Saint Antoine-Marie Claret

Fondateur des Missionnaires Fils du Cœur Immaculé de

Marie (+ 1870)

Catalan, originaire des environs de Barcelone. Il fut

d'abord apprenti-tisserand, profession familiale. Puis il fut typographe, juste

le temps d'aimer la diffusion de la Parole de Dieu par la presse. Il trouva sa

voie à 22 ans en entrant au séminaire de Vicq. Prêtre, il parcourt la

Catalogne, chapelet en main, distribuant des brochures édifiantes qu'il avait

lui-même imprimées. Mais ces horizons étaient encore trop étriqués à ses yeux.

En 1849, il fonde une nouvelle congrégation à vocation missionnaire : « les

Fils de Marie Immaculée » qu'on appelle les Clarétins. En 1850, le Pape le

nomme archevêque de Santiago de Cuba, et cela ne le déconcerte pas. Il y exerce

un intense apostolat, homme de feu brûlé par l'amour du Christ. Là encore il

imprime et distribue images et brochures, prend la défense des esclaves,

condamne les exactions des grands propriétaires. Ce qui lui attire bien des

ennemis. Il échappe alors à quinze tentatives d'assassinat. En 1857, après 6

années d'un tel ministère, la reine Isabelle l'appelle en Espagne comme

conseiller et confesseur. En 1868, la révolution éclate. Saint Antoine-Marie

suit la reine, réfugiée à Paris. Les Claretains sont expulsés de leurs six

maisons et fondent en France celle de Prades. Il prend part au concile du

Vatican en 1869 et 1870. Au retour, il se retirera au monastère cistercien de

Fontfroide où il meurt.

Mémoire de saint Antoine-Marie Claret, évêque. Après

son ordination presbytérale, il parcourut pendant plusieurs années la

Catalogne, en prêchant au peuple, et fonda la Société des Missionnaires Fils du

Cœur Immaculé de Marie. Devenu évêque de Santiago de Cuba, il se soucia plus

que tout du salut des âmes. Revenu en Espagne, il eut beaucoup à souffrir pour

l’Église et finit ses jours en exil chez les moines cisterciens de Fontfroide

près de Narbonne, en 1870.

Martyrologe romain

La meilleure disposition à l’union avec Dieu, c’est

l’intimité avec Notre-Seigneur et la vie d’amour.

Saint Antoine-Marie - Lettre à Micael

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/2070/Saint-Antoine-Marie-Claret.html

Sant'Antonio María Claret y Clará

Homélie de Pie XII pour la canonisation de St. Antoine

Marie Claret

ROME, Mercredi 25 octobre 2006 (ZENIT.org)

– Antoine Marie Claret y Clara a donné aux travailleurs « des exemples

admirables et imitables d’honneur et de sainteté », a souligné Pie XII le

jour de la canonisation du saint catalan.

Voici le texte complet de l’homélie du pape Pie XII

pour la canonisation de l’évêque St. Antoine Marie Claret y Clara, en 1950.

Homélie (cf. Missel)

« Lorsque Nous évoquons la vie de saint

Antoine-Marie Claret, dit Pie XII dans l’homélie de la canonisation, Nous ne

savons ce qu’il faut le plus admirer : l’innocence de son âme que, dès sa

plus tendre enfance, des soins attentifs et sa prudence conservèrent intacte,

tel un lis entre les épines ; ou l’ardeur de sa charité qui le faisait

tendre au soulagement de toutes les misères ; ou enfin son zèle

apostolique qui le fit contribuer si fortement, par une activité de jour et de

nuit, par des prières instantes pour le salut des âmes, par de nombreux

voyages, par des discours enflammés d’amour pour Dieu, à la réforme des mœurs

privées et publiques selon l’esprit de l’Évangile.

Lorsque, jeune homme, il exerçait le métier de

tisserand pour obéir à la volonté de son père, il donna à ses compagnons de

travail de tels exemples de vertu chrétienne, qu’il excitait l’admiration de

tous. Et dès qu’il pouvait cesser le travail et se reposer, il gagnait une

église où il passait ses meilleures heures en prières et en contemplation

devant l’autel du Saint Sacrement ou l’image de la Vierge. Car il était dans

les vues de la Providence qu’avant même d’être élevé à un état de vie

supérieure, il donnerait aux travailleurs des exemples admirables et imitables

d’honneur et de sainteté.

Après quelques années, surmontant bien des obstacles,

il put enfin réaliser, le cœur rempli de gratitude pour Dieu, ce qu’il avait

toujours souhaité et se consacrer totalement à Dieu. Admis au séminaire

diocésain, il se donna avec joie et courage à l’étude, obéissant avec soin au

règlement, et s’efforça partout de développer en son âme les dons naturels pour

reproduire par ses paroles et ses actes la vivante image de Jésus-Christ. Aussi

est-ce comme un infatigable soldat qu’ayant achevé ses études et devenu prêtre,

il se lança tout heureux dans le champ de l’apostolat, comptant moins sur les

moyens humains que sur la puissance divine ; et, dès le début de son ministère

sacerdotal, il obtint d’admirables fruits de salut. En s’acquittant de ce

ministère, il prit toujours un soin particulier à rechercher ce qui lui

paraissait répondre le mieux aux besoins de son époque.

C’est ainsi que voyant une ignorance assez générale

des préceptes divins et la tiédeur d’un grand nombre vis-à-vis de la religion

être cause d’un affaiblissement de la piété chrétienne, d’une désertion des

églises et de la ruine lamentable des mœurs, il forma avec opportunité le

projet d’entreprendre des courses missionnaires pour organiser dans diverses

villes et villages des prédications de plusieurs jours. Pendant qu’il prêchait,

son visage rayonnait de la charité dont brillait son âme : les paroles qui

sortaient de ses lèvres, ou plutôt de son cœur, étaient telles que les

assistants étaient souvent émus jusqu’aux larmes et, qui plus est, inclinés à

tendre d’un cœur sincère vers une vie meilleure et plus sainte.

Aussi lui arrivait-il d’obtenir plus que de salutaires

améliorations, le renouvellement des mœurs, qu’il confirmait efficacement en

accomplissant au nom de Dieu d’extraordinaires miracles. Comme sa réputation de

sainteté se répandait chaque jour davantage, il fut jugé digne d’être promu

archevêque et de se voir confier l’île de Cuba. Bien qu’il y rencontrât de

graves difficultés et des obstacles sans cesse renaissants, il ne se laissa pas

décourager par les travaux les plus durs, ni les périls de tous genres ;

ce qu’en bon soldat du Christ il avait fait en Espagne, cet excellent, cet

intrépide pasteur s’efforça de le réaliser dans l’île.

Rappelé ensuite dans sa patrie, et choisi comme

confesseur de la Reine et son conseiller, il n’eut pas d’autres préoccupations

que la recherche de ce qui était le plus utile au salut de son auguste

pénitente : la défense des droits de l’Eglise et le développement de tout

ce qui pouvait concourir à l’expansion de la religion catholique.

L’œuvre si utile qu’il avait déjà commencée depuis

longtemps, à savoir la fondation d’un groupe de missionnaires consacrés au Cœur

Immaculé de la Vierge Marie fut achevée et si bien affermie et dotée de Règles

très sages qu’elle se propagea peu à peu avec succès en Espagne, dans presque

toutes les nations d’Europe et jusqu’aux Amériques, ainsi qu’en Afrique et en

Asie.

Tels sont, vénérables frères et chers fils, les

principaux traits de la physionomie de ce saint et le très bref résumé de ses

œuvres. On voit clairement combien saint Antoine-Marie Claret s’est signalé par

sa sublime vertu, et par tout ce qu’il accomplit pour le salut de son prochain.

Si les ouvriers, les prêtres, les évêques et tout le peuple chrétien tournent

leurs regards vers lui, ils auront certes tous des raisons d’être frappés par

ses exemples lumineux et d’être entraînés, chacun selon son état, à l’acquisition

de la perfection chrétienne, seule source d’où pourront sortir les remèdes que

réclame la situation troublée actuelle et d’où pourront naître des temps

meilleurs.

Puisse le nouveau saint nous obtenir cela du Divin

Rédempteur et de sa Mère Immaculée. Et que ce soit le fruit béni de cette

solennelle célébration. Amen.

SOURCE : http://news.catholique.org/12242-homelie-de-pie-xii-pour-la-canonisation-de

Sant'Antonio María Claret y Clará

SAINT-ANTOINE MARIE CLARET

Naissance

Saint Antoine-Marie Claret est né le 23 Décembre, 1807

à Sallent (Espagne). Sa famille, une famille nombreuse de onze enfants, se

distinguait par deux caractéristiques : une ambiance chrétienne intense et

une grande ardeur au travail. Il est issu d'une famille de tisserands.

Les premières pensées qui ont occupé son esprit

enfantin se rapportent à l’éternité. Cette pensée l’a poussé á travailler á la

conversion des pécheurs. Pendant son enfance et son adolescence il sentit une

très tendre dévotion à la Vierge Marie et à l’Eucharistie.

Ouvrier

Antoine passa son adolescence entre les métiers à

tisser de son père. Il y devint bientôt maître dans l’art du tissage. Pour se

perfectionner dans la fabrication, il demanda à son père

l’autorisation de se rendre à Barcelone. Il travaillait

dans une manufacture le jour et étudiait la nuit. Et bien qu’il continuât

d’être un bon chrétien, sa piété s’est réfroidie, car sa grande préoccupation

était la fabrication et l’étude. Quelques contrariétées l’ont amené à se

poser des questions sérieuses sur son avenir. Et c’est dans cette situation de

réflexion qu’il fut frappé par cette parole de l’Évangile : «De quoi sert

à l’homme de gagner le monde entier, s’il se perd lui-même ? ». Cette

phrase l’ébranla profondément.

