Giovanni Marchiori. Statue de Saint Laurent Justinien, Église San Rocco, Venise

Giovanni Marchiori. Statue de Saint Laurent Justinien, Église San Rocco, Venise

Giovanni Marchiori. Statue de Saint Laurent Justinien, Église San Rocco, Venise

Saint Laurent Justinien

Premier patriarche de

Venise (+ 1455)

Originaire d'une famille

vénitienne, il perd très tôt son père. Sa mère reste à 24 ans avec cinq

enfants. Elle voudrait bien marier ce fils, mais il choisit d'entrer dans une

communauté de chanoines réguliers où il vit dans la pauvreté et la

prière.

Élu prieur général de sa

congrégation, il sera appelé par le Pape Eugène IV à devenir évêque de

Castello, puis de Venise. Il y garde un mode de vie très pauvre, s'occupe avec

zèle de son diocèse dont il est le premier patriarche nommé.

Par sa prédication et son

enseignement théologique, il donne une grande impulsion à sa communauté,

accueillant tout le monde avec bonté et simplicité.

Martyrologe romain au 8

janvier: À Venise, en 1456, saint Laurent Justinien, évêque, premier patriarche

de cette église, qu'il illustra par sa doctrine de la sagesse éternelle.

Martyrologe romain

Il faut éviter les

affaires trop compliquées. Il y a toujours du démon dans les complications.

saint Laurent Justinien -

Perles de sagesse

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/1802/Saint-Laurent-Justinien.html

Gentile Bellini (1429–1507). Portrait

of Lorenzo Giustiniani, 1465, tempera on panel, 41 x 29,5, National Museum in Warsaw

Saint Laurent

Justinien (+1455)

Fêté le 05 septembre

Originaire d’une famille

vénitienne, Laurent Justinien perd très tôt son père. Sa mère reste à 24 ans

avec cinq enfants. Elle voudrait bien marier ce fils, mais il choisit d’entrer

dans une communauté de chanoines réguliers où il vit dans la pauvreté et la

prière. Elu prieur général de sa congrégation, il sera appelé par le Pape

Eugène IV à devenir évêque de Castello, puis de Venise. Il y garde un mode de

vie très pauvre, s’occupe avec zèle de son diocèse dont il est le

premier patriarche nommé. Par sa prédication et son enseignement théologique,

il donne une grande impulsion à sa communauté, accueillant tout le monde avec

bonté et simplicité.

Il faut éviter les

affaires trop compliquées. Il y a toujours du démon dans les complications.

(Saint Laurent Justinien

– Perles de sagesse)

La véritable science

tient dans ces deux propositions : Dieu est tout. Je ne suis rien !

(Saint Laurent Justinien

– Perles de sagesse)

SOURCE : https://eglise.catholique.fr/saint-du-jour/05/09/saint-laurent-justinien/

Gentile Bellini (1429–1507), Blessed Lawrence Giustiniani / Le bienheureux Laurent Justinien / Beato Lorenzo Giustiniani, 1465, tempera on canvas, 221 x 155, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice, northern Italy. Acquisition in 1852, from the church of the Madonna dell'Orto. Last Restoration 2004-2005 / Acquisition en 1852, provenant de l'église de la Madonna dell'Orto. Dernière restauration en 2004-2005 / Acquisizione 1852, dalla chiesa della Madonna dell'Orto. Ultimo restauro 2004-2005

Saint Laurent Justinien

Patriarche de Venise

(1381-1455)

|

L |

orenzo Giustiniani naît

à Venise. On remarqua en lui, dès son enfance, une docilité peu commune. Sa

pieuse mère le grondait quelques fois pour le prémunir contre l'orgueil, le

tenir dans l'humilité et le porter à ce qu'il y avait de plus parfait. Il

répondait alors qu'il tâcherait de mieux faire, et qu'il ne désirait rien tant

que de devenir un saint. Une vision de la sagesse éternelle le porta vers la

vocation religieuse ; il s'y essaya d'abord par la pénitence, coucha sur

le bois ou la terre nue, et brisa son corps par les macérations. Laurent ne

tarda pas à s'enfuir chez les chanoines réguliers de Saint-Georges-d'Alga, où

il prit l'habit.

Ses premiers pas dans la

vie religieuse montrèrent en lui le modèle de tous ses frères : jamais de

récréations non nécessaires, jamais de feu, jamais de boisson en dehors des

repas, fort peu de nourriture, de sévères disciplines : c'était là sa

règle.

Quand, par une grande

chaleur, on lui proposait de boire : « Si nous ne pouvons

supporter la soif, disait-il, comment supporterons-nous le feu du

purgatoire ? » Il dut subir une opération par le fer et par le

feu ; aucune plainte ne sortit de sa bouche : « Allons,

disait-il au chirurgien dont la main tremblait, coupez hardiment ;

cela ne vaut pas les ongles de fer avec lesquels on déchirait les martyrs. »

« Allons quêter des

mépris, disait-il à son compagnon de quête, lorsqu'il y avait quelque avanie à

souffrir ; nous n'avons rien fait, si nous n'avons renoncé au

monde. » À un frère qui se lamentait parce que le grenier de la communauté

avait brûlé : « Pourquoi donc, dit-il, avons-nous fait le vœu de

pauvreté ? Cet incendie est une grâce de Dieu pour nous ! »

Il ne célébrait jamais la

Sainte Messe sans larmes, et souvent il y était favorisé de ravissements. Ses

vertus l'élevèrent d'abord aux fonctions de général de son ordre, puis au

patriarcat de Venise, malgré ses supplications et ses larmes. Il parut aussi

admirable pontife qu'il avait été saint religieux ; son zèle lui attira

des injures qu'il reçut avec joie ; sa charité le faisait bénir de tous

les pauvres ; sa ponctualité ne laissait jamais attendre personne, sa

bonté agréait tout le monde : il était regardé de tous comme un ange sur

la terre. Après de longs travaux, il sentit sa fin prochaine : « Un

chrétien, dit-il, après saint Martin, doit mourir sur la cendre et le

cilice. »

Abbé L. Jaud, Vie des Saints pour tous les jours de l'année, Tours, Mame, 1950.

SOURCE : https://levangileauquotidien.org/FR/display-saint/8d5d7212-51b9-4f5e-b4c0-d430581b6630 et

St Laurent Justinien,

évêque et confesseur

Né en 1381, sacré évêque le 5 septembre 1433, mort patriarche de Venise en 1455. Canonisé en 1690, fête depuis 1692.

(Leçons des Matines (avant 1960)

Quatrième leçon. Laurent, né à Venise de l’illustre famille des Justinien, montra dès son enfance une très grande gravité de mœurs. Les pratiques d’une piété fervente sanctifièrent son adolescence, et l’appel de la Sagesse divine ayant convié son âme aux chastes fiançailles du Christ, il s’appliqua à connaître dans quel institut religieux il se consacrerait à Dieu. Voulant donc se préparer en secret à cette nouvelle milice, il se mit, entre autres mortifications, à coucher sur des planches nues. Un jour qu’il considérait, d’une part les plaisirs du monde et une alliance négociée par sa mère à son intention, et d’autre part les rudes austérités du cloître, il jeta les yeux sur la croix du Christ souffrant et s’écria : « C’est vous, Seigneur, qui êtes mon espérance, et c’est en vous que se trouve la consolation et la force. » Laurent dirigea ses pas vers la communauté des Chanoines de Saint-Georges in Alga, où, ingénieux à trouver de nouveaux moyens de se mortifier, il engagea contre lui-même le plus opiniâtre des combats, comme s’il se fût agi de son ennemi le plus redoutable. Ne s’accordant aucune satisfaction, il s’interdit même l’entrée du jardin de la maison paternelle, et ne franchit jamais le seuil de cette demeure, si ce n’est pour remplir auprès de sa mère mourante les derniers devoirs de la piété, ce qu’il fit sans verser de larmes. Égal à son esprit de pénitence se montrait son zèle pour la pratique de l’obéissance, de la douceur et surtout de l’humilité, qui lui faisait rechercher les emplois les plus abjects du monastère, mendier dans les endroits les plus fréquentés de la ville, en y recueillant moins de vivres que de moqueries, et supporter, impassible et silencieux, les injures ainsi que les calomnies. C’était principalement dans une oraison assidue, où souvent l’extase le ravissait en Dieu, que s’enflammait la grande ardeur dont son cœur brûlait, ardeur telle qu’elle excitait à la persévérance les frères chancelants et les embrasait d’amour pour Jésus-Christ

Cinquième leçon. Désigné par Eugène IV pour occuper le siège épiscopal de Venise, Laurent fit tous ses efforts pour décliner cette dignité, dont il remplit les devoirs d’une manière digne des plus grands éloges. Il ne changea absolument rien à son genre de vie accoutumé ; conserva dans ses repas, ses meubles et son coucher, la même pauvreté qu’il avait toujours pratiquée et ne prit qu’un petit nombre de domestiques, disant qu’il possédait une grande famille, les pauvres du Christ. A quelque heure du jour qu’on l’abordât, il était tout à tous, prodiguant à chacun sa charité paternelle et n’hésitant même pas à se charger de dettes pour venir en aide à l’indigence du prochain. Quand on lui demandait sur quoi il comptait : « Sur mon Seigneur, qui pourra facilement acquitter mes dettes, répondait-il. » Sa confiance n’avait jamais été trompée par la divine Providence, comme le montraient les secours inespérés qui lui arrivaient. Il construisit plusieurs monastères de vierges, qu’il forma par sa vigilance à la pratique de la vie parfaite, s’appliqua avec grand soin à arracher les dames aux pompes du siècle et à la vanité des parures, et n’apporta pas moins d’ardeur à la réforme de la discipline et des mœurs dans le clergé, se montrant digne assurément d’être proclamé par le Pape Eugène III, devant les Cardinaux, la gloire et l’honneur de l’épiscopat, et d’être nommé par Nicolas V, son successeur, le premier Patriarche de Venise, quand ce titre eut été transféré de Grado dans cette cité.

