Bienheureux Frédéric Ozanam

Fondateur de la société saint Vincent de Paul (+ 1853)

Homme d’une érudition et d’une piété remarquables, il mit sa science éminente au service de la défense et de la propagation de la foi, montra aux pauvres une charité assidue dans la Société de Saint-Vincent de Paul et, père exemplaire, fit de sa famille une église domestique. Son père était médecin à Milan et ancien officier de cavalerie dans les armées napoléoniennes. En 1815, quand la ville repassa sous domination autrichienne, la famille Ozanam rentra en France, où Frédéric fit ses études de droit. Il était alors logé par Ampère. C'est alors que ses opinions politiques se dirigèrent vers le républicanisme, car il fut très marqué par la révolte des ouvriers tisserands, les Canuts à Lyon. Sa vie s'orienta vers l'aide aux plus démunis. Il décida, en avril 1833, avec des amis parisiens de fonder une petite société vouée au soulagement des pauvres, qui prit le nom de Conférence de la charité. La conférence se plaça sous le patronage de saint Vincent de Paul. Il fut alors aidé dans sa tâche par la bienheureuse Rosalie Rendu, des Filles de la Charité. En 1839, il obtint son doctorat ès lettres, puis l'agrégation pour devenir professeur de littérature comparée à la Sorbonne. Il s'engagea également en politique, se présentant, sans succès, aux élections législatives de 1848. En 1841, il se maria. Peu après, il fut atteint par la maladie et mourut à Marseille en 1853.

Béatification de Frédéric Ozanam - Homélie le Vendredi 22 août 1997 - Notre-Dame de Paris

société saint Vincent de Paul , Frédéric Ozanam, un modèle chrétien pour notre temps.

- D’origine lyonnaise, Ozanam vient très jeune à Paris pour faire carrière dans l’enseignement. Il n’entend pas seulement affirmer sa foi dans ses paroles et ses écrits, il veut la mettre en œuvre auprès des déshérités... (diocèse de Paris)

- Frédéric Ozanam (1813-1853) Après avoir fondé, à 20 ans, la société Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, ce laïc père de famille, béatifié par Jean-Paul II, a manifesté, sa vie durant, une foi ardente et une charité inventive au service des plus pauvres. (Témoins - site de l'Église catholique en France)

À Marseille, en 1853, le trépas du bienheureux Frédéric Ozanam. Homme d’une érudition et d’une piété remarquables, il mit sa science éminente au service de la défense et de la propagation de la foi, montra aux pauvres une charité assidue dans la Société de Saint-Vincent de Paul et, père exemplaire, fit de sa famille une église domestique.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/9927/Bienheureux-Frederic-Ozanam.html

Béatification de Frédéric OZANAM - Homélie du Pape Jean-Paul II

Vendredi 22 août 1997 - Notre-Dame de Paris

1. «L'amour vient de Dieu» (1 Jn 4,7). L'Évangile de ce jour nous présente la figure du bon Samaritain. Par cette parabole, le Christ veut montrer à ses auditeurs qui est le prochain cité dans le plus grand commandement de la Loi divine: «Tu aimeras le Seigneur ton Dieu de tout ton cœur, de toute ton âme, de toute ta force et de tout ton esprit, et ton prochain comme toi-même» (Lc 10,27). Un docteur de la Loi demandait que faire pour avoir part à la vie éternelle: il trouva dans ces paroles la réponse décisive. Il savait que l'amour de Dieu et du prochain est le premier et le plus grand des commandements. Malgré cela, il demande: «Et qui donc est mon prochain? » (Lc 10,29).

Le fait que Jésus propose un Samaritain en exemple pour répondre à cette question est significatif. En effet, les Samaritains n'étaient pas particulièrement estimés par les Juifs. De plus, le Christ compare la conduite de cet homme à celle d'un prêtre et d'un lévite qui virent l'homme blessé par les brigands gisant à demi mort sur la route, et qui passèrent leur chemin sans lui porter secours. Au contraire le Samaritain, qui vit l'homme souffrant, «fut saisi de pitié» (Lc 10,33); sa compassion l'entraîna à toute une série d'actions. D'abord il pansa les plaies, puis il porta le blessé dans une auberge pour le soigner; et, avant de partir, il donna à l'aubergiste l'argent nécessaire pour s'occuper de lui (cf. Lc 10,34-35). L'exemple est éloquent. Le docteur de la Loi reçoit une réponse claire à sa question: qui est mon prochain? Le prochain, c'est tout être humain, sans exception. Il est inutile de demander sa nationalité, son appartenance sociale ou religieuse. S'il est dans le besoin, il faut lui venir en aide. C'est ce que demande la première et la plus grande Loi divine, la loi de l'amour de Dieu et du prochain.

Fidèle à ce commandement du Seigneur, Frédéric Ozanam, a cru en l'amour, l'amour que Dieu a pour tout homme. Il s'est lui-même senti appelé à aimer, donnant l'exemple d'un grand amour de Dieu et des autres. Il allait vers tous ceux qui avaient davantage besoin d'être aimés que les autres, ceux auxquels Dieu Amour ne pouvait être effectivement révélé que par l'amour d'une autre personne. Ozanam a découvert là sa vocation, il y a vu la route sur laquelle le Christ l'appelait. Il a trouvé là son chemin vers la sainteté. Et il l'a parcouru avec détermination.

2. «L'amour vient de Dieu». L'amour de l'homme a sa source dans la Loi de Dieu; la première lecture de l'Ancien Testament le montre. Nous y trouvons une description détaillée des actes de l'amour du prochain. C'est comme une préparation biblique à la parabole du bon Samaritain.

La deuxième lecture, tirée de la première Lettre de saint Jean, développe ce que signifie la parole «l'amour vient de Dieu». L'Apôtre écrit à ses disciples: «Mes bien-aimés, aimons-nous les uns les autres, puisque l'amour vient de Dieu. Tous ceux qui aiment sont enfants de Dieu et ils connaissent Dieu. Celui qui n'aime pas ne connaît pas Dieu, car Dieu est amour» (1 Jn 4,7-8). Cette parole de l'Apôtre est vraiment le cœur de la Révélation, le sommet vers lequel nous conduit tout ce qui a été écrit dans les Évangiles et dans les Lettres apostoliques. Saint Jean poursuit: «Voici à quoi se reconnaît l'amour: ce n'est pas nous qui avons aimé Dieu, c'est lui qui nous a aimés, et il a envoyé son Fils qui est la victime offerte pour nos péchés» (ibid., 10). La rédemption des péchés manifeste l'amour que nous porte le Fils de Dieu fait homme. Alors, l'amour du prochain, l'amour de l'homme, ce n'est plus seulement un commandement. C'est une exigence qui découle de l'expérience vécue de l'amour de Dieu. Voilà pourquoi Jean peut écrire: «Puisque Dieu nous a tant aimés, nous devons aussi nous aimer les uns les autres» (1 Jn 4,11).

L'enseignement de la Lettre de Jean se prolonge; l'Apôtre écrit: «Dieu, personne ne l'a jamais vu. Mais si nous nous aimons les uns les autres, Dieu demeure en nous, et son amour atteint en nous sa perfection. Nous reconnaissons que nous demeurons en lui, et lui en nous, à ce qu'il nous donne part à son Esprit» (1 Jn 4,12-13). L'amour est donc la source de la connaissance. Si, d'un côté, la connaissance est une condition de l'amour, d'un autre côté, l'amour fait grandir la connaissance. Si nous demeurons dans l'amour, nous avons la certitude de l'action de l'Esprit Saint qui nous fait participer à l'amour rédempteur du Fils que le Père a envoyé pour le salut du monde. En connaissant le Christ comme Fils de Dieu, nous demeurons en Lui et, par Lui, nous demeurons en Dieu. Par les mérites du Christ, nous avons cru en l'amour, nous connaissons l'amour que Dieu a pour nous, nous savons que Dieu est amour (cf. 1 Jn 4,16). Cette connaissance par l'amour est en quelque sorte la clé de voûte de toute la vie spirituelle du chrétien. «Qui demeure dans l'amour demeure en Dieu, et Dieu en lui» (ibid.).

3. Dans le cadre de la Journée mondiale de la Jeunesse, qui a lieu à Paris cette année, je procède aujourd'hui à la béatification de Frédéric Ozanam. Je salue cordialement Monsieur le Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger, Archevêque de Paris, ville où se trouve le tombeau du nouveau bienheureux. Je me réjouis aussi de la présence à cet événement d'Évêques de nombreux pays. Je salue avec affection les membres de la Société de Saint-Vincent de Paul venus du monde entier pour la béatification de leur fondateur principal, ainsi que les représentants de la grande famille spirituelle héritière de l'esprit de Monsieur Vincent. Les liens entre vincentiens furent privilégiés dès les origines de la Société puisque c'est une Fille de la Charité, sœur Rosalie Rendu, qui a guidé le jeune Frédéric Ozanam et ses compagnons vers les pauvres du quartier Mouffetard, à Paris. Chers disciples de saint Vincent de Paul, je vous encourage à mettre en commun vos forces, pour que, comme le souhaitait celui qui vous inspire, les pauvres soient toujours mieux aimés et servis et que Jésus Christ soit honoré en leurs personnes !

