Jacopo del Casentino (–1358), Saint

Thomas d'Aquin, circa 1325, tempera and gold on poplar wood, 96 x 43, Musée du Petit Palais, Avignon

Saint Thomas d'Aquin

Frère prêcheur, docteur de l'Église (+ 1274)

Né dans une noble famille napolitaine, élevé à l'abbaye bénédictine du Mont-Cassin, Thomas choisit cependant, à 19 ans, d'entrer chez les Frères Prêcheurs. Ce n'est guère du goût de sa famille, qui le fait enlever et enfermer. L'ordre dominicain est un ordre mendiant, fondé quelques années plus tôt, et il n'avait pas bonne presse dans l'aristocratie. Au bout d'un an, Thomas peut enfin suivre sa vocation. On l'envoie à Paris pour y suivre les cours de la bouillonnante Université. Il a comme professeur saint Albert le Grand. Pour ce dernier, il faut faire confiance à la raison et à l'intelligence de l'homme pour chercher Dieu. Le philosophe le plus approprié à cette recherche est Aristote. Saint Thomas retient la leçon. Devenu professeur, il s'attelle à un gigantesque travail pour la mettre en œuvre. Connaissant très bien Aristote et ses commentateurs, mais aussi la Bible et la tradition patristique chrétienne, il élabore une pensée originale, qu'il expose dans de multiples ouvrages, dont le plus connu est la "Somme Théologique". Comme professeur, il doit aussi soutenir de véhémentes controverses avec des intellectuels chevronnés. Il voyage aussi à la demande des Papes. Mais c'est l'étude qui a toute sa faveur : à la possession de "Paris la grande ville", il dit préférer "le texte correct des homélies de saint Jean Chrysostome sur l'évangile de saint Matthieu". Il meurt sur la route, en chemin vers Lyon où il devait participer au grand concile de 1274.

Le 23 juillet 2010 - catéchèse sur saint Thomas d'Aquin consacrée à la Summa Theologiae, l'apogée de son œuvre en 512 questions et 2.669 articles. Le Docteur Angélique y expose avec précision et pertinence les vérités de la foi découlant de l'Écriture et des Pères, principalement de saint Augustin. "Comme la vie entière, rappelle Thomas, l'esprit humain doit être sans cesse éclairé par la prière et par la lumière qui vient du Ciel". Dans la Somme, a dit Benoît XVI, saint Thomas décrit les trois modes d'existence de Dieu: Dieu existe en lui même, il est principe et fin de toute chose, tout vient de lui et en dépend. Ensuite, Dieu se manifeste par la grâce dans la vie et l'action du chrétien et des saints. Enfin il est tout particulièrement présent en la personne du Christ et dans les sacrements découlant de sa mission rédemptrice".

Puis le Pape a rappelé que saint Thomas s'est tout spécialement intéressé au mystère eucharistique, pour lequel il avait une grande dévotion... A la suite des saints, attachons-nous à ce sacrement. Participons avec ferveur à la messe afin d'en retirer des fruits spirituels. Nourrissons nous du corps et du sang du Seigneur afin de recevoir continuellement la grâce divine. Arrêtons nous souvent devant le Saint Sacrement! Ce que Thomas d'Aquin a exposé avec rigueur dans son œuvre, et en particulier dans la Somme, il l'a également transmis dans sa prédication. Son contenu...correspond pratiquement entièrement à la structure du Catéchisme de l'Église Catholique... Dans une époque marquée par un fort souci de reévangélisation, ces thèmes fondamentaux ne doivent pas manquer car ils sont ce en quoi nous croyons, le symbole de la foi, ce que nous récitons comme le Pater et l'Ave Maria, ce que nous vivons en vertu de la révélation biblique, ainsi que la loi de l'amour...de Dieu et du prochain".

Dans son "opuscule sur le Symbole des Apôtres", Thomas explique la valeur de la foi. Grâce à elle les âmes s'unissent à Dieu..., la vie trouve sa juste voie et nous le moyen d'éviter les tentations. A qui pense que la foi est obtuse car on ne peut la prouver par nos sens, il offre une réponse complète. Ce doute est sans consistance car l'intelligence est limité et ne saurait tout connaître. Seulement si nous pouvions tout connaître du visible comme de l'invisible, ce serait une véritable faute d'accepter des vérités sur la simple base de la foi. Il est d'ailleurs impossible de vivre sans l'expérience de l'autre, là où la connaissance personnelle n'arrive pas. Il est donc raisonnable de croire en un Dieu qui se révèle, et dans le témoignage des apôtres".

Revenant sur l'article de la Somme consacré à l'incarnation du Verbe de Dieu, le Saint-Père a rappelé que pour saint Thomas la foi chrétienne doit être renforcée par le mystère de l'incarnation. L'espérance s'accroît et se renforce en pensant que le Fils de Dieu est venu parmi nous, comme un de nous, pour communiquer sa divinité aux hommes. La charité est renforcée car il n'y a pas de signe plus évident de l'amour que nous porte Dieu, ni de voir le Créateur se faire créature". Saint Thomas d'Aquin, a conclu Benoît XVI, "fut comme tous les saints un grand dévot de Marie, qu'il a magnifiquement baptisée trône de la Trinité, lieu où elle trouve son repos. Par l'incarnation, dans aucune créature autre qu'elle les trois personnes divines ne séjournent en plénitude de grâce et n'accordent d'aide par l'intercession de la prière". (source: VIS 20100623 610)

- Audiences générales du pape Benoît XVI, catéchèse sur la méditation de certains grands penseurs du Moyen-Age - Saint Thomas d'Aquin.

le 2 juin 2010 - le 16 juin 2010 - le 23 juin 2010

- Site officiel de l'Académie pontificale de Saint Thomas d'Aquin (en anglais)

- livres de Jean-Pierre Torrell (ordre des dominicains)

- Les œuvres de Thomas d'Aquin disponibles en ligne à la Éditions du Cerf (Dominicains)

Mémoire de saint Thomas d'Aquin, prêtre de l'Ordre des Prêcheurs et docteur de

l'Église. Doué des plus hautes qualités intellectuelles, il transmit aux

autres, par ses prières et ses écrits, sa sagesse éminente. Appelé par le pape

lui-même, le bienheureux Grégoire

X, au deuxième Concile général de Lyon, il s'y rendait, quand il mourut au

monastère de Fossanova dans le Latium, le 7 mars 1274 et, bien des années

après, en 1369, son corps fut transféré à Toulouse en ce jour.

Martyrologe romain

La paix entre les hommes est mieux garantie si chacun

se trouve satisfait de ce qui lui appartient. Ce qui convient le mieux à

l'homme par rapport aux biens extérieurs, c'est de s'en servir. Sous cet angle,

toutefois, l'homme ne doit pas posséder ces biens comme s'ils lui étaient

propres, mais comme étant à tous. Il doit donc être disposé à en faire part aux

plus pauvres, suivant le conseil de saint Paul.

Saint Thomas - Somme théologique

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/524/Saint-Thomas-d-Aquin.html

Bernardo Daddi (1290–1348), Die

Versuchung des Heilige Thomas von Aquin, 1338, 38 x 34, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

Saint Thomas

d'Aquin, prêtre et docteur de l'Eglise

Né dans une noble famille

napolitaine, élevé à l'abbaye bénédictine du Mont-Cassin, Thomas choisit

cependant, à 19 ans, d'entrer chez les Frères Prêcheurs. Sa famille,

contrariée, le fait enlever et enfermer. Au bout d'un an, Thomas peut enfin

suivre sa vocation. On l'envoie à Paris pour y suivre les cours en Sorbonne où

il étudie sous la férule de saint Albert le Grand. Devenu professeur à son

tour, Thomas s'attelle à un gigantesque travail pour mettre en œuvre la

correspondance entre la philosophie d’Aristote, la Bible et la tradition

patristique ; il élabore une pensée originale, qu'il expose dans de

multiples ouvrages, dont le plus connu est la "Somme Théologique". Il

déploie une activité prodigieuse entre l’enseignement, la participation aux

débats philosophiques et théologiques du temps, les missions à l’étranger,

l’étude et la vie spirituelle qui reste première et où il puise les ressources

de son génie. Il meurt en Italie sur la route de Lyon où il devait participer

au grand concile de 1274.

Master of Saint Cecilia (fl. 1250–1350),

Saint Thomas Aquinas at his desk, circa 1323, fresco

painting, Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, Florence. Durante

la sua prima lezione all'Università di Parigi contornato dai simboli dei

quattro evangelisti ed ispirato da s. Domenico. La cattedra è una bella prova

di rappresentare la profondità degli oggetti nello spazio. Questo e gli altri

affreschi dietro le pale cinquecentesche sono visibili solo la prima domenica

del mese, nel pomeriggio

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Place Saint-Pierre,

Mercredi 2 juin 2010

Saint Thomas d'Aquin (1)

Chers frères et sœurs,

Après quelques catéchèses

sur le sacerdoce et mes derniers voyages, nous revenons aujourd'hui à notre

thème principal, c'est-à-dire la méditation de certains grands penseurs du

Moyen-Age. Nous avions vu dernièrement la grande figure de saint Bonaventure,

franciscain, et je voudrais aujourd'hui parler de celui que l'Eglise appelle le

Doctor communis: c'est-à-dire saint Thomas d'Aquin. Mon vénéré prédécesseur,

le Pape

Jean-Paul II, dans son encyclique Fides

et ratio, a rappelé que saint Thomas "a toujours été proposé à juste

titre par l'Eglise comme un maître de pensée et le modèle d'une façon correcte

de faire de la théologie" (n. 43). Il n'est donc pas surprenant que, après

saint Augustin, parmi les écrivains ecclésiastiques mentionnés dans le

Catéchisme de l'Eglise catholique, saint Thomas soit cité plus que tout autre,

pas moins de soixante et une fois! Il a également été appelé Doctor Angelicus,

sans doute en raison de ses vertus, en particulier le caractère sublime de sa

pensée et la pureté de sa vie.

Thomas naquit entre 1224

et 1225 dans le château que sa famille, noble et riche, possédait à Roccasecca,

près d'Aquin, à côté de la célèbre abbaye du Mont Cassin, où il fut envoyé par

ses parents pour recevoir les premiers éléments de son instruction. Quelques

années plus tard, il se rendit dans la capitale du Royaume de Sicile, Naples,

où Frédéric II avait fondé une prestigieuse Université. On y enseignait, sans

les limitations imposées ailleurs, la pensée du philosophe grec Aristote,

auquel le jeune Thomas fut introduit, et dont il comprit immédiatement la

grande valeur. Mais surtout, c'est au cours de ces années passées à Naples, que

naquit sa vocation dominicaine. Thomas fut en effet attiré par l'idéal de

l'Ordre fondé quelques années auparavant par saint Dominique. Toutefois,

lorsqu'il revêtit l'habit dominicain, sa famille s'opposa à ce choix, et il fut

contraint de quitter le couvent et de passer un certain temps auprès de sa

famille.

