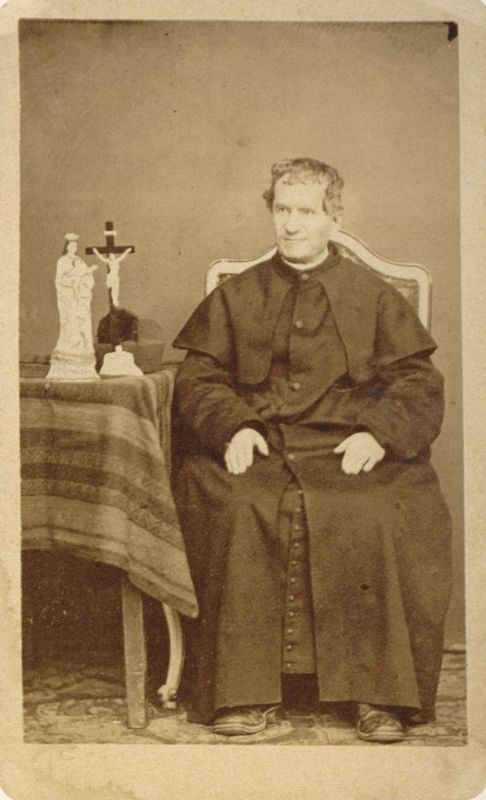

Attributed

to Carlo

Felice Deasti, Don Bosco la Torino în 1880 (fotografie originală).

Saint Jean

Bosco, prêtre

Fils de pauvres paysans

piémontais, devenu prêtre à force de sacrifices, il se dévoue aux jeunes

ouvriers de Turin abandonnés à eux-mêmes. Il crée pour eux un centre de

loisirs, un patronage, puis un centre d'accueil, puis des ateliers. Ses

"enfants" seront bientôt des centaines. Très marqué par la

spiritualité de saint François de Sales, Jean Bosco invente une éducation par

la douceur, la confiance et l'amour. Pour ses garçons, il fonde l'Oratoire,

l'Oeuvre, qui sera à l'origine de la congrégation des prêtres salésiens. Pour

les filles, il fonde la congrégation de Marie-Auxiliatrice. Don Bosco mourra,

épuisé, en 1888, entouré de ses disciples.

Saint Jean Bosco

Fondateur et

éducateur (+ 1888)

Fondateur de la société

de Saint-François-de-Sales et de l'Institut des Filles de Marie-Auxiliatrice.

C'était un fils de

pauvres paysans piémontais. Adolescent, il joue à l'acrobate pour distraire

sainement les garnements de son village. Devenu prêtre à force de sacrifices,

il se dévoue aux jeunes ouvriers de Turin abandonnés à eux-mêmes. Il crée

pour eux un centre de loisirs, un patronage, puis un centre d'accueil, puis des

ateliers. Rien de tout cela n'était planifié à l'avance, mais ce sont les

besoins immenses qui le pressent. Jamais il ne refuse d'accueillir un jeune,

même si la maison est petite, même si l'argent manque. Plutôt que de refuser,

il multipliera les châtaignes comme son maître multipliait les pains en

Palestine. Sa confiance absolue en la Providence n'est jamais déçue. Ses

"enfants" seront bientôt des centaines et tous se feraient couper en

morceaux pour Don Bosco. Sa mère, Maman Marguerite, vient s'installer près de

lui et jusqu'à sa mort, elle leur cuira la polenta et ravaudra leurs vêtements.

Très marqué par la spiritualité de saint

François de Sales, Jean Bosco invente une éducation par la douceur, la

confiance et l'amour. Pour ses garçons, il fonde l'Oratoire, l’œuvre, qui

sera à l'origine de la congrégation des prêtres salésiens. Pour les filles, il

fonde la congrégation de Marie-Auxiliatrice. Don Bosco mourra, épuisé, en butte

à l'hostilité de son évêque qui ne le comprend pas, mais entouré de ses

disciples.

Site

des religieux Salésiens de Don Bosco.

Don

Bosco par thèmes - Pour découvrir la pédagogie et la spiritualité

salésienne, il y a aussi la "méthode

Don Bosco"...

Portail

de la Famille Salésienne de Don Bosco.

- ADAFO,

Bureau de Planification et Développement, Afrique francophone occidentale.

- Bicentenaire

Don Bosco, Histoire, Pédagogie, Spiritualité, 1815-2015, un songe qui

continue... L'Oratoire salésien... changer le monde par l'éducation... (vidéo)

Mémoire de saint Jean

Bosco, prêtre. Il connut une enfance pauvre et dure, et après son ordination,

il mit à Turin toute son énergie à l'éducation des jeunes et fonda la Société

de Saint-François de Sales et, avec l'aide de sainte

Marie-Dominique Mazzarello, l'Institut des Filles de Marie Auxiliatrice,

pour enseigner aux jeunes un métier et la vie chrétienne. Après avoir réalisé

tant de projets, il mourut à Turin en 1888.

Martyrologe romain

Le salésien "saisit

les valeurs du monde et refuse de gémir sur son temps: il retient tout ce qui

est bon, surtout si cela plaît aux jeunes. Celui qui est toujours prêt à se

plaindre n'a pas le véritable esprit salésien"

Article 22 - L'optimisme

et la joie de l'espérance

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/534/Saint-Jean-Bosco.html

Saint Jean Bosco

Jean Bosco est né le

16 août 1815, sur la colline des Becchi, un petit hameau près de Castelnuovo

d'Asti, aujourd'hui Castelnuovo Don Bosco. Issu d'une famille pauvre, orphelin

à l'âge de 2 ans, il fut élevé par sa mère Marguerite, ainsi que son frère aîné

Joseph et son demi frère Antoine.

Travaillant dur et ferme, il s'est préparé à la mission qui lui avait été

indiquée dans un songe, alors qu'il avait à peine 9 ans, et qu'il s'est vu

confirmer par la suite à maintes reprises, de manière extraordinaire.Il a

étudié à Chieri, tout en apprenant divers métiers. Il est ordonné prêtre à 26

ans. Arrivé à Turin, il est immédiatement frappé par le spectacle des enfants

et des jeunes livrés à eux-mêmes, sans travail et sans guide. Il prend alors la

décision de consacrer sa vie aux jeunes pour les sauver.

Le 8 décembre 1841, dans l'église St François d'Assise, Don Bosco rencontrait

un pauvre garçon, nommé Barthélemy Garelli, le premier d'une multitude de

jeunes. C'est ainsi que commence l'Oratoire, itinérant au début, puis, dès

Pâques 1846, définitivement installé au Valdocco, faubourg malfamé, qui

deviendra la maison mère de toutes les œuvres salésiennes.Les garçons affluent

par centaines : ils étudient et apprennent un métier dans les ateliers que Don

Bosco a construit pour eux. En 1859, Don Bosco invite ses premiers

collaborateurs à se joindre à lui dans la Congrégation Salésienne : ainsi,

rapidement, devaient se multiplier partout des « oratoires » (centres de

loisirs et de formation humaine et chrétienne pour les jeunes), des écoles

professionnelles, des collèges, des centres de vocations (sacerdotales,

religieuses, missionnaires), des paroisses, des centres en pays de mission...

Ainsi, en 1875, son action déborde l'Italie, une première expédition

missionnaire s'embarque pour l'Argentine, et les salésiens ouvrent leur

première œuvre en France, à Nice .Les filles et les laïcs aussiEn 1872, Don

Bosco fonde l'institut des Filles de Marie Auxiliatrice (Sœurs salésiennes) qui

travailleront pour les jeunes filles dans des œuvres variées, avec le même

esprit et la même pédagogie. La cofondatrice et première supérieure a été Marie

Dominique Mazzarello (1837-1881), canonisée par le pape Pie XII le 21 juin

1951.Mais Don Bosco a su s'entourer de nombreux laïcs pour partager avec les

Salésiens et les Salésiennes son projet éducatif. Dès 1869, il fondait

l'Association des Coopérateurs, qui font partie à part entière de la Famille

Salésienne, se mettant au service de l'Eglise à la manière de Don Bosco.A 72

ans, épuisé par le travail, Don Bosco avait réalisé ce qu'il avait déclaré un

jour : « J'ai promis à Dieu que tant qu'il me resterait un souffle de vie, ce

serait pour mes chers enfant. » Il meurt à Turin, au Valdocco, à l'aube du 31

janvier 1888. Béatifié le 2 juin 1929 et proclamé saint par le pape Pie XI, le

dimanche de Pâques 1er avril 1934, Don Bosco est considéré, à juste titre,

comme un des plus grands éducateurs.

SOURCE :

Saint Jean Bosco

Prêtre, confesseur,

fondateur des Salésiens

(1815-1888)

Jean Bosco naquit en 1815

dans un village du Piémont. Ses parents étaient de pauvres paysans; mais sa

mère, demeurée veuve avec trois enfants, était une sainte femme. Le caractère

jovial de Jean lui donnait une grande influence sur les enfants de son âge. Il

les attirait par ses manières aimables et il entremêlait avec eux les

divertissements et la prière. Doué d'une mémoire extraordinaire, il se plaisait

à leur répéter les sermons qu'il avait entendus à l'église. C'étaient là les

premiers signes de sa vocation apostolique. Son coeur, soutenu par celui de sa

mère et d'un bon vieux prêtre, aspirait au sacerdoce. La pauvreté, en

l'obligeant au travail manuel, semblait lui interdire l'étude. Mais, par la

grâce de Dieu, son courage et sa vive intelligence surmontèrent tous les

obstacles.

En 1835, il était admis

au grand séminaire. "Jean, lui dit sa mère, souviens-toi que ce qui honore

un clerc, ce n'est pas l'habit, mais la vertu. Quand tu es venu au monde je

t'ai consacré à la Madone; au début de tes études je t'ai recommandé d'être Son

enfant; sois à Elle plus que jamais, et fais-La aimer autour de toi."

