Saint Isidore de Séville

Docteur de l'Église -

Évêque et confesseur (+ 636)

Son père Severianus avait dû fuir Carthagène devant les Wisigoths qui, non contents d'être des barbares (*), avaient adopté l'hérésie arienne et persécutaient les catholiques. Il se réfugia à Séville. Ses quatre enfants deviendront des saints : Léandre, Florentine, Fulgence et Isidore. A la mort de ses parents, Isidore est encore bien jeune, mais son frère ainé, saint Léandre, devenu évêque de Séville, l'élève comme un fils. Isidore se nourrit, se gave, des livres dont regorge la bibliothèque fraternelle. En 599, à la mort de Léandre, Isidore lui succède comme évêque de Séville. Il présidera des conciles et travaillera à la conversion des Goths à la vraie foi. Son "Histoire des Goths" nous est très utile car, sans elle, nous ne saurions presque rien des Goths et des Vandales. Tout en gouvernant avec un grand dévouement son diocèse, il écrit sans relâche. Toutes les richesses de la culture classique qui ont enchanté sa jeunesse, il les sent menacées par les invasions barbares. Or ce sont des trésors qui peuvent être utiles pour une meilleure compréhension des Écritures. Il rédige donc de très nombreux ouvrages, dont le plus connu "les Étymologies" (de l'origine des choses) est une encyclopédie qui transmettra aux siècles suivants l'essentiel de la culture antique. C'est à lui, avant les Arabes, que l'Occident doit sa connaissance d'Aristote. Ce sera une des bases des études en Occident jusqu'à l'époque de la Renaissance. Il occupera le siège épiscopal de Séville durant quarante ans, y fonda de grands collèges et influença les conseils royaux. On le considère aussi comme l'un des initiateurs de la liturgie mozarabe. Il meurt dans sa cathédrale, étendu sur le sol, tout en continuant de parler à l'assistance.

(*) au sens étymologique du terme, c'est à dire parlant une autre langue que le grec.

- Le 18 juin 2008, Benoît XVI a consacré la catéchèse de l'audience générale à Isidore de Séville (560-636), défini en 653 par le concile de Tolède comme "la gloire de l'Église catholique": L'enseignement de saint Isidore de Séville sur les relations entre vie active et vie contemplative.

- Un saint pour internet: Saint Isidore de Séville - portail des jeunes de l'Eglise catholique

Mémoire de saint Isidore, évêque et docteur de l'Église. Disciple de son frère

saint Léandre, il lui succéda sur le siège de Séville en Espagne, écrivit

beaucoup d'ouvrages d'érudition, convoqua et dirigea de nombreux conciles et se

livra avec sagesse au zèle de la foi catholique et à l'observance de la

discipline ecclésiastique. Il mourut à Séville en 636.

Martyrologe romain

SOURCE : https://nominis.cef.fr/contenus/saint/915/Saint-Isidore-de-Seville.html

BENOÎT XVI

AUDIENCE GÉNÉRALE

Mercredi 18 juin 2008

L'enseignement de saint Isidore de Séville sur les relations entre vie active et vie contemplative

Chers frères et sœurs,

Je voudrais parler

aujourd'hui de saint Isidore de Séville: il était le petit frère de Léandre,

évêque de Séville, et grand ami du Pape Grégoire le Grand. Ce fait est

important, car il permet de garder à l'esprit un rapprochement culturel et

spirituel indispensable à la compréhension de la personnalité d'Isidore. Il

doit en effet beaucoup à Léandre, une personne très exigeante, studieuse et

austère, qui avait créé autour de son frère cadet un contexte familial

caractérisé par les exigences ascétiques propres à un moine et par les rythmes

de travail demandés par un engagement sérieux dans l'étude. En outre, Léandre

s'était préoccupé de prédisposer le nécessaire pour faire face à la situation

politico-sociale du moment: en effet, au cours de ces décennies les Wisigoths,

barbares et ariens, avaient envahi la péninsule ibérique et s'étaient emparé

des territoires qui avaient appartenu à l'empire romain. Il fallait donc les

gagner à la romanité et au catholicisme. La maison de Léandre et d'Isidore

était fournie d'une bibliothèque très riche en œuvres classiques, païennes et

chrétiennes. Isidore, qui se sentait attiré simultanément vers les unes et vers

les autres, fut donc éduqué à développer, sous la responsabilité de son frère

aîné, une très grande discipline en se consacrant à leur étude, avec discrétion

et discernement.

Dans l'évêché de Séville,

on vivait donc dans un climat serein et ouvert. Nous pouvons le déduire des

intérêts culturels et spirituels d'Isidore, tels qu'ils apparaissent dans ses

œuvres elles-mêmes, qui comprennent une connaissance encyclopédique de la

culture classique païenne et une connaissance approfondie de la culture

chrétienne. On explique ainsi l'éclectisme qui caractérise la production

littéraire d'Isidore, qui passe avec une extrême facilité de Martial à

Augustin, de Cicéron à Grégoire le Grand. La lutte intérieure que dut soutenir

le jeune Isidore, devenu successeur de son frère Léandre sur la chaire

épiscopale de Séville en 599, ne fut pas du tout facile. Peut-être doit-on

précisément à cette lutte constante avec lui-même l'impression d'un excès de

volontarisme que l'on perçoit en lisant les œuvres de ce grand auteur,

considéré comme le dernier des Pères chrétiens de l'antiquité. Quelques années

après sa mort, qui eut lieu en 636, le Concile de Tolède de 653 le définit:

"Illustre maître de notre époque, et gloire de l'Eglise catholique".

Isidore fut sans aucun

doute un homme aux contrastes dialectiques accentués. Et, également dans sa vie

personnelle, il vécut l'expérience d'un conflit intérieur permanent, très

semblable à celui qu'avaient déjà éprouvé Grégoire le Grand et saint Augustin,

partagés entre le désir de solitude, pour se consacrer uniquement à la

méditation de la Parole de Dieu, et les exigences de la charité envers ses frères,

se sentant responsable de leur salut en tant qu'évêque. Il écrit, par exemple,

à propos des responsables des Eglises: "Le responsable d'une Eglise (vir

ecclesiasticus) doit d'une part se laisser crucifier au monde par la

mortification de la chair et, de l'autre, accepter la décision de l'ordre

ecclésiastique, lorsqu'il provient de la volonté de Dieu, de se consacrer au

gouvernement avec humilité, même s'il ne voudrait pas le faire"

(Sententiarum liber III, 33, 1: PL 83, col 705 B). Il ajoute ensuite, à peine

un paragraphe après: "Les hommes de Dieu (sancti viri) ne désirent pas du

tout se consacrer aux choses séculières et gémissent lorsque, par un mystérieux

dessein de Dieu, ils sont chargés de certaines responsabilités... Ils font de

tout pour les éviter, mais ils acceptent ce qu'ils voudraient fuir et font ce

qu'ils auraient voulu éviter. Ils entrent en effet dans le secret du cœur et, à

l'intérieur de celui-ci, ils cherchent à comprendre ce que demande la

mystérieuse volonté de Dieu. Et lorsqu'ils se rendent compte de devoir se

soumettre aux desseins de Dieu, ils humilient le cou de leur cœur sous le joug

de la décision divine" (Sententiarum liber III, 33, 3: PL 83, coll.

705-706).

Pour mieux comprendre

Isidore, il faut tout d'abord rappeler la complexité des situations politiques

de son temps dont j'ai déjà parlé: au cours des années de son enfance, il avait

dû faire l'expérience amère de l'exil. Malgré cela, il était envahi par un

grand enthousiasme apostolique: il éprouvait l'ivresse de contribuer à la

formation d'un peuple qui retrouvait finalement son unité, tant sur le plan

politique que religieux, avec la conversion providentielle de l'héritier au

trône wisigoth, Ermenégilde, de l'arianisme à la foi catholique. Il ne faut

toutefois pas sous-évaluer l'immense difficulté à affronter de manière

appropriée les problèmes très graves, tels que ceux des relations avec les

hérétiques et avec les juifs. Toute une série de problèmes qui apparaissent

très concrets aujourd'hui également, surtout si l'on considère ce qui se passe

dans certaines régions où il semble presque que l'on assiste à nouveau à des

situations très semblables à celles qui étaient présentes dans la péninsule

ibérique de ce VI siècle. La richesse des connaissances culturelles dont disposait

Isidore lui permettait de confronter sans cesse la nouveauté chrétienne avec

l'héritage classique gréco-romain, même s'il semble que plus que le don

précieux de la synthèse il possédait celui de la collatio, c'est-à-dire celui

de recueillir, qui s'exprimait à travers une extraordinaire érudition

personnelle, pas toujours aussi ordonnée qu'on aurait pu le désirer.

Il faut dans tous les cas

admirer son souci de ne rien négliger de ce que l'expérience humaine avait

produit dans l'histoire de sa patrie et du monde entier. Isidore n'aurait rien

voulu perdre de ce qui avait été acquis par l'homme au cours des époques

anciennes, qu'elles fussent païenne, juive ou chrétienne. On ne doit donc pas

s'étonner si, en poursuivant ce but, il lui arrivait parfois de ne pas réussir

à transmettre de manière adaptée, comme il l'aurait voulu, les connaissances

qu'il possédait à travers les eaux purificatrices de la foi chrétienne. Mais de

fait, dans les intentions d'Isidore, les propositions qu'il fait restent

cependant toujours en harmonie avec la foi pleinement catholique, qu'il

soutenait fermement. Dans le débat à propos des divers problèmes théologiques,

il montre qu'il en perçoit la complexité et il propose souvent avec acuité des

solutions qui recueillent et expriment la vérité chrétienne complète. Cela a

permis aux croyants au cours des siècles de profiter avec reconnaissance de ses

définitions jusqu'à notre époque. Un exemple significatif en cette matière nous

est offert par l'enseignement d'Isidore sur les relations entre vie active et

vie contemplative. Il écrit: "Ceux qui cherchent à atteindre le repos de

la contemplation doivent d'abord s'entraîner dans le stade de la vie active; et

ainsi, libérés des scories des péchés, ils seront en mesure d'exhiber ce coeur

pur qui est le seul qui permette de voir Dieu" (Differentiarum Lib II, 34,

133: PL 83, col 91A). Le réalisme d'un véritable pasteur le convainc cependant

du risque que les fidèles courent de n'être que des hommes à une dimension.

