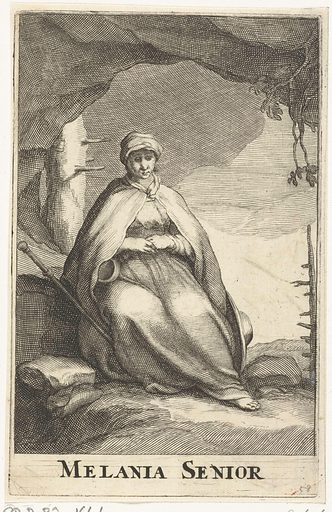

Frederick Bloemaert, print maker (1614–1669). Saint Melania the Elder. 1 January 1636. Origin: Utrecht. Date: after 1636– c 1670. Object ID: RP-P-BI-1644, Rijksmuseum

Sainte Mélanie

Veuve romaine (+ 410)

que l'on appelle

également Mélanie l'ancienne parce qu'elle est la grand-mère paternelle de

sainte Mélanie

la jeune. Elle s'enfuit d'Italie au moment de l'invasion des Goths et

alla s'établir en Terre Sainte pour le reste de ses jours. On dit qu'elle avait

un caractère irascible dont souffrit sa petite-fille. Ce qui ne l'empêcha pas

d'être reconnue comme sainte. Ceci peut nous consoler de nos emportements, et

nous rendre confiance en la bonté de Dieu à notre égard.

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/506/Sainte-Melanie.html

A partir du IVe siècle,

de nombreux Romains s'installent dans le même temps en Palestine, et nous

retrouvons parmi eux quelques noms des nobles Romaines que nous évoquerons dans

le contexte monastique occidental, car elles avaient auparavant organisé leur

demeure romaine en communauté : Mélanie l'Ancienne, veuve du Préfet de Rome,

s'installe vers 380 sur le mont des Oliviers, à Jérusalem, et fonde un

monastère double, le couvent masculin étant confié à Rufin

d'Aquilée (Rufinus, 345-410), connu pour ses traductions d'Origène.

Mélanie et Rufin se lient d'amitié avec Egérie,

venue de Gaule ou d'Hispanie, qui débarque à Jérusalem en 381. Paula, qui fonde

à Bethléem, en 386, un monastère double, dont celui des hommes est dirigé par

saint Jérôme ; sa cousine, Mélanie

la Jeune, petite-fille de Mélanie l'Ancienne, est une des plus grandes

fortunes de Rome. Elle voyage beaucoup, rencontre Augustin à Thagaste, se

défaisant progressivement de sa colossale fortune en immenses dons aux quatre

coins de la chrétienté naissante. Elle installera en 417 un monastère de 80

vierges sur le mont des Oliviers puis en 432, à la mort de Pinien, son époux,

aussi fortuné qu'elle, elle fondera cette fois un monastère d'hommes, où

s'installera un prince géorgien, Nabarnugi (Pierre Ibère) qui fondera lui-même

un monastère près de l'église de Sion. Jérusalem se couvrira bientôt de

nombreux monastères.

Une « route de

femmes »

samedi 24 mai 2008

par Pascal

G. DELAGE

En 384, alors que Jérôme

se prépare à repartir en Orient, il écrit à Paula, une des ses élèves romaines,

veuve de son état, pour la décider à entreprendre le même pèlerinage, et il lui

rappelle un fait-divers qui défraya la chronique romaine plus d’une dizaine

d’années plus tôt : « Mais pourquoi ressasser de vieilles

histoires ? Suis donc les exemples du présent : vois sainte Mélanie

[femme d’un Préfet de Rome], vraie noblesse des chrétiens de notre époque… Le

cadavre de son mari était encore chaud, on ne l’avait pas encore inhumé qu’elle

perdit en même temps ses deux fils. Je vais dire une chose incroyable mais non

pas fausse, j’en atteste le Christ. Qui, dans cette conjoncture, ne l’eût

imaginée hors d’elle-même, les cheveux épars, déchirant ses vêtements et

lacérant sa poitrine avec frénésie ? Pas une larme ne coula. Elle tint bon

sans broncher… après avoir cédé tout ce qu’elle possédait au seul fils qui lui

restât, bien qu’on fût au début de l’hiver, elle s’embarqua pour Jérusalem ».

En fait, Mélanie fit d’abord voile pour l’Egypte afin de se mettre à l’école

des moines, ces chrétiens qui initiaient une nouvelle manière d’être disciple

du Christ en abandonnant famille et richesses pour être seuls avec l’Unique.

Athanase d’Alexandrie ayant fait connaître en Occident Antoine, le Père des

moines, par un petit livre, cette première « vie de saint » avait

déclenché un enthousiasme sans précédent chez les chrétiens, mais plus encore

chez les chrétiennes militantes de Rome qui, comme Asella ou Marcella, se

mirent à refuser mariage et honneurs – souvent au grand dam de leurs familles –

pour se regrouper en petites communautés vivant dans la prière et l’étude de la

Parole de Dieu.