4. Frédéric Ozanam aimait tous les démunis. Dès sa jeunesse, il a pris conscience qu'il ne suffisait pas de parler de la charité et de la mission de l'Église dans le monde: cela devait se traduire par un engagement effectif des chrétiens au service des pauvres. Il rejoignait ainsi l'intuition de Monsieur Vincent: «Aimons Dieu, mes frères, aimons Dieu, mais que ce soit aux dépens de nos bras, que ce soit à la sueur de nos visages» (Saint-Vincent de Paul, XI, 40). Pour le manifester concrètement, à l'âge de vingt ans, avec un groupe d'amis, il créa les Conférences de Saint-Vincent de Paul, dont le but était l'aide aux plus pauvres, dans un esprit de service et de partage. Très vite, ces Conférences se répandirent en dehors de France, dans tous les pays d'Europe et du monde. Moi-même, comme étudiant, avant la deuxième guerre mondiale, je faisais partie de l'une d'entre elles.

Désormais l'amour des plus misérables, de ceux dont personne ne s'occupe, est au cœur de la vie et des préoccupations de Frédéric Ozanam. Parlant de ces hommes et de ces femmes, il écrit : «Nous devrions tomber à leurs pieds et leur dire avec l'Apôtre : "Tu es Dominus meus". Vous êtes nos maîtres et nous serons vos serviteurs; vous êtes pour nous les images sacrées de ce Dieu que nous ne voyons pas et, ne sachant pas l'aimer autrement, nous l'aimons en vos personnes» (à Louis Janmot).

5. Il observe la situation réelle des pauvres et cherche un engagement de plus en plus efficace pour les aider à grandir en humanité. Il comprend que la charité doit conduire à travailler au redressement des injustices. Charité et justice vont de pair. Il a le courage lucide d'un engagement social et politique de premier plan à une époque agitée de la vie de son pays, car aucune société ne peut accepter la misère comme une fatalité sans que son honneur n'en soit atteint. C'est ainsi qu'on peut voir en lui un précurseur de la doctrine sociale de l'Église, que le Pape Léon XIII développera quelques années plus tard dans l'encyclique Rerum novarum.

Face aux pauvretés qui accablent tant d'hommes et de femmes, la charité est un signe prophétique de l'engagement du chrétien à la suite du Christ. J'invite donc les laïcs et particulièrement les jeunes à faire preuve de courage et d'imagination pour travailler à l'édification de sociétés plus fraternelles où les plus démunis seront reconnus dans leur dignité et trouveront les moyens d'une existence respectable. Avec l'humilité et la confiance sans limites dans la Providence, qui caractérisaient Fréderic Ozanam, ayez l'audace du partage des biens matériels et spirituels avec ceux qui sont dans la détresse !

6. Le bienheureux Frédéric Ozanam, apôtre de la charité, époux et père de famille exemplaire, grande figure du laïcat catholique du dix-neuvième siècle, a été un universitaire qui a pris une part importante au mouvement des idées de son temps. Étudiant, professeur éminent à Lyon puis à Paris, à la Sorbonne, il vise avant tout la recherche et la communication de la vérité, dans la sérénité et le respect des convictions de ceux qui ne partagent pas les siennes. «Apprenons à défendre nos convictions sans haïr nos adversaires, écrivait-il, à aimer ceux qui pensent autrement que nous, [...] plaignons-nous moins de notre temps et plus de nous-mêmes» (Lettres, 9 avril 1851). Avec le courage du croyant, dénonçant tous les égoïsmes, il participe activement au renouveau de la présence et de l'action de l'Église dans la société de son époque. On connaît aussi son rôle dans l'institution des Conférences de Carême en cette cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris, dans le but de permettre aux jeunes de recevoir un enseignement religieux renouvelé face aux grandes questions qui interrogent leur foi. Homme de pensée et d'action, Frédéric Ozanam demeure pour les universitaires de notre temps, enseignants et étudiants, un modèle d'engagement courageux capable de faire entendre une parole libre et exigeante dans la recherche de la vérité et la défense de la dignité de toute personne humaine. Qu'il soit aussi pour eux un appel à la sainteté !

7. L'Église confirme aujourd'hui le choix de vie chrétienne fait par Ozanam ainsi que le chemin qu'il a emprunté. Elle lui dit: Frédéric, ta route a été vraiment la route de la sainteté. Plus de cent ans ont passé, et voici le moment opportun pour redécouvrir ce chemin. Il faut que tous ces jeunes, presque de ton âge, qui sont rassemblés si nombreux à Paris, venant de tous les pays d'Europe et du monde, reconnaissent que cette route est aussi la leur. Il faut qu'ils comprennent que, s'ils veulent être des chrétiens authentiques, ils doivent prendre ce même chemin. Qu'ils ouvrent mieux les yeux de leur âme aux besoins si nombreux des hommes d'aujourd'hui. Qu'ils comprennent ces besoins comme des défis. Que le Christ les appelle, chacun par son nom, afin que chacun puisse dire: voilà ma route! Dans les choix qu'ils feront, ta sainteté, Frédéric, sera particulièrement confirmée. Et ta joie sera grande. Toi qui vois déjà de tes yeux Celui qui est amour, sois aussi un guide sur tous les chemins que ces jeunes choisiront, en suivant aujourd'hui ton exemple!

© Copyright - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Février 1833, Frédéric Ozanam fait une rencontre

décisive

Aliénor Goudet - Publié le 09/09/20

Fondateur de la Société Saint-Vincent-de-Paul en 1834,

avec l’aide de la jeunesse catholique de Paris, Frédéric Ozanam a provoqué un

élan salvateur de charité qui s’est propagé dans le monde. Amoureux de Dieu et

grand intellectuel, il n’a pas laissé sa jeunesse le ralentir dans son combat

contre la misère sociale. Imaginons la naissance de cette idée révolutionnaire

dans l’esprit du jeune Frédéric.

Paris, février 1833. La neige de la veille craque sous

les pas de Frédéric, tandis qu’il déambule dans le quartier de l’église

Saint-Médard. Malgré le ciel ensoleillé et une belle messe matinale, le jeune

Lyonnais est perdu dans ses pensées.

Les paroles troublantes d’un camarade de l’université

le travaille depuis quelques temps. Le catholicisme est-il réellement mort ?

Les temps des prodiges de la foi sont-ils révolus ? Non, c’est impossible.

L’amour de Dieu est pour tous les temps et toutes les générations. Mais alors

pourquoi la France souffre-t-elle ainsi ? Aller à la messe, communier et

écouter les homélies n’est pas suffisant. Enseigner le catéchisme et distribuer

la soupe aux mendiants ont leurs limites.

Il lève enfin la tête lorsque les cloches de

Saint-Médard sonnent, appelant les fidèles à la messe de 10h. Il songe y

retourner une seconde fois pour demander de l’aide à Dieu. Quelques personnes

accélèrent le pas et se hâtent vers le sanctuaire.

– V’la les bons chrétiens qui vont à la messe du

dimanche comme des gens bien, ricane une voix. Et ça file tout aussi vite quand

faut aider les pauvres, hein ? Elle est belle la charité chrétienne !

Une bonne femme toute menue couverte d’un châle troué

se trouvant sur le parvis lance un regard mauvais aux fidèles. Ses cheveux mal

coiffés sous son bonnet et les cernes sur son visage trahissent un grand manque

de sommeil. D’un air agacé, elle secoue la tête avant de croiser le regard de

Frédéric. Avec un sourire en coin aussi peu sincère que son rire, elle

s’approche de lui et vient lui prendre le bras.

– Et alors, mon bon m’sieur, on n’offre pas d’verre

aux demoiselles dans le froid ?

Une odeur nauséabonde de whisky et d’humidité monte à

la tête de Frédéric, mais celui-ci combat son dégoût et s’interdit un mouvement

de recul.

– Je trouve qu’il est un peu tôt pour de l’alcool,

répond-t-il en s’efforçant de sourire. Mais si vous l’acceptez, je vous offre

volontiers un café.

La femme écarquille les yeux, abasourdie, avant

d’éclater d’un rire gras mais sincère cette fois.

– Z’êtes marrant vous ! – Pardonnez mon indiscrétion,

demande-t-il. J’ai cru comprendre que vous aviez besoin d’aide.

Elle le dévisage avec méfiance quelques instants,

avant de hausser les épaules, et de lui raconter l’état pitoyable de sa maison,

qu’avec son travail d’ouvrière, elle n’a ni le temps, ni les moyens de s’en

occuper.

– Je serai pas aussi embêtée si y’avait que moi

dedans, continue-t-elle. Mais avec le mari qu’est plus de ce monde, ma fifille

elle est toute seule. J’veux pas qu’elle se blesse, moi, mais j’peux pas la

mettre dehors par ce froid.

Lire aussi :

« Pour saint Vincent de Paul là où se trouve le pauvre, se

trouve le Christ »

C’est au tour de Frédéric d’être bouche bé. Bien sûr !

