Statue de Saint Gérard à Székesfehérvár.

Saint Gérard de Csanad

Évêque

de Csanad et martyr (✝ 1047)

Moine bénédictin

vénitien, il devint évêque de Csanad en Hongrie, à la demande du roi saint Étienne. Après

la mort du roi, les guerres de succession amenèrent au pouvoir le prince André

qui voulut rétablir l'idolâtrie. Au cours d'une des missions d'évangélisation

que saint Gérard menait avec deux autres évêques, ils furent tous trois agressés

par des païens opposés à leur ministère. Gérard fut précipité du haut d'une

falaise au bord du Danube et il y sacrifia sa vie. Les autres deux évêques

furent martyrisés avec lui.

En Hongrie, l’an 1046, saint Gérard Sagredo, évêque de Csanad et

martyr. Originaire de Venise et moine bénédictin en route pour la Terre Sainte,

il devint le précepteur du jeune prince Émeric, fils du roi de Hongrie saint

Étienne et, dans une révolte des Hongrois, mourut lapidé, non loin du Danube.

Martyrologe romain

Statue de

Gherardo Sagredo di it:Giusto le Court à San Francesco della

Vigna a Venezia

Saint Gérard Sagredo

Évêque et martyr

(† 1046)

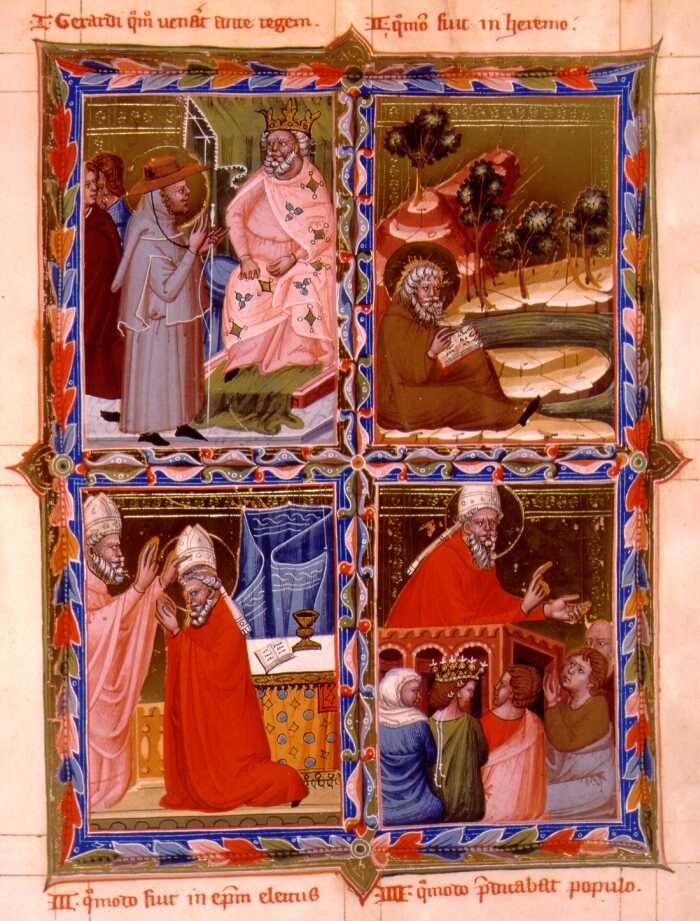

D'origine vénitienne, Gérard se fit moine bénédictin et se vit confier

l'éducation du prince Émeric à la cour de Saint Étienne, roi de Hongrie.

Il devint évêque de Csanád et instaura le culte marial et la liturgie dans son

diocèse. Il aimait beaucoup se retirer dans la solitude d'une forêt pour prier.

À la mort de son protecteur, saint Étienne, un usurpateur prit le pouvoir et

fit lapider Gérard qui lui résistait, restant inébranlable sur ses positions.