L’ensemencement

monastique ne prit pas d’ailleurs que dans la vieille aristocratie romaine, qui

pouvait y voir encore, par le relais de ses femmes, un moyen de cultiver

l’excellence que lui refusait maintenant le nouveau pouvoir politique siégeant

au loin, à Constantinople. Des bourgeoises - comme la sœur de Basile de Césarée

ou celle d’Augustin - fondent des communautés d’un type nouveau dans les villae

familiales avec leurs parentes et leurs servantes à la fin du IVe siècle.

Les communautés monastiques se multiplient en Syrie, en Palestine à Jérusalem

et à Bethléem – autour des Romaines Mélanie et de Paula, la disciple fidèle et

l’égérie de Jérôme ; cependant c’est l’Egypte qui reste la terre des

moines et des moniales : à la fin du IVe siècle, la ville d’Antinoé

rassemble douze communautés de femmes ; celle de Tabennèse comptait

environ 400 femmes vivant dans une stricte clôture et sous la direction d’un

abba . Des femmes pouvaient aussi se voir reconnaître un charisme de direction

spirituelle et reçurent de la Tradition le titre prestigieux d’amma

(« Mère ») comme Sara, Théodora ou Synclétique que venaient consulter

laïcs, moines et évêques.

Le prestige des moines

est tel que l’Egypte devint une véritable terre sainte, visitée pieusement à

l’instar de Jérusalem et de Bethléem par les riches matrones venant même

d’extrême occident, de Galice comme Egérie, l’auteur d’un pittoresque récit de

pèlerinage, ou comme Poemonia, une parente de l’empereur Théodose, au point que

l’ermite Jean de Lycopolis se désolait de ce que la mer Méditerranée soit

devenue une « route de femmes », femmes que les moines auraient de

plus en plus de mal à garder à distance. Si certaines matrones venaient

seulement demander une grâce ou une guérison, d’autres demeuraient à la limite

du désert pour s’initier à l’ascèse et pratiquer la « vie évangélique ».

L’école pouvait être rude ; Mélanie – encore elle - fit apporter trois

cent livres d’argenterie au désert de Nitrie pour les donner à abba

Pambo : « Sans se lever, continuant de tresser ses feuilles de

palmier, il me bénit en me disant simplement : « Que Dieu te donne la

récompense » [Pambo ordonne à son disciple que cette somme soit attribuée

aux monastères les plus pauvres]. Quant à moi, je restais là, poursuit Mélanie,

m’attendant à ce qu’il me félicite ou me loue pour ce don. Comme il ne disait

toujours rien, je repris « Pour que tu le saches, maître, il y a trois

cents livres ». Sans relever la tête, il me répondit : « Celui à

qui tu l’as apporté, mon enfant, n’a pas besoin de poids. Celui qui pèse les

montagnes sait bien davantage la quantité de cet argent. A la vérité, si c’est

à moi que tu le donnais, tu faisais bien de me le dire, mais si c’est à Dieu,

Lui qui n’a pas dédaigné les deux oboles de la veuve, tais-toi » .

A la génération suivante,

l’exemple de Mélanie fut imité par sa petite fille prénommée aussi Mélanie. A

la veille de la prise de Rome par les Goths d’Alaric, elle obtint de son époux

Pinianus qu’il vécût auprès d’elle comme un frère (elle lui avait donné

auparavant deux enfants qui ne vécurent pas) et qu’il la suivît dans sa

conversion à la « vie parfaite » en se dépouillant de leurs immenses

propriétés, qui se répartissaient sur trois continents, et en affranchissant 8

000 de leurs esclaves. Ce ne fut pas sans susciter un tollé d’indignation de la

part des sénateurs romains, encore largement païens. Même le très chrétien

Théodose voit d’un très mauvais œil la conversion ascétique d’une de ses jeunes

parentes, du nom d’Olympias : ne va-t-elle pas dilapider l’héritage

familial au profit des églises et des pauvres, alors qu’un si bon parti récompenserait

fort à propos un général ou un ministre zélé ? Olympias refuse le mariage,

l’empereur place ses biens sous séquestre. La jeune femme ne s’en réjouit que

davantage , s’estimant libérée d’un pesant fardeau qui mettait en péril son

propre salut ! Devant tant d’opiniâtreté, Théodose céda et Olympias fut

ordonnée diaconesse en dépit de son jeune âge (elle a trente ans et les canons

ecclésiastiques n’admettent pas au diaconat des femmes de moins de soixante

ans). C’est elle qui accueillera à Constantinople Jean Chrysostome devenu

évêque de la capitale, le secondant fidèlement dans sa tâche de pasteur et de

réformateur, le soutenant aux moments d’épreuve lors du conflit avec la cour et

les puissants, ce qui l’entraîna dans la disgrâce de Jean et elle mourra comme

lui, en exil, loin de sa communauté religieuse. S’il nous reste 17 lettres de

Jean en exil à Olympias, la tradition, hélas, ne jugea pas utile de conserver

les lettres de la diaconesse, pas plus que celles de Marcella, de Paula ou

autres Mélanie.

