Saint Athanase

Bazzekuketta

Martyr en Ouganda (+1886)

Il fait partie des martyrs

en Ouganda.

À Nakiwubo en Ouganda,

l’an 1886, saint Athanase Bazzekuketta, martyr. Il était un des pages du roi,

récemment baptisé et brûlant du désir du martyre. Pendant qu’on le conduisait,

avec les autres, vers le lieu du supplice, il demanda aux bourreaux de le tuer

sur le champ et, percé de coups, il acheva son martyre.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/11739/Saint-Athanase-Bazzekuketta.html

Saint Athanase

BAZZEKUKETTA

Nom: BAZZEKUKETTA

Prénom: Athanase

Pays: Ouganda

Naissance:

Mort:

27.05.1886 à Nakiwubo

Etat:

Laïc - Martyr du Groupe des 22

martyrs de l’Ouganda

Note: Thésaurier royal.

Baptisé en 1885.

Béatification:

06.06.1920 à Rome par Benoît XV

Canonisation:

18.10.1964 à Rome par Paul VI

Fête: 3 juin

Réf. dans l’Osservatore

Romano:

Réf. dans la Documentation

Catholique: 1964 col.1345-1352

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/hagiographie/fiches/f0629.htm

Saints Martyrs de

l’Ouganda

Martyrologe Romain :

Mémoire des saints Charles Lwanga et ses douze compagnons :

les saints Mbaga Tuzindé, Bruno Serunkerma, Jacques Buzabaliawo, Kizito,

Ambroise Kibuka, Mgagga, Gyavira, Achille Kiwanuka, Adolphe Ludigo Mkasa,

Mukasa Kiriwawanvu, Anatole Kiriggwajjo ; Luc Banabakintu, martyrs en

Ouganda l’an 1886. Âgés de 14 à 30 ans, ils faisaient partie du groupe des

pages ou de la garde du roi Mwanga. Néophytes et fermement attachés à la foi

catholique, ils refusèrent de se soumettre aux désirs impurs du roi et furent

soit égorgés par l’épée, soit jetés au feu sur la colline Nemugongo.

Avec eux sont commémorés

neuf autres martyrs : les saints Joseph Mukasa Balikuddembe, Denis

Sebuggwawo, André Kaggwa, Pontien Ngondwe, Athanase Bazzekuketta, Gonzague

Gonza, Matthias Kalemba, Noé Mawaggali, Jean-Marie Muzei. qui subirent le

martyre dans la même persécution, à des jours différents, entre 1885 et 1889.

SOURCE : http://dioceseobala.net/

QUI SONT LES MARTYRS DE

L’OUGANDA ?

Charles Lwanga et ses

compagnons martyrs de l'Ouganda/ Wikipédia

Le 3 juin, l’Église

catholique commémore 22 martyrs africains torturés puis tués en Ouganda entre

1885 et 1887, sous le règne du roi Mwanga. Qui sont-ils ?

De nombreuses paroisses

en Afrique ont comme saints patrons les Martyrs de l’Ouganda fêtés le 3 juin.

Voici leur histoire.

L’évangélisation du

Buganda (sud de l’actuel Ouganda) commence en 1879.

Deux Missionnaires

d’Afrique (Pères blancs), Simon Lourdel et Léon Livinhac arrivent à Entebbé

(ancienne capitale d’Ouganda) et sont pacifiquement reçus par le roi, Mutesa

qui les autorise à ouvrir un catéchuménat, préparant au baptême quelques

autochtones. Les pères Lourdel et Livinhac baptisent alors quelques

catéchumènes mais également des enfants agonisant suite à une épidémie de

variole. Ils quittent ensuite Entebbé de 1882 à 1885, pressentant déjà la

persécution.

Joseph Mukasa

À la mort du roi Mutesa,

son fils Mwanga est, a priori, favorable au christianisme et demande aux

missionnaires de revenir après trois ans d’exil. Aidés par les nouveaux

baptisés, notamment Joseph Mukasa, intendant du roi, les missionnaires

continuent leur évangélisation. Mais leurs activités commencent à gêner le

premier ministre ainsi que dignitaires locaux. Ils finissent par convaincre le

roi que les chrétiens ourdissaient un complot dans le but de le renverser.

Joseph Mukasa est la

première victime de la persécution du roi Mwanga contre les catholiques. Il est

décapité et son corps, brûlé le 15 novembre 1885. Le tyran espérait décourager

tous les néophytes en tuant leur chef. Mais rien n’y fait. Le lendemain du

martyre de Joseph, 12 catéchumènes demandent le baptême et 500 autres sont

baptisés la même semaine.

Denis Sebuggwao, André

Kaggwa, Achille Kiwanuka, Pontien Ngondwe

Le 25 mai 1886, le roi

Mwanga, égorge un page de 14 ans, Denis Sebuggwao, après avoir été informé

qu’il apprenait la catéchèse. Le 26 mai, il déclare ouverte la persécution

contre les chrétiens. André Kaggwa, un autre page est amputé puis tué.

Le même jour, le roi

ordonne que tous les pages chrétiens soient brûlés vifs. En plus de Joseph,

Denis et André, Achille Kiwanuka, un clerc qui servait à la cour du roi, et 14

autres pages sont condamnés à mort. Alors qu’ils marchaient, attachés les uns

autres, ils rencontrèrent un jeune nommé Pontien Ngondwe. « Tu sais prier ? »,

lui demanda l’un des bourreaux qui lui trancha la tête à sa réponse par

l’affirmative.

Charles Lwanga, Kizito

Les condamnés sont livrés

au feu le 3 juin.

Charles Lwanga, un des 22

martyrs, est un grand athlète d’une vigueur peu commune. Le roi lui a confié un

groupe de pages à qui il enseigne, en cachette, le catéchisme. Le roi décide de

le brûler à part, d’une manière particulièrement cruelle.

Quand le bourreau alluma

le feu, pour brûler les pieds de Charles, celui-ci lui dit : « tu me brûles,

mais c’est comme si tu versais de l’eau pour me laver ! » Lorsque les flammes

attaquèrent la région du cœur, avant d’expirer, Charles murmura : « Mon Dieu !

mon Dieu ! »

L’un des martyrs les plus

connus est Kizito, 13 ans, page du roi, le plus jeune du groupe. « Donne-moi la

main : j’aurai moins peur », dit-il à Charles Lwanga, dans l’attente du bûcher.

« C’est ici que nous

verrons Jésus ! », s’exclamait un autre. Pendant qu’on les brûlait, les martyrs

récitaient le « Notre Père ». On sut qu’ils étaient morts quand cessa leur

prière.

Jean-Marie Muzei et les

autres martyrs

Le dernier des martyrs

est Jean-Marie Muzei. Il se livre lui-même au roi, las de se cacher pour vivre

sa foi. Il est décapité le 27 janvier 1887 et son corps jeté dans un marécage.

Les autres martyrs de

l’Ouganda sont : Adolphe Ludigo Mkasa, Ambroise Kibuka, Anatole

Kiriggwajjo, Athanase Bazzekuketta, Bruno Seronuma, Jacques Buzabali,

Gonzague Gonza, Gyavira, Luc Banabakintu, Matthias Kalemba, Mbaya Tuzinde,

Mgagga, Mukasa Kiriwanwu, Noé Mawaggali.

En plus des 22 martyrs

catholiques 23 chrétiens anglicans sont tués dans la même période.

Le 16 août 1912, le pape

saint Pie X déclare vénérables les Charles Lwanga et ses compagnons. Ils sont

béatifiés le 6 juin 1920, puis canonisés le 18 octobre 1964.

Saint Kizito et Saint

Charles Lwanga sont proclamés patrons de la jeunesse africaine.

Lucie Sarr

Source: africa.la-croix

SOURCE : https://mafr.net/nouvelles-en-details/2020-11-02/ouganda_140

Les Saints Martyrs de l'Ouganda

Ces Saints habitaient une

contrée au milieu de l'Afrique, appelée Ouganda. Personne n'y avait jamais

prononcé le nom de Dieu et le démon y régnait par l'esclavage, la sorcellerie

et le cannibalisme. Deux Pères Blancs, le P. Lourdel et le P. Livinhac débarquèrent

un jour chez ces pauvres indigènes. Ils se présentèrent aussitôt au roi Mutesa

qui les accueillit pacifiquement et leur accorda droit de cité.

Les dévoués missionnaires

se faisaient tout à tous en rendant tous les services possibles. Sept mois à

peine après l'ouverture du catéchuménat, ils désignaient quelques sujets dignes

d'être préparés au baptême. Le roi Mutesa s'intéressait à ce que prêchaient les

Pères, mais leur prédication alluma bientôt la colère des sorciers jaloux et

des Arabes qui pratiquaient le commerce des Noirs.

Pressentant la

persécution, les Pères Lourdel et Livinhac baptisèrent les indigènes déjà

préparés et se retirèrent au sud du lac Victoria avec quelques jeunes Noirs

qu'ils avaient rachetés. Comme la variole décimait la population de cette

contrée, les missionnaires baptisèrent un grand nombre d'enfants près de

mourir.

Après trois ans d'exil,

le roi Mutesa vint à mourir. Son fils Mwanga, favorable à la nouvelle religion,

rappela les Pères Blancs au pays. Le 12 juillet 1885, la population ougandaise

qui n'avait rien oublié des multiples bienfaits des missionnaires, accueillait

triomphalement les Pères Lourdel et Livinhac. Les Noirs qu'ils avaient baptisés

avant de partir, en avaient baptisé d’autres ; l'apostolat s'avérait

florissant. Le ministre du nouveau roi prit ombrage du succès des chrétiens,

surtout du chef des pages, Joseph Mukasa, qui combattait leur immoralité.

