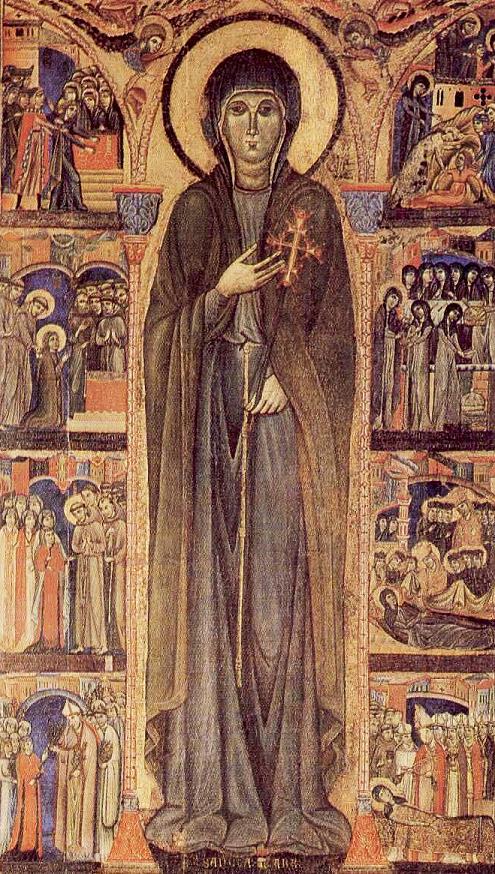

Maestro

della Santa Chiara (attr.), Santa Chiara d'Assisi e storie della sua

vita (1283),

tempera su tavola; Assisi, Basilica di Santa Chiara

Santa Chiara d'Assisi, 1283, tempera on panel, 273 x 165, Altarpiece of St Clare, Basilica di Santa Chiara

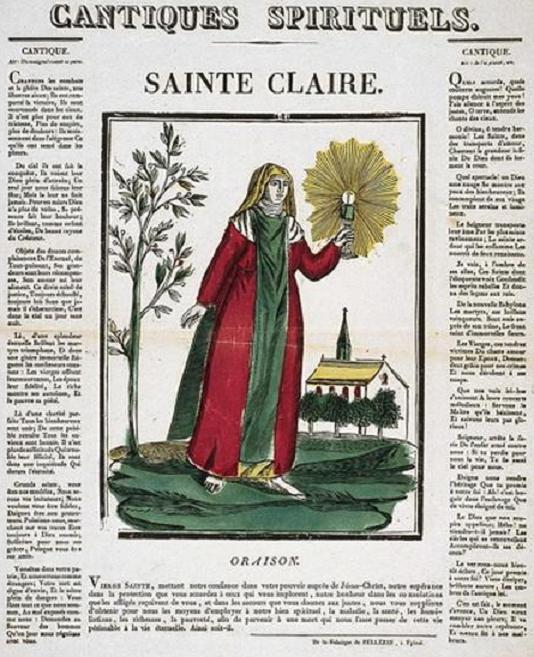

Sainte Claire d'Assise

Fondatrice des clarisses (+1253)

Il n'est pas possible de séparer l'histoire de sainte Claire de celle de saint François d'Assise. Née à Assise, elle a 11 à 12 ans de moins que lui. Elle est de famille noble et lui fils de marchand. Au moment de la 'commune' d'Assise vers 1200, soulèvement violent contre le pouvoir féodal, auquel participe saint François, les parents de Claire quittent la ville par sécurité et se réfugient à Pérouse, la ville rivale. Ils ne reviendront à Assise que 5 à 6 ans plus tard. Claire ne commence à connaître saint François que vers 1210, quand celui-ci, déjà converti à la vie évangélique, se met à prêcher dans Assise. Elle est séduite par lui et par cette vie pauvre toute donnée au Christ. Elle cherche donc à rencontrer François par l'intermédiaire de son cousin Rufin qui fait partie du groupe des frères. Ensemble, ils mettent au point son changement de vie. Le soir des Rameaux 1212, elle quitte la demeure paternelle et rejoint saint François à la Portioncule. Elle a 18 ans et se consacre à Dieu pour toujours. L'opposition de sa famille n'y pourra rien. Rapidement d'autres jeunes filles se joignent à Claire, dont sa sœur Agnès, sa maman Ortolana et son autre sœur Béatrice. La vie des 'Pauvres Dames' prospère rapidement et d'autres monastères doivent être fondés. Le Pape Innocent III leur accorde 'le privilège de pauvreté'. Mais après la mort de saint François, les papes interviendront pour aménager la vie matérielle des Clarisses et leur permettre une relative sécurité. Claire refuse de toutes ses forces. Elle veut la pauvreté totale et la simplicité franciscaine. En 1252, le pape Innocent IV rend visite aux Sœurs, accepte leur Règle de vie et la bulle d'approbation arrive le 9 août 1253. Claire meurt le 11 août tenant la bulle dans ses mains dans la paix et la joie.

- méditation sur les symboles dans la vie et les écrits de sainte Claire d'Assise, vidéo de la WebTV de la CEF.

Le 15 septembre 2010, Benoît XVI a consacré sa catéchèse à Claire d'Assise (1193-1253), une des saintes les plus aimées dans l'Église. Son témoignage "montre ce que l'Église doit aux femmes courageuses et remplies de foi, capables de donner une forte impulsion à sa rénovation". Puis il a rappelé qu'elle naquit dans une famille aristocratique, qui décida de la marier à un bon parti. Mais à dix huit ans, Claire et son amie Bonne quittèrent leurs foyers et décidèrent de suivre le Christ en entrant dans la communauté de la Portioncule. C'est François qui l'y accueillit, lui tailla les cheveux et la revêtit d'un grossier vêtement de pénitence. Dès lors fut elle une vierge, épouse du Christ, humble et pauvre, totalement consacrée au Seigneur".

Dès le début de sa vie religieuse, a ensuite rappelé le Pape, "Claire trouva en François un maître avec ses enseignements, et plus encore un ami fraternel. Cette amitié fut considérable car, lorsque deux âmes pures brûlent ensemble du même amour de Dieu, elles trouvent dans l'amitié un encouragement à la perfection. L'amitié est l'un des sentiments les plus nobles et élevés que la grâce divine purifie et transfigure". L'évêque Jacques de Vitry, qui connut les débuts du mouvement franciscain, a rapporté que la pauvreté radicale, liée à la confiance absolue en la Providence, était caractéristique de sa spiritualité, et que Claire y était très sensible. C'est pourquoi elle obtint du Pape "le Privilegium Paupertatis, confirmant que Claire et ses compagnes du couvent de San Damiano ne pourraient jamais posséder de biens fonciers. "Ce fut une exception totale au droit canonique de l'époque, accordée par les autorités ecclésiastiques devant les fruits de sainteté évangélique produits par le mode de vie de la sainte et de ses sœurs".

Ce point, a-t-il ajouté, "montre combien au Moyen Âge le rôle de la femme

était important. D'ailleurs, Claire fut la première femme de l'histoire de

l'Église à rédiger une règle qui fut soumise à l'approbation papale, par

laquelle elle voulut que le charisme de saint François fut conservé dans toutes

les communautés féminines s'inspirant de leur exemple". A San Damiano,

elle "pratiqua les vertus héroïques qui devraient distinguer tous les

chrétiens, l'humilité, la piété, la pénitence et la charité. Sa réputation de

sainteté et les prodiges opérés grâce à elle conduisirent Alexandre IV à

canoniser Claire en 1255, à peine deux ans après sa mort". Ses filles

spirituelles, les clarisses, poursuivent dans la prière une œuvre inappréciable

au sein de l'Église.

(source: VIS 20100915 430)

Pie XII, Lettre Apostolique (en forme brève) proclamant Ste Claire Patronne Céleste de la Télévision (21 août 1958)

- Sainte Claire est présente sur les vitraux de plusieurs églises du diocèse d'Autun.

Mémoire de sainte Claire, vierge. Première plante des pauvres Dames de l'Ordre

des Mineurs, elle suivit saint François d'Assise et mena au couvent de

Saint-Damien une vie très austère, mais riche d’œuvres de charité et de piété.

Aimant par-dessus tout la pauvreté, elle n'accepta jamais de s'en écarter, pas

même dans l'extrême indigence ou dans la maladie. Elle mourut à Assise en 1253.

Martyrologe romain

Ce que tu tiens, tiens-le. Ce que tu fais, fais-le et

ne le lâche pas. Mais d'une course rapide, d'un pas léger, sans entraves aux

pieds, pour que tes pas ne ramassent pas la poussière, sûre, joyeuse et alerte,

marche prudemment sur le chemin de la béatitude.

Sainte Claire à sainte Agnès de Prague

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1654/Sainte-Claire-d-Assise.html

Lippo Memmi (1291–1356), Santa Chiara d'Assisi / Clare of Assisi, circa 1330, tempera on wood, gold ground, 39.4 x 19.1, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

SAINTE CLAIRE D'ASSISE

Vierge et Fondatrice

d'Ordre

(1194-1253)

Sainte Claire naquit à

Assise, en Italie. Dès son enfance, on put admirer en elle un vif attrait pour

la retraite, l'oraison, le mépris du monde, l'amour des pauvres et de la

souffrance; sous ses habits précieux, elle portait un cilice.

A l'âge de seize ans,

fortement émue de la vie si sainte de François d'Assise, elle va lui confier

son désir de se donner toute à Dieu. Le Saint la pénètre des flammes du divin

amour, accepte de diriger sa vie, mais il exige des actes: Claire devra, revêtue

d'un sac, parcourir la ville en mendiant son pain de porte en porte. Elle

accomplit de grand coeur cet acte humiliant, et, peu de jours après, quitte les

livrées du siècle, reçoit de François une rude tunique avec une corde pour lui

ceindre les reins, et un voile grossier sur sa tête dépouillée de ses beaux

cheveux.

Elle triomphe de la

résistance de sa famille. Quelques jours après, sa soeur Agnès la supplie de

l'agréer en sa compagnie, ce que Claire accepte avec joie, en rendant grâce au

Ciel. "Morte ou vive, qu'on me ramène Agnès!" s'écria le père,

furieux à cette nouvelle; mais Dieu fut le plus fort, et Agnès meurtrie,

épuisée, put demeurer avec sa soeur. Leur mère, après la mort de son mari, et

une de leurs soeurs, vinrent les rejoindre.

