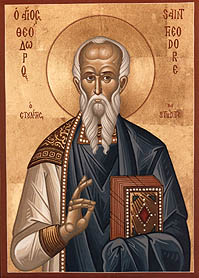

Saint Théodore le Studite

Higoumène

du monastère du Stoudion (+ 826)

Né dans une noble

et très chrétienne famille de Constantinople. Il entre dans un monastère dirigé

par l'un de ses oncles, mais les moines sont exilés parce qu'ils réprouvent la

conduite de l'empereur qui répudie sa femme et en épouse religieusement une

autre. Lorsque les raids arabes chassent les moines byzantins de leurs

monastères d'Asie Mineure, saint Théodore revient à Constantinople où ses

difficultés se sont aplanies. Il est placé à la tête du monastère du 'Stoudios'

à qui il fait retrouver la pureté du monachisme primitif. Le règlement du

Stoudios servira d'ailleurs de règle à un grand nombre de monastères orientaux.

Chaque jour, il adresse à ses frères des catéchèses célèbres. Mais la tempête

revient. L'empereur Léon V met hors la loi les saintes images. Théodore résiste

et il passera le reste de sa vie dans un exil douloureux. "O philanthropie

indicible du Christ, dit-il. Du non-être, il nous a amenés à l'être."

Le 27 mai 2009, Benoît XVI a tracé durant l'audience générale un portrait de saint Théodore Le Studite. Né en 759 dans une famille riche et religieuse, il se fit moine à 22 ans. Son opposition au mariage adultère de l'empereur Constantin VI, le fit exiler à Salonique en 796. Il peut retrouver son monastère de Sakkudion grâce à l'impératrice Irène qui le fit venir à celui de Studios, loin des incursions sarrasines. Il guida ensuite la résistance contre l'iconoclaste Léon V, ce qui lui valut de nouveaux exils à travers l'Asie Mineure. Finalement de retour à Constantinople, il mourut en 826.

Le Pape a d'abord rappelé que Théodore "s'est distingué dans l'histoire de l’Église comme grand réformateur de la vie monastique, puis comme défenseur des icônes avec le Patriarche Nicéphore au cours de la seconde crise iconoclaste... Il insista sur la valeur du monachisme et la nécessaire obéissance des moines...pour que le monastère soit une communauté fonctionnelle, une véritable famille, un corps du Christ comme il disait... Une de ses convictions profondes était que le moine doit observer les devoirs chrétiens avec rigueur et intensité afin d'offrir un exemple aux autres. Pour cela il doit prononcer ses vœux particuliers...comme un second baptême". Puis il a souligné l'importance pour saint Théodore de la pauvreté, de la chasteté et de l'obéissance, qui distinguent les moines des laïcs". La pauvreté personnelle "constitue un élément essentiel du monachisme, qui peut indiquer aussi un cheminement pour les autres fidèles. Les moines vivent radicalement la renonciation à la propriété et aux biens matériels, la sobriété et la simplicité dans un esprit d'égalité. Sans dépendre des choses matérielles, il faut apprendre à renoncer et à être sobre pour qu'une société solidaire puisse surmonter enfin la grave question de la misère du monde... Ces renonciations, Théodore Le Studite les appelaient "un martyre de la soumission". D'ailleurs, le tissu social ne peut tenir qu'en appliquant pour le bien commun ces limites aux règles générales. Ainsi créera-t-on une société libérée de la superbe qui conduit ce monde.

Pour saint Théodore, a ajouté le Pape, "l'humilité était aussi une importante vertu, la Philergia, c'est-à-dire l'amour du travail... Sous prétexte de la prière et de la contemplation, le moine ne doit pas se dispenser de travailler, le travail manuel étant un moyen de rencontrer Dieu... Père spirituel de ses moines, il était toujours prêt à écouter leurs confidences, mais conseillait spirituellement aussi de nombreuses personnes hors de la communauté... La règle du Studite ne fut codifiée qu'après sa mort et adoptée presque complètement au Mont Athos, où elle est toujours en usage, singulièrement d'actualité". Benoît XVI a conclu son exposé en disant qu'il existe de nos jours nombre de "courants qui menacent l'unité de la foi et poussent à un dangereux individualisme spirituel. Il faut donc s'engager dans la défense et dans la croissance de l'unité parfaite de l’Église, dans laquelle paix et ordre peuvent s'articuler harmonieusement avec les rapports personnels dans l'Esprit. L'enseignement du Studite est éclairant en la matière".

(source: VIS 090527)

À Constantinople, en 826, saint Théodore Studite, abbé, qui fit de son monastère une école de sages, de saints et de martyrs, victime des persécutions perpétrées par les iconoclastes; trois fois envoyé en exil, il eut en grand honneur les traditions des pères de l’Église et, pour l’exposé de la foi catholique, il écrivit les célèbres Institutions de la doctrine chrétienne.

Martyrologe

romain

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 27 mai 2009

Saint Théodore le Studite

Chers

frères et sœurs!

Le saint que nous rencontrons aujourd'hui, saint

Théodore le Studite, nous conduit en plein Moyen Age byzantin, à une période

assez tourmentée du point de vue religieux et politique. Saint Théodore naquit

en 759 dans une famille noble et pieuse: sa mère, Théoctiste, et un

oncle, Platon, abbé du monastère de Saccoudion en Bithynie, sont vénérés

comme des saints. Ce fut précisément son oncle qui l'orienta vers la vie

monastique, qu'il embrassa à l'âge de 22 ans. Il fut ordonné prêtre par le

patriarche Tarasius, mais rompit ensuite la communion avec lui en raison de la

faiblesse dont celui-ci fit preuve à l'occasion du mariage adultérin de

l'empereur Constantin vi. La conséquence en fut l'exil de Théodore, en 796, à

Thessalonique. La réconciliation avec l'autorité impériale advint l'année

suivante sous l'impératrice Irène, dont la bienveillance conduisit Théodore et

Platon à s'installer dans le monastère urbain de Stoudios, avec une

grande partie de la communauté des moines de Saccoudion, pour éviter les

incursions des sarrasins. C'est ainsi que débuta l'importante "réforme

studite".

Toutefois, l'histoire personnelle de Théodore

continua d'être mouvementée. Avec son énergie habituelle, il devint le chef de

la résistance contre l'iconoclasme de Léon v l'Arménien, qui s'opposa de

nouveau à l'existence d'images et d'icônes dans l'Eglise. La procession

d'icônes organisée par les moines de Stoudios déchaîna la réaction de la

police. Entre 815 et 821, Théodore fut flagellé, incarcéré et exilé en divers

lieu de l'Asie Mineure. En fin de compte, il put rentrer à Constantinople, mais

pas dans son monastère. Il s'installa alors avec ses moines de l'autre côté du

Bosphore. Il mourut, semble-t-il, à Prinkipo, le 11 novembre 826, jour

où il est célébré dans le calendrier byzantin. Théodore se distingua dans

l'histoire de l'Eglise comme l'un des grands réformateurs de la vie monastique

et également comme défenseur des images sacrées pendant la deuxième phase de

l'iconoclasme, aux côtés du patriarche de Constantinople, saint Nicéphore.

Théodore avait compris que la question de la vénération des icônes avait à voir

avec la vérité même de l'Incarnation. Dans ses trois livres Antirretikoi (Réfutations),

Théodore établit une comparaison entre les relations éternelles

intratrinitaires, où l'existence de chaque Personne divine ne détruit pas

l'unité, et les relations entre les deux natures en Christ, qui ne

compromettent pas, en lui, l'unique Personne du Logos. Et il

argumente: abolir la vénération de l'icône du Christ signifierait effacer

son œuvre rédemptrice elle-même, du moment que, assumant la nature humaine,

l'invisible Parole éternelle est apparue dans la chair visible humaine et de

cette manière a sanctifié tout le cosmos visible. Les icônes, sanctifiées par

la bénédiction liturgique et par les prières des fidèles, nous unissent avec la

Personne du Christ, avec ses saints et, par leur

intermédiaire, avec le Père céleste et témoignent de l'entrée dans la réalité

divine de notre cosmos visible et matériel.

Théodore et ses moines, témoins du courage au temps

des persécutions iconoclastes, sont liés de façon inséparable à la réforme de

la vie cénobitique dans le monde byzantin. Leur importance s'impose déjà en

vertu d'une circonstance extérieure: le nombre. Tandis que les monastères

de l'époque ne dépassaient pas trente ou quarante moines, nous apprenons de La

vie de Théodore l'existence de plus d'un millier, au total, de moines

studites. Théodore lui-même nous informe de la présence dans son monastère

d'environ trois cents moines; nous voyons donc l'enthousiasme de la foi qui est

né autour de cet homme réellement informé et formé par la foi elle-même.

