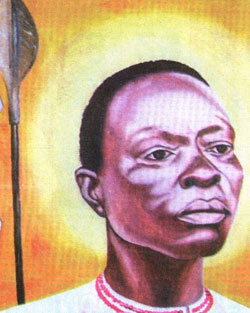

Saint Noé Mawaggali

Martyr en Ouganda (+1886)

Page du roi Mwanga, quand

commença la persécution, il refusa, sans peur, de fuir et offrit spontanément

sa poitrine aux lances des soldats. Percé de coups, il fut alors pendu à un

arbre, jusqu'à ce qu'il rendît l'esprit pour le Christ à Mityana en Ouganda.

Béatifié par Benoît XV en

1920 et canonisé par Paul VI en 1964, membre du groupe des 22 martyrs

de l'Ouganda.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/10924/Saint-Noe-Mawaggali.html

Mawaggali, Noé

1850-1886

Église Catholique

Ouganda

Noé Mawaggali était un

des trois martyrs catholiques de Mityana, Ouganda, les deux autres étant

Matthias Kalemba et Luc Banabakintu. Mawaggali était le fils de Musazi et

membre du clan des cerfs de la brousse (Ngabi), et sa mère s’appelait Meme. Il

est né à Nkazibaku dans le compté Ssingo de Buganda, vers 1850. Il était maître

potier, et avait été nommé potier du chef de compté, car celui-ci admirait

beaucoup son travail. Après avoir vécu un certain temps dans la maison du chef,

Mawaggali est devenu locataire de Matthias Kalemba et a bâti une maison sur la

propriété de celui-ci. Kalemba était non seulement son propriétaire mais aussi

son ami, et c’est cette amitié, ajoutée au zèle et à l’exemple chrétien de

Matthias, qui a attiré Mawaggali vers lui et qui l’a persuadé à s’inscrire au

catéchisme catholique. Il a éventuellement été baptisé le 1er novembre, 1885,

avec un groupe de vingt-deux personnes.

En plus de la poterie,

Mawaggali faisait aussi du tannage de peaux, et avait la réputation d’être un

ouvrier industrieux et stable. Physiquement parlant, il était grand et mince.

Quoiqu’il ne se soit toujours pas marié avant l’époque de son martyre, son

comportement moral était rigoureusement correct. Par la suite, sa mère Meme a

été baptisée, et a pris le nom de Valeria, alors que sa sœur Munaku, qui avait

dix-huit ans de moins, a souffert pour sa foi au temps du martyre de son frère.

Elle aussi à été baptisée, prenant le nom de Maria Matilda, et elle a vécu

jusqu’à l’âge de soixante-seize ans.

En 1881, Mawaggali faisait

partie d’un groupe de plusieurs catéchumènes catholiques qui prenaient des

cours sur l’évangile de St. Matthieu et sur les Actes des Apôtres donnés par le

missionnaire anglican Alexander Mackay. Quand la persécution de 1886 a éclaté,

Mawaggali était à Mityana, à quelques soixante kilomètres de la capitale, mais

la communauté chrétienne qui existait là était bien connue et n’échappa pas au

regard. Les détails de la mort de son frère ont été racontés plus tard par

Munaku. Mawaggali était à la tête de la maison de Matthias Kalemba, qui était à

Mengo avec Luc Banabakintu. Les chrétiens à Mityana avaient pris l’habitude

d’envoyer des représentants chaque semaine au cours de catéchisme qui était

donné à la mission catholique. Le matin du 31 mai, Mawaggali était allé à

Kawingo pour voir les hommes à qui c’était le tour. Pendant qu’il était parti,

le groupe qui faisait le raid est arrivé.

Mawaggali était dans la

maison de Banabakintu en train de donner des instructions finales aux hommes,

et discutant avec eux la nouvelle de l’arrestation de Matthias et de Luc. Le

parti du raid dirigé par Mbugano, le légat royal, arrivait enfin à la maison.

Mawaggali est allé à leur rencontre, donnant ainsi à ses frères chrétiens le

temps de s’échapper. “Est-ce que c’est toi, Mawaggali ?” a crié un des membres

du raid. “Oui, c’est moi,” il a répondu, tirant en même temps sur la tête le

tissu qu’il portait, pour qu’il ne voie pas le coup mortel qui allait arriver.

Le maître des tambours du roi, Kamanyi, a plongé sa lance dans le dos de

Mawaggali, qui est tombé, mortellement blessé. Un des membres du raid a suggéré

qu’on devrait le donner à manger aux chiens. Ils ont donc attaché le martyre

blessé à un arbre, et ont lâché les chiens. De plus en plus excités par l’odeur

du sang qui venait des lacérations successives, les chiens l’ont déchiré. On

dit que son agonie a duré jusqu’au soir. A la tombée de la nuit, son corps

mutilé a été détaché de l’arbre et laissé sur la route comme avertissement aux

autres chrétiens. Lorsque les bourreaux ont quitté Mityana le jour suivant, il

ne restait pratiquement rien du corps car les hyènes avaient achevé le travail

commencé par les chiens.

Noé Mawaggali a été

béatifié par le Pape Bénédicte XV en 1920, et déclaré saint canonisé par le

Pape Paul VI en 1964. Une partie de l’arbre auquel on avait attaché le martyr a

été préservé à Mityana, où un tombeau moderne magnifique commémore les trois

martyrs de Mityana.

Aylward Shorter M. Afr.

Bibliographie

J.F. Faupel, African

Holocaust, the Story of the Uganda Martyrs [Holocauste africain,

l’histoire des martyrs de l’ouganda] (Nairobi, St. Paul’s Publications Africa,

1984 [1962]).

J.P. Thoonen, Black

Martyrs [Martyres noirs] (London: Sheed and Ward, 1941).

Cet article, soumis en

2003, a été recherché et rédigé par le dr. Aylward Shorter M. Afr., directeur

émérite de Tangaza College Nairobi, université catholique de l’Afrique de

l’Est.

SOURCE : https://dacb.org/fr/stories/uganda/mawaggali-noe/

Saint Nowa Mawaggali

Also

known as

Noah Mawaggali

Noè Mawaggali

Memorial

31 May

3 June as

one of the Martyrs

of Uganda

Profile

Member of the Ngabi

clan. Convert.

One of the Martyrs

of Uganda who died in

the Mwangan persecutions.

Born

at Buganda, Uganda

Died

stabbed with

a spear and

torn apart by wild

dogs on 31 May 1886 at

Mityana, Uganda

Venerated

29 February 1920 by Pope Benedict

XV (decree of martyrdom)

Beatified

6 June 1920 by Pope Benedict

XV

Canonized

18 October 1964 by Pope Paul

VI at Rome, Italy

Additional

Information

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

Catholic

Online

images

Santi e Beati

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

Dicastero delle Cause dei Santi

Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

Santi e Beati

MLA

Citation

“Saint Nowa

Mawaggali“. CatholicSaints.Info. 27 June 2023. Web. 3 June 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-nowa-mawaggali/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-nowa-mawaggali/

Mawaggali, Noé

1850-1886

Catholic Church

Uganda

Noé (Noah) Mawaggali was

one of the three Catholic martyrs of Mityana, Uganda, the other two being

Matthias Kalemba and Luke Banabakintu. Mawaggali was the son of Musazi and a

member of the Bush-Buck (Ngabi) Clan. His mother’s name was Meme. He was born

at Nkazibaku in the Ssingo County of Buganda about 1850. He was an expert

potter and was appointed potter to the county chief who greatly admired his

work. After living for a time in the chief’s household, Mawaggali became a

tenant of Matthias Kalemba and built a house on his land. Kalemba was his

friend, as well as his landlord, and it was this friendship, as well as the

zeal and Christian example of Matthias, which drew Mawaggali to him and which

induced him to join the Catholic catechumenate. He was eventually baptized on

November 1st, the Feast of All Saints, 1885 in a group of twenty-two.

Besides making pots,

Mawaggali also tanned hides, and had a reputation as a steady and industrious

worker. In appearance, he was tall and slender. Although he had not married by

the time of his martyrdom, his moral behaviour was scrupulously correct. His mother

Meme was later baptized and took the name Valeria, while his sister Munaku, who

was eighteen years younger, suffered for her faith at the time of her brother’s

martyrdom. She, too, was baptized, taking the name Maria Matilda, and lived to

the age of seventy-six.

In 1881, Mawaggali was

among several Catholic catechumens who attended classes on St. Matthew’s Gospel

and the Acts of the Apostles, given by the Anglican missionary, Alexander

Mackay. When the persecution of 1886 broke out, Mawaggali was at Mityana, some

forty-five miles from the capital, but the Christian community there was too

well known to escape notice. The details of her brother’s death were later

related by Munaku. Mawaggali was in charge of the household of Matthias

Kalemba, who was away at Mengo with Luke Banabakintu. It was the custom for the

Christians of Mityana to send representatives each week to the catechetical

class at the Catholic mission. On the morning of May 31, Mawaggali went to

Kawingo to see the men whose turn it was. While he was gone, the raiders

arrived.