Sixième

leçon. Favorisé du don des larmes, Laurent offrait chaque jour au Dieu tout-puissant

l’hostie de propitiation. Une fois même, la nuit de la Nativité du Seigneur, en

accomplissant les saints Mystères, il mérita de contempler Jésus-Christ sous la

forme d’un gracieux petit enfant. Si grande était l’efficacité de ses prières

pour le troupeau confié à ses soins, que la République devait son salut à

l’intercession et au mérite de son Pontife, d’après un témoignage qu’en a rendu

le ciel. Doué de l’esprit prophétique, il prédit plusieurs fois des événements

qu’on ne pouvait humainement prévoir. Ses prières eurent souvent pour effet de

guérir les malades et de chasser les démons. Il composa des ouvrages remplis

d’une doctrine toute céleste et respirant la piété, bien qu’il sût à peine les

règles du style. Enfin une maladie mortelle étant venue l’atteindre, comme ses

domestiques lui préparaient un lit plus commode pour un vieillard et pour un

malade, il refusa des soulagements qui lui semblaient trop contraster avec la

très dure croix sur laquelle avait expiré son Seigneur, et voulut qu’on le

déposât sur sa couche habituelle. Puis voyant sa fin approcher, il leva les

yeux au ciel, et dit ces paroles : « Je vais à vous, ô bon

Jésus. » Et le huitième jour du mois de janvier, il s’endormit dans le

Seigneur. Sa mort fut précieuse devant Dieu. Ce qui le prouve ce sont les

concerts angéliques entendus par des religieux Chartreux ; c’est aussi la

conservation de son saint corps, qui demeura dans toute son intégrité et sans

trace de corruption, exhalant une odeur suave, conservant un visage vermeil, durant

plus de deux mois qu’il resta sans sépulture ; ce sont enfin les nouveaux

miracles qui suivirent cette mort. En considération de ces prodiges, le

souverain Pontife Alexandre VIII l’inscrivit au nombre des Saints, et Innocent

XII fixa la célébration de sa Fête au cinq septembre, jour où le Saint était

monté sur la chaire épiscopale

SOURCE : http://www.introibo.fr/05-09-St-Laurent-Justinien-eveque

San Lorenzo Giustiniani

Il Pordenone (1484–1539). Le Bienheureux Lorenzo

Giustiniani entre deux moines et Saint Louis de Toulouse, saint Francois

d'Assise, saint Bernard et saint Jean Baptiste, 1532, Gallerie dell'Accademia de Venise

Il Pordenone (1484–1539). Le Bienheureux Lorenzo Giustiniani entre deux moines et Saint Louis de Toulouse, saint Francois d'Assise, saint Bernard et saint Jean Baptiste, 1532, Gallerie dell'Accademia de Venise

SAINT LAURENT JUSTINIEN,

ÉVÊQUE ET CONFESSEUR.

VENEZ, vous tous que

sollicite l'attrait du bien immuable, et qui vainement le demandez à ce siècle

qui passe; je vous dirai ce que le ciel a fait pour moi. Comme vous jadis je

cherchais fiévreusement ; et ce monde extérieur ne donnait point satisfaction à

mon désir brûlant. Mais, par la divine grâce qui nourrissait mon angoisse,

enfin m'est apparue, plus belle que le soleil, plus suave que le baume, Celle

dont alors le nom m'était ignoré. Venant à moi, combien son visage, était doux

!combien pacifiante était sa voix, me disant : « O toi dont la

jeunesse est toute pleine de l'amour que je t'inspire, pourquoi répandre ainsi

ton cœur ? La paix que tu cherches par tant de sentiers divers est avec moi;

ton désir sera comblé, je t'en donne ma foi : si, cependant, tu veux de moi

pour épouse. » J'avoue qu'à ces mots défaillit mon cœur ; mon âme fut

transpercée du trait de son amour. Comme toutefois je désirais savoir son nom,

sa dignité, son origine, die me dit qu'elle se nommait la Sagesse de Dieu,

laquelle, invisible d'abord au sein du Père, avait pris d'une Mère une nature

visible pour être plus facilement aimée. Alors, en grande allégresse, je lui

donnai consentement; et elle, me donnant le baiser, se retira joyeuse.

« Depuis, la flamme de

son amour a été croissant, absorbant mes pensées. Ses délices durent toujours;

c'est mon épouse bien-aimée, mon inséparable compagne. Par elle, la paix que je

cherchais fait maintenant ma joie. Aussi, écoutez-moi, vous tous : allez à elle

de même; car elle met son bonheur à ne rebuter personne (1). »

Lisons l'histoire de

celui qui vient de nous livrer dans ces lignes le secret du ressort de sa vie.

Laurent naquit à Venise

de l'illustre famille des Justiniani. Il montra dès l'enfance une gravité

rare. Son adolescence se passait dans les exercices de la piété, lorsque,

invité par In Sagesse divine aux noces très pures du Verbe et de l'âme, il

conçut la pensée d'embrasser l'état religieux. C'est pourquoi, préludant

secrètement à cette milice nouvelle, il affligeait son corps en différentes

manières et couchait sur la planche nue. Puis, comme un arbitre appelé à

prononcer, il prenait séance entre, d'une part, les austérités du cloître, de

l'autre, les douceurs du siècle et le mariage que lui préparait sa mère ;

alors, tournant les yeux vers la croix du Christ souffrant : «C'est vous,

disait-il, Seigneur, qui êtes mon espérance ; c'est là que vous avez placé pour

moi votre asile très sûr. » Ce fut vers

la congrégation des

chanoines de Saint-Georges in Alga que le porta

sa ferveur. On l'y vit inventer de nouveaux tourments pour sévir plus durement

contre lui-même, se déclarant une guerre d'ennemi acharné,

ne se permettant aucun plaisir. Plus jamais il n'entra dans

le jardin de sa famille, ni dans la maison paternelle, si

ce n'est pour rendre les derniers devoirs à

sa mère mourante, ce qu'il fit sans une larme. Non

moindre était son zèle pour l'obéissance, la douceur,

l'humilité surtout : il allait au-devant des offices les plus

abjects du monastère; il se plaisait à mendier par les lieux les

plus fréquentés de la ville, cherchant moins la nourriture que l'opprobre ; les

injures, les calomnies ne pouvaient l'émouvoir ni lui

l'aire rompre le silence. Son grand secours était

dans la prière continuelle; souvent l'extase

le ravissait en Dieu; telle était l'ardeur dont brûlait son âme, qu'elle

embrasait ses compagnons, les prémunissant contre la défaillance, les

affermissant dans la persévérance et l'amour de

Jésus-Christ.

Élevé par Eugène IV à

l'épiscopat de sa patrie, l'effort qu'il fit pour décliner l'honneur

ne fut dépassé que par le mérite avec lequel il s'acquitta de la

charge. Il ne changea en rien sa manière de vivre, gardant jusqu'à la fin pour

la table, le lit, l'ameublement, la pauvreté qu'il avait toujours pratiquée. Il

ne retenait à ses gages qu'un personnel réduit de familiers, disant qu'il avait

une autre grande famille, par laquelle il entendait les pauvres du Christ.

Quelle que fût l'heure, on le trouvait toujours abordable ; sa paternelle

charité se donnait a tous, n'hésitant pas à s'endetter pour soulager la misère.

Comme on lui demandait sur quelles ressources il comptait, ce faisant, il

répondait : « Sur celles de mon Seigneur, qui pourra facilement payer pour moi.

» Et toujours, par les secours les plus inattendus, la Providence divine

justifiait sa confiance. Il bâtit plusieurs monastères de vierges, et forma

diligemment leurs habitantes à marcher dans les voies de la vie parfaite. Son

zèle s'employa à détourner les matrones vénitiennes des pompes du siècle et des

vaines parures, comme à réformer la discipline ecclésiastique et les mœurs.

Aussi fût-ce à bon droit que le même Eugène IV l'appela, en présence des

cardinaux, la gloire et l'honneur de la prélature. Ce fut

également pour reconnaître son mérite, que le successeur d'Eugène, Nicolas V,

ayant transféré le titre patriarcal de Grado à Venise, l'institua

premier patriarche de cette ville.