La communauté fut bientôt

nombreuse et florissante; on y vit pratiquer, sous la direction de sainte

Claire, devenue, quoique jeune, une parfaite maîtresse de vie spirituelle, une

pauvreté admirable, un détachement absolu, une obéissance sublime: l'amour de

Dieu était l'âme de toutes ses vertus.

Claire dépassait toutes

ses soeurs par sa mortification; sa tunique était la plus rude, son cilice le

plus terrible à la chair; des herbes sèches assaisonnées de cendre formaient sa

nourriture; pendant le Carême, elle ne prenait que du pain et de l'eau, trois

fois la semaine seulement. Longtemps elle coucha sur la terre nue, ayant un

morceau de bois pour oreiller.

Claire, supérieure, se

regardait comme la dernière du couvent, éveillait ses soeurs, sonnait matines,

allumait les lampes, balayait le monastère. Elle voulait qu'on vécût dans le

couvent au jour le jour, sans fonds de terre, sans pensions et dans une clôture

perpétuelle.

Claire est célèbre par

l'expulsion des Sarrasins, qui, après avoir pillé la ville, voulaient piller le

couvent. Elle pria Dieu, et une voix du Ciel cria: "Je vous ai gardées et

Je vous garderai toujours." Claire, malade, se fit transporter à la porte

du monastère, et, le ciboire en main, mit en fuite les ennemis. Sa mort arriva

le 12 août 1253.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950.

SOURCE : https://livres-mystiques.com/partieTEXTES/Jaud_Saints/calendrier/Vies_des_Saints/08-12.htm

Giotto (1266–1337), Saint Francis and Saint Clare, circa 1279, fresco, Upper Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi

Ad perpetuam rei memoriam

Par un bienfait de la

divine Sagesse le génie de l'homme brille d'un plus vif éclat et fait, surtout

de nos jours, des découverts qui suscitent l'admiration générale. Et l'Église,

qui ne se montra jamais contraire au progrès de la civilisation et de la technique,

encourage cette assistance nouvelle apportée à la culture et à la vie

journalière, et s'en sert même volontiers pour l'enseignement de la vérité et

l'extension de la religion. Parmi ces inventions si utiles, la Télévision a sa

place, elle qui "permet en effet de voir et d'entendre à distance des

événements à l'instant même où ils se produisent, et cela de façon si

suggestive que l'on croit y assister." (Litt. Encycl. "Miranda

prorsus", 8 sept. 1957; A.A.S. XLIX, p. 800). Ce merveilleux instrument -

comme chacun le sait et Nous l'avons dit clairement Nous-même - peut être la

source des très grands biens, mais aussi de profonds malheurs en raison de

l'attraction singulière qu'il exerce sur les esprits à l'intérieurs même de la

maison familiale. Aussi Nous a-t-il semblé bon de donner à cette invention une

sauvegarde céleste qui interdise ses méfaits et en favorise un usage honnête,

voir salutaire. On a souhaité pour ce patronage sainte Claire. On rapporte en

effet qu'à Assise, une nuit de Noël, Claire, alitée dans son couvent par la

maladie, entendit les chants fervents qui accompagnaient les cérémonies sacrée

et vit la crèche du Divin Enfant, comme si elle était présente en personne dans

l'Église franciscaine. Dans la splendeur de la gloire de son innocence et la

clarté qu'elle jette sur nos si profondes ténèbres, que Claire protège donc

cette technique et donne à l'appareil translucide de faire briller la vérité et

la vertu, soutiens nécessaires de la société. Nous avons donc décidé

d'accueillir avec bienveillance les prières que Nous ont adressés à ce sujet

Notre Vénérable Frère Joseph Placide Nicolini, évêque d'Assise, le Supérieurs

des quatre familles franciscaines, enfin d'autres personnes remarquables, et

qu'ont approuvées de nombreux Cardinaux de la Sainte Eglise Romaine, des

Archevêques et des Évêques. En consequence, ayant consulté la Sacrée

Congrégation des Rites, de science certaine et après mûre réflexion, en vertu

de la plénitude du pouvoir Apostolique, par cette Lettre et pour toujours, Nous

faisons, Nous constituons et Nous déclarons Sainte Claire, vierge d'Assise,

céleste Patronne auprès de Die de la Télévision, en lui attribuant tous les

privilèges et honneurs liturgiques qu'un tel patronage comporte, nonobstant

toutes choses contraires. Nous annonçons, Nous établissons, Nous ordonnons que

cette présente Lettre soit ferme et valide, qu'elle sorte et produise tous ses

effets dans leur intégrité et leur plénitude, maintenant et à l'avenir, pour

ceux qu'elle concerne ou pourra concerner; qu'il en faut régulièrement juger et

décider ainsi; que dès maintenant est tenu pour nul et sans effet tout ce qui

pourrait être tenté par quiconque, en vertu de n'importe quelle autorité, en

connaissance de cause ou par ignorance, contre les mesures décrétées par cette

Lettre.

Donnée à Rome, près Saint

Pierre, sous l'anneau du Pêcheur, le 14 février 1957, de Notre Pontifical la

19éme année.

PIUS PP. XII

*La lettre Apostolique,

en "forme breve" - dont nous donnons ci-dessous la traduction du

latin - a été publiée dans les Acta Apostolica Sedis du 21 août 1958, vol. L,

p. 512-513.

© Copyright - Libreria

Editrice Vaticana

Bartolomeo Vivarini (1430–1499),

Saint Clare of Assisi, 1451, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna,

Très chères soeurs!

1. Le 11 août 1253

achevait son pèlerinage terrestre sainte Claire d'Assise, disciple de saint

François et fondatrice de votre Ordre, dit des Soeurs pauvres ou Clarisses, qui

compte aujourd'hui, dans ses diverses ramifications, environ neuf cents

monastères répartis sur les cinq continents. A 750 ans de sa mort, le souvenir

de cette grande sainte continue à être très vivant dans le coeur des fidèles,

et je suis donc particulièrement heureux, en cette circonstance, d'adresser à

votre famille religieuse une pensée cordiale et mes salutations affectueuses.

En un anniversaire

jubilaire aussi significatif, sainte Claire exhorte chacun à comprendre de

manière toujours plus profonde la valeur de la vocation, qui est un don

de Dieu à faire fructifier. Elle écrivait à ce propos dans son

Testament: "Parmi les autres bénéfices que nous avons reçus et

que nous continuons chaque jour de recevoir de notre Donateur, le Père des

miséricordes, pour lesquels nous sommes hautement tenues de Lui rendre, en sa

gloire, de vives actions de grâces, grand est le don de notre vocation. Et plus

celle-ci est grande et parfaite, plus encore Lui sommes-nous obligées. C'est à

quoi l'Apôtre nous exhorte: Connais bien ta vocation" (2-4).

2. Née à Assise

autour des années 1193-1194 dans la noble famille de Favarone di Offreduccio,

sainte Claire reçut, notamment de sa mère Ortolana, une solide éducation

chrétienne. Illuminée par la grâce divine, elle se laissa attirer par la

nouvelle forme évangélique initiée par saint François et par ses compagnons, et

elle décida d'entreprendre à son tour une "sequela Christi" plus

radicale. Après avoir quitté la maison paternelle dans la nuit entre le

Dimanche des Rameaux et le Lundi Saint de 1211 (ou 1212), sur les

conseils du saint lui-même, elle se rendit à la petite église de la

Portioncule, berceau de l'expérience franciscaine, où au pied de l'autel, elle

se dévêtit de toutes ses richesses, pour revêtir l'humble habit de pénitence en

forme de croix.

Après une courte période

de recherche, elle aboutit au petit monastère de Saint-Damien, où la rejoignit

sa jeune soeur Agnès. Là s'unirent à elles d'autres compagnes souhaitant

incarner l'Evangile dans une dimension contemplative. Face à la détermination

avec laquelle la nouvelle communauté monastique suivait les traces du Christ,

voyant en la pauvreté, l'effort, les difficultés, l'humiliation et le mépris du

monde des raisons de grande joie spirituelle, saint François ressentit à leur

égard une affection paternelle et leur écrivit: "Etant

devenues, par une inspiration divine, filles et servantes du très-haut et

souverain Roi, le Père céleste, et ayant épousé l'Esprit Saint, faisant le

choix de vivre selon la perfection du saint Evangile, je veux et promets, pour

ma part et celle de mes frères, d'avoir pour vous, comme je l'ai pour eux, un

soin attentif et une sollicitude particulière" (Règle de sainte

Claire, chap. VI, 3-4).

3. Claire inséra ces

paroles dans le chapitre central de sa Règle, en y reconnaissant non seulement

l'un des enseignements reçus du saint, mais le noyau fondamental de son

charisme, qui s'inscrit dans le cadre trinitaire et marial de l'Évangile de

l'Annonciation. Saint François, en effet, envisageait la vocation des Soeurs

Pauvres à la lumière de la Vierge Marie, l'humble servante du Seigneur qui,

sous la protection de l'Esprit Saint, devint la Mère de Dieu. L'humble servante

du Seigneur est le modèle de l'Église, Vierge, Épouse et Mère.

Claire percevait sa

vocation comme un appel à vivre selon l'exemple de Marie, qui offrit sa

virginité à l'action de l'Esprit Saint pour devenir Mère du Christ et de son

Corps mystique. Elle se sentait étroitement associée à la Mère du Seigneur et

c'est pourquoi elle exhortait en ce sens sainte Agnès de Prague, la princesse

de Bohême devenue Clarisse: "Attache-toi à la très douce Mère,

qui donna naissance à un Fils si grand que les cieux eux-mêmes ne pouvaient le

contenir, et elle le recueillit pourtant dans l'humble cloître de son corps

saint et le porta en son sein virginal" (Troisième Lettre à Agnès de

Prague, 18-19).

La figure de Marie

accompagna le chemin vocationnel de la sainte d'Assise jusqu'au dernier jour de

sa vie. Selon un témoignage significatif rapporté lors du procès de

canonisation, la Madone s'approcha du chevet de Claire mourante, en penchant

son visage sur elle, dont la vie avait été une radieuse image de la sienne.