Ami et confident du roi,

supérieurement doué, Joseph aurait pu devenir le second personnage du royaume,

mais sa seule ambition était de réaliser en lui et autour de lui, les

enseignements du Christ. Le ministre persuada le jeune roi que les chrétiens

voulaient s'emparer de son trône ; les sorciers insistaient pour que les

prétendus conspirateurs soient promptement punis de mort. Mwanga céda à ces

fausses accusations et fit brûler Joseph Mukasa, le 15 novembre 1885.

« Quand j'aurai tué

celui-là, dit le tyran, tous les autres auront peur et abandonneront la

religion des Pères ». Contrairement à ces prévisions, les conversions ne

cessèrent de se multiplier. La nuit qui suivit le martyre de Joseph, douze catéchumènes

sollicitèrent la grâce du baptême. Cent cinq autres catéchumènes furent

baptisés dans la semaine qui suivit la mort de Joseph, parmi lesquels

figuraient onze des futurs martyrs.

Le 25 mai 1886, six mois

après l'odieux meurtre de Joseph, le roi revenant de chasse fit appeler un de

ses pages, nommé Denis, âgé de quatorze ans. En l'interrogeant, Mwanga apprit

qu'il étudiait le catéchisme avec Muwafu, un jeune baptisé. Transporté de rage,

il l'égorgea avec sa lance empoisonnée. Les bourreaux l'achevèrent le lendemain

matin, 26 mai, jour où le despote déclara officiellement la persécution ouverte

contre les chrétiens.

Le même jour, Mwanga fit

mutiler et torturer le jeune Honorat, mit la cangue au cou à un néophyte appelé

Jacques qui avait essayé autrefois de le convertir à la religion chrétienne.

Ensuite, il fit assembler tous les pages chrétiens et ordonna qu'on les amena

pour être brûlés vifs sur le bûcher de Namugongo. Jacques périt sur ce bûcher

en compagnie des autres martyrs, le 3 juin 1886, fête de l'Ascension.

« On avait lié

ensemble les jeunes de 18 à 25 ans, écrira le Père Lourdel ; les enfants

étaient également liés, et si étroitement serrés les uns près des autres qu'ils

ne pouvaient marcher sans se heurter un peu. Je vis le petit Kizito rire de cette

bousculade comme s'il eût été en train de jouer avec ses compagnons ». Ils

sont en tout quinze catholiques. Trois seront graciés à la dernière minute. On

compte officiellement vingt-deux martyrs catholiques canonisés dont le martyre

s'échelonne de l'année 1885 à 1887.

Le groupe des condamnés

marchait vers le lieu de leur supplice, lorsqu'ils rencontrèrent un Noir nommé

Pontien. « Tu sais prier ? » questionna le bourreau ; sur

la réponse affirmative de Pontien, le bourreau lui trancha la tête d'un coup de

lance. C'était le 26 mai 1886. Le soir venu, on immobilisa les martyrs dans une

cangue et on ramena de force à la maison, le fils du bourreau, au nombre des

victimes. Après une longue marche exténuante, doublée de mauvais traitements,

les captifs arrivèrent, le 27 mai, à Namugongo. Les bourreaux, au nombre d'une

centaine, répartirent les prisonniers entre eux.

Les cruels exécuteurs

travailleront jusqu'au 3 juin afin de rassembler tout le bois nécessaire au

bûcher. Les prisonniers doivent donc attendre six longues journées de

privations et de souffrances, nuits de froid et d'insomnie, mais plus encore

d'ardentes prières, avant que la mort ne vienne couronner leur héroïque combat.

Le martèlement frénétique des tam-tams qui se fit entendre toute la nuit du 2 juin

indiqua aux martyrs qui languissaient, garrottés dans des huttes, que l'immense

brasier de leur suprême holocauste s'allumerait très bientôt.

Charles Lwanga,

magnifique athlète d'une vigueur peu commune, à qui le roi avait confié un

groupe de pages auxquels il avait enseigné le catéchisme en cachette, fut

séparé de ses compagnons afin d'être brûlé à part, d'une manière

particulièrement atroce. Le bourreau alluma les branchages de manière à ne

brûler d'abord que les pieds de sa victime. « Tu me brûles, dit Charles,

mais c'est comme si tu versais de l'eau pour me laver ! » Lorsque les

flammes attaquèrent la région du cœur, avant d'expirer, Charles murmura :

« Mon Dieu ! Mon Dieu ! »

Comme le groupe des

martyrs avançait vers le bûcher, un cri de triomphe retentit : Nwaga, le

fils du chef des bourreaux, avait réussi à s'enfuir de la maison pour voler au

martyre ! Il bondissait de joie en se retrouvant dans la compagnie de ses

amis. On l'assomma d'abord d'un coup de massue, puis il fut roulé avec les

autres dans des claies de roseaux pour devenir dans un instant la proie des

flammes.

Après leur avoir brûlé

les pieds, ils reçurent la promesse d'une prompte délivrance s'ils renonçaient

à la prière. Mais ces héros ne craignaient pas la mort de leur corps et devant

leur refus catégorique d'apostasier, on commença à incendier le bûcher.

Par-dessus le crépitement du brasier et les clameurs des bourreaux

sanguinaires, la prière des saints martyrs s'éleva calme, ardente et

sereine : « Notre Père qui êtes aux cieux... » On sut qu'ils

étaient morts lorsqu'ils cessèrent de prier.

Le dernier des martyrs

s'appelait Jean-Marie. Longtemps obligé de se cacher, las de sa vie vagabonde,

il désirait ardemment mourir pour sa foi. Malgré les conseils de ses amis qui

essayaient de le dissuader de ce projet, Jean-Marie résolut d'aller voir le roi

Mwanga. Nul ne le revit plus jamais, car le 27 janvier 1887, Mwanga le fit

décapiter et jeter dans un étang.

La dévotion populaire aux

martyrs de l'Ouganda prit un essor universel, après que saint Pie X les

proclama Vénérables, le 16 août 1912. Leur béatification eut lieu le 6 juin

1920 et ils reçurent les honneurs de la canonisation, le 18 octobre

1964. Tiré de Marteau de Langle de Cary, 1959, tome II, p. 305-308 --

Vivante Afrique, No 234 - Bimestriel - Sept - Oct. - 1964. Ils sont fêtés

le 3 juin.

Source : http://christroi.over-blog.com

Prière Litanique aux

Saints Martyrs d'Ouganda

O Jésus, notre Seigneur

et Rédempteur, à travers votre passion et la mort nous Vous adorons et vous

louons par Votre douloureuse passion et Votre mort.

Sainte Marie, Mère et

Reine des Martyrs, obtenez-nous la sanctification par l'offrande de nos

souffrances.

Saints Martyrs, disciples

du Christ souffrant, obtenez-nous la grâce de vous imiter.

Saint Joseph

Balikuddembe, premier martyr de l'Ouganda, qui a inspiré et encouragé Nephyte,

obtenez-nous l'esprit de vérité et de justice.

Saint Charles Lwanga,

patron de la jeunesse et de l'Action catholique, obtenez-nous une foi ferme et

zélée.

Saint Matthias Mulumba,

idéal chef et disciple du Christ doux et humble de cœur, obtenez-nous une

douceur chrétienne.

Saint Denis Sebuggwawo,

rempli zèle pour la foi chrétienne et renommé pour votre modestie, obtenez-nous

la grâce de rester modestes.

Saint André Kaggwa,

modèle des catéchistes et des enseignants, obtenez-nous, un grand amour pour

l'enseignement du Christ.

Saint Kizito, enfant

resplendissant de la pureté et de joie chrétienne, obtenez-nous le don de la

joie des enfants de Dieu.

Saint Gyaviira, brillant

modèle du pardon, obtenez-nous la grâce de pardonner à ceux qui nous blessent

et nous offensent.

Saint Mukasa, fervent

catéchumène qui avez reçu le baptême de sang, obtenez-nous de toujours

persévérer dans la Foi jusqu'à la mort.

Saint Adolphe Ludigo,

remarquable par votre service envers le Seigneur et par votre esprit de service

aux autres, obtenez-nous l'amour du service désintéressé.

Saint Anatole

Kiriggwajjo, humble serviteur préférant une vie pieuse aux honneurs terrestres,

obtenez-nous de préférer l'amour de la piété aux choses terrestres.

Saint Ambroise Kibuuka,

jeune homme plein de joie et d'amour du prochain, obtenez-nous la grâce d'une

charité fraternelle.

Saint Achille Kiwanuka,

qui pour l'amour du Christ avez détesté les vaines pratiques superstitieuses,

obtenez-nous une sainte haine de ces pratiques.

Saint Jean Muzeeyi,

conseiller sage et prudent, réputé pour la pratique des œuvres de miséricorde,

d'obtenir pour nous l'amour des œuvres de miséricorde.

Bienheureux Jildo Irwa et

le bienheureux Daudi Okello qui avez donné vos vies pour la propagation de la

foi catholique, obtenez-nous un zèle ardent pour la propagation de la foi

catholique.

Saint Pontaianus Ngondwe,

soldat fidèle, désirant la couronne du martyre, obtenez nous la grâce d'être

toujours fidèle à notre devoir.

Saint Athanase

Bazzekuketta, fidèle gardien du trésor royal, obtenez-nous l'esprit de

responsabilité.

Saint Mbaaga, qui a

préféré la mort aux persuasions de vos parents ; obtenez-nous de suivre

généreusement la grâce divine.

Saint Gonzague Gonza,

rempli de sympathie pour les prisonniers, et tous ceux qui sont en difficulté,

obtenez-nous un esprit miséricordieux.

Saint Noé Mawaggali,

humble travailleur et amoureux de la pauvreté évangélique, obtenez-nous un

grand amour de la pauvreté évangélique.

Saint Luc Baanabakintu,

qui a ardemment souhaité imiter le Christ souffrant le martyre, obtenez-nous

l'amour pour notre patrie.

Saint Bruno Serunkuuma,

le soldat qui a donné un exemple de repentir et de tempérance, obtenez-nous une

vie de repentir et tempérance.

Saint Mugagga, jeune

homme reconnu pour votre chasteté héroïque, obtenez-nous la persévérance dans

la chasteté.

