Columba banging on the gate of Bridei, son of Maelchon, King of Fortriu. Henrietta Elizabeth Marshall, Scotland's Story,

1906. J. R. Skelton (Joseph Ratcliffe Skelton; 1865–1927) (illustrator), erroneously credited as John R. Skelton

Saint Colomba

Abbé d'Iona (+ 597)

ou Columba.

Abbé dans l'île d'Iona au

large de l'Écosse. L'un de ses successeurs trace de lui ce portrait:

"Nature d'élite, brillant dans ses paroles, grand dans ses conseils, plein

d'amour envers tous, rempli au fond du cœur de la sérénité et de la joie du

Saint-Esprit."

Il fonda plusieurs

monastères en Irlande avant de fonder celui d'Iona en Écosse, monastère célèbre

qui fut une pépinière de saints moines et de missionnaires.

Il est vénéré en Irlande

à l'égal de saint Patrick et de sainte Brigitte de Kildare, cette Irlande qu'il

chantait: "Sur chaque branche de chêne, je vois posé un ange du ciel...

tout y respire la paix, tout n'y est que délice."

Ascèse, prière

contemplative et charité sont les grandes réalités de sa vie comme de sa règle;

celle-ci franchira la mer et sera suivie par les ermites et les moines bretons.

(diocèse de Quimper et Léon - saint Colomba)

Dans l’île d’Iona, en

Écosse, vers 597, saint Colomba ou Colum Cille, prêtre et abbé. Né en Irlande

et formé aux préceptes de la vie monastique, il établit son monastère dans

cette île, qu’il rendit célèbre par la discipline de vie et le culte des

lettres. Enfin, recru de vieillesse et prévoyant son dernier jour, il mourut

devant l’autel du Seigneur.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1296/Saint-Colomba.html

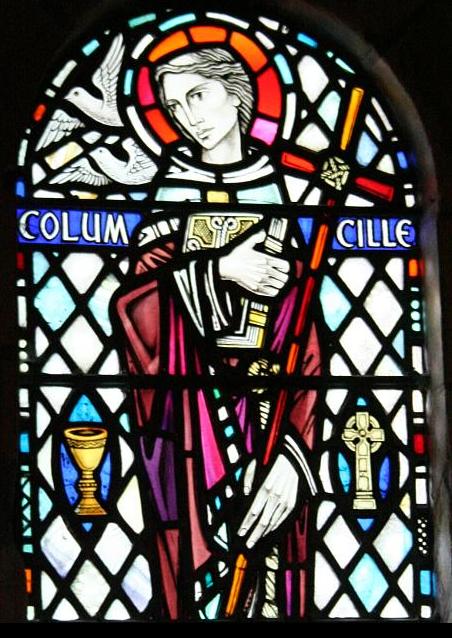

St.

Patrick's Cathedral of the Church of Ireland, Armagh, County Armagh, Northern

Ireland

Detail of the stained glass window W12 in the south aisle (4th from east), depicting Saint Columba. The window is signed “Leadlines & David Esler” in the lower right corner of this panel. (See W. R. H. Carson, The Stained Glass Windows of the Cathedral Church of St. Patrick Armagh, p. 20; gloine.ie.)

Saint Saint Colomba

d’Iona

Saint Colomba d’Iona (521-597)

est un irlandais qui participa à l’évangélisation de l’Irlande, de l’Écosse et

du Nord de l’Angleterre. Considéré comme l’un des saint patron des irlandais,

Saint Colomba mena tout au long de sa vie un combat en faveur de la conversion

complète de peuples n’ayant pas encore été évangélisés par le christianisme en

Irlande, en Écosse et en Angleterre.

Biographie de Saint

Colomba d’Iona

Un irlandais qui

participe à la christianisation de l’Irlande

Saint Colomba naît le 7

décembre 521, au sein d’un riche clan irlandais : les O’Neill de Tyrconnel, une

famille royale régnant à cette époque sur le Donegal. Son père, Feidlimid mac

Fergus Cendfota mac Conall Gulban est le fondateur même du clan, et fils du roi

suprême (Ard ri Érenn) Niall Noigiallach (399-432).

Durant sa jeunesse, Saint

Colomba découvre le christianisme et entre à l’Abbaye de Clonard, et travaille

sous l’influence de son mentor, Saint Finian de Clonard. Très vite, Saint

Colomba crée plusieurs monastères et écoles dans toute l’Irlande, dont :

un monastère à Derry en

545,

un monastère à Durrow en

553,

un monastère à Kells en

554

Egalement très impliqué

dans le domaine politique, Saint Colomba est parfois au centre de conflits et

rivalités au sein même de sa famille. Son engagement est tel, qu’il devient

alors dérangeant, et se voit forcé à l’exil en Écosse. Selon la légende, il

partit donc avec 12 compagnons (en analogie au Christ est ses apôtres), pour

l’île d’Iona en 563, et bénéficie dès lors de la protection du roi d’Écosse

Conall mac Comgaill de Dalriada.

Il fait alors de l’île de

Iona son QG pour participer à la christianisation de l’Écosse et du Nord de

l’Angleterre. Il convertit le peuple Picte, étend le christianisme sur l’ensemble

de l’Écosse, et devient une figure emblématique religieuse.

Saint Colomba décède le 9

juin 597, et est rapatrié en Irlande, à Downpatrick où il est enterré au

cimetière du village aux côtés de 2 autres saints : Saint Patrick (385-461) et

Sainte Brigitte (451-525).

De nos jours, les

irlandais commémorent Saint Colomba le 9 juin de chaque année au travers de

cérémonies religieuses.

SAINT COLOMBA

Le pèlerin du Christ

Né dans le comté de

Donegal, de la famille royale irlandaise des Tirconaill, Colomba reçut son

éducation à Moville (où il devint diacre), à Leinster et à l’école monastique

de Clonard sous l’autorité de saint Finnian. Il fut probablement ordonné prêtre

avant de partir pour Glasnevin. Quand la peste ravagea le pays en 543, les

moines furent dispersés et Colomba passa les quinze années qui suivirent à

voyager à travers l’Irlande : il fondait des monastères (Derry en 546),

prêchait et convertissait la population. Un jour, une dispute survint entre

Colomba et saint Finnian : le premier avait copié un psautier appartenant au

second, lequel, soucieux de réserver ses droits de reproduction, revendiqua la

copie en question. Colomba en appela au roi Diarmaid qui lui donna tort. Ce fut

la première ébauche de la législation sur le copyright. L’affaire n’en resta

pas là. Colomba incita sa famille à se battre contre les troupes de Diarmaid.

Ses hommes gagnèrent la bataille mais ce fut un massacre. Certains racontent

que ce fut le remords qui poussa Colomba à partir en Écosse.

L'Écosse

Colomba s’embarqua pour

Iona en 563 avec douze compagnons. Il y fonda un monastère très célèbre, centre

de la Chrétienté celtique. Iona fut une base pour les missions chez les Pictes

du Nord. Il fit grande impression sur le roi Brude en faisant sortir le monstre

du Loch Ness. On lui attribue aussi la conversion du roi irlandais Aidan de

Dalriada. Colomba resta à Iona jusqu’à la fin de sa vie, mais il visita

l’Irlande à plusieurs reprises. Il fonda tant d’églises dans les Hébrides qu’on

lui attribua le nom gaélique Colmcille (colombe des églises). Les traditions

monastiques d’Iona furent suivies dans l’Europe entière, l’ordre bénédictin

finit par s’imposer à quelques-unes. Colomba passa beaucoup de temps à la fin

de sa vie, à transcrire des livres. Il mourut à Iona le 9 juin 597.

Le portrait du saint

« Il avait, dit saint

Adamman, une figure angélique : c’était une nature d’élite ; il était brillant

dans ses paroles, saint dans ses actions, grand dans ses conseils. Il ne

perdait pas un moment, toujours à prier, à lire ou à écrire ; il supportait le

poids des jeûnes et des veilles sans répit. »

Faits et gestes

Toute sa vie porte

l’empreinte d’une ardente et spéciale sympathie pour les travailleurs des

champs. Pendant un des derniers étés, en revenant de moissonner les maigres

récoltes de leur île, les religieux s’arrêtèrent émus et charmés. Baïthen,

l’économe du monastère, ami et successeur de Colomba, leur demanda : «

N’éprouvez-vous ici rien de particulier ? - Oui, vraiment, répondit le plus

ancien, tous les jours à cette heure, je respire un parfum délicieux, comme si

toutes les fleurs du monde étaient ici réunies ; je sens aussi comme la flamme

d’un foyer qui ne me brûle pas, mais me réchauffe doucement ; j’éprouve enfin,

dans mon cœur, une joie si inaccoutumée, si incomparable, que je ne sens plus

ni chagrin ni fatigue. Les gerbes que je porte sur le dos ne pèsent plus rien,

il me semble qu’on me les enlève des épaules.

