Die

selige Schwester Maria Restituta Kafka SFCC (um 1919)

Bienheureuse

Marie-Restitute Kafka

Religieuse franciscaine

autrichienne martyre (+ 1943)

Franciscaine autrichienne, elle s'opposa au nazisme et refusa que les crucifix soient enlevés dans l'hôpital où se trouvaient les religieuses. En octobre 1942, elle fut arrêtée pour haute trahison, jetée en prison et condamnée à mort. Une pétition demanda sa grâce au général des S.S., Martin Bormann qui la refuse et elle fut décapitée le 30 mars 1943, après avoir demandé à l'aumônier de la prison de tracer une croix sur son front.

Voir aussi: Homélie de Jean-Paul II lors de la Messe de Béatification de Jakob Kern, Restituta Kafka et Anton Maria Schwartz (Vienne, 21 Juin 1998) [Anglais, Espagnol, Portugais]

Près de Vienne en Autriche, l’an 1943, la bienheureuse Hélène Kafka

(Marie-Restituta), vierge, des Sœurs franciscaines de la Charité et martyre.

Originaire de Bohême, elle était infirmière; pendant la seconde guerre mondiale

quand elle fut arrêtée par le régime nazi et décapitée.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : http://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/6368/Bienheureuse-Marie-Restitute-Kafka.html

Bienheureuse Marie Restituta

KAFKA

Nom: KAFKA

Prénom: Hélène

Nom de religion: Marie

Restituta (Maria Restituta)

Pays: Autriche

Naissance: 1894

Mort:

30.03.1943 à Vienne

Etat:

Religieuse - Martyre

Note: Religieuse

franciscaine de la charité. Infirmière. Elle lutta contre le nazisme. Elle

refusa de retirer les crucifix des chambres des malades. Arrêtée pour avoir

composé un poème satirique sur Hitler. Condamnée pour haute trahison le

29.10.1942. Guillotinée à la prison de Vienne.

Béatification:

21.06.1998 à Vienne par Jean Paul II

Canonisation:

Fête: 30 mars

Réf. dans l’Osservatore

Romano : 1998 n.26 p.4

Réf. dans la Documentation

Catholique : 1998 n.14 p.690

Notice

Le 21 juin 1998 Jean Paul

II béatifie trois Autrichiens (Jacob

Kern 2, Anton

Schwartz 2 et

Restituta Kafka) sur la "Place des héros" de Vienne. 60 ans

auparavant en 1938 - rappelle le Pape - Hitler du balcon qui domine cette place

a fait acclamer l'Anschluss (rattachement de l'Autriche à l'Allemagne) par une

foule en délire de 250'000 personnes. Sur cette même "Heldenplatz",

devant une foule enthousiaste de 50'000 personnes (on en attendait plus, mais

l'Église d'Autriche, quoique bien vivante, traverse à ce moment-là une crise),

Jean Paul II béatifie une martyre de Nazisme, Sœur Restituta Kafka. Hitler

avait proclamé que le salut était en lui; les "héros selon l'Église"

annoncent que le salut ne se trouve pas dans l'homme mais dans le Christ, Roi

et Sauveur.

Restituta Kafka naît en

1894. Avant d'être majeure, elle exprime son intention d'entrer au couvent. Ses

parents s'y opposent, mais elle ne perd pas de vue son projet: devenir sœur

"par amour de Dieu et des hommes" et servir en particulier les pauvres

et les malades. Les "Sœurs franciscaines de la Charité"

l'accueillent, lui permettant de réaliser sa vocation dans le monde

hospitalier: un engagement quotidien souvent dur et monotone. Sœur infirmière

dans l'âme, elle fait bientôt figure "d'institution" à Mödling. Sa

compétence, sa résolution et sa cordialité sont telles que de nombreuses

personnes l'appellent Sœur Resoluta et non Sœur Restituta. Son courage et sa

fermeté ne lui permettent pas de se taire face au régime national-socialiste. Elle

refuse de retirer le crucifix des chambres des malades et même lorsqu'on bâtit

une nouvelle aile à l'hôpital, elle y fait mettre des crucifix, prête à payer

de sa vie plutôt que de renoncer à ses convictions. Effectivement, à la suite

d'une perquisition chez elle, on découvre un poème satirique contre Hitler. Le

mercredi des Cendre 1942, elle est arrêtée par la Gestapo. C'est alors que

commence pour elle en prison un 'Calvaire' qui dure plus d'un an. Malgré de

nombreux recours en grâce, elle est condamnée à mort. Conservant le crucifix

dans son cœur, elle lui rend encore témoignage peu de temps avent d'être

conduite au lieu de l'exécution: elle demande à l'aumônier de la prison de lui

faire "le signe de la croix sur le front". Ses dernières paroles connues

sont: "J'ai vécu pour le Christ, je veux mourir pour le Christ". Elle

est décapitée dans la prison de Vienne le 30 mars 1943. La Gestapo prend soin

que son corps ne soit pas rendu à la Communauté de peur qu'on en fasse une

martyre.

"Tant de choses

peuvent nous être enlevées à nous chrétiens, mais nous ne permettront à

personne de nous enlever la Croix comme signe de salut - conclut le Pape - Nous

ne permettrons pas qu'elle soit exclue de la vie publique". Puis

s'adressant aux jeunes: "Plantez dans votre vie la Croix du Christ! La

Croix est le véritable arbre de vie". Et les jeunes d'apprécier ce message

avec enthousiasme.

Note d'humour: Pour fêter

cette béatification, les Sœurs franciscaines ont fait brasser des bières avec

l'étiquette "Restituta", rappelant ainsi qu'après chaque opération

difficile, la bienheureuse se faisait servir au bistrot une chope de bière avec

une goulache…

SOURCE : http://www.abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/hagiographie/fiches/f0433.htm

Stift

Heiligenkreuz : monument aux morts

Bienheureuse Maria

Restitua

Maria Restitua, née

le 1er mai 1884 à Husovice, près de Brünn (aujourd'hui Brno) en Moravie

(actuellement République tchèque) et décapitée le 30 mars 1943 à Vienne est une

religieuse catholique.

Son nom séculier était

Hélène Kafka (ou Kafková).

En 1896, ses parents

s'installent avec leurs six autres enfants à Vienne, où le père était

cordonnier. Elle fut vendeuse, et en 1914, entra dans la congrégation

hospitalière des Franciscaines de la Charité à Vienne. A sa profession, elle

prit le nom de Marie Restituta. Elle devint infirmière anesthésiste à l'hôpital

de Mödling en 1919.

Après l'Anschluss en mars

1938, elle s'opposa au régime nazi et refusa que les crucifix soient enlevés

dans l'hôpital où se trouvaient les religieuses. Elle fut dénoncée comme

opposante et arrêtée le Mercredi des Cendres 1942, sous le prétexte d'avoir

écrit des poèmes satiriques à l'encontre d'Hitler.

Une pétition demanda sa

grâce au général des S.S., Martin Bormann qui la refusa et elle fut décapitée

le 30 mars 1943 à la prison de Vienne, après avoir demandé à l'aumônier de la

prison de tracer une croix sur son front.

Elle fut béatifiée à

Vienne par le Pape Jean-Paul II le 21 juin 1998.

SOURCE : http://nova.evangelisation.free.fr/maria_restituta_kafka.htm

Also

known as

Helen Kafka

Helena Kafka

Maria Restituta Kafka

Sister Restituta

30

October on some calendars

Profile

Sixth daughter

of a shoemaker.

Grew up in Vienna, Austria.

Worked as a sales

clerk. Nurse.

Joined the Franciscan Sisters

of Christian Charity (Hartmannschwestern) in 1914,

taking the name Restituta after an early Church martyr.

Worked for twenty years as a surgical nurse,

beginning in 1919.

Known as a protector of the poor and

oppressed. Vocal opponent of the Nazis after Anschluss, the German take

over of Austria.

Sister Restituta hung a crucifix in

every room of a new hospital wing.

The Nazis ordered them removed; Restituta refused. She was arrested by

the Gestapo in 1942.

Sentenced to death on 28

October 1942 for

“aiding and abetting the enemy in the betrayal of the fatherland and for

plotting high treason”; Martin Bormann decided that her execution would provide

“effective intimidation” for other opponents of the Nazis. She spent her

remaining time in prison caring

for other prisoners;

even the Communist prisoners spoke

well of her. She was offered her freedom if she would abandon her religious

community; she declined. Martyr.

Born

1 May 1894 in

Brno, Czechoslovakia (modern

Czech Republic) as Helena Kafka

beheaded on 30

March 1943 at Vienna, Austria

6 April 1998 by Pope John

Paul II (decree of martyrdom)

21 June 1998 by Pope John

Paul II

Additional

Information

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

other

sites in english

webseiten

auf deutsch

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

Dicastero delle Cause dei Santi

Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

nettsteder

i norsk

Readings

I have lived for Christ;

I want to die for Christ. – Blessed Mary’s

last recorded words

MLA

Citation

“Blessed Mary Restituta

Kafka“. CatholicSaints.Info. 4 July 2023. Web. 30 March 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/blessed-mary-restituta-kafka/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/blessed-mary-restituta-kafka/

Maria

Restituta in der Brigittakirche,

Wien-Brigittenau

BL. MARIA RESTITUTA KAFKA was

born in Brno (in what is now the Czech Republic) on 10 May 1894, the sixth

daughter of a shoemaker, and was given the name Helena at Baptism. She grew up

with her family in Vienna and was employed as a salesgirl and later as a nurse.

