Saint Dunstan

Archevêque de Cantorbery (✝ 988)

abbé bénédictin, il devint évêque de Worchester et de Londres, puis archevêque de Cantorbery. Durant ce siècle de fer, il ranima la ferveur monastique en Grande-Bretagne. C'était un homme assez extraordinaire. On dit de lui qu'il n'était pas seulement théologien, mais aussi orfèvre, peintre, fondeur, architecte. L'Église anglicane en conserve la mémoire.

À Cantorbéry en Angleterre, l’an 988, saint Dunstan, évêque. D’abord abbé de Glastonbury, il y restaura la vie monastique et la propagea au-delà. Sur le siège épiscopal de Worcester, puis de Londres et enfin de Cantorbéry, il travailla à promouvoir une règle commune pour les moines et les moniales.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/6992/Saint-Dunstan.html

DUNSTAN DE CANTORBÉRY

Évêque, Saint

+ 988

S. Dunstan, issu d'une

famille illustre, naquit à Glastenbury. Il eut pour maîtres dans les sciences

certains moines irlandais qui avaient beaucoup de réputation, et qui s'étaient

établis dans le lieu de sa naissance. La ville de Glastenbury se trouvait

alors, par une suite des ravages de la guerre, dans un état de désolation.

Dunstan se distingua de

tous ses compagnons d'étude par la rapidité de ses progrès; Athelnie, son

oncle, archevêque de Cantorbéry, avec lequel il vécut quelque temps, le mena à

la cour avec lui, et le fit connaître au roi Athelstan. Ce prince, qui aimait

la vertu et qui protégeait les talents, conçut pour lui une grande estime, le

retint auprès de lui, et lui donna plus de marques de bienveillance qu'à tous

ceux qui approchaient de sa personne. Mais l'envie, qui ne peut souffrir les

distinctions du mérite, chercha les moyens de le mettre mal dans l'esprit du

roi, et elle vint à bout d'y réussir. Dunstan comprit alors mieux que jamais

combien peu l'on doit compter sur la faveur des grands. Il avait reçu dans sa

jeunesse la tonsure et les ordres mineurs; toujours il avait vécu d'une manière

conforme à l'Evangile ; et quoiqu'il eût pratiqué toutes les vertus

chrétiennes, il s'était spécialement rendu recommandable par son humilité, sa

modestie et la pureté de ses mœurs.

Lorsqu'il eut quitté la

cour, il prit l'habit monastique, de l'avis d'Elphège, son oncle, évêque de

Winchester, qui peu de temps après l'éleva au sacerdoce. S'étant parfaitement

affermi dans la connaissance et la pratique des devoirs de sa profession, il

fut envoyé à Glastenbury pour en desservir l'église. Il s'y bâtit une petite

cellule qui n'avait que cinq pieds de long sur deux pieds et demi de large. Il

s'y bâtit aussi un oratoire attenant à la muraille de la grande église dédiée

sous l'invocation de la Mère de Dieu. Dans cet ermitage, il joignait le jeûne à

la prière. Il avait aussi des heures marquées pour le travail des mains. Par là

il se proposait d'éviter l'oisiveté, et de s'entretenir dans l'esprit de

pénitence. Son travail consistait à faire des croix, des vases, des encensoirs

et autres choses destinées au culte divin. D'autres fois, il s'occupait à

peindre ou à copier des livres,

Le roi Athelstan étant

mort en 900, après avoir régné seize ans avec beaucoup de gloire, Edmond, son

frère, monta sur le trône. Comme ce prince allait souvent par dévotion à

l'église de Glastenbury , qui n'était qu'à neuf milles de son palais de

Chedder, il eut occasion de connaître par lui-même la sainteté de Dunstan.

Il i crut ne pouvoir mieux faire que de lui donner le gouvernement du

monastère. Dunstan fut le dix-neuvième abbé de Glastenbury, à compter de S.

Brithwald, le premier Anglais qui avait eu la même dignité deux cent

soixante-dix ans auparavant. Edmond fut massacré après un règne de six ans et

demi. On enterra son corps à Glastenbury. Ses fils Edwi et Edgar étant trop

jeunes pour gouverner, on plaça sur le trône Edred, leur oncle. Ce prince

religieux se conduisit toujours par les conseils de S. Dunstan. Il mourut en

955, et la couronne retourna à Edwi dont les mœurs étaient fort déréglées. En

voici un exemple : le jour de son sacre, il quitta brusquement la table où

était rassemblée toute la noblesse, pour aller se livrer à d'infâmes plaisirs.

S. Dunstan le suivit et lui représenta avec une généreuse liberté ce qu'il

devait à Dieu et aux hommes. L'exil fut la récompense de son zèle. Edwi

persécuta les moines de son royaume, et ruina toutes les abbayes qui avaient

échappé aux déprédations des Danois. Il n'épargna que celles de Glastenbury et

d'Abbington.

S. Dunstan, exilé, se

retira en Flandre, où il passa un an. Il y répandit de toutes parts la

bonne odeur de Jésus-Christ, par l'exemple de ses vertus et par la force de ses

discours.

Cependant les Merciens et

les peuples du nord de l'Angleterre accablés sous la pesanteur du joug qu'ils

portaient, ôtèrent la couronne à Edwi, pour la mettre sur la tête d'Edgar, son

frère. Le nouveau roi rappela S. Dunstan, et lui donna une place distinguée

parmi ceux qui composaient son conseil. En 957, il le nomma évêque de

Worcester. La cérémonie de son sacre fut faite par S. Odon, archevêque de

Cantorbéry. Le siège de Loudvet étant venu à vaquer peu de temps après, Dunstan

fut obligé d'en prendre le gouvernement malgré lui. C'était l'homme qui

paraissait le plus en état de rétablir dans cette église et la discipline et la

pureté des mœurs.

Edwi, qui s'était

toujours maintenu dans la souveraineté des provinces du midi, termina, en 958,

une vie souillée de crimes, par une mort malheureuse. Edgar réunit alors en sa

personne toute la monarchie anglaise, qu'il gouverna toujours avec beaucoup de

sagesse et de gloire, il continua de donner à notre saint des marques de son

estime et de sa confiance.

S. Odon, archevêque de

Cantorbéry, étant mort en 961, Duns tan fut élu pour lui succéder. Il employa

toutes sortes de moyens pour ne pas accepter cette dignité; mais il lui fut

impossible de réussir. Le pape Jean XII, qui l'estimait singulièrement, le fit

légat du saint Siège. Dunstan, revêtu de cette autorité, ne pensa plus qu'à

rétablir partout la discipline ecclésiastique, qui avait beaucoup souffert des

incursions des Danois et des troubles occasionnés par la tyrannie d'Edwi. Il

avait la consolation de se voir puissamment protégé par le roi Edgar. Il

recevait aussi de grands secours de deux de ses disciples, de S. Ethelwold,

évêque de Winchester, et de S. Oswald, évêque de Worcester et archevêque d'Yorck.

Les trois prélats commencèrent par la réformation des monastères; et afin

d'entretenir partout l'uniformité de discipline, S. Dunstan publia la

Concorde des règles, qui était un recueil des anciennes constitutions

monastiques, combinées avec celles de l'ordre de Saint-Benoît. La réformation

des moines fut suivie de celle des clercs. Le saint fit aussi, pour l'usage de

ces derniers, de sages règlements connus sous le titre de Canons publiés

sous le roi Edgar. Quelques clercs étaient tombés par le malheur du temps dans

plusieurs désordres; ils avaient même osé se marier, contre Va disposition des

anciens canons. Le saint les chassa des églises et des monastères dont ils

s'étaient emparés, et mit en leur place des religieux fervents. C'était une

espèce de restitution que l'on faisait à ceux-ci, puisque, avant les guerres

des Danois, ils avaient été en possession des églises et des monastères dont il

s'agissait.

S. Ethelwoid, voyant que

les chanoines de sa cathédrale menaient une vie scandaleuse, leur substitua

aussi des moines. Les coupables appelèrent de la sentence rendue contre eux. Il

se tint pour cet effet un synode à Winchester, en 968. On rapporte qu'une voix,

paraissant sortir d'un crucifix qui était dans le lieu de l'assemblée, fit

entendre ces paroles : « Dieu défend de réformer ce qui a été fait. On a bien

jugé, ce serait un mal que de juger autrement. » Le synode confirma la

sentence de S. Ethelwold, et le roi Edouard, le Martyr, fit de ce

décret une loi de l'État.

L'archevêque de

Cantorbéry montra aussi beaucoup de zèle contre les laïques, violateurs de la

discipline ecclésiastique. Il n'y avait point de considération qui pût le faire

mollir, lorsqu'il s'agissait de maintenir le bon ordre. Les pécheurs scandaleux

surtout, de quelque rang qu'ils fussent, redoutaient sa fermeté, et étaient

obligés de se soumettre aux règles de la pénitence canonique. Nous allons en

citer un exemple.