Mawaggali was in

Banabakintu’s house giving the men their final instructions and discussing with

them the news of the arrest of Matthias and Luke. The raiding party led by

Mbugano, the royal legate, closed in on the house. Mawaggali went to meet them,

thus giving his fellow Christians the chance to escape. “Is that you

Mawaggali?” called out one of the raiders. “Yes, it is,” he replied, at the

same time drawing over his head the bark cloth he was wearing, so that he

should not see the death stroke coming. Kamanyi, the king’s chief drummer,

plunged his spear into Mawaggali’s back, who fell grievously wounded. One of

the raiders suggested that Noë should be fed to the dogs. The wounded martyr

was therefore tied to a tree and dogs were set upon him. Maddened by the scent

of blood from further lacerations, they tore him to pieces. It is said that his

agony lasted until evening. At nightfall his mangled remains were untied from

the tree and left on the road as a warning to other Christians. By the time the

executioners left Mityana the following day, there was virtually nothing left

of the body. Hyenas had finished the work begun by the dogs.

Noé Mawaggali was

beatified by Pope Benedict XV in 1920, and declared a canonized saint by Pope

Paul VI in 1964. A portion of the tree to which the martyr was tied is

preserved at Mityana, where a magnificent modern shrine commemorates all three

martyrs of Mityana.

Aylward Shorter M.Afr.

Bibliography

J. F. Faupel, African

Holocaust, the Story of the Uganda Martyrs (Nairobi: St. Paul Publications

Africa, 1984 [1962]).

J. P. Thoonen, *Black

Martyrs * (London: Sheed and Ward, 1941).

This article, submitted

in 2003, was researched and written by Dr. Aylward Shorter M.Afr., Emeritus

Principal of Tangaza College Nairobi, Catholic University of Eastern Africa.

SOURCE : https://dacb.org/stories/uganda/mawaggali-noe/

Saint

Noa Mawaggali Cathedral, Mityana, Uganda.

St. Noe Mawaggali

Mawaggali’s parentage and conversion

to Catholicism

Noe Mawaggali was a son of Musaazi and a member of the Bush-Buck (Ngabi) Clan.

He was a native of Ssingo County, having been born at Nkazibaku about 1850.

Mawaggali was an expert potter, turning out all manner of articles such as

earthenware dishes, water-pots, cooking-pots, jugs, bowls and pipes. He became

by appointment potter to the county chief, who greatly admired his work, and

lived for a time in the chief’s household. Later, he built a simple house for

himself on the land of Matthias Kalemba Mulumba, a move that seems to have been

prompted partly by friendship for the Mulumba and largely by the desire to

remove himself from the pagan atmosphere of the chiefs court, because it was

about the same time that the zeal and example of Matthias won him over to the

Catholic Faith. He was not, however, baptized until the Feast of All Saints,

1885.

As well as making pots, Mawaggali used to tan hides and, unlike his fellows,

who spent most of their time visiting and taking part in the interminable

beer-parties, was known as a steady and industrious worker, quiet and

unassuming in manner. He was tall and slender, with a head that narrowed

towards the crown. He never married and was scrupulously correct in his moral

behaviour.

After the death of his father, Mawaggali took his ageing mother and his young

sister to live with him and provided for them. His mother Meeme was later

baptized, taking the name Valeria. His sister Munaku, about eighteen years his

junior, suffered cruelly and heroically in the persecution and was later, after

her freedom had been purchased by the missionaries, baptized Maria Mathilda. She

lived to the age of seventy-six, devoted to prayer and good works, and is the

source of much of the information about her brother.

Mawaggali evangelizes in difficulty

The Mityana Christian group, Luke Banabakintu and Noa Mawaggali in particular,

used to walk from Mityana to Nalukolongo every week, a distance of 42 miles or

64 kilometers, for Sunday masses and Sunday sermons. Either Baanabakintu or

Mawaggali had to set off on this tedious and difficult journey on Friday and

spend the night at Nswanjere. He would arrive at Kampala (Mmengo) on Saturday

evening, spending the night at Mulumba’s official residence near the palace. He

had to attend the Sunday Mass and endeavour to commit the sermon to memory and

then after Mass he would start off for Mityana spending the night at the

Nswanjere Christian station where he had spent the night on his way to Mmengo.

The journey was not easy, the traveler had to go through thick and extensive

forests and jungles to cross River Mayanja twice, wade through deep, and strong

and wide currents in some places. That was not all, he would on a number of

occasions encounter wild animals, highway robbers, dangerous snakes etc.

Noe’s last moments

After King Mwanga had condemned Christians to death, and many of them had been

arrested at Munyonyo, various raiding groups were sent all other Christian

centres to seize all followers of Christ they find there. Mawaggali was at

Mityana Christian centre where Mathias Mulumba had left him with their

catechumens.

It was still early in the morning and Noe Mawaggali was inside Baanabakintu’s

house, giving final instruction to the two catechumens who were going to the

capital and discussing with them the news of the arrest of Matthias and Luke.

Suddenly, the raiding party under Mbugano closed in on the house, shouting as

they did so that they were looking for Christians. Noe, walking-stick in hand,

came out from the house to meet the raiders, saying, ‘Here we are!’ and,

incidentally, giving his companions an opportunity, of which they availed themselves,

to escape through the back of the house.

‘Is that you, Mawaggali?’ called out one of the raiders.

‘Yes, it is I,’ replied the potter, at the same time drawing over his head the

bark-cloth he was wearing, so that he might not see the death-stroke that he

was expecting. It came from the spear of Kamanyi, the chief’s drummer, acting

as legate, who well knew Mawaggali to be one of the leading Christians.

Levelling his spear, Kamanyi plunged it into the martyr’s back, and Noe fell to

the ground grievously wounded. At this, one of Mbugano’s followers, attempting

to outvie his companions in cruelty, proposed: ‘Now that this Christian can no

longer defend himself, let us feed him to the dogs.’

This horrible suggestion was adopted. The wounded martyr was lashed to a tree,

and the dogs of the village set upon him, further wounds being first inflicted

upon his defenceless body so that the animals might become maddened by the

scent of blood.

Archbishop Streicher mentions reports to the effect that Mawa¬ggali’s agony

lasted until evening. Throughout the day, until con¬sciousness mercifully left

him, he could feel the savage dogs leaping at him and tearing at his flesh,

which they devoured before his eyes. At nightfall, his mangled remains were

untied from the tree and thrown on to the main road, to serve as a warning to

other Christians, and to those with leanings towards that religion.

The brutal treatment of Noe Mawaggali seems to have shocked one at least of his

executioners, men hardened to cruelty.

Noe’s sister Munaku, from her place of concealment, overheard one of them

addressing his companions: ‘What men these Christians are!’ he exclaimed. ‘How

obstinate in their religion and how hardened to pain! This Mawaggali now, we

gave him what he deserved, but, all the same, it was cruel to feed him to the

dogs.’

Then Munaku, with her mother a captive and her brother dead, decided to give

herself up. She emerged hastily from her place of concealment and ran after the

murderers of her brother, crying out, ‘I am Mawaggali’s sister. You have killed

my brother:

Kill me too!’ The men, taken aback, looked at her in astonish¬ment. ‘My brother

has died for his religion,’ insisted the girl, ‘I wish to die also. Plunge your

spears into me!’ ‘You are mad!’ answered the men, ignoring the girl’s plea and

continuing on their way.

Munaku refused to be put off. She followed the men to the square before the

county headquarters, where she found some thirty Christ¬ians in bonds,

including her own mother, Meeme, the widow and daughter of Matthias Kalemba,

the boy, Arsenius or Anselm and a boy who lodged with this family. Mbugano, the

legate, seeing in this comely young girl of eighteen an unexpected windfall,

decided to take her as part of his share of the spoils and had her tied up with

the others.

During the evening, the boy who had been captured in the Mulumba’s house, and

also Meeme, the mother of Noe and Munaku, managed to free themselves from their

bonds and escape. When Mbugano and his captives finally left Mityana, their

route led them past the spot where Noe Mawaggali’s body had been thrown, but

hyenas had completed the work begun by the dogs, and very few traces of the

body remained on the road.

Noe’s tells his sister ‘Never to

abandon Christ’

On Sunday 30 May, when rumours of the outbreak of persecution were circulating

in Mityana, Noe took me aside after the instruction. When we were alone, he

said, ‘Munaku, I see that you are a good girl; you keep the commandments of

God; you are industrious and neat at your work and you pray well; but you have

yet to learn what the priests made very clear to us on the eve of our baptism.

To be a Christian implies a readiness to follow Our Lord to Calvary and even,

if need be, to a painful death. As for myself, I am convinced that there is a

life after death, and I am not afraid of losing this one; but what about you?