Honoré du don des larmes,

il offrait tous les jours au Dieu tout-puissant l'hostie d'expiation. C'est en

s'en acquittant une fois dans la nuit de la Nativité du Seigneur,

qu'il mérita de voir sous l'aspect d'un très bel enfant le Christ

Jésus. Efficace était sa garde autour du bercail à lui confié; un jour, on

sut du ciel que l'intercession et les mérites du Pontife avaient sauvé la

république. Eclairé de l'esprit de prophétie, il annonça d'avance plusieurs

événements que nul homme ne pouvait prévoir. Maintes fois

ses prières mirent en fuite maladies et démons. Bien qu'il n'eût

presque point étudié la grammaire, il a laissé des livres remplis d'une céleste

doctrine et respirant l'amour. Cependant la maladie qui

devait l'enlever de ce monde venait de l'atteindre; ses gens

lui préparaient un lit plus commode pour sa vieillesse et son infirmité ; mais

lui, manifestant sa répulsion pour des délices trop peu

en rapport avec la dure croix de son Seigneur mourant,

voulut qu'on le déposât sur sa couche ordinaire. Sentant venue la fin de sa vie

: « Je viens à vous, ô bon Jésus ! » dit-il, les yeux levés au ciel. Ce fut le

huit janvier qu'il s'endormit dans le Seigneur. Combien sa mort avait été

précieuse, c'est ce qu'attestèrent les concerts angéliques entendus par plu

sieurs Chartreux, et la conservation de son saint corps qui , pendant

plus de deux mois que la sépulture en fut différée, demeura sans

corruption, avec les couleurs de la vie et exhalant un suave parfum. D'autres

miracles suivirent aussi cette mort, lesquels amenèrent le Souverain

Pontife Alexandre VIII à l'inscrire au nombre des Saints. Innocent XII désigna

pour sa fête le cinquième jour de septembre, où il avait été d'abord élevé sur

la chaire des pontifes.

O Sagesse qui résidez sur

votre trône sublime, Verbe par qui tout fut fait, soyez-moi propice dans la

manifestation des secrets de votre saint amour (2). » C'était, Laurent, votre

prière, lorsque craignant d'avoir à répondre du talent caché si vous gardiez

pour vous seul ce qui pouvait profitera plusieurs (3), vous résolûtes de

divulguer d'augustes mystères. Soyez béni d'avoir voulu nous faire partager le

secret des cieux. Par la lecture de vos dévots ouvrages, par votre

intercession près de Dieu, attirez-nous vers les hauteurs comme la

flamme purifiée qui ne sait plus que monter toujours. Pour l'homme, c'est déchoir

de sa noblesse native que de chercher son repos ailleurs qu'en Celui dont il

est l'image (4). Tout ici-bas n'est que pour nous traduire l'éternelle beauté,

nous apprendre à l'aimer, chanter avec nous notre amour (5).

Quelles délices ne furent

pas les vôtres, à ces sommets de la charité, voisins du ciel, où conduisent les

sentiers de la vérité qui sont les vertus (6) ! C'est bien de vous-même en

cette vie mortelle que vous faites le portrait, quand vous dites de l'âme

admise à l'ineffable intimité de la Sagesse du Père : Tout lui profite; où

qu'elle se tourne, elle n'aperçoit qu'étincelles d'amour; au-dessous d'elle, le

monde qu'elle a méprisé se dépense à servir sa flamme; sons, spectacles,

suavités, parfums, aliments délectables, concerts de la terre et rayonnement

des cieux, elle n'entend plus, elle ne voit plus dans la nature entière qu'une

harmonie d'épithalame et le décor de la fête où le Verbe l'a épousée (7).

Oh! puissions-nous marcher comme vous à la divine lumière, vivre

d'union et de désir, aimer plus toujours, pour toujours être aimé davantage.

1. Laurent Justinian. Fasciculus amoris,

cap. XVI.

2. De casto connubio Verbi et animae. Proœmium.

3. Ibid.

4.De castoconnubio Verbi et animae, cap. I.

5. Ibid. cap.

XXV.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

Dom Guéranger, L’Année

liturgique

SOURCE : http://abbaye-saint-benoit.ch/gueranger/anneliturgique/pentecote/pentecote05/012.htm

Portrait de Saint Laurent Justinien, vers 1622, 100 x 74, Madonna dell'Orto

Saint Laurent Justinien:

Histoire et Fête Liturgique

Premier Patriarche de

Venise, + 1455

Date : 1455

Fête : 05 septembre

Pape : Calixte III

Saint Laurent Justinien naquit

à Venise, en 1380, de parents nobles. On remarqua toujours en lui une grandeur

d’âme extraordinaire.

Il ne perdait point son

temps comme les enfants de son âge ; il aimait à s’entretenir avec des

personnes raisonnables, ou à s’occuper de choses sérieuses. Sa pieuse mère

veillait à le prémunir contre l’orgueil, et le portait à ce qu’il y a de plus

parfait.

À l’âge de dix-neuf ans,

il se sentit intérieurement appelé à se consacrer au service du Seigneur d’une

manière particulière ; mais il ne voulut se déterminer qu’après avoir, avec

ferveur, prié Dieu de l’éclairer, et avoir pris l’avis de personnes dignes de

toute confiance.

Il entra d’abord dans la

congrégation des chanoines réguliers de Saint-Georges, dont il devint général,

et qu’il gouverna avec tant de sagesse, en est regardé comme le second

fondateur.

Nommé en 1433 évêque de

Venise, il ne changea rien à la vie qu’il avait menée dans le

cloître. Il distribuait

aux pauvres tous ses revenus, parce qu’un évêque, disait-il, ne doit pas avoir

d’autre famille.

Il réforma les abus qui

s’étaient glissés dans la célébration de l’office divin et dans

l’administration des sacrements, augmenta le nombre des paroisses dans la ville

de Venise, fonda plusieurs monastères, et établit un si bel ordre dans son diocèse,

qu’on le citait pour modèle.

Ses soins s’étendaient

jusqu’aux affaires temporelles de sa patrie, à laquelle il rendit d’importants

services. Il mourut saintement en 1405. Il a laissé des ouvrages précieux pour

la piété.

On lui met souvent la croix

à la main, pour marquer non

seulement sa haute dignité, mais aussi le souvenir

de l’abnégation qu’il professa dès

sa première jeunesse. Parfois, on peint près de lui

la

ville de Venise, d’où il détourne la foudre

que Notre-Seigneur s’apprête à lancer. C’est que ses

prières sauvèrent plus d’une fois celte cité menacée par les fléaux du ciel.

Que peut un saint dans

une haute position ? 1° Son exactitude et sa régularité lui font

toujours trouver du temps pour travailler d’abord à sa propre sanctification et

pour rendre service au prochain. 2° Son humilité et son esprit de

justice l’habituent à recevoir et à traiter avec égards aussi bien le pauvre

que le riche. 3° Sa douceur et sa charité le rendent sensible à

toutes les misères, et il devient le soutien et le consolateur de l’affligé,

quel qu’il soit.

Iconographie

La sainteté de saint Laurent

ayant été attestée par plusieurs miracles

après sa mort, le pape Sixte IV commença à faire

faire les procédures de sa canonisation, qui furent continuées par

les papes Léon X et Adrien VI.

Enfin, le pape

Clément VII donna le décret de sa

béatification en 1524, avec permission d’en faire la fête

et l’office public dans toutes les

églises de la république de Venise.

Longtemps auparavant,

on avait commencé à dresser des autels sous

son nom à Venise, à placer ses statues dans les

Églises, à lui bâtir des chapelles et à

l’invoquer ; on le regardait

déjà comme le protecteur, ou le saint tutélaire de la ville

et de toute la seigneurie, après saint Marc.

En 1597, le

cardinal Laurent Priolo, patriarche de Venise, se disposait

à faire la translation solennelle de ses

reliques, en vertu d’un décret

de la sacrée Congrégation

des Rites, en date du 1ᵉʳ février, quand la mort

du patriarche en fit suspendre l’exécution.

Le pape Clément VIII

accorda, par un bref apostolique, des

indulgences à ceux qui visiteraient les églises

des Chanoines réguliers de la Congrégation de Saint-George d’Alga,

dans toute l’Italie, le jour de la fête de

saint Laurent Justinien.

Son culte fut

introduit en Sicile, et surtout

à Palerme, qui le mit au nombre de ses saints

patrons, parce qu’elle fut

garantie de la peste, en 1626, par son intercession.

Cette dévotion

publique fut autorisée par

un décret de la Congrégation des

Rites, le 26 février 1628.

Saint Laurent fut canonisé le 1ᵉʳ novembre

1690 par le pape Alexandre VIII. Sa fête,

érigée en semi-double dans l’office romain, fut remise

au 5 septembre par ordre du Saint-Siège

et de la Congrégation des Rites.

Ses reliques sont

conservées à Venise dans l’église cathédrale

de Saint-Pierre du Château, et placées

sous le maître-autel.

Saint Laurent Justinien nous a

laissé un grand nombre de traités et de

sermons, recueillis en un fort volume in-folio, imprimé à Bresse

en 1560, et à Venise en 1755.

