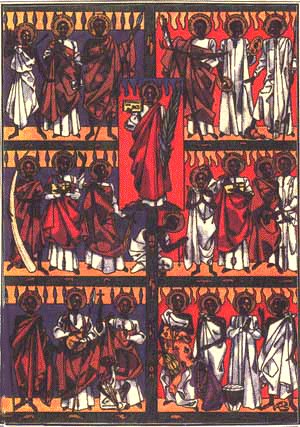

Saint Charles

Lwanga (in the center) and his 21 followers.

Der

Heilige Karl Lwanga (in der Mitte) und seine 21

Anhänger.

De

Hillige Korl Lwanga (in de Merr) un siene 21 Folgers.

Saint Matthias Kalemba

Martyr en Ouganda (+1886)

Magistrat en Ouganda, il quitta l'Islam et se convertit au Christ pour qui il donna sa vie.

À Kampala en Ouganda, l'an 1886, saint Matthias Kalemba, surnommé Mulumba,

c'est-à-dire Fort, martyr. Après avoir abandonné la religion musulmane et reçu

le baptême, il abdiqua son office de juge et se dépensa beaucoup à répandre la

foi chrétienne. Pour cela, sous le roi Mwanga, il fut soumis à des tortures et,

privé de tout soulagement, rendit son âme à Dieu.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/7126/Saint-Matthias-Kalemba.html

Kalemba, Matthias Mulumba

1836-1886

Église Catholique

Ouganda

Kalemba était membre de

la tribu Soga, et il est né dans le compté de Bunya, dans l’est de l’Ouganda.

Il a été capturé, avec sa mère, par un groupe de Ganda du clan des loutres, qui

faisaient un raid. Ses ravisseurs l’ont vendu comme esclave à Magatto, l’oncle

du chancelier Mukasa, et membre du clan des rats comestibles. Kalemba a grandi

dans cette famille, étant traité comme membre du clan et homme libre. Suite à

la mort de son père adoptif, il est resté un certain temps chez le frère de

Magatto, Buzibwa. Quand il a atteint la maturité, il s’est engagé chez Ddumba,

le chef du compté de Ssingo. C’est là qu’il est devenu chef de la maison de son

maître, et superviseur de tous les autres serviteurs. Quand Ddumba est mort,

son frère a reconnu la position de Kalemba de manière officielle en lui créant

un poste en mémoire de Ddumba. A partir de ce moment là, Kalemba était connu

comme le Mulumba.

Kalemba était un homme

plutôt grand, de teint clair. Il avait une petite barbe, chose rare chez un

Ganda. Physiquement parlant, il était extrêmement fort, de caractère joyeux, et

c’était quelqu’un qui cherchait la vérité. Cette passion l’a d’abord amené à

l’Islam, mais ensuite - suite à l’arrivée des missionnaires anglicans, - vers

leur instruction chrétienne. C’était le devoir du chef de Ssingo d’entreprendre

la construction au palais royal. Quand le roi Mutesa I a décidé de bâtir des

maisons pour les missionnaires catholiques, c’est à Kalemba que la tâche est

revenue. Il a donc rencontré des catholiques pour la première fois, et a

découvert que les préjudices protestants à leur égard n’étaient pas vrais. Le

31 mai 1880, il s’est inscrit comme catéchumène catholique, mais a parfois

continué à aller aux cours bibliques anglicans.

Kalemba a pris son

allégiance chrétienne au sérieux. Malgré le fait qu’il possédait un grand

nombre de femmes, il a fait d’autres provisions pour toutes celles-ci sauf une,

appelée Kikuvwa, qu’il a gardé comme femme. Il a été baptisé par le Père

Ludovic Girault le 28 mai, 1882. Kalemba s’est auto inscrit dans l’école de

l’humilité en acceptant de faire des tâches serviles, en travaillant dans son

jardin, en portant des fardeaux, et même en acceptant des coups qu’il ne

méritait pas de la part des soldats du roi. Il déclarait fièrement qu’il était

esclave - “l’esclave de Jésus-Christ.” On dit qu’il a chassé un buffle sauvage

à l’aide d’un bâton. Il prenait part aux raids de guerre organisés par son

chef, mais refusait de participer au pillage, qui était le vrai but des raids.

Il refusait aussi d’accepter les pots-de-vin quand il administrait la justice

de la part de son maître.

Dans sa maison à Mityana,

à une soixantaine de kilomètres de la capitale, Kalemba vivait une vie humble

et pratiquait comme métiers la poterie et le tannage. Pendant l’absence des missionnaires

catholiques en Ouganda, de 1882 à 1885, Kalemba a organisé une communauté

chrétienne à Mityana. C’est là qu’il a fait de l’instruction chrétienne avec

les futurs martyrs Noe Mawaggali et Luc Banabakintu. Quand la persécution a

éclaté en 1886, il y avait à peu près deux cent croyants dans cette communauté

de chrétiens et de catéchumènes.

Quand l’orage a commencé,

Kalemba se trouvait dans la capitale, où il était occupé à rebâtir le palais du

roi qui avait brûlé en février 1886. Bien qu’il se trouvait en danger imminent,

il n’a pas quitté son poste. Le maître de Kalemba, qui était chef de Ssingo, a

pensé qu’il vaudrait mieux l’arrêter lui-même, ainsi que son compagnon, Luc

Banabakintu. Ils ont passé la nuit du 26 mai en ville à la résidence du chef,

leurs pieds dans les fers et le cou dans un joug d’esclave. Le jour suivant, on

les a amenés au palais, où le chancelier les a condamnés à une mort terrible

simplement parce qu’ils avaient reconnu qu’ils étaient chrétiens. Alors qu’ils

étaient en route pour Namugongo, l’endroit traditionnel des exécutions, Kalemba

s’est arrêté et a demandé qu’on le mette à mort tout de suite, là où il était

encore, dans l’ancienne partie de la ville de Kampala. Les bourreaux se sont

attaqués à lui sur l’endroit même, lui coupant les bras et les jambes, et lui

arrachant des lambeaux de chair pour les brûler devant lui. Son courage et sa

résistance ont été extraordinaires, et les seules paroles à lui échapper aux

lèvres ont été, “Mon Dieu! Mon Dieu!” Les bourreaux lui ont ensuite ligoté les

artères et l’ont laissé sur place pour qu’il meure lentement.

La passion de Matthias

Kalemba a commencé à midi le jeudi 27 mai, et ne s’était toujours pas terminée

le Samedi. Quelques hommes qui venaient couper des roseaux dans le marais ont

entendu une voix qui criait, “De l’eau! De l’eau!” Ils ont été tellement

terrifiés par ce qu’ils ont vu qu’ils ont pris la fuite. On suppose qu’il est

mort le Dimanche, le 30 mai. Dieu seul peut savoir à quel point il aura

souffert l’agonie. Luc est mort avec Charles Lwanga et ses compagnons à

Namugongo le 27 mai. Matthias Kalemba, le Mulumba, a été déclaré “Béni” par le

Pape Bénédicte XV en 1920, avec les vingt-et-un autres martyrs. Ils ont été

proclamés saints canonisés en 1964 par le Pape Paul VI.

Aylward Shorter M. Afr.

Bibliographie

J.F. Faupel, African

Holocaust [Holocauste africain] (Nairobi, St. Paul’s Publications Africa,

1984 [1962]).

J.P. Thoonen, Black

Martyrs [Martyres noirs] (London: Sheed and Ward, 1941).

Cet article, soumis en

2003, a été recherché et rédigé par le dr. Aylward Shorter M. Afr., directeur

émérite de Tangaza College Nairobi, université catholique de l’ Afrique de

l’Est.

SOURCE : https://dacb.org/fr/stories/uganda/kalemba-matthias/

Also

known as

Mattias Kalemba Murumba

3 June as

one of the Martyrs

of Uganda

27 May on

some calendars

Profile

Born to the Lugave clan.

A man who was seeking God, he converted first to Islam, and then to Christianity.

One of the Martyrs

of Uganda who died in

the Mwangan persecutions.

Born

at Busoga, Uganda

Died

hacked

to pieces on 27 May 1886 at

Old Kampala, Uganda

29 February 1920 by Pope Benedict

XV (decree of martyrdom)

6 June 1920 by Pope Benedict

XV

18 October 1964 by Pope Paul

VI at Rome, Italy

Additional

Information

books

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

other

sites in english

images

sitios

en español

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

fonti

in italiano

Dicastero delle Cause dei Santi

Martirologio Romano, 2005 edition

MLA

Citation

“Saint Matiya

Mulumba“. CatholicSaints.Info. 27 June 2023. Web. 3 June 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-matiya-mulumba/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-matiya-mulumba/

Kalemba, Matthias Mulumba

1836-1886

Catholic Church

Uganda

Kalemba was a member of

the Soga tribe, born in Bunya County in eastern Uganda. Together with his

mother, he was captured by Ganda raiders belonging to the Otter clan. His

captors sold him as a slave to Magatto, uncle of the Chancellor Mukasa, and a

member of the Edible-Rat Clan. Kalemba grew up in this family, treated as a

member of the clan and as a free man. After the death of his adoptive father,

he remained for a time with Magatto’s brother, Buzibwa. On attaining manhood,

he took service with Ddumba, the chief of Ssingo County, becoming effectively

the head of his household and supervisor of all the other servants. On Ddumba’s

death, his brother gave official recognition to Kalemba’s position, by creating

an office for him in memory of Ddumba. Henceforth, Kalemba was known as The

Mulumba.