Are you determined to remain loyal to the Faith?’ ‘Certainly, I am,’ I replied.

‘Very well then,’ he continued, ‘when we have been killed, never cease to be a

good Christian and to love the Christians who will come after us.’ He said this

to strengthen me in the faith, because I was not yet baptized.

When Noe left me, he said that he was going to Kiwanga, Luke Baanabakintu’s

place, to appoint a man to go to the capital. The Christians of Ssingo were

accustomed to send one of their members every week to the mission at the

capital to attend the priest’s explanation of the catechism, so that he could

repeat what he had learnt to his fellow-Christians at home. On this occasion,

the man was also to bring back tidings of Matthias and Luke.

Next morning, Monday 31 May, after saying our morning prayers, my mother and I

went to cultivate our plot, and Noe went across the swamp to Kiwanga, about a

mile away, to see the man who was to leave that morning for the capital.

We were working in the bananary when we heard the approach of the raiders who

had come from the capital to arrest us and loot our property. They entered the

house of Matthias not far from that of Noe, and seized his wife, Kikuvwa, his

two children, Arsenius aged ten and Julia aged two or three, and a boy who only

slept there. When my mother and I heard them coming, we ran into the

elephant-grass that surrounded the bananary and tried to hide. However, they

overtook my mother and arrested her. Then they went on to the house of Luke

Baanabakintu.

I did not see with my own eyes the manner of my brother’s death, but, from my

place of concealment in the elephant-grass, I overheard some of the villagers,

who had accompanied the raiders, discussing the details as they walked along

the nearby path.

Munaku indeed kept the promise as she fought had to keep her virtue of chastity

up to the age of 76 when she breathed her last.

Noe’s last message to his sister

On Sunday 30 May, when rumours of the outbreak of persecution were circulating

in Mityana, Noe took me aside after the instruction. When we were alone, he

said, ‘Munaku, I see that you are a good girl; you keep the commandments of

God; you are industrious and neat at your work and you pray well; but you have

yet to learn what the priests made very clear to us on the eve of our baptism.

To be a Christian implies a readiness to follow Our Lord to Calvary and even,

if need be, to a painful death. As for myself, I am convinced that there is a

life after death, and I am not afraid of losing this one; but what about you?

Are you determined to remain loyal to the Faith?’ ‘Certainly, I am,’ I replied.

‘Very well then,’ he continued, ‘when we have been killed, never cease to be a

good Christian and to love the Christians who will come after us.’ He said this

to strengthen me in the faith, because I was not yet baptized.

Munaku indeed kept the promise as she fought had to keep her virtue of chastity

up to the age of 76 when she breathed her last.

Noe Mawaggali’s sister follows her

brother determination

When Mbugano and his captives finally left Mityana, their route led them past

the spot where Noe Mawaggali’s body had been thrown, but hyenas had completed

the work begun by the dogs, and very few traces of the body remained on the

road.

Munaku had confided to the Mulumba’s widow Kikuvwa, her intention of forcing

the soldiers to kill her when they reached this spot, by refusing to go any

further. The older woman managed to dissuade her young companion from this course

of action and offered her some wise and timely advice. She explained that

although martyrdom was a noble and glorious death, God did not desire his

followers to seek it for themselves. She also warned the girl that the greatest

danger to which her captors were likely to expose her was not to her life, but

to her chastity and to her soul. Munaku pondered over this warning. She had

already promised her brother that she would not, after his death, endanger her

new-found faith by going to live with their pagan relatives. She therefore

decided that she would renounce these entirely and begged the older woman not

to reveal to anyone who they were.

What Kikuvwa had foretold soon came to pass. Mbugano de¬clared his intention of

taking Munaku as one of his wives and began to question her about her male

relatives, so that he might learn which was entitled to receive the

bride-price. The girl asserted that, since her father was dead and he had

killed her brother, she had no male relatives. She also refused to reveal the

name of her clan, de¬claring that her status was now that of a slave. As for

becoming his wife, she would rather die. Greatly offended by this rejection,

Mbugano determined to break the spirit of this courageous girl.

On reaching the capital, Mbugano went to report to the Chan¬cellor the success

of his mission.

The boy Arsenius escaped and took refuge at the Catholic mission, and

Mawaggali’s sister, Munaku, was taken by Mbugano to his home in Kyaggwe County,

where heavy stocks were fastened to both her feet. For a full month he tried

every means to bend her to his will. After a few days in the stocks, all the

skin had gone from the girl’s ankles and raw wounds encircled her legs.

Mbugano’s other women, moved with pity, wished to pack the apertures of the

stocks with soft fibres to lessen the friction, but their master would not

allow it. ‘Her feet will be cared for,’ he said, ‘and even freed entirely, when

she has come to her senses.’ He resorted also to daily beatings and threats to

sell her to the Arab slave-traders but nothing he could do was able to break

down her resistance.

Finally, baffled by Munaku’s constancy, Mbugano decided to cut his losses.

Professing pity and admiration for his victim, he offered Pere Lourdel the

chance to redeem her. The priest was de¬lighted and a bargain was struck. That

same night, July 1886, in exchange for a gun and some ammunition, Mbugano

handed the girl over to the care of the mission.

Pere Lourdel decided that the heroic profession of faith made by this young

catechumen merited her exemption from the customary four years’ period of

probation before baptism. She was therefore given an intensive course of

instruction and some weeks later, on 22 August, baptized and given the name

Maria-Mathilda. She became a religious (Sister)

Munyonyo Martyrs' Shrine

SOURCE : https://www.munyonyo-shrine.ug/martyrs/other-uganda-martyrs/st-noe-mawaggali/

San Noè Mawaggali Martire

Festa: 31 maggio

>>> Visualizza la

Scheda del Gruppo cui appartiene

† Mityana, Uganda, 31

maggio 1886

Tra i ventidue martiri

ugandesi beatificati da Papa Benedetto XV nel 1920, spicca la figura di San Noè

Mawaggali, un servo del re Mwanga convertito al cattolicesimo. La sua storia,

inserita nel contesto delle persecuzioni anticristiane scatenate dal sovrano,

offre spunti di riflessione sulla fede, il coraggio e la testimonianza.

Mawaggali, originario del clan Ngabi, era un esperto vasaio al servizio del re.

La sua conversione al cattolicesimo lo pose in contrasto con le dissolutezze di

Mwanga, che vedeva nella fede un ostacolo al suo potere e alle sue

inclinazioni. Quando la persecuzione iniziò ad infierire, Mawaggali rimase

saldo nella sua fede, rifiutando di abiurare anche di fronte alle minacce e

alle torture. Il 31 maggio 1886, dopo un'estenuante "via crucis" da

Munyonyo a Namugongo, Mawaggali fu trafitto con le lance dei soldati e

inchiodato ad un albero.

Martirologio

Romano: In località Mityana in Uganda, san Noè Mawaggali, martire, che fu

domestico del re: rifiutando impavidamente di cercare la fuga durante la

persecuzione, offrì spontaneamente il petto alle lance dei soldati e, dopo

esserne stato trafitto, fu appeso ad un albero, finché rese lo spirito per

Cristo.

Fece un certo scalpore,

nel 1920, la beatificazione da parte di Papa Benedetto XV di ventidue martiri

di origine ugandese, forse perché allora, sicuramente più di ora, la gloria

degli altari era legata a determinati canoni di razza, lingua e cultura. In

effetti, si trattava dei primi sub-sahariani (dell’”Africa nera”, tanto per

intenderci) ad essere riconosciuti martiri e, in quanto tali, venerati dalla

Chiesa cattolica.

La loro vicenda terrena si svolge sotto il regno di Mwanga, un giovane re che,

pur avendo frequentato la scuola dei missionari (i cosiddetti “Padri Bianchi”

del Cardinal Lavigerie) non è riuscito ad imparare né a leggere né a scrivere

perché “testardo, indocile e incapace di concentrazione”. Certi suoi

atteggiamenti fanno dubitare che sia nel pieno possesso delle sue facoltà

mentali ed inoltre, da mercanti bianchi venuti dal nord, ha imparato quanto di

peggio questi abitualmente facevano: fumare hascisc, bere alcool in gran

quantità e abbandonarsi a pratiche omosessuali. Per queste ultime, si

costruisce un fornitissimo harem costituito da paggi, servi e figli dei nobili

della sua corte.

Sostenuto all’inizio del suo regno dai cristiani (cattolici e anglicani) che

fanno insieme a lui fronte comune contro la tirannia del re musulmano Kalema,

ben presto re Mwanga vede nel cristianesimo il maggior pericolo per le

tradizioni tribali ed il maggior ostacolo per le sue dissolutezze. A sobillarlo

contro i cristiani sono soprattutto gli stregoni e i feticisti, che vedono

compromesso il loro ruolo ed il loro potere e così, nel 1885, ha inizio

un’accesa persecuzione, la cui prima illustre vittima è il vescovo anglicano

Hannington, ma che annovera almeno altri 200 giovani uccisi per la fede.