La meilleure édition que

nous en ayons, est celle qui parut à Venise en 1751, 2 vol.

In-fol. On y trouve une vaste érudition, une

profonde sagesse, beaucoup de véhémence, de force et de

noblesse dans le style.

Oraison

O Dieu, qui traitez vos

peuples avec indulgence et régnez sur eux avec amour, et qui leur donnez pour

les diriger de dignes ministres de votre charité : accordez, nous vous en

supplions, par l’intercession du bienheureux Laurent Justinien, pontife, à

ceux que vous avez placés à la tête de votre Église, l’esprit de sagesse, afin

que le progrès spirituel des ouailles soit la joie éternelle des pasteurs.

Par Jésus-Christ Notre- Seigneur. Ainsi soit-il.

SOURCE : https://www.laviedessaints.com/saint-laurent-justinien/

Svatý Vavřinec Giustiniani. Freska č. 26, kostel Nejsvětější Trojice, Fulnek, Česko, Evropa.

Saint

Lorenzo Giustiniani. Fresco No. 26, Most Holy Trinity Church, Fulnek, Czechia, Europe.

Sankta

Laŭrenco Giustiniani. Fresko n-ro 26, kirko de la Plej Sankta Triunuo, Fulnek, Ĉeĥujo, Eŭropo.

Also

known as

Lawrence Justinian

Laurence…

Laurentius…

Lorenzo…

Patriarch of Venice

formerly 5

September (based on the date of his ordination)

Profile

Born to the Venetian nobility;

his ancestors had fled Constantinople for

political reasons. Against his widowed mother‘s

wishes, he chose against marriage and

for the religious

life. Augustinian canon regular

at San Giorgio, Alga, Italy in 1400.

Spent his days wandering the island, begging for the poor. Ordained in 1406.

Noted preacher and teacher of

the faith.

Held assorted administrative positions within his Order.

Reluctant bishop of Castello, Italy in 1433.

General of the canons regular. Bishop of Grado, Italy in 1451;

the see was

then moved to Venice, Italy,

and Laurence was named archbishop and

patriarch by Pope Nicholas

V. Noted writer on mystical contemplation.

Had the gift of prophecy. Miracle worker.

Born

1

September 1381 at Venice, Italy

8

January 1455 at Venice, Italy of

natural causes

interred at

the basilica of

San Pietro di Castello, Venice

7

October 1524 by Pope Clement

VII

16

October 1690 by Pope Alexander

VIII (approval of canonization)

4 June 1724 by Pope Benedict

XIII (proclamation of canonization)

Additional

Information

Book

of Saints, by the Monks of

Ramsgate

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Alban

Butler

Lives

of the Saints, by Father Francis

Xavier Weninger

Lives

of the Saints, by Sabine Baring-Gould

Roman

Martyrology, 1914 edition

Saints

of the Day, by Katherine Rabenstein

Short

Lives of the Saints, by Eleanor Cecilia Donnelly

books

Lives of the Saints, by Omer Englebert

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Saints

Saints

and Their Attributes, by Helen Roeder

other

sites in english

History of

Giustiniani from Genova

images

video

webseiten

auf deutsch

Die Geschichte

der Giustiniani von Genua

sitios

en español

Historia de

los Giustiniani de Genova

Martirologio Romano, 2001 edición

sites

en français

L’histoire des

Giustiniani de Gênes

fonti

in italiano

Dicastero delle Cause dei Santi

Storia dei Giustiniani di

Genova

Wikipedia: Santi patroni della città di Venezia

nettsteder

i norsk

MLA

Citation

“Saint Lawrence

Giustiniani“. CatholicSaints.Info. 6 April 2024. Web. 10 August 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/saint-lawrence-giustiniani/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/saint-lawrence-giustiniani/

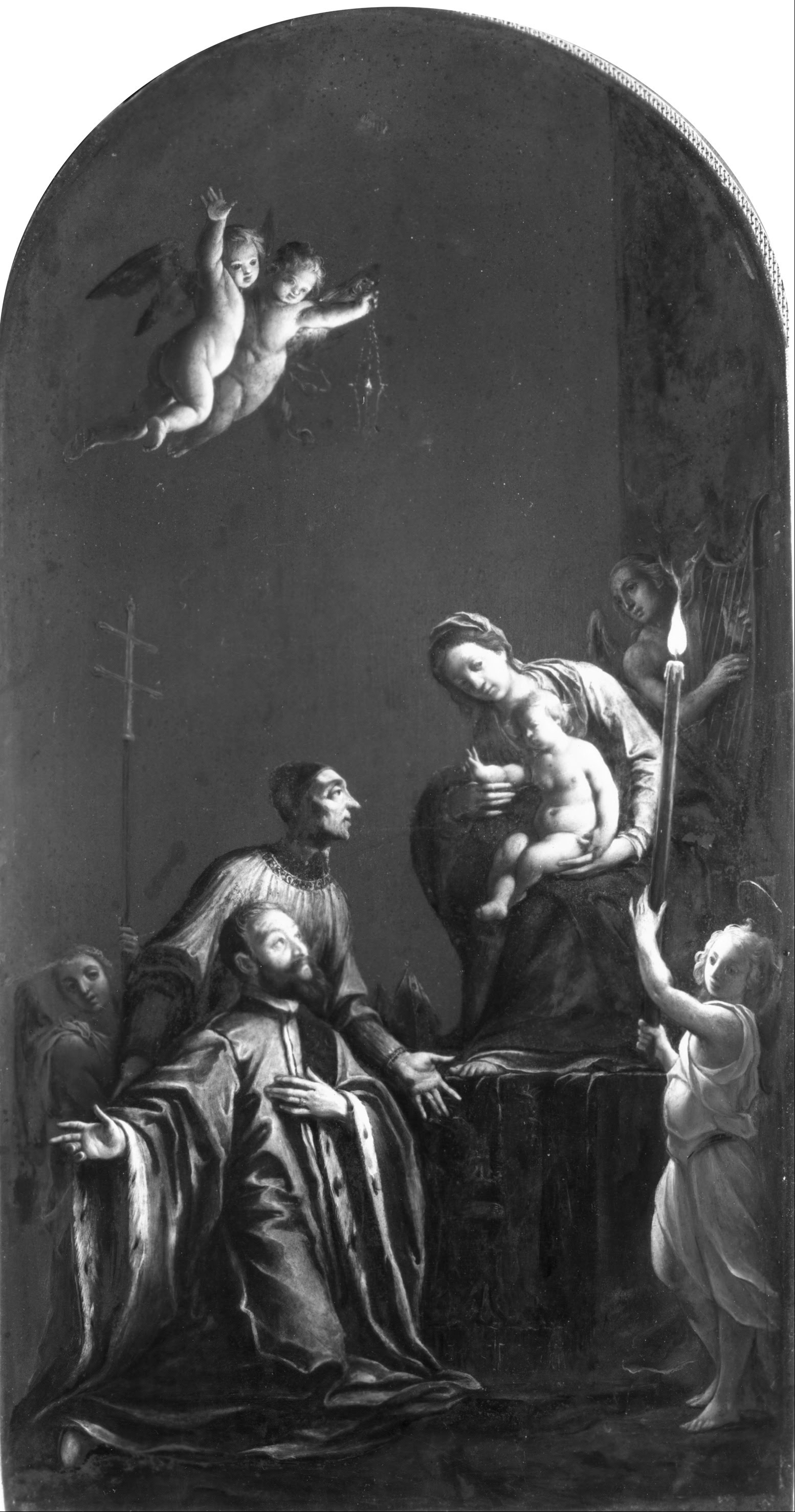

Madonna dell'Orto, Venice Interior.

Chapel Vendramin . St. Vincent between Saints Dominic Lawrence

giustiniani, Elena and Pope Eugene IV by Palma

il Vecchio (1480-1528). Two of the characters (St. Helen and St. Dominic)

were added during the restoration carried out in 1867 by Placido

Fabris

Église de la Madonna dell'Orto à

Venise, vue de la chapelle Vendramin - Saint Vincent entre Saints

Dominique Laurent Giustiniani, Hélène et le pape Eugène IV par Palma

le Vieux. Deux des personnages (Sainte-Hélène et Saint-Dominique) ont été

ajoutés au cours de la restauration effectuée en 1867 par Placido Fabris.

Chiesa della Madonna dell'Ortoa Venezia,

interno. La Cappella Vendramin - San Vincenzo fra i santi Domenico,

Lorenzo giustiniani, Elena e papa Eugenio IV di Palma il Vecchio. Due delle figure (S.Elena e

S.Domenico) sono state inserite nel corso di restauri eseguiti nel 1867

da Placido Fabris.

Book of Saints –

Laurence Justiniani

Article

(Saint) Bishop (January

8) (15th

century) A scion of a noble Venetian family who, at the age of nineteen,

being already favoured with the grace of supernatural prayer,

joined the austere Congregation of the Canons Regular of Saint Giorgio in Alga,

of which in due time he became the General. Pope Eugene

IV (A.D. 1433)

compelled him to accept the Bishopric of Venice, of which city he became the

first Patriarch, when that dignity was transferred from Grado to Venice

(A.D. 1451). Saint Laurence,

by his zeal for the salvation of the souls committed to his charge, was the

model of the Prelates of his age; but his private life was ever one of penance

and high prayer.

