvre du saint et, en particulier, sa Règle se révélèrent détentrices d'un

authentique ferment spirituel qui transforma le visage de l'Europe au cours des

siècles, bien au-delà des frontières de sa patrie et de son temps, suscitant

après la chute de l'unité politique créée par l'empire romain une nouvelle

unité spirituelle et culturelle, celle de la foi chrétienne partagée par les

peuples du continent. C'est précisément ainsi qu'est née la réalité que nous

appelons "Europe".

La naissance de saint Benoît se situe autour de l'an 480. Il provenait, comme

le dit saint Grégoire, "ex provincia Nursiae" - de la région de la

Nursie. Ses parents, qui étaient aisés, l'envoyèrent suivre des études à Rome

pour sa formation. Il ne s'arrêta cependant pas longtemps dans la Ville

éternelle. Comme explication, pleinement crédible, Grégoire mentionne le fait

que le jeune Benoît était écoeuré par le style de vie d'un grand nombre de ses

compagnons d'étude, qui vivaient de manière dissolue, et qu'il ne voulait pas

tomber dans les mêmes erreurs. Il voulait ne plaire qu'à Dieu seul; "soli

Deo placere desiderans" (II Dial. Prol. 1). Ainsi, avant même la

conclusion de ses études, Benoît quitta Rome et se retira dans la solitude des

montagnes à l'est de Rome. Après un premier séjour dans le village d'Effide

(aujourd'hui Affile), où il s'associa pendant un certain temps à une

"communauté religieuse" de moines, il devint ermite dans la proche

Subiaco. Il vécut là pendant trois ans complètement seul dans une grotte qui,

depuis le Haut Moyen-âge, constitue le "coeur" d'un monastère

bénédictin appelé "Sacro Speco". La période à Subiaco, une période de

solitude avec Dieu, fut un temps de maturation pour Benoît. Il dut supporter et

surmonter en ce lieu les trois tentations fondamentales de chaque être humain:

la tentation de l'affirmation personnelle et du désir de se placer lui-même au

centre, la tentation de la sensualité et, enfin, la tentation de la colère et

de la vengeance. Benoît était en effet convaincu que ce n'était qu'après avoir

vaincu ces tentations qu'il aurait pu adresser aux autres une parole pouvant

être utile à leur situation de besoin. Et ainsi, son âme désormais pacifiée

était en mesure de contrôler pleinement les pulsions du "moi" pour

être un créateur de paix autour de lui. Ce n'est qu'alors qu'il décida de

fonder ses premiers monastères dans la vallée de l'Anio, près de Subiaco.

En l'an 529, Benoît quitta Subiaco pour s'installer à Montecassino. Certains

ont expliqué ce déplacement comme une fuite face aux intrigues d'un

ecclésiastique local envieux. Mais cette tentative d'explication s'est révélée

peu convaincante, car la mort soudaine de ce dernier n'incita pas Benoît à

revenir (II Dial. 8). En réalité, cette décision s'imposa à lui car il était

entré dans une nouvelle phase de sa maturation intérieure et de son expérience

monastique. Selon Grégoire le Grand, l'exode de la lointaine vallée de l'Anio

vers le Mont Cassio - une hauteur qui, dominant la vaste plaine environnante,

est visible de loin - revêt un caractère symbolique: la vie monastique cachée a

sa raison d'être, mais un monastère possède également une finalité publique

dans la vie de l'Eglise et de la société, il doit donner de la visibilité à la

foi comme force de vie. De fait, lorsque Benoît conclut sa vie terrestre le 21

mars 547, il laissa avec sa Règle et avec la famille bénédictine qu'il avait

fondée un patrimoine qui a porté des fruits dans le monde entier jusqu'à

aujourd'hui.

Dans tout le deuxième livre des Dialogues, Grégoire nous montre la façon dont

la vie de saint Benoît était plongée dans une atmosphère de prière, fondement

central de son existence. Sans prière l'expérience de Dieu n'existe pas. Mais

la spiritualité de Benoît n'était pas une intériorité en dehors de la réalité.

Dans la tourmente et la confusion de son temps, il vivait sous le regard de

Dieu et ne perdit ainsi jamais de vue les devoirs de la vie quotidienne et

l'homme avec ses besoins concrets. En voyant Dieu, il comprit la réalité de

l'homme et sa mission. Dans sa Règle, il qualifie la vie monastique

d'"école du service du Seigneur" (Prol. 45) et il demande à ses

moines de "ne rien placer avant l'Œuvre de Dieu [c'est-à-dire l'Office

divin ou la Liturgie des Heures]" (43, 3). Il souligne cependant que la

prière est en premier lieu un acte d'écoute (Prol. 9-11), qui doit ensuite se

traduire par l'action concrète. "Le Seigneur attend que nous répondions

chaque jour par les faits à ses saints enseignements", affirme-t-il (Prol.

35). Ainsi, la vie du moine devient une symbiose féconde entre action et

contemplation "afin que Dieu soit glorifié en tout" (57, 9). En

opposition avec une réalisation personnelle facile et égocentrique, aujourd'hui

souvent exaltée, l'engagement premier et incontournable du disciple de saint

Benoît est la recherche sincère de Dieu (58, 7) sur la voie tracée par le

Christ humble et obéissant (5, 13), ne devant rien placer avant l'amour pour

celui-ci (4, 21; 72, 11) et c'est précisément ainsi, au service de l'autre,

qu'il devient un homme du service et de la paix. Dans l'exercice de

l'obéissance mise en acte avec une foi animée par l'amour (5, 2), le moine

conquiert l'humilité (5, 1), à laquelle la Règle consacre un chapitre entier

(7). De cette manière, l'homme devient toujours plus conforme au Christ et

atteint la véritable réalisation personnelle comme créature à l'image et à la

ressemblance de Dieu.

A l'obéissance du disciple doit correspondre la sagesse de l'Abbé, qui dans le

monastère remplit "les fonctions du Christ" (2, 2; 63, 13). Sa

figure, définie en particulier dans le deuxième chapitre de la Règle, avec ses

qualités de beauté spirituelle et d'engagement exigeant, peut-être considérée

comme un autoportrait de Benoît, car - comme l'écrit Grégoire le Grand -

"le saint ne put en aucune manière enseigner différemment de la façon dont

il vécut" (Dial. II, 36). L'Abbé doit être à la fois un père tendre et

également un maître sévère (2, 24), un véritable éducateur. Inflexible contre

les vices, il est cependant appelé à imiter en particulier la tendresse du Bon

Pasteur (27, 8), à "aider plutôt qu'à dominer" (64, 8), à

"accentuer davantage à travers les faits qu'à travers les paroles tout ce

qui est bon et saint" et à "illustrer les commandements divins par

son exemple" (2, 12). Pour être en mesure de décider de manière

responsable, l'Abbé doit aussi être un personne qui écoute "le conseil de

ses frères" (3, 2), car "souvent Dieu révèle au plus jeune la

solution la meilleure" (3, 3). Cette disposition rend étonnamment moderne

une Règle écrite il y a presque quinze siècles! Un homme de responsabilité

publique, même à une petite échelle, doit toujours être également un homme qui

sait écouter et qui sait apprendre de ce qu'il écoute.

Benoît qualifie la Règle de "Règle minimale tracée uniquement pour le

début" (73, 8); en réalité, celle-ci offre cependant des indications

utiles non seulement aux moines, mais également à tous ceux qui cherchent un

guide sur leur chemin vers Dieu. En raison de sa mesure, de son humanité et de

son sobre discernement entre ce qui est essentiel et secondaire dans la vie

spirituelle, elle a pu conserver sa force illuminatrice jusqu'à aujourd'hui.

Paul VI, en proclamant saint Benoît Patron de l'Europe le 24 octobre 1964,

voulut reconnaître l'œuvre merveilleuse accomplie par le saint à travers la

Règle pour la formation de la civilisation et de la culture européenne.