C'est pourquoi il ajoute: "La voie médiane, composée par l'une et par

l'autre forme de vie, apparaît généralement plus utile pour résoudre ces

tensions qui sont souvent accentuées par le choix d'un seul genre de vie et qui

sont, en revanche, mieux tempérées par une alternance des deux formes"

(o.c., 134: ibid., col 91B).

Isidore recherche dans

l'exemple du Christ la confirmation définitive d'une juste orientation de vie:

"Le sauveur Jésus nous offrit l'exemple de la vie active, lorsque pendant

le jour il se consacrait à offrir des signes et des miracles en ville, mais il

montrait la voie contemplative lorsqu'il se retirait sur la montagne et y

passait la nuit en se consacrant à la prière" (o.c. 134: ibid.). A la

lumière de cet exemple du divin Maître, Isidore peut conclure avec cet enseignement

moral précis: "C'est pourquoi le serviteur de Dieu, en imitant le Christ,

doit se consacrer à la contemplation sans se refuser à la vie active. Se

comporter différemment ne serait pas juste. En effet, de même que l'on aime

Dieu à travers la contemplation, on doit aimer son prochain à travers l'action.

Il est donc impossible de vivre sans la présence de l'une et de l'autre forme

de vie à la fois, et il n'est pas possible d'aimer si l'on ne fait pas

l'expérience de l'une comme de l'autre" (o.c., 135: ibid., col 91C). Je

considère qu'il s'agit là de la synthèse d'une vie qui recherche la

contemplation de Dieu, le dialogue avec Dieu dans la prière et dans la lecture

de l'Ecriture Sainte, ainsi que l'action au service de la communauté humaine et

du prochain. Cette synthèse est la leçon que le grand évêque de Séville nous

laisse à nous aussi, chrétiens d'aujourd'hui, appelés à témoigner du Christ au

début d'un nouveau millénaire.

* * *

Je suis heureux

d’accueillir ce matin les pèlerins de langue française. Je salue

particulièrement les étudiants de l’Institut de philosophie comparée, de Paris,

la paroisse de Rodez, et tous les jeunes. Je vous invite à faire dans votre vie

l’unité entre la contemplation de Dieu et le service de vos frères. Avec ma Bénédiction

apostolique.

© Copyright 2008 -

Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Saint Isidore, évêque

et docteur de l'Église

Isidore de Séville

(560-636) est le grand docteur de l'Espagne. Successeur de son frère Léandre

comme évêque de Séville (601), il travailla à organiser l'Eglise dans le

royaume wisigothique, spécialement en tenant des Conciles. Il aimait par-dessus

tout enseigner. La somme des connaissances qu'il a recueillies servit de manuel

scolaire durant des générations.

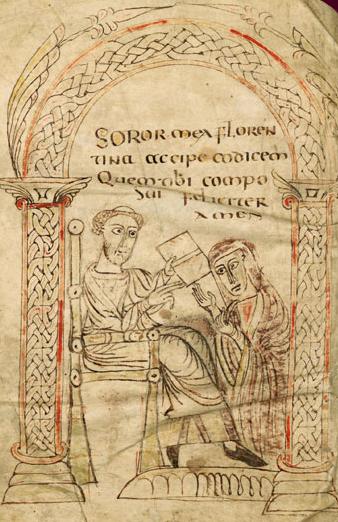

Saint Isidore de Séville présentant le livre " De fide catholica contra judaeos " à sa soeur, sainte Florentine.

Abbaye de Corbie. VIIIe

Un

saint pour internet : Saint Isidore de Séville

Le service d’observation

d’internet, promu par le Vatican, a mené une enquête et a choisi comme saint

patron, le plus apprécié dans le monde des informaticiens, Saint Isidore de

Séville né en Espagne au VIème siècle.

Ce Saint devint le génie

de la compilation en écrivant une oeœuvre encyclopédique admirable, “Etymologies”,

et en donnant à son travail une structure proche du concept de la base de

données, utilisé en informatique et dans l’Internet. D’autre part, il était en

avance sur son temps et son œoeuvre constitua un pont culturel entre l’Antiquité

et le Moyen Âge. Ces faits le rapprochent des internautes qui sont au tournant

d’une nouvelle étape de l’Histoire.

Le Pape Innocent III

conféra à Saint Isidore le titre de “docteur de l’Eglise”. En effet la culture

espagnole bénéficia de la lumière de sa connaissance qui lui permit d’émerger

des âges noirs du barbarisme. Mais plus célèbre encore que son esprit

exceptionnel, était le génie de son coeœur qui lui permit de voir au-delà du

rejet et du découragement, la joie et l’ouverture possible.

A l’aube de ce nouveau

siècle, que nous enseigne Saint Isidore ? Venez et voyez comment Isidore de

Séville réussit à réaliser ce pont entre deux époques en vivant ses engagements

de chrétien au plus près des événements socio-politique et religieux du VIème

siècle ; quelle place pouvons-nous donner à l’Internet, cet outil d’information

universelle et de communication “sans frontières” ?

Sa vie : quelques points

de repère

C’est en cette fin du

VIème siècle, en Andalousie, la province d’Espagne la plus ouverte aux

influences de l’orient et de l’Afrique, qu’Isidore est né et a vécu.

D’une famille de leaders

et de fortes têtes, il subit l’éducation de son frère aîné impliquant force et

punition. Blessé par le traitement de celui-ci, il sombra dans un sentiment

d’échec et de rejet. Jusqu’au jour où son attention se posa sur l’eau tombant

sur le rocher où il était assis : les gouttes d’eau qui tombaient de façon

répétée sans force semblaient n’avoir aucun effet sur le roc ; puis avec le

temps elles finirent par user et faire des trous dans la roche. C’est ainsi

qu’Isidore pris conscience que ses petits efforts vraisemblablement

seraient payants dans l’apprentissage. Ils le furent, son amour de l’étude fit

de lui l’un des esprits les plus érudits de son temps. Avant Charlemagne,

Isidore est connu comme “le Maître d’école du Moyen Age”.

Il choisit la carrière

ecclésiastique, et monta sur le siège métropolitain de Séville. Tout au long

des 35 années de son pontificat, il assista aux luttes pour l’unification

nationale de l’Espagne, succédant à l’invasion des Wisigoths. Après la conversion

des Wisigoths de l’arianisme au catholicisme, il usa de son autorité pour

réorganiser l’Eglise catholique. Il conseilla les princes, participa à

l’affermissement de la royauté wisigothique.

Par ses écrits et œuvres,

il a recueilli et transmis tout le savoir de son temps, linguistique,

historique, culturel et scientifique mais aussi théologique et profane du

Moyen- âge. Il a le souci permanent d’apprendre autant que d’instruire. Son

œoeuvre connaîtra une diffusion extraordinaire aux siècles suivants en Europe

entière.

Se laisser enseigner

chaque jour sous le regard de Dieu

Le Christ dit : “je suis

la Vérité”.

Saint Paul dit “…transformez-vous en renouvelant votre façon de penser pour

savoir reconnaître quelle est la volonté de Dieu” (Rm 12, 2).

Nous avons à nous laisser enseigner pour que cette vérité qui est le Christ

nous transforme. Une des devises de Saint Isidore de Séville est : ” Etudiez

comme si vous deviez vivre toujours ; vivez comme si vous deviez mourir demain

“.

Quand nous prions, nous

parlons à Dieu ; mais quand nous étudions la Parole de Dieu, Dieu nous parle.

C’est pourquoi Isidore nous incite à approfondir notre connaissance de

l’héritage spirituel pour vivre fidèlement au Christ, idée qu’a repris le Saint

Père dans son message aux jeunes du monde.

Celui qui ne cultive pas

sa capacité intellectuelle donnée par Dieu en est réduit à mépriser ses dons et

pêcher par paresse. Par contre, l’homme qui tente avec persévérance et labeur,

d’acquérir la connaissance, est gratifié par l’extraordinaire puissance de Dieu

et peut mettre ses talents au service des hommes par grâce.

Choisir et faire

d’Internet, un lieu de croissance fraternelle

Internet ne peut-il pas

être un outil d’Amour et de paix, de partage et de fraternité dans le

monde ?

Comment utilisons-nous

Internet ? Est-ce un outil d’apprentissage, de connaissance et de

partage, ou un lieu de dispersion, de gaspillage de temps et de fuite de

certaines réalités ? Par cet accès “facile” aux cultures diverses, à quoi

sommes-nous sensibilisés ? Qu’engendrent ces informations en nous et

autour de nous ? Ces informations, changent-elles notre façon d’être et

d’agir dans notre quotidien ? Quels nouveaux liens pouvons-nous créer

par cet outil ? Par ailleurs, restons-nous présents à ceux qui nous sont

proches ?

Related Posts:

Saint Robert Bellarmin (1542-1621)

Saint Silouane, la nostalgie de

Dieu

Saint Jean

Bosco, homme de rupture et modèle de sainteté

Saint Louis Marie Grignon de

Montfort

Saint Isidore de Séville

Archevêque et docteur de l'église catholique - saint patron de

l'Internet

vers 560 - 636

article du Dictionnaire

de Théologie Catholique, version word

La

Foi Catholique selon l'Ancien et le Nouveau Testament contre les Juifs (ouvrage

en 2 livres)

De fide catholica ex

Veteri et Novo Testamento contra judæos

(Sur le même thème de

l'annonce de l'Evangile à nos frères bien aimés de religion juive, on peut lire

l'excellent Dialogue avec Tryphon de Saint Justin)

I.

Vie de Saint Isidore. II.

Ses Œuvres. III.

Sa Doctrine.

1. Sa famille. On ignore

la date exacte et le vrai lieu de sa naissance ; les précisions données plus

tard par les auteurs espagnols ne sont que des conjectures. Ses parents étaient

catholiques de race hispano-romaine. Son père Sévérien dut occuper un rang

distingué à Carthagène : lequel ? Sobre de détails sur sa famille, saint

Isidore, en parlant de son frère dans son De viris illustribus, XLI, se borne à

cette phrase : Leander genitus patre Severiano, carthaginensis provinciæ.