Kalemba was a man of

fairly large stature and light colouring. He sported a small beard, unusual for

a Ganda. He was immensely strong, of a joyful disposition and a passionate

searcher after truth. This passion led him first to Islam, and then - after the

arrival of the Anglican missionaries - to their Christian instructions. It was

the duty of the chief of Ssingo to carry out construction at the royal palace.

When King Mutesa I decided to build houses for the Catholic missionaries,

Kalemba was assigned to the task. Coming into contact with Catholics for the

first time, he discovered that Protestant prejudices about them were not true.

On May 31, 1880 he enrolled as a Catholic catechumen, but continued

occasionally to attend Anglican Bible classes.

Kalemba took his

Christian allegiance seriously. Although he was the owner of a large number of

women, he made other provisions for all except one, called Kikuvwa, whom he

kept as wife. He was baptized by Father Ludovic Girault on May 28, 1882.

Kalemba schooled himself in humility by undertaking menial tasks, working in

his garden, carrying loads and even accepting unmerited blows from the king’s

soldiers. He declared proudly that he was a slave - “the slave of Jesus

Christ.” He is said to have driven off a wild buffalo with the aid of a stick.

He took part in the war-raids organized by his chief, but refused to take share

in the looting which was their main object. He also refused to take bribes when

administering justice on behalf of his master.

At his home in Mityana,

forty-seven miles from the capital, Kalemba lived a humble life, taking up the

trades of pottery and tanning. During the absence from Uganda of the Catholic

missionaries from 1882 to 1885, Kalemba organized a Christian community at

Mityana where, together with the future martyrs Noe Mawaggali and Luke

Banabakintu, he gave Christian instruction. When persecution broke out in 1886

this community of Christians and catechumens numbered about two hundred.

When the storm broke,

Kalemba was at the capital rebuilding the king’s palace that had burned down in

February 1886. Although in imminent danger, he did not leave his post.

Kalemba’s master, the chief of Ssingo, deemed it best to arrest him and his

companion, Luke Banabakintu, himself. They spent the night of May 26 at the

chief’s town residence, with their feet in the stocks and their necks in slave

yokes. The following day they were taken to the palace, where the chancellor

sentenced them to a savage death for acknowledging that they were Christians.

On the way to Namugongo, the traditional place of execution, Kalemba stopped

and asked to be put to death there and then in Old Kampala. His executioners

butchered him on the spot, cutting off his limbs and tearing strips of flesh

from his body, burning them before his eyes. His courage and endurance were

extraordinary and the only sound that came from his lips were the words: “My

God ! My God !” The executioners then tied up his arteries and left him to die

a lingering death.

Matthias Kalemba’s

passion began at noon on Thursday, May 27. On Saturday it had not ended. Some

men coming to cut reeds in the swamp heard a voice calling: “Water! Water!”

They were so horrified by the sight that they fled. He died presumably on

Sunday, May 30. God alone knows the full extent of his agony. Luke died with

Charles Lwanga and his companions at Namugongo on May 27. Matthias Kalemba, the

Mulumba, was declared “Blessed” by Pope Benedict XV in 1920, together with

twenty-one other martyrs. They were proclaimed canonized saints in 1964 by Pope

Paul VI.

Aylward Shorter M.Afr.

Bibliography

J. F. Faupel, African

Holocaust (Nairobi, St. Paul’s Publications Africa, 1984 [1962]).

J. P. Thoonen, Black

Martyrs (London: Sheed and Ward, 1941).

This article, submitted

in 2003, was researched and written by Dr. Aylward Shorter M.Afr., Emeritus

Principal of Tangaza College Nairobi, Catholic University of Eastern Africa.

SOURCE : https://dacb.org/stories/uganda/kalemba-matthias/

The Uganda Martyrs

Their countercultural

Witness Still Speaks Today

BY: BOB FRENCH

In his living room wall,

Matthew Segaali has a painting of twenty-two young men and boys in Ugandan

tribal dress. Some of them are standing in front of a backdrop of upraised

spears; the rest, in front of flames as tall as they are.

While it appears that they

are about to be put to death, the expressions on their faces are of peace,

trust, and even joy. One of them is holding a palm branch; others have their

hands folded in prayer; and others are clasping a cross or a rosary.

They are the men and boys

whose martyrdom in 1886 is considered the spark that ignited the flame of

Christianity in modern Africa. Canonized in 1964, the Uganda Martyrs are

revered for their faith, their courage, and their countercultural witness to

Christ.

These saints are highly

honored in the Segaali home. Matthew's son Joseph is named after one of them.

The whole family regularly prays litanies for their intercession in their

native language of Ugandan. Their prayers have been answered so often that

Matthew has lost count. "I would not be who I am without the Uganda

Martyrs," he says proudly.

You may be surprised to

learn that the Segaalis don't actually live in Uganda. As residents of Boston,

Massachusetts, they are among the many African expatriates around the world who

feel a close connection to the martyrs.

Why are these men so

important to the Segaalis and to Africans all over the world? Perhaps because,

as Pope John Paul II pointed out during his visit to their shrine, their

sacrifice was the seed that "helped to draw Uganda and all of Africa to

Christ." Despite the martyrs' youth—most were in their teens and

twenties—they are truly "founding fathers" of the modern African

church, which displays so much vigor today.

Planting the Seed. Their

story begins with the Protestant missionaries who began arriving in Buganda

(now Uganda) in 1877. Mutesa—the king, or Kabaka—welcomed them and seemed open

to Christianity, perhaps because it had points of contact with his people's

belief in the afterlife and in a creator god. He even allowed it to be taught

at his court.

When the Catholic White

Fathers (now the Missionaries of Africa) arrived in 1879, Mutesa welcomed them

as well. However, he also flirted with Islam, which Arab traders had introduced

into Buganda decades before, and began favoring now one religious group and

then another, mainly for political gain.

The king's shifting favor

created an uncertain, often dangerous climate for Christians, but White Father

Simeon Lourdel and his companions took advantage of every opportunity Mutesa

gave. They founded missions where they could teach people about the faith, and

about medicine and agriculture as well.

In the Fathers'

Footsteps. Unlike some missionaries of the day, the White Fathers took

their time preparing people for baptism. They wanted their new converts to

understand what it means to enter into new life with Jesus and to follow him.

Many Bugandans were

hungry for their teaching and responded eagerly to this approach. "They

were offered the living word of God, not just the historical facts of

salvation," says Caroli Lwanga Mpoza, a historian from Uganda. "They

grabbed onto it, and it changed them."

The depth of their faith

became obvious during a three-year period when Mutesa's hostility forced the

White Fathers out of the country. The priests returned from exile after

Mutesa's death in 1884 and were pleased to find that their converts had taken

it upon themselves to bring their families and friends to the Lord. Many had

renounced polygamy and slavery and were devoting their energies to serving and

caring for the needy around them.

Hero of the Faith. One

exceptionally active convert was Joseph Mukasa, who served as personal

attendant for both Mutesa and the new king, his son Mwanga. He had brought

Christ to many of the five hundred young men and boys who worked as court

pages, and they relied on his leadership and his clear grasp of the faith.

Mukasa had the king's

respect, too, for he had once killed a poisonous snake with his bare hands as

it was about to strike his master. But King Mwanga was even more unstable than

his father. He was soon affected by the poisonous lies of jealous advisors, who

called Mukasa disloyal for his allegiance to another king, the "God of the

Christians."

Their accusations were

reinforced when Mukasa reprimanded King Mwanga for trying to have the newly

arrived Anglican bishop put to death. Furious that anyone would dare to oppose

him, the Kabaka went ahead with the assassination.

Mukasa could have played

it safe and chosen not to cross the king again. Instead, he enraged Mwanga even

more by repeatedly opposing his attempts to use the younger pages as his sex

partners. Mukasa not only taught the boys to resist but made sure they stayed

out of Mwanga's reach.

The Kabaka finally

decided to make Mukasa an example, ordering him to be burned alive as a

conspirator. But here, too, Mukasa proved the stronger and braver. He assured

his executioner that "a Christian who gives his life for God has no reason

to fear death. . . . Tell Mwanga," he also said, "that he has

condemned me unjustly, but I forgive him with all my heart." The

executioner was so impressed with Mukasa that he beheaded him swiftly before

tying him to the stake and burning his body.

A Terrible Vengeance. Now

on a rampage, King Mwanga threatened to have all his Christian pages killed

unless they renounced their faith. This failed to intimidate them, however, for

Mukasa's example had inspired them. Even the catechumens among them followed

Mukasa's bravery by asking to be baptized before they died.

Among them was Charles

Lwanga, who took over both Mukasa's position as head of the pages and his role

of spiritual leader. Like Mukasa, Lwanga professed loyalty to the king but fell

into disfavor for protecting the boys and holding onto his faith.