Aujourd'hui, l'Europe - à peine sortie d'un siècle profondément blessé par deux

guerres mondiales et après l'effondrement des grandes idéologies qui se sont révélées

de tragiques utopies - est à la recherche de sa propre identité. Pour créer une

unité nouvelle et durable, les instruments politiques, économiques et

juridiques sont assurément importants, mais il faut également susciter un

renouveau éthique et spirituel qui puise aux racines chrétiennes du continent,

autrement on ne peut pas reconstruire l'Europe. Sans cette sève vitale, l'homme

reste exposé au danger de succomber à l'antique tentation de vouloir se

racheter tout seul - une utopie qui, de différentes manières, a causé dans

l'Europe du XX siècle, comme l'a remarqué le Pape Jean-Paul II, "un recul

sans précédent dans l'histoire tourmentée de l'humanité" (Insegnamenti,

XIII/1, 1990, p. 58). En recherchant le vrai progrès, nous écoutons encore

aujourd'hui la Règle de saint Benoît comme une lumière pour notre chemin. Le

grand moine demeure un véritable maître à l'école de qui nous pouvons apprendre

l'art de vivre le véritable humanisme.

* * *

Je suis heureux de vous accueillir chers pèlerins francophones. Je salue en

particulier le groupe de la Vallée de l’Andelle dans le diocèse d’Évreux ainsi

que les jeunes venus notamment de Neuilly, de Rueil-Malmaison et de Pontivy. A

l’exemple de saint Benoît, donnez une place importante à la prière et à la

contemplation du visage du Christ ressuscité présent et agissant dans votre

vie! Bon temps pascal!

© Copyright 2008 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

LETTRE ENCYCLIQUE

FULGENS RADIATUR (*)

DE S. S. PIE XII

À L’OCCASION DU 14ème

CENTENAIRE DE

LA MORT DE SAINT BENOÎT

Vénérables Frères,

Salut et Bénédiction Apostolique.

Rayonnant comme un astre dans les ténèbres de la nuit, Benoît de Nursie honore

non seulement l’Italie, mais l’Eglise tout entière. Celui qui observe sa vie

illustre et étudie sur les documents authentiques l’époque ténébreuse et

trouble qui fut la sienne, éprouve sans aucun doute la vérité des divines

paroles par lesquelles le Christ promit à ses Apôtres et à la société fondée

par lui : « Je serai avec vous tous les jours jusqu’à la fin des siècles. » (Mt

28, 20). Certainement à aucune époque, ces paroles et cette promesse ne perdent

de leur force, mais elles se réalisent au cours de tous les siècles, qui sont

entre les mains de la divine Providence. Davantage, quand les ennemis du nom

chrétien l’attaquent avec plus de fureur, quand la barque portant le sort de

Pierre est agitée par des bourrasques plus violentes, quand tout semble aller à

la dérive et que ne luit plus aucun espoir de secours humain, voici qu’alors

apparaît le Christ, garant, consolateur, pourvoyeur de force surnaturelle, par

laquelle il excite ses nouveaux athlètes à défendre le monde catholique, à le

renouveler, et à lui susciter, avec l’inspiration et le secours de la grâce

divine, des progrès toujours plus étendus.

Parmi eux resplendit d’une vive lumière notre Saint « Benoît » « qui l’est et

de grâce et de nom » (1), et qui par une disposition spéciale de la divine

Providence, se dresse au milieu des ténèbres du siècle, à l’heure où se

trouvaient très gravement compromises les conditions d’existence, non seulement

de l’Eglise, mais de toute la civilisation politique et humaine. L’Empire

romain, qui était parvenu au faîte d’une si grande gloire et qui s’était

aggloméré tant de peuples, de races et de nations grâce à la sage modération et

à l’équité de son droit, de telle sorte qu’on « aurait pu l’appeler avec plus

de vérité un patronat sur le monde entier qu’un Empire » (2), désormais, comme toutes

les choses terrestres, en était venu à son déclin ; car, affaibli et corrompu à

l’intérieur, ébranlé sur ses frontières par les invasions barbares, se ruant du

septentrion, il avait été écrasé dans les régions occidentales, sous ses ruines

immenses.

Dans une si violente tempête et au milieu de tant de remous, d’où vint luire

l’espérance sur la communauté des hommes, d’où se levèrent pour elle le secours

et la défense capables de la sauver du naufrage, elle-même et quelques restes à

tout le moins de ses biens ? Justement de l’Eglise catholique. Les entreprises

de ce monde, en effet, et toutes les institutions de l’homme, l’une après

l’autre au cours des âges, s’accroissent, atteignent à leur sommet, et puis de

leur propre poids, déclinent, tombent et disparaissent ; au contraire la

communauté fondée par notre divin Rédempteur, tient de lui la prérogative d’une

vie supérieure et d’une force indéfectible ; ainsi entretenue et soutenue par

lui, elle surmonte victorieusement les injures des temps, des événements et des

hommes, au point de faire surgir de leurs disgrâces et de leurs ruines une ère

nouvelle et plus heureuse en même temps qu’elle crée et élève dans la doctrine

chrétienne et dans le sens chrétien une nouvelle société de citoyens, de

peuples et de nations. Or il Nous plaît, Vénérables Frères, de rappeler

brièvement et à grands traits dans cette Encyclique la part que prit Benoît à

l’œuvre de cette restauration et de ce renouveau, l’année même, à ce qu’il

semble, du quatorzième centenaire, depuis le jour où, ayant achevé ses

innombrables travaux pour la gloire de Dieu et le salut des hommes, il changea

l’exil de cette terre pour la patrie du ciel.

I. La figure historique de saint Benoît

« Né de noble race dans la province de Nursie » (3), Benoît « fut rempli de

l’esprit de tous les justes » (4), et il soutint merveilleusement le monde

chrétien par sa vertu, sa prudence et sa sagesse. Car, tandis que le siècle

s’était vieilli dans le vice, que l’Italie et l’Europe offraient l’affreux

spectacle d’un champ de bataille pour les peuples en conflit, et que les

institutions monastiques, elle-mêmes, souillées par la poussière de ce monde,

étaient moins fortes qu’il n’aurait fallu pour résister aux attraits de la

corruption et les repousser, Benoît, par son action et sa sainteté éclatantes,

témoigna de l’éternelle jeunesse de l’Eglise, restaura par la parole et par

l’exemple la discipline des mœurs, et entoura d’un rempart de lois plus

efficaces et plus sanctifiantes la vie religieuse des cloîtres. Plus encore :

par lui-même et par ses disciples, il fit passer les peuplades barbares d’un

genre de vie sauvage à une culture humaine et chrétienne, et les convertissant

à la vertu, au travail, aux occupations pacifiques des arts et des lettres, il

les unit entre eux par les liens des relations sociales et de la charité

fraternelle.

Dès sa prime jeunesse, il se rend à Rome, pour s’occuper de l’étude des

sciences libérales (5) ; mais, à sa très grande tristesse, il se rend compte

que des hérésies et des erreurs de toute sorte s’insinuent, les trompant et les

déformant, en beaucoup d’esprits ; il voit les mœurs privées et publiques

tomber en décadence, un grand nombre de jeunes surtout, mondains et efféminés,

se vautrer lamentablement dans la fange des voluptés ; si bien qu’avec raison

on pouvait affirmer de la société romaine : « Elle meurt et elle rit. C’est

pourquoi, dans toutes les parties du monde, des larmes suivent nos rires » (6).

Cependant Benoît, prévenu par la grâce de Dieu, « ne s’adonna à aucun de ces plaisirs,…

mais, voyant beaucoup de ses compagnons côtoyer les abîmes du vice et y tomber,

il retira le pied qu’il y avait posé presque dès son entrée dans le monde...

Renonçant aux études littéraires, il quitta la maison paternelle et tous ses

biens, ne désirant plaire désormais qu’à Dieu, et il chercha une sainte manière

de vivre » (7). Il dit un cordial adieu aux commodités de la vie et aux appâts

d’un monde corrompu, de même qu’à l’attrait de la fortune et aux emplois

honorables auxquels son âge mûr pouvait prétendre. Quittant Rome, il se retira

dans des régions boisées et solitaires où il lui serait loisible de vaquer à la

contemplation des réalités surnaturelles. Il gagna ainsi Subiaco, où

s’enfermant dans une étroite caverne, il commença à mener une vie plus divine

qu’humaine.