His writings on

Mystical Contemplation are sublime in their simplicity. He died mourned

by all, January 8, A.D. 1455,

at the age of seventy-four, and was canonised A.D. 1690.

MLA

Citation

Monks of Ramsgate.

“Laurence Justiniani”. Book of Saints, 1921. CatholicSaints.Info.

11 August 2018. Web. 10 August 2025.

<https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-laurence-justiniani/>

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/book-of-saints-laurence-justiniani/

Pictorial

Lives of the Saints – Saint Laurence Giustiniani

Laurence

from a child longed to be a Saint; and when he was nineteen years of age there

was granted to him a vision of the Eternal Wisdom. All earthly things paled in

his eyes before the ineffable beauty of this sight, and as it faded away a void

was left in his heart which none but God could fill. Refusing the offer of a

brilliant marriage, he fled secretly from his home at Venice, and joined the

Canons Regular of Saint George. One by one he crushed every natural instinct

which could bar his union with his Love. When Laurence first entered religion,

a nobleman went to dissuade him from the folly of thus sacrificing every earthly

prospect. The young monk listened patiently in turn to his friend’s

affectionate appeal, scorn, and violent abuse. Calmly and kindly he then

replied. He pointed out the shortness of life, the uncertainty of earthly

happiness, and the incomparable superiority of the prize he sought to any his

friend had named. The nobleman could make no answer; he felt in truth that

Laurence was wise, himself the fool. He left the world, became a fellow-novice,

with the Saint, and his holy death bore every mark that he too had secured the

treasures which never fail. As superior and as general, Laurence enlarged and

strengthened his Order, and as bishop of his diocese, in spite of slander and

insult, thoroughly reformed his see. His zeal led to his being appointed the first

patriarch of Venice, but he remained ever in heart and soul an humble priest

thirsting for the sight of heaven. At length the eternal vision began to dawn.

“Are you laying a bed of feathers for me?” he said. “Not so; my Lord was

stretched on a hard and painful tree.” Laid upon the straw, he exclaimed in

rapture, “Good Jesus, behold I come.” He died 1435, aged seventy-four.

Reflection – Ask Saint

Laurence to vouchsafe you such a sense of the sufficiency of God that you too

may fly to Him and be at rest.

SOURCE : https://catholicsaints.info/pictorial-lives-of-the-saints-saint-laurence-giustiniani/

Laurence Giustiniani

(Lawrence Justinian) B (RM)

Born at Venice, Italy, July 1, 1381; died in Venice on January 8, 1456;

canonized in 1670; feast day formerly January 8; September 4 was the date of

his episcopal consecration.

Saint Laurence was born into a prominent Venetian family that had produced

important scholars, statesmen, prelates, and saints. Although his father,

Bernard Giustiniani, died while he was still young, his pious mother lived only

for her children and ensured they had an excellent education. From the cradle

she recognized in Laurence an uncommon docility and generosity of soul that

might point to a religious vocation, yet she desired to keep him for herself.

When he was 19, Laurence had a vision of the Eternal Wisdom in the guise of a

maiden encircled with light. She invited him to seek her with happiness, rather

than satiate his baser lusts. The youth confided his vision to his uncle,

Marino Querino, an Augustinian canon of San Giorgio on Alga Island one mile

from Venice. Don Querino recommended that he take on the austerities of a monk

at home, that is, try on the role of a religious by putting aside honors,

riches, and worldly pleasures, before entering religious life. His mother

feared he would damage his health and tried to divert him by arranging a

marriage.

Heeding his uncle's advice, he refused his mother's wish for him to marry and

instead joined Querino in the monastery. As a young monk, he practice the most

severe austerities and went about the city with a sack over his should to beg

alms and food for the community. In 1406, Laurence was ordained to the

priesthood and made prior of San Giorgio. His deep prayer life that often led

to raptures and his spirit of penance provided him with experiential knowledge

of the paths of the interior life and a wonderful ability to direct souls. The

tears that he shed while offering Mass strongly affected all who assisted and

awakened in them a renewed faith.

Thereafter he was general of the congregation, which at the time of his entry

into the position had adopted a different rule. Laurence completed this rule by

writing its constitutions, so that he became its second founder of this

congregation of secular canons. He also preached widely during this time and

taught theology.

In 1433, Pope Eugene IV forced Laurence to accept the see of Castello, which

then included part of Venice in its diocesan boundaries. He would not be

persuaded by the saint to change his mind and appoint a worthier bishop. He

took possession of his cathedral so quietly that his own friends knew nothing

about it until after the ceremony was complete. He was impatient with the

temporal administration of his diocese, and delegated this work to others so

that he might be free to personally look after his flock. In 1451, Pope

Nicholas suppressed the see of Castello and transferred the patriarchal title

of Grado to Venice with Laurence as archbishop.

The senate of the Venetian Republic, wary that this change might lead to a

diminution of its prerogatives, began a debate over Laurence's jurisdiction.

Laurence sought an audience with the assembled senate and declared his desire

to resign a charge for which he was unfit, rather than to feel his burden

increased by this additional dignity. His bearing so strongly affected the

whole senate that the doge himself asked him not to entertain such a thought or

to raise any obstacle to the pope's decree, and he was supported by the whole

assembly. Laurence therefore accepted the new office and continually acted in

such way that his reputation for goodness and charity increased.

He drew from his prayer life the light, vigor, and courage to direct the

diocese as easily as if it had been a single, well- regulated monastery. As

bishop of the Jewel of the Adriatic, Laurence did a great deal to restore Saint

Mark's and other churches; he also enhanced the beauty of the service. He added

parishes, tried to elevate the pastoral work, and to inspire both the secular

and the cloistered clergy with his zeal. Not only was he known for his piety,

but also for his ability as a peace maker, his spiritual knowledge, and his

gifts of prophecy and miracles. He overcame opposition by meekness and

patience. Under his direction, the whole spirit of the diocese was changed;

crowds flocked to him for spiritual and material aid.

He was of a boundless generosity toward the poor and needy, and stinted himself

as regards his dwelling, table, and dress to a point which the strictest orders

could not surpass. It is interesting to note that he rarely gave monetary aid

except in small amounts because he thought it might be ill-spent. In fact, when

a relative asked him for a dowry for his daughter, he replied: "A little

is not enough for you; and if I gave you much, I would be robbing the

poor." Nevertheless he was open-handed with food and clothes. He even

employed married women to seek out those who might need relief but who were too

bashful to ask for it.

The writings of Saint Laurence on mystical contemplation, especially The

degrees of perfection, are sublime in their simplicity. They are practical, not

speculative, and intended to assist the clergy. He had just finished The

degrees of perfection when he was seized with a sharp fever. As he lay dying,

someone tried to give him a featherbed, but he refused it, saying: "My

Savior did not die on a featherbed, but upon the hard wood of the Cross."

He was troubled and restless until they laid him on straw.

The saint had no will to make, because he no longer possessed anything of which

he could have disposed. During the two days of his illness after he received

the last sacraments, many of the city came to receive his blessing. He insisted

that the beggars be admitted, as well as the elite, and gave to each a short,

final instruction.

Laurence was venerated by popes even in his lifetime. When Eugene IV met him

once in Bologna, he greeted Laurence: "Welcome, ornament of bishops!"

The saint's nephew and biographer, Bernardo Giustiniani, relates that the

corpse remained 67 days without burial. He emphasizes that it was on view for

the multitudes that came from afar, and that doctors examined the body and

could give no explanation for its incorrupted state (Benedictines, Bentley,

Delaney, Schamoni, Walsh).

In art, Saint Laurence is best recognized by his face, which is typically

Venetian: thin, long-nosed, and austere. He has dark, hollow eyes, and an

ascetic, rather Dantesque mouth. Laurence seldom wore the grandiose insignia of

a bishop. Most often he is portrayed in a severe Venetian gown and

close-fitting cap. He may also be shown (1) distributing the vessels of the

Church during a famine; (2) as an episcopal cross and banner are carried in

front of him and a mitre carried behind him; (3) holding a book, his hand

raised to bless; or (4) giving alms (Roeder).

SOURCE : http://www.saintpatrickdc.org/ss/0905.shtml

Lorenzo : Giustiniani. De disciplina et perfectione monastica

conversationis. Dottrina della vita monastica. - [Venezia] :

[Bernardino Benali], Anno MCCCCLXXXXIIII […] a XX de octobrio del anno supra

notato. - 114 c. ; [a-n⁸, o¹⁰] ; 4º. - Alcune copie hanno il titolo

stampato sopra l'incisione a c. 1r (BMC) Anno MCCCCLXXXXIIII […] a XX de

octobrio del anno supra notato AD

St. Lawrence Justinian

Bishop and

first Patriarch of Venice,

b. in 1381, and d. 8 January, 1456. He was a descendant of the Giustiniani,

a Venetian patrician family which

numbered several saints among

its members. Lawrence's pious mother

sowed the seeds of a devout religious

life in the boy's youth. In 1400 when he was about nineteen years old,

he entered the monastery of

the Canons

Regular of St. Augustine on the Island of Alga near Venice.