King Mwanga's simmering

rage boiled over one evening, when he returned from a hunting trip and learned

that a page named Denis Ssebuggwawo had been teaching the catechism to a

younger boy, Mwanga's favorite. The king gave Denis a brutal beating and handed

him to the executioners, who hacked him to pieces.

The following day, Mwanga

gathered all the pages in front of his residence. "Let all those who do

not pray stay here by my side," he shouted. "Those who pray" he

commanded to stand before a fence on his left. Charles Lwanga led the way,

followed by the other Christian pages, Catholic and Anglican. The youngest,

Kizito, was only fourteen.

The king's vengeance was

terrible: He sentenced the group to be burnt alive at Namugongo, a village

twenty miles away.

No Cause for Sadness. The

prisoners were strikingly peaceful and joyful in the face of this verdict. Fr.

Lourdel, who tried to save them, reported that afterwards, "they were tied

so closely that they could scarcely walk, and I saw little Kizito laughing

merrily at this, as though it were a game." Another page asked the priest,

"Mapera [Father], why be sad? What I suffer now is little compared with

the eternal happiness you have taught me to look forward to!"

The prisoners suffered

greatly during the long march to the execution site, but they prayed aloud and

recited the catechism all along the way. Three of them were speared to death

before reaching the village. The others were led out to a massive funeral pyre.

It was Ascension Thursday morning.

Eyewitnesses said that

the martyrs were lighthearted, cheering and encouraging one another as the

executioners sent up menacing chants. Each of the pages was wrapped in reeds

and placed on the giant bonfire, which soon became an inferno.

"Call on your God,

and see if he can save you," called one executioner. "Poor madman,"

replied Lwanga. "You are burning me, but it is as if you are pouring water

over my body."

The other prisoners were

equally calm. From the raging flames, only their prayers and songs could be

heard, growing fainter and fainter. Those who witnessed the fire said they had

never seen men die that way.

But the martyrs at

Namugongo were not Mwanga's only victims. Dozens more Christians were killed in

the surrounding countryside, and some of those who had taught the faith were

singled out for special retribution.

Andrew Kaggwa, a friend

of the king's, was beheaded. Impatient to meet his fate, he said to his

executioner, "Why don't you carry out your orders? I'm afraid delay will

get you into serious trouble." Noe Mawaggali was speared, then attacked by

wild dogs. Matthias Kalemba was dismembered and pieces of his flesh roasted

before his eyes. Before he died, he said, "Surely Katonda [God] will

deliver me, but you will not see how he does it. He will take my soul and leave

you my body."

Against the Grain. The

martyrs of Uganda were young, but they were not seduced by the values of the

royal court. They took a stand for God's law, even when it meant defying the

king himself. Out of allegiance to a higher king and a nobler law, they

rejected the earthly security that could have been theirs had they given in to

the king's lusts.

Their example is

extremely important today, Caroli Mpoza points out. It shows how faith can

become a "rudder" that sustains us in times of trial and temptation.

It also shows how critical it is to instill godliness in our children. If they

learn to honor God and put him first, he says, they too will stand firm against

the seductive values of our culture.

Like the parable of the

sower, the story of the Uganda Martyrs invites us to examine our commitment to

the Lord. Here are young people whose whole life of faith was marked by simple,

luminous, joyful trust in God—even in the face of a gruesome death. They were

"rich soil" indeed—not just for Africa, but for the whole church.

Bob French lives in

Alexandria, Virginia. This story was based mainly on J.F Faupel's African

Holocaust and Caroli Lwanga Mpoza's Heroes of African Origin Are Our

Ancestors in the Faith, as well as personal interviews.

SOURCE : https://wau.org/archives/article/the_uganda_martyrs/

ST. MATTIAS MULUMBA KALEMBA

The capture of Matthias

and his mother from Busoga and how he became a Christian

This most remarkable man

was a Musoga. Born about 1836 in Bunya County in Busoga, the country lying

across the Nile from Buganda, he, together with his mother, was captured by a

raiding party of Baganda belonging to the Otter Clan and, at a very early age,

carried off to Buganda as a slave.

His captors sold him to a

member of the Edible-Rat (Musu) Clan, named Magatto, an uncle of the Chancellor

Mukasa, who seems to have treated the little fellow as a member of the family

rather than as a slave. As often happened in such cases he was, as he grew up,

grad¬ually treated as a member of the clan and as a free man. Possibly it was

in recognition of this that he changed his name from the original Wante to

Kalemba.

After the death of his

adopted father, Kalemba remained for a time with Magatto’s brother, Buzibwa,

but, on attaining manhood, he left and took service with Ddumba, the county

chief of Ssingo. In this service he displayed such loyalty and trustworthiness

that Ddumba came to rely upon him more and more until he became, in fact if not

in name, head of the chief’s household and supervisor of all the other

servants.

On the death of Ddumba,

his brother Kabunga who succeeded to the chieftainship seems to have realized

the treasure he had in Kalemba, for not only did he confirm him in his many

duties but gave them official recognition by creating for him the post of

Ekirumba, so called in memory of Ddumba. As holder of this office, Kalemba

became known as the Mulumba.

Matthias Kalemba, the

Mulumba, was of fairly large stature and rather light colouring. His face,

somewhat longer than the average and adorned with a small beard, an unusual

feature amongst Baganda, was slightly pock-marked. He was immensely strong,

quite fearless and endowed with a powerful voice, a joyous disposition and a

passionate love for the truth. His search for the truth led him first to the

Muslim faith, which appealed to him by its obvious super¬iority to the paganism

that surrounded him. When the Protestant missionaries arrived, he was at once

attracted by Christianity and began to attend their instructions; but before he

had made up his mind to ask for baptism he came, in the course of his duties,

into contact with the Catholic Fathers. It was the traditional duty of the

chief of Ssingo to erect and repair the buildings of the royal enclo¬sure, so

that when Kabaka Muteesa undertook to build houses for the Catholic

missionaries he naturally commissioned this chief to build them. The chief in

turn placed his trusted headman, Kalemba, in charge of the work. The rest of

the story is best told in Kalemba’s own words to Pere Livinhac:

My father (almost

certainly Magatto, his father by adoption) had always believed that the Baganda

had not the truth, and he sought it in his heart. He had often mentioned this

to me, and before his death he told me that men would one day come to teach us

the right way.

These words made a

profound impression on me and, whenever the arrival of some stranger was

reported, I watched him and tried to get in touch with him, saying to myself

that here perhaps was the man foretold by my father. Thus I associated with the

Arabs who came first in the reign of Ssuuna. Their creed seemed to me superior

to our superstitions. I received instructions and, together with a number of

Baganda, I embraced their religion. Muteesa himself, anxious to please the

Sultan of Zanzibar, of whose power and wealth he had been given an exaggerated

account, declared that he also wanted to become a Muslim. Orders were given to

build mosques in all the counties. For a short time, it looked as if the whole

country was going to embrace the religion of the false prophet, but Muteesa had

an extreme repugnance to circumcision. Consequently, changing his mind all of a

sudden, he gave orders to exterminate all who had become Muslims. Many perished

in the massacre, two or three hundred managed to escape and, with Arab

caravans, made their way to the Island of Zanzibar. I succeeded with a few

others in concealing the fact of my conversion, and continued to pass for a

friend of our own gods, though in secret I remained faith¬ful to the practices

of Islam.

That was how things stood

when the Protestants arrived. Muteesa received them very well; he had their

book read in public audience, and seemed to incline to their religion, which he

declared to be much superior to that of the Arabs. I asked myself whether I had

not made a mistake, and whether, perhaps, the newcomers were not the true

messengers of God. I often went to visit them and attended their instructions.

It seemed to me that their teaching was an improvement on that of my first

masters. I therefore abandoned Islam, without however asking for baptism.

Several months had

elapsed when Mapeera (Lourdel) arrived.

My instructor, Mackay,

took care to tell me that the white men who had just arrived did not know the

truth. He called their religion the ‘worship of the woman’; they adored, he

said, the Virgin Mary. He also advised me to avoid them with the greatest care.

I therefore kept away from you and, probably, I would never have set foot in

your place if my chief had not ordered me to supervise the building of one of

your houses. But God showed his love for me.

The first time when I saw

you nearby, I was very much impressed.

Nevertheless, I continued

to watch you closely at your prayers and in your dealings with the people. Then

seeing your goodness, I said to myself, ‘How can people who appear so good be

the messengers of the devil?’

I talked with those who

had placed themselves under instruction and questioned them on your doctrine.

What they told me was just the contrary of what Mackay had assured me. Then I

felt strongly urged to attend personally your catechetical instructions. God

gave me the grace to understand that you taught the truth, and that you really

were the man of God of whom my father had spoken. Since then, I have never had

the slightest doubt about the truth of your religion, and I feel truly happy.

Kalemba’s actual

enrolment as a catechumen seems to have taken place on 31 May 1880.