Caché avec le Christ en Dieu (Cf. Col 3, 3), il s’efforça très efficacement

durant trois ans à poursuivre cette perfection évangélique et cette sainteté

auxquelles il se sentait appelé par une inspiration divine. Fuir tout ce qui est

terrestre pour n’aspirer de toutes ses forces qu’à ce qui est céleste ;

converser jour et nuit avec Dieu, et Lui adresser de ferventes prières pour son

salut et celui du prochain ; réprimer et maîtriser le corps par une

mortification volontaire ; réfréner et dominer les mouvements désordonnés des

sens : telle fut sa règle. Dans cette manière de vivre et d’agir, il goûtait

une si douce suavité intérieure qu’il prenait en suprême dégoût les richesses

et commodités de la terre et en oubliait même les charmes qu’il avait éprouvés

jadis. Un jour que l’ennemi du genre humain le tourmentait des plus violents

aiguillons de la concupiscence, Benoît, âme noble et forte, résista sur le

champ avec toute l’énergie de sa volonté ; et se jetant au milieu des ronces et

des orties, il éteignit par leurs piqûres volontaires le feu qui le brûlait au

dedans ; sorti de la sorte vainqueur de lui-même, il fut en récompense confirmé

dans la grâce divine. « Depuis lors, comme il le raconta plus tard à ses

disciples, la tentation impure fut si domptée en lui qu’il n’éprouvât plus rien

de semblable... Libre ainsi du penchant au vice, il devint désormais à bon

droit maître de vertus » (8).

Renfermé dans la grotte de Subiaco durant ce long espace de vie obscure et

solitaire, Notre Saint se confirma et s’aguerrit dans l’exercice de la sainteté

; il jeta ces solides fondements de la perfection chrétienne sur lesquels il

lui serait permis d’élever par la suite un édifice d’une prodigieuse hauteur.

Comme vous le savez bien, Vénérables Frères, les œuvres d’un saint zèle et d’un

saint apostolat restent sans aucun doute vaines et infructueuses si elles ne

partent pas d’un cœur riche en ces ressources chrétiennes, grâce auxquelles les

entreprises humaines peuvent, avec le secours divin, tendre sans dévier à la

gloire de Dieu et au salut des âmes. De cette vérité Benoît avait une intime et

profonde conviction ; c’est pourquoi, avant d’entreprendre la réalisation et

l’achèvement de ces grandioses projets auxquels il se sentait appelé par le

souffle de l’Esprit Saint, il s’efforça de tout son pouvoir, et il demanda à

Dieu par d’instantes prières, de reproduire excellemment en lui ce type de

sainteté, composé selon l’intégrité de la doctrine évangélique, qu’il désirait

enseigner aux autres.

Mais la renommée de son extraordinaire sainteté se répandait dans les environs,

et elle augmentait de jour en jour. Aussi non seulement les moines qui

demeuraient à proximité voulurent se mettre sous sa direction, mais une foule

d’habitants eux-mêmes commencèrent à venir en groupes auprès de lui, désireux

d’entendre sa douce voix, d’admirer son exceptionnelle vertu et de voir ces

miracles que par un privilège de Dieu il opérait assez souvent. Bien plus,

cette vive lumière qui rayonnait de la grotte obscure de Subiaco, se propagea

si loin qu’elle parvint en de lointaines régions. Aussi « nobles et personnes

religieuses de la ville de Rome commencèrent à venir à lui, et ils lui

donnaient leurs fils à élever pour le Tout-Puissant » (9).

Notre Saint comprit alors que le temps fixé par le décret de Dieu était venu de

fonder un ordre religieux, et de le conformer à tout prix à la perfection

évangélique. Cette œuvre débuta sous les plus heureux auspices. Beaucoup, en

effet, « furent rassemblés par lui en ce lieu pour le service du Dieu

Tout-Puissant..., si bien qu’il put, avec l’aide du Tout-Puissant Seigneur

Jésus-Christ, y construire douze monastères, à chacun desquels il assigna douze

moines sous des supérieurs désignés ; il en retint quelques-uns avec lui, ceux

qu’il jugea devoir être formés en sa présence » (10).

Toutefois, au moment où, — comme Nous l’avons dit ,— l’initiative procédait

heureusement, où elle commençait à produire d’abondants fruits de salut et en

promettait plus encore pour l’avenir, Notre Saint, avec une immense tristesse

dans l’âme, vit se lever sur les moissons grandissantes une noire tempête,

soulevée par une jalousie aiguë et entretenue par des désirs d’ambition

terrestre. Benoît était guidé par une prudence non humaine, mais divine ; pour

que cette haine, qui s’était déchaînée surtout contre lui, ne tournât point,

par malheur, au dommage de ses fils, « il céda le pas à l’envie ; mit ordre à

tous les lieux de prière construits par lui, en remplaçant les supérieurs et en

ajoutant de nouveaux frères ; puis, ayant pris avec lui quelques moines, il

changea l’endroit de sa résidence » (11). C’est pourquoi, se fiant à Dieu et

sûr de son très efficace secours, il s’en alla vers le sud, et s’établit dans

la localité « appelée Mont Cassin, au flanc d’une haute montagne... ; sur

l’emplacement d’un très ancien temple, où un peuple ignorant et rustique

vénérait Apollon à la manière des vieux païens. Tout à l’entour, des bois

consacrés au culte des démons avaient grandi, et, à cette époque encore, une

multitude insensée d’infidèles s’y livrait à des sacrifices sacrilèges. A peine

arrivé l’homme de Dieu brisa l’idole, renversa l’autel, incendia les bosquets

sacrés ; sur le temple même d’Apollon il édifia la chapelle du Bienheureux

Martin, et là où se trouvait l’autel du même Apollon il construisit l’oratoire

de S. Jean ; enfin, par sa continuelle prédication, il convertit à la foi les

populations qui habitaient aux environs » (12).

Le Mont-Cassin, tout le monde le sait, a été la demeure principale du S.

Patriarche et le principal théâtre de sa vertu et de sa sainteté. Des sommets

de ce mont, quand presque de toutes parts les ténèbres de l’ignorance et des

vices se propageaient dans un effort pour tout recouvrir et pour tout ruiner,

resplendit une lumière nouvelle qui, alimentée par les enseignements et la

civilisation des peuples anciens, et surtout échauffée par la doctrine

chrétienne ; éclaira les peuples et les nations qui erraient à l’aventure, les

rappela et les dirigea vers la vérité et le droit chemin. Si bien qu’on peut

affirmer à bon droit que le saint monastère édifié là devint le refuge et la

forteresse des plus hautes sciences et de toutes les vertus, et en ces temps

troublés « comme le soutien de l’Eglise et le rempart de la foi » (13).

C’est là que Benoît porta l’institution monastique à ce genre de perfection,

auquel depuis longtemps il s’était efforcé par ses prières, ses méditations et

ses expériences. Tel semble bien être, en effet, le rôle spécial et essentiel à

lui confié par la divine Providence : non pas tant apporter de l’Orient en

Occident l’idéal de la vie monastique, que l’harmoniser et l’adapter avec

bonheur au tempérament, aux besoins et aux habitudes des peuples de l’Italie et

de toute l’Europe. Par ses soins donc, à la sereine doctrine ascétique qui

florissait dans les monastères de l’Orient, se joignit la pratique d’une

incessante activité, permettant de « communiquer à autrui les vérités

contemplées » (14), et, non seulement de rendre fertiles des terres incultes,

mais de produire par les fatigues de l’apostolat des fruits spirituels. Ce que

la vie solitaire avait d’âpre, d’inadapté à tous et même parfois de dangereux

pour certains, il l’adoucit et le tempéra par la communauté fraternelle de la

famille bénédictine, où, successivement adonnée à la prière, au travail, aux

études sacrées et profanes, la douce tranquillité de l’existence ne connaît

cependant ni oisiveté ni dégoût ; où l’action et le travail, loin de fatiguer

l’esprit et l’âme, de les dissiper et de les absorber en futilités, les

rassérènent plutôt, les fortifient et les élèvent aux choses du ciel. Ni excès

de rigueur, en effet, dans la discipline, ni excès de sévérité dans les

mortifications, mais avant tout l’amour de Dieu et une charité fraternellement

dévouée envers tous : voilà ce qui est ordonné. Si tant est que Benoît «

équilibra sa règle de manière que les forts désirent faire davantage et que les

faibles ne soient pas rebutés par son austérité... Il s’appliquait à régir les

siens par l’amour plutôt qu’à les dominer par la crainte » (15). Prévenu,

certain jour, qu’un anachorète s’était lié avec des chaînes et enfermé dans une

caverne, pour ne plus pouvoir retourner au péché et à la vie du siècle, il le

réprimanda doucement en disant : « Si tu es un serviteur de Dieu, ce n’est pas

une chaîne de fer, mais la chaîne du Christ qui doit te retenir » (16).