Il 15 novembre 1885 Mwanga fa decapitare il maestro dei paggi e prefetto della

sala reale. La sua colpa maggiore? Essere cattolico e per di più catechista, aver

rimproverato al re l’uccisione del vescovo anglicano e aver difeso a più

riprese i giovani paggi dalle “avances” sessuali del re. Giuseppe Mkasa

Balikuddembè apparteneva al clan Kayozi ed ha appena 25 anni.

Viene sostituito nel prestigioso incarico da Carlo Lwanga, del clan Ngabi, sul

quale si concentrano subito le attenzioni morbose del re. Anche Lwanga, però,

ha il “difetto” di essere cattolico; per di più, in quel periodo burrascoso in

cui i missionari sono messi al bando, assume una funzione di “leader” e

sostiene la fede dei neoconvertiti.

Il 25 maggio 1886 viene condannato a morte insieme ad un gruppo di cristiani e

quattro catecumeni, che nella notte riesce a battezzare segretamente; il più

giovane, Kizito, del clan Mmamba, ha appena 14 anni. Il 26 maggio vemgono

uccisi Andrea Kaggwa, capo dei suonatori del re e suo familiare, che si era

dimostrato particolarmente generoso e coraggioso durante un’epidemia, e Dionigi

Ssebuggwawo.

Si dispone il trasferimento degli altri da Munyonyo, dove c’era il palazzo

reale in cui erano stati condannati, a Namugongo, luogo delle esecuzioni

capitali: una “via crucis” di 27 miglia, percorsa in otto giorni, tra le

pressioni dei parenti che li spingono ad abiurare la fede e le violenze dei

soldati. Qualcuno viene ucciso lungo la strada: il 26 maggio viene trafitto da

un colpo di lancia Ponziano Ngondwe, del clan Nnyonyi Nnyange, paggio reale,

che aveva ricevuto il battesimo mentre già infuriava la persecuzione e per

questo era stato immediatamente arrestato; il paggio reale Atanasio

Bazzekuketta, del clan Nkima, viene martirizzato il 27 maggio.

Alcune ore dopo cade trafitto dalle lance dei soldati il servo del re Gonzaga

Gonga del clan Mpologoma, seguito poco dopo da Mattia Mulumba del clan Lugane,

elevato al rango di “giudice”, cinquantenne, da appena tre anni convertito al

cattolicesimo.

Il 31 maggio viene inchiodato ad un albero con le lance dei soldati e quindi

impiccato Noè Mawaggali, un altro servo del re, del clan Ngabi.

Il 3 giugno, sulla collina di Namugongo, vengono arsi vivi 31 cristiani: oltre

ad alcuni anglicani, il gruppo di tredici cattolici che fa capo a Carlo Lwanga,

il quale aveva promesso al giovanissimo Kizito: “Io ti prenderò per mano, se

dobbiamo morire per Gesù moriremo insieme, mano nella mano”. Il gruppo di

questi martiri è costituito inoltre da: Luca Baanabakintu, Gyaviira Musoke e

Mbaga Tuzinde, tutti del clan Mmamba; Giacomo Buuzabalyawo, figlio del

tessitore reale e appartenente al clan Ngeye; Ambrogio Kibuuka, del clan Lugane

e Anatolio Kiriggwajjo, guardiano delle mandrie del re; dal cameriere del re,

Mukasa Kiriwawanvu e dal guardiano delle mandrie del re, Adolofo Mukasa Ludico,

del clan Ba’Toro; dal sarto reale Mugagga Lubowa, del clan Ngo, da Achilleo

Kiwanuka (clan Lugave) e da Bruno Sserunkuuma (clan Ndiga).

Chi assiste all’esecuzione è impressionato dal sentirli pregare fino alla fine,

senza un gemito. E’ un martirio che non spegne la fede in Uganda, anzi diventa

seme di tantissime conversioni, come profeticamente aveva intuito Bruno

Sserunkuuma poco prima di subire il martirio “Una fonte che ha molte sorgenti

non si inaridirà mai; quando noi non ci saremo più altri verranno dopo di noi”.

La serie dei martiri cattolici elevati alla gloria degli altari si chiude il 27

gennaio 1887 con l’uccisione del servitore del re, Giovanni Maria Musei, che

spontaneamente confessò la sua fede davanti al primo ministro di re Mwanga e

per questo motivo venne immediatamente decapitato.

Carlo Lwanga con i suoi 21 giovani compagni è stato canonizzato da Paolo VI nel

1964 e sul luogo del suo martirio oggi è stato edificato un magnifico

santuario; a poca distanza, un altro santuario protestante ricorda i cristiani

dell’altra confessione, martirizzati insieme a Carlo Lwanga. Da ricordare che

insieme ai cristiani furono martirizzati anche alcuni musulmani: gli uni e gli

altri avevano riconosciuto e testimoniato con il sangue che “Katonda” (cioè il

Dio supremo dei loro antenati) era lo stesso Dio al quale si riferiscono sia la

Bibbia che il Corano.

Autore: Gianpiero Pettiti

SOURCE : https://www.santiebeati.it/dettaglio/55460

Carlo Lwanga, Mattia

Maulumba Kalemba e 20 compagni

(† 1885 - 1887)

Beatificazione:

- 06 giugno 1920

- Papa Benedetto XV

Celebrazione

Canonizzazione:

- 18 ottobre 1964

- Papa Paolo VI

- Basilica Vaticana

Celebrazione

Ricorrenza:

- 3 giugno

Vatican News nell'anniversario

Re Mwanga, sobillato

dagli stregoni locali che vedono il loro potere compromesso dalla forza del

Vangelo, il sovrano dà inizio a una vera e propria persecuzione contro i

cristiani, soprattutto perché non cedono al suo volere dissoluto. Carlo Lwanga

viene condannato a morte, insieme ad altri. Il giorno seguente, cominciano le

prime esecuzioni Il 3 giugno Carlo Lwanga e i suoi compagni, insieme ad alcuni

fedeli anglicani, vengono arsi vivi. Pregano fino alla fine, senza emettere un

gemito, dando una prova luminosa di fede feconda. Uno tra loro, Bruno

Ssrerunkuma, dirà, prima di spirare: “Una fonte che ha molte sorgenti non si

inaridirà mai. E quando noi non ci saremo più, altri verranno dopo di noi

“Io ti prenderò per mano.

Se dobbiamo morire per Gesù, moriremo insieme, mano nella mano”

Nel 1875 arrivarono in

Uganda i primi missionari, all'inizio il re provò simpatia per la religione

cattolica ma dopo un pò preferì l'islam. Nonostante tutto, la missione

prosperava e vi erano molti catecumeni, ma il re temendo che l'Inghilterra

desiderasse appropriarsi del suo regno allontanò dalla sua tribù i missionari

cristiani. Morto lui, però, il figlio Mwanga che ne prese il posto, richiamò i

Padri ed essi trovarono una comunità cristiana piuttosto fiorente, con oltre

800 catecumeni.

Inoltre, dopo averli accolti

con cordialità al ritorno, promise pubblicamente (poiché era succeduto al

padre) che, dopo aver pregato il Dio dei cristiani, avrebbe non soltanto

chiamato a sé i migliori tra i sudditi cristiani e attribuito loro le alte

cariche del regno, ma che avrebbe egli stesso sollecitato tutti i pagani del

suo dominio ad abbracciare la religione. Ordinò pure che molti cristiani e

catecumeni lo assistessero nella reggia, e ciò non senza vantaggio per lui

stesso.

Infatti, avendo i

maggiorenti, ostili al nuovo, ordito una congiura per uccidere il re, e

avendolo scoperto, alcuni dei suoi cortigiani cristiani avvertirono

segretamente Muanga perché stesse in guardia, e aggiunsero che egli poteva fare

pieno assegnamento su tutti i cristiani e sui loro servi, cioé su duemila

uomini in armi.

Ma nel contempo il primo

ministro del re, che era anche il capo della congiura, pur avendo ottenuto il

perdono per sé e per i propri compagni da Muanga, concepì tuttavia un odio

ancor più forte verso i cristiani; e come stupirsene, quando venne a sapere che

sarebbe stato destituito e che al suo posto sarebbe stato designato il

cristiano Giuseppe Mkasa? Egli cominciò quindi a cogliere ogni occasione per

sussurrare all’orecchio del re che avrebbe dovuto guardarsi da coloro che

professavano la religione cristiana, come fossero i peggiori nemici: essi gli

sarebbero rimasti fedeli finché fossero una piccola minoranza; ma una volta

diventati maggioranza lo avrebbero tolto di mezzo ed avrebbero elevato alla

dignità regia uno di loro. Ma a questo si aggiunse un altro e maggiore motivo

di ostilità che indusse il re Muanga a perseguitare i cristiani.