La réponse à ses questions est là, sous son nez. Il ne faut pas attendre que

les pauvres viennent à lui. C’est lui qui doit aller chez eux. Pour les visiter,

les aider à faire ce qu’ils n’ont pas le temps de faire, leur donner du temps…

Comme le faisait saint Vincent de Paul. Il faut absolument en parler à l’abbé

Noirot !

– Z’êtes un drôle d’oiseau, m’sieur, dit alors la

bonne femme, à écouter les tourments d’une sotte qui a trop bu. – Je suis

vraiment navré, lui dit Frédéric. Je vais devoir y aller. Mais dîtes moi où

vous habitez. J’aimerai vous aider à réparer votre toit.

Il s’attend à l’entendre rire à nouveau, et dire

qu’elle ne croit pas à son hypocrite charité chrétienne. Mais au lieu de cela,

un sourire radieux se dessine sur son visage, lui retirant dix ans d’âge.

Frédéric le sait à présent : c’est ce regard plein d’espoir et de confiance

qu’il souhaite offrir aux miséreux.

– Je suis du quartier, de la rue Mouffetard. Ici, tout

le monde connait Hélène Guibout. Suffit de demander. Et vous m’sieur, votre nom

? – Frédéric Ozanam. – Ah, ça ! s’exclame Hélène. M’sieur Hosanna, vous

l’portez bien !

Frédéric meurt le 8 septembre 1853 et est béatifié le 22 août 1997 par Jean Paul II, après une vie de service auprès des miséreux. La Société Saint-Vincent-de-Paul est présente dans 150 pays et compte près de 800.000 bénévoles qui continuent l’œuvre de son fondateur, pour combattre la misère.

Lire aussi :

Frédéric Ozanam, un laïc à l’assaut de la misère

Lire aussi :

Amélie Ozanam, l’épouse inspiratrice de Frédéric

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/2020/09/09/frederic-ozanam-idee-creation-societe-saint-vincent-de-paul/

Frédéric Ozanam, un bienheureux à l’origine de la

démocratie chrétienne

Jean-Michel

Castaing - Publié le 31/05/21

À l'occasion des JMJ de Paris en 1997, Jean Paul II

béatifia le penseur politique Frédéric Ozanam. Pour le fondateur de la Société

Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, et selon l’historien Charles Vaugirard qui vient de

faire paraître un essai sur sa pensée politique, « la question sociale est une

question morale avant tout ».

Àl’instar de ses semblables, le chrétien est inséré

dans la cité. Pas moyen pour lui de faire comme si la politique n’existait pas

! Déjà, au Moyen Âge, saint Thomas d’Aquin réfléchit à la notion de bien commun. Mais existe-il une politique typiquement

chrétienne ? La vie et l’œuvre de Frédéric Ozanam (1813-1853) offrent une excellente

introduction à la tentative de réponse à cette question. Même s’il refusa

toujours de fonder un parti catholique, Ozanam tient cependant à ne jamais

dissocier sa réflexion politique de sa foi. Cet universitaire érudit peut être

considéré comme le père de la démocratie chrétienne. Certes, il ne fut pas le seul

penseur catholique de son temps. Mais son originalité tient à ce qu’il se

revendiqua très tôt comme républicain tandis que ses pairs coreligionnaires

restaient légitimistes et royalistes. En effet, le catholicisme français était

encore traumatisé, en ce milieu du XIXe siècle, par la séquence historique

de la Révolution.

Sans jamais abdiquer la rigueur de l’analyse, il

considéra la question sociale avant tout comme une problématique morale et

spirituelle

De plus, Frédéric Ozanam ne cantonna pas la

revendication de liberté aux domaines de la presse et de l’enseignement, mais

il l’étendit à celui de la question sociale. Les événements de le révolution

1848 furent, à cet égard, décisifs pour sa réflexion. Original, Ozanam le fut

également en se tenant à égale distance du socialiste matérialiste et du

libéralisme qui flattait les tendances égoïstes des possédants. Sans jamais

abdiquer la rigueur de l’analyse, il considéra la question sociale avant tout

comme une problématique morale et spirituelle. A cet égard, ses réflexions sur

le travail n’ont rien perdu de leur pertinence.

Un intellectuel cohérent

On est frappé, en suivant le parcours intellectuel et

existentiel de Frédéric Ozanam, de constater combien sa pensée fut en

adéquation avec ses engagements de foi. Ses écrits politiques ne sont jamais

déconnectés de son expérience religieuse. Sa volonté de concilier liberté

politique et christianisme n’en acquiert que plus de force. Par exemple, en

tant que fondateur de la Société Saint-Vincent-de-Paul en 1833, il ne s’en tint pas à

la mise en œuvre de la charité individuelle, mais cette expérience lui servit

de tremplin pour réfléchir de façon plus systématique à l’organisation de la

cité et à la question sociale prise dans sa globalité. La charité de Frédéric

Ozanam est toujours incarnée. Rien n’illustre mieux cette vérité que les

circonstances historiques qui amenèrent le surgissement de la démocratie

chrétienne.

Sa postérité prestigieuse

La postérité de la démocratie chrétienne, dont Ozanam

fut l’initiateur, est immense. Des hommes politiques prestigieux, venus souvent

d’horizons sociologiques ou idéologiques différents, ont revendiqué son

héritage. Nul ne peut nier que la démocratie chrétienne fut à l’origine du

projet de l’Union européenne. La pensée de Frédéric Ozanam constitue

une aide précieuse pour réfléchir à la nature de l’apport de la charité chrétienne à une politique qu’elle informerait

de l’intérieur — et cela sans jamais céder à la tentation trop facile (et

improductive) de « confessionnaliser » l’engagement politique ni à celle de faire l’impasse

sur l’autonomie des réalités temporelles et contingentes. Un éclairage précieux

pour s’orienter dans la séquence politique inédite que traverse la France

actuellement.

La pensée politique de Frédéric Ozanam, par Charles

Vaugirard, Éditions Pierre Téqui, 2021.

Katholische Pfarrkirche Saint-Hubert in Aubel in der Provinz Lüttich (Belgien), Bleiglasfenster, Darstellung im Maßwerk: Frédéric Ozanam (1813—1853) (Ausschnitt)

Blessed

Antoine-Frédéric Ozanam

Profile

Born to Jean and Marie Ozanam, the fifth of 14 children;

only three of them survived to adulthood. Married layman scholar, teacher and author in

the archdioceses of Paris and Marseilles, France. Studied law in Paris.

Worked in the judicial service in Lyons, France.

Obtained a doctorate based on his work on Dante. Taught in Lyons, Paris and

the Sorbonne. His writing and teaching always

revolved around the benefits to individuals and society of Christianity.

One of the founders of the Conference of Charity which became the

modern Society of Saint Vincent de Paul.

Born

8

September 1853 in

Marseilles, Bouches-du-Rhône, France of

natural causes

6

July 1993 by Pope John

Paul II (decree of heroic

virtues)

22

August 1997 by Pope John

Paul II

beatification recognition

celebrated at Notre Dame de Paris cathedral

Additional Information

Frederic

Ozanam, Founder of the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul, by John J Horgan

New Catholic Dictionary

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

other sites in english

images

video

sitios en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti in italiano

Writings

Etudes Germaniques (Germanic Studies)

Poetes franciscains en Italie (Franciscan poets in

Italy)

La civilisation chretienne chez les Francs (Christian

civilization among the Franks)

MLA Citation

“Blessed Antoine-Frédéric Ozanam“. CatholicSaints.Info.

29 May 2021. Web. 1 June 2021.

<https://catholicsaints.info/blessed-antoine-frederic-ozanam/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/blessed-antoine-frederic-ozanam/

Portrait

de Frédéric Ozanam (Gravure d'Antoine Maurin dit "Maurin l'aîné"

(1793-1860) à partir d'un dessin de Louis Janmot (1814-1892), mis en

frontispice de l'édition de ses Oeuvres complètes, éditions Lecoffre, Paris,

1862 (seconde édition)

Blessed Frédèric Ozanam

Born in Lyons, France, in

1813; died 1853; beatified in 1997 by Pope John Paul II.

For the first 17 years of

his life, Frédèric Ozanam saw Catholicism practiced daily by his devout

parents. His father was a physician who gave his services freely to the poor.

Frédèric's first enthusiasm was for philosophy, but defense of the faith became

his chief intellectual concern. He studied the comparative history of religions

in his leisure time, while he was a full-time law student in Paris. Both

mystical and practical. Humble, no pride of intellect

In Paris, he lived with

the famous scientist Ampère. His faith was tested by the secularism that

surrounded him, by the unbelief. Ampère's faith created abut Ozanam an

atmosphere unfavorable to doubt. His confessor Abbé Noirot really saved Ozanam

by his instructions.

Ozanam worked with the

publication L'Avenir, which aimed at cementing bonds between the Church and the

working class, and at securing political liberty and equal rights for all

people. Soon in conflict with Socialism, so aimed at the liberals. Pope

disapproved, so the publication stopped in 1833.

Soon Ozanam realized that

Christianity is not just an intellectual pursuit, which led him to understand

there cannot be faith without works and to the founding of the Society of Saint

Vincent de Paul. Active charity throughout the rest of his life. "The

defense of the faith and the love of the poor became the two master passions of

his life."

