Saint Étienne

Harding, abbé

Il était né en

Angleterre. Il se fit moine à Molesme. En 1098, il quitte son monastère avec

une vingtaine de moines, dont le futur saint Robert pour essaimer et fonder à

100 kilomètres de là un monastère plus austère. Ainsi naquit Cîteaux, en

Bourgogne, dont il devint le troisième abbé, en 1108, après saint Robert et

saint Albéric. Il venait d'entrer dans cette charge quand saint Bernard et ses

trente compagnons arrivèrent en 1112. L'abbaye qui peinait à se développer

reprit vie et la réforme cistercienne ne tarda pas à se répandre dans toute

l'Europe. Saint Etienne fonda douze monastères, qu’il unit par le lien de la

Charte de Charité, pour qu’il n’y ait aucune discorde, mais que les moines

agissent par une même charité, avec une même Règle et des coutumes semblables.

Il mourut en 1134.

Saint Etienne Harding

Abbé de Cîteaux (+ 1134)

Confesseur.

Il était né en Angleterre

et regagnait son pays après un voyage en Italie et en France. Passant par la

Bourgogne, il rencontra sur sa route l'abbaye de Molesme. Il y entra et s'y fit

moine. En 1098, il quitta Molesme, avec une vingtaine de moines, dont le futur

saint Robert

de Molesmes, pour essaimer et fonder à 100 kilomètres de là un monastère

plus austère. Ainsi naquit Citeaux dont il devint le Père abbé. Il venait

d'entrer dans cette charge quand saint Bernard et

ses trente compagnons arrivèrent (1112). L'abbaye reprit vie et la réforme

cistercienne ne tarda pas à se répandre dans toute l'Europe. Un de ses moines

écrit de lui: "C'était un bel homme, toujours abordable et toujours de

bonne humeur."

L'ordre de Cîteaux nous

communique: les 3 Fondateurs ne sont objet d'une solennité commune que depuis

peu, le 26 janvier: Saint Robert, saint Albéric et saint

Étienne, abbés de Cîteaux, solennité dans l'OCSO (l'Ordre Cistercien de la

Stricte Observance) - source: rituel

cistercien

Au 28 mars au martyrologe

romain: À Cîteaux en Bourgogne, l’an 1134, saint Étienne Harding, abbé. Venu de

Molesme en ce monastère avec d’autres moines, il en devint l’abbé, institua les

frères convers, accueillit le futur saint Bernard avec huit compagnons et fonda

douze monastères, qu’il unit par le lien de la Charte de Charité, pour qu’il

n’y ait aucune discorde, mais que les moines agissent par une même charité,

avec une même Règle et des coutumes semblables.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/994/Saint-Etienne-Harding.html

Satue

de Saint Étienne Harding, Abbaye de Citeaux, Côte-d'Or, Bourgogne, France.

Saint Étienne Harding

Troisième abbé de

Cîteaux. Né vers 1060 dans le Dorset, Angleterre, il entre dans la vie

monastique à Sherborne près de Winchester. Au retour d'un pèlerinage à Rome, il

entre à Molesmes vers 1085. Il participe à la fondation de Cîteaux, dont il

devint sous-prieur sous saint Robert, prieur sous saint Albéric et enfin

troisième abbé. Étienne reçut saint Bernard et ses trente compagnons à Cîteaux

et, deux ans plus tard, il envoya Bernard à Clairvaux comme abbé-fondateur.

Etienne a présidé à la

croissance spectaculaire de l'entreprise cistercienne pendant plus de 25 ans.

En 1119 la fédération comptait déjà 12 monastères. Etienne se chargea de la

rédaction des constitutions de son ordre, ainsi que de l'amendement de la

Charte de Charité, qu'il présenta au chapitre général de Cîteaux en 1119. Il

présenta également ces documents au Pape Callixte II en vue de la

reconnaissance de la nouvelle branche des moines bénédictins. C'est donc plus à

Saint Etienne qu'à Saint Robert que les cisterciens doivent leur statut

définitif et la spécificité des relations entre les différents monastères.

Saint Etienne fut

canonisé en 1623.

SOURCE : http://www.abbayes.fr/histoire/cisterciens/etienne.htm

Sarlat-la

-Canéda ( Dordogne ). Saint-Sacerdos de Sarlat cathedral - Stained glass window

dedicated to Saint Bernard of Clairvaux ( detail ): Stephan Harding. abbot of

Citeaux abbey, accepts Bernard in his monastery ( 1112 )

Sarlat-la -Canéda ( Dordogne ). Kathedrale Saint-Sacerdos de Sarlat - Buntglasfenster mit Szenen aus dem Leben ded heiligen Bernhard von Clairvaux: Stephan Harding, Abt von Citeaux, nimmt Bernhard in den Zisterzienserorden auf.

Saint Étienne de Harding

"Séparés par le corps dans les diverses parties

du monde, qu'ils soient indissolublement unis par l'âme...

Vivant dans la même Règle, avec les mêmes

coutumes."

La très sainte et des plus pieuses vie de Saint

Étienne, fondateur de l'Ordre de Cîteaux (Ordo Cistercensis), rédacteur de la

règle cistercienne et de la charte de charité, qui toute sa vie durant

travailla pour l'épanouissement de l'idéal monastique prôné par Saint

Benoît.

Premières années

Saint Étienne naquit vers 1060, dans le Dorset, région

méridionale de l'Albion, au sein de la grande, ancienne et noble famille de

Harding. On ne sait peu de choses sur ses parents, si ce n'est que son père fut

un administrateur admiré et aimé par ses censitaires, auprès desquels il était

fort généreux. On sait aussi qu'Étienne reçut une éducation religieuse et

pratique poussée, au point où ses connaissances impressionnèrent les autorités

religieuses locales.

Ceci dit, la part d'ombre sur sa vie se lève

complètement quand Étienne de Harding choisit la vie monastique. En effet, à

partir de ce moment là, grâce à l'assidu travail des moines qui côtoyèrent le

saint, de nombreux écrits et registres nous permettent de connaître avec

précision le déroulement de sa vie. On sait qu'il entra à l'abbaye bénédictine

de Sherborne à l'âge de 15 ans. Après un noviciat rapide et fructueux, il fut

élevé frère par l'abbé Roger de Lisieux, d'origine normande, qui le nomma

chantre, où ses connaissances déjà très complètes en Christologie lui furent

très utiles. Étienne resta cloitré à Sherborne pendant quatre ans, priant avec

ferveur et sans relâche. Ces quatre années, il les utilisa à bon escient, ayant

lu tous les ouvrages de la bibliothèque de l'abbaye, faisant de lui un érudit

hors pair. D'ailleurs, il fut, après le décès de l'abbé de Lisieux et le

remplacement de ce-dernier par un nouvel abbé, Richard de MacGroar, d'origine

écossaise, rapidement nommé par ce-dernier chapitrain, qui en plus de le

récompenser pour son érudition, voulait fait un contrepoids aux français très

présents au sein du chapitre. En effet, l'abbé de MacGroar souhaitait que le

monachisme s'internationalise, au lieu de rester une mode française. En quelque

sorte, on peut dire qu'il était un précurseur du concept d'intertionalisation,

et son influence fut grande sur Sainte Étienne, qui en fit un but, un objectif

et un devoir des cisterciens.

Cependant, Saint Étienne ne resta pas chapitrain bien

longtemps, puisque l'abbé le fit nommer lecteur au séminaire de Winchester,

fondé quelques années auparavant, comme de nombreux autres à travers l'Europe,

grâce à des lettres patentes de Grégoire VII, qui souhaitait une meilleure

formation des prêtres, ce qui était à ses yeux essentiel et primordial pour

lutter contre le nicolaïsme et la simonie. C'est au sein de ce séminaire

qu'Étienne put s'initier à l'aristotélisme, doctrine alors réservée à une

petite élite au sein des prélats et des plus éminents théologiens.

L'affirmation de la sociabilité de l'homme est un choc. Étienne découvre alors

la futilité de l'idéal monastique bénédictin, qu'il tente de réformer.

Il réussit à fonder un hospice sous l'autorité de

l'ordre, qu'il administre seul, puisqu'il est le seul à maîtriser des concepts

de médecine, acquis au séminaire, mais ses autres tentatives resteront sans

suite. Un nouvel abbé succède à MacGroar, Nicolo Aldobrandeschi, d'origine

italienne, qui ne veut rien savoir des idées d'Étienne et l'expulse de

Sherborne.