Évangile

au Quotidien

St. Gerard Sagredo

(980-1046) joined a Benedictine monastery when he was a young man, because he

knew from an early age he wanted to serve the Lord with a ministry of some

kind. While on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem he befriended Stephen, the king of

Hungary, and became the tutor of the king’s son. Stephen established an

Episcopal see in Csanad, and made Gerard its first bishop. Even though most of

the people in the area did not believe in God, Gerard’s preaching brought many

of them into the church. However, after the death of King Stephen, the country

fell back on its heathen roots and Christians were persecuted. Gerard himself

was a target of the anti-Christian movement, and he died a brave martyr’s

death. We honor him on Sept. 24. -

See more at: http://www.catholiccourier.com/faith-family/kids-chronicle/saint-for-today/st-gerard-sagredo1/#sthash.6lAlB7nz.dpuf

See more at: http://www.catholiccourier.com/faith-family/kids-chronicle/saint-for-today/st-gerard-sagredo1/#sthash.6lAlB7nz.dpuf

SOURCE : http://www.catholiccourier.com/faith-family/kids-chronicle/saint-for-today/st-gerard-sagredo1/

September 24

ST GERARD,

BISHOP OF CSANAD, MARTYR (A.D. 1046)

ST GERARD,

sometimes surnamed Sagredo, the apostle of a large district in Hungary, was a

Venetian, born about the beginning of the eleventh century. At an early age he

consecrated himself to the service of God in the Benedictine monastery of San

Giorgio Maggiore at Venice, but after some time left it to undertake a

pilgrimage to Jerusalem. While passing through Hungary he became known to the

king, St Stephen, who made him tutor to his son, Bd Emeric, and Gerard began as

well to preach with success. When St Stephen established the episcopal see of

Csanad he appointed Gerard to be its first bishop. The greater part of the

people were heathen, and those that bore the name of Christian were ignorant,

brutish and savage, but St Gerard laboured among them with much fruit. He

always so far as possible joined to the perfection of the episcopal state that

of the contemplative life, which gave him fresh vigour in the discharge of his

pastoral duties. But Gerard was also a scholar, and wrote an unfinished

dissertation on the Hymn of the Three Young Men (Daniel iii), as well as other

works which are lost.

King Stephen seconded the

zeal of the good bishop so long as he lived, but on his death in 1038 the realm

was plunged into anarchy by competing claimants to the crown, and a revolt

against Christianity began. Things went from bad to worse, and eventually, when

celebrating Mass at a little place on the Danube called Giod, Gerard had

prevision that he would on that day receive the crown of martyrdom. His party

arrived at Buda and were going to cross the river, when they were set upon by

some soldiers under the command of an obstinate upholder of idolatry and enemy

of the memory of King St Stephen. They attacked St Gerard with a shower of

stones, overturned his conveyance, and dragged him to the ground. Whilst in

their hands the saint raised himself on his knees and prayed with St Stephen,

"Lord, lay not this sin to their charge. They know not what they do."

He had scarcely spoken these words when he was run through the body with a

lance; the insurgents then hauled him to the edge of the cliff called the

Blocksberg, on which they were, and dashed his body headlong into the Danube

below. It was September 24, 1046. The heroic death of St Gerard had a profound

effect, he was revered as a martyr, and his relics were enshrined in 1083 at

the same time as those of St Stephen and his pupil Bd Emeric. In 1333 the

republic of Venice obtained the greater part of his relics from the king of

Hungary, and with great solemnity translated them to the church of our Lady of

Murano, wherein St Gerard is venerated as the protomartyr of Venice, the place

of his birth.

The most reliable

source for the history of St Gerard is, it appears, the short biography printed

in the Acta Sanctorum, September, vol. vi (pp. 722-724). Contrary to the

opinion previously entertained, it is not an epitome of the longer life which

is found in Endlicher, Monumenta Arpadiana (pp. 205-234), but dates from the

twelfth, or even the end of the eleventh, century. This, at least, is the

conclusion of R. F. Kaindl in the Archiv f. Oesterreichische Geschichte, vol.

xci (1902), pp. 1-58. The other biographies are later expansions of the first

named, and not so trustworthy. St Gerard's story and episcopate have also been

discussed by C. Juhász in Studien und Mittheilungen O.S.B., 1929, pp. 139-145,

and 1930, pp. 1-35; and see C. A. Macartney, in Archivum Europae

centro-orientalis, vol. iv (1938), pp. 456-490, on the Lives of St Gerard, and

his Medieval Hungarian Historians (1953)

September 24

St. Gerard, Bishop of

Chonad, Martyr

From his

exact life in Surius, Bonfinius, Hist. Hung. Dec. 2, l. 1, 2. Fleury, t. 9.