SOURCE : https://www.causesanti.va/it/santi-e-beati/martiri-dell-uganda.html

I MARTIRI

Sono stati i primi

africani sub-sahariani ad essere venerati come santi dalla Chiesa cattolica.

Essi si possono distinguere in due gruppi, in relazione al tipo di pena

capitale subita: tredici furono bruciati vivi e gli altri nove vennero uccisi

con diversi generi di supplizio.

Nel primo gruppo sono

compresi giovani quasi tutti cortigiani: Carlo Lwanga, Mbaga Tuzindé, Bruno

Séron Kuma, Giacomo Buzabaliao, Kizito, Ambrogio Kibuka, Mgagga, Gyavira,

Achille Kiwanuka, Adolfo Ludigo Mkasa, Mukasa Kiriwanvu, Anatolio Kiriggwajjo,

Luca Banabakintu.

Carlo Lwanga, nato nella

città di Bulimu e battezzato il 15 novembre 1885, si attirò ammirazione e

benevolenza di tutti per le sue grandi doti spirituali; lo stesso Muanga lo

teneva in grande considerazione per aver saputo portare a termine con la

massima diligenza gl’incarichi a lui affidati. Posto a capo dei giovani del

palazzo regio, rafforzò in loro l’impegno a preservare la propria fede e la

castità, respingendo gli allettamenti dell’empio e impudico re; imprigionato,

incoraggiò apertamente anche i catecumeni a perseverare nell’amore per la

religione, e si recò al luogo del supplizio con mirabile forza d’animo, all’età

di vent’anni.

Mbaga Tuzindé, giovane di

palazzo (figlio di Mkadjanga, il primo e il più crudele dei carnefici) ancora

catecumeno quando si scatenò la persecuzione, fu battezzato da Carlo Lwanga

poco prima di essere con lui mandato a morte. Il padre, cercando di sottrarlo

in ogni modo all’esecuzione, lo supplicò più e più volte affinché abiurasse la

religione cattolica, o almeno si lasciasse nascondere e promettesse di cessare

di pregare. Ma il nobile giovane rispose che conosceva la causa della propria

morte e che l’accettava, ma non voleva che l’ira del re ricadesse sul padre:

pregò di non venir risparmiato. Allora Mkadjanga, mentre il figlio, all’età di

appena sedici anni, stava per essere condotto al rogo, comandò ad uno dei

carnefici ai suoi ordini che lo colpisse al capo con un bastone e che ne

collocasse poi il corpo esanime sul rogo perché venisse bruciato insieme agli

altri.

Bruno Séron Kuma, nato

nel villaggio Mbalé e battezzato il 15 novembre 1885, lasciò la tenda dove

viveva col fratello perché questi seguiva una setta non cattolica. Divenuto

servitore del re Mtesa, quando Muanga successe al padre lasciò il suo incarico

per il servizio militare. Accolto fra i giovani cristiani che facevano servizio

a corte, a ventisei anni sostenne con la parola e con l’esempio i compagni

della gloriosa schiera.

Giacomo Buzabaliao,

cosparso con l’acqua battesimale il 15 novembre 1885, acceso di singolare

ardore religioso, compì ogni sforzo per convincere e spronare altri, fra cui lo

stesso Muanga, non ancora salito al trono paterno, ad abbracciare la fede di

Cristo; e il re stesso rinfacciò tale colpa al fortissimo giovane, quando lo

mandò a morte, all’età di vent’anni.

Kizito, anima innocente,

più giovane degli altri, dato che subì il martirio nel suo tredicesimo anno di

vita, figlio di uno dei più alti dignitari del regno, splendente di purezza e

forza d’animo, poco prima di essere gettato in prigione ricevette il battesimo

da Carlo Lwanga. Il re, spinto dalla sua libidine, cercò invano di attrarre a

sé, con più accanimento che verso gli altri, questo fortissimo giovinetto.

Kizito biasimò così aspramente alcuni cristiani che avevano determinato di

darsi alla fuga, che essi deposto il timore, rimasero presso il re Muanga; e

quando giunse per loro il momento di essere condotti al supplizio, affinché i

compagni non si perdessero d’animo li convinse ad avanzare tutti insieme,

tenendosi per mano.

Ambrogio Kibuka, anch’egli

giovane di palazzo, battezzato il 17 novembre 1885, conservò la propria ferma e

ardente fede fino all’atrocissima morte, che affrontò nel nome di Cristo

all’età di ventidue anni.

Mgagga, giovinetto di

corte, ancora catecumeno, resistette impavido alle oscene lusinghe del re e,

essendosi dichiarato cristiano, fu gettato in carcere con gli altri; prima di

essere imprigionato ricevette il battesimo da Carlo Lwanga, e, non diversamente

dagli altri, andò al martirio con animo tranquillo, all’età di sedici anni.

Gyavira, anch’egli

giovane di palazzo, di bell’aspetto, era prediletto da Muanga, il quale si

adoperò invano per piegarlo a soddisfare la propria libidine. Ancora catecumeno

quando, dopo la professione di fede, fu da Muanga condannato a morte, durante

la notte fu asperso col battesimo da Carlo Lwanga e, a diciassette anni, fu dai

carnefici condotto al luogo del supplizio insieme agli altri.

Achille Kiwanuka, giovane

di corte, nato a Mitiyana, fu battezzato il 17 novembre 1885. Dopo che ebbe

impavidamente professato la propria fede davanti al re, posto in ceppi con i

compagni e gettato in carcere, dichiarò ancora una volta che mai avrebbe

abiurato la religione cattolica e si avviò con coraggio all’ultimo supplizio,

nel suo diciassettesimo anno di età.

Adolfo Ludigo Mkasa,

cortigiano, si mise in luce per la purezza dei costumi e così pure per la

costanza e la sopportazione nelle sventure. Ricevuto il battesimo il 17

novembre 1885, osservò santamente e professò con fermezza insieme agli altri la

fede cattolica, fino alla morte che affrontò in nome di Cristo a venticinque

anni.

Mukasa Kiriwanu, giovane

del palazzo regio, addetto al servizio della tavola, mentre i carnefici stavano

conducendo Carlo Lwanga e i suoi compagni al colle Namugongo, alla domanda se

fosse cristiano disse di sì, e fu condotto con gli altri al supplizio.

Catecumeno, non ancora asperso con l’acqua del battesimo, conseguì gloria

eterna attraverso il battesimo di sangue, all’età di diciotto anni.

Anatolio Kiriggwajjo,

giovane di palazzo, battezzato il 17 novembre 1885, osservò con tanta fermezza

d’animo i precetti della vita cristiana, che respinse senza esitazione una

carica che gli era offerta dal re, ritenendo che essa potesse in qualche modo

pregiudicare il conseguimento della salvezza eterna. Avendo poi professato

apertamente, insieme agli altri, la fede cattolica, affrontò con loro una

comune morte, nel suo sedicesimo anno di vita.

Infine, ricordiamo di

questa schiera Luca Banabakintu, che, nato nel villaggio Ntlomo, era

servitore amatissimo di un patrizio di nome Mukwenda. Il 28 maggio 1882,

ricevuti il battesimo e la confermazione, si accostò per la prima volta alla

sacra celebrazione eucaristica: da quel faustissimo giorno si pose in luce a

tutti come esempio per integrità di costumi e per osservanza dei precetti, e

nulla gli era più caro che parlare di religione con gli amici. Sebbene potesse

facilmente sottrarsi alla morte, preferì, quando fu ricercato per essere

condotto al supplizio, rimanere presso il padrone, dal quale fu consegnato agli

inviati del re. Gettato in carcere, vi dimorò con animo sereno finché, con gli

altri, nel suo trentesimo anno donò la vita nel nome di Cristo.

Tutti costoro che abbiamo

nominato, il 3 giugno 1886, all’alba, sono condotti sul colle Namugongo. Qui

giunti, le mani legate dietro la schiena e i piedi in ceppi, ciascuno di loro è

avvolto in una stuoia di canne intrecciate; viene innalzato un rogo, sul quale

essi vengono collocati come fascine umane. Il fuoco viene accostato ai piedi,

perché quel tenero gregge di vittime sia avvolto più lentamente e più a lungo;

crepita la fiamma, alimentata dai santi corpi; dal rogo di diffondono per

l’aria mormorii di preghiere che aumentano col crescere dei tormenti; i

carnefici si stupiscono che non un lamento, non un gemito si levino dai

morenti, dacché a nulla di simile è loro capitato di assistere.

Nel secondo gruppo di

martiri si annoverano i venerabili servi di Dio Mattia Kalemba Murumba,

Attanasio Badzekuketta, Pontiano Ngondwé, Gonzaga Gonza, Andrea Kagwa, Noe

Mawgalli, Giuseppe Mkasa Balikuddembé, Giovanni Maria Muzéi (Iamari), Dionisio

Sebugwao.