C’est ainsi qu’aux coutumes et préceptes propres à la vie érémitique, qui la

plupart du temps n’étaient pas nettement fixés et codifiés, mais dépendaient

souvent du caprice du supérieur, succéda la règle monastique de S. Benoît, chef

d’œuvre de la sagesse romaine et chrétienne, où les droits, les devoirs et les

offices des moines sont tempérés par la bonté et la charité évangéliques, et

qui a eu et a encore tant d’efficacité pour stimuler un grand nombre à la

poursuite de la vertu et de la sainteté.

Dans cette règle bénédictine, la prudence se joint à la simplicité, l’humilité

chrétienne s’associe au courage généreux ; la douceur tempère la sévérité et

une saine liberté ennoblit la nécessaire obéissance. En elle, la correction

conserve toute sa vigueur, mais l’indulgence et la bonté l’agrémentent de

suavité ; les préceptes gardent toute leur fermeté, mais l’obéissance donne

repos aux esprits et paix aux âmes ; le silence plaît par sa gravité, mais la

conversation s’orne d’une douce grâce ; enfin l’exercice de l’autorité ne

manque pas de force, mais la faiblesse ne manque pas de soutien (17).

Il n’y a donc pas à s’étonner que tous les gens sensés d’aujourd’hui exaltent

de leurs louanges la « règle monastique écrite par S. Benoît, règle fort

remarquable par sa discrétion et par la lumineuse clarté de son expression »

(18) ; et il Nous plaît d’en souligner ici et d’en dégager les traits

essentiels, avec la confiance que Nous ferons œuvre agréable et utile non

seulement à la nombreuse famille du S. Patriarche, mais à tout le clergé et à

tout le peuple chrétien.

La communauté monastique est constituée et organisée à l’image d’une maison

chrétienne, dont l’abbé, ou cénobiarche, comme un père de famille, a le

gouvernement, et tous doivent dépendre entièrement de sa paternelle autorité. «

Nous jugeons expédient — écrit S. Benoît — pour la sauvegarde de la paix et de

la charité, que le gouvernement du monastère dépende de la volonté de l’abbé »

(19). Aussi tous et chacun doivent-ils lui obéir très fidèlement par obligation

de conscience (20), voir et respecter en lui l’autorité divine elle-même.

Toutefois que celui qui, en fonction de la charge reçue, entreprend de diriger

les âmes des moines et de les stimuler à la perfection de la vie évangélique,

se souvienne et médite avec grand soin qu’il devra un jour en rendre compte au

Juge suprême (21) ; qu’il se comporte donc, dans cette très lourde charge, de

manière à mériter une juste récompense « quand se fera la reddition des comptes

au terrible jugement de Dieu » (22). En outre, toutes les fois que des affaires

de plus grande importance devront être traitées dans son monastère, qu’il

rassemble tous ses moines, qu’il écoute leurs avis librement exposés et qu’il

en fasse un sérieux examen avant d’en venir à la décision qui lui paraîtra la

meilleure (23).

Dès les débuts pourtant, une grave difficulté et une épineuse question furent

soulevées, à propos de la réception ou du renvoi des candidats à la vie

monastique. En effet, des hommes de toute origine, de tout pays, de toute

condition sociale accouraient dans les monastères pour y être admis : Romains

et barbares, hommes libres et esclaves, vainqueurs et vaincus, beaucoup de

nobles patriciens et d’humbles plébéiens. C’est avec magnanimité et délicatesse

fraternelle que Benoît résolut heureusement ce problème ; « car, dit-il,

esclaves ou hommes libres, nous sommes tous un dans le Christ, et sous le même

Seigneur nous servons à égalité dans sa milice... Que la charité soit donc la

même en tous ; qu’une même discipline s’exerce pour tous selon leurs mérites »

(24). A tous ceux qui ont embrassé son Institut, il ordonne que « tout soit

commun pour l’avantage de tous » (25), non par force ou contrainte en quelque

sorte, mais spontanément et avec une volonté généreuse. Que tous en outre

soient maintenus dans l’enceinte du monastère par la stabilité de la vie

religieuse, de telle façon pourtant qu’ils vaquent non seulement à la prière et

à l’étude,(26) mais aussi à la culture des champs (27), aux métiers manuels

(28) et enfin aux saints travaux de l’apostolat. Car « l’oisiveté est l’ennemie

de l’âme ; c’est pourquoi à des heures déterminées les frères doivent être

occupés au travail des mains... » (29). Toutefois que, pour tous, le premier

devoir, celui qu’ils doivent s’efforcer de remplir avec le plus de diligence et

de soin, soit de ne rien faire passer avant l’office divin (« opus Dei ») (30).

Car bien que « nous sachions que Dieu est présent partout... nous devons

cependant le croire sans la plus minime hésitation quand nous assistons à

l’office divin... Réfléchissons donc sur la manière qu’il convient de nous

tenir en présence de Dieu et des anges, et psalmodions de façon que notre

esprit s’harmonise avec notre voix. » (31)

Par ces normes et maximes plus importantes, qu’il Nous a paru bon de déguster

pour ainsi dire dans la Règle bénédictine, il est facile de discerner et

d’apprécier non seulement la prudence de cette règle monastique, son

opportunité et sa merveilleuse correspondance et accord avec la nature de

l’homme, mais aussi son importance et son extrême élévation. Car, dans ce

siècle barbare et turbulent, la culture des champs, les arts mécaniques et

industriels, l’étude des sciences sacrées et profanes, étaient totalement

dépréciés et malheureusement délaissés de tous ; dans les monastères

bénédictins, au contraire, alla sans cesse croissante une foule presque

innombrable d’agriculteurs, d’artisans et de savants qui, chacun selon ses

talents, parvinrent, non seulement à conserver intactes les productions de

l’antique sagesse, mais à pacifier de nouveau, à unir et à occuper activement

des peuples vieux et jeunes souvent en guerre entre eux ; et ils réussirent à

les faire passer de la barbarie renaissante, des haines dévastatrices et des

rapines à des habitudes de politesse humaine et chrétienne, à l’endurance dans

le travail, à la lumière de la vérité et à la reprise des relations normales

entre nations, s’inspirant de la sagesse et de la charité.

Mais ce n’est pas tout ; car, dans l’Institut de la vie Bénédictine,

l’essentiel est que tous, autant les travailleurs manuels qu’intellectuels,

aient à cœur et s’efforcent le plus possible d’avoir l’âme continuellement

tournée vers le Christ, et brûlant de sa très parfaite charité. En effet, les

biens de ce monde, même tous rassemblés, ne peuvent rassasier l’âme humaine que

Dieu a créée pour le chercher lui-même ; mais ils ont bien plutôt reçu de leur

Auteur la mission de nous mouvoir et de nous convertir, comme par paliers

successifs, jusqu’à sa possession. C’est pourquoi il est tout d’abord

indispensable que « rien ne soit préféré à l’amour du Christ » (32), « que rien

ne soit estimé de plus haut prix que le Christ » (33) ; « qu’absolument rien ne

soit préféré au Christ, qui nous conduit à la vie éternelle ». (34)

A cet ardent amour du Divin Rédempteur doit correspondre l’amour des hommes,

que nous devons tous embrasser comme des frères, et aider de toute façon. C’est

pourquoi, à l’encontre des haines et des rivalités qui dressent et opposent les

hommes les uns aux autres ; des rapines, des meurtres et des innombrables maux

et misères, conséquences de cette trouble agitation de gens et de choses,

Benoît recommande aux siens ces très saintes lois : « Qu’on montre les soins

les plus empressés dans l’hospitalité, spécialement à l’égard des pauvres et

des pèlerins, car c’est le Christ que l’on accueille davantage en eux » (35). «

Que tous les hôtes qui nous arrivent soient accueillis comme le Christ, car

c’est Lui qui dira un jour : J’ai été étranger, et vous m’avez accueilli »

(36). « Avant tout et par-dessus tout, que l’on ait soin des malades, afin de

les servir comme le Christ lui-même, car il a dit : J’étais malade, et vous

m’avez visité » (37).