Séminariste

C'est en 1829, à l'âge de 22 ans, que le saint décide de faire son entrée au Séminaire de Vic, capitale de son diocèse natal. Il se fera remarquer par sa piété et son engagement en faveur des pauvres et des malades. Il se découvre une vraie passion pour la Parole de Dieu.

À la fin de l’année académique, Antoine crut venu le moment de mettre en œuvre

sa décision d’entrer à la Chartreuse et il s’en alla vers celle de Monte

Alegre, près de Barcelone. Mais il fit demi-tour et retourna à Vic.Malgré les

vicissitudes sociales et politiques de l'époque, Antoine parvient au sacerdoce

le 13 Juin,1835. Il est ordonné à Solsona (Espagne).

Au cours de cette deuxième année de séminaire, il

traversa l’épreuve du feu de la chasteté. Alité, il se sentit tout à coup

assailli par une tentation qu’il n’arrivait pas à chasser. Il vit alors la

Vierge lui apparaître et lui dire, en lui montrant une couronne : « Antoine,

cette couronne sera à toi si tu vainc s». Et, tout à coup, toutes les images

malsaines et obsédantes s’évanouirent.

Sacerdoce

Claret fut ordonné prêtre le 13 juin 1835. C’est à

Sallent, sa ville natale, qu’il fut nommé à son premier poste en qualité de

vicaire et, peu de temps après, comme curé.

Son esprit apostolique ne connaissait pas de bornes.

C’est pourquoi les limites d’une paroisse ne pouvaient pas satisfaire l’ardeur

apostolique de Claret. Il consulta et décida de partir pour Rome avec

l’intention de se mettre à la disposition de la Congrégation de la Propagation

de la Foi, dans le but d’aller prêcher l’Évangile aux infidèles...

Claret profita d’un temps libre pour faire les

exercices spirituels sous la direction d’un père de la Compagnie de Jésus. Ce

fut une occasion providentielle pour mieux discerner sa vocation missionnaire

et s’y préparer à travers quelques mois comme novice jésuite. Une maladie assez

inexplicable -une forte douleur à la jambe droite- lui fera comprendre que sa

mission était en Espagne.

Missionaire Apostolique en Catalogne et Canarias

De retour en Espagne, il fut envoyé provisoirement à

Viladrau, une petite paroisse rurale dans les montagnes du sud de Gérone. Il y

entreprit son ministère avec un grand zèle

Ses traces sont restées imprimées sur tous les chemins

de la Catalogne.

En 1843, apparaît la première édition du «Camino

Recto» (Le Droit Chemin), le livre de piété le plus lu au XIX siècle en

Espagne. Claret avait 35 ans. En 1847, il fondait une maison d’éditions, la

« Librería Religiosa ». Cette même année, il fondait également

l’Archiconfrérie du Cœur de Marie et rédigeait les statuts de la Fraternité du

Cœur Immaculé de Marie et des Amis de l’Humanité, composée de prêtres et de

laïcs (hommes et femmes) qui s’engageaient à la bienfaisance et à l’apostolat.

Il prêcha et confessa infatigablement dans les Îles

Canaries pendant quinze mois, laissant derrière lui des conversions, des

miracles, des prophéties et des légendes. Les habitants de ces îles virent

partir un jour leur Padrito (petit Père) et, les larmes aux yeux, lui

firent leurs adieux. Cela se passait les derniers jours du mois de mai 1849.

Fondateur et Archevêque de Cuba

Peu de temps après, le 16 juillet 1849, à quinze

heures, dans une cellule du séminaire de Vic, il fondait la Congrégation des

Missionnaires Fils du Cœur Immaculé de Marie.

Un mois après la fondation, il reçut un Décret Royal,

par lequel on le nommait archevêque de Santiago de Cuba. Après avoir essayé par

tous les moyens d’y renoncer, il accepta la charge le 4 octobre 1849 et fut

consacré Évêque le 6 octobre 1850 dans la cathédrale de Vic.

Avant de s’embarquer pour Cuba Il eut encore le temps,

avant son départ, de fonder les Religieuses chez Elles ou Filles du Cœur

Immaculé de Marie, une sorte d’Institut séculier, connu aujourd’hui sous le nom

de Filiation du Cœur Immaculé de Marie.

Claret restera six ans au diocèse de Santiago de Cuba,

travaillant sans prendre le moindre repos, prêchant des missions, semant

l’amour et la justice, en cette île où regnaient la discrimination raciale et

l’injustice sociale. Il a fondé dans son diocèse des institutions religieuses

et sociales pour les enfants et les adultes ; il a créé une grande école

d’agriculture pour la formation des enfants des paysans. Il a établi et

développé partout à Cuba les Caisses d’Épargne et fondé des asiles. Il a visité

quatre fois, à pied ou à cheval, toutes les villes et tous les villages de son

immense diocèse. L’une des œuvres les plus importantes que le Père Claret

ait réalisées à Cuba fut la fondation, avec la Mère Antonia París, de la

Congrégation des « Religieuses de Marie Immaculée », Missionnaires

Clarétaines

Son travail missionnaire, surtout son action sociale

en faveur des esclaves noirs, lui attira la persécution de ses ennemis. La

fureur des attentats atteignit son plus haut point à Holguín, où il fut

grièvement blessé, alors qu’il sortait de l’église, par un sicaire à la solde

de ses ennemis. Le Père Claret, en danger de mort, demanda que le criminel soit

pardonné. Malgré tout, ses ennemis continuèrent à harceler le Père Claret.

Confesseur de la Reine et missionnaire

Au bout de six ans de séjour à Cuba, on lui remit une

dépêche urgente qui lui communiquait que sa Majesté la Reine Isabelle II

l’appelait à Madrid. C’était le 18 mars 1857.

Arrivé à Madrid, le Père Claret apprit, à sa grande

surprise, que sa charge à Madrid était celle de confesseur de la

Reine. Bien que contrarié, il accepta, tout en y posant ces trois

conditions : qu’il ne demeurerait pas au Palais, qu’il ne serait pas impliqué

dans la politique et qu’il ne serait pas obligé à faire antichambre. Il voulait

assurer toute sa liberté apostolique.Il développa une inlassable

activité. Le grand Apôtre catalan n’était pas né courtisan. Durant les

onze années qu’il resta à Madrid, son activité apostolique à la Cour fut très

intense et ininterrompue.

Il profitait des déplacements de la Reine, qu’il

accompagnait à travers l’Espagne, pour déployer un apostolat intense. La Reine

le nomma Président du Monastère Royal de l’Escurial.

Claret est l’auteur de 96 ouvrages (15 livres et 81

opuscules). Il édita aussi 27 livres d’autres auteurs, annotés ou traduits par

lui. Ce n’est qu’en tenant compte de son zèle apostolique, de son tempérament

actif et des forces que Dieu lui communiquait, que l’on peut comprendre qu’il

ait pu écrire et publier autant, tout en se consacrant à une si intense

activité missionnaire. Claret n’était pas seulement un écrivain, il était aussi

un propagandiste. Il distribuait copieusement les livres et les feuilles

volantes. « Les livres -disait-il- sont la meilleure aumône qu’on peut

faire ». Une de ses œuvres fut l’Académie de Saint Michel (1858).

Elle prétendait réunir les artistes, journalistes et écrivains catholiques,

épaulés par des zélateurs. Il a également fondé les Bibliothèques

Populaires.

Il n’est pas étonnant qu’un homme de l’influence du

Père Claret, qui attirait les multitudes, soit devenu l’objet de la haine et la

colère des ennemis de l’Église. Mais les menaces et les attentats étaient

autant d’échecs, parce que la Providence veillait sur lui et qu’il se

réjouissait dans les persécutions. Les attentats personnels dont il fut l’objet

dans sa vie furent nombreux. La plupart furent un échec et se terminèrent même

par la conversion des hommes engagés pour l’assassiner.

Exile et Padre en el Concilio Vaticano I

Le 30 septembre 1868, la famille royale, avec quelques

amis et son confesseur, le Père Claret, partait en exil pour la France. D’abord

à Pau, puis à Paris.

Le 8 décembre 1869, commencèrent à arriver à Rome les

700 évêques du monde entier. Le Concile Oecuménique, Vatican I, commençait. Le

Père Claret était là. Parmi les thèmes les plus débattus, il y avait celui de

l’infaillibilité pontificale concernant les questions de foi et de mœurs. La

voix de Claret s’éleva dans la Basilique vaticane : «Je porte dans mon corps

les stigmates de la passion du Christ, dit-il, faisant allusion aux

blessures d’Holguín. Puissé-je verser tout mon sang en affirmant

l’infaillibilité du Pape». Claret est le seul Père présent à ce Concile à

parvenir à l’honneur des autels.

Muerte y glorificación

Le 23 juillet 1870, le Père Claret savait que sa mort

était proche et arrivait à Prades, dans les Pyrénées Orientales Mais ses

ennemis ne le laissèrent pas en paix, même en cette paisible retraite.

Même exilé et malade, le Père Claret fut

contraint de fuir. Il trouva asile dans le monastère cistercien de Fontfroide,

proche de la ville de Narbonne.