Saint Martyrs, fermes et

courageux dans la fidélité à la véritable Église du Christ, aidez-nous à être

toujours fidèles à la véritable Église du Christ.

Prions : O Seigneur

Jésus-Christ, qui a merveilleusement renforcé les Saint Martyrs de l'Ouganda,

Charles Lwanga, Matthias Mulumba, les Bienheureux Jildo Irwa et Daudi Okello et

tous leurs compagnons, et qui nous les avez donné comme exemples de foi et de courage,

de chasteté, de charité et de fidélité ; faites, nous vous en supplions,

que, par leur intercession, les même vertus croissent en nous, pour que nous

méritions ainsi de devenir propagateurs de la vraie foi. Vous qui vivez et

régnez avec le Père, dans l'Unité du Saint Esprit, maintenant et pour les

siècles et les siècles. Amen.

Source : http://imagessaintes.canalblog.com

SOURCE : http://laviedesparoisses.over-blog.com/2019/06/les-22-martyrs-de-l-ouganda.html

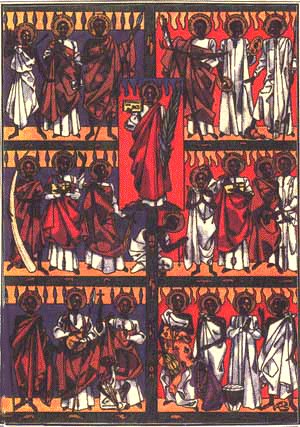

Saint Charles Lwanga (in the center) and his 21

followers.

Der

Heilige Karl Lwanga (in der Mitte) und seine 21

Anhänger.

De

Hillige Korl Lwanga (in de Merr) un siene 21 Folgers.

Also

known as

Atanasio

3 June as

one of the Martyrs

of Uganda

Profile

Nkima clan. Convert.

One of the Martyrs

of Uganda who died in

the Mwangan persecutions.

Born

hacked

to pieces on 27 May 1886 at

Nakivubo, Uganda

29

February 1920 by Pope Benedict

XV (decree of martyrdom)

6 June 1920 by Pope Benedict

XV

18

October 1964 by Pope Paul

VI at Rome, Italy

Additional

Information

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

Dicastero delle Cause dei Santi

Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

MLA

Citation

“Saint Antanansio

Bazzekuketta“. CatholicSaints.Info. 27 June 2023. Web. 27 May 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-antanansio-bazzekuketta/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-antanansio-bazzekuketta/

St. Athanasius

Badzekuketta

Feastday: June 3

Death: 1886

A martyr of

Uganda. He was a page in the court of King Mwanga of Uganda and the keeper of

the royal treasury. When it was discovered that Athanasius had been baptized,

he was slain.

SOURCE : https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=1588

ATHANASIUS BAZZEKUKETTA

Bazzekuketta’s

early life and how he joined Christianity

Mwanga appoints Bazzekuketta his treasurer

The

heroism and death of Bazzekuketta

Bazzekuketta’s

early life and how he joined Christianity

Bazzekuketta, another

page who served both Muteesa and Mwanga was the second of the eleven children

of Kafeero Kabalu Sebaggala of the Monkey (Nkima) clan and Namukwaya of the

Buffalo (Mbogo) clan. Bazzekuketta is first heard of as belonging to the

household of Sembuzzi, the chief chosen by Stanley to command his escort on his

journey through Bunyoro, the same who later deserted and ab¬sconded with one

hundred and eighty pounds of beads. He was known as Sembuzzi's brother-in-law

although actually a nephew-in-¬law, one of Sembuzzi's wives, Namuddu, a sister

of Ddumba, being his aunt. The name Bazzekuketta, which means

they-have-come-¬to-see-whether- their-brother-in -law- treats-them-well-or-ill,

was given him when he first joined Sembuzzi's household; there is no informa¬tion

about his original name, nor any certainty about the place of his birth.

It was while he was still

at Sembuzzi's that Bazzekuketta caught the small-pox that left its scars upon

his face and, in the throes, of the sickness, was approached by Raphael

Sembuya, one of his com¬panions, with the suggestion that baptism was the only

remedy for his illness. He agreed to be baptized and was taught the Sign of the

Cross and other prayers but not then given the sacrament, as he began to mend.

This incident illustrates the charity shown by these early Baganda Christians

and their zeal for sharing the good-tidings with others. It also provides an

object-lesson for the complacent Christian who considers his religion to be a

purely private and per¬sonal matter between himself and God.

After his recovery,

Bazzekuketta persevered with the study of the Catholic religion and, on

entering the Kabaka's service, evidently in a humble capacity because he was

nicknamed Bisasiro (Rubbish) by his companions, he found there able instructors

in Joseph Mukasa, Jean-Marie Muzeeyi and, later, Charles Lwanga. He could also

often be found sitting at the feet of Andrew Kaggwa in the latter's com¬pound

at Nateete and, later, at Kigoowa.

Bazzekuketta, who was

about twenty at the time of his martyrdom, was one of Muteesa's pages

re-appointed by Kabaka Mwanga. He was then put in charge of the Kabaka's

ceremonial robes and ornaments, to keep them clean and polished, and also had

the duty of polishing the palace mirrors.

Mwanga

appoints Bazzekuketta his treasurer

Bazzekuketta was one of

the pages served King Muteesa I and later reappointed by King Mwanga after the

death of Muteesa. He was a clean, orderly, faithful and obedient young man of

about twenty years of age.

Because of his sleekness,

he was selected to be in charge of the king's ceremonial robes and ornaments.

Athanasius was chosen to be in charge of the king's treasury of money and

ivory, in spite of the fact that he was still young.

It is crystal clear that

Athanasius' trustworthiness was so great that it drew the king's confidence in

him to the extent of entrusting his treasury and other property with this young

man.

The

heroism and death of Bazzekuketta

Immediately after his

condemnation by the Kabaka, while being led to the executioners' quarters for

detention, he had remarked, 'So you want us to bite through the stocks (i.e.

keep us in prison)? Are you not going to kill us? We are the Kabaka's meat.

Take us away and kill us at once!'

'This fellow talks as if

he longs for death,' said one of the execu¬tioners, hitting him with a

stick.

When taken out of prison

at Munyonyo, Bazzekuketta again objected to the delay: 'The Kabaka ordered you

to put us to death. Where are you taking us? Why don't you kill us here?'

Perhaps the sight of

Ngondwe's blood, which Denis Kamyuka says they saw on the road, encouraged the

youth to hope that he could at last goad the executioners into granting him the

martyr's crown, for at Ttaka Jjunge, near the residence of Kulekaana, he

stopped and sat himself down on the road, exclaiming, 'I am not going to walk

after death all the way to Namugongo. Kill me here!'

The guards laid about him

with sticks until he said, 'Very well!

You can stop beating me.

I will march. I was only thinking that you would kill me here.'

The prisoners reached

Mmengo late in the evening, and were lodged for the night in the executioners'

encampment.

In the morning, the executioners

informed them that they intended putting one of them to death at the near-by

execution- site, where Joseph Mukasa had met his death some six months earlier.

Immediately, Athanasius Bazzekuketta, still thirsting for martyrdom,

volunteered. 'Take me!' he exclaimed. Mukaajanga, who had been informed of the

youth's behaviour on the previous evening, gave his assent. 'Since he has given

you trouble,' he said to his assistants, 'go and kill him at once. Later on the

Kabaka might remember (i.e. pardon) him.'

Athanasius was promptly

taken to the spot at the foot of Mmengo Hill, just at the back of the present

Nakivubo Stadium, and there hacked to pieces, his executioners chanting, as

they went about their task, 'The gods of Kampala will rejoice'. Thus died the

fifth of the Blessed Martyrs of Uganda, on the morning of 27 May 1886, aged

about twenty.

Having butchered the

gallant Bazzekuketta and granted him the martyr’s crown which he had craved

with such holy impatience, the group of executioners returned to their other

victims and glee¬fully told them what they had done. 'The Christians,' they

said, 'are getting what they deserve; they are simply asking for death.' Far

from being dismayed by the gruesome recital, their prisoners said to one

another, 'Our friend Athanasius has proved his courage; he did not shrink from

laying down his life in God's cause. Let us be brave like him!' The cortege was

then assembled and, shortly after, set out on what was to be for most of the

prisoners their last journey on earth, the journey to Namugongo.

SOURCE : http://www.ugandamartyrsshrine.org.ug/martyrs.php?id=9

Namugongo Martyrs’ Shrine,

Uganda (1973). Architect: Justus Dahinden, Zurich

Wallfahrtskirche

in Namugongo, Uganda (1973)

Eglise

de pèlerinage à Namugongo, Uganda (1973)

Sant' Atanasio

Bazzekuketta Martire

>>>

Visualizza la Scheda del Gruppo cui appartiene

Uganda, 1866 - Nakiwubo,

27 maggio 1886

Atanasio Bazzekuketta fa

parte del gruppo - venerato oggi con la dizione Carlo Lwanga e compagni - di 22

martiri ugandesi. Questi furono uccisi in diverse fasi sotto il re Muanga,

durante una persecuzione che costò la vita in poco più di un anno, dal novembre

1885 al febbraio 1887, a un centinaio di cristiani. Muanga e il predecessore,

re Mutesa, avevano accolto favorevolmente l'annuncio del Vangelo da parte dei

missionari Padri Bianchi. Ma l'erede, salito al trono, mutò tragicamente

parere. Atanasio era il custode del regio tesoro e fu ucciso il 3 giugno del

1886 a soli 20 anni. Si offrì ai carnefici che durante una marcia di

trasferimento dei cristiani imprigionati ne uccidevano uno a ogni crocicchio

per incutere terrore agli altri. I martiri ugandesi sono stati beatificati nel

1920 da Benedetto XV e canonizzati nel 1964 da Paolo VI, che nel 1969 consacrò

il santuario a loro dedicato nella località ugandese di Namugongo. (Avvenire)

Martirologio Romano: In

località Nakiwubo in Uganda, sant’Atanasio Bazzekuketta, martire, che, giovane

della casa reale, essendo stato da poco battezzato, mentre veniva condotto con

gli altri al luogo del supplizio per aver accolto la fede di Cristo, implorò i

carnefici di ucciderlo subito e, preso a bastonate, portò a compimento il suo

martirio.