Gowget Mezangui and Roussel, Vies des Saints, 1730. Stilting, t. 6, Sept. p.

713. Mabillon, Act. Ben. sæc. 6, par. 1, p. 628.

A.D. 1046.

ST. GERARD,

the apostle of a large district in Hungary, was a Venetian, and born about the

beginning of the eleventh century. He renounced early the enjoyments of the

world, forsaking family and estate to consecrate himself to the service of God

in a monastery. By taking up the yoke of our Lord from his youth he found it

light, and bore it with constancy and joy. Walking always in the presence of

God, and nourishing in his heart a spirit of tender devotion by assiduous holy

meditation and prayer, he was careful that his studies should never extinguish

or impair it, or bring any prejudice to the humility and simplicity by which he

studied daily to advance in Christian perfection. After some years, with the

leave of his superiors, he undertook a pilgrimage to the holy sepulchre at

Jerusalem. Passing through Hungary, he became known to the holy king St.

Stephen, who was wonderfully taken with his sincere piety, and with great

earnestness persuaded him that God had only inspired him with the design of

that pilgrimage, that he might assist, by his labours, the souls of so many in

that country, who were perishing in their infidelity. Gerard, however, would by

no means consent to stay at court, but built a little hermitage at Beel, where

he passed seven years with one companion called Maur, in the constant practice

of fasting and prayer. The king having settled the peace of his kingdom, drew

Gerard out of his solitude, and the saint preached the gospel with wonderful

success. Not long after, the good prince nominated him to the episcopal see of

Chonad or Chzonad, a city eight leagues from Temeswar. Gerard considered

nothing in this dignity but labours, crosses, and the hopes of martyrdom. The

greater part of the people were infidels, those who bore the name of Christians

in this diocess were ignorant, brutish, and savage. Two-thirds of the

inhabitants of the city of Chonad were idolaters; yet the saint, in less than a

year, made them all Christians. His labours were crowned with almost equal

success in all the other parts of the diocess. The fatigues which he underwent

were excessive, and the patience with which he bore all kinds of affronts was

invincible. He commonly travelled on foot, but sometimes in a waggon: he always

read or meditated on the road. He regulated everywhere all things that belonged

to the divine service with the utmost care, and was solicitous that the least

exterior ceremonies should be performed with great exactness and decency, and

accompanied with a sincere spirit of religion. To this purpose he used to say,

that men, especially the grosser part, (which is always the more numerous,)

love to be helped in their devotion by the aid of their senses.

The example

of our saint had a more powerful influence over the minds of the people than

the most moving discourses. He was humble, modest, mortified in all his senses,

and seemed to have perfectly subdued all his passions. This victory he gained

by a strict watchfulness over himself. Once finding a sudden motion to anger

rising in his breast, he immediately imposed upon himself a severe penance,

asked pardon of the person who had injured him, and heaped upon him great

favours. After spending the day in his apostolic labours, he employed part of

the night in devotion, and sometimes in cutting down wood and other such

actions for the service of the poor. All distressed persons he took under his

particular care, and treated the sick with uncommon tenderness. He embraced

lepers and persons afflicted with other loathsome diseases with the greatest

joy and affection; often laid them in his own bed, and had their sores dressed

in his own chamber. Such was his love of retirement, that he caused several

small hermitages or cells to be built near the towns in the different parts of

his diocess, and in these he used to take up his lodging wherever he came in

his travels about his diocess, avoiding to lie in cities, that, under the

pretence of reposing himself in these solitary huts, he might indulge the

heavenly pleasures of prayer and holy contemplation; which gave him fresh

vigour in the discharge of his pastoral functions. He wore a rough hair shirt

next his skin, and over it a coarse woollen coat.