Le roi Edgard, maîtrisé

par une passion honteuse, abusa d'une vierge qui résistait depuis longtemps à

ses désirs, et qui, pour mettre son honneur en sûreté, avait pris le voile de

religieuse, sans toutefois faire profession. Cette dernière circonstance

ajoutait un nouveau degré d'énormité au crime du roi. S. Dunstan fut informé de

ce qui s'était passé. Il se rendit aussitôt à la cour, et comme un autre

Nathan, il dit au prince, avec un zèle mêlé de 'respect, qu'il avait offensé le

Seigneur. Edgar, agité de salutaires remords, s'avoua coupable, témoigna son

repentir par ses larmes, et demanda une pénitence proportionnée à son crime. Le

saint lui en imposa une de sept ans, qui consistait à ne point porter la

couronne durant tout ce temps-là, à jeûner deux fois la semaine, et à faire

d'abondantes aumônes. Il lui enjoignit en outre, pour expier son crime d'une

manière plus spéciale, de fonder un monastère où plusieurs vierges pussent se

consacrer à Jésus-Christ. Edgar accomplit fidèlement tous les articles de sa

pénitence, et fonda le monastère de Shaftsbury. Les sept ans écoulés,

c'est-à-dire en 973, le saint archevêque lui remit la couronne sur la tête,

dans une assemblée composée des évêques et des seigneurs de la nation.

Edgar étant mort dans la

seizième année de son règne, et la trente-deuxième de son âge, Édouard, son

fils aîné, lui succéda. Ce prince avait beaucoup de piété, et donnait de

grandes espérances. Mais il périt bientôt par la trahison d'Elfride, sa

belle-mère. C'est lui que l'on appelle Edouard le Martyr. Sa mort

tragique causa une vive douleur à S. Dunstan ; et lorsqu'il couronna son jeune

frère, en 979, il lui prédit tous les malheurs qui devaient arriver sous son

règne.

Le saint sacra Gaeon,

évêque de Landaff, vers l'an 983. Les évêques du pays de Galles avaient été

soumis jusque là à l'archevêque de Saint-David. Ce prélat perdit alors la

juridiction de métropolitain, sans qu'on puisse précisément en assigner la

raison. S. Dunstan faisait souvent la visite des différentes églises du

royaume. Partout il prêchait et instruisait les fidèles. Ses discours étaient

si touchants et si persuasifs, que les cœurs les plus insensibles ne pouvaient

s'empêcher de se rendre. Ses revenus étaient employés au soulagement des

pauvres. Il conciliait les différends, réfutait les erreurs, et s'appliquait

continuellement à extirper les vices et à corriger les abus. Malgré les soins

qu'il était obligé de donner à son diocèse, aux églises du royaume, et souvent

aux affaires de l'État, il trouvait encore du temps pour vaquer aux exercices

de piété ; il consacrait à la prière une bonne partie de la nuit. Quelquefois

il se retirait à Glastenbury, afin de converser avec Dieu plus librement. Étant

à Cantorbéry, il visitait, dans la saison même la plus rigoureuse, l'église de

Saint-Augustin, située hors les murs, et celle de la Mère de Dieu, qui était

attenante.

Ce fut dans cette ville

qu'il tomba malade. Il se prépara à sa dernière heure par un redoublement de

ferveur dans tous ses exercices. Le jour de l'Ascension, il prêcha trois fois

sur la fête, pour exhorter les fidèles à suivre leur chef en esprit, et par la

k vivacité de leurs désirs. Pendant qu'il parlait, son visage paraissait tout

rayonnant de gloire. A la fin de son troisième discours, il se recommanda aux

prières de son auditoire, et dit à son troupeau qu'il ne tarderait pas à être

séparé de lui. A ces dernières paroles, tout le monde fondit en larmes. Après

midi, le saint retourna à l'église, et indiqua le lieu où il voulait être

enterré. Il se mit ensuite au lit; puis, ayant reçu le saint viatique le samedi

suivant,

II est assez probable que

ce fut par un effet de la grande puissance d'Edgar, qui par là voulait

commencer à unir les Gallois avec les Anglais.

Dunstan passa de cette

vie à l'immortalité bienheureuse. Sa mort arriva le 19 mai 988. Il vécut

soixante-quatre ans, et en gouverna dix-sept l'église de Cantorbéry. Son corps fut

enterré dans la cathédrale, à l'endroit qu'il avait lui-même marqué.

SOURCE : Alban Butler : Vie

des Pères, Martyrs et autres principaux Saints… – Traduction :

Jean-François Godescard.

SOURCE : http://nouvl.evangelisation.free.fr/dunstan_de_cantorbery.htm

DUNSTAN saint

(909-988)

Né près de Glastonbury,

en Angleterre, Dunstan fut élevé dans l'abbaye de ce nom, où l'on ne suivait

plus aucune règle monastique, mais où l'on avait conservé la précieuse

bibliothèque. Il pensait à se marier quand il fut atteint d'une grave maladie

dont il devait souffrir toute sa vie. Il se rendit alors à Winchester, où

l'évêque, son oncle, lui imposa la consécration monastique et l'ordonna prêtre.

En 943, le roi Edmond le nomma abbé de Glastonbury.

D'après ce que ses

lectures lui avaient appris, Dunstan essaya d'y rétablir l'observance de la

règle de saint Benoît. Exilé en 955 par le roi Edwig, Dunstan se réfugia au

Mont-Blandin, près de Gand, où, pour la première fois de sa vie, il rencontra

des moines. Rappelé en 957 par le roi Edgar, il devint évêque de Worcester,

puis de Londres et,

dès 959, archevêque de Cantorbéry. Primat d'Angleterre, conseiller et ami des

rois, réformateur de l'Église et du clergé, organisateur de la vie monastique,

initiateur d'un vaste mouvement artistique, créateur de l'unité anglaise,

Dunstan eut, jusqu'à la mort du roi Edgar (975), un rôle prépondérant. Durant

ses dernières années, il se cantonna dans sa charge pastorale, mais son œuvre

se prolongea après lui. À sa mort, il laissa une telle renommée qu'il fut le

saint le plus populaire d'Angleterre jusqu'au martyre de son successeur Thomas

Becket (mort en 1170).

Jacques DUBOIS,

« DUNSTAN saint (909-988) », Encyclopædia Universalis [en

ligne], consulté le 19 mai 2015. URL : http://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/dunstan/

SOURCE : http://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/dunstan/

Saint Dunstan de

Canterbury,

Abbé de Glastonbury,

26ième archévêque de Canterbury

Né à Baltonsborough près de Glastonbury, Angleterre, vers 909; mort en 988.

Dunstan, né d'une noble famille Anglo-Saxonne apparentée à la maison dirigeante

du Wessex, fut une des grandes figures de l'Histoire Anglaise. Il reçut sa

prime éducation des moines Irlandais à Glastonbury. Pendant qu'il était jeune,

il fut envoyé comme page auprès de la cour d'Athelstan.

Il avait déjà reçu la tonsure, et son oncle, l'évêque Saint Alphege le Chauve

(12 mars) de Winchester, l'encouragea à s'engager dans la vie religieuse.

Dunstan hésita quelque temps et faillit même se marier, mais après avoir été

sauvé d'une maladie de peau qu'il pensait être la lèpre, il reçut l'habit (en

934) et les saints ordres de son oncle le même jour que Saint Ethelwold (1er

Août) vers 939.

Il retourna à Glastonbury et on pense qu'il s'y construisit une petite cellule

près de la vieille église, où il entama une vie de prière, d'étude, et de

travail manuel qui inclut la réalisation de cloches et de vases sacrés pour

l'église, et la copie ou l'enluminure de livres. On le décrit comme excellant

dans la peinture, la brodure, la harpe, comme fondeur de cloche, et comme

artisan du métal. Dunstan jouait de la harpe pendant que les moniales de

l'abbaye brodaient ses dessins. On rapporte qu'un jour qu'il avait raccroché sa

harpe au mur et quitté la pièce quelque temps, la harpe continua de jouer sur

son propre accord. Les moniales prirent cela comme un signe de la future

grandeur de Dunstan.

Dunstan aimait aussi la musique vocale : quand il chantait à l'autel, rapporte

un contemporain, "il semblait être occupé à converser face à face avec le

Seigneur". Etant très habille dans les arts, Dunstan stimula la

renaissance de l'art ecclésial.

Le successeur d'Athelstan, Edmund, l'appela à la court pour devenir conseiller

royal et trésorier. En 943, le roi Edmond I échappa de peu à la mort durant une

chasse, il nomma Dunstan abbé de Glastonbury avec pour tâche d'y restaurer la

vie monastique et de richement doter le monastère. Selon la vieille Chronique

Saxone, Dunstan n'avait que 18 ans quand il devint abbé de Glastonbury.