Le prestige du modèle

ascétique est tel que même les princesses de la famille impériale, comme les

trois filles de l’empereur Arcadius font vœu de célibat et mènent au palais une

véritable vie monacale. En raison de cette inflexion religieuse, les impératrices,

à l’instar de leurs pères ou de leurs époux, s’estiment en droit de se mêler de

théologie : Eudoxie soutient un temps Nestorius, condamné au concile

d’Ephèse en 431, et Pulchérie s’empresse de réunir le concile de Chalcédoine en

451 qui mit fin – pour un temps court – aux querelles christologiques.

Cependant, si nos sources (vies de saints, correspondances…) sont bien

documentées sur les « femmes bien-nées », bien plus rares sont les

éclairages que l’on peut porter sur les autres femmes, c’est à dire leur

immense majorité, qui restent encore attachées aux cultes traditionnels et

familiers, principalement dans les campagnes. Encore entrevoit-on au détour

d’une lettre de Jérôme que Paula avait fondé à Bethléem trois monastères de

femmes correspondant à leurs origines sociales (les nobles, les bourgeoises et

les servantes), ou encore que l’entrée au couvent avait pu être décidée par le

père ou le reste de la famille : « De malheureux parents, chrétiens à

la foi imparfaite, vouent à la virginité leurs filles, si elles sont laides ou

faibles de quelque membre, parce qu’ils ne trouvent pas de gendre à leur

goût » . Palladius admire ingénument une vieille moniale d’Egypte, amma

Talis : « avec elle habitaient soixante jeunes filles qui l’aimaient

tellement qu’il n’y avait pas de clé à la clôture du monastère comme dans les

autres : l’amour de la vieille femme les retenait ». Ailleurs, une

solide fermeture était nécessaire, sous peine de voir s’envoler quelques

novices moins motivées que les autres !

SOURCE : http://caritaspatrum.free.fr/spip.php?article75

Mélanie dite l’ancienne

ou sainte Mélanie (350-410)

Veuve d’un Préfet romain,

est mère de Publicola le père de Mélanie la Jeune.

C’est à la suite de ses

conseils que sa petite fille, Mélanie la jeune avec l’accord de Pinien, son

mari, vendit leurs biens et affranchit leurs esclaves estimés à 8 000 pour en

faire dons à des monastères et Églises.

En 410, lors des

invasions goths [1] d’Alaric 1er, elle

quitte l’Espagne, avec la famille de sa petite fille Mélanie la jeune, pour

l’Italie, l’Afrique et s’exile en Terre sainte. Elle fit la visite des déserts

d’Égypte en compagnie de Rufin d’Aquilée.

À Jérusalem, elle rencontra Évagre le Pontique et

le convainc d’embrasser la vie monastique.

Mélanie l’ancienne aurait

fondé vers 380 le monastère double du Mont des Oliviers [2],

que sa petite fille améliora et rendit célèbre.

Durant son périple, elle

rencontra Saint

Jérôme. Elle rencontra aussi Pallade de Galatie qui en fit ses

louanges.

P.-S.

Source : Cet article

est partiellement ou en totalité issu de l’article de Alan D. Booth,

« Quelques dates hagiographiques : Mélanie l’Ancienne, Saint Martin,

Melanie la Jeune », Phoenix, vol. 37, no. 2 (Summer, 1983)

Notes

[1]

Les Goths faisaient partie des peuples germaniques. Selon leurs propres

traditions, ils seraient originaires de la Scandinavie. Ils provenaient

peut-être de l’île de Gotland. Mais ils pourraient également être issus du

Götaland en Suède méridionale ou bien du Nord de la Pologne actuelle. Au début

de notre ère, ils s’installèrent dans la région de l’estuaire de la Vistule.

Dans la seconde partie du 2ème siècle, une partie des Goths migrèrent vers le sud-est

en direction de la mer Noire. Dès le 3ème siècle les Goths étaient fixés dans

la région de l’Ukraine moderne et de la Biélorussie où ils furent probablement

rejoints par d’autres groupes qui ont été plus ou moins intégrés dans la tribu.

Les Goths formaient un seul peuple jusqu’à la fin du 3ème siècle. Après un

premier affrontement avec l’Empire romain dans le sud-est de l’Europe au début

du siècle, ils se séparèrent en deux groupes : les Greuthunges à l’Est et

les Tervinges à l’Ouest qui deviendront par la suite les Ostrogoths ou

« Goths brillants », à l’Est, et les Wisigoths ou « Goths

sages » à l’Ouest.

[2]

Le monastère du Mont des Oliviers, à Jérusalem (Palestine), est fondé vers 380

par Mélanie l’Ancienne. La communauté des hommes est confiée à Rufin d’Aquilée.

SOURCE : https://www.ljallamion.fr/spip.php?article6579

Orante

(particolare), catacombe di priscilla, cubicolo della velatio, roma (metà III

secolo)

Profile

Married; mother; grandmother of Saint Melania

the Younger. Widowed at

age 21. Travelled through Palestine for

several years, and founded a monastery on

the Mount of Olives.

Born

c.342

c.410 of

natural causes

Additional

Information

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

MLA

Citation

“Saint Melania the

Elder“. CatholicSaints.Info. 7 October 2022. Web. 31 December 2022.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-melania-the-elder/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-melania-the-elder/

Melania the Elder, Widow

(AC)

Died in Jerusalem c.