Le matin du 24 octobre, son état s’est aggravé d’une

façon alarmante. Aux côtés du mourant, se trouvaient les Pères Clotet et Puig.

Tous les religieux se tenaient autour de son lit ; pendant les prières de cette

assemblée, Claret remit son esprit entre les mains du Créateur à 8 h 45. Il

avait 62 ans.

Sa dépouille mortelle fut déposée au cimetière du

monastère. Sur la pierre tombale, on grava cette inscription de Grégoire VII :

«J’ai aimé la justice et haï l’iniquité, c’est pourquoi je meurs en

exil».

En 1897, le corps du Père Claret fut transféré à Vic

où il est vénéré aujourd’hui. Le 25 février 1934, l’Église l’inscrivit au

nombre des Bienheureux. L’humble missionnaire apparut à la vénération du monde

entier dans la gloire du Bernin. Les cloches de la Basilique du Vatican

proclamaient sa gloire.

Le 7 mai 1950, le Pape Pie XII le proclama saint.

Voici les paroles du Pape en ce jour de gloire :

«Saint Antoine-Marie Claret fut une grande homme, né

pour réunir des contrastes : il put être d’humble origine et glorieux aux yeux

du monde ; petit de corps, mais géant d’esprit ; modeste d’apparence, mais tout

à fait capable d’imposer le respect même aux grands de la terre ; fort de

caractère, mais doué de la douceur suave de celui qui connaît le frein de

l’austérité et de la pénitence ; toujours en présence de Dieu, même au milieu

de sa prodigieuse activité extérieure ; admiré et calomnié ; fêté et

persécuté. Et, parmi toutes ces merveilles, comme une douce lumière illuminant

tout, sa dévotion à la Mère de Dieu».

SOURCE : http://www.claret.org/fr/biographie-saint-antoine-marie-claret

Sant'Antonio María Claret y Clará

24 octobre

Saint Antoine-Maire Claret y Clara

Homélie

de Pie XII lors de la canonisation

A Saint-Martin d’Heuille, dans le Nivernais, on vient

prier Notre-Dame de Pitié en souvenir de la résurrection d’un petit

enfant. Le 24 octobre 1879, un petit enfant, n’ayant aucune apparence de

vie, fut apporté à l’église de Saint-Martin et déposé sur le marchepied de

l’autel de Notre-Dame de Pitié. Devant le petit cadavre, les fidèles désolés,

mais confants, tombent à genoux et chantent avec ferveur le « Salve

Regina ». Soudain, la vie semble renaître ; le visage se colore, les yeux

s’ouvrent, l’enfant donne tous les signes d’une véritable résurrection. Il est

baptisé, et une prière d’actions de grâces jaillit de tous les cœurs.

Le 24 octobre 1859, la ville d’Avignon renouvelle sa

confiance à Marie en plaçant au faîte de la basilique Notre-Dame des Doms une

statue monumentale. Plus de cent mille personnes conduites par sept évêques.

Cinquième des onze enfants du tisserand Jean Claret et

de Joséphine Clara, Antoine naquit le 23 décembre 1807, à Sallent, dans le

diocèse de Vich, en Catalogne. En même temps qu'il s'initiait au métier de

tisserand, il étudiait le latin avec le curé de sa paroisse qui lui donna une

solide formation religieuse et une tendre dévotion à la Sainte Vierge ; à

dix-sept ans, son père l'envoya se perfectionner dans une entreprise de

Barcelone où, aux cours du soir, il apprit, sans abandonner le latin, le

français et l'imprimerie. Après une terrible crise spirituelle où il fut au

bord du suicide, il avait songé à se faire chartreux mais, sur les conseils de

son directeur de conscience, il choisit d'entrer au séminaire de Vich (29

septembre 1829). Tonsuré le 2 février 1832, minoré le 21 décembre 1833, il

reçut le sous-diaconat le 24 mai 1834, fut ordonné diacre le 20 décembre 1834

et prêtre le 13 juin 1835. Il acheva ses études de théologie en exerçant le ministère

de vicaire puis d'économe de sa ville natale.

Désireux de partir en mission, il se rendit à Rome

pour se mettre à la disposition de la Congrégation de la Propagande. Le

cardinal préfet étant absent, Antoine suivit les Exercices de saint Ignace chez

les Jésuites qui lui proposèrent d'entrer dans leur compagnie. Il commença son

noviciat (2 novembre 1839) qu'une plaie à la jambe l'obligea à quitter (3 mars

1840).

Revenu en Espagne, il fut curé de Viladrau où, à peine

arrivé, pour le 15 août, il prêcha une mission qui eut tant de succès qu'on le

demanda ailleurs et l'évêque le déchargea de sa cure pour qu'il se consacrât

aux missions intérieures (mai 1843) ; il prêcha et confessa dans toute la

Catalogne et soutint ses prédications par plus de cent cinquante livres et

brochures. Sa vie étant menacée, l'évêque l'envoya aux îles Canaries (février

1848 à mars 1849) où il continua son ministère missionnaire. Avec cinq prêtres

du séminaire de Vich, il fondait la congrégation des Missionnaires Fils du

Coeur Immaculé de Marie (16 juillet 1849).

A la demande de la reine Isabelle II d'Espagne, Pie IX

le nomma archevêque de Santiago de Cuba dont le siège était vacant depuis

quatorze ans ; il fut sacré le 6 octobre 1850 et ajouta le nom de Marie à son

prénom ; il s'embarqua, le 28 décembre 1850, à Barcelone, et arriva dans son

diocèse le 16 février 1851. Il s'efforça d'abord d'instruire le peu de prêtres

de son diocèse (vingt-cinq pour quarante paroisses) et de leur assurer un

revenu suffisant ; il fit venir des religieux ; il visita son diocèse et y

prêcha pendant deux ans où il distribua 97 217 livres et brochures, 83 500

images, 20 665 chapelets et 8 397 médailles ; en six ans, il visita trois

fois et demi son diocèse où il prononça 11 000 sermons, régularisa 30 000

mariages et confirma 300 000 personnes. Il prédit un tremblement de terre, une

épidémie de choléra et même la perte de Cuba par l'Espagne ; il fonda une

maison de bienfaisance pour les enfants et les vieillards pauvres où il attacha

un centre d'expérimentation agricole ; il créa 53 paroisses et ordonna 36

prêtres. Les esclavagistes lui reprochaient d'être révolutionnaire, les

autonomistes lui reprochaient d'être espagnol et les pouvoirs publics lui

reprochaient d'être trop indépendant : il n'y eut pas moins de quinze attentats

contre lui et l'on pensa que le dernier, un coup de couteau qui le blessa à la

joue, lui serait fatal (1° février 1856).

Le 18 mars 1857, l'archevêque fut mandé en Espagne par

la reine Isabelle qui le voulait pour confesseur et il fut nommé archevêque

titulaire (in partibus) de Trajanopolis sans pour autant cesser d'assurer de

Madrid l'administration de Cuba. Confesseur de la Reine, il eut assez

d'influence pour faire nommer de bons évêques, pour organiser un centre

d'études ecclésiastiques à l'Escurial et pour imposer la morale à la cour.

Voyageant avec la Reine à travers l'Espagne, il continua de prêcher et ne

manqua pas de s'attirer la haine des nombreux ennemis du régime. Quand Isabelle

II fut chassée de son trône (novembre 1868), Mgr. Claret y Clara suivit sa

souveraine en France : il quitta définitivement l'Espagne le 30 septembre 1868.

Pendant ce temps, la congrégation des Missionnaires

Fils du Coeur Immaculé de Marie se développait lentement : elle avait reçu

l'approbation civile (9 juillet 1859) et ses constitutions avaient été

approuvées par Rome (decretum laudis du 21 novembre 1860) et

définitivement reconnues le 27 février 1866 ; l'approbation perpétuelle, donnée

le 11 février 1870, fut confirmée le 2 mai 1870. D'abord établie au séminaire

de Vich, puis installée dans l'ancien couvent des Carmes, la congrégation,

dirigée depuis 1858 par le P. Xifré, fonde à Barcelone (1860) et dans d'autres

villes espagnoles avant d'ouvrir des maisons à l'étranger : en France (1869), au

Chili (1870), à Cuba (1880), en Italie (1884), au Mexique (1884), au Brésil

(1895), au Portugal (1898), en Argentine (1901), aux Etats-Unis (1902), en

Uruguay (1908), en Colombie (1909), au Pérou (1909), en Autriche (1911), en

Angleterre (1912), en Bolivie (1919), au Vénézuéla (1923), à Saint-Domingue

(1923), au Panama (1923), en Allemagne (1924), en Afrique portugaise (1927), en

Chine (1933), à Porto-Rico (1946), aux Philippines (1947), en Belgique

(1949).

Après la révolution de 1868 ou un prêtre de la

congrégation fut assassiné, le nouveau gouvernement ferma les six maisons

espagnoles et les missionnaires s'exilèrent en France (Prades).

Mgr. Antoine-Marie Claret y Clara bien que sa santé

fut de plus en plus mauvaise, s'occupa de la colonie espagnole de Paris ;

le 30 mars 1869, il partit pour Rome, afin de participer aux travaux du premier

concile du Vatican, mais il y tomba si malade qu'il dut se retirer à Prades où

il arriva le 23 juillet 1870. Il parut pour la dernière fois en public à la distribution

des prix au petit séminaire où il fit un discours en Catalan (27 juillet 1870).