Dunstan restaura les bâtiments du monastère et l'église de Saint-Pierre. En

introduisant des moines parmi les prêtres qui y vivaient déjà, il mit en

vigueur la disciple régulière sans que cela ne provoque de troubles. Il

transforma l'abbaye en grand centre d'enseignement. Dunstan revitalisa aussi

les autres monastères de Glastonbury.

Le meurtre du roi Edmund fut suivit par l'accession de son frère Edred, qui fit

de Dunstan un de ses principaux conseillers. Dunstan devint profondément

impliqué dans la politique séculière, et encouru la colère des nobles Saxons

de l'Ouest pour avoir dénoncé leur immoralité et pour son appel urgent à faire

la paix avec les Danois.

En 955, Edred mourrut et ce fut son neveu de 16 ans, Edwy, qui lui succéda. Le

jour de son couronnement, Edwy quitta le banquet royal pour aller voir une

fille appelée Elgiva et sa mère. Pour cela, il fut vertement tancé par Dunstan,

et le prince n'accepta pas l'admonition. Avec le soutien des partis opposants,

Dunstan tomba en disgrâce, sa propriété fut confisquée et il fut exilé.

Il passa une année à Gand, dans les Flandres [B], et là il entra en contact

avec le monachisme continental réformé. Cette expérience alimenta sa vision

d'un parfait monachisme Bénédictin, ce qui inspirera ses travaux ultérieurs.

Une rébellion éclata en Angleterre; le Nord et l'Est déposèrent Edwy et

choisirent son frère Edgar le Pacifique (cfr 8 juillet) pour le trône. Edgar

rappela Dunstan et en fit son conseiller principal, en 957 l'évêque de

Worcester, et l'évêque de Londres en 958.

A la mort d'Edwy en 959,

le royaume fut réunifié sous Edgar, qui nomma Dunstan archevêque de Canterbury

en 961.

Ensemble, ils initièrent

une politique de réforme pour renforcer tant l'Église que le pays. A

Canterbury, Dunstan fonda une abbaye à l'est de la ville, et 3 églises :

Sainte-Marie, Saints Pierre-et-Paul, et Saint-Pancrace.

En 961, Dunstan partit pour Rome pour recevoir le pallium et fut nommé par le

pape [de Rome] Jean XII comme légat du Saint-Siège. Avec cette autorité, il

entreprit de rétablir la discipline ecclésiastique, sous la protection du roi

Edgar, et assisté par saint Ethelwold, évêque de Winchester, et Saint Oswald

(28 février), évêque de Worcester et l'archevêque d'York. En ces jours, la vie

monastique Anglaise avait quasiment disparu, résultat des invasions Danoises.

Ils restaurèrent la plupart des grand monastères, comme Abingdon, qui avait été

détruits durant les invasions Danoises, et en fondèrent de nouveaux.

Dunstan fonda des monastères à Bath, Exeter, Westminster, Malmesbury, et

d'autre lieux. Il rédigea des Règles pour chaque, afin d'y insuffler le bon

ordre. Les prêtres séculiers récalcitrants furent éjectés et remplacés par des

moines à Winchester,

Chertsey, Surrey, et

Dorset. Vers 970 une conférence d'évêques, d'abbés et d'abbesses établit un

code national d'observances monastiques, le "Regularis Concordia." En

harmonie avec les coutumes continentales et la Règle de Saint-Benoît, il avait

néanmoins ses particularités : les monastères devaient être intégrés dans la

vie des gens, et leur influence ne devait pas rester confinée à l'intérieur des

murs du monastère.

Le clergé qui avait vécu une vie scandaleuse et des situations irrégulières fut

réformé. Dunstan demeura ferme dans ses normes morales, au point de faire

postposer le couronnement d'Edgar pour 14 ans - probablement à cause de sa

désapprobation du comportement scandaleux d'Edgar. Il modifia le rite de

couronnement, et certaines de ses modifications réalisées pour le couronnement

d'Edgar à Bath en 973 ont survécu jusqu'à nos jours.

Durant les 16 ans de règne d'Edgar, Dunstan fut son principal conseiller, le

critiquant librement. Un jour que le roi s'était rendu coupable d'immoralité,

Dunstan se tint debout devant sa face, refusant de prendre sa main tendue et

faisant brusquement demi-tour en disant : "Je ne suis pas l'ami de

l'ennemi du Christ". Plus tard, il imposa comme pénitence au roi de ne pas

porter sa couronne 7 ans durant.

Dunstan continua à diriger le pays durant le court règne du roi successeur,

Edouard le Martyr (18 mars http://www.amdg.be/sankt/mar18.html ), le protégé de

Dunstan. La mort du jeune roi, reliée aux réactions anti-monastiques ayant

suivit la mort du roi Edgar, affectèrent terriblement Dunstan. Sa carrière

politique étant terminée, il retourna à Canterbury pour enseigner à l'école

cathédrale, où on lui attribue des visions, des prophéties et des miracles. Il

eut une dévotion particulière pour les saints de Canterbury, dont il visitait

la tombe de nuit.

A la fête de l'Ascenscion en 988 l'archevêque tomba malade, mais il offrit la

Messe et prêcha 3 fois à son peuple, à qui il déclara qu'il mourrait bientôt. 2

jours plus tard, il mourut. Il est considéré comme le restaurateur du

monachisme en Angleterre. On dit que le 10ième siècle forma l'Histoire

Anglaise, et que Dunstan forma le 10ième siècle. Il composa nombre d'hymnes,

notamment le "Kyrie Rex spendens" (Attwater, Bénédictins, Bentley,

Delaney, Duckett, Fisher, Gill, White).

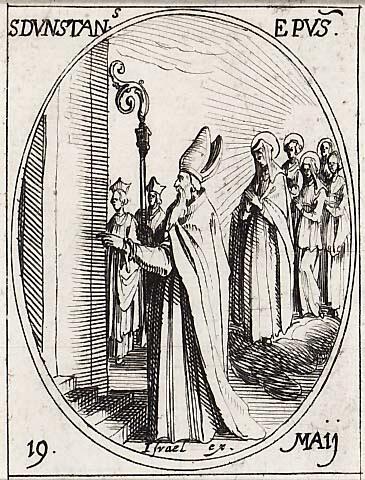

Dans l'art, on le montre comme un évêque tenant le diable (ou son nez) avec

une paire de tenailles; ou avec un crucifix lui parlant (White). On peut aussi

le voir représenté (1) tenant les pinces; (2) travaillant comme orfèvre; (3)

jouant de la harpe; (4) avec un groupe d'anges près de lui; (5) avec une

colombe; ou (6) comme un moine prosterné aux pieds du Christ (dans un dessin

qu'on lui attribue)

(Roeder).

Il est le saint patron des armuriers, des orfèvres, des bijoutiers et des

serruriers (Delaney, White), des forgerons, des musiciens et des aveugles

(Roeder).

Office à notre saint Père Dunstan, Archevêque de Canterbury

Vêpres et Matines [en anglais]

http://www.orthodoxengland.btinternet.co.uk/servduns.htm

Par les prières de saint Dunstan et de tous les Saints d'Angleterre, Christ

notre Dieu, fais-nous miséricorde et sauve-nous.

* * *

Liturgie du Rite Occidental pour Saint Dunstan:

Bénédiction de l'Archevêque

chantée sur le Peuple

Puisse Dieu, l'Illuminateur de tous les Âges, Qui fit briller l'illustre et

exalté hiérarque Dunstan comme un d'entre les Apôtres, faire que vous soyez

remplis de toutes les célestes bénédictions par ses justes prières, qu'en suivant

les pas d'un si radieux prédécesseurs, vous puissiez devenir le peuple qui

gravit l'échelle vers le Ciel.

Le peule : Amen.

And may He that granted him such noble standing with Himself that being

reverenced and glorified by all the people he might blossom as an unsurpassed

and angelic patron for all the English, Himself kindle the ardour of your hopes

towards that place where this magnificent Saint flourisheth amidst a choir of

Angels. People: Amen.

And may ye that glory to be honoured with such a sublime patron, being filled

with great joy by his miracles and illumined by his teachings, attain this from

the Lord: that ye may be reunited with him in the kingdom of heaven. Amen.

Which may He deign to grant, Whose kingdom & dominion abideth, etc. ... May

the blessing, etc. ...