400-410. This Melania, a Roman patrician of the Valerii family, was the

paternal grandmother of the saint by the same name. Left a widow at age 22, she

was away from Rome from 372 to 379, mostly in Palestine where she was

associated with Saint Jerome. Melania left Italy for good following the

Visigoth invasion. She had a somewhat domineering personality, and her

relationship with her granddaughter was not always easy. The relationship with

Saint Jerome was a clash of titans (Attwater, Benedictines). Saint Melania is

portrayed in art as a widow praying in a cave with a water-pot, bread, and a

pilgrim's staff near her (Roeder).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0608.shtml

St. Melania the Elder

Commemorated on June 8

St. Melania was a wealthy

and noble woman, born in Spain in the fourth century. Upon turning fourteen,

she married and moved with her husband to the suburbs of Rome.

At 22 years old, she was

left a widow, when her husband and two of her children died. Immediately

following their deaths, she converted to Christianity. When her remaining son

turned ten, she placed him with a guardian and set off for Alexandria where she

joined other Christian desert ascetics to visit the monks at Nitria.

She gave away most of her

great wealth to the needy, and to Egyptian Christians being persecuted by the

Arians. It is said that in three days she fed some 5,000 people.

When the Orthodox in

Egypt were exiled to Palestine, she went with them to Jerusalem, where she

built a convent for virgins on the Mount of Olives. Eventually, over 50 nuns

found the path to salvation at her monastery.

Melania founded more

monasteries and promoted theological tolerance and the unity of Christianity.

On a visit to Rome to see her son, she also influenced his daughter, Melania.

Known as Melania the Younger, she too took up the religious calling and

followed her grandmother back to Jerusalem.

St. Melania entered the

convent herself, and entered into eternal life there in 410. Her granddaughter,

Melania the Younger, is commemorated on December 31.

By permission of www.abbamoses.com

SOURCE : http://www.antiochian.org/node/18794

MELANIA THE ELDER

CHAPTER XLVI: MELANIA THE

ELDER

[1] The thriceblessed

Melania Divas a Spaniard by origin, but afterwards belonged to Rome. She was

the daughter of Marcellinus the axconsul, and wife of a certain man of high

official rank, whom I do not quite remember. Having become a widow at

twenty-two, she was favored with the divine love, and having said nothing to

any onefor she would have been preventedin the time when Valens had the rule

in the empire, she had a guardian nominated for her son and took all her

movable property and put it on a ship; then she sailed with all speed to

Alexandria, accompanied by various highborn women and children. [a] After that,

having sold her goods and turned them into money, she went to the mountain of

Nitria, where she met the following fathers and their companionsPambo,

Arsisius, Sarapion the Great, Paphnutius of Scete, Isidore the Confessor,

bishop~of Hermopolis, and Dioscorus. And she sojourned with them for half a

year, travailing about in the desert and visiting all the saints. [3] But after

this, when the prefects of Alexandria banished Isidore, Pisimius, Adelphius,

Paphoutius and Pambo, with them also Ammonius Paroles, and twelve bishops and

priests, to Palestine in the neighborhood of Dioczesarea, she followed them and

ministered to them from her own money. But, servants being forbidden them, so

they told mefor I met the holy Pisimius and Isidore and Paphnutius and

Ammoniuswearing the dress of a young slave she brought them in the evenings

what they required. But the consular of Palestine got to know of it, and

wishing to fill his pocket thought he would terrify her. [4] And having

arrested her hethrew her into prison, ignorant that she was a lady. But she

told him: " For my part, I am SoandSo's daughter and SoandSo's wife, but

I am Christ's slave. And do not despise the cheapness of my clothing. For I am

able to exalt myself if I like, and you cannot terrify me in this way or take

any of my goods. So then I have told you this, lest through ignorance you

should incur judicial accusations. For one must in dealing with insensate folk

be as audacious as a hawk." Then the judge, recognizing the situation,

both made an apology and honored her, and gave orders that she should succor

the saints without hindrance.

[5] After they were

recalled she founded a monastery in Jerusalem, and spent twentyseven years

there in charge of a convent of fifty virgins. With her lived also the most

noble Rufinus, from Italy, of the city of Aquileia, a man similar to her in

character and very steadfast, who was afterwards judged worthy of the

priesthood. A more learned man or a kinder than he was not to be found among

mend [6] So these two during twentyseven years receiving at their own charges

those who visited Jerusalem in pursuance of a vow, bishops and monks and

virgins, edified all who visited them, and they reconciled the schism of

Paulinus, some 400 monks in all, and winning over every heretic that denied the

Holy Spirit they brought him to the Church; and they honored the clergy of the

district with gifts and food, and so continued to the end, without offending

anyone.

CHAPTER LIV: THE ELDER

MELANIA

[I] THOUGH I have told

above in a superficial way of the wonderful and saintly Melania, nevertheless I

will now weave into my narrative at this point what remains to be said. What

stores of goods she used up in her divine zeal, as it were burning them in a

fire, is not for me to dwell on, but for those who dwell in Persia. For no one

escaped her benevolence, neither East nor West nor North nor South. [2] For

thirtyseven years she had been giving hospitality, and at her own costs had

succored both churches and monasteries and strangers and prisoners, her family

and her son himself and her stewards providing the money. She persevered so

long in the practice of hospitality that she possessed not even a span of land.