L'ambassadeur d'Espagne demanda son internement mais le gouvernement français

fit en sorte que l'évêque de Perpignan l'avertît et, lorsqu'on vint l'arrêter

(6 août 1870), il était réfugié chez les Cisterciens de Fontfroide où il mourut

le 24 octobre 1870. Il fut béatifié en 1934 et canonisé en 1950.

Sant'Antonio María Claret y Clará

Homélie

de Pie lors de la canonisation

« Lorsque Nous évoquons la vie de saint

Antoine-Marie Claret, dit Pie XII dans l’homélie de la canonisation,

Nous ne savons ce qu'il faut le plus admirer : l'innocence de son âme que,

dès sa plus tendre enfance, des soins attentifs et sa prudence conservèrent

intacte, tel un lis entre les épines ; ou l'ardeur de sa charité qui le

faisait tendre au soulagement de toutes les misères ; ou enfin son zèle

apostolique qui le fit contribuer si fortement, par une activité de jour et de

nuit, par des prières instantes pour le salut des âmes, par de nombreux

voyages, par des discours enflammés d'amour pour Dieu, à la réforme des mœurs

privées et publiques selon l'esprit de l'Évangile.

Lorsque, jeune homme, il exerçait le métier de

tisserand pour obéir à la volonté de son père, il donna à ses compagnons de

travail de tels exemples de vertu chrétienne, qu'il excitait l'admiration de

tous ; et dès qu'il pouvait cesser le travail et se reposer, il gagnait

une église où il passait ses meilleures heures en prières et en contemplation

devant l'autel du Saint Sacrement ou l'image de la Vierge. Car il était dans

les vues de la Providence qu'avant même d'être élevé à un état de vie

supérieure, il donnerait aux travailleurs des exemples admirables et imitables

d'honneur et de sainteté.

Après quelques années, surmontant bien des obstacles,

il put enfin réaliser, le cœur rempli de gratitude pour Dieu, ce qu'il avait

toujours souhaité et se consacrer totalement à Dieu. Admis au séminaire

diocésain, il se donna avec joie et courage à l'étude, obéissant avec soin au

règlement, et s'efforça partout de développer en son âme les dons naturels pour

reproduire par ses paroles et ses actes la vivante image de Jésus-Christ. Aussi

est-ce comme un infatigable soldat qu'ayant achevé ses études et devenu prêtre,

il se lança tout heureux dans le champ de l'apostolat, comptant moins sur les

moyens humains que sur la puissance divine ; et, dès le début de son

ministère sacerdotal, il obtint d'admirables fruits de salut. En s'acquittant

de ce ministère, il prit toujours un soin particulier à rechercher ce qui lui

paraissait répondre le mieux aux besoins de son époque. C'est ainsi que voyant

une ignorance assez générale des préceptes divins et la tiédeur d'un grand

nombre vis-à-vis de la religion être cause d'un affaiblissement de la piété

chrétienne, d'une désertion des églises et de la ruine lamentable des mœurs, il

forma avec opportunité le projet d'entreprendre des courses missionnaires pour

organiser dans diverses villes et villages des prédications de plusieurs jours.

Pendant qu'il prêchait, son visage rayonnait de la charité dont brillait son

âme : les paroles qui sortaient de ses lèvres, ou plutôt de son cœur,

étaient telles que les assistants étaient souvent émus jusqu'aux larmes et, qui

plus est, inclinés à tendre d'un cœur sincère vers une vie meilleure et plus

sainte.

Aussi lui arrivait-il d'obtenir plus que de salutaires

améliorations, le renouvellement des mœurs, qu'il confirmait efficacement en

accomplissant au nom de Dieu d'extraordinaires miracles. Comme sa réputation de

sainteté se répandait chaque jour davantage, il fut jugé digne d'être promu

archevêque et de se voir confier l'île de Cuba. Bien qu'il y rencontrât de

graves difficultés et des obstacles sans cesse renaissants, il ne se laissa pas

décourager par les travaux les plus durs, ni les périls de tous genres ;

ce qu'en bon soldat du Christ il avait fait en Espagne, cet excellent, cet

intrépide pasteur s'efforça de le réaliser dans l'île.

Rappelé ensuite dans sa patrie, et choisi comme

confesseur de la Reine et son conseiller, il n'eut pas d'autres préoccupations

que la recherche de ce qui était le plus utile au salut de son auguste

pénitente : la défense des droits de l'Eglise et le développement de tout

ce qui pouvait concourir à l'expansion de la religion catholique.

L'œuvre si utile qu'il avait déjà commencée depuis

longtemps, à savoir la fondation d'un groupe de missionnaires consacrés au Cœur

Immaculé de la Vierge Marie fut achevée et si bien affermie et dotée de Règles

très sages qu'elle se propagea peu à peu avec succès en Espagne, dans presque

toutes les nations d'Europe et jusqu'aux Amériques, ainsi qu'en Afrique et en

Asie.

Tels sont, vénérables frères et chers fils, les

principaux traits de la physionomie de ce saint et le très bref résumé de ses

œuvres. On voit clairement combien saint Antoine-Marie Claret s'est signalé par

sa sublime vertu et par tout ce qu'il accomplit pour le salut de son prochain.

Si les ouvriers, les prêtres, les évêques et tout le peuple chrétien tournent

leurs regards vers lui, ils auront certes tous des raisons d'être frappés par

ses exemples lumineux et d'être entraînés, chacun selon son état, à

l'acquisition de la perfection chrétienne, seule source d'où pourront sortir

les remèdes que réclame la situation troublée actuelle et d'où pourront naître

des temps meilleurs.

Puisse le nouveau saint nous obtenir cela du Divin

Rédempteur et de sa Mère Immaculée. Et que ce soit le fruit béni de cette

solennelle célébration. Amen.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/10/24.php

Saint Antoine-Marie

Claret

Enfance

Saint Antoine-Marie

Claret est né à Sallent (Barcelone), à environ 15 km de Manresa, en 1807, dans

une famille profondément chrétienne, dédiée à la fabrication de textiles.

L’enfance du Saint ne

s’est pas déroulée dans la plus grande tranquillité. La guerre napoléonienne,

l’influence des idées de la révolution française, le serment de la Constitution

de 1812 et les tensions entre absolutistes et libéraux ont en quelque sorte

marqué la vie du Saint. En ce qui concerne l’aspect religieux, il était marqué,

d’une part, par l’expérience de la providence de Dieu et, d’autre part, par

l’idée de l’éternité. Sa piété a été influencée par sa dévotion à la Vierge

Marie et à l’Eucharistie.

Étudiant et ouvrier

A 12 ans, son père l’a

mis au travail sur le métier de tisserand. Reconnaissant ses compétences en

matière de fabrication, il se rend à Barcelone pour perfectionner l’art

textile. Il s’est consacré au travail de tisserand avec un réel intérêt. Ses

prières, en revanche, n’étaient pas aussi nombreuses ni aussi ferventes, bien

qu’il n’ait pas renoncé à la messe dominicale ni à la prière du rosaire.

Peu à peu, il oublia son

désir enfantin de devenir prêtre, mais Dieu le dirigeait selon ses plans. De

dures déceptions, et surtout la parole de l’Évangile : « A quoi bon gagner

le monde entier si à la fin on perd la vie », ébranlent sa conscience.

Malgré les offres de créer sa propre usine, il refuse de satisfaire le désir de

son père et décide de devenir chartreux.

Vocation sacerdotale

missionnaire

À l’âge de 22 ans, il

entre au séminaire de Vic, sans perdre de vue son intention de devenir

chartreux. Lorsqu’il se rend à la chartreuse de Montealegre, l’année suivante,

une tempête le force à se retirer et son rêve d’une vie retirée commence à

s’évanouir.

Il poursuit ses études

artistiques à Vic. Il y a subi une forte tentation contre la chasteté, dans

laquelle il a reconnu l’intercession maternelle de la Vierge Marie en sa faveur

et surtout la volonté de Dieu, qui voulait qu’il soit missionnaire et évangélisateur.

Bien qu’il n’ait pas

terminé ses études de théologie, le 13 juin 1835, il est ordonné prêtre parce

que son évêque voit en lui quelque chose d’extraordinaire. Il a pris en charge

sa paroisse natale à Sallent. L’appel du Seigneur à évangéliser devenait de

plus en plus fort. La situation politique en Catalogne, divisée par la guerre

civile entre libéraux et carlistes, et celle de l’Église, soumise à la méfiance

des dirigeants, ne lui laisse d’autre solution que de quitter la Catalogne et

de s’offrir à Propaganda Fide, qui est alors chargée de toute l’œuvre

d’évangélisation.

Après un voyage plein de

dangers, il est arrivé à Rome. Il a profité des quelques jours libres pour

faire une retraite spirituelle chez les jésuites du Gesù. Son directeur

l’a encouragé à demander à rejoindre la Compagnie de Jésus. Au début de 1840,

quatre mois après avoir commencé le noviciat, il est affligé d’une douleur

intense à la jambe droite qui l’empêche de marcher. La main de Dieu se faisait

sentir. Le Père Général des Jésuites lui a dit avec résolution : « C’est

la volonté de Dieu que vous alliez bientôt en Espagne ; n’ayez pas peur ;

courage ! »

Missionnaire apostolique

en Catalogne et les Îles Canaries

Une fois de plus en

Catalogne, la paroisse de Viladrau lui est confiée. Comme elle est très

fréquentée, il peut se déplacer pour offrir des missions et des exercices

spirituels aux villes voisines. Son évêque, connaissant sa vocation et les

fruits de sa prédication, le laisse libre de tout lien paroissial pour pouvoir

évangéliser de village en village. En raison de son désir de communion avec la

hiérarchie et des facultés pastorales qu’elle implique, il a demandé à Propaganda

Fide le titre de « Missionnaire apostolique », qu’il a rempli de

contenu spirituel et apostolique.