The Preface of the Mass, May 19:

It is truly meet and just, right and availing to salvation, that we should

always and in all places give thanks to Thee, pay our vows to Thee, and

consecrate our gifts to Thee, O holy Lord, Father almighty, everlasting God:

Who didst beforehand elect Thy blessed confessor Dunstan for Thyself, a Bishop

of sanctified confession, a man shining brightly with the ncircumscribable

light, prevailing by the gentleness of his ways, afire with the fervour of the

Faith, and flowing over with the brook of eloquence. And in what his glory lay,

the multitudes at his sepulchre reveal, and their purification from demonic

assaults, their healing from diseases, and the miracles of his power, of which

we stand in awe. For even if he made an end here by his passing, according to

nature, the hierarch's righteous deeds live on after the grave, in that place

where there is the presence of the Saviour, Jesus Christ our Lord. By Whom

Angels praise Thy majesty, Dominions worship, the Powers tremble. The heavens,

and the heavenly Virtues, and the blessed Seraphim, concelebrate in one

exultation:- with whom command our voices also to have entrance, we beseech

Thee, humbly confessing Thee and saying: Holy, Holy, Holy, ...etc.

(The blessing, sequence, and preface are given in full in the complete Old

Sarum Rite Missal, (c) 1998 St. Hilarion Press 1998)

Icones de Saint Dunstan:

http://www.holycross-hermitage.com/pages/Icons/Samples/fj_st_dunstan.htm

Allez ici pour accéder à toutes leurs icônes, http://www.holycross-hermitage.com/ et

utilisez le menu déroulant pour aller à "Our

Products." ["nos produits"]

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/temporary-celt/message/7624

http://www.odox.net/Icons-Dunstan.htm##1

Sources:

Attwater, D. (1983). The Penguin Dictionary of Saints, NY: Penguin Books.

Benedictine Monks of St. Augustine Abbey, Ramsgate. (1947). The Book of

Saints. NY: Macmillan.

Benedictine Monks of St. Augustine Abbey, Ramsgate. (1966). The Book of

Saints. NY: Thomas Y. Crowell.

Bentley, J. (1986). A Calendar of Saints: The Lives of the Principal

Saints of the Christian Year, NY: Facts on File.

Delaney, J. J. (1983). Pocket Dictionary of Saints, NY: Doubleday Image.

Duckett, E. S. (1955). St. Dunstan of Canterbury.

Fisher, D. J. V. (1965). The Earliest Lives of St. Dunstan, St. Ethelwold,

and St. Oswald.

Gill, F. C. (1958). The Glorious Company: Lives of Great Christians for

Daily Devotion, vol. I. London: Epworth Press.

Roeder, H. (1956). Saints and Their Attributes, Chicago: Henry Regnery.

White, K. E. (1992). Guide to the Saints. NY: Ivy Books.

SOURCE : http://home.scarlet.be/amdg/oldies/sankt/mai19.html

Profile

Son of Heorstan, a Wessex

nobleman. Nephew of Saint Athelm,

and related to Saint Alphege

of Winchester. Educated at Glastonbury

Abbey by Irish monks. Hermit. Monk.

Expert goldsmith, metal-worker,

and harpist. Ordained by Saint Alphege.

Appointed abbot of Glastonbury in 944 by King Edmund

I of England.

He rebuilt the abbey,

introduced the Benedictine

Rule, and established a famous school.

Close advisor to King Eadred

and King Eadgar. Bishop of Worcester, England,

and of London, England. Archbishop of Canterbury, England in 960.

The combination of spiritual authority and political influence made him the

virtual regent of the kingdom. Spiritual

director of Saint Wulsin

of Sherborne. Reformed church life in 10th

century England.

Advisor to King Edwy

until he commented on the king‘s

profligate sexual ways – which caused the bishop to

be exiled.

In 978,

with the ascension of King Ethelred

the Unready, he retired from political life to Canterbury.

Had the gift of prophecy.

Born

909 at

Baltonsborough, Glastonbury, England

19

May 988 at Canterbury, England of

natural causes

buried in Canterbury

his burial site was lost

for years, but rediscovered by Archbishop Washam

relics destroyed

during the Reformation

–

Charlottetown,

Prince Edward Island, Canada, diocese of

Worshipful

Company of Goldsmiths

gold cup

man holding a pair

of smith‘s tongs

man putting a horseshoe on

the devil‘s

cloven foot

man with a dove hovering

near him

man with a troop of angels before

him

man working with gold or

metal, usually in a monastery or

cloister, sometimes with an angel speaking

to him

metal working tools

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Dunstan,

the Friend of Kings, by Leonora Blanche Lang

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Roman

Martyrology, 1914 edition

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

True

Legend of Saint Dunstan and the Devil, by Edward G Flight

books

Our

Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

1001

Patron Saints and Their Feast Days, Australian Catholic Truth Society

A

Clerk of Oxford: Dunstan and the Devil

A

Clerk of Oxford: The Death of Saint Dunstan

Christian

Biographies, by James Keifer

sitios

en español

Martirologio

Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

MLA

Citation

“Saint Dunstan of

Canterbury“. CatholicSaints.Info. 13 June 2020. Web. 23 January 2021.

<http://catholicsaints.info/saint-dunstan-of-canterbury/>

SOURCE : http://catholicsaints.info/saint-dunstan-of-canterbury/

Saint Dunstan, Vitrail, Église Saint-Dunstan, Cantorbéry

St. Dunstan

Archbishop and confessor, and one of the greatest saints of the Anglo-Saxon Church; b. near Glastonbury on the estate of his father, Heorstan, a West Saxon noble. His mother, Cynethryth, a woman of saintly life, was miraculously forewarned of the sanctity of the child within her. She was in the church of St. Mary on Candleday, when all the lights were suddenly extinguished. Then the candle held by Cynethryth was as suddenly relighted, and all present lit their candles at this miraculous flame, thus foreshadowing that the boy "would be the minister of eternal light" to the Church of England. In what year St. Dunstan was born has been much disputed. Osbern, a writer of the late eleventh century, fixes it at "the first year of the reign of King Aethelstan", i.e. 924-5. This date, however, cannot be reconciled with other known dates of St. Dunstan's life and involves many obvious absurdities. It was rejected, therefore, by Mobillon and Lingard; but on the strength of "two manuscripts of the Chronicle" and "an entry in an ancient Anglo-Saxon paschal table", Dr. Stubbs argued in its favour, and his conclusions have been very generally accepted. Careful examination, however, of this new evidence reveals all three passages as interpolations of about the period when Osbern was writing, and there seem to be very good reasons for accepting the opinion of Mabillon that the saint was born long before 925. Probably his birth dates from about the earliest years of the tenth century.

In early youth Dunstan was brought by his father and committed to the care of the Irish scholars, who then frequented the desolate sanctuary of Glastonbury. We are told of his childish fervour, of his vision of the great abbey restored to splendour, of his nearly fatal illness and miraculous recovery, of the enthusiasm with which he absorbed every kind of human knowledge and of his manual skill. Indeed, throughout his life he was noted for his devotion to learning and for his mastery of many kinds of artistic craftsmanship. With his parent's consent he was tonsured, received minor orders and served in the ancient church of St. Mary. So well known did he become for devotion of learning that he is said to have have been summoned by his uncle Athelm, Archbishop of Canterbury, to enter his service. By one of St. Dunstan's earliest biographers we are informed that the young scholar was introduced by his uncle to King Aethelstan, but there must be some mistake here, for Athelm and probably died about 923, and Aethelstan did not come to the throne till the following year. Perhaps there is confusion between Athelm and his successor Wulfhelm. At any rate the young man soon became so great a favourite with the king as to excite the envy of his kingfolk court. They accused him of studying heathen literature and magic, and so wrought on the king that St. Dunstan was ordered to leave the court. As he quitted the palace his enemies attacked him, beat him severely, bound him, and threw him into a filthy pit (probably a cesspool), treading him down in the mire. He managed to crawl out and make his way to the house of a friend whence he journeyed to Winchester and entered the service of Bishop Aelfheah the Bald, who was his relative. The bishop endeavoured to persuade him to become a monk, but St. Dunstan was at first doubtful whether he had a vocation to a celibate life. But an attack of swelling tumours all over his body, so severe that he thought it was leprosy, which was perhaps some form of blood-poisoning caused by the treatment to which he had been subjected, changed his mind. He made his profession at the hands of St. Aelfheah, and returned to live the life of a hermit at Glastonbury. Against the old church of St. Mary he built a little cell only five feet long and two and a half feet deep, where he studied and worked at his handicrafts and played on has harp. Here the devil is said (in a late eleventh legend) to have tempted him and to have been seized by the face with the saint's tongs.