She was not drawn (from her purpose) by desire for her son, nor did yearning

after her only son separate her from love towards Christ. [3] But thanks to her

prayers the young man attained a high standard of education and a good

character and an illustrious marriage, and participated in the honors of the

world; he had also two children. A long while after, hearing how her

granddaughter was situated, that she was married and was proposing to renounce

the world, afraid lest they should be injured by bad teaching or heresy or evil

living, though an old woman of sixty years, she flung herself into a ship and

sailing from Caesarea reached Rome in twenty days. [4] And having met there

that most blessed and worthy man Apronianus, a pagan, she instructed him and

made him a Christian, persuading him to be continent as regards his wife,

Melania's niece named Avita. And having also strengthened the will of her own

granddaughter Melania, with her husband Pinianus, and instructed her daughter

inlaw Albina, wife of her son, and having induced all these to sell their

goods, she led them out from Rome and brought them into the holy and calm

harbor of the (religious) life. And in so doing she fought with beasts a in the

shape of all the senators and their wives who tried to prevent her, in view of

(similar) renunciation of the world on the part of the other (senatorial)

houses. But she said to them: " Little children, it was written 400 years

ago, It is the last hour. Why do you love to linger in life's vanities?

Perchance the days of antichrist will surprise you, and you will cease to enjoy

your wealth and your ancestral property." [6] And having liberated all

these she led them to the monastic life. And after instructing the younger son

of Publicola she brought him to Sicily, and having sold all her remaining goods

and receded their value, she came to Jerusalem. Then, having got rid of her

possessions, within forty days she fell asleep in a good old age and profound

meekness, leaving behind both a monastery in Jerusalem and an endowment for it.

[7] But when all these

persons had left Rome there fell on Rome a hurricane of barbarians, which was

ordained long ago in prophecies, and it did not spare even the bronze statues

in the Forum, but sacking them all with barbaric frenzy delivered them to

destruction, so that Rome, which had been beautified by loving hands for 1200

years, became a ruin. Then those who had been instructed (by Melania) and those

who had opposed her instruction glorified God, Who had persuaded the

unbelievers by a reversal of fortune, in that, when all the other families had

been made prisoners, these ones only were preserved, having been made by

Melania's zeal burntofferings to the Lord.

CHAPTER LV: SILVANIA

(MELANIA continued)

[1] IT SO happened that

we traveled together from Aelia to Egypt, escorting the blessed Silvania the

virgin, sisterinlaw of Rufinus the exprefect. Among the party there was

Jovinus also with us, then a deacon, but now bishop of the church of Ascalon, a

devout and learned man. We came into an intense heat and, when we reached

Pelusium, it chanced that Jovinus took a basin and gave his hands and feet a

thorough wash in icecold water, and after washing flung a rug on the ground

and lay down to rest. id] She came to him like a wise mother of a true son and

began to scoff at his softness, saying: " How dare you at your age, when

your blood is still vigorous, thus coddle your flesh, not perceiving the

mischief that is engendered by it? Be sure of this, be sure of it, that I am in

the sixtieth year of my life and except for the tips of my fingers neither my

feet nor my face nor any one of my limbs have touched water, although I am a

victim to various ailments and the doctors try to force me. I have not consented

to make the customary concessions to the flesh, never in my travels have I

rested on a bed or used a litter."

[3] Being very learned

and loving literature she turned night into day by perusing every writing of

the ancient commentators, including 3,000,000 (lines) of Origen and 2,500,000

(lines) of Gregory, Stephen, Pierius, Basil, and other standard writers. Nor

did she read them once only and casually, but she laboriously went through each

book seven or eight times. Wherefore also she was enabled to be freed from

knowledge falsely so called (I Tim. 6:20) and to fly on wings, thanks to the

grace of these books; elevated by kindly hopes she made herself a spiritual

bird and journeyed to Christ.

Palladius: The

Lausiac History

SOURCE : https://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/palladius-lausiac.asp#

St. Melania the Elder

Source

Several sources for the

life of Melania the Elder, the most complete first hand record being

Palladius's Lausiac History (trans. R.T. Meyer, Ancient Christian

Writers, Paulist Press, ©1964), containing three chapters, numerous additional

references, and the life of her granddaughter, St. Melania the Younger.

Important additional first-hand information is located in the writings of

Rufinus of Aquileia, St. Jerome, and in the lives several Fathers of the

Egyptian Desert.[1] The

accounts are not consistent in every detail, especially with regard to her son.[2]

Life

St.Melania was the

daughter of the Roman consul, Marcellinus, and born Spain in 341. She moved to

Rome following her marriage at age 14, to a proconsul and prefect of Rome. She

was widowed eight years later, age 22.