Qu’est-ce donc que cette

merveille ? Et tous de raconter une impression identique. « Je vais vous le

dire, reprit l’économe, ce qu’il en est. C’est notre vieux maître Colomba,

toujours plein d’anxiété pour nous, qui s’inquiète de notre retard, qui se

tourmente de notre fatigue et qui ne pouvant plus venir au-devant de nous avec

son corps, nous envoie son souffle pour nous rafraîchir, nous réjouir et nous

consoler. »

Saint Colomba est fêté le

9 juin

Les Saints, Alison Jones

; éd. Bordas, 1995.

SOURCE : http://www.orthodoxie-celtique.net/saint_colomba.html

Saint Columba

Saint Columba (également

connu sous le nom Columcille, qui signifie "Colombe de

l'Église") est né à Donegal sur le7 Décembre 521 de nobles parents

irlandais. Il devint moine et fut bientôt ordonné prêtre. La Tradition affirme

qu'aux environs de 560, il y eut un litige sur le droit de copier une édition

du Psautier Le différend a finalement conduit à la bataille de Cul Dremhe en

561, au cours de laquelle beaucoup d'hommes furent tués. Comme pénitence pour

ces morts, il fut ordonné à Columba de faire le même nombre de nouveaux

convertis que d'hommes qui avaient été tués dans la bataille. Il lui fut aussi

ordonné de quitter l'Irlande et d'être assez éloigné pas ne pas voir son pays

natal.

Il alla en Écosse, où il

est réputé, il débarqua à la pointe sud de la péninsule de Kintyre, près de

Southend. Toutefois, étant encore en vue de sa terre natale il déménagea plus

au nord jusqu'à la côte ouest de l'Écosse. En 563, il fonda un monastère sur

l'île de Iona au large de la côte ouest de l'Écosse, lieu qui devint le centre

de sa mission évangélisatrice vers l'Ecosse.

Il y a beaucoup

d'histoires de miracles qu'il accomplit au cours de sa mission pour convertir

les Pictes, peuple qui vivait en Écosse à cette époque. Dans une histoire de sa

vie, en 565 le saint rencontra un groupe de Pictes qui enterraient un homme tué

par un monstre qui vivait dans les eaux du Loch Ness, et il fit revenir l'homme

à la vie. Dans une autre version, il aurait sauvé l'homme alors qu'il était

attaqué, chassant le monstre avec le signe de la Croix.

La principale source de

la vie de saint Columba est la Vie de saint Columba, hagiographie de saint

Adamnan d'Iona.

Saint Columba est censé

être enterré avec saint Patrick et Saint-Brigitte de Kildare, à Downpatrick

dans le comté de Down, au fond de la célèbre colline de Down.

Sa fête est au 9 juin.

Version française Claude

Lopez-Ginisty

d'après

http://www.oodegr.com/english/biographies/arxaioi/Columba_Iona.htm

SOURCE : http://orthodoxologie.blogspot.ca/2010/04/saint-columba-higoumene-diona-597.html

St

Columba statue, St Cuthberts

Also

known as

Apostle of the Picts

Apostle to Scotland

Coim

Colmcille

Colum

Columbkill

Columbkille

Columbus

Columcille

Columkill

Combs

6

January as one of the Twelve

Apostles of Ireland

17

June (translation of relics)

Profile

Born to the Irish royalty,

the son of Fedhlimidh and Eithne of the Ui Neill clan. Bard. Miracle worker. Monk at

Moville. Spiritual student of Saint Finnian. Priest.

Itinerant preacher and teacher throughout Ireland and Scotland.

Spiritual teacher of Saint Corbmac, Saint Phelim, Saint Drostan, Saint Colman

McRhoi and Saint Fergna

the White; uncle of Saint Ernan. Travelled to Scotland in 563. Exiled to Iona on

Whitsun Eve, he founded a monastic community

there and served as its abbot for

twelve years. He and the monks of Iona,

including Saint Baithen

of Iona and Saint Eochod,

then evangelized the Picts, converting many,

including King Brude.

Attended the Council of Drumceat, 575.

Legend says he wrote 300

books.

Born

7

December 521 at

Garton, County Donegal, Ireland

9

June 597 at Iona, Scotland,

and buried there

relics translated

to Dunkeld, Scotland in 849

—

—

Youngstown, Ohio, diocese of

—

Pemboke,

Ontario, Canada,

city of

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Book

of Saints and Heroes, by Leonora Blanche Lang

Book

of Saints and Wonders, by Lady Gregory

Catholic

World: An Irish Saint

Folk-Lore

and Legends of Scotland

Legends

of Saints and Birds, by Agnes Aubrey Hilton

Little

Lives of the Great Saints

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Our

Island Saints, by Amy Steedman

Roman

Martyrology, 1914 edition

Saint

Columba, Apostle of Scotland, by A C Storer

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

Life of Saint Columba, by

Mother Frances Alice Monica Forbes

Life of Saint Columba,

by Saint Adamnan

of Iona

download in EPub format

Summary of Principal

Events in the Life of Saint Columba, by Wentworth Huyshe

books

Battersby’s Registry for

the Whole World

Our

Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

Patron

Saints and Their Feast Days, by the Australian Catholic

Truth Society

other

sites in english

British

Broadcasting Corporation

Christian

Today: Saint Columba’s cell discovered by scientists on Scottish island of

Iona

Saint

Columba of Iona Orthodox Christian Monastery

images

audio

The

Life of Saint Columba, Apostle of Scotland – audio book

video

ebooks

Life

of Saint Columba, Apostle of the Highlands, by John Smith, DD

Saint

Columba, Apostle of Caledonia, by Charles Forbes, comte de Montalembert

sitios

en español

Martirologio

Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

Readings

My Druid is Christ, the

son of God, Christ, Son of Mary, the Great Abbot, The Father, the Son and the

Holy Ghost. – Saint Columba

O Lord, grant us that

love which can never die, which will enkindle our lamps but not extinguish

them, so that they may shine in us and bring light to others. Most dear Savior,

enkindle our lamps that they may shine forever in your temple. May we receive

unquenchable light from yo so that our darkness will be illuminated and the

darkness of the world will be made less. Amen. – Saint Columba

The holy Columba was born

of noble parents, having as his father Fedelmith,

Fergus’ son, and his mother, Ethne by name, whose father may

be called in Latin “son of a ship,” and in the Irish tongue Mac-naue.

In the second year after the battle of Cul-drebene, the forty-second year of

his age, Columba sailed away from Ireland to Britain, wishing to be a pilgrim

for Christ. Devoted even from boyhood to the Christian novitiate and

the study of philosophy,

preserving by God‘s

favour integrity of body and purity of soul, he showed himself, though placed

on earth, ready for the life of heaven; for he was angelic in aspect, refined

in speech, holy in work, excellent in ability, great in counsel. Living as an

island soldier for thirty-four years, he could not pass even the space of a

single hour without applying himself to prayer, or to reading, or to writing or

some kind of work. Also by day and by night, without any intermission, he was

so occupied with unwearying labours of fasts and vigils that the burden of each

several work seemed beyond the strength of man. And with all this he was loving

to everyone, his holy face ever showed gladness, and he was happy in his inmost

heart with the joy of the Holy

Spirit. – Adomnan, from his biography of Columba

MLA

Citation

“Saint Columba of

Iona“. CatholicSaints.Info. 6 April 2021. Web. 9 June 2021.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-columba-of-iona/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-columba-of-iona/

William Hole (1846–1917), Saint

Columba converting King Brude of the Picts to Christianity, circa 1899, Mural

painting in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, photographed by uploader

Book of Saints –

Columba – 9 June

Article

COLUMBA (COLUMBUS, COLM,

COLUMBKILL) (Saint) Abbot (June 9) (6th century) Of the blood of Irish

chieftains, born in Donegal (December 7, A.D. 521), Columba was destined to be

the founder of a hundred monasteries and the Apostle of Caledonia. From boyhood

devoted to the study of Holy Scripture and day-by-day advancing in sanctity of

life, he was ordained priest at the age of twenty-five. After founding Derry,

Durrow and other religious houses, he with twelve disciples, crossed in the

year 563 to Scotland, and landed in the Island of I or Hy (now called Iona),

where he built the world-famed monastery which was for two centuries the

nursery of Bishops and Saints. For thirty-four years Columba travelled about

evangelising the Highlands of Scotland. At last, weighed down by age and

infirmities, he died kneeling before the Altar (June 9, 597), and was buried at

Iona. But in the ninth century his relics were translated to Down in Ulster,

and laid by the side of those of Saint Patrick. Saint Adamnan, one of his

successors at Iona, has left us an important and interesting Life of Saint

Columba.