En 1245, désormais

majeur, il put reprendre son chemin de réponse à l'appel de Dieu. Il fut envoyé

à Paris pour étudier la théologie sous la direction d'un autre saint, Albert le

Grand, dont j'ai récemment parlé. Albert et Thomas nouèrent une véritable et

profonde amitié, et apprirent à s'estimer et à s'aimer, au point qu'Albert voulut

que son disciple le suivît également à Cologne, où il avait été envoyé par les

supérieurs de l'Ordre pour fonder une école de théologie. Thomas se familiarisa

alors avec toutes les œuvres d'Aristote et de ses commentateurs arabes,

qu'Albert illustrait et expliquait.

A cette époque, la

culture du monde latin avait été profondément stimulée par la rencontre avec

les œuvres d'Aristote, qui étaient demeurées longtemps inconnues. Il s'agissait

d'écrits sur la nature de la connaissance, sur les sciences naturelles, sur la

métaphysique, sur l'âme et sur l'éthique, riches d'informations et

d'intuitions, qui apparaissaient de grande valeur et convaincants. Il

s'agissait d'une vision complète du monde, développée sans et avant le Christ,

à travers la raison pure, et elle semblait s'imposer à la raison comme

"la" vision elle-même: cela était donc une incroyable attraction pour

les jeunes de voir et de connaître cette philosophie. De nombreuses personnes

accueillirent avec enthousiasme, et même avec un enthousiasme acritique, cet

immense bagage de savoir antique, qui semblait pouvoir renouveler

avantageusement la culture, ouvrir des horizons entièrement nouveaux. D'autres,

toutefois, craignaient que la pensée païenne d'Aristote fût en opposition avec

la foi chrétienne, et se refusaient de l'étudier. Deux cultures se

rencontrèrent: la culture pré-chrétienne d'Aristote, avec sa rationalité

radicale, et la culture chrétienne classique. Certains milieux étaient conduits

au refus d'Aristote également en raison de la présentation qui était faite de

ce philosophe par les commentateurs arabes Avicenne et Averroès. En effet,

c'était eux qui avaient transmis la philosophie d'Aristote au monde latin. Par

exemple, ces commentateurs avaient enseigné que les hommes ne disposaient pas

d'une intelligence personnelle, mais qu'il existe un unique esprit universel,

une substance spirituelle commune à tous, qui œuvre en tous comme

"unique": par conséquent, une dépersonnalisation de l'homme. Un autre

point discutable véhiculé par les commentateurs arabes était celui selon lequel

le monde est éternel comme Dieu. De façon compréhensible, des discussions sans

fin se déchaînèrent dans le monde universitaire et dans le monde

ecclésiastique. La philosophie d'Aristote se diffusait même parmi les personnes

communes.

Thomas d'Aquin, à l'école

d'Albert le Grand, accomplit une opération d'une importance fondamentale pour

l'histoire de la philosophie et de la théologie, je dirais même pour l'histoire

de la culture: il étudia à fond Aristote et ses interprètes, se procurant de

nouvelles traductions latines des textes originaux en grec. Ainsi, il ne

s'appuyait plus seulement sur les commentateurs arabes, mais il pouvait

également lire personnellement les textes originaux, et commenta une grande

partie des œuvres d'Aristote, en y distinguant ce qui était juste de ce qui

était sujet au doute ou devant même être entièrement rejeté, en montrant la

correspondance avec les données de la Révélation chrétienne et en faisant un

usage ample et précis de la pensée d'Aristote dans l'exposition des écrits

théologiques qu'il composa. En définitive, Thomas d'Aquin démontra qu'entre foi

chrétienne et raison, subsiste une harmonie naturelle. Et telle a été la grande

œuvre de Thomas qui, en ce moment de conflit entre deux cultures - ce moment où

il semblait que la foi devait capituler face à la raison - a montré que les

deux vont de pair, que ce qui apparaissait comme une raison non compatible avec

la foi n'était pas raison, et que ce qui apparaissait comme foi n'était pas la

foi, si elle s'opposait à la véritable rationalité; il a ainsi créé une

nouvelle synthèse, qui a formé la culture des siècles qui ont suivi.

En raison de ses

excellentes capacités intellectuelles, Thomas fut rappelé à Paris comme

professeur de théologie sur la chaire dominicaine. C'est là aussi que débuta sa

production littéraire, qui se poursuivit jusqu'à sa mort, et qui tient du

prodige: commentaires des Saintes Ecritures, parce que le professeur de

théologie était surtout un interprète de l'Ecriture, commentaires des écrits

d'Aristote, œuvres systématiques volumineuses, parmi elles l'excellente Summa

Theologiae, traités et discours sur divers sujets. Pour la composition de ses

écrits, il était aidé par des secrétaires, au nombre desquels Réginald de Piperno,

qui le suivit fidèlement et auquel il fut lié par une amitié sincère et

fraternelle, caractérisée par une grande proximité et confiance. C'est là une

caractéristique des saints: ils cultivent l'amitié, parce qu'elle est une des

manifestations les plus nobles du cœur humain et elle a quelque chose de divin,

comme Thomas l'a lui-même expliqué dans certaines quaestiones de la Summa

Theologiae, où il écrit: "La charité est l'amitié de l'homme avec Dieu

principalement, et avec les êtres qui lui appartiennent" (II, q. 23, a.

1).

Il ne demeura pas

longtemps ni de façon stable à Paris. En 1259, il participa au Chapitre général

des Dominicains à Valenciennes, où il fut membre d'une commission qui établit

le programme des études dans l'Ordre. De 1261 à 1265, ensuite, Thomas était à

Orvieto. Le Pape Urbain iv, qui nourrissait à son égard une grande estime, lui

commanda la composition de textes liturgiques pour la fête du Corpus Domini,

que nous célébrons demain, instituée suite au miracle eucharistique de Bolsena.

Thomas eut une âme d'une grande sensibilité eucharistique. Les très beaux

hymnes que la liturgie de l'Eglise chante pour célébrer le mystère de la

présence réelle du Corps et du Sang du Seigneur dans l'Eucharistie sont

attribués à sa foi et à sa sagesse théologique. De 1265 à 1268, Thomas résida à

Rome où, probablement, il dirigeait un Studium, c'est-à-dire une maison des

études de l'ordre, et où il commença à écrire sa Summa Theologiae (cf.

Jean-Pierre Torell, Thomas d'Aquin. L'homme et le théologien, Casale Monf.,

1994).

En 1269, il fut rappelé à

Paris pour un second cycle d'enseignement. Les étudiants - on les comprend -

étaient enthousiastes de ses leçons. L'un de ses anciens élèves déclara qu'une

très grande foule d'étudiants suivaient les cours de Thomas, au point que les

salles parvenaient à peine à tous les contenir et il ajoutait dans une remarque

personnelle que "l'écouter était pour lui un profond bonheur".

L'interprétation d'Aristote donnée par Thomas n'était pas acceptée par tous,

mais même ses adversaires dans le domaine académique, comme Godefroid de

Fontaines, par exemple, admettaient que la doctrine du frère Thomas était

supérieure à d'autres par son utilité et sa valeur et permettait de corriger

celles de tous les autres docteurs. Peut-être aussi pour le soustraire aux

vives discussions en cours, les supérieurs l'envoyèrent encore une fois à

Naples, pour être à disposition du roi Charles I, qui entendait réorganiser les

études universitaires.

Outre les études et

l'enseignement, Thomas se consacra également à la prédication au peuple. Et le

peuple aussi venait volontiers l'écouter. Je dirais que c'est vraiment une

grande grâce lorsque les théologiens savent parler avec simplicité et ferveur

aux fidèles. Le ministère de la prédication, d'autre part, aide à son tour les

chercheurs en théologie à un sain réalisme pastoral, et enrichit leur recherche

de vifs élans.

Les derniers mois de la

vie terrestre de Thomas restent entourés d'un climat particulier, mystérieux

dirais-je. En décembre 1273, il appela son ami et secrétaire Réginald pour lui

communiquer sa décision d'interrompre tout travail, parce que, pendant la célébration

de la Messe, il avait compris, suite à une révélation surnaturelle, que tout ce

qu'il avait écrit jusqu'alors n'était qu'"un monceau de paille".

C'est un épisode mystérieux, qui nous aide à comprendre non seulement

l'humilité personnelle de Thomas, mais aussi le fait que tout ce que nous

réussissons à penser et à dire sur la foi, aussi élevé et pur que ce soit, est

infiniment dépassé par la grandeur et par la beauté de Dieu, qui nous sera

révélée en plénitude au Paradis. Quelques mois plus tard, absorbé toujours

davantage dans une profonde méditation, Thomas mourut alors qu'il était en

route vers Lyon, où il se rendait pour prendre part au Concile œcuménique

convoqué par le Pape Grégoire X. Il s'éteignit dans l'Abbaye cistercienne de

Fossanova, après avoir reçu le Viatique avec des sentiments de grande piété.