While Dunstan was living thus at Glastonbury he became the trusted adviser of the Lady Aethelflaed, King Aethelstan's niece, and at her death found himself in control of all her great wealth, which he used in later life to foster and encourage the monastic revival. About the same time his father Heorstan died, and St. Dunstan inherited his possessions also. He was now become a person of much influence, and on the death of King Aethelstan in 940, the new King, Eadmund, summoned him to his court at Cheddar and numbered him among his councillors. Again the royal favour roused against him the jealousy of the courtiers, and they contrived so to enrage the king against him that he bade him depart from the court. There were then at Cheddar certain envoys from the "Eastern Kingdom", by which term may be meant either East Anglia or, as some have argued, the Kingdom of Saxony. To these St. Dunstan applied, imploring them to take him with them when they returned. They agreed to do so, but in the event their assistance was not needed. For, a few days later, the king rode out to hunt the stag in Mendip Forest. He became separated from his attendants and followed a stag at great speed in the direction of the Cheddar cliffs. The stag rushed blindly over the precipice and was followed by the hounds. Eadmund endeavoured vainly to stop his horse; then, seeing death to be imminent, he remembered his harsh treatment of St. Dunstan and promised to make amends if his life was spared. At that moment his horse was stopped on the very edge of the cliff. Giving thanks to God, he returned forthwith to his palace, called for St. Dunstan and bade him follow, then rode straight to Glastonbury. Entering the church, the king first knelt in prayer before the altar, then, taking St. Dunstan by the hand, he gave him the kiss of peace, led him to the abbot's throne and, seating him thereon, promised him all assistance in restoring Divine worship and regular observance.

St. Dunstan at once set vigorously to work at these tasks. He had to re-create monastic life and to rebuild the abbey. That it was Benedictine monasticism which he established at Glastonbury seems certain. It is true that he had not yet had personal experience of the stricter Benedictinism which had been revived on the Continent at great centres like Cluny and Fleury. Probably, also, much of the Benedictine tradition introduced by St. Augustine had been lost in the pagan devastations of the ninth century. But that the Rule of St. Benedict was the basis of his restoration is not only definitely stated by his first biographer, who knew the saint well, but is also in accordance with the nature of his first measures as abbot, with the significance of his first buildings, and with the Benedictine prepossessions and enthusiasm of his most prominent disciples. And the presence of secular clerks as well as of monks at Glastonbury seems to be no solid argument against the monastic character of the revival. St. Dunstan's first care was to reerect the church of St. Peter, rebuild the cloister, and re-establish the monastic enclosure. The secular affairs of the house were committed to his brother; Wulfric, "so that neither himself nor any of the professed monks might break enclosure". A school for the local youth was founded and soon became the most famous of its time in England. But St. Dunstan was not long left in peace. Within two years after the appointment King Eadmund was assassinated (946). His successor, Eadred, appointed the Abbot of Glastonbury guardian of the royal treasure of the realm to his hands. The policy of the government was supported by the queen-mother, Eadgifu, by the primate, Oda, and by the East Anglian party, at whose head was the great ealddorman, Aethelstan, the "Half-king". It was a policy of unification, of conciliation of the Danish half of the nation, of firm establishment of the royal authority. In ecclesiatical matters it favoured the spread of regular observance, the rebuilding of churches, the moral reform of the secular clergy and laity, the extirpation of heathendom. Against all this ardour of reform was the West-Saxon party, which included most of the saint's own relations and the Saxon nobles, and which was not entirely disinterested in its preference for established customs. For nine years St. Dunstan's influence was dominant, during which period he twice refused an bishopric (that of Winchester in 951 and Credition in 953), affirming that he would not leave the king's side so long as he lived and needed him.

In 955 Eadred died, and the situation was at once changed. Eadwig, the elder son of Eadmund, who then came to the throne, was a dissolute and headstrong youth, wholly devoted to the reactionary party and entirely under the influence of two unprincipled women. These were Aethelgifu, a lady of high rank, who was perhaps the king's foster-mother, and her daughter Aelfgifu, whom she desired to marry to Eadwig. On the day of his coronation, in 956, the king abruptly quit the royal feast, in order to enjoy the company of these two women. The indignation of the assembled nobles was voiced by Archbishop Oda, who suggested that he should be brought back. None, however, were found bold enough to make the attempt save St. Dunstan and his kinsman Cynesige, Bishop of Lichfield. Entering the royal chamber they found Eadwig with the two harlots, the royal crown thrown carelessly on the ground. They delivered their message, and as the king took no notice, St. Dunstan compelled him to rise and replace his crown on his head, then, sharply rebuking the two women, he led him back to the banquet-hall. Aethelgifu determined to be revenged, and left no stone unturned to procure the overthrow of St. Dunstan. Conspiring with the leaders of the West-Saxon party she was soon able to turn his scholars against the abbot and before long induced Eadwig to confiscate all Dunstan's property in her favour. At first Dunstan took refuge with his friends, but they too felt the weight of the king's anger. Then seeing his life was threatened he fled the realm and crossed over to Flanders, where he found himself ignorant alike of the language and of the customs of the inhabitants. But the ruler of Flanders, Count Arnulf I, received him with honour and lodged him in the Abbey of Mont Blandin, near Ghent. This was one of the centres of the Benedictine revival in that country, and St. Dunstan was able for the first time to observe the strict observance that had had its renascence at Cluny at the beginning of the century. But his exile was not of long duration. Before the end of 957 the Mercians and Northumbrians unable no longer to endure the excesses of Eadwig, revolted and drove him out, choosing his brother Eadzar as king of all the country north of the Thames. The south remained faithful to Eadwig. At once Eadgar's advisers recalled St. Dunstan, caused Archbishop Oda to consecrate him a bishop, and on the death of Cynewold of Worcester at the end of 957 appointed the saint to that see. In the following year the See of London also became vacant and was conferred on St. Dunstan, who held it in conjunction with Worcester. In October, 959, Eadwig died and his brother was readily accepted as ruler of the West-Saxon kingdom. One of the last acts of Eadwig had been to appoint a successor to Archbishop Oda, who died on 2 June, 958. First he appointed Aelfsige of Winchester, but he perished of cold in the Alps as he journeyed to Rome for the pallium. In his place Eadwig nominated Brithelm, Bishop of Wells. As soon as Eadgar became king he reversed this act on the ground that Brithelm had not been able to govern even his former diocese properly. The archbishopric was conferred on St. Dunstan, who went to Rome 960 and received the pallium from Pope John XII. We are told that, on his journey thither, the saint's charities were so lavish as to leave nothing for himself and his attendants. The steward remonstrated, but St. Dunstan merely suggested trust in Jesus Christ. That same evening he was offered the hospitality of a neighbouring abbot.

On his return from Rome Dunstan at once regained his position as virtual ruler of the kingdom. By his advice Aelfstan was appointed to the Bishopric of London, and St. Oswald to that of Worcester. In 963 St. Aethelwold, the Abbot of Abingdon, was appointed to the See of Winchester. With their aid and with the ready support of King Eadgar, St. Dunstan pushed forward his reforms in Church and State. Throughout the realm there was good order maintained and respect for law. Trained bands policed the north, a navy guarded the shores from Danish pirates. There was peace in the kingdom such as had not been known within memory of living man. Monasteries were built, in some of the great cathedrals ranks took the place of the secular canons; in the rest the canons were obliged to live according to rule. The parish priests were compelled to live chastely and to fit themselves for their office; they were urged to teach parishioners not only the truths of the Catholic Faith, but also such handicrafts as would improve their position. So for sixteen years the land prospered. In 973 the seal was put on St. Dunstan's statesmanship by the solemn coronation of King Eadgar at Bath by the two Archbishops of Canterbury and York. It is said that for seven years the king had been forbidden to wear his crown, in penance for violating a virgin living in the care of the nunnery of Wilton. That some severe penance had been laid on him for this act by St. Dunstan is undoubted, but it took place in 961 and Eadgar wore no crown till the great day at Bath in 973. Two years after his crowning Eadgar died, and was succeeded by his eldest son Eadward. His accession was disputed by his step-mother, Aelfthryth, who wished her own son Aethelred to reign. But, by the influence of St. Dunstan, Eadward was chosen and crowned at Winchester. But the death of Eadgar had given courage to the reactionary party. At once there was an determined attack upon the monks, the protagonists of reform. Throughout Mercia they were persecuted and deprived of their possessions by Aelfhere, the ealdorman. Their cause, however, was supported by Aethelwine, the ealdorman of East Anglia, and the realm was in serious danger of civil war. Three meetings of the Witan were held to settle these disputes, at Kyrtlington, at Calne, and at Amesbury. At the second place the floor of the hall (solarium) where the Witan was sitting gave way, and all except St. Dunstan, who clung to a beam, fell into the room below, not a few being killed. In March, 978, King Eadward was assassinated at Corfe Castle, possibly at the instigation of his step-mother, and Aetheled the Redeless became king. His coronation on Low Sunday, 978, was the last action of the state in which St. Dunstsn took part. When the young king took the usual oath to govern well, the primate addressed him in solemn warning, rebuking the bloody act whereby he became king and prophesying the misfortunes that were shortly to fall on the realm. But Dunstan's influence at court was ended. He retired to Canterbury, where he spent the remainder of his life. Thrice only did he emerge from this retreat: once in 980 when he joined Aelfhere of Mercia in the solemn translation of the relics of King Eadward from their mean grave at Wareham to a splendid tomb at Shaftesbury Abbey; again in 984 when, in obedience to a vision of St. Andrew, he persuaded Aethelred to appoint St. Aelfheah to Winchester in succession to St. Aethelwold; once more in 986, when he induced the king, by a donation of 100 pounds of silver, to desist from his persecution of the See of Rochester.

