« Mariage de saint Julien d'Antioche et de sainte Basilisse ». Speculum historiale. V. de Beauvais. XVe.

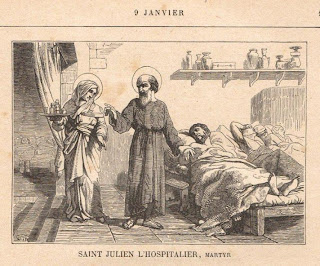

Saints Julien et

Basilisse

Époux, martyrs à

Antinoé (+ 309)

Ils consacrèrent leurs biens au soulagement des pauvres et leurs forces à soigner les malades qu'ils abritaient dans leur maison.

À Antinoé en Thébaïde, au IVe siècle, les saints Julien et Basilisse, martyrs.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/397/Saints-Julien-et-Basilisse.html

Bas-relief

évoquant la légende de saint Julien au no 42 rue Galande, Paris Ve

San

Giuliano traghetta i lebbrosi sul fiume Potenza, bassorilievo del XIV secolo,

Parigi

Saint Julien

l'Hospitalier et sainte Basilisse

Saint Julien naquit à

Antioche, capitale de la Syrie, de parents illustres et craignant DIEU. A l'âge

de dix-huit ans, ils le sollicitèrent de s'engager dans les liens du mariage.

Après quelques jours de réflexion, ayant eu une vision, DIEU lui promit que sa

future épouse conserverait avec lui sa virginité et que leur union serait pour

beaucoup une occasion de salut.

Il consentit alors à

épouser une jeune fille, nommée Basilisse, que ses parents lui présentèrent. Le

soir même des noces, les pieux époux s'étant mis en prière, Basilisse sentit

dans la chambre un suave parfum de fleurs, quoiqu'on fût au cœur de l'hiver.

Son époux lui expliqua comment ces fleurs signifiaient la bonne odeur de la

virginité, et il obtint sans peine qu'elle consentît à vivre avec lui dans la

continence parfaite.

Leur vœu fut aussitôt

récompensé, car un chœur de saints et de saintes, conduit par JÉSUS et MARIE,

leur apparut dans une nuée brillante, et les deux époux entendirent une

harmonie toute céleste qui remplit leur âme d'une joie inénarrable.

Leurs parents étant

morts, ils consacrèrent tous leurs revenus au soulagement des pauvres et des

malades ; ils firent même de leur maison une espèce d'hôpital. Il y avait des

logements séparés pour les hommes et pour les femmes.

Basilisse avait soin des

personnes de son sexe, et Julien, que son immense charité avait fait surnommer

l'hospitalier, avait soin des hommes. La pieuse épouse mourut la première,

après avoir reçu un avertissement céleste, et prédit à son époux qu'il

recevrait bientôt la palme du martyre.

En effet, la persécution

s'étant élevée, Julien, connu par son zèle pour la religion de JÉSUS-CHRIST, ne

tarda pas à être jeté en prison. Son interrogatoire, ses supplices, furent

accompagnés d'étonnants prodiges et surtout de nombreuses conversions.

DIEU permit que son

épouse Basilisse lui apparût pour lui annoncer que la fin de ses combats était

venue et que bientôt il recevrait la palme tant désirée du martyre. Epargné par

le feu et par les bêtes féroces, Julien eut enfin la tête tranchée, le 9

janvier 313.

Ce fut par une jeunesse

sainte et mortifiée et par une fidèle correspondance à la grâce que Julien obtint

tant de faveurs du Ciel. Jamais DIEU ne se laisse vaincre en générosité. —

LE SEIGNEUR a illustré

Saint Julien par plusieurs miracles, non seulement à son tombeau, où dix

lépreux furent guéris le même jour, mais aussi en plusieurs endroits de la

chrétienté.

Pratique. Évitez l'égoïsme ; vivez pour DIEU et le prochain.

SOURCE : http://je-n-oeucume-guere.blogspot.ca/2010/01/09-janvier-saint-julien-lhospitalier.html

Le calendrier civil, en

lien avec la tradition populaire, se réfère à un autre saint Julien, dit

l'Hospitalier, patron des bateliers, des aubergistes et des voyageurs. Il nous

est surtout connu par un beau conte de Gustave Flaubert, reprenant une histoire

déjà propagée depuis des siècles par Jacques de Voragine dans sa Légende

dorée.

On y racontait que Julien

était un grand chasseur devant l'Éternel, selon une référence au Livre de la

Genèse dans la Bible. Un jour, Julien traquait un cerf qui se met à lui parler,

lui prédisant qu'il deviendrait le meurtrier de ses propres parents. Ce qui

arriva par une erreur tragique. Désespéré, parricide sans l'avoir voulu, Julien

décide de tout faire pour se racheter. Il se dépouille de tous ses biens et

construit près d'un fleuve dangereux une maison d'accueil pour les voyageurs.

Il assure gratuitement leur passage : on le nomme l'hospitalier. Par une nuit

de tempête, il risque sa vie pour faire passer un lépreux qui se révèle à lui

comme étant le Christ. On pense tout de suite à saint Christophe : à invoquer

comme protecteur de tous les voyageurs, des vacanciers en ce début du mois

d'août.

Le prénom Julien vient du

latin Julia, famille illustre de romains qui prétendaient être descendants

directs de Vénus ! Le membre le plus célèbre de cette famille est bien sûr

Jules César.