Matthias Kalemba Mulumba

separates with his women for Christianity

Matthias Kalemba Mulumba,

a man of about 50, was an assistant county chief to Mukwenda (the county chief

of Ssingo) and had many wives. In the African tradition, it was prestigeous to

marry many wives, the bigger the number of wives one had, the greater the

honour. The exact number of wives Mulumba had is not known. But Matthew Kirevu,

the eyewitness remembered the following three:

(a) Bwamunnyondo

Taakulaba: She was a Muganda of the Ndiga (sheep/Ovil) clan in the family of

Muguluka. When Kalemba’s master known as Kaabunga succeeded his father Ddumba

as county chief of Ssingo, he gave Bwamunnyondo, Kaabunga’s widowed

step-mother, to Kalemba Mulumba to be his wife. When Mulumba embraced

Christianity, he separated with Bwamunnyondo without fear of annoying his

master Kaabunga, to whom Mulumba was the Assistant. But he gave out some

property to support her for a considerable length of time.

Bwamunnyondo went back to

his father Muguluka in Buddu County. She had been a young lady, but her beauty

had faded away with age. Thus she named herself “ATAAKULABA,” which means “he

or she who never saw you in your youth, cannot understand your former beauty.”

Later Bwamunnyondo became a catholic and was baptized and given the name Berta

at Villa Maria Parish in 1907. She died a very pius and devoted catholic in

1932.

(b) Tibajjukira: This was

a Musoga of Mulumba’s tribe (a Musoga). When Kalemba Mulumba became a catholic,

he separated from her according to the Christian law as he had done to

Bwamunnyondo. He also surrendered some property for her upkeep. She named

herself ”TIBAJJUKIRA,” which means “the Christians do not remember the good

done to them.” She also later became a catholic, but Matthew Kirevu, the

eyewitness and the informer did not remember her Christian name. Tibajjukira

died during the Muslim/Christian wars of 1888.

(c) Kikuwambazza or

Kikuwa: was a Muganda, with whom Kalemba Mulumba got properly married in the

Catholic Church. Both were faithful to each other. Kikuwa soon embraced the

catholic religion. By the time Mulumba died for his religion they had two

children, a girl Julia “Baalekatebaawudde” (they left before identifying) who

was 4 years and a boy who was about 2 years of age.

Kikuwa was a pius and

devoted Catholic. When her husband was arrested for being a Christian, she

voluntarily gave up herself to the executioners to be killed for her religion.

But Mbugano, the leader of the Mityana executioners’ expedition refused,

saying, “We do not kill women.” Instead one of the executioners wanted take her

for his wife. But she totally refused. After the martyrdom of her husband,

Kikuwa lived a very pius, devoted and self-sacrificial life.

Though Mulumba had had

many wives from whom he separated remaining with only one, Kikuwa, still the

priests hesitated in giving him the sacrament of Baptism. They had fear that

Mulumba would bring back some of his former wives after receiving baptism. This

was revealed to Mulumba before receiving that sacrament.

But Mulumba assured them,

saying: ”Do not be afraid, I have made up my mind through my own free will, I

am a mature man, I am determined to be a Catholic and abide by all the Catholic

laws, never to turn back to my old ways be that as it may.”

On hearing that, the

priests resolved to baptize him. Kalemba Mulumba was baptized on Pentecost

Sunday 28th May 1882 and was given the name MATTHIAS.

When Mulumba sent away

his other wives and retained only one for God’s Sake, he was brought to the

Katikkiro’s (Prime Minister) tribunal on Wednesday 26th May 1886. Besides being

a Christian, the Mulumba was furiously rebuked by the Katikkiro saying: “This

was certainly an act of putting chiefs to shame by sending away all your wives

and cooking your own food”. To which Mulumba retorted: “Have I been arrested

and brought before you because I am thin or for the religion I am practicing?”

Mulumba evangelises with

utmost difficulty

When Mulumba embraced the

Catholic faith, he set free all his servants and treated them in the best way

possible, allowing them all full liberty for their well-being and prosperity.

Out of humility Mulumba often carried his luggage on journeys instead of giving

it to his servants to carry it, an act that was considered very humiliating.

When the Catholic

Missionaries had fled Uganda to Tanganyika (Tanzania), from November 1882 to

July 1885, Matthias Mulumba was allocated a big part of the country for evangelizing.

He was in charge of evangelizing the whole Buganda excluding the palace,

Kampala and the neighbourhood.

His headquarters were at

Mityana in Ssingo county, a distance of 42 miles or 64 kilometers from Kampala

(the capital).

For evangelization purposes

Mulumba had opened up three other stations, namely:

1. NSEEGE: Near Bbowa

Buzinde in Bulemeezi county, about 60 miles or 96 kilometres from Mityana.

2. KIYEGGA (MUKONO): This

was 65 miles or 104 kilometres from Mityana.

3. MASAKA (Headquarterss

of Buddu county): 100 miles or 160 kilometers (short-cut) from Mityana, but 120

miles or 192 kilometres from Mityana via Kampala.

To reach out to each of

these centres, Mulumba had to travel on foot all the way from Mityana. He was

working very hard to spread and stabilize Catholicism in all these centers.

Although he was extremely busy with evangelization work, he never neglected or

abandoned his work as a chief. It was never heard of that Mulumba ever failed

to carry out his duties as a civil servant.

During the time of Lent

Mulumba used to fast the whole day, and even at supper he used to take very

little food. He worked vigorously and unceasingly almost the whole day. At

other times, i.e. outside Lenten period: on Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays

of every week, Mulumba did not eat meat and very often on those days he would

fast.

Mulumba dies the most

cruel, brutal and lingering death

When the storm of

persecution broke, Matthias was at Mmengo with his chief, who had the task of

rebuilding the royal palace, des¬troyed by fire in February.

Because Mulumba had sent

away his other wives and retained only one for God’s Sake, he was brought to

the Katikkiro’s (Prime Minister) tribunal on Wednesday 26th May 1886.

The Chancellor began by

asking: ‘Are you the Mulumba?’ Matthias replied, ‘Yes I am.’

‘Why do you pray? What

has induced a man of your standing to adopt the white men’s religion, at your

age too?’

‘I follow that religion

because I wish to.’

‘You have sent away all

your wives, I am told. So you cook your own food, I suppose?’

‘Is it because I am thin,

or because of my religion that I have been brought before you?’ asked Matthias.

Addressing Mulumba and

Luke Baanabakintu, another Christian who had been arrested, the Chancellor said

with a sneer, ‘So you are the people who are content to marry only one woman?

And you are trying to persuade other people to agree to such a monstrosity!’

Besides being a

Christian, the Mulumba was furiously rebuked by the Katikkiro saying: “This was

certainly an act of putting chiefs to shame by sending away all your wives and

cooking your own food”. To this Mulumba retorted: “Have I been arrested and

brought before you because I am thin or for the religion I am practicing?”

The Katikkiro became more

furious and ordered the executioners, Tabawomuyombi and Lukowe in particular to

take Mulumba to Namugongo to be killed in the cruelest manner.

On reaching Old Kampala,

and for fear of his being pardoned by the King, Mulumba told the executioners:

“Why do you take me all the way to Namugongo as if there is no death here, kill

me here.” Then he said to Luke Baanabakintu, ‘Au revoir, my friend. We shall

meet again in Heaven.’ ‘Yes, with God,’ answered Luke. The executioners were

annoyed, took Mulumba a little distance into the jungle of elephant grass and

proceeded to butcher him on the Spot, employing every refinement of cruelty of

which they were capable.

They cut off his arms at

the elbows, then cut off his legs at the ankles and knees. Finally, they cut

off strips of flesh from his back and roasted them before him. The executioners

used skillful means of stopping the bleeding so that he could stay longer in

pain and poor Mulumba was left there a victim to be devoured by vouchers, wild

animals, dogs, insects etc. But he suffered quietly without any complaint; only

one word came repeatedly to his lips, the invocation, ‘Katonda! Katonda! (My

God!, My God!)’, and for three days and three nights he lay there mortionless,

until he died.

Mulumba died the

cruelest, brutal and lingering death, from Thursday 27th to Sunday 30th May

1886.

The suffering

Left alone, in untold

agony and without the consolation of anyone save his Lord and Master, Matthias

suffered in silence both the excruciating thirst caused by the loss of so much

blood, and the smarting pains of the wounds which had been inflicted over his

whole body. Deprived of his limbs and attacked by swarms of flies and other

biting insects, and exposed to the scorching heat, Mulumba lay suffering at his

place of sacrifice for two full days, and on the second day, hearing human

voices near, Matthias called out to them, and when they approached, asked them

for a drop of water. But the men, instead of taking pity on the poor sufferer,

ran away instead, fearing to come near such a spectacle any more. And thus

Matthias, deserted by all, passed away in agony and went to his reward.

Mulumba’s pains can

better be imagined than described. And the heroism with which he bore his

sufferings for two long days is beyond comprehension. God alone can know to the

full the extent of the agonies of his martyrs; we poor mortals can only feebly

imagine and less accurately describe them.

Matthias Kalemba, the

Mulumba, died, presumably on Sunday 30 May on Kampala Hill, now generally known

as Old Kampala.

Chancellor regrets

killing Mulumba

It was then that the

Chancellor learnt that Matthias Kalemba, whom he had so cruelly done to death a

few days before, had been adopted and brought up by his own uncle, Magatto. On

hearing this, he said, ‘If I had known that, I would not have put him to death,

but I would have installed him in my household, and given him charge over all

my goods, for I know that those who practise religion do not steal!’ Because of

the newly discovered relationship the Chancellor ordered his brother to

establish Matthias’s widow on their own family estate.