St. Dunstan's life at Canterbury is characteristic; long hours, both day and night, were spent in private prayer, besides his regular attendance at Mass and the Office. Often he would visit the shrines of St. Augustine and St. Ethelbert, and we are told of a vision of angels who sang to him heavenly canticles. He worked ever for the spiritual and temporal improvement of his people, building and restoring churches, establishing schools, judging suits, defending the widow and the orphan, promoting peace, enforcing respect for purity. He practised, also, his handicrafts, making bells and organs and correcting the books in the cathedral library. He encouraged and protected scholars of all lands who came to England, and was unwearied as a teacher of the boys in the cathedral school. There is a sentence in the earliest biography, written by his friend, that shows us the old man sitting among the lads, whom he treated so gently, and telling them stories of his early days and of his forebears. And long after his death we are told of children who prayed to him for protection against harsher teachers, and whose prayers were answered. On the vigil of Ascension Day, 988 he was warned by a vision of angels that he had but three days to live. On the feast itself he pontificated at Mass and preached three times to the people: once at the Gospel, a second time at the benediction (then given after the Pater Noster), and a third time after the Agnus Dei. In this last address he announced his impending death and bade them farewell. That afternoon he chose the spot for his tomb, then took to his bed. His strength failed rapidly, and on Saturday morning (19 May), after the hymn at Matins, he caused the clergy to assemble. Mass was celebrated in his presence, then he received Extreme Unction and the Holy Viaticum, and expired as he uttered the words of thanksgiving: "He hath made a remembrance of his wonderful works, being a merciful and gracious Lord: He hath given food to them that fear Him." They buried him in his cathedral; and when that was burnt down in 1074, his relics were translated with great honour by Lanfranc to a tomb on the south side of the high altar in the new church. The monks of Glastonbury used to claim that during the sack of Canterbury by the Danes in 1012, the saint's body had been carried for safety to their abbey; but this claim was disproved by Archbishop Warham, by whom the tomb at Canterbury was opened in 1508 and the holy relics found. At the Synod of Winchester in 1029, St. Dunstan's feast was ordered to be kept solemnly throughout England on 19 May. Until his fame was overshadowed by that of St. Thomas the Martyr, he was the favourite saint of the English people. His shrine was destroyed at the Reformation. Throughout the Middle Ages he was the patron of the goldsmiths' guild. He is most often represented holding a pair of smith's tongs; sometimes, in reference to his visions, he is shown with a dove hovering near him, or with a troop of angels before him.

Ecclesiastical approbation. Nihil Obstat. May

1, 1909. Remy Lafort, Censor. Imprimatur. +John M. Farley, Archbishop

of New York.

Copyright © 2020 by Kevin

Knight. Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05199a.htm

Here followeth the Life of Saint Dunstan.

Saint Dunstan was born in England, and our Lord showed

miracles for him ere he was born. It was so that on a Candlemas day, as all the

people were in the church with tapers in their hands, suddenly all the lights

in the church were quenched at once, save only the taper which Saint Dunstan’s

mother bare, for that burned still fair. Whereof all the people marvelled

greatly; howbeit her taper was out, but by the power of our Lord it lighted

again by itself, and burned full bright, so that all the others came and

lighted their tapers at the taper of Saint Dunstan’s mother. Wherefore all the

people gave laud and thankings unto our Lord God for this great miracle. And

then there was a holy man that said that the child that she then bare should

give light to all England by his holy living.

This holy child Dunstan was born in the year of our

Lord nine hundred and twenty-five, that time reigning in this land king

Athelstan. And Saint Dunstan’s father hight Herston, and his mother hight

Quendred, and they set their son Dunstan to school in the abbey of Glastonbury,

whereafter he was abbot for his holy living. And within a short time after he

went to his uncle Ethelwold, that then was bishop of Canterbury, to whom he was

welcome and was glad of his conversation of holy living. And then he brought

him to King Athelstan, the which made full much of him also for his good

living, and then he was made abbot of Glastonbury by consent of the king and

his brother Edmond, and in that place ruled full well and religiously the monks

his brethren, and drew them to holy living by good ensample giving. Saint

Dunstan and Saint Ethelwold were both made priests

in one day, and he was holy in contemplation. And whenso was that Saint Dunstan

was weary of prayer, then used he to work in goldsmith’s work with his own

hands for to eschew idleness, and he gave alway alms to poor people for the

love of God.

And on a time as he sat at his work his heart was on

Jesu Christ, his mouth occupied with holy prayers, and his hands busy on his

work. But the devil, which ever had great envy at him, came to him in an

eventide in the likeness of a woman, as he was busy to make a chalice, and with

smiling said that she had great things to tell him, and then he bade her say

what she would, and then she began to tell him many nice trifles, and no manner

virtue therein, and then he supposed that she was a wicked spirit, and anon

caught her by the nose with a pair of tongs of iron, burning hot, and then the

devil began to roar and cry, and fast drew away, but Saint Dunstan held fast

till it was far within the night, and then let her go, and the fiend departed

with a horrible noise and cry, and said, that all the people might hear: Alas!

what shame hath this carle done to me, how may I best quit him again? But never

after the devil had lust to tempt him in that craft. And in short time after

died king Athelstan, and Edmond his brother reigned king after him, to whom

Saint Dunstan was chief of counsel, for he gave to him right good counsel to

his life’s end; and then died Edmond the king, and after him reigned his son

Edwin, and soon after Saint Dunstan and he fell at strife for his sinful

living. For Saint Dunstan rebuked the king sharply therefor, but there was none

amendment, but always worse and worse. Wherefore Saint Dunstan was right sorry,

and did all that pain he might to bring the king to amendment, but it would not

be. But the king, within a while after, exiled Saint Dunstan out of this land,

and then he sailed over the sea and came to the abbey of Saint Amand in France,

and there he dwelled long time in full holy life till king Edwin was dead. And

after him reigned Edgar king, a full holy man. And then he heard of the

holiness of Saint Dunstan, and sent for him to be of his council, and received

him with great reverence, and made him again abbot of Glastonbury. And soon

after the bishop of Worcester died, and then Saint Dunstan was made bishop

there by the will of king Edgar. And within a little while after the see of

London was void, to which king Edgar promoted Saint Dunstan also, and so he

held both bishoprics in his hand, that is to wit both the bishopric of

Worcester and the bishopric of London. And after this died the archbishop of

Canterbury, and then king Edgar made Saint Dunstan archbishop of Canterbury,

which he guided well and holily to the pleasure of God, so that in that time of

king Edgar, and Dunstan archbishop, was joy and mirth through the realm of

England, and every man praised greatly Saint Dunstan for his holy life, good

rule, and guiding. And in divers places, whereas he visited and saw curates

that were not good, ne propice for the weal of the souls that they had cure of,

he would discharge them and put them out of their benefices, and set in such as

would entend and were good men, as ye shall find more plainly of this matter in

the life of Saint Oswald.

And on a time as he sat at a prince’s table, he looked

up and saw his father and mother above in heaven, and then he thanked our Lord

God of his great mercy and goodness that it pleased him to show him that sight.

And another time as he lay in his bed he saw the brightness of heaven, and

heard angels singing Kyrie eleison after the note of Kyrie rex splendens, which

was to him a full great comfort. And another time he was in his meditations, he

had hanging on the wall in his chamber an harp, on which otherwhile he would

harp anthems of our Lady, and of other saints, and holy hymns, and it was so

that the harp sounded full melodiously without touching of any hand that he

could see, this anthem was, Gaudent in celis animæ sanctorum, wherein this holy

saint Dunstan had great joy. He had a special grace of our Lord that such

heavenly joys and things were showed to him in this wretched world for his

great comfort. And after this he became all sick and feeble, and upon holy

Thursday he sent for all his brethren and asked of them forgiveness, and also

forgave them all trespasses and assoiled them of all their sins, and the third day

after he passed out of this world to God, full of virtues, the year of our Lord

nine hundred and eighty-eight. And hls soul was borne up to heaven with merry

song of angels, all the people hearing that were at his death. And his body

lieth at Canterbury in a worshipful shrine, whereas our Lord showeth for his

servant Saint Dunstan many fair and great miracles, wherefore our Lord be

praised, world without end. Amen.

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/golden-legend-saint-dunstan/

The True Legend of Saint Dunstan and the Devil

The Horse Shoe: The True Legend of Saint Dunstan and the Devil

by Edward G. Flight

illustrated by George Cruikshank

Preface to the Second Edition

The success of the first edition of this little work,

compels its author to say a few words on the issue of a second. “Expressive

silence” would now be in him the excessive impudence of not acknowledging, as

he respectfully does acknowledge, that success to be greatly ascribable to the

eminent artists who have drawn and engraved the illustrations.