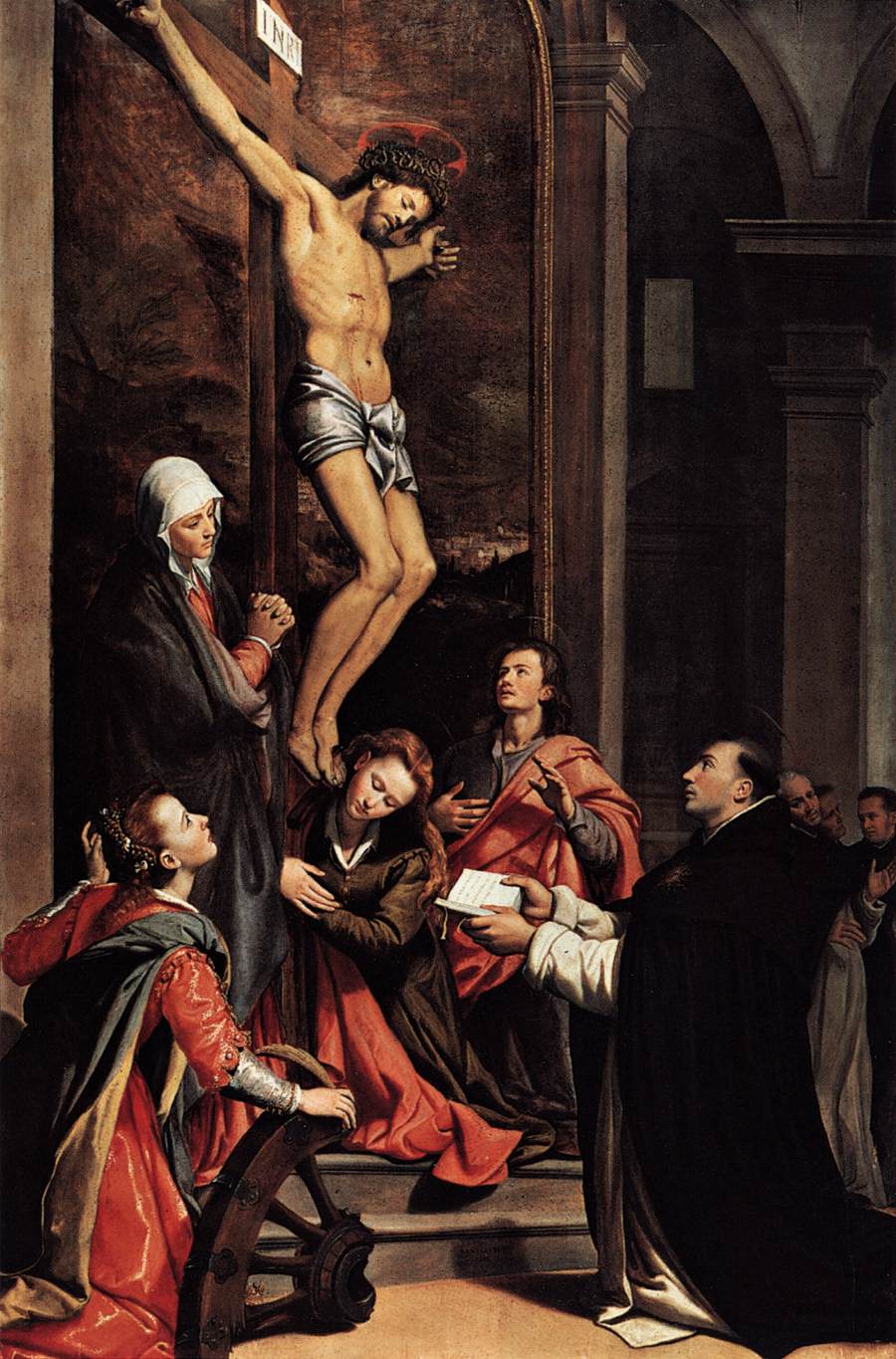

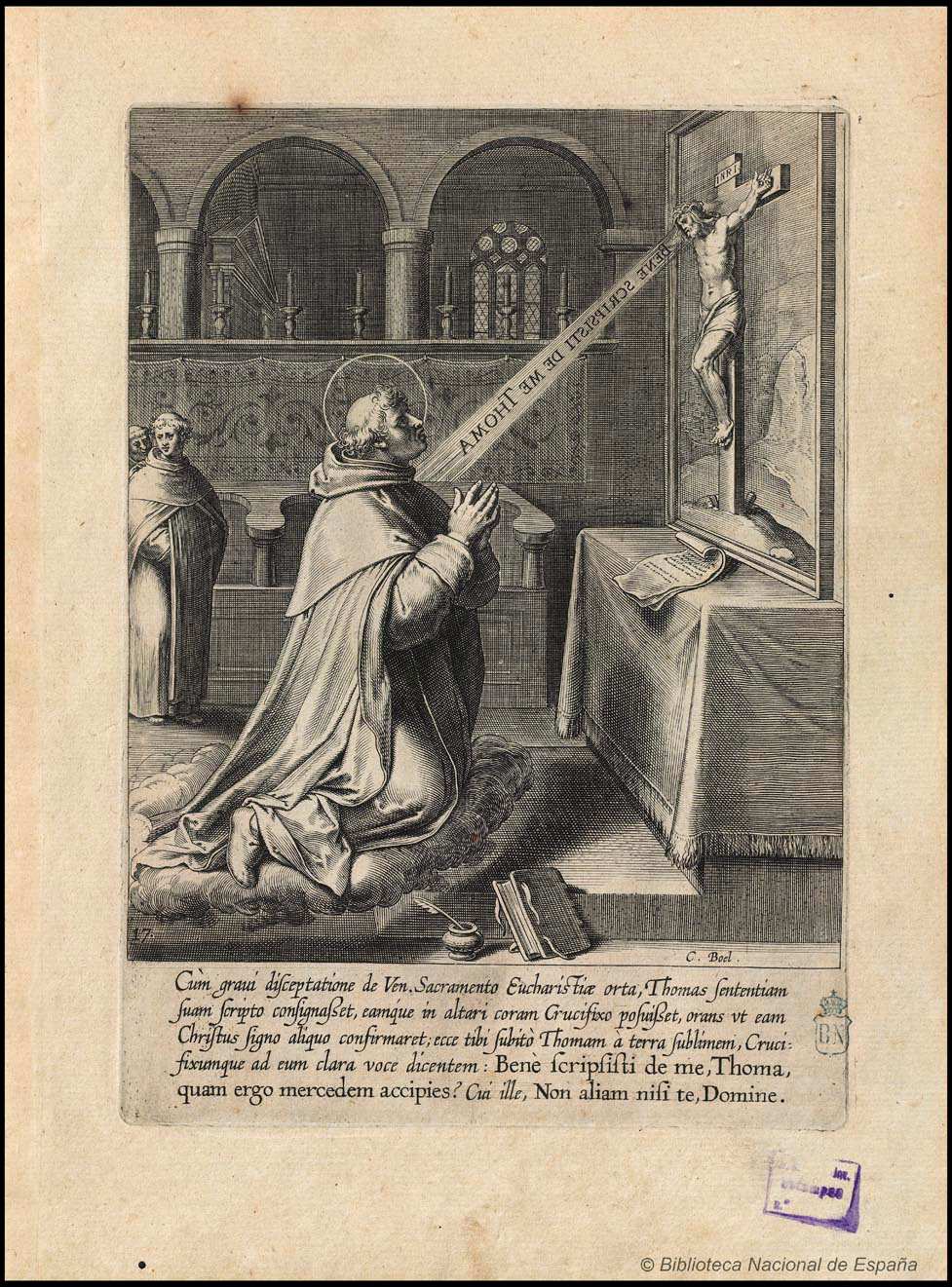

La vie et l'enseignement

de saint Thomas d'Aquin pourrait être résumés dans un épisode rapporté par les

anciens biographes. Tandis que le saint, comme il en avait l'habitude, était en

prière devant le crucifix, tôt le matin dans la chapelle "San Nicola"

à Naples, Domenico da Caserta, le sacristain de l'Eglise, entendit un dialogue.

Thomas demandait inquiet, si ce qu'il avait écrit sur les mystères de la foi

chrétienne était juste. Et le Crucifié répondit: "Tu as bien parlé de moi,

Thomas. Quelle sera ta récompense?". Et la réponse que Thomas donna est

celle que nous aussi, amis et disciples de Jésus, nous voudrions toujours lui

dire: "Rien d'autre que Toi, Seigneur!" (Ibid., p. 320).

* * *

Je confie à votre prière,

chers pèlerins francophones, mon Voyage

Apostolique à Chypre et tous les Chrétiens du Moyen Orient. Priez

aussi pour les prêtres et les séminaristes. Puisse le Seigneur Jésus vous

accompagner dans votre vie! Que Dieu vous bénisse!

APPEL DU PAPE

C'est avec

une profonde inquiétude que je suis les tragiques épisodes qui ont eu lieu à

proximité de la Bande de Gaza. Je ressens le besoin d'exprimer mes sincères

condoléances pour les victimes de ces douloureux événements, qui inquiètent

tous ceux qui ont à cœur la paix dans la région. Encore une fois, je répète

avec une grande tristesse que la violence ne résout pas les différends, mais

qu'elle en accroît au contraire les douloureuses circonstances et engendre

d'autres violences. Je fais appel à tous ceux qui ont des responsabilités

politiques au niveau local et international afin qu'ils recherchent sans

attendre des solutions justes à travers le dialogue, de manière à garantir aux

populations de la région de meilleures conditions de vie, dans la concorde et

la sérénité. Je vous invite à vous unir à moi dans la prière pour les victimes,

pour leurs proches et pour tous ceux qui souffrent. Que le Seigneur soutienne

les efforts de ceux qui ne se lassent pas d'œuvrer pour la réconciliation et

pour la paix.

© Copyright 2010 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Lippo

Memmi (1291–1356), Le Triomphe de Saint Thomas Aquinas, circa 1340, 375 x 258, Santa Caterina, Pisa

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Place Saint-Pierre, Mercredi 16 juin 2010

Saint Thomas d'Aquin (2)

Chers frères et sœurs,

Je voudrais aujourd'hui

continuer la présentation de saint Thomas d'Aquin, un théologien d'une telle

valeur que l'étude de sa pensée a été explicitement recommandée par le Concile

Vatican II dans deux documents, le décret Optatam

totius, sur la formation au sacerdoce, et la déclaration Gravissimum

educationis, qui traite de l'éducation chrétienne. Du reste, déjà en 1880,

le Pape Léon

XIII, son grand amateur et promoteur des études thomistes, voulut déclarer

saint Thomas Patron des écoles et des universités catholiques.

La principale raison de cette estime réside non seulement dans le contenu de

son enseignement, mais aussi dans la méthode qu'il a adoptée, notamment sa

nouvelle synthèse et distinction entre philosophie et théologie. Les Pères de

l'Eglise se trouvaient confrontés à diverses philosophies de type platonicien,

dans lesquelles était présentée une vision complète du monde et de la vie, y

compris la question de Dieu et de la religion. En se confrontant avec ces

philosophies, eux-mêmes avaient élaboré une vision complète de la réalité, en

partant de la foi et en utilisant des éléments du platonisme, pour répondre aux

questions essentielles des hommes. Cette vision, basée sur la révélation

biblique et élaborée avec un platonisme corrigé à la lumière de la foi, ils

l’appelaient «notre philosophie». Le terme de «philosophie» n'était donc pas

l'expression d'un système purement rationnel et, en tant que tel, distinct de

la foi, mais indiquait une vision d'ensemble de la réalité, construite à la

lumière de la foi, mais faite sienne et pensée par la raison; une vision qui,

bien sûr, allait au-delà des capacités propres de la raison, mais qui, en tant

que telle, était aussi satisfaisante pour celle-ci. Pour saint Thomas, la

rencontre avec la philosophie pré-chrétienne d'Aristote (mort vers 322 av.

J.-C.) ouvrait une perspective nouvelle. La philosophie aristotélicienne était,

évidemment, une philosophie élaborée sans connaissance de l’Ancien et du

Nouveau Testament, une explication du monde sans révélation, par la raison

seule. Et cette rationalité conséquente était convaincante. Ainsi, l'ancienne

formule de «notre philosophie» des Pères ne fonctionnait plus. La relation

entre philosophie et théologie, entre foi et raison, était à repenser. Il

existait une «philosophie» complète et convaincante en elle-même, une

rationalité précédant la foi, et puis la «théologie», une pensée avec la foi et

dans la foi. La question pressante était celle-ci: le monde de la rationalité,

la philosophie pensée sans le Christ, et le monde de la foi sont-ils

compatibles? Ou bien s'excluent-ils? Il ne manquait pas d'éléments qui

affirmaient l'incompatibilité entre les deux mondes, mais saint Thomas était

fermement convaincu de leur compatibilité — et même que la philosophie élaborée

sans la connaissance du Christ attendait en quelque sorte la lumière de Jésus

pour être complète. Telle a été la grande «surprise» de saint Thomas, qui a

déterminé son parcours de penseur. Montrer cette indépendance entre la

philosophie et la théologie et, dans le même temps, leur relation réciproque a

été la mission historique du grand maître. Et on comprend ainsi que, au XIXe

siècle, alors que l'on déclarait avec force l'incompatibilité entre la raison

moderne et la foi, le Pape Léon

XIII indiqua saint Thomas comme guide dans le dialogue entre l'une et

l'autre. Dans son travail théologique, saint Thomas suppose et concrétise cette

relation. La foi consolide, intègre et illumine le patrimoine de vérité que la

raison humaine acquiert. La confiance que saint Thomas accorde à ces deux

instruments de la connaissance — la foi et la raison — peut être reconduite à

la conviction que toutes deux proviennent de l'unique source de toute vérité,

le Logos divin, qui est à l'œuvre aussi bien dans le domaine de la création que

dans celui de la rédemption.