1830-1850 saw the rise of

secularism and anti-clericalism in Europe. Ozanam fought these trends wherever

possible. In 1832, he wrote to a friend, "It is most necessary to make it

clear to the student body that one can be a Catholic and have common sense, and

that one can love both religion and liberty." He initiated the Lenten

Conferences at Notre Dame de Paris, which were still on- going a hundred years

later and are now heard on the radio.

Saint Vincent de Paul

Society is not simply for works of Christian charity, but primarily for

sanctification of its members. Faith only maintained by the practice of

charity. Also intended for the Society to be a practical exemplification of the

principles of true democracy; rights of men founded on charity, not justice.

Catholic men must become the servants of the poor, giving their hearts as well

as their substance. He who was given gave as much as the one who helped him.

"Almsgiving is a reward for service done which has no salary."

Partial payment of the debt we owe the poor. "They suffer where we do not;

they serve God by suffering in a way we do not: they win for us graces from Him,

which without them we would never have; they make humanity itself more like

Jesus."

Ozanam maintained that

almsgiving is an honor, "when it takes hold of a man and lifts him up;

when it looks first and foremost to his soul, . . . when it leads him to real

independence and makes him a truer man. Help is an honor and not a humiliation

when to the gift of bread is joined a visit that comforts, a word of advice

that clears away a cloud, a shake of the hand that revives a dying courage;

when it treats the poor man with respect, not only as an equal, but in many

ways as one above us, since he is with us as one sent by God himself, to test

our justice and our charity, and by our own attitudes towards him to enable us

to save our souls."

Ozanam started a new

journal L'ère Nouvelle. In July 1835, Ozanam won his doctorate in law and soon

felt a spiritual dryness. In 1837 his father died from a fall down a dark

staircase while visiting a poor patient and Ozanam became the head of the

family. Sad, he poured out his soul to a priest who responded, "Rejoice in

the Lord always!" which Ozanam realized was audaciously the right

response. At this time he was trying to discern his vocation. By the end of

1840, he was engaged to Amélie Soulacroix, daughter of the Rector of the

University of Lyons. He left the decision of his teaching in Paris or Lyons to

her and she chose Paris.

For Amélie, Frédèric was

consecrated to God, a man upon whom God and the poor held prior claims. Ozanam

loved and cherished his wife; she was like Dante's Beatrice, the source of

truth and virtue. In his The history of civilization in the fifth century,

Ozanam wrote: "Christian marriage is a double oblation, offered in two

chalices. . . . These two cups must both be full to the brim, in order that the

union may be holy, and that heaven may bless it." Within one year after

his marriage, he was elected to succeed Fauriel in the Sorbonne chair of

comparative literature. His lectures and writings did much to make the Church more

respected in the intellectual world of his day.

He was a man of unusual

personal magnetism. His method of apologetic was primarily historical--he

showed what the Church had done for mankind in the past, and argued from that

to what it could and should do in the present. He said once in an address to

working men that we work out our destinies here below, but without knowledge of

the functions they will fulfill in the purposes of God. Another time: "The

greatest men are those who have never drawn up in advance the plan of their

lives, but have let themselves be led by the hand."

Five years after their

marriage, their daughter Marie was born. Ozanam died in 1853 (age 40) when she

was only eight.

From: Delany, Selden P.

1950. Married Saints (Westminster, MD, The Newman Press).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0909.shtml

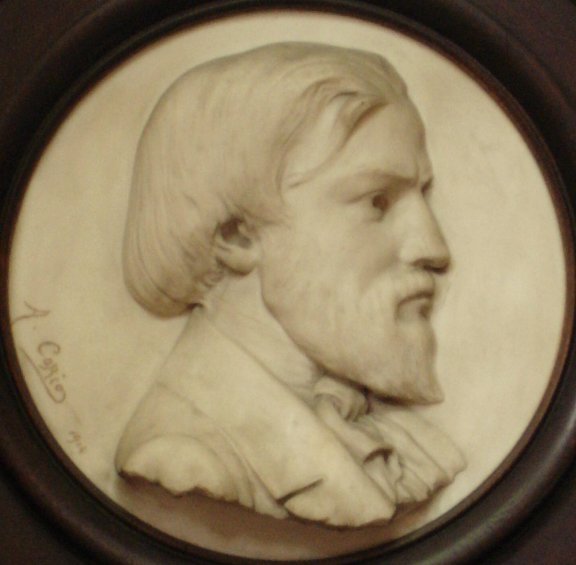

Frédéric Ozanam, Gründer der karitativen

katholischen Vinzenzgemeinschaft, Gedächtnisplakette der

Stiftung der Société Saint-Vincent de Paul mit der

Inschrift: "Frédéric Ozanam et ses amis fondèrent la Société

Saint-Vincent de Paul en mai 1833 sur la paroisse de

Saint-Étienne-du-Mont", Paris, St. Étienne-du-Mont

Frédéric Ozanam, the founder of the Society

of Saint Vincent de Paul a Catholic charity

Frédéric Ozanam, fondateur de l'organisation

caritative catholique Société de Saint-Vincent-de-Paul,

plaque commémorative de la fondation de la Société Saint-Vincent de Paul,

portant l'inscription : « Frédéric Ozanam et ses amis fondèrent la

Société Saint-Vincent de Paul en mai 1833 sur la paroisse de

Saint-Étienne-du-Mont », Paris, Église Saint-Étienne-du-Mont

Antoine-Frédéric Ozanam

Great grand-nephew

of Jacques

Ozanam. Born at Milan,

23 April, 1813; died at Marseilles,

8 September, 1853. His father, settled at first in Lyons as a

merchant, after reverses of fortune decided to go to Milan.

Later he returned to Lyons and became a physician. At

eighteen Frédéric, in defence of the Faith, wrote Réflexions sur

la doctrine de Saint-Simon. Later he studied law in Paris,

and lived for eighteen months with the illustrious physician Ampère. He

formed an intimate friendship with the latter's son, Jean-Jacques Ampère,

well known later for his works on literature and history.

Meanwhile he became a prey of doubt. He

said,

God gave

me the grace to be born in the Faith.

Later the confusion of an unbelieving world surrounded me. I knew all

the horror of the doubts that

torment the soul.

It was then that the instructions of a priest and philosopher (Abbé Noirot) saved me.

I believed thenceforth with an assured faith,

and touched by so rare a goodness.

I promised God to devote my life to

the services of the truth which

had given me peace.

Rarely was a promise

more faithfully fulfilled.

In 1836 he left Paris,

where he had known Chateaubriand, Ballanche, Montalembert,

and Lacordaire,

and was appointed to the bench at Lyons,

but two years later returned to Paris to

submit his thesis on Dante for

his doctorate in letters. His defence was a triumph. "Monsieur

Ozanam", Cousin said to the candidate, "there is no one

more eloquent than you have just proved yourself."

He was given the chair of

commercial law, just created at Lyons.

The following year he competed for admission to

the Faculties at Paris,

and was appointed to substitute for one of the judges of the Sorbonne, Fauriel, philosopher and

professor of foreign literature. At the same time he taught at Stanislas

College, where he had been called by Abbé

Gratry. On Fauriel's death

in 1844,

the Faculty unanimously elected Ozanam his successor.

Like his friend Lacordaire he believed that

a Christian

democracy was the end towards which Providence was leading

the world, and after the Revolution of 1848 aided him by his writings

in the Ere Nouvelle. In 1846 he visited Italy to

regain his strength, undermined by a fever. On his return he published Etudes

germaniques (1847); Poètes franciscains en Italie au XIIIe siècle;

finally, in 1849, the greatest of his works: La civilisation chretienne

chez les Francs. The Academy of Inscriptions awarded him

the "Grand Prix Gobert" for two successive years. In 1852 he made a

short journey to Spain an

account of which is found in the posthumous work: Un pélérinage au pays

du Cid.

In the beginning of the next year, his doctors again

sent him to Italy,

but he returned to Marseilles to

die. When the priest exhorted

him to have confidence in God,

he replied "Oh why should I fear God,

whom I love so

much?" Complying with his desire the Government allowed him to

be interred in

the crypt of

the "Carmes".

A brilliant apologist,

impressed by the benefits of the Christian

religion, he desired that they should be made known to all who might read

his works or hear his words. To him the Gospel had renewed or

revivified all the germs of good to be found in the ancient and in

the barbarian world. In his many miscellaneous studies he endeavored to develop

this idea,

but was unable to fully realize his plan. In the two volumes of the Etudes

germaniques he did for one nation what he desired to do for all. He also

published, with the same view, a valuable collection of hitherto unpublished

material: Documents inédits pour servir a l'histoire de l'Italie, depuis

le VIII siecle jusqu'au XIIe (Paris, 1850). Ozanam was untiring

in energy, had a rare gift for precision

and historical insight, and at the same time a naturalness in his

verse and a spontaneous, pleasing eloquence, all the more charming because of

his frankness. He wrote,

Those who wish

no religion introduced into a scientific work accuse me of

a lack of independence. But I pride myself

on such an accusation. . . I do not aspire to an independence, the result of

which is to love and

to believe nothing.