Cantorbéry, puis Rome

Saint Étienne déménage alors à Cantorbéry, siège de la

primatie des angles, et se place sous la protection du nouvel archevêque,

Baudoin d'Exeter, proche de la famille royale normande. Étienne, élevé

chanoine, devient alors clerc séculier, tandis que l'archevêque lui confie la

doyenné de la cathédrale. Étienne de Harding a alors 25 ans. Les théologiens de

la ville, et ses confrères du cloître de la cathédrale, sont beaucoup plus

réceptifs à ses propositions de réforme de l'Ordre Bénédictin, et se tiennent

au fait des actualités romaines. Saint Étienne se fait remarquer pour ses

prêches et est élevé seigneur par le roi Henri II.

Finalement, Monseigneur Baudoin propose à Étienne

d'effectuer un pélerinage à Rome. Enthousiaste, et voulant profiter de

l'occasion pour discuter de son idéal avec nombre de théologiens du continent,

Étienne se prépare quelque peu et met de côté quelques sous pour le voyage

avant de recevoir le bourdon après une courte messe célébrée dans le choeur de

la cathédrale.

Son voyage débuta par une traversée de la Manche qui

fut plutôt calme selon les dires même d'Étienne, et il prit ensuite la direction

de Paris, où il ne fit qu'un bref arrêt, déçu par les théologiens de la ville,

et emprunta ensuite la Via Agrippa, qui l'amena jusqu'à Rome en passant par les

principales villes italiennes. À Boulogne, l'université lui réserva un bon

acceuil, et ses thèses ne furent pas autant décriées qu'elles le furent à

Florence. Néanmoins, les conditions météorologiques furent avec lui.

Arrivé à Rome, il se plongea dans la lecture d'ouvrage

sur Aristote. Il y découvrit les livres du panégyrique et du siège d'Aornos,

qu'il dévora, mais qui furent pour lui très décevant, n'y trouvant pas

d'arguments pour étayer ses idées de réforme. Cependant, il se lie d'amitié

avec l'archevêque de Lyon et primat des Gaules, Hugues de Bourgogne. Après

quoi, Étienne se fait connaître grâce à ses messes, mais aussi, et surtout,

grâce aux débats théologiques qu'il mène et organise au sein de la faculté des

sciences théologiques de Rome. Il entre même dans l'entourage du pape, mais son

aristotélicisme un peu trop marqué lui vaut des critiques, et il préfère

finalement suivre l'archevêque Hugues, qui retournait dans son diocèse.

Molesme et Cîteaux

La remontée sur la Via Agrippa se fit sans problème,

la région n'étant pas alors infestée de Lion de Judas comme elle l'est

aujourd'hui. Arrivé à Lyon, Étienne fit la connaissance de Robert de Molesme,

qui visait le même saint et noble objectif que lui. En effet, Robert avait

souhaité lui aussi réformer le monachisme, et avait pour ce faire fondé une

abbaye, l'abbaye de Molesme. Cependant, cette-dernière était en grande

difficulté. Établie sur un flanc de montagne, une terre infertile et loin de

toute bourgade, un endroit dont personne ne voulait, l'abbaye sombrait dans

l'acédie. Au départ, l'établissement n'était composé que de cabanes de branches

autour d'une chapelle dédiée à Saint Hubert. Rapidement, la maison de nouveaux

moines, rétifs à tant d'austérité. Ces moines, désespérés par leur situation,

ne voulaient surtout pas suivre les enseignements de Robert, encore plus

draconiens, et continuaient malgré tout d'honorer l'interprétation bénédictine

de la règle de Saint Benoît. Étienne promit toutefois à Robert de venir le

seconder à Molesme, mais après quelques temps, la tâche s'avérait tellement

ardue que Robert et Étienne se décidèrent à trouver une solution.

Les deux moines avaient un rêve, celui de fonder une

abbaye sur une vraie terre, une terre fertile et acceuillante. Mais pour cela,

il fallait obtenir une concession de la part d'un seigneur ou d'un propriétaire

terrien, et peu s'étaient prononcés en faveur d'une réforme de ce qui était

alors l'ordre le plus puissant d'Europe. Néanmoins, Étienne était convaincu que

ses idées, de par leur originalité, mais aussi de par leur sérieux, séduirait

un important vassal de Sa Majesté. Ce noble, ce fut Renaud de Beaune. Après

qu'Étienne soit passé à sa cour, séduit par son discours, le vicomte de Beaune

lui offrit une terre fertile au milieu d'une grande forêt.

Avec quelques moines de Molesme, Étienne de Harding et

Robert fondèrent l'abbaye de Cîteaux. Dans les premiers temps, la nouvelle

communauté travailla à défricher la terre. Ils revendirent les stères de bois

et purent acheter des pierres pour l'enbelissement de leur abbatiale. Dès la

première année, les moines réussirent à tirer profit des champs. La récolte fut

très variée. En effet, prévoyants et instruits, Étienne et Robert avaient

organisés les cultures de manière à tirer profit des grandes terres du domain

abbatial, c'est-à-dire en y cultivant le plus possible. Grâce à la technique de

l'assolement triennal, les moines réussirent à récolter une quantité de

légumes, mais aussi une quantité de grains, que ce soit du blé, que les frères

boulangers transformèrent en pain, du houblon, que les frères brasseurs

transformèrent en bière et alcools divers, qu'on vendait, tout comme les

surplus des autres cultures, aux villageois, ce qui permit à l'abbaye d'amasser

des sommes considérables, ou encore de l'orge. La structure était là, il ne

manquait que l'organisation pour avoir la règle d'un ordre monastique des plus

solide.

Toutefois, les débuts de Cîteaux ne furent pas

toujours faciles. S'il y eut discorde dans la nouvelle abbaye, ce fut surtout à

savoir qui de Robert de Molesme ou d'Étienne de Harding serait élu abbé. Les

moines furent séparés en deux factions, et le chaos fut maître des lieux

jusqu'à ce que le sage Saint Étienne décide de reconnaître son frère comme

abbé, pour mettre un terme à la désolation causée pas la désunion de ceux que

l'on appelait déjà les cisterciens.

Ceci dit, les moines de Molesme vinrent à Cîteaux pour

se repentirent, et implorèrent Robert de redevenir leur abbé, en échange de

quoi il se soumettrait aux principes et coutumes de Cîteaux, ce qu'il accepta.

Étienne de Harding et Robert avait réussi à mener à bien leur réforme du

monachisme.

La Charte de Charité

Suite au départ de Robert, Étienne fut proclamé abbé

par acclamation. Il nomma ensuite le frère Albéric comme prieur de l'abbaye,

ainsi qu'un chapitre. Entre-temps, l'idéal monastique cistercien s'était

grandement répandu en France, et il devenait urgent d'établir les structures

d'un nouvel ordre. Étienne se pencha alors sur la rédaction ce qui devrait être

le texte fondateur pour tous les frères cisterciens.

La nouvelle règle énonçait les valeurs fondamentales

de l'Ordre Cistercien : la charité, qui consiste en l'aide du plus démuni et le

refus et le rejet de l'égoïsme, l'exemplarité, qui est le respect d'un code

d'honneur implicite ainsi que la foi.

L'abbé de Cîteaux, soucieux de l'intertionalisation de

l'ordre et du bon fonctionnement de ce-dernier, inclut aussi dans la charte des

mesures administratives. Il fixa d'abord les modalités d'établissement de

l'ordre. Ainsi, une abbaye cistercienne ne peut être ouverte que si trois

moines se trouvent dans la même région, et avec l'accord du chapitre d'une

abbaye-mère de l'ordre. La nouvelle abbaye devenant donc fille de

l'abbaye-mère. Ensuite, il établit le fonctionnement des élections pour les

abbés, ainsi que les charges, les fonctions et les statuts de chacun.

Saint Étienne, voulant donner à la règle cistercienne

un nom évocateur, la baptisa Carta Caritatis, ou Charte de Charité, pour

signifier la principale et plus importante valeur de l'ordre.

Saint Bernard et dernières années

L'abbaye de Cîteaux florissait et devenait de plus en

plus importantes, et sa réputation dépassa largement la Bourgogne. La réforme

cistercienne intéressait beaucoup de gens, et les théologiens les plus

respectés se penchaient régulièrement sur la situation de l'ordre

naissant.

Évidemment, Cîteaux accueillait chaque année un

incessant flot de novices, venus pour y vivre dans la vertu, dans l'espoir

d'obtenir le salut de leur âme et ainsi atteindre le soleil. C'est dans ce

contexte qu'un jeune nobliaux venu directement de sa région de Dijon natale,

qui deviendra plus tard Saint Bernard de La Bussière, intégra l'Ordre

Cistercien. Tel Saint Étienne, qui aimait, en tant qu'abbé, admirer sa

réussite, Saint Bernard passa avec brio le noviciat, et fut rapidement promu

aux charges les plus importantes et les plus prestigieuses de l'abbaye. En

effet, il en vint même à être nommé recteur de l'abbatiale, devenant en quelque

sorte le bras droit d'Albéric. Chargé de la célébration des offices, il

prêchait, chaque dimanche, les vertus et les bienfaits du cistercianisme, et

ses qualités lui valurent d'être grandement considéré, même partie le clergé

séculier et la société laïque. Après s'être entretenu avec le collège des

nobles bourguignons, Saint Bernard, qui avait entre-temps été élevé chapitrain

de Cîteaux, vint voir Saint Étienne pour obtenir l'autorisation de fonder une

abbaye-fille sur les terres de La Bussière sur Ouche.