Il a parcouru

pratiquement toute la Catalogne de 1843 à 1847, prêchant la Parole de Dieu,

toujours à pied, sans accepter d’argent ou de cadeaux pour ses besoins. Malgré

sa neutralité politique, il a rapidement dû subir les persécutions des

dirigeants et les calomnies de ceux qui combattaient la foi.

Mais Saint Antoine-Marie

Claret ne voulait pas se contenter d’être un infatigable prédicateur de

missions et d’exercices pour des prêtres et des religieux. Il découvre bientôt

d’autres moyens plus efficaces d’apostolat : il publie des livres de dévotion,

des petits livrets destinés aux prêtres, aux religieuses, aux enfants, aux

jeunes, aux femmes mariées, aux parents… il fonde la Librairie religieuse en

1848, qui publie 2 811 000 exemplaires de livres en deux ans, 2 059 500 livrets

et 4 249 200 dépliants. Comme moyen efficace de persévérance et de progrès dans

la vie chrétienne, il fonda et renforça les Confréries, parmi lesquelles la

Confrérie du cœur très saint et immaculé de Marie, qui fut le précurseur des « religieuses

dans leur maison » ou « filles du Cœur très saint et immaculé de

Marie », qui devinrent avec le temps l’Institut séculier « Filiation

cordimarianne ». Comme il lui était totalement impossible de prêcher en

Catalogne en raison de la rébellion armée, son évêque l’envoya aux îles

Canaries.

De février 1848 à mai

1849, il fait le tour des îles. Bientôt et sur un ton familier, il commence à

être appelé « le petit père ». Il est devenu si populaire qu’il a été

co-patron du diocèse de Las Palmas à la « Virgen del Pino ».

Fondateur et archevêque

de Cuba

De retour en Catalogne,

le 16 juillet 1849, il fonde la Congrégation des Missionnaires Fils du Cœur

Immaculé de Marie dans une cellule du séminaire de Vic. Le grand travail de

Claret a commencé humblement avec cinq prêtres dotés du même esprit que le

Fondateur. Quelques jours plus tard, le 11 août, ils ont informé le père Claret

de sa nomination comme archevêque de Cuba. Malgré sa résistance et ses

objections dues à la Librairie religieuse et à la Congrégation des

Missionnaires récemment fondée, il dut accepter cette charge par obéissance et

fut consacré à Vic le 6 octobre 1850.

La situation sur l’île de

Cuba est déplorable : exploitation et esclavage, immoralité publique,

insécurité familiale, désaffection envers l’Église et surtout la

déchristianisation progressive. En arrivant sur l’île, il a immédiatement

compris que le plus nécessaire était d’entreprendre un travail de renouveau de

la vie chrétienne et il a promu une série de campagnes missionnaires, auxquelles

il a lui-même participé, pour apporter la Parole de Dieu à tous les peuples. Il

a donné à son ministère épiscopal une dynamique missionnaire. En six ans, il a

visité trois fois l’ensemble de son diocèse. Il s’est intéressé au renouveau

spirituel et pastoral du clergé et à la fondation de communautés religieuses.

Pour l’éducation de la jeunesse et le soin des institutions caritatives, il

réussit à faire établir des communautés à Cuba les Piaristes, les Jésuites et

les Filles de la Charité ; avec M. Antonia Paris, il fonde les Religieuses de

Marie Immaculée, les Missionnaires Clarétaines, le 27 août 1855. Il lutte

contre l’esclavage, il crée une ferme-école pour les enfants pauvres, il

propose une caisse d’épargne à caractère social et il fonde des bibliothèques

populaires. Des activités si nombreuses et si diverses lui ont valu des

confrontations, des calomnies, des persécutions et des attaques. L’attentat

d’Holguín (1er février 1856) a failli lui coûter la vie, bien qu’il ait fait

verser son sang pour le Christ.

Confesseur royal de la

Reine Isabelle II et apôtre á Madrid et en Espagne

La reine Elizabeth II l’a

personnellement choisi comme son confesseur en 1857 et il a été obligé de

déménager à Madrid. Il devait se rendre au moins une fois par semaine au palais

pour exercer son ministère de confesseur et pour s’occuper de l’éducation

chrétienne du prince Alphonse et de ses filles. En raison de son influence

spirituelle et de sa fermeté, la situation religieuse et morale de la Cour

changeait. Il vit dans l’austérité et la pauvreté.

Les ministères du palais

n’occupent pas le temps ni l’esprit apostolique de l’évêque Claret, qui est

très actif dans la ville : il prêche et il confesse, il écrit des livres, il

visite les prisons et les hôpitaux. Il profite des voyages avec les rois à

travers l’Espagne pour prêcher partout. Il promeut l’Académie de San Miguel, un

projet dans lequel il essaie de rassembler les intellectuels et les artistes

pour promouvoir les sciences et les arts sous l’aspect religieux, pour unir

leurs efforts, pour combattre les erreurs, pour propager les bons livres et

avec eux les bonnes doctrines.

La Reine le nomme

protecteur de l’église et de l’hôpital de Montserrat à Madrid, et président de

l’Escorial en 1859. Sa gestion ne pouvait être plus efficace et plus large :

restauration du bâtiment, équipement de l’église, création d’une communauté et

d’un séminaire. Une de ses plus grandes préoccupations serait de fournir des

évêques zélés en Espagne et de protéger et promouvoir la vie consacrée, en

particulier celle des Instituts fondés par lui, les Missionnaires et les

Religieuses de Marie Immaculée, ou d’autres.

Il continue à maintenir

son indépendance et sa neutralité politique, ce qui implique de multiples

inimitiés. Il est devenu la cible de la haine et de la vengeance de beaucoup :

« bien qu’ayant toujours essayé de traiter ce sujet avec prudence – en

référence au favoritisme – je ne pouvais pas échapper aux mauvaises

langues », avoue-t-il.

Son union avec

Jésus-Christ atteint un point culminant dans la grâce de la préservation des

espèces sacramentelles accordée à La Granja de Segovia le 26 août 1861.

Exil et père conciliaire

de Vatican I

Après la révolution de

septembre 1868, le père Claret s’exila avec la reine. À Paris, il maintient son

ministère auprès de la Reine, fonde les Conférences de la Sainte Famille et

participe à de nombreuses activités apostoliques.

Pour la célébration de

l’anniversaire d’or du sacerdoce du pape Pie IX, il se rend à Rome. Il a

participé à la préparation du premier Concile du Vatican, dans lequel il est

intervenu pour défendre l’infaillibilité papale. A la fin des sessions, sa

santé étant déjà très précaire et sa mort très proche, il s’installe dans la

communauté clarétaine à Prades (France).

Mort et glorification

Ses persécuteurs arrivent

à Prades et tentent de le capturer et de l’emmener en Espagne pour être jugé et

condamné. Il doit fuir comme un criminel et se réfugier dans le monastère

cistercien de Fontfroide. Dans ce monastère de Fontfroide, à l’âge de 63 ans, entouré

de l’affection des moines et de certains de ses missionnaires, il meurt le 24

octobre 1870. Sa dépouille mortelle a été transférée à Vic en 1897.

Il a été béatifié par Pie

XI le 25 février 1934. Pie XII l’a canonisé le 7 mai 1950.

Pour plus d’informations,

visitez le Centre de Spiritualité Clarétaine.

SOURCE : https://claretpaulus.org/fr/nous-sommes-claretains/notre-fondateur/

Sant'Antonio María Claret y Clará

Also known as

Antonio María Claret y Clará

formerly 23

October

Profile

Worked as a weaver in

his youth. Seminary student with Saint Francisco

Coll Guitart. Ordained on 13 June 1835. Missionary in

Catalonia and the Canary Islands. Directed retreats. Founded the Congregation

of Missionary Sons of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (Claretians). Archbishop of Santiago

de Cuba on 20 May 1850.

Founded the Teaching Sisters of Mary Immaculate. Following his work in the

Caribbean, Blessed Pope Pius

IX ordered Anthony back to Spain. Confessor to Queen Isabella

II, and was exiled with

her. Had the gifts of prophecy and miracles.

Reported to have preached 10,000

sermons, published 200 works. Spread devotion to the Blessed Sacrament and the

Immaculate Heart of Mary.

Born

23

December 1807 at

Sallent, Catalonia, Spain

24

October 1870 in

a Cistercian monastery at

Fontfroide, Narbonne, France

6

January 1926 by Pope Pius

XI

25

February 1934 by Pope Pius

XI

Blessed Jacinto

Blanch Ferrer served as Vice-Postulator for Saint Anthony’s Caused from 1916 until

his death in 1936

Missionary

Sons of the Immaculate Heart of Mary

Additional Information

Book

of Saints, by Father Lawrence

George Lovasik, S.V.D.