MLA

Citation

Monks of Ramsgate. “Columba”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info. 12 October 2012. Web. 12 December 2024. <http://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-columba-9-june/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-columba-9-june/

Calendar

of Scottish Saints – Saint Colum Cille or Columba, Abbot

Article

A.D. 597. The apostle of

the northern regions of Scotland was born in Ireland in A.D. 521. Both father

and mother were of royal race. Though offered the crown of his native province,

Columba preferred rather to enrol himself in the monastic state. He studied in

the schools of Moville, Clonard, and Glasnevin, and in course of time was

ordained priest. At twenty-five years of age he founded his first monastery at

Derry; this was to be the precursor of the hundred foundations which Ireland

owed to his zeal and energy. In these monasteries the transcription of the Holy

Scriptures formed the chief labour of the inmates, and so much did Columba love

the work that he actually wrote three hundred manuscripts of the Gospels and

Psalms with his own hand.

But Columba was not

destined to remain in Ireland. From his earliest years he had looked forward to

the time when he might devote himself to missionary efforts for the benefit of

those who knew not the Christian faith. In the forty-second year of his age he

exiled himself voluntarily from his beloved country to preach the Gospel to the

pagan Picts. The story of his having been banished from Ireland for using his

influence to bring about a bloody conflict between chieftains is rejected by

the greatest modern historians as a fable. Early writers speak of the saint as

a man of mild and gentle nature.

On Whit Sunday, A.D. 563,

Saint Columba landed with twelve companions on the bleak, unsheltered island

off the coast of Argyll, known as Hii-Coluim-Cille or Iona. For thirty-four

years the saint and his helpers laboured with such success, that through their

efforts churches and centres of learning sprang up everywhere, both on the

mainland and the adjacent islands. Iona became the centre whence the Faith was

diffused throughout the country north of the Grampians. The monastic

missionaries were untiring in their efforts. They penetrated even to Orkney and

Shetland.

On Sunday, June 9, A.D.

597, Saint Columba was called to his reward. He died in the church, kneeling

before the altar and surrounded by his religious brethren. His remains, first

laid to rest at Iona, were afterwards carried over to Ireland and enshrined in

the Cathedral of Down by the side of those of Saint Patrick and Saint Bridget.

All these relics perished when the cathedral was burned by Henry VIII’s

soldiers.

Saint Columba was a man

of singular purity of mind, boundless love for souls, and a gentle, winning

nature which drew men irresistibly to God. His labours were furthered by Divine

assistance, which was evidenced by numerous miracles. Among the saints of

Scotland he takes a foremost rank, and in Catholic ages devotion to him was

widespread. The churches dedicated to him are too numerous to mention. He

himself founded no less than fifty during his residence in the land which he

had chosen as the scene of his labours. Annual fairs were held on his feast at

Aberdour (Fife), Dunkeld each for eight days Drymen (Stirlingshire), Largs

(Argyllshire), and Fort-Augustus (Inverness-shire). Saint Columba’s holy wells

were very numerous, for an old Irish record relates of him: “He blessed three

hundred wells which were constant.” In Scotland they are to be traced at Birse

(Aberdeenshire), Alvah and Portsoy (Banffshire), Invermoriston

(Inverness-shire), Calaverock (Forfarshire), Cambusnethan (Lanarkshire), Alness

(Ross-shire), Kirkholm (Wigtonshire), and on the islands of Garvelloch, Eigg

and Iona.

MLA

Citation

Father Michael

Barrett, OSB.

“Saint Colum Cille or Columba, Abbot”. The

Calendar of Scottish Saints, 1919. CatholicSaints.Info.

28 May 2014. Web. 12 December 2024.

<https://catholicsaints.info/calendar-of-scottish-saints-saint-colum-cille-or-columba-abbot/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/calendar-of-scottish-saints-saint-colum-cille-or-columba-abbot/

New Catholic

Dictionary – Saint Columba

Article

(521-597) Confessor,

apostle of the Picts, Abbot of

Iona, born Gartan, Ireland; died Iona, Scotland.

He entered the monastic life

at Moville, studied under Saint Finnian,

and was later ordained by Bishop Etchen

of Clonfad. In 563 he

left Ireland;

journeyed to Scotland, and founded a large monastery on

the island of Iona. He made numerous conversions among the Picts,

having won over their king, Brude. During his exile he returned twice to Ireland,

and was prominent at the Council of Drumceat, 575.

The Benedictine rule

has, since Columba’s time, replaced his monastic rule, which was prevalent

in Germany, Gaul,

Britain, and northern Italy.

Besides his missionary work, he is said to have written 300 books. Patron

of Ireland and

Scotland. His remains are interred at Downpatrick with those of Saint Patrick

and Saint Brigid. Feast, 9

June.

MLA

Citation

“Saint Columba”. New Catholic Dictionary. CatholicSaints.Info. 16

September 2012.

Web. 12 December 2024. <http://catholicsaints.info/new-catholic-dictionary-saint-columba/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/new-catholic-dictionary-saint-columba/

St. Columba

Abbot of Iona,

b. at Garten, County Donegal, Ireland,

7 December, 521; d. 9 June, 597. He belonged to the ClanO'Donnell, and was of

royal descent. His father's name was Fedhlimdh and that of his

mother Eithne. On his father's side

he was great-great-grandson of Niall of the Nine Hostages,

an Irish king

of the fourth century. His baptismal

name was Colum, which signifies a dove, hence the

latinized form Columba. It assumes another formin Colum-cille, the

suffix meaning "of the Churches". He was baptized at

Tulach-Dubhglaise, now Temple-Douglas, by a priest named

Cruithnechan, who afterwards became his tutor or foster-father. When

sufficiently advanced in letters he entered the monastic school of

Movilla under St.

Finnian who had studied at St.

Ninian's"Magnum Monasterium" on the shores of Galloway. Columba at

Movilla monastic life and received the diaconate.

In the same place his sanctity first

manifested itself by miracles.

By his prayers, tradition says,

he convertedwater into wine for the Holy

Sacrifice (Adam., II, i). Having completed his training at Movilla, he

travelled southwards into Leinster, where he became a pupil of an aged bard

named Gemman. On leaving him, Columbaentered the monastery of Clonard,

governed at that time by Finnian, a remarkable, like his namesake of

Movilla, for sanctity and

learning. Here he imbibed the traditions of the Welsh

Church, for Finnian had been trained in theschools of St.

David. Here also he became one those

twelve Clonard disciples known in

subsequent history as the Twelve

Apostles of Ireland.

About this same time he was promoted to the priesthood by

Bishop Etchen of Clonfad. The story that St.

Finnian wished Columba to be consecrated bishop,

but through a mistake only priest'sorders were

conferred, is regarded by competent authorities as the invention of a

later age (Reeves, Adam., 226).

Another preceptor

of Columba was St. Mobhi, whose monastery at

Glasnevin was frequented by such famous men as St.

Canice, St.

Comgall, and St. Ciaran. A pestilence which devastated Ireland in

544 caused the dispersion of Mobhi's disciples,

and Columba returned to Ulster, the land of his kindred. The

following years were marked by the foundation of several

important monasteries, Derry, Durrow,

and Kells. Derry and Durrow were always specially dear

to Columba. While at Derry it is said that he planned a pilgrimage to Rome and Jerusalem,

but did not proceed farther than Tours. Thence he brought a copy of

those gospels that had lain on the bosom ofSt.