Rédacteur : Frère Bernard

Pineau, OP

SOURCE : http://www.lejourduseigneur.com/Web-TV/Saints/Julien-l-hospitalier

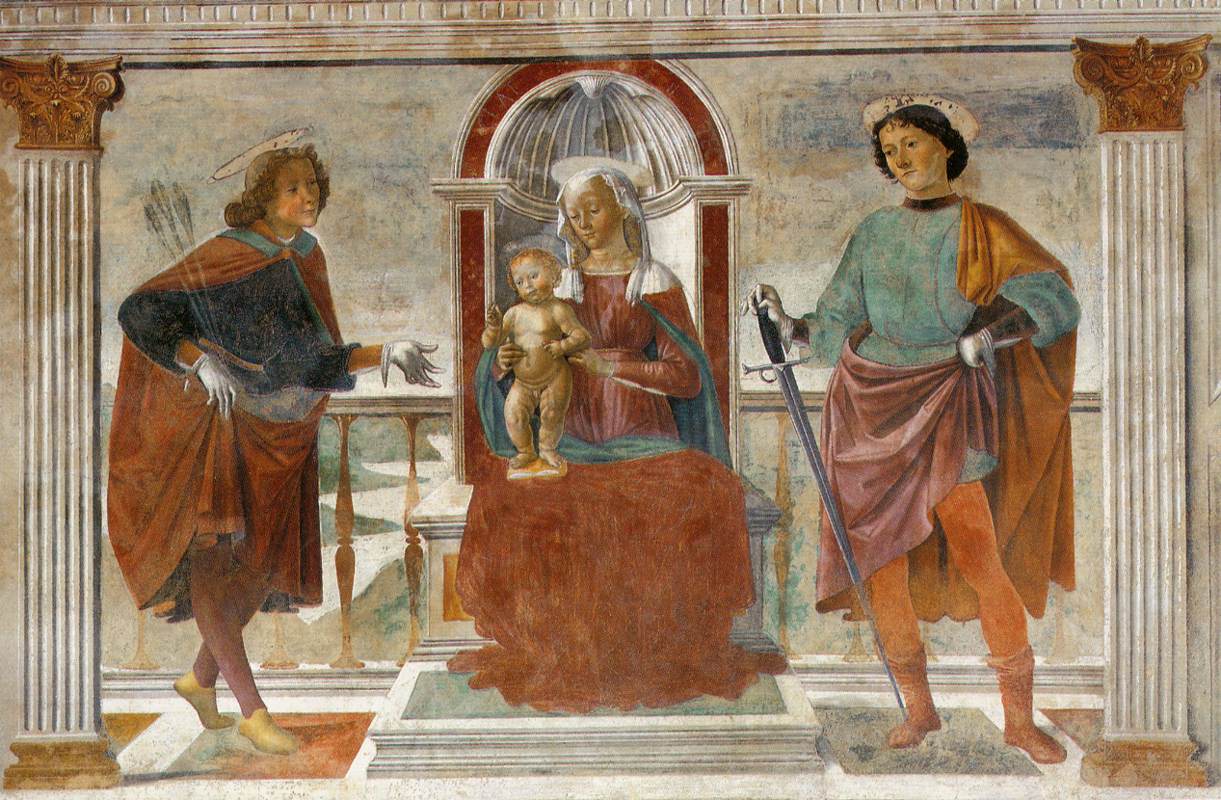

Masolino da Panicale (1383–1447),

Scènes de l'histoire de Saint Julien (Julien assassinant son père), 1426,

24 x 43, Musée Ingres

SAINT JULIEN

L’HOSPITALIER

Texte résumé et modifié.

Inspiré de Gustave Flaubert.

Le père et la mère de

Julien habitaient un château, au milieu des bois, sur la pente d’une colline.

On y vivait en paix

depuis si longtemps que la herse ne s’abaissait plus; les fossés étaient pleins

d’eau et des hirondelles faisaient leur nid dans la fente des créneaux.

L’archer qui se promenait

toute la journée sur la courtine, dès que le soleil brillait trop fort,

rentrait dans l’échauguette et s’endormait.

A l’intérieur, tous

respirait l’abondance : les armoires regorgeaient de linge, les tapisseries

protégeaient du froid, les tonnes de vins s’empilaient dans les celliers et les

coffres craquaient sous le poids des sacs d’argent.

Le bon seigneur du lieu,

se promenait dans sa maison, rendant la justice, apaisant les querelles.

Pendant l’hiver, il se faisait lire des histoires. Dès les premiers beaux

jours, il allait se promener le long des chemins et causait avec les manants auxquels

il donnait des conseils.

Après beaucoup

d’aventures, il avait pris pour femme une demoiselle de haut lignage. Elle

était très blanche, un peu fière et sérieuse. A force de prier Dieu, il lui

vint un fils.

Alors, il y eut de

grandes réjouissances qui durèrent trois jours et quatre nuits. On y mangea les

plus rares épices avec des poules grosses comme des moutons.

La mère n’assista pas à

ces fêtes. Elle se tenait dans son lit tranquillement.

Un soir, elle se

réveilla, et elle aperçut, à travers la fenêtre, un vieillard en froc de bure,

avec un chapelet au côté, qui avait toute l’apparence d’un ermite.

Il s’approcha de son

chevet et lui dit :

- “ Réjouis-toi ô mère !

ton fils sera un saint !”

Elle allait crier mais le

vieillard disparut.

Elle entendit les voix

des anges mais sa tête retomba sur l’oreiller. Le lendemain, elle eut soin de

n’en rien dire, ayant peur qu’on ne l’accusât d’orgueil.

Les convives s’en

allèrent au petit jour; et le père de Julien se trouvait en dehors de la poterne.

Quand soudain un mendiant se dressa devant lui, c’était un Bohème à barbe

tressée, avec des yeux aux prunelles flamboyantes.

Il bégaya ces mots :

- “ Ah ! ah! ton fils !…

beaucoup de sang!… beaucoup de gloire!… toujours heureux ! La famille d’un empereur.”

Puis il disparut.

Le châtelain attribua

cette vision à la fatigue “si j’en parle, on se moquera de moi”.

Les époux cachèrent leur

secret. Tous deux chérissaient l’enfant d’un pareil amour.

Quand il eut sept ans, sa

mère lui appris à chanter. Son père, pour le rendre courageux, le hissa sur un

gros cheval. Il ne tarda pas à savoir tout ce qui concerne les destriers. Un

vieux moine très savant lui enseigna l’Écriture sainte, la numération des

Arabes, les lettres latines.

Julien écoutait souvent,

avec émotion, le châtelain et ses compagnons raconter leurs faits d’armes. mais

le soir, au sortir de l’angélus, il puisait dans son escarcelle et, avec

modestie, donnait aux pauvres inclinés devant lui.

Sa place dans la chapelle

était aux côtés de ses parents. Il était très pieux.

Un jour, pendant la

messe, il aperçut, en relevant la tête, une petite souris blanche qui sortait

d’un trou dans la muraille. Après deux ou trois tours, elle s’enfuit par le

trou.

Elle revint chaque

dimanche. Il en était importuné. Pris de haine contre elle il décida de s’en

défaire. Il mit donc des miettes de gâteau sur les marches, et, attendit une

baguette à la main. Au bout d’un long moment, quand la souris parut, il la

frappa avec son bâton et demeura stupéfait devant ce petit corps sanglant qui

ne bougeait plus.

Beaucoup d’oisillons

picoraient les graines du jardin. Il imagina de mettre des pois dans un roseau

creux. Quand il entendait gazouiller, il s’approchait avec douceur puis, en

enflant ses joues, il levait son tube et les bestioles lui pleuvaient

abondamment sur les épaules. Il ne pouvait alors s’empêcher de rire.

Un matin, il vit un gros

pigeon sur le rempart. Avec une pierre, il abattit l’oiseau. Le pigeon aux

ailes cassées palpitait toujours. Julien était irrité de ce qu’il vivait encore

et se mit à l’étrangler. Au dernier raidissement, il faillit s’évanouir.

Un soir, son père décida

qu’il devait être initié à la chasse. Il lui constitua une grande meute et une

fauconnerie avec des piqueurs et des rabatteurs. Mais cela n’intéressait pas

vraiment Julien qui préférait chasser loin du monde, seul avec son cheval, son

faucon et ses chiens.

Quand le cerf commençait

à gémir sous les morsures, il l’abattait prestement puis se délectait à la

furie des chiens qui le dévoraient. Il tua des ours, des taureaux, des

sangliers et des loups…

Un matin d’hiver, il

partit en forêt malgré la neige. Remarquant un coq de bruyère qui, engourdi par

le froid, dormait la tête sous l’aile, il lui faucha les deux pattes. Il

enfonça son poignard dans le corps d’un bouquetin, assomma, avec son fouet, les

grues qui passaient au dessus de sa tête, tua, de loin, à l’aide d’une flèche,

un castor au museau noir.

Il tua bien des

chevreuils, des blaireaux, des daims qui tournaient autour de lui avec un

regard plein de douceur et de supplications. Mais il ne se fatiguait pas de

tuer et n’en gardait pas le souvenir.

Un jour, il vit de

nombreux cerfs entassés dans un vallon. Ils se réchauffaient de leur haleine

que l’on voyait fumer dans le brouillard. L’espoir d’un pareil carnage le

suffoqua de plaisir.

Puis, il se mit à tirer.

Au sifflement de la première flèche, un mouvement agita le troupeau. Le rebord

du vallon était trop haut pour le franchir. Ils bondissaient dans l’enceinte,

cherchant à s’échapper. Les cerfs rendus furieux se battaient. Les flèches

tombaient comme une pluie d’orage. Ils moururent couchés sur le sable.