Au grand séminaire, comme

au village et au collège, Jean Bosco préludait à sa mission d'apôtre de la

jeunesse et donnait à ses condisciples l'exemple du travail et de la vertu dans

la joie. Prêtre en 1841, il vint à Turin. Ému par le spectacle des misères

corporelles et spirituelles de la jeunesse abandonnée, il réunit, le dimanche,

quelques vagabonds qu'il instruisait, moralisait, faisait prier, tout en leur

procurant d'honnêtes distractions. Mais cette oeuvre du dimanche ne suffisait

pas à entretenir la vie chrétienne, ni même la vie corporelle, de ces pauvres

enfants.

Jean Bosco, bien que

dépourvu de toute ressource, entreprit donc d'ouvrir un asile aux plus

déshérités. Il acheta pour 30.000 francs une maison payable dans la quinzaine.

"Comment! lui dit sa mère devenue son auxiliaire, mais tu n'as pas un sou

vaillant!" -- "Voyons! reprit le fils, si vous aviez de l'argent,

m'en donneriez-vous? Eh bien, mère, croyez-vous que la Providence, qui est

infiniment riche, soit moins bonne que vous?"

Voilà le trésor divin de

foi, d'espérance et de charité dans lequel Jean Bosco, malgré toutes les

difficultés humaines, ne cessa de puiser, pour établir ses deux Sociétés

Salésiennes de Religieux et de Religieuses, dont la première dépasse le nombre

de 8 000, et la seconde celui de 6 000, avec des établissements charitables

multipliés aujourd'hui dans le monde entier.

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie

des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950

SOURCE : http://magnificat.ca/cal/fr/saints/saint_jean_bosco.html

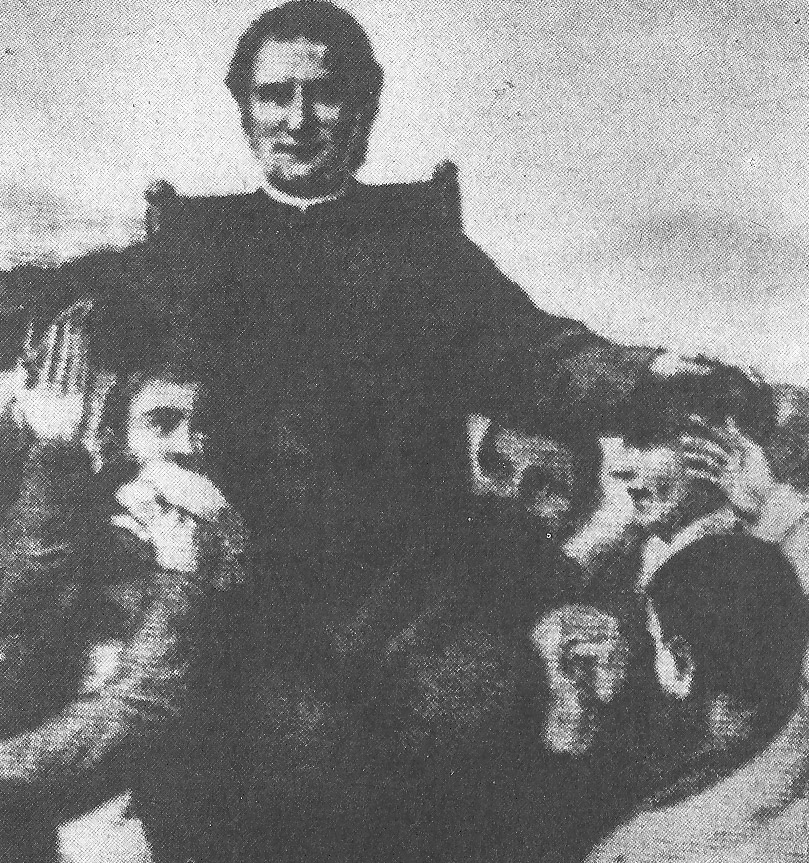

Don

Bosco la Barcelona (Spania), 1886

JEAN BOSCO

Prêtre, Fondateur, Saint

1815-1888

EXTRAIT BIOGRAPHIQUE

Dans une ferme, au cœur

du Piémont agricole, à Morialdo, hameau de Castelnuovo, naît Jean Bosco,

fils d'un petit métayer, en août 1815. Son père François, meurt deux ans plus

tard, laissant sa veuve, Marguerite éduquer ses trois enfants. Ce sont trois

garçons, dont l'aîné, Antoine, qui n'a que 10 ans, va très vite s'occuper de la

ferme avec sa mère. Le second, Joseph, a 4 ans. La maman Marguerite apprit elle

même les prières du chrétien à ses trois enfants qui priaient tous ensemble

matin et soir. C'est dans cette ambiance chrétienne et rurale que le petit Jean

fit, dans cette chambre, un rêve vers l'âge de neuf ans. Ce rêve lui laissa

pour toute la vie une profonde impression. Le lendemain il s'empressa de le

raconter à sa famille. Bien des années plus tard, il en comprit la

signification profonde, et le redit souvent à ses enfants et à ses disciples

les salésiens.

C'est devenu un texte

fondateur :

« A neuf ans j'ai

fait un songe qui m'est resté profondément gravé dans l'esprit pendant toute ma

vie. Dans ce songe, il me semblait que j'étais près de notre maison dans une

cour très spacieuse où étaient rassemblés une foule d'enfants qui jouaient. Les

uns riaient, beaucoup blasphémaient. En entendant ces blasphèmes je me suis

tout de suite jeté au milieu d'eux, donnant du poing et de la voix pour les

faire taire.

A ce moment, apparut un

Homme imposant, noblement vêtu. Son visage était si lumineux qu'on ne pouvait

pas le regarder en face. Il m'appela par mon nom et me dit : “Ce n'est pas avec

des coups mais avec la douceur et la charité que tu devras faire d'eux tes

amis. Commence dont tout de suite à leur parler de la laideur du péché et de la

valeur de la vertu”.

Intimidé, craintif, je

répondis que j'étais un pauvre enfant ignorant. Alors, les garçons, cessant de

se battre et de crier, se groupèrent tous autour de Celui qui parlait. Comme si

je ne savais plus ce que je disais, je demandai :

“Qui êtes-vous pour

m'ordonner des choses impossibles ?

– C'est justement parce

que ces choses te paraissent impossibles que tu devras les rendre possibles en

obéissant et en acquérant la science.

– Comment pourrai-je

acquérir la science ?

– Je te donnerai une

institutrice. Sous sa conduite, tu pourras devenir savant.

– Mais qui

êtes-vous ?

– Je suis le Fils de

cette Femme que ta mère t'a appris à prier trois fois par jour. Mon nom,

demande-le à ma Mère.”

Aussitôt, je vis à ses

côtés une Dame d'aspect majestueux, vêtue d'un manteau qui resplendissait comme

le soleil. S'approchant de moi tout confus, elle me fit signe d'avancer et me

prit par la main avec bonté :

“Regarde !

dit-elle”.

En regardant, je m'aperçus

que les enfants avaient tous disparu. A leur place je vis une multitude de

cabris, de chiens, de chats, d'ours et beaucoup d'autres animaux.

“Voilà ton domaine !

Voilà où tu devras travailler. Deviens humble, courageux, et vigoureux :

et ce que tu vois arriver en ce moment à ces animaux, tu le feras pour mes

enfants”.

Je tournai donc les yeux

et voilà qu'à la place des bêtes sauvages apparurent autant de paisibles

agneaux qui sautaient, couraient, bêlaient autour de cet Homme et de cette

Femme comme pour leur rendre hommage.

Alors, toujours dans mon

rêve, je me mis à pleurer et je priai cette Dame de vouloir bien s'expliquer

d'une façon plus claire, car je ne comprenais pas ce que tout cela signifiait.

Elle posa sa main sur ma

tête et me dit :

“Tu comprendras tout au

moment voulu”.

Elle avait à peine dit

cela qu'un bruit me réveilla. Tout avait disparu. J'étais abasourdi. J'avais

l'impression que les mains me faisaient mal à cause des coups de poings que

j'avais distribués et que le visage me cuisait d'avoir reçu des gifles de tous

ces galopins.

Le matin, j'ai raconté le

songe d'abord à mes frères qui se mirent à rire, puis à ma mère et à la

grand-mère. Chacun donnait son interprétation : “Tu deviendras berger”, dit

Joseph. “Chef de brigands”, insinua perfidement Antoine. Ma mère : “Qui sait si

tu ne deviendras pas prêtre”. C'est la grand-mère qui prononça le jugement

définitif : “Il ne faut pas s'occuper des rêves”. J'étais de l'avis de l'aïeule

et pourtant je ne réussis jamais à m'ôter tout cela de l'esprit. »

Toutes les années qui

suivirent furent profondément influencées par ce songe. Maman Marguerite avait

compris (et Jean le comprit aussi très vite) que ce songe indiquait une

direction. (Don Bosco, Souvenirs Autobiographiques)

Ayant fini ses cours

primaires, Jean Bosco vient à Chieri suivre ses études secondaires. A la fin de

celles-ci, il rentre au séminaire de Chieri. Il a 19 ans .Six ans d'étude à

nouveau, mais avec de bons compagnons et de bons professeurs. Pendant les

vacances, il revient aux Becchi. Il aide à la ferme familiale. Il s'occupe

aussi des jeunes du village. Il enseigne le catéchisme à beaucoup d'entre eux

qui à 16 ou 17 ans étaient totalement ignares des vérités de la foi. Il leur

demande aussi l'assiduité aux offices, et la confession mensuelle. Quelques uns

abandonnèrent, mais beaucoup continuèrent. Une fois devenu prêtre, on lui

proposa plusieurs postes, mais rien ne l'attirait. Don Cafasso, son confesseur,

lui conseilla de rester avec lui pour continuer des études de spiritualité. Il

lui fit découvrir aussi la vie dans les banlieues pauvres de Turin. Étant

aumônier de prison il lui fait rencontrer des condamnés à mort, et surtout

beaucoup de jeunes dont certains étaient déjà des criminels endurcis. Il décida

alors de se consacrer à la jeunesse en péril. Le dimanche, les jeunes apprentis

de Turin viennent de plus en plus nombreux chez Don Bosco. Après le catéchisme,

il leur apprend à lire et à écrire. Don Bosco renonce à s'occuper des filles du

refuge de la marquise Barollo, pour se consacrer à ses garçons de la rue. C'est

l'époque du patronage volant, où il se fait chasser de partout avec sa bande

bruyante de jeunes. Pendant plusieurs mois, il doit changer de lieu sans cesse.