En plus de l'accord entre la raison et la foi, il faut reconnaître, d'autre

part, que celles-ci font appel à des processus de connaissance différents. La

raison accueille une vérité en vertu de son évidence intrinsèque, médiate ou

immédiate; la foi, en revanche, accepte une vérité sur la base de l'autorité de

la Parole de Dieu qui est révélée. Saint Thomas écrit au début de sa Summa

Theologiae: «L'ordre des sciences est double; certaines procèdent de principes

connus à travers la lumière naturelle de la raison, comme les mathématiques, la

géométrie et équivalents; d'autres procèdent de principes connus à travers une

science supérieure, c'est-à-dire la science de Dieu et des saints» (I, q. 1, a.

2).

Cette distinction assure l'autonomie autant des sciences humaines que des

sciences théologiques. Celle-ci n'équivaut pas toutefois à une séparation, mais

implique plutôt une collaboration réciproque et bénéfique. La foi, en effet,

protège la raison de toute tentation de manquer de confiance envers ses propres

capacités, elle l'encourage à s'ouvrir à des horizons toujours plus vastes,

elle garde vivante en elle la recherche des fondements et, quand la raison

elle-même s'applique à la sphère surnaturelle du rapport entre Dieu et l'homme,

elle enrichit son travail. Selon saint Thomas, par exemple, la raison humaine

peut sans aucun doute parvenir à l’affirmation de l'existence d'un Dieu unique,

mais seule la foi, qui accueille la Révélation divine, est en mesure de puiser

au mystère de l'Amour du Dieu Un et Trine.

Par ailleurs, ce n'est pas seulement la foi qui aide la raison. La raison elle

aussi, avec ses moyens, peut faire quelque chose d'important pour la foi, en

lui rendant un triple service que saint Thomas résume dans le préambule de son

commentaire au De Trinitate de Boèce: «Démontrer les fondements de la foi;

expliquer à travers des similitudes les vérités de la foi; repousser les

objections qui sont soulevées contre la foi» (q. 2, a. 2). Toute l'histoire de

la théologie est, au fond, l'exercice de cet engagement de l'intelligence, qui

montre l'intelligibilité de la foi, son articulation et son harmonie interne,

son caractère raisonnable, sa capacité à promouvoir le bien de l'homme. La

justesse des raisonnements théologiques et leur signification réelle de

connaissance se basent sur la valeur du langage théologique, qui est, selon

saint Thomas, principalement un langage analogique. La distance entre Dieu, le

Créateur, et l'être de ses créatures est infinie; la dissimilitude est toujours

plus grande que la similitude (cf. DS 806). Malgré tout, dans toute la

différence entre le Créateur et la créature, il existe une analogie entre

l'être créé et l'être du Créateur, qui nous permet de parler avec des paroles

humaines sur Dieu.

Saint Thomas a fondé la doctrine de l'analogie, outre que sur des thèmes

spécifiquement philosophiques, également sur le fait qu'à travers la

Révélation, Dieu lui-même nous a parlé et nous a donc autorisés à parler de

Lui. Je considère qu'il est important de rappeler cette doctrine. En effet,

celle-ci nous aide à surmonter certaines objections de l'athéisme contemporain,

qui nie que le langage religieux soit pourvu d'une signification objective, et

soutient au contraire qu'il a uniquement une valeur subjective ou simplement

émotive. Cette objection découle du fait que la pensée positiviste est

convaincue que l'homme ne connaît pas l'être, mais uniquement les fonctions qui

peuvent être expérimentées par la réalité. Avec saint Thomas et avec la grande

tradition philosophique, nous sommes convaincus qu'en réalité, l'homme ne

connaît pas seulement les fonctions, objet des sciences naturelles, mais

connaît quelque chose de l'être lui-même, par exemple, il connaît la personne,

le Toi de l'autre, et non seulement l'aspect physique et biologique de son

être.

A la lumière de cet enseignement de saint Thomas, la théologie affirme que,

bien que limité, le langage religieux est doté de sens — car nous touchons

l'être — comme une flèche qui se dirige vers la réalité qu'elle signifie. Cet

accord fondamental entre raison humaine et foi chrétienne est présent dans un

autre principe fondamental de la pensée de saint Thomas d'Aquin: la Grâce

divine n'efface pas, mais suppose et perfectionne la nature humaine. En effet,

cette dernière, même après le péché, n'est pas complètement corrompue, mais

blessée et affaiblie. La grâce, diffusée par Dieu et communiquée à travers le

Mystère du Verbe incarné, est un don absolument gratuit avec lequel la nature

est guérie, renforcée et aidée à poursuivre le désir inné dans le cœur de chaque

homme et de chaque femme: le bonheur. Toutes les facultés de l'être humain sont

purifiées, transformées et élevées dans la Grâce divine.

Une application importante de cette relation entre la nature et la Grâce se

retrouve dans la théologie morale de saint Thomas d'Aquin, qui apparaît d'une

grande actualité. Au centre de son enseignement dans ce domaine, il place la

loi nouvelle, qui est la loi de l'Esprit Saint. Avec un regard profondément

évangélique, il insiste sur le fait que cette loi est la Grâce de l'Esprit

Saint donnée à tous ceux qui croient dans le Christ. A cette Grâce s'unit

l'enseignement écrit et oral des vérités doctrinales et morales, transmises par

l'Eglise. Saint Thomas, en soulignant le rôle fondamental, dans la vie morale,

de l'action de l'Esprit Saint, de la Grâce, dont jaillissent les vertus

théologales et morales, fait comprendre que chaque chrétien peut atteindre les

autres perspectives du «Sermon sur la montagne» s’il vit un rapport authentique

de foi dans le Christ, s'il s'ouvre à l'action de son Saint Esprit. Mais —

ajoute saint Thomas d'Aquin — «même si la grâce est plus efficace que la

nature, la nature est plus essentielle pour l'homme» (Summa Theologiae, Ia,

q.29. a. 3), c'est pourquoi, dans la perspective morale chrétienne, il existe

une place pour la raison, qui est capable de discerner la loi morale naturelle.

La raison peut la reconnaître en considérant ce qu'il est bon de faire et ce

qu'il est bon d'éviter pour atteindre le bonheur qui tient au cœur de chacun,

et qui impose également une responsabilité envers les autres, et donc, la

recherche du bien commun. En d'autres termes, les vertus de l'homme,

théologales et morales, sont enracinées dans la nature humaine. La Grâce divine

accompagne, soutient et pousse l'engagement éthique, mais, en soi, selon saint

Thomas, tous les hommes, croyants et non croyants, sont appelés à reconnaître

les exigences de la nature humaine exprimées dans la loi naturelle et à

s'inspirer d'elle dans la formulation des lois positives, c'est-à-dire de celles

émanant des autorités civiles et politiques pour réglementer la coexistence

humaine.

Lorsque la loi naturelle et la responsabilité qu'elle implique sont niées, on

ouvre de façon dramatique la voie au relativisme éthique sur le plan individuel

et au totalitarisme de l'Etat sur le plan politique. La défense des droits

universels de l'homme et l'affirmation de la valeur absolue de la dignité de la

personne présupposent un fondement. Ce fondement n'est-il pas la loi naturelle,

avec les valeurs non négociables qu'elle indique? Le vénérable Jean-Paul

II écrivait dans son encyclique Evangelium

vitae des paroles qui demeurent d'une grande actualité: «Pour l'avenir

de la société et pour le développement d'une saine démocratie, il est donc

urgent de redécouvrir l'existence de valeurs humaines et morales essentielles

et originelles, qui découlent de la vérité même de l'être humain et qui

expriment et protègent la dignité de la personne: ce sont donc des valeurs

qu'aucune personne, aucune majorité ni aucun Etat ne pourront jamais créer,

modifier ou abolir, mais que l'on est tenu de reconnaître, respecter et

promouvoir» (n.

71).

En conclusion, Thomas nous propose un concept de la raison humaine ample et

confiant: ample, car il ne se limite pas aux espaces de la soi-disant raison

empirique-scientifique, mais il est ouvert à tout l'être et donc également aux

questions fondamentales et auxquelles on ne peut renoncer de la vie humaine; et

confiant, car la raison humaine, surtout si elle accueille les inspirations de

la foi chrétienne, est promotrice d'une civilisation qui reconnaît la dignité

de la personne, le caractère intangible de ses droits et le caractère coercitif

de ses devoirs. Il n'est pas surprenant que la doctrine sur la dignité de la

personne, fondamentale pour la reconnaissance du caractère inviolable de

l'homme, se soit développée dans des domaines de pensée qui ont recueilli

l'héritage de saint Thomas d'Aquin, qui avait une conception très élevée de la

créature humaine. Il la définit, à travers son langage rigoureusement

philosophique, comme «ce qui se trouve de plus parfait dans toute la nature,

c'est-à-dire un sujet subsistant dans une nature rationnelle» (Summa

Theologiae, Ia, q. 29, a. 3).

La profondeur de la pensée de saint Thomas d'Aquin découle — ne l'oublions

jamais — de sa foi vivante et de sa piété fervente, qu'il exprimait dans des

prières inspirées, comme celle où il demande à Dieu: «Accorde-moi, je t'en

prie, une volonté qui te recherche, une sagesse qui te trouve, une vie qui te

plaît, une persévérance qui t'attend avec patience et une confiance qui

parvienne à la fin à te posséder».

* * *

Je suis heureux de vous accueillir, chers pèlerins de langue française, venus

particulièrement de France et de Belgique. Que votre pèlerinage à Rome soit

pour vous l'occasion de découvrir toujours plus profondément le visage du

Seigneur. Que Dieu vous bénisse!