In spite of his youth he excited admiration by his poverty, mortifications,

and fervour in prayer.

At that time the convent was

changed into a congregation of secular canons living in community. After his ordination in

1406 Lawrence was chosen prior of

the community, and shortly after that general of the congregation. He gave them

their constitution, and was so zealous in

spreading the same that he was looked upon as the founder. His reputation for

saintliness as well as his zeal for souls attracted

the notice of Eugene

IV and on 12 May, 1433, he was raised to the Bishopric of Castello.

The newprelate restored

churches, established new parishes in Venice,

aided the foundation of convents,

and reformed the life of the canons. But above all he was noted for his Christian

charity and his unbounded liberality. All the money he could raise he

bestowed upon the poor,

while he himself led a life of simplicity and poverty. He was greatly respected

both in Italy and

elsewhere by the dignitaries of both Church

and State. He tried to foster the religious

life by his sermons as

well as by his writings. The Diocese

of Castello belonged to the Patriarchate of Grado. On 8 October,

1451, Nicholas

V united the See

of Castello with the Patriarchate of Grado, and the see of

the patriarch was transferred to Venice,

and Lawrence was named the first Patriarch of Venice,

and exercised his office till his death somewhat more than four years later.

His beatification was

ratified by Clement

VII in 1524, and he was canonized in

1690 by Alexander

VIII. Innocent

XII appointed 5 September for the celebration of his feast.

The saint's ascetical writings

have often been published, first in Brescia in

1506, later in Paris in

1524, and in Basle in 1560, etc. We are indebted to his nephew, Bernardo

Giustiniani, for his biography.

Sources

BERNARDUS

JUSTINIANUS, Opusculum de vita beati Laurentii Justiniani (Venice,

1574); SURIUS, De vitis sanctorum, ed. 1618, I, 126-35; Acta SS.,

January, I, 551-63; Bibliotheca hagiographica latina, ed. BOLLANDISTS, II,

1708; Bullarium Romanum, ed. TAURIN., V, 107 sqq.; EUBEL, Hierarchia

catholica medii aevi, II, 134-290; ROSA, Summorum Pontificum, illustrium

virorum . . . de b. Laurentii Justiniani vita, sanctitate ac miraculis

testimoniorum centuria (Venice, 1614); BUTLER, Lives of the Saints,

III (Baltimore, 1844), 416-422; REGAZZI, Note storiche edite ed inedite di

S. Lorenzo Giustiniani (Venice, 1856); CUCITO, S. Lorenzo

Giustiniani, primo patriarca di Venezia (Venice, 1895).

Kirsch, Johann

Peter. "St. Lawrence Justinian." The Catholic

Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton

Company, 1910. 8 Jan.

2018 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09091a.htm>.

Transcription. This

article was transcribed for New Advent by Herman F. Holbrook. O Saint

Lawrence, and all ye holy Pastors, pray for us.

Ecclesiastical approbation. Nihil

Obstat. October 1, 1910. Remy Lafort, Censor. Imprimatur. +John

M. Farley, Archbishop of New York.

Copyright © 2021 by Kevin

Knight. Dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

SOURCE : http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09091a.htm

_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall'Orto%2C_8-Dec-2007.jpg)

Plaque to Lorenzo Giustiniani (1551) in the

Giustiniani chapel inside the church of San Francesco della Vigna in Venice. Picture by Giovanni Dall'Orto, December 8 2007.

Saint Laurence

Giustiniani

Jul 10, 2015 /

Written by: America

Needs Fatima

Feast September 5

Laurence was born of

noble parentage in Venice in 1381. His father having died when Laurence was

still very young, his mother was left a widow at a very young age indeed.

Rejecting any thoughts of

remarrying, she resolutely turned her attention to her own sanctification and

her young children’s early training in the practice of virtue.

In this she was aided by

Laurence’s innate attraction to all that pertained to God, an inclination of

soul he demonstrated from his most tender years. Devoting herself to her

children and to works of charity, fasting, assiduous prayer and her own

mortification, the young widow was nevertheless perturbed by the extreme

severity with which her son treated his body and the continual application of

his mind to the exercises of religion.

Religious Life and the

Priesthood

In his nineteenth year,

she endeavored to divert him from this course by arranging a marriage for him.

However, having consulted a reliable spiritual director, prayed earnestly and

humbly for light and guidance, and tested his own resolve in the matter,

Laurence fled secretly to the monastery of St. George in Alga, on an island

situated a mile from Venice.

Here, even his superiors

in this austere congregation judged it necessary to mitigate the rigor of his

penances as Laurence at nineteen easily surpassed all his religious brethren in

his fasts and prayerful vigils.

He was ordained to the

priesthood in 1406, and much against his will, he was chosen general of the

Order, which he governed with exemplary prudence and sanctity. The first thing

in which he labored to ground his religious brothers was a profound and sincere

humility by which the soul places entire confidence in God alone, the only

source of the soul’s strength.

Bishop of Venice

In the year 1433 Pope

Eugenius IV obliged Laurence to quit his cloister by appointing him to the

episcopal see of Venice. His wisdom, goodness and charity drew crowds of people

to him and his humility dissolved all forms of contention and disagreement even

among the most proud. The salutary affect of his discourses and example worked

as effectively among his people as it had in the confines of his cloister with

his brethren: he animated the tepid, filled the presumptuous with a holy fear,

raised the fearful to confidence, and inflamed the fervor of all.

On one occasion, overcome

by admiration for his sanctity, Pope Eugenius IV saluted Laurence as “the

ornament of bishops.” His successor, Nicholas V, in consideration of his

sanctity and virtue, transferred the patriarchal dignity from the see of Grado

to that of Venice in 1451, making Laurence the first Patriarch of Venice.

A Humble Patriarch

Notwithstanding the

dignity this would confer upon the commonwealth of Venice, the Venetian Senate

contested it, only embracing it after the bishop personally pleaded with the

senators to reject the honor, attesting his willingness to put aside the weight

of the office he had carried unworthily for eighteen years rather than to feel

his burden increased by the additional dignity.

His pure humility and

charity so strongly affected the whole senate that the Doge himself was not

able to refrain from tears, and he entreated Laurence to desist from raising

any obstacle to the pope’s decree. The installation of the new patriarch was

subsequently celebrated with great joy by the entire city.

Laurence died in 1455 at

the age of seventy-four. Before his death, he personally gave blessings to all

those who had come to visit him in his illness. Canonized in 1690, St. Laurence

is also revered for his great works on mystical contemplation.

SOURCE : https://americaneedsfatima.org/articles/saint-laurence-giustiniani

Tiburzio

Passarotti, L'elezione di san Lorenzo Giustiniani al Patriarcato di

Venezia, vers 1585

St.

Laurence Justinian, Bishop and Confessor

From his original Life

written by his nephew, Bernard Justinian, in Bollandus, Jan. 8, and from his

Italian Life, elegantly compiled by F. Maffei. See also Helyot, Hist. des Ord.

Relig. t. 2, p. 359; and Opera S. Laurentii Justiniani, Proto-Patriarchæ

Venetiarum, published by F. Nicolas Antony Justiniani, a Benedictin monk, at

Venice, in two volumes, 1756.

A.D. 1455.

[First Patriarch of

Venice.] ST. LAURENCE was born at Venice, in 1380. His

father Bernardi Justiniani 1 held

an illustrious rank among the prime nobility of the commonwealth; nor was the

extraction of his mother Querini less noble. By the death of Bernardo she was

left a disconsolate widow with a nursery of tender children; though very young,

she thought it her duty to sanctify her soul by the great means and advantages

which her state afforded for virtue, and resolutely rejected all thoughts of

any more altering her condition. She looked upon herself as called by her very

state to a penitential and retired life, and devoted herself altogether to the

care of her children’s education, to works of charity, fasting, watching,

assiduous prayer, and the exercises of all virtues. Under her inspection her

children were brought up in the most perfect maxims of Christian piety.

Laurence discovered, even from the cradle, an uncommon docility, and an

extraordinary generosity of soul; and disdaining to lose any part of his time,

loved only serious conversation and employs. His mother fearing some spark of

pride and ambition, chid him sometimes for aiming at things above his age; but

he humbly answered that it was his only desire, by the divine grace, to become

a saint. Reflecting from his infancy that he was made by God only to serve him,

and to live eternally with him, he kept this end always in view, and governed

all his thoughts and actions so as to refer them to God and eternity.