Martin for the space of 100 years. This relic was

deposited in Derry (Skene, Celtic Scotland,

II, 483). Columbaleft Ireland and

passed over into Scotland in

563. The motives for this migration have been frequently discussed. Bede simply

says: "Venit de Hibernia . . . praedicaturus verbum Dei" (H. E., III,

iv); Adarnnan: "pro Christo perigrinari volens enavigavit" (Praef.,

II). Later writers state that his departure was due to the fact that he

had induced the clan Neill to rise and engage in battle

against King Diarmait at Cooldrevny in 561. The reasons

alleged for this action of Columba are: (1) The king's

violation of the right of sanctuary belonging

to Columba's person as

a monk on

the occasion of the murder of

Prince Curnan, the saint's kinsman;

(2) Diarmait's adversejudgment concerning the

copy Columba had secretly made of St.

Finnian's psalter. Columba is said to have supported by

his prayers the men of

the North who were fighting while Finnian did the same

for Diarmait's men. The latter were defeated with a loss of three

thousand. Columba's conscience smote

him, and he had recourse to his confessor, St. Molaise, who imposed this

severe penance:

to leave Ireland and

preach the Gospel so as to gain as many souls to Christ as

lives lost at Cooldrevny, and never more to look upon his native land.

Some writers hold that these are legends invented by the bards and

romancers of a later age, because there is no mention of them by the

earliest authorities (O'Hanlon,

Lives of the Ir. Saints, VI, 353). Cardinal

Moran accepts no other motive than that assigned by Adamnan,

"a desire to carry the Gospel to a pagan nation

and to win souls to God".

(Lives of Irish Saints in Great Britain, 67). Archbishop Healy, on

the contrary, considers that the saint did

incite to battle, and exclaims: "O felix culpa . . . which produced

so much good both for Erin and Alba (Schools and

Scholars, 311).

Iona

Columba was in his

forty-fourth year when he departed from Ireland.

He and his twelve companions crossed the sea in a currach of wickerwork covered

with hides. They landed at Iona on

the eve of Pentecost, 12 May, 563. The island, according

to Irish authorities,

was granted to the monastic colonists by

King Conall of Dalriada,Columba's kinsman. Bede attributes the gift to

the Picts (Fowler, p. lxv). It was a convenient situation, being midway between

his countrymen along the western coast and the Picts of Caledonia. He and

his brethren proceeded at once to erect their humble dwellings,

consisting of a church, refectory, and cells, constructed of wattles and

rough planks. After spending some years among

the Scots of Dalriada, Columba began the great work of

his life, the conversion of the Northern Picts. Together with St.

Comgall and St.

Canice (Kenneth) he visited King Brude in his royal

residence near Inverness. Admittance was refused to the missionaries,

and the gates were closed and bolted, but before the sign

of the cross the bolts flew back, the doors stood open, and the monks entered

the castle. Awe-struck by so evident a miracle,

the king listened to Columba with reverence; and was baptized.

The people soon followed the example set them, and thus was inaugurated a

movement that extended itself to the whole of Caledonia. Opposition was

not wanting, and it came chiefly from the Druids, who officially

represented the paganism of

the nation.

The thirty-two remaining

years of Columba's life were mainly spent in preaching the Christian

Faith to the inhabitants of the glens and wooded straths of

Northern Scotland.

His steps can be followed not only through the Great Glen, but eastwards also,

into Aberdeenshire. The "Book of Deer" (p. 91) tells us how he

and Drostancame, as God had

shown them to Aberdour in Buchan, and how Bede,

a Pict, who was high steward of Buchan, gave them the town in freedom

forever. The preaching of the saint was confirmed by

many miracles,

and he provided for the instruction of his converts by the erection

of numerous churches and monasteries.

One of his journeys brought him to Glasgow,

where he met St.

Mungo, the apostle of Strathclyde. He frequently visited Ireland;

in 570 he attended the synod of Drumceatt, in company with

the Scottish King Aidan, whom shortly before he had

inaugurated successor of Conall of Dalriada. When not

engaged in missionary journeys, he always resided at Iona.

Numerous strangers sought him there, and they received help for soul and

body. From Iona he

governed those numerous communities in Ireland and Caledonia,

which regarded him as their father and founder. This accounts for the unique

position occupied by the successors of Columba, who governed the

entireprovince of the Northern Picts although they had received priest's orders only.

It was considered unbecoming that any successor in the office

of Abbot of Iona should

possess a dignity higher than of the founder. The bishopswere

regarded as being of a superior order, but subject nevertheless to the jurisdiction of

the abbot.

At Lindisfarne the monks reverted

to the ordinary law and were subject to a bishop (Bede,

H.E., xxvii).

Columba is said never to

have spent an hour without study, prayer,

or similar occupations. When at home he was frequently engaged in transcribing.

On the eve of his death he was engaged in the work of transcription.

It is stated that he wrote 300 books with his own hand, two of which, "The

Book of Durrow" and the psalter called "The Cathach",

have been preserved to the present time. The psalter enclosed in a

shrine, was originally carried into battle by the O'Donnells as a pledge of

victory. Several of his compositions in Latin and Irish have

come down to us, the best known being the poem "Altus Prosator",

published in the "Liber Hymnorum", and also in

another form by the late Marquess

of Bute. There is not sufficient evidence to prove that the rule

attributed to him was really his work.

In the spring of 597 he knew that

his end was approaching. On Saturday, 8 June, he ascended the hill

overlooking his monastery and blessed for

the last time the home so dear to him. That afternoon he was present at Vespers,

and later, when the bell summoned the community to the midnight

service, he forestalled the others and entered the church without

assistance. But he sank before the altar, and in that place breathed forth

his soulto God,

surrounded by his disciples. This happened a little after midnight between

the 8th and 9th of June, 597. He was in the seventy-seventh year of his age.

The monks buried him

within the monastic

enclosure. After the lapse of a century or more his bones were disinterred

and placed within a suitable shrine. But as Northmen andDanes more

than once invaded the island, the relics of

St. Columba were carried for purposes of safety intoIreland and

deposited in the church of Downpatrick. Since the twelfth

century history is silent regarding them. His books and

garments were held in veneration at Iona,

they were exposed and carried in procession,

and were the means of working miracles (Adam.,

II, xlv). His feast is

kept in Scotland and Ireland on

the 9th of June. In the Scottish Province of st Andrews

and Edinburgh there is a Mass and Office proper

to the festival, which ranks as a double of the second class with

an octave. He is patron of two Scottish dioceses Argyle and

the Isles andDunkeld.

According to tradition St. Columba was tall and of dignified

mien. Adamnan says:

"He was angelic in appearance, graceful in

speech, holy in work" (Praef., II). His voice was strong, sweet,

and sonorous capable at times of being heard at a great distance. He inherited

the ardent temperament and strong passions of his race. It has been

sometimes said that he was of an angry and

vindictive spirit not only because of his supposed part in the battle

of Cooldrevny but also because of irritant related by Adamnan (II,

xxiii sq.) But the deeds that roused his indignation were wrongs done

to others, and the retribution that overtook the perpetrators was rather

predicted than actually invoked. Whatever faults were inherent in

his nature he overcame and he stands before the world conspicuous

for humility and charity not

only towards has brethren, but towards strangers also. He was generous and

warm-hearted, tender and kind even to dumb creatures. He was ever

ready to sympathize with thejoys and sorrows of others. His fasts and vigils were

carried to a great extent. The stone pillow on which he slept is said

to be still preserved in Iona.

His chastity of body and purity of mind are extolled by all

his biographers. Notwithstanding his wonderful austerities, Adamnan assures

us he was beloved by all, "for a holy joyousness that

ever beamed from his countenance revealed the gladness with

which the Holy Spirit filled his soul". (Praef.,

II.)

Influence, and attitude

towards Rome

He was not only a great

missionary saint who won a whole kingdom to Christ,

but he was a statesman, a scholar, a poet, and the founder of

numerous churches and monasteries.

His name is dear to Scotsmen and Irishmenalike.

And because of his great and noble work even non-Catholics hold

his memory in veneration. For the purposes of controversy it has

been maintained some that St. Columba ignored papal supremacy,

because he entered upon his mission without the pope's authorization. Adamnan is silent on

the subject; but his work is neither exhaustive as to Columba's life,

nor does it pretend to catalogue the implicit and explicit belief of

hispatron. Indeed, in those days a mandate from the pope was

not deemed essential for the work which St. Columba undertook. This

may be gathered from the words of St.