Puis tout fut immobile.

la nuit allait venir, le ciel était rouge comme une nappe de sang.

Julien s’adossa à un

arbre, contemplant l’énormité du massacre et ne comprenant pas comment il avait

pu le faire.

De l’autre coté du

vallon, il aperçut un énorme cerf noir, une biche et son faon qui tétait les

mamelles de sa mère. Encore une fois, l’arbalète ronfla. Le faon fut tué. Sa

mère regarda le ciel en bramant d’une voix profonde, déchirante, humaine.

Julien la tua.

Le grand cerf l’avait vu.

Il fit un bond mais Julien lui envoya sa dernière flèche. Elle l’atteignit au

front et y resta plantée.

Enjambant par dessus les

morts, le grand cerf s’approcha de Julien comme s’il voulait l’éventrer. Julien

eut une épouvante indicible. L’animal s’arrêta, les yeux flamboyant, solennel

comme un patriarche et comme un justicier. Pendant qu’une cloche tintait au

loin, il répéta trois fois :

“Maudit ! maudit ! maudit

! Un jour, coeur féroce, tu assassineras ton père et ta mère !”

Puis, le cerf mourut.

Julien fut stupéfait. Un

dégoût et une tristesse l’envahit. Accablé, il pleura longtemps.

De retour au château, il

ne dormit pas la nuit. la prédiction du cerf noir l’obsédait. “Non, non, je ne

peux pas les tuer ! “ Puis, “Si je le voulais pourtant?...” et il

avait peur que le diable lui en souffle l’envie.

Durant trois mois, les

parents de Julien s’inquiétèrent du mal de leur fils. Puis, quand il fut

rétabli, il pris la résolution de ne plus chasser.

Son père lui fit cadeau

d’une épée sarrasine. Julien monta sur une échelle pour la prendre en haut d’un

pilier où elle était accrochée. Mais l’épée trop lourde lui échappa des mains.

En tombant, elle coupa le manteau de son père. Julien qui crut l’avoir tué

s’évanouit.

Dès lors, il redouta les

armes. Le vieux moine qui lui avait tout enseigné lui commanda de reprendre de

l’exercice. Il s’initia au maniement de la javeline et y excella bien vite.

Un soir d’été, il

aperçut, tout au fond du jardin, deux ailes blanches qui voletaient. Il pensa

que c’était une cigogne et lança son javelot. Un cri déchirant partit. C’était

sa mère dont le bonnet à longues barbes restait cloué au mur.

Julien s’enfuit du

château et ne reparut plus.

Il s’engagea dans une

troupe d’aventuriers. Grâce à son courage, il commanda sans peine toute la

compagnie. Il échappa toujours à la mort grâce à la faveur divine, car il

protégeait les gens d’église, les veuves les orphelins et les vieillards. Il se

mit au service des grands de ce monde. Il sauva même la vie de l’empereur

d’Occitanie, qui, pour le remercier, lui donna sa fille en mariage. Elle était

très belle. Julien accepta et l’épousa. Il vécurent dans un grand palais de

marbre blanc.

Julien ne faisait plus la

guerre. Il se reposait entouré d’un peuple tranquille. Quelquefois, dans un

rêve, il se voyait comme notre père Adam, au milieu du paradis, entre toutes

ses bêtes; en allongeant les bras, il les faisait toutes mourir.

Des amis l’invitèrent à

chasser, il refusait toujours. Sa femme, pour le divertir faisait venir

jongleurs et danseuses. Ils se promenaient longuement dans la campagne.

Un jour, Julien lui avoua

son horrible pensée. Elle la combattit en raisonnant très bien : son père et sa

mère étaient probablement morts.

Un soir qu’ils étaient

dans leur chambre, Julien entendit le jappement d’un renard puis entrevit dans

l’ombre comme des apparences d’animaux. La tentation était trop forte, il

décrocha son carquois et partit dans la forêt. “Au lever du soleil, je serai revenu

!”

Après son départ,

Arrivèrent au château, deux vieillards poussiéreux. Ils dirent qu’ils

apportaient à Julien des nouvelles de ses parents. Le maître étant absent,

c’est la seigneuresse qui les reçut. Ils demandèrent à la jeune femme si Julien

aimait toujours ses parents, s’il parlait d’eux ? Celle-ci répondait que oui.

Ils avouèrent alors qu’ils étaient eux-mêmes ses parents et donnèrent des

preuves en décrivant leur fils en détail.

Ils racontèrent le long

voyage qu’ils avaient dû faire pour retrouver leur fils ainsi que l’argent

qu’ils avaient dépensés à tel point que maintenant, ils étaient obligés de

mendier.

Lorsque les parents de

Julien découvrirent les richesses du château, ils pensèrent à la prophétie de

l’ermite et du mendiant, de nombreuses années auparavant.

La femme de Julien les

engagea à ne pas l’attendre mais à aller se reposer. Elle les coucha alors dans

son propre lit puis ferma la fenêtre, ils s’endormirent.

Le jour allait paraître

et les petits oiseaux commençaient à chanter.

Pendant ce temps, Julien

marchait d’un pas nerveux dans la forêt. Il vit des sangliers, des loups, des

hyènes qu’il ne put atteindre de ses flèches. Il s’en affligeât et sentait

qu’un pouvoir supérieur avait détruit sa force.

Il y avait dans les

feuillages, des yeux d’animaux, des chats sauvages, des écureuils, des hiboux,

des perroquets, des singes. Julien tira contre eux ses flèches mais elles se

posaient sur les feuilles comme des papillons blancs. Il leur jeta des pierres,

les pierres sans rien toucher retombaient. Il aurait voulu se battre, hurla des

imprécations, étouffait de rage.

Tous les animaux qu’il

avait poursuivis se représentèrent en faisant autour de lui un cercle étroit

comme pour le narguer. Julien se mit à courir, ils le poursuivirent. Le serpent

sifflait, les bêtes puantes bavaient, les singes le pinçaient en grimaçant. Un

ours, d’un revers, lui enleva son chapeau. Une ironie perçait dans leurs

allures sournoises.

Les animaux semblaient

méditer un plan de vengeance.

Le coq chanta. Julien

reconnut au loin les toits de son château et courut de plus belle. Sur le bord

du champ, il vit des perdrix. Il jeta sur elles son manteau tel un filet. Quand

il les eut découvertes, il n’en trouva plus qu’une seule, et morte depuis

longtemps, pourrie.

Cette déception

l’exaspéra. Sa soif de carnage le reprit. Les bêtes manquant, il aurait voulu

massacrer des hommes.

Il arriva enfin chez lui

et se détendit en pensant à sa femme. Elle dormait sans doute, et il allait la

surprendre. Ayant retiré ses sandales, il tourna doucement la serrure, et

entra. Les vitraux garnis de plombs obscurcissaient la chambre. Perdu dans les ténèbres,

il s’approcha du lit.

Quand il voulut embrasser

sa femme, il sentit contre sa bouche l’impression d’une barbe. Il se recula

croyant devenir fou; mais revint auprès du lit et ses doigt touchèrent des

cheveux qui étaient très longs. A côté, c’était bel et bien une barbe qu’il

sentait. La barbe d’un homme, un homme couché avec sa femme. Eclatant d’une

colère démesurée, il bondit sur eux à coups de poignard; il trépignait,

écumait, avec des hurlements de bêtes fauves.