Toutefois, plus que le nombre, c'est le nouvel esprit imprimé par le fondateur

à la vie cénobitique qui se révéla influent. Dans ses écrits, il insiste sur

l'urgence d'un retour conscient à l'enseignement des Pères, surtout à saint

Basile, premier législateur de la vie monastique et à saint Dorothée de Gaza,

célèbre père spirituel du désert palestinien. La contribution caractéristique

de Théodore consiste à insister sur la nécessité de l'ordre et de la soumission

de la part des moines. Au cours des persécutions, ceux-ci s'étaient dispersés,

s'habituant à vivre chacun selon son propre jugement. A présent qu'il était

possible de reconstituer la vie commune, il fallait s'engager pleinement pour

faire du monastère une véritable communauté organisée, une véritable famille

ou, comme il le dit, un véritable "Corps du Christ". Dans cette

communauté se réalise de façon concrète la réalité de l'Eglise dans son

ensemble.

Une autre conviction de fond de Théodore est la

suivante: les moines, par rapport aux séculiers, prennent l'engagement

d'observer les devoirs chrétiens avec une plus grande rigueur et intensité.

Pour cela, ils prononcent une profession particulière, qui appartient aux hagiasmata

(consécrations), et est presque un "nouveau baptême", dont

la vêture représente le symbole. En revanche, par rapport aux séculiers,

l'engagement à la pauvreté, à la chasteté et à l'obéissance est caractéristique

des moines. S'adressant à ces derniers, Théodore parle de façon concrète,

parfois presque pittoresque, de la pauvreté, mais celle-ci, dans la suite du

Christ, est depuis le début un élément essentiel du monachisme et indique

également un chemin pour nous tous. Le renoncement à la possession des choses

matérielles, l'attitude de liberté vis-à-vis de celle-ci, ainsi que la sobriété

et la simplicité valent de façon radicale uniquement pour les moines, mais

l'esprit de ce renoncement est le même pour tous. En effet, nous ne devons pas

dépendre de la propriété matérielle, nous devons au contraire apprendre le

renoncement, la simplicité, l'austérité et la sobriété. Ce n'est qu'ainsi

que peut croître une société solidaire et que peut être surmonté le grand

problème de la pauvreté de ce monde. Donc, dans ce

sens, le signe radical des moines pauvres indique en substance

également une voie pour nous tous. Lorsqu'il expose ensuite les tentations

contre la chasteté, Théodore ne cache pas ses expériences et montre le chemin

de lutte intérieure pour trouver le contrôle de soi et ainsi, le respect de son

corps et de celui de l'autre comme temple de Dieu.

Mais les renoncements principaux sont pour lui ceux

exigés par l'obéissance, car chacun des moines a sa propre façon de vivre et

l'insertion dans la grande communauté de trois cents moines implique réellement

une nouvelle forme de vie, qu'il qualifie de "martyre de la soumission".

Ici aussi, les moines donnent uniquement un exemple de combien celui-ci est

nécessaire pour nous-mêmes, car, après le péché originel, la tendance de

l'homme est de faire sa propre volonté, le principe premier est la vie du

monde, tout le reste doit être soumis à sa propre volonté. Mais de cette façon,

si chacun ne suit que lui-même, le tissu social ne peut fonctionner. Ce n'est

qu'en apprenant à s'insérer dans la liberté commune, à la partager et à s'y

soumettre, à apprendre la légalité, c'est-à-dire la soumission et l'obéissance

aux règles du bien commun et de la vie commune, qu'une société peut être

guérie, de même que le moi lui-même, de l'orgueil d'être au centre du

monde. Ainsi, saint Théodore aide ses moines et en définitive, nous aussi, à

travers une délicate introspection, à comprendre la vraie vie, à résister à la

tentation de placer notre volonté comme règle suprême de vie, et de conserver

notre véritable identité personnelle - qui est toujours une identité avec les

autres - et la paix du cœur.

Pour Théodore le Studite, une autre vertu, aussi

importante que l'obéissance et que l'humilité, est la philergia,

c'est-à-dire l'amour du travail, dans lequel il voit un critère pour éprouver

la qualité de la dévotion personnelle: celui qui est fervent dans les

engagements matériels, qui travaille avec assiduité, soutient-il, l'est

également dans les engagements spirituels. Il n'admet donc pas que, sous le

prétexte de la prière et de la contemplation, le moine se dispense du travail,

également du travail manuel, qui est en réalité, selon lui et selon toute la

tradition monastique, le moyen pour trouver Dieu. Théodore ne craint pas de

parler du travail comme du "sacrifice du moine", de sa

"liturgie", et même d'une sorte de Messe à travers laquelle la vie

monastique devient angélique. C'est précisément ainsi que le monde du travail

doit être humanisé et que l'homme à travers le travail devient davantage

lui-même, plus proche de Dieu. Une conséquence de cette vision singulière

mérite d'être rappelée: précisément parce qu'étant le fruit d'une forme

de "liturgie", les richesses tirées du travail commun ne doivent pas

servir au confort des moines, mais être destinées à l'assistance des pauvres.

Ici, nous pouvons tous saisir la nécessité que le fruit du travail soit un bien

pour tous. Bien évidemment, le travail des "studites" n'était pas

seulement manuel: ils eurent une grande importance dans le développement

religieux et culturel de la civilisation byzantine comme calligraphes,

peintres, poètes, éducateurs des jeunes, maîtres d'école, bibliothécaires.

Bien qu'exerçant une très vaste activité, Théodore

ne se laissait pas distraire de ce qu'il considérait comme strictement lié à sa

fonction de supérieur: être le père spirituel de ses moines. Il

connaissait l'influence décisive qu'avaient eu dans sa vie aussi bien sa bonne

mère que son saint oncle Platon, qu'il qualifiait du titre significatif de

"père". Il exerçait donc à l'égard des moines la direction

spirituelle. Chaque jour, rapporte son biographe, après la prière du soir, il

se plaçait devant l'iconostase pour écouter les confidences de tous. Il

conseillait également spirituellement de nombreuses personnes en dehors du

monastère lui-même. Le Testament spirituel et les Lettres

soulignent son caractère ouvert et affectueux, et montrent que de sa paternité

sont nées de véritables amitiés spirituelles dans le milieu monastique et

également en dehors de celui-ci.

La Règle, connue sous le nom d'Hypotyposis,

codifiée peu après la mort de Théodore, fut adoptée, avec quelques modifications,

sur le Mont Athos, lorsqu'en 962 saint Athanase Athonite y fonda la Grande

Lavra, et dans la Rus' de Kiev, lorsqu'au début du deuxième millénaire,

saint Théodose l'introduisit dans la Lavra des Grottes. Comprise dans sa

signification authentique, la Règle se révèle singulièrement actuelle.

Il existe aujourd'hui de nombreux courants qui menacent l'unité de la foi

commune et qui poussent vers une sorte de dangereux individualisme spirituel et

d'orgueil intellectuel. Il est nécessaire de s'engager pour défendre et faire

croître la parfaite unité du Corps du Christ, dans laquelle peuvent se composer

de manière harmonieuse la paix de l'ordre et les relations personnelles

sincères dans l'Esprit.

Il est peut-être utile de reprendre, pour conclure,

certains des éléments principaux de la doctrine spirituelle de Théodore. Amour

pour le Seigneur incarné et pour sa visibilité dans la Liturgie et dans les

icônes. Fidélité au baptême et engagement à vivre dans la communion du Corps du

Christ, entendue également comme communion des chrétiens entre eux. Esprit de

pauvreté, de sobriété, de renoncement; chasteté, maîtrise de soi, humilité et

obéissance contre le primat de sa propre volonté, qui détruit le tissu social

et la paix des âmes. Amour pour le travail matériel et spirituel. Amitié

spirituelle née de la purification de sa propre conscience, de son âme, de sa

propre vie. Cherchons à suivre ces enseignements qui nous montrent réellement

la voie de la vraie vie.

* * *

Je salue avec joie les pèlerins francophones,

particulièrement les groupes de jeunes de Bitche, d’Aix-en-Provence et du

Luxembourg, ainsi que les pèlerins de l’Archidiocèse de Clermont-Ferrand. A la

suite de saint Théodore le Studite, n’ayez pas peur de vous laisser guider par

l’Esprit Saint « hôte très doux de nos âmes ». Avec ma Bénédiction

apostolique.