4. Seul le choix

radical du Christ crucifié, qu'elle fit emplie d'un ardent amour, explique la

décision de sainte Claire de suivre la voie de la "très haute pauvreté",

expression qui renferme dans toute sa signification l'expérience de

dépouillement, vécue par le Fils de Dieu dans l'Incarnation. Par le

qualificatif de "très haute", Claire voulait en quelque sorte

exprimer l'abaissement du Fils de Dieu, qui la remplissait

d'émerveillement: "Un tel et si grand Seigneur -

remarquait-elle - en descendant dans le sein de la Vierge, voulut apparaître

dans le monde comme un homme dérisoire, nécessiteux et pauvre, afin que les

hommes - qui étaient extrêmement pauvres et indigents, affamés en raison de

l'excessive pénurie de nourriture céleste - devinsent en lui riches de la

possession des royaumes célestes" (Première Lettre à Agnès de Prague,

19-20). Elle percevait cette pauvreté dans toute l'expérience terrestre de Jésus,

de Bethléem au Calvaire, où le Seigneur "nu, demeura sur la croix" (Testament

de sainte Claire, 45).

Suivre le Fils de Dieu,

qui s'est fait notre chemin, impliquait pour elle de ne rien désirer d'autre

que de se perdre avec le Christ dans une expérience d'humilité et de pauvreté

radicale, qui faisait appel à chaque aspect de l'expérience humaine, jusqu'au

dépouillement de la Croix. Le choix de la pauvreté était pour sainte Claire une

exigence de fidélité à l'Évangile, au point qu'elle demanda au Pape de lui

accorder un "privilège de pauvreté", comme prérogative à la

forme de vie monastique qu'elle avait fondée. Elle inscrivit ce "privilège",

défendu avec ténacité durant toute sa vie, dans la Règle qui reçut

l'approbation pontificale l'avant-veille de sa mort par la Bulle Solet

annuere du 9 août 1253, il y a 750 ans.

5. Le regard de

Claire demeura jusqu'au bout fixé sur le Fils de Dieu, dont elle contemplait

sans trêve les mystères. Son regard était le regard empli d'amour de l'épouse,

empli du désir d'un partage toujours plus complet. Elle se

plongeait en particulier dans la méditation de la Passion, en contemplant le

mystère du Christ, qui du haut de la Croix l'appelait et l'attirait. Elle

écrivait ces mots: "O vous tous qui passez sur cette route, arrêtez-vous

pour voir s'il existe une douleur semblable à la mienne; et nous répondons, je

Lui dis, Lui qui appelle et gémit, d'une seule voix et avec un coeur

unique: Jamais ne m'abandonnera ton souvenir et mon âme en sera

rongée" (Quatrième Lettre à Agnès de Prague, 25-26). Et elle

exhortait: "Laisse-toi donc toujours plus consumer par cette

ardeur de charité!... et crie avec toute l'ardeur de ton désir et de ton

amour: Attire-moi à toi, ô céleste Époux" (ibid., 27.29-32).

Cette pleine communion

avec le mystère du Christ l'introduit dans l'expérience de la possession

trinitaire, dans laquelle l'âme prend une conscience de plus en plus vive de la

présence de Dieu en elle: "Alors que les cieux et toutes les

autres choses créées ne peuvent contenir le Créateur, l'âme fidèle en revanche,

et elle seule, est sa demeure et son séjour, et ce pour la seule raison de la

charité, dont les impies sont privés" (Troisième Lettre à Agnès de

Prague, 22-23).

6. Guidée par

Claire, la communauté réunie à Saint-Damien choisit de vivre selon la forme du

saint Évangile dans un cadre contemplatif de clôture, qui se distinguait par le

désir de "vivre de manière communautaire dans l'unité de

l'esprit" (Règle de sainte Claire, Prologue, 5), selon une

"façon de sainte unité" (ibid., 16). Il semble que la compréhension

particulière que Claire manifesta à l'égard de la valeur de l'unité dans la

fraternité puisse être rapportée à la maturité de son expérience contemplative

du Mystère trinitaire. La contemplation authentique, en effet, ne se renferme

pas dans l'individualisme mais réalise la vérité de l'être unique dans le Père,

dans le Fils et dans l'Esprit Saint. Claire imposa non seulement dans sa Règle

la vie fraternelle sur les valeurs du service réciproque, de la participation et

du partage, mais elle se préoccupa aussi que la communauté soit solidement

édifiée sur l'"unité de la charité réciproque et de la paix" (Chap.

IV, 22), et que les soeurs soient "attentives à toujours conserver les

unes pour les autres l'unité de la charité réciproque, qui est le chemin qui

porte à la perfection" (Chap. X, 7).

Elle était en effet

convaincue que l'amour mutuel édifie la communauté et conduit à une croissance

dans la vocation; aussi exhortait-elle dans son Testament: "En

vous aimant les unes les autres dans l'amour du Christ, montrez à l'extérieur

cet amour que vous avez dans le coeur à travers les oeuvres, afin que les

Soeurs, encouragées par cet exemple, croissent toujours davantage dans l'amour

de Dieu et dans la charité mutuelle" (59-60).

7. Cette valeur de

l'unité fut également perçue par Claire comme s'inscrivant dans une dimension

plus vaste. C'est pourquoi elle voulut que la communauté de clôture fut

pleinement inscrite dans l'Église et solidement ancrée à elle par le lien de

l'obéissance et de l'assujettissement filial (cf. Règles, chap. I, XII).

Elle était tout à fait consciente que la vie des soeurs de clôture devait

devenir un miroir pour d'autres soeurs appelées à suivre la même vocation,

ainsi qu'un témoignage lumineux pour ceux qui vivent dans le monde.

Les quarante années

vécues à l'intérieur du petit monastère de Saint-Damien ne réduisirent pas les

horizons de son coeur, mais firent croître sa foi dans la présence de Dieu,

oeuvrant au salut de l'histoire. Deux épisodes sont bien connus: lorsque grâce

à la force de sa foi dans l'Eucharistie et l'humilité de la prière, Claire

obtint la libération de la ville d'Assise et du monastère, menacés par une

destruction imminente.

8. Comment ne pas

souligner qu'à 750 ans de la confirmation pontificale, la Règle de sainte

Claire conserve tout son attrait spirituel et sa richesse théologique?

L'harmonie parfaite de valeurs humaines et chrétiennes, le savant équilibre

d'ardeur contemplative et de rigueur évangélique vous confirment, chères

Clarisses du troisième millénaire, qu'elle est une voie maîtresse qu'il faut

suivre, sans accommodements ni concessions à l'esprit du monde.

A chacune de vous, Claire

adresse les paroles qu'elle laissa à Agnès de Prague: "Quelle

merveilleuse chance as-tu! Il t'est permis de jouir de ce saint banquet, pour

pouvoir adhérer de toutes les fibres de ton coeur à Celui dont la beauté fait

l'inlassable admiration des bienheureuses foules du ciel" (Quatrième

Lettre à Agnès de Prague, 9).

La commémoration de ce

centenaire vous offre l'opportunité de réfléchir sur le charisme propre à votre

vocation de Clarisses. Un charisme qui se caractérise, en premier lieu, par un

appel à vivre selon la perfection du saint Évangile, avec une référence précise

au Christ, comme unique et véritable programme de vie. N'est-ce pas un défi

proposé aux hommes et aux femmes d'aujourd'hui? Il s'agit d'une proposition

alternative à l'insatisfaction et à la superficialité du monde contemporain,

qui semble souvent avoir perdu sa propre identité, parce qu'il n'a plus conscience

qu'il a été créé par l'amour de Dieu et qu'il est attendu par Lui dans la

communion sans fin.

Quant à vous, chères

Clarisses, vous réalisez la "sequela Christi" dans sa

dimension sponsale, en renouvelant le mystère de virginité féconde de la Vierge

Marie, Épouse de l'Esprit Saint, la femme accomplie. Puisse la présence de vos

monastères entièrement voués à la vie contemplative être encore aujourd'hui

une "mémoire du coeur sponsal de l'Église" (Verbi Sponsa,

1), pleine du désir brûlant de l'Esprit, qui implore incessamment la venue du

Christ-Époux (cf. Ap 22, 17).

Face au besoin d'un

engagement renouvelé de sainteté, sainte Claire offre par ailleurs un exemple

de cette pédagogie de la sainteté qui, en se nourrissant d'incessantes prières,

conduit à devenir des contemplateurs du Visage de Dieu, en ouvrant grand son

coeur à l'Esprit du Seigneur, qui transforme toute la personne, esprit, coeur

et actions, selon les exigences de l'Évangile.

9. Mon souhait le

plus vif, renforcé par la prière, est que vos monastères continuent d'offrir à

l'exigence diffuse de spiritualité et de prière du monde d'aujourd'hui la

proposition exigeante d'une pleine et authentique expérience de Dieu, Un et

Trine, qui devienne un rayonnement de sa présence d'amour et de salut.

Que Marie, la Vierge de

l'écoute, vous vienne en aide. Que sainte Claire et les saintes et

bienheureuses de votre ordre intercèdent pour vous.

Quant à moi, chères

soeurs, je vous assure d'un souvenir cordial, ainsi qu'à tous ceux qui

partagent avec vous la grâce de cet événement jubilaire significatif, et

j'accorde de tout coeur à tous une Bénédiction apostolique particulière.

Du Vatican, le 9 août

2003

IOANNES PAULUS II

Copyright © Dicastero per

la Comunicazione - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Pietro

da Rimini e bottega, SS. Francesco e Chiara, affreschi dalla Chiesa di S.

Chiara a Ravenna, 1310-20 ca.

Frescos from Santa Chiara, Museo Nazionale di Ravenna, Ravenna

Pietro

da Rimini e bottega, SS. Francesco e Chiara, affreschi dalla Chiesa di S.

Chiara a Ravenna, 1310-20 ca.

Frescos from Santa Chiara, Museo Nazionale di Ravenna, Ravenna

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Salle Paul VI

Mercredi 15 septembre

2010

Claire d’Assise

Chers frères et sœurs,

L’une des saintes les

plus aimées est sans aucun doute sainte Claire d’Assise, qui vécut au XIIIe

siècle, et qui fut contemporaine de saint François. Son témoignage nous montre

combien l’Eglise tout entière possède une dette envers des femmes courageuses et

riches de foi comme elle, capables d’apporter une impulsion décisive au

renouveau de l’Eglise.