Among the richest women

of her day, she gave away her son to the care of a trustee, and took all her

household goods to Alexandria, where she sold them and befriended the ascetics

and teachers there. She made extended pilgrimages to the Nitrian desert,

learning true philosophy from the great fathers, including Pambo, Paphnutius,

Isidore, and Evagrius. When the Arian bishop Alexandria, Theophilos, banished

many ascetics and hierarchs during the anthropomorphite controversy, St.

Melania followed them into Palestine.

The depth of her

compassion for the needy is reflected in an Egyptian tradition holding that to

alleviate suffering at the hands of the Arians, she feed out of her own wealth

some 5,000 people over the course of three days.

In Palestine, St Melania

supported the ascetics from her own wealth. To serve them, she wore slave's

clothing, an action that resulted in her being cast into prison. When brought

before the judge she defended her action declaring herself a slave of Christ.

St. Melania remained in

Jerusalem when the exiled ascetics were allowed to return to Egypt, and out of

her own wealth established a female cenobium on the Mount of Olives that

exceeded fifty monastics, energetically practiced hospitality, and funded

churches and monasteries in the Roman and Persian Empires, and charitable

works. Erudite, she constantly read and re-read the works of Origen, Basil the

Basil the Great, and Gregory of Nazianzus, turning night into day, she once

reproached a young man, saying How can a warm-blooded young man like you dare

to pamper your flesh...Do you not know that this is the source of much harm?

Look, I am sixty years old and neither my feet nor my face, nor any of members,

except for the tips of my fingers, touched water, although I am afflicted with

many aliments and my doctors urge me. I have not yet made concessions to my

bodily desires, nor have I used a couch for resting, nor have I ever made a

journey on a litter.

As in Alexandria, in

Jerusalem she used the nobility of her character and hospitality in service of

the unity and peace of the Church. In the words of Palladius describing her,

and her coenobium's, work:

So, for twenty-seven

years they both entertained with their own private funds the bishops,

solitaries, and virgins who visited them, coming to Jerusalem to fulfill a vow.

They edified all their visitors and united the four hundred monks of the

Pauline schism by persuading every heretic who denied the Holy Spirit and so

brought them back to the Church. They bestowed gifts on the local clergy, and

so finished their days without offending anyone.

At age sixty, she

traveled to Rome and promoting and teaching the ascetic, peace-loving life.

Among those choosing to follow her in the practice of self-control and

renunciation were her daughter-in-law, Albina, her granddaughter, St. Melania

the Younger and her husband, Pinianus. In doing so, she challenged the Roman

Senators and their wives, for whom notions of asceticism within marriage,

chastity, and virginity were deeply scandalous. Palladius records her prophetic

response: Little children, it was written over four hundred years

ago, it is the last hour. Why are you fond of the vain things of life?

Beware lest the days of the Antichrist overtake you and you not enjoy your

wealth and your ancestral property. Prophetic, for Rome was soon sacked Alaric

in 410, the year of her repose.

Prior to her repose, St.

Melania disposed of all her wealth, sending it to Jerusalem.

Understanding Her

St. Melania and her

social network was one of the most important in the fourth and early fifth

century Christianity. Fluent and well read in both Latin and Greek, her

geographical connections reached from Spain to Persia. She grew-up as a member

of the first generation in which members of the nobility and social elites were

expected to take Christianity seriously, and lived to see it become the

official religion of the Empire. This she did without hypocrisy or compromise

in her way of living, first becoming both an icon of repentance and then an

evangelist to her social peers, urging them to understand the way of salvation

through a life in Him upon whose shoulders rested the government of the

universe.

Her connections to

Hellenistic Christianity of Alexandria, Origen and Evagrius, is no more a basis

for skepticism than the use of these important authors by most of the great Church

Fathers. Indeed, both the breadth of her reading and her political savvy is

reflected in her opposition to Arianism, and how personally she understood the

Psalmist when he said Jerusalem is builded as a city which its dwellers share

in concord. (Ps. 121, LXX) and again Behold now, what is so good or so joyous

as for the brethren to dwell together in unity?...For the Lord commanded the

blessing, life forevermore. (Ps. 132, LXX). In age which saw both the apostasy

of Julian, the destructiveness of Arianism, and proclamations of the Council of

Nicaea, providing erudite hospitality at the center of Christian pilgrimage was

no plain piety.

Making Jerusalem, and not

Alexandria, the center of her activity during the difficult period between the

Councils of Nicaea and Chalcedon, St. Melania and her community on the Mount of

Olives were profoundly important to the sifting of ascetical wisdom and

liturgical expression (that is theological) synthesis that based Palestinian

monasticism.[3]

Humbling herself by

submitting all her wealth, erudition, and daily activity to the hosting of

Christ, acquiring poverty by elevating those poor in body and mind, she

acquired a mature Christian soul, thus, in Palladius words, became a female Man

of God. The comparison to St. Alexis, the Man of God is instructive,

for both profound saints, the highest reality is the anticipation of fully

unity with the true Bridegroom, Christ God. Her life gives no room for

effeminate sentimentality, let alone then, as now, contemporary sociological

agendas: St. Melania the Elder's asceticism is as needed as it is

uncompromising.

Odes of Solomon: Ode II

I am putting on the Love

of the Lord.