Il est surveillé par la police, mais aussi par le clergé de Turin qui veut le

faire interner, le croyant devenu fou. En 1847, une occasion se présente

enfin : Don Bosco loue un local appartenant à un certain Pinardi, et le

terrain qui l'entoure. Le dimanche suivant, les petits maçons, plâtriers et autres

ouvriers du bâtiment commencent les travaux avec un enthousiasme

indescriptible. Dans la semaine, Don Bosco passe les voir chez leurs patrons,

sur leurs chantiers, et prend leur défense quand ils sont exploités. Plusieurs

fois, il obtient même d'établir un contrat de travail. Cette fois, l'œuvre

semble stabilisée. Don Bosco a 32 ans. Mais il s'est trop dépensé, une

bronchite infectieuse se déclare, pendant plusieurs jours il est entre la vie

et la mort. Une fois rétabli, les médecins envoient Don Bosco en convalescence

dans son village natal. Quand il revient, il n'est pas seul. Il a convaincu sa

mère de l'accompagner, car ses enfants ont besoin d'une maman. Elle fait la

cuisine pour tout le monde. Surtout qu'il arrive de recueillir des jeunes mis à

la porte par leurs parents... Un internat commence. Don Bosco se souvenant de

ce qu'il avait appris pendant son enfance, reprise les vêtements usages,

entaille d'autres, et enseigne cela à plusieurs jeunes, créant ainsi ses

premiers cours professionnels !

Abandonné par ses aides

bénévoles à la suite des troubles politiques de 1848, Don Bosco

se souvient du songe de son enfance : les jeunes loups qui se

transformaient en agneaux et certains en bergers. C'est parmi ses jeunes qu'il

trouvera ses collaborateurs. Il propose à Rua de partager les responsabilités

avec lui ; à 17 ans il lui confie un nouveau patronage à l'autre bout de

la ville. Buzetti se chargera des finances et Cagliero de l'animation du

Valdocco. Plusieurs de ces jeunes demandent alors à devenir prêtres comme Don

Bosco. Don Bosco achète la maison Pinardi en 1851, lui fait construire une

aile, et bâtit une chapelle. Ces bâtiments deviennent de nouvelles classes

professionnelles, et des classes de latin, car Don Bosco veut former lui-même

ses futurs collaborateurs. Mais Don Bosco a de nombreux ennemis chez les

anticléricaux et les vaudois. Il lutte contre eux sur le terrain de la presse,

créant ses propres journaux catholiques : “le Bulletin Salésien” et les

“Lectures catholiques”. Pour cela, il fonde sa propre imprimerie, avec des

cours de typographie et une formation aux métiers du livre. Il échappe de

justesse à plusieurs attentats. Plusieurs fois sur le chemin désert du Valdocco

il eut la vie sauvée par la présence d'un gros chien gris qui l'accompagnait.

Aux difficultés extérieures et au manque d'argent s'ajoutent les épreuves

internes. Maman Marguerite meurt en 1856. La maman de Michel Rua vient la

remplacer pour l'internat, la cuisine et le rôle de maman des jeunes du

Valdocco. L'œuvre est fragile. Don Bosco cherche une solution pour stabiliser

son oeuvre. Il rédige un projet de constitution, et le soumet au pape Pie IX,

qui le reçoit avec beaucoup d'intérêt. Après diverses modifications, elles

deviennent les Constitutions de la Société de Saint François de Sales. Don

Bosco attend encore 18 mois pour en parler à ses jeunes animateurs. Après une

discussion très agitée, 16 jeunes répondent à l'appel de Don Bosco, et le

prient de devenir leur supérieur.

Maintenant Don Bosco peut

se consacrer à un autre projet. En songe, la Vierge lui a demandé de construire

à Turin une basilique dédiée à Marie Auxiliatrice. Il n'a pas d'argent, mais

organise loteries, quêtes, etc. La basilique sera consacrée en 1867. Don Bosco

était venu prêcher à Mornèse en 1864. Il y avait rencontré une jeune fille qui

apprenait la couture à quelques jeunes pauvres de son village. Or le Pape

demande à Don Bosco de faire quelque chose pour les filles. L'équipe de Mornèse

accepte. 15 jeunes filles prennent l'habit à la suite de Marie Dominique

Mazzarello. Don Bosco leur donne des constitutions inspirées de celles des

salésiens. Elles prennent le nom de Filles de Marie Auxiliatrice (FMA) ou

salésiennes. En 1875 partit la première mission salésienne en Amérique, suivie

de plusieurs autres. L'évangélisation de la Patagonie commençait. Don Bosco est

maintenant connu dans toute l'Italie. Malgré les multiples tracasseries de la

police et du gouvernement, il multiplie écoles et patronages. Les premiers

appels lui viennent de l'Europe. En 1880, le nouveau pape Léon XIII convoque

Don Bosco. Alors que celui-ci, fatigué, voudrait s'occuper de l'organisation de

ses œuvres, il reçoit mission de construire à Rome une église dédiée au

Sacré-Coeur. Mais Don Bosco a épuisé la générosité de ses bienfaiteurs italiens.

Il va s'adresser à la France. En 1883, son voyage dure 4 mois, c'est un vrai

triomphe. On se bouscule pour le voir. On coupe des morceaux de sa soutane pour

faire des reliques. Il fait des miracles. sa prière obtient des guérisons. Tout

Paris veut l'entendre. Il passe son temps à recevoir des gens, aussi bien

l'ouvrier que le prince. Un saint traversa la France... et la basilique du

Sacré-Cœur fut achevée 4 ans plus tard. En 1886, Don Bosco fait un dernier

voyage en Espagne. Il déchaîne encore plus d'enthousiasme qu'à Paris. Il

entrait dans la gloire de son vivant. Mais à son retour il est totalement

épuisé. Le 3 décembre 1887, il ne peut dire la messe. Le 23 il renonce à

recevoir. Il s'éteint le 31 janvier 1888, à Turin.

Vénérable le 20 février

1927, il fut béatifié le 2 juin 1929 et enfin canonisé le 1er avril 1934.

SOURCE : http://voiemystique.free.fr/jean_bosco_extrait.htm

Jean Bosco, l’homme aux

rêves prophétiques

Anne

Bernet - publié le 30/01/23

Connu pour son génie

d’éducateur, saint Jean Bosco l’est moins pour ses prédispositions aux rêves

prophétiques. En pleine tempête politique italienne, il prévint par exemple le

roi des dangers auquel celui-ci s’exposait en s’attaquant à l’Église.

Même si Jésus annonce

qu’à la fin des temps, « les vieillards prophétiseront et les jeunes gens

auront des songes », l’Église a

toujours pris soin de ne pas trop encourager à croire aux rêves. Il arrive

toutefois que certains saints, tel Joseph dans l’Ancien Testament, méchamment

surnommé « l’homme aux songes » par ses frères jaloux, soient avertis

dans leur sommeil d’événements à venir qui, en effet, se réalisent. En ce

domaine, Jean Bosco est un champion hors catégorie mais ce don, qu’il a

lui-même longtemps regardé avec méfiance, ne lui a pas toujours simplifié la

vie…

Des visions pas toujours

plaisantes

Il est un garçon de neuf

ans au caractère déjà prononcé et violent quand il se voit en rêve au milieu

d’une vaste troupe d’enfants qui s’insultent, se disputent et en viennent aux

mains ; les entendant blasphémer, Giovanni, indigné, se précipite dans la

mêlée, décidé à ramener l’ordre à coups de poings. Le Christ apparaît alors et

lui dit : « Ce n’est pas par la violence mais par la douceur que tu

devras conquérir tes amis. » Ce rêve prémonitoire en plusieurs phases qui

aboutissent à la transformation des jeunes sauvages en doux agneaux, est connu,

comme celui dit des « trois blancheurs » où Don Bosco voit l’Église,

sous la forme d’un navire amiral entouré d’une flottille éparpillée aux prises

avec une flotte ennemie qui menace de la détruire. Deux colonnes surgissent

alors de la mer, l’une portant une hostie rayonnante, l’autre l’Immaculée, auxquelles

l’homme en blanc, le Pape, peut arrimer solidement sa nef en détresse. Célèbre

aussi le songe de 1857 où Giovanni voit le jeune Dominique Savio, décédé depuis

peu, s’avancer vers lui au milieu d’un paysage magnifique, l’assurer qu’il est

au Ciel et lui expliquer que les merveilles entrevues sont une pauvre

représentation d’une réalité autrement plus belle mais impossible à appréhender

par les vivants.

Le problème est que ces

visions ne sont pas toujours plaisantes. Le monde onirique de Don Bosco est peuplé

de créatures monstrueuses qui, sous la forme de chats énormes et terrifiants,

d’éléphants féroces, de crapauds horribles ou d’un cheval rouge emballé, celui

d’un des cavaliers de l’Apocalypse, menacent les âmes ou dévastent la

chrétienté. Beaucoup, à commencer par le romancier italien Eugenio Corti, qui

intitulera justement Le Cheval rouge son terrible récit de

l’engagement des troupes du régime fasciste en Russie aux côtés des Allemands,

identifieront la cavale écarlate au communisme. C’est aussi l’interprétation

d’Irène Corona dans Les Prophéties de Don Bosco (Éd. du Parvis,

2013).