What Catholic

Missionaries had to say about Matthias Mulumba

Kalemba was baptized on

the feast of Pentecost. After their baptism, he and Luke and the other two

neophytes were confirmed by Pere Livinhac and then, at the High Mass sung by

Pere Levesque, made their first Holy Communion. Profoundly impressed by at

least one of those he had been privileged to admit into the Church, Pere

Girault wrote:

Among those who have been

baptized this morning there is one in whom the action of Grace has been truly

apparent, namely the Mulumba, a man of about thirty to forty years of age

(actually nearer fifty), who throughout his whole life has had a fervent desire

to know the true religion.

Before admitting Kalemba

to baptism, the mission superior, Pere Livinhac, had asked him whether he was

resolved to persevere and intimated that, if not, it would be better for him

not to receive the sacrament. ‘Have no fear, Father,’ was the reply. ‘It is two

years now since I made up my mind, and nothing can make me change it. I am a

Catholic and I shall die a Catholic.’

Naturally of a haughty

and violent disposition, Matthias Kalemba began to school himself in Christian

humility and meekness, even in the smallest details of his daily life.

Within a week he had

complied with the conditions and set his affairs in order. Pere Lourdel’s diary

has the following entry for 7 June 1880:

“Yesterday, a young man

among our catechumens, an overseer of the slaves of a great chief called

Mukwenda, an ex-disciple of the Protestants and owner of a large number of

women, sent them all away except one, and then came to ask us to baptize him.”

It was not, however,

until two years later that Kalemba received the sacrament he so ardently

desired. It was only then that, taking advantage of the permission given by

Bishop Lavigerie to make some exceptions to the rule of the four years’

catechumenate, Pere Lourdel baptized four on 30 April 1882 and Pere Girault

four more on 28 May. Both priests had the great privilege of baptizing two

future martyrs, Pere Lourdel baptizing Joseph Mukasa and Andrew Kaggwa, and

Pere Girault J: having in his group Matthias Kalemba and Luke Baanabakintu.

Munyonyo Martyrs' Shrine

SOURCE : http://www.munyonyo-shrine.ug/martyrs/other-uganda-martyrs/st-mattias-mulumba-kalemba/

San Mattia Kalemba Martire

>>>

Visualizza la Scheda del Gruppo cui appartiene

† Kampala, Uganda, 30

maggio 1886

Martirologio

Romano: A Kampala in Uganda, san Mattia Kalemba, detto Mulumba o il Forte,

martire, che, lasciata la religione maomettana, ricevette il battesimo in

Cristo e, deposto l’incarico di giudice, si impegnò nella diffusione della fede

cristiana; per questo, sotto il re Mwanga fu sottoposto a tortura e, privo di

ogni conforto, rese il suo spirito a Dio.

Fece un certo scalpore,

nel 1920, la beatificazione da parte di Papa Benedetto XV di ventidue martiri

di origine ugandese, forse perché allora, sicuramente più di ora, la gloria

degli altari era legata a determinati canoni di razza, lingua e cultura. In

effetti, si trattava dei primi sub-sahariani (dell’”Africa nera”, tanto per

intenderci) ad essere riconosciuti martiri e, in quanto tali, venerati dalla

Chiesa cattolica.

La loro vicenda terrena

si svolge sotto il regno di Mwanga, un giovane re che, pur avendo frequentato

la scuola dei missionari (i cosiddetti “Padri Bianchi” del Cardinal Lavigerie)

non è riuscito ad imparare né a leggere né a scrivere perché “testardo,

indocile e incapace di concentrazione”. Certi suoi atteggiamenti fanno dubitare

che sia nel pieno possesso delle sue facoltà mentali ed inoltre, da mercanti

bianchi venuti dal nord, ha imparato quanto di peggio questi abitualmente

facevano: fumare hascisc, bere alcool in gran quantità e abbandonarsi a

pratiche omosessuali. Per queste ultime, si costruisce un fornitissimo harem

costituito da paggi, servi e figli dei nobili della sua corte.

Sostenuto all’inizio del

suo regno dai cristiani (cattolici e anglicani) che fanno insieme a lui fronte

comune contro la tirannia del re musulmano Kalema, ben presto re Mwanga vede

nel cristianesimo il maggior pericolo per le tradizioni tribali ed il maggior

ostacolo per le sue dissolutezze. A sobillarlo contro i cristiani sono

soprattutto gli stregoni e i feticisti, che vedono compromesso il loro ruolo ed

il loro potere e così, nel 1885, ha inizio un’accesa persecuzione, la cui prima

illustre vittima è il vescovo anglicano Hannington, ma che annovera almeno

altri 200 giovani uccisi per la fede.

Il 15 novembre 1885

Mwanga fa decapitare il maestro dei paggi e prefetto della sala reale. La sua

colpa maggiore? Essere cattolico e per di più catechista, aver rimproverato al

re l’uccisione del vescovo anglicano e aver difeso a più riprese i giovani

paggi dalle “avances” sessuali del re. Giuseppe Mkasa Balikuddembè apparteneva

al clan Kayozi ed ha appena 25 anni.

Viene sostituito nel

prestigioso incarico da Carlo Lwanga, del clan Ngabi, sul quale si concentrano

subito le attenzioni morbose del re. Anche Lwanga, però, ha il “difetto” di

essere cattolico; per di più, in quel periodo burrascoso in cui i missionari

sono messi al bando, assume una funzione di “leader” e sostiene la fede dei

neoconvertiti.

Il 25 maggio 1886 viene

condannato a morte insieme ad un gruppo di cristiani e quattro catecumeni, che

nella notte riesce a battezzare segretamente; il più giovane, Kizito, del clan

Mmamba, ha appena 14 anni. Il 26 maggio vemgono uccisi Andrea Kaggwa, capo dei

suonatori del re e suo familiare, che si era dimostrato particolarmente

generoso e coraggioso durante un’epidemia, e Dionigi Ssebuggwawo.

Si dispone il

trasferimento degli altri da Munyonyo, dove c’era il palazzo reale in cui erano

stati condannati, a Namugongo, luogo delle esecuzioni capitali: una “via

crucis” di 27 miglia, percorsa in otto giorni, tra le pressioni dei parenti che

li spingono ad abiurare la fede e le violenze dei soldati. Qualcuno viene

ucciso lungo la strada: il 26 maggio viene trafitto da un colpo di lancia

Ponziano Ngondwe, del clan Nnyonyi Nnyange, paggio reale, che aveva ricevuto il

battesimo mentre già infuriava la persecuzione e per questo era stato

immediatamente arrestato; il paggio reale Atanasio Bazzekuketta, del clan

Nkima, viene martirizzato il 27 maggio.

Alcune ore dopo cade

trafitto dalle lance dei soldati il servo del re Gonzaga Gonga del clan

Mpologoma, seguito poco dopo da Mattia Mulumba del clan Lugane,

elevato al rango di “giudice”, cinquantenne, da appena tre anni convertito al

cattolicesimo.

Il 31 maggio viene

inchiodato ad un albero con le lance dei soldati e quindi impiccato Noè

Mawaggali, un altro servo del re, del clan Ngabi.

Il 3 giugno, sulla

collina di Namugongo, vengono arsi vivi 31 cristiani: oltre ad alcuni

anglicani, il gruppo di tredici cattolici che fa capo a Carlo Lwanga, il quale

aveva promesso al giovanissimo Kizito: “Io ti prenderò per mano, se dobbiamo

morire per Gesù moriremo insieme, mano nella mano”. Il gruppo di questi martiri

è costituito inoltre da: Luca Baanabakintu, Gyaviira Musoke e Mbaga Tuzinde,

tutti del clan Mmamba; Giacomo Buuzabalyawo, figlio del tessitore reale e appartenente

al clan Ngeye; Ambrogio Kibuuka, del clan Lugane e Anatolio Kiriggwajjo,

guardiano delle mandrie del re; dal cameriere del re, Mukasa Kiriwawanvu e dal

guardiano delle mandrie del re, Adolofo Mukasa Ludico, del clan Ba’Toro; dal

sarto reale Mugagga Lubowa, del clan Ngo, da Achilleo Kiwanuka (clan Lugave) e

da Bruno Sserunkuuma (clan Ndiga).

Chi assiste

all’esecuzione è impressionato dal sentirli pregare fino alla fine, senza un

gemito. E’ un martirio che non spegne la fede in Uganda, anzi diventa seme di

tantissime conversioni, come profeticamente aveva intuito Bruno Sserunkuuma

poco prima di subire il martirio “Una fonte che ha molte sorgenti non si

inaridirà mai; quando noi non ci saremo più altri verranno dopo di noi”.

La serie dei martiri cattolici

elevati alla gloria degli altari si chiude il 27 gennaio 1887 con l’uccisione

del servitore del re, Giovanni Maria Musei, che spontaneamente confessò la sua

fede davanti al primo ministro di re Mwanga e per questo motivo venne

immediatamente decapitato.