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

The

Holiness of the Church in the 19th Century

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other sites in english

Claretian Missionaries of the United Kingdom and Ireland

Professor Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

images

video

sitios en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites en français

Abbé Christian-Philippe Chanut

fonti in italiano

Readings

Driven by the fire of the Holy

Spirit, the holy apostles traveled throughout the earth. Inflamed with the

same fire, apostolic missionaries have reached, are now reaching, and will

continue to reach the ends of the earth, from one pole to the other, in order

to proclaim the word of God. They are deservedly able to apply to themselves

those words of the apostle Paul: “The love of Christ drives us on.” The love of

Christ arouses us, urges us to run, and to fly, lifted on the wings of holy

zeal. The zealous man desires and achieve all great things and he labors

strenuously so that God may always be better known, loved and served in this

world and in the life to come, for this holy love is without end. Because he is

concerned also for his neighbor, the man of zeal works to fulfill his desire

that all men be content on this earth and happy and blessed in their heavenly

homeland, that all may be saved, and that no one may perish for ever, or offend

God, or remain even for a moment in sin. Such are the concerns we observe in

the holy apostles and in all who are driven by the apostolic spirit. For

myself, I say this to you: The man who burns with the fire of divine love is a

son of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, and wherever he goes, he enkindles that

flame; he deserves and works with all this strength to inflame all men with the

fire of God’s love. Nothing deters him: he rejoices in poverty; he labors

strenuously; he welcomes hardships; he laughs off false accusations; he

rejoices in anguish. He thinks only of how he might follow Jesus Christ and

imitate him by his prayers,

his labors, his sufferings, and by caring always and only for the glory

of God and

the salvation of souls. – from a work by Saint Anthony

Mary Claret

MLA Citation

“Saint Anthony Mary Claret“. CatholicSaints.Info.

16 September 2021. Web. 25 October 2021.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-anthony-mary-claret/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-anthony-mary-claret/

Picture of painted tiles to commemorate the stay

of Saint Anthony Mary Claret in Santa Lucía de Tirajana in January

1849, wall-mounted to the 150th anniversary of his stay; Santa Lucía de Tirajana, Gran

Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain.

Bild aus bemalten Kacheln zur Erinnerung an den

Aufenthalt von Antonius Maria Claret y Clará in Santa Lucía de Tirajana im Januar

1849, angebracht zum 150. Jahrestages seines Aufenthaltes; Santa Lucía de Tirajana, Gran

Canaria, Kanarische Inseln, Spanien.

Saint Anthony Mary Claret

St. Anthony Mary Claret was born in Catalonia, the

northeastern corner of Spain, in a town called Sallent on December 23, 1807. He

was the fifth son of Juan Claret and Josefa Clará’s eleven children. His father

owned a small textile factory, but was not rich. Anthony grew up in a Christian

environment, and at a very early age had a strong sense of the eternal life

that Christ wanted all men and women to enjoy. He wanted to spare sinners

eternal unhappiness, and felt moved to work for their salvation. When he was

about eleven years old, a bishop visited his school and asked him what he

wanted to be when he grew up. Without hesitation he responded: “A priest.”

As soon as Anthony was old enough, he began working as

an apprentice weaver. When he turned 17, his father sent him to Barcelona to

study the latest techniques in textile manufacturing and to work in the large

textile mills. He did so well in the textile design school that he began

receiving offers from large textile companies. Even though he had the talent to

succeed, he turned down the offer and returned home after experiencing the

emptiness of worldly achievements.

The words of the Gospel kept resounding in his heart:

“what good is it for man to win the world if he loses his soul?” He began to

study Latin to prepare to enter the Seminary. He wanted to be a Carthusian

Monk. His father was ready to accept the will of God, but preferred to see him

become a diocesan priest. Anthony decided to enter the local diocesan seminary

in the city of Vic. He was 21 years old. After a year of studies, he decided to

pursue his monastic vocation and left for a nearby monastery. On the way there,

he was caught in a big storm. He realized that his health was not the best, and

retracted from his decision to go to the monastery.

He was ordained a priest at 27 years of age and was

assigned to his hometown parish. The town soon became too small for his

missionary zeal, and the political situation -hostile to the Church- limited

his apostolic activity. He decided to go to Rome to offer himself to serve in

foreign missions. Things did not work out as expected, and he decided to join

the Jesuits to pursue his missionary dream. While in the Jesuit Novitiate, he

developed a strange illness, which led his superiors to think that God may have

other plans for him. Once again, he had to return home to keep searching for

God’s will in his life.

Back in a parish of Catalonia, Claret begins preaching

popular missions all over. He traveled on foot, attracting large crowds with

his sermons. Some days he preached up to seven sermons in a day and spent 10

hours listening to confessions. He dedicated to Mary all his apostolic efforts.

He felt forged as an apostle and sent to preach by Mary.

The secret of his missionary success was LOVE. In his

words: “Love is the most necessary of all virtues. Love in the person who

preaches the word of God is like fire in a musket. If a person were to throw a

bullet with his hands, he would hardly make a dent in anything; but if the

person takes the same bullet and ignites some gunpowder behind it, it can kill.

It is much the same with the word of God. If it is spoken by someone who is

filled with the fire of charity- the fire of love of God and neighbor- it will

work wonders.”

His popularity spread; people sought him for spiritual

and physical healing. By the end of 1842, the Pope gave him the title of

“apostolic missionary.” Aware of the power of the press, in 1847, he organized

with other priests a Religious Press. Claret began writing books and pamphlets,

making the message of God accessible to all social groups. The increasing

political restlessness in Spain continued to endanger his life and curtail his

apostolic activities. So, he accepted an offer to preach in the Canary Islands,

where he spent 14 months. In spite of his great success there too, he decided

to return to Spain to carry out one of his dreams: the organization of an order

of missionaries to share in his work.

On July 16, 1849, he gathered a group of priests who

shared his dream. This is the beginning of the Missionary Sons of the

Immaculate Heart of Mary, today also known as Claretian Fathers and Brothers.

Days later, he received a new assignment: he was named Archbishop of Santiago

de Cuba. He was forced to leave the newly founded community to respond to the

call of God in the New World. After two months of travel, he reached the Island

of Cuba and began his episcopal ministry by dedicating it to Mary.

He visited the church where the image of Our Lady of

Charity, patroness of Cuba was venerated. Soon he realized the urgent need for

human and Christian formation, specially among the poor. He called Antonia

Paris to begin there the religious community they had agreed to found back in

Spain. He was concerned for all aspects of human development and applied his

great creativity to improve the conditions of the people under his pastoral

care.

Among his great initiatives were: trade or vocational

schools for disadvantaged children and credit unions for the use of the poor.

He wrote books about rural spirituality and agricultural methods, which he

himself tested first. He visited jails and hospitals, defended the oppressed

and denounced racism. The expected reaction came soon. He began to experience persecution,

and finally when preaching in the city of Holguín, a man stabbed him on the

cheek in an attempt to kill him. For Claret this was a great cause of joy. He

writes in his Autobiography: “I can´t describe the pleasure, delight, and joy I

felt in my soul on realizing that I had reached the long desired goal of

shedding my blood for the love of Jesus and Mary and of sealing the truths of

the gospel with the very blood of my veins.”. During his 6 years in Cuba he

visited the extensive Archdiocese three times…town by town. In the first years,

records show, he confirmed 100,000 people and performed 9,000 sacramental

marriages.

Claret was called back to Spain in 1857 to serve as

confessor to the Queen of Spain, Isabella II. He had a natural dislike for aristocratic

life. He loved poverty and the simplest lifestyle. He accepted in obedience,

but requested to be allowed to continue some missionary work. Whenever he had

to travel with the Queen, he used the opportunity to preach in different towns

throughout Spain.

In a time where the Queens and Kings chose the bishops

for vacant dioceses, Claret played an important role in the selection of holy

and dedicated bishops for Spain and its colonies.

The eleven years he spent as confessor to the Queen of

Spain were particularly painful, because the enemies of the Church directed

toward him all kinds of slanders and personal ridicule. In 1868 a new

revolution dethroned the Queen and sent her with her family into exile.

Claret’s life was also in danger, so he accompanied her to France. This gave

him the opportunity to preach the Gospel in Paris. He stayed with them for a

while, then went to Rome where he was received by Pope Pius IX in a private

audience.

On December 8, 1869, seven hundred bishops from all

over the world gathered in Rome for the First Vatican Council. Claret was one

of the Council Fathers. His presence became noticeable when the subject of

papal infallibility was discussed, which Claret defended vehemently. This

teaching became a dogma of faith for all Catholics at this Council. The Italian

revolution interrupted the process of the Council, which is never concluded.

Claret’s health is deteriorated, so he returned to France accompanied by the

Superior General of the Sons of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, his congregation.

In France, Claret joined his missionaries who are also

in exile. Soon he found out, that there was a warrant for his arrest. He

decided to go into hiding in a Cistercian Monastery in the French southern town

of Fontfroide. There he died on October 24, 1870 at the age of 62. As his last

request, he dictated to his missionaries the words that are to appear on his

tombstone: “I have loved justice and hated iniquity; therefore I die in exile.”

His remains are venerated in Vic. Claret was beatified in 1934 and in 1950

canonized by Pope Pius XII.