Si personne ne fait

pénitence…

Pour Don Bosco, cet

avenir, révélé dans un songe de 1870 annonciateur de cataclysmes pour l’Italie,

l’Europe et l’Église, est conjurable, à condition que le clergé prenne

l’avertissement au sérieux : « Mais vous, les prêtres, pourquoi ne

courez-vous pas pleurer entre le vestibule et l’autel pour invoquer la

suspension des fléaux ? Pourquoi ne saisissez-vous pas le bouclier de la

foi et n’allez-vous pas sur les toits, dans les maisons, sur les routes, les

places et en tous lieux, même inaccessibles, pour porter la semence de ma

Parole ? Ne savez-vous pas qu’elle est l’épée terrible à deux tranchants

qui abat mes ennemis et apaise la colère de Dieu et des hommes ? »

Mais, si personne ne fait pénitence pour, comme le roi de Ninive, empêcher

l’accomplissement de ces maux, alors « ces choses, inexorablement, se

produiront une à une ». Don Bosco ne sera pas plus entendu, hélas, que

Notre-Dame ne l’a été rue

du Bac en 1830, à La

Salette en 1846, à Fatima en

1917, et ailleurs encore…

Pourtant, à l’instar de

la Vierge du Rosaire annonçant : « À la fin, mon cœur immaculé

triomphera », Giovanni prédit l’apparition d’un « soleil

lumineux » annonciateur du feu du Saint-Esprit sur le monde. Dieu, et Il

ne cesse de le redire à l’humanité par la voix de Marie et des saints, ne veut

pas la mort des pécheurs mais qu’ils se convertissent et vivent. Cela implique

de leur part un retour sur eux-mêmes. Dans le cas contraire, la justice divine

frappera, en effet. C’est ce que le prêtre visionnaire annonce, en décembre

1854, au roi Victor-Emmanuel II.

La suppression des ordres

contemplatifs

Nous sommes au cœur de la

crise qui durera jusqu’à la chute de Rome en septembre 1870, opposant partisans

de l’unité italienne et défenseurs des États pontificaux qui font du pape un

souverain temporel aussi bien que spirituel. L’unification de l’Italie implique

la disparition de cette souveraineté, ce à quoi Pie IX ne veut, ni ne peut,

consentir. Le jeune Victor-Emmanuel II, qui ambitionne de régner sur des

possessions plus vastes que celles léguées par ses aïeux en Savoie, Piémont et

Sardaigne, est entré, contre promesse de la couronne italienne, dans le jeu

d’une gauche révolutionnaire, franc-maçonne, décidée à renverser les monarchies

catholiques des Bourbons-Sicile à Naples ou des Habsbourg en Lombardie et

Vénétie ; décidée, surtout, à en finir, non seulement avec le pouvoir temporel

de la papauté, incarnée par les États pontificaux, mais avec le catholicisme.

Cette année 1854, le roi

a donné des gages aux adversaires de l’Église en acceptant le projet de loi

Ratazzi qui prévoit la suppression dans son royaume de tous les ordres religieux

contemplatifs et la confiscation de leurs biens, ne laissant subsister que ceux

voués à l’enseignement, la prédication et les œuvres de charité. Pour faire

passer la pilule auprès de la hiérarchie catholique piémontaise, la loi Ratazzi

affirme que l’argent ainsi récupéré sera attribué aux paroisses pauvres et à

l’entretien des édifices cultuels. Don Bosco, à l’instar des promoteurs de la

loi qui, eux, ne mésestiment pas la puissance de la prière et du sacrifice,

sait que détruire les ordres contemplatifs, c’est priver l’Église de ses

troupes d’élite et la livrer désarmée ou presque à l’Ennemi…

Morts annoncées

Seul le roi peut arrêter

le processus en opposant son veto ; Victor-Emmanuel, emporté par

l’ambition, n’en a pas l’intention. Fin novembre 1854, Don Bosco fait un

rêve : il se trouve au palais royal entouré d’autres prêtres. Soudain, un

valet déboule dans la salle ; il crie : « Grande

nouvelle ! » « Laquelle ? » demande Don Bosco et

l’autre de répondre : « Grand enterrement à la Cour ! »

Giovanni ne se rendort pas : « J’en ai été malade le reste de la nuit

… » Il est si frappé qu’il écrit au roi afin de l’avertir. À cinq jours de

là, il refait le même songe, à un détail près ; le domestique crie :

« Pas un mais plusieurs grands enterrements à la Cour ! » Don

Bosco réécrit à Victor-Emmanuel ; il l’avertit que, s’il signe la loi, il

attirera sur la Maison royale de Savoie de grands malheurs.

Je n’ai écrit au roi que

la vérité ; je regrette de l’avoir fâché mais j’ai fait cela pour son bien

et celui de l’Église.

Ce n’est pas un

avertissement à prendre à la légère. Don Bosco a déjà prophétisé des drames,

accidents, morts, en en précisant souvent la date ; toujours, les faits

lui ont donné raison dans les délais indiqués. Victor-Emmanuel, plus frappé

qu’il l’admet, envoie l’un de ses proches rencontrer Giovanni. Cet envoyé

s’emporte : « Croyez-vous raisonnable de mettre de la sorte la Cour

sens dessus dessous ? Le roi est furieux, très impressionné, très

troublé ! » Le message est clair ; il faut arrêter de vaticiner.

Imperturbable, Don Bosco rétorque : « Je n’ai écrit au roi que la

vérité ; je regrette de l’avoir fâché mais j’ai fait cela pour son bien et

celui de l’Église. » Victor-Emmanuel ne recule pas, de peur d’être

ridicule en prêtant foi à ce prêtre tenu par son ministre de l’Intérieur pour

un dangereux réactionnaire. Le 5 janvier 1855, la loi passe en première lecture

au parlement. Dans la soirée, la reine mère tombe brusquement très malade et

meurt. Elle avait 54 ans.

« Ouvre les

yeux ! »

C’est un coup très dur

pour le roi, le premier. Le jour des obsèques, sa femme, accouchée huit jours

plus tôt, et qui paraît très bien se remettre de la naissance, est emportée par

des complications inattendues. Don Bosco, à l’annonce du premier décès, a envoyé

un dernier courrier au souverain : « Une personne éclairée du Ciel

prévient : ouvre les yeux. Si la loi passe, de grands malheurs s’abattront

sur ta famille car ceci n’est que le début des maux… » En vain… Après les

deux reines, c’est le frère de Victor-Emmanuel, le duc de Gênes qui meurt le 11

février. Le roi ne bouge pas. Mi-mai, alors que le processus législatif touche

à son terme son dernier-né succombe à une maladie infantile. Son père signe

malgré tout le décret qui supprime 334 couvents de son royaume. Dans des notes

personnelles, Don Bosco écrit : « La famille qui vole Dieu subira

maintes tribulations et ne passera pas la quatrième génération. »

La prédiction se

réalisera. Le successeur de Victor-Emmanuel, Umberto Ier, est assassiné. Son

fils, Victor-Emmanuel III, qui a déjà perdu l’essentiel de son pouvoir au

profit de Mussolini, abdique en 1946, son fils est contraint d’en faire avant

de quitter l’Italie avec sa famille, frappé par la loi d’exil. La Maison de

Savoie ne règnera pas au-delà de cette quatrième génération marquée par le

Ciel…

Lire aussi :Où

en est la cause de Mamma Margherita, la mère de Don Bosco ?

Lire aussi :Dix

conseils très simples de Don Bosco à l’intention des parents

Lire aussi :Saint

Jean Bosco, un pionnier de l’éducation bienveillante?

"Centoventicinquesimo

anniversario" allegato al giornale L'Arena

PREMIÈRE PARTIE

LA VIE DE SAINT JEAN

BOSCO

3-Un

remarquable conseiller: Don Cafasso

5-D’autres

missions pour don Bosco

6-Le

développement des principales œuvres de Don Bosco

7-Don

Bosco constructeur d’églises

DEUXIÈME PARTIE

LES FAITS EXTRAORDINAIRES

DE LA VIE DE SAINT JEAN BOSCO

2-Les

prémonitions et les visions

TROISIÈME PARTIE

SAINT JEAN BOSCO -

L’HOMME

QUATRIÈME PARTIE

LA SPIRITUALITÉ DE DON

BOSCO

2-Le

fondateur d’ordres religieux

4-La

spiritualité de don Bosco

ANNEXES

Annexe

2-Résurrection d’un adolescent

Annexe

3-Vie de Dominique Savio

Annexe

4-Quelques repères chronologiques

Annexe

5-Les œuvres écrites de don Bosco

SOURCE : http://voiemystique.free.fr/jean_bosco_bio_tab.htm

中文(台灣): 天主教台北總教區聖若望鮑思高天主堂的聖若望鮑思高雕像。

Statue

of Don Bosco at St. John Bosco Parish Church, Taipei, Taiwan

Statue

de Saint Jean Bosco à l'église Saint Jean Bosco à Taipei, Taiwan. Photographie :

Bernard Gagnon

QUELQUES REPÈRES

CHRONOLOGIQUES

1815-(16 août): Naissance

de Jean Bosco aux Becchi (Asti-Piémont).

1817-Jean perd son père à

l’âge de deux ans.

1825-Jean voit en songe

la préfiguration de sa mission.

1835 Jean Bosco reçoit la

soutane et entre au séminaire.

1837-(9 mai) :

Naissance à Mornese de Marie Dominique Mazzarello, cofondatrice des FMA.

(Filles de Marie Immaculée)

1841-(5 juin): Jean Bosco

est ordonné prêtre à Turin.

1841-(8 décembre): Don

Bosco débute par une leçon de catéchisme son apostolat auprès des jeunes à

Turin.

1842-(2 avril) :

Naissance de Dominique Savio.

1845-Don Bosco lance les

cours du soir.

1846-(12 avril): Don

Bosco s’établit au Valdocco.

1847-Don Bosco ouvre un

deuxième Oratoire à Turin-Porta Nuova.

1848-Don Bosco est pris

pour un fou par ceux à qui il confie son projet apostolique.

1852-(31 mars) : Don

Bosco est officiellement reconnu par son évêque comme directeur des trois

Oratoires de Turin.