Fece un certo scalpore,

nel 1920, la beatificazione da parte di Papa Benedetto XV di ventidue martiri

di origine ugandese, forse perché allora, sicuramente più di ora, la gloria

degli altari era legata a determinati canoni di razza, lingua e cultura. In

effetti, si trattava dei primi sub-sahariani (dell’”Africa nera”, tanto per

intenderci) ad essere riconosciuti martiri e, in quanto tali, venerati dalla

Chiesa cattolica.

La loro vicenda terrena

si svolge sotto il regno di Mwanga, un giovane re che, pur avendo frequentato

la scuola dei missionari (i cosiddetti “Padri Bianchi” del Cardinal Lavigerie)

non è riuscito ad imparare né a leggere né a scrivere perché “testardo,

indocile e incapace di concentrazione”. Certi suoi atteggiamenti fanno dubitare

che sia nel pieno possesso delle sue facoltà mentali ed inoltre, da mercanti

bianchi venuti dal nord, ha imparato quanto di peggio questi abitualmente

facevano: fumare hascisc, bere alcool in gran quantità e abbandonarsi a

pratiche omosessuali. Per queste ultime, si costruisce un fornitissimo harem

costituito da paggi, servi e figli dei nobili della sua corte.

Sostenuto all’inizio del

suo regno dai cristiani (cattolici e anglicani) che fanno insieme a lui fronte

comune contro la tirannia del re musulmano Kalema, ben presto re Mwanga vede

nel cristianesimo il maggior pericolo per le tradizioni tribali ed il maggior

ostacolo per le sue dissolutezze. A sobillarlo contro i cristiani sono

soprattutto gli stregoni e i feticisti, che vedono compromesso il loro ruolo ed

il loro potere e così, nel 1885, ha inizio un’accesa persecuzione, la cui prima

illustre vittima è il vescovo anglicano Hannington, ma che annovera almeno

altri 200 giovani uccisi per la fede.

Il 15 novembre 1885

Mwanga fa decapitare il maestro dei paggi e prefetto della sala reale. La sua

colpa maggiore? Essere cattolico e per di più catechista, aver rimproverato al

re l’uccisione del vescovo anglicano e aver difeso a più riprese i giovani

paggi dalle “avances” sessuali del re. Giuseppe Mkasa Balikuddembè

apparteneva al clan Kayozi ed ha appena 25 anni.

Viene sostituito nel

prestigioso incarico da Carlo Lwanga, del clan Ngabi, sul quale si concentrano

subito le attenzioni morbose del re. Anche Lwanga, però, ha il “difetto” di

essere cattolico; per di più, in quel periodo burrascoso in cui i missionari

sono messi al bando, assume una funzione di “leader” e sostiene la fede dei

neoconvertiti.

Il 25 maggio 1886 viene

condannato a morte insieme ad un gruppo di cristiani e quattro catecumeni, che

nella notte riesce a battezzare segretamente; il più giovane, Kizito, del clan

Mmamba, ha appena 14 anni. Il 26 maggio vemgono uccisi Andrea Kaggwa, capo dei

suonatori del re e suo familiare, che si era dimostrato particolarmente

generoso e coraggioso durante un’epidemia, e Dionigi Ssebuggwawo.

Si dispone il

trasferimento degli altri da Munyonyo, dove c’era il palazzo reale in cui erano

stati condannati, a Namugongo, luogo delle esecuzioni capitali: una “via

crucis” di 27 miglia, percorsa in otto giorni, tra le pressioni dei parenti che

li spingono ad abiurare la fede e le violenze dei soldati. Qualcuno viene

ucciso lungo la strada: il 26 maggio viene trafitto da un colpo di lancia

Ponziano Ngondwe, del clan Nnyonyi Nnyange, paggio reale, che aveva ricevuto il

battesimo mentre già infuriava la persecuzione e per questo era stato

immediatamente arrestato; il paggio reale Atanasio Bazzekuketta, del clan

Nkima, viene martirizzato il 27 maggio.

Alcune ore dopo cade

trafitto dalle lance dei soldati il servo del re Gonzaga Gonga del clan

Mpologoma, seguito poco dopo da Mattia Mulumba del clan Lugane, elevato al

rango di “giudice”, cinquantenne, da appena tre anni convertito al

cattolicesimo.

Il 31 maggio viene

inchiodato ad un albero con le lance dei soldati e quindi impiccato Noè

Mawaggali, un altro servo del re, del clan Ngabi.

Il 3 giugno, sulla

collina di Namugongo, vengono arsi vivi 31 cristiani: oltre ad alcuni

anglicani, il gruppo di tredici cattolici che fa capo a Carlo Lwanga, il quale

aveva promesso al giovanissimo Kizito: “Io ti prenderò per mano, se dobbiamo

morire per Gesù moriremo insieme, mano nella mano”. Il gruppo di questi martiri

è costituito inoltre da: Luca Baanabakintu, Gyaviira Musoke e Mbaga Tuzinde,

tutti del clan Mmamba; Giacomo Buuzabalyawo, figlio del tessitore reale e

appartenente al clan Ngeye; Ambrogio Kibuuka, del clan Lugane e Anatolio

Kiriggwajjo, guardiano delle mandrie del re; dal cameriere del re, Mukasa Kiriwawanvu

e dal guardiano delle mandrie del re, Adolofo Mukasa Ludico, del clan Ba’Toro;

dal sarto reale Mugagga Lubowa, del clan Ngo, da Achilleo Kiwanuka (clan

Lugave) e da Bruno Sserunkuuma (clan Ndiga).

Chi assiste

all’esecuzione è impressionato dal sentirli pregare fino alla fine, senza un

gemito. E’ un martirio che non spegne la fede in Uganda, anzi diventa seme di

tantissime conversioni, come profeticamente aveva intuito Bruno Sserunkuuma

poco prima di subire il martirio “Una fonte che ha molte sorgenti non si

inaridirà mai; quando noi non ci saremo più altri verranno dopo di noi”.

La serie dei martiri

cattolici elevati alla gloria degli altari si chiude il 27 gennaio 1887 con

l’uccisione del servitore del re, Giovanni Maria Musei, che spontaneamente confessò

la sua fede davanti al primo ministro di re Mwanga e per questo motivo venne

immediatamente decapitato.

Carlo Lwanga con i suoi

21 giovani compagni è stato canonizzato da Paolo VI nel 1964 e sul luogo del

suo martirio oggi è stato edificato un magnifico santuario; a poca distanza, un

altro santuario protestante ricorda i cristiani dell’altra confessione, martirizzati

insieme a Carlo Lwanga. Da ricordare che insieme ai cristiani furono

martirizzati anche alcuni musulmani: gli uni e gli altri avevano riconosciuto e

testimoniato con il sangue che “Katonda” (cioè il Dio supremo dei loro

antenati) era lo stesso Dio al quale si riferiscono sia la Bibbia che il

Corano.

Autore: Gianpiero

Pettiti

SOURCE : http://www.santiebeati.it/dettaglio/92074

Carlo Lwanga, Mattia Maulumba Kalemba e 20 compagni

(† 1885 - 1887)

Beatificazione:

- 06 giugno 1920

- Papa Benedetto XV

Canonizzazione:

- 18 ottobre 1964

- Papa Paolo VI

- Basilica Vaticana

Ricorrenza:

- 3 giugno

Vatican News nell'anniversario

Re Mwanga, sobillato

dagli stregoni locali che vedono il loro potere compromesso dalla forza del

Vangelo, il sovrano dà inizio a una vera e propria persecuzione contro i

cristiani, soprattutto perché non cedono al suo volere dissoluto. Carlo Lwanga

viene condannato a morte, insieme ad altri. Il giorno seguente, cominciano le

prime esecuzioni Il 3 giugno Carlo Lwanga e i suoi compagni, insieme ad alcuni

fedeli anglicani, vengono arsi vivi. Pregano fino alla fine, senza emettere un

gemito, dando una prova luminosa di fede feconda. Uno tra loro, Bruno

Ssrerunkuma, dirà, prima di spirare: “Una fonte che ha molte sorgenti non si

inaridirà mai. E quando noi non ci saremo più, altri verranno dopo di noi

“Io ti prenderò per mano.

Se dobbiamo morire per Gesù, moriremo insieme, mano nella mano”

Nel 1875 arrivarono in

Uganda i primi missionari, all'inizio il re provò simpatia per la religione

cattolica ma dopo un pò preferì l'islam. Nonostante tutto, la missione

prosperava e vi erano molti catecumeni, ma il re temendo che l'Inghilterra

desiderasse appropriarsi del suo regno allontanò dalla sua tribù i missionari

cristiani. Morto lui, però, il figlio Mwanga che ne prese il posto, richiamò i

Padri ed essi trovarono una comunità cristiana piuttosto fiorente, con oltre

800 catecumeni.

Inoltre, dopo averli

accolti con cordialità al ritorno, promise pubblicamente (poiché era succeduto

al padre) che, dopo aver pregato il Dio dei cristiani, avrebbe non soltanto

chiamato a sé i migliori tra i sudditi cristiani e attribuito loro le alte

cariche del regno, ma che avrebbe egli stesso sollecitato tutti i pagani del

suo dominio ad abbracciare la religione. Ordinò pure che molti cristiani e

catecumeni lo assistessero nella reggia, e ciò non senza vantaggio per lui

stesso.

Infatti, avendo i

maggiorenti, ostili al nuovo, ordito una congiura per uccidere il re, e

avendolo scoperto, alcuni dei suoi cortigiani cristiani avvertirono

segretamente Muanga perché stesse in guardia, e aggiunsero che egli poteva fare

pieno assegnamento su tutti i cristiani e sui loro servi, cioé su duemila

uomini in armi.