And His members are with

Him,

And I am dependent on

them; and He loves me.

For I should not have

know how to love the Lord

If He had not

continuously loved me.

Who is able to

distinguish love,

Except him who is loved?

I love the Beloved and I

myself love Him,

And where His rest is,

there also am I.

And I shall be no

stranger,

Because there is no jealousy

with the Lord Most High and Merciful.

I have been united to

Him, because the lover has found the Beloved,

Because I live Him that

is the Son, I shall become a son.

Indeed, he who is joint

to Him who is immortal,

Truly shall be immortal.

And he who delights in

the Life,

Will become living.

This is the Spirit of the

Lord, which is not false,

Which teaches the sons of

men to know His ways.

Be wise and understanding

and vigilant.

Hallelujah.

translated by James H

Charlesworth, Scholars Press, ©1977

Troparion and Kontakion

Troparion for St. Melania

the Edler, in the Eigth Tone

Scorning perishable

riches and worldly dignity, thou sought heavenly glory through self-denial and

toils. By humility, thou made noble rank noble in heaven. Thou didst build a

holy house in Jerusalem, where thou guided souls to salvation. O Mother Melania

grant us the alms of thy rich prayers to God.

Kontakion for St. Melania

the Elder, in the Fourth Tone

O wise Melania in using

thine earthly to comfort and help the poor, together with the riches of thy

mind, thou led many of noble rank to the joy of poverty in spirit for Jesus'

sake.

Feast day: June 8

[1] cf.

Tim Vivian, "Introduction" to Four Desert Fathers, SVS Press,

©2004 for an informative discussion of St. Melania's relationship to the

Egyptian desert.

[2] Some

modern biographies, including official ones, wrongly claim she had three sons,

two of which died. While understandable, this is a confusion with her

granddaughter, St. Melania the Younger, who, according to both Palladius and

Rufinius in Apology Against Jerome, Book 2 (in Nicene and

Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series vol. 3), had two children, both of which

died prior to the parents entry into asceticism.

[3] For

a useful introduction, cf. John Binns, Ascetics and Ambassadors of Christ:

The Monasteries of Palestine 314-631 Oxford University Press, 1996/©Binns,

1994.

SOURCE : http://andronicus-athanasia.org/Melania_the_Elder.html

Melania the Elder (c. 350–c. 410)

Roman who founded two of

the earliest Christian religious communities. Born around 350 ce; died

around 410 ce; granddaughter of Antonius Marcellinus; grandmother of Melania

the Younger; married possibly Valerius Maximus (a praetorian praefect),

probably in 365; children: three sons, including Valerius Publicola (father of

Melania the Younger).

Melania the Elder (so

called to distinguish her from her namesake granddaughter) was from a Roman

Senatorial family (her paternal grandfather, Antonius Marcellinus, served as

consul in 341) with Spanish roots. Her family was also extremely wealthy and Christian—a

religion which Melania the Elder avidly pursued as a young woman in Rome. Her

husband was of an equally prestigious family, the Valerian, and was perhaps the

Valerius Maximus who held the office of praetorian praefect in the 360s. If

this was so, then a young Melania married a much older man, probably about the

year 365. Despite the probable difference in their ages, this union produced

three sons before Melania was widowed at the age of 22. The death of her

husband was followed within months by the deaths of two of her children,

leaving only Valerius Publicola (the eventual father of Melania

the Younger ) to reach adulthood.

In one sense the tragedy

of these triple deaths liberated Melania the Elder, for instead of remarrying,

she left Rome for Egypt and Palestine, there to associate with the holy men and

women who dominated the Church of the period as priests, bishops, monks and

nuns. Rome was then, in Christian terms, far less developed than were

Jerusalem, Alexandria and their surrounding areas. Melania the Elder was able

to pursue her dream of visiting the East because she had given birth to three

children who had lived past the age of two. By Roman

law, she thus had earned the right to certain freedoms denied women who

could not boast of that accomplishment. What Melania the Elder originally

intended to do with her surviving son is unclear. One source reports that she

took him at least as far as Sicily when she left Rome, seemingly intent upon

bringing him with her to the East. If so, she changed her mind, for Valerius Publicola

was reared in Rome under the care of a guardian, where, although without a

mother's care, he never suffered for the lack of money. Mother and son would

not see each other again until she returned to Rome, probably some 37 years

later.

Like many Christians of

her time, Melania the Elder wished to disassociate herself from material

possessions (although she retained control of a huge estate throughout her life

which she used to fund her religious career) and to deny as many bodily

pleasures as possible in order to cultivate the spirit, thus to prepare for the

hereafter. It was common especially for Roman women bent upon such purification

to withdraw from the world into their own homes, where they fasted and prayed

in a self-imposed isolation—albeit one which could be reversed simply by

walking out into any public thoroughfare. Melania the Elder, however, both knew

of the monastic movement which had only recently swept the Christian East and

had the financial wherewithal to travel there and experience it firsthand.