© Copyright 2009 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

SOURCE :

http://w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/fr/audiences/2009/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20090527.html

Pope Benedict XVI

St Theodore the Studite

On Wednesday, 27 May [2009], at the General Audience in St Peter's Square the Holy Father spoke about St Theodore the Studite, a monk of the medieval Byzantine period who vigorously opposed the iconoclastic movement. The following is a translation of the Pope's Catechesis, which was given in Italian. Dear Brothers and Sisters, The Saint we meet today, St Theodore the Studite, brings us to the middle of the medieval Byzantine period, in a somewhat turbulent period from the religious and political perspectives. St Theodore was born in 759 into a devout noble family: his mother Theoctista and an uncle, Plato, Abbot of the Monastery of Saccudium in Bithynia, are venerated as saints. Indeed it was his uncle who guided him towards monastic life, which he embraced at the age of 22. He was ordained a priest by Patriarch Tarasius, but soon ended his relationship with him because of the toleration the Patriarch showed in the case of the adulterous marriage of the Emperor Constantine This led to Theodore's exile in 796 to Thessalonica. He was reconciled with the imperial authority the following year under the Empress Irene, whose benevolence induced Theodore and Plato to transfer to the urban monastery of Studios, together with a large portion of the community of the monks of Saccudium, in order to avoid the Saracen incursions. So it was that the important "Studite Reform" began. Theodore's personal life, however, continued to be eventful. With his usual energy, he became the leader of the resistance against the iconoclasm of Leo V, the Armenian who once again opposed the existence of images and icons in the Church. The procession of icons organized by the monks of Studios evoked a reaction from the police. Between 815 and 821, Theodore was scourged, imprisoned and exiled to various places in Asia Minor. In the end he was able to return to Constantinople but not to his own monastery. He therefore settled with his monks on the other side of the Bosporus. He is believed to have died in Prinkipo on 11 November 826, the day on which he is commemorated in the Byzantine Calendar. Theodore distinguished himself within Church history as one of the great reformers of monastic life and as a defender of the veneration of sacred images, beside St Nicephorus, Patriarch of Constantinople, in the second phase of the iconoclasm. Theodore had realized that the issue of the veneration of icons was calling into question the truth of the Incarnation itself. In his three books, the Antirretikoi (Confutation), Theodore makes a comparison between eternal intra-Trinitarian relations, in which the existence of each of the divine Persons does not destroy their unity, and the relations between Christ's two natures, which do not jeopardize in him the one Person of the Logos. He also argues: abolishing veneration of the icon of Christ would mean repudiating his redeeming work, given that, in assuming human nature, the invisible eternal Word appeared in visible human flesh and in so doing sanctified the entire visible cosmos. Theodore and his monks, courageous witnesses in the period of the iconoclastic persecutions, were inseparably bound to the reform of coenobitic life in the Byzantine world. Their importance was notable if only for an external circumstance: their number. Whereas the number of monks in monasteries of that time did not exceed 30 or 40, we know from the Life of Theodore of the existence of more than 1,000 Studite monks overall. Theodore himself tells us of the presence in his monastery of about 300 monks; thus we see the enthusiasm of faith that was born within the context of this man's being truly informed and formed by faith itself. However, more influential than these numbers was the new spirit the Founder impressed on coenobitic life. In his writings, he insists on the urgent need for a conscious return to the teaching of the Fathers, especially to St Basil, the first legislator of monastic life, and to St Dorotheus of Gaza, a famous spiritual Father of the Palestinian desert. Theodore's characteristic contribution consists in insistence on the need for order and submission on the monks' part. During the persecutions they had scattered and each one had grown accustomed to living according to his own judgement. Then, as it was possible to re-establish community life, it was necessary to do the utmost to make the monastery once again an organic community, a true family, or, as St Theodore said, a true "Body of Christ". In such a community the reality of the Church as a whole is realized concretely. Another of St Theodore's basic convictions was this: monks, differently from lay people, take on the commitment to observe the Christian duties with greater strictness and intensity. For this reason they make a special profession which belongs to the hagiasmata (consecrations), and it is, as it were, a "new Baptism", symbolized by their taking the habit. Characteristic of monks in comparison with lay people, then, is the commitment to poverty, chastity and obedience. In addressing his monks, Theodore spoke in a practical, at times picturesque manner about poverty, but poverty in the following of Christ is from the start an essential element of monasticism and also points out a way for all of us. The renunciation of private property, this freedom from material things, as well as moderation and simplicity apply in a radical form only to monks, but the spirit of this renouncement is equal for all. Indeed, we must not depend on material possessions but instead must learn renunciation, simplicity, austerity and moderation. Only in this way can a supportive society develop and the great problem of poverty in this world be overcome. Therefore, in this regard the monks' radical poverty is essentially also a path for us all. Then when he explains the temptations against chastity, Theodore does not conceal his own experience and indicates the way of inner combat to find self control and hence respect for one's own body and for the body of the other as a temple of God. However, the most important renunciations in his opinion are those required by obedience, because each one of the monks has his own way of living, and fitting into the large community of 300 monks truly involves a new way of life which he describes as the "martyrdom of submission". Here too the monks' example serves to show us how necessary this is for us, because, after the original sin, man has tended to do what he likes. The first principle is for the life of the world, all the rest must be subjected to it. However, in this way, if each person is self-centred, the social structure cannot function. Only by learning to fit into the common freedom, to share and to submit to it, learning legality, that is, submission and obedience to the rules of the common good and life in common, can society be healed, as well as the self, of the pride of being the centre of the world. Thus St Theodore, with fine introspection, helped his monks and ultimately also helps us to understand true life, to resist the temptation to set up our own will as the supreme rule of life and to preserve our true personal identity — which is always an identity shared with others — and peace of heart. For Theodore the Studite an important virtue on a par with obedience and humility is philergia, that is, the love of work, in which he sees a criterion by which to judge the quality of personal devotion: the person who is fervent and works hard in material concerns, he argues, will be the same in those of the spirit. Therefore he does not permit the monk to dispense with work, including manual work, under the pretext of prayer and contemplation; for work — to his mind and in the whole monastic tradition — is actually a means of finding God. Theodore is not afraid to speak of work as the "sacrifice of the monk", as his "liturgy", even as a sort of Mass through which monastic life becomes angelic life. And it is precisely in this way that the world of work must be humanized and man, through work, becomes more himself and closer to God. One consequence of this unusual vision is worth remembering: precisely because it is the fruit of a form of "liturgy", the riches obtained from common work must not serve for the monks' comfort but must be ear-marked for assistance to the poor. Here we can all understand the need for the proceeds of work to be a good for all. Obviously the "Studites'" work was not only manual: they had great importance in the religious and cultural development of the Byzantine civilization as calligraphers, painters, poets, educators of youth, school teachers and librarians. Although he exercised external activities on a truly vast scale, Theodore did not let himself be distracted from what he considered closely relevant to his role as superior: being the spiritual father of his monks. He knew what a crucial influence both his good mother and his holy uncle Plato — whom he described with the significant title "father" — had had on his life. Thus he himself provided spiritual direction for the monks. Every day, his biographer says, after evening prayer he would place himself in front of the iconostasis to listen to the confidences of all. He also gave spiritual advice to many people outside the monastery. The Spiritual Testament and the Letters highlight his open and affectionate character, and show that true spiritual friendships were born from his fatherhood both in the monastic context and outside it. The Rule, known by the name of Hypotyposis, codified shortly after Theodore's death, was adopted, with a few modifications, on Mount Athos when in 962 St Athanasius Anthonite founded the Great Laura there, and in the Kievan Rus', when at the beginning of the second millennium St Theodosius introduced it into the Laura of the Grottos. Understood in its genuine meaning, the Rule has proven to be unusually up to date. Numerous trends today threaten the unity of the common faith and impel people towards a sort of dangerous spiritual individualism and spiritual pride. It is necessary to strive to defend and to increase the perfect unity of the Body of Christ, in which the peace of order and sincere personal relations in the Spirit can be harmoniously composed. It may be useful to return at the end to some of the main elements of Theodore's spiritual doctrine: love for the Lord incarnate and for his visibility in the Liturgy and in icons; fidelity to Baptism and the commitment to live in communion with the Body of Christ, also understood as the communion of Christians with each other; a spirit of poverty, moderation and renunciation; chastity, self-control, humility and obedience against the primacy of one's own will that destroys the social fabric and the peace of souls; love for physical and spiritual work; spiritual love born from the purification of one's own conscience, one's own soul, one's own life. Let us seek to comply with these teachings that really do show us the path of true life.

Taken from:

L'Osservatore Romano Weekly Edition in English 3 June 2009, page 15 The Weekly Edition in English is published for the US by: The Cathedral Foundation L'Osservatore Romano English Edition 320 Cathedral St. Baltimore, MD 21201 Subscriptions: (410) 547-5315 Fax: (410) 332-1069 lormail@catholicreview.org

Provided Courtesy of:

Eternal Word Television Network 5817 Old Leeds Road Irondale, AL 35210 www.ewtn.com |

St.