As a nurse she came into contact with the Franciscan Sisters of Christian

Charity (known as the "Hartmannschwestern") and entered their

congregation in 1914, taking the name of an ancient martyr, Restituta.

From 1919 she worked for

20 years as a surgical nurse and soon gained the reputation not only of a

devoted and capable nurse but one who was particularly close to the poor, the

persecuted and the oppressed. She even protected a Nazi doctor from arrest

which she thought was unjustified.

When Hitler took over

Austria, Sr Restituta made her total rejection of Nazism quite clear. She

called Hitler "a madman" and said of herself: "A Viennese cannot

keep her mouth shut". Her reputation spread rapidly when she hung a

crucifix in every room of a new hospital wing. The Nazis demanded that the

crosses be removed, threatening Sr Restituta's dismissal. The crucifixes were

not removed, nor was Sr Restituta, since her community said they could not

replace her. Sr Restituta was arrested and accused not only of hanging the

crosses but also of having written a poem mocking Hitler.

On 28 October 1942 she

was sentenced to death for "aiding and abetting the enemy in the betrayal

of the fatherland and for plotting high treason". She was later offered

her freedom if she would leave her religious congregation, but she refused.

When asked to commute her sentence, Martin Bormann expressly rejected the

request, saying: "I think the execution of the death penalty is necessary

for effective intimidation.

While in prison she cared

for the other prisoners, as even communist prisoners later attested. After

various requests for clemency were rejected by the authorities, Sr Restituta

was decapitated on 30 March 1943.

SOURCE : https://web.archive.org/web/20190126075842/http://www.ewtn.com/library/mary/bios98.htm#KAFKA

Kostel

blahoslavené Marie Restituty v Brně-Lesné

Church of Blessed Maria Restituta, Brno

Kostel

blahoslavené Marie Restituty v Brně-Lesné

Church of Blessed Maria Restituta, Brno

Kostel

blahoslavené Marie Restituty v Brně-Lesné

Church of Blessed Maria Restituta, Brno

Kostel

blahoslavené Marie Restituty v Brně-Lesné

Church

of Blessed Maria Restituta, Brno

Blessed Maria Restituta

Kafka M (AC)

(also known as Helena

Kafka)

Born at Brno, Czech

Republic, May 10, 1894; died in Vienna, Austria, March 30, 1943; beatified June

21, 1998.

Blessed Maria Restituta

Kafka, baptized Helena, was the sixth daughter of a shoemaker. Her family moved

to Vienna, Austria, where she grew up and worked as a salesgirl, then as a

nurse, which brought her into contact with the Franciscan Sister of Christian

Charity (Hartmannschwestern).

Impressed by their lives,

she joined the congregation in 1914 and took the name Restituta. After her

novitiate, she was a surgical nurse for twenty years, during which she gained a

particular reputation for her devotion to the materially and socially poor.

After the Anschluss, when

Austria was united to Germany, Sister Restituta was vocal in her opposition to

Nazism and Hitler, whom she called a "madman." Her first personal

encounter with the Nazis occurred when she hung a crucifix in every room of a

new hospital wing. The Nazis demanded that they or Sister Restituta be removed;

neither were. Her community declared that Sister Restituta was irreplaceable.

The blessed nun was

arrested and, on October 28, 1942, sentenced to death for "aiding and

abetting the enemy in the betrayal of the fatherland and for plotting high

treason" because she had hung the crucifixes and allegedly written a poem

that mocked the Nazi leader. Sister Restituta was later offered her freedom in

exchange for leaving the order. She refused. Martin Bormann expressly rejected

the requested commutation of her sentence with the words: "I think the

execution of the death penalty is necessary for effective intimidation."

For the next five month, Blessed Maria Restituta tended to the needs of others

in prison. On March 30, 1943, the sentence of decapitation was executed

(L'Osservatore Romano English Edition).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0330.shtml

Büste

im Wiener Stephansdom

Büste der sel. Schwester Maria Restituta Kafka von Alfred Hrdlicka in der

Barbara-Kapelle des Wiener Stephansdoms

Bust

of Sister Maria Restituta Kafka by Alfred Hrdlicka in Barbara Chapel of St.

Stephen's Cathedral, Vienna

BLESSED MARIA RESTITUTA

KAFKA

Helen Kafka was born in

1894 to a shoemaker and grew up in Vienna, Austria. At the age of 20, she

decided to join the Franciscan Sisters of Christian Charity and took the name

Restituta after an early Church martyr.

In 1919, she began

working as a surgical nurse in Austria. When the Germans took over the

country, she became a local opponent of the Nazi regime. Her conflict with

them escalated after they ordered her to remove all the crucifixes she had hung

up in each room of a new hospital wing.

Sister Maria Restitua

refused, and was arrested by the Gestapo in 1942. She was sentenced to

death for "aiding and abetting the enemy in the betrayal of the fatherland

and for plotting high treason.”

She spent the rest of her

days in prison caring for other prisoners, who loved her. The Nazis

offered her freedom if she would abandon the Franciscan sisters, but she

refused. She was beheaded March 30, 1943 in Vienna, and was beatified by Pope

John Paul II on June 21, 1998.

SOURCE : http://www.catholicnewsagency.com/saint.php?n=639

Sr.

Maria Restituta Kafka (* 1. Mai 1894 in Hussowitz bei Brünn, Österreich-Ungarn;

† 30. März 1943 in Wien hingerichtet), mit dem bürgerlichen Namen Helene Kafka,

war eine österreichische Ordens- und Krankenschwester und Märtyrin, die sich

während der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus den Machthabern widersetzte. Papst

Johannes Paul II. sprach Sr. M. Restituta 1998 selig.

Die

Gedenktafel befindet sich im Gebäude des Landesklinikum Mödling;

Sr.

M. Restituta-Gasse 12, 2340 Mödling

HOMILY OF POPE JOHN PAUL

II

Sunday, 21 June 1998

1. "Who do the

people say I am?" (Lk 9:18).

Jesus asked his disciples

this question one day as they were walking together. He also puts this question

to Christians on the paths of our time: "Who do the people say I

am?".

As it was 2,000 years ago

in an obscure part of the then known world, so today, human opinions about

Jesus are divided. Some attribute to him the gift of prophetic speech. Others

consider him an extraordinary personality, an idol that attracts people.

Others, again, believe he is even capable of ushering in a new era.

"But who do you say

that I am?" (Lk 9:20). The question cannot be given a "neutral"

answer. It requires a taking of sides and involves everyone. Today, as well,

Christ is asking: you Catholics of Austria, you Christians of this

country, you citizens, "who do you say that I am?".

It is a question that

comes from Jesus' heart. He who opens his own heart wants the person before him

not to answer with his mind alone. The question that comes from Jesus' heart

must move ours: Who am I for you? What do I mean to you? Do you really

know me? Are you my witnesses? Do you love me?

2. Then Peter, the

disciples' spokesman, answered: "We consider you the Christ of God"

(Lk 9:20). The Evangelist Matthew reports Peter's profession in greater detail:

"You are the Christ, the Son of the living God!" (Mt 16:16). Today

the Pope, as Successor of the Apostle Peter by the grace of God, professes on

your behalf and with you: "You are the Messiah of God. You are the Christ,

the Son of the living God".

3. Down the

centuries, there has been a continual struggle for the correct profession of

faith. Thanks be to Peter, whose words have become the norm!

They should be used to

measure the Church's efforts in seeking to express in time what Christ means to

her. In fact, it is not enough to profess with one's lips alone. Knowledge of

Scripture and Tradition is important, the study of the Catechism is valuable;

but what good is all this if faith lacks deeds?

Professing Christ calls

for following Christ. The correct profession of faith must be accompanied by a

correct conduct of life. Orthodoxy requires orthopraxis. From the start, Jesus

never concealed this demanding truth from his disciples. Actually, Peter had

barely made an extraordinary profession of faith when he and the other

disciples immediately heard Christ clarify what the Master was expecting of

them: "If any man would come after me, let him deny himself and take up

his cross daily and follow me" (Lk 9:23).

As it was in the

beginning, so it is today: Jesus does not only look for people to acclaim

him. He looks for people to follow him.

4. Dear brothers and

sisters, whoever reflects on the history of the Church with eyes of love will

discover that despite the many faults and shadows, there were and still are men

and women everywhere whose lives highlight the credibility of the Gospel.

Today I am given the joy

to enrol three Christians from your land among the blesseds. Each of them

individually confirmed his or her profession of faith in the Messiah through

personal witness of life. All three blesseds show us that "Messiah"

is not only a title for Christ but also means a willingness to co-operate in

the messianic work: the great become small and the weak take the lead.

It is not the heroes of

the world who are speaking today in Heroes' Square, but the heroes of the

Church. Sixty years ago from the balcony overlooking this square, a man

proclaimed himself salvation. The new blesseds have another message. They tell

us: Salvation [Heil] is not found in a man, but rather: Hail

[Heil] to Christ, the King and Redeemer!

5. Jakob Kern came

from a humble Viennese family of workers. The First World War tore him abruptly

from his studies at the minor seminary in Hollabrunn. A serious war injury made

his brief earthly life in the major seminary and the Premonstratensian

monastery of Geras - as he said himself - a "Holy Week". For love of

Christ he did not cling to life but consciously offered it to others. At first

he wanted to become a diocesan priest. But one event made him change direction.

When a Premonstratensian left the monastery to follow the Czech National Church

formed after the separation from Rome which had just occurred, Jakob Kern

discovered his vocation in this sad event. He wanted to atone for this

religious. Jakob Kern joined the monastery of Geras in his place, and the Lord accepted

his offering a "substitute".