Saint Étienne de Harding

Étienne, trop heureux d'assister à la fondation d'une

seconde abbaye soumise à la règle cistercienne, accepta avec enthousiasme.

Cette nouvelle abbaye ne fut que la première d'une longue série, et grâce aux

mesures prises par Saint Étienne en matière d'intertionalisation, mais aussi

grâce aux connaissances et au charisme de Saint Bernard, l'Ordre put

s'installer en Irlande, en Scandinavie, dans la péninsule Ibérique, etc.

Même s'il aurait voulu lui-même participer à

l'expansion de l'Ordre Cistercien, Saint Étienne ne le put en raison de son

grand âge. Malgré cet ultime regret, il restait fidèle à la règle qu'il avait

écrite, faisant toujours preuve de grande charité. Petit à petit, il déléguait

ses responsabilités à Albéric, qui devint le troisième abbé de Cîteaux, mais

aussi aux jeunes qui s'étaient joints à la grande famille cistercienne et

faisait preuve d'enthousiasme et de motivation.

Chaque jour, on pouvait le voir méditer tout en se

promenant dans les grands domaines de l'abbaye.

Le trépas

Saint Étienne de Harding, fondateur de l'Ordre

Cistercien et rédacteur de la Charte de Charité, s'éteignit paisiblement en sa

cellule de l'abbaye de Cîteaux, entouré de ses frères de la famille

cistercienne, un beau jour de mai alors que les arbres et les arbustes du

domaine étaient en fleur. On pleura beaucoup sa mort, et plusieurs dignitaires,

qu'ils soient religieux ou laïques, assistèrent à ses funérailles ainsi qu'à

son inhumnation.

On l'enterra sous l'abbatiale de Cîteaux, et on marqua

l'emplacement de sa tombe par un gisant qui fut réalisé par un sculpteur

bourguignon. On conserva son coeur, dont le reliquaire fut déposé à la

primatiale Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Lyon, sa mitre, qui fut donnée à l'abbaye de

La Bussière sur Ouche, et sa crosse, que l'on offrit à la jeune abbaye de

Noirlac.

Attributs

Saint Étienne de Harding est souvent dépeint en

vêtements d'abbé, avec mitre et crosse, mais aussi souvent tenant dans ses

mains une maquette de l'abbaye de Cîteaux, rappelant ainsi que c'est lui qui en

fut le fondateur. Son apparence générale est plutôt sobre, et rappelle donc son

voeu de pauvreté.

Reliques

L'histoire des reliques de Saint Étienne de Harding

est particulière. Premièrement, son gisant, de même que l'abbaye de Cîteaux,

furent détruits par les Armagnacs lors de la guerre civile qui les opposa aux

Bourguignons. Ne restait que du corps du Saint son coeur, qui put être admiré à

Lyon jusqu'à ce que Monseigneur de Bouviers l'amène à Sens pour être adoré par

les fidèles qui visiteraient la cathédrale Saint-Étienne. Sa mitre fut, quant à

elle, ramenée à Noirlac après l'abandon de l'abbaye de La Bussière, où elle a

rejoint la crosse du Saint. Ces deux dernières reliques se trouvent toujours à

Noirlac.

SOURCE : http://cathedrale-aix-arles.actifforum.com/t1941-saint-etienne-de-harding

Saint Etienne Harding

Etienne, surnommé Harding, troisième abbé de

Cîteaux, né en Angleterre, d'une famille noble, fit ses premières études et

prit l'habit religieux au monastère de Schirburn. Il en sortit pour passer en

Ecosse, et de là en France. Après avoir achevé sa réthorique et sa philosophie

dans les écoles de Paris, il partit pour Rome, avec un jeune ecclésiastique de ses

amis. A son retour, il s'arrêta à l'abbaye de Molesme, où il ne put retenir son compagnon de voyage. Cependant, cette abbaye tomba bientôt dans un extrême relâchement, effet

d'une dangereuse abondance. Saint Robert, qui en était abbé, en remit la direction au

prieur Alberic, et s'exila dans la solitude de Vinay. Alberic ne tarda pas à suivre Robert, et le fidèle

Etienne à les joindre tous deux. Il leur offrit ses secours pour une

réforme ; mais le peu de succès qu'obtint leur nouvelle tentative les ayant

découragés, ils allèrent, avec 18 autres religieux de Molesme, jeter, en 1098, les fondements de l'abbaye de Cîteaux, dans une forêt du diocèse de Challon. Ils vinrent heureusement à bout de

leur entreprise, avec la permission du légat de Rome et l'assistance du duc de Bourgogne. Les services rendus par Etienne à

l'établissement nouveau ne furent pas sans récompense. Après la mort d'Alberic,

second abbé de Cîteaux, il fut choisi à l'unanimité pour lui succéder. Sous la

conduite d'Etienne, ses religieux pratiquèrent à la lettre ce précepte de l'Evangile : Cherchez premièrement le royaume des

cieux, et le reste vous sera donné comme par surcroît. Aussi, dans la disette

où ils se trouvaient souvent, quelques aumônes qui venaient à propos leur

semblaient venir par miracle. Etienne, en tout ennemi du luxe, le bannit même du service divin. Il

remplaça l'or et l'argent par le cuivre et le fer, et ne fit grâce qu'aux

calices de vermeil. Il eut à craindre un moment que cette sévérité de moeurs ne

nuisît à l'accroissement de sa communauté : plusieurs frères étaient morts en moins de deux ans, et personne ne

se présentait pour les remplacer.

Etienne était plongé dans une affliction

profonde, quand tout à coup arriva saint Bernard, qui venait, à la tête de trente gentils-hommes

français, solliciter leur commune admission dans un ordre dont il a fait la

gloire. Son exemple ne fut point stérile. Cîteaux eut en peu de

temps une surabondance de population, dont Etienne forma des colonies, qui

fondèrent, sous ses auspices, les monastères de la Ferté, de Pontigny, de Clairvaux et de Morimond. On a appelé ces

quatre abbayes les quatre filles de Cîteaux. Etienne,

considérant ces rapides progrès de l'ordre, ne voulut plus être le seul juge des intérêts de tous, et convoqua, en 1116, le premier

chapitre général de Cîteaux. Satisfait de cet essai, il en convoqua un second,

en 1119, pour soumettre à son examen des statuts intitulés Charta

charitatis, ayant pour but de réunir en un même corps les différentes abbayes dont Cîteaux était, en quelque sorte, la

métropole.

Lorsque Étienne sentit l'affaiblissement de ses forces, il se démit, en plein chapitre, de sa dignité d'abbé,

demandant la permission de s'occuper de lui, puisqu'il ne pouvait plus

s'occuper des autres. Il fut remplacé par un hypocrite, que sa mauvaise

conduite fit déposer au bout d'un mois ; mais il eut, de son vivant,

un second successeur plus digne de lui, et mourut, avec cette consolation, le

28 mars 1134. (Biographie universelle ancienne et moderne - Tome

24 - Page 546)

ÉTIENNE

HARDING saint (1060-1134)

Issu de la noble famille

de Harding, Étienne naquit à Meriot dans le comté de Dorset (Angleterre). Il

entra à l'abbaye voisine de Sherborne, la quitta quelques années plus tard pour

aller en Écosse, puis se rendit à Paris pour étudier. De là, il fit le

pèlerinage de Rome. Au retour, il se fixa à Molesmes, où l'abbé Robert

cherchait désespérément une formule nouvelle de vie monastique. En 1098,

Étienne Harding fut du groupe des fondateurs de Cîteaux, où il resta malgré les

difficultés des premières années, difficultés accrues par la pauvreté et

l'absence de recrutement. En 1109, l'abbé Albéric mourut et Étienne Harding lui

succéda. Il mit au point un texte de la Bible, qu'il présenta magnifiquement , ne

voulant pas que la simplicité soit confondue avec l'indigence (Dijon, Mss, de

12 à 15). L'arrivée de saint Bernard et de nombreux novices donna un essor

inattendu à l'abbaye de Cîteaux, qui essaima en 1113 à La Ferté, en 1114 à

Pontigny, en 1115 à Clairvaux et à Morimond, puis dans toute l'Europe. Sous

l'abbatiat d'Étienne Harding, le nombre des abbayes cisterciennes dépassa

soixante-dix. Pour maintenir leur union, il promulgua la Charte de charité et

les premières coutumes de l'ordre, qui furent approuvées par le pape en 1119.