In the nineteenth year of

his age he was called by God to consecrate himself in a special manner to his

service. He seemed one day to see in a vision the eternal wisdom in the

disguise and habit of a damsel, shining brighter than the sun, and to hear from

her the following words: “Why seekest thou rest to thy mind out of thyself, sometimes

in this object, and sometimes in that? What thou desirest is to be found only

with me: behold, it is in my hands. Seek it in me who am the wisdom of God. By

taking me for thy spouse and thy portion, thou shalt be possessed of its

inestimable treasure.” That instant he found his soul so pierced with the

charms, incomparable honour, and advantages of this invitation of divine grace,

that he felt himself inflamed with new ardour to give himself up entirely to

the search of the holy knowledge and love of God. 2 A

religious state appeared to him that in which God pointed out to him the path

in which he might most securely attain to the great and arduous end which he

proposed to himself. But, before he determined himself, he make his application

to God by humble prayer, and addressed himself for advice to a holy and learned

priest called Marino Querini, who was his uncle by the mother’s side, and a

regular canon in the austere Congregation of St. George in Alga, established in

a little isle which bears that name, situate a mile from the city of Venice,

towards the continent. 3 The

prudent director, understanding that he was most inclined to a religious state,

advised him first to make trial of his strength, by inuring himself to the

habitual practice of austerities. Laurence readily obeyed, and in the night,

leaving his soft bed, lay on knotty sticks on the floor. During this deliberation,

he one day represented to himself on one side honours, riches, and worldly

pleasures, and on the other, the hardships of poverty, fasting, watching, and

self-denial. Then said to himself: “Hast thou courage, my soul, to despise

these delights, and to undertake a life of uninterrupted penance and

mortification?” After standing some time in a pause, he cast his eyes on a

crucifix, and said: “Thou, O Lord, art my hope.” In this tree are found comfort

and strength. The ardour of his resolution to walk in the narrow path of the

cross, showed itself in the extreme severity with which he treated his body,

and the continual application of his mind to the exercises of religion. His

mother and other friends, fearing lest his excessive mortifications should

prove prejudicial to his health, endeavoured to divert him from that course,

and, with that view, contrived a proposal of an honourable match to be made

him. The saint perceiving in this stratagem that his friends had entered into a

conspiracy to break his measures, fled secretly to the monastery of St. George

in Alga, and was admitted to the religious habit.

By the change of his

state he found no new austerities which he had not before practised; his

superiors even judged it necessary to mitigate the rigours which he exercised

upon himself. He was only nineteen years of age, but surpassed in his watchings

and fasts all his religious brethren. To make a general assault upon sensuality

he never took any useless recreation, subdued his body by severe discipline,

and never came near a fire in the sharpest weather in winter, though his hands

were often benumbed with cold; he allowed to hunger only what the utmost

necessity required, and never drank out of meals; when asked to do it under

excessive heats and weariness, he used to say: “If we cannot bear this thirst,

how shall we endure the fire of purgatory?” From the same heroic disposition

proceeded his invincible patience in every kind of sickness. During his

novitiate he was afflicted with dangerous scrofulous swellings in his neck. The

physicians prescribed cupping, lancing, and searing with fire. Before the

operation, seeing others tremble for his sake, he courageously said to them:

“What do you fear? Let the razors and burning irons be brought in. Cannot he

grant me constancy, who not only supported but even preserved from the flames

the three children in the furnace?” Under the cutting and burning he never so

much as fetched a sigh, and only once pronounced the holy name of Jesus. In his

old age, seeing a surgeon tremble who was going to make a ghastly incision in a

great sore in his neck, he said to him: “Cut boldly, your razor cannot exceed

the burning irons of the martyrs.” The saint stood the operation of this

timorous surgeon without stirring, and as if he had been a stock that had no

feeling. At all public devotions he was the first in the church, and left it

the last; he remained there from matins, whilst others returned to their rest,

till they came to prime at sunrise.

Humiliations he always

embraced with singular satisfaction. The meanest and most loathsome offices,

and the most tattered habit were his desire and delight. The beck of any

superior was to him as an oracle; even in private conversation he was always

ready to yield to the judgment and will of others, and he sought every where

the lowest place as much as was possible to be done without affectation. When

he went about the streets begging alms with a wallet on his back, he often

thrust himself into the thickest crowds, and into assemblies of the nobility,

that he might meet with derision and contempt. Being one day put in mind, that

by appearing loaded with his wallet in a certain public place, he would expose

himself to the ridicule of the company, he answered to his companion: “Let us

go boldly in quest of scorn.” We have done nothing if we have renounced the

world only in words. Let us to-day triumph over it with our sacks and crosses.

Nothing is of greater advantage towards gaining a complete victory over

ourselves, and the fund of pride which is our greatest obstacle to virtue, than

humiliations accepted and borne with cheerfulness and sincere humility. To

those which providence daily sends us opportunities of, it is expedient to add

some that are voluntary, provided the choice be discreet, and accompanied with

heroic dispositions of soul, clear of the least tincture of affectation or

hypocrisy. Our saint frequently came to beg at the house where he was born, but

only stood in the street before the door, crying out: “An alms for God’s sake.”

His mother never failed to be exceedingly moved at hearing his voice, and to

order the servants to fill his wallet. But he never took more than two loaves,

and wishing peace to those who had done him that charity, departed as if he had

been some stranger. The store-house, in which were laid up the provisions of

the community for a year, happening to be burned down, St. Laurence hearing a

certain brother lament for the loss, said cheerfully: “Why have we embraced and

vowed poverty? God has granted us this blessing that we may feel it.” Thus he

discovered his ardour for suffering the humiliations, hardships, and

inconveniences of that state, for the exercise and improvement of the heroic

virtues of which they afford the occasions, and in which consists its chief

advantages. When he first renounced the world, as often as he felt a violent

inclination to justify or excuse himself, (so natural to the children of Adam,

upon being unjustly reprehended or injured,) in order to repress it, he used to

bite his tongue; and he at length obtained a perfect mastery over himself in

this particular. Whilst he was superior, he was one day rashly accused in

chapter of having done something against the rule. The saint could have easily

confuted the slander, and given a satisfactory account of his conduct; but he

rose instantly from his seat, and walking gently, with his eyes cast down, into

the middle of the chapter-room, there fell on his knees, and begged penance and

pardon of the fathers. The sight of his astonishing humility covered the

accuser with such confusion and shame, that he threw himself at the saint’s

feet, proclaimed him innocent, and loudly condemned himself.

St. Laurence so much

dreaded the danger of worldly dissipation breaking in upon his solitude, that

from the day on which he first entered the monastery, to that of his death, he

never set foot in his father’s house, only when with dry eyes he assisted his

mother and brothers on their death-beds. Some months after his retreat from the

world, a certain nobleman who had been his intimate friend, and then filled one

of the first dignities in the commonwealth, returning from the East, and

hearing of the state he had embraced, determined to use all his endeavours to

change his purpose. With this design he went to St. George’s with a band of

musicians, and, on account of his dignity, got admittance; but the issue of the

interview proved quite contrary to his expectation. Upon the first sight of the

new soldier of Christ he was struck by the modesty of his countenance, and the gravity

and composure of his person, and stood for some time silent and astonished.

However, at length offering violence to himself he spoke, and both by the

endearments of the most tender friendship, and afterwards by the sharpest

reproaches and invectives, undertook to shake the resolution of the young

novice. Laurence suffered him to vent his passion: then with a cheerful and

mild countenance he discoursed in so feeling a manner on death and the vanity

of the world, that the nobleman was disarmed, and so penetrated with

compunction, that cutting off all his worldly schemes he resolved upon the spot

to embrace the holy rule which he came to violate; and the fervour with which

he went through the novitiate, and persevered to his death in this penitential

institute, was a subject of admiration and edification to the whole city.

St. Laurence was promoted

to the priesthood, and the fruit of the excellent spirit of prayer and

compunction with which he was endowed was a wonderful experimental knowledge of

spiritual things, and of the paths of interior virtue, and a heavenly light and

prudence in the direction of souls. The tears which he abundantly shed at his

devotions, especially whilst he offered the adorable sacrifice of the mass,

strongly affected all the assistants, and awakened their faith; and the

raptures with which he was favoured in prayer were wonderful, especially in

saying mass one Christmas-night. Much against his inclination he was chosen

general of his Order, which he governed with singular prudence, and

extraordinary reputation for sanctity. He reformed its discipline in such a

manner as to be afterwards regarded as its founder. Even in private

conversation he used to give pathetic lessons of virtue, and that sometimes in

one short sentence; and such was the unction with which he spoke on spiritual

matters in private discourses, as to melt the heart of those who heard him. By

his inflamed entertainments he awaked the tepid, filled the presumptuous with

saving fear, raised the pusillanimous to confidence, and quickened the fervour

of all. It was his usual saying, that a religious man ought to tremble at the

very name of the least transgression. He would receive very few into his Order,

and these thoroughly tried, saying, that a state of such perfection and

obligations is only for few, and its essential spirit and fervour are scarcely

to be maintained in multitudes; yet in these conditions, not in the number of a

religious community, its advantages and glory consist. It is not therefore to

be wondered at that he was very attentive and rigorous in examining and trying

the vocation of postulants. The most sincere and profound humility was the

first thing in which he laboured to ground his religious disciples, teaching

them that it not only purges the soul of all lurking pride, but also that this

alone inspires her with true courage and resolution, by teaching her to place

her entire confidence in God alone, the only source of her strength. Whence he

compared this virtue to a river which is low and still in summer, but loud and

high in winter. So, said he, humility is silent in prosperity, never elated or

swelled by it; but it is high, magnanimous, and full of joy and invincible

courage under adversity. He used to say, that there is nothing in which men

more frequently deceive themselves than humility; that few comprehend what it

is, and they only truly possess it who, by strenuous endeavours, and an

experimental spirit of prayer, have received this virtue by infusion from God.