Bl. Jakob Kern stands

before us as a witness of fidelity to the priesthood. At the beginning, it

was a childhood desire that he expressed in imitating the priest at the altar.

Later this desire matured. The purification of pain revealed the profound

meaning of his priestly vocation: to unite his own life with the sacrifice of

Christ on the Cross and to offer it vicariously for the salvation of others.

May Bl. Jakob Kern, who

was a vivacious and enthusiastic student, encourage many young men generously

to accept Christ's call to the priesthood. The words he spoke then are

addressed to us: "Today more than ever there is a need for authentic and

holy priests. All the prayers, all the sacrifices, all the efforts and all the

suffering united with a right intention become the divine seed which sooner or

later will bear its fruit".

6. In Vienna 100

years ago, Fr Anton Maria Schwartz was concerned with the lot of

workers. He first dedicated himself to the young apprentices in the period of

their professional training. Ever mindful of his own humble origins, he felt

especially close to poor workers. To help them, he founded the Congregation of

Christian Workers according to the rule of St Joseph Calasanz, and it is still

flourishing. He deeply longed to convert society to Christ and to renew it in

him. He was sensitive to the needs of apprentices and workers, who frequently

lacked support and guidance. Fr Schwartz dedicated himself to them with love

and creativity, finding the ways and means to build "the first workers'

church in Vienna". This humble house of God hidden among the modest

dwellings, resembles the work of its founder, who filled it with life for 40

years.

Opinions on the "worker

apostle" of Vienna varied. Many found his dedication exaggerated. Others

felt he deserved the highest esteem. Fr Schwartz stayed faithful to himself and

also took some courageous steps. His petitions for training positions for the

young and a day of rest on Sunday even reached Parliament.

He leaves us a message:

Do all you can to protect Sunday! Show that it cannot be a work day because it

is celebrated as the Lord's day! Above all, support young people who

are unemployed! Those who give today's young people an opportunity to earn

their living help make it possible for tomorrow's adults to pass the meaning of

life on to their children. I know that there are no easy solutions. This is why

I repeat the words which guided Bl. Fr Schwarz in his many efforts: "We

must pray more!".

7. Sr Restituta

Kafka was not yet an adult when she expressed her intention to enter the

convent. Her parents were against it, but the young girl remained faithful to

her goal of becoming a sister "for the love of God and men". She

wanted to serve the Lord especially in the poor and the sick. She was accepted

by the Franciscan Sisters of Charity to fulfil her vocation in everyday

hospital life, which was often hard and monotonous. A true nurse, she soon

became an institution in Mödling. Her nursing ability, determination and warmth

caused many to call her Sr Resoluta instead of Sr Restituta.

Because of her courage

and fearlessness, she did not wish to be silent even in the face of the

National Socialist regime. Challenging the political authority's prohibitions,

Sr Restituta had crucifixes hung in all the hospital rooms. On Ash Wednesday

1942 she was taken away by the Gestapo. In prison her "Lent" began,

which was to last more than a year and to end in execution. Her last words

passed on to us were: "I have lived for Christ; I want to die for Christ".

Looking at Bl. Sr

Restituta, we can see to what heights of inner maturity a person can be led by

the divine hand. She risked her life for her witness to the Cross. And she

kept the Cross in her heart, bearing witness to it once again before being led

to execution, when she asked the prison chaplain to "make the Sign of the

Cross on my forehead".

Many things can be taken

from us Christians. But we will not let the Cross as a sign of salvation be

taken from us. We will not let it be removed from public life! We will listen

to the voice of our conscience, which says: "We must obey God rather than

men" (Acts 5:29).

8. Dear brothers and

sisters, today's celebration has a particularly European tone. In addition to

the distinguished President of the Republic of Austria, Mr Thomas Klestil, the

Presidents of Lithuania and Romania, political leaders from home and abroad,

have honoured us with their presence. I offer them my cordial greetings and

through them I also greet the people they represent.

With joy for the gift of

three new blesseds which we are offered today, I turn to all my brothers and

sisters in the People of God who are gathered here or have joined us through

radio or television. In particular, I greet the Pastor of the Archdiocese of Vienna,

Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, and the President of the Austrian Bishops'

Conference, Bishop Johann Weber, as well as my Brothers in the Episcopate who

have come to Heroes' Square from near and far. Then I cannot forget the many

priests and deacons, religious and pastoral assistants in the parishes and

communities.

Dear young people! I

extend a special greeting to you today. Your presence in such large numbers is

a great joy for me. Many of you have come a long way, and not only in a

geographical sense.... But now you are here: the gift of youth which life

is waiting for! May the three heroes of the Church who have just been enrolled

among the blesseds sustain you on your way: young Jakob Kern, who precisely

through his illness won the trust of young people; Fr Anton Maria Schwartz, who

knew how to touch the hearts of apprentices; Sr Restituta Kafka, who gave

courageous witness to her convictions.

They were not

"photocopied Christians", but each was authentic, unrepeatable and

unique. They began like you: as young people, full of ideals, seeking to give

meaning to their life.

Another thing makes the

three blesseds so attractive: their biographies show us that their

personalities matured gradually. Thus your life too has yet to become a

ripe fruit. It is therefore important that you cultivate life in such a way

that it can bloom and mature. Nourish it with the vital fluid of the Gospel!

Offer it to Christ, the sun of salvation! Plant the Cross of Christ in

your life! The Cross is the true tree of life.

9. Dear brothers and

sisters! "But who do you say that I am?".

In a short time we will

profess our faith. To this profession, which puts us in the community of the

Apostles and of the Church's Tradition, as well as in the ranks of the saints

and blesseds, we must also add our personal response. The persuasive power

of the message also depends on the credibility of its messengers. Indeed, the

new evangelization starts with us, with our life-style.

The Church today does

not need part-time Catholics but full-blooded Christians. This is what the

three new blesseds were! We can learn from them!

Thank you, Bl. Jakob

Kern, for your priestly fidelity!

Thank you, Bl. Anton

Maria Schwartz, for your commitment to workers!

Thank you, Sr Restituta

Kafka, for swimming against the tide of the times!

All of you saints and

blesseds of God, pray for us. Amen.

© Copyright - Libreria

Editrice Vaticana

Countering the Swastika

with the Cross of Christ

L'Osservatore Romano

Relic of Blessed

Restituta Kafka in the Basilica of St Bartholomew on Tiber Island

A strong and courageous

woman. Ward sister and head nurse in an Austrian hospital, she firmly, opposed

the anti-religious measures of the Nazi regime and defended the rights of the

weak and the sick, speaking of peace and democracy. She was denounced by the

SS, was imprisoned, condemned to death and then decapitated in Vienna on 30

March 1943, at the age of 49. She was killed together with some Communist

workmen whom she managed to comfort on the eve of their death.

The sacrifice of Bl.

Maria Restituta (in the world: Helen Kafka) — the only nun to be condemned to

death under the National-Socialist regime and judged after a court hearing —

was recently commemorated in the Basilica of St Bartholomew on Tiber Island.

Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, Archbishop of Vienna, celebrated on 4 March a

Mass at which the Franciscan Sisters of Christian Charity gave to the Basilica

a small cross which Maria Restituta carried on the belt of her habit. The relic

was placed in the altar — which commemorates the martyrs of

Nationalist-Socialism — by a woman who was born in 1941 in very the hospital

where the religious served in those years. Immediately following the Great

Jubilee of 2000, John Paul II decided that the Roman Basilica of St Bartholomew

on Tiber Island was to become a memorial of the "new martyrs" and

witnesses of the faith from the 20th and 21st century.

Born on 1 May 1894 at

Brno-Husovice, in modern day Czech Republic, of humble background, Helen Kafka

grew up in the Austrian capital where she worked in the Lainz hospital with the

Franciscan Sisters of Christian Charity. In 1914 she entered the convent and

received the name Maria Restituta. From 1919 until 1942 she served in the

hospital in Mödling, Vienna, where she became a surgical nurse and an

anaesthetist, esteemed for her professional competence, beloved for her

sensitivity and respected for her energetic character, so much so that she soon

earned the nickname "Sister Resoluta" .

After Germany annexed

Austria, the religious worked for justice and the dignity of every human being.

Faced with the anti-religious suppression of the Nazis, she responded by

reaffirming religious freedom and by refusing to remove the crucifixes in the hospital.

She also countered Hitler's swastika with the Cross of Christ. She also spread

"A soldier's song" that spoke of democracy, peace, and a free

Austria. Spied on by two ladies, she was denounced by a doctor close to the SS,

who for some time sought an opportunity to distance her from the hospital.

After her arrest by the

Gestapo on Ash Wednesday, 18 February 1942, she was condemned to death on 29

October 1942 (the day chosen for her liturgical memorial). The sentence was

carried out 30 March 1943. Before her death she asked the chaplain to make the

sign of the cross on her forehead. "She was a saint because in that

situation she encouraged everyone, she transmitted a power, a positive spirit

and one of confidence", a fellow-prisoner later recalled.

On 21 June 1998 Restituta

Kafka was beatified in Vienna, together with the servants of God, Jakob

Kern and Anton Maria

Schwartz, by John Paul II, who said: "Looking at Bl. Sr Restituta, we can

see to what heights of inner maturity a person can be led by the divine hand.

She risked her life for her witness to the Cross. And she kept the Cross in her

heart, bearing witness to it once again before being led to execution, when she

asked the prison chaplain to make the Sign of the Cross on my forehead".