Sévérien était-il duc de Carthagène, comme l’ont soutenu dans la suite certains

écrivains espagnols ? Ni saint Isidore, ni aucun témoignage contemporain

n’autorisent à l’affirmer ; ce titre, en tout cas, ne lui a pas été donné dans

les offices de l’Eglise de Tolède. Lors de l’invasion d’Agila, l’an 587 de

l’ère espagnole, c’est-à-dire ne 549, Sévérien dut fuir sa cité d’origine,

ruinée par les Goths ariens : il se réfugia à Séville. Il eut quatre enfants,

tous inscrits au catalogue des saints. Les deux premiers, Léandre et

Florentine, étaient nés certainement à Carthagène ; les deux autres, Fulgence

et Isidore, naquirent vraisemblablement dans la capitale de la Bétique, le

dernier vers l’an 560. Le père et la mère, morts peu après, avaient confié aux

soins des deux aînés le plus jeune et le plus aimé de leurs enfants ; et c’est

ainsi qu’Isidore, devenu orphelin, fut élevé par son frère Léandre, qui devint

archevêque de Séville, et par sa sœur Florentine, qui embrassa la vie

religieuse.

2. Son éducation.

Léandre, en effet, traita

toujours dans la suite Isidore comme son fils, et veilla avec sa sœur à son

instruction et à son éducation. Florentine ayant manifesté un jour le désir de

revoir les lieus de son enfance, Léandre l’en dissuada, parce que Dieu avait

jugé bon de la retirer de Sodome. Malum quod illa experta fuit, lui écrivit-il

en parlant de leur mère, tu prudenter evita ; ce sol natal, du reste, avait

perdu sa liberté, sa beauté et sa fertilité. Mieux valait don, ajouta-t-il,

qu’elle restât dans son nid et qu’elle veillât tout particulièrement sur le

plus jeune de leurs frères. Regula, XXI, P. L., t. LXXII, col. 892. Isidore fut

confié, tout enfant, à l’un des monastères de la ville ou des environs, où il

fit des fortes études et puisa des connaissances vraiment étonnantes pour

l’époque et dans le milieu où il vécut. Il n’est pas, en effet, d’auteur sacré

ou profane, surtout parmi les latins, dont il n’ait lu et mis à profit les

ouvrages. Mais il n’étudia pas uniquement pour le vain plaisir de savoir ; il

poursuivit un double but : celui d’être utile à son pays pour le soustraire à

la barbarie et celui de faire triompher la foi catholique contre l’hérésie

arienne.

3. Son prosélytisme.

L’Espagne presque toute

entière était au pouvoir des Goths ariens, et la difficulté était de ramener

ces hérétiques à la vraie foi. Il y eut une lueur d’espoir, lorsque le fils

aîné du roi Léovigilde (569-585), Herménégilde, qui avait épousé la fille du

roi Franc Sigebert et de Brunehaut, passa au catholicisme. Il est vrai qu’il

dut aussitôt s’enfuir à Séville ou qu’il y fut exilé. Mais là, loin des menaces

paternelles, et très vraisemblablement sous l’inspiration de Léandre, il

chercha à former un parti pour la conversion de l’Espagne. Il sollicita le

concours du lieutenant de l’empereur de Byzance et envoya Léandre en mission à

Constantinople ; c’est là, en effet, que Léandre se rencontra [col.98 fin /

col.99 début] avec le futur pape saint Grégoire le Grand, qui lui écrivait plus

tard : Te illuc injuncta pro causis fidei Wisigothorum. Moral., epist., I, P.

L., t. LXXV, col. 510. Durant cette mission, Isidore, alors âgé de plus de

vingt ans, crut le moment propice pour faire œuvre de propagande en combattant

ouvertement l’arianisme. Ce ne fut pas sans horreur qu’en 585 il apprit le

guet-apens tendu à Herménégilde et le meurtre qui en fut la suite. Mais survint

presque aussitôt la mort du roi persécuteur, suivie de l’avènement de Recarède,

qui, comme son frère, abjura l’arianisme et entraîna par son exemple la

conversion en masse de tout le royaume goth. Ce grand évènement, si conforme

aux vœux d’Isidore, fut célébré au IIIe concile de Tolède, en 589n où siégea et

signa, comme métropolitain de la Bétique, saint Léandre. Isidore rentra dès

lors dans le cloître, comme clerc, ou comme moine, pour y continuer la lecture

attentive des auteurs et enrichir de plus en plus sa collection d’extraits.

2° Son épiscopat.

1. Il remplace son frère

Léandre sur le siège de Séville. A la mort de Léandre, du temps de l’empereur

Maxime († 602) et du roi Recarède († 601), donc au plus tard en 601, Isidore

fut élu pour remplacer son frère sur le siège métropolitain de la Bétique ; c’est

la date consignée par un contemporain et un ami d’Isidore, saint Braulio,

évêque de Saragosse, dans sa Prænotatio in libros divi Isidori, P. L., t.

LXXXI, col. 15-17. Saint Ildefonse ajoute qu’il occupa ce siège une quarantaine

d’années, De viris illustribus, IX, P. L., t. LXXXI, col. 28 ; exactement

jusqu’au début du règne de Chintilla en 636, comme a eu soin de le préciser un

disciple d’Isidore, qui a raconté la mort édifiante de son maître. P. L., t.

LXXXI, col. 32. Ce long épiscopat fut consacré par Isidore aux intérêts de son

siège, de sa province et de l’Espagne ; il ne fut pas sans fruits ; n’en

retenons que les faits principaux.

2. Il signe à un synode

de la province de Carthagène. En 610, se tint à Tolède, à la cour du roi

Gondemar, un synode de la province carthaginoise, où il fut décidé que le titre

de métropolitain de cette province n’appartiendrait plus au siège de

Carthagène, amis à celui de Tolède, la capitale du royaume. Bien qu’étranger à

cette province, Isidore, alors l’hôte du roi, fut invité à signer le premier ce

décret ; c’est ce qu’il fit en ces termes : Ego Isidorus, Hispalensis ecclesiæ

provinciæ metropolitanus episcopus, dum in urbem Toletanam, pro occursu regis,

advenissem, agnitis his constitutionibus, assensum præbui et subscripi.

3. Il convoque lui-même

des synodes. Par deux fois, en 619 et en 625, Isidore convoqua à Séville les

évêques de la Bétique pour régler certaines affaires litigieuses et délicates.

Dans le premier de ces synodes, il trancha d’abord le différend survenu entre

son frère Fulgence, évêque d’Astigi (Ecija), et Honorias, évêque de Cordoue, au

sujet de la délimitation de leurs diocèses ; puis il traita l’affaire de

l’évêque eutychien Grégoire, de la secte des acéphales, qui, chassé de la

Syrie, avait trouvé un refuge en Espagne. Pour couper court à toute suspicion

et à toute propagande d’erreur de sa part, Isidore exigea de lui une abjuration

formelle de l’hérésie monophysite et une confession de foi orthodoxe. Dans le

second, il déposa le successeur de Fulgence, Martianus, et le remplaça par

Habentius. Cf. Florez, España sagrada, t. X, p. 106.

4. Il préside le IVe

concile international de Tolède. A titre du plus ancien métropolitain de

l’Espagne, Isidore eut à présider, en 633, le IVe concile national, qui est

resté le plus célèbre de la péninsule, à cause des décisions qui y furent

prises tant au point de vue religieux et ecclésiastique qu’au point de vue

civil et politique ; il en fut vraiment l’âme.

a) Au point de vue

religieux. Le concile commença d’abord par promulguer un symbole ; puis il

imposa à [col.99 fin / col.100 début] toute l’Espagne ainsi qu’à la Gaule

narbonnaise l’uniformité pour le chant de l’office et les rites de la messe :

Ut unus ordo orandi atque psallendi per omnem Hispaniam atque Galliam

conservaretur, unus modus in missarum solemnitate, unus in matutinis

vespertinisque officiis, can. 2. Il régla ensuite plusieurs points de

discipline et de liturgie, 7-19. Il rappela aux prêtres l’obligation de la

chasteté, can. 21-27, et aux évêques le devoir de surveiller les juges civils

et de dénoncer leurs abus, can. 32. Il déclara tous les clercs exempts de

redevances et de corvées, can. 47.

b) Relativement aux

juifs. La question juive, en 633, n’était pas nouvelle en Espagne et ne devait

pas de sitôt recevoir une solution définitive, mais elle s’imposait à

l’attention du pouvoir civil et ecclésiastique dans l’intérêt de la paix et du

bien public. Déjà, en 589, le IIIe concile de Tolède s’en était occupé. Il

avait interdit aux juifs : toute fonction qui leur aurait permis d’édicter des

peines contre les chrétiens ; toute union avec une femme chrétienne, soit comme

épouse, soit comme concubine, les enfants nés d’une telle union devant être

baptisés ; tout achat d’esclaves chrétiens, ceux-ci ayant droit à

l’affranchissement gratuit s’ils avaient été l’objet de quelque rite judaïque ;

autant de mesures sages qui, sans léser les juifs, protégeaient les chrétiens.

Quelques années plus tard, Sisebut obligea les juifs à recevoir le baptême ; c’est

ce que note simplement Isidore dans son Chronicon, CXX, P. L., t. LXXXIII, col.

1056, mais ce qu’il blâme avec raison dans son Historia de regibus Gothorum,

LX, ibid., col. 1093, où il dit de Sisebut : Initio regni judæos in fidem

christianam promovens æmulationem, quidem habuit, sed non secundum scientiam,

potestate enim compulit quos provocare fidei ratione oportuit. Aussi, ayant

lui-même à s’occuper des juifs, maintint-il tout d’abord les décisions prises

au IIIe concile de Tolède, mais il eut soin de faire décréter qu’on ne

forcerait plus désormais aucun juif à se faire chrétien. Les juifs restaient

exclus des emplois publics et ne pouvaient plus posséder d’esclaves chrétiens ;

si l’un d’eux avait épousé une femme chrétienne, il était mis en demeure ou de

se séparer d’elle ou de se convertir. Restait à liquider le passé et à prendre

des mesures pour l’avenir ; car la plupart de ceux qui avaient été contraints

sous Sisebut à recevoir le baptême étaient retombés dans le judaïsme ; ceux-là

devaient être ramenés de force à la vraie foi ; leurs enfants, s’ils étaient

circoncis, devaient être soustraits à leur autorité pour être confiés à des

communautés ou à des fidèles recommandables, et leurs esclaves, s’ils avaient

été circoncis par eux, devaient être affranchis aussitôt. Désormais tout juif

baptisé, qui viendrait à renier son baptême, serait condamné à la perte de tous

ses biens au profit de ses enfants, si ces derniers étaient chrétiens, can.