The holy king

St. Stephen seconded the zeal of the good bishop as long as he lived. But that

prince’s nephew and successor Peter, a debauched and cruel prince, declared

himself the persecutor of our saint: but was expelled by his own subjects in

1042, and Abas, a nobleman of a savage disposition, was placed on the throne.

This tyrant soon gave the people reason to repent of their choice, putting to

death all those noblemen whom he suspected not to have been in his interest.

St. Stephen had established a custom, that the crown should be presented to the

king by some bishop on all great festivals. Abas gave notice to St. Gerard to

come to court to perform that ceremony. The saint, regarding the exclusion of

Peter as irregular, refused to pay the usurper that compliment, and foretold

him that if he persisted in his crime, God would soon put an end both to his

life and reign. Other prelates, however, gave him the crown; but, two years

after, the very persons who had placed him on the throne turned their arms against

him, treated him as a rebel, and cut off his head on a scaffold. Peter was

recalled, but two years after banished a second time. The crown was then

offered to Andrew, son of Ladislas, cousin-german to St. Stephen, upon

condition that he should restore idolatry, and extirpate the Christian

religion. The ambitious prince made his army that promise. Hereupon Gerard and

three other bishops set out for Alba Regalis, in order to divert the new king

from this sacrilegious engagement.

When the four

bishops were arrived at Giod near the Danube, St. Gerard, after celebrating

mass, said to his companions: “We shall all suffer martyrdom to-day, except the

bishop of Benetha.” They were advanced a little further, and going to cross the

Danube, when they were set upon by a party of soldiers, under the command of

Duke Vatha, the most obstinate patron of idolatry, and the implacable enemy of

the memory of St. Stephen. They attacked St. Gerard first with a shower of

stones, and, exasperated at his meekness and patience, overturned his chariot,

and dragged him on the ground. Whilst in their hands the saint raised himself

on his knees, and prayed with the protomartyr St. Stephen: “Lord, lay not this

to their charge; for they know not what they do.” He had scarcely spoken these

words when he was run through the body with a lance, and expired in a few

minutes. Two of the other bishops, named Bezterd and Buld, shared the glory of

martyrdom with him: but the new king coming up, rescued the fourth bishop out

of the hands of the murderers. This prince afterwards repressed idolatry, was

successful in his wars against the Germans who invaded his dominions, and

reigned with glory. St. Gerard’s martyrdom happened on the 24th of September,

1046. His body was first interred in a church of our Lady near the place where

he suffered; but soon after removed to the cathedral of Chonad. He was declared

a martyr by the pope, and his remains were taken up, and put in a rich shrine

in the reign of St. Ladislas. At length the republic of Venice, by repeated

importunate entreaties, obtained his relics of the king of Hungary, and with

great solemnity translated them to their metropolis, where they are venerated

in the church of our Lady of Murano

The good

pastor refuses no labour, and declines no danger for the good of souls. If the

soil where his lot falls be barren, and he plants and waters without increase,

he never loses patience, out redoubles his earnestness in his prayers and

labours. He is equally secure of his own reward if he perseveres to the end;

and can say to God, as St. Bernard remarks: “Thou, O Lord, wilt not less reward

my pains, if I shall be found faithful to the end.” Zeal and tender charity

give him fresh vigour, and draw floods of tears from his eyes for the souls

which perish, and for their contempt of the infinite and gracious Lord of all

things. Yet his courage is never damped, nor does he ever repine or disquiet

himself. He is not authorized to curse the fig-tree which produces no fruit,

but continues to dig about it, and to dung the earth, waiting to the end,

repaying all injuries with kindness and prayers, and never weary with renewing

his endeavours. Impatience and uneasiness in pastors never spring from zeal or

charity; but from self-love, which seeks to please itself in the success of

what it undertakes. The more deceitful this evil principle is, and the more

difficult to be discovered, the more careful must it be watched against. All

sourness, discouragement, vexation, and disgust of mind are infallible signs

that a mixture of this evil debases our intention. The pastor must imitate the

treasures of God’s patience, goodness, and long-suffering. He must never

abandon any sinner to whom God, the offended party, still offers mercy.

Rev. Alban

Butler (1711–73). Volume IX: September. The Lives of the Saints. 1866.