SOURCE : HTTP://UCATHOLIC.COM/SAINTS/ANTHONY-MARY-CLARET/

Sant'Antonio María Claret y Clará

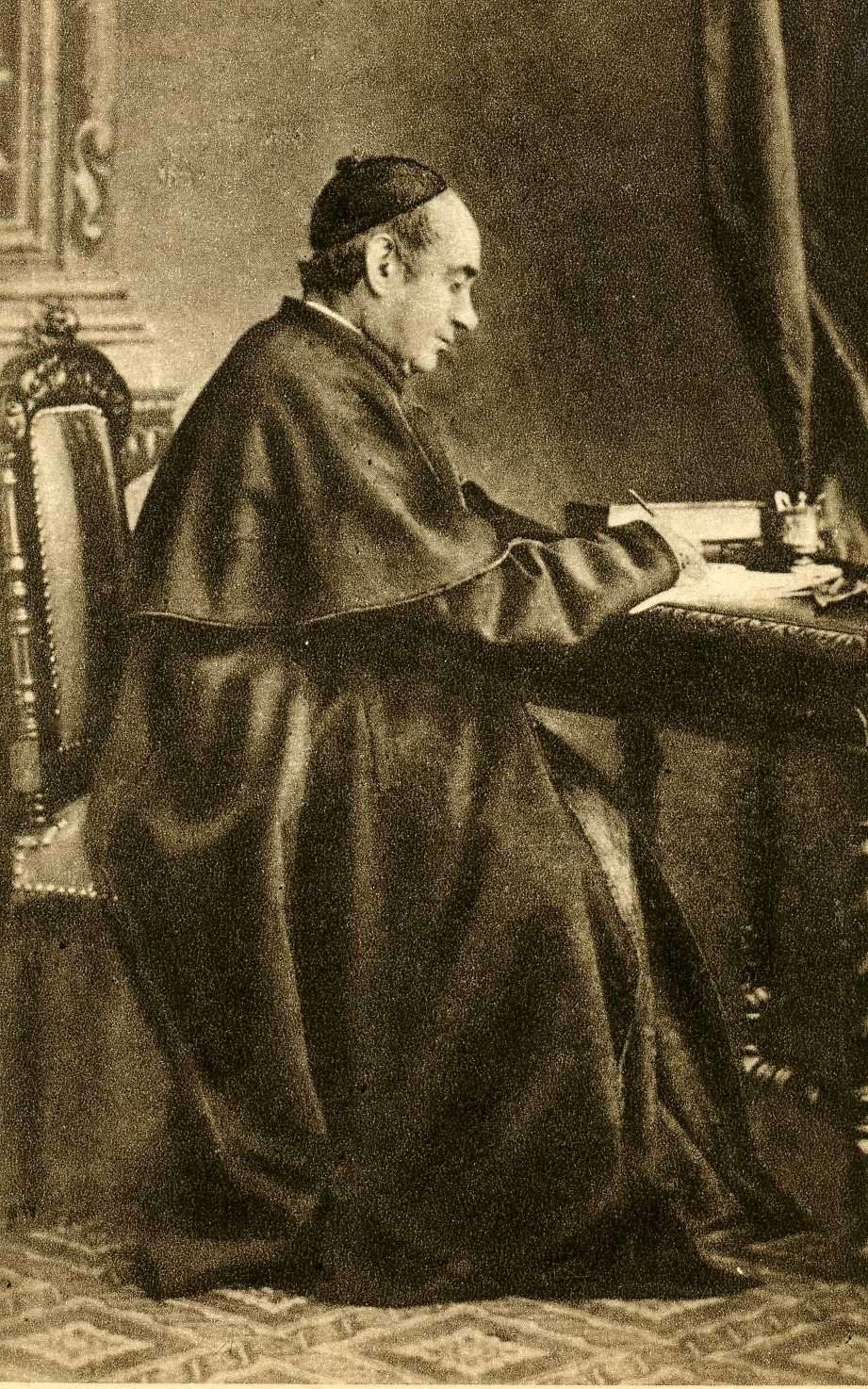

Foto del P. Claret escribiendo. A. Trinquarts, París, 29

December 1868.

Ven. Antonio María Claret y Clará

Spanish prelate and

missionary, born at Sallent, near Barcelona, 23 Dec.,

1807; d. at Fontfroide, Narbonne, France, on 24 Oct.,

1870. Son of a small woollen manufacturer, he received an elementary education in his

native village, and at the age of twelve became a weaver. A little later he

went to Barcelona to specialize in his trade, and remained there till he was

twenty. Meanwhile he devoted his spare time to study and became proficient in

Latin, French, and engraving; in addition he enlisted in the army as a

volunteer. Recognizing a call to a higher life, he left Barcelona, entered

the seminary at Vich in 1829, and

was ordained on

13 June, 1835. He received a benefice in his

native parish,

where he continued to study theology till 1839.

He now wished to become a Carthusian; missionary

work, however, appealing strongly to him he proceeded to Rome. There he entered

the Jesuit novitiate but

finding himself unsuited for that manner of life, he returned shortly to Spain and exercised

his ministry at Valadrau and Gerona, attracting notice by his efforts on behalf

of the poor. Recalled by his superiors to Vich, he was engaged in

missionary work throughout Catalonia. In 1848 he was sent to the Canary Islands where

he gave retreats for fifteen months. Returning to Vich he established the

Congregation of the Missionary Sons of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (16 July,

1849), and founded the great religious library at

Barcelona which bears his name, and which has issued several million cheap

copies of the best ancient and modern Catholic works.

Such had been the fruit of his zealous labours and

so great the wonders he had worked, that Pius IX at the

request of the Spanish sovereign appointed him Archbishop of

Santiago de Cuba in 1851. He was consecrated at Vich and embarked

at Barcelona on 28 Dec. Having arrived at his destination he began at once a

work of thorough reform. The seminary was

reorganized, clerical discipline

strengthened, and over nine thousand marriages validated within the first two

years. He erected a hospital and

numerous schools.

Three times he made a visitation of the entire diocese, giving local missions

incessantly. Naturally his zeal stirred up the

enmity and calumnies of

the irreligious, as had happened previously in Spain. No less than

fifteen attempts were made on his life, and at Holguin his cheek was laid open

from ear to chin by a would-be assassin's knife. In February, 1857, he was

recalled to Spain by

Isabella II, who made him her confessor. He obtained permission to resign

his see and

was appointed to the titular

see of Trajanopolis.

His influence was now directed solely to help the poor and to propagate

learning; he lived frugally and took up his residence in an Italian hospice.

For nine years he was rector of

the Escorial monastery where he

established an excellent scientific laboratory, a museum of natural history,

a library,

college, and schools of

music and languages. His further plans were frustrated by the revolution of

1868. He continued his popular missions and distribution of good books wherever

he went in accompanying the Spanish Court. When Isabella recognized the new

Government of United Italy he

left the Court and hastened to take his place by the side of the pope; at the latter's

command, however, he returned to Madrid with

faculties for absolving the queen from the censures she had incurred. In 1869

he went to Rome to

prepare for the Vatican

Council. Owing to failing health he withdrew to Prades in France, where he was

still harassed by his calumnious Spanish

enemies; shortly afterwards he retired to the Cistercian abbey at Fontfroide

where he expired.

His zealous life and

the wonders he

wrought both before and after his death testified to his sanctity. Informations

were begun in 1887 and he was declared Venerable by Leo XIII in 1899.

His relics were

transferred to the mission house at Vich in 1897, at

which time his heart was found incorrupt, and his grave is constantly visited

by many pilgrims.

In addition to the Congregation of the Missionary Sons of the Heart of Mary

(approved definitively by Pius IX, 11 Feb., 1870)

which has now over 110 houses and 2000 members, with missions in W. Africa, and

in Chocó (Columbia), Archbishop Claret founded or drew up the rules of several

communities of nuns.

By his sermons and

writings he contributed greatly to bring about the revival of the Catalan

language. His printed works number over 130, of which we may mention: "La

escalade Jacob"; "Maximas de moral la más pura";

"Avisos"; "Catecismo explicado con láminas"; "La llave

de oro"; "Selectos panegíricos" (11 vols.); "Sermones de

misión" (3 vols.); "Misión de la mujer"; "Vida de Sta.

Mónica"; "La Virgen del Pilar y los Francmasones"; and his

"Autobiografia", written by order of his spiritual director, but

still unpublished.

Sources

AGUILAR, Vida admirable del Venerable Antonio María

Claret (Madrid, 1894); BLANCH, Vida del Venerable Antonio María Claret

(Barcelona, 1906); CLOTET, Compendio de la vida del Siervo de Dios Antonio

María Claret (Barcelona, 1880); Memorias ineditas del Padre Clotet in the

archives of the missionaries of Aranda de Duero; VILLABA HERVAS, Recuerdos de

cinco lustros 1843-1868 (Madrid, 1896); Estudi bibliografich de los obres del

Venerable Sallenti (Barcelona, 1907).

[Note: Antonio María Claret was canonized by Pope

Pius XII in 1950.]

MacErlean, Andrew. "Ven. Antonio María

Claret y Clará." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 16

(Index). New York: The Encyclopedia Press, 1914. 25 Oct.

2021 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/16026a.htm>.

Transcription. This article was transcribed for

New Advent by Herman F. Holbrook. Ad Dei gloriam honoremque Sancti Antonii

Mariae.

Ecclesiastical approbation. Nihil Obstat. March

1, 1914. Remy Lafort, S.T.D., Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal

Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2020 by Kevin Knight.

Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/16026a.htm

Anthony (Antony)

Mary Claret B, Founder (RM)

Born in Sallent,

Spain, December 23, 1807; died in Narbonne, France, October 24, 1870; canonized

1950.

"When I see the need there is for divine teaching

and how hungry people are to hear it, I am atremble to be off and running

throughout the world, preaching the Word of God. I have no rest. My soul finds no other relief than to rush about and

preach."

"If God's

Word is spoken by a priest who is filled with the fire of charity--the fire of

love of God and neighbor--it will wound vices, kill sins, convert sinners, and

work wonders."