John Paul II continued: "Many things can be taken from us Christians but

the Cross as the sign of salvation will not be taken from us. We will not let

it be removed from public life! We will listen to the voice of our conscience,

which says: 'We must obey God rather than men' (Acts 5:29)."

Bl. Maria Restituta Helen

Kafka was a lady who, with a power for renewal, was able to give an example of

freedom of expression and of responsibility of the individual conscience — even

in difficult circumstances, animated by a virtue that is at times inconvenient:

courage. "No matter how far we are from everything we are, no matter what

is taken from us", the religious wrote in a letter from prison, "no

one can take from us the faith we have in our heart. In this way we can build

an altar in our own heart".

Taken from:

L'Osservatore Romano

Weekly Edition in English

10 April 2010, page 10

For subscriptions:

Online: L'Osservatore

Romano

Or write to:

Weekly Edition in English

00120 Vatican City State

Europe

Provided Courtesy of:

Eternal Word Television

Network

5817 Old Leeds Road

Irondale, AL 35210

www.ewtn.com

SOURCE : https://www.ewtn.com/library/MARY/blrestituta.htm

Gedenktafel

für NS-Opfer. Wien, Währinger Gürtel, Maria Restituta Kafka

A SHORT BIOGRAPHY OF

BLESSED MARIA RESTITUTA KAFKA

21Jul

WE MUST OBEY GOD RATHER

THAN MEN (ACTS 5:29).

“A strong and courageous

woman, Ward Sister and Head Nurse in an Austrian hospital, she firmly opposed

the anti-religious measures of the Nazi regime and defended the rights of the

weak and the sick, speaking of peace and democracy. She was denounced by the

SS, was imprisoned, condemned to death and then beheaded in Vienna on the 30th

March 1943, at the age of 49. She was killed together with some communist

workmen whom she managed to comfort on the eve of their death.

THE FRANCISCAN SISTERS OF

CHRISTIAN CHARITY

The sacrifice of Blessed

Maria Restituta (Helene Kafka) – the only nun to be condemned to death under

the National-Socialist regime and judged after a court hearing – was recently

commemorated in the Basilica of St Bartholomew on Tiber Island. Cardinal

Christoph Schoenborn, Archbishop of Vienna, celebrated a Mass at which the

Franciscan Sisters of Christian Charity gave to the Basilica a small cross

which Maria Restituta carried on the belt of her habit. The relic was placed in

the altar – which commemorates the martyrs of National-Socialism – by a woman

who was born in 1941 in the very hospital where the religious served in those

years. Immediately following the great jubilee of 2000, John Paul II decided

that the Roman Basilica of St Bartholomew on Tiber Island was to become a

memorial of the ‘new martyrs’ and witnesses of the faith from the 20th and 21st

centuries.

ENERGETIC CHARACTER

Born on 1 May 1894 [at

Hussowitz bei Bruenn in the Austria-Hungary Empire, today] Brno-Husovice, in

modern day Czech Republic, of humble background, Helene Kafka grew up in the

Austrian capital where she worked in the Lainz hospital with the Franciscan

Sisters of Christian Charity. In 1914 she entered the convent and received the

name Maria Restituta. From 1919 until 1942 she served in the hospital in

Moedling, Vienna, where she became a surgical nurse and an anaesthetist,

esteemed for her professional competence, beloved for her sensitivity and

respected for her energetic character, so much that she soon earned the

nickname ‘Sister Resoluta’.

THE CROSS OF CHRIST

After Germany annexed

Austria, the religious worked for justice and the dignity of every human being.

Faced with the anti-religious suppression of the Nazis, she responded by

reaffirming religious freedom and by refusing to remove the crucifixes in the hospital.

She also countered Hitler’s swastika with the Cross of Christ. She also spread

‘A soldier’s song’ that spoke of democracy, peace, and a free Austria. Spied on

by two ladies, she was denounced by a doctor close to the SS, who for some time

sought an opportunity to distance her from the hospital.

‘SHE WAS A SAINT’

After her arrest by the

Gestapo on Ash Wednesday, 18 February 1942, she was condemned to death on 29th

October 1942 (the day chosen for her liturgical memorial). The sentence was

carried out on 30th March 1943. Before her death she asked the chaplain to make

the sign of the cross on her forehead. ‘She was a saint because in that

situation she encouraged everyone, she transmitted a power, a positive spirit

and one of confidence’, a fellow prisoner later recalled.

On 21 June 1998 Restituta

Kafka was beatified in Vienna, together with the servants of God, Jakob Kern

and Anton Maria Schwartz, by John Paul II, who said: ‘Looking at Blessed Sister

Restituta, we can see to what heights of inner maturity a person can be led by

the divine hand.

She risked her life for

her witness to the Cross. And she kept the Cross in her heart, bearing witness

to it once again before being led to execution, when she asked the prison

chaplain to ‘make the Sign of the Cross on my forehead’. John Paul II

continued: ‘Many things can be taken from us Christians but the Cross as the

sign of salvation will not be taken from us. We will not let it be removed from

public life! We will listen to the voice of our conscience, which says: ‘We

must obey God rather than men’ (Acts 5:29).

‘NO ONE CAN TAKE FROM US

THE FAITH’

Blessed Maria Restituta

Helene Kafka was a lady who, with a power for renewal, was able to give an

example of freedom of expression and of responsibility of the individual

conscience – even in difficult circumstances, animated by a virtue that is at

times inconvenient: courage. ‘No matter how far we are from everything we are,

no matter what is taken from us,’ the religious wrote in a letter from prison,

‘no one can take from us the faith we have in our heart. In this way we can

build an altar in our own heart.'”

– This article was

published in “The Crusader” issue June 2013. For donations towards the

Restoration Appeal and subscriptions, please contact: The Secretary, All Saints

Friary, Redclyffe Road, Urmston, Manchester M41 7LG

Side-altar Holy

Family, Church of Münchendorf (St. Leonard), Lower Austria. paintings: Sacred

Heart middle, Maria Restituta Kafka right

Seitenaltar Heilige

Familie (Altarbild darüber), Pfarrkirche Münchendorf St. Leonhard, Bezirk

Mödling, NÖ. Bilder: Herz Jesu Mitte, wikipedia:de:Maria Restituta Kafka rechts

Blessed Marie Restituta

The brutal murder of

American journalist, James Foley, is just the latest act inspired by Satan, and

carried out by his malevolent followers. James Foley was not killed

because he was James Foley. He was killed because, like so many before him,

he represented GOODNESS. The evil that has given us the heinous

torture and bloodletting of Christians, since ISIS reared its Satanic head, is

nothing new. It has been with us throughout history. I would

like you to take a trip back to Nazi Germany, circa 1943. Meet Helena

Kafka, who grew up to be become Sister

Maria Restituta, a Franciscan Sister of Charity.

May 1, 1894, was

a happy day for Anton and Marie Kafka. Marie had just given birth

to her sixth child, a girl, and mom and her daughter were both doing

fine. The proud parents named their new baby, Helena. Devout Catholics,

Anton and Marie had Helena baptized into the faith thirteen days

after her birth in their parish, The Church of the Assumption, in the town of

Husovice, located in Austria. Before Helena reached her second birthday,

and due to financial circumstances, the family had to move. They settled in the

city of Vienna, where Helena and her siblings would remain and grow up.

Helena was a good student

and worked hard. She received her First Holy Communion in May of 1905 in St.

Brigitta Church, and was confirmed in the same church a year later. After eight

years of school, Helena spent another year in housekeeping school. By the

age of 15, she was working as a servant, a cook and was earning nursing. She

became an assistant nurse at Lainz City Hospital in 1913. This was Helena's

first contact with the Franciscan Sisters of Christian Charity, and she was

immediately moved to become a Sister herself. On April 25, 1914, Helena

Kafka joined the Franciscan sisters, and on October 23, 1915, she became Sister

Maria Restituta. She made her final vows one year later, and began working

solely as a nurse.

When World War I ended,

Sister Maria was the lead surgical nurse at Modling Hospital in Vienna.

She and all other Austrians had never heard of Adolf Hitler, and could

never have imagined that one day their beloved nation would be annexed

into the German Republic because of this man. After a successful coup

d'etat by the Austrian Nazi Party on March 12, 1938, these unforeseen and

unimagined things came to pass. The Nazis, under Hitler, now controlled the

once proud Austrian nation.

Sister Restituta was very

outspoken in her opposition to the Nazi regime. When a new wing to the hospital

was built, she hung a Crucifix in each of the new bedrooms. The Nazis demanded

that they be removed, telling Sister Restituta that she would be dismissed if

she did not comply. She refused, and the crucifixes remained hanging on the

walls One of the doctors on staff, a fanatical Nazi, would have none of

it. He denounced her to the Nazi Party, and on Ash Wednesday, 1942, she was

arrested by the Gestapo after coming out of the operating room. The "charges"

against her included "hanging crucifixes and writing a poem that mocked

Hitler".

Sister Maria Restituta,

the former Helena Kafka, loved her Catholic faith, and, filled with the Spirit,

she wanted to do nothing more than serve the sick. The Nazis promptly sentenced

her to death by the guillotine for "favouring the enemy and conspiracy to

commit high treason". The Nazis offered her freedom if she would

abandon the Franciscans she loved so much. She adamantly refused. An

appeal for clemency went as far as the desk of Martin Bormann, Hitler's

personal secretary and Nazi Party Chancellor. His response was that her

execution "would provide effective intimidation for others who might want

to resist the Nazis". Sister Maria Restituta spent her final days in

prison caring for the sick. Because of her love for the Crucifix, and the

Person who was nailed to it and died on it, she was beheaded on March 30, 1943.