SOURCE : http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/audiences/2010/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20100616_fr.html

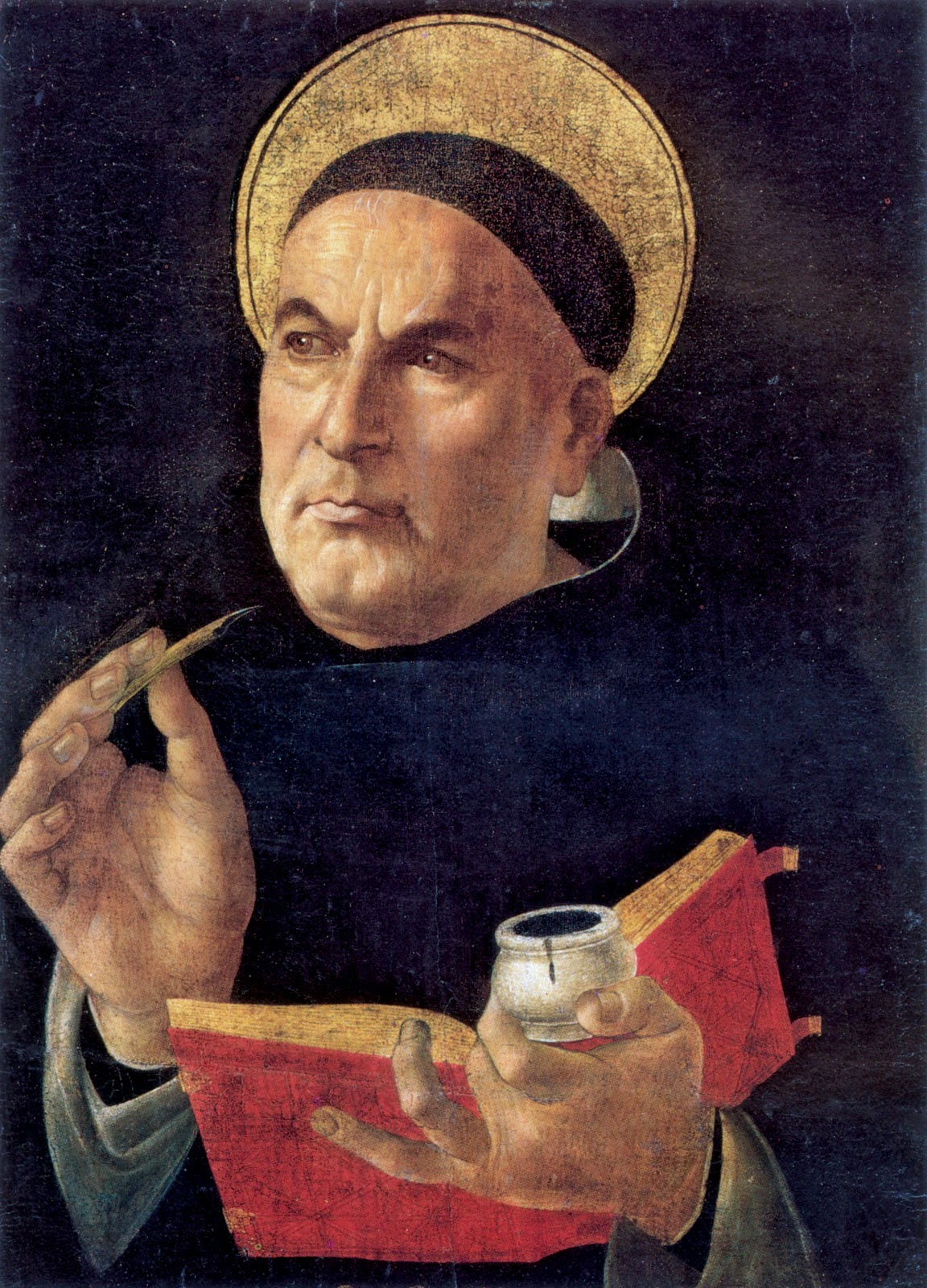

Fra Angelico (circa 1395 –1455). Saint Thomas Aquinas, 1438-1440, Cini Foundation $ Fondazione Giorgio Cini, located in the former San Giorgio Monastery on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Salle Paul VI, Mercredi 23 juin 2010

Saint Thomas d'Aquin (3)

Chers frères et sœurs,

Je voudrais aujourd’hui

compléter, par une troisième partie, mes catéchèses sur saint Thomas d’Aquin.

Même à 700 ans de sa mort nous pouvons beaucoup apprendre de lui. C’est ce que

rappelait également mon prédécesseur, le Pape Paul

VI, qui, dans un discours prononcé à Fossanova le 14 septembre 1974, à

l’occasion du septième centenaire de la mort de saint Thomas, se demandait:

«Maître Thomas, quelle leçon peux-tu nous donner?». Et il répondit ainsi: «La

confiance dans la vérité de la pensée religieuse catholique, telle qu’il la

défendit, l’exposa, l’ouvrit à la capacité cognitive de l’esprit humain»

(Insegnamenti di Paolo VI, XII [1974], pp. 833-834). Et, le même jour, à Aquin,

se référant toujours à saint Thomas, il affirmait: «Tous, nous qui sommes des

fils fidèles de l'Eglise, nous pouvons et nous devons, au moins dans une

certaine mesure, être ses disciples!» (ibid., p. 836).

Mettons-nous donc nous aussi à l’école de saint Thomas et de son chef-d’œuvre,

la Summa Theologiae. Celle-ci, bien qu’étant inachevée, est une œuvre

monumentale: elle contient 512 questions et 2669 articles. Il s’agit d’un

raisonnement serré, dans lequel l’application de l’intelligence humaine aux

mystères de la foi procède avec clarté et profondeur, mêlant des questions et

des réponses, dans lesquelles saint Thomas approfondit l’enseignement qui vient

de l'Ecriture Sainte et des Pères de l'Eglise, en particulier saint Augustin.

Dans cette réflexion, dans la rencontre de vraies questions de son époque, qui

sont aussi et souvent des questions de notre temps, saint Thomas, utilisant

également la méthode et la pensée des philosophes antiques, en particulier

Aristote, arrive à des formulations précises, lucides et pertinentes des

vérités de la foi, où la vérité est don de la foi, où elle resplendit et nous

devient accessible, ainsi qu’à notre réflexion. Cependant, cet effort de

l’esprit humain — rappelle saint Thomas à travers sa vie elle-même — est

toujours éclairé par la prière, par la lumière qui vient d’En-haut. Seul celui

qui vit avec Dieu et avec ses mystères pour comprendre ce qu’ils disent.

Dans la Summa de théologie, saint Thomas part du fait qu’il existe trois différentes

façons de l'être et de l’essence de Dieu: Dieu existe en lui-même, il est le

principe et la fin de toute chose, c’est pourquoi toutes les créatures

procèdent et dépendent de Lui; ensuite, Dieu est présent à travers sa Grâce

dans la vie et dans l’activité du chrétien, des saints; enfin, Dieu est présent

d’une manière toute particulière en la Personne du Christ et dans les

Sacrements, qui naissent de son œuvre rédemptrice. Mais la structure de cette

œuvre monumentale (cf. Jean-Pierre Torrell, La «Summa» di San Tommaso, Milan

2003, pp. 29-75), une recherche de la plénitude de Dieu avec un «regard

théologique» (cf. Summa Theologiae, Ia, q. 1, a. 7), est articulée en trois

parties, et est illustrée par le Doctor Communis lui-même — saint Thomas — avec

ces mots: «Le but principal de la sainte doctrine est celui de faire connaître

Dieu, et pas seulement en lui-même, mais également en tant que principe et fin

des choses, et spécialement de la créature raisonnable. Dans l’intention

d’exposer cette doctrine, nous traiterons en premier de Dieu; en deuxième du

mouvement de la créature vers Dieu; et en troisième du Christ, qui, en tant

qu’homme, est pour nous le chemin pour monter vers Dieu» (ibid., i, q. 2).

C’est un cercle: Dieu en lui-même, qui sort de lui-même et nous prend par la

main, afin qu’avec le Christ nous retournions à Dieu, nous soyons unis à Dieu,

et Dieu sera tout en tous.

La première partie de la Summa Theologiae enquête donc sur Dieu en lui-même,

sur le mystère de la Trinité et sur l’activité créatrice de Dieu. Dans cette

partie, nous trouvons également une profonde réflexion sur la réalité

authentique de l’être humain en tant que sorti des mains créatrices de Dieu,

fruit de son amour. D’une part nous sommes un être créé, dépendant, nous ne

venons pas de nous-mêmes, mais de l’autre, nous avons une véritable autonomie,

ainsi nous ne sommes pas seulement quelque chose d’apparent — comme disent

certains philosophes platoniciens — mais une réalité voulue par Dieu comme

telle, et qui possède une valeur en elle-même.

Dans la deuxième partie, saint Thomas considère l’homme, animé par la grâce,

dans son aspiration à connaître et à aimer Dieu pour être heureux dans le temps

et pour l’éternité. L’auteur présente tout d’abord les principes théologiques

de l’action morale, en étudiant comment, dans le libre choix de l’homme

d’accomplir des actes bons, s’intègrent la raison, la volonté et les passions,

auxquelles s’ajoute la force que donne la Grâce de Dieu à travers les vertus et

les dons de l’Esprit Saint, ainsi que l’aide qui est offerte également par la

loi morale. Ainsi, l'être humain est un être dynamique qui se cherche lui-même,

qui aspire à être lui-même et cherche, de cette manière, à accomplir des actes

qui l’édifient, qui le font devenir vraiment homme; et celui qui pénètre dans

la loi morale, pénètre dans la grâce, dans sa propre raison, sa volonté et ses

passions. Sur ce fondement, saint Thomas trace la physionomie de l’homme qui

vit selon l’Esprit et qui devient, ainsi, une icône de Dieu. Saint Thomas

s’arrête ici pour étudier les trois vertus théologales — la foi, l’espérance et

la charité —, suivies de l’examen approfondi de plus de cinquante vertus

morales, organisées autour des quatre vertus cardinales: la prudence, la

justice, la tempérance et la force. Il termine ensuite par une réflexion sur

les différentes vocations dans l'Eglise.

Dans la troisième partie de la Summa, saint Thomas étudie le Mystère du Christ

— le chemin et la vérité — au moyen duquel nous pouvons rejoindre Dieu le Père.

Dans cette section, il écrit des pages presque uniques sur le Mystère de

l’Incarnation et de la Passion de Jésus, en ajoutant ensuite une vaste

réflexion sur les sept Sacrements, car en eux le Verbe divin incarné étend les

bénéfices de l’Incarnation pour notre salut, pour notre chemin de foi vers Dieu

et la vie éternelle et demeure presque présent matériellement avec la réalité

de la création et nous touche ainsi au plus profond de nous-mêmes.

En parlant des Sacrements, saint Thomas s’arrête de manière particulière sur le

Mystère de l’Eucharistie, pour lequel il eut une très grande dévotion, au point

que, selon ses antiques biographes, il avait l’habitude d’approcher son visage

du Tabernacle comme pour sentir battre le Cœur divin et humain de Jésus. Dans

l’une de ses œuvres de commentaire de l'Ecriture, saint Thomas nous aide à

comprendre l’excellence du Sacrement de l’Eucharistie, lorsqu’il écrit:

«L’Eucharistie étant le Sacrement de la Passion de notre Seigneur, elle

contient Jésus Christ qui souffrit pour nous. Et donc, tout ce qui est l’effet

de la Passion de notre Seigneur, est également l’effet de ce sacrement, n’étant

autre que l’application en nous de la Passion du Seigneur» (In Ioannem, c.6,

lect. 6, n. 963). Nous comprenons bien pourquoi saint Thomas et d’autres saints

ont célébré la Messe en versant des larmes de compassion pour le Seigneur, qui

s’offre en sacrifice pour nous, des larmes de joie et de gratitude.

Chers frères et sœurs, à l'école des saints, tombons amoureux de ce Sacrement!

Participons à la Messe avec recueillement, pour en obtenir des fruits

spirituels, nourrissons-nous du Corps et du Sang du Seigneur, pour être sans

cesse nourris par la Grâce divine! Entretenons-nous volontiers et fréquemment,

familièrement, avec le Très Saint Sacrement!