Inspiré et emporté de la sorte par un amour très parfait de Dieu et du

prochain, Benoît conduisit son entreprise à bonne fin, jusqu’à la perfection.

Et quand tressaillant de joie et rempli de mérites, il aspirait déjà les brises

célestes de l’éternelle félicité et en goûtait à l’avance les douceurs, « le

sixième jour avant sa mort..., il fit creuser sa tombe. Consumé bientôt de

fièvre, il commença à ressentir l’ardente brûlure du feu intérieur ; et comme

la maladie s’aggravait de plus en plus, le sixième jour il se fit porter par

ses disciples à l’église ; là il se pourvut, pour l’ultime voyage, de la

réception du Corps et du Sang du Seigneur, et entre les bras de ses fils qui

soutenaient ses membres déficients, les mains levées vers le ciel, il se tint

immobile et, en murmurant encore des paroles de prière, il rendit le dernier

soupir » (38).

II. Bienfaits de S. Benoît et de son Ordre pour l’Eglise et la Civilisation

Lorsque, par une pieuse mort, le très saint Patriarche se fut envolé au ciel,

l’ordre de moines qu’il avait fondé, loin de tomber en décadence, sembla bien

plutôt, non seulement conduit, nourri et façonné à chaque instant par ses

vivants exemples, mais encore maintenu et fortifié par son céleste patronage,

au point de connaître d’année en année de plus larges développements.

Avec quelle force et efficacité l’Ordre bénédictin exerça son heureuse

influence au temps de sa première fondation, que de nombreux et grands services

il rendit aux siècles suivants, tous ceux-là doivent le reconnaître, qui

discernent et apprécient sainement les événements humains, non selon des idées

préconçues, mais au témoignage de l’histoire. Car, outre que, nous l’avons dit,

les moines Bénédictins furent presque les seuls, en des siècles ténébreux, au

milieu d’une telle ignorance des hommes et de si grandes ruines matérielles, à

garder intacts les savants manuscrits et les richesses des belles lettres, à

les transcrire très soigneusement et à les commenter, ils furent encore des

tout premiers à cultiver les arts, les sciences, l’enseignement, et à les

promouvoir de toutes leurs industries. De la sorte, ainsi que l’Eglise

catholique, surtout pendant les trois premiers siècles de son existence, se

fortifia et s’accrut d’une façon merveilleuse par le sang sacré de ses martyrs,

et ainsi qu’à cette date et aux époques suivantes l’intégrité de sa divine

doctrine fut sauvegardée contre les attaques perfides des hérétiques par

l’activité vigoureuse et sage des Saints Pères, on est de même en droit

d’affirmer que l’Ordre bénédictin et ses florissants monastères furent suscités

par la sagesse et l’inspiration de Dieu : cela pour qu’à l’heure même où

s’écroulait l’Empire romain et où des peuples barbares, qu’excitait la furie

guerrière, l’envahissaient de tous côtés, la chrétienté pût réparer ses pertes,

et de plus, avec une vigilance inlassable, amener des peuples nouveaux,

qu’avaient domptés la vérité et la charité de l’Evangile, à la concorde

fraternelle, à un travail fécond, en un mot à la vertu, qui est régie par les

enseignements de notre Rédempteur et alimentée par sa grâce.

Car, de même qu’aux siècles passés les légions Romaines s’en allaient sur les

routes consulaires pour tenter d’assujettir toutes les nations à l’empire de la

Ville Eternelle, ainsi des cohortes innombrables de moines, dont les armes ne «

sont pas celles de la chair, mais la puissance même de Dieu » (2 Cor 10, 4),

sont alors envoyées par le Souverain Pontife pour propager efficacement le

règne pacifique de Jésus-Christ jusqu’aux extrémités de la terre, non par

l’épée, non par la force, non par le meurtre, mais par la Croix et par la

charrue, par la vérité et par l’amour.

Partout où posaient le pied ces troupes sans armes, formées de prédicateurs de

la doctrine chrétienne, d’artisans, d’agriculteurs et de maîtres dans les sciences

humaines et divines, les terres boisées et incultes étaient ouvertes par le fer

de la charrue ; les arts et les sciences y élevaient leurs demeures ; les

habitants sortis de leur vie grossière et sauvage, étaient formés aux relations

sociales et à la culture, et devant eux brillait en un vivant exemple la

lumière de l’Evangile et de la vertu. Des apôtres sans nombre, qu’enflammait la

céleste charité, parcoururent les régions encore inconnues et agitées de

l’Europe ; ils arrosèrent celles-ci de leurs sueurs et de leur sang généreux,

et, après les avoir pacifiées, ils leur portèrent la lumière de la vérité

catholique et de la sainteté. Si bien que l’on peut affirmer à juste titre que,

si Rome, déjà grande par ses nombreuses victoires avait étendu le sceptre de

son empire sur terre et sur mer, grâce à ces apôtres pourtant, « les gains que

lui valut la valeur militaire furent moindres que ce que lui assujettit la paix

chrétienne » (39). De fait, non seulement l’Angleterre, la Gaule, les Pays

Bataves, la Frise, le Danemark, la Germanie et la Scandinavie, mais aussi de

nombreux pays Slaves se glorifient d’avoir été évangélisés par ces moines

qu’ils considèrent comme leurs gloires, et comme les illustres fondateurs de

leur civilisation. De leur Ordre, combien d’Evêques sont sortis, qui

gouvernèrent avec sagesse des diocèses déjà constitués, ou qui en fondèrent un

bon nombre de nouveaux, rendus féconds par leur labeur ! Combien d’excellents

maîtres et docteurs élevèrent des chaires illustres de lettres et d’arts libéraux,

éclairèrent de nombreuses intelligences, qu’obnubilait l’erreur, et donnèrent à

travers le monde entier aux sciences sacrées et profanes une forte impulsion !

Combien enfin, rendus célèbres par leur sainteté, qui, dans les rangs de la

famille bénédictine s’efforcèrent d’atteindre selon leurs forces la perfection

évangélique et propagèrent de toutes manières le Règne de Jésus-Christ par

l’exemple de leurs vertus, leurs saintes prédications et même les miracles que

Dieu leur permit d’opérer ! Beaucoup d’entre eux, vous le savez, Vénérables

Frères, furent revêtus de la dignité épiscopale, ou de la majesté du Souverain

Pontificat. Les noms de ces apôtres, de ces Evêques, de ces Saints, de ces

Pontifes suprêmes sont écrits en lettres d’or dans les annales de l’Eglise, et

il serait trop long de les rapporter ici nommément ; au reste, brillent-ils

d’une si vivante splendeur et tiennent-ils dans l’histoire une si grande place,

qu’il est facile à tous de se les rappeler.

III. Enseignements de la « Règle bénédictine » au monde actuel

Nous croyons, en conséquence, très opportun que ces faits, rapidement esquissés

dans Notre lettre, soient attentivement médités durant les solennités de ce

centenaire et qu’à tous les regards ils revivent en pleine lumière, afin que

plus aisément tous en conçoivent, non seulement le désir d’exalter et de louer

ces fastueuses grandeurs de l’Eglise, mais la résolution de suivre d’un cœur

prompt et généreux les exemples de vie et les enseignements qui en découlent.