The early monastic

movement involved holy men and women who sought the isolation of inhospitable

locales where they lived lives of bodily denial, so as to subordinate all

physical desires to the will of the spirit, to study and interpret sacred

scripture without any distractions, and to engage in what was thought a very

real struggle against demons, who thus engaged would be unable to tempt less

resolute Christians back in everyday society. These hermits were among the

"stars" of the late 4th-century Christian world, and their passion to

root out evil in themselves and in the world was deemed charismatic by just

about everyone. Although their wish to live in the wilderness was in large part

generated by the fact that they would thus be removed from other human beings,

the self-imposed isolation of these holy figures was self-defeating, for as

their fame grew, more and more of their Christian brethren followed them into

the desert in order to be in their physical proximity. This soon necessitated a

second stage of monastic development: that in which communities of voluntary

disciples had to be organized, both to prevent them from being a distraction to

the original attraction and to give them something constructive, and hopefully,

"orthodox," to do. The idea of organized Christian communities

somehow set aside from everyday society—and therefore also set aside from

religious authority—thus arose. These communities were at once both

inspirational and troublesome: the former because "God's soldiers" were

known to be "out there" leading the struggle against the forces of

Satan, and the latter because, without the proper over-sight by religious

authority, there was the potential for these communities to be side-tracked

into doctrinal deviancy.

Whatever the potential

pitfalls, Melania the Elder wished to devote herself to physical denial,

spiritual struggle, and religious study, and found what she needed to do so in

the East. Upon her arrival there, she familiarized herself with the vibrant

religious life of Egypt by visiting both the influential See of Alexandria and

the hermits of the desert. Perhaps one of the more important reasons Melania

the Elder did so was that she had become very fond of the theological writings

of Origen (born c. 185 in Alexandria), which she had come to know through the

Latin translations of her contemporary Rufinus. Later, when she moved on to

Jerusalem in the late 370s, Melania founded and endowed a convent for herself

and a monastery in honor of Rufinus (who remained in the West) on the Mount

of Olives. These were not only among the earliest such establishments

founded, they also fostered the asceticism Melania the Elder thought essential

for salvation and a study of scripture in the tradition of Origen. This

tradition, popular especially in the East, interpreted the Bible in the light

of significant philosophical principles which had first been set forth by pagan

thinkers. Although for a long time no one questioned the orthodoxy of such an

approach to the Gospels, this began to change in the 390s, especially in the

West. Thereafter, the orthodoxy of those working in the tradition of Origen

came increasingly under fire.

Melania the Elder never

thought of herself as a heretic. Indeed, she thought of herself as a bastion of

orthodoxy. For example, when the Arian emperor Valens persecuted those in Egypt

who espoused the orthodoxy of the

Trinity, Melania gave them shelter. Because she was a disciple of Origen,

however, others began to question her orthodoxy. Even as the weight of Church

opinion began to swing toward the anti-Origenists, Melania the Elder maintained

her allegiance to Origen's interpretive assumptions, and kept close ties with

others (such as Rufinus, Evagrius Ponticus, and Palladius) who did likewise.

This choice eventually set her at odds with the likes of the famous Jerome and

his female associate Paula ,

both of whom had monastic communities of their own near Bethlehem. As the

argument over the orthodoxy of Origen's tradition heated up, so did the rivalry

between the houses of Melania the Elder and Rufinus on the one hand and those

of Jerome and Paula on the other—violence even occasionally flared. Indeed, by

about 399 the controversy was so intense that Melania decided to return to Rome

for a period. This decision, however, probably had less to do with a desire to

let things in the East cool off than it did to Melania's desire to put forth

the case for Origen to her granddaughter. Melania the Younger's Senatorial

status, kinship to Melania the Elder, and growing fame as a religious zealot in

her own right made her an attractive target for proselytizing by the

anti-Origen faction—if the younger Melania could be won over by them, then the

elder's position could be seriously weakened.

Thus Melania the Elder

returned to Rome (by way of Sicily, where she gave to Paulinus of Nola a piece

of wood thought to be from the true cross) and to her kin. If doctrinal matters

were Melania the Elder's primary reason for her homecoming, it probably failed,

for although Melania the Younger did not go out of her way to embarrass her

grandmother, neither did she fall into Origen's camp. In fact during her own

religious career, Melania the Younger took some pains to disassociate herself

from her grand-mother's memory and foundation, while simultaneously cultivating

good relations with Jerome. It is not surprising, therefore, that tradition has

it that the personal relationship between the two Melanias was a stormy one.

It is not known how long

Melania the Elder remained in the West, but she probably did not stay long.

Returning to her beloved community in Jerusalem, Melania continued her work in

the manner of Origen and the defense of her orthodoxy until she died about the

year 410.

William Greenwalt ,

Associate Professor of Classical History, Santa

Clara University, Santa

Clara, California

Women in World History: A

Biographical Encyclopedia

Voir aussi : Mélanie

l'Ancienne (Antonia Melania) (v. 343, à Rome - 410, dans un monastère à Jérusalem) © France-Spiritualités™ : http://www.histoireetspiritualite.com/religions-fois-philosophie/christianisme/biographies-portraits/melanie-l-ancienne.html

%2C_catacombe_di_priscilla%2C_cubicolo_della_velatio%2C_roma_(met%C3%A0_III_secolo).jpg)