Ce que saint Thomas a illustré avec une grande rigueur scientifique dans ses

œuvres théologiques majeures, comme justement la Summa Theologiae, et également

la Summa contra Gentiles a été exposé dans sa prédication, adressée aux

étudiants et aux fidèles. En 1273, un an avant sa mort, pendant toute la

période du Carême, il tint des prédications dans l'église San Domenico Maggiore

à Naples. Le contenu de ces sermons a été recueilli et conservé: ce sont les

Opuscules, où il explique le Symbole des Apôtres, interprète la prière du Notre

Père, illustre le Décalogue et commente l'Ave Maria. Le contenu des

prédications du Doctor Angelicus correspond presque tout entier à la structure

du Catéchisme de l'Eglise catholique. En effet, dans la catéchèse et dans la prédication,

à une époque comme la nôtre d'engagement renouvelé pour l'évangélisation, ces

arguments fondamentaux ne devraient jamais faire défaut: ce que nous croyons,

et voici le Symbole de la foi; ce que nous prions, et voici le Notre Père et

l'Ave Maria; et ce que nous vivons comme nous l'enseigne la Révélation

biblique, et voici la loi de l'amour de Dieu et du prochain et les Dix

Commandements comme explication de ce mandat de l’amour.

Je voudrais proposer quelques exemples du contenu, simple, essentiel et

convaincant, de l'enseignement de saint Thomas. Dans son Opuscule sur le

Symbole des Apôtres, il explique la valeur de la foi. Par l'intermédiaire de

celle-ci, dit-il, l'âme s'unit à Dieu, et il se produit comme un bourgeon de

vie éternelle; la vie reçoit une orientation sûre, et nous dépassons avec

aisance les tentations. A qui objecte que la foi est une stupidité, parce

qu’elle fait croire en quelque chose qui n'appartient pas à l'expérience des

sens, saint Thomas offre une réponse très articulée, et il rappelle que cela

est un doute inconsistant, parce que l'intelligence humaine est limitée et ne

peut pas tout connaître. Ce n'est que dans le cas où nous pourrions connaître

parfaitement toutes les choses visibles et invisibles, que ce serait alors une

authentique sottise d'accepter des vérités par pure foi. Par ailleurs, il est

impossible de vivre, observe saint Thomas, sans se fier à l'expérience des

autres, là où la connaissance personnelle n'arrive pas. Il est donc raisonnable

de prêter foi à Dieu qui se révèle et au témoignage des Apôtres: ils étaient un

petit nombre, simples et pauvres, bouleversés par la Crucifixion de leur

Maître; pourtant beaucoup de personnes sages, nobles et riches se sont

converties en peu de temps à l'écoute de leur prédication. Il s'agit, en effet,

d'un phénomène historiquement prodigieux, auquel on peut difficilement donner

une autre réponse raisonnable, sinon celle de la rencontre des Apôtres avec le

Christ ressuscité.

En commentant l'article du Symbole sur l'Incarnation du Verbe divin, saint

Thomas fait certaines considérations. Il affirme que la foi chrétienne, si l'on

considère le mystère de l'Incarnation, se trouve renforcée; l'espérance s'élève

plus confiante, à la pensée que le Fils de Dieu est venu parmi nous, comme l'un

de nous pour communiquer aux hommes sa divinité; la charité est ravivée, parce

qu'il n'y a pas de signe plus évident de l'amour de Dieu pour nous, que de voir

le Créateur de l'univers se faire lui-même créature, un de nous. Enfin, si l'on

considère le mystère de l'Incarnation de Dieu, nous sentons s'enflammer notre

désir de rejoindre le Christ dans la gloire. Pour faire une comparaison simple

mais efficace, saint Thomas observe: «Si le frère d'un roi était loin, il

brûlerait certainement de pouvoir vivre à ses côtés. Eh bien, le Christ est

notre frère: nous devons donc désirer sa compagnie, devenir un seul cœur avec

lui» (Opuscoli teologico-spirituali, Rome 1976, p. 64).

En présentant la prière du Notre Père, saint Thomas montre qu'elle est en soit

parfaite, ayant les cinq caractéristiques qu'une oraison bien faite devrait

posséder: l'abandon confiant et tranquille; un contenu convenable, car —

observe saint Thomas — «il est très difficile de savoir exactement ce qu'il est

opportun de demander ou non, du moment que nous sommes en difficulté face à la

sélection des désirs» (Ibid., p. 120); et puis l'ordre approprié des requêtes,

la ferveur de la charité et la sincérité de l'humilité.

Saint Thomas a été, comme tous les saints, un grand dévot de la Vierge. Il l'a

appelée d'un nom formidable: Triclinium totius Trinitatis, triclinium,

c'est-à-dire lieu où la Trinité trouve son repos, parce qu'en raison de

l'Incarnation, en aucune créature comme en elle, les trois Personnes divines

habitent et éprouvent délice et joie à vivre dans son âme pleine de Grâce. Par

son intercession nous pouvons obtenir tous les secours.

Avec une prière qui est traditionnellement attribuée à saint Thomas et qui,

quoi qu'il en soit, reflète les éléments de sa profonde dévotion mariale, nous

disons nous aussi: « O bienheureuse et très douce Vierge Marie, Mère de

Dieu..., je confie à ton cœur miséricordieux toute ma vie... Obtiens-moi, ô ma

très douce Dame, la véritable charité, avec laquelle je puisse aimer de tout

mon cœur ton très saint Fils et toi, après lui, par dessus toute chose, et mon

prochain en Dieu et pour Dieu ».

* * *

Je salue les pèlerins francophones, particulièrement les jeunes collégiens et

les Vietnamiens présents. Puissions-nous suivre avec générosité le chemin que saint

Thomas d’Aquin nous indique ! Que la Vierge Marie vous accompagne ! Bon

pèlerinage à tous !

SOURCE : http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/audiences/2010/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20100623_fr.html

Giovanni di Paolo, Saint Thomas d'Aquin confond Averroès, 1445, 24,7 x 26,2, Saint-Louis, Art museum

750 ans après sa mort, le

formidable héritage de saint Thomas d’Aquin

Mathilde de Robien - publié

le 06/03/24

Le 7 mars 2024 marque les

750 ans de la mort de saint Thomas d’Aquin, survenue le 7 mars 1274 alors qu’il

était en route pour le Concile de Lyon. Déclaré docteur de l’Église en 1567,

son héritage théologique et philosophique continue d’éclairer l’Église

universelle.

De "bœuf muet"

à "docteur angélique". Une sacrée évolution ! Thomas

d’Aquin est né à Aquino en 1225, dans la région de Naples, et est issu d’une

grande famille italienne. Il fait ses études chez les Dominicains et, à 19 ans,

entre au noviciat de l’Ordre des Prêcheurs contre l’avis de ses parents. Il

poursuit sa formation à Paris puis à Cologne sous la direction d’Albert le

Grand. À Cologne, il est affublé par ses pairs du sobriquet de "bœuf muet", en raison de sa stature imposante et de

son caractère taciturne. Il consacre sa vie à l’enseignement universitaire en

France et en Italie, et à la rédaction de sa grande œuvre La Somme

théologique. Thomas d'Aquin est canonisé le 18 juillet 1323 par le pape Jean

XXII, et proclamé docteur de l'Église en 1567 par le pape Pie V. C’est à cette

époque qu’il reçoit le titre de "docteur angélique".

La Somme théologique

Œuvre majeure de saint Thomas d’Aquin, la Somme

théologique ou Somme de théologie est un

traité théologique et philosophique qui présente, de manière

organique, l’ensemble de la doctrine chrétienne. Un ouvrage conséquent (trois

fois la taille de la Bible !), destiné initialement à l’instruction des

jeunes clercs, et à la formation continue de religieux, de prêtres et de laïcs.

Il demeure néanmoins accessible aux moins "avancés", comme saint

Thomas le souligne dans le Prologue : "Le docteur de la vérité

catholique doit non seulement enseigner les plus avancés, mais aussi instruire

les commençants, selon ces mots de l’Apôtre (1 Co 3, 1-2) :

"Comme à de petits enfants dans le Christ, c’est du lait que je vous ai

donné à boire, non de la nourriture solide." Notre intention est

donc, dans cet ouvrage, d’exposer ce qui concerne la religion chrétienne de la

façon la plus convenable à la formation des débutants."

En répondant à 512

questions, saint Thomas essaie d’opérer une synthèse entre la foi et l’ensemble

de la sagesse chrétienne. La Somme se compose de trois parties : la

première est consacrée à la connaissance de Dieu, à la fois Un et Trinité de personnes, la deuxième, plus longue, à

l’agir de l’homme en tant que créature à l’image de Dieu, et la troisième au

Christ et à sa vie sur terre, et aux sacrements. Rédigée durant les dernières

années de sa vie, en pleine maturité intellectuelle, elle représente sept ans

de travail. Elle est inachevée car après avoir vécu une extase pendant la messe

le 6 décembre 1273, saint Thomas cesse d’écrire. Tout ce qu'il a écrit lui

paraît "comme de la paille", comparé à ce qu'il a

"vu".

Même inachevée, la Somme

théologique rayonne dans toute l’Europe et bien au-delà du Moyen Âge. Six

siècles plus tard, en 1879, le pape Léon XIII déclare que les écrits

de saint Thomas d'Aquin expriment adéquatement la doctrine de l'Église. Il

écrit dans son encyclique Æterni Patris : "Les

Pères du concile de Trente voulurent que, au milieu de leur assemblée, avec le

livre des divines Écritures et les décrets des pontifes suprêmes, sur l'autel

même, la Somme de Thomas d'Aquin fut déposée ouverte, pour pouvoir y

puiser des conseils, des raisons, des oracles." Le Concile Vatican II

recommande explicitement l'étude de sa pensée dans deux documents, le

décret Optatam totius sur la formation au sacerdoce, et la

déclaration Gravissimum educationis qui traite de l'éducation

chrétienne.

Le Docteur angélique

Au XVIe siècle, saint

Thomas reçoit le titre de "docteur angélique". Réputé pour sa pureté,

(Léon XIII souligne son "intégrité parfaite de mœurs"), doté d’une

intelligence lumineuse, saint Thomas est comparé à un ange. Dans son motu

proprio Doctoris Angelici, le pape Pie X évoque en ce sens "la

qualité presque angélique de son intellect". Mais saint Thomas doit sans

doute aussi ce qualificatif à sa profonde réflexion sur les anges. Il est le

premier à avoir défini l’ange comme une créature purement immatérielle, purement

spirituelle. Il a également développé une pensée sur les anges gardiens. Pour saint Thomas, les

anges gardiens sont des amis fidèles, des tuteurs personnels. À la naissance,

chaque être reçoit un tuteur. Tant qu’il pèlerine sur la terre, l’homme, menacé

par de nombreux dangers qui viennent "de l’intérieur et de

l’extérieur", se voit attribuer un gardien spécial : "son ange

gardien" (Somme I, 113, 4).