She was 48 years old.

Pope John Paul II visited

Vienna on June 21,1998. That was the day Helena Kafka, the girl who

originally went to housekeeping school to learn how to be a servant, was

beatified by the Pope, and declared Blessed Maria Restituta. She had

learned how to serve extremely well, always serving others before herself.

Blessed Marie Restituta,

please pray for us.

Meet the Only Nun

Sentenced to Death by a Nazi Court

Larry Peterson - published

on 04/12/16

Defiant Sister Maria

Restituta hung crucifixes on the walls of her hospital, and wouldn’t take them

down

Sister Maria Restituta

began Lent of 1942 under arrest. She was taken on Ash Wednesday. Her crime:

“hanging crucifixes.” She was sentenced to death. The following year, on

Tuesday of Holy Week, she was executed.

May 1, 1894, was a happy

day for Anton and Marie Kafka. Marie had just given birth to her sixth

child and mom and daughter were both doing fine. The proud parents named their

new baby girl Helena. Devout Catholics, Anton and Marie had Helena

baptized into the faith only 13 days after her birth.

The ceremony took place

in the Church of the Assumption, in the town of Husovice, located in Austria.

Before Helena reached her second birthday, the family had settled in the

city of Vienna.

Helena was a good student

and worked hard. She received her First Holy Communion in St. Brigitta Church

during May of 1905 and was confirmed in the same church a year later. After

eight years of school she spent another year in housekeeping school and,

by the age of 15, was working as a servant, a cook, and being trained as a

nurse.

At age 19, she became an

assistant nurse at Lainz City Hospital. This was Helena’s first contact with

the Franciscan

Sisters of Christian Charity and she was immediately moved to become a

sister herself, and on October 23, 1915, became Sister Maria Restituta. She

made her final vows a year later and began working as a nurse.

By the end of World War

I, Sister Restituta was the lead surgical nurse at Modling Hospital in Vienna.

She had never heard of Adolf Hitler and could never have imagined that

one day, because of this man, her beloved nation would be annexed into the

German Republic.

On March 12, 1938,

the Austrian

Nazi Party pulled off a successful coup d’etat taking control of the

government. The unforeseen and unimagined had come to pass, and Hitler now

controlled the once proud Austrian nation.

Sister Restituta was very

outspoken in her opposition to the Nazi regime. When a new wing to the hospital

was built she hung a crucifix in each of the new rooms. The Nazis demanded that

they be removed. Sister Restituta was told she would be dismissed if she did

not comply.

She refused. The

crucifixes remained on the walls.

One of the doctors on

staff, a fanatical Nazi, would have none of it. He denounced her to the Party

and on Ash Wednesday, 1942, she was arrested by the Gestapo as she came out of

the operating room. The charges against her included, “hanging crucifixes, and

writing a poem that mocked Hitler.”

The Nazis promptly

sentenced her to death by the guillotine for “favouring the enemy and

conspiracy to commit high treason.” They offered her freedom if she would

abandon the Franciscans she loved so much. She adamantly refused. Although many

nuns lost their lives in the extermination camps, Sister Restituta would be the

only Catholic nun ever charged, tried, and sentenced to death by a Nazi court.

An appeal for clemency

went as far as the desk of Hitler’s personal secretary and Nazi Party

Chancellor, Martin

Bormann. His response was that her execution “would provide effective

intimidation for others who might want to resist the Nazis.” Sister Maria

Restituta spent her final days in prison caring for the sick. Because of her

love for the crucifix — or rather, the One who was died upon it — she was

beheaded on March 30, 1943.

The day she died happened

to be Tuesday of Holy Week. She was 48 years old.

Pope

John Paul II visited Vienna in 1998 and there beatified Helena Kafka,

the girl whose destiny was service. She was declared Blessed

Maria Restituta. She had learned how to serve others extremely well. But

the One she served best of all was her Savior. She gave Him her life.

Blessed Marie Restituta,

please pray for us.

Larry Peterson is a

Christian author, writer and blogger who has written hundreds of columns

on various topics. His books include the novel The Priest and the

Peaches and the children’s book Slippery Willie’s Stupid, Ugly Shoes. His

latest book, The Demons of Abadon, will become available during the

spring of 2016. He has three kids and six grandchildren, and they all

live within three miles of each other in Florida.

SOURCE : https://aleteia.org/2016/04/12/meet-the-only-nun-sentenced-to-death-by-a-nazi-court

The Tough Nun Nurse Who

Stood Up to the Nazis

March 30, 2016Bl. Maria Restituta Kafka (1894-1943)

Feast: March 30

Beatified: June 21, 1998

We know the Nazis’

wickedness cowed many into silence, but not everyone. Take, for instance, Bl.

Maria Restituta.

Born Helen Kafka, she was

from a family of Czech extraction, and she grew up in Vienna. After leaving

school at 15, Helen tried her hand at various jobs before settling on a nursing

career with the Franciscan Sisters of Christian Charity.

After several months,

Helen asked her parents to join the order. When they refused, she ran away from

home. Ultimately, her parents relented, and so the congregation accepted her.

Helen took the name Restituta after an early martyr who had been beheaded and

made her final vows at age 23 in 1918. (One source says that one of the

meanings of “Restituta” is “obese.” Given her keen sense of humor, maybe she

also chose the name as a joke? We can only speculate.)

Her hospital’s best

surgeon was difficult. Nobody wanted to work with him … except Sr.

Restituta, and within a short time, she was running his operating room.

Eventually, she became a world-class surgical nurse.

Sister was tough. People

called her “Sr. Resolute” because of her stubbornness. Mostly, however,

Restituta was easy-going and funny. After work, she’d visit the local pub and

order goulash and “a pint of the usual.”

Given her very vocal

opposition to the Nazis, she was also brave. After Restituta hung a crucifix in

every room of her hospital’s new wing, the Nazis ordered them taken down. She

refused. The crucifixes stayed.

However, when the Gestapo

found anti-Nazi propaganda on her, she was arrested and later sentenced to

death for treason.

Bl. Restituta spent her

remaining days ministering to other prisoners. As she approached the guillotine

wearing a paper shirt and weighing just half her previous weight, her last

words were, “I have lived for Christ; I want to die for Christ.”

She was the only “German”

religious living in “Greater Germany” martyred during the Second World War. St.

Edith Stein and her sister were living in the Netherlands before their

deportation to Auschwitz.)

Fearing that Catholic

Christians would promote her as a martyr, the Nazis did not hand over her body.

Rather they buried it in a mass grave.

In the Basilica of St.

Bartholomew on the Tiber in Rome is a chapel dedicated to 20th century martyrs.

The crucifix that hung from Bl. Restituta’s belt is kept there as a relic.

SOURCE : https://catholicsaintsguy.wordpress.com/2016/03/30/the-tough-nun-nurse-who-stood-up-to-the-nazis/