Carlo Lwanga con i suoi

21 giovani compagni è stato canonizzato da Paolo VI nel 1964 e sul luogo del

suo martirio oggi è stato edificato un magnifico santuario; a poca distanza, un

altro santuario protestante ricorda i cristiani dell’altra confessione,

martirizzati insieme a Carlo Lwanga. Da ricordare che insieme ai cristiani

furono martirizzati anche alcuni musulmani: gli uni e gli altri avevano

riconosciuto e testimoniato con il sangue che “Katonda” (cioè il Dio supremo

dei loro antenati) era lo stesso Dio al quale si riferiscono sia la Bibbia che

il Corano.

Autore: Gianpiero

Pettiti

SOURCE : http://www.santiebeati.it/dettaglio/55180

Carlo Lwanga, Mattia

Maulumba Kalemba e 20 compagni

(† 1885 - 1887)

Beatificazione:

- 06 giugno 1920

- Papa Benedetto XV

Canonizzazione:

- 18 ottobre 1964

- Papa Paolo VI

- Basilica Vaticana

Ricorrenza:

- 3 giugno

Vatican News nell'anniversario

Re Mwanga, sobillato

dagli stregoni locali che vedono il loro potere compromesso dalla forza del

Vangelo, il sovrano dà inizio a una vera e propria persecuzione contro i

cristiani, soprattutto perché non cedono al suo volere dissoluto. Carlo Lwanga

viene condannato a morte, insieme ad altri. Il giorno seguente, cominciano le

prime esecuzioni Il 3 giugno Carlo Lwanga e i suoi compagni, insieme ad alcuni

fedeli anglicani, vengono arsi vivi. Pregano fino alla fine, senza emettere un

gemito, dando una prova luminosa di fede feconda. Uno tra loro, Bruno

Ssrerunkuma, dirà, prima di spirare: “Una fonte che ha molte sorgenti non si

inaridirà mai. E quando noi non ci saremo più, altri verranno dopo di noi

“Io ti prenderò per mano.

Se dobbiamo morire per Gesù, moriremo insieme, mano nella mano”

Nel 1875 arrivarono in

Uganda i primi missionari, all'inizio il re provò simpatia per la religione

cattolica ma dopo un pò preferì l'islam. Nonostante tutto, la missione

prosperava e vi erano molti catecumeni, ma il re temendo che l'Inghilterra

desiderasse appropriarsi del suo regno allontanò dalla sua tribù i missionari

cristiani. Morto lui, però, il figlio Mwanga che ne prese il posto, richiamò i

Padri ed essi trovarono una comunità cristiana piuttosto fiorente, con oltre

800 catecumeni.

Inoltre, dopo averli

accolti con cordialità al ritorno, promise pubblicamente (poiché era succeduto

al padre) che, dopo aver pregato il Dio dei cristiani, avrebbe non soltanto

chiamato a sé i migliori tra i sudditi cristiani e attribuito loro le alte

cariche del regno, ma che avrebbe egli stesso sollecitato tutti i pagani del

suo dominio ad abbracciare la religione. Ordinò pure che molti cristiani e

catecumeni lo assistessero nella reggia, e ciò non senza vantaggio per lui

stesso.

Infatti, avendo i

maggiorenti, ostili al nuovo, ordito una congiura per uccidere il re, e

avendolo scoperto, alcuni dei suoi cortigiani cristiani avvertirono

segretamente Muanga perché stesse in guardia, e aggiunsero che egli poteva fare

pieno assegnamento su tutti i cristiani e sui loro servi, cioé su duemila

uomini in armi.

Ma nel contempo il primo

ministro del re, che era anche il capo della congiura, pur avendo ottenuto il

perdono per sé e per i propri compagni da Muanga, concepì tuttavia un odio

ancor più forte verso i cristiani; e come stupirsene, quando venne a sapere che

sarebbe stato destituito e che al suo posto sarebbe stato designato il

cristiano Giuseppe Mkasa? Egli cominciò quindi a cogliere ogni occasione per

sussurrare all’orecchio del re che avrebbe dovuto guardarsi da coloro che professavano

la religione cristiana, come fossero i peggiori nemici: essi gli sarebbero

rimasti fedeli finché fossero una piccola minoranza; ma una volta diventati

maggioranza lo avrebbero tolto di mezzo ed avrebbero elevato alla dignità regia

uno di loro. Ma a questo si aggiunse un altro e maggiore motivo di ostilità che

indusse il re Muanga a perseguitare i cristiani.

SOURCE : https://www.causesanti.va/it/santi-e-beati/martiri-dell-uganda.html

I MARTIRI

Sono stati i primi

africani sub-sahariani ad essere venerati come santi dalla Chiesa cattolica.

Essi si possono distinguere in due gruppi, in relazione al tipo di pena

capitale subita: tredici furono bruciati vivi e gli altri nove vennero uccisi

con diversi generi di supplizio.

Nel primo gruppo sono

compresi giovani quasi tutti cortigiani: Carlo Lwanga, Mbaga Tuzindé, Bruno

Séron Kuma, Giacomo Buzabaliao, Kizito, Ambrogio Kibuka, Mgagga, Gyavira,

Achille Kiwanuka, Adolfo Ludigo Mkasa, Mukasa Kiriwanvu, Anatolio Kiriggwajjo,

Luca Banabakintu.

Carlo Lwanga, nato nella

città di Bulimu e battezzato il 15 novembre 1885, si attirò ammirazione e

benevolenza di tutti per le sue grandi doti spirituali; lo stesso Muanga lo

teneva in grande considerazione per aver saputo portare a termine con la

massima diligenza gl’incarichi a lui affidati. Posto a capo dei giovani del

palazzo regio, rafforzò in loro l’impegno a preservare la propria fede e la

castità, respingendo gli allettamenti dell’empio e impudico re; imprigionato,

incoraggiò apertamente anche i catecumeni a perseverare nell’amore per la

religione, e si recò al luogo del supplizio con mirabile forza d’animo, all’età

di vent’anni.

Mbaga Tuzindé, giovane di

palazzo (figlio di Mkadjanga, il primo e il più crudele dei carnefici) ancora

catecumeno quando si scatenò la persecuzione, fu battezzato da Carlo Lwanga

poco prima di essere con lui mandato a morte. Il padre, cercando di sottrarlo

in ogni modo all’esecuzione, lo supplicò più e più volte affinché abiurasse la religione

cattolica, o almeno si lasciasse nascondere e promettesse di cessare di

pregare. Ma il nobile giovane rispose che conosceva la causa della propria

morte e che l’accettava, ma non voleva che l’ira del re ricadesse sul padre:

pregò di non venir risparmiato. Allora Mkadjanga, mentre il figlio, all’età di

appena sedici anni, stava per essere condotto al rogo, comandò ad uno dei

carnefici ai suoi ordini che lo colpisse al capo con un bastone e che ne

collocasse poi il corpo esanime sul rogo perché venisse bruciato insieme agli

altri.

Bruno Séron Kuma, nato

nel villaggio Mbalé e battezzato il 15 novembre 1885, lasciò la tenda dove

viveva col fratello perché questi seguiva una setta non cattolica. Divenuto

servitore del re Mtesa, quando Muanga successe al padre lasciò il suo incarico

per il servizio militare. Accolto fra i giovani cristiani che facevano servizio

a corte, a ventisei anni sostenne con la parola e con l’esempio i compagni

della gloriosa schiera.

Giacomo Buzabaliao,

cosparso con l’acqua battesimale il 15 novembre 1885, acceso di singolare

ardore religioso, compì ogni sforzo per convincere e spronare altri, fra cui lo

stesso Muanga, non ancora salito al trono paterno, ad abbracciare la fede di

Cristo; e il re stesso rinfacciò tale colpa al fortissimo giovane, quando lo

mandò a morte, all’età di vent’anni.

Kizito, anima innocente,

più giovane degli altri, dato che subì il martirio nel suo tredicesimo anno di

vita, figlio di uno dei più alti dignitari del regno, splendente di purezza e

forza d’animo, poco prima di essere gettato in prigione ricevette il battesimo

da Carlo Lwanga. Il re, spinto dalla sua libidine, cercò invano di attrarre a

sé, con più accanimento che verso gli altri, questo fortissimo giovinetto.

Kizito biasimò così aspramente alcuni cristiani che avevano determinato di

darsi alla fuga, che essi deposto il timore, rimasero presso il re Muanga; e

quando giunse per loro il momento di essere condotti al supplizio, affinché i

compagni non si perdessero d’animo li convinse ad avanzare tutti insieme,

tenendosi per mano.

Ambrogio Kibuka,

anch’egli giovane di palazzo, battezzato il 17 novembre 1885, conservò la

propria ferma e ardente fede fino all’atrocissima morte, che affrontò nel nome

di Cristo all’età di ventidue anni.

Mgagga, giovinetto di

corte, ancora catecumeno, resistette impavido alle oscene lusinghe del re e,

essendosi dichiarato cristiano, fu gettato in carcere con gli altri; prima di

essere imprigionato ricevette il battesimo da Carlo Lwanga, e, non diversamente

dagli altri, andò al martirio con animo tranquillo, all’età di sedici anni.

Gyavira, anch’egli

giovane di palazzo, di bell’aspetto, era prediletto da Muanga, il quale si

adoperò invano per piegarlo a soddisfare la propria libidine. Ancora catecumeno

quando, dopo la professione di fede, fu da Muanga condannato a morte, durante

la notte fu asperso col battesimo da Carlo Lwanga e, a diciassette anni, fu dai

carnefici condotto al luogo del supplizio insieme agli altri.