57-66.

c) Relativement à l’Etat.

C’était là, à vrai dire, l’un des points plus importants à traiter, car on

était au lendemain d’une révolution : il s’agissait de mettre un terme aux

discordes civiles et d’assurer la paix, en tranchant le différend survenu entre

Suinthila et Sisenand. Sisenand, en effet, avait pris les armes pour détrôner

le roi régnant, et Suinthila, devant la révolte triomphante, avait dû

abandonner le pouvoir. Sisenand, intéressé à se faire reconnaître, s’était

montré plein de déférence à l’égard de l’épiscopat et ne ménagea pas les

promesses. Loin d’être inquiété pour sa révolte et son élection, qui avaient

tous les caractères d’une usurpation, il fut acclamé et solennellement reconnu

comme roi légitime. Quant à Suinthila, il fut condamné à la dégradation et à la

perte de tous ses biens. Le concile, disposant ainsi des affaires de l’Etat,

menaça d’anathème quiconque attenterait aux jours du nouveau roi, le

dépouillerait du pouvoir ou usurperait son trône, et décida qu’à la mort de

Sisenand son successeur serait [col.100 fin / col.101 début] élu par tous les

grands de la nation et par les évêques, can. 75. Ainsi s’affirmait, en Espagne,

l’action politique du clergé et l’union étroite de l’Eglise et de l’Etat.

d) Relativement à

l’instruction et à l’éducation du clergé. Isidore, qui avait tant profité de

son séjour dans les écoles monastiques et qui comprenait l’importance capitale

de l’instruction et de l’éducation pour le clergé, avait fondé à Séville un

collège pour les jeunes clercs sous la direction d’un supérieur qui fût à la

fois un magister doctrinæ et un festis vitæ. C’est là que fut élevé saint

Ildefonse. Il eut soin en outre de faire décréter qu’un établissement semblable

serait institué dans chaque diocèse, can. 24. Voir les canons du IVe concile de

Tolède, dans Hefele, Histoire des conciles, trad. Leclercq, Paris, 1909, t.

III, p. 267-276.

3° Sa mort.

Isidore ne devait

survivre que trois ans au IVe concile de Tolède. Déjà vieux et "sentant

approcher sa fin", raconte son disciple, P. L., t. LXXXI, col. 30-32, il

redoubla ses aumônes avec une telle profusion que, pendant les six derniers

mois de sa vie, on voyait venir chez lui de tous côtés ou une foule de pauvres

depuis le matin jusqu’au soir. Quelques jours avant sa mort il pria deux

évêques, Jean et Eparchius, de le venir voir. Il se rendit avec eux à l’église,

suivi d’une grande partie de son clergé et du peuple. Quand il fut au milieu du

chœur, l’un des évêques mit sur lui un calice, l’autre de la cendre. Alors,

levant les mains vers le ciel, il pria et demanda à haute voix pardon de ses

péchés. Ensuite il reçut de la main de ces évêques le corps et le sang du

Christ, se recommanda aux prières des assistants, remit les obligations à ses

débiteurs et fit distribuer aux pauvres tout ce qu’il restait d’argent. De

retour à son logis, il mourut en paix le 4 avril 636. " Cf. Ceillier,

Histoire générale des auteurs sacrés et ecclés., t. XI, p. 711 ; Leclercq,

L’Espagne chrétienne, Paris, 1906, p. 310.

4° Sa célébrité.

L’opinion des

contemporains. Très renommé pendant sa vie, Isidore est resté l’une des gloires

de l’Espagne. Déjà son ami, Braulio, évêque de Saragosse, prit soin d’insérer

son nom dans le De viris illustribus d’Isidore lui-même et d’y dresser la liste

de ses principaux ouvrages. Il y vante son éloquence, sa science, sa charité ;

il le considère comme le plus grand érudit de son époque, comme le restaurateur

des études, comme l’homme providentiellement suscité par Dieu pour sauver les

documents des anciens, relever l’Espagne et l’empêcher de tomber dans la

rusticité. Prænotatio librorum divi Isidori, P. L., t. LXXXI, col. 15-17.

2. Sa vaste érudition.

Cet éloge enthousiaste était mérité en grande partie ; car, sans être un homme

de génie, Isidore fut un grand érudit. Il connaissait une grande partie des

œuvres de l’antiquité sacrée et profane, et il y puisa à pleines mains,

transcrivant textuellement, au fur et à mesure de ses multiples lectures, tout

ce qui lui paraissait digne d’être retenu, et amassant ainsi pour ses futurs

travaux des extraits précieux qu’il n’avait plus qu’à mettre en ordre. Il fut

surtout un compilateur, comme le montre l’étendue encyclopédique de ses

citations.

Ayant ainsi recueilli

tout ce qui touche à l’exégèse, à la théologie, à la morale, à la grammaire,

liturgie, à l’histoire, à la grammaire, aux sciences cosmologiques,

astronomiques et physiques, Isidore se contenta, quand il eut à traiter à

traiter du sujet, d’utiliser la collection de ses notes, exprimant ainsi, comme

un écho fidèle, moins sa propre pensée que celle de ses devanciers. Et telle

fut constamment sa méthode ainsi qu’il a eu soin à plusieurs reprises d’en

prévenir loyalement ses lecteurs, P. L., t. LXXXII, col. 73 ; LXXXIII, col.

207, 737, 964 ; si bien qu’il aurait pu écrire en tête de chacun de ses

nombreux ouvrages ou qu’il a mis dans la préface de ses Questiones in [col.101

fin / col.102 début] Vetus Testamentum : Lector non nostra leget sed veterum

releget, P. L., t. LXXXII, col. 209.

3. Son titre de docteur

de l’Eglise.

Traduisant la pensée des

contemporains, le VIIIe concile de Tolède, en 653, parle d’Isidore en ces

termes : Doctor egregius, Ecclesiæ catholicæ novissimum decus, præcedentibus

ætate postremus, doctrina et comparatione non infimus et, quod majus est, in

sæculorum fine doctissimus. Mansi, Concil., t. X, col. 1215.

C’est ce même titre de

docteur que lui donne encore le concile de Tolède de 688.

Aussi l’Eglise de Séville

n’hésita pas à insérer dans l’office de son saint évêque l’antienne : O doctor

optime, et dans la messe l’évangile propre à la fête des docteurs : Vos estis

sal terræ : office et messe qui reçurent, pour l’Espagne et le pays soumis au

roi catholique, l’approbation de Grégoire XIII (1572-1585).

Finalement ce titre fut

reconnu pour toute l’Eglise, le 25 avril 1722, par Innocent XIII.

Cf. Benoît XIV De beati

sanct., l. IV, part. II, c. XI, n. 15.

Comme ses deux frères,

Léandre et Fulgence, et comme sa sœur Florentine, Isidore a été inscrit au

catalogue des saints ; sa fête est fixée au 4 avril. Acta sanctorum, aprilis,

t. I, p. 325-361.

II. ŒUVRES.

Durant son long

épiscopat, Isidore composa un grand nombre d’ouvrages, dont quelques-uns ne

sont point parvenus jusqu’à nous. Braulio, en effet, après en avoir signalé 17,

ajoute ces mots : sunt et alia multa opuscula. Prænotatio, P. L., t. LXXXI,

col. 17. Ceux qui restent sont caractéristiques quant au genre et à la méthode

du saint. Ils roulent sur les matières les plus variées ; car, ainsi que l’a

observé Arevalo, Isidoriana, part. I, c. I, n. 3, P. L., t. LXXXI, col. 11, il

n’est pas de sujet qu’Isidore n’ait abordé : nil intentatum reliquit. Laissant

de côté tout ce qui a trait au droit canon et à la la liturgie, et qui trouvera

sa place dans les dictionnaires consacrés à ces deux sciences, nous nous

bornerons à parcourir succinctement ses œuvres, non dans leur suite

chronologique, car il n’y en a guère que quatre ou cinq que l’on puisse dater

approximativement, mais dans l’ordre des matières adopté par Arevalo, le

dernier et le meilleur éditeur des ouvrages de saint Isidore.

1° Etymologie. C’est

le plus long et le principal ouvrage du saint. Isidore y travailla longtemps

sans pouvoir l’achever comme il l’aurait voulu. Mais sollicité plusieurs années

de suite par Braulio pour qu’il le lui envoyât complet et en ordre, il finit

par céder, vers 630. Il l’expédia à son ami avec une dédicace, mais tel qu’il

était encore, inemendatum, en lui laissant le soin de l’amender lui-même. Son

titre général est celui d’Etymologiæ, sous lequel Isidore le désigne plusieurs

fois ; mais comme il est qualifié dans la préface d’opus de origine quarumdam

rerum, Margarin de la Bigne et du Breul lui ont donné aussi le titre

d’Origines. Sa division actuelle en vingt livres est-elle due à Isidore ou à

Braulio ? C’est ce qu’on ne saurait dire, car les manuscrits varient et pour le

nombre et pour l’ordre de ces livres.

En voici le résumé : le

Ier livre traite de la grammaire ; le IIe de la rhétorique et de la dialectique

; ces deux livres sont plus développés dans les Differentiæ, mais dans le même

esprit, selon le même plan et la même méthode ; le IIIe, de l’arithmétique, de

la géométrie, de la musique et de l’astronomie ; le IVe, de la médecine ; le

Ve, des lois et des temps : celui-ci est un résumé ou Chronicon, ou abrégé de

l’histoire universelle, en six époques, depuis les origines du monde jusqu’à

l’an 627 après Jésus-Christ ; le VIe, des livres et des offices de l’Eglise :

il y est question du cycle pascal et il est plus développé dans le De officiis

; le VIIe, de Dieu, dans anges et des différentes classes de fidèles : c’est un

abrégé de théologie ; le VIIIe, de l’Eglise et des sectes ; le IXe, des

langues, des peuples, des royaumes, des armées, de la population civile, des

degrés de parenté ; le Xe, des mots : c’est un index alphabétique des plus

curieux ; le XIe, de [col.102 fin / col.103 début] l’homme et des monstres ; le

XIIe, des animaux ; le XIIIe, du monde et de ses parties : c’est une sorte de

cosmologie générale ; le XIVe, de la terre et de ses parties : c’est une

géographie ; le XVe, des pierres et des métaux ; le XVIe, de la culture des

champs et des jardins ; le XVIIe, de la guerre et des jeux ; le XIXe, des

vaisseaux, des constructions et de costumes ; le XXe, des mets et des boissons,

des ustensiles de ménage et des instruments aratoires.