His daily life was

animated by an apostolic

zeal. He was one of those who signed the petition addressed to

the Archbishop of Paris to

obtain a large body of religious teachers for the Catholic school children,

whose faith was

endangered by the current unbelief. As a result of

this petition Monseigneur de Quelen created the famous

"Conférences de Notre Dame", which Lacordaire inaugurated

in 1835. When but twenty, Ozanam with seven companions had laid the

foundations of the Society

of St. Vincent de Paul, in order, as he said to "insure my faith by works

of charity". During his life he was an active member and a zealous propagator

of the society.

With all his zeal,

he was, however, tolerant. His strong, sincere books exhibit a brilliant

and animated style, enthusiasm and erudition, eloquence and exactness, and are

yet very useful introductions to the subjects of which they treat.

[Note: Frédéric Ozanam was beatified by

Pope John Paul II on August 22, 1997.]

Bertrin, Georges. "Antoine-Frédéric Ozanam." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton

Company, 1911. 13 Sept.

2015 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11378a.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Kathy Schneider.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. February 1, 1911. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2020 by Kevin

Knight. Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11378a.htm

The

Church of Saint-Joseph-des-Carmes, a Roman Catholic church situated at 70 rue

de Vaugirard in the 6th arrondissement of Paris in the heart of the Séminaire

des Carmes.

Blessed Frédéric Antoine

Ozanam

Contents

[hide]

· 1 Life

Life

Frédéric Antoine Ozanam

(April 23, 1813 - September 8, 1853) founded with fellow students the Conference of Charity, later known as the Saint Vincent de Paul Society. He

was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1997.

Important dates

· 1813

- Birth of Frederic in Milan, April 23, to Jean-Antoine and Marie Ozanam.

· 1815

- Move of Ozanam Family to Lyons.

· 1829

- Experiences a "crisis of doubt" about his faith.

· 1831

- Enters Sorbonne in Paris to study law.

· 1833

- Establishes the Conference of Charity with other Sorbonne students.

· 1834

- Leads petition to Archbishop for relevant sermons.

· 1835

- Conference officially becomes Society of St. Vincent de Paul.

· 1836

- Awarded Doctor of Laws degree.

· 1837

- Publishes THE ORIGINS OF FRENCH LAW; death of Frederic's father.

· 1839

- Awarded Doctorate in Literature.

· 1840

- Named Professor of Commercial Laws at Lyons; death of Frederic's mother.

· 1841

- Marriage to Amelie Soulacroix of Lyons.

· 1842

- Represents Church in negotiations with the government.

· 1844

- Assumes Chair of Foreign Literature at Sorbonne.

· 1845

- Birth of daughter Marie. Society is recognized by Pope Gregory XVI.

· 1847

- Publication of GERMAN STUDIES I.

· 1848

- Cofounder of JOURNAL L´ERE NOUVELLE.

· 1849

- Publication of GERMAN STUDIES II.

· 1852

- Mediates in student riots at Sorbonne.

· 1853

- Death in Marseilles of kidney ailment, September 8.

· 1855

- Posthumous publication of CIVILIZATION IN THE FIFTH CENTURY.

· 1989

- Society of St. Vincent de Paul established at St. John's University, NYC.

· 1997

- Declaration of Frederic as "Blessed Frederic" on August 22 in

Paris.

Frederic Ozanam was born

on April 23, 1813 in Milan, Italy. He was the fifth child of fourteen born to

Jean-Antoine- Francoise and Marie Nantas Ozanam, ardent French Catholics of

middle-class circumstances. His father had served with distinction as an officer

under Napoleon, retiring early to become a tutor and later to practice

medicine. When the city of Milan fell to the Austrians in 1815, the Ozanams

returned to their native city of Lyons in France where Frederic spent his early

years.

At seven he suffered the

loss of his sister, Elise, which came as a great grief to him because they had

grown close as she patiently helped him with his early lessons. Frederic became

a day student at the Royal College of Lyons where he quickly showed an aptitude

for and an interest in literature and where he would later become editor of a

college journal, The Bee.

In a letter written when

he was sixteen we have something of an autobiographical account of these early

years:

...They say 1 was very

gentle and docile as a child, and they attribute this to my feeble health; but

1 account for it in another way. 1 had a sister, such a beloved sister! who

used to take turns with my mother to teach me, and whose lessons were so sweet,

so well-explained, so admirably suited to my childish comprehension as to be a

real delight to me. All things considered, 1 was pretty good at this stage of

my life, and, with the exception of some trifling peccadilloes, 1 have not much

to reproach myself with.

At seven years old I had

a serious illness, which brought me so near death that everybody said I was

saved by a miracle,. not that I wanted kind care, my dear father and mother

hardly left my bedside for fifteen days and nights. I was on the point of

expiring when suddenly I asked for some beer. I had always disliked beer but it

saved me. I recovered, and six months later, my sister, my darling sister,

died. Oh! what a grief that was. Then I began to learn Latin, and to be

naughty; really and truly I believe I never was so wicked as at eight years old.

And yet I was being educated by a kind father and a kind mother and an

excellent brother; I loved them dearly, and at this period I had no friends

outside my family,. yet I was obstinate, passionate, disobedient. I was

punished, and I rebelled against it. I used to write letters to my mother

complaining of my punishments. I was lazy to the last degree, and used to plan

all sorts of naughtiness in my mind. This is a true portrait of me as I was

first going to school at nine and a half years old. By degrees I improved;

emulation cured my laziness. I was very fond of my master; I had some little

successes, which encouraged me. I studied with ardor, and at the same time I

began to feel some emotions of pride. I must also confess that I exchanged a

great number of blows with my companions. But I changed very much for the

better when I entered the fifth class. I fell ill, and was obliged to go for a

month to the country, to the house of a very kind lady, where I acquired some

degree of polish, which I lost in great part soon after.

I grew rather idle in the

fourth class, but I pulled up again in the third. It was then that I made my

first Communion. O glad and blessed day! may my right hand wither and my tongue

cleave to the roof of my mouth if I ever forget thee!

I had changed a good deal

by this time; I had become modest, gentle, and docile, more industrious and

unhappily rather scrupulous. I still continued proud and impatient. 12

At sixteen the young

Ozanam started his course in philosophy and became greatly disturbed by doubts

of faith for about a year. However, he was able to survive the ordeal with the

help of a wise teacher and guide, Abbe Noirot, who was to exercise a strong

influence on Frederic throughout his life. In the midst of this crisis, he made

a promise that if he could see the truth, then he would devote his entire life

to its defense. Subsequently he emerged from the crisis with a consolidation of

the intellectual bases for his faith, a life commitment to the defense of Truth

and a deep sense of compassion for unbelievers.

Despite a leaning toward

literature and history, Frederic's father decided on a law career for him and

apprenticed him to a local attorney, M. Coulet. But, in his spare time, the

young man pursued the study of language and managed to contribute historical

and philosophical articles to the college journal.

In the Spring of 1831

Ozanam published his first work of any length, "Reflections on the

Doctrine of Saint-Simon," which was a defense against some false social

teaching that was capturing the fancy of young people at the time. His efforts

were rewarded with favorable notice from some of the leading social thinkers of

the day including Lamartine, Chateaubriand and Jean-Jacques Ampere.

Ozanam also found time

outside of work to help organize and write for the Propagation of the Faith

which had begun in this same city of Lyons.

In Autumn of the same

year, Frederic was sent to the University of Paris to study law. :At first

he suffered a great deal from homesickness and unsuitable company in boarding

house surroundings. But after moving in with the family of the renowned

Andre-Marie Ampere where he stayed for two years, he had not only the

nourishment of a very Christian and intellectual milieu, but also the

opportunity to meet some of the bright lights of the Catholic Revival like

Chateaubriand, Montalembert, Lacordaire and Ballanche.

It was at this time that

Frederic's attraction to history took on the dimensions of a life's task as

apologist, to write a literary history of the Middle Ages from the fifth to the

thirteenth centuries with a focus on the role of Christianity in guiding the

progress of civilization. His aim was to help restore Catholicism to France

where materialism and rationalism, irreligion and anti-clericalism prevailed.

He made plans for the extensive studies he would need to equip him for this

vocation.

It was not long before

Ozanam found the climate of the University hostile to Christian belief. So he

seized the opportunity to find kindred spirits among the students to join in

defending the faith with notable success. Among these was one who was to become

his best friend, Francoise Lallier .

Under the sponsorship of

an older ex-professor, J. Emmanuel Bailly, these young men revived a discussion

group called a "Society of Good Studies" and formed it into a

"Conference of History" which quickly became a forum for large and

lively discussions among students. Their attentions turned frequently to the

social teachings of the Gospel.

At one meeting during a

heated debate in which Ozanam and his friends were trying to prove from

historical evidence alone the truth of the Catholic Church as the one founded

by Christ, their adversaries declared that, though at one time the Church was a

source of good, it no longer was. One voice issued the challenge, "What is

your church doing now? What is she doing for the poor of Paris? Show us your

works and we will believe you!" In response, one of Ozanam's companions,

Auguste de Letaillandier, suggested some effort in favor of the poor. "Yes,"

Ozanam agreed, "let us go to the poor!"