Achille Kiwanuka, giovane

di corte, nato a Mitiyana, fu battezzato il 17 novembre 1885. Dopo che ebbe

impavidamente professato la propria fede davanti al re, posto in ceppi con i

compagni e gettato in carcere, dichiarò ancora una volta che mai avrebbe

abiurato la religione cattolica e si avviò con coraggio all’ultimo supplizio,

nel suo diciassettesimo anno di età.

Adolfo Ludigo Mkasa,

cortigiano, si mise in luce per la purezza dei costumi e così pure per la

costanza e la sopportazione nelle sventure. Ricevuto il battesimo il 17

novembre 1885, osservò santamente e professò con fermezza insieme agli altri la

fede cattolica, fino alla morte che affrontò in nome di Cristo a venticinque

anni.

Mukasa Kiriwanu, giovane

del palazzo regio, addetto al servizio della tavola, mentre i carnefici stavano

conducendo Carlo Lwanga e i suoi compagni al colle Namugongo, alla domanda se

fosse cristiano disse di sì, e fu condotto con gli altri al supplizio.

Catecumeno, non ancora asperso con l’acqua del battesimo, conseguì gloria

eterna attraverso il battesimo di sangue, all’età di diciotto anni.

Anatolio Kiriggwajjo,

giovane di palazzo, battezzato il 17 novembre 1885, osservò con tanta fermezza

d’animo i precetti della vita cristiana, che respinse senza esitazione una

carica che gli era offerta dal re, ritenendo che essa potesse in qualche modo

pregiudicare il conseguimento della salvezza eterna. Avendo poi professato

apertamente, insieme agli altri, la fede cattolica, affrontò con loro una

comune morte, nel suo sedicesimo anno di vita.

Infine, ricordiamo di

questa schiera Luca Banabakintu, che, nato nel villaggio Ntlomo, era

servitore amatissimo di un patrizio di nome Mukwenda. Il 28 maggio 1882,

ricevuti il battesimo e la confermazione, si accostò per la prima volta alla

sacra celebrazione eucaristica: da quel faustissimo giorno si pose in luce a

tutti come esempio per integrità di costumi e per osservanza dei precetti, e

nulla gli era più caro che parlare di religione con gli amici. Sebbene potesse

facilmente sottrarsi alla morte, preferì, quando fu ricercato per essere

condotto al supplizio, rimanere presso il padrone, dal quale fu consegnato agli

inviati del re. Gettato in carcere, vi dimorò con animo sereno finché, con gli

altri, nel suo trentesimo anno donò la vita nel nome di Cristo.

Tutti costoro che abbiamo

nominato, il 3 giugno 1886, all’alba, sono condotti sul colle Namugongo. Qui

giunti, le mani legate dietro la schiena e i piedi in ceppi, ciascuno di loro è

avvolto in una stuoia di canne intrecciate; viene innalzato un rogo, sul quale

essi vengono collocati come fascine umane. Il fuoco viene accostato ai piedi,

perché quel tenero gregge di vittime sia avvolto più lentamente e più a lungo;

crepita la fiamma, alimentata dai santi corpi; dal rogo di diffondono per

l’aria mormorii di preghiere che aumentano col crescere dei tormenti; i

carnefici si stupiscono che non un lamento, non un gemito si levino dai

morenti, dacché a nulla di simile è loro capitato di assistere.

Nel secondo gruppo di

martiri si annoverano i venerabili servi di Dio Mattia Kalemba Murumba,

Attanasio Badzekuketta, Pontiano Ngondwé, Gonzaga Gonza, Andrea Kagwa, Noe

Mawgalli, Giuseppe Mkasa Balikuddembé, Giovanni Maria Muzéi (Iamari), Dionisio

Sebugwao.

Mattia Kalemba Murumba aveva

cinquant’anni quando ricevette il martirio. Scelto per svolgere la mansione di

giudice, dopo essersi convertito da una setta maomettana e protestante alla

religione cattolica, ricevette il battesimo il 28 maggio 1882; dopo di che si

dimise dall’incarico, temendo di poter recar danno a qualcuno con le sue

sentenze. Dotato di modestia e dolcezza d’animo, era così fervido nel suo zelo

di apostolato religioso che non solo educò i propri figli a vivere santamente,

ma cercò d’insegnare a quanti più poté la dottrina cristiana. Il primo ministro

del re, al cui cospetto fu trascinato, comandò che a quell’uomo nobilissimo,

che aveva impavidamente professato la propria fede, fossero tagliati le mani e

i piedi, e gli fossero strappati frammenti di carne dalla schiena perché

fossero bruciati davanti ai suoi occhi. I carnefici dunque, per non essere disturbati

da testimoni del loro atrocissimo ufficio, conducono su un colle incolto e

deserto questo venerabile servitore di Dio, animoso e sereno nell’aspetto;

eseguono gli ordini alla lettera, perché il glorioso martire soffra più a

lungo, trattengono con tale abilità il sangue che fuoriesce dalle membra, che

tre giorni dopo alcuni servi, giunti sul posto per tagliare legna, odono la

voce di Mattia, debole e sommessa, che chiede un sorso d’acqua; e avendolo

visto così orribilmente mutilato fuggono via atterriti e lo lasciano là, a

imitazione di Cristo morente, privo di ogni conforto.

Atanasio Badzekuketta,

scelto fra i giovani in servizio nel palazzo reale e battezzato il 17 novembre

1885, seguiva con grande devozione i comandamenti di Dio e della Chiesa. Era così

desideroso di cingersi della corona del martirio che supplicò vivamente i

carnefici, i quali lo stavano conducendo con altri al luogo stabilito, di

ucciderlo sul posto. Così quel valoroso giovane fu dilaniato da ripetuti colpi,

il 26 maggio 1886, nel suo diciottesimo anno d’età.

Pontiano Ngondwé, nato

nel villaggio Bulimu e cortigiano del re Mtesa, una volta salito al trono

Muanga entrò nell’esercito, e ancora catecumeno apparve così animato di

cristiana spiritualità da saper vincere in sé, e trasformare, il proprio

carattere aspro e difficile. Quando era iniziata la persecuzione, ricevette il

battesimo il 18 novembre 1885; per questo, poco dopo fu gettato in carcere con

gli altri. Condannato a morte, accadde che il carnefice Mkadjanga, mentre lo

conduceva al colle Namugongo, gli chiedesse ripetutamente durante il cammino se

fosse seguace della religione cristiana; ed egli due volte confermò la sua

fede, e due volte quello lo trafisse con la lancia; e il suo capo, troncato dal

corpo, fu fatto rotolare lungo la via; era il 26 maggio 1886.

Gonzaga Gonza, ragazzo di

corte, battezzato il 17 novembre 1885, assolse con devozione agli obblighi

religiosi e si distinse particolarmente per la virtù della carità. Mentre

procedeva verso il luogo del supplizio, poiché i ceppi, che non avevano potuto

essere sciolti, gli impedivano di camminare speditamente, fu più volte trafitto

dai carnefici con la lancia; fu così martirizzato, nel suo diciottesimo anno di

vita, il 27 maggio 1886.

Andrea Kagwa, nato nel

villaggio Bunyoro e vissuto in grande familiarità con Muanga, sia quando era

principe, sia quando era re, ricevette il 30 aprile 1882 i sacramenti del

battesimo, della confermazione e dell’Eucaristia. Caro a tutti per le grandi

qualità d’animo, non soltanto istruiva nella dottrina cristiana quanti lo

avvicinavano, ma altresì, in occasione di una pestilenza che si era diffusa

nella regione, aiutando tutti si prodigò con singolare carità a favore degli

infermi, ne avvicinò moltissimi a Cristo aspergendoli con l’acqua battesimale,

e dando poi sepoltura ai defunti. Ma il primo ministro del re vedeva assai di

malocchio che i propri figli venissero da lui istruiti nella dottrina

cristiana, e infine, con il consenso del re, comandò che fosse catturato e

ucciso, aggiungendo che non sarebbe andato a cena prima che il carnefice gli

avesse presentato la mano mozzata del morto Andrea. Così il 26 maggio 1886, nel

suo trentesimo anno, il venerabile servo di Dio subì il martirio e raggiunse la

gloria celeste.

Noe Mawgalli, servitore

del nobile Mukwenda nella preparazione delle imbandigioni, risplendette

grandemente di virtù cristiane. Battezzato il 1° novembre 1885, colpito dalla

lancia dei sicari che il re Muanga aveva mandato in giro per distruggere le

case dei Cristiani, morì nel trentesimo anno d’età il 31 maggio 1886.