1853-Don Bosco ouvre des

écoles professionnelles dans ses internats, crée sa première fanfare et lance

les “Lectures Catholiques”, sa première revue populaire.

1854-(26 janvier) :

Don Bosco donne le nom de “Salésiens” à ses premiers assistants.

1854-(2 octobre) :

Rencontre entre don Bosco et Dominique Savio.

1855-(25 mars) :

Naissance de la Société Salésienne: l’abbé Michel Rua émet les voeux privés en

présence de Don Bosco.

1855-Don Dominique

Pestarino fonde à Mornese (Alessandria-Piémont) une association qui deviendra

l’Institut des Filles de Marie Auxiliatrice.

1856-(25 novembre) :

Décès de Maman Marguerite.

1857-(9 mars) : Mort

de Dominique Savio.

1858-Première visite de Don

Bosco à Rome et au Pape.

1859-(9 décembre) :

Don Bosco annonce sa décision de fonder la Congrégation Salésienne.

1859-(18 décembre) :

Don Bosco installe le premier Chapitre Supérieur salésien.

1860-(12 juin) : 26

salésiens adoptent les Règles de la Congrégation.

1860-Don Bosco accepte

parmi les salésiens le premier laïc: le coadjuteur Joseph Rossi.

1861-Don Bosco ouvre la

première typographie.

1862-(14 mai) : les

22 premiers salésiens émettent leurs voeux en présence de don Bosco.

1863-(20 octobre) :

Don Bosco ouvre la première maison hors de Turin (à Mirabello Monferrato).

1864-(23 juillet) :

La Congrégation Salésienne reçoit la première reconnaissance du Saint-Siège

(Décret de louange).

1864-(octobre) : Don

Bosco rencontre Marie Mazzarello à Mornese.

1865-(13 novembre) :

Premier diplôme obtenu par un salésien (Don Jean Baptiste Francesia).

1868-(9 juin) :

Consécration de la basilique Marie Auxiliatrice à Turin.

1869-(18 avril) :

Don Bosco fonde à Turin l'Archiconfrérie de Marie Auxiliatrice.

1870-(septembre) :

Ouverture de la première maison hors du Piémont (à Alassio, province de

Savona).

1872-(5 août) :

Fondation à Mornese de l'Institut des FMA.

1874-(3 avril) : Le

Saint-Siège approuve les Constitutions salésiennes.

1875-(11 novembre) :

La première expédition missionnaire salésienne part pour l'Amérique.

1875-(21 novembre) :

Ouverture de la première maison salésienne hors d’Italie (Nice, France)

1876-(9 mai) : Le

Saint-Siège approuve l'Association des Salésiens Coopérateurs.

1877-(5 septembre) :

Les Salésiens tiennent leur premier Chapitre Général.

1877-(14 novembre) :

Les 6 premières FMA partent d’Italie pour les missions d’Amérique.

1879-Premier contact des

missionnaires salésiens avec les Indiens de Patagonie.

1880-Salésiens et FMA

ouvrent les premières œuvres missionnaires en Patagonie (Argentine).

1881-(14 mai) : Mort

de Mère Marie Mazzarello.

1883-(février-mai) :

Visite de Don Bosco en France.

1884-(7 décembre) :

Premier salésien évêque (Mgr Jean Cagliero).

1886-Visite de Don Bosco

à Barcelone.

1887-(14 mai) :

Consécration de la Basilique du Sacré Coeur à Rome.

1888-(31 janvier) :

Mort de Don Bosco (il laisse 773 Salésiens et 393 FMA).

1890-Ouverture du procès

de canonisation de Don Bosco.

1897-(septembre): Début

de l’œuvre salésienne en Amérique Centrale.

1915 Premier cardinal

salésien (Mgr Jean Cagliero)

1929-(2 juin):

Béatification de Don Bosco.

1934-(1 avril):

Canonisation de Don Bosco.

1938-(20 novembre) :

Béatification de Mère Marie Mazzarello.

1946-(24 mai) : Don

Bosco est déclaré patron des éditeurs catholiques.

1950-Les missionnaires

expulsés de Chine transplantent l'œuvre salésienne aux Philippines, au Vietnam,

à Taiwan et en Corée du Sud.

1950-(5 mars) :

Béatification de Dominique Savio.

1951-(24 juin) :

Canonisation de Mère Marie Mazzarello.

1954-(12 juin) :

Canonisation de Dominique Savio.

1972-(29 octobre) :

Béatification de don Michel Rua.

1988-Premier centenaire

de la mort de Don Bosco. Une "année de grâces" enrichies

d’indulgences par le pape Jean-Paul II, est ouverte le 31 janvier par une

célébration solennelle à Turin, en présence du Recteur Majeur et du Conseil

Général, quatre cardinaux et 58 évêques salésiens.

1989-(24 janvier) :

Le Pape Jean-Paul II proclame officiellement don Bosco “Père et Maître de la

jeunesse”.

SOURCE : http://voiemystique.free.fr/jean_bosco_bio_25.htm

Carlo

Felice Deasti. San Giovanni Bosco, santo italiano, 1887

LES ŒUVRES ÉCRITES DE

JEAN BOSCO

Écrits de caractère

scolaires

Système métrique décimal

(1849)[1]

Histoire de l’Église

(1845)

Histoire Sainte (1847)

Histoire d’Italie (1855)

Biographies :

Saint Martin de Tours (1855)

Saint Pancrace martyr

(1856)

Saint Pierre apôtre

(1856)

Saint Paul (1857)

Les papes des trois

premiers siècles (1857-1865)

La bienheureuse Marie des

Anges, carmélite (1865)

Louis Comollo (1844)

Saint Dominique Savio

(1859)

Michel Magon (1861)

François Besucco (1864)

Joseph Cafasso (1864)

Charles-Louis de Haller,

protestant converti (1855)

Les mémoires de

l’Oratoire Saint François de Sales (de 1815 à 1855)

Récits “agréables”

La conversion d’une

vaudoise (1854)

Pierre ou la force de la

bonne éducation (1855)

Récit agréable d’un vieux

soldat de Napoléon 1er (1862) etc. ...

Doctrine, apologétique,

dévotion

Avis aux catholiques

(1850)

Le catholique instruit

dans sa religion (1853)

Une dispute entre un

avocat et un ministre protestant (1853)

L’Église catholique et sa

hiérarchie (1869)

Les conciles généraux et

l’Église catholique (1869)

Œuvres mariales

Le mois de mai (1858)

Neuf jours consacrés à

l’auguste Mère du Sauveur sous le titre de Marie Auxiliatrice (1870),

etc. ...

Sur l’œuvre salésienne

Règlements de l’Oratoire

(1877)

Les Coopérateurs

Salésiens (1876)

Constitutions de la

Société de saint François de Sales (à partir de 1867)

À cela il faut ajouter la

revue intitulée “Les Lectures Catholiques” à partir de 1853...

Enfin, sur l’ordre exprès

du pape Pie IX, don Bosco écrivit aussi ses Souvenirs autobiographiques.

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

A. Auffray. Un grand

Éducateur, Saint Jean Bosco (1815-1888). Édité chez Emmanuel Vitte en 1929

Don Bosco. Souvenirs

autobiographiques. Agence internationale Salésienne d’Information

(www.sdb.org).

Jean Bosco - Écrits

spirituels. Textes présentés par Joseph Aubry. Édité par Nouvelle

Cité en 1979

[1] Les

nombres entre parenthèses sont les dates de la première parution

SOURCE : http://voiemystique.free.fr/jean_bosco_bio_26.htm

Qui est Don Bosco ?

30 janvier 2021 à 10:00

Un prêtre éducateur du

XIXe siècle qui a donné sa vie aux jeunes abandonnés de la ville de Turin…

Voici résumer en quelques mots la vie d’une personne qui aura marqué son époque

et aura laissé un trésor pour aimer les jeunes : le système préventif. Son projet a conquis

des jeunes et des adultes de son temps… et aujourd’hui, ils sont des centaines

de milliers, dans plus de 130 pays, à vivre du style d’éducation proposé

par Don Bosco.

voir une vidéo sur Don Bosco

Son enfance

Né le 16 août 1815 aux

Becchi, un hameau situé à 30 kilomètres au sud de Turin, Jean Bosco est le

troisième fils d’un couple de paysans. Très tôt orphelin de père, il est

forcé d’aider sa mère aux travaux des champs pour ne pas mourir de faim. Malgré

cela, il trouve le temps de s’instruire, et fait profiter de ses connaissances

aux garçons de son âge. Enfant joyeux, mais impulsif, il doit quitter le foyer

familial à l’âge de onze ans du fait de sa mésentente avec l’un de ses frères.

Après avoir effectué plusieurs petits métiers, il bénéficie de l’enseignement

d’un prêtre, Don Calosso, ce qui nourrit en lui la vocation de rentrer

dans les ordres.

Attentif aux jeunes

Ordonné prêtre le 5 juin

1841, Don Bosco est invité par Don Cafasso à arpenter les faubourgs de

Turin. Il y découvre une jeunesse livrée à elle-même, en proie à la misère

et à l’exploitation. Il faut dire qu’à cette époque, la capitale piémontaise

est en pleine effervescence industrielle, et les jeunes constituent, pour les

patrons, une main d’oeuvre bon marché et corvéable à merci. Ses visites dans

les prisons finissent de le convaincre d’agir rapidement. C’est ainsi qu’il

conçoit le projet du Valdocco (littéralement : « val des occis» en

italien, puisque c’était dans ce quartier de Turin que les exécutions avaient

lieu), un centre de jeunes qui ouvre en 1846.

Au Valdocco, Don Bosco

fait construire une chapelle, dédiée à Saint-François de

Sales. Parallèlement, il met en place des ateliers pour former ses jeunes

aux métiers de l’industrie : menuiserie, cordonnerie, reliure, etc. Sur les

chantiers, il fait signer aux patrons des contrats de travail en bonne et due

forme, ce qui n’est pas monnaie courante à l’époque. Enfin, il tient à créer

une ambiance familiale au sein du centre et, pour cela, persuade sa mère de le

rejoindre.