Ma nel contempo il primo

ministro del re, che era anche il capo della congiura, pur avendo ottenuto il

perdono per sé e per i propri compagni da Muanga, concepì tuttavia un odio

ancor più forte verso i cristiani; e come stupirsene, quando venne a sapere che

sarebbe stato destituito e che al suo posto sarebbe stato designato il

cristiano Giuseppe Mkasa? Egli cominciò quindi a cogliere ogni occasione per

sussurrare all’orecchio del re che avrebbe dovuto guardarsi da coloro che

professavano la religione cristiana, come fossero i peggiori nemici: essi gli

sarebbero rimasti fedeli finché fossero una piccola minoranza; ma una volta

diventati maggioranza lo avrebbero tolto di mezzo ed avrebbero elevato alla

dignità regia uno di loro. Ma a questo si aggiunse un altro e maggiore motivo

di ostilità che indusse il re Muanga a perseguitare i cristiani.

SOURCE : https://www.causesanti.va/it/santi-e-beati/martiri-dell-uganda.html

I MARTIRI

Sono stati i primi

africani sub-sahariani ad essere venerati come santi dalla Chiesa cattolica.

Essi si possono distinguere in due gruppi, in relazione al tipo di pena

capitale subita: tredici furono bruciati vivi e gli altri nove vennero uccisi

con diversi generi di supplizio.

Nel primo gruppo sono

compresi giovani quasi tutti cortigiani: Carlo Lwanga, Mbaga Tuzindé, Bruno

Séron Kuma, Giacomo Buzabaliao, Kizito, Ambrogio Kibuka, Mgagga, Gyavira,

Achille Kiwanuka, Adolfo Ludigo Mkasa, Mukasa Kiriwanvu, Anatolio Kiriggwajjo,

Luca Banabakintu.

Carlo Lwanga, nato nella

città di Bulimu e battezzato il 15 novembre 1885, si attirò ammirazione e

benevolenza di tutti per le sue grandi doti spirituali; lo stesso Muanga lo

teneva in grande considerazione per aver saputo portare a termine con la

massima diligenza gl’incarichi a lui affidati. Posto a capo dei giovani del

palazzo regio, rafforzò in loro l’impegno a preservare la propria fede e la

castità, respingendo gli allettamenti dell’empio e impudico re; imprigionato,

incoraggiò apertamente anche i catecumeni a perseverare nell’amore per la

religione, e si recò al luogo del supplizio con mirabile forza d’animo, all’età

di vent’anni.

Mbaga Tuzindé, giovane di

palazzo (figlio di Mkadjanga, il primo e il più crudele dei carnefici) ancora

catecumeno quando si scatenò la persecuzione, fu battezzato da Carlo Lwanga

poco prima di essere con lui mandato a morte. Il padre, cercando di sottrarlo

in ogni modo all’esecuzione, lo supplicò più e più volte affinché abiurasse la

religione cattolica, o almeno si lasciasse nascondere e promettesse di cessare

di pregare. Ma il nobile giovane rispose che conosceva la causa della propria

morte e che l’accettava, ma non voleva che l’ira del re ricadesse sul padre:

pregò di non venir risparmiato. Allora Mkadjanga, mentre il figlio, all’età di

appena sedici anni, stava per essere condotto al rogo, comandò ad uno dei

carnefici ai suoi ordini che lo colpisse al capo con un bastone e che ne

collocasse poi il corpo esanime sul rogo perché venisse bruciato insieme agli altri.

Bruno Séron Kuma, nato

nel villaggio Mbalé e battezzato il 15 novembre 1885, lasciò la tenda dove

viveva col fratello perché questi seguiva una setta non cattolica. Divenuto

servitore del re Mtesa, quando Muanga successe al padre lasciò il suo incarico

per il servizio militare. Accolto fra i giovani cristiani che facevano servizio

a corte, a ventisei anni sostenne con la parola e con l’esempio i compagni

della gloriosa schiera.

Giacomo Buzabaliao,

cosparso con l’acqua battesimale il 15 novembre 1885, acceso di singolare

ardore religioso, compì ogni sforzo per convincere e spronare altri, fra cui lo

stesso Muanga, non ancora salito al trono paterno, ad abbracciare la fede di

Cristo; e il re stesso rinfacciò tale colpa al fortissimo giovane, quando lo mandò

a morte, all’età di vent’anni.

Kizito, anima innocente,

più giovane degli altri, dato che subì il martirio nel suo tredicesimo anno di

vita, figlio di uno dei più alti dignitari del regno, splendente di purezza e

forza d’animo, poco prima di essere gettato in prigione ricevette il battesimo

da Carlo Lwanga. Il re, spinto dalla sua libidine, cercò invano di attrarre a

sé, con più accanimento che verso gli altri, questo fortissimo giovinetto.

Kizito biasimò così aspramente alcuni cristiani che avevano determinato di

darsi alla fuga, che essi deposto il timore, rimasero presso il re Muanga; e

quando giunse per loro il momento di essere condotti al supplizio, affinché i

compagni non si perdessero d’animo li convinse ad avanzare tutti insieme,

tenendosi per mano.

Ambrogio Kibuka,

anch’egli giovane di palazzo, battezzato il 17 novembre 1885, conservò la

propria ferma e ardente fede fino all’atrocissima morte, che affrontò nel nome

di Cristo all’età di ventidue anni.

Mgagga, giovinetto di

corte, ancora catecumeno, resistette impavido alle oscene lusinghe del re e,

essendosi dichiarato cristiano, fu gettato in carcere con gli altri; prima di

essere imprigionato ricevette il battesimo da Carlo Lwanga, e, non diversamente

dagli altri, andò al martirio con animo tranquillo, all’età di sedici anni.

Gyavira, anch’egli

giovane di palazzo, di bell’aspetto, era prediletto da Muanga, il quale si

adoperò invano per piegarlo a soddisfare la propria libidine. Ancora catecumeno

quando, dopo la professione di fede, fu da Muanga condannato a morte, durante

la notte fu asperso col battesimo da Carlo Lwanga e, a diciassette anni, fu dai

carnefici condotto al luogo del supplizio insieme agli altri.

Achille Kiwanuka, giovane

di corte, nato a Mitiyana, fu battezzato il 17 novembre 1885. Dopo che ebbe

impavidamente professato la propria fede davanti al re, posto in ceppi con i

compagni e gettato in carcere, dichiarò ancora una volta che mai avrebbe

abiurato la religione cattolica e si avviò con coraggio all’ultimo supplizio,

nel suo diciassettesimo anno di età.

Adolfo Ludigo Mkasa,

cortigiano, si mise in luce per la purezza dei costumi e così pure per la

costanza e la sopportazione nelle sventure. Ricevuto il battesimo il 17

novembre 1885, osservò santamente e professò con fermezza insieme agli altri la

fede cattolica, fino alla morte che affrontò in nome di Cristo a venticinque

anni.

Mukasa Kiriwanu, giovane

del palazzo regio, addetto al servizio della tavola, mentre i carnefici stavano

conducendo Carlo Lwanga e i suoi compagni al colle Namugongo, alla domanda se

fosse cristiano disse di sì, e fu condotto con gli altri al supplizio.

Catecumeno, non ancora asperso con l’acqua del battesimo, conseguì gloria

eterna attraverso il battesimo di sangue, all’età di diciotto anni.

Anatolio Kiriggwajjo,

giovane di palazzo, battezzato il 17 novembre 1885, osservò con tanta fermezza

d’animo i precetti della vita cristiana, che respinse senza esitazione una

carica che gli era offerta dal re, ritenendo che essa potesse in qualche modo

pregiudicare il conseguimento della salvezza eterna. Avendo poi professato

apertamente, insieme agli altri, la fede cattolica, affrontò con loro una

comune morte, nel suo sedicesimo anno di vita.

Infine, ricordiamo di

questa schiera Luca Banabakintu, che, nato nel villaggio Ntlomo, era

servitore amatissimo di un patrizio di nome Mukwenda. Il 28 maggio 1882,

ricevuti il battesimo e la confermazione, si accostò per la prima volta alla

sacra celebrazione eucaristica: da quel faustissimo giorno si pose in luce a

tutti come esempio per integrità di costumi e per osservanza dei precetti, e

nulla gli era più caro che parlare di religione con gli amici. Sebbene potesse

facilmente sottrarsi alla morte, preferì, quando fu ricercato per essere

condotto al supplizio, rimanere presso il padrone, dal quale fu consegnato agli

inviati del re. Gettato in carcere, vi dimorò con animo sereno finché, con gli

altri, nel suo trentesimo anno donò la vita nel nome di Cristo.

Tutti costoro che abbiamo

nominato, il 3 giugno 1886, all’alba, sono condotti sul colle Namugongo. Qui

giunti, le mani legate dietro la schiena e i piedi in ceppi, ciascuno di loro è

avvolto in una stuoia di canne intrecciate; viene innalzato un rogo, sul quale

essi vengono collocati come fascine umane. Il fuoco viene accostato ai piedi,

perché quel tenero gregge di vittime sia avvolto più lentamente e più a lungo;

crepita la fiamma, alimentata dai santi corpi; dal rogo di diffondono per

l’aria mormorii di preghiere che aumentano col crescere dei tormenti; i

carnefici si stupiscono che non un lamento, non un gemito si levino dai

morenti, dacché a nulla di simile è loro capitato di assistere.

Nel secondo gruppo di

martiri si annoverano i venerabili servi di Dio Mattia Kalemba Murumba,

Attanasio Badzekuketta, Pontiano Ngondwé, Gonzaga Gonza, Andrea Kagwa, Noe

Mawgalli, Giuseppe Mkasa Balikuddembé, Giovanni Maria Muzéi (Iamari), Dionisio

Sebugwao.