En 1125, des moniales de Juilly, abbaye qui fut fondée par des moines de

Molesmes et qui resta sous son obédience, instaurèrent à Notre-Dame-du-Tart la

première abbaye de cisterciennes. Étienne Harding démissionna en 1133 et mourut

le 28 mars 1134. Sa fête fut fixée au 17 avril par le chapitre général de 1623.

Actuellement, saint Étienne Harding est, avec ses prédécesseurs Robert et

Albéric, honoré par les cisterciens et

par les bénédictins le 26 janvier en une fête commune aux pères de

Cîteaux.

SOURCE : http://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/etienne-harding/

Maria Vergine dona lo scapolare dell'Ordine

Cistercense a

Santo

Stefano Harding

(part.), affresco; Szentgotthárd (Ungheria), Chiesa di Santo Stefano Harding in Apátistvánfalva

Also

known as

Stephen of Citeaux

Esteban…

Etienne…

Stefano…

Stevan…

formerly 17 April

formerly 16 July

formerly 26 January

Profile

Born to the English nobility.

After a somewhat mis-spent youth, he was drawn to religious life and entered

the Benedictine Sherborne

Abbey. Following the Norman conquest of England in 1066,

Stephen left the monastic life,

moved to Scotland and

then to Paris, France to study. Pilgrim to Rome, Italy,

seeking forgiveness for having abandoned monasticism. Monk at Molesme

Abbey. With Saint Robert

of Molesme, he helped begin the Cistercian reform

by helping found Citeaux

Abbey in 1098.

Chosen abbot of

the house in 1109,

he came in with a reformer’s zeal and administrative skill. Accepted Saint Bernard

of Clairvaux into the Order with

all the reform and expansion that he and his brothers brought with them. Helped

found a dozen other Cistercian houses.

amd gave the statutes that started the Cistician nuns.

His reform work aimed at simplicity in all things including liturgical rites,

church decor, monastic dress,

and life in the Order.

Born

c.1060 in

Meriot, Sherborne, England

28 March 1134 at

Citeaux, France of

natural causes

1623 by Pope Urban

VIII

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Harding

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

Roman Martyrology, 3rd Turin edition

other

sites in english

images

video

webseiten

auf deutsch

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

spletne

strani v slovenšcini

MLA

Citation

“Saint Stephen

Harding“. CatholicSaints.Info. 6 August 2022. Web. 27 March 2023.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-stephen-harding/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-stephen-harding/

Klosterkirche

Wald (Landkreis Sigmaringen),

Stephen Harding, OSB Cist. Abbot

(RM)

Born probably in Sherborne, Dorsetshire, England; died at Cîteaux, France,

March 28, 1134; canonized in 1623; his feast is celebrated on July 16 among the

Cistercians.

Saint Stephen, one of the founders of the Cistercians, was an Englishman of

unknown parentage. While he was yet a child, they offered him as an oblate to

Sherborne Abbey in Dorsetshire, where he was educated. When he reached

maturity, he detested the monastic lifestyle and set out to see the world. He

travelled to Scotland, and then on to Paris to study further.

As a Benedictine monk he travelled on pilgrimage to Rome, reciting the Psalms

daily as he went, but it was no perfunctory repetition, for he drew from them a

strength which refreshed his spirit, and their influence deeply affected the

rest of his life.

Some say that he had wandered through Europe seeking a community where the

Benedictine Rule was strictly kept and had almost given up hope, when he met

Saint Robert of Molesmes, a native of Champagne. On Stephen's return from Rome,

he and a friend came across a community of monks living a very austere and

solitary life in the forest of Langres in Burgundy. Their life of prayer, hard

work, and strict adherence to the austere rule of Saint Benedict attracted

Stephen, and he settled there. Among the monks were Saint Robert, the abbot,

and Saint Alberic.

Everything went well until the bishop of Troyes took it upon himself to

moderate the austerities of these enfants terribles and to give them property

so they would not be "devoured" by their zeal. The community's

devotion to poverty was bypassed and little by little the Benedictines of

Molesmes became canons.

Disappointed to find that its discipline had become slack and that wealth and

worldliness had bred indifference, Robert no longer desired to be the abbot and

left. But the monks of Molesmes increasingly deviated from the rule and the

other two, each becoming abbot for a time, in turn departed for the diocese of

Langres following Robert's example.

The bishop of Troyes ordered all three to return to Molesmes, but they could

not rekindle the flame of enthusiasm, so the three left again. In order to escape

the jurisdiction of the bishop of Troyes, they sought refuge in another

jurisdiction. Stephen accompanied Robert and Alberic to Lyons to ask the

Archbishop Hugh, the papal legate to France, for permission to leave Molesmes

to create a stricter order.

The legate made known his opinion in 1098: "We have thought that the best

thing would be for you to retire to another convent which the Divine Goodness

will grant you. We have therefore permitted you who have appeared before us,

Abbot Robert, Brothers Alberic and Stephen and all those who are determined to

follow you, to execute this good plan and we exhort you to persevere

therein." What is comforting to note is that in the Church, if a work is

good, the Holy Spirit gets involved in it and sooner or later, someone always

presents himself to support and activate it.

Thus, the permission was granted, and Saint Robert and 20 others, built a

monastery at Cîteaux, diocese of Châlon-sur- Saône, in the heart of the forest.

The site was chosen, not for its majestic beauty, but because Rainald, the lord

of Beaune, gladly donated the site to them. The monastery opened in 1098 with

Robert as abbot, Alberic as prior, and Stephen as subprior. Saint Robert

returned to Molesmes about a year later at the order of Urban II. The other two

shifted positions respectively to abbot and prior.

During Alberic's reign, the new order received definitive approval from Pope

Pascal II and was placed under the protection of the Holy See. The Benedictines

of Cîteaux received a white habit and made their solemn professions on March

21, 1098, Passion Sunday.

Stephen assisted at the death of Alberic on January 26, 1109. Alberic was the

first of the trio to prepare a meeting place for them with God. Stephen missed

Alberic, his friend, his "companion in arms," his "general in

the battles of the Lord," in the time that they were placed "in the

front line of the battle." Stephen's character and temperament are well

expressed in this military language.

In the following year, on March 21, 1110, there was a second departure for

eternity. Robert died. Stephen was the sole survivor of the three. This

vouched-safe, original Cistercian, however, was not to conform in all points

with the Benedictine prototype because he was to become the champion of the most

absolute poverty with an almost Franciscan insistence.

With the death of Alberic, Stephen found himself elected abbot of Cîteaux

against his will. He was now to induce the others to follow him on the path to

poverty that was his preferred route. Stephen decreed that magnates could no

longer hold their courts at Cîteaux, and thus cut off feudal sources of income,

from which the abbey had derived most of its revenue. Until that time the duke

of Burgundy and his court could break the sacred silence of Cîteaux whenever he

desired.

At Cîteaux they framed the rule of a new order, that of the Cistercians, the

Charter of Charity with its insistence on poverty, solitude, and simplicity,

and here for years they lived out their poor and barren life. They passed their

days in hard manual labor in the fields and vineyards. They raised their own

food. They avoided every form of religious corruption and ostentation,

forebearing the use of rich vestments, stained glass, and altar vessels of gold

and silver, wearing the simplest dress, and allowing only a crucifix of painted

wood. Their church was unadorned, their worship plain and severe, but along

with such bare austerity they combined grace and beauty.

During those 15 years nothing remarkable happened. On the contrary, the little

company made no headway, attracted no new followers, and it seemed a hopeless

enterprise. Stephen's changes discouraged visitors, which had been a source of

new recruits. Combined with a disease that killed several monks, this caused

the number of monks to dwindle significantly, and Stephen began to doubt his

actions. But they had great faith and patience, pursuing their work with

untiring devotion, and in the end their perseverance was rewarded.

One time Stephen sent a friar to the market of Vézelay with three pennies and

the instruction to bring back to Cîteaux "all the necessaries of

life." The friar actually came back to Cîteaux with three wagons, drawn by

three horses, laden with clothes and food because at just the right moment he

had found in the market place a man who wanted to bequeath a part of his

fortune to the monks. Stephen's trust in God's providence was warranted again.

Yet, because the order did not flourish, Stephen asked a dying monk to

"come back after your death, when God wills and if He will allow it, to

tell us if our way of life is pleasing to Him, and if our work is to

perish." The response came a few days later when Stephen was working in

the fields: "I say unto you, in truth, dispel all your doubts, consider it

certain that your life is holy and agreeable to God."

Then there came a dramatic day in 1112 when a company of 30 men made their way

through the forest to Cîteaux to join them and changed the destiny of the

order. The company was of excellent quality, for they belonged to some of the

noblest families of Burgundy, and were led by Bernard, afterwards famous as

Saint Bernard of Clairvaux. They presented themselves as novices and their

arrival brought new hope and strength to the community; there followed an era of

remarkable expansion, which, in time, infused fresh life into Western

Christendom.