Avec l’aide des

éducateurs, laïcs et prêtres, Don Bosco assure une présence permanente auprès

des garçons qu’il accueille : il joue avec eux, mange avec eux, veille à leur

bien-être. Le succès du centre est retentissant : en six ans, les effectifs

passent de 17 à plus de 600 ! Du coup, un deuxième oratoire est ouvert dès

1853, dans le quartier de Porta Nuova. Ce succès, cependant, ne fait pas que

des heureux, et son refus catégorique de voir ses jeunes s’enrôler dans la

révolution qui secoue le Piémont attise le ressentiment. Don Bosco est ainsi la

cible de tentatives d’attentats, auxquels il échappe miraculeusement.

Développer son oeuvre

En 1859, il propose à 17

garçons, parmi les plus âgés, de l’aider à fonder une congrégation. Les Salésiens sont nés. En 1872, sa

rencontre avec Marie-Dominique Mazzarello aboutit à la fondation des

« Filles de Marie Auxiliatrice »,

appelées aussi Salésiennes de Don Bosco. Enfin, en 1875, il conçoit le projet

des Coopérateurs, qui rassemble laïcs, prêtres et religieux soucieux de

l’éducation des jeunes dans leurs lieux de vie. La même année, les premiers

missionnaires embarquent pour l’Argentine, première étape de

l’internationalisation de la jeune congrégation.

Don Bosco s’éteint le 31

janvier 1888 à Turin, à 73 ans. Il est proclamé Saint par Pie XI en 1934,

et nommé « Père et maître de la jeunesse » par Jean-Paul

II en janvier 1988. Son élève et disciple Dominique

Savio (1842-1857) est, lui, canonisé en 1954 par Pie XII, et nommé

Saint-patron des enfants et des adolescents.

SOURCE : https://www.don-bosco.net/actualites/famille-salesienne/qui-est-don-bosco/

Stamp

of India, 1989, Colnect 165292, St John Bosco founder of Salesian Brothers, Commemoratio.

https://colnect.com/en/stamps/stamp/165292-St_John_Bosco_founder_of_Salesian_Brothers_-_Commemoratio-Commemorations_1989-India

À l'école de Don Bosco,

être toujours dans la joie

Edifa - Publié

le 30/01/21

Proclamé "patron des

apprentis" par le pape Pie XII, Jean Bosco était un éducateur hors du

commun. Fêté ce 31 janvier, il pourrait aussi être le protecteur des parents,

des catéchistes et des enseignants.

Don Bosco est né le 16

août 1815, dans un petit hameau du nord de l’Italie. Il fut ordonné prêtre le 5

juin 1841. Comme un songe le lui avait fait pressentir durant sa jeunesse,

l’essentiel de son ministère fut consacré aux jeunes, qu’il accueillit par

centaines à l’Oratoire saint François-de-Sales, les sauvant ainsi de la misère

matérielle et surtout spirituelle à laquelle ils étaient livrés. Éducateur hors

pair, il sert encore aujourd’hui d’exemple aux parents et à tous ceux qui

travaillent avec les enfants.

Être toujours dans la joie

et garder confiance

La joie est vraiment la

tonalité de la vie de Don

Bosco : une joie puisée à la source de la prière et des sacrements,

une joie qui s’incarne très concrètement. Agé d’une douzaine d’années, il fait

le pitre sur une corde tendue à la manière des funambules de foire, histoire

d’attirer des spectateurs qu’il invite ensuite à prier ! Plus tard, avec les

garçons de l’Oratoire, il passe des heures à jouer et à raconter des histoires.

Et quand le petit Dominique

Savio, qui est son élève, se croit obligé de rester sérieux par amour du

Seigneur, Don Bosco lui fait très vite comprendre qu’« un saint triste est

un triste saint ».

« Ayons confiance en

Dieu, quoi qu’il arrive » : ce sont les derniers mots du père de Jean, qui

meurt alors que ce dernier n’a pas deux ans. Cette confiance restera la règle

de Don Bosco. Il aime à répéter à ses jeunes : « Gardez confiance ».

Avec sa mère, venue travailler avec lui à Turin, il vit cette confiance au

quotidien, qu’il s’agisse de trouver un toit pour ses garçons, de les nourrir,

ou de rassembler des fonds pour construire une église. Don Bosco et

« Maman Marguerite » ne s’appuient pas sur le contenu de leur

porte-monnaie (vide, le plus souvent !), mais sur Dieu seul. Et Dieu ne les

déçoit jamais. Nous pouvons demander à Jean Bosco de nous apprendre la

confiance lorsque les factures à payer s’amoncellent, ou que le chômage met en

péril les finances familiales. Don Bosco fit tant de fois l’expérience d’avoir

plus de bouches à nourrir que d’argent pour acheter du pain, que l’on peut

certainement le choisir comme protecteur des fins de mois difficiles.

Dieu a besoin d’hommes et

de femmes bien formés du corps, du cœur et de l’intelligence

Développez vos talents et

profitez de toutes les occasions pour apprendre : telle est la leçon que nous

donne la vie de Don Bosco. Certes, il était doué et sans doute plus que

d’autres : il jouissait d’une mémoire prodigieuse, chantait à merveille, était

souple et agile, habile de ses mains, etc. Mais il sut développer tous ces

dons, pour les mettre au service de Dieu. Tout jeune, il ne perd pas une minute

pour étudier « afin, disait-il, de devenir prêtre », ce qui ne

l’empêche pas de travailler aux champs ou de s’exercer à diverses acrobaties et

jongleries !

Lire aussi :

Bosco,

ou quand la vie d’un saint inspire un prénom

Lorsqu’il est collégien,

il n’a pas de quoi payer sa pension. Qu’à cela ne tienne : puisqu’il habite

chez un tailleur, il lui propose de travailler pour lui après l’école,

acquérant ainsi une compétence qui lui sera précieuse lorsqu’il s’agira de

ravauder les vêtements usés de ses garçons. Il apprendra ensuite la menuiserie,

la reliure, la serrurerie, la cordonnerie. Jean Bosco nous rappelle qu’il ne

faut perdre aucune occasion de développer ses compétences, surtout lorsqu’on

est jeune. Sa vie nous rappelle que Dieu a besoin de bons ouvriers pour sa

moisson, d’hommes et de femmes solides, bien formés dans tous les domaines du

corps, du cœur et de l’intelligence.

Conduire les enfants à

Dieu avec une fermeté qui n’exclut jamais la miséricorde

Faites-vous aimer,

attirez l’affection des enfants pour les conduire à Dieu : voilà comment Don

Bosco éduqua les jeunes qui lui furent confiés. Il les conduisait par la

douceur, avec une fermeté qui n’excluait jamais la miséricorde. Il faisait

aimer le Bon Dieu parce que lui-même était bon. Quand il voyait les fautes de

ses garçons – et il avait reçu le don de lire avec clairvoyance dans leurs âmes

– , il ne les accablait pas de reproches, mais cherchait avec beaucoup de

délicatesse et de bienveillance à les conduire jusqu’au pardon de Dieu.

« Dites à mes

enfants que je les attends tous au Paradis, et recommandez-leur toujours une

grande dévotion à l’Eucharistie et à la Sainte Vierge. Ainsi, ils n’auront jamais

rien à craindre ». Ces ultimes conseils de Don Bosco, mort le 31

janvier 1888, ne tracent-ils pas un beau programme pour toutes les familles

chrétiennes ?

Christine Ponsard

Lire aussi :

Tout

savoir sur Don Bosco, le père de la jeunesse

Saint Jean BOSCO

Mort en 1888. Canonisé en

1934. Fête en 1936.

Leçon des Matines 1960

Troisième leçon. Jean

Bosco naquit d’une humble famille ; après une enfance éprouvée et pure, il fit

ses études à Chieri et fut estimé pendant ce temps pour son intelligence et

pour ses vertus. Ordonné prêtre, il vint à Turin, où il se fit tout à tous ; mais

c’est surtout à aider les adolescents pauvres et abandonnés qu’il consacra ses

efforts. Par une éducation libérale, des écoles professionnelles, des

patronages il s’employa de toutes ses forces à préserver l’enfance des poisons

de l’erreur et du vice : à cette fin, il suscita dans l’Église deux instituts,

l’un d’hommes, l’autre de vierges. Il publia de nombreux livres, riches de

sagesse chrétienne. Il contribua aussi au salut des infidèles en envoyant ses

religieux en mission. L’âme constamment élevée vers Dieu, cet homme très saint

ne semblait être ni effrayé par les menaces, ni fatigué par les labeurs, ni

accablé par les soucis, ni troublé par l’adversité. Il mourut en 1888, dans sa

soixante-treizième année. Il fut inscrit au nombre des saints par le Souverain

Pontife Pie XI.

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/31-01-St-Jean-Bosco-confesseur

San

Felice (Fierozzo, Trentino), chiesa di San Felice da Nola - Vetrata con san

Giovanni Bosco

San

Felice (Fierozzo, Trentino, Italy), Saint Felix of Nola church - Stained-glass

window with don Bosco

Saint Jean Bosco

De l'éducation des

enfants

Je consacrerai ma vie aux

enfants. Je les aimerai et m'en ferai aimer. Quand ils tournent mal, c'est que

personne ne s'est occupé d'eux. Je me dépenserai sans mesure pour eux.

Si vous voulez vraiment

faire du bien à l'âme de vos enfants et les plier au devoir, il faut vous rappeler,

sans cesse, que vous tenez la place de leurs parents. Si vous vous regardez

comme les pères de cette jeunesse, vous en prendrez le cœur... Un cœur, c'est

une citadelle inexpugnable, dit saint Grégoire ; seules l'affection et la

douceur la peuvent forcer : fermeté à vouloir le bien et empêcher le mal, mais

douceur et prudence pour atteindre cette double fin.

Les maîtres qui ne

pardonnent rien aux enfants sont ceux qui se pardonnent tout à eux-mêmes. Pour

apprendre à commander, commençons par apprendre à obéir, et cherchons à nous

faire aimer avant de nous faire craindre.