Saint patron des écoles

catholiques

Le 4 août

1880, Léon XIII déclare saint Thomas patron des écoles

catholiques. "Le patronage de cet homme très grand et très saint sera très

puissant pour la restauration des études philosophiques et théologiques, au

grand avantage de la société. Car, dès que les écoles catholiques se seront

mises sous la direction et la tutelle du Docteur Angélique, on verra fleurir

aisément la vraie science", écrit-il dans Cum hoc sit. Voilà pourquoi tant

d’établissements de l’enseignement catholique sont placés sous la protection de

saint Thomas d’Aquin.

Le pape Pie X va plus

loin en demandant avec forte insistance aux professeurs italiens de philosophie

d’enseigner les principes du thomisme. Dans son motu proprio Doctoris

Angelici pour encourager l'étude de la philosophie de saint Thomas d'Aquin

dans les écoles catholiques du 29 juin 1914, il exhorte : "Les

principes de philosophie posés par saint Thomas d'Aquin doivent être observés

religieusement et inviolablement, car ils sont le moyen d'acquérir une

connaissance de la création la plus conforme à la foi". Et d’affirmer

fermement : "Nous souhaitions donc que tous les professeurs de

philosophie et de théologie sacrée soient avertis que s'ils s'écartaient ne

serait-ce qu'un pas, en métaphysique notamment, de Thomas d'Aquin, ils

s'exposaient à de graves risques."

Le thomisme

Comme l'indique son nom,

le thomisme est une école de pensée qui s'inspire directement des écrits de

saint Thomas d'Aquin. Il consiste en un réalisme philosophique. L'originalité

de sa pensée réside dans la conciliation entre les acquis de la pensée

d’Aristote et les exigences de la foi chrétienne. Elle met en pleine lumière la

cohérence entre foi et raison. "À une époque où les penseurs chrétiens

redécouvraient les trésors de la philosophie antique, et plus directement

aristotélicienne, il eut le grand mérite de mettre au premier plan l'harmonie

qui existe entre la raison et la foi", souligne Jean Paul II dans Fides et ratio. "La lumière de

la raison et celle de la foi viennent toutes deux de Dieu, expliquait-il; c'est

pourquoi elles ne peuvent se contredire."

Au fil des siècles, le

thomisme a revêtu plusieurs formes, s'éloignant plus ou moins des réflexions

initiales développées dans la Somme théologique. À la fin du XIXe, à

l'initiative du pape Léon XIII, le thomisme se renouvelle en un mouvement

appelé le néothomisme, dont les représentants les plus importants

sont Jacques Maritain et Étienne Gilson.

Ses reliques

Le corps de saint Thomas

d’Aquin est conservé sous le maître-autel de l'église de l'ancien couvent

des Dominicains de Toulouse. L’une de ses reliques, son crâne, conservé depuis 1369 dans le couvent des

Jacobins à Toulouse, a été confié en 2023 pour trois ans aux Dominicains de la

Ville Rose, en l’honneur des trois années jubilaires qui célèbrent les 700 ans

de sa canonisation (1323), les 750 ans de sa mort (1274) et les 800 ans de sa

naissance (1225).

Nouveau reliquaire pour le

crâne Saint Thomas d'Aquin I Dominican Province of Toulouse I YouTube

Le chef de saint Thomas a

donc déjà entamé des visites dans toute la France, organisées par l’Association pour

le Centenaire Saint Thomas d’Aquin (ACTA). Il est actuellement à Paris

(du samedi 2 au 9 mars 2024), exposé à l’église saint Étienne du Mont puis à

Stanislas, avant de rejoindre la Lorraine du 13 au 19 mars, à Nancy puis Metz.

"Les paroisses, les communautés, les diocèses qui veulent actualiser

quelque chose de la grâce reçue par saint Thomas peuvent recevoir ces reliques

et organiser des veillées de prière, mais aussi vivifier leur recherche de Dieu

à travers la figure de saint Thomas", expliquait le père Olivier de

Saint-Martin, supérieur du couvent des dominicains de Toulouse. Par décret du

pape François, une indulgence plénière est

accordée aux fidèles qui vénèrent ces reliques.

Les dix plus belles

citations de saint Thomas d'Aquin :

Lire aussi :Le

saint cordon de Thomas d’Aquin

Lire aussi :Alcool

: quand s’arrêter ? La juste limite de saint Thomas d’Aquin

Lire aussi :La

prière de saint Thomas d’Aquin juste avant de mourir

Master of the Urbino Coronation (fl. 14th century ). Madonna con il

Bambino, un frate domenicano, i Santi Giacomo Maggiore, Tommaso d'Aquino,

Leonardo e un committente, Pinacoteca San Domenico

Les plus belles citations

de saint Thomas d’Aquin

Mathilde de Robien - publié

le 06/03/24

Grand philosophe,

brillant théologien, docteur de l'Église... Grâce à ses nombreux écrits, saint

Thomas d'Aquin nous éclaire encore aujourd'hui sur notre rapport à Dieu, à la

foi, au bien et au mal.

Saint Thomas d'Aquin mérite

à plus d'un titre le qualificatif de docteur "angélique". Ce frère prêcheur italien,

proclamé docteur de l’Église en 1567 par le pape Pie V, était réputé pour sa

pureté, - Léon XIII souligne son "intégrité parfaite de mœurs" -, et

son intelligence lumineuse. Dans son motu proprio Doctoris Angelici, le

pape Pie X évoque "la qualité presque angélique de son intellect".

Florilège de citations, extraites de la Somme de théologie, de la Somme

contre les Gentils et des Sermons catéchétiques sur le Symbole des

Apôtres, qui reflètent merveilleusement la clarté de son âme :

Lire aussi :750

ans après sa mort, le formidable héritage de saint Thomas d’Aquin

Lire aussi :Jubilé

de saint Thomas d’Aquin : comment obtenir l’indulgence plénière ?

Lire aussi :Le

saint cordon de Thomas d’Aquin

SOURCE : https://fr.aleteia.org/2024/03/06/les-plus-belles-citations-de-saint-thomas-daquin

Beato Angelico, San Tommaso d'Aquino con la

"Summa Theologiae", circa 1442, affresco; Firenze, Museo di San Marco, chiostro di S. Antonino,

lunetta

Les cinq voies de Saint

Thomas d'Aquin

PROLOGUE DE SAINT JEAN

« Dans le Principe était Le Logos, et le Verbe était tourné vers Dieu. Et c’est

Dieu qui était Verbe. Ainsi en était-il dans le Principe en Dieu. Et tout ce

qui devient est par lui, et rien de ce qui est devenu n’est devenu sans Lui. Et

ce qui est devenu était vie en lui. Et la Vie était la Lumière des hommes. Et

la Lumière luit dans la Ténèbre, et la Ténèbre n’a pas compris. [...] La

Lumière véritable existait, éclairant tout homme qui vient dans ce monde. Elle

était dans le monde, et le monde a été fait par elle et le monde ne la

connaissait pas. Et elle vint dans son domaine, et ses vassaux ne la reçurent

point. Mais à ceux qui la reçurent elle donna le pouvoir de devenir enfants de

Dieu : à ceux qui croient en son nom qui sont nés, non pas du mélange des

sangs, ni de la volonté de la chair ni de la volonté de l’homme, mais de Dieu.

Car le Verbe s’est fait chair et a habité parmi nous ; et nous avons vu sa

gloire : une gloire digne de l’Unique Engendré du Père ; la plénitude de la

grâce et de la Vérité ».

PREMIERE VOIE : Elle est fondée sur « l’observation du mouvement des êtres dans

le monde ». Le mouvement, défini comme le passage à l’acte d’un être en

puissance relativement à cet acte, est causé par un autre être qui joue le rôle

de moteur ou d’agent du changement, celui-ci à son tour est mû par un autre,

mais on ne saurait remonter à l’infini dans la série des mouvements, car alors

on ne pourrait assigner un commencement (fini) au mouvement. Mais si

éternellement rien ne se meut, éternellement rien ne se mouvra et il n’y aurait

pas de mouvement. Il faut donc poser l’existence d’un « Moteur Premier » non mû

seul à même d’expliquer le mouvement, que tous reconnaissent comme Dieu !

DEUXIEME VOIE : Elle est fondée sur la notion et la réalité tout aussi

aristotélicienne de cause. Tout être ou toute modification d’être advient comme

l’effet d’un être antérieur (logique !) qui joue à son égard le rôle de cause

et qui est lui-même l’effet d’un autre et ainsi de suite… Toutefois, comme le

première voie, on ne peut aller à l’infini dans la série des causes, cela

signifierait qu’il n’y aurait pas de commencement assignable et donc pas de

suite ni de série causale. Il faut donc poser l’existence d’une « Cause

Première » incausée « que tous appellent Dieu » !

TROISIEME VOIE : Elle est fondée sur la distinction qui n’avait pas retenu

l’attention d’Aristote de « l’être possible » ou contingent et de « l’être

nécessaire » (Dieu). Ici, Saint Thomas tire une partie de la pensée des

philosophes arabes, en particulier d’Avicenne. Pour ce dernier, parmi les

objets intelligibles que contemple le métaphysicien, il en est un qui jouit

d’un privilège particulier : c’est l’être. Etre un homme n’est pas être un

cheval ou un arbre, mais dans les trois cas, c’est être un être ou un existant

! Pourtant, cette notion n’est pas simple : elle se dédouble immédiatement en

être nécessaire et être possible. On appelle possible un être qui peut exister

mais qui n’existera jamais s’il n’est pas produit par une cause, on appelle

nécessaire ce qui n’a pas de cause et, en vertu de sa propre essence, ne peut

pas ne pas exister. Dans une métaphysique dont l’objet propre est l’essence,

ces distinctions conceptuelles équivalent à une division des êtres. En fait,

l’expérience ne nous fait connaître que des êtres dont l’existence dépend de

certaines causes : chacun est possible mais leur causes aussi. La série totale

des êtres est donc un simple possible. Il ne sert à rien d’allonger

indéfiniment la série des causes : si les possibles existent, c’est qu’existe

aussi un être nécessaire, cause de leur existence. Le Dieu d’Avicenne est donc

le « Necesse esse » par définition, l’Être Nécessaire : il possède l’existence

en vertu de sa seule essence ou encore, dit autrement, essence et existence ne

font qu’un en lui, c’est pourquoi il est indéfinissable. Il est, quod est, mais

si l’on demande ce qu’il est, quid est, il n’y a pas de réponse ! Son cas est

unique. Dans cette troisième voie, (un peu longue, désolé !) Saint Thomas

reprend donc à son compte non seulement la distinction entre le possible et le

nécessaire mais aussi la marche générale de la preuve qui conduit à poser

l’existence d’un Être Nécessaire que tous appellent Dieu !