From that point, Cistercian communities thrived and spread rapidly, and there

were no less than 90 of them--including Pontigny, Morimond, and Clairvaux--when

Stephen Harding died. Although Bernard was only 24, Stephen appointed him abbot

of Clairvaux. Stephen ruled that the abbots of the monasteries must meet at

Clairvaux each year, and that the abbot of the motherhouse must make a

visitation of each abbey every year; these rules served to safeguard the

original spirit and observance.

In addition to being a Biblical scholar, and perhaps an artist, Stephen was an

excellent administrator. In 1119, when there were already ten monasteries,

Stephen drew up and presented to the general chapter at Cîteaux a constitution

for the Cistercians--the Charter of Charity (Carta caritatis). This charter

defined the spirit of the order and provided for the unity of the association

of Cistercian abbeys. It is a document of prime importance in Western monastic

history because it would influence other orders. The high ideals, the careful

organization, the austerity and simplicity of the Cistercian life are an index

to the character of Stephen Harding.

He also made emendations to the Vulgate Bible that were designed for the use of

Cîteaux. He continued directing the monasteries until 1133, when he was quite

old and losing his sight. His last words, uttered on March 28, 1134, were:

"I am going to God as I had never done any good. If I have done some good,

it was through the help of the grace of God. But perhaps I have received this

grace unworthily, without turning it sufficiently to account."

In England, beginning with a thatched barn situated in a wild and narrow glen,

there rose their most famous and glorious Cistercian abbey of Fountains. Thus

the story of the Cistercians, which is linked for ever with the names of

Stephen Harding and Bernard of Clairvaux, is of the reform of the Benedictine

Order (for that also resulted) and of a great spiritual awakening. Harding's

fellow countryman, William of Malmesbury, wrote of him that he was

"approachable, good-looking, always cheerful in the Lord--everyone liked

him" (Attwater, Attwater2, Benedictines, Bentley, Dalgairns, Delaney,

Encyclopedia, Gill, White).

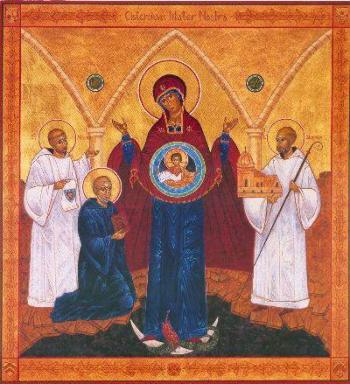

In art, Saint Stephen

Harding is depicted as a Cistercian abbot with the Virgin Mary and the Infant

appearing to him (Roeder, White). He may also be pictured with Robert of Molesme (Roeder).

SOURCE: http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0417.shtml

St. Stephen Harding

Confessor, the third Abbot of Cîteaux, was born at Sherborne in Dorsetshire, England, about the middle of the eleventh century; died 28 March, 1134. He received his early education in the monastery of Sherborne and afterwards studied in Paris and Rome. On returning from the latter city he stopped at the monastery of Molesme and, being much impressed by the holiness of St. Robert, the abbot, joined that community. Here he practised great austerities, became one of St. Robert's chief supporters and was one of the band of twenty-one monks who, by authority of Hugh, Archbishop of Lyons, retired to Cïteaux to institute a reform in the new foundation there. When St. Robert was recalled to Molesme (1099), Stephen became prior of Cïteaux under Alberic, the new abbot. On Alberic's death (1110) Stephen, who was absent from the monastery at the time, was elected abbot. The number of monks was now very reduced, as no new members had come to fill the places of those who had died. Stephen, however, insisted on retaining the strict observance originally instituted and, having offended the Duke of Burgundy, Cïteaux's great patron, by forbidding him or his family to enter the cloister, was even forced to beg alms from door to door. It seemed as if the foundation were doomed to die out when (1112) St. Bernard with thirty companions joined the community. This proved the beginning of extraordinary prosperity. The next year Stephen founded his first colony at La Ferté, and before is death he had established thirteen monasteries in all. His powers as an organizer were exceptional, he instituted the system of general chapters and regular visitations and, to ensure uniformity in all his foundations, drew up the famous "Charter of Charity" or collection of statutes for the government of all monasteries united to Cïteaux, which was approved by Pope Callistus II in 1119 (see CISTERCIANS). In 1133 Stephen, being now old, infirm, and almost blind, resigned the post of abbot, designating as his successor Robert de Monte, who was accordingly elected by the monks. The saint's choice, however, proved unfortunate and the new abbot only held office for two years.

Stephen was buried in

the tomb of

Alberic, his predecessor, in the cloister of Cîteaux.

In the Roman calendar his feast is

17 April, but the Cistercians themselves

keep it on 15 July, with an octave, regarding him as the true founder

of the order. Besides the "Carta Caritatis" he is commonly credited

with the authorship of the "Exordium Cisterciencis cenobii", which

however may not be his. Two of his sermons are

preserved and also two letters (Nos. 45 and 49) in the "Epp. S.

Bernardi".

Huddleston, Gilbert.

"St. Stephen Harding." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. New York:

Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 28 Mar. 2015

<http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/14290d.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Michael C. Tinkler.

Ecclesiastical

approbation. Nihil Obstat. July 1, 1912. Remy Lafort, S.T.D.,

Censor. Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2021 by Kevin Knight.

Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/14290d.htm

Harding Szent István-oltár a zirci apátsági

templomban

Saint

Stephen Harding side altar in Abbey Church of Zirc, Hungary

Heiliger

Stephan Harding Seitenaltar in der Abteikirche von Zirc, Ungarn

April 17

St. Stephen, Abbot of

Citeaux, Confessor

From the Exordiom of

Citeaux; the Annals of that Order by Manriquez; the short ancient Life of St.

Stephen, published by Henriquez in his Fasciculus, printed at Brussels in 1624,

and by Henschenius, 17 Apr. t. 2, p. 497; also from the Little Exordium of

Citeaux, and the Exordium Magnum Cisterc. both in the first tome of Teissier’s

Bibliotheca Patrum Cisterc. See De Visch’s Bibliotheca Cisterciensis, or

History of the Writers of this Order, in 4to. printed in 1656. Le Nain,

Hist. de l’Ordre de Citeaux, t. 1. Stephens, Monast. Anglic. t. 2. Britannia

Sancta, and Hist. Litéraire de la. France, t. 11, p. 213.

A.D. 1134.

ST. STEPHEN HARDING was

an Englishman of an honourable family, and heir to a plentiful estate. He had

his education in the monastery of Sherbourne, in Dorsetshire, and there laid a

very solid foundation of literature and sincere piety. A cheerfulness in his

countenance always showed the inward joy of his soul, and a calm which no

passions seemed ever to disturb. Out of a desire of learning more perfectly the

means of Christian perfection, he, with one devout companion, travelled into

Scotland, and afterwards to Paris, and to Rome. They every day recited together

the whole psalter, and passed the rest of their time on the road in strict

silence, occupied in holy meditation and private prayer. Stephen, in his

return, heard at Lyons of the great austerity and sanctity of the poor

Benedictin monastery of Molesme, lately founded by St. Robert, in 1075, in the

diocess of Langres. Charmed with the perpetual recollection and humility of

this house, he made choice of it to accomplish there the sacrifice of himself

to God. Such was the extreme poverty of this place, that the monks, for want of

bread, were often obliged to live on the wild herbs of the wilderness. The

compassion and veneration of the neighbourhood at length supplied their wants

to profusion: but, with plenty and riches, a spirit of relaxation and self-love

crept in, and drew many aside from their duty. St. Robert, Alberic his prior,

and Stephen, seeing the evil too obstinate to admit a cure, left the house: but

upon the complaint of the monks, were called back again; Robert, by an order of

the pope, the other two by the diocesan. Stephen was then made superior. The

monks had promised a reformation of their sloth and irregularities; but their

hearts not being changed, they soon relapsed. They would keep more clothes than

the rule allowed; did not work so long as it prescribed, and did not prostrate

to strangers, nor wash their feet when they came to their house. St. Stephen

made frequent remonstrances to them on the subject of their remissness. He was

sensible that as the public tranquillity and safety of the state depend on the

ready observance and strict execution of the laws, so much more do the

perfection and sanctification of a religious state consist in the most

scrupulous fidelity in complying with all its rules. These are the pillars of

the structure: he who shakes and undermines them throws down the whole edifice,

and roots up the very foundations. Moreover, in the service of God, nothing is

small: true love is faithful, and never contemns or wilfully fails in the least

circumstance or duty in which the will of God is pointed out. Gerson observes,

how difficult a matter it is to restore the spirit of discipline when it is

once decayed, and that, of the two, it is more easy to found a new Order. From

whence arises his just remark, how grievous the scandal and crime must be of

those who, by their example and tepidity, first open a gap to the least

habitual irregularity in a religious Order or house.