Gregory the Great, relative to the neglect of theBritish clergy towards

the pagan Saxons (Haddan

and Stubbs, III, 10). Columba was a son of the Irish Church,

which taught from the days of St.

Patrick that matters of greater moment should be referred to the Holy

See for settlement. St.

Columbanus, Columba's fellow-countryman and fellow-churchman, asked

for papal judgment(judicium)

on the Easter question;

so did the bishops and abbots of Ireland.

There is not the slightest evidence toprove that St. Columba differed on

this point from his fellow-countrymen. Moreover, the Stowe Missal,

which, according to the best authority, represents the Mass of

the Celtic Church during the early part of the seventh century,

contains in its Canon prayers for

the pope more

emphatic than even those of the Roman Liturgy. To the further

objection as to the supposed absence of the cultus

of Our Lady, it may be pointed out that the same Stowe Missal contains

before its Canon the invocation "Sancta Maria,

ora pro nobis", which epitomizes all Catholic devotion

to the Blessed Virgin. As to the Easter difficulty Bede thus

sums up the reasons for the discrepancy: "He [Columba] left successors distinguished

for great charity, Divine love,

and strict attention to the rules ofdiscipline following indeed uncertain

cycles in the computation of the great festival of Easter,

because, far away as they were out of the world, no one had supplied them with

the synodal decrees relating to the Paschalobservance"

(H.E., III, iv). As far as can be ascertained no

proper symbolical representation of St. Columba exists. The few

attempts that have been made are for the most part mistaken. A suitable

pictorial representation would exhibit him, clothed in the habit and cowl usually

worn by the Basilian or Benedictine monks,

with Celtic tonsure and crosier.

His identity could be best determined by showing him standing near the

shell-strewn shore, with currach hard by, and

the Celtic cross and ruins of Iona in

the background.

Edmonds,

Columba. "St. Columba." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton

Company, 1908. 15 Mar. 2015 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04136a.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Joseph P. Thomas.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. Remy Lafort,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John M. Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2020 by Kevin

Knight. Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04136a.htm

Point

of Departure The famous missionary, Saint Colmcille (Saint Columba) left here

and ended up in Iona http://www.isle-of-iona.com/abbey.htm.

Columba (RM)

(also known as Colum, Columbus, Combs, Columkill, Columcille, Colmcille)

Born in Garton, County Donegal, Ireland, c. 521; died June 9, 597.

"Alone with none but Thee, my God,

I journey on my way;

What need I fear when Thou art near,

Oh King of night and day?

More safe am I within Thy hand

Than if a host did round me stand."

--Attributed to Saint Columba.

"We know for certain that Columba left successors distinguished for their

purity of life, their love of God, and their loyalty to the rules of the

monastic life." --The Venerable Bede.

Ireland has many saints and three great ones: Patrick, Brigid, and Columba.

Columba outshines the others for his pure Irishness. He loved Ireland with all

his might and hated to leave it for Scotland. But he did leave it and laid the

groundwork for the conversion of Britain. He had a quick temper but was very

kind, especially to animals and children. He was a poet and an artist who did

illumination, perhaps some of those in the Book of Kells itself. His skill as a

scribe can be seen in the Cathach of Columba at the Irish Academy, which is the

oldest surviving example of Irish majuscule writing. It was latter enshrined in

silver and bronze and venerated in churches.

About the time that Patrick was taken to Ireland as a slave, Columba was born.

He came from a race of kings who had ruled in Ireland for six centuries,

directly descended from Niall of the Nine Hostages, and was himself in close

succession to the throne. From an early age he was destined for the priesthood;

he was given in fosterage to a priest. After studying at Moville under Saint

Finnian and then at Clonard with another Saint Finnian, he surrendered his

princely claims, he became a monk at Glasnevin under Mobhi and was ordained.

He spent the next 15 years preaching and teaching in Ireland. As was the custom

in those days, he combined study and prayer with manual labor. By his own

natural gifts as well as by the good fortune of his birth, he soon gained

ascendancy as a monk of unusual distinction. By the time he was 25, he had

founded no less than 27 Irish monasteries, including those at Derry (546),

Durrow (c. 556), and probably Kells, as well as some 40 churches.

Columba was a poet, who had learned Irish history and poetry from a bard named

Gemman. He is believed to have penned the Latin poem Altus Prosator and two

other extant poems. He also loved fine books and manuscripts. One of the famous

books associated with Columbia is the Psaltair, which was traditionally the

Battle Book of the O'Donnells, his kinsmen, who carried it into battle. The

Psaltair is the basis for one of the most famous legends of Saint Columba.

It is said that on one occasion, so anxious was Columba to have a copy of the

Psalter that he shut himself up for a whole night in the church that contained

it, transcribing it laboriously by hand. He was discovered by a monk who

watched him through the keyhole and reported it to his superior, Finnian of

Moville. The Scriptures were so scarce in those days that the abbot claimed the

copy, refusing to allow it to leave the monastery. Columba refused to surrender

it, until he was obliged to do so, under protest, on the abbot's appeal to the

High King Diarmaid, who said: "Le gach buin a laogh" or "To

every cow her own calf," meaning to every book its copy.

An unfortunate period followed, during which, owing to Columba's protection of

a refugee and his impassioned denunciation of an injustice by King Diarmaid,

war broke out between the clans of Ireland, and Columba became an exile of his

own accord. Filled with remorse on account of those who had been slain in the

battle of Cooldrevne, and condemned by many of his own friends, he experienced

a profound conversion and an irresistible call to preach to the heathen.

Although there are questions regarding Columba's real motivation, in 563, at

the age of 42, he crossed the Irish Sea with 12 companions in a coracle and

landed on a desert island now known as Iona (Holy Island) on Whitsun Eve. Here

on this desolate rock, only three miles long and two miles wide, in the grey

northern sea off the southwest corner of Mull, he began his work; and, like

Lindisfarne, Iona became a center of Christian enterprise. It was the heart of

Celtic Christianity and the most potent factor in the conversion of the Picts,

Scots, and Northern English.

Columba built a monastery consisting of huts with roofs of branches set upon

wooden props. It was a rough and primitive settlement. For over 30 years he

slept on the hard ground with no pillow but a stone. But the work spread and

soon the island was too small to contain it. From Iona numerous other

settlements were founded, and Columba himself penetrated the wildest glens of

Scotland and the farthest Hebrides, and established the Caledonian Church. It

is reputed that he anointed King Aidan of Argyll upon the famous stone of

Scone, which is now in Westminster Abbey. The Pictish King Brude and his people

were also converted by Columba's many miracles, including driving away a water

"monster" from the River Ness with the Sign of the Cross. Columba is

said to have built two churches at Inverness.

Just one year before Columba's migration to Iona, Saint Moluag established his

mission at Lismore on the west coast of Scotland. There are constant references

to a rivalry between the two saints over spheres of influence, which are

probably without foundation. Columba was primarily interested in Gaelic life in

Scotland, while Moluag was drawn to the conversion of the Picts.

While leading the Irish in Scotland, Columba appears to have retained some sort

of overlordship over his monasteries in Ireland. About 580, he participated in

the assembly of Druim-Cetta in Ulster, where he mediated about the obligations

of the Irish in Scotland to those in Ireland. It was decided that they should

furnish a fleet, but not an army, for the Irish high-king. During the same

assembly, Columba, who was a bard himself, intervened to effectively swing the

nation away from its declared intention of suppressing the Bardic Order.

Columba persuaded them that the whole future of Gaelic culture demanded that

the scholarship of the bards be preserved. His prestige was such that his views

prevailed and assured the presence of educated laity in Irish Christian

society.

He is personally described as "A man well-formed, with powerful frame; his

skin was white, his face broad and fair and radiant, lit up with large, gray,

luminous eyes. . . ." (Curtayne). Saint Adamnan, his biographer wrote of

him: "He had the face of an angel; he was of an excellent nature, polished

in speech, holy in deed, great in counsel . . . loving unto all." It is

clear that Columba's temperament changed dramatically during his life. In his

early years he was intemperate and probably inclined to violence. He was

extremely stern and harsh with his monks, but towards the end he seems to have

softened. Columba had great qualities and was gay and lovable, but his chief

virtue lay in the conquest of his own passionate nature and in the love and

sympathy that flowed from his eager and radiant spirit.