Mattia Kalemba Murumba aveva

cinquant’anni quando ricevette il martirio. Scelto per svolgere la mansione di

giudice, dopo essersi convertito da una setta maomettana e protestante alla

religione cattolica, ricevette il battesimo il 28 maggio 1882; dopo di che si

dimise dall’incarico, temendo di poter recar danno a qualcuno con le sue

sentenze. Dotato di modestia e dolcezza d’animo, era così fervido nel suo zelo

di apostolato religioso che non solo educò i propri figli a vivere santamente,

ma cercò d’insegnare a quanti più poté la dottrina cristiana. Il primo ministro

del re, al cui cospetto fu trascinato, comandò che a quell’uomo nobilissimo,

che aveva impavidamente professato la propria fede, fossero tagliati le mani e

i piedi, e gli fossero strappati frammenti di carne dalla schiena perché

fossero bruciati davanti ai suoi occhi. I carnefici dunque, per non essere

disturbati da testimoni del loro atrocissimo ufficio, conducono su un colle

incolto e deserto questo venerabile servitore di Dio, animoso e sereno

nell’aspetto; eseguono gli ordini alla lettera, perché il glorioso martire

soffra più a lungo, trattengono con tale abilità il sangue che fuoriesce dalle

membra, che tre giorni dopo alcuni servi, giunti sul posto per tagliare legna,

odono la voce di Mattia, debole e sommessa, che chiede un sorso d’acqua; e

avendolo visto così orribilmente mutilato fuggono via atterriti e lo lasciano

là, a imitazione di Cristo morente, privo di ogni conforto.

Atanasio Badzekuketta,

scelto fra i giovani in servizio nel palazzo reale e battezzato il 17 novembre

1885, seguiva con grande devozione i comandamenti di Dio e della Chiesa. Era

così desideroso di cingersi della corona del martirio che supplicò vivamente i

carnefici, i quali lo stavano conducendo con altri al luogo stabilito, di

ucciderlo sul posto. Così quel valoroso giovane fu dilaniato da ripetuti colpi,

il 26 maggio 1886, nel suo diciottesimo anno d’età.

Pontiano Ngondwé, nato

nel villaggio Bulimu e cortigiano del re Mtesa, una volta salito al trono

Muanga entrò nell’esercito, e ancora catecumeno apparve così animato di

cristiana spiritualità da saper vincere in sé, e trasformare, il proprio

carattere aspro e difficile. Quando era iniziata la persecuzione, ricevette il

battesimo il 18 novembre 1885; per questo, poco dopo fu gettato in carcere con

gli altri. Condannato a morte, accadde che il carnefice Mkadjanga, mentre lo

conduceva al colle Namugongo, gli chiedesse ripetutamente durante il cammino se

fosse seguace della religione cristiana; ed egli due volte confermò la sua

fede, e due volte quello lo trafisse con la lancia; e il suo capo, troncato dal

corpo, fu fatto rotolare lungo la via; era il 26 maggio 1886.

Gonzaga Gonza, ragazzo di

corte, battezzato il 17 novembre 1885, assolse con devozione agli obblighi

religiosi e si distinse particolarmente per la virtù della carità. Mentre

procedeva verso il luogo del supplizio, poiché i ceppi, che non avevano potuto

essere sciolti, gli impedivano di camminare speditamente, fu più volte trafitto

dai carnefici con la lancia; fu così martirizzato, nel suo diciottesimo anno di

vita, il 27 maggio 1886.

Andrea Kagwa, nato nel

villaggio Bunyoro e vissuto in grande familiarità con Muanga, sia quando era

principe, sia quando era re, ricevette il 30 aprile 1882 i sacramenti del

battesimo, della confermazione e dell’Eucaristia. Caro a tutti per le grandi

qualità d’animo, non soltanto istruiva nella dottrina cristiana quanti lo

avvicinavano, ma altresì, in occasione di una pestilenza che si era diffusa

nella regione, aiutando tutti si prodigò con singolare carità a favore degli

infermi, ne avvicinò moltissimi a Cristo aspergendoli con l’acqua battesimale,

e dando poi sepoltura ai defunti. Ma il primo ministro del re vedeva assai di

malocchio che i propri figli venissero da lui istruiti nella dottrina

cristiana, e infine, con il consenso del re, comandò che fosse catturato e

ucciso, aggiungendo che non sarebbe andato a cena prima che il carnefice gli

avesse presentato la mano mozzata del morto Andrea. Così il 26 maggio 1886, nel

suo trentesimo anno, il venerabile servo di Dio subì il martirio e raggiunse la

gloria celeste.

Noe Mawgalli, servitore

del nobile Mukwenda nella preparazione delle imbandigioni, risplendette grandemente

di virtù cristiane. Battezzato il 1° novembre 1885, colpito dalla lancia dei

sicari che il re Muanga aveva mandato in giro per distruggere le case dei

Cristiani, morì nel trentesimo anno d’età il 31 maggio 1886.

Giuseppe Mkasa

Balikuddembé, nato nel villaggio Buwama, fu scelto dal re Mtesa, per la sua

provata lealtà, come proprio inserviente personale per il giorno e per la

notte, e come infermiere. Il figlio di lui Muanga, non diversamente dal padre,

riponeva la più totale fiducia in questo venerabile servo di Dio; pertanto non

solo lo pose a capo di tutti i servitori del palazzo reale, ma volle che fosse

lui ad avvertirlo, quando il suo operato prestasse il fianco a critiche. Il 30

aprile 1882, Giuseppe ricevette il battesimo e la confermazione e si accostò

per la prima volta alla santa comunione, alla quale in seguito si accostò di

frequente. Con la propria dolcezza d’animo, con la carità e l’afflato religioso

che mostrava non solo seppe avvicinare a Cristo molti giovani, ma in

particolare fece pressioni, con consigli ed esortazioni, sui ragazzi della

corte reale e sugli altri cortigiani perché non accondiscendessero alla

libidine del re Muanga. Il re, essendo venuto a conoscenza di ciò, cominciò a

nutrire avversione per il venerabile servo di Dio, finché, vinto dalle

sollecitazioni del primo ministro, che provava invidia per Giuseppe, comandò

che questi fosse condannato a morte. Giuseppe, rinforzato dal cibo divino,

viene condotto nella località Mengo, dove, dopo aver dichiarato di voler dare al

re sia il perdono, sia il consiglio di pentirsi, viene dal carnefice decapitato

e gettato nel fuoco, prima vittima della persecuzione, a ventisei anni, il 15

novembre 1885.

Giovanni Maria

Muzéi (Iamari), nato nel villaggio Minziro, aveva un aspetto di tale

gravità che venne onorato col nome di Muzéi, cioé vecchio; insigne anche per

prudenza, carità, dolcezza d’animo, generosità verso i poveri, sollecitudine

verso gli ammalati, dedicò le proprie sostanze e il proprio impegno a

riscattare i prigionieri, che poi istruiva nella fede cristiana. Si dice che

egli avesse in un solo giorno appreso tutta la dottrina del catecumenato; fu

poi battezzato il 1° novembre 1885 e unto del sacro crisma il 3 giugno

dell’anno seguente. Dopo l’esecuzione capitale del suo grande amico Giuseppe

Mkasa, pur avendo saputo che il re intendeva farlo uccidere, non volle

nascondersi, né darsi alla fuga; al contrario, accompagnato da un certo Kulugi,

si presentò al re, dal quale ricevette l’ordine di recarsi, per una causa

qualsiasi, dal primo ministro. Obbedì, sebbene sospettasse l’inganno, poiché

riteneva indegno di sé l’esitare e il temere a motivo della propria fede

religiosa. E il primo ministro del re ordinò che fosse gettato in uno stagno

che si trovava in un suo podere, il 27 gennaio 1887.

Dionisio Sebuggwao, nato

nel villaggio Bunono, ragazzo di corte, ricevette il battesimo il 17 novembre

1885 e rifulse per integrità di costumi. Avendogli il re Muanga chiesto se

fosse vero che egli aveva insegnato i rudimenti della fede cristiana a due

cortigiani, egli rispose di sì, e quello lo trapassò con un colpo di lancia, e

comandò che gli fosse tagliato il capo. Così morì Dionisio, martire, all’età di

quindici anni, il 26 maggio 1886.

SOURCE : https://www.causesanti.va/it/santi-e-beati/martiri-dell-uganda.html

CANONIZACIÓN DE LOS

MÁRTIRES DE UGANDA

HOMILÍA DE SU SANTIDAD

PABLO VI

Basílica de San Pedro

Domingo 18 de octubre de

1964

«Estos que están

cubiertos de vestiduras blancas, ¿quiénes son y de dónde han venido?» (Ap 7,

13).