Seeing no hopes of a sufficient reformation, St. Robert appointed another abbot

at Molesme, and with B. Alberic, St. Stephen, and other fervent monks, they

being twenty-one in number, with the permission of Hugh, archbishop of Lyons,

and legate of the holy see, retired to Citeaux, a marshy wilderness, five

leagues from Dijon. The viscount of Beaune gave them the ground, and Eudes,

afterwards duke of Burgundy, built them a little church, which was dedicated

under the patronage of the Blessed Virgin, as all the churches of this Order

from that time have been. The monks with their own hands cut down trees, and

built themselves a monastery of wood, and in it made a new profession of the

rule of St. Bennet, which they bound themselves to observe in its utmost

severity. This solemn act they performed on St. Bennet’s-day, 1098: which is

regarded as the date of the foundation of the Cistercian Order. After a year

and some months St. Robert was recalled to Molesme, and B. Alberic chosen the

second abbot of Citeaux. These holy men, with their rigorous silence,

recollection, and humility, appeared to strangers, by their very countenances,

as angels on earth, particularly to two legates of Pope Paschal II., who,

paying them a visit, could not be satiated with fixing their eyes on their

faces; which, though emaciated with extreme austerities, breathed an amiable

peace and inward joy, with an heavenly air resulting from their assiduous

humble conversation with God, by which they seemed transformed into citizens of

heaven. Alberic obtained from Paschal II. the confirmation of his Order, in

1100, and compiled several statutes to enforce the strict observance of the

rule of St. Bennet, according to the letter. Hugh, duke of Burgundy, after a

reign of three years, becoming a monk at Cluni, resigned his principality to

his brother Eudes, who was the founder of Citeaux, and who, charmed with the

virtue of these monks, came to live in their neighbourhood, and lies buried in

their church with several of his successors. He was great grandson to Robert,

the first duke of Burgundy, son to Robert, king of France, and brother to King

Henry I. The second son of Duke Eudes, named Henry, made his religious

profession under B. Alberic, and died holily at Citeaux. B. Alberic finished

his course on sackcloth and ashes, on the 26th of January, 1109, and St.

Stephen was chosen the third abbot. 1 The

Order seemed then in great danger of failing: it was the astonishment of the

universe, but had appeared so austere, that hitherto scarce any had the courage

to embrace that institute. St. Stephen, who had been the greatest assistant to

his two predecessors in the foundation, carried its rule to the highest

perfection, and propagated the Order exceedingly, so as to be regarded as the

principal among its founders, as Le Nain observes.

It was his first care to secure, by the best fences, the essential spirit of

solitude and poverty. For this purpose, the frequent visits of strangers were

prevented, and only the Duke of Burgundy permitted to enter. He also was

entreated not to keep his court in the monastery on holydays, as he had been

accustomed to do. Gold and silver crosses were banished out of the church, and

a cross of painted wood, and iron candlesticks were made use of: no gold

chalices were allowed, but only silver gilt; the vestments, stoles, and

maniples, &c., were made of common cloth and fringes, without gold or

silver. The intention of this rule was, that every object might serve to

entertain the spirit of poverty in this austere Order. The founder, with this

holy view, would have poverty to reign even in the church, where yet he

required the utmost neatness and decency, by which this plainness and

simplicity appeared with a majesty well becoming religion and the house of God.

If riches are to be displayed, this is to be done in the first place to the

honour of Him who bestowed them, as God himself was pleased to show in the

temple built by King Solomon. Upon this consideration, the monks of Cluni used

rich ornaments in the service of the church. But a very contrary spirit moved

some of that family afterward to censure this rule of the Cistercians, which

St. Bernard justified by his apology. Let not him that eateth, despise him that

eateth not. 2 And

many saints have thought a neat simplicity and plainness, even in their

churches, more suitable to that spirit of extraordinary austerity and poverty

which they professed. The Cistercian monks allotted several hours in the day to

manual labour, copying books, or sacred studies. St. Stephen, who was a most

learned man, wrote in 1109, being assisted by his fellow-monks, a very correct

copy of the Latin Bible, which he made for the use of the monks, having

collated it with innumerable manuscripts, and consulted many learned Jews on

the Hebrew text. 3 But

God was pleased to visit him with trials, that his virtue might be approved

when put to the test. The Duke of Burgundy and his court were much offended at

being shut out of the monastery, and withdrew their charities and protection:

by which means the monks, who were not able totally to subsist by their labour,

in their barren woods and swampy ground, were reduced to extreme want: in which

pressing necessity St. Stephen went out to beg a little bread from door to

door: yet refused to receive any from a simoniacal priest. For though this

Order allows not begging abroad, as contrary to its essential retirement, such

a case of extreme necessity must be excepted, as Le Nain observes. The saint

and his holy monks rejoiced in this their poverty, and in the hardships and

sufferings which they felt under it; but were comforted by frequent sensible

marks of the divine protection. This trial was succeeded by another. In the two

years 1111 and 1112, sickness swept away the greater part of this small

community. St. Stephen feared he should leave no successors to inherit, not

worldly riches, but his poverty and penance; and many presumed to infer that

their institute was too severe, and not agreeable to heaven. St. Stephen, with

many tears, recommended to God his little flock, and after repeated assurances

of his protection, had the consolation to receive at once into his community

St. Bernard, with thirty gentlemen: whose example was followed by many others.

St. Stephen then founded other monasteries, which he peopled with his monks; as

La Ferté, in the diocess of Challons, in 1113; Pontigni, near Auxerre, in 1114;

Clairvaux, in 1115, for several friends of St. Bernard, who was appointed the

first abbot; and Morimond, in the diocess of Langres. St. Stephen held the first

general chapter in 1116. Cardinal Guy, archbishop of Vienne, legate of the holy

see, in 1117, made a visit to Citeaux, carried St. Stephen to his diocess, and

founded there, in a valley, the abbey of Bonnevaux. He was afterwards pope,

under the name of Calixtus II., and dying in 1124, ordered his heart to be

carried to Citeaux, and put into the hands of St. Stephen. It lies behind the

high altar, in the old church. St. Stephen lived to found himself thirteen

abbeys, and to see above a hundred founded by monks of his Order under his

direction. In order to maintain strict discipline and perfect charity, he

established frequent visitations to be made of every monastery, and instituted

general chapters. The annalist of this Order thinks he was the first author of

general chapters; nor do we find any mention of them before his time. The

assemblies of abbots, sometimes made in the reigns of Charlemagne and Lewis le

Debonnaire, &c., were kinds of extraordinary synods; not regular chapters.

St. Stephen held the first general chapter of his Order in 1116; the second in

1119. In this latter he published several statutes called the Charte of

Charity, confirmed the same year by Calixtus II. 4

He caused afterwards a collection of sacred ceremonies and customs to be drawn

up, under the name of the Usages of Citeaux, and a short history of the

beginning of the Order to be written, called the Exordium of Citeaux. The holy

founder made a journey into Flanders in 1125; in which he visited the abbey of

St. Vast, at Arras, where he was received by the Abbot Henry and his community,

as if he had been an angel from heaven; and the most sacred league of spiritual

friendship was made between them, of which several monuments are preserved in

the library of Citeaux, described by Mabillon. In 1128, he and St. Bernard

assisted at the council of Troyes, being summoned to it by the Bishop of

Albano, legate of the apostolic see. In 1132, St. Stephen waited on Pope

Innocent II., who was come into France. The Bishop of Paris, the Archbishop of

Sens, and other prelates, besought the mediation of St. Stephen with the King

of France and with the Pope, in affairs of the greatest importance. The

Cistercian monks came over also into England in the time of St. Stephen. The

extreme austerity and sanctity of the professors of this Order, which did not

admit any relaxation in its discipline for two hundred years after its

institution, were a subject of astonishment and edification to the whole world,

as is described at large by Oderic Vitalis; St. Peter, abbot of Cluni; William

of St. Thierry; William of Malmesbury; Peter, abbot of Celles; Stephen, bishop

of Tournay; Cardinal James of Vitry; Pope Innocent III., &c., who mention,

with amazement, their rigorous silence, their abstinence from flesh-meat, and,

for the most part, from fish, eggs, milk, and cheese; their lying on straw,

long watchings from midnight till morning, and austere fasts; their bread as

hard as the earth itself; their hard labour in cultivating desert lands to

produce the pulse and herbs on which they subsisted; their piety, devotion, and

tears, in singing the divine office; the cheerfulness of their countenances

breathing an holy joy in pale and mortified faces; the poverty of their houses;

the lowliness of their buildings, &c.