Avant toute chose, voici

ce qui importe : attendez pour punir d'être maître de vous-même.

Second principe aussi

important que le premier : ne punissez jamais un enfant à l'instant de sa

faute.

Oublier et faire oublier

l'heure de la faute est l'art suprême du bon éducateur. Où lisons-nous que

Notre Seigneur ait rappelé ses écarts à Marie-Madeleine ? Et avec quelle

paternelle délicatesse le Sauveur fit confesser et expier sa faute à Pierre !

Après son pardon, l'enfant veut se persuader que son maître nourrit l'espoir de

son retournement : rien ne l'aide autant à reprendre la route du devoir.

Rappelons-nous toujours

que la force punit la faute, mais ne guérit pas le coupable. La culture d'une

plante ne doit jamais être violente, et l'on n'éduque pas la volonté en

l'écrasant sous un joug excessif.

Rappelez-vous que

l'éducation est une affaire de cœur : Dieu seul est le maître de cette place

forte ; s'il ne nous enseigne l'art de la forcer, s'il ne nous en livre les

clefs, nous perdons notre temps.

Post

of India, Stamp of India, 2006 Colnect 158963. Don Bosco Salesians.

https://colnect.com/en/stamps/stamp/158963-Don_Bosco_Salesians-Religions_beliefs_Christianity-India

Saint Jean Bosco

Manière facile

d’apprendre l’Histoire Sainte (1850)

Les adultes qui vivent et

meurent séparés de l’Eglise catholique ne peuvent pas se sauver, parce que

celui qui n’est pas avec l’Eglise catholique n’est pas avec Jésus-Christ ; et

qui n’est pas avec lui est contre lui, dit l’Évangile

Saint Jean Bosco

Brochure sur le

centenaire de saint Pierre (1867)

Heureux les peuples qui

sont unis à Pierre dans la personne des papes ses successeurs. Ils marchent sur

la route du salut. tandis que tous ceux qui se trouvent hors de cette route et

n’appartiennent pas à l’union de Pierre n’ont aucun espoir de salut. Car Jésus-Christ

nous assure que la sainteté et le salut ne se peuvent trouver que dans l’union

avec Pierre, sur qui repose le fondement inamovible de son Eglise.

Salesian

church in Nazareth, photographie de Don Bosco et inscriptions en arabe

Saint Jean Bosco

Lettre à ses confrères

Avant tout, si nous

voulons nous montrer les amis du vrai bien de nos élèves et les amener à faire

leur devoir, nous ne devons jamais oublier que nous représentons les parents de

cette chère jeunesse qui fut toujours le tendre sujet de mes occupations, de

mes études, de mon ministère sacerdotal, et de notre congrégation salésienne.

Que de fois, mes chers

fils, dans ma longue carrière, j'ai dû me persuader de cette grande vérité ! Il

est toujours plus facile de s'irriter que de patienter, de menacer un enfant,

que de le persuader. Je dirai même qu'il est plus facile, pour notre impatience

et pour notre orgueil, de châtier les récalcitrants que de les corriger, en les

supportant avec fermeté et douceur.

Je vous recommande la

charité que saint Paul employait envers les nouveaux convertis à la religion du

Seigneur, et qui le faisait souvent pleurer et supplier quand il les voyait peu

dociles et répondant mal à son zèle.

Ecartez tout ce qui

pourrait faire croire qu'on agit sous l'effet de la passion. Il est difficile,

quand on punit, de conserver le calme nécessaire pour qu'on ne s'imagine pas

que nous agissons pour montrer notre autorité ou pour décharger notre

emportement.

Considérons comme nos

enfants ceux sur lesquels nous avons un pouvoir à exercer. Mettons-nous à leur

service, comme Jésus qui est venu pour obéir, non pour commander. Redoutons ce

qui pourrait nous donner l'air de vouloir dominer, et ne les dominons que pour

mieux les servir.

C'est ainsi que Jésus se

comportait avec ses apôtres, supportant leur ignorance, leur rudesse et même

leur manque de foi. Il traitait les pécheurs avec gentillesse et familiarité,

au point de susciter chez les uns l'étonnement, chez d'autres le scandale, et

chez beaucoup l'espoir d'obtenir le pardon de Dieu. C'est pourquoi il nous a

dit d'apprendre de lui à être doux et humbles de cœur.

Puisqu'ils sont nos

enfants, éloignons toute colère, quand nous devons corriger leurs manquements,

ou du moins modérons-la pour qu'elle semble tout à fait étouffée.

Pas d'agitation dans

notre cœur, pas de mépris dans nos regards, pas d'injures sur nos lèvres. Ayons

de la compassion pour le présent, de l'espérance pour l'avenir : alors vous

serez de vrais pères, et vous accomplirez un véritable amendement.

Dans les cas très graves,

il vaut mieux vous recommander à Dieu, lui adresser un acte d'humilité, que de

vous laisser aller à un ouragan de paroles qui ne font que du mal à ceux qui

les entendent, et d'autre part ne procurent aucun profit à ceux qui les

méritent.

SOURCE : http://missel.free.fr/Sanctoral/01/31.php

Eugénie Marie Salanson (1836–1912), Portrait

of John Bosco, 1883 (signed)

Also

known as

Don Bosco

Giovanni Bosco

Giovanni Melchior Bosco

John Melchoir Bosco

Profile

Son of Venerable Margaret

Bosco. John’s father died when

the boy was

two years old; and as soon as he was old enough to do odd jobs, John did so to

help support his family. Bosco would go to circuses,

fairs and carnivals, practice the tricks that he saw magicians perform, and

then put on one-boy shows.

After his performance, while he still had an audience of boys,

he would repeat the homily he had heard earlier that day in church.

He worked as a tailor, baker, shoemaker,

and carpenter while

attending college and seminary. Ordained in 1841.

A teacher,

he worked constantly with young people,

finding places where they could meet, play and pray, teaching catechism to orphans and apprentices. Chaplain in

a hospice for girls. Wrote short

treatises aimed at explaining the faith to children,

and then taught children how

to print them.

Friend of Saint Joseph

Cafasso, whose biography he wrote,

and confessor to Blessed Joseph

Allamano. Founded the Salesians of Don Bosco (SDB) in 1859, priests who

work with and educate boys,

under the protection of Our Lady, Help of

Chistians, and Saint Francis

de Sales. Founded the Daughters of Mary, Help

of Christians in 1872,

and Union of Cooperator Salesians in 1875.

Born

16 August 1815 at

Becchi, Castelnuovo d’Asti, Piedmont, Italy as Giovanni

Melchior Bosco

31 January 1888 at Turin, Italy of

natural causes

24 July 1907 by Pope Pius X (decree

of heroic

virtues)

apprentices (traditional,

and given to Italian apprentices by Pope Pius XII on 17 January 1958)

magicians (performers,

not black magic)

schools,

colleges, universities

–

Institución

Educadiva Juan Pablo I Paz y Futuro

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints by Father Lawrence

George Lovasik, S.V.D.

Book

of Saints, by the Monk of

Ramsgate

Saint

John Bosco, by Edward Fitzgerald, S.D.B.

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

The

Holiness of the Church in the 19th Century

The

Nineteenth Century Apostle of the Little Ones, by E. Uhlrich

–

First

Panegyric on Saint Joseph Cafasso

Second

Panegyric on Saint Joseph Cafasso

–

Don Bosco, The Friend of

Youth, by Mother Frances Alice Monica Forbes

download in EPub format

The Life of Dominic

Savio, by Saint John

Bosco

A Sketch of the Life and

Works of the Venerable Don Bosco, by M S Pine

Librivox audio book + image montage on YouTube

Don Bosco – A Sketch of

His Life and Miracles, by Dr Charles d’Espiney

Virtue and Christian

Refinement According to the Spirit of Saint Vincent

de Paul, by Saint John

Bosco

Venerable Don Bosco, by R

F O’Connor

books

1001 Patron Saints and Their Feast Days, by Australian

Catholic Truth Society

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

Oxford Dictionary of Saints, by David Hugh Farmer

Patron Saints and Their Feast Days, by the Australian Catholic

Truth Society

other

sites in english

Angelo Stagnaro: Why Don Bosco is the Patron Saints of

Magicians

Catholic Exchange: Conquering Souls for Christ

Catholic Exchange: The Ghost, The Blessed Sacrament and The

Devil

Catholic Exchange: The Danger of Tolerance

Catholic Exchange: Six Ways to Live a Joyful Life from

Saint John Bosco

Catholic

Online, by Terry Metz

Domestic-Church, by Catherine Fournier

images

audio

The Venerable Don Bosco the Apostle of Youth, by M S Pine

(Librivox audio book)

video

The Venerable Don Bosco the Apostle of Youth, by M S Pine

(Librivox audio book + image montage)

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites

en français

Abbé

Christian-Philippe Chanut

Les idées

pédagogiques de Don Bosco

Vie

de Dom Bosco, fondateur de la société salésienne

fonti

in italiano

Calendario Francescano Secolare

Dicastero delle Cause dei Santi

spletne

strani v slovenšcini

Readings

Fly from bad companions

as from the bite of a poisonous snake. If you keep good companions, I can

assure you that you will one day rejoice with the blessed in Heaven; whereas if

you keep with those who are bad, you will become bad yourself, and you will be

in danger of losing your soul. – Saint John

Bosco

When tempted, invoke your

Angel. he is more eager to help you than you are to be helped! Ignore the devil

and do not be afraid of him: He trembles and flees at the sight of your

Guardian Angel. – Saint John

Bosco

Enjoy yourself as much as

you like – if only you keep from sin. – Saint John

Bosco

Do you want our Lord to

give you many graces? Visit him often. Do you want him to give you few graces?