Qui était donc Claire

d’Assise? Pour répondre à cette question, nous possédons des sources sûres: non

seulement les anciennes biographies, comme celles de Thomas de Celano, mais

également les Actes du procès de canonisation promu par le Pape quelques mois

seulement après la mort de Claire et qui contiennent les témoignages de ceux

qui vécurent à ses côtés pendant longtemps.

Née en 1193, Claire

appartenait à une riche famille aristocratique. Elle renonça à la noblesse et à

la richesse pour vivre dans l’humilité et la pauvreté, adoptant la forme de vie

que François d’Assise proposait. Même si ses parents, comme cela arrivait

alors, projetaient pour elle un mariage avec un personnage important, à 18 ans,

Claire, à travers un geste audacieux inspiré par le profond désir de suivre le

Christ et par son admiration pour François, quitta la maison paternelle et, en

compagnie de son amie, Bona de Guelfuccio, rejoignit en secret les frères

mineurs dans la petite église de la Portioncule. C’était le soir du dimanche

des Rameaux de l’an 1211. Dans l’émotion générale, fut accompli un geste

hautement symbolique: tandis que ses compagnons tenaient entre les mains des

flambeaux allumés, François lui coupa les cheveux et Claire se vêtit d’un habit

de pénitence en toile rêche. A partir de ce moment, elle devint l’épouse vierge

du Christ, humble et pauvre, et se consacra entièrement à Lui. Comme Claire et

ses compagnes, d’innombrables femmes au cours de l’histoire ont été fascinées

par l’amour pour le Christ qui, dans la beauté de sa Personne divine, remplit

leur cœur. Et l’Eglise tout entière, au moyen de la mystique vocation nuptiale

des vierges consacrées, apparaît ce qu’elle sera pour toujours: l’Epouse belle

et pure du Christ.

L’une des quatre lettres

que Claire envoya à sainte Agnès de Prague, fille du roi de Bohême, qui voulut

suivre ses traces, parle du Christ, son bien-aimé Epoux, avec des expressions

nuptiales qui peuvent étonner, mais qui sont émouvantes: «Alors que vous le

touchez, vous devenez plus pure, alors que vous le recevez, vous êtes vierge.

Son pouvoir est plus fort, sa générosité plus grande, son apparence plus belle,

son amour plus suave et son charme plus exquis. Il vous serre déjà dans ses

bras, lui qui a orné votre poitrine de pierres précieuses... lui qui a mis sur

votre tête une couronne d'or arborant le signe de la sainteté» (Première

Lettre: FF, 2862).

En particulier au début

de son expérience religieuse, Claire trouva en François d’Assise non seulement

un maître dont elle pouvait suivre les enseignements, mais également un ami

fraternel. L’amitié entre ces deux saints constitue un très bel et important

aspect. En effet, lorsque deux âmes pures et enflammées par le même amour pour

le Christ se rencontrent, celles-ci tirent de leur amitié réciproque un

encouragement très profond pour parcourir la voie de la perfection. L’amitié

est l’un des sentiments humains les plus nobles et élevés que la Grâce divine purifie

et transfigure. Comme saint François et sainte Claire, d’autres saints

également ont vécu une profonde amitié sur leur chemin vers la perfection

chrétienne, comme saint François de Sales et sainte Jeanne-Françoise de

Chantal. Et précisément saint François de Sales écrit: «Il est beau de pouvoir

aimer sur terre comme on aime au ciel, et d’apprendre à s’aimer en ce monde

comme nous le ferons éternellement dans l’autre. Je ne parle pas ici du simple

amour de charité, car nous devons avoir celui-ci pour tous les hommes; je parle

de l’amitié spirituelle, dans le cadre de laquelle, deux, trois ou plusieurs

personnes s’échangent les dévotions, les affections spirituelles et deviennent

réellement un seul esprit» (Introduction à la vie de dévotion, III, 19).

Après avoir passé une

période de quelques mois auprès d’autres communautés monastiques, résistant aux

pressions de sa famille qui au début, n’approuvait pas son choix, Claire

s’établit avec ses premières compagnes dans l’église Saint-Damien où les frères

mineurs avaient préparé un petit couvent pour elles. Elle vécut dans ce

monastère pendant plus de quarante ans, jusqu’à sa mort, survenue en 1253. Une

description directe nous est parvenue de la façon dont vivaient ces femmes au

cours de ces années, au début du mouvement franciscain. Il s’agit du

compte-rendu admiratif d’un évêque flamand en visite en Italie, Jacques de

Vitry, qui affirme avoir trouvé un grand nombre d’hommes et de femmes, de toute

origine sociale, qui «ayant quitté toute chose pour le Christ, fuyaient le

monde. Ils s’appelaient frères mineurs et sœurs mineures et sont tenus en

grande estime par Monsieur le Pape et par les cardinaux... Les femmes...

demeurent ensemble dans divers hospices non loin des villes. Elles ne reçoivent

rien, mais vivent du travail de leurs mains. Et elles sont profondément

attristées et troublées, car elles sont honorées plus qu’elles ne le

voudraient, par les prêtres et les laïcs» (Lettre d’octobre 1216: FF,

2205.2207).

Jacques de Vitry avait

saisi avec une grande perspicacité un trait caractéristique de la spiritualité

franciscaine à laquelle Claire fut très sensible: la radicalité de la pauvreté

associée à la confiance totale dans la Providence divine. C'est pour cette

raison qu'elle agit avec une grande détermination, en obtenant du Pape Grégoire

IX ou, probablement déjà du Pape Innocent III, celui que l’on appela le

Privilegium Paupertatis (cf. FF, 3279). Sur la base de celui-ci, Claire et ses

compagnes de Saint-Damien ne pouvaient posséder aucune propriété matérielle. Il

s'agissait d'une exception véritablement extraordinaire par rapport au droit

canonique en vigueur et les autorités ecclésiastiques de cette époque le

concédèrent en appréciant les fruits de sainteté évangélique qu’elles

reconnaissaient dans le mode de vie de Claire et de ses consœurs. Cela montre

que même au cours des siècles du Moyen âge, le rôle des femmes n'était pas

secondaire, mais considérable. A cet égard, il est bon de rappeler que Claire a

été la première femme dans l'histoire de l'Eglise à avoir rédigé une Règle

écrite, soumise à l'approbation du Pape, pour que le charisme de François

d'Assise fût conservé dans toutes les communautés féminines qui étaient fondées

de plus en plus nombreuses déjà de son temps et qui désiraient s'inspirer de

l'exemple de François et de Claire.

Dans le couvent de

Saint-Damien, Claire pratiqua de manière héroïque les vertus qui devraient

distinguer chaque chrétien: l'humilité, l'esprit de piété et de pénitence, la

charité. Bien qu'étant la supérieure, elle voulait servir personnellement les

sœurs malades, en s'imposant aussi des tâches très humbles: la charité en

effet, surmonte toute résistance et celui qui aime accomplit tous les

sacrifices avec joie. Sa foi dans la présence réelle de l'Eucharistie était si

grande que, par deux fois, un fait prodigieux se réalisa. Par la seule

ostension du Très Saint Sacrement, elle éloigna les soldats mercenaires

sarrasins, qui étaient sur le point d'agresser le couvent de Saint-Damien et de

dévaster la ville d'Assise.

Ces épisodes aussi, comme

d'autres miracles, dont est conservée la mémoire, poussèrent le Pape Alexandre

IV à la canoniser deux années seulement après sa mort, en 1255, traçant un

éloge dans la Bulle de canonisation, où nous lisons: «Comme est vive la puissance

de cette lumière et comme est forte la clarté de cette source lumineuse.

Vraiment, cette lumière se tenait cachée dans la retraite de la vie de clôture

et dehors rayonnaient des éclats lumineux; elle se recueillait dans un étroit

monastère, et dehors elle se diffusait dans la grandeur du monde. Elle se

protégeait à l'intérieur et elle se répandait à l'extérieur. Claire en effet,

se cachait: mais sa vie était révélée à tous. Claire se taisait mais sa

renommée criait» (FF, 3284). Et il en est véritablement ainsi, chers amis: ce

sont les saints qui changent le monde en mieux, le transforment de manière

durable, en insufflant les énergies que seul l'amour inspiré par l'Evangile

peut susciter. Les saints sont les grands bienfaiteurs de l'humanité!

La spiritualité de sainte

Claire, la synthèse de sa proposition de sainteté est recueillie dans la

quatrième lettre à sainte Agnès de Prague. Sainte Claire a recours à une image

très répandue au Moyen âge, d'ascendance patristique, le miroir. Et elle invite

son amie de Prague à se refléter dans ce miroir de perfection de toute vertu

qu'est le Seigneur lui-même. Elle écrit: «Heureuse certes celle à qui il est

donné de prendre part au festin sacré pour s'attacher jusqu'au fond de son cœur

[au Christ], à celui dont toutes les troupes célestes ne cessent d'admirer la

beauté, dont l'amitié émeut, dont la contemplation nourrit, dont la

bienveillance comble, dont la douceur rassasie, dont le souvenir pointe en

douceur, dont le parfum fera revivre les morts, dont la vue en gloire fera le

bonheur des citoyens de la Jérusalem d'en haut. Tout cela puisqu'il est la

splendeur de la gloire éternelle, l'éclat de la lumière éternelle et le miroir

sans tache. Ce miroir, contemple-le chaque jour, ô Reine, épouse de Jésus

Christ, et n'arrête d'y contempler ton apparence afin que... tu puisses,

intérieurement et extérieurement, te parer comme il convient... En ce miroir

brillent la bienheureuse pauvreté, la sainte humilité et l'ineffable charité»

(Quatrième lettre: FF, 2901-2903).

Reconnaissants à Dieu qui

nous donne les saints qui parlent à notre cœur et nous offrent un exemple de

vie chrétienne à imiter, je voudrais conclure avec les mêmes paroles de

bénédiction que sainte Claire composa pour ses consœurs et qu'aujourd'hui

encore les Clarisses, qui jouent un précieux rôle dans l'Eglise par leur prière

et leur œuvre, conservent avec une grande dévotion. Ce sont des expressions où

émerge toute la tendresse de sa maternité spirituelle: «Je vous bénis dans ma

vie et après ma mort, comme je peux et plus que je le peux, avec toutes les

bénédictions par lesquelles le Père des miséricordes pourrait bénir et bénira

au ciel et sur la terre les fils et les filles, et avec lesquelles un père et

une mère spirituelle pourraient bénir et béniront leurs fils et leurs filles

spirituels. Amen» (FF, 2856).