After this, the

"Conference of History" became the "Conference of Charity"

which eventually was named the "Conference of St. Vincent de Paul." Now, instead of engaging in

mere discussion and debate, seven of the group (M. Bailly, Frederic Ozanam,

Francois Lallier, Paul Lamanche, Felix Clave, Auguste Letaillandier and Jules

De Vaux) met on a May evening in 1833 for the first time and determined to

engage in practical works of charity. This little band was to expand rapidly

over France and around the world even during the lifetime of Ozanam.

In the meantime, Frederic

continued his law studies, but kept his interest in literary and historical matters.

He was also able to initiate other ventures like the famed "Conferences of

Notre Dame" which provided thousands with the inspired and enlightening

sermons of Pere Lacordaire. This was another expression of Ozanam's

life-commitment to work for the promotion of the Truth of the Church.

In 1834, after passing

his bar examination, Frederic turned to Lyons for the holidays and then went to

Italy where he was to gain his first appreciation of medieval art. After this,

he returned to Paris to continue studying for his doctorate in Law. When he

finished, he took up a practice of law in Lyons, but with little satisfaction.

His attention turned more and more to literature. When his father died in 1837,

he found himself the sole support of his mother which kept him in the field of

law to make a living.

In 1839, after finishing

a brilliant thesis on Dante which revolutionized critical work on the poet, the

Sorbonne awarded him a doctorate in literature. In the same year he was given a

chair of Commercial Law at Lyons where his lectures received wide acclaim and

where, after an offer to assume a chair of Philosophy at Orleans, he was asked

to lecture also on Foreign Literature at Lyons which enabled him to support his

mother. She died early in 1840, leaving him quite unsettled about his future.

At the time, Lacordaire was on his way to Rome to join the Dominicans with the

hope of returning to France to restore religious life. For a while, Ozanam

entertained the idea of joining him, but again under the guidance of Abbe

Noirot and with the consideration of his commitment to the constantly expanding

work of the Conference of Charity which were multiplying around France, he

decided against pursuing a life of celibacy and the cloister.

In the same year (1840),

to qualify for the Chair of Foreign Literature at Lyons, Ozanam had to take a

competitive examination which demanded six months of grueling preparation. He

took first place easily with the result that he was offered an assistantship to

a professor of Foreign Literature at the prestigious Sorbonne, M. Fauriel. When

Fauriel died three years later, Ozanam replaced him with the rank of full

professor, no mean accomplishment for a man of his early years. This

established him in the midst of the intellectual world of Paris. He now began a

course of lectures on German Literature in the Middle Ages. To prepare, he went

on a short tour of Germany. His lectures proved highly successful despite the

fact that, contrary to his predecessors and most colleagues in the

anti-Christian climate of the Sorbonne, he attached fundamental importance to

Christianity as the primary factor in the growth of European civilization.

After years of hesitation

concerning marriage, Frederic was introduced by his old friend and guide, Abbe

Noirot, to Amelie Soulacroix, the daughter of the rector of the Lyons Academy.

They married on June 23,1844, and spent an extended honeymoon in Italy during

which he continued his research. After four years of happy marriage, an only

daughter, Marie, was born to the delighted Ozanams.

All during this time,

Ozanam, who had never enjoyed robust health, found his work-load increasing

between the teaching, writing and work with the Conference of St. Vincent de

Paul. In 1846 he was named to the Legion of Honor. But at this time his health broke

down and ,he was forced to take a year's rest in Italy where he continued his

research.

When the Revolution of

1848 broke out, Ozanam served briefly and reluctantly in the National Guard.

Later he made a belated and unsuccessful bid for election to the National

Assembly at the insistence of friends. This was followed by a short and stormy

effort at publishing a liberal Catholic journal called The New Era which was

aimed at securing justice for the poor and working classes. This evoked the ire

of conservative Catholics and the consternation of some of Ozanam's friends for

seeming to side with the Church's enemies. In its pages he advocated that

Catholics play their part in the evolution of a democratic state.

At this time, too, he

wrote another of his important works, The Italian Franciscan Poets of the

Thirteenth Century, which reflected his admiration for Franciscan ideals.

During the academic year

1851/52, Ozanam barely managed to get through his teaching responsibilities as

a complete breakdown of his health was in progress. The doctors ordered him to

surrender his teaching duties at the Sorbonne and he again went with his family

to Southern Europe for rest. It did not deter him, however, from continuing to

promote the work of the Conferences.

In the Spring of 1853,

the Ozanams moved to a seaside cottage at Leghorn, Italy, on the Mediterranean,

where Frederic spent his last days peacefully. Though not fearing death, he ex-

pressed the wish to die on French soil, so his brothers came to assist him and

his family to Marseilles where Frederic died on September 8, 1853.

He has been revered since

as an exemplar of the lay apostle in family, social and intellectual life. The

work he began with the Conferences of St. Vincent de Paul has continued to

flourish. At his death, the membership numbered about 15,000. Today (in 1979)

it numbers 750,000, serving the poor in 112 countries, a living monument to

Frederic Ozanam and his companions.

The first formal step for

his beatification was taken in Paris on June 10, 1925. On January 12, 1954,

Pope Pius XII signed the decree of the introduction of the cause. He now (in

1979) enjoys the official title, "Servant of God."

From

A Layman for Now (Reproduced with permission of the author, Shaun

McCarty)

Cultural Context

...the environment in

which Frederic Ozanam sought to realize the Christian ideal was much like our

contemporary culture. [t was a world full of violence and turmoil -secular,

unstable, crisis-ridden. [t was a world of uncertainty and fear 3

Thus writes an American

biographer of Ozanam in the mid-1960's.

From the time of the

fourth century when Christianity was declared the official religion of the

Roman Empire, French Catholics, like most Western Christians, assumed that

their culture was Christian. It took the Enlightenment and the French

Revolution of the eighteenth century to bring to a boil the secular trends that

were simmering beneath the surface of the culture.

The French Revolution had

left in its wake the uprooting of old beliefs and traditions as well as the

destruction of old institutions. With the coming of Napoleon, the country was

almost without religion. (To this day, ancient churches like the Cathedral at

Chartres bear the scars of vicious destruction and profanation.) Reason was

literally enthroned as goddess in the Pantheon, once a sacred shrine to St.

Genevieve, one of France's great patronesses of the poor whose relics were

desecrated at the time of the Revolution. Atheism and freethinking had become

vogue. Religious instruction was absent outside the home. Religious orders had

been banished, the faithful clergy scattered. The philosophers declared the

"death of Christianity." In 1797 Napoleon himself named religion as

"one of those prejudices which French people had yet to eradicate." 4

Yet a Concordat was signed

in 1801 which pleased no one, but provided at least some room for a

reconstruction of a new order on the ruins of the old.

Understandably, the

Church had grown very defensive about the encroachments made upon its claims.

In Ozanam's time, Catholics were divided as to what stand to take. 'there was a

widespread rejection not just of the excesses of the Revolution, but also of

its ideals of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity. Conservative Catholics grimly

favored retrenchment. Liberal Catholics sought reconciliation and, though

rejecting the anti-Catholic dimensions of secular liberalism, saw the

acceptance of those ideals of the Revolution and the meeting of legitimate

demands of the oppressed as vital to the reconciliation of the Church and

modern society.

The basic issue between

conservative and liberal Catholics was not a political one, but rather one of

defending what the attitude to be taken by the Church toward modernity. On the

one hand, should there be a withdrawal from or reconciliation with it? An

unyielding defense against it or a search for new applications of Christian

principles? To regard change with pessimism and resist it or to look with

optimism and hope at the possibilities of development?

We will see that Ozanam

made a clear and consistent choice in the liberal direction of bringing the

Church to a more positive view of the modern world. This put him out of step

with the prevailing conservative mood of French Catholics. But it would

anticipate the more universally Catholic view that would surface in the social

encyclicals and more recent pronouncements like those of Vatican II.

There was also a strong

anti-clerical ( or perhaps anti-Church is a more accurate term) spirit in many

quarters. Certain features of it are worth noting.

First, not all enemies of

the Church were enemies of religion. Anti-clericalism was due primarily to the

political involvement of Church and State.

It was originally a

protest against the political pretensions of the Church. In 1798 and again in

1848 the Church cooperated in revolutions which destroyed privilege, but on

both occasions it quickly abandoned the popular cause and emerged on the

winning, reactionary side. It was rewarded with a reinforcement of its

position. 5

Socialism and

Christianity had grown close in France by 1848.

...but the Church was too

deeply instilled with the medieval idea that. ..the government of lay and

spiritual matters was inextricable and that the state should lend its authority

to the Church to ensure that religious principles were obeyed. 6

It is further noted...

For a whole century,

Catholicism and democracy seemed incompatible. ..Politics thus made the people

increasingly reject religion -or in occasional reactions, adopt it -for reasons

which were not inherently religious. 7

Second, anti-clericalism

was strongest in areas where the monastic orders had large land holdings under

the ancien regime where the presence of the Church had been felt most strongly

and especially where the Jansenists had been most deeply entrenched.