San Gerardo Sagredo Apostolo d'Ungheria

Venezia, 23 aprile 980 – Pest (Ungheria), 24 settembre 1046

Patronato: Ungheria

Martirologio Romano: In

Pannonia, nel territorio dell’odierna Ungheria, san Gerardo Sagredo,

vescovo di

Csanád e martire, che fu maestro di sant’Emerico, principe adolescente, figlio

del re santo Stefano, e morì lapidato presso il Danubio nella rivolta di alcuni

pagani del luogo.

Il santo vescovo accomuna nella sua vita, dalle origini alla morte vari

Paesi europei; egli nacque a Venezia in un anno imprecisato intorno al 980 un

23 aprile, perciò al battesimo ebbe il nome Giorgio, da una famiglia oriunda

della Dalmazia, che secondo una tradizione cinquecentesca discendeva dalla

stirpe Sagredo.

Giorgio all’età di cinque anni fu colpito da grave febbre ed i genitori impetrarono la grazia a s. Giorgio per la sua guarigione.

Una volta guarito e raggiunta un’età adatta, entrò nel monastero benedettino di S. Giorgio Maggiore all’Isola Maggiore di Venezia e in ricordo del padre da poco deceduto, prese il nome di Gerardo.

Dopo alcuni anni divenne priore del monastero e poi abate, ma dopo un po’ rinunciò alla carica, perché voleva partire per un pellegrinaggio a Betlemme in Palestina.

Partito con una nave, giunse fino a Zara, da dove invece di proseguire per la Terra Santa, ripartì per l’Ungheria dove si stabilì.

Ebbe l’incarico di “magister” (maestro) del principe Emerico, figlio del re Stefano I ‘il santo’ (969-1038) primo re d’Ungheria, in seguito si ritirò a Bakonybél per vivere da eremita.

Ma dopo un certo periodo di tempo, il re Stefano I lo richiamò dall’eremo affidandogli il vescovado di Csanád. Il vescovo Gerardo Sagredo partecipò attivamente all’opera di evangelizzazione del popolo magiaro, voluta fortemente dal re Stefano ‘il santo’, tanto da meritarsi il titolo di apostolo dell’Ungheria.

Risulta che scrisse di sua mano varie opere, ma allo stato si conosce solo il “Commento a Daniele”. Gerardo Sagredo morì il 24 settembre 1046 alla porta di Pest sulla riva destra del Danubio, per mano di un gruppo di pagani, che lo spinsero giù dal monte Kelen che prese poi il suo nome, tuttora si chiama Monte Gerardo.

Apostolo dell’Ungheria, l’antica Pannonia, il santo vescovo e martire ebbe un culto ufficiale dal 1083 con l’approvazione di papa Gregorio VII.

Nei secoli successivi si ebbe una vasta produzione biografica che lo riguarda.

Autore: Antonio Borrelli

GERARDO di Csanád

di Luigi Canetti - Dizionario Biografico degli

Italiani - Volume 53 (2000)

GERARDO di Csanád (Gerardus

Moresenae "Aecclesiae" seu Csanadiensis episcopus). - Di origine

veneziana o veneta, nacque sul finire del X secolo; le notizie storicamente

accertabili sul suo conto sono scarse fino al 1030, quando divenne vescovo

della diocesi missionaria di Marosvar, poi Csanád, in Ungheria.