On June 8, 597, Columba was copying out the psalms once again. At the verse,

"They that love the Lord shall lack no good thing," he stopped, and

said that his cousin, Saint Baithin must do the rest. Columba died the next day

at the foot of the altar. He was first buried at Iona, but 200 years later the

Danes destroyed the monastery. His relics were translated to Dunkeld in 849,

where they were visited by pilgrims, including Anglo-Saxons of the 11th

century.

The year Columba died was the same year in which Saint Gregory the Great sent

Saint Augustine of Canterbury to convert England. Perhaps because the Roman

party gained ascendancy at the Synod of Whitby, much of the credit that belongs

to Saint Columba and his followers for the conversion of Britain has been

attributed to Augustine. It should not be forgotten that both saints played

important roles.

Saint Columba is also important as patron of the Knights of Saint Columba,

known in the United States as the Knights of Columbus and by other names in

various parts of the world. Like Saint Malachy, whose apocryphal prophecies

concerning the succession of popes are universally known, Saint Columba left a

series of predictions about the future of Ireland. These were published in 1969

by Peter Blander under the title, The Prophecies of Saint Malachy and Saint

Columbkille (4th ed. 1979, Colin Smythe, Gerrards Cross Buckshire).

Unsurprisingly, devotion to Columba is especially strong in Derry. On April 13,

the king signed the Catholic Emancipation Act in London. On that same day in

Derry, the statue of a Protestant leader of the siege of Derry, which stood on

the city walls was smashed apart of its own accord. The destruction of this

symbol of dominion was attributed to the intercession of Saint Columba

(Anderson, Attwater, Benedictines, Bentley, Encyclopedia, Farmer, Gill,

Menzies, Montague, Simpson).

The following legends about Saint Columba are the gentlest things recorded

about the heroic and tempestuous abbot who founded Iona. The countryside where

he was fathered is Gartan in Donegal, at the ingoing of the mountains and the

great lake; a gentle countryside, and more apt a birthplace for the bird than

the saint. The life written about 690 by Saint Adamnan, himself an Irishman and

an abbot of Iona, is a rugged piece of work: but the deathdays of Saint

Columba, and the crowding torches that discovered him dying in the dark before

the high altar at midnight on June 9, are one of the tidemarks in medieval

prose. The work itself owes much to Adamnan's imagination and more to

unreliable sources, but it is a primarily a narrative of the miracles worked

through Columba.

In the first story Columba bids his brother monk to go in three days to a far

hilltop and wait, "'For when the third hour before sunset is past, there

shall come flying from the northern coasts of Ireland a stranger guest, a

crane, wind tossed and driven far from her course in the high air; tired out

and weary she will fall upon the beach at thy feet and lie there, her strength

nigh gone. Tenderly lift her and carry her to the steading near by; make her

welcome there and cherish her with all care for three days and nights; and when

the three days are ended, refreshed and loath to tarry longer with us in our

exile, she shall take flight again towards that old sweet land of Ireland

whence she came, in pride of strength once more. And if I commend her so

earnestly to thy charge, it is that in the countryside where thou and I were

reared, she too was nested.'"

The brother obeyed and all happened as Columba had foretold. "And on his

return that evening to the monastery the Saint spoke to him, not as one

questioning but as one speaks of a thing past. 'May God bless thee, my son,'

said he, 'for thy kind tending of this pilgrim guest; that shall make no long

stay in her exile, but when three suns have set shall turn back to her own

land.'" And so it happened (Adamnan; also in Curtayne).

The second story recalls how Columba's heart would be touched when he saw a sad

child. From time to time he would leave Iona to preach to the Picts of

Scotland. "Once he visited a Pictish ruler who was also a druid, or pagan

priest. When he was there he noticed a thin little girl with a face like a

ghost. He asked who she was and was told that she was just a slave from

Ireland. The way it was said seemed to mean: 'Why do you ask such silly

questions? Who cares who she is, as long as she brushes and scrubs and does

what she is told?'

"Columcille was troubled; he could see plainly that the little girl was

miserable. So he asked the druid to give her freedom and he would get her home

to Ireland. The druid refused. Columcille went away with a picture of an

unhappy little girl in his mind.

"Shortly afterward, the important druid became ill; there was nobody near

to tell him what to do to get well so he sent for the Abbot of Iona, who had a

great reputation for curing people. Columcille did not leave Iona but sent a

message back that he would cure the druid if he let the little girl free.

"The druid was angry and again refused. 'What on earth is he troubling

himself for about that little bit of a good-for-nothing?' grumbled the druid as

he tossed about in bed. But the messenger had hardly left for Iona with the

refusal when the druid got worse; he had much pain and he thought he would die.

So he sent off another message to Columcille: 'Yes, you can have the

slave-girl, only come and do something for me. I am very bad and will die if

you don't come soon.'" Columcille, however, did not trust the priest, so

he sent two of his monks to bring the girl back. When the girl was safe,

Columcille set out for the druid's house and cured him of his sickness

(Curtayne).

Anther story occurs in May, when Columba set out in a cart to visit the

brethren at their work. He found them busy in the western fields and said, 'I

had a great longing on me this April just now past, in the high days of the

Easter feast, to go to the Lord Christ; and it was granted me by Him, if I so

willed. But I would not have the joy of your feast turned into mourning, and so

I willed to put off the day of my going from the world a little longer.' The

monks were saddened to hear this and Columba tried to cheer them. He blessed

the island and islanders and returned in his cart to the monastery.

On that Saturday, the venerable old saint and his faithful Diarmid went to

bless a barn and two heaps of grain stored therein. Then with a gesture of

thanksgiving, he spoke, 'Truly, I give my brethren at home joy that this year,

if so be I might have to go somewhere away from you, you will have what

provision will last you the year.'

Diarmid was grieved to hear this again and the saint promised to share his

secret. "'In the Holy Book this day is called the Sabbath, which is, being

interpreted, rest. And truly is this day my Sabbath, for it is the last day for

me of this present toilsome life, when from all weariness of travail I shall

take my rest, and at midnight of this Lord's Day that draws n, I shall, as the

Scripture saith, go the way of my fathers. For now my Lord Jesus Christ hath

deigned to invite me; and to Him, I say, at this very midnight and at His own

desiring, I shall go. For so it was revealed to me by the Lord Himself.' At

this sad hearing his man began bitterly to weep, and the Saint tried to comfort

him as best he might.

"And so the Saint left the barn, and took the road back to the monastery;

and halfway there sat down to rest. Afterwards on that spot they set a cross,

planted upon a millstone, and it is to be seen by the roadside to this day. And

as the Saint sat there, a tired old man taking his rest awhile, up runs the

white horse, his faithful servitor that used to carry the milk pails, and

coming up to the Saint he leaned his head against his breast and began to

mourn, knowing as I believe from God Himself--for to God every animal is wise

in the instinct his Maker hath given him--that his master was soon to go from

him, and that he would see his face no more. And his tears ran down as a man's

might into the lap of the Saint, and he foamed as he wept.

"Seeing it, Diarmid would have driven the sorrowing creature away, but the

Saint prevented him, saying, 'Let be, let be, suffer this lover of mine to shed

on my breast the tears of his most bitter weeping. Behold, you that are a man

and have a reasonable soul could in no way have known of my departing if I had

not but now told you; yet to this dumb and irrational beast, his Creator in

such fashion as pleased Him has revealed that his master is to go from him.'

And so saying, he blessed the sad horse that had served him, and it turned

again to its way" (Adamnan; also in Curtayne).

In art, Saint Columba is depicted with a basket of bread and an orb of the

world in a ray of light. He might also be pictured with an old, white horse

(Roeder). He is venerated in Dunkeld and as the Apostle of Scotland (Roeder).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0609.shtml#feli

SAINT COLUMBA, ABBOT,

CONFESSOR—521-597

Feast: June 6

Columba, the most famous

of the saints associated with Scotland, was actually an Irishman of the O'Neill

or O'Donnell clan, born about the year 521 at Garton, County Donegal, in north

Ireland. Of royal lineage on both sides, his father, Fedhlimidh, or Phelim, was

great-grandson to Niall of the Nine Hostages, Overlord of Ireland, and

connected with the Dalriada princes of southwest Scotland; his mother, Eithne,

was descended from a king of Leinster. The child was baptized Colum, or Columba.[1]

In later life he was given the name of Columcille or Clumkill, that is, Colum

of the Cell or Church, an appropriate title for one who became the founder of

so many monastic cells and religious establishments.