"When I am before the Blessed Sacrament I feel

such a lively faith that I cannot describe it. Christ in the Eucharist is

almost tangible to me. . . . When

it is time for me to leave, I have to tear myself away from His sacred

presence."

--St. Antony Claret

As the son of a weaver, Antony became a weaver himself

and in his free time he learned Latin and printing. At the age of 22 he entered

the seminary at Vich, Catalonia, Spain, and was ordained in 1835. After a few

years he began to entertain the idea of a Barthusian vocation but it seemed

beyond his strength, so he travelled to Rome to join the Jesuits with the idea

of becoming a foreign missionary. Ill health, however, caused him to leave the

Jesuit novitiate and he returned to pastoral work at Sallent in 1837. He spent

the next decade preaching parochial missions and retreats throughout Catalonia.

During this time he helped

Blessed Joachima de Mas to establish the Carmelites of Charity.

He went to the Canary Islands and after 15 months

there (1848-49) with Bishop Codina, Anthony returned to Vich. His evangelical

zeal inspired other priests to join in the same work, so in 1849 he founded the

Missionary Sons of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (the Claretians), dedicated to

preaching missions. The

Claretians have spread far beyond Spain to the Americas and beyond.

In 1850, Queen Isabella II, appointed him archbishop

of Santiago, Cuba. The people of this diocese were in a shocking state, and

Claret made bitter enemies in his efforts to reform the see--some of whom made

threats on his life. In

fact, he was wounded in an assassination attempt against his life at Holguin in

1856, by a man angered that his mistress was won back to an honest life.

At the request of Queen Isabella, he returned to Spain

in 1857 to become her confessor. He resigned his Cuban see in 1858, but spent

as little time at the court as his official duties required. Throughout this

period he was also deeply occupied with the missionary activities of his

congregation and with the diffusion of good literature, especially in his

native Catalan. He was also appointed rector of the Escorial, where he

established a science laboratory, a natural history museum, and schools of

music and languages. He also founded a religious library in Barcelona.

He followed Isabella to France when a revolution drove

her from the throne in 1868. He attended Vatican Council I (1869-70) where he

influenced the definition of papal infallibility. An attempt was made to lure

him back to Spain, but it failed. Antony retired to Prades, France, but was forced to flee to a Cistercian

monastery at Fontfroide near Narbonne when the Spanish ambassador demanded his

arrest.

Anthony Claret was a leading figure in the revival of

Catholicism in Spain, preached over 25,000 sermons, and published some 144

books and pamphlets during his lifetime. His continual union with God was

rewarded by many supernatural graces. He was reputed to have performed

miraculous cures and to have had gifts of prophecy. Both in Cuba and in Spain he encountered the hostility

of the Spanish anti-clerical politicians (Attwater, Benedictines, Delaney,

Encyclopedia, Walsh, White).

He is the patron

saint of weavers; and of savings and savings banks, a result of his opening

savings banks in Santiago in an effort to help the poor (White).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/1024.shtml

Sant'Antonio María Claret y Clará

St Anthony Mary

Claret~"When we say, I believe in the Holy Catholic Church [...]"

Posted by Dawn Marie on September 3, 2013 at 7:06pm

St Anthony Mary Claret (died A.D. 1870) :

"When we say, I believe in the Holy Catholic

Church, we are not speaking of the material church, the place in which we

faithful unite to pay God that tribute of love, honour, and attention which we

owe to Him, and which is called religion. In this sense "church"

means temple, house of God, or house of prayer. But by those words of the

Creed, we affirm belief in the Church as the society or congregation of the

faithful, united by the profession of one and the same Faith, united also by

participation in the same Sacraments, and by submission to the legitimate

prelates, principally to the Roman Pontiff. [...] In the first place He made it

One. Not having more than One God, nor been given more than One Faith, as Saint

Paul says, and One Baptism, which is the door of His Church and of the other

Sacraments, neither can there be more than One True Religion in which men can

please God and accomplish His most holy will. [...] By this the true Church is

distinguished from the synagogues of Satan or heretical sects, of which some

teach one thing, others another. [...] And, actually, there have been, there

are now, and there always will be saints in the Catholic Church. But heretical

sects can count not even one, nor will they ever have them. Do you know how

they evade this argument? They make fun of the saints and even of the Most Holy

Virgin Mary. But they will stop laughing when they are presented to the

tribunal of God, where they will find that those Catholics who observed the

laws and doctrine taught by our Holy Church are saved ‑ while heretics, even

though they observed their own laws, are condemned! [...]

She is Catholic also with respect to places, or to Her reach and diffusion

throughout all the world, clasping to Her breast all groups of people without

distinction of nations, classes, ages, or sexes. In all times, in all

countries, and in all groups of people where She is found, She has held, and

will continue to hold, one and the same Faith, one and the same doctrine or

morality, and one and the same form of government under the Roman Pontiff.

And Her members, wherever they are found, will always be united by the same

beliefs, by the same hope, and by charity, being alive by grace. Thus, She

embraces all those who are to be saved. For She is another ark of Noah. Outside

of the ark everyone drowned in the flood; and so also will everyone drown or be

damned who does not choose to enter into this mystical ark, the Church of Jesus

Christ. "Who does not have the Church for a mother," says Saint

Cyprian, "cannot have God for a father." [...] Here you have

explained for you, my son, the four marks which I told you God left us in order

that we may know the true Church. By these we cannot confuse Her with the many

synagogues of Satan, which also pretend to be the Church of God. We can see

that none are in peace or unity except ours. Furthermore, we can conclude that

ours is the only truth, in which and with which we must live and die united in

order to be able to go to heaven. [...] Consequently, the evasions of the heretics

are futile. For this reason you cannot doubt that the only true Church is our

Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman Church, in which you must persevere, inwardly

and outwardly. And with all preciseness must you observe Her holy laws if you

want to save your soul. Otherwise, you will be lost forever." (The

Catechism Explained)

Sant'Antonio María Claret y Clará

A Very Special

Patron: Saint Anthony Mary Claret

by The Slaves of the Immaculate Heart

of Mary January

3, 2006

“And who,” comes the usual response, “is Anthony Mary

Claret?”

It happens nearly every time we introduce the name of

this remarkable saint in the course of conversation. Which we do frequently,

since St. Anthony Mary is very fittingly invoked in connection with a great

many of our religious discussions nowadays.

But our reply to the question only prompts

bewilderment on the part of our uninformed inquirers, leaving each in turn to

wonder aloud, “How is it that I never heard of him?” For this is how we must

answer their first query:

Anthony Claret was a renowned apostle — one to be

compared to no lesser figure than Saint Francis Xavier. Too, he was a miracle

worker whose prodigious cures would rival the marvels of Saint Anthony of

Padua. And, like Saint Vincent Ferrer, he was a mystic, as well whose

prophecies unfolded the events of our very day.

What is more, as was told him by Our Lady, he was to

be the Saint Dominic of the latter times spreading devotion to the Holy Rosary.

In his own era, however, he would best be remembered as “the most calumniated

man of the nineteenth century.”

Yes, he was all these and more — much, much more!

Indeed, in the last analysis, Saint Anthony Mary Claret was perhaps the

greatest of our great modern Saints. And yet, strangely enough, scarcely a

century after his death he is also probably the least known.

This is a phenomenon without precedence in Christian

annals. Never before has the fame of so illustrious and conspicuous a hero of

the Church been forced into obscurity, and in such a short time! Yet never has

the world needed more the example, the inspiration, and the heavenly assistance

of so splendid a saint. So,

America, allow us to introduce Saint Anthony Mary Claret.

Early years

Catalonia, a region of Spain with a dialect all its

own, lies against the Pyrenees in the northeastern corner of that country. It

was there, in the town of Sallent, that Senor Juan Claret made a special visit

to the parish church on Christmas morning, 1807, to have his day-old son

baptized. Surely, he reasoned, in favor of his haste, God would especially

bless a child regenerated in grace on the very birthday of Our Lord. And, of

course, he was right.

The infant was christened Antonio Juan Adjutorio

Claret y Clara. Years later when consecrated archbishop, “out of devotion to

Mary Most Holy I added the sweet name of Maria, my mother, my patroness, my

mistress, my directress, and, after Jesus, my all.” But in childhood he was

known simply as “Tonin.” And that’s the long and the short of the heralded

name, Anthony Mary Claret.

There was something exceptional about “poco Tonin.”

There was, for example, his rare disposition and charitable nature which he

would later attribute entirely to God’s good grace. Constrained by his

confessor under formal obedience later in life to write his autobiography,

Saint Anthony affirmed, “I am by nature so softhearted and compassionate that I

cannot bear seeing misfortune or misery without doing something to help.”

This explains his struggling with thoughts about

eternity at the mere age of five. “Siempre, siempre, siempre ” — “forever

and ever and ever” was the shuddering notion that robbed the little fellow of

sleep, contemplating the endless horrible suffering that was the lot of the

damned. “Yes, forever and ever they will have to bear their pain.”

It was “this idea of a lost eternity” that would

actuate the extraordinarily holy and eventful career of the apostle, and that

would provoke him one day to remark, “I simply cannot understand how other

priests who believe the same truths that I do, and as we all should, do not

preach and exhort people to save themselves from falling into hell. I wonder,

too, how the laity, men and women who have the Faith, can help crying out.”

The diminutive aspirant for the priesthood began

school at the age of six and proved to be a diligent student. It was during

these years of primary education that the stalwart champion of sound

catechetical training learned his most important lesson in life: “Just as the