The saint having assembled the chapter of his Order in 1133, when all the other

business was dispatched, alleging his great age, infirmities, and incapacity,

begged most earnestly to be discharged from his office of general, that he

might in holy solitude have leisure to prepare himself to appear at the

judgment seat of Christ. All were afflicted, but durst not oppose his desire.

The chapter chose one Guy; but the saint discovering him unworthy of such a

charge, in a few days he was deposed, and Raynard, a holy disciple of St.

Bernard, created general. St. Stephen did not long survive the election of

Raynard. Twenty neighbouring abbots of his Order assembled at Citeaux, to

attend at his death. Whilst he was in his agony, he heard many whispering that,

after so virtuous and penitential a life, he could have nothing to fear in dying:

at this he said to them, trembling: “I assure you that I go to God in fear and

trembling. If my baseness should be found to have ever done any good, even in

this I fear, lest I should not have preserved that grace with the humility and

care I ought.” He passed to immortal glory on the 28th of March, 1134, and was

interred in the tomb of B. Alberic, in which also many of his successors lie

buried, in the cloister, near the door of the church. 5 His

Order keeps his festival on the 15th of July, as of the first class, with an

octave, and with greater solemnity than those of St. Robert, or St. Bernard,

having always looked upon him as the principal of its founders. The Roman

Martyrology honours him on the 17th of April, supposed to be the day on which

he was canonized, of which mention is made by Benedict XIV. 6

Note 1. B. Alberic is honoured with an office on the 26th of January, by

the Cistercian Order in Italy, by a grant of the Congregation of Sacred Rites.

See Bened. XIV. de Canon. l. 1, c. 13. Tu. 17, p. 100. [back]

Note 2. Rom. xiv.

3, 6. [back]

Note 3. This most valuable MS. copy of the Bible is preserved at Citeaux,

in four volumes in folio. Mauriquez in his Annals, and Henriquez in his

Fasciculus, give us a short pathetic discourse on the death of B. Alberic,

ascribed by many to St. Stephen, and not unworthy his pen. [back]

Note 4. St. Robert, in the foundation of Citeaux, proposed to himself, and

prescribed to his companions, nothing else but the reformation of the Order of

St. Bennet, and the observance of his rule to the letter, as Benedict XIV.

takes notice, (de Canoniz. l. 1, c. 13, n. 17. p. 101,) nor did the legate

grant him leave for his removal and new establishment with any other view or on

any other condition. (Exordium Magn. l. 1, c. 12, Hist. Lit. Fr. t. 11, p.

225.) St. Stephen in the Charte, or Charter of Charity, prescribes the rule of

St. Bennet to be observed to the letter, in all his monasteries, as it was kept

at Citeaux, (c. 1.) It is ordained that the abbot of Citeaux shall visit all

the monasteries of the Order, as the superior of the abbots themselves, and

shall take proper measures with the abbot of each house for the reformation of

all abuses, (c. 4.) Upon this rule the grand Conseil at Paris decreed, in the

year 1761, that the abbot of Citeaux could not establish in the four first

abbeys of the Order, and their filiations or dependencies, the reformation

which he attempted, without the free consent of the four abbots of those

houses. St. Stephen orders other abbots to perform every year the visitation of

all the houses subject to them, (c. 8.) and appoints the four first abbots of

the Order, viz. of La Ferte, Pontigni, Clairvaux, and Morimond, to visit every

year, in person, the abbey of Citeaux, (c. 8,) and to take care of its

administration upon the death of an abbot, and assemble the abbots of the

filiations of Citeaux, and some others, to choose a new abbot, (c. 19.) If any

abbot busies himself too much in temporal affairs, or falls into any other

irregularity, he is to be accused, to confess his fault, and be punished in the

next general chapter, (c. 19.) If any abbot commits or allows any transgression

against the rule, he is to be reprimanded by the abbot of Citeaux, and if

obstinate, to be deposed by him, (c. 23,) and in like manner the abbot of

Citeaux by the four first abbots, (c. 27, 28, 29, 30.)

The Usages of Citeaux, Liber Usuum, were compiled about the same

time, and according to Bale, Pits, Possevin, and Seguin, by St. Stephen; though

Brito, Pritero, and Henriquez are of opinion they were completed by St.

Bernard. In it all the regular observances of Citeaux are committed to writing

in five parts, which comprise one hundred and eighty chapters. B. Alberic had

before published certain regulations for this Order in 1101, assisted

principally by St. Stephen, who was at that time prior under the abbot Alberic.

The Usages were approved by the holy see, at or about the same time with the

Charte of Charity, and were probably published in the same general chapter. At

least they are mentioned among the acts of the general chapters compiled by

Rainard, the fourth abbot of Citeaux, in 1134. These have always made the code

of this Order: the best edition is that in the Nomasticon Cisterciense,

published at Paris in 1664, by F. Julian Paris.

The Exordium Parvum, or Short History of the Origin of Citeaux, was

composed by St. Stephen’s order, by some of his first companions. This most

edifying golden book, as it is justly called by the annalist of the Order, is

inserted by F. Teissier, in the Bibliotheca Patrum Cisterciensium, which he

published in three volumes in folio, in 1660. We have in the same place the

Exordium Magnum Cisterciense, or larger history of the beginning of this Order,

compiled near one hundred years later, in the thirteenth century. [back]

Note 5. A description of this saint’s tomb, and of those of several dukes

of Burgundy, and other great and holy men interred in this church, is given in

Descript. Historique des principaux Monumens de l’Abbaye de Cisteaux, in

the Mémoires de l’Acad. des Inscript. t. 9, p. 193. [back]

Note 6. De Canoniz. l. 1, c. 13, n. 17, t. 1, p. 100. [back]

Rev. Alban Butler (1711–73). Volume IV: April. The Lives

of the Saints. 1866.

SOURCE : http://www.bartleby.com/210/4/172.html

ST. STEPHEN HARDING

St. Stephen Harding is

regarded as the founder of the Cistercian monasteries. He was born in Dorset,

England, and educated at Sherborne Abbey.

After studying in Paris

and Rome, he visited the monastery of Molesme. Impressed by its

holy abbot, Robert of Molesme, and the prior, Alberic (both of

which were later canonized), Stephen joined the community.

After a few years, the

three men, along with 20 other monks, established a more austere monastery

in Citeaux. Eventually Robert was called back to his position of abbot

at Molesme(1099), and Alberic, who became the new abbot of

Citeaux, died in 1110. Following Alberic's death, Stephen was elected

as abbot.

Stephen drew up the

famous "Charter of Charity," which became the basis for Cistercian

monasticism. However, very few men were joining the community and the monastery

was suffering from hunger and sickness. It seemed for awhile as if thier

new order was destined to die out. However, in1112 the man who was to be known

as St. Bernard of Clairvaux, joined the community along with 30

other companions, including almost his entire family. The very next year

Stephen founded his first colony at La Ferté.

Before his death in

1134, Stephen had established 13 monasteries. By the end of the 12th

century there were 500 in Europe.

SOURCE : http://www.catholicnewsagency.com/saint.php?n=439

Church

of St. Stephen Harding (Apátistvánfalva)

Saint Stephen Harding

Confessor, the third

Abbot of Cîteaux, was born at Sherborne in Dorset, about the middle of

the eleventh century; died 28 March, 1134. He received his early education in

the monastery of Sherborne and afterwards studied in Paris and Rome. On

returning from the latter city he stopped at the monastery of Molesme and,

being much impressed by the holiness of St. Robert, the abbot, joined that

community. Here he practised

great austerities, became one of St. Robert’s chief supporters and was one of

the band of twenty-one monks who, by authority of Hugh, Archbishop of Lyons,

retired to Cïteaux to institute a reform in the new foundation there.

When St. Robert was

recalled to Molesme (1099), Stephen became prior of Cïteaux under Alberic, the

new abbot. On Alberic’s death (1110) Stephen, who was absent from the monastery

at the time, was elected abbot. The number of monks was now very reduced, as no

new members had come to fill the places of those who had died. Stephen,

however, insisted on retaining the strict observance originally instituted and,

having offended the Duke of Burgundy, Cïteaux’s great patron, by forbidding him

or his family to enter the cloister, was even forced to beg alms from door to

door. It seemed as if the foundation were doomed to die out when (1112) St.

Bernard with thirty companions joined the community. This proved the

beginning of extraordinary prosperity.

The next year Stephen

founded his first colony at La Ferté, and before is death he had established

thirteen monasteries in all. His powers as an organizer were exceptional, he

instituted the system of general chapters and regular visitations and, to

ensure uniformity in all his foundations, drew up the famous “Charter of

Charity” or collection of statutes for the government of all monasteries united

to Cïteaux, which was approved by Pope Callistus II in 1119. In 1133 Stephen,

being now old, infirm, and almost blind, resigned the post of abbot,

designating as his successor Robert de Monte, who was accordingly elected by

the monks. The saint’s

choice, however, proved unfortunate and the new abbot only held office for two

years.