Theodore of Studium

A zealous champion of the veneration

of images and the last geat

representative of the unity and

independence of the Church in the East, b. in 759; d. on the

Peninsula of Tryphon, near the

promontory Akrita on 11 November, 826. He belonged to a very

distinguished family and like his two brothers, one of

whom, Joseph, became Archbishop of Thessalonica, was highly educated. In 781 theodore

entered the monastery of Saccudion

on the Asiatic side of the Bosphorus near Constantinople,

where his uncle Plato was abbot. In 787 or 788 Theodore

was ordained priest and in 794 succeeded his uncle. He insisted

upon the exact observance of the monastic

rules. During the Adulterine heresy dispute (see SAINT NICEPHORUS), concerning the divorce and remarriage

of the Emperor Constantine VI, he was banished by Constantine VI to Thessalonica, but returned in triumph after the emperor's

overthrow. In 799 he left Saccudion,

which was threatened by the Arabs, and took charge of the monastery of the Studium at Constantinople.

He gave the Studium an excellent organization which was

taken as a model by the entire Byzantine

monastic world, and still exists

on Mount Athos and in Russian

monasticism. He supplemented the

somewhat theoretical rules of St. Basil by specific regulations concerning enclosure, poverty,

discipline, study, religious

services, fasts, and manual labour. When the Adulterine

heresy dispute broke out again in 809, he was exiled

a second time as the head of the strictly orthodox church

part, but was recalled in 811. The administration of the iconoclastic Emperor Leo V brought new and more severe trials. Theodore

courageously denied the emperor's right

to interfere in ecclesiastical affairs. He was consequently

treated with great cruelty, exiled, and his monastery filled with iconoclastic monks. Theodore

lived at Metopa in Bithynia from 814, then at Bonita from 819, and finally at Smyrna. Even in banishment he was the central point

of the opposition to Cæsaropapism

and Iconoclasm. Michael

II (810-9) permitted the exiles to return, but did not annul the laws of his predecessor. Thus Theodore

saw himself compelled to continue the struggle. He did not return to the Studium, and died without having attained his ideals.

In the Roman Martyrology

his feast is placed on 12 November; in the Greek

martyrologies on 11 November.

Theodore was a man

of practical bent and never wrote any theological works, except a dogmatic

treatise on the veneration of images.

Many of his works are still unprinted or exist

in Old Slavonic and Russian

translations. Besides several polemics against the enemies of images, special

mention should be made of the "Catechesis magna", and the

"Catechesis parva" with their sonorous sermons

and orations. His writings on monastic life

are: the iambic verses on the monastic

offices, his will addressed to

the monks, the "Canones", and the "Pænæ

monasteriales", the regulations for the monastery and for the church

services. His hymns and epigrams show fiery feeling and

a high spirit. He is one of the

first of hymn-writers in productiveness, in a peculiarly creative technic, and

in elegance of language. 550 letters testify to his ascetical

and ecclesiastico-political labours.

Sources

Theodorus Studites, Opera varia,

ed. SIRMOND (Paris, 1696); P.G., XCIX; Nova patrum bibl., V,

VIII, IX, X (Rome, 1849, 1871, 1888, 1905); Theodorus Studites, Parva

Catechesis, ed. AUVRAT-TOUGARD (Paris, 1891); Bibl. hagiogr. Græca

(2nd ed., Brussels, 1909), 249; THOMAS, Theodor von Studien (Osnabrück,

1892); GARDNER, Theodore of Studium (London, 1905).

Löffler, Klemens. "St. Theodore of Studium." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 11 Nov. 2015

<http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/14574a.htm>.

Transcription. This article was transcribed for

New Advent by WGKofron. In memory of Fr. John Hilkert, Akron, Ohio — Fidelis servus et

prudens, quem constituit Dominus super familiam suam.

Ecclesiastical approbation. Nihil Obstat. July 1, 1912. Remy Lafort, S.T.D., Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of

New York.

Theodore the Studite,

Abbot (RM)

Born at Constantinople in 759; died at Akrita, 826. Saint Theodore was the son

of an imperial treasury official. Theodore became a novice at a monastery

established by his father on his estate at Saccudium (Sakkoudion) near

Constantinople, where he was sent to study by his uncle Abbot Saint Plato of

Symboleon.

He was ordained in

787 in Constantinople, returned to the monastery, and in 794 succeeded his

uncle as abbot of the monastery of Sakkoudion in Bithynia. He and his monks

were banished for a short time in 796 for his refusal to countenance Emperor

Constantine VI's divorce and remarriage to Theodota but they returned when

Constantine's mother, Irene, seized power, dethroned and then blinded her son.

Theodore reopened

Sakkoudion but in 799 he transferred his community to Constantinople to escape

the Saracen raids. There they occupied the monastery founded by the Roman

consul Studius in 463 and he was again named abbot. The Studios Monastery was

famous partly because of its age, but it had been neglected and rundown. Under

Theodore's direction this house developed remarkably from 12 monks to a

thousand.

Theodore's ideals

and regulations have had a far-reaching influence in Byzantine monasticism. He

encouraged learning and the arts, founded a school of calligraphy, and wrote a

rule for the monastery that was adopted in Russia, Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia,

and even on Mount Athos. He restored liturgical prayer, community life,

enclosure, poverty, and manual labor among his monks. These reforms and

developments were brought about under great external difficulties.

When he opposed the

emperor's appointment of a layman, Nicephorus, to succeed Tarasius, who had

died in 806 as patriarch of Constantinople, Theodore was imprisoned by the

emperor.

From 809 to 811

Theodore was in exile on Prince's Island with his uncle Plato and his brother

Archbishop Joseph of Thessalonica on account of further troubles arising out of

the late emperor's adultery. At that time the emperor dispersed the monks of

Studios. Theodore returned to Constantinople on the emperor's death and was reconciled

to Patriarch Nicephorus in a common fight against Emperor Leo V the Armenian,

who revived iconoclasm as an imperial policy. When Nicephorus was banished,

Theodore organized public resistance, and he was again exiled to Mysia in 813.

For seven years he

was confined at various places with extreme rigor, even to being flogged by his

jailers. But he continued by letter to encourage his followers to keep up the

struggle, and he sent an appeal to Pope Paschal I (emphasizing the primacy of

the bishop of Rome), who sent legates to Constantinople; but they achieved

nothing except Theodore's removal to Bonita in Anatolia (now in Turkey). He

endured great hardships for the three years he was imprisoned there and was

then transferred to Smyrna and placed in the custody of an iconoclast bishop

who wanted him beheaded and treated him with great harshness.

After the violent

death of Leo V in 820, Theodore was released, but was again faced with a

renewed iconoclasm under Emperor Michael the Stammerer, and was not allowed to

return permanently to the Studite monastery. Theodore left Constantinople and

visited monasteries in Bithynia, founded a monastery on Akrita for many of his

monks who had followed him, and he died there in semi-exile on November 11.

Saint Theodore stands out as a champion of the Church's religious independence

of civil power, a defender of the legitimacy of sacred images, and a monastic

reformer of genius. He has been called an incomparable agitator: he was

certainly strong-willed and intransigent, even domineering; but there was a

less rigid side to him, which can be seen in some of the more personal of his

very numerous extant letters. There have also survived, as well as polemical

writings, catechetical works, sermons, hymns, and epigrams. Saint Theodore was

also a skilled calligrapher, an art which he fostered among his monks

(Attwater, Benedictines, Delaney, Gardner).

This anonymous

Russian icon shows Saint Theodore with Saint Theodosius the Great.

Saint Theodore the Confessor,

Abbot of the Studion was born in the year 758 at Constantinople into a family

of the imperial tax-collector Photinus and his spouse Theoctiste, both pious

Christians. St Theodore received a good education from the best rhetoricians,

philosophers and theologians in the capital city.

During this time the

Iconoclast heresy had become widespread in the Byzantine Empire, and it was

supported also by the impious emperor Constantine Kopronymos (741-775). The

views of the emperor and his court conflicted with the religious beliefs of

Photinus, who was a fervent adherent of Orthodoxy, and so he left government

service. Later, St Theodore’s parents, by mutual consent, gave away their

substance to the poor, took their leave of each other and accepted monastic

tonsure. Their son Theodore soon became widely known in the capital for his

participation of the numerous disputes concerning icon-veneration.

St Theodore was

accomplished in oratory, and had a command of the terminology and logic of the

philosophers, so he frequently debated with the heretics. His knowledge of Holy

Scripture and Christian dogma was so profound that no one could get the better

of him.