Car ce n’est pas uniquement les siècles passés qui ont profité des bienfaits

incalculables de ce grand Patriarche et de son Ordre ; notre époque elle aussi

doit apprendre de lui de nombreuses et importantes leçons. En tout premier lieu

— Nous n’en doutons nullement — que les membres de sa très nombreuse famille

apprennent à suivre ses traces avec une générosité chaque jour plus grande et à

faire passer dans leur propre vie les principes et les exemples de sa vertu et

de sa sainteté. Et sûrement, il arrivera que, non seulement ils correspondront

magnanimement, activement et fructueusement à cette voix céleste, dont ils

suivirent un jour l’appel surnaturel, lorsqu’ils ont débuté dans la vie

monastique ; que non seulement ils assureront la paix sereine de leur

conscience et surtout leur salut éternel, mais encore qu’ils pourront

s’adonner, d’une façon très fructueuse, au bien commun du peuple chrétien et à

l’extension de la gloire de Dieu.

De plus, si toutes les classes de la société, avec une studieuse et diligente

attention, observent la vie de S. Benoît, ses enseignements et ses hauts faits,

elles ne pourront pas ne pas être attirées par la douceur de son esprit et la

force de son influence ; et elles reconnaîtront d’elles-mêmes que notre siècle,

rempli et désaxé lui aussi par tant de graves ruines matérielles et morales,

par tant de dangers et de désastres, peut lui demander des remèdes nécessaires

et opportuns. Qu’elles se souviennent pourtant avant tout et considèrent

attentivement que les principes sacrés de la religion et les normes de vie

qu’elle édicte sont les fondements les plus solides et les plus stables de

l’humaine société ; s’ils viennent à être renversés ou affaiblis, il s’ensuivra

presque fatalement que tout ce qui est ordre, paix, prospérité des peuples et des

nations sera détruit progressivement. Cette vérité, que l’histoire de l’Ordre

Bénédictin, comme Nous l’avons vu, démontre si éloquemment, un esprit distingué

de l’antiquité païenne l’avait déjà comprise lorsqu’il traçait cette phrase : «

Vous autres, Pontifes... vous encerclez plus efficacement la ville par la

religion que ne le font les murailles elles-mêmes » (40). Le même auteur

écrivait encore : « ...Une fois disparues (la sainteté et la religion), suit le

désordre de l’existence, avec une grande confusion ; et je ne sais si, la piété

envers les dieux supprimée, ne disparaîtront pas également la confiance et la

bonne entente entre les mortels, ainsi que la plus excellente de toutes les

vertus, la justice » (41).

Le premier et le principal devoir est donc celui-ci : révérer la divinité,

obéir en privé et en public à ses saintes lois ; celles-ci transgressées, il

n’y a plus aucun pouvoir qui ait des freins assez puissants pour contenir et

modérer les passions déchaînées du peuple. Car la religion seule constitue le

soutien du droit et de l’honnêteté.

Notre saint Patriarche nous fournit encore une autre leçon, un autre

avertissement, dont notre siècle a tant besoin : à savoir, que Dieu ne doit pas

seulement être honoré et adoré ; il doit aussi être aimé, comme un Père, d’une

ardente charité. Et parce que cet amour s’est malheureusement aujourd’hui

attiédi et alangui, il en résulte qu’un grand nombre d’hommes recherchent les

biens de la terre plus que ceux du ciel, et avec une passion si immodérée,

qu’elle engendre souvent des troubles, qu’elle entretient les rivalités et les

haines les plus farouches. Or, puisque le Dieu éternel est l’auteur de notre

vie et que de Lui nous viennent des bienfaits sans nombre, c’est un devoir

strict pour tous de l’aimer par-dessus toutes choses, et de tourner vers Lui,

avant tout le reste, nos personnes et nos biens. De cet amour envers Dieu doit

naître ensuite une charité fraternelle envers les hommes, que tous, à quelque

race, nation ou condition sociale qu’ils appartiennent, nous devons considérer

comme nos frères dans le Christ ; en sorte que de tous les peuples et de toutes

les classes de la société se constitue une seule famille chrétienne, non pas

divisée par la recherche excessive de l’utilité personnelle, mais cordialement

unie par un mutuel échange de services rendus. Si ces enseignements, qui

portèrent jadis Benoît, ému par eux, à construire, recréer, éduquer et

moraliser la société décadente et troublée de son époque, retrouvaient

aujourd’hui le plus grand crédit possible, plus facilement aussi, sans nul

doute, notre monde moderne pourrait émerger de son formidable naufrage, réparer

ses ruines matérielles ou morales, et trouver à ses maux immenses d’opportuns

et efficaces remèdes.

Le législateur de l’Ordre Bénédictin nous enseigne encore, Vénérables Frères,

une autre vérité — vérité que l’on aime aujourd’hui à proclamer hautement, mais

que trop souvent on n’applique pas comme il conviendrait et comme il faudrait —

à savoir que le travail de l’homme n’est pas chose exempte de dignité, odieuse

et accablante, mais bien plutôt aimable, honorable et joyeuse. La vie de

travail, en effet, qu’il s’agisse de la culture des champs, des emplois

rétribués ou des occupations intellectuelles, n’avilit pas les esprits, mais

les ennoblit ; elle ne les réduit pas en servitude, mais plus exactement elle

les rend maîtres en quelque sorte et régisseurs des choses qui les environnent

et qu’ils traitent laborieusement. Jésus lui-même, adolescent, quand il vivait

à l’ombre de la demeure familiale, ne dédaigna pas d’exercer le métier de

charpentier dans la boutique de son père nourricier et il voulut consacrer de

sa sueur divine le travail humain. Que donc, non seulement ceux qui se livrent

à l’étude des lettres et des sciences, mais aussi ceux qui peinent dans des

métiers manuels, afin de se procurer leur pain quotidien, réfléchissent qu’ils

ont une très noble occupation, leur permettant de pourvoir à leurs propres

besoins, tout en se rendant utiles au bien de la société entière. Qu’ils le fassent

pourtant, comme le Patriarche Benoît nous l’enseigne, l’esprit et le cœur levés

vers le ciel ; qu’ils s’y adonnent non par force, mais par amour ; enfin, quand

ils défendent leurs droits légiTimes New Roman, qu’ils le fassent, non en

jalousant le sort d’autrui, non désordonnément et par des attroupements, mais

d’une manière tranquille et avec droiture. Qu’ils se souviennent de la divine

sentence : « Tu mangeras ton pain à la sueur de ton front » (Gn 3, 19) ;

précepte que tous les hommes doivent observer en esprit d’obéissance et

d’expiation.

Qu’ils n’oublient pas surtout que nous devons nous efforcer chaque jour

davantage de nous élever des réalités terrestres et caduques, qu’il s’agisse de

celles qu’élabore ou découvre un esprit aiguisé, ou de celles qui sont

façonnées par un métier pénible, à ces réalités célestes et perdurables, dont

l’atteinte peut seule nous donner la véritable paix, la sereine quiétude et

l’éternelle félicité.

IV. La reconstruction du Monastère du Mont-Cassin, juste tribut de reconnaissance

Quand la guerre, toute récente, se porta sur les limites de la Campanie et du

Latium, elle frappa violemment, vous le savez, Vénérables Frères, les hauteurs

sacrées du Mont Cassin ; et bien que, de tout Notre pouvoir, par des conseils,

des exhortations, des supplications, Nous n’ayons rien omis pour qu’une si

cruelle atteinte ne soit pas portée à une très vénérable religion, à de

splendides chefs-d’œuvre et à la civilisation elle-même, le fléau a néanmoins

détruit et anéanti cette illustre demeure des études et de la piété, qui, tel

un flambeau vainqueur des ténèbres, avait émergé au-dessus des flots

séculaires. C’est pourquoi, tandis que, tout autour, villes, places fortes,

bourgades devenaient des monceaux de ruines, il s’avéra que le monastère du

Mont Cassin lui-même, maison-mère de l’Ordre bénédictin, dût comme partager le

deuil de ses fils et prendre sa part de leurs malheurs. Presque rien n’en resta

intact, sauf le caveau sacré où sont très religieusement conservées les

reliques du S. Patriarche.