Mattia Kalemba Murumba aveva

cinquant’anni quando ricevette il martirio. Scelto per svolgere la mansione di

giudice, dopo essersi convertito da una setta maomettana e protestante alla

religione cattolica, ricevette il battesimo il 28 maggio 1882; dopo di che si

dimise dall’incarico, temendo di poter recar danno a qualcuno con le sue

sentenze. Dotato di modestia e dolcezza d’animo, era così fervido nel suo zelo

di apostolato religioso che non solo educò i propri figli a vivere santamente,

ma cercò d’insegnare a quanti più poté la dottrina cristiana. Il primo ministro

del re, al cui cospetto fu trascinato, comandò che a quell’uomo nobilissimo,

che aveva impavidamente professato la propria fede, fossero tagliati le mani e

i piedi, e gli fossero strappati frammenti di carne dalla schiena perché

fossero bruciati davanti ai suoi occhi. I carnefici dunque, per non essere

disturbati da testimoni del loro atrocissimo ufficio, conducono su un colle

incolto e deserto questo venerabile servitore di Dio, animoso e sereno

nell’aspetto; eseguono gli ordini alla lettera, perché il glorioso martire

soffra più a lungo, trattengono con tale abilità il sangue che fuoriesce dalle

membra, che tre giorni dopo alcuni servi, giunti sul posto per tagliare legna,

odono la voce di Mattia, debole e sommessa, che chiede un sorso d’acqua; e

avendolo visto così orribilmente mutilato fuggono via atterriti e lo lasciano

là, a imitazione di Cristo morente, privo di ogni conforto.

Atanasio Badzekuketta,

scelto fra i giovani in servizio nel palazzo reale e battezzato il 17 novembre

1885, seguiva con grande devozione i comandamenti di Dio e della Chiesa. Era

così desideroso di cingersi della corona del martirio che supplicò vivamente i

carnefici, i quali lo stavano conducendo con altri al luogo stabilito, di

ucciderlo sul posto. Così quel valoroso giovane fu dilaniato da ripetuti colpi,

il 26 maggio 1886, nel suo diciottesimo anno d’età.

Pontiano Ngondwé, nato

nel villaggio Bulimu e cortigiano del re Mtesa, una volta salito al trono

Muanga entrò nell’esercito, e ancora catecumeno apparve così animato di

cristiana spiritualità da saper vincere in sé, e trasformare, il proprio

carattere aspro e difficile. Quando era iniziata la persecuzione, ricevette il

battesimo il 18 novembre 1885; per questo, poco dopo fu gettato in carcere con

gli altri. Condannato a morte, accadde che il carnefice Mkadjanga, mentre lo

conduceva al colle Namugongo, gli chiedesse ripetutamente durante il cammino se

fosse seguace della religione cristiana; ed egli due volte confermò la sua

fede, e due volte quello lo trafisse con la lancia; e il suo capo, troncato dal

corpo, fu fatto rotolare lungo la via; era il 26 maggio 1886.

Gonzaga Gonza, ragazzo di

corte, battezzato il 17 novembre 1885, assolse con devozione agli obblighi

religiosi e si distinse particolarmente per la virtù della carità. Mentre

procedeva verso il luogo del supplizio, poiché i ceppi, che non avevano potuto

essere sciolti, gli impedivano di camminare speditamente, fu più volte trafitto

dai carnefici con la lancia; fu così martirizzato, nel suo diciottesimo anno di

vita, il 27 maggio 1886.

Andrea Kagwa, nato nel

villaggio Bunyoro e vissuto in grande familiarità con Muanga, sia quando era

principe, sia quando era re, ricevette il 30 aprile 1882 i sacramenti del

battesimo, della confermazione e dell’Eucaristia. Caro a tutti per le grandi

qualità d’animo, non soltanto istruiva nella dottrina cristiana quanti lo

avvicinavano, ma altresì, in occasione di una pestilenza che si era diffusa

nella regione, aiutando tutti si prodigò con singolare carità a favore degli

infermi, ne avvicinò moltissimi a Cristo aspergendoli con l’acqua battesimale,

e dando poi sepoltura ai defunti. Ma il primo ministro del re vedeva assai di

malocchio che i propri figli venissero da lui istruiti nella dottrina

cristiana, e infine, con il consenso del re, comandò che fosse catturato e

ucciso, aggiungendo che non sarebbe andato a cena prima che il carnefice gli

avesse presentato la mano mozzata del morto Andrea. Così il 26 maggio 1886, nel

suo trentesimo anno, il venerabile servo di Dio subì il martirio e raggiunse la

gloria celeste.

Noe Mawgalli, servitore

del nobile Mukwenda nella preparazione delle imbandigioni, risplendette

grandemente di virtù cristiane. Battezzato il 1° novembre 1885, colpito dalla

lancia dei sicari che il re Muanga aveva mandato in giro per distruggere le

case dei Cristiani, morì nel trentesimo anno d’età il 31 maggio 1886.

Giuseppe Mkasa

Balikuddembé, nato nel villaggio Buwama, fu scelto dal re Mtesa, per la sua

provata lealtà, come proprio inserviente personale per il giorno e per la

notte, e come infermiere. Il figlio di lui Muanga, non diversamente dal padre,

riponeva la più totale fiducia in questo venerabile servo di Dio; pertanto non

solo lo pose a capo di tutti i servitori del palazzo reale, ma volle che fosse

lui ad avvertirlo, quando il suo operato prestasse il fianco a critiche. Il 30

aprile 1882, Giuseppe ricevette il battesimo e la confermazione e si accostò

per la prima volta alla santa comunione, alla quale in seguito si accostò di

frequente. Con la propria dolcezza d’animo, con la carità e l’afflato religioso

che mostrava non solo seppe avvicinare a Cristo molti giovani, ma in

particolare fece pressioni, con consigli ed esortazioni, sui ragazzi della

corte reale e sugli altri cortigiani perché non accondiscendessero alla

libidine del re Muanga. Il re, essendo venuto a conoscenza di ciò, cominciò a

nutrire avversione per il venerabile servo di Dio, finché, vinto dalle

sollecitazioni del primo ministro, che provava invidia per Giuseppe, comandò

che questi fosse condannato a morte. Giuseppe, rinforzato dal cibo divino,

viene condotto nella località Mengo, dove, dopo aver dichiarato di voler dare al

re sia il perdono, sia il consiglio di pentirsi, viene dal carnefice decapitato

e gettato nel fuoco, prima vittima della persecuzione, a ventisei anni, il 15

novembre 1885.

Giovanni Maria Muzéi (Iamari),

nato nel villaggio Minziro, aveva un aspetto di tale gravità che venne onorato

col nome di Muzéi, cioé vecchio; insigne anche per prudenza, carità, dolcezza

d’animo, generosità verso i poveri, sollecitudine verso gli ammalati, dedicò le

proprie sostanze e il proprio impegno a riscattare i prigionieri, che poi

istruiva nella fede cristiana. Si dice che egli avesse in un solo giorno

appreso tutta la dottrina del catecumenato; fu poi battezzato il 1° novembre

1885 e unto del sacro crisma il 3 giugno dell’anno seguente. Dopo l’esecuzione

capitale del suo grande amico Giuseppe Mkasa, pur avendo saputo che il re

intendeva farlo uccidere, non volle nascondersi, né darsi alla fuga; al

contrario, accompagnato da un certo Kulugi, si presentò al re, dal quale

ricevette l’ordine di recarsi, per una causa qualsiasi, dal primo ministro.

Obbedì, sebbene sospettasse l’inganno, poiché riteneva indegno di sé l’esitare

e il temere a motivo della propria fede religiosa. E il primo ministro del re

ordinò che fosse gettato in uno stagno che si trovava in un suo podere, il 27

gennaio 1887.

Dionisio Sebuggwao, nato

nel villaggio Bunono, ragazzo di corte, ricevette il battesimo il 17 novembre

1885 e rifulse per integrità di costumi. Avendogli il re Muanga chiesto se

fosse vero che egli aveva insegnato i rudimenti della fede cristiana a due

cortigiani, egli rispose di sì, e quello lo trapassò con un colpo di lancia, e

comandò che gli fosse tagliato il capo. Così morì Dionisio, martire, all’età di

quindici anni, il 26 maggio 1886.

SOURCE : https://www.causesanti.va/it/santi-e-beati/martiri-dell-uganda.html

CANONIZACIÓN DE LOS

MÁRTIRES DE UGANDA

«Estos que están cubiertos de vestiduras

blancas, ¿quiénes son y de dónde han venido?» (Ap 7, 13).

Nos viene al pensamiento

esta frase bíblica mientras inscribimos en la lista gloriosa de los santos

victoriosos en el cielo a estos veintidós hijos de África, cuyo singular mérito

había ya reconocido nuestro predecesor, de venerada memoria, el Papa Benedicto

XV, el 6 de junio de 1920, al declararlos Beatos y autorizar así su culto

particular.

¿Quiénes son? Son

africanos, verdaderos africanos, de color, de raza y de cultura, dignos

exponentes de los fabulosos pueblos Bantúes y Nilóticos explorados en el siglo

pasado por la audacia de Stanley y Livingstone, establecidos en las regiones

del África oriental, que se llama de los Grandes Lagos, en el ecuador, en el

terrible clima ecuatorial, sólo atenuado por la elevación de los altiplanos y

por las grandes lluvias estacionales. Su patria, en el tiempo en que vivían,

era un protectorado británico, pero desde 1962 ha logrado, como tantas otras

naciones de aquel continente, su propia independencia, que afirma actualmente

con rápidos y espléndidos progresos de civilización moderna. La capital es

Kampala, pero la circunscripción eclesiástica principal tiene su centro en

Rubaga, sede del primer Vicariato apostólico local, erigido en 1878 y elevada

ahora a la dignidad de archidiócesis con siete diócesis sufragáneas. Es este un

campo de apostolado misional que acogió primeramente a los ministros de

confesión anglicana, ingleses, a los cuales se sumaron dos años después los

misioneros católicos de lengua francesa llamados Padres Blancos, misioneros de

África, hijos del célebre y valeroso cardenal Lavigerie (1825-1892), a quien no

sólo África, sino la civilización misma debe recordar entre los hombres

providenciales más insignes, y fueron los Padres Blancos los que introdujeron

el catolicismo en Uganda, predicando el Evangelio en amigable competencia con

los misioneros anglicanos y los que tuvieron la dicha —ganada con riesgos y

fatigas incalculables— de formar a estos mártires para Cristo, a estos a

quienes hoy nosotros honramos cómo héroes y hermanos en la fe e invocamos como

protectores en el cielo. Sí, son africanos y son mártires. «Son —prosigue la

Sagrada Escritura— los que han venido de la gran tribulación y lavaron sus

vestidos y los blanquearon en la sangre del Cordero. Por eso están ante el

trono de Dios» (Ib. 14-15).