* * *

Je salue les francophones

présents et plus particulièrement les participants au pèlerinage promu par la

Conférence épiscopale de Guinée, et conduits par l’Evêque de N’Zérékoré, Mgr

Guilavogui, et ceux du Diocèse de Nancy, en France, guidés par Mgr Papin. Je

n’oublie pas les pèlerins de la Martinique, de Dijon et d’ailleurs. Puisse Dieu

vous bénir! Bon séjour à Rome!

APPEL DU SAINT-PÈRE

Je suis avec

préoccupation les événements qui se déroulent ces jours-ci dans les diverses

régions de l'Asie du sud, notamment en Inde, au Pakistan et en Afghanistan. Je

prie pour les victimes et je demande que le respect de la liberté religieuse et

la logique de la réconciliation prévalent sur la haine et la violence.

© Copyright 2010 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

SOURCE : https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/fr/audiences/2010/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20100915.html

Carlo Crivelli (circa 1435–circa 1495),

Santa Chiara, 1470, Montefiore,

Sainte Claire

Sainte Claire (née en

1193 ou 1194) fille du noble et chevalier Favarone di Offreduccio, l'un des

plus puissants et des plus riches d'Assise, est expulsée de la ville avec sa

famille lors de l'insurrection bourgeoise de 1198-1199 et se réfugie à Pérouse où

ses parents possèdent un château. Lorsqu'en 1211, à Assise, elle entend une

prédication de saint François à la cathédrale Saint-Rufin, elle se sent

irrésistiblement attirée par son idéal de pauvreté évangélique et décide de

le prendre, après Dieu, pour guide de sa vie. Dans la nuit qui suit le

dimanche des Rameaux 1212, elle s'enfuit de chez elle et rejoint les frères à

Sainte-Marie de la Portioncule où elle fait promesse de suivre le Christ

pauvre ; saint François la conduit chez les bénédictines de Saint-Paul

(sur la route de Sainte-Marie des Anges à Pérouse) où elle reste jusqu'à ce que

la famille soit apaisée, puis l'installe à Saint-Damien où elle fonde l'ordre

des Pauvres Dames aujourd'hui connu sous le nom de Clarisses. A la

tête d'une communauté de cinquante religieuses dont sa soeur Agnès, elle est

faite abbesse par le pape (1216). De nouvelles communautés se forment en Italie

(on en compte 24 en 1228), en France (le couvent de Reims est fondé en 1220) et

en Espagne (Pampelune) ; sainte Agnès de Bohême fonde, en 1233 la communauté de

Prague. La règle est approuvée par Innocent IV, le 9 août 1253, deux jours

avant la mort de Claire (11 août). Cinquante ans après la mort de sainte

Claire, l'ordre compte soixante-seize monastères, il y en aura 372 en 1316

(dont 47 en France) et 425 à la fin du XIV° siècle.L'ordre des clarisses

comprend aujourd'hui 18 000 religieuses réparties en 897 maisons : 617 couvents

en Europe (270 en Espagne, 160 en Italie, 54 en France, 25 en Belgique, 24 en

Allemagne, 22 en Pologne, 19 en Angleterre, 17 au Portugal, 8 en Hollande, 6 en

Irlande, 4 dans l'ancienne Yougoslavie, 3 en Suisse, 1 à Malte), 39 en Amérique

du Nord (32 aux Etats-Unis, 7 au Canada), 159 en Amérique Latine (96 au

Mexique,17 en Colombie, 7 au Pérou, 7 au Brésil, 6 en Bolivie, 5 en Argentine,

5 au Chili, 3 en Equateur, 3 en Uruguay, 3 au Venezuela, 2 au Guatemala, 2 au

Nicaragua, 2 au Paraguay, 1 en République dominicaine), 27 en Afrique (4 en

Ethiopie, 3 en Tanzanie, 2 en Afrique du Sud, 2 en Angola, 2 au Cameroun, 2 au

Zaïre, 1 en Algérie, 1 au Burundi, 1 en Côte d'Ivoire, 1 en Egypte, 1 au Gabon,

1 à Madagascar, 1 au Malawi, 1 en République Centre Africaine, 1 au Rwanda, 1

en Ouganda, 1 en Zambie), 2 en Israël, 1 au Liban, 47 en Asie (17 au

Philippines, 8 aux Indes, 7 en Thaïlande, 4 en Indonésie, 4 au Japon, 2 en

Corée du Sud, 2 au Sri-Lanka, 1 au Bangla-Desh, 1 à Taïwan, 1 au Viet-Nam), 5

en Océanie (3 en Australie, 1 en Papouasie, 1 en Polynésie française).

Les plus anciens

monastères français de Clarisses existant aujourd'hui sont : Tinqueux (Marne),

fondé en 1220, refondé en 1933, reconstruit en 1965 ; Béziers, fondé en 1240,

rétabli en 1819 ; Nîmes, fondé en 1240, détruit en 1567, restauré en 1891,

bombardé en 1944, reconstruit en 1956 ; Perpignan, fondé en 1240, reconstruit

en 1878 ; Besançon, fondé en 1250, réformé par sainte Colette en 1410, rétabli

en 1879 ; Nérac, fondé en 1358, restauré en 1935 ; Azille (Aude) fondé en 1361,

restauré en 1891 ; Marseille, fondé en 1254, rétabli en 1892 ; Poligny

(Jura), fondé en 1415 par Marguerite de Bavière, rétabli en 1817 ; Le Puy,

fondé par sainte Colette en 1432 ; Arras, fondé en 1457 ; Nantes, fondé en

1457, rétabli en 1859 ; Paris, fondé par Anne de Beaujeu en 1484, rétabli en

1876 ; Haubourdin (Nord), fondé en 1490, refondés à Esquermes en 1866, rétabli

à Haubourdin en 1931 ; Cambrai, fondé en 1496, rétabli en 1827 ; Alençon, fondé

en 1498 par Marguerite de Lorraine et refondé en 1819 ; Motbrison, fondé en

1500 ; Evian-les-Bains, fondé en 1536, restauré en 1875, refondé en 1924,

établi à Thony en 1978 ; Romans (Drome), fondé en 1621, reconstruit en 1834 ;

Lavaur, fondé en 1642, restauré en 1802 ; Mur-de-Barrez (Aveyron), fondé en

1653, rétabli en 1868.

Giovanni di Paolo (–1482), Sts Clare and Elizabeth of Hungary, circa 1445, 32 x 12, Private collection

Sainte Claire, vénère en

même temps le Christ comme le Divin Enfant « couché dans la crèche et

enveloppé de quelques méchants langes » et le Crucifié qui a voulu « souffrir

sur le bois de la croix et... mourir du genre de mort le plus infamant aui soit. »

En cela, elle est bien la fille de saint François d’Assise qui fit venir

l’Enfant Jésus dans la crèche à Greccio, et qui reçut les stigmates sur

l'Alverne. L'Homme-Dieu est l'Enfant et le Crucifié, mais aussi le Roi de

Gloire, le Seigneur.

Sainte Claire médite sans

cesse le mystère de l'lncarnation par lequel « Celui qui était riche s'est

fait pauvre pour nous » ; elle contemple le Verbe divin devenu

« le dernier des humains, méprisé, frappé, tout le corps déchiré à coups

de fouets, mourant sur la croix dans les pires douleurs. » De la Crèche au

crucifiement, elle voit le même et profond mystère, adorant déjà dans le corps

du Divin Enfant les plaies du Divin Crucifié. Si on ne peut lui attribuer la

composition de la prière aux Cinq Plaies du Seigneur, on sait qu'elle la disait

chaque jour.

A l’école de saint

François d’Assise, elle découvre la sainte humanité du Sauveur Jésus, sans pour

autant être uniquement fascinée par l'aspect sanglant du Crucifié :

l’Enfant Jésus de la Crèche n’est pas moins l'Oint, le Messie, le Seigneur, le

Fils du Trés-Haut que l’Homme Dieu de la passion et de la Croix. Elle découvre

la sainte humanité du Sauveur Jésus, sans pour autant perdre de vue que « Celui

s'est fait pauvre pour nous » est toujours le Seigneur qu’elle

n’appelle, avec la révérence que l’on doit à sa divinité, le Christ ou le

Christ-Jésus, le Seigneur ou le Roi. Le Crucifié de Saint-Damien qui a parlé à

saint François, celui que sainte Claire contemple n'est pas tant l’Homme des

douleurs que le Christ serein et victorieux au sein même de la plus extrême

abjection. Sous le Crucifié, elle voit encore « le plus beau des enfants

des hommes », « de race noble », « celui dont la beauté

fait l'admiration des anges pour l'éternité », celui « dont le soleil

et la lune admirent la beauté », celui qui est « splendeur de la

gloire éternelle, éclat de la Lumière sans fin et miroir sans tache. »

Comme saint François, parce qu’elle perçoit la « Beauté de Dieu » elle

s'attache à Lui seul comme son épouse.

L'ardent

désir du Crucifix pauvre

La lumineuse figure de

sainte Claire d'Assise a été évoquée par le Saint-Père dans une Lettre, en date

du 11 août 1993, adressée aux Clarisses à l'occasion du VIII° centenaire de la

naissance de la sainte fondatrice. Voici une traduction du texte du message de

Jean-Paul II :

Très chères religieuses

de clôture !

1. Il y a huit cents ans

naissait Claire d'Assise du noble Favarone d'Offreduccio.

Cette " femme

nouvelle ", comme l'ont écrit d'elle dans une Lettre récente les Ministres

généraux des familles franciscaines, vécut comme une " petite plante

" à l'ombre de saint François qui la conduisit au sommet de la perfection

chrétienne. La commémoration d'une telle créature véritablement évangélique

veut surtout être une invitation à la redécouverte de la contemplation, de cet

itinéraire spirituel dont seuls les mystiques ont une profonde expérience. Lire

son ancienne biographie et ses écrits - la Forme de vie, le Testament et

les quatre Lettres qui nous sont restées des nombreuses qu'elle a

adressées à sainte Agnès de Prague - signifie s'immerger à tel point dans le

mystère de Dieu Un et Trine et du Christ, Verbe incarné, que l'on en reste

comme ébloui. Ses écrits sont tellement marqués par l'amour suscité en elle par

le regard ardent et prolongé posé sur le Christ Seigneur, qu'il n'est pas

facile de redire ce que seul un coeur de femme a pu expérimenter.