La

letteratura erudita e devozionale di ambito veneto-ungherese ha alimentato la

pia leggenda della sua appartenenza alla nobile famiglia veneziana dei Sagredo,

appartenenza accreditata per la prima volta nella seconda edizione del Catalogus

sanctorum di Pietro Natali (Petrus de Natalibus), apparsa nel 1516 a

Venezia (c. 99v). Deve essere interpretata in questa prospettiva la stessa

tradizione che vuole che G. (nato un 23 aprile e battezzato perciò con il nome

del patrono Giorgio) sia stato, sin dalla più tenera infanzia, oblato e poi

(assunto il nome del padre, Gerardo, morto nel frattempo in Terrasanta), monaco

benedettino, priore e abate del monastero veneziano di S. Giorgio in Isola (più

tardi S. Giorgio Maggiore), secondo quanto è dato ricavare dalla biografia

assai fantasiosa della Vita s. Gerhardi più nota come Legenda

maior (Bibliotheca hagiographica Latina [BHL],

3424). È probabile che il legame con la famiglia Sagredo abbia trovato appiglio

in un episodio attestato dalla tradizione agiografica, lo sbarco fortunoso di

G. a Zara, città dalmata di cui i Sagredo si volevano oriundi, durante il

viaggio devozionale che avrebbe dovuto portare G. in Terrasanta e che invece

doveva condurlo, grazie all'incontro con l'abate ungherese Rasina, a farsi

evangelizzatore dei pagani nel Regno magiaro di Stefano il santo. Il legame con

il cenobio veneziano di S. Giorgio in Isola doveva invece probabilmente

giustificarsi, sempre a posteriori, con la fondazione da parte di G. di un monastero

dedicato allo stesso martire sulla riva del fiume Maros, ciò che poteva

suggerire una qualche analogia di ubicazione geografica con l'omonima sede

lagunare. L'origine veneziana o quantomeno veneta sembra comunque confermata

anche dalla più sobria Passiob. Gerardi (BHL, 3426)

o Legenda minor ("per Venetos parentes sortitus",

ed. Madzsar, p. 471), che, insieme con la Vita, costituisce, in

mancanza di notizie documentarie dirette, la principale fonte relativa alla

vita di Gerardo. Anche la Vita maior Stephani regis (BHL,

7918), attribuibile come la Passio ai primi decenni del secolo

XII, conferma tale provenienza ("Gerardus de Venetia veniens", ed.

Wattenbach, p. 236). Di dubbio, o addirittura di nessun valore, appaiono tutte

le altre speculazioni genealogiche sulle origini di G. contenute nella

letteratura del Cinque-Seicento e talora anche del Novecento, animata da

evidenti ragioni encomiastico-celebrative.

I dati

relativamente sicuri della biografia di G. sono scarsi e in ogni caso limitati

al periodo ungherese ed episcopale della sua vita, giacché tutti gli episodi

relativi alla fase monastica ed eremitica sino al 1030 appaiono costruiti

piuttosto ingenuamente sulla base di tòpoi del genere

agiografico e della spiritualità monastica e comunque gravati da patenti

anacronismi, come per esempio il presunto soggiorno presso lo Studium di

Bologna (cfr. Legenda maior, ed. Madzsar, p. 483): analisi

spregiudicate come quella di J. Leclercq hanno indotto persino a dubitare della

reale appartenenza di G. al monachesimo benedettino.

Nonostante

tutte le ragionevoli ipotesi formulate a riguardo (dalla vocazione

ascetico-missionaria alle avviate relazioni politico-diplomatico-commerciali

veneto-ungheresi tra X e XI secolo), dobbiamo rassegnarci a ignorare anche i

motivi reali che dovettero spingere o portare G. in Ungheria nel corso del

terzo decennio del sec. XI: qui, forse dopo un periodo di relativo isolamento

presso l'eremo di Beel, avviò i contatti con re Stefano, che, dopo avergli

affidato l'educazione del figlio Emerico, lo coinvolse a pieno titolo nella sua

politica di consolidamento della cristianizzazione del Regno, affidandogli nel

1037 la nuova diocesi di Csanád, base di partenza per vaste campagne

missionarie e per l'erezione di nuove fondazioni ecclesiastiche.

Ben

scarsi sono i lumi autobiografici che ci provengono dall'opera, incompiuta, di

G., la Deliberatio supra hymnum trium puerorum, trasmessaci da un

solo manoscritto (Monaco, Bayerische Staatsbibl., Lat. 6211) e

oggetto di un'edizione critica: Gerardi Moresenae Aecclesiae seu Csanadiensis

episcopi Deliberatio supra hymnum trium puerorum, a cura G. Silagi,

Turnholti 1978 (Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio mediaevalis, XLIX).