Nos viene al pensamiento

esta frase bíblica mientras inscribimos en la lista gloriosa de los santos

victoriosos en el cielo a estos veintidós hijos de África, cuyo singular mérito

había ya reconocido nuestro predecesor, de venerada memoria, el Papa Benedicto

XV, el 6 de junio de 1920, al declararlos Beatos y autorizar así su culto

particular.

¿Quiénes son? Son

africanos, verdaderos africanos, de color, de raza y de cultura, dignos

exponentes de los fabulosos pueblos Bantúes y Nilóticos explorados en el siglo

pasado por la audacia de Stanley y Livingstone, establecidos en las regiones

del África oriental, que se llama de los Grandes Lagos, en el ecuador, en el terrible

clima ecuatorial, sólo atenuado por la elevación de los altiplanos y por las

grandes lluvias estacionales. Su patria, en el tiempo en que vivían, era un

protectorado británico, pero desde 1962 ha logrado, como tantas otras naciones

de aquel continente, su propia independencia, que afirma actualmente con

rápidos y espléndidos progresos de civilización moderna. La capital es Kampala,

pero la circunscripción eclesiástica principal tiene su centro en Rubaga, sede

del primer Vicariato apostólico local, erigido en 1878 y elevada ahora a la

dignidad de archidiócesis con siete diócesis sufragáneas. Es este un campo de

apostolado misional que acogió primeramente a los ministros de confesión

anglicana, ingleses, a los cuales se sumaron dos años después los misioneros

católicos de lengua francesa llamados Padres Blancos, misioneros de África,

hijos del célebre y valeroso cardenal Lavigerie (1825-1892), a quien no sólo

África, sino la civilización misma debe recordar entre los hombres

providenciales más insignes, y fueron los Padres Blancos los que introdujeron

el catolicismo en Uganda, predicando el Evangelio en amigable competencia con

los misioneros anglicanos y los que tuvieron la dicha —ganada con riesgos y

fatigas incalculables— de formar a estos mártires para Cristo, a estos a

quienes hoy nosotros honramos cómo héroes y hermanos en la fe e invocamos como

protectores en el cielo. Sí, son africanos y son mártires. «Son —prosigue la

Sagrada Escritura— los que han venido de la gran tribulación y lavaron sus vestidos

y los blanquearon en la sangre del Cordero. Por eso están ante el trono de

Dios» (Ib. 14-15).

Todas las veces que

pronunciamos la palabra “mártires” en el sentido que tiene en la hagiografía

cristiana, debería presentársenos a la mente un drama horrible y maravilloso:

horrible por la injusticia, armada de autoridad y de crueldad, que es la que

provoca el drama; horrible también por la sangre que corre y por el dolor de la

carne que sufre sometida despiadadamente a la muerte; maravilloso por la inocencia

que, sin defenderse, físicamente se rinde dócil al suplicio, feliz y orgullosa

de poder testimoniar la invencible verdad de una fe que se ha fundido con la

vida humana; la vida muere, la fe vive. La fuerza contra la fortaleza; la

primera, venciendo, queda derrotada; ésta, perdiendo, triunfa. El martirio es

un drama; un drama tremendo y sugestivo, cuya violencia injusta y depravada,

casi desaparece del recuerdo allí mismo donde se produjo mientras permanece en

la memoria de los siglos siempre fúlgida y amable la mansedumbre que supo hacer

de su propia oblación un sacrificio, un holocausto; un acto supremo de amor y

de fidelidad a Cristo; un ejemplo, un testimonio, un mensaje perenne a los

hombres presentes y futuros. Esto es el martirio.

Esta es la gloria de la

Iglesia a través de los siglos. Y es un acontecimiento tan grande que la

Iglesia se apresuró a recoger las narraciones de la «pasión de los mártires» y

hacer de ellas el libro de oro de sus hijos más ilustres, el martirologio. Y

fue tal la irradiación de belleza y grandeza que emanaron de ese libro que pudo

ofrecer a la leyenda y al arte nuevas amplificaciones legendarias y

fantásticas; pero la historia verdadera, que todavía halla su documentación en

este libro, merece una admiración sin límites, es una alabanza a Dios, que obra

grandes cosas en hombres frágiles, y es testimonio de honor para los héroes,

que con su sangre han escrito las páginas de ese libro incomparable.

Ahora estos mártires

africanos vienen a añadir a ese catálogo de vencedores que es el martirologio,

una página trágica y magnífica, verdaderamente digna de sumarse a aquellas

maravillosas de la antigua África, que nosotros, modernos, hombres de poca fe,

creíamos que no podrían tener jamás adecuada continuación. ¿Quién podía

suponer, por ejemplo, que a las emocionantísimas historias de los mártires

escilitanos, de los mártires cartagineses, de los mártires de la “Masa Cándida”

de Útica —de quienes San Agustín (cf. PL 36,571 y 38, 1405) y Prudencio nos han

dejado el recuerdo—, de los mártires de Egipto —cuyo elogio trazó San Juan

Crisóstomo (cf, PG 50, 693 ss) —, de los mártires de la persecución vandálica,

hubieran venido a añadirse nuevos episodios no menos heroicos, no menos

espléndidos, en nuestros días? ¿Quién podía prever que a las grandes figuras

históricas de los Santos Mártires y Confesores africanos, como Cipriano,

Felicidad y Perpetua, y al gran Agustín, habríamos asociado un día los nombres

queridos de Carlos Lwanga y de Matías Mulumba Kalemba, con sus veinte

compañeros Y no queremos olvidar tampoco a aquellos otros que, perteneciendo a

la confesión anglicana, han afrontado la muerte por el nombre de Cristo.

Estos mártires africanos

abren una nueva época, no queremos decir ciertamente de persecuciones y de

luchas religiosas, sino de regeneración cristiana y civilizada. El África,

bañada por la sangre de estos mártires, primicias de la nueva era —y Dios

quiera que sean los últimos, pues tan precioso y tan grande fue su holocausto—,

resurge libre y redimida. La tragedia que los devoró fue tan inaudita y

expresiva que ofrece elementos representativos suficientes para la formación

moral de un pueblo nuevo, para la fundación de una nueva tradición espiritual,

para simbolizar y promover el paso desde una civilización primitiva —no desprovista

de magníficos valores humanos, pero contaminada y enferma, como esclava de sí

misma— hacia una civilización abierta a las expresiones superiores del espíritu

y a las formas superiores de la vida social.

No pretendáis que os

narremos aquí la historia de los mártires que estamos honrando. Es demasiado

larga y compleja: se refiere a veintidós hombres, en su mayor parte muy

jóvenes, cada uno de los cuales merecería un elogio particular; a ellos,

además, debería añadirse una doble y larga lista de otras víctimas de esa feroz

persecución: una de católicos —neófitos y catecúmenos— y otra de anglicanos,

como se refiere también ellos, sacrificados por el nombre de Cristo. Y sería

una historia demasiado cruda; el suplicio de la carne y la arbitraria tiranía de

la autoridad son ahí tan fáciles y tan despiadados, que conturban profundamente

nuestra sensibilidad. Sería una historia casi inverosímil; no es fácil darse

cuenta de las condiciones bárbaras, para nosotros paradójicas e intolerables,

en las que se mantiene y desenvuelve la vida de muchas comunidades tribales del

África casi hasta nuestros días. Sería historia digna de meditarse largamente,

ya que los motivos morales que constituyen su sentido y su valor, es decir, los

motivos simplicísimos y altísimos de la religión y del pudor, aparecen con tan

impresionante y edificante evidencia. Leed más bien esta conmovedora historia,

la tenéis en las manos. Pocas narraciones de las actas de los mártires se

hallan tan documentadas como ésta. Aquí no hay leyenda, sino la crónica de una

«Passio martyrum» fielmente descrita. El que la lee, contempla; el que

contempla, se estremece, y el que se estremece, llora. Hay que concluir

finalmente: ¡Sí, son mártires; «son aquellos —decíamos con el autor del

Apocalipsis— que vienen de la gran tribulación, y que han lavado y purificado

sus vestiduras en la sangre del Cordero»!

Permítasenos hacer

algunas sencillas consideraciones.

Este martirio colectivo

que tenemos delante nos presenta un fenómeno cristiano estupendo. Nos demuestra

muchas, cosas: ¿qué era el África antes que el mensaje evangélico le fuera

anunciado? Nos ofrece uno de los cuadros más interesantes y genuinos de aquella

sociedad humana primitiva, que tanto ha apasionado a los estudiosos modernos.