That humility which is required by repeated acts is necessary and preparatory

to the other; but this first is always blind and imperfect. Infused humility

enlightens the soul in all her views, and makes her clearly see and feel her

own miseries and baseness; it gives her perfectly that true science which

consists in knowing that God alone is the great All, and that we are nothing.

The saint never ceased to

preach to the magistrates and senators in times of war and all public

calamities, that, to obtain the divine mercy, and the remedy of all the evils

with which they were afflicted, they ought, in the first place, to become

perfectly sensible that they were nothing; for, without this disposition of

heart they could never hope for the divine assistance. His confidence in God’s

infinite goodness and power accordingly kept pace with his humility and entire

distrust in himself, and assiduous prayer was his constant support. From the

time he was made priest he never failed saying mass every day, unless he was

hindered by sickness; and he used to say, that it is a sign of little love if a

person does not earnestly endeavour to be united to his Saviour as often as he

can. It was a maxim which he frequently repeated, that for a person to pretend

to live chaste amid softness, ease, and continual gratifications of sense, is

as if a man should undertake to quench fire by throwing fuel upon it. He often

put the rich in mind, that they could not be saved but by abundant alms-deeds.

His discourses consisted more of effective amorous sentiments than of studied

thoughts; which sufficiently appears from his works. 4

Pope Eugenius IV. being

perfectly acquainted with the eminent virtue of our saint, obliged him to quit

his cloister, and nominated him to the episcopal see of Venice in 1433. The

holy man employed all manner of entreaties and artifices to prevent his

elevation, and engaged his whole Order to write in the same strain, in the most

pressing manner, to his Holiness: but to no effect. When he could no longer

oppose the repeated orders of the pope, he acquiesced with many tears; but such

was his aversion to pomp and show, that he took possession of his church so

privately that his own friends knew nothing of the matter till the ceremony was

over. The saint passed that whole night in the church at the foot of the altar,

pouring forth his soul before God, with many tears; and he spent in the same

manner the night which preceded his consecration. He was a prelate, says Dr.

Cave, 5 admirable

for his sincere piety towards God, the ardour of his zeal for the divine

honour, and the excess of his charity to the poor. In this dignity he remitted

nothing of the austerities which he had practised in the cloister, and from his

assiduity in holy prayer he drew a heavenly light, an invincible courage, and

indefatigable vigour which directed and animated him in his whole conduct, and

with which he pacified the most violent public dissensions in the state, and

governed a great diocess in the most difficult times, and the most intricate

affairs, with as much ease as if it had been a single well regulated convent.

Though he was bishop of

so distinguished a see, in the ordering of his household he consulted only

piety and humility; and when others told him that he owed some degree of state

to his illustrious birth, to the dignity of his church, and to the

commonwealth, his answer was, that virtue ought to be the only ornament of the

episcopal character, and that all the poor of the diocess composed the bishop’s

family. His household consisted only of five persons; he had no plate, making

use only of earthen ware; he lay on a scanty straw bed covered with a coarse

rag, and wore no clothes but his ordinary purple cassock. His example, his

severity to himself, and the affability and mildness with which he treated all

others, won every one’s heart, and effected with ease the most difficult

reformations which he introduced both among the laity and clergy. The flock loved

and respected too much so holy and tender a parent and pastor not to receive

all his ordinances with docility and the utmost deference. When any private

persons thwarted or opposed his pious designs, he triumphed over their

obstinacy by meekness and patience. A certain powerful man who was exasperated

at a mandate the zealous bishop had published against stage entertainments,

called him a scrupulous old monk, and endeavoured to stir up the populace

against him. Another time, an abandoned wretch reproached him in the public

streets as a hypocrite. The saint heard them without changing his countenance,

or altering his pace. He was no less unmoved amidst commendations and applause.

No sadness or inordinate passions seemed ever to spread their clouds in his

soul, and all his actions demonstrated a constant peace and serenity of mind

which no words can express. By the very first visitation which he made, the

face of his whole diocess was changed. He founded fifteen religious houses, and

a great number of churches, and reformed those of all his diocess, especially

with regard to the most devout manner of performing the divine office, and the

administration of the sacraments. Such was the good order and devotion he

established in his cathedral, that it was a model to all Christendom. The

number of canons that served it being too small, St. Laurence founded several

new canonries in it, and also in many other churches; and he increased the

number of parishes in the city of Venice from twenty to thirty.

It is incredible what

crowds every day resorted to the holy bishop’s palace for advice, comfort, or

alms; his gate, pantry, and coffers were always open to the poor. He gave alms

more willingly in bread and clothes than in money, which might be ill spent;

when he gave money it was always in small sums. He employed pious matrons to

find out and relieve the bashful poor, or persons of family in decayed

circumstances. In the distribution of his charities, he had no regard to flesh

and blood. When a poor man came to him, recommended by his brother Leonard, he

said to him: “Go to him who sent you, and tell him, from me, that he is able to

relieve you himself.” No man ever had a greater contempt of money than our

saint. He committed the care of his temporals to a faithful steward, and used

to say, that it is an unworthy thing for a pastor of souls to spend much of his

precious time in casting up farthings.

The popes held St.

Laurence in great veneration. Eugenius IV. having ordered our holy bishop to

give him a meeting once at Bologna, saluted him in these words: “Welcome the

ornament of bishops.” His successor, Nicholas V., earnestly sought an

opportunity of giving him some singular token of his particular esteem; when

Dominic Michelli, patriarch of Grado, happened to die in 1451, 6 his

holiness, barely in consideration of the saint, transferred the patriarchal

dignity to the see of Venice. The senate, always jealous of its prerogatives

and liberty above all other states in the world, formed great difficulties lest

such an authority should in any cases trespass upon their jurisdiction. Whilst

this affair was debated in the senate-house, St. Laurence repaired thither,

and, being admitted, humbly declared his sincere and earnest desire of rather

resigning a charge for which he was most unfit, and which he had borne against

his will eighteen years, than to feel his burden increased by this additional

dignity. His humility and charity so strongly affected the whole senate, that

the doge himself was not able to refrain from tears, and cried out to the

saint, conjuring him not to entertain such a thought, or to raise any obstacle

to the pope’s decree, which was expedient to the church, and most honourable to

their country. In this he was seconded by the whole house, and the ceremony of

the installation of the new patriarch was celebrated with great joy by the

whole city.

St. Laurence, after this

new exaltation, considered himself as bound by a new tie to exert his utmost

strength in labouring for the advancement of the divine honour, and the

sanctification of all the souls committed to his care. Nor did it perhaps ever

appear more sensible than in this zealous prelate, how much good a saint, when

placed in such a station, is, with the blessing of heaven, capable of doing;

nor how much time a person is able to find for himself and the service of his

neighbour, who husbands all his moments to the best advantage, and is never

taken up with any inordinate care of his body, or gratification of self-love.

St. Laurence never, on his own account, made any one wait to speak to him, but

immediately interrupted his writing, studies, or prayers to give admittance to

others, whether rich or poor; and received all persons who addressed themselves

to him with so much sweetness and charity, comforted and exhorted them in so

heavenly a manner, and appeared in his conversation so perfectly exempt from

all inordinate passions, that he scarcely seemed clothed with human flesh,

infected with the corruption of our first parent. Every one looked upon him as

if he had been an angel living on earth. His advice was always satisfactory and

healing to the various distempers of the human mind; and such was the universal

opinion of his virtue, prudence, penetration, and judgment, that causes decided

by him were never admitted to a second hearing at Rome; but in all appeals his

sentence was forthwith confirmed. Grounded in the most sincere and perfect

contempt of himself, he seemed insensible and dead to the flattering temptation

of human applause; which appeared to have no other effect upon him than to make

him more profoundly to humble himself in his own soul, and before both God and

men. His good works he studied as much as possible to hide from the eyes of

others. When he was not able to refrain his tears, which proceeded from the

tenderness and vehemence of the divine love, and from the wonderful spirit of

compunction with which he was endowed, he used to accuse himself of weakness

and too tender and compassionate a disposition of mind. But these he freely

indulged at his private devotions, and by them he purified his affections more

and more from earthly things, and moved the divine mercy to shower down the

greatest blessings on others.

The republic was at that

time shaken with violent storms, and threatened with great dangers. 7 A

holy hermit, who had served God with great fervour above thirty years in the

isle of Corfu, assured a Venetian nobleman, as if it were from a divine

revelation, that the city and republic of Venice had been preserved by the

prayers of the good bishop. The saint’s nephew, who has accurately wrote his

life in an elegant and pure style, mentions several miracles wrought by him,

and certain prophecies, of which he was himself witness. It appeared in many