Là où l’on admirait des monuments superbes, il n’y a plus aujourd’hui que des

murs chancelants, des décombres et des ruines, que de misérables ronces

recouvrent ; seule une petite demeure pour les moines a été récemment élevée à

proximité. Mais pourquoi ne serait-il pas permis d’espérer que, durant la

commémoraison du XIVe centenaire depuis le jour où, après avoir commencé et

conduit à bon terme une si grandiose entreprise, notre Saint alla jouir de la

céleste béatitude, pourquoi, disons-Nous, ne pourrions-nous pas espérer qu’avec

le concours de tous les gens de bien, surtout des plus riches et des plus

généreux, cet antique monastère ne soit rétabli au plus vite dans sa primitive

splendeur ? C’est assurément une dette à Benoît de la part du monde civilisé,

qui, s’il est éclairé aujourd’hui d’une si grande lumière doctrinale et s’il se

réjouit d’avoir conservé les antiques monuments des lettres, en est redevable à

ce Saint et à sa famille laborieuse. Nous formons donc l’espoir que l’avenir

réponde à ces vœux, qui sont Nôtres ; et que pareille entreprise soit non

seulement une œuvre de restauration intégrale, mais un augure également de

temps meilleurs, où l’esprit de l’Institut bénédictin et ses très opportuns

enseignements viennent de jour en jour à refleurir davantage. Dans cette très

douce espérance, à chacun de vous, Vénérables Frères, ainsi qu’au troupeau

confié à vos soins, comme à l’universelle famille monacale, qui se glorifie

d’un tel législateur, d’un tel maître et d’un tel père, Nous accordons de toute

Notre âme, en gage des grâces célestes et en témoignage de Notre bienveillance,

la Bénédiction Apostolique.

Donné à Rome, près Saint Pierre, le 21e jour du mois de Mars, en la fête de

Saint Benoît, l’an 1947, neuvième de Notre Pontificat.

PIUS PP. XII

NOTES

(*) Pius PP. XII, Litt. enc. Fulgens radiatur decimoquarto exacto saeculo a

pientissimo S. Benedicti obitu, [Ad venerabiles Fratres Patriarchas, Primates,

Archiepiscopos, Episcopos, aliosque locorum Ordinarios pacem et communionem cum

Apostolica Sede habentes], 21 martii 1947: AAS 39(1947), pp.137-155 ; texte

officiel français dans DC 44 (1947), col. 513-528.

I. L'incomparable figure historique du patriarche : origines et premières

orientations de saint Benoît ; à Subiaco ; au Mont-Cassin ; prière et travail ;

vie de famille ; frères en Jésus-Christ ; le monastère bénédictin, petit «

royaume de Dieu » ; sa sainte mort. - II. Immenses bienfaits de saint Benoît et

de son Ordre pour l’Eglise et la civilisation. - III. Enseignements de la «

Règle bénédictine » au monde actuel. IV. La reconstruction du monastère du

Mont-Cassin, tribut juste et général de reconnaissance.

(1) S. Grégoire le Grand, Dialogues, II, Prol. : PL 66, 126.

(2) Cf. Cicéron, De Officiis, II, 8.

(3) S. Grégoire le Grand, Dialogues, II, Prol. : PL 66, 126.

(4) S. Grégoire le Grand, Dialogues, II, 8 : PL 66, 150.

(5) Cf. S. Grégoire le Grand, Dialogues, II, Prol. : PL 66, 126.

(6) Salvien, De gubernatione mundi, VII, 1 : PL 53, 130.

(7) S. Grégoire le Grand, Dialogues, II, Prol. : PL 66, 126.

(8) S. Grégoire le Grand, Dialogues, II, 3 : PL 66, 132.

(9) S. Grégoire le Grand, Dialogues, II, 3 : PL 66, 140.

(10) S. Grégoire le Grand, Dialogues, II, 3 : PL 66, 140.

(11) S. Grégoire le Grand, Dialogues, II, 8 : PL 66, 148.

(12) S. Grégoire le Grand, Dialogues, II, 8 : PL 66, 152.

(13) Pie X, Lettre apost. Archicoenobium Casinense, 10 fév. 1913 : AAS 5(1913),

p. 113.

(14) S. Thomas d’Aquin, Somme théologique, II-II, q. 188, a. 6.

(15) Mabillon, Annales Ord. S. Bened., Lucae 1739, t. I, p. 107.

(16) S. Grégoire le Grand, Dialogues, III, 16 : PL 67, 261.

(17) Cf. Bossuet, Panégyrique de S. Benoît : Oeuvres compl., vol. XII, Paris

1863, p. 165.

(18) S. Grégoire le Grand, Dialogues, II, 36 : PL 66, 200.

(19) Règle de S. Benoît, c. 65.

(20) Cf. Règle de S. Benoît, c. 3.

(21) Cf. Règle de S. Benoît, c. 2.

(22) Règle de S. Benoît, c. 2.

(23) Cf. Règle de S. Benoît, c. 3.

(24) Règle de S. Benoît, c. 2.

(25) Règle de S. Benoît, c. 33.

(26) Cf. Règle de S. Benoît, c. 48.

(27) Cf. Règle de S. Benoît, c. 48.

(28) Cf. Règle de S. Benoît, c. 57.

(29) Règle de S. Benoît, c. 48.

(30) Règle de S. Benoît, c. 43.

(31) Règle de S. Benoît, c. 19.

(32) Règle de S. Benoît, c. 4.

(33) Règle de S. Benoît, c. 5.

(34) Règle de S. Benoît, c. 72.

(35) Règle de S. Benoît, c. 53.

(36) Règle de S. Benoît, c. 53.

(37) Règle de S. Benoît, c. 36.

(38) S. Grégoire le Grand, Dialogues, II, 37 : PL 67, 202.

(39) Cf. S. Léon le Grand, Sermon I pour la fête des Apôtres Pierre et Paul :

PL 54, 423.

(40) Cicéron, De natura Deorum, II, c. 40.

(41) Cicéron, De natura Deorum, I, c. 2.

SOURCE : http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/pius_xii/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xii_enc_21031947_fulgens-radiatur_fr.html

Spinello Aretino (1350–1410), St

Benedict (wing of a polyptych, 1383-1384, 127.5 x 44.5, Hermitage Museum

Saint Benoît

Les disciples de St Benoît, réfugiés au Latran suite aux ravages des Lombards au Mont-Cassin en 580, apportèrent à Rome le culte de leur patriarche, mort vers 547. Rome était la ville monastique par excellence, entre le Ve et le Xe siècle, on y recense 157 monastères.

Odon de Cluny vint y insuffler l’esprit de la réforme lui-même en 936.

Il n’est pas étonnant que tous les témoins liturgiques du XIe siècle attestent

la fête de St Benoît.

Saint Benoît était célébré par deux fêtes au Moyen-Âge : son natale le 21 mars,

et la translation de ses reliques le 11 juillet.

Leçons des Matines avant 1960

Quatrième leçon. Benoît né à Nursie, de famille noble, commença ses études à

Rome, puis, afin de se donner tout entier à Jésus-Christ se retira dans une

profonde caverne en un lieu appelé Subiaco. Il y demeura caché pendant trois

ans, sans que personne d’autre le sût qu’un moine nommé Romain, qui lui

fournissait les choses nécessaires à la vie. Le diable ayant un jour excité en

lui une violente tentation d’impureté, il se roula sur des épines, jusqu’à ce

que, son corps étant tout déchiré, le sentiment de la volupté fût étouffé par

la douleur. Déjà la renommée de sa sainteté se répandant hors de sa retraite,

quelques moines se mirent sous sa conduite ; mais parce qu’ils ne pouvaient

supporter des réprimandes méritées par leur vie licencieuse, ils résolurent de

lui donner du poison dans un breuvage. Quand ils le lui présentèrent, le Saint

brisa le vase d’un signe de croix, puis, quittant le monastère, il retourna

dans la solitude.