The Seventh Ecumenical

Council put an end to dissension and brought peace to the Church under the

empress Irene. The Ecumenical Council, as the highest authority in the life of

the Church, forever condemned and rejected Iconoclasm.

Among the Fathers of the

Council was St Platon (April 5), an uncle of St Theodore, and who for a long

time had lived the ascetic life on Mount Olympos. An Elder filled with the

grace of the Holy Spirit, St Platon, at the conclusion of the Council, summoned

his nephew Theodore and his brothers Joseph and Euthymius to the monastic life

in the wilderness.

After leaving

Constantinople, they went to Sakkoudion, not far from Olympos. The solitude and

the beauty of the place, and its difficulty of access, met with the approval of

the Elder and his nephews, and they decided to remain here. The brothers built

a church dedicated to St John the Theologian, and gradually the number of monks

began to increase. A monastery was formed, and St Platon was the igumen.

St Theodore’s life was

truly ascetic. He toiled at heavy and dirty work. He strictly kept the fasts,

and each day he confessed to his spiritual Father, the Elder Platon, revealing

to him all his deeds and thoughts, carefully fulfilling all his counsels and

instructions.

Theodore made time for

daily spiritual reflection, baring his soul to God. Untroubled by any earthly

concern, he offered Him mystic worship. St Theodore unfailingly read the Holy

Scripture and works of the holy Fathers, especially the works of St Basil the

Great, which were like food for his soul.

After several years of

monastic life, St Theodore was ordained a priest according to the will of his

spiritual Father. When St Platon went to his rest, the brethren unanimously

chose St Theodore as Igumen of the monastery. Unable to oppose the wish of his

confessor, St Theodore accepted the choice of the brethren, but imposed upon

himself still greater deeds of asceticism. He taught the others by the example

of his own virtuous life and also by fervent fatherly instruction.

When the emperor

transgressed against the Church’s canons, the events of outside life disturbed

the tranquility in the monastic cells. St Theodore bravely distributed a letter

to the other monasteries, in which he declared the emperor Constantine VI

(780-797) excommunicated from the Church by his own actions for abusing the

divine regulations concerning Christian marriage.

St Theodore and ten of

his co-ascetics were sent into exile to the city of Thessalonica. But there

also the accusing voice of the monk continued to speak out. Upon her return to

the throne in 796, St Irene freed St Theodore and made him igumen of the

Studion monastery (dedicated to St John the Baptist) in Constantinople, in

which there were only twelve monks. The saint soon restored and enlarged the

monastery, attracting about 1,000 monks who wished to have him as their spiritual

guide.

St Theodore composed a

Rule of monastic life, called the “Studite Rule” to govern the monastery. St

Theodore also wrote many letters against the Iconoclasts. For his dogmatic

works, and also for his Canons and Three-Ode Canons, St Theoctistus called St

Theodore “a fiery teacher of the Church.”

When Nicephorus seized

the imperial throne, deposing the pious Empress Irene, he also violated Church

regulations by restoring to the Church a previously excommunicated priest on

his own authority. St Theodore again denounced the emperor. After torture, the

monk was sent into exile once again, where he spent more than two years.

St Theodore was freed by

the gentle and pious emperor Michael, who succeeded to the throne upon the

death of Nicephoros and his son Staurikios in a war against barbarians. Their

death had been predicted by St Theodore for a long while. In order to avert

civil war, the emperor Michael abdicated the throne in favor of his military

commander Leo the Armenian.

The new emperor proved to

be an iconoclast. The hierarchs and teachers of the Church attempted to reason

with the impious emperor, but in vain. Leo prohibited the veneration of holy

icons and desecrated them. Grieved by such iniquity, St Theodore and the

brethren made a religious procession around the monastery with icons raised

high, singing of the troparion to the icon of the Savior Not-Made-by-Hands

(August 16). The emperor angrily threatened the saint with death, but he

continued to encourage believers in Orthodoxy. Then the emperor sentenced St

Theodore and his disciple Nicholas to exile, at first in Illyria at the

fortress of Metopa, and later in Anatolia at Bonias. But even from prison the

confessor continued his struggle against heresy.

Tormented by the

executioners which the emperor sent to Bonias, deprived almost of food and

drink, covered over with sores and barely alive, Theodore and Nicholas endured

everything with prayer and thanksgiving to God. At Smyrna, where they sent the

martyrs from Bonias, St Theodore healed a military commander from a terrible

illness. The man was a nephew of the emperor and of one mind with him. St

Theodore told him to repent of his wicked deeds of Iconoclasm, and to embrace

Orthodoxy. But the fellow later relapsed into heresy, and then died a horrible

death.

Leo the Armenian was

murdered by his own soldiers, and was replaced by the equally impious though

tolerant emperor Michael II Traulos (the Stammerer). The new emperor freed all

the Orthodox Fathers and confessors from prison, but he prohibited icon-veneration

in the capital.

St Theodore did not want

to return to Constantinople and so decided to settle in Bithynia on the

promontory of Akrita, near the church of the holy Martyr Tryphon. In spite of

serious illness, St Theodore celebrated Divine Liturgy daily and instructed the

brethren. Foreseeing his end, the saint summoned the brethren and bade them to

preserve Orthodoxy, to venerate the holy icons and observe the monastic rule.

Then he ordered the brethren to take candles and sing the Canon for the Departure

of the Soul From the Body. Just before singing the words “I will never forget

Thy statutes, for by them have I lived,” St Theodore fell asleep in the Lord,

in the year 826. At the same hour St Hilarion of Dalmatia (June 6) saw a vision

of a heavenly light during the singing and the voice was heard, “This is the

soul of St Theodore, who suffered even unto blood for the holy icons, which now

departs unto the Lord.”

St Theodore worked many

miracles during his life and after his death. Those invoking his name have been

delivered from fires, and from the attacks of wild beasts, they have received

healing, thanks to God and to St Theodore the Studite. On January 26 we

celebrate the transfer of the relics of Theodore the Studite from Cherson to

Constantinople in the year 845.

Those with stomach

ailments entreat the help of St Theodore.

SOURCE

: http://oca.org/saints/lives/2015/11/11/103281-venerable-theodore-the-confessor-the-abbot-of-the-studion

November 22

St. Theodorus the Studite, Abbot

ST. PLATO, the holy abbot of Symboleon upon Mount Olympus, in Bithynia, being obliged to come to Constantinople for certain affairs, was received there as an angel sent from heaven, and numberless conversions were the fruit of his example and pious exhortations. He reconciled families that were at variance, promoted all virtue, and corrected vice. Soon after his return to Symboleon, the whole illustrious family of his sister Theoctista resolved to imitate his example, and, renouncing the world, founded the abbey of Saccudion near Constantinople in 781. Among these novices no one was more fervent in every practice of virtue than Theodorus, the son of Theoctista, then in the twenty-second year of his age. St. Plato was with difficulty prevailed upon to resign his abbacy in Bithynia to take upon him the government of this new monastery, in 782. Theodorus made so great progress in virtue and learning that, in 794, his uncle abdicated the government of the house, and, by the unanimous consent of the community, invested him in that dignity, shutting himself up in a narrow cell.

The young emperor Constantine having, in 795, put away Mary, his lawful wife, after seven years’ cohabitation, and taken to his bed Theodota, a near relation of SS. Plato and Theodorus, the saints declared loudly against such scandalous enormities. The emperor desired exceedingly to gain Theodorus, and employed for that purpose his new empress Theodota; but though she used her utmost endeavours, by promises of large sums of money and great presents, and by the consideration of their kindred, her attempts were fruitless. The emperor then went himself to the monastery; but neither the abbot nor any of his monks were there to receive him. The prince returned to his palace in a great rage, and sent two officers with an order to see Theodorus and those monks who were his most resolute adherents severely scourged. The punishment was inflicted on the abbot and ten monks with such cruelty that the blood ran down their bodies in streams; which they suffered with great meekness and patience. After this they were banished to Thessalonica, and a strict order was published, forbidding any one to receive or entertain them, so that even the abbots of that country durst not afford them any relief. St. Plato was confined in the abbey of St. Michael. St. Theodorus wrote him from Thessalonica an account of his sufferings, with the particulars of his journey. 1 He wrote also to Pope Leo III. and received an answer highly commending his wisdom and constancy. The emperor’s mother, Irene, having gained the principal officers, dethroned her son, and ordered his eyes to be put out: which was executed with such violence that he died of the wounds in 797. After this Irene reigned five years alone, and recalled the exiles. St. Theodorus returned to Saccudion, and reassembled his scattered flock; but finding this monastery exposed to the insults of the Mussulmans or Saracens, who made incursions to the gates of Constantinople, took shelter within the walls of the city. The patriarch and the empress pressed him to settle in the famous monastery of Studius, so called from its founder, a patrician and consul, who, coming from Rome to Constantinople, had formerly built that monastery. Constantine Copronymus had expelled the monks; but St. Theodorus restored this famous abbey, and had the comfort to see in it above a thousand monks.