Visit him seldom. Visits to the Blessed Sacrament are powerful and

indispensable means of overcoming the attacks of the devil. Make frequent

visits to Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament and the devil will be powerless

against you. – Saint John

Bosco

My sons, in my long

experience very often I had to be convinced of this great truth. It is easier

to become angry than to restrain oneself, and to threaten a boy than to persuade

him. Yes, indeed, it is more fitting to be persistent in punishing our own

impatience and pride than to correct the boys. We must be firm but kind, and be

patient with them. See that no one finds you motivated by impetuosity or

willfulness. It is difficult to keep calm when administering punishment, but

this must be done if we are to keep ourselves from showing off our authority or

spilling out our anger. Let us regard those boys over whom we have some

authority as our own sons. Let us place ourselves in their service. Let us be

ashamed to assume an attitude of superiority. Let us not rule over them except

for the purpose of serving them better. This was the method that Jesus used

with the apostles. He put up with their ignorance and roughness and even their

infidelity. He treated sinners with a kindness and affection that caused some

to be shocked, others to be scandalized and still others to hope for God’s

mercy. And so he bade us to be gentle and humble of heart. – from a letter

by Saint John

Bosco

All past persecutors of

the Church are now no more, but the Church still lives on. The same fate awaits

modern persecutors; they, too, will pass on, but the Church of Jesus Christ

will always remain, for God has pledged His Word to protect Her and be with Her

forever. – Saint John

Bosco

Most Holy Virgin Mary,

Help of Christians, how sweet it is to come to your feet imploring your

perpetual help. If earthly mothers cease not to remember their children, how

can you, the most loving of all mothers forget me? Grant then to me, I implore

you, your perpetual help in all my necessities, in every sorrow, and especially

in all my temptations. I ask for your unceasing help for all who are now

suffering. Help the weak, cure the sick, convert sinners. Grant through your

intercessions many vocations to the religious life. Obtain for us, O Mary, Help

of Christians, that having invoked you on earth we may love and eternally thank

you in heaven. Amen. – Saint John

Bosco

MLA

Citation

“Saint John Bosco“. CatholicSaints.Info.

21 April 2024. Web. 20 August 2025. <https://catholicsaints.info/saint-john-bosco/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-john-bosco/

(Blessed) (19th century)

Founder of the Salesian Society. He was born in Piedmont in 1815 and worked as

a secular priest in Turin. He was especially remarkable for his influence over

boys and young men. In 1842 he founded his Oratory, for the housing and religious

education of poor boys, and from this has sprung the world-wide organisation of

the Salesian Society, a congregation of priests devoted to the care of boys. He

also founded a congregation of nuns (Sisters of Marie Auxiliatrice) dedicated

to similar work among girls. He died in 1888 and was beatified in 1929.

MLA

Citation

Monks of

Ramsgate. “John Bosco”. Book of Saints, 1931. CatholicSaints.Info.

19 April 2024. Web. 20 August 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-john-bosco/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-john-bosco/

St. John Bosco

Feastday: January 31

Patron: of apprentices, editors and publishers, schoolchildren, magicians, and juvenile delinquents

Birth: August 16, 1815

Death: January 31, 1888

Beatified: June 2, 1929 by Pope Pius XI

Canonized: April 1, 1934 by Pope Pius XI

John Bosco, also known as

Giovanni Melchiorre Bosco and Don Bosco, was born in Becchi, Italy, on August

16, 1815. His birth came just after the end of the Napoleonic Wars which

ravaged the area. Compounding the problems on his birthday, there was also a

drought and a famine at the time of his birth.

At the age of two, John

lost his father, leaving him and his two older brothers to be raised by his

mother, Margherita. His "Mama Margherita Occhiena" would herself be

declared venerable by the Church in 2006.

Raised primarily by his

mother, John attended church and became very devout. When he was not in church,

he helped his family grow food and raise sheep. They were very poor, but

despite their poverty his mother also found enough to share with the homeless

who sometimes came to the door seeking food, shelter or clothing.

When John was nine years

old, he had the first of several vivid dreams that would influence his life. In

his dream, he encountered a multitude of boys who swore as they played. Among

these boys, he encountered a great, majestic man and woman. The man told him

that in meekness and charity, he would "conquer these your friends."

Then a lady, also majestic said, "Be strong, humble and robust. When the

time comes, you will understand everything." This dream influenced John

the rest of his life.

Not long afterwards, John

witnessed a traveling troupe of circus performers. He was enthralled by their

magic tricks and acrobatics. He realized if he learned their tricks, he could

use them to attract others and hold their attention. He studied their tricks

and learned how to perform some himself.

One Sunday evening, John

staged a show for the kids he played with and was heartily applauded. At the

end of the show, he recited the homily he heard earlier in the day. He ended by

inviting his neighbors to pray with him. His shows and games were repeated and

during this time, John discerned the call to become a priest.

To be a priest, John

required an education, something he lacked because of poverty. However, he

found a priest willing to provide him with some teaching and a few books.

John's older brother became angry at this apparent disloyalty, and he

reportedly whipped John saying he's "a farmer like us!"

John was undeterred, and

as soon as he could he left home to look for work as a hired farm laborer. He

was only 12 when he departed, a decision hastened by his brother's hostility.

John had difficulty

finding work, but managed to find a job at a vineyard. He labored for two more

years before he met Jospeh Cafasso, a priest who was willing to help him.

Cafasso himself would later be recognized as a saint for his work, particularly

ministering to prisoners and the condemned.

In 1835, John entered the

seminary and following six years of study and preparation, he was ordained a

priest in 1841.

His first assignment was

to the city of Turin. The city was in the throes of industrialization so it had

slums and widespread poverty. It was into these poor neighborhoods that John,

now known as Fr. Bosco, went to work with the children of the poor.

While visiting the

prisons, Fr. Bosco noticed a large number of boys, between the ages of 12 and

18, inside. The conditions were deplorable, and he felt moved to do more to

help other boys from ending up there.

He went into the streets

and started to meet young men and boys where they worked and played. He used

his talents as a performer, doing tricks to capture attention, then sharing

with the children his message for the day.

When he was not

preaching, Fr. Bosco worked tirelessly seeking work for boys who needed it, and

searching for lodgings for others. His mother began to help him, and she became

known as "Mamma Margherita." By the 1860s, Fr. Bosco and his mother were

responsible for lodging 800 boys.

Fr. Bosco also negotiated

new rights for boys who were employed as apprentices. A common problem was the

abuse of apprentices, with their employers using them to perform manual labor

and menial work unrelated to their apprenticeship. Fr. Bosco negotiated

contracts which forbade such abuse, a sweeping reform for that time. The boys

he hired out were also given feast days off and could no longer be beaten.

Fr. Bosco also identified

boys he thought would make good priests and encouraged them to consider a

vocation to the priesthood. Then, he helped to prepare those who responded

favorably in their path to ordination.

Fr. Bosco was not without

some controversy. Some parish priests accused him of stealing boys from their

parishes. The Chief of Police of Turin was opposed to his catechizing of boys

in the streets, which he claimed was political subversion.

In 1859, Fr. Bosco

established the Society of St. Francis de Sales. He organized 15 seminarians

and one teenage boy into the group. Their purpose was to carry on his

charitable work, helping boys with their faith formation and to stay out of

trouble. The organization still exists today and continues to help people,

especially children around the world.

In the years that

followed, Fr. Bosco expanded his mission, which had, and still has, much work

to do.

Fr. Bosco died on January

31, 1888. The call for his canonization was immediate. Pope Pius XI knew Fr.

Bosco personally and agreed, declaring him blessed in 1929. St. John Bosco was

canonized on Easter Sunday, 1934 and he was given the title, "Father and

Teacher of Youth."

In 2002, Pope John Paul

II was petitioned to declare St. John Bosco the Patron of Stage Magicians. St.

Bosco had pioneered the art of what is today called "Gospel Magic,"

using magic and other feats to attract attention and engage the youth.

Saint John Bosco is the

patron saint of apprentices, editors and publishers, schoolchildren, magicians,

and juvenile delinquents. His feast day is on January 31.

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=63

Estatua

de Don Bosco, La Coruña

Saint DON BOSCO

Also known as Don

Bosco or Giovanni Melchior Bosco, he was the founder of the Salesian

Society. Born of poor parents in a little cabin at Becchi, a hill-side hamlet

near Castelnuovo, Piedmont, Italy, 16 August, 1815; died January 31, 1888;

declared Venerable by Pius X, July 21, 1907.

When he was little more

than two years old his father died, leaving the support of three boys to the

mother, Margaret Bosco. John’s early years were spent as a shepherd and he

received his first instruction at the hands of the parish priest. He possessed

a ready wit, a retentive memory, and as years passed his appetite for study

grew stronger. Owing to the poverty of the home, however, he was often obliged

to turn from his books to the field, but the desire of what he had to give up

never left him. In 1835 he entered the seminary at Chieri and after six years

of study was ordained priest on the eve of Trinity Sunday by Archbishop

Franzoni of Turin.

Leaving the seminary, Don

Bosco went to Turin where he entered zealously upon his priestly labours. It

was here that an incident occurred which opened up to him the real field of

effort of his afterlife. One of his duties was to accompany Don Cafasso upon

his visits to the prisons of the city, and the condition of the children

confined in these places, abandoned to the most evil influences, and with

little before them but the gallows, made such a indelible impression upon his

mind that he resolved to devote his life to the rescue of these unfortunate

outcasts.

On the eighth of December

1841, the feast of the Immaculate Conception, while Don Bosco was vesting for

Mass, the sacristan drove from the Church a ragged urchin because he refused to

serve Mass. Don Bosco heard his cries and recalled him, and in the friendship

which sprang up between the priest and Bartollomea Garelli was sown the first

seed of the “Oratory”, so called, no doubt, after the example of St. Philip

Neri and because prayer was its prominent feature. Don Bosco entered eagerly

upon the task of instructing thus first pupil of the streets; companions soon

joined Bartholomeo, all drawn by a kindness they had never known, and in

February 1842, the Oratory numbered twenty boys, in March of the same year,

thirty, and in March 1846, four hundred.

As the number of boys

increased, the question of a suitable meeting-place presented itself. In good

weather walks were taken on Sundays and holidays to spots in the country to