QUATRIEME VOIE : « On voit en effet dans les choses du plus ou moins bon, du

plus ou moins vrai, du plus ou moins noble » (Saint Thomas). Elle part de la

constatation qu’il y a des degrés dans les êtres. En effet, il y a des degrés

de beauté, de bonté dans les choses, qui ne s’entendent que par rapport au

Beau, au Vrai, au Bon en soi. D’inspiration platonicienne et donc assez

différente des trois premières, cette voie ne s’écarte pas néanmoins de

l’inspiration aristotélicienne. Pour être clair, cette voie peut-être mise sous

la forme syllogistique suivante : Des êtres possédant imparfaitement leur

perfection la tiennent d’un être qui la possède par soi, ou sont causés par un être

qui possède cette perfection dans ce genre (du bon, du vrai, du beau). Donc

quelque Être possédant la perfection par soi est existant. En conclusion, « il

y a donc un être qui est, pour tous les êtres, causes d’êtres, de bonté et de

toute perfection. C’est lui que nous appelons Dieu ! »

CINQUIEME VOIE : Elle part de la constatation de « l’ordre du monde ». Elle

peut-être considérée comme une application de la cause finale (quatrième cause

reconnue par Aristote). Les divers êtres que nous voyons, les astres, les

plantes, les animaux suivent un ordre qui délimite leur place, c’est l’ordre

statique ou structurel, et leur mouvement ou évolution, c’est l’ordre

dynamique. Il y a donc un Être intelligent par lequel toutes choses naturelles

sont ordonnées à leur fin, et cet Être, c’est lui que nous appelons tous Dieu !

POUR CONCLURE… Si le mouvement (première voie), les causes efficientes

(deuxième voie), ce qui naît et meurt ou le devenir des êtres (troisième voie),

les degrés de perfection des êtres (quatrième voie), l’ordre manifesté par les

choses inanimées (cinquième voie) permettent de conclure à l’existence de Dieu,

c’est parce qu’ils existent ! Il suffit d’assigner la raison suffisante

complète d’une seule existence quelconque empiriquement donnée pour prouver

l’existence de Dieu.

--> En conclusion finale, pour continuer dans la pure logique de ce qui

vient d’être dit, tout ce qui existe vient nécessairement de Dieu. Ceux qui

affirmeraient le contraire même par un discours rationnellement

"décoré" se trouvent dans l’erreur et non dans la Vérité. Ne

l’oublions pas, notre Vérité Incarnée, c’est seulement Jésus-Christ, notre «

LOGOS SUPRÊME » à tous !

SOURCE : http://notredamedesneiges.over-blog.com/article-3574621.html

Carlo Crivelli (circa 1435–circa 1495), Saint Thomas Aquinas, 1476, 61 x 40, tempera on poplar panel, National Gallery, City of Westminster, Central London

Thomas d’Aquin :

antidote au divorce entre foi et raison

par Simon Lessard

28 janvier 2025

Religion et science

sont-elles condamnées à s’opposer ? Saint Thomas d’Aquin (1225-1274), figure

emblématique de la théologie chrétienne, a montré qu’elles peuvent au contraire

dialoguer et même collaborer. Alors que nous célébrons en 2025 les 800 ans de

sa naissance, Le Verbe vous invite à redécouvrir la vie de celui qui

a su marier foi et raison avec brio.

« Défendre la

vérité, la proposer avec humilité et conviction et en témoigner dans la vie

sont des formes exigeantes et irremplaçables de la charité. » Ces mots du

pape Benoît XVI expriment parfaitement l’appel spécifique du saint docteur

de l’Église, Thomas d’Aquin, qui fut toute sa vie fidèle à cette vocation de

chercher, de contempler et de prêcher la vérité. Né vers 1225 au sein de la noble

famille d’Aquin dans le royaume de Sicile, Thomas est offert comme oblat aux

moines du Mont-Cassin dès l’âge de cinq ans par ses parents. Durant ses neuf

années au monastère où saint Benoît a jeté les bases de la vie contemplative en

Occident, le jeune Thomas apprend naturellement la grammaire, premier outil de

la pensée, mais il développe surtout le gout de Dieu, premier moteur de la vie

humaine.

Qu’est-ce que Dieu ?

Sa première parole connue

est une question : « Qu’est-ce que Dieu? », demande-t-il un jour

à l’un de ses instituteurs. Le reste de sa vie n’est que la recherche de la

réponse à cette question sur celui qui est la cause première et ultime de toute

chose. « Tous les hommes sont tenus de chercher la vérité, surtout en ce

qui concerne Dieu et son Église; et quand ils l’ont connue, de l’embrasser et

de lui être fidèles » (Dignitatis humanae, paragr. 1).

En 1239, alors que

l’empereur Frédéric II se trouve en guerre contre le pape Grégoire IX

et que le monastère où il étudie est menacé, Thomas est envoyé poursuivre ses

études à l’académie de Naples. Cette école est alors le refuge de tous les

penseurs les moins orthodoxes d’Europe, que l’empereur se plaît à rassembler et

à protéger en signe de résistance à l’Église. Les maitres de cette école sont

pour la plupart des philosophes qui, par désir d’indépendance, se coupent de la

faculté de théologie, amorçant ainsi une rupture entre foi et raison que le

saint docteur passera sa vie à vouloir résorber. Ainsi, entre 13 et

18 ans, Thomas se trouve exposé aux erreurs de la vie intellectuelle de

son temps, ce qui ne fait qu’augmenter son amour de la vérité, en plus de

l’exercer à répondre aux objections des dissidents.

Contempler et prêcher

En 1244, alors âgé de

19 ans, Thomas décide de se joindre à l’ordre des Prêcheurs, fondé moins

de trente ans auparavant par saint Dominique. Il est attiré par cette nouvelle

forme de vie religieuse imitant la vie des apôtres, toute consacrée à la

prédication dans la pauvreté mendiante, l’amitié fraternelle et l’étude

priante. Plus question pour le religieux de rester enfermé silencieusement dans

un cloitre : il faut sortir, marcher et parler pour enseigner la vérité en

des temps et des lieux où l’erreur se répand. Il écrira ainsi : « Il

est plus beau d’éclairer que de briller seulement, de transmettre aux

autres ce qu’on a contemplé que de contempler seulement » (Somme

théologique, IIa-IIae, q. 188, a. 6).

Le choix de Thomas

déplait à sa mère Théodora, qui voit plutôt son fils devenir le successeur de

saint Benoît à l’abbaye du Mont-Cassin. Avec la complicité de ses autres fils,

cette mère à l’amour contrôlant fait enlever puis enfermer Thomas dans le

donjon du château familial de Roccasecca. Mais la Providence ne permettant un

mal que pour en tirer du bien, c’est au cœur de cette « roche sèche »

que jaillit en abondance l’eau de sa sagesse.

Durant une année que l’on

peut comparer à un noviciat, Thomas, avec pour seul maitre le Saint-Esprit, médite

la Bible, faisant de la Parole de Dieu le principe de toute sa théologie.

« Pour saint Thomas, nous confie le dominicain Serge-Thomas Bonino,

professeur à l’université pontificale Saint-Thomas-d’Aquin, la théologie

n’est pas une simple « science religieuse », mais une exigence

spirituelle de la foi. Elle s’enracine dans la méditation de l’Écriture et de

la Tradition et veut être un regard de sagesse qui ressaisit toutes choses sous

la lumière de Dieu. »

Le « bœuf

muet »

Après une étrange année

de « noviciat » reclus au terme de laquelle Thomas ne change pas

d’idée, sa famille accepte de lui redonner sa liberté. Dès lors, il entame des

études à Paris, puis à Cologne, où il se fait disciple du maitre Albert le

Grand. On dit qu’il parle peu, étudie beaucoup et prie sans cesse, ce qui lui

vaut de la part de ses confrères le sobriquet de « bœuf muet ». À ce

sujet, saint Albert prophétise: « Vous l’appelez le « bœuf

muet », et moi je vous dis que le mugissement de sa science ébranlera

l’univers! »

À 26 ans, Thomas

entreprend son enseignement à l’université de Paris, où il commente entre

autres le livre d’Isaïe et les Sentences de Pierre Lombard. Sa vive

intelligence lui permet de distinguer et d’ordonner là où d’autres ne sont

capables que d’opposer et de confondre. À 30 ans, il devient le plus jeune

« maitre-régent » de Paris. Ses cours connaissent un « succès

bœuf » auprès des étudiants parisiens grâce à leur profondeur et à leur

clarté, deux qualités qu’il est très rare de voir si bien réunies. « On

apprend plus avec saint Thomas en une année qu’avec tous les autres saints

ensemble pendant toute la vie », confia ainsi le pape Jean XXII

(bulle de canonisation de saint Thomas d’Aquin).

Durant les 17 années

qui suivent, le jeune docteur enseigne partout où l’obéissance religieuse

l’appelle. Entre la France et l’Italie, il rédige des œuvres – à l’aide de

secrétaires, parfois jusqu’à trois en même temps! – qui illuminent encore

aujourd’hui tous ceux qui cherchent sincèrement la vérité. Toujours selon le

professeur Bonino : « La foi chrétienne est, entre autres choses, une

lumière et une nourriture pour l’intelligence en quête de vérité. Le Verbe,

Sagesse de Dieu, vient s’incarner aussi dans l’intelligence. C’est pourquoi le

croyant ne peut pas se dispenser de chercher l’intelligence de la foi. Non

seulement il scrute les raisons de croire, mais il cherche aussi à mettre en

évidence la cohérence et la beauté des mystères révélés et la manière dont ils

répondent aux interrogations de l’humanité. Sur ce chemin, saint Thomas est

exemplaire. »

Une cathédrale

théologique

Entre 1263 et 1265,

Thomas d’Aquin planche sur sa première synthèse théologique, la Somme contre les gentils, comme on

appelait à l’époque tous ceux qui, n’étant ni juifs ni chrétiens, ne croyaient

pas aux Saintes Écritures. À ce jour, cet ouvrage demeure l’un des plus utiles

pour entrer en dialogue avec les musulmans et les non-croyants, puisqu’il

s’appuie non pas sur la foi, mais sur « la raison naturelle à laquelle

tous sont obligés de donner leur adhésion »

(livre 1, ch. 2). « Thomas d’Aquin, nous explique, depuis

l’université de Fribourg, le professeur Gilles Émery, o. p., est un modèle

qui nous montre comment une réflexion croyante peut et doit faire appel à la

philosophie, sans contradictions et sans soumettre la foi à la raison humaine,

mais en élevant la raison humaine par la lumière qu’apporte la

foi. »

En 1266, il amorce son chef-d’œuvre

inachevé, la Somme théologique. Souvent comparé à une

cathédrale gothique en raison de leur comparable structure, grandeur, splendeur

et orientation céleste, ce monument de plus de 3 000 articles vise à

présenter aux débutants en théologie l’essentiel de la doctrine sacrée de

manière brève, claire et ordonnée, tout en évitant les répétitions et les

questions inutiles. Aujourd’hui encore, la Somme demeure l’une des

plus belles démonstrations de l’harmonie possible entre la foi surnaturelle et

la raison naturelle. Si l’on doit en croire le pape Jean XXII, qui

écrivait dans sa bulle de canonisation « autant ce Docteur a composé

d’articles, autant il a opéré de miracles », on peut conclure qu’il est

l’un des saints les plus prolifiques en prodiges de tout le Moyen Âge!

« Rien d’autre que

toi! »

Le matin du

6 décembre 1273 à Naples, le sacristain de la chapelle Saint-Nicolas