Il y a là, comme on le

voit, une sorte de d’encyclopédie. Tout y est traité d’une manière uniforme,

l’étymologie des mots servant à l’explication des choses. Mais il y a

l’étymologie secundum naturam et l’étymologie secundum propositum. A défaut de

la première, Isidore recourt à la seconde. Or, quelque ingéniosité qu’on y

déploie, il y a toujours place alors pour l’arbitraire. Aussi, à côté

d’étymologies pertinentes et parfois fort remarquables, combien qui prêtent à

sourire ou même semblent ridicules ! Isidore, il est vrai, ne les a pas

inventées, mais alors à quoi bon les transcrire sans tenir compte de leur

invraisemblance, ni même de leur contradiction ou de leur absurdité ? Arevalo a

vainement essayé de l’en excuser, quand il a écrit : Scriptores collectaneorum

magis excusandi sunt, si quædam aliquantutum absurda aut minus credibilia

proferand. Propositum enim illis erat, non tam ut vera a falsis discernerent,

quam ut aliorum dicta congererent et aliis dijudicanda

proponerent. Isidoriana, part. II, c. LXI, n. 10, P. L., t. LXXXI, col.

386. Un choix plus judicieux s’imposait. A vrai dire, dans une œuvre de ce

genre, Isidore n’a pas été plus heureux que Platon chez les grecs, Varron chez

les latins et Philon chez les juifs. Mais telle quelle, sa compilation n’en fut

pas moins, pour tout le moyen âge, une mine de renseignements et un manuel à la

portée de tous.

2. Differentiæ, sive

de proprietate sermonum. Isidore dit avoir eu en vie ici le traité

correspondant de Caton, mais il a aussi emprunté à d’autres. Il a divisé son

travail en deux livres. Le Ier, De differentiis verborum, disposé par ordre

alphabétique, comprend 610 différences, quelques-unes subtiles et bien

approfondies ; par exemple : entre aptum et utile ; aptum, ad tempus ; utiles,

ad perpetuum ; entre ante et antea ; ante locum significat et personam ; antea,

tantum tempus ; entre alterum et alium ; alter de duobus dicitur ; allius, de

multis, etc. Le IIe, De differentiis rerum, en 40 sections et 170 paragraphes,

marque la différence des choses, comme par exemple entre Deus et Dominus,

Trinitas et Unitas, substantia et essentia, animus et anima, anima et spiritus,

etc. C’est en fait, un vrai petit traité de théologie sur la Trinité, le

pouvoir et la nature du Christ, le paradis, les anges, les hommes, le libre

arbitre, la chute, la grâce, la loi et l’Evangile, la vie active et la vie

contemplative, etc.

3° Allegoriæ.

Ouvrage dédié à Orosio, personnage inconnu, ou plutôt Orontio, qui fut

métropolitain de Mérida avant 638, ces Allégories forment une suite

d’interprétations ou d’explications spirituelles, d’à peine quelques lignes

chacune, sur des noms, des caractéristiques, des personnages de l’écriture :

129 pour l’Ancien Testament, d’Adam aux Machabées ; 121 pour le Nouveau, la

plupart de celles-ci concernant les paraboles et les miracles du Sauveur. Hæc,

dit Isidore dans sa préface, P. L., t. LXXXIII, col. 97, non meo conservavi

arbitrio, sed tuo commisi corrigenda judicio. Même esprit et même méthode que

dans les Etymologiæ.

4° De ortu et habitu

Patrum qui in scriptura laudibus efferuntur. C’est une série de très courtes

notices biographiques sur 64 personnages de l’Ancien Testament, d’Adam aux

Machabées, et 22 du nouveau, de Zacharie à Tite. Son attribution à saint

Isidore, dans sa forme actuelle, n’est pas acceptable, dit Mgr Duchesne,

[col.103 fin / col.104 début] S. Jacques de Galice, p. 156-157, dans les

Annales du Midi, 1890, t. XII, p.145-179. C’est là que se trouve, en effet, De

ortu, LXI, P. L., t. LXXXIII, col. 151, le passage interpolé qui, de saint

Jacques le Majeur, frère de saint jean, fait l’apôtre de l’Espagne, l’auteur de

l’Epître et la victime d’Hérode le Tétrarque. Or saint Jacques le Majeur n’a

pas écrit l’épître en question et fut mis à mort à Jérusalem par Hérode Agrippa

Ier.

5°In libros Veteris ac

Novi Testamenti proæmia. Très courtes introductions à plusieurs livres de la

Bible, y compris Tobie, Judith, les Machabées, précédées d’une introduction

générale également très courte. A remarquer simplement que, dans la liste des

livres du Nouveau Testament, les Actes sont placés à la fin de l’Epître de

saint Jude et l’Apocalypse de saint Jean, Proæmia, XIII, P. L., t. LXXXIII,

col. 160 ; c’est du reste la même place qu’Isidore leur assigne dans son De

officiis ecclesiasticis, I, XI, P. L., t. LXXXIII, col. 746.

6° Liber numerorum

qui in sanctis Scripturis occurunt. Il est question dans ce petit traité de

divers nombres qui se trouvent dans l’Ecriture, à savoir de 1 à 16 de 18 à 20,

puis des nombres suivants : 24, 30, 40, 46, 50 et 60. Isidore en donne une

explication mystique qu’il clôture en faisant remarquer, à la suite de saint

Augustin, que le nombre de 350 est la somme des dix-sept premiers chiffres. Or

153 est le nombre est le nombre de poissons pris dans le coup de filet de la

pêche miraculeuse.

7°De Veteri et Novo

Testamento quæstiones. D’un intérêt plus relevé que le précédent, cet opuscule,

quoique beaucoup plus court, quatre pages à peine dans Migne, fait passer sous

les yeux, dans une suite de 41 questions, la substance et l’enseignement de

l’Ecriture. Dic mihi qui est inter Novum et Vetus Testamentum ? Vetus est

peccatum Adæ, unde dicit Apostolus : Regnavit mors ab Adam usque ad Moysen,

etc. Novum est Christus de Virgine natus ; unde Propheta dicit : Cantate Domino

canticum novum ; quia homo novus venit ; nova præcepta attulit, etc.

Quæstiones, I, P. L., t. LXXXIII, col. 201.

8°Mysticorum expositiones

sacramentorum, seu quæstiones in Vetus Testamentus. Dans ce traité assez

étendu, Isidore donne une interprétation mystique des principaux évènements

rapportés dans les livres de Moïse, de Josué, des Juges, de Samuel, des Rois,

d’Esdras et des Machabées : il y voit autant de figures de l’avenir. C’est,

selon sa constante méthode, une série d’emprunts, que tantôt il abrège ou

modifie, et auxquels il ajoute parfois. Veterum ecclesiasticorum sententias

congregantes. . veluti ex diversis prati flores lectos. . . et pauca de multis

breviter perstringentes, pleraque etiam adjicientes vel aliqua ex parte

mutantes. Præf., P. L., t. LXXXIII, col. 207. L’allégorie y est souvent poussée

jusqu’à l’excès, elle est du moins d’un ton très moralisant.

9° De fide catholica

ex Veteri et Novo Testamento contra judæos. Ce titre pourrait faire croire à un

traité d’apologétique ou de controverse, mais il n’en est pas tout à fait

ainsi. Sans doute, dans son épître dédicatoire à sa sœur Florentine, Isidore

dit : Ut prophetarum auctoritas fidei gratiam firmet et infidelium judæorum

imperitiam probet, ce qui semble annoncer une thèse, mais il ajoute : Hæc,

sancta soror te petente, ob ædificationem studit tui tibi dicavi, P. L., t.

LXXXIII, col. 449 ; c’est, en effet, une exposition sereine plutôt qu’une œuvre

de polémique. Dans le premier livre, on traite, texte en mains, de la personne

du Christ, de son existence dans le sein du Père avant la création, de son

incarnation, de sa passion, de sa mort, de sa résurrection, de son ascension et

de retour futur pour le jugement, le tout terminé par cette observation :

Tenent ista omnia libri Hebræorum, legunt cuncta judæi sed non intelligunt.

Cont. judæos, I, 62, P. L., t. LXXXIII, col. 498. [col.104 fin / col.105 début]

Dans le second, on montre les suites de l’incarnation, à savoir ; la vocation

des gentils, la dispersion des juifs et la cessation du sabbat ; après quoi

vient simplement cette exclamation : O infelicium judæorum defienda demential.

Cont. judæos, II, 28 ; ibid., col. 536. Cette manière d’argumenter contre les

juifs, quelque intérêt qu’elle offre pour l’époque, est loin de rappeler le

célèbre Dialogue avec Tryphon, de saint Justin.

10° Sententiarum

libri tres. Autrement dit, ajoute Braulio, De summo bono. Voici un manuel de

doctrine et de pratique chrétiennes, empruntés surtout à saint Augustin et à

saint Grégoire le Grand. Il est divisé en trois livres. Dans le Ier, il est

question de Dieu et de ses attributs, de la création, de l’origine du mal, des

anges, de l’homme, de l’âme et des sens, du Christ, du Saint-Esprit, de

l’Eglise et des hérésies, de la loi, du symbole et de la prière, du baptême et

de la communion, du martyre, des miracles des saints, de l’Antechrist, de la

résurrection et du jugement, du châtiment des damnés et de la récompense des

justes. Dans le IIe, de la sagesse, de la foi, de la charité, de l’espérance,

de la grâce, de la prédestination, de l’exemple des saints, de la confession

des péchés et de la pénitence, du désespoir, de ceux que Dieu abandonne, de la

rechute, des vices et des vertus. Dans le IIIe, qui est d’une grande utilité

pratique, il s’agit des châtiments de Dieu et de la patience qu’il faut avoir à

les supporter, de la tentation, et de ses remèdes, prière, lecture et étude, de

la science sans la grâce, de la contemplation, de l’action, de la vie des

moines, des chefs de l’Eglise, des princes, des juges et des jugements, de la

brièveté de la vie et de la mort.