In 802 the empress Irene was deposed by Nicephorus, her chief treasurer, and banished to a monastery in Prince’s Island, and afterwards to the Isle of Lesbos, where she died in close confinement in 803. Nicephorus assumed the imperial diadem on the last day of October, in 802. He was one of the most treacherous and perfidious of men, dissimulation being his chief talent, and it was accompanied with the basest cruelty against all whom he but suspected to be his enemies; of which the chronicles of Theophanes and Nicephorus have preserved most shocking instances. He was a fast friend to the Manichees or Paulicians. who were numerous in Phrygia and Lycaonia, near his own country, and was fond of their oracles and superstitions to a degree of frenzy. He grievously oppressed the Catholic bishops and monasteries, and when remonstrances were made to him by a prudent friend, how odious he had rendered himself to the whole empire by his avarice and impiety, his answer was, “My heart is hardened. Never expect any thing but what you see from Nicephorus.” Setting out in May, in 811, to invade Bulgaria, he desired to gain St. Theodorus, who had boldly reproved him for his impiety. He sent certain magistrates to the holy abbot for this purpose. The saint answered them as if he was speaking to the emperor, and said: “You ought to repent, and not make the evil incurable. Not content to bring yourselves to the brink of the precipice, you drag others headlong after you. He, whose eye beholdeth all things, declareth by my mouth that you shall not return from this expedition.” Nicephorus entered Bulgaria with a superior force, and refused all terms which Crummius, king of the Bulgarians, offered him. The barbarian, being driven to despair, came upon him by surprise, enclosed, attacked, and slew him in his tent on the 25th of July, in 811, when he had reigned eight years and nine months. Many patricians and the flower of the Christian army perished in this action. Great numbers were made prisoners, and many of these were tormented, hanged, beheaded, or shot to death with arrows, rather than consent to renounce their faith, as the Bulgarians, who were then pagans, would have forced them to do. These are honoured by the Greeks as martyrs on the 23rd of July. King Crummius caused a drinking-cup to be made of the emperor’s head, to be used on solemn festivals, according to the custom of the ancient Scythians. Stanricius, the son of Nicephorus, was proclaimed emperor; but he, being wounded in the late battle, took the monastic habit, and died of his wounds in the beginning of the following year. Two months after the death of Nicephorus, Michael Curopolates, surnamed Rangabè, who had married Procopia, the daughter of Nicephorus, was crowned emperor on the 2nd of October. He was magnificent, liberal, pious, and a zealous Catholic. By his endeavours all divisions in the church of Constantinople were made up, and the patriarch St. Nicephorus reconciled with St. Plato and St. Theodorus. Michael commanded the Paulicians to be punished with death; and some were beheaded. But St. Nicephorus put a stop to the further execution of that edict, by persuading him that it was better to leave those heretics room for repentance, though the abominations which they practised were most execrable. An Armenian called Paul, who made his escape from Constantinople into Cappadocia, and there, setting up a school, and pretending to inspiration, continued chief of this sect for thirty years: from him these Manichees were called Paulicians, but, by his sons and others, were soon divided into several sects, all infamous for abominable impurities. 2 St. Plato died in 813, on the 19th of March, and the Emperor Michael having been shamefully defeated by the Bulgarians, resolved to resign the empire. This design he communicated to Leo the Armenian, governor of Natolia, and son of the patrician Bardas, who thereupon was chosen and crowned emperor, on the 11th of July. Michael, with his wife and children, took sanctuary in a church, and all of them embraced the monastic state. Leo defended Constantinople against the barbarians; but having perfidiously attempted to kill their king, under pretence of a conference, that prince, in a rage, took Adrianople, and carried the archbishop Manuel and the rest of the inhabitants captives into Bulgaria, where they converted many to the Christian faith. For their zeal in preaching Christ, the archbishop and three hundred and seventy-six other Christian captives were put to cruel deaths by order of the successor of Crummius. The Greek church honours them as martyrs on the 22nd of January.

During these public commotions, St. Theodorus enjoyed the sweet calm of his retirement, studying every day to advance in the perfection of holy charity, and to die more perfectly to himself. He was versed in the sciences, but was the more solicitous to acquire a settled humility of heart, without which learning serves only to puff up. Humility and purity of heart give light of understanding, purge the affections, and illustrate the mind; for it is impossible, as Cassian remarks, 3 that an unclean mind should obtain the gift of spiritual knowledge, or an unmortified heart that of divine charity. Our saint’s solitude was disturbed by a storm which threatened the Eastern church. The heresy of the Iconoclasts, which Leo the Isaurian had set up in the East in 725, was espoused by Leo the Armenian, who, in December, 814, signified his intention of abolishing holy images to the patriarch St. Nicephorus. The patriarch replied: “We cannot alter the ancient traditions. We venerate images as we do the cross and the book of the gospels, though there is nothing written concerning them,” (for the Iconoclasts agreed to reverence the cross and the gospels.) The holy patriarch was deprived in 815, and Theodotus Cassiterus, an Iconoclast, at that time equerry to the emperor, an illiterate layman, was ordained in his room. As soon as Nicephorus was deposed, the enemies of holy images began to deface, pull down, burn, and profane them all manner of ways. St. Theodorus the Studite, to repair this scandal as much as in him lay, ordered all his monks to take images in their hands, and to carry them solemnly lifted up in the procession on Palm-Sunday, singing a hymn which begins, “We reverence thy most pure image,” and others of the like nature, in honour of Christ. The emperor, upon notice hereof, sent him a prohibition to do the like upon pain of scourging and death. The holy abbot, nevertheless, continued to encourage all to honour holy images, for which the emperor banished him into Mysia, and commanded him to be there closely confined in the castle of Mesope, near Apollonia. He forbore not still to animate the Catholics by letters, of which a great number are extant. His correspondence being discovered, the emperor ordered him to be conveyed to the tower Bonitus, at a greater distance, in Natolia; and afterwards sent Nicetas, his commissary, to see him severely scourged. Nicetas, seeing the cheerfulness with which St. Theodorus put off his tunic, and offered his naked body, wasted with fasting, to the blows, was moved with compassion, and conceived the highest veneration for the servant of God. In order to spare him, as often as the sentence was to be executed, he contrived, under pretence of decency, to send all others out of the dungeon; then, throwing a sheep-skin over Theodorus’s back, he discharged upon it a great number of blows, which were heard by those without; then pricking his arm, to stain the whips with blood, he showed them when he came out, and seemed out of breath with the pains he had taken. By his indulgence, St. Theodorus was able to write several letters in support of the Catholic cause. The most remarkable are those which he sent to all the patriarchs, and to Pope Paschal. To this last he writes: “Give ear, O apostolic prelate, shepherd appointed by God over the flock of Jesus Christ; who have received the keys of the kingdom of heaven; the rock on which the Catholic church is built; for you are Peter, since you fill his see. Come to our assistance.” 4 The pope having vigorously ejected from his communion Theodotus and all the Iconoclasts, St. Theodorus wrote him a letter of thanks, in which he said: “You are from the beginning the pure source of the orthodox faith: you are the secure harbour of the universal church, her shelter against the storms of heretics, and the city of refuge chosen by God for safety.” 5 All the five patriarchs were unanimous in the condemnation of the Iconoclasts, as appears by the letters of St. Theodorus, and other monuments.

Several famous Iconoclasts having been converted by our saint, he and his disciple Nicholas were both hung in the air, and cruelly torn with whips, each receiving a hundred stripes. After this they were shut up in a close and noisome prison, so strictly guarded, that no one could come near them. Here they remained three years, enduring extreme cold in winter, and almost stifled in summer; eaten by all sorts of vermin, and tormented with hunger and thirst: for their guards, who were continually scoffing at them, threw them in at a hole in a window only a little piece of bread every other day. St. Theodorus testifies, that he expected they would be left very soon to perish with hunger; and adds, “God is yet but too merciful to us.” 6 He strenuously maintained the rigorous discipline of canonical penances, which all penitents were to undergo, who, for fear of torments or otherwise, had conformed to the Iconoclasts. 7 One of his letters being at length intercepted, the emperor sent orders to the governor of the East, to cause him to be severely chastised. The governor committed the execution to an officer, who caused Nicholas, the disciple who had written the letter, to be cruelly scourged; then a hundred stripes to be given to Theodorus; and after this, Nicholas to be again scourged, and then to be left lying on the ground, exposed to the cold air, in the month of February. The abbot Theodorus also lay stretched on the ground, out of breath, and was a long time unable to take any rest, or receive almost any nourishment. His disciple, seeing him in this condition, forgetting his own pain, moistened his tongue with a little broth, and, after he had brought him to himself, endeavoured to dress his wounds, from which he was forced to cut away a great deal of mortified and corrupted flesh. Theodorus was in a high fever, and for three months in excessive pain. Before he was recovered, an officer arrived, sent by the emperor to conduct him and Nicholas to Smyrna, in June, 819. They were forced to walk in the day-time, and at night were put in irons.