Puis il s’arrêta, il

écoutait maintenant deux râles qui s’affaiblissaient. Cette voix plaintive se

rapprochait, s’enfla, devint cruelle; et il reconnut, terrifié, le bramement du

grand cerf noir.

Alors, il crut voir dans

l’encadrure de la porte, le fantôme de sa femme, une lumière à la main.

Celle-ci épouvantée comprit et s’enfuit en courant , et laissa tomber son

flambeau. Julien le ramassa. Son père et sa mère étaient devant lui, étendus

sur le dos avec un trou dans la poitrine. Leur visages majestueux et doux

avaient l’air de garder comme un secret éternel.

A la fin du jour, il se

présenta à sa femme et lui commanda de ne pas lui répondre, de ne pas

l’approcher et de ne pas le regarder. Il lui donna des instructions pour les

funérailles de ses parents puis partit en abandonnant tout.

Pendant la messe, un

moine, cagoule rabattue resta à plat ventre, les bras en croix et le front dans

la poussière.

Puis il disparut.

Julien s’en alla de par

le monde, recherchant la solitude de la campagne. Mais chaque nuit, en rêve,

son parricide recommençait. Il mendiait çà et là, et son visage était si triste

que jamais on ne lui refusait l’aumône. Le temps qui passait n’apaisait pas sa

souffrance. Il ne se révoltait pas contre Dieu qui lui avait infligé cette

action, et pourtant se désespérait de l’avoir pu commettre. Il résolut alors de

mourir.

Un jour qu’il était au

bord d’une fontaine et qu’il se penchait pour juger de la profondeur de l’eau,

il vit l’image d’un vieillard tout décharné. Sans reconnaître son image,

il se rappela confusément du visage de son père et ne pensa plus à se tuer.

Portant ainsi le poids de

son souvenir, il arriva près d’un fleuve dont la traversée était dangereuse. Il

eu l’idée de mettre son existence au service des autres.

Il aménagea la berge,

répara une vieille barque et s’installa modestement dans une cahute qu’il fit

avec de la terre glaise. Une petite table, un escabeau, un lit de

feuilles mortes et trois coupes d’argile lui servaient de mobilier.

Des gens se présentèrent,

il les fit traverser sans épargner ses peines. Il ne demandait rien en échange.

Certains lui donnaient des restes de victuailles ou des habits usés. D’autres

vociféraient des blasphèmes. Il les reprenait avec douceur et, s’ils

l’injuriaient, il se contentait de les bénir.

Une nuit qu’il dormait,

il crut entendre quelqu’un l’appeler. Il tendit l’oreille mais ne distingua que

le mugissement des flots. Mais la même voix reprit :

- “Julien !”

Elle venait de l’autre

bord. Ce qui paraissait extraordinaire vu la largeur du fleuve.

Une deuxième fois, on

l’appela :

- “Julien !”

Il sortit en tenant sa

lanterne à la main. Un ouragan furieux emplissait la nuit. Les ténèbres étaient

profondes. Julien ne vit rien.

Une troisième fois, la voix se fit entendre :

- “Julien !”

Après un moment

d’hésitation, Julien dénoua l’amarre. L’eau devint tranquille et la barque

glissa jusqu’à l’autre berge où un homme l’attendait.

En s’approchant de lui,

Julien s’aperçut qu’une lèpre hideuse le recouvrait. Cependant, son attitude

avait la majesté d’un roi.

Dès qu’il entra dans sa

barque, elle enfonça prodigieusement, écrasée par son poids. Une secousse la

remonta et Julien se mit à ramer. La grêle cinglait ses mains et la pluie

coulait dans son dos, la traversée dura longtemps.

Quand ils furent arrivé

dans la cahute, Julien ferma la porte et le vit siégeant sur l’escabeau. Le

linceul qui le recouvrait était tombé jusqu’à ses hanches? Sa poitrine et ses

bras étaient recouverts de pustules écailleuses. Il avait un trou à la place du

nez et ses lèvres bleuâtre dégageaient une haleine nauséabonde.

- “ J’ai faim ! “ dit-il.

Julien lui donna ce qu’il

possédait : un vieux morceau de lard et un croûton de pain. Quand il les eut

dévorés, il dit encore :

- “ J’ai soif ! “

Julien lui apporta une

cruche d’eau dont il vit qu’elle était devenue du vin.

- “ J’ai froid ! “ dit

l’homme.

Julien enflamma un paquet

de fougères, au milieu de la cabane.

Le lépreux vint s’y

chauffer.

Puis, d’une voix presque

éteinte, il murmura :

- “ Ton lit ! “.

Julien l’aida doucement à

l’y traîner et étendit sur lui la toile de son bateau. Le lépreux gémissait,

les coins de sa bouche découvraient ses dents, un râle accéléré lui secouait la

poitrine. Puis il ferma ses paupières.

- “ C’est comme de la

glace dans mes os ! Viens près de moi ! “

Julien, écartant la

toile, se coucha sur les feuilles mortes, près de lui, côte à côte.

Le lépreux tourna la

tête.

- “ Déshabille-toi, pour

que j’aie la chaleur de ton corps ! “

Julien ôta ses vêtements;

puis, nu comme le jour de sa naissance, se replaça dans le lit. Il sentait

contre lui la peau du lépreux plus froide qu’un serpent, rude comme une lime.

- “ Ah, je vais mourir…

rapproche-toi, réchauffe-moi avec toute ta personne ! “

Julien s’étala dessus

bouche contre bouche, poitrine contre poitrine.

Alors le lépreux

l’étreignit; ses yeux tout à coup prirent une clarté d’étoile, ses cheveux

s’allongèrent comme les rais du soleil; le souffle de ses narines avait la

douceur des roses.

Puis il se mit à grandir,

touchant de sa tête les murs de la cabane. Le toit s’envola, le firmament se

déployait.

Et Julien monta vers les

espaces bleus, face à face avec Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ qui l’emportait

vers le ciel.

Et voilà l’histoire de

Saint Julien l’hospitalier, telle, à peu près, qu’on la trouve, sur un

vitrail d’église, dans mon pays.

Fête le 27 janvier ou le

12 février.

SOURCE : http://carmina-carmina.com/carmina/Mytholosaints/julien.htm

Cristofano Allori (1577–1621), Saint

Julien offre I'hospitalité aux pèlerins, circa 1610, 259 x 202, Palazzo

Pitti

SAINT-JULIEN

D'après La Légende

Dorée de jacques de Voragine

On trouve encore un autre

julien qui tua son père et sa mère sans le savoir. Un jour, ce jeune noble

prenait le plaisir de la chasse et poursuivait un cerf qu'il avait fait lever,

quand tout à coup le cerf se tourna vers lui miraculeusement et lui dit : "

Tu me poursuis, toi qui tueras ton père et ta mère ? " Quand Julien eut

entendu cela, il fut étrangement saisi, et dans la crainte que tel malheur

prédit par le cerf lui arrivât, il s'en alla sans prévenir personne, et se

retira dans un pays fort éloigné, où il se mit au service d'un prince; il se

comporta si honorablement partout, à la guerre, comme à la cour, que le prince

le fit son lieutenant et le maria à une châtelaine veuve, en lui donnant un

château pour dot. Cependant, les parents de Julien, tourmentés de la perte de

leur fils, se mirent à sa recherche en parcourant avec soin les lieux où ils

avaient l'espoir de le trouver. Enfin ils arrivèrent au château dont Julien,

était le seigneur : Pour lors saint julien se trouvait absent. Quand sa femme

les vit et leur eut demandé qui ils étaient, et qu'ils eurent raconté tout ce

qui était arrivé à leur fils, elle reconnut que c'était le père et la mère de

son époux, parce qu'elle l'avait entendu souvent lui raconter son histoire.