11° De

ecclesiasticis officiis. Dédié à Fulgence († 620), frère du saint, ce traité

d’Isidore contient des renseignements précieux sur l’état du culte divin et des

fonctions ecclésiastiques dans l’Eglise gothique du VIIe siècle. Le premier

livre, relatif au culte, passe en revue les chants, les cantiques, les psaumes,

les hymnes, les antiennes, les prières, les répons, les leçons, l’alléluia, les

offertoires, l’ordre et les prières de la messe dans la liturgie gallicane, cf.

Duchesne, Les origines du culte chrétien, 2e édit., Paris, 1898, p. 189 sq., le

symbole, les bénédictions, le sacrifice, les offres de tierce, sexte, none,

vêpres et complies, les vigiles, les matines, le dimanche, le samedi, la Noël,

l’Epiphanie, les Rameaux, les trois derniers jours du carême, les fêtes de

Pâques, de l’Ascension, de la Pentecôte, des martyrs, de la dédicace ; les

jeûnes du carême, de la Pentecôte, du septième mois, des calendes de novembre

et de janvier, l’abstinence. Le second livre, relatif aux membres du clergé et

aux diverses catégories de fidèles, traite des clercs : évêques, archevêques,

prêtres, diacres, sous-diacres, lecteurs, chantres, exorcistes, acolytes,

portiers ; des moines, des pénitents, des vierges, des veuves, des personnes

mariées, des catéchumènes, des compétents, du symbole et de la règle de foi qui

précèdent la collation du baptême, de la chrismation, de l’imposition des mains

ou de la confirmation.

12° Synonyma, de

lamentatione animæ peccatricis. Ces deux titres, dont le premier fit plutôt

penser à quelque traité de grammaire, et dont le second des gémissements d’un

pécheur, se justifient également, l’un pour la forme, l’autre pour le fond. En

effet, chaque idée est présentée plusieurs fois par des expressions

différentes, mais équivalentes : de là le titre de Synonyma. Mais comme il

s’agit d’un pauvre pécheur qui gémit son propre état, le second titre explique

la matière du traité. C’est une sorte de soliloque ou plutôt de dialogue intime

entre l’homme et sa raison. L’homme, sous le poids des maux qui l’oppriment, en

vient à désirer la mort ; mais la raison intervient pour relever son courage,

lui rendre l’espoir du pardon, le ramener dans la bonne voie et pousser

jusqu’au som- [col.105 fin / col.106 début] met de la perfection. Il a tort, en

effet, de se plaindre, car les épreuves ont leur utilité : Dieu les permet pour

notre amendement, et elles sont la juste punition de nos fautes. Mieux vaut

donc lutter, se convertir, opposer de bonnes habitudes aux mauvaises,

persévérer dans la crainte de mourir comme un impie et d’encourir les

châtiments éternels : tel est l’objet du premier livre, au commencement duquel

se lit cette sentence : Melius est bene mori quam male vivere ; melius est non

esse quam infeliciter esse. Syn., I, 21, P. L., t. LXXXIII, col. 832. Dans le

second livre, la raison continue à donner des approprié et détaillés pour

conserver la chasteté, résister aux tentations, pratiquer la prière, la

vigilance, la mortification, et poursuivre la conquête des biens célestes,

etc., et elle conclut : Donum scientiæ acceptum retine, imple opere quod

didicisti prædicatione. Syn., II, 100, ibid., col. 868. Et le pécheur aussitôt

de remercier la raison. Cette œuvre de direction morale est, du point de vue de

la piété, la plus intéressante de saint Isidore.

13° Regula

monachorum. Résumé de tout ce que l’on trouve épars dans les ouvrages des Pères

relativement à la disposition et à la distribution d’un monastère, à l’élection

de l’abbé et à la vie des moines.

14° Epistolæ. En

dehors des lettres, qui servent de préface ou de dédicace à cinq de ses

ouvrages, on n’en a conservé que quelques autres : trois à Braulio, évêque de

Saragosse ; nue à Leudefeld, de Cordoue, concernant les membres et les fonctions

du clergé dans l’Eglise ; une à Massona, de Mérida, sur la réintégration, après

pénitence, des clercs tombés dans le péché ; une à Helladius, sur la chute de

l’évêque de Cordoue ; une au duc Claude, sur ses victoires ; une à

l’archidiacre Redemptus, sur certains points de liturgie ; une autre enfin à

Eugène, sur l’éminente dignité des évêques, en tant que successeurs des

apôtres, et plus particulièrement du pontife romain, tête de l’Eglise.

15° De ordine

creaturarum. Cet opuscule, retenu comme authentique par Arevalo, traite d’abord

de la Trinité, puis des créatures spirituelles, c’est-à-dire des anges

distribués en neuf chœurs, du diable et des démons, ensuite des eaux

supérieures du firmament, du soleil, de la lune, de l’espace supérieur et

inférieur, des eaux et de l’océan, du paradis, et enfin de l’homme après le

péché, de la diversité des pécheurs et du lieu de leur peine, du feu du

purgatoire et de la vie future.

16° De natura reum.

Dédié au roi Sisebut, après avoir été composé sur sa demande, ce petit travail

résume tout ce que les anciens ont écrit sur le jour, la nuit, la semaine, le

mois, l’année, les saisons, le solstice et l’équinoxe, le monde et ses parties,

le ciel et les sept planètes alors connues, le cours du soleil et de la lune, les

éclipses, les étoiles filantes et les comètes, le tonnerre et les éclairs,

l’arc-en-ciel, les nuages, la pluie, la neige, la grêle, les vents, les

tremblements de terre, etc. Pour les diverses sources, voir Becker, De natura

rerum, Berlin, 1857.

17° Chronicon.

Toujours fidèle à sa méthode, Isidore résume dans cette chronique, en une suite

de 122 paragraphes, les six âges de l’histoire du monde, depuis la création

jusqu'à l’an 654 de l’ère espagnole, c’est-à-dire jusqu’en 616, en empruntant

ses matériaux aux travaux de Jules l’Africain, d’Eusèbe, de saint Jérôme et de

Victor de Tunnunum, et en y rajoutant quelques renseignement sur l’histoire de

l’Espagne. Il a soin, à la fin, de rappeler la victoire de Léovigilde, sur les

Suèves, le soulèvement d’Herménégilde, mais sans faire la moindre allusion à sa

mort violente, la conversion de Recarède et de tous les Goths d’Espagne, et la

part que prît à ce grand évènement son frère Léandre. Pour les sources, voir

Hertzberg, Ueber die Croniken des Isidorus von Sevilla, dans [col.106 fin /

col.107 début] Forschungen zur deutschen Geschichte, 1875, t. XV, p.

289-360.

18° Historia de

regibus Gothorum, Wandalorum et Suevorum. Ce résumé historique, tout à

l’honneur de l’Espagne dont il célèbre la richesse, la fécondité et la gloire,

est d’une valeur inappréciable et constitue la source principale pour

l’histoire des Visigoths, depuis leur origines jusqu’à la cinquième année du

règne de Suintila, en 621, c’est-à-dire pendant 256 années ; pour l’histoire

des Vandales, depuis leur entrée en Espagne sous Gundéric, en 408, jusqu’à

l’invasion de l’Afrique et la défaite de Gélimer, en 522 ; et enfin pour

l’histoire des Suèves, qui, entrés en Espagne en même temps que les Alains, les

Vandales s’y maintinrent jusqu’en 585, lors de leur incorporation au royaume

des Goths. Cf. Hertzberg, Die Historien und die Chroniken des Isidorus von

Sevilla, Gœttingue, 1874.

19° De viris

illustribus. Sur une liste de 46 noms dont il est question dans ce traité,

treize appartiennent à des auteurs espagnols, ce qui nous vaut des

renseignements précieux sur plusieurs évêques d’Espagne, antérieurs au VIIe

siècle. On y trouve une note sévère sur la mort d’Osius et un éloge mérité de

Léandre au sujet de son influence religieuse et de la part qu’il prit à la

conversion des Goths.

III. DOCTRINE.

1° Observation

préliminaire. Sur l’Ecriture, le dogme, la morale, la discipline et la

liturgie, saint Isidore a résumé la science de son temps ; mais c’est moins sa

pensée qu’il nous donne que celle des autres. Il s’est contenté d’être l’écho

de la tradition, dont il a pris soin de recueillir et de reproduire les

témoignages, et, à ce point de vue ; son œuvre des plus précieuse ; c’est celle

d’un disciple très averti, d’un témoin autorisé, mais ce n’est pas celle d’un

initiateur ou d’un maître. S’en tenant trop exclusivement à sa méthode de

collectionneur et de rapporteur, il n’a pas donné, dans quelque œuvre originale

et forte, toute la mesure de son talent. Dans ces conditions, il serait

difficile de parler de son enseignement personnel ; il suffira de signaler

quelques points particuliers sur lesquels son témoignage est bon à recueillir

ou à propos desquels il a été l’objet d’accusations injustifiées.

2° Sur l’Ecriture.