Todas las veces que

pronunciamos la palabra “mártires” en el sentido que tiene en la hagiografía

cristiana, debería presentársenos a la mente un drama horrible y maravilloso:

horrible por la injusticia, armada de autoridad y de crueldad, que es la que

provoca el drama; horrible también por la sangre que corre y por el dolor de la

carne que sufre sometida despiadadamente a la muerte; maravilloso por la

inocencia que, sin defenderse, físicamente se rinde dócil al suplicio, feliz y

orgullosa de poder testimoniar la invencible verdad de una fe que se ha fundido

con la vida humana; la vida muere, la fe vive. La fuerza contra la fortaleza;

la primera, venciendo, queda derrotada; ésta, perdiendo, triunfa. El martirio

es un drama; un drama tremendo y sugestivo, cuya violencia injusta y depravada,

casi desaparece del recuerdo allí mismo donde se produjo mientras permanece en

la memoria de los siglos siempre fúlgida y amable la mansedumbre que supo hacer

de su propia oblación un sacrificio, un holocausto; un acto supremo de amor y

de fidelidad a Cristo; un ejemplo, un testimonio, un mensaje perenne a los hombres

presentes y futuros. Esto es el martirio.

Esta es la gloria de la

Iglesia a través de los siglos. Y es un acontecimiento tan grande que la

Iglesia se apresuró a recoger las narraciones de la «pasión de los mártires» y

hacer de ellas el libro de oro de sus hijos más ilustres, el martirologio. Y

fue tal la irradiación de belleza y grandeza que emanaron de ese libro que pudo

ofrecer a la leyenda y al arte nuevas amplificaciones legendarias y

fantásticas; pero la historia verdadera, que todavía halla su documentación en

este libro, merece una admiración sin límites, es una alabanza a Dios, que obra

grandes cosas en hombres frágiles, y es testimonio de honor para los héroes,

que con su sangre han escrito las páginas de ese libro incomparable.

Ahora estos mártires

africanos vienen a añadir a ese catálogo de vencedores que es el martirologio,

una página trágica y magnífica, verdaderamente digna de sumarse a aquellas

maravillosas de la antigua África, que nosotros, modernos, hombres de poca fe,

creíamos que no podrían tener jamás adecuada continuación. ¿Quién podía

suponer, por ejemplo, que a las emocionantísimas historias de los mártires

escilitanos, de los mártires cartagineses, de los mártires de la “Masa Cándida”

de Útica —de quienes San Agustín (cf. PL 36,571 y 38, 1405) y Prudencio nos han

dejado el recuerdo—, de los mártires de Egipto —cuyo elogio trazó San Juan

Crisóstomo (cf, PG 50, 693 ss) —, de los mártires de la persecución vandálica,

hubieran venido a añadirse nuevos episodios no menos heroicos, no menos

espléndidos, en nuestros días? ¿Quién podía prever que a las grandes figuras

históricas de los Santos Mártires y Confesores africanos, como Cipriano,

Felicidad y Perpetua, y al gran Agustín, habríamos asociado un día los nombres

queridos de Carlos Lwanga y de Matías Mulumba Kalemba, con sus veinte

compañeros Y no queremos olvidar tampoco a aquellos otros que, perteneciendo a

la confesión anglicana, han afrontado la muerte por el nombre de Cristo.

Estos mártires africanos

abren una nueva época, no queremos decir ciertamente de persecuciones y de

luchas religiosas, sino de regeneración cristiana y civilizada. El África,

bañada por la sangre de estos mártires, primicias de la nueva era —y Dios

quiera que sean los últimos, pues tan precioso y tan grande fue su holocausto—,

resurge libre y redimida. La tragedia que los devoró fue tan inaudita y

expresiva que ofrece elementos representativos suficientes para la formación

moral de un pueblo nuevo, para la fundación de una nueva tradición espiritual,

para simbolizar y promover el paso desde una civilización primitiva —no

desprovista de magníficos valores humanos, pero contaminada y enferma, como

esclava de sí misma— hacia una civilización abierta a las expresiones

superiores del espíritu y a las formas superiores de la vida social.

No pretendáis que os

narremos aquí la historia de los mártires que estamos honrando. Es demasiado

larga y compleja: se refiere a veintidós hombres, en su mayor parte muy

jóvenes, cada uno de los cuales merecería un elogio particular; a ellos,

además, debería añadirse una doble y larga lista de otras víctimas de esa feroz

persecución: una de católicos —neófitos y catecúmenos— y otra de anglicanos,

como se refiere también ellos, sacrificados por el nombre de Cristo. Y sería

una historia demasiado cruda; el suplicio de la carne y la arbitraria tiranía

de la autoridad son ahí tan fáciles y tan despiadados, que conturban

profundamente nuestra sensibilidad. Sería una historia casi inverosímil; no es

fácil darse cuenta de las condiciones bárbaras, para nosotros paradójicas e

intolerables, en las que se mantiene y desenvuelve la vida de muchas

comunidades tribales del África casi hasta nuestros días. Sería historia digna

de meditarse largamente, ya que los motivos morales que constituyen su sentido

y su valor, es decir, los motivos simplicísimos y altísimos de la religión y

del pudor, aparecen con tan impresionante y edificante evidencia. Leed más bien

esta conmovedora historia, la tenéis en las manos. Pocas narraciones de las

actas de los mártires se hallan tan documentadas como ésta. Aquí no hay

leyenda, sino la crónica de una «Passio martyrum» fielmente descrita. El que la

lee, contempla; el que contempla, se estremece, y el que se estremece, llora.

Hay que concluir finalmente: ¡Sí, son mártires; «son aquellos —decíamos con el

autor del Apocalipsis— que vienen de la gran tribulación, y que han lavado y

purificado sus vestiduras en la sangre del Cordero»!

Permítasenos hacer

algunas sencillas consideraciones.

Este martirio colectivo

que tenemos delante nos presenta un fenómeno cristiano estupendo. Nos demuestra

muchas, cosas: ¿qué era el África antes que el mensaje evangélico le fuera

anunciado? Nos ofrece uno de los cuadros más interesantes y genuinos de aquella

sociedad humana primitiva, que tanto ha apasionado a los estudiosos modernos.

Es como una prueba, o una muestra de la vida africana, antes de la colonización

del siglo pasado: una vida mísera y heroica, en la cual la naturaleza humana,

todavía casi en estado instintivo, pone delante sus debilidades y dolencias en

forma y medida impresionantes, pero manifiesta al mismo tiempo ciertas

fundamentales virtudes reveladoras del divino modelo de donde proviene el

hombre. Dentro de este cuadro, un día llega el mensaje cristiano; nada parece

más diverso, nada más extraño. Sin embargo, he aquí que inmediatamente

encuentra acogida, encuentra simpatía, asimilación. El terreno, que parecía

árido y estéril, estaba en realidad por cultivar; la semilla evangélica lo

encuentra fecundo. Más todavía: se diría que lo encuentra ávido de aquella

nueva vegetación; como si la estuviera esperando, como si le fuese connatural.

Los tallos de la nueva mies son bellos, crecen rectilíneos, vigorosos; hablan

de una espléndida primavera. El cristianismo encuentra en África: una

predisposición particular que no dudamos en considerar como un arcano de Dios,

una vocación indígena, una promesa histórica. África es tierra de Evangelio,

África es patria nueva de Cristo. La sencillez recta y lógica y la inflexible

fidelidad de estos jóvenes cristianos de África nos lo aseguran y nos lo

prueban; por una parte la fe, don de Dios, y la capacidad humana de progreso;

por otra, se unen con prodigiosa correspondencia. Que la semilla evangélica

encuentre obstáculo en las espinas de un terreno tan selvático, causa dolor, no

extrañeza; pero que la semilla eche inmediatamente raíces y brote pujante y

llena de flores por la bondad del suelo, causa alegría y admiración al mismo

tiempo: es la gloria espiritual del continente de los rostros negros y de las

almas blancas, que anuncia una nueva civilización: la civilización cristiana de

África.

Este fenómeno es tan

bello y está de tal modo representado en la trágica y gloriosa historia de los

mártires de Uganda que sugiere el parangón entre la evangelización cristiana y

el colonialismo, del que hoy tanto se habla. Estas dos importaciones de la

civilización en territorios de antiguas culturas respetables bajo muchos

aspectos, pero rudimentarias e inmóviles, introducen briosos factores de

desarrollo y traban relaciones revolucionarias. Pero mientras la evangelización

introduce un principio —la religión cristiana— que tiende a hacer brotar las

energías propias, las virtudes innatas, las capacidades latentes de la

población indígena, o, lo que es lo mismo, tiende a libertarla, a hacerla

autónoma y adulta, a capacitarla para expresarse de manera más amplia y mejor

en las formas de cultura y de arte propios de su genio; la colonización, en

cambio, si tan sólo se guía por criterios utilitarios y temporales, pretende

otras finalidades no siempre conformes al honor y a la utilidad de los

indígenas. El cristianismo educa, liberta, ennoblece, humaniza en el sentido

más alto de la palabra; abre los caminos a las riquezas interiores del espíritu

y a las mejores organizaciones comunitarias. El cristianismo es la verdadera

vocación de la humanidad; y estos mártires nos lo confirman.