As soon as he was old

enough, Columba was taken from the care of his priest-guardian at

Tulach-Dugblaise, or Temple Douglas, to St. Finnian's training school at

Moville, at the head of Strangford lough. He was about twenty, and a deacon,

when he left to study in the school of Leinster under an aged theologian and

bard called Gemman. With their songs of heroes, the bards were the preservers

of Irish lore, and Columba himself became a poet. Still later he attended the

famous monastic school of Clonard, presided over by another Finnian, who in later

times was known as the "tutor of Erin's saints." At one time three

thousand students were gathered here from all over Ireland, Scotland, and

Wales, and even from Gaul and Germany. It was probably at Clonard that Columba

was ordained priest, although it may have been later, when he was living with

his friends, Comgall, Kieran, and Kenneth, under the most gifted of all his

teachers, St. Mobhi, by a ford in the river Tolca, called Dub Linn, the site of

the future city of Dublin. In 543 an outbreak of plague compelled Mobhi to

close his school, and Columba, now twenty-five years old and fully trained,

returned to Ulster. He was a striking figure of great stature and powerful

build, with a loud, melodious voice which could be heard from one hilltop to

another. For the next fifteen years Columba went about Ireland preaching and

founding monasteries, the chief of which were those at Derry, Durrow, and

Kells.

The powerful stimulus

given to Irish learning by St. Patrick in the previous century was now

beginning to burgeon. Columba himself dearly loved books, and spared no pains

to obtain or make copies of Psalters, Bibles, and other valuable manuscripts

for his monks. His former master Finnian had brought back from Rome the first

copy of St. Jerome's Psalter to reach Ireland. Finnian guarded this precious

volume jealously, but Columba got permission to look at it, and surreptitiously

made a copy for his own use. Finnian, on being told of this, laid claim to the

copy. Columba refused to give it up, and the question of ownership was put

before Ring Diarmaid, Overlord of Ireland. His curious decision in this early

"copyright" case went against Columba. "To every cow her

calf," reasoned the King, "and to every book its son-book. Therefore

the copy you made, O Colum Cille, belongs to Finnian." Columba was soon to

have a more serious grievance against the King. Prince Curnan of Connaught, who

had fatally injured a rival in a hurling match and had taken refuge with

Columba, was dragged from his protector's arms and slain by Diarmaid's men, in

defiance of the rights of sanctuary.

The war which soon broke

out between Columba's clan and the clans loyal to Diarmaid was instigated, it

is said, by Columba. At the battle of Cuil Dremne his cause was victorious, but

Columba was accused of being morally responsible for driving three thousand

unprepared souls into eternity. A church synod was held at Tailltiu (Telltown)

in County Meath, which passed a vote of censure and would have followed it by

excommunication but for the intervention of St. Brendan. Columba's own

conscience was uneasy, and on the advice of an aged hermit, Molaise, he

resolved to expiate his offense by exiling himself and trying to win for Christ

in another land as many souls as had perished in the terrible battle of Cuil

Dremne.

This traditional account

of the events which led to Columba's departure from Ireland may well be

correct, although missionary zeal and love of Christ are the motives mentioned

for his going by the earliest biographers and by Adamnan,[2] our chief

authority for his subsequent history. Whatever the impulse that prompted him,

in the year 563, Columba embarked with twelve companions in a wicker coracle

covered with leather, and on the eve of Pentecost landed on the island of Hi,

or Iona.[3] The first thing he did there was to erect a high stone cross; then

he built a monastery, which was to be his home for the rest of his life. The

island itself was made over to him by his kinsman Conall, king of the British

Dalriada, who perhaps had invited him to come to Scotland in the first place.

Lying across from the border country between the Picts of the north and the

Scots of the south, Iona made an ideal center for missionary work. Columba

seems to have first devoted himself to teaching the imperfectly instructed

Christians of Dalriada, most of whom were of Irish descent, but after some two

years he turned to the work of converting the Scottish Picts. With his old

comrades, Comgall and Kenneth, both of them Irish Picts, he made his way

through Loch Ness northward to the castle of the redoubtable King Brude, near

modern Inverness. That pagan monarch had given strict orders that they were not

to be admitted, but when Columba raised his arm and made the sign of the cross,

it was said that bolts fell out and gates swung open, permitting the strangers

to enter. Impressed by such powers, the King listened to them and ever after

held Columba in high regard. As Overlord of Scotland he confirmed him in

possession of Iona. We know from Adamnan that on several occasions Columba

crossed the mountain chain which divides Scotland and that his travels also

took him far north, and through the Western Isles. He is said to have planted

churches as far east as Aberdeenshire and to have evangelized nearly the whole

of the country of the Picts. When the descendants of the Dalriada kings became

the rulers of Scotland, they were naturally eager to magnify the achievements

of their hero and distant kinsman, Columba, and may have attributed to him

victories won by others.

Columba never lost touch

with Ireland. In 575 he was at the synod of Drumceatt in County Meath in

company with King Conall's successor, Aidan, whom he had helped to place on the

throne and had crowned at Iona, in his role as chief ecclesiastical ruler. His

immense influence is shown by his veto of a proposal to abolish the order of

bards and his securing for women exemption from all military service. When not

on missionary journeys, Columba was to be found in his cell on Iona, where

persons of all conditions visited him, some in want of spiritual or material

help, some drawn by his miracles and sanctity. His biographer gives us a

picture of a serene old age. His manner of life was austere; he slept on a bare

slab of rock and ate barley or oat cakes, drinking only water. When he became

too weak to travel, he spent long hours copying manuscripts, as he had done in

his youth. On the day before his death he was at work on a Psalter, and had

just traced the words, "They that love the Lord shall lack no good thing,"

when he paused and said, "Here I must stop; let Baithin do the rest."

Baithin was his cousin. whom he had already nominated as his successor. When

the monks entered the church for Matins, they found their beloved abbot lying

helpless and dying before the altar. As his faithful attendant Diarmaid gently

upraised him, he made a feeble effort to bless his brethren and then expired.

Iona was for centuries

one of the famous centers of Christian learning For a long time afterwards,

Scotland, Ireland, and Northumbria followed the observances Columba had set for

the monastic life, in distinction to those that were brought from Rome by later

missionaries. His rule, based on the Eastern Rule of St. Basil, was that of

many monasteries of Western Europe until superseded by the milder ordinance of

St. Benedict. Adamnan, who must have bee n brought up on memories and

recollections of Columba, writes eloquently of him: "He had the face of an

angel; he was of excellent nature, polished in speech, holy in deed, great in council.

He never let a single hour pass without engaging in prayer or reading or

writing or some other occupation. He endured the hardships of fasting and

vigils without intermission by day and night; the burden of a single one of his

labors would have seemed beyond the powers of man. And, in the midst of all his

toils, he appeared loving unto all, serene and holy, rejoicing in the joy of

the Holy Spirit in his inmost heart."

M'Oenuran[4]

Alone am I upon the

mountain;

O Royal Sun, be the way

prosperous;

I have no more fear of

aught

Than if there were six

thousand with me.

If there were six

thousand with me

Of people, though they

might defend my body,

When the appointed moment

of my death shall come,

There is no fortress that

can resist it.

They that are ill-fated

are slain even in a church,

Even on an island in the

middle of a lake;

They that are well-fated

are preserved in life,

Though they were in the

first rank of battle, . . .

Whatever God destines for

one,

He shall not go from the

world till it befall him;

Though a Prince should

seek anything more

Not as much as a mite

shall he obtain....

O Living God, O Living

God!

Woe to him who for any

reason does evil.

What thou seest not come

to thee,

What thou seest escapes

from thy grasp.

Our fortune does not

depend on sneezing.

Nor on a bird on the

point of a twig,

Nor on the trunk of a

crooked tree,

Nor on a sordan hand in

hand,

Better is He on whom we

depend,

The Father,—the One,—and

the Son....

I reverence not the

voices of birds,

Nor sneezing, nor any

charm in the wide world,

Nor a child of chance,

nor a woman;

My Druid is Christ, the

Son of God.

Christ the Son of Mary,

the great Abbot,

The Father, Son, and Holy

Ghost;

My Possession is the King

of Kings;

My Order is in Kells and

Moone.

Alone am I.