Elle les reçut donc avec bonté, et pour l'amour de son mari, elle leur donne

son lit et prend pour elle une autre chambre. Le matin arrivé, la châtelaine

alla à l'église; pendant ce temps, arriva Julien qui entra dans sa chambre à

coucher comme pour éveiller sa femme; mais trouvant deux personnes endormies,

il suppose que c'est sa femme avec un adultère, tire son épée sans faire de

bruit et les tue l'un et l'autre ensemble. En sortant de chez soi, il voit son

épouse revenir de l'église; plein de surprise, il lui demande qui sont ceux qui

étaient couchés dans son lit : " Ce sont, répond-elle, votre père et votre

mère qui vous ont cherché bien longtemps et que j'ai fait mettre en votre

chambre. " En entendant cela, il resta à demi mort, se mit à verser des

larmes très amères et à dire : " Ah! malheureux! Que ferais-je ? J'ai tué

mes bien-aimés parents. La voici accomplie, cette parole du cerf; en voulant

éviter le plus affreux des malheurs, je l'ai accompli. Adieu donc, ma chère

sueur, je ne me reposerai désormais que je n'aie su que Dieu a accepté ma

pénitence. " Elle répondit : " Il ne sera pas dit, très cher frère,

que je te quitterai; mais si j'ai partagé tes plaisirs, je partagerai aussi ta

douleur. " Alors, ils se retirèrent tous les deux sur les bords d'un grand

fleuve, où plusieurs perdaient la vie, ils y établirent un grand hôpital où ils

pourraient faire pénitence; sans cesse occupés à faire passer la rivière à ceux

qui se présentaient, et à recevoir tous les pauvres. Longtemps après, vers

minuit, pendant que julien se reposait de ses fatigues et qu'il y avait grande

gelée, il entendit une voix qui se lamentait pitoyablement et priait julien

d'une façon lugubre, de le vouloir passer. A peine l'eut-il entendu qu'il se

leva de suite, et il ramena dans sa maison un homme qu'il avait trouvé mourant

de froid; il alluma le feu et s'efforça de le réchauffer, comme il ne pouvait

réussir, dans la crainte qu'il ne vînt à mourir, il le porta dans son petit lit

et le couvrit soigneusement. Quelques instants après, celui qui paraissait si

malade et comme couvert de lèpre se lève blanc comme neige vers le ciel, et dit

à son hôte : " Julien, le Seigneur m'a envoyé pour vous avertir qu'il a

accepté votre pénitence et que dans peu de temps tous deux vous reposerez dans

le Seigneur. " Alors il disparut, et peu de temps après Julien mourut dans

le Seigneur avec sa femme, plein de bonnes oeuvres et d'aumônes.

Traduction J.-B. M. Roze

GARNIER-FLAMARION, Paris, 1967.

SOURCE : http://www.rouen-histoire.com/Vitraux/Saint_Julien/Legende_Doree.htm

Saint-Julien. Tableau du retable de Saint-Julien de l'église Saint-Léger de Saint-Léger-des-Prés (35).

Saint-Julien. Tableau du retable de Saint-Julien de l'église Saint-Léger de Saint-Léger-des-Prés (35).

Saint-Julien.

Tableau du retable de Saint-Julien de l'église Saint-Léger de

Saint-Léger-des-Prés (35).

Also

known as

Julian Hospitator

Julian the Poor

Giuliano…

Julijan Ubogi

31

August (city and diocese of Macerata, Italy)

last Sunday in August (hunters in Malta)

12

February on some calendars

Profile

Noble layman;

friend and counselor to the king,

he was married to

a wealthy widow.

A stag he

was hunting predicted

he would kill his

own parents. Julian moved far away to avoid his parents, but they found him,

and came to make a surprise visit. His wife gave

them her and Julian’s bed; Julian killed them,

thinking they were his wife and

another man.

As penance, he and

his wife travelled to Rome, Italy as pilgrims seeking absolution.

On his way home, to continue his penance, Julian built a hospice beside a

river, cared for the poor and sick,

and rowed travellers across

the river for free.

Once, after having helped

many, many travellers,

Julian gave his own bed to a pilgrim leper who

had nearly frozen to death. When they had him safely settled, the man suddenly

revealed himself to be an angel. The visitor announced that Christ had accepted

Julian’s penance; the angel then

disappeared.

Immensely popular in

times past; scholars today think the story is likely to be pious fiction,

mistaken for history.

to

obtain lodging while travelling

–

–

Worshipful

Company of Innholders

carrying a leper through

a river

holding an oar

man listening to a

talking stag

with Jesus and Saint Martha as patrons of travellers

young

man killing his parents in bed

young

man wearing a fur-lined cloak, sword,

and gloves

young,

well-dressed man holding a hawk on

his finger

Additional

Information

A

Garner of Saints, by Allen Banks Hinds, M.A.

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

Oxford Dictionary of Saints, by David Hugh Farmer

Saints

and Their Attributes, by Helen Roeder

Some Patron Saints, by

Padraic Gregory

other

sites in english

Life of Saint Julian

the Hospitaller, translated by Tony Devaney Morinelli

images

videos

fonti

in italiano

spletne

strani v slovenšcini

MLA

Citation

“Saint Julian the

Hospitaller“. CatholicSaints.Info. 16 June 2024. Web. 7 January 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-julian-the-hospitaller/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-julian-the-hospitaller/

Křivoklát, okres Rakovník, Amalín, č. p. 27, restaurace Nad Hradem,

malba svatého Juliána Chudého.

Křivoklát, Rakovník District, Central Bohemian Region, the Czech

Republic. Amalín, house No. 27, restaurant Nad Hradem, a mural of Saint

Julian the Hospitaller.

St. Julian

Feastday: February 12

Patron: of hotel

keepers, travelers, and boatman

According to a pious

fiction that was very popular in the Middle Ages, Julian was of noble birth and

while hunting one day, was reproached by a hart for hunting him and told that

he would one day kill his mother and father. He was richly rewarded for his services

by a king and married a widow. While he was away his mother and father arrived

at his castle seeking him; When his wife realized who they were, she put them

up for the night in the master's bed room. When Julian returned unexpectedly

later that night and saw a man and

a woman in

his bed, he suspected the worst and killed them both. When his wife returned

from church and he found he had killed his parents, he was overcome with

remorse and fled the castle, resolved to do a fitting penance. He was joined by

his wife and they built an inn for travelers near a wide river, and a hospital

for the poor. He was forgiven for his crime when he gave help to a leper in his

own bed; the leper turned out to be a messenger from God who

had been sent to test him. He is the patron of hotel keepers, travelers, and

boatmen. His feast day is

February 12th.

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=400

San

Giuliano, santo altare Natività, Chiesa di San Giuliano, Vicenza

St. Julian the Hospitaler

Feastday: February 12

Patron: of

Boatmen, carnival workers, childless people, circus workers, clowns, ferrymen,

fiddlers, fiddle players, hospitallers, hotel-keepers, hunters, innkeepers,

jugglers, knights, murderers, pilgrims, shepherds, to obtain lodging while

traveling, travelers

Death: unknown

Patron saint of boatmen,

innkeepers, and travelers, also called "the Poor." Reported in the

doubtful Golden Legend, Julian slew his noble parents in

a case of mistaken identity. He believed his wife was with another man and

struck them both. His wife returned home from church soon after. In penance,

Julian and his wife went to Rome. Returning after receiving absolution, Julian

built an inn and a hospital for the poor. He even put a leper into his own bed.