La Deliberatio si presenta formalmente come un commento

teologico al cantico dei tre fanciulli rinchiusi nella fornace del Libro del

profeta Daniele (Dan. III, 57-65), ma in realtà è infarcita di

ampie divagazioni di svariato argomento, che tradiscono una notevole cultura

filosofico-letteraria, anche nutrita di autori antichi e profani, sia pur

mediati il più delle volte da Isidoro di Siviglia; notevole è l'influsso dello

Pseudo-Dionigi, forse conosciuto direttamente dal testo greco. Alcune prese di

posizione esplicite rendono comunque difficile non collocare G. tra i

rappresentanti della corrente antidialettica o comunque tra gli esponenti della

tradizionale esegesi simbolico-allegorica di ambiente monastico, che si

opponeva ai primi tentativi di applicazione del metodo razionale all'analisi

del dato rivelato. La compiaciuta veste retorico-stilistica e il linguaggio

criptico, ricchissimo di neologismi, rendono assai dubbia la valutazione di

particolari quali ad esempio le affermazioni secondo cui egli avrebbe compiuto

numerosi viaggi in Francia e in altri paesi d'Europa (Deliberatio, l. IV,

p. 41; l. VIII, p. 152). Dal punto di vista storico religioso sono inoltre di

un certo interesse i numerosi riferimenti alla minacciosa presenza di movimenti

ereticali nei Balcani (bogomili) e, in Italia, a Verona, Venezia e Ravenna (Deliberatio,

l. IV, p. 51). G. stesso afferma di avere scritto altre opere, tra le quali un

commento alla Lettera agli Ebrei, uno alla prima Lettera di

Giovanni (Deliberatio, l. V, p. 75) e un Libellus de

divino patrimonio (Deliberatio, l. VIII, p. 153). Sono stati

ritrovati, anche in anni recenti (Heinzer), frammenti di sermoni mariani a lui

attribuibili, che dovettero avere una certa diffusione, come sembra attestare

una citazione diretta nella Legenda aurea di Jacopo da Varazze

(ed. a cura di T. Graesse, Lipsiae 1850, cap. CXIX, p. 511).

Dopo la

morte di re Stefano (1038), nel periodo dei disordini conseguenti alla

successione, G. sembra essersi allontanato dalla corte tentando di mantenere

una posizione di cauta equidistanza, pur non potendo sottrarsi all'appoggio

della fazione di Pietro Orseolo, il nipote di Stefano designato alla

successione e sostenuto dall'imperatore Enrico III, che si opponeva

all'usurpatore Samuele Aba, appoggiato dagli eretici bogomili. Questi fu

sconfitto nel 1044, ma a costo di una crescente sudditanza del regno di Pietro

all'Impero germanico, situazione che provocò forte scontento, disordini e

congiure nobiliari, nonché una grande sollevazione pagana capeggiata dal

"pecenego" Vata. G. si schierò a favore del partito nazionale del

principe Andras, figlio di un cugino di Stefano Árpád: il 24 sett. 1046, nei

pressi del traghetto di Pest, il drappello di armati che scortava G. diretto a

Buda per accogliere il pretendente arpadiano fu assalito da una pioggia di

pietre lanciate dai sostenitori di Vata. Il vescovo, legato a un carretto, fu

trascinato sul vicino monte Kelen (che da lui prese poi il nome di monte S.

Gerardo che conserva ancor oggi) e da lì venne fatto precipitare nel Danubio.

La

fioritura agiografico-leggendaria conseguente al suo martirio gli valse, nel

1083, il riconoscimento da parte di papa Gregorio VII di un culto pubblico.

Fonti e Bibl.: Vita maior Stephani regis, a cura di W.

Wattenbach, in Mon. Germ. Hist., Script., XI, Hannoverae 1854, p.

236; Passio b. Gerardi…, in Acta sanctorumseptembris,

VI, Antverpiae 1757, pp. 722-724; Vita s. Gerhardi episcopi…, a

cura di E. Madzsar, in E. Szentpétery, Scriptores rerum Hungaricarum…,

II, Budapestini 1938, pp. 480-505; Passio b. Gerardi…, a cura di E.