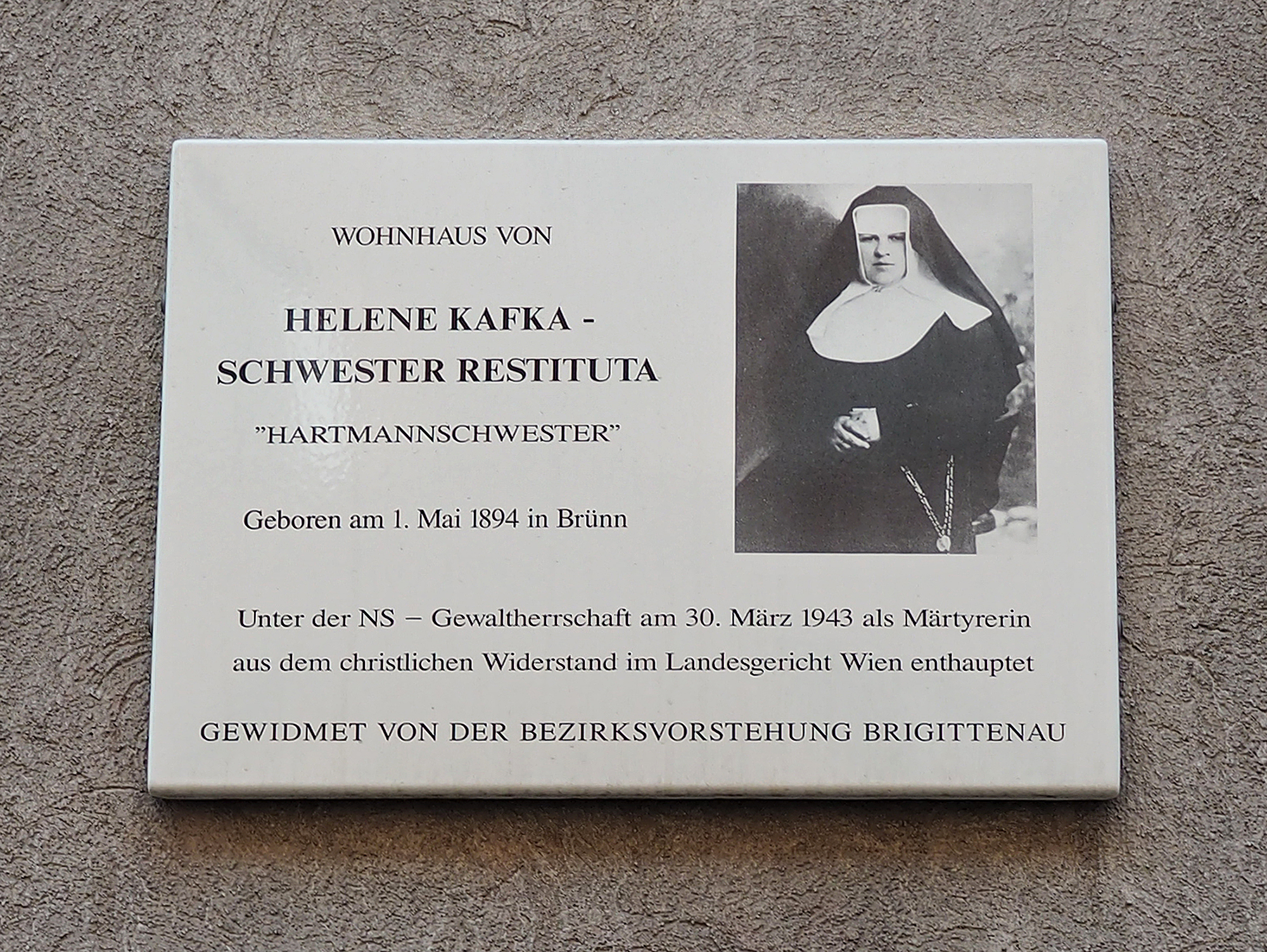

Gedenktafel

für Sr. Maria Restituta Kafka (1894–1943) an ihrem Wohnhaus, Denisgasse 24,

1200 Wien

Here-lived

plaque of Sr. Maria Restituta Kafka (1894–1943), Denisgasse 24, 1200 Vienna

Beata Restituta Kafka Vergine

e martire

Brno, Repubblica Ceca, 1°

maggio 1894 - Vienna, Austria, 30 marzo 1943

Martirologio Romano: A

Vienna in Austria, beata Maria Restituta (Elena) Kafka, vergine delle Suore

Francescane della Carità Cristiana e martire, che, originaria della Moravia,

svolse servizio di infermiera e, arrestata durante la guerra dai nemici della

fede, morì decapitata.

La sua è l’umile famiglia

di un calzolaio con sette figli; lei è povera e perdipiù balbuziente. Anche un

po’ testarda, a giudicare almeno dal carattere forte e dal suo modo di fare,

sbrigativo e risoluto, che l’accompagnerà per tutta la vita. A 15 anni vorrebbe

continuare a studiare, ma la mandano a far la cameriera; a 18 vorrebbe farsi

suora, ma i suoi sono decisamente contrari. Si rassegna così ad aspettare

i 20 anni e, quando li raggiunge, scappa di casa per andare in

convento. Le Suore Francescane della Carità Cristiana di Vienna le danno

il nome di Suor Restituta e la mandano a fare l’infermiera: è sempre stato

quello il suo desiderio più grande, perché le piace servire Gesù nei malati.

Come infermiera ci sa davvero fare: medici e colleghi l’apprezzano e la stimano

sia come infermiera di sala operatoria che come anestesista. Qui e là continua

a far capolino quel suo carattere cordiale ma deciso, tanto che suor Restituta

viene presto ribattezzata “suor Resoluta” . Al letto dei malati, però, nessuno

la può superare, perché è di una delicatezza e di una amorevolezza uniche.

Scoppia la prima guerra mondiale e suor Restituta è accanto ai feriti ,

sollecita ad ogni chiamata, pronta per ogni emergenza. Nel 1938 i nazisti

invadono Vienna e sono due tra le prime disposizioni di Hitler che cercano di

applicare: far sparire i crocifissi dai luoghi pubblici e allontanare le suore

dalle corsie degli ospedali. Suor Restituta, però, è così indispensabile per la

sua indiscussa competenza, che più o meno segretamente può continuare la sua

opera di carità al letto dei malati. Il crocifisso nelle stanze e nelle corsie

dell’ospedale diventa invece quasi una questione personale: Suor Restituta,

risoluta come sempre, si prende l’incarico di personalmente andare a

rimpiazzarli là dove sono stati tolti: sa di rischiare parecchio con quel suo

gesto provocatorio, ma intanto più crocifissi vengono eliminati e più lei ne

risistema. Tanto, tra lei e il nazismo c’è un’incompatibilità dichiarata,

perché non può condividere l’ideologia di morte e di razzismo che Hitler va

professando. E così la furia nazista si scatena anche su di lei: viene

arrestata il mercoledì delle Ceneri del 1942 e messa in prigione, ma nella sua

cella continua ad aiutare donne incinte e compagni deperiti, oltre a consolare

e sostenere i condannati a morte. Per lei la condanna a morte arriva quasi un

anno dopo e viene decapitata il 30 marzo 1943. Prima di morire chiede al

cappellano di tracciarle in fronte il segno della croce: quasi il timbro di

autenticità su una vita che si è sempre ispirata al crocifisso. Il 21 giugno

1998 il Papa proclama beata Suor Restituta Kafka, la martire del crocifisso,

fissando al 29 ottobre la sua memoria liturgica.

Autore: Gianpiero Pettiti

La sua terra di Moravia è soggetta all’imperatore austriaco Francesco Giuseppe: lei, Helene, è la sesta dei sette figli di Anton e Maria Kafka, che nel 1896 si sono trasferiti dalla regione nativa a Vienna, capitale dell’Impero. Helene si avvia alla professione di infermiera e vuole anche farsi suora. I genitori dicono di no, lei si rassegna ad aspettare i vent’anni, e infine la accolgono le Francescane della Carità Cristiana in Vienna. Qui, come religiosa, prende il nome di sua madre e quello di una martire dei primi secoli. Si chiamerà dunque suor Maria Restituta.

Abbastanza presto, però, molti cominciano a chiamarla suor Resoluta, per i modi cordiali e decisi e per la sua sicurezza e capacità come infermiera di sala operatoria e come anestesista. Nell’ospedale regionale di Mödling, presso Vienna, la religiosa diventa un’istituzione: per i medici, per le altre infermiere, ma soprattutto per i malati, ai quali sa comunicare con straordinaria efficacia il suo amore per la vita, la sua e quella degli altri, nella gioia e nella sofferenza. Una donna, diremmo oggi, splendidamente realizzata.

Nel marzo 1938, Hitler manda il suo esercito a occupare l’Austria, a tradimento. Vienna, già capitale di un Impero multietnico e multilingue, si ritrova capoluogo di una provincia del Reich tedesco, sottoposta a brutale nazificazione. Suor Restituta si trova naturalmente, fisiologicamente avversa a tutto questo. E non vuole, non può nasconderlo. Essendo per la vita è contro il nazismo. A tutti i costi.

E quando i nazisti tolgono il Crocifisso anche dagli ospedali, lei tranquillamente lo va a rimettere, a testa alta, sfidando comandi e comandanti.

Non potendola piegare, i nazisti la sopprimono. Arrestata il mercoledì delle Ceneri 1942, è condannata a morte nell’ottobre, poi trascorre 5 mesi nel braccio della morte, e il 30 marzo 1943 muore decapitata. Alle consorelle ha mandato un messaggio: "Per Cristo sono vissuta, per Cristo voglio morire".

E in faccia agli assassini, prima che il carnefice alzi la mannaia, suor Restituta dice al cappellano: "Padre, mi faccia sulla fronte il segno della Croce".

Papa Giovanni Paolo II l’ha beatificata il 21 giugno 1998 a Vienna.

Autore: Domenico Agasso

Non c'è dubbio: il secolo XX è stato un grande secolo per l'umanità, con molteplici luci ma anche con grandi zone d'ombra. Tra le prime ricordiamo i progressi nel campo dei diritti civili e del rispetto della persona, e, in Europa il superamento di tante inimicizie fra le nazioni con la conseguente nascita della Unione Europea (ancora 'in progress'); in campo tecnologico, l'avvento della rivoluzione informatica, con l'invenzione del computer che è stato veramente il motore di questo travolgente progresso che ha rivoluzionato la nostra vita di tutti i giorni. Ma non mancano anche le ombre, e che ombre! E' stato il secolo delle ideologie (fascismo, comunismo e nazismo) a carattere onnicomprensivo (volevano dare ogni risposta all'uomo e sull'uomo), ma anche aggressivo e repressivo. Ed è anche un secolo che ha visto, a causa di queste ideologie, ben due guerre mondiali con uno spaventoso bilancio di distruzione e morte.

Non dimentichiamo che è stato anche il "Secolo dei Martiri" della fede cristiana, a causa proprio dell'ideologia comunista, con le sue scuole di ateismo ed i corsi di rieducazione che miravano di estirpare "la superstizione della religione" dalla testa della gente. E di quella nazista, di stampo antisemita, anticristiana e antiumana (mito della razza e della eugenetica). Il nazismo fu anche fautore del neopaganesimo. Sulla propria bandiera aveva la 'croce uncinata' (o svastica) che, secondo loro, doveva soppiantare la croce di Cristo dal cuore dei cristiani con la propaganda e con il terrore della persecuzione.

Il papa Giovanni Paolo II nell'anno del Giubileo 2000, in una memorabile cerimonia al Colosseo di Roma, ha parlato proprio di Secolo dei Martiri, invitando tutti a ricordare i tantissimi cristiani, testimoni fino a donare la propria vita per la loro fede in Cristo.