1. Le canon. Par

trois fois, saint Isidore a donné le catalogue des livres de la Bible. Etym.,

VI, I ; In libros Veteris et Novi Testamenti proæmia, prol. 2-13 ; De officiis

ecclesiasticis, I, XI, P. L., t. LXXXIII, col. 150-160 ; 229 ; 746. Pour

l’Ancien Testament, c’est la liste du Prologus galeatus. Aux trois classes des

protocanoniques, livres historiques, prophétiques et hagiographes, Isidore

joint celle des deut rocanoniques, la Sagesse, l’Ecclésiastique, Tobie, Judith

et les deux livres des Machabées, parce que l’Eglise, dit-il, les tient pour

des livres divins. Pour le Nouveau testament, c’est l’ordo evangelicus ou les

quatre Evangiles ; l’ordo apostolicus : les quatorze épîtres de saint Paul, les

sept Epîtres catholiques rangées dans l’ordre suivant : Pierre, Jacques, Jean

et Jude, et enfin les Actes et l’Apocalypse. Ce dernier livre était encore

contesté en Espagne, mais Isidore eut soin, au IVe concile de Tolède, de faire

porter ce décret : " L’autorité de plusieurs conciles et les décrets

synodaux des pontifes romains déclarent que le livre de l’Apocalypse est de

Jean l’Evangéliste et ordonnent de le recevoir parmi les livres divins. Mais il

y a beaucoup de gens qui contestent son autorité et qui ne veulent pas

l’expliquer dans l’Eglise de Dieu. Si désormais quelqu’un ne le reçoit ou ne le

prend pas pour texte d’explication pendant la messe, de Pâques à la Pentecôte,

il sera excommunié. " Can. 17.

2. L’inspiration.

Saint Isidore affirme le fait de l’inspiration divine de tous les auteurs

sacrés, mais sans en spécifier la nature ; il se contente de dire : Auctor

earumdem Scripturarum Spiritus Sanctus esse credit- [col.107 fin / col. 108

début] tur ; ipse enim scripsit qui prophetis suis scribenda dictavit. De

offic. eccle., I, XII, 13, P. L., t. LXXXIII, col. 750. Quant au rôle et à la

part de l’écrivain sacré dans la rédaction de son œuvre, il n’en parle pas,

cette question n’ayant pas encore été pleinement élucidée.

3. L’interprétation.

Isidore connaît la multiple signification du texte sacré ; il sait que l’on

peut entendre au sens littéral et au sens spirituel, au sens propre ou

métaphorique. Scriptura non solum historialiter sed etiam mysterio sensu, id

est spiritualiter, sentienda est. De fide cath., II, XX, 1, P. L., t. LXXXIII,

col. 528. Scriptura sacra ratione tripartita intellegitur ; d’abord secundum

litteram sine ulla figurali intentione ; ensuite secundum figuralem

intellegentiam absque aliquo rerum respectu ; enfin salva historica rerum

narratione, mystica ratione. De ord. creat., X, 6-7, P. L., t. LXXXIII, col.

939. Pour l’intelligence des passagers les plus obscurs, il rappelle, à la

suite de saint Augustin, mais sans y joindre les judicieuses réflexions de l’évêque

d’Hippone dans son De doctrina christiana, III, XXX-XXXVIII, 42-56, les sept

règles du donatiste Tichonius. Sent., I, IXI, P. L., t. LXXXIII, col.

581-586.

3° Sur le dogme. Deux

points de doctrine ont paru répréhensibles dans saint Isidore : l’un sur la

prédestination, l’autre sur la transsubstantiation ; qu’en est-il ?

1. La prédestination.

Saint Isidore parle dans un passage de la gemina prædestinatio, sive electorum

ad requiem, sive reproborum ad mortem. Sent., II, VI, 1, P. L., t. LXXXIII,

col. 606. Hincmar de Reims, au IXe siècle, a conclu de là que l’évêque de

Séville était un successeur des Gaulois qu’avait combattu saint Augustin dans

son De prædestinatione sanctorum et son De bono perseverantiæ. C’est bien à

tort, car il n’y a pas de preuve que le prédestinatianisme ait paru en Espagne,

soit de provenance gauloise, soit d’ ailleurs. L’erreur des prédestinatiens du

IXe siècle fut de croire que Dieu prédestine les pécheurs, non seulement à la

damnation, mais aussi au péché. Or, saint Isidore distingue avec raison l’une

de l’autre, il nie la prédestination au péché ; car Dieu ne veut pas le péché,

il ne fait que le permettre ; et s’il est question de l’endurcissement ou de

l’aveuglement du pécheur, il faut prendre garde au rôle négatif de Dieu.

Obdurare dicitur Deus hominem, non ejus faciendo duritiam, sed non auferendo

eam, quam sibi ipse nutrivit. Non aliter et obcæcare dicitur quosdam Deus, non

ut in eis eamdem ipse cæcitatem eorum ab eis ipse non auferat. Sent. II, V, 13,

P. L., t. LXXXIII, col. 605. Quant à la prédestination à la peine, Isidore

l’enseigne : Miro modo æquus omnibus Conditor alios prædestinando præeligit,

alios in suis moribus pravis justo judicio derelinquit ; quidam enim gratissimæ

misericordiæ ejus prævenientis dono salvantur, effecti vasa misericordiæ ;

quidam vero reprobi habiti ad pœnam prædestinati damnantur, effecti vasa iræ.

Different., II, XXXII, 117-118, P. L., t. LXXXIII, col. 88.

Au sens propre et

rigoureux qu’il aura dans la langue théologique, le mot de prédestination ne

s’applique qu’à certaines créatures raisonnables qui doivent avoir la gloire du

ciel en partage ; c’est la prescience, non des mérites de la créature, mais des

bienfaits de Dieu ; c’est le plan éternel de Dieu statuant en lui-même l’obtention

du ciel pour ceux qui, en effet, doivent un jour et pour l’éternité, être admis

à ce bonheur. Il ne s’applique au pécheur que dans un sens impropre ; car la

réprobation implique de la part de Dieu deux choses, d’abord la permission de

la faute, ensuite la volonté de la punir. Dieu permet le péché : pourquoi ?

C’est le grand mystère, dont il n’est point permis de demander compte à Dieu ;

et Dieu très justement châtie le péché non pardonné et non expié. Cf.

Arevalo, Isidoriana, part. I, c. XXX, n. 1-14, P. L., t. LXXXI, col.

150-157. [col.108 fin / col.109 début]

2. La

transsubstantiation. D’après Bingham, Origines eccles., l. XV, c. V, sect. 4,

Londres, 1710-1719, t. VI, p. 801, saint Isidore aurait nié la

transsubstantiation. S’il s’agit du mot, il est certain que saint Isidore ne

l’a pas employé, pour la bonne raison qu’il n’existait pas encore pour exprimer

la nature du changement qui s’opère au sacrifice de la messe par la

consécration ; mais s’il s’agit du sens exprimé si bien plus part par le mot de

transsubstantiation, on ne peut pas soutenir qu’Isidore ne l’a pas enseigné.

Car, dans un passage, il dit qu’on appelle corps et sang du Christ le pain et

le vin, quand ils sont sanctifiés et deviennent sacrement par l’invisible

opération du Saint-Esprit. Unde hoc, eo jubente corpus Christi et sanguinem

dicimus, quod, dum sit ex fructibus terræ, sanctificantur et fit sacramentum

operante invisibiliter Spiritu Dei. Etym., VI, XIX. Resteraient-ils pain et vin

tout en devenant sacrement ? Nullement, car, dans un autre passage, après avoir

dit comme saint Paul : panis, quem frangimus, corpus Christi est, il ajoute :

Hæc autem, dum sunt visibilia, sanctificata per Spiritum Sanctum, in

sacramentum divini corporis transeunt. De offic. eccl., I, XVIII. Transeunt,

qu’est-ce à dire ? Il s’agit bien d’un changement, d’une transformation, et

n’est-ce pas là l’équivalent du mot transsubstantiation ? Cf. Arevalo,

Isidoriana, part. I, c. XXX, n. 15-24, P. L., t. LXXXI, col. 157-160.

4° Sur les sacrements.

Bingham, Origines eccles., l. XII, c. I, accuse encore saint Isidore de n’avoir

fait qu’un seul sacrement du baptême et de la confirmation. En effet, l’évêque

de Séville a écrit : Sunt autem sacramenta baptismus et chrisma, corpus et

sanguis. Etym., VI, XIX. D’où Bingham de conclure : de même que corpus et

sanguis ne désignent qu’un seul et même sacrement, de même baptismus et

chrisma. Conclusion erronée, car Isidore, loin de confondre le sacrement du

baptême avec celui de la confirmation, les distingue l’un de l’autre : Sicut in

baptismo peccatorum remissio datur, ita per unctionem sanctificatio Spiritus

adhibetur, et il traite ailleurs, De offic. eccles., II, XXV-XXVIII, P. L., t.

LXXXIII, col. 822-826, séparément et distinctement du baptême, de la chrismatio

et de l’imposition des mains. Ce que l’on peut reprocher à son langage, c’est,

tout au plus, un certain manque de précision fort excusable à une époque où la

théorie sacramentaire n’était pas encore rigoureusement fixée. Cf.

Arevalo, Isidoriana, part. I, c. XXX, n. 22-25, P. L., t. LXXXI, col.

160-162.

5° Sur l’origine de l’âme

des enfants d’Adam. L’âme de l’enfant qui vient au monde a-t-elle été créée dès

l’origine, ou n’est-t-elle créée par Dieu qu’au moment de la conception, ou

bien encore ne serait-elle pas transmise du père au fils par voie de génération

? Autant de questions soulevées parmi les Pères grecs et latins et résolues en

sens divers. Saint Augustin est mort sans avoir pu y trouver une solution qui

le satisfît. Saint Isidore, cela va sans dire, rappelle les opinions anciennes,

en constatant que la question est des plus difficiles et n’a pas été tranchée.

Differ., II, XXX, 105 ; De offic. eccl., II, XXIV, 3 ; De ord. creat., XV, 10,

P. L., t. LXXXIII, col. 85, 818, 952. Toutefois il se prononce pour la création

de l’âme au moment où elle doit animer un corps humain : Animam non esse partem

divinæ substantiæ, vel naturæ, nec esse eam priusquam corporis misceatur,

constat ; sed tunc creari eam quando et corpus creatur, cui admisceri videtur. Sent.,

I, XII, 4, P. L., t. LXXXIII, col. 562.