At Smyrna, the archbishop, who was one of the most furious among the Iconoclasts, kept Theodorus confined in a dark dungeon under ground eighteen months, and caused him to receive a third time a hundred stripes. When the saint set out from thence to be conveyed to Constantinople, the inhuman archbishop said, he would desire the emperor to send an officer to cut off his head, or at least to cut out his tongue. The persecution ended the same year, with the life of him who had raised it. Michael, commander of the confederates, (a body of troops so called), was cast into prison by the emperor for a conspiracy against him, and his execution was only deferred one day, out of respect to the feast of Christmas, at the intercession of the empress. In the meantime the rest of the conspirators slew Leo at matins on Christmas night: his four sons and their mother were banished to the isle of Prote; and Michael was taken out of his dungeon, and, his fetters being knocked off, was crowned emperor. He was a native of Phrygia, and, from an impediment in his speech, is surnamed Michael the Stutterer. He had been educated in a certain heresy, in which was a mixture of Judaism, most of its laws being observed by this sect, except that baptism is substituted for circumcision, as Theophanes informs us. He denied the resurrection, maintained fornication to be lawful, and contemned studies, valuing himself only in the knowledge of mules, horses, and sheep. He at first affected great moderation towards the Catholics, but soon threw off the mask, and became a great persecutor. In the beginning of his reign the exiles were restored, and, among others, St. Theodorus the Studite came out of his dungeon, after full seven years’ imprisonment, from 815 to 821. He wrote a letter of thanks to Michael, exhorting him to be united with Rome, the first of the churches, and by her with the patriarchs, &c. Going towards Constantinople, he was received with the greatest honours, and wrought many miracles on the road. The new emperor refused to suffer any images in the city of Constantinople: on which account St. Theodorus, after making fruitless remonstrances to that prince, left it, and retired into the peninsula of St. Tryphon, and was followed by his disciples. He was taken ill in the beginning of November, yet walked to church on the fourth day, which was Sunday, and celebrated the holy sacrifice. His distemper increasing, he was not able to speak aloud, but he dictated to a secretary his last instructions, and to a great number of bishops and devout persons, who came to visit him in his sickness; and he left his monks an excellent testament, recommending to them fervour in all monastic duties, never to have any property, not so much as of a needle; to leave the care of temporal things to their stewards, exacting from them an account, and reserving to themselves only the care of souls; to admit no delicacy in eating, not even in the entertainment of guests; to keep no money in the monastery, and to give all superfluity to the poor; to walk on foot, and, when necessary to ride in long journeys, to make use only of an ass; not to open the gate of the monastery to any woman, nor ever to speak to any except in presence of two witnesses; to catechise or hold conferences three times a week; to transact no business, spiritual or temporal, without taking the advice of the master, &c. These rules were then observed by the monks in the East, and are more enlarged upon in his greater catechism. When his last hour approached, he desired the usual prayers of the church to be read, received extreme unction, and afterwards the viaticum. After this, the wax tapers were lighted, and his brethren, placing themselves round about him in a circle, began the prayers appointed for dying persons. They were singing the hundred and eighteenth psalm, which the Greeks still sing at funerals, when he expired, in the sixty-eighth year of his age. He died in the peninsula of Tryphon, on the coast of Bithynia, near Constantinople, on the 11th of November, and is commemorated by the Latins on the day following. His successor, Naucratius, abbot of Studius, wrote the circumstances of his death in a circular letter. His body was translated to the monastery of Studius, eighteen years after his death. See the letter of Naucratius, and the saint’s authentic anonymous life; also Theophanes in Chronogr., &c.

Note 1. Ep. 3. [back]

Note 2. See Theophan. Contin. [back]

Note 3. Collat. 14, c. 10. [back]

Note 4. S. Theod. Studit. ep. 3. [back]

Note 5. Ep. 15. [back]

Note 6. Ep. 34. [back]

Note 7. Ep. 11. &c. [back]

Rev. Alban Butler (1711–73). Volume XI: November. The Lives of the Saints. 1866.

SOURCE : http://www.bartleby.com/210/11/222.html

Tutto iniziò nel gennaio 795 quando l’imperatore romano di Oriente (basileus) Costantino VI (771-797) fece rinchiudere la moglie Maria di Armenia in monastero e iniziò una illecita unione con Teodota, dama d’onore della madre Irene. Pochi mesi dopo l’imperatore fece proclamare “augusta” Teodota, ma non riuscendo a convincere il patriarca Tarasio (730-806) a celebrare il nuovo matrimonio, trovò finalmente un ministro compiacente nel prete Giuseppe, igumeno del monastero di Kathara, nell’isola di Itaca, che benedisse ufficialmente l’unione adulterina.

San Teodoro, nato a Costantinopoli nel 759, era allora monaco nel monastero di Sakkudion in Bitinia, di cui era abate lo zio Platone, venerato anche lui come santo. Teodoro ricorda che l’ingiusto divorzio produsse un profondo turbamento in tutto il popolo cristiano: concussus est mundus (Epist. II, n. 181, in PG, 99, coll. 1559-1560CD) e, assieme a san Platone, protestò energicamente, in nome dell’indissolubilità del vincolo. L’imperatore deve ritenersi adultero – scrisse – e perciò deve ritenersi gravemente colpevole il prete Giuseppe per avere benedetto gli adulteri e per averli ammessi all’Eucarestia. «Incoronando l’adulterio», il prete Giuseppe si è opposto all’insegnamento di Cristo e ha violato la legge divina (Epist. I, 32, PG 99, coll. 1015/1061C). Per Teodosio era da condannare altresì il patriarca Tarasio che, pur non approvando le nuove nozze, si era mostrato tollerante, evitando sia di scomunicare l’imperatore che di punire l’economo Giuseppe.

Questo atteggiamento era tipico di un settore della Chiesa orientale che proclamava l’indissolubilità del matrimonio ma nella prassi dimostrava una certa sottomissione nel confronti del potere imperiale, seminando confusione del popolo e suscitando la protesta dei cattolici più ferventi. Basandosi sull’autorità di san Basilio, Teodoro rivendicò la facoltà concessa ai sudditi di denunciare gli errori del proprio superiore (Epist. I, n. 5, PG, 99, coll. 923-924, 925-926D) e i monaci di Sakkudion ruppero la comunione con il patriarca per la sua complicità nel divorzio dell’imperatore. Scoppiò così la cosiddetta “questione moicheiana” (da moicheia= adulterio) che pose Teodoro in conflitto non solo con il governo imperiale, ma con gli stessi patriarchi di Costantinopoli. E’ un episodio poco conosciuto sul quale, qualche anno fa, ha sollevato il velo il prof. Dante Gemmiti in un’attenta ricostruzione storica, basata sulle fonti greche e latine (Teodoro Studita e la questione moicheiana, LER, Marigliano 1993), che conferma come nel primo millennio la disciplina ecclesiastica della Chiesa d’Oriente rispettava ancora il principio dell’indissolubilità del matrimonio.

Nel settembre 796, Platone e Teodoro, con un certo numero di monaci del Sakkudion, furono arrestati, internati e poi esiliati a Tessalonica, dove giunsero il 25 marzo 797. A Costantinopoli però il popolo giudicava Costantino un peccatore che continuava a dare pubblico scandalo e, sull’esempio di Platone e Teodoro, l’opposizione aumentava di giorno in giorno. L’esilio fu di breve durata perché il giovane Costantino, in seguito a un complotto di palazzo, fu fatto accecare dalla madre che assunse da sola il governo dell’impero. Irene richiamò gli esiliati, che si trasferirono nel monastero urbano di Studios, insieme alla gran parte della comunità dei monaci di Sakkudion. Teodoro e Platone si riconciliarono con il patriarca Tarasio che, dopo l’avvento di Irene al potere, aveva pubblicamente condannato Costantino e il prete Giuseppe per il divorzio imperiale. Anche il regno di Irene fu breve. Il 31 ottobre 802 un suo ministro, Niceforo, in seguito a una rivolta di palazzo, si proclamò imperatore. Quando poco dopo morì Tarasio, il nuovo basileus fece eleggere patriarca di Costantinopoli un alto funzionario imperiale, anch’egli di nome Niceforo (758-828). In un sinodo da lui convocato e presieduto, verso la metà dell’806, Niceforo reintegrò nel suo ufficio l’egumeno Giuseppe, deposto da Tarasio. Teodoro, divenuto capo della comunità monastica dello Studios, per il ritiro di Platone a vita di recluso, protestò vivamente contro la riabilitazione del prete Giuseppe e, quando quest’ultimo riprese a svolgere il ministero sacerdotale, ruppe la comunione anche con il nuovo patriarca.