L'idea di martirio è sempre stata presente nella storia della Chiesa, ed è tornata alla ribalta, prepotentemente, proprio nel secolo scorso. Gesù stesso aveva messo in guardia i suoi discepoli con le famose parole: "Un servo non è più grande del suo padrone. Se hanno perseguitato me, perseguiteranno anche voi. Ma tutto questo vi faranno a causa del mio nome" (Gv 15,20). Il destino dei discepoli è dunque quello di Gesù: la persecuzione. Perché questo? Perché la Chiesa continua nella storia umana quello che ha fatto Gesù, la sua missione che non fu soltanto quella di annunciare il regno di Dio e chiamare gli uomini alla conversione, ma anche quella della suprema testimonianza della propria vita sulla croce per la salvezza del mondo. Ed i martiri di tutti i secoli avevano questa coscienza di seguire il Cristo, di portare il peso della croce dell'umanità insieme a lui, di continuare la sua passione a beneficio dell'umanità intera. Vissero per Cristo, morirono martiri per Cristo e con Cristo.

Tra questi testimoni ricordiamo una Suora Francescana della Carità Cristiana,

morta martire per la propria fede, (conosciuta anche come "Martire per il

Crocifisso") per mano dei nazisti, a Vienna nel 1943: Sr. Maria Restituta,

al secolo Elena Kafka, dichiarata beata nel 1998 proprio nella capitale

austriaca da Giovanni Paolo II.

"Per aiutare quelli che soffrono…."

Elena Kafka, questo era il suo nome, nacque nel 1896 a Brno, città nell'odierna

Cekia (allora faceva parte dell'impero austro-ungarico), ma visse a Vienna,

dove la famiglia era emigrata, fin da bambina. A sei anni Elena era

balbuziente… e la sua maestra con una 'cura' originale che si usava allora, non

sappiamo se con qualche fondamento scientifico, le impose il silenzio per tre

mesi. Per una bambina un ordine…. tremendo. Ma la cura riuscì. Ed Elena,

felicissima come non mai, cominciò ad esprimersi con fierezza e con correttezza

di pronuncia, come gli altri bambini di pari età.

A 15 anni dovette lasciare la scuola per lavorare come cameriera e così aiutare la propria famiglia. Proprio in quegli anni cominciò a maturare l'idea che realizzerà con costanza e coraggio, di farsi religiosa ed infermiera così da poter "aiutare quelli che soffrono e hanno bisogno di aiuto". Ideale questo che cresceva sempre di più nel suo cuore, fortemente voluto e perseguito da lei ma anche ostacolato dai genitori. Forse avevano paura di perdere una preziosa fonte di sostentamento per la famiglia e anche la constatazione di non poterle pagare o dare la dote per tale scelta. Sua madre specialmente cercò con forza di farle cambiare idea. Ma Elena, come farà anche in seguito da adulta e infermiera, perseverò con risolutezza. Fino a scappare di casa all'età di 19 anni (per quegli anni ancora minorenne). Il rifugio scelto fu la Casa Madre delle Suore della Carità Cristiana sempre a Vienna.

Anche con questa decisione i suoi genitori si convinsero che non si trattava di un capriccio adolescenziale o di una semplice infatuazione passeggera. Elena aveva le idee chiare e faceva sul serio. E le diedero il permesso. E così entrò nel noviziato il 23 ottobre 1915 prendendo il nome, da religiosa, di Maria Restituta, in ricordo di una martire dei primi secoli.

Erano gli anni della Prima Guerra mondiale, e ben presto anche Elena dovette

fare esperienza della sofferenza umana e delle tragedie che il conflitto

portava e fu chiamata a dare il proprio contributo in un ospedale che operava e

curava i soldati feriti in guerra. Erano giovani traumatizzati dall'esperienza

bellica, ed avevano bisogno di aiuto psicologico, di una parola buona, di molta

pazienza… e lei dava tutto questo. Sentiva che quella era la sua missione, e la

stava svolgendo con impegno e dedizione.

Da Sr. Maria Restituta… a Sr. Risoluta!

Questa sua totale carità e donazione di servizio nel contatto con i malati la

attuò anche nell'ospedale di Moedling dove fu trasferita nel 1919, e che sarà

la sua ultima destinazione. Qui lavorò certo con dedizione, con pazienza ma

anche con risolutezza: era sicura di sé e risoluta nel portare avanti le

decisioni. Tanto da essere talvolta chiamata… Sr. Risoluta! Fu chiamata a

lavorare come infermiera in sala operatoria, ed in questo compito dimostrò

eccezionali qualità professionali, molto apprezzate, come testimonieranno

persone che la conobbero. "Era una persona buona e caritatevole…Una volta

doveva essere trasferita; il primario Stoehr disse: "Se Sr. Restituta se

ne va me ne andrò anch'io. Allora non venne trasferita. Ella era risoluta,

sicura di sé".

Professionalmente era diventata un'eccellente anestesista. Disse un altro testimone: "Era assoluta padrona del suo mestiere. Nelle operazioni in cui non operava il primario, ma uno dei medici più giovani, si aveva l'impressione che ella dirigesse l'operazione. Ella porgeva già il bisturi ancor prima che l'operatore l'avesse chiesta. Si poteva imparare molto da lei. Maria Restituta era pienamente impegnata nel suo lavoro, irradiando grande calma e sicurezza".

Dato il suo carattere deciso e sicuro di sé, pur essendo piccola e piuttosto

grassa non era consigliabile a nessuno contraddirla quando aveva deciso

qualcosa che riteneva giusta. Sapeva però anche essere affettuosa e piena di

premure materne. Ed era dotata perfino di un fine senso dell'umorismo, qualità

apprezzata nelle corsie dell'ospedale e non solo nella sua comunità religiosa.

Quando tornava a casa dal lavoro ordinava la cena ed anche "una pinta della

solita birra". E le consorelle, sorridenti, capivano perfettamente.

"Padre, mi faccia il segno di croce in fronte"

Il nazismo era salito al potere in Germania nel 1933, e per gli Ebrei

cominciarono le persecuzioni e le deportazioni nei campi di concentramento

(l'Olocausto). Anche per la Chiesa Cattolica (e protestante) incominciarono i

giorni difficili, che sfoceranno in migliaia di sacerdoti e (in numero minore

di pastori ) deportati e uccisi nei campi di concentramento durante la guerra.

Questa persecuzione religiosa fu estesa anche all'Austria nel 1938 con l'annessione (o Anschluss) alla Germania nazista. Hitler stesso non voleva assolutamente la presenza delle suore negli ospedali. E arrivò anche l'ordine di togliere il Crocifisso dai luoghi pubblici. Un'altra conseguenza fu la proibizione di ogni attività di tipo religioso all'interno degli ospedali.

La situazione per sr. Maria Restituta si fece estremamente difficile e pericolosa per la propria vita. Ella continuò ad assistere religiosamente i morenti, e anche a far avere l'Unzione degli infermi. Era anche sorvegliata da due spie all'interno dell'ospedale.

Il medico chirurgo, un fanatico nazista, sapeva bene delle sue convinzioni religiose… ma non la denunciò, non per rispetto o per un improvviso soprassalto di coscienza, che non aveva… ma semplicemente perché aveva bisogno di lei in sala operatoria. Puro opportunismo pragmatico il suo. Ma un giorno la vide appendere il Crocifisso in ogni stanza di un nuovo reparto e venne anche scoperta a fare delle copie di un volantino antinazista. La denunciò alla polizia, la Gestapo, e il 18 febbraio 1942 venne arrestata e messa in prigione. Accusa: alto tradimento. Prospettiva: la condanna a morte. Era solo una questione di tempo.

L'anno passato in prigione lo visse nella preghiera, nella pazienza e nella carità, a parole ed in opere. Era anche solita dare buona parte della sua razione di cibo ad una donna incinta che ne aveva bisogno. Aiutava i condannati nel braccio della morte, i prigionieri, i compagni di prigionia, donando a tutti un po' di incoraggiamento, una buona parola, un sorriso… e talvolta anche un po' del suo umorismo.

Dopo un anno, nel marzo 1943, arrivò per ordine dello stesso Martin Bormann, un gerarca molto importante del nazismo, la condanna a morte: esecuzione il 30 marzo. Al cappellano che l'accompagnava al patibolo per la decapitazione chiese un ultimo desiderio: "Padre, mi faccia il segno della croce sulla fronte".

Precedentemente aveva scritto alle consorelle un ultimo messaggio: "Non vi mortificate, perché quel che Dio fa è sempre ben fatto. Personalmente non mi sento colpevole e, se devo lasciare la mia vita volentieri faccio questo sacrificio, perché spero che sarò accolta benevolmente dal mio Salvatore. Ho perdonato di cuore a tutti coloro che hanno contribuito alla mia condanna. Vi prego di non serbare rancore a nessuno, ma perdonate a tutti di cuore, come anch'io lo faccio".

Scrisse anche quelle parole che riassumono tutta la sua vita: "Per Gesù sono vissuta, per Gesù voglio morire".

E così moriva martire l'unica suora uccisa dai nazisti in Austria, in odio alla sua fede cristiana, e per aver difeso il suo amore a Cristo e alla sua Croce.

Autore: Mario Scudu sdb

SOURCE : http://www.santiebeati.it/dettaglio/90397

Maria Restituta Helena

Kafka

(1894-1943)

Beatificazione:

- 21 giugno 1998

- Papa Giovanni

Paolo II

Ricorrenza:

- 30 marzo

Vergine delle Suore

Francescane della Carità Cristiana e martire, che, originaria della Moravia,

svolse servizio di infermiera e, arrestata durante la guerra dai nemici della

fede, morì decapitata

"Ho vissuto per

Cristo, voglio morire per Cristo!"