2. L'itinéraire

contemplatif de Claire, qui se conclura par la vision du " Roi de gloire

" (Proc. IV, 19 : FF 3017 ),commence précisément lorsqu'elle se remet

totalement à l'Esprit du Seigneur, à la manière de Marie lors de l'Annonciation

: c'est-à-dire qu'il commence par cet esprit de pauvreté ( cf.. Lc I, 26-38 )

qui ne laisse plus rien en elle si ce n'est la simplicité du regard fixé sur

Dieu.

Pour Claire, la pauvreté

- tant aimée et si souvent invoquée dans ses écrits - est la richesse de l'âme

qui, dépouillée de ses propres biens, s'ouvre à l' "Esprit du Seigneur et

à sa sainte opération " (cf. Reg. S. Ch. X, 10 : FF 2811 ),

comme une coquille vide où Dieu peut déverser l'abondance de ses dons. Le

parallèle Marie - Claire apparaît dans le premier écrit de saint François, dans

la " Forma vivendi " donnée à Claire : " Par inspiration divine,

vous vous êtes faites filles et servantes du très haut Roi suprême, le Père

céleste, et vous avez épousé l'Esprit Saint, en choisissant de vivre selon la

perfection du saint Evangile " ( Forma vivendi,in Reg. S. Ch.

VI, 3 : FF 2788 ).

Claire et ses soeurs sont

appelées " épouses de l'Esprit Saint " : terme inusité dans

l'histoire de l'Eglise, où la soeur, la religieuse, est toujours qualifiée d'

"épouse du Christ". Mais on retrouve là certains thèmes du récit de

Luc de l'Annonciation ( cf. Lc 1, 26-38 ), qui deviennent des paroles-clefs

pour exprimer l'expérience de Claire : le " Très Haut ", l'

"Esprit Saint ", le " Fils de Dieu ", la " servante du

Seigneur " et, enfin, cet " ensevelissement "qu'est pour Claire

la prise du voile, alors que ses cheveux, coupés, tombent au pied de l'autel de

la Vierge Marie dans la Portioncule, " presque devant la chambre nuptiale

" (cf. Legg. S. Ch. 8 : FF 3170-3172 ).

3. L'" opération de

l'Esprit du Seigneur ", qui nous est donné dans le baptême, est de créer

chez le chrétien le visage du Fils de Dieu. Dans la solitude et dans le

silence, que Claire choisit comme forme de vie pour elle et pour ses compagnes

entre les pauvres murs de son monastère, à mi-côte entre Assise et la Portioncule,

se dissipe le voile de fumée des paroles et des choses terrestres, et la

communion avec Dieu devient réalité : amour qui naît et qui se donne.

Claire, penchée en

contemplation sur l'enfant de Bethléem, nous exhorte ainsi : " Puisque

cette vision de lui est splendeur de la gloire éternelle, clarté de la lumière

éternelle et miroir sans tache, chaque jour porte ton âme dans ce miroir...

Admire la pauvreté de celui qui fut déposé dans la crèche et enveloppé de

pauvres linges. O admirable humilité et pauvreté qui stupéfie ! Le Roi des

anges, le Seigneur du ciel et de la terre, est couché dans une mangeoire !

" ( Lett. IV, 14. 19-21 : FF 2902. 2904 ).

Elle ne se rend pas même

compte que son sein de vierge consacrée et de " vierge pauvre "

attachée au " Christ pauvre " (cf.Lett. II, 18 : FF 2878 ) devient

aussi, au moyen de la contemplation et de la transformation, un berceau du Fils

de Dieu (Proc. IX, 4 : FF 3062 ) . C'est la voix de cet enfant qui, de

l'Eucharistie, dans un moment de grand danger - quand le monastère va tomber

aux mains des troupes sarrazines au service de l'empereur Frédéric II - la

rassure : " Je vous protègerai toujours ! " (Legg. S. Ch. 22 :

FF 3202 ).

Dans la nuit de Noël de

1252, Jésus enfant transporte Claire loin de son lit d'infirme et l'amour, qui

n'a ni lieu ni époque, l'enveloppe dans une expérience mystique qui l'immerge

dans la profondeur infinie de Dieu.

4. Si Catherine de Sienne

est la sainte pleine de passion pour le sang du Christ, si Thérèse la Grande

est la femme qui s'avance de " demeure " en " demeure "

jusqu'à la porte du Grand Roi, dans le Château intérieur, et si Thérèse de

l'Enfant-Jésus est celle qui parcour avec simplicité évangélique la petite

voie, Claire est l'amante passionnée du Crucifix pauvre, avec lequel

elle veut absolument s'identifier.

Dans une de ses lettres

elle s'exprime ainsi : " Vois que Lui, pour toi, s'est fait objet de

mépris, et suis son exemple, en devenant, par amour de lui, méprisable en ce

monde. Admire ... ton Epoux, le plus beau parmi les fils des hommes, méprisé,

frappé et plusieurs fois flagellé sur tout le corps, et allant jusqu'à mourir

dans les douleurs les plus atroces sur la croix. Médite et contemple et aspire

à l'imiter. Si tu souffres avec Lui, avec Lui tu règneras ; si tu pleures avec

Lui, avec Lui tu te réjouiras ; si tu meurs avec lui sur la croix des

tribulations, tu possèderas avec Lui les demeures célestes dans la splendeur

des saints, et ton nom sera écrit dans le Livre de vie ... " (Lett.

II, 19-22 : FF 2879-2880 ).

Claire, entrée au

monastère à dix-huit ans à peine, y meurt à cinquante-neuf ans, après une vie

de souffrance, de prière jamais relâchée, de restriction et de pénitence. Pour

cet " ardent désir du Crucifix pauvre ", rien ne lui pèsera jamais, au

point qu'elle dira en mourant au frère Rainaldo qui l'assistait " dans le

long martyr d'aussi graves infirmités ... : Depuis que j'ai connu la grâce de

mon Seigneur Jésus-Christ au moyen de son serviteur François, aucune peine ne

m'a pesée, aucune pénitence n'a été lourde, aucune infirmité n'a été dure, très

cher frère ! " ( Legg. S. Ch. 44 : FF 3247 ).

5. Mais celui qui souffre

sur la croix est aussi celui qui reflète la gloire du Père et qui entraîne avec

lui dans sa Pâque qui l'a aimé jusqu'à en partager les souffrances par amour.

La fragile jeune fille de

dix-huit ans qui, fuyant de chez elle la nuit du dimanche des Rameaux de l'an

1212, s'aventure sans hésitations dans la nouvelle expérience, en croyant en

l'Evangile que lui a indiqué François et en rien d'autre, entièrement plongée

avec les yeux du visage et ceux du coeur dans le Christ pauvre et crucifié,

fait l'expérience de cette union qui la transforme : " Place tes yeux -

écrit-elle à sainte Agnès de Prague - devant le miroir de l'éternité, place ton

âme dans la splendeur de la gloire, place ton coeur en Celui qui est image de

la substance divine et transforme-toi entièrement, au moyen de la

contemplation, en l'image de sa divinité. Alors, toi aussi tu éprouveras ce qui

est réservé à ses seuls amis, et tu goûteras la douceur secrète que Dieu

lui-même a réservée dès le début à ceux qui l'aiment. Sans même accorder un

regard aux séductions, qui dans ce monde trompeur et agité tendent des pièges

aux aveugles qui y attachent leur coeur, aime de toute ta personne Celui qui,

par amour pour toi, s'est donné " ( Lett. III, 12-15 : FF 2888-2889

).

Alors, le terrible lieu

de la croix devient le doux lit nuptial et la " recluse à vie par amour

" trouve les accents les plus passionnés de l'Epouse du Cantique : "

Attire-moi à toi, ô céleste Epoux ! ... Je courrai sans jamais me fatiguer,

jusqu'à ce que tu m'introduise dans ta cellule " (Lett. IV, 30-32 :

FF 2906 ).

Enfermée dans le

monastère de saint Damien, menant une vie marquée par la pauvreté, par la

fatigue, par les tribulations, par la maladie, mais aussi par une communion

fraternelle si intense qu'elle est qualifiée dans le langage de la " Forma

di vita " par le nom de " sainte unité " ( Bulle initiale,

18 : FF 2749 ), Claire connaît la joie la plus pure qui ait jamais été donnée

d'expérimenter à une créature : celle de vivre dans le Christ la parfaite union

des Trois personnes divines, en entrant presque dans l'ineffable circuit de

l'amour trinitaire.

6. La vie de Claire, sous

la conduite de François, ne fut pas une vie érémitique, même si elle fut

contemplative et claustrale. Autour d'elle, qui voulait vivre comme les oiseaux

du ciel et les lys des champs ( Mt. VI, 26-28 ), se rassembla un premier groupe

de soeurs, satisfaites de Dieu seulement. Ce " petit troupeau " , qui

s'agrandit rapidement - en août 1228 les monastères des clarisses étaient au

moins 25 (cf. Lett. du Cardinal Rainaldo ; AFH 5, 1912, pp. 444-446 )

- ne nourrissait aucune crainte ( cf. Lc XII, 32 ) : la foi était pour

elles un motif de sécurité tranquille au milieu de tous les dangers. Claire et

les soeurs avaient un coeur grand comme le monde : étant contemplatives, elles

intercédaient pour toute l'humanité. En tant qu'âmes sensibles aux problèmes

quotidiens de chacun, elles savaient prendre en charge chaque peine : il n'y

avait pas de préoccupation d'autrui, de souffrance, d'angoisse, de désespoir

qui ne trouvât un écho dans leur coeur de femmes priantes. Claire pleura et

supplia le Seigneur pour la ville bien-aimée d'Assise, assiégée par les troupes

de Vitale d'Aversa, obtenant la libération de la ville de la guerre ; elle

priait chaque jour pour les malades et de nombreuses fois elle les guérit d'un

signe de croix. Persuadée qu'il n'y a pas de vie apostolique si on ne s'immerge

pas dans le flanc déchiré du Christ crucifié, elle écrivait à Agnès de Prague

avec les paroles de saint Paul : " Je te considère comme une

collaboratrice de Dieu lui-même ( Rm XVI, 3 ) et un soutien des membres faibles

et vacillants de son ineffable Corps " ( Lett. III, 8 : FF 2886 ).