That leper was an angel.

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=4129

Andrea del Castagno (1420–1457),

San Giuliano e il Redentore, circa 1453, tempera, gesso e affresco ,

223 x 209, basilica della Santissima

Annunziata, Firenze

St. Julian the Hospitaller

Feast day: Feb 12

St. Julian the

Hospitaller, or "the Poor Man," came from a wealthy, noble family in

the early 4th century and is a popular saint in Western Europe.

According to a legend,

while Julian was a baby, he was cursed to one-day kill his own parents. His

father wanted him killed, but his mother kept him alive. When he was old enough

to learn of the curse, he left his family to preserve their safety.

While he was hunting, his

mother and father made an unexpected visit to his castle. His wife gave them

one of the best rooms. He received a vision from the devil that his wife was in

his bed with another man, and he returned home to kill whoever was in his bed.

When Julian returned from his hunt and saw the two figures in bed, he assumed

it was his wife with a lover. In a jealous rage, Julian killed his mother and

father.

Julian was so horrified

upon learning the truth that he swore to devote the remainder of his life to

good works. He and his wife then undertook a pilgrimage to a distant country

where he established a hospital.

The hospital was near a

river that was frequently crossed by people prompted to travel by the Holy

Crusades. People frequently drowned crossing this river so Julian took

responsibility of ferrying travelers across and tending to the sick.

One night, the devil

vandalized his house, and blaming it on those he helped, Julian said that he

would never house anyone else ever again. God showed up at his door, asking for

help, and he denied Him. After recognizing him, he retracted his statement and

decided to help all those who needed it once again. /p>

One night, thieves came

into their hospital and killed Julian and his wife in the same way Julian had

killed his mother and father.

“There were great

miracles without end in that place and land,” recounts the legend. “So many

that, as it pleased God, their bodies were brought to Brioude (France).”

St. Julian is considered

the patron of ferrymen, innkeepers and circus performers.

SOURCE : https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/saint/st-julian-the-hospitaller-145

Giovanni del Biondo (fl 1356–99). Der

heilige Julian trägt einen Wanderer durch den Fluss, Gemäldegalerie, Berlino

Sts. Julian and Basilissa

Husband and wife; died

at Antioch or, more probably, at Antinoe,

in the reign of Diocletian,

early in the fourth century, on 9 January, according to

the Roman Martyrology, or 8 January, according to

the Greek Menaea. We have no historically certain data

relating to these two holy personages, and more than one

this Julian of Antinoe has

been confounded with Julian of Cilicia. The confusion is easily

explained by the fact that thirty-nine saints of

this name are mentioned in the Roman Martyrology, eight of whom are

commemorated in the one month of January. But little is known of this saint,

one we put aside the exaggerations of his Acts. Forced by his family to marry,

he agreed with his spouse, Basilissa, that they should both preserve

their virginity, and further encouraged her to found a convent for women,

of which she became the superior. while he himself gathered a large number

of monks and

undertook their direction. Basilissa died a

very holy death, but martyrdom was

reserved for Julian. During the persecution of Diocletian he

was arrested, tortured, and put

to death at Antioch,

in Syria,

by the order of the governor, Martian, according to the Latins,

at Antinoe,

in Egypt,

according to the Greeks, which seems more probable. Unfortunately,

the Acts of this martyr belong

to those pious romances

so much appreciated in early times, whose authors, unearned only for the

edification of their readers, drowned the few known facts in a mass

of imaginary details. Like many similar lives of saints,

it offers miracles,

prodigies, and improbable utterances, that lack the

least historical value. In any ease these two saints must

have enjoyed a great reputation in antiquity, and

their veneration was well established before the eighth century. In

the "Martyrologium Hieronymianum" they are mentioned under 6

January; Usuard, Ado, Notker,

and others place them under the ninth, and Rabanus

Maurus under the thirteenth of the same month, while Vandelbert

puts them under 13 February, and the Menology of Canisius under

21 June, the day to which the Greek Menaea assign St.

Julian of Caesarea. There used

to exist at Constantinople a church under

the invocation of these saints,

the dedication of which is inscribed in

the Greek Calendar under 5 July.

Sources

Acta SS. Bolland. Jan. I

(1643), 570-75; MARCHINI, I SS. Giuliano e Basilissa sposi, vergini e

martiri, protettori dei conjugati (Genoa, 1873); TILLEMONT, Mémoires

pour servir à l'hist. eccl. V (Paris, 1698), 799 sqq.; SURIUS, Vit.

Sanct., I (Venice 1581), 61-62.

Clugnet,

Léon. "Sts. Julian and Basilissa." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton

Company, 1910. 12 Feb. 2016 http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08556b.htm.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Joseph E. O'Connor.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. October 1, 1910. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2023 by Kevin Knight.

Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08556b.htm

Julian the Hospitaler

(AC)

(also known as Julian the

Poor Man)

Fictitious; feast day of

January 29 in the Acta Sanctorum appears to be arbitrary. Of the many churches,

hospitals, and other charitable institutions in western Europe which bore or

bear the name of Saint Julian, most commemorate this hero of a romance, a pious

fiction that was very popular in the Middle Ages. There is no evidence to

suggest any historicity whatsoever.

According to the James

Voragine's Golden Legend, Julian the Hospitaler accidentally committed one of

the worst crimes possible: He killed his parents. This was predicted one day

while the nobleman was hunting. A deer reproached Julian for hunting him and

said that in the future he would commit the crime. Afraid of committing such a

terrible crime, Julian migrated to a far land and served the king there so well

that he was knighted and given a rich widow in marriage with a castle for her

dowry.

One day he returned to

his castle and went to the bedroom. Unknown to him, his parents had arrived

unexpectedly, and being tired had got into Julian's own bed. Julian saw two

figures there and not recognizing them under the bedclothes, he supposed them

to be intruders and impetuously stabbed them both to death. He suspected that

another man had been in bed with Julian's own wife. However, he met her as she

was returning home from church. Distraught with grief and guilt, he told her he

was about to leave her, no longer fit to live with decent people. She refused

to abandon him. Together they set out to attempt to make amends for his crime.

They forsook their fine castle and journeyed first to Rome to obtain

absolution, then as far as a swiftly flowing, wide river where they built a

hospital for the poor and an inn for travellers. In addition to this work, they

did penance for Julian's crime by helping travellers across the swift river.

After many years Julian

was awakened one freezing night by a voice from the other side of the river

crying for help. He got up, crossed over, and discovered a man almost frozen to

death. Julian carried the man across the river and warmed him back to life in

his own bed. The poor sufferer appeared to be a leper, but this did not stop

Julian. And when the man recovered, he revealed himself to be a special

messenger from God, sent to test the saint's kindness. "Julian," the

leper said, "Our Lord sends you word that He has accepted your

penance"

There are many saints

named Julian. Some of their stories have mixed with the tale of the Hospitaler

and vice versa. The one with which he is most confused is Julian the Martyr, whose

wife was also named Basilissa. Nevertheless, Julian the Hospitaller's story is

recorded in the sermons of Antoninus of Florence, the 13th-century work of

Vincent of Beauvais, and in one of Gustave Flaubert's Trois Contes (Attwater,

Benedictines, Bentley, Delaney, Farmer).