Helena Kafka, questo era

il suo nome, nacque il 1° maggio 1894 Brno, nell'attuale Repubblica Ceca

(allora faceva invece parte dell'impero austro-ungarico), ma fin da bambina,

visse a Vienna, dove la famiglia era emigrata.

Non ancora maggiorenne

espresse la sua intenzione di entrare in convento. I genitori si opposero, ma

la giovane restò fedele al suo obiettivo di farsi suora "per amore di Dio

e degli uomini". Voleva servire il Signore specialmente nei poveri e nei

malati.

Ella trovò accoglienza

presso le Suore Francescane della Carità per realizzare la sua vocazione nel

quotidiano impegno ospedaliero, spesso duro e monotono. Autentica infermiera,

diventò presto a Mödling un'istituzione. La sua competenza infermieristica, la

sua risolutezza e la sua cordialità fecero sì che molti la chiamassero suor

Resoluta e non suor Restituta.

Per il suo coraggio e il

suo animo deciso essa non volle tacere neanche di fronte al regime

nazionalsocialista. Sfidando i divieti dell'autorità politica, suor Restituta

fece appendere in tutte le stanze dell'ospedale dei Crocifissi. Il mercoledì

delle Ceneri del 1942 venne portata via dalla Gestapo. In prigione cominciò per

lei un "Calvario" che durò più di un anno, per concludersi alla fine

sul patibolo. Le sue ultime parole a noi trasmesse furono: "Ho vissuto per

Cristo, voglio morire per Cristo!"

Guardando alla Beata suor

Restituta, possiamo intravedere a quali vette di maturità interiore una persona

può essere condotta dalla mano divina. Essa rischiò la vita con la sua

testimonianza per il Crocifisso. E il Crocifisso conservò nel suo cuore

testimoniandolo di nuovo poco prima di essere condotta all'esecuzione capitale,

quando chiese al cappellano carcerario di farle "il segno della croce

sulla fronte".

SOURCE : https://www.causesanti.va/it/santi-e-beati/maria-restituta-helena-kafka.html

OMELIA DI GIOVANNI PAOLO

II

21 Giugno 1998

1. "Chi sono io

secondo la gente?" (Lc 9,18).

Questa domanda Gesù la

pose un giorno ai suoi discepoli in cammino con lui. Anche ai cristiani in

cammino sulle strade del nostro tempo Gesù pone la stessa domanda: "Chi

sono io secondo la gente?".

Come avvenne duemila anni

or sono in un luogo appartato del mondo conosciuto di allora, anche oggi di

fronte a Gesù le opinioni umane sono divise. Alcuni gli attribuiscono la

qualifica di profeta. Altri lo ritengono una personalità straordinaria, un

idolo che attira la gente. Altri ancora lo credono persino capace di aprire una

nuova era.

"Ma voi chi dite che

io sia?" (Lc 9,20). La domanda è tale da non consentire una risposta

"neutrale". E' una domanda che esige una scelta di campo ed è domanda

che coinvolge tutti. Anche oggi Cristo chiede: voi cattolici dell'Austria, voi

cristiani di questo Paese, voi cittadini, uomini e donne, chi dite che io sia?

La domanda sgorga dal

cuore stesso di Gesù. Colui che apre il proprio cuore vuole che la persona che

gli è davanti non risponda solo con la mente. La domanda proveniente dal cuore

di Gesù deve toccare i nostri cuori! Chi sono io per voi? Che cosa rappresento

io per voi? Mi conoscete veramente? Siete i miei testimoni? Mi amate?

2. Allora Pietro,

portavoce dei discepoli, rispose: Noi crediamo che tu sei "il Cristo di

Dio" (Lc 9,20). L'evangelista Matteo riferisce la professione di

Pietro più dettagliatamente: "Tu sei il Cristo, il Figlio del Dio

vivente!" (Mt 16,16). Oggi il Papa, quale successore per volontà

divina dell'Apostolo Pietro, professa a nome vostro e assieme a voi: Tu sei il

Messia di Dio, tu sei il Cristo, il Figlio del Dio vivente.

3. Nel corso dei secoli

la giusta professione di fede è stata ripetutamente oggetto di affannosa

ricerca. Sia ringraziato Pietro le cui parole sono divenute normative.

Con esse si devono

misurare gli sforzi della Chiesa che cerca di esprimere nel tempo che cosa

rappresenta Cristo per essa. Infatti, non basta solo la professione con le

labbra. La conoscenza della Scrittura e della Tradizione è importante, lo

studio del Catechismo è prezioso: ma a che cosa serve tutto questo se alla fede

cognitiva mancano i fatti?

La professione di fede in

Cristo chiama alla sequela di Cristo. La giusta professione di fede deve essere

accompagnata da una giusta condotta di vita. L'ortodossia richiede l'ortoprassi.

Fin dall'inizio Gesù non ha mai nascosto ai suoi discepoli questa esigente

verità. Infatti, Pietro ha appena pronunciato una straordinaria professione di

fede, e subito, lui e gli altri discepoli si sentono dire da Gesù ciò che il

Maestro si aspetta da loro: "Se qualcuno vuol venire dietro a me, rinneghi

se stesso, prenda la sua croce ogni giorno e mi segua" (Lc 9,23).

Com'è stato all'inizio,

così continua ad essere ora: Gesù non cerca solo delle persone che l'acclamino.

Egli cerca persone che lo seguano.

4. Cari Fratelli e

Sorelle! Chi riflette sulla storia della Chiesa con gli occhi dell'amore,

scorge con gratitudine che, malgrado tutti i difetti e tutte le ombre, ci sono

stati e ci sono tuttora e dappertutto uomini e donne la cui esistenza mette in

luce la credibilità del Vangelo.

Oggi mi è data la gioia

di poter annoverare nel libro dei Beati tre cristiani della vostra Terra.

Ciascuno di essi ha confermato la professione di fede nel Messia mediante la

testimonianza personale resa nel proprio ambiente. Tutti e tre i Beati ci

dimostrano che col titolo di "Messia" non si riconosce solamente un

attributo a Cristo, ma ci si impegna anche a cooperare con l'opera messianica:

i grandi diventano piccoli, i deboli diventano protagonisti.

Non gli eroi del mondo

hanno la parola oggi qui sulla Heldenplatz, ma gli eroi della Chiesa, i tre

nuovi Beati. Dal balcone che si affaccia su questa piazza, sessant'anni or

sono, un uomo ha proclamato in se stesso la salvezza. I nuovi Beati portano un

altro annuncio: la salvezza non si trova nell'uomo, ma in Cristo, Re e

Salvatore!

5. Jakob Kern proveniva

da una modesta famiglia viennese di operai. La prima guerra mondiale lo strappò

bruscamente dagli studi nel Seminario Minore di Hollabrunn. Una grave ferita di

guerra rese la sua breve esistenza terrena nel Seminario Maggiore e nel

Monastero di Geras - come lui stesso diceva - un Calvario. Per amore di Cristo

egli non si aggrappò alla vita, ma la offrì consapevolmente per gli altri. In

un primo momento voleva diventare sacerdote diocesano. Ma un evento gli fece

cambiare strada. Quando un religioso premonstratense abbandonò il convento,

seguendo la Chiesa nazionale ceca formatasi a seguito della separazione da Roma

avvenuta da poco, Jakob Kern scoprì in questo triste evento la sua vocazione.

Egli volle riparare l'azione di quel religioso. Jakob Kern entrò al posto suo

nel Monastero di Geras e il Signore accettò l'offerta del

"sostituto". Il Beato Jakob Kern si presenta a noi come testimone

della fedeltà al sacerdozio. All'inizio era un desiderio d'infanzia, che

s'esprimeva nell'imitare il sacerdote all'altare. Successivamente il desiderio

maturò. Attraverso la purificazione del dolore, apparve il profondo significato

della sua vocazione sacerdotale: unire la propria vita al sacrificio di Cristo

sulla Croce e offrirla in sostituzione per la salvezza degli altri.

Possa il Beato Jakob

Kern, che era uno studente vivace e impegnato, incoraggiare molti giovani ad

accogliere generosamente la chiamata al sacerdozio per seguire Cristo. Le sue

parole di allora sono rivolte a noi: "Oggi più che mai c'è bisogno di

sacerdoti autentici e santi. Tutte le preghiere, tutti i sacrifici, tutti gli

sforzi e tutte le sofferenze unite alla retta intenzione diventano seme divino

che prima o poi porterà il suo frutto".

6. Padre Anton Maria

Schwartz a Vienna, cento anni or sono, si preoccupò delle condizioni degli

operai, dedicandosi in primo luogo ai giovani apprendisti in fase di formazione

professionale. Tenendo sempre presenti le proprie umili origini, si sentì

specialmente unito ai poveri operai. Per la loro assistenza fondò, adottando la

regola di San Giuseppe Calasanzio, la Congregazione dei Pii Operai, tuttora

fiorente. Il suo grande desiderio fu quello di convertire la società a Cristo e

di restaurarla in Lui. Egli fu sensibile ai bisogni degli apprendisti e degli

operai, che spesso mancavano di sostegno e di orientamento. Padre Schwartz si

dedicava a loro con amore e creatività trovando mezzi e vie per costruire la

prima "Chiesa per gli operai di Vienna". Questo tempio umile e

nascosto dalle case popolari assomiglia all'opera del suo fondatore, che l'ha

vivificata per ben quarant'anni.

Di fronte

all'"apostolo operaio" di Vienna le opinioni erano divise. Molti

trovavano il suo impegno esagerato. Altri lo ritenevano degno della più alta

considerazione. Padre Schwartz rimase fedele a se stesso e intraprese anche