7. Claire d'Assise, également

en raison d'un genre d'iconographie qui a eu un vaste succès à partir du XVII°

siècle, est souvent représentée l'ostensoir à la main. Le geste rappelle, bien

qu'avec une attitude plus solennelle, l'humble réalité de cette femme qui, déjà

très malade, se prosternait, soutenue par deux soeurs, devant le ciboire

d'argent contenant l'Eucharistie ( cf. Legg. S. Ch. 21 : FF 3201 ),

placé devant la porte du réfectoire, où devait s'abattre la furie des troupes

de l'Empereur. Claire vivait de ce pain, que pourtant, suivant l'usage de

l'époque, elle ne pouvait recevoir que sept fois par an. Sur son lit de malade,

elle brodait du linge d'autel et l'envoyait aux églises pauvres de la vallée de

Spolète.

En réalité, toute la vie

de Claire était une eucharistie, car - à l'instar de François - elle

élevait de sa clôture un continuel " remerciement " à Dieu par la

prière, la louange, la supplication, l'intercession, les pleurs, l'offrande et

le sacrifice. Tout était accueilli par elle et offert au Père en union avec le

" merci " infini du Fils unique, enfant, crucifié, ressuscité, vivant

à la droite du Père.

En cette fête jubilaire,

très chères soeurs, l'attention de toute l'Eglise se tourne avec un intérêt

accru vers la figure lumineuse de votre Mère profondément aimée. Avec une

ferveur encore plus grande votre regard doit converger sur elle, pour tirer de

ses exemples une stimulation à intensifier l'élan à répondre à la grâce du

Seigneur, avec un dévouement quotidien à cet engagement contemplative dont

l'Eglise tire tant de force pour son action missionnaire dans le monde

d'aujourd'hui.

Que le Christ, notre

Seigneur, soit votre lumière et la joie de vos coeurs.

Avec ces souhaits, en

signe de profonde affection, je donne à tous une spéciale Bénédiction

apostolique.

Du Vatican, le 11 août,

mémoire liturgique de sainte Claire d'Assise, de l'an 1993, quinzième de mon

pontificat.

Jean-Paul II

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/08/11.php

Unknown

Alsatian Master, St Mary Magdalene, St Odile of Alsace and St Clare of Assi.

/

Šv. Marija Magdalietė, šv. Odilė Elzasietė ir šv. Klara / Св. Марія Магдалина,

св. Одилія та св. Клара. 15th century, 9 x 73, Borys Voznytskyi Lviv

National Art Gallery

11 août: Sainte Claire

d'Assise

Le projet de vie de

Claire d’Assise et de ses Pauvres Dames, mieux connues sous le nom de

Clarisses, tient en une humilité toute joyeuse au service de « dame

pauvreté ». Le Christ donne tout son sens à un tel engagement. Claire, qui

se voyait comme une petite plante à l’ombre de saint

François, découvrira la sainte humanité du Seigneur Jésus qui s’est fait

pauvre pour nous, de la crèche à la Croix. Elle ne séparera pas l’Enfant Jésus

du Crucifié.

Deux enfants d’Assise

Claire est née à Assise,

vers 1193, du chevalier Favarone et de dame Ortolana. D’une douzaine d’années

de moins que François et d’une famille plus noble que la sienne, son histoire

sera pourtant inséparable du Poverello. Elle fait sa connaissance vers

1210, quand celui-ci prêche dans Assise. Elle est séduite par cette vie pauvre

et joyeuse toute donnée au Christ. Son désir est de prendre François comme

guide de sa vie, après Dieu.

Dans la nuit qui suit le

dimanche des Rameaux 1212, elle s’enfuit de chez elle et rejoint François et

les frères à Sainte-Marie de la Portioncule qu’il avait restaurée. François lui

coupe les cheveux et lui remet un voile et une robe de toile grossière pour

bien signifier sa promesse de suivre le Christ pauvre. François conduit la

jeune femme de dix-huit ans chez les bénédictines de Saint-Paul, puis il

l’installe à Saint-Damien, où le Christ lui avait parlé. D’autres jeunes filles

se joindront à cette femme forte et tendre.

Fondatrice des Pauvres

Dames

Claire fonde rapidement

l’ordre des Pauvres Dames, les Clarisses, qui vivront l’idéal franciscain dans

la prière. À la tête d’une communauté de cinquante religieuses, dont sa sœur

Agnès, elle est faite abbesse par le pape en 1216. Sa mère Ortolana sera plus

tard de la communauté. Après la mort de François en 1226, les papes

interviennent pour aménager la vie matérielle des Clarisses, même si Claire

refuse. Elle rédige une Règle qui marque les liens étroits avec la pauvreté,

les frères franciscains et la simplicité joyeuse de l’Esprit. Les sœurs sont

appelées « épouses de l’Esprit Saint » et non « épouses du

Christ », ce qui est assez inusité dans l’histoire de l’Église.

De nouvelles communautés

se forment en Italie (on en compte 24 en 1228), en France, dont le couvent de

Reims est fondé en 1220, et en Espagne. En 1252, le pape Innocent IV visite les

Sœurs et approuve leur Règle. La bulle d’approbation arrivera l’année suivante.

Claire meurt le 11 août 1253 en serrant la bulle dans ses mains.

En quarante-trois années

de vie monastique à Saint-Damien, dont vingt-neuf de maladie, Claire a donné

l’exemple d’une vie dépouillée et d’une union à Dieu, vécue dans la joie. On a

dit que par ses prières elle éloigna à deux reprises les Sarrasins de la ville

d’Assise. Ses dernières paroles sont une prière de louange que j'aimerais bien

dire à ma mort. Elles révèlent la paix profonde et la joie intérieure qui

l’habitaient : « Ô Dieu, béni sois-tu de m’avoir créée. » Ses

obsèques se déroulent en présence du pape Innocent IV et de la curie romaine.

Fait inhabituel dans l’Église, elle est canonisée deux ans plus tard. L’ordre

des clarisses comprend aujourd’hui environ 17 000 religieuses réparties en 850

maisons.

La dame pauvre meurt donc

comme elle a vécu, dans l’action de grâce d’une prière. Sa vie offerte fut une

eucharistie, un immense merci fait de silences et de cris, de rires et de

larmes. Elle a tout accueilli pour Jésus Ressuscité, avec lui et en lui, en

louange au Très-Haut tout aimant.

La joie du dépouillement

Pour Claire, la vraie

pauvreté est toujours joyeuse, car l’âme dépouillée de ses propres biens

s’ouvre à l’action de l’Esprit Saint. L’âme marche ainsi vers son Seigneur,

alerte et libre, comme elle l’écrit à Agnès de Prague : « Ce que tu

fais, fais-le et ne le lâche pas, mais d’une course rapide, d’un pas léger,

sans entraves aux pieds, pour que tes pas ne ramassent pas la poussière, sûre,

joyeuse et alerte, marche prudemment sur le chemin de la béatitude. » (Sources

chrétiennes 325, p. 92).

À la suite des premiers

franciscains, les Clarisses font de l’imitation du Christ une source de joie.

Claire aime la vie, les autres, la nature qui l’entoure. Sa vie est une sorte

de Cantique des créatures où transpire cette jubilation qui lui vient

de l’Évangile et de la découverte de la joie parfaite. Le Crucifié de

Saint-Damien qu’elle contemple n’est pas tant l’Homme des douleurs que le

Christ victorieux de la mort. Elle se donne à cette beauté de Dieu qui

resplendit sur la face de son Christ, « pour qu’ils aient en eux ma joie,

et qu’ils en soient comblés » (Jn 17, 13).

Jean-Paul II, dans une

lettre datée du 11 août 1993, adressée aux Clarisses à l’occasion du VIIIe centenaire

de la naissance de leur sainte fondatrice, évoqua la figure lumineuse de Claire

: « Si Catherine de Sienne est la sainte pleine de passion pour le sang du

Christ, si Thérèse la Grande est la femme qui s’avance de demeure en demeure

jusqu’à la porte du Grand Roi, dans le Château intérieur, et si Thérèse de

l’Enfant-Jésus est celle qui parcourt avec simplicité évangélique la petite

voie, Claire est l’amante passionnée du Crucifié pauvre, avec lequel elle

veut absolument s’identifier. »

Prière

Jésus, celle qui murmure

ton nom en silence

porte sa pauvreté à la suite de François d’Assise.

Elle coupe sa chevelure pour revêtir ta grâce

et partager avec d’autres ton secret.

Tu l’as séduite, elle

s’ouvre à tes noces.

Perle sans prix au jardin du Père,

elle entre dans la chapelle de Saint-Damien.

Ton Esprit l’inonde de tendresse.

Elle tient sa lampe

allumée dans la nuit.

Elle se fiance à toi pour toujours.

Elle fonde l’ordre des Pauvres Dames,

ces Clarisses qui n’aspirent qu’à s’unir à toi.

Tu es l’Époux qui va à

leur rencontre.

Tu les guides vers toi, ces filles de Claire,

dont la bure couleur de terre

nous dit jusqu’où va la joie de tout donner.

Pour aller plus

loin, Les

saints, ces fous admirables et Prières

de toutes les saisons,

SOURCE : https://www.jacquesgauthier.com/blog/entry/11-aout-sainte-claire-d-assise.html

Piero della Francesca (1415–1492), : Polyptych

of St Anthony: St Clare, circa 1460, color on panel, 21 x 38, National Gallery of Umbria, Palazzo dei Priori, Perugia,

Piero della Francesca (1415–1492), : Polyptych

of St Anthony: St Clare, circa 1460, color on panel, 21 x 38, National Gallery of Umbria, Palazzo dei Priori, Perugia,

La prière de sainte

Claire d’Assise pour apaiser l’angoisse de la mort

Marzena

Devoud - publié le 16/10/21 - mis à jour le 07/08/24

Écrite au moment de sa

mort, la prière de louange de sainte Claire d’Assise est saisissante. Elle met

la lumière sur l’essence de la vie même. Pleine de gratitude, elle révèle que

Dieu veille sur chaque personne à chaque instant.