“A man’s worst wish for his enemy is that he might

write a book,” is a generally-received notion, of whose accuracy it is hoped

there is no impertinence in suggesting a doubt. To reflect on having

contributed, however slightly, to the innocent amusement of others, without

giving pain to any, is alone an enjoyment well worth writing for. But when even

so unpretending a trifle as this is, can, besides, bring around its obscure

author fresh and valuable friendships, the hackneyed exclamation would appear

more intelligible if rendered thus: “Oh, that my friend would write a

book!”

In former days, possibly, things may have been very

different from what they now are. Haply, the literary highway may, heretofore,

have been not particularly clean, choked with rubbish, badly drained, ill

lighted, not always well paved even with good intentions, and beset with

dangerous characters, bilious-looking Thugs, prowling about, ready to pounce

upon, hocus, strangle, and pillage any new arrival. But all that is now

changed. Now, the path of literature is all velvet and roses. The race of

quacks and impostors has become as extinct, as are the saurian and the dodo;

and every honest flourisher of the pen, instead of being tarred and feathered,

is hailed as a welcome addition to “the united happy family” – of letters.

Much of this agreeable change is owing to the

improvement of the literary police, which is become a respectable, sober,

well-conducted body of men, who seldom go on duty as critics, without a

horse-shoe. Much is owing to the propagation of the doctrines of the Peace

Society, even among that species of the genus irritabile, authors

themselves, who have at last learned

“That brother should not war with brother

And worry and devour each other;

But sing and shine by sweet consent

Till life’s poor transient night is spent.”

Chiefly, however, is the happy change attributable to

the discriminating and impartial judgment of the reading public of this golden

Victorian era. In the present day, it may be considered a general rule, that no

picture is admired, no book pronounced readable, no magazine or newspaper

circulated, unless in each case it developed intrinsic merit. The mere name of

the artist, or author, or editor, has not the slightest weight with our present

intelligent, discriminating community, who are never enslaved, or misled, by

whim, caprice, or fashion. It has been said, but it seems too monstrous for

belief, that, formerly, persons were actually to be found so extremely

indolent, or stupid, or timid, as never to think for themselves; but who

followed with the crowd, like a swarm of bees, to the brazen tinkle of a mere

name! Happily, the minds of the present age are far too active, enlightened,

independent, and fearless, for degradation so unworthy. In our day, the

professed wit hopes not for the homage of a laugh, on his “only asking for the

mustard;” the artist no longer trusts to his signature on the canvas for its

being admired; no amount of previous authorship-celebrity preserves a book from

the trunk-maker; and the newspaper-writer cannot expect an extensive sale,

unless his leaders equal, at least, the frothy head of “Barclay’s porter,” or

possess the Attic salt of “Fortnum and Mason’s hams.” At the same time, the

proudest notable in literature can now no longer swamp, or thrust aside, his

obscurer peers; nor is the humblest votive offering at the shrine of intellect,

in danger, as formerly, from the hoofs of spurious priests, alike insensible to

receive, and impotent to reflect or minister, light or warmth, from the sacred

fire they pretend to cherish. In short, such is the pleasant change which has

come over literary affairs, that, however apposite in past times, there is not,

in the present, any fitness in the exclamation, “Oh, that mine enemy would

write a book!”

With reference to the observation, made by more than

one correspondent, that the horse-shoe has not always proved an infallible

charm against the devil, the author, deferentially, begs to hazard an opinion

that, in every one of such cases, the supposed failure may have resulted from

an adoption of something else than the real shoe, as a protection. Once upon a

time, a witness very sensibly accounted for the plaintiff’s horse having broken

down. “‘Twasn’t the hoss’s fault,” said he; “his plates was wore so thin and so

smooth, that, if he’d been Hal Brook his self, he couldn’t help slipping.”

“You mean,” said the judge, “that the horse, instead

of shoes, had merely slippers?”

Peradventure, the alleged failures may be similarly

accounted for; the party, in each case, having perhaps nailed up, not a shoe,

but a slipper, the learned distinction respecting which was thus judicially

recognized. The deed which the devil signed, must, like a penal statute, be

construed strictly. It says nothing of a slipper; and it has been held by all

our greatest lawyers, from Popham and Siderfin, down to Ambler and Walker, that

a slipper is not a shoe.

Another solution suggests itself. Possibly the

horse-shoe, even if genuine, was not affixed until after the Wicked One had

already got possession. In that case, not only would the charm be inefficacious

to eject him, but would actually operate as a bar to his quitting the premises;

for that eminent juris consult, Mephistopheles himself, has distinctly laid it

down as “a law binding on devils, that they must go out the same way they stole

in.” Nailing up a shoe to keep the devil out, after he has once got in, is

indeed too late; and is something like the literary pastime of the

“Englishman,” who kept on showing cause against the Frenchman’s rule, long

after the latter had, on the motion of his soldiers, already made it absolute

with costs.

There is one other circumstance the author begs to

refer to, from a desire to dispel any uneasiness about our relations with the

Yezidi government. The late distinguished under-secretary for foreign affairs,

as every one knows, not regarding as infra dig. certain great,

winged, human-headed bulls, that would have astonished Mr. Edgeworth, not less

than they puzzle all Smithfield, and the rest of the learned “whose speech is

of oxen,” has imported those extraordinary grand-junction specimens, which,

with their country-folk, the Yezidis, Dr. Layard has particularly described in

his book on Nineveh. When speaking of the Yezidis, he has observed, “The name

of the evil spirit is, however, never mentioned; and any allusion to it by

others so vexes and irritates them, that it is said they have put to death

persons who have wantonly outraged their feelings by its use. So far is their

dread of offending the evil principle carried, that they carefully avoid every expression

which may resemble in sound the name of Satan, or the Arabic word for

‘accursed.’ Thus, in speaking of a river, they will not say Shat, because

it is too nearly connected with the first syllable in Sheitan, the devil;

but substitute Nahr. Nor, for the same reason, will they utter the

word Keitan, thread or fringe. Naal, a horse-shoe, and naal-band,

a farrier, are forbidden words; because they approach to laan, a curse,

and māloun, accursed.” – Layard

Notwithstanding all this, the author has the pleasant

satisfaction of most respectfully assuring his readers, on the authority of the

last Yezidi Moniteur, that the amicable relations of this country with the

Yezidi government are not in the slightest danger of being disturbed by this

little book; and that John Bull is, at present, in no jeopardy of being

swallowed up by those monstrous distant cousins of his, of whom Mr. Layard has

brought home the above-mentioned speaking likenesses.

“And it is for trouth reported, that where this signe

dothe appere, there the Evill Spirite entreth not.” – SERMON ON WITCHES.

“Your wife’s a witch, man; you should nail a

horse-shoe on your chamber-door.” – RED GAUNTLET.

Saint Dunstan and the Devil

In days of yore, when saints were plenty

(For each one now, you’d then find twenty,)

In Glaston’s fruitful vale

Saint Dunstan had his dwelling snug

Warm as that inmate of a rug

Named in no polished tale

The holy man, when not employed

At prayers or meals, to work enjoyed

With anvil, forge, and sledge

These he provided in his cell

With saintly furniture as well;

So chroniclers allege

The peaceful mattock, ploughshare,

spade

Sickle, and pruning-hook he made

Eschewing martial labours

Thus bees will rather honey bring

Than hurtfully employ their sting

In warfare for their neighbours

A cheerful saint too, oft would he

Mellow old Time with minstrelsy, –

But such as gave no scandal;

Than his was never harp more famed;

For Dunstan was the blacksmith named

Harmonious by Handel

And when with tuneful voice he sang

His well-strung harp’s melodious twang

Accompaniment lending;

So sweetly wedded were the twain

The chords flowed mingled with the strain

Mellifluently blending

Now ’tis well known mankind’s great

foe

Oft lurks and wanders to and fro

In bailiwicks and shires;

Scattering broad-cast his mischief-seeds

Planting the germs of wicked deeds

Choking fair shoots with poisonous weeds

Till goodness nigh expires

Well, so it chanced, this tramping

vagrant

Intent on villanies most flagrant

Ranged by Saint Dunstan’s gate;

And hearing music so delicious

Like hooded snake, his spleen malicious

Swelled up with envious hate

Thought Nick, I’ll make his harp a fool;

I’ll push him from his music-stool;

Then, skulking near the saint

The vilest jars Nick loudly sounded

Of brayings, neighings, screams compounded;

How the musician’s ears were wounded

Not Hogarth e’en could paint

The devil fancied it rare fun

“Well! don’t you like my second, Dun?

Two parts sound better sure than one,”

Said he, with queer grimace:

“Come sing away, indeed you shall;

Strike up a spicy madrigal

And hear me do the bass.”