Su testimonio, para quien

lo escucha atentamente en esta hora decisiva de la historia de África, se hace

voz que llama: voz que parece repetir, como un eco potente, la invitación

misteriosa, oída durante una noche en una visión por San Pablo: «Adiuva nos»,

ven a ayudarnos (Hch 16,9). Estos mártires imploran ayuda. África tiene

necesidad de misioneros: de sacerdotes especialmente, de médicos, de maestros,

de hermanas y de enfermeras, de almas generosas, que ayuden a la joven y

floreciente, pero tan necesitada comunidad católica a crecer en número y

calidad para hacerse pueblo: pueblo africano de la Iglesia de Dios. Nos hemos

recibido, precisamente en estos días, una carta firmada por muchos obispos de

países de África Central, en la: que se implora el envío de sacerdotes, de

nuevas escuadras de sacerdotes, muchos y pronto. Hoy, no mañana. África tiene

gran necesidad de ellos. África hoy les abre la puerta y el corazón; es éste

quizá el momento de gracia que podría pasar y no repetirse. Por nuestra parte

lanzamos a la Iglesia la invitación del África y esperamos que las diócesis y

las familias religiosas de Europa y de América, de la misma manera que han

acogido la invitación de Roma para la América latina, ofreciendo ayudas tan

dignas de encomio y todavía necesarias de hombres y de medios, querrán también

unir a este esfuerzo generoso otro no menos próvido y meritorio a beneficio del

África cristiana. ¿Nuevos sacrificios? ¡Sí!, pero esta es ley del Evangelio,

hecha hoy extraordinariamente imperiosa; la caridad se enciende como fuego, a

fin de que la fe resplandezca en el mundo.

Este pensamiento, que

llena de certeza y de vigor la conciencia de la Iglesia ya desde sus primeros

días, se hace urgente en nuestro espíritu en estos años en que el mundo entero

parece despertar y buscar el camino de su porvenir. Pueblos nuevos, que hasta

ahora habían permanecido estáticos e inertes y que no aspiraban a otra forma de

vida sino a aquella que habían ya alcanzado con una lenta elaboración secular,

ahora se despiertan y se levantan. El progreso científico y técnico de nuestros

días los ha vuelto capaces de nuevos ideales y de nuevas empresas, les ha dado

un ansia de lograr para sí una fórmula plena y nueva de vida que, interpretando

sus virtudes nativas, los habilite para conquistar y gozar los beneficios de la

civilización presente y venidera.

Pues bien, frente a este

despertar de los pueblos nuevos, sentimos que en Nos crece la persuasión de que

es un deber nuestro, un deber de amor, de acercarnos con un diálogo más

fraternal a estos mismos pueblos, de darles muestra de nuestra estima y de

nuestro afecto, de manifestarles cómo la Iglesia católica comprende sus legítimas

aspiraciones, de ayudar su libre y justo desarrollo por los caminos pacíficos

de la fraternidad humana y de hacerles así más fácil el acceso, cuando

libremente lo quieran, al conocimiento de aquel Cristo que nosotros creemos que

constituye para todos la verdadera salvación y el intérprete original y

maravilloso de sus mismas aspiraciones más profundas.

Tal es la fuerza de esta

persuasión que nos parece que no debemos rehusar la ocasión, mejor dicho, la

invitación que insistentemente se nos dirige de ir a encontrarnos con un gran

pueblo, en el cual nos complacemos en ver simbolizada la inmensa población de

un entero continente para llevarle nuestro sincero mensaje de fe cristiana.

Así, pues, os comunicamos, hermanos, que hemos decidido intervenir en el próximo

Congreso Eucarístico Internacional de Bombay.

Es la segunda vez que

anunciamos en esta basílica un viaje nuestro, hasta ahora del todo extraño a

las costumbres de nuestro ministerio apostólico pontificio. Pero creemos que de

la misma manera que el primer viaje a Tierra Santa, éste a las puertas del Asia

inmensa, del mundo nuevo moderno, no es ajeno a la índole, más aún, al mandato

de nuestro ministerio apostólico. Oímos en nuestro interior solemnes y

apremiantes, las palabras siempre vivas de Jesucristo: “Id y anunciad a todas

las gentes” (Mt 28,19).

En verdad, no es el deseo

de novedad o de viajar el que nos mueve a esta decisión, sino sólo el celo

apostólico de lanzar nuestro saludo evangélico a los inmensos horizontes

humanos que los nuevos tiempos abren ante nuestros pasos y el sólo propósito de

ofrecer a Cristo Señor un testimonio de fe y de amor más amplio, más vivo y más

humilde.

El Papa se hace

misionero, diréis. Sí, el Papa se hace misionero, que quiere decir testigo,

pastor, apóstol en camino. Nos alegramos de repetirlo en este día mundial de

las misiones. Nuestro viaje, aunque brevísimo y sencillísimo, limitado a una

sola estación, en la que se le rinde a Cristo presente en la Eucaristía solemne

homenaje, quiere ser un testimonio de reconocimiento para todos los misioneros

de ayer y de hoy que han consagrado su vida a la causa del Evangelio y para

aquellos especialmente que, siguiendo las huellas de San Francisco Javier, han

«establecido la Iglesia» con tanta entrega y tanto fruto en Asia y particularmente

en la India; quiere ser además una simbólica adhesión, exhortación y aliento a

todo el esfuerzo misionero de la Santa Iglesia católica; quiere ser una primera

y diligente respuesta a la invitación misionera que el Concilio ecuménico en

curso lanza a la Iglesia misma para que cada uno, miembro fiel, acoja en sí

mismo el ansia de la dilatación del reino de Cristo; quiere ser un estímulo y

un aplauso a todos nuestros misioneros esparcidos por el mundo entero y a los

que los sostienen y ayudan; quiere ser señal de amor y de confianza para todos

los pueblos de la tierra,

Y sean benditos los

mártires declarados hoy ciudadanos del cielo que abren nuestro espíritu a tales

propósitos; y que sean ellos los que os infundan valor, gozo y esperanza, in

nomine Domini.

Copyright © Dicastero per

la Comunicazione - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

PAULUS PP.VI

Venerabiles Fratres ac

dilecti filii,

«Hi, qui amicti sunt

stolis albis, qui sunt et unde venerunt?» (Apoc. 7, 13).

Haec verba de Sanctis

Bibliis deprompta in mentem Nostram occurrunt, dum in gloriosum album Sanctorum,

qui in caelum victores ascenderunt, hos viginti duos filios Africae ascribimus;

eos Benedictus XV, Decessor Noster recolendae memoriae, merita eorum singularia

agnoscens, iam die sexta mensis Iunii anno millesimo nongentesimo vicesimo

Beatos renuntiavit atque adeo peculiarem cultum probavit iis tribuendum.

Qui sunt? sunt Africani,

veri Africani colore, genere, ingenii cultu, digni alumni gentium «Bantu», quae

dicuntur, et Niloticarum, quas, fabulosas olim, Ioannes Stanley ac David

Livingstone saeculo praeterito animose exploraverunt. Quae quidem gentes

regiones Africae orientalis, amplis lacubus distinctae, incolunt, ad circulum

scilicet meridianum, ubi aer caelique status sunt gravissimi, nempe torrido

loco proprii, quibus levamen affertur tantummodo ubi regio est in montium dorso

porrecta, et cum pluviae certis anni temporibus violentius effunduntur.

Eorum patria, cum vitam

agerent, Britanniae patrocinio erat subiecta, sed anno millesimo nongentesimo

sexagesimo secundo, ut plures aliae regiones eiusdem continentis, sui iuris est

facta; eademque libertatem adeptam nunc confirmat velocibus et egregiis

incrementis cultus civilis, qui hac aetate viget. Urbs princeps est

quidem Kampala, sed territorium in re ecclesiastica praecipuum est

Rubagaense, olim sedes primi Vicariatus apostolici ea in regione anno millesimo

octingentesimo septuagesimo octavo constituti, nunc vero ad dignitatem

archidioecesis evecti, ad quam septem dioeceses suffraganeae pertinent. In hunc

apostolatus missionalis campum primum administri sacrorum anglicani, natione

Britanni, advenerunt, quos post duos annos subsecuti sunt Missionarii

catholici, scilicet Patres Albi, qui dicuntur, seu Missionarii Africae,

filii Caroli Martialis Cardinalis Lavigerie (qui vixit ab anno millesimo

octingentesimo vicesimo quinto ad nonagesimum secundum); quem non solum Africa

sed etiam homines cultu civili ornati celebrent oportet ut virum e

praeclarissimis, quos divina Providentia misit. Hi Patres Albi religionem

catholicam in Ugandam intulerunt, Evangelium annuntiantes eaque in re

certationem amicalem quandam ineuntes cum Missionariis Anglicanis. Illis igitur

feliciter contigit, ac merito quidem propter pericula et labores ingentes

susceptos, ut Christo Martyres educarent, quos hodie ut fratres in fide praestantissimos

colimus et ut protectores gloria caelesti circumfusos invocamus. Re quidem vera

sunt Africani et sunt Martyres. «Hi sunt - ut in memorato loco Sacrorum

Bibliorum legere pergimus - qui venerunt de tribulatione magna et laverunt

stolas suas, et dealbaverunt eas in sanguine Agni. Ideo sunt ante thronum Dei»

(ibid. 14-15).

Quotiescumque nomen

martyris enuntiamus, ea quidem vi et sententia, quam christiani hagiographi ei

subiecerunt, spectaculum taeterrimum sed simul admirabile menti nostrae obversatur;

taeterrimum propter iniustitiam, quae, auctoritate et crudelitate potens, causa

est facinoris huiusmodi gravissimi, taeterrimum propter sanguinem, qui

profluit, et cruciatus corporum, quae doloribus vexantur et morti atroci