Parmi les tableaux qui

illustrent sainte Claire d’Assise (1193-1253) sur son lit de mort, il y a cette

représentation de maître anonyme de Heiligenkreuz (Autriche) où on aperçoit la

Vierge Marie accompagner la moniale au moment de la mort. Une apparition

confirmée par sœur Benvenuta de Diambra, présente alors au couvent. Vêtue d’une

robe de brocart rouge et or et escortée par des saintes martyres, la Vierge

Marie caresse la joue de Claire sous le regard tendre de deux anges. En haut de

l’icône, dans le ciel bleu, on aperçoit le Christ avec dans ses bras l’âme de

la future sainte…

Cette scène, peinte selon

la tradition byzantine, surprend par la douceur et la tendresse du grand

passage vers l’au-delà. Les dernières paroles de la disciple et amie de

François d’Assise sur son lit de mort complètent de façon surprenante ce

tableau. En 43 années de vie monastique, dont 29 de maladie, la fondatrice de

l’ordre des Pauvres Dames nommé « les Clarisses ,» est encore une fois fidèle à

son union à Dieu, vécue dans la joie et la gratitude profondes. Cette prière de

louange "Celui qui te créa a toujours veillé sur toi" révèle la

grande paix intérieure qui l’habitait au moment de mourir :

"Va en paix, sans

inquiétude, tu auras une bonne escorte. Car Celui qui te créa t'a sanctifiée.

Car Celui qui te créa t'a envoyé l'Esprit-Saint. Il a toujours veillé sur toi,

comme une mère veille sur son petit enfant qu'elle aime. Sois béni, ô Toi,

Seigneur, Toi qui m'as créée".

Lire aussi :Quand

saint Augustin dit “À Dieu” à sa mère

Lire aussi :La

prière de saint Thomas d’Aquin juste avant de mourir

Lire aussi :Prière

de saint Ambroise pour un proche en train de mourir

Lire aussi :Qui

prie Marie, se sauve : ce saint avait tout compris

Lire aussi :Que

dire à un proche en fin de vie ? Sept pistes pour vivre ce temps en vérité

Lire aussi :Sainte

Claire et saint François d’Assise, des amis inséparables

Lire aussi :Qu’y

a-t-il après la mort ? Le message plein d’espérance de Thérèse de Lisieux

Pere Serra (1403-1408). Sainte Eulalie de Barcelone et Sainte Claire

d'Assise, retable, Cathédrale de Segorbe

SAINTE CLAIRE, vierge

Morte le 11 août 1253,

canonisée en 1255 par Alexandre IV. Fête immédiate diffusée par les

Franciscains.

Fête double jusqu’en 1568

au calendrier romain. Réduite à une simple mémoire dans l’Octave de St Laurent

par St Pie V. Innocent X en fit un double ad libitum et Clément X à

nouveau un double de précepte en 1670.

die 12 augusti

SANCTÆ CLARÆ

Virginis

III classis (ante CR

1960 : duplex)

Missa Dilexísti, de

Communi Virginum III loco.

le 12 août

SAINTE CLAIRE

Vierge

IIIème classe (avant

1960 : double)

Messe Dilexísti, du

Commun des Vierges III.

Leçons des Matines avant

1960.

Au deuxième nocturne.

Quatrième leçon. La

vierge Claire naquit d’une famille illustre, à Assise, en Ombrie. A l’exemple

de saint François, qui était de la même ville, elle distribua et convertit tous

ses biens en aumônes et secours aux pauvres. Fuyant le tumulte du siècle, elle

se rendit dans l’église de la Portioncule, où le même Saint lui coupa les

cheveux. Ses parents firent tous leurs efforts pour la ramener dans le monde ;

mais elle y opposa une ferme résistance. Conduite par saint François à l’église

de Saint-Damien, elle s’associa plusieurs compagnes et institua ainsi elle-même

une communauté de religieuses consacrées à Dieu, dont elle n’accepta le

gouvernement que pour céder aux saintes importunités du Bienheureux. Elle

exerça pendant quarante-deux ans la charge de supérieure, et se montra

admirable par sa sollicitude, sa prudence et le soin qu’elle prit de maintenir

dans sa communauté la parfaite observance des règles et des statuts de l’Ordre.

Sa vie, en effet, était pour ses sœurs un enseignement et un exemple, d’où elles

apprirent à régler leur vie.

Cinquième leçon. Afin de

fortifier l’esprit en soumettant la chair, elle avait pour lit la terre nue ou

des sarments, et pour oreiller un dur morceau de bois. Une seule tunique et un

manteau d’étoffe rude et grossière lui suffisaient ; un âpre cilice ne quittait

point sa chair. Telle était son abstinence que, pendant un temps assez long,

elle ne goûta aucun aliment corporel, trois jours par semaine ; se restreignant

les autres jours à une si petite quantité de nourriture, que ses sœurs

s’étonnaient qu’elle pût subsister. Avant de tomber malade, elle s’imposait

deux carêmes chaque année, sa seule réfection consistant alors en du pain et de

l’eau. Adonnée aux veilles et assidue à l’oraison, elle passait dans ce saint

exercice la plupart des jours et des nuits. Quand, éprouvée par de longues

infirmités, elle ne pouvait se lever d’elle-même pour se livrer au labeur

matériel, Claire se soulevait avec l’aide de ses sœurs, puis, le dos appuyé,

travaillait des mains pour ne pas demeurer oisive, même dans ses maladies. Son

amour passionné de la pauvreté lui fit constamment refuser les biens que

Grégoire IX lui offrait pour le soutien de sa communauté.

Sixième leçon. Des

miracles nombreux et variés répandirent l’éclat de sa sainteté. A l’une des

sœurs de son monastère, elle rendit l’usage de la parole, guérit une seconde de

sa surdité, et en délivra d’autres de la fièvre, d’une enflure d’hydropisie,

d’une fistule douloureuse et de diverses maladies qui les accablaient. Un frère

de l’Ordre des Mineurs lui dut de recouvrer la raison. L’huile étant venue à

manquer totalement dans le monastère, Claire prit une cruche, la lava, et tout

à coup ce vase se trouva rempli d’huile par un miracle de la divine bonté. Elle

multiplia la moitié d’un pain, de manière à ce qu’il y en eût assez pour

cinquante sœurs. Les Sarrasins, assiégeant Assise, s’efforçaient d’envahir le

couvent de Claire : la Sainte, toute malade qu’elle était, se fit porter à

l’entrée de la maison, tenant elle-même le vase où était renfermé le très saint

sacrement de l’Eucharistie ; là, elle adressa à Dieu cette prière : « Seigneur,

ne livrez pas aux bêtes féroces des âmes qui vous louent ; protégez vos

servantes, que vous avez rachetées de votre sang précieux. » Pendant qu’elle priait,

on entendit cette parole : « Moi, je vous garderai toujours. » En effet, une

partie des Sarrasins prit la fuite, et ceux d’entre eux qui étaient déjà montés

sur les murailles furent aveuglés et tombèrent à la renverse. Enfin cette

Vierge, à ses derniers moments, fut visitée par un chœur de bienheureuses

Vierges vêtues de blanc parmi lesquelles s’en distinguait une surpassant en

beauté toutes les autres. Alors, munie de la sainte Eucharistie et enrichie par

Innocent IV de l’indulgence plénière, elle rendit son âme à Dieu, la veille des

ides d’août. Les nombreux miracles qui la glorifièrent après sa mort,

déterminèrent le Pape Alexandre IV à la mettre au nombre des saintes Vierges.

Au troisième nocturne. Du

Commun.

Lecture du saint Évangile

selon saint Matthieu. Cap. 25, 1-13.

En ce temps-là : Jésus

dit à-ses disciples cette parabole : Le royaume des cieux sera semblable à dix

vierges qui ; ayant pris leurs lampes, altèrent au-devant de l’époux et de

l’épouse. Et le reste.

Homélie de saint

Grégoire, Pape. Homilia 12 in Evang.

Septième leçon. Je vous

recommande souvent, mes très chers frères, de fuir le mal et de vous préserver

de la corruption du monde ; mais aujourd’hui la lecture du saint Évangile

m’oblige à vous dire de veiller avec beaucoup de soin à ne pas perdre le mérite

de vos bonnes actions. Prenez garde que vous ne recherchiez dans le bien que

vous faites, la faveur ou l’estime des hommes, qu’il ne s’y glisse un désir

d’être loué, et que ce qui paraît au dehors ne recouvre un fond vide de mérite

et peu digne de récompense. Voici que notre Rédempteur nous parle de dix

vierges, il les nomme toutes vierges et cependant toutes ne méritèrent pas

d’être admises au séjour de la béatitude, car tandis qu’elles espéraient

recueillir de leur virginité une gloire extérieure, elles négligèrent de mettre

de l’huile dans leurs vases.

Huitième leçon. Il nous

faut d’abord examiner ce qu’est le royaume des cieux, ou pourquoi il est

comparé à dix vierges, et encore quelles sont les vierges prudentes et les vierges

folles. Puisqu’il est certain qu’aucun réprouvé n’entrera dans le royaume des

cieux, pourquoi nous dit-on qu’il est semblable à des vierges parmi lesquelles

il y en a de folles ? Mais nous devons savoir que l’Église du temps présent est

souvent désignée dans le langage sacré sous le nom de royaume des cieux ; d’où

vient que le Seigneur dit en un autre endroit : « Le Fils de l’homme enverra

ses anges, et ils enlèveront de son royaume tous les scandales » [1]. Certes,

ils ne pourraient trouver aucun scandale à enlever, dans ce royaume de la

béatitude, où se trouve la plénitude de la paix.

Neuvième leçon. L’âme

humaine subsiste dans un corps doué de cinq sens. Le nombre cinq, multiplié par

deux, donne celui de dix. Et parce que la multitude des fidèles comprend l’un

et l’autre sexe, la sainte Église est comparée à dix vierges. Comme, dans cette

Église, les méchants se trouvent mêlés avec les bons et ceux qui seront

réprouvés avec les élus, ce n’est pas sans raison qu’on la dit semblable à des

vierges, dont les unes sont sages et les autres insensées. Il y a en effet,

beaucoup de personnes chastes qui veillent sur leurs passions quant aux choses

extérieures et sont portées par l’espérance vers les biens intérieurs ; elles

mortifient leur chair et aspirent de toute l’ardeur de leur désir vers la

patrie d’en haut ; elles recherchent les récompenses éternelles, et ne veulent

pas recevoir pour leurs travaux de louanges humaines : celles-ci ne mettent

assurément pas leur gloire dans les paroles des hommes, mais la cachent au fond

de leur conscience. Et il en est aussi plusieurs qui affligent leur corps par