This was somewhat of a

paradox as one historian has noted:

Jansenism ...was also a

source of individualism and of a certain kind of egalitarianism -but its moral

rigorism undoubtedly had the effect of turning people away from the Church. It

set up traditions of anti- clericalism and it was by no means a mere memory in

the nineteenth century.

Finally, anti-clericalism

to a certain extent was France's alternative to Protestantism elsewhere, but

which had been largely stamped out in France by the combined efforts of Church

and monarchy. Thus. .."It was no accident that Protestants took a leading

part in the anti-clerical movement. ..and its revenge was therefore

twofold." 9

A word must be said about

the socio-economic scene. The France of Ozanam's time was marked by increasing

numbers of poor people and inadequate measures of assistance for them. The

Napoleonic system left public charities to the discretion of each of the

nation's communes most of which had very limited re- sources. Cities like Paris

had a disproportionate number of very poor people. In 1829, one in twelve were

classified as "indigent." By 1856, the figure had declined one in

sixteen. 10 Thus there was enormous need and scope for charitable efforts at

the time.

An economic survey of the

time summed up the plight of the urban poor in this way:

When work is continual,

the salary average, (and) the price of bread moderate, a family could live with

a sort of ease and even make some savings if there are no children. If there is

one, it is difficult; impossible if there are two or three. Then it can survive

only with the assistance of the government or some private charity. 11

In addition to the more

obvious problems of the poor - wages, living conditions, lack of necessities of

life -a new, industrial, mass society was being born. And its violent birth was

met with fear and resistance by the upper-classes.

It was not merely a

matter of low wages and long work hours. Living conditions, especially in the

rapidly growing cities were dreadful. Violence, disease and immorality were

rampant.

Furthermore, the plight

of the poor was worsened by the greed and indifference of the upper-classes.

The power of the State only strengthened the position of the wealthy. The whole

spirit of society was hostile to the poor.

In the midst of this

exploitation of the wealthy, indifference of the State and alliance between

Church and State, it is little wonder that the workers responded with hatred

and violence. And it became imperative for Christians like Ozanam to speak and

to act so that the Church could be a Church incarnating Jesus in a modern

world.

From Shaum McCarty

Model for Today

An Appreciation by Amin

A. De Tarrazi former International President of the Society of

St. Vincent de Paul

Bibliography

Bibliography from -

"A Layman for Now" by Shaun McCarty

Reproduced with

permission of the author, Shaun McCarty

Auge, T. E., Frederic

Ozanam and His World, Milwaukee: Bruce, 1966.

Baunard, L., Ozanam

in His Correspondence, by the Right Reverend Monsignor Baunard. Trans. by a

member of the Council of Ireland of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul. New

York: Benzinger Brothers, 1925.

__________, Ozanam

in His Correspondence, trans, by a member of the Council of Ireland of the

Society of St. Vincent de Paul. Dublin: Catholic Truth Society of Ireland,

1925. _

________, Ozanam in

His Correspondence, trans. by a member of the Council of Ireland of the Society

of St. Vincent de Paul, Australia: National Council, 1925.

Brody, T. A., Frederic

Ozanam Speaks To Us, St. Louis: Society of St. Vincent de Paul.

Brodrick, J., Frederic

Ozanam and His Society, London: Burns, Oats & Washbourne, Ltd., 1933.

Camus, L. Y ., Pionnier

de son époque, précurseur de la nôtre: Frédéric Ozanam, 1813-1853; Paris: 1953.

Cassidy, J R., Frederic

Ozanam: A Study in Sanctity and Scholarship, Dublin: Talbot Press Ltd., 1943.

Celier, L., Frederic

Ozanam (1813-1853) Préface de Robert d'Harcourt de l'Academie Francaise, Paris:

P. Lethielleux, 1956.

Celier, L., Federico

Ozanam 1813-1853. Préf. de Robert d'Harcourt, Rome: Edizioni 5 lune, 1958.

Chauveau, P., Frédéric

Ozanam, sa vie et ses oeuvres, Avec une introduction par M. Chauveau, membre de

la Societe royale du Canada, Montreal: Beauchemin & Fils, 1887.

Coates, A., trans. Letters

of Frederic Ozanam, New York: Benziger, 1886.

Deflandre, M., Frédéric

Ozanam: son oeuvre, son temps, Bruxelles: Editions LaLecture au Foyer, 1953.

Delany, S., Frederic

Ozanam (1813-1853) (In his Married saints). New York: 1935, p. 269-290.

Derum, J., Apostle

In A Top Hat, New York: All Saints Press, 1962, c1960.

__________, Apostle

In A Top Hat; The Life Of Frederic Ozanam. Garden City, N.Y.: Hanover House,

1960.

Drury, T., Ozanam

and the Saint Vincent de Paul Society, Webster Groves, Mo.: Kenrick papers, v.

1., no.1 (1933), p. 60-68.

Drzazgowska, M. B.,

Sr., Frederic Ozanam as a Historian; A Critical Study. St. Louis: Thesis

St. Louis University, 1954.

Dunn, A. J., Frederic

Ozanam And The Establishment Of The Society Of St. Vincent de Paul. New

York: Benziger Brothers, 1877. ___

_______, Frederic

Ozanam And The Establishment Of The Society Of St. Vincent de Paul, London: R.

& T. Washbourne, Ltd., 1913.

Duroselle, J. B., Ozanam

et la société de Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, Paris: In his Les débuts du

catholicisme social en France, 1822-1870), 1951. Cf. The First 100 Years

Particular Council, St. Vincent de Paul Society (1865-1965) Baltimore: St.

Vincent de Paul Society, 1965.

Galopin, E., Essai

de bibliographie chronologique sur Antoine- Frédéric Ozanam ( 1813-1853) Paris:

Societe d'edition "Les Belles lettres", 1933, 168 p.

Gautier, L., Portraits

du XIXe siècle. Paris: Sanard et Derangeon, (1894?) "Ozanam:" v. 2,

p. (129)-144.

Girard, H., Un

catholique romantique: Frédéric Ozanam, Paris: Editions de la Nouvelle revue

critique, 1930, 220 p.

Goyau, G., Ozanam.

Nouv. ed. rev. et completes. Paris: E. Flemmarion (c1931) 203p. (Les

grands coeurs) Previously published under title: Frederic Ozanam.

Heneghan, G. E., Frederic

Ozanam. St. Louis Society of St. Vincent de Paul. (n.d.) (Annual Meeting

Society of St. Vincent de Paul)

Hess, M. A. G., Frederic

Ozanam, trans. Cahiers Ozanam, Nos. 37/38/39, (January/June 1974)

Hughes, H. L., Frederic

Ozanam, St. Louis: Herder, 1933.

Joly, H.,

1839-1925, Ozanam et ses continuateurs, Paris: Libraine, V. Lecoffre,

1913. 235p.

Jones, J. V., 1924-

, Frederic Ozanam: Liberal Catholic. St. Louis: Society of St. Vincent de

Paul (n.d.) 11p. (Ozanam Sunday observance)

Labelle, E., Frédéric

Ozanam, message d'un voyant. Paris: Bloud & Gay, 1939. 190p. (La vie

inteneure pour notre temps)

Lacordaire, J. B.

H., Frédéric Ozanam. Paris: J. Lecoffre et cie., 1856. 80p.

Sound with Power, G. D. Frederic Ozanam. St. Louis, 1878.

Lacordaire, J. B.

H., Frédéric Ozanam. Paris: J. Lecoffre et cie., 1856. Microfilm

copy, made in 1964, of the original in Pius XII Memorial Library, St. Louis.

Negative. Collation of the original: 80p. With this is bound: Power, G.D.

Fredenc Ozanam, St. Louis, 1878.

Lauscher, H., Frédéric

Ozanam et les conférences de Saint Vincent de Paul. 2e. ed. Liege, H. Desain;

Verviers, J. Piette & cie (1890) 16p. (Tracts populaires, no.7)

Leone, G., Attualita di

Antonio Federico Ozanam. (Milano) Edizioni del Segretariato N ationale

della Societa di S. Vincenzo de'Paoli (n.d.)

Louvain, Universite

catholique. Fondation Jules Becucci. Fredenc Ozanam (1813-1853) (Louvain)

Publications Universitaires de Louvain, 1954. 43p.

Manual of the Society of

St. Vincent de Paul. Dublin, Ireland: Society of St. Vincent De Paul. 1944

McColgan, Daniel

T., A Century of Charity. Milwaukee: Bruce, 1951. 2 vols. First 100 yrs.

in the U.S.

Mejecaze, Francoi. L'âme

d'un saint laïque, Frederic Ozanam. Paris: B. Grasset, (1935) 272p. (Collection

"LaVie chretienne". 3. serie 3.)

Murphy, Charles K., The

Spirit of the Society of St. Vincent De Paul., New York: Longmans Green, 1940.

Neill, Thomas Patrick,

1915- , Frederic Ozanam And The Intellectual Apostolate. St. Louis,

Society of St. Vincent de Paul (n.d.) 10p. (Ozanam Sunday Observance)

O'Connor, Vincent

M., Organization and Program of the St. Vincent de Paul Society of St.

Louis, Mo., Washington, D. C.: Unpublished Dissertation, School of Social

Service, CUA, June 1953.