Stephen was buried in the

tomb of Alberic, his predecessor, in the cloister of Cîteaux. In the Roman

calendar his feast is 17 April, but the Cistercians themselves keep it on 15

July, with an octave, regarding him as the true founder of the order. Besides

the “Carta Caritatis” he is commonly credited with the authorship of the

“Exordium Cisterciencis cenobii”, which however may not be his. Two of his sermons are preserved and also two letters

(Nos. 45 and 49) in the “Epp. S. Bernardi”.

Insisting on simplicity

in all aspects of monastic life, Stephen was largely responsible for the

severity of Cistercian architecture. Drawing on Jewish authorities, he prepared his own

edition of the Bible (1112; the manuscript is preserved at Dijon).

SOURCE : http://www.ss-thomas-stephen.org.uk/?page_id=118

St. Stephen Harding: Monk, Abbott, Founder of the Cistercian Order

The

three founders of the monastery at Citeaux: from left to right, Stephen

Harding, Saint Robert of Molesme, and Saint Alberic.

The saint of the day for April 17 is St. Stephen Harding (1060-1134), an

English-born monk and abbot, who was one of the founders of the Cistercian

Order in what is now France.

Stephen Harding, son of an English noble, was born at Sherborne in Dorsetshire,

England in 1060. He consecrated himself to the monastic life in the Abbey of

Sherbonne in Dorsetshire, where he received his early education. He later

studied in Paris and Rome, where he pursued a brilliant course in humanities,

philosophy and theology.

After studying in Paris and Rome, he visited the monastery of Molesmes.

Impressed by its leaders, Robert of Molesmes and Alberic (who were later

canonized), Stephen joined the community.

After a few years, the three men, along with another 20 monks, established a

more austere monastery in Citeaux. Eventually, Robert was recalled to Molesme

(1099), Alberic died (1110), and Stephen was elected abbot.

Stephen Harding is credited with writing the famous Carta Caritatis (Charter of

Charity - often referred to as the Charter of Love). It was a six page

constitution which laid out the relationship between the Cistercian houses and

their abbots, set out the obligations and duties inherent in these, and ensured

the accountability of all the abbots and houses to the underlying themes of

charity and living according to the rule of Benedict.

Since the monastery received very few novices, he began to have doubts that the

new institution was pleasing to God. He prayed for enlightenment and received a

response that encouraged him and his small community. From Bourgogne a noble

youth arrived with 30 companions, asking to be admitted to the abbey. This

noble was the future St. Bernard. In 1115 St. Stephen built the abbey of

Clairvaux, and installed St. Bernard as its Abbot. From it 800 abbeys were

born.

In 1133, Stephen resigned as the head of the order, due to age and disability,

and died the following year. He was canonized in 1623 by Pope Urban VIII.

SOURCE : https://catholicfire.blogspot.com/2015/04/st-stephen-harding-monk-abbott-founder.html

Romanesque

miniature with the three founders of the Citeaux order: Robert of Molesme,

Alberic of Citeaux and Stephen Harding, XIIIe sec.

St Stephen Harding

April 28, 2009 by Mark

Armitage

In the latter half of the eleventh century, when

Stephen was still a child, his parents presented him to Sherborne Abbey in

Dorset as an oblate. He received a monastic education, but, frustrated at the

restrictions inherent in monastic life, decided to leave the abbey and see the

world, traveling first to Scotland and then to Paris as a wandering scholar

(this, of course, was an age of wandering scholars).

Stephen’s dissatisfaction

with monasticism at Sherborne did nothing to weaken his Christian devotion,

and, nourished on the Psalms (which were for him the root and source of all his

spiritual life), he began – perhaps unusually for a wandering scholar – to

experience a desire not for a less restrictive kind of monasticism, but for a

Benedictine monastery where the Rule was observed with full strictness and

austerity.

He appeared to have discovered just such a monastery

when he happened upon a community living in the forest of Langres in Burgundy

under the abbot St Robert of Molesmes, where long hours of prayer and hard

manual labour underpinned a rigorous interpretation of St Benedict’s Rule.

The Bishop of Troyes, however, was hostile towards

this reformed kind of Benedictinism, and took it upon himself to burden the

community with property in the hope that this would have the effect of

mitigating the zeal and austerity of the monks.

His plan was so successful that, appalled at the

descent into mediocrity and indiscipline, St Robert decided to leave, being

followed by St Stephen and St Alberic (both of whom succeeded him briefly as

abbot).

The Bishop of Troyes ordered them to return, but,

increasingly disillusioned with lax spirit which the bishop had engendered

within the monastery, the fled the region and took refuge in Lyons under the

Archbishop Hugh, who happened to be the papal legate.

Thanks to Hugh’s support, Robert, Stephen and Alberic

were permitted to start a new, stricter religious order modeled on the original

spirit of the monastery from which they had come, and the new monastery of

Cîteaux opened in 1098 with Robert as abbot, Alberic as prior and Stephen as

subprior, though Robert was later ordered by Pope Urban II to return to

Molesmes for the purpose of extending the reform movement.

Alberic succeeded Robert

as Abbot of Cîteaux, and, after his death in 1109, was in turn succeeded by

Stephen. Stephen was

determined to move the new Cistercian order in the direction of a commitment to

radical poverty, and cut Cîteaux off from the usual sources of feudal income on

which monasteries normally depended.

Due to a chronic lack of

vocations, the new venture made little headway, and it was only Stephen’s

unshakeable trust in divine providence that kept Cîteaux going. However, almost

miraculously, in 1112 a group of thirty men, led by the future St Bernard of

Clairvaux, appeared out of the forests which surrounded Cîteaux and entered the

monastery as novices.

The Cistercian movement now exploded into life,

expanding to around ninety monasteries by the time of Stephen’s death in 1134.

In 1119 Stephen framed the new Cistercian

constitution, the “Charter of Charity”, which emphasized those principles of

the reformed monasticism – radical poverty, solitary silence, hard manual

labour, economic self-sufficiency, and a spirit of austere (even severe)

liturgical simplicity – which set the Cistercian charism apart from that of

less observant Benedictine houses.

Stephen’s dying words

were: “I am going to God as I had never done any good. If I have done some

good, it was through the help of the grace of God. But perhaps I have received this grace unworthily,

without turning it sufficiently to account”.

In fact, he had turned

the grace of God to very good account. Having co-founded a reform-movement within

Benedictinism, he went on to shape and preside over a monastic renaissance

which did much to transform the spiritual, intellectual and economic landscape

of mediaeval Europe.

Most images of Stephen

including some of those reproduced here, depict him as an abbot presenting his

church to the Virgin Mary. In this images he is invariable the figure at the

left of the painting or icon.

SOURCE : https://saintsandblesseds.wordpress.com/2009/04/28/st-stephen-harding/

Les

trois fondateurs de Citeaux: Saints Robert, Albéric, et Étienne Harding.

Cette

peinture commémore et décrit la fondation en 1111, montrant les trois saints vénérant la Vierge Marie.

I tre fondatori

dell'Abbazia di Cîteaux (Santo

Stefano Harding, San Roberto di Molesme e Sant'Alberico di Cîteaux)

Santo Stefano

Harding Abate

Meriot, Sherborne,

Inghilterra, 1060 ca. – Citeaux, Francia, 28 marzo 1134

La storia di Stefano

Harding rimanda alle origini dell'ordine monastico dei cistercensi, tra la fine

dell'XI e l'inizio del XII secolo. Questo monaco inglese originario di

Shelburne è infatti accanto a san Roberto di Molesme e ad Alberico quando nel

1098 fondano il nuovo monastero a Citeaux in Borgogna. Il principio ispiratore

di questa nuova comunità era la volontà di ristabilie l'obbedienza alla Regola

benedettina nella sua integrità. Di Citeaux Stefano Harding diverrà anche

abate. E sarà lui ad accogliere qui san Bernardo, la figura che col suo carisma

contribuirà alla grande fioritura del nuovo ordine monastico. Già sotto la

guida di Stefano Harding furono dodici le fondazioni nate da Citeaux. Morto nel

1134, è stato canonizzato nel 1623.

Etimologia: Stefano

= corona, incoronato, dal greco

Emblema: Bastone

pastorale

Martirologio

Romano: A Cîteaux in Burgundia, nell’odierna Francia, santo Stefano

Harding, abate: giunto da Molesme insieme ad altri monaci, resse questo celebre

cenobio, istituendovi i fratelli laici e accogliendo in esso il famoso Bernardo

con trenta suoi compagni; fondò dodici monasteri, che vincolò tra loro con la

Carta della Carità, affinché non esistesse tra i monaci discordia alcuna e

tutti vivessero sotto il medesimo dettame della carità, sotto la stessa regola

e secondo consuetudini simili.