Saint Julian is depicted

in his identifying scene: killing his parents in bed. Sometimes he is shown (1)

as young, richly dressed with a hawk on his finger (making him difficult to

distinguish from Saint Bavo); (2) holding an oar; (3) wearing a fur-lined

cloak, sword, and gloves; (4) with a stag; or (5) carrying a leper over the

river to his waiting wife Saint Basilissa (Roeder). Julian's legend is

portrayed in several important cycles of 13th-century stained glass at both

Chartres and Rouen, as well as medieval paintings elsewhere (Farmer).

He is the patron of

boatmen, ferrymen, innkeepers, musicians, travellers, and wandering minstrels

(Roeder).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0212.shtml

Agnolo

Gaddi (1350–1396), San Nicola e San Giuliano, circa 1393, 200 x 68,

Bayerische

Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek

Saint Julian

According to a pious

legend that was very popular in the Middle Ages, St. Julian was of noble

birth and while hunting one day, was reproached by a hart for hunting him and

told that he would one day kill his mother and father.

He was richly rewarded

for his services by a king and married a widow. While he was away his mother

and father arrived at his castle seeking him; When his wife realized who they

were, she put them up for the night in the master’s bed room. When St. Julian

returned unexpectedly later that night and saw a man and a woman in his bed, he

suspected the worst and killed them both. When his wife returned from church

and he found he had killed his parents, he was overcome with remorse and fled

the castle, resolved to do a fitting penance.

He was joined by his wife

and they built an inn for travelers near a wide river, and a hospital for the

poor. He was forgiven for his crime when he gave help to a leper in his own

bed; the leper turned out to be a angel from God who had been sent to test him.

He is the patron of hotel keepers, travelers, and boatmen. His feast day is

February 12th.

SOURCE : http://ucatholic.com/saints/julian/

Agnolo Gaddi (1350–1396), St. Julian murders his parents , Storie di san Giuliano l'ospitaliere, circa 1393, 24,9 x 28,3, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek

Agnolo

Gaddi (1350–1396), Penance of St. Julian, Storie di san Giuliano l'ospitaliere, circa 1393, 24,6

x 28,6, Bayerische

Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek

St. Julian the Hospitaller

Feast day: February 12

St. Julian the

Hospitaller, or "the Poor Man," came from a wealthy, noble family in

the early 4th century and is a popular saint in Western Europe.

According to a legend,

while Julian was a baby, he was cursed to one-day kill his own parents. His

father wanted him killed, but his mother kept him alive. When he was old enough

to learn of the curse, he left his family to preserve their safety.

While he was hunting, his

mother and father made an unexpected visit to his castle. His wife gave them

one of the best rooms. He received a vision from the devil that his wife was in

his bed with another man, and he returned home to kill whoever was in his bed.

When Julian returned from his hunt and saw the two figures in bed, he assumed

it was his wife with a lover. In a jealous rage, Julian killed his mother and

father.

Julian was so horrified

upon learning the truth that he swore to devote the remainder of his life to

good works. He and his wife then undertook a pilgrimage to a distant country

where he established a hospital.

The hospital was near a

river that was frequently crossed by people prompted to travel by the Holy

Crusades. People frequently drowned crossing this river so Julian took

responsibility of ferrying travelers across and tending to the sick.

One night, the devil

vandalized his house, and blaming it on those he helped, Julian said that he

would never house anyone else ever again. God showed up at his door, asking for

help, and he denied Him. After recognizing him, he retracted his statement and

decided to help all those who needed it once again.

One night, thieves came

into their hospital and killed Julian and his wife in the same way Julian had

killed his mother and father.

“There were great

miracles without end in that place and land,” recounts the legend. “So many

that, as it pleased God, their bodies were brought to Brioude (France).”

St. Julian is considered

the patron of ferrymen, innkeepers and circus performers.

SOURCE : https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/saint/st-julian-the-hospitaller-145

Biagio

Puccini (1675-1721), Saint Julian the Hospitaller, chiesa Sant'Eustachio, Roma

A Garner

of Saints – Saint Julian Hospitator

Article

(French: Julian

Hospitalier; Italian: Giuliano Ospitate): A young nobleman. One day while he

was hunting a stag, the animal turned and said, “You who pursue me shall one

day kill both your father and your mother.” On hearing this he abandoned

everything and departing secretly from home, he entered the service of a prince

with whom he speedily distinguished himself both in war and at the court. The

prince made him a knight and gave him a widow lady to wife with a castle as

dowry. Meanwhile Julian’s parents went about seeking him far and near, and at

length they arrived at his castle at a time when he was away. The wife received

them, and on discovering who they were she gave them her own bed. While the

wife was absent at church Julian returned, and finding a man and a woman in his

bed, concluded that they were his wife and a stranger, and in his fury he slew

them both. On leaving the castle he met his wife retuming from the church, and

filled with surprise he asked her who were the two who were sleeping in their

bed. When she told him, he fell to weeping bitterly, recalling the words of the

stag. Then, bidding his wife farewell he swore that he would allow himself no

rest until he knew that the Lord had pardoned him. But she would not leave him,

and accordingly they went together to the banks of a great river where many had

perished, and in this desert they founded a hospital as a penance and for the

purpose of carrying to the other side of the water those who wished to cross,

receiving there all poor travellers. Long afterwards, as Julian was about to

rest and when he was feeling very fatigued, he heard a voice calling him, it

being the middle of a bitterly cold night, and asking to cross the river.

Julian rose and found a man who was dying of the cold. He took him into the

house, lighted a fire and employed every means to revive him, putting him in

his own bed. Soon afterwards the man, who had appeared sick and leprous, became

transformed into a splendid apparition, and as he ascended into Heaven he said,

“Julian, the Lord has sent me to you to make known to you that he has accepted

your penance, and you and your wife shall shortly repose in Our Lord.”

Instantly he disappeared, and shortly afterwards it happened to them as the

angel had predicted. 29th

January.

Attributes

Stag beside him, carries

boat in hand; or sits in boat crossing a river; usually dressed as a hermit.

MLA

Citation

Allen Banks Hinds, M.A.

“Saint Julian Hospitator”. A Garner of Saints, 1900. CatholicSaints.Info.

20 April 2017. Web. 7 January 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/a-garner-of-saints-saint-julian-hospitator/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/a-garner-of-saints-saint-julian-hospitator/

Taddeo Gaddi, Scomparto

di polittico con San

Giuliano l'ospitaliere (1330-1366),

tempera su tavola; New York (USA), collezione

privata

San Giuliano

l'ospitaliere

Patronato: Albergatori,

Viaggiatori, Macerata

Etimologia: Giuliano

= appartenente alla 'gens Julia', illustre famiglia romana, dal latino

San Giuliano L'Ospitaliere, protettore della città, è rappresentato a Macerata dappertutto, come protagonista o come santo laterale, nelle chiese, sulle porte d'accesso intorno alle mura, nelle opere conservate in pinacoteca, nell'antico sigillo dell'università, nelle medaglie commemorative del comune, nei palazzi signorili, sugli stendardi.

La sua immagine più antica, a cavallo, è del 1326, una scultura in pietra un tempo nella Fonte maggiore e oggi nell'atrio della pinacoteca comunale; la più scenografica nelle chiesa delle Vergini mentre tiene in mano il modellino della città; la più moderna nel ciclo della vota del presbiterio del Duomo dove negli anni 30 è stata affrescata la storia della sua redenzione dopo un tragico, incredibile evento. Gustave Flubert ne aveva già tratto una novella-romanzo, Saint Julien l'Hospitalier, raccontando con tinte fosche la giovinezza di questo fiammingo patito per la caccia anche violenta, cavaliere infaticabile e carattere vendicativo che non aveva esitato a uccidere il padre e la madre coricati nel suo letto credendoli la moglie e il suo presunto amante.