This chaffing Dunstan could not

brook

His clenched fist, his crabbed look

Betrayed his irritation

‘Twas nuts for Nick’s derisive jaw

Who fairly chuckled when he saw

The placid saint’s vexation

“Au revoir, friend, adieu till noon;

Just now you are rather out of tune

Your visage is too sharp;

Your ear perhaps a trifle flat:

When I return, ‘All round my hat’

We’ll have upon the harp.”

A tale, I know, has gone about

That Dunstan twinged him by the snout

With pincers hotly glowing;

Levying, by fieri facias tweak

A diabolic screech and squeak

No tender mercy showing

But antiquarians the most curious

Reject that vulgar tale as spurious;

His reverence, say they

Instead of giving nose a pull

Resolved on vengeance just and full

Upon some future day

Dunstan the saying called to mind

“The devil through his paw behind

Alone shall penal torture find

From iron, lead, or steel.”

Achilles thus had been eternal

Thanks to his baptism infernal

But for his mortal heel

And so the saint, by wisdom guided

To fix old Clootie’s hoof decided

With horse-shoe of real metal

And iron nails quite unmistakable;

For Dunstan, now become implacable

Resolved Nick’s hash to settle

Satan, of this without forewarning

Worse luck for him! the following morning

With simper sauntered in;

Squinted at what the saint was doing

But never smoked the mischief brewing

Putting his foot in’t; soon the shoeing

Did holy smith begin

Oh! ’twas worth coin to see him

seize

That ugly leg, and ‘twixt his knees

Firmly the pastern grasp

The shoe he tried on, burning hot

His tools all handy he had got

Hammer, and nails, and rasp

A startled stare the devil lent

Much wondering what St. Dunstan meant

This preluding to follow

But the first nail from hammer’s stroke

Full soon Nick’s silent wonder broke

For his shrill scream might then have woke

The sleepiest of Sleepy Hollow

And distant Echo heard the sound

Vexing the hills for leagues around

But answer would not render

She may not thus her lips profane:

So Shadow, fearful of a stain

Avoids the black offender

The saint no pity had on Nick

But drove long nails right through the quick;

Louder shrieked he, and faster

Dunstan cared not; his bitter grin

Without mistake, showed Father Sin

He had found a ruthless master

And having driven, clenched, and

filed

The saint reviewed his work, and smiled

With cruel satisfaction;

And jeering said, “Pray, ere you go

Dance me the pas seul named ‘Jim Crow,’

With your most graceful action.”

To tell how Horny yelled and cried

And all the artful tricks he tried

To ease his tribulations

Would more than fill a bigger book

Than ever author undertook

Since the Book of Lamentations

His tail’s short, quick, convulsive

coils

Told of more pain than all Job’s boils

When Satan brought, with subtle toils

Job’s patience to the scratch

For sympathetic tortures spread

From hoof to tail, from tail to head:

All did the anguish catch

And yet, though seemed this sharp correction

Stereotyped in Satan’s recollection

As in his smarting hocks;

Not until he the following deed

Had signed and sealed, St. Dunstan freed

The vagabond from stocks

To all good folk in Christendom to whom this

instrument shall come the Devil sendeth greeting: Know ye that for

himself and heirs said Devil covenants and declares, that never at morn or

evening prayers at chapel church or meeting, never where concords of sweet

sound sacred or social flow around or harmony is woo’d, nor where the

Horse-Shoe meets his sight on land or sea by day or night on lowly sill or

lofty pinnacle on bowsprit helm mast boom or binnacle, said Devil will intrude.

The horse-shoe now saves keel, and

roof

From visits of this rover’s hoof

The emblem seen preventing

He recks the bond, but more the pain

The nails went so against the grain

The rasp was so tormenting

He will not through Granāda march

For there he knows the horse-shoe arch

At every gate attends him

Nor partridges can he digest

Since the dire horse-shoe on the breast

Most grievously offends him

The name of Smith he cannot bear;

Smith Payne he’ll curse, and foully swear

At Smith of Pennsylvania

With looks so wild about the face;

Monro called in, pronounced the case

Clear antismithymania;

And duly certified that Nick

Should be confined as lunatic

Fit subject for commission

But who the deuce would like to be

The devil’s person’s committee?

So kindred won’t petition

Now, since the wicked fiend’s at

large

Skippers, and housekeepers, I charge

You all to heed my warning

Over your threshold, on your mast

Be sure the horse-shoe’s well nailed fast

Protecting and adorning

Here note, if humourists by trade

On waistcoat had the shoe displayed

Lampoon’s sour spirit might be laid

And cease its spiteful railing

Whether the humour chanced to be

Joke, pun, quaint ballad, repartee

Slang, or bad spelling, we should see

Good humour still prevailing

And oh! if Equity, as well

As Nisi Prius, would not sell

Reason’s perfection ever

To wrangling suitors sans horse-shoe

Lawyers would soon have nought to do

Their subtle efforts ceasing too

Reason from right to sever

While Meux the symbol wears, tant

mieux

Repelling sinful aid to brew

His liquid strains XX;

Still, I advise, strong drinks beware

No horse-shoe thwarts the devil there

Or demon-mischief checks

And let me rede you, Mr. Barry

Not all your arms of John, Dick, Harry

Plantagenet, or Tudor;

Nor your projections, or your niches

Affluent of crowns and sculptile riches

Will scare the foul intruder

He’ll care not for your harp a

whistle

Nor lion, horse, rose, shamrock, thistle

Horn’d head, or Honi soit;

Nor puppy-griffs, though doubtless meant

Young senators to represent

Like Samson, armed with jaw

Only consult your sober senses

And ponder well the consequences

If in some moment evil

The old sinner should take Speaker’s chair

Make Black Rod fetch the nobles there

And with them play the devil!

Then do not fail, great architect

Assembled wisdom to protect

From Satan’s visitation

With horse-shoe fortify each gate

Each lion’s paw; and then the State

Is safe from ruination

Postscript

The courteous reader’s indulgence will, it is hoped,

extend to a waiver of all proofs and vouchers in demonstration of the

authenticity of this tale, which is “simply told as it was told to me.” Any one

who can show that it is not the true tale, will greatly oblige, if he can and

will a tale unfold, that is the true one. If this is not the true

story and history of the horse-shoe’s charm against the wicked one, what is?

That’s the question.

There’s nothing like candour; and so it is here

candidly and ingenuously confessed that the original deed mentioned in the

poem, has hitherto eluded the most diligent searches and researches. As yet, it

cannot be found, notwithstanding all the patient, zealous, and persevering

efforts of learned men, erudite antiquarians, law and equity chiffonniers, who

have poked and pored, in, through, over, and among, heaps, bundles, and

collections, of old papers, vellums, parchments, deeds, muniments, documents,

testaments, instruments, ingrossments, records, writings, indentures, deed

polls, escrows, books, bills, rolls, charters, chirographs, and

exemplifications, in old English, German text, black letter, red letter,

round-hand, court-hand, Norman French, dog Latin, and law gibberish, occupying

all sorts of old boxes, old bookcases, old chests, old cupboards, old desks,

old drawers, old presses, and old shelves, belonging to the Dunstan branch of

the old Smith family. At one moment, during the searches, it is true, hopes

were excited on the perception of a faint brimstone odour issuing from an

antiquated iron box found among some rubbish; but instead of any vellum or

parchment, there were only the unused remains of some bundles of veteran

matches, with their tinder-box accomplice, which had been thrown aside and

forgotten, ever since the time when the functions of those old hardened

incendiaries, flint and steel, were extinguished by the lucifers. All further

search, it is feared, will be in vain; and the deed is now believed to be as

irrecoverably lost, as the musty muster-roll of Battle Abbey.

A legal friend has volunteered an opinion, that

certain supposed defects in the alleged deed evince its spuriousness, and even

if genuine, its inefficiency. His words are, “The absence of all legal

consideration, that is to say, valuable consideration, such as money, or

money’s worth; or good consideration, such as natural love and affection, would

render the deed void, or voidable, as a mere nudum pactum. [See Plowden.]

Moreover, an objection arises from there being no Anno Domini, [Year Book,

Temp. Ric. III.] and no Anno Regni, [Croke Eliz.] and no condition in

pœnam. [Lib. Ass.] Now, if the original deed had been thus defective, the

covenanting party thereto is too good a lawyer, not to have set it aside.”

To these learned subtleties it may be answered, that

the deed was evidently intended, not so much as an instrument effectively

binding “the covenanting party,” as a record whereby to justify a renewal of

punishment, in case of contravention of any of the articles of treaty. It would

have been informal to make mention of money as the consideration, it being

patent that this “covenanting party” considers it of no value at all. For

however dearly all “good folk in Christendom” may estimate and hug the precious

bane, as the most valuable consideration on earth, he, old sinner that he is,

wickedly disparages it, as being mere filthy lucre, only useful