(D. Macgregor, Saint

Columba, Edinburgh, 1897.)

Endnotes

1 Some records say he was

baptized Crimthan, meaning the Fox, but that hisgentleness and goodness as a

child so won all hearts that he was rechristened Colum, or Columba, Latin for

dove.

2 The historian Adamnan

was born in Donegal about 624. He became abbot of Iona, being ninth in

succession after Columba. His is a rich mine of anecdote.

3 The original form of

the word was Hy or I, which is Irish for island. Iona is one of the Inner

Hebrides, just off the west coast of Scotland. It became known also as

Icolmkill, "the island of Columba of the Cell." It had been a sacred

place to the Druids before Columba landed there, and was to become the center

of Celtic Christianity.

4 Columba sang this song

as he walked alone, it was thought to be a protection to anyone who sang it on

a journey, like the "Lorica" of St. Patrick.

Saint Columba, Abbot,

Confessor. Celebration of Feast Day is June 6.

Taken from "Lives

of Saints", Published by John J. Crawley & Co., Inc.

Provided Courtesy of:

Eternal Word Television Network, 5817 Old Leeds Road, Irondale, AL 35210

SOURCE : http://www.ewtn.com/library/mary/columba.htm

Paisley

Abbey, Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland. Door with depiction of St Mirin and St

Columba.

Paisley

Abbey, Paisley, Renfrewshire, Schotland. Schip. Deur met afbeelding van St

Mirin en St Columba.

June 9

Columba (Colum,

Colm, Columkill, Columcille, Colmcille, Combs, Columbus), the most famous of

the saints associated with Scotland, was actually born in Ireland, of the

O'Neill or O'Donnell clan, at Garton, County Donegal. Some say his birth date

was December 7; most sources agree that the year of his birth was 521. His

father, Fedhlimidh, or Phelim, was great-grandson to Niall of the Nine

Hostages, Overlord of Ireland, and connected with the Dalriada princes of

southwest Scotland; his mother, Eithne, was descended from a king of Leinster.

He was of the blood royal on both sides, and might indeed have become High King

of Ireland had he not chosen to be a priest.

A few records say his

original name was Crimthan, meaning "fox", but his gentleness and

goodness as a child so won all hearts that he was rechristened Colum, Latin for

dove. Later he was commonly known as Colum-kill or Colum-cille, the suffix

"kill" or "cill" meaning "of the cell" or

"of the church" -- an appropriate title for the founder of so many

religious establishments.

Like many children

destined for a holy life, as an infant he was given into the foster care of a

priest named Cruithnechan, who also served as his tutor. He was baptized by

Cruithnechan at Tulach-Dubhglaise, now Temple-Douglas, and his early life

education began. When sufficiently advanced in letters Columba was taken from

the care of his priest-guardian and sent to the school of Moville (County

Down), where he began his training in the monastic life under a St. Finnian who

had studied with St. Colman of Dromore. He was ordained to the diaconate before

the age of twenty, and, after completing his training at Moville, he travelled

southwards to Leinster, the land of his mother's ancestors, to study under an

aged theologian and bard named Gemman. The bards were the preservers of Irish

lore, and Columba himself was inspired to become a poet. He is believed to have

penned the Latin poem Altus Prosator and two other extant poems.

Following some years with

Gemman, Columba finally entered the famous monastic school of Clonard, presided

over by the more famous St. Finnian who was known as the "tutor of Erin's

saints." At one time three thousand students were gathered here from all

over Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, and even from Gaul and Germany. By his own

natural gifts as well as by the good fortune of his birth, he soon gained

ascendancy as a monk of unusual distinction. He became one those Clonard

disciples known in subsequent history as the Twelve Apostles of Ireland. It was

probably at Clonard that Columba was ordained priest, although it may have been

later, when he was living with his friends, Comgall, Kieran, and Kenneth, under

the most gifted of all his teachers, St. Mobhi. St. Mobhi's monastery at

Glasnevin was located by a ford in the river Tolca at a place called Dub Linn,

the site of the future city of Dublin. In 543 an outbreak of plague devastated

Ireland and in 544 Mobhi was compelled to close his school. Columba returned to

Ulster, the land of his kindred.

He was fully trained by the

time he was twenty-five years old, and he was a striking figure of great

stature and powerful build. His loud, melodious voice could be heard from one

hilltop to another. As was the custom in those days, he combined study and

prayer with manual labor. Amongst many other accomplishments, Columba was a

splendid sailor. With his imposing presence, holy personality and self-denying

discipline, Columba went about Ireland for the next fifteen years preaching and

founding monasteries, including those at Derry, Durrow, and Kells.

The powerful stimulus

given to Irish learning by St. Patrick in the previous century was rapidly

spreading and growing. Columba himself dearly loved books, and spared no pains

to obtain or make copies of Psalters, Bibles, and other valuable manuscripts

for his monks. In 540 his first master Finnian brought back from Rome the first

copy of St. Jerome's Vulgate to reach Ireland. Finnian guarded this precious

volume jealously, but Columba got permission to look at it, and surreptitiously

made a copy of the Psalter for his own use. Finnian, on being told of this,

laid claim not only to the original but to the copy made by Columba's own hand.

Columba refused to give it up, and the question of ownership was put before

King Diarmaid, Overlord of Ireland. Columba lost this early

"copyright" case when the King said: "To every cow her calf, and

to every book its son-book. Therefore the copy you made, O Colum Cille, belongs

to Finnian."

Columba was soon to have

a more serious grievance against King Diarmaid, when a prince had fatally

injured a rival and had taken refuge with Columba was dragged from his

protector's arms and slain by Diarmaid's men, in defiance of the sacred rights

of sanctuary. The resulting war which broke out between Columba's clan and the

clans loyal to Diarmaid was instigated, it is said, by Columba. At the battle

of Cuil Dremne Columba's cause was victorious, but he was accused of being

morally responsible for driving three thousand unprepared souls into eternity.

A synod was held at Tailltiu (Telltown) in County Meath, which passed a vote of

censure. Were it not for the intervention of St. Brendan, Columba would have

been excommunicated. Though he still felt he was in the right, his conscience

remained uneasy, and at last he made his confession to an aged hermit, Molaise.

As penance, he resolved to exile himself and win for Christ in another land as

many souls as had perished in the battle of Cuil Dremne.

Whatever the impulse that

prompted him, in 563 Columba embarked with twelve companions in a wicker

coracle covered with leather, and on the eve of Pentecost landed on one of the

Inner Hebrides, just off the west coast of Scotland, at the place we now know

as Iona. The first thing he did there was to erect a high stone cross; then he

built a monastery, which was to be his home for the rest of his life. Iona was

a desolate rock originally known only as Hy or I, Irish for "island".

Years later it also became known also as Icolmkill, "the island of Columba

of the Cell." It had been a sacred place to the Druids long before Columba

landed there, and was to become the center of Celtic Christianity.

Columba and his Celtic

monks at Iona combined contemplative life with extensive missionary activity.

Lying across from the border country between the Picts of the north and the

Scots of the south, Iona made an ideal center for missionary work. Columba

seems to have first devoted himself to teaching the imperfectly instructed

Christians of Dalriada, most of whom were of Irish descent, but after two years

he turned to the work of converting the Scottish Picts. With his old comrades,

Comgall and Kenneth, Columba made his way through Loch Ness northward to the

castle of the redoubtable King Brude, near modern Inverness. The pagan monarch

had given strict orders that they were not to be admitted, but when Columba

raised his arm and made the sign of the cross, it was said that bolts fell out

and gates swung open, permitting the strangers to enter. Impressed by such

powers, the King listened to them and ever after held Columba in high regard.

As Overlord of Scotland he confirmed him in possession of Iona. Columba is said

to have planted churches as far east as Aberdeenshire and to have evangelized

nearly the whole of the country of the Picts.

Columba never lost touch

with Ireland. In 575 he was at the synod of Drumceatt in County Meath in

company with King Conall's successor, Aidan, whom he had helped to place on the

throne and had crowned at Iona, in his role as chief ecclesiastical ruler. His

immense influence is shown by his veto of a proposal to abolish the order of

bards, and his success at securing for women exemption from all military

service. When not on missionary journeys, Columba was to be found in his cell

on Iona, where persons of all conditions visited him, some in want of spiritual

or material help, some drawn by his miracles and sanctity. Iona was for

centuries one of the famous centers of Christian learning. For a long time