Giuseppe Mkasa

Balikuddembé, nato nel villaggio Buwama, fu scelto dal re Mtesa, per la sua

provata lealtà, come proprio inserviente personale per il giorno e per la

notte, e come infermiere. Il figlio di lui Muanga, non diversamente dal padre,

riponeva la più totale fiducia in questo venerabile servo di Dio; pertanto non

solo lo pose a capo di tutti i servitori del palazzo reale, ma volle che fosse

lui ad avvertirlo, quando il suo operato prestasse il fianco a critiche. Il 30

aprile 1882, Giuseppe ricevette il battesimo e la confermazione e si accostò

per la prima volta alla santa comunione, alla quale in seguito si accostò di

frequente. Con la propria dolcezza d’animo, con la carità e l’afflato religioso

che mostrava non solo seppe avvicinare a Cristo molti giovani, ma in

particolare fece pressioni, con consigli ed esortazioni, sui ragazzi della

corte reale e sugli altri cortigiani perché non accondiscendessero alla

libidine del re Muanga. Il re, essendo venuto a conoscenza di ciò, cominciò a

nutrire avversione per il venerabile servo di Dio, finché, vinto dalle

sollecitazioni del primo ministro, che provava invidia per Giuseppe, comandò

che questi fosse condannato a morte. Giuseppe, rinforzato dal cibo divino,

viene condotto nella località Mengo, dove, dopo aver dichiarato di voler dare

al re sia il perdono, sia il consiglio di pentirsi, viene dal carnefice

decapitato e gettato nel fuoco, prima vittima della persecuzione, a ventisei

anni, il 15 novembre 1885.

Giovanni Maria Muzéi (Iamari),

nato nel villaggio Minziro, aveva un aspetto di tale gravità che venne onorato

col nome di Muzéi, cioé vecchio; insigne anche per prudenza, carità, dolcezza

d’animo, generosità verso i poveri, sollecitudine verso gli ammalati, dedicò le

proprie sostanze e il proprio impegno a riscattare i prigionieri, che poi

istruiva nella fede cristiana. Si dice che egli avesse in un solo giorno

appreso tutta la dottrina del catecumenato; fu poi battezzato il 1° novembre

1885 e unto del sacro crisma il 3 giugno dell’anno seguente. Dopo l’esecuzione

capitale del suo grande amico Giuseppe Mkasa, pur avendo saputo che il re

intendeva farlo uccidere, non volle nascondersi, né darsi alla fuga; al

contrario, accompagnato da un certo Kulugi, si presentò al re, dal quale

ricevette l’ordine di recarsi, per una causa qualsiasi, dal primo ministro.

Obbedì, sebbene sospettasse l’inganno, poiché riteneva indegno di sé l’esitare

e il temere a motivo della propria fede religiosa. E il primo ministro del re

ordinò che fosse gettato in uno stagno che si trovava in un suo podere, il 27

gennaio 1887.

Dionisio Sebuggwao, nato

nel villaggio Bunono, ragazzo di corte, ricevette il battesimo il 17 novembre

1885 e rifulse per integrità di costumi. Avendogli il re Muanga chiesto se

fosse vero che egli aveva insegnato i rudimenti della fede cristiana a due

cortigiani, egli rispose di sì, e quello lo trapassò con un colpo di lancia, e

comandò che gli fosse tagliato il capo. Così morì Dionisio, martire, all’età di

quindici anni, il 26 maggio 1886.

SOURCE : https://www.causesanti.va/it/santi-e-beati/martiri-dell-uganda.html

CANONIZACIÓN DE LOS

MÁRTIRES DE UGANDA

Domingo 18 de octubre de 1964

«Estos que están cubiertos de vestiduras

blancas, ¿quiénes son y de dónde han venido?» (Ap 7, 13).

Nos viene al pensamiento

esta frase bíblica mientras inscribimos en la lista gloriosa de los santos

victoriosos en el cielo a estos veintidós hijos de África, cuyo singular mérito

había ya reconocido nuestro predecesor, de venerada memoria, el Papa Benedicto

XV, el 6 de junio de 1920, al declararlos Beatos y autorizar así su culto

particular.

¿Quiénes son? Son

africanos, verdaderos africanos, de color, de raza y de cultura, dignos

exponentes de los fabulosos pueblos Bantúes y Nilóticos explorados en el siglo

pasado por la audacia de Stanley y Livingstone, establecidos en las regiones

del África oriental, que se llama de los Grandes Lagos, en el ecuador, en el

terrible clima ecuatorial, sólo atenuado por la elevación de los altiplanos y

por las grandes lluvias estacionales. Su patria, en el tiempo en que vivían,

era un protectorado británico, pero desde 1962 ha logrado, como tantas otras

naciones de aquel continente, su propia independencia, que afirma actualmente

con rápidos y espléndidos progresos de civilización moderna. La capital es

Kampala, pero la circunscripción eclesiástica principal tiene su centro en

Rubaga, sede del primer Vicariato apostólico local, erigido en 1878 y elevada

ahora a la dignidad de archidiócesis con siete diócesis sufragáneas. Es este un

campo de apostolado misional que acogió primeramente a los ministros de

confesión anglicana, ingleses, a los cuales se sumaron dos años después los

misioneros católicos de lengua francesa llamados Padres Blancos, misioneros de

África, hijos del célebre y valeroso cardenal Lavigerie (1825-1892), a quien no

sólo África, sino la civilización misma debe recordar entre los hombres

providenciales más insignes, y fueron los Padres Blancos los que introdujeron

el catolicismo en Uganda, predicando el Evangelio en amigable competencia con

los misioneros anglicanos y los que tuvieron la dicha —ganada con riesgos y

fatigas incalculables— de formar a estos mártires para Cristo, a estos a

quienes hoy nosotros honramos cómo héroes y hermanos en la fe e invocamos como

protectores en el cielo. Sí, son africanos y son mártires. «Son —prosigue la

Sagrada Escritura— los que han venido de la gran tribulación y lavaron sus

vestidos y los blanquearon en la sangre del Cordero. Por eso están ante el

trono de Dios» (Ib. 14-15).

Todas las veces que

pronunciamos la palabra “mártires” en el sentido que tiene en la hagiografía

cristiana, debería presentársenos a la mente un drama horrible y maravilloso:

horrible por la injusticia, armada de autoridad y de crueldad, que es la que provoca

el drama; horrible también por la sangre que corre y por el dolor de la carne

que sufre sometida despiadadamente a la muerte; maravilloso por la inocencia

que, sin defenderse, físicamente se rinde dócil al suplicio, feliz y orgullosa

de poder testimoniar la invencible verdad de una fe que se ha fundido con la

vida humana; la vida muere, la fe vive. La fuerza contra la fortaleza; la

primera, venciendo, queda derrotada; ésta, perdiendo, triunfa. El martirio es

un drama; un drama tremendo y sugestivo, cuya violencia injusta y depravada,

casi desaparece del recuerdo allí mismo donde se produjo mientras permanece en

la memoria de los siglos siempre fúlgida y amable la mansedumbre que supo hacer

de su propia oblación un sacrificio, un holocausto; un acto supremo de amor y

de fidelidad a Cristo; un ejemplo, un testimonio, un mensaje perenne a los

hombres presentes y futuros. Esto es el martirio.

Esta es la gloria de la

Iglesia a través de los siglos. Y es un acontecimiento tan grande que la

Iglesia se apresuró a recoger las narraciones de la «pasión de los mártires» y

hacer de ellas el libro de oro de sus hijos más ilustres, el martirologio. Y

fue tal la irradiación de belleza y grandeza que emanaron de ese libro que pudo

ofrecer a la leyenda y al arte nuevas amplificaciones legendarias y

fantásticas; pero la historia verdadera, que todavía halla su documentación en

este libro, merece una admiración sin límites, es una alabanza a Dios, que obra

grandes cosas en hombres frágiles, y es testimonio de honor para los héroes,

que con su sangre han escrito las páginas de ese libro incomparable.

Ahora estos mártires

africanos vienen a añadir a ese catálogo de vencedores que es el martirologio,

una página trágica y magnífica, verdaderamente digna de sumarse a aquellas

maravillosas de la antigua África, que nosotros, modernos, hombres de poca fe,

creíamos que no podrían tener jamás adecuada continuación. ¿Quién podía

suponer, por ejemplo, que a las emocionantísimas historias de los mártires

escilitanos, de los mártires cartagineses, de los mártires de la “Masa Cándida”

de Útica —de quienes San Agustín (cf. PL 36,571 y 38, 1405) y Prudencio nos han

dejado el recuerdo—, de los mártires de Egipto —cuyo elogio trazó San Juan

Crisóstomo (cf, PG 50, 693 ss) —, de los mártires de la persecución vandálica,

hubieran venido a añadirse nuevos episodios no menos heroicos, no menos

espléndidos, en nuestros días? ¿Quién podía prever que a las grandes figuras

históricas de los Santos Mártires y Confesores africanos, como Cipriano,

Felicidad y Perpetua, y al gran Agustín, habríamos asociado un día los nombres

queridos de Carlos Lwanga y de Matías Mulumba Kalemba, con sus veinte

compañeros Y no queremos olvidar tampoco a aquellos otros que, perteneciendo a

la confesión anglicana, han afrontado la muerte por el nombre de Cristo.

Estos mártires africanos

abren una nueva época, no queremos decir ciertamente de persecuciones y de

luchas religiosas, sino de regeneración cristiana y civilizada. El África,

bañada por la sangre de estos mártires, primicias de la nueva era —y Dios

quiera que sean los últimos, pues tan precioso y tan grande fue su holocausto—,

resurge libre y redimida. La tragedia que los devoró fue tan inaudita y