I. EDITIONS. Margarin

de la Bigne fut le premier à publier les œuvres de l’évêque de Séville sous ce

titre : S. Isidori Hispalensis episcopi opera omnia, Paris, 1580. Son édition

était incomplète et laissait à désirer. près de vingt ans après, Grial donna

une autre édition beaucoup plus soignée, mais qui est encore loin d’être

satisfaisante : [col.109 fin/col.110 début] Divi Isidori Hispalensis episcopi

opera, Madrid, 1599 ; 2 vol. 1778. Le bénédiction Jacques du Breuil, profitant

du travail de ses devanciers, améliora celle de Margarin de la Bigne et

compléta celle de Grial sans la rendre plus correcte : S. Isidori Hispalensis

episcopi opera omnia, Paris, 1601 ; Cologne, 1617. Au XVIIIe siècle, Ulloa

reprit l’édition de Grial et la publia à Madrid, en 1778, revue, corrigée et

augmentée de notes de Gomez. Mais il restait un examen critique à faire sur

tous les ouvrages, authentiques ou supposés, de saint Isidore ; ce fut l’œuvre

d’Arevalo. Ce dernier, grâce à un examen attentif et à une connaissance

approfondie du sujet, passa en revue les manuscrits et les éditions et ne

retint comme authentique que les ouvrages dont l’analyse a été donnée dans cet

article, en suivant l’ordre de la dignité des matières et, dans chaque matière,

le genre d’abord, les espèces ensuite ; c’est jusqu’ici la meilleure de toutes

les éditions : S. Isidori Hispalensis episcopi opera omnia, 4 vol., Rome,

1797-1803. Migne l’a reproduite : P. L., t. LXXXI-LXXXIV, en y joignant la

Collectio canonum attribuée à saint Isidore, ainsi que la Liturgia mozarabica

secundum regulam beati Isidori, P. L., t. LXXXV-LXXXVI. Depuis lors quelques

ouvrages de saint Isidore ont fait l’objet d’éditions critiques nouvelles. La

partie historique, sous ce titre : Isidori junioris Hispalensis historia

Gothorum, Wandalorum, Sueborum ad annum 624, a été insérée dans les Monumenta

Germaniæ historica. Auctores antiquissimi, Berlin, 1894, t. XI, p. 304-390. G.

Becker a donné une édition critique du De natura rerum, Berlin, 1857. K.

Weinhold, a publié quelques fragments en vieil allemand de l’opuscule contre

les juifs : Di altdeutschen Bruckstücke des Tractats des Bischofs Isidorus von

Sevilla De fide catholica contra judæos, Paderborn, 1874. G. A. Hench, a publié

un fac-similé du codex de Paris : Der althochdeusche Isidor. Fac-Simile Ausgabe

der Pariser Codex, nebst kritischen Texte der Pariser und Monseer Bruchstücke,

Strasbourg, 1893. Il reste encore beaucoup à faire. W. M. Lindsay, Isidori

Hispalensis Etymologiarum seu Originum libri XX, 2 vol. Oxford, 1911 : Beer,

Isidori Etymologiarum cod. Toletanus phototypice editus, Leyde, 1909.

II. SOURCES. S. Braulio,

évêque de Saragosse, contemporain et ami de saint Isidore ; Prænotatio librorum

divi Isidori, P. L., t. LXXXI, col. 15-17 ; S. Ildefonse, De viris illustribus,

IX, ibid., col. 27-28 ; un récit de la mort de l’évêque de Séville, ibid., col.

30-32 ; Acta sanctorum, avril, t. I, p. 325-361.

III. TRAVAUX. Des

biographies ont été publiées par Cajétan, Rome, 1616, par Dumesnil, 1843, par

l’abbé Colombet, 1846. Sur la vie et les œuvres de saint Isidore, Noël

Alexandre, Historia ecclesiastica, Paris, 1743, t. X, p. 195, 411-413 ; Dupin,

Nouvelle bibliothèque des auteurs ecclésiastiques, Mons, 1691, t. VI, p. 1-6 ;

Ceillier, Histoire générale des auteurs sacrés et ecclésiastiques, Paris,

1858-1868, t. XI, p. 720-728 ; N. Antonio, Bibliotheca hispana vetus, Madrid,

1788, p. 321 sq. ; Florez, España sagrada, Madrid, 1754-1777, t. III, p.

101-109 ; t. V, p. 417-420 ; t. VI, P. 441-452, 477-482 ; t. IX, p. 173,

406-412 ; Arevalo, Isidoriana, P. L., t. LXXXI ; Bourret, L’école chrétienne de

Séville sous la monarchie des Wisigoths, Paris, 1855 ; Gams, Die

Kirchengeschichte von Spanien, Ratisbonne, 1862-1874, t. II, sect. II, p. 102-113

; Ebert, Histoire générale de la littérature du moyen âge en Occident, trad.

franç., Paris, 1883, t. I, p. 621-636 ; Teuffel, Geschichte der römischen

Litteratur, Leipzig, 1870 ; trad. franç., Paris, 1883, t. III, p. 337-345 ;

Dressel, De Isidori Originum fontibus, Turin, 1874 ; Hertzberg, Ueber die

Chroniken des Isidorus von Sevilla, dans les Forschungen zur deutschen

Geschichte, 1875, t. XV, p. 289-360 ; Menendez y Pelayo, S. Isidore et

l’importance de son rôle dans l’histoire intellectuelle de l’Espagne, trad.

franç., dans les Annales de philosophie chrétienne, 1882, t. VII, p. 258-269 ;

Manitius, Geschichte der christ.-latein. Poesie, Stuttgart, 1891, p. 414-420 ;

Klusmann, Excerpta Tertullianea in Isidori Hispa. Etymologiis, Hambourg, 1892 ;

Dzialowski, Isidor und Ildefons als Litterarhistoriker, Munster, 1899 ;

Bardenhewer, Patrologie, 3e édit., Fribourg-en-Brisgau, 1910, p. 568 sq. ;

Realencyklopädie für protestantische Theologie und Kirche, 3e édit., Leipzig,

1901, t. IX, p. 447-453 ; Leclercq, L’Espagne chrétienne, Paris, 1906, p.

302-306 ; Kirchenlexicon, 2e édit., t. VI, p. 969, 976 ; Smith et Wace, A

dictionary of christian biography, t. III, p. 305-313 ; U. Chevalier,

Répertoire. Bio-bibliographie, t. I, p. 2283-2285 ; Schwarz, Observationes

criticæ in Isidori Hispalensis Origines, Hirschberg, 1895 ; Schulte, Studien

über den Schriftstellerkatalog des h. Isidorus, dans Kirchengeschitliche.

Abhandlugen de Sdralek, Breslau, 1902, [col.110 fin / col.111 début] t. VI ;

Endt, Isidor und Lukasscholien, dans Wiener Studien, 1909 ; Valenti, S.

Isidoro, noticia de sua vida y escritos, Valladolid, 1909 ; Schenk, De Isidori

Hispalensis de natura rerum libelli fontibus (diss.), Iéna, 1909 ; C. H.

Besson, Isidor Studien, Munich, 1913 ; J. Tixeront, Précis de patrologie,

Paris, 1918, p. 492-496.

G. BAREILLE.

SOURCE : http://jesusmarie.free.fr/isidore_de_seville.html

St Isidore de Séville,

évêque, confesseur et docteur

Mort à Séville le 4 avril

636. Culte immédiat en Espagne.

Innocent XIII inscrivit sa fête comme docteur, au rite double, en 1722.

die 4 aprilis

SANCTI ISIDORI

Ep., Conf. et Eccl. Doct.

III classis (ante CR

1960 : duplex)

Missa In

médio, de Communi Doctorum.

Oratio C

Deus, qui pópulo tuo

ætérnæ salútis beátum Isidórum minístrum tribuísti : præsta,

quǽsumus ; ut, quem Doctórem vitæ habúimus in terris, intercessórem habére

mereámur in cælis. Per Dóminum.

Ante 1960 : Credo

Secreta C 1

Sancti Isidóri Pontíficis

tui atque Doctóris nobis, Dómine, pia non desit orátio : quæ et múnera

nostra concíliet ; et tuam nobis indulgéntiam semper obtíneat. Per

Dóminum.

Postcommunio C 1

salútem : beátus

Isidórus Póntifex tuus et Doctor egrégius, quǽsumus, precátor accédat. Per

Dóminum nostrum.

Ut nobis, Dómine, tua

sacrifícia dent

(En Carême, on fait

seulement mémoire du Saint avec les trois oraisons de la Messe suivante)

le 4 avril

SAINT ISIDORE

Evêque, Confesseur et

Docteur de l’Église

IIIème classe (avant

1960 : double)

Messe In

médio, du Commun des Docteurs

Collecte C

O Dieu qui avez fait à

votre peuple la grâce d’avoir le bienheureux Isidore, pour ministre du salut

éternel, faites, nous vous en prions, que nous méritions d’avoir pour

intercesseur dans les cieux celui qui nous a donné sur terre la doctrine de vie

Avant 1960 : Credo

Secrète C 1

Que la pieuse

intercession de saint Isidore, Pontife et Docteur, ne nous fasse point défaut,

Seigneur, qu’elle vous rende nos dons agréables et nous obtienne toujours votre

indulgence.

Postcommunion C 1

Afin, Seigneur, que votre

saint sacrifice nous procure le salut, que le bienheureux Isidore, votre

Pontife et votre admirable Docteur intercède pour nous.

Leçons des Matines avant 1960

Au deuxième nocturne.

Quatrième leçon. Isidore, Docteur illustre, était Espagnol de nation ; il

naquit à Carthagène ; son père, Sévérien, était gouverneur de la province. Les

saints Évêques, Léandre de Séville, et Fulgence de Carthagène, ses frères,

prirent soin de lui enseigner la piété et les lettres. Formé aux littératures

latine, grecque et hébraïque, et instruit dans les lois divines et humaines, il

acquit à un degré éminent toutes les sciences et toutes les vertus chrétiennes.

Dès sa jeunesse, il combattit avec tant de courage l’hérésie aérienne, depuis

longtemps déjà répandue chez les Goths alors maîtres de l’Espagne, que peu s’en

fallut qu’il ne fût mis à mort par les hérétiques. Léandre ayant quitté cette

vie, Isidore fut élevé, malgré lui, au siège épiscopal de Séville, sur les

instances du roi Récarède, avec l’assentiment unanime du clergé et du peuple.

On rapporte que saint Grégoire le Grand ne se contenta pas de confirmer cette

élection par l’autorité apostolique, mais qu’il envoya, selon l’usage, le

pallium au nouvel élu, et l’établit son vicaire ainsi que celui du Siège

apostolique dans toute l’Espagne.

Cinquième leçon. On ne peut dire combien Isidore fut, durant son épiscopat,