Es como una prueba, o una muestra de la vida africana, antes de la colonización

del siglo pasado: una vida mísera y heroica, en la cual la naturaleza humana,

todavía casi en estado instintivo, pone delante sus debilidades y dolencias en

forma y medida impresionantes, pero manifiesta al mismo tiempo ciertas

fundamentales virtudes reveladoras del divino modelo de donde proviene el

hombre. Dentro de este cuadro, un día llega el mensaje cristiano; nada parece

más diverso, nada más extraño. Sin embargo, he aquí que inmediatamente encuentra

acogida, encuentra simpatía, asimilación. El terreno, que parecía árido y

estéril, estaba en realidad por cultivar; la semilla evangélica lo encuentra

fecundo. Más todavía: se diría que lo encuentra ávido de aquella nueva

vegetación; como si la estuviera esperando, como si le fuese connatural. Los

tallos de la nueva mies son bellos, crecen rectilíneos, vigorosos; hablan de

una espléndida primavera. El cristianismo encuentra en África: una

predisposición particular que no dudamos en considerar como un arcano de Dios,

una vocación indígena, una promesa histórica. África es tierra de Evangelio,

África es patria nueva de Cristo. La sencillez recta y lógica y la inflexible

fidelidad de estos jóvenes cristianos de África nos lo aseguran y nos lo

prueban; por una parte la fe, don de Dios, y la capacidad humana de progreso;

por otra, se unen con prodigiosa correspondencia. Que la semilla evangélica

encuentre obstáculo en las espinas de un terreno tan selvático, causa dolor, no

extrañeza; pero que la semilla eche inmediatamente raíces y brote pujante y

llena de flores por la bondad del suelo, causa alegría y admiración al mismo

tiempo: es la gloria espiritual del continente de los rostros negros y de las

almas blancas, que anuncia una nueva civilización: la civilización cristiana de

África.

Este fenómeno es tan

bello y está de tal modo representado en la trágica y gloriosa historia de los

mártires de Uganda que sugiere el parangón entre la evangelización cristiana y

el colonialismo, del que hoy tanto se habla. Estas dos importaciones de la

civilización en territorios de antiguas culturas respetables bajo muchos

aspectos, pero rudimentarias e inmóviles, introducen briosos factores de

desarrollo y traban relaciones revolucionarias. Pero mientras la evangelización

introduce un principio —la religión cristiana— que tiende a hacer brotar las

energías propias, las virtudes innatas, las capacidades latentes de la

población indígena, o, lo que es lo mismo, tiende a libertarla, a hacerla

autónoma y adulta, a capacitarla para expresarse de manera más amplia y mejor

en las formas de cultura y de arte propios de su genio; la colonización, en

cambio, si tan sólo se guía por criterios utilitarios y temporales, pretende

otras finalidades no siempre conformes al honor y a la utilidad de los

indígenas. El cristianismo educa, liberta, ennoblece, humaniza en el sentido

más alto de la palabra; abre los caminos a las riquezas interiores del espíritu

y a las mejores organizaciones comunitarias. El cristianismo es la verdadera

vocación de la humanidad; y estos mártires nos lo confirman.

Su testimonio, para quien

lo escucha atentamente en esta hora decisiva de la historia de África, se hace

voz que llama: voz que parece repetir, como un eco potente, la invitación

misteriosa, oída durante una noche en una visión por San Pablo: «Adiuva nos»,

ven a ayudarnos (Hch 16,9). Estos mártires imploran ayuda. África tiene

necesidad de misioneros: de sacerdotes especialmente, de médicos, de maestros,

de hermanas y de enfermeras, de almas generosas, que ayuden a la joven y

floreciente, pero tan necesitada comunidad católica a crecer en número y

calidad para hacerse pueblo: pueblo africano de la Iglesia de Dios. Nos hemos

recibido, precisamente en estos días, una carta firmada por muchos obispos de

países de África Central, en la: que se implora el envío de sacerdotes, de

nuevas escuadras de sacerdotes, muchos y pronto. Hoy, no mañana. África tiene

gran necesidad de ellos. África hoy les abre la puerta y el corazón; es éste

quizá el momento de gracia que podría pasar y no repetirse. Por nuestra parte

lanzamos a la Iglesia la invitación del África y esperamos que las diócesis y

las familias religiosas de Europa y de América, de la misma manera que han

acogido la invitación de Roma para la América latina, ofreciendo ayudas tan

dignas de encomio y todavía necesarias de hombres y de medios, querrán también

unir a este esfuerzo generoso otro no menos próvido y meritorio a beneficio del

África cristiana. ¿Nuevos sacrificios? ¡Sí!, pero esta es ley del Evangelio,

hecha hoy extraordinariamente imperiosa; la caridad se enciende como fuego, a

fin de que la fe resplandezca en el mundo.

Este pensamiento, que

llena de certeza y de vigor la conciencia de la Iglesia ya desde sus primeros

días, se hace urgente en nuestro espíritu en estos años en que el mundo entero

parece despertar y buscar el camino de su porvenir. Pueblos nuevos, que hasta

ahora habían permanecido estáticos e inertes y que no aspiraban a otra forma de

vida sino a aquella que habían ya alcanzado con una lenta elaboración secular,

ahora se despiertan y se levantan. El progreso científico y técnico de nuestros

días los ha vuelto capaces de nuevos ideales y de nuevas empresas, les ha dado

un ansia de lograr para sí una fórmula plena y nueva de vida que, interpretando

sus virtudes nativas, los habilite para conquistar y gozar los beneficios de la

civilización presente y venidera.

Pues bien, frente a este

despertar de los pueblos nuevos, sentimos que en Nos crece la persuasión de que

es un deber nuestro, un deber de amor, de acercarnos con un diálogo más

fraternal a estos mismos pueblos, de darles muestra de nuestra estima y de

nuestro afecto, de manifestarles cómo la Iglesia católica comprende sus

legítimas aspiraciones, de ayudar su libre y justo desarrollo por los caminos

pacíficos de la fraternidad humana y de hacerles así más fácil el acceso,

cuando libremente lo quieran, al conocimiento de aquel Cristo que nosotros

creemos que constituye para todos la verdadera salvación y el intérprete

original y maravilloso de sus mismas aspiraciones más profundas.

Tal es la fuerza de esta

persuasión que nos parece que no debemos rehusar la ocasión, mejor dicho, la

invitación que insistentemente se nos dirige de ir a encontrarnos con un gran

pueblo, en el cual nos complacemos en ver simbolizada la inmensa población de

un entero continente para llevarle nuestro sincero mensaje de fe cristiana.

Así, pues, os comunicamos, hermanos, que hemos decidido intervenir en el

próximo Congreso Eucarístico Internacional de Bombay.

Es la segunda vez que

anunciamos en esta basílica un viaje nuestro, hasta ahora del todo extraño a

las costumbres de nuestro ministerio apostólico pontificio. Pero creemos que de

la misma manera que el primer viaje a Tierra Santa, éste a las puertas del Asia

inmensa, del mundo nuevo moderno, no es ajeno a la índole, más aún, al mandato

de nuestro ministerio apostólico. Oímos en nuestro interior solemnes y

apremiantes, las palabras siempre vivas de Jesucristo: “Id y anunciad a todas

las gentes” (Mt 28,19).

En verdad, no es el deseo

de novedad o de viajar el que nos mueve a esta decisión, sino sólo el celo

apostólico de lanzar nuestro saludo evangélico a los inmensos horizontes

humanos que los nuevos tiempos abren ante nuestros pasos y el sólo propósito de

ofrecer a Cristo Señor un testimonio de fe y de amor más amplio, más vivo y más

humilde.

El Papa se hace

misionero, diréis. Sí, el Papa se hace misionero, que quiere decir testigo,

pastor, apóstol en camino. Nos alegramos de repetirlo en este día mundial de

las misiones. Nuestro viaje, aunque brevísimo y sencillísimo, limitado a una

sola estación, en la que se le rinde a Cristo presente en la Eucaristía solemne

homenaje, quiere ser un testimonio de reconocimiento para todos los misioneros

de ayer y de hoy que han consagrado su vida a la causa del Evangelio y para

aquellos especialmente que, siguiendo las huellas de San Francisco Javier, han

«establecido la Iglesia» con tanta entrega y tanto fruto en Asia y

particularmente en la India; quiere ser además una simbólica adhesión,

exhortación y aliento a todo el esfuerzo misionero de la Santa Iglesia

católica; quiere ser una primera y diligente respuesta a la invitación

misionera que el Concilio ecuménico en curso lanza a la Iglesia misma para que

cada uno, miembro fiel, acoja en sí mismo el ansia de la dilatación del reino

de Cristo; quiere ser un estímulo y un aplauso a todos nuestros misioneros

esparcidos por el mundo entero y a los que los sostienen y ayudan; quiere ser

señal de amor y de confianza para todos los pueblos de la tierra,

Y sean benditos los

mártires declarados hoy ciudadanos del cielo que abren nuestro espíritu a tales

propósitos; y que sean ellos los que os infundan valor, gozo y

esperanza, in nomine Domini.

Copyright © Dicastero per

la Comunicazione - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

SOURCE : https://www.vatican.va/content/paul-vi/es/homilies/1964/documents/hf_p-vi_hom_19641018_martiri-uganda.html

Voir aussi : https://www.lastampa.it/vatican-insider/it/2014/05/30/news/noe-mawaggali-1.35760572