Cinquième leçon. Mais comme de nouveaux disciples venaient chaque jour en grand

nombre trouver Benoît, il édifia douze monastères et les munit de lois très

saintes. Il se rendit ensuite au mont Cassin, où, trouvant une idole d’Apollon

qu’on y honorait encore, il la brisa, renversa son autel, mit le feu au bois

sacré, et construisit en ce lieu un petit sanctuaire à saint Martin et une chapelle

à saint Jean ; il enseigna aussi aux habitants de cette contrée les préceptes

de la religion chrétienne. Benoît croissait de jour en jour dans la grâce de

Dieu ; il annonçait l’avenir par un esprit prophétique. Totila, roi des Goths,

l’ayant appris, voulut éprouver s’il en était ainsi. 11 alla le trouver en se

faisant précéder de son écuyer à qui il avait donné une suite et des ornements

royaux, et qui feignait d’être le roi. Dès que Benoît l’eut aperçu, il lui dit

: « Dépose, mon fils, dépose ce que tu portes, car cela n’est pas à toi ». Le

Saint prédit à Totila lui-même qu’il entrerait dans Rome, qu’il passerait la

mer, et qu’il mourrait au bout de neuf ans.

Sixième leçon. Quelques mois avant de sortir de cette vie, Benoît annonça à ses

disciples le jour de sa mort. Il commanda d’ouvrir le tombeau dans lequel il

voulait être inhumé ; c’était six jours avant que l’on y déposât son corps. Le

sixième jour, il voulut être porté à l’église, et c’est là, qu’après avoir reçu

l’Eucharistie, et priant, les yeux au ciel, il rendit l’âme, entre les mains de

ses disciples. Deux moines le virent monter au ciel paré d’un manteau très

précieux, et environné de flambeaux resplendissants ; et ils entendirent un

homme à l’aspect vénérable et tout éclatant qui se tenait un peu plus haut que

la tête du Saint, et qui disait : Ceci est le chemin par lequel Benoît, le

bien-aimé du Seigneur, est monté au ciel.

Pietro Perugino (1448–1523), San

Benedetto, 1495-1498, Pinacoteca Vaticana

Dom Guéranger, l’Année Liturgique

Quarante jours s’étaient à peine écoules depuis l’heureux moment où la blanche

colombe du Cassin s’éleva au plus haut des cieux ; et Benoît, son glorieux

frère, montait à son tour, par un chemin lumineux, vers le séjour de bonheur

qui devait les réunir à jamais. Le départ de l’un et de l’autre pour la patrie

céleste eut lieu dans cette période du Cycle qui correspond, selon les années,

au saint temps du Carême ; mais souvent il arrive que la fête de la vierge

Scholastique a déjà été célébrée, lorsque la sainte Quarantaine ouvre son cours

; tandis que la solennité de Benoît tombe constamment dans les jours consacrés

à la pénitence quadragésimale. Le Seigneur, qui est le souverain maître des

temps, a voulu que ses fidèles, durant les exercices de leur pénitence, eussent

sous les yeux, chaque année, un si illustre modèle et un si puissant

intercesseur.

Avec quelle vénération profonde nous devons approcher aujourd’hui de cet homme

merveilleux, de qui saint Grégoire a dit « qu’il fut rempli de l’esprit de tous

les justes » ! Si nous considérons ses vertus, elles l’égalent à tout ce que

les annales de l’Église nous présentent de plus saint ; la charité de Dieu et

du prochain, l’humilité, le don de la prière, l’empire sur toutes les passions,

en font un chef-d’œuvre de la grâce du Saint-Esprit. Les signes miraculeux

éclatent dans toute sa vie par la guérison des infirmités humaines, le pouvoir

sur les forces de la nature, le commandement sur les démons, et jusqu’à la

résurrection des morts. L’Esprit de prophétie lui découvre l’avenir ; et les

pensées les plus intimes des hommes n’ont rien de caché aux yeux de son esprit.

Ces traits surhumains sont relevés encore par une majesté douce, une gravité

sereine, une charité compatissante, qui brillent à chaque page de son admirable

vie ; et cette vie, c’est un de ses plus nobles enfants qui l’a écrite : c’est

le pape et docteur saint Grégoire le Grand, qui s’est chargé d’apprendre à la

postérité tout ce que Dieu voulut opérer de merveilles dans son serviteur

Benoît.

La postérité, en effet, avait droit de connaître l’histoire et les vertus de

l’un des hommes dont l’action sur l’Église et sur la société a été le plus

salutaire dans le cours des siècles : car, pour raconter l’influence de Benoît,

il faudrait parcourir lus annales de tous les peuples de l’Occident, depuis le

VIIe siècle jusqu’aux âges modernes. Benoît est le père de l’Europe ; c’est lui

qui, par ses enfants, nombreux comme les étoiles du ciel et comme les sables de

la mer, a relevé les débris de la société romaine écrasée sous l’invasion des

barbares ; présidé à l’établissement du droit public et privé des nations qui

surgirent après la conquête ; porté l’Évangile et la civilisation dans

L’Angleterre, la Germanie, les pays du Nord, er jusqu’aux peuples slaves ; enseigné

l’agriculture ; détruit l’esclavage ; sauvé enfin le dépôt des lettres et des

arts, dans le naufrage qui devait les engloutir sans retour, et laisser la race

humaine en proie aux plus désolantes ténèbres.

Et toutes ces merveilles, Benoît les a opérées par cet humble livre qui est

appelé sa Règle. Ce code admirable de perfection chrétienne et de discrétion a

discipliné les innombrables légions de moines par lesquels le saint Patriarche

a opéré tous les prodiges que nous venons d’énumérer. Jusqu’à la promulgation

de ces quelques pages si simples et si touchantes, l’élément monastique, en

Occident, servait à la sanctification de quelques âmes ; mais rien ne faisait

espérer qu’il dût être, plus qu’il ne l’a été en Orient, l’instrument principal

de la régénération chrétienne et de la civilisation de tant de peuples. Cette

Règle est donnée ; et toutes les autres disparaissent successivement devant

elle, comme les étoiles pâlissent au ciel quand le soleil vient à se lever.

L’Occident se couvre de monastères, et de ces monastères se répandent sur

l’Europe entière tous les secours qui en ont fait la portion privilégiée du

globe.

Un nombre immense de saints et de saintes qui reconnaissent Benoit pour leur

père, épure et sanctifie la société encore à demi-sauvage ; une longue série de

souverains Pontifes, formés dans le cloître bénédictin, préside aux destinées

de ce monde nouveau, et lui crée des institutions fondées uniquement sur la loi

morale, et destinées à neutraliser la force brute, qui sans elles eût prévalu ;

des évoques innombrables, sortis de l’école de Benoît, appliquent aux provinces

et aux cités ces prescriptions salutaires ; les Apôtres de vingt nations

barbares affrontent des races féroces et incultes, portant d’une main

l’Évangile et de l’autre la Règle de leur père ; durant de longs siècles, les

savants, les docteurs, les instituteurs de l’enfance, appartiennent presque

tous à la famille du grand Patriarche qui, par eux, dispense la plus pure

lumière aux générations. Quel cortège autour d’un seul homme, que cette armée

de héros de toutes les vertus, de Pontifes, d’Apôtres, de Docteurs, qui se

proclament ses disciples, et qui aujourd’hui s’unissent à l’Église entière pour

glorifier le souverain Seigneur dont la sainteté et la puissance ont paru avec un

tel éclat dans la vie et les œuvres de Benoît !

L’Ordre Bénédictin célèbre son illustre Patriarche par les trois Hymnes

suivantes.

HYMNE.

Faites entendre, ô fidèles, des chants harmonieux ; temples, retentissez

d’hymnes solennelles : aujourd’hui Benoît s’élève dans les hauteurs des cieux.

C’est à l’âge où la vie commence à fleurir, qu’on le vit enfant quitter une

patrie qui lui était chère, et se retirer seul au fond d’un antre silencieux.

Sur les buissons semés d’orties et d’épines, il terrassa les passions coupables

de la jeunesse : par la il devint digne d’écrire les règles admirables de la

vie parfaite.

Il renversa la statue d’airain du profane Apollon : il détruisit le bois

consacre à Vénus ; et sur le sommet de la sainte montagne il éleva un temple à

Jean-Baptiste.

Maintenant, fixé dans l’heureuse région du ciel, mêlé au chœur ardent des

Séraphins, il voit encore ses protégés, et ranime leurs âmes de ses douces

influences.

Gloire au Père et au Fils qu’il engendre ! à vous honneur égal, Esprit de l’un

et de l’autre ! gloire au Dieu unique dans tout le cours des siècles ! Amen.

IIe HYMNE