La reazione non tardò. Lo Studios venne occupato militarmente, Platone, Teodoro e il fratello Giuseppe, arcivescovo di Tessalonica, vennero arrestati, condannati ed esiliati. Nell’808 l’imperatore convocò un altro sinodo che si riunì nel gennaio 809. Fu quello che, in una lettera dell’809 al monaco Arsenio, Teodoro definisce “moechosynodus”, il “Sinodo dell’adulterio” (Epist. I, n. 38, PG 99, coll. 1041-1042c). Il Sinodo dei vescovi riconobbe la legittimità del secondo matrimonio di Costantino, confermò la riabilitazione dell’egumene Giuseppe e anatemizzò Teodoro, Platone e il fratello Giuseppe, che fu deposto dalla sua carica di arcivescovo di Tessalonica. Per giustificare il divorzio dell’imperatore, il Sinodo utilizzava il principio della “economia dei santi” (tolleranza nella prassi). Ma per Teodoro nessun motivo poteva giustificare la trasgressione di una legge divina. Richiamandosi all’insegnamento di san Basilio, di san Gregorio di Nazianzo e di san Giovanni Crisostomo, egli dichiarò priva di fondamento scritturale la disciplina dell’“economia dei santi”, secondo cui in alcune circostanze si poteva tollerare un male minore – come in questo caso il matrimonio adulterino dell’imperatore.

Qualche anno dopo l’imperatore Niceforo morì nella guerra contro i Bulgari (25 luglio 811) e salì al trono un altro funzionario imperiale, Michele I. Il nuovo basileus richiamò dall’esilio Teodoro, che divenne il suo consigliere più ascoltato. Ma la pace fu di breve durata. Nell’estate dell’813, i Bulgari inflissero a Michele I una gravissima sconfitta presso Adrianopoli e l’esercito proclamò imperatore il capo degli Anatolici, Leone V, detto l’Armeno (775-820). Quando Leone depose il patriarca Niceforo e fece condannare il culto delle immagini, Teodoro assunse la guida della resistenza contro l’iconoclastia. Teodoro infatti si distinse nella storia della Chiesa non solo come l’oppositore al “Sinodo dell’adulterio”, ma anche come uno dei grandi difensori delle sacre immagini durante la seconda fase dell’iconoclasmo. Così la domenica delle Palme dell’815 si poté assistere ad una processione dei mille monaci dello Studios che all’interno del loro monastero, ma bene in vista, portavano le sante icone, al canto di solenni acclamazioni in loro onore. La processione dei monaci dello Studios scatenò la reazione della polizia. Tra l’815 e l’821, Teodoro fu flagellato, incarcerato ed esiliato in diversi luoghi dell’Asia Minore. Alla fine poté tornare a Costantinopoli, ma non nel proprio monastero. Egli allora si stabilì con i suoi monaci dall’altra parte del Bosforo, a Prinkipo, dove morì l’11 novembre 826.

Il “non licet” (Mt 14, 3-11) che san Giovanni Battista oppose al tetrarca Erode, per il suo adulterio, risuonò più volte nella storia della Chiesa. San Teodoro Studita, un semplice religioso che osò sfidare il potere imperiale e le gerarchie ecclesiastiche del tempo, può essere considerato uno dei protettori celesti di chi, anche oggi, di fronte alle minacce di cambiamento della prassi cattolica sul matrimonio, ha il coraggio di ripetere un inflessibile non licet.

Nel 797, dopo la morte dell’imperatore, Teodoro fu richiamato in patria con tutti gli onori, lasciò Sakkoudion che nel frattempo era stata saccheggiata dagli Arabi e si trasferì nel monastero di Studion in Costantinopoli, dal quale prese il suo soprannome. Qui intraprese una forte campagna in favore dell’ascetismo e di radicali riforme monastiche. I punti focali della sua regola, utilizzata in seguito sia nei monasteri bizantini che in quelli russi, come Pečerska Lavra e Pocaiv Lavra, furono la clausura, la povertà, la disciplina, lo studio, i servizi religiosi ed il lavoro manuale.

L’abate Teodoro viene ricordato anche per aver autorizzato i suoi monaci a sbriciolare noce moscata, una delle spezie più costose all’epoca, sulla loro zuppa di piselli quando questi erano costretti a mangiarla. Questo aneddoto, la cui veridicità ci è difficile appurare, lungi dal ridicolizzare il santo ci è invece di aiuto nell’accostarci a lui negli aspetti della sua vita quotidiana quale pastore di una comunità, certamente salda guida spirituale, ma al tempo stesso impelagato in molteplici questioni logistiche che la vita comune di un gruppo di uomini necessariamente comporta.

Nel 809 Teodoro fu nuovamente bandito a causa del suo rifiuto di ricevere la comunione dal patriarca Niceforo, il quale aveva reintegrato il sacerdote Giuseppe reo di aver officiato le nozze tra Costantino e Teodota. Due anni dopo l’imperatore Michele I, sul quale aveva molta influenza, lo richiamò dall’esilio, ma fu di nuovo bandito nonché flagellato nel 814 a causa della sua strenua opposizione all'editto iconoclasta promulgato dall’imperatore Leone V, col quale si proibiva la venerazione delle immagini sacre. Liberato nel 821 dall’imperatore Michele II, promosse nel 824 un’insurrezione contro lo stesso, dal santo giudicato troppo indulgente nei confronti degli iconoclasti. Quando però i suoi piani fallirono, Teodoro ritenne allora opportuno allontanarsi da Costantinopoli.

Da quel momento visse peregrinando fra vari monasteri in Bitinia e morì in quello di Calkite l’11 novembre 826. Sepolto inizialmente proprio in tale monastero, il suo corpo fu successivamente traslato nel monastero di Studion il 26 gennaio 844. E’ festeggiato come santo dalla Chiesa cattolica nell’anniversario della morte, mentre nelle Chiese orientali si dedica alla sua memoria anche l’anniversario della traslazione.

San Teodoro compose parecchie opere letterarie. Innanzitutto, quale intrepido lottatore per la difesa dell’indissolubilità del matrimonio, sulla questione moichiana, ovvero l’unione adulterina di Costantino VI, scrisse un trattato ed uno scritto “Sull’economia in genere” che andarono purtroppo dispersi o più probabilmente distrutti per ordine del patriarca Metodio. Alla sua produzione sono inoltre attribuite lettere la cui importanza è costituita dal quadro della vita e del carattere del santo che in esse si desume e facenti inoltre luce sulle dispute teologiche cui intervenne; opere di catechesi suddivise in due collezioni rivolte ai monaci e contenti moniti e consigli connessi con la vita spirituale e con l’organizzazione monasteriale; orazioni funerarie per la propria madre e per lo zio Plato; opere teologiche incentrate sull’adorazione delle immagini sacre, epigrammi su vari soggetti, alcuni dei quali dimostrano una considerabile originalità, ed alcuni inni sacri. Inoltre, come tutti i monaci dello Studion, San Teodoro fu inoltre celebre per la sua calligrafia e per la sua bravura nel copiare manoscritti.

Autore: Fabio Arduino

November 22

St. Theodorus the Studite, Abbot

ST. PLATO, the holy abbot of Symboleon upon Mount Olympus, in Bithynia, being obliged to come to Constantinople for certain affairs, was received there as an angel sent from heaven, and numberless conversions were the fruit of his example and pious exhortations. He reconciled families that were at variance, promoted all virtue, and corrected vice. Soon after his return to Symboleon, the whole illustrious family of his sister Theoctista resolved to imitate his example, and, renouncing the world, founded the abbey of Saccudion near Constantinople in 781. Among these novices no one was more fervent in every practice of virtue than Theodorus, the son of Theoctista, then in the twenty-second year of his age. St. Plato was with difficulty prevailed upon to resign his abbacy in Bithynia to take upon him the government of this new monastery, in 782. Theodorus made so great progress in virtue and learning that, in 794, his uncle abdicated the government of the house, and, by the unanimous consent of the community, invested him in that dignity, shutting himself up in a narrow cell.