Poi una vita di espiazione e di preghiera dedicata all'accoglienza dei poveri e al traghetto dei pellegrini da una riva all'altra di un periglioso fiume. Ma sull'identità del santo ci sono non pochi dubbi, in parte espressi anche dalla curia maceratese e che un viaggio a Parigi per confrontare la storia del San Giuliano cui è dedicato il duomo di Macerata con quella della chiesa gemella ; Saint Julien-le Pauvre nel quartiere latino, non hanno chiarito del tutto. La chiesa parigina, costruita dai benedettini tra il 1170 e il 1240 su una originaria cappella del VI secolo dedicata a Saint Julien-l'Hospitalier, faceva parte della ventina di chiese edificate nei dintorni di Notre -Dame, tutte scomparse tranne quella. Situata nel cuore del centro universitario del XII e XIV secolo, fu luogo d'incontro di studenti e mastri, quando le lezioni si tenevano all'aria aperta, e al suo interno si riuniva l'assemblea per l'elezione del Rector Magnificus.

Pare che Dante vi ascoltò le lezioni di Sigieri e che certamente la frequentarono Alberto Magno, Tommaso d'Aquino e Petrarca e più tardi Villon e Rabelais. Solo quando furono costruiti nelle vicinanze i collegi della Montagne Sainte Geneviève tra i quali si impose quello della Sorbona,, la chiesa perdette di importanza. Quanto al santo cui è intitolata, la fama popolare ha sempre fatto coincidere il Giuliano storico con l'ospitaliere, tant'è che in veste di traghettatore compare in piedi sulla barca in un bassorilievo medievale incastrato nella facciata numero 42 della rue de Galande, di fianco alla chiesa: nel vicino giardino, che la separa dalla Senna e dalla fiancata destra dell'imponente Notre-Dame, una fontana in bronzo, questa recente, porta scolpiti tutti intorno a cascata i fatti salienti della sua storia. Ma l'opuscolo predisposto dalla parrocchia di rito greco-melkita e il prete interpellato propendono per l'identificazione del santo con Giuliano martire di Brioude. Il Giuliano leggendario, al quale la voce popolare ha dato il nome di ospitaliere rendendolo patrono di fatto anche nella chiesa di Parigi, sarebbe perciò usurpatore del titolo e in ogni caso, come ribadisce anche l'attento custode, non sarebbe riconosciuto come santo dall'autorità ecclesiastica. Un bell'impiccio per tutte le chiese francesi, italiane e spagnole che lo hanno scelto come loro protettore.

E la reliquia del braccio sinistro conservata nel duomo di Macerata a chi dovrebbe appartenere? Il miracoloso ritrovamento avvenne il 6 gennaio del 1442, e l'atto notarile che lo descrive è depositato nell'archivio priorale mentre le ossa, dopo varie collocazioni, sono conservate in una urna d'argento cesellata dall'orafo Domenico Piani.

Quello che conta è che in nome del patrono, santo reale o possibile, si aggreghino interessi culturali e iniziative utili alla città proprio nel senso e nella direzione dell'"ospitalità". La pensa così il comitato "Amici di San Giuliano" che si è costituito con spirito attivo e che non si preoccupa tanto dei riconoscimenti ufficiali quanto il promuovere in suo nome in tempi tanto angoscianti il valore dell'accoglienza.

Il 14 gennaio 2001, riprendendo un'antica tradizione, è stata innalzata in cielo una stella luminosa in onore del santo e la sua storia raccontata per le vie, quasi in veste di banditore, dall'attore Giorgio Pietroni mentre risuonavano i canti della Pasquella, continuazione allegra di un evento che sarebbe durato troppo poco se esaurito nel giorno dell'Epifania.

Non è citato nel Martirologio Romano, mentre la Bibliotheca Sanctorum lo pone al 29 gennaio.

E' patrono della Diocesi e della città di Macerata che lo festeggiano il 31 agosto.

Autore: Donatella Donati

Domenico Ghirlandaio (1448–1494),

Saint Julien l'Hospitalier, 1473, étail de http://www.wga.hu/art/g/ghirland/domenico/1early/3brozzi1.jpg,

La storia di San Giuliano l’Ospitaliere non è certa. Ne parla per primo nella sua Leggenda Aurea, dove viene descritta la vita di molti santi, il Beato Jacopo da Varazze, frate domenicano vissuto nel XIII secolo. In seguito, la leggenda di questo santo è stata soprattutto diffusa dallo scrittore francese Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880) con la novella Saint Julien l’Hospitalier.

Giuliano sarebbe vissuto nel VII secolo in Belgio. È un nobile cavaliere dal carattere impulsivo e vendicativo. Si narra che un giorno, mentre è a caccia, un cervo, prima di morire, gli abbia profetizzato una tragedia: Giuliano avrebbe ucciso i propri genitori. Il cavaliere, sconvolto, scappa via da casa e si trasferisce lontano. Passano gli anni e si sposa con una castellana.

Un giorno Giuliano si allontana da casa e i suoi genitori, che lo cercano da anni, per caso arrivano nella sua nuova dimora. La nuora li accoglie con calore e affetto e offre loro il letto matrimoniale per farli riposare. Giuliano rincasa prima del previsto, nella notte. Si reca in camera da letto e, convinto di aver scoperto la moglie con l’amante, uccide i propri genitori con la spada, come aveva previsto il cervo. Quando si accorge del tragico errore, Giuliano si dispera e, pentito, per espiare la tremenda colpa, decide di dedicare la sua vita alla preghiera e ai bisognosi. La moglie, sentendosi responsabile dell’accaduto, segue il marito.

La coppia lascia lusso e ricchezze e viaggia per l’Europa aiutando il prossimo. Giuliano apre, poi, una locanda in Italia, in riva a un fiume, nei pressi di Macerata (Marche): ospita i viandanti e li traghetta da una sponda all’altra, soprattutto aiuta i bisognosi e i malati. Da questa accoglienza deriva il nome San Giuliano l’Ospitaliere. La leggenda narra che un giorno Giuliano abbia prestato soccorso a un povero malato di lebbra intirizzito dal freddo. L’uomo si rivela un angelo inviato da Gesù per dire a Giuliano che il suo pentimento è stato accolto.

Patrono di Macerata, il santo protegge albergatori, barcaioli, traghettatori, giostrai, osti, addetti alle mense, pellegrini, viaggiatori.

Autore: Mariella Lentini

Note: Non è citato

nel Martirologio Romano, mentre la Bibliotheca Sanctorum lo pone al 29 gennaio.

E' patrono della Diocesi e della città di Macerata che lo festeggiano il 31

agosto.

SOURCE : http://www.santiebeati.it/dettaglio/36750

Saint Julien d'Antioche, XVIIIe s., 240 x 110, Église Saint-Julien et Sainte-Basilisse de Servian.

Saint

Julien d'Antioche, XVIIIe s., 240 x 110, Église Saint-Julien et

Sainte-Basilisse de Servian. Détail du tableau

Medieval Sourcebook. The Life of St. Julian the Hospitaller ©Translation by Tony Devaney Morinelli : https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/julian.asp

Saint Julian the

Hospitaller: The Iconography : https://www.christianiconography.info/julian.html

Voir aussi : http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/bude_1247-6862_1988_num_47_4_1736

https://www.christianiconography.info/julian.html

_%C3%89glise_Retable_de_Saint-Julien_03.jpg)