O'Meara, Kathleen,

1839-1888. Frederic Ozanam, Professor At The Sorbonne,. His Life And Works,

with a preface by His Eminence Cardinal Manning. N.Y.; Catholic School Book

Co., (c1911). 345p.

Ozanam, Charles

Alsphonse, b. 1804. Vie de Frédéric Ozanam, professeur de littérature

étrangère à la Sorbonne. Paris: Poussiegue freres, 1879. 644p.

Ozanam: livre du

centenaire, par mm. Georges Goyau ( et. a1. ) Préface de m. René Doumic. Bibliographie

par m l’Abbe Corbierre. Paris: G. Beauchesne, 1913. 479p.

Power, Gerard D., Frederic

Ozanam, Founder Of The Society Of St. Vincent de Paul. A Sketch Of His Life And

Labors. A lecture. St. Louis: P. Fox, 1878. 52p.

Power, Gerard D., Frederic

Ozanam, founder of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul; a sketch of his life and

labors. A lecture delivered in St. John's Church (St. Louis) on Sunday, March

11, for the benefit of the poor. St. Louis: P. Fox, 1878.

Proceedings of the

International convention of the St. Vincent de Paul Society, 1904, St. Louis:

Little & Becker, 1905.

Renner, Emmanuel,

Sr., The Historical Thought Of Frederic Ozanam, Washington: Catholic

University of America Press, 1906.86p.

Rochford, John, Frederic

Ozanam, Founder of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul. Dublin: the Catholic

Truth Society of Ireland (1924) 36p.

Romero Carranza,

Ambrosio. Ozanam e i suol contemporanie. Pref. di Girogio La Pira,

Traduzione di Luisa e Lamberto Lattanzi. Firenze, Edizioni Libreria fiorentina

(1956). 512p.

Rooy, N. Frederic

Ozanam. de's-Gravenhage, Uitgeverij Pax, 1948.285p.

Roths, Tarcisia, Sr.,

1930- , Frederic Ozanam's "Philosophy of History." St.

Louis: 1959. 308 numb. 1.

Schimberg, Albert Paul,

1885- , The Great Friend: Frederic Ozanam. Milwaukee: The Bruce

Publishing Co., (1946). 344p.

Horgan, John J. Great

Catholic Laymen. New York, Cincinnati, etc.: Benzinger Brothers,

1905. 388p.

Somerville, Henry. A

Contrast In France: Ozanam and Marx. In his Studies in the Catholic Social

movement. 1933. p. 19-28.

Zeldin, Theodore, France

1848-1945. The Oxford History of Modern Europe, vols. I & II. Oxford:

The Clarendon Press, 1973.

ARTICLES

Baker, D., "St.

Vincent de Paul, Society of," New Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 12,

N.Y.: McGraw-Hill, 1966, pp. 957-59.

Dattilo, F ., "The

Youth Who Shook Pagan Paris," Our Sunday Visitor 61 (August 20,

1972), pp. 1ff

Hanley, G., "For

your Love Alone," The Anthonian. Paterson, N.J.: St. Anthony's Guild,

1976. 30pp.

Macmillan, F.

"Ozanam, Frederic, New Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 10, N.Y.:

McGraw-Hi1l, 1966, pp. 847-48.

Murphy, M. P., "The

Frederic Ozanam Story." St. Louis, Mo.: St. Vincent de Paul Society, 1976,

16pp.

Recent works

Sister M. Teresa

Candelas, D.C. Biography of Frederic Ozanam (Translated

from the Spanish)

External Links

Frédéric

Antoine Ozanam Wikipedia article - Excellent background on his

scholarly activities.

Frederic

Ozanam - Life, Times, Words a brief introduction at The Vincentian

Center Web site, St John's University

Ozanam

Feast Day Mass - pdf format from the Canadian SVDP site, Litany,

Prayers and readings for the mass for Frédéric Ozanam's feast day.

SOURCE : https://famvin.org/wiki/Fr%C3%A9d%C3%A9ric_Ozanam

Portrait

de Frédéric Ozanam en 1852, Il s'agit de la copie en miniature du portrait fait

par Louis Janmot (1814-1892), probablement réalisée par Louis Janmot, lui-même.

Beato Federico Ozanam Padre

di Famiglia

Milano, 23 aprile 1813 -

Marsiglia, Francia, 8 settembre 1853

Il francese Federico

Ozanam, fondatore della Società di San Vincenzo, è un esempio di carità e

santità laicale. Nato a Milano nel 1813 (il padre era nell'esercito

napoleonico), dopo Waterloo rientrò in patria. A Parigi si legò ai circoli

intellettuali cattolici intorno al fisico André-Marie Ampère e a Emmanuel

Bailly. Nel 1833 diede vita alle «conferenze» che insieme, formano la «Società

di San Vincenzo de' Paoli», un'istituzione «cattolica, ma laica; povera, ma

carica di poveri da sollevare; umile, ma numerosa» secondo una definizione che

ne diede lo stesso fondatore. Federico Ozanam si laureò in Legge e

Lettere, insegnò alla Sorbona, fu accademico della Crusca di Firenze. Nel 1841

si sposò ed ebbe una figlia. Sempre in viaggio per l'Europa, però, trovava sempre

tempo da dedicare al suo mondo povero, alla Società di San Vincenzo, che seguì

e stimolò nel suo sviluppo. Morì a Marsiglia nel 1853. È stato proclamato beato

da Papa Giovanni Paolo II a Parigi il 27 agosto 1997. (Avvenire)

Etimologia: Federico

= potente in pace, dal tedesco

Martirologio

Romano: A Marsiglia in Francia, transito del beato Federico Ozanam, che,

uomo di insigne cultura e pietà, difese e propagò con la sua alta dottrina le

verità della fede, mise la sua assidua carità a servizio dei poveri nella

Società di San Vincenzo de’ Paoli e, padre esemplare, fece della sua famiglia

una vera chiesa domestica.

Sono presenti in 130 Paesi del mondo con centinaia di migliaia di volontari, in lotta da un secolo e mezzo contro la povertà, quella palese e quella che si nasconde. Sono gruppi detti “conferenze” di parrocchia, di paese, di quartiere, di azienda. Insieme, formano la “Società di San Vincenzo de’ Paoli”, che è istituzione "cattolica, ma laica; povera, ma carica di poveri da sollevare; umile, ma numerosa". Così ne parla Federico Ozanam, uno dei fondatori dell’Opera a Parigi, il 23 aprile 1833.

Nato in Italia quando il padre era ufficiale medico nell’esercito napoleonico, dopo Waterloo torna con la famiglia a Lione. E’ il secondo di tre fratelli, uno dei quali diventerà sacerdote e l’altro medico. Dopo il liceo, va a Parigi per studiare legge, ed è ospite in casa di André-Marie Ampère, il grande esploratore dell’elettrodinamica (anche ora si chiama ampere l’unità di misura per l’intensità della corrente elettrica).

Pilotato dallo scienziato, che è grande uomo di fede, Ozanam si unisce ai giovani intellettuali cattolici raccolti intorno a Emmanuel Bailly, un capofila della riscossa culturale cattolica. Si laurea in legge nel 1836 e in lettere nel 1839, con una tesi sulla filosofia in Dante Alighieri: "Il poeta", così lo chiama, "del nostro presente come lo fu del suo tempo; il poeta della libertà, dell’Italia e del cristianesimo". La sua tesi viene subito pubblicata anche in inglese, tedesco e italiano, e Ozanam ottiene una cattedra alla Sorbona. Ma resta sempre l’uomo della “San Vincenzo”. E continua a metterci l’anima, per stimolare e orientare; spiega che l’Opera agisce sotto piena responsabilità dei laici, e non si dedica a pura beneficenza; essa vive la carità innanzitutto con la vicinanza fisica e regolare con i poveri, nelle loro case. L’aiuto materiale soccorre sì una necessità immediata, ma ha il fine di strappare il povero alla sua condizione: "La terra si è raffreddata, tocca a noi cattolici rianimare il calore vitale che si estingue!".

Si sposa nel 1841 con la concittadina Amalia Soulacroix, da cui ha una figlia. Amico dell’intellettualità parigina più illustre, viaggiatore di continuo attraverso l’Europa, sempre però ritorna al suo mondo povero, alla Società di San Vincenzo, che segue e stimola nel suo irradiarsi. E torna al singolo povero, alla singola famiglia, con la visita personale che è il contrassegno dell’Opera e anche della vita sua privata: quando sta con i poveri, Ozanam parla con Dio. Per lui non c’è responsabilità o carica che dispensi il confratello dalla visita e dall’immaginare novità per meglio aiutare i poveri, per meglio camminare sulla via della promozione umana: (La cosa, per opera sua, precede il nome, di cui farà variamente uso il XX secolo).

Federico Ozanam muore a Marsiglia tornando dalla Toscana, dove è stato accolto

nell’Accademia della Crusca con Cesare Balbo. Il 27 agosto 1997, Giovanni Paolo

II lo ha proclamato beato a Parigi.

Autore: Domenico Agasso

Ozanam - Semaine religieuse du diocèse de Lyon 23 mai 1913

.jpg)