Madzsar, ibid., pp. 471-479; P. de Natalibus, Catalogus

sanctorum, Venetiis 1516, cc. 99v-100; G. Morin, Un théologien

ignorée du XIe siècle: l'évêque-martyr Gérard de Csanád O.S.B., in Revue

bénédictine, XXVII (1910), pp. 516-521; M. Manitius, Geschichte der

lateinischen Literatur des Mittelalters, II, München 1923, pp. 74-81; A.

Bacotich, Tribuni antichi di Venezia di origine dalmata, in Archivio

storico per la Dalmazia, XXV (1938), pp. 101 s., 104; F. Banfi, Vita

di s. G. da Venezia nel Leggendario di Pietro Calò, in Janus

Pannonius (Roma), I (1947), pp. 224-228; Id., Vita di s. G. da

Venezia nel codice 1622 della Biblioteca universitaria di Padova, in Benedictina,

II (1948), pp. 262-330 (BHL, Suppl., 3424); A. Borst, Die

Katharer, Stuttgart 1953, pp. 78 s.; J. Horváth, A Gellért-legendák

forrásértéke [La valutazione delle leggende di G. come fonti

storiche], in A Magyar tudományos akadémia Nyelv és

Irodalomtudományi osztályának közleményei. Acta linguistica Academiae

scientiarum Hungaricae, XIII (1958), pp. 21-82; E. von Ivánka, Das

"Corpus areopagiticum" bei Gerhard von Csanád…, in Traditio,

XV (1959), pp. 205-222; E. Pásztor, Problemi di datazione della

"Legenda maior s. Gerhardi episcopi", in Bull. dell'Ist.

stor. ital. per il Medio Evo e Arch. muratoriano, LXXIII (1961), pp.

113-140; H. Barré, L'oeuvre mariale de Saint Gérard de Csanád,

in Marianum, XXV (1963), pp. 262-296; G. Silagi, Untersuchungen

zur "Deliberatio supra hymnum trium puerorum" des Gerhard von Csanád,

München 1967; S. Tramontin, Pagine di santi veneziani. Antologia,

Brescia 1968, pp. 17-26; Z.J. Kosztolnyik, The importance of Gerard of

Csanád as the first author in Hungary, in Traditio, XXV (1969),

pp. 376-386; B. Smalley, Lo studio della Bibbia nel Medioevo,

Bologna 1972, p. 115; É. Gilson, La filosofia nel Medioevo, Firenze

1973, pp. 283 s.; J. Leclercq, San G. di Csanád e il monachesimo,

in Venezia e Ungheria nel Rinascimento, a cura di V. Branca,

Firenze 1973, pp. 3-22; L. Szegfü, La missione politica e ideologica di

san G. in Ungheria, ibid., pp. 23-36; R. Manselli, L'eresia

del male, Napoli 1980, pp. 149 s.; F. Heinzer, Neues zu Gerhard von

Csanád: die Schlussschrift einer Homeliensammlung, in Internationale

Zeitschrift für Geschichte, Kultur und Landeskunde Südosteuropas, LXI

(1982), pp. 1-7; S. Tramontin, Problemi agiografici e profili di santi,

in La Chiesa di Venezia nei secoli XI-XIII, a cura di F. Tonon,

Venezia 1988, pp. 160-166; G. D'Onofrio, L'itinerario dalle arti alla

teologia nell'Alto Medioevo, in XXXVI Convegno di studi

bonaventuriani, Bagnoregio 1989, in Doctor seraphicus, XXXVI

(1989), pp. 111-142; G. Cracco, I testi agiografici: religione e

politica nella Venezia del Mille, in Storia di Venezia, I, Roma

1992, p. 934; Bibliotheca sanctorum, VI, coll. 184-186; Dict.

de spiritualité, VI, 1967, coll. 264 s.; Rep. fontium hist. Medii

Aevi, IV, pp. 697 s.;Bibliotheca hagiographica Latina…, I, pp. 510

s., Idem, Novum supplementum, p. 386; Dict.

d'hist. et de géogr. ecclésiastiques, XX, coll. 761-763.

_-_Chapel_St_Mauro_-_Gerard_of_Csan%C3%A1d.jpg)

_-_Statue_of_Saint_Gerard